Title: The Weans at Rowallan

Author: Kathleen Fitzpatrick

Illustrator: A. Guy Smith

Release date: February 22, 2010 [eBook #31362]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | WHY MRS M'REA RETURNED TO THE FAITH OF HER FATHERS |

| II. | UNDER THE SHADOW OF THE MOUNTAINS |

| III. | JANE'S CONVERSION |

| IV. | A DAY OF GROWTH |

| V. | THE CHILD SAMUEL |

| VI. | THE BEST FINDER |

| VII. | A STOCKING FULL OF GOLD |

| VIII. | THE BANTAM HEN |

| IX. | THE DORCAS SOCIETY |

| X. | THE CRUEL HARM |

| XI. | A CHIEF MOURNER |

| XII. | A SAFEGUARD FOR HAPPINESS |

| XIII. | JIMMIE BURKE'S WEDDING |

| XIV. | JANE AT MISS COURTNEY'S SCHOOL |

| XV. | AN ENGLISH AUNT |

One soaking wet day in September Patsy was sitting by the kitchen fire eating bread and sugar for want of better amusement when he was cheered by the sight of a tall figure in a green plaid shawl hurrying past the window in the driving rain. He got up from his creepie stool to go for the other children, who were playing in the schoolroom, when Lull, sprinkling clothes at the table, exclaimed:

"Bad luck to it, here's that ould runner again."

Patsy quietly moved his stool back into the shadow of the chimney corner. In that mood Lull, if she saw him, would chase him from the kitchen when the news began; and clearly Teressa was bringing news worth hearing. As far back as Patsy or any of the children could remember, Teressa had brought the village gossip to Rowallan. Neither rain nor storm could keep the old woman back when there was news to tell. One thing only—a dog in her path—had power to turn her aside. The quietest dog sent her running like a hare, and the most obviously imitated bark made her cry.

She came in, shaking the rain from her shawl.

"Woman, dear, but that's the saft day. I'm dreepin' to the marrow bone."

"What an' iver brought ye out?" said Lull shortly.

Teressa sank into a chair, and wiped her wet face with the corner of her apron. "'Deed, ye may weel ast me. My grandson was for stoppin' me, but says I to myself, says I, the mistress be to hear this before night."

"She'll hear no word of it, then," said Lull. "She's sleepin' sound, an' I'd cut aff my han' afore I'd wake her for any ould clash."

Teressa paid no heed. "Such carryin's-on, Lull, I niver seen. Mrs M'Rea, the woman, she bates Banagher. She's drunk as much whiskey these two days as would destroy a rigiment, an' now she has the whole village up with her talk."

"Andy was tellin' me she was at it again," said Lull.

"Och, I wisht ye'd see her," said Teressa. "She was neither to bind nor to stay. An' the tongue of her. Callin' us a lock a' papishes an' fenians! Sure, she was sittin' on Father Ryan's dour-step till past twelve o'clock wavin' an or'nge scarf, an' singin' 'Clitter Clatter, Holy Watter.'"

"Dear help us," said Lull.

"'Deed, I'm sayin' it," said Teressa. "An when his riverence come out to her it was nothin' but a hape of abuse, an' to hell wid the Pope, that she give him."

"That's forty shillin's an' costs if the polis heard her," said Patsy, forgetting he was in hiding.

Teressa jumped. "Lord love ye, did ye iver hear the like a' that?" she said. "It's a wee ould man the chile is."

"Be off wid ye, Patsy," said Lull; "what call has the likes a' yous to know that?" But Patsy wanted to hear more.

"What did Father Ryan say to her, Teressa?" he asked.

"Troth, he tould her she'd be in hell herself before the Pope for all her cursin'," said Teressa.

"An' will she?" said Patsy.

"As sure as an egg's mate," said Teressa. "If she doesn't give over drinkin' the ould gentleman's comin' for her one of these fine nights to take her aff wid him."

"Does she know when he's comin'?" Patsy asked.

"Not her, the black-mouthed Protestant divil," said Teressa.

"Whist!" said Lull, "that's no talk before the chile."

"And a fine child he is," said Teressa, "an' a fine man he'll be makin' one a' these days."

But Patsy had heard enough, and was off to tell the others. They were playing in the schoolroom when he brought the news. Mrs M'Rea was drunk again, and had cursed the Pope on Father Ryan's doorstep, and the devil was coming to take her away if she did not stop drinking. It was bitter news, for Mrs M'Rea kept the one sweetie shop in the village.

"I'll go an' see her," said Jane.

"What good'll that do?" said Mick.

"I'll tell her the divil's comin'," said Jane.

"She won't heed ye," said Mick.

"I know," said Fly, who had said nothing so far but had been thinking seriously; "let's send her a message from the divil to tell her to give over or he'll come for her."

This plan commended itself to the others as a brilliant solution of a difficulty. Mrs M'Rea had been known to see devils and rats before when she was drunk—they had only been dancing devils, and had come to no good purpose that the children knew of—she would, therefore, be quite prepared for another visit, and a devil with a warning would have to be taken seriously. It was well worth trying, for Mrs M'Rea, in spite of her drunken habits and the fact that she was a turncoat—had been born a Roman Catholic, and had married into the other camp—was a great favourite with the children. She often gave them sweets when they had not a farthing between them to pay.

As the idea was hers Fly was to go with the message. Mick raked down a handful of soot from the chimney, and rubbed her face and hands till they were black, then dressed her in a pair of old bathing-drawers and a black fur cape. Patsy got the pitchfork from the stable for her to carry in her hand.

Fly started off for the village. The others waited patiently for her to come back. She was gone nearly two hours, and came back wet to the skin, and frightened at the success of her mission.

"Go on; tell us right from the start," said Jane.

"Well, when I got outside the gate who should I meet but Teressa goin' home, so I just dodged down behind her, an' barked—an' she tuk to her heels, an' run the whole way. An' when we come to the village I hid behind a tree, an' then I dodged round to Mrs M'Rea's. The door was shut, so I knocked with the pitchfork. Sez she: 'Who's there?' Sez I: 'Come out a' that, Mrs M'Rea.' Sez she: 'What would I be doin' that for?' 'Because,' sez I, 'it's the divil himself come to see ye, Mrs M'Rea.'"

"But ye wern't to be the divil," Jane interrupted. "Ye were only one of his wee divils."

"I clean forgot," said Fly; "'deed, indeed, I clean forgot. An' oh, Jane, I wisht ye'd seen her. She opened the dour, and when she seen me she give a yell, an' went down on her knees, an' began prayin' like mad. I danced round, an' poked her with the pitchfork, an', sez I: 'I'll larn ye to curse the Pope, Mrs M'Rea, ye black-mouthed ould Protestant,'—that's what Teressa said, wasn't it, Patsy? 'Look here, my girl,' sez I, 'I'm comin' for ye at twelve the night, so see an' be ready.' An' with that she give another big yell, an' run in an' shut the dour, an' I could hear her cryin'. An' oh, Jane, Jane, I've scared the very sowl out of her." And Fly began to cry too.

"Ye've just spoilt it all, Fly," said Jane. "The divil wasn't to be goin' to come for her on'y if she wouldn't give over drinkin'."

Fly shivered, and sobbed.

"Yes, ye jackass; an' how can we take her away at twelve?" said Mick.

"An' if we don't she won't believe it was the divil," said Patsy.

But Fly only shivered, and sobbed the more.

"Look here," said Jane, "she'll be sick if we don't dry her." So they all went upstairs, and Fly was washed, and dressed in her own clothes, and sent down to sit by the kitchen fire, having first sworn to cut her throat if she let out one word to Lull. Then the four went back to the schoolroom to think the matter over.

"We can't have Mrs M'Rea goin' round sayin' the divil tould her a lie," said Jane.

"An' we can't have her sittin' there all night scared to death," said Mick.

"We'll have to send her another message," said Jane.

"Another divil?" said Patsy.

"No," said Jane; "it must be some person from heaven this time to tell her that if she'll quit drinkin' the divil won't be let come!"

They agreed that this was the only plan; but who was it to be? "I'll be the Blessed Virgin," said Jane; "there's mother's blue muslin dress in the nursery cupboard, an' I can have the wax flowers out of the glass shade in my hair."

"But Mrs M'Rea's a Protestant," Mick objected, "an' what would she care for the Blessed Virgin?"

"Let's send a ghost of Mister M'Rea," said Patsy. But here again there was a difficulty, for Mr M'Rea could only have come from purgatory—and who would have let him out?

"Is there niver a Protestant saint?" said Mick.

"Not a one but King William," said Jane.

"An' he's the very ould boy," Mick shouted, and upstairs they ran to search for suitable clothes. Jane begged to be King William; but by the time she was dressed it was dark, and she was afraid to go alone, so Mick and Patsy went with her.

Honeybird was sent downstairs to the kitchen to wait with Fly till they came back, and if Lull asked where they were she was not to tell. When they dropped out of the dressing-room window into the garden the rain was over. The wind now chased the clouds in wild shapes across the sky, now piled them up to hide the moon. The children crept along the road, terrified that they might meet Sandy M'Glander, the ghost with the wooden leg, or see Raw Head and Bloody Bones ride by on his black horse. When they reached Mrs M'Rea's cottage all was in darkness, but they could hear through the door the crying that had frightened Fly.

"Hide quick yous two," said Jane; "I'm goin' to knock."

There was a yell of terror from inside.

"It's all right, Mrs M'Rea," said Jane; "come out, I want to speak to ye."

"Who are ye?" said Mrs M'Rea.

"Sure, I'm King William, of Glorious, Pious, an' Immortal memory, come to save ye from the divil."

They heard Mrs M'Rea fumbling with the latch, and then the door opened. Jane stood up straight, and, as luck would have it, the clouds parted, and the moon shone bright on King William in an old hunting-coat stuffed out with pillows, a pair of white-frilled knickerbockers, and a top hat with a peacock's feather in it.

"God help us," said Mrs M'Rea, "but the quare things do happen."

"Ay; an' quarer things will happen if yer don't give over drinkin', Mrs M'Rea," said King William. "Fine goin's-on these are when dacent people can't rest in heaven for the likes a' you and yer vagaries."

"It's Himself," said Mrs M'Rea, and got down on her knees.

"If it hadn't been for me meeting the divil this evenin' ye'd have been in hell by this time; but sez I to him, sez I: 'Give her another chance,' sez I."

"God save us," sobbed Mrs M'Rea.

"An' sez he: 'No.' Do ye hear what I'm sayin', Mrs M'Rea? Sez he: 'No; the black-mouthed Protestant, she cursed the Pope, and waved an or'nge scarf, on Father's Ryan's dourstep,' sez he."

"Whist!" said a warning voice round the corner, "King William's a Protestant."

"What do I care about Protestants?" shouted King William, getting excited. "If I didn't know ye for a dacent woman I'd 'a' let the divil have ye; but sez I to myself, sez I: 'Where would the childer be without their wee sweetie shop?'"

Jane was losing her head. The whispers round the corner began again. King William took no notice, but went on: "An' he'll let you off this wanst, Mrs M'Rea; but ye'll go down first thing in the mornin', an' take the pledge with Father Ryan."

"Did yer honour say Father Ryan?" gasped Mrs "M'Rea.

"'Deed, I did; an' who else would I be sayin'?" said King William.

"But I'm a Protestant, yer honour," said Mrs M'Rea.

"So ye are; an' I'm tellin' ye, Mrs M'Rea, ye'll be sorry for it. Sure, there's niver a Protestant in heaven but myself, an' me got in by the skin a' my teeth. There's nothin' but rows an' rows a' Popes there. Sure, there's many the time I be sorry for ye when I hear ye down here shoutin' 'Clitter clatter' an' wearin' or'nge scarfs when I know where ye're goin' through it."

"Och-a-nee, an' me knew no better," said Mrs M'Rea.

"Ye did know better wanst, an' ye know better again now. Go down to Father Ryan, an' take the pledge; an' let me hear no more about it, or it'll not be tellin' ye, for divil a fut I'll stir out of heaven again for you or anybuddy else." Mrs M'Rea was rocking to and fro on her knees. The clouds once more hid the moon, and in the darkness Mick and Patsy seized King William, and hurried her away.

"Ye very near spoilt it all," said Mick.

"But I didn't," said Jane. "Let's hide, an' see what she'll do."

Mrs M'Rea only got up from her knees, and went into the cottage, and shut the door. It was late when they got home. Jane crept upstairs, and changed her clothes before she went into the kitchen for supper.

Next morning Teressa came with the strange news that Mrs M'Rea had been converted, and had been to Father Ryan to take the pledge. "Small wonder, for the divil himself come to see her," said Teressa. "An' sure, I seen him myself wid me own two eyes. As I was goin' home last night who should come after me but a black baste wid the ugliest face on him ye iver seen. An' it wasn't long after that the neighbours heard her yellin' 'Murder!' She sez herself that he come to her as bould as brass, like a wee ould black man, an' poked holes in her wid a fiery fork, an' by strake a' dawn she was down at Father Ryan's tellin' him she was converted. An' not a drop of drink on her. An' the whole parish is callogueing wid her now. But she houlds to it that King William's a great saint in glory."

Rowallan was an old, rambling house that stood in a wilderness of weeds and trees under the shadow of the Mourne Mountains. It was a house with a strange name; people said it was never free from sorrow. Others went so far as to say there was a curse on the place, and many went miles out of their way rather than pass the big gates after dark, and crossed themselves when they passed them in broad daylight. There was not a man or woman in the countryside who could not have given you the reason for this feeling about Rowallan. Anyone could have told you that the master had been murdered not five years ago at his own gates. Most of them could have told how his father before him had died on the same spot—died cursing a son and daughter who had turned to be Roman Catholics. And in some of the cottages there still lived a man or a woman old enough to remember the master before that: a bad man, for he had believed in neither God nor devil, and had broken his neck, riding home one night full of drink, at the gates. God save us! was it any wonder people were afraid to pass them? The present, too, had its own share of sorrow. The children, they would tell you, lived almost alone; there was no one to take care of them but two old servants, both over sixty, for the mistress, though still alive, was a broken-hearted woman, who had never left her room since her husband's death. This they might have told a stranger, but no one would have dreamt of telling the children these tales about their home. They, though they had friends in every cottage, had never heard one word of either haunting sorrow or curse. It is true that sometimes, coming home in the evening from a long day's expedition across the mountains, they felt a strange sense of depression when they came to the big iron gates. For no reason, it seemed, a foreboding of calamity chilled their spirits, and sent them, at a run, up the avenue into the house to the warm shelter of the kitchen, to be assured by Lull's cheerful presence that their mother had not died in their absence, and life was still happy.

There were five of them: Mick, Jane, Fly, Patsy, and Honeybird. The tales people told of their home were not the strangest part of their history. Their father had been a man hated by his own class for his broad and generous views at a time when the whole country was disturbed, and loved by his poorer neighbours for the same reason. He had been murdered by a terrible mistake. It was not the master, Michael Darragh, but his Roman Catholic brother Niel, the murderer had meant to kill. Niel Darragh, when he and his sister had been driven out of their father's house for their religious views, had taken a farm about a mile from Rowallan, and it was over his title to this farm the quarrel had arisen that had ended in the master being murdered, mistaken in the dark for his brother. The children's mother was an Englishwoman, who came of an old Puritan stock, and had married against the wishes of her family. Her husband's death was God's judgment for her wickedness, she thought. She had never recovered from the shock of the murder, and was only able to move with Lull's help from her bed to a couch by the window, and she was so entirely occupied with her own troubles that she often forgot the children existed. So it came that they were being brought up by Lull, their father's old nurse, and Andy Graham, the coachman. Lull had so much else to do, with all the work of the house, and an invalid mistress to wait on, that the children were left to come and go as they pleased. Twice a week they went to old Mr Rannigan, the rector, for lessons, but on other days they roamed for miles over the country, making friends at every cottage they passed. When they came home in the evening Lull was always waiting with supper by the kitchen fire, ready to hear their adventures, to sympathise or reprove as she saw fit. So long as they were well fed and clothed, and did nothing Quality would be ashamed of, she said she was content. Days spent on the mountains, fishing in some brown stream, helping an old peasant to herd his cow, or watching a woman spin by her door, taught the children more than they learnt from Mr Rannigan. They brought back to Lull stories of ghosts, Orange and Papist, who fought by night on the bridge that had once been slippery with their blood; of the devil's strange doings in the mountains: how he had bitten a piece out of one—the marks of his teeth showed to this day; or milder tales of fairy people—leprachauns, and the fiddlers whose music only the good could hear. Lull believed them all, crossed herself at the mention of ghosts and devil—her own mother had seen fairies dancing on the rocks one day as she was coming home from school. Lull herself, though she had never seen anything, had heard the banshee wailing round the house the night the master's mother died. The children were sure Lull could have heard the fairy fiddlers if she would have come with them to the right place up the mountains; she was good enough to hear it—they knew that.

Lull was a good old woman. The children were right; she was never cross, but always loving and kind, always ready to help them whatever they might want. Any spare minute she had was spent at her beads, and often while she worked they could tell by her lips she was saying her prayers. Blessed saints and holy angels filled her world, and her tales, if they were not of the days when she first came to Rowallan, were about these wonderful beings. They were far better than fairies, she said; for the best of fairies were mischievous at times, but the saints could be depended on. But the children thought her tales about their home were even more interesting than tales of the saints.

There was a time, she said, when the dilapidated old house and garden had been the finest in Ireland. When she came to Rowallan, a slip of a girl, more than forty years ago, there had been no less than seven gardeners about the place. Ould Davy, who worked in the kitchen garden now, was all that was left of them. Now the house was falling to pieces, great patches of damp discoloured the walls, and most of the rooms were shut up; but Lull had seen the day when all was light and colour, when the rooms were filled with guests, and the children, who slept in the nursery then, had heard the rustle of silk dresses, not the scamper of rats, on the stairs at night. The children could see, when they opened the shutters in the disused drawing-room, how beautiful everything had been then, though the yellow damask, the satin chairs, and the big sconces on the wall were faded, moth-eaten, and dusty now. And in the garden, where Lull's thoughts loved to dwell on the flowers she had seen—lupins, phlox, roses, pinks, bachelor's buttons, and more whose names she had forgotten, that had fought others for leave to grow, she said—a strange flower would now and again push its way up through weeds and grass to witness that her tales were true. Lull always ended her talks as she rose to take the children off to bed, with a promise that all would come back again, that one fine day their ship would come in.

Andy Graham, in the stable, said the same thing. On Sunday mornings, when they watched him getting ready to take them to church, he would say, as he put on the old top hat and faded blue coat that were his livery: "Troth, the day'll come when I'll not be wispin' hay round me head to keep on a hat that was made for a man twiced me size, an' it's more than an ould coat that has only one tail to it I'll be wearin'. I'll be the smartest lad in Ireland, with livery to me legs forby, when yer fortune comes back to yez all again."

This hopeful view of the future, a romantic fiction half believed by Lull and Andy themselves, was taken quite seriously by the children. They imagined their home was under some kind of enchantment that would one day be broken. It was true Lull had told them the present state of Rowallan was God's will, and Andy said God alone knew when their fortune would come back; but the children, whose mind held fairies, saints, banshees, and angels, and their mother's Puritan God, had no difficulty in reconciling God's will and an enchantment. One thing had helped to confirm this belief. Mick and Jane remembered the night their father died—it was the night Honeybird was born—and, thinking back over it now, they were sure they had heard the incantation that had wrought the spell. They had been waked by a noise, a muttering, and a tramp of feet on the gravel beneath the nursery window. They had been frightened, for Lull was not in the nursery, and when they ran out into the passage to call her they saw their mother standing in a white dress at the top of the stairs and a crowd of strange faces in the hall below. That was all they had seen, for someone had pushed them back into the nursery, and locked them in, but they had heard shrieks and horrible laughter through the night. No one knew when the spell would be broken, but when the one fine day did come the children believed that in some mysterious way the house would shake off its air of ruin and decay; the six gardeners would come back to join ould Davy, who, though he was so cross, had been faithful all these years; the horses and carriages and dogs that Andy remembered would return; their mother would come downstairs; and, perhaps, their father would come to life again, if he were really dead, and had not been whipped away to some remote island, they thought it was quite possible, till the time when the enchantment would cease.

Their chief reason for looking with joy to this day was that then their mother would be quite well, and their anxiety about her would be over. Twice a day they went to her room—to bid her good-morning and good-night. Then she read them a chapter from the Bible, and made them promise to say their prayers. From her they got their ideas of God's terrible judgments, and of the Last Day, when the heavens would roll back like a scroll, and they would be caught up in the clouds. Jane was afraid it might happen when she was bathing some day, and she would be caught up in her bare skin. She always put her boots and stockings under her pillow when she went to bed, in case it came like a thief in the night. Occasionally Mrs Darragh was well enough to forget her own trouble, and then she would keep the children with her, and tell them stories of the time when she was a child. These were the children's happiest days. They would sit on the floor round her sofa, listening, fascinated by her description of a life so unlike their own. Their mother, like a child in a book, had never gone outside the garden gates without her nurse, and they laughed at the difference between their life and hers. She never went fishing, and brought home enough fish to feed her family for three days; she never tramped for miles over mountains or spent whole days catching glasen off the rocks. The country she had lived in had been different, too—a red-roofed village, where every cottage had a garden neat and trim, and all the children had rosy cheeks and tidy yellow hair. But on their mother's bad days, when she remembered another past, they would creep to her door, and listen with troubled faces to her wild talk of sins and punishment, and hear her praying for forgiveness and death. Their love for their mother was a passionate devotion, and through it came the only real trouble they knew—they were afraid that God would answer her prayer, and take her from them. So her bad days came to mean days of black misery for them, when they spent their time beseeching God not to take her prayers seriously: it was only because she was ill that she thought she wanted to die, and would have changed her mind by the morning. If after one of these bad days a stormy night followed, misery changed to terror. On such a night the Banshee had wailed for their grandmother, and if they heard her now it would be for a sign that their mother must die too.

Lull would do her best to comfort them. "Banshee daren't set fut in the garden, or raise wan skirl of a cry, after all the prayers yez have been sayin'," she would tell them. But when she left them it was only to go to the kitchen fire and pray against the same fear herself. But, apart from this shadow, that often lifted for weeks at a time, their life was very happy. Mick, the eldest, was twelve years old, and Honeybird was five; the others, Jane, Fly, and Patsy, came between. The two eldest, Mick and Jane, led the others, though Fly and Patsy criticised their leaders' opinions when they saw fit; Honeybird was content to blindly obey. After one of their good days they would go to bed in the big nursery, sure that no children in the world were so content. When there was no frightening wind in the trees they could hear through the open window the sea across the fields. "It's a quare, good world," Jane would mutter sleepily; and Fly would reply: "The sea's the nicest ould thing in it; you'd think it was hooshin' us to sleep"; and then Patsy's voice would come from the dressing-room: "Mebby it's bringin' our ship in to us."

On Sunday morning the children went to church by themselves. They would rather have gone to Mass with Lull in the Convent Chapel, but Lull said they were Protestants. Everybody else was a Roman Catholic—Uncle Niel, Aunt Mary, Andy Graham, even ould Davy, though he never went to Mass.

None of the children liked going to church; they went to please Lull. The service was long and dull, and though each one of them had a private plan to while away the time they found it very tedious.

Jane was the luckiest, for under the carpet in the corner where she sat—Jane and Mick sat in the front pew—there was a fresh crop of fungi every Sunday; all prayer-time she was occupied in scraping it off with a pin. Honeybird came next; she had collected all the spare hassocks into the second pew, and played house under the seat. So long as they made no noise they felt they were behaving well, for old Mr Rannigan, the rector, was nearly blind, and could not see what they were doing. Sometimes Mick followed the service in the big prayer-book, just for the fun of hearing Mr Rannigan making mistakes when he lost his place or fell asleep, as he did one Sunday in the middle of a prayer, and woke up with a start, and prayed for our Sovereign Lord King William.

Fly played that she was a princess, but she always stopped pretending when the Litany came. Not that she understood the strange petitions, but she felt when she had repeated them all that there was no calamity left that had not been prayed against.

The sermon was the most wearisome part for them all. When the text was given out Jane read the Bible. Nebuchadnezzar was her favourite character. She pictured the fun he must have had prancing round in the grass playing he was a horse or a cow. Mick read the hymn-book, Fly fell in love with the prince whom she saved up for the sermon, while Patsy and Honeybird built a ship of hassocks, and sailed as pirates to unknown seas.

One Sunday morning they had just settled themselves in their seats—Jane had discovered what looked like a mushroom under the carpet, and was waiting for the general confession that she might see if it would peel—when the vestry door opened, and, instead of the familiar little figure in a surplice trailing on the ground, that had tottered in as long as the children could remember, a strange clergyman came in. He began the service in a loud voice that startled them, and read the prayers so quickly that the people were on their feet again before Jane had half peeled the mushroom.

When he came to the Psalms he glared at the children till Jane thought he was going to scold her for not reading too. She had not listened to hear what morning of the month it was, but she got so frightened that she had to pretend to be reading by opening and shutting her mouth. But it was worse when he came to the sermon. Jane, who had not dared to go back once to the mushroom, but had followed his movements all through the service, saw with horror when he went into the pulpit that Patsy and Honeybird had forgotten that he was not Mr Rannigan, and were stowing away all the books they could reach in the hold of their pirate ship. She reached over the back of the pew to poke Honeybird, but at that moment a loud voice startled her.

"Except ye be converted ye shall all likewise perish," the clergyman said. Then, fixing his eyes on a thin woman, who sat near the pulpit, he repeated the text in a louder tone.

"Do you know what that means?" he said, pointing to Miss Green. "It means that you will go to hell."

"What has she done?" Jane wondered. But the preacher had turned round, and was pointing to old Mr Byers. "You will go to hell," he said. Then he looked round the church. Jane saw that Patsy and Honeybird were sitting on their seats watching him.

"You will go to hell," he said again. This time he picked out Mrs Maxwell. Jane waited, expecting he would tell them some awful sins these three had committed. But after a long pause he said: "Everyone seated before me this morning will go to hell."

A chill seemed to have fallen on the congregation. Patsy said afterwards he thought the devil was waiting outside with a long car to drive them off at once. "Except ye be converted," the preacher added.

He went on to describe what hell was like, and told them a story of a godless death-bed he had stood beside, where he had heard the sinner's groans of remorse—useless then, for God had said he must perish. Jane's eyes never for a moment wandered from the man's face. Even when he turned to her she still looked at him, though she was cold with fear. "The young too will perish except they be converted," he said.

At last the sermon came to an end. The children went out to the porch to wait for the car. But the sermon had been so long that Andy Graham was waiting for them. The others ran down the path, but Jane turned back, and went into the church. All the people had gone. The strange clergyman was just coming through the vestry door. Jane went up to him. "I want to get converted," she said; "quick, for Andy Graham's waitin'."

"Pray to God, and He will give you an assurance that your sins are forgiven," the clergyman said.

"Come on, Jane," Patsy shouted at the porch door.

"Thank ye," said Jane, and went out to the car.

On Sunday afternoon they generally weeded Patsy's garden or played with the rabbits, but this day Jane went up to the nursery the minute dinner was over. Fly, who was sent up by Mick to tell her to come out, found the door locked.

"Who's there?" said Jane.

"It's me; Mick wants ye," said Fly.

"I can't come."

"What're ye doin'?"

"Mind yer own business," was the reply.

"Let me in; I want a hanky," said Fly.

There was no answer, but as Fly went on trying to turn the handle and banging at the door it suddenly opened, and Jane faced her.

"Can't ye go away ar that an' quit botherin' me?" she said.

"What're ye doin'?" said Fly, trying to look round the door, but Jane slammed it in her face.

"If ye don't go away I'll give ye the right good thumpin'," she said. Fly went downstairs.

At tea Jane appeared with a grave face.

"We'll play church after tea," she said, "an' I'll be the preacher."

They arranged the chairs for pews. Patsy rang the dinner bell. Fly was the organist, and played on the table. Jane leant over the back of an arm-chair to preach.

"Mind ye," she said, "I'm not making fun. I'm converted, an' ye've all got to get converted too, or ye'll go to hell for iver and iver. An' ye can't think about for iver an' iver, for it's for iver, an' then it's for iver after that, till it hurts yer head to go on thinkin' any more. We'll all have to quit bein' bad, an' niver fight any more an' tell no lies an' niver think a cross word, an' if we say our prayers God'll give us an insurance, an' then we'll be good for iver after."

Then she read a chapter out of the Bible. But it was not a part the others liked—about Daniel or Joseph or Moses and the plagues—it was a chapter of Revelation. They listened patiently to that, but when Jane said she was going to pray Patsy got up.

"I'm tired," he said, "an' I don't want to get converted. I don't believe that ould boy knowed what he was talkin' about. Andy Graham said he was bletherin' when I told him about us all goin' to hell."

Fly and Honeybird said they wanted to paint, so Jane came out of the pulpit.

"Ye'll just have to get converted by yer own selves," she said, "for I'm not goin' to help ye any more."

When they went to bed Jane read the Bible to herself, and was such a long time saying her prayers that Fly thought she had gone to sleep, and tried to wake her.

"I'm niver goin' to be cross any more," she said as she got into bed.

The next day was wet, so wet that Lull would not allow them to go out. Jane began the morning by making clothes for Bloody Mary, Honeybird's doll. But Honeybird would have the clothes made as she liked. Though Jane tried to persuade her that Bloody Mary had worn a ruff and not a bustle Honeybird insisted on the bustle, and would not have the ruff. At last Jane said she would make the clothes her own way or not at all.

"Then ye needn't make them at all," said Honeybird, picking up Bloody Mary, and going out of the room.

When she got to the door she added, over her shoulder: "Girney-go-grabby, the cat's cousin," and ran.

But Jane was at her heels, and caught her at the foot of the stairs. She pulled Bloody Mary from under Honeybird's arm.

"I'll make a ruff, an' sew it on tight," she said grimly.

Honeybird began to cry. Jane was just going to give her back the doll when Fly appeared at the top of the stairs, and looked over the banisters.

"Let her alone," said Fly.

"Shut up," said Jane.

"I thought ye were converted," said Fly. In a minute Jane was at the top of the stairs, and slaps and howls told that Fly's remark was answered.

There was nothing Fly hated so much as being slapped. If they had fought properly, and she had been beaten, she would not have minded so much, but when Jane slapped her she felt she was degraded.

Having punished her Jane walked slowly downstairs. When she got to the last step she looked up. Fly spat over the banister.

"Cat!" Jane yelled running up the stairs again two at a time; but Fly raced down the passage, and was just in time to shut and lock the nursery door in Jane's face.

"All right, me girl," Jane shouted through the keyhole. "You wait an' see what ye'll get when ye come out."

"I'm not coming out," said Fly, "I'm goin' to see what ye've got in yer drawer."

Jane went down to the schoolroom. No one was there. Honeybird had gone to play in the kitchen. She sat down, with her elbows on the table, her head in her hands.

"It wasn't my fault," she muttered—"I didn't want to fight—but I'll kill her now when I catch her. I don't care. God had no business to let her spit at me, an' I will just kill her."

Soon she heard Fly coming downstairs, and got under the table to wait for her. Fly pushed the door open, looked in, then came in, and shut the door behind her. She went up to the bookcase, and was looking for a book when, with a yell of fury, Jane pounced on her. Jane thumped on Fly's back and Fly tore Jane's hair. They rolled over on the ground, biting and thumping, till Jane was on the top. She held Fly down, and very deliberately slapped her, counting the slaps out loud, six times on each hand. "That's for spittin'," she said as she got up.

Fly sobbed on the floor. Lull came in to lay the table for dinner.

"'Deed, ye ought to be ashamed a' yerselves," she said, "fightin' like Kilkenny cats. What would yer mother say if she heard ye?"

Jane banged out of the schoolroom, and out of the house. She went across the yard to the stables, climbed up into the loft, and threw herself down on a bundle of hay.

Lull called her to come in to dinner, but she did not move. Mick and Patsy came out to look for her. After a few minutes she heard them go back into the house. When all was quiet again she sat up. "I'll go to hell," she said—"an' I don't care a bit. I wisht I was dead." She had thought only yesterday, when she was converted, and had been all warm and happy inside, that God would never let her fight any more. But God had failed her. He had allowed her to fight the very next day.

"He might 'a' made me good when I ast Him," she muttered. "I hate fightin'; but I can't help it, an' now I'll niver be good."

By-and-by she heard Honeybird at the kitchen door. "Janie, come in," she was calling, "there's awful nice pancakes for pudden." Jane didn't want the pancakes; she wanted very much to go in, and be happy, but something held her. "Come on in, Jane," Honeybird called. "Fly's awful sorry she spit at ye." Honeybird called once more, then Jane heard the kitchen door shut.

"It's the divil," she muttered; "he won't let me be good." In a burst of despair she beat her head against the wall till she fell back exhausted on the hay.

The next thing she heard—she must have been asleep—was the tea bell ringing. Still she did not go in, but when the loft began to get dark she was so frightened that she crept down the ladder, and went into the kitchen. There was no one in the kitchen but Lull.

"Och, now ye'll be sick if ye cry like that," said Lull. "Sit down here by the fire, an' have a drop milk an' a bit a' soda bread."

But Jane could not eat. She managed to swallow the milk, then as Lull stroked her rough hair she began to cry again.

"Whisht, whisht, chile dear," Lull said; "sure, ye can't help fightin' now an' then. Come on upstairs, an' have a nice hot bath, an' go to yer bed, an' ye'll be as good as Saint Patrick in the mornin'."

When the others came to bed she was asleep, but she woke before they were undressed.

"I'm sorry I was cross," she said.

"So am I," said Fly.

"Ye were just as cross as I was yerself," Jane said sharply.

"That's what I mane," said Fly.

"Then ye should say what ye mane," said Jane. "Ye just want to make me fight again."

"'Deed, I don't," Fly began.

But Jane threw back the clothes, and jumped out of bed. "There!" she said, "ye've done it. Ye've made me cross again."

Fly and Honeybird both began to cry. They got undressed, crying all the time. When they were ready for bed Fly said: "Aren't ye goin' to get into bed, Jane?"

"No!" said Jane.

"But ye'll catch yer death a' cold," said Fly.

"I just wisht I could," said Jane. She sat down on the floor by the window.

"I'll just sit here till I die," she said, "an' then I'll go to hell."

Fly and Honeybird began to howl. The boys came in from the dressing-room.

"What's the matter?" said Mick.

"I'm goin' to hell," said Jane; "I can't help it. I don't want to go, but Fly makes me fight. She's sendin' me to hell, an' I'll just sit here till I'm dead."

Mick begged her to get back into bed. Fly and Honeybird sobbed and shivered. "Don't go to hell, Jane," they pleaded; "get into bed, an' we'll niver make ye cross any more."

But Jane shook her head. "I'm goin'; I can't help it," she said.

Patsy looked at her.

"Let her go if she wants to," he said, "I'm goin' to sleep." He went back into the dressing-room. Jane looked after him, and then began to laugh.

"I declare to my goodness I'm an ould divil myself," she said, "makin' ye all miserable." She got up, and kissed them all.

"An I'll make Bloody Mary a bustle in the mornin'," she said as she got into bed.

"I think I'd rather have a ruff," said Honeybird.

Next Sunday Mr Rannigan was at church. When he gave out his text Jane looked at him. "Brethren, it is my duty to preach the simple gospel," he began, and Jane opened the Bible at Nebuchadnezzar.

Fly sat on the wall in the wood at the back of the garden simmering with excitement. Two wonderful things had happened to her, each of which by itself would have been enough to make her happy for a week. First, she had got a letter in the morning addressed to herself. She was so pleased that she did not think of opening it till Jane took it from her. The inside, however, was still more delightful. Somebody called Janette Black said she had a little present for Fly, and was bringing it to Rowallan that afternoon. Lull said Miss Black was Fly's godmother. She used to live at Rose Cottage years ago, but for a long time she had been away in Dublin. Fly was too much excited to eat her breakfast. The others as they watched her dancing round the room could not help being a little bit envious at her good fortune. They had never heard of anybody before, except Cinderella, who had had a visit from a godmother. Their godmothers were all dead, or away in England. Fly in her happiness had a pang of regret that she could not share this delightful relative with the others. She said she would share the gift. She had thought that morning would never pass. Lull was getting the drawing-room ready for the visitor, and once or twice she had warned Fly that she might be disappointed.

"I wouldn't marvel if she niver come near the place at all," she said. "She's a bird-witted ould lady, an' niver in the wan way a' thinkin' two minutes thegether." But Fly could not have been calm if she had tried. She had spent her time going backwards and forwards to look at the kitchen clock. Now the time had come, dinner was over, Fly had her clean pinafore on, the godmother was, perhaps, already in the house, but Fly was so busy thinking of something else that she had almost forgotten her. The second wonderful thing had happened. There were days, Fly told herself, when things took jumps—when, instead of growing up at the usual pace, so slow you could not feel it, something happened that made you older and richer and cleverer all in a minute. To-day life had taken two jumps. As she was sitting there quietly on the wall, thinking only of her godmother, a big yellow cat had come out of the wood. Everybody at Rowallan hated cats—they were deadly enemies, poachers, and destroyers. Andy had been in trouble for the past week over the wickedness of a cat who, night after night, had been at the rabbits in his traps. Rabbits were a source of income to Rowallan, and it was a serious matter when six rabbits were destroyed in one night. Fly had been in the kitchen that morning when Andy came in to tell Lull his trouble.

"I niver seen the cat that could get the better av me afore," he said dejectedly. "I'm thinkin' I'm gettin' too ould for this game." Fly remembered this as she watched the cat coming towards her through the wood. If only Andy were there now with his gun. It was a terrible pity that such a chance should be lost. She sat quite still, waiting to see what the cat would do. It never seemed to notice her, but came boldly on, with no sense of shame, straight towards her, till it was beneath her feet. The wall was high, and the cat had jumped before Fly realised that it meant to use her legs as a ladder to the top. Indignation on Andy's account now gave place to wild rage at personal injury. The cat's claws were in her leg. She kicked it off, then, quick as thought, seized a big flat stone off the top of the wall, and dropped it on the cat's neck. The yellow head bowed, and without a sound the body rolled over on the grass. Fly saw that she had killed it. Her heart jumped for joy. She could hardly believe she had really done this wonderful thing. Andy's enemy lay dead at her feet, struck down by her unerring aim. What would the others say? What would Andy say? How they would all praise her! She felt that God had helped her. It must be He who had brought the cat within her reach and given her power to kill it with one blow of a stone. Honeybird's voice called from the garden. Fly gave a little gasp—her heart was beating so quickly with excitement. To find a godmother and to kill a cat in one day!—had anybody else ever had such happiness? She got down from the wall, and took the dead cat in her arms. She must go to the godmother now, and wait till she had gone before she could tell the others. There was nobody at home to tell except Honeybird, for Jane had gone with Andy on the car to bring Mick and Patsy home from school. She would hide the cat in the stables, she thought, and when the others came home she would produce it dramatically, and see what they would do. On the way through the garden she met Honeybird coming to find her.

"She's come," said Honeybird, "in a wee donkey carriage an' a furry cloak; but I'm feared she's got nuthin' with her, 'cause I walked all round her to see."

Fly held up the cat. "I've just kilt it with wan blow av a stone," she said.

"Well done you," said Honeybird joyfully. "Bad auld divil," addressing the dead cat, "what for did ye eat the neck out a' Andy's rabbits?" Then her tone changed. "Give him to me, Fly, to play feeneral with. Sure, you've got a godmother, an' I've got nuthin' at all." Fly had not the heart to refuse. She gave Honeybird the dead cat, but explained that she must be allowed to dig it up again to show it to Andy. Then she ran quickly towards the house. A smell of pancakes came from the kitchen. Lull was getting tea ready for the visitor. Fly felt that life was richer than she had ever known it to be. At the drawing-room door she paused to mutter a little prayer of thanksgiving. She hardly knew what she had been expecting, but she was a little bit disappointed when she opened the door and went in. Her godmother was sitting on a sofa. She was a little woman, dressed in dull black; an old-fashioned fur-lined cloak fell from her shoulders; a lace veil, turned over her bonnet, hung down like a curtain behind. She wore gloves several sizes too big for her, and the ends of the fingers were twisted into spikes. But her voice pleased Fly's ear. She had been to see Mrs Darragh, she said, but had only stayed a minute. In spite of her disappointment there was something about the little lady that attracted Fly's fancy. Her eyes were just the colour of the sea on a clear, sunny day. She talked a good deal, holding Fly's hand and patting it all the time. Fly did not understand much of what she said—she mentioned so many people Fly had never heard of before.

"You know you are my only god-child," she said; "when I die you shall have all my money if you are a good girl." Fly thought this was very kind, but she begged her godmother not to think of dying for years yet. The little lady smiled. Then she began to talk again about people Fly did not know, nodding and smiling as though it were all very funny. Fly wondered when she would come to the gift.

"There now, I've talked enough," she said at last. "Tell me all about yourself and the other dear children now."

Fly told her everything she could remember. Miss Black said "Yes, yes," "How delightful," "How pleasant," but she did not seem to be listening; her eyes were looking all round the room, and once she said "How pleasant" when Fly was telling her about the time Patsy hurt his foot. Fly was in the middle of the tale of Andy's trouble that morning when Miss Black interrupted her.

"You must come and see me, my dear, and bring the others with you, and you shall make the acquaintance of my darling Phoebus."

Here was another person Fly had never heard of. She wondered who he could be.

"Naughty darling Phoebus," Miss Black went on. "Oh, he has been so naughty since we left Dublin. Out for hours by himself, frightening me into fits. But he doesn't care how anxious I am."

He must be her son, Fly thought; rather a horrid little boy to frighten his mother like that. She asked Miss Black if he were her only child.

Miss Black laughed. "He is, indeed, my darling only one; you must come and see him. You will be sure to love him. He is not very fond of children, but I shall tell him he must love you and not scratch."

Fly thought she would not love him at all, but she was too polite to say so. She wished Miss Black would say something about her present. But Miss Black went on talking about Phoebus. She called him her golden boy, her heart's delight and only treasure. Fly was rather bewildered by this talk. It seemed to her that Phoebus must be a very nasty little boy: he ate nothing but kidney and fish, his mother said, and never a bite of bread with it.

Lull brought in tea, and when Miss Black had finished her tea she became silent. Fly did not like to speak. She thought her godmother must be thinking of something important. She waited a little while, then, as Miss Black continued silent, she cautiously introduced the subject of godmothers. It might, perhaps, remind the little lady of what her letter had promised. She told Miss Black about the other children's godmothers, and how lucky the others thought she was to have a godmother alive and in Ireland. Miss Black patted her hand absently, and gazed round the room.

"I know there is something I wanted to remember," she said at last. Fly waited eagerly. She knew what it was, though, of course, she could not say so. "I have it," said Miss Black. "I wanted to ask for a rabbit for Phoebus. He has no appetite, these days. This morning he touched nothing but his saucerful of cream. Do you think you could get me a rabbit, my dear? Phoebus adores rabbit."

"To be sure I can get ye wan," said Fly, swallowing her disappointment. "I'll get ye wan to-morra from Andy."

Miss Black got up to go. "That is kind of you," she said; "and, now that I remember, I had a little gift for you, but I forgot to bring it. Come to-morrow, and you shall have it. And don't forget the rabbit for Phoebus."

"I'll hould ye I'll not forgit," said Fly. "We've been havin' bad luck this wee while back with the rabbits. Some ould cat's been spoilin' them on us. But just a minute before you came I kilt the ould baste." Fly looked for applause, but her godmother's attention had wandered again.

"How very pleasant," she said. Then suddenly she looked at Fly. "What did you say, dear child?"

"I said I kilt an ould thief of a cat," said Fly proudly.

The godmother grasped her by the arm. "Killed a——" Her voice was almost a scream. "Merciful heavens! what do you mean?"

Fly was frightened. Her godmother seemed to have changed into another person. She looked at Fly with burning eyes.

"Wicked, wicked, cruel child!"

"I couldn't help it," Fly stammered. "I done it by accident." Had she all unconsciously done some awful thing? Surely everybody killed cats. They were like rats—a plague to be exterminated.

"What was it like?" demanded her godmother.

"The nastiest-lukin' baste I iver set eyes on," said Fly earnestly.

"If it had been Phoebus I think I should have killed you," said Miss Black.

Fly looked at her in a bewildered way.

"You are quite sure it wasn't Phoebus—not my darling cat?" said her godmother sternly.

A horrid fear seized Fly. Phoebus was not a boy, he was a cat—surely, surely not that yellow cat—such a thing would be too terrible.

"Was it a large, dignified creature with yellow fur?" her godmother questioned.

"It was not," said Fly emphatically. "It was a wee, scraggy cat, black all over, with a white spot on its tail."

"Thank God for it," said Miss Black. "If it had been Phoebus I should have died."

Fly was shaking all over; she felt like a murderess. If only her godmother knew the truth! It was, of course, hopeless to ask God to make the cat alive again. The only thing was to get her godmother safely away from Rowallan, and pray that she might never come back. Anxiously she watched the lady go down the steps. The donkey carriage was waiting. In another minute she would be gone; but, with her foot on the step of the carriage, Miss Black paused.

"I must see the garden; it was so pretty once, and I may never be back again," she said. Fly led the way. The burden on her chest lifted a little as she heard that her godmother would not be likely to come again. It would not take long to see the garden, and then she would go for ever. When they were half way down the path the garden gate opened, and Honeybird came through, wheeling a barrow. She had Lull's old crape bonnet on her head. Fly had a moment of sickening fright.

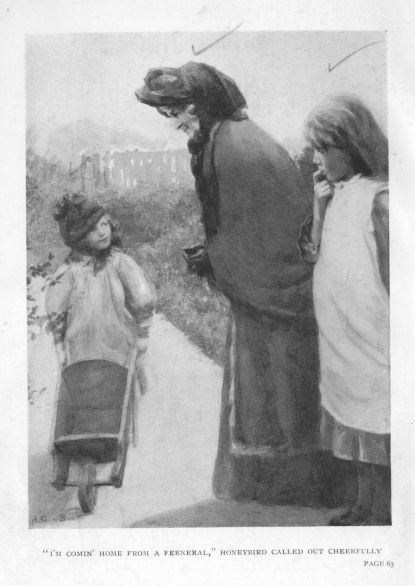

"I'm comin' home from a feeneral," Honeybird called out cheerfully. "I've just been buryin' my ould husband, an' now I'm a widdy woman."

Fly breathed again: Phoebus was safely buried.

"How very nice," said Miss Black.

"Ye wouldn't say that if ye knowed who her husband was," Fly thought.

"Would ye 'a' liked to be a mourner?" Honeybird asked, with a smile at Miss Black. "'Cause if ye would I can dig him up, an' bury him again."

Fly grimaced at her in an agony of terror. "Lull wants ye this very minute," she said hurriedly. Honeybird nodded to them, and took her barrow again, and went on round the house.

By this time the sun had set, and the garden was full of that strange, luminous twilight that comes with frost in the air.

A cluster of late roses in Patsy's garden glowed against the fuchsia hedge; a white flower stood out in almost startling distinctness. Above the pear-tree the sky was clear, cold green; a flush of red mounted from the south-west. The garden, shut in by the convent wall and high hedge, seemed to Fly like a box without a lid at the bottom of a deep well of clear sky.

She sniffed the cold air. Her happiness had gone from her, but she had been mercifully delivered from her trouble. Suddenly a hand gripped her. Her godmother pointed with the spiked finger of a black kid glove to Honeybird's garden. It was a bare patch—nothing grew there—for what Honeybird planted one day she dug up the next. To-day Honeybird evidently had made a new bed-centre, and bordered it with cockle shells. Fly's knees shook under her. In the middle of that bed, coming up through the newly-turned earth, with a ring of cockle shells round its neck, was the head of a big yellow cat. It was here Honeybird had buried her husband—buried him, unfortunately, as she always buried birds, with his head out, in case he felt lonely in the dark. Miss Black was down on her knees, clearing the earth away. Fly never thought of escape. She felt as though she were tied to the path. She stood there while her godmother lifted the dead cat in her arms and tenderly brushed the earth from its fur. Then the little lady turned round. "Now she'll kill me," Fly thought. She lifted her terrified eyes to Miss Black's face. How would she do it, she wondered. But her godmother never seemed to notice her. Without a word she turned, and walked quickly from the garden. A moment later Fly heard the gate shut. She was too bewildered to move. The sound of wheels going down the avenue roused her to the fact that her godmother had gone. She had been found out, and no awful punishment had followed, but to her surprise there was no relief in this. Fly felt as miserable as ever. She looked up at the sky. A star showed above the pear-tree. She had not meant to do anything wrong, but she had hurt somebody terribly. Whose fault was it? Almighty God's or her own? The donkey carriage was going slowly up the road; she could hear the whacking of a stick and the driver's "gone a' that." Suddenly through the frosty air her ear caught the sound of bitter weeping. Then Fly turned, and ran from the garden, dashing wildly through Patsy's flower-bed in her haste to get away from that heart-breaking sound.

Fly and Honeybird introduced Samuel Brown to Rowallan. They found him sitting at the gate one day, and mistook him for the child Samuel. For a long time they had been expecting the coming of a mysterious beggar, who would turn out to be a saint or an angel in disguise. Such things had often happened in Ireland, Lull said. But, although scores of beggars came to Rowallan, so far no saint or angel had appeared. Most of the beggars were too well known to cast off a disguise worn long and successfully and suddenly declare themselves to be celestial visitors. But now and then an unknown beggar came from nobody knew where, and disappeared again into the same silent country. These nameless ones kept the two children's faith and hope alive. Samuel was one of these. Fly had spied his likeness to the child Samuel the minute she saw him sitting at the gate tired and dejected. They went to work cautiously to find out the truth, for they had got into trouble with Lull a few days before for bringing into the house a possible St Anne, who had stolen the schoolroom tablecloth. But when they asked his name, and he said it was Samuel, they did not need much further proof.

Was he the real child Samuel out of the Bible? Honey bird asked, to make sure. The boy confessed he was. He had come straight from heaven on purpose to visit them, he said.

As they were taking him up to the house they met Patsy, and told him. Patsy jeered at their tale, and reminded them of St Anne. But, in spite of Patsy's warning, they took the beggar into the kitchen. Patsy, disgusted at their folly, left them to do as they pleased. If he had remembered that Lull was out he might have been more careful. Half-an-hour later he caught sight of the child Samuel running down the avenue wearing his best Sunday coat. Lull was very angry with Fly and Honeybird when she came home. Mick and Jane said it was the beggar who was to blame. Patsy had given chase, and did not come home till ten o'clock that night. When he did come back he brought his Sunday coat with him, as well as a black eye. He had followed the child Samuel to the town, he said, and Eli had never given the boy as good a beating. In spite of this beating and the discovery of his fraud Samuel came back a few days later. His mother was sick, he said, and he had come to borrow sixpence. Jane wanted Mick to give him a second beating.

"Nasty wee ruffan, comin' here cheatin' two wee girls," she said.

Samuel took no notice of her. He addressed his remarks to Patsy.

"Anybuddy could chate them, but I'm thinkin' it'd be the divil's own job to chate yerself," he said flatteringly.

Patsy smiled. "Don't you try it on, that's all," he said.

"Do ye think I want another batin'?" Samuel grinned. He stayed, and played with them all afternoon, in spite of Jane's plain-spoken requests for him to be off. Before he left he had a good tea in the kitchen, and got sixpence from Lull, who had a tender heart for the poor. After that he came frequently. He said his mother was dying, and wrung Lull's heart by his tales of the poor woman's sufferings. Jane noticed, and did not fail to point out, that grief never spoilt his appetite for pears. Now and then Samuel would silence her by a wild fit of weeping. Patsy got angry with Jane for her cruelty.

"Let the poor wee soul alone, an' quit yer naggin' at him," he said one day, when Jane's repeated hints had made Samuel throw himself on the grass to cry.

"I wisht I believed he was tellin' no lies," was Jane's answer.

Lull agreed with Patsy that Jane was too suspicious.

"No good iver comes to them that's hasky with the poor," she told Jane. Lull was Samuel's best friend. Every time he came she gave him something for his dying mother. There was one thing the children did not like about Samuel: he never seemed to be content with what he got. He begged for more and more, till even Patsy was ashamed of him. One evening he grumbled because Lull had only given him a penny. He had had a good tea, and his pockets were lined with apples to eat on the way home.

"It's hardly worth my while comin' if that's all I'm going to get," he said.

"Then don't be troublin' yerself to come anymore," said Jane; "we'll niver miss ye."

Samuel looked reproachfully at her. "How would ye like your own mother to be dyin'?" he asked. Jane's heart melted at once. She offered him flowers to take back. Samuel refused the flowers. "Thon half-crown ye have in yer money-box'll be more to her than yer whole garden full," he said.

But Jane was not sympathetic enough for this. She said she was saving up to buy Lull a pair of boots at Christmas. After he had gone she wondered how he could have known about her money-box, and then remembered that Fly and Honeybird had told him most of the history of the house on his first visit. The very next day Samuel came to tell them that his mother was dead. His eyes were red and swollen with weeping. For half-an-hour after he came he sat in the kitchen sobbing bitterly, and refusing to be comforted. Fly and Honeybird cried in sympathy, and Jane would have cried too if she had not been so busy watching him. He cried steadily, only stopping every now and then, to wipe his nose on his sleeve. She decided she would give him the black-bordered handkerchief she had treasured away in her drawer upstairs; also, she would make a beautiful wreath for his mother's coffin. But soon the terrible truth came out that there was no coffin. Between bursts of sobs Samuel explained that his father was in gaol, and he himself had not a penny to pay for the funeral.

"An' her laid out an' all," he wept. "The neighbours done that much for her. In as nice a shroud as ye'd wish to wear. She had it by her this many's the day. But sorra a coffin has she, poor soul, an' God knows where she's goin' to get wan."

Lull was greatly distressed. "To be sure, the parish would bury the woman," she said; "but God save us from a burial like that." She took her teapot out of the cupboard, and gave Samuel five shillings.

"If I had more ye'd be welcome to it, but that's every penny piece I've got," she said. Samuel thanked her kindly, and murmured something about money-boxes. Mick responded at once.

"I'll bet ye we've got a good wee bit in them," he said joyfully. The money-boxes were opened, and found to contain nearly ten shillings. The children handed over their savings gladly to help Samuel in his need. Even Jane rejoiced that she had her half-crown to give. Samuel went away immediately after this, and not until he had been gone some time did Jane remember the black-bordered pocket handkerchief. However, she determined to take it to him, and also to take a wreath for the coffin. After dinner she made the wreath in private. Lull might have forbidden it if she had known. Then she called Mick and Patsy, and they started for Samuel's house. He lived near the town, so they had a long walk before they reached the squalid street. Some boys were playing marbles when the children turned the street corner. One of them looked up, then rose, and fled into a house. Jane thought he looked like Samuel, but she said nothing. Patsy had led the way so far; now he stopped, and said they must ask which was the house. They asked some women sitting on a doorstep.

"If it's Mrs Brown ye want, she's been in her grave this six years," one of them said.

"Why, Samuel tould us ye helped to lay her out this mornin'," said Jane indignantly. A drunken-looking woman came forward.

"To be sure we did," she said. Jane fancied she saw her wink at the others. "Samuel tould ye his poor mother was dead, didn't he, dear? I suppose ye've brought a trifle for him, the poor orphan."

"Which house does he live in?" Jane asked.

"Don't trouble yerselves to be goin' up. The place is not fit for quality. Lave yer charity with me, an' I'll give it to the childe." Jane insisted on going up. The woman said she would bring Samuel down to them. She seemed anxious to keep them back. But suddenly Samuel himself appeared at a door.

"I knowed ye'd mebby come," he said in a hushed voice as he led them up the stairs. He pushed open a door, and invited them to step in.

"The place is that dirty I hardly like to ask ye," he said. The room was very dirty, but the children hardly noticed this. All their attention was concentrated on the bed where the corpse lay, straight and stiff, covered with a sheet. They stood silently by, awed by the outlines of that rigid figure. Jane began to wish she had not insisted on coming upstairs. But it was their duty to look at the dead. Samuel would be hurt if they did not; he would think they were wanting in respect. She dreaded the moment when he would turn back the sheet, and show them the cold, unnatural face, that would haunt her eyes for days. Breathing a prayer that God would not let her be frightened she stepped forward, and put the wreath at the foot of the bed. As she did so her hand touched something hard. At once fear gave place to suspicion. Under cover of the wreath she felt again, and made sure the corpse was wearing a pair of hobnailed boots. She looked carefully, and saw that the sheet was moved as if by gentle breathing. Samuel, weeping at the head of the bed, never offered to turn back the sheet.

"I'd like to luk at her face," said Jane at last.

Samuel cried more than ever. "Don't ast me," he said. "The poor soul got that thin that I'd be feared for ye to see her."

"God rest her, anyhow," said Mick piously.

"Well, I'm thinkin' that's the quare thing," said Jane, looking hard at Samuel, "not to show a buddy the corpse. I niver heard tell a' the like." Samuel's answer was more tears. Mick and Patsy were both ashamed of their sister.

"I'm thinkin' she's not dead at all," Jane went on.

"Whisht, Jane; are ye clean mad?" Mick remonstrated. Samuel stopped crying. "Can't ye see for yerself she's dead right enough?" he said.

"I'd be surer if I seen her face," said Jane.

Mick in disgust turned to go, but Jane stood still.

"Wait a minute till I fix this flower that's fallen out," she said, noting with satisfaction that Samuel looked uneasy. She watched the figure under the sheet, and made sure it was breathing regularly then she took a pin out of her dress, and bent over to arrange the wreath. Suddenly her hand dropped on the sheet. There was a yell of pain, and the corpse sat bolt upright. Samuel's fraud was laid bare. His dead mother was a man with a black beard.

"God forgive ye, ye near tuk the leg aff me," he shouted, "jabbin' pins into a buddy like that."

"Shame on ye!"—Jane's eyes blazed; "lettin' on to be dead; I've the quare good mind to tell the polis." She turned to Samuel, but he had gone. Patsy had gone too; only Mick stood there, with a white, scared face.

"Come on ar this for a polisman," she said wrathfully, and swept Mick before her. The corpse was still rubbing his leg. Out on the street the women crowded round to know what had happened. Jane pushed her way through them.

"I think ye all a pack a' rogues," was the only answer she would give to their questions. Patsy was nowhere to be seen, so they turned sorrowfully homeward, to tell Lull for what they had parted with their savings. Patsy followed them a few hours later. He had been looking for Samuel to beat him, but Samuel had got away. He never came back to Rowallan. They watched for him for weeks, but never saw him again. The thought of the first beating Patsy had given him was the only satisfaction they ever got from the memory of Samuel Brown.

The children had gone on an excursion that would have been too far for Honeybird, and had left her playing on the grassy path. It was a favourite place, especially in May, when the apple-trees, that made a thick screen on one side, were in blossom, and the grass was starred with dandelions and daisies. There was not a safer spot in the garden, the hedge was thick, the path was sunny, and it was a part ould Davy, the cross gardener, never came near. Patsy had allowed her to play with his rabbits and call them hers while he was away. He had carried out the hutches for her before he started. Honeybird was quite content to be left at home when she could play with the rabbits. She played being mother to them. Mr Beezledum, the white Angora, was her eldest son. Together, mother and son, they went to market to buy dandelions for the children at home, bathed in the potato patch that was the sea, and went to church under the hedge. It was the nature of children to hate going to church, she knew, so when Beezledum struggled and protested against having his fur torn by thorns she only gripped him closer, and sternly sang a hymn. Beezledum suffered a great deal; for Honeybird liked this part of the game best, and went to church more often than to market. When Mick looked back from the far end of the path as he started she was already under the hedge, with Beezledum struggling in her arms. He heard her shrill voice singing: "Shall we gather at the river?"

The day was warm and bright. The children tramped for miles, and it was nearly eight o'clock when they came home, tired and hungry, and clamouring for food. But the minute they saw Lull's face they saw that something had happened. Her eyes were red with crying. Teressa was in the kitchen too, wiping her eyes on the corner of her old plaid shawl. It was Honeybird, Lull said when she could speak, for the sight of the children made her cry again. Honeybird was lost; she had been missing since dinner-time. Andy Graham and ould Davy were out scouring the countryside for her. The children did not wait to hear more. They ran at once to the grassy path where they had left Honeybird in the morning. Mrs Beezledum was turning over half a ginger biscuit in her hutch, the other rabbits were nibbling at the bars for food, but all that was left of Honeybird and Mr Beezledum was a tuft of white fur in the hedge. For a minute the children looked at each other, afraid to speak. One of their terrors had come at last. Honeybird had been stolen. Either the Kidnappers or the Wee People had taken her. The children stared at each other's white faces as they realised what had happened. If the Kidnappers, those tall, thin, half men, half devils, had taken her they would carry her away behind the mountains, and there they would cut the soles off her feet, and put her in a hot bath till she bled to death. And if the Wee People had got her it would be to take her under the ground, where she would sigh for evermore to come back to earth. Mick's voice was thick when he spoke. "We'll hunt for the wee sowl till we drop down dead," he said.

The fear of the Kidnappers was the most urgent, so towards the mountains they must go first. The rest started at a run that soon left Fly behind; but they dared not wait for her, and though she did her best to keep up they were soon out of sight. But Fly never for a moment thought of going back. Left to herself she jogged along with her face to the mountains. The sun, setting behind Slieve Donard, threw an unearthly glow over the fields. The mountains looked bigger and wilder than ever, the sky farther away. Everything seemed to know what had happened, even the birds were still, and a silence like an enchantment made the whole country strange.

At last, in the middle of the field, Fly stopped, with a stitch in her side. A flaming red sky stared her in the face, a wild, unknown land stretched away on every side. Things she had been afraid of but had only half believed in crowded round her. She saw now that they had been real all the time, and had only been waiting for a chance to come out of their hiding-places. Strange faces grinned at her from the whins, cold eyes frowned at her from the stones. In another minute that ragged bramble would turn back into an old witch. And behind the mountains the Kidnappers were cutting the soles off Honeybird's feet. With a wail of anguish Fly began to run again. She was not afraid of the fiends and witches. They might grin and frown and laugh that low, shivering laugh behind her if they liked—her Honeybird, her own Honeybird, was behind the mountains, alone with those awful Kidnappers.

"Almighty God, make them ould Kidnappers drop our wee Honeybird," she wailed.

Then she stopped again. She had forgotten that Almighty God could help.

But He would not help unless He were asked properly. For a moment she doubted the wisdom of stopping to ask. She was conscious of many grudges against her. This very day she had promised she would not do one naughty thing if God would let it be fine—and then had forgotten, and played being Moses when they were bathing, and struck the sea with a tail of seaweed to make it close over Patsy, who was Pharaoh's host. But her trouble was so great that, perhaps, if she confessed her sin He would forgive her this time. So she knelt down, and folded her hands. "Almighty God," she began, "I'm sorry I didn't keep my promise about being good, I'm sorry I was Moses, I'm sorry I'm such a bad girl, but as sure as I kneel on this grass I'll be good for iver an' iver if ye'll send back our wee Honeybird."

Tears blinded and choked her for a moment. Almighty God could do everything, could help her now so easily. It wouldn't hurt Him just for once, she thought. She went on repeating her promise to be good, begging and coaxing, but no sign came from the flaring heavens. At last she got desperate. "If ye don't I'll niver believe in ye again," she shouted, then added: "Oh, please, I didn't mean to be rude, but we want our poor, poor, wee Honeybird." She laid her face down on the grass, and sobbed.

Almighty God might have helped her, she thought. It wasn't much she had done to make Him cross after all—but, then, He was just—and she had made Moses cross too. But Honeybird must be saved from the Kidnappers, and if Almighty God would not help Fly knew she must go on herself. She dried her eyes on her sleeve, and was getting up from her knees, when something white hopped out from behind a whin. It was Beezledum; and when Fly looked in under the whin there was Honeybird fast asleep. She knelt down, and folded her hands again. "Almighty God," she said, "I'll niver, niver to my dyin' day forget this on ye." Then with a yell of joy she ran to wake Honeybird.

There was great rejoicing when they got home. Lull hugged and kissed them both, and made Honeybird tell her story over and over again.

"It was that ould Beezledum," Honeybird said; "he didn't like goin' to church, an' he ran away through the hedge. An he run on an' on, an' I thought I'd niver catch him. An' when I catched him, an begun to come home, I was awful tired, an' I just sat down to get my breath, and Fly came and woke me up."

About ten o'clock the others came home, despairing of ever seeing Honeybird again. They had met ould Davy at the gates, who told them to run on and see what was sitting by the kitchen fire.

What was sitting by the kitchen fire when they came in was Honeybird eating hot buttered toast.

Lull pulled up their stools to the fire, and took a plate of toast that she had made for them out of the oven. The rest of the evening was spent in rejoicing. Fly began to be elated.

It was she who had found Honeybird. The others had run on and left her, but she was the best finder after all. They praised her till she was only second to Honeybird in importance. The desire to shine still more got the better of her; though her conscience hurt she would not heed it.

"Ye'll find I knowed where to look," she said; "ye'll find I know things."

Lull and the four others listened with breathless interest to her tale. Andy Graham came in from the stables to hear it. Fly got more and more excited. "When ye all left me," she said, "I just run on till I come to the quarest place, all whins an' big stones an' trees, an' I can tell ye I was brave an' scared; I was just scared out a' my skin. But I keep on shoutin': 'Where's our wee Honeybird? Give us back our wee Honeybird,' an' all the time I run on like mad, shoutin' hard, an' I lifted a big stick, an' sez I: 'If ye don't give us back our wee Honeybird I'll wreck yer ould country an' I'll burn yer ould thorn-trees,' an' I shook the big stick. 'Do ye hear me?' sez I—'for I will, as sure as I'm standin' on this green grass.' An' with that something white jumped out, an', sure enough, this was Beezledum, and Honeybird fast asleep in under a whin."

"God love ye, but ye were the brave chile," said Lull.

"An' as I was comin' away," Fly went on, "I throwed down the big stick, an' I shouted out: 'I'll thank ye all, an' I'll niver, niver to my dyin' day forget it on ye.'"

They praised her again and again. No one had ever such a triumph. But in the middle of the night yells of terror from the nursery brought Lull from her bed. Fly was sitting up in bed howling, the others were huddled round her. Mick and Honeybird were crying with her, but Jane and Patsy were dry-eyed and severe. Almighty God's eye had looked in at the window at her, Fly said. He had come to send her to hell for the awful lie she had told. Patsy said she deserved to go. "It's in the Bible," Jane said: "all liars shall have a portion of the lake of burnin' fire an' brimstone."

"Sure, she's only a wee chile, an' how could she know any better?" Mick remonstrated. "God'd be the quare old tyrant if He sent her to hell for a wee lie like thon."