Title: Free Joe and Other Georgian Sketches

Author: Joel Chandler Harris

Release date: February 2, 2010 [eBook #31160]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from scans of public domain material produced by

Microsoft for their Live Search Books site.)

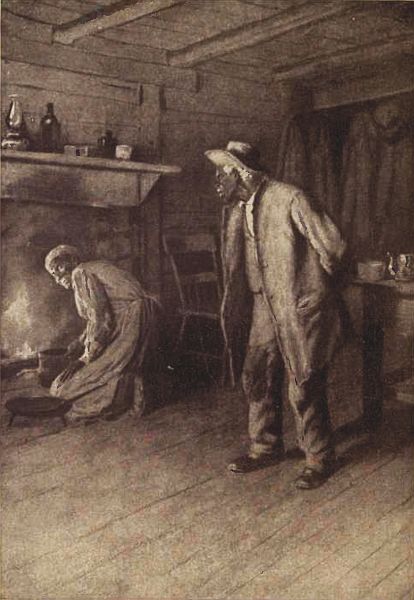

"Den I tell him 'bout de man down dar in de gully"

"Den I tell him 'bout de man down dar in de gully"

The problems of one generation are the paradoxes of a succeeding one, particularly if war, or some such incident, intervenes to clarify the[4] atmosphere and strengthen the understanding. Thus, in 1850, Free Joe represented not only a problem of large concern, but, in the watchful eyes of Hillsborough, he was the embodiment of that vague and mysterious danger that seemed to be forever lurking on the outskirts of slavery, ready to sound a shrill and ghostly signal in the impenetrable swamps, and steal forth under the midnight stars to murder, rapine, and pillage—a danger always threatening, and yet never assuming shape; intangible, and yet real; impossible, and yet not improbable. Across the serene and smiling front of safety, the pale outlines of the awful shadow of insurrection sometimes fell. With this invisible panorama as a background, it was natural that the figure of Free Joe, simple and humble as it was, should assume undue proportions. Go where he would, do what he might, he could not escape the finger of observation and the kindling eye of suspicion. His lightest words were noted, his slightest actions marked.

Under all the circumstances it was natural that his peculiar condition should reflect itself[5] in his habits and manners. The slaves laughed loudly day by day, but Free Joe rarely laughed. The slaves sang at their work and danced at their frolics, but no one ever heard Free Joe sing or saw him dance. There was something painfully plaintive and appealing in his attitude, something touching in his anxiety to please. He was of the friendliest nature, and seemed to be delighted when he could amuse the little children who had made a playground of the public square. At times he would please them by making his little dog Dan perform all sorts of curious tricks, or he would tell them quaint stories of the beasts of the field and birds of the air; and frequently he was coaxed into relating the story of his own freedom. That story was brief, but tragical.

In the year of our Lord 1840, when a negro speculator of a sportive turn of mind reached the little village of Hillsborough on his way to the Mississippi region, with a caravan of likely negroes of both sexes, he found much to interest him. In that day and at that time there were a number of young men in the village who had[6] not bound themselves over to repentance for the various misdeeds of the flesh. To these young men the negro speculator (Major Frampton was his name) proceeded to address himself. He was a Virginian, he declared; and, to prove the statement, he referred all the festively inclined young men of Hillsborough to a barrel of peach-brandy in one of his covered wagons. In the minds of these young men there was less doubt in regard to the age and quality of the brandy than there was in regard to the negro trader's birthplace. Major Frampton might or might not have been born in the Old Dominion—that was a matter for consideration and inquiry—but there could be no question as to the mellow pungency of the peach-brandy.

In his own estimation, Major Frampton was one of the most accomplished of men. He had summered at the Virginia Springs; he had been to Philadelphia, to Washington, to Richmond, to Lynchburg, and to Charleston, and had accumulated a great deal of experience which he found useful. Hillsborough was hid in the woods of Middle Georgia, and its general aspect[7] of innocence impressed him. He looked on the young men who had shown their readiness to test his peach-brandy as overgrown country boys who needed to be introduced to some of the arts and sciences he had at his command. Thereupon the major pitched his tents, figuratively speaking, and became, for the time being, a part and parcel of the innocence that characterized Hillsborough. A wiser man would doubtless have made the same mistake.

The little village possessed advantages that seemed to be providentially arranged to fit the various enterprises that Major Frampton had in view. There was the auction block in front of the stuccoed court-house, if he desired to dispose of a few of his negroes; there was a quarter-track, laid out to his hand and in excellent order, if he chose to enjoy the pleasures of horse-racing; there were secluded pine thickets within easy reach, if he desired to indulge in the exciting pastime of cock-fighting; and variously lonely and unoccupied rooms in the second story of the tavern, if he cared to challenge the chances of dice or cards.[8]

Major Frampton tried them all with varying luck, until he began his famous game of poker with Judge Alfred Wellington, a stately gentleman with a flowing white beard and mild blue eyes that gave him the appearance of a benevolent patriarch. The history of the game in which Major Frampton and Judge Alfred Wellington took part is something more than a tradition in Hillsborough, for there are still living three or four men who sat around the table and watched its progress. It is said that at various stages of the game Major Frampton would destroy the cards with which they were playing, and send for a new pack, but the result was always the same. The mild blue eyes of Judge Wellington, with few exceptions, continued to overlook "hands" that were invincible—a habit they had acquired during a long and arduous course of training from Saratoga to New Orleans. Major Frampton lost his money, his horses, his wagons, and all his negroes but one, his body-servant. When his misfortune had reached this limit, the major adjourned the game. The sun was shining brightly, and all[9] nature was cheerful. It is said that the major also seemed to be cheerful. However this may be, he visited the court-house, and executed the papers that gave his body-servant his freedom. This being done, Major Frampton sauntered into a convenient pine thicket, and blew out his brains.

The negro thus freed came to be known as Free Joe. Compelled, under the law, to choose a guardian, he chose Judge Wellington, chiefly because his wife Lucinda was among the negroes won from Major Frampton. For several years Free Joe had what may be called a jovial time. His wife Lucinda was well provided for, and he found it a comparatively easy matter to provide for himself; so that, taking all the circumstances into consideration, it is not matter for astonishment that he became somewhat shiftless.

When Judge Wellington died, Free Joe's troubles began. The judge's negroes, including Lucinda, went to his half-brother, a man named Calderwood, who was a hard master and a rough customer generally—a man of many eccentricities of mind and character. His neighbors[10] had a habit of alluding to him as "Old Spite"; and the name seemed to fit him so completely that he was known far and near as "Spite" Calderwood. He probably enjoyed the distinction the name gave him, at any rate he never resented it, and it was not often that he missed an opportunity to show that he deserved it. Calderwood's place was two or three miles from the village of Hillsborough, and Free Joe visited his wife twice a week, Wednesday and Saturday nights.

One Sunday he was sitting in front of Lucinda's cabin, when Calderwood happened to pass that way.

"Howdy, marster?" said Free Joe, taking off his hat.

"Who are you?" exclaimed Calderwood abruptly, halting and staring at the negro.

"I'm name' Joe, marster. I'm Lucindy's ole man."

"Who do you belong to?"

"Marse John Evans is my gyardeen, marster."

"Big name—gyardeen. Show your pass."

Free Joe produced that document, and Calderwood[11] read it aloud slowly, as if he found it difficult to get at the meaning:

"To whom it may concern: This is to certify that the boy Joe Frampton has my permission to visit his wife Lucinda."

This was dated at Hillsborough, and signed "John W. Evans."

Calderwood read it twice, and then looked at Free Joe, elevating his eyebrows, and showing his discolored teeth.

"Some mighty big words in that there. Evans owns this place, I reckon. When's he comin' down to take hold?"

Free Joe fumbled with his hat. He was badly frightened.

"Lucindy say she speck you wouldn't min' my comin', long ez I behave, marster."

Calderwood tore the pass in pieces and flung it away.

"Don't want no free niggers 'round here," he exclaimed. "There's the big road. It'll carry you to town. Don't let me catch you here no more. Now, mind what I tell you."

Free Joe presented a shabby spectacle as he[12] moved off with his little dog Dan slinking at his heels. It should be said in behalf of Dan, however, that his bristles were up, and that he looked back and growled. It may be that the dog had the advantage of insignificance, but it is difficult to conceive how a dog bold enough to raise his bristles under Calderwood's very eyes could be as insignificant as Free Joe. But both the negro and his little dog seemed to give a new and more dismal aspect to forlornness as they turned into the road and went toward Hillsborough.

After this incident Free Joe appeared to have clearer ideas concerning his peculiar condition. He realized the fact that though he was free he was more helpless than any slave. Having no owner, every man was his master. He knew that he was the object of suspicion, and therefore all his slender resources (ah! how pitifully slender they were!) were devoted to winning, not kindness and appreciation, but toleration; all his efforts were in the direction of mitigating the circumstances that tended to make his condition so much worse than that of the negroes[13] around him—negroes who had friends because they had masters.

So far as his own race was concerned, Free Joe was an exile. If the slaves secretly envied him his freedom (which is to be doubted, considering his miserable condition), they openly despised him, and lost no opportunity to treat him with contumely. Perhaps this was in some measure the result of the attitude which Free Joe chose to maintain toward them. No doubt his instinct taught him that to hold himself aloof from the slaves would be to invite from the whites the toleration which he coveted, and without which even his miserable condition would be rendered more miserable still.

His greatest trouble was the fact that he was not allowed to visit his wife; but he soon found a way out of his difficulty. After he had been ordered away from the Calderwood place, he was in the habit of wandering as far in that direction as prudence would permit. Near the Calderwood place, but not on Calderwood's land, lived an old man named Micajah Staley and his sister Becky Staley. These people were[14] old and very poor. Old Micajah had a palsied arm and hand; but, in spite of this, he managed to earn a precarious living with his turning-lathe.

When he was a slave Free Joe would have scorned these representatives of a class known as poor white trash, but now he found them sympathetic and helpful in various ways. From the back door of their cabin he could hear the Calderwood negroes singing at night, and he sometimes fancied he could distinguish Lucinda's shrill treble rising above the other voices. A large poplar grew in the woods some distance from the Staley cabin, and at the foot of this tree Free Joe would sit for hours with his face turned toward Calderwood's. His little dog Dan would curl up in the leaves near by, and the two seemed to be as comfortable as possible.

One Saturday afternoon Free Joe, sitting at the foot of this friendly poplar, fell asleep. How long he slept, he could not tell; but when he awoke little Dan was licking his face, the moon was shining brightly, and Lucinda his wife stood before him laughing. The dog, seeing[15] that Free Joe was asleep, had grown somewhat impatient, and he concluded to make an excursion to the Calderwood place on his own account. Lucinda was inclined to give the incident a twist in the direction of superstition.

"I 'uz settn' down front er de fireplace," she said, "cookin' me some meat, w'en all of a sudden I year sumpin at de do'—scratch, scratch. I tuck'n tu'n de meat over, en make out I ain't year it. Bimeby it come dar 'gin—scratch, scratch. I up en open de do', I did, en, bless de Lord! dar wuz little Dan, en it look like ter me dat his ribs done grow terge'er. I gin 'im some bread, en den, w'en he start out, I tuck'n foller 'im, kaze, I say ter myse'f, maybe my nigger man mought be some'rs 'roun'. Dat ar little dog got sense, mon."

Free Joe laughed and dropped his hand lightly on Dan's head. For a long time after that he had no difficulty in seeing his wife. He had only to sit by the poplar tree until little Dan could run and fetch her. But after a while the other negroes discovered that Lucinda was meeting Free Joe in the woods, and information[16] of the fact soon reached Calderwood's ears. Calderwood was what is called a man of action. He said nothing; but one day he put Lucinda in his buggy, and carried her to Macon, sixty miles away. He carried her to Macon, and came back without her; and nobody in or around Hillsborough, or in that section, ever saw her again.

For many a night after that Free Joe sat in the woods and waited. Little Dan would run merrily off and be gone a long time, but he always came back without Lucinda. This happened over and over again. The "willis-whistlers" would call and call, like fantom huntsmen wandering on a far-off shore; the screech-owl would shake and shiver in the depths of the woods; the night-hawks, sweeping by on noiseless wings, would snap their beaks as though they enjoyed the huge joke of which Free Joe and little Dan were the victims; and the whip-poor-wills would cry to each other through the gloom. Each night seemed to be lonelier than the preceding, but Free Joe's patience was proof against loneliness. There came a time, however, when little Dan refused to go after Lucinda.[17] When Free Joe motioned him in the direction of the Calderwood place, he would simply move about uneasily and whine; then he would curl up in the leaves and make himself comfortable.

One night, instead of going to the poplar tree to wait for Lucinda, Free Joe went to the Staley cabin, and, in order to make his welcome good, as he expressed it, he carried with him an armful of fat-pine splinters. Miss Becky Staley had a great reputation in those parts as a fortune-teller, and the schoolgirls, as well as older people, often tested her powers in this direction, some in jest and some in earnest. Free Joe placed his humble offering of light-wood in the chimney corner, and then seated himself on the steps, dropping his hat on the ground outside.

"Miss Becky," he said presently, "whar in de name er gracious you reckon Lucindy is?"

"Well, the Lord he'p the nigger!" exclaimed Miss Becky, in a tone that seemed to reproduce, by some curious agreement of sight with sound, her general aspect of peakedness. "Well, the Lord he'p the nigger! hain't you been a-seein'[18] her all this blessed time? She's over at old Spite Calderwood's, if she's anywheres, I reckon."

"No'm, dat I ain't, Miss Becky. I ain't seen Lucindy in now gwine on mighty nigh a mont'."

"Well, it hain't a-gwine to hurt you," said Miss Becky, somewhat sharply. "In my day an' time it wuz allers took to be a bad sign when niggers got to honeyin' 'roun' an' gwine on."

"Yessum," said Free Joe, cheerfully assenting to the proposition—"yessum, dat's so, but me an' my ole 'oman, we 'uz raise terge'er, en dey ain't bin many days w'en we 'uz' 'way fum one 'n'er like we is now."

"Maybe she's up an' took up wi' some un else," said Micajah Staley from the corner. "You know what the sayin' is: 'New master, new nigger.'"

"Dat's so, dat's de sayin', but tain't wid my ole 'oman like 'tis wid yuther niggers. Me en her wuz des natally raise up terge'er. Dey's lots likelier niggers dan w'at I is," said Free Joe, viewing his shabbiness with a critical eye, "but[19] I knows Lucindy mos' good ez I does little Dan dar—dat I does."

There was no reply to this, and Free Joe continued:

"Miss Becky, I wish you please, ma'am, take en run yo' kyards en see sump'n n'er 'bout Lucindy; kaze ef she sick, I'm gwine dar. Dey ken take en take me up en gimme a stroppin', but I'm gwine dar."

Miss Becky got her cards, but first she picked up a cup, in the bottom of which were some coffee-grounds. These she whirled slowly round and round, ending finally by turning the cup upside down on the hearth and allowing it to remain in that position.

"I'll turn the cup first," said Miss Becky, "and then I'll run the cards and see what they say."

As she shuffled the cards the fire on the hearth burned low, and in its fitful light the gray-haired, thin-featured woman seemed to deserve the weird reputation which rumor and gossip had given her. She shuffled the cards for some moments, gazing intently in the dying[20] fire; then, throwing a piece of pine on the coals, she made three divisions of the pack, disposing them about in her lap. Then she took the first pile, ran the cards slowly through her fingers, and studied them carefully. To the first she added the second pile. The study of these was evidently not satisfactory. She said nothing, but frowned heavily; and the frown deepened as she added the rest of the cards until the entire fifty-two had passed in review before her. Though she frowned, she seemed to be deeply interested. Without changing the relative position of the cards, she ran them all over again. Then she threw a larger piece of pine on the fire, shuffled the cards afresh, divided them into three piles, and subjected them to the same careful and critical examination.

"I can't tell the day when I've seed the cards run this a-way," she said after a while. "What is an' what ain't, I'll never tell you; but I know what the cards sez."

"W'at does dey say, Miss Becky?" the negro inquired, in a tone the solemnity of which was heightened by its eagerness.[21]

"They er runnin' quare. These here that I'm a-lookin' at," said Miss Becky, "they stan' for the past. Them there, they er the present; and the t'others, they er the future. Here's a bundle"—tapping the ace of clubs with her thumb—"an' here's a journey as plain as the nose on a man's face. Here's Lucinda—"

"Whar she, Miss Becky?"

"Here she is—the queen of spades."

Free Joe grinned. The idea seemed to please him immensely.

"Well, well, well!" he exclaimed. "Ef dat don't beat my time! De queen er spades! W'en Lucindy year dat hit'll tickle 'er, sho'!"

Miss Becky continued to run the cards back and forth through her fingers.

"Here's a bundle an' a journey, and here's Lucinda. An' here's ole Spite Calderwood."

She held the cards toward the negro and touched the king of clubs.

"De Lord he'p my soul!" exclaimed Free Joe with a chuckle. "De faver's dar. Yesser, dat's him! W'at de matter 'long wid all un um, Miss Becky?"[22]

The old woman added the second pile of cards to the first, and then the third, still running them through her fingers slowly and critically. By this time the piece of pine in the fireplace had wrapped itself in a mantle of flame, illuminating the cabin and throwing into strange relief the figure of Miss Becky as she sat studying the cards. She frowned ominously at the cards and mumbled a few words to herself. Then she dropped her hands in her lap and gazed once more into the fire. Her shadow danced and capered on the wall and floor behind her, as if, looking over her shoulder into the future, it could behold a rare spectacle. After a while she picked up the cup that had been turned on the hearth. The coffee-grounds, shaken around, presented what seemed to be a most intricate map.

"Here's the journey," said Miss Becky, presently; "here's the big road, here's rivers to cross, here's the bundle to tote." She paused and sighed. "They hain't no names writ here, an' what it all means I'll never tell you. Cajy, I wish you'd be so good as to han' me my pipe."[23]

"I hain't no hand wi' the kyards," said Cajy, as he handed the pipe, "but I reckon I can patch out your misinformation, Becky, bekaze the other day, whiles I was a-finishin' up Mizzers Perdue's rollin'-pin, I hearn a rattlin' in the road. I looked out, an' Spite Calderwood was a-drivin' by in his buggy, an' thar sot Lucinda by him. It'd in-about drapt out er my min'."

Free Joe sat on the door-sill and fumbled at his hat, flinging it from one hand to the other.

"You ain't see um gwine back, is you, Mars Cajy?" he asked after a while.

"Ef they went back by this road," said Mr. Staley, with the air of one who is accustomed to weigh well his words, "it must 'a' bin endurin' of the time whiles I was asleep, bekaze I hain't bin no furder from my shop than to yon bed."

"Well, sir!" exclaimed Free Joe in an awed tone, which Mr. Staley seemed to regard as a tribute to his extraordinary powers of statement.

"Ef it's my beliefs you want," continued the old man, "I'll pitch 'em at you fair and free. My beliefs is that Spite Calderwood is gone an' took Lucindy outen the county. Bless your[24] heart and soul! when Spite Calderwood meets the Old Boy in the road they'll be a turrible scuffle. You mark what I tell you."

Free Joe, still fumbling with his hat, rose and leaned against the door-facing. He seemed to be embarrassed. Presently he said:

"I speck I better be gittin' 'long. Nex' time I see Lucindy, I'm gwine tell 'er w'at Miss Becky say 'bout de queen er spades—dat I is. Ef dat don't tickle 'er, dey ain't no nigger 'oman never bin tickle'."

He paused a moment, as though waiting for some remark or comment, some confirmation of misfortune, or, at the very least, some endorsement of his suggestion that Lucinda would be greatly pleased to know that she had figured as the queen of spades; but neither Miss Becky nor her brother said anything.

"One minnit ridin' in the buggy 'longside er Mars Spite, en de nex' highfalutin' 'roun' playin' de queen er spades. Mon, deze yer nigger gals gittin' up in de pictur's; dey sholy is."

With a brief "Good night, Miss Becky, Mars Cajy," Free Joe went out into the darkness, followed[25] by little Dan. He made his way to the poplar, where Lucinda had been in the habit of meeting him, and sat down. He sat there a long time; he sat there until little Dan, growing restless, trotted off in the direction of the Calderwood place. Dozing against the poplar, in the gray dawn of the morning, Free Joe heard Spite Calderwood's fox-hounds in full cry a mile away.

"Shoo!" he exclaimed, scratching his head, and laughing to himself, "dem ar dogs is des a-warmin' dat old fox up."

But it was Dan the hounds were after, and the little dog came back no more. Free Joe waited and waited, until he grew tired of waiting. He went back the next night and waited, and for many nights thereafter. His waiting was in vain, and yet he never regarded it as in vain. Careless and shabby as he was, Free Joe was thoughtful enough to have his theory. He was convinced that little Dan had found Lucinda, and that some night when the moon was shining brightly through the trees, the dog would rouse him from his dreams as he[26] sat sleeping at the foot of the poplar tree, and he would open his eyes and behold Lucinda standing over him, laughing merrily as of old; and then he thought what fun they would have about the queen of spades.

How many long nights Free Joe waited at the foot of the poplar tree for Lucinda and little Dan no one can ever know. He kept no account of them, and they were not recorded by Micajah Staley nor by Miss Becky. The season ran into summer and then into fall. One night he went to the Staley cabin, cut the two old people an armful of wood, and seated himself on the doorsteps, where he rested. He was always thankful—and proud, as it seemed—when Miss Becky gave him a cup of coffee, which she was sometimes thoughtful enough to do. He was especially thankful on this particular night.

"You er still layin' off for to strike up wi' Lucindy out thar in the woods, I reckon," said Micajah Staley, smiling grimly. The situation was not without its humorous aspects.

"Oh, dey er comin', Mars Cajy, dey er comin', sho," Free Joe replied. "I boun' you dey'll[27] come; en w'en dey does come, I'll des take en fetch um yer, whar you kin see um wid you own eyes, you en Miss Becky."

"No," said Mr. Staley, with a quick and emphatic gesture of disapproval. "Don't! don't fetch 'em anywheres. Stay right wi' 'em as long as may be."

Free Joe chuckled, and slipped away into the night, while the two old people sat gazing in the fire. Finally Micajah spoke.

"Look at that nigger; look at 'im. He's pine-blank as happy now as a killdee by a mill-race. You can't faze 'em. I'd in-about give up my t'other hand ef I could stan' flat-footed, an' grin at trouble like that there nigger."

"Niggers is niggers," said Miss Becky, smiling grimly, "an' you can't rub it out; yit I lay I've seed a heap of white people lots meaner'n Free Joe. He grins—an' that's nigger—but I've ketched his under jaw a-tremblin' when Lucindy's name uz brung up. An' I tell you," she went on, bridling up a little, and speaking with almost fierce emphasis, "the Old Boy's[28] done sharpened his claws for Spite Calderwood. You'll see it."

"Me, Rebecca?" said Mr. Staley, hugging his palsied arm; "me? I hope not."

"Well, you'll know it then," said Miss Becky, laughing heartily at her brother's look of alarm.

The next morning Micajah Staley had occasion to go into the woods after a piece of timber. He saw Free Joe sitting at the foot of the poplar, and the sight vexed him somewhat.

"Git up from there," he cried, "an' go an' arn your livin'. A mighty purty pass it's come to, when great big buck niggers can lie a-snorin' in the woods all day, when t'other folks is got to be up an' a-gwine. Git up from there!"

Receiving no response, Mr. Staley went to Free Joe, and shook him by the shoulder; but the negro made no response. He was dead. His hat was off, his head was bent, and a smile was on his face. It was as if he had bowed and smiled when death stood before him, humble to the last. His clothes were ragged; his hands were rough and callous; his shoes were literally[29] tied together with strings; he was shabby in the extreme. A passer-by, glancing at him, could have no idea that such a humble creature had been summoned as a witness before the Lord God of Hosts.

Not many years ago a representative of this class visited the old town. He was from the North, and, being much interested in what he saw, was duly inquisitive. Among other things that attracted his attention was a little one-armed man who seemed to be the life of the place. He was here, there, and everywhere; and wherever he went the atmosphere seemed to lighten and brighten. Sometimes he was flying around town in a buggy; at such times he was driven by a sweet-faced lady, whose smiling air of proprietorship proclaimed her to be his wife: but more often he was on foot. His cheerfulness and good humor were infectious. The old men sitting at Perdue's Corner, where they had been gathering for forty years and more, looked up and laughed as he passed; the ladies shopping in the streets paused to chat with him; and even the dry-goods clerks and lawyers, playing chess or draughts under the China trees that shaded the sidewalks, were willing to be interrupted long enough to exchange jokes with him.

"Rather a lively chap that," said the observant commercial traveler.[32]

"Well, I reckon you won't find no livelier in these diggin's," replied the landlord, to whom the remark was addressed. There was a suggestion of suppressed local pride in his tones. "He's a little chunk of a man, but he's monst'us peart."

"A colonel, I guess," said the stranger, smiling.

"Oh, no," the other rejoined. "He ain't no colonel, but he'd 'a' made a prime one. It's mighty curious to me," he went on, "that them Yankees up there didn't make him one."

"The Yankees?" inquired the commercial traveler.

"Why, yes," said the landlord. "He's a Yankee; and that lady you seen drivin' him around, she's a Yankee. He courted her here and he married her here. Major Jimmy Bass wanted him to marry her in his house, but Captain Jack Walthall put his foot down and said the weddin' had to be in his house; and there's where it was, in that big white house over yander with the hip roof. Yes, sir."

"Oh," said the commercial traveler, with a[33] cynical smile, "he stayed down here to keep out of the army. He was a lucky fellow."

"Well, I reckon he was lucky not to get killed," said the landlord, laughing. "He fought with the Yankees, and they do say that Little Compton was a rattler."

The commercial traveler gave a long, low whistle, expressive of his profound astonishment. And yet, under all the circumstances, there was nothing to create astonishment. The lively little man had a history.

Among the genial and popular citizens of Hillsborough, in the days before the war, none were more genial or more popular than Little Compton. He was popular with all classes, with old and with young, with whites and with blacks. He was sober, discreet, sympathetic, and generous. He was neither handsome nor magnetic. He was awkward and somewhat bashful, but his manners and his conversation had the rare merit of spontaneity. His sallow face was unrelieved by either mustache or whiskers, and his eyes were black and very small, but they glistened with good-humor and[34] sociability. He was somewhat small in stature, and for that reason the young men about Hillsborough had given him the name of Little Compton.

Little Compton's introduction to Hillsborough was not wholly without suggestive incidents. He made his appearance there in 1850, and opened a small grocery store. Thereupon the young men of the town, with nothing better to do than to seek such amusement as they could find in so small a community, promptly proceeded to make him the victim of their pranks and practical jokes. Little Compton's forbearance was wonderful. He laughed heartily when he found his modest signboard hanging over an adjacent barroom, and smiled good-humoredly when he found the sidewalk in front of his door barricaded with barrels and dry-goods boxes. An impatient man would have looked on these things as in the nature of indignities, but Little Compton was not an impatient man.

This went on at odd intervals, until at last the fun-loving young men began to appreciate Little Compton's admirable temper; and then[35] for a season they played their jokes on other citizens, leaving Little Compton entirely unmolested. These young men were boisterous, but good-natured, and they had their own ideas of what constituted fair play. They were ready to fight or to have fun, but in neither case would they willingly take what they considered a mean advantage of a man.

By degrees they warmed to Little Compton. His gentleness won upon them; his patient good-humor attracted them. Without taking account of the matter, the most of them became his friends. This was demonstrated one day when one of the Pulliam boys from Jasper County made some slurring remark about "the little Yankee." As Pulliam was somewhat in his cups, no attention was paid to his remark; whereupon he followed it up with others of a more seriously abusive character. Little Compton was waiting on a customer; but Pulliam was standing in front of his door, and he could not fail to hear the abuse. Young Jack Walthall was sitting in a chair near the door, whittling a piece of white pine. He put his knife in his[36] pocket, and, whistling softly, looked at Little Compton curiously. Then he walked to where Pulliam was standing.

"If I were you, Pulliam," he said, "and wanted to abuse anybody, I'd pick out a bigger man than that."

"I don't see anybody," said Pulliam.

"Well, d—— you!" exclaimed Walthall, "if you are that blind, I'll open your eyes for you!"

Whereupon he knocked Pulliam down. At this Little Compton ran out excitedly, and it was the impression of the spectators that he intended to attack the man who had been abusing him; but, instead of that, he knelt over the prostrate bully, wiped the blood from his eyes, and finally succeeded in getting him to his feet. Then Little Compton assisted him into the store, placed him in a chair, and proceeded to bandage his wounded eye. Walthall, looking on with an air of supreme indifference, uttered an exclamation of astonishment, and sauntered carelessly away.

Sauntering back an hour or so afterward, he found that Pulliam was still in Little Compton's[37] store. He would have passed on, but Little Compton called to him. He went in prepared to be attacked, for he knew Pulliam to be one of the most dangerous men in that region, and the most revengeful; but, instead of making an attack, Pulliam offered his hand.

"Let's call it square, Jack. Your mother and my father are blood cousins, and I don't want any bad feelings to grow out of this racket. I've apologized to Mr. Compton here, and now I'm ready to apologize to you."

Walthall looked at Pulliam and at his proffered hand, and then looked at Little Compton. The latter was smiling pleasantly. This appeared to be satisfactory, and Walthall seized his kinsman's hand, and exclaimed:

"Well, by George, Miles Pulliam! if you've apologized to Little Compton, then it's my turn to apologize to you. Maybe I was too quick with my hands, but that chap there is such a d—— clever little rascal that it works me up to see anybody pester him."

"Why, Jack," said Compton, his little eyes glistening, "I'm not such a scrap as you make[38] out. It's just your temper, Jack. Your temper runs clean away with your judgment."

"My temper! Why, good Lord, man! don't I just sit right down, and let folks run over me whenever they want to? Would I have done anything if Miles Pulliam had abused me?"

"Why, the gilded Queen of Sheba!" exclaimed Miles Pulliam, laughing loudly, in spite of his bruises; "only last sale day you mighty nigh jolted the life out of Bill-Tom Saunders, with the big end of a hickory stick."

"That's so," said Walthall reflectively; "but did I follow him up to do it? Wasn't he dogging after me all day, and strutting around bragging about what he was going to do? Didn't I play the little stray lamb till he rubbed his fist in my face?"

The others laughed. They knew that Jack Walthall wasn't at all lamblike in his disposition. He was tall and strong and handsome, with pale classic features, jet-black curling hair, and beautiful white hands that never knew what labor was. He was something of a dandy in Hillsborough, but in a large, manly,[39] generous way. With his perfect manners, stately and stiff, or genial and engaging, as occasion might demand, Mr. Walthall was just such a romantic figure as one reads about in books, or as one expects to see step from behind the wings of the stage with a guitar or a long dagger. Indeed, he was the veritable original of Cyrille Brandon, the hero of Miss Amelia Baxter's elegant novel entitled "The Haunted Manor; or, Souvenirs of the Sunny Southland." If those who are fortunate enough to possess a copy of this graphic book, which was printed in Charleston for the author, will turn to the description of Cyrille Brandon, they will get a much better idea of Mr. Walthall than they can hope to get in this brief and imperfect chronicle. It is true, the picture there drawn is somewhat exaggerated to suit the purposes of fictive art, but it shows perfectly the serious impression Mr. Walthall made on the ladies who were his contemporaries.

It is only fair to say, however, that the real Mr. Walthall was altogether different from the ideal Cyrille Brandon of Miss Baxter's powerfully[40] written book. He was by no means ignorant of the impression he made on the fair sex, and he was somewhat proud of it; but he had no romantic ideas of his own. He was, in fact, a very practical young man. When the Walthall estate, composed of thousands of acres of land and several hundred healthy, well-fed negroes, was divided up, he chose to take his portion in money; and this he loaned out at a fair interest to those who were in need of ready cash. This gave him large leisure; and, as was the custom among the young men of leisure, he gambled a little when the humor was on him, having the judgment and the nerve to make the game of poker exceedingly interesting to those who sat with him at table.

No one could ever explain why the handsome and gallant Jack Walthall should go so far as to stand between his own cousin and Little Compton; indeed, no one tried to explain it. The fact was accepted for what it was worth, and it was a great deal to Little Compton in a social and business way. After the row which has just been described, Mr. Walthall was usually[41] to be found at Compton's store—in the summer sitting in front of the door under the grateful shade of the China trees, and in the winter sitting by the comfortable fire that Compton kept burning in his back room. As Mr. Walthall was the recognized leader of the young men, Little Compton's store soon became the headquarters for all of them. They met there, and they made themselves at home there, introducing their affable host to many queer antics and capers peculiar to the youth of that day and time, and to the social organism of which that youth was the outcome.

That Little Compton enjoyed their company is certain; but it is doubtful if he entered heartily into the plans of their escapades, which they freely discussed around his hearth. Perhaps it was because he had outlived the folly of youth. Though his face was smooth and round, and his eye bright, Little Compton bore the marks of maturity and experience. He used to laugh, and say that he was born in New Jersey, and died there when he was young. What significance this statement possessed no one ever[42] knew; probably no one in Hillsborough cared to know. The people of that town had their own notions and their own opinions. They were not unduly inquisitive, save when their inquisitiveness seemed to take a political shape; and then it was somewhat aggressive.

There were a great many things in Hillsborough likely to puzzle a stranger. Little Compton observed that the young men, no matter how young they might be, were absorbed in politics. They had the political history of the country at their tongues' ends, and the discussions they carried on were interminable. This interest extended to all classes: the planters discussed politics with their overseers; and lawyers, merchants, tradesmen, and gentlemen of elegant leisure discussed politics with each other. Schoolboys knew all about the Missouri Compromise, the fugitive slave law, and States rights. Sometimes the arguments used were more substantial than mere words, but this was only when some old feud was back of the discussion. There was one question, as Little Compton discovered, in regard to which there[43] was no discussion. That question was slavery. It loomed up everywhere and in everything, and was the basis of all the arguments, and yet it was not discussed: there was no room for discussion. There was but one idea, and that was that slavery must be defended at all hazards, and against all enemies. That was the temper of the time, and Little Compton was not long in discovering that of all dangerous issues slavery was the most dangerous.

The young men, in their free-and-easy way, told him the story of a wayfarer who once came through that region preaching abolitionism to the negroes. The negroes themselves betrayed him, and he was promptly taken in charge. His body was found afterward hanging in the woods, and he was buried at the expense of the county. Even his name had been forgotten, and his grave was all but obliterated. All these things made an impression on Little Compton's mind. The tragedy itself was recalled by one of the pranks of the young men, that was conceived and carried out under his eyes. It happened after he had become well used to the ways of Hillsborough.[44] There came a stranger to the town, whose queer acts excited the suspicions of a naturally suspicious community. Professedly he was a colporteur; but, instead of trying to dispose of books and tracts, of which he had a visible supply, he devoted himself to arguing with the village politicians under the shade of the trees. It was observed, also, that he would frequently note down observations in a memorandum book. Just about that time the controversy between the slaveholders and the abolitionists was at its height. John Brown had made his raid on Harper's Ferry, and there was a good deal of excitement throughout the State. It was rumored that Brown had emissaries traveling from State to State, preparing the negroes for insurrection; and every community, even Hillsborough, was on the alert, watching, waiting, suspecting.

The time assuredly was not auspicious for the stranger with the ready memorandum book. Sitting in front of Compton's store, he fell into conversation one day with Uncle Abner Lazenberry, a patriarch who lived in the country, and[45] who had a habit of coming to Hillsborough at least once a week "to talk with the boys." Uncle Abner belonged to the poorer class of planters; that is to say, he had a small farm and not more than half a dozen negroes. But he was decidedly popular, and his conversation—somewhat caustic at times—was thoroughly enjoyed by the younger generation. On this occasion he had been talking to Jack Walthall, when the stranger drew a chair within hearing distance.

"You take all your men," Uncle Abner was saying—"take all un 'em, but gimme Hennery Clay. Them abolishioners, they may come an' git all six er my niggers, if they'll jess but lemme keep the ginnywine ole Whig docterin'. That's me up an' down—that's wher' your Uncle Abner Lazenberry stan's, boys." By this time the stranger had taken out his inevitable note-book, and Uncle Abner went on: "Yes, siree! You may jess mark me down that away. 'Come,' sez I, 'an' take all my niggers an' the ole gray mar',' sez I, 'but lemme keep my Whig docterin',' sez I. Lord, I've seed sights wi' them[46] niggers. They hain't no manner account. They won't work, an' I'm ablidge to feed 'em, else they'd whirl in an' steal from the neighbors. Hit's in-about broke me for to maintain 'em in the'r laziness. Bless your soul, little children! I'm in a turrible fix—a turrible fix. I'm that bankruptured that when I come to town, ef I fine a thrip in my britches-pocket for to buy me a dram I'm the happiest mortal in the county. Yes, siree! hit's got down to that."

Here Uncle Abner Lazenberry paused and eyed the stranger shrewdly, to whom, presently, he addressed himself in a very insinuating tone:

"What mought be your name, mister?"

"Oh," said the stranger, taken somewhat aback by the suddenness of the question, "my name might be Jones, but it happens to be Davies."

Uncle Abner Lazenberry stared at Davies a moment as if amazed, and then exclaimed:

"Jesso! Well, dog my cats ef times hain't a-changin' an' a-changin' tell bimeby the natchul world an' all the hummysp'eres 'll make the'r[47] disappearance een'-uppermost. Yit, whiles they er changin' an' a-disappearin', I hope they'll leave me my ole Whig docterin', an' my name, which the fust an' last un it is Abner Lazenberry. An' more'n that," the old man went on, with severe emphasis—"an' more'n that, they hain't never been a day sence the creation of the world an' the hummysp'eres when my name mought er'been anything else under the shinin' sun but Abner Lazenberry; an' ef the time's done come when any mortal name mought er been anything but what hit reely is, then we jess better turn the nation an' the federation over to demockeracy an' giner'l damnation. Now that's me, right pine-plank."

By way of emphasizing his remarks, Uncle Abner brought the end of his hickory cane down upon the ground with a tremendous thump. The stranger reddened a little at the unexpected criticism, and was evidently ill at ease, but he remarked politely:

"This is just a saying I've picked up somewhere in my travels. My name is Davies, and I am traveling through the country selling a[48] few choice books, and picking up information as I go."

"I know a mighty heap of Davises," said Uncle Abner, "but I disremember of anybody named Davies."

"Well, sir," said Mr. Davies, "the name is not uncommon in my part of the country. I am from Vermont."

"Well, well!" said Uncle Abner, tapping the ground thoughtfully with his cane. "A mighty fur ways Vermont is, tooby shore. In my day an' time I've seed as many as three men folks from Vermont, an' one un 'em, he wuz a wheelwright, an' one wuz a tin-pedler, an' the yuther one wuz a clock-maker. But that wuz a long time ago. How is the abolishioners gittin' on up that away, an' when in the name er patience is they a-comin' arter my niggers? Lord! if them niggers wuz free, I wouldn't have to slave for 'em."

"Well, sir," said Mr. Davies, "I take little or no interest in those things. I have to make a humble living, and I leave political questions to the politicians."[49]

The conversation was carried an at some length, the younger men joining in occasionally to ask questions; and nothing could have been friendlier than their attitude toward Mr. Davies. They treated him with the greatest consideration. His manner and speech were those of an educated man, and he seemed to make himself thoroughly agreeable. But that night, as Mr. Jack Walthall was about to go to bed, his body-servant, a negro named Jake, began to question him about the abolitionists.

"What do you know about abolitionists?" Mr. Walthall asked with some degree of severity.

"Nothin' 'tall, Marse Jack, 'cep'in' w'at dish yer new w'ite man down dar at de tavern say."

"And what did he say?" Mr. Walthall inquired.

"I ax 'im, I say, 'Marse Boss, is dese yer bobolitionists got horns en huffs?' en he 'low, he did, dat dey ain't no bobolitionists, kaze dey er babolitionists, an' dey ain't got needer horns ner huffs."

"What else did he say?"[50]

Jake laughed. It was a hearty and humorous laugh.

"Well, sir," he replied, "dat man des preached. He sholy did. He ax me ef de niggers' roun' yer wouldn' all like ter be free, en I tole 'im I don't speck dey would, kaze all de free niggers w'at I ever seed is de mos' no-'countes' niggers in de lan'."

Mr. Walthall dismissed the negro somewhat curtly. He had prepared to retire for the night, but apparently thought better of it, for he resumed his coat and vest, and went out into the cool moonlight. He walked around the public square, and finally perched himself on the stile that led over the court-house enclosure. He sat there a long time. Little Compton passed by, escorting Miss Lizzie Fairleigh, the schoolmistress, home from some social gathering; and finally the lights in the village went out one by one—all save the one that shone in the window of the room occupied by Mr. Davies. Watching this window somewhat closely, Mr. Jack Walthall observed that there was movement in the room. Shadows played on the white window-curtains—human[51] shadows passing to and fro. The curtains, quivering in the night wind, distorted these shadows, and made confusion of them; but the wind died away for a moment, and, outlined on the curtains, the patient watcher saw a silhouette of Jake, his body-servant. Mr. Walthall beheld the spectacle with amazement. It never occurred to him that the picture he saw was part—the beginning indeed—of a tremendous panorama which would shortly engage the attention of the civilized world, but he gazed at it with a feeling of vague uneasiness.

The next morning Little Compton was somewhat surprised at the absence of the young men who were in the habit of gathering in front of his store. Even Mr. Jack Walthall, who could be depended on to tilt his chair against the China tree and sit there for an hour or more after breakfast, failed to put in an appearance. After putting his store to rights, and posting up some accounts left over from the day before, Little Compton came out on the sidewalk, and walked up and down in front of the door. He was in excellent humor, and as he walked he hummed[52] a tune. He did not lack for companionship, for his cat, Tommy Tinktums, an extraordinarily large one, followed him back and forth, rubbing against him and running between his legs; but somehow he felt lonely. The town was very quiet. It was quiet at all times, but on this particular morning it seemed to Little Compton that there was less stir than usual. There was no sign of life anywhere around the public square save at Perdue's Corner. Shading his eyes with his hand, Little Compton observed a group of citizens apparently engaged in a very interesting discussion. Among them he recognized the tall form of Mr. Jack Walthall and the somewhat ponderous presence of Major Jimmy Bass. Little Compton watched the group because he had nothing better to do. He saw Major Jimmy Bass bring the end of his cane down upon the ground with a tremendous thump, and gesticulate like a man laboring under strong excitement; but this was nothing out of the ordinary, for Major Jimmy had been known to get excited over the most trivial discussion; on one occasion, indeed, he had even[53] mounted a dry-goods box, and, as the boys expressed it, "cussed out the town."

Still watching the group, Little Compton saw Mr. Jack Walthall take Buck Ransome by the arm, and walk across the public square in the direction of the court-house. They were followed by Mr. Alvin Cozart, Major Jimmy Bass, and young Rowan Wornum. They went to the court-house stile, and formed a little group, while Mr. Walthall appeared to be explaining something, pointing frequently in the direction of the tavern. In a little while they returned to those they had left at Perdue's Corner, where they were presently joined by a number of other citizens. Once Little Compton thought he would lock his door and join them, but by the time he had made up his mind the group had dispersed.

A little later on, Compton's curiosity was more than satisfied. One of the young men, Buck Ransome, came into Compton's store, bringing a queer-looking bundle. Unwrapping it, Mr. Ransome brought to view two large pillows. Whistling a gay tune, he ran his keen[54] knife into one of these, and felt of the feathers. His manner was that of an expert. The examination seemed to satisfy him; for he rolled the pillows into a bundle again, and deposited them in the back part of the store.

"You'd be a nice housekeeper, Buck, if you did all your pillows that way," said Compton.

"Why, bless your great big soul, Compy," said Mr. Ransome, striking an attitude, "I'm the finest in the land."

Just then Mr. Alvin Cozart came in, bearing a small bucket, which he handled very carefully. Little Compton thought he detected the odor of tar.

"Stick her in the back room there," said Mr. Ransome; "she'll keep."

Compton was somewhat mystified by these proceedings; but everything was made clear when, an hour later, the young men of the town, reenforced by Major Jimmy Bass, marched into his store, bringing with them Mr. Davies, the Vermont colporteur, who had been flourishing his note-book in the faces of the inhabitants. Jake, Mr. Walthall's body-servant, was prominent[55] in the crowd by reason of his color and his frightened appearance. The colporteur was very pale, but he seemed to be cool. As the last one filed in, Mr. Walthall stepped to the front door and shut and locked it.

Compton was too amazed to say anything. The faces before him, always so full of humor and fun, were serious enough now. As the key turned in the lock, the colporteur found his voice.

"Gentlemen!" he exclaimed with some show of indignation, "what is the meaning of this? What would you do?"

"You know mighty well, sir, what we ought to do," cried Major Bass. "We ought to hang you, you imperdent scounderl! A-comin' down here a-pesterin' an' a-meddlin' with t'other people's business."

"Why, gentlemen," said Davies, "I'm a peaceable citizen; I trouble nobody. I am simply traveling through the country selling books to those who are able to buy, and giving them away to those who are not."

"Mr. Davies," said Mr. Jack Walthall, leaning[56] gracefully against the counter, "what kind of books are you selling?"

"Religious books, sir."

"Jake!" exclaimed Mr. Walthall somewhat sharply, so sharply, indeed, that the negro jumped as though he had been shot. "Jake! stand out there. Hold up your head, sir!—Mr. Davies, how many religious books did you sell to that nigger there last night?"

"I sold him none, sir; I—"

"How many did you try to sell him?"

"I made no attempt to sell him any books; I knew he couldn't read. I merely asked him to give me some information."

Major Jimmy Bass scowled dreadfully; but Mr. Jack Walthall smiled pleasantly, and turned to the negro.

"Jake! do you know this man?"

"I seed 'im, Marse Jack; I des seed 'im; dat's all I know 'bout 'im."

"What were you doing sasshaying around in his room last night?"

Jake scratched his head, dropped his eyes, and shuffled about on the floor with his feet.[57] All eyes were turned on him. He made so long a pause that Alvin Cozart remarked in his drawling tone:

"Jack, hadn't we better take this nigger over to the calaboose?"

"Not yet," said Mr. Walthall pleasantly. "If I have to take him over there I'll not bring him back in a hurry."

"I wuz des up in his room kaze he tole me fer ter come back en see 'im. Name er God, Marse Jack, w'at ail' you all w'ite folks now?"

"What did he say to you?" asked Mr. Walthall.

"He ax me w'at make de niggers stay in slave'y," said the frightened negro; "he ax me w'at de reason dey don't git free deyse'f."

"He was warm after information," Mr. Walthall suggested.

"Call it what you please," said the Vermont colporteur. "I asked him those questions and more." He was pale, but he no longer acted like a man troubled with fear.

"Oh, we know that, mister," said Buck Ransome. "We know what you come for, and we[58] know what you're goin' away for. We'll excuse you if you'll excuse us, and then there'll be no hard feelin's—that is, not many; none to growl about.—Jake, hand me that bundle there on the barrel, and fetch that tar-bucket.—You've got the makin' of a mighty fine bird in you, mister," Ransome went on, addressing the colporteur; "all you lack's the feathers, and we've got oodles of 'em right here. Now, will you shuck them duds?"

For the first time the fact dawned on Little Compton's mind that the young men were about to administer a coat of tar and feathers to the stranger from Vermont; and he immediately began to protest.

"Why, Jack," said he, "what has the man done?"

"Well," replied Mr. Walthall, "you heard what the nigger said. We can't afford to have these abolitionists preaching insurrection right in our back yards. We just can't afford it, that's the long and short of it. Maybe you don't understand it; maybe you don't feel as we do; but that's the way the matter stands. We are in a[59] sort of a corner, and we are compelled to protect ourselves."

"I don't believe in no tar and feathers for this chap," remarked Major Jimmy Bass, assuming a judicial air. "He'll just go out here to the town branch and wash 'em off, and then he'll go on through the plantations raising h—— among the niggers. That'll be the upshot of it—now, you mark my words. He ought to be hung."

"Now, boys," said Little Compton, still protesting, "what is the use? This man hasn't done any real harm. He might preach insurrection around here for a thousand years, and the niggers wouldn't listen to him. Now, you know that yourselves. Turn the poor devil loose, and let him get out of town. Why, haven't you got any confidence in the niggers you've raised yourselves?"

"My dear sir," said Rowan Wornum, in his most insinuating tone, "we've got all the confidence in the world in the niggers, but we can't afford to take any risks. Why, my dear sir," he went on, "if we let this chap go, it won't be six months before the whole country'll be full[60] of this kind. Look at that Harper's Ferry business."

"Well," said Compton somewhat hotly, "look at it. What harm has been done? Has there been any nigger insurrection?"

Jack Walthall laughed good-naturedly. "Little Compton is a quick talker, boys. Let's give the man the benefit of all the arguments."

"Great God! You don't mean to let this d—— rascal go, do you, Jack?" exclaimed Major Jimmy Bass.

"No, no, sweet uncle; but I've got a nicer dose than tar and feathers."

The result was that the stranger's face and hands were given a coat of lampblack, his arms were tied to his body, and a large placard was fastened to his back. The placard bore this inscription:

Mr. Davies was a pitiful-looking object after the young men had plastered his face and hands[61] with lampblack and oil, and yet his appearance bore a certain queer relation to the humorous exhibitions one sees on the negro minstrel stage. Particularly was this the case when he smiled at Compton.

"By George, boys!" exclaimed Mr. Buck Ransome, "this chap could play Old Bob Ridley at the circus."

When everything was arranged to suit them, the young men formed a procession, and marched the blackened stranger from Little Compton's door into the public street. Little Compton seemed to be very much interested in the proceeding. It was remarked afterward that he seemed to be very much agitated, and that he took a position very near the placarded abolitionist. The procession, as it moved up the street, attracted considerable attention. Rumors that an abolitionist was to be dealt with had apparently been circulated, and a majority of the male inhabitants of the town were out to view the spectacle. The procession passed entirely around the public square, of which the court-house was the centre, and then across the square[62] to the park-like enclosure that surrounded the temple of justice.

As the young men and their prisoner crossed this open space, Major Jimmy Bass, fat as he was, grew so hilarious that he straddled his cane as children do broomsticks, and pretended that he had as much as he could do to hold his fiery wooden steed. He waddled and pranced out in front of the abolitionist, and turned and faced him, whereat his steed showed the most violent symptoms of running away. The young men roared with laughter, and the spectators roared with them, and even the abolitionist laughed. All laughed but Little Compton. The procession was marched to the court-house enclosure, and there the prisoner was made to stand on the sale-block so that all might have a fair view of him. He was kept there until the stage was ready to go; and then he was given a seat on that swaying vehicle, and forwarded to Rockville, where, presumably, the "boys" placed him on the train and "passed him on" to the "boys" in other towns.

For months thereafter there was peace in[63] Hillsborough, so far as the abolitionists were concerned; and then came the secession movement. A majority of the citizens of the little town were strong Union men; but the secession movement seemed to take even the oldest off their feet, and by the time the Republican President was inaugurated, the Union sentiment that had marked Hillsborough had practically disappeared. In South Carolina companies of minutemen had been formed, and the entire white male population was wearing blue cockades. With some modifications, these symptoms were reproduced in Hillsborough. The modifications were that a few of the old men still stood up for the Union, and that some of the young men, though they wore the blue cockade, did not aline themselves with the minutemen.

Little Compton took no part in these proceedings. He was discreetly quiet. He tended his store, and smoked his pipe, and watched events. One morning he was aroused from his slumbers by a tremendous crash—a crash that rattled the windows of his store and shook its very walls. He lay quiet a while, thinking that a small[64] earthquake had been turned loose on the town. Then the crash was repeated; and he knew that Hillsborough was firing a salute from its little six-pounder, a relic of the Revolution, that had often served the purpose of celebrating the nation's birthday in a noisily becoming manner.

Little Compton arose, and dressed himself, and prepared to put his store in order. Issuing forth into the street, he saw that the town was in considerable commotion. A citizen who had been in attendance on the convention at Milledgeville had arrived during the night, bringing the information that the ordinance of secession had been adopted, and that Georgia was now a sovereign and independent government. The original secessionists were in high feather, and their hilarious enthusiasm had its effect on all save a few of the Union men.

Early as it was, Little Compton saw two flags floating from an improvised flagstaff on top of the court-house. One was the flag of the State, with its pillars, its sentinel, and its legend of "Wisdom, Justice, and Moderation." The design of the other was entirely new to Little[65] Compton. It was a pine tree on a field of white, with a rattlesnake coiled at its roots, and the inscription, "DON'T TREAD ON ME!" A few hours later Uncle Abner Lazenberry made his appearance in front of Compton's store. He had just hitched his horse to the rack near the court-house.

"Merciful heavens" he exclaimed, wiping his red face with a red handkerchief, "is the Ole Boy done gone an' turned hisself loose? I hearn the racket, an' I sez to the ole woman, sez I: 'I'll fling the saddle on the gray mar' an' canter to town an' see what in the dingnation the matter is. An' ef the worl's about to fetch a lurch, I'll git me another dram an' die happy,' sez I. Whar's Jack Walthall? He can tell his Uncle Abner all about it."

"Well, sir," said Little Compton, "the State has seceded, and the boys are celebrating."

"I know'd it," cried the old man angrily. "My min' tole me so." Then he turned and looked at the flags flying from the top of the court-house. "Is them rags the things they er gwine to fly out'n the Union with?" he exclaimed[66] scornfully. "Why, bless your soul an body, hit'll take bigger wings than them! Well, sir, I'm sick; I am that away. I wuz born in the Union, an' I'd like mighty well to die thar. Ain't it mine? ain't it our'n? Jess as shore as you're born, thar's trouble ahead—big trouble. You're from the North, ain't you?" Uncle Abner asked, looking curiously at Little Compton.

"Yes, sir, I am," Compton replied; "that is, I am from New Jersey, but they say New Jersey is out of the Union."

Uncle Abner did not respond to Compton's smile. He continued to gaze at him significantly.

"Well," the old man remarked somewhat bluntly, "you better go back where you come from. You ain't got nothin' in the roun' worl' to do with all this hellabaloo. When the pinch comes, as come it must, I'm jes gwine to swap a nigger for a sack er flour an' settle down; but you had better go back where you come from."

Little Compton knew the old man was friendly; but his words, so solemnly and significantly uttered, made a deep impression. The[67] words recalled to Compton's mind the spectacle of the man from Vermont who had been paraded through the streets of Hillsborough, with his face blackened and a placard on his back. The little Jerseyman also recalled other incidents, some of them trifling enough, but all of them together going to show the hot temper of the people around him; and for a day or two he brooded rather seriously over the situation. He knew that the times were critical.

For several weeks the excitement in Hillsborough, as elsewhere in the South, continued to run high. The blood of the people was at fever heat. The air was full of the portents and premonitions of war. Drums were beating, flags were flying, and military companies were parading. Jack Walthall had raised a company, and it had gone into camp in an old field near the town. The tents shone snowy white in the sun, uniforms of the men were bright and gay, and the boys thought this was war. But, instead of that, they were merely enjoying a holiday. The ladies of the town sent them wagon-loads of provisions every day, and the occasion was a veritable[68] picnic—a picnic that some of the young men remembered a year or two later when they were trudging ragged, barefooted, and hungry, through the snow and slush of a Virginia winter.

But, with all their drilling and parading in the peaceful camp at Hillsborough, the young men had many idle hours, and they devoted these to various forms of amusements. On one occasion, after they had exhausted their ingenuity in search of entertainment, one of them, Lieutenant Buck Ransome, suggested that it might be interesting to get up a joke on Little Compton.

"But how?" asked Lieutenant Cozart.

"Why, the easiest in the world," said Lieutenant Ransome. "Write him a note, and tell him that the time has come for an English-speaking people to take sides, and fling in a kind of side-wiper about New Jersey."

Captain Jack Walthall, leaning comfortably against a huge box that was supposed to bear some relation to a camp-chest, blew a cloud of smoke through his sensitive nostrils and laughed.[69] "Why, stuff, boys!" he exclaimed somewhat impatiently, "you can't scare Little Compton. He's got grit, and it's the right kind of grit. Why, I'll tell you what's a fact—the sand in that man's gizzard would make enough mortar to build a fort."

"Well, I'll tell you what we'll do," said Lieutenant Ransome. "We'll sling him a line or two, and if it don't stir him up, all right; but if it does, we'll have some tall fun."

Whereupon, Lieutenant Ransome fished around in the chest, and drew forth pen and ink and paper. With some aid from his brother officers he managed to compose the following:

"Little Mr. Compton. Dear Sir—The time has arrived when every man should show his colors. Those who are not for us are against us. Your best friends, when asked where you stand, do not know what to say. If you are for the North in this struggle, your place is at the North. If you are for the South, your place is with those who are preparing to defend the rights and liberties of the South. A word to the wise is sufficient. You will hear from me again in due time. Nemesis."

This was duly sealed and dropped in the Hillsborough post-office, and Little Compton received it the same afternoon. He smiled as he broke the seal, but ceased to smile when he read the note. It happened to fit a certain vague feeling of uneasiness that possessed him. He laid it down on his desk, walked up and down behind his counter, and then returned and read it again. The sprawling words seemed to possess a fascination for him. He read them again and again, and turned them over and over in his mind. It was characteristic of his simple nature that he never once attributed the origin of the note to the humor of the young men with whom he was so familiar. He regarded it seriously. Looking up from the note, he could see in the corner of his store the brush and pot that had been used as arguments on the Vermont abolitionist. He vividly recalled the time when that unfortunate person was brought up before the self-constituted tribunal that assembled in his store.

Little Compton thought he had gaged accurately the temper of the people about him;[71] and he had, but his modesty prevented him from accurately gaging or even thinking about, the impression he had made on them. The note troubled him a good deal more than he would at first confess to himself. He seated himself on a low box behind his counter to think it over, resting his face in his hands. A little boy who wanted to buy a thrip's worth of candy went slowly out again after trying in vain to attract the attention of the hitherto prompt and friendly storekeeper. Tommy Tinktums, the cat, seeing that his master was sitting down, came forward with the expectation of being told to perform his famous "bouncing" trick, a feat that was at once the wonder and delight of the youngsters around Hillsborough. But Tommy Tinktums was not commanded to bounce; and so he contented himself with washing his face, pausing every now and then to watch his master with half-closed eyes.

While sitting thus reflecting, it suddenly occurred to Little Compton that he had had very few customers during the past several days; and it seemed to him, as he continued to think[72] the matter over, that the people, especially the young men, had been less cordial lately than they had ever been before. It never occurred to him that the threatened war, and the excitement of the period, occupied their entire attention. He simply remembered that the young men who had made his modest little store their headquarters met there no more. Little Compton sat behind his counter a long time, thinking. The sun went down, and the dusk fell, and the night came on and found him there.

After a while he lit a candle, spread the communication out on his desk, and read it again. To his mind, there was no mistaking its meaning. It meant that he must either fight against the Union, or array against himself all the bitter and aggressive suspicion of the period. He sighed heavily, closed his store, and went out into the darkness. He made his way to the residence of Major Jimmy Bass, where Miss Lizzie Fairleigh boarded. The major himself was sitting on the veranda; and he welcomed Little Compton with effusive hospitality—a hospitality that possessed an old-fashioned flavor.[73]

"I'm mighty glad you come—yes, sir, I am. It looks like the whole world's out at the camps, and it makes me feel sorter lonesome. Yes, sir; it does that. If I wasn't so plump I'd be out there too. It's a mighty good place to be about this time of the year. I tell you what, sir, them boys is got the devil in 'em. Yes, sir; there ain't no two ways about that. When they turn themselves loose, somebody or something will git hurt. Now, you mark what I tell you. It's a tough lot—a mighty tough lot. Lord! wouldn't I hate to be a Yankee, and fall in their hands! I'd be glad if I had time for to say my prayers. Yes, sir; I would that."

Thus spoke the cheerful Major Bass; and every word he said seemed to rime with Little Compton's own thoughts, and to confirm the fears that had been aroused by the note. After he had listened to the major a while, Little Compton asked for Miss Fairleigh.

"Oho!" said the major. Then he called to a negro who happened to be passing through the hall: "Jesse, tell Miss Lizzie that Mr. Compton is in the parlor." Then he turned to Compton.[74] "I tell you what, sir, that gal looks mighty puny. She's from the North, and I reckon she's homesick. And then there's all this talk about war. She knows our boys'll eat the Yankees plum up, and I don't blame her for being sorter down-hearted. I wish you'd try to cheer her up. She's a good gal if there ever was one on the face of the earth."

Little Compton went into the parlor, where he was presently joined by Miss Fairleigh. They talked a long time together, but what they said no one ever knew. They conversed in low tones; and once or twice the hospitable major, sitting on the veranda, detected himself trying to hear what they said. He could see them from where he sat, and he observed that both appeared to be profoundly dejected. Not once did they laugh, or, so far as the major could see, even smile. Occasionally Little Compton arose and walked the length of the parlor, but Miss Fairleigh sat with bowed head. It may have been a trick of the lamp, but it seemed to the major that they were both very pale.

Finally Little Compton rose to go. The major[75] observed with a chuckle that he held Miss Fairleigh's hand a little longer than was strictly necessary under the circumstances. He held it so long, indeed, that Miss Fairleigh half averted her face, but the major noted that she was still pale. "We shall have a wedding in this house before the war opens," he thought to himself; and his mind was dwelling on such a contingency when Little Compton came out on the veranda.

"Don't tear yourself away in the heat of the day," said Major Bass jocularly.

"I must go," replied Compton. "Good-by!" He seized the major's hand and wrung it.

"Good night," said the major, "and God bless you!"

The next day was Sunday. But on Monday it was observed that Compton's store was closed. Nothing was said and little thought of it. People's minds were busy with other matters. The drums were beating, the flags flying, and the citizen soldiery parading. It was a noisy and an exciting time, and a larger store than Little Compton's might have remained closed for several[76] days without attracting attention. But one day, when the young men from the camp were in the village, it occurred to them to inquire what effect the anonymous note had had on Little Compton; whereupon they went in a body to his store; but the door was closed, and they found it had been closed a week or more. They also discovered that Compton had disappeared.

This had a very peculiar effect upon Captain Jack Walthall. He took off his uniform, put on his citizen's clothes, and proceeded to investigate Compton's disappearance. He sought in vain for a clue. He interested others to such an extent that a great many people in Hillsborough forgot all about the military situation. But there was no trace of Little Compton. His store was entered from a rear window, and everything found to be intact. Nothing had been removed. The jars of striped candy that had proved so attractive to the youngsters of Hillsborough stood in long rows on the shelves, flanked by the thousand and one notions that make up the stock of a country grocery store. Little Compton's disappearance was a mysterious[77] one, and under ordinary circumstances would have created intense excitement in the community; but at that particular time the most sensational event would have seemed tame and commonplace alongside the preparations for war.

Owing probably to a lack of the faculty of organization at Richmond—a lack which, if we are to believe the various historians who have tried to describe and account for some of the results of that period, was the cause of many bitter controversies, and of many disastrous failures in the field—a month or more passed away before the Hillsborough company received orders to go to the front. Fort Sumter had been fired on, troops from all parts of the South had gathered in Virginia, and the war was beginning in earnest. Captain Jack Walthall of the Hillsborough Guards chafed at the delay that kept his men resting on their arms, so to speak; but he had ample opportunity, meanwhile, to wonder what had become of Little Compton. In his leisure moments he often found himself sitting on the dry-goods boxes in the neighborhood[78] of Little Compton's store. Sitting thus one day, he was approached by his body-servant. Jake had his hat in his hand, and showed by his manner that he had something to say. He shuffled around, looked first one way and then another, and scratched his head.

"Marse Jack," he began.

"Well, what is it?" said the other, somewhat sharply.

"Marse Jack, I hope ter de Lord you ain't gwine ter git mad wid me; yit I mos' knows you is, kaze I oughter done tole you a long time ago."

"You ought to have told me what?"

"'Bout my drivin' yo' hoss en buggy over ter Rockville dat time—dat time what I ain't never tole you 'bout. But I 'uz mos' 'blige' ter do it. I 'low ter myse'f, I did, dat I oughter come tell you right den, but I 'uz skeer'd you mought git mad, en den you wuz out dar at de camps, 'long wid dem milliumterry folks."

"What have you got to tell?"

"Well, Marse Jack, des 'bout takin' yo' hoss en buggy. Marse Compton 'lowed you wouldn't[79] keer, en w'en he say dat, I des went en hich up de hoss en kyar'd 'im over ter Rockville."

"What under heaven did you want to go to Rockville for?"

"Who? me, Marse Jack? 'Twa'n't me wanter go. Hit 'uz Marse Compton."

"Little Compton?" exclaimed Walthall.

"Yes, sir, dat ve'y same man."

"What did you carry Little Compton to Rockville for?"

"Fo' de Lord, Marse Jack, I dunno w'at Marse Compton wanter go fer. I des know'd I 'uz doin' wrong, but he tuck'n 'low dat hit'd be all right wid you, kaze you bin knowin' him so monst'us well. En den he up'n ax me not to tell you twell he done plum out'n yearin'."

"Didn't he say anything? Didn't he tell you where he was going? Didn't he send any word back?"

This seemed to remind Jake of something. He clapped his hand to his head, and exclaimed:

"Well, de Lord he'p my soul! Ef I ain't de beatenest nigger on de top side er de yeth! Marse Compton gun me a letter, en I tuck'n[80] shove it un' de buggy seat, en it's right dar yit ef somebody ain't tored it up."

By certain well-known signs Jake knew that his Marse Jack was very mad, and he was hurrying out. But Walthall called him.

"Come here, sir!" The tone made Jake tremble. "Do you stand up there, sir, and tell me all this, and think I am going to put up with it?"

"I'm gwine after dat note, Marse Jack, des ez hard ez ever I kin."

Jake managed to find the note after some little search, and carried it to Jack Walthall. It was crumpled and soiled. It had evidently seen rough service under the buggy seat. Walthall took it from the negro, turned it over and looked at it. It was sealed, and addressed to Miss Lizzie Fairleigh.

Jack Walthall arrayed himself in his best, and made his way to Major Jimmy Bass's, where he inquired for Miss Fairleigh. That young lady promptly made her appearance. She was pale and seemed to be troubled. Walthall explained his errand, and handed her the note. He thought her hand trembled, but he may[81] have been mistaken, as he afterward confessed. She read it, and handed it to Captain Walthall with a vague little smile that would have told him volumes if he had been able to read the feminine mind.

Major Jimmy Bass was a wiser man than Walthall, and he remarked long afterward that he knew by the way the poor girl looked that she was in trouble, and it is not to be denied, at least, it is not to be denied in Hillsborough, where he was known and respected, that Major Bass's impressions were as important as the average man's convictions. This is what Captain Jack Walthall read: