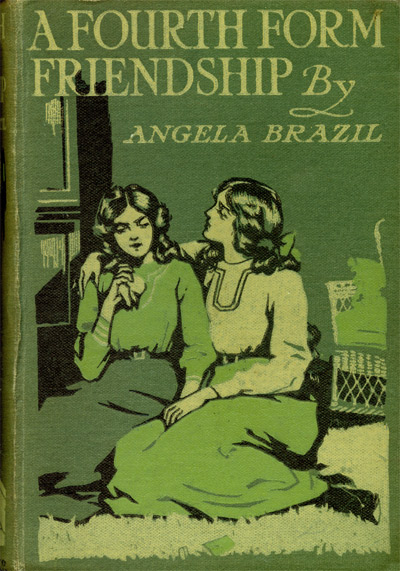

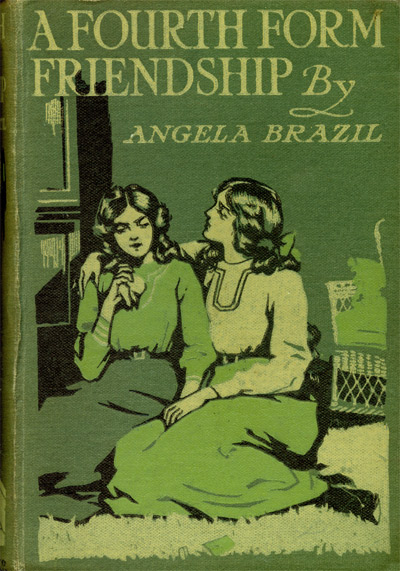

Title: A Fourth Form Friendship: A School Story

Author: Angela Brazil

Illustrator: Frank Wiles

Release date: May 25, 2010 [eBook #32524]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

"Angela Brazil has proved her undoubted talent for writing a story of schoolgirls for other schoolgirls to read."—Bookman.

The Madcap of the School.

"A capital school story, full of incident and fun, and ending with a mystery."—Spectator.

The Luckiest Girl in the School.

"A thoroughly good girls' school story."—Truth.

The Jolliest Term on Record.

"A capital story for girls."—Record.

The Girls of St. Cyprian's: A Tale of School Life.

"St. Cyprian's is a remarkably real school, and Mildred Lancaster is a delightful girl."—Saturday Review.

The Youngest Girl in the Fifth: A School Story.

"A very brightly-written story of schoolgirl character."—Daily Mail.

The New Girl at St. Chad's: A Story of School Life.

"The story is one to attract every lassie of good taste."—Globe.

For the Sake of the School.

"Schoolgirls will do well to try to secure a copy of this delightful story, with which they will be charmed."—Schoolmaster.

The School by the Sea.

"One always looks for works of merit from the pen of Miss Angela Brazil. This book is no exception."—School Guardian.

The Leader of the Lower School: A Tale of School Life.

"Juniors will sympathize with the Lower School at Briarcroft, and rejoice when the new-comer wages her successful battle."—Times.

A Pair of Schoolgirls: A Story of School-days.

"The story is so realistic that it should appeal to all girls."—Outlook.

A Fourth Form Friendship: A School Story.

"No girl could fail to be interested in this book."—Educational News.

The Manor House School.

"One of the best stories for girls we have seen for a long time."—Literary World.

The Nicest Girl in the School.

The Third Class at Miss Kaye's: A School Story.

The Fortunes of Philippa: A School Story.

LONDON: BLACKIE & SON, Ltd., 50 OLD BAILEY, E.C.

A Fourth Form

Friendship

A School Story

BY

Author of "The New Girl at St. Chad's" "The Manor House School"

"The Nicest Girl in the School" &c.

ILLUSTRATED BY FRANK E. WILES

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

| Chap. | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Aldred's Sketch | 9 |

| II. | Mabel Farrington | 27 |

| III. | The Model Cottage | 43 |

| IV. | Domestic Economy | 60 |

| V. | Out of Bounds | 75 |

| VI. | An Awkward Predicament | 88 |

| VII. | False Colours | 102 |

| VIII. | Amateur Theatricals | 116 |

| IX. | Chinese Lanterns | 127 |

| X. | A Frosty January | 139 |

| XI. | Venus in the Snow | 152 |

| XII. | The New Teacher | 166 |

| XIII. | Aldred Pays a Visit | 186 |

| XIV. | An Alarm | 200 |

| XV. | On the River | 214 |

| XVI. | An Opportunity | 227 |

| XVII. | Loss and Gain | 245 |

| Page | |

|---|---|

| An Alarming Discovery | Frontispiece 134 |

| Aldred Overhears a Surprising Story | 38 |

| "With a shriek she drew swiftly back" | 65 |

| Four Unhappy Truants | 97 |

| "'I think I understand,' said Aldred" | 183 |

"Two pencils, an india-rubber, a penknife, camp stool, easel, paint-box, a tube of Chinese white, a piece of sponge, paint rag, and water tin," said Aldred Laurence, checking each item off on her fingers. "Let me see! Can I possibly want anything else? It's so extremely aggravating to get to a place and find you've left at home what you most particularly need. My block, of course! How could I be so stupid as to forget it? It's no good taking pencils and paints if I've nothing to draw upon!"

"Hello, Aldred! What a spread!" exclaimed Keith, rousing himself from the luxuries of a comfortable chair and an absorbing book to notice that his sister had put on her hat, that her gloves lay on a chair, and that she was already beginning to pack some of the articles in question inside a home-made portfolio of dark-green American cloth. "The table looks like an art repository!" he continued. "Have[10] you suddenly turned into a Rubens, or a Raphael? Where are you going with all those traps?"

Aldred paused to count her paint brushes, fitted the spare tube of Chinese white into a vacant corner of her paint-box, and slipped the penknife into her pocket.

"I want to make a sketch of old Mrs. Barker's cottage," she replied. "The clematis is out over the porch, and it looks lovely. I heard Mr. Bowden say yesterday that it was a splendid subject. Don't you remember, he made a picture of it last year?"

"So he did, and a jolly good one too. Yours won't be anything like up to that, Sis!"

"I dare say not, but you needn't discourage me from trying, at any rate."

"Oh, I'm not discouraging you. Go by all means, and good luck to your efforts! You can show me the masterpiece when you come back;" and the boy, flinging his legs over one arm of the chair, settled himself in an even more inelegant and reposeful attitude than before, and plunged again into the fascinating adventures of Captain Kettle.

That, however, did not at all content his sister.

"I thought you were coming with me," she said reproachfully. "I was counting upon you to hold my water tin while I painted."

Keith detached his mind from tropical Africa with an effort.

"Then you counted without your host, my dear girl!" he responded. "I'm extremely comfortable here, and I assure you I haven't the smallest intention of pounding half a mile down the dusty road, on a baking afternoon, to look at a picturesque cottage and act water-carrier when I get there!"

[11] "The tin upsets when I hold it on my paint-box," said Aldred, in a rather aggrieved voice, "and if I put it on the ground I have to stoop every time I want to dip my brush."

"Then make a hole in each side, tie a piece of string across, and hang it on the peg of your easel. I'll fix it up for you in half a second, if you'll find me the hammer and a nail. Girls have no invention! The thing's as simple as possible. I wonder you couldn't think of it for yourself. Where's a piece of string? Now, isn't this A1? Put it inside your case. There! Off you go!"

Aldred could not but acknowledge the improvement in her painting tin, but she seemed, nevertheless, in no hurry to start. She re-arranged her paints, took off her hat and put it on again, and loitered about in so marked a manner that her brother could not fail to notice her hesitation.

"What's the matter now?" he enquired.

"You might come with me, Keith!"

"Oh, bother!"

"You know quite well I can't go alone."

"Why not?"

"Because Father said I mustn't sit sketching by myself."

"That's a horse of another colour. In that case, why did Aunt Bertha let you get ready?"

"She didn't. She's out, so I couldn't ask her."

"Taking French leave?" chuckled Keith.

"I thought it would be all right if you went too."

Keith groaned in reply.

"We need only walk for five minutes along the road, and then turn into the path through the wood," suggested Aldred. "There's a field of cut corn in[12] front of the cottage; you could sit on the corn and read if you like."

"Not half so cool as here."

"Oh, Keith, you might be nice when it's holidays!" pleaded Aldred. "It's the only time I ever have anybody to go about with. I'm sure I do heaps of things for you; I was playing cricket with you all morning, wasn't I?"

"Yes, and a precious butterfingers you were, too. There, then, you needn't look so blue! I'll go, but on the one condition that you let me read in peace and quiet, and don't bother."

"I won't say a single word, if you don't want to talk. I'll be absolutely dumb and mum!"

"Well, I hardly believe you'll be able to hold your tongue to that extent. I'll allow you an occasional remark, but you mustn't keep up a continual flow of conversation. Where's my straw hat?—it's too hot for a cap. I think I'm an absolute saint to turn out on such a blazing afternoon!"

Having gained her point, Aldred ran readily enough to fetch her brother's hat, and set off with him down the drive in a state of beaming satisfaction.

Dingfield, the place where they lived, though only an hour's distance from London, was sufficiently in the country to afford a pleasant prospect of trees, meadows, and winding reaches of river. The hedgerows were thick with twining bryony and feathery traveller's joy; here and there the hips were reddening, and a ripe blackberry or two tempted them to linger upon the way. It was cooler than Keith had anticipated, for a fresh breeze was blowing from the Surrey Hills, sending white clouds in long streamers across the blue of the sky, and shaking down a few[13] windfalls from the apple trees that overhung Farmer Walton's gate.

The two soon left the high road, and, after strolling leisurely through the welcome shade of the wood, climbed over a stile into a pasture, and after another five minutes' walking found themselves in a stubble field, within sight of the river. Here was the subject upon which Aldred had determined to try her brush. It was a picturesque old cottage, with red-tiled roof, lattice windows, a porch wreathed in purple clematis, and a garden gay with dahlias, looking attractive enough in the September sunshine to make even an amateur wish to commit its beauties to paper.

Aldred chose her point of view with great deliberation, and considerable taste for a girl of only fourteen. She fixed her easel where a couple of elders would make a background for the red roof, and where she could catch a pleasant angle of the gable window and a peep of the distance beyond. Having unpacked her portfolio, she settled herself on her camp stool and began to put in her sketch with rapid lines, working, indeed, more quickly than correctly, but nevertheless obtaining rather a good effect. Keith, finding a pile of corn stooks conveniently near, flung himself down in the shade, and, with a fern leaf to flip away flies, lay with half-closed eyes watching his sister's energetic pencil.

"How you go at it!" he remarked. "It makes me hot just to look at you!"

"Then don't look! I thought you wanted to read? You made me promise not to open my lips, and I haven't spoken a word since we came."

"Most heroic self-denial on your part, I'm sure! I believe I'm too lazy even to read. I like to lounge[14] in the holidays, especially when it's getting so near the end."

"Only a week now to the fourteenth," said Aldred.

"Yes, worse luck! I wish it were a month!"

"And I am counting the days. I want the time to come so much!"

"It's a case of 'where ignorance is bliss', my dear girl. You've never been to school before; I have! You won't find yourself in such an anxious hurry to start off by next September, if I'm anything of a true prophet."

"I expect I shall. All the stories I've read about school sound delightful—the girls have such fun. I'm looking forward to going most immensely. It will be far nicer than having a governess at home. It's so fearfully slow while you're away at Stavebury. Aunt Bertha grows more prim and particular every day, and I never seem able to do a single thing right; it's scold and lecture, lecture and scold, from morning till night! As for Miss Perkins, I was sick of the very sight of her! You can't imagine how glad I was when she took her final departure. I said good-bye as nicely as I could, for decency's sake, and then rushed into the empty schoolroom and danced a jig and clapped my hands for joy, to think I need never do lessons with her there again."

Keith laughed. "I don't suppose she's crying her eyes out over you either," he observed.

"I'm sure she isn't. I've no doubt she's almost as delighted as I am. She's going to The Thorns, to teach Blanche and Minna Lawson. They're absolutely pattern girls, warranted never to do anything they shouldn't, so I hope she'll be happy at last. I find them insufferably dull."

[15] "You may get a far worse mistress at school than Miss Perkins."

"I don't think so. You know, Mary Kennedy has been at The Grange, and she says Miss Drummond is a perfect dear. They have all kinds of games there too. It will be lovely to learn hockey and lacrosse; I've never played either before."

"School isn't all games, I can tell you," said Keith, pulling a straw from the stook and chewing it meditatively. "There's a jolly lot of grind to be gone through. You'll find you'll have to set that young head of yours to work in good earnest."

"I can easily do that," declared Aldred, tossing back her dark curls, "I've no fear at all of not managing my lessons. Why, when I cared to take the trouble, I could simply astonish Miss Perkins. I could work sums far quicker than she did, and I used to reel off French verbs so fast that sometimes she could hardly follow me, even with the book in her hand."

"All very well with a private governess, Madam Conceit! You've had no competition. Wait till you work with a class. At The Grange you'll probably find several other girls who can reel things off a little quicker."

"Then I shall go quicker still. I tell you, I mean to be top of my class, and head of the examinations too."

"Don't boast too much beforehand, or pride may bring a fall!" said Keith, speaking with the superior authority of his sixteen years. "You'll have to find your own level, Sis. The other girls may have ambitions as well as you, and will be ready to dispute for the head place."

"Then they won't get it! It's booked already for[16] Aldred Laurence, and so is the tennis championship, and anything that's first and foremost in the way of hockey and lacrosse."

"Great Scott! What more?" exclaimed Keith, looking at his sister with quizzical amusement. "Are there no bounds to your ambition?"

"Well, I've often heard you say yourself that if one is to get on at school one must do well at games."

"No one tolerates slackers, certainly I'll allow that."

"I mean to be a general favourite," continued Aldred. "I want the girls to be tremendously fond of me, and ready to do anything for me."

"They won't jump into your arms all at once, I assure you."

"I'll make them like me! Just you wait and see! I can always make people care about me when I try hard enough."

"How about Miss Perkins?" suggested Keith dryly.

"Miss Perkins? Oh, well, I didn't even try! I disliked her so much, I wanted to get rid of her. But it will be a very different matter indeed when I go to The Grange. I don't mind undertaking that by the time I've been there a year I shall be the most popular girl, not only in my class, but in the whole school."

"Whew! That's a large order! Popularity isn't so easy to come by, Sis. It depends on a dozen things—sometimes, indeed, it seems almost an accident. If you work too hard for it, you may overstep the line, and find yourself sent to Coventry instead. I've known two or three fellows served that way."

[17] "You always want to discourage me," declared Aldred, with a flush on her cheeks.

"No, I don't. But I think you've far too good an opinion of yourself. You need taking down considerably, and fortunately school will soon do that for you. You'll talk very differently from this at the end of your first term, or I'm much mistaken."

Aldred shrugged her shoulders. She was confident of her own success, and regarded Keith's warnings simply in the light of brotherly teasing. She said no more for the present, but gave her whole attention to her sketch, which had now arrived at the painting stage. She dabbed on the colours with the greatest assurance; there was no hesitation in the bold, rather clever strokes, and the picture, though somewhat "slap-dash" in style, was already beginning to bear a very fair resemblance to the scene before her.

"You're not the only one out working to-day," remarked Keith, after an interval of silence. "Here's Mr. Bowden himself sauntering down the field in search of a subject."

Aldred looked round and waved her hand to a tall, grey-haired gentleman, who, armed with a sketchbook, appeared to be jotting down the outlines of some of the corn stooks. On seeing her smiling face he came at once in her direction, and stopped critically behind her easel.

Mr. Bowden was an artist of considerable repute; he was a friend of their father's, and always had a pleasant word for Aldred when he visited at the house. Therefore she awaited his verdict with some anxiety.

"Very good, Aldred! I had heard you were fond[18] of drawing, though I did not know you could do so well as this. But, my dear child, it's full of faults, all the same. The perspective of the front of the house is completely wrong."

"I'm afraid I don't know anything about perspective," pleaded Aldred. "I just drew it as I thought it looked. The cottage is so pretty, I felt I simply must paint it."

"That is the right spirit. Go on and try, even if you don't always succeed. I am glad to see you make an effort to sketch out-of-doors. There is no teacher like Mother Nature, and the attempt to reproduce a living tree, or a house, on paper will do you more good than a hundred copies. Why did you make the lines of your windows run up, when they so clearly ought to run down?"

"I don't quite understand," said Aldred, looking puzzled.

"Give me your pencil a moment, and I will show you."

"Oh, thank you!" cried Aldred, jumping up with alacrity. "Please take my camp stool, and then you will have exactly the same view as I have. It looks so different when one is sitting down."

Mr. Bowden good-naturedly installed himself in Aldred's place, and, taking her paint-box and brushes, began to give her a practical lesson in sketching from nature.

"The composition is not bad," he remarked, "but if you had brought in that far tree, which is considerably taller than the cottage, it would have raised the subject on the left-hand side of the picture, and given a pleasanter result. Shall I put in a touch to show you what I mean?"

[19] "Oh, please!—as many as you like. It would be such a help to watch you!" replied Aldred.

"Very well, then. In the first place, I make the lines of your perspective slope down to their right vanishing point. Is not that better? Now, a dab of brighter blue in the sky, with a raw edge to give the effect of that white cloud. The trees need massing together, with a greater depth of shade to give roundness to them, and a branch just indicated here and there among the foliage. The stubble field needs a tone of richer and warmer yellow, while a few stooks here in the foreground would be the utmost improvement. Look how I am blocking them in, with strong light and shadow, and two or three ears marked definitely at the top, to show against the dark of the hedge beyond. There! Go on working yourself at the field and the distance. Paint moistly, and don't spare your cobalt blue."

"It's like magic!" said Aldred, reviewing the improvement in her sketch with immense satisfaction. "I hardly know how to thank you. I'm afraid I've been wasting your time dreadfully."

"No matter, if it has helped you," said Mr. Bowden, picking up his sketch-book. "I must go now, though, for I want to catch the effect of the late afternoon light on those marshy pools beyond the cottage. Don't forget the hints I have given you," and with a friendly nod to Keith he walked rapidly away, and was soon out of sight.

For some little time after Mr. Bowden had left, Aldred painted away industriously at her foreground. Keith, in the shelter of the stooks close by, was deep in his book; and there was no sound except the chirping of birds, or the lowing of cattle, to disturb her.[20] How pleasant it was! She keenly enjoyed each touch of her brush, and tried hard to follow the directions which her kind old friend had given.

Fully half an hour had passed away, and her stubble field had made considerable progress, when voices in the pathway behind her caused her to look round.

It was Mr. and Mrs. Silvester, the vicar and his wife, who, bearing a basket, were walking in the direction of the cottage, no doubt with the intention of paying a visit to old Mrs. Barker.

Recognizing the little figure at the easel, they came at once to see what she was working at so briskly.

"Aldred, my dear! have you turned artist? This is an extremely good sketch. How long has it taken you?" asked Mrs. Silvester.

"I only began it this afternoon," answered Aldred. "We came here about three o'clock—didn't we, Keith?"

"It is really excellent!" exclaimed the Vicar. "I myself have had a little experience in painting, so I am able to judge. The composition of the picture is most artistic; I admire the way the tree has been arranged to just overtop the chimney, and the large corn stook to bring the eye down to the foreground. The perspective is correct, the light and shade have been handled in quite a masterly fashion, and the sky with the patch of cloud is particularly happy. I hope you are going to have drawing lessons at school. I am sure you have unusual talent, which ought certainly to be cultivated."

Keith, who had risen from his seat among the corn to greet the visitors, gave a peculiar, rather suggestive[21] cough, but did not volunteer any remark. Aldred's eyes were very bright, and her cheeks pink, as she replied:

"I'm certainly fond of painting. I don't think I can do any more to the distance. I was just finishing the foreground when you came."

"Don't put another touch to it," said the vicar. "It is excellent just as it is. I beg that you will shut your paint-box, and leave it; it would be a mistake to work at it any more."

"I am most interested to have seen it," declared Mrs. Silvester; "it is delightful to find anyone with such a decided gift for art. You must make it your special study, and we shall look for great things from you when you have finished school."

She passed on with her husband, and as they walked towards the cottage the words "marvellous talent" and "astonishing cleverness" were wafted back by the summer breeze.

Aldred closed her paint-box as the Vicar had suggested. Somehow she did not feel inclined to continue her work; all the pleasure had suddenly faded away from it.

Keith had subsided once more into his former lazy attitude, and sat idly picking ears of corn, preserving an ominous silence. He waited until Mr. and Mrs. Silvester were safely inside old Mrs. Barker's garden, then burst forth.

"Well, of all the sneaks you're the biggest! Call that your work? Why, it's Mr. Bowden's!—all the best parts, at any rate, that they were praising so much. And you calmly took the credit for the whole! I wasn't going to speak and give you away, but I'll let you know what I think of you now."

[22] "Oh, Keith! What could I do?" stammered Aldred, the tears welling up in her eyes and splashing down upon the paint-box. "Don't scold me so! I can't bear you to be cross with me."

"But you deserve it! Why didn't you say it wasn't really your own painting?"

"They never asked me if I had been helped," answered Aldred; "and, after all, it's my sketch, not Mr. Bowden's."

"Yes, your sketch, but improved absolutely beyond recognition. Look here! if you play these tricks at school you'll pretty soon find yourself the reverse of popular. Boys wouldn't stand it, and I don't suppose girls will either."

"It didn't strike me to say anything," sobbed Aldred. "Oh, Keith, don't look at me like that! Shall I run after them and tell them? I will, if you want. I'll go at once, if you'll only be friends with me again."

"No, they're inside the cottage, condoling with Mrs. Barker over her rheumatism. You'd only make yourself ridiculous if you followed them, and came out with a dramatic confession in the middle of the kitchen. I hate scenes. Do turn off the water-works, there's a good girl! Be a little straighter in future if you want to keep chums with me, though. Here, I'll help you to pack up your traps, and we'll go home to tea. Your sketch is still wet; if you carry that I'll bring on the rest."

Very crestfallen and miserable, Aldred took up her unfortunate painting, and began to walk away down the path towards the wood, leaving her brother to follow. In her brown holland dress and red poppy hat she made such a sweet picture against the yellow[23] of the corn stooks that, in spite of his disapproval, Keith could not help looking after her with a certain amount of admiration. No one who met Aldred Laurence could have failed to be struck by her personality. She was very neatly and trimly made, and had a way of holding herself erect and looking alert that gave her a distinguished appearance, and seemed to raise her above the level of the average girl. Her lovely dark eyes, long, curling brown hair, and warm, rich colouring had a gipsy effect that was particularly picturesque. Her eyes were so bright and soft and expressive, her cheeks had two such bewitching dimples, and she smiled so readily and winningly in response to the smallest advance, that she generally made friends easily, and had won notice from strangers since the days of her babyhood.

To sober, downright, matter-of-fact Keith his sister was often a sore puzzle. Her eager, impetuous, excitable disposition, and many impulsive acts, were as foreign to him as an unknown language.

"Why need you work yourself up so tremendously over every trifle? What's the use of taking life so stormily?" he once remonstrated.

"I don't know," replied Aldred. "I seem to care so much more about everything than you do. I can't help it; I suppose it was born in me."

"Then it's high time you got it out of you!" remarked Keith, whose ideal was a state of unruffled calm on all occasions.

In spite of the difference in their temperaments the two were really attached to each other, and though Keith might not be demonstrative, he tolerated Aldred's devotion when they were strictly alone, though he would not allow her, as he expressed[24] it, to "make an exhibition of him before other fellows".

Poor Aldred! She had a very warm and loving heart, and a perpetual hunger for affection that, so far, had failed to be entirely satisfied. Since the day, seven years before, when her mother had started on that long journey from which none return, nobody had seemed to understand her quite, or to know how to manage her aright. Her father, a clever barrister who went daily from Dingfield into London, was too absorbed in his profession to give much time or sympathy to his children. Having sent his son to school, and provided a daily governess for his daughter, he felt that he had done all that was required of him. The masters at Stavebury were responsible for Keith, and as for Aldred, if anything more was needful for her upbringing than Miss Perkins could give, surely his sister, who managed his house so admirably, could look after his motherless girl?

Unfortunately, though Aunt Bertha had great experience and excellent skill in the making of jams and the care of linen, she had no aptitude for the handling of human souls. She was a stout, bustling, unimaginative, prosaic person, without an atom of romance or sentiment in her composition. A nature such as Aldred's was beyond her comprehension. She tried to do her best for the child, but it was such an unsympathetic best that it had the unhappy effect of setting a barrier between herself and her niece which neither seemed able to pass. Long and lucidly would Aunt Bertha reason and expound, and enjoin habits of neatness, order, and punctuality. All to no purpose! Arguments never appealed to[25] Aldred. She would listen with an air of don't-care indifference, and do just the same next time. Yet if her aunt could have given her one warm kiss, the battle would have been won. It was a sad pity, for the girl had in reality a very sweet disposition, though at present it was like a neglected garden, where a few choice blossoms might be found, struggling with ugly weeds that threatened sometimes almost to strangle the flowers.

The precise governess carefully chosen by Aunt Bertha had not helped matters. She found her pupil bright indeed, but only ready to work by fits and starts, and quite unmoved by fear of punishment, or promise of reward. So strong at last had the friction grown that Miss Perkins had herself resigned her post, and recommended that Aldred should be packed off to school.

"I have done my utmost," she said to Miss Laurence, "but I feel that I am a complete failure. I have no influence over Aldred, and she is not making the slightest progress. In the circumstances I cannot honestly continue to teach her. In my opinion a little strict discipline is what she requires, and the sooner she experiences it the better."

The decision to send her away (long held over her head as a threat), instead of daunting Aldred, had delighted her. Aunt Bertha was much relieved. She had dreaded a storm when the question was raised, and though she considered it a bad characteristic in a girl to be glad to leave home, she felt it removed a difficulty when her niece accepted the situation so readily.

To Aldred the idea of forming herself on the prim pattern of her aunt was intolerable. She was[26] ready to copy anybody whom she loved and admired, but to be obliged to repress her enthusiasms, and reduce her ideals to the level of the commonplace, seemed like being forced into a box too small to contain her.

"Aunt Bertha never understands," she thought. "She says I must try to grow up now, and be sensible. If growing up means getting cold and calm and stupid, and taking everything as a matter of course, I'd rather not. I'll just stop a child always, however hard they may try to make me different!"

Such was Aldred at the time our story begins,—a mass of contradictions, so wayward and yet so winning, a mixture of good impulses and weak points, equally ready to join a crusade or to follow the multitude to do evil; waiting, like a gaily painted but rudderless vessel, to be launched on to the stormy ocean of school life.

Birkwood Grange was a rambling, roomy stone house, built at the edge of a breezy common, within sight and sound of the sea. It was a pleasant spot for a school; beyond stretched the broad downs, covered with short, fine grass, through which the dazzling white road wound like a ribbon to the distant horizon. There was a sense of air and space as one looked over the green upland, where for miles the view was interrupted only by the sails of a windmill, or an occasional storm-swept tree, the slanting branches of which showed the direction of the prevailing gale. In front, the chalky cliffs descended sharply to the beach; and beyond them, now blue as turquoise, now gleaming silver, now inky black, as calm as a lake, or lashing into foaming spray, always changing, yet ever beautiful, lay the wide waters of the English Channel. On one side of the house was a walled kitchen-garden, and on the other a field for hockey; while in front a large lawn provided ample space for several tennis courts.

On the afternoon of September 14th The Grange presented an extremely lively and animated scene. Girls were everywhere—tall girls, short girls, fat girls, slim girls; some fair, some dark, some pretty and some plain; and all in a state of excitement, and[28] chattering as fast as their tongues would wag. No anthill, or hive of bees about to swarm, could have seemed in a greater ferment; there was a constant hum of conversation, a continual patter of feet, and a succession of young people, always moving in and out, searching for friends, claiming old acquaintances, exchanging greetings, and passing on items of news. It was the first day of the autumn term; a fresh school year had begun, and the party of thirty-nine girls who constituted Miss Drummond's little community were once more assembled for a season of work and play. Several changes had taken place; most of the rooms had been re-papered and painted, and there were alterations in the time-table, a revised practising list, and an entirely modified arrangement of some of the classes.

Small wonder, therefore, that a babel of talk prevailed in every corner of the house, and that various groups of hair ribbons kept collecting and dispersing with the bewildering effect of a kaleidoscope, while such a general atmosphere of bustle and commotion pervaded the establishment as to turn the head of any onlooker in a complete whirl. Aldred, ensconced in an angle of a bow window, surveyed the whole spectacle, as yet, from the standpoint of an outsider. It is true, she had received a cordial welcome from Miss Drummond; she had been duly entered as a member of the Fourth Form; she had been allotted a desk in a classroom, a locker in the recreation-room, and a cubicle in a big, airy bedroom; and was already possessed of a pile of new books, a chest expander, and a hockey stick: yet, in spite of this initiation she was feeling decidedly like a fish out of water. She was not usually afflicted with shyness, but to find[29] herself in the midst of a medley of strangers, all too occupied with their own affairs even to realize her existence, was a little disconcerting to even her easy self-confidence. She was beginning to wonder how long she would remain unnoticed, and was trying to screw up her courage to venture a remark to one of her nearest neighbours, when a plain girl in spectacles broke the ice.

"What's your name, and where do you come from?"

Aldred started at the abruptness of the question and turned to face the speaker, who continued with a smile: "We always put new-comers through a catechism. I want to know your age, and what class and dormitory you're in, and which teacher you're to learn music from, and whether you're going to take dancing and wood-carving. Oh! so you're in the Fourth—that's my form, as it happens. My name's Ursula Bramley, and I'm fourteen and a half. We have a very decent time at Birkwood. There's any amount of fun going on, as you'll soon find out. Wait till we start the Debating Society and the Cooking Class! Have you been measured yet for a gymnasium costume? Of course, there has not been an opportunity, but Miss Drummond is sure to see about it to-morrow—and a cooking apron too, if you haven't already got one."

Aldred replied as briefly as possible to these various interrogations, but Ursula seemed quite satisfied with "Yes" and "No" for an answer, and rattled on: "I'm rather sorry for you, being put in No. 2 dormitory, because you'll be with Fifth Form girls, and you can't expect them to be particularly chummy with you. If there had only been room, now, in No. 5![30] But we're full up, all six beds; there isn't even a corner for a shakedown. We have such jokes in the mornings, when we're getting up! It's a pity you'll be out of it. I'd like you to see Dora Maxwell acting a peacock; you'd simply scream! Of course, we daren't make too much noise, or we should have a monitress pouncing down upon us; but it's ever such fun, all the same. They're a very prim set in No. 2. They never lost a single order mark last term! Well, if you can't be in our dormitory you'll be with us in class, at any rate, and it isn't dull there by any means, I can tell you."

"How many girls are there in the Fourth Form?" asked Aldred.

"There were seven before, but you'll make eight. Why, most of them are in the room now, or on the lawn just outside, so I can point them out to you. That's Phœbe Stanhope standing by the fireplace,—the one with the long light pigtail and the blue blouse; she's talking to Lorna Hallam, and Agnes Maxwell is showing her camera to them both. Now, if you'll look through the window you'll see two girls walking arm in arm round the sundial; the fair one is Dora Maxwell, and the dark one is Myfanwy James. Dora is tremendously jolly; she and Myfanwy think of the most outlandish things to do. Why, one night they went to bed right underneath their bottom sheets, and put their pillows over their faces, and when Freda Martin (that's our prefect) came to turn out the lights she thought they weren't there at all, and was just going to make a tremendous fuss, when Myfanwy couldn't stand it any longer, and exploded! We six are in the same dormitory, and we're the greatest chums. We call ourselves[31] 'The Clan', and each is pledged to back the others up through thick and thin, whatever happens."

"Who's the seventh girl in the class?"

"Mabel Farrington."

"And doesn't she belong to 'The Clan'?"

"Oh, no! Mabel wouldn't dream of such a thing."

"Why not?"

"Oh! because—well, she's rather particular. She's not very great friends with anybody."

"Don't you like her?"

"Like her? Yes; everybody likes Mabel. That's not the reason at all. Somehow she's a little different from other people. You see, her grandfather is Bishop of Holcombe, and her uncle is Lord Ribchester."

"You mean, she gives herself airs?"

"Not in the least; she's not at all conceited. But she never cares about playing tricks, and having all kinds of jokes, like the rest of us."

"Then she's a prig!"

"No, she isn't. Wait till you've seen her; she's extremely nice. As I said before, she always seems different—just a trifle above everyone else, perhaps."

"Which dormitory is she in?"

"She's allowed a bedroom to herself, and she's the only girl in the school who has one—even the monitresses have to sleep in cubicles."

"Why is she so specially privileged?"

"Her mother, Lady Muriel Farrington, is a friend of Miss Drummond's. I believe Mabel was sent here rather as a favour, because Miss Drummond was so anxious to have her at The Grange."

"Then you all make a fuss over her?"

[32] "No, not particularly; but we certainly like her."

"I'm sure I shan't."

"You can't help it, when you know her. By the way, here she is now, coming in at the door. I must tell her who you are."

Aldred turned, and saw a girl of her own age, so remarkably pretty and attractive that, in spite of her preconceived prejudice against the aristocrat of the school, she could not repress a certain amount of admiration.

Mabel had a very fair complexion, with cheeks pink as apple blossom, a pair of frank, thoughtful blue eyes, straight features, and a quantity of beautiful red-gold hair that hung almost to her waist. Her expression was particularly pleasant and winning, and as she crossed the room in response to Ursula's call, and smiled a welcome to the new-comer, Aldred began already to reverse her unfavourable opinion.

"I'm glad we shall be eight in class now," said Mabel. "It's a much nicer number than seven. Don't you remember, last term Miss Drummond said she hoped we should get a new girl? Of course, we were Third Form then, but it has not made any difference to be moved up to the Fourth, except that we are going to have Miss Bardsley for a teacher, instead of Miss Chambers—we're just the same set altogether."

"I like our new classroom far better than the old one," remarked Ursula. "The desks are more comfortable, and there's a nicer view out of the window. From my place I can catch a little glimpse of the sea, if I screw my neck."

"Miss Bardsley won't let you crane your neck in school, I'm sure," said Phœbe Stanhope, who[33] had joined the group. "She has the reputation of being much stricter than Miss Chambers."

"Ugh! Then I wish I could go back to the Third," declared Ursula.

"We'd a fairly easy time with Miss Chambers," said Lorna Hallam. "One could always give a headache as an excuse, if one didn't know one's lessons."

"I don't care for a slack teacher like poor Miss Chambers," put in Agnes Maxwell. "She has no more idea of keeping order than a jellyfish; I could teach as well myself."

"Go and tell Miss Drummond so, and propose that you should take the Third," laughed Ursula. "I should like to see her face when you suggest it!"

"There's the dressing-bell! Aldred, you must go and get tidy for tea, which will be ready in exactly ten minutes."

There was no doubt that Mabel Farrington was a particularly nice girl; the more Aldred saw of her, the more she liked her. Her popularity at The Grange was thoroughly well deserved, for it rested more on her character than on her social standing. She was extremely high-principled and conscientious, a plodding worker, and always anxious to uphold the general tone and credit of the school. If she had a fault, it was her exclusiveness. So far, though she was pleased with everyone, she had made no bosom friend, and, as Ursula had said, kept slightly aloof from the other girls in the form.

Aldred also found herself rather left out; "the clan" of six were so thoroughly absorbed in their own[34] interests, so taken up with various amusements, secrets, and private jokes that could not be shared by anyone who did not sleep in their dormitory, that it was impossible for them to include her in their fun.

They were not unkind to her, but they simply took no notice of her; and as the Fifth Form girls in No. 2 dormitory were equally stand-off, Aldred's first week at The Grange was a very lonely one.

It was an unpleasant and unwelcome experience for her; she had come to school full of confidence that she would win immediate favour, and it was humiliating to find herself not appreciated as she had expected.

After her first catechism by Ursula no one had exhibited further curiosity about her home or her family; and any information which she volunteered was received without enthusiasm. It was plain that "The Clan" thought her of small consequence, and did not trouble to cultivate her acquaintance.

Aldred was not used to being overlooked; she felt both indignant and offended at this neglect. She almost wished she had never left home, or, at any rate, that she had been sent to some other school than The Grange.

"If I can't make them like me, I shall never be happy here," she said to herself. "They're a stupid set! Well, if I don't get along any better than this, I shall ask Father to take me away, and send me to Oakdene with the Ropers. They always admire me; Doris writes two letters to my one, and Sibyl fights with Daisy to sit next to me at tea!"

It is generally the unexpected that happens. Aldred[35] had nearly made up her mind that she would never be popular with the Fourth Form, and would be obliged to remain a permanent outsider, when quite suddenly the whole aspect of affairs was altered.

The change arose from a most unanticipated quarter. One day Mabel Farrington came up to Aldred with an unusual warmth of manner, and an evidently newly awakened interest.

"By the by, Aldred, do you happen to live at Watersham?" she began.

"At Dingfield. It's really a part of Watersham, only the river runs between," replied Aldred, rather astonished at the question, for no one had seemed to care to hear about her home before.

"And were you staying at Seaforth in June?"

"Yes; we had rooms on the Promenade."

"I thought you must be the same girl! I've just had a letter from a cousin. I don't expect you've met her, but at any rate she has heard all about you, and she wrote to tell me. I'm so glad you have come to The Grange! I hope we shall be great friends. Will you sit next to me in class?"

Aldred's amazement was extreme. That Mabel Farrington, so exclusive and particular, should have singled her out, and actually wished to sit near her, was an honour which had been bestowed upon no one else in the school. It was evidently no empty compliment, but a genuine offer of friendship, for Mabel went promptly to Miss Bardsley and arranged for an exchange of desks, with the result that she and Aldred were placed side by side. At lunch-time she took Aldred's arm as they walked down the passage, she chose her for a partner at[36] tennis during the afternoon, and sat talking to her during evening recreation.

She even made a more astonishing proposal.

"It's horrid for you to be obliged to sleep in No. 2, with Fifth Form girls," she said. "There's plenty of room in my bedroom for another bed. Would you care to join me? I should be delighted to have you, if you will."

The sudden fancy which Mabel had taken for Aldred could not fail to attract the notice of the other members of the Fourth Form. It was so unlike her to seek to be on such intimate terms with a classmate that at first they could scarcely believe the evidence of their own eyes. When they saw, however, that she appeared to have formed, not only an affection, but also an intense admiration for Aldred, they began to yield the latter a higher place in their estimation. As an ordinary new-comer, she had seemed of little importance; but as the chosen friend and elect companion of Mabel Farrington, she was at once raised to a very superior and important position. Girls who had hardly noticed her before, now made much of her; and her opinions were consulted, her remarks listened to, and her suggestions well received. It was an understood thing that to offend her would be to offend Mabel also, and to please the one was the best way of pleasing the other.

Aldred found this new state of things extremely gratifying. It was exactly what she had hoped for; success had come with a bound, and granted her the popularity for which she had craved. Added to this, she liked Mabel immensely, and keenly enjoyed her society. Once Mabel had unbent and thrown off her usual cloak of reserve, she proved a most delightful[37] and winning comrade, and it gave a special zest to her confidences to feel they were shared by no one else. Aldred knew well that she was regarded as supremely lucky by the rest of the class, each one of whom would have jumped at the chance of being Mabel's room-mate, and envied her good fortune. She held her head a little high in consequence, and was ready almost to patronize those who, while they had had a much longer acquaintance with the school favourite, had not been considered worthy of her particular esteem.

It was about a fortnight after the establishment of this friendship, when the two girls had already grown very fond of each other, that Aldred happened one day to be standing inside the book cupboard in the classroom. It was quite a large cupboard, almost like a separate little room; and it had shelves all round, where spare exercise-books, bottles of ink, and boxes of chalk for the blackboard were kept. No one but the monitress was supposed to enter, and that only by the mistress's orders; so Aldred had no business there, and had gone in out of curiosity to see what it contained. She was examining the new pens, paper fasteners, bundles of pencils, and other articles which she found, when she heard voices in the classroom. Mabel Farrington and one or two other girls had evidently come in, and, to judge from their conversation, were discussing no less a person than herself. Aldred pricked up her ears. What were they saying about her? Strict honour urged her to step out of the cupboard at once, before she heard any more; but prudence advised her to stay where she was, and not to let her companions know that she had been prying in a place where[38] she was not allowed to go: and it was the latter counsel that prevailed.

"Yes, I think she's pretty," said Phœbe Stanhope, "and she's very clever, and can make herself pleasant; but (if you'll excuse my saying so, Mabel) I can't quite see why you admire her so blindly as you do."

"Because she deserves it!" exclaimed Mabel, with enthusiasm. "She did such an absolutely splendid thing that I feel proud to know her."

"What do you mean?"

"I'll tell you. I didn't say a word about it before because I wanted to see if Aldred would mention it herself; but she's never hinted at the matter, and that's raised her higher still in my opinion. There are few girls who would not have made some reference to it."

"But what did she do?" asked Dora Maxwell.

"She was staying at Seaforth last June, and while she was there a terrible fire broke out in the middle of the night at the house where she was lodging. The people got safely on to the Promenade, and had sent for the fire engines, when suddenly it was discovered that the landlady's youngest little boy had been left asleep in the attic. The flames were blazing out at the windows, and the hall was filled with horrible, dense smoke. Nobody dared to go inside, and everybody said: 'Wait for the Brigade, and the proper fire-escape. One of the men will fetch him.' But Aldred knew that every moment wasted might mean the loss of the child's life. She ran and dipped her pocket-handkerchief in the sea, and tied it over her mouth; then, without consulting anyone, she dashed into the house, and[39] crept on her hands and knees up the stairs. She could just manage to breathe, but she reached the bedroom, and groped her way to the crib where the little boy lay whimpering with fright. He was only two years old, and luckily not very heavy, so she took him in her arms and crawled down the stairs in the same way as she had gone up, so as to get the purer air close to the floor. The people nearly went wild with excitement as they saw her stumble out at the door carrying the baby; and its mother was ready to worship her. The Brigade was such a long time in arriving that the flames had gained a complete hold before it came, and the attics were flaring like a bonfire. If Aldred had not seized the opportunity, and gone the very moment she did, the child would have been burnt to death! I believe it made a stir in Seaforth at the time. The newspapers wanted to print her portrait, but her father wouldn't allow it. He said 'his daughter had no wish for notoriety, and did not desire any public recognition of an act she had only been too happy to perform. She would be grateful if people would kindly take no further notice of it.' Now, you see why I think so well of Aldred! She's as brave as anyone in the Book of Golden Deeds, and yet so modest about what she has done that she's content to let it be quite forgotten."

"How did you hear, then?"

"I happened to mention in a letter to a cousin that we had a new girl at The Grange, called Aldred Laurence; and Cousin Marion wrote back, sending me a newspaper cutting that she had kept describing the fire, and saying she was sure that was the name of the 'little heroine' whom everybody at Seaforth had been talking about when she stayed there in June.[40] She knew her home was at Watersham, and could tell me that she was dark and pretty, for she had sat next to her at a concert, one afternoon, on the pier. To make quite sure, I asked Aldred if she lived at Watersham, and if she had been at Seaforth in June; so when she answered 'Yes' to both questions, I was certain that Cousin Marion must be right."

"Aldred was brave!"

"Yes, and she showed such particularly nice, delicate feeling afterwards. It's a privilege to have such a girl at the school! Although she mayn't want us to say anything about it, she can't help our honouring her for it. I shall always feel quite different towards her for the sake of this."

In the shelter of the book cupboard Aldred had overheard every word. Mabel's account almost took her breath away. It was all a mistake. She had certainly never been in a fire, or risen to any such pitch of heroism. She remembered the circumstances, which had occurred just before her visit to Seaforth, and she had been struck at the time with the fact that the author of the deed bore the same surname as herself. The latter's name was, however, spelt with a W instead of a U, and the two families were not related, nor even acquainted. Aldred had not, indeed, been aware that the Lawrences lived at Watersham.

[41] So this was the explanation of Mabel's violent attachment! She had been attracted, not by Aldred's real personality, but by qualities which she believed her to possess. What would she think, when she learnt that Aldred was not the girl she imagined? Suppose she were to drop the friendship as suddenly as she had taken it up? She might possibly prefer to have her bedroom to herself once more, and would feel no further interest in one who had not done anything particularly worthy of admiration. Aldred turned quite cold at the idea. If such a catastrophe occurred, all her popularity in the school would be lost. She was shrewd enough to realize that it depended entirely upon Mabel's goodwill, and that her position really resembled that of a Court favourite. It would be worse, far worse, to have to fall again into comparative obscurity than if she had never been thus made much of. Her pride could not tolerate the thought of being once more a nonentity in her class. To be held in high repute by her companions was the salt of life to her.

She knew perfectly well that she ought to walk out of the cupboard, confess to Mabel and the others that she had been listening to their talk, and explain the exact state of the case. It was the only straightforward course to take, and would prevent any further misconceptions. And yet, she hesitated. A swift and strong temptation had assailed her. After all, why need she tell? No one was aware that she had overheard this conversation, and nobody had so far made the slightest reference to her fictitious deed. She would act as if she were quite unconscious that they credited her with it, and it would be time enough to disclaim it when it was alluded to in unmistakable terms. The longer she could keep Mabel's friendship the stronger it would be likely to prove; and if the rest of the class had grown accustomed to treating her opinions with deference, they would probably continue to accord[42] her a certain amount of consideration, from sheer force of habit.

She could not deliberately give up all that she had gained; it was too great a sacrifice to be expected from anybody! On some future occasion, when she had had sufficient opportunity to win their approbation on her own merits, she could casually enlighten the girls, and set the mistake right. She was confident that when they knew her better they could not fail to value her for herself alone, and this exploit would sink into insignificance. Besides, it was surely Mabel's fault, for jumping at once to a conclusion without making adequate enquiries. She could not help all the absurd things people might set down to her account, and it was not her business to go about the world correcting them.

The girls had left the classroom and run downstairs. She could now emerge from the cupboard quite unobserved, and no one but herself would be any the wiser for what had happened. For the present, at any rate, she would temporize; she would let matters remain as they were, and be guided by future contingencies. There was really no deception about it, because she fully intended to tell some time, when it was more convenient.

Thus Aldred drugged her conscience, and allowed herself deliberately to take the first step in a course which she knew in her heart was dishonourable and unworthy, and which she was afterwards most bitterly to regret.

In her supposed character of a modest and retiring heroine, Aldred rapidly secured the favour she wanted in the school. Since the afternoon when Mabel had confided to Phœbe and Dora the story of the rescue, the whole class had waxed enthusiastic. Though nobody openly mentioned the subject, she could feel a marked difference in the general attitude towards her; she was no longer only Mabel's friend, but somebody on her own account. That this new esteem was not truly her due caused her an occasional pang, but she would put the thought hurriedly away, consoling herself by reflecting that the girls were beginning to discover her good qualities, and to appreciate her as she deserved.

Her intimacy with Mabel increased daily. The latter seemed hardly able to make enough of her. The two were always together, and Mabel, who possessed many luxuries that do not usually fall to the lot of the average schoolgirl, was ready to share everything with her room-mate. Aldred found it decidedly pleasant to be, not only encouraged, but actually begged to help herself to an unlimited quantity of the most delicious scent, to use dainty notepaper, or a delicate pair of scissors; to be lent a most superior tennis racket, and allowed to[44] borrow any of the delightful volumes that filled the bookcase in the bedroom. To do her justice, she was really grateful for all this kindness, and absolutely adored Mabel. Had she loved her less, she might, perhaps, have been more willing to hazard the loss of her affection; but the thought of the blank which such a calamity would entail made her keep silence, in spite of the reproachful accusations of her better self.

"It's such a delight to me to have found a real friend!" said Mabel one day. "I've told Mother about you, and she wrote that she was so glad. I think I must read you a little scrap of her letter. She says: 'Your description of Aldred Laurence pleased me very much—she seems just the kind of high-minded girl with whom I should wish you to be associated; and though I stipulated for you to have a bedroom to yourself, I do not object to your sharing it with her, if you like. Our friends naturally exercise a great influence over our characters, so I am glad you have made such a good choice. I am sure that, knowing our home standards, I can rely upon your judgment, and that you would not allow yourself to be intimate with anyone who is not thoroughly worthy of your confidence.' You needn't turn so red!" continued Mabel, who misunderstood the cause of Aldred's blushes. "Of course, Mother is extremely particular, but she seems quite satisfied. I hope she'll see you some day, and then she'll love you on her own account."

"Suppose she didn't?" hazarded Aldred.

"She couldn't help it. Mother and I have just the same tastes; we admire courage and spirit, and people who do things in the world. Nearly[45] all Mother's friends are interesting in some way. Mr. Joyce is an explorer, and Mr. Hall has done grand temperance work; Miss Abercombie is an artist, and Miss Verney is helping to run a settlement in the slums. Mother says it does her good to know them, and spurs her on to try to do more herself."

"What does she do?"

"Oh, heaps! No one could live a busier life than Mother. She's president of ever so many societies and guilds! She looks after poor girls, and finds employment for them, and sends them to the country when they need holidays. Then, in our own village there are the Orphanage and the Cottage Hospital to visit, and the district nurse and the deaconess to help, and clothing clubs and local charities to manage. She opens bazaars, and gives the prizes at schools, and acts as judge at flower shows. When Father was in Parliament it was really dreadful; Mother could hardly get through her enormously long list. But he lost his seat at the last election, and she has had a little easier time since then."

"But need she do it, if she doesn't like it?" objected Aldred.

There was a puzzled look on Mabel's face as she answered: "You, of all people, to ask such a question! Of course, she feels bound to give what help she can. She says her social influence is her one talent, and she must use it wherever a good cause needs a champion. She would be terribly missed, if she stopped supporting those various societies. It's what I'm to take up myself when I leave school. You, I expect, will go in for some splendid work, like Florence Nightingale, or Sister Dora. I have a presentiment[46] that your name will be handed down to fame."

The idea of devoting her life to such self-sacrifice absolutely staggered Aldred. She did not attempt, however, to shatter Mabel's dreams for her future, but only gave an ambiguous reply. When her friend was in this exalted mood, she evidently did not like to be checked, and the least hint that her high ideals were not shared would make a little rift within the lute, and destroy her confidence.

Now that she had secured what she considered her rightful place at Birkwood, Aldred was thoroughly happy in her new life. The Grange was a very up-to-date school, and Miss Drummond was an exceedingly enterprising and go-ahead principal, who kept in touch with all the latest educational methods, and was ever ready to give some fresh system a trial. This term she was devoting herself to an experiment which found great favour among her pupils. It was one of her pet theories that every woman, whether rich or poor, ought to have a thoroughly practical acquaintance with all the details of housekeeping, and she was determined to put this into operation. She had had a small cottage built in one corner of the grounds, and classes were held there regularly for cookery and still-room lore. The girls were taught to mix puddings, bake bread, make light pastry, and concoct many old-world salves and cordials. Miss Drummond would wax both enthusiastic and didactic when she aired her views on the subject.

"We can very well emulate our great grandmothers in this respect," she would say, "and thus make a happy combination of ancient and modern. Because you are studying French and algebra is no reason at all why you should not also know how to fry an omelette[47] or boil a potato. A cultivated brain ought surely to be able to grasp domestic economy better than an untrained one, and an educated woman who is really helpful is worth more than an ignorant one. Even if you are never called upon to do things yourselves at home, you ought at least to know how they should be done, so that you need not set your maids unreasonable tasks, and expect impossibilities in the way of service. I think, also, that a great future for many of our English girls lies in the Colonies, where domestic help is often at a premium, and the most delicately nurtured lady must sometimes set to work, and be her own cook and laundress. If you profit by the classes you attend at the cottage, you will have an invaluable accomplishment, and one which may in some emergency prove more useful than anything else you have learnt."

Miss Drummond believed in putting all knowledge to the test of practice, so she instituted the plan of sending the girls in relays of three to the cottage every Saturday, and letting them undertake the entire work of the little establishment. Everything must be done by their own hands: the stove lighted—after the flues had first been intelligently cleaned—the rooms swept, dusted, and tidied; the midday dinner prepared, dished up, and cleared away; the crockery washed, and the kitchen left in apple-pie order. Miss Drummond herself and one of the other teachers were permanent guests at dinner; and the three housekeepers were each allowed to ask one friend to afternoon tea, so that there should be visitors to appreciate the various viands prepared.

The girls welcomed the experiment with the utmost enthusiasm. The cottage was to them a veritable[48] doll's house, and they were supremely delighted at the prospect of directing the internal arrangements. As three were told off weekly for "domestic duty" there was just time during the term for each of the thirty-nine to have one trial, and "Cottage Saturday" became an event to which they looked forward with the greatest eagerness.

Instead of giving the upper forms the entire precedence, Miss Drummond sandwiched elder and younger girls in alternate weeks, so that several members of the Fourth Form secured an early chance. Aldred's turn happened to come the first week in October. To her great satisfaction, Mabel was bracketed with her for the same day, and Dora Maxwell completed the trio.

"It will be such fun!" declared Mabel. "We shall have to get our own breakfast. I hope we shan't make any idiotic mistakes."

"Grind the bacon, and fry the coffee?" laughed Aldred.

"Well, hardly so bad as that. But we shan't have anybody to ask. Miss Drummond says we're to be absolutely and entirely by ourselves."

"I wish we could do something rather out of the common," said Aldred; "something that nobody else has thought of yet! It would be such fun to surprise Miss Drummond!"

"Suppose we were to make some jam?" suggested Dora. "There are heaps of blackberries growing round the playing-field and the paddock. We could pick them this afternoon, and hide the basket."

"How about the sugar? There wouldn't be enough in the stores that are given out."

"We shall have to let Miss Reade into the secret,[49] and ask her to buy it for us. We can pay for it out of our pocket-money."

"All right. I know there's a preserving-pan and plenty of jam pots at the cottage. It would be such a triumph, when Miss Drummond came to look round in the evening, if we could show her a row of jars neatly labelled 'Blackberry'."

"We'll do it, then. Let us get the basket and go to the paddock now."

There was no lack of fruit on the brambles, and the hedgerows yielded such a prolific harvest that in an hour the girls had picked all they required. They concealed their spoils carefully in a cupboard under the stairs, where hockey sticks, tennis rackets, and other possessions were generally kept. Miss Reade was sympathetic when they took her into their confidence, and promised readily to get them the sugar.

"Cook will bring it across and smuggle it into the scullery," she said. "I think Miss Drummond will be quite pleased to find you have tried something on your own initiative. By the by, I suppose you know how to make jam?"

"I do," replied Aldred. "I've often watched my aunt make it at home, and helped her, too. I remember exactly."

"Would you like a recipe?"

"I really don't think we need it, thanks."

"Well, I wish you all success," said Miss Reade "It is not my turn to have a meal at the cottage to-morrow, but perhaps the blackberry jam will appear at The Grange afterwards, and we shall taste it sometime at tea."

By half-past seven next morning the three housewives[50] were ready, and attired in the regulation costume for the day's work. Each wore a holland overall with sleeves, and had her hair tightly plaited, to keep it out of the way.

Miss Drummond presented them solemnly with the key of the cottage.

"You will find most of the stores ready, either in the cupboard or in the larder," she said; "but the meat will be delivered at ten o'clock. It is a loin of mutton, and you may cook it in any one of the ways that Miss Reade has taught you. You can get what vegetables you want from the garden, and I leave both the pudding and the cakes for afternoon tea to your choice. Mademoiselle and I will come to dinner punctually at one o'clock, and I have no doubt you will have everything ready and hot and very nice."

"We'll do our best," replied the trio.

They rushed across to the cottage in great excitement, eager to commence operations. The place was a tiny bungalow, containing a sitting-room, a kitchen, a scullery, a larder, and a coal-shed. Most of its adornments were of amateur origin. Miss Drummond had wished it to be the special toy of the school; so while it was in progress of construction, she had encouraged the girls to prepare everything for it that they could possibly make themselves, even allowing them to help with the decorations. Handicrafts were much in vogue at Birkwood, and it was really astonishing what a number of charming articles had been contrived, all at a very small cost. The walls of the sitting-room were colour-washed a pale, duck-egg green, and the Sixth Form had painted round them a frieze, consisting of long,[51] trailing sprays of wild roses, quite simply and broadly done, but giving a most artistic effect. The curtains of cream-coloured casement cloth were embroidered in pale-green appliqué by the Fifth Form; the Fourth had undertaken the cushions; and the Third had worked an elaborate and dainty table-cover. The pictures were mostly chalk and pastel drawings done by the best students of the art class; while the wood-carving class had contributed the frames. Carpentry lessons had produced the bookcase, the cosy corner, the two arm-chairs, and also many neat little contrivances, in the way of shelves and handy brackets. Every item spent on the furnishing had been carefully entered and added up by the girls, so that each should have an adequate idea of the cost of the wee establishment, and what it was possible to do at trifling expense.

Though the sitting-room was more æsthetic than the kitchen, the latter was regarded as the most important feature of the house. The walls were a pale terra-cotta, and were hung with a few brown bromide photographs; but there art ended and utility began. All the rest was strictly business-like. There was a small "settler's stove", with oven and boiler; and a complete stock of requisites for simple cookery—pots, pans, dishes, pastry-board and roller, lemon squeezer, egg whisk, and even a coffee grinder, a knife cleaner, and a mincing machine.

The three girls felt quite important as they took possession of their little kingdom for the day. It was almost like "playing at house", but there was a "grown-up" sensation of responsibility which differed from mere amusement. With two guests for dinner and three for tea, they certainly could not afford[52] to waste their time, if they wished to make a worthy effort at hospitality.

"We'll get the stove going first," said Mabel, "and have our breakfast; then, as soon as we've cleared away and washed up, we can begin at once to think about dinner."

She set the example by seizing the flue brush and beginning to clear the soot from under the oven, while Aldred fetched sticks, and Dora ran with a bucket to the shed to break coals, hammering away at the largest lumps she could find with keen satisfaction. The fire was soon blazing and the kettle filled, and with so many hands to help breakfast was not long in preparation. The energetic Dora turned the handle of the coffee grinder, Mabel cut dainty slices of bacon and presided over the frying-pan, and Aldred laid the table and made the toast. They all agreed that their first meal was delicious, although Mabel had forgotten to warm the plates for the bacon, and the coffee was just a trifle muddy.

"It oughtn't to be," said poor Dora anxiously. "I'm sure I made it exactly the same way as Miss Reade showed us. I must manage better if we intend to serve any after dinner to Miss Drummond and Mademoiselle."

"And I must remember hot plates!" said Mabel. "I should be ashamed to face Miss Drummond if we left out such an important item as that. By the by, Aldred, did you fill the kettle again, so that we can have plenty of hot water for washing up? It takes a long time to heat the boiler."

Aldred jumped up rather guiltily. As a matter of fact, she had drained the kettle, and thoughtlessly[53] placed it empty upon the stove. By good luck it had not been there long enough to crack, but the vision of what might have happened made her pensive.

"There seem so many little things to think about!" she declared. "While you're doing one, you just forget another. I can quite believe the story of King Alfred burning the cakes, though Miss Bardsley always says it's 'not based on sound historical evidence'."

"It's most natural, and has the ring of truth," agreed Mabel, "especially the woman saying he would be ready enough to eat them afterwards. I should have told him so myself, I'm sure."

"What are we going to give Miss Drummond for dinner?" enquired Dora. "Let us arrange that before we begin to clear away. The kettle can't boil for quite five minutes, so we may as well hold our council of war now."

After considerable discussion they decided to cut the loin of mutton into chops, and stew it with carrots and turnips; to have kidney beans for the second vegetable, and a plum tart and a corn-flour blancmange for the pudding.

"Couldn't we have some soup?" suggested Aldred.

"There's nothing to make it with. We've no stock or bones."

"You don't need any. It can be bouillon maigre, instead of bouillon gras—just water and vegetables, without any meat. A lady who lives in France was staying with us this summer, and she said they always have it like that on Fridays. They put all kinds of things from the garden into it[54]—things we never think of using. It will be a compliment to Mademoiselle to give her a French dish."

"Hadn't we better stick to what Miss Reade has taught us?" returned Dora doubtfully.

"We're to have 'soups and broths' at the next lesson," said Mabel.

"We can't wait for the next lesson!" urged Aldred. "I'll undertake the soup, and you can do the stew. I might make some bread sauce as well."

"But no one ever takes bread sauce with stewed mutton!"

"Why shouldn't they? It will be a novelty. I believe they have it in Germany. It will make an extra dish on the table, at any rate. We want to give Miss Drummond a good spread."

Mabel and Dora demurred, but Aldred was so insistent that in the end they agreed to let her include both the soup and the bread sauce.

"But you'll have to be answerable for them," maintained Dora, "because we haven't learnt to make either, and we wanted to practise what we really know to-day, not to try too many fresh experiments."

"Oh, I'll take the responsibility!" declared Aldred lightly. "We shall have a splendid dinner now. We'll pick a few apples, and those big yellow plums, for dessert."

"We'd better write a menu, if we've so many courses," said Mabel.

"A good idea! We'll put it in French; it will just delight Mademoiselle. What a pity we didn't think of it sooner, and we'd have painted a lovely card on purpose! I suppose there wouldn't be time now, if I ran and fetched my paint-box?"

[55] "Aldred! With all this cooking still to be done! We haven't even put away the breakfast things yet!"

"Well, the kettle's just singing; we'll wait till it boils. Have you a pencil, Dora, and a scrap of paper?"

The list of dishes looked quite imposing and elegant, when written in a foreign language. Aldred regarded it with pride, and copied it in her best handwriting:

MENU.

Potage aux Herbes.

Côtelettes de Mouton aux Légumes.

Sauce Anglaise.

Pommes de Terre au Naturel.

Haricots Verts.

Blancmange.

Pâté de Prunes.

Fromage.

Dessert.

Café.

"But why have you called the bread sauce Sauce Anglaise?" asked Mabel.

"I didn't know what to put. Sauce de pain doesn't sound quite right, somehow; and don't you remember some old Frenchman—was it Voltaire?—said the English were a nation of forty religions, and only one sauce? It's always supposed to be bread sauce, so I think Sauce Anglaise is a very good name for it."

The kettle by this time had boiled over, which necessitated a careful wiping of the fender and fire-irons. After the washing-up had been successfully[56] accomplished, and the stove stoked, and the damper turned to heat the oven, the girls sallied forth with baskets to the kitchen-garden, to pick fruit and vegetables. Aldred, who was determined to concoct what she imagined to be a really French soup, made a selection of almost every herb she could find—sage, sweet marjoram, thyme, fennel, chervil, sorrel, and parsley, as well as lettuces, leeks, and a few artichokes.

"It shall be exactly like what Madame Pontier described to Aunt Bertha," she thought; "and I won't forget the soupçon of vinegar and olive oil, which she said was so indispensable. Miss Drummond will be quite amazed when she hears I've evolved it myself. I suppose some people have a natural talent for cooking, the same as they have for painting. Who first thought of all the recipes in the cookery books, I wonder? It's far more interesting to try something original than to make the same stew as we had last week with Miss Reade."

Mabel and Dora had hurried back with their baskets, and when Aldred, having secured her miscellaneous collection, followed them leisurely to the cottage, she found them already hard at work, disjointing chops, cutting up carrots and turnips, slicing beans, and peeling potatoes.

"We want to get the meat on in good time, and let it cook gently," announced Mabel; "then we can turn our attention to the sweets. Would you rather make the blancmange or the pastry?"

"I don't care much about either, if you and Dora want to make them," said Aldred. "I shall have quite enough with the soup and the bread sauce. I might look after the vegetables, if you like."

[57] As the others agreed to this division of labour, Aldred retired to the scullery, and started operations. There was a small oil cooker here, which she thought she had better use, as there would not be room for everything on the kitchen stove. She chopped up all her various herbs, put them into a pan with some water, and then began to consider the question of seasonings.

"Even Aunt Bertha admitted that French people are cleverer than English at flavourings," she thought. "Madame Pontier said there ought to be a dash of so many things. I'll try a combination of all sorts of spices, not just plain pepper and salt." So in went a stick of cinnamon, a blade of mace, a few cloves, a teaspoonful of ginger, some grated nutmeg, and some caraway seeds. Aldred had not the least notion of how much or how little constituted a "dash", so she put a liberal interpretation on the term and added a teacupful of vinegar, and half a bottle of salad oil.

"There! That ought to be worthy of a cordon bleu," she said to herself. "Now I must let it simmer away, and it will be delicious."

She set her pan on the oil cooker, and ran out to the garden, to pick some flowers for the table. This was a part of the day's work that appealed to her more than the cookery, so she lingered for some time making an artistic combination of poppies, grasses, and sweet scabious. When she arrived back at the cottage, she was greeted by both Mabel and Dora with rueful faces.

"Your lamp has been flaring up in the scullery, and has made such a mess!" began Dora. "It's sent black smuts over everything! They came right[58] through into the kitchen, and fell into the blancmange. I had hard work to fish them out."

"And the scullery looks as if it wants spring cleaning," added Mabel. "I'm afraid we shall have to put clean paper on the shelves."

Aldred rushed to ascertain the fate of her pan. Mabel had taken it off and turned the lamp out, but there was still a very nasty, oily smell in the air. Dora, who was the most practical of the three, examined the cooker and re-trimmed the wick.