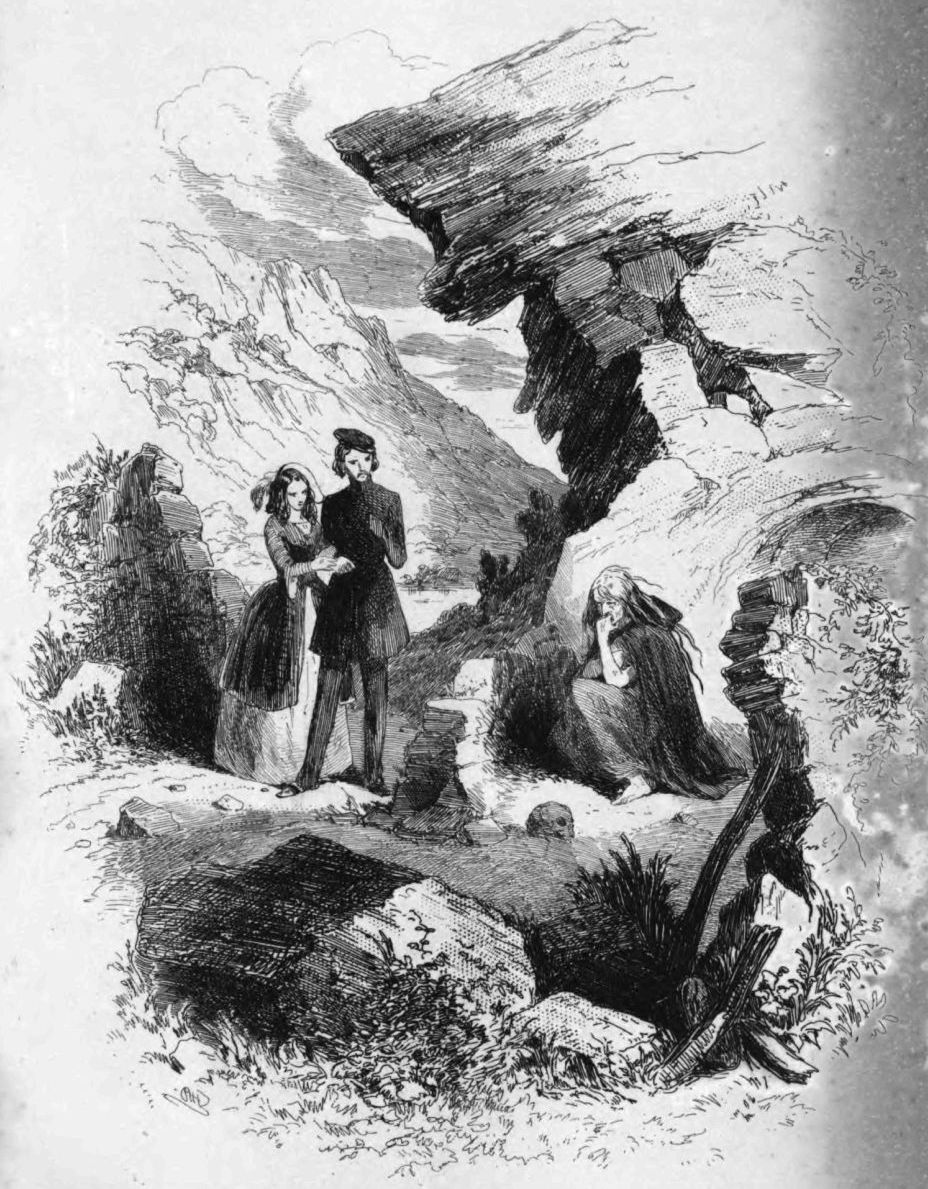

Title: The O'Donoghue: Tale of Ireland Fifty Years Ago

Author: Charles Lever

Illustrator: Hablot Knight Browne

Release date: May 11, 2010 [eBook #32340]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

TO JOHN WILSON, ESQ., Professor of Moral Philosophy In the

University of Edinburgh, &c.

Dear Sir, It is but seldom that the few lines of a dedication can give the pleasure I now feel in availing myself of your kind permission to inscribe this volume to you. As a boy, the greatest happiness of my life was in your writings; and among all my faults and failures, I can trace not one to your influence, while, if I have ever been momentarily successful in upholding the right, and denouncing the wrong, I owe more of the spirit that suggested the effort to yourself than to any other man breathing. With my sincerest respects, and, if I dared, I should say, with my warmest regards, I am, yours truly, CHARLES LEVER. Carlsruhe, October 18th, 1845.

CONTENTS

THE O'DONOGHUE

CHAPTER I. GLENFLESK

CHAPTER II. THE WAYSIDE INN

CHAPTER III. THE “COTTAGE AND THE CASTLE.”

CHAPTER IV. KERRY O'LEARY

CHAPTER V. IMPRESSIONS OF IRELAND

CHAPTER VI. THE BLACK VALLEY

CHAPTER VII. SIR ARCHY'S TEMPER TRIED

CHAPTER VIII. THE HOUSE OF SICKNESS

CHAPTER IX. A DOCTOR'S VISIT

CHAPTER X. AN EVENING AT “MARY” M'KELLY's

CHAPTER XI. MISTAKES ON ALL SIDES

CHAPTER XII. THE GLEN AT MIDNIGHT

CHAPTER XIII. THE GUARDSMAN

CHAPTER XIV. THE COMMENTS ON A HURRIED DEPARTURE

CHAPTER XV. SOME OF THE PLEASURES OF PROPERTY

CHAPTER XVI. THE FOREIGN LETTER

CHAPTER XVII. KATE O'DONOGHUE

CHAPTER XVIII. A HASTY PLEDGE

CHAPTER XIX. A DIPLOMATIST DEFEATED

CHAPTER XX. TEMPTATION IN A WEAK HOUR

CHAPTER XXI. THE RETURN OF THE ENVOY

CHAPTER XXII. A MORNING VISIT

CHAPTER XXIII. SOME OPPOSITE TRAITS OF CHARACTER

CHAPTER XXIV. A WALK BY MOONLIGHT

CHAPTER XXV. A DAY OF DIFFICULT NEGOCIATIONS

CHAPTER XXVI. A LAST EVENING AT HOME

CHAPTER XXVII. A SUPPER PARTY

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE CAPITAL AND ITS PLEASURES

CHAPTER XXIX. FIRST IMPRESSIONS

CHAPTER XXX. OLD CHARACTERS WITH NEW FACES

CHAPTER XXXI. SOME HINTS ABOUT HARRY TALBOT

CHAPTER XXXII. A PRESAGE OF DANGER

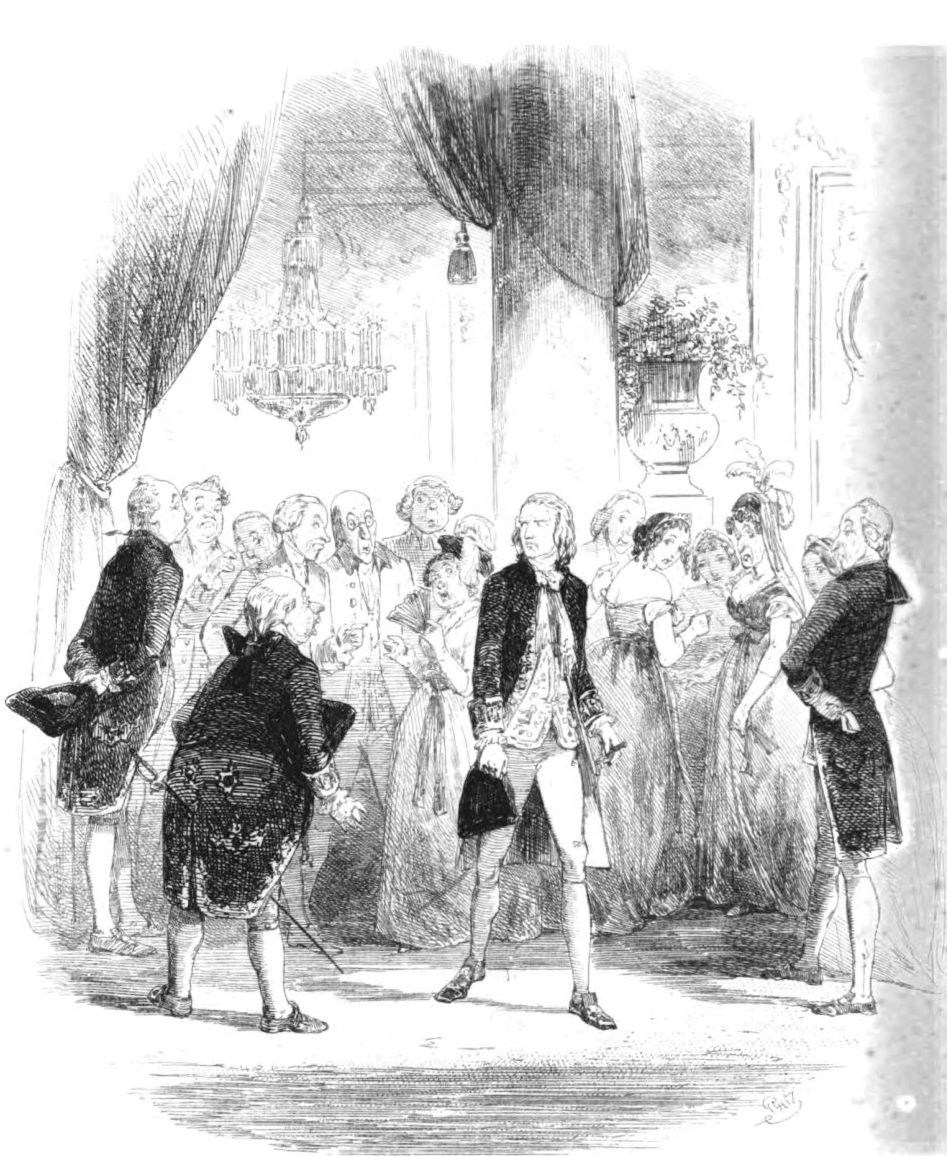

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE ST. PATRICK'S BALL

CHAPTER XXXIV. THE DAYBREAK ON THE STRAND

CHAPTER XXXV. THE WANDERER'S RETURN

CHAPTER XXXVI. SUSPICIONS ON EVERY SIDE

CHAPTER XXXVII. HEMSWORTH'S LETTER

CHAPTER XXXVIII. TAMPERING AND PLOTTING

CHAPTER XXXIX. THE BROTHERS

CHAPTER XL. THE LULL BEFORE THE STORM

CHAPTER XLI. A DISCOVERY

CHAPTER XLII. THE SHEALING

CHAPTER XLIII. THE CONFEDERATES

CHAPTER XLIV. THE MOUNTAIN AT SUNRISE

CHAPTER XLV. THE PROGRESS OF TREACHERY

CHAPTER XLVI. THE PRIEST'S COTTAGE

CHAPTER XLVII. THE DAY OF RECKONING

CHAPTER XLVIII. THE GLEN AND THE BAY

CHAPTER XLIX. THE END

In that wild and picturesque valley which winds its way between the town of Macroom and Bantry Bay, and goes by the name of Glenflesk, the character of Irish scenery is perhaps more perfectly displayed than in any other tract of the same extent in the island. The mountains, rugged and broken, are singularly fanciful in their outline; their sides a mingled mass of granite and straggling herbage, where the deepest green and the red purple of the heath-bell are blended harmoniously together. The valley beneath, alternately widening and narrowing, presents one rich meadow tract, watered by a deep and rapid stream, fed by a thousand rills that come tumbling, and foaming down the mountain sides, and to the traveller are seen like white streaks marking the dark surface of the precipice. Scarcely a hut is to be seen for miles of this lonely glen, and save for the herds of cattle and the flocks of sheep here and there to be descried, it would seem as if the spot had been forgotten by man, and left to sleep in its own gloomy desolation. The river itself has a character of wildness all its own-now, brawling over rugged rocks-now foaming between high and narrow sides, abrupt as walls, sometimes, flowing over a ledge of granite, without a ripple on the surface-then plunging madly into some dark abyss, to emerge again, lower down the valley, in one troubled sea of foam and spray: its dull roar the only voice that echoes in the mountain gorge. Even where the humble roof of a solitary cabin can be seen, the aspect of habitation rather heightens than diminishes the feeling of loneliness and desolation around. The thought of poverty enduring its privations unseen and unknown, without an eye to mark its struggles, or a heart to console its griefs, comes mournfully on the mind, and one wonders what manner of man he can be, who has fixed his dwelling in such solitude.

In vain the eye ranges to catch sight of one human being, save that dark speck be such which crowns the cliff, and stands out from the clear sky behind. Yes, it is a child watching the goats that are browsing along the mountain, and as you look, the swooping mist has hidden him from your view. Life of dreariness and gloom! What sad and melancholy thoughts must be his companions, who spends the live-long day on these wild heaths, his eye resting on the trackless waste where no fellow-creature moves! how many a mournful dream will pass over his mind! what fearful superstitions will creep in upon his imagination, giving form and shape to the flitting clouds, and making the dark shadows, as they pass, seem things of life and substance.

Poor child of sorrow! How destiny has marked you for misery! For you no childish gambols in the sun—no gay playfellow—no paddling in the running stream, that steals along bright and glittering, like happy infancy—no budding sense of a fair world, opening in gladness; but all, a dreary waste—the weariness of age bound up with the terrors of childhood.

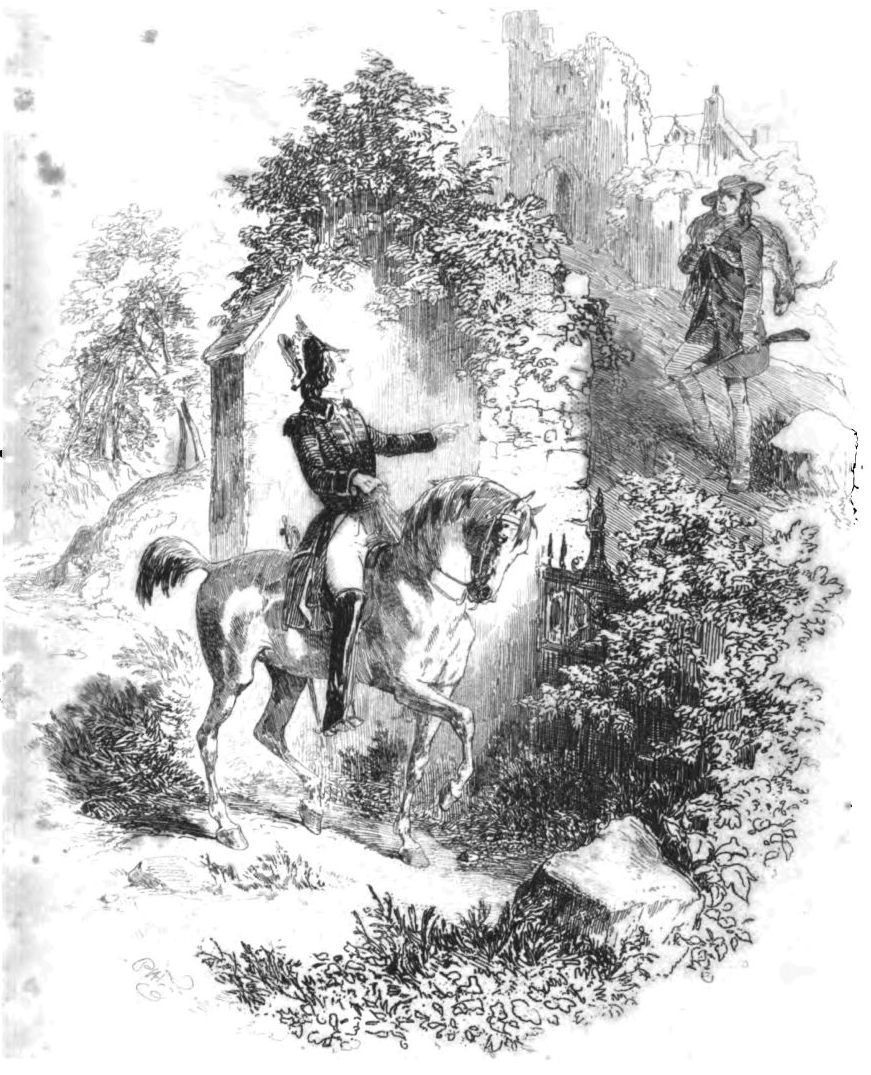

The sun was just setting on a mellow evening, late in the autumn of a year towards the close of the last century, as a solitary traveller sat down to rest himself on one of the large rocks by the road-side; divesting himself of his gun and shot-pouch, he lay carelessly at his length, and seemed to be enjoying the light breeze which came up the valley.

He was a young and powerfully-built man, whose well-knit frame and muscular limbs showed how much habitual exercise had contributed to make the steepest paths of the mountain a task of ease to him. He was scarcely above the middle height, but with remarkable breadth of chest, and that squareness of proportion which indicates considerable physical strength; his countenance, except for a look of utter listlesness and vacuity, had been pleasing; the eyes were large and full, and of the deep grey which simulates blue; the nose large and well-formed; the mouth alone was unprepossessing-the expression it wore was of ill-humour and discontent, and this character seemed so habitual that even as he sat thus alone and in solitude, the curl of the upper lip betrayed his nature.

His dress was a shooting-jacket of some coarse stuff, stained and washed by many a mountain streamlet; loose trowsers of grey cloth, and heavy shoes-such as are worn by the peasantry, wherever such luxuries are attainable. It would have been difficult, at a mere glance, to have decided what class or condition of life he pertained to; for, although certain traits bespoke the person of a respectable rank, there was a general air of neglect about him, that half contradicted the supposition. He lay for some time perfectly motionless, when the tramp of horses at a distance down the glen suddenly roused him from his seeming apathy, and resting on his elbow he listened attentively. The sounds came nearer and nearer, and now, the dull roll of a carriage could be heard approaching. Strange noises these in that solitary valley, where even the hoofs of a single horse but rarely routed the echoes. A sudden dip of the road at a little distance from where he lay, concealed the view, and he remained in anxious expectancy, wondering what these sounds should portend, when suddenly the carriage seemed to have halted, and all was still.

For some minutes the youth appeared to doubt whether he had not been deceived by some swooping of the wind through the passes in the mountains, when the sound of voices fell on his ear, and at the same moment, two figures appeared over the crest of the hill, slowly advancing up the road. The one was a man advanced in years, but still hale and vigorous, in look-his features even yet eminently handsome, wore an air of mingled frankness and haughtiness; there was in their expression the habitual character of one accustomed to exert a degree of command and influence over others-a look, which of all the characteristics of temper, is least easily mistaken.

At his side walked one who, even at a passing glance, might be pronounced his daughter, so striking the resemblance between them, She did not seem above sixteen years of age, but through the youthful traits of her features you could mark the same character of expression her father's wore, modified by the tender beauty, which at that age, blends the loveliness of the girl with the graces of womanhood. Bather above than below the middle height, her figure had that distinguishing mark of elegance high birth impresses, and in her very walk a quick observer might detect an air of class.

They both stopped short as they gained the summit of the hill, and appeared wonder-struck at the scene before them. The grey gloom of twilight threw its sombre shadows over the valley, but the mountain peaks were tipped with the setting sun, and shone in those rich violet and purple hues the autumn heath displays so beautifully. The dark-leaved holly and the bright arbutus blossom lent their colour to every jutting cliff and promontory, which, to eyes unacquainted with the scenery, gave an air of culture strangely at variance with the desolation around.

“Is this wild enough for your fancy, Sybella,” said the father, with a playful smile, as he watched the varying expression of the young girl's features, “or would you desire something still more dreary?” But she made no answer. Her gaze was fixed on a thin wreath of smoke that curled its way upwards from what appeared a low mound of earth, in the valley below the road; some branches of trees, covered with sods of earth, grass-grown and still green, were heaped up together, and through these the vapour found a passage and floated into the air.

“I am wondering what that fire can mean,” said she, pointing downwards with her finger.

“Here is some one will explain it,” said the old man, as for the first time he perceived the youth, who still maintained his former attitude on the bank, and with a studied indifference, paid no attention to those whose presence had before so much surprised him.

“I say, my good fellow, what does that smoke mean we see yonder?”

The youth sprung to his feet with a bound that almost startled his questioner, so sudden and abrupt the motion; his features, inactive and colourless the moment before, seemed almost convulsed now, while they became dark with blood.

“Was it to me you spoke?” said he, in a low guttural tone, which his passion made actually tremulous.

“Yes—”

But before the old man could reply, his daughter, with the quick tact of womanhood, perceiving the mistake her father had fallen into, hastily interrupted him by saying,—

“Yes, sir, we were asking you the cause of the fire at the foot of that cliff.”

The tone and the manner in which the words were uttered seemed at once to have disarmed his anger; and although for a second or two he made no answer, his features recovered their former half-listless look, as he said—

“It is a cabin—There is another yonder, beside the river.”

“A cabin! Surely you cannot mean that people are living there?” said the girl, as a sickly pallor spread itself across her cheeks.

“Yes, to be sure,” replied the youth; “they have no better hereabouts.”

“What poverty—what dreadful misery is this!” said she, as the great tears gushed forth, and stole heavily down her face.

“They are not so poor,” answered the young man, in a voice of almost reproof. “The cattle along that mountain all belong to these people—the goats you see in that glen are theirs also.”

“And whose estate may this be?” said the old man.

Either the questioner or his question seemed to have called up again the youth's former resentment, for he fixed his eyes steadily on him for some time without a word, and then slowly added—

“This belongs to an Englishman—a certain Sir Marmaduke Travers—It is the estate of O'Donoghue.”

“Was, you mean, once,” answered the old man quickly.

“I mean what I say,” replied the other rudely. “Confiscation cannot take away a right, it can at most—”

This speech was fortunately not destined to be finished, for while he was speaking, his quick glance detected a dark object soaring above his head. In a second he had seized his gun, and taking a steady aim, he fired. The loud report was heard repeated in many a far-off glen, and ere its last echo died away, a heavy object fell upon the road not many yards from where they stood.

“This fellow,” said the youth, as he lifted the body of a large black eagle from the ground—“This fellow was a confiscator too, and see what he has come to. You'd not tell me that our lambs were his, would you?”

The roll of wheels happily drowned these words, for by this time the postillions had reached the place, the four post-horses labouring under the heavy-laden travelling carriage, with its innumerable boxes and imperials.

The post boys saluted the young man with marked deference, to which he scarcely deigned an acknowledgment, as he replaced his shot-pouch, and seemed to prepare for the road once more.

Meanwhile the old gentleman had assisted his daughter to the carriage, and was about to follow, when he turned around suddenly and said—

“If your road lies this way, may I offer you a seat with us?”

The youth stared as if he did not well comprehend the offer, and his cheek flushed, as he answered coldly—

“I thank you; but my path is across the mountain.”

Both parties saluted distantly, the door of the carriage closed, and the word to move on was given, when the young man, taking two dark feathers from the eagle's wing, approached the window.

“I was forgetting,” said he, in a voice of hesitation and diffidence, “perhaps you would accept these feathers.”

The young girl smiled, and half blushing, muttered some words in reply, as she took the offered present. The horses sprung forward the next instant, and a few minutes after, the road was as silent and deserted as before; and save the retiring sound of the wheels, nothing broke the stillness.

As the glen continues to wind between the mountains, it gradually becomes narrower, and at last contracts to a mere cleft, flanked on either side by two precipitous walls of rock, which rise to the height of several hundred feet above the road; this is the pass of Keim-an-eigh, one of the wildest and most romantic ravines of the scenery of the south.

At the entrance to this pass there stood, at the time we speak of, a small wayside inn, or shebeen-house, whose greatest recommendation was in the feet, that it was the only place where shelter and refreshment could be obtained for miles on either side. An humble thatched cabin abutting against the granite rock of the glen, and decorated with an almost effaced sign of St. Finbar converting a very unprepossessing heathen, over the door, showed where Mary M'Kelly dispensed “enthertainment for man and baste.”

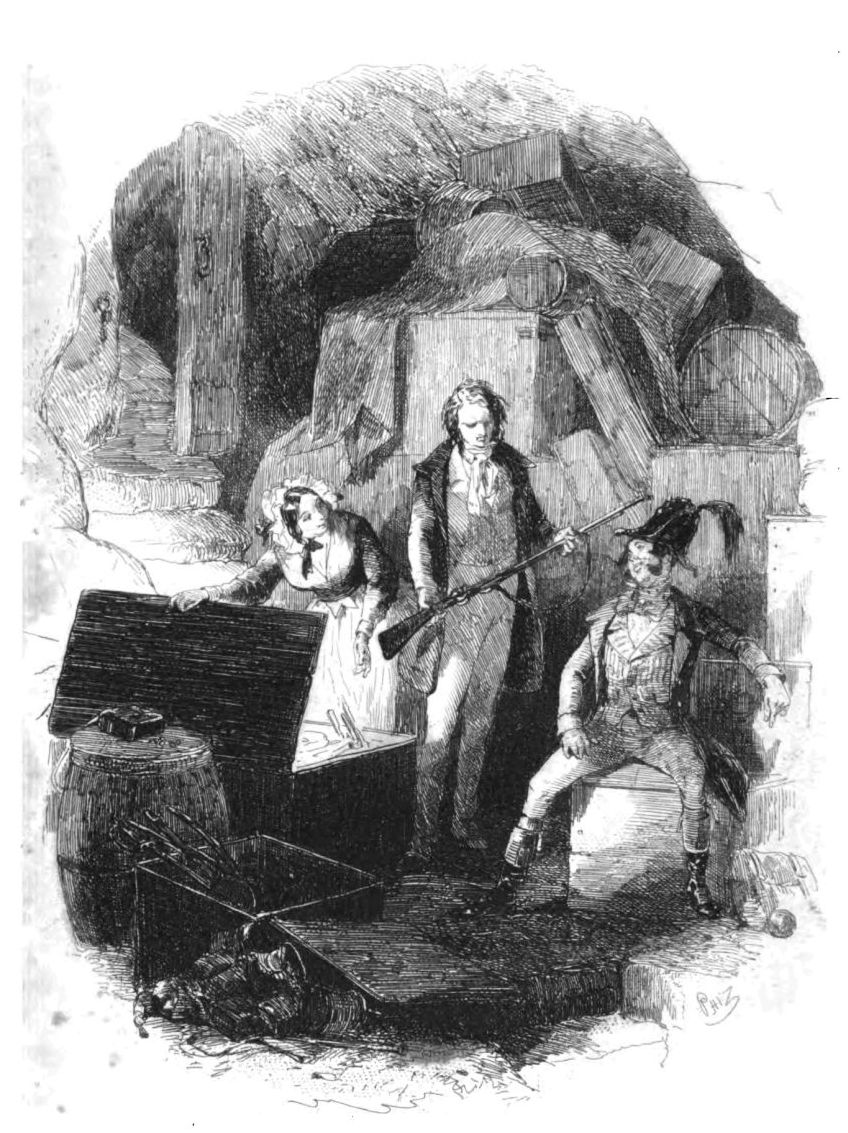

A chance traveller, bestowing a passing glance upon this modest edifice, might deem that an inn in such a dreary and unfrequented valley, must prove a very profitless speculation—few, very few travelled the road—fewer still would halt to bait within ten miles of Bantry. Report, however, said differently; the impression in the country was, that “Mary's”—as it was briefly styled—had a readier share of business than many a more promising and pretentious hotel; in fact, it was generally believed to be the resort of all the smugglers of the coast; and the market, where the shopkeepers of the interior repaired in secret to purchase the contraband wares and “run goods,” which poured into the country from the shores of France and Holland.

Vast storehouses and caves were said to exist in the rock behind the house, to store away the valuable goods, which from time to time arrived; and it was currently believed that the cargo of an Indiaman might have been concealed within these secret recesses, and never a cask left in view to attract suspicion.

It is not into these gloomy receptacles of contraband that we would now conduct our reader, but into a far more cheerful and more comfortable locality—the spacious kitchen of the cabin, or, in fact, the apartment which served for the double purpose of cooking and eating—the common room of the inn, where around a blazing fire of black turf was seated a party of three persons.

At one side sat the fat and somewhat comely figure of Mary herself, a woman of some five-and-forty years, with that expression of rough and ready temperament, the habits of a wayside inn will teach. She had a clear, full eye—a wide, but not unpleasant mouth—and a voice that suited well the mellifluous intonation of a Kerry accent. Opposite to her were two thin, attenuated old men, who, for dress, look, age, voice, and manner, it would have been almost impossible to distinguish from each other; for while the same weather-beaten, shrivelled expression was common to both, their jackets of blue cloth, leather breeches, and top boots, were so precisely alike, that they seemed the very Dromios brought back to life, to perform as postillions. Such they were—such they had been for above fifty years. They had travelled the country from the time they were boys—they entered the career together, and together they were jogging onward to the last stage of all, the only one where they hoped to be at rest! Joe and Jim Daly were two names no one ever heard disunited; they were regarded as but one corporeally, and although they affected at times to make distinctions themselves, the world never gave them credit for any consciousness of separate identity. These were the postillions of the travelling carriage, which having left at its destination, about two miles distant, they were now regaling themselves at Mary's, where the horses were to rest for the night.

“Faix, ma'am, and it's driving ye may call it,” said one of the pair, as he sipped a very smoking compound the hostess had just mixed, “a hard gallop every step of the way, barrin' the bit of a hill at Carrignacurra.”

“Well, I hope ye had the decent hansel for it, any how, Jim?”

“I'm Joe, ma'am, av its plazing to ye; Jim is the pole-end boy; he rides the layders. And it's true for ye—they behaved dacent.”

“A goold guinea, divil a less”—said the other, “there's no use in denying it. Begorra, it was all natural, them's as rich as Crasis; sure didn't I see the young lady herself throwing out the tenpenny bits to the gossoons, as we went by, as if it was dirt; bad luck to me, but I was going to throw down the Bishop of Cloyne.”

“Throw down who?” said the hostess.

“The near wheeler, ma'am; he's a broken-kneed ould divil, we bought from the bishop, and called him after him; and as I was saying, I was going to cross them on the pole, and get a fall, just to have a scramble for the money, with the gaffers.”

“'They look so poor,' says she. God help her—it's little poverty she saw—there isn't one of them crayters hasn't a sack of potatoes.”

“Ay—more of them a pig.”

“And hens,” chimed in the first speaker, with a horror at the imposition of people so comfortably endowed, affecting to feel any pressure or poverty.

“And what's bringing them here at all?” said Mrs. M'Kelly, with a voice of some asperity; for she foresaw no pleasant future in the fact of a resident great man, who would not be likely to give any encouragement to the branch of traffic her principal customers followed.

“Sorrow one of me knows,” was the safe reply of the individual addressed, who not being prepared with any view of the matter, save that founded on the great benefit to the country, preferred this answer to a more decisive one.

“'Tis to improve the property, they say,” interposed the other, who was not equally endowed with caution. “To look after the estate himself he has come.”

“Improve, indeed!” echoed the hostess. “Much we want their improving! Why didn't they leave us the ould families of the country? It's little we used to hear of improving, when I was a child. God be good to us.—There was ould Miles O'Donoghue, the present man's father, I'd like to see what he'd say, if they talked to him about improvement. Ayeh! sure I mind the time a hogshead of claret didn't do the fortnight. My father, rest his soul, used to go up to the house every Monday morning for orders; and ye'd see a string of cars following him at the same time, with tay, and sugar, and wine, and brandy, and oranges, and lemons. Them was the raal improvements!”

“'Tis true for ye, ma'am. It was a fine house, I always heerd tell.”

“Forty-six in the kitchen, besides about fourteen colleens and gossoons about the place; the best of enthertainment up stairs and down.”

“Musha! that was grand.”

“A keg of sperits, with a spigot, in the servants' hall, and no saying by your leave, but drink while ye could stand over it.”

“The Lord be good to us!” piously ejaculated the twain.

“The hams was boiled in sherry wine.”

“Begorra, I wish I was a pig them times.”

“And a pike daren't come up to table without an elegant pudding in his belly that cost five pounds!”

“'Tis the fish has their own luck always,” was the profound meditation at this piece of good fortune.

“Ayeh! ayeh!” continued the hostess in a strain of lamentation, “When the ould stock was in it, we never heerd tell of improvements. He'll be making me take out a license, I suppose,” said she, in a voice of half contemptuous incredulity.

“Faix, there's no knowing,” said Joe, as he shook the ashes out of his pipe, and nodded his head sententiously, as though to say, that in the miserable times they'd fallen upon, any thing was possible.

“Licensed for sperits and groceries,” said Mrs. M'Kelly, with a sort of hysterical giggle, as if the thought were too much for her nerves.

“I wouldn't wonder if he put up a pike,” stammered out Jim, thereby implying that human atrocity would have reached its climax.

The silence which followed this terrible suggestion, was now loudly interrupted by a smart knocking at the door of the cabin, which was already barred and locked for the night.

“Who's there?” said Mary, as she held a cloak across the blaze of the fire, so as to prevent the light being seen through the apertures of the door—“'tis in bed we are, and late enough, too.”

“Open the door, Mary, it's me,” said a somewhat confident voice. “I saw the fire burning brightly—and there's no use hiding it.”

“Oh, troth, Mr. Mark, I'll not keep ye out in the cowld,” said the hostess, as, unbarring the door, she admitted the guest whom we had seen some time since in the glen. “Sure enough, 'tisn't an O'Donoghue we'd shut the door agin, any how.”

“Thank ye, Mary,” said the young man; “I have been all day in the mountains, and had no sport; and as that pleasant old Scotch uncle of mine gives me no peace, when I come home empty-handed, I have resolved to stay here for the night, and try my luck to-morrow. Don't stir, Jim—there's room enough, Joe: Mary's fire is never so grudging, but there's a warm place for every one. What's in this big pot here, Mary?”

“It's a stew, sir; more by token, of your honour's providin'.” “Mine—how is that?”

“The hare ye shot afore the door, yesterday morning; sure it's raal luck we have it for you now;” and while Mary employed herself in the pleasant hustle of preparing the supper, the young man drew near to the fire, and engaged the others in conversation.

“That travelling carriage was going on to Bantry, Joe, I suppose?” said the youth, in a tone of easy indifference.

“No sir; they stopped at the lodge above.”

“At the lodge!—surely you can't mean that they were the English family—Sir Marmaduke.”

“'Tis just himself, and his daughter. I heerd them say the names, as we were leaving Macroom. They were not expected here these three weeks; and Captain Hemsworth, the agent, isn't at home; and they say there's no servants at the lodge, nor nothin' ready for the quality at all; and sure when a great lord like that—”

“He is not a lord you fool; he has not a drop of noble blood in his body: he's a London banker—rich enough to buy birth, if gold could do it.” The youth paused in his vehemence; then added, in a muttering voice—“Rich enough to buy up the inheritance of those who have blood in their veins.”

The tone of voice in which the young man spoke, and the angry look which accompanied these words, threw a gloom over the party, and for some time nothing was said on either side. At last he broke silence abruptly by saying—

“And that was his daughter, then?”

“Yes, sir; and a purty crayture she is, and a kind-hearted. The moment she heerd she was on her father's estate, she began asking the names of all the people, and if they were well off, and what they had to ate, and where was the schools.”

“The schools!” broke in Mary, in an accent of great derision—“musha, it's great schooling we want up the glen, to teach us to bear poverty and cowld, without complaining: learning is a fine thing for the hunger—”

Her irony was too delicate for the thick apprehension of poor Jim, who felt himself addressed by the remark, and piously responded—

“It is so, glory be to God!”

“Well,” said the young man, who now seemed all eagerness to resume the subject—“well, and what then?”

“Then, she was wondering where was the roads up to the cabins on the mountains, as if the likes of them people had roads!”

“They've ways of their own—the English,” interrupted Jim, who felt jealous of his companion being always referred to—“for whenever we passed a little potatoe garden, or a lock of oak, it was always, 'God be good to us, but they're mighty poor hereabouts;' but when we got into the raal wild part of the glen, with divil a house nor a human being near us, sorrow word out of their mouths but 'fine, beautiful, elegant!' till we came to Keim-an-eigh, and then, ye'd think that it was fifty acres of wheat they were looking at, wid all the praises they had for the big rocks, and black cliffs oyer our heads.”

“I showed them your honour's father's place on the mountains,” said Joe.

“Yes, faith,” broke in Jim; “and the young lady laughed and said, 'you see, father, we have a neighbour after all.'”

The blood mounted to the youth's cheek, till it became almost purple, but he did not utter a word.

“'Tis the O'Donoghue, my lady,' said I,” continued Joe, who saw the difficulty of the moment, and hastened to relieve it—“that's his castle up there, with the high tower. 'Twas there the family lived these nine hundred years, whin the whole country was their own; and they wor kings here.”

“And did you hear what the ould gentleman said then?” asked Jim.

“No, I didn't—I wasn't mindin' him,” rejoined Joe; endeavouring with all his might to repress the indiscreet loquacity of the other.

“What was it, Jim?” said the young man, with a forced smile.

“Faix, he begun a laughing, yer honour, and says he, 'We must pay our respects at Coort,' says he; 'and I'm sure we'll be well received, for we know his Royal Highness already—that's what he called yer honour.”

The youth sprang to his feet, with a gesture so violent and sudden, as to startle the whole party.

“What,” he exclaimed, “and are we sunk so low, as to be a scoff and a jibe to a London money-changer? If I but heard him speak the words—”

“Arrah, he never said it at all,” said Joe, with a look that made his counterpart tremble all over. “That bosthoon there, would make you believe he was in the coach, convarsing the whole way with him. Sure wasn't I riding the wheeler, and never heerd a word of it. Whisht, I tell ye, and don't provoke me.”

“Ay, stop your mouth with some of this,” interposed Mary, as she helped the smoking and savoury mess around the table.

Jim looked down abashed and ashamed; his testimony was discredited; and without knowing why or wherefore, he yet had an indistinct glimmering that any effort to vindicate his character would be ill-received; he therefore said nothing more: his silence was contagious, and the meal which a few moments before promised so pleasantly, passed off with gloom and restraint.

All Mary M'Kelly's blandishments, assisted by a smoking cup of mulled claret—a beverage which not a Chateau on the Rhone could rival in racy flavour—failed to recall the young man's good-humour: he sat in gloomy silence, only broken at intervals by sounds of some low muttering to himself. Mary at length having arranged the little room for his reception, bade him good night, and retired to rest. The postillions sought their dens over the stable, and the youth, apparently lost in his own thoughts, sat alone by the embers of the turf fire, and at last sunk to sleep where he was, by the chimney-corner.

Of Sir Marmaduke Travers, there is little to tell the reader beyond what the few hints thrown out already may have conveyed to him. He was a London banker, whose wealth was reputed to be enormous. Originally a younger son, he succeeded somewhat late in life to the baronetcy and large estates of his family. The habits, however, of an active city life—the pursuits which a long career had made a second nature to him—rendered him both unfit to eater upon the less exciting duties of a country gentleman's existence, and made him regard such as devoid of interest or amusement. He continued therefore to reside in London for many years after he became the baronet; and it was only at the death of his wife, to whom he was devotedly attached, that these habits became distasteful; he found that he could no longer continue a course which companionship and mutual feeling had rendered agreeable, and he resolved at once to remove to some one of his estates, where a new sphere of occupation might alleviate the sorrows of his loss. To this no obstacle of any kind existed. His only son was already launched into life as an officer in the guards; and, except his daughter, so lately before the reader, he had no other children. The effort to attain forgetfulness was not more successful here, than it is usually found to be. The old man sought, but found not in a country life the solace he expected; neither his tastes nor his habits suited those of his neighbours; he was little of a sportsman, still less of a farmer. The intercourse of country social life was a poor recompense for the unceasing flow of London society. He grew wearied very soon of his experiment, and longed once more to return to his old haunts and habits. One more chance, however, remained for him, and he was unwilling to reject without trying it. This was, to visit Ireland, where he possessed a large estate, which he had never seen. The property, originally mortgaged to his father, was represented as singularly picturesque and romantic, possessing great mineral wealth, and other resources, never examined into, nor made available. His agent, Captain Hemsworth, a gentleman who resided on the estate, at his annual visit to the proprietor, used to dilate upon the manifold advantages and capabilities of the property, and never ceased to implore him to pay a visit, if even for a week or two, sincerely trusting the while that such an intention might never occur to him. These entreaties, made from year to year, were the regular accompaniment of every settlement of account, and as readily replied to by a half promise, which the maker was certainly not more sincere in pledging.

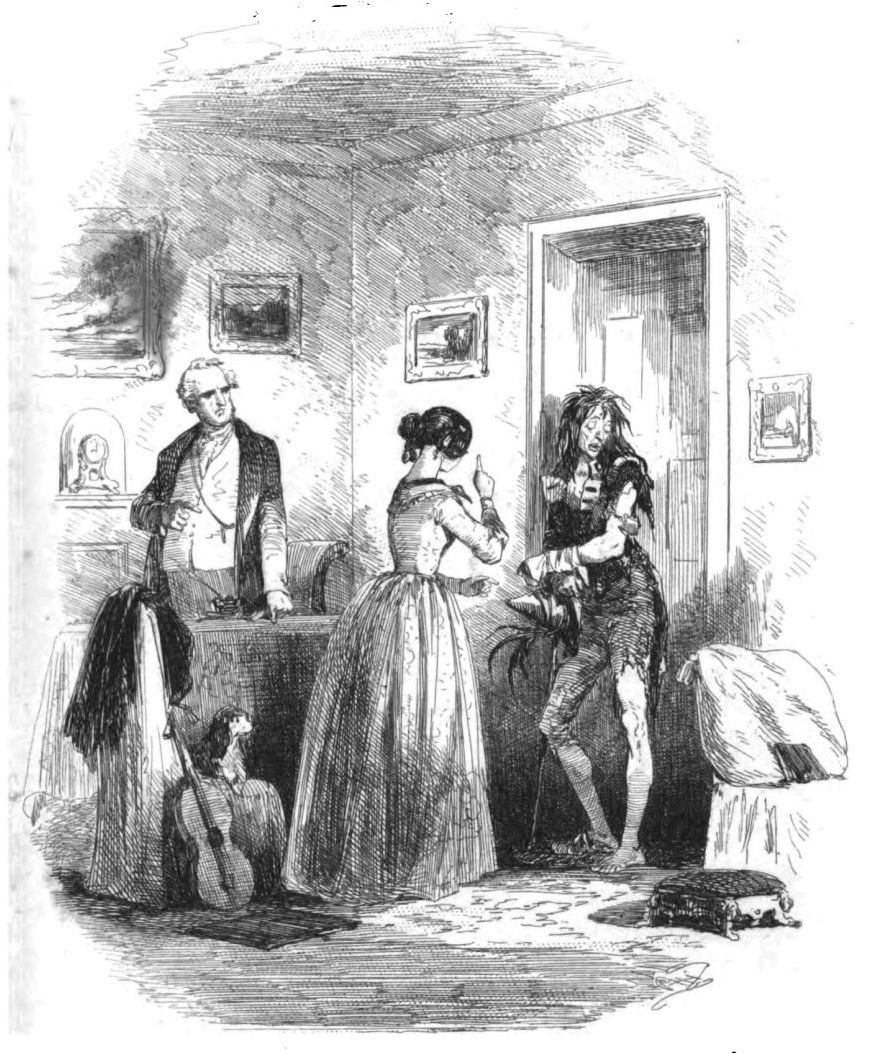

Three years of country life had now, however, disposed Sir Marmaduke to reflect on this long unperformed journey; and, regardless of the fact that his agent was then grouse-shooting in Scotland, he set out at a moment's notice, and without a word to apprise the household at the lodge of his intended arrival, reached the house in the evening of an autumn day, by the road we have already been describing.

It is but justice to Sir Marmaduke to add, that he was prompted to this step by other than mere selfish considerations. The state of Ireland had latterly become a topic of the press in both countries. The poverty of the people—interpreted in various ways, and ascribed to very opposite causes—was a constant theme of discussion and conversation. The strange phenomenon of a land teeming with abundance, yet overrun by a starving population, had just then begun to attract notice; and theories were rife in accounting for that singular and anomalous social condition, which unhappily the experience of an additional half century has not succeeded in solving.

Sir Marmaduke was well versed in these popular writings; he had the “Whole State of Ireland” by heart; and so firmly was he persuaded that his knowledge of the subject was perfect, that he became actually impatient until he had reached the country, and commenced the great scheme of regeneration and civilization, by which Ireland and her people were to be placed among the most favoured nations. He had heard much of Irish indolence and superstition—Irish bigotry and intolerance—the indifference to comfort—the indisposition to exertion—the recklessness of the present—the improvidence of the future; he had been told that saint-days and holydays mulcted labour of more than half its due—that ignorance made the other half almost valueless; he had read, that, the easy contentment with poverty, had made all industry distasteful, and all exertion, save what was actually indispensable, a thing to be avoided.

“Why should these things be, when they were not so in Norfolk, nor in Yorkshire?” was the question he ever asked, and to which his knowledge furnished no reply. There, superstitions, if they existed—and he knew not if they did—came not in the way of daily labour. Saints never unharnessed the team, nor laid the plough inactive—comfort was a stimulant to industry that none disregarded; habits of order and decorum made the possessor respected—poverty almost argued misconduct, and certainly was deemed a reproach. Why then not propagate the system of these happy districts in Ireland? To do this was the great end and object of his visit.

Philanthropy would often seem unhappily to have a dislike to the practical—the generous emotions appear shorn of their freedom, when trammelled with the fruit of experience or reflection. So, certainly it was, in the case before us. Sir Marmaduke had the very best intentions—the weakest notions of their realization; the most unbounded desire for good—the very narrowest conceptions of how to effect it. Like most theorists, no speculative difficulty was great enough to deter—no practical obstacle was so small as not to affright him. It never apparently occurred to him that men are not every where alike, and this trifling omission was the source of difficulties, which he persisted in ascribing to causes outside of himself. Generous, kind-hearted, and benevolent, he easily forgave an injury, never willingly inflicted one; he was also, however, hot-tempered and passionate; he could not brook opposition to his will, where its object seemed laudable to himself, and was utterly unable to make allowance for prejudices and leanings in others, simply because he had never experienced them in his own breast.

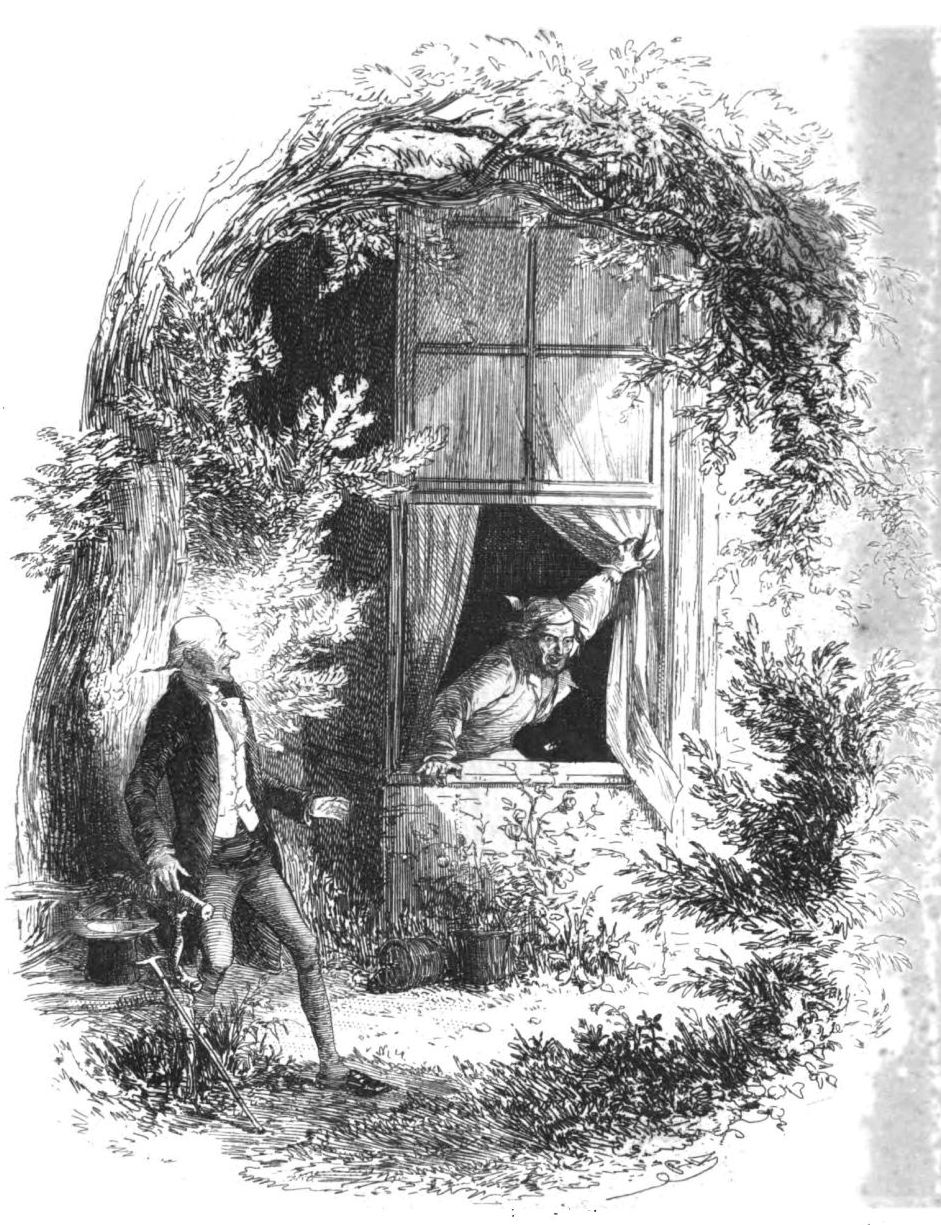

Such was, in a few words, the present occupant of “the Lodge”—as the residence of the agent was styled. Originally a hunting box, it had been enlarged and ornamented by Captain Hemsworth, and converted into a cottage of singular beauty, without, and no mean pretension to comfort, within doors. It occupied an indenture of the glen of Keim-an-eigh, and stood on the borders of a small mountain-lake, the surface of which was dotted with wooded islands. Behind the cottage, and favoured by the shelter of the ravine, the native oaks grew to a great size, and contrasted by the rich foliage waving in the breeze, with the dark sides of the cliff opposite, rugged, barren and immutable.

In all the luxuriance of this mild climate, shrubs attained the height of trees; and flowers, rare enough elsewhere to demand the most watchful care, grew here, unattended and unregarded. The very grass had a depth of green, softer and more pleasing to the eye than in other places. It seemed as if nature had, in compensation for the solitude around, shed her fairest gifts over this lonely spot, one bright gem in the dreary sky of winter.

About a mile further down the glen, and seated on a lofty pinnacle of rock, immediately above the road, stood the once proud castle of the O'Donoghue. Two square and massive towers still remained to mark its ancient strength, and the ruins of various outworks and bastions could be traced, extending for a considerable distance on every side. Between these square towers, and occupying the space where originally a curtain wall stood, a long low building now extended, whose high-pitched roof and narrow windows vouched for an antiquity of little more than a hundred years. It was a strange incongruous pile, in which fortress and farm-house seemed welded together—the whole no bad type of its past and its present owners. The approach was by a narrow causeway, cut in the rock, and protected by a square keep, through whose deep arch the road penetrated—flanked on either hand by a low battlemented wall; along these, two rows of lime trees grew, stately and beautiful in the midst of all the ruin about them. They spread their waving foliage around, and threw a mellow, solemn shadow along the walk. Except these, not a tree, nor even a shrub, was to be seen—the vast woods of nature's own planting had disappeared—the casualties of war—the chances of times of trouble, or the more ruinous course of poverty, had laid them low, and the barren mountain now stood revealed, where once were waving forests and shady groves, the home of summer birds, the lair of the wild deer.

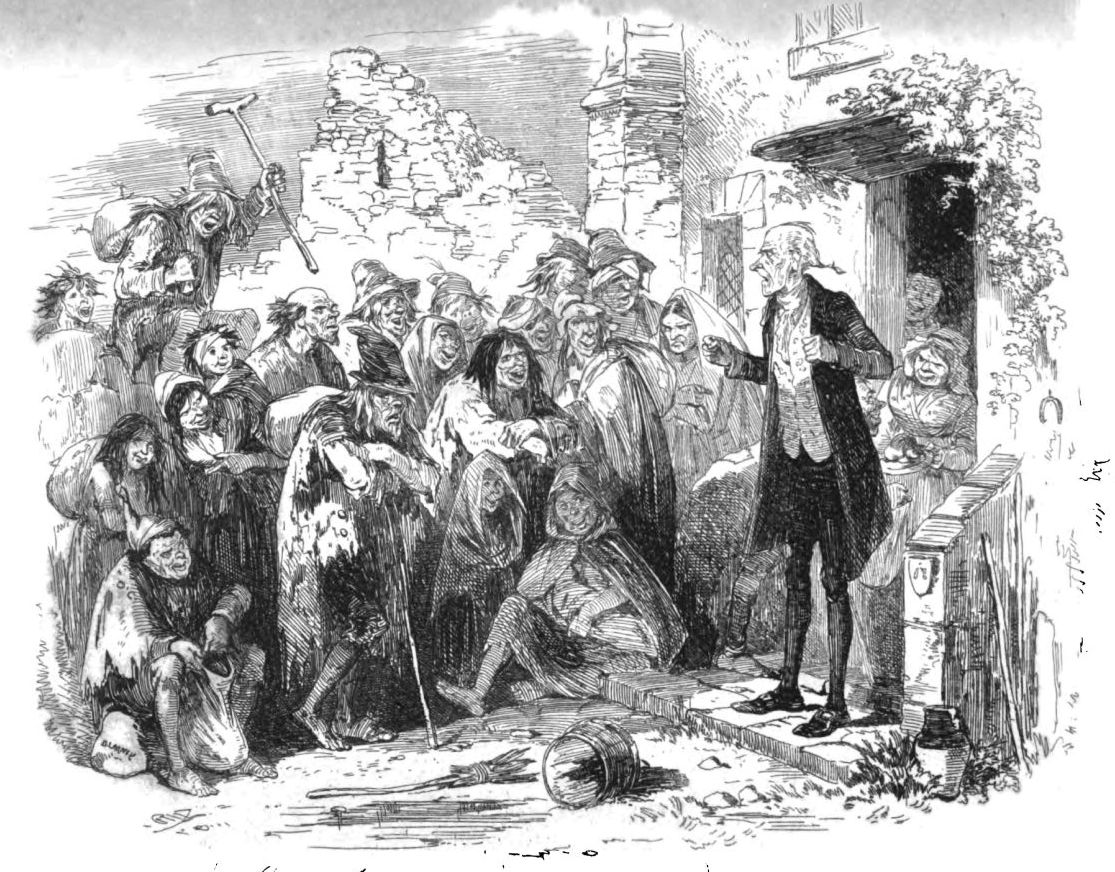

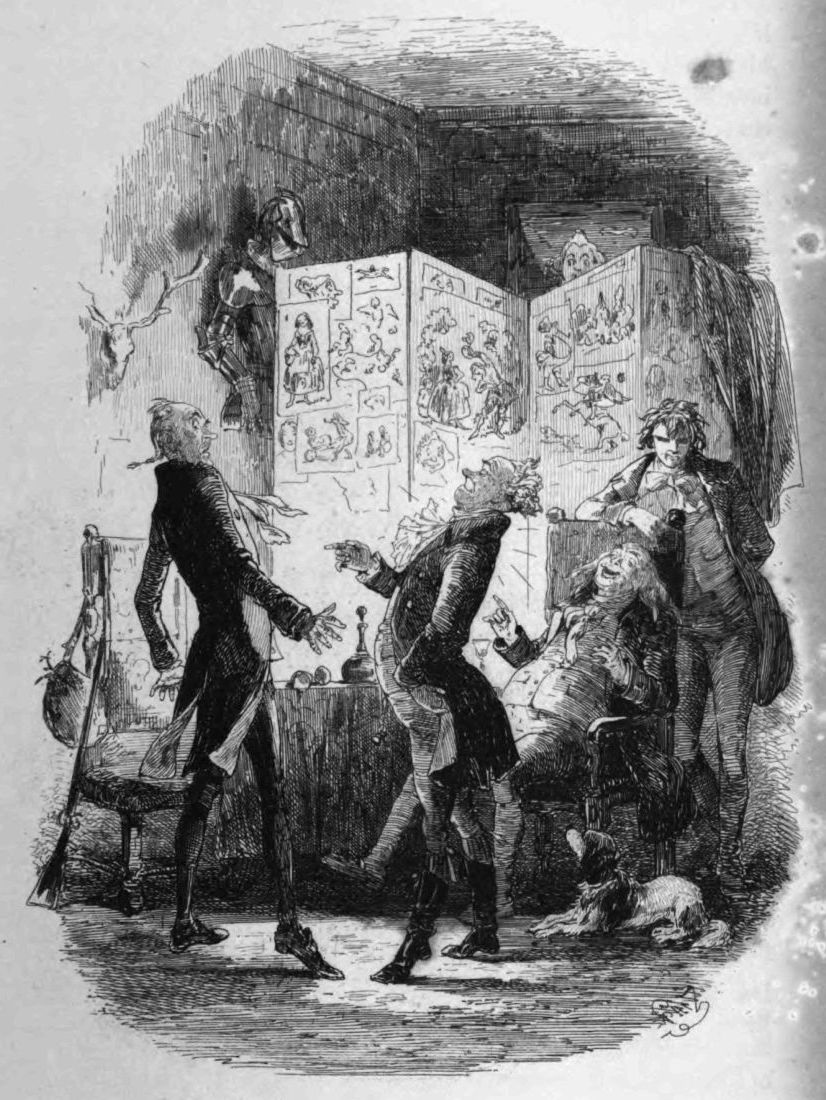

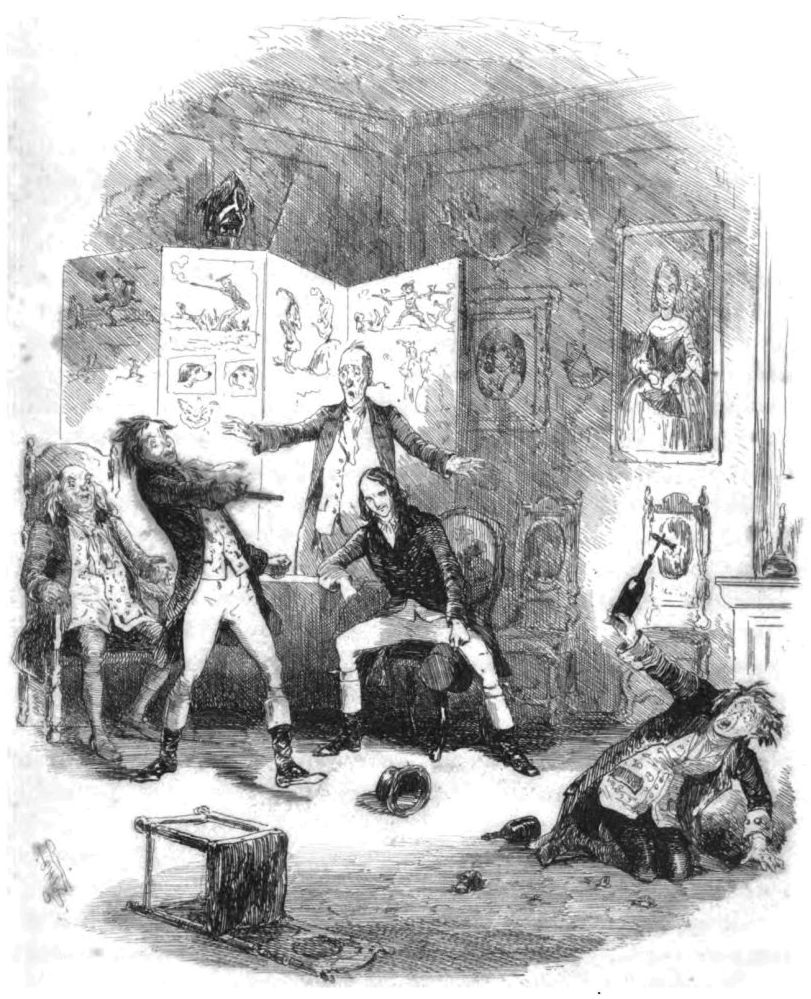

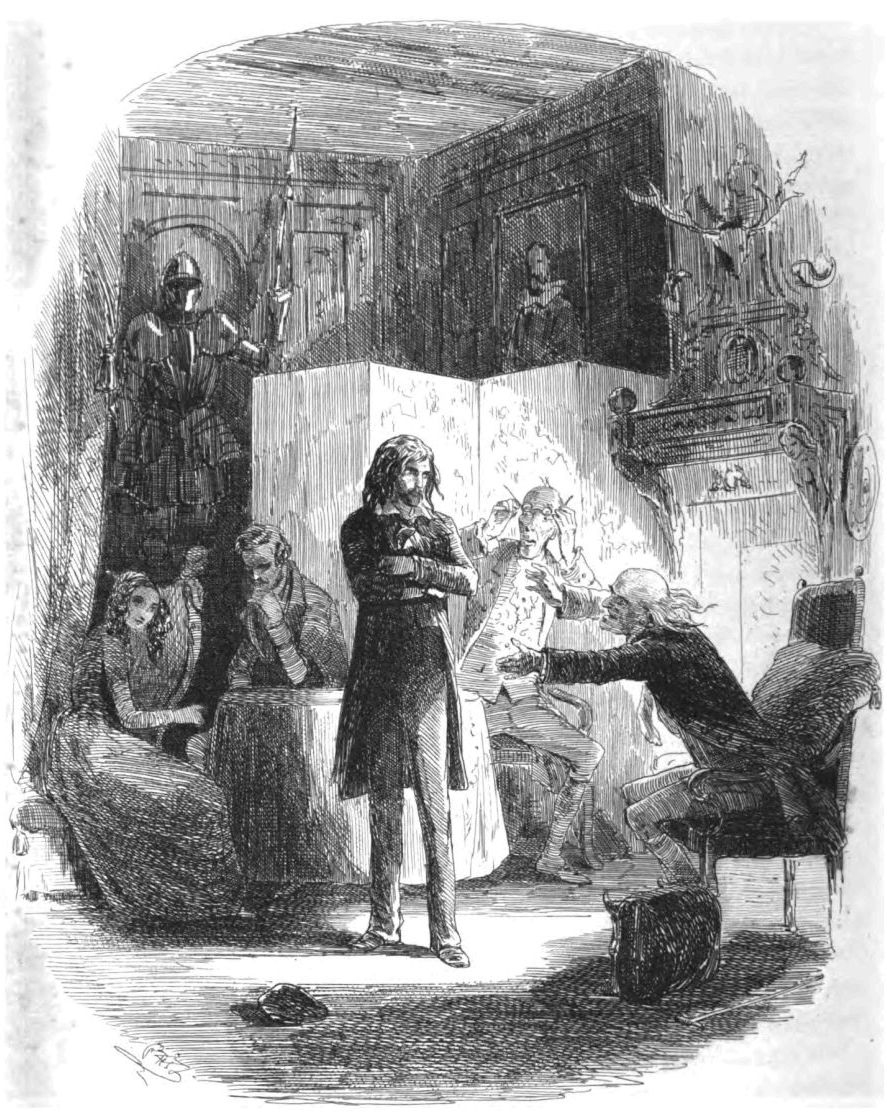

Cows and farm-horses were stabled in what once had been the outworks of the castle. Implements of husbandry lay carelessly on all sides, neglect and decay marked every thing, the garden-wall was broken down in many places, and cattle strayed at will among the torn fruit-trees and dilapidated terraces, while, as if to add to the dreary aspect of the scene, the ground for a considerable distance around had been tilled, but never subsequently restored to grass land, and now along its ridged surface noisome weeds and thistles grew rankly, tainting the air with their odour, and sending up heavy exhalations from the moist and spongy earth. If, without, all looked sad and sorrow-struck, the appearances within, were not much better. A large flagged-hall, opened upon two long ill-lighted corridors, from which a number of small sitting-rooms led off. Many of these were perfectly devoid of furniture; in the others, what remained seemed to owe its preservation to its want of value rather than any other quality. Cracked looking-glasses—broken chairs, rudely mended by some country hand—ragged and patched carpets, were the only things to be found, with here and there some dirt-disfigured piece of framed canvas, which, whether tapestry or painting, no eye could now discover. These apartments bore little or no trace of habitation; indeed, for many years they were rarely entered by any one. A large square room in one of the towers, of some forty feet in dimensions, was the ordinary resort of the family, serving the purposes of drawing and dining-room. This was somewhat better in appearance: whatever articles of furniture had any pretension to comfort or convenience were here assembled; and here, were met, old-fashioned sofas, deep arm-chairs, quaint misshapen tables like millipedes, and fat old footstools, the pious work of long-forgotten grandmothers. A huge screen, covered with a motley array of prints and caricatures, cut off the group around the ample fire-place from the remainder of the apartment, and it is within this charmed circle we would now conduct our reader.

In the great arm-chair, to the right of the ample fire-place, sat a powerfully built old man, whose hair was white as snow, and fell in long waving masses at either side of his head. His forehead, massive and expanded, surmounted two dark, penetrating eyes, which even extreme old age had not deprived of their lustre. The other features of his face were rather marked by a careless, easy sensuality, than by any other character, except that in the mouth the expression of firmness was strongly displayed. His dress was a strange mixture of the costume of gentleman and peasant. His coat, worn and threadbare, bore traces of better days, in its cut and fashion; his vest also showed the fragment of tarnished embroidery along the margin of the flapped pockets; but the coarse knee breeches of corduroy, and the thick grey lambswool stockings, wrinkled along the legs, were no better than those worn by the poorer farmers of the neighbourhood.

This was the O'Donoghue himself. Opposite to him sat one as unlike him in every respect as it was possible to conceive. He was a tall, spare, raw-boned figure, whose grey eyes and high cheek-bones bore traces of a different race from that of the aged chieftain. An expression of intense acuteness pervaded every feature of his face, and seemed concentrated about the angles of the mouth, where a series of deep wrinkles were seen to cross and intermix with each other, omens of a sarcastic spirit, indulged without the least restraint on the part of its possessor. His wiry grey hair was brushed rigidly back from his bony temples, and fastened into a short queue behind, thus giving greater apparent length to his naturally long and narrow face. His dress was that of a gentleman of the time: a full-skirted coat of a dark brown, with a long vest descending below the hips; breeches somewhat a deeper shade of the same colour, and silk stockings, with silver-buckled shoes, completed an attire which, if plain, was yet scrupulously neat and respectable. As he sat, almost bolt upright, in his chair, there was a look of vigilance and alertness about him very opposite to the careless, nearly drooping air of the O'Donoghue. Such was Sir Archibald M'Nab, the brother of the O'Donoghue's late wife, for the old man had been a widower for several years. Certain circumstances of a doubtful and mysterious nature had made him leave his native country of Scotland many years before, and since that, he had taken up his abode with his brother-in-law, whose retired habits and solitary residence afforded the surest guarantee against his ever being traced. His age must have been almost as great as the O'Donoghue's; but the energy of his character, the lightness of his frame, and the habits of his life, all contributed to make him seem much younger.

Never were two natures more dissimilar. The one, reckless, lavish, and improvident; the other, cautious, saving, and full of forethought. O'Donoghue was frank and open—his opinions easily known—his resolutions hastily formed. M'Nab was close and secret, carefully weighing every thing before he made up his mind, and not much given to imparting his notions, when he had done so.

In one point alone was there any similarity between them—pride of ancestry and birth they both possessed in common; but this trait, so far from serving to reconcile the other discrepancies of their naturess, kept them even wider apart, and added to the passive estrangement of ill-matched associates, an additional element of active discord.

There was a lad of some fifteen or sixteen years of age, who sat beside the fire on a low stool, busily engaged in deciphering, by the fitful light of the bog-wood, the pages of an old volume, in which he seemed deeply interested. The blazing pine, as it threw its red gleam over the room, showed the handsome forehead of the youth, and the ample locks of a rich auburn, which hung in clusters over it; while his face was strikingly like the old man's, the mildness of its expression—partly the result of youth, partly the character imparted by his present occupation—was unlike that of either his father or brother; for Herbert O'Donoghue was the younger son of the house, and was said, both in temper and appearance, to resemble his mother.

At a distance from the fire, and with a certain air of half assurance, half constraint, sat a man of some five-and-thirty years of age, whose dress of green coat, short breeches, and top boots, suggested at once the jockey, to which the mingled look of confidence and cunning bore ample corroboration. This was a well-known character in the south of Ireland at that time. His name was Lanty Lawler. The sporting habits of the gentry—their easiness on the score of intimacy—the advantages of a ready-money purchaser, whenever they wished “to weed their stables,” admitted the horse-dealer pretty freely among a class, to which neither his habits nor station could have warranted him in presenting himself. But, in addition to these qualities, Lanty was rather a prize in remote and unvisited tracts, such as the one we have been describing, his information being both great and varied in every thing going forward. He had the latest news of the capital—the fashions of hair and toilet—the colours worn by the ladies in vogue, and the newest rumours of any intended change—he knew well the gossip of politics and party—upon the probable turn of events in and out of parliament he could hazard a guess, with a fair prospect of accuracy. With the prices of stock and the changes in the world of agriculture he was thoroughly familiar, and had besides a world of stories and small-talk on every possible subject, which he brought forth with the greatest tact as regarded the tastes and character of his company, one-half of his acquaintances being totally ignorant of the gifts and graces, by which he obtained fame and character with the other.

A roving vagabond life gave him a certain free-and-easy air, which, among the majority of his associates, was a great source of his popularity; but he well knew when to lay this aside, and assume the exact shade of deference and respect his company might require. If then with O'Donoghue himself, he would have felt perfectly at ease, the presence of Sir Archy, and his taciturn solemnity, was a sad check upon him, and mingled the freedom he felt with a degree of reserve far from comfortable. However, he had come for a purpose, and, if successful, the result would amply remunerate him for any passing inconvenience he might incur; and with this thought he armed himself, as he entered the room some ten minutes before.

“So you are looking for Mark,” said the O'Donoghue to Lanty. “You can't help hankering after that grey mare of his.”

“Sure enough, sir, there's no denying it. I'll have to give him the forty pounds for her, though, as sure as I'm here, she's not worth the money; but when I've a fancy for a beast, or take a conceit out of her—it's no use, I must buy her—that's it!”

“Well, I don't think he'll give her to you now, Lanty; he has got her so quiet—so gentle—that I doubt he'll part with her.”

“It's little a quiet one suits him; faix, he'd soon tire of her if she wasn't rearing or plunging like mad! He's an elegant rider, God bless him. I've a black horse now that would mount him well; he's out of 'Divil-may-care,' Mooney's horse, and can take six foot of a wall flying, with fourteen stone on his back; and barring the least taste of a capped hock, you could not see speck nor spot about him wrong.”

“He's in no great humour for buying just now,” interposed the O'Donoghue, with a voice to which some suddenly awakened recollection imparted a tone of considerable depression.

“Sure we might make a swop with the mare,” rejoined Lanty, determined not to be foiled so easily; and then, as no answer was forthcoming, after a long pause, he added, “and havn't I the elegant pony for Master Herbert there; a crame colour—clean bred—with white mane and tail. If he was the Prince of Wales he might ride her. She has racing speed—they tell me, for I only have her a few days; and, faix, ye'd win all the county stakes with her.”

The youth looked up from his book, and listened with glistening eyes and animated features to the description, which, to one reared as he was, possessed no common attraction.

“Sure I'll send over for her to-morrow, and you can try her,” said Lanty, as if replying to the gaze with which the boy regarded him.

“Ye mauna do nae sich a thing,” broke in M'Nab. “Keep your rogueries and rascalities for the auld generation ye hae assisted to ruin; but leave the young anes alane to mind ither matters than dicing and horse-racing.”

Either the O'Donoghue conceived the allusion one that bore hardly on himself, or he felt vexed that the authority of a father over his son should have been usurped by another, or both causes were in operation together, but he turned an angry look on Sir Archy, and said—

“And why shouldn't the boy ride? was there ever one of his name or family that didn't know how to cross a country? I don't intend him for a highland pedlar.”

“He might be waur,” retorted M'Nab, solemnly, “he might be an Irish beggar.”

“By my soul, sir,” broke in O'Donoghue; but fortunately an interruption saved the speech from being concluded, for at the same moment the door opened, and Mark O'Donoghue, travel-stained and weary-looking, entered the room.

“Well, Mark,” said the old man, as his eyes glistened at the appearance of his favourite son—“what sport, boy?”

“Poor enough, sir; five brace in two days is nothing to boast of, besides two hares. Ah, Lanty—you here; how goes it?”

“Purty well, as times go, Mr. Mark,” said the horse-dealer, affecting a degree of deference he would not have deemed necessary had they been alone. “I'm glad to see you back again.”

“Why—what old broken-down devils have you now got on hand to pass off upon us? It's fellows like you destroy the sport of the country. You carry away every good horse to be found, and cover the country with spavined, wind-galled brutes, not fit for the kennel.”

“That's it, Mark—give him a canter, lad,” cried the old man, joyfully.

“I know what you are at well enough,” resumed the youth, encouraged by these tokens of approval; “you want that grey mare of mine. You have some fine English officer ready to give you an hundred and fifty, or, may be, two hundred guineas, for her, the moment you bring her over to England.”

“May I never—

“That's the trade you drive. Nothing too bad for us—nothing too good for them.”

“See now, Mr. Mark, I hope I may never———”

“Well, Lanty, one word for all; I'd rather send a bullet through her skull this minute, than let you have her for one of your fine English patrons.”

“Won't you let me speak a word at all,” interposed the horse-dealer, in an accent half imploring, half deprecating. “If I buy the mare—and it isn't for want of a sporting offer if I don't—she'll never go to England—no—devil a step. She's for one in the country here beside you; but I won't say more, and there now.” At these words he drew a soiled black leather pocket-book from the breast of his coat, and opening it, displayed a thick roll of bank notes, tied with a piece of string—“There now—there's sixty pounds in that bundle there—at least I hope so, for I never counted it since I got it—take it for her or leave it—just as you like; and may I never have luck with a beast, but there's not a gentleman in the county would give the same money for her.” Here he dropped his voice to a whisper, and added, “Sure the speedy cut is ten pounds off her price any day, between two brothers.”

“What!” said the youth, as his brows met in passion, and his heightened colour showed how his anger was raised.

“Well, well—it's no matter, there's my offer; and if I make a ten pound note of her, sure it's all I live by; I wasn't born to an estate and a fine property, like yourself.”

These words, uttered in such a tone as to be inaudible to the rest, seemed to mollify the young man's wrath, for, sullenly stretching forth his hand, he took the bundle and opened it on the table before him.

“A dry bargain never was a lucky one, they say, Lanty—isn't that so?” said the ODonoghue, as, seizing a small hand-bell, he ordered up a supply of claret, as well as the more vulgar elements for punch, should the dealer, as was probable, prefer that liquor.

“These notes seem to have seen service,” muttered Mark: “here's a lagged fellow. There's no making out whether he's two or ten.”

“They were well handled, there's no doubt of it,” said Lanty, “the tenants was paying them in; and sure you know yourself how they thumb and finger a note before they part with it. You'd think they were trying to take leave of them. There's many a man can't read a word, can tell you the amount of a note, just by the feel of it!—Thank you, sir, I'll take the spirits—it's what I'm most used to.”

“Who did you get them from, Lanty?” said the ODonoghue.

“Malachi Glynn, sir, of Cahernavorra, and, by the same token, I got a hearty laugh at the same house once before.”

“How was that?” said the old man, for he saw by the twinkle of Lanty's eye, that a story was coming.

“Faix, just this way, sir. It was a little after Christmas last year that Mr. Malachi thought he'd go up to Dublin for a month or six weeks with the young ladies, just to show them, by way of; for ye see, there's no dealing at all downi here; and he thought he'd bring them up, and see what could be done. Musha! but they're the hard stock to get rid of! and somehow they don't improve by holding them over. And as there was levees, and drawing-rooms, and balls going on, sure it would go hard but he'd get off a pair of them anyhow. Well, it was an elegant scheme, if there was money to do it; but devil a farthin' was to be had, high or low, beyond seventy pounds I gave for the two carriage horses and the yearlings that was out in the field, and sure that wouldn't do at all. He tried the tenants for 'the November,' but what was the use of it, though he offered a receipt in full for ten shillings in the pound?—when a lucky thought struck him. Troth, and it's what ye may call a grand thought too. He was walking about before the door, thinking and ruminating how to raise the money, when he sees the sheep grazing on the lawn fornint him—not that he could sell one of them, for there was a strap of a bond or mortage on them a year before. 'Faix,' and says he, when a man's hard up for cash, he's often obliged to wear a mighty thread-bare coat, and go cold enough in the winter season—and sure it's reason sheep isn't better than Christians; and begorra,' says he, I'll have the fleece off ye, if the weather was twice as cowld.' No sooner said than done. They were ordered into the haggard-yard the same evening, and, as sure as ye're there, they cut the wool off them three days after Christmas. Musha! but it was a pitiful sight to see them turned out shivering and shaking, with the snow on the ground. And it didn't thrive with him; for three died the first night. Well, when he seen what come of it, he had them all brought in again, and they gathered all the spare clothes and the ould rags in the house together, and dressed them up, at least the ones that were worst; and such a set of craytures never was seen. One had an old petticoat on; another a flannel waistcoat; many, could only get a cravat or a pair of gaiters; but the ram beat all, for he was dressed in a pair of corduroy breeches, and an ould spencer of the master's; and may I never live, if I didn't roll down full length on the grass when I seen him.”

For some minutes before Lanty had concluded his story, the whole party were convulsed with laughter; even Sir Archy vouchsafed a grave smile, as, receiving the tale in a different light, he muttered, to himself—

“They're a the same—ne'er-do-well, reckless deevils.”

One good result at least followed the anecdote—the good-humour of the company was restored at once—the bargain was finally concluded; and Lanty succeeded by some adroit flattery in recovering five pounds of the price, under the title of luck-penny—a portion of the contract M'Nab would have interfered against at once, but that, for his own especial reasons, he preferred remaining silent.

The party soon after separated for the night, and as Lanty sought the room usually destined for his accommodation, he muttered, as he went, his self-gratulations on his bargain. Already he had nearly reached the end of the long corridor, where his chamber lay, when a door was cautiously opened, and Sir Archy, attired in a dressing-gown, and with a candle in his hand, stood before him..

“A word wi' ye, Master Lawler,” said he, in a low dry tone, the horse-dealer but half liked. “A word wi' ye, before ye retire to rest.”

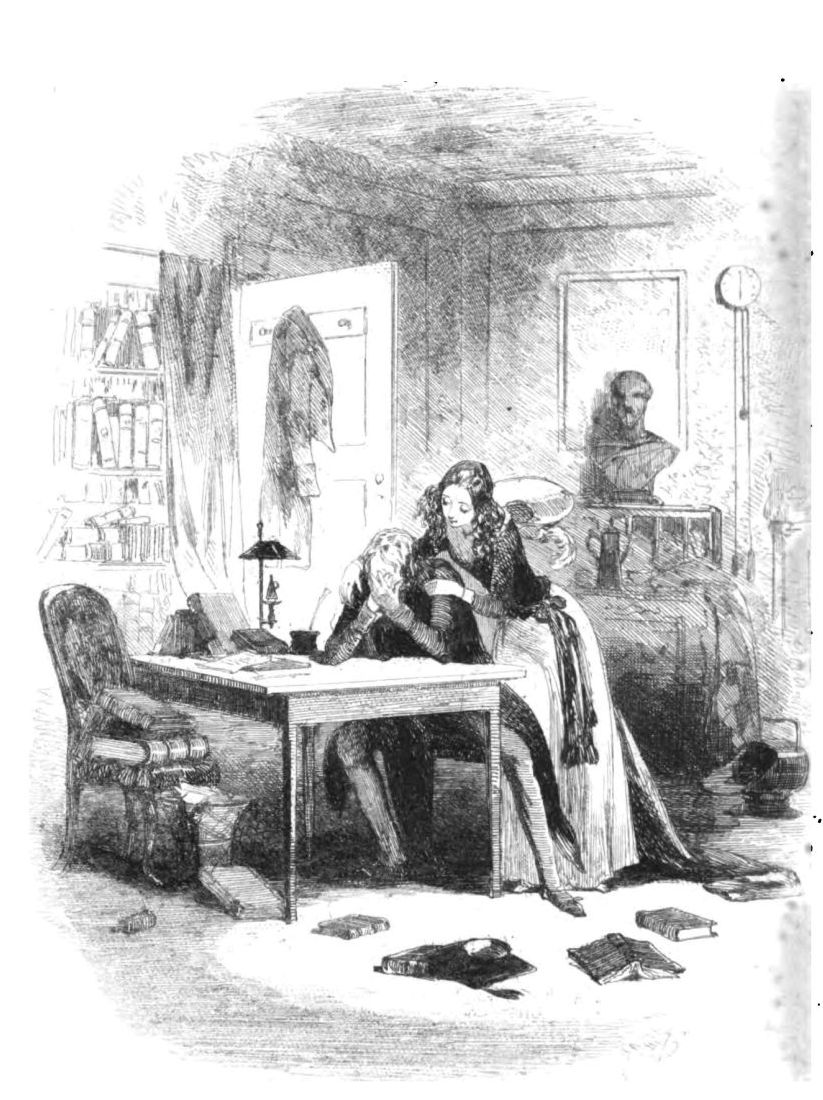

Lanty followed the old man into the apartment with an air of affected carelessness, which soon, however, gave way to surprise, as he surveyed the chamber, so little like any other in that dreary mansion. The walls were covered with shelves, loaded with books; maps and prints lay scattered about on tables; an oak cabinet of great beauty in form and carving, occupied a deep recess beside the chimney; and over the fireplace a claymore of true Highland origin, and a pair of silver-mounted pistols, were arranged like a trophy, surmounted by a flat Highland cap, with a thin black eagle's feather.

Sir Archy seemed to enjoy the astonishment of his guest, and for some minutes made no effort to break silence. At length he said—

“We war speaking about a sma' pony for the laird's son, Mister Lawler—may I ask ye the price?”

The words acted like a talisman—Lanty was himself in a moment. The mere mention of horse flesh brought back the whole crowd of his daily associations, and with his native volubility he proceeded, not to reply to the question, but to enumerate the many virtues and perfections of the “sweetest tool that ever travelled on four legs.”

Sir Archy waited patiently till the eloquent eulogy was over, and then, drily repeated his first demand.

“Is it her price!” said Lanty, repeating the question to gain time to consider how far circumstances might warrant him in pushing a market. “It's her price ye're asking me, Sir Archibald? Troth, and I'll tell you: there's not a man in Kerry could say what's her price. Goold wouldn't pay for her, av it was value was wanted. See now, she's not fourteen hands high, but may I never leave this room if she wouldn't carry me—ay, myself here, twelve stone six in the scales—over e'er a fence between this and Inchigeela.”

“It's no exactly to carry you that I was making my inquiry,” said the old man, with an accent of more asperity than he had used before.

“Well then, for Master Herbert—sure she is the very beast—”

“What are you, asking for her?—canna you answer a straightforred question, man?” reiterated Sir Archy, in a voice there was no mistaking.

“Twenty guineas, then,” replied Lanty, in a tone of defiance; “and if ye offer me pounds I won't take it.”

Sir Archy made no answer; but turning to the old cabinet, he unlocked one of the small doors, and drew forth a long leather pouch, curiously embroidered with silver; from this he took ten guineas in gold, and laid them leisurely on the table. The horse dealer eyed them askance, but without the slightest sign of having noticed them.

“I'm no goin' to buy your beast, Mr. Lawler,” said the old man, slowly; “I'm just goin' merely to buy your ain good sense and justice. You say the powney is worth twenty guineas.”

“As sure as I stand here. I wouldn't—”

“Weel, weel, I'm content. There's half the money; tak' it, but never let's hear anither word about her here: bring her awa wi' ye; sell or shoot her, do what ye please wi' her; but, mind me, man”—here, his voice became full, strong, and commanding—“tak' care that ye meddle not wi' that young callant, Herbert. Dinna fill his head wi' ranting thoughts of dogs and horses. Let there be one of the house wi' a soul above a scullion or a groom. Ye have brought ruin enough here; you can spare the boy, I trow: there, sir, tak' your money.”

For a second or two, Lanty seemed undecided whether to reject or accept a proposal so humiliating in its terms; and when at length he acceded, it was rather from his dread of the consequences of refusal, than from any satisfaction the bargain gave him.

“I'm afraid, Sir Archibald,” said he, half timidly, “I'm afraid you don't understand me well.”

“I'm afraid I do,” rejoined the old man, with a bitter smile on his lip; “but it's better we should understand each other. Good night.”

“Well, good night to you, any how,” said Lanty, with a slight sigh, as he dropped the money into his pocket, and left the room.

“I have bought the scoundrel cheap!” muttered Sir Archy, as the door closed.

“Begorra, I thought he was twice as knowing!” was Lanty's reflection, as he entered his own chamber.

Lanty Lawler was stirring the first in the house. The late sitting of the preceding evening, and the deep potations he had indulged in, left little trace of weariness on his well-accustomed frame. Few contracts were ratified in those days without the solemnity of a drinking bout, and the habits of the O'Donoghue household were none of the most abstemious. All was still and silent then as the horse-dealer descended the stairs, and took the path towards the stable, where he had left his hackney the night before.

It was Lanty's intention to take possession of his new purchase, and set out on his journey before the others were stirring; and with this object he wended his way across the weed-grown garden, and into the wide and dreary court-yard of the building.

Had he been disposed to moralize—assuredly an occupation he was little given to—he might have indulged the vein naturally enough, as he surveyed on every side the remains of long past greatness and present decay. Beautifully proportioned columns, with florid capitals, supplied the place of gate piers. Richly carved armorial bearings were seen upon the stones used to repair the breaches in the walls. Fragments of inscriptions and half obliterated dates appeared amid the moss-grown ruins; and the very, door of the stable had been a portal of dark oak, studded with large nails, its native strength having preserved it when even the masonry was crumbling to decay. Lanty passed these with perfect indifference. Their voice awoke no echo within his breast; and even when he noticed them, it was to mutter some jeering allusion to their fallen estate, rather than with any feeling of reverence for what they once represented.

The deep bay of a hound now startled him, however. He turned suddenly round, and close beside him, but within the low wall of a ruined kennel-yard, lay a large foxhound, so old and feeble that, even roused by the approach of a stranger, he could not rise from the ground, but lay helplessly on the earth, and with uplifted throat sent forth a long wailing note. Lanty leaned upon the wall, and looked at him. The emotions which other objects failed to suggest, seemed to flock upon him now. That poor dog, the last of a once noble pack, whose melody used to ring through every glen and ravine of the wild mountains, was an appeal to his heart he could not withstand; and he stood with his gaze fixed upon him.

“Poor old fellow,” said he compassionately, “it's a lonely thing for you to be there now, and all your old friends and companions dead and gone. Rory, my boy, don't you know me?”

The tones of his voice seemed to soothe the animal, for he responded in a low cadence indescribably melancholy.

“That's my boy. Sure I knew you didn't forget me;” and he stooped over and patted the poor beast upon the head.

“The top of the morning to you, Mister Lawler,” cried out a voice straight over his head—and at the same instant a strange-looking face was protruded from a little one-paned window of a hay loft—“'tis early you are to-day.”

“Ah, Kerry, how are you, my man? I was taking a look at Rory here.”

“Faix, he's a poor sight now,” responded the other with a sigh; “but he wasn't so once. I mind the time he could lead the pack over Cubber-na-creena mountain, and not a dog but himself catch the scent, after a hard frost and a north wind. I never knew him wrong. His tongue was as true as the priest's—sorra he in it.”

A low whine from the poor old beast seemed to acknowledge the praise bestowed upon him; and Kerry continued—

“It's truth I'm telling; and if it wasn't, it's just himself would contradict me.—Tallyho! Rory—tallyho! my ould boy;” and both man and dog joined in a deep-toned cry together.

The old walls sent back the echoes, and for some seconds the sounds floated through the still air of the morning.

Lanty listened with animated features and lit-up eyes to notes which so often had stirred the strongest cords of his heart, and then suddenly, as if recalling his thoughts to their former channel, cried out—

“Come down, Kerry, my man—come down here, and unlock the door of the stable. I must be early on the road this morning.”

Kerry O'Leary—for so was he called, to distinguish him from those of the name in the adjoining county—soon made his appearance in the court-yard beneath. His toilet was a hasty one, consisting merely of a pair of worn corduroy small clothes and an old blue frock, with faded scarlet collar and cuffs, which, for convenience, he wore on the present occasion buttoned at the neck, and without inserting his arms in the sleeves, leaving these appendages to float loosely at his side. His legs and feet were bare, as was his head, save what covering it derived from a thick fell of strong black hair that hung down on every side like an ill-made thatch.

Kerry was not remarkable for good looks. His brow was low, and shaded two piercing black eyes, set so closely together, that they seemed to present to the beholder one single continuous dark streak beneath his forehead: a short snubby nose, a wide thick-lipped mouth, and a heavy massive under-jaw, made up an assemblage of features, which, when at rest, indicated little of remarkable or striking; but when animated and excited, displayed the strangest possible union of deep cunning and simplicity, intense curiosity and apathetic indolence. His figure was short, almost to dwarfishness, and as his arms were enormously long, they contributed to give that air to his appearance. His legs were widely bowed, and his gait had that slouching, shambling motion, so indicative of an education cultivated among horses and stable-men. So it was, in fact, Kerry had begun life as a jockey. At thirteen he rode a winning race at the Curragh, and came in first on the back of Blue Blazes, the wickedest horse of the day in Ireland. From that hour he became a celebrity, and until too old to ride, was the crack jockey of his time. From jockey he grew into trainer—the usual transition of the tadpole to the frog; and when the racing stud was given up by the O'Donoghue in exchange for the hunting field, Kerry led the pack to their glorious sport. As time wore on, and its course brought saddening fortunes to his master, Kerry's occupation was invaded; the horses were sold, the hounds given up, and the kennel fell to ruins. Of the large household that once filled the castle, a few were now retained; but among these was Kerry. It was not that he was useful, or that his services could minister to the comfort or convenience of the family; far from it, the commonest offices of in-door life he was ignorant of, and, even if he knew, would have shrunk from performing them, as being a degradation. His whole skill was limited to the stable-yard, and there, now, his functions were unneeded. It would seem as if he were kept as a kind of memento of their once condition, rather than any thing else. There was a pride in maintaining one who did nothing the whole day but lounge about the offices and the court-yard, in his old ragged suit of huntsman. And so, too, it impressed the country people, who seeing him, believed that at any moment the ancient splendour of the house might shine forth again, and Kerry, as of yore, ride out on his thoroughbred, to make the valleys ring with music. He was, as it were, a kind of staff, through which, at a day's notice, the whole regiment might be mustered. It was in this spirit he lived, and moved, and spoke. He was always going about looking after a “nice beast to carry the master,” and a “real bit of blood for Master Mark,” and he would send a gossoon to ask if Barry O'Brien of the bridge “heard tell of a fox in the cover below the road.” In fact, his preparations ever portended a speedy resumption of the habits in which his youth and manhood were spent.

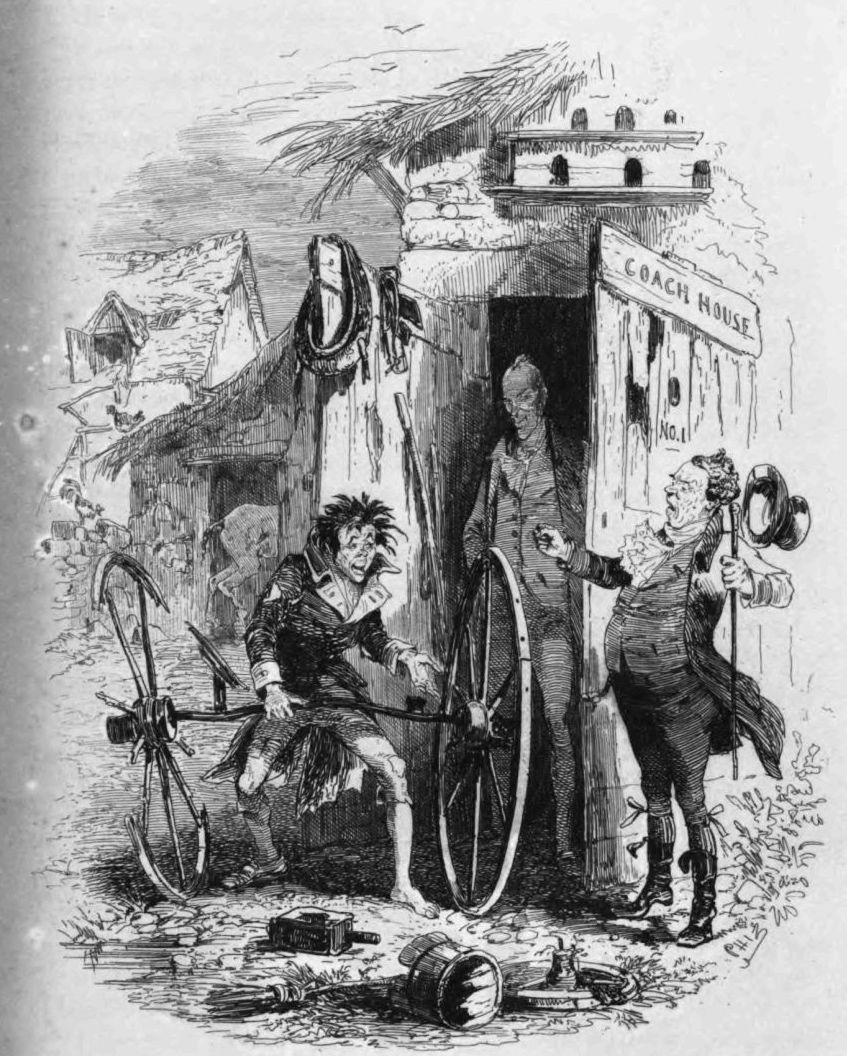

Such was the character who now, in the easy deshabille described, descended into the court-yard with a great bunch of keys in his hand, and led the way towards the stable.

“I put the little mare into the hack-stable, Mr. Lawler,” said he, “because the hunters is in training, and I didn't like to disturb them with a strange beast.”

“Hunters in training!” replied Lanty in astonishment. “Why, I thought he had nothing but the grey mare with the black legs.”

“And sure, if he hasn't,” responded Kerry crankily, “couldn't he buy them when he wants them.”

“Oh, that's it,” said the other, laughing to himself. “No doubt of it Kerry. Money will do many a thing.”

“Oh, it's wishing it I am for money! Bad luck to the peace or ease I ever seen since they became fond of money. I remember the time it was, 'Kerry go down and bring this, or take that,' and devil a more about it; and lashings of every thing there was. See now! if the horses could eat pease pudding, and drink punch, they'd got it for askin'; but now it's all for saving, and saving. And sure, what's the use of goold? God be good to us, as I heard Father Luke say, he'd do as much for fifteen shillings as for fifty pounds, av it was a poor boy wanted it.”

“What nonsense are you talking, you old sinner, about saving. Why man, they haven't got as much as they could bless themselves on, among them all. You needn't be angry, Kerry. It's not Lanty Lawler you can humbug that way. Is there an acre of the estate their own now? Not if every perch of it made four, it wouldn't pay the money they owe.”

“And if they do,” rejoined Kerry indignantly, “who has a better right, tell me that? Is it an O'Donoghue would be behind the rest of the country—begorra, ye're bould to come up here and tell us that.”

“I'm not telling you any thing of the kind—I'm saying that if they are ruined entirely—”

“Arrah! don't provoke me. Take your baste and go, in God's name.”

And so saying, Kerry, whose patience was fast ebbing, pushed wide the stable-door, and pointed to the stall where Lanty's hackney was standing.

“Bring out that grey mare, Master Kerry,” said Lanty in a tone of easy insolence, purposely assumed to provoke the old huntsman's anger, “Bring her out here.”

“And what for, would I bring her out?”

“May be I'll tell you afterwards,” was the reply. “Just do as I say, now.”

“The devil a one o' me will touch the beast at your bidding; and what's more, I'll not let yourself lay a finger on her.”

“Be quiet, you old fool,” said a deep voice behind him. He turned, and there stood Mark O'Donoghue himself, pale and haggard after his night's excess. “Be quiet, I say. The mare is his—let him have her.”

“Blessed Virgin!” exclaimed Kerry, “here's the hunting season beginning, and sorrow thing you'll have to put a saddle on, barrin'—barrin'—”

“Barring what?” interposed Lanty, with an insolent grin.

The young man flushed at the impertinence of the insinuation, but said not a word for a few minutes, then suddenly exclaimed—

“Lanty, I have changed my mind; I'll keep the mare.”

The horse-dealer started, and stared him full in the face—

“Why Mr. Mark, surely you're not in earnest? The beast is paid for—the bargain all settled.”

“I don't care for that. There's your money again. I'll keep the mare.”

“Ay, but listen to reason. The mare is mine. She was so when you handed me the luck-penny, and if I don't wish to part with her, you cannot compel me.”

“Can't I?” retorted Mark, with a jeering laugh; “can't I, faith? Will you tell me what's to prevent it? Will you take the law of me? Is that your threat?”

“Devil a one ever said I was that mean, before!” replied Lanty, with an air of deeply-offended pride. “I never demeaned myself to the law, and I'm fifteen years buying and selling horses in every county in Munster. No, Mr. Mark, it is not that; but I'll just tell you the truth, The mare is all as one as sold already;—there it is now, and that's the whole secret.”

“Sold! What do you mean?—that you had sold that mare before you ever bought her?”

“To be sure I did,” cried Lanty, assuming a forced look of easy assurance he was very far from feeling at the moment. “There's nothing more common in my trade. Not one of us buys a beast without knowing where the next owner is to be had.”

“And do you mean, sir,” said Mark, as he eyed him with a steady stare, “do you mean to tell me that you came down here, as you would to a petty fanner's cabin, with your bank-notes, ready to take whatever you may pitch your fancy on, sure and certain that our necessities must make us willing chapmen for all you care to deal in—do you dare to say that you have done this with me?”

For an instant Lanty was confounded. He could not utter a word, and looked around him in the vain hope of aid from any other quarter, but none was forthcoming. Kerry was the only unoccupied witness of the scene, and his face beamed with ineffable satisfaction at the turn matters had taken, and as he rubbed his hands he could scarcely control his desire to laugh outright, at the lamentable figure of his late antagonist.

“Let me say one word, Master Mark,” said Lanty at length, and in a voice subdued to its very softest key—“just a single word in your own ear,” and with that he led the young man outside the door of the stable, and whispered for some minutes, with the greatest earnestness, concluding in a voice loud enough to be heard by Kerry—

“And after that, I'm sure I need say no more.”

Mark made no answer, but leaned his back against the wall, and folded his arms upon his breast.

“May I never if it is not the whole truth,” said Lanty, with a most eager and impassioned gesture; “and now I leave it all to yourself.”

“Is he to take the mare?” asked Kerry, in anxious dread lest his enemy might have carried the day.

“Yes,” was the reply, in a deep hollow voice, as the speaker turned away and left the stable.

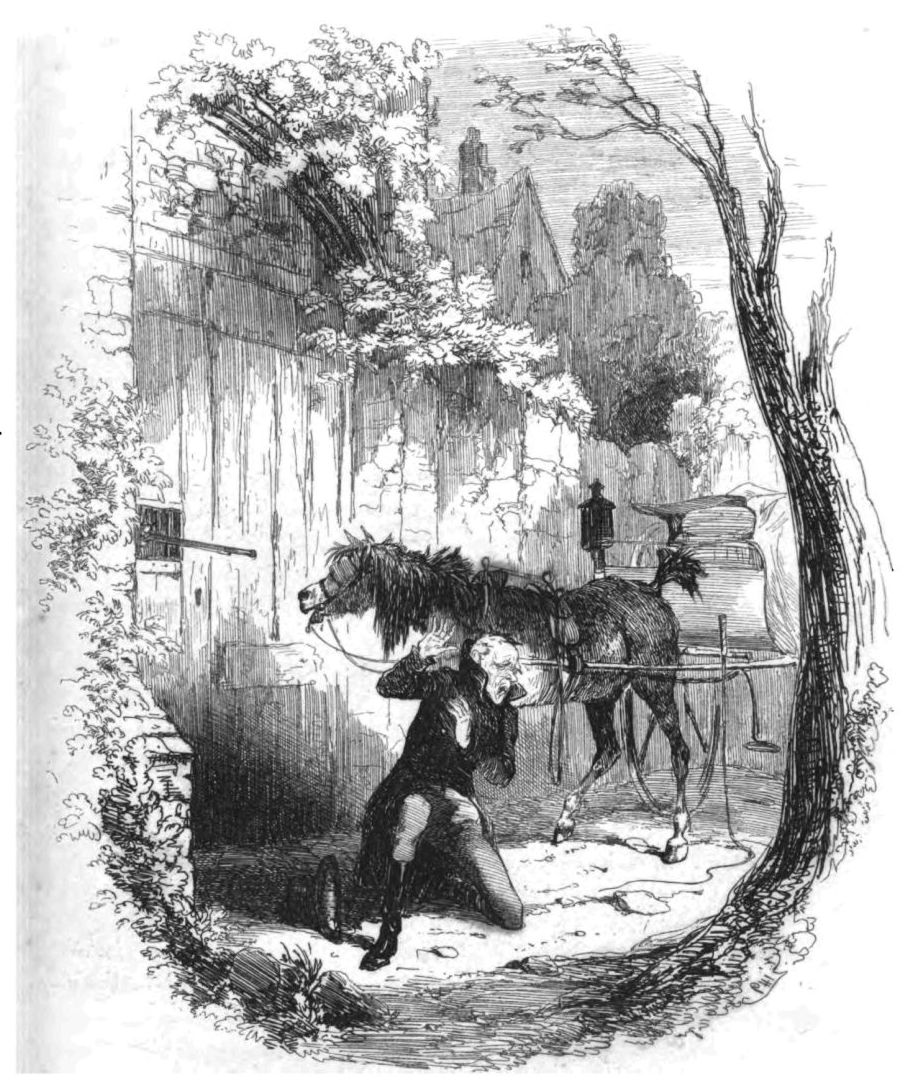

While Lanty was engaged in placing his saddle on his new purchase, an operation in which Kerry contrived not to afford him any assistance whatever, Mark O'Donoghue paced slowly to and fro in the courtyard, with his arms folded, and his head sunk upon his breast; nor was he aroused from his reverie until the step of the horse was heard on the pavement beside him.

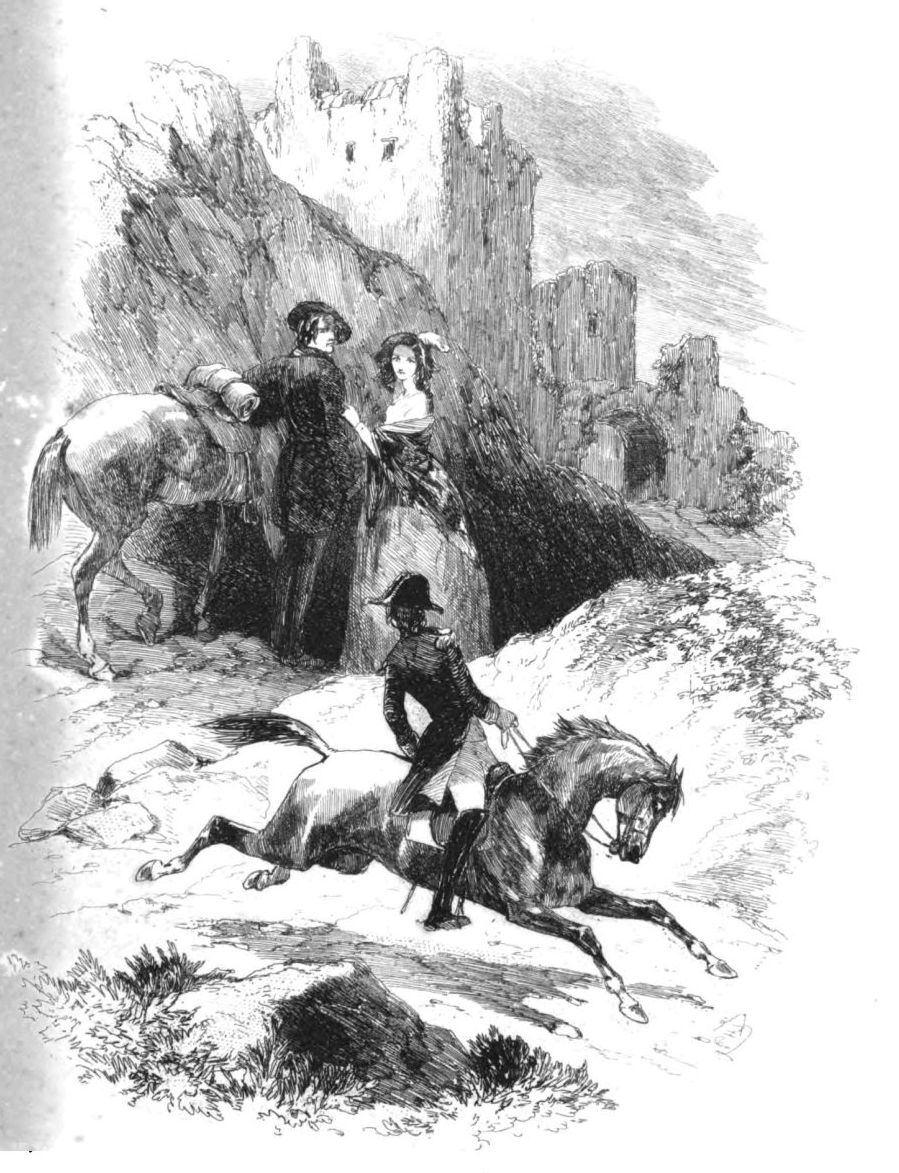

“Poor Kittane,” said he, looking up suddenly, “you were a great pet: I hope they'll be as kind to you as I was; and they'd better, too,” added he, half-savagely, “for you've a drop of the Celt in your blood, and can revenge harsh treatment when you meet with it. Tell her owner that she is all gentleness, if not abused, but get her temper once up, and, by Jove, there's not a torrent on the mountain can leap as madly! She knows her name, too: I trust they'll not change that. She was bred beside Lough Kittane, and called after it. See how she can follow;” and with that, the youth sprang forward, and placing his hand on the top bar of a gate, vaulted lightly over; but scarcely had he reached the ground, when the mare bounded after him, and stood with her head resting on his shoulder.

Mark turned an elated look on the others, and then surveyed the noble animal beside him with all the pride and admiration of a master regarding his handiwork. She was, indeed, a model of symmetry, and well worthy of all the praise bestowed on her.

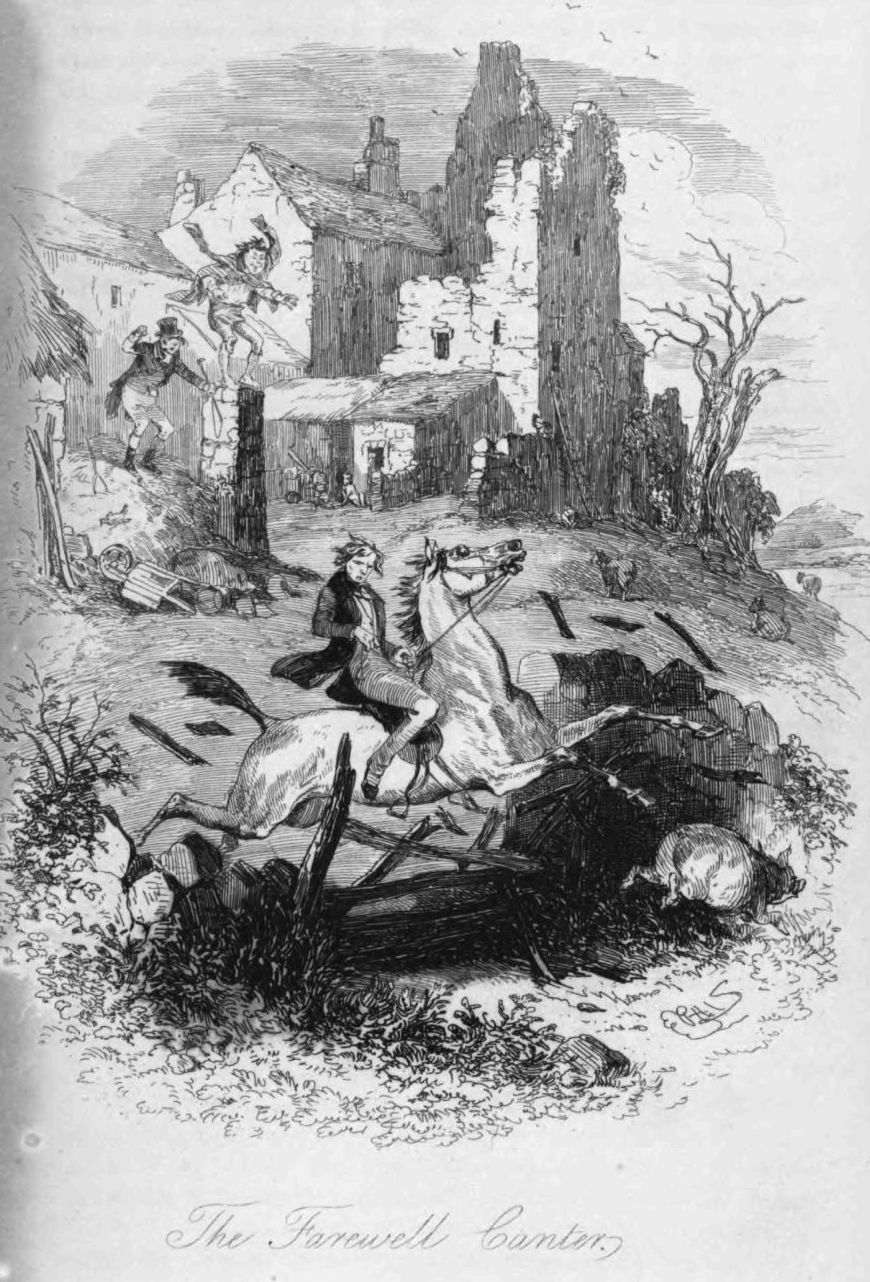

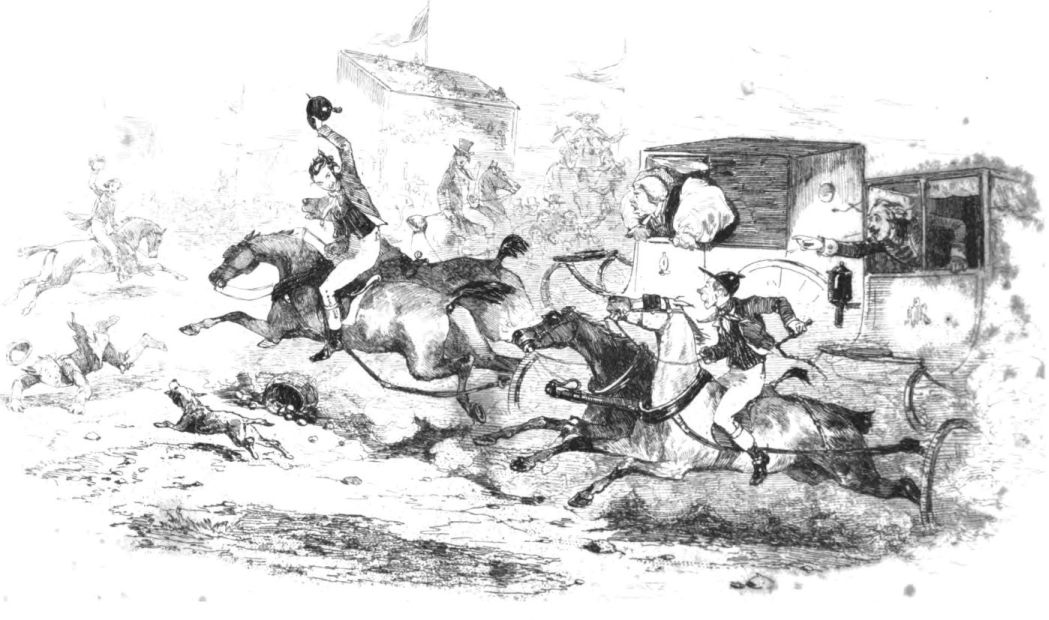

For a moment or two the youth gazed on her, with a flashing eye and quivering lip, while the mare, catching excitement from the free air of the morning, and the spring she had made, stood with swelled veins and trembling limbs, his counterpart in eagerness. One spirit seemed to animate both. So Mark appeared to feel it, as with a bound he sprung into the saddle, and with a wild cheer dashed forward. With lightning's speed they went, and in a moment disappeared from view. Kerry jumped up on a broken gate-pier, and strained his eyes to catch them, while Lanty, muttering maledictions to himself, on the hair-brained boy, turned everywhere for a spot where he might view the scene.

“There he goes,” shouted Kerry; “look at him now; he's coming to the furze ditch into the big field: see! see! she does not see the fence; her head's in the air. Whew—elegant, by the mortial—never touched a hoof to it!—murther! murther! how she gallops in the deep ground, and the wide gripe that's before her! Ah, he won't take it; he's turning away.”

“I wish to the Lord he'd break a stirrup-leather,” muttered Lanty.

“Oh, Joseph!” screamed Kerry, “there was a jump—twenty feet as sure as I'm living. Where is he now?—I don't see him.”

“May you never,” growled Lanty, whose indignant anger had burst all bounds: “that's not treatment for another man's horse.”

“There he goes, the jewel; see him in the stubble field; sure it's a real picture to see him going along at his ease. Whurroo—he's over the wall. What the devil's the matter now?—they're away;” and so it was: the animal that an instant before was cantering perfectly in hand, had now set off at top speed, and at full stretch. “See the gate—mind the gate—Master Mark—tear-and-ages, mind the gate,” shouted Kerry, as though his admonition could be heard half a mile away. “Oh! holy Mary! he's through it,” and true enough—the wild and now affrighted beast dashed through the frail timbers, and held on her course, without stopping. “He's broke the gate to flitters.”

“May I never, if I don't wish it was his neck,” said Lanty, in open defiance.