Title: The Everett Massacre: A history of the class struggle in the lumber industry

Author: Walker C. Smith

Release date: March 28, 2010 [eBook #31810]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber's Note:

A Table of Contents and List of Illustrations have been added.

This book is dedicated to those loyal soldiers of the great class war who were murdered on the steamer Verona at Everett, Washington, in the struggle for free speech and free assembly and the right to organize:

FELIX BARAN,

HUGO GERLOT,

GUSTAV JOHNSON,

JOHN LOONEY,

ABRAHAM RABINOWITZ,

and those unknown martyrs whose bodies were swept out to unmarked ocean graves on Sunday, November Fifth, 1916.

PRINTED BY THE

MEMBERS OF THE

GENERAL RECRUITING

UNION I. W. W.

| Chapter | Page | |

| PREFACE | 5 | |

| EVERETT, NOVEMBER FIFTH | 7 | |

| I. | THE LUMBER KINGDOM | 9 |

| II. | CLASS WAR SKIRMISHES | 27 |

| III. | A REIGN OF TERROR | 49 |

| IV. | BLOODY SUNDAY | 84 |

| V. | BEHIND PRISON BARS | 115 |

| VI. | THE PROSECUTION | 142 |

| VII. | THE DEFENSE | 177 |

| VIII. | PLEADINGS AND THE VERDICT | 230 |

| IX. | SOLIDARITY SCORES A SUCCESS | 289 |

| X. | THE BANKRUPTCY OF "LAW AND ORDER" | 297 |

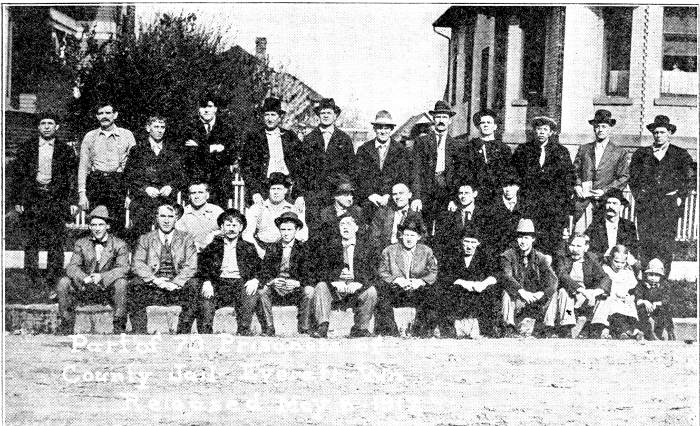

| Released Free Speech prisoners who visited the graves of

their murdered Fellow Workers at Mount Pleasant Cemetery, May 12, 1917. |

8 |

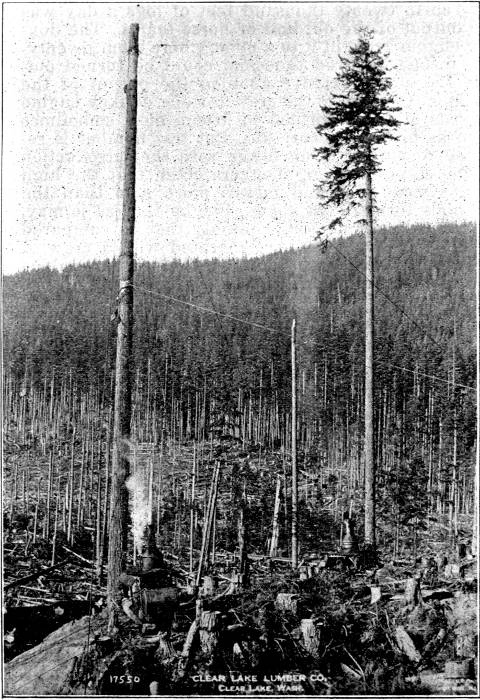

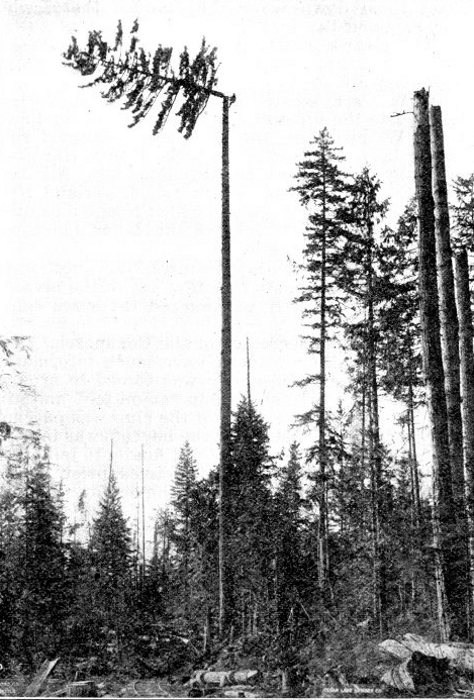

| The Flying Machine as now used in Western logging. | 21 |

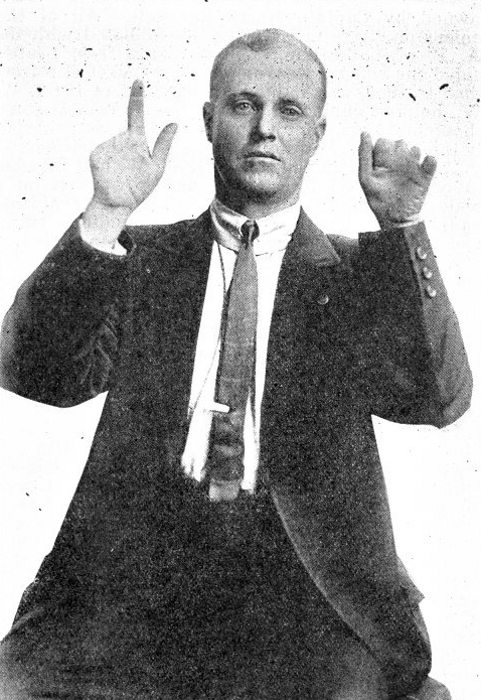

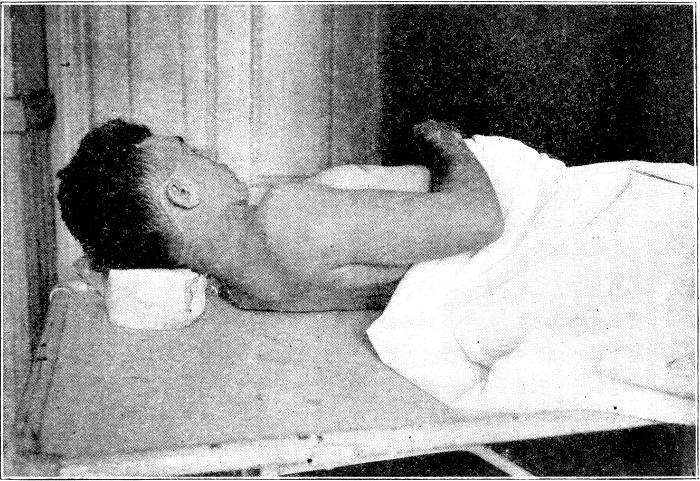

| One of the thousands who donate their fingers to the Lumber Trust. The Trust compensated all with poverty and some with bullets on November 5, 1916. |

33 |

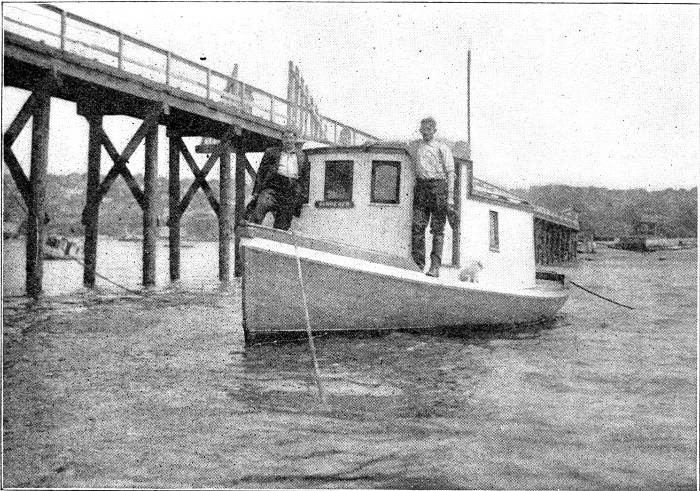

| Joe (Red) Doran Capt. Jack Mitten The Launch Wanderer. | 48 |

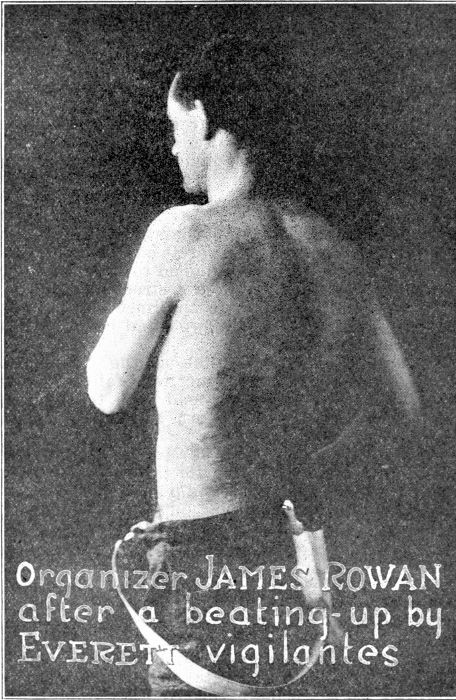

| Organizer James Rowan; Showing his back lacerated by Lumber Trust thugs. |

55 |

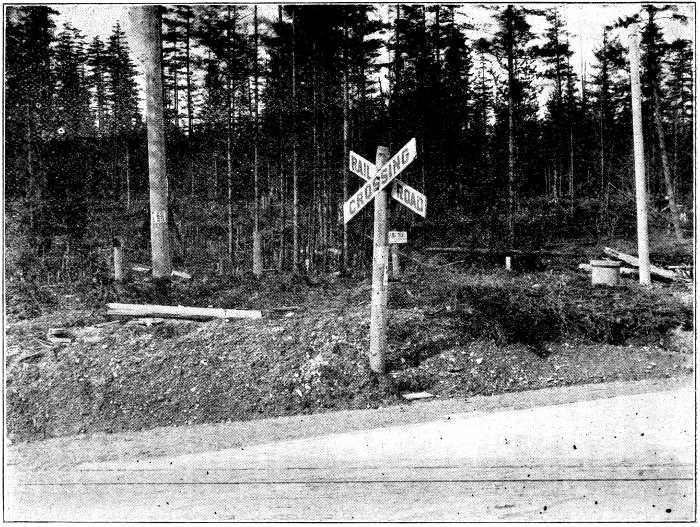

| Beverly Park | 70 |

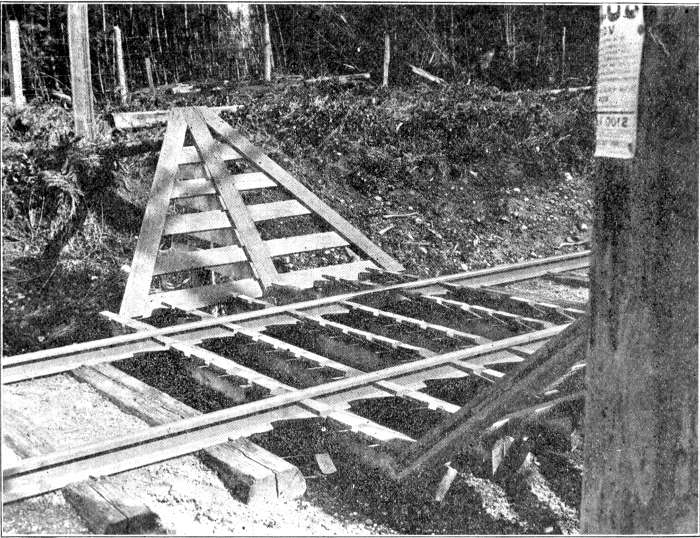

| A close up view of Beverly Park showing cattle guards. | 71 |

| The Ketchum Home near Beverly Park | 83 |

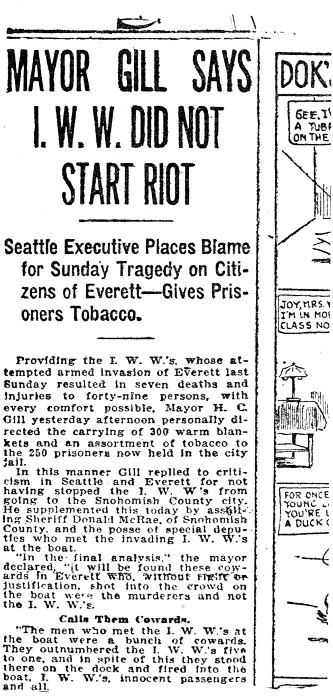

| Mayor Gill says I. W. W. did not start riot | 102 |

| Jail at Everett | 116 |

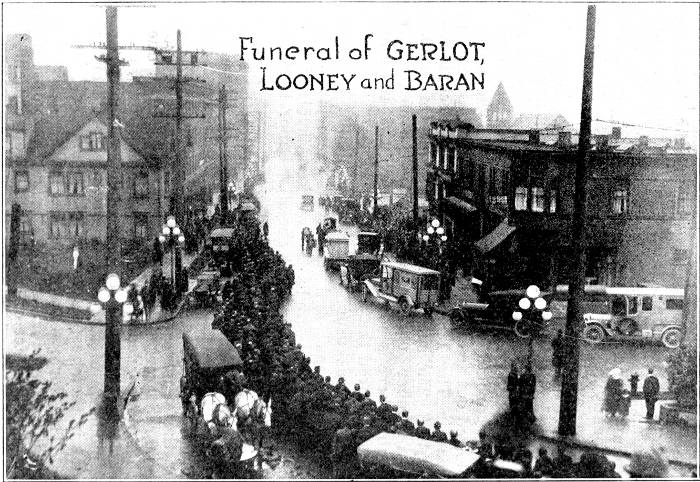

| Funeral of Gerlot, Looney and Baran | 119 |

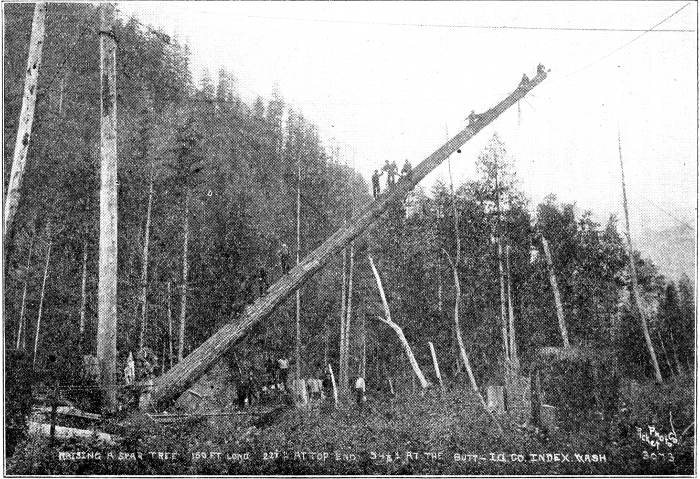

| An all-I. W. W. crew raising a spar tree 160 ft. long,

22½ inches at top and 54½ inches at butt, at Index, Wash. |

132 |

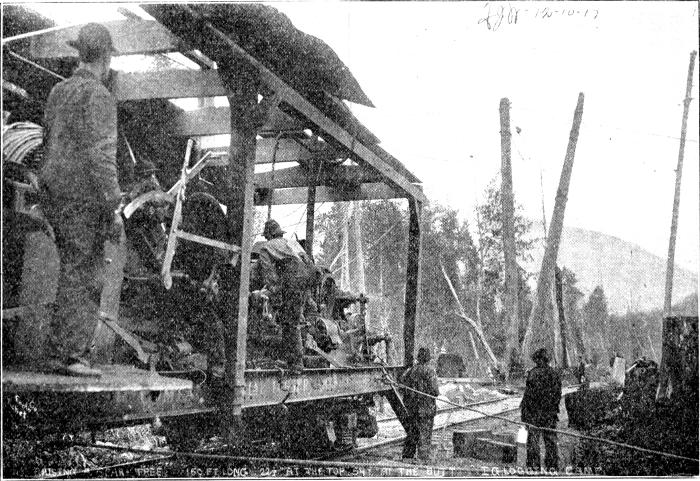

| Another view of the same operation. | 133 |

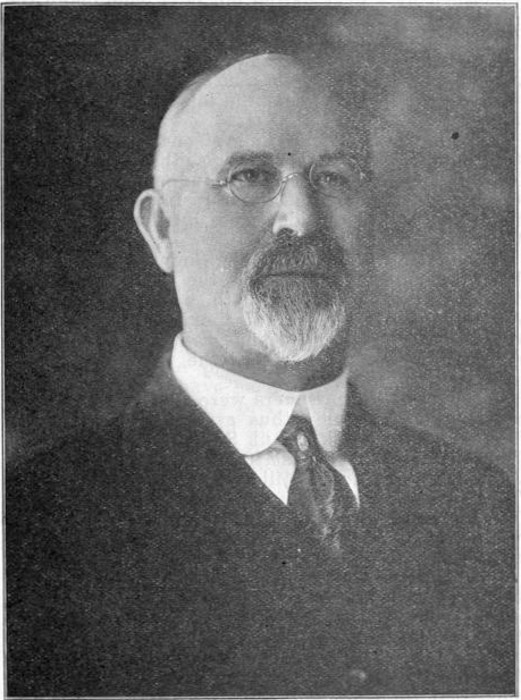

| Judge J. T. Ronald | 139 |

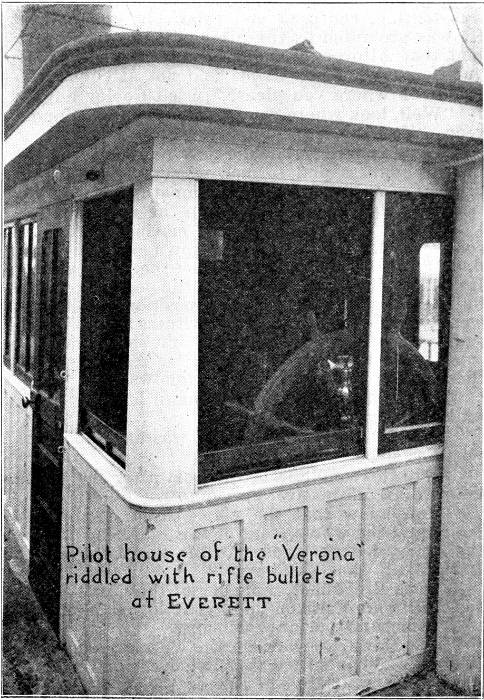

| Pilot house of the "Verona" riddled with rifle bullets at Everett | 162 |

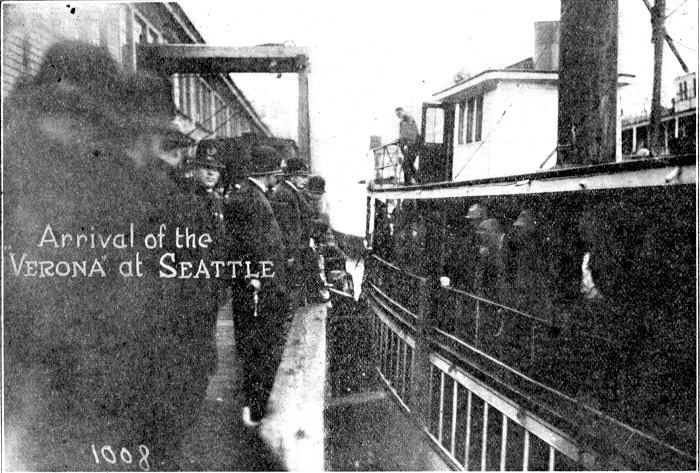

| Arrival of the "Verona" at Seattle | 169 |

| Cutting off top of tree to fit block for flying machine. | 189 |

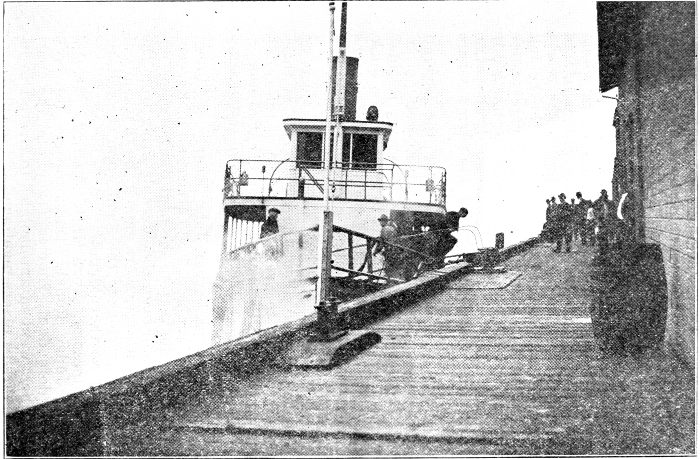

| VERONA AT EVERETT DOCK, under same tide condition as at time of Massacre. |

200 |

| View of Beverly Park, showing County Road. | 210 |

| THOMAS H. TRACY | 216 |

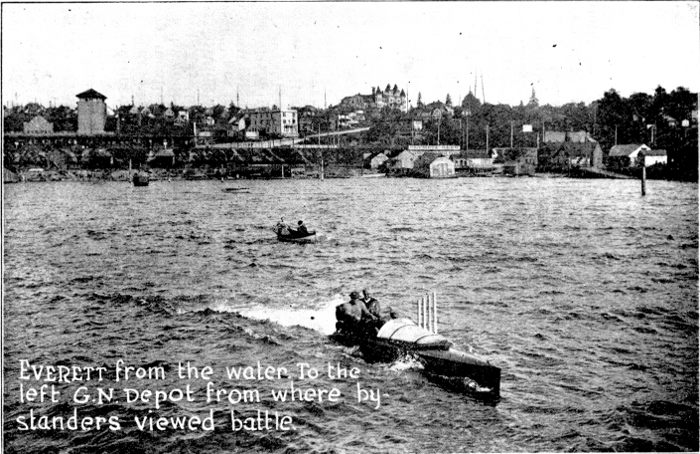

| Everett from the water. To the left G. N. Depot from where by-standers viewed battle. |

223 |

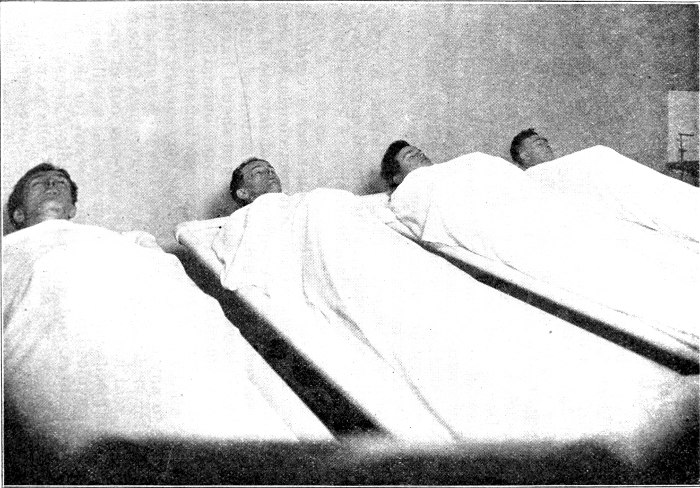

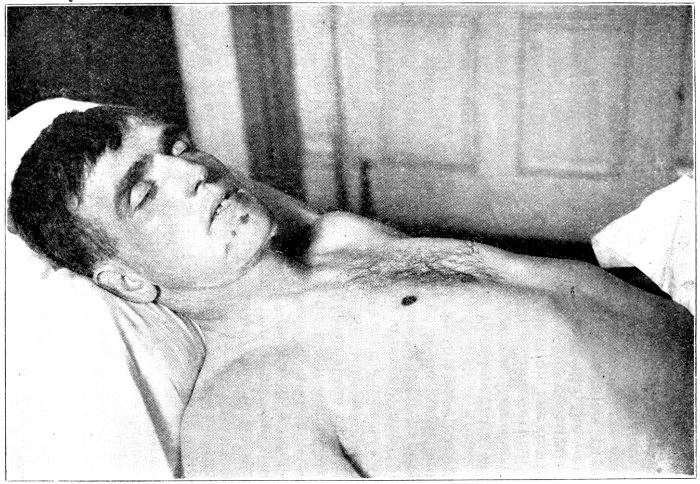

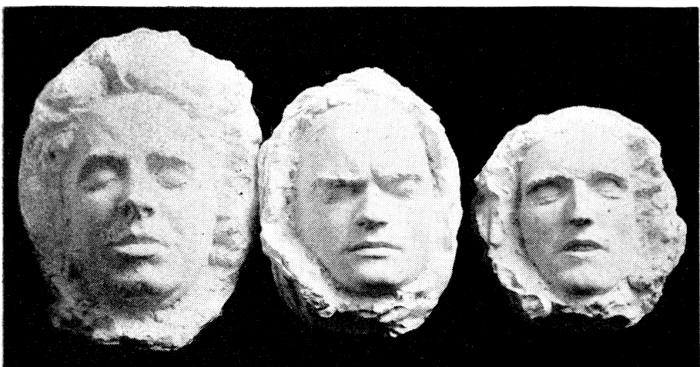

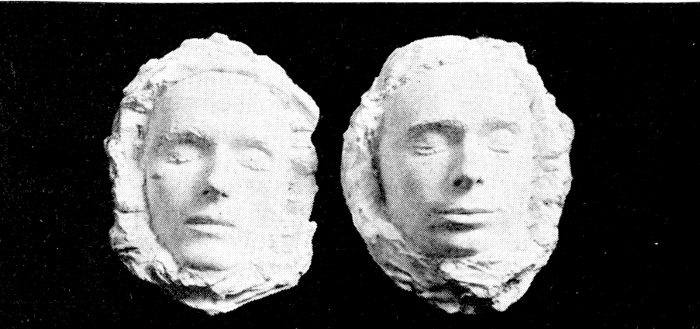

| Victims at Morgue. John Looney Hugo Gerlot, Felix Baran Abe Rabinowitz |

235 |

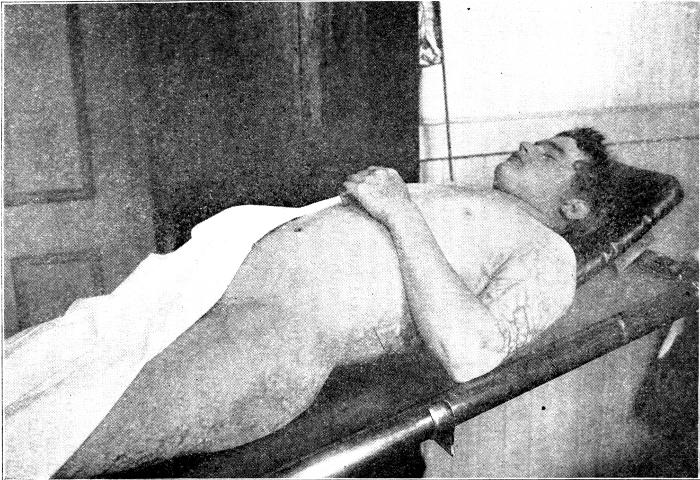

| JOHN LOONEY | 243 |

| FELIX BARAN Dark lines on body caused by internal hemorrhage; Portland doctor said life might have been saved by operation. |

252 |

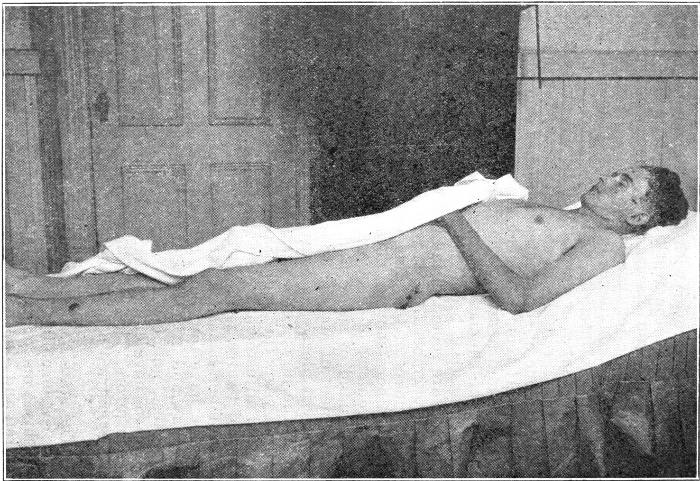

| HUGO GERLOT | 260 |

| Dead body of Abraham Rabinowitz. | 264 |

| Part of 78 prisoners of County Jail Everett Wn. Released May 8, 1917. |

272 |

| Singing to the Prisoners. | 277 |

| Charles Ashleigh speaking at the funeral, of Looney, Baran and Gerlot. | 282 |

| Gus Johnson Felix Baran John Looney Hugo Gerlot Abraham Rabinowitz |

290 |

| May First at Graveside of Gerlot, Baran and Looney. | 294 |

In ten minutes of seething, roaring hell at the Everett dock on the afternoon of Sunday, November 5, 1916, there was more of the age-old superstition regarding the identity of interests between capital and labor torn from the minds of the working people of the Pacific Northwest than could have been cleared away by a thousand lecturers in a year. It is with regret that we view the untimely passing of the seven or more Fellow Workers who were foully murdered on that fateful day, but if the working class of the world can view beyond their mangled forms the hideous brutality that was the cause of their deaths, they will not have died in vain.

This book is published with the hope that the tragedy at Everett may serve to set before the working class so clear a view of capitalism in all its ruthless greed that another such affair will be impossible.

C. E. PAYNE.

With grateful acknowledgments to C. E. Payne for valuable

assistance in

preparing the subject matter, to Harry

Feinberg in consultation, to

Marie B. Smith

in revising manuscript, and to J. J.

Kneisle for photographs.

["* * * and then the Fellow Worker died, singing 'Hold

the Fort' * *

*"—From the report of a witness.]

Perhaps the real history of the rise of the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest will never be written. It will not be set down in these pages. A fragment—vividly illustrative of the whole, yet only a fragment—is all that is reproduced herein. But if that true history be written, it will tell no tales of "self-made men" who toiled in the woods and mills amid poverty and privation and finally rose to fame and affluence by their own unaided effort. No Abraham Lincoln will be there to brighten its tarnished pages. The story is a more sordid one and it has to do with the theft of public lands; with the bribery and corruption of public officials; with the destruction and "sabotage," if the term may be so misused, of the property of competitors; with base treachery and double-dealing among associated employers; and with extortion and coercion of the actual workers in the lumber industry by any and every means from the "robbersary" company stores to the commission of deliberate murder.

No sooner had the larger battles among the lumber barons ended in the birth of the lumber trust than there arose a still greater contest for control of the industry. Lumberjack engaged lumber baron in a[Pg 10] struggle for industrial supremacy; on the part of the former a semi-blind groping toward the light of freedom and for the latter a conscious striving to retain a seat of privilege. Nor can the full history of that struggle be written here, for the end is not yet, but no one who has read the past rightly can doubt the ultimate outcome. That history, when finally written, will recite tales of heroism and deeds of daring and unassuming acts of bravery on the part of obscure toilers beside which the vaunted prowess of famous men will seem tawdry by comparison. Today the perspective is lacking. Time alone will vindicate the rebellious workers in their fight for freedom. From all this travail and pain is to be born an Industrial Democracy.

The lumber industry dominated the whole life of the Northwest. The lumber trust had absolute sway in entire sections of the country and held the balance of power in many other places. It controlled Governors, Legislatures and Courts; directed Mayors and City Councils; completely owned Sheriffs and Deputies; and thru threats of foreclosure, blackmail, the blacklist and the use of armed force it dominated the press and pulpit and terrorized many other elements in each community. The sworn testimony in the greatest case in labor history bears out these statements. Out of their own mouths were the lumber barons and their tools condemned. For, let it be known, the great trial in Seattle, Wash., in the year 1917, was not a trial of Thomas H. Tracy and his co-defendants. It was a trial of the lumber trust, a trial of so-called "law and order," a trial of the existing method of production and exchange and the social relations that spring from it,—and the verdict was that Capitalism is guilty of Murder in the First Degree.

To get even a glimpse into the deeper meaning of the case that developed from the conflict at Everett, Wash., it is necessary to know something of the lives of the migratory workers, something of the vital necessity of free speech to the working class[Pg 11] and to all society for that matter, and also something about the basis of the lumber industry and the foundation of the city of Everett. The first two items very completely reveal themselves thru the medium of the testimony given by the witnesses for the defense, while the other matters are covered briefly here.

The plundering of public lands was a part of the policy of the lumber trust. Large holdings were gathered together thru colonization schemes, whereby tracts of 160 acres were homesteaded by individuals with money furnished by the lumber operators. Often this meant the mere loaning of the individual's name, and in many instances the building of a home was nothing more than the nailing together of three planks. Other rich timber lands were taken up as mineral claims altho no trace of valuable ore existed within their confines. All this timber fell into the hands of the lumber trust. In addition to this there were large companies who logged for years on forty acre strips. This theft of timber on either side of a small holding is the basis of many a fortune and the possessors of this stolen wealth can be distinguished today by their extra loud cries for "law and order" when their employes in the woods and mills go on strike to add a few more pennies a day to their beggarly pittance.

Altho cheaper than outright purchase from actual settlers, these methods of timber theft proved themselves quite costly and the public outcry they occasioned was not to the liking of the lumber barons. To facilitate the work of the lumber trust and at the same time placate the public, nothing better than the Forest Reserve could possibly have been devised. The establishment of the National Forest Reserves was one of the long steps taken in the United States in monopolizing both the land and the timber of the country.

The first forest reserves were established February 22, 1898, when 22,000,000 acres were set aside as National Forests. Within the next eight[Pg 12] years practically all the public forest lands in the United States that were of any considerable extent had been set off into these reserves, and by 1913 there had been over 291,000 square miles included within their confines.[1] This immense tract of country was withdrawn from the possibility of homestead entry at approximately the time that the Mississippi Valley and the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains had been settled and brought under private ownership. Whether the purpose was to put the small sawmills out of business can not be definitely stated, but the lumber trust has profited largely from the establishment of the forest reserves.

So long as there was in the United States a large and open frontier to be had for the taking there could be no very prolonged struggle against an owning class. It has been easier for those having nothing to go but a little further and acquire property for themselves. But on coming to what had been the frontier and finding a forest reserve with range riders and guards on its boundaries to prevent trespassing; on looking back and seeing all land and opportunities taken; on turning again to the forest reserve and finding a foreman of the lumber trust within its borders offering wages in lieu of a home, it was inevitable that a conflict should occur.

With the capitalistic system of industry in operation, the conflict between the landless homeseekers and the owners of the vast accumulations of capital would inevitably have taken place, but this clash has come at least a generation earlier because of the establishment of the National Forests than it otherwise would. The land now in reserves would furnish homes and comfortable livings for ten million people, and have absorbed the surplus population for another generation. It is also true that the establishment of the National Forests has been one of the[Pg 13] vital factors that made the continued existence of the lumber trust possible.

Prior to 1895 the shipments of lumber to the prairie states from west of the Rocky Mountains were very small, and of no effect on the domination of the lumber industry by the trust. Also, prior to that date but a small part of the valuable timber west of the Rocky Mountains had been brought under private ownership. But about this time the pioneer settlers began swarming over the Pacific Slope and taking the free government land as homesteads. As the timber land was taken up, floods of lumber from the Pacific Coast met the lumber of the trust on the great prairies. The lumber trust had looted the government land and the Indian reservations in the middle states of their timber, and had almost full control of the prairie markets until the lumber of the Pacific Slope began to arrive. In 1896 lumber from the Puget Sound was sold in Dakota for $16.00 per thousand feet, and it kept coming in a constantly increasing volume and of a better quality than the trust was shipping from the East. It was but natural that the trust should seek a means to stifle the constantly increasing competition from the homesteads of the West, and the means was found in the establishment of the National Forest Reserves.

While the greater portion of North America was yet a wilderness, the giving of vast tracts of valuable land on the remote frontier to private individuals and companies could be accomplished. But at this time such a procedure would have been impossible, tho it was imperative for the life of the trust that the timber of the Pacific Slope should be withdrawn from the possibility of homestead entry. In order to carry out this scheme it was necessary to raise a cry of "Benefit to the Public" and make it appear that this new public policy was in the interest of future generations. The cry was raised that the public domain was being used for private gain, that the timber was being wastefully handled, that unnecessary amounts were being cut, that the future generations would find themselves without timber,[Pg 14] that the watersheds were being denuded and that drought and floods would be the certain result, that the nation should receive a return for the timber that was taken, together with many other specious pleas.

That the public domain was being used for private gain was in some instances true, but the vast majority of the timber land was being taken as homesteads, and thus taking the timber outside the control of the trust. That the timber was being wastefully handled was to some extent true, but this was inevitable in the development of a new industry in a new country, and so far as the Pacific Slope is concerned there is but little change from the methods of twenty years ago. That unnecessary amounts were being cut was sometimes true, but this served only to keep prices down, and from the standpoint of the trust was unpardonable on that account alone. The market is being supplied now as formerly, and with as much as it will take. The only means that has been used to restrict the amount cut has been to raise the price to about double what it was in 1896. The denuding of the watersheds of the continent goes on today the same as it did twenty-five years ago, the only consideration being whether there is a market for the timber. Some reforesting has been done, and some protection has been established for the prevention of fires, but these things have been much in the nature of an advertisement since the government has taken charge of the forests, and was done automatically by the homesteaders before the Reserves were established. There has never been any restriction in the amount of timber that any company could buy, and the more it wanted, the better chance it had of getting it. The nation is receiving some return from the sale of timber from the government land, but it is in the nature of a division of the spoils from a raid on the homes of the landless.

When the Reserve were established, the Secretary of the Interior was empowered to "make rules and regulations for the occupancy and the use of the forests and preserve them from destruction." No[Pg 15] attempt was made in the General Land Office to develop a technical forestry service. The purpose of the administration was mainly protection against trespass and fire. The methods of the administration were to see to it first that there were no trespassers. Fire protection came later. When the Reserves were established, people who were at the time living within their boundaries were compelled to submit the titles of their homesteads to the most rigid scrutiny, and many people who had complied with the spirit of the law were dispossessed on mere technicalities, while before the establishment of the Reserve system the spirit of the compliance with the homestead law was mainly considered, and very seldom the technicality. And while the Forestry Service was examining all titles to homesteads within the boundaries of the Reserve with the utmost care, the large lumbering companies were given the best of consideration, and were allowed all the timber they requested and a practically unlimited time to remove it.

The system of dealing with the lumber trust has been most liberal on the part of the government. A company wanting several million feet of timber makes a request to the district office to have the timber of a certain amount and on a certain tract offered for sale. The Forestry Service makes an estimate of the minimum value of the timber as it stands in the tree and the amount of timber requested within that tract is then offered for sale at a given time, the bids to be sent in by mail and accompanied by certified checks. The bids must be at least as large as the minimum price set by the Forestry Service, and highest bidder is awarded the timber, on condition that he satisfies the Forestry Service that he is responsible and will conduct the logging according to rules and regulations. The system seems fair, and open to all, until the conditions are known.

But among the large lumber companies there has never been any real competition for the possession of any certain tract of timber that was listed for sale by request. When one company has decided on [Pg 16]asking for the allotment of any certain tract of timber, other companies operating within that forest seldom make bids on that tract. Any small company that is doing business in opposition to the trust companies, and may desire to bid on an advertised tract, even tho its bid may be greater than the bid of the trust company, will find its offer thrown out as being "not according to the Government specifications," or the company is "not financially responsible," or some other suave explanation for refusing to award the tract to the competing company. On the other hand, when a small company requests that some certain tract shall be listed for sale, it very frequently happens that one of the large companies that is commonly understood to be affiliated with the lumber trust will have a bid in for that tract that is slightly above that of the non-trust company, and the timber is solemnly awarded to "the highest bidder."

When a company is awarded a tract of timber, the payment that is required is ten per cent of the purchase price at the time of making the award, and the balance is to be paid when the logs are on the landing, or practically when they can be turned into ready cash, thus requiring but a comparatively small outlay of money to obtain the timber. When the award is made, it is the policy of the Forestry Service to be on friendly terms with the customers, and the men who scale the logs and supervise the cutting are the ones who come into direct contact with the companies, and it is inevitable that to be on good terms with the foreman the supervision and scaling must be "satisfactory." Forestry Service men who have not been congenial with the foremen of the logging companies have been transferred to other places, and it is almost axiomatic that three transfers is the same as a discharge. The little work that is required of the companies in preventing fires is much more than offset by the fact that no homesteaders have small holdings within the area of their operations, either to interfere with logging or to compete with their small mills for the control of the lumber market.

That the forest lands of the nation were being denuded, and that this would cause droughts and floods was a fact before the establishment of the Reserves, and the fact is still true. Where a logging company operates, the rule is that it shall take all the timber on the tract where it works, and then the forest guards are to burn the brush and refuse. A cleaner sweep of the timber could not have been made under the old methods. The only difference in methods is that where the forest guards now do the fire protecting for the lumber trust, the homesteaders formerly did it for their own protection. In January, 1914, the Forestry Service issued a statement that the policy of the Service for the Kaniksu Forest in Northern Idaho and Northeastern Washington would be to have all that particular reserve logged off and then have the land thrown open to settlement as homesteads. As the timber in that part of the country will but little more than pay for the work of clearing the land ready for the plow, but is very profitable where no clearing is required, it can be readily seen that the Forestry Service was being used as a means of dividing the fruit—the apples to the lumber trust, the cores to the landless homeseekers.

One particular manner in which the Government protects the large lumber companies is in the insurance against fire loss. When a tract has been awarded to a bidder it is understood that he shall have all the timber allotted to him, and that he shall stand no loss by fire. Should a tract of timber be burned before it can be logged, the government allots to the bidder another tract of timber "of equal value and of equal accessibility," or an adjustment is made according to the ease of logging and value of the timber. In this way the company has no expense for insurance to bear, which even now with the fire protection that is given by the Forestry Service is rated by insurance companies at about ten per cent. of the value of the timber for each year.

No taxes or interest are required on the timber[Pg 18] that is purchased from the government. Another feature that makes this timber cheaper than that of private holdings, is that to buy outright would entail the expense of the first cost of the land and timber, the protection from fire, the taxes and the interest on the investment. In addition to this there is always the possibility that some homesteader would refuse to sell some valuable tract that was in a vital situation, as holding the key to a large tract of timber that had no other outlet than across that tract. There has been as yet no dispute with the government about an outlet for any timber purchased on the Reserves; the contract for the timber always including the proviso that the logging company shall have the right to make and use such roads as are "necessary," and the company is the judge of what is necessary in that line.

The counties in which Reserves are situated receive no taxes from the government timber, or from the timber that is cut from the Reserves until it is cut into lumber, but in lieu of this they receive a sop in the form of "aid" in the construction of roads. In the aggregate this aid looks large, but when compared with the amount of road work that the people who could make their homes within what is now the Forest Reserves could do, it is pitifully small and very much in the nature of the "charity" that is handed out to the poor of the cities. It is the inevitable result of a system of government that finds itself compelled to keep watch and ward over its imbecile children.

So in devious ways of fraud, graft, coercion, and outright theft, the bulk of the timber of the Northwest has been acquired by the lumber trust at an average cost of less than twelve cents a thousand feet. In the states of Washington and Oregon alone, the Northern Pacific and the Southern Pacific railways, as allies of the Weyerhouser interests of St. Paul, own nearly nine million acres of timber; the Weyerhouser group by itself dominating altogether more than thirty million acres, or an area almost[Pg 19] equal to that of the state of Wisconsin. The timber owned by a relatively small group of individuals is sufficient to yield enough lumber to build a six-room house for every one of the twenty million families in the United States.

Why then should conservation, or the threat of it, disturb the serenity of the lumber trust? If the government permits the cutting of public timber it increases the value of the trust holdings in multiplied ratio, and if the government withdraws from public entry any portion of the public lands, creating Forest Reserves, it adds marvelously to the value of the trust logs in the water booms. Even forest fires in one portion of these vast holdings serve but to send skyward the values in the remaining parts, and by some strange freak of nature the timber of trust competitors, like the "independent" and co-operative mills, seems to be more inflammable than that of the "law-abiding" lumber trust. And so it happens that the government's forest policy has added fabulous wealth and prestige and power to the rulers of the lumber kingdom.

But whether the timber lands were stolen illegally or acquired by methods entirely within the law of the land, the exploitation of labor was, and is, none the less severe. The withholding from Labor of any portion of its product in the form of profits—unpaid wages—and the private ownership by individuals or small groups of persons, of timber lands and other forms of property necessary to society as a whole, are principles utterly indefensible by any argument save that of force. Such legally ordained robbery can be upheld only by armies, navies, militia, sheriffs and deputies, police and detectives, private gunmen, and illegal mobs formed of, or created by, the propertied classes. Alike in the stolen timber, the legally acquired timber, and in the Government Forest Reserves, the propertyless lumberjacks are unmercifully exploited, and any difference in the degree of exploitation does not arise because of the "humanity" of any certain set[Pg 20] of employers but simply because the cutting of timber in large quantities brings about a greater productivity from each worker, generally accompanied with a decrease in wages due to the displacement of men.

With the development of large scale logging operations there naturally came a development of machinery in the industry. The use of water power, the horse, and sometimes the ox, gave way to the use of the donkey engine. This grew from a crude affair, resembling an over-sized coffee mill, to a machine with a hauling power equal to that of a small sized locomotive. Later on came "high lead" logging and the Flying Machine, besides which the wonderful exploits of "Paul Bunyan's old blue ox" are as nothing.

The overhead system was created as a result of the additional cost of hauling when the increased demand for a larger output of logs forced the erection of more and more camps, each new camp being further removed from the cities and towns. Today its use is almost universal as there remains no timber close to the large cities, even the stumps having been removed to make room for farming operations.

Roughly the method of operation is to leave a straight tall tree standing near the logging track in felling timber. The machine proper is set right at the base of this tree, and about ninety feet up its trunk a large chain is wrapped to allow the hanging of a block. From this spar tree a cable, two inches in diameter, is stretched to another tree some distance in the woods. On this cable is placed what is known as a bicycle or trolley. Various other lines run back and forth thru this trolley to the engine. At the end of one of these lines an enormous pair of hooks is suspended. These grasp the timber and convey it to the cars.

Ten to twenty thousand feet of logs a day was the output of the old bull or horse teams. The donkey engine brought it to a point where from seventy-five to one hundred thousand could be turned out, and the steam skidder doubled the output of the donkey. Ordinarily the crew for one donkey engine consists of from thirteen to fifteen men, sometimes even as high as twenty-five, but this number is reduced to nine or even lower with the introduction of the steam skidder. Loggers claim that the high lead system kills and maims more men than the methods formerly in vogue, but be that as it may, the fact stands out quite plainly that as compared with a line horse donkey, operated with a crew of twenty-five men, the flying machine will produce enough lumber to mean the displacement of one hundred men.

At the same time the sawmills of the old type have disappeared with their rotary or circular saws, dead rollers, and obsolete methods of handling lumber, and in their place is the modern mill with its band saw, shot-gun feed, steam nigger, live rollers, and resaw. Nor do the mills longer turn out rough lumber to be re-handled by trained specialists and highly skilled carpenters with large and costly kits of intricate hand tools. Relatively unskilled workers send forth the finished products, window sashes, doors, siding, etc., carpenters armed only with square, hammer and saw, and classed with unskilled labor, put these in place, and a complete house can be ordered by parcel post.

As is usual with the introduction of new machinery and methods where the workers are not in control, the actual producers find that all these innovations force them to work at a higher rate of speed under more hazardous conditions for a lower rate of pay. It is true of all industry in the main, particularly true of the lumber industry, and the mills of Everett and camps of Snohomish county have no exceptions to test this rule.

The story of Everett has no hint of romance. Some time in the late seventies the representatives[Pg 23] of John D. Rockefeller gained possession of a tract of land in Western Washington, on Puget Sound, about thirty miles north of Seattle. The land was heavily timbered and water facilities made it a perfect site for mill and shipping purposes. The Everett Land Company was organized, the tract was plotted, and the city of Everett laid out. The leading streets, Rockefeller, Colby, Hoyt, etc., were named for these early promoters. Hewitt Avenue was given the name of a man who is today recognized as the leading capitalist of the state of Washington. Even the building of those streets reflected no credit upon the city. The work was done by what amounted to convict labor. Unemployed workers, even tho they were plentifully supplied with money, were arrested and without being allowed the alternative of a fine were set to work clearing, grading, planking and, later on, paving the streets. Perhaps it is too much to expect freedom of speech to be allowed on slave-built streets.

In their articles of incorporation the promoters reserved to themselves all right to the ownership and control of public utilities, such as water, light and power and street railway systems. A mortgage of $1,500,000 was placed upon the property. After a time the company failed, the mortgage was foreclosed and the property purchased by Rucker Brothers. The Everett Improvement Company was then organized with J. T. McChesney as president. It held all rights to dispose of public utility franchises. The firm of Stone & Webster, the construction, light, heat, power and traction trust, secured franchises granting them the right to furnish light and power for the city of Everett and also to operate the street railway system for 99 years. The Everett Improvement Company owns a dock lying to the south of the municipally owned City Dock where the Everett tragedy was staged. Thru its alliances the shipping of Everett is in the hands of the same group of capitalists that control all other public utilities. The waterworks was sold to the city but has remained in the hands of the same officials who were in charge[Pg 24] when its title was a private one. Everett operates under the commission form of government.

The American National Bank was organized with McChesney as president. The only other bank of importance in Everett was the First National. These two institutions consolidated with Wm. C. Butler as president and McChesney as one of the directors. The Everett Savings and Trust Company was later organized, with the same stockholders and under the same management as the First National Bank. The control of every public service corporation in Everett is directly in the hands of these two banks, and, indirectly, thru loans to industrial corporations, they control both the lumber and the shingle mills of Snohomish County in which Everett is situated.

Everett, the "City of Smokestacks," as its promoters have named it, is an industrial community of approximately 35,000 people. Its main activities are the production of lumber and shingles, and shipping. The practically undiversified nature of its economic life binds all those engaged in the employment of labor into a common body. The owners of the lumber and shingle mills, the owners and officials of the banks where the lumber men do business, the lawyers representing the mills and the banks, the employers engaged in shipping lumber and supplies for the lumber industry, their lawyers and their bank connections, the owners of hardware stores that supply equipment for the mills and allied industries, all are united by common ties and common interests and they all support one policy. Not only are they banded together against the wage workers but they also oppose the entrance of any kind of business that will in any way menace their rule. They arose almost as one in opposition to the entrance of the ship building industry into Everett, despite the fact that it would add measurably to the general prosperity of the city, and with a full knowledge that their harbor offered wonderful natural facilities for that line of endeavor. In the face of[Pg 25] an action that threatened their autocratic power their alleged "patriotism" vanished.

In 1912 the Everett Commercial Club was organized. In the month of December, 1915, following a visit from a San Francisco representative of the Merchants and Manufacturers' Association, it was re-organized on the Bureau plan as a stock concern. Stock memberships were issued to employers and business houses and were subsequently distributed among the employers and their employes. Memberships were doled out to persons who would be subservient to the wishes of the small group of capitalists representing the great corporate interests. W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club, testified, under oath, that the Everett Improvement Company took 25 memberships, the First National Bank took 10, the Weyerhouser Lumber Company 10, the Clough-Hartley Mill Company 5, the Jamison Mill Company 5, and other mills and allied industries also purchased memberships in bulk. Organized labor, however, had no representation at the Commercial Club.

There is nothing in the history of Everett to suggest the usual spontaneous outgrowth of the honest endeavors of hardy pioneer settlers. From the first day the Rockefeller interests set foot in the virgin forests of Snohomish County up to the present time, the spirit of democracy has been crushed by the greed and cupidity of this small and powerful group.

The struggle at Everett was but one of the inevitable phases of the larger struggle that takes place when a class or group that has no property comes in contact with those who have monopolized the earth and its resources. It was no new, marvelous, isolated case of violence. It was the normal accompaniment of industry based upon the exploitation of wage workers, and was of one piece with the outbreak on the Mesaba Range, in Bayonne, Ludlow, Paint Creek, Paterson, Lawrence, San Diego, Fresno, Spokane, Homestead and in countless other places. All these apparently [Pg 26]disconnected and sporadic uprisings of labor and the accompanying capitalist violence are joined together in a whole that spells wage slavery. As one of the manifestations of the class conflict, the Everett tragedy cannot be considered apart from that age-long and world-wide struggle between the takers of profits and the makers of values.

[1] Data on Forest Reserve taken from 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica articles by Gifford Pinchot.

"Shingle-weaving is not a trade; it is a battle. For ten hours a day the sawyer faces two teethed steel discs whirling around two hundred times a minute. To the one on the left he feeds heavy blocks of cedar, reaching over with his left hand to remove the rough shingles it rips off. He does not, he cannot stop to see what his left hand is doing. His eyes are too busy examining the shingles for knot holes to be cut out by the second saw whirling in front of him.

"The saw on his left sets the pace. If the singing blade rips fifty rough shingles off the block every minute, the sawyer must reach over to its teeth fifty times in sixty seconds; if the automatic carriage feeds the odorous wood sixty times into the hungry teeth, sixty times he must reach over, turn the shingle, trim its edge on the gleaming saw in front of him, cut out the narrow strip containing the knot hole with two quick movements of his right hand and toss the completed board down the chute to the packers, meanwhile keeping eyes and ears open for the sound that asks him to feed a new block into the untiring teeth. Hour after hour the shingle weaver's hands and arms, plain, unarmored flesh and blood, are staked against the screeching steel that cares not what it severs. Hour after hour the steel sings its crescendo note as it bites into the wood, the sawdust cloud thickens, the wet sponge under the sawyer's nose, fills with fine particles. If 'cedar asthma,' the shingle weaver's occupational disease, does not get him, the steel will. Sooner or later he reaches over a little[Pg 28] too far, the whirling blade tosses drops of deep red into the air, and a finger, a hand or part of an arm comes sliding down the slick chute."[2]

This description of shingle weaving was given by Walter V. Woehlke, managing editor of the Sunset Magazine, in an article which had as its purpose the justification of the murders committed by the Everett mob, and it contains no over-statement. Shingle weavers are set apart from the rest of the workers by their mutilated hands and the dead grey pallor of their cheeks.

"The nature of a man's occupation, his daily working environment, marks in a large degree the nature of the man himself, and cannot help but mold the early years, at least, or his economic organization. Men who flirt with death in their daily calling become inured to physical danger, they become contemptuous of the man whose calling fails to bring forth physical prowess. So do they in their organizations become irritated and contemptuous at the long-drawn-out process of bargaining, the duel of wits and brain power engaged in by the more conservative organizations to win working concessions. Their motto becomes 'Strike quick and strike hard,'* * *" So says E. P. Marsh, President of the Washington State Federation of Labor, in speaking of the shingle weavers.[3]

Logging, no less than shingle weaving, is a dangerous occupation. The countless articles of wood in every-day use have claimed their toll of human blood. A falling tree or limb, a mis-step on the river, a faulty cable, a weakened trestle; each may mean a still and mangled form. Time and again the loggers have organized to improve their working conditions only to find themselves beaten[Pg 29] or betrayed. Playing upon the natural desire of the woodsmen for organization, shrewd swindlers have formed unions which were nothing more than dues collection agencies. Politicians have fathered organizations for their own purposes. Unions built by the men themselves have fallen into the hands of officials who used them for selfish personal gain. Over and over the employers have crushed the embryonic unions only to see them rise again with added strength. Forced by the very necessities of their daily lives, the workers always returned to the fight with a new and better form of unionism.

Like the loggers, the shingle weavers were routed time and again, but their spirit never died. The Everett shingle weavers formed their union as a result of a successful strike in 1901. In 1905 they were strong enough to resist a proposed reduction of wages. In 1906 they struck in sympathy with the Ballard weavers, and lost. Within a year the defeated union was back as strong as before. By 1911 the International Shingle Weavers Union had attained a membership of nearly 2,000, the majority of whom were in accord with the Industrial Workers of the World. The question of affiliation with the I. W. W. was widely discussed and was only prevented from going to a referendum vote by the efforts of a few officials. Further discussion of the question was excluded from the columns of their official organ, "The Shingle Weaver," by the Ninth Annual Convention.[4]

Following this slap in the face, the progressive members quit the union in large numbers, leaving affairs in the hands of conservative and reactionary elements. Endeavors were made to negotiate contracts with the employers; and in 1913 the officials secured $30,000 from the American Federation of Labor and made a pretense at the organization of all workers in the woods and mills into one body. This was a move aimed at the Forest and Lumber[Pg 30] Workers of the I. W. W., which was feared alike by the employers and the craft union officials because of its new strength gained thru the affiliation of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers in the southern states. Instead of gaining ground by the move, the shingle weavers union lost in membership and subsequently claimed that industrial unionism was a failure in the lumber industry.

The industrial depression of 1914-15 found all unions in bad shape. Employers used the army of unemployed as an axe to cut wages. In the spring of 1915 notice of a wage reduction was posted in the Everett shingle mills. The weavers promptly struck. Scabs, gunmen, injunctions, and violence followed. The strike failed, the wage reduction was made, but the men returned to work relying upon a "gentlemen's agreement" that the employers would voluntarily raise the wages of the shingle weavers when shingles again sold for what they were bringing before the depression. Faith in agreements had gotten in its deadly work; the shingle weavers believed that the employers meant to keep their word.

In the spring of 1916 shingles soared to a price higher than had prevailed for years, but the promised raise failed to materialize. With but a skeleton of an organization to back them, a handful of determined delegates met in Seattle in April and decided to demand the restoration of the 1915 scale thruout the entire jurisdiction of the Shingle Weavers' Union, setting May 1st as the date when the raise should take effect.

At the time set, or shortly thereafter, most of the mills in the Northwest paid the scale. Everett, where the employers had given their "word of honor," refused the strikers' demand. The fight was on! The Seaside Shingle Company, which held no membership in the Commercial Club, soon granted the raise. Many of the other companies, notably the Jamison Mill, began the importation of scabs within the month. The cry of "outside agitators" was forgotten long enough to go outside in search of [Pg 31]notorious gunmen and scab-herders. The slums, the hells of Capitalism, were raked with a fine-toothed comb for degenerates with a record for lawless deviltry. The strikers threw out their picket line and the ever-present class war began to show itself in other than peaceful ways.

During May, June and July the picket line had to be maintained in the face of strong opposition by the local authorities who were the pliant tools of the lumber trust. The ranks of the pickets were constantly being thinned by false arrest and imprisonment on every charge and no charge, until on August 19th there were but eighteen men on the picket line.

On that particular morning the Everett police searched the little handful of pickets in front of the Jamison Mill to make sure that they were unarmed, and when that fact was determined, they started the men across the narrow trestle bridge that extended over an arm of the bay. When the pickets were well out on the bridge, the imported thugs, some seventy in number, personally directed and urged on by their employer, Neil Jamison, poured in from either side, leaving no means of escape save that of making a thirty foot leap into the deep waters of the bay, and with brass knuckles and blackjacks made an attack upon the defenseless weavers. The pickets were unmercifully beaten. Robert H. Mills, business agent of the Shingle Weavers' Union, was knocked down by one of the open-shop thugs and kicked in the ribs and face as he lay senseless in the roadway. From a vantage point, thoughtfully removed from the danger zone, the police calmly surveyed the scene.

When darkness fell that night, the pickets, aided by irate citizens, returned to the attack with clubs and fists. The tables were turned. The "moral heroes" had their heads cracked. Seeing that the scabs were thoroly whipped, the "guardians of the peace" rushed to the rescue with drawn revolvers. In the melee one union picket was shot thru the leg.

About ten nights later, Mr. Jamison herded his scabs into military formation and after a short parade thru the main streets led them to the Everett Theater; the party being in appreciation of their "efficiency." This arrogant display incensed the strikers and citizens, and when the scabs emerged from the show a near-riot occurred. Mills was present and altho too weak from his recent injuries to have taken any active part in the fray, he was arrested and thrown in jail in default of bail. The man who had murderously assaulted him at the mill swore out the complaint. Mills was subsequently tried and acquitted on a charge of inciting to riot. Nothing was done to his assailant. And in none of these acts of violence was the I. W. W. in any way a participant.

During this period there existed a strike of longshoremen on the entire Pacific Coast, including the port of Everett. The wrath of the employers fell heavily upon the Riggers and Stevedores because that body was not in sympathy with the idea of craft contracts or agreements, and because of the adoption by a large majority of a proposal to "amalgamate all the unions of the Maritime Transportation Industry, between the Warehouse at the Shipping Point and Warehouse at the Receiving Point into one big powerful organization, meeting, thinking, and acting together at all times."[5] The industrially united employers of the Pacific Coast did not relish the idea of the workers grouping themselves together along lines similar to those on which the owners were associated. The longshoremen's strike started on June 1st and was marked by more or less serious disorders at various points, most of the violence being precipitated by detectives placed in the unions by the employers. The tug boat men were also on strike in Everett, particularly against the American Tug Boat Company owned by Captain Harry Ramwell. All of the unions on strike in Everett were affiliated with the A. F. of L. Striking longshoremen from Seattle aided the shingle weavers on their picket line from time to time, and individual members of the I. W. W., holding duplicate cards in the A. F. of L. stood shoulder to shoulder with the strikers, but officially the I. W. W. had no part in any of the strikes.

[Pg 34]Meanwhile in Seattle the I. W. W. had planned to organize the forest and lumber workers on a scale never before attempted. Calls for organizers had been coming in from the surrounding district and there were demands for a mass convention to discuss conditions in the industry. Yet, strange as it may seem to those who do not know of the ebb and flow of labor unions, there were at that time less than half a hundred paid-up members in the Seattle loggers branch, so great had been the depression from 1914 to 1916. The conference was set for July 4th and five hundred logger delegates responded, representing nearly as many camps in the district. Enthusiasm ran high! The assembled workers suggested the adoption of a plan of district organization along lines more in keeping with the modern trend of the lumber industry. The loggers' union, then known as Local 432, ratified the actions of the conference. As a preliminary move it was decided that an organizer be secured to make a survey of the lumber situation in the surrounding territory. General Headquarters in Chicago was communicated with, James Rowan was found to be available, and on July 31st he was sent to Everett to find out the sentiment for industrial unionism at that point.

That night Rowan spoke on Wetmore Avenue fifty feet back from Hewitt Avenue, in compliance with the street regulations. No mention was made of local conditions as Rowan had just come from another part of the country and was unaware that a shingle weavers strike was in progress. His speech consisted mainly of references to the Industrial Relations Commission Report, a pamphlet[Pg 35] summarizing that report being the only literature offered for sale at the meeting. Toward the end of his speech Rowan declared:

"The A. F. of L. believes in signing agreements with the employers. The craft unions regard these contracts as sacred. When one craft goes on strike the others are forced to remain at work. This makes the craft unions scab on each other."

"You are a liar!" cried Jake Michel, an A. F. of L. representative, staunchly defending his organization.

From an automobile near the edge of the crowd, Donald McRae, Sheriff of Snohomish County, called to Michel:

"Jake, I will run that guy in if you say so."

"I don't see any need to run him in;" remonstrated Michel. "He hasn't said anything yet to run him in for."

Nevertheless McRae, usurping the powers of the local police department, made Rowan leave the platform and go with him to the county jail. McRae was drunk.

Rowan was held for an hour. Immediately upon his release he returned to the corner to resume his speech. Police Officer Fox thereupon arrested him and took him to the city jail. He was thrown into a dark cell for refusing to do jail work, was taken into court next morning and absurdly charged with peddling without a license, was denied a jury trial, refused a postponement, not allowed a chance to secure counsel, and was sentenced to thirty days imprisonment with an alternative of leaving town. No ordinance against street speaking at Wetmore and Hewitt then existed. Rowan chose to leave town. No time was set as to how long he was to remain away. He then left for Bellingham and from there went to Sedro-Woolley. Using an assumed name to avoid the blacklist he worked at the latter place for a short time to familiarize himself with job conditions, subsequently returning to Everett.

Levi Remick, a one-armed veteran of the industrial war, was next sent to Everett on August 4th[Pg 36] to act as temporary delegate. He interviewed a number of people and sold some literature. Receiving orders to stop selling the pamphlets and papers, he inquired the price of a peddler's license and finding it prohibitive he returned to Seattle to secure funds to open an office. A small hall was found at 1219½ Hewitt Avenue, a month's rent was paid, and on August 9th Remick placed a sign in the window and started to sell literature and transact business for the I. W. W.

The little hall remained open until late in August. Migratory workers, strikers, and citizens generally, dropped in from time to time to ask about the organization or to purchase papers. Solidarity and the Industrial Worker were particularly in demand, the latter paper having commenced publication in Seattle on April 1st, 1916. A number of Everett citizens, desiring to hear a lecture by James P. Thompson, who had spoken in Everett without molestation in 1915 and in March and April of 1916, made donations to Remick sufficient to cover all expenses, and it was arranged that Thompson speak on August 22nd. Attempts to secure a hall met with failure; the halls of Everett were closed to the I. W. W. The conspiracy against free speech and free assembly was on in earnest! No other course was left but to hold the proposed meeting on the street, so Hewitt and Wetmore, the spot where the Salvation Army and various religious and political bodies spoke almost nightly, was selected and the meeting advertised.

Early in the morning on the day before the scheduled meeting, Sheriff McRae, commanding a body of police officers over whom he had no official control, stormed into the I. W. W. hall and tore from the wall all bills advertising Thompson's meeting, saying with an oath:

"That man won't be allowed to speak in Everett!"

Turning to Remick and throwing back his coat to display the badge, he yelled:

"I order you out of this town! Get out by afternoon or you go to jail!"

McRae was drunk. Stalking out as rapidly as his condition would permit he staggered down the street to a near-by pool hall where the order was repeated to the men assembled therein. These, with other workingmen, 25 in all were rounded up, seized, roughly questioned, searched, and all those who had no families or property in Everett were forcibly deported. That night ten more were taken from the shingle weaver's picket line and sent out of town without due process of law. Treatment of this kind became general.

"Not a man in overalls is safe!" declared the secretary of the Everett Building Trades Council. "Men just off the job with their pay checks in their pocket have been unceremoniously thrown out of town just because they were workingmen."[6]

Remick closed the little hall and left for Seattle the next morning to place the question of the Thompson meeting before the Seattle membership. Shortly before noon Rowan, who had just returned to Everett, went to the hall and finding it closed and locked he proceeded to open it up. Within a few minutes Sheriff McRae, in company with police officer Fox, entered the place and ordered Rowan to leave town by two o'clock. He then tore up the balance of the advertising matter for the Thompson meeting. McRae was drunk. Rowan went to Seattle, where the report of this occurrence made the members more determined than ever to hold the meeting that night.

With about twenty other members of the I. W. W., Thompson went to Everett. The Salvation Army was holding services on the corner. Placing his platform even further back from the street intersection Thompson waited until the Army had concluded and then commenced his lecture. Using the Industrial Relations Commission Report as the basis[Pg 38] of his talk, he spoke for about twenty minutes without interruption. Then a body of fifteen policemen marched down the street and swung into the crowd. The officer in charge stepped up to Thompson and requested him to go to see the chief of police at the police station. After addressing a few remarks to the crowd Thompson withdrew from the platform. His place was taken at once by Rowan, who was immediately dragged from the stand and turned over to the same officer who had charge of Thompson and his wife. Mrs. Edith Frennette then spoke briefly and called for a song. The audience responded with "The Red Flag," but meanwhile Mrs. Frennette and Mrs. Lorna Mahler had been placed under arrest. In succession several others attempted to speak but were pulled or pushed off the stand. The police then formed a circle by holding hands around those who were close to the platform. One by one the citizens were allowed to slip outside the "ring-around-a-rosy" until only "desperadoes" were left. These made no effort to resist arrest, and were started toward the city jail. The officer entrusted with Thompson was so interested in his captive that Rowan was able to quietly remove himself from the scene, returning to the street corner where he spoke for more than half an hour before being rearrested.

Aroused by this invasion of liberty, Mrs. Letelsia Fye, an Everett citizen, arose to recite the Declaration of Independence, but even that proved too revolutionary for the tools of the lumber trust. A threatening move on the part of the police brought back the thought of her two unprotected children and caused her to cease her efforts to declare independence in Everett.

"Is there a red-blooded man in the audience who will take the stand?" called out the gallant little woman as she stepped from the platform. Jake Michel promptly accepted the challenge and was as promptly suppressed by the police at the first mention of free speech.

In the jail the arrested persons were searched one by one and thrown into the "receiving tank."[Pg 39] When Thompson's turn came, Commissioner of Public Safety, as Chief of Police Kelly was known under Everett's form or government, said to him:

"Mr. Thompson, I don't want to lock you up."

"That's interesting," replied Thompson. "Why have you got me down here?"

"We don't want you to speak on the street at this time."

"Have you any ordinance against it, that is, have I broken any law?" enquired Thompson.

"Oh no, no. That isn't the idea," rejoined Kelly. "We have strikes on, labor troubles here, and we don't want you to speak here at all. You are welcome at any other time, but not now."

"Well," said Thompson, "as a representative of labor, when labor is in trouble is the time I would like to speak, but I am not going to advocate anything that I think you could object to."

"Now, Thompson," said Kelly, "if you will agree to get right out of town I will let you go. I don't want to lock you up."

"Do you believe in free speech?" asked Thompson.

"Yes."

"And I am not arrested?"

"No, you are not arrested."

"Come up to the meeting then," Thompson said with a smile, "for I am going back and speak."

"Oh no, you are not!"—and Kelly kind of laughed. "No, you are not!"

"If you let me go I will go right up to the corner and speak, and if you send me out of town I will come back," said Thompson emphatically. "I don't know what you are going to do, but that's how I stand."

"Lock him up with the rest!" was the abrupt reply of the "Commissioner of Public Safety."

At this juncture James Rowan was brought in from the patrol wagon, and searched. As the officers were about to put him in the cell with the others, Sheriff McRae called out:

"Don't put him in there, he is instigator of the whole damn business. Turn him over to me." He then took Rowan in his automobile to the county jail and threw him in a cell, along with B. E. Peck, who had previously been given a "floater" out of town for having spoken on the street on or about August 15th. McRae was drunk.

More than half a thousand indignant citizens followed the twenty-one arrested persons to the jail, loudly condemning the outrage against their constitutional rights. Editor H. W. Watts, of the Northwest Worker, a union and socialist paper published in Everett, forcibly expressed his opinion of the suppression of free speech and was thereupon thrown into jail. Fearing a serious outbreak, Michel secured permission to address the people surrounding the jail. The crowd, upon receiving assurances from Michel that the men would be well treated and could be seen in the morning, quietly dispersed and returned to their homes.

The free speech prisoners were charged with vagrancy on the police blotter, but no formal charge was ever made, nor were they brought to trial. Next morning, Thompson and his wife, who had return tickets on the Interurban, were deported by rail, together with Herbert Mahler, secretary of the Seattle I. W. W. Mrs. Mahler, Mrs. Frennette and the balance of the prisoners were taken to the City Dock and deported by boat. At the instigation of McRae, and without a court order, the sum of $13. was seized from the personal funds of James Orr and turned over to the purser of the boat to pay the fares of the deportees to Seattle. Protests against this legalized robbery were of no avail; the amount of the fares was never repaid. Mayor Merrill of Everett, replying to a letter from Mahler, promised that this money would be refunded to Orr. His word proved to be as good as that of the Everett shingle mill owners. Prominent members of the Commercial Club lent civic dignity to the deportation by their profane threats to use physical force in the event that any of the deported prisoners dared to return.

Upon their arrival in Seattle the deported men conferred with other members of the union, telling of the beating some of them had received while in jail, and as a result there was organized a free speech committee composed of Sam Dixon, Dan Emmett and A. E. Soper. Telegrams were then sent to General Headquarters, to Solidarity and to various branches of the organization, notifying them of what had happened. At a street meeting that night, Mrs. Frennette, Mrs. Mahler and James P. Thompson, gave the workers the facts and collected over $50.00 for the committee to use in its work. In Everett the Labor Council passed a resolution stating that the unions there were back of the battle for free speech and condemning McRae and the authorities for their illegal actions. The Free Speech Fight was on!

Remick, in the meantime, had returned to Everett and found that all the literature had been confiscated from the hall. The day following his return, August 24th, Sheriff McRae blustered into the hall with a police officer in his train. Leering at Remick he exclaimed:

"You God damn son of a b——, are you back here again? Get on your coat and get into that auto!"

Seizing an I. W. W. stencil that was lying on the table he tore it to shreds.

"If anybody asks who tore that up,"—bombastically—"tell them Sheriff McRae tore it!"

Shoving Remick into the automobile with the remark that jail was too easy for him and they would therefore take him to the Interurban and deport him, the sheriff drove off to make good his threat. McRae was drunk.

On the corner that night, Harry Feinberg spoke to a large audience and was not molested. That this was due to no change of policy on the part of the lumber trust tools was shown when secretary Herbert Mahler went to Everett the following day in reference to the situation. He was met at the depot by Sheriff McRae who asked him what he had come to Everett for. "To see the Mayor," answered [Pg 42]Mahler. "Anything you have to say to the Mayor, you can say to me," was McRae's rejoinder. After a brief conversation Mahler was deported to Seattle by the same car on which he had made the trip over. McRae was drunk.

F. W. Stead reopened the hall on the 26th and managed to hold it down for a couple of days. Three speakers appeared and spoke that night. J. A. MacDonald, editor of the Industrial Worker, opened the meeting. George Reese spoke next, but upon commencing to advocate the use of violence he was pulled from the platform by Harry Feinberg, who concluded the meeting. No arrests were made.

It was during this period that Secretary Herbert Mahler addressed a letter to Governor Ernest Lister, informing him of the state of lawlessness existing in Everett. A second letter was sent to Mayor Merrill and in it was enclosed a copy of the letter to Lister. No reply was received to the communication.

For a time following this there was no interference with street meetings. Feinberg spoke without molestation on Monday night and Dan Emmett opened up the hall once more. On Tuesday evening, the same night as the theater riot, Thompson addressed an audience of thousands of Everett citizens, giving them the facts of the arrests made the previous week, and advising the workers against the use of violence in any disputes with employers.

After having been held by McRae for eight days without any commitment papers, Rowan was turned over to the city police and released on September 1st. He returned to the street corner and spoke for several succeeding nights including "Labor Day" which fell on the 4th. Incidentally he paid a visit to the home of Jake Michel and, after industrial unionism was more fully explained, Michel agreed that the craft union contract system forced scabbery upon the workers. Rowan left shortly thereafter for Anacortes to find out the sentiment for organization in that section.

This period of comparative peace was due to the fact that the lumber barons realized that their [Pg 43]actions reflected no credit upon themselves or their city and they wished to create a favorable impression upon Federal Mediator Blackman who was in Everett at the request of U. S. Commissioner of Labor Wilson. It was during this time, too, that the protagonists of the open shop were secretly marshalling their forces for a still more lawless and brutal campaign.

Affairs gradually slipped from the hands of the Everett authorities into the grasp of those Snohomish County officials who were more completely dominated by the lumber interests.

"Tom," remarked Jake Michel one day to Chief of Police Kelley, "it seems funny that you can't handle the situation."

"I can handle it all right," replied Kelley, bitterly, "but McRae has been drunk around here for the last two or three weeks and he has butted into my business."

It was on August 30th that the lumber trust definitely stripped the city officials of all power and turned affairs over to the sheriff. On this point a quotation from the Industrial Relations Commission Report is particularly illuminating in showing a common industrial condition:

"Free speech in informal and personal intercourse was denied the inhabitants of the coal camps. It was also denied public speakers. Union organizers would not be permitted to address meetings. Periodicals permitted in the camps were censored in the same fashion. The operators were able to use their power of summary discharge to deny free press, free speech, and free assembly, to prevent political activities for the suppression of popular government and the winning of political control. I find that the head of the political machinery is the sheriff."

In Everett the sheriff's office was controlled by the Commercial Club and the Commercial Club in turn was dominated, thru an inner circle, by the lumber trust. Acting for the trust a small committee meeting was held on the morning of the 30th with[Pg 44] the editor of a trust-controlled newspaper, the secretary of the Commercial Club, two city officials, a banker and a lumber trust magnate in attendance. A larger meeting of those in control met in the afternoon and, pursuant to a call already published in the Everett Herald, several hundred scabs, gunmen, and other open shop advocates were brought together that night at the Commercial Club.

Commissioner of Finance, W. H. Clay, suggested that as Federal Mediator Blackman, an authority on labor questions, was in the city it might be well to confer with him regarding a settlement. Banker Moody said he did not think a conference would be advisable as Mr. Blackman might be inclined to lean toward the side of the laboring men, and at a remark by "Governor" Clough, formerly Governor of Minnesota and spokesman for the mill owners, to the effect that there was nothing to be settled the suggestion was not considered further.

H. D. Cooley, special counsel for a number of the mills, Governor Clough, a prominent mill owner, and others then addressed the meeting in furtherance of the plans already laid. Clough asked McRae if he could handle the situation. McRae said he did not have enough deputies.

"Swear in the members of the Commercial Club, then!" demanded Clough. This was done. Nearly two hundred of the men whose membership had been paid for by the mill owners "volunteered" their services. McRae swore in a few and then, for the first time in his life, found swearing a difficulty, so W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club, who was neither a city nor a county official, administered the remainder of such oaths as were taken by the deputies. The whole meeting was illegal.

From time to time the deputy force was added to until it ran way up in the hundreds. It was divided into sections A, B, C, etc. Each division was assigned to a special duty, one to watch incoming trains for free speech advocates, another to watch the boats for I. W. W. members, and others for various duties such as deporting and beating up workers.[Pg 45] This marked the beginning of a reign of terror during which no propertyless worker or union sympathizer was safe from attack.

About this same time the Commercial Club made a pretense of investigating the shingle weavers' strike. Not one of the strikers was called to give their side of the controversy, and J. G. Brown, international president of the Shingle Weavers' Union, was refused permission to testify. The committee claimed that the employers could not pay the wages asked. An adverse report was returned and was adopted by the club.

Attorneys E. C. Dailey, Robert Fassett, and George Loutitt, along with a number of other fair minded members who did not favor the open shop program, withdrew from membership on account of these various actions. Their names were placed on the bulletin board and a boycott advised. Feeling against the organization responsible for the chaotic conditions in Everett finally became so strong that practically all of the merchants whose places were not mortgaged or who were not otherwise dependent upon the whims of the lumber barons, posted notices in their windows,

"WE ARE NOT MEMBERS OF THE

COMMERCIAL CLUB."

Their names, too, were placed on the bulletin board, and the boycott and other devices used in an endeavor to force them into bankruptcy.

Prior to these occurrences and for some time thereafter, the club was addressed by emissaries of the open shop interests. A. L. Veitch, special counsel for the Merchants' and Manufacturers' Association, on one occasion addressed the deputies on labor troubles in San Francisco and the methods used to handle them. Veitch was later one of the attorneys in the case against Thomas H. Tracy, and he was employed by the state, it being stipulated that he receive no state compensation. H. D. Cooley,[Pg 46] lumber mill lawyer and former prosecuting attorney, also spoke at different times on the open shop questions. Cooley was likewise an attorney for the prosecution in the Tracy case and he, like Veitch, was retained by "interested parties." Cooley was one of the anti-union speakers at a meeting of the deputies which was also addressed by F. C. Beach, of San Francisco, president of the M. & M., Robert Moody, president of the First National Bank of Everett, Governor Clough, mill magnate, F. K. Baker, president of the Commercial Club, and Col. Roland H. Hartley, open shop candidate for the nomination as governor of Washington at the pending election. Leigh Irvine, of Seattle, secretary of the Employers' Association, and Murray, president of the National Association of Manufacturers, were also active in directing the destinies of the Commercial Club.

A special open shop committee was formed, the nature of its operations being apparent when the following two quotations from its minutes, taken from among others of similar purport, are considered:

"Decided to go after advertisements in labor journals and the Northwestern Worker."[7]

"Matter of how far to go on open shop propaganda at the deputies meeting this morning was discussed. Also the advisability of submitting pledges. Mr. Moody to take up matter of the legality of pledges with Mr. Coleman. Note: At deputies meeting all speakers touched quite strongly on the open shop, and as far as it was possible to see all in attendance seemed favorable."[8]

Just how far they finally did go is a matter of history. At the time, however, there were appropriations made for the purchase of blackjacks, leaded clubs, guns and ammunition, and for the [Pg 47]employment of detectives, labor spies, and "agents provocateur."[9]

[2] Sunset Magazine, February 1917. "The I. W. W. and the Golden Rule."

[3] Supplemental report on "Everett's Industrial Warfare," by President Ernest P. Marsh to State Federation of Labor convention held at Everett, Wash., from January 22 to 26, 1917.

[4] Vol. 9, No. 2, The Shingle Weaver, Special Convention Number, February, 1911.

[5] Proposition No. 5, submitted to referendum of membership of Pacific Coast District I. L. A., Riggers and Stevedores Local 38, at their annual election on Jan. 6, 1916.

[6] Dreamland Rink Meeting, Seattle, Nov. 19th, over 5,000 in attendance.

[7] Minutes of Open Shop Committee, Sept. 27th.

[8] Minutes of Open Shop Committee, October 29.

[9] The incidents of the foregoing chapter are corroborated by the sworn testimony of prosecution witnesses Donald McRae, sheriff of Snohomish County; and D. D. Merrill, Mayor of Everett; and by witnesses called by the Defense, W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club: J. G. Brown, International president of the Shingle Weavers' Union; W. H. Clay, Commissioner of Finance in Everett; Robert Faussett, Everett attorney; Harry Feinberg, one of the defendants; Mrs. Letelsia Fye, Everett citizen; Jake Michel, Secretary Everett Building Trades Council; Herbert Mahler, Secretary Seattle I. W. W. and subsequently secretary of the Everett Prisoners' Defense Committee; Robert Mills, business agent Everett Shingle Weavers' Union; James Orr, and Levi Remick, I. W. W. members; James Rowan, I. W. W. organizer; and James P. Thompson, National Organizer for the I. W. W. and a speaker of international reputation.

No sooner had Mediator Blackman left Everett than the "law and order" forces resumed their hostilities with a bitterness and brutality that seems almost incredible. On September 7th Mrs. Frennette, H. Shebeck, Bob Adams, J. Johnson, J. Fred, and Dan Emmett were dragged from the platform at Hewitt and Wetmore Avenues and were literally thrown into their cells. Next morning Mrs. Frenette was released but the men were "kangarood" for 30 days each. Petty abuses were heaped upon them and Johnson was cast into the "black hole" by the sheriff. Some of the men were severely beaten just before their release a few days afterward.

When Fred Reed and James Dwyer were arrested the next night for street speaking, the crowd of Everett citizens, in company with the few I. W. W. members present, followed the deputies to the county jail, demanding the release of Reed, Dwyer and Peck, and those who had been arrested the night before. In its surging to and from the crowd pushed over a post-rotted picket fence that had been erected in the early days of Everett. This violence, together with cries of "You've got the wrong bunch in jail! Let those men out and put the 'bulls' in!" was the basis from which the trust-owned press built up a story of a riot and attempted jail delivery. On the same flimsy basis a warrant was issued charging Mrs. Frennette with inciting a riot.

The free speech committee sent John Berg to Everett that same day to retain an attorney for the men held without warrants. He secured the services of E. C. Dailey, and, while waiting to learn the result[Pg 50] of the lawyer's efforts, he went to the I. W. W. hall only to find it closed. A man was there waiting to get his blankets to go to work and Berg volunteered to get them for him. He then went to the county jail and asked for McRae. When McRae came in and learned that Berg wanted to see the secretary in order to get the keys to the hall, he yelled out:

"You are another I. W. W. Throw him in jail, the old son-of-a-b——!"

Without having any charges placed against him, Berg was held until the next morning, when McRae and a deputy took him out in a roadster to a lonely spot on the county road. Forcing him to dismount, McRae ordered Berg to walk to Seattle under threats of death if he returned, and then knocked Berg down and kicked him in the groin as he lay prostrate. McRae was drunk. Berg subsequently developed a severe rupture as a result of this treatment. He managed to make his way to Seattle and in spite of his condition returned to Everett that same night.

Undaunted by their previous deportations, and determined to circumvent the deputies who were seizing men from the railroad trains and regular boats, a body of free speech fighters, on September 9th, took the train to Mukilteo, a village about four miles from Everett, and there, by pre-arrangement, were taken aboard the launch "Wanderer."

The little boat would not hold the entire party and six men were towed behind in a large dory. There were 17 first class life preservers on board, the captain borrowing some to supplement his equipment.

When the "Wanderer" reached a point about a mile and a half from the Weyerhouser dock a boat was seen approaching. It was the scab tug "Edison," belonging to the American Tugboat Company. On board was Captain Harry Ramwell, Sheriff McRae and a body of about sixty deputies. When the "Edison" was about 200 feet away the sheriff commenced shooting—but let Captain Jack Mitten tell his own story.

"The first shot went over the bow. I don't know whether there was one or two shots fired, then there was a shot struck right over my head onto the big cast iron muffler. The next shot came on thru the boat,—I had my bunk strapped up against the wall,—and thru the blanket,—and the cotton in the blanket turned the bullet,—and it struck flat on the bottom of the bunk.

"I shut the engine down and went out to the stern door and just as I stepped out there was a shot went right by my head and at the same time McRae hollered out and says 'You son-of-a-b—, you come over here!' Says I, "If you want me, you come over here." With that they brought their boat and my boat up together. Six shots in all were fired.

"McRae commenced to take the people off the boat and when he had them all off he kicked the pilot house open and says, 'Oho, there is a woman here!' Mrs. Frennette was sitting in the pilot house. Anyhow, they took her and he says, 'You'll get a one piece suit on McNeil's island for this,' and then he says to Cap Ramwell—Cap Ramwell was sitting on the side—'This is Oscar Lindstrom, drag him along too.'