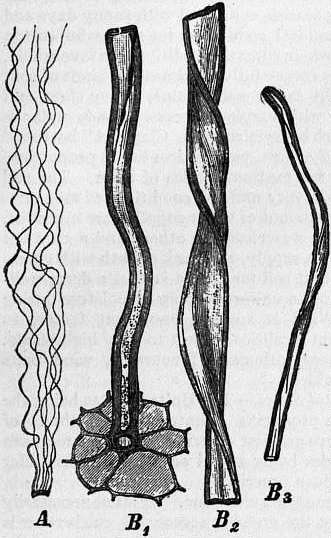

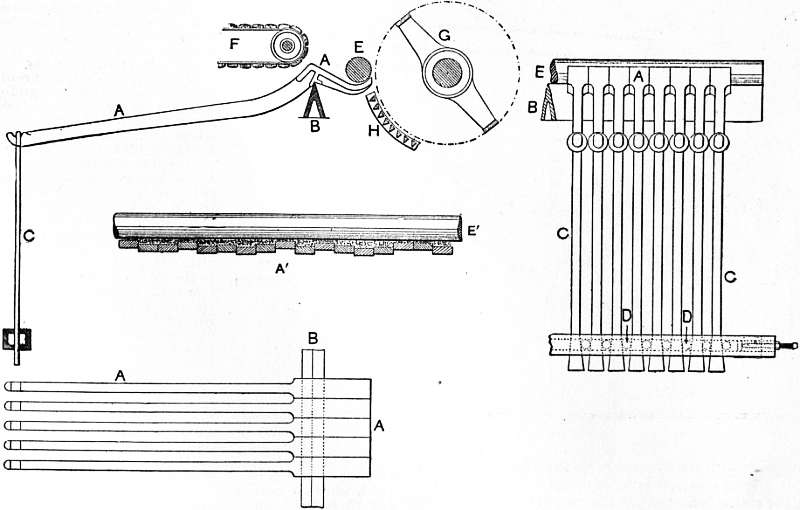

Fig. 1.—Seed-hairs of the Cotton, Gossypium herbaceum. A, Part of seed-coat with hairs; B1, insertion and lower part; B2, middle part; and B3, upper part of a hair.

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Cosway, Richard" to "Coucy, Le Châtelain de"

Author: Various

Release date: May 8, 2010 [eBook #32294]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz, Juliet Sutherland and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

COSWAY, RICHARD (c. 1742-1821), English miniature painter, was baptized in 1742; his father was master of Blundell’s school, Tiverton, where Cosway was educated, and his uncle mayor of that town. He it was who, in conjunction with the boy’s godfather, persuaded the father to allow Richard to proceed to London before he was twelve years old, to take lessons in drawing, and undertook to support him there. On his arrival, the youthful artist won the first prize given by the newly founded Society of Arts, of the money value of five guineas. He went to Thomas Hudson for his earliest instruction, but remained with him only a few months, and then attended William Shipley’s drawing class, where he remained until he began to work on his own account in 1760. He was one of the earliest members of the Royal Academy, Associate in 1770 and Royal Academician in 1771. His success in miniature painting is said to have been started by his clever portrait of Mrs Fitzherbert, which gave great satisfaction to the prince of Wales, and brought Cosway his earliest great patron. He speedily became one of the most popular artists of the day, and his residence at Schomberg House, Pall Mall, was a well-known aristocratic rendezvous. In 1791 he removed to Stratford Place, where he lived in a state of great magnificence till 1821, when after selling most of the treasures he had accumulated he went to reside in Edgware Road. He died on the 4th of July 1821, when driving in a carriage with his friend Miss Udney. He was buried in Marylebone New church.

He married in 1781 Maria Hadfield, who survived him many years, and died in Italy in January 1838, in a school for girls which she had founded, and which she had attached to an important religious order devoted to the cause of female education, known as the Dame Inglesi. She had been created a baroness of the Empire on account of her devotion to female education by the emperor Francis I. in 1834. Her college still exists, and in it are preserved many of the things which had belonged to her and her husband.

Cosway had one child who died young. She is the subject of one of his most celebrated engravings. He painted miniatures of very many members of the royal family, and of the leading persons who formed the court of the prince regent. Perhaps his most beautiful work is his miniature of Madame du Barry, painted in 1791, when that lady was residing in Bruton Street, Berkeley Square. This portrait, together with many other splendid works by Cosway, came into the collection of Mr J. Pierpont Morgan. There are many miniatures by this artist in the royal collection at Windsor Castle, at Belvoir Castle and in other important collections. His work is of great charm and of remarkable purity, and he is certainly the most brilliant miniature painter of the 18th century.

For a full account of the artist and his wife, see Richard Cosway, R.A., by G. C. Williamson (1905).

COTA DE MAGUAQUE, RODRIGO (d. c. 1498), Spanish poet, who flourished towards the end of the 15th century, was born at Toledo. Little is known of him save that he was of Jewish origin. The Coplas de Mingo Revulgo, the Coplas del Provincial, and the first act of the Celestina have been ascribed to him on insufficient grounds. He is undoubtedly the author of the Dialogo entre el amor y un viejo, a striking dramatic poem first printed in the Cancionero general of 1511, and of a burlesque epithalamium written in 1472 or later. He abjured Judaism about the year 1497, and is believed to have died shortly afterwards.

See “Épithalame burlesque,” edited by R. Foulché-Delbosc, in the Revue hispanique (Paris, 1894), i. 69-72; A. Bonilla y San Martín, Anales de la literatura española (Madrid, 1904), pp. 164-167.

CÔTE-D’OR, a department of eastern France, formed of the northern region of the old province of Burgundy, bounded N. by the department of Aube, N.E. by Haute-Marne, E. by Haute-Saône and Jura, S. by Saône-et-Loire, and W. by Nièvre and Yonne. Area, 3392 sq. m. Pop. (1906) 357,959. A chain of hills named the Plateau de Langres runs from north-east to south-west through the centre of the department, separating the basin of the Seine from that of the Saône, and forming a connecting-link between the Cévennes and the Vosges mountains. Extending southward from Dijon is a portion of this range which, on account of the excellence of its vineyards, bears the name of Côte-d’Or, whence that of the department. The north-west portion of the department is occupied by the calcareous and densely-wooded district of Châtillonais, the south-west by spurs of the granitic chain of Morvan, while a wide plain traversed by the Saône extends over the eastern region. The Châtillonais is watered by the Seine, which there takes its rise, and by the Ource, both fed largely by the douix or abundant springs characteristic of Burgundy. The Armançon and other affluents of the Yonne, and the Arroux, a tributary of the Loire, water the south-west.

The climate of Côte-d’Or is temperate and healthy; the rainfall is abundant west of the central range, but moderate, and, in places, scarce, in the eastern plain. Husbandry flourishes, the wealth of the department lying chiefly in its vineyards, especially those of the Côte-d’Or, which comprise the three main groups of Beaune, Nuits and Dijon, the latter the least renowned of the three. The chief cereals are wheat, oats and barley; potatoes, hops, beetroot, rape-seed, colza and a small quantity of tobacco are also produced. Sheep and cattle-raising is carried on chiefly in the western districts. The department has anthracite mines and produces freestone, lime and cement. The manufactures include iron, steel, nails, tools, machinery and other iron goods, paper, earthenware, tiles and bricks, morocco leather goods, biscuits and mustard, and there are flour-mills, distilleries, oil and vinegar works and breweries. The imports of the department are inconsiderable, coal alone being of any importance; there is an active export trade in wine, brandy, cereals and live stock and in manufactured goods. The Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée railway serves the department, its main line passing through Dijon. The canal of Burgundy, connecting the Saône with the Yonne, has a length of 94 m. in the department, while that from the Marne to the Saône has a length of 24 m.

Côte-d’Or is divided into the arrondissements of Dijon, Beaune, Châtillon and Semur, with 36 cantons and 717 communes. It forms the diocese of the bishop of Dijon, and part of the archiepiscopal province of Lyons and of the 8th military region. Dijon is the seat of the educational circumscription (académie) and court of appeal to which the department is assigned. The more noteworthy places are Dijon, the capital, Beaune, Châtillon, Semur, Auxonne, Flavigny and Cîteaux, all separately treated. St Jean de Losne, at the extremity of the Burgundy canal, is famous for its brave and successful resistance in 1636 to an immense force of Imperialists. Châteauneuf has a château of the 249 15th century, St Seine-l’Abbaye, a fine Gothic abbey church, and Saulieu, a Romanesque abbey church of the 11th century. The château of Bussy Rabutin (at Bussy-le-Grand), founded in the 12th century, has an interesting collection of pictures made by Roger de Rabutin, comte de Bussy, who also rebuilt the château. Montbard, the birthplace of the naturalist Buffon, has a keep of the 14th century and other remains of a castle of the dukes of Burgundy. The remarkable Renaissance chapel (1536) of Pagny-le-Château, belonging to the château destroyed in 1768, contains the tomb of Jean de Vienne (d. 1455) and that of Jean de Longwy (d. 1460) and Jeanne de Vienne (d. 1472), with alabaster effigies. At Fontenay, near Marmagne, a paper-works occupies the buildings of a well-preserved Cistercian abbey of the 12th century. At Vertault there are remains of a theatre and other buildings marking the site of the Gallo-Roman town of Vertilium.

COTES, ROGER (1682-1716), English mathematician and philosopher, was born on the 10th of July 1682 at Burbage, Leicestershire, of which place his father, the Rev. Robert Cotes, was rector. He was educated at Leicester school, and afterward at St Paul’s school, London. Proceeding to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1699, he obtained a fellowship in 1705, and in the following year was appointed Plumian professor of astronomy and experimental philosophy in the university of Cambridge. He took orders in 1713; and the same year, at the request of Dr Richard Bentley, he published the second edition of Newton’s Principia with an original preface. He died on the 5th of June 1716, leaving unfinished a series of elaborate researches on optics, and a large amount of unpublished manuscript. He contributed two memoirs to the Philosophical Transactions, one, “Logometria,” which discusses the calculation of logarithms and certain applications of the infinitesimal calculus, the other, a “Description of the great fiery meteor seen on March 6th, 1716.” After his death his papers were collected and published by his cousin and successor in the Plumian chair, Dr Robert Smith, under the title Harmonia Mensurarum (1722). This work included the “Logometria,” the trigonometrical theorem known as “Cotes’ Theorem on the Circle” (see Trigonometry), his theorem on harmonic means, subsequently developed by Colin Maclaurin, and a discussion of the curves known as “Cotes’ Spirals,” which occur as the path of a particle described under the influence of a central force varying inversely as the cube of the distance. In 1738 Dr Robert Smith published Cotes’ Hydrostatical and Pneumatical Lectures, a work which was held in great estimation. The exceptional genius of Cotes earned encomiums from both his contemporaries and successors; Sir Isaac Newton said, “If Mr Cotes had lived, we should have known something.”

CÔTES-DU-NORD, a maritime department of the north-west of France, formed in 1790 from the northern part of the province of Brittany, and bounded N. by the English Channel, E. by the department of Ille-et-Vilaine, S. by Morbihan, and W. by Finistère. Pop. (1906) 611,506. Area, 2786 sq. m. In general conformation, Côtes-du-Nord is an undulating plateau including in its more southerly portion three well-marked ranges of hills. A granitic chain, the Monts du Méné, starting in the south-east of the department runs in a north-westerly direction, forming the watershed between the rivers running respectively to the Channel and the Atlantic Ocean. Towards its western extremity this chain bifurcates to form the Montagnes Noires in the south-west and the Montagne d’Arrée in the west of the department. The rivers of the Channel slope are the Rance, Arguenon, Gouessan, Gouet, Trieux, Tréguier and Léguer, while the Blavet, Meu, Oust and Aulne belong to the southern slope. Off the coast, which is steep, rocky and much indented, are the Sept-Iles, Bréhat and other small islands. The principal bays are those of St Malo and St Brieuc.

The climate is mild and not subject to extremes; in the west it is especially humid. Agriculture is more successful on the coast, where seaweed can be used as a fertilizer, than in the interior. Cereals are largely grown, wheat, oats and buck-wheat being the chief crops. Potatoes, flax, mangels, apples, plums, cherries and honey are also produced. Pasture and various kinds of forage are abundant, and there is a large output of milk and butter. The horses of the department are in repute. It produces slate, building-stone, lime and china-clay. Flour-mills, saw-mills, sardine factories, tanneries, iron-works, manufactories of polish, boat-building yards, and rope-works employ many of the inhabitants, and cloth, agricultural implements and nails are manufactured. The chief imports are coal, wood and salt. Exports include agricultural products (eggs, butter, vegetables, &c.), horses, flax and fish. The chief commercial ports are Le Légué and Paimpol; and Paimpol also equips a large fleet for the Icelandic fisheries. The coast fishing is important and large quantities of sardines are preserved. The department is served by the Ouest-État railway; its chief waterway is the canal from Nantes to Brest which traverses it for 73 m.

Côtes-du-Nord is divided into the five arrondissements of St Brieuc, Dinan, Guingamp, Lannion and Loudéac, which contain 48 cantons and 390 communes. Bas Breton is spoken in the arrondissements of Guingamp and Lannion, and in part of those of Loudéac and St Brieuc. The department belongs to the ecclesiastical province, the académie (educational division), and the appeal court of Rennes, and in the region of the X. army corps. St Brieuc, Dinan, Guingamp, Lamballe, Paimpol and Tréguier, the more noteworthy towns, are separately treated. Extensive remains of an abbey of the Premonstratensian order, dating chiefly from the 13th century, exist at Kerity; and Lehon has remains of a priory, which dates from the same period. The department is rich in interesting churches, among which those of Ploubezre (12th, 14th and 16th centuries), Perros-Guirec (12th century), Plestin-les-Grèves (16th century) and Lanleff (12th century) may be mentioned. The church of St Mathurin at Moncontour, which is a celebrated place of pilgrimage, contains fine stained glass of the 16th century, and the mural paintings of the chapel of Kermaria-an-Isquit near Plouha, which belongs to the 13th and 14th centuries, are celebrated. Near Lannion (pop. 5336), itself a picturesque old town, is the ruined castle of Tonquédec, built in the 14th century and sometimes known as “the Pierrefonds of Brittany,” owing to its resemblance to the more famous castle. At Corseul are a temple and other Roman remains.

COTGRAVE, RANDLE (?-1634), English lexicographer, came of a Cheshire family, and was educated at Cambridge, entering St John’s College in 1587. He became secretary to Lord Burghley, and in 1611 published his French-English dictionary (2nd ed., 1632), a work of real historical importance in lexicography, and still valuable in spite of such errors as were due to contemporary want of exact scholarship.

CÖTHEN, or Köthen, a town of Germany, in the duchy of Anhalt on the Ziethe, at the junction of several railway lines, 42 m. N.W. of Leipzig by rail. Pop. (1905) 22,978. It consists of an old and a new town with four suburbs. The former palace of the dukes of Anhalt-Cöthen, in the old town, has fine gardens and contains collections of pictures and coins, the famous ornithological collection of Johann Friedrich Naumann (1780-1857), and a library of some 20,000 volumes. Of the churches the Lutheran Jakobskirche (called the cathedral), a Gothic building with some fine old stained glass, is noteworthy. Besides the usual classical and modern schools (Gymnasium and Realschule) Cöthen possesses a technical institute, a school of gardening and a school of forestry. The industries include iron-founding and the manufacture of agricultural and other machinery, malt, beet-root sugar, leather, spirits, &c.; a tolerably active trade is carried on in grain, wool, potatoes and vegetables. Among others, there is a monument to Sebastian Bach, who was music director here from 1717 to 1723.

In the 10th century Cöthen was a Slav settlement, which was captured and destroyed by the German king Henry I. in 927. By the 12th century it had secured town rights and become a considerable centre of trade in agricultural produce. In 1300 it was burned by the margrave of Meissen. In 1547 the town was taken from its prince, Wolfgang (a cadet of the house of Anhalt), who had joined the league of Schmalkalden, and given by the emperor Charles V., with the rest of the prince’s possessions, to the Spanish general and painter, Felipe Ladron y Guevara 250 (1510-1563), from whom it was, however, soon repurchased. Hahnemann, the founder of homoeopathy, lived and worked in Cöthen. From 1603 to 1847 Cöthen was the capital of the principality, later duchy, of Anhalt-Cöthen.

COTMAN, JOHN SELL (1782-1842), English landscape-painter and etcher, son of a well-to-do silk mercer, was born at Norwich on the 16th of May 1782. He showed a talent for art and was sent to London to study, where he became the friend of Turner, T. Girtin and other artists. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1800. In 1807 he went back to Norwich and joined the Norwich Society of Artists, of which in 1811 he became president. In 1825 he was made an associate of the Society of Painters in Water-colours; in 1834 he was appointed drawing-master at King’s College, London; and in 1836 he was elected a member of the Institute of British Architects. He died in London on the 24th of July 1842. Cotman’s work was not considered of much importance in his own day, and his pictures only procured small prices; but he now ranks as one of the great figures of the Norwich school. He was a fine draughtsman, and a remarkable painter both in oil and water-colour. One of his paintings is in the National Gallery. His fine architectural etchings, published in a series of volumes, the result of tours in Norfolk and Normandy, are valuable records of his interest in archaeology. He married early in life, and had five children, his sons, Miles Edmund (1810-1858) and Joseph John (1814-1878), both becoming landscape-painters of merit; and his younger brother Henry’s son, Frederic George Cotman (b. 1850), the water-colour artist, continued the family reputation.

COTONEASTER, a genus of the rose family (Rosaceae), containing about twenty species of shrubs and small trees, natives of Europe, North Africa and temperate Asia. C. vulgaris is native on the limestone cliffs of the Great Orme in North Wales. Several species are grown in shrubberies and borders, or as wall plants, mainly for their clusters of bright red or yellow berry-like fruits. Plants are easily raised by seeds, cuttings or layers, and grow well in ordinary soil.

COTOPAXI, a mountain of the Andes, in Ecuador, South America, 35 m. S.S.E. of Quito, remarkable as the loftiest active volcano in the world. The earliest outbursts on record took place in 1532 and 1533; and since then the eruptions have been both numerous and destructive. Among the most important are those of 1744, 1746, 1766, 1768 and 1803. In 1744 the thunderings of the volcano were heard at Honda on the Rio Magdalena, about 500 m. distant; in 1768 the quantity of ashes ejected was so great that it covered all the lesser vegetation as far as Riobamba; and in 1803 Humboldt reports that at the port of Guayaquil, 160 m. from the crater, he heard the noise day and night like continued discharges of a battery. There were considerable outbursts in 1851, 1855, 1856, 1864 and 1877. In 1802 Humboldt made a vain attempt to scale the cone, and pronounced the enterprise impossible; and the failure of Jean Baptiste Boussingault in 1831, and the double failure of M. Wagner in 1858, seemed to confirm his opinion. In 1872, however, Dr Wilhelm Reiss succeeded on the 27th and 28th of November in reaching the top; in the May of the following year the same feat was accomplished by Dr A. Stübel, and he was followed by T. Wolf in 1877, M. von Thielmann in 1878 and Edward Whymper in 1880.

Cotopaxi is frequently described as one of the most beautiful mountain masses of the world, rivalling the celebrated Fujiyama of Japan in its symmetry of outline, but overtopping it by more than 7000 ft. It is more than 15,000 ft. higher than Vesuvius, over 7000 ft. higher than Teneriffe, and nearly 2000 ft. higher than Popocatepetl. Its slope, according to Orton, is 30°, according to Wagner 29°, the north-western side being slightly steeper than the south-eastern. The apical angle is 122° 30′. The snowfall is heavier on the eastern side of the cone which is permanently covered, while the western side is usually left bare, a phenomenon occasioned by the action of the moist trade winds from the Atlantic. Its height according to Whymper is 19,613 ft., and its crater is 2300 ft. in diameter from N. to S., 1650 ft. from E. to W., and has an approximate depth of 1200 ft. It is bordered by a rim of trachytic rock, forming a black coronet above the greyish volcanic dust and sand which covers its sides to a great depth. Whymper found snow and ice under this sand. On the southern slope, at a height of 15,059 ft., is a bare cone of porphyritic andesite called El Picacho, “the beak,” or Cabeza del Inca, “the Inca’s head,” with dark cliffs rising fully 1000 ft., which according to tradition is the original summit of the volcano blown off at the first-known eruption of 1532. The summit of Cotopaxi is usually enveloped in clouds; and even in the clearest month of the year it is rarely visible for more than eight or ten days. Its eruptions produce enormous quantities of pumice, and deep layers of mud, volcanic sand and pumice surround it on the plateau. Of the air currents about and above Cotopaxi, Wagner says (Naturw. Reisen im trop. Amerika, p. 514): “On the Tacunga Plateau, at a height of 8000 Paris feet, the prevailing direction of the wind is meridional, usually from the south in the morning, and frequently from the north in the evening; but over the summit of Cotopaxi, at a height of 18,000 ft., the north-west wind always prevails throughout the day. The gradually-widening volcanic cloud continually takes a south-eastern direction over the rim of the crater; at a height, however, of about 21,000 ft. it suddenly turns to the north-west, and maintains that direction till it reaches a height of at least 28,000 ft. There are thus from the foot of the volcano to the highest level attained by its smoke-cloud three quite distinct regular currents of wind.”

COTRONE (anc. Croto, Crotona), a seaport and episcopal see on the E. coast of Calabria, Italy, in the province of Catanzaro, 37 m. E.N.E. of Catanzaro Marina by rail, 143 ft. above sea-level. Pop. (1901) town, 7917; commune, 9545. It has a castle erected by the emperor Charles V. and a small harbour, which even in ancient times was not good, but important as the only one between Taranto and Reggio. It exports a considerable quantity of oranges, olives and liquorice.

COTTA, the name of a family of German publishers, intimately connected with the history of German literature. The Cottas were of noble Italian descent, and at the time of the Reformation the family was settled in Eisenach in Thuringia.

Johann Georg Cotta (1) (1631-1692), the founder of the publishing house of J. G. Cotta, married in 1659 the widow of the university bookseller, Philipp Braun, in Tübingen, and took over the management of his business, thus establishing the firm which was subsequently associated with Cotta’s name. On his death, in 1692, the undertaking passed to his only son, Johann Georg (2); and on his death in 1712, to the latter’s eldest son, also named Johann Georg (3), while the second son, Johann Friedrich (see below), became the distinguished theologian.

Although the eldest son of Johann Georg (3), Christoph Friedrich Cotta (1730-1807), established a printing-house to the court at Stuttgart, the business languished, and it was reserved to his youngest son, Johann Friedrich, Freiherr Cotta Von Cottendorf (1764-1832), who was born at Stuttgart on the 27th of April 1764, to restore the fortunes of the firm. He attended the gymnasium of his native place, and was originally intended to study theology. He, however, entered the university of Tübingen as a student of mathematics and law, and after graduating spent a considerable time in Paris, studying French and natural science, and mixing with distinguished literary men. After practising as an advocate in one of the higher courts, Cotta, in compliance with his father’s earnest desire, took over the publishing business at Tübingen. He began in December 1787, and laboured incessantly to acquire familiarity with all the details. The house connexions rapidly extended; and, in 1794, the Allgemeine Zeitung, of which Schiller was to be editor, was planned. Schiller was compelled to withdraw on account of his health; but his friendship with Cotta deepened every year, and was a great advantage to the poet and his family. Cotta awakened in Schiller so warm an attachment that, as Heinrich Döring tells us in his life of Schiller (1824), when a bookseller offered him a higher price than Cotta for the copyright of Wallenstein, the poet firmly declined it, replying “Cotta deals honestly with me, and I with him.” In 1795 Schiller and Cotta founded 251 the Horen, a periodical very important to the student of German literature. The poet intended, by means of this work, to infuse higher ideas into the common lives of men, by giving them a nobler human culture, and “to reunite the divided political world under the banner of truth and beauty.” The Horen brought Goethe and Schiller into intimate relations with each other and with Cotta; and Goethe, while regretting that he had already promised Wilhelm Meister to another publisher, contributed the Unterhaltung deutscher Ausgewanderten, the Roman Elegies and a paper on Literary Sansculottism. Fichte sent essays from the first, and the other brilliant German authors of the time were also represented. In 1798 the Allgemeine Zeitung appeared at Tübingen, being edited first by Posselt and then by Huber. Soon the editorial office of the newspaper was transferred to Stuttgart, in 1803 to Ulm, and in 1810 to Augsburg; it is now in Munich. In 1799 Cotta entered on his political career, being sent to Paris by the Württemberg estates as their representative. Here he made friendships which proved very advantageous for the Allgemeine Zeitung. In 1801 he paid another visit to Paris, also in a political capacity, when he carefully studied Napoleon’s policy, and treasured up many hints which were useful to him in his literary undertakings. He still, however, devoted most of his attention to his own business, and, for many years, made all the entries into the ledger with his own hand. He relieved the tedium of almost ceaseless toil by pleasant intercourse with literary men. With Schiller, Huber, and Gottlieb Konrad Pfeffel (1736-1809) he was on terms of the warmest friendship; and he was also intimate with Herder, Schelling, Fichte, Richter, Voss, Hebel, Tieck, Therese Huber, Matthisson, the brothers Humboldt, Johann Müller, Spittler and others, whose works he published in whole or in part. In the correspondence of Alexander von Humboldt with Varnhagen von Ense we see the familiar relations in which the former stood to the Cotta family. In 1795 he published the Politischen Annalen and the Jahrbücher der Baukunde, and in 1798 the Damenalmanach, along with some works of less importance. In 1807 he issued the Morgenblatt, to which Schorn’s Kunstblatt and Menzel’s Literaturblatt were afterwards added. In 1810 he removed to Stuttgart; and from that time till his death he was loaded with honours. State affairs and an honourable commission from the German booksellers took him to the Vienna congress; and in 1815 he was deputy-elect at the Württemberg diet. In 1819 he became representative of the nobility; then he succeeded to the offices of member of committee and (1824) vice-president of the Württemberg second chamber. He was also appointed Prussian Geheimrat, and knight of the order of the Württemberg crown; King William I. of Württemberg having already revived the ancient nobility in his family by granting him the patent of Freiherr (Baron) Cotta von Cottendorf. Meanwhile such publications as the Polytechnische Journal, the Hesperus, the Württembergische Jahrbücher, the Hertha, the Ausland, and the Inland issued from the press. In 1828-1829 appeared the famous correspondence between Schiller and Goethe. Cotta was an unfailing friend of young struggling men of talent. In addition to his high standing as a publisher, he was a man of great practical energy, which flowed into various fields of activity. He was a scientific agriculturist, and promoted many reforms in farming. He was the first Württemberg landholder to abolish serfdom on his estates. In politics he was throughout his life a moderate liberal. In 1824 he set up a steam printing press in Augsburg, and, about the same time, founded a literary institute at Munich. In 1825 he started steamboats, for the first time, on Lake Constance, and introduced them in the following year on the Rhine. In 1828 he was sent to Berlin, on an important commission, by Bavaria and Württemberg, and was there rewarded with orders of distinction at the hands of the three kings. He died on the 29th of December 1832 leaving a son and a daughter as coheirs.

His son, Johann Georg (4), Freiherr Cotta Von Cottendorf (1796-1863), succeeded to the management of the business on the death of his father, and was materially assisted by his sister’s husband, Freiherr Hermann von Reischach. He greatly extended the connexions of the firm by the purchase, in 1839, of the publishing business of G. J. Göschen in Leipzig, and in 1845 of that of Vogel in Landshut; while, in 1845, “Bible” branches were established at Stuttgart and Munich. He was succeeded by his younger son, Karl, and by his nephew (the son of his sister), Hermann Albert von Reischach. Under their joint partnership, the before-mentioned firms in Leipzig and Landshut, and an artistic establishment in Munich passed into other hands, leaving on the death of Hermann Albert von Reischach, in 1876, Karl von Cotta the sole representative of the firm, until his death in 1888. In 1889 the firm of J. G. Cotta passed by purchase into the hands of Adolf and Paul Kröner, who took others into partnership. In 1899 the business was converted into a limited liability company.

See Albert Schäffle, Cotta (1895); Verlags-Katalog der J. G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung, Nachfolger (1900); and Lord Goschen’s Life and Times of G. J. Göschen (1903).

Johann Friedrich Cotta (1701-1779), the theologian, was born on the 12th of March 1701, the son of Johann Georg Cotta (2). After studying theology at Tübingen he began his public career as lecturer in Jena University. He then travelled in Germany, France and Holland, and, after residing several years in London, became professor at Tübingen in 1733. In 1736 he removed to the chair of theology in the university of Göttingen, which had been instituted as a seat of learning, two years before, by George II. of England, in his capacity as elector of Hanover. In 1739, however, he returned, as extraordinary professor of theology, to his Alma Mater, and, after successively filling the chairs of history, poetry and oratory, was appointed ordinary professor of theology in 1741. Finally he died, as chancellor of Tübingen University, on the 31st of December 1779. His learning was at once wide and accurate; his theological views were orthodox, although he did not believe in strict verbal inspiration. He was a voluminous writer. His chief works are his edition of Johann Gerhard’s Loci Theologici (1762-1777), and the Kirchenhistorie des Neuen Testaments (1768-1773).

COTTA, BERNHARD VON (1808-1879), German geologist, was born in a forester’s lodge near Eisenach, on the 24th of October 1808. He was educated at Freiberg and Heidelberg and from 1842 to 1874 he held the professorship of geology in the Bergakademie of Freiberg. Botany at first attracted him, and he was one of the earliest to use the microscope in determining the structure of fossil plants. Later on he gave his attention to practical geology, to the study of ore-deposits, of rocks and metamorphism; and he was regarded as an excellent teacher. His Rocks classified and described: a Treatise on Lithology (translated by P. H. Lawrence, 1866) was the first comprehensive work on the subject issued in the English language, and it gave great impetus to the study of rocks in Britain. He died at Freiberg on the 14th of September 1879.

Publications.—Geognostische Wanderungen (1836-1838); Grundriss der Geognosie und Geologie (1846); Geologische Briefe aus den Alpen (1850); Praktische Geologie (1852); Geologische Bilder (1852, ed. 4, 1861); Die Gesteinslehre (1855, ed. 2, 1862).

COTTA, GAIUS AURELIUS (c. 124-73 B.C.), Roman statesman and orator. In 92 he defended his uncle P. Rutilius Rufus, who had been unjustly accused of extortion in Asia. He was on intimate terms with the tribune M. Livius Drusus, who was murdered in 91, and in the same year was an unsuccessful candidate for the tribunate. Shortly afterwards he was prosecuted under the lex Varia, directed against all who had in any way supported the Italians against Rome, and, in order to avoid condemnation, went into voluntary exile. He did not return till 82, during the dictatorship of Sulla. In 75 he was consul, and excited the hostility of the optimates by carrying a law that abolished the Sullan disqualification of the tribunes from holding higher magistracies; another law de judiciis privatis, of which nothing is known, was abrogated by his brother. In 74 Cotta obtained the province of Gaul, and was granted a triumph for some victory of which we possess no details; but on the very day before its celebration an old wound broke out, and he died suddenly. According to Cicero, P. Sulpicius Rufus and Cotta were the best speakers of the young men of their time. Physically incapable of rising to passionate heights of oratory, Cotta’s 252 successes were chiefly due to his searching investigation of facts; he kept strictly to the essentials of the case and avoided all irrelevant digressions. His style was pure and simple. He is introduced by Cicero as an interlocutor in the De oratore and De natura deorum (iii.), as a supporter of the principles of the New Academy. The fragments of Sallust contain the substance of a speech delivered by Cotta in order to calm the popular anger at a deficient corn-supply.

See Cicero, De oratore, iii. 3, Brutus, 49, 55, 90, 92; Sallust, Hist. Frag.; Appian, Bell. Civ. i. 37.

His brother, Lucius Aurelius Cotta, when praetor in 70 B.C. brought in a law for the reform of the jury lists, by which the judices were to be eligible, not from the senators exclusively as limited by Sulla, but from senators, equites and tribuni aerarii. One-third were to be senators, and two-thirds men of equestrian census, one-half of whom must have been tribuni aerarii, a body as to whose functions there is no certain evidence, although in Cicero’s time they were reckoned by courtesy amongst the equites. In 66 Cotta and L. Manlius Torquatus accused the consuls-elect for the following year of bribery in connexion with the elections; they were condemned, and Cotta and Torquatus chosen in their places. After the suppression of the Catilinarian conspiracy, Cotta proposed a public thanksgiving for Cicero’s services, and after the latter had gone into exile, supported the view that there was no need of a law for his recall, since the law of Clodius was legally worthless. He subsequently attached himself to Caesar, and it was currently reported that Cotta (who was then quindecimvir) intended to propose that Caesar should receive the title of king, it being written in the books of fate that the Parthians could only be defeated by a king. Cotta’s intention was not carried out in consequence of the murder of Caesar, after which he retired from public life.

See Cicero, Orelli’s Onomasticon; Sallust, Catiline, 18; Suetonius, Caesar, 79; Livy, Epit. 97; Vell. Pat. ii. 32; Dio Cassius xxxvi. 44, xxxvii. 1.

COTTABUS (Gr. κότταβος), a game of skill for a long time in great vogue at ancient Greek drinking parties, especially in the 4th and 5th centuries B.C. It is frequently alluded to by the classical writers of the period, and not seldom depicted on ancient vases. The object of the player was to cast a portion of wine left in his drinking cup in such a way that, without breaking bulk in its passage through the air, it should reach a certain object set up as a mark, and there produce a distinct noise by its impact. Both the wine thrown and the noise made were called λάταξ. The thrower, in the ordinary form of the game, was expected to retain the recumbent position that was usual at table, and, in flinging the cottabus, to make use of his right hand only. To succeed in the aim no small amount of dexterity was required, and unusual ability in the game was rated as high as corresponding excellence in throwing the javelin. Not only was the cottabus the ordinary accompaniment of the festal assembly, but at least in Sicily a special building of a circular form was sometimes erected so that the players might be easily arranged round the basin, and follow each other in rapid succession. Like all games in which the element of chance found a place, it was regarded as more or less ominous of the future success of the players, especially in matters of love; and the excitement was sometimes further augmented by some object of value being staked on the event.

Various modifications of the original principle of the game were gradually introduced, but for practical purposes we may reckon two varieties, (1) In the Κότταβος δἰ ὀξυβάφων shallow saucers (ὀξύβαφα) were floated in a basin or mixing-bowl filled with water; the object was to sink the saucers by throwing the wine into them, and the competitor who sank the greatest number was considered victorious, and received the prize, which consisted of cakes or sweetmeats. (2) Κότταβος κατακτός1 is not so easy to understand, although there is little doubt as to the apparatus. This consisted of a ῥάβδος or bronze rod; a πλάστιγξ, a small disk or basin, resembling a scale-pan; a larger disk (λεκανίς); and (in most cases) a small bronze figure called μάνης. The discovery (by Professor Helbig in 1886) of two sets of actual apparatus near Perugia and various representations on vases help to elucidate the somewhat obscure accounts of the method of playing the game contained in the scholia and certain ancient authors who, it must not be forgotten, wrote at a time when the game itself had become obsolete, and cannot therefore be looked to for a trustworthy description of it.

The first specimen of the apparatus found at Perugia resembles a candelabrum on a base, tapering towards the top, with a blunt end, on which the small disk (found near the rod), which has a hole near the edge and is slightly hollow in the middle, could be balanced. At about a third of the height of the rod is a large disk with a hole in the centre through which the rod runs; in a socket at the top is a small bronze figure, with right arm and right leg uplifted. In the second specimen there is no large disk, and the figure is holding up what is apparently a rhyton or drinking-horn.

According to Prof. Helbig in Mittheilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts (Römische Abtheilung i., 1886) three games were played with this apparatus. In the first the smaller disk was placed on the top of the rod, and the object of the player was to dislodge it with a cast of the wine, so that it would fall with a clatter on the larger disk below. In the second (as in the third) the bronze figure was used; the smaller disk was placed above the figure, upon which it fell when hit, and thence on to the larger disk below. In the third, there was no smaller disk; the wine was thrown at the figure, and fell on to the larger disk underneath. Another supposed variety, in which two scales were balanced in such a manner that the weight of the liquid cast into either scale caused it to dip down and touch the top of an image placed under each, probably had no real existence, but is due to a confusion of the πλάστιγξ with a scale-pan by reason of its shape. The game appears to have been of Sicilian origin, but it spread through Greece from Thessaly to Rhodes, and was especially fashionable at Athens. Dionysius, Alcaeus, Anacreon, Pindar, Bacchylides, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, Antiphanes, make frequent and familiar allusion to the κότταβος; but in the writers of the Roman and Alexandrian period such reference as occurs shows that the fashion had died out. In Latin literature it is almost entirely unknown.

The most complete treatise on the subject is C. Sartori’s Das Kottabos-Spiel der alten Griechen (1893), in which a full bibliography of ancient and modern authorities is given. English readers may be referred to an article by A. Higgins on “Recent Discoveries of the Apparatus used in playing the Game of Kottabos” (Archaeologia, li. 1888); see also “Kottabos” in Daremberg and Saglio’s Dictionnaire des antiquités, and L. Becq de Fouquières, Les Jeux des anciens (1873).

1 The epithet κατακτὀς (let down) may refer to the rod, which might be raised or lowered as required; to the lower disk, which might be moved up and down the stem; to the moving up and down of the scales, in the supposed variety of the game mentioned below.]

COTTBUS, a town of Germany, in the kingdom of Prussia, on the Spree, 72 m. S.E. of Berlin by the main railway to Görlitz, and at the intersection of the lines Halle-Sagan and Grossenhain-Frankfort-on-Oder. Pop. (1905) 46,269. It has four Protestant churches, a Roman Catholic church and a synagogue. The chief industry of the town is the manufacture of cloth, which has flourished here for centuries and now employs more than 6000 hands. Wool-spinning, cotton-spinning and the manufacture of tobacco, machinery, beer, brandy, &c., are also carried on. The town is also a considerable trading centre, and is the seat of a chamber of commerce and of a branch of the Imperial Bank (Reichsbank). In the Stadtwald, close to the town, is a women’s hospital for diseases of the lungs, a government institution in connexion with the state system of insurance against incapacity and old age. At Branitz, a neighbouring village, are the magnificent château and park of Prince Pückler-Muskau.

At one time Cottbus formed an independent lordship of the Empire, but in 1462 it passed by the treaty of Guben to Brandenburg. From 1807 to 1813 it belonged to the kingdom of Saxony.

COTTENHAM, CHARLES CHRISTOPHER PEPYS, 1st Earl of (1781-1851), lord chancellor of England, was born in London on the 29th of April 1781. He was the second son of Sir William W. Pepys, a master in chancery, who was descended from John Pepys, of Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, a great-uncle of Samuel Pepys, the diarist. Educated at Harrow and Trinity College, 253 Cambridge, Pepys was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1804. Practising at the chancery bar, his progress was extremely slow, and it was not till twenty-two years after his call that he was made a king’s counsel. He sat in parliament, successively, for Higham Ferrars and Malton, was appointed solicitor-general in 1834, and in the same year became master of the rolls. On the formation of Lord Melbourne’s second administration in April 1835, the great seal was for a time in commission, but eventually Pepys, who had been one of the commissioners, was appointed lord chancellor (January 1836) with the title of Baron Cottenham. He held office until the defeat of the ministry in 1841. In 1846 he again became lord chancellor in Lord John Russell’s administration. His health, however, had been gradually failing, and he resigned in 1850. Shortly before his retirement he had been created Viscount Crowhurst and earl of Cottenham. He died at Pietra Santa, in the duchy of Lucca, on the 29th of April 1851.

Both as a lawyer and as a judge, Lord Cottenham was remarkable for his mastery of the principles of equity. An indifferent speaker, he nevertheless adorned the bench by the soundness of his law and the excellence of his judgments. As a politician he was somewhat of a failure, while his only important contribution to the statute-book was the Judgments Act 1838, which amended the law for the relief of insolvent debtors.

The title of earl of Cottenham descended in turn to two of the earl’s sons, Charles Edward (1824-1863), and William John (1825-1881), and then to the latter’s son, Kenelm Charles Edward (b. 1874).

Authorities.—Campbell, Lives of the Lord Chancellors (1869); E. Foss, The Judges of England (1848-1864); E. Manson, Builders of our Law (1904); J. B. Atlay, The Victorian Chancellors (1906).

COTTER, Cottar, or Cottier, a word derived from the Latin cota, a cot or cottage, and used to describe a man who occupies a cottage and cultivates a small plot of land. This word is often employed to translate the cotarius of Domesday Book, a class whose exact status has been the subject of some discussion, and is still a matter of doubt. According to Domesday the cotarii were comparatively few, numbering less than seven thousand, and were scattered unevenly throughout England, being principally in the southern counties; they were occupied either in cultivating a small plot of land, or in working on the holdings of the villani. Like the villani, among whom they were frequently classed, their economic condition may be described as “free in relation to every one except their lord.”

See F. W. Maitland, Domesday Book and Beyond (Cambridge, 1897); and P. Vinogradoff, Villainage in England (Oxford, 1892).

COTTESWOLD HILLS, or Cotswolds, a range of hills in the western midlands of England. The greater part lies in Gloucestershire, but the system covered by the name also extends into Worcestershire, Warwickshire, Oxfordshire, Wiltshire and Somersetshire. It extends on a line from N.E. to S.W., forming a part of the great Oolitic belt extending through the English midlands. On the west the hills overlook the vales of Evesham, Gloucester and Berkeley (valleys of the Worcestershire Avon and the Severn), with a bold escarpment broken only by a few abrupt spurs, such as Bredon hill, between Tewkesbury and Evesham. On the east they slope more gently towards the basins of the upper Thames and the Bristol Avon. The watershed lies close to the western line, except where the Stroud valley, with the Frome, draining to the Severn, strikes deep into the heart of the hills. The principal valleys are those of the Windrush, Lech, Coln and Churn, feeders of the Thames, the Thames itself, and the Bristol Avon. The last, wherein lie Bath and Bristol, forms the southern boundary of the Cotteswolds; the northern is formed by the valleys of the Evenlode (draining to the Thames) and the Stour (to the Worcestershire Avon), with the low divide between them. The crest-line from Bath at the south to Meon Hill at the north measures 57 m. The breadth varies from 6 m. in the south to 28 towards the north, and the area is some 300 sq. m. The features are those of a pleasant sequestered pastoral region, rolling plateaus or wolds and bare uplands alternating with deep narrow valleys, well wooded and traversed by shallow, rapid streams. The average elevation is about 600 ft., but Cleeve Cloud above Cheltenham in the Vale of Gloucester reaches 1134 ft., and Broadway Hill, in the north, 1086 ft. These heights command splendid views over the rich vales towards the distant hills of Herefordshire and the Forest of Dean. The picturesque village of Broadway at the foot of the hill of that name is much in favour with artists.

In the soil of the hill country is so much lime that a liberal supply of manure is required. With this good crops of barley and oats are obtained, and even of wheat, if the soil is mixed with clay. But the poorest land of the hill country affords excellent pasturage for sheep, the staple commodity of the district; and the sainfoin, which grows wild, yields abundantly under cultivation. The Cotteswolds have been famous for the breed of sheep named from them since the early part of the 15th century, a breed hardy and prolific, with lambs that quickly put on fleece, and become hardened to the bracing cold of the hills, where vegetation is a month later than in the vales. Improved by judicious crossing with the Leicester sheep, the modern Cotteswold has attained high perfection of weight, shape, fleece and quality. An impulse was given to Cotteswold farming by the chartering in 1845 of the Royal Agricultural College at Cirencester.

A number of small market-towns or large villages lie on the outskirts of the hills, but in the inner parts of the district villages are few. The “capital of the Cotteswolds” is Cirencester, in the east. In the north is Chipping Campden, its great Perpendicular church and the picturesque houses of its wide street commemorating the wealth of its wool-merchants between the 14th and 17th centuries. Near this town, in the parish of Weston-sub-Edge, Robert Dover, an attorney, founded the once famous Cotteswold games early in the 17th century. Horse-racing and coursing were included with every sort of athletic exercise from quoits and skittles to wrestling, cudgels and singlestick. The games were suppressed by act of parliament in 1851.

See Proceedings of the Cotteswold Naturalists’ Field Club, passim; W. H. Hutton, By Thames and Cotswold (London, 1903).

COTTET, CHARLES (1863- ), French painter, was born at Puy. He studied at the École des Beaux-Arts, and under Puvis de Chavannes and Roll. He travelled and painted in Egypt, Italy, and on the Lake of Geneva, but he made his name with his sombre and gloomy, firmly designed, severe and impressive scenes of life on the Brittany coast. His signal success was achieved by his painting of the triptych, “Au pays de la mer,” now at the Luxembourg museum. The Lille gallery has his “Burial in Brittany.”

COTTII REGNUM, a district in the north of Liguria, including a considerable part of the important road which led over the pass (6119 ft.) of the Alpis Cottia (Mont Genèvre) into Gaul. Whether Hannibal crossed the Alps by this route is disputed, but it was certainly in use about 100 B.C. (see Punic Wars). In 58 B.C. Caesar met with some resistance on crossing it, but seems afterwards to have entered into friendly relations with Donnus, the king of the district; he must have used it frequently, and refers to it as the shortest route. Donnus’s son Cottius erected the triumphal arch at his capital Segusio, the modern Susa, in honour of Augustus. Under Nero, after the death of the last Cottius, it became a province under the title of “Alpes Cottiae,” being governed by a procurator Augusti, though it still kept its old name also.

COTTIN, MARIE [called Sophie] (1770-1807), French novelist, née Risteau (not Ristaud), was born in Paris in 1770. At seventeen she married a Bordeaux banker, who died three years after, when she retired to a house in the country at Champlan, where she spent the rest of her life. In 1799 she published anonymously her Claire d’Albe. Malvina (1801) was also anonymous; but the success of Amélie Mansfield (1803) induced her to reveal her identity. In 1805 appeared Mathilde, an extravagant crusading story, and in 1806 she produced her last tale, the famous Élisabeth, ou les exilés de Sibérie, the subject of which was treated later with an admirable simplicity by Xavier de Maistre. Sainte-Beuve asserted that she committed suicide on account of an unfortunate attachment. This story is, however, 254 unauthenticated. She died at Champlan (Seine et Oise) on the 25th of April 1807.

A complete edition of her works, with a notice by A. Petitot, was published, in five volumes, in 1817.

COTTINGTON, FRANCIS COTTINGTON, Baron (1578-1652), English lord treasurer and ambassador, was the fourth son of Philip Cottington of Godmonston in Somersetshire. According to Hoare, his mother was Jane, daughter of Thomas Biflete, but according to Clarendon “a Stafford nearly allied to Sir Edward Stafford,” through whom he was recommended to Sir Charles Cornwallis, ambassador to Spain, becoming a member of his suite and acting as English agent on the latter’s recall, from 1609 to 1611. In 1612 he was appointed English consul at Seville. Returning to England, he was made a clerk of the council in September 1613. His Spanish experience rendered him useful to the king, and his bias in favour of Spain was always marked. He seems to have promoted the Spanish policy from the first, and pressed on Gondomar, the Spanish ambassador, the proposal for the Spanish in opposition to the French marriage for Prince Charles. He was a Roman Catholic at least at heart, becoming a member of that communion in 1623, returning to Protestantism, and again declaring himself a Roman Catholic in 1636, and supporting the cause of the Roman Catholics in England. In 1616 he went as ambassador to Spain, making in 1618 James’s proposal of mediation in the dispute with the elector palatine. After his return he was appointed secretary to the prince of Wales in October 1622, and was knighted and made a baronet in 1623. He strongly disapproved of the prince’s expedition to Spain, as an adventure likely to upset the whole policy of marriage and alliance, but was overruled and chosen to accompany him. His opposition greatly incensed Buckingham, and still more his perseverance in the Spanish policy after the failure of the expedition, and on Charles’s accession Cottington was through his means dismissed from all his employments and forbidden to appear at court. The duke’s assassination, however, enabled him to return. On the 12th of November 1628 he was made a privy councillor, and in March 1629 appointed chancellor of the exchequer. In the autumn he was again sent ambassador to Spain; he signed the treaty of peace of the 5th of November 1630, and subsequently a secret agreement arranging for the partition of Holland between Spain and England in return for the restoration of the Palatinate. On the 10th of July 1631 he was created Baron Cottington of Hanworth in Middlesex.

In March 1635 he was appointed master of the court of wards, and his exactions in this office were a principal cause of the unpopularity of the government. He was also appointed a commissioner for the treasury, together with Laud. Between Cottington and the latter there sprang up a fierce rivalry. In these personal encounters Cottington had nearly always the advantage, for he practised great reserve and possessed great powers of self-command, an extraordinary talent for dissembling and a fund of humour. Laud completely lacked these qualities, and though really possessing much greater influence with Charles, he was often embarrassed and sometimes exposed to ridicule by his opponent. The aim of Cottington’s ambition was the place of lord treasurer, but Laud finally triumphed and secured it for his own nominee, Bishop Juxon, when Cottington became “no more a leader but meddled with his particular duties only.”1 He continued, however, to take a large share in public business and served on the committees for foreign, Irish and Scottish affairs. In the last, appointed in July 1638, he supported the war, and in May 1640, after the dismissal of the Short Parliament, he declared it his opinion that at such a crisis the king might levy money without the Parliament. His attempts to get funds from the city were unsuccessful, and he had recourse instead to a speculation in pepper. He had been appointed constable of the Tower, and he now prepared the fortress for a siege. In the trial of Strafford in 1641 Cottington denied on oath that he had heard him use the incriminating words about “reducing this kingdom.” When the parliamentary opposition became too strong to be any longer defied, Cottington, as one of those who had chiefly incurred their hostility, hastened to retire from the administration, giving up the court of wards in May 1641 and the chancellorship of the exchequer in January 1642. He rejoined the king in 1643, took part in the proceedings of the Oxford parliament, and was made lord treasurer on the 3rd of October 1643. He signed the surrender of Oxford in July 1646, and being excepted from the indemnity retired abroad. He joined Prince Charles at the Hague in 1648, and became one of his counsellors. In 1649, together with Hyde, Cottington went on a mission to Spain to obtain help for the royal cause, having an interview with Mazarin at Paris on the way. They met, however, with an extremely ill reception, and Cottington found he had completely lost his popularity at the Spanish court, one cause being his shortcomings and waverings in the matter of religion. He now announced his intention of remaining in Spain and of keeping faithful to Roman Catholicism, and took up his residence at Valladolid, where he was maintained by the Jesuits. He died there on the 19th of June 1652, his body being subsequently buried in Westminster Abbey. He had amassed a large fortune and built two magnificent houses at Hanworth and Founthill. Cottington was evidently a man of considerable ability, but the foreign policy pursued by him was opposed to the national interests and futile in itself. According to Clarendon’s verdict “he left behind him a greater esteem of his parts than love of his person.” He married in 1623 Anne, daughter of Sir William Meredith and widow of Sir Robert Brett. All his children predeceased him, and his title became extinct at his death.

Bibliography.—Article in the Dict. of Nat. Biography and authorities there quoted; Clarendon’s Hist. of the Rebellion, passim, and esp. xiii. 30 (his character), and xii., xiii. (account of the Spanish mission in 1649); Clarendon’s State Papers and Life; Strafford’s Letters; Gardiner’s Hist. of England and of the Commonwealth; Hoare’s Wiltshire; Laud’s Works, vols, iii.-vii.; Winwood’s Memorials: A Refutation of a False and Impious Aspersion cast on the late Lord Cottington; Dart, Westmonasterium, i. 181 (epitaph and monument).

1 Strafford’s Letters, ii. 52.

COTTON, the name of a well-known family of Anglo-Indian administrators, of whom the following are the most notable.

Sir Arthur Thomas Cotton (1803-1899), English engineer, tenth son of Henry Calveley Cotton, was born on the 15th of May 1803, and was educated at Addiscombe. He entered the Madras engineers in 1819, served in the first Burmese war (1824-26), and in 1828 began his life-work on the irrigation works of southern India. He constructed works on the Cauvery, Coleroon, Godavari and Kistna rivers, making anicuts (dams) on the Coleroon (1836-1838) for the irrigation of the Tanjore, Trichinopoly and South Arcot districts; and on the Godivari (1847-1852) for the irrigation of the Godavari district. He also projected the anicut on the Kistna (Krishna), which was carried out by other officers. Before the beginning of his work Tanjore and the adjoining districts were threatened with ruin from lack of water; on its completion they became the richest part of Madras, and Tanjore returned the largest revenue of any district in India. He was the founder of the school of Indian hydraulic engineering, and carried out much of his work in the face of opposition and discouragement from the Madras government; though, in the minute of the 15th of May 1858, that government paid an ample tribute to the genius of Cotton’s “master mind.” He was knighted in 1861. Sir Arthur Cotton believed in the possibility of constructing a complete system of irrigation and navigation canals throughout India, and devoted the whole of a long life to the partial realization of this project. He died on the 24th of July 1899.

See Lady Hope, General Sir Arthur Cotton (1900).

Sir Henry John Stedman Cotton (1845- ), Anglo-Indian administrator, son of J. J. Cotton of the Madras Civil Service, was born on the 13th of September 1845, and was educated at Magdalen College school and King’s College, London. He entered the Bengal Civil Service in 1867, and held various appointments of increasing importance until he became chief secretary to the Bengal government (1891-1896), acting home secretary to the government of India (1896), and chief commissioner of Assam (1896-1902). He retired in 1902, and soon became known as the leading English champion of the Indian 255 nationalists. In 1906 he entered parliament as Liberal member for East Nottingham. He was the author of New India (1885; revised 1904-1907).

His brother, James Sutherland Cotton (1847- ), was born in India on the 17th of July 1847, and was educated at Magdalen College school and Trinity College, Oxford. For many years he was editor of the Academy; he published various works on Indian subjects, and was the English editor of the revised edition of the Imperial Gazetteer of India (1908).

COTTON, CHARLES (1630-1687), English poet, the translator of Montaigne, was born at Beresford in Staffordshire on the 28th of April 1630. His father, Charles Cotton, was a man of marked ability, and counted among his friends Ben Jonson, John Selden, Sir Henry Wotton and Izaak Walton. The son was apparently not sent to the university, but he had as tutor Ralph Rawson, one of the fellows ejected from Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1648. Cotton travelled in France and perhaps in Italy, and at the age of twenty-eight he succeeded to an estate greatly encumbered by lawsuits during his father’s lifetime. The rest of his life was spent chiefly in country pursuits, but from his Voyage to Ireland in Burlesque (1670) we know that he held a captain’s commission and was ordered to that country. His friendship with Izaak Walton began about 1655, and the fact of this intimacy seems a sufficient answer to the charges sometimes brought against Cotton’s character, based chiefly on his coarse burlesques of Virgil and Lucian. Walton’s initials made into a cipher with his own were placed over the door of his fishing cottage on the Dove; and to the Compleat Angler he added “Instructions how to angle for a trout or grayling in a clear stream.” He married in 1656 his cousin Isabella, who was a sister of Colonel Hutchinson. It was for his wife’s sister, Miss Stanhope Hutchinson, that he undertook the translation of Corneille’s Horace (1671). His wife died in 1670 and five years later he married the dowager countess of Ardglass; she had a jointure of £1500 a year, but it was secured from his extravagance, and at his death in 1687 he was insolvent. He was buried in St James’s church, Piccadilly, on the 16th of February 1687. Cotton’s reputation as a burlesque writer may account for the neglect with which the rest of his poems have been treated. Their excellence was not, however, overlooked by good critics. Coleridge praises the purity and unaffectedness of his style in Biographia Literaria, and Wordsworth (Preface, 1815) gave a copious quotation from the “Ode to Winter.” The “Retirement” is printed by Walton in the second part of the Compleat Angler. His masterpiece in translation, the Essays of M. de Montaigne (1685-1686, 1693, 1700, &c.), has often been reprinted, and still maintains its reputation; his other works include The Scarronides, or Virgil Travestie (1664-1670), a gross burlesque of the first and fourth books of the Aeneid, which ran through fifteen editions; Burlesque upon Burlesque, ... being some of Lucian’s Dialogues newly put into English fustian (1675); The Moral Philosophy of the Stoicks (1667), from the French of Guillaume du Vair; The History of the Life of the Duke d’Espernon (1670), from the French of G. Girard; the Commentaries (1674) of Blaise de Montluc; the Planter’s Manual (1675), a practical book on arboriculture, in which he was an expert; The Wonders of the Peake (1681); the Compleat Gamester and The Fair one of Tunis, both dated 1674, are also assigned to Cotton.

William Oldys contributed a life of Cotton to Hawkins’s edition (1760) of the Compleat Angler. His Lyrical Poems were edited by J. R. Tutin in 1903, from an unsatisfactory edition of 1689. His translation of Montaigne was edited in 1892, and in a more elaborate form in 1902, by W. C. Hazlitt, who omitted or relegated to the notes the passages in which Cotton interpolates his own matter, and supplied his omissions.

COTTON, GEORGE EDWARD LYNCH (1813-1866), English educationist and divine, was born at Chester on the 29th of October 1813. He received his education at Westminster school, and at Trinity College, Cambridge. Here he joined the Low Church party, and was also the intimate friend of several disciples of Thomas Arnold, among whom were C. J. Vaughan and W. J. Conybeare. The influence of Arnold determined the character and course of his life. He graduated B.A. in 1836, and became an assistant-master at Rugby. Here he worked devotedly for fifteen years, inspired with Arnold’s spirit, and heartily entering into his plans and methods. He became master of the fifth form about 1840 and was singularly successful with the boys. In 1852 he accepted the appointment of headmaster at Marlborough College, then in a state of almost hopeless disorganization, and in his six years of rule raised it to a high position. In 1858 Cotton was offered the see of Calcutta, which, after much hesitation about quitting Marlborough, he accepted. For its peculiar duties and responsibilities he was remarkably fitted by the simplicity and strength of his character, by his large tolerance, and by the experience which he had gained as teacher and ruler at Rugby and Marlborough. The government of India had just been transferred from the East India Company to the crown, and questions of education were eagerly discussed. Cotton gave himself energetically to the work of establishing schools for British and Eurasian children, classes which had been hitherto much neglected. He did much also to improve the position of the chaplains, and was unwearied in missionary visitation. His sudden death was widely mourned. On the 6th of October 1866 he had consecrated a cemetery at Kushtea on the Ganges, and was crossing a plank leading from the bank to the steamer when he slipped and fell into the river. He was carried away by the current and never seen again.

A memoir of his life with selections from his journals and correspondence, edited by his widow, was published in 1871.

COTTON, JOHN (1585-1652), English and American Puritan divine, sometimes called “The Patriarch of New England,” born in Derby, England, on the 4th of December 1585. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating B.A. in 1603 and M.A. in 1606, and became a fellow in Emmanuel College, Cambridge, then a stronghold of Puritanism, where, during the next six years, according to his friend and biographer, Rev. Samuel Whiting, he was “head lecturer and dean, and Catechist,” and “a dilligent tutor to many pupils.” In June 1612 he became vicar of the parish church of St Botolphs in Boston, Lincolnshire, where he remained for twenty-one years and was extremely popular. Becoming more and more a Puritan in spirit, he ceased, about 1615, to observe certain ceremonies prescribed by the legally authorized ritual, and in 1632 action was begun against him in the High Commission Court. He thereupon escaped, disguised, to London, lay in concealment there for several months, and, having been deeply interested from its beginning in the colonization of New England, he eluded the watch set for him at the various English ports, and in July 1633 emigrated to the colony of Massachusetts Bay, arriving at Boston early in September. On the 10th of October he was chosen “teacher” of the First Church of Boston, of which John Wilson (1588-1667) was pastor, and here he remained until his death on the 23rd of December 1652. In the newer, as in the older Boston, his popularity was almost unbounded, and his influence, both in ecclesiastical and in civil affairs, was probably greater than that of any other minister in theocratic New England. According to the contemporary historian, William Hubbard, “Whatever he delivered in the pulpit was soon put into an order of court, if of a civil, or set up as a practice in the church, if of an ecclesiastical concernment.” His influence, too, was generally beneficent, though it was never used to further the cause of religious freedom, or of democracy, his theory of government being given in an oft-quoted passage: “Democracy, I do not conceyve that ever God did ordeyne as a fitt government eyther for church or commonwealth.... As for Monarchy and aristocracy they are both for them clearly approved, and directed in Scripture yet so as (God) referreth the sovereigntie to himselfe, and setteth up Theocracy in both, as the best form of government.” He naturally took an active part in most, if not all, of the political and theological controversies of his time, the two principal of which were those concerning Antinomianism and the expulsion of Roger Williams. In the former his position was somewhat equivocal—he first supported and then violently opposed Anne Hutchinson,—in the latter he approved Williams’s expulsion as “righteous in the eyes of God,” and subsequently in a pamphlet discussion with 256 Williams, particularly in his Bloudy Tenent, Washed and made White in the Blood of the Lamb (1647), vigorously opposed religious freedom. He was a man of great learning and was a prolific writer. His writings include: The Keyes to the Kingdom of Heaven and the Power thereof (1644), The Way of the Churches of Christ in New England (1645), and The Way of Congregational Churches Cleared (1648), these works constituting an invaluable exposition of New England Congregationalism; and Milk for Babes, Drawn out of the Breasts of Both Testaments, Chiefly for the Spirituall Nourishment of Boston Babes in either England, but may be of like Use for any Children (1646), widely used for many years, in New England, for the religious instruction of children.

See the quaint sketch by Cotton Mather, John Cotton’s grandson, in Magnalia (London, 1702), and a sketch by Cotton’s contemporary and friend, Rev. Samuel Whiting, printed in Alexander Young’s Chronicles of the First Planters of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay from 1623 to 1636 (Boston, 1846); also A. W. McClure’s The Life of John Cotton (Boston, 1846), a chapter in Arthur B. Ellis’s History of the First Church in Boston (Boston, 1881), and a chapter in Williston Walker’s Ten New England Leaders (New York, 1901). (W. Wr.)

COTTON, SIR ROBERT BRUCE, Bart. (1571-1631), English antiquary, the founder of the Cottonian library, born at Denton in Huntingdonshire on the 22nd of January 1571, was a descendant, as he delighted to boast, of Robert Bruce. He was educated at Westminster school under William Camden the antiquary, and at Jesus College, Cambridge. His antiquarian tastes were early displayed in the collection of ancient records, charters and other manuscripts, which had been dispersed from the monastic libraries in the reign of Henry VIII.; and throughout the whole of his life he was an energetic collector of antiquities from all parts of England and the continent. His house at Westminster had a garden going down to the river and occupied part of the site of the present House of Lords. It was the meeting-place in the last years of Elizabeth’s reign of the antiquarian society founded by Archbishop Parker. In 1600 Cotton visited the north of England with Camden in search of Pictish and Roman monuments and inscriptions. His reputation as an expert in heraldry led to his being asked by Queen Elizabeth to discuss the question of precedence between the English ambassador and the envoy of Spain, then in treaty at Calais. He drew up an elaborate paper establishing the precedence of the English ambassador. On the accession of James I. he was knighted, and in 1608 he wrote a Memorial on Abuses in the Navy, that resulted in a navy commission, of which he was made a member. He also presented to the king an historical Inquiry into the Crown Revenues, in which he speaks freely about the expenses of the royal household, and asserts that tonnage and poundage are only to be levied in war time, and to “proceed out of good will, not of duty.” In this paper he supported the creation of the order of baronets, each of whom was to pay the crown £1000; and in 1611 he himself received the title.

Cotton helped John Speed in the compilation of his History of England (1611), and was regarded by contemporaries as the compiler of Camden’s History of Elizabeth. It seems more likely that it was executed by Camden, but that Cotton exercised a general supervision, especially with regard to the story of Mary queen of Scots. The presentation of his mother’s history was naturally important to James I., and Cotton himself took a keen interest in the matter. He had had the room in Fotheringay where Mary was executed transferred to his family seat at Connington. Meanwhile he was enlarging his collection of documents. In 1614 Arthur Agarde (q.v.) left his papers to him, and Camden’s manuscripts came to him in 1623. In 1615 Cotton, as the intimate of the earl of Somerset, whose innocence he always maintained, was placed in confinement on the charge of being implicated in the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury; he confessed that he had acted as intermediary between Sarmiento, the Spanish ambassador, and Somerset, and had altered the dates of Somerset’s correspondence. He was released after about eight months’ imprisonment without formal trial, and obtained a pardon on payment of £500. His friendship with Gondomar, Spanish ambassador in England from 1613 to 1621, brought further suspicion, probably undeserved, upon Cotton, of unduly favouring the Catholic party. From Charles I. and Buckingham Cotton received no favour; his attitude towards the court had begun to change, and he became the intimate friend of Sir John Eliot, Sir Simonds d’Ewes and John Selden. He had entered parliament in 1604 as member for Huntingdon; in 1624 he sat for Old Sarum; in 1625 for Thetford; and in 1628 for Castle Rising, Norfolk. In the debate on supply in 1625 Cotton provided Eliot with full notes defending the action of the opposition in parliament, and in 1628 the leaders of the party met at Cotton’s house to decide on their policy. In 1626 he gave advice before the council against debasing the standard of the coinage; and in January 1628 he was again before the council, urging the summons of a parliament. His arguments on the latter occasion are contained in his tract entitled The Danger in which the Kingdom now standeth and the Remedy. In October of the next year he was arrested, together with the earls of Bedford, Somerset, and Clare, for having circulated, with ironical purpose, a tract known as the Proposition to bridle Parliament, which had been addressed some fifteen years before by Sir Robert Dudley to James I., advising him to govern by force; the circulation of this by Parliamentarians was regarded as intended to insinuate that Charles’s government was arbitrary and unconstitutional. Cotton denied knowledge of the matter, but the original was discovered in his house, and the copies had been put in circulation by a young man who lived after him and was said to be his natural son. Cotton was himself released the next month; but the proceedings in the star chamber continued, and, to his intense vexation, his library was sealed up by the king. He died on the 6th of May 1631, and was buried in Connington church, Huntingdonshire, where there is a monument to his memory.

Many of Cotton’s pamphlets were widely read in manuscript during his lifetime, but only two of his works were printed, The Reign of Henry III. (1627) and The Danger in which the Kingdom now Standeth (1628). His son, Sir Thomas (1594-1662), added considerably to the Cottonian library; and Sir John, the fourth baronet, presented it to the nation in 1700. In 1731 the collection, which had in the interval been removed to the Strand, and thence to Ashburnham House, was seriously damaged by fire. In 1753 it was transferred to the British Museum.

See the article Libraries, and Edwards’s Lives of the Founders of the British Museum, vol. i. Several of Cotton’s papers have been printed under the title Cottoni Posthuma; others were published by Thomas Hearne.

COTTON (Fr. coton; from Arab, qutun), the most important of the vegetable fibres of the world, consisting of unicellular hairs which occur attached to the seeds of various species of plants of the genus Gossypium, belonging to the Mallow order (Malvaceae). Each fibre is formed by the outgrowth of a single epidermal cell of the testa or outer coat of the seed.

Botany and Cultivation.—The genus Gossypium includes herbs and shrubs, which have been cultivated from time immemorial, and are now found widely distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of both hemispheres. South America, the West Indies, tropical Africa and Southern Asia are the homes of the various members, but the plants have been introduced with success into other lands, as is well indicated by the fact that although no species of Gossypium is native to the United States of America, that country now produces over two-thirds of the world’s supply of cotton. Under normal conditions in warm climates many of the species are perennials, but, in the United States for example, climatic conditions necessitate the plants being renewed annually, and even in the tropics it is often found advisable to treat them as annuals to ensure the production of cotton of the best quality, to facilitate cultural operations, and to keep insect and fungoid pests in check.

Microscopic examination of a specimen of mature cotton shows that the hairs are flattened and twisted, resembling somewhat in general appearance an empty and twisted fire hose. This characteristic is of great economic importance, the natural twist facilitating the operation of spinning the fibres into thread or yarn. It also distinguishes the true cotton from the silk cottons or flosses, the fibres of which have no twist, and do not readily 257 spin into thread, and for this reason, amongst others, are very considerably less important as textile fibres. The chief of these silk cottons is kapok, consisting of the hairs borne on the interior of the pods (but not attached to the seeds) of Eriodendron anfractuosum, the silk cotton tree, a member of the Bombacaceae, an order very closely allied to the Malvaceae.

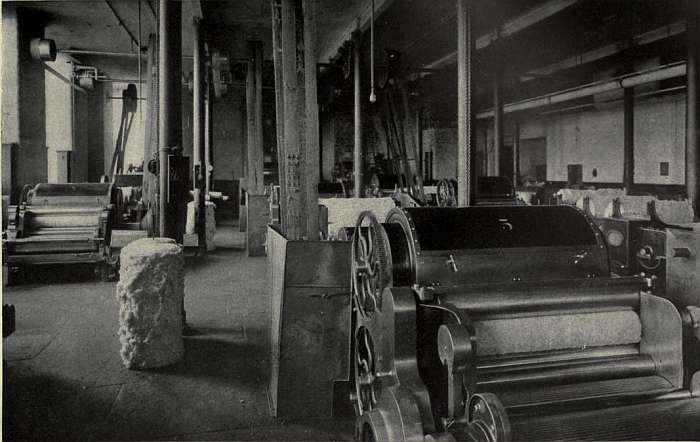

|

| From Strasburger’s Lehrbuch der Botanik, by

permission of Gustav Fischer. Fig. 1.—Seed-hairs of the Cotton, Gossypium herbaceum. A, Part of seed-coat with hairs; B1, insertion and lower part; B2, middle part; and B3, upper part of a hair. |