REV. SAMUEL MARSDEN.

Title: A History of the English Church in New Zealand

Author: Henry Thomas Purchas

Release date: February 9, 2010 [eBook #31234]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Heiko Evermann, Rob Reid, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/historyofenglish00purc |

Transcriber's Note:

The spelling in this text has been left as it appears in the

original book except where it was inconsistent within the text.

Details of changes made are shown within the text with mouse-hover popups

and are listed in full at the end of the text.

To the

RIGHT REVEREND

WILLIAM LEONARD WILLIAMS,

sometime Bishop of Waiapu.

THIS BOOK

is respectfully dedicated in memory of

the eminent services rendered to the New Zealand Church

by himself and others of his name.

BY

H. T. PURCHAS, M.A.

Vicar of Glenmark, N.Z.

Canon of Christchurch Cathedral, and Examining

Chaplain to the Bishop.

Author of

"Bishop Harper and the Canterbury Settlement,"

"Johannine Problems and Modern Needs."

SIMPSON & WILLIAMS LIMITED

CHRISTCHURCH, N.Z.

G. ROBERTSON & CO. PROPY. LTD., MELBOURNE.

SAMPSON LOW & CO. LTD., LONDON.

1914

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Bishop Harper and the Canterbury Settlement.

PRESS NOTICES

Original Edition.

"We are glad to welcome this book. It has been very well written; it is interesting throughout; one's attention never flags; it is exactly what was wanted by churchmen, and should be on the book-shelf of every churchman in at least this Colony.... We simply advise every one of our readers to buy it and read it, and let their boys and girls read it too."

Auckland Church Gazette.

"One reads it as eagerly as though it were a novel."

N. Z. Guardian (Dunedin).

"Just the book to present to any young clergyman who wishes to have the life of an ideal pastor before him."

Nelson Diocesan Gazette.

"A valuable addition to our growing library of historical literature."

Lyttelton Times.

"In many respects the book is a model biography."

Evening Post (Wellington).

"A very valuable contribution to the early history of New Zealand.... Throws considerable light on the pioneering days in Canterbury."

The Outlook.

REVISED AND ENLARGED EDITION

"To some extent re-written.... The additions considerably exceed the omissions.... Generally, in all respects in which the book is fuller it may be said to be more full of interest."

Guardian (England).

Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd. - Publishers

If asked why I took in hand a task of such difficulty and delicacy as that of writing a History of the Church in our Dominion, I can really find no more truthful answer than that of the schoolboy, "Please, Sir, I couldn't help it." From boyhood's days in the old country, when a copy of the Life of Marsden fell into my hands, I felt drawn to the subject; the reading of Selwyn's biography strengthened the attraction; the urging of friends in later years combined with my own inclinations; and thus the work was well on its way when the General Synod of 1913 committed it to my hands as a definite duty.

For the last quarter of a century the Church of this Dominion has indeed possessed a history by my honoured teacher, Dean Jacobs. That scholarly volume could hardly be bettered on the constitutional side. In this department the Dean wrote as one who had taken no mean part in the events which he describes. His ecclesiastical learning and his judicial temper rendered him admirably qualified for the task. In working over the same ground I have perhaps been able to point out a few facts which he had missed or ignored, but on the whole I have left this part of the field to him. This is not a constitutional history: it seeks rather to depict the general life of the Church, and the ideals which guided its leading figures.

The Dean's description of the missionary period is also an admirable piece of work, but he had not the advantage of the stores of material which are now available. Through the indefatigable enthusiasm of the late Dr. Hocken the journals of the early missionaries have been brought to this country, and are made available to the student. His comprehensive collection enables us to come into close touch with days which are already far distant from our own. Of course the historian must be guided by the principle, summa sequi fastigia rerum; but he[vi] cannot estimate aright the work of the heroic leaders and rulers of the Church unless he can follow the thoughts and careers of the less conspicuous agents—the humble missionary or catechist, the native convert or thinker.

In acknowledging my obligations to the late Dr. Hocken, I would wish to express my gratitude to the authorities of the Dunedin Museum, where his library is kept; and also to my friend Archdeacon Woodthorpe, who kindly placed at my service the unpublished volume in which Dr. Hocken's researches into the life of Marsden are contained. For permission to consult the Godley correspondence in the Christchurch Museum I have to thank the Board of Governors of Canterbury College; and for the loan of a rare and valuable pamphlet on the death of the Rev. C. S. Volkner I am greatly indebted to Mr. Alexander Turnbull, of Wellington. Archdeacon Fancourt, of the same city, has afforded me generous help in recovering some of the early history of the diocese he has so long served; while, in Auckland, the Rev. J. King Davis—a descendant of the two missionaries whose names he bears—has enabled me to identify the positions of some long forgotten pas, and has furnished valuable information on other points. Other correspondents, from the Bay of Islands to Otago, have assisted generously with their local knowledge. Outside of New Zealand I have to acknowledge help from Mrs. Hobhouse, of Wells, and the Ven. Archdeacon Hobhouse, of Birmingham, the widow and son of the first Bishop of Nelson.

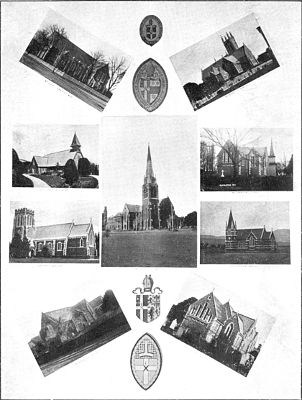

Many clergy have kindly acceded to my application for photographs of their churches. A fair number of these I have been able to use, and to all the senders I desire to express my thanks. For the view of the ruined church at Tamaki I am indebted to Miss Brookfield, of Auckland, and for the excellent representation of the scene at the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi to Mr. A. F. McDonnell, of Dunedin. In the preparation of the MS. for the press I have been greatly assisted by the Rev. H. East, Vicar of Leithfield.

But the greatest help of all remains to be told. To the aged and venerable Bishop Leonard Williams this book owes more than I can estimate. Not only has he furnished me with abundant information from the stores of his own unique and first-hand knowledge, but, on many points, he has engaged in[vii] fresh and laborious research. Every chapter has been sent to him as soon as written, and has benefited immensely by his careful and judicial criticism. Without this thorough testing my book would be far more imperfect than it is.

It is due, however, to the bishop, as well as to my readers, to state emphatically that he is in no way responsible for the views expressed in this book. There are, in fact, a few points on which we do not quite agree. The intricacies of high policy or of mingled motive will never appeal in exactly the same way to different minds. My aim throughout has been to arrive at the simple truth, and I have often been driven to abandon long-cherished ideas by its imperative demand.

In the spelling of Maori names Bishop Williams' authority has always been followed except when a place is looked at from the pakeha or colonial point of view. Then it is spelt in the colonial manner. Readers may be glad to be warned against confusing Turanga (Poverty Bay) with Tauranga in the Bay of Plenty. Similarly, it may be well to call attention to the wide difference between Tamihana Te Waharoa and Tamihana Te Rauparaha. Both were notable men, but their characters were not alike, and they took opposite sides in the great war.

The scope of this book has not permitted me to trace the history of the Melanesian Mission, nor to deal with the island dependencies of our Dominion. Even within the limits of New Zealand itself the treatment of the later period may perhaps seem inadequate. But the events of the years 1850-1890 have been already covered to some extent in my book, "Bishop Harper and the Canterbury Settlement," while for the latest stage of all I have the pleasure of appending to this preface a valuable letter from the present Primate, whose high office and long experience enable him to speak with unique authority upon the life of the Church of to-day.

H. T. P.

Glenmark Vicarage, Canterbury, N.Z.,

March, 1914.

LETTER FROM THE MOST REVEREND THE PRIMATE.

Dear Canon Purchas—

In consideration of my long career as a church-worker in New Zealand, you have honoured me with a request to add to your forthcoming volume of the History of the Church here a short account of my impressions as to her life and progress since 1871, and also my ideas as to her prospects and the chief tasks which lie before her.

I think the most convenient form in which I could attempt to supply the need would be by addressing a letter to you embracing these topics, which letter, should you esteem it worthy, could be printed with your Preface.

In turning, then, to your first question, I have to premise that the life and progress of any institution are very largely affected by attendant circumstances and surroundings for which perhaps the leaders of the institution itself are not responsible. Thus, with reference to our Provincial Church at the period you mention, she was weakened by the loss of not a few of those upon whom she had leaned for counsel and stimulating influence. Bishops Hobhouse and Abraham, Sir William Martin and Mr. Swainson, besides other prominent churchmen, such as Sir George Arney, and others less known, speedily followed their great leader, Bishop Selwyn, to England, or were removed by other causes. Without any surrender to the weakness of a mere laudator temporis acti, I look back to the time of my arrival in New Zealand with a feeling that there were giants in the earth in those days. Many whom we have more recently lost were also with us then—men like Messrs. Acland and Hanmer and Maude and Sewell, Col. Haultain, Mr. Hunter-Brown, and, of course, Bishop Hadfield and Dean Jacobs. Many of these were men of marked ability, men who made the synod halls ring with their forcible utterances, men full of knowledge of the Church and love for her, full of self-sacrificing spirit and determination to make her a praise in the[ix] faithful guardian of our Church's influence, Primate Harper. The loss of such fathers of the Church has been felt in the interval under review, and could not but affect the life and progress of the Church. It is not for me to say anything of those by whom their places have been filled.

Another adverse circumstance which must be called to mind in such a review is the long period of commercial depression which followed a short period of fictitious prosperity and inflated values. Misled by the apparently fair prospect of making money rapidly—of which prospect a shoal of interested persons sprang up to make the most—undertakings were entered upon on borrowed capital and properties were bought at prices which could not be realised upon them perhaps twenty years afterwards. The consequence of all this was a widespread desolation. My diocesan visitations were in those days largely made on horseback, and in a journey of perhaps many hundred miles I had to look upon stations and homesteads at which I had formerly been hospitably received, whether their owners belonged to our communion or not, either closed altogether or left in charge of a shepherd.

Many of the proprietors of these sheep stations had been liberal supporters of the Church, and their ruin spelt disaster to the authorities of the nearest clerical charge, if not also the weakness of diocesan institutions. During those long, long years, diocesan management was a weariness indeed, and not the less so because it was so hard to keep up the courage even of our church-workers themselves. I am thankful to say that no organised charge within my own diocese was closed in that period, but it was manifestly impossible to subdivide districts and so to introduce additional clergy. Little else could be thought of than holding on.

By these circumstances, then, the life of the Church was affected and her progress hindered. New conditions were developed, and the rulers of the Church had to accept and provide for these new conditions. I am far from saying that the large displacement of the pastoral industry by the agricultural was a misfortune either to the country or the Church: as regards the latter, the large increase of the population upon the land has given the Church more scope for the exercise of her ministerial activities; but for vestries and church committees[x] the work is harder, demanding, as it does, so much closer attention to details. In the old days one man might ride round the eight or ten stations within a district, and by collecting £10 to £20 from each would thus easily raise a large part of the stipend of the clergyman, and at the same time enjoy a pleasant visit to his friends. The collecting from a large number of scattered persons is a different matter, and means many workers and much patience. It is not unnatural, therefore, that this outlying work is avoided, and that the church officials rely too much upon the residents in towns and villages. This is a danger of the present, and needs close attention. A vestry easily becomes content so soon as in one way or another it has got together enough money wherewith to discharge its obligations; but there can be no free and elastic expansion unless the interest of all her members is enlisted by the Church, and each is willing to do his part in the establishment of the kingdom of Christ.

I think the progress of the Church of late years has been satisfactory. We have a body of clergy who, in devotion to their work and ability for the performance of it, need not fear comparison with those of other countries, not excluding the average of the English clergy themselves; and I think it high time that that insulting enactment known as the "Colonial Clergy Act" was rescinded. It is an unworthy bar to full inter-communion between areas of the Church which profess to be at one. As to our lay people I can only say that I often stand amazed at the willing and patient sacrifice they make of time and effort in the management of church affairs in synods, on vestries, and committees of every kind for the promotion of her work.

As to the future, the great task of the Church is, to my mind, the instruction both of the young clergy and the young laity as to the Divine Commission and real nature of the Church. Since union through the truth is the only method authorised by Holy Scripture, we must teach and teach and teach. That is the task of our divinity schools and of the clergy in preparing their candidates for confirmation: line upon line and precept upon precept, definite and clear instruction should be given so that the future heads of families may know and value[xi] their privileges, and the whole population will be impressed by the strength of our convictions.

I am afraid I have allowed my pen to run beyond the limits you had in view, but you must do what you think well with this letter, and believe me to remain,

Faithfully yours,

S. T. DUNEDIN, Primate.

Bishopsgrove, January, 1914.

The Keystone Printing Co.,

552-4 Lonsdale Street, Melb.

Slow progress of Christianity towards Antipodes—Moslem barrier—Effect of the Renaissance—Europeans south of the barrier—Dutch in East Indies—Tasman's discovery of New Zealand—"Three Kings Island"—Cook's visit—Convict settlement at Port Jackson—Conclusions.

FIRST PERIOD.

the preparation (1805-1813).

The Bay of Islands—Te Pahi—His visit to New South Wales—Meeting with Marsden—Te Pahi's return and death—Ruatara—His arrival in England—Marsden at Home—The Church Missionary Society—Its plans for New Zealand Mission—Hall and King—Marsden meets Ruatara on Active—Boyd massacre—Delay—Ruatara's return to New Zealand—The years of waiting.

the enterprise (1813-1815).

Conditions more favourable—Preliminary voyage of Active—"Noah's Ark"—Arrival of mission in New Zealand—Interview with Whangaroans—"Rangihoo"—Landing of Marsden, &c.—Preparation for service—Christmas Day, 1814—Marsden's narrative—Planting of settlement—Gathering timber—Ruatara's illness and death—His work.

the reception (1815-1822).

Position of settlers—Hall at Waitangi—Communistic experiment—Difficulty with Kendall—The mission in trouble—Visit of Rev. S. Leigh—Renewed zeal—Second visit of Marsden—Foundation of Kerikeri station[xiv]—Marsden's third visit—Hongi and Kendall leave for England—Reception by King George IV—Marsden's journeys in New Zealand—Hinaki of Mokoia—Return of Hongi and Kendall—Change in Hongi—Siege of Mokoia—Devastation of Thames district—Miserable plight of missionaries—Closing of seminary at Parramatta.

the new beginning (1823-1830).

Need of the mission—Arrival of Rev. H. Williams—His character—Settlement at Paihia—New workers—Difficulties in farming—Richard Davis—Building of the Herald—Schools—Flight of Wesleyans from Whangaroa—Death of Hongi—Peace-making—The "Girls' War"—Conversions—Taiwhanga—Baptisms—Effectiveness of schools—Evidences of progress.

the forward move (1831-1837).

Exploration—Expedition to Kaitaia—Station formed—Cape Reinga—Expedition to Thames—Evening service—Surprising reception—Visit to Te Waharoa—Station at Puriri—Visit to Waikato—Station at Mangapouri—Tauranga—Rotorua—The Rotorua-Thames war—Looting of Ohinemutu station—Flight from Matamata—Mrs. Chapman's bonnet—Withdrawal of missionaries—Ngakuku and Tarore—Marsden's last visit—Progress in the north—Departure of Marsden—Estimate of his work and character.

years of the right hand (1838-1840).

Re-occupation of Rotorua and Tauranga—Visit to Opotiki—Station there—Maunsell at Waikato Heads—Visit of Bishop Broughton—Influenza—Octavius Hadfield—The east coast—Taumatakura—W. Williams moves to Poverty Bay—Ripahau at Cook Strait—Rauparaha—Tamihana learns from Ripahau—Tamihana and Te Whiwhi come to Bay of Islands—Hadfield offers to return with them—H. Williams and Hadfield visit Port Nicholson—Kapiti—Work of Ripahau—Peace-making[xv]—Williams at Whanganui—Ascends the river—Village bells—March to Taupo—Tauranga—Wairarapa—The instructions of Karepa.

retrospect (1814-1841).

Arrival of Hobson—Treaty of Waitangi—Opposition of New Zealand Company—The work of the missionaries—Absence of authority—Kendall the Gnostic—The new workers—Bible translation—Simplicity in worship—And in life—Buying of land—Motives tested by selection of Auckland—Darwin's verdict—Missionaries and Methodists—Friendly relations—Disagreement on West Coast—Arrival of Roman mission—Hardships—Koinaki's taua—Causes of rapid spread of Christianity among Maoris—Gifts of civilisation—Religiousness of Maori nature—Letters of converts—The old heart—Marvellous memory—Hopes for the future.

SECOND PERIOD.

the beginnings of the new order (1839-1842).

Arrival of immigrants—Principles of the New Zealand Company—Opposition of the C.M.S.—Henry Williams and the Wellington settlers—Arrival of Bishop Selwyn—His ideals—His choice of Waimate—Condition of the country—Bishop's first tour—Nelson—Wellington—Whanganui—New Plymouth—Journey across the island—Waiapu—Bay of Plenty—Waikato—Return to Waimate.

adjustment (1843-1844).

Bishop Selwyn's ecclesiastical position—Religious divisions—Formation of St. John's College—Death of Whytehead—Communism in practice—A lesson to the world—Ordinations—Bishop's second tour—White Terraces—Whanganui River—Wairau tragedy—Hadfield and Wiremu Kingi save Wellington—Tamihana Te Rauparaha[xvi]—His mission to the south—Bishop's visit to Canterbury—Otago—Stewart Island—Akaroa—Return to Waimate—Difference with C.M.S.—Bonds of fellowship—Ordinations—Synod—Bishop leaves Waimate.

conflict and trouble (1845-1850).

Settlement in Auckland—College founded at Tamaki—Continued disagreement with C.M.S.—Heke's rebellion—His tactics—Burning of Kororareka—Charge against Henry Williams—Ohaeawai—Governor Grey—The Bats' Nest—"Blood and Treasure Despatch"—"Substantiation or Retractation"—Bishop joins Governor—His motives—Dismissal of Henry Williams by C.M.S.—Removal to Pakaraka—Subsequent history of Bay of Islands.

sacrifice and healing (1850-1856).

Selwyn visits Chatham Islands—Melanesia—Progress at Otaki and Wanganui—Troubles—Epidemic at St. John's—Failure of communistic system—Lutherans at Chatham Island—Porirua—Effect of H. Williams' dismissal—Journey of W. Williams to England—Improvement of relations between bishop and missionaries—Arrival of Rev. C. J. Abraham—Of Canterbury colonists—Ideals of Canterbury Association—Godley captured by Selwyn—Disagreement between them and the Association—Bishop wins affections of colonists—Break-up of Maori side of St. John's College—Visit of Bishop to England—Concordat between him and the C.M.S.—Return to New Zealand—Election of Rev. H. J. C. Harper to Christchurch—Arrival and installation of Bishop Harper.

organisation and progress (1850-1859).

Difficulty of creating ecclesiastical government in the colonies—Governor Grey drafts constitution—Its favourable reception—Discussed by Australian bishops—The Royal Supremacy—Godley's advocacy of freedom—Meetings to discuss constitution—C.M.S. opposition disarmed[xvii]—"Voluntary compact"—Taurarua Conference—Struggle over ecclesiastical franchise—Promulgation of Constitution—Legal recognition—The new bishoprics—Wellington, Nelson, Waiapu—Completion of organisation of Church.

trouble and anguish (1859-62).

Sudden darkness—Working of constitution—Paucity of Maori clergy—Inadequacy of mission Staff—Tamihana Te Waharoa—His ideals—The king movement—Suspicion of its loyalty—Governor Gore-Browne precipitates war in Taranaki—Sympathy of "king" natives—Growth of king movement—Good order of its rule—Defeat of Taranaki natives—Truce—Attempt at justice to Maoris—General Synod at Nelson—Discontent of Canterbury churchmen.

ruin and desolation (1862-1868).

Position in 1862—Meeting at Peria—Position of Waikato Maoris—Grey brings on another war—Rangiaohia—Defeat of "king" forces—Henare Taratoa—His rules—Heroic action—Death—Devastation by British forces—Hauhauism—Wiremu Hipango—Hauhaus at Opotiki—Murder of Rev. C. S. Volkner—A night of horror—The trial—Bishop Patteson's memorial sermon—Selwyn starts to the rescue of Rev. T. Grace—Critical situation of Bishop Williams—Rescue of Grace—Removal of Bishop Williams—The third General Synod—Death of Tamihana—And of Henry Williams—Journey of Bishop Selwyn to England—Offer of Lichfield bishopric—Refusal—Acceptance—Tribute to his character and work.

THIRD PERIOD.

after the war. the maoris.

Changes produced by war and immigration—Separateness of Maori and pakeha—Maoris and Sir George Grey[xviii]—Siege of Waerenga-a-hika—S. Williams at Te Aute—Return of Bishop Williams—Reconstitution of diocese of Waiapu—Te Kooti at Chatham Island—His prayers—Poverty Bay massacre—Ringa-tu—Depressed state of Maori Christianity—Present condition of Maoris.

after the war. the colonists (1868-1878).

Troubles in the colonial Church—Dunedin—Nomination of the Rev. H. L. Jenner—Opposition to his appointment—His rejection by General Synod—And by the Synod of Dunedin—Illness of Bishop Patteson—His last voyage—His death—Weakness in the dioceses—Education Act of 1877—Episcopal changes.

the church of to-day (1878-1914).

The Blue Gum period—The Pine period—The Macrocarpa period—Recovery—New churches—Bishop Harper's resignation—Disputed election—Bishop Hadfield, primate—Labour movement—Retirement of bishops—Fresh episcopal appointments—The General Mission of 1910.

the church at work.

Doctrine and discipline—Worship—Hymns—Clergy—Theological colleges—Parish priests of the past—Church buildings—ADMINISTRATION—Legal position of priests and people—The General Synod—Patronage—Finance—EDUCATION—Grammar schools—Primary education—Bible-in-schools movement—Sunday-schools—CHARITABLE RELIEF—MISSIONARY EFFORTS—Maori Mission—Melanesian Mission—the Church Missionary Association—Conclusion.

| 1. | Portrait of Samuel Marsden | Frontispiece | ||

| 2. | Map of North Island, showing Missionary Routes | Facing | page | 16 |

| 3. | View of Paihia | " | " | 33 |

| 4. | Henry Williams at the Treaty of Waitangi | " | " | 49 |

| 5. | Portrait of Bishop Selwyn | " | " | 64 |

| 6. | Ruins of St. Thomas', Tamaki | " | " | 82 |

| 7. | Old Church at Russell | " | " | 89 |

| 8. | Nelson Cathedral | " | " | 97 |

| 9. | A Village Church, Stoke, near Nelson | " | " | 113 |

| 10. | St. Matthew's Church, Auckland | " | " | 128 |

| 11. | St. Matthew's Church, Dunedin | " | " | 145 |

| 12. | Canterbury Churches | " | " | 161 |

| 13. | Map of the Bay of Islands | " | " | 169 |

| 14. | St. John's Cathedral, Napier | " | " | 177 |

| 15. | All Saints' Church, Palmerston North | " | " | 193 |

| 16. | St. John's, Invercargill | " | " | 200 |

| 17. | St. Luke's, Oamaru | " | " | 209 |

| 18. | Wanganui School Chapel | " | " | 225 |

| 19. | Baptistery of St. Matthew's, Auckland | " | " | 233 |

| 20. | New Zealand Bishops | " | " | 240 |

Beginning from Jerusalem.

—Acts.

A commercial message of trifling import may now be flashed in a few minutes from Jerusalem to the Antipodes: the message of Christ's love took nearly eighteen centuries to make the journey. For a time, indeed, the advance was direct and swift, for before the third century after Christ a Church had established itself in South India. But there the missionary impulse failed. Had the first rate of progress been maintained, the message would have reached our shores a whole millennium before it actually arrived.

But what would have been then its form and content? Had it made its way from island to island, passing through the minds of Malay, Papuan, or Melanesian on its passage, how much of its original purity would have been preserved? And who would have been here to receive it? Possibly, only the moa and the apteryx. Who knows?

These considerations enable us to look with less regret upon the check which the Christian message received after its first rapid advance. The rise of Mohammedanism in the sixth century drove the faith of Christ from Asia and from Africa, but it kept it "white." It threw a barrier across the old road which led from Jerusalem to the Antipodes, but the barrier enabled preparation to be made on either side for a grander and more fruitful intercourse. On the south of the Islamic empire the migrations of the peoples brought to our islands the Maori race, who made them their permanent home. On the north, the Christian faith took firm hold of the maritime nations[2] of Europe, from whom the missionaries of the future were to spring.

The capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1452 may be taken as the turning point. It closed more firmly than ever the land-route to the south, but the libraries of this great city, in which was preserved nearly all that remained of ancient learning, were scattered by the captors, and their contents carried far and wide. New Testament manuscripts awakened fresh study in the western world, and led to a cleansing and quickening of religion; narratives of old Greek explorers made men impatient of the barrier which blocked them from the lands which the ancients had known, and thus drove them to seek new routes by sea.

Marvellous was the energy which now awoke. By 1492 Columbus had crossed the Atlantic, and Vasco da Gama, having rounded the African continent, had reached India by an ocean road which had nothing to fear from the Mussulman power.

Two routes, in fact, had now been opened, for not only did the Portuguese follow up da Gama's discoveries in the Indian Ocean, but the Spaniards from the American side soon entered the Pacific. But neither of these nations quite reached our distant islands. Their ships were swept from the sea in the seventeenth century by the Dutch, whose eastern capital was Batavia. From this port there started in 1642 a small expedition of two ships under the command of Abel Tasman. Heading his journal with the words, "May the Almighty God give His blessing to this voyage," the courageous Hollander went forth, and, sailing round the Australian continent, struck boldly across the sea which now bears his name. On December 16th the mountainous coast of our South Island rose before him, and what we may now call New Zealand was seen by European eyes. The ferocity of the inhabitants prevented the explorer from landing on its shores, but his expedition spent some[3] weeks along the coast. His austere Calvinism prevented Tasman from observing in any special manner the festival of Christmas, but as a Rhinelander he could not forget the "Three Kings of Cologne," whom legend had associated with the Magi of the Gospels. On Twelfth Night his ships were abreast of the small island which lies at the extreme north of the country, and "this island," wrote Tasman, "we named Drie Koningen Eyland (i.e., Three Kings Island), on account of this being the day of Epiphany."

Here then, at last, was a spot of New Zealand soil to which a name was attached which told of something Christian. The name stood alone as yet, but it contained a promise of the time when the Gentile tribes should come to Christ's light, and their kings to the brightness of His rising.

For nearly a century and a half the startled Maoris treasured the memory of the white-winged ships of the Hollander, before they saw any others like them. At length, in 1769, there appeared the expedition of Captain Cook. England had now wrested from the Dutch the sovereignty of the seas, and Cook was looking for the "New Zealand" which appeared on the Dutch maps, but which no living European had ever seen. More tactful and more fortunate than his forerunner, Cook was able to open a communication with the islanders and to conciliate their good-will.

Not yet, however, was England prepared to follow up the lead thus given. Not until her defeat by the American colonists, which closed the "New World" against her convicts, did Britain's statesmen bethink them of the still newer world which had been made known by the explorer. In 1787 an expedition went forth from England—not indeed to New Zealand, but—to South-east Australia, where a penal colony was established at Port Jackson. A strange and repulsive spectacle the enterprise presented, yet these convict ships were the instruments for carrying on the message which had been sent out from Jerusalem by apostolic[4] bearers. "Did God send an army of pious Christians to prepare His way in the wilderness?" asked Samuel Marsden, the second chaplain of this colony. "Did He establish a colony in New South Wales for the advancement of His glory and the salvation of the heathen nations in those distant parts of the globe by men of character and principle? On the contrary, He takes men from the dregs of society, the sweepings of gaols, hulks, and prisons. Men who had forfeited their lives to the laws of their country, He gives them their lives for a prey, and sends them forth to make a way for His chosen, for them that should bring glad tidings of good things. How unsearchable are His judgments, and His ways past finding out!"

Advance and retreat; check and recovery; failure of methods which seemed direct and divine; compensating success through agencies that looked hostile; the winds of the Spirit blowing where they list—none able to tell beforehand whence they are coming or whither they will go: such are the outstanding features of the long journey of the Christian faith across the globe; such will be found to mark its history when established in this land.

THE PREPARATION.

(1805-1813).

Every noble work is at first "impossible." In very truth: for every noble work the possibilities will lie diffused through immensity, inarticulate, undiscoverable except to faith.

—Carlyle.

For the seed-plot of Christianity and of civilisation in New Zealand we must look away from the present centres of population to the beautiful harbours which cluster round the extreme north of the country. Chief among these stands the Bay of Islands. This noble sheet of water, with its hundred islands, its far-reaching inlets, its wooded coves and sheltered beaches, was for more than a quarter of a century the focus of whatever intellectual or spiritual light New Zealand enjoyed. Here the Gospel of Christ was first proclaimed, and the first Mission stations were established. Here were founded the first schools, the first printing press, the first theological college, the first library. Here the first bishop fixed his headquarters, and here he convened the first synod. Here was signed the Treaty of Waitangi, by which the islands passed under British rule, and here was the temporary capital of the first governor. Here, too, was the theatre of the first war between Maoris and white men; here stood the flagstaff which Heke cut down; from these hills on the west the missionaries beheld the burning of Kororareka, whose smoke went up "like the smoke of a furnace."

At the opening of the nineteenth century this important locality was occupied by the warlike and enterprising tribe of the Ngapuhi. The soil was generally infertile, but the waters teemed with fish, while[8] the high clay cliffs and the narrow promontories lent themselves readily to the Maori system of fortification. The safe anchorage which the Bay afforded early drew to it the whaling ships of Europe, especially as the harbour was accessible from the ocean in all weathers. The Ngapuhi eagerly welcomed these new comers, and prepared to take full advantage of whatever benefits the outside world might offer.

Among the various hapus of this tribe stands out pre-eminent that which owed allegiance to the chief Te Pahi. This warrior had fortified an island close to Te Puna on the north side of the bay. In readiness to receive new ideas, and in the power to assimilate them, he and his kinsmen, Ruatara and Hongi, were striking examples of the height to which the Maori race could attain. Hardly had the century dawned which was to bring New Zealand within the circle of the Christian world, when word came to Te Pahi of the wonders to be seen at Norfolk Island, and of the friendly nature of its governor, Captain King. To test for himself the truth of these tidings, the chief, with his four sons, set forth (about 1803) across the sea to the great convict station. The friendly governor had left the island, but Te Pahi followed him on to New South Wales, little thinking of the mighty consequences which would result from his journey. Everyone at Port Jackson was struck with the handsome presence and dignified manners of the New Zealander. He was received by the governor into his house at Parramatta; he went regularly to church, where he behaved "with great decorum;" and loved nothing so much as to talk to the chaplain about the white man's God. His enquiries met with ready sympathy, for the chaplain was no other than the Reverend Samuel Marsden.

This remarkable man had hitherto found little to encourage him in his labours, but his light shone all the more brightly from its contrast with the surrounding darkness. Selected while still a student at Cambridge,[9] by no less a person than the philanthropist Wilberforce, for this difficult position, Marsden had brought to his work a heart full of evangelical fervour, a strong Yorkshire brain, and "the clearest head in Australia." During the eleven years which had passed since his arrival, he had been fighting a courageous fight against vice in high places and in low, but nothing had daunted his spirit nor soured his temper. His large heart had a place for all classes and for all races. When he met Te Pahi his sympathies were at once excited. Like Gregory in the marketplace at Rome, he had found a people who must be brought into the fold of Christ. Years were indeed to pass before active steps could be taken, but the new-born project never died within him. Amidst all the difficulties of his lot the thought of the New Zealanders was ever in his mind, and their evangelisation the constant subject of his prayers. Many years afterwards, on one of his journeys through their country, Marsden remarked to those about him, "Te Pahi just planted the acorn, but died before the sturdy oak appeared above the surface of the ground."

What this Maori pioneer had done may seem little enough, but that little cost him his life. The presents which he carried home, and the house built for him by Governor King upon his island, excited the envy of his neighbours, who eventually found a way to compass his destruction by means of the Europeans themselves. Te Pahi happened to be at Whangaroa when the Boyd was captured in 1809, and he did his best to save some of the crew from the terrible slaughter that followed. But his presence at the scene was enough to give a handle to his enemies. They accused him to the whalers of participation in the outrage, and these stormed the island pa by night and slaughtered the unsuspecting inhabitants. Te Pahi himself escaped with a wound, but he was soon afterwards killed by the real authors of the Boyd massacre for his known sympathy with the Europeans.[10]

It is a piteous story, and one that reflects only too faithfully the temper of the times. Hardly less piteous is the history of his young kinsman, Ruatara, the inheritor of his influence over the tribe. This notable man, while still young, determined that he too would see the world, and in the year 1805 engaged himself as a common sailor on board a whaling vessel. The roving life suited his adventurous temperament, and in spite of many hardships and much foul play he served in one ship after another. His duties carried him more than once to Port Jackson, where he, too, met Samuel Marsden and talked about the projected mission to his race. After many vicissitudes he at length nearly attained the object of his desire, for his ship reached the Thames and cast anchor below London Bridge. Now he would see the king, and would learn the secret of England's power.

But the London of those days was a cruel place. There were no kindly chaplains, no sailors' institutes nor waterside missions for the care of those who thronged its waterways. There was little care for the poor anywhere, and little religion among employers or employed. The close of the eighteenth century was indeed the low-water mark of English religion and morality. But by 1809—the year of Ruatara's arrival—an improvement had begun. What is known as the Evangelical movement was changing the tone of life and thought. The excesses of the French Revolution had led to a reaction among the upper classes and made them think more seriously. This revival did not at once lead to much thought for the poor at home; it reached out rather towards the heathen abroad. The "Romantic" school was in the ascendant, and a black skin under a palm-tree formed a picture which appealed to the awakened conscience. Much of the fervour of the time had its being outside the historic Church of England, but in the last year of the old century a few earnest clergy and laity—without much encouragement from the bishops or[11] others in high places—had formed what was afterwards known as "The Church Missionary Society." This Society had the New Zealanders under its consideration at the very time when Ruatara was being starved and beaten in the docks of London itself.

What had drawn its attention to a place so distant? It was the presence of Marsden in England. He had come thither in 1807 on business of grave and various import. The Government of the day had recognised the value of his practical knowledge, and had sought his advice on many matters concerning the welfare of Australia. But he did not forget New Zealand, and it was to the young Church Missionary Society that he betook himself. So great, in fact, and so various were the plans which Marsden entertained for the welfare of the many races in which he was interested, that the grandiloquent words of his biographer seem not too strong: "As the obscure chaplain from Botany Bay paced the Strand, from the Colonial Office at Whitehall to the chambers in the city where a few pious men were laying plans for Christian missions in the southern hemisphere, he was in fact charged with projects upon which not only the civilisation, but the eternal welfare, of future nations were suspended."

Marsden's proposals were the outcome of his own original mind. He appealed for a mission to the Maoris, but he wished it to be an industrial mission. He proposed that artisans should be sent out who should prepare the way for ordained clergy. A carpenter, a smith, and a twine-spinner should form the missionary staff. They must be men of sound piety and lively interest in the spiritual welfare of the heathen; but their religious lessons should be given whilst they were instructing the Maoris in the building of a house, the forging of a bolt, or the spinning of their native flax.

Such a scheme was only half relished by the Committee of the Society. These excellent men had hardly[12] yet realised that the dark-skinned savage was a real human being. They had begun by picturing the whole population of a heathen island as rushing gladly to meet the missionary, receiving his message with unquestioning belief, and crying out in an agony of terror, "What must we do to be saved?" Now that apparent failure had met their efforts in different parts of the world, they were inclined to go to the opposite extreme and to despair of the heathen ever accepting Christianity at all. Marsden's unromantic proposals jarred upon their old ideas, but in their perplexity they could not help feeling that at least here was a man who had had experience of real, not of imaginary, heathen; a man who did not despair, and who had a definite and carefully prepared plan. Gradually they yielded to his influence, and, especially as clerical missionaries were not to be found, they agreed to seek for the artisans.

Even these were hard enough to find. There were as yet no colleges for the training of young aspirants; outside the newly-formed societies there was little interest in the welfare of heathen people; the best that could be done was to seek for men who had the love of God and men in their hearts, and should seem to possess the qualities of patience, perseverance, and tact. Through the good offices of friendly clergy two young men were found. From distant Carlisle came the carpenter, William Hall; the Midlands supplied a shoemaker, John King. These were given further technical training—Hall in shipbuilding, King in rope-making. By the month of August, 1809, they were ready for their enterprise. Their earthly prospects were not tempting. They were to receive £20 each per annum until they should be able to grow corn enough for their own support. To meet this and all other expenses the Committee advanced Marsden the sum of £100. With this small sum and his two plain and poorly paid mechanics, this undaunted man started out from his native land to undertake the evangelisation of a country as large as England itself.[13]

But a mightier coadjutor was at hand. Many prayers were offered as the Ann was about to sail, and it must surely have been in answer to these that, when the vessel with her freight of convicts had already reached Gravesend, there appeared a boat in which were a half-naked Maori together with a seafaring Englishman. These were Ruatara and his employer who had robbed him of his wages and had now no further use for him. "Will you take him back to Australia?" said the heartless master. "Not unless you find him some clothes," said the captain of the Ann. The clothes were procured, and the Maori was allowed to go below. There he lay sick in body and mind. He had tried to play the part of the Russian Peter, but he was bringing back nothing for the benefit of his country. What was left but to die?

When the ship reached Portsmouth, Marsden came on board, and on August 25th she finally started on her six months' voyage. Not for some days did the chaplain know of the Maori's presence, but, as the ship entered warmer latitudes, Marsden observed on the forecastle among the sailors a man whose dark skin and forlorn condition appealed strongly to his sympathy. Ruatara was wrapped in an old great coat, racked with a violent cough, and was bleeding from the lungs. Though young, he seemed to have but a few days to live. Marsden at once went to him and found in the miserable stranger the nephew of his old acquaintance Te Pahi. Kindness and attention soon had their effect; the health of the invalid rapidly improved; the remembrance of past injuries melted away before the sunshine of Christian love; and, before the ship reached Australia, Ruatara was once again a man, and now almost a Christian.

This meeting was momentous in its results. "Mr. Marsden and Ruatara," as Carleton says, "were each necessary to the other; each furnished means without which the labour of his associate must have been thrown away. But for the determined support which[14] Ruatara as a high chief was able to afford, Marsden could never have gained a footing in the land; and without the sustained labour of the civilised European, the work of the Maori innovator, too much in advance of its time, would have withered like Jonah's gourd, and have come to an end with the premature decease of Ruatara."

For a few days after the arrival of the Ann at Port Jackson, it seemed as though Marsden's project were going to be helped by another unexpected agency. The Sydney merchants had resolved to form a trading settlement in New Zealand; the settlers were chosen, and the ship was ready to sail. But at the last moment news came from the land of their destination of an event already referred to—news which for many a long day checked every thought of adventure thither, and had the effect of throwing New Zealand back into its old position of isolation and aloofness. The ship Boyd, which had sailed from Sydney not many months previously, had been surprised by the Maoris in the harbour of Whangaroa, and with four exceptions all its white crew, to the number of about 70 persons, had been killed and cooked and eaten.

The report of this awful tragedy—the most horrible that has ever been enacted on our shores, at least with white folk for the victims—threw the people of New South Wales into a fever heat of indignation. This condition was further intensified when the intelligence arrived that among the murderers had been seen the "worthy and respectable" Te Pahi, who had been an honoured guest at the Governor's table. No Maori dared now to be seen in the streets of Sydney, and it required all Marsden's influence to protect Ruatara, who was known to be Te Pahi's relative. His protector kept him for six months quietly working with a few other Maoris on his farm at Parramatta, and the expedition to New Zealand was for the time abandoned.[15]

This sudden interruption of his favourite project was a severe trial to Marsden's hopeful temperament. But he never lost heart. "We have not heard the natives' side of the case," he said. As for Te Pahi, he refused, and rightly refused, to believe in his guilt. When the passion for vengeance had somewhat calmed, he found opportunity to ship Ruatara and some other Maoris on board a whaling craft which was on her way to fish on the New Zealand shores, and he gave them seed wheat and agricultural tools.

Even now Ruatara's adventures were not ended. In the following year he was again at Port Jackson with another tale of woe. He had never reached his home, though he had actually been within sight of it. Instead of being allowed to land there, he had been carried away by the unprincipled captain, robbed again of his wages, and then marooned on Norfolk Island. Again he found a friend in Marsden. Once more he was despatched to the Bay of Islands with wheat and hoes and spades. This time he arrived safely, and Marsden had the satisfaction of feeling that however long the time of waiting might still be, there was a quiet but effective influence at work in New Zealand on behalf of himself and of the message which he still hoped to proclaim.

At any time, in fact, during those years of suspense, Marsden was willing to venture forth among the cannibals, but he was forbidden by Governor Macquarie. That all-powerful functionary was determined that such a valuable life should not be thrown away on what appeared to be a quixotic scheme. But the chaplain was not to be altogether balked. He received into his parsonage whatever Maoris of good standing he could find; showed them the varied activities of his model farm; and explained to them the principles of the laws which he was called to administer from the magisterial bench. In this way several young chiefs acquired a knowledge of the elements of civilisation, and were disposed to welcome Christianity.[16]

But it was not only upon his Maori visitors that Marsden's influence was at work. The two artisans whom he kept near himself must have learned during these years that absolute loyalty upon which so much was to depend thereafter. They laboured diligently at their trades, and each was soon earning as much as £400 a year; but the zeal and unselfishness of the chaplain kept them true to their original purpose, and prevented them from yielding to the fascinations of Mammon.

Thus the years passed—not uselessly nor unhopefully. One bit of intelligence seemed like an augury of good for the future: Ruatara's wheat had been sown and was growing well!

THE ENTERPRISE.

(1813-1815).

—R. Browning.

The fourth year of waiting brought signs of approaching change. The Society at home, encouraged by Marsden's hopeful letters, sent out another catechist, Thomas Kendall. They were less sure of him than of King and Hall, but he pleaded earnestly to be sent, and, being a schoolmaster, he was a man of more education than the two others. During the last days of the year 1813, Marsden organised an influential meeting in Sydney, and succeeded in carrying fifteen resolutions in favour of a forward movement. Armed with these he again approached the Governor, who reluctantly consented to allow the missionaries to make a trial visit to New Zealand if a captain could be found sufficiently courageous to take them. The shipping problem was indeed a great difficulty, but Marsden at last overcame it by buying a vessel with money which he raised on the security of his farm. The Active was a brig of 110 tons, and claims the honour of being the first missionary craft of modern times.

Hall and Kendall were the men chosen for the preliminary visit. They were instructed to open up communication with Ruatara, and, if possible, to bring him back with them to Sydney. With good supply of articles for trade and for presents they set sail on the 4th of March, and arrived safely at the Bay of[18] Islands. Here they were welcomed by the faithful Ruatara, to whom they presented a small hand-mill as a gift from his friend at Parramatta. This machine played its part in preparing the way for the mission. Ruatara's wheat had long been harvested, but his neighbours were still sceptical as to the possibility of converting it into bread. While this doubt remained, Ruatara's words carried little weight. In vain did the poor Maori try one expedient after another; in vain did he send appeals to Marsden. His own efforts always failed; his benefactor's gifts never reached him. But now the situation was changed. The mill was at once charged with New Zealand grown wheat; eager eyes watched the mealy stream issuing from beneath; a cake was quickly made and cooked; and all incredulity was at an end. Several chiefs volunteered to accompany Ruatara to Sydney, and the Active reached that port on August 22nd, after a thoroughly successful voyage.

The Governor could no longer withhold his consent to the enterprise, and Marsden was granted leave of absence for four months from his duties at Parramatta.

Before starting for New Zealand he spent three busy months in preparation. The mission was to take the form of a "settlement," and the missionaries were to be "settlers" as well as catechists. The Active was loaded with all that was necessary for this object, and in the words of Mr. Nicholas, who accompanied the expedition as a friend, it "bore a perfect resemblance to Noah's Ark." The resemblance was indeed a close one. The vessel carried horses and cattle, sheep and pigs, goats and poultry; Maori chiefs and convict servants; the three missionaries with their wives and children; while the place of the patriarch was filled by Samuel Marsden himself, who, like Noah, had been "warned of God of things not seen as yet," had laboured on amidst the incredulity of his neighbours, and now bore with him the seeds of a new world.[19] Stormy weather delayed the progress of the brig and brought much misery to those on board. Three weeks passed before the New Zealand coast was sighted, but Saturday, December 17th, brought the travellers opposite to Tasman's "Three Kings," and on the following Tuesday they were off the harbour of Whangaroa, where the remains of the Boyd still lay. The brig did not enter this dreaded haven, but, seeing an armed force on the coast to the south, Marsden resolved to land and to attempt to conciliate these hostile people. Ruatara and Hongi acted as intermediaries, and friendly relations were soon established between the missionaries and the cannibals. Marsden and his companion even spent the night with the savages, sleeping among them without fear under the starlit sky.

Two days later the expedition reached its destination, and the Active cast anchor off the Bay of Rangihoua. From her deck the mission families could now gaze upon the scene of their future home. The bracken and manuka with which the farther slopes were clad might remind them of the fern and heather of old England, but their gaze would be chiefly attracted to an isolated hill of no great height which rose steeply from the sea on the left side of the little bay. To this hill had come the remnant of Te Pahi's people after the slaughter on the island, and it was now crowned with a strongly fortified pa. Ruatara's residence was on the highest point; around it were crowded about fifty other dwellings; outside the mighty palisade neat plantations of potatoes and kumaras seemed to hang down the steep declivity; an outer rampart encircled the whole. At sight of the vessel the inhabitants rushed down to the beach with cries of welcome, and greeted Marsden, on his landing, with affectionate regard. He seemed to be no stranger among them, for his name and his fame were familiar to all. The horses and cows caused a temporary panic among people who had never seen animals[20] so large before, but fear soon gave way to admiration and a general sense of excited expectancy.

Ruatara's home-coming was not free from pain to himself. Misconduct had occurred in his household during his absence, and the next morning was occupied with a trial for adultery. The case was referred to Marsden, who advised the application of the lash to the male offender. Thirty strokes were given, and the honour of the chief was vindicated. Next morning (Saturday) he treated his guests to a scene of mimic warfare. Led by himself and Korokoro, four hundred warriors in all the pomp of paint and feathers rehearsed the details of a naval engagement. The brandished spears and blood-curdling yells brought forcibly to the imagination of the white men the perils which might be in store for them, but as the day wore on the arts of war were succeeded by preparations for the preaching of the Gospel of peace. Ruatara caused about half an acre of land by the Oihi beach to be fenced in; within this area he improvised some rough seats with planks and an upturned boat; in a convenient spot he erected a reading desk and pulpit which he draped with black native cloth, and with white duck which he had brought from Sydney; on the top of the hill he reared a flagstaff; and thus prepared his church for the coming festival.

The account of that Christmas Day of 1814 must be given in Marsden's own words, which have already attained a classical celebrity:

"On Sunday morning when I was upon deck, I saw the English flag flying, which was a pleasing sight in New Zealand. I considered it as the signal and the dawn of civilisation, liberty, and religion in a benighted land. I never viewed the British colours with more gratification, and flattered myself they would never be removed till the natives of that island enjoyed all the happiness of British subjects.

"About ten o'clock we prepared to go ashore, to publish for the first time the glad tidings of the Gospel.[21] I was under no apprehensions for the safety of the vessel, and therefore ordered all on board to go on shore to attend divine service, except the master and one man. When we landed we found Korokoro, Ruatara, and Hongi dressed in regimentals which Governor Macquarie had given them, with their men drawn up ready to be marched into the enclosure to attend divine service. They had swords by their sides, and switches in their hands. We entered the enclosure, and were placed on the seats on each side of the pulpit. Korokoro marched his men and placed them on my right hand, in the rear of the Europeans; and Ruatara placed his men on the left. The inhabitants of the town, with the women and children and a number of other chiefs, formed a circle round the whole. A very solemn silence prevailed: the sight was truly impressive. I rose up and began the service with singing the Old Hundredth Psalm, and felt my very soul melt within me when I viewed my congregation and considered the state they were in. After reading the service, during which the natives stood up and sat down at the signals given by Korokoro's switch, which was regulated by the movements of the Europeans, it being Christmas Day, I preached from the second chapter of St. Luke's Gospel, and tenth verse, 'Behold, I bring you glad tidings of great joy,' etc. The natives told Ruatara that they could not understand what I meant. He replied that they were not to mind that now, for they would understand by and by, and that he would explain my meaning as far as he could. When I had done preaching, he informed them what I had been talking about. Ruatara was very much pleased that he had been able to make all necessary preparations for the performance of divine worship in so short a time, and we felt much obliged to him for his attention. He was extremely anxious to convince us that he would do everything in his power, and that the good of his country was his principal consideration. In this manner the Gospel has been[22] introduced into New Zealand, and I fervently pray that the glory of it may never depart from its inhabitants till time shall be no more."

For the moment it seemed as though Marsden's congregation had not been very deeply impressed. Three or four hundred natives (says Nicholas) began a furious war-dance, apparently to express gratitude and appreciation. With conflicting feelings the missionaries at length withdrew to their ship, and there, in the evening, Marsden "administered the Holy Sacrament in remembrance of our Saviour's birth and what He had done and suffered for us."

What would be the reflections of this far-sighted man as he lay in his berth that summer night? Fresh from the scene of the Boyd tragedy, and in the very presence of Te Pahi's desolated citadel, he had ventured to take up the angels' song of peace on earth, goodwill to men. He might perhaps have drawn some hope from the peace which the world at large was then enjoying after years of desperate strife. Napoleon was a prisoner in Elba, and the dogs of war were chained. But a few more months would bring another outburst and the awful carnage of Waterloo. So would it be in New Zealand also, and its Napoleon was a small quiet man who stood listening thoughtfully on that Christmas Day to Marsden's message of peace.

The planting of the settlement occupied the next fortnight. By the second Sunday in the new year a large building was sufficiently advanced to serve as a church. In a few days more this was divided into separate apartments for the residence of the mission families.

Marsden was now at liberty to think of certain subordinate objects of his visit—exploration and trade. In obedience to the Governor's instructions, he took his brig on an exploring tour down the Hauraki Gulf. On his return he had the vessel loaded with timber and flax for conveyance to New South Wales.[23] The expedition had, of course, been an expensive matter, and it must be remembered that he had strained his own private resources to provide means for its equipment. He had all along looked to recoup himself for some of his outlay by a trade in logs and spars. By the middle of February the vessel had received her cargo, the missionaries were settling down in their new home, and his leave of absence was nearing its expiration. But before he set sail two duties claimed his attention. A child had been born to Mr. and Mrs. King, and Marsden determined to make the first administration of Holy Baptism in this heathen land as impressive as possible. The infant was brought out into the open air. Many of the Maoris as well as the white folk stood around while the little one was solemnly admitted into the congregation of Christ's flock.

The other duty was less pleasant, and called for all the missionary's skill and resource. Poor Ruatara had fallen ill in the hour of his triumph—a victim, it would seem, to his admiration for the white man's ways. At the service on Sunday, February 12th, he had been present in European clothes, which had set off to advantage his manly form and European-like features. The day was rainy, and probably he had gone home in his wet clothes and thus contracted pneumonia. On the next day he was suffering from a chill and fever which defied the kindly attentions of Nicholas, who visited him daily until the tohunga forbad his admission. When Marsden returned from his trading enterprise he could only force an entrance by threatening to bombard the town with the ship's guns. The invalid seemed grateful for his visit and rallied for a little time, but as soon as Marsden sailed for Australia he grew rapidly worse. On the third day he was carried from his home and deposited on the top of a bare hill to await his end. Ruatara has been often compared with the Russian Peter, and like him he had purposed to build a new town in which he could[24] carry out the ideas he had gained abroad. It was to the site of this projected metropolis that he was now borne, and it was there that, after death, his body was laid on a stage erected for the purpose. To complete the tragedy the same stage received the remains of his favourite wife, who hung herself out of grief at her loss.

In spite of this noble Maori's enlightened efforts for the civilisation of his countrymen, his mind seems to have been not wholly without misgiving as to the possible consequences of his policy. He could not altogether throw off the suggestions of the reactionary party, that the coming of the white man would eventually lead to the slavery and dispossession of the Maori. Could he look down from his lofty eminence now that a century has passed, what would be his thoughts? He would see his countrymen still residing on their own lands, their children carefully taught, their houses fitted with mechanical appliances which would have surprised even Marsden himself. But, on the other hand, the crowded pas and the vigorous life have passed away. Instead of the long canoe with its stalwart tatooed rowers, he would see perhaps a small motor-boat with one half-caste engineer. As for his "town of Rangihoo," he would see no trace of its existence. Maori dwellings, mission-station—all are gone. Nothing now remains to show that man has ever occupied the spot, save the rose-covered graves of one or two of the original "settlers," and the lofty stone cross which marks the place where Christ was first preached on New Zealand soil.

THE RECEPTION.

(1815-1822).

He that soweth discord among brethren.

—Proverbs.

The position of the missionaries when left alone at Rangihoua was not an easy one. Ruatara was dead, and there was no one to fill his place. His successor at Rangihoua, though friendly and genial, seems to have had but little influence. Korokoro cared for nothing but war. The real ruler was Ruatara's uncle, Hongi, who lived some miles away; and Hongi's character had yet to disclose itself. His behaviour was quiet and gentlemanly; he assured the missionaries of his protection, and he kept his word.

This protection, however, was subject to limitations. The settlers were naturally anxious to grow corn and vegetables, but the cold clay of Te Puna[1] was not a favourable soil. At the very beginning some of them had pleaded for a more fertile spot, but their sagacious leader had set his veto on the proposal. Not many months, however, after Marsden's departure, Kendall and Hall crossed the Bay to a sunny spot at the mouth of the Waitangi River. Here they bought 50 acres of fertile land, and thither Hall transferred his family. He soon saw around him a prolific growth of maize and vegetables, but just as he was congratulating himself on the wisdom of the move, a scene occurred which quickly altered his views. He was felled to the ground by a savage visitor who brandished an axe over his head, and he struggled to his feet only to behold his wife's countenance suffused with[26] blood from a smashing blow dealt her by another ruffian. His furniture and tools were carried off, and the poor missionary was glad to return to his colleagues, and to share the protection of the tapu which Ruatara had placed upon their settlement. Barren as Te Puna might be, it was a safe refuge, and so long as the missionaries stayed there they suffered nothing worse from the natives than a little pilfering and an occasional threat.

Their real troubles arose within their own circle. The settlement (including children) consisted of twenty-five people, and it was organised by Marsden on what may be called a communistic basis. His original plan had been for each settler to be allowed to trade with the Maoris on his own account, and for this purpose he had given them a stock of goods before leaving Sydney. This concession was intended to compensate those who, like King and Hall, had given up large incomes on leaving New South Wales. But a very short experience convinced Marsden that such traffic was open to grave objections. With characteristic promptitude he remodelled his scheme. Calling the settlers together, he told them that he could allow no private trade whatever. All traffic with the natives was to be carried on by the whole community, and the profits were to go towards defraying the expenses of the mission. Rations of food and other necessaries would be served out to the mission families, and each settler would receive a small percentage on whatever profit might accrue from the trading voyages of the brig.

These terms were not accepted without protest, but such was the weight of Marsden's authority that they were at length adopted by all. The scheme is interesting as foreshadowing the communism of Selwyn, and as being the earliest example of socialism in white New Zealand. But all such experiments need the constant presence of the inspiring mind, and this is just what the Te Puna community lacked. Marsden[27] did not return for more than four years, and in the meantime the settlers were left with no head whatever. Kendall was the cleverest of the group, and his ambitious spirit chafed at the restrictions imposed by his distant superior. He bore a commission of the Peace from the Governor of New South Wales, but his magisterial powers were mostly exercised on runaway sailors. In the mission his vote counted for no more than the vote of King or of Hall.

For a time, indeed, the experiment promised well. Hall spoke in later years of the "zeal, warmth, and sanguinity" with which they began their work. Kendall was successful with the school, in which a son of the noble Te Pahi acted as an assistant. One or two new settlers arrived from Australia, and glowing reports reached the Committee in London.

But evil was at work. As early as 1816, Kendall was sending to Marsden grave accusations against his colleagues. His letters were plausible and carried weight. Quarrels arose between him and Hall, who was so wearied with the "difficulties, discouragements, and insults" of his life that he wished to retire from his post. The rules of the community were not kept; the forbidden trade in firearms was not altogether avoided; the early fervour cooled, and little mission work was done.

Marsden grieved over this sad declension, yet could not at once apply a remedy. But in the early months of 1819 he had staying at his parsonage a singularly devoted Methodist preacher whose health had broken down. The chaplain suggested to his guest that he should try the effect of a voyage to New Zealand, and should investigate the state of the Mission there. Like a mediæval bishop, Marsden called in the assistance of a preaching order to infuse new life into his failing "seculars." The boldness of the plan was justified by the result. Mr. Leigh tactfully mediated between the separated brethren; by prayer and exhortation he rekindled their flagging zeal; and, Methodist[28]-like, he drew up a "plan" for their future operations. Soon after his departure King and Kendall went on a missionary tour to Hokianga on the western coast; Hall boated along the eastern coast, and preached as far as Whangaruru.

On the reception of Leigh's report, Marsden wrote a hopeful letter to London. "The place," he said, "will now be changed, and I trust we shall be able to lay down such rules and keep those who are employed in the work to their proper duty, so as to prevent the existence of any great differences among them." But he himself must initiate the changes, and by August of that same year (1819) he was again at the Bay of Islands. The meeting between himself and his catechists was marked by satisfaction on both sides. Kendall and King could report hopefully of their recent reception on the Hokianga River, which they were the first white men to see; Hall could relate how he had found and forgiven the people who had assaulted him at Waitangi, and how prosperous had been his tour until he reached a pa where the demand for iron was so great that the inhabitants stole the rudder-hangings of his boat, and left the poor missionary to find his way back as best he might in stormy weather to the shelter of Rangihoua. Marsden, on his part, could introduce a party of new helpers whom he had brought from Sydney—the Rev. John Butler and his wife, Francis Hall, a schoolmaster, and James Kemp, a smith.

New plans were at once formed for an extension of the work. An offer from Hongi of a site opposite to his own pa was accepted, and Marsden bought for four dozen axes a large piece of ground on the Kerikeri River, at the extreme north-west of the Bay. Here, in a sheltered vale and amid the sound of waterfalls, the new mission station was established. To it the fresh workers were assigned, Butler taking the chief place. Marsden himself pushed on across the island to the mouth of the Hokianga, and on his return[29] was surprised to see much of the new ground broken up, maize growing upon it, and vines in leaf.

Agriculture formed indeed an important feature in Marsden's plans for the mission. Seeing Hongi's blind wife working hard in a potato field, he was much affected by the miserable condition of many of the Maoris: "Their temporal situation must be improved by agriculture and the simple arts, in order to lay a permanent foundation for the introduction of Christianity." No spiritual results were as yet visible, but the chiefs attended Marsden's services and "behaved with great decorum." On the evening of September 5 he administered the Holy Communion to the settlers at Rangihoua. The service was held in a "shed," but "the solemnity of the occasion did not fail to excite in our breasts sensations and feelings corresponding with the peculiar situation in which we were. We had retrospect to the period when this holy ordinance was first instituted in Jerusalem in the presence of our Lord's disciples, and adverted to the peculiar circumstances under which it was now administered at the very ends of the earth."

In spite of the more promising appearances, however, Marsden seems to have realised that the missionaries must never be left so long again unvisited. In little more than three months he was again in New Zealand. There had been no difficulty about leave of absence this time, for the Admiralty needed kauri timber, and was glad to avail itself of his influence with the Maoris, and his knowledge of their ways. Marsden made the most of this unlooked for opportunity, and stayed nine months in the country. Of all his visits this was the longest and the most full of arduous effort, but its results were almost nullified by subsequent events. For it happened that on his arrival at Te Puna he found another enterprise in contemplation—one which would leave its mark upon history, and make the year memorable with an evil memory in the annals of New Zealand. This was the journey of[30] Kendall and Hongi to England. To understand the course of events and to appreciate its fell significance, it is necessary to keep in mind both what the Englishman was doing in New Zealand, and what the New Zealander was doing in England, during those same months of the year 1820. They will meet again next year in the parsonage of Parramatta, and then the results of their separate courses will begin to show themselves.

Hongi, though less definitely favourable to the mission than had been his nephew Ruatara, had hitherto always stood its friend. On Marsden's last visit he had indeed disbanded a large army at his request, and had seemed ready to relinquish his design of obtaining utu for the blood of several Ngapuhi chiefs who had been lately slain in battle. But the obtaining of utu was almost the main object of the heathen Maori. An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, blood for blood and death for death—this was his creed. If the blood of the murderer could not be had, then someone else's blood must be shed—someone, too, of equal rank and dignity. Hongi could not bring himself to accept the new message of peace, and his dissatisfaction was, it would seem, fanned by Kendall, who had ambitions of his own to serve. The other settlers, fearing to lose the protection of Hongi's restraining hand, did their utmost to dissuade him from taking the journey, but in vain. "I shall die," said the chief, "if I do not go."

Four days accordingly after Marsden's arrival the two set sail, having with them Waikato, another chief of the same tribe. The story of their visit to England is to a large extent familiar. They were received with great interest at the Missionary House, but the authorities treated Hongi as a heathen soul to be saved, and this was not what he wanted. Together they went to Cambridge, and here Kendall found scope for his abilities in furnishing to Professor Lee the materials for a scientific orthography of the Maori[31] language. He stayed on at Cambridge to prepare for Holy Orders, which the Society had agreed that he should receive. The chiefs meanwhile were entertained at the houses of nobles and prelates in different parts of the country, and at length were presented to King George IV. "How do you do, Mr. King George?" said the gentlemanly Hongi. "How do you do, Mr. King Hongi?" replied that easy monarch. This was the kind of reception that the Maori appreciated, and with the craft of his race he immediately seized his advantage. "You have ships and guns in plenty," said he to the King; "have you said that the New Zealanders are not to have any?" "Certainly not," replied His Majesty, and gave him a suit of armour from the Tower. Hongi's object was now attained. In spite of the missionaries he would have his guns, and he would be a king.

This determination was not shaken by the Christianity which came under the notice of the chiefs. At Norwich Cathedral they were given a seat in the episcopal pew close to the altar, on the occasion of Kendall's ordination. Hongi was chiefly impressed by the bishop's wig, which he thought must be emblematic of wisdom. His conclusion was that the Church was a very venerable institution and a necessary part of the English State, but it did not seem to follow very consistently the doctrines which he had heard proclaimed by the missionaries. Its official representatives seemed to be on good terms with the world: why should he be better than they? Like the king and great people of England he would uphold the Church and—go his own way.

Marsden meanwhile had been working hard in the opposite direction. On landing in February, 1820, he found that some of the missionaries had been using muskets and powder as articles of barter. It was very hard to avoid doing so, for the Maoris were no longer satisfied with hoes and axes. Guns were becoming necessary to self-defence in New Zealand, and guns[32] they would have. Marsden took a firm stand and informed the chiefs that if there were any more trading for firearms the mission would be withdrawn. The Maoris were far too keenly alive to the advantages of European settlement not to be alarmed at this threat. They agreed to deal with the settlers by means of peaceful articles of commerce.