Title: Uncle Daniel's Story Of "Tom" Anderson, and Twenty Great Battles

Author: John McElroy

Release date: March 25, 2010 [eBook #31769]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/31769

Credits: Produced by David Widger

“UNCLE DANIEL” IS PRESENTED TO THE PUBLIC. A TRUTHFUL

PICTURE, IN STORY, BASED UPON EVENTS OF THE LATE WAR. THIS

VOLUME IS DEDICATED TO THE UNION SOLDIERS AND THEIR

CHILDREN.

The Author

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Uncle Daniel Telling his Story --

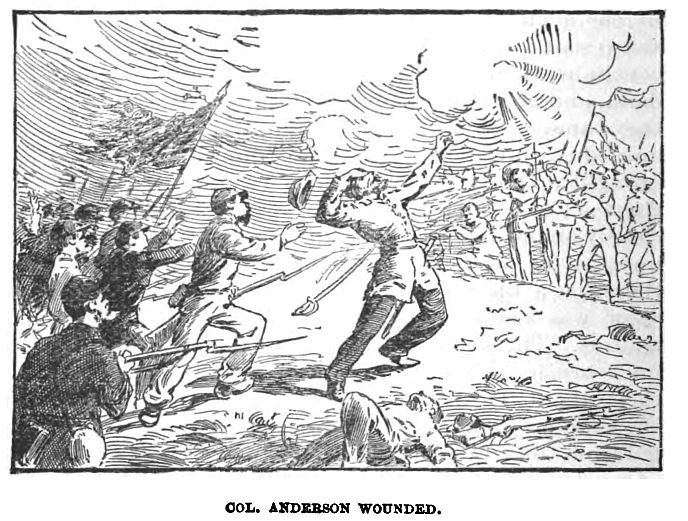

The Charge of Col. Anderson's Regiment --

Pupils Attacking the Little Abolitionist --

Uncle Daniel Meets Aunt Martha --

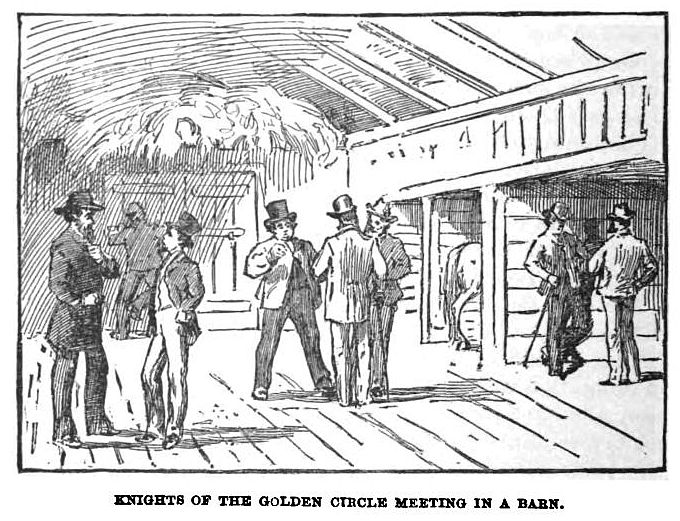

Knights of the Golden Circle Meeting in a Barn --

Drinking to the Success of Treason --

General Anderson Taking Command --

Anderson Overhears the Conspiracy --

A Spector Appears to the General --

Seraine With Henry at Pine Forest Prison --

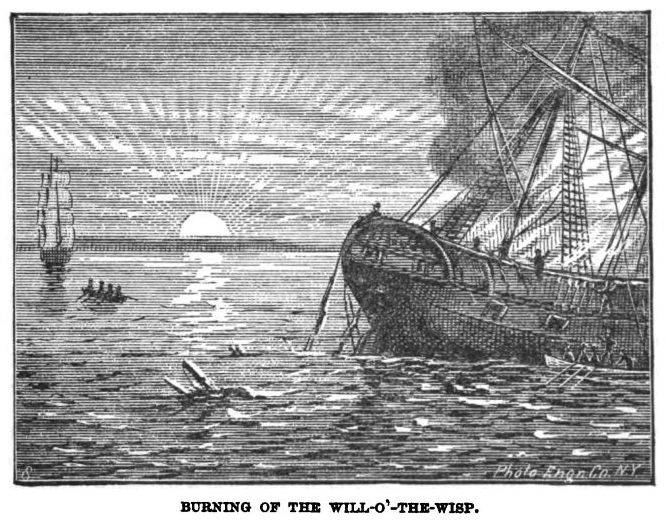

The Burning of the Will-o-the-wisp --

Thomlinson and Friends in Consultation --

Marriage of Henry and Seraine --

Gens. Silent and Meador in Conversation --

Mrs. Lyon Dies at Peter's Coffin --

Uncle Daniel Conferring With Lincoln and Stanton --

The Shooting of President Lincoln by Wilkes --

DARK DAYS OF 1861.—A FATHER WHO GAVE HIS CHILDREN TO THE

COUNTRY.—RALLYING TO THE FLAG.—RAISING VOLUNTEERS IN

SOUTHERN INDIANA.

“The more solitary, the more friendless, the more

unsustained I am, the more I will respect and rely upon

myself.”—Charlotte Bronte

ALLENTOWN is a beautiful little city of 10,000 inhabitants, situated on the Wabash River, in Vigo County, Ind., in the vicinity of which several railroads now center. It is noted for its elevated position, general healthfulness, and for its beautiful residences and cultivated society. Daniel Lyon located here in 1850. He was a man of marked ability and undoubted integrity; was six feet two inches in height, well proportioned, and of very commanding and martial appearance. In 1861, he was surrounded by a large family, seven grown sons—James, David, Jackson, Peter, Stephen, Henry and Harvey—all of whom were well educated, fond of field sports and inclined to a military life. The mother, “Aunt Sarah,” as she was commonly called by the neighbors, was a charming, motherly, Christian woman, whose heart and soul seemed to be wrapped up in the welfare of her family. She was of short, thick build, but rather handsome, with dark brown hair and large blue eyes, gentle and kind. Her politeness and generosity were proverbial. She thought each of her seven sons a model man; her loving remarks about them were noticeable by all.

Daniel Lyon is at present 85 years old, and lives with one of his granddaughters—Jennie Lyon—now married to a man by the name of James Wilson, in Oakland, Ind., a small town conspicuous only for its rare educational facilities.

On the evening of the 22d of February, 1884, a number of the neighbors, among whom was Col. Daniel Bush, a gallant and fearless officer of the Union side during the late war, and Dr. Adams, President of ——— College, dropped in to see Uncle Daniel, as he is now familiarly called. During the evening, Col. Bush, turning to the old veteran, said:

“'Uncle Daniel,' give us a story from some of your experiences during the war.”

The old man arose from his easy-chair and stood erect, his hair, as white as snow, falling in profusion over his shoulders. His eyes, though dimmed by age, blazed forth in youthful brightness; his frame shook with excitement, his lips quivered, and tears rolled down the furrows of his sunken cheeks. All were silent. He waved his hand to the friends to be seated; then, drawing his big chair to the centre of the group, he sat down. After a few moments' pause he spoke, in a voice tremulous with emotion:

“My experience was vast. I was through the whole of the war. I saw much. My story is a true one, but very sad. As you see, my home is a desolate waste. My family consists now of only two grand-children; wife and sons are all gone. I am all that is now left of my once happy family. My God! My God! Why should I have been required to bear this great burden? But pardon this weakness in an old man. I will now begin my story.

“In the month of ———, 1861, my nephew, 'Tom' Anderson,—I called the boy Tom, as I learned to do so many years before, while visiting at his father's; he was the son of my eldest sister,—his wife, Mary, and their only child, a beautiful little girl of two years (called Mary, for her mother), were visiting at my house. Their home was in Jackson, Miss. One evening my good wife, Tom, his wife, my son Peter, and I were sitting on our front porch discussing the situation, when we heard a great noise a couple of blocks south of us. The young men stepped out to see what the trouble was and in a very short time they returned greatly excited. A company of men were marching down the street bearing the American flag, when a number of rebel sympathizers had assaulted them with stones, clubs, etc., and had taken their flag and torn it to shreds. It seemed that a Mr. 'Dan' Bowen, a prominent man in that part of the State, had been haranguing the people on the question of the war, and had denounced it as 'an infamous Abolition crusade,' and the President as a villainous tyrant,' and those who were standing by the Union as 'Lincoln's hirelings, and dogs with collars around their necks.' This language stirred up the blood of the worst element of the people, who sympathised with secession, and had it not been for the timely interposition of many good and worthy citizens, blood would have been shed upon the streets.”

Here Col. Bush asked:

“What became of this man Bowen?”

“I understand that he now occupies one of the highest positions the people of Indiana can give to one of her citizens. You see, my friends, that we American people are going so fast that we pass by everything and forget almost in a day the wrongs to our citizens and our country.”

“But to return to what I was saying in connection with the young men. Tom Anderson was in a state of great excitement. He said he had almost been mobbed before leaving home for entertaining Union sentiments, and feared that he could not safely return with his family. My son Peter suggested that, perhaps, they (being young) owed a duty to their country and could not perform it in a more satisfactory manner than to enter the service and do battle for the old flag. To this suggestion no reply was made at the time. I said to them:

“'This seems to me a very strange condition of things, to see a Government like this threatened in its permanency by the very people that have controlled and profited most by it.' Tom replied:

“'Uncle, I have given a great deal of thought to this subject. You know I was born in Ohio. My father was an Episcopal minister, and settled in Mississippi while I was but a boy. My father and mother are both buried there, leaving me an only child. I grew up and there married my good wife, Mary Whitthorne. We have lived happily together. I have had a good practice at the law; have tried to reconcile myself to their theories of human rights and 'rope-of-sand' government, but cannot. They are very different from our Northern people—have different theories of government and morals, with different habits of thought and action. The Pilgrim Fathers of the North who landed at Plymouth Rock were men of independence of thought; believed in Christianity, in education and universal liberty. They and their progeny have moved almost on a line due west, to the Pacific Ocean, infusing their energy, their ideas of government, of civil liberty, of an advanced Christian civilization, with a belief in man's equality before the law. These ideas and thoughts have become imbedded in the minds of the Northern people so firmly that they will fight to maintain them; will make them temporarily a success, and would make them permanent but for their habit of moving so rapidly in the direction of business and the accumulation of wealth, which prepares the mind to surrender everything to the accomplishment of this single object. The Southern inhabitants are almost entirely descended from impetuous, hot-blooded people. Their ancestors that landed at Jamestown, and later along the Southern Atlantic coast within our borders, were of an adventurous and warlike people. Their descendants have driven westward almost on a parallel line with the Northern people to the borders of Mexico, occasionally lapping over the Northern line. Their thoughts, ideas, manners and customs have been impressed upon the people wherever they have gone, by the pretense, always foremost and uppermost, as if a verity, that they were the most hospitable and chivalric of any people in America. Their civilization was different. Their arguments were enforced by the pistol and bowie-knife upon their equals, and slaves subjected to their will by the lash and bloodhound—the death of a man, white or black, being considered no more than merely a reduction of one in the enumeration of population. They have opposed common schools for fear the poorer classes of whites might have an opportunity of contesting at some time the honors of office, that being the great ambition of Southern society. They would not allow the slave to be educated for fear he might learn that he was a man, having rights above the brute with which he has always been held on a par. The aristocracy only were educated. And this was generally done in the North, where the facilities were good; and by sending them from home it kept down the envy and ambition of the poorer classes, where, if they could have seen the opportunity of acquiring knowledge it might have stimulated them to greater exertion for the purpose of storing their minds with something useful in extricating themselves from an obedience to the mere will of the dominating class. Those people, one and all, no matter how ignorant, are taught to consider themselves better than any other people save the English, whose sentiments they inculcate. They are not in sympathy with a purely Republican system of Government. They believe in a controlling class, and they propose to be that class. I have heard them utter these sentiments so often that I am sure that I am correct. They all trace their ancestry back to some nobleman in some mysterious way, and think their blood better than that which courses in the veins of any Northern man, and honestly believe that one of them in war will be the equal of five men of the North. They think because Northern men will not fight duels, they must necessarily be cowards. In the first contest my judgment is that they will be successful. They are trained with the rifle and shotgun; have taken more pains in military drill than the people of the North, and will be in condition for war earlier than the Union forces. They are also in better condition in the way of arms than the Government forces will be. The fact that they had control of the Government and have had all the best arms turned over to them by a traitorous Secretary of War, places them on a war footing at once, while the Government must rely upon purchasing arms from foreign countries, and possibly of a very inferior character. Until foundries and machinery for manufacturing arms can be constructed, the Government will be in poor condition to equip troops for good and effective service. This war now commenced will go on; the North will succeed; slavery will go down forever; the Union will be preserved, and for a time the Union sentiment will control the Government; but when reverses come in business matters to the North, the business men there, in order to get the trade of the South, under the delusion that they can gain pecuniarily by the change, will, through some 'siren song,' turn the Government over again to the same blustering and domineering people who have ever controlled it. This, uncle, is the fear that disturbs me most at present.'”

“How prophetic,” spoke up Dr. Adams.

“Yes, yes,” exclaimed all present.

Col. Bush at this point arose and walked across the floor. All eyes were upon him. Great tears rolled down his bronzed cheeks. In suppressed tones he said:

“For what cause did I lose my right arm?”

He again sat down, and for the rest of the evening seemed to be in deep meditation.

Uncle Daniel, resuming his story, said:

“Just as Tom had finished what he was saying, I heard the garden gate open and shut, and David and Harvey appeared in the moonlight in front of the porch. These were my second and youngest sons. David lived some five miles from Allentown, on a farm, and Harvey had been staying at his house, helping do the farm work. They were both very much excited. Their mother, who had left. Mary Anderson in the parlor, came out to enjoy the fresh air with us, and observing the excited condition of her two sons, exclaimed:

“'Why, my dear boys! what is the matter?'

“David spoke to his mother, saying:

“'Do not get excited or alarmed when I tell you that Harvey and I have made a solemn vow this evening that we will start to Washington city in the morning.'

“'For what, my dear sons, are you going?' inquired the mother, much troubled.

“'We are going to tender our services to the President in behalf of the Union. Harvey is going along with me, believing it his duty. As I was educated by the Government for the military service, I deem it my duty to it, when in danger from this infamous and unholy rebellion, to aid in putting it down.'

“Their mother raised her hands and thanked God that she had not taught them lessons of patriotism in vain. She laid her head upon David's manly breast and wept, and then clasped Harvey in her arms and blessed him as her young and tender child, and asked God to preserve him and return him safely to her, as he was her cherished hope. Peter, who had been silent during the entire evening, except the bare suggestion to Tom to enter the service, now arose from where he was sitting, and extending his hand to David, said:

“'My old boy, I am with you. I shall commence at once to raise a company.'

“David turned to his mother and laughingly said:

“'Mother, you seem to have taught us all the same lesson.'

“His mother's eyes filled with tears as she turned away to seek Mary. She found her in the parlor teaching her sweet little daughter her prayers. My wife stood looking at the pretty picture of mother and child until little Mary Anderson finished, kissed her mamma, and ran off to bed; then entering the room she said:

“'Mary, my child, I am too weak to speak. I have held up as long as I can stand it,' and then burst into tears. Mary sprang to her at once, clasping her in her arms.

“'Dearest auntie, what is the matter? Are you ill?

“'No! no! my child; I am full of fear and grief; I tremble. My sons are going to volunteer. I am grieved for fear they will never return. Oh! Mary! I had such a terrible dream about all the family last night. Oh! I cannot think of it; and yet I want them to go. God knows I love my country, and would give all—life and everything—to save it. No, I will not discourage them. I will tell you my dream when I have more strength.'

“Just then my blessed old wife fainted. Mary screamed, and we all rushed into the parlor and found her lying on the floor with Mary bending over, trying to restore her. We were all startled, and quickly lifted her up, when she seemed to revive, and was able to sit in a chair. In a few moments she was better, and said:

“'I am all right now; don't worry. I was so startled and overcome at the thought that so many of my dear children were going to leave me at once and on such a perilous enterprise.'

“To this Peter answered:

“'Mother, you ought not to grieve about me. Being an old bachelor, there will be but few to mourn if I should be killed.'

“'Yes; but, my son, your mother loves you all the same.'

“Just then a rap was heard at the window. It being open, a letter was thrown in upon the floor. I picked it up. It was addressed to 'Thos. Anderson.' I handed it to him. He opened it, and read it to himself, and instantly turned very pale and walked the floor. His wife took his arm and spoke most tenderly, asking what it was that troubled him.

“'Mary, dear, I will read it,' he said, and unfolding the letter, he read aloud:

“'Jackson, Miss., June — 1861.

“'Dear Tom—You have been denounced to-day in resolutions as

a traitor to the Southern cause, and your property

confiscated. Serves you right. I am off to-morrow morning

for the Confederate Army.

Good-by.

Love to sister.

“'Your enemy in war,

“'JOS. WHITTHORNE.

“'Mary sank into a chair. For a moment all were silent. At last Tom exclaimed:

“'What is there now left for me?”

“His wife, with the stateliness of a queen, as she was, her black hair clustering about her temples and falling around her shoulders and neck, her bosom heaving, her eyes flashing fire, on her tip-toes arose to her utmost height. All gazed upon her with admiration, her husband looking at her with a wildness almost of frenzy. She clenched both hands and held them straight down by her side, and exclaimed in a tone that would have made a lion cower:

“'Would that I were a man! I would not stop until the last traitor begged for quarter!'

“Tom flew to her and embraced her, exclaiming:

“'I was only waiting for that word.'

“She murmured:

“'My heavens, can it be that there are any of my blood traitors to this country?'

“The household were by this time much affected. A long silence ensued, which was broken by David, saying:

“'Father, Harvey and I having agreed to go to Washington to enter the army, I wish to make some arrangements for my family. You know I have plenty for Jennie and the babies, and I want to leave all in your hands to do with as if it were your own, so that the family will have such comforts as they desire.'

“David's wife, Jennie, was a delightful little woman, with two beautiful children—Jennie, named for her mother, and Sarah, for my wife. I said to David that I would write to his brother James, who was a widower, having no children, to come and stay with Jennie. I at once wrote James, who was practicing medicine at Winchester, Va., that I feared it would be 'unhealthy' for him there, so to come to me at once. This being done and all necessary arrangements made, David and Harvey bade all an affectionate farewell and started for their farm, leaving their mother and Mary in tears. As their footsteps died away their mother went to the door, exclaiming, “'Oh, my children! will I ever see you again?' “That night we all joined in a general conversation on the subject of the war. It was arranged that Peter should start next morning for Indianapolis to see the Governor, and, if possible, obtain authority to raise a regiment under the call of the President. This having been decided upon we all retired, bidding each other good night. I presume there was little sleeping in our house that night save what little Mary did, the poor child being entirely unconscious of the excitement and distress in the family. The next morning Peter took the train for Indianapolis, Tom went down town to ascertain the latest news, and I took my horse and rode out to David's farm, leaving the two women in tears, and little Mary inquiring: “'What is the matter, mamma and aunty?' “I rode on in a deep study as to the outcome of all this trouble. I came to David's house, unconscious for a moment as to where I was, aroused, however, by hearing some one crying as if in despair. I looked around and saw it was Jennie. She stood on the door-step in great grief, the two children asking where their father had gone. “'Good morning, my daughter,' I said, and, dismounting, I took her in my arms, and laying her head on my shoulder she sobbed as if her heart would break.

“'O! my dear husband, shall I ever see him again? O! my children, what shall I do?' was all she could say.

“I broke down completely, this was too much; the cries of the little children for their papa and the tears of their mother were more than I could stand. He had never left them before to be gone any great length of time. I took Jennie and the children into the house. There was a loneliness and a sadness about the situation that was unendurable, and I at once ordered one of the farm hands to hitch the horses to the wagon and put the family and their little traps in and get ready to take them to my house, and turned David's house over to his head man, Joseph Dent (he being very trusty) to take charge of until David should return. With these arrangements I left with the family for Allentown. On our arrival the meeting of the three women would have melted the heart of a stone. I walked out to the barn and remained there for quite awhile, thinking matters over to myself. When I returned to the house all had become quiet and seemingly reconciled. For several days all was suspense; nothing had been heard from any of our boys; I tried to keep away from the house as much as possible to avoid answering questions asked by the women and the poor little children, which I knew no more about than they did. But while we were at breakfast on the morning of ———, Jennie was speaking of going out to her house that day to look after matters at home and see that all was going well. Just at this moment a boy entered with a letter, saying:

“'Mr. Burton sent me with this, thinking there might be something that you would like to see.'

“Mr. B. was the Postmaster, and very kind to us. He was a true Union man, but the opposition there was so strong that he was very quiet; he kept the American flag flying over his office, which was burned on that account a few nights later, as was supposed, by Southern sympathizing incendiaries. These were perilous times in Southern Indiana.”

“Yes! Yes!” said Col. Bush. “We had a taste of it in Southern Ohio, where I then resided; I know all about it. The men who were for mobbing us at that time are now the most prominent 'reformers,' and seem to be the most influential persons.

Uncle Daniel continued:

“I opened the letter and read it aloud. It ran substantially as follows:

“'We arrived at Columbus, O., on the morning of ———, when

there was some delay. While walking about the depot I

chanced to meet your old friend the Governor. He was very

glad to see me, and said to me, “Lyon, you are the very man

I am looking for.” I asked, “Why, Governor? I am on my way

to Washington to tender my services to the President in

behalf of the Union.” The Governor answered, “You are

hunting service, I see. Well, sir, I have a splendid

regiment enlisted, but want to have a man of some experience

for their Colonel, and as you have been in the Regular Army

and maintained a good reputation, I will give you the

position if you will take it. I grasped him by the hand and

thanked him with all my heart. This was more than I could

have expected. So, you see, I start off well. We are now in

camp. I am duly installed as Colonel. Harvey has been

mustered in and I have him detailed at my headquarters. He

seems to take to soldiering very readily. I have written

Jennie all about matters. I hope she and my darling children

are well and as happy as can be under the circumstances.

“'Your affectionate son,

“'David Lyon.'

“He did not know that I had them at my house, and all were assisting one another to keep up courage. This letter affected the whole family, and caused many tears to fall, in joy as well as grief; joy that he had succeeded so well at the beginning, and grief at his absence. That evening Jennie received her letter from the 'Colonel' as we now called him, all becoming very military in our language. Her letter was of the same import, but much of it devoted to family affairs. This made Jennie happy. We all retired and rested well that night, after pleasing the children by telling them about their father being a great soldier, and that they must be good children, and in that way cause their mother to write pleasant things about them to their good papa.”

BATTLE OF THE “GAPS.”—YOUNG HARVEY LYON BRUTALLY MURDERED.—

UNCLE DANIEL'S RETURN.—RAISING TROOPS IN SOUTHERN

INDIANA.

“When sorrows come they come not single spies, but in

battalion.” —-Shakespeare.

“Three days later Peter returned from Indianapolis, with full authority for Tom Anderson to recruit a regiment for the Union service. This was very gratifying to him, and he said to his wife, 'Mary, my time will come.' She appeared happy over the news, but her quivering lip, as she responded, gave evidence of her fears that the trial to her was going to be severe. My good wife then called us into tea, and when we were all seated, Mary said to her:

“'Aunt Sarah, you have not yet told us your dream. Don't you remember, you promised to tell it to me? Now let us hear it, please.”

“'Yes, my child. It has troubled me very much; and yet I don't believe there is any cause for alarm at what one may dream.'

“'Mother, let us hear it,' spoke up Peter; 'it might be something that I could interpret. You know I try to do this sometimes; but I am not as great a success as Daniel of old.'

“'Well, my son, it was this: I thought your father and I were in the garden. He was pulling some weeds from the flower-bed, when he was painfully stung on both hands by some insect. Soon his fingers began dropping off—all five from his right hand and his thumb and little finger from his left.'

“Tom laughingly said, 'Uncle, hold up your hands;' which I did, saying, 'You see my fingers are not gone.' Whereupon they all laughed except Peter.

“My wife said to him:

“'My son, what is your interpretation of my dream! It troubles me.'

“'Well, mother, I will not try it now. Let the war interpret it; it will do it correctly, doubtless. Let us talk about something else. You know dreams amount to nothing now-a-days.'

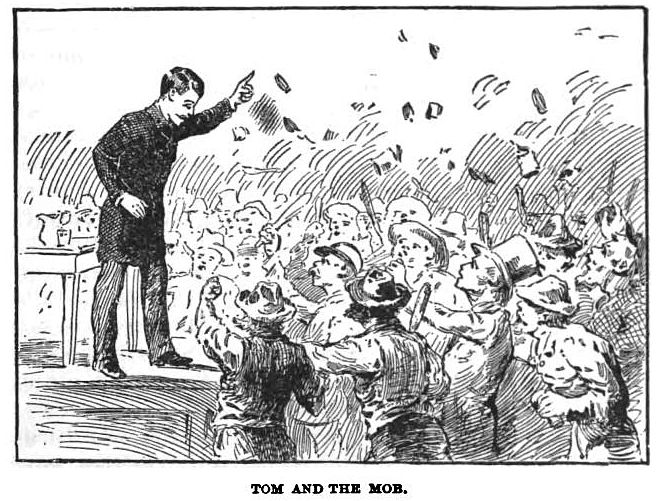

“During all this time, Peter wore a serious countenance. We discussed the matter as to how Tom should go about raising his regiment. It was understood that he should start out at once, and that Peter should take the recruits, as fast as organized into companies, and place them in the camp of instruction at Indianapolis. The next morning Tom opened a recruiting office in Allentown, placed Peter temporarily in charge, and started through the country making speeches to the people (he was quite an orator), and soon succeeded in arousing patriotic sentiments in and about Allentown. After raising two companies, he extended his operations, going down on the O. & M. R. R. to Saco, a town then of about 1,000 inhabitants. While addressing the people, a mob gathered and were about to hang him. He stood them off until the Union people came to his rescue and saved his life.”

“That is just as it was where I lived,” said Col. Bush. “I know of just such a case, where a mob tried the same thing; some of them, however, repented before they went to heaven, I hope.”

Uncle Daniel continued:

“He left the town, however, under a guard and returned home. Soon after this he made a second effort, by arming 20 resolute men of his recruits with Colt's revolvers, which he procured from the Governor of the State, and returned to Saco. He at once gave notice that he would speak the next day. When the time arrived, he told his men to take positions in the crowd, scattering as well as they could in his front. This done he commenced his speech. Soon mutterings of the crowd could be heard, and finally the storm came and they rushed towards the stand. He shouted at the top of his voice, “Hold!” at the same time drawing his revolver, declaring he would shoot the first man that advanced another step, and also raising his left hand above his head. This was a signal for his men to “fall in,” and they all rushed into line in his front with drawn weapons. The crowd instantly ran in all directions, much to the amusement and gratification of Tom.

“There were some loyal men in that community, and before leaving Saco, Tom had raised a full company. When the day came for them to leave, they marched with the flag presented to them by the ladies of the town proudly waving, and with drum and fife making all the noise possible. There was no more disturbance there, except in secret. The 'secesh' element murdered several soldiers afterwards, and continued secretly hostile to the success of our army. In a few days after this Tom had recruited another company. There seemed then to be an immediate demand for a regiment, with a brave and daring officer, at the Capital, for some reason not then made known. Tom was ordered to have his four companies mustered in, and, attached to six already in camp; he was commissioned Colonel, and the regiment was numbered the —— Indiana Infantry Volunteers. Tom Anderson looked the soldier in every respect. He was five feet eleven, straight as an arrow, well-built, large, broad shoulders, black eyes and hair, and martial in his bearing.

“He placed his family in my charge. The next day after Tom had left (Peter Lyon, my son, having gone before him with the recruits), my wife, Mary, Jennie, the three children and myself, were all on the porch, when a tall man, fully six feet, rather fine looking, made his appearance at the gate, and asked if that was where Daniel Lyon lived. As I answered in the affirmative, he opened the gate and walking in, saluted us all with:

“'How do you do? Do you not recognize me? I am James Lyon.'

“I sprang to him and grasped his hand, his mother threw her arms around his neck and wept for joy, the other women greeted him heartily, and the little children rushed to him. Although they had never seen him before, they knew he was some one they were glad to see, as their fathers and uncles, whom they knew, were gone from them. We all sat down and the Doctor, as I must call him (being a physician by profession), gave us some of his experiences of the last few weeks. When he received my letter and commenced getting ready to leave, the people of Winchester suspected him of preparing to go North to aid the Union, and so they threw his drugs into the street, destroyed his books, and made him leave town a beggar. He walked several miles, and finally found an old friend, who loaned him money enough to get to my place.”

Mr. Reeves, who was of the party, said:

“I have been through all that and more, too. I had to leave my wife and family, and was almost riddled with bullets besides; but it is all past now.”

“I have been greatly interested, Uncle Daniel,” said Dr. Adams, “and am taking down all you say in shorthand, and intend to write it up.”

“The next day,” continued Uncle Daniel, “the newspapers had telegrams stating that the troops at Columbus and other places had been ordered to the East for active operations. I said to Dr. James that he must stay with the family while I went to Washington, as I wanted to see the President on matters of importance. The truth was, I wanted to see David and Harvey, as well as the President. I started the next morning, after telling the women and children to be of good cheer.

“When I reached Washington I found the army had moved to the front, and was daily expecting an engagement, but I could not understand where. I at once visited the President, to whom I was well known, and told him my desire, which was to see my sons. He promptly gave me a note to the Provost-Marshal, which procured me a pass through the lines. That night I was in the camp of my son David, who, you remember, was a Colonel. After our greeting we sat down by his camp chest, upon which was spread his supper of cold meat, hard crackers and coffee, the whole lighted by a single candle inserted in the shank of a bayonet which was stuck in the ground. While enjoying the luxury of a soldier's fare I told him all about the family, his own in particular. Harvey enjoyed the things said of him by the children which I repeated. The Colonel, however, seemed thoughtful, and did not incline to very much conversation. Looking up with a grave face he said to me:

“'Father, to-morrow may determine the fate of the Republic. I am satisfied that a battle, and perhaps a terrible one, will be fought very near here.'”

'I asked him about the armies, and he replied that we had a very large army, but poorly drilled and disciplined; that the enemy had the advantage in this respect. As to commanding officers, they were alike on both sides, with but little experience in handling large armies. He suggested that we retire to rest, so that we could be up early, but urged me to stay at the rear, and not go where I would be exposed. To this I assented. Soon we retired to our couches, which were on the ground, with but one blanket apiece and no tent over us. I did not sleep that night. My mind was wandering over the field in anticipation of what was to occur.

Early next morning I heard the orders given to march in the direction of the gaps. Wagons were rolling along the road, whips were cracking, and teamsters in strong language directing their mules; artillery was noisy in its motion; the tramp of infantry was steady and continuous; cavalrymen were rushing to and fro. I started to the rear, as my son had directed, and ate my breakfast as I rode along. About 10 o'clock I heard musket shots, and soon after artillery; then the musketry increased. I listened for awhile. Troops were rushing past me to the front. As I was dressed in citizen's clothes, the boys would occasionally call out to me, 'Old chap, you had better get back;' but I could not. I was moved forward by some strong impulse, I knew not what, and finally found myself nearing the front with my horse on the run. Soon I could see the lines forming, and moving forward into the woods in the direction of the firing, I watched closely for my son's command, and kept near it, but out of sight of the Colonel, as I feared he would be thinking of my being in danger, and might neglect his duty. The battle was now fully opened—the artillery in batteries opening along the line, the infantry heavily engaged, the cavalry moving rapidly to our flanks. Steadily the line moved on, when volley after volley rolled from one end of the line to the other. Now our left was driven back, then the line adjusted and advanced again. The rebel left gave way; then the center. Our cavalry charged, and our artillery was advanced. A shout was heard all along the line, and steadily on our line moved. The rebels stubbornly resisted, but were gradually giving way. The commanding General rode along the line, encouraging all by saying:

“'The victory is surely ours, Press forward steadily and firmly; keep your line closed up;' and to the officers, 'Keep your commands well in hand.'

“He felt that he had won the day. For hours the battle went steadily on in this way. I rode up and down the line watching every movement. I took position finally where I could see the enemy. I never expected to see officers lead their men as the rebels did on that day. They would rally their shattered ranks and lead them back into the very jaws of death. Many fell from their horses, killed or wounded; the field was strewn with the dead and dying; horses were running in different directions riderless. I had never seen a battle, and this was so different from what I had supposed from reading, I took it for granted that, both sides being unacquainted with war, were doing many things not at all military. I learned more about it afterward, however. From an eminence, where I had posted myself, I could see a large column of fresh troops filing into the plain from the hills some miles away. They were moving rapidly and coming in the direction of the right flank of our army. I at once rode as fast as I could to the left, where my son was inline, and for the first time that day showed myself to him. He seemed somewhat excited when he saw me, and asked: 'In Heaven's name what are you doing here?'

“I said: 'Never mind me, I am in no danger.'

“I then told him what I had seen, and he at once sent an orderly, with a note to the General commanding. In a short time, however, we heard the assault made on our right. It was terrific. Our troops gave way and commenced falling back. The alarm seemed to go all along the line, and a general retreat began without orders. Soon the whole army was leaving the field, and without further resistance gave away the day. The rebel army was also exhausted, and seemed to halt, in either joy or amazement, at the action of our forces.

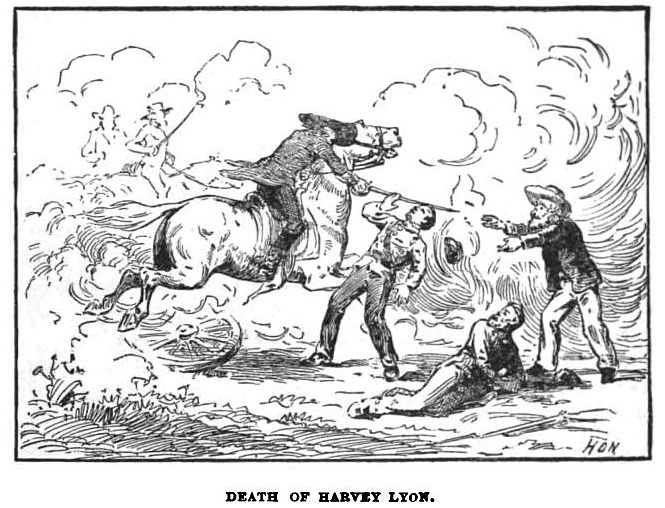

“Just as our army retired I found a poor young officer wounded. I let him take my horse, thinking that I could walk as fast as the army could march. I came to the place formerly occupied by my son's regiment. There I found quite a number of wounded men, and my young son Harvey trying to help one of his comrades from the field.

“Neither army was then in sight. I heard the sound of horses' hoofs; looked up, and saw a cavalry troop coming. I supposed it to be our own, and did not move. They dashed up where we were, and Col. Hunter, in command, drew his sabre and cut my dear boy down. I caught him as he fell, his head being cleft open. I burst out loudly in grief, and was seized as a prisoner. I presume my dress and gray hair saved my life. I was torn from my son and made to walk some three miles, to the headquarters of Gen. Jones, who heard my story about my adventure and my dead boy. He at once released me and sent an officer with me to that part of the field where my dead child lay.

“I shall ever respect Gen. Jones. He is still living, and respected highly for his great soldierly qualities. I walked on the line of our retreat until I came up with a man driving an ambulance. I took him back with me and brought my son away from the field to the camp of his brother, whom I found in great distress about Harvey, but he was not aware of what had befallen him. I pointed to the ambulance, he looked and saw him lying there dead. He fell on my neck and accused himself for having brought the young boy away from home to encounter the perils of war. I was going to take his body back to his mother, but the Colonel said:

“'No; bury him like a soldier on the battlefield.'

“So I gave way, and we buried him that night in the best manner we could. He now lies in the cemetery at Arlington. My sorrow was great then, but I am past it all now, and can grieve no more.”

Col Bush here interrupted, saying:

“'Uncle Daniel, you made a narrow escape. My heavens! to think of a father carrying his young son dead from the battlefield, slain by an enemy in such a villainous and dastardly way.”

“What a blow to a father,” said Dr. Adams. “Uncle Daniel, this Colonel was a demon to strike down a youth while assisting a wounded comrade. He deserved to be killed.”

“Yes, it would seem so. I felt just as you do, and my son David uttered many imprecations against him. But, you see, we forgave all these men and acquited them of all their unholy deeds. Col. Hunter has become a very prominent man since the war, and now holds a high position in one of the Southern States. You know, in the South, the road to high position since the war has been through the rebel camps.”

“Yes, yes! Uncle Daniel, that is true. Not so, however, with us in the North. The road to high position here is not through the Union camps, but through wealth and the influence of what is called elegant society, where no questions are asked as to how or where you got your money, so you have it.”

“It does seem so, Doctor, now; but it was not so in our earlier days. I am sorry to confess that this change has taken place.

“After going through the scenes of this battle, now called the battle of the 'Gaps,' and burying my son, I felt for the time as if I could have no heart in anything the only thought on my mind was how to break the sad news to his mother. The Colonel said he would keep the name from the list of the dead until I could return home to be with the mother, so as to console her in her grief. I bade my son, the Colonel, farewell. There he stood, quiet and erect, the great tears rolling down his cheeks. I commenced my sad journey alone. In going to Washington I overtook straggling detachments, teams without drivers, and found on the road general waste of army materials, and equipage of all kinds in large quantities. Arriving in Washington, everything was in great confusion. The old General then in command of all the forces was dignified and martial in his every look and movement, but evidently much excited. There was no danger, however, as both armies were willing to stand off without another trial of arms for the present. I saw the President and told him what I had witnessed, as well as my misfortune. I advised that no movement of our forces be again attempted without further drilling and better discipline, as I was sure good training would have prevented the disaster of that day. On my way home I was oppressed with grief, causing many inquiries of me as to my distress, which only made it necessary for me to repeat my sad story over and over again until I reached Allentown. My friends, there was the great test of my strength and manhood. How could I break this to my wife? They had all heard the news of the battle, and were in sorrow over our country's misfortune. On entering the gate all rushed out on the porch to welcome me back, eager for news; but my countenance told the sad story. The Doctor was the first to speak:

“'We know about the battle, father,' said he; 'but your face tells me something has happened to the boys. What is it?'

“Sarah and the women stood as pale as death, but could not speak. Then I broke down, but tried to be as calm as I could, and said:

“'Our dear Harvey is killed.'

“My wife fell upon my neck and sobbed and cried aloud in despair until I thought her heart would break. The children ran out to their mother, crying:

“'Oh! mother, what is the matter? Is papa hurt? Is he shot?'

“They screamed, and the scene was one that would have melted the strongest heart. James stood and gazed on the scene. When all 'became somewhat calm, my wife was tenderly placed in bed, and Jennie, after hearing that the Colonel was safe, staid with her. To the others I related my experience on the battlefield, and the death of Harvey, his burial, my capture and release, my arrival at and departure from Washington, and all up to the time I reached home. The saddest time I ever spent in my life was during the long, weary hours of that night; the attempt to reconcile my wife to our sad fate, the fears expressed by the wives of the Colonel and Tom, the questions of the children, and their grief and sobs for their Uncle Harvey—they all loved him dearly; he had petted them and played with them frequently, entertaining them in a way that children care so much for. Many days my wife was confined to her bed, the Doctor keeping close watch over her. Weeks of sadness and gloom in our household passed before we seemed to take the matter as a part of what many would have to experience in this dreadful and wicked attempt to destroy the peace and happiness of our people. In the meantime, Col. Tom Anderson (as he was now a Colonel), and my son Peter, who had been made a Captain in Col. Anderson's regiment, came home to see us, and tried to make it as pleasant for us as could be done under the circumstances. When Peter heard of Harvey's death, through Col. Anderson, he was very much affected and wept bitterly.

“'That dream haunts me,' he said, 'by day and by night. I know my fate so well.'

“This amazed the Colonel, and he asked Peter what he meant by this nonsense.

“'I know,' said Peter, 'but—'

“'But what?' asked the Colonel.

“'Nothing,' replied Peter, and the conversation on that subject dropped for the time being.

“The visit of Col. Tom and Capt. Peter, as we now out of courtesy called them, made the time pass much more pleasantly. Col. Tom and the Doctor, both being good conversationalists, kept the minds of the family as much away from the battle of the Gaps as possible. The Doctor having lived in Virginia and Col. Anderson in Mississippi, their conversation naturally turned on the condition of the South. The Doctor said 'there are in Virginia many Union men, but they were driven into secession by the aggressiveness and ferocity of those desiring a separation from the Government.

“'Those people are opposed to a Republican form of Government, and if they succeed in gaining a separation and independence, sooner or later they will take on the form of the English Government. They now regard the English more favorably than they do the Northern people, and the most surprising thing to me is to see the sentiment in the North in favor of the success of this (the Southern) rebellion. True, it is confined to one political party, but that is a strong party in the North as well as the South.

“'One of the dangers that will confront us is the tiring out of our Union people at some stage of the war, and following on that the success by the sympathizers with the rebellion in the elections North. If this can be brought about it will be done. This is part of the Southern programme, and they have their men selected in every Northern State.'”

“'I have heard this discussed frequently, and their statements as to the assurances that they have from all over the North—in New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Illinois, and so on. In Ohio, their chief adviser from the North, Mr. Valamburg, resides. Such men as “Dan” Bowen and Thos. A. Stridor, both very influential and prominent men, are regarded as ready to act in concert with them at any moment. Should that party succeed, with such men as I have mentioned as leaders, the independence of the Confederacy would at once be acknowledged, on the ground that we have failed to suppress the rebellion, and that a further continuance of the war would only prove an absolute failure; and I fear that our Northern peacemakers would then cry “peace! peace!” and acquiesce in this outrage upon our Republic and our Christian civilization,” 'Yes,' replied Col. Tom; 'but, Doctor—there is a feature preceding that which should be carefully considered. I fear, since I have heard what is going on here, that these Northern secessionists and sympathizers will organize in our rear and bring on war here at home. I was ordered to the Capital to watch this movement. They are organizing all around us. I was about to be mobbed near here for trying to raise troops for the Union army. Thos. A. Strider, of whom you spoke, is doing everything he can to discourage enlistments. He speaks of the Republican President as “a tyrant and this war as an unholy abolition war,” and people listen to him. He has been considered a kind of oracle in this State for many years, as you know.'

“Just then Jennie returned from the post-office with two letters from Col. David—one to her and one to the Doctor. This concluded the conversation between Col. Tom and the Doctor. Jennie's letter gave her a more complete description of the battle of the Gaps than any he had heretofore sent. He spoke of my appearance on the ground and the tragic death of Harvey. The household assembled and listened with great attention, except my wife, who went weeping to her room, as she could not hear of her boy without breaking down, wondering why it was her fate to be so saddened thus early in the contest. The Doctor opened his letter and found that the Assistant Surgeon of Col. David's regiment had died from a wound received at the battle of the Gaps, and the Governor of Ohio had commissioned Dr. James Lyon Assistant Surgeon at the request of the Colonel. He was directed to report to his regiment at once. This was very gratifying to the Doctor, as he felt inclined to enter the service.

When his mother heard this she again grew very melancholy, and seemed to think her whole family were, sooner or later, to enter the army and encounter the perils and vicissitudes of war. The next morning the Doctor bade us all good-by, and left for the army of the East. The visit of Col. Anderson and Pefer helped to distract our attention from the affliction which was upon us. Peter, however, was very quiet and seemed in a deep study most of the time. His mother finally asked him if he had thought of her dream, saying it troubled her at times. He smiled, and answered:

“'Mother, I think this war will interpret it. You know there is nothing in dreams,' thus hoping to put her mind at rest by his seeming indifference; but he afterwards told Col. Anderson his interpretation.”

Dr. Adams here asked Uncle Daniel if he knew Peter's interpretation.

“Yes; it was certainly correct, and so it will appear to you as we proceed in this narrative, should you wish to hear me through.”

“My dear sir, I have never been so interested in all my life, and hope you will continue until you tell us all. I am preserving every sentence.”

“The day passed off quietly, and next morning Col. Anderson and Peter left for their command. Mary was brave; she gave encouragement to her husband and all others who left for the Union army. She was very loyal, and seemed to be full of a desire to see the Union forces succeed in every contest. In fact, the letter of her brother to her husband seemed to arouse her almost to desperation; she went about quietly, but showed determination in every movement. She taught her little daughter patriotism and devotion to the cause of our country, and religiously believed that her husband would yet make his mark as a gallant and brave man. She gave encouragement to my good wife Sarah, and to Jennie, Col. David's wife. She told me afterwards, out of the hearing of the others, that she hoped every man on the Union side would enter the army and help crush out secession forever.”

BATTLE OF TWO RIVERS.—COL. TOM ANDERSON MEETS HIS BROTHER-

IN-LAW.—UNCLE DANIEL BECOMES AN ABOLITIONIST.—A WINTER

CAMPAIGN AGAINST A REBEL STRONGHOLD.

“Cease to consult; the time for action calls,

War, horrid war approaches.”—Homer

For a season battles of minor importance were fought with varying success. In the meantime Col. Anderson had been ordered with his command to join the forces of Gen. Silent, at Two Rivers.

Here there was quiet for a time.

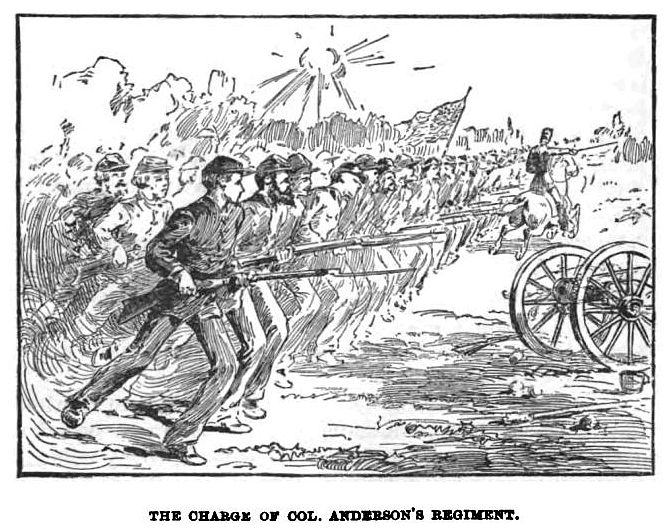

“At length, however, orders came for them to move to the front. For a day or so all was motion and bustle. Finally the army moved out, and after two days' hard marching our forces struck the enemy's skirmishers. Our lines moved forward and the battle opened. Col. Anderson addressed his men in a few eloquent words, urging them to stand, never acknowledge defeat or think of surrender. The firing increased and the engagement became general. Gen. Silent sat on his horse near by, his staff with him, watching the action. Col. Anderson was pressing the enemy in his front closely, and as they gave way he ordered a charge, which was magnificently executed.

“As the enemy gave back, evidently becoming badly demoralized, he looked and beheld before him Jos. Whitthorne.

“The recognition was mutual, and each seemed determined to outdo the other. Anderson made one charge after another, until the enemy in his front under command of his wife's brother retreated in great confusion. Col. Anderson, in his eagerness to capture Whitthorne, advanced too far to the front of the main line, and was in great danger of being surrounded. He perceived the situation in time, and at once changed front, at the same time ordering his men to fix bayonets. Drawing his sword and rising in his stirrups, he said:

“'Now, my men, let us show them that a Northern man is equal to any other man.'

“He then ordered them forward at a charge bayonets, riding in the centre of his regiment. Steadily on they went, his men falling at every step, but not a shot did they fire, though they were moving almost up to the enemy's lines. The rebel commander shouted to his men:

“'What are these? Are they men or machines?'

“The rebel line wavered a moment, and then gave way. At that instant a shot struck Col. Anderson's horse and killed it, but the Colonel never halted. He disengaged himself, and pushing forward on foot, regained his line, and left the enemy in utter rout and confusion. Whitthorne was not seen again that day by Anderson. The battle was still raging on all the other parts of the line. First one side gained an advantage, then the other, and so continued until night closed in on the combatants. A truce was agreed to, and hostilities ceased for the time being.

“The Colonel worked most of the night, collecting his wounded and burying his dead. His loss was quite severe, in fact, the loss was very heavy throughout both armies. Late in the night, while searching between the lines for one of his officers, he met Whitthorne. They recognized each other. Col. Anderson said to him:

“'Jo, I am glad to see you, but very sorry that we meet under such circumstances.'

“Whitthorne answered:

“'I cannot say that I am glad to see you, and had it not been for making my sister a widow, you would have been among the killed to-day.'

“The Colonel turned and walked away without making any reply, but said to himself:

“'Can that man be my wife's brother? I will not, however, condemn him; his blood is hot now; he may have a better heart than his speech would indicate.”

“Thus meditating, he returned to his bivouac. In the morning the burying parties were all that was to be seen of the enemy. He had retreated during the night, and very glad were our forces, as the battle was well and hard fought on both sides. The forces were nearly equal as to numbers.

“Col. Anderson did not see the General commanding for several days; when he did the latter said to him:

“Colonel, you handle your men well; were you educated at a military school?'

“The Colonel answered:

“'No; I am a lawyer.'

“General Silent remarked:

“'I am very sorry for that,' and walked on.

“Tom wrote his wife a full report of this battle. He called it the battle of Bell Mountain. It is, however, called Two Rivers. He said that Gen. Silent was a curious little man, rather careless in his dress; no military bearing whatever, quite unostentatious and as gentle as a woman; that he did not give any orders during the battle, but merely sat and looked on, the presumption being that while everything was going well it was well enough to let it alone. In his report he spoke highly of Col. Anderson as an officer and brave man.

“This letter of the Colonel's filled his wife's heart with all the enthusiasm a woman could possess. She was proud of her husband. She read and re-read the letter to my wife and Jennie, and called her little daughter and told her about her father fighting so bravely. We were all delighted. He spoke so well of Peter also. Said 'he was as cool as an icebox during the whole engagement.' He never mentioned to his wife about meeting her brother Jo on the field until long afterwards.

“The troops of this army were put in camp and shortly recruited to their maximum limit. Volunteering by this time was very active. No longer did our country have to wait to drum up recruits. The patriotic fires were lighted up and burning brightly: drums and the shrill notes of the fife were heard in almost every direction. Sympathizers with rebellion had hushed in silence for the present—but for the present only.”

“Uncle Daniel,” said Major Isaac Clymer, who had been silent up to this time, “I was in that engagement, in command of a troop of cavalry, and saw Col. Anderson make his bayonet charge. He showed the most cool and daring courage that I have ever witnessed during the whole war, and I was through it all. Gen. Pokehorne was in command of the rebels, and showed himself frequently that day, urging his men forward. He was afterwards killed at Kensington Mountain, in Georgia. We got the information very soon after he fell, from our Signal Corps. They had learned to interpret the rebel signals, and read the news from their flags.”

“Yes, I have heard it said by many that our Signal Corps could do that, and I suppose the same was true of the other side.”

“O, yes,” said Col. Bush, “that was understood to be so, and towards the end of the war we had to frequently change our signal signs to prevent information being imparted in that way to our enemy.”

“There was a Colonel,” said Major Clymer, “from Arkansas, in command of a rebel brigade, in that battle, who acted with great brutality. He found some of our Surgeons on the field dressing the wounds of soldiers and drove them away from their work and held them as prisoners while the battle lasted, at the same time saying, with an oath, that the lives of Abolitionists were not worth saving.”

“Yes. The Colonel mentioned that in his letter and spoke of it when I saw him. He said it was only one of the acts of a man instinctively barbarous. His name was Gumber—Col. Gumber. He has been a prominent politician since the war, holding important positions. You know, these matters are like Rip Van Winkle's drinks—they don't count, especially against them.”

“'But among Christian people they should,' said Dr. Adams.

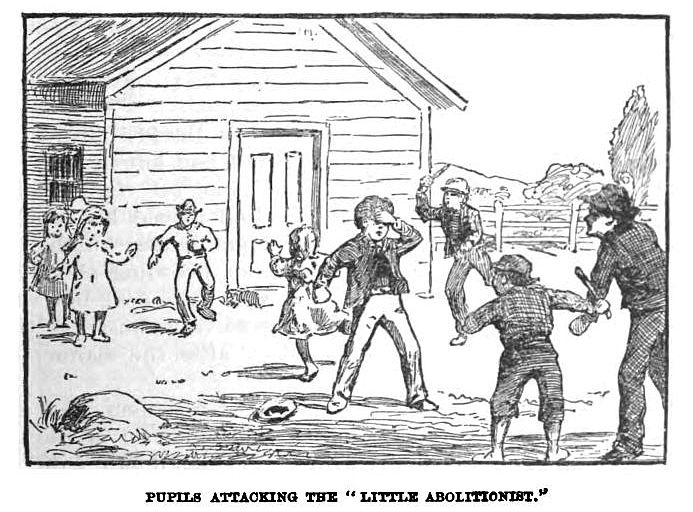

“'That is true, but it does not. There are two distinct civilizations in this country, and the sooner our people recognize this fact the sooner they will understand what is coming in the future. But, returning to my story, the winter was now coming on, and I had to make provision for the families that were in my charge, so I called the women together and had a council as to what we would do for the best; the first thing was to arrange about sending the little girls to school. After discussing it, we concluded to start them the next day to the common school. Our public schools were said to be very good. So the next morning my wife, Mary and Jennie all started with the children to school. They saw the teacher and talked with her, telling her that their fathers were in the army, and she entered them in school. They came and went, back and forth, and seemed greatly pleased during the first week, but on Wednesday of the second week, they came running home crying and all dirty, saying that some of the school children had pelted them with clods and pebbles, calling them Abolitionists. Little Jennie said to me:

“'Grandpa, what is an Abolitionist?'

“I replied: 'One who desires the colored people to be free, and not sold away to strangers like cattle.'

“'Grandpa, do white people sell colored people like they sell cows?'

“'Yes, my child.'

“'Well, grandpa, is that right?'

“'I think not, my child. Would it be right for me to sell you away from your mother and send you where you would never see her again?'

“'Oh! no, grandpa; you would not be so wicked as that. I would cry myself to death; and mamma—what would she do without me, she loves me so?'

“'Yes, said little Sarah, 'I love sister, too. I would cry, too, if you sent her away where I could not see her. Why, grandpa, people don't do that, do they? Your are only fooling sister.'

“'No, no, child; in the South, where the war is, there are a great many colored people living. They are called slaves. They work for their masters and only get what they eat and wear, and their masters very often sell them and send the men away from their wives and children, and their babies away from their mothers and fathers.'

“'Grandpa, do they ever sell white people?' asked Jennie.

“'No, my child.'

“'Well, why don't they sell white people, too?'

“'Oh, my child, the law only allows colored people to be sold.'

“'Well, grandpa, I don't think any good people ever sell the little children away from their mothers, any way.'

“'No, my child, nor any grown people either.'

“'Well, grandpa, you wouldn't sell anybody, would you?'

“'No, my child, I would not.'

“'Well, then, grandpa, you are an Abolitionist.'

“'Yes, in that sense I am.'

“'Well, grandpa, I am one, too, and I will just say so at school, and will tell the boys and girls who threw clods at us and called us Abolitionists that they sell people like cows, and that they are not good people.'

“'Yes,' said little Mary Anderson, 'I know what colored people are. They've plenty of them down where we came from. They call them “niggers”. They are mighty good to me, grandpa, and my papa doesn't sell 'em. He is a good man. He don't do bad like those rebels, does he, ma?'

“'No, my child, your papa does not sell anybody. He is against it. He never owned anyone. He does not think it right to own people.'

“'No; my papa don't, does he, ma? He is going to fight the people that sell other people, ain't he, ma?'

“'Yes, my darling; but don't say any more. Let us go in and get our tea, and you will feel better.'

“This interference of little Mary and her mother let me out of a scrape, for I say to you, friends, that I was getting into deep water and would have very soon lost my soundings if Jennie and little Sarah had kept after me much longer. You see, the truth is that I had never been an Abolitionist, but a Freesoil Democrat; but soon I became a full-fledged Abolitionist after our flag was fired upon by the Secessionists.

“However, we all entered the house, and after tea, the children being put to bed, we held another council and decided that inasmuch as there was such great excitement in the country, and Allentown being such a hot-hole of rebel sympathizers, it was not safe even to allow our children to attend the schools. Jennie, however, being a good scholar and having prior to her marriage taught school, we unanimously elected her our family teacher, and setting apart a room, duly installed her on the next Monday morning over our Abolition school, as we found on the evening of our discussion with the children that they had converted the household by their innocent questions.

“The next day I rode out to my son David's farm and saw Joseph Dent, the man whom I had left in charge. I inquired of him if everything was all right about the place, and he told me that he had moved his family into David's house, as he feared some damage might be done to it, having seen several persons prowling about at different times. He did not know who they were, but was sure they meant mischief, as they were very abusive of the Colonel, calling him a 'Lincoln dog,' after the manner of Dan Bowen in his speech.

“Joseph said he was now prepared for them; that he had another man staying with him, and if I would go with him he would show me what they had done. I did as he asked me, he led the way into the house and upstairs, where he showed me a couple of holes cut through the wall in each room, just beneath the eaves, and standing in the corner was a regular arsenal of war materials. I said to him that he seemed to be in for war. The tears started in his eyes, and he said:

“'Uncle Daniel, I am an old soldier; was in Capt. David's company when he was in the Regular Army. I came to him three years ago when my enlistment was out. I will defend everything on these premises with my life. I would be in the army now with the Colonel (I am used to calling him Captain) if he had not asked me to stay here and take care of his farm. These “secesh” will not get away with me and my partner very easily, and should you hear of this fort being stormed, you bring some men with you to pick up the legs and pieces of the fellows who shall undertake it. Do not be afraid; we will take care of all here.'

“'Yes, Joseph, I see that. I will tell Jennie, and also write the Colonel how splendidly you are doing.'

“'Thanks,' said Joseph, giving me the regular soldier's salute. 'Is there anything wanted at your house, sir? Tell the Colonel's wife that I will bring down anything that she may be wanting at any time. I will certainly bring a load of wood in to-morrow.'

“We were in the habit of getting many things from the farm—butter, eggs, chickens, potatoes, etc. All our wood came from there. Joseph was very useful in many ways. I returned home satisfied that all was going well at the farm.

“The weather was now getting cold and disagreeable; too much so, it was thought, for any very serious army movements on our Western lines. The rebels had collected a very heavy force at Dolinsburg, situated on a high ridge, with hills sloping down to Combination River, one of the tributaries of the Ohio. Here they had built an immense fortress, with wings running out from either side for a great distance; on the outer walls were placed large guns, sweeping and commanding the river to the north. The rebels were well prepared with all kinds of war materials, as well as in the numbers of their effective force, to defend their works against great odds.

“Gen. Silent, who, it seems, always did everything differently from what the enemy expected him to do, conceived the idea that he would try to dislodge them. When the enemy heard that he was preparing to move against them, they but laughed at such an attempt.

“The General, however, made ready, gave his orders, and his army was soon in motion. The direction in which our army was to march was very soon known, as it was impossible to keep any of our movements a secret, on account of the great desire of newspapers to please everybody and keep every one posted on both sides, the rebels as well as friends; which prompted them to publish every movement made. This was called 'enterprise,' and it has been considered patriotic devotion by many, especially the gold gamblers and money kings. This was not permitted by our enemies; the publication of any secret expedition or movement of their forces, by any one inside of their lines, would cost him his life; and so in any army save our Union army. Why was this? It does seem to me that this ought not to have been so. I have often thought of it, and concluded it must have been fear. 'The pen is mightier than the sword' has been truthfully said.

“Our Congress was afraid of the press, and were not willing to make laws stringent enough for the army on this subject. The President was nervous in this respect, and commanding Generals were afraid of criticisms; so it was the only class that had the privilege of doing and saying what it wished to, and, my friends, that is one of our troubles even now. Our statesmen are afraid to speak out and give their opinions, without first looking around to see if any one has a pencil and notebook in his hand. This is getting to be almost unbearable, to find some person in nearly every small assemblage of people, on the street, in the hotel, in the store, even in your own private house, reporting what you have for dinner, what this one said about some other one, what this one did or said, or expects to do or say in the future. But I am wandering from my story.”

“Well, Uncle Daniel, your discussions on all subjects are interesting,” replied the Doctor.

“I have been thinking of what you said about the press during the war,” said Col. Bush; “and taking what you said upon the subject of our great ambition here in the North to get money, and let all else take care of itself, I can see that the same sordid spirit pervaded the press during our war; fortunes were made by many newspapers in that way; everybody bought papers then; we sold the news to our own people for money and furnished it to the rebels gratis. Get money, get money; that is our worst feature, and most dangerous one it is, for the country's welfare.”

“I agree with you, Colonel,” spoke up Maj. Clymer, “but I would rather hear Uncle Daniel talk. On any other occasion I would be delighted to hear you.”

“I beg pardon, Uncle Daniel,” replied the Colonel. “I will hereafter be a patient and delighted auditor.”

“Well, when the army was under way there was great excitement and alarm throughout the North among the Union people. Our armies in the East had not been successful, and the sympathizers with the rebellion all over the country were again beginning to be rather saucy. They would enjoy getting together and reading of our defeats and discuss, to our disadvantage, the failures of our attempts to subdue the rebellion, and in this way made it very uncomfortable for any person who loved his country and desired its success. They would in every way try to discourage our people by saying 'this movement now commencing will only be a repetition of what we have already had so often lately in the East.'

“But our army moved on, and during the march to the vicinity of Combination River they were met by the enemy frequently, who were trying to impede their march, and several severe skirmishes and minor engagements occurred. They were now within some twenty miles of Dolinsburg Fortress, when a sharp and very decisive engagement took place between one battalion of cavalry, two batteries of artillery, and three regiments of infantry on our side, where Col. Anderson was the ranking officer, and therefore in command, and five regiments of infantry, two batteries and one troop of cavalry on the side of the rebels. They were posted behind a small stream, known as Snake Creek, having steep banks. The action commenced, as usual, with the skirmishers. After reconnoitering the position well, the Colonel determined to send his cavalry and one regiment around some distance, so as to cross the stream and strike the enemy's left flank. He could not expect re-enforcements, if they might be needed, very soon, as he marched on the extreme southern road, so as to form the junction with the other troops on their extreme right, touching Combination River to the south of the enemy's works, so as to be the extreme right flank of our army. The enemy, finding his force was superior in numbers, attempted to cross the stream with his infantry. The two batteries were opened and poured shrapnel into the advancing column, dealing havoc and slaughter on all sides. They tried to keep their line, but they soon staggered, halted, and fell back. The Colonel then opened a destructive musketry fire all along the line. Just at this moment he heard the attack of his regiment of infantry and troop of cavalry on their flank. He quickly advanced across the stream, and the enemy was in utter rout.

“He captured all his guns—six 12-pound Napoleons and four howitzers—and a large number of prisoners. He followed closely on the rear of the enemy, gathering in stragglers and squads of men until night closed in and compelled him to desist and go into camp. When safety from surprise was assured, he sent for one of the prisoners to get some information about the road and the fortifications, commands, etc. After ascertaining many things that he considered important, he found, upon further inquiry, that his enemy upon that afternoon was commanded by Col. Jos. Whitthorne, his wife's brother. He turned and said to Peter, who was standing near:

“'This man seems to be my evil genius. I hope I will not meet him again. It seems hard that I am to continually meet my own kindred in combat. Is it possible that these people are willing to spill the blood of their own friends and kindred, merely because they have failed to retain power longer, and for that reason will destroy the Government?'

“'Yes,” said Peter; 'they will never be content except when they can control other people as well as the Government. But see here, Colonel, do you see this?' showing him a great rent in the breast of his coat and vest; 'a pretty close call, wasn't it?'

“'By George! it was that!'

“'Well, never mind; but was not this about as nice a little fight as you would wish to have for an appetiser?'

“'Yes, you are quite right; and that reminds me that I have not had a bite to eat since four o'clock this morning. By the way, have you any cold coffee in your canteen?'

“'O, yes, I have learned to keep that on hand. Here, help yourself.'

“The Colonel took a good drink, and turned to Peter and said:

“'What is the matter with that coffee?

“'Nothing; it is only laced a little.'

“'Laced? What is that?'

“'Why, I put a little brandy in it, that's all.'

“'That's all, is it? Well! that is something I have learned. Let me taste it again.'

“Which he did, as Peter afterwards said, until there was none left. I tell you these poor fellows were excusable for occasionally warming up after a hard march or a battle. I have learned to look very leniently on the shortcomings in that direction of the poor old unfortunate fellows who are going through this hard world without a penny, after having served their country faithfully. I see them nearly every day, forgotten, neglected, no home, no friends to care for them; and to see them when they pass by the American flag always salute it. I hope their fate will be a better one in the next world.

“I well remember that during the war every one who cared for his country would say, 'God bless the Union soldier and his family.' We all prayed for them then; the good women in church, at home, in the hospital, at the side of the sick, wounded or dying soldier, prayed fervently for their safety here and hereafter. We loved him then, and say we do yet; but we find the same men who reviled him then, complaining about the pension list, and some saying: 'The Confederates fought for what they believed to be right. We are all American citizens. Why not put all on the same footing? Let us be brothers.' I tell you, my friends, the people of this country are hard to understand. I heard the President of the Southern Confederacy applauded this year. I was saddened by this, and was glad that my time here could not be regarded as of great duration. Can such things be? Am I dreaming? Where am I? Is it possible that I am in Indiana and not in South Carolina? Am I under the Union flag, and not the Confederate?”

Uncle Daniel here bowed his head, and in a whisper to himself, said:

“Is it so? Is it so?”

BATTLE OF DOLINSBURG.—HEROIC CONDUCT OF COL. TOM ANDERSON

—REPORTED DEAD.—HIS WIFE REFUSES TO BELIEVE THE REPORT.

“There was speech in their dumbness, language in their very

gesture, they looked as they had heard of a world ransomed,

or one destroyed, a notable passion of wonder appeared in

them; but the wisest beholder, that knew no more but seeing

could not say, if the importance were joy or sorrow; but in

the extremity of the one it must needs be.”—Shakespeare

The next morning the march was resumed. At an early hour the whole army was in motion on different roads with the general understanding that the command would close in line around the west side of the fortress that afternoon. The weather being very disagreeable for marching, there was delay on the roads, but, finally, late in the evening the army commenced closing in and forming its line. The centre was commanded by General Smote; the left, resting north, on the river, commanded by General Waterberry, and the right, resting on an almost impassable slough, connecting with the river, commanded by General McGovern. In moving into position the place was found to be well protected by a heavy abatis and chevaux-de-frise, from point to point, above and below the fortress. This seemed impassable, and the enemy, seeing our army closing in around them, kept up a terrible fire on our advancing columns, causing us very severe loss in getting into position. It was at a late hour in the night (when our lines were only partially formed) that our army rested, as best as they could, in the snow and sleet; but not a murmur was heard. The next morning our lines were advanced to the front and the impediments removed as much as possible; though a severe and deadly fire was poured upon our men most of the day. Late in the afternoon an assault was ordered in the centre, and a bloody affair it was; again and again our brave fellows moved on the works, but were as often driven back with severe loss. About 'o'clock Gen. Silent came riding along with an orderly by his side, his staff having been sent in different directions with orders. He came up to where Col. Anderson was sitting on his horse, watching the engagement in the centre. Gen. Silent, after passing the compliments of the day, said to the Colonel:

“'Your engagement at Snake Creek (that being the name of the creek where the Colonel met the enemy the day before) was a rather brilliant affair as I learn it.'

“'Yes,' said the Colonel; 'it was my first attempt at commanding in a battle, but we had the best of it.'

“'Yes,' said the General; 'and now I want to see if you can do as well here. I wish you to assault the enemy's works in this low ground on the right, in order to draw some of his forces away from the centre; our forces are having a hard time of it there.'

“Col. Anderson gave the order at once to prepare for action—knapsacks and blankets were thrown off, and the assaulting column formed. The General rode away after saying:

“'It is not imperative that you enter their works; but make the assault as effectual as you can without too great a sacrifice of men.'

“The Colonel looked at the ground over which they must pass and viewed the works with his glass, but said not one word save to give the command 'Forward!' On, on they went, and as they moved under a torrent of leaden hail, men fell dead and wounded at every step; but they went right up to the mouths of the cannon. There they stood and poured volley after volley into the enemy, until at last he began to give way, when re-enforcements came from the centre, as was desired. The Colonel's force could stand no longer. Sullenly they fell back to a strip of woods when night closed in, and the battle ceased for the day.

“Our lines were much nearer the enemy than in the morning.