THE THAMES EMBANKMENT

Title: Old and New London, Volume I

Author: Walter Thornbury

Release date: February 26, 2010 [eBook #31412]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Eric Hutton, Jane Hyland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Illustrated with Numerous Engravings

FROM THE MOST AUTHENTIC SOURCES.

CASSELL, PETTER & GALPIN:

LONDON, PARIS & NEW YORK

[Pg 13]

ROMAN LONDON

Buried London—Our Early Relations—The Founder of London—A Distinguished Visitor at Romney Marsh—Cæsar re-visits the "Town on the Lake"—The Borders of Old London—Cæsar fails to make much out of the Britons—King Brown—The Derivation of the Name of London—The Queen of the Iceni—London Stone and London Roads—London's Earlier and Newer Walls—The Site of St. Paul's—Fabulous Claims to Idolatrous Renown—Existing Relics of Roman London—Treasures from the Bed of the Thames—What we Tread underfoot in London—A vast Field of Story

TEMPLE BAR

Temple Bar—The Golgotha of English Traitors—When Temple Bar was made of Wood—Historical Pageants at Temple Bar—The Associations

of Temple Bar—Mischievous Processions through Temple Bar—The First Grim Trophy—Rye-House Plot Conspirators

FLEET STREET:—GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Frays in Fleet Street—Chaucer and the Friar—The Duchess of Gloucester doing Penance for Witchcraft—Riots between Law Students and Citizens—'Prentice Riots—Oates in the Pillory—Entertainments in Fleet Street—Shop Signs—Burning the Boot—Trial of Hardy—Queen Caroline's Funeral

FLEET STREET (continued)

Dr. Johnson in Ambuscade at Temple Bar—The First Child—Dryden and Black Will—Rupert's Jewels—Telson's Bank—The Apollo Club at

the "Devil"—"Old Sir Simon the King"—"Mull Sack"—Dr. Johnson's Supper to Mrs. Lennox—Will Waterproof at the "Cock"—The

Duel at "Dick's Coffee House"—Lintot's Shop—Pope and Warburton—Lamb and the Albion—The Palace of Cardinal Wolsey—Mrs.

Salmon's Waxwork—Isaak Walton—Praed's Bank—Murray and Byron—St. Dunstan's—Fleet Street Printers—Hoare's Bank and

the "Golden Bottle"—The Real and Spurious "Mitre"—Hone's Trial—Cobbett's Shop—"Peele's Coffee House"

FLEET STREET (continued)

The "Green Dragon"—Tompion and Pinchbeck—The Record—St. Bride's and its Memories—Punch and his Contributors—The Dispatch—The

Daily Telegraph—The "Globe Tavern" and Goldsmith—The Morning Advertiser—The Standard—The London Magazine—A

Strange Story—Alderman Waithman—Brutus Billy—Hardham and his "37"

FLEET STREET (NORTHERN TRIBUTARIES—SHIRE LANE AND BELL YARD)

The Kit-Kat Club—The Toast for the Year—Little Lady Mary—Drunken John Sly—Garth's Patients—Club Removed to Barn Elms—Steele

at the "Trumpet"—Rogues' Lane—Murder—Beggars' Haunts—Thieves' Dens—Coiners—Theodore Hook in Hemp's Sponging-house—Pope

in Bell Yard—Minor Celebrities—Apollo Court

FLEET STREET (NORTHERN TRIBUTARIES—CHANCERY LANE)

The Asylum for Jewish Converts—The Rolls Chapel—Ancient Monuments—A Speaker Expelled for Bribery—"Remember Cæsar"—Trampling

on a Master of the Rolls—Sir William Grant's Oddities—Sir John Leach—Funeral of Lord Gifford—Mrs. Clark and the Duke of York—Wolsey

in his Pomp—Strafford—"Honest Isaak"—The Lord Keeper—Lady Fanshawe—Jack Randal—Serjeants' Inn—An Evening

with Hazlitt at the "Southampton"—Charles Lamb—Sheridan—The Sponging Houses—The Law Institute—A Tragical Story

FLEET STREET (NORTHERN TRIBUTARIES—continued)

Clifford's Inn—Dyer's Chambers—The Settlement after the Great Fire—Peter Wilkins and his Flying Wives—Fetter Lane—Waller's Plot and its Victims—Praise-God Barebone and his Doings—Charles Lamb at School—Hobbes the Philosopher—A Strange Marriage—Mrs. Brownrigge—Paul Whitehead—The Moravians—The Record Office and its Treasures—Rival Poets [Pg 14]

FLEET STREET TRIBUTARIES—CRANE COURT, JOHNSON'S COURT, BOLT COURT

Removal of the Royal Society from Gresham College—Opposition to Newton—Objections to Removal—The First Catalogue—Swift's Jeer at

the Society—Franklin's Lightning Conductor and King George III.—Sir Hans Sloane insulted—The Scottish Society—Wilkes's Printer—The

Delphin Classics—Johnson's Court—Johnson's Opinion on Pope and Dryden—His Removal to Bolt Court—The John Bull—Hook

and Terry—Prosecutions for Libel—Hook's Impudence

FLEET STREET TRIBUTARIES

Dr. Johnson in Bolt Court—His Motley Household—His Life there—Still existing—The Gallant "Lumber Troop"—Reform Bill Riots—Sir

Claudius Hunter—Cobbett in Bolt Court—The Bird Boy—The Private Soldier—In the House—Dr. Johnson in Gough Square—Busy at

the Dictionary—Goldsmith in Wine Office Court—Selling "The Vicar of Wakefield"—Goldsmith's Troubles—Wine Office Court—The

Old "Cheshire Cheese"

FLEET STREET TRIBUTARIES—SHOE LANE

The First Lucifers—Perkins' Steam Gun—A Link between Shakespeare and Shoe Lane—Florio and his Labours—"Cogers' Hall"—Famous

"Cogers"—A Saturday Night's Debate—Gunpowder Alley—Richard Lovelace, the Cavalier Poet—"To Althea, from Prison"—Lilly

the Astrologer and his Knaveries—A Search for Treasure with Davy Ramsay—Hogarth in Harp Alley—The "Society of Sign Painters"—Hudson,

the Song Writer—"Jack Robinson"—The Bishop's Residence—Bangor House—A Strange Story of Unstamped Newspapers—Chatterton's

Death—Curious Legend of his Burial—A well-timed Joke

FLEET STREET TRIBUTARIES—SOUTH

Worthy Mr. Fisher—Lamb's Wednesday Evenings—Persons one would wish to have seen—Ram Alley—Serjeants' Inn—The Daily News—"Memory"

Woodfall—A Mug-House Riot—Richardson's Printing Office—Fielding and Richardson—Johnson's Estimate of Richardson—Hogarth

and Richardson's Guest—An Egotist Rebuked—The King's "Housewife"—Caleb Colton: his Life, Works, and Sentiments

THE TEMPLE.—GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Origin of the Order of Templars—First Home of the Order—Removal to the Banks of the Thames—Rules of the Order—The Templars at the

Crusades, and their Deeds of Valour—Decay and Corruption of the Order—Charges brought against the Knights—Abolition of the Order

THE TEMPLE CHURCH AND PRECINCT

The Temple Church—Its Restorations—Discoveries of Antiquities—The Penitential Cell—Discipline in the Temple—The Tombs of the

Templars in the "Round"—William and Gilbert Marshall—Stone Coffins in the Churchyard—Masters of the Temple—The "Judicious"

Hooker—Edmund Gibbon, the Historian—The Organ in the Temple Church—The Rival Builders—"Straw Bail"—History of the

Precinct—Chaucer and the Friar—His Mention of the Temple—The Serjeants—Erection of New Buildings—The "Roses"—Sumptuary

Edicts—The Flying Horse

THE TEMPLE (continued)

The Middle Temple Hall: its Roof, Busts, and Portraits—Manningham's Diary—Fox Hunts in Hall—The Grand Revels—Spenser—Sir J.

Davis—A Present to a King—Masques and Royal Visitors at the Temple—Fires in the Temple—The Last Great Revel in the Hall—Temple

Anecdotes—The Gordon Riots—John Scott and his Pretty Wife—Colman "Keeping Terms"—Blackstone's "Farewell"—Burke—Sheridan—A

Pair of Epigrams—Hare Court—The Barber's Shop—Johnson and the Literary Club—Charles Lamb—Goldsmith: his Life,

Troubles, and Extravagances—"Hack Work" for Booksellers—The Deserted Village—She Stoops to Conquer—Goldsmith's Death and

Burial

THE TEMPLE (continued)

Fountain Court and the Temple Fountain—Ruth Pinch—L.E.L.'s Poem—Fig-tree Court—The Inner Temple Library—Paper Buildings—The

Temple Gate—Guildford North and Jeffreys—Cowper, the Poet: his Melancholy and Attempted Suicide—A Tragedy in Tanfield

Court—Lord Mansfield—"Mr. Murray" and his Client—Lamb's Pictures of the Temple—The Sun-dials—Porson and his Eccentricities—Rules>

of the Temple—Coke and his Labours—Temple Riots—Scuffles with the Alsatians—Temple Dinners—"Calling" to the Bar—The

Temple Gardens—The Chrysanthemums—Sir Matthew Hale's Tree—Revenues of the Temple—Temple Celebrities

WHITEFRIARS

The Present Whitefriars—The Carmelite Convent—Dr. Butts—The Sanctuary—Lord Sanquhar murders the Fencing-Master—His Trial—Bacon

and Yelverton—His Execution—Sir Walter Scott's "Fortunes of Nigel"—Shadwell's Squire of Alsatia—A Riot in Whitefriars—Elizabethan

Edicts against the Ruffians of Alsatia—Bridewell—A Roman Fortification—A Saxon Palace—Wolsey's Residence—Queen

Katherine's Trial—Her Behaviour in Court—Persecution of the first Congregationalists—Granaries and Coal Stores destroyed by the

Great Fire—The Flogging in Bridewell—Sermon on Madame Creswell—Hogarth and the "Harlot's Progress"—Pennant's Account of

Bridewell—Bridewell in 1843—Its Latter Days—Pictures in the Court Room—Bridewell Dock—The Gas Works—Theatres in Whitefriars—Pepys'

Visits to the Theatre—Dryden and the Dorset Gardens Theatre—Davenant—Kynaston—Dorset House—The Poet-Earl

[Pg 15]

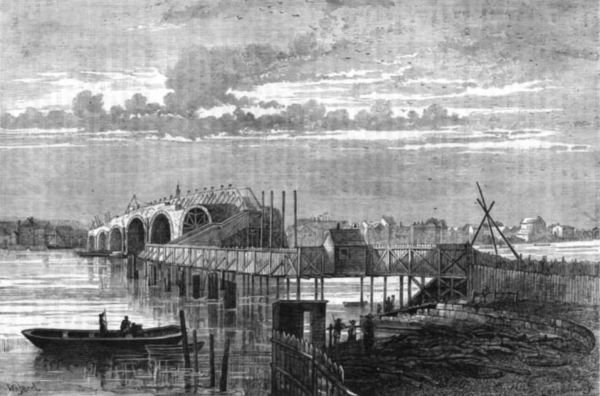

BLACKFRIARS

Three Norman Fortresses on the Thames' Bank—The Black Parliament—The Trial of Katherine of Arragon—Shakespeare a Blackfriars

Manager—The Blackfriars Puritans—The Jesuit Sermon at Hunsdon House—Fatal Accident—Extraordinary Escapes—Queen Elizabeth

at Lord Herbert's Marriage—Old Blackfriars Bridge—Johnson and Mylne—Laying of the Stone—The Inscription—A Toll Riot—Failure

of the Bridge—The New Bridge—Bridge Street—Sir Richard Phillips and his Works—Painters in Blackfriars—The King's Printing

Office—Printing House Square—The Times and its History—Walter's Enterprise—War with the Dispatch—The gigantic Swindling

Scheme exposed by the Times—Apothecaries' Hall—Quarrel with the College of Physicians

LUDGATE HILL

An Ugly Bridge and "Ye Belle Savage"—A Radical Publisher—The Principal Gate of London—From a Fortress to a Prison—"Remember the

Poor Prisoners"—Relics of Early Times—St. Martin's, Ludgate—The London Coffee House—Celebrated Goldsmiths on Ludgate Hill—Mrs.

Rundell's Cookery Book—Stationers' Hall—Old Burgavenny House and its History—Early Days of the Stationers' Company—The

Almanacks—An Awkward Misprint—The Hall and its Decorations—The St. Cecilia Festivals—Dryden's "St. Cecilia's Day" and

"Alexander's Feast"—Handel's Setting of them—A Modest Poet—Funeral Feasts and Political Banquets—The Company's Plate—Their

Charities—The Pictures at Stationers' Hall—The Company's Arms—Famous Masters

ST. PAUL'S

London's Chief Sanctuary of Religion—The Site of St. Paul's—The Earliest authenticated Church there—The Shrine of Erkenwald—St. Paul's

Burnt and Rebuilt—It becomes the Scene of a Strange Incident—Important Political Meeting within its Walls—The Great Charter

published there—St. Paul's and Papal Power in England—Turmoils around the Grand Cathedral—Relics and Chantry Chapels in St.

Paul's—Royal Visits to St. Paul's—Richard, Duke of York, and Henry VI.—A Fruitless Reconciliation—Jane Shore's Penance—A

Tragedy of the Lollards' Tower—A Royal Marriage—Henry VIII. and Cardinal Wolsey at St. Paul's—"Peter of Westminster"—A

Bonfire of Bibles—The Cathedral Clergy Fined—A Miraculous Rood—St. Paul's under Edward VI. and Bishop Ridley—A Protestant

Tumult at Paul's Cross—Strange Ceremonials—Queen Elizabeth's Munificence—The Burning of the Spire—Desecration of the Nave—Elizabeth

and Dean Nowell—Thanksgiving for the Armada—The "Children of Paul's"—Government Lotteries—Executions in the

Churchyard—Inigo Jones's Restorations and the Puritan Parliament—The Great Fire of 1666—Burning of Old St. Paul's, and Destruction

of its Monuments—Evelyn's Description of the Fire—Sir Christopher Wren called in

ST. PAUL'S (continued)

The Rebuilding of St. Paul's—Ill Treatment of its Architect—Cost of the Present Fabric—Royal Visitors—The First Grave in St. Paul's—Monuments

in St. Paul's—Nelson's Funeral—Military Heroes in St. Paul's—The Duke of Wellington's Funeral—Other Great Men in

St. Paul's—Proposal for the Completion and Decoration of the Building—Dimensions of St. Paul's—Plan of Construction—The Dome,

Ball, and Cross—Mr. Horner and his Observatory—Two Narrow Escapes—Sir James Thornhill—Peregrine Falcons on St. Paul's—Nooks

and Corners of the Cathedral—The Library, Model Room, and Clock—The Great Bell—A Lucky Error—Curious Story of a

Monomaniac—The Poets and the Cathedral—The Festivals of the Charity Schools and of the Sons of the Clergy

ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

St Paul's Churchyard and Literature—Queen Anne's Statue—Execution of a Jesuit in St. Paul's Churchyard—Miracle of the "Face in the

Straw"—Wilkinson's Story—Newbery the Bookseller—Paul's Chain—"Cocker"—Chapter House of St. Paul's—St. Paul's Coffee House—Child's

Coffee House and the Clergy—Garrick's Club at the "Queen's Arms," and the Company there—"Sir Benjamin" Figgins—Johnson

the Bookseller—Hunter and his Guests—Fuseli—Bonnycastle—Kinnaird—Musical Associations of the Churchyard—Jeremiah

Clark and his Works—Handel at Meares' Shop—Young the Violin Maker—The "Castle" Concerts—An Old Advertisement—Wren at

the "Goose and Gridiron"—St. Paul's School—Famous Paulines—Pepys visiting his Old School—Milton at St. Paul's

PATERNOSTER ROW

Its Successions of Traders—The House of Longman—Goldsmith at Fault—Tarleton, Actor, Host, and Wit—Ordinaries around St. Paul's:

their Rules and Customs—The "Castle"—"Dolly's"—The "Chapter" and its Frequenters—Chatterton and Goldsmith—Dr. Buchan

and his Prescriptions—Dr. Gower—Dr. Fordyce—The "Wittinagemot" at the "Chapter"—The "Printing Conger"—Mrs. Turner, the

Poisoner—The Church of St. Michael "ad Bladum"—The Boy in Panier Alley

BAYNARD'S CASTLE AND DOCTORS' COMMONS

Baron Fitzwalter and King John—The Duties of the Chief Bannerer of London—An Old-fashioned Punishment for Treason—Shakesperian

Allusions to Baynard's "Castle"—Doctors' Commons and its Five Courts—The Court of Probate Act, 1857—The Court of Arches—The

Will Office—Business of the Court—Prerogative Court—Faculty Office—Lord Stowell, the Admiralty Judge—Stories of him—His

Marriage—Sir Herbert Jenner Fust—The Court "Rising"—Doctor Lushington—Marriage Licences—Old Weller and the "Touters"—Doctors'

Commons at the Present Day

HERALDS' COLLEGE

Early Homes of the Heralds—The Constitution of the Heralds' College—Garter King at Arms—Clarencieux and Norroy—The Pursuivants—Duties

and Privileges of Heralds—Good, Bad, and Jovial Heralds—A Notable Norroy King at Arms—The Tragic End of Two Famous

Heralds—The College of Arms' Library

[Pg 16]

CHEAPSIDE—INTRODUCTORY AND HISTORICAL

Ancient Reminiscences of Cheapside—Stormy Days therein—The Westchepe Market—Something about the Pillory—The Cheapside Conduits—The

Goldsmiths' Monopoly—Cheapside Market—Gossip anent Cheapside by Mr. Pepys—A Saxon Rienzi—Anti-Free-Trade Riots in

Cheapside—Arrest of the Rioters—A Royal Pardon—Jane Shore

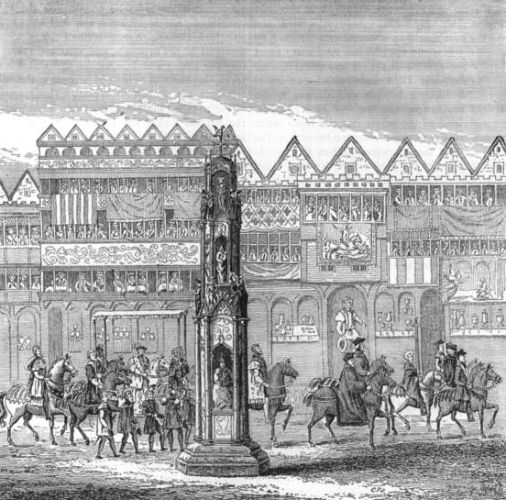

CHEAPSIDE SHOWS AND PAGEANTS

A Tournament in Cheapside—The Queen in Danger—The Street in Holiday Attire—The Earliest Civic Show on Record—The Water Processions—A

Lord Mayor's Show in Queen Elizabeth's Reign—Gossip about Lord Mayors' Shows—Splendid Pageants—Royal Visitors at

Lord Mayors' Shows—A Grand Banquet in Guildhall—George III. and the Lord Mayor's Show—The Lord Mayor's State Coach—The

Men in Armour—Sir Claudius Hunter and Elliston—Stow and the Midsummer Watch

CHEAPSIDE—CENTRAL

Grim Chronicles of Cheapside—Cheapside Cross—Puritanical Intolerance—The Old London Conduits—Mediæval Water-carriers—The Church

of St. Mary-le-Bow—"Murder will out"—The "Sound of Bow Bells"—Sir Christopher Wren's Bow Church—Remains of the Old

Church—The Seldam—Interesting Houses in Cheapside and their Memories—Goldsmiths' Row—The "Nag's Head" and the Self-consecrated

Bishops—Keats' House—Saddlers' Hall—A Prince Disguised—Blackmore, the Poet—Alderman Boydell, the Printseller—His

Edition of Shakespeare—"Puck"—The Lottery—Death and Burial

CHEAPSIDE TRIBUTARIES—SOUTH

The King's Exchange—Friday Street and the Poet Chaucer—The Wednesday Club in Friday Street—William Paterson, Founder of The Bank

of England—How Easy it is to Redeem the National Debt—St. Matthew's and St. Margaret Moses—Bread Street and the Bakers'

Shops—St. Austin's, Watling Street—Fraternity of St. Austin's—St. Mildred's, Bread Street—The Mitre Tavern—A Priestly Duel—Milton's

Birthplace—The "Mermaid"—Sir Walter Raleigh and the Mermaid Club—Thomas Coryatt, the Traveller—Bow Lane—Queen

Street—Soper's Lane—A Mercer Knight—St. Bennet Sherehog—Epitaphs in the Church of St. Thomas Apostle—A Charitable

Merchant

CHEAPSIDE TRIBUTARIES—NORTH

Goldsmiths' Hall—Its Early Days—Tailors and Goldsmiths at Loggerheads—The Goldsmiths' Company's Charters and Records—Their Great

Annual Feast—They receive Queen Margaret of Anjou in State—A Curious Trial of Skill—Civic and State Duties—The Goldsmiths

break up the Image of their Patron Saint—The Goldsmiths' Company's Assays—The Ancient Goldsmiths' Feasts—The Goldsmiths at

Work—Goldsmiths' Hall at the Present Day—The Portraits—St. Leonard's Church—St. Vedast—Discovery of a Stone Coffin—Coachmakers'

Hall

CHEAPSIDE TRIBUTARIES, NORTH:—WOOD STREET

Wood Street—Pleasant Memories—St. Peter's in Chepe—St. Michael's and St. Mary Staining—St. Alban's, Wood Street—Some Quaint

Epitaphs—Wood Street Compter and the Hapless Prisoners therein—Wood Street Painful, Wood Street Cheerful—Thomas Ripley—The

Anabaptist Rising—A Remarkable Wine Cooper—St. John Zachary and St. Anne-in-the-Willows—Haberdashers' Hall—Something

about the Mercers

CHEAPSIDE TRIBUTARIES, NORTH (continued)

Milk Street—Sir Thomas More—The City of London School—St. Mary Magdalen—Honey Lane—All Hallows' Church—Lawrence Lane and

St. Lawrence Church—Ironmonger Lane and Mercers' Hall—The Mercers' Company—Early Life Assurance Companies—The Mercers'

Company in Trouble—Mercers' Chapel—St. Thomas Acon—The Mercers' School—Restoration of the Carvings in Mercers' Hall—The

Glories of the Mercers' Company—Ironmonger Lane

GUILDHALL

The Original Guildhall—A fearful Civic Spectacle—The Value of Land increased by the Great Fire—Guildhall as it was and is—The Statues

over the South Porch—Dance's Disfigurements—The Renovation in 1864—The Crypt—Gog and Magog—Shopkeepers in Guildhall—The

Cenotaphs in Guildhall—The Court of Aldermen—The City Courts—The Chamberlain's Office—Pictures in the Guildhall—Sir

Robert Porter—The Common Council Room—Pictures and Statues—Guildhall Chapel—The New Library and Museum—Some Rare

Books—Historical Events in Guildhall—Chaucer in Trouble—Buckingham at Guildhall—Anne Askew's Trial and Death—Surrey—Throckmorton—Garnet—A

Grand Banquet

THE LORD MAYORS OF LONDON

The First Mayor of London—Portrait of him—Presentation to the King—An Outspoken Mayor—Sir N. Farindon—Sir William Walworth—Origin

of the prefix "Lord"—Sir Richard Whittington and his Liberality—Institutions founded by him—Sir Simon Eyre and his

Table—A Musical Lord Mayor—Henry VIII. and Gresham—Loyalty of the Lord Mayor and Citizens to Queen Mary—Osborne's

Leap into the Thames—Sir W. Craven—Brass Crosby—His Committal to the Tower—A Victory for the Citizens

[Pg 17]

THE LORD MAYORS OF LONDON (continued)

John Wilkes: his Birth and Parentage—The North Briton—Duel with Martin—His Expulsion—Personal Appearance—Anecdotes of

Wilkes—A Reason for making a Speech—Wilkes and the King—The Lord Mayor at the Gordon Riots—"Soap-suds" versus "Bar"—Sir

William Curtis and his Kilt—A Gambling Lord Mayor—Sir William Staines, Bricklayer and Lord Mayor—"Patty-pan" Birch—Sir

Matthew Wood—Waithman—Sir Peter Laurie and the "Dregs of the People"—Recent Lord Mayors

THE POULTRY

The Early Home of the London Poulterers—Its Mysterious Desertion—Noteworthy Sites in the Poultry—The Birthplace of Tom Hood,

Senior—A Pretty Quarrel at the Rose Tavern—A Costly Sign-board—The Three Cranes—The Home of the Dillys—Johnsoniana—St.

Mildred's Church, Poultry—Quaint Epitaphs—The Poultry Compter—Attack on Dr. Lamb, the Conjurer—Dekker, the Dramatist—Ned

Ward's Description of the Compter—Granville Sharp and the Slave Trade—Important Decision in favour of the Slave—Boyse—Dunton

OLD JEWRY

The Old Jewry—Early Settlements of Jews in London and Oxford—Bad Times for the Israelites—Jews' Alms—A King in Debt—Rachel

weeping for her Children—Jewish Converts—Wholesale Expulsion of the Chosen People from England—The Rich House of a Rich

Citizen—The London Institution, formerly in the Old Jewry—Porsoniana—Nonconformists in the Old Jewry—Samuel Chandler,

Richard Price, and James Foster—The Grocers Company—Their Sufferings under the Commonwealth—Almost Bankrupt—Again

they Flourish—The Grocers' Hall Garden—Fairfax and the Grocers—A Rich and Generous Grocer—A Warlike Grocer—Walbrook—Bucklersbury

THE MANSION HOUSE

The Palace of the Lord Mayor—The Old Stocks' Market—A Notable Statue of Charles II.—The Mansion House described—The

Egyptian Hall—Works of Art in the Mansion House—The Election of the Lord Mayor—Lord Mayor's Day—The Duties of a Lord

Mayor—Days of the Year on which the Lord Mayor holds High State—The Patronage of the Lord Mayor—His Powers—The

Lieutenancy of the City of London—The Conservancy of the Thames and Medway—The Lord Mayor's Advisers—The Mansion

House Household and Expenditure—Theodore Hook—Lord Mayor Scropps—The Lord Mayor's Insignia—The State Barge—The

Maria Wood

SAXON LONDON

A Glance at Saxon London—The Three Component Parts of Saxon London—The First Saxon Bridge over the Thames—Edward the Confessor

at Westminster—City Residences of the Saxon Kings—Political Position of London in Early Times—The first recorded Great Fire of

London—The Early Commercial Dignity of London—The Kings of Norway and Denmark besiege London in vain—A great Gemot held

in London—Edmund Ironside elected King by the Londoners—Canute besieges them, and is driven off—The Seamen of London—Its

Citizens as Electors of Kings

THE BANK OF ENGLAND

The Jews and the Lombards—The Goldsmiths the first London Bankers—William Paterson, Founder of the Bank of England—Difficult

Parturition of the Bank Bill—Whig Principles of the Bank of England—The Great Company described by Addison—A Crisis at the Bank—Effects

of a Silver Re-coinage—Paterson quits the Bank of England—The Ministry resolves that it shall be enlarged—The Credit of

the Bank shaken—The Whigs to the Rescue—Effects of the Sacheverell Riots—The South Sea Company—The Cost of a New Charter—Forged

Bank Notes—The Foundation of the "Three per Cent. Consols"—Anecdotes relating to the Bank of England and Bank Notes—Description

of the Building—Statue of William III.—Bank Clearing House—Dividend Day at the Bank

THE STOCK EXCHANGE

The Kingdom of Change Alley—A William III. Reuter—Stock Exchange Tricks—Bulls and Bears—Thomas Guy, the Hospital Founder—Sir

John Barnard, the "Great Commoner"—Sampson Gideon, the famous Jew Broker—Alexander Fordyce—A cruel Quaker Criticism—Stockbrokers

and Longevity—The Stock Exchange in 1795—The Money Articles in the London Papers—The Case of Benjamin Walsh,

M.P.—The De Berenger Conspiracy—Lord Cochrane unjustly accused—"Ticket Pocketing"—System of Business at the Stock

Exchange—"Popgun John"—Nathan Rothschild—Secrecy of his Operations—Rothschild outdone by Stratagem—Grotesque Sketch of

Rothschild—Abraham Goldsmid—Vicissitudes of the Stock Exchange—The Spanish Panic of 1835—The Railway Mania—Ricardo's

Golden Rules—A Clerical Intruder in Capel Court—Amusements of Stockbrokers—Laws of the Stock Exchange—The Pigeon Express—The

"Alley Man"—Purchase of Stock—Eminent Members of the Stock Exchange

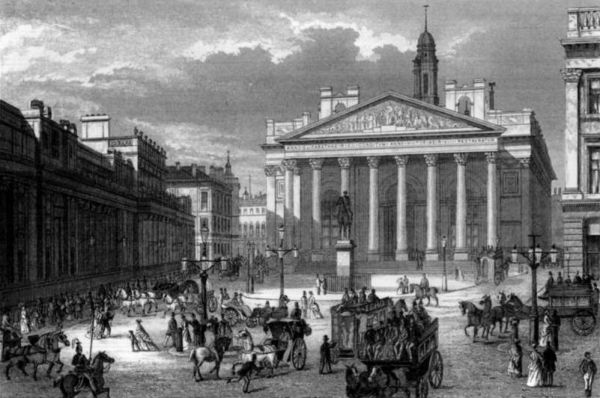

THE ROYAL EXCHANGE

The Greshams—Important Negotiations—Building of the Old Exchange—Queen Elizabeth visits it—Its Milliners' Shops—A Resort for Idlers—Access

of Nuisances—The various Walks in the Exchange—Shakespeare's Visits to it—Precautions against Fire—Lady Gresham and

the Council—The "Eye of London"—Contemporary Allusions—The Royal Exchange during the Plague and the Great Fire—Wren's

Design for a New Royal Exchange—The Plan which was ultimately accepted—Addison and Steele upon the Exchange—The Shops of

the Second Exchange

[Pg 18]

The Second Exchange on Fire—Chimes Extraordinary—Incidents of the Fire—Sale of Salvage—Designs for the New Building—Details of the

Present Exchange—The Ambulatory, or Merchants' Walk—Royal Exchange Assurance Company—"Lloyd's"—Origin of "Lloyd's"—Marine

Assurance—Benevolent Contributions of "Lloyd's"—A "Good" and "Bad" Book

NEIGHBOURHOOD OF THE BANK:—LOTHBURY

Lothbury—Its Former Inhabitants—St. Margaret's Church—Tokenhouse Yard—Origin of the Name—Farthings and Tokens—Silver Halfpence

and Pennies—Queen Anne's Farthings—Sir William Petty—Defoe's Account of the Plague in Tokenhouse Yard

THROGMORTON STREET.—THE DRAPERS' COMPANY

Halls of the Drapers' Company—Throgmorton Street and its many Fair Houses—Drapers and Wool Merchants—The Drapers in Olden Times—Milborne's

Charity—Dress and Livery—Election Dinner of the Drapers' Company—A Draper's Funeral—Ordinances and Pensions—Fifty-three

Draper Mayors—Pageants and Processions of the Drapers—Charters—Details of the present Drapers' Hall—Arms of the

Drapers' Company

BARTHOLOMEW LANE AND LOMBARD STREET

George Robins—His Sale of the Lease of the Olympic—St. Bartholomew's Church—The Lombards and Lombard Street—William de la Pole—Gresham—The

Post Office, Lombard Street—Alexander Pope's Father in Plough Court—Lombard Street Tributaries—St. Mary

Woolnoth—St. Clement's—Dr. Benjamin Stone—Discovery of Roman Remains—St. Mary Abchurch

THREADNEEDLE STREET

The Centre of Roman London—St. Benet Fink—The Monks of St. Anthony—The Merchant Taylors—Stow, Antiquary and Tailor—A

Magnificent Roll—The Good Deeds of the Merchant Taylors—The Old and the Modern Merchant Taylors' Hall—"Concordia parvæ

res crescunt"—Henry VII. enrolled as a Member of the Taylors' Company—A Cavalcade of Archers—The Hall of Commerce in

Threadneedle Street—A Painful Reminiscence—The Baltic Coffee-house—St. Anthony's School—The North and South American Coffee-house—The

South Sea House—History of the South Sea Bubble—Bubble Companies of the Period—Singular Infatuation of the Public—Bursting

of the Bubble—Parliamentary Inquiry into the Company's Affairs—Punishment of the Chief Delinquents—Restoration of Public

Credit—The Poets during the Excitement—Charles Lamb's Reverie

CANNON STREET

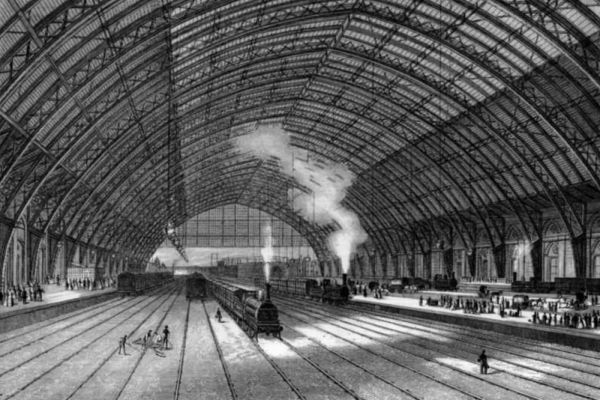

London Stone and Jack Cade—Southwark Bridge—Old City Churches—The Salters' Company's Hall, and the Salters' Company's History—Oxford

House—Salters' Banquets—Salters' Hall Chapel—A Mysterious Murder in Cannon Street—St. Martin Orgar—King William's

Statue—Cannon Street Station

CANNON STREET TRIBUTARIES AND EASTCHEAP

Budge Row—Cordwainers' Hall—St. Swithin's Church—Founders' Hall—The Oldest Street in London—Tower Royal and the Wat Tyler Mob—The

Queen's Wardrobe—St. Antholin's Church—"St. Antlin's Bell"—The London Fire Brigade—Captain Shaw's Statistics—St.

Mary Aldermary—A Quaint Epitaph—Crooked Lane—An Early "Gun Accident"—St. Michael's and Sir William Walworth's Epitaph—Gerard's

Hall and its History—The Early Closing Movement—St. Mary Woolchurch—Roman Remains in Nicholas Lane—St.

Stephen's, Walbrook—Eastcheap and the Cooks' Shops—The "Boar's Head"—Prince Hal and his Companions—A Giant Plum-pudding—Goldsmith

at the "Boar's Head"—The Weigh-house Chapel and its Famous Preachers—Reynolds, Clayton, Binney

THE MONUMENT AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD

The Monument—How shall it be fashioned?—Commemorative Inscriptions—The Monument's Place in History—Suicides and the Monument—The

Great Fire of London—On the Top of the Monument by Night—The Source of the Fire—A Terrible Description—Miles Coverdale—St.

Magnus, London Bridge

CHAUCER'S LONDON

London Citizens in the Reigns of Edward III. and Richard II.—The Knight—The Young Bachelor—The Yeoman—The Prioress—The Monk

who goes a Hunting—The Merchant—The Poor Clerk—The Franklin—The Shipman—The Poor Parson

[Pg 19]

Introduction of Randolph to Ben Jonson (Frontispiece)

The Old Wooden Temple Bar

Burning the Pope in Effigy at Temple Bar

Bridewell in 1666

Part of Modern London, showing the Ancient Wall

Plan of Roman London

Ancient Roman Pavement

Part of Old London Wall, near Falcon Square

Proclamation of Charles II. at Temple Bar

Penance of the Duchess of Gloucester

The Room over Temple Bar

Titus Oates in the Pillory

Dr. Titus Oates

Temple Bar and the "Devil Tavern"

Temple Bar in Dr. Johnson's Time

Mull Sack and Lady Fairfax

Mrs. Salmon's Waxwork, Fleet Street

St. Dunstan's Clock

An Evening with Dr. Johnson at the "Mitre"

Old Houses (still standing) in Fleet Street

St. Bride's Church, Fleet Street, after the Fire, 1824

Waithman's Shop

Alderman Waithman, from an Authentic Portrait

Group at Hardham's Tobacco Shop

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and the Kit-Kats

Bishop Butler

Wolsey in Chancery Lane

Izaak Walton's House

Old Serjeants' Inn

Hazlitt

Clifford's Inn

Execution of Tomkins and Challoner

Roasting the Rumps in Fleet Street (from an old Print)

Interior of the Moravian Chapel in Fetter Lane

House said to have been occupied by Dryden in Fetter Lane

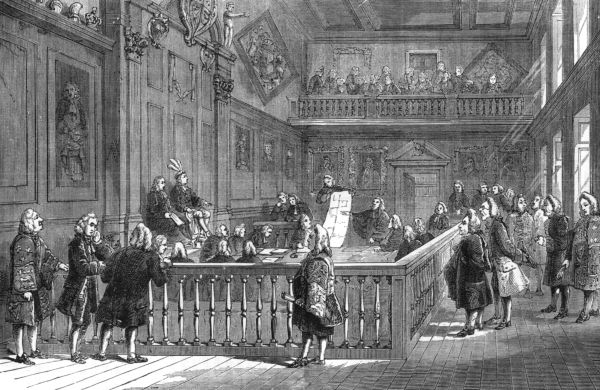

A Meeting of the Royal Society in Crane Court

The Royal Society's House in Crane Court

Theodore E. Hook

Dr. Johnson's House in Bolt Court

A Tea Party at Dr. Johnson's

Gough Square

Wine Office Court and the "Cheshire Cheese"

Cogers' Hall

Lovelace in Prison

Bangor House, 1818

Old St. Dunstan's Church

The Dorset Gardens Theatre, Whitefriars

Attack on a Whig Mug-house

Fleet Street, the Temple, &c., 1563

Fleet Street, the Temple, &c., 1720

[Pg 20]

A Knight Templar

Interior of the Temple Church

Tombs of Knights Templars

The Temple in 1671

The Old Hall of the Inner Temple

Antiquities of the Temple

Oliver Goldsmith

Goldsmith's Tomb in 1860

The Temple Fountain, from an Old Print

A Scuffle between Templars and Alsatians

Sun-dial in the Temple

The Temple Stairs

The Murder of Turner

Bridewell, as Rebuilt after the Fire, from an Old Print

Beating Hemp in Bridewell, after Hogarth

Interior of the Duke's Theatre

Baynard's Castle, from a View published in 1790

Falling-in of the Chapel at Blackfriars

Richard Burbage, from an Original Portrait

Laying the Foundation-stone of Blackfriars Bridge

Printing House Square and the "Times" Office

Blackfriars Old Bridge during its Construction, 1775

The College of Physicians, Warwick Lane

Outer Court of La Belle Sauvage in 1828

The Inner Court of the Belle Sauvage

The Mutilated Statues from Lud Gate, 1798

Old Lud Gate, from a Print published about 1750

Ruins of the Barbican on Ludgate Hill

Interior of Stationers' Hall

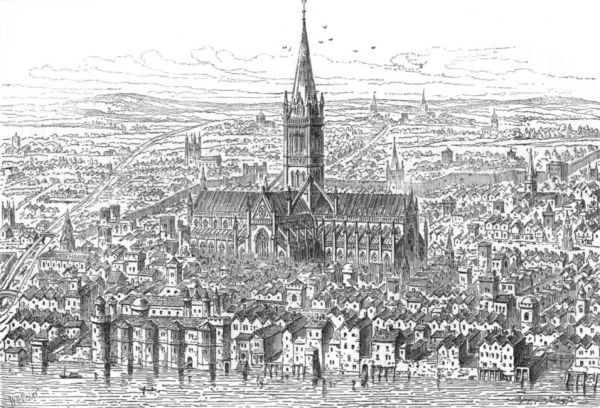

Old St. Paul's, from a View by Hollar

Old St. Paul's—the Interior, looking East

The Church of St. Faith, the Crypt of Old St. Paul's

St. Paul's after the Fall of the Spire

The Chapter House of Old St. Paul's

Dr. Bourne preaching at Paul's Cross

The Rebuilding of St. Paul's

The Choir of St. Paul's

The Scaffolding and Observatory on St. Paul's in 1848

St. Paul's and the Neighbourhood in 1540

The Library of St. Paul's

The "Face in the Straw," 1613

Execution of Father Garnet

Old St. Paul's School

Richard Tarleton, the Actor

Dolly's Coffee House

The Figure in Panier Alley

The Church of St. Michael ad Bladum

The Prerogative Office, Doctors' Commons

St. Paul's and Neighbourhood, from Aggas' Plan, 1563

Heralds' College (from an Old Print)

The Last Heraldic Court (from an Old Picture)

[Pg 21]

Sword, Dagger, and Ring of King James of Scotland

Linacre's House

Ancient View of Cheapside

Beginning of the Riot in Cheapside

Cheapside Cross, as it appeared in 1547

The Lord Mayor's Procession, from Hogarth

The Marriage Procession of Anne Boleyn

Figures of Gog and Magog set up in Guildhall

The Royal Banquet in Guildhall in 1761

The Lord Mayor's Coach

The Demolition of Cheapside Cross

Old Map of the Ward of Cheap—about 1750

The Seal of Bow Church

Bow Church, Cheapside, from a View taken about 1750

No. 73, Cheapside, from an Old View

The Door of Saddlers' Hall

Milton's House and Milton's Burial-place

Interior of Goldsmiths' Hall

Trial of the Pix

Exterior of Goldsmiths' Hall

Altar of Diana

Wood Street Compter, from a View published in 1793

The Tree at the Corner of Wood Street

Pulpit Hour-glass

Interior of St. Michael's, Wood Street

Interior of Haberdashers' Hall

The "Swan with Two Necks," Lad Lane

City of London School

Mercers' Chapel, as Rebuilt after the Fire

The Crypt of Guildhall

The Court of Aldermen, Guildhall

Old Front of Guildhall

The New Library, Guildhall

Sir Richard Whittington

Whittington's Almshouses, College Hill

Osborne's Leap

A Lord Mayor and his Lady

Wilkes on his Trial

Birch's Shop, Cornhill

The Stocks' Market, Site of the Mansion House

John Wilkes

The Poultry Compter

Richard Porson

Sir R. Clayton's House, Garden Front

Exterior of Grocers' Hall

Interior of Grocers' Hall

The Mansion House Kitchen

[Pg 22]

The Mansion House in 1750

Interior of the Egyptian Hall

The "Maria Wood"

Broad Street and Cornhill Wards

Lord Mayor's Water Procession

The Old Bank, looking from the Mansion House

Old Patch

The Bank Parlour, Exterior View

Dividend Day at the Bank

The Church of St. Benet Fink

Court of the Bank of England

"Jonathan's," from an Old Sketch

Capel Court

The Clearing House

The Present Stock Exchange

On Change (from an Old Print, about 1800)

Inner Court of the First Royal Exchange

Sir Thomas Gresham

Wren's Plan for Rebuilding London

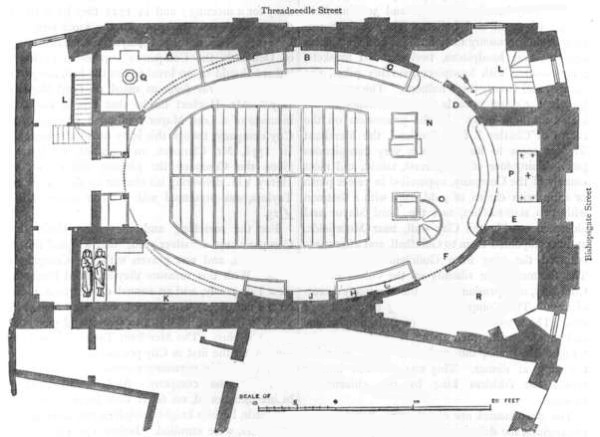

Plan of the Exchange in 1837

The First Royal Exchange

The Second Royal Exchange, Cornhill

The Present Royal Exchange

Blackwell Hall in 1812

Interior of Lloyd's

The Subscription Room at "Lloyd's"

Interior of Drapers' Hall

Drapers' Hall Garden

Cromwell's House, from Aggas's Map

Pope's House, Plough Court, Lombard Street

St. Mary Woolnoth

Interior of Merchant Taylors' Hall

Ground Plan of the Church of St. Martin Outwich

March of the Archers

The Old South Sea House

London Stone

The Fourth Salters' Hall

Cordwainers' Hall

St. Antholin's Church, Watling Street

The Crypt of Gerard's Hall

Old Sign of the "Boar's Head"

Exterior of St. Stephen's, Walbrook, in 1700

The Weigh-house Chapel

Miles Coverdale

Wren's Original Design for the Summit of the Monument

The Monument and the Church of St. Magnus, 1800

[Pg 23]

Writing the history of a vast city like London is like writing a history of the ocean—the area is so vast, its inhabitants are so multifarious, the treasures that lie in its depths so countless. What aspect of the great chameleon city should one select? for, as Boswell, with more than his usual sense, once remarked, "London is to the politician merely a seat of government, to the grazier a cattle market, to the merchant a huge exchange, to the dramatic enthusiast a congeries of theatres, to the man of pleasure an assemblage of taverns." If we follow one path alone, we must neglect other roads equally important; let us, then, consider the metropolis as a whole, for, as Johnson's friend well says, "the intellectual man is struck with London as comprehending the whole of human life in all its variety, the contemplation of which is inexhaustible." In histories, in biographies, in scientific records, and in chronicles of the past, however humble, let us gather materials for a record of the great and the wise, the base and the noble, the odd and the witty, who have inhabited London and left their names upon its walls. Wherever the glimmer of the cross of St. Paul's can be seen we shall wander from street to alley, from alley to street, noting almost every event of interest that has taken place there since London was a city.[Pg 24]

Had it been our lot to write of London before the Great Fire, we should have only had to visit 65,000 houses. If in Dr. Johnson's time, we might have done like energetic Dr. Birch, and have perambulated the twenty-mile circuit of London in six hours' hard walking; but who now could put a girdle round the metropolis in less than double that time? The houses now grow by streets at a time, and the nearly four million inhabitants would take a lifetime to study. Addison probably knew something of London when he called it "an aggregate of various nations, distinguished from each other by their respective customs, manners, and interests—the St. James's courtiers from the Cheapside citizens, the Temple lawyers from the Smithfield drovers;" but what would the Spectator say now to the 168,701 domestic servants, the 23,517 tailors, the 18,321 carpenters, the 29,780 dressmakers, the 7,002 seamen, the 4,861 publicans, the 6,716 blacksmiths, &c., to which the population returns of thirty years ago depose, whom he would have to observe and visit before he could say he knew all the ways, oddities, humours—the joys and sorrows, in fact—of this great centre of civilisation?

The houses of old London are incrusted as thick with anecdotes, legends, and traditions as an old ship is with barnacles. Strange stories about strange men grow like moss in every crevice of the bricks. Let us, then, roll together like a great snowball the mass of information that time and our predecessors have accumulated, and reduce it to some shape and form. Old London is passing away even as we dip our pen in the ink, and we would fain erect quickly our itinerant photographic machine, and secure some views of it before it passes. Roman London, Saxon London, Norman London, Elizabethan London, Stuart London, Queen Anne's London, we shall in turn rifle to fill our museum, on whose shelves the Roman lamp and the vessel full of tears will stand side by side with Vanessas' fan; the sword-knot of Rochester by the note-book of Goldsmith. The history of London is an epitome of the history of England. Few great men indeed that England has produced but have some associations that connect them with London. To be able to recall these associations in a London walk is a pleasure perpetually renewing, and to all intents inexhaustible.

Let us, then, at once, without longer halting at the gate, seize the pilgrim staff and start upon our voyage of discovery, through a dreamland that will be now Goldsmith's, now Gower's, now Shakespeare's, now Pope's, London. In Cannon Street, by the[Pg 25] old central milestone of London, grave Romans will meet us and talk of Cæsar and his legions. In Fleet Street we shall come upon Chaucer beating the malapert Franciscan friar; at Temple Bar, stare upwards at the ghastly Jacobite heads. In Smithfield we shall meet Froissart's knights riding to the tournament; in the Strand see the misguided Earl of Essex defending his house against Queen Elizabeth's troops, who are turning towards him the cannon on the roof of St. Clement's church.

But let us first, rather than glance at scattered pictures in a gallery which is so full of them, measure out, as it were, our future walks, briefly glancing at the special doors where we shall billet our readers. The brief summary will serve to broadly epitomise the subject, and will prove the ceaseless variety of interest which it involves.

We have selected Temple Bar, that old gateway, as a point of departure, because it is the centre, as near as can be, of historical London, and is in itself full of interest. We begin with it as a rude wooden building, which, after the Great Fire, Wren turned into the present arch of stone, with a room above, where Messrs. Childs, the bankers, store their books and archives. The trunk of one of the Rye House conspirators, in Charles II.'s time, first adorned the Bar; and after that, one after the other, many rash Jacobite heads, in 1715 and 1745, arrived at the same bad eminence. In many a royal procession and many a City riot, this gate has figured as a halting-place and a point of defence. The last rebel's head blew down in 1772; and the last spike was not removed till the beginning of the present century. In the Popish Plot days of Charles II. vast processions used to come to Temple Bar to illuminate the supposed statue of Queen Elizabeth, in the south-east niche (though it probably really represents Anne of Denmark); and at great bonfires at the Temple gate the frenzied people burned effigies of the Pope, while thousands of squibs were discharged, with shouts that frightened the Popish Portuguese Queen, at that time living at Somerset House, forsaken by her dissolute scapegrace of a husband.

Turning our faces now towards the old black dome that rises like a half-eclipsed planet over Ludgate Hill, we first pass along Fleet Street, a locality full to overflowing with ancient memorials, and in its modern aspect not less interesting. This street has been from time immemorial the high road for royal processions. Richard II. has passed along here to St. Paul's, his parti-coloured robes jingling with golden bells; and Queen Elizabeth, be-ruffled and be-fardingaled, has glanced at those gable-ends east[Pg 26] of St. Dunstan's, as she rode in her cumbrous plumed coach to thank God at St. Paul's for the scattering and shattering of the Armada. Here Cromwell, a king in all but name and twice a king by nature, received the keys of the City, as he rode to Guildhall to preside at the banquet of the obsequious Mayor. William of Orange and Queen Anne both clattered over these stones to return thanks for victories over the French; and old George III. honoured the street when, with his handsome but worthless son, he came to thank God for his partial restoration from that darker region than the valley of the shadow of death, insanity. We recall many odd and pleasant figures in this street; first the old printers who succeeded Caxton, who published for Shakespeare or who timidly speculated in Milton's epic, that great product of a sorry age; next, the old bankers, who, at Child's and Hoare's, laid the foundations of permanent wealth, and from simple City goldsmiths were gradually transformed to great capitalists. Izaak Walton, honest shopkeeper and patient angler, eyes us from his latticed window near Chancery Lane; and close by we see the child Cowley reading the "Fairy Queen" in a window-seat, and already feeling in himself the inspiration of his later years. The lesser celebrities of later times call to us as we pass. Garrick's friend Hardham, of the snuff-shop; and that busy, vain demagogue, Alderman Waithman, whom Cobbett abused because he was not zealous enough for poor hunted Queen Caroline. Then there is the shop where barometers were first sold, the great watchmakers, Tompion and Pinchbeck, to chronicle, and the two churches to notice. St. Dunstan's is interesting for its early preachers, the good Romaine and the pious Baxter; and St. Bride's has anecdotes and legends of its own, and a peal of bells which have in their time excited as much admiration as those giant hammermen at the old St. Dunstan's clock, which are now in Regent's Park. The newspaper offices, too, furnish many curious illustrations of the progress of that great organ of modern civilisation, the press. At the "Devil" we meet Ben Jonson and his club; and at John Murray's old shop we stop to see Byron lunging with his stick at favourite volumes on the shelves, to the bookseller's great but concealed annoyance. Nor do we forget to sketch Dr. Johnson at Temple Bar, bantered by his fellow Jacobite, Goldsmith, about the warning heads upon the gate; at Child's bank pausing to observe the dinnerless authors returning downcast at the rejection of brilliant but fruitless proposals; or stopping with Boswell, one hand upon a street post, to shake the night air with his Cyclopean laughter. Varied as the[Pg 27] colours in a kaleidoscope are the figures that will meet us in these perambulations; mutable as an opal are the feelings they arouse. To the man of facts they furnish facts; to the man of imagination, quick-changing fancies; to the man of science, curious memoranda; to the historian, bright-worded details, that vivify old pictures now often dim in tone; to the man of the world, traits of manners; to the general thinker, aspects of feelings and of passions which expand the knowledge of human nature; for all these many-coloured stones are joined by the one golden string of London's history.

But if Fleet Street itself is rich in associations, its side streets, north and south, are yet richer. Here anecdote and story are clustered in even closer compass. In these side binns lies hid the choicest wine, for when Fleet Street had, long since, become two vast rows of shops, authors, wits, poets, and memorable persons of all kinds, still inhabited the "closes" and alleys that branch from the main thoroughfare. Nobles and lawyers long dwelt round St. Dunstan's and St. Bride's. Scholars, poets, and literati of all kind, long sought refuge from the grind and busy roar of commerce in the quiet inns and "closes," north and south. In what was Shire Lane we come upon the great Kit-Kat Club, where Addison, Garth, Steele, and Congreve disported; and we look in on that very evening when the Duke of Kingston, with fatherly pride, brought his little daughter, afterwards Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, and, setting her on the table, proposed her as a toast. Following the lane down till it becomes a nest of coiners, thieves, and bullies, we pass on to Bell Yard, to call on Pope's lawyer friend, Fortescue; and in Chancery Lane we are deep among the lawyers again. Ghosts of Jarndyces v. Jarndyces, from the Middle Ages downwards, haunt this thoroughfare, where Wolsey once lived in his pride and state. Izaak Walton dwelt in this lane once upon a time; and that mischievous adviser of Charles I., Earl Strafford, was born here. Hazlitt resided in Southampton Buildings when he fell in love with the tailor's daughter and wrote that most stultifying confession of his vanity and weakness, "The New Pygmalion." Fetter Lane brings us fresh stores of subjects, all essentially connected with the place, deriving an interest from and imparting a new interest to it. Praise-God-Barebones, Dryden, Otway, Baxter, and Mrs. Brownrigg form truly a strange bouquet. By mutual contrast the incongruous group serves, however, to illustrate various epochs of London life, and the background serves to explain the actions and the social position of each and all these motley beings.[Pg 28]

In Crane Court, the early home of the Royal Society, Newton is the central personage, and we tarry to sketch the progress of science and to smile at the crudity of its early experiments and theories. In Bolt Court we pause to see a great man die. Here especially Dr. Johnson's figure ever stands like a statue, and we shall find his black servant at the door and his dependents wrangling in the front parlour. Burke and Boswell are on their way to call, and Reynolds is taking coach in the adjoining street. Nor is even Shoe Lane without its associations, for at the north-east end the corpse of poor, dishonoured Chatterton lies still under some neglected rubbish heap; and close by the brilliant Cavalier poet, Lovelace, pined and perished, almost in beggary.

The southern side of Fleet Street is somewhat less noticeable. Still, in Salisbury Square the worthy old printer Richardson, amid the din of a noisy office, wrote his great and pathetic novels; while in Mitre Buildings Charles Lamb held those delightful conversations, so full of quaint and kindly thoughts, which were shared in by Hazlitt and all the odd people Lamb has immortalised in his "Elia"—bibulous Burney, George Dyer, Holcroft, Coleridge, Hone, Godwin, and Leigh Hunt.

Whitefriars and Blackfriars are our next places of pilgrimage, and they open up quite new lines of reading and of thought. Though the Great Fire swept them bare, no district of London has preserved its old lines so closely; and, walking in Whitefriars, we can still stare through the gate that once barred off the brawling Copper Captains of Charles II.'s Alsatia from the contemptuous Templars of King's Bench Walk. Whitefriars was at first a Carmelite convent, founded, before Blackfriars, on land given by Edward I.; the chapter-house was given by Henry VII. to his physician, Dr. Butts (a man mentioned by Shakespeare), and in the reign of Edward VI. the church was demolished. Whitefriars then, though still partially inhabited by great people, soon sank into a sanctuary for runaway bankrupts, cheats, and gamblers. The hall of the monastery was turned into a theatre, where many of Dryden's plays first appeared. The players favoured this quarter, where, in the reign of James I., two henchmen of Lord Sanquire, a revengeful young Scottish nobleman, shot at his own door a poor fencing-master, who had accidentally put out their master's eye several years before in a contest of skill. The two men were hung opposite the Whitefriars gate in Fleet Street. This disreputable and lawless nest of river-side alleys was called Alsatia, from its resemblance to the seat of the war then raging on the frontiers of France, in the dominions[Pg 29] of King James's son-in-law, the Prince Palatine. Its roystering bullies and shifty money-lenders are admirably sketched by Shadwell in his Squire of Alsatia, an excellent comedy freely used by Sir Walter Scott in his "Fortunes of Nigel," who has laid several of his strongest scenes in this once scampish region. That great scholar Selden lived in Whitefriars with the Countess Dowager of Kent, whom he was supposed to have married; and, singularly enough, the best edition of his works was printed in Dogwell Court, Whitefriars, by those eminent printers, Bowyer & Son. At the back of Whitefriars we come upon Bridewell, the site of a palace of the Norman kings. Cardinal Wolsey afterwards owned the house, which Henry VIII. reclaimed in his rough and not very scrupulous manner. It was the old palace to which Henry summoned all the priors and abbots of England, and where he first announced his intention of divorcing Katherine of Arragon. After this it fell into decay. The good Ridley, the martyr, begged it of Edward VI. for a workhouse and a school. Hogarth painted the female prisoners here beating hemp under the lash of a cruel turnkey; and Pennant has left a curious sketch of the herd of girls whom he saw run like hounds to be fed when a gaoler entered.

If Whitefriars was inhabited by actors, Blackfriars was equally favoured by players and by painters. The old convent, removed from Holborn, was often used for Parliaments. Charles V. lodged here when he came over to win Henry against Francis; and Burbage, the great player of "Richard the Third," built a theatre in Blackfriars, because the Precinct was out of the jurisdiction of the City, then ill-disposed to the players. Shakespeare had a house here, which he left to his favourite daughter, the deed of conveyance of which sold, in 1841, for £165 15s. He must have thought of his well-known neighbourhood when he wrote the scenes of Henry VIII., where Katherine was divorced and Wolsey fell, for both events were decided in Blackfriars Parliaments. Oliver, the great miniature painter, and Jansen, a favourite portrait painter of James I., lived in Blackfriars, where we shall call upon them; and Vandyke spent nine happy years here by the river side. The most remarkable event connected with Blackfriars is the falling in of the floor of a Roman Catholic private chapel in 1623, by which fifty-nine persons perished, including the priest, to the exultation of the Puritans, who pronounced the event a visitation of Heaven on Popish superstition. Pamphlets of the time, well rummaged by us, describe the scene with curious exactness, and mention the singular[Pg 30] escapes of several persons on the "Fatal Vespers," as they were afterwards called.

Leaving the racket of Alsatia and its wild doings behind us, we come next to that great monastery of lawyers, the Temple—like Whitefriars and Blackfriars, also the site of a bygone convent. The warlike Templars came here in their white cloaks and red crosses from their first establishment in Southampton Buildings, and they held it during all the Crusades, in which they fought so valorously against the Paynim, till they grew proud and corrupt, and were suspected of worshipping idols and ridiculing Christianity. Their work done, they perished, and the Knights of St. John took possession of their halls, church, and cloisters. The incoming lawyers became tenants of the Crown, and the parade-ground of the Templars and the river-side terrace and gardens were tenanted by more peaceful occupants. The manners and customs of the lawyers of various ages, their quaint revels, fox-huntings in hall, and dances round the coal fire, deserve special notice; and swarms of anecdotes and odd sayings and doings buzz round us as we write of the various denizens of the Temple—Dr. Johnson, Goldsmith, Lamb, Coke, Plowden, Jefferies, Cowper, Butler, Parsons, Sheridan, and Tom Moore; and we linger at the pretty little fountain and think of those who have celebrated its praise. Every binn of this cellar of lawyers has its story, and a volume might well be written in recording the toils and struggles, successes and failures, of the illustrious owners of Temple chambers.

Thence we pass to Ludgate, where that old London inn, the "Belle Sauvage," calls up associations of the early days of theatres, especially of Banks and his wonderful performing horse, that walked up one of the towers of Old St. Paul's. Hone's old shop reminds us of the delightful books he published, aided by Lamb and Leigh Hunt. The old entrance of the City, Ludgate, has quite a history of its own. It was a debtors' prison, rebuilt in the time of King John from the remains of demolished Jewish houses, and was enlarged by the widow of Stephen Forster, Lord Mayor in the reign of Henry VI., who, tradition says, had been himself a prisoner in Ludgate, till released by a rich widow, who saw his handsome face through the grate and married him. St. Martin's church, Ludgate, is one of Wren's churches, and is chiefly remarkable for its stolid conceit in always getting in the way of the west front of St. Paul's.

The great Cathedral has been the scene of events that illustrate almost every age of English history. This is the third St. Paul's. The first, falsely supposed to have been built on the site of a Roman[Pg 31] temple of Diana, was burnt down in the last year of William the Conqueror. Innumerable events connected with the history of the City happened here, from the killing a bishop at the north door, in the reign of Edward II., to the public exposure of Richard II.'s body after his murder; while at the Cross in the churchyard the authorities of the City, and even our kings, often attended the public sermons, and in the same place the citizens once held their Folkmotes, riotous enough on many an occasion. Great men's tombs abounded in Old St. Paul's—John of Gaunt, Lord Bacon's father, Sir Philip Sydney, Donne, the poet, and Vandyke being very prominent among them. Fired by lightning in Elizabeth's reign, when the Cathedral had become a resort of newsmongers and a thoroughfare for porters and carriers, it was partly rebuilt in Charles I.'s reign by Inigo Jones. The repairs were stopped by the civil wars, when the Puritans seized the funds, pulled down the scaffolding, and turned the church into a cavalry barracks. The Great Fire swept all clear for Wren, who now found a fine field for his genius; but vexatious difficulties embarrassed him at the very outset. His first great plan was rejected, and the Duke of York (afterwards James II.) is said to have insisted on side recesses, that might serve as chantry chapels when the church became Roman Catholic. Wren was accused of delays and chidden for the faults of petty workmen, and, as the Duchess of Marlborough laughingly remarked, was dragged up and down in a basket two or three times a week for a paltry £200 a year. The narrow escape of Sir James Thornhill from falling from a scaffold while painting the dome is a tradition of St. Paul's, matched by the terrible adventure of Mr. Gwyn, who when measuring the dome slid down the convex surface till his foot was stayed by a small projecting lump of lead. This leads us naturally on to the curious monomaniac who believed himself the slave of a demon who lived in the bell of the Cathedral, and whose case is singularly deserving of analysis. We shall give a short sketch of the heroes whose tombs have been admitted into St. Paul's, and having come to those of the great demi-gods of the old wars, Nelson and Wellington, pass to anecdotes about the clock and bells, and arrive at the singular story of the soldier whose life was saved by his proving that he had heard St. Paul's clock strike thirteen. Queen Anne's statue in the churchyard, too, has given rise to epigrams worthy of preservation, and the progress of the restoration will be carefully detailed.

Cheapside, famous from the Saxon days, next invites our wandering feet. The north side remained an open field as late as Edward III.'s reign,[Pg 32] and tournaments were held there. The knights, whose deeds Froissart has immortalised, broke spears there, in the presence of the Queen and her ladies, who smiled on their champions from a wooden tower erected across the street. Afterwards a stone shed was raised for the same sights, and there Henry VIII., disguised as a yeoman, with a halbert on his shoulder, came on one occasion to see the great City procession of the night watch by torchlight on St. John's Eve. Wren afterwards, when he rebuilt Bow Church, provided a balcony in the tower for the Royal Family to witness similar pageants. Old Bow Church, we must not forget to record, was seized in the reign of Richard I. by Longbeard, the desperate ringleader of a Saxon[Pg 33] rising, who was besieged there, and eventually burned out and put to death. The great Cross of Cheapside recalls many interesting associations, for it was one of the nine Eleanor crosses. Regilt for many coronations, it was eventually pulled down by the Puritans during the civil wars. Then there was the Standard, near Bow Church, where Wat Tyler and Jack Cade beheaded several objectionable nobles and citizens; and the great Conduit at the east end—each with its memorable history. But the great feature of Cheapside is, after all, Guildhall. This is the hall that Whittington paved and where Walworth once ruled. In Guildhall Lady Jane Grey and her husband were tried; here the Jesuit Garnet was arraigned [Pg 35][Pg 34]for his share in the Gunpowder Plot; here it was Charles I. appealed to the Common Council to arrest Hampden and the other patriots who had fled from his eager claws into the friendly City; and here, in the spot still sacred to liberty, the Lords and Parliament declared for the Prince of Orange. To pass this spot without some salient anecdotes of the various Lord Mayors would be a disgrace; and the banquets themselves, from that of Whittington, when he threw Henry V.'s bonds for £60,000 into a spice bonfire, to those in the present reign, deserve some notice and comment. The curiosities of Guildhall in themselves are not to be lightly passed over, for they record many vicissitudes of the great City; and Gog and Magog are personages of importance only secondary to that of Lord Mayor, and not in any way to be disregarded. The Mansion House, built in 1789, leads us to much chat about "gold chains, warm furs, broad banners and broad faces;" for a folio might be well filled with curious anecdotes of the Lord Mayors of various ages—from Sir John Norman, who first went in procession to Westminster by water, to Sir John Shorter (James II.), who was killed by a fall from his horse as he stopped at Newgate, according to custom, to take a tankard of wine, nutmeg, and sugar. There is a word to say of many a celebrity in the long roll of Mayors—more especially of Beckford, who is said to have startled George III. by a violent patriotic remonstrance, and of the notorious John Wilkes, that ugly demagogue, who led the City in many an attack on the King and his unwise Ministers.

The tributaries of Cheapside also abound in interest, and mark various stages in the history of the great City. Bread Street was the bread market of the time of Edward I., and is especially honoured for being the birthplace of Milton; and in Milk Street (the old milk market) Sir Thomas More was born. Gutter Lane reminds us of its first Danish owner; and many other turnings have their memorable legends and traditions.

The Halls of the City Companies, the great hospitals, and Gothic schools, will each by turn detain us; and we shall not forget to call at the Bank, the South-Sea House, and other great proofs of past commercial folly and present wealth. The Bank, projected by a Scotch theorist in 1691 (William III.), after many migrations, settled down in Threadneedle Street in 1734. It has a history of its own, and we shall see during the Gordon Riots the old pewter inkstands melted down for bullets, and, prodigy of prodigies! Wilkes himself rushing out to seize the cowardly ringleaders![Pg 36]

By many old houses of good pedigree and by several City churches worthy a visit, we come at last to the Monument, which Wren erected and which Cibber decorated. This pillar, which Pope compared to "a tall bully," once bore an inscription that greatly offended the Court. It attributed the Great Fire of London, which began close by there, to the Popish faction; but the words were erased in 1831. Littleton, who compiled the Dictionary, once wrote a Latin inscription for the Monument, which contained the names of seven Lord Mayors in one word:—

"Fordo-Watermanno-Harrisono-Hookero-Vinero-Sheldono-Davisonam."

But the learned production was, singularly enough, never used. The word, which Littleton called "an heptastic vocable," comprehended the names of the seven Lord Mayors in whose mayoralties the Monument was begun, continued, and completed.

On London Bridge we might linger for many chapters. The first bridge thrown over the Thames was a wooden one, erected by the nuns of St. Mary's Monastery, a convent of sisters endowed by the daughter of a rich Thames ferryman. The bridge figures as a fortified place in the early Danish invasions, and the Norwegian Prince Olaf nearly dragged it to pieces in trying to dispossess the Danes, who held it in 1008. It was swept away in a flood, and its successor was burnt. In the reign of Henry II., Pious Peter, a chaplain of St. Mary Colechurch, in the Poultry, built a stone bridge a little further west, and the king helped him with the proceeds of a tax on wool, which gave rise to the old saying that "London Bridge was built upon woolpacks." Peter's bridge was a curious structure, with nineteen pointed arches and a drawbridge. There was a fortified gatehouse at each end, and a gothic chapel towards the centre, dedicated to St. Thomas à Becket, the spurious martyr of Canterbury. In Queen Elizabeth's reign there were shops on either side, with flat roofs, arbours, and gardens, and at the south end rose a great four-storey wooden house, brought from Holland, which was covered with carving and gilding. In the Middle Ages, London Bridge was the scene of affrays of all kinds. Soon after it was built, the houses upon it caught fire at both ends, and 3,000 persons perished, wedged in among the flames. Henry III. was driven back here by the rebellious De Montfort, Earl of Leicester. Wat Tyler entered the City by London Bridge; and, later, Richard II. was received here with gorgeous ceremonies. It was the scene of one of Henry V.'s greatest triumphs, and also[Pg 37] of his stately funeral procession. Jack Cade seized London Bridge, and as he passed slashed in two the ropes of the drawbridge, though soon after his head was stuck on the gatehouse. From this bridge the rebel Wyatt was driven by the guns of the Tower; and in Elizabeth's reign water-works were erected on the bridge. There was a great conflagration on the bridge in 1632, and eventually the Great Fire almost destroyed it. In the Middle Ages countless rebels' heads were stuck on the gate-houses of London Bridge. Brave Wallace's was placed there; and so were the heads of Henry VIII.'s victims—Fisher, Bishop of Rochester and Sir Thomas More, the latter trophy being carried off by the stratagem of his brave daughter. Garnet, the Gunpowder-Plot Jesuit, also contributed to the ghastly triumphs of justice. Several celebrated painters, including Hogarth, lived at one time or another on the bridge; and Swift and Pope used to frequent the shop of a witty bookseller, who lived under the northern gate. One or two celebrated suicides have taken place at London Bridge, and among these we may mention that of Sir William Temple's son, who was Secretary of War, and Eustace Budgell, a broken-down author, who left behind him as an apology the following sophism:—

"What Cato did and Addison approved of cannot be wrong."

Pleasanter is it to remember the anecdote of the brave apprentice, who leaped into the Thames from the window of a house on the bridge to save his master's infant daughter, whom a careless nurse had dropped into the river. When the girl grew up, many noble suitors came, but the generous father was obdurate. "No," said the honest citizen; "Osborne saved her, and Osborne shall have her." And so he had; and Osborne's great grandson throve and became the first Duke of Leeds. The frequent loss of lives in shooting the arches of the old bridge, where the fall was at times five feet, led at last to a cry for a new bridge, and one was commenced in 1824. Rennie designed it, and in 1831 William IV. and Queen Adelaide opened it. One hundred and twenty thousand tons of stone went to its formation. The old bridge was not entirely removed till 1832, when the bones of the builder, Pious Peter of Colechurch, were found in the crypt of the central chapel, where tradition had declared they lay. The iron of the piles of the old bridge was bought by a cutler in the Strand, and produced steel of the highest quality. Part of the old stone was purchased by Alderman[Pg 38] Harmer, to build his house, Ingress Abbey, near Greenhithe.

Southwark, a Roman station and cemetery, is by no means without a history. It was burned by William the Conqueror, and had been the scene of battle against the Danes. It possessed palaces, monasteries, a mint, and fortifications. The Bishops of Winchester and Rochester once lived here in splendour; and the locality boasted its four Elizabethan theatres. The Globe was Shakespeare's summer theatre, and here it was that his greatest triumphs were attained. What was acted there is best told by making Shakespeare's share in the management distinctly understood; nor can we leave Southwark without visiting the "Tabard Inn," from whence Chaucer's nine-and-twenty jovial pilgrims set out for Canterbury.

The Tower rises next before our eyes; and as we pass under its battlements the grimmest and most tragic scenes of English history seem again rising before us. Whether Cæsar first built a tower here or William the Conqueror, may never be decided; but one thing is certain, that more tears have been shed within these walls than anywhere else in London. Every stone has its story. Here Wallace, in chains, thought of Scotland; here Queen Anne Boleyn placed her white hands round her slender neck, and said the headsman would have little trouble. Here Catharine Howard, Sir Thomas More, Cranmer, Northumberland, Lady Jane Grey, Wyatt, and the Earl of Essex all perished. Here, Clarence was drowned in a butt of wine and the two boy princes were murdered. Many victims of kings, many kingly victims, have here perished. Many patriots have here sighed for liberty. The poisoning of Overbury is a mystery of the Tower, the perusal of which never wearies though the dark secret be unsolvable; and we can never cease to sympathise with that brave woman, the Countess of Nithsdale, who risked her life to save her husband's. From Laud and Strafford we turn to Eliot and Hutchinson—for Cavaliers and Puritans were both by turns prisoners in the Tower. From Lord William Russell and Algernon Sydney we come down in the chronicle of suffering to the Jacobites of 1715 and 1745; from them to Wilkes, Lord George Gordon, Burdett, and, last of all the Tower prisoners, to the infamous Thistlewood.

Leaving the crimson scaffold on Tower Hill, we return as sightseers to glance over the armoury and to catch the sparkle of the Royal jewels. Here is the identical crown that that daring villain Blood stole and the heart-shaped ruby that the Black Prince once wore; here we see the swords, sceptres, and diadems of many of our monarchs. In the[Pg 39] armoury are suits on which many lances have splintered and swords struck; the imperishable steel clothes of many a dead king are here, unchanged since the owners doffed them. This suit was the Earl of Leicester's—the "Kenilworth" earl, for see his cognizance of the bear and ragged staff on the horse's chanfron. This richly-gilt suit was worn by James I.'s ill-starred son, Prince Henry, whom many thought was poisoned by Buckingham; and this quaint mask, with ram's horns and spectacles, belonged to Will Somers, Henry VIII.'s jester.

From the Tower we break away into the far east, among the old clothes shops, the bird markets, the costermongers, and the weavers of Whitechapel and Spitalfields. We are far from jewels here and Court splendour, and we come to plain working people and their homely ways. Spitalfields was the site of a priory of Augustine canons, however, and has ancient traditions of its own. The weavers, of French origin, are an interesting race—we shall have to sketch their sayings and doings; and we shall search Whitechapel diligently for old houses and odd people. The district may not furnish so many interesting scenes and anecdotes as the West End, but it is well worthy of study from many modern points of view.

Smithfield and Holborn are regions fertile in associations. Smithfield, that broad plain, the scene of so many martyrdoms, tournaments, and executions, forms an interesting subject for a diversified chapter. In this market-place the ruffians of Henry VIII.'s time met to fight out their quarrels with sword and buckler. Here the brave Wallace was executed like a common robber; and here "the gentle Mortimer" was led to a shameful death. The spot was the scene of great jousts in Edward III.'s chivalrous reign, when, after the battle of Poictiers, the Kings of France and Scotland came seven days running to see spears shivered and "the Lady of the Sun" bestow the prizes of valour. In this same field Walworth slew the rebel Wat Tyler, who had treated Richard II. with insolence, and by this prompt blow dispersed the insurgents, who had grown so dangerously strong. In Henry VIII.'s reign poisoners were boiled to death in Smithfield; and in cruel Mary's reign the Protestant martyrs were burned in the same place. "Of the two hundred and seventy-seven persons burnt for heresy in Mary's reign," says a modern antiquary, "the greater number perished in Smithfield;" and ashes and charred bodies have been dug up opposite to the gateway of Bartholomew's Church and at the west end of Long Lane. After the Great Fire the houseless citizens were sheltered here in tents. Over against the corner where the[Pg 40] Great Fire abated is Cock Lane, the scene of the rapping ghost, in which Dr. Johnson believed and concerning which Goldsmith wrote a catchpenny pamphlet.

Holborn and its tributaries come next, and are by no means deficient in legends and matter of general interest. "The original name of the street was the Hollow Bourne," says a modern etymologist, "not the Old Bourne;" it was not paved till the reign of Henry V. The ride up "the Heavy Hill" from Newgate to Tyburn has been sketched by Hogarth and sung by Swift. In Ely Place once lived the Bishop of Ely; and in Hatton Garden resided Queen Elizabeth's favourite, the dancing chancellor, Sir Christopher Hatton. In Furnival's Inn Dickens wrote "Pickwick." In Barnard's Inn died the last of the alchemists. In Staple's Inn Dr. Johnson wrote "Rasselas," to pay the expenses of his mother's funeral. In Brooke Street, where Chatterton poisoned himself, lived Lord Brooke, a poet and statesman, who was a patron of Ben Jonson and Shakespeare, and who was assassinated by a servant whose name he had omitted in his will. Milton lived for some time in a house in Holborn that opened at the back on Lincoln's Inn Fields. Fox Court leads us to the curious inquiry whether Savage, the poet, was a conscious or an unconscious impostor; and at the Blue Boar Inn Cromwell and Ireton discovered by stratagem the treacherous letter of King Charles to his queen, that rendered Cromwell for ever the King's enemy. These are only a few of the countless associations of Holborn.

Newgate is a gloomy but an interesting subject for us. Many wild faces have stared through its bars since, in King John's time, it became a City prison. We shall look in on Sarah Malcolm, Mrs. Brownrigg, Jack Sheppard, Governor Wall, and other interesting criminals; we shall stand at Wren's elbow when he designs the new prison, and follow the Gordon Rioters when they storm in over the burning walls.

The Strand stands next to Fleet Street as a central point of old memories. It is not merely full, it positively teems. For centuries it was a fashionable street, and noblemen inhabited the south side especially, for the sake of the river. In Essex Street, on a part of the Temple, Queen Elizabeth's rash favourite (the Earl of Essex) was besieged, after his hopeless foray into the City. In Arundel Street lived the Earls of Arundel; in Buckingham Street Charles I.'s greedy favourite began a palace. There were royal palaces, too, in the Strand, for at the Savoy lived John of Gaunt; and Somerset House was built by the Protector Somerset with[Pg 41] the stones of the churches he had pulled down. Henrietta Maria (Charles I.'s Queen) and poor neglected Catherine of Braganza dwelt at Somerset House; and it was here that Sir Edmondbury Godfrey, the zealous Protestant magistrate, was supposed to have been murdered. There is, too, the history of Lord Burleigh's house (in Cecil Street) to record; and Northumberland House still stands to recall to us its many noble inmates. On the other side of the Strand we have to note Butcher Row (now pulled down), where the Gunpowder Plot conspirators met; Exeter House, where Lord Burleigh's wily son lived; and, finally, Exeter 'Change, where the poet Gay lay in state. Nor shall we forget Cross's menagerie and the elephant Chunee; nor omit mention of many of the eccentric old shopkeepers who once inhabited the 'Change. At Charing Cross we shall stop to see the old Cromwellians die bravely, and to stare at the pillory, where in their time many incomparable scoundrels ignominiously stood. The Nelson Column and the surrounding statues have stories of their own; and St. Martin's Lane is specially interesting as the haunt of half the painters of the early Georgian era. There are anecdotes of Hogarth and his friends to be picked up here in abundance, and the locality generally deserves exploration, from the quaintness and cleverness of its former inhabitants.

In Covent Garden we break fresh ground. We found St. Martin's Lane full of artists, Guildhall full of aldermen, the Strand full of noblemen—the old monastic garden will prove to be crowded with actors. We shall trace the market from the first few sheds under the wall of Bedford House to the present grand temple of Flora and Pomona. We shall see Evans's a new mansion, inhabited by Ben Jonson's friend and patron, Sir Kenelm Digby, alternately tenanted by Sir Harry Vane, Denzil Holles (one of the five refractory members whom Charles I. went to the House of Commons so imprudently to seize), and Admiral Russell, who defeated the French at La Hogue. The ghost of Parson Ford, in which Johnson believed, awaits us at the doorway of the Hummums. There are several duels to witness in the Piazza; Dryden to call upon as he sits, the arbiter of wits, by the fireside at Will's Coffee House; Addison is to be found at Button's; at the "Bedford" we shall meet Garrick and Quin, and stop a moment at Tom King's, close to St. Paul's portico, to watch Hogarth's revellers fight with swords and shovels, that frosty morning that the painter sketched the prim old maid going to early service. We shall look in at the Tavistock to see Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller at work at portraits of[Pg 42] beauties of the Carolean and Jacobean Courts; remembering that in the same rooms Sir James Thornhill afterwards painted, and poor Richard Wilson produced those fine landscapes which so few had the taste to buy. The old hustings deserve a word, and we shall have to record the lamentable murder of Miss Ray by her lover, at the north-east angle of the square. The neighbourhood of Covent Garden, too, is rife with stories of great actors and painters, and nearly every house furnishes its quota of anecdote.