Title: In the Early Days along the Overland Trail in Nebraska Territory, in 1852

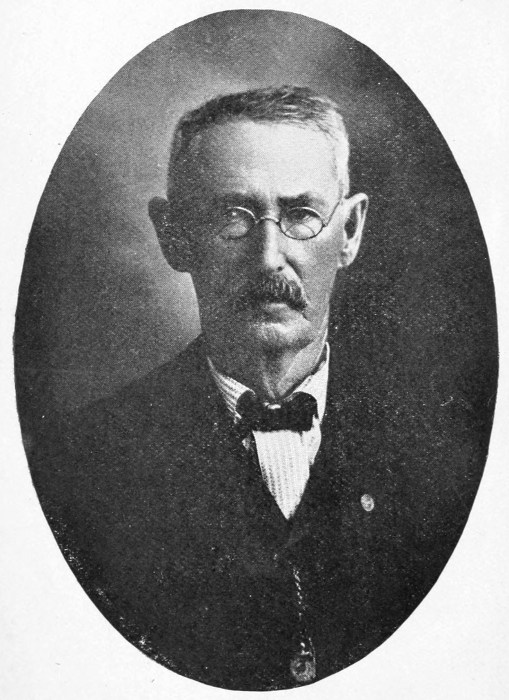

Author: Gilbert L. Cole

Compiler: Mrs. A. S. Hardy

Release date: February 25, 2010 [eBook #31384]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A true story plainly told, of immense historical value and fascinating interest from beginning to end.

Dr. Geo. W. Crofts,

Beatrice, Nebraska.

I have read every word of "In the Early Days," written by Mr. Gilbert L. Cole, with great interest and profit. The language is well chosen, the word-pictures are vivid, and the subject-matter is of historic value. The story is fascinating in the extreme, and I only wished it were longer. The story should be printed and distributed for the people in general to read.

July 27, 1905.

C. A. Fulmer,

Superintendent of Public Schools,

Beatrice, Neb.

At a single sitting, with intense interest, I have read the manuscript of "In the Early Days." It is a very entertaining narrative of adventure, a vivid portrayal of conditions and an instructive history of events as they came into the personal experience and under the observation of the writer fifty-three years ago. An exceedingly valuable contribution to the too meager literature of a time so near in years, but so distant in conditions as to[Pg vi] make the truth about it seem stranger than fiction.

Rev. N. A. Martin,

Pastor, Centenary M. E. Church,

Beatrice, Neb.

Nebraska State Historical Society.

Lincoln, Nebraska, July 28, 1905.

To whom it may concern: The manuscript account of the overland trip by Mr. Gilbert L. Cole of Beatrice, Nebraska, in my opinion is a very carefully written story of great interest to the whole public, and particularly to Nebraskans. It reads like a novel, and the succession of adventures holds the interest of the reader to the end. The records of trips across the Nebraska Territory as early as this one are very incomplete, and Mr. Cole has done a real public service in putting into print so complete a record of these experiences. I predict that it will find a wide circulation among lovers of travel and of Nebraska history.

Very sincerely,

Jay Amos Barrett,

Curator and Librarian Nebraska

State Historical Society,

Author of "Nebraska and the Nation";

"Civil Government of Nebraska."

Executive Chamber,

Lincoln, Nebraska, July 28, 1905.

To whom it may concern: It gives me great pleasure to say that the publication, "In the Early Days," written by Mr. Gilbert L. Cole, of Beatrice,[Pg vii] Nebraska, is a very interesting and profitable work to read. It bears upon many subjects of great historical value and no doubt will prove a very interesting book to all who read it and I take pleasure in recommending the same.

Very respectfully,

John H. Mickey,

Governor.

To whom it may concern: It is with pleasure I write a few words of commendation for the book written by Mr. Gilbert L. Cole, of Beatrice, Nebraska, entitled "In the Early Days." It is well prepared and full of interest from beginning to the end. It is of great value to every Nebraskan.

July 28, 1905.

D. L. Thomas,

Pastor Grace M. E. Church,

Lincoln, Neb.

An interesting, thrilling and delightful bit of prairie history hitherto unwritten and unsung, which most opportunely and completely supplies a missing link in the stories of the great Westland.

Mrs. A. Hardy,

President Beatrice Woman's Club,

Beatrice, Neb.

Beatrice, Neb., July 30, 1905.

I have just read "In the Early Days," by Col. G. L. Cole, and I find it an interesting and instructive narrative, clothed in good diction and pleasing style. Few of the Argonauts took time or trouble to make note of the events of their journey and our California gold episode is remarkably barren of literature, a fact which makes Col. Cole's book doubly interesting and valuable.

M. T. Cummings

| Chapter I.—Setting up Altars of Remembrance, | 13 |

| Chapter II.—"God Could Not Be Everywhere, and so He Made Mothers," | 23 |

| Chapter III.—"But Somewhere the Master Has a Counterpart of Each," | 32 |

| Chapter IV.—Our Prairies are a Book Whose Pages Hold Many Stories, | 41 |

| Chapter V.—A Worthy Object Reached For and Missed is a First Step Toward Success, | 51 |

| Chapter VI.—"'Tis Only a Snowbank's Tears, I Ween," | 58 |

| Chapter VII.—We Stepped Over the Ridge and Courted the Favor of New and Untried Waters, | 67 |

| Chapter VIII.—We Had No Flag to Unfurl, but Its Sentiment Was Within Us, | 77 |

| Chapter IX.—We Listened to Each Other's Rehearsals, and Became Mutual Sympathizers and Encouragers, | 87 |

| Chapter X.—Boots and Saddles Call, | 98 |

| Chapter XI.—"But All Comes Right in the End," | 108 |

| Chapter XII.—Each Day Makes Its Own Paragraphs and Punctuation Marks, | 123 |

If one is necessary, the only apology I can offer for presenting this little volume to the public is that it may serve to record for time to come some of the adventures of that long and wearisome journey, together with my impressions of the beautiful plains, mountains and rivers of the great and then comparatively unknown Territory of Nebraska. They were presented to me fresh from the hand of Nature, in all their beauty and glory. And by reference to the daily journal I kept along the trail, the impressions made upon my mind have remained through these long years, bright and clear.

The Author.

It has been said that once upon a time Heaven placed a kiss upon the lips of Earth and therefrom sprang the fair State of Nebraska.

It was while the prairies were still dimpling under this first kiss that the events related in this little volume became part and parcel of my life and experience, as gathered from a trip made across the continent in the morning glow of a territory now occupying high and honorable position in the calendar of States and nations.

On the 16th day of March, 1852, a caravan consisting of twenty-four men, one woman (our captain, W. W. Wadsworth being accompanied by his wife),[Pg 14] forty-four head of horses and mules and eight wagons, gathered itself together from the little city of Monroe, Michigan, and adjacent country, and, setting its face toward the western horizon, started for the newly found gold fields of California, where it expected to unloose from the storage quarters of Nature sufficient of shining wealth to insure peace and plenty to twenty-five life-times and their dependencies. As is usual upon such occasions, this March morning departure from home and friends was a strange commingling of sadness and gladness, of hope and fear, for in those days whoever went into the regions beyond the Missouri River were considered as already lost to the world. It was going into the dark unknown and untried places of earth whose farewells always surrounded those who remained at home with an atmosphere of foreboding.

Nothing of importance occurred during our travel through the States, except the general bad roads, which caused us to make slow progress. Crossing the Mississippi River at Warsaw, Illinois, we kept along the northern tier of counties in Missouri, which were heavily timbered and sparsely settled. Bearing [Pg 15]south-west, we arrived at St. Joseph, Missouri, on the first day of May.

The town was a collection of one-story, cheap, wooden buildings, located along the river and Black Snake Hollow.

The inhabitants appeared to be chiefly French and half-breed Indians. The principal business was selling outfits to immigrants and trading horses, mules and cattle. There was one steam ferry-boat, which had several days crossing registered ahead.

The level land below the town was the camping-place of our colony. After two or three days at this point, we drove up to the town of Savannah, where we laid in new supplies and passed on to the Missouri River, where we crossed by hand-ferry at Savannah Landing, now called Amazonia. Here we pressed for the first time the soil of the then unsettled plains of the great West. Working our way through the heavily timbered bottom, we camped under the bluffs, wet and weary.

We remained here over Sunday, it having been decided to observe the Sabbath days as a time of rest. We usually rested Wednesday afternoons also.

Just after crossing the river, we had a number of set-backs; beginning with the crippling of a wheel while passing through a growth of timber. As we examined the broken spokes, we realized that they would soon have to be replaced by new ones, and that the wise thing to do was to provide for them while in the region of timber; so we stopped, cut jack-oak, made it into lengths and stored them in the wagon until time and place were more opportune for wheel-wrighting. This broken wheel proved to be a hoodoo, as will appear at intervals during the story of the next few weeks.

In attempting to cross the slough which lies near to and parallel with the river for a long distance, my team and wagon, leading the others, no sooner got fairly on to the slough, which was crusted over, than the wagon sank in clear to its bed, and the horses sank until they were resting on their bellies as completely as though they were entirely without legs.

And there we were, the longed-for bluffs just before us, and yet as unapproachable as if they were located in Ireland. A party of campers, numbering some fifty or seventy-five, who were resting near by, came to our relief. The horses[Pg 17] were extricated, and, after we had carried the contents of the wagon to the bluff shore, they drew the wagon out with cow-teams, whose flat, broad hoofs kept them from sinking. Cow-teams were used quite extensively in those days, being very docile and also swift walkers.

Here under the bluffs over-hanging the Missouri, we completed our organization, for it was not only necessary that every man go armed, but also each man knew his special duty and place. W. W. Wadsworth, a brave and noble man, was by common consent made captain. Four men were detailed each night to stand guard, two till 1 o'clock, when they were relieved by two others, who served till daylight.

Monday morning came, and at sunrise we started on the trail that led up the hollow and on to the great plains of Kansas and Nebraska. The day was warm and bright and clear. The sight before us was the most beautiful I had ever seen. Not a tree nor an obstacle was in sight; only the great rolling sea of brightest green beneath us and the vivid blue above. I think it must have been just such a scene as this that inspired a[Pg 18] modern writer to pen those expressive and much admired lines:

Sky, air, grass; what an abundance of them! in all the pristine splendor of fifty-three years ago, was ours upon that spring morning. This, then, was the land which in later years was called the "Great American Desert." I have now lived in Nebraska for a quarter of a century and know whereof I speak when I say that in those days the grass was as green and luxuriant as it is today; the rivers were fringed with willow green as they are today; the prairie roses, like pink stars, dotted the trail sides through which we passed; and, later on, clumps of golden-rod smiled upon us with their sun-hued faces; the rains fell as they have been falling all these years, and several kinds of birds sang their praises of it all. This was "the barren, sandy desert," as I saw it more than half a hundred years ago.

Perhaps right here it will be well to ask the reader to bear in mind the fact[Pg 19] that the boundary lines of Nebraska in 1852, were different from the boundary lines of today. They extended many miles farther south, and so many miles farther west, that we stepped out of Nebraska on to the summit of the Sierra Nevada Mountains into California.

It was at this stage of our journey, that, in going out, very early in the morning to catch my horse, I noticed ahead of me something sticking up above the grass. Stepping aside to see what it might be, I found a new-made grave; just a tiny grave; at its head was the object I had seen—a bit of board bearing the inscription,

"Our only child,

Little Mary."

How my heart saddened as I looked upon it! The tiny mound seemed bulging with buried hopes and happiness as the first rays of a new sun fell across it, for well I knew that somewhere on the trail ahead of us there were empty arms, aching hearts, and bitter longings for the baby who was sleeping so quietly upon the bosom of the prairie.

The first Indians we saw were at Wolf Creek, where they had made a bridge of logs and brush, and charged us fifty cents[Pg 20] per wagon to pass over it. We paid it and drove on, coming northwest to the vicinity of the Big Blue River, at a point near where Barneston, Gage County, is now located.

As a couple of horsemen, a comrade and myself, riding in advance, came suddenly to the Big Blue, where, on the opposite bank stood a party of thirty or forty Indians. We fell back, and when the train came up a detail was made of eight men to drive the teams and the other sixteen were to wade the river, rifles in hand.

In making preparations to ford the river, Captain Wadsworth, as a precaution of safety, placed his wife in the bottom of their wagon-bed, and piled sacks of flour around her as a protection in case of a fight.

Being one of the skirmish line, I remember how cold and blue the water was, and that it was so deep as to come into our vest pockets. We walked up to the Indians and said "How," and gave some presents of copper cents and tobacco. We soon saw that they were merely looking on to see us ford the stream. They were Pawnees, and were gaily dressed and armed with bows and arrows. We passed[Pg 21] several pipes among them, and, seeing that they were quiet, the train was signalled, and all came through the ford without any mishap, excepting, that the water came up from four to six inches in the wagon-bed, making the ride extremely hazardous and uncomfortable for Mrs. Wadsworth, who was necessarily drawn through the water in an alarming and nerve-trying manner. But she was one of the bravest of women, and in this instance, as in many others of danger and fatigue before we reached our journey's end, she displayed such courage and good temper, as to win the admiration of all the company. The sacks of flour and other contents of the wagons were pretty badly wet, and, after we were again on the open prairie, we bade the Indians good-bye, and all hands proceeded to dismount the wagons, and spread their contents on the grass to dry.

An "Altar of remembrance," is sure to be established at each of these halting places along life's trail. A company of kin-folk and neighbor-folk hitting the trail simultaneously, having a common goal and actuated by common interests, are drawn wonderfully close together by the varied incidents and conditions of the[Pg 22] march, and, at the spots thus made sacred, memory never fails to halt, as in later life it makes its rounds up and down the years. Not fewer in number than the stars, which hang above them at night, are the altars of remembrance, which will forever mark the line of immigration and civilization from east to west across our prairie country.

We now moved on in the direction of Diller and Endicott, where we joined the main line of immigration coming through from St. Joe, and, crossing the Big Blue where Marysville, Kansas, is located, we were soon coming up the Little Blue, passing up on the east side, and about one-half mile this side of Fairbury.

Our trail now lay along the uplands through the day, where we could see the long line of covered wagons, sometimes two or three abreast, drawing itself in its windings like a huge white snake across this great sea of rolling green. This line could be seen many miles to the front and rear so far that the major portion of it seemed to the observer to be motionless.

This immense concourse of travellers was self-divided into trail families or travelling neighborhoods, as it were; and while each party was bound together by local ties of friendship and affection, there still ran through the entire procession a[Pg 24] chord of common interest and sympathy, a something which, in a sense, made the whole line kin. This fact was most touchingly exemplified one day in the region of the Blue.

I was driving across a bad slough, close behind a man who belonged to another party, from where I did not know. Himself, wife and little daughter lived in the covered wagon he was driving. The piece of ground was an unusually bad one, and both his wagon and mine being heavily loaded, we stopped as soon as we had pulled through, in order that the horses might rest; our wagons standing abreast and about ten or twelve feet apart. In the side of his wagon cover next to me was a flap-door, which, the day being fine, was fastened open. As we sat our loads and exchanged remarks, his little girl, a beautiful child, apparently three or four years old, came from the recesses of the wagon-home, and standing in the opening of the door, looked coyly and smilingly out at her father and myself. She made a beautiful picture, with her curls and dimples, and, as I didn't know any baby talk at that time, I playfully snapped my fingers at her. The thought of moving on evidently came to the father[Pg 25] very suddenly, for, without any preliminary symptoms and not realizing that the little one was standing so nearly out of the door, he swung his long whip, and, as it cracked over the horses' backs, they gave a sudden lurch, throwing the little girl out of the door and directly in front of the hind wheel of the heavily laden wagon, which, in an instant had passed over the child's body at the waist line, the pretty head and hands reaching up on one side of the wheel, and the feet on the other, as the middle was pressed down into the still boggy soil. The little life was snuffed out in the twinkling of an eye. The mother, seeing her darling fall, jumped from the door, and such excruciating sobs of agony I hope never to hear again. But why say it in that way when I can hear them still, even as I write? It seemed but a moment of time till men and women were gathered about the wagon, helping to gather the crushed form from the prairie, and giving assistance and sympathy in such measure and earnestness as verified the truth of the words, "A touch of sorrow makes the whole world kin."

When started again, the trail soon led to a stream, called the Big Sandy; I [Pg 26]believe it is in the northwest part of Fillmore County, where, about nine o'clock, A. M., we were suddenly alarmed by the unearthly whoops and yells of one hundred or more Indians (Pawnees), all mounted and riding up and down across the trail on the open upland opposite us, about a good rifle shot distant.

Our company was the only people there. A courier was immediately sent back for reinforcements. We hastily put our camp in position of defense (as we had been drilled) by placing our wagons in a circle with our stock and ourselves inside. The Indians constantly kept up their noise, and rode up and down, brandishing their arms at us, and every minute we thought they would make a break for us.

We soon had recruits mounted and well armed coming up, when our Captain assumed command, and all were assigned to their positions. This was kept up until about four P. M., when we decided that our numbers would warrant us in making a forward movement.

As a preliminary, skirmishers were ordered forward toward the creek, through some timber and underbrush, I being one of them. My pardner and I, coming[Pg 27] to the creek first, discovered an empty whiskey barrel, and going a little farther into the brush, discovered two tents. Creeping carefully up to them, we heard groans as of some one in great pain. Peeping through a hole in the tent we saw two white men, who, on entering the tent, we learned were badly wounded by knife and bullet. From them we learned the following facts, which caused all our fear and trouble of the morning: The two white men were post-keepers at that point, and, of course, had whiskey to sell. Two large trains had camped there the night before; the campers got on a drunk, quarreled, and had a general fight, during which the post-keepers were wounded. On the trail over where the Indians were, some immigrants were camped, and a guard had been placed at the roadside. One of the Indians, hearing the noise down at the post, started out to see what was going on. Coming along the trail, the guard called to him to halt, but as he did not do so the guard fired, killing him on the spot. The campers immediately hitched up and moved on. Later the dead Indian was found by the other Indians lying in the road. It was this that aroused their[Pg 28] anger and kept us on the ragged edge for several hours.

The Indians all rode off as we approached them, and as the trail was now clear our train moved ahead, travelling all night and keeping out all the mounted ones as front and rear guards.

We now come to the "last leaving of the Little Blue," and pass on to the upland without wood or water, thirty-three miles east of Ft. Kearney, leading to the great Platte Valley.

Meanwhile my broken wheel had completely collapsed. Having a kit of tools with me, I set about shaping spokes out of the oak wood gathered several days before. While I was doing this others of the men rode a number of miles in search of fuel with which to make a fire to set the tire. It was nearly night and in a drizzling rain when we came to the line of the reservation. A trooper, sitting on his horse, informed us that we would have to keep off of the reservation or else go clear through if once we started. This meant three or four miles' further ride through the darkness and rain, and so we camped right there, without supper or even fire to make some coffee. We hitched up in the morning and drove into the[Pg 29] Fort, where we were very kindly treated by the commanding officer, whose name, I think, was McArthur. He tendered us a large room with tables, pen and ink, paper and "envelope paper," where we wrote the first letters home from Nebraska, which, I believe, were all received with much joy. The greater part of the troops were absent from the Fort on a scout.

After buying a few things we had forgotten to bring with us and getting rested, we moved on our journey again, going up on the south side of the Platte River.

Before leaving this region I want to speak of the marvelous beauty of the Platte River islands, a magnificent view of which could be had from the bluffs. Looking out upon the long stretch of river either way were islands and islands of every size whatever, from three feet in diameter to those which contained miles of area, resting here and there in the most artistic disregard of position and relation to each other, the small and the great alike wearing its own mantle of sheerest willow-green. There are comparatively few of these island beauty spots in the whole wide world. When the Maker of the universe gathered up his emeralds[Pg 30] and then dropped them with careless hand upon a few of earth's waters. He wrought nowhere a more beautiful effect than in the Platte islands of Nebraska. It was well that at this point we had an extra amount of kindness tendered us and so much unusual beauty to look upon, for a great sorrow was about to come upon us.

Just as we were leaving the Little Blue, thirty-three miles back, one of our party, Robert Nelson, became ill, and in spite of the best nursing and treatment that the company could give he rapidly grew worse, and it soon became evident that his disease was cholera, which was already quite prevalent thereabout. Mrs. Wadsworth, that most excellent woman, gave to him her special care, taking him into the tent occupied by herself and husband, which, in fact, was the only tent in the outfit. It was Lew Wallace who once said that "God couldn't be everywhere, and so He made mothers." Our captain's wife was a true mother to the sick boy, but she couldn't save him. At 3 o'clock Sunday afternoon, May 27th, about sixty miles beyond Kearney, his soul passed on, and we were bowed under our first bereavement. We dug his grave in[Pg 31] the sand a little way off the trail. We wrapped his blanket about him and sewed it, and at sunrise Monday morning laid him to rest. The end-gate from my wagon had been shaped into a grave-board and, with his name cut upon it, was planted to mark his resting-place. It was a sorrowful little company that performed these last services for one who was beloved by all.

Just before dying, Robert had requested that his grave might be covered with willow branches, and so a comrade and myself rode our horses out to one of the islands and brought in big bunches of willows and tucked them about him, as he had desired.

Truly our prairies have been a stage upon which much more of tragedy than of comedy has been enacted.

"O Lord Almighty, aid Thou me to see my way more clear. I find it hard to tell right from wrong, and I find myself beset with tangled wires. O God, I feel that I am ignorant, and fall into many devices. These are strange paths wherein Thou hast set my feet, but I feel that through Thy help and through great anguish, I am learning."

This modern prayer, as prayed by the hero of a modern tale, would have fitted most completely into the spirit and conditions prevailing in our camp on a certain morning in early June, 1852, as we were completing arrangements preparatory to the extremely dangerous crossing of the Platte River, owing to its treacherous quicksand bottom.

Despite the old proverb, "Never cross a bridge till you get to it," we had, because of the very absence of a bridge, been running ahead of ourselves during the entire trip, to make the dreaded [Pg 33]crossing over this deceptive and gormandizing stream. We had now caught up with our imaginings and found them to be realities. There was not much joshing among the boys that morning as we made the rounds of the horses and wagons and saw that every buckle and strap and gear was in the best possible condition, for to halt in the stream to adjust a mishap would mean death. "Once started, never stop," was the ominous admonition of the hour.

About 9 o'clock, all things being in readiness, two of us were sent out to wade across the river and mark the route by sticking in the sand long willow branches, with which we were laden for that purpose. The route staked, we returned and the train lined up. It need not require any great feat of imagination on the part of the reader to hear how dirge-like the first hoofs and wheels sounded as they parted the waters and led the way. Every man except the drivers waded alongside the horses to render assistance if it should be required. Mrs. Wadsworth was remarkably brave, sitting her wagon with white, but calm face. Scarcely a word was spoken during the entire crossing, which occupied about twenty-five [Pg 34]minutes. We passed on the way the remains of two or three wagons standing on end and nearly buried in the sand. They were grewsome reminders of what had been, as well as of what might be. But without a halt or break, we drove clear through and on to dry land. To say that we all felt happy at seeing the crossing behind us does not half express our feelings. The nervous strain had been terrible, and at no time in our journey had we been so nearly taxed to the utmost. One man dug out a demijohn of brandy from his traps and treated all hands, remarking, "That the success of that undertaking merits something extraordinary."

The crossing was made at the South Fork of the Platte, immediately where it flows into the main river. What is now known as North Platte and South Platte was then known as North Fork and South Fork of Platte River.

It was at the South Fork and just before we crossed that I shot and killed my first buffalo. It was also very early in the morning, and while I was still on guard duty. A bunch of five of them came down to the river to drink, buffalo being as plentiful in that region, and time, as domestic cattle are here today. My[Pg 35] first shot only wounded the creature, who led me quite a lively chase before I succeeded in killing him. We soon had his hide off, and an abundance of luscious, juicy steak for breakfast. I remember that we sent some to another company that was camping not far distant. This was our first and last fresh meat for many a day.

A few days after this an incident occurred in camp that bordered on the tragic, but finally ended in good feeling. My guard mate, named Charley Stewart, and myself were the two youngest in the company, and, being guards together, were great friends. He was a native of Cincinnati, well educated, and had a fund of stories and recitations that he used to get off when we were on guard together. This night we were camped on the side of some little hills near some ravines. The moon was shining, but there were dark clouds occasionally passing, so that at times it was quite dark. It was near midnight and we would be relieved in an hour. We had been the "grand rounds" out among the stock, and came to the nearest wagon which was facing the animals that were picketed out on the slope. Stewart was armed with a "Colt's Army,"[Pg 36] while I had a double-barreled shot-gun, loaded with buckshot. I was sitting on the double-tree, on the right side of the tongue, which was propped up with the neck-yoke. Stewart sat on the tongue, about an arm's length ahead of me, I holding my gun between my knees, with the butt on the ground. Stewart was getting off one of his stories, and, had about reached the climax, when I saw something running low to the ground, in among the stock. Thinking it was an Indian, on all fours, to stampede the animals, I instantly leveled my gun, and, as I was following it to an opening in the herd, my gun came in contact with Stewart's face at the moment of discharge, Stewart falling backward, hanging to the wagon-tongue by his legs and feet. My first thought was that I had killed him. He recovered in a moment, and began cursing and calling me vile names; accusing me of attempting to murder him, etc. During these moments, in his frenzy, he was trying to get his revolver out from under him, swearing he would kill me. Taking in the situation, I dropped my gun, jumped over the wagon tongue, as he was getting on to his feet, and engaged in what proved to be a desperate[Pg 37] fight for the revolver. We were both sometimes struggling on the ground, then again on our knees, he repeatedly striking me in the face and elsewhere, still accusing me of trying to murder him. As I had no chance to explain things, the struggle went on. Finally I threw him, and held him down until he was too much exhausted to continue the fight any longer, and, having wrested the revolver from him, I helped him to his feet. In trying to pacify him, I led him out to where the object ran that I had fired at, and there lay the dead body of a large gray wolf, with several buckshot holes in his side.

Stewart was speechless. Looking at the wolf, and then at me, he suddenly realized his mistake, and repeatedly begged my pardon. We agreed never to mention the affair to any one in the company. Taking the wolf by the ears, we dragged him back to the wagon, where I picked up my gun, and gave Stewart his revolver. I have often thought what would have been the consequence of that shot, had I not killed the wolf.

Along in this vicinity, the bluff comes down to the river, and, consequently, we had to take to the hills, which were [Pg 38]mostly deep sand, making heavy hauling. This trail brought us into Ash Hollow, a few miles from its mouth. Coming down to where it opened out on the Platte, about noon, we turned out for lunch. Here was a party of Sioux Indians, camped in tents made of buffalo skins. They were friendly, as all of that tribe were that summer. This is the place where General Kearney, several years later, had a terrific battle with the same tribe, which was then on the war-path along this valley.

My hoodoo wheel had recently been giving me trouble. The spokes that I made of green oak, having become dry and wobbly, I had been on the outlook for a cast-off wheel, that I might appropriate the spokes. Hence it was, that, after luncheon I took my rifle, and started out across the bottom, where, within a few rods of the river, and about a half a mile off the road which turned close along the bluff, I came upon an old broken-down wagon, almost hidden in the grass. Taking the measure of the spokes, I found to my great joy, that they were just the right size and length. Looking around, I saw the train moving on, at a good pace, almost three-quarters of a mile away. I was delayed some time in getting the[Pg 39] wheel off the axle-tree. Succeeding at last, I fired my rifle toward the train, but no one looked around, all evidently supposing that I was on ahead.

It was an awful hot afternoon, and I was getting warmed up myself. I reloaded my rifle, looked at the receding train, and made up my mind to have that wheel if it took the balance of the day to get it into camp. I started by rolling it by hand, then by dragging it behind me, then I ran my rifle through the hub and got it up on my shoulder, when I moved off at a good pace. The sun shining hot, soon began to melt the tar in the hub, which began running down my back, both on the inside and outside of my clothes, as well as down along my rifle. I finally got back to the road, very tired, stopping to rest, hoping a wagon would come along to help me out, but not one came in sight that afternoon. In short, I rolled, dragged and carried that wheel; my neck, shoulders and back daubed over with tar, until the train turned out to camp, when, I being missed, was discovered away back in the road with my wheel. When relief came to me, I was nearly tired out with my exertions, and want of water to drink.

Some of the men set to work taking[Pg 40] the wheel apart and fitting the spokes and getting the wheel ready to set the tire. Others had collected a couple of gunny-sacks full of the only fuel of the Platte Valley, viz., "buffalo-chips," and they soon had the job completed. The boys nearly wore themselves out, laughing and jeering at me, saying they were sorry they had no feathers to go with the tar, and calling me a variety of choice pet names.

The wheel, when finished and adjusted, proved to be the best part of the wagon, and, better than all else, had provided a season of mirth to the whole company, which, considering the all too serious environments of our march, was really a much needed tonic and diversion.

We learned so many wonderful lessons in those days, lessons that have never been made into books. We learned from nature; we learned from animal nature; we learned from human nature; and where are they who studied from the same page as did I? So often and so completely have the slides been changed, that among all the faces now shown by life's stereopticon, mine alone remains of the original twenty-five, of the trail of '52. But somewhere the Master has a counterpart of each.

We have just been passing through an extremely interesting portion of Nebraska, a portion which today is known as Western Nebraska, where those wonderful formations, Scott's Bluff, Courthouse Rock and Chimney Rock, are standing now, even as they did in the early '50's. Courthouse Rock a little way off really looked a credit to its name. It was a huge affair, and, in its ragged, irregular outline, seemed to impart to the traveller a sense of protection and fair dealing.

Scott's Bluff was an immense formation, and sometime during its history nature's forces had cleft it in two parts, making an avenue through its center at least one hundred feet wide, through which we all passed, as the trail led through instead of around the bluff.

Chimney Rock in outline resembled an immense funnel. The whole thing was at least two hundred feet in height, the chimney part, starting about midway,[Pg 42] was about fifty feet square; its top sloped off like the roof of a shanty. Beginning at the top, the chimney was split down about one quarter of its length. On the perpendicular part of this rock a good many names had been cut by men who had scaled the base, and, reaching as far on to the chimney as they could, cut their names into its surface. So clear was the atmosphere that when several miles distant we could see the rock and men who looked like ants as they crept and crawled up its sides.

As one stops to decipher the inscriptions upon this boulder the sense of distance is entirely lost, and the traveller finds himself trying to compare it with that other obelisk in Central Park, New York. As he thinks about them, the truth comes gradually to him that there can be no comparison, since the one is a masterpiece from the hand of Nature and the other is but a work of art.

These formations are not really rock, but of a hard marle substance, and while each is far remote from the others, the same colored strata is seen in all of them, showing conclusively that once upon a time the surface of the ground in that region was many feet higher than it was[Pg 43] in 1852 or than it is today, and that by erosion or upheaval large portions of the soil were displaced and carried away, these three chunks remaining intact and as specimens of conditions existing many centuries ago.

I have been through the art galleries of our own country and through many of those in Europe; I have seen much of the natural scenery in the Old World as well as in the New; but not once have I seen anything which surpassed in loveliness and grandeur the pictures which may be seen throughout Nature's gallery in Nebraska and through which the trail of '52 led us. Landscapes, waterscapes, rocks, and skies and atmosphere were here found in the perfection of light, shadow, perspective, color, and effect. Added to these fixed features were those of life and animation, contributed by herds of buffalo grazing on the plains, here and there a bunch of antelope galloping about, and everywhere wolf, coyote, and prairie dog, while a quaint and picturesque charm came from the far-reaching line of covered wagons and the many groups of campers, each with its own curl of ascending smoke, which, to the immigrant, always indicated that upon that particular patch of[Pg 44] ground, for that particular time, a home had been established.

In this connection I find myself thinking about the various modes of travel resorted to in those primitive days, when roads and bridges as we have them today were still far in the future. The wagons were generally drawn by cattle teams, from two to five yokes to the wagon. The number of wagons would be all the way from one to one hundred. The larger trains were difficult to pass, as they took up the road for so long a distance that sometimes we would move on in the night in order to get past them. Among the smaller teams we would frequently notice that one yoke would be of cows, some of them giving milk right along. The cattle teams as a rule started out earlier in the morning and drove later at night than did the horse and mule teams; hence, we would sometimes see a certain train for two or three days before we would have an opportunity to get ahead of them. This was the cause of frequent quarrels among drivers of both cattle and horse teams; the former being largely in the majority and having the road, many of them seemed to take delight in keeping the horse teams out of the road and[Pg 45] crowding them into narrow places. These little pleasantries were indulged in generally by people from Missouri, as many of them seemed to think their State covered the entire distance to California.

As to classes and conditions constituting the immigration, they might be divided up somewhat as follows: There were the proprietors or partners, owners of the teams and outfits; then there were men going along with them who had bargained with the owners before leaving home, some for a certain amount paid down, some to work for a certain time or to pay a certain amount at the journey's end. This was to pay for their grub and use of tents and wagons. These men were also to help drive and care for the stock, doing their share of camp and guard duty. There were others travelling with a single pack animal, loaded with their outfits and provisions. These men always travelled on foot. Then there were some with hand-carts, others with wheelbarrows, trudging along and making good time. Occasionally we would see a man with a pack like a knapsack on his back and a canteen strapped on to him and a long cane in either hand. These men would just walk away from everybody.[Pg 46] A couple of incidents along here will serve to show how these conditions sometimes worked.

We were turned into camp one evening, and as we were getting supper there came along a man pushing a light handcart, loaded with traps and provisions, and asked permission to camp with us, which was readily granted. He was a stout, hearty, good-natured fellow, possessed of a rich Irish accent, and in the best of humor commenced to prepare his supper. Just about this time there came into camp another lone man, leading a diminutive donkey, not much larger than a good-sized sheep. The donkey, on halting, gave us a salute that simply silenced the ordinary mule. The two men got acquainted immediately, and by the time their supper was over they had struck a bargain to put their effects together by way of hitching the donkey to the cart, and so move on together. They made a collar for the donkey out of gunny-sack, and we gave them some rope for traces. Then, taking off the hand-bar of the cart, they put the donkey into the shafts and tried things on by leading it around through the camp till it was time to turn in.

Everything went first-rate, and they were so happy over their transportation prospects that they scarcely slept during the whole night. In the morning they were up bright and early, one making the coffee and the other oiling the iron axle-trees and packing the cart. Starting out quite early, they bade us goodby with hearty cheer, saying they would let the folks in California know that we were coming, etc. About 10 o'clock we came to a little narrow creek, the bottom being miry and several feet below the surface of the ground. There upon the bank stood the two friends who had so joyously bidden us goodby only a few hours before. The cart was a wreck, with one shaft and one spindle broken. It appeared that the donkey had got mired in crossing the creek and in floundering about had twisted off the shaft and broken one of the wheels. We left them there bewailing their misfortune and blaming each other for the carelessness which worked the mishap. We never saw them again.

This incident is an illustration of those cases where a man obtained his passage by contributing something to the outfit and working his way through. There[Pg 48] were quite a number of this class, they having no property rights in the train.

At the usual time we turned in for dinner near by a camp of two or three wagons. On the side of one wagon was a doctor's sign, who, we afterwards learned, was the proprietor of the train. As we were quietly eating and resting we suddenly heard some one cursing and yelling in the other camp, and saw two men, one the hired man and the other the doctor, the latter being armed with a neck-yoke and chasing the hired man around the wagon, and both running as fast as they could. They had made several circuits, the doctor striking at the man with all his might at each turn, when some of us went over to try to stop the fight. Just at this point, the hired man, as he turned the rear of the wagon, whipped out an Allen revolver and turning shot the doctor in the mouth, the charge coming out nearly under the ear. The doctor and the neckyoke struck the ground about the same time. His eyes were blinded by powder and he had the appearance of being dangerously if not fatally wounded. Everybody was more or less excited except the hired man. From expressions all around in both trains, the hired man[Pg 49] seemed to have the most friends. There were many instances of this kind, though none quite so tragic, the quarrels usually arising from the owner of the wagons constantly brow-beating and finding fault with the hired man.

Again I saw an instance where two men were equal partners all around, in four horses, harness and wagon. They seemed to have quarreled so much that they agreed to divide up and quit travelling together. They divided up their horses and provisions, and then measured off the wagon-bed and sawed it in two parts, also the reach, and then flipped a copper cent to see which should have the front part of the wagon. After the division they each went to work and fixed up his part of the wagon as best he could, and drove on alone.

The entire trip from Monroe, Michigan, our starting-point, to Hangtown, the point of landing in California, covered 2,542 miles, and we were five months, lacking six days, in making it. Today the same trip can be made in a half week, with every comfort and luxury which money and invention can provide. There is probably nothing that marks the progress of civilization more distinctly than[Pg 50] do the perfected modes and conveniences of travel. It is strange, but true, however, that so long as our prairies shall stretch themselves from river to ocean the imprint of the overland trail can never be obliterated. Today, after a lapse of over fifty years, whoever passes within seeing distance of the old trail can, upon the crest of grain and grass, note its serpentine windings, as marked by a light and sickly color of green. I myself have followed it from a car-window as traced in yellow green upon an immense field of growing corn. No amount of cultivation can ever restore to that long-trodden path its pristine vigor and productiveness.

Who, among the many persons contributing for a wage, to the convenience of everyday life in these latter times, is more waited and watched for, and brings more of joy, and more of sorrow when he comes, than the postman.

In the days of trailing, our post accommodations were extremely few and very far between. There were no mailing points, except at the government forts, Fort Kearney and Laramie being the only two on the entire trip, soldiers carrying the mail to and from the forts either way. After leaving Fort Kearney, the next mailing point east, was Fort Laramie.

Before leaving home, I had been entrusted with a package of letters by Hon. Isaac P. Christiancy, from his wife, to her brother, James McClosky, who had been on the plains some fourteen years, and who was supposed to be living near Fort Laramie. When within a couple of days' drive of the fort we came to a [Pg 52]building which proved to be a store, and which was surrounded by several wigwams. Upon halting and going into the store, we found ourselves face to face with the man we were wanting to meet, Mr. McClosky. He was glad to see us, and overjoyed to receive the package of letters. He stepped out of doors and gave a whoop or two, and immediately Indians began to come in from all directions. He ordered them to take our stock out on the ranch, feed and guard it, and bring it in in the morning. He treated us generously to supper and breakfast, including many delicacies to which we had long been strangers. In consideration of my bringing the letters to him, he invited me to sleep in his store, and, in the morning, introduced me to his Indian wife and two sons, also, to several other women who were engaged in an adjoining room, in cutting and making buckskin coats, pants and moccasins, presenting me with an elegant pair of the latter. His wife was a bright and interesting woman, to whom he was deeply attached. His two boys were bright, manly fellows, the oldest of whom, about ten years old, was soon to be taken to St. Joe or Council Bluffs and placed in school.

At an early hour in the morning, the Indians brought in the stock, in fine condition, and we hitched up and bade our host goodbye. He sent word to his sister at home, and seemed much affected at our parting. This was the first morning when, in starting out, we knew anything about what was ahead of us; what we would meet, or what the roads and crossings would be. In fact, every one we saw, were going the same as ourselves, consequently, all were quite ignorant of what the day might bring forth. On this morning, we knew the conditions of the roads for several days ahead, and, that Fort Laramie was thirty-six miles before us.

Shortly after going into camp toward sunset, a party of horsemen was seen galloping toward us, who, on nearer approach, proved to be a band of ten or twelve Indians. When within about one hundred yards, they halted and dismounted, each holding his horse. The chief rode up to us, saluted and dismounted. He was a sharp-eyed young fellow, showing beneath his blanket the dress-coat of a private soldier and non-commissioned officer's sword. He gave us to [Pg 54]understand that they were Sioux, and had been on the warpath for some Pawnees, also that they were hungry and would like to have us give them something to eat. After assuring him that we would do so, he ordered his men to advance, which they did after picketing their ponies, coming up and setting themselves on the grass in a semi-circle.

We soon noticed that they carried spears made of a straight sword-blade thrust into the end of a staff. On two or three of the spears were dangling one or more fresh scalps, on which the blood was yet scarcely dry. On pointing to them, one of the Indians drew his knife, and taking a weed by the top, quickly cut it off, saying as he did so, "Pawnees." His illustration of how the thing was done was entirely satisfactory.

We gave the grub to the chief, who in turn, handed it out to the men as they sat on the ground. When through eating, they mounted their ponies, waved us a salute and were off.

The balance of the day was spent in writing home letters, which we expected to deliver on the morrow at the post.

About 9 o'clock the next morning, we came to Laramie River, near where it[Pg 55] empties into the North Platte, which we crossed on a bridge, the first one we had seen on the whole route. At this point a road turns off, leading up to the fort, about one mile distant. Being selected to deliver the mail, I rode out to the fort, which was made up of a parade-ground protected by earth-works, with the usual stores, quarters, barracks, etc., the sutler and post-office being combined. On entering the sutler's, about the first person I saw was the young leader of the Indians, who had lunched at our camp the afternoon before. He was now dressed in the uniform of a soldier, recognizing me as soon as we met with a grunt and a "How."

Delivering the mail, I rode out in another direction to intercept the train. When about one-half mile from the fort I came to a sentinel, pacing his beat all alone. He was just as neat and clean as though doing duty at the general's headquarters, with his spotless white gloves, polished gun, and accoutrements. In a commanding tone of voice, he ordered me to halt. Asking permission to pass, which was readily granted, I rode on a couple of miles, when I met some Indians with their families, who were on the march with ponies, dogs, women, and papooses.

Long spruce poles were lashed each side of the ponies' necks, the other ends trailing on the ground. The poles, being slatted across, were made to hold their plunder or very old people and sometimes the women and children. The dogs, like the ponies, were all packed with a pole or two fastened to their necks; the whole making an interesting picture.

Overtaking the train about noon, we camped at Bitter Cottonwood Creek, the location being beautifully described by the author of the novel, "Prairie Flower."

Our standard rations during these days consisted of hardtack, bacon, and coffee; of course, varying it as we could whenever we came to a Government fort. I recall how, on a certain Sunday afternoon, we men decided to make some doughnuts, as we had saved some fat drippings from the bacon. Not one of us had any idea as to the necessary ingredients or the manner of compounding them, but we remembered how doughnuts used to look and taste at home. So we all took a hand at them, trying to imitate the pattern as well as our ignorance and poor judgment would suggest. Well, they looked a trifle peculiar, but we thoroughly enjoyed them, for they were[Pg 57] the first we had since leaving home, and proved to be the last until we were boarding in California.

One thing was sure; our outdoor mode of living gave us fine appetites and a keen relish for almost anything. And then again, persons can endure almost any sort of privation as long as they can see a gold mine ahead of them, from which they are sure to fill their pockets with nuggets of the pure stuff. What a happy arrangement it is on the part of Providence that not too much knowledge of the future comes to us at any one time! Just enough to keep us pushing forward and toward the ideal we have set for ourselves, which, even though we miss it, adds strength to purpose as well as to muscle. A worthy object reached for and missed is a first step towards success.

We are now approaching the foot-hills of the Rocky Mountains. The fertile plains through which we have been passing are being merged into rocky hills, the level parts being mostly gravelly barrens. The roads are hard and flinty, like pounded glass, which were making some of the cattle-teams and droves very lame and foot-sore. When one got so it could not walk, it was killed and skinned. Other lame ones were lashed to the side of a heavy wagon, partially sunk in the ground, their lame foot fastened on the hub of a wheel, when a piece of the raw hide was brought over the hoof and fastened about the fet-lock, protecting the hoof until it had time to heal. This mode of veterinary treatment, although crude, lessened the suffering among the cattle very materially.

The streams along here, the La Barge, La Bonte, and Deer Creek, were all shallow with rocky bottoms and excellent water.[Pg 59] Here we frequently took the stock upon the hills at night, where the bunch-grass grows among the sage brush. This grass, as its name indicates, grows in bunches about a foot high and about the same in diameter, bearing a profusion of yellow seeds about the size of a kernel of wheat. This makes excellent feed, and the stock is very fond of it.

At this point Mother Nature is gradually changing the old scenes for new ones. The big brawny mountains with their little ones clustered at their feet are just before us; while the Platte River, which for many miles has been our constant companion, will soon be a thing of the past, as we are close to the crossing, and once over we shall see the river no more. This river which stretches itself in graceful curves across an entire State, is one of peculiar construction and characteristics. At a certain point it is terrifying, even to its best friends. In curve, color, contour, and graceful foliage, it is a magnificent stretch of beauty; while as a stream of utility its presence has ever been a benediction to the country through which it passes. As a tribute to its general excellence, I place here the beautiful lines[Pg 60] (name of author unknown to me), entitled:

We crossed the river on a ferry-boat that was large enough to hold four wagons and some saddle-horses. The boat was run by a cable stretched taut up[Pg 62] stream fifteen or twenty feet from the boat. A line from the bow and stern of the boat connected it with a single block which ran on the cable. When ready to start, the bow-line was hauled taut, the stern line slacked off to the proper angle, when, the current passing against the side of the boat, it was propelled across very rapidly. The river here was rapid, the water cold and deep, with a strong undercurrent.

We had to wait nearly a whole day before it came our turn to take our wagons over. In the meantime we were detailed as follows: Ten men were selected to get the wagons aboard the boat, cross over with them and guard them until all were carried over; three or four men were sent across and up the river to catch and care for the stock as it came out of the river near a clump of cottonwoods. One of the company, named Owen Powers, a strong, courageous young man and a good swimmer, volunteered to ride the lead horse in and across to induce the other animals to follow, the balance of the company herding them, as they were all loose near the edge of the river. When everything was ready, Powers stripped off, and mounting the horse he had selected, rode[Pg 63] out into the stream. The other animals, forty-seven of them followed, and when a few feet from the shore had to swim. Everything was going all right until Powers reached the middle of the river, when an undercurrent struck his horse, laying him over partly on his side. Powers leaned forward to encourage his horse, when the animal suddenly threw up his head, striking him a terrible blow squarely in the face. He was stunned and fell off alongside the horse. It now seemed as though both he and his horse would be drowned, as all the other stock began to press close up to them. He soon recovered, however, and as he partially pulled himself on to his horse, we could plainly see that his face and breast were covered with blood. We shouted at him words of encouragement, cheering him from both sides of the river. While his struggling form was hanging to the horse's mane, the other animals all floundered about him, pulling for the shore for dear life. The men on the other side were ready to catch him as he landed, nearly exhausted by his struggles and the blow he had received. They carried him up the bank and leaned him against a tree, one man taking care of him while the[Pg 64] others caught the animals, or rather corralled them, until the rest of us got across and went to their assistance. We brought the young man's clothes with us and fixed him up, washing him and stanching his bleeding nose and mouth. He had an awful looking face; his eyes were blackened, nose flattened and mouth cut. However, he soon revived and was helped by a couple of the men down to the wagons. We then gathered the stock, went down to the train, hitched up, and drove into camp.

We now soon came to the Sweetwater River. The country here is more hilly and rocky, and the valleys narrower and more barren. The main range of Wind River Mountains could be plainly seen in the distance, while close upon our left were the Sweetwater Mountains. The difference in scenery after leaving the river and plains was such as to awaken new emotions and fire one with a new kind of admiration. The immensity and fixedness of the mountains awakened a keener sense of stability, of firmness of purpose, and a sort of expect great things and do great things spirit; while the sense of beauty appreciation was in no wise narrowed as it followed the lights and shades[Pg 65] of jut and crevice, and the rosy, scintillating bits of sun as a new day dropped them with leisure hand upon summit and sides, or later the tender glow of crimson and blue and gold, as the gathered sun-bits trailed themselves behind the mountains for the night.

When making up our outfit back in the States, by oversight or want of knowledge of what we would need, we had neglected to lay in a supply of horse-nails, which we now began to be sorely in need of, as the horses' shoes were fast wearing out and becoming loose. It was just here that we came one day to a man sitting by the roadside with a half-bushel measure full of horse nails to sell at the modest price of a "bit" or twelve and one-half cents apiece. No amount of remonstrance or argument about taking advantage of one's necessity could bring down the price; so I paid him ten dollars in gold for eighty nails. I really wanted to be alone with that man for awhile, I loved him so. He, like some others who had crossed the plains before, knew of the opportunity to sell such things as the trailers might be short of at any price they might see fit to ask.

It was here, too, that we came upon the great Independence Rock, an immense boulder, lying isolated on the bank of the Sweetwater River. It was oblong, with an oval-shaped top, as large as a block of buildings. It was of such form that parties could walk up and over it lengthwise, thereby getting a fine view of the surrounding country.

About a mile beyond was the Devil's Gate, a crack or rent in the mountain, which was probably about fifty feet wide, the surface of the walls showing that by some sort of force they had been separated, projections on one side finding corresponding indentations on the other. The river in its original course had run around the range, but now it ran leaping and roaring through the Gate.

There was considerable alkali in this section. We had already lost two horses from drinking it, and several others barely recovered from the effects.

Between Independence Rock and Devil's Gate we cross the river, which is about four feet deep and thirty or forty feet wide. There was a man lying down in the shade of his tent, who had logs enough fastened together to hold one wagon, which he kindly loaned the use of for fifty cents for each wagon, we to do the work of ferrying. Rather than to wet our traps, we paid the price. The stock was driven through the ford.

We camped at the base of some rocky cliffs, and while we were getting our supper an Indian was noticed peering from behind some rocks, taking a view of the camp. One of the boys got his rifle from the wagon and fired at him. He drew in his head and we saw no more of him, but kept a strong guard out all night.

The trail that followed up the Sweetwater was generally a very good road, with good camping-place's and fair grass[Pg 68] for stock; while grass and sage brush for fuel and excellent water made the trip of about ninety miles very pleasant, as compared with some of the former route.

We now came to the last-leaving of the Sweetwater, which is within ten miles of the highest elevation of the South Pass. The springs and the little stream on which we were camped, across which one could have stepped, was the last water we saw that flowed into the Atlantic. We were upon the summit or dividing line of the continent. With our faces to the southward, the stream at our left flowed east and into the Atlantic, while that upon our right flowed west into the Pacific.

There was something not altogether pleasant in considering the conditions. Following and crossing and studying the streams as we had so long been doing, it was not without a tinge of regret and broken fellowship that we stepped over the ridge and courted the favor of new and untried waters.

The abrupt ending of the great Wind River Mountain range was at our right. These mountains are always more or less capped with snow. To the south, perhaps one hundred miles, could be seen the[Pg 69] main ridge of the Rocky Mountains looming up faintly against the sky. The landscape, looking at it from the camp, was certainly pleasing, if not beautiful. During the day there could be seen bunches of deer, antelope, and elk grazing and running about on the ridges, the whole making a picture never to be forgotten. The sky was clear, the air pure and invigorating, the sun shone warm by day and the stars bright at night.

The spot proved to be a "parting of the ways" in more than one sense, for it was here, before the breaking of camp, that the company decided to separate, not as to interests, but as to modes of travel.

Some of our wagons were pretty nearly worn out, and, as we had but little in them, there were sixteen men who that night decided to give up their five wagons and resort to "packing." Consequently the remaining three wagons, including Captain and Mrs. Wadsworth, bade us goodby and pulled out in the morning. This parting of the trail, as had been the case in the parting of the waters, was not without its smack of regret. For four months we had travelled as one family, each having at heart the interest and [Pg 70]comfort of the others. There had been days of sickness and an hour of death; there was a grave at the roadside; there had had been times of danger and disheartenment; all of which marshalled themselves to memory's foreground as the question of division was talked pro and con by the entire family while camped at the base of the snow-capped mountains on that midsummer night.

After the departure of the three wagons we who remained resolutely set ourselves to work to prepare, as best we could, ourselves and our belongings for the packing mode of travel. For three days and nights we remained there busily engaged. We took our wagons to pieces, cutting out such pieces as were necessary to make our pack saddles. One bunch of men worked at the saddles, another bunch separated the harnesses and put them in shape for the saddles, while others made big pouches or saddle-bags out of the wagon covers, in which to carry provisions and cooking utensils.

The spot upon which our camp was located was in the vicinity of what is now known as Smith's Pass, Wyoming. During one of our afternoons here Nature treated us to one of the grandest [Pg 71]spectacles ever witnessed by mortal eyes. We first noticed a small cloud gathering about the top of the mountain, which presently commenced circling around the peak, occasionally reaching over far enough to drop down upon us a few sprinkles of water, although the sun was shining brightly where we were. As the cloud continued to circle, it increased in size, momentum, and density of color, spreading out like a huge umbrella. Soon thunder could be heard, growing louder and more frequent until it became one continuous roar, fairly shaking the earth. Long, vivid flashes of lightning chased each other in rapid succession over the crags and lost themselves in crevice and ravine. All work was forgotten. In fact, one would as soon think of making saddles in the immediate presence of the Almighty as in the presence of that terrific, but sublime spectacle upon the mountain heights. Every man stood in reverential attitude and gazed in speechless wonder and admiration. David and Moses and the Christ had much to do with mountains in their day; and, as we watched the power of the elements that afternoon, we realized as never before how David could hear the floods clap their[Pg 72] hands and see expressions of joy or anger upon the faces of the mountains; and how Mount Sinai might have looked as it became the meeting-place of the Lord and Moses and the tables of stone. The storm lasted about an hour, and when at last Nature seemed to have exhausted herself the great mountain-top stood out again in the clear sunlight, wearing a new mantle of the whitest snow.

During our three-days' camp we had a number of callers from other trains, also six or eight Indians, among whom we divided such things as we could not take with us.

In the evening of the last day, we made a rousing camp-fire out of our wagon wheels, which we piled on top of each other, kindling a fire under them, around which we became reminiscent and grew rested for an early start on the morrow.

All things finally ready, we brought up the animals in the morning to fit their saddles and packs to them. One very quiet animal was packed with some camp-kettles, coffee-pots, and other cooking traps. As soon as he was let loose and heard the tinware rattle he broke and ran, bringing up in a quagmire up to his sides. The saddle had turned, and his hind feet[Pg 73] stepping into the pack well nigh ruined all our cooking utensils.

We managed to pull him out of the mire and quieted him down, but we could never again put anything on him that rattled. We took our guns and provisions and only such clothing as we had on, leaving all else behind. I remember putting on a pair of new boots that I had brought from home, which I did not take off until I had been some time in California, nor any other of my clothes, lying down in my blanket on the ground, like the rest of the animals.

As we turned out for noon, we saw off toward the mountain a drove of eleven elk. I took my rifle and creeping behind rocks and through ravines, tried to get in range of them, but with all my caution, they kept just beyond my reach. But I had a little luck toward night just as we were turning into camp. Out by a bunch of sagebrush sat the largest jack rabbit I ever saw. I raised my rifle and hit him squarely in the neck, killing him. I took him by the hind feet and slung him over my shoulder, and as I hung hold of his feet in front, his wounded neck came down to my heels behind. His ears were as long as a mule's ears. We dressed it[Pg 74] and made it into rabbit stew by putting into the kettle first a layer of bacon and then one of rabbit, and then a layer of dumpling, which we made from flour and water, putting in layer after layer of this sort until our four camp-kettles were filled. We had a late supper that night. It was between 9 and 10 o'clock before our stews were done to a turn, but what a luscious feast was ours when they were finally ready. I can think of no supper in my whole life that I have enjoyed so much as I did that one. We had plenty left over for our sixteen breakfasts the next morning, and some of the boys packed the remainder as a relish for the noon meal.

Soon after our start in the morning, we came to the Big Sandy, a stream tributary to Green River. The land here had more of the appearance of a desert than any we had yet seen. Out on the plain the trail forked, the left hand leading via Fort Bridges and Salt Lake City, while the right hand led over what is known as Sublett's Cut-off. Being undecided as to which fork to follow, we finally submitted it to vote, which proved to be a large majority in favor of the Cut-off, it having[Pg 75] been reported that the Mormons were inciting the Indians to attack immigrants.

The road here was hard and flinty, and, for more than a mile passed down a steep hill, at the bottom of which we noticed that wagon tires were worn half through owing to the wheels being locked for such a long distance.

This was Green River valley, and, where we made our crossing, the water being deep and cold, with a swift current. There was a good ferry boat, on which, after nearly a day's waiting, we ferried over our pack animals at one dollar per head; the balance of the stock we swam across. A short way on we had to ford a fork of the same river, and were then in an extremely mountainous country, up one side and down the other, until we reached Bear River valley.

We came down off the uplands into the valley and beside the river to camp, where we had an experience as exasperating as it was unexpected. Seeing some fine looking grass, half knee high, we started for it, when all at once clouds of the most persistent and venomous mosquitos filled the air, covering the animals, which began stamping and running about, some of them lying down and rolling in great [Pg 76]torment. We hurried the packs and saddles off them and sent a guard of men back to the hills with them. The rest of us wrapped ourselves head and ears and laid down in the grass without supper or water for man or beast. About 3 o'clock in the morning, the mosquitos having cooled down to some extent, the guard brought in the pack animals, which we loaded, and, like the Arab, "silently stole away." Returning to the road and getting the balance of the stock, we moved along the base of the hills, and about sunrise came to a beautiful spring branch, which crossed the trail, refreshing us with its cool, sparkling water. Here we went up into the hills and into camp for a day and a night, to rest and recuperate from our terrible experience of the night before.

It was now the first of July. By keeping close to the base of the hills we found good travelling and an abundance of clear spring-water. At nights we camped high up in the hills, where the mosquito was not.

"It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, bells, bonfires and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward for evermore."

These words, written by John Adams to his wife the day following the Declaration of Independence, and regarding that act and day, were evidently the sounding of the key-note of American patriotism.

It has long been one of Uncle Sam's legends that "he who starts across the continent is most sure to leave his religion on the east side of the Missouri river." Conditions in Nebraska to-day refute the truth of this statement, however. Whatever may be the rule or exception concerning an American traveller's religion, the genuineness of his patriotism and his fidelity to it are rarely questioned. Hence[Pg 78] it was that during the early July days the varied events of the past few months betook themselves to the recesses of our natures, and patriotism asserted its right of pre-emption.

The day of July 3d was somewhat eventful and perhaps somewhat preparatory to the 4th, in that I did a bit of horse-trading, as my riding-horse, through a hole in his shoe, had got a gravel into his foot, which made him so lame that I had been walking and leading him for the last ten days. We had just come to Soda Springs, where there was a village of Shoshone Indians, numbering about one thousand, among whom was an Indian trader named McClelland, who was buying or trading for broken-down stock. I soon struck him for a trade. He finally offered me, even up, a small native mule for my lame horse, and we soon traded. I then bought an Indian saddle for two dollars, and, mounting, rode back to camp with great joy to myself and amusement of the balance of the company. I had walked for the last two hundred miles, keeping up with the rest of them, and consequently was nearly broken down; and now that I had what proved to be the toughest and easiest riding [Pg 79]animal in the bunch, I was to be congratulated. I afterwards saw the horse I had traded for the mule in Sacramento, hitched to a dray. His owner valued him at four hundred dollars.

We had gone into camp close to the Indians, right among their wigwams, in fact, and, though it was Independence eve, the weather was cool and chilling, which, together with the jabbering and grunting of the Indians and their papooses, made sleeping almost impossible.

We had not been in camp more than an hour when three or four packers rode up on their way to the "States." They were the first persons travelling eastward that we had met since leaving the Missouri River. One of the men had been wounded with a charge of buckshot a few hours before, and there being no surgeon present, some of us held him while others picked out the shot and dressed his wounds.

Soda Springs was in the extreme eastern part of what is now the State of Idaho, at which point there is a town bearing the same name, Soda Springs. Indeed, the 4th of July found us in a settlement of springs, Beer Spring and Steamboat Spring being in close proximity to Soda[Pg 80] Springs. Beer Spring is barrel-shaped, its surface about level with the ground surface. It was always full to the top, and we could look down into the water at least twenty feet and see large bubbles that were constantly rising, a few feet apart, one chasing another to the surface, where they immediately collapsed. The peculiarity of the water was that one could sip down a gallon at a time without any inconvenience. The celebrated Steamboat Spring came out of a hole in a level rock. The water was quite hot, and the steam, puffing out at regular intervals, presented an interesting sight.

We remained in camp during the forenoon and celebrated the 4th of July as best we could. I am quite positive that we could not have repeated in concert the memorable words which open this chapter, but, while the letter of the injunction was absent, the spirit was with us and we carried it out in considerable detail, the Indians joining with us. We shot at a mark, we ran horse-races with the Indians and also foot-races. We had no bells to ring, but we had plenty of noise and games and sports. We had no flag to unfurl, but its sentiment was within us;[Pg 81] and when we had finished we were prouder than ever to be Americans.

After dinner we packed up and started out again, our trail leading us up in the top of the mountains, where, after going into camp for the night, it began to snow, so I had to quit writing in my diary. We spent a very uncomfortable night, and got out of the place early, going down into a warmer atmosphere and to a level stretch of deep sand covered with a thick growth of sagebrush. Having neglected to fill our canteens while on the mountain, we had to travel all day in the sand, under a scorching sun, without a drop of water. This was our first severe experience in water-hunger, and we thought of the deserts yet to be crossed.

At night we were delighted with coming to a stream, by the side of which we made camp, ourselves and our animals quite exhausted with the day's experiences. The country along here was very rough and mountainous, making travelling very difficult, so much so that two or more men dropped out to rest up.

We were soon in the region of the "City of Rocks," which was not a great distance south of Fort Hall, in Oregon.[Pg 82] This place, to all appearance, was surrounded by a range of high hills, circular in form and perhaps a quarter mile in diameter. A small stream of mountain water ran through it, near which we made our noon meal.

From about the center of this circle arose two grand, colossal steeples of solid rock, rising from two hundred to three hundred feet high; in outline they resembled church steeples. From the base of these great turrets, allowing the eyes to follow the circular mountains, could be seen a striking resemblance to a great city in ruins. Tall columns rose with broad facades and colossal archings over the broad entrances, which seemed to lead into those great temples of nature. Many of the formations strongly resembled huge lions crouched and guarding the passageways. Altogether the spot was one of intense interest and stood as strong evidence that