Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Coucy-le-Château" to "Crocodile"

Author: Various

Release date: May 19, 2010 [eBook #32423]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz, Marius Masi, Juliet

Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

COUCY-LE-CHÂTEAU, a village of northern France, in the department of Aisne, 18 m. W.S.W. of Laon on a branch of the Northern railway. Pop. (1906) 663. It has extensive remains of fortifications of the 13th century, the most remarkable feature of which is the Porte de Laon, a gateway flanked by massive towers and surmounted by a fine apartment. Coucy also has a church of the 15th century, preserving a façade in the Romanesque style. The importance of the place is due, however, to the magnificent ruins of a feudal fortress (see Castle) crowning the eminence on the slope of which the village is built. The remains, which embrace an area of more than 10,000 sq. yds., form an irregular quadrilateral built round a court-yard and flanked by four huge towers. The nucleus of the stronghold is a donjon over 200 ft. high and over 100 ft. in diameter, standing on the south side of the court. Three large vaulted apartments, one above the other, occupy its interior. The court-yard was surrounded on the ground-floor by storehouses, kitchens, &c., above which on the west and north sides were the great halls known as the Salle des preux and the Salle des preuses. A chapel projected from the west wing. The bailey or base-court containing other buildings and covering three times the area of the château extended between it and the village. The architectural unity of the fortress is due to the rapidity of its construction, which took place between 1230 and 1242, under Enguerrand III., lord of Coucy. A large part of the buildings was restored or enlarged at the end of the 14th century by Louis d’Orléans, brother of Charles VI., by whom it had been purchased. The place was dismantled in 1652 by order of Cardinal Mazarin. It is now state property. In 1856 researches were carried on upon the spot by Viollet-le-Duc, and measures for the preservation of the ruins were subsequently undertaken.

Sires de Coucy.—Coucy gave its name to the sires de Coucy, a feudal house famous in the history of France. The founder of the family was Enguerrand de Boves, a warlike lord, who, at the end of the 11th century seized the castle of Coucy by force. Towards the close of his life, he had to fight against his own son, Thomas de Marle, who in 1115 succeeded him, subsequently becoming notorious for his deeds of violence in the struggles between the communes of Laon and Amiens. He was subdued by King Louis VI. in 1117, but his son Enguerrand II. continued the struggle against the king. Enguerrand III., the Great, fought at Bouvines under Philip Augustus (1214), but later he was accused of aiming at the crown of France, and he took part in the disturbances which arose during the regency of Blanche of Castile. These early lords of Coucy remained till the 14th century in possession of the land from which they took their name. Enguerrand IV., sire de Coucy, died in 1320 without issue and was succeeded by his nephew Enguerrand, son of Arnold, count of Guines, and Alix de Coucy, from whom is descended the second line of the house of Coucy. Enguerrand VI. had his lands ravaged by the English in 1339 and died at Crécy in 1346. Enguerrand VII., sire de Coucy, count of Soissons and Marle, and chief butler of France, was sent as a hostage to England, where he married Isabel, the eldest daughter of King Edward III. Wishing to remain neutral in the struggle between England and France, he went to fight in Italy. Having made claims upon the domains of the house of Austria, from which he was descended through his mother, he was defeated in battle (1375-1376). He was entrusted with various diplomatic negotiations, and took part in the crusade of Hungary against the Sultan Bayezid, during which he was taken prisoner, and died shortly after the battle of Nicopolis (1397). His daughter Marie sold the fief of Coucy to Louis, duke of Orleans, in 1400. The Châtelain de Coucy (see above) did not belong to the house of the lords of Coucy, but was castellan of the castle of that name.

COUES, ELLIOTT (1842-1899), American naturalist, was born at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on the 9th of September 1842. He graduated at Columbian (now George Washington) University, Washington, D.C., in 1861, and at the Medical school of that institution in 1863. He served as a medical cadet at Washington in 1862-1863, and in 1864 was appointed assistant-surgeon in the regular army. In 1872 he published his Key to North American Birds, which, revised and rewritten in 1884 and 1901, has done much to promote the systematic study of ornithology in America. In 1873-1876 Coues was attached as surgeon and naturalist to the United States Northern Boundary Commission, and in 1876-1880 was secretary and naturalist to the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, the publications of which he edited. He was lecturer on anatomy in the medical school of the Columbian University in 1877-1882, and professor of anatomy there in 1882-1887. He resigned from the army in 1881 to devote himself entirely to scientific research. He was a founder of the American Ornithologists’ Union, and edited its organ, The Auk, and several other ornithological periodicals. He died at Baltimore, Maryland, on the 25th of December 1899. In addition to ornithology he did valuable work in mammalogy; his book Fur-Bearing Animals (1877) being distinguished by the accuracy and completeness of its description of species, several of which are already becoming rare. In 1887 he became president of the Esoteric Theosophical Society of America. Among the most important of his publications, in several of which he had collaboration, are A Field Ornithology (1874); Birds of the North-west (1874); Monographs on North American Rodentia, with J. A. Allen (1877); Birds of the Colorado Valley (1878); A Bibliography of Ornithology (1878-1880, incomplete); New England Bird Life (1881); A Dictionary and Check List of North American Birds (1882); Biogen, A Speculation on the Origin and Motive of Life (1884); The Daemon of Darwin (1884); Can Matter Think? (1886); and Neuro-Myology (1887). He also contributed numerous articles to the Century Dictionary, wrote for various encyclopaedias, and edited the Journals of Lewis and Clark (1893), and The Travels of Zebulon M. Pike (1895).

COULISSE (French for “groove,” from couler, to slide), a term for a groove in which a gate of a sluice, or the side-scenes in a theatre, slide up and down, hence applied to the space on the stage between the wings, and generally to that part of the theatre “behind the scenes” and out of view of the public. It is also a term of the Paris Bourse, derived from a coulisse, or passage in which transactions were carried on without the authorized agents de change. The name coulissier was thus given to unauthorized agents de change, or “outside brokers” who, after many attempts at suppression, were finally given a recognized status in 1901. They bring business to the agents de change, and act as intermediaries between them and other parties. (See Stock Exchange: Paris.)

COULOMB, CHARLES AUGUSTIN (1736-1806), French natural philosopher, was born at Angoulême on the 14th of June 1736. He chose the profession of military engineer, spent three years, to the decided injury of his health, at Fort Bourbon, Martinique, and was employed on his return at Rochelle, the Isle of Aix and Cherbourg. In 1781 he was stationed permanently at Paris, but on the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789 he resigned his appointment as intendant des eaux et fontaines, and retired to a small estate which he possessed at Blois. He was recalled to Paris for a time in order to take part in the new determination of weights and measures, which had been decreed by the Revolutionary government. Of the National Institute he was one of the first members; and he was appointed inspector of public instruction in 1802. But his health was already very feeble, and four years later he died at Paris on the 23rd of August 1806. Coulomb is distinguished in the history alike of mechanics and of electricity and magnetism. In 1779 he published an important investigation of the laws of friction (Théorie des machines simples, en ayant regard au frottement de leurs parties et à la roideur des cordages), which was followed twenty years later by a memoir on fluid resistance. In 1785 appeared his Recherches théoriques et expérimentales sur la force de torsion et sur l’élasticité des fils de métal, &c. This memoir contained a description of different forms of his torsion balance, an instrument used by him with great success for the experimental investigation of the distribution of electricity on surfaces and of the laws of electrical and magnetic action, of the mathematical theory of which he may also be regarded as the founder. The practical unit of quantity of electricity, the coulomb, is named after him.

COULOMMIERS, a town of northern France, capital of an arrondissement in the department of Seine-et-Marne, 45 m. E. of Paris by rail. Pop. (1906) 5217. It is situated in the fertile district of Brie, in a valley watered by the Grand-Morin. The church of St Denis (13th and 16th centuries), and the ruins of a castle built by Catherine of Gonzaga, duchess of Longueville, in the early 17th century, are of little importance. There is a statue to Commandant Beaurepaire, who, in 1792, killed himself rather than surrender Verdun to the Prussians. Coulommiers is the seat of a subprefect, and has a tribunal of first instance and a communal college. Printing is the chief industry, tanning, flour-milling and sugar-making being also carried on. Trade is in agricultural products, and especially in cheeses named after the town.

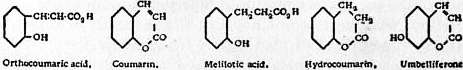

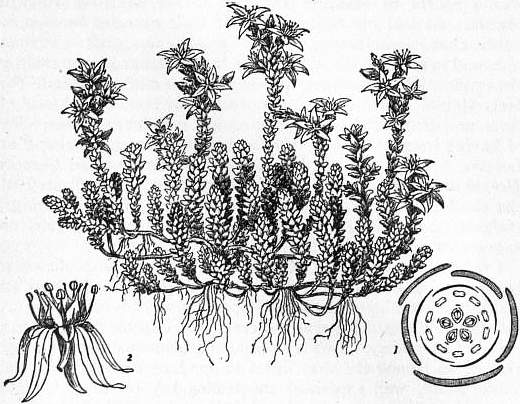

COUMARIN, C9H6O2, a substance which occurs naturally in sweet woodruff (Asperula odorata), in the tonka bean and in yellow melilot (Melilotus officinalis). It can be obtained from the tonka bean by extraction with alcohol. It is prepared artificially by heating aceto-ortho-coumaric acid (which is formed from sodium salicyl aldehyde) or from the action of acetic anhydride and sodium acetate on salicyl aldehyde (Sir W. H. Perkin, Berichte, 1875, 8, p. 1599). It can also be prepared by heating a mixture of phenol and malic acid with sulphuric acid, or by passing bromine vapour at 107° C. over the anhydride of melilotic acid. It forms rhombic crystals (from ether) melting at 67° C. and boiling at 290° C., which are readily soluble in alcohol, and moderately soluble in hot water. It is applied in perfumery for the preparation of the Asperula essence. On boiling with concentrated caustic potash it yields the potassium salt of coumaric acid, whilst when fused with potash it is completely decomposed into salicylic and acetic acids. Sodium amalgam reduces it, in aqueous solution, to melilotic acid. It forms addition products with bromine and hydrobromic acid. By the action of phosphorus pentasulphide it is converted into thiocoumarin, which melts at 101° C.; and in alcoholic solution, on the addition of hydroxylamine hydrochloride and soda, it yields coumarin oxime.

Ortho-coumaric acid (o-oxycinnamic acid) is obtained from coumarin as shown above, or by boiling coumarin for some time with sodium ethylate. It melts at 208° C. and is easily soluble in hot water and in alcohol. It cannot be converted into coumarin by heating alone, but it is readily transformed on heating with acetic anhydride or acetyl chloride. By the action of sodium amalgam it is readily converted into melilotic acid, which melts at 81° C., and on distillation furnishes its lactone, hydrocoumarin, melting at 25° C. For the relations of coumaric and coumarinic acid see Annalen, 254, p. 181. The homologues of coumarin may be obtained by the action of sulphuric acid on phenol and the higher fatty acids (propionic, butyric and isovaleric anhydrides), substitution taking place at the carbon atom in the α position to the -CO- group, whilst by the condensation of acetoacetic ester and phenols with sulphuric acid the β substituted coumarins are obtained.

Umbelliferone or 4-oxycoumarin, occurs in the bark of Daphne mezereum and may be obtained by distilling such resins as galbanum or asafoetida. It may be synthesized from resorcin and malic anhydride or from β resorcyl aldehyde, acetic anhydride and sodium acetate. Daphnetin and Aesculetin are dioxycoumarins.

The structural formulae of coumarin and the related substances are:

|

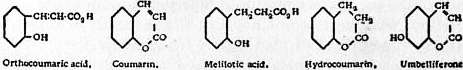

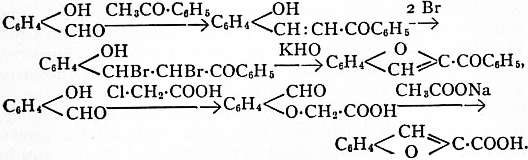

COUMARONES or Benzofurfuranes, organic compounds

containing the ring system

This ring system

may be synthesized in many different ways, the chief methods

employed being as follows: by the action of hot alcoholic

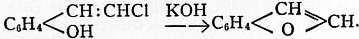

potash on α-bromcoumarin (R. Fittig, Ann., 1883, 216, p. 162),

This ring system

may be synthesized in many different ways, the chief methods

employed being as follows: by the action of hot alcoholic

potash on α-bromcoumarin (R. Fittig, Ann., 1883, 216, p. 162),

|

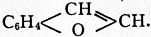

from sodium salts of phenols and α-chloracetoacetic ester (A. Hantzsch, Ber., 1886, 19, p. 1292),

|

or from ortho-oxyaldehydes by condensation with ketones (S. Kostanecki and J. Tambor, Ber., 1896, 29, p. 237), or with chloracetic acid (A. Rossing, Ber., 1884, 17, p. 3000),

|

The parent substance coumarone, C8H6O, is also obtained by heating ω-chlor-ortho-oxystyrol with concentrated potash solution (G. Komppa, Ber., 1893, 26. p. 2971),

|

It is a colourless liquid which boils at 171-172° C. and is readily volatile in steam, but is insoluble in water and in potash solution. Concentrated acids convert it into a resin. When heated with sodium and absolute alcohol, it is converted into hydrocoumarone, C8H8O, and ethyl phenol.

COUNCIL (Lat. concilium, from cum, together, and the root cal, to call), the general word for a convocation, meeting, assembly. The Latin word was frequently confused with consilium (from consulere, to deliberate, cf. consul), advice, i.e. counsel, and thus specifically an advisory assembly. Du Cange (Gloss. Med. Infim. Latin.) quotes the Greek words σύνοδος, συνέδριον, συμβούλιον as the equivalent of concilium. In French the distinction between conseil (from consilium), advice, and concile, council (i.e. ecclesiastical—its only meaning) has survived, but the two English derivatives are much confused. In the New Testament, “council” is the rendering of the Hebrew Sanhedrin, Gr. συνέδριον. The word is generally used in English for all kinds of congregations or convocations assembled for administrative and deliberative purposes.1

The present article is confined to a history of the development of the ecclesiastical council, summoned to adjust matters in dispute with the civil authority or for the settlement of doctrinal and other internal disputes. For details see under separate headings, Nicaea, &c.

From a very early period in the history of the Church, councils or synods have been held to decide on matters of doctrine and discipline. They may be traced back to the second half of the 2nd century A.D., when sundry churches in Asia Minor held consultations about the rise of Montanism. Their precise origin is disputed. The common Roman Catholic view is that they are apostolic though not prescribed by divine law, and the apostolic precedent usually cited is the “council” of Jerusalem (Acts xv.; Galatians ii.). Waiving the consideration of vital critical questions and accepting Acts xv. at its face value, the assembly at Jerusalem would scarcely seem to have been a council in the technical sense of the word; it was in essence a meeting of the Jerusalem church at which delegates from Antioch were heard but apparently had no vote, the decision resting solely with the mother church. R. Sohm argues that synods grew from the custom of certain local churches which, when confronted with a serious problem of their own, augmented their numbers by receiving delegates from the churches of the neighbourhood. Hauck, however, holds that these augmented church meetings, which dealt with the affairs of but a single church, are to be distinguished from the synods, which took cognizance of matters of general interest. Older Protestant writers have contented themselves with saying either that synods were of apostolic origin, or that they were the inevitable outcome of the need of the leaders of churches to take counsel together, and that they were perhaps modelled on the secular provincial assemblies (concilia provincialia).

Every important alteration in the constitution of the Church has affected the composition and function of synods; but the changes were neither simultaneous nor precisely alike throughout the Roman empire. The synods of the 2nd century were extraordinary assemblies which met to deliberate upon pressing problems. They had no fixed geographical limits for membership, no ex-officio members, nor did they possess an authority which did away with the independence of the local church. In the course of the 3rd century came the decisive change, which increased the prestige of the councils: the right to vote was limited to bishops. This was the logical outgrowth of the belief that each local church ought to have but one bishop (monarchical episcopate), and that these bishops were the sole legitimate successors of the apostles (apostolic succession), and therefore official organs of the Holy Spirit. Although as late as 250 the consensus of the priests, the deacons and the people was still considered essential to the validity of a conciliar decision at Rome and in certain parts of the East, the development had already run its course in northern Africa. It was a further step in advance when synods began to meet at regular intervals. They were held annually in Cappadocia by the middle of the 3rd century, and the council of Nicaea commanded in 325 that semiannual synods be held in every province, an arrangement which was not systematically enforced, and was altered in 692, when the Trullan Council reduced the number to one a year.

With the multiplication of synods came naturally a differentiation of type. In text-books we find clear lines drawn between diocesan, provincial, national, patriarchal and oecumenical synods; but the first thousand years of church history do not justify the sharpness of the traditional distinction. The provincial synods, presided over by the metropolitan (archbishop), were usually held at the capital of the province, and attempted to legislate on all sorts of questions. The state had nothing to do with calling them, nor did their decrees require governmental sanction. Various abortive attempts were made to set up synods of patriarchal or at least of more than provincial rank. In North Africa eighteen such synods were held between 393 and 424; during part of the 5th and 6th centuries primatial councils assembled at Arles; and the patriarchs of Constantinople were accustomed to invite to their “endemic synods” ( σύνοδοι ἐνδημοῦσαι) all bishops who happened to be sojourning at the capital. Papal synods from the 5th and especially from the 9th century onward included members such as the archbishops of Ravenna, Milan, Aquileia and Grado, who resided outside the Roman archdiocese; but the territorial limits from which the membership was drawn do not appear to have been precisely defined.

Before the form of the provincial synod had become absolutely fixed, there arose in the 4th century the oecumenical council. The Greek term σύνοδος οἰκουμενική2 (1) (used by Eusebius, Vita Constantini, iii. 6) is preferable to the Latin concilium universale or generale, which has been applied loosely to national and even to provincial synods. The oecumenical synods were not the logical outgrowth of the network of provincial synods; they were creations of the imperial power. Constantine, who had not even been baptized, laid the foundations when, in response to a petition of the Donatists, he referred their case to a committee of bishops that convened at Rome, which meeting Eusebius calls a 310 synod. After that the emperor summoned the council of Arles to settle the matter. For both of these assemblies it was the emperor that decided who should be summoned, paid the travelling expenses of the bishops, determined where the council should be held and what topics should be discussed. He regarded them as temporary advisory bodies, to whose recommendations the imperial authority might give the force of law. In the same manner he appointed the time and place for the council of Nicaea, summoned the episcopate, paid part of the expenses out of the public purse, nominated the committee in charge of the order of business, used his influence to bring about the adoption of the creed, and punished those who refused to subscribe. To be sure, the council of Nicaea commanded great veneration, for it was the first attempt to assemble the entire episcopate; but no more than the synods of Rome and of Arles was it an organ of ecclesiastical self-government—it was rather a means whereby the Church was ruled by the secular power. The subsequent oecumenical synods of the undivided Church were patterned on that of Nicaea. Most Protestant scholars maintain that the secular authorities decided whether or not they should be convened, and issued the summons; that imperial commissioners were always present, even if they did not always preside; that on occasion emperors have confirmed or refused to confirm synodal decrees; and that the papal confirmation was neither customary nor requisite. Roman Catholic scholars to-day tend to recede from the high ground very generally taken several centuries ago, and Funk even admits that the right to convoke oecumenical synods was vested in the emperor regardless of the wishes of the pope, and that it cannot be proved that the Roman see ever actually had a share in calling the oecumenical councils of antiquity. Others, however, while acknowledging the futility of seeking historical proofs that the popes formally called, directed and confirmed these synods, yet assert that the emperor performed these functions not of his own right but in his quality as protector of the Church, that this involved his acting at the request or at least with the permission and approval of the Church, and in particular of the pope, and that a special though not a stereotyped papal confirmation of conciliar decrees was necessary to their validity.

In the Germanic states which arose on the ruins of the Western Empire we find national and diocesan synods; provincial synods were unusual. National synods were summoned by the king or with his consent to meet special needs; and they were frequently concilia mixta, at which lay dignitaries appeared. Although the Frankish monarchs were not absolute rulers, nevertheless they exercised the right of changing or rejecting synodal decrees which ran counter to the interests of the state. Clovis held the first French national synod at Orleans in 511; Reccared, the first in Spain in 589 at Toledo. Under Charlemagne they were occasionally so representative that they might almost be ranked as general synods of the West (Regensburg, 792, Frankfort, 794). Contemporaneous with the evolution of the national synod was the development of a new type of diocesan synod, which included the priests of separate and mutually independent parishes and also the leaders of the monastic clergy.

The papal synods came into the foreground with the success of the Cluniac reform of the Church, especially from the Lateran synod of 1059 on. They grew in importance until at length Calixtus II. summoned to the Lateran the synod of 1123 as “generale concilium.” The powers which the pope as bishop of the church in Rome had exercised over its synods he now extended to the oecumenical councils. They were more completely under his control than the ancient ones had been under the sway of the emperor. The Pseudo-Isidorean principle that all major synods need papal authorization was insisted on, and the decrees were formulated as papal edicts.

The absolutist principles cherished by the papal court in the 12th and 13th centuries did not pass unchallenged; but the protests of Marsilius of Padua and the less radical William of Occam remained barren until the Great Schism of 1378. As neither the pope in Rome nor his rival in Avignon would give way, recourse was had to the idea that the supreme power was vested not in the pope but in the oecumenical council. This “conciliar theory,” propounded by Conrad of Gelnhausen and championed by the great Parisian teachers Pierre d’Ailly and Gerson, proceeded from the nominalistic axiom that the whole is greater than its part. The decisive revolutionary step was taken when the cardinals independently of both popes ventured to hold the council of Pisa (1409). The council of Constance asserted the supremacy of oecumenical synods, and ordered that these be convened at regular intervals. The last of the Reform councils, that of Basel, approved these principles, and at length passed a sentence of deposition against Pope Eugenius IV. Eugenius, however, succeeded in maintaining his power, and at the council of Florence (1439) secured the condemnation of the conciliar theory; and this was reiterated still more emphatically, on the eve of the Reformation, by the fifth Lateran council (1516). Thenceforward the absolutist theories of the 13th and 14th centuries increasingly dominated the Roman Church. The popes so distrusted oecumenical councils that between 1517 and 1869 they called but one; at this (Trent, 1545-1563), however, all treatment of the question of papal versus conciliar authority was purposely avoided. Although the Declaration of the French clergy of 1682 reaffirmed the conciliar doctrines of Constance, since the French Revolution this “Gallicanism” has shown itself to be but a passing phase of constitutional theory; and in the 19th century the ascendancy of Ultramontanism became so secure that Pius IX. could confidently summon to the Vatican a synod which set its seal on the doctrine of papal infallibility. Yet it would be a misconception to suppose that the Vatican decrees mean the surrender of the ancient belief in the infallibility of oecumenical synods; their decisions may still be regarded as more solemn and more impressive than those of the pope alone; their authority is fuller, though not higher. At present it is agreed that the pope has the sole right of summoning oecumenical councils, of presiding or appointing presidents and of determining the order of business and the topics which shall come up. The papal confirmation is indispensable; it is conceived of as the stamp without which the expression of conciliar opinion lacks legal validity. In other words, the oecumenical council is now practically in the position of the senate of an absolute monarch. It is in fact an open question whether a council is to be ranked as really oecumenical until after its decrees have been approved by the pope. (See Vatican Council, Ultramontanism, Infallibility.)

The earlier oecumenical councils have well been called “the pitched battles of church history.” Summoned to combat heresy and schism, in spite of degrading pressure from without and tumultuous disorder within, they ultimately brought about a modicum of doctrinal agreement. On the one side as time went on they bound scholarship hand and foot in the winding-sheet of tradition, and also fanned the flames of intolerance; yet on the other side they fostered the sense of the Church’s corporate oneness. The diocesan and provincial synods have formed a valuable system of regularly recurring assemblies for disposing of ecclesiastical business. They have been held most frequently, however, in times of stress and of reform, for instance in the 11th, 16th and 19th centuries; at other periods they have lapsed into disuse: it is significant that to-day the prelate who neglects to convene them suffers no penalty. At present the main function of both provincial and oecumenical synods seems to be to facilitate obedience to the wishes of the central government of the Church.

The right to vote (votum definitivum) has been distinguished from early times from the right to be heard (votum consultativum). The Reform Synods of the 15th century gave a decisive vote to doctors and licentiates of theology and of laws, some of them sitting as individuals, some as representatives of universities. Roman Catholic canonists now confine the right to vote at oecumenical councils to bishops, cardinal deacons, generals or vicars general of monastic orders and the praelati nullius (exempt abbots, &c.); all other persons, lay or clerical, who are admitted or invited, have merely the votum consultativum—they are chiefly procurators of absent bishops, or very learned priests. It was but a clumsy and temporary expedient, designed to offset the preponderance of Italian bishops dependent on the pope 311 when the council of Constance subdivided itself into several groups or “nations,” each of which had a single vote. In voting, the simple majority decides; yet such is the importance attached to a unanimous verdict that an irreconcilable minority may absent itself from the final vote, as was the case at the Vatican Council.

The numbering of oecumenical synods is not fixed; the list most used in the Roman Church to-day is that of Hefele (Conciliengeschichte, 2nd ed., I. 59 f.):

| A.D. | ||

| 1. | Nicaea I. | 325 |

| 2. | Constantinople I. | 381 |

| 3. | Ephesus | 431 |

| 4. | Chalcedon | 451 |

| 5. | Constantinople II. | 553 |

| 6. | Constantinople III. | 680 |

| 7. | Nicaea II. | 787 |

| 8. | Constantinople IV. | 869 |

| 9. | Lateran I. | 1123 |

| 10. | Lateran II. | 1139 |

| 11. | Lateran III. | 1179 |

| 12. | Lateran IV. | 1215 |

| 13. | Lyons I. | 1245 |

| 14. | Lyons II. | 1274 |

| 15. | Vienne | 1311 |

| 16. | Constance (in part) | 1414-1418 |

| 17a. | Basel (in part) | 1431 ff. |

| 17b. | Ferrara-Florence (a continuation of Basel) | 1438-1442 |

| 18. | Lateran V. | 1512-1517 |

| 19. | Trent | 1545-1563 |

| 20. | Vatican | 1869-1870 |

(Each of these and certain other important synods are treated in separate articles.)

By including Pisa (1409) and by treating Florence as a separate synod, certain writers have brought the number of oecumenical councils up to twenty-two. These standard lists are of the type which became established through the authority of Cardinal R. F. Bellarmine (1542-1621), who criticized Constance and Basel, while defending Florence and the fifth Lateran council against the Gallicans. As late as the 16th century, however, “the majority did not regard those councils in which the Greek Church did not take part as oecumenical at all” (Harnack, History of Dogma, vi. 17). The Greek Church accepts only the first seven synods as oecumenical; and it reckons the Trullan synod of 692 (the Quinisextum) as a continuation of the sixth oecumenical synod of 680. But concerning the first seven councils it should be remarked that Constantinople I. was but a general synod of the East; its claim to oecumenicity rests upon its reception by the West about two centuries later. Similarly the only representatives of the West present at Constantinople II. were certain Africans; the pope did not accept the decrees till afterwards and they made their way in the West but gradually. Just as there have been synods which have come to be considered oecumenical though not convoked as such, so there have been synods which though summoned as oecumenical, failed of recognition: for instance Sardica (343), Ephesus (449), Constantinople (754). The last two received the imperial confirmation and from the legal point of view were no whit inferior to the others; their decrees, however, were overthrown by subsequent synods. As the Protestant leaders of the 16th century held fast the traditional christology, they regarded with veneration the dogmatic decisions of Nicaea I., Constantinople I., Ephesus and Chalcedon. These four councils had enjoyed a more or less fortuitous pre-eminence both in Roman and in canon law, and by many Catholics at the time of the Reformation were regarded, along with the three great creeds (Apostles’, Nicene, Athanasian), as a sort of irreducible minimum of orthodoxy. In the 17th century the liberal Lutheran George Calixtus based his attempts at reuniting Christendom on this consensus quinquesaecularis. Many other Protestants have accepted Constantinople II. and III. as supporting the first four councils; and still others, notably many Anglican high churchmen, have felt bound by all the oecumenical synods of the undivided Church. The common Protestant attitude toward synods is, however, that they may err and have erred, and that the Scriptures and not conciliar decisions are the sole infallible standard of faith, morals and worship.

Protestant Councils.—The churches of the Reformation have all had a certain measure of synodal life. The Church of England has maintained its ancient provincial synods or convocations, though for the greater part of the 18th and the first part of the 19th centuries they transacted no business. In the Lutheran churches of Germany there was no strong agitation in favour of introducing synods until the 19th century, when a movement, designed to render the churches less dependent on the governmental consistories, won its way, until at length Prussia itself fell into line (1873 and 1876). As the powers granted to the German synods are very limited, many of their advocates have been disillusioned; but the Lutheran churches of America, being independent of the state, have developed synods both numerous and potent. In the Reformed churches outside Germany synodal life is vigorous; its forms were developed by the Huguenots in days of persecution, and passed thence to Scotland and other presbyterian countries. Even many of the churches of congregational polity have organized national councils (see Congregationalism); but here the principle of the independence of the local church prevents the decisions from binding those congregations which do not approve of the decrees. Moreover, in the last decade of the 19th century a growing desire for a rapprochement between the Free Churches in the United Kingdom as a whole led to the annual assembly of the Free Church Council for the consideration of all matters affecting the dissenting bodies. This body has no executive or doctrinal authority and is rather a conference than a council. In general it may be said that synods are becoming more and more powerful in Protestant lands, and that they are destined to still greater prominence because of the growing sentiment for Christian unity.

Authorities.—General Collections: Collectio regia (Paris, 1644, 37 vols.) (the first very extensive work); P. Labbe (not Labbé) and G. Cossart, Sacrosancta concilia (Paris, 1672, 17 vols.), with supplement by Étienne Baluze (Baluzius), 1683 (based on above); J. Hardouin (Harduinus), Conciliorum collectio regia maxima (Paris, 1715), 11 tomi in 12 vols, (to 1714; more exact; indexed; serious omissions); enlarged edition by N. Coletus (Venice, 1728-1732), supplemented by J. D. Mansi, Sanctorum conciliorum et decretorum nova collectio (Lucca, 1748, 6 tomi). Convenient but fallible is Mansi’s Sacrorum conciliorum et decretorum nova et amplissima collectio (Florence, 1759-1767; completed Venice, 1769-1798, 31 vols.); facsimile reproduction by Welter (Paris, 1901 ff.), adding (tom. O) Introductio seu apparatus ad sacrosancta concilia, and (tom. 17B and 18B) Baluze, Capitularia regum Francorum, and continuing to date by reproducing parts of Coletus and of Mansi’s supplement to Coletus, and furnishing (tom. 37 ff.) a new edition of the councils from 1720 on by J. B. Martin and L. Petit. A careful text of Roman Catholic synods from 1682 to 1870 is Collectio Lacensis (Acta et decreta sacrorum conciliorum recentiorum, Friburgi, 1870 ff.), 7 vols.

Special Collections: Great Britain: Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae, ed. D. Wilkins (London, 1737, 4 vols.); Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents relating to Great Britain and Ireland, ed. by A. W. Haddan and W. Stubbs (Oxford, 1869 ff., 4 vols.); J. W. Joyce, Handbook of the Convocations or Provincial Synods of the Church of England (London, 1887); Concilia Scotiae (1225-1559), ed. Joseph Robertson (Edinburgh, Bannatyne Club, 1866, 2 tom.).

United States: Collectio Lacensis (Roman Catholic synods); The American Church History Series (New York, 1893 ff. 13 vols.) gives information on the various Protestant synods.

France.—Concilia aevi Merovingici, rec. F. Maassen (Hanover, 1893) (Monumenta Germaniae historica, Legum sectio iii., Concilia, tom. i.); Concilia antiqua Galliae, cur. J. Sirmond (Paris, 1629, 3 vols.); supplement by P. de la Lande (Paris, 1666); L. Odespun, Concilia novissima Galliae (Paris, 1646); Conciliorum Galliae tam editorum quam ineditorum, stud. congreg. S. Mauri, tom. i. (Paris, 1789). Synods of the Reformed Churches of France are contained in J. Quick, Synodicon in Gallia reformata (London, 1692, 2 vols.); J. Aymon, Tous les synodes nationaux des églises réformées de France (La Haye, 1710, 2 vols.); E. Hugues, Les Synodes du désert (Paris, 1885 f., 3 vols.). For the synods of other countries see Herzog-Hauck, 3rd ed., 19,262 f., and Wetzer and Welte, 2nd ed., 3809 f.

Less Elaborate Texts: Canones apostolorum et conciliorum saeculorum, iv.-vii., rec. H. T. Bruns (Berlin, 1839, 2 vols.) (still useful); J. Fulton, Index Canonum (3rd ed., New York, 1892) (3rd and 4th centuries); W. Bright, Notes on the Canons of the First Four General Councils (2nd ed., Oxford, 1892); Die Kanones der 312 wichtigsten altkirchlichen Conzilien nebst den apostolischen Kanones, ed. F. Lauchert (Freiburg i. B., 1896); Enchiridion symbolorum et definitionum, quae de rebus fidei et morum a conciliis oecumenicis et summis pontificibus emanarunt, ed. H. Denzinger (7th ed., Würzburg, 1895); Bibliothek der Symbole und Glaubensregeln der alten Kirche, ed. by A. Hahn (3rd edition, revised and enlarged, Breslau, 1897), with variant readings; C. Mirbt, Quellen zur Geschichte des Papsttums und des römischen Katholizismus (2nd much enlarged ed., Tübingen, 1901); E. F. Karl Müller, Die Bekenntnisschriften der reformierten Kirche (Leipzig, 1903) (for all countries). These last five are elaborately indexed.

Translations: John Johnson, A Collection of the Laws and Canons of the Church of England [601-1519], 2 parts (London, 1720; reprinted Oxford, 1850 f., in the Library of Anglo-Catholic Theology); P. Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom (New York, 1877, 3 vols.) (texts and translations parallel); Canons and Creeds of the First Four Councils, ed. by E. K. Mitchell, in Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History, published by the Department of History of the University of Pennsylvania, vol. iv. 2 (1897); H. R. Percival, The Ecumenical Councils (New York, 1900) (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, second series, vol. xiv.; translates canons and compiles notes; bibliography in Introduction).

General Histories of Councils: C. J. von Hefele, Conciliengeschichte (Freiburg i. B., 1855); English translation of the earlier volumes to A.D. 787, from A.D. 326 on, based on the second German edition (Edinburgh, 1871 ff.); French, by Delarc (Paris, 1869-1874, 10 vols.). This first edition not entirely superseded by the second, made after the Vatican council, and continued by Knöpfler and by Hergenröther (Freiburg, 1873-1890, 9 vols.); a French translation, with continuation and critical and bibliographical notes, par un religieux bénédictin de Farnborough, tome i. 1re partie (Paris, Létouzey, 1907); Paul Viollet, Examen de l’histoire des conciles de Mgr Hefele (Paris, 1876) (Extrait de la Revue historique); W. P. du Bose, The Ecumenical Councils (New York, 1896) (popular); P. Guérin, Les Conciles généraux et particuliers (Paris, 1868, 3rd impression, 1897, 3 tom.); see also A. Harnack, History of Dogma (Boston, 1895-1900, 7 vols.); F. Loofs, Leitfaden der Dogmengeschichte (4th ed., enlarged, Halle, 1906).

Literature: Dictionnaire universel et complet des conciles, rédigé par A. C. Peltier, publié par Migne (Paris, 1847, 2 vols.) (Migne, Encyclopédie théologique, vol. 13 f.); Z. Zitelli-Natali, Epitome historico-canonica conciliorum generalium (Rome, 1881); F. X. Kraus, Realencyklopädie der christlichen Altertümer, vol. i. (Freiburg-i.-B., 1882) (art. “Concilien” by Funk); William Smith and S. Cheetham, Dictionary of Christian Antiquities (London, 1876-1880, 2 vols.) (erudite detail); Wetzer und Welte’s Kirchenlexikon, 2nd ed. by Hergenröther and Kaulen (Freiburg i. B., 1882-1903, 13 vols.) (art. “Concil” by Scheeben); La Grande Encyclopédie (Paris, s.d., 31 vols.) (numerous articles); P. Hinschius, Das Kirchenrecht der Katholiken und Protestanten in Deutschland, vol. 3 (Berlin, 1883) (fundamental and masterly); R. von Scherer, Handbuch des Kirchenrechtes, vol. i. (Graz, 1886) (excellent notes and references); E. H. Landon, A Manual of Councils of the Holy Catholic Church, (revised ed., London, [1893], 2 vols.) (paraphrases chief canons; needs revision); Martigny, Dictionnaire des antiquités chrétiennes (3rd ed., Paris, 1889) (for ceremonial); R. Sohm, Kirchenrecht, vol. i. (Leipzig, 1892) (brilliant); A. Kneer, Die Entstehung der konziliaren Theorie (Rome, 1893); Realencyklopädie für protestantische Theologie und Kirche, begründet von J. J. Herzog, 3rd revised ed. by A. Hauck (Leipzig, 1896 ff.) (in vol. 19 Hauck’s excellent Synoden, 1907); F. X. Funk, Kirchengeschichtliche Abhandlungen und Untersuchungen (Paderborn, 1897); A. V. G. Allen, Christian Institutions (New York, 1897), chap. xi.; C. A. Kneller, “Papst und Konzil im ersten Jahrtausend” (Zeitschrift für katholische Theologie, vols. 27 and 28, Innsbruck, 1893 f.); F. Bliemetzrieder, Das Generalkonzil im grossen abendländischen Schisma (Paderborn, 1904); Wilhelm and Scannell, Manual of Catholic Theology (3rd ed., London, 1906, sect. 32); J. Forget, “Conciles,” in A. Vacant and E. Mangeot, Dictionnaire de théologie catholique, tome 3, 636-676 (Paris, 1906 ff.), with elaborate bibliography; The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York, 1907 ff.).

1 For the Greek Council see Boule; for the Hebdomadal Council see Oxford; see also England: Local Government.

2 From ἡ οἰκουμἐνη (γῆ). the inhabited world; Latin oecumenicus or universalis. The English forms “oecumenical” and “ecumenical” are both used.

COUNCIL BLUFFS, a city and the county-seat of Pottawattamie county, Iowa, U.S.A., about 2½ m. E. of the Missouri river opposite Omaha, Nebraska, with which it is connected by a road bridge and two railway bridges. Pop. (1890) 21,474; (1900) 25,802, of whom 3723 were foreign-born; (1910) 29,292. It is pre-eminently a railway centre, being served by the Union Pacific, of which it is the principal eastern terminus, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, the Chicago, Milwaukee & Saint Paul, the Chicago & Northwestern, the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific, the Chicago Great-Western, the Illinois Central, and the Wabash, which together have given it considerable commercial importance. It is built for the most part on level ground at the foot of high bluffs; and has several parks, the most attractive of which, commanding fine views, is Fairmount Park. With the exception of bricks and tiles, carriages and wagons, agricultural implements, and the products of its railway shops, its manufactures are relatively unimportant, the factory product in 1905 being valued at only $1,924,109. Council Bluffs is the seat of the Western Iowa Business College, and of the Iowa school for the deaf. On or near the site of Council Bluffs, in 1804, Lewis and Clark held a council with the Indians, whence the city’s name. In 1838 the Federal government made this the headquarters of the Pottawattamie Indians, removed from Missouri. They remained until 1846-1847, when the Mormons came, built many cabins, and named the place Kanesville. The Mormons remained only about five years, but on their departure for Utah their places were speedily taken by new immigrants. During 1849-1850 Council Bluffs became an important outfitting point for California gold seekers—the goods being brought by boat from Saint Louis—and in 1853 it was incorporated as a city.

COUNSEL AND COUNSELLOR, one who gives advice, more particularly in legal matters. The term “counsel” is employed in England as a synonym for a barrister-at-law, and may refer either to a single person who pleads a cause, or collectively, to the body of barristers engaged in a case. Counsellor or, more fully, counsellor-at-law, is practically an obsolete term in England, but is still in use locally in Ireland as an equivalent to barrister. In the United States, a counsellor-at-law is, specifically, an attorney admitted to practice in all the courts; but as there is no formal distinction of the legal profession into two classes, as in England, the term is more often used loosely in the same sense as “lawyer,” i.e. one who is versed in, or practises law.

COUNT (Lat. comes, gen. comitis, Fr. comte, Ital. conte, Span. conde), the English translation of foreign titles equivalent generally to the English “earl.”1 In Anglo-French documents the word counte was at all times used as the equivalent of earl, but, unlike the feminine form “countess,” it did not find its way into the English language until the 16th century, and then only in the sense defined above. The title of earl, applied by the English to the foreign counts established in England by William the Conqueror, is dealt with elsewhere (see Earl). The present article deals with (1) the office of count in the Roman empire and the Frankish kingdom, (2) the development of the feudal count in France and under the Holy Roman Empire, (3) modern counts.

1. The Latin comes meant literally a companion or follower. In the early Roman empire the word was used to designate the companions of the emperor (comites principis) and so became a title of honour. The emperor Hadrian chose senators as companions on his travels and to help him in public business. They formed a permanent council, and Hadrian’s successors entrusted these comites with the administration of justice and finance, or placed them in military commands. The designation comes thus developed into a formal official title of high officers of state, some qualification being added to indicate the special duties attached to the office in each case. Thus in the 5th century, among the comites attached to the emperor’s establishment, we find, e.g., the comes sacrarum largitionum and the comes rei privatae; while others, forming the council, were styled comites consistorii. Others were sent into the provinces as governors, comites per provincias constituti; thus in the Notitia dignitatum we find a comes Aegypti, a comes Africae, a comes Belgicae, a comes Lugdunensis and others. Two of the generals of the Roman province of Britain were styled the comes Britanniae and the comes littoris Saxonici (count of the Saxon shore).

At Constantinople in the latter Roman empire the Latin word comes assumed a Greek garb as κόμης and was declined as a Greek noun (gen. κόμητος); the comes sacrarum largitionum (count of the sacred bounties) was called at Constantinople ὁ κόμης τῶν σακρῶν λαργιτιώνων and the comes rerum privatarum 313 (count of the private estates) was called κόμης τῶν πριβάτων. The count of the sacred bounties was the lord treasurer or chancellor of the exchequer, for the public treasury and the imperial fisc had come to be identical; while the count of the private estates managed the imperial demesnes and the privy purse. In the 5th century the “sacred bounties” corresponded to the aerarium of the early Empire, while the res privatae represented the fisc. The officers connected with the palace and the emperor’s person included the count of the wardrobe (comes sacrae vestis), the count of the residence (comes domorum), and, most important of all, the comes domesticorum et sacri stabuli (graecized as κόμης τοῦ στάβλου). The count of the stable, originally the imperial master of the horse, developed into the “illustrious” commander-in-chief of the imperial army (Stilicho, e.g., bore the full title as given above), and became the prototype of the medieval constable (q.v.).

An important official of the second rank (spectabilis, “respectable” as contrasted with those of highest rank who were “illustrious”) was the count of the East, who appears to have had the control of a department in which 600 officials were engaged. His power was reduced in the 6th century, when he was deprived of his authority over the Orient diocese, and became civil governor of Syria Prima, retaining his “respectable” rank. Another important officer of the later Roman court was the comes sacri patrimonii, who was instituted by the emperor Anastasius. In this connexion it should be observed that the word patrimonium gradually changed in meaning. In the beginning of the 3rd century patrimonium meant crown property, and res privata meant personal property: at the beginning of the 6th century patrimonium meant personal property, and res privata meant crown property. It is difficult to give briefly a clear idea of the functions of the three important officials comes sacrarum largitionum, comes rei privatae and comes sacri patrimonii; but the terms have been well translated by a German author as Finanzminister des Reichsschatzes (finance minister of the treasury of the Empire), F. des Kronschatzes (of the crown treasury), and F. des kaiserlichen Privatvermögens (of the emperor’s private property).

The Frankish kings of the Merovingian dynasty retained the Roman system of administration, and under them the word comes preserved its original meaning; the comes was a companion of the king, a royal servant of high rank. Under the early Frankish kings some comites did not exercise any definite functions; they were merely attached to the king’s person and executed his orders. Others filled the highest offices, e.g. the comes palatii and comes stabuli (see Constable). The kingdom was divided for administrative purposes into small areas called pagi (pays, Ger. Gau), corresponding generally to the Roman civitates (see City).2 At the head of the pagus was the comes, corresponding to the German Graf (Gaugraf, cf. Anglo-Saxon scire-gerefa,3 sheriff). The comes was appointed by the king and removable at his pleasure, and was chosen originally from all classes, sometimes from enfranchised slaves. His essential functions were judicial and executive, and in documents he is often described as the king’s agent (agens publicus) or royal judge (judex publicus or fiscalis). As the delegate of the executive power he had the right to military command in the king’s name, and to take all the measures necessary for the preservation of the peace, i.e. to exercise the royal “ban” (bannus regis). He was at once public prosecutor and judge, was responsible for the execution of the sentences of the courts, and as the king’s representative exercised the royal right of protection (mundium regis) over churches, widows, orphans and the like. He enjoyed a triple wergeld, but had no definite salary, being remunerated by the receipt of certain revenues, a system which contained the germs of discord, on account of the confusion of his public and private estates. He also retained a third of the fines which he imposed in his judicial capacity.

Under the early Carolings the title count did not indicate noble birth. A comes was generally raised from childhood in the king’s palace, and rose to be a count through successive stages. The count’s office was not yet a dignity, nor hereditary; he was not independent nor appointed for life, but exercised the royal power by delegation, as under the Merovingians. While, however, he was theoretically paid by the king, he seems to have been himself one of the sources of the royal revenue. The counties were, it appears, farmed out; but in the 7th century the royal choice became restricted to the larger landed proprietors, who gradually emancipated themselves from royal control, and in the 8th century the term comitatus begins to denote a geographical area, though there was little difference in its extent under the Merovingian kings and the early Carolings. The count was about to pass into the feudatory stage. Throughout the middle ages, however, the original official and personal connotation of the title was never wholly lost; or perhaps it would be truer to say, with Selden, that it was early revived with the study of the Roman civil law in the 12th century. The unique dignity of count of the Lateran palace,4 bestowed in 1328 by the emperor Louis IV. the Bavarian on Castrucio de’ Antelminelli, duke of Lucca, and his heirs male, was official as well as honorary, being charged with the attendance and service to be performed at the palace at the emperor’s coronation at Rome (Du Cange, s.v. Comites Palatii Lateranensis; Selden, op. cit. p. 321). This instance, indeed, remained isolated; but the personal title of “count palatine,” though honorary rather than official, was conferred on officials—especially by the popes on those of the Curia—had no territorial significance, and was to the last reminiscent of those early comites palatii whose relations to the sovereign had been purely personal and official (see Palatine). A relic of the old official meaning of “count” still survives in Transylvania, where the head of the political administration of the Saxon districts is styled count (comes, Graf) of the Saxon Nation.

2. Feudal Counts.—The process by which the official counts were transformed into feudal vassals almost independent is described in the article Feudalism. In the confusion of the period of transition, when the title to possession was usually the power to hold, designations which had once possessed a definite meaning were preserved with no defined association. In France, by the 10th century, the process of decomposition of the old organization had gone far, and in the 11th century titles of nobility were still very loosely applied. That of “count” was, as Luchaire points out, “equivocal” even as late as the 12th century; any castellan of moderate rank could style himself comte who in the next century would have been called seigneur (dominus). Even when, in the 13th century, the ranks of the feudal hierarchy in France came to be more definitely fixed, the style of “count” might imply much, or comparatively little. In the oldest register of Philip Augustus counts are reckoned with dukes in the first of the five orders into which the nobles are divided, but the list includes, besides such almost sovereign rulers as the counts of Flanders and Champagne, immediate vassals of much less importance—such as the counts of Soissons and Dammartin—and even one mediate vassal, the count of Bar-sur-Seine. The title was still in fact “equivocal,” and so it remained throughout French history. In the official lists it was early placed second to that of duke (Luchaire, Manuel, p. 181, note 1), but in practice at least the great comtes-pairs (e.g. of Champagne) were the equals of any duke and the superiors of many. Thus, too, in modern times royal princes have been given the title of count (Paris, Flanders, Caserta), the heir of Charles X. actually changing his style, without sense of loss, from that of duc de Bordeaux to that of comte de Chambord. From the 16th 314 century onwards the equivocal nature of the title in France was increased by the royal practice of selling it, either to viscounts or barons in respect of their fiefs, or to rich roturiers.

In Germany the change from the official to the territorial and hereditary counts followed at the outset much the same course as in France, though the later development of the title and its meaning was different. In the 10th century the counts were permitted by the kings to divide their benefices and rights among their sons, the rule being established that countships (Grafschaften) were hereditary, that they might be held by boys, that they were heritable by females and might even be administered by females. The Grafschaft became thus merely a bundle of rights inherent in the soil; and, the count’s office having become his property, the old counties or Gauen rapidly disappeared as administrative units, being either amalgamated or subdivided. By the second half of the 12th century the official character of the count had quite disappeared; he had become a territorial noble, and the foundation had been laid of territorial sovereignty (Landeshoheit). The first step towards this was the concession to the counts of the military prerogatives of dukes, a right enjoyed from the first by the counts of the marches (see Margrave), then given to counts palatine (see Palatine) and, finally, to other counts, who assumed by reason of it the style of landgrave (Landgraf, i.e. count of a province). At first all counts were reckoned as princes of the Empire (Reichsfürsten); but since the end of the 12th century this rank was restricted to those who were immediate tenants of the crown,5 the other counts of the Empire (Reichsgrafen) being placed among the free lords (barones, liberi domini). Counts of princely rank (gefürstete Grafen) voted among the princes in the imperial diet; the others (Reichsgrafen) were grouped in the Grafenbänke—originally two, to which two more were added in the 17th century—each of which had one vote. In 1806, on the formation of the Confederation of the Rhine, the sovereign counts were all mediatized (see Mediatization). Even before the end of the Empire (1806) the right of bestowing the title of count was freely exercised by the various German territorial sovereigns.

3. Modern Counts.—Any political significance which the feudal title of count retained in the 18th century vanished with the changes produced by the Revolution. It is now simply a title of honour and one, moreover, the social value of which differs enormously, not only in the different European countries, but within the limits of the same country. In Germany, for instance, there are several categories of counts: (1) the mediatized princely counts (gefürstete Grafen), who are reckoned the equals in blood of the European sovereign houses, an equality symbolized by the “closed crown” surmounting their armorial bearings. The heads of these countly families of the “high nobility” are entitled (by a decree of the federal diet, 1829) to the style of Erlaucht (illustrious, most honourable); (2) Counts of the Empire6 (Reichsgrafen), descendants of those counts who, before the end of the Holy Roman Empire (1806), were Reichsständisch i.e. sat in one of the Grafenbänke in the imperial diet, and entitled to a ducal coronet; (3) Counts (a) descended from the lower nobility of the old Empire, titular since the 15th century, (b) created since; their coronet is nine-pointed (cf. the nine points and strawberry leaves of the English earl). The difficulty of determining in any case the exact significance of the title of a German count, illustrated by the above, is increased by the fact that the title is generally heritable by all male descendants, the only exception being in Prussia, where, since 1840, the rule of primogeniture has prevailed and the bestowal of the title is dependent on a rent-roll of £3000 a year. The result is that the title is very widespread and in itself little significant. A German or Austrian count may be a wealthy noble of princely rank, a member of the Prussian or Austrian Upper House, or he may be the penniless cadet of a family of no great rank or antiquity. Nevertheless the title, which has long been very sparingly bestowed, always implies a good social position. The style Altgraf (old count), occasionally found, is of some antiquity, and means that the title of count has been borne by the family from time immemorial.

In medieval France the significance of the title of count varied with the power of those who bore it; in modern France it varies with its historical associations. It is not so common as in Germany or Italy; because it does not by custom pass to all male descendants. The title was, however, cheapened by its revival under Napoleon. By the decree of the 1st of March 1808, reviving titles of nobility, that of count was assigned ex officio to ministers, senators and life councillors of state, to the president of the Corps Législatif and to archbishops. The title was made heritable in order of primogeniture, and in the case of archbishops through their nephews. These Napoleonic countships, increased under subsequent reigns, have produced a plentiful crop of titles of little social significance, and have tended to lower the status of the counts deriving from the ancien régime. The title of marquis, which Napoleon did not revive, has risen proportionately in the estimation of the Faubourg St Germain. As for that of count, it is safe to say that in France its social value is solely dependent on its historical associations.

Of all European countries Italy has been most prolific of counts. Every petty Italian prince, from the pope downwards, created them for love or money; and, in the absence of any regulating authority, the title was also widely and loosely assumed, while often the feudal title passed with the sale of the estate to which it was attached. Casanova remarked that in some Italian cities all the nobles were baroni, in others all were conti. An Italian conte may or may not be a gentleman; he has long ceased, qua count, to have any social prestige, and his rank is not recognized by the Italian government. As in France, however, there are some Italian conti whose titles are respectable, and even illustrious, from their historic associations. The prestige belongs, however, not to the title but to the name. As for the papal countships, which are still freely bestowed on those of all nations whom the Holy See wishes to reward, their prestige naturally varies with the religious complexion of the country in which the titles are borne. They are esteemed by the faithful, but have small significance for those outside. In Spain, on the other hand, the title of conde, the earlier history of which follows much the same development as in France, is still of much social value, mainly owing to the fact that the rule of primogeniture exists, and that, a large fee being payable to the state on succession to a title, it is necessarily associated with some degree of wealth. The Spanish counts of old creation, some of whom are grandees and members of the Upper House, naturally take the highest rank; but the title, still bestowed for eminent public services or other reasons, is of value. The title, like others in Spain, can pass through an heiress to her husband. In Russia the title of count (graf, fem. grafinya), a foreign importation, has little social prestige attached to it, being given to officials of a certain rank. In the British empire the only recognized counts are those of Malta, who are given precedence with baronets of the United Kingdom.

See Selden, Titles of Honor (London, 1672); Du Cange, Glossarium Med. Lat. (ed. Niort, 1883) s.v. “Comes”; La Grande Encyclopédie, s.v. “Comte”; A. Luchaire, Manuel des institutions françaises (Paris, 1892); P. Guilhiermoz, Essai sur l’origine de la noblesse en France au moyen âge (Paris, 1902); Brunner, Deutsche Rechtsgeschichte, Band ii. (Leipzig, 1892).

1 The exact significance of a title is difficult to reproduce in a foreign language. Actually, only some foreign counts could be said to be equivalent to English earls; but “earl” is always translated by foreigners by words (comte, Graf) which in English are represented by “count,” itself never used as the synonym of “earl.” Conversely old English writers had no hesitation in translating as “earl” foreign titles which we now render “count.”

2 The changing language of this epoch speaks of civitates, subsequently of pagi, and later of comitatus (counties).

3 The A.S. gerefa, however, meaning “illustrious,” “chief,” has apparently, according to philologists, no connexion with the German Graf, which originally meant “servant” (cf. “knight,” “valet,” &c.). It is the more curious that the gerefa should end as a servant (“reeve”), the Graf as a noble (count).

4 “Count of the Lateran Palace” (Comes Sacri Lateranensis Palatii) was later the title usually bestowed by the popes in creating counts palatine. The emperors, too, continued to make counts palatine under this title long after the Lateran had ceased to be an imperial palace.

5 Of these there were four who, as counts of the Empire par excellence, were sometimes styled “simple counts” (Schlechtgrafen), i.e. the counts of Cleves, Schwarzburg, Cilli and Savoy; they were entitled to the ducal coronet. Three of these had become dukes by the 17th century, but the count (now prince) of Schwarzburg still styled himself “Of the four counts of the Holy Roman Empire, count of Schwarzburg” (see Selden, ed. 1672, p. 312).

6 This title is borne by certain English families, e.g. by Lord Arundell of Wardour. In other cases it has been assumed without due warrant. See J. H. Round, “English Counts of the Empire,” in The Ancestor, vii. 15 (Westminster, October 1903).

COUNTER. (1) (Through the O. Fr. conteoir, modern comptoir, from Lat. computare, to reckon), a round piece of metal, wood or other material used anciently in making calculations, and now for reckoning points in games of cards, &c., or as tokens representing actual coins or sums of money in gambling games such as roulette. The word is thus used, figuratively, of something of no real value, a sham. In the original sense of “a means of counting money, 315 or keeping accounts,” “counter” is used of the table or flat-topped barrier in a bank, merchant’s office or shop, on which money is counted and goods handed to a customer. The term was also applied, usually in the form “compter,” to the debtors’ prisons attached to the mayor’s or sheriff’s courts in London and some other boroughs in England. The “compters” of the sheriff’s courts of the city of London were, at various times, in the Poultry, Bread St., Wood St. and Giltspur St.; the Giltspur St. compter was the last to be closed, in 1854. (2) (From Lat. contra, opposite, against), a circular parry in fencing, and in boxing, a blow given as a parry to a lead of an opponent. The word is also used of the stiff piece of leather at the back of a boot or shoe, of the rounded angle at the stern of a ship, and, in a horse, of the part lying between the shoulder and the under part of the neck. In composition, counter is used to express contrary action, as in “countermand,” “counterfeit,” &c.

COUNTERFEITING (from Lat. contra-facere, to make in opposition or contrast), making an imitation without authority and for the purpose of defrauding. The word is more particularly used in connexion with the making of imitations of money, whether paper or coin. (See Coinage Offences; Forgery.)

COUNTERFORT (Fr. contrefort), in architecture, a buttress or pier built up against the wall of a building or terrace to strengthen it, or to resist the thrust of an arch or other constructional feature inside.

COUNTERPOINT (Lat. contrapunctus, “point counter point,” “note against note”), in music, the art happily defined by Sir Frederick Gore Ouseley as that “of combining” melodies: this should imply that good counterpoint is the production of beautiful harmony by a combination of well-characterized melodies. The individual audibility of the melodies is a matter of which current criticism enormously overrates the importance. What is always important is the peculiar life breathed into harmony by contrapuntal organization. Both historically and aesthetically “counterpoint” and “harmony” are inextricably blended; for nearly every harmonic fact is in its origin a phenomenon of counterpoint. And if in later musical developments it becomes possible to treat chords as, so to speak, harmonic lumps with a meaning independent of counterpoint, this does not mean that they have really changed their nature; but it shows a difference between modern and earlier music precisely similar to that between modern English, in which metaphorical and abstract expressions are so constantly used that they have become a mere shorthand for the literal and concrete expression, and classical Greek, where metaphors and abstractions can appear only as elaborate similes or explicit philosophical ideas. The laws of counterpoint are, then, laws of harmony with the addition of such laws of melody as are not already produced by the interaction of harmonic and melodic principles. In so far as the laws of counterpoint are derived from purely harmonic principles, that is to say, derived from the properties of concord and discord, their origin and development are discussed in the article Harmony. In so far as they depend entirely on melody they are too minute and changeable to admit of general discussion; and in so far as they show the interaction of melodic and harmonic principles it is more convenient to discuss them under the head of harmony, because they appear in such momentary phenomena as are more easily regarded as successions of chords than as principles of design. All that remains, then, for the present article is the explanation of certain technical terms.

1. Canto Fermo (i.e. plain chant) is a melody in long notes given to one voice while others accompany it with quicker counterpoints (the term “counterpoint” in this connexion meaning accompanying melodies). In the simplest cases the Canto Fermo has notes of equal length and is unbroken in flow. When it is broken up and its rhythm diversified, the gradations between counterpoint on a Canto Fermo and ordinary forms of polyphony, or indeed any kind of melody with an elaborate accompaniment, are infinite and insensible.

2. Double Counterpoint is a combination of melodies so designed that either can be taken above or below the other. When this change of position is effected by merely altering the octave of either or both melodies (with or without transposition of the whole combination to another key), the artistic value of the device is simply that of the raising of the lower melody to the surface. The harmonic scheme remains the same, except in so far as some of the chords are not in their fundamental position, while others, not originally fundamental, have become so. But double counterpoint may be in other intervals than the octave; that is to say, while one of the parts remains stationary, the other may be transposed above or below it by some interval other than an octave, thus producing an entirely different set of harmonies.

Double Counterpoint in the 12th has thus been made a powerful means of expression and variety. The artistic value of this device depends not only on the beauty and novelty of the second scheme of harmony obtained, but also on the change of melodic expression produced by transferring one of the melodies to another position in the scale. Two of the most striking illustrations of this effect are to be found in the last chorus of Brahms’s Triumphlied and in the fourth of his variations on a theme by Haydn.

Double Counterpoint in the 10th has, in addition to this, the property that the inverted melody can be given in the new and in the original positions simultaneously.

Double counterpoint in other intervals than the octave, 10th and 12th, is rare, but the general principle and motives for it remain the same under all conditions. The two subjects of the Confiteor in Bach’s B minor Mass are in double counterpoint in the octave, 11th and 13th. And Beethoven’s Mass in D is full of pieces of double counterpoint in the inversions of which a few notes are displaced so as to produce momentary double counterpoint in unusual intervals, obviously with the intention of varying the harmony. Technical treatises are silent as to this purpose, and leave the student in the belief that the classical composers used these devices, if at all, in a manner as meaningless as the examples in the treatises.

3. Triple, Quadruple and Multiple Counterpoint.—When more than two melodies are designed so as to combine in interchangeable positions, it becomes increasingly difficult to avoid chords and progressions of which some inversions are incorrect. In triple counterpoint this difficulty is not so great; although a complete triad is dangerous, as it is apt to invert as a “6/46⁄4” which requires careful handling. On the other hand, in triple counterpoint the necessity for strictness is at its greatest, because there are only six possible inversions, and in a long polyphonic work most of these will be required. Moreover, the artistic value of the device is at its highest in three-part polyphonic harmony, which, whether invertible or not, is always a fine test of artistic economy, while the inversions are as evident to the ear, especially where the top part is concerned, as those in double counterpoint. Triple counterpoint (and a fortiori multiple counterpoint) is normally possible only at the octave; for it will be found that if three parts are designed to invert in some other interval this will involve two of them inverting in a third interval which will give rise to incalculable difficulty. This makes the fourth of Brahms’s variations on a theme of Haydn almost miraculous. The plaintive expression of the whole variation is largely due to the fact that the flowing semiquaver counterpoint below the main theme is on each repeat inverted in the 12th, with the result that its chief emphasis falls upon the most plaintive parts of the scale. But in the first eight bars of the second part of the variation a third contrapuntal voice appears, and this too is afterwards inverted in the 12th, with perfectly natural and smooth effect. But this involves the inversion of two of the counterpoints with each other in the 9th, a kind of double counterpoint which is almost impossible. The case is unique, but it admirably illustrates the difference between artistic and merely academic mastery of technical resource.

Quadruple Counterpoint is not rare with Bach. It would be more difficult than triple, but for the fact that of its twenty-four possible inversions not more than four or five need be correct. Quintuple counterpoint is admirably illustrated in the finale of Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony, in which everything in the successive statement and gradual development of the five themes conspires 316 to give the utmost effect to their combination in the coda. Of course Mozart has not room for more than five of the 120 possible combinations, and from these he selects such as bring fresh themes into the outside parts, which are the most clearly audible. Sextuple Counterpoint may be found in Bach’s great double chorus, Nun ist das Heil, and in the finale of his concerto for three claviers in C, and probably in other places.

4. Added Thirds and Sixths.—An easy and effective imitation of triple and quadruple counterpoint, embodying much of the artistic value of inversion, is found in the numerous combinations of themes in thirds and sixths which arise from an extension of the principle which we mentioned in connexion with double counterpoint in the 10th, namely, the possibility of performing it in its original and inverted positions simultaneously. The Pleni sunt coeli of Bach’s B minor Mass is written in this kind of transformation of double into quadruple counterpoint; and the artistic value of the device is perhaps never so magnificently realized as in the place, at bar 84, where the trumpet doubles the bass three octaves and a third above while the alto and second tenor have the counter subjects in close thirds in the middle.

Almost all other contrapuntal devices are derived from the principle of the canon and are discussed in the article Contrapuntal Forms.

As a training in musical grammar and style, the rhythms of 16th-century polyphony were early codified into “the five species of counterpoint” (with various other species now forgotten) and practised by students of composition. The classical treatise on which Haydn and Beethoven were trained was Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum (1725). This was superseded in the 19th century by Cherubini’s, the first of a long series of attempts to bring up to date as a dead language what should be studied in its original and living form.

COUNTERSCARP ( = “opposite scarp,” Fr. contrescarpe), a term used in fortification for the outer slope of a ditch; see Fortification and Siegecraft.

COUNTERSIGN, a military term for a sign, word or signal previously arranged and required to be given by persons approaching a sentry, guard or other post. In some armies the “countersign” is strictly the reply of the sentry to the pass-word given by the person approaching.

COUNTRY (from the Mid. Eng. contre or contrie, and O. Fr. cuntrée; Late Lat. contrata, showing the derivation from contra, opposite, over against, thus the tract of land which fronts the sight, cf. Ger. Gegend, neighbourhood), an extent of land without definite limits, or such a region with some peculiar character, as the “black country,” the “fen country” and the like. The extension from such descriptive limitation to the limitation of occupation by particular owners or races is easy; this gives the common use of the word for the land inhabited by a particular nation or race. Another meaning is that part of the land not occupied by towns, “rural” as opposed to “urban” districts; this appears too in “country-house” and “country town”; so too “countryman” is used both for a rustic and for the native of a particular land. The word appears in many phrases, in the sense of the whole population of a country, and especially of the general body of electors, as in the expression “go to the country,” for the dissolution of parliament preparatory to a general election.