Title: Bible Studies in the Life of Paul, Historical and Constructive

Author: Henry T. Sell

Release date: February 22, 2010 [eBook #31350]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

The book of Acts shows in a very graphic way the rapid growth and marvelous progress of Christianity in the midst of great opposition. We see in process of fulfillment the promise of Jesus Christ to his disciples that they should receive power after the Holy Ghost had come upon them and that they should be witnesses unto Him "both in Jerusalem and in all Judea and in Samaria and unto the uttermost part of the earth." Those were earnest times and full of stirring events, when men went forth to conquer a hostile world not with swords, but by the preaching of a gospel of peace and good will. As soon as this proclamation was made in Judea and Samaria a new instrument was chosen by Jesus Christ, in Paul, to carry His message to the uttermost part of the earth. He thus became at once the chief character in the larger work of planting and developing churches outside of Palestine. The study of Paul's life shows the difficulties encountered, the doctrines taught, and the organization perfected in the early churches. "We here watch the dawn of the gospel which the Savior preached as it broadens gradually into the boundless day."

Bible Studies in the Life of Paul is designed to follow the author's Bible Studies in the Life of Christ and to show the work of the Great Apostle in carrying the gospel to a Gentile world. The aim is to present the work of Paul in a constructive and historical way. While there has been a careful consideration, on the part of the author, of disputed questions, only conclusions upon which there is a general agreement amongst scholars, and which can be consistently held, are presented. The great main facts of Paul's life and work stand forth unchallenged and the emphasis is placed upon them. This book is divided into three parts, Paul's preparation for his work, his missionary journeys, and his writings. This is a text book, and, with the analysis of each study and questions, is prepared for the use of normal and advanced Sunday-school classes, teachers' meetings, schools, colleges, and private study. This is the sixth book of the kind which the author has prepared and sent forth. The large favor with which the other books have been received, and the desire, first of all, of making the life and work of Paul even better known, have been the motives which have led to its preparation.

CHICAGO, ILL.

HENRY T. SELL.

| STUDY | |

| I. | Early Life |

| II. | Conversion |

| III. | First Missionary Journey |

| IV. | Second Missionary Journey |

| V. | Third Missionary Journey |

| VI. | Jerusalem to Rome |

| VII. | The Future of Christ's Kingdom |

| VIII. | The Old Faiths and the New |

| IX. | The Supremacy of Christ |

| X. | Pastoral and Personal |

The Place of Paul—The Man. The Work of the Apostle. The Leading Thought.

Birth—Place. Time. Family.

Training—Home. Mental, Moral and Religious. Industrial.

The World as Paul Saw It—The World. Political. Religious. The Difficulties.

The Man, Paul, judged by the influence he has exerted in the world, is one of the greatest characters in all history. He is pre-eminent not only as a missionary, but as a marvelous thinker and writer. "He was a personality of vast power, force, and individuality." There are some men who seem to be born and prepared to do a large work for the world; Paul makes the impression upon those who carefully read the record of his life that he stands first in this class of men.

The Work of the Apostle.—As John the Baptist preceded Christ and prepared the way for His coming, so Paul succeeded Christ and went throughout the heathen world proclaiming that the Christ had come, and calling upon all men, Jews and Gentiles, to repent and accept Him as their Lord and Savior. So wide was his work as a missionary of the cross, and an interpreter of the Christ, that a certain class of critics have sought to make him the creator of Christianity, as we know it; a position which Paul would be the first to repudiate. He sought of himself, before he was apprehended by Christ on the way to Damascus, to drive Christianity from the face of the earth.

The Leading Thought in Paul's mind, after his conversion, was personal devotion to Christ; this was the mainspring of every act. He said, "I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless, I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me": (Gal. 2:20). "For me to live is Christ" (Phil. 1:21). In his letters to the churches which he founded, there are found no picturesque descriptions of cities or of scenery; his one thought is to make known the Christ. He says, writing to the Corinthian church, "and I, brethren, when I came to you, came not with excellency of speech or of wisdom, declaring unto you the testimony of God. For I determined not to know anything among you, save Jesus Christ and Him crucified" (1 Cor. 2:1, 2). In the evangelization of the heathen world, for which task he had been set apart by the Holy Spirit (Acts 13:2) and which he had accepted with all his heart, it is not only his leading, but his only thought to make known Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior.

To miss this supreme purpose of Paul in the study of his life is to miss its whole significance (Phil. 2:1-11; Col. 1:12-20).

Place.—The world is interested in the birthplaces of its great men. Some of these birthplaces are in doubt. There is no doubt about the place in which Paul was born. He says, in making a speech to the Jews, "I am verily a man which am a Jew, born in Tarsus, a city in Cilicia" (Acts 22:3). This city was the capital of Cilicia and was situated in the southeastern part of Asia Minor. It was but a few miles from the coast and was easily accessible from the Mediterranean sea by a navigable river. A large commerce was controlled by the merchants, on sea and on land. Tarsus, while one of three university centers of the period, ranking with Athens and Alexandria, was an exceedingly corrupt city. It was the chief seat of "a special Baal worship of an imposing but unspeakably degrading character."

Time.—The date of Paul's birth is nowhere recorded, but from certain dates given in the Acts, from which we reckon back, it is thought that he was born about the same time as Jesus Christ.

Family.—We are left, in this matter, without any uncertainty. Paul says, "I am a Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee" (Acts 23:6). I was "circumcised the eighth day, of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, an Hebrew of the Hebrews, as touching the law, a Pharisee" (Phil. 3:5). Paul's father and mother were Jews of the stricter sort. The expression which Paul uses, "An Hebrew of the Hebrews" is very significant. The Jews of the Dispersion were known at this time as Hebrews and Hellenists. The Hebrews clung to the Hebrew tongue and followed Hebrew customs. The Hellenists spoke Greek by preference and adopted, more or less, Greek views and civilization. Paul had a married sister who lived in Jerusalem (Acts 23:16) and relatives in Rome (Rom. 16:7, 11).

Home.—The instruction received in the home has often more influence and is more lasting than any other. Paul received the usual thorough training of the Jew boy accentuated in his case, in all probability, by the open iniquity which was daily practised in his native city. We never hear him expressing any regret that he received such thorough religious instruction at the hands of his parents.

Mental, Moral, and Religious.—Good teachers were employed to instruct the boy, who was afterwards to make such a mark in the world. After going through the school, under the care of the synagogue at Tarsus, he was sent to Jerusalem to complete his education. Paul, speaking in this chief Jewish city, says, I was "brought up in this city at the feet of Gamaliel, and taught according to the perfect manner of the law of the fathers" (Acts 22:3). It is very evident that He had a profound knowledge of the Scriptures from the large use he makes of them in his Epistles. He seems also to have been quite well acquainted with Greek philosophy and literature. He quotes from the Greek poets, Aratus, Epimenides, and Menander. No man ever studied men and the motives which actuate them more than he. His inward life was pure (Acts 23:1; 24:16). Paul differed from Christ in that he was a man who sought the cities and drew his illustrations from them, while Christ was much in the country and drew his illustrations from country life. But in this study of and work for the city Paul was but carrying out the commands of Christ.

Industrial.—It was required of every Jew father that his boy should learn some trade by which he might support himself should necessity require it. It was a common Jewish proverb that "he who taught his son no trade taught him to be a thief." Paul was taught the trade of tent making. "The hair of the Cicilian goats was used to make a cloth which was especially adapted for tents for travelers, merchants, and soldiers." He afterwards found this trade very useful in his missionary work (Acts 18:3; 20:34; 1 Cor. 4:12; 1 Thess. 2:9; 2 Thess. 3:8).

This World was very different from the world as we see it to-day. This makes it difficult for us to appreciate his work at its full value. Now, Christianity is the great religion of the world; then it was unknown, outside a very limited circle of believers. The state and society were organized upon a different basis and were in strong opposition to the new religion.

Political.—The world was under the dominion of the Romans. They, in conquering it, broke down the barriers that had separated tribe from tribe and nation from nation. Yet it was a comparatively small world for all interests centered about the Mediterranean Sea. Before the Romans the Greeks had been in possession of a part of this world and had permeated and penetrated the whole of it, with their art, language, and commerce. With the upheavals of war and the tribulations that had befallen the Jews, they were everywhere scattered abroad and had their synagogues in most of the cities.

Religious.—For the Romans, Greeks, and conquered nations and tribes, it was an age of scepticism. While the gods and goddesses in the great heathen temples still had their rites and ceremonies observed yet the people, to a large degree, had ceased to believe in them. The Roman writers of the period are agreed in the slackening of religious ties and of moral restraints. Yet it was the policy of the state to maintain the worship of the gods and goddesses. Any attack upon them or their worship was regarded as an offense against the state.

The Difficulties of the situation were threefold: (a) To seek to overturn the religion of the state constituted an offense which was punishable by stripes and imprisonment; (b) To rebuke men's sins and the evils of the times stirred up bitter opposition on their part; (c) To proclaim a crucified and risen Christ as the Messiah to the Jews, when they expected a great conquering hero, often excited and put them in a rage.

That Paul could preach Christ and establish churches, under all the opposition that he encountered, shows how fully and implicitly he believed in his Lord.

What impression has the man, Paul, made upon the world? What was his work as an apostle? What his leading thought? Where is the place of his birth? What can be said of his family? How was he educated and trained, in the home, in school, and for a trade? What was the political and religious condition of the world as Paul saw it? What were the three difficulties in the way of his work in preaching Christ?

Paul the Persecutor—Order of Events. The Inevitable Conflict. Cruelty of the Persecutor.

Conversion—Cause. Effects (physical, mental and spiritual, penalty, relief to the Christians, triumph of Christ, and estimates of the results).

Period of Waiting—Retirement of Paul. Reasons. The Gospel for the Gentiles. Paul Brought to Antioch.

Order of Events.—It seems to be quite evident, when Paul finished his studies in Jerusalem, that he left the city and engaged in work somewhere else, during the years when John the Baptist and Jesus were preaching and teaching. In all probability he did not return until after the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ.

Paul first appears in the narrative of the Acts, under the name of Saul, at the martyrdom of Stephen, where he takes charge of the clothes of the witnesses (Acts 7:58, 59).

From the Ascension of Christ to the martyrdom of Stephen is an important period in the history of the infant church. On and after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2) the apostles and followers of the risen Lord assumed a very bold attitude. They did not hesitate to speak openly in the temple (Acts 3:12-16) of the crime of putting "The Prince of Life" to death and asserted that He was risen from the dead. The priests and Sadducees strongly objected to this kind of preaching (Acts 4), laid hands upon the preachers, and put them in prison. When they were examined the next day before (Acts 4:5-13) the Jewish tribunal, the apostles spoke even more boldly of Jesus and his resurrection and refused to be silenced (Acts 4:13-20, 33). Again an attempt was made to stop the preaching of the apostles, but they refused to keep still (Acts 5:16-33). A remarkable prison deliverance by the "Angel of the Lord" (Acts 5:19, 20) gave them great courage in proclaiming "all the words of this life."

At this point Gamaliel (Acts 5:34-42) proposes in the Jewish council a new policy, which was to let the followers of Christ alone, arguing that then they would speedily give up their preaching. This policy was adopted (Acts 5:40). But with the election of Stephen as a deacon (Acts 6:1-8) the followers of Christ began to multiply with great rapidity and it was soon seen that "the let-alone policy" was a mistake (Acts 6:9-15). Persecution again breaks out which results in the death of Stephen (Acts 7), the bringing out of Saul as the arch persecutor, and the scattering of the church (Acts 8:1-4).

The Inevitable Conflict.—Had the early Christians been content to have proclaimed Jesus Christ to be but a great teacher and prophet, they would in all probability have become a Jewish sect and been speedily lost to sight. But extraordinary claims were put forth that Jesus Christ was the promised Messiah (Acts 2:25-40), the Son of God (Acts 3:26), the Forgiver of sins (Acts 2:38; 5:31), that He was risen from the dead (Acts 4:33), that obedience to Him was above that to the Jewish rulers (Acts 4:18-20), that the Jews had wickedly slain Christ (Acts 3:14, 15), and that salvation was only through Him (Acts 4:12). Further than this they wrought miracles in the name of Jesus Christ (Acts 3:2-8, 16; 2:43; 5:12).

It was very soon plainly seen that Christianity could keep no truce, and proposed to keep no truce, which called in question or denied the supremacy of Christ.

The Cruelty of the Persecutor.—To a man of Paul's temperament and zeal there could be no half way measures in a case like this. He could not be content to bide his time. Either the claims of Christ were true or false. If false, then they were doing harm and His doctrine and teaching must be eradicated at any cost. All the aggressive forces of the Jews found a champion in this Saul of Tarsus. Drastic measures were at once inaugurated. There was to be no more temporizing. The cruelty and thoroughness of the persecutor, in his work, are shown in his instituting a house to house canvass seeking for the Christians and sparing neither age nor sex (Acts 8:1, 3).

In the first persecutions the Jews had been content to arrest and imprison those who publicly preached Christ, but now the policy was changed and Christianity was to be exterminated root and branch. All believers in Christ were to be hunted out.

The character of Saul, the arch persecutor, is shown in the characterization of him by Luke, when he represented him as breathing out, "threatenings and slaughter against the disciples of the Lord" (Acts 9:1).

Cause.—The book of the Acts, opened at one place, shows a fierce hater and persecutor of the Christians (8:3), opened at another place it shows this same persecutor as an ardent and enthusiastic preacher of the faith in Jesus Christ (13:16-39) We seek for the cause of this remarkable change. Luke tells us that Saul was on his way to Damascus, seeking victims for his persecuting zeal, when Jesus suddenly appeared to him and Saul was changed from a persecutor to a believer in Christ (Acts 9:3-7). The account is very brief. For an event which has had such tremendous results, the narrator is very reticent; a light from heaven, a voice speaking, and a person declaring that He is Jesus. Paul gives us two accounts of his conversion and how it took place (Acts 22:6-15; 26:12-18). The men who were with Paul saw a light and heard a voice, but not what was said. It is impossible to describe or exaggerate what took place in Paul's mind in those brief moments while Jesus talked to him; but his beliefs, and his whole life plan were radically changed. It had been well if no explanation of this conversion had been attempted and the great fact had been left to stand as it does in the Acts. Attempts, however, have been made to minimize the power of this conversion and the marvelous and sudden change it wrought in the character and life of Paul. Some critics seeking a natural, rather than a supernatural, cause have attributed to Paul certain compunctions of conscience and misgivings about his persecution of the Christians, together with a hot day and a certain temperament, which led him to have a subjective experience, which he thought was real. But there is no recorded evidence forthcoming that Paul ever had any compunctions of conscience about persecuting the Christians. Paul was an honest man to the very core of his being; in the two accounts he gives us of this conversion, and in incidental references to it, he never even hints at any such state of mind. The expression used by Jesus, "It is hard for thee to kick against the pricks" (Acts 9-5), of which so much has been made, means no more than that Saul's opposition and hard work against the Christians (Acts 8:3; 9:1), would be of no avail. In doing what he did Paul thought he was doing God's service. Again the language which Paul uses and the references which he makes to this appearance of Christ forbid us to think that it was only a mere vision of Christ which he saw. "He ranks it as the last of the appearances of the risen Savior to His disciples and places it on the same level as the appearances to Peter, to James, to the eleven, and to the five hundred" (1 Cor. 15:1-8). In these appearances Jesus had eaten with his disciples and been touched by them (John 20:24-31; Luke 24:36-43), appearing as a real being, according to the narrative.

"It was the appearance to Paul of the risen Lord, which made him a Christian, gave him a gospel to preach, and sent him forth as the apostle of the Gentiles."

The time of Paul's conversion was about 36 A.D.

Effects.—There is no question as to the very marked results which followed the appearance of the risen Lord to Saul on the way to Damascus.

1. Physical. He was smitten with blindness (Acts 9:8), and was without food for three days (Acts 9:9). His sight was restored by Ananias at the command of the Lord (Acts 9:15-18).

2. Mental and spiritual. His whole outlook upon life and its significance was changed. He received baptism and was filled with the Holy Spirit (Acts 9:17). From being a persecutor he became an enthusiastic witness for Christ (Acts 9:20-22).

3. Penalty. The consequences of his former course of action were visited upon him; for the Jews sought to kill him and the disciples of Christ were at first afraid of him (Acts 9:23-26). But Barnabas vouched for his sincerity (Acts 9:27).

4. The relief to the Christians at Damascus, when Saul was converted, was very great. They had looked forward to his coming with dread.

5. The triumph of Christ. In Paul Christianity won its most efficient missionary and, next to Christ, its greatest thinker, preacher, and teacher.

6. The estimates of the results of this conversion of Saul cannot be too large; they are world wide.

Retirement of Paul.—From the conversion of Paul (Acts 9:3-7) to his call to the missionary work (Acts 13:2) is a period of about ten years. During this time we have only incidental notices of him and what he was doing. When we think of it there is nothing strange in this retirement. It is the divine method, as in the case of Moses, when a man is to do a very large work for God that he should be well prepared for it. The chief scripture notices of this period of retirement are found in Acts 9:19-30; Gal. 1:15-24; (Acts 11:25-30; 12:25). From these notices it is quite plain: (a) That Paul retired into Arabia. (b) That he preached in Damascus and Jerusalem, but was compelled to flee from both cities on account of the persecutions of the Jews, who sought his life. (c) That he went to Tarsus and "into the regions of Syria and Cilicia." (d) That he came to Antioch, where there was a great revival (Acts 11:25-30), at the solicitation of Barnabas. Luke in his account (Acts 9:19-30) does not mention the trip to Arabia spoken of by Paul in his epistle to the Galatians (1:15-24). It must be remembered however that each is writing from a different point of view. Luke is a historian recording only the most salient facts and passing over the mention of many events. We see this in the compression in eight and a half short chapters of the events of the three missionary journeys. Paul writing to the Galatians is anxious to establish the fact that he received his commission, as an apostle, not from man, but from Christ himself (Gal. 1:1); hence he enters more into details and we get from him the inside view. The accounts of Luke and Paul if read carefully, keeping in mind all the circumstances, are seen not to be in any way antagonistic, but to supplement each other.

Reasons.—Many reasons have been given for the retirement of Paul to Arabia, and what seems to be the period of comparative inactivity that followed it.

1. Fierce opposition on the part of the Jews whenever Paul attempted to preach, as in the cities of Damascus and Jerusalem.

2. A preparation of mind and heart for his great work. As a thinker he needed to look upon all sides of the gospel, which he was afterwards to preach so effectively to the Gentiles.

3. A careful rereading of the Old Testament. As a Jew he had read the Scriptures in one way, now he reread them seeing Christ there.

4. System of doctrine. He may at this time have wrought out that magnificent system of Christian doctrine which he afterwards presented to the churches in his Epistles.

The Gospel for the Gentiles.—While Paul was waiting for the call to his great missionary work there came a new crisis in the history of the early church, and a new era was inaugurated. In the tenth and eleventh chapters of the book of Acts Luke tells us of the conversion of the Gentile Cornelius, "a centurion of the band called the Italian band" (Acts 10:1-8), and of the instructions given to Peter to receive him (Acts 10:9-44).

Cornelius was the first Gentile convert and we note here the beginning of the preaching of the gospel to the Gentiles, which was to have such large results. "The day of Pentecost, the conversion of Saul of Tarsus, the call of Cornelius and the foundation of the Gentile church at Antioch are, if we are to pick and choose amid the events related by Luke, the turning points of the earliest ecclesiastical history." How great and epoch making was this new departure of preaching the gospel to the Gentiles, and receiving them into the church, is shown in the eleventh chapter of the Acts (11:1-18) where, when Peter goes up to Jerusalem, he is put on the defensive and compelled to explain why he received Cornelius into the church. When however the matter was fully explained the early disciples rejoiced over the fact that to the Gentiles was granted by God repentance unto life (Acts 11:18).

Paul Brought to Antioch by Barnabas, on account of the revival that had broken out in that city, is another step which he takes up to his work as the great missionary to the Gentiles (Acts 11:25-26). It was here that the disciples were first called Christians (Acts 11:26). It was from this city that Paul went forth on his missionary journeys and it was here that he returned (Acts 13:1-3; 14:26; 15:24-41; 18:22; 18:23).

"Antioch was the capital of the Greek kingdom of Syria, and afterwards the residence of the Roman governor of the province. It was made a free city by Pompey the Great, and contained an aqueduct, amphitheater, baths, and colonnades. It was situated on the Orontes about twenty miles from the mouth of the river. Its sea-port was Seleucia. It was intimately connected with apostolic Christianity. Here the first Gentile church was formed" (Acts 11:20, 21).

Give the order of events which led to the persecution in which Paul was so prominent. Why was the conflict between Christianity and Judaism inevitable? What can be said of the cruelty of Paul, the persecutor? Give the cause of Paul's conversion. What were some of the effects? What can be said of the period of waiting; the retirement of Paul? What are some of the probable reasons for this retirement? What can be said about the beginning of the gospel to the Gentiles? By whom was Paul brought to Antioch and for what purpose? In what relation does Antioch stand to the missionary journeys of Paul?

Introduction to the Three Missionary Journeys—The call. The Significance. Extent and Time. The Record. Other Long Journeys. Method of Work and Support. The Message.

The First Journey—Preparation. Companions. Paul Comes to the Front. Time and Extent. Rulers.

The Itinerary—Salamis. Paphos. Perga. Antioch. Iconium. Lystra and Derbe. The Return Journey.

The Jerusalem Council—One Problem of the Early Church. The Decision of the Council.

Before taking up the study of the first missionary journey, attention is called to certain points which should be considered in regard to all three of them (Acts 13:1-21:17).

We have now arrived at what we might call the watershed of the Acts of the Apostles. Hitherto we have had various scenes, characters, personages to consider. Henceforth Paul, his labors, his disputes, his speeches, occupy the entire field, and every other man who is introduced into the narrative plays a subordinate part.

Our attention is now turned from the Jewish world, considered so largely in the first twelve chapters of the Acts, to the heathen world and the struggle which Paul and his fellow laborers had with it, in bringing it to Christ.

The Call to this work was by the Holy Ghost in the city of Antioch (Acts 13:1-4). Luke says, "As they ministered to the Lord and fasted, the Holy Ghost said, separate me Barnabas and Saul for the work whereunto I have called them" (Acts 13:2, 4). Contrast this with the beginning of the work in Jerusalem which was also inaugurated by the Holy Ghost on the day of Pentecost (Acts 1:14; 2:1-4). This call was in accordance with what Jesus had told his disciples before His ascension (Acts 1:8).

The agency of the Holy Ghost in directing and promoting this missionary work is very manifest (Acts 13:2, 4, 9, 52; 15:8, 28; 16:6; 19:2, 6; 20:23, 28; 21:11; 28:25).

The Significance and importance of these journeys cannot be overestimated. It is probable, when the call came, that Paul had but little idea of their magnitude and that in the end they would result in changing not only the religion, but the philosophy and civilization of the world.

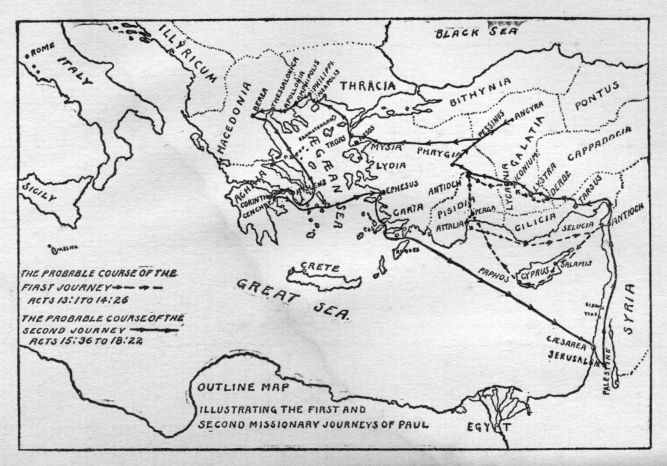

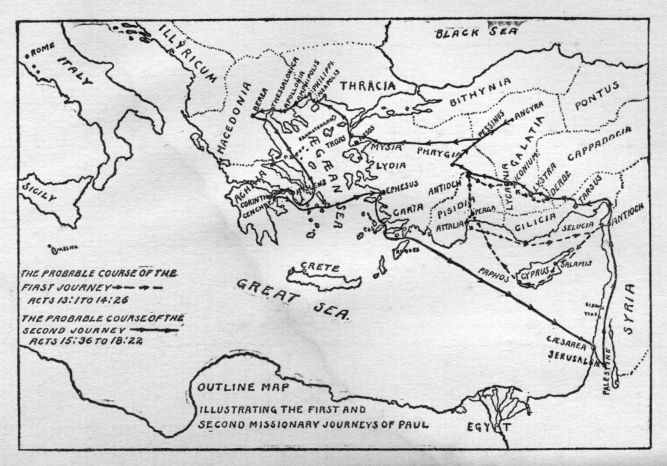

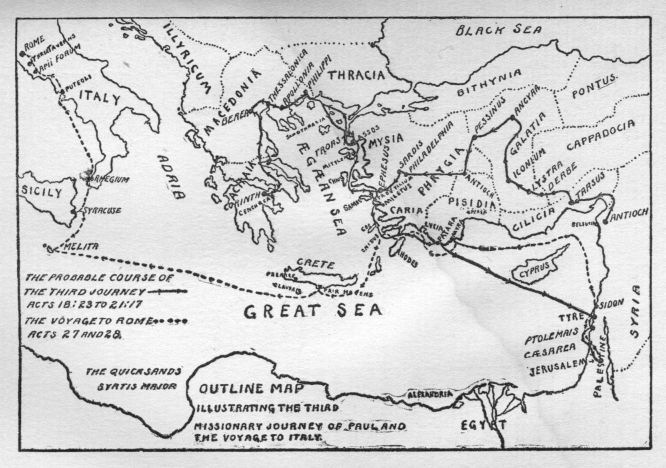

Extent and Time.—It is estimated that the first journey was 1,400 miles long, the second 3,200, and the third 3,500, making 8,100 miles traveled by Paul. The time occupied for the three journeys was about ten years.

The Record of the three missionary journeys, is briefly comprised in eight and a half chapters (Acts 13:1-21:17), and it does not profess to be a complete one. Only the most striking incidents and events, and probably not all of these, are given. There were side trips not recorded by Luke; Paul speaks of one to Illyricum (Rom. 15:19), and of others in which he underwent great perils (2 Cor. 11:24-27).

The purpose of Luke seems to be to show how, in accordance with the command and promise of Christ, the knowledge and power of the gospel was spread, beginning in Jerusalem, through Judea, and Samaria, throughout the heathen world (Acts 1:8); everything seems to be made to bend to this purpose. Certainly there could be no more graphic and concise account of these epoch making events than that given us by this wonderful narrator.

Other Long Journeys.—1. Paul's voyage to Rome as a prisoner. Luke gives a full account of this voyage, its many interesting incidents (Acts 27:1-28:16), and of the circumstances which led up to it (Acts 21:17-27:1).

2. There is every reason to believe that Paul was released at the end of his two years imprisonment in Rome (Acts 28:30) and that he made an Eastern journey as far as Colossæ and a Western journey as far as Spain.

NOTE.—These last journeys are considered in chapter ten.

Method of Work and Support.—Paul and his companion, or company, when they entered into a city would first seek for a lodging and then for work, going from one tent maker's door to another until finally a place was found. Then upon the following Sabbath they would seek the Jewish synagogue and after the reading of the Scriptures, when an opportunity was given, Paul would arise and begin to speak, (Acts 13:14-16) leading up through the Old Testament message (Acts 13:17-43) to the great topic of Jesus Christ as the promised Messiah and closing with an exhortation to believe on Him. Such a speech would naturally excite great interest coming from the lips of one, who by his speech and the handling of the Old Testament, would be recognized as a cultivated Jewish Rabbi. Paul would be asked to speak again the next Sabbath (Acts 13:44-52), the synagogue would be full of people and he would set forth Jesus Christ more plainly as the Savior both of Jew and Gentile. This would generally be a signal for the Jews to contradict and oppose Paul, but some Jews would believe with a number of Gentiles. This would be the starting point of the Christian church in that community. The Jews, however, who were untouched by what Paul preached, and who looked upon him as the destroyer of their religion, would raise a cry against him and seek to have him expelled from the city. This experience was frequently repeated. There were great difficulties also to be encountered when the heathen thought that their worship was in danger (Acts 19:20-30).

The Message which Paul bore to Jew and Gentile was the moving force of all his work. The starting point was the memorable day when Jesus Christ appeared to him on his way to Damascus. Paul believed that he received his commission as an apostle directly from Jesus Christ (Gal. 1:1-24). The four main positions of Paul, set forth so plainly in his Epistle to the Romans, are: (a) All are guilty before God (Jew and Gentile). (b) All need a Savior. (c) Christ died for all. (d) We are all (through faith) one body in Christ. Paul leaves us in no doubt as to how he regards Jesus Christ. He is to him the Son of God, through whom God created all things and who is the Divine Savior of man (Eph. 3:9-21; Phil. 2:9-11; Rom. 9:5). There is no doubt, no hesitation on Paul's part in delivering his message. He is a witness, testifying to the glory of his Divine Lord. He is a messenger who cannot alter or tamper with that which has been entrusted to him. To the rude inhabitants of the mountain regions of Asia Minor, to the philosophers in Athens, to the Roman governors in Cæsarea, to the dwellers in Corinth and in Rome the purport of the Message is always the same.

Preparation.—First, on the part of Paul. About ten years have passed since his conversion. During this time we have few notices of him, but he was undoubtedly making ready for this very important work of a missionary. Second, on the part of the church. The first step had already been taken, in the conversion of Cornelius, in the giving of the gospel to the Gentile world. Third, Paul was brought to Antioch by Barnabas to assist the church in the great revival which broke out in that second early center of Christian work and teaching (Acts 11:21-26). Fourth, the large success of the disciples who went throughout Judea and Samaria, preaching the gospel, after the death of Stephen (Acts 7:5-8:4; 11:19-21) made possible this new aggressive movement to the regions beyond. Fifth, the Christian prophets and teachers at Antioch "ministered to the Lord and fasted." They desired to know the will of the Lord and it was made known to them by the Holy Ghost. "And when they had fasted and prayed, and laid their hands on them, they sent them away." "So they being sent forth by the Holy Ghost, departed unto Seleucia (Acts 13:3, 4).

Companions of the Journey, Barnabas and Saul (Acts 13:2) and John Mark (Acts 13:5). Barnabas has been called the discoverer of Saul. He was probably a convert of the day of Pentecost. He was a land proprietor of the island of Cyprus and early showed his zeal for Christ by selling his land and devoting the proceeds to the cause in which he so heartily believed (Acts 4:36, 37). He early sought out and manifested, in a very practical way, his friendship for Paul (Acts 9:27; 11:22, 25, 30; 12:25). John Mark, who started on this journey with Barnabas and Saul, was a nephew of Barnabas (Acts 13:5, 13; 12:25; Col. 4:10).

Paul Comes to the Front when his company leave Paphos and ever after he has the first place (Acts 13: 13). Here also he is called Paul for the first time, a name which he retains.

Extent and Time—This was the shortest of the three journeys (about 1,400 miles). It extended over the island of Cyprus and a part of Asia Minor. In time it occupied about three years, 47-50 A.D.

Rulers—Claudius was the emperor of Rome, since 41 A.D. Herod Agrippa was king of Chalcis, Ananias was high priest in Jerusalem.

NOTE.—The cities, which Paul visited in this and the other journeys, should be located upon the map by the student. It will greatly increase the interest to consult some good Bible dictionary and get well acquainted also with the history of the places.

Salamis, on the island of Cyprus, was the first place reached, after sailing from Seleucia (Acts 13:4, 5) the sea-port of Antioch. It was the natural thing to go first to this island as it had been the home of Barnabas and many Jews had settled there; it was about eighty miles to the southwest of Seleucia.

Paphos.—After passing through the island from east to west the missionaries came to Paphos. This city was the seat of the worship of Venus, the goddess of love. This worship was carried on with the most degrading of immoralities.

The chief incidents in the ministry here were the smiting of the Jewish sorcerer, Elymas, with blindness for his persistent opposition and the conversion of the deputy of the country, Sergius Paulus (Acts 13:6-12). Saul is filled with an unusual power of the Spirit for his work in this city and takes the name of Paul. It is now no longer Barnabas and Saul, but Paul and Barnabas.

Perga in Pamphylia—(Acts 13:13, 14). The missionaries take ship from Paphos and sail in a north-easterly direction across the Mediterranean Sea to this city of Asia Minor. John Mark, doubtless appalled by the difficulties which had already been experienced and now that the journey seemed to promise still greater hardships, left the company and returned to Jerusalem.

Antioch in Pisidia (Acts 13:14-52) was about ninety miles directly north of Perga. It was a good-sized city with a large Jewish population. Luke's account of this visit is notable in that we have the chief points in Paul's speech in the synagogue set down. This address is worth study from the fact that it is the first sermon of Paul of which we have any record, and is probably the usual way in which he began his work in a great many Jewish synagogues. Paul is asked to speak to the assembled Jews. He begins upon the common ground of the history of Israel. He declares the promise of a Savior. This Savior is to be of the seed of David. Then Paul sets forth that Jesus is the promised Savior. He reminds them of the testimony of John and of those who had seen Jesus before and after His resurrection. He declares unto them the glad tidings of a Savior. He warns them of their peril in rejecting Jesus Christ. Paul is invited to speak upon the next Sabbath, but there is a division and those who oppose Paul try to drive him out of their city which they finally succeed in doing. But the Word has fallen into good soil and there is the beginning of a Christian church.

Iconium in Lycaonia (Acts 14:1-5) is over one hundred miles distant from Antioch. The missionaries were now in a country of a people with strange ways. They remained here for some time and their ministry was attested by "signs and wonders." But again some of the Jews opposed them and stirred up the multitude. A plan was made by the ringleaders of the opposition to stone them, but being made aware of it Paul and Barnabas "fled unto Derbe and Lystra." They had, however, the satisfaction of leaving behind "a great multitude of believing Jews and Greeks" (Acts 14:1).

Lystra and Derbe in Lycaonia (Acts 14:6-21).—"And there they preached the gospel." There is no mention of any Jewish synagogue at either of these cities. The inhabitants were worshippers of the heathen gods. The healing of a lame man at Lystra brought Paul and Barnabas directly into touch with the heathen priests and populace. When they saw this miracle of healing, they thought that the gods had come down to earth in the likeness of men. Barnabas was called Jupiter "and Paul Mercurius, because he was the chief speaker." When Paul and Barnabas sought to restrain the priests and people from doing sacrifice to them, it is interesting to note what words Paul uses in addressing them. As with the Jews he here seeks first of all a common ground. He says, "We are men of like passions with you and preach unto you that you should turn from these vanities unto the living God, which made heaven, and earth, and the sea, and all things that are therein; who in times past suffered all nations to walk in their own ways. Nevertheless He left not Himself without a witness, in that He did good, and gave us rain from heaven, and fruitful seasons, filling our hearts with food and gladness" (Acts 14:15-17). We find the same earnestness the same desire to preach the gospel to the heathen here as to the Jews elsewhere. But the Jews who had made trouble in Antioch and Iconium for the missionaries came to Lystra and, forming a plot against Paul, persuaded the people and stoned him so that he was drawn out of the city, they "supposing he had been dead." But he was not dead, he soon rose up and came back into the city and the next day departed with Barnabas to Derbe, where they preached the gospel and taught many.

The Return Journey is very briefly recorded (Acts 14:21-28). The missionaries returned through the same cities, Lystra, Iconium, Antioch, and so back to Perga. But from the last city they did not sail to the island of Cyprus, but took a different course, westerly along the coast to Attalia in Pamphylia and from thence they sailed to Antioch, the starting point of their trip. During this return journey they proved to their friends and enemies that, in departing from the cities where mobs threatened them, it was through no cowardice on their part, but for other reasons and for the purpose of preaching the gospel in the regions beyond. They "confirmed the souls of the disciples exhorting them to continue in the faith." They also further perfected the organization of the churches, ordaining elders in every church. They prayed with and for the disciples and commended them to the Lord.

When the missionaries at last entered the city of Antioch, "they rehearsed all that God had done with them, and how He had opened the door of faith unto the Gentiles." There must have been great rejoicing over this happy return of Paul and Barnabas.

One Problem of the Early Church was how to reconcile the commandments of Moses with the new law of liberty in Jesus Christ. Ought the Gentile Christians to observe the law of Moses? Ought they to become Jews before they became Christians? Were there to be two churches? One for Jewish and another for Gentile Christians? These questions are obsolete now, but then they were burning ones and hotly debated. Hence this Jerusalem Council, where the matter was debated and settled, was exceedingly important and fraught with great and grave consequences for the future welfare of the church. Because certain of the Jewish brethren came to Antioch and began to teach that it was necessary to salvation that a certain Jewish ordinance and the law of Moses be kept, it was determined to send Paul and Barnabas to Jerusalem.

A council of "the apostles and elders came together for to consider of this matter" (Acts 15:6). At this council in Jerusalem, Peter, Paul, Barnabas, and James were the chief speakers. All matters were carefully gone over. Of all the speeches made, Luke records only the two made by Peter (Acts 15:7-12) and James (Acts 15:13-2l), which must have embodied the sense of the meeting in that both spoke for liberty, from the Mosaic yoke, in Christ.

The Decision of the council was for the freedom of the Gentile Christians and that they should not be obliged to become Jews before they became Christians. Thus was one of the grave crises of the early church safely passed. Paul and Barnabas went back happy in that great victory for Gentile Christianity to their brethren at Antioch.

It should be borne in mind, however, that while the question of the relation of the Gentile Christians to the law of Moses was decided at this council, it was one which came up again and again to hamper and bother Paul in his missionary work.

What is to be considered in the introduction to the three missionary journeys? By whom was the call to this work? What is the significance of the journeys? The extent and time? What can be said of the record? Were there other long journeys by Paul? What was the method of work and support? What was the message? The first journey; what was the preparation for it? Who the companions? Time and extent? Rulers? Give some of the incidents that took place upon the Itinerary, at Salamis, Paphos, Perga, Antioch, Iconium, Lystra, and Derbe? What can be said of the return journey? Why was the Jerusalem Council necessary, and what was decided by it?

Second Missionary Journey—The Inception. The Companions. The Wide Scope. Value to the World. Time and Rulers. Epistles to the Churches.

The Itinerary—Through Asia Minor. In Europe (Philippi. Thessalonica. Berea. Athens. Corinth).

The Return Voyage—Ephesus. Cæsarea. Antioch.

The Inception—After the Jerusalem Council Paul returned to Antioch where he spent some time, "teaching and preaching the Word of the Lord with many others also." "And some days after Paul said unto Barnabas, Let us go again and visit our brethren in every city where we have preached the Word of the Lord, and see how they do" (Acts 15:35, 36). He felt that he must be advancing the work of Jesus Christ.

The Companions (Acts 15:37-40).—Barnabas proposed to take John Mark, his nephew, with them on this second journey. But Paul strenuously objected, basing his objection on the ground that this young man had deserted them (Acts 13:13) at a very important juncture in the first journey. We are told that the contention was very sharp between Barnabas and Paul over this matter. It was finally settled by Barnabas taking John Mark and sailing for the island of Cyprus and Paul choosing Silas for his companion. When Paul came to Derbe and Lystra Timotheus was invited to join him, which he did (Acts 16:1-4). Luke, the author of the Acts, goes with this company into Macedonia (Acts 16:10). We can trace Luke's connection with the missionaries by the "we" passages.

That Paul was afterwards reconciled to Barnabas and John Mark is shown by his kindly mention of them in his Epistles (1 Cor. 9:6; Col. 4:10; 2 Tim 4:11; Philem. 24).

The Wide Scope is a marked feature of this journey of about 3,200 miles.

The first journey was through Cyprus, where Barnabas was well acquainted, and through that section of Asia Minor roundabout the province of Cilicia, where Paul was practically at home. Paul was born in Tarsus in Cilicia and it was to this region that he went for some part of the time between his conversion and his call to the missionary work (Acts 9:30; Gal. 1:21).

The second journey carries Paul into entirely, to him, new provinces of Asia Minor and into Macedonia and Achaia. He comes into close contact not only with the rough native populations of the Asian provinces but with the cultivated philosophers of Greece and the effeminate voluptuaries of the heathen temples. Here are new tests for this missionary and the gospel which he preaches, but he meets them all. This journey had a large significance for the spread of Christianity. Had the gospel failed to meet the wants of all sorts and conditions of men, there would have been no further triumphs for it.

Value to the World.—"This journey was not only the greatest which Paul achieved but perhaps the most momentous recorded in the annals of the human race. In its issues it far outrivalled the expedition of Alexander the Great when he carried the arms and civilization of Greece into the heart of Asia, or that of Cæsar when he landed on the shores of Britain, or even the voyage of Columbus when he discovered a new world."

To Paul's turning westward, instead of eastward, through the guidance of the Spirit, and his entering upon his work in Macedonia (Acts 16:7-11) Europe to-day owes her advancement and Christian civilization. It is stating a sober fact when it is asserted that without Christianity Europeans would now be worshipping idols, the same as the inhabitants of other sections of the world where the gospel of Christ has not been made known.

Time and Rulers.—In time this journey extended over about three years, 51-54 A.D. The rulers were: Claudius, Emperor of Rome (Nero became Emperor in 54 A.D.); Herod Agrippa II., King of Chalcis (who also gets Batanea and Trachontis); and Gallio, Procurator of Achaia.

Epistles to the Churches.—Upon this journey Paul makes a new departure. With the multiplication of the churches and the impossibility of visiting them often, when occasions demanded it, Paul begins the writing of special and circular letters to the churches. The two first Epistles, of which we have any record, were those to The Thessalonians from Corinth, written probably in the winter of 52-53 A.D.

NOTE.—For an account of and an analysis of these Epistles see study 7.

Through Asia Minor (Acts 15:40-16:8).—It was Paul's custom to revisit the churches which he had organized, and to care for them. Following out this plan he went through Syria and Cilicia confirming the churches, then to Derbe and Lystra, where he found Timotheus who joined his company. After visiting the churches founded on the first missionary journey, Paul and his company turned northward and "went throughout Phrygia and the region of Galatia" (Acts 16:6) though there is no record of any church having been founded in these regions. "After they were come to Mysia, they assayed to go into Bithynia; but the Spirit suffered them not" (Acts 16:7).

It is important to note that the Holy Ghost now forbade Paul, at this time, to further preach the word in Asia (Acts 16:7). Paul and his company tried after this to go into Bithynia but they were prevented from doing so by the Spirit, and came down to Troas (Acts 16:8-12). Of this long journey through Asia Minor, of its perils and difficulties, of the rejoicings of the former Christian converts, when they saw Paul again, and of the many interesting facts and incidents we have only a glimpse.

In Europe (Acts 16:9-18:18).—Paul, following what was to him a clear indication of the guidance of the Holy Ghost (Acts 16:6-11), left Troas and set out by ship, by way of Samothracia, for Neapolis, which he reached on the following day. There have been many conjectures as to what the fortunes of the Christian church would have been had Paul been allowed to carry out his intention to visit Bithynia, and to preach the gospel in the regions of the east. Had he done so, however, it is quite certain, that the history of the world would have been quite different from what it is to-day. In this invasion of Europe Paul came within the charmed circle of what was then the highest civilization. The gospel was now to try its strength with the keenest philosophers and the most seductive fascinations of immorality, masquerading under the guise of religion in the licentious rites of the heathen temples and groves. What could this missionary do? What could he preach? If philosophy, if art, if beauty could have saved the souls of men then they would not have needed the gospel which Paul preached. But this was a gilded age, and the gilding hid the corruption, beneath. The message of Paul to the men in this charmed circle of civilization was the same that he had set forth in the rough mountain towns of Asia Minor. Human nature, under a rough or a polished exterior, is the same the world over. Paul was seeking men, to bring them to a knowledge of their alienation from God through sin, and to show them the way of salvation through repentance and faith in Jesus Christ? Greece, over whom the Romans held sway at this time, had been divided into two parts: Achaia on the south and Macedonia on the north. A great Roman road ran from east to west through Macedonia. It was by this road that the missionaries traveled.

1. Philippi (Acts 16:12-40) will be forever memorable as the first city in Europe in which a Christian church was established. It had the character of a Roman rather than a Greek city; both the civil and the military authorities being Roman. It had the rank of a Roman colony. Situated as it was on the great Egnatian way travelers and traders passed through it, eastward and westward, from all parts of the Roman world. "The Greek character in this northern province of Macedonia was more vigorous and much less corrupted than in the more polished society of the south. The churches which Paul established here gave him more comfort than any he established elsewhere." The beginning of the work at Philippi was not very promising and to most men would have been very discouraging. Luke tells us that "on the Sabbath we went out of the city by a riverside where prayer was wont to be made; and we sat down, and spake unto the women which resorted hither." But there they met Lydia, an energetic business woman and a work was begun which has had far reaching consequences. Paul and his company had been but a short time in the city when they came in conflict with the Roman authorities. A damsel, possessed with a spirit of divination, who brought much gain to her masters, testified to Paul and his work; this spirit Paul cast out and in consequence the owners of the girl brought the charge against Paul and Silas that they were Jews who taught customs not lawful for Romans to receive. Notice, the shrewdness of the trumped-up charge against Paul and Silas. Nothing is said about the real state of the case. In this charge the status of the Jews is shown in this city. Paul and Silas are beaten and thrown into prison; their feet are made fast in the stocks; their wounds are left unwashed and undressed. But in the earthquake, which opens the prison doors and gives release to the prisoners, Paul has an opportunity to preach the gospel to the jailer. How magnificently, forgetting himself, he sets forth the way of salvation through Christ! We turn to the Epistle to the Philippians (see Study 9) to see how Paul loved this church, and how this church loved him.

2. Thessalonica (Acts 17:1-9). Thinking it best to leave Philippi, Paul and his company passed on their way along the Egnatian road through the two beautiful Greek cities of Amphipolis and Apollonia to Thessalonica, distant about seventy-three miles from Philippi. Thessalonica is one of the few cities which has retained its importance up to the present time. It was founded by Cassander, King of Macedon in 315 B.C. It came under the Roman rule in 168 B.C. In Paul's time it was a great commercial center, the inhabitants being Greeks, Romans, and Jews. Here was a Jewish synagogue and for three Sabbath days Paul went into it and reasoned with the assembled Jews about Jesus Christ, declaring to them that He was the promised Messiah, and had suffered and was risen from the dead. We have the same results here which followed similar preaching elsewhere (1 Thess. 1:8). Out of the storm again emerges a Christian church. Paul and his company, after the usual tumult, pass on to another city but the church remains to send its blessed influence through all that region. The Epistles to the Thessalonians (see Study 7) give us some graphic pictures of the converts and their ways of working.

3. Berea (Acts 17:10-14) was a secluded inland city. It must have been somewhat of a surprise to Paul to find the Jews of this place so ready to receive the Word of God, which he preached to them in their synagogue. There was great searching of the Scriptures and many believed. A large work was in progress when Jews from Thessalonica, hearing of the success of Paul in Berea, came down and stirred up the people against him. It became quite evident now that there was a persistent and organized effort being made to drive Paul out of this section. As the opposition seemed to be directed against Paul alone, the brethren proposed to send him away, and to have Silas and Timotheus remain for a short time. This plan was carried out.

4. Athens (Acts 17:15-34) was the most cultivated city of the old world; a statue was set upon every corner and an altar in every street. "Here the human mind had blazed forth with a splendor it has never exhibited elsewhere. In the golden age of its history Athens possessed more men of the very highest genius than have ever lived in any other city. To this day their names invest her with glory. Yet even in Paul's day the living Athens was a thing of the past. Four hundred years had elapsed since its golden age, and in the course of these centuries it had experienced a sad decline. Philosophy had degenerated into sophistry, art into dilettanteism, oratory into rhetoric, poetry into verse making. It was a city living on its past." Paul entered into the open places where the people gathered and talked with them. So much interest was aroused by what he had to say that he was asked to speak to them upon Mars Hill. Thither they all went. Paul as his custom was sought a common starting point in the altar to the unknown God. So long as he spoke of God and man in general terms he was listened to, but when he came to touch their hearts and consciences and to apply what he said, speaking of the judgment through Christ and His resurrection from the dead, he was left alone. Paul did not fail, the trouble with the Athenians was that they possessed only intellectual curiosity; they had no appetite for the truth. But still some converts were made. "Certain men clave unto him and believed; among whom were Dionysius the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris and others with them" (Acts 17:34).

5. Corinth. (Acts 18:1-18) was the largest and most important city in Greece. From Athens Paul came to Corinth and remained over a year and a half. We have a graphic picture of this church in the Epistles to the Corinthians. (See Study 8.) Probably no better place than this highway of all peoples could have been selected in which to preach the gospel. No one knew better than Paul how to select strategic places. A stream of travelers, merchants, scholars, and sailors was constantly passing through this great commercial city; what was preached here would be carried to the ends of the earth. It was a city of art and culture and yet a place where the vices of the east and west met and held high carnival. Religion itself was put to ignoble uses; a thousand priestesses ministered to a base worship in the magnificent temple of the goddess Aphrodite. Greek philosophy showed its decay in endless discussions about words and the tendency to set intellectual above moral distinctions. There was a denial of the future life for the sake of unlimited enjoyment in the present. Paul, when he came into the city, found a lodging with Aquila and his wife Priscilla, and wrought with them at the occupation of tent making. When Silas and Timotheus joined him he openly testified to the Jews that Jesus was the Christ. Crispus, the chief ruler of the synagogue, was converted together with many Corinthians. Paul was comforted at this time by a vision of the Lord which bade him to speak and not to hold his peace. After a year and a half of earnest preaching an attempt was made by the Jews to drive Paul out of the city by bringing accusations against him before the Roman proconsul Gallio, but in this they were unsuccessful. Paul tarried and worked here until it seemed best for him to turn his steps homeward again to Antioch. The keynote of his preaching in this city is given by him in his First Epistle to the Corinthians where he says (2:2), "For I determined not to know anything among you save Jesus Christ and him crucified." If this gospel could win converts in Corinth, it can win converts anywhere.

The Return Voyage (Acts 18:18-22) was by way of Ephesus where he entered into the synagogue and reasoned with the Jews. Leaving Ephesus he sailed for Cæsarea where he landed. After he had gone up and saluted the church he went down to Antioch.

Who proposed the second missionary journey? Who were the companions? What can be said of the wide scope? What was its value to the world? Time and Rulers? What can be said of the new departure in writing Epistles to the churches? What can be said of the itinerary through Asia Minor? Give the incidents, of preaching the gospel, that occurred during the trip in Europe, in the different cities; Philippi, Thessalonica, Berea, Athens, and Corinth. How was the return voyage made?

Third Missionary Journey—Method. The Chief City. Time and Extent. Epistles Written.

Itinerary—Through Galatia and Phygia. Ephesus. Through Macedonia and Greece. The Return Voyage.

Method.—A study of the three missionary journeys shows the method of evangelization of the ancient world. The first journey was comparatively near home. The second was a review of the work done in the first and a pushing on to new work in Asia Minor and the larger conquests in Europe. In the third we have a review visit to the churches of Asia Minor, a long stop at Ephesus, and a review visit to the churches of Macedonia and Achaia, which were organized upon the second missionary journey. There was always a method in what Paul did. He was not only a missionary preaching and testifying to Jesus Christ, but he was an organizer and leader of men. The churches formed were visited again and again; messengers were sent to them to instruct, to chide, and to encourage them; circular and special letters from Paul's own hand were dispatched to them, when occasion required. Wherever Paul preached, whatever might be the tumults raised, he always won some adherents for Jesus Christ, who were brought together and organized into a church.

On this third journey he was already planning to go to Rome (Acts 19:21) and wrote an epistle to the Romans announcing his coming (Rom. 1:7, 15).

The Chief City, in which Paul spent most of his time (Acts 19:1, 8, 10), between two and three years upon this journey, was Ephesus in Asia Minor. This city situated midway between the extreme points of his former missionary journeys was a place where he could have an intelligent oversight over all the work which he had previously accomplished.

Ephesus has been thus described: "It had been one of the early Greek colonies, later the capital of Ionia, and in Paul's day it was by far the largest and busiest of all the cities of proconsular Asia. All the roads in Asia Minor centered in Ephesus and from its position it was almost as much a meeting place of eastern and western thought as Alexandria. Its religion was oriental. Its goddess called Artemis or Diana, had a Greek name but was the representative of an old Phrygian nature worship. The goddess was an inartistic, many-breasted figure, the body carved with strange figures of animals, flowers, and fruits. The temple built by Alexander the Great was the most magnificent religious edifice in the world. It was kept by a corporation of priests and priestesses, who were supported by the rents of vast estates. For centuries Ephesus was a great center of pilgrimage, and pilgrims came from all parts of Asia to visit the famous shrine."

"The first great blow which this worship received was given by Paul during his two years' stay in Ephesus, and the story told in this chapter is the history of the beginning of a decline from which the worship of Diana never recovered. The speech of Demetrius perhaps exaggerates the effects of Paul's work, but it should be remembered that the gospel took firm hold of proconsular Asia from a very early period. Paul's Epistles tell us of the churches in Ephesus, Laodicea, and Colossæ, and the Apocalypse adds churches in Pergamos, Smyrna, Thyatira, Sardis, and Philadelphia. Half a century later, Pliny asserted that in this region the temples were deserted, the worship was neglected, and the sacrificial victims were unsold."

During his long stay in Ephesus, Paul doubtless received many delegations and visitors from the churches formerly organized by him.

The character of the Ephesian Christians can be seen from the Epistle addressed to them (See Study 9).

Time and Extent.—About four years, 54-58 A.D., were occupied by Paul in going about among the churches and about 3,500 miles were traveled.

Epistles.—This journey was prolific in masterly writings. Paul wrote the First and Second Epistles to the Corinthians from Ephesus about 57 A.D., Galatians from the same city (somewhere between 54 and 56 A.D.), and Romans at Corinth in 58 A.D. (See Study 8).

Through Galatia and Phrygia (Acts 18:23).—After Paul had spent some time at Antioch, at the close of the second missionary journey, "He departed and went over all the country of Galatia and Phrygia in order strengthening all the disciples." Thus Luke briefly sums up in a few words all the incidents of a journey of hundreds of miles of travel.

Ephesus (Acts 19:1-20:1).—Evidently with the purpose of showing what is new and of chief importance in each journey Luke, as is his habit, calls attention to the work of Paul in Ephesus; other parts of this journey are passed over with slight mention.

Having gone through the upper coasts, Paul comes to Ephesus. The chief events in this city, during the visit of the Apostle, were:

1. The incident of the work of Apollos is given (Acts 18:24-19:1) to show how Paul found about twelve disciples of John the Baptist (Acts 19:7) at Ephesus and instructed them further, baptizing them in the name of the Lord Jesus (Acts 19:5, compare Acts 19:1-7).

2. Three months were spent by Paul (Acts 19:8, 9) with the Jews in their synagogue, "disputing and persuading the things pertaining to the kingdom of God." But when certain of them became hardened and it was plainly seen that little good was being done he left the synagogue.

3. About two years' time was given, after the apostle had separated himself and followers from the Jewish synagogue, to teaching in the school or lecture room of Tyrannus (Acts 19:9, 10). The result of this preaching and teaching was that a great multitude of men and women was brought to a confession of faith in Christ, throughout Asia.

4. The mighty growth of the Word of God (Acts 19:20) was attested by the miracles which Paul did in the name of Christ (Acts 19:11, 12). He confounded the Jewish exorcists, who attempted to imitate these miracles (Acts 19:13-20). This great work was shown to be a thorough one from the fact that many who used curious arts brought their books and burned them amounting in value to over $31,000.

5. Paul now proposed, thinking the Ephesian church could stand alone (Acts 19:21, 22), "after he had passed through Macedonia and Achaia to go to Jerusalem, saying, after I have been there, I must also see Rome." In anticipation of this visit he sent Timotheus and Erastus into Macedonia, "but he himself stayed in Asia for a season."

6. The tumult made by Demetrius (Acts 19:23-40) is a strong proof of the large impression made by the gospel of Jesus Christ upon not only the city of Ephesus but all Asia Minor. The burning of the magical books had arrested the attention of many people, but when the sale of the silver images of the idol, Diana, began to fall off so as to touch the trade of the silversmiths they were up in arms at once. Demetrius showed how the power of Christ had prevailed with men when he declared that, "Paul hath persuaded and turned away much people, saying that there be no gods which are made with hands." The violence of the men who composed the mob showed how deeply Christianity had taken hold upon large numbers of people. Paul, after the uproar had quieted down, carried out his intention of departing for Macedonia.

Through Macedonia and Greece (Acts 21:1-6).—"The order of events seems to have been: (a) Timotheus and Erastus were sent to look after the church discipline at Corinth (Acts 19:22). Stephanas and others came from Corinth and returned with the First Epistle to the Corinthians (1 Cor. 16:17). (b) Paul meant to visit Corinth (1 Cor. 4:18, 19); instead he went to Macedonia by Troas (2 Cor. 2:12, 13). (c) He waited at Troas for news from Corinth, and his anxiety told on his health (2 Cor. 2:12; 1:8; 4:10, 11; 12:7). (d) In spite of illness he pressed on to Macedonia (2 Cor. 2:13), where he met Titus, who brought him good news of the state of the Corinthian church (2 Cor. 7:5-9). (e) He wrote the Second Epistle to the Corinthians and sent it by Titus, and resolved to wait sometime longer before going to Corinth, for he wished to take a contribution from the Corinthians to Jerusalem (2 Cor. 9:1-5). (f) In Macedonia he probably visited Berea, Thessalonica, and Philippi, with perhaps a journey to Illyricum (Rom. 15:19). (g) He went to Greece (Corinth and Cenchrea). (h) He proposed sailing for Syria with the contributions of the various churches, and with delegates who carried the money; Sopater from Berea, Aristarchus and Secundus from Thessalonica, Gaius from Derbe, Timotheus from Lystra, Tychicus and Trophimus from Ephesus (Acts 20:4; 21:29). (i) The Jews of Corinth conspired to murder Paul on his embarkation, so his friends went by ship, and he eluded the conspirators by going by land to Philippi. (j) Then he took ship for Troas, having Luke who had been at Philippi for his companion ("We sailed").

The Return Journey, Troas to Jerusalem (Acts 20:6-21:15).

1. Troas. Luke and Paul were five days in reaching Troas, from Philippi, where they found a number of the brethren who had preceded them (Acts 20:6, compare Acts 20:4-6). Seven days were spent at Troas (Acts 20:6). We have here the record of how the disciples spent the Sabbath day in breaking bread together and in listening to the preaching of Paul. (Acts 20:7-12). This last day here came near being marred by Eutychus meeting his death, when he fell down from the third loft. But Paul was there and Eutychus's life was spared. The meeting did not break up until the next morning, so interested were they in talking over "The Way."

2. Troas to Miletus (Acts 20:13-15). Paul's company went by ship first to Assos, where Paul met them; he having covered the distance of about twenty miles on foot. At Assos Paul joined the company on the ship and they sailed from Assos to Mitylene. "And we sailed thence," says Luke, "and came the next day over against Chios; and the next day we arrived at Samos, and tarried at Trogyllium; and the next day we came to Miletus."

3. At Miletus (Acts 20:17-38) Paul sent for the elders of the Ephesian church to come to him. When they came he spoke to them in a very touching and tender way. This address has been divided into four parts: (a) What was behind Paul; he called them to witness that he had been faithful in declaring to them the full gospel of Jesus Christ, repentance toward God and faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. (b) What was before Paul; he said that in every city the Holy Ghost witnessed that bonds and afflictions awaited him. (c) What was before the elders of the Ephesian church; it was theirs to take care of the flock over which they presided and "to feed the church of God." (d) Commendation of the elders to God in their good work. (e) Paul's earnest prayer for their welfare. (f) The farewell words.

4. Miletus to Cæsarea and Jerusalem (Acts 21:1-15) by way of Coos, Rhodes, Patara, Tyre, and Cæsarea. At Tyre there was a wait of seven days and a change of ships; in this city it was testified to Paul that he should not go up to Jerusalem. At the parting, when Paul and his company took ship to go to Cæsarea, the disciples of Tyre came out to see them off and all kneeled down on the shore and prayed. At Cæsarea where Paul's company tarried many days, it was again made known to Paul by the Holy Ghost that bonds and imprisonment awaited him at Jerusalem, but still he pressed on saying, "The will of the Lord be done." Arriving in Jerusalem they were gladly received by the brethren.

What was the method of evangelizing the ancient world? How did the three missionary journeys differ from each other? What can be said of the chief city in which Paul spent so much of the time of this journey? Time and extent of this journey? What Epistles were written? Give the chief incidents of the itinerary; through Galatia and Phrygia; in Ephesus; through Macedonia and Greece; the return voyage.

This Journey—From Jerusalem to Rome. The Seven Speeches. The Writings. Time and Extent. The Historical Connections.

Paul at Jerusalem—The Return to Jerusalem. The Meeting with James and the Elders of the Church. The Temple Riot. The Speech of Paul to the Rioters. Before the Jewish Council. Paul Comforted by God. Conspiracy of Jewish Fanatics.

Paul at Cæsarea—The First Defense, before Jewish Accusers and the Roman Governor Felix. Second Defense, before Felix. Third Defense, before Festus. Fourth Defense, before Festus and King Agrippa II.

The Voyage to Rome—Cæsarea to Myra. Myra to Melita. Melita to Rome.

Paul at Rome—Testifying to the Jews. Testifying to the Gentiles. Incidental Notices of the Imprisonment. The Further Travels of Paul.

From Jerusalem to Rome.—This portion of the book of the Acts comprises more than one quarter of the whole, or seven and a half chapters. There must have been some important purpose to be served by thus relating so fully the incidents of this period in Paul's life; for Luke elsewhere narrates only the incidents of the missionary journeys which are of great interest. It may be that his purpose was to show, with the full connecting incidents, how clearly and strongly Paul testified, to the Jews in the temple (Acts 22:1-23), and before the Roman tribunal (Acts 25:13, 14, 26; 26:1-32), that Jesus was the Christ. Jesus himself, before his death, gave the same testimony to the Sanhedrin (Matt. 26:63, 64; Mark 14:61, 62; Luke 22:67-69), and the Roman tribunal (John 18:33-37). The testimony of Paul was further carried to imperial Rome, the capital of the world (Acts 28:17-24).

The Seven Speeches.—The last recorded addresses of the Great Apostle are a striking feature of this period. They show his faith after it had been tried and tested in his toilsome years of missionary labors. They reveal the courage and character of the man in that they were given when he was in bonds and in imminent peril of his life.

1. The speech before the Jewish mob in the temple (Acts 22:1-29) in which Paul tells the Jews how he was changed from a persecutor to a believer in Christ. He relates also the story of his conversion.

2. The speech before the Jewish council (Acts 22:30; 23:1-10) in which he creates confusion by raising the question of the resurrection. But the provocation was great for the high-priest had commanded that Paul be smitten on the mouth when he began to speak.

3. The speech before Felix, the Roman governor (Acts 24:10-22) in which he makes his defense against Jewish accusers, and affirms his belief in the new "Way" and in the resurrection.

4. The speech before Felix and Brasilia, his wife, (Acts 24:24-27). Paul, being sent for by Felix to tell him of his faith in Christ, reasons "of righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come."

5. The speech before Festus the Roman governor (Acts 25:7-11) in which Paul appeals to Cæsar.

6. The speech before Festus, the Roman governor, and King Agrippa and his wife, Bernice, (Acts 25:13; 26:1-32). Here Paul again relates the story of his conversion and shows that Jesus is the Christ.

7. The speech before the chief Jews in Rome (Acts 28:17-31) showing that Jesus is the Christ.

The Writings.—During the two years' imprisonment of Paul in Cæsarea we have no account of any Epistles written by him. But when he arrives in Rome he again begins to indite those writings which have made his name so famous. From his prison in Rome he sent out four letters which have been called, "The Epistles of the First Imprisonment"; Colossians, Philemon, Ephesians, and Philippians (See Chapter 9). For profound expositions of the Christian doctrines, lofty ethical teaching, and mellowness of feeling they stand unequalled.

Time and Extent.—Paul arrived in Jerusalem in 58 A.D. He was imprisoned two years in Cæsarea, 58 to 60 A.D. The voyage to Rome was in the winter of 60 and 61 A D. He was imprisoned in Rome two years, 61 to 63 A.D. In extent the journey which Paul took from Cæsarea to Rome was about 2,300 miles.

The Historical Connections.—Nero was Emperor of Rome (since 54 A.D.). Felix was Procurator of Judea from 51 to 60 A.D., when he was succeeded by Festus. We fix the date of Paul's going to Rome by the fact that when Festus came in 60 A.D., he made his appeal to Cæsar.

The Return to Jerusalem (Acts 21:17-23:23) was at the feast of Pentecost when it was crowded with strangers from all parts of the world. Paul had been warned not to come back to this city (Acts 21:10-14) and it might have been possible for him to have remained away, passing the last years of his life in high honor and peace as the Great Apostle and Head of the Gentile churches. But he seems to have felt it incumbent upon him to return to Jerusalem and testify for his faith (Acts 21:14), and to carry alms (Acts 24:17). Paul was now about sixty years of age and for more than ten years had been engaged in the most arduous missionary labors, enduring stonings, beatings, and contumelies of all kinds, for the sake of preaching Jesus Christ. More than twenty years had elapsed since his conversion; and before his well-known three missionary journeys he had been actively engaged in the work which he loved so well. In his body he must have borne the marks of these incessant labors, but his spirit was as fresh and undaunted as ever. Whatever awaited him in Jerusalem he was ready for it.

The Meeting with James and the Elders of the Church (Acts 21:17-25) seems to have been a pleasant one. Paul told his story of the wonders wrought in the Gentile world, and God was glorified, but there seems to have been a certain constraint upon the company. Paul was well known everywhere as an exponent of that liberty in Christ by which the Gentiles when they became Christians were not obliged to become Jews and obey the laws of Moses. We find the elders, while freely admitting the binding nature of the decision of the Jerusalem Council upon this matter, advising him to show the many thousands of Jews who believed and kept the law, that he himself still held to the observance of the law. Hence the urgency with which they requested him to purify himself in the temple, with certain men who had a vow, so that the Jews might see that he was not a renegade. The consequences of this advice soon became evident.

The Temple Riot and Paul's Imprisonment (Acts 21:26-39).—When the days of purification for his companions were almost completed some Jews of Asia saw him and at once raised a great tumult. It is a wonder that he was not seen and recognized earlier. Doubtless the Asian Jews had been restrained in their own cities from wreaking their hatred upon Paul to the full, by the strong arm of the Roman magistrate. At once a great outcry was raised and Paul would have fared badly if he had not been rescued by the Roman soldiers, to be imprisoned by them.

The Speech of Paul to the Rioters (Acts 21:40-22:23).—He requested that he be permitted to speak to this angry crowd of fanatic Jews, who were howling for his life. What would he say? What defense could he make? Listen to him! He is telling the story of his life and conversion, on the way to Damascus. He is glorifying Jesus and urging them to believe in Him. There is not one word about the indignities that have been heaped upon himself. This personal testimony in this city where Paul had been the chief persecutor was wonderful. But as the Jews had demanded the life of Christ, when he was upon earth and testified to His mission, so now they demanded the life of Paul.

Before the Jewish Council (Acts 22:24-23:10).—Paul, rescued from the clutches of the mob, would have been scourged by the Romans had he not declared himself a Roman. On the morrow, taken before the Sanhedrin, and seeing no hope of any justice being done him, he sets one party of it over against the other by declaring that he was a Pharisee and "of the hope of the resurrection of the dead I am called in question." So great was the dissension that arose over this matter that Paul was faring badly when he was rescued by the chief captain and his soldiers.

Paul Comforted by God (Acts 23:10).—Paul must have been quite worn out with the tumults and mobs of the last two days. The encouragement of God speaking to him and telling him to be of good cheer, and that as he had testified of Him in Jerusalem, he must also bear witness in Rome, put a new heart in him. It had been Paul's great desire to visit Rome and preach Christ in that city (Rome 1:11-15; Acts 19:21).