Title: Merchantmen-at-arms : the British merchants' service in the war

Author: David W. Bone

Illustrator: Sir Muirhead Bone

Release date: April 11, 2010 [eBook #31953]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tor Martin Kristiansen and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive) In memory of Thomas A. Noster,

American Merchant Marine, from June 29, 1942-August 15,

1945.

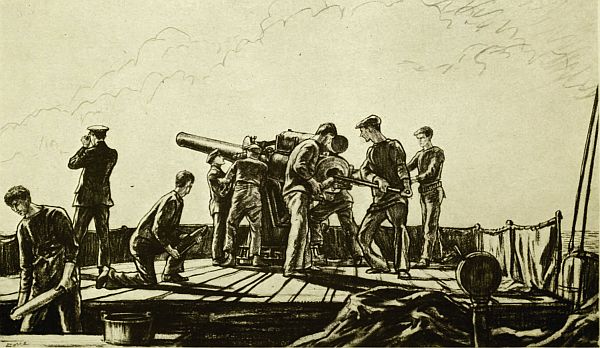

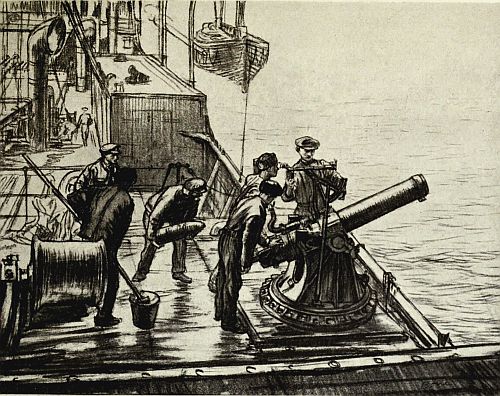

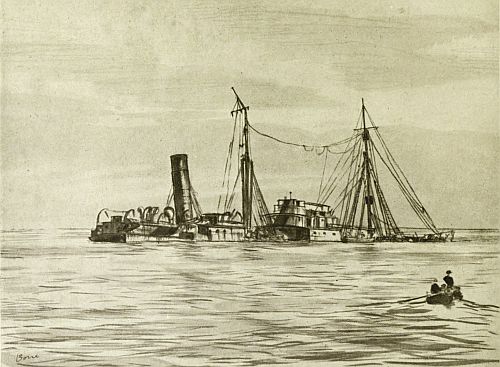

Frontispiece MERCHANTMEN AT GUN PRACTICE

Frontispiece MERCHANTMEN AT GUN PRACTICE

| PART I | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I | THE MERCHANTS' SERVICE | |

| Our Foundation | 3 | |

| The Structure | 14 | |

| II | OUR RELATIONS WITH THE NAVY | |

| Joining Forces | 21 | |

| At Sea | 26 | |

| Our War Staff | 30 | |

| III | THE LONGSHORE VIEW | 44 |

| IV | CONNECTION WITH THE STATE | |

| Trinity House, our Alma Mater | 53 | |

| The Board of Trade | 61 | |

| V | MANNING | 67 |

PART II | ||

| VI | THE COASTAL SERVICES | |

| The Home Trade | 77 | |

| Pilots | 87 | |

| Lightships | 91 | |

| VII | 'THE PRICE O' FISH' | 97 |

| VIII | THE RATE OF EXCHANGE | 103 |

| [viii]IX | INDEPENDENT SAILINGS | 110 |

| X | BATTLEDORE AND SHUTTLECOCK | 116 |

| XI | ON SIGNALS AND WIRELESS | 120 |

| XII | TRANSPORT SERVICES | 125 |

| Interlude | 132 | |

| 'The Man-o'-War's 'er 'usband' | 134 | |

| XIII | THE SALVAGE SECTION | |

| The Tidemasters | 141 | |

| A Day on the Shoals | 147 | |

| The Dry Dock | 156 | |

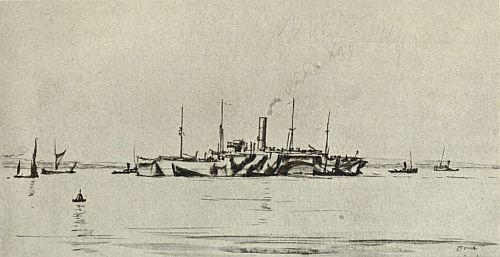

| XIV | ON CAMOUFLAGE—AND SHIPS' NAMES | 163 |

| XV | FLAGS AND BROTHERHOOD OF THE SEA | 169 |

PART III | ||

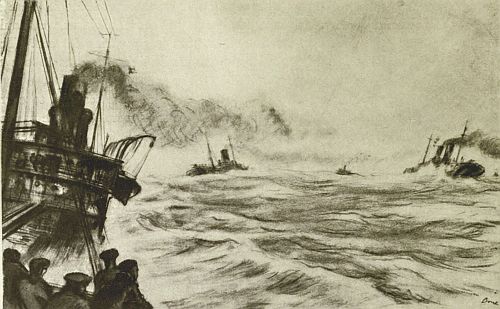

| XVI | THE CONVOY SYSTEM | 177 |

| XVII | OUTWARD BOUND | 184 |

| XVIII | RENDEZVOUS | 190 |

| XIX | CONFERENCE | 198 |

| XX | THE SAILING | |

| Fog, and the Turn of the Tide | 205 | |

| 'In Execution of Previous Orders' | 212 | |

| XXI | THE NORTH RIVER | 217 |

| XXII | HOMEWARDS | |

| The Argonauts | 224 | |

| On Ocean Passage | 230 | |

| 'One Light on all Faces' | 236 | |

| XXIII | 'DELIVERING THE GOODS' | 244 |

| XXIV | CONCLUSION: 'M N' | 252 |

| | ||

| APPENDIX | 255 | |

| INDEX | 257 | |

| PAGE | |

| Merchantmen at Gun Practice | Frontispiece |

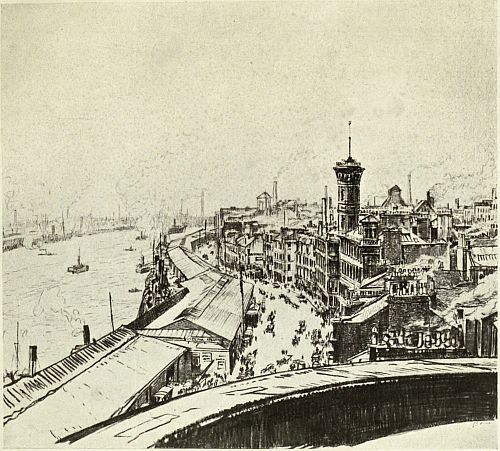

| The Clyde from the Tower of the Clyde Trust Buildings | xi |

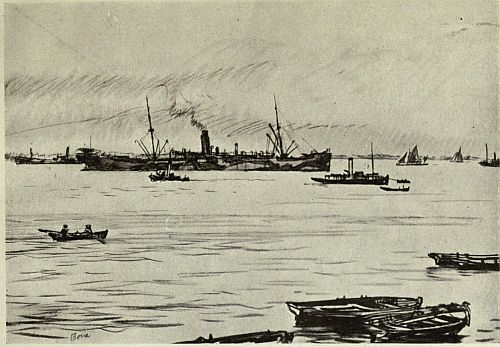

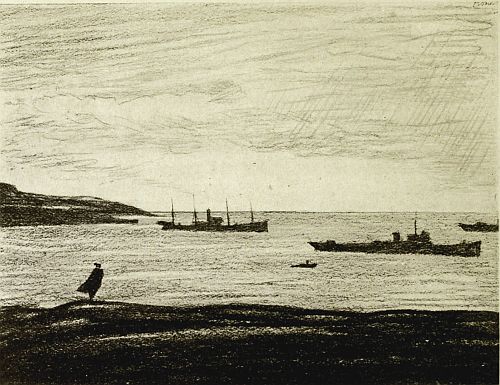

| Gravesend: A Merchantman Outward Bound | 3 |

| The Bridge of a Merchantman | 7 |

| The Old and the New: The Margaret of Dublin and R.M.S. Tuscania | 15 |

| In a Merchantman—Bomb-Thrower Practice | 21 |

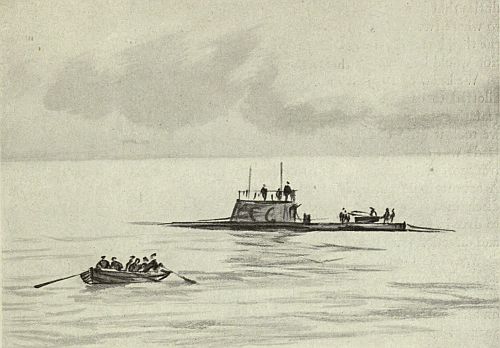

| A British Submarine detailed for Instruction of Merchant Officers | 31 |

| The D.A.M.S. Gunwharf at Glasgow | 33 |

Instructional Anti-Submarine Course for Merchant Officers at Glasgow | 39 |

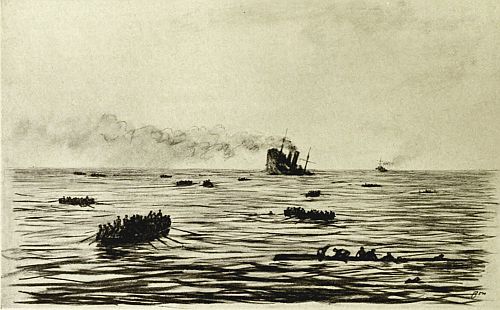

| The Loss of a Liner | 44 |

| The Mersey from the Liver Buildings, Liverpool | 49 |

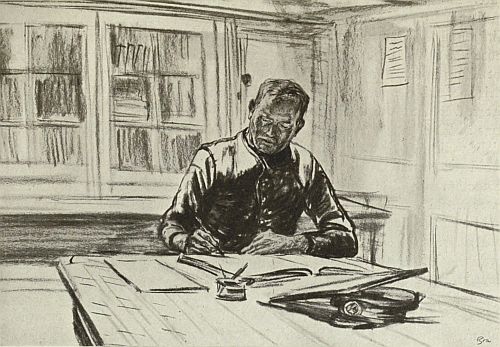

| The Master of the Gull Lightship writing the Log | 53 |

| At Gravesend: Pilots awaiting an Inward-Bound Convoy | 59 |

| Transports leaving Southampton on the Night Passage to France | 67 |

| Liverpool: Merchantmen signing on for Oversea Voyages | 69 |

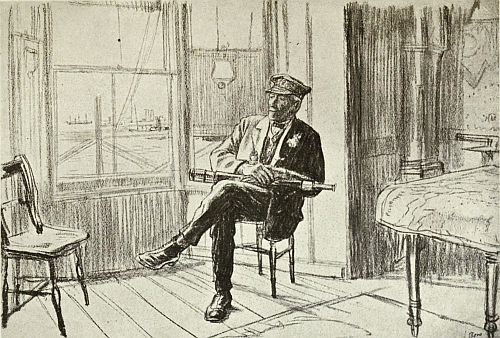

| The Ruler of Pilots at Deal | 77 |

| A Heavily Armed Coasting Barge | 83 |

| The Lampman of the Gull Lightship | 93 |

| Minesweepers going out | 97 |

| Southampton Water | 103 |

| 'Out-Boats' in a Merchantman | 105 |

| Firemen standing by to relieve the Watch | 111 |

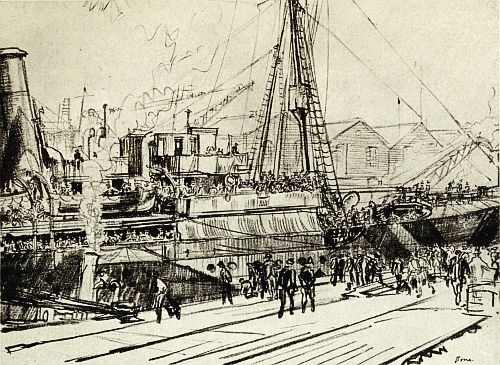

| Queen's Dock, Glasgow | 116 |

| The Bridge-Boy repairing Flags | 121 |

| A Transport Embarking Troops for France | 125 |

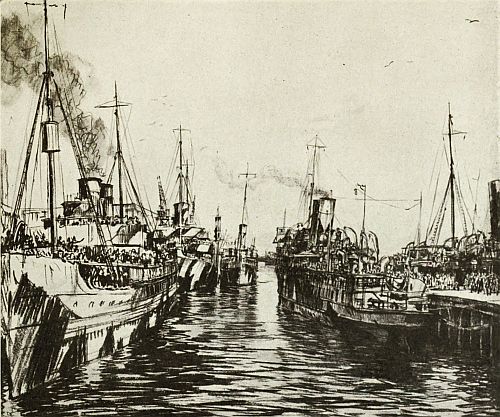

| Transports in Southampton Docks | 129 |

| [x]The Leviathan docking at Liverpool | 135 |

| Salvage Vessels off Yarmouth, Isle of Wight | 141 |

| In a Salvage Vessel: Overhauling the Insulation of the Power Leads | 145 |

A Torpedoed Merchantman on the Shoals: Salvage Officers making a Survey | 151 |

| A Torpedoed Ship in Dry Dock | 157 |

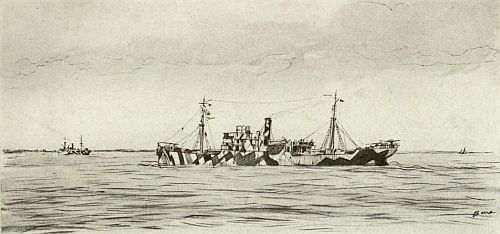

| Dazzle | 163 |

| An Apprentice in the Merchants' Service | 171 |

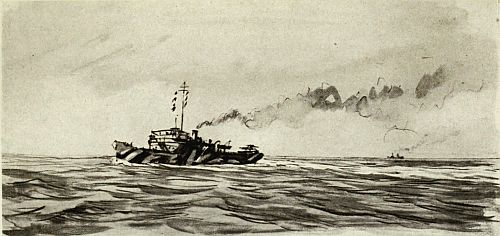

| A Standard Ship at Sea | 177 |

| Building a Standard Ship | 179 |

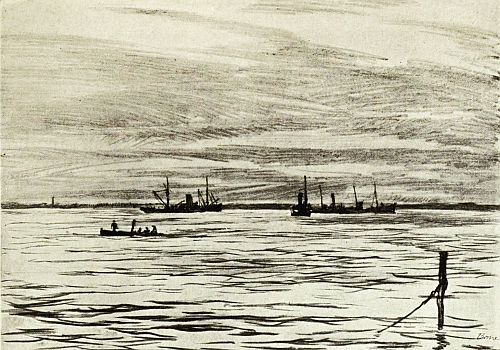

| The Thames Estuary in War-Time | 184 |

| Dropping the Pilot | 187 |

| Examination Service Patrol boarding an Incoming Steamer | 190 |

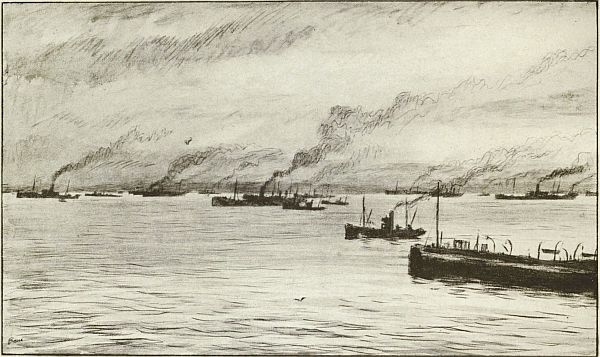

| Dawn: Convoy preparing to put to Sea | 193 |

| Evening: Plymouth Hoe | 198 |

| A Convoy Conference | 201 |

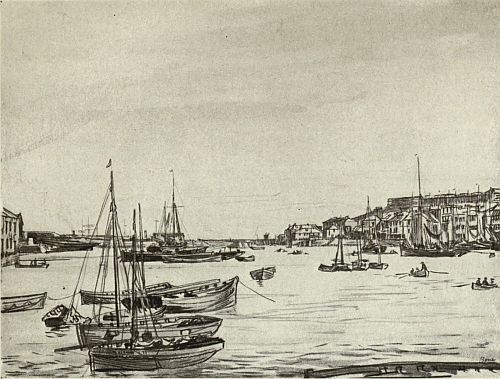

| The Old Harbour, Plymouth | 205 |

| Convoy sailing from Plymouth Sound | 207 |

| Inward Bound | 217 |

| A Transport Loading | 219 |

| A Convoy in the Atlantic | 224 |

| The Bows of the Kashmir damaged by Collision | 227 |

| The Mayflower Quay, the Barbican, Plymouth | 233 |

| Evening: The Mersey from the Landing-Stage | 241 |

| The Steersman | 243 |

| The Work of a Torpedo | 244 |

| Transports Discharging in Liverpool Docks | 245 |

| Troop Transports disembarking at the Landing-Stage, Liverpool | 249 |

| 'M N' | 252 |

THE CLYDE FROM THE TOWER OF THE CLYDE TRUST BUILDINGS

THE CLYDE FROM THE TOWER OF THE CLYDE TRUST BUILDINGS

It is necessarily halting and incomplete. The extent of the subject is perhaps beyond the safe traverse of a mariner's dead reckoning. Policies of governmental control and of the economics of our management do not come within the[xii] scope of the book except as text to the diary of seafaring. Out at sea it is not easy to keep the right proportions in forming an opinion of measures devised on a grand scale, and of the operation of which we see only a small part. Our slender thread of communication with longshore happenings is often broken, and understanding is warped by conjecture.

In pride of his ancient trade, the seaman may perceive an importance and vital instrumentality in the ships and their voyages that may not be so evident to the landsman. By this is the mariner constantly impressed: that, without the merchant's enterprise on the sea—the adventure of his finance, his ships, his gear, his men—the armed and enlisted resources of the State could not have prevailed in averting disaster and defeat.

The unique experiences of individual seamen—the trials of seafaring under less favourable circumstances than was the writer's good fortune—the plaints and grievances of our internal affairs—are but lightly sketched. Many brother seamen may feel that the harassing and often despairing case of the average tramp steamer has not adequately been dealt with; that—in "Outward Bound," as an instance—the writer presents a tranquil and idyllic picture which cannot be accepted as typical. The bitter hardship of proceeding on a voyage under war conditions, with the same small crew that was found inadequate in peace-time, is hardly suggested; the extent of the work to be overtaken is perhaps camouflaged in that description of setting out. Reality would more frequently show a vessel being hurried out of dock on the top of the tide, putting to sea into heavy weather, with the hatchways open over hasty stowage, and all the litter of a week's harbour disroutine standing to be cleared by a raw and semi-mutinous crew.

Criticism on these grounds is just: but it was ever the seaman's custom to dismiss heavy weather—when it was past and gone—and recall only the fine days of smooth sailing. If the hard times of our strain and labouring are not wholly over, at least we have fallen in with a more favouring wind from the land. Conditions in the Merchants' Service are vastly improved since Germany challenged our right to pass freely on our lawful occasions. Relations between the owner and the seamen are less strained. Remuneration for sea-service is now more adequate. The sullen atmosphere of harsh treatment on the one hand, and grudging service on the other, has been cleared away by the hurricane threat to our common interests.[xiii]

Throughout the book there are some few extracts—all indicated by quotation marks—from the works of modern authors. The writer wishes to acknowledge their use and to mention the following: "Trinity House," by Walter H. Mayo; "The Sea," by F. Whymper; "The Merchant Seamen in War," by L. Cope Cornford; "Fleets behind the Fleet," by W. Macneile Dixon; "North Sea Fishers and Fighters" and "Fishermen in Wartime," both by Walter Wood; the pages of the Nautical Magazine.

The grateful thanks of writer and artist are tendered to Rear-Admiral Sir Douglas Brownrigg, Chief Naval Censor, and to Lord Beaverbrook and Mr. Arnold Bennett, of the Ministry of Information, for facilities and kindly assistance in preparation of the work. The writer's indebtedness to his Owners for encouragement and for generous leave of absence (without which the book could not have been written) is especially acknowledged.

Mr. Muirhead Bone's drawings reproduced in this book were executed during the war for the Ministry of Information with the co-operation of the Admiralty. They are now in the possession of the Imperial War Museum. With the exception of the illustrations on pages 44, 224, and 252, these drawings were made on the spot.

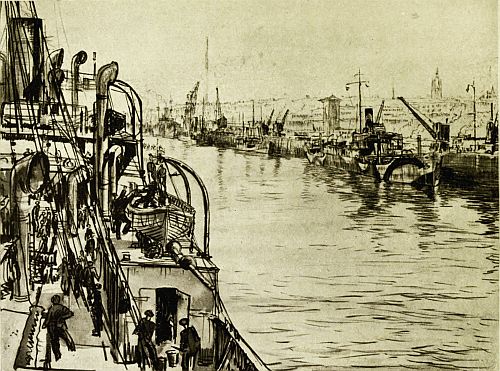

GRAVESEND: A MERCHANTMAN OUTWARD BOUND

GRAVESEND: A MERCHANTMAN OUTWARD BOUND

Grandeur of the fleets, the might of sea-ordnance, the intense dramatic decision of a landing, stand out in the great pieces the early writers and painters[4] designed. Brave kingly figures wind in and out against the predominant background of rude hulls and rigging and weathered sails. The outline of the ships and the ungainly figures of the mariners are definitely placed to impel our thoughts to the distant sea-marches.

Happily for us, the passengers of early days included clerks and learned men on their pilgrimages, else we had known but little of bygone ship life. With interest narrowed by bounds of the bulwarks, they noted and recorded a worthy description. In the mystery of unknown seas, as in detail of the sea-tackle and the forms and usages of the ship, they penned a perfect register: down to the tunnage of the butts, we know the ships—to the 'goun of faldying' and the extent of their lodemanage, we recognize the men.

At later date we come on the seaman and his ships recorded and portrayed with a loving enthusiasm. Richard Hakluyt—"with great charges and infinite cares, after many watchings, toiles and travels, and wearying out" of his weak body—sets out for us a wonderful chronicle of the shipping to his day. He grew familiarly acquainted with the chiefest 'Captaines,' the greatest merchants, and the best mariners of our nation, and acquired at first hand somewhat more than common knowledge of the sea. He saw not only the waving banners of sea-warriors and the magnificence of their martial encounters, but lauded victory in far voyages, the opening to commerce of distant lands, the hardihood of the Merchant Venturers. He realized the value of the seaman to the nation, not alone to fight battles on the sea, but as skilful navigators to further trade and intercourse. He was not ignorant "that shippes are to litle purpose without skillfull Sea-men; and since Sea-men are not bred up to perfection of skill in much lesse time than in the time of two prentiships; and since no kinde of men of any profession in the commonwealth passe their yeres in so great and continuall hazard of life; and since of so many, so few grow to gray heires; how needful it is that . . . these ought to have a better education, than hitherto they have had."

His matchless patience and care and exactitude were only equalled by his pride in the doings of the seamen and the merchants. With a joyful humility he exults in the hoisting of our banners in the Caspian Sea—not as robber marauders, but as peaceful traders under licence and ambassade—at the station of an English Ligier in the stately porch of the Grand Signior at Constantinople, at consulates at Tripolis and Aleppo, in Babylon and Balsara—"and which is more, at English Shippes coming to anker in the mighty river of Plate." In script and tabulation he glories in the tale of the ships, and sets out the names and stations of humble merchant supercargoes with the same meticulous care as the rank and titles of the Captain-General of the Armada.[5]

Alas! There was none to set a similarly gifted hand to the further course of his lone furrow. Purchas tried, but there was no great love of his subject-matter to spread a glamour on the pages. Perhaps the magnitude of the task, ever growing and gathering, and the minute and unwearying succession of Hakluyt's "Navigations and Traffiques," discouraged and deterred less ardent followers. Of voyages and expeditions and discoveries there are volumes enough, but few such intimate records as "the Oathe ministered to the servants of the Muscovie company," or the instructions given by the Merchant Adventurers unto Richard Gibbs, William Biggatt, and John Backhouse, masters of their ships, have been written since Hakluyt turned his last page.

As outposts to our field, roving bands on a frontier that rises and falls with the tide, the seamen were ever the first to apprehend the mutterings of war. With but little needed to set spark to the torch, they came in to foreign seaport or littoral with a fine confidence in their ships and arms. Truculent perhaps, and overbearing in their pride of long voyaging over a mysterious and threatening sea, they were hardly the ambassadors to aid settlement of a dispute by frank goodwill and prudence. Sailing outwith the confines of ordered government, their lawless outlook and freebooting found a ready rejoinder in restraint of trade and arbitrary imprisonment. Long wars had their seed in tavern brawls, enforcement "to stoope gallant [lower topsail] and vaile their bonets" for a puissant king or queen, brought a reckoning of strife and bloodshed.

Although military sea-captains, the glory of their victories, the worthiness of their ships and appurtenances, figure largely on the pages of subsequent sea-history, not a great deal has been written of the sailor captains and their mates and crews. Later chroniclers were concerned that their subjects should be grand and combatant: there was little room in their text for trading ventures, or for such humble recitals as the tale and values of hogshead or caisse or bale. A line of demarcation was slowly but inevitably ruling a division of our sea-forces. The service of the ships, devoted indifferently to sea-warfare or oversea trading—as the nation might be at war or peace—was in process of adjustment to meet the demands of a new sea-attack. The vessels were no longer merely floating platforms from which a military leader could direct a plan of rude assault and engage the arms of his soldiery, leaving to the masters and seamen the duty of handling the way of the ship. A new aristocracy had arisen from the decks who saw, in the pull of their sails, a weapon more powerful than shock ordnance, and resented the dictation of landsmen on their own sea-province. Sea-warfare had become a contest, more of seamanship and manœuvre, less of stunning impact and a weight of military arms.

In division of the ships and their service, it may quite properly be claimed[6] that the Merchants' Service remained the parent trunk from which the new Navy—a gallant growing limb—drew sap and sustenance, perhaps, in turn, improving the growth of the grand old tree. Certainly their service was an offshoot, for, since Henry VIII ordered laying of the first especial war keel, the sea-battles to the present day have been largely joined by the ships and men and furniture of the merchants, carrying on in the historic traditional manner of a fight when there was fighting to be done, a return to trade and enterprise when the great sea-roads were cleared to commerce. Stout old Sir John Hawkins, Frobisher, Drake, Davis, Amadas, and Barlow were merchant masters, shrewd at a venture, in intervals of, and combination with, their deeds of arms. Only a small proportion of State ships were in issue with the merchants' men to scourge the great Armada from our shores. Perhaps the existence of such a vast reserve in ships and men delayed the progress of purely naval construction. Only with the coming of steam was the line drawn sharply and definitely—the branch outgrowing the interlock of the parent stem.

With partial severance and division of the ships, the seamen—who had been for so long of one breed, laying down sail-needle and caulking-iron to serve ordnance and hand-cutlass or boarding-pike—had reached a parting of the ways, and become naval or mercantile as their habits lay. The State war vessels, built and manned and maintained for strictly military uses, increased in strength and numbers. Their officers and crews developed a new seamanship and discipline that had little counterpart on the commercial vessels. For a time the two services sailed, if not in company, within sight and hail of one another. On occasion they joined to effect glorious issues, but, with the last broadside of war, courses were set that quickly swerved the fleets apart.

Longer terms of peace gave opportunity for development on lines that were as poles apart. The Naval Service perfected and exercised their engines of war, and drilled and seasoned their men to automaton-like subservience to their plans. A broadening to democratic freedom, quickened by familiar intercourse with other nationals, had effect with the merchantmen in rousing a reluctance to a resort to arms; they desired but a free continuance of trading relations. Although differing in their operations and ideals, both services were striving to enhance the sea-power of the nation. Thomas Cavendish, Middleton, Monson, Hudson, and Baffin—merchant masters—explored the unknown and extended a field for mercantile ventures, but that field could have been but indifferently maintained if naval power had not been advanced to protect the merchantmen in their voyaging.

As their separation developed, relations grew the more distant between the seamen. While certainly protecting the traders from any foreign interference,[9] the new Navy did little to effect a community of interest with their sea-fellows. Prejudices and distrust grew up. State jealousies and trade monopolies formed a confusion of interests and made for strained relations between the merchants and the naval chancelleries on shore. At sea, the arbitrary exercise of authority by the King's officers was opposed by revolutionary instincts for a free sea on the part of the merchants' seamen. Forcible impressment to naval service was the worst that could befall the traders' men. For want of energy or ability to carry through the drudgery of early sea-training, the naval officers took toll of the practised commercial seamen as they came in from sea. Bitter hardship set wedge to the cleavage. After long and perilous voyaging, absent from a home port for perhaps two or three years, the homeward-bound sailor had little chance of being allowed a term of liberty on shore—a brief landward turn to dissolve the salt casing of his bones. Within sound of his own church bells, in sight of the windmills and the fields and the home dwelling he had longed for, he was haled to hard and rigorous sea-service on vessels of war. The records of the East India Company have frequent references to this cruel exercise of naval tyranny.

"On Thursday morning the Directors received the agreeable news of the safe arrival of the Devonshire, Captain Prince, from Bengal. . . . Her men have all been impressed by the Men-of-War in the Downs, and other hands were put on board to bring her up to her moorings in the River."

". . . On Sunday morning the Purser of the William, Captain Petre, arrived in town, who brought advice of the said ship in the Downs, richly laden, on Account of the Turkey Company: the Ships of War in the Downs impressed all her men, and put others on board to bring her up."

"Notwithstanding the Report spread about, fourteen days ago, that no more sailors would be impressed out of the homeward-bound ships, several ships that arrived last week had all their men taken from them in the Downs."

Serving by turns, as his agility to dodge the gangs was rated, on King's ship for a turn, then hauling bowline on a free vessel; forced and hunted and impressed, the shipmen had perhaps sorry records to offer the historian, then busy with the enthralling chronicles of fleet engagements and veiling with glamour the toll of battles. Perhaps it was, after all, the better course to preserve a silence on the traders' doings and leave to romantic conjecture a continuance of Hakluyt's patient story.

Since the date of naval offgrowth, the chronicles have not often turned[10] on our commercial path. Lone voyages and encounters with the sea and storm are minor enterprises to the sack of cities and the clash of arms at sea. Unlike the Naval Service, we merchants' men hold few recorded titles to our keystone in the national fabric. The deeds and documents may exist, but they are lost to us and forgotten in the files of musty ledgers. The fruits of our efforts stand in the balances of commercial structure, and are perhaps more enduring than a roll of record. But, if we are insistent in our search, we may borrow from the naval charters, and read that not all the glory of our sea-history lies with the thunder of broadsides and the impact of a close boarding. Engagement with the elements—a contest with powers more cruel and implacable than keen steel—efforts to further able navigation, the standard of our seamanship—drew notable recruits to the humbler sea-life. The small crews and less lavish gear on the freighters brought the essentials of the sea-trade to each individual of the ship's company. Idlers and landsmen learned quickly and bitterly that their only claim to existence on a merchant's ship lay in a rapid acquisition of a skill in seamanship. The lessons and the threats and enforcements did not come wholly from their superiors, to whose tyranny they might expose a sullen obstinance, and gain, perhaps, a measure of sympathy from their rude sea-fellows. Then—as later, in the keen sailing days of our clipper ships—their hardest taskmasters were foremast hands, watchmates, the men they lived with and ate with and worked with—bitter critics, unpersuadable, who saw only menace and a threat to their own safety in the shipping of a man who could not do man's work. On the decks and about the spars of a merchant vessel, each man of the few seamen carried two lives—his own and a shipmate's—in his ability to 'hand, reef, and steer.' There was no place on board for a 'waister,' a 'swabber,' longshoreman, or sea labourer. Every man had quickly to prove his ability: the unrelenting sea gave time for few essays.

Fertility of resource, dexterity to serve at all duties, skill at handling ship and canvas, were the results of sea-ship training. In the merchantmen great opportunities offered for advancement in all branches of the seaman's art. Long voyaging was better exercise for a progression in navigation than the daily pilotage of the war vessels. Blake, in his early days as a merchant supercargo, learnt his seafaring on rough trading voyages, and his training could not have been other than sound to persist, through twenty years shore-dwelling as a merchant at Bridgwater, until he was called from his counting-house to command our naval forces. Dampier was a tarry foremast hand in his day: whatever we may judge of his conduct, we can have nothing but admiration for his seamanship. Ill-equipped and short-handed, racked by sea-sores and scurvy, his expeditions were unparalleled as a triumph of merchant sea-skill. James Cook[11] learned his trade on the grimy hull of an east-coast collier—to this day we are working on charts of his masterly surveys.

In later years the merit of the trading vessels as sterling sea-schools was equally plain. During intervals of combatant service, or as prelude to a naval career, training on the merchants' ships was eagerly sought by ardent naval seamen who saw the value of its resource in practical seamanship, in navigation, and weather knowledge. Great captains did not disdain the measure of the instruction. They sent their heirs to sea in trading vessels to draw an essence in practice from their sea-cunning. Hardy, Foley, and Berry had borne a hand at the sheets and braces, and had steered a lading of goods abroad, before they came to high command of the King's ships. Who knows what actions in the victories of Copenhagen, the Nile, and Trafalgar (hinged on the cast of the winds) were governed by Nelson's early sea-lessons, under Master John Rathbone, on the decks of a West India merchantman?

For long after, relations and interchange between the two Services were not so intimate. Until coming of the Great War, with a mutual appreciation, we had little in common. Our friend and peacemaker—the influence of seafaring under square sail—languished a while, then died. In steam-power, with its growth of development and intricacy of application, we found no worthy successor to present as good an office. In the long span of a hundred years of sea-peace we grew apart. The gulf between the two great Services widened to a breach that only the rigours of a world-conflict could reconcile.

As though exhausted by the indefinite sea-campaign of 1812, the Royal Navy lay on their oars and saw their commercial sea-fellows forge ahead on a course that revolutionized sea-transport and sea-warfare alike. The Lords of the Admiralty would listen to no deprecation of their gallant old wooden walls: steam propulsion was laughed at. To the Merchants' Service they left the risk and the responsibility of venturing afar in the rude new ships. In this wise, to us fell the honour of leading the State service to a new order of seafaring. Iron hulls and steam propulsion came first under our hands. It was not long before our new command of the sea was noted. Somewhat grudgingly, the conservative sea-mandarins were brought to a knowledge that their torpor was fatal. The Navy stirred and lost little time in traversing the leeway. They progressed on a path of experiment and probation suited to their needs, striving to construct mightier vessels and to forge new and greater arms. Exploring every avenue in their quest for aid and material, every byway for furtherance of their aims, they drew strange road-fellows within their ranks, new workmen to the sea. The engines of their adoption called for crafty hands to serve and adjust them. Steam we knew in our time and could understand, but auxiliary[12] mechanics outgrew the limits of our comprehension; naval practice became a science outwith the bounds of our sea-lore, a new trade, whose only likeness to ours lay in its service on the same wide sea.

Parted from the need to draw arms, secure in the knowledge of adequate naval protection, the Merchants' Service developed their ships and tackle in the ways of a free world trade. By shrewd engagement and industry in the counting-house, diligence and forethought in the building-yards, keen sailing and efficiency on the sea, the structure of our maritime supremacy was built up and maintained. Monopolies and hindering trade reservations and restrictions barred the way, but yielded to the spirit of our progress. Vested interests in seas and continents had to be fought and conquered, and there was room and scope for lingering combative instincts in the keen competition that arose for the world's carrying trade. Other nations came on the free seas, secure in the peace our arms had wrought, and entered the lists against us. The challenge to our seafaring we met by skill and hardihood—keener and more polished arms than the weapons of our sea-fathers. The coming of competitors spurred us to sea-deeds in the handling of our ships and cargoes, dispatch in the ports, and activity in the yards, that brought acknowledged victory to our flag. Every sense and thought that was in us was used to further our supremacy. The craft and workmanship of the builders and enterprise of the merchants provided us with the most beautiful of man's creations on the sea—the square-rigged sailing ship of the nineteenth century. With pride we sailed her. We, too, brought science to our calling; rude, perhaps, and not readily defined save by a long, hard pupilage. Not less than the calibre of the new naval ordnance was the measure of our sail spread, not inferior to ironclad hulls the speed and beauty of our clippers—we paralleled the roads of their strategy by the masterly handling of a cloud in sail. With a regularity and precision as noted as our naval sea-brothers' advance in gunfire, we served the trade and the mails, and spread the flood of emigration to the rise and glory of the Empire.

With the decline of square sail, a new way of seafaring opened to us. In the first of our steam pioneering, we took our yards and canvas with us, as good part of our sea-kit; a safe provision, as we thought, against the inevitable failure we looked for in the new navigation. We were conservatively jealous of our gallant top hamper, and scorned the promise of a power that only dimly as yet we understood. But—the promise held. In a few years we became converts to the new order, in which we found a greater security, a more definite reliance, than in the angles of our sail plane. There was no longer a need for our precious 'stand by,' and we unrigged the wind tackle and accepted our new shipmate, the marine engineer, as a worthy brother seaman. It was not only[13] the spars and the cordage and the sails we put ashore. With all the gallant litter we unloaded, condemned to the junk-heap, went a part of our seamanship as closely woven to the canvas as the seams our hands had sewn.

In steam practice, new problems required to be studied and resolved; challenges to our vaunted sea-lore came up that called for radical revision of older methods and ideas. Changes, as wide and drastic as the evolutions of a decade in sail, were presented in a swift succession of as many days. With eyes now turned from aloft to ahead, we retyped our seamanship to meet the altered conditions of the veer in our outlook. Unhelped, if unhindered, in our efforts, we adapted our calling to the sudden and revolutionary innovations in construction and power of the new ships. We grew sensible of gaps in our knowledge, of voids in education that our earlier handicraft had not revealed. Severed, by press of our sea-work, from the facilities for study that now offered advancement to the landsman, we sought in alert and constant practice a substitute for technical instruction. By step and stride and canter we jockeyed each new starter from the shipyards, and studied their paces and behaviour on the vexed testing courses of the open sea. If our methods were rude in trial, they settled to efficiency in service. We paced in step with the rapid developments of the shipwright's art, the not less active contrivance of the engineers. We kept no man waiting for a sea-controller to his new and untried machine: there was no whistling for a pilot on the grounds of our reaches. From oversea dredger and frail harbour tug to the magnitude of an Aquitania, we were ever ready to board her on the launching ways and steer her to the limits of her draught.

A Hakluyt of the day would have a full measure for his enthusiasm in the shear of our keels on every sea, the flutter of our flags to all the winds. By virtue of worthy vessels and good seamanship, the Red Ensign was devoted to a world service; by good guardianship and commercial rectitude the Merchants' Service held charge of the world's wealth in transport—the burden of the ships. All nations put trust in us for sea-carriage. The Spanish onion-grower on the slopes of Valencia, the Java sugar merchants, the breeders of Plata, looked to their harbours for sight of our hulls to load their products. Greek boatmen took payment for their cases on a scrap of dingy paper; the tide-labourers of the world demanded no earnest of their fees ere setting to work—our flag was their guarantor. The incoming of our ships brought throng to the quay-sides of far seaports; the outgoing sent the prospering merchants to the bank counters, to draw value from our skill in navigation, our integrity, and sea-care.[14]

On such a stage the gage was thrown. Right on the heels of the courier with challenge accepted, went the ships laden with a new and precious cargo—our gallant men-at-arms. Before a shot of ours was fired, the first blow in the conflict was swung by passage of the ships: throughout the length of it, only by the sea-lanes could the shock be maintained.

Viewing the numbers and tonnage of the ships, the roll and character of the seamen, we were not uneasy for the sea-front. With the most powerful war fleet in the world boarding on the coasts of the enemy, we had little to fear. The transports and war-service vessels could be adequately safeguarded: the peaceful traders on their lawful occasions could trust in international law of the civilized seas, on which no destruction may be effected without cause, prefaced by examination. Of raiders and detached war units there might be some apprehension, but the White Ensign was abroad and watchful—it was impossible that the shafts of the enemy could reach us on the sea. For a time we set out on our voyages and returned without interference.

Anon, an amazing circumstance shocked our blythe assurance. In a new warfare, by traverse of a route we thought was barred, the impossible became a stern reality! While able, by power of their ships and skill and gallantry of[17] the men, to keep the surface naval forces of the enemy doomed to ignoble harbour watch, the mightiest war fleet the seas had ever carried was impotent wholly to protect us! Our Achilles heel was exposed to merciless under-water attack, to a new weapon, deadly in precision and difficult to counter or evade. Throwing to the winds all shreds of honour and conscionable restraint, all vestiges of a sea-respect for non-combatants and neutrals, the pacts and bounds of international law—the humane sea-usages that spared women and children and stricken wounded—the decivilized German set up the banners of a stark piracy, an ocean anarchy, to whose lieutenants the sea-wolves of an earlier age were but feeble enervated weaklings.

Piracy, gloried in and undisguised, faced us. Well and definite! We had known piracy in the long years of our sea-history: we had dealt with their trade to a full settlement at yard-arm or gallows. The course of our seafaring was not to be arrested by even the deep roots and deadly poison of this not unknown sea-growth: we had scaled the foul barnacles and cut the rank weeds before in the course of sea-development. If our ways had become peaceful in the long years of unchallenged trading, our habits were never less than combatant throughout a life of struggle with storm and tide. Not while we had a ship and a man to the helm would we be driven from the sea; our hard-won heritage was not to be delivered under threat or operation of even the most surpassing frightfulness. Jealousy for our seafaring, for our name as sailors, forbade that we should skulk in harbour or linger behind the nets and booms. Our work, our livelihood, our proud sea-trade, our honour was on the open sea. Our pride was this—that, in our action, we would be followed by the seafarers of the world. It was for no idle vaunt we boasted our supremacy at sea. If we could take first place of the world's seamen in time of peace, our station was to lead in war. We put out to sea—the neutrals followed. Had we held to port, German orders would have halted the sea-traffic of the world. With no shield but our seamanship, no weapon but the keenness of our eyes, no power of defence or assault other than the swing of a ready helm, we met the pirates on the sea, with little pretension in victory and no whining in defeat.

Challenged to stand and submit, the Vosges answered with a cant of the helm and hoist of her flag, and stood on her way under a merciless hail of shot. Unarmed, outsped, there was little prospect of escape—only, in an obstinate sea-pride, lay acceptance of the challenge. With decks littered by wreckage and wounded, bridge swept by shrapnel, water making through her torn hull, there was no thought to lay-to and droop the flag in surrender. When, at length, the ensign was shot away, there were men enough to hoist another. In hours their agony was measured, until, in despair of completing his foul work,[18] the enemy gave up the contest. Reeking of the combat, the Vosges foundered under her wounds. The sea took her from her gallant crew, but they had not given up the ship—their flag still fluttered at the peak as she went down. Anglo-Californian fought a grim, silent fight for four hours, matching the intensity of the German gunfire by the dogged quality of her mute defiance. Palm Branch turned away from galling fire at short range, double-banked the press in the stokehold, and cut and turned on her course to confuse the ranges. Her stern was shattered by shell, the lifeboats blown away; the apprentice at the wheel stood to his job with blood running in his eyes. Fire broke out and added a new terror to the situation. There was no flinching. Through it all the engines turned steadily, driven to their utmost speed by the engineers and firemen. A one-sided affair—a floating hell for seamen to stand by, helpless, and take a frightful gruelling! But they stood to it, and came to port.

If, under new and treacherous blows, our hearts beat the faster, there was little pause, no stoppage, in the steady coursing of our sea-arteries. We fought the menace with the same spirit our old sea-fathers knew. Undeterred by the ghastly handicap against us—the galling fetters of a policy that kept us unarmed, we pitted our brains and seamanship against the murderous mechanics of the enemy. To the new under-water attack there were few adequate counter-measures in the records of our old seafaring. We revised the standard manual, drew text from old games, shield from the cuttlefish, models for our sweeps from discarded sea-tackle. Special devices, new plans, stern services were called for; we devised, we specialized—our readiness was never more instant. Out of our strength we built up a new Service. Instruction and equipment came from the Royal Navy, but the men were ours. In the throes of our exertions the Merchants' Service repeated a tradition. The stout aged tree shot forth another worthy limb—a second Navy—not less ardent or resourceful than the first offshoot, now grown to be our guardian.

Our branches twined and interlocked in service of a joint endeavour. Under the fierce blast of war we swayed and weighed together in shield of our ancient foundation. Within our ranks we had cunning fishers, keen, resolute sea-fighters of the banks, to whom the coming of a strange mechanical devil-fish offered a new zest to the chase, a famous netting. Enrolled to Special Service, they engaged the enemy at his doorstep and patrolled the areas of his outset. Undaunted by the odds, deterred by no risk or threat, they ranged and searched the sea-channels and cleared the lanes for our safe passage. To detect, to warn, to meet and counter-charge the submarine in his depths, to safeguard the narrow seas from hazard of the mines, was all in the day's work of the Temporary R.N.R.[19]

Throughout all the enrolments, the divisions, the changes, and the training for new and special duties, there was no easing of the engines: we effected our adjustments and allotments under a full head of steam. All that the enemy could do could not prevent the steady reinforcement of our arms, the passage of our men, the transport of our trade. The long lines of our sea-communications remained unbroken, despite our losses and the grim spectre of the raft and the open boat. It could not be otherwise—and Britain stand. There could be no halt in the sea-traffic. Only from abroad could we draw supplies to raise the new leaguer of our island garrison; only by way of the sea could we retain and renew our strength.

In time the intolerable shackles of inactive resistance were struck from our hands. Somewhat tardily we were supplied with weapons of defence and instructed in their use and maintainance. We went to school again, under tutelage of the Naval Service, and drew a helpful assistance from the tale of their courses since we had parted company. We were heartened by the new spirit of co-operation with the fighting service. Ungrudgingly they lent experts to direct our movement. They turned a stream of their inventive talent in the ways of gear and apparatus to protect our ships. They shipped our ordnance, and supplied skilled gunners to leaven our rude crews. More, they helped to strip the veneer of convention that hampered us—our devotion to standard practice in rules and lights and equipment. We learned our lessons. Even though the peaceful years had lessened our fighting spring, we had lost no aptitude for service of the guns in defence of our rights, nor for measure to deceive or evade. Armed and alert, we returned to the sea, confident in the discard of a weight in our handicap. We could strike back, and with no feeble blow—as the pirates soon learned.

There were scores to settle. Palm Branch, belying her tranquil name, took a payment in full for her shattered stern and the blood running in the steersman's eyes. Keen eyes sighted a periscope in time. The helm was put over and the white track raced across the stern, missing by feet. Baffled in under-water attack, the enemy hove up from his depths to open surface fire. He never had opportunity. If look-out was good, gun action was as quick and ready in Palm Branch. Her first shot struck the conning-tower, the second drove home on the submarine, which sank. While all eyes were focused on the settling wash and spreading scum of oil, a new challenge came and was as speedily accepted. A shell, fired by a second submarine at long range, passed over the steamer. Slewing round to a new target, the gunners kept up a steady return, shot for shot. The submarine dropped farther astern, fearing the probe of a bracket: he angled his course to bring both his guns in action. Two pieces[20] against the steamer's one! At that, he fared no better. Firing continuously, eighty rounds in less than an hour, he registered not one hit.

At length Palm Branch's steady, methodical search for the range had effect. Her gunners capped the day's fine shooting by a direct hit on the submarine's after-gun, shattering the piece. At evens again—the U-boat ceased fire and drew off, possibly under threat of British patrols approaching at full speed, more probably for the good and sufficient reason that he had had enough.

Not all our contests were as happily decided. If—shirking the issue of the guns, with no zest for a square fight—the German went to his depths, he had still the deadly torpedo to enforce a toll. The toll we paid and are paying, but there is no stoppage in the round by which the nation is fed and her arms served. The burden is heavy and our losses great, but we have not failed. We dare not fail.

IN A MERCHANTMAN—BOMB-THROWER PRACTICE

IN A MERCHANTMAN—BOMB-THROWER PRACTICE

[22]We seamen, naval or mercantile, are a stout unmovable breed. Tenacity to our convictions is deeply rooted. The narrow trends of shipboard life give licence to a conservatism that out-Herods Herod in intensity, unreason—in utter sophistry. We extend this atmosphere to our relationships, to the associations with the beach, with other sea-services, with other ships—to the absurd pretensions of the other watch. "A sailorman afore a landsman, an' a shipmate afore all," may be a useful creed, but it engenders a contentious outlook, an intolerance difficult to reconcile. In the fo'c'sle, the upholding of a 'last ship' may lead to a broken nose; aft, the officers may quarrel, wordily, over the grades of their service; ashore, the captain may only reserve his confidences for a peer of his tonnage; over all, the distance between the Naval and Merchants' Services was immeasurable and complete.

If it was so to this date, it was perhaps more intense in the old days when common seafaring had not set as broad a distinction, as widely divergent a sea-practice, as our modern services shew. That such a contentious atmosphere existed we have ample witness. After experience as a merchants' man, Nelson wrote of his re-entry. "I returned a practical seaman with a horror of the Royal Navy. . . . It was many weeks before I got the least reconciled to a man-o'-war, so deep was the prejudice rooted!" We have no such noted record of a merchant seaman re-entering from the Navy. Doubtless the laxity and indiscipline he might observe would produce a not dissimilar revulsion.

In the years that have elapsed since Nelson wrote, we have had few opportunities to compose our differences, to get on better terms with one another. The course of naval development took the great war fleets hull down on our commercial horizon, beyond casual intercommunication. On rare and widely separated occasions we fell into an expedition together, but the unchallenged power of the naval forces only served to heighten the barriers that stood between us. At the Crimea, in India, on the Chinese and Egyptian expeditions, during the Boer War, we were important links in the venture, but no more important than the cargoes we ferried. There was no call for any service other than our usual sea-work. The Navy saw to it that our comings and goings were unmolested. We were sea-civilians, purely and simply; there was nothing more to be said about it.

If little was said, it was with no good grace we took such a station. There were those who saw that seafaring could not thus arbitrarily be divided. Other nations were stirring and striving to a naval strength and power, drawing aid and personnel from their mercantile services. Sea-strength and paramountcy might not wholly come to be measured in terms of thickness of the armour-plating—in calibre of the great guns. Auxiliary services would be required.[23] The Navy could no more work without us than the Army without a Service Corps.

The Royal Naval Reserve came as a link to our intercourse. Certain of our shipmates left us for a period of naval training. They came back changed in many particulars. They had acquired a social polish, were perhaps less 'sailor-like' in their habits. As a rule they were discontented with the way of things in their old ships; the quiet rounds bored them after the crowded life in a warship. We were frequently reminded of how well and differently things were done in the Service. Perhaps, in return, we took the wrong line. We made no effort to sift their experiences, to find out how we might improve our ways. Often our comrade's own particular shrewdness was cited as a reason for the better ways of naval practice. We were rather irritated by the note of superiority assumed, perhaps somewhat jealous. Had commissions been granted on a competitive basis, we might have accepted such a tone, but we had our own way of assessing sea-values, and saw no reason why we should stand for these new airs. What was in it, what had wrought the change, we were never at pains to investigate. It was enough for us to note that, though his watch-keeping was certainly improved, our re-entered shipmate did not seem to be as efficient as a navigator or cargo supervisor as once we had thought him. All his talk of drills and guns and station-keeping considered, he seemed to have quite forgotten that groundnuts are thirteen hundredweights to the space ton and ought not to be stowed near fine goods!

On the other hand, he might reasonably be expected to see his old shipmates in a new light. Rude, perhaps. Of limited ideas. Tied to the old round of petty bickerings and small intrigues. He would note the want of trusty brotherhood. His sojourn among better-educated men may have roused his ideas to an appreciation of values that deep-sea life had obscured. The lack of the discipline to which he had become accustomed would appal and disquiet him. In time he would be worn to the rut again, but who can say the same rut? Unconsciously, we were influenced by his quieter manners. In self-study we saw faults that had been unnoticed before his return. Reviewing our hard sea-life, we recalled our exclusion from benefits of instruction that went a-begging on the beach. We stirred. There might yet be time to make up the leeway.

The influence of naval training was never very pronounced among the seamen and firemen of the Merchants' Service who were attached to the R.N.R. Their periods of training were too short for them to be permanently influenced by the discipline of the Navy (or our indiscipline on their return to us may have blighted a promising growth!) On short-term training they were rarely allotted to important work. The governing attitude was rather that they should be used as[24] auxiliaries, mercantile handymen, in a ship. If there was a stowage of stores, cleaning up of bilges, chipping and scaling of iron rust—well, here was mercantile Jack, who was used to that kind of work; who better for the job? Generally, he returned to his old ways rather tired of Navy 'fashion' and discipline, and one saw but little influence of his temporary service on a cruiser. Usually, he was a good hand, to begin with: he sought a post on good ships: with his papers in order we were very glad to have him back.

In few other ways did we come in touch with the Navy. At times the misfortune of the sea brought us into a naval port for assistance in our distress. Certainly, assistance was readily forthcoming, a full measure, but in a somewhat cold and formal way that left a rankling impression that we were not—well, we were not perhaps desirable acquaintances. The naval manner was not unlike that of a courteous prescribing chemist over his counter. "Have you had the pain—long?" "Is there any—coughing?" We had always the feeling that they were bored by our custom, were anxious to get back to the mixing of new pills, to their experiments. We were not very sorry when our repairs were completed and we could sail for warmer climates.

With the outbreak of war the R.N.R. was instantly mobilized. Their outgoing left a sensible gap in our ranks, a more considerable rift than we had looked for. Example drew others on their trodden path, our mercantile seamen were keen for fighting service; the unheralded torpedo had not yet struck home on their own ships. Commissions to a new entry of officers were still limited and capricious—the Hochsee Flotte had not definitely retired behind the booms at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, to weave a web of murder and assassination. For a short term we sailed on our voyages, on a steady round, differing but little from our normal peace-time trade.

A short term. The enemy did not leave us long secure in our faith in civilized sea-usage. Our trust in International Law received a rude and shattering shock from deadly floating mine and racing torpedo. Paralysed and impotent to venture a fleet action, the German Navy was to be matched not only against the commercial fleets of Britain and her Allies, but against every merchant ship, belligerent or neutral. There was to be no gigantic clash of sea-arms; action was to be taken on the lines of Thuggery. The German chose his opponents as he chose his weapons. Assassins' weapons! The knife in the dark—no warning, no quarter, sink or swim! The 'sea-civilians' were to be driven from the sea by exercise of the most appalling frightfulness and savagery that the seas had ever known.

Under such a threat our sea-services were brought together on a rapid sheer, a close boarding, in which there was a measure of confusion. It could not have[25] been otherwise. The only provision for co-operation, the R.N.R. organization, was directed to augment the forces of the Navy: there was no anticipation of a circumstance that would sound a recall. Our machinery was built and constructed to revolve in one direction; it could not instantly be reversed. Into an ordered service, ruled by the most minute shades of seniority, the finest influences of precedence and tradition, there came a need to fit the mixed alloy of the Merchants' Service. Ready, eager, and willing, as both Services were, to devote their energies to a joint endeavour, it took time and no small patience to resolve the maze and puzzle of the jig-saw. Naval officers detailed for our liaison were of varied moulds. Not many of the Active List could be spared; our new administrators were mostly recalled from fishing and farming to take up special duties for which they had few qualifications other than the gold lace on their sleeves. Some were tactful and clever in appreciation of other values than a mere readiness to salute, and those drew our affection and a ready measure of confidence. Others set up plumed Gessler bonnets, to which we were in no mood to bow. Only our devotion to the emergency exacted a jerk of our heads. To them we were doubtless difficult and trying. Our free ways did not fit into their schemes of proper routine. Accustomed to the lines of their own formal service, to issuing orders only to their juniors, they had no guide to a commercial practice whereby there can be a concerted service without the usages of the guard-room. They made things difficult for us without easing their own arduous task. They objected to our manners, our appearance, to the clothes we wore. Our diffidence was deemed truculence: our reluctance to accept a high doctrine of subservience was measured as insubordination.

The flames of war made short work of our moods and jealousies, prejudices, and dislikes. A new Service grew up, the Temporary R.N.R., in which we were admitted to a share in our own governance and no small part in combatant operations at sea. The sea-going section found outlet for their energy and free scope for a traditional privateering in their individual ventures against the enemy. Patrolling and hunting gave high promise for their capacity to work on lines of individual control. Minesweeping offered a fair field for the peculiar gifts of seamanship that mercantile practice engenders. Commissioned to lone and perilous service, they kept the seas in fair weather or foul. Although stationed largely in the narrow seas, there were set no limits to the latitude and longitude of their employment. The ice of the Arctic knew them—riding out the bitter northern gales in their small seaworthy drifters, thrashing and pitching in the seaway, to hold a post in the chain of our sea-communications. In the Adriatic warmer tides lapped on their scarred hulls, but brought no relaxing variance to their keen look-out. For want of a match of their own size, they had the[26] undying temerity to call three cheers and engage cruiser ordnance with their pipe-stems! A service indeed! If but temporary in title, there is permanence in their record!

Coincident with our actions on the sea—not alone those of our fighting cubs, but also those of our trading seamen—a better feeling came to cement our alliance. First in generous enthusiasm for our struggle against heavy odds, as they came to understand our difficulties, naval officers themselves set about to create a happier atmosphere. We were admitted to a voice in the league of our defence. Administration was adjusted to meet many of our grievances. Our capacity for controlling much of the machinery of our new movements was no longer denied. The shreds of old conservatism, the patches of contention and envy were scattered by a strong free breeze of reasoned service and joint effort.

We meet the naval man on every turn of the shore-end of our seafaring. We have grown to admire him, to like him, to look forward to his coming and association in almost the same way that we are pleased at the boarding of our favoured pilots. He fits into our new scheme of things as readily as the Port Authorities and the Ship's Husband. The plumed bonnets are no longer set up to attract our awed regard: by a better way than caprice and petulant discourtesy, the naval officer has won a high place in our esteem. We have borrowed from his stock to improve our store; better methods to control our manning, a more dispassionate bearing, a ready subordinance to ensure service. His talk, too. We use his phrases. We 'carry on'; we ask the 'drill' for this or that; we speak of our sailing orders as 'pictures,' our port-holes are become 'scuttles.' The enemy is a 'Fritz,' a depth-charge a 'pill,' torpedoes are 'mouldies.' In speaking of our ships we now omit the definite article. We are getting on famously together.

The operation of a threat to shipping—at three thousand miles distance—was dramatic in intensity under the light of acute contrast. Entering New York a few days after war had been declared, we berthed alongside a crack German liner. Her voyage had been abandoned: she lay at the pier awaiting events. At the first, we stared at one another curiously. Her silent winches and closed hatchways, deserted decks and passages, were markedly in contrast to the stir and animation with which we set about unloading and preparing for the return voyage. The few sullen seamen about her forecastle leant over the bulwarks and noted the familiar routine that was no longer theirs. Officers on the bridge-deck eyed our movements with interest, despite their apparent unconcern. We were respectfully hostile: submarine atrocities had not yet begun. The same newsboy served special editions to both ships. The German officers grouped together, reading of the fall of Liége. Doubtless they confided to one another that they would soon be at sea again. Five days we lay. At eight o'clock 'flags,' our bugle-call accompanied the raising of the ensign: the red, white, and black was hoisted defiantly at the same time. We unloaded, re-loaded, and embarked passengers, and backed out into the North River on our way to sea again. The Fürst ranged to the wash of our sternway as we cleared the piers; her hawsers strained and creaked, then held her to the bollards of the quay.

Time and again we returned on our regular schedule, to find the German berthed across the dock, lying as we had left her, with derricks down and her hatchways closed. . . . We noted the signs of neglect growing on her; guessed at the indiscipline aboard that inaction would produce. For a while her men were set to chipping and painting in the way of a good sea-custom, but the days passed with no release and they relaxed handwork. Her topsides grew rusty, her once trim and clean paintwork took on a grimy tint. Our doings were plain to her officers and crew: we were so near that they could read the tallies on the mailbags we handled: there were no mails from Germany. Loading operations, that included the embarkation of war material, went on by night and day: we were busied as never before. The narrow water space between her hull and ours was crowded by barges taking and delivering our cargo; the shriek of steam-tugs and clangour of their engine-bells advertised our stir and activity. On occasion, the regulations of the port obliged the Fürst to haul astern, to allow working space for the Merritt-Chapman crane to swing a huge piece of ordnance to our decks. There were rumours of a concealed activity on the German. "She was coaling silently at night, in preparation for a dash to sea." . . . "German spies had their headquarters in her." The evening papers had a[28] new story of her secret doings whenever copy ran short. All the while she lay quietly at the pier; we rated her by her draught marks that varied only with the galley coal she burnt.

At regular periods her hopeless outlook was emphasized by our sailings. Officers and crew could not ignore the stir that attended our departure. They saw the 'blue peter' come fluttering from the masthead, and heard our syren roar a warning to the river craft as we backed out. We were laden to our marks and the decks were thronged with young Britons returning to serve their country. The Fatherland could have no such help: the Fürst could handle no such cargo. For her there could be no movement, no canting on the tide and heading under steam for the open sea: the distant ships of the Grand Fleet held her in fetters at the pier.

While the Battle Fleet opened the oceans to us, we were not wholly safe from enemy interference on the high seas in the early stages of the war. German commerce raiders were abroad; there was need for a more tangible protection to the merchants' ships on the oversea trade routes. The older cruisers were sent out on distant patrols. They were our first associates of the huge fleet subsequently detailed for our defence and assistance. We were somewhat in awe of the naval men at sea on our early introduction. The White Ensign was unfamiliar. Armed to the teeth, an officer from the cruiser would board us: the bluejackets of his boat's crew had each a rifle at hand. "Where were we from . . . where to . . . our cargo . . . our passengers?" The lieutenant was sternly courteous; he was engaged on important duties: there was no mood of relaxation. He returned to his boat and shoved off with not one reassuring grin for the passengers lining the rails interested in every row-stroke of his whaler. In time we both grew more cordial: we improved upon acquaintance. The drudgery and monotony of a lone patrol off a neutral coast soon brought about a less punctilious boarding. Our procès-verbal had unofficial intervals. "How were things at home? . . . Are we getting the men trained quickly? . . . What about the Russians?" The boarding lieutenants discovered the key to our affections—the secret sign that overloaded their sea-boat with newspapers and fresh mess. "A fine ship you've got here, Captain!" We parted company at ease and with goodwill. The boat would cast off to the cheers of our passengers. The great cruiser, cleared for action with her guns trained outboard, would cant in to close her whaler. Often her band assembled on the upper deck: the favourite selections were 'Auld Lang Syne' and 'Will ye no' come back again'—as she swung off on her weary patrol.

Submarine activities put an end to these meetings on the sea. Except while under ocean escort of a cruiser—when our relations by flag signal are studied and[29] impersonal—we have now little acquaintance with vessels of that class. Counter-measures of the new warfare demand the service of smaller vessels. Destroyers and sloops are now our protectors and co-workers. With them, we are drawn to a familiar intimacy; we are, perhaps, more at ease in their company, dreading no formal routine. Admirals are, to us, awesome beings who seclude themselves behind gold-corded secretaries: commodores (except those who control our convoys) are rarely sea-going, and we come to regard them as schoolmasters, tutors who may not be argued with; post-captains in command of the larger escorts have the brusque assumption of a super-seamanship that takes no note of a limit in manning. The commanders and lieutenants of the destroyers and sloops that work with us are different; they are more to our mind—we look upon them as brother seamen. Like ourselves, they are 'single-ship' men. They are neither concerned with serious plans of naval strategy nor overbalanced by the forms and usages of great ship routine. While 'the bridge' of a cruiser may be mildly scornful upon receipt of an objection to her signalled noon position, the destroyer captain is less assured: he is more likely to request our estimate of the course and speed. His seamanship is comparable to our own. The relatively small crew he musters has taught him to be tolerant of an apparent delay in carrying out certain operations. In harbour he is frequently berthed among the merchantmen, and has opportunity to visit the ships and acquire more than a casual knowledge of our gear and appliances. He is ever a welcome visitor, frank and manly and candid. Even if there is a dispute as to why we turned north instead of south-east 'when that Fritz came up,' and we blanked the destroyer's range, there is not the air of superior reproof that rankles.

In all our relations with the Navy at sea there was ever little, if any, friction. We saw no empty plumed bonnet in the White Ensign. We were proud of the companionship and protection of the King's ships. Our ready service was never grudged or stinted to the men behind the grey guns; succour in our distress was their return. Incidents of our co-operation varied, but an unchanging sea-brotherhood was the constant light that shone out in small occurrences and deathly events.

Dawn in the Channel, a high south gale and a bitter confused sea. Even with us, in a powerful deep-sea transport, the measure of the weather was menacing; green seas shattered on board and wrecked our fittings, half of the weather boats were gone, others were stove and useless. A bitter gale! Under our lee the destroyer of our escort staggered through the hurtling masses that burst and curled and swept her fore and aft. Her mast and one funnel were gone, the bridge wrecked; a few dangling planks at her davits were all that was[30] left of her service boats. She lurched and faltered pitifully, as though she had loose water below, making through the baulks and canvas that formed a makeshift shield over her smashed skylights. In the grey of the murky dawn there was yet darkness to flash a message: "In view of weather probably worse as wind has backed, suggest you run for Waterford while chance, leaving us to carry on at full speed." An answer was ready and immediate: "Reply. Thanks. I am instructed escort you to port."

The Mediterranean. A bright sea and sky disfigured by a ring of curling black smoke—a death-screen for the last agonies of a torpedoed troopship. Amid her littering entrails she settles swiftly, the stern high upreared, the bows deepening in a wash of wreckage. Boats, charged to inches of freeboard, lie off, the rowers and their freight still and open-mouthed awaiting her final plunge. On rafts and spars, the upturned strakes of a lifeboat, remnants of her manning and company grip safeguard, but turn eyes on the wreck of their parent hull. Into the ring, recking nothing of entangling gear or risk of suction, taking the chances of a standing shot from the lurking submarine, a destroyer thunders up alongside, brings up, and backs at speed on the sinking transport. Already her decks are jammed to a limit, by press of a khaki-clad cargo she was never built to carry. This is final, the last turn of her engagement. The foundering vessel slips quickly and deeper. "Come along, Skipper! You've got 'em all off! You can do no more! Jump!"

A BRITISH SUBMARINE DETAILED FOR INSTRUCTION OF MERCHANT OFFICERS

A BRITISH SUBMARINE DETAILED FOR INSTRUCTION OF MERCHANT OFFICERS

The work was sound and no small ingenuity was advanced in planning adaptations, but the spirit of emergency did not show an evidence in their careful papers. The proposed voyage was distinctly stated to be from Newhaven to Dieppe, and it seemed to us that the elaborate accommodation for a prison, a guard-room, a hospital, were somewhat ambitious for a six-hour sea-passage. In conversation with the Commandant, we were of opinion that, to a degree, their work and pains were rather needless. Carrying passengers (troops and others) was our business; a trade in which we had been occupied for some few years. He agreed. He regarded their particular exercise in the same light as the 'herring-and-a-half' problem of the schoolroom: it was good for the young braves to learn something of their only gangway to a foreign[32] field. "Of course," he said, "if war comes it will be duty for the Navy to supervise our sea-transport." We understood that their duty would be to safeguard our passage, but we had not thought of supervision in outfit. The Commandant was incredulous when we remarked that we had never met a naval transport officer, that we knew of no plans to meet such an emergency as that submitted to his officers. It was evident that his trained soldierly intendance could not contemplate a situation in which the seamen of the country had no foreknowledge of a war service; it was amazing to him that we were not already drilled for duties that might, at any moment, be thrust upon us. Pointing across the dock to where two vessels of the Bremen Hansa Line were working in haste to catch the tide, he affirmed that they would be better prepared: their place in mobilization would be detailed, their duties and services made clear.

We knew of no plans for our employment in war service; we had no position allotted to us in measures for emergency. We were sufficiently proud of our seafaring to understand a certain merit in this apparent lack of prevision: we took it as in compliment to the efficiency and resource with which our sea-trade was credited. Was it not on our records that the Isle of Man steamers transported 58,000 people in the daylight hours of an August Bank Holiday. A seventy-mile passage. Trippers. Less amenable to ordered direction than disciplined troops. A day's work, indeed. Unequalled, unbeaten by any record to date in the amazing statistics of the war. There was no need for supervision and direction: we knew our business, we could pick up the tune as we marched.

We did. On the outbreak of war we fell into our places in transport of troops and military material with little more ado than in handling our peace-time cargoes. The ship on which the Staff students worked their problems set out on almost the very route they had planned for her, but with no prison or guard-room or hospital, and sixteen hundred troops instead of eleven: the time taken to fit her (including discharge of a cargo) occupied exactly four days. We saw but little of the naval authority.

Later, in our war work, we made the acquaintance of the naval transport officer. Generally, he was not intimate with the working of merchant ships. His duties were largely those of interpretation. Through him Admiralty passed their orders: it devolved on the mercantile shore staff of the shipping companies to carry these orders into execution. If, in transport services, our marine superintendents and ships' husbands did not share in the honours, it was not for want of merit. They could not complain of lack of work in the early days of the war when the transport officer was serving his apprenticeship to the trade. The absence of a keen knowledge and interest in commercial ship-practice at the transport office made for complex situations; hesitancies and[35] conflicting orders added to the arduous business. Under feverish pressure a ship would be unloaded on to quay space already congested, ballast be contracted for—and delivered; a swarm of carpenters, working day and night, would fit her for carriage of troops. At the eleventh hour some one idly fingering a tide-table would discover that the vessel drew too much water to cross the bar of her intended port of discharge. (The marine superintendent was frequently kept in ignorance of the vessel's intended destination.) Telegraph and telephone are handy—"Requisition cancelled" is easily passed over the wires! As you were is a simple order in official control, but it creates an atmosphere of misdirection almost as deadly as German gas. Only our tremendous resources, the sound ability of our mercantile superintendents, the industry of the contractors and quay staffs, brought order out of chaos and placed the vessels in condition for service at disposal of the Admiralty.

Despite all blunders and vacillations our expedition was not unworthy of the emergency. How much better we could have done had there been a considered scheme of competent control must ever remain a conjecture. Four years of war practice have improved on the hasty measures with which we met the first immediate call. Sea-transport of troops and munitions of war has become a highly specialized business for naval directorate and mercantile executant alike. Ripe experience in the thundering years has sweetened our relations. The naval transport officer has learnt his trade. He is better served. He has now an adequate executant staff, recruited largely from the Merchants' Service. With liberal assistance he relies less on telegraph and telephone to advance his work: our atmosphere is no longer polluted by the miasma of indecision, and by the chill airs of the barracks.

Of our Naval War Staff, the transport officer was the first on the field, but his duties were only concerned with ships requisitioned for semi-naval service. For long we had no national assistance in our purely commercial seafaring. Our sea-rulers (if they existed) were unconcerned with the judicious employment of mercantile tonnage: some of our finest liners were swinging the tides in harbour, rusting at their cables—serving as prison hulks for interned enemies. Our service on the sea was as lightly held. We made our voyages as in peace-time. We had no means of communication with the naval ships at sea other than the universally understood International Code of Signals. Any measures we took to keep out of the way of enemy war vessels, then abroad, were our own. We had no Intelligence Service to advise us in our choice of sea-routes, and act as distributors of confidential information. We were far too 'jack-easy' in our seafaring: we estimated the enemy's sea-power over-lightly.[36]

In time we learned our lesson. Tentative measures were advanced. Admiralty, through the Trade Division, took an interest in our employment. Orders and advices took long to reach us. These were first communicated to the War Risks Associations, who sent them to our owners. We received them as part of our sailing orders, rather late to allow of considered efforts on our part to conform with their tenor. There was no channel of direct communication. When on point of sailing, we projected our own routes, recorded them in a sealed memorandum which we left with our owners. If we fell overdue Admiralty could only learn of our route by application to the holders of the memorandum. A short trial proved the need for a better system. Shipping Intelligence Officers were appointed at the principal seaports. At this date some small echo of our demand for a part in our governance had reached the Admiralty. In selecting officers for these posts an effort was made to give us men with some understanding of mercantile practice; a number of those appointed to our new staff were senior officers of the R.N.R. who were conversant with our way of business. (If they did, on occasion, project a route for us clean through the Atlantic ice-field in May, they were open to accept a criticism and reconsider the voyage.) With them were officers of the Royal Navy who had specialized in navigation, a branch of our trade that does not differ greatly from naval practice. They joined with us in discussion of the common link that held few opportunities for strained association. Certainly we took kindly to our new directors from the first; we worked in an atmosphere of confidence. The earliest officer appointed to the West Coast would blush to know the high esteem in which he is held, a regard that (perhaps by virtue of his tact and courtesy) was in course extended to his colleagues of a later date.

The work of the S.I.O. is varied and extensive. His principal duty is to plan and set out our oversea route, having regard to his accurate information of enemy activities. All Admiralty instructions as to our sea-conduct pass through his hands. He issues our confidential papers and is, in general, the channel of our communication with the Naval Service. He may be likened to our signal and interlocking expert. On receipt of certain advices he orders the arm of the semaphore to be thrown up against us. The port is closed to the outward-bound. His offices are quickly crowded by masters seeking information for their sailings: with post and telephone barred to us in this connection, we must make an appearance in person to receive our orders. A tide or two may come and go while we wait for passage. We have opportunity, in the waiting-room, to meet and become intimate with our fellow-seafarers. It is good for the captain of a liner to learn how the captain of a North Wales schooner makes his bread, the difficulties of getting decent yeast at the salt-ports; how the[37] schooner's boy won't learn ("indeed to goodness") the proper way his captain shows him to mix the dough!

On telegraphic advice the arm of the semaphore rattles down. The port is open to traffic again. The waiting-room is emptied and we are off to the sea, perhaps fortified by the S.I.O.'s confidence that the cause of the stoppage has been violently removed from the sea-lines.

Under the pressure of ruthless submarine warfare we were armed for defence. Gunnery experts were added to our war complement. A division for organization of our ordnance was formed, the Defensively Armed Merchant Ships Department of the Admiralty. We do not care for long titles; we know this division as the "Dam Ships." Most of the officers appointed to this Service are R.N.R. They are perhaps the most familiar of the war staff detailed to assist us. Their duties bring them frequently on board our ships, where (on our own ground) relations grow quickly most intimate and cordial. The many and varied patterns of guns supplied for our defence made a considerable shore establishment necessary, not alone for the guns and mountings, but for ammunition of as many marks as a Geelong wool-bale. In the first stages of our war-harnessing, the supply of guns was limited to what could be spared from battlefield and naval armament. The range of patterns varied from pipe-stems to what was at one time major armament for cruisers; we had odd weapons—soixante-quinze and Japanese pieces; even captured German field-guns were adapted to our needs in the efforts of the D.A.M.S. to arm us. Standardization in mounting and equipment was for long impossible. Our outcry for guns was cleverly met by the department. We could not wait for weapons to be forged: by working 'double tides' they ensured a twenty-four-hour day of service for the guns in issue, by a system that our ordnance should not remain idle during our stay in port. Incoming ships were boarded in the river, their guns and ammunition dismounted and removed to serve the needs of a vessel bound out on the same tide. The problem of fitting a 12-pounder on a 4.7 emplacement taxed the department's ingenuity and resource, but few ships were held in port for failure of their prompt action.