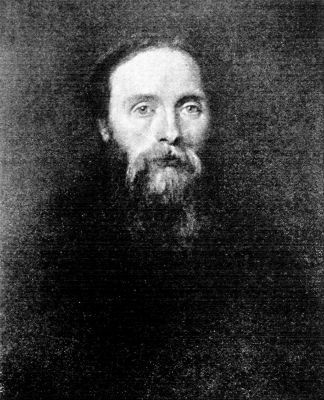

GENERAL ALEXEI NICHOLAEVITCH KUROPATKIN

Title: McClure's Magazine, Vol. XXXI, No. 4, August 1908

Author: Various

Release date: April 1, 2010 [eBook #31851]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Katherine Ward, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Copyright, 1908, by The S. S. McClure Co. All rights reserved

PAGE |

|

| A DISCLOSURE OF THE SECRET POLICIES OF RUSSIA. By General Kuropatkin. | 363 |

| TALKS WITH BISMARCK. By Carl Schurz. | 367 |

| THE FOREHANDED COLQUHOUNS. By Margaret Wilson. | 378 |

| LAST YEARS WITH HENRY IRVING. By Ellen Terry. | 386 |

| THE LOST MOTHER. By Blanche M. Kelly. | 399 |

| PATSY MORAN. THE BOOK AND ITS COVERS. By Arthur Sullivan Hoffman. | 401 |

| ARCTIC COLOR. By Sterling Heilig. | 411 |

| THE TAVERN. By Willa Sibert Cather. | 419 |

| A STORY OF HATE. By Gertrude Hall. | 420 |

| HIS NEED OF MIS’ SIMONS. By Lucy Pratt. | 432 |

| PROHIBITION AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY. By Hugo Münsterberg. | 438 |

| THE MOVING FINGER WRITES. By Marie Belloc Lowndes. | 445 |

| A BUNK-HOUSE AND SOME BUNK-HOUSE MEN. By Alexander Irvine. | 455 |

| THE KING OF THE BABOONS. By Perceval Gibbon. | 467 |

| ONE HUNDRED CHRISTIAN SCIENCE CURES. By Richard C. Cabot | 472 |

| SOUTH STREET. By Francis E. Falkenbury. | 476 |

| THE INABILITY TO INTERFERE. By Mary Heaton Vorse. | 477 |

| PROHIBITION AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY. By Dr. Münsterberg. | 482 |

| General Alexei Nicholaevitch Kuropatkin | 363 |

| Kaiser Wilhelm I | 369 |

| Prince Otto Von Bismarck | 372 |

| Count Hellmuth Von Moltke | 373 |

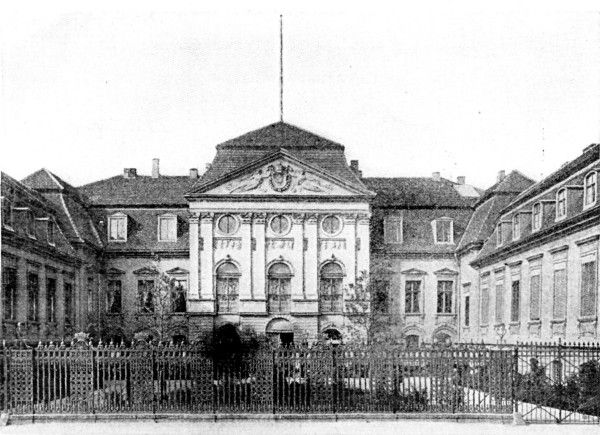

| The Chancellor’s Palace on the Wilhelmstrasse | 374 |

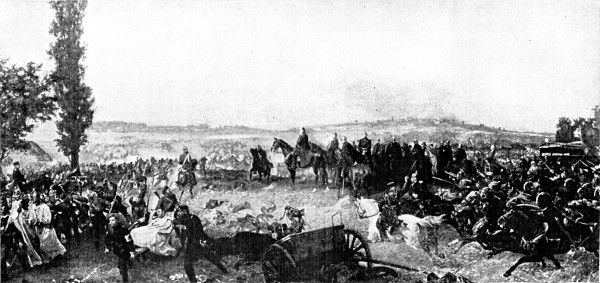

| The Battle of Königgrätz | 374 |

| Emperor Napoleon III | 376 |

| “Jane and Selina ... Looked at Patient and Nurse with Disapproving Gloom” | 378 |

| “She Could Not Help Seeing That Selina Found Some Strange Pleasure in all These Incidents of a Last Illness” | 382 |

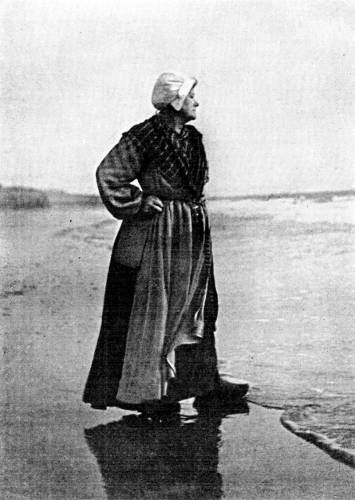

| Ellen Terry as Kniertje in “The Good Hope” | 387 |

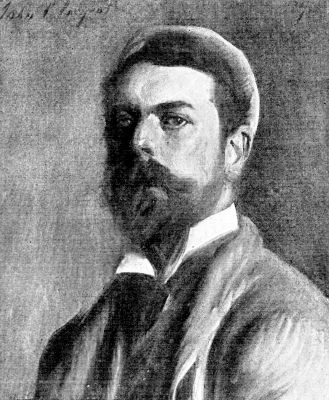

| John Singer Sargent | 388 |

| Sir Edward Burne-Jones | 388 |

| Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth | 389 |

| Peggy, Madame Sans-Gene, Madame Sans-Gene, Cordelia | 390 |

| Imogen, Lucy Ashton, Catherine Duval, Lucy Ashton | 390 |

| Cardinal Wolsey, Lady Macbeth, Guinevere, Thomas Becket | 391 |

| Nancy Oldfield, Hermione, Alice-Sit-by-the-Fire, Lady Cicely, Wayneflete | 391 |

| Miss Ellen Terry | 392 |

| Sir Henry Irving | 392 |

| Ellen Terry as Queen Katherine in Henry VIII | 395 |

| The Book and Its Covers | 401 |

| “Pardon Me,” He Said, “But What Are You Doing That for?” | 402 |

| “Ye’d Better Be Usin’ Your Brains to Walk With, and Not Strainin’ Thim Like That” | 407 |

| Midnight in the Kara Sea | 411 |

| “The Country of the Dead”—A Study of the Kara Sea in August | 413 |

| Samoyed Love of Color | 414 |

| Painting of a Sledge Set Upon End for the Night, With Skins and Meat Hung Upon It So as to Be Out of Reach of the Dogs | 415 |

| A Study Made in Nova Zembla at the Time of the Complete Eclipse of the Sun, July 27, 1896 | 416 |

| Painting of a Church Built by M. Seberjakow | 417 |

| In the Midnight Sunshine | 418 |

| His Need of Mis’ Simons | 432 |

| ‘I Couldn’ Git ’Long ’Thout Yer Noways, Could I?’ She Say | 433 |

| ‘She Keep on A-Readin’, an’ I Keep on A-Wukkin’ on de Paff’ | 434 |

| ‘It’s Time Fer You ter Go to Baid, Ain’t It, ’Zekiel?’ She Say | 435 |

| ‘’Tain’ Gwine Nobody Else Git—Fru—Dat—Do’,’ She Say | 436 |

| The Bunk-House | 459 |

| One Night the Graf Was Prevailed Upon to Tell His Story | 461 |

| The Sitting-Room of the Bismarck | 462 |

| I Noticed a Profile Silhouetted against the Window | 463 |

| St. Francis of the Bunk-House | 464 |

| They Sat on Their Rumps Outside the Circle of Kafirs | 467 |

A DISCLOSURE OF THE SECRET POLICIES OF RUSSIA

BY

GENERAL KUROPATKIN

Once in a generation the intimate and vital secrets of a great nation may be made public through one of the little circle of men to whom they are entrusted; but rarely, if ever, till the men are dead, and the times are entirely changed. Beginning next month, McClure’s Magazine will present to the reading world a striking exception to this rule. It will print for the first time a frank and startling official revelation of the present political plans and purposes of Russia—the great nation whose guarded and secret movements have been the concern of modern European civilization for two centuries.

General Kuropatkin—Minister of War and later Commander-in-Chief of the Russian forces in the great and disastrous Manchurian campaign—became a target for abuse at the close of the Russo-Japanese War. He returned to St. Petersburg and constructed, from the official material accessible to him, an elaborate history of the war, and a detailed statement of the condition, purposes, and development of the Russian Empire. Documents and dispatches endorsed “Strictly Confidential,” matters involving the highest officials, information obviously intended for no eyes but those of the innermost government circles, are laid forth with the utmost abandon in this work. No sooner had 364 it been completed, than it was confiscated by the government. Its manuscript has never been allowed to pass out of the custody of the Czar’s closest advisers.

An authentic copy of this came into the hands of McClure’s Magazine this spring; it is not essential and obviously would not be wise to state just how. George Kennan, the well-known student of Russian affairs, now has it in his possession and is engaged in translating and arranging material taken from it for magazine publication. A series of five or six articles, constructed from Kuropatkin’s 600,000 words, will be issued in McClure’s, beginning next month. These will contain astonishing revelations concerning matters of great international importance, and accusations that are audacious to the point of recklessness.

Remarkable among these are the letters to the Czar. Kuropatkin’s correspondence with him is given in detail, documents which naturally would not appear within fifty or a hundred years from the time when they were written. And upon the letters and reports of the General appear the comments and marginal notes of the Emperor. The war was forced against the will of the sovereign and the advice of the War Department. It was ended, Kuropatkin shows, when Russia was just beginning to discipline and dispose her great forces, because of the lack of courage and firmness in the Czar.

Japan certainly would have been crushed, says Kuropatkin, if war had continued. At the time of the Treaty at Portsmouth, the military struggle, from Russia’s standpoint, had only begun. She was then receiving ammunition and supplies properly for the first time; her men were becoming disciplined soldiers; and the railroad, whose service had increased from three to fourteen military trains a day, had now, at last, brought the Russian forces into the distant field. For the first time, just when treaty negotiations were begun, Russia had more soldiers in her army than Japan. There were a million men, well equipped and abundantly supplied, under General Linevitch, who succeeded General Kuropatkin as Commander-in-Chief; and he was about to take the offensive when peace was declared.

Beyond the individual conflict General Kuropatkin shows the Russian nation, a huge, unformed giant, groping along its great borders in every direction to find the sea.

“Can an Empire,” he asks, “with such a tremendous population, be satisfied with its existing frontiers, cut off from free access to the sea on all sides?”

There are in existence in the secret archives of the government, Kuropatkin’s work discloses, documents containing the definite program of Russia, fixed by headquarters years ago, for its future growth and aggrandizement. Results of campaigns and diplomacy are checked up according to this great program, and decade after decade Russia is working secretly and quietly to carry it out. The Japanese War constituted a great mistake in the development of this national plan.

During the twentieth century, says Kuropatkin, Russia will lose no fewer than two million men in war, and will place in the field not fewer than five million. No matter how peaceful and purely defensive her attitude may be, she will be forced into war along her endless borders by the conflict with other national interests and the age-long unsatisfied necessity of her population to reach the sea.

Russia will furnish in this century the advance guard of an inevitable conflict between the white and yellow races. For within a hundred years there must be a great struggle in Asia between the Christian and non-Christian nations. To prepare for this, an understanding between Russia and England is essential for humanity. Kuropatkin deals with this necessity at length; and the future relations of Russia with Japan and China are treated with an impressive grasp.

His exposition of the sensitive and dangerous situation on the Empire’s western border contains matters of consequence to the whole world. The relations he discloses, between Russia, on the one hand, and Austria and Germany on the other, are important in the extreme. Within a fortnight these two latter countries could throw two million men across the Russian frontier, and a war would result much more colossal than that just finished with Japan.

General Kuropatkin has had an education and a career which eminently qualify him as a judge and critic of the Russian nation. For forty years, as an active member of its military establishment, he has watched its development, from the viewpoint of important posts in St. Petersburg, Turkey, Central Asia, and the far East.

Kuropatkin was born in 1848 and was educated in the Palovski Military School and the Nikolaiefski Academy of the general staff in St. Petersburg. From there he went at once into the army, and, at the early age of twenty, took part in the march of the Russian expeditionary force to the central Asian city of Samarkand. He won 366 distinction in the long and difficult march of General Skobeleff’s army to Khokand. In 1875 he acted as Russia’s diplomatic agent in Chitral, and a year or two later he headed an embassy to Kashgar and concluded a treaty with Yakub Bek.

When the Russo-Turkish War broke out in 1877, he became General Skobeleff’s chief of staff and took part in the battle of Loftcha and in many of the attacks on Plevna. While forcing the passage of the Balkans with Skobeleff’s army, on the 25th of December, 1877 (O.S.), he was so severely wounded that he had to leave the theater of war and return to St. Petersburg. There, as soon as he recovered, he was put in charge of the Asiatic Department of the Russian General Staff, and, at the same time, was made adjunct-professor of military statistics in the Nikolaiefski Military Academy. In 1879 the rank of General was conferred upon him and he was appointed to command the Turkestan rifle brigade in Central Asia. In 1880 he led a Russian expeditionary force to Kuldja, and when the trouble with the Chinese there had been adjusted, he was ordered to organize and equip a special force in the Amu Daria district and march to the assistance of General Skobeleff in the Akhal-Tekhinski oasis. After conducting this force across seven hundred versts of nearly waterless desert, he joined General Skobeleff in front of the Turkoman fortress of Geok Tepe, and in the assault upon that famous stronghold, a few weeks later, he led the principal storming column. After the Turkomen had been subdued, he returned to European Russia, and during the next eight years served on the General Staff in St. Petersburg, where he was entrusted with important strategic work. In 1890 he was made Lieutenant-General and was sent to govern the trans-Caspian region and to command the troops there stationed.

He occupied this position six or eight years, and then, shortly after his return to St. Petersburg, was appointed Minister of War. In 1902, while still holding the war portfolio, he was promoted to Adjutant-General; in 1903 he visited Japan and made the acquaintance of its political and military leaders; and in 1904, when hostilities began in the Far East, he took command of the Russian armies in Manchuria under the general direction of Viceroy Alexeieff. Besides, he has written and published three important books.

No man perhaps, is better equipped, by education and experience, to explain Russia’s plans and movements in Asia; to tell the true story of the Japanese war. And probably never, at least in this generation, has an international matter of this magnitude been treated with such frankness by a person so thoroughly and eminently qualified to discuss it.

BY

CARL SCHURZ

ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS

In the autumn of 1867 my family went to Wiesbaden, where my wife was to spend some time on account of her health, and I joined them there about Christmas time for a few weeks. Great changes had taken place in Germany since that dark December night in 1861 when I rushed through the country from the Belgian frontier to Hamburg on my way from Spain to America. The period of stupid reaction after the collapse of the revolutionary movements of 1848 was over. King Frederick William IV. of Prussia, who had been so deeply convinced and arduous an upholder of the divine right of kings, had died a helpless lunatic. King William I., afterwards Emperor William I., his brother and successor, also a believer in that divine right, but not to the extent of believing as well in the divine inspiration of kings—in other words, a man of good sense and capable of recognizing the superior ability of others—had found in Bismarck a minister of commanding genius. The sweeping victory of Prussia over Austria in 1866 had resulted in the establishment of the North German Confederacy under Prussian hegemony, which was considered a stepping-stone to the unification of all Germany as a constitutional empire. Several of the revolutionists of 1848 now sat in the Reichstag of the North German Confederacy, and one of the ablest of them, Lothar Bucher, was Bismarck’s confidential counsellor. The nation was elated with hope, and there was a liberal wind blowing even in the sphere of the government.

I did not doubt that under these circumstances I might venture into Germany without danger of being seriously molested; yet, as my personal case was technically not covered by any of the several amnesties which had been proclaimed in Prussia from time to time, I thought that some subordinate officer, either construing his duty with the strictness of a thorough Prussian, or wishing to distinguish himself by a conspicuous display of official watchfulness, might give me annoyance. I did not, indeed, entertain the slightest apprehension as to my safety, but I might have become involved in sensational proceedings, which would have been extremely distasteful to me, as well as unwelcome to the government. I therefore wrote to Mr. George Bancroft, the American Minister at Berlin, requesting him if possible to inform himself privately whether the Prussian government had any objection to my visiting Germany for a few weeks, and to let me have his answer at Bremerhaven upon the arrival there of the steamer on which I had taken passage. My intention was, in case the answer were unfavorable, to sail at once from Bremen to England and to meet my family there. Mr. Bancroft very kindly complied with my request, and assured me in his letter which I found at Bremerhaven that the Prussian government not only had no objection to my visiting Germany, but that I should be welcome.

After having spent Christmas with my family in Wiesbaden, I went to Berlin. I wrote a note to Lothar Bucher, whom I had last seen sixteen 368 years before as a fellow refugee in London, and whom I wished very much to meet again. Bucher answered promptly that he would be glad indeed to see me again, and asked if I would not like to make the acquaintance of “the Minister” (Bismarck), who had expressed a wish to have a talk with me. I replied, of course, that I should be happy, etc., whereupon I received within an hour an invitation from Count Bismarck himself (he was then only a count) to visit him at eight o’clock that same evening at the Chancellor’s palace on the Wilhelmstrasse. Promptly at the appointed hour I was announced to him, and he received me at the door of a room of moderate size, the table and some of the furniture of which were covered with books and papers,—evidently his working cabinet. There I beheld the great man whose name was filling the world—tall, erect, and broad-shouldered, and on those Atlas shoulders that massive head which everybody knows from pictures—the whole figure making the impression of something colossal—then at the age of fifty-three, in the fulness of physical and mental vigor.

He was dressed in a General’s undress uniform, unbuttoned. His features, which evidently could look very stern when he wished, were lighted up with a friendly smile. He stretched out his hand and gave me a vigorous grasp. “Glad you have come,” he said, in a voice which appeared rather high-keyed, issuing from so huge a form, but of pleasing timbre.

“I think I must have seen you before,” was his first remark, while we were still standing up facing one another. “It was some time in the early fifties on a railway train from Frankfort to Berlin. There was a young man sitting opposite me who, from some picture of you which I had seen in a pictorial paper, I thought might be you.”

I replied that this could not be, since at that period I was not in Germany. “Besides,” I added—a little impudently perhaps—“would you not have had me arrested as a malefactor?”

“Oh,” he exclaimed, with a good, natural laugh, “you mistake me. I would not have done such a thing. You mean on account of that Kinkel affair? Oh, no! I rather liked that. And if it were not that it would be highly improper for His Majesty’s minister and the Chancellor of the North German Confederacy, I should like to go with you to Spandau and have you tell me the whole story on the spot. Now let us sit down.”

He pointed out to me an easy-chair close to his own and then uncorked a bottle which stood, with two glasses, on a tray at his elbow. “You are a Rhinelander,” he said, “and I know you will relish this.” We touched glasses, and I found the wine indeed very excellent.

“You smoke, of course,” he continued, “and here are some good Havanas. I used to be very fond of them, but I have a sort of superstitious belief that every person is permitted to smoke only a certain number of cigars in his life, and no more. I am afraid I have exhausted my allowance, and now I take to the pipe.” With a lighted strip of paper, called in German “Fidibus,” he put the tobacco in the porcelain bowl of his long German student pipe in full blast, and presently he blew forth huge clouds of smoke.

This done, he comfortably leaned back in his chair and said: “Now tell me, as an American Republican and a Forty-eighter of the revolutionary kind, how the present condition of Germany strikes you. I would not ask you that question,” he added, “if you were a privy counsellor (a Geheimrath), for I know what he would answer. But you will tell me what you really think.”

I replied that I had been in the country only a few weeks and had received only superficial impressions, but that I had become sensible of a general atmosphere of newly inspired national ambition and a confident hope for the development of more liberal political institutions. I had found only a few old fogies in Nassau and a banker in Frankfort who seemed to be in a disappointed and depressed state of mind. Bismarck laughed heartily. The disgruntled Nassauers, he said, had probably been some sort of purveyors to the late ducal court, and he would wager that the Frankfort banker was either a member of one of the old patrician families, who thought they were the highest nobility in all the land, or a money-maker complaining that Frankfort was no longer, as it had been, the financial center of southern Germany. Here Bismarck gave full reign to his sarcastic humor. He had spent years in Frankfort as the representative of the defunct “Bundestag,” and had no end of funny anecdotes about the aristocratic pretensions of the patrician burghers of that ancient free city, and about their lofty wrath at the incorporation of that commonwealth in the Prussian monarchy.

Then he began to tell me about the great difficulties he had been obliged to overcome in bringing about the decisive struggle with Austria. One of the most serious of these difficulties, as 369 he said, consisted in the scrupulous hesitancy of old King William to consent to anything that seemed to be in any sense unconstitutional or not in harmony with the strictest notion of good faith. In our conversation Bismarck constantly called the king “der alte Herr”—“the old gentleman,” or, as it might also have been translated, “the old master.” One moment he would speak of the old gentleman with something like sentimental tenderness, and then again in a tone of familiar freedom which smacked of anything but reverential respect. He told me anecdotes about him which made me stare, for at the moment I could not help remembering that I was listening to the prime minister of the crown, to whom I was an entire stranger and who knew nothing of my discretion or sense of responsibility.

As if we had been confidential chums all our lives, he gave me, with apparently the completest abandon and exuberant vivacity, inside views of the famous “conflict” period between the crown and the Prussian parliament, when, seeing the war with Austria inevitably coming, he had, without legislative authorization, spent millions upon millions of the public funds upon 370 the army in preparation for the great crisis; how the liberal majority of the chambers, and an indignant public opinion which did not recognize the great object of national unification in view, had fiercely risen up against that arbitrary stretch of power; how the king himself had recoiled from such a breach of the constitution; how the king had apprehended a new revolution which might cost each of them his head—which would possibly have come about if they had failed in the Austrian war; how then he had “desperately used his spurs to make the noble old horse clear the ditch and take the risk”; and how, the victory having been won, on their return from the war they were received by the people with the most jubilant acclamations instead of having their heads cut off, which had pleased the old gentleman immensely and taught him a lesson as to his reckless prime minister.

It was not the cautious and conservative spirit of the king alone that he had occasionally to overcome. Still more was he clogged and not seldom exasperated by what he called the stupid old bureaucracy, which had to be got out of its accustomed ruts whenever anything new and bold was to be done. He fairly bubbled over with humorous anecdotes, evidently relishing, himself, his droll descriptions of the antiquated “Geheimrath” (privy counsellor), as he stared with his bleared eyes wide open, whenever anything unusual was proposed, seeing nothing but insuperable difficulties before him and then exhausting his whole ingenuity in finding the best sort of red tape with which to strangle the project. His patience tried to the utmost, he, the minister would then go to the king and tell him that such and such a rusty official could no longer be got along with and must necessarily give place to a more efficient person; whereupon the “old gentleman,” melting with pity, would say, “Oh, he has so long been a faithful servant of the State, would it not be cruel to cast him aside like a squeezed-out orange?—no, I cannot do it.” “And there,” said Bismarck, “there we are.”

I ventured to suggest that an offer to resign on his part, if he could not have his way, might make the king less tender of his inefficient friends in high places. “Oh,” said Bismarck with a laugh, “I have tried that so often, too often, perhaps, to make it impressive! What do you think happens when I offer my resignation? My old gentleman begins to sob and cry—he actually sheds tears, and says, ‘Now you want to leave me too?’ Now when I see him shed tears, what in the world can I do then?” So he went on for a while, from one funny anecdote to another and from one satirical description to another.

Bismarck then came back to the Austrian war and told me much about the diplomatic fencing which led up to it. With evident gusto he related story after story, showing how his diplomatic adversaries at that critical period had been like puppets in his hands, and how he had managed the German princes as they grouped themselves on one side or the other. Then he came to speak of the battle of Königgrätz, and especially of that “anxious moment” in it before the arrival of the Crown Prince in the rear of the Austrians, when some Prussian attacks had failed and there were signs of disorder among the repulsed troops.

“It was an anxious moment,” said Bismarck, “a moment on the decision of which the fate of empire depended. What would have become of us if we had lost that battle? Squadrons of cavalry, all mixed up, hussars, dragoons, uhlans, were streaming by the spot where the king, Moltke, and myself stood, and although we had calculated that the Crown Prince might long have appeared behind the Austrian rear, no sign of the Crown Prince! Things began to look ominous. I confess I felt not a little nervous. I looked at Moltke, who sat quietly on his horse and did not seem to be disturbed by what was going on around us. I thought I would test whether he was really as calm as he appeared. I rode up to him and asked him whether I might offer him a cigar, since I noticed he was not smoking. He replied that he would be glad if I had one to spare. I presented to him my open case in which there were only two cigars, one a very good Havana, and the other of rather poor quality. Moltke looked at them and even handled them with great attention, in order to ascertain their relative value, and then with slow deliberation chose the Havana. ‘Very good,’ he said composedly. This reassured me very much. I thought, If Moltke can bestow so much time and attention upon the choice between two cigars, things cannot be very bad. Indeed, a few minutes later we heard the Crown Prince’s guns, we observed unsteady and confused movements on the Austrian positions, and the battle was won.”

I said that we in America who had followed the course of events with intense interest were rather surprised, at the time, that the conclusion of peace followed the battle of Königgrätz so quickly and that Prussia did not take greater advantage of her victory. Bismarck replied that the speedy conclusion of peace had been a great surprise to many people, but that he thought it was the best thing he had ever done, 371 and that he had accomplished it against the desire of the king and of the military party, who were greatly elated by that splendid triumph of the Prussian arms and thought that so great and so successful an effort should have a greater reward. Sound statesmanship required that the Austrian Empire, the existence of which was necessary for Europe, should not be reduced to a mere wreck; that it should be made a friend and, as a friend, not too powerless; that what Prussia had gone to war for was the leadership of Germany, and that this leadership in Germany would not have been fortified, but rather weakened, by the acquisition from Austria of populations which would not have fitted into the Prussian scheme.

Besides, the Chancellor thought that, the success of the Prussians having been so decisive, it was wise to avoid further sacrifices and risks. The cholera had made its appearance among the troops, and so long as the war lasted there would have been danger of French intervention. He had successfully fought off that French intervention, he said, by all sorts of diplomatic manœuvres, some of which he narrated to me in detail. But Louis Napoleon had become very restless at the growth of Prussian power and prestige, and he would, probably, not have hesitated to put in his hand, had not the French army been so weakened by his foolish Mexican adventure. But now, when the main Prussian army was marching farther and farther away from the Rhine and had suffered serious losses, and was threatened by malignant disease, he might have felt encouraged by these circumstances to do what he would have liked to do all the time.

“That would have created a new situation,” said Bismarck. “But to meet that situation, I should have had a shot in my locker which, perhaps, will surprise you when I mention it.”

I was indeed curious. “What would have been the effect,” said Bismarck, “if under those circumstances I had appealed to the national feeling of the whole people by proclaiming the constitution of the German Empire made at Frankfort in 1848 and 1849?”

“I think it would have electrified the whole country and created a German nation,” I replied. “But would you really have adopted that great orphan left by the revolution of 1848?”

“Why not?” said the Chancellor. “True, that constitution contained some features very objectionable to me. But, after all, it was not so very far from what I am aiming at now. But whether the old gentleman would have adopted it is doubtful. Still, with Napoleon at the gates, he might have taken that jump too. But,” he added, “we shall have that war with France anyhow.”

I expressed my surprise at this prediction,—a prediction all the more surprising to me when I again recalled that the great statesman, carrying on his shoulders such tremendous responsibilities, was talking to an entire stranger,—and his tone grew quite serious, grave, almost solemn, as he said: “Do not believe that I love war. I have seen enough of war to abhor it profoundly. The terrible scenes I have witnessed will never cease to haunt my mind. I shall never consent to a war that is avoidable, much less seek it. But this war with France will surely come. It will be forced upon us by the French Emperor. I see that clearly.”

Then he went on to explain how the situation of an “adventurer on a throne,” such as Louis Napoleon, was different from that of a legitimate sovereign, like the King of Prussia. “I know,” said he with a smile, “you do not believe in such a thing as the divine right of kings. But many people do, especially in Prussia—perhaps not as many as did before 1848, but even now more than you think. People are attracted to the dynasty by traditional loyalty. A King of Prussia may make mistakes or suffer misfortunes, or even humiliations, but that traditional loyalty will not give way. But the adventurer on the throne has no such traditional sentiment behind him. His security depends upon personal prestige, and that prestige upon sensational effects which must follow one another in rather rapid succession to remain fresh and satisfactory to the ambition, or the pride, or, if you will, the vanity of the people—especially to such a people as the French.

“Now, Louis Napoleon has lost much of his prestige by two things—the Mexican adventure, which was an astounding blunder, a fantastic folly on his part; and then by permitting Prussia to become so great without obtaining some sort of ‘compensation’ in the way of an acquisition of territory that might have been made to appear to the French people as a brilliant achievement of his diplomacy. It was well known that he wanted such a compensation, and tried for it, and was manœuvered out of it by me without his knowledge of what was happening to him. He is well aware that thus he has lost much of his prestige, more than he can afford, and that such a loss, unless soon repaired, may become dangerous to his tenure as emperor. He will, therefore, as soon as he thinks that his army is in good fighting condition, again make an effort to recover that prestige which is so vital to him, by using some pretext 372 for picking a quarrel with us. I do not think he is personally eager for that war, I think he would rather avoid it, but the precariousness of his situation will drive him to it. My calculation is that the crisis will come in about two years. We have to be ready, of course, and we are. We shall win, and the result will be just the contrary of what Napoleon aims at—the total unification of Germany outside of Austria, and probably Napoleon’s downfall.”

PRINCE OTTO VON BISMARCK

FROM THE PAINTING BY FRANZ VON LENBACH

Photographed by the Berlin Photographic Co.

This was said in January, 1868. The war between France and Prussia and her allies broke out in July, 1870, and the foundation of the German Empire and the downfall of Napoleon 373 were the results. No prediction was ever more shrewdly made and more accurately and amply fulfilled.

COUNT HELLMUTH VON MOLTKE

FROM THE PAINTING BY FRANZ VON LENBACH

Photographed by the Berlin Photographic Co.

I have introduced here Bismarck as speaking in the first person. I did this to present the substance of what he said to me in a succinct form. But this does not pretend to portray the manner in which he said it—the bubbling vivacity of his talk, now and then interspersed with French or English phrases; the lightning flashes of his wit scintillating around the subjects of his remarks and sometimes illuminating, as with a search-light, a public character, or an event, or a situation; his laugh, now contageously 374 genial, and then grimly sarcastic; the rapid transitions from jovial, sportive humor to touching pathos; the evident pleasure taken by the narrator in his tale; the dashing, rattling rapidity with which that tale would at times rush on; and behind all this that tremendous personality—the picturesque embodiment of a power greater than any king’s—a veritable Atlas carrying upon his shoulders the destinies of a great nation. There was a strange fascination in the presence of the giant who appeared so peculiarly grand and yet so human.

THE CHANCELLOR’S PALACE ON THE WILHELMSTRASSE WHERE CARL SCHURZ VISITED BISMARCK IN 1878.

Photographed by the Berlin Photographic Co.

While he was still speaking with unabated animation I looked at the clock opposite me and was astounded when I found that midnight was long behind us. I rose in alarm and begged the Chancellor’s pardon for having intruded so long upon his time. “Oh,” said the Chancellor, “I am used to late hours, and we have not talked yet about America. However, you have a right to be tired. But you must come again. You must dine with me. Can you do so to-morrow? I have invited a commission on the Penal Code—mostly dull old jurists, I suppose—but I may find some one among them fit to be your neighbor at the table and to entertain you.”

I gladly accepted the invitation and found myself the next evening in a large company of serious and learned-looking gentlemen, each one of whom was adorned with one or more decorations. I was the only person in the room who had none, and several of the guests seemed to eye me with some curiosity, when Bismarck in a loud voice presented me to the Countess as “General Carl Schurz from the United States of America.” Some of the gentlemen looked somewhat surprised, but I at once became a person of interest, and many introductions followed. At the table I had a judge from Cologne for my neighbor, who had enough of the Rhenish temperament to be cheerful company. The dinner was a very rapid affair—lasting hardly three quarters of an hour, certainly not more.

THE BATTLE OF KÖNIGGRÄTZ—FROM THE PAINTING BY GEORG BLEISTREW

THE DECISIVE BATTLE OF THE SEVEN WEEKS’ WAR, BY WHICH PRUSSIA BECAME THE LEADING POLITICAL AND MILITARY POWER IN GERMANY. IN THE CENTER OF THE PICTURE IS SHOWN KING WILLIAM, SURROUNDED BY BISMARCK, VON MOLTKE, AND THE MEMBERS OF HIS STAFF.

Photographed by the Berlin Photographic Co.

Before the smokers could have got half through with their cigars, the Minister of Justice, who seemed to act as mentor and guide to the gentlemen of the Penal Code Commission, took leave of the host, which was accepted by the whole company as a signal to depart. I followed 376 their example, but the Chancellor said: “Wait a moment. Why should you stand in that crowd struggling for your overcoat? Let us sit down and have a glass of Apollinaris.” We sat down by a small round table, a bottle of Apollinaris water was brought, and he began at once to ply me with questions about America.

EMPEROR NAPOLEON III

WHOM BISMARCK CALLED “THE ADVENTURER ON THE THRONE,” AND WHOSE DOWNFALL HE PREDICTED IN A CONVERSATION WITH CARL SCHURZ TWO YEARS BEFORE SEDAN

He was greatly interested in the struggle going on between President Johnson and the Republican majority in Congress, which was then approaching its final crisis. He said that he looked upon that struggle as a test of the strength of the conservative element in our political fabric. Would the impeachment of the President, and, if he were found guilty, his deposition from office, lead to any further conflicts dangerous to the public peace and order? I replied that I was convinced it would not; the executive power would simply pass from the hands of one man to the hands of another, according to the constitution and laws of the country, without any resistance on the part of anybody; and on the other hand, if President Johnson were acquitted, there would be general submission to the verdict as a matter of course, although popular excitement stirred up by the matter would run very high throughout the country.

The Chancellor was too polite to tell me point-blank that he had grave doubts as to all this, but he would at least not let me believe that he thought as I did. He smilingly asked me whether I was still as firmly convinced a republican as I had been before I went to America and studied republicanism from the inside; and when I assured him that I was, and that, 377 although I had in personal experience found the republic not as lovely as my youthful enthusiasm had pictured it to my imagination, but much more practical in its general beneficence to the great masses of the people, and much more conservative in its tendencies than I had imagined, he said that he supposed our impressions or views with regard to such things were largely owing to temperament, or education, or traditional ways of thinking.

“I am not a democrat,” he went on, “and cannot be. I was born an aristocrat and brought up an aristocrat. To tell you the truth, there was something in me that made me instinctively sympathize with the slaveholders, as the aristocratic party, in your Civil War. But,” he added with earnest emphasis, “this vague sympathy did not in the least affect my views as to the policy to be followed by our government with regard to the United States. Prussia, notwithstanding her monarchical and aristocratic sympathies, is, and will steadily be by tradition, as well as by thoroughly understood interest, the firm friend of your republic. You may always count upon that.”

He asked me a great many questions concerning the political and social conditions in the United States. Again and again he wondered how society could be kept in tolerable order where the powers of the government were so narrowly restricted and where there was so little reverence for the constituted or “ordained” authorities. With a hearty laugh, in which there seemed to be a suggestion of assent, he received my remark that the American people would hardly have become the self-reliant, energetic, progressive people they were, had there been a privy-counsellor or a police captain standing at every mud-puddle in America to keep people from stepping into it. And he seemed to be much struck when I brought out the apparent paradox that in a democracy with little government things might go badly in detail but well on the whole, while in a monarchy with much and omni-present government things might go very pleasingly in detail but poorly on the whole. He saw that with such views I was an incurable democrat; but would not, he asked, the real test of our democratic institutions come when, after the disappearance of the exceptional opportunities springing from our wonderful natural resources which were in a certain sense common property, our political struggles became, as they surely would become, struggles between the poor and the rich, between the few who have, and the many who want? Here we entered upon a wide field of conjecture.

The conversation then turned to international relations, and especially public opinion in America concerning Germany. Did the Americans sympathize with German endeavors towards national unity?—I thought that so far as any feeling with regard to German unity existed in America, it was sympathetic; among the German-Americans it was warmly so.—Did Louis Napoleon, the emperor of the French, enjoy any popularity in America?—He did not enjoy the respect of the people at large and was rather unpopular except with a comparatively small number of snobs who would feel themselves exalted by an introduction at his court.—There would, then, in case of a war between Germany and France, be no likelihood of American sympathy running in favor of Louis Napoleon?—There would not, unless Germany forced war on France for decidedly unjust cause.

Throughout our conversation Bismarck repeatedly expressed his pleasure at the friendly relations existing between him and the German Liberals, some of whom had been prominent in the revolutionary troubles of 1848. He mentioned several of my old friends, Bucher, Kapp, and others, who, having returned to Germany, felt themselves quite at home under the new conditions and had found their way open to public positions and activities of distinction and influence, in harmony with their principles. As he repeated this, or something like it, in a manner apt to command my attention, I might have taken it as a suggestion inviting me to do likewise. But I thought it best not to say anything in response.

Our conversation had throughout been so animated that time had slipped by us unaware, and it was again long past midnight when I left. My old friends of 1848 whom I met in Berlin were of course very curious to know what the great man of the time might have had to say to me, and I thought I could without being indiscreet communicate to them how highly pleased he had expressed himself with the harmonious coöperation between him and them for common ends. Some of them thought that Bismarck’s conversion to liberal principles was really sincere. Others were less sanguine, believing as they did that he was indeed sincere and earnest in his endeavor to create a united German empire under Prussian leadership; that he would carry on a gay flirtation with the Liberals so long as he thought that he could thus best further his object, but that his true autocratic nature would assert itself again and he would throw his temporarily assumed Liberalism overboard as soon as he felt that he did not need its support any longer, and especially when he found it to stand in the way of his will.

BY

MARGARET WILSON

ILLUSTRATIONS BY A. E. CEDERQUIST

“Perhaps I’m too old to be wearing such things, but I love bright colors, and there’s not a bit of use denying it.”

Mary Ann gathered one end of the fancy tartan into a handful, and looked approvingly at its soft, heavy folds.

“Particularly at this time of year. It’s warming to the blood on a cold autumn day just to see a dress like this on the street. I always did like a good rich tartan. It becomes me, too. Look, Selina’n’Jane.”

She held the dress material against one cheek, and her sisters looked—but somehow failed to see what a pleasing picture she made. She had just come in from shopping and had not yet removed her hat, and its trimming of foliage repeated the colors of her face—autumnal tints of red and bronze and healthy yellow. She, the eldest of the family and the only unmarried one, was forty-five, but she was rosy and fat and matronly, while her sisters were pinched and anemic. They were old maids by nature, she by chance.

“It becomes you well enough, but under the circumstances,” Jane said, exchanging glances with Selina, “it seems a pity to buy all these things.”

Mary Ann opened her eyes wide.

“Circumstances? What circumstances? It’s no more than I buy every fall,” protested the puzzled Mary Ann. “The flowered piece is for a morning wrapper, the tartan’s for a street suit, and the blue-gray’s a company dress.”

Jane and Selina again exchanged glances, and Selina nodded.

“You never did seem to look ahead, Mary Ann,” said Jane, thus encouraged. “I don’t believe you realize that an attack of bronchitis is serious at Ma’s age. I wouldn’t have got all my clothes colored. It’s never any harm to have one black dress.”

Mary Ann gasped.

“Good gracious!” was all she said.

“Well, Mary Ann,” said Selina, coming to Jane’s rescue, “there’s not a particle of use shutting your eyes to plain facts. Ma’s in a serious condition, and if anything happens to her, what’ll you do with all that stuff? You may dye the blue, but that tartan won’t take a good black.”

“Why,” Mary Ann said, recovering speech, “Ma has bronchitis at the beginning of cold weather every year. She’ll be downstairs in a week or two, the same as she always is.”

“I hope so, Mary Ann. I hope, when next she comes down, it won’t be feet first. But we’re told to prepare for the worst while we hope for the best,” said Jane solemnly, imagining that she was quoting scripture. “You and Ma act as if there was nothing to prepare for. To see you, sitting by her sick-bed, reading trashy love-stories out of the magazines, and both of you as much interested!—it gives me a creepy feeling.”

“When my poor husband lay in his last illness,” sighed Selina, “he was only too willing to be flattered into the belief that he was going to get well, but I wouldn’t let him deceive himself, and it’s a comfort to me now I didn’t. I had everything ready but my crape when he died. I didn’t have to depend on the neighbors for a dress for the funeral, as I’ve known some do.”

“Many a time I’ve lent, but never borrowed,” Jane boasted.

“And of course, never laying off widow’s weeds, I’m ready for whatever comes.” Selina stroked her tarletan cuffs complacently, yet modestly withal, as if not wishing to make others feel too keenly the difference in their position.

Mary Ann gathered the dress goods together and threw them in a heap on the sofa. “There, I’m sorry I showed them to you,” she cried; “you’ve got me almost turned against them. 380 I declare, I’d be melancholy in two minutes more. Now you listen to me, Selina’n’Jane. There’s no need to worry about Ma’s preparations for the next world; she’s not thinking of leaving this world yet, and there’s no reason why she should. The day you two go away, she’ll be standing at the gate to say good-by to you, just the same as she always is. You see if she’s not, Selina’n’Jane.”

She left the room with something as like a flounce as her figure would permit. Stealing softly into the half-darkened bedroom at the head of the stairs, she stood looking down at the sleeping woman in the bed. The indignant moisture in her eyes turned to a mist of tenderness that blotted out the sight until a few drops formed and fell.

She was too unsuspicious to observe an unsleeplike flickering of the eyelids. She turned to tiptoe out of the room again. There was a quick peep, a look of relief, a husky whisper, “Is that you, Mary Ann?”

“Well now, I never did see anything like the regular way you wake up at medicine time,” Mary Ann said, opening the shutters and consulting her watch. “Anybody’d think you had an alarm inside of you to go off at the right time.”

She administered the dose and then went on with a cheerful monologue. She had got into this habit in the sick-room, because her mother hated silence and had to save her own voice.

“What kept me so long was that everybody I met wanted to stop me and ask how you were. Everybody seemed pleased to hear you were getting along so nicely. Mrs. Dowling said Dr. Corbett told her you were the most satisfactory patient he had, because you always did everything he told you and always got well.”

The sick woman smiled up at her. She had a smile that came and went easily, and Mary Ann had become skilful in the art of conducting a conversation in such a way that it served as well as words.

“And Caroline Sibbet said to tell you she was counting on going with us to the reception to the minister, and she didn’t believe she’d go at all unless you were well by then.”

It was a wistful smile now.

“So I told her she needn’t be afraid, you’d be there.”

A smile of appeal, as if to ask, “Do you really think so?”

Mary Ann gave her a puzzled glance. Something was wrong.

“Of course you’ll be well by then, dearie. You heard what the doctor said to-day—that you might go back to having your cup of tea again to-morrow. That’s always the first sign you’re getting well, then you get leave to sit up. A week sitting up in your room, a week going downstairs——” Mary Ann began to check off the weeks on her fingers, but her mother interrupted.

“Was that Jane the doctor was talking to so long in the hall to-day?”

“Let me see. No, that was Selina.”

“What was he saying to her?”

“He was saying every blessed thing that he’s said to me since you took sick, and that I’ve repeated over again to her. But you know how it is with those two, Ma. I believe they think there’s some kind of magic in the marriage ceremony that gives a woman sense—they don’t give me credit for a speck. When Selina told me she was going to speak to the doctor herself to-day, says she, ‘You know that it stands to reason, Mary Ann, that you can’t be as experienced as one that has been a wife five years and a widow seven’; and then Jane seemed to think it was being cast up to her that she wasn’t a widow, so she speaks up real snappy, ‘Nor one that’s brought up a family of four boys,’ and then Selina she looked mad.” Mary Ann went off into a peal of laughter at the remembrance.

“Jane told me he said at my age the heart was weak and there was always more or less danger.”

“He always says that after he’s told what good sound lungs you have, and what steady progress you’re making, and how he’d rather pass you for insurance than most women half your age. It means we’re not to be too reckless, all the same.”

“She says if I should recover from this attack——”

“Sakes alive! Did she come over all that with you too? ‘If you should recover from this attack, you’d better sell the house and visit round among your married children?’ Visit round as much as you like, Ma, but have a house of your own to come back to; that’s my advice.”

“She said you wouldn’t want to keep up a house after you were left alone——”

Mary Ann threw up her hands. “No wonder Selina’n’Jane are thin—they wear the flesh off their bones providing for the future. They’re born Colquhouns. I’m glad I take after your side of the family. Do you know what Selina told me, Ma? The preserves she put up this year won’t have to be touched till winter after next. She has enough to last her over two years. ‘Land sakes!’ I said, ‘what do you want to eat stale jam for, when you might have fresh?’ The two get competing which will be furthest ahead in their work; from the way 381 they talk, I shouldn’t wonder if before long their fall house-cleaning would be done in the spring. It makes me think of what Pa used to tell about his uncle Alick Colquhoun—how he was earlier and earlier with the milking, till at last the evening milking was done in the morning, and the morning’s was done the night before. Then there was Eva Meldrum; you remember she had all her marriage outfit ready before she was asked—sheets, tablecloths, and everything. As soon as Fred Healey proposed, she got right to work with the final preparations, and when she found herself left with nothing else to do—she just sat down and wrote out notes of thanks for the wedding gifts, leaving blanks for the names of the articles. I laughed till I was sore when she told me. ‘You’re a Colquhoun,’ I said, ‘though you do only get it from your grandma; you’re a Colquhoun by nature if not by name.’ You know I always say it comes from having such a name. It’s enough to make an anxious streak in the family, having to spell it, one generation after another.”

Mary Ann laughed so heartily that the sound reached her sisters, who wondered what “Ma’n’Mary Ann” were at now. And still the little cloud lingered, and the smile only flitted waveringly.

“I called at the library, Ma, and brought home the magazine. Now we’ll find out for sure whether Lady Geraldine marries the earl—I don’t believe but what she’s in love with the private secretary.”

“Did you do the shopping?” her mother whispered.

“Yes, and if you feel rested with your sleep, I’ll show you what I got. Mr. Merrill opened out such a heap of pretty things, I didn’t hardly know what to take. I was thinking, Ma, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to have Miss Adams in to sew, the first week you’re downstairs, when we’ve got to be in the house anyway.”

At this moment Jane and Selina came into the room to see what the sounds of merriment meant. They looked at patient and nurse with disapproving gloom. Jane settled herself at once to her knitting; Selina, who never worked in the afternoon when she was wearing her widow’s collar and cuffs, sat regarding her mother with an expression of grieved wonder. Mrs. Colquhoun was uncomfortably conscious of being judged by something in her own child of other heritage than hers—one of the strangest sensations a parent can have.

“You’d ought to be kept quiet, Ma,” Selina said, after a prolonged scrutiny. “If you had any suitable book in the house, I’d read to you. There was one my poor husband used to listen to by the hour in his last illness—‘Preparations for the Final Journey.’”

“I’m going to run down and fetch that stuff I bought to-day to show it to Ma and get her opinion,” Mary Ann interrupted, and a minute later she was standing by the bed with the three dress lengths piled in confusion upon her arms. To the woman in the bed it was as if an angel looked out from over a tumbled rainbow and smiled a message of hope to her from the sky.

“Take an end of this tartan, will you, Jane, and stand off a little with it. There, I knew you’d like it, Ma. I said so to Mr. Merrill the minute he showed it to me. That flowered piece? That’s for a morning wrapper. I know it’s gay, but somehow, after the flowers are all over, I do hanker after gay colors. In summer I don’t feel to want them so much on my back when I can have them in the garden. The gray-blue’s for a company dress. I’ll have it made up in time for the reception to the new minister. You’ll need a dress for that too, Ma. We’ll get samples as soon as you’re well enough to choose. It was between this and a shot silk, but I thought this was more becoming at my age. To tell the truth,” confessed Mary Ann with a laugh, “I’d rather have had it than this, and more than either I’d love to have bought a dress off a piece of crimson velvet Mr. Merrill had just got in.”

She rested an elbow on her knee and sank the length of a forefinger in her plump cheek.

“When I was a little girl,” she ruminated, “I was awfully fond of the rose-in-campin’ that grew in our garden at home—you mind it, mother; mullein pink, some call it. I used to say to myself that if ever I could get what clothes I liked, I’d have a dress as near like that as I could find. Well, there I was to-day looking at the very thing, the same color, the same downy look, and all, and money enough in my purse to buy it. Of course I know it would be silly. But don’t it seem a pity that the things we dream of having some day—when the day comes, we don’t want ’em? I feel somehow as if I’m cheating that little girl that wished for the dress like a rose-in-campin’.”

She began to fold the dress pieces thoughtfully. “Made up handsomely with a train,” she said, half to herself, “and worn on suitable occasions, it wouldn’t seem so silly, either. I believe I’ll have that crimson velvet yet,” she concluded, with a laughing toss of the head. Her mother looked from the bright materials to the bright face above them.

“She would never have gone and bought all these colors just after the doctor said I wasn’t going to get well,” she thought, and turned over and fell into a real sleep. The last had been 382 feigned—to escape Jane’s disquieting remarks and to ponder their significance.

Mary Ann’s prophecy was fulfilled. Her mother stood beside her at the garden gate when Jane and Selina drove away, her glances up and down the sunny street evincing all a convalescent’s freshened interest in the outside world. The two faces were alike and yet unlike. The joy of living was in both; but a little uncertainty, a little appeal in the older woman’s told that with her it depended to some degree upon the steadier flow of animal spirits in the younger.

Jane and Selina turned for a last look at the portly figures and waving handkerchiefs.

“Who would think to look at them,” said Jane, “that Ma had only just returned from the jaws of death! It ought to be a warning to them. Some day she’ll go off in one of those attacks.”

“Ma’n’Mary Ann are as like as two peas,” said Selina. “They’re Maberlys. There never was a Maberly yet that knew how to look ahead. I declare, it gave me the shivers to see these two plunging right out of a sick-bed into colors and fashions the way they did. Ma’d ought to listen to us and sell her house and live round with her married children; at her age she’d ought to be some place where sickness and death are treated in a serious way.”

Upon this point Mrs. Colquhoun was firm. She could never go back to life on a farm again, she said; “living in town was living.” But she compromised by agreeing to devote the whole of the next summer to visiting her married children.

That was a long summer to Mary Ann. There was something wanting in all the small accustomed pleasures of her simple life, until the middle of August came, and the time set for her mother’s return was within counting distance. Then her spirits rose higher with every hour. As a toper would celebrate his happiness at the saloon, she went to Mr. Merrill’s dry-goods shop, and after a revel in that part of it where color most ran riot, she bought new chintz covering for the parlor furniture, a chrysanthemum pattern in various shades of fawn and glowing crimson.

The next step was to plan a reception to welcome her mother home and exhibit the new covering. Then a mighty idea struck her—this was the opportunity for the crimson velvet dress!

“I mayn’t never have as good an excuse for it again,” she said to the sewing-girl, “and it’s the one thing needed to make everything complete. Me in that crimson and Ma in the fawn silk she had made when the Reverend Mr. Ellis came will be a perfect match for the furniture.”

She patted the sofa back with affectionate pride.

“It does make you feel good to have anything new,” she said, sighing contentedly. “Anything, I don’t care if it’s only a kitchen stove-lifter. But this!—There are an awful lot of things in the world do make you feel good; aren’t there, Miss Adams? I mean common things, like putting on dry stockings when your feet are wet, or reading in bed, or sitting in a shady spot on a hot summer’s day, with a muslin dress on—yes, or even eating your tea, if you happen to be feeling hungry and have something particularly nice,” added this cheerful materialist.

The crimson velvet dress was being fitted for the last time when a letter was handed to Mary Ann. Her spectacles were downstairs, so she asked the sewing-girl to read it.

“‘My dear aunt,’” Miss Adams began, “‘Grandma took cold in church a week ago last Sunday and has been laid up——’”

There was a quick rustling of the velvet train. Mary Ann was vanishing into the clothes-closet. In a moment she reappeared with a small valise in her hand, and Miss Adams saw in her face what no one had ever seen there before—the shadow of a fear that hovered always on the outer edge of her happy existence and now stood close by her side. Mary Ann might be nine-tenths Maberly, but the other tenth was Colquhoun, after all.

“Put a dress into it, please,” she said, handing the valise to Miss Adams. “No, I won’t wait to take this off—I’ve a waterproof that will cover it all up. Pin the train up with safety pins—never mind if it does make pin-holes—I’ve just ten minutes to catch the train. A week ago Sunday! Oh, why didn’t they let me know before?”

When she alighted from the train at the flag station, she was clutching the waterproof close at the neck. She held it in the same unconscious grasp when she entered Jane’s big farm-house, by way of the kitchen. Selina was there, making a linseed poultice, and the odor was mingled with another which she knew afterwards to be the odor of black dye.

“SHE COULD NOT HELP SEEING THAT SELINA FOUND SOME STRANGE PLEASURE IN ALL THESE INCIDENTS OF A LAST ILLNESS”

In her mother’s bedroom the same acid odor was in the air, and Jane was sitting at the window with a piece of black sewing in her hands. Jane’s husband and John Maberly were standing at the foot of the bed, silent and melancholy, looking as awkward as men always do in a sick-room; Jane’s stern gloom was tinged with a 383 condescending pity for beings so out of place. Mary Ann saw them all at the first glance. Then she forgot everything; she was snuggling down against the bed, making the little, tender, glad, sorry sounds a mother makes when she has been separated from her baby.

When she lifted her head the men were leaving the room, John’s face working. Selina was there with the poultice. She took it from her. One look into her mother’s face had been enough. From that moment she seemed to be holding her back by sheer force of will from the edge over which she was slipping.

There was no merry gossip and laughter now, 384 there were no love stories, no monologues with pauses for smiles. Mary Ann felt that a careless word or look would be enough to loosen that frail hold on life. When the doctor came, he found his patient in charge of a stout woman in a fresh linen dress, whose self-command was so perfect that he did not waste many words in softening the opinion for which she followed him to the door.

“Your mother’s age is against her,” he said. “The bronchitis in itself is not alarming, but her heart is weak, and I fear you must not expect her recovery.”

He knew at once that she refused to accept his verdict, though she only said, “I’d like to telegraph for our doctor at home, if you don’t mind.”

When Dr. Corbett came, he confirmed the opinion.

“The bronchitis is no worse than usual,” he added, “the treatment has been the same; but she seems to have lost her grip.”

“There’s no reason why she shouldn’t catch a hold of it again,” said poor Mary Ann, choking down her agony with the thought that she must return immediately to her mother’s room.

“I don’t quite understand it,” the doctor said, with a questioning look. “The nursing—that’s been good? Dr. Black tells me so.”

“Yes, Jane and Selina are both good nurses, better’n what I am, if it wasn’t that Ma’s used to me.”

“And there’s no obstacle to her recovery that you know of?” Mary Ann shook her head. “Well, Miss Mary Ann, we must just conclude that it’s the natural wearing out of a good machine. And we’ll do what we can.”

When Mary Ann went back to her mother’s room, she found her a little roused from the stupor in which she had been lying. The visit of her own doctor, the accustomed tendance, had touched some spring that set old wheels running. With the clairvoyance love so often gives to the sick-nurse, Mary Ann knew that she had something to say to her.

She sat by the bed and waited. A fluttering whisper came at last.

“Did you see Jane’s hands?”

Mary Ann’s mind, seeking desperately for a clue, flashed from the stains on her sister’s hands, which she had vaguely set down to black currant jelly, to the acid smell in the kitchen—to the black sewing—to the forgotten shock of a year ago.

“They asked me where I’d like to lie—beside Pa or in the cemetery in town.”

“It’s their forehandedness, Ma. I never did know such a forehanded pair. Talk about meeting trouble half way—Selina’n’Jane don’t wait for it to start out at all.”

“Selina read out of the paper that bronchitis was nearly always fatal after seventy.”

“Well, now, what will those papers say next? Do you know what I read out of our own Advertiser the other day? That every woman over thirty has had at least one offer of marriage. Now, that’s a lie, for I never had an offer in my life. I’m kind of glad I didn’t, Ma, for I suppose I’d have took it; and you and me do have an awfully good time together, don’t we?”

But her mother was not listening now; it had been a flash merely of the old self. Mary Ann looked around the room until she found Jane’s lap-board with a pile of black sewing on it. She gathered up the carefully pressed pieces and poked them roughly in between a large clothes cupboard and the wall.

“There!” she said to herself, “it will be a while before they find that, and when they do they can call it Mary Ann’s flighty way of redding up a room.”

She heard her sisters whispering in the hall and went out to them. Selina was tying her bonnet-strings.

“I’m going home to do a lot of cooking,” she said in an important undertone. “John’s wrote to Ma’s relatives in Iowa, and some of them’s sure to come.”

Mary Ann looked into the wrinkled face; the past weeks had added new lines of genuine grief to it, yet she could not help seeing that Selina found some strange pleasure in all these incidents of a last illness. The words she had meant to say seemed futile. She was turning to go into her mother’s room again when an idea came to her.

“Don’t go yet,” she said. “I want to show you two something.”

She went into her bedroom and returned in a few minutes with the crimson dress over her arm.

“I was getting it fitted when the news of Ma’s sickness came, and I just put a waterproof over it. The seams have got a little ravelled. I thought maybe you two would help me top-sew them.”

“Mary Ann——!”

“You’re so much cleverer than me with the needle. I was having it made for—for—” Mary Ann could not trust her voice to tell what she had been having it made for—“for an occasion. It won’t be needed now as soon as I expected, but you know, Selina’n’Jane, you always say yourselves there’s nothing like taking time by the forelock.”

“Mary Ann——”

“A few hours would finish it up if we all got at it. Oh, there’s Ma coughing. I must run and get the pail of water and hot brick to steam up the room.”

She threw the dress into her sister’s hands and was gone. They stood looking at each other across it.

“Poor Mary Ann!”

“She talked about an occasion. I don’t know more’n one kind of occasion people get dresses like this for. Can she mean——?”

“At her age? Nonsense!”

“Dr. Corbett appears to think a pile of her. He’s a widower——”

“Now you speak of it, Selina, he does look at her in an admiring sort of way. If there was anything of that kind in prospect—and of course she’d lay off black sooner——”

The sun came out and streamed through the high window upon the dress in their hands. It was like a drink of wine to look at it.

“There’s no denying it’s a handsome thing,” Jane said. “It does seem a pity to have the edges ravel. We might finish it, anyway, and sew it up in a bag with camphor.”

Through the gray languor that overlay Mrs. Colquhoun’s consciousness, glints of crimson began to find their way. Now the spot of color was disappearing under Mary Ann’s white apron; now it was in Jane’s stained hands; now it was passing from Jane to Selina.

Then she heard Dr. Corbett say, as he handed Mary Ann a small parcel, “It’s the first sewing-silk I ever bought, Miss Mary Ann, and I don’t know whether it’s a good match, but it’s crimson, anyhow, Merrill gave me his word for that”; and when Mary Ann made a warning gesture towards the bed, the faint stirring of interest almost amounted to curiosity.

“What did he mean?” she asked, after the doctor had gone. Mary Ann bent down to catch the husky whisper. “The silk—what is it for?”

“You’re a little stronger to-day, aren’t you, Ma? I’ve a secret I meant to keep till you were well; but there! Wait till I get back and I’ll tell you.”

Mrs. Colquhoun let her eyelids close and forgot all about it. When she opened them again, Mary Ann stood before her arrayed in the velvet dress. The radiant vision seemed part of the train of visions that had been passing before her closed eyes; but this stayed, and the smiling creases of the cheeks were substantial and firm.

Then Mary Ann fell on her knees beside the bed and made a crimson frame of her arms for the nightcapped head on the pillow.

“I’m not a bit of good at keeping a secret, Ma. Jane and Selina and me have just finished it, but you weren’t to know anything about it till you got home. It was to be a surprise. And there’s new covering on the parlor furniture, a handsome flower pattern, all fawn and crimson, like our dresses, and we’re going to have a home-coming party. I don’t want to be impatient, but I wish you’d hurry up and get well.”

Mrs. Colquhoun was gazing into her daughter’s eyes.

“Do you really think I’m going to get well, Mary Ann?” she asked, and the wistfulness of old desire revived was in the feeble voice.

“Of course you’re going to get well, dearie. Why shouldn’t you?”

“It seemed kind of settled I wasn’t—and it’s so upsetting to stay when you’re expected to go. I didn’t care much.”

She put up her hand weakly and stroked the velvet.

“But now—if you think so—perhaps——”

At his next visit Dr. Corbett said, “Your mother’s caught her grip again, Miss Mary Ann,” and Dr. Black added heartily, “And if you’ll only tell us how you did it, Miss Mary Ann, you’ll be putting dollars in our pockets.”

But the cunning of love, with all its turnings and twistings, is only half-conscious—the rest is instinct.

“I don’t know that there’s anything to tell, doctor,” Mary Ann said slowly, wiping away a tear. “Only you might just keep a watch out and see that none of your patients are being hurried out of the world by the preparations for their own mourning. That’s what was happening to Ma.”

BY

ELLEN TERRY

ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS

Copyright, 1908, by Ellen Terry (Mrs. Carew)

Perhaps Henry Irving and I might have gone on with Shakespeare to the end of the chapter if he had not been in such a hurry to produce “Macbeth.”

We ought to have done “As You Like It” in 1888, or “The Tempest.” Henry thought of both these plays. He was much attracted by the part of Caliban in “The Tempest,” but, he said, “the young lovers are everything, and where are we going to find them?” He would have played Touchstone in “As You Like It,” not Jacques, because Touchstone is in the vital part of the play.

He might have delayed both “Macbeth” and “Henry VIII.” He ought to have added to his list of Shakespearian productions “Julius Cæsar,” “King John,” “As You Like It,” “Antony and Cleopatra,” “Richard II.,” and “Timon of Athens.” There were reasons “against,” of course. In “Julius Cæsar” he wanted to play Brutus. “That’s the part for the actor,” he said, “because it needs acting. But the actor-manager’s part is Antony. Antony scores all along the line. Now when the actor and actor-manager fight in a play, and when there is no part for you in it, I think it’s wiser to leave it alone.”

Every one knows when luck first began to turn against Henry Irving. It was in 1896, when he revived “Richard III.” On the first night he went home, slipped on the stairs in Grafton Street, broke a bone in his knee, aggravated the hurt by walking, and had to close the theatre. It was that year, too, that his general health began to fail. For the ten years preceding his death he carried on an indomitable struggle against ill-health. Lungs and heart alike were weak. Only the spirit in that frail body remained as strong as ever. Nothing could bend it, much less break it.

But I have not come to that sad time yet.

“We all know when we do our best,” said Henry once. “We are the only people who know.” Yet he thought he did better in “Macbeth” than in “Hamlet!”

Was he right, after all?

ELLEN TERRY AS KNIERTJE IN “THE GOOD HOPE”

TAKEN ON THE BEACH AT SWANSEA, WALES, IN 1906, BY EDWARD CRAIG

“WE HAVE TO PAY DEAR FOR THE FISH”

From the collection of H. McM. Painter

His view of Macbeth, though attacked and derided and put to shame in many quarters, is as clear to me as the sunlight itself. To me it seems as stupid to quarrel with the conception as to deny the nose on one’s face. But the carrying out of the conception was unequal. Henry’s imagination was sometimes his worst enemy. When I think of his Macbeth, I remember him most distinctly in the last act, after the battle, when he looked like a great famished wolf, weak with the weakness of a giant exhausted, spent as one whose exertions have been ten times as great as those of commoner men of rougher fibre and coarser strength.

“Of all men else I have avoided thee.”

Once more he suggested, as he only could suggest, 388 the power of fate. Destiny seemed to hang over him, and he knew that there was no hope, no mercy.

JOHN SINGER SARGENT

FROM A PORTRAIT PAINTED BY HIMSELF IN 1892 AND PRESENTED BY HIM TO THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF DESIGN

The rehearsals for “Macbeth” were very exhausting, but they were splendid to watch. In this play Henry brought his manipulation of crowds to perfection. My acting edition of the play is riddled with rough sketches by him of different groups. Artists to whom I have shown them have been astonished by the spirited impressionism of these sketches. For his “purpose” Henry seems to have been able to do anything, even to drawing and composing music. Sir Arthur Sullivan’s music at first did not quite please him. He walked up and down the stage humming and showing the composer what he was going to do at certain situations. Sullivan with wonderful quickness and open-mindedness caught his meaning at once.

“Much better than mine, Irving,—much better—I’ll rough it out at once!”

SIR EDWARD BURNE-JONES

FROM THE PAINTING BY GEORGE FREDERICK WATTS

By courtesy of G. P. Putnam’s Sons

When the orchestra played the new version based on that humming of Henry’s, it was exactly what he wanted!

Knowing what a task I had before me, I began to get anxious and worried about “Lady Mac.” Henry wrote me such a nice letter about this:

“To-night, if possible, the last act. I want to get these great multitudinous scenes over and then we can attack our scenes.... Your sensitiveness is so acute that you must suffer sometimes. You are not like anybody else—you see things with such lightning quickness and unerring instinct that dull fools like myself grow irritable and impatient sometimes. I feel confused when I’m thinking of one thing, and disturbed by another. That’s all. But I do feel very sorry afterwards when I don’t seem to heed what I so much value....

“I think things are going well, considering the time we’ve been at it, but I see so much that is wanting that it seems almost impossible to get through properly. ‘To-night commence Matthias. If you sleep, you are lost!’”[*]

At this time we were able to be of the right use to each other. Henry could never have worked with a very strong woman. I should have deteriorated in partnership with a weaker man whose ends were less fine, whose motives were less pure. I had the taste and artistic knowledge that his upbringing had not developed in him. For years he did things to please 390 me. Later on I gave up asking him. In “King Lear” Mrs. Nettleship made him a most beautiful cloak, but he insisted on wearing a brilliant purple velvet cloak with “glits” all over it which spoiled his beautiful make-up and his beautiful acting. Poor Mrs. Nettle was almost in tears.

“I’ll never make you anything again,” she said. “Never!”

Copyrighted by Window and Grove|From the collection of Miss

One of Mrs. Nettle’s greatest triumphs was my Lady Macbeth dress, which she carried out from Mrs. Comyns Carr’s design. I am glad to think it is immortalized in Sargent’s picture. From the first I knew that picture was going to be splendid. In my diary for 1888 I was always writing about it:

“The picture of me is nearly finished and I think it magnificent. The green and blue of the dress is splendid, and the expression as Lady Macbeth holds the crown over her head is quite wonderful.”

“Sargent’s ‘Lady Macbeth’ in the New Gallery is a great success. The picture is the sensation of the year. Of course opinions differ about it, but there are dense crowds round it day after day. There is talk of putting it on an exhibition by itself.”

Since then it has gone over nearly the whole of Europe, and now is resting for life at the Tate Gallery. Sargent suggested by this picture all that I should have liked to be able to convey in my acting as Lady Macbeth. Of Sargent’s portrait of Henry Irving, I wrote in my dairy:

“Everybody hates Sargent’s head of Henry. Henry also. I like it, but not altogether. I think it perfectly wonderfully painted and like him, only not at his best by any means. There sat Henry and there by his side the picture, and I could scarce tell one from t’other. Henry looked white, with tired eyes, and holes in his cheeks, and bored to death! And there was the picture with white face, tired eyes, holes in the cheeks, and boredom in every line. Sargent tried to paint his smile and gave it up.”

Copyrighted by Window and Grove

Sargent said to me, I remember, upon Henry 391 Irving’s first visit to the studio to see the “Macbeth” picture of me, “What a saint!” This to my mind promised well—that Sargent should see that side of Henry so swiftly. So then I never left off asking Henry Irving to sit to Sargent, who wanted to paint him into the bargain, and said to me continually, “What a head!”

Terry and Miss Frances Johnson

Copyrighted by Window and Grove and by W. & D. Downey

Again from my diary: