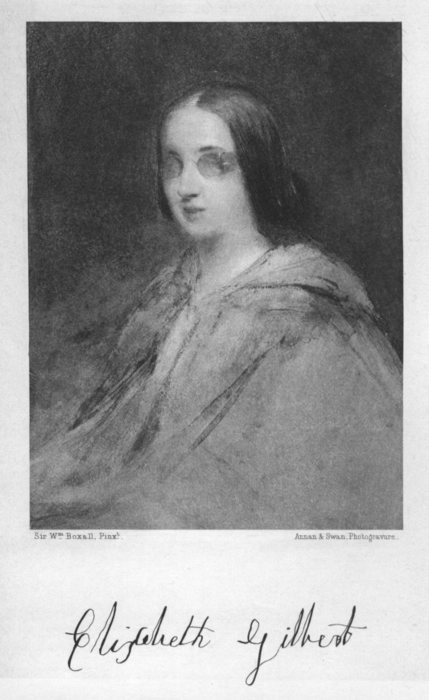

Title: Elizabeth Gilbert and Her Work for the Blind

Author: Frances Martin

Release date: March 21, 2010 [eBook #31721]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Audrey Longhurst, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

There is a sacred privacy in the life of a blind person. It is led apart from much of the ordinary work of the world, and is unaffected by many external incidents which help to make up the important events of other lives. It is passed in the shade and not in the open sunlight of eager activity. At first we should be disposed to say that such a life, with its inevitable restrictions and compulsory isolation, could offer little of public interest, and might well remain unchronicled. But in the rare cases where blindness, feeble health, and suffering form scarcely any bar to activity; where they are not only borne with patience, but by heroic effort are compelled to minister to great aims, we are eager to learn the secret of such a life. No details connected with it are devoid of interest; and we are stimulated, encouraged, and strengthened by seeing obstacles overcome which appeared insurmountable, and watching triumph where we dreaded defeat.

Elizabeth Gilbert was born at a time when kindly and intelligent men and women could gravely implore "the Almighty" to "take away" a child merely because it was blind; when they could argue that to teach the blind to read, or to attempt to teach them to work, was to fly in the face of Providence. And her whole life was given to the endeavour to overcome prejudice and superstition; to show that blindness, though a great privation, is not a disqualification. Blind men and women can learn, labour, and fulfil all the duties of life if their fellow-men are merciful and helpful, and God is on the side of all those who work honestly for themselves and others.

The life of Elizabeth Gilbert and her work for the blind are so inextricably interwoven, that it is impossible to tell one without constant reference to the other.

A small cellar in Holborn at a rent of eighteen-pence a week was enough for a beginning. But before her death she could point to large and well-appointed workshops in almost every city of England, where blind men and women are employed, where tools have been invented by or modified for them, where agencies have been established for the sale of their work.

Her example has encouraged, her influence has[Pg ix] promoted the work which she never relinquished throughout life.

Nothing was too great for her to attempt on behalf of the blind, nothing seemed impossible of achievement. One success suggested a new endeavour, one achievement opened a door for fresh effort.

Free from any taint of selfishness or self-seeking, all her thought was for others, for the helpless, the poor, the friendless. Her pity was boundless. There was nothing she could not forgive the blind, no error, no ignorance, no crime. She knew the desolation of their lives, their friendless condition, and understood how they might sink down and down in the darkness because no friendly hand was held out to them.

And yet she was unsparing to herself, and a rigid censor of her own motive and conduct. This she could not fail to be, because she believed in her vocation as from God. She never doubted that her work had been appointed for her; she never wavered in her belief that strength given by God, supported her. She knew that she was the servant of God, sent by Him to minister to others. This knowledge was joy; but it made her inexorable and inflexible towards herself.

There are but few incidents in her peaceful life. It was torn by no doubt, distracted by no [Pg x]apprehensions, it reached none of the heights of human happiness, and sounded none of the depths of despair. If there were unfulfilled hopes, aspirations, affections, they left no bitterness, no sense of disappointment. A beautiful life and helpful; for who need despair where she overcame and gained so great a victory?

The materials for recording the history of Elizabeth Gilbert are scanty, but all that were possessed by her sisters and friends have been placed at my disposal. My love for her, and our long friendship, have enabled me, I hope, to interpret them aright.

FRANCES MARTIN.

October 1887.

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Childhood | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| In the Dark | 14 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Little Blossom | 27 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| What the Prophetess Foresaw | 39 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Palace Garden | 51 |

| [Pg xii] | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| A Sense of Loss | 70 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Blind Manager | 82 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Royal Bounty | 94 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Removing Stumbling-Blocks | 110 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Trials and Temptations | 129 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Reflections and Suggestions | 142 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Her Diary | 150 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| The Fear of God and no other | 158 |

| [Pg xiii] | |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Everyday Life | 175 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Time of Trouble | 192 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The First Loss | 212 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| How the Work went on | 221 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Blind Children of the Poor | 238 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| In Time of Need | 249 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| The Valley of the Shadow | 259 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| Life in the Sick-Room | 279 |

| [Pg xiv] | |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| Twilight | 293 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| The End | 304 |

"Moving about in worlds not realised."—Wordsworth.

Elizabeth Margaretta Maria, born on the 7th of August 1826, was the second daughter and third of the eleven children of Ashhurst Turner Gilbert, Principal of Brasenose College, Oxford, afterwards Bishop of Chichester, and of Mary Ann his wife, only surviving child of the Rev. Robert Wintle, Vicar of Culham, near Abingdon.

The little girl, Bessie, as she was always called, was christened at St. Mary's Church, which is close to the old-fashioned house in High Street known as the Principal's Lodgings, in which Dr. Gilbert lived.

"A fine handsome child, with flashing black eyes," she is said to have been; and then for three years we hear nothing more. There was a nest of little children in the nursery, and in the spring of 1829 a fifth baby was to be added to them. In the diary of the[Pg 2] grandfather, Mr. Wintle, we find the following entries:—

| 1829.—April 6. | Little Elizabeth alarmingly ill with scarlet fever. |

| " 7. | Child very ill. |

| " 8. | Child somewhat better. |

| " 18. | Letter from Mary Ann [Mrs. Gilbert], stating that little Elizabeth had lost one eye. |

| " 21. | Went to Oxford. Little girl blind. |

| July 9. | Dr. Farre and Mr. Alexander say there is no chance of little Bessie seeing. |

And so the "flashing black eyes," scarcely opened upon the world, were closed for ever, and all memory of sight was very speedily obliterated. Mrs. Gilbert had not been allowed to nurse or even to see her little girl, who had been removed from the nursery to a north wing, stretching back and away from the house. It was the father who watched over and scarcely left her. Mrs. Gilbert believed that the child's recovery was owing to his unremitting care. Dr. Gilbert's common sense seems to have been in advance of the medical treatment of that period; and he insisted on open windows, change of bedding and clothing to suit the exigencies of the case. When the child was thought to be sinking, he took upon himself the responsibility of administering port wine; this may or may not have saved her life, it is certain she struggled through and survived a dangerous, almost fatal attack.

But the handsome, healthy baby was sightless; one eye was entirely and the other partly destroyed, the throat ragged and certain to be always delicate, ears and nose also affected. A childhood of much suffering was inevitable—and then?

It was the father who bore the first brunt of this sorrow. It was he who listened to the pathetic appeal of the little one, "Oh, nursie, light a candle," to her entreaty to be taken "out of the dark room," to the softly-whispered question, "If I am a very good 'ittle girl may I see my dolly to-morrow?" He had been full of courage, hope, and resource at the most critical times, but he was broken-hearted now, and would rush weeping from the child's bedside.

It was not until July, by that time a fifth baby was in the nursery, that the parents took their little Bessie to London, and there, as Mr. Wintle's diary tells, the case was pronounced to be hopeless. The renowned oculist of that day, Mr. Alexander, told them that there was no possibility of sight; the eyes were destroyed, the child was blind. Dr. Farre, whom they also consulted, showed much sympathy with the parents in their affliction, and they looked upon him as a friend raised up to advise and comfort them. Many years later they appealed to him on behalf of their blind child, and reminded him of the encouragement and help he had given them. It was doubtless he who suggested that blindness should be made as little as possible of a disability to the child, what other help could he give in such a[Pg 4] case?—that she should be trained, educated, and treated like the other children; that she should share their pleasures and their experience, and should not be kept apart from the mistaken notion of shielding her from injury.

It was with these views that the parents returned to Oxford, and it was these that they consistently carried out henceforward. There was no invention, no educational help for the blind which they did not inquire into and procure; but these were only used in the same way that one child might have one kind of pencil and another child another pencil.

The sisters who were nearest her own age speak of Bessie as gay and happy, "so like the others that it is difficult to pick her out from them." Surviving friends who remember the Gilbert children, the sisterhood, as the eight little girls came ultimately to be called, say that the group is ineffaceably stamped upon the memory, but that there was nothing special to attract attention to the individual members of it. And yet the figure of the blind child does emerge, distinct and apart, and the reminiscences of youth and childhood are numerous enough to manifest the interest with which every part of her career was followed in her own family.

The parents had decided that she was to be treated exactly like her sisters. When she came into a room they were not to give her a chair; she was to find one for herself. Dr. Gilbert specially could not endure to have it suggested[Pg 5] that she could not do what the others did. "Let her try," he would say. So Bessie tried, and, ordinarily, succeeded. He was specially anxious that she should behave like the others at table, should be as particular in eating and drinking as they were, and should manage the food on her plate without offence to others. He encouraged her in ready repartee and swift intellectual insight. When the father joined his children in their walks it was always Bessie who took his hand. She invariably sat by him at breakfast, and when the children went in to dessert it was Bessie who sat by his side and poured out his glass of wine. "How do you know when it is full?" some one asked. "By the weight," she replied. The father, we may be sure, was training her in the transfer of the work of one sense to another, and helping her to supplement the lost eyesight by touch and sound, raising her up to the level of other children; and his initiative was followed in the family.

A special tie between the father and his blind child was always recognised. If any favour was to be asked it was Bessie who was sent to the father, and also if any difficulty arose amongst the children they would say, "We will tell Bessie," "We will ask Bessie."

There seems to have been no jealousy of her influence, no opposition to it. The sisters thought it her right to be first, and looked upon it as a great distinction, honour, and privilege to have a blind sister. It was their part to make her feel as little as possible the difference between herself[Pg 6] and them, and to help her to be as independent as they were. She was taught to dress herself unaided as early as the other children. She was full of fun, and enjoyed a romping game; she would much rather risk being knocked over than allow any one to lead her by the hand when they were all at play. She was passionate as a child, liable to sudden violent outbursts of anger; and as there were a good many passionate children together, she was quite as often mixed up in a quarrel as any of the others.

One incident remembered against her was that at seven or eight years old she seized one of the high schoolroom chairs and hurled it, or intended to do so, at a governess who had offended her. Another was that when she was somewhat younger, at the close of their daily walk, she and a little sister hurried on to enjoy the luxury of ringing the front door bell. It was just out of reach, and the little girls on tiptoe were straining to get at it. An undergraduate, passing by, thought to do them a kindness and pulled the bell. Bessie stamped with anger, and turned upon him a little blind passionate face: "Why did you do it? You knew I wanted to ring."

"A most affectionate nature, unselfish, generous, but passionate and obstinate; so obstinate no one could turn her from the thing she had resolved on," says one of the sisters.

In after life we find a temper under perfect control, and a will developed and trained to sweet firmness and unwavering endurance; but[Pg 7] these showed themselves in the fitful irregularity of a somewhat wilful childhood.

In accordance with the precept of her father, Bessie wanted to do everything that other children did. She would try, and nothing but her own individual experience would convince her of the limitations of her powers. The fire and the kettle were great temptations to her. One day in the nursery at Oxford she tried to reach the kettle, slipped and fell in front of the fire, tried to save herself by grasping the hot bars of the grate, and the poor little hands were badly burnt. We may be sure how the parents would suffer with their blind child in such an accident, and yet they would not encourage a panic, or allow any unnecessary restrictions to be put upon her actions.

A few years after scarlet fever the Gilbert children had measles. All memory of the occurrence would have faded out had it not been for Bessie. Her throat, as we have said, was ragged and impeded, and throughout life the only way in which she could swallow any liquid was in very small sips and with a curious little twist of nose and mouth. In after life she used to compare herself to Pascal, saying how much better her own case was, for Pascal was obliged to have his medicine warmed before he could sip it, whilst she could take hers cold.

There are some who still remember how they pitied her when they saw Bessie sitting up in bed sipping a black draught, and they can recall the resolution with which she did it, and the [Pg 8]conscientiousness with which she took all, to the last drop.

Some twenty years later she was walking in the garden at Eversley with Charles Kingsley, and he said to her, "When you take medicine you drink it all up. I spill some on my frock, and then I have to take it over again." It was one of those swift intuitive glances of his; he saw in the delicate woman the same patient courage that had characterised the child. She had much suffering from her throat throughout life, and as a little girl was nearly choked by a lozenge. The noteworthy point of the incident is that in the wildest tumult of alarm of those around her, the child was quite calm.

There was so little sense of her inferiority to others in early youth that it was only as the sisters grew up that they realised how much Bessie knew, and how much she could do, in spite of her blindness. As a child they all looked upon her as very clever. One of their Sunday amusements was to play at Sunday school, and Bessie was invariably made the mistress.

For a long time she and her sister Fanny, little more than a year younger, were companions in their lessons, which were in every respect alike. Bessie's were read aloud to her; she learnt easily, her memory was good, and she made rapid progress. In French and German the grammar was read to her, and she worked the exercises verbally. The governess, Miss Lander, was devoted to her pupils, and specially interested in Bessie, so that[Pg 9] she turned to account every hint and suggestion as to special methods for the blind. She drew threads across a piece of paper, which was fixed to a frame, and taught the child to write in the ordinary way. There was a box of raised letters which could be used for spelling lessons, and there was leaden type with raised figures for arithmetic lessons. The letters were arranged on an ordinary board; but the figures were placed in a grooved board. Now arithmetic was the most difficult and distasteful of all Bessie's lessons; the placing of the figures correctly was a very perplexing task, and the working of sums an intricate problem. But she did her duty and made her way steadily to compound division, a stage beyond which no woman was expected to advance fifty years ago. Miss Lander did her best to explain the various processes, but the sums, alas, were only too often wrong, and a passionate outburst would succeed the announcement of failure. That little episode of the chair was probably not unconnected with arithmetic. She was keenly interested in astronomical lessons, and the home-made orrery, which explained the relative position of sun, moon, and planets, was a source of unfailing interest. The little fingers fluttered over the planets and followed their movements with great delight.

An eager, intelligent child, with parents and teachers all anxious to smoothe her way and remove difficulties, we need not wonder that youth was a happy time for her: "the brightest and happiest of all the children," she is said to have been.

"The Principal's Lodgings," as the old-fashioned, rambling house in High Street, Oxford, was called, has no garden whatever. The front door opens into a dark hall; spacious cupboards to the right; to the left the dining-room; in front of you passages, doors, and two difficult staircases. There was no one, we are told, who had not fallen up or down these dark winding stairs except Bessie. On the first floor to the front, with five windows looking into High Street, is the drawing-room. This was divided, and one part of it was converted into a schoolroom. The Principal's study was on the same floor at the back of the house. What is known as the north wing stretches back, and has two or three small rooms which can easily be isolated. It was in them that Bessie was nursed through scarlet fever.

There is also a south wing with excellent kitchens and good servants' rooms.

On the second floor the space above the drawing-room and schoolroom was occupied by Mrs. Gilbert's room and the two nurseries; whilst a large bedroom at the back, away from the street and over the study, the spare room, was that in which all the children saw the light, and from which eleven of them successively emerged. The second and ninth were boys, and there were nine daughters. A little girl died in 1834, and is buried in the adjacent churchyard of St. Mary's. Bessie, who was eight years old, was taken into the room to bid farewell to her sister Gertrude, and laid her little hand upon her. She never[Pg 11] forgot it; and would say in after years in a low tone of awe: "She was so cold." The impression produced on a sensitive organisation was so painful that she was never again taken into the chamber of death.

There is a large "flat" or leaden roof above this "spare" room over the study, to which there is access from an adjacent passage; but this roof is too dangerous a place for a playground, and the children had none in or near the house. The south windows in the front look into High Street; an east window high up in the nursery looks out upon St. Mary's; and all the windows to the north at the back of the house look over walls, and houses, and chimney pots, and brick and mortar. The children played at home in ordinary times, but in the long vacation they played in the quadrangle, a grassy, treeless enclosure, but a very garden of delight to them. The favourite part of it was near the figures called "Cain and Abel," long since removed, and long since known not to have represented Cain and Abel, but to have been a copy of antique sculpture. There were grand games of hide and seek around "Cain and Abel," in which Bessie always joined.

Sometimes the children dined in the College Hall during vacation, and were joined after dinner in the quadrangle by their friends amongst the Fellows of Brasenose, who all had a kind word for the little blind girl. She was also a special favourite with the College servants, and led, as it were, a[Pg 12] charmed life, watched over by every one, and unconscious of their care.

All memory of vision seems to have faded from her before she left the sick-room; but, taught by those around her, she soon began to take an imaginary interest in colour, and a very real one in form and texture. An old nurse is still alive who remembers making a pink frock for her when she was a child, her delight at its being pink, and her pleasure in stroking down the folds. In 1835 or 1836 the young Princess Victoria, with her mother the Duchess of Kent, visited Oxford. Bessie was amongst those who went to "see" them enter the city. Returning home she exclaimed, "Oh, mamma, I have seen the Duchess of Kent, and she had on a brown silk dress." The language is startling; but how else could the blind child express the impression she had received except by saying "I have seen." Throughout life she continued to say, "I have seen," and throughout life the words continued to represent a reality as clear and true to the blind as the facts of sight are to those who have eyes.

Very early Bessie knew the songs of birds and delighted in them. Very early also she learned to love flowers. She liked to have them described, and to hear the minutest particulars about them. Nothing made her so happy as to gather them for herself. There were fields near Hincksey which the Gilberts called "The Happy Valley." Thither they resorted in the spring with baskets to gather forget-me-nots, the flowering rush, and[Pg 13] other blossoms, which they prized highly. In all these expeditions Bessie was happy, and a source of happiness to others. The tender and reverent way in which she examined a flower, the little fluttering fingers touching every petal and bruising none, was a lesson never to be forgotten.

Her youthful admiration of Wordsworth was chiefly based upon his love of flowers, but also upon personal knowledge. When she was about ten years old, Wordsworth went to Oxford to receive the honorary degree of D.C.L. from the University. He stayed with the Principal, in that large spare room we know of, and won Bessie's heart the first day by telling at the dinner-table how he had almost leapt off the coach in Bagley Wood to gather the little blue veronica. But she had a better reason for remembering that visit. One day she was in the drawing-room alone, and Wordsworth entered. For a moment he stood silent before the blind child. The little sensitive face, with its wondering, inquiring look, turned towards him. Then he gravely said, "Madam, I hope I do not disturb you." She never forgot that "Madam," grave, solemn, almost reverential.

The Gilbert children had a very happy home. In Oxford they were constantly under the eyes of parents who loved them tenderly, and loved to have them at hand. The schoolroom was between drawing-room and study, the nurseries adjacent to the parents' bedroom.

Mrs. Gilbert, a very handsome, large-hearted, attractive woman, was devoted to her husband, and gave him constant and loving care so long as she lived. She dearly loved her children; but she thought, though perhaps she was mistaken, that she liked boys better than girls; and she had so few boys! Husband and children were all the world to her; she was happy in their midst, full of plans for them, greatly preoccupied with their future, and looked up to and beloved by all.

Dr. Gilbert was a schoolfellow of De Quincey, and in his Confessions[1] De Quincey thus speaks of him: "At this point, when the cause of Grotius seemed desperate, G——[2] (a boy whom subsequently I had reason to admire as equally courageous, truthful, and far-seeing) suddenly changed the whole field of view."

And again referring to his leaving school, De Quincey writes: "To three inferior servants I found that I ought not to give less than one guinea each; so much therefore I left in the hands of G——[2], the most honourable and upright of boys."

What weeks and months of anguish must have been passed by these parents, when the bright little three-year-old child was struck down into darkness, and the light of the "handsome black eyes" extinguished for ever. She was smitten into the ranks of the blind; and of the blind nearly sixty years ago, when their privation was a stigma, an affliction, "a punishment sent by the Almighty;" when even good and merciful people looked upon it as "rebellion" to endeavour to mitigate and alleviate the lot of those who lived in the dark. Bessie's parents did not and could not accept this view. They saw their child rise from her bed of sickness unchanged, though grievously maimed; but she was the same little Bessie who had been given to them bright and[Pg 16] clever and happy, and by God's grace they resolved that she should never lose her appointed place in the family circle. From the very first they were, as we have seen, advised to educate her with her sisters. This advice they followed; and at the same time inquired in all directions as to the methods and material and implements which might give special help to their blind child. Packets of letters yellow with age, long paragraphs copied from old newspapers by Mrs. Gilbert and sent to people living in distant parts, accounts of apparatus, lists of inventions and suggestions bear constant and touching tribute to the loving care of a mother upon whose time and strength in that large young family there must have been so many demands. The surviving members of the family do not even remember by name many of those whose letters have been preserved; letters now valuable, not in themselves, but as showing that if Bessie Gilbert lived to do a great work on behalf of the blind, and did it, undaunted by obstacles and difficulty that might well have seemed beyond her strength, she did but inherit the strong will and indomitable courage, the power of endurance and devotion which characterised her parents.

These letters throw much light upon the condition of the blind at the beginning of this century. One packet is specially interesting as the story of the successful effort of a person unknown, and without influence, to effect an improvement in a public institution. It may, probably it must, have[Pg 17] been told in later years to Bessie herself; it would encourage her, and may encourage others, to persevere in efforts on behalf of those who are helpless and afflicted.

Mrs. Wood, wife of the Rev. Peter Wood, Broadwater Rectory, Worthing, was interested in the condition of the blind. She had visited institutions in Zurich, in Paris, had heard of work being done on their behalf in Edinburgh, and was acquainted with the condition of the School for the Indigent Blind, St. George's Fields, London.

She wrote in 1831 to Mr. Henry V. Lynes, Mr. Gaussen, Mr. Dodd, Mr. Pigou, Mr. Capel Cure, and other members of the Committee of the St. George's Fields School, begging them to inquire into the methods for teaching the blind to read, recently discovered, and at that time attracting attention. With her letter she sent specimens of books and other data to be submitted to the Committee.

Mr. Gaussen, writing from the Temple, 12th March 1831, replies that he will have much pleasure in forwarding her excellent views, and that Mr. Vynes has secured the reference of her plan to the Committee; that it will be well considered, but for his own part he is bound to express the greatest doubt as to the result. He suggests that instead of teaching the blind to read there should be more reading aloud to them, "so as to stimulate their minds to more exertion, which in many cases is the source of the kind treatment they meet with."

A brother of the Secretary, Mr. Dodd, writes that he also will do what he can, although he has heard that the benefit of the plan "is so limited that quite as much good may be accomplished by teaching the pupils to commit portions of Scripture to memory as by teaching them to read."

Mr. Vynes informs Mrs. Wood that he has, at her request, attended the meeting of the Committee, that only two of the other gentlemen she had written to were present, Mr. Pigou and Mr. Gaussen. "The latter is not favourable to the plan, neither is Mr. Dodd, the Secretary." The gentlemen present who spoke were all "well satisfied with the amount of religious knowledge which their blind pupils already possess, so that I much fear they will take little trouble to increase it." He refers to a "rumour" that the "art of reading" has been introduced into the Edinburgh School for the Blind, but adds that the "Meeting did not seem inclined to give any credit to it;" and suggests that, if it is true, Mrs. Wood might let them hear more about it, as he had secured a reference of the whole matter to the consideration of the House Committee.

Now Mrs. Wood was nothing daunted by these successive splashes of cold water. She wrote afresh to members of the Committee. She obtained facts from Edinburgh, and she wisely limited her appeal to a petition that the blind should be enabled to read the Scriptures for themselves. But whether at that time she recognised the fact or not, there can be no doubt that[Pg 19] the whole question of what the blind could do themselves would be opened by this step, and must be decided.

Mr. Vynes writes to her again on the 29th March, and it is interesting to observe that a Committee in 1831 was very much the same sort of thing that it is now.

Among the seven or eight gentlemen present I found Mr. Jackman, the Chaplain of the Institution, being the first time I had ever the pleasure of meeting him. Both Mr. Jackman and Mr. Dodd [the Secretary] affirm that these poor blind pupils are already as well instructed as it is possible they should be, under their afflicting circumstances. They are correctly moral in their general conduct, influenced by religious feelings and principles, with contented and pious minds. Mr. Jackman mentioned as a proof that they do think beyond the present moment, the average number who now participate at every celebration of the Lord's Supper is one or two and twenty, though formerly there had been but three or four. They can repeat a large portion of the Psalms, not merely the singing Psalms, but take the alternate verse of the reading version without requiring any prompting. And all the pupils have a variety of the most important texts strongly impressed upon their memories. Their memories are generally good, and they assure me they are fully exercised upon sound truths. These gentlemen are of opinion that more is to be learned by the ear than ever can be acquired by the fingers, and therefore see no advantage attending the new plan which can at all compensate the trouble and expense of introducing it.

Two of the gentlemen present, Mr. Capel Cure and Mr. Meller, very handsomely supported your view of the subject, and recommended a trial to be made. At[Pg 20] the same time they candidly confessed themselves quite unable to point out the best way, or indeed any way, to set about it; upon which the Committee very naturally threw the burthen upon me, or, my dear madam, you must allow me to say, rather upon you. I read to them the plan which you had sketched out, which, however, the Committee do not think very practicable. They will not seek out an idle linguist as you recommend; but if you will bring a qualified man to their door, with all appliances to boot—that is, all the books requisite for introducing the system, then they will be ready to treat with him. And here the matter rests for the present.

"Here" probably the Committee expected it to rest. But not so Mrs. Wood, who reconsidered and amended her suggestion as to "an idle linguist."

The next letter from Mr. Vynes, 15th April 1831, announces that Mr. Gall of Edinburgh "has offered to come to London to put our Committee in more complete possession of his plan, and to instruct some of our teachers gratuitously." The Sub-committee recommended that this offer should be accepted; the General Committee had resolved to adopt the recommendation. "They have also very properly," he continues, "agreed to reimburse Mr. Gall the expenses of his journey and of his necessary residence in London. The account which Mr. Gall has given of his invention is doubtless overcharged; it exhibits all the enthusiasm which generally attends all new discoveries. His estimate of the expense is somewhat vague. He requires very little time to enable his poor blind pupils to read and to write as[Pg 21] correctly, and almost as quickly, as the more fortunate poor who have the blessing of sight. However, if Mr. G. does but accomplish one-half of what he has promised, our Committee will be quite satisfied.

"Thus far, then, I may congratulate you, my dear madam, on the successful result of your active and persevering exertions."

After this there is a long pause; and the next letter from Mr. Vynes is dated Clapton, 24th August 1831. We can picture to ourselves the feelings with which Mrs. Wood would read it in the far-off Broadwater rectory.

Dear Madam—I have now the pleasure of returning to you the various books and papers which you so kindly sent up for the inspection of the Committee of our Blind School, and have to give you our best thanks for the use of them. You will be pleased to hear this new system of reading and writing is making some progress in the London school. As a proof that the General Committee are satisfied, I will report to you the results of their meeting on the 13th of this month. They first voted fifty guineas to Mr. Gall as a compliment for the service he has already done to the Institution. But when Mr. G. was called in and acquainted with their vote, he at once, respectfully, but very positively, declined to accept of any remuneration for what he had done, saying his object was to introduce the new system to serve the poor blind and not himself.

The Committee then elected Mr. Gall as Honorary Member of the Corporation, and requested the House Committee to find out (if possible) something acceptable to Mrs. Gall, and empowered them to present it to her. I mention all this in justice to Mr. Gall. It is indeed[Pg 22] highly creditable to him, for we are told that he is by no means in affluent circumstances. Mr. Gall continues in almost daily attendance at the school, and will remain some short time longer, so anxious is he to establish his system permanently in this school. On the female side he has already pretty well succeeded; Miss Grove, the sub-matron, and also one of the blind inmates having qualified themselves to become teachers.

On the male side, Mr. G. has hitherto been baffled, and therefore has asked the Committee for some extra aid. This matter is still under consideration.... On the whole, then, I think I may now venture to congratulate you, my dear madam, on the attainment of the object you have so much at heart—that these poor blind shall be enabled to read those oracles which will give them comfort in this world and lead them to perfect happiness hereafter.

And thus cautiously and quietly, with the inevitable resistance of officials to any change, and the caution of a Committee on their guard against enthusiasm, and not sanguine as to results, an important change was inaugurated. Henceforward the blind were no longer to be treated as incurables in a hospital, capable of no instruction and able to do no more than commit to memory moral precepts and religious truths. They were to learn reading and writing, a door was set open that would never again be closed. Education was shown to be possible, and work would follow.

In August 1832 Mrs. Gilbert received the copy of a letter written by Mr. Edward Lang, teacher of mathematics, St. Andrew Square, Edinburgh, to a Mr. Alexander Hay. Mr. Lang had invented a system of printing for the use of the blind,[Pg 23] with simplifications of letters and the introduction of single signs for many "redundant sounds." He is in favour of these modifications, and adds:

Were not the prejudice so strong in favour of ordinary spellings of words, I would, had I been engaged in the formation of such an alphabet, have innovated much more extensively. But words, like men, must carry their genealogy, not their qualifications, on their coats-of-arms; and though this arrangement conceals many obliquities of descent, and more than many real characters, it must be acquiesced in, since the law of prescription in this, as in many other cases, prevents the exercise of reason. He concludes: Most warmly do I recommend your whole system to the attention of all who feel interested in the diffusion of knowledge; and I trust that its advantages will soon be felt by those who were once consigned by barbarous laws, or by dark superstition, to destruction or to neglect, but who now are re-elevated to their own station through the light of a milder and nobler humanity.

At the close of this year, 1832, a Mrs. Wingfield sent to Mrs. Gilbert a newspaper paragraph giving an account of a meeting of the Managers of the Blind Asylum, Edinburgh. After some routine business these managers had proceeded to examine the "nature and efficiency" of the books lately printed for the use of the blind. Some of the blind boys in the Asylum, who had been using the books for "only a few weeks," picked out words and letters and read "slowly but correctly." By repeated trials, and by varying the exercises, the directors were of opinion that the art promised to be of "the greatest practical utility to the[Pg 24] blind." Mr. Gall also stated that the apparatus for writing to and by the blind was in a state of considerable forwardness. This paragraph Mrs. Gilbert copied and sent, on the 10th of January 1833, to her father's cousin, Mr. J. Wintle of Lincoln's Inn Fields, who had, as she learnt, a friend in Edinburgh. To this friend, Mr. Ellis, application was duly made, and he set about instituting inquiries which resulted, on the 13th of April 1833, in the despatch of a portentous epistle, such a letter as at that time was considered worthy of heavy postage. He had obtained for Mr. Wintle every possible scrap of information on the subject in question. Letters follow from him direct to Mrs. Gilbert, and on the 2d of November 1833 Mr. Ellis "presents his compliments, and, after many delays, is happy in being able at last to forward the articles he was commissioned to procure for Mrs. Gilbert's little girl."

The following list shows how much had been done in two years:—

1. Gall's First Book. Three other Lesson Books and the Gospel of St. John.

2. Hay's Alphabet and Lessons (Mr. Lang's friend), with outline sketch of Map.

3. The string alphabet, with a printed statement of its invention and use.

4. Seven brass types constructed on the principles of the string alphabet.

5. Several packets of metallic pieces representing the notes in music.

Another letter preserved by Mrs. Gilbert was[Pg 25] from a Mr. Richardson, of 11 Lothian Street, Edinburgh, to her uncle, Mr. Morrell, at that time staying in Edinburgh, dated 14th January 1837. It gives an account of the globes, maps, boards, etc., in use in the Edinburgh Asylum, and shows what rapid advance has been made since the little boys were examined by the managers in 1833.

Mrs. Gilbert would learn not so much from the account of the things done, as the manner of doing them; from the explanation of the method of adapting ordinary maps and globes to the use of the blind, and of employing gum and sand and string and pieces of cork; the little holes in the map instead of the names of cities, and the movable pegs. All these hints were very valuable to her; and every one of them was turned to good account in the schoolroom at Oxford.

In 1839 Mr. J. Wintle sends raised books from London. In 1840 he has gone, out of health, on a visit to his friend Mr. Ellis, Inverleith Row, Edinburgh. One of his first visits was to the Edinburgh Asylum, and he writes an account of it to Mrs. Gilbert, "in the hope of being useful to your daughter Bessie." He promises further information from Glasgow, which is, so he learns, "the fountain-head of all works for the blind, save those published in America," and he announces a copy of the New Testament as almost ready, price £2: 2s. It was ultimately procured by Mrs. Gilbert and presented to Bessie.

And now we may lay aside the time-worn, yellow paper, the large and copious letters, the[Pg 26] anxious inquiries and the willing replies. They did not, however, end at this period, they went on throughout the whole life of these good parents. There was no new invention, no new system into which they did not at once inquire, nothing that could be procured which they did not obtain for their child.

But they never swerved from their original intention to educate Bessie at home in the schoolroom with her sisters. The apparatus which replaced pen and pencil and slate might differ, as slate differs from paper. She had to put her fingers on the globe upon which her sisters cast their eyes, and to feel the movements of the planets around the sun, in the orrery which gave her so much pleasure; but her lessons were given and learnt at the same time, and she lost none of the happiness and stimulating effect of companionship in work and play.

There can be no doubt that she was influenced throughout life by her own early training, which had made it impossible for her to believe in the numerous so-called "disabilities" of the blind. Some of her friends thought that she had not an adequate notion of what these really were. Perhaps those who are born blind, or who have lost sight at so early an age that no memory of it remains, do not adequately realise their privation. Sight is to them a "fourth dimension," a something that it is absolutely impossible to realise. They can talk about it, but it is impossible for them to understand it.

[1] Confessions of an English Opium Eater, pp. 48 and 73, by Thomas de Quincey. Edinburgh, 1862.

[2] Gilbert.

Mr. Wintle gave his little grand-daughter a new name after her loss of sight. He called her "Little Blossom." She was never to develop into flower or fruit, he said, on account of her great affliction, and the limitations that it must entail. Miss Trotwood may have had a similar theory as to David Copperfield's Dora, but these were days before Dickens had written of Little Blossom. The theory was by no means adopted by Bessie's parents; and the name of Blossom was used by Mr. Wintle only.

Dr. Kynaston, in lines addressed "to Bessie," in 1835, tells how his "soul" reproved

"That friend, as once I heard him say,

Oh, may it please Almighty God

To take that child away!"

We do not know who "that friend" was, who prayed for the removal, at nine years old, of a[Pg 28] singularly happy and engaging child; but the prayer is indicative of the condition of the blind, the probable outlook for the child, and the point of view from which blindness was regarded even by people of culture and means. If such a one could pray for the death of a blind child, what would the poor do?

Despite the "Blossom" theory, or perhaps because of it, Bessie was a great favourite with her grandfather. He liked to have her with him at Culham Vicarage. She often stayed there for weeks together, and would learn more about flowers and birds than she could do in Oxford. There was also a delightful companion and friend at Culham, the black pony, Toby. Bessie was a fearless little rider, and delighted in a gallop round the field. But Mr. Wintle would not trust her alone with Toby, and there was always a servant to walk or run by his side. The grandfather makes an entry in his diary as to Bessie's first ride, and adds that he "was much pleased with Blossom."

It was at Culham that she was introduced to Robinson Crusoe. Mr. Wintle gave it to the servant who was to walk out with her, and who read aloud as she walked. Bessie was deeply interested, and would allow of no pause in the reading: "She kept her going all the time:" says a sister. Sometimes there were three or four little girls at Culham, and then in the evening, grandpapa read aloud to them James's Naval History. It was very little to their taste, and all[Pg 29] but one paid little attention, or if attending, could remember or understand but little. When, however, the reading was ended, and grandpapa began to ask questions, it was Bessie who knew how the vessels were manned and rigged, the complement of men and guns, and all the details connected with the fitting out of a man-of-war. And again Mr. Wintle had good reason to be "much pleased with Blossom."

The little girl learnt needlework with her sisters. She could hem and sew, but never liked doing either. A very neatly hemmed duster, done before she was ten years old, and presented to an aunt, is still preserved in the family. Knitting and crochet she liked better, and a knitted purse in bands of very bright colours has been kept unused by the friend to whom she gave it as a child. Her favourite occupation of this kind was the making of slender watch chains with fine silk on a little ivory frame. All her friends will remember these chains, which in many cases were an annual present.

But needlework of any kind was always "against the grain." She liked any other occupation better.

Perhaps the chief characteristic of early youth was her love of poetry and music. Wordsworth's poems, especially those that referred to flowers; Mary Howitt, Mrs. Hemans, these were her favourites. A sister says she cannot remember the time when Bessie was not in the habit of sitting down to the piano to improvise. She set Mary Howitt's "Sea Gull" to her own music before[Pg 30] she was twelve years old. It was published at the time of the Irish famine, and realised £20, which she gave to the Famine Fund.

Bessie's first music-mistress was the widow of an organist in Oxford, but when her talent for music was more pronounced she had lessons from Dr. Elvey, the brother of Sir George Elvey. Whilst she was learning a new piece, a sister would sit by her side and read the notes aloud. She quickly discovered if a single one had been omitted; and, as with Robinson Crusoe, she kept her reader "going all the time." But her enthusiasm and pleasure kindled the interest of those who certainly had a dry part of the work.

Bessie was not the only blind child in Oxford. Dr. Hampden, afterwards Bishop of Hereford, had two blind daughters. The three blind children used often to meet and walk together; but Bessie preferred the companionship of the merry girls at home, in whose games she always shared. She did not bowl a hoop, however, and in formal walks she was the companion of the governess.

Children's parties in Oxford were a source of much pleasure; she danced with girls, she was very fond of dancing, but seldom with boys. She wanted a little guiding, and the boys were possibly too shy to undertake this; certainly very few of them were disposed to try.

Bessie's birthday was, for the Gilbert children, the festival of the year. This was owing partly[Pg 31] to the fact that it fell in August, during the long vacation, the time associated with out-door games in the grassy quadrangle, whispered conferences near the mysterious and awe-inspiring Cain and Abel, with dinners in the Hall and visits in the schoolroom from friendly dons. There were three birthdays in August: a younger sister and a brother were also born in that month; all three were celebrated on the 7th, and Bessie was the "lady of the day." There was always a water party to Nuneham in the house-boat or the barge. On landing, the children would run to the top of a grassy slope and then slide and roll down the slippery grass. Bessie joined in this game with keen delight, untroubled by the silent watchfulness of a father, ever alert to protect her from danger, and ever anxious that she should be ignorant of special precautions on her behalf.

Dr. Kynaston, "High Master of St. Paul's," and former Philological Lecturer of Christ Church, Oxford, was nearly always included in the birthday party, and was very fond of Bessie. When she was a very little child she was leaning far out of the window of the boat so as to put her hands in the water, and her father was alarmed. "I am holding her tight by the frock," said Dr. Kynaston. "Yes," replied the father, "but I must have something more solid than that held by."

Of all these birthday parties, the most memorable to the blind child was that on which she was[Pg 32] ten years old. The day was fine, every one was very good to her. Her special favourites, Dr. Kynaston and Mr. Bazely (father of Mr. Henry Bazely, of whom a short biography has recently appeared), were both present. A vase with a bouquet of the flowers she loved, mignonette, heliotrope, roses, geraniums, was presented to her. All her life she treasured those dried flowers and the little vase. But the thing that made this birthday memorable was that not only her music but her poems were beginning to receive consideration, and one written at this time was considered worthy of being copied and sent to her godmother, Miss Hales. A copy in her mother's writing is still extant, and may be read with interest:

The child's verses are neither better nor worse[Pg 33] than those of many a little versifier of her age, but they are remarkable because they are obviously untouched by elders, who could so easily have corrected rhythm and metre; they are genuine, and they are written by a child who had apparently forgotten that she had ever seen the light. She had learnt to love it for some occult and mysterious reason which she could not explain, perhaps for the physical effect which light exercises upon the human organism. She loved light, she loved nature, and from early childhood she loved beautiful scenery. Dreams were always a source of delight to her, and her dreams were a feature in her life. She would say that she constantly dreamt about beautiful landscapes. Did some memory of sight revisit her in dreams? "There were beautiful intuitions in her music," we are told. Had she "beautiful intuitions" as to sight? Had she, in her dreams, visions of the scenes that passed before her in those three first years of which she retained not the slightest recollection in her waking hours? Beautiful scenery gave her pleasure; there was always a response to any description of it. Once when a sister was describing mountains she said: "I don't want to know how high they are, how many hours it takes to climb them, and what they are made of. I want you to tell me if they make you afraid, if they make you happy, or," drawing herself up, "if they give you a kind of a proud feeling."

In the April before this tenth birthday she had attempted to express in verse her feeling as to the[Pg 34] light; and on this day three sonnets were addressed to her by Dr. Kynaston.

What little girl would not be proud of such homage from a "High Master of St. Paul's," and so dear a friend?

The sonnets appear in Miscellaneous Poetry, by Rev. Herbert Kynaston, M.A.,[3] and two of them are here given:—

In this same year, 1836, Bessie took her first long journey away from home. Her father and mother had arranged to pay visits to some old friends, and they took with them the two eldest girls, Mary and Bessie. They stayed with the Bishop of Lincoln, Dr. Kaye, with an old college friend, Mr. Stephens, at Belgrave, Leicester, and with several other old college friends of the Principal's. They visited Matlock; and on her return Bessie described to the younger sisters the excitement of going into the caves, of crossing the Styx, and of listening to the blasting of rocks. It is recorded of her at this time that she never hesitated or shrank from anything required of her. She sat down in the boat, or stood up, or bent her head just as she was told to do. The loving care of the parents was not in vain, they saw their blind child fearless and happy, and well able to take the place due to her as second daughter. It is recorded that at Liverpool she was present for the first time at a really good concert, and that the music she then heard was a great stimulus to her, as well as a keen delight.

Dr. Gilbert preached at Liverpool, and from Liverpool they went to Stockport. In the church at the latter place there was a brass band, the sudden braying of which was a shock to her[Pg 36] nerves which Bessie never forgot. She was too young to dine or spend much time downstairs in the houses where they stayed, but she always remembered the kindness with which she was treated in schoolrooms and nurseries, and looked back upon these early visits with great pleasure.

The family hurried back to Oxford on account of the unexpected death of Dr. Rowley before his term of office had expired, and Dr. Gilbert at once entered upon the duties of Vice-Chancellor of the University.

Many little incidents connected with her father's tenure of office were a source of amusement to Bessie throughout life.

The University marshal made daily reports to the Vice-Chancellor, and informed him of any disturbance. One morning he stated that he had found two men fighting near Wadham College and separated them. Some time afterwards he came upon them in another place and did not interfere. "And pray, why not?" asked the Vice-Chancellor. "Well, sir, you see, they were very comfortably at it."

This story was repeated at the breakfast table and made a great impression upon Bessie. She told it and laughed over it throughout life. If she was seated near a table when telling it, she would push herself away with her two hands as if she wanted more room to laugh, a way she had when very much amused.

It was also about the same time that the butler, standing one day by the open door, saw a [Pg 37]freshman pursued by the proctor coming at full speed down the street. Seeing the open door the young man darted in, and rushed up the staircase. Silence for a few moments, and then peeping over the banisters the youth said in an urgent whisper, "Is he gone, is he gone?"

Now, the humour of the situation was that whilst he was so eager to escape from the proctor, nothing but a thin partition separated him from the Vice-Chancellor in his study.

We can picture to ourselves the butler's "Do you wish to see the Vice-Chancellor, sir?" and the hasty exit!

Meanwhile the child Bessie returned to her poems, her songs, her improvisings at the piano, to lessons in the schoolroom, to that terrible frame and the leaden type and raised figures, and the sums which would not "come right"; to the brothers and sisters and the happy home life. But she too had seen something of the great world lying on the outside of Oxford, and could refer back to "my visit to the North."

An old friend of the family remembers the first sight of Bessie as a girl of about twelve years old. She was in the Magdalen Gardens with a nurse and the little brother Tom, the youngest boy, of whom she was always very fond. She was standing apart on the grass; standing peaceful, motionless, with a sweet still face, and all the sad suggestion of the large darkened glasses that encased her eyes. The little boy picked daisies and took them to her and showed[Pg 38] her the gold in the centre. She smiled as she took them, and her slender fingers fluttered about them. And the children, the flowers, the sunlight, and those beautiful gardens in the early summer, made a picture in which this friend always loved to enshrine her memory of "Little Blossom."

[3] Published by B. Fellowes, Ludgate Street, 1841.

The early summer of 1838 was spent by the Vice-Chancellor and his family at Malvern. Bessie greatly enjoyed long walks on the hills, but either from over fatigue, or because the air was too keen for her, she began to suffer at that time from what she always spoke of as "my long headache." It was a headache that lasted many months and caused the parents almost as much suffering as the child. On their return to Oxford the family doctor was called in and promptly applied a blister to the back of the ears.

The blister did no good; the child was often quite prostrate with pain, probably neuralgia, but the doctor was a man of resource. The diary of Mrs. Gilbert is instructive as to the treatment of such a case fifty years ago. The entry "Gave Bessie two grains of calomel," begins in August[Pg 40] and is continued at short intervals throughout the month. "Blisters behind the ears, to be kept open," are added to the calomel in September. In October we have reached the more advanced stage of calomel blisters, black draught (to be sipped, poor child), and leeches. The treatment was continued, with additions, throughout November, and on the 21st of December Mrs. Gilbert makes the not very surprising entry, "Bessie was worse this evening."

The parents were by this time alarmed; and the doctor acknowledged that he could do no more. Casting about for help, they bethought them of the physician whom they had seen in London some years previously, of his tenderness and sympathy.

The rough draft of a letter written to him by Mrs. Gilbert still remains to testify to the grave consideration given by the parents to the adequate statement of the case, to their endeavour to recall it to his mind and to their acknowledgment of his previous kindness and courtesy. One point in their letter may be mentioned. "She is very fond of, and has good talents for music," writes the mother, "but her pain is so much increased by it that her music has had to be discontinued."

Poor little girl! No privation could be greater.

Of the answer sent by Dr. Farre there is no trace. But all drugs disappear from the records, and there is an account of "veratrine ointment," "a preparation of Hellebore known to Hippocrates," sent down from London, and needing so much care in the application that the[Pg 41] Oxford doctor himself came every night to rub it on the child's brow.

Early in 1839 she had quite recovered not only from the headache but from the effects of the remedies.

The music lessons were resumed, and before long she began the study of the harp. A younger sister remembers sitting by her to teach the pieces note by note. Bessie found it also very easy to play by ear and learnt much in this way; but the harp was a difficult instrument, and the management of it always fatigued her.

During her childhood, Cardinal, then the Rev. J. H. Newman was incumbent of St. Mary's, the church close to the house in High Street, and that which the family attended. Even up to the last days of her life Bessie used to say that she could not listen to a chapter in Isaiah, especially any of those read in Advent, without hearing the sound of his voice.

Cardinal Newman mentions in his Apologia that, on account of his doctrine and teaching, the Vice-Chancellor threatened no longer to allow his children to attend St. Mary's. But the children knew nothing of the proposed prohibition.[4]

Augustus Short, afterwards Bishop of Adelaide, was one of Mr. Wintle's curates at Culham.[Pg 42] He remembers Bessie as a child, and visited her for the last time when he was in England in 1884. Mr. Coxe, the late Librarian of the Bodleian, was another of the Culham curates, the friend of a lifetime, whose farewell letter to Bessie was written shortly before his own death in 1881. He lived in Oxford, and went over to Culham every Sunday. At first he was accompanied by his young wife, but Mrs. Coxe was speedily overtaken by the cares of a family and could not go with him. Mrs. Gilbert, with her warm, kind heart, took pity upon the lonely wife, and invited her to spend the Sundays with them. In this way she saw much of the sisterhood, the pretty name by which the eight girls were known.

They generally walked out on Sunday afternoons, and when they reached a certain spot in Christ Church Meadows, Bessie would stop and say, "Here you have the best view of Christ Church Towers." Other friends of this and later times were Bishop Gray of Cape Town, Bishop Mackenzie, and Dr. Barnes, Canon of Christ Church. The Provost of Oriel, Dr. Hawkins, and Dr. Gilbert were great friends, and it was possibly on this account that Bessie was a special favourite with the Provost. Mrs. Gilbert's uncle, Mr. Wintle, was a fellow of St. John's. He was a wealthy bachelor, had a fine voice, sang well, and was very fond of the society of his great-nieces. The Gilberts were acquainted with nearly all the families of the heads of colleges in Oxford, and the handsome, clever little girls were favourites[Pg 43] and were "made much of." When there was a dinner party at home they came in to dessert, and accompanied the ladies to the drawing-room, where Bessie would play and sing. She lived thus not merely in a world of ideas, but in the external world of facts, of things. When a friend once spoke of another lady as handsome, Bessie exclaimed, "Oh, Mrs. ——, with such a nose!"

Many of the fellows of Brasenose College were frequent visitors at the Vice-Chancellor's Lodgings, and the old friends, Dr. Kynaston and Mr. Bazely, were constant as ever. They joined the girls in their walks, and paid frequent visits to the schoolroom, where the younger ones would hide their caps to prevent them from leaving.

Bessie used to delight in these visits, and looked back upon them as the very sunshine of life at Oxford. Her poetry and music gained her much sympathy. At this time, when she was about fourteen, she wrote a poem on the violet which was much praised. At fifteen her intellectual activity was the most remarkable point in her character, whilst at the same time there was an equally remarkable absence of that rebellion against authority which marks an epoch in so many young lives. Boys and girls of that age begin to fret against the restrictions of childhood and youth; they endeavour to cast aside laws and restraints; they are eager to "live their own life" and to enjoy a freedom which they are all unfit to use. Bessie knew nothing of this, or rather, she knew it in a very modified, even[Pg 44] attenuated form. The one extravagant desire which marked her adolescence, was to be allowed the privilege of pouring out tea!

It was urged in vain that she would not know if cups were full or half full, that she could not give to each one what they wanted of tea or water, milk or sugar. Her reply was always the same, she would know by the weight. The decision of the parents, however, went against her, and she had her one small grievance. She did not "take turns" in making tea.

In the summer of 1841 Bessie, with a sister of nearly her own age, and one of the little ones, went on a long visit to Culham. They took the harp with them and practised diligently. They read history together. Bessie gave daily lessons to her young sister, reading with her Scott's Tales of a Grandfather, and teaching the child to love them as she herself did. Whenever she had charge of a younger sister, poetry entered largely into her scheme of education, and the "little sister" still remembers the Scott, Wordsworth, and Mrs. Hemans, "Hymns for Childhood" which she learnt at this time.

Bessie loved romantic ballads and stories. She was more imaginative than any of "the others;" and "the others" thought that the loss of sight acted upon her like the want of a drag upon a wheel, when the coach goes down hill. During this visit Bessie had such a constant craving and eager desire for books, that even in their walks she induced her sister to read aloud.[Pg 45] They thus read Southey's Curse of Kehama, and she was so much excited by it that somewhat to the alarm of younger persons she went about repeating aloud "the words of that awful curse."

There were plenty of books at Culham. Mr. Wintle interdicted two or three, but amongst the rest his grandchildren were at liberty to select. They picked out all that promised to be "most exciting," and this free pasture made the visit memorable. Bessie was still "Blossom" to her grandfather, a Blossom that he admired and loved, but Blossom only. Never was a Blossom whose words and deeds have been treasured in such loving hearts.

"We looked upon her as a sort of prophetess;" and this view was confirmed by incidents that occurred in 1842. The sisters were walking together, and first one and then another suggested strange things that might happen. "Why, who knows," said Bessie, "in less than a month our house may be burnt down and we may be living in a palace!" Now within a month it is recorded that a rocket let off in the street, and badly aimed, went through the windows of the nursery in which several children were asleep. The governess happened to be in the room, and with great presence of mind seized the rocket and threw it back into the street. Now here was at any rate the possibility of a fire. Still more impressive was the fact that within the month Dr. Gilbert was appointed to the See of Chichester. They would really live in a palace.

Much excitement and no little awe in the[Pg 46] nursery, not so much because the father was a bishop as because Bessie was a prophetess. The bishop would be comparatively innocuous in the nursery, but who could tell what a prophetess might foresee!

And so the pleasant Oxford life came to an end; and in spite of a prospective palace, the sisterhood thought the change a calamity. Bessie specially disliked leaving her old friends, and her regret at parting from them did not diminish but increased with time. Doubtless in later years the inevitable restraint of her life lent an additional charm to the memory of her youth in Oxford. The constant solicitude of parents, friends, and sisters had kept from her in early days the knowledge of limitations; but in the time that was at hand she was to go forth to face the world and to learn more of the meaning of the mysterious word blind. Canon Melville, who knew her in Oxford, writes to one of her sisters as follows:—

The College, Worcester, 1885.

I have a very clear memory of the person and character of your sister Bessie; it is a pleasure to me to recall them.

The natural gifts and graces of her mind and disposition were only heightened by the loss of her eyesight. That wonderful compensating power which often makes amends for loss of faculty in one sense by corresponding intensity in another, her moral and spiritual sensitiveness with that inward joyfulness recording itself in outward expression of a pleased and happy countenance, were remarkably evident. Out of many little traits indicative[Pg 47] of this and her quiet intuition of what favourably or otherwise might strike her moral sense, I remember once when the appearance of some one she personally, for some unknown reason, disliked, was being remarked upon, and I had pronounced my admiration of it, she turned quite gravely to me, and with deep earnestness, as if she was then seeing or had recently seen the form and figure of him of whom we were talking, exclaimed, "Oh, Mr. Melville, I cannot agree with you! How can you admire him!" Something that had jarred with her moral perceptions having made her transfer her judgment on the character to the form and features of the person, as though she had seen the analogy she felt there must be between the outward and the inward.

Of the history of her self-devotion to the personal and industrial improvement of those under like affliction with herself her whole life was an illustration. Of that many must have much to tell.

During the removal from Oxford the Bishop and Mrs. Gilbert were in London with two daughters, of whom Bessie was one; Fanny and the younger ones were left under the charge of the faithful governess, Miss Lander, and in bright and copious epistles they inform Bessie of all that is going on in the old home. They tell how they had heard Adelaide Kemble in Oxford, whom Bessie is shortly to hear at Covent Garden; how they met many friends at the concert; how one gentleman told them that Adelaide Kemble sang better than Catalani; and how three who had not heard Catalani said she was equal to Grisi. How some of the "Fellows" went home to supper with them, and how they all stayed up till twelve o'clock, a great event for the little girls and their[Pg 48] governess, who all send "love and duty to papa and mamma."

There is another letter to Bessie, still in London, though the parents have returned to Oxford, which gives a happy picture of last days there. Bessie sends as farewell presents some of the little chains which she makes, and the sisters sew them together for her. The father receives a farewell presentation of plate, the elder girls darn rents in the gowns of their friends, the Fellows of Brasenose, and so on it runs:—

My dear Bessie—I write to you now in a great hurry to tell you to send Mr. Melville's chain to-morrow by Mr. ——, as I expect we shall see him some time to-morrow, and I could sew it for him. I sent the mat on Tuesday, and when he came to tea in the evening he said he must come to thank you for it to-day; but as I told him he would not be able to see Sarah and Henrietta after this week, he seemed to say that he should wait till next week to see you, which I hope you will think quite fair. The plate was presented to papa yesterday. The address was short, but a very nice one, and I suspect chiefly written by Mr. ——. Papa's answer I have not seen, as he had only one copy, which he left with the Vice-Principal. We were none of us there, which I am almost sorry for, although it would very likely have been too much for us. Papa is delighted beyond measure with it.... We went last night to drink tea at aunt's, and then went to sleep at the Barnes's. We are going to dinner there to-night and sleep, for there is not a bed here. The glasses and all the pictures are gone, and that has made the house more deplorable than ever. Miss A. is here now, and seems pretty well. You know that Mary and I have been mending Mr. A.'s gown for him.

He came this morning for it and stayed some time. He said he could not have got it done anywhere else so nicely; that is a long darn that Mary did for him. The B.'s have told Mr. W. that they will keep their acquaintance with him for our sakes, so that he will not be quite deserted; are not you glad of it? Will you ask Miss Lander to send word where she left her Punch and Judy? If she doesn't remember, I daresay it will be found; but we have not seen it. There is a chance, I believe, of Mr. A.'s taking Selham, but you must not say anything about it. All send love to everybody.—Believe me to be your affectionate sister, F. H. L. G.

Whilst the parents were in London this year, Bessie paid one visit which produced a great and lasting effect upon her. She accompanied her mother to the blind school in the Avenue Road; and this seems to have been the first time that the blind, as a class of the community, apart from the majority, and separated by a great loss and privation, came under her notice. The experience could not fail to be painful. She contrasted the lot of these young people with her own in her happy home, and shrank back in pain from institutions in which the afflicted are herded together, the one common bond that of the fetters of a hopeless fate. The matron of the girls' school, afterwards Mrs. Levy, remembers this visit, and says the impression produced on her by the bishop's daughter was that she was "delightful, beautiful, full of sympathy for the blind." She remembers also that the Bishop preached in Marylebone Church in aid of the blind school, taking as his text words that must often have comforted[Pg 50] and strengthened his own heart, "Who hath made the blind and deaf, but I the Lord?"

This year, 1842, was altogether a memorable one. Bessie's grandfather, as a young man, had a living or curacy at Acton, where his chief friend, the squire of the parish, was a Mr. Wegg. Another friend of whom he saw much at this time was Mr. Bathurst, afterwards General Sir James Bathurst, aide-de-camp to the Duke of Wellington. A third was Miss Hales, companion and friend of Mrs. Wegg. The Gilberts and the Bathursts were Miss Hales's dearest friends; and she had a god-daughter in each family, they were Catherine, younger daughter of Sir James Bathurst, and Bessie, the blind grand-daughter of Mr. Wintle. Mrs. Gilbert always corresponded with Miss Hales, sent her copies of Bessie's verses, and information as to the health and progress of the child. Miss Hales died in 1842, and by will divided her fortune between her two god-daughters.

Bessie was thus placed in a different position from that of any of her sisters; she alone when she attained her majority would have an independent income during her father's lifetime. The Bishop was relieved from anxiety as to the future of his blind daughter, and the necessity of ample provision for her; but he felt strongly, and wished her also to feel, that the possession of money brings with it duties and responsibilities.

[4] "Added to this the authorities of the University, the appointed guardians of those who form great part of the attendants on my sermons, have shown a dislike to my preaching. One dissuades men from coming, the late Vice-Chancellor threatens to take his own children away from the church."—Apologia pro Vita Sua, p. 133. John Henry Newman, D.D. Longmans, 1879.

By the autumn of 1842 the removal from Oxford to Chichester had been accomplished. The Bishop and his family were installed in the palace, which was to be their home for twenty-eight years. A new life was beginning for Bessie, and one which, when the inevitable pain of parting from old friends was over, she learnt to love very dearly. She had a keen imaginative delight in the beauties of nature. She loved to hear of clouds and sunset; of sunrise and the dawn, of green fields, of hills and valleys. She loved the outer air, flowers, and the song of birds; and she had passed the first sixteen years of her life in a house in the High Street, Oxford. She was very proud of the architectural beauty of Oxford, and always thought it a distinction to belong to Oxford; but her whole heart was soon in the home at Chichester.

The Bishop's palace has a beautiful old-fashioned[Pg 52] garden, of which the city wall forms the west and part of the southern boundary. A sloping mound leads from the garden to within a few feet of the top of the wall, and there is a green walk around the summit. There are grassy plots, umbrageous trees, flowering shrubs, roses, roses everywhere; and there are birds that sing all the long day in the spring-time. The black-cap was a special favourite of Bessie's and of the Bishop's. A garden door in the palace opens upon a straight gravel walk, with a southern aspect, leading towards the western boundary wall. On the southern side of the walk lies the garden, on the north a bank of lilacs, laburnums, and shrubs. Here Bessie could walk alone; she needed no companion, no guide. It was a new pleasure to her, and one of which she never grew weary. The song of birds, the hum of insects, the rustle of the trees, all made the garden a fairy palace of delight. A sister remembers how one summer morning at three o'clock she found Bessie standing at her bedside begging her to get up and dress, and go with her to the garden "to hear the birds waking up." Her father always gave a shilling to whoever saw the first swallow, and Bessie was delighted when the shilling had been earned.

The hall of the palace is a confusing place; there are many doors, passages, rooms opening into and leading from it There was always a moment of hesitation before Bessie opened the garden door or found the turning which she[Pg 53] wanted; but she quickly accommodated herself to all other eccentricities in one of the most puzzling of old-fashioned houses.

She spent less time in the schoolroom at Chichester than she had done at Oxford; she was indeed soon emancipated from the schoolroom altogether. She was much with her mother in the pleasant morning-room adjoining the bed and dressing rooms used by her parents. A steep spiral staircase, without a rail of any kind, with half a stair cut away at intervals for convenience of access to a cupboard or a small room, led from her father's dressing-room to rooms above. One of these with a western window so darkened by trees that no sunlight and very little daylight entered, was assigned to Bessie and one sister, whilst another sister was close at hand in another small room. The Bishop made a window to the south in Bessie's room, which greatly improved it, admitting light and air and all the sweet garden sounds and scents. The drawing-room is on the first floor near the morning-room. You ascend to it by a few broad stairs. A passage on the same floor leads to the private chapel attached to the palace, where Bessie knelt daily in prayer. The dining-room on the ground floor, the best room in the house, with its oak panels and fine painted ceiling, was a great pleasure to her. Some years later, when her work made it necessary that she should have a private sitting-room, two rooms were assigned to her in the centre of the house, one of which had been the schoolroom. Access[Pg 54] to these is gained by a long passage barely high enough to allow a full-grown person to stand erect at the highest part, near the bedroom door; and sloping on the other side to the floor and outer wall of the palace. Windows in the steep roof look north into West Street. Bessie's rooms were close to the angle formed by the centre and west wing of the palace, and had windows facing south.