Title: Dorothy on a House Boat

Author: Evelyn Raymond

Illustrator: Rudolf Mencl

Release date: May 30, 2010 [eBook #32606]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

◆◆◆◆

ILLUSTRATED

◆◆◆◆

These stories of an American girl by an American author have made “Dorothy” a household synonym for all that is fascinating. Truth and realism are stamped on every page. The interest never flags, and is ofttimes intense. No more happy choice can be made for gift books, so sure are they to win approval and please not only the young in years, but also “grown-ups” who are young in heart and spirit.

Dorothy

Dorothy at Skyrie

Dorothy’s Schooling

Dorothy’s Travels

Dorothy’s House Party

Dorothy in California

Dorothy on a Ranch

Dorothy’s House-Boat

Dorothy at Oak Knowe

Dorothy’s Triumph

Dorothy’s Tour

Illustrated, 12mo, Cloth

Price per Volume, 50 Cents

Copyright, 1909, by

The Platt & Peck Co.

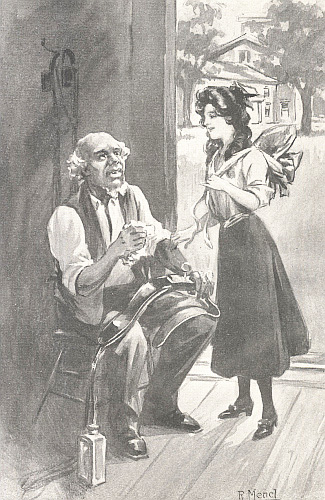

“EPHRAIM, DID YOU EVER LIVE IN A HOUSE-BOAT?”—P 15

Dorothy’s House-Boat

“EPHRAIM, DID YOU EVER LIVE IN A HOUSE-BOAT?”—P 15

Dorothy’s House-Boat

Those who have followed the story of Dorothy Calvert’s life thus far will remember that it has been full of interest and many adventures—pleasant and otherwise. Beginning as a foundling left upon the steps of a little house in Brown street, Baltimore, she was adopted by its childless owners, a letter-carrier and his wife. When his health failed she removed with them to the Highlands of the Hudson. There followed her “Schooling” at a fashionable academy; her vacation “Travels” in beautiful Nova Scotia; her “House Party” at the home of her newly discovered great aunt, Mrs. Betty Calvert; their winter together “In California”; a wonderful summer “On a Ranch” in Colorado; and now the early autumn has found the old lady and the girl once more in the ancestral home of the Calverts. Enjoying their morning’s mail in the pleasant library of old Bellvieu, they are both astonished by the contents of one letter which offers for Dorothy’s acceptance the magnificent gift of a “House-Boat.” What follows the receipt of this letter is now to be told.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Foreword | 9 | |

| I. | A Big Gift for a Small Maid | 11 |

| II. | Invitations To a Cruise of Loving Kindness |

25 |

| III. | The Difficulties of Getting Under Way |

44 |

| IV. | Matters Are Settled | 62 |

| V. | The Storm and What Followed | 76 |

| VI. | A Mule and Melon Transaction | 92 |

| VII. | Visitors | 105 |

| VIII. | The Colonel’s Revelation | 121 |

| IX. | Fish and Monkeys | 138 |

| X. | A Mere Anne Arundel Gust | 154 |

| XI. | A Morning Call of Monkeys | 165 |

| XII. | Under the Persimmon Tree | 180 |

| XIII. | What Lay Under the Walking Fern |

195 |

| XIV. | The Redemption of a Promise | 213 |

| XV. | In the Heart of an Ancient Wood | 229 |

| XVI. | When the Monkeys’ Cage Was Cleaned |

243 |

| XVII. | Conclusion | 254 |

“Well, of all things!” exclaimed Mrs. Betty Calvert, shaking her white head and tossing her hands in a gesture of amazement. Then, as the letter she had held fell to the floor, her dark eyes twinkled with amusement and she smilingly demanded: “Dorothy, do you want an elephant?”

The girl had been reading her own letters, just come in the morning’s mail, but she paused to stare at her great-aunt and to ask in turn:

“Aunt Betty, what do you mean?”

“Because if you do here’s the chance of your life to get one!” answered the old lady, motioning toward the fallen letter.

Dolly understood that she was to pick it up and read it, and, having done so, remarked:

“Auntie dear, this doesn’t say anything about an elephant, as I can see.”

“Amounts to the same thing. The idea of a house-boat as a gift to a girl like you! My cousin Seth Winters must be getting into his dotage! Of course, girlie, I don’t mean that fully, but isn’t it a queer notion? What in the world can you, could you, do with a house-boat?”

“Live in it, sail in it, have the jolliest time in it! Why not, Auntie, darling?”

Dorothy’s face was shining with eagerness and she ran to clasp Mrs. Calvert with coaxing arms. “Why not, indeed, Aunt Betty? You’ve been shut up in this hot city all summer long; you haven’t had a bit of an outing, anywhere; it would do you lots of good to go sailing about on the river or bay; and—and—do say ‘yes,’ please, to dear Mr. Seth’s offer! Oh! do!”

The old lady kissed the uplifted face, merrily exclaiming:

“Don’t pretend it’s for my benefit, little wheedler! The idea of such a thing is preposterous—simply preposterous! Run away and write the silly man that we’ve no use for house-boats, but if he does happen to have an elephant on hand, a white elephant, we might consider accepting it as a gift! We could have it kept at the park Zoo, maybe, and some city youngsters might like that.”

Dorothy’s face clouded. She had become accustomed to receiving rich gifts, during her Summer on a Ranch, as the guest of the wealthy Fords, and now to have a house-boat offered her was only one more of the wonderful things life brought to her.

Going back to her seat beside the open window she pushed her own letters aside, for the moment, to re-read that of her old teacher and guardian, during her life on the mountain by the Hudson. [Pg 13]She had always believed Mr. Winters to be the wisest of men, justly entitled to his nickname of the “Learned Blacksmith.” He wasn’t one to do anything without a good reason and, of course, Aunt Betty’s remarks about him had been only in jest. That both of them understood; and Dorothy now searched for the reason of this surprising gift. This was the letter:

“Dear Cousin Betty:

“Mr. Blank has failed in business, just as you warned me he would, and all I can recover of the money I loaned him is what is tied up in a house-boat, one of his many extravagances—though, in this case, not a great one.

“Of course, I have no use for such a floating structure on top of a mountain and I want to give it to our little Dorothy. As she has now become a shareholder in a mine with a small income of her own, she can afford to accept the boat and I know she will enjoy it. I have forwarded the deed of gift to my lawyers in your town and trust your own tangled business affairs are coming out right in the end. All well at Deerhurst. Jim Barlow came down to say that Dr. Sterling is going abroad for a few months and that the manse will be closed. I wish the boy were ready for college, but he isn’t. Also, that he wasn’t too proud to accept any help from Mr. Ford—but he is. He says the discovery of that mine on that gentleman’s property was an ‘accident’ on his own part, and he ‘won’t yet awhile.’ He wants [Pg 14]‘to earn his own way through the world’ and, from present appearances, I think he’ll have a chance to try. He’s on the lookout now for another job.”

There followed a few more sentences about affairs in the highland village where the writer lived, but not a doubt was expressed as to the fitness of his extraordinary gift to a little girl, nor of its acceptance by her. Indeed, it was a puzzled, disappointed face which was now raised from the letter and an appealing glance that was cast upon the old lady in the chair by the desk.

Meanwhile Aunt Betty had been doing some thinking of her own. She loved novelty with all the zest of a girl and she was fond of the water. Mr. Winters’s offer began to seem less absurd. Finally, she remarked:

“Well, dear, you may leave the writing of that note for a time. I’m obliged to go down town on business, this morning, and after my errands are done we will drive to that out-of-the-way place where this house-boat is moored and take a look at it. Are all those letters from your summer-friends? For a small person you have established a big correspondence, but, of course, it won’t last long. Now run and tell Ephraim to get up the carriage. I’ll be ready in twenty minutes.”

Dorothy hastily piled her notes on the wide window-ledge and skipped from the room, clapping her hands and singing as she went. To her [Pg 15]mind Mrs. Calvert’s consent to visit the house-boat was almost proof that it would be accepted. If it were—Ah! glorious!

“Ephraim, did you ever live in a house-boat?” she demanded, bursting in upon the old colored coachman, engaged in his daily task of “shinin’ up de harness.”

He glanced at her over his “specs,” then as hastily removed them and stuffed them into his pocket. It was his boast that he could see as “well as evah” and needed no such aids to his sight. He hated to grow old and those whom he served so faithfully rarely referred to the fact.

So Dorothy ignored the “specs,” though she couldn’t help smiling to see one end of their steel frame sticking out from the pocket, while she repeated to his astonished ears her question.

“Evah lib in a house-boat? Evah kiss a cat’s lef’ hind foot? Nebah heered o’ no such contraption. Wheah’s it at—dat t’ing?”

“Away down at some one of the wharves and we’re going to see it right away. Oh! I forget. Aunt Betty wants the carriage at the door in twenty minutes. In fifteen, now, I guess because ‘time flies’ fairly away from me. But, Ephy, dear, try to put your mind to the fact that likely, I guess, maybe, you and I and everybody will go and live on the loveliest boat, night and day, and every day go sailing—sailing—sailing—on pretty rivers, between green banks and heaps of flowers, and——”

Ephraim rose from his stool and waved her away.

“Gwan erlong wid yo’ foolishness honey gell! Yo’ dreamin’, an’ my Miss Betty ain’ gwine done erlow no such notionses. My Miss Betty done got sense, she hab, bress her! She ain’ gwine hab not’in’ so scan’lous in yo’ raisin’ as dat yeah boat talk. Gwan an’ hunt yo’ bunnit, if you-all ’spects to ride in ouah bawoosh.”

Dorothy always exploded in a gale of laughter to hear Ephraim’s efforts to pronounce “barouche,” as he liked to call the old carriage; and she now swept a mocking curtsey to his pompous dismissal, as she hurried away to put on her “bunnit” and coat. To Ephraim, any sort of feminine headgear was simply a “bunnit” and every wrap was a “shawl.”

Soon the fat horses drew the glistening carriage through the gateway of Bellvieu, the fine old residence of the Calverts, and down through the narrow, crowded streets of the business part of old Baltimore. To loyal Mrs. Betty, who had passed the greater part of her long life in the southern city, it was very dear and even beautiful; but to Dorothy’s young eyes it seemed, on that early autumn day, very “smelly” and almost squalid. Her mind still dwelt upon visions of sunny rivers and green fields, and she was too anxious for her aunt’s acceptance of Mr. Winters’s gift to keep still.

Fidgetting from side to side of the carriage [Pg 17]seat, where she had been left to wait, the impatient girl felt that Aunt Betty’s errands were endless. Even the fat horses, used to standing quietly on the street, grew restless during a long delay at the law offices of Kidder and Kidder, Mrs. Calvert’s men of business. This, the lady had said, would be the last stop by the way; and when she at length emerged from the building, she moved as if but half conscious of what she was doing. Her face was troubled and looked far older than when she had left the carriage; and, with sudden sympathy and pity, Dorothy’s mood changed.

“Aunt Betty, aren’t you well? Let’s go straight home, then, and not bother about that boat.”

Mrs. Calvert smiled and bravely put her own worries behind her.

“Thank you, dear, for your consideration, but ‘the last’s the best of all the game,’ as you children say. I’ve begun to believe that this boat errand of ours may prove so. Ephraim, drive to Halcyon Point.”

If his mistress had bidden him drive straight into the Chesapeake, the old coachman would have attempted to obey; but he could not refrain from one glance of dismay as he received this order. He wouldn’t have risked his own respectability by a visit to such a “low down, ornery” resort, alone; but if Miss Betty chose to go there it was all right. Her wish was “sutney cur’us” but being hers not to be denied.

And now, indeed, did Dorothy find the city with its heat a “smelly” place, but a most interesting one as well. The route lay through the narrowest of streets, where tumble-down old houses swarmed with strange looking people. To her it all seemed like some foreign country, with its Hebrew signs on the walls, its bearded men of many nations, and its untidy women leaning from the narrow windows, scolding the dirty children in the gutters beneath.

But after a time, the lane-like streets gave place to wider ones, the air grew purer, and soon a breath from the salt water beyond refreshed them all. Almost at once, it seemed, they had arrived; and Dorothy eagerly sought to tell which of the various craft clustered about the Point was her coveted house-boat.

The carriage drew up beside a little office on the pier and a man came out. He courteously assisted Aunt Betty to descend, while he promptly pointed out a rather squat, but pretty, boat which he informed her was the “Water Lily,” lately the property of Mr. Blank, but now consigned to one Mr. Seth Winters, of New York, to be held at the commands of Miss Dorothy Calvert.

“A friend of yours, Madam?” he inquired, concluding that this stately old lady could not be the “Miss” in question and wholly forgetting that the little maid beside her might possibly be such.

Aunt Betty laid her hand on Dolly’s shoulder and answered:

“This is Miss Dorothy Calvert and the ‘Water Lily’ is a gift from Mr. Winters to her. Can we go on board and inspect?”

The gentleman pursed his lips to whistle, he was so surprised, but instead exclaimed:

“What a lucky girl! The ‘Water Lily’ is the most complete craft of its kind I ever saw. Mr. Blank spared no trouble nor expense in fitting her up for a summer home for his family. She is yacht-shaped and smooth-motioned; and even her tender is better than most house-boats in this country. Blank must be a fanciful man, for he named the tender ‘The Pad,’ meaning leaf, I suppose, and the row-boat belonging is ‘The Stem.’ Odd, isn’t it, Madam?”

“Rather; but will just suit this romantic girl, here,” she replied; almost as keen pleasure now lighting her face as was shining from Dorothy’s. At her aunt’s words she caught the lady’s hand and kissed it rapturously, exclaiming:

“Then you do mean to let me accept it, you precious, darling dear! You do, you do!”

They all laughed, even Ephraim, who was close at his lady’s heels, acting the stout body-guard who would permit nothing to harm her in this strange place.

The Water Lily lay lower in the water than the dock and Mrs. Calvert was carefully helped down the gang plank to its deck. Another plank [Pg 20]rested upon the top of the cabin, or main room of the house-boat, and Dorothy sped across this and hurried down the steep little winding stair, leading from it to the lower deck, to join in her aunt’s inspection of the novel “ship.”

Delighted astonishment hushed for the time her nimble tongue. Then her exclamations burst forth:

“It’s so big!”

“About one hundred feet long, all told, and eighteen wide;” the wharf master explained.

“It’s all furnished, just like a really, truly house!”

“Indeed, yes; with every needful comfort but not one superfluous article. See this, please. The way the ‘bedrooms’ are shut off;” continued the gentleman, showing how the three feet wide window-seats were converted into sleeping quarters. Heavy sail cloth had been shaped into partitions, and these fastened to ceiling and side wall separated the cots into cosy little staterooms. Extra seats, pulled from under the first ones, furnished additional cots, if needed.

The walls of the saloon had been sunk below the deck line, giving ample head room, and the forward part was of solid glass, while numerous side-windows afforded fine views in every direction. The roof of this large room could be covered by awnings and became a charming promenade deck.

Even Aunt Betty became speechless with pleasure [Pg 21]as she wandered over the beautiful boat, examining every detail, from the steam-heating arrangements to the tiny “kitchen,” which was upon the “tender” behind.

“I thought the tug, or towing boat was always in front,” she remarked at length.

“Mr. Blank found this the best arrangement. The ‘Pad’ has a steam engine and its prow fastened to the stern of the Lily propels it ahead. None of the smoke comes into the Lily and that, too, was why the galley, or kitchen, was built on the smaller boat. A little bridge is slung between the two for foot passage and—Well, Madam, I can’t stop admiring the whole affair. It shows what a man’s brain can do in the way of invention, when his heart is in it, too. I fancy that parting with his Water Lily was about the hardest trial poor old Blank had to bear.”

Silence fell on them all and Dorothy’s face grew very sober. It was a wonderful thing that this great gift should come to her but it grieved her to know it had so come by means of another’s misfortune. Aunt Betty, too, grew more serious and she asked the practical question:

“Is it a very expensive thing to run? Say for about three months?”

The official shrugged his shoulders, replying:

“That depends on what one considers expensive. It would smash my pocket-book to flinders. The greatest cost would be the engineer’s salary. One might take the job for three dollars a day [Pg 22]and keep. He might—I don’t know. Then the coal, the power for the electric lights—the lots of little things that crop up to eat up cash as if it were good bread and butter. Ah! yes. It’s a lovely toy—for those who can afford it. I only wish I could!”

The man’s remarks ended in a sigh and he looked at Dorothy as if he envied her. His expression hurt her, somehow, and she turned away her eyes, asking a practical question of her own:

“Would three hundred dollars do it?”

“Yes—for a time, at least. But——”

He broke off abruptly and helped Aunt Betty to ascend the plank to the wharf, while Dorothy followed, soberly, and Ephraim with all the pomposity he could assume.

There Methuselah Bonaparte Washington, the small colored boy who had always lived at Bellvieu and now served as Mrs. Betty’s page as well as footman, descended from his perch and untied the horses from the place where careful Ephraim had fastened them. His air was a perfect imitation of the old man’s and sat so funnily upon his small person that the wharf master chuckled and Dorothy laughed outright.

“Metty,” as he was commonly called, disdained to see the mirth he caused but climbed to his seat behind, folded his arms as well as he could for his too big livery, and became as rigid as a statue—or as all well-conducted footmen should be.

Then good-byes were exchanged, after the [Pg 23]good old Maryland fashion and the carriage rolled away.

As it vanished from view the man left behind sighed again and clenched his fists, muttering:

“This horrible, uneven world! Why should one child have so much and my Elsa—nothing! Elsa, my poor, unhappy child!”

Then he went about his duties and tried to forget Dorothy’s beauty, perfect health, and apparent wealth.

For some time neither Mrs. Calvert nor Dorothy spoke; then the girl said:

“Aunt Betty, Jim Barlow could tend that engine. And he’s out of a place. Maybe——”

“Yes, dear, I’ve been thinking of him, too. Somehow none of our plans seem quite perfect without good, faithful James sharing them.”

“And that poor Mr. Blank——”

“A very dishonest scoundrel, my child, according to all accounts. Don’t waste pity on him.”

“But his folks mayn’t be scoundrels. He loved them, too, same as we love or he wouldn’t have built such a lovely Water Lily. Auntie, that boat would hold a lot of people, wouldn’t it?”

“I suppose so,” answered the lady, absently.

“When we go house-boating may I invite anybody I choose to go with us?”

“I haven’t said yet that we would go!”

“But you’ve looked it and that’s better.”

Just then an automobile whizzed by and the horses pretended to be afraid. Mrs. Calvert was [Pg 24]frightened and leaned forward anxiously till Ephraim had brought them down to quietness again. Then she settled back against her cushions and became once more absorbed in her own sombre thoughts. She scarcely heard and wholly failed to understand Dorothy’s repeated question:

“May I, dear Aunt Betty?”

She answered carelessly:

“Why, yes, child. You may do what you like with your own.”

But that consent, so rashly given, was to bring some strange adventures in its train.

“Huh! Dolly’s caught the Ford fashion of sending telegrams where a letter would do!” exclaimed Jim Barlow, after he had opened the yellow envelope which Griselda Roemer gave him when he came in from work.

He was back at Deerhurst, living with old Hans and Griselda, the caretakers, and feeling more at home in his little room above the lodge doorway than anywhere else. He had come to do any sort of labor by which he might earn his keep, and to go on with his studies whenever he had leisure. Mr. Seth Winters, the “Learned Blacksmith,” and his faithful friend, would give him such help as was needed; and the lad had settled down in the prospect of a fine winter at his beloved books. After his long summer on the Colorado mountains he felt rested and keener for knowledge than ever.

Now as he held the telegram in his hand his face clouded, so that Griselda, watching, anxiously inquired:

“Is something wrong? Is our good lady sick?”

“It doesn’t say so. It’s from Dorothy. She wants me to come to Baltimore and help her fool away lots more time on a house-boat! I wish she’d mind her business!”

The friendly German woman stared. She had grown to look upon her lodger, Jim, very much as if he were her own son. He wasn’t often so cross as this and never had been so against Dorothy.

“Well, well! Ah so! Well!”

With this brief comment she made haste to set the dinner on the table and to call Hans from his own task of hoeing the driveway. Presently he had washed his face and hands at the little sink in the kitchen, rubbed them into a fine glow with the spotless roller-towel, and was ready for the great meal of the day—his generous “Dutch dinner.”

Usually Jim was as ready as Hans to enjoy it; but, to-day, he left his food untasted on his plate while he stared gloomily out of the window, and for so long that Griselda grew curious and went to see what might be happening without.

“What seest thou, lad? Is aught wrong beyond already?”

“No. Oh! come back to table, Mrs. Roemer. I’ll tell you. I’d just got fixed, you know, to do a lot of hard work—both kinds. Now comes this silly thing! I suppose Mrs. Calvert must have let Dolly ask me else she wouldn’t have done it. [Pg 27]It seems some simpleton or other, likely as not that Mr. Ford——”

“Call no names, son!” warned Hans, disposing of a great mouthful, to promptly reprimand the angry youth. Hans was a man of peace. He hated nothing so much as ill temper.

Jim said no more, but his wrath cooling began to eat his dinner with a zeal that made up for lost time. Having finished he went out saying:

“I’ll finish my job when I come back. I’m off now for the Shop.”

He always spoke of the smithy under the Great Balm of Gilead Tree as if it began with a capital letter. The old man who called himself a “blacksmith”—and was, in fact, a good one—and dwelt in the place stood to eager James Barlow as the type of everything good and great. He was sure, as he hurried along the road, that Mr. Seth would agree with him in regard to Dorothy’s telegram.

“Hello, Jim! What’s up? You look excited,” was the blacksmith’s greeting as the lad’s shadow darkened the smithy entrance.

“Read that, will you, Mr. Winters?”

The gentleman put on his “reading specs,” adjusted the yellow slip of paper conveniently, and exclaimed:

“Good enough! Mistress Betty has allowed the darling to accept it then! First rate. Well?”

Then he looked up inquiringly, surprised by the impatience of the boy’s expression.

“Well—of course I sha’n’t go. The idea of [Pg 28]loafing for another two, three months is—ridiculous! And what fool would give such a thing as a house-boat to a chit of a girl like our Dorothy?”

Mr. Seth laughed and pointed to the settee.

“Sit down, chap, and cool off. The world is as full of fools as it is of wise men. Which is which depends upon the point of view. I’m sorry to have you number me amongst the first; because I happen to be the stupid man who gave the ‘Water Lily’ and its belongings to little Dorothy. I knew she’d make good use of it, if her aunt would let her accept the gift, and she flatters you, I think, by inviting you to come and engineer the craft. You’ll go, of course.”

Jim did sit down then, rather suddenly, while his face reddened with shame, remembering what he had just called the wise man before him. Finally, he faltered:

“I know next to nothing about a steam engine.”

“I thought you had a good idea of the matter. Not as a trained expert, of course, but enough to manage a simple affair like the one in question. Dr. Sterling told me that you were often pottering about the machine shops in Newburgh and had picked up some good notions about steam and its force. He thought you might, eventually, turn your attention to such a line of work. From the beginning I had you in mind as helping Dolly to carry out her pleasant autumn plans.”

“I’d likely enough blow up the whole concern—through dumb ignorance. And—and—I was going to study double hard. I do want to get to college next year!”

“This trip will help you. I wish I could take it myself, though I couldn’t manage even a tiny engine. Besides, lad, as I understand, the ‘Water Lily’ doesn’t wholly depend upon steam for her ‘power.’ She—but you’ll find out in two minutes of inspection more than I can suggest in an hour. If you take the seven-thirty train to New York, to-morrow morning, you can reach Baltimore by three in the afternoon, easily enough. ‘James Barlow. Been given house-boat. You’re engineer. Be Union Station, three, Wednesday.’ Signed: ‘Dorothy.’”

This was the short dispatch which Mr. Winters now re-read, aloud, with the comment:

“The child is learning to condense. She’s got this message down to the regulation ten-words-for-a-quarter.”

Then he crossed to the bookcase and began to select certain volumes from its shelves, while Jim watched eagerly, almost hungrily. One after another, these were the beloved books whose contents he had hoped to master during the weeks to come. To see them now from the outside only was fresh disappointment and he rose to leave, saying:

“Well, if I must I must an’ no bones about it. I wouldn’t stir hand nor foot, ’cept it’s Mrs. Calvert and——”

“Don’t leave out Dolly Doodles, boy! She was your first friend among us all, and your first little teacher in the art of spelling. Oh! I know. Of course, such a boy as you would have learned, anyway, but ‘Praise the bridge that carries you safe over.’ Dorothy was the first ‘bridge’ between you and these volumes, in those far-back days when you both picked strawberries on Miranda Stott’s truck-farm. There. I think these will be all you can do justice to before you come back. There’s an old ‘telescope’ satchel of mine in the inner closet that will hold them nicely. Fetch it and be off with you.”

“Those—why, those are your own best beloved books! Would you trust them with me away from home? Will they be of any use on a house-boat?”

“Yes, yes, you ‘doubting Thomas.’ Now—how much money have you on hand?”

“Ten dollars. I’d saved it for a lexicon and some—some other things.”

“This bulky fellow is a lexicon I used in my youth; and since Latin is a ‘dead language’ it’s as much alive and as helpful now as ever. That book is my parting gift to you; and ten dollars is sufficient for your fare and a day’s needs. good-bye.”

All the time he had been talking Mr. Winters had been deftly packing the calf-bound volumes in the shabby “telescope,” and now strapped it securely. [Pg 31]Then he held out his hand with a cheerful smile lighting his fine face, and remarking:

“When you see my dear ones just say everything good to them and say I said it. Good-bye.”

Jim hurried away lest his friend should see the moisture that suddenly filled his eyes. He “hated good-byes” and could never get used to partings. So he fairly ran over the road to the gates of Deerhurst and worked off his troublesome emotion by hoeing every vestige of a weed from the broad driveways on its grounds. He toiled so swiftly and so well that old Hans felt himself relieved of the task and quietly went to sleep in his chair by the lodge door.

Gradually, too, the house-boat idea began to interest him. He had but a vague notion of what such a craft was like and found himself thinking about it with considerable pleasure. So that when, at three o’clock the next afternoon, he stepped down from the train at Union Station he was his old, eager, good-natured self.

“Hello, Doll!”

“O Jim! The three weeks since I saw you seems an age! Isn’t it just glorious? I’m so glad!”

With that the impulsive girl threw her arms around the lad’s neck and tip-toed upwards to reach his brown cheek with her lips. Only to find her arms unclasped and herself set down with considerable energy.

“Quit that, girlie. Makes me look like a fool!”

“I should think it did. Your face is as red—as red! Aren’t you glad to see me, again?” demanded Miss Dorothy, folding her arms and standing firmly before him.

She looked so pretty, so bewitching, that some passers-by smiled, at which poor Jim’s face turned even a deeper crimson and he picked up his luggage to go forward with the crowd.

“But aren’t you glad, Jim?” she again mischievously asked, playfully obstructing his progress.

“Oh! bother! Course. But boys can be glad without such silly kissin’. I don’t know what ails girls, anyway, likin’ so to make a feller look ridic’lous.”

Dorothy laughed and now marched along beside him, contenting herself by a clasp of his burdened arms.

“Jim, you’re a dear. But you’re cross. I can always tell when you’re that by your ‘relapsing into the vernacular,’ as I read in Aunt Betty’s book. Never mind, Jim, I’m in trouble!”

“Shucks! I’d never dream it!”

They had climbed the iron stairway leading to the street above and were now waiting for a street-car to carry them to Bellvieu. So Jim set down his heavy telescope and light bag of clothing to rest his arms, while old Ephraim approached from the rear. He had gone with his “li’l miss” to meet the newcomer but had kept out of sight until now.

“Howdy, Marse Jim. Howdy.”

Then he picked up the bag of books and shrugged his shoulders at its weight. Setting it back on the sidewalk he raised his hand and beckoned small Methuselah, half-hiding behind a pillar of the building. That youngster came tremblingly forward. He was attired in his livery, that he had been forbidden to wear when “off duty,” or save when in attendance upon “Miss Betty.” But having been so recently promoted to the glory of a uniform he appeared in it whenever possible.

On this trip to the station he had lingered till his grandfather had already boarded the street-car and too late for him to be sent home to change. Now he cowered before Ephraim’s frown and fear of what would happen when they two were alone together in the “harness room” of the old stable. On its walls reposed other whips than those used for Mrs. Calvert’s horses.

“Yeah, chile. Tote dem valeeshes home. Doan’ yo let no grass grow, nudder, whiles yo’ doin’ it. I’ll tend to yo’ case bimeby. I ain’ gwine fo’get.”

Then he put the little fellow aboard the first car that came by, hoisted the luggage after him, and had to join in the mirth the child’s appearance afforded—with his scrawny body half-buried beneath the livery “made to grow in.”

Jim was laughing, too, yet anxious over the disappearance of his books, and explained to Dorothy:

“That gray telescope’s full of Mr. Seth’s books. We better get the next car an’ follow, else maybe he’ll lose ’em.”

“He’ll not dare. And we’re not going home yet. We’re going down to the Water Lily. Oh! she’s a beauty! and think that we can do just what we like with her! No, not that one! This is our car. It runs away down to the jumping-off place of the city and out to the wharves beyond. Yes, of course, Ephraim will go with us. That’s why Metty was brought along. To take your things home and to let Aunt Betty know you had come. O Jim, I’m so worried!”

He looked and laughed his surprise, but she shook her head, and when they were well on their way disclosed her perplexities, that were, indeed, real and serious enough.

“Jim Barlow, Aunt Betty’s got to give up Bellvieu—and it’s just killing her!”

“Dolly Doodles—what you sayin’?”

It sounded very pleasant to hear that old pet name again and proved that this was the same loving, faithful Jim, even if he did hate kissing. But then he’d always done that.

“I mean just what I say and I’m so glad to have you to talk it over with. I daren’t say a word to her about it, of course, and I can’t talk to the servants. They get just frantic. Once I said something to Dinah and she went into a fit, nearly. Said she’d tear the house down stone by stone ’scusin’ she’d let her ‘li’l Miss Betty [Pg 35]what was borned yeah be tu’ned outen it.’ You see that dear Auntie, in the goodness of her heart, has taken care of a lot of old women and old men, in a big house the family used to own down in the country. Something or somebody has ‘failed’ whatever that means and most of Aunt Betty’s money has failed too. If she sells Bellvieu, as the ‘city’ has been urging her to do for ever so long, she’ll have enough money left to still take care of her ‘old folks’ and keep up their Home. If she doesn’t—Well there isn’t enough to do everything. And, though she doesn’t say a word of complaint, it’s heart-breaking to see the way she goes around the house and grounds, laying her old white hand on this thing or that in such a loving way—as if she were saying good-bye to it! Then, too, Jim, did you know that poor Mabel Bruce has lost her father? He died very suddenly and her mother has been left real poor. Mabel grieves dreadfully; so, of course, she must be one of our guests on the Water Lily. She won’t cheer up Aunt Betty very well, but you must do that. She’s very fond of you, Jim, Aunt Betty is, and it’s just splendid that you’re free from Dr. Sterling now and can come to manage our boat. Why, boy, what’s the matter? Why do you look so ‘sollumcolic?’ Didn’t you want to come? Aren’t you glad that ‘Uncle Seth’ gave me the ‘Water Lily’?”

“No. I didn’t want to come. And if Mrs. Betty’s so poor, what you doing with a house-boat, anyway?”

Promptly, they fell into such a heated argument that Ephraim felt obliged to interfere and remind his “li’l miss” that she was in a public conveyance and must be more “succumspec’ in yo’ behavesomeness.” But she gaily returned that they were now the only passengers left in the car and she must make stupid Jim understand—everything.

Finally, she succeeded so far that he knew the facts:

How and why the house-boat had become Dorothy’s property; that she had three hundred dollars in money, all her own; and that, instead of putting it in the bank as she had expected, she was going to use it to sail the Water Lily and give some unhappy people a real good time; that Jim was expected to work without wages and must manage the craft for pure love of the folks who sailed in it; that Aunt Betty had said Dorothy might invite whom she chose to be her guests; and that, first and foremost, Mrs. Calvert herself must be made perfectly happy and comfortable.

“Here we are! There she is! That pretty thing all white and gold, with the white flag flying her own sweet name—Water Lily! Doesn’t she look exactly like one? Wasn’t it a pretty notion to paint the tender green like a real lily ‘Pad?’ and that cute little row-boat a reddish brown, like an actual ‘Stem?’ Aren’t you glad you came? Aren’t we going to be gloriously [Pg 37]happy? Does it seem it can be true that it’s really, truly ours?” demanded Dorothy, skipping along the pier beside the soberer Jim.

But his face brightened as he drew nearer the beautiful boat and a great pride thrilled him that he was to be in practical charge of her.

“Skipper Jim, the Water Lily. Water Lily, let me introduce you to your Commodore!” cried Dorothy, as they reached the gang-plank and were about to go aboard. Then her expression changed to one of astonishment. Somebody—several somebodies, indeed—had presumed to take possession of the house-boat and were evidently having “afternoon tea” in the main saloon.

The wharf master came out of his office and hastily joined the newcomers. He was evidently annoyed and hastened to explain:

“Son and daughter of Mr. Blank with some of their friends. Come down here while I was off duty and told my helper they had a right to do that. He didn’t look for you to come, to-day, and anyway, he’d hardly have stopped them. Sorry. Ah! Elsa! Afraid to stay alone back there?”

A girl, about Dorothy’s age, had followed the master and now slipped her hand about his arm. She was very thin and sallow, with eyes that seemed too large for her face, and walked with a painful limp. There was an expression of great timidity on her countenance, so that she shrank half behind her father, though he patted her hand to reassure her and explained to Dorothy:

“This is my own motherless little girl. She’s not very strong and rather nervous. I brought her down here this afternoon to show her your boat, but we haven’t been aboard. Those people—they had no right—I regret—”

Dolly, vexatious with the “interlopers,” as she considered the party aboard the Water Lily, gave place to a sudden, keen liking for the fragile Elsa. She looked as if she had never had a good time in her life and the more fortunate girl instantly resolved to give her one. Taking Elsa’s other hand in both of hers, she exclaimed:

“Come along with Jim and me and pick out the little stateroom you’ll have for your own when we start on our cruise—next Monday morning! You’ll be my guest, won’t you? The first one invited.”

Elsa’s large eyes were lifted in amazed delight; then as quickly dropped, while a fit of violent trembling shook her slight frame. She was so agitated that her equally astonished father put his arm about her to support her, and the look he gave Dorothy was very keen as he said:

“Elsa has always lived alone. She isn’t used to the jests of other girls, Miss Calvert.”

“Isn’t she? But I wasn’t jesting. My aunt has given me permission to choose my own guests and I choose Elsa, first, if she will come. Will you, dear?” and again Dolly gave the hand she held an affectionate squeeze. “Come and help us make our little cruise a perfectly delightful one.”

Once more the great, dark eyes looked into Dorothy’s brown ones and Elsa answered softly: “Ye-es, I’ll come. If—if you begin like this—with a poor girl like me—it should be called ‘The Cruise of Loving Kindness.’ I guess—I know—God sent you.”

Neither Dorothy nor Jim could find anything to say. It was evident that this stranger was different from any of their old companions, and it scarcely needed the father’s explanation to convince them that “Elsa is a deeply religious dreamer.” Jim hoped that she wouldn’t prove a “wet blanket” and was provoked with Dorothy’s impulsive invitation; deciding to warn her against any more such as soon as he could get her alone.

Already the lad was feeling as if he, too, were proprietor of this wonderful Water Lily, and carried himself with a masterful air which made Dolly smile, as he now stepped across the little deck into the main cabin.

It was funny, too, to see the “How-dare-you” sort of expression with which he regarded the “impudent” company of youngsters that filled the place, and he was again annoyed by the graciousness with which “Doll” advanced to meet them. In her place—hello! what was that she was saying?

“Very happy to meet you, Miss Blank—if I am right in the name.”

A tall girl, somewhat resembling Helena Montaigne, though with less refinement of appearance, had risen as Dorothy moved forward and stood defiantly awaiting what might happen. Her face turned as pink as her rose-trimmed hat but she still retained her haughty pose, as she stiffly returned:

“Quite right. I’m Aurora Blank. These are my friends. That’s my brother. My father owns—I mean—he ought—We came down for a farewell lark. We’d all expected to cruise in her all autumn till—. Have a cup of tea, Miss—Calvert, is it?”

“Yes, I’m Dorothy. This is Elsa Carruthers and this—James Barlow. You seem to be having a lovely time and we won’t disturb you. We’re going to inspect the tender. Ephraim, please help Elsa across when we come to the plank.”

The silence which followed proved that the company of merrymakers was duly impressed by Dolly’s treatment of their intrusion. Also, the dignity with which the old colored man followed and obeyed his small mistress convinced these other Southerners that his “family” was “quality.” Dorothy’s simple suit, worn with her own unconscious “style,” seemed to make the gayer costumes of the Blank party look tawdry and loud; while the eager spirituality of Elsa’s face became a silent reproof to their boisterous fun, which ceased before it.

Only one member of the tea-party joined the [Pg 41]later visitors. This was the foppish youth whom Aurora had designated as “my brother.” Though ill at ease he forced himself to follow and accost Dorothy with the excuse:

“Beg pardon, Miss Calvert, but we owe you an apology. We had no business down here, you know, and I say—it’s beastly. I told Rora so, but—I mean, I’m as much to blame as she. And I say, you know, I hope you’ll have as good times in the Lily as we expected to have—and—I’ll bid you good day. We’ll clear out, at once.”

But Dorothy laid her hand on his arm to detain him a moment.

“Please don’t. Finish your stay—I should be so sorry if you didn’t, and you’ve saved me a lot of trouble.”

Gerald Blank stared and asked:

“In what way, please? I’m glad to think it.”

“Why, I was going to hunt up your address, or that of your family. I’d like to have you and your sister go with us next week on our cruise. We mayn’t take the same route you’d have chosen, but—will you come? It’s fair you should and I’d be real glad. Talk it over with your sister and let me know, to-morrow, please, at this address. good-bye.”

She had slipped a visiting-card into his hand and while he stood still, surprised by her unexpected invitation, she hurried after her own friends—and to meet the disgusted look on Jim Barlow’s face.

“I say, Dolly Calvert, have you lost your senses?”

“I hope not. Why?”

“Askin’ that fellow to go with us! The idea! Well, I’ll tell you right here and now, there won’t be room enough on this boat for that popinjay an’ me at the same time. I don’t like his cut. Mrs. Calvert won’t, either, and you’d ought to consult your elders before you launch out promiscuous, this way. All told, it’s nothing but a boat. Where you going to stow them all, child?”

“Oh, there’ll be room enough, and you should be studying your engine instead of scolding me. You’re all right, though, Jimmy-boy, so I don’t mind telling you that whatever invitations I’ve given so far, were planned from the very day I was allowed to accept the Lily. Now get pleasant right away and find out how much or little you know about that engine.”

Jim laughed. Nobody could be offended with happy Dorothy that day, and he was soon deep in exploration of his new charge; his pride in his ability to handle such a perfect bit of machinery increasing every moment.

When they returned from the tender to the main saloon they found it empty and in order. Everything was as shipshape as possible, the young Blanks having proudly demonstrated their father’s skill in arrangement, and then quietly departing. Gerald’s whispered announcement to his sister had secured her prompt help in breaking [Pg 43]up their tea-party, and she now felt as ashamed of the affair as he had been.

At last, even Jim was willing to leave the Water Lily, reminded by hunger that he’d eaten nothing since his early breakfast; and returning the grateful Elsa to her father’s care, he and Dorothy walked swiftly down the pier to the car line beyond, to take the first car which came. It was full of workmen returning from the factories beyond and for a time Dorothy found no seat, while Jim went far forward and Ephraim remained on the rear platform, whence, by peering through the back window, he could still keep a watchful eye over his beloved “li’l miss.”

Somebody left the car and he saw the girl pushed into a vacant place beside a rough, seafaring man with crutches, and poorly clad. He resented the “old codger’s” nearness to his dainty darling and his talking to her. Next he saw that the talk was mostly on Dorothy’s side and that when the cripple presently left the car it was with a cordial handshake of his little lady, and a smiling good-bye from her. Then the “codger” limped to the street and Ephraim looked after him curiously. Little did he guess how much he would yet owe that vagrant.

How that week flew! How busy was everybody concerned in the cruise of the wonderful Water Lily!

Early on the morning after his arrival, Jim Barlow repaired to Halcyon Point, taking an expert engineer with him, as Aunt Betty had insisted, and from that time till the Water Lily sailed he spent every moment of his waking hours in studying his engine and its management. At the end he felt fully competent to handle it safely and was as impatient as Dorothy herself to be off; and, at last, here they all were waiting on the little pier for the word of command or, as it appeared, for one tardy arrival.

From her own comfortable steamer-chair, Aunt Betty watched the gathering of the company and wondered if anybody except Dolly could have collected such a peculiar lot of contrasts. But the girl was already “calling the roll” and she listened for the responses as they came.

“Mrs. Elisabeth Cecil Somerset Calvert?”

“Present!”

“Mrs. Charlotte Bruce?”

“Here.”

“Mabel Bruce?”

“Present!”

“Elsa Carruthers?”

“Oh! I—don’t know—I guess—.” But a firm voice, her father’s, answered for the hesitating girl, whose timidity made her shrink from all these strangers.

“Aurora Blank? Gerald Blank?”

“Oh, we’re both right on hand, don’t you know? Pop’s pride rather stood in the way, but—Present!”

“Mr. Ephraim Brown-Calvert?”

The old man bowed profoundly and answered:

“Yeah ’m I, li’l miss!”

“That ends the passengers. Now for the crew. Captain Jack Hurry?”

Nobody responded. Whoever owned the rapid name was slow to claim it. But Dorothy smiled and proceeded. “Cap’n Jack” was a surprise of her own. He would keep for a time.

“Engineer James Barlow?”

“At his post!”

“Master Engineer, John Stinson?”

“Present!” called that person, laughing. He was Jim’s instructor and would see them down the bay and into the quiet river where they would make their first stop.

“Mrs. Chloe Brown, assistant chef and dishwasher?”

“Yeah ’m I?” returned the only one of Aunt Betty’s household-women who dared to trust herself on board a boat “to lib.” She was Methuselah’s mother and as his imposing name was read, answered for him; while the “cabin boy and general utility man” ducked his woolly head beneath her skirts, for once embarrassed by the attention he received.

“Miss Calvert, did you know that you make the thirteenth person?” asked Aurora Blank, who had kept tally on her white-gloved fingers.

“I hope I do—there’s ‘luck in odd numbers’ one hears. But I’m not—I’m not! Auntie, Jim, look yonder—quick! It’s Melvin! It surely is!”

With a cry of delight Dorothy now rushed down the pier to where a street-car had just stopped and a lad alighted. She clasped his hands and fairly pumped them up and down in her eagerness, but she didn’t offer to kiss him though she wanted to do so. She remembered in time that the young Nova Scotian was even shyer than James Barlow and mustn’t be embarrassed. But her questions came swiftly enough, though his answers were disappointing.

However, she led him straight to Mrs. Calvert, his one-time hostess at Deerhurst, and there was now no awkward shyness in his respectful greeting of her, and the acknowledgment he made to the general introductions which followed.

Seating himself on a rail close to Mrs. Betty’s chair he explained his presence.

“The Judge sent me to Baltimore on some errands of his own, and after they were done I was to call upon you, Madam, and say why her father couldn’t spare Miss Molly so soon again. He missed her so much, I fancy, while she was at San Leon ranch, don’t you know, and she is to go away to school after a time—that’s why. But——”

The lad paused, colored, and was seized by a fit of his old bashfulness. He had improved wonderfully during the year since he had been a member of “Dorothy’s House Party” and had almost conquered that fault. No boy could be associated for so long a time with such a man as Judge Breckenridge and fail to learn much; but it wasn’t easy to offer himself as a substitute for merry Molly, which he had really arrived to do.

However, Dolly was quick to understand and caught his hands again, exclaiming:

“You’re to have your vacation on our Water Lily! I see, I see! Goody! Aunt Betty, isn’t that fine? Next to Molly darling I’d rather have you.”

Everybody laughed at this frank statement, even Dolly herself; yet promptly adding the name of Melvin Cook to her list of passengers. Then as he walked forward over the plank to where Jim Barlow smilingly awaited him, carrying his small suit-case—his only luggage, she called after him:

“I hope you brought your bugle! Then we can have ‘bells’ for time, as on the steamer!”

He nodded over his shoulder and Dorothy strained her eyes toward the next car approaching over the street line, while Mrs. Calvert asked:

“For whom are we still waiting, child? Why don’t we go aboard and start?”

“For dear old Cap’n Jack! He’s coming now, this minute.”

All eyes followed hers and beheld an old man approaching. Even at that distance his wrinkled face was so shining with happiness and good nature that they smiled too. He wore a very faded blue uniform made dazzlingly bright by scores of very new brass buttons. His white hair and beard had been closely trimmed, and the discarded cap of a street-car conductor crowned his proudly held head. The cap was adorned in rather shaky letters of gilt: “Water Lily. Skipper.”

Though he limped upon crutches he gave these supports an airy flourish between steps, as if he scarcely needed them but carried them for ornaments. Nobody knew him, except Dorothy; not even Ephraim recognizing in this almost dapper stranger the ragged vagrant he had once seen on a street car.

But Dorothy knew and ran to meet him—“last but not least of all our company, good Cap’n Jack, Skipper of the Water Lily.”

Then she brought him to Aunt Betty and formally [Pg 49]presented him, expressing by nods and smiles that she would “explain him” later on. Afterward, each and all were introduced to “our Captain,” at whom some stared rather rudely, Aurora even declining to acknowledge the presentation.

“Captain Hurry, we’re ready to embark. Is that the truly nautical way to speak? Because, you know, we long to be real sailors on this cruise and talk real sailor-talk. We cease to be ‘land lubbers’ from this instant. Kind Captain, lead ahead!” cried Dorothy, in a very gale of high spirits and running to help Aunt Betty on the way.

But there was no hurry about this skipper, except his name. With an air of vast importance and dignity he stalked to the end of the pier and scanned the face of the water, sluggishly moving to and fro. Then he pulled out a spy glass, somewhat damaged in appearance, and tried to adjust it to his eye. This was more difficult because the lens was broken; but the use of it, the old man reckoned, would be imposing on his untrained crew, and he had expended his last dollar—presented him by some old cronies—in the purchase of the thing at a junk shop by the waterside. Indeed, the Captain’s motions were so deliberate, and apparently, senseless, that Aunt Betty lost patience and indignantly demanded:

“Dorothy, who is this old humbug you’ve [Pg 50]picked up? You quite forgot—or didn’t forget—to mention him when you named your guests.”

“No, Auntie, I didn’t forget. I kept him as a delightful surprise. I knew you’d feel so much safer with a real captain in charge.”

“Humph! Who told you he was a captain, or had ever been afloat?”

“Why—he did;” answered the girl, under her breath. “I—I met him on a car. He used to own a boat. He brought oysters to the city. I think it was a—a bugeye, some such name. Auntie, don’t you like him? I’m so sorry! because you said, you remember, that I might choose all to go and to have a real captain who’ll work for nothing but his ‘grub’—that’s food, he says——”

“That will do. For the present I won’t turn him off, but I think his management of the Water Lily will be brief. On a quiet craft—Don’t look so disappointed. I shall not hurt your skipper’s feelings though I’ll put up with no nonsense.”

At that moment the old man had decided to go aboard and leading the way with a gallant flourish of crutches, guided them into the cabin, or saloon, and made his little speech.

“Ladies and gents, mostly ladies, welcome to my new ship—the Water Lily. Bein’ old an’ seasoned in the knowledge of navigation I’ll do my duty to the death. Anybody wishin’ to consult me will find me on the bridge.”

With a wave of his cap the queer old fellow [Pg 51]stumped away to the crooked stairway, which he climbed by means of the baluster instead of the steps, his crutches thump-thumping along behind him.

By “bridge” he meant the forward point of the upper deck, or roof of the cabin, and there he proceeded to rig up a sort of “house” with pieces of the awning in which there had been inserted panes of glass.

But the effect of his address was to put all these strangers at ease, for none could help laughing at his happy pomposity, and after people laugh together once stiffness disappears.

Gerald Blank promptly followed Melvin Cook to Jim’s little engine-room on the tender, and the colored folks as promptly followed him. Their own bunks were to be on the small boat and Chloe was anxious to see what they were like.

Then Mrs. Bruce roused from her silence and asked Aunt Betty about the provisions that had been brought on board and where she might find them. She had been asked to join the party as housekeeper, really for Mabel’s sake, from whom she couldn’t be separated now, and because Dorothy had argued:

“That dear woman loves to cook better than anything else. She always did. Now she hasn’t anybody left to cook for, ’cept Mabel, and she’ll forget to cry when she has to get a dinner for lots of hungry sailors.”

The first sight of Mrs. Bruce’s sad face, that [Pg 52]morning, had been most depressing; and she was relieved to find a change in its aspect as the woman roused to action. There hadn’t been much breakfast eaten by anybody and Dorothy had begged her old friend to:

“Just give us lots of goodies, this first meal, Mrs. Bruce, no matter if we have to do with less afterwards. You see—three hundred dollars isn’t so very much——”

“It seems a lot to me, now,” sighed the widow.

But Dorothy went on quickly:

“And it’s every bit there is. When the last penny goes we’ll have to stop, even if the Lily is right out in the middle of the ocean.”

“Pshaw, Dolly! I thought you weren’t going out of sight of land!”

“Course, we’re not. That is—we shall never go anywhere if my skipper doesn’t start. I’ll run up to his bridge and see what’s the matter. You see I don’t like to offend him at the beginning of things and though Jim Barlow is really to manage the boat, I thought it would please the old gentleman to be put in charge, too.”

“Foolish girl, don’t you know that there can’t be two heads to any management?” returned the matron, now really smiling. “It’s an odd lot, a job lot, seems to me, of widows and orphans and cripples and rich folks all jumbled together in one little house-boat. More ’n likely you’ll find yourself in trouble real often amongst us all. That old chap above is mighty pleasant to look at [Pg 53]now, but he’s got too square a jaw to be very biddable, especially by a little girl like you.”

“But, Mrs. Bruce, he’s so poor. Why, just for a smell of salt water—or fresh either—he’s willing to sail this Lily; just for the sake of being afloat and—his board, course. He’ll have to eat, but he told me that a piece of sailor’s biscuit and a cup of warmed over tea would be all he’d ever ‘ax’ me. I told him right off then I couldn’t pay him wages and he said he wouldn’t touch them if I could. Think of that for generosity!”

“Yes, I’m thinking of it. Your plans are all right—I hope they’ll turn out well. A captain for nothing, an engineer the same, a housekeeper who’s glad to cook for the sake of her daughter’s pleasure, and the rest of the crew belonging—so no more wages to earn than always. Sounds—fine. By the way, Dorothy, who deals out the provisions on this trip?”

“Why, you do, of course, Mrs. Bruce, if you’ll be so kind. Aunt Betty can’t be bothered and I don’t know enough. Here’s a key to the ‘lockers,’ I guess they call the pantries; and now I must make that old man give the word to start! Why, Aunt Betty thought we’d get as far as Annapolis by bed-time. She wants to cruise first on the Severn river. And we haven’t moved an inch yet!”

“Well, I’ll go talk with Chloe about dinner. She’ll know best what’ll suit your aunt.”

Dorothy was glad to see her old friend’s face [Pg 54]brighten with a sense of her own importance, as “stewardess” for so big a company of “shipmates,” and slipping her arm about the lady’s waist went with her to the “galley,” or tiny cook-room on the tender. There she left her, with strict injunctions to Chloe not to let her “new mistress” overtire herself.

It was Aunt Betty’s forethought which had advised this, saying:

“Let Chloe understand, in the beginning, that she is the helper—not the chief.”

Leaving them to examine and delight in the compact arrangements of the galley she sped up the crooked stair to old Captain Jack. To her surprise she found him anything but the sunny old fellow who had strutted aboard, and he greeted her with a sharp demand:

“Where’s them papers at?”

“Papers? What papers?”

“Ship’s papers, child alive? Where’s your gumption at?”

Dorothy laughed and seated herself on a camp-stool beside him.

“Reckon it must be ‘at’ the same place as the ‘papers.’ I certainly don’t understand you.”

“Land a sissy! ’Spect we’d be let to sail out o’ port ’ithout showin’ our licenses? Not likely; and the fust thing a ship’s owner ought to ’tend to is gettin’ a clean send off. For my part, I don’t want to hug this dock no longer. I want to take her out with the tide, I do.”

Dorothy was distressed. How much or how little this old captain of an oyster boat knew about this matter, he was evidently in earnest and angry with somebody—herself, apparently.

“If we had any papers, and we haven’t—who’d we show them to, anyway?”

Captain Hurry looked at her as if her ignorance were beyond belief. Then his good nature made him explain:

“What’s a wharf-master for, d’ye s’pose? When you hand ’em over I’ll see him an’ up anchor.”

But, at that moment, Mr. Carruthers himself appeared on the roof of the cabin, demanding:

“What’s up, Cap’n Jack? Why don’t you start—if it’s you who’s to manage this craft, as you claim? If you don’t cut loose pretty quick, my Elsa will get homesick and desert.”

The skipper rose to his feet, or his crutches, and retorted:

“Can’t clear port without my dockyments, an’ you know it! Where they at?”

“Safe in the locker meant for them, course. Young Barlow has all that are necessary and a safe keeper of them, too. Better give up this nonsense and let him go ahead. Easier for you, too, Cap’n, and everything’s all right. Good-bye, Miss Dorothy. I’ll slip off again without seeing Elsa, and you understand? If she gets too homesick for me, or is ill, or—anything happens, telegraph [Pg 56]me from wherever you are and I’ll come fetch her. Good-bye.”

He was off the boat in an instant and very soon the Water Lily had begun her trip. The engineer, Mr. Stinson, was a busy man and made short work of Captain Hurry’s fussiness. He managed the start admirably, Jim and the other lads watching him closely, and each feeling perfectly capable of doing as much—or as little—as he. For it seemed so very simple; the turning of a crank here, another there, and the thing was done.

However, they didn’t reach Annapolis that night, as Mrs. Calvert had hoped. Only a short distance down the coast they saw signs of a storm and the lady grew anxious at once.

“O Dolly! It’s going to blow, and this is no kind of a boat to face a gale. Tell somebody, anybody, who is real captain of this Lily, to get to shore and anchor her fast. She must be tied to something strong. I never sailed on such a craft before nor taken the risk of caring for so many lives. Make haste.”

This was a new spirit for fearless Aunt Betty to show and, although she herself saw no suggestions of a gale in the clouding sky, Dorothy’s one desire was to make that dear lady happy. So, to the surprise of the engineers, she gave her message, that was practically a command, and a convenient beach being near it was promptly obeyed.

“O, Mr. Captain, stop the ship—I want to get out and walk!” chanted Gerald Blank, in irony; “Is anybody seasick? Has the wild raging of the Patapsco scared the lady passengers? I brought a lemon in my pocket——”

But Dorothy frowned at him and he stopped.

“It is Mrs. Calvert’s wish,” said the girl, with emphasis.

“But Pop would laugh at minding a few black clouds. He built the Water Lily to stand all sorts of weather. Why, he had her out in one of the worst hurricanes ever blew on the Chesapeake and she rode it out as quiet as a lamb. Fact. I wasn’t with him, course, but I heard him tell. I say, Miss Dolly, Stinson’s got to leave us, to-night, anyway, or early to-morrow morning. I wish you’d put me in command. I do so, don’t you know. I understand everything about a boat. Pop has belonged to the best clubs all his life and I’m an ‘Ariel’ myself—on probation; that is, I’ve been proposed, only not voted on yet, and I could sail this Lily to beat the band. Aw, come! Won’t you?” he finished coaxingly.

John Stinson was laughing, yet at the same time, deftly swinging both boats toward the shore; while Jim Barlow’s face was dark with anger, Cap’n Jack was nervously thumping his crutches up and down, and even gentle Melvin had retreated as far from the spot as the little tender allowed. His shoulders were hunched in the fashion which showed him, also, to be provoked [Pg 58]and, for an instant Dorothy was distressed. Then the absurdity of the whole matter made her laugh.

“Seems if everybody wants to be captain, on this bit of a ship that isn’t big enough for one real one! Captain Hurry, Captain Barlow, Captain Blank, Captain Cook——”

“What do Barlow and Cook know about the water? One said he was a ‘farmer,’ and the other a ‘lawyer’s clerk’——”

“But a lawyer’s clerk that’s sailed the ocean, mind you, Gerald. Melvin’s a sailor-lad in reality, and the son of a sailor. You needn’t gibe at Melvin. As for Jim, he’s the smartest boy in the world. He understands everything about engines and machinery, and—Why, he can take a sewing-machine to pieces, all to pieces, and put it together as good as new. He did that for mother Martha and Mrs. Smith back home on the mountain, and at San Leon, last summer, he helped Mr. Ford decide on the way the new mine should be worked, just by the books he’d studied. Think of that! And Mr. Ford’s a railroad man himself and is as clever as he can be. He knows mighty well what’s what and he trusts our Jim——”

“Dorothy, shut up!”

This from Jim, that paragon she had so praised! The effect was a sudden silence and a flush of anger on her own face. If the lad had struck her she couldn’t have been more surprised, [Pg 59]nor when Melvin faced about and remarked:

“Better stow this row. If Captain Murray, that I sailed under on the ‘Prince,’ heard it he’d say there’d be serious trouble before we saw land again. If we weren’t too far out he’d put back to port and set every wrangler ashore and ship new hands. It’s awful bad luck to fight at sea, don’t you know?”

Sailors are said to be superstitious and Melvin had caught some of their notions and recalled them now. He had made a longer speech than common and colored a little as he now checked himself. Fortunately he just then caught Mrs. Bruce’s eye and understood from her gestures that dinner was ready to serve. Then from the little locker he had appropriated to his personal use, he produced his bugle and hastily blew “assembly.”

The unexpected sound restored peace on the instant. Dorothy clapped her hands and ran to inform Aunt Betty:

“First call for dinner; and seats not chosen yet!”

All unknown to her two tables had been pulled out from somewhere in the boat’s walls and one end of the long saloon had been made a dining-room. The tables were as neatly spread as if in a stationary house and chairs had been placed beside them on one side, while the cushioned [Pg 60]benches which ran along the wall would seat part of the diners.

With his musical signals, Melvin walked the length of the Water Lily and climbed the stairs to cross the “promenade deck,” as the awning-covered roof was always called. As he descended, Aunt Betty called him to the little room off one end the cabin, which was her own private apartment, and questioned him about his bugle.

“Yes, Madam, it’s the one you gave me at Deerhurst, at the end of Dorothy’s house-party. My old one I gave Miss Molly, don’t you know? Because she happened to fancy—on account of her hearing it in the Nova Scotia woods, that time she was lost. It wasn’t worth anything, but she liked it. Yours, Madam, is fine. I often go off for a walk and have a try at it, just to keep my hand in and to remind me of old Yarmouth. Miss Molly begged me to fetch it. She said Miss Dolly would be pleased and I fancy she is.”

Then again conquering his shyness, he offered his arm to the lady and conducted her to dinner. There was no difficulty in seeing what place was meant for her, because of the fine chair that was set before it and the big bunch of late roses at her plate. These were from the Bellvieu garden, and were another of Dolly’s “surprises.”

As Melvin led her to her chair and bowed in leaving her, old Ephraim placed himself behind [Pg 61]it and stood ready to serve her as he had always done, wherever she might happen to be.

Then followed a strange thing. Though Mrs. Bruce and Chloe had prepared a fine meal, and the faces of all in the place showed eagerness to enjoy it, not one person moved; but each stood as rigid as possible and as if he or she would so remain for the rest of the day.

Only Dorothy. She had paused between the two tables and was half-crying, half-laughing over the absurd dilemma which had presented itself.

“Why, good people, what’s the matter?” asked Mrs. Calvert, glancing from one to another. But nobody answered; and at this mark of disrespect she colored and stiffened herself majestically in her chair.

“Aunt Betty, it’s Captain Hurry, again!” explained Dorothy, close to her aunt’s ear. “He claims that the captain of any boat always has head table. He’s acted so queer even the boys hate to sit near him, and the dinner’s spoiling and—and I wish I’d never seen him!”

“Very likely. Having seen him it would have been better for you to ask advice before you invited him. He was the picture of happiness when he appeared but—we must get rid of him right away. He must be put ashore at once.”

“But, Aunt Betty, I invited him. Invited him, don’t you see? How can a Calvert tell a guest to go home again after that?”

Mrs. Calvert laughed. This was quoting her own precepts against herself, indeed. But she was really disturbed at the way their trip was beginning and felt it was time “to take the helm” herself. So she stood up and quietly announced:

“This is my table. I invite Mrs. Bruce to take the end chair, opposite me. Aurora and Mabel, the wall seats on one side; Dorothy and [Pg 63]Elsa, the other side, with Elsa next to me, so that she may be well looked after.

“Captain Hurry, the other table is yours. Arrange it as you choose.”

She reseated herself amid a profound silence; but one glance into her face convinced the old Captain that here was an authority higher than his own. The truth was that he had been unduly elated by Dorothy’s invitation and her sincere admiration for the cleverness he boasted. He fancied that nobody aboard the Water Lily knew anything about “Navigation” except himself and flattered himself that he was very wise in the art. He believed that he ought to assert himself on all occasions and had tried to do so. Now, he suddenly resumed his ordinary, sunshiny manner, and with a grand gesture of welcome motioned the three lads to take seats at the second table.

Engineer Stinson was on the tender and would remain there till the others had finished; and the colored folks would take their meals in the galley after the white folks had been served.

“Well, that ghost is laid!” cried Dorothy, when dinner was over and she had helped Aunt Betty to lie down in her own little cabin. “But Cap’n Jack is so different, afloat and ashore!”

“Dolly, dear, I allowed you to invite whom you wished, but I’m rather surprised by your selections. Why, for instance, the two Blanks?”

“Because I was sorry for them.”

“They’re not objects of pity. They’re quite the reverse and the girl’s manners are rude and disagreeable. Her treatment of Elsa is heartless. Why didn’t you choose your own familiar friends?”

“Elsa! Yes, indeed, Auntie, dear, without her dreaming of it, Elsa changed all my first plans for this house-boat party. I fell in love with her gentle, sad little face the first instant I saw it and I just wanted to see it brighten. She looked as if she’d never had a good time in her life and I wanted that she should have. Then she said it would be ‘A cruise of loving kindness’ and I thought that was beautiful. I just longed to give every poor, unhappy body in the world some pleasure. The Blanks aren’t really poor, I suppose, for their clothes are nice and Aurora has brought so many I don’t see where she’ll keep them. But she seemed poor in one way—like this: If you’d built the Water Lily for me and had had to give it up for debt I shouldn’t have felt nice to some other girl who was going to get it. I thought the least I could do was ask them to come with us and that would be almost the same thing as if they still owned the house-boat themselves. They were glad enough to come, too; and I know—I mean, I hope—they’ll be real nice after we get used to each other. You know we asked Jim because we were sort of sorry for him, too, and because he wouldn’t charge any wages for taking care the engine! Mrs. Bruce [Pg 65]and Mabel—well, sorry for them was their reason just the same. You don’t mind, really, do you, Auntie, darling? ’Cause——”

Dorothy paused and looked anxiously into the beloved face upon the pillow.

Aunt Betty laughed and drew the girl’s own face down to kiss it fondly. Dorothy made just as many mistakes as any other impulsive girl would make, but her impulses were always on the side of generosity and so were readily forgiven.

“How about me, dear? Were you sorry for me, along with the rest?”

Dorothy flushed, then answered frankly:

“Yes, Aunt Betty, I was. You worried so about that horrid ‘business,’ of the Old Folks’ Home and Bellvieu, that I just wanted to take you away from everything you’d ever known and let you have everything new around you. They are all new, aren’t they? The Blanks and Elsa, and the Bruces; yes and Captain Jack, too. Melvin’s always a dear and he seems sort of new now, he’s grown so nice and friendly. I’d rather have had dear Molly, course, but, since I couldn’t, Melvin will do. He’ll be company for Jim—he and Gerald act like two pussy cats jealous of one another. But isn’t it going to be just lovely, living on the Water Lily? I mean, course, after everybody gets used to each other and we get smoothed off on our corners. I guess it’s like the engine in the Pad. Mr. Stinson says it’ll run [Pg 66]a great deal better after it’s ‘settled’ and each part gets fitted to its place.

“There! I’ve talked you nearly to sleep, so I’ll go on deck with the girls. It isn’t raining yet, and doesn’t look as if it were going to. Sleep well, dear Aunt Betty, and don’t you dare to worry a single worry while you’re aboard the Lily. Think of it, Auntie! You are my guest now, my really, truly guest of honor! Doesn’t that seem queer? But you’re mistress, too, just the same.”

Well, it did seem as if even this brief stay on the house-boat were doing Mrs. Calvert good, for Dorothy had scarcely slipped away before the lady was asleep. No sound came to her ears but the gentle lapping of the water against the boat’s keel and a low murmur of voices from the narrow deck which ran all around the sides.

When she awoke the craft was in motion and the sun shining far in the west. She was rather surprised at this, having expected the Lily to remain anchored in that safe spot which had been chosen close to shore. However, everything was so calm and beautiful when she stepped out, the smooth gliding along the wooded banks was so beautiful, that she readily forgave anybody who had disobeyed her orders. Indeed, she smilingly assured herself that she was now:

“Nothing and nobody but a guest and must remember the fact and not interfere. Indeed, it will be delightful just to rest and idle for a time.”

Dorothy came to meet her, somewhat afraid to explain:

“I couldn’t help it this time, Aunt Betty. Mr. Stinson says he must leave at midnight and he wants to ‘make’ a little town a few miles further down the shore, where he can catch a train back to city. That will give him time to go on with his work in the morning. Old Cap’n Jack, too, says we’d better get along. The storm passed over, to-day, but he says we’re bound to get it soon or late.”

Mrs. Calvert’s nap had certainly done her good, for she was able now to laugh at her own nervousness and gaily returned:

“It would be strange, indeed, if we didn’t get a storm sometime or other. But how is the man conducting himself now?”

“Why, Aunt Betty, he’s just lovely. Lovely!”

“Doesn’t seem as if that adjective fitted very well, but—Ah! yes. Thank you, my child, I will enjoy sitting in that cosy corner and watching the water. How low down upon it the Water Lily rides.”

Most of this was said to Elsa, who had timidly drawn near and silently motioned to a sheltered spot on the deck and an empty chair that waited there. She had never seen such a wonderful old lady as this; a person who made old age seem even lovelier than youth.

Aunt Betty’s simple gown of lavender suited her fairness well, and she had pinned one of [Pg 68]Dorothy’s roses upon her waist. Her still abundant hair of snowy whiteness and the dark eyes, that were yet bright as a girl’s, had a beauty which appealed to the sensitive Elsa’s spirit. A fine color rose in the frail girl’s face as her little attention was so graciously accepted, and from that moment she became Aunt Betty’s devoted slave.

Her shyness lessened so that she dared to flash a look of scorn upon Aurora, who shrugged her shoulder with annoyance at the lady’s appearance on deck and audibly whispered to Mabel Bruce that:

“She didn’t see why an old woman like that had to join a house-boat party. When we had the Water Lily we planned to have nobody but the jolliest ones we knew. We wouldn’t have had my grandmother along, no matter what.”

Mabel looked at the girl with shocked eyes. She had been fascinated by Aurora’s dashing appearance and the stated fact that she had only worn her “commonest things,” which to Mabel’s finery-loving soul seemed really grand. But to hear that aristocratic dame yonder spoken of as an “old woman,” like any ordinary person, was startling.

“Why Aurora—you said I might call you that——”

“Yes, you may. While we happen to be boatmates and out of the city, you know. At home, I don’t know as Mommer would—would—You [Pg 69]see she’s very particular about the girls I know. I shall be in ‘Society’ sometime, when Popper makes money again. But, what were you going to say?”

“I was going to say that maybe you don’t know who that lady is. She is Mrs. Elisabeth Cecil-Somerset-Calvert!”

“Well, what of it? Anybody can tie a lot of names on a string and wear ’em that way. Even Mommer calls herself Mrs. Edward Newcomer-Blank of R.”

“Why ‘of R?’ What does it mean?” asked Mabel, again impressed.

“Doesn’t mean anything, really, as far as I know. But don’t you know a lot of Baltimoreans, or Marylanders, write their names that way? Haven’t you seen it in the papers?”

“No. I never read a paper.”

“You ought. To improve your mind and keep you posted on—on current events. I’m in the current event class at school—I go to the Western High. I was going to the Girls’ Latin, this year, only—only—Hmm. So I have to keep up with the times.”

Aurora settled her silken skirts with a little swagger and again Mabel felt it a privilege to know so exalted a young person, even if their acquaintance was limited to a few weeks of boat life. Then she listened quite humbly while Aurora related some of her social experiences and discussed [Pg 70]with a grown-up air her various flirtations.