Title: Susanna and Sue

Author: Kate Douglas Smith Wiggin

Illustrator: Alice Barber Stephens

N. C. Wyeth

Release date: April 28, 2010 [eBook #32169]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Linda Hamilton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

![]()

Susanna and Sue. Illustrated by Alice Barber Stephens.

The Old Peabody Pew. Illustrated by Alice Barber Stephens.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm.

New Chronicles of Rebecca. Illustrated by F. C. Yohn.

Rose o' the River. Illustrated by George Wright.

The Affair at the Inn. Illustrated by Martin Justice.

The Birds' Christmas Carol. Illustrated.

The Story of Patsy. Illustrated.

The Diary of a Goose Girl. Illustrated by C. A. Shepperson.

A Cathedral Courtship and Penelope's English Experiences. Illustrated by Clifford Carleton.

A Cathedral Courtship. Holiday Edition. Enlarged, and with illustrations by Charles E. Brock.

Penelope's Progress. Experiences in Scotland.

Penelope's Irish Experiences.

Penelope's Experiences. Holiday Edition. In three volumes. Illustrated by Charles E. Brock. I. England; II. Scotland; III. Ireland.

Marm Lisa.

The Village Watch-Tower. Short Stories.

Polly Oliver's Problem. A Story for Girls. Illustrated.

Timothy's Quest. A Story for Anybody, Young or Old, who cares to read it.

Timothy's Quest. Holiday Edition. Illustrated by Oliver Herford.

A Summer in a Cañon. A California Story. Illustrated by Frank T. Merrill.

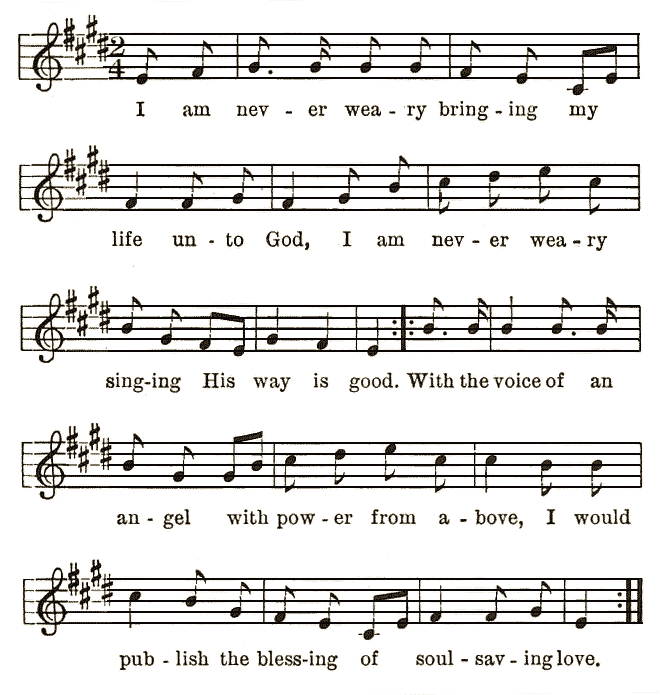

Nine Love Songs and a Carol. Poems set to music by Mrs. Wiggin.

![]()

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY KATE DOUGLAS RIGGS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published October 1909

| I. | Mother Ann's Children | 1 |

| II. | A Son of Adam | 23 |

| III. | Divers Doctrines | 43 |

| IV. | Louisa's Mind | 67 |

| V. | The Little Quail Bird | 87 |

| VI. | Susanna speaks in Meeting | 107 |

| VII. | "The Lower Plane" | 121 |

| VIII. | Concerning Backsliders | 141 |

| IX. | Love Manifold | 163 |

| X. | Brother and Sister | 177 |

| XI. | "The Open Door" | 195 |

| XII. | The Hills of Home | 211 |

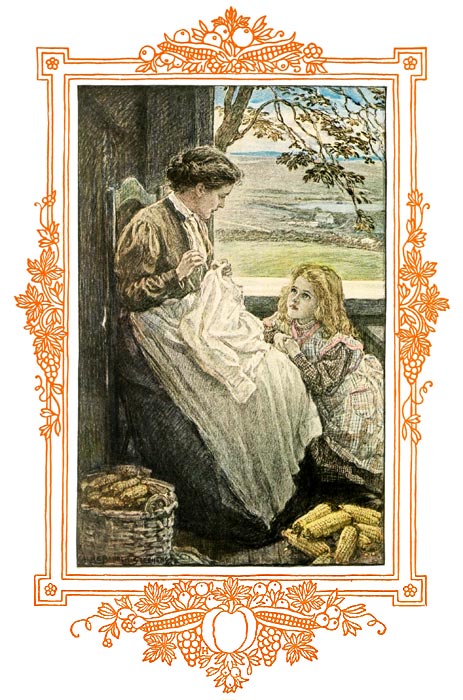

| Looking up into her mother's face expectantly (page 102) | Frontispiece |

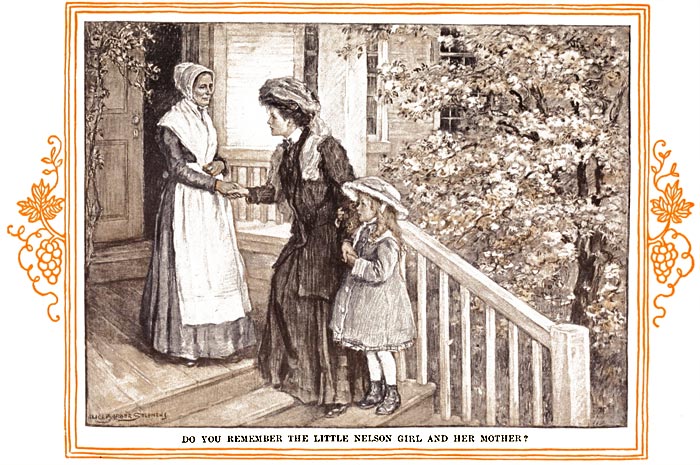

| Do you remember the little Nelson girl and her mother? | 12 |

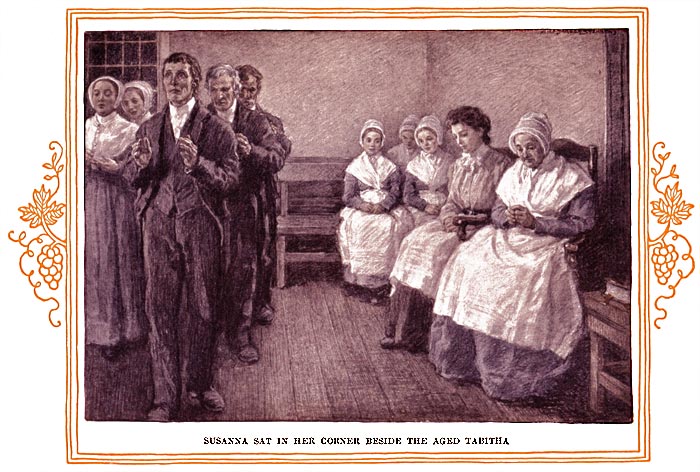

| Susanna sat in her corner beside the aged Tabitha | 112 |

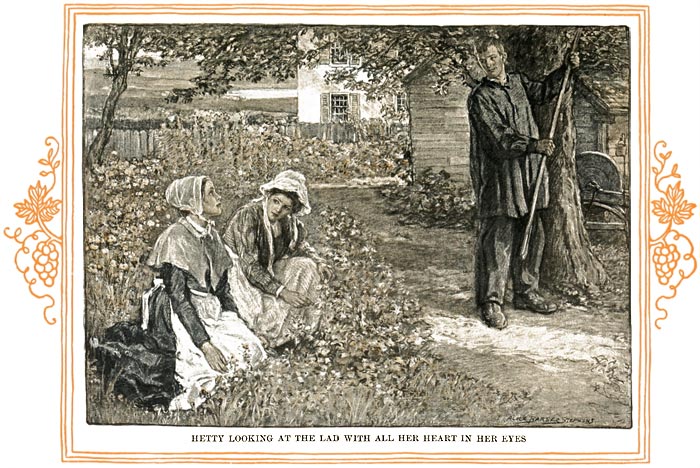

| Hetty looking at the lad with all her heart in her eyes | 130 |

It was the end of May, when "spring goeth all in white." The apple trees were scattering their delicate petals on the ground, dropping them over the stone walls to the roadsides, where in the moist places of the shadows they fell on beds of snowy innocence. Here and there a single tree was tinged with pink, but so faintly, it was as if the white were blushing. Now and then a tiny white butterfly danced in the sun and pearly clouds strayed across the sky in fleecy flocks.

Everywhere the grass was of ethereal greenness, a greenness drenched with the pale yellow of spring sunshine. Looking from earth to sky and from blossom to blossom, the little world of the apple orchards, shedding its falling petals like fair-weather snow, seemed made of alabaster and porcelain, ivory and mother-of-pearl, all shimmering on a background of tender green.

After you pass Albion village, with its streets shaded by elms and maples and its outskirts embowered in blossoming orchards, you wind along a hilly country road that runs between grassy fields. Here the whiteweed is already budding, and there are pleasant pastures dotted with rocks and fringed with spruce and fir; stretches of woodland, too, where the road is lined with giant pines and you lift your face gratefully to catch the cool balsam breath of the forest. Coming from out this splendid shade, this silence too deep to be disturbed by light breezes or vagrant winds, you find yourself on the brow of a descending hill. The first thing that strikes the eye is a lake that might be a great blue sapphire dropped into the verdant hollow where it lies. When the eye reluctantly leaves the lake on the left, it turns to rest upon the little Shaker Settlement on the right—a dozen or so large comfortable white barns, sheds, and houses, standing in the wide orderly spaces of their own spreading acres of farm and timber land. There again the spring goeth all in white, for there is no spot to fleck the dazzling quality of Shaker paint, and their apple, plum, and pear trees are so well cared for that the snowy blossoms are fairly hiding the branches.

The place is very still, although there are signs of labor in all directions. From a window of the girls' building a quaint little gray-clad figure is beating a braided rug; a boy in homespun, with his hair slightly long in the back and cut in a straight line across the forehead, is carrying milk-cans from the dairy to one of the Sisters' Houses. Men in broad-brimmed hats, with clean-shaven, ascetic faces, are ploughing or harrowing here and there in the fields, while a group of Sisters is busy setting out plants and vines in some beds near a cluster of noble trees. That cluster of trees, did the eye of the stranger realize it, was the very starting-point of this Shaker Community, for in the year 1785, the valiant Father James Whittaker, one of Mother Ann Lee's earliest English converts, stopped near the village of Albion on his first visit to Maine. As he and his Elders alighted from their horses, they stuck into the ground the willow withes they had used as whips, and now, a hundred years later, the trees that had grown from these slender branches were nearly three feet in diameter.

From whatever angle you look upon the Settlement, the first and strongest impression is of quiet order, harmony, and a kind of austere plenty. Nowhere is the purity of the spring so apparent. Nothing is out of place; nowhere is any confusion, or appearance of loose ends, or neglected tasks. As you come nearer, you feel the more surely that here there has never been undue haste nor waste; no shirking, no putting off till the morrow what should have been done to-day. Whenever a shingle or a clapboard was needed it was put on, where paint was required it was used,—that is evident; and a look at the great barns stored with hay shows how the fields have been conscientiously educated into giving a full crop.

To such a spot as this might any tired or sinful heart come for rest; hoping somehow, in the midst of such frugality and thrift, such self-denying labor, such temperate use of God's good gifts, such shining cleanliness of outward things, to regain and wear "the white flower of a blameless life." The very air of the place breathed peace, so thought Susanna Hathaway; and little Sue, who skipped by her side, thought nothing at all save that she was with mother in the country; that it had been rather a sad journey, with mother so quiet and pale, and that she would be very glad to see supper, should it rise like a fairy banquet in the midst of these strange surroundings.

It was only a mile and a half from the railway station to the Shaker Settlement, and Susanna knew the road well, for she had driven over it more than once as child and girl. A boy would bring the little trunk that contained their simple necessities later on in the evening, so she and Sue would knock at the door of the house where visitors were admitted, and be undisturbed by any gossiping company while they were pleading their case.

"Are we most there, Mardie?" asked Sue for the twentieth time. "Look at me! I'm being a butterfly, or perhaps a white pigeon. No, I'd rather be a butterfly, and then I can skim along faster and move my wings!"

The airy little figure, all lightness and brightness, danced along the road, the white cotton dress rising and falling, the white-stockinged legs much in evidence, the arms outstretched as if in flight, straw hat falling off yellow hair, and a little wisp of swansdown scarf floating out behind like the drapery of a baby Mercury.

"We are almost there," her mother answered. "You can see the buildings now, if you will stop being a butterfly. Don't you like them?"

"Yes, I 'specially like them all so white. Is it a town, Mardie?"

"It is a village, but not quite like other villages. I have told you often about the Shaker Settlement, where your grandmother brought me once when I was just your age. There was a thunder-storm; they kept us all night, and were so kind that I never forgot them. Then your grandmother and I stopped off once when we were going to Boston. I was ten then, and I remember more about it. The same sweet Eldress was there both times."

"What is an El-der-ess, Mardie?"

"A kind of everybody's mother, she seemed to be," Susanna responded, with a catch in her breath.

"I'd 'specially like her; will she be there now, Mardie?"

"I'm hoping so, but it is eighteen years ago. I was ten and she was about forty, I should think."

"Then o' course she'll be dead," said Sue, cheerfully, "or either she'll have no teeth or hair."

"People don't always die before they are sixty, Sue."

"Do they die when they want to, or when they must?"

"Always when they must; never, never when they want to," answered Sue's mother.

"But o' course they wouldn't ever want to if they had any little girls to be togedder with, like you and me, Mardie?" And Sue looked up with eyes that were always like two interrogation points, eager by turns and by turns wistful, but never satisfied.

"No," Susanna replied brokenly, "of course they wouldn't, unless sometimes they were wicked for a minute or two and forgot."

"Do the Shakers shake all the time, Mardie, or just once in a while? And shall I see them do it?"

"Sue, dear, I can't explain everything in the world to you while you are so little; you really must wait until you're more grown up. The Shakers don't shake and the Quakers don't quake, and when you're older, I'll try to make you understand why they were called so and why they kept the name."

"Maybe the El-der-ess can make me understand right off now; I'd 'specially like it." And Sue ran breathlessly along to the gate where the North Family House stood in its stately, white-and-green austerity.

Susanna followed, and as she caught up with the impetuous Sue, the front door of the house opened and a figure appeared on the threshold. Mother and child quickened their pace and went up the steps, Susanna with a hopeless burden of fear and embarrassment clogging her tongue and dragging at her feet; Sue so expectant of new disclosures and fresh experiences that her face beamed like a full moon.

Eldress Abby (for it was Eldress Abby) had indeed survived the heavy weight of her fifty-five or sixty summers, and looked as if she might reach a yet greater age. She wore the simple Shaker afternoon dress of drab alpaca; an irreproachable muslin surplice encircled her straight, spare shoulders, while her hair was almost entirely concealed by the stiffly wired, transparent white-net cap that served as a frame to the tranquil face. The face itself was a network of delicate, fine wrinkles; but every wrinkle must have been as lovely in God's sight as it was in poor unhappy Susanna Hathaway's. Some of them were graven by self-denial and hard work; others perhaps meant the giving up of home, of parents and brothers or sisters; perhaps some worldly love, the love that Father Adam bequeathed to the human family, had been slain in Abby's youth, and the scars still remained to show the body's suffering and the spirit's triumph. At all events, whatever foes had menaced her purity or her tranquillity had been conquered, and she exhaled serenity as the rose sheds fragrance.

"Do you remember the little Nelson girl and her mother that stayed here all night, years ago?" asked Susanna, putting out her hand timidly.

"DO YOU REMEMBER THE LITTLE NELSON GIRL AND HER MOTHER?"

"Why, seems to me I do," assented Eldress Abby, genially. "So many comes and goes it's hard to remember all. Didn't you come once in a thunder-storm?"

"Yes, one of your barns was struck by lightning and we sat up all night."

"Yee, yee.[1] I remember well! Your mother was a beautiful spirit. I couldn't forget her."

"And we came once again, mother and I, and spent the afternoon with you, and went strawberrying in the pasture."

"Yee, yee, so we did; I hope your mother continues in health."

"She died the very next year," Susanna answered in a trembling voice, for the time of explanation was near at hand and her heart failed her.

"Won't you come into the sitting-room and rest awhile? You must be tired walking from the deepot."

"No, thank you, not just yet. I'll step into the front entry a minute.—Sue, run and sit in that rocking-chair on the porch and watch the cows going into the big barn.—Do you remember, Eldress Abby, the second time I came, how you sat me down in the kitchen with a bowl of wild strawberries to hull for supper? They were very small and ripe; I did my best, for I never meant to be careless, but the bowl slipped and fell,—my legs were too short to reach the floor, and I couldn't make a lap,—so in trying to pick up the berries I spilled juice on my dress, and on the white apron you had tied on for me. Then my fingers were stained and wet and the hulls kept falling in with the soft berries, and when you came in and saw me you held up your hands and said, 'Dear, dear! you have made a mess of your work!' Oh, Eldress Abby, they've come back to me all day, those words. I've tried hard to be good, but somehow I've made just such a mess of my life as I made of hulling the berries. The bowl is broken, I haven't much fruit to show, and I am all stained and draggled. I shouldn't have come to Albion on the five-o'clock train—that was an accident; I meant to come at noon, when you could turn me away if you wanted to."

"Nay, that is not the Shaker habit," remonstrated Abby. "You and the child can sleep in one of the spare chambers at the Office Building and be welcome."

"But I want much more than that," said Susanna, tearfully. "I want to come and live here, where there is no marrying nor giving in marriage. I am so tired with my disappointments and discouragements and failures that it is no use to try any longer. I am Mrs. Hathaway, and Sue is my child, but I have left my husband for good and all, and I only want to spend the rest of my days here in peace and bring up Sue to a more tranquil life than I have ever had. I have a little money, so that I shall not be a burden to you, and I will work from morning to night at any task you set me."

"I will talk to the Family," said Eldress Abby, gravely; "but there are a good many things to settle before we can say yee to all you ask."

"Let me confess everything freely and fully," pleaded Susanna, "and if you think I'm to blame, I will go away at once."

"Nay, this is no time for that. It is our duty to receive all and try all; then if you should be gathered in, you would unburden your heart to God through the Sister appointed to receive your confession."

"Will Sue have to sleep in the children's building away from me?"

"Nay, not now; you are company, not a Shaker, and anyway you could keep the child with you till she is a little older; that's not forbidden at first, though there comes a time when the ties of the flesh must be broken! All you've got to do now's to be 'pure and peaceable, gentle, easy to be entreated, and without hypocrisy.' That's about all there is to the Shaker creed, and that's enough to keep us all busy."

Sue ran in from the porch excitedly and caught her mother's hand.

"The cows have all gone into the barn," she chattered; "and the Shaker gentlemen are milking them, and not one of them is shaking the least bit, for I 'specially noticed; and I looked in through the porch window, and there is nice supper on a table—bread and butter and milk and dried-apple sauce and gingerbread and cottage cheese. Is it for us, Mardie?"

Susanna's lip was trembling and her face was pale. She lifted her swimming eyes to the Sister's and asked, "Is it for us, Eldress Abby?"

"Yee, it's for you," she answered; "there's always a Shaker supper on the table for all who want to leave the husks and share the feast. Come right in and help yourselves. I will sit down with you."

Supper was over, and Susanna and Sue were lying in a little upper chamber under the stars. It was the very one that Susanna had slept in as a child, or that she had been put to bed in, for there was little sleep that night for any one. She had leaned on the window-sill with her mother and watched the pillar of flame and smoke ascend from the burning barn; and once in the early morning she had stolen out of bed, and, kneeling by the open window, had watched the two silent Shaker brothers who were guarding the smoldering ruins, fearful lest the wind should rise and bear any spark to the roofs of the precious buildings they had labored so hard to save.

The chamber was spotless and devoid of ornament. The paint was robin's egg blue and of a satin gloss. The shining floor was of the same color, and neat braided rugs covered exposed places near the bureau, washstand, and bed. Various useful articles of Shaker manufacture interested Sue greatly: the exquisite straw-work that covered the whisk-broom; the mending-basket, pincushion, needle-book, spool and watch cases, hair-receivers, pin-trays, might all have been put together by fairy fingers.

Sue's prayers had been fervent, but a trifle disjointed, covering all subjects from Jack and Fardie, to Grandma in heaven and Aunt Louisa at the farm, with special references to El-der-ess Abby and the Shaker cows, and petitions that the next day be fair so that she could see them milked. Excitement at her strange, unaccustomed surroundings had put the child's mind in a very whirl, and she had astonished her mother with a very new and disturbing version of the Lord's prayer, ending: "God give us our debts and help us to forget our debtors and theirs shall be the glory, Amen." Now she lay quietly on the wall side of the clean, narrow bed, while her mother listened to hear the regular breathing that would mean that she was off for the land of dreams. The child's sleep would leave the mother free to slip out of bed and look at the stars; free to pray and long and wonder and suffer and repent,—not wholly, but in part, for she was really at peace in all but the innermost citadel of her conscience. She had left her husband, and for the moment, at all events, she was fiercely glad; but she had left her boy, and Jack was only ten. Jack was not the helpless, clinging sort; he was a little piece of his father, and his favorite. Aunt Louisa would surely take him, and Jack would scarcely feel the difference, for he had never shown any special affection for anybody. Still he was her child, nobody could possibly get around that fact, and it was a stumbling-block in the way of forgetfulness or ease of mind. Oh, but for that, what unspeakable content she could feel in this quiet haven, this self-respecting solitude! To have her thoughts, her emotions, her words, her self, to herself once more, as she had had them before she was married at seventeen. To go to sleep in peace, without listening for a step she had once heard with gladness, but that now sometimes stumbled unsteadily on the stair; or to dream as happy women dreamed, without being roused by the voice of the present John, a voice so different from that of the past John that it made the heart ache to listen to it.

Sue's voice broke the stillness: "How long are we going to stay here, Mardie?"

"I don't know, Sue; I think perhaps as long as they'll let us."

"Will Fardie come and see us?"

"Who'll take care of Jack, Mardie?"

"Your Aunt Louisa."

"She'll scold him awfully, but he never cries; he just says, 'Pooh! what do I care?' Oh, I forgot to pray for that very nicest Shaker gentleman that said he'd let me help him feed the calves! Hadn't I better get out of bed and do it? I'd 'specially like to."

"Very well, Sue; and then go to sleep."

Safely in bed again, there was a long pause, and then the eager little voice began, "Who'll take care of Fardie now?"

"He's a big man; he doesn't need anybody."

"What if he's sick?"

"We must go back to him, I suppose."

"To-morrow's Sunday; what if he needs us to-morrow, Mardie?"

"I don't know, I don't know! Oh, Sue, Sue, don't ask your wretched mother any more questions, for she cannot bear them to-night. Cuddle up close to her; love her and forgive her and help her to know what's right."

When Susanna Nelson at seventeen married John Hathaway, she had the usual cogent reasons for so doing, with some rather more unusual ones added thereto. She was alone in the world, and her life with an uncle, her mother's only relative, was an unhappy one. No assistance in the household tasks that she had ever been able to render made her a welcome member of the family or kept her from feeling a burden, and she belonged no more to the little circle at seventeen, than she did when she became a part of it at twelve. The hope of being independent and earning her own living had sustained her through the last year; but it was a very timid, self-distrustful, love-starved little heart that John Hathaway stormed and carried by assault. Her girl's life in a country school and her uncle's very rigid and orthodox home had been devoid of emotion or experience; still, her mother had early sown seeds in her mind and spirit that even in the most arid soil were certain to flower into beauty when the time for flowering came; and intellectually Susanna was the clever daughter of clever parents. She was very immature, because, after early childhood, her environment had not been favorable to her development. At seventeen she began to dream of a future as bright as the past had been dreary and uneventful. Visions of happiness, of goodness, and of service haunted her, and sometimes, gleaming through the mists of dawning womanhood, the figure, all luminous, of The Man!

When John Hathaway appeared on the horizon, she promptly clothed him in all the beautiful garments of her dreams; they were a grotesque misfit, but when we intimate that women have confused the dream and the reality before, and may even do so again, we make the only possible excuse for poor little Susanna Nelson.

John Hathaway was the very image of the outer world that lay beyond Susanna's village. He was a fairly prosperous, genial, handsome young merchant, who looked upon life as a place furnished by Providence in which to have "a good time." His parents had frequently told him that it was expedient for him to "settle down," and he supposed that he might finally do so, if he should ever find a girl who would tempt him to relinquish his liberty. (The line that divides liberty and license was a little vague to John Hathaway!) It is curious that he should not have chosen for his life-partner some thoughtless, rosy, romping young person, whose highest conception of connubial happiness would have been to drive twenty miles to the seashore on a Sunday, and having partaken of all the season's delicacies, solid and liquid, to come home hilarious by moonlight. That, however, is not the way the little love-imps do their work in the world; or is it possible that they are not imps at all who provoke and stimulate and arrange these strange marriages—not imps, but honest, chastening little character-builders? In any event, the moment that John Hathaway first beheld Susanna Nelson was the moment of his surrender; yet the wooing was as incomprehensible as that of a fragile, dainty little hummingbird by a pompous, greedy, big-breasted robin.

Susanna was like a New England anemone. Her face was oval in shape and as smooth and pale as a pearl. Her hair was dark, not very heavy, and as soft as a child's. Her lips were delicate and sensitive, her eyes a cool gray,—clear, steady, and shaded by darker lashes. When John Hathaway met her shy, maidenly glance and heard her pretty, dovelike voice, it is strange he did not see that there was a bit too much saint in her to make her a willing comrade of his gay, roistering life. But as a matter of fact, John Hathaway saw nothing at all; nothing but that Susanna Nelson was a lovely girl and he wanted her for his own. The type was one he had never met before, one that allured him by its mysteries and piqued him by its shy aloofness.

John had a "way with him,"—a way that speedily won Susanna; and after all there was a best to him as well as a worst. He had a twinkling eye, an infectious laugh, a sweet disposition, and while he was over-susceptible to the charm of a pretty face, he had a chivalrous admiration for all women, coupled, it must be confessed, with a decided lack of discrimination in values. His boyish light-heartedness had a charm for everybody, including Susanna; a charm that lasted until she discovered that his heart was light not only when it ought to be light, but when it ought to be heavy.

He was very much in love with her, but there was nothing particularly exclusive, unique, individual, or interesting about his passion at that time. It was of the every-day sort which carries a well-meaning man to the altar, and sometimes, in cases of exceptional fervor and duration, even a little farther. Stock sizes of this article are common and inexpensive, and John Hathaway's love when he married Susanna was, judged by the highest standards, about as trivial an affair as Cupid ever put upon the market or a man ever offered to a woman. Susanna on the same day offered John, or the wooden idol she was worshiping as John, her whole self—mind, body, heart, and spirit. So the couple were united, and smilingly signed the marriage-register, a rite by which their love for each other was supposed to be made eternal.

Cinderella, when the lover-prince discovers her and fits the crystal slipper to her foot, makes short work of flinging away her rags; and in some such pretty, airy, unthinking way did Susanna fling aside the dullness, inhospitality, and ugliness of her uncle's home and depart in a cloud of glory on her wedding journey. She had been lonely, now she would have companionship. She had been of no consequence, now she would be queen of her own small domain. She had been last with everybody, now she would be first with one, at least. She had worked hard and received neither compensation nor gratitude; henceforward her service would be gladly rendered at an altar where votive offerings would not be taken as a matter of course. She was only a slip of a girl now; marriage and housewifely cares would make her a woman. Some time perhaps the last great experience of life would come to her, and then what a crown of joys would be hers,—love, husband, home, children! What a vision it was, and how soon the chief glory of it faded!

Never were two beings more hopelessly unlike than John Hathaway single and John Hathaway married, but the bliss lasted a few years, nevertheless: partly because Susanna's charm was deep and penetrating, the sort to hold a false man for a time and a true man forever; partly because she tried, as a girl or woman has seldom tried before, to do her duty and to keep her own ideal unshattered.

John had always been convivial, but Susanna at seventeen had been at once too innocent and too ignorant to judge a man's tendencies truly, or to rate his character at its real worth. As time went on, his earlier leanings grew more definite; he spent on pleasure far more than he could afford, and his conduct became a byword in the neighborhood. His boy he loved. He felt on a level with Jack, could understand him, play with him, punish him, and make friends with him; but little Sue was different. She always seemed to him the concentrated essence of her mother's soul, and when unhappy days came, he never looked in her radiant, searching eyes without a consciousness of inferiority. The little creature had loved her jolly, handsome, careless father at first, even though she feared him; but of late she had grown shy, silent, and timid, for his indifference chilled her and she flung herself upon her mother's love with an almost unchildlike intensity. This unhappy relation between the child and the father gave Susanna's heart new pangs. She still loved her husband,—not dearly, but a good deal; and over and above that remnant of the old love which still endured she gave him unstinted care and hopeful maternal tenderness.

The crash came in course of time. John transcended the bounds of his wife's patience more and more. She made her last protests; then she took one passionate day to make up her mind,—a day when John and the boy were away together; a day of complete revolt against everything she was facing in the present, and, so far as she could see, everything that she had to face in the future. Prayer for light left her in darkness, and she had no human creature to advise her. Conscience was overthrown; she could see no duty save to her own outraged personality. Often and often during the year just past she had thought of the peace, the grateful solitude and shelter of that Shaker Settlement hidden among New England orchards; that quiet haven where there was neither marrying nor giving in marriage. Now her bruised heart longed for such a life of nun-like simplicity and consecration, where men and women met only as brothers and sisters, where they worked side by side with no thought of personal passion or personal gain, but only for the common good of the community.

Albion village was less than three hours distant by train. She hastily gathered her plainest clothes and Sue's, packed them in a small trunk, took her mother's watch, her own little store of money and the twenty-dollar gold piece John's senior partner had given Sue on her last birthday, wrote a letter of good-by to John, and went out of her cottage gate in a storm of feeling so tumultuous that there was no room for reflection. Besides, she had reflected, and reflected, for months and months, so she would have said, and the time had come for action. Susanna was not unlettered, but she certainly had never read Meredith or she would have learned that "love is an affair of two, and only for two that can be as quick, as constant in intercommunication as are sun and earth, through the cloud, or face to face. They take their breath of life from each other in signs of affection, proofs of faithfulness, incentives to admiration. But a solitary soul dragging a log must make the log a God to rejoice in the burden." The demigod that poor, blind Susanna married had vanished, and she could drag the log no longer, but she made one mistake in judging her husband, in that she regarded him, at thirty-two, as a finished product, a man who was finally this and that, and behaved thus and so, and would never be any different.

The "age of discretion" is a movable feast of extraordinary uncertainty, and John Hathaway was a little behindhand in overtaking it. As a matter of fact, he had never for an instant looked life squarely in the face. He took a casual glance at it now and then, after he was married, but it presented no very distinguishable features, nothing to make him stop and think, nothing to arouse in him any special sense of responsibility. Boys have a way of "growing up," however, sooner or later, at least most of them have, and that possibility was not sufficiently in the foreground of Susanna's mind when she finished what she considered an exhaustive study of her husband's character.

"I am leaving you, John [she wrote], to see if I can keep the little love I have left for you as the father of my children. I seem to have lost all the rest of it living with you. I am not perfectly sure that I am right in going, for everybody seems to think that women, mothers especially, should bear anything rather than desert the home. I could not take Jack away, for you love him and he will be a comfort to you. A comfort to you, yes, but what will you be to him now that he is growing older? That is the thought that troubles me, yet I dare not take him with me when he is half yours. You will not miss me, nor will the loss of Sue make any difference. Oh, John! how can you help loving that blessed little creature, so much better and so much more gifted than either of us that we can only wonder how we came to be her father and mother? Your sin against her is greater than that against me, for at least you are not responsible for bringing me into the world. I know Louisa will take care of Jack, and she lives so near that you can see him as often as you wish. I shall let her know my address, which I have asked her to keep to herself. She will write to me if you or Jack should be seriously ill, but not for any other reason.

"As for you, there is nothing more that I can say except to confess freely that I was not the right wife for you and that mine was not the only mistake. I have tried my very best to meet you in everything that was not absolutely wrong, and I have used all the arguments I could think of, but it only made matters worse. I thought I knew you, John, in the old days. How comes it that we have traveled so far apart, we who began together? It seems to me that some time you must come to your senses and take up your life seriously, for this is not life, the sorry thing you have lived lately, but I cannot wait any longer! I am tired, tired, tired of waiting and hoping, too tired to do anything but drag myself away from the sight of your folly. You have wasted our children's substance, indulged your appetites until you have lost the respect of your best friends, and you have made me—who was your choice, your wife, the head of your house, the woman who brought your children into the world—you have made me an object of pity; a poor, neglected thing who could not meet her neighbors' eyes without blushing."

When Jack and his father returned from their outing at eight o'clock in the evening, having had supper at a wayside hotel, the boy went to bed philosophically, lighting his lamp for himself, the conclusion being that the two other members of the household were a little late, but would be in presently.

The next morning was bright and fair. Jack waked at cockcrow, and after calling to his mother and Sue, jumped out of bed, ran into their rooms to find them empty, then bounced down the stairs two at a time, going through the sitting-room on his way to find Ellen in the kitchen. His father was sitting at the table with the still-lighted student lamp on it; the table where lessons had been learned, books read, stories told, mending done, checkers and dominoes played; the big, round walnut table that was the focus of the family life—but mother's table, not father's.

John Hathaway had never left his chair nor taken off his hat. His cane leaned against his knee, his gloves were in his left hand, while the right held Susanna's letter.

He was asleep, although his lips twitched and he stirred uneasily. His face was haggard, and behind his closed lids, somewhere in the centre of thought and memory, a train of fiery words burned in an ever-widening circle, round and round and round, ploughing, searing their way through some obscure part of him that had heretofore been without feeling, but was now all quick and alive with sensation.

"You have made me—who was your choice, your wife, the head of your house, the woman who brought your children into the world—you have made me an object of pity; a poor, neglected thing who could not meet her neighbors' eyes without blushing."

Any one who wished to pierce John Hathaway's armor at that period of his life would have had to use a very sharp and pointed arrow, for he was well wadded with the belief that a man has a right to do what he likes. Susanna's shaft was tipped with truth and dipped in the blood of her outraged heart. The stored-up force of silent years went into the speeding of it. She had never shot an arrow before, and her skill was instinctive rather than scientific, but the powers were on her side and she aimed better than she knew—those who took note of John Hathaway's behavior that summer would have testified willingly to that. It was the summer in which his boyish irresponsibility slipped away from him once and for all; a summer in which the face of life ceased to be an indistinguishable mass of meaningless events and disclosed an order, a reason, a purpose hitherto unseen and undefined. The boy "grew up," rather tardily it must be confessed. His soul had not added a cubit to its stature in sunshine, gayety, and prosperity; it took the shock of grief, hurt pride, solitude, and remorse to make a man of John Hathaway.

It was a radiant July morning in Albion village, and when Sue first beheld it from the bedroom window at the Shaker Settlement, she had wished ardently that it might never, never grow dark, and that Jack and Fardie might be having the very same sunshine in Farnham. It was not noon yet, but experience had in some way tempered the completeness of her joy, for the marks of tears were on her pretty little face. She had neither been scolded nor punished, but she had been dragged away from a delicious play without any adequate reason. She had disappeared after breakfast, while Susanna was helping Sister Tabitha with the beds and the dishes, but as she was the most docile of children, her mother never thought of anxiety. At nine o'clock Eldress Abby took Susanna to the laundry house, and there under a spreading maple were Sue and the two youngest little Shakeresses, children of seven and eight respectively. Sue was directing the plays: chattering, planning, ordering, and suggesting expedients to her slower-minded and less-experienced companions. They had dragged a large box from one of the sheds and set it up under the tree. The interior had been quickly converted into a commodious residence, one not in the least of a Shaker type. Small bluing-boxes served for bedstead and dining-table, bits of broken china for the dishes, while tiny flat stones were the seats, and four clothes-pins, tastefully clad in handkerchiefs, surrounded the table.

"Do they kneel in prayer before they eat, as all Believers do?" asked Shaker Mary.

"I don't believe Adam and Eve was Believers, 'cause who would have taught them to be?" replied Sue; "still we might let them pray, anyway, though clothes-pins don't kneel nicely."

"I've got another one all dressed," said little Shaker Jane.

"We can't have any more; Adam and Eve didn't have only two children in my Sunday-school lesson,—Cain and Abel," objected Sue.

"Can't this one be a company?" pleaded Mary, anxious not to waste the clothes-pin.

"But where could comp'ny come from?" queried Sue. "There wasn't any more people anywheres but just Adam and Eve and Cain and Abel. Put the clothes-pin in your apron-pocket, Jane, and bimeby we'll let Eve have a little new baby, and I'll get Mardie to name it right out of the Bible. Now let's begin. Adam is awfully tired this morning; he says, 'Eve, I've been workin' all night and I can't eat my breakfuss.' Now, Mary, you be Cain, he's a little boy, and you must say, 'Fardie, play a little with me, please!' and Fardie will say, 'Child'en shouldn't talk at the—'"

What subjects of conversation would have been aired at the Adamic family board before breakfast was finished will never be known, for Eldress Abby, with a firm but not unkind grasp, took Shaker Jane and Mary by their little hands and said, "Morning's not the time for play; run over to Sister Martha and help her shell the peas; then there'll be your seams to oversew."

Sue watched the disappearing children and saw the fabric of her dream fade into thin air; but she was a person of considerable individuality for her years. Her lip quivered, tears rushed to her eyes and flowed silently down her cheeks, but without a glance at Eldress Abby or a word of comment she walked slowly away from the laundry, her chin high.

"Sue meant all right, she was only playing the plays of the world," said Eldress Abby, "but you can well understand, Susanna, that we can't let our Shaker children play that way and get wrong ideas into their heads at the beginning. We don't condemn an honest, orderly marriage as a worldly institution, but we claim it has no place in Christ's kingdom; therefore we leave it to the world, where it belongs. The world's people live on the lower plane of Adam; the Shakers try to live on the Christ plane, in virgin purity, long-suffering, meekness, and patience."

"I see, I know," Susanna answered slowly, with a little glance at injured Sue walking toward the house, "but we needn't leave the children unhappy this morning, for I can think of a play that will comfort them and please you.—Come back, Sue! Wait a minute, Mary and Jane, before you go to Sister Martha! We will play the story that Sister Tabitha told us last week. Do you remember about Mother Ann Lee in the English prison? The soap-box will be her cell, for it was so small she could not lie down in it. Take some of the shingles, Jane, and close up the open side of the box. Do you see the large brown spot in one of them, Mary? Push that very hard with a clothes-pin and there'll be a hole through the shingle;—that's right! Now, Sister Tabitha said that Mother Ann was kept for days without food, for people thought she was a wicked, dangerous woman, and they would have been willing to let her die of starvation. But there was a great key-hole in the door, and James Whittaker, a boy of nineteen, who loved Mother Ann and believed in her, put the stem of a clay pipe in the hole and poured a mixture of wine and milk through it. He managed to do this day after day, so that when the jailer opened the cell door, expecting to find Mother Ann dying for lack of food, she walked out looking almost as strong and well as when she entered. You can play it all out, and afterwards you can make the ship that brought Mother Ann and the other Shakers from Liverpool to New York. The clothes-pins can be—who will they be, Jane?"

"William Lee, Nancy Lee, James Whittaker, and I forget the others," recited Jane, like an obedient parrot.

"And it will be splendid to have James Whittaker, for he really came to Albion," said Mary.

"Perhaps he stood on this very spot more than once," mused Abby. "It was Mother Ann's vision that brought them to this land,—a vision of a large tree with outstretching branches, every leaf of which shone with the brightness of a burning torch! Oh! if the vision would only come true! If Believers would only come to us as many as the leaves on the tree," she sighed, as she and Susanna moved away from the group of chattering children, all as eager to play the history of Shakerism as they had been to dramatize the family life of Adam and Eve.

"There must be so many men and women without ties, living useless lives, with no aim or object in them," Susanna said, "I wonder that more of them do not find their way here. The peace and goodness and helpfulness of the life sink straight into my heart. The Brothers and Sisters are so friendly and cheery with one another; there is neither gossip nor hard words; there is pleasant work, and your thoughts seem to be all so concentrated upon right living that it is like heaven below, only I feel that the cross is there, bravely as you all bear it."

quoted Eldress Abby, devoutly.

"It is easy enough for me," continued Susanna, "for it was no cross for me to give up my husband at the time; but oh, if a woman had a considerate, loving man to live with, one who would strengthen her and help her to be good, one who would protect and cherish her, one who would be an example to his children and bring them up in the fear of the Lord—that would be heaven below, too; and how could she bear to give it all up when it seems so good, so true, so right? Mightn't two people walk together to God if both chose the same path?"

"It's my belief that one can find the road better alone than when somebody else is going alongside to distract them. Not that the Lord is going to turn anybody away, not even when they bring Him a lot of burned-out trash for a gift," said Eldress Abby, bluntly. "But don't you believe He sees the difference between a person that comes to Him when there is nowhere else to turn—a person that's tried all and found it wanting—and one that gives up freely pleasure, and gain, and husband, and home, to follow the Christ life?"

"Yes, He must, He must," Susanna answered faintly. "But the children, Eldress Abby! If you hadn't any, you could perhaps keep yourself from wanting them; but if you had, how could you give them up? Jesus was the great Saviour of mankind, but next to Him it seems as if the children had been the little saviours, from the time the first one was born until this very day!"

"Yee, I've no doubt they keep the worst of the world's people, those that are living in carnal marriage without a thought of godliness,—I've no doubt children keep that sort from going to the lowest perdition," allowed Eldress Abby; "and those we bring up in the Community make the best converts; but to a Shaker, the greater the sacrifice, the greater the glory. I wish you was gathered in, Susanna, for your hands and feet are quick to serve, your face is turned toward the truth, and your heart is all ready to receive the revelation."

"I wish I needn't turn my back on one set of duties to take up another," murmured Susanna, timidly.

"Yee; no doubt you do. Your business is to find out which are the higher duties, and then do those. Just make up your mind whether you'd rather replenish earth, as you've been doing, or replenish heaven, as we're trying to do.—But I must go to my work; ten o'clock in the morning's a poor time to be discussing doctrine! You're for weeding, Susanna, I suppose?"

Brother Ansel was seated at a grindstone under the apple trees, teaching (intermittently) a couple of boys to grind a scythe, when Susanna came to her work in the herb-garden, Sue walking discreetly at her heels.

Ansel was a slow-moving, humorously-inclined, easy-going Brother, who was drifting into the kingdom of heaven without any special effort on his part.

"I'd 'bout as lives be a Shaker as anything else," had been his rather dubious statement of faith when he requested admittance into the band of Believers. "No more crosses, accordin' to my notion, an' consid'able more chance o' crowns!"

His experience of life "on the Adamic plane," the holy estate of matrimony, being the chief sin of this way of thought, had disposed him to regard woman as an apparently necessary, but not especially desirable, being. The theory of holding property in common had no terrors for him. He was generous, unambitious, frugal-minded, somewhat lacking in energy, and just as actively interested in his brother's welfare as in his own, which is perhaps not saying much. Shakerism was to him not a craving of the spirit, not a longing of the soul, but a simple, prudent theory of existence, lessening the various risks that man is exposed to in his journey through this vale of tears.

"Women-folks makes splendid Shakers," he was wont to say. "They're all right as Sisters, 'cause their belief makes 'em safe. It kind o' shears 'em o' their strength; tames their sperits; takes the sting out of 'em an' keeps 'em from bein' sassy an' domineerin'. Jest as long as they think marriage is right, they'll marry ye spite of anything ye can do or say—four of 'em married my father one after another, though he fit 'em off as hard as he knew how. But if ye can once get the faith o' Mother Ann into 'em, they're as good afterwards as they was wicked afore. There's no stoppin' women-folks once ye get 'em started; they don't keer whether it's heaven or the other place, so long as they get where they want to go!"

Elder Daniel Gray had heard Brother Ansel state his religious theories more than once when he was first "gathered in," and secretly lamented the lack of spirituality in the new convert. The Elder was an instrument more finely attuned; sober, humble, pure-minded, zealous, consecrated to the truth as he saw it, he labored in and out of season for the faith he held so dear; yet as the years went on, he noted that Ansel, notwithstanding his eccentric views, lived an honest, temperate, God-fearing life, talking no scandal, dwelling in unity with his brethren and sisters, and upholding the banner of Shakerism in his own peculiar way.

As Susanna approached him, Ansel called out, "The yairbs are all ready for ye, Susanna; the weeds have been on the rampage sence yesterday's rain. Seems like the more uselesser a thing is, the more it flourishes. The yairbs grow; oh, yes, they make out to grow; but you don't see 'em come leapin' an' tearin' out o' the airth like weeds. Then there's the birds! I've jest been stoppin' my grindin' to look at 'em carry on. Take 'em all in all, there ain't nothin' so lazy an' aimless an' busy'boutnothin' as birds. They go kitin' 'roun' from tree to tree, hoppin' an' chirpin', flyin' here an' there 'thout no airthly objeck 'ceptin' to fly back ag'in. There's a heap o' useless critters in the univarse, but I guess birds are 'bout the uselyest, 'less it's grasshoppers, mebbe."

"I don't care what you say about the grasshoppers, Ansel, but you shan't abuse the birds," said Susanna, stooping over the beds of tansy and sage, thyme and summer savory. "Weeds or no weeds, we're going to have a great crop of herbs this year, Ansel!"

"Yee, so we be! We sowed more'n usual so's to keep the two 'jiners' at work long's we could.—Take that scythe over to the barn, Jacob, an' fetch me another, an' step spry."

"What's a jiner, Ansel?"

"Winter Shakers, I call 'em. They're reg'lar constitooshanal dyed-in-the-wool jiners, jinin' most anything an' hookin' on most anywheres. They jine when it comes on too cold to sleep outdoors, an' they onjine when it comes on spring. Elder Gray's always hopin' to gather in new souls, so he gives the best of 'em a few months' trial. How are ye, Hannah?" he called to a Sister passing through the orchard to search for any possible green apples under the trees. "Make us a good old-fashioned deep-dish pandowdy an' we'll all do our best to eat it!"

"I suppose the 'jiners' get discouraged and fear they can't keep up to the standard. Not everybody is good enough to lead a self-denying Shaker life," said Susanna, pushing back the close sunbonnet from her warm face, which had grown younger, smoother, and sweeter in the last few weeks.

"Nay, I s'pose likely; 'less they're same as me, a born Shaker," Ansel replied. "I don't hanker after strong drink; don't like tobaccer (always could keep my temper 'thout smokin'), ain't partic'lar 'bout meat-eatin', don't keer 'bout heapin' up riches, can't 'stand the ways o' worldly women-folks, jest as lives confess my sins to the Elder as not, 'cause I hain't sinned any to amount to anything sence I made my first confession; there I be, a natural follerer o' Mother Ann Lee."

Susanna drew her Shaker bonnet forward over her eyes and turned her back to Brother Ansel under the pretense of reaching over to the rows of sweet marjoram. She had never supposed it possible that she could laugh again, and indeed she seldom felt like it, but Ansel's interpretations of Shaker doctrine were almost too much for her latent sense of humor.

"What are you smiling at, and me so sad, Mardie?" quavered Sue, piteously, from the little plot of easy weeding her mother had given her to do. "I keep remembering my game! It was such a Christian game, too. Lots nicer than Mother Ann in prison; for Jane said her mother and father was both Believers, and nobody was good enough to pour milk through the key-hole but her. I wanted to give the clothes-pins story names, like Hilda and Percy, but I called them Adam and Eve and Cain and Abel just because I thought the Shakers would 'specially like a Bible play. I love Elderess Abby, but she does stop my happiness, Mardie. That's the second time to-day, for she took Moses away from me when I was kissing him because he pinched his thumb in the window."

"Why did you do that, Sue?" remonstrated her mother softly, remembering Ansel's proximity. "You never used to kiss strange little boys at home in Farnham."

"Moses isn't a boy; he's only six, and that's a baby; besides, I like him better than any little boys at home, and that's the reason I kissed him; there's no harm in boy-kissing, is there, Mardie?"

"You don't know anybody here very well yet; not well enough to kiss them," Susanna answered, rather hopeless as to the best way of inculcating the undesirability of the Adamic plane of thought at this early age. "While we stay here, Sue, we ought both to be very careful to do exactly as the Shakers do."

By this time mother and child had reached the orchard end of a row, and Brother Ansel was thirstily waiting to deliver a little more of the information with which his mind was always teeming.

"Them Boston people that come over to our public meetin' last Sunday," he began, "they was dretful scairt 'bout what would become o' the human race if it should all turn Shakers. 'I guess you needn't worry,' I says; 'it'll take consid'able of a spell to convert all you city folks,' I says, 'an' after all, what if the world should come to an end?' I says. 'If half we hear is true 'bout the way folks carry on in New York and Chicago, it's 'bout time it stopped,' I says, 'an' I guess the Lord could do a consid'able better job on a second one,' I says, 'after findin' out the weak places in this.' They can't stand givin' up their possessions, the world's folks; that's the principal trouble with 'em! If you don't have nothin' to give up,—like some o' the tramps that happen along here and convince the Elder they're jest bustin' with the fear o' God,—why, o' course 't ain't no trick at all to be a Believer."

"Did you have much to give up, Brother Ansel?" Susanna asked.

"'Bout's much as any sinner ever had that jined this Community," replied Ansel, complacently. "The list o' what I consecrated to this Society when I was gathered in was: One horse, one wagon, one two-year-old heifer, one axe, one saddle, one padlock, one bed and bedding, four turkeys, eleven hens, one pair o' plough-irons, two chains, and eleven dollars in cash.—Can you beat that?"

"Oh, yes, things!" said Susanna, absent-mindedly. "I was thinking of family and friends, pleasures and memories and ambitions and hopes."

"I guess it don't pinch you any worse to give up a hope than it would a good two-year-old heifer," retorted Ansel; "but there, you can't never tell what folks'll hang on to the hardest! The man that drove them Boston folks over here last Sunday,—did you notice him? the one that had the sister with a bright red dress an' hat on?—Land! I could think just how hell must look whenever my eye lighted on that girl's git-up!—Well, I done my best to exhort that driver, bein' as how we had a good chance to talk while we was hitchin' an' unhitchin' the team; an' Elder Gray always says I ain't earnest enough in preachin' the faith;—but he didn't learn anything from the meetin'. Kep' his eye on the Shaker bunnits, an' took notice o' the marchin' an' dancin', but he didn't care nothin' 'bout doctrine.

"'I draw the line at bein' a cerebrate,' he says. 'I'm willin' to sell all my goods an' divide with the poor,' he says, 'but I ain't goin' to be no cerebrate. If I don't have no other luxuries, I will have a wife,' he says. 'I've hed three, an' if this one don't last me out, I'll get another, if it's only to start the kitchen fire in the mornin' an' put the cat in the shed nights!'"

Louisa otherwise Mrs. Adlai Banks, the elder sister of Susanna's husband, was a rock-ribbed widow of forty-five summers,—forty-five winters would seem a better phrase in which to assert her age,—who resided on a small farm twenty miles from the manufacturing town of Farnham.

When the Fates were bestowing qualities of mind and heart upon the Hathaway babies, they gave the more graceful, genial, likable ones to John,—not realizing, perhaps, what bad use he would make of them,—and endowed Louisa with great deposits of honesty, sincerity, energy, piety, and frugality, all so mysteriously compounded that they turned to granite in her hands. If she had been consulted, it would have been all the same. She would never have accepted John's charm of personality at the expense of being saddled with his weaknesses, and he would not have taken her cast-iron virtues at any price whatsoever.

She was sweeping her porch on that day in May when Susanna and Sue had wakened in the bare upper chamber at the Shaker Settlement—Sue clear-eyed, jubilant, expectant, unafraid; Susanna pale from her fitful sleep, weary with the burden of her heart.

Looking down the road, Mrs. Banks espied the form of her brother John walking in her direction and leading Jack by the hand.

This was a most unusual sight, for John's calls had been uncommonly few of late years, since a man rarely visits a lady relative for the mere purpose of hearing "a piece of her mind." This piece, large, solid, highly flavored with pepper, and as acid as mental vinegar could make it, was Louisa Banks's only contribution to conversation when she met her brother. She could not stop for any airy persiflage about weather, crops, or politics when her one desire was to tell him what she thought of him.

"Good-morning, Louisa. Shake hands with your aunt, Jack."

"He can't till I'm through sweeping. Good-morning, John; what brings you here?"

John sat down on the steps, and Jack flew to the barn, where there was generally an amiable hired man and a cheerful cow, both infinitely better company than his highly respected and wealthy aunt.

"I came because I had to bring the boy to the only relation I've got in the world," John answered tersely. "My wife's left me."

"Well, she's been a great while doing it," remarked Louisa, digging her broom into the cracks of the piazza floor and making no pause for reflection. "If she hadn't had the patience of Job and the meekness of Moses, she'd have gone long before. Where'd she go?"

"I don't know; she didn't say."

"Did you take the trouble to look through the house for her? I ain't certain you fairly know her by sight nowadays, do you?"

John flushed crimson, but bit his lip in an attempt to keep his temper. "She left a letter," he said, "and she took Sue with her."

"That was all right; Sue's a nervous little thing and needs at least one parent; she hasn't been used to more, so she won't miss anything. Jack's like most of the Hathaways; he'll grow up his own way, without anybody's help or hindrance. What are you going to do with him?"

"Leave him with you, of course. What else could I do?"

"Very well, I'll take him, and while I'm about it I'd like to give you a piece of my mind."

John was fighting for self-control, but he was too wretched and remorseful for rage to have any real sway over him.

"Is it the same old piece, or a different one?" he asked, setting his teeth grimly. "I shouldn't think you'd have any mind left, you've given so many pieces of it to me already."

"I have some left, and plenty, too," answered Louisa, dashing into the house, banging the broom into a corner, coming out again like a breeze, and slamming the door behind her. "You can leave the boy here and welcome; I'll take good care of him, and if you don't send me twenty dollars a month for his food and clothes, I'll turn him outdoors. The more responsibility other folks rid you of, the more you'll let 'em, and I won't take a feather's weight off you for fear you'll sink into everlasting perdition."

"I didn't expect any sympathy from you," said John, drearily, pulling himself up from the steps and leaning against the honeysuckle trellis. "Susanna's just the same. Women are all as hard as the nether millstone. They're hard if they're angels, and hard if they're devils; it doesn't make much difference."

"I guess you've found a few soft ones, if report says true," returned Louisa, bluntly. "You'd better go and get some of their sympathy, the kind you can buy and pay for. The way you've ruined your life turns me fairly sick. You had a good father and mother, good education and advantages, enough money to start you in business, the best of wives, and two children any man could be proud of, one of 'em especially. You've thrown 'em all away, and what for? Horses and cards and gay company, late suppers, with wine, and for aught I know, whiskey,—you the son of a man who didn't know the taste of ginger beer! You've spent your days and nights with a pack of carousing men and women that would take your last cent and not leave you enough for honest burial."

"It's a pity we didn't make a traveling preacher of you!" exclaimed John, bitterly. "Lord Almighty, I wonder how such women as you can live in the world, you know so little about it, and so little about men."

"I know all I want to about 'em," retorted Louisa, "and precious little that's good. They're a gluttonous, self-indulgent, extravagant, reckless, pleasure-loving lot! My husband was one of the best of 'em, and he wouldn't have amounted to a hill of beans if I hadn't devoted fifteen years to disciplining, uplifting, and strengthening him!"

"You managed to strengthen him so that he died before he was fifty!"

"It don't matter when a man dies," said the remorseless Mrs. Banks, "if he's succeeded in living a decent, God-fearing life. As for you, John Hathaway, I'll tell you the truth if you are my brother, for Susanna's too much of a saint to speak out."

"Don't be afraid; Susanna's spoken out at last, plainly enough to please even you!"

"I'm glad of it, for I didn't suppose she had spunk enough to resent anything. I shall be sorry to-morrow, 's likely as not, for freeing my mind as much as I have, but my temper's up and I'm going to be the humble instrument of Providence and try to turn you from the error of your ways. You've defaced and degraded the temple the Lord built for you, and if He should come this minute and try to turn out the crowd of evil-doers you've kept in it, I doubt if He could!"

"I hope He'll approve of the way you've used your 'temple,'" said John, with stinging emphasis. "I shouldn't want to live in such a noisy one myself; I'd rather be a bat in a belfry. Good-by; I've had a pleasant call, as usual, and you've been a real sister to me in my trouble. You shall have the twenty dollars a month. Jack's clothes are in that valise, and there'll be a trunk to-morrow. Susanna said she'd write and let you know her whereabouts."

So saying, John Hathaway strode down the path, closed the gate behind him, and walked rapidly along the road that led to the station. It was a quiet road and he met few persons. He had neither dressed nor shaved since the day before; his face was haggard, his heart was like a lump of lead in his breast. Of what use to go to the empty house in Farnham when he could stifle his misery by a night with his friends?

No, he could not do that, either! The very thought of them brought a sense of satiety and disgust; the craving for what they would give him would come again in time, no doubt, but for the moment he was sick to the very soul of all they stood for. The feeling of complete helplessness, of desertion, of being alone in mid-ocean without a sail or a star in sight, mounted and swept over him. Susanna had been his sail, his star, although he had never fully realized it, and he had cut himself adrift from her pure, steadfast love, blinding himself with cheap and vulgar charms.

The next train to Farnham was not due for an hour. His steps faltered; he turned into a clump of trees by the wayside and flung himself on the ground to cry like a child, he who had not shed a tear since he was a boy of ten.

If Susanna could have seen that often longed-for burst of despair and remorse, that sudden recognition of his sins against himself and her, that gush of penitent tears, her heart might have softened once again; a flicker of flame might have lighted the ashes of her dying love; she might have taken his head on her shoulder, and said, "Never mind, John! Let's forget, and begin all over again!"

Matters did not look any brighter for John the next week, for his senior partner, Joel Atterbury, requested him to withdraw from the firm as soon as matters could be legally arranged. He was told that he had not been doing, nor earning, his share; that his way of living during the year just past had not been any credit to "the concern," and that he, Atterbury, sympathized too heartily with Mrs. John Hathaway to take any pleasure in doing business with Mr. John.

John's remnant of pride, completely humbled by this last withdrawal of confidence, would not suffer him to tell Atterbury that he had come to his senses and bidden farewell to the old life, or so he hoped and believed.

To lose a wife and child in a way infinitely worse than death; to hear the unwelcome truth that as a husband you have grown so offensive as to be beyond endurance; to have your own sister tell you that you richly deserve such treatment; to be virtually dismissed from a valuable business connection;—all this is enough to sober any man above the grade of a moral idiot, and John was not that; he was simply a self-indulgent, pleasure-loving, thoughtless, willful fellow, without any great amount of principle. He took his medicine, however, said nothing, and did his share of the business from day to day doggedly, keeping away from his partner as much as possible.

Ellen, the faithful maid of all work, stayed on with him at the old home; Jack wrote to him every week, and often came to spend Sunday with him.

"Aunt Louisa's real good to me," he told his father, "but she's not like mother. Seems to me mother's kind of selfish staying away from us so long. When do you expect her back?"

"I don't know; not before winter, I'm afraid; and don't call her selfish, I won't have it! Your mother never knew she had a self."

"If she'd only left Sue behind, we could have had more good times, we three together!"

"No, our family is four, Jack, and we can never have any good times, one, two, or three of us, because we're four! When one's away, whichever it is, it's wrong, but it's the worst when it's mother. Does your Aunt Louisa write to her?"

"Yes, sometimes, but she never lets me post the letters."

"Do you write to your mother? You ought to, you know, even if you don't have time for me. You could ask your aunt to enclose your letters in hers."

"Do you write to her, father?"

"Yes, I write twice a week," John answered, thinking drearily of the semi-weekly notes posted in Susanna's empty work-table upstairs. Would she ever read them? He doubted it, unless he died, and she came back to settle his affairs; but of course he shouldn't die,—no such good luck. Would a man die who breakfasted at eight, dined at one, supped at six, and went to bed at ten? Would a man die who worked in the garden an hour every afternoon, with half a day Saturday; that being the task most disagreeable to him and most appropriate therefore for penance?

Susanna loved flowers and had always wanted a garden, but John had been too much occupied with his own concerns to give her the needed help or money so that she could carry out her plans. The last year she had lost heart in many ways, so that little or nothing had been accomplished of all she had dreamed. It would have been laughable, had it not been pathetic, to see John Hathaway dig, delve, grub, sow, water, weed, transplant, generally at the wrong moment, in that dream-garden of Susanna's. He asked no advice and read no books. With feverish intensity, with complete ignorance of Nature's laws and small sympathy with their intricacies, he dug, hoed, raked, fertilized, and planted during that lonely summer. His absent-mindedness caused some expensive failures, as when the wide expanse of Susanna's drying ground, which was to be velvety lawn, "came up" curly lettuce; but he rooted out his frequent mistakes and patiently planted seeds or roots or bulbs over and over and over and over, until something sprouted in his beds, whether it was what he intended or not. While he weeded the brilliant orange nasturtiums, growing beside the magenta portulacca in a friendly proximity that certainly would never have existed had the mistress of the house been the head-gardener, he thought of nothing but his wife. He knew her pride, her reserve, her sensitive spirit; he knew her love of truth and honor and purity, the standards of life and conduct she had tried to hold him to so valiantly, and which he had so dragged in the dust during the blindness and the insanity of the last two years.

He, John Hathaway, was a deserted husband; Susanna had crept away all wounded and resentful. Where was she living and how supporting herself and Sue, when she could not have had a hundred dollars in the world? Probably Louisa was the source of income; conscientious, infernally disagreeable Louisa!

Would not the rumor of his changed habit of life reach her by some means in her place of hiding, sooner or later? Would she not yearn for a sight of Jack? Would she not finally give him a chance to ask forgiveness, or had she lost every trace of affection for him, as her letter seemed to imply? He walked the garden paths, with these and other unanswerable questions, and when he went to his lonely room at night, he held the lamp up to a bit of poetry that he had cut from a magazine and pinned to the looking-glass. If John Hathaway could be brought to the reading of poetry, he might even glance at the Bible in course of time, Louisa would have said. It was in May that Susanna had gone, and the first line of verse held his attention.

The Hathaway house was in the suburbs, on a rise of ground, and as John turned to the window he saw the full moon hanging yellow in the sky. It shone on the verdant slopes and low wooded hills that surrounded the town, and cast a glittering pathway on the ocean that bathed the beaches of the near-by shore.

"How long shall I have to wait," he wondered, "before my hills of home look higher, and my sea bluer, because Susanna has come back to 'hearth and board'!"

Susanna had helped at various household tasks ever since her arrival at the Settlement, for there was no room for drones in the Shaker hive; but after a few weeks in the kitchen with Martha, the herb-garden had been assigned to her as her particular province, the Sisters thinking her better fitted for it than for the preserving and pickling of fruit, or the basket-weaving that needed special apprenticeship.

The Shakers were the first people to raise, put up, and sell garden seeds in our present-day fashion, and it was they, too, who began the preparation of botanical medicines, raising, gathering, drying, and preparing herbs and roots for market; and this industry, driven from the field by modern machinery, was still a valuable source of income in Susanna's day. Plants had always grown for Susanna, and she loved them like friends, humoring their weakness, nourishing their strength, stimulating, coaxing, disciplining them, until they could do no less than flourish under her kind and hopeful hand.

Oh, that sweet, honest, comforting little garden of herbs, with its wholesome fragrances! Healing lay in every root and stem, in every leaf and bud, and the strong aromatic odors stimulated her flagging spirit or her aching head, after the sleepless nights in which she tried to decide her future life and Sue's.

The plants were set out in neat rows and clumps, and she soon learned to know the strange ones—chamomile, lobelia, bloodroot, wormwood, lovage, boneset, lemon and sweet balm, lavender and rue, as well as she knew the old acquaintances familiar to every country-bred child—pennyroyal, peppermint or spearmint, yellow dock, and thoroughwort.

There was hoeing and weeding before the gathering and drying came; then Brother Calvin, who had charge of the great press, would moisten the dried herbs and press them into quarter and half-pound cakes ready for Sister Martha, who would superintend the younger Shakeresses in papering and labeling them for the market. Last of all, when harvesting was over, Brother Ansel would mount the newly painted seed-cart and leave on his driving trip through the country. Ansel was a capital salesman, but Brother Issachar, who once took his place and sold almost nothing, brought home a lad on the seed-cart, who afterward became a shining light in the community. ("Thus," said Elder Gray, "does God teach us the diversity of gifts, whereby all may be unashamed.")

If the Albion Shakers were honest and ardent in faith, Susanna thought that their "works" would indeed bear the strictest examination. The Brothers made brooms, floor and dish mops, tubs, pails, and churns, and indeed almost every trade was represented in the various New England Communities. Physicians there were, a few, but no lawyers, sheriffs, policemen, constables, or soldiers, just as there were no courts or saloons or jails. Where there was perfect equality of possession and no private source of gain, it amazed Susanna to see the cheery labor, often continued late at night from the sheer joy of it, and the earnest desire to make the Settlement prosperous. While the Brothers were hammering, nailing, planing, sawing, ploughing, and seeding, the Sisters were carding and spinning cotton, wool, and flax, making kerchiefs of linen, straw Shaker bonnets, and dozens of other useful marketable things, not forgetting their famous Shaker apple sauce.

Was there ever such a busy summer, Susanna wondered; yet with all the early rising, constant labor, and simple fare, she was stronger and hardier than she had been for years. The Shaker palate was never tickled with delicacies, yet the food was well cooked and sufficiently varied. At first there had been the winter vegetables: squash, yellow turnips, beets, and parsnips, with once a week a special Shaker dinner of salt codfish, potatoes, onions, and milk gravy. Each Sister served her turn as cook, but all alike had a wonderful hand with flour, and the whole-wheat bread, cookies, ginger cake, and milk puddings were marvels of lightness. Martha, in particular, could wean the novitiate Shaker from a too riotous devotion to meat-eating better than most people, for every dish she sent to the table was delicate, savory, and attractive.

Dear, patient, devoted Martha! How Susanna learned to love her as they worked together in the big sunny, shining kitchen, where the cooking-stove as well as every tin plate and pan and spoon might have served as a mirror! Martha had joined the Society in her mother's arms, being given up to the Lord and placed in "the children's order" before she was one year old.

"If you should unite with us, Susanna," she said one night after the early supper, when they were peeling apples together, "you'd be thankful you begun early with your little Sue, for she's got a natural attraction to the world, and for it. Not but that she's a tender, loving, obedient little soul; but when she's among the other young ones, there's a flyaway look about her that makes her seem more like a fairy than a child."

"She's having rather a hard time learning Shaker ways, but she'll do better in time," sighed her mother. "She came to me of her own accord yesterday and asked: 'Bettent I have my curls cut off, Mardie?'"

"I never put that idea into her head," Martha interrupted. "She's a visitor and can wear her hair as she's been brought up to wear it."

"I know, but I fear Sue was moved by other than religious reasons. 'I get up so early, Mardie,' she said,—'and it takes so long to unsnarl and untangle me, and I get so hot when I'm helping in the hayfield,—and then I have to be curled for dinner, and curled again for supper, and so it seems like wasting both our times!' Her hair would be all the stronger for cutting, I thought, as it's so long for her age; but I couldn't put the shears to it when the time came, Martha. I had to take her to Eldress Abby. She sat up in front of the little looking-glass as still as a mouse, while the curls came off, but when the last one fell into Abby's apron, she suddenly put her hands over her face and cried: 'Oh, Mardie, we shall never be the same togedder, you and I, after this!'—She seemed to see her 'little past,' her childhood, slipping away from her, all in an instant. I didn't let her know that I cried over the box of curls last night!"

"You did wrong," rebuked Martha. "You shouldn't make an idol of your child or your child's beauty."

"You don't think God might put beauty into the world just to give His children joy, Martha?"

Martha was no controversialist. She had taken her opinions, ready-made, from those she considered her superiors, and although she was willing to make any sacrifice for her religion, she did not wish to be confused by too many opposing theories of God's intentions.

"You know I never argue when I've got anything baking," she said; and taking the spill of a corn-broom from a table-drawer, she opened the oven door and delicately plunged it into the loaf. Then, gazing at the straw as she withdrew it, she said: "You must talk doctrine with Eldress Abby, Susanna, not with me; but I guess doctrine won't help you so much as thinking out your life for yourself."

Martha was the chief musician of the Community, and had composed many hymns and tunes—some of them under circumstances that she believed might entitle them to be considered directly inspired. Her clear full voice filled the kitchen and floated out into the air after Susanna, as she called Sue and, darning-basket in hand, walked across the road to the great barn.

The herb-garden was one place where she could think out her life, although no decision had as yet been born of those thoughtful mornings.