Title: The Child's Book of American Biography

Author: Mary Stoyell Stimpson

Illustrator: Frank T. Merrill

Release date: May 31, 2010 [eBook #32628]

Most recently updated: May 7, 2014

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Carla Foust, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Carla Foust,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Corrections are indicated with a mouse-hover and are also listed at the end of this book.

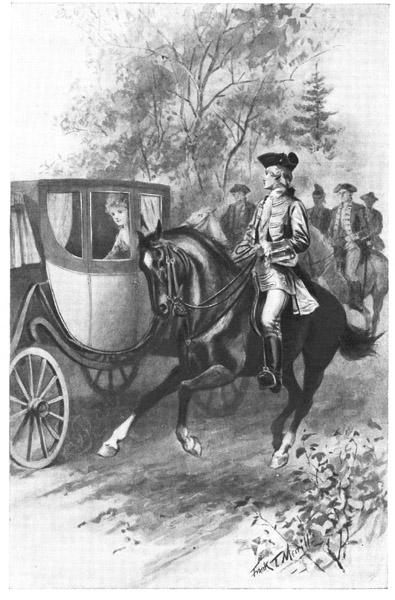

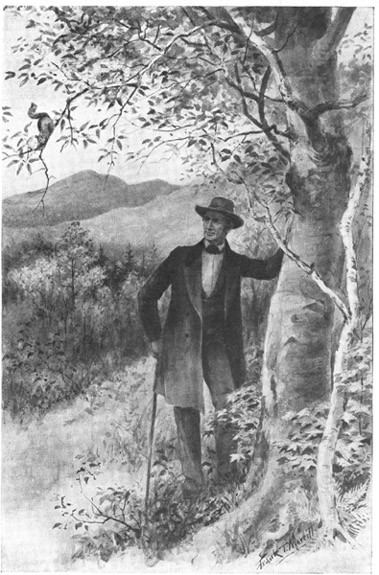

He rode beside the coach on a chestnut horse.

Frontispiece. See Page 6.

He rode beside the coach on a chestnut horse.

Frontispiece. See Page 6.

BY

MARY STOYELL STIMPSON

ILLUSTRATED BY

FRANK T. MERRILL

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1924

Copyright, 1915,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Set up and electrotyped by J. S. Cushing Co., Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

In every country there have been certain men and women whose busy lives have made the world better or wiser. The names of such are heard so often that every child should know a few facts about them. It is hoped the very short stories told here may make boys and girls eager to learn more about these famous people.

| PAGE | |

| George Washington | 1 |

| William Penn | 9 |

| John Paul Jones | 17 |

| John Singleton Copley | 27 |

| Benjamin Franklin | 36 |

| Louis Agassiz | 46 |

| Dorothea Lynde Dix | 54 |

| Ulysses Simpson Grant | 62 |

| Clara Barton | 75 |

| Abraham Lincoln | 81 |

| Robert Edward Lee | 91 |

| John James Audubon | 98 |

| Robert Fulton | 106 |

| George Peabody | 116 |

| Daniel Webster | 124 |

| Augustus St. Gaudens | 132 |

| Henry David Thoreau | 141 |

| Louisa May Alcott | 149 |

| Samuel Finley Breese Morse | 155 |

| William Hickling Prescott | 164 |

| Phillips Brooks | 173 |

| Samuel Clemens | 181 |

| Joe Jefferson | 188 |

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | 197 |

| James McNeill Whistler | 204 |

| Ralph Waldo Emerson | 215 |

| Jane Addams | 222 |

| Luther Burbank | 229 |

| Edward Alexander MacDowell | 236 |

| Thomas Alva Edison | 243 |

| He rode beside the coach on a chestnut horse | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

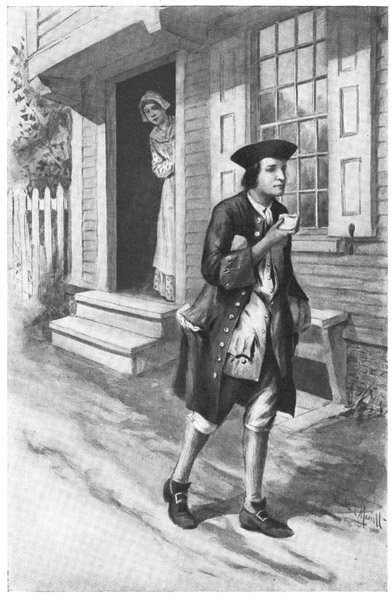

| He began munching one of these as he went back into the street | 41 |

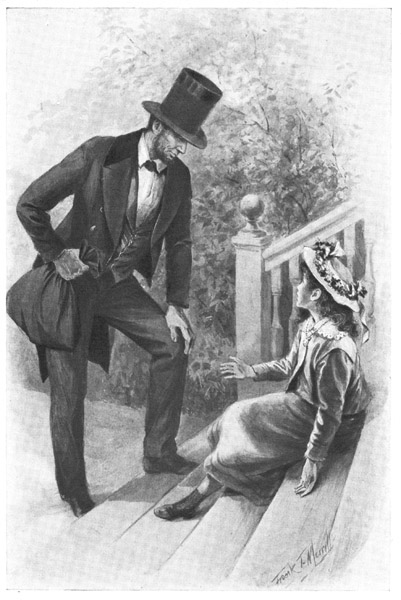

| "How big is your trunk?" | 88 |

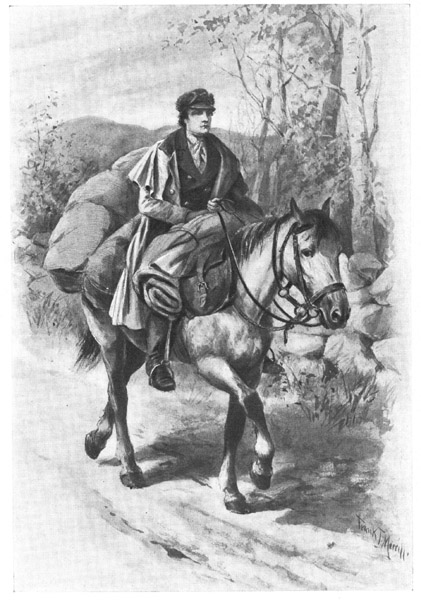

| He rode there on horseback | 129 |

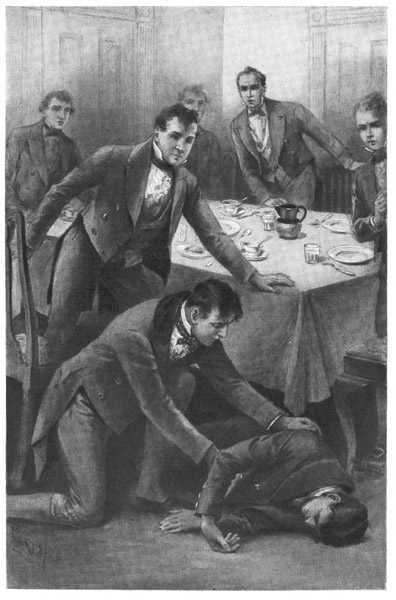

| The poor fellow fell to the floor as if he were dead | 166 |

| He generally went out alone | 221 |

No one ever tells a story about the early days in America without bringing in the name of George Washington. In fact he is called the Father of our country. But he did not get this name until he was nearly sixty years old; and all kinds of interesting things, like taming wild colts, fighting Indians, hunting game, fording rivers, and commanding an army, had happened to him before that. He really had a wonderful life.

George Washington was born in Virginia almost two hundred years ago. Virginia was not a state then. Indeed, there were no states. Every colony from Maine to Georgia was owned by King George, who sent men from England to govern them.

At the time of George Washington's birth,[2] Virginia was the richest of the thirteen colonies. George's father, Augustine Washington, had a fine old southern farmhouse set in the midst of a large tobacco plantation. This farm of a thousand acres was on the Potomac River. The Washington boys (George had two older brothers and several younger ones) had plenty of room to play in, and George had a pony, Hero, of his own.

George was eleven years old when his father died, and his mother managed the plantation and brought up the children. George never gave her any trouble. He had good lessons at school and was willing to help her at home. He was a fine wrestler and could row and swim. Indeed, he liked the water so well, that he fancied he might lead the life of a sailor, carrying tobacco from the Potomac River to England. He heard stories of vessels meeting pirates and thought it would be very exciting. But his English uncle warned Mrs. Washington that it would be a hard life for her son, and she coaxed him to give up the idea.

George had shown that he could do the[3] work of a man on the farm when he was only sixteen. He was tall and strong and had a firm will. He had great skill in breaking colts and understood planting and harvesting, as well as tobacco raising. Being good at figures, he learned surveying. Surveying is the science of measuring land so that an owner will know just how much he has, how it lies, and what it adjoins, so that he can cut it into lots and set the measurements all down on paper. George was a fine land surveyor, and when he went to visit a half-brother, Lawrence Washington, who had a beautiful new home on the Potomac, which he called Mount Vernon, an English nobleman, Lord Fairfax, who owned the next estate, hired George to go all over his land in Virginia and put on paper for him the names of the people who lived in the Shenandoah valley, the way the roads ran, and the size of his different plantations. He really did not know how much land he owned, for King Charles the Second had given an immense amount of land to his grandfather. But he thought it was quite[4] time to find out, and he was sure George Washington was an honest lad who would do the work well.

Lord Fairfax spoke so highly of George that he was made surveyor of the colony. The outdoor life, and the long tramps in the sunshine made George's tall frame fill out, and he became one of the stoutest and handsomest young men in the colony.

Lawrence Washington was ill and had to go to a warmer climate, so he took George with him for help and company. Lawrence did not live and left the eight-thousand-acre estate, Mount Vernon, to George. This made George Washington a rich man at twenty.

The French and English began to discover that there was fine, rich land on either side of the Ohio River, and each laid claim to it. Now the Indians had been wandering through the forests of that region, camping and fishing where they chose, and they felt the land belonged to them. They grew ugly and sulky toward the English with whom up to this time they had been very friendly. It looked as if there would be war.[5]

"Some one must go and talk to these Frenchmen," said Dinwiddie, the English governor at Virginia, "whom shall we send?"

Lord Fairfax, the old neighbor of George, answered: "I know just the man you want. Your messenger must be young, strong, and brave. He must know the country and be able to influence both the French and the Indians. Send George Washington."

Washington served through these troubled times one year with Dinwiddie and three years with General Braddock, an English general. Always he proved himself brave. He had plenty of dangers. He was nearly drowned, four bullets went crashing through his clothes, in two different battles the horse on which he was riding was killed, but he kept calm and kept on fighting. He was soon made commander-in-chief of all the armies in Virginia.

After five hard years of fighting, Washington went back to Mount Vernon, where he lived quietly and happily with a beautiful widow to whom he was married a few weeks after meeting her. When he and his bride[6] rode home to Mount Vernon, she was dressed in white satin and wore pearl jewels. Her coach was drawn by six white horses. Washington was dressed in a suit of blue, lined with red satin and trimmed with silver lace. He rode beside the coach on a chestnut horse, with soldiers attending him.

Mrs. Washington had two children, Jack Custis, aged six, and Martha, who was nicknamed Patty, aged four. George Washington was very fond of these children, and one of the first things he did after they came to Mount Vernon was to send to England for ten shillings' worth of toys, six little books, and a fashionable doll. Patty broke this doll, but Washington only laughed and ordered another that was better and larger.

George Washington was having a fine time farming, raising horses and sheep, having the negro women weave and spin cloth and yarn, carrying on a fishery, and riding over his vast estate, when there was trouble between the colonists and England. Again a man was needed that was brave, wise, and honest. And when the colonists decided to[7] fight unless the king would either stop taxing them or let them vote in Parliament, they said: "George Washington must be our commander-in-chief." So he left his wife, children, and home, and led the American troops for seven years.

The colonists won their freedom from the English yoke, but they knew if they were to govern themselves, they needed a very wise man at their head. They made George Washington the first President of the United States of America. Of course it pleased him that such honor should be shown him, but he would have preferred to be just a Virginian farmer at Mount Vernon. However, he went to New York and took the oath of office—that is he promised, as all presidents have to, to work for the good of the United States. He was dressed in a suit of dark brown cloth (which was made in America) with knee-breeches and white silk stockings, and shoes with large silver buckles. He wore a sword at his side, and as the sun shone on his powdered hair, he looked very noble and handsome. He kissed the Bible as he took the oath; the[8] chancellor lifted his hand and shouted: "Long live George Washington, President of the United States."

The people did some wild cheering, cannons boomed, bells rang, hats were tossed in the air, and there was happiness everywhere.

America had her first President!

Washington ruled the people for eight years wisely and well. He was greatly beloved at home and he was praised in other countries. A German ruler said Washington was the greatest general in the world. A prime minister of England said Washington was the purest man in history. But we like to say Washington was the Father of our country, and we like to remember that he said: "Do justice to all, but never forget that we are Americans!"

When Charles the Second was King of England, there lived in London a wealthy admiral of the British navy, Sir William Penn. He had been such a brave sailor that he was a favorite at court. He had a son who was a handsome, merry lad, whom he meant to educate very highly, for he knew the king would find some great place for him in his kingdom.

So young William was sent early to school and college, where he learned Greek and Latin, French, German, and Dutch. He was quick motioned and strong. At Oxford College there was hardly a student who could equal him in swimming, rowing, and outdoor sports. His father grew prouder and prouder of his son each day. "William," he said to himself, "will do honor to me, to his king, and to his country." And he kept urging money and luxuries upon his son, whom he dressed like a prince.[10]

Imagine the Admiral's despair when he learned one morning that his son was hobnobbing with the Quakers! Just then a new sect of religious people who called themselves Quakers, or Friends, had sprung up in England. They were much despised. A Quaker believed that all men are equal, so he never took his hat off to any one, not even the king. The Quakers would not take an oath in court; would not go to war or pay money in support of war; always said "thee" and "thou" in addressing each other, and wore plain clothes and sober colors. They thought they ought always to act as their consciences told them to.

In England and Massachusetts, Quakers were treated like criminals. Some of them were put to death. But the more they were abused, the more their faith became known, and the more followers they had.

A traveling Quaker preacher went to Oxford, and when young William Penn heard him, he decided that he had found a religion that suited him. He stopped going to college services, declared he would not wear the[11] college gown, and even tore the gowns from other students. He was expelled from Oxford.

The Admiral was very angry. He told his son he had disgraced him. But he knew William had a strong will, and instead of having many harsh words with him, sent his son off to Paris. "I flatter myself," laughed the Admiral, "that in gay, fashionable Paris, William will soon forget his foolish ideas about the Quakers."

The young people of Paris made friends with William at once, for he was handsome and jolly. He was eighteen years old. He had large eyes and long dark hair which fell in curls about his shoulders. For a time he entered into all the gay doings of Paris and spent a long time in Italy. So when he returned to England, two years later, his father nodded approval at the change in his looks and ways. He seemed to have forgotten the new religion entirely. But presently an awful plague swept over London, and William grew serious again. The Admiral now packed the boy off to Ireland. He was bound to stop this Quaker business.[12]

There was some kind of a riot or war in Ireland, and William fought in the thickest of it, for he liked to be in the midst of whatever was going on. One evening he heard that the old Quaker preacher he had liked at Oxford was preaching near by. He, with some other soldiers, went to hear him, and all his love for the Quaker faith came back to him, and he joined the society. He was imprisoned with other Quakers, and then his father said he would never speak to him again. But he really loved his son and was so pleased when he got out of prison that he agreed to forgive him, if he would only promise to take off his hat when he met his father, the king, or the Duke of York. But after young William had thought about it, he told his father that he could not make such a promise.

William was sometimes in prison, sometimes driven from home by his father, then forgiven for the sake of his mother; often he was tired out with writing and preaching, but he kept true to his belief.

When William's father died, he left his[13] son great wealth, which he used for the good of others, especially the Quakers. William knew the Crown owed the Admiral nearly a hundred thousand dollars. As the king was something of a spendthrift, it was not likely that the debt would be paid very soon, so William asked the king to pay him in land. This the monarch was glad to do, so he granted an immense tract of land on the Delaware River, in America, to the Admiral's son.

William planned to call this tract Sylvania, or Woodland, but when King Charles heard this, he said: "One thing I insist on. Your grant must be called after your father, for I had great love for the brave Admiral." Thus the name decided on was Pennsylvania (Penn's Woods).

William Penn lost no time in sending word to all the Quakers in England that in America they could find a home and on his land be free from persecution. As many as three thousand of them sailed at once for America, and the next year William visited his new possessions. He did not know just how the tract might[14] please him, so he left his wife and child behind, in England. He laid out a city himself on the Delaware River and called it the City of Brotherly Love, because he hoped there would be much love and harmony in the colony of Quakers. The other name for city of brotherly love is Philadelphia. If you visit this city to-day, you will find many of its streets bearing the names William Penn gave them more than two hundred years ago. Some of these are Pine, Mulberry, Cedar, Walnut, and Chestnut streets.

Of course Indians were to be found along all the rivers in the American colonies. Penn really owned the land along the Delaware, but he thought it better to pay them for it as they had held it so many years, so he called a council under a big tree, where he shook hands with the red men and said he was of the same blood and flesh as they; and he gave them knives, beads, kettles, axes, and various things for their land. The Indians were pleased and vowed they would live in love with William Penn as long as the[15] moon and sun should shine. This treaty was never broken. And one of the finest things to remember about William Penn is his honesty with the much persecuted Indians.

Penn left the Quaker colony after a while and went back to England. But he returned many years later with his wife and daughter. He had two fine homes, one in the city of Philadelphia, the other in the country. At the country home there was a large dining-hall, and in it Penn entertained strangers and people of every color and race. At one of his generous feasts his guests ate one hundred roast turkeys.

Penn, who was so gentle and loving to all the world, had many troubles of his own. One son was wild and gave him much anxiety. He himself was suspected of being too friendly with the papist King James, and of refusing to pay his bills. For one thing and another, he was cast into prison until he lost his health from the cold, dark cells. It seems strange that the rich, honest William Penn should from boyhood be doomed to imprison[16]ment because of his religion, his loyalty, and from trying to obey the voice of his conscience. While he was not born in this country, the piety and honesty of William Penn will always be remembered in America.

Along the banks of the River Dee, in Scotland, the Earls of Selkirk owned two castles. John Paul was landscape gardener at Saint Mary's Isle, and his brother George made the grounds beautiful at the Arbigland estate. Little John Paul stayed often with his uncle. At either place he could see the blue water, and he loved everything about it. At Arbigland he watched the ships sail by and could see the English mountains in the distance. From the sailors he heard all kinds of sea stories and tales of wild border warfare. When a tiny child, he used to wander down to the mouth of the river Nith and coax the crews of the sailing vessels to tell him stories. They liked him and taught him to manage small sailboats. He quickly learned sea phrases and used to climb on some high rock and give off orders to his small play-fellows, or perhaps launch his boat[18] alone upon the waters and just make believe that he had a crew of men on board with whom he was very stern.

For a few years this son of the Scotch gardener went to parish school, but his mind was filled with the wild stories of adventure, and he longed to see the world. John had a feeling that his life was going to be exciting, and he could not keep his mind on his books some days. He was not sorry when his mother told him that as times were hard, he must leave school and go to work.

John's older brother, William, had gone to America, and his uncle George had ceased working for the Earls of Selkirk because he had saved enough money to go to America. He was a merchant, with a store of his own in South Carolina.

John heard such glowing accounts of men getting rich and famous in that land across the sea that he felt it must be almost like fairy-land. Think how pleased he must have been when at the age of twelve he shipped aboard the ship Friendship, bound for Virginia! And best of all, this ship anchored[19] a few miles from Fredericksburg, where his brother lived. When in port, John stayed with William. He loved America from the first moment he saw a bit of her coast, and he never left off loving our country as long as he lived.

John went back and forth from America to Scotland on the Friendship a great many times. He had made up his mind that he would always go to sea, and he meant to understand everything about ships, countries to which they might sail, and all laws about trading in different ports. So he studied all the books he could get hold of that would teach him these things.

Sometimes he changed vessels, shipping with a different captain. Sometimes he went to strange countries. But he was one who kept his eyes open, and he learned to be more and more skilful in all sea matters.

About two years before the Revolutionary War, he was feeling discouraged. He knew his employers were pirates in a way. He had met with some trouble on his last voyage, so that he knew it was best not to go to his[20] brother's when he reached North Carolina from the West Indies, and that he had best avoid using his own name. As he sat alone on a bench in front of a tavern one afternoon, his head in his hands, a jovial, handsome man came along. The man was well dressed, a kind-hearted, rich Southerner. He hated to see people unhappy. After he had passed John Paul, he turned back and going close to him, asked: "What's your name, my friend?"

"I have none," was the answer.

"Where's your home?"

"I have none."

The stranger was struck with the face and figure of John Paul and noticed that his handsome black eyes had a commanding expression. He said to himself: "Here is a lad that will be of importance some day, or my name is not Willie Jones!"

Then Willie Jones took John by the arm and said: "Come home with me. My home is big enough for us both."

This was quite true, for Willie Jones had a beautiful estate called "The Grove." The house was like a palace with its immense[21] drawing-rooms, wide fireplaces, carved halls, and spacious dining-room which overlooked the owner's race track. For Willie Jones owned blooded horses, went to country hunts, played cards, and had overseers to manage his fifteen hundred slaves, who worked in Jones's tobacco fields and salt mines. His clothes were of the first quality and his linen fine.

On a neighboring estate across the river lived Willie's brother, Allen Jones. He was married to a dark-eyed beauty who gave parties in her large ballroom, and who led the minuets and gavottes better than any of her guests.

Just as John Paul had been at home on the estates of the Earl of Selkirk in Scotland, he was now at home on both these southern plantations. By both families he was petted and soon beloved. He seemed like one of their own blood.

The people of North Carolina talked constantly of Liberty. They declared themselves anxious to be independent of England. Soon after the famous Boston Tea-party,[22] the women of North Carolina pledged their word to drink no more tea that was taxed.

John Paul took the same stand as his good friends. And he more than ever felt he was born to do great deeds. And he hoped to prove his gratitude to the Joneses by winning fame. From this time he took the name of John Paul Jones. All his navy papers are signed that way. And he became an American citizen.

Paul Jones's rise was rapid. In 1776 he became a lieutenant in the Continental navy. The colonists had but five armed vessels; the Alfred, on which Paul Jones served, was one of them. These five ships were the beginning of the American navy. The captain of the Alfred was slow in reaching his vessel, and so Paul Jones had to get the ship ready for sea. He was so quick and sure in all his acts that the sailors all liked him.

The ship was visited by the commodore of the squadron of five ships. He found everything in such fine condition that he said: "My confidence in you is so great that if the captain does not reach here by the time[23] we should get away, I shall hoist my flag on your ship and give you command of her!"

"Thank you, Commodore," and Paul bowed, "when your flag is hoisted on the Alfred, I hope a flag of the United Colonies will fly at the peak. I want to be the man to raise that flag on the ocean."

The commodore laughed and replied: "As Congress is slow, I am afraid there will not be time to make a flag after it actually decides what that shall be."

"I think there will, Sir," answered Paul Jones.

It seems he knew almost for a certainty that the Continental Congress had planned their first flag of the Revolution. It was to be of yellow silk, showing a pine tree with a rattlesnake under it, and bearing the daring motto: "Don't tread on me." Paul Jones had bought the material to make one, out of his own pocket, and Bill Green, a quarter-master, sat up all night to cut and sew the cloth into a flag.

Captain Saltonstall arrived in time to take command, but Paul Jones kept his disappoint[24]ment to himself and faithfully did the lieutenant's duties. He had been drilling the men, and when the commodore came again to inspect the ship, some four hundred, with one hundred marines, were drawn up on deck. Bill Green and Paul Jones were very busy for a minute, and just as the commodore came over the ladder at the ship's side, the flag with the pennant flew up the staff, under Paul Jones's hand. Every man's hat came off, the drummer boys beat a double ruffle on the drums, and such cheers burst from every throat!

The commodore said to Paul Jones: "I congratulate you; you have been enterprising. Congress adopted that flag but yesterday, and this one is the first to fly."

Bill Green was thanked, too, and the squadron sailed for the open sea, the Alfred leading the way.

Paul Jones was very daring, but his judgment and knowledge were so perfect that in the twenty-three great battles which he fought upon the seas, though many times wounded, he was never defeated. He made[25] the American flag, which he was the first to raise, honored, and he kept it flying in the Texel with a dozen, double-decked Dutch frigates threatening him in the harbor, while another dozen English ships were waiting just beyond to capture him. He was offered safety if he would hoist the French colors and accept a commission in the French navy, but he never wavered. It was his pride to be able to say to the American Congress: "I have never borne arms under any but the American flag, nor have I ever borne or acted under any commission except that of the Congress of America."

Paul Jones served without pay and used nearly all of his private fortune for the cause of independence. Congress made him the ranking officer of the American navy and gave him a gold medal. France conferred the cross of a military order upon him and a gold sword. It was a beautiful day when this cross was given him. The French minister gave a grand fête in Philadelphia. All Congress was there, army and navy officers, citizens, and sailors who had served under[26] Jones. Against the green of the trees, the uniforms of the officers and the white gowns of the ladies showed gleamingly.

Paul Jones wore the full uniform of an American captain and his gold sword. He carried his blue and gold cap in his hand. A military band played inspiring airs as the French minister and Paul Jones walked toward the center of the lawn. Paul Jones was pale but happy. He was receiving an honor never before given a man who was not a citizen of France, but as his eyes lighted on the stars and stripes floating above him, they filled with tears, for his greatest joy of all was that he had left the sands of Dee to become a citizen and defender of his beloved America.

When the city of Boston, Massachusetts, was just a small town in which there were no schools where boys and girls could learn to draw and paint, one little fellow by the name of John Singleton Copley was quite sure to be waiting at the door when his stepfather, Peter Pelham, came home to dinner or supper, to ask why the pictures he had been drawing of various people did not look like them. Peter Pelham could nearly always tell John what the matter was, because he knew a good deal about drawing. He made maps and engravings himself.

John remembered what his stepfather told him and practised until he made really fine drawings. Then he began to color them. He did love gay tints, and as both men and women wore many buckles and jewels, and brocades and velvets of every hue in those days, he could make these portraits as dazzling as he chose.[28]

There is no doubt John loved to make pictures. He had drawn many a one on the walls of his nursery when he was scarcely more than a baby. He later covered the blank pages and margins of his school-books with faces and animals. And instead of playing games with the other boys in holidays, he was apt to spend such hours with chalks and paints.

When John was fourteen or fifteen, his portraits were thought so lifelike that Boston people paid him good prices for them. He was glad to earn money, for his kind stepfather died, leaving his wife to the care of John and his stepbrother, Henry. He had been working and saving for years when he married the daughter of a rich Boston merchant. This wife, Suzanne, was a beautiful girl, proud of her husband's talent and anxious for him to get on in the world. The artist soon bought a house on Beacon Hill which had a fine view from its windows. He called this estate, which covered eleven acres, his "little farm." You can guess how large it looked when I tell you that the farm is to-day practically the western side of Beacon Hill.[29]

The young couple were happy and must have prospered, for a man who saw the house on the hill wrote to his friends: "I called on John Singleton Copley and found him living in a beautiful home on a fine open common; dressed in red velvet, laced with gold, and having everything about him in handsome style." It is evident John still liked bright colors.

John had never seen any really good paintings; he had never had any teacher; and he longed to see the works of the old masters in other countries. But at first he did not want to leave his old mother; then it was the young wife who kept him here; and by and by he felt he could not be away from his own dear little children, so it was not until he was nearly forty that he went abroad.

In one of the first letters that Suzanne got from her husband he told of the fine shops in Genoa. She laughed when she read that in a few hours after he landed he bought a suit of black velvet lined with crimson satin, lace ruffles for his neck and sleeves, and silk stockings. "I'd know," she said to herself, "the[30] suit would have a touch of crimson—John does love rich colors!"

All his letters told how wonderful he found the old paintings and often described his attempts to copy them. After he had visited the galleries and museums of Italy, he went to England. He was delighted to find that his wife and family had already fled there because of the Revolution in America. He had heard of the trouble between the Colonists in America and England and had worried night and day for fear harm would come to Suzanne and the children. Of course he worried about the "little farm" too, but it was no time to go back to Boston, and he could only hope his agent would protect it.

The Copleys liked London, but some days they felt homesick for Beacon Hill. Still he must keep earning money, and there were plenty of English people who wanted to sit for their portraits, while of course, with the fierce Revolution raging, and with soldiers camping everywhere, Boston people did not care much about having their pictures painted.[31]

In London John began to paint pictures that showed events in history. Sometimes he would take for a subject a famous battle, sometimes a scene from the English Parliament, or perhaps a king or lord doing some act which we have read about in their lives. These pictures were immense in size and took a long time to do, because Copley was particular to have everything exactly true. George the Third was so much pleased with his work that when he was going to paint the large work "The Siege of Gibraltar", his Majesty sent him, with his wife and eldest daughter, to Hanover, to take the portraits of four great generals of that country, who had proved their bravery and skill on the rock of Gibraltar. All the uniforms, swords, banners, and scenery were as perfect as if Copley had been at the siege himself, and the officers' faces were just like photographs. The king was very kind and generous. He told Copley not to hurry back to England but to enjoy Hanover thoroughly, and to give his wife and daughter a holiday they would never forget. To enable Copley to go into private[32] homes and look at art treasures which the public never saw, the king gave him a letter asking this courtesy, written with his own hand.

This large canvas, "The Siege of Gibraltar", is owned by the city of London. There is another huge painting, "The Death of Lord Chatham", at Kensington Museum, which Americans like to see. It shows old Lord Chatham falling in a faint at the House of Lords. The poor man was too sick to be there, but he was a strong friend to the American Colonies and had declared over and over again that the king ought not to tax them. When he heard there was to be voting on the question, he rose from his bed and drove in a carriage to the House to say once more how wicked it was. The members of the House of Lords look very imposing with their grave faces and robes of scarlet, trimmed with ermine, but they sometimes act in a childish manner and show temper. One man who almost hated Chatham for so defending the Colonies sat as still as if he were carved out of stone when the poor old lord dropped[33] to the floor. This picture shows him sitting as cold and stiff as a ramrod while all the other members have sprung to their feet or have rushed to help the fainting man.

The Boston Public Library holds one of Copley's historical pictures. It shows a scene from the life of Charles the First of England. He is standing in the speaker's chair in the House of Commons, demanding something which the speaker, kneeling before him, is unwilling to tell. There is plenty of chance for John Copley to show his love for brilliant coloring, for the suits of the king, his nephew, Prince Rupert, and his followers are of velvets and satins, the slashed sleeves showing facings of yellow, cherry, and green. The knee breeches are fastened with buckles over gaudy silk stockings and high-heeled slippers. The men wear deep collars of lace, curled wigs, and velvet hats with sweeping plumes.

But in a picture at Buckingham Palace called "The Three Princesses" there is a riot of color. The scene is a garden, beyond which the towers of Windsor Castle show, with the flag of England floating above it;[34] there are fruit-trees and flowers, parrots of gay plumage, and pet dogs. The little girls' gowns are rainbow-like, and one of them is dancing to the music of a tambourine. It is a darling picture, and the royal couple prized it greatly.

When John Copley was only a young man, he sent a picture from Boston to England, asking that it might be placed on exhibition at the Royal Academy. It was called "The Boy and the Flying Squirrel." The boy was a portrait of his half-brother, Henry Pelham. Copley sent no name or letter, and it was against the rules of the Academy to hang any picture by an unknown artist, but the coloring was so beautiful that the rule was broken, and crowds stopped before the Boston lad's canvas to admire it. When it was discovered that John Copley painted it, and it was known he had received no lessons at that time, he was urged to go abroad at once. At the time he could not. But the praise encouraged him to keep on, and before he had a chance to visit Italy, he had painted nearly three hundred pictures. Nearly all[35] of these were painted at the "little farm" on Beacon Hill, when he or Suzanne would hardly have dreamed the day would come when he should be the favorite of kings and courts.

One of the greatest Americans that ever lived was Benjamin Franklin. The story of his life sounds like a fairy tale. Though he stood before queens and kings, dressed in velvet and laces, before he died, he was the son of a poor couple who had to work very hard to find food and clothes for their large family—for there were more than a dozen little Franklins!

Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston, one bright Sunday morning more than two hundred years ago. That same afternoon his father took the baby boy across the street to the Old South Church, to be baptized. He was named for his uncle Benjamin, who lived in England.

As Benjamin grew up, he made friends easily. People liked his eager face and merry ways. He was never quiet but darted about like a kitten. The questions he asked[37]—and the mischief he got into! But the neighbors loved him. The women made little cakes for him, and the men were apt to toss him pennies.

One day when Benjamin was about seven, some one gave him all the pennies he could squeeze into one hand. Off he ran to the toy shop, but on his way he overtook a boy blowing a whistle. Ben thought that whistle was the nicest thing he had ever seen and offered his handful of pennies for it. The boy took them, and Ben rushed home with his prize. Well, he tooted that whistle all over the house until the family wished there had never been a whistle in the world. Then an older brother told him he had paid the other boy altogether too much for it, and when Ben found that if he had waited and bought it at a store, he would have had some of the pennies left for something else, he burst out crying. He did not forget about this, either. When he was a grown man and was going to buy something, he would wait a little and say to himself: "Careful, now—don't pay too much for your whistle!" An Italian sculptor who[38] had heard this story made a lovely statue called "Franklin and his Whistle." If you happen to be in the beautiful Public Library in Newark, New Jersey, you must ask to see it.

Ben always loved the water and was a wonderful swimmer as a little fellow. He could manage a boat, too, and spent half his play hours down at the wharves. One day he had been flying kites, as he often did, and thought he would see what would happen if he went in swimming with a kite tied to his waist. He tried it and the kite pulled him along finely. If he wanted to go slowly, he let out a little bit of string. If he wanted to move through the water fast, he sent the kite up higher in the air.

But it was in school that Ben did his best. He studied so well that his father wanted to make a great scholar of him, but there was not money enough to do this, so when he was ten he had to go into his father's soap and candle shop to work. The more he worked over the candles, the worse he hated to, and by and by he said to his father: "Oh, let me go to sea!"[39]

"No," said Mr. Franklin, "your brother ran away to sea. I can't lose another boy that way. We will look up something else."

So the father and son went round the city, day after day, visiting all kinds of work-shops to see what Benjamin fancied best. But when it proved that the trade of making knives and tools, which was what pleased Benjamin most, could not be learned until Mr. Franklin had paid one hundred dollars, that had to be given up, like the school. There was never any spare cash in the Franklin purse.

As James Franklin, an older brother, had learned the printing business in England and had set up an office in Boston, Ben was put with him to learn the printer's trade. Poor Ben found him a hard man to work for. If it had not been for the books he found there to read and the friends who loaned him still more books, he could not have stayed six months. But Ben knew that since he had to leave school when he was only ten, the thing for him to do was to study by himself every minute he could get. He sat up half the nights[40] studying. When he needed time to finish some book, he would eat fruit and drink a glass of water at noon, just to save a few extra minutes for studying. James never gave him a chance for anything but work; it seemed as if he could not pile enough on him. When he found Ben could write poetry pretty well, he made him write ballads and sell them on the streets, putting the money they brought into his own pocket. He was very mean to the younger brother, and when he began to strike Ben whenever he got into a rage, the boy left him.

Benjamin went to New York but found no work there. He worked his way to Philadelphia. By this time his clothes were ragged. He had no suitcase or traveling bag and carried his extra stockings and shirts in his pockets. You can imagine how bulgy and slack he looked walking through the streets! He was hungry and stepped into a baker's for bread. He had only one silver dollar in the world. But he must eat, whether he found work or not. When he asked for ten cents' worth of bread, the baker gave him three[41] large loaves. He began munching one of these as he went back into the street. As his pockets were filled with stockings and shirts, he had to carry the other two loaves under his arms. No wonder a girl standing in a doorway giggled as he passed by! Years afterwards, when Franklin was rich and famous, and had married this very girl, the two used to laugh well over the way he looked the first time she saw him.

He began munching one of these as he went back into the

street. Page 41.

He began munching one of these as he went back into the

street. Page 41.

After one or two useless trips to England, Franklin settled down to the printing business in Philadelphia. He was the busiest man in town. Deborah, his wife, helped him, and he started a newspaper, a magazine, a bookstore; he made ink, he made paper, even made soap (work that he hated so when a boy!). Then he published every year an almanac. Into this odd book, which people hurried to buy, he put some wise sayings, which I am sure you must have heard many times. Such as: "Haste makes waste"; "Well done is better than well said"; and "Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise."[42]

Franklin and his wife did so many things and did them well that they grew rich. So when he was only forty-two, Franklin shut up all his shops and took his time for studying out inventions. When you hear about the different things he invented, you will not wonder that the colleges in the country thought he ought to be honored with a degree and made him Doctor Franklin. Here are some of his inventions: lightning-rods, stoves, fans to cool hot rooms, a cure for smoking chimneys, better printing-presses, sidewalks, street cleaning. He opened salt mines and drained swamps so that they were made into good land. Then he founded the first public library, the first police service, and the first fire company. Doesn't it seem as if he thought of everything?

But better than all, Franklin always worked for the glory of America. When King George was angry and bitter against our colonies, Franklin went to England and stood his ground against the king and all his council. He said the king had no right to make the colonies pay a lot of money for everything[43] that was brought over from England unless they had some say as to how much money it should be. If they paid taxes, they wanted to vote. They were not willing to be just slaves under a hard master.

"Very well, then," said the council, "then you colonists can't have any more clothes from England."

Mr. Franklin answered back: "Very well, then, we will wear old clothes till we can make our own new ones!"

In a week or so word was sent from England that clothing would not be taxed, and the colonists had great rejoicings. They built bonfires, rang bells, and had processions; and Benjamin Franklin's name was loudly cheered.

But England still needed money and decided to make the colonists pay a tax on tea and a few other things. Then the American colonists were as angry as they could be. They tipped the whole cargo of tea into Boston Harbor, and in spite of Franklin's trying to make the king and the colonists understand each other, there was a long war (it is called[44] the Revolutionary War) and it ended in the colonists declaring themselves independent of Great Britain. A paper telling the king and the world that the colonists should not obey the English rule any longer, but would make laws of their own was signed by men from all thirteen colonies. Benjamin Franklin was one of the men from Pennsylvania who signed it. As this paper—The Declaration of Independence—was first proclaimed July 4, 1776, the people always celebrate the fourth day of July throughout the United States.

Franklin was postmaster-general of the colonies; he was our first minister to the Court of France, the governor (or president, as the office was then called) of Pennsylvania, and helped, more than almost any other man, to make America the great country she is.

Franklin was admired in France and England for his good judgment and clever ideas. Pictures of him were shown in public places; prints of his face were for sale in three countries; medallions of his head were set in[45] rings and snuff-boxes; he traveled in royal coaches, and was treated like a prince. But although it was "the Great Doctor Franklin" here, and "the Noble Patriot" there, he did not grow vain. Benjamin Franklin was just a modest, good American!

Louis Agassiz was a Swiss boy who knew how to keep his eyes open. Some people walk right by things without seeing them, but Louis kept a sharp lookout, and nothing escaped him.

Louis was born in a small Swiss village near a lake. His father was a minister and school teacher. His mother was a fine scholar and was very sure that she wanted her children to love books, but two brothers of Louis's had died and she meant to have Louis and another son, Auguste, get plenty of play and romping in the fields so that they would grow up healthy and strong, first of all; there would be time for study afterwards.

The Agassiz boys had a few short lessons in the morning with their father or mother, and then they roamed through the woods and fields the rest of the day. Of course they found plenty to interest them and never came[47] home from these jaunts with empty hands. They had pet mice, birds, rabbits, and fish.

There was a stone basin in his father's yard, with spring water flowing through it. In this Louis put his fish and then watched their habits. As I told you, nothing escaped his eyes. He proved this more than once.

It was the custom in Swiss cantons for different kinds of workmen to travel from house to house, making such things at the door as each family might need. Louis watched the cobbler, and after he had gone away surprised his sister with a pair of boots he himself had made for her doll. And after the cooper had made his father some casks and barrels, Louis made a tiny, water-tight barrel, as perfect as could be. He kept his sharpest gaze on the tailor, and Papa Agassiz said to his wife: "Let us see, now, if Louis can make a suit!" They did not, in the end, ask him to try, but no doubt he knew pretty well how it was done.

At the age of ten, Louis was sent to a college twenty miles from Motier, where his parents lived. He was keen at his lessons and asked[48] questions until he mastered whatever he studied. The second year he went to this college he was joined by his brother, Auguste. The two boys liked the same things and never wanted to be away from each other. Whenever a vacation came, the boys walked home—all that twenty miles—and did not make any fuss about it!

By and by the boys wanted to own books which would tell them about birds, fishes, and rocks. These were the things Louis was thinking of all the time. The boys saved every cent of their spending money for these books. They were always talking about animals. One day, as they were walking from Zurich to Motier, they were overtaken by a gentleman in a carriage. He asked them to ride with him and to share his lunch. They did so and talked to him about their studies. He was greatly taken with Louis, who was a handsome, graceful lad, as he told the stranger his fondness for books. The gentleman hardly took his eyes from the boy, and a few days later Reverend Mr. Agassiz had a letter from him saying that he was very rich[49] and that he wanted to adopt Louis. He said he was sure that the boy was a genius.

Louis was not willing, though, to be any one's boy but his own parents', and so the matter was dropped.

The boys did not have much spending money, and it took, oh, such a long time to save enough to buy even one book! So they often went to a library, or borrowed a book from a teacher, then copied every word of it with pen and ink, so as to own it. You can see from this that they were very much in earnest.

When not studying or copying, the brothers were busy outdoors, watching animals. In this way they learned just what kinds of fishes could be found in certain lakes, and almost the exact day when different birds would come or go from the woods. In their rooms the cupboards and shelves were crammed with shells, stuffed fishes, plants, and odd specimens. On the ledges of the windows hovered often as many as fifty kinds of birds who had become tamed and who made their home there.[50]

At seventeen Louis was bending over his desk a good many hours of the day. He learned French, German, Latin, Greek, Italian, and English. But he was wise enough to keep himself well and strong by walking, swimming, and fencing.

Because Louis's parents and his uncle wanted him to be a doctor, he studied medicine. He carried home his diploma when he was twenty-three and earned a degree in philosophy, too. But in his own heart he knew he would not be happy unless he could hunt the world over for strange creatures and try to find out the secrets of the old, old mountains.

Louis traveled all he could and became so excited over the different things he discovered that he sometimes stopped in cities and towns and talked to the people, in their public halls, about them. He had a happy way of telling his news, and crowds went to listen to the young Swiss.

The King of Prussia thought that any one who used his eyes in such good fashion ought to visit many places. He said to Louis:[51] "Here is money for you to travel with, so that you may find out more of these strange things. You are a clever young man and can do much for the world!"

In the course of his travels, Louis Agassiz came to America. At that time he could not speak English very well, but all his stories were so charming that the halls were never large enough to hold the men and women who wanted to hear him.

Louis Agassiz loved America so well that he made up his mind to spend the rest of his life here. As time passed, he decided, also, to give this country the benefit of all that he discovered. He was so bright that the whole world was beginning to wonder at him. France got jealous of America's keeping such a great man. So Napoleon offered him a high office and great honors; but Louis said "No," adding courageously: "I'd rather have the gratitude of a free people than the patronage of Emperors!"

The city of Zurich begged him to return.

"No," he wrote, "I cannot. I love America too well!"[52]

Then the city of Paris urged him to be at the head of their Natural History Museum, but this was no use, either. Nothing could win Louis Agassiz away from America.

At Harvard College Agassiz was made professor of natural history, and there is to-day at Cambridge a museum of zoology, the largest of its kind in the world, which Agassiz founded and built. At his home in Cambridge the professor still kept strange pets, quite as he used to do when a boy. Visitors to his garden never knew when they might step on a live turtle, or when they might come suddenly upon an alligator, an eagle, or a timid rabbit.

The precious dream of going to Brazil came true when Louis Agassiz was fifty years old. With a party of seventeen and his wife, he went on an exploring expedition to South America. It was a great adventure.

Agassiz had been to many cold countries and had slept on glaciers night after night, with only a single blanket under him, but never in his life had he been in the tropics.

When Agassiz arrived in South America,[53] Don Pedro, the Emperor of Brazil, was glad to see the man who was known as a famous scientist and heaped all kinds of honors upon him. Better than all, he helped Agassiz get into many out-of-the-way places.

If you want to know about a fish that has four eyes, about dragon-flies that are flaming crimson and green, and floating islands that are as large as a school playground, yet go sailing along like a ship, bearing birds, deer, and wild looking jaguars, read: A Journey to Brazil by Professor and Mrs. Agassiz.

When you have heard the story of all these strange things, you will agree that Louis Agassiz did certainly know how to keep his eyes open.

Doctor Elisha Dix of Orange Court, Boston, was never happier than when his pet grandchild, little Dorothea Dix, came to visit his wife and himself. Every morning he had to drive about the city, in his old-fashioned chaise, to see how the sick people were getting along, and he did love to have Dorothea sitting beside him, her tongue going, as he used to declare "like a trip-hammer." She was a wide-awake, quick-motioned creature and said such droll things that the doctor used to shout with laughter, until the dappled gray horse which he drove sometimes stopped short and looked round at the two in the chaise as if to say: "Whatever in the world does all this mean?"

But when the time drew near for Dorothea to go back home, she always looked sober enough. One day she burst out: "Oh, Grandpa, I almost hate tracts!"[55]

Doctor Dix glanced down at her in his kind way and answered: "I don't know as I blame you, Child!"

You see, Joseph Dix, Dorothea's father, was a strange man. He had fine chances to make money because the doctor had bought one big lot of land after another and had to hire agents to look after these farms and forests. Naturally he sent his own son to the pleasantest places, but the only thing Joseph Dix, who was very religious in the gloomiest sort of a way, really wanted to do, was to repeat hymns and write tracts. To publish these dismal booklets, he used nearly all the money he earned, so that the family had small rations of food, cheap clothing, and no holidays.

Besides having to live in such sorry fashion, the whole household were forced to stitch and paste these tracts together. Year after year Mrs. Dix, Dorothea, and her two brothers sat in the house, doing this tiresome work. No matter whether, as agent, Mr. Dix was sent to Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, or Massachusetts; no matter whether their[56] playmates in the neighborhood were berrying, skating, or picnicking; no matter how the birds sang, the brooks sparkled, the nuts and fruit ripened; the wife and children of Joseph Dix had no outdoor pleasures, no, they just bent over those old tracts, pasting and sewing till they fairly ached.

When Dorothea was twelve, she decided to stand such a life no longer. Fortunately the family was then living in Worcester, near Boston, and it did not cost much to get there. Doctor Dix was dead, but Dorothea ran away to her grandmother, who still lived at Orange Court (now it is called Dix Place), and although Madam Dix was very strict, life was better there than with the tract-maker.

At Orange Court, Dorothea was allowed no time to play. She was taught to sew and cook and knit and was sometimes punished if the tasks were not well done. "Poor thing," she said in after life, "I never had any childhood!" But she went to school and was so quick at her lessons that in two years she went back to Worcester and opened a school for little children. She was only[57] fourteen and rather small for her age, so she put on long dresses and piled her hair on top of her head with a high comb. I think people never guessed how young she was. Anyway, she proved a good teacher, and the children loved her and never disobeyed her.

After keeping this school for a year, she studied again in Boston until she was nineteen. Then she not only taught a day and boarding-school in that city, but looked after her brothers and opened another school for poor children whose parents could not afford to pay for their lessons. She took care of her grandmother's house, too. While every one was wondering how one young girl could do so much, she made them open their eyes still wider by writing three or four books.

By and by her health broke down, and she began to think that she could never work any more, but after a long rest in England she came back to America and did something far greater than teaching or writing—she went through the whole country making prisons, jails, and asylums more comfortable. Up to the time of Dorothea Dix's interest, no[58] one had seemed to bother his head about prisoners and insane people. Any kind of a place that had a lock and key was good enough for such to sleep in. And what did it matter if a wicked man or a crazy man was cold or hungry? But it mattered very much to Dorothea Dix that human beings were being ill-treated, and she meant to start a reform. She talked with senators, governors, and presidents. She visited the places in each State where prisoners, the poor, and the crazy were shut up. She talked kindly to these shut-ins, and she talked wrathfully to the men who ill-treated them. She made speeches before legislatures; she wrote articles for the papers, and begged money from millionaires to build healthy almshouses and asylums. This was seventy years ago, when traveling was slow and dangerous in the west and south. She had so many delays on account of stage-coaches breaking down on rough or muddy roads that finally she made a practice of carrying with her an outfit of hammer, wrench, nails, screws, a coil of stout rope, and straps of strong leather. Some of[59] the western rivers had to be forded, and many times she nearly lost her life. Once, when riding in a stage-coach in Michigan, a robber sprang out of a dark place in the forest through which they were passing and demanded her purse. She did not scream or faint. She asked him if he was not ashamed to molest a woman who was going through the country to help prisoners. She told him if he was really poor, she would give him some money. And what do you think? Before she finished speaking, the robber recognized her voice. He had heard her talk to the prisoners when he was a convict in a Philadelphia prison! He begged her to go on her way in peace.

For twelve years Miss Dix went through the United States in the interests of the deaf and dumb, the blind, and the insane. Then she went to Europe to rest. But she found the same suffering there as here. In no time she was busy again. She tried to get audience with the Pope in Rome to beg him to stop some prison cruelties but was always put off. Any one else would have[60] given up, but Dorothea Dix always carried her point. One day she met the Pope's carriage in the street. She stopped it, and as she knew no Italian, began talking fast to him in Latin. She was so earnest and sensible that he gave her everything she asked for.

It was not long after her return to America before the Civil War broke out. She went straight to Washington and offered to nurse the soldiers without pay. As she was appointed superintendent, she had all the nurses under her rule. She hired houses to keep supplies in, she bought an ambulance, she gave her time, strength, and fortune to her country. In the whole four years of the Civil War, Dorothea Dix never took a holiday. She was so interested in her work that often she forgot to eat her meals until reminded of them.

After this war was over, the Secretary of War, Honorable Edwin M. Stanton, asked her how the nation could show its gratitude to her for the grand work she had done. She told him she would like a flag. Two very beautiful ones were given her, made with[61] special printed tributes on them. In her will Miss Dix left these flags to Harvard College. They hang over the doors of Memorial Hall.

Nobody ever felt sorry that Dorothea ran away from those tiresome tracts. For probably all the tracts ever written by Joseph Dix never did as much good as a single day's work of his daughter, among the wounded soldiers. And as for her reforms—they will go on forever. She has been called the most useful woman of America. That is a great name to earn.

Once upon a time, at Point Pleasant, a small town on the Ohio River, there lived a young couple who could not decide how to name their first baby. He was a darling child, and as the weeks went by, and he grew prettier every minute, it was harder and harder to think of a name good enough for him.

Finally Jesse Grant, the father, told his wife, Hannah, he thought it would be a good plan to ask the grandparents' advice. So off they rode from their little cottage, carrying the baby with them.

But at grandpa's it was even worse. In that house there were four people besides themselves to suit. At last, the father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, and the two aunts each wrote a favorite name on a bit of paper. These slips of paper were all put into grandpa's tall, silk hat which was[63] placed on the spindle-legged table. "Now," said the father to one of the aunts, "draw from the hat a slip of paper, and whatever name is written on that slip shall be the name of my son."

The slip she drew had the name "Ulysses" on it.

"Well," murmured the grandfather, "our dear child is named for a great soldier of the olden days. But I wanted him to be called Hiram, who was a good king in Bible times."

Then Hannah Grant, who could not bear to have him disappointed, answered: "Let him have both names!" So the baby was christened Hiram Ulysses Grant.

While Ulysses was still a baby, his parents moved to Georgetown, Ohio. There his father built a nice, new, brick house and managed a big farm, besides his regular work of tanning leather. As Ulysses got old enough to help at any kind of work, it was plain he would never be a tanner. He hated the smell of leather. But he was perfectly happy on the farm. He liked best of all to be around the horses, and before he was six years old he[64] rode horseback as well as any man in Georgetown. When he was seven, it was part of his work to drive the span of horses in a heavy team that carried the cord-wood from the wood-lot to the house and shop. He must have been a strong boy, for at the age of eleven he used to hold the plow when his father wanted to break up new land, and it makes the arms and back ache to hold a heavy plow! He was patient with all animals and knew just how to manage them. His father and all the neighbors had Ulysses break their colts.

In the winters Ulysses went to school, but he did not care for it as much as he did for outdoor life and work with his hands. Still he usually had his lessons and was decidedly bright in arithmetic. Because he was not a shirk and always told the truth, his father was in the habit of saying, after the farm chores were done: "Now, Ulysses, you can take the horse and carriage and go where you like. I know I can trust you."

When he was only twelve, his father began sending him seventy or eighty miles away from[65] home, on business errands. These trips would take him two days. Sometimes he went alone, and sometimes he took one of his chums with him. Talking so much with grown men gave him an old manner, and as his judgment was pretty good he was called by merchants a "sharp one." He would have been contented to jaunt about the country, trading and colt-breaking, all his life, but his father decided he ought to have military training and obtained for him an appointment at West Point (the United States' school for training soldiers that was started by George Washington) without Ulysses knowing a thing about it. Now Ulysses did not have the least desire to be a soldier and did not want to go to this school one bit, but he had always obeyed his father, and started on a fifteen days' journey from Ohio without any more talk than the simple statement: "I don't want to go, but if you say so, I suppose I must."

He found, when he reached the school, that his name had been changed. Up to this time his initials had spelled HUG, but[66] the senator who sent young Grant's appointment papers to Washington had forgotten Ulysses' middle name. He wrote his full name as Ulysses Simpson Grant, and as it would make much trouble to have it changed at Congress, Ulysses let it stand that way. So instead of being called H-U-G Grant (as he had been by his mates at home) the West Point boys, to tease him, caught up the new initials and shouted "Uncle Sam" Grant, or "United States" Grant—and sometimes "Useless" Grant.

But the Ohio boy was good-natured and only laughed at them. He was a cool, slow-moving chap, well-behaved, and was never known to say a profane word in his life. At this school there was plenty of chance to prove his skill with horses. Ulysses was never happier than when he started off for the riding-hall with his spurs clanking on the ground and his great cavalry sword dangling by his side. Once, mounted on a big sorrel horse, and before a visiting "Board of Directors," he made the highest jump that had ever been known at West Point. He was[67] as modest as could be about this jump, but the other cadets (as the pupils were called) bragged about it till they were hoarse.

After his graduation, Grant, with his regiment, was sent to the Mexican border. In the battle of Palo Alto he had his first taste of war. Being truthful, he confessed afterwards that when he heard the booming of the big guns, he was frightened almost to pieces. But he had never been known to shirk, and he not only rode into the powder and smoke that day, but for two years proved so brave and calm in danger that he was promoted several times. But he did not like fighting. He was sure of that.

At the end of the Mexican War, Ulysses married a girl from St. Louis, named Julia Dent, and she went to live, as soldiers' wives do, in whatever military post to which he happened to be sent. First the regiment was stationed at Lake Ontario, then at Detroit, and then, dear me! it was ordered to California!

There were no railroads in those days. People had to go three thousand miles on[68] horseback or in slow, lumbering wagons. This took months and was both tiresome and dangerous. Every little while there would be a deep river to ford, or some wicked Indians skulking round, or a wild beast threatening. The officers decided to take their regiments to California by water. This would be a hard trip but a safer one.

It was lucky that Mrs. Grant and the babies stayed behind with the grandparents, for besides the weariness of the long journey, there was scarcity of food; a terrible cholera plague broke out, and Ulysses Grant worked night and day. He had to keep his soldiers fed, watch out for the Indians, and nurse the sick people.

Well, after eleven years of army life, Grant decided to resign from the service. He thought war was cruel; he wanted to be with his wife and children; and a soldier got such small pay that he wondered how he was ever going to be able to educate the children. Farming would be better than fighting, he said.

He was welcomed home with great joy.[69] His wife owned a bit of land, and Grant built a log cabin on it. He planted crops, cut wood, kept horses and cows, and worked from sunrise till dark. But the land was so poor that he named the place Hardscrabble. Even with no money and hard work, the Grants were happy until the climate gave Ulysses a fever; then they left Missouri country life and moved into the city of St. Louis.

In this city Grant tried his hand at selling houses, laying out streets, and working in the custom-house; but something went wrong in every place he got. He had to move into poorer houses, he had to borrow money, and finally he walked the streets trying to find some new kind of work. Nobody would hire him. The men said he was a failure. Friends of the Dent family shook their heads as they whispered: "Poor Julia, she didn't get much of a husband, did she?"

Then he went back to Galena, Illinois, and was a clerk in his brother's store, earning about what any fifteen-year-old boy gets to-day. He worked quietly in the store all[70] day, stayed at home evenings, and was called a very "commonplace man." He was bitterly discouraged, I tell you, that he could not get ahead in the world. And his father's pride was hurt to think that his son who had appeared so smart at twelve could not, as a grown man, take care of his own family. But Julia Dent Grant was sweet and kind. She kept telling him that he would have better luck pretty soon.

In 1861 the Americans began to quarrel among themselves. Several of the States grew very bitter against each other and were so stubborn that the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, said he must have seventy-five thousand men to help him stop such rebellion. Ulysses Grant came forward, and said he would be one of these seventy-five thousand, and enlisted again in the United States Army. He was asked to be the colonel of an Illinois regiment by the governor of that State. Then, you may be sure, what he had learned at West Point came into good play. He soon showed that he knew just how to train men into fine soldiers.[71] He did so well that he was made Brigadier-general.

He stormed right through the enemies' lines and took fort after fort. Oh, his work was splendid—this man who had been called a failure!

A general who was fighting against him began to get frightened, and by and by he sent Grant a note saying: "What terms will you make with us if we will give in just a little and do partly as you want us to?"

Grant laughed when he read the letter and wrote back: "No terms at all but unconditional surrender!" Finally the other general did surrender, and when the story of the two letters and the victory for Grant was told, the initials of his name were twisted into another phrase; he was called Unconditional Surrender Grant. This saying was quoted for months, every time his name was mentioned. At the end of that time, he had said something else that pleased the people and the President.

You see, the war kept raging harder and harder. It seemed as if it would never end.[72] Grant was always at the front of his troops, watching everything the enemy did and planned, but he grew sadder and sadder. He felt sure there would be fighting until dear, brave Robert E. Lee, the southern general, laid down his sword. The whole country was sad and anxious. They said: "It is time there was a change—what in the world is Grant going to do?" And he answered: "I am going to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer!" No one doubted he would keep his word. It did take all summer and all winter, too. Then, when poor General Lee saw that his men were completely trapped, and that they would starve if he did not give in, he yielded. Grant showed how much of a gentleman he was by his treatment of the general and soldiers he had conquered. There was no lack of courtesy toward them, I can tell you. When the cruel war was ended, Grant was the nation's hero.

Later, Grant was made President of the United States he had saved. When he had finished his term of four years, he was chosen for President again. After that he traveled[73] round the world. I cannot begin to tell you the number of presents he received or describe one half the honors which were paid him—paid to this man who, at one time, could not get a day's work in St. Louis. This farmer from Hardscrabble dined with kings and queens, talked with the Pope of Rome, called on the Czar of Russia, visited the Mikado of Japan in his royal palace, and was given four beautiful homes of his own by rich Americans. One house was in Galena, one in Philadelphia, one in Washington, and another in New York. New York was his favorite city, and in a square named for him you can see a statue showing General Grant on his pet horse, in army uniform. On Claremont Heights where it can be seen from the city, the harbor, and the Hudson River, stands a magnificent tomb, the resting-place of the great hero who was born in the tiny house at Point Pleasant.

There was always a good deal of fighting blood in the Grants. The sixth or seventh great-grandfather of Ulysses, Matthew Grant, came to Massachusetts in 1630, almost three[74] hundred years ago; over in Scotland, where he was born, he belonged to the clan whose motto was "Stand Fast." I think that old Scotchman and all the other ancestors would agree with us that the boy from Ohio stood fast. And how well the name suited him which his aunt drew from the old silk hat—Ulysses—a brave soldier of the olden time!

It was on the brightest, sunniest kind of a Christmas morning, nearly one hundred years ago, that Clara Barton was born, in the State of Massachusetts. Besides the parents, there were two grown-up sisters and two big brothers to pet the new baby. There was plenty of love and plenty of money in the Barton household, so the child knew nothing but happiness.

Clara was a bright little thing. As she grew old enough to walk and talk, she followed the family about, repeating all their words and phrases like a parrot. She was not sure as to the meaning of all these words, but she liked the sound of them. Her father, who had fought in the French and Indian wars, had a fondness for the rules and forms that are used among soldiers. He taught her the names and rank of army officers.[76] Also the name of the United States' president, the vice-president, and members of the president's cabinet.

Clara's eyes looked so big, and her voice was so solemn when she babbled these names that her mother asked her one day what she thought these men looked like. "Oh," gasped Clara, "Papa always says 'the great president' so I guess he's almost a giant. I guess the president is as big as the meeting-house, and prob'ly the vice-president is the size of the school-house."

The school-teacher sisters were busy with Clara so that she was reading and spelling almost as soon as she could talk. One of these gave her a geography, and Clara was so excited over it that she used to wake this poor sister up long before daylight, and make her hold a candle close to the maps so that she could find rivers, mountains, and cities.

Stephen Barton, the older brother, was a wonder in arithmetic. It was he who taught Clara how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide. She made such good figures and so often had the examples right that she en[77]joyed her little slate next best to riding horseback with her brother David.

David did not care much for study, but did like farm work and horses. He taught Clara to ride, and the two used to gallop across the country at a mad pace. She felt as safe on the back of a horse as in a rocking-chair. She did not look much larger than a doll when the neighbors first noticed her dashing by on the back of a colt which wore neither saddle nor bridle, clinging to the animal's mane, keeping close to David's horse, and laughing with joy. Sometimes Button, the white dog, tore along after them, trying his best to keep up with them. Button belonged to Clara. He had taken care of her when she was a baby, and very gravely picked her up each time she fell in the days when she was learning to walk.

Stephen and David went to a school that was several miles away. They wanted to take Clara with them. It was one of the old-fashioned, ungraded schools, and the pupils were all ages. The snowdrifts were high, and Stephen carried Clara on his shoulder.[78] Clara sat very quiet with her slate until the primer class was called. Then she stepped before the teacher with the other little ones. The serious man pointed to the letters of different words for each child, then he asked them to spell short words like dog and cat. When Clara was asked to do the same, she smiled at the teacher and said: "But I do not spell there!"

"Where do you spell?" he inquired.

"I spell in artichoke," she answered, looking very dignified.

"In that case," he laughed, "I think you belong with the scholars who spell in three and four syllables." So after that, she spelled in the class of her big brothers.

When Clara was twelve, she was very shy of strangers, and her parents thought it might help her to get over it if she went away from home to school in New York. She was a bright pupil and decided she would like to be a teacher like her two sisters.

Clara made an excellent teacher, but was not very well and went to Washington, D.C., to work. While there, the Civil War broke out,[79] and she offered her services as a nurse. Nobody doubted she would be good at nursing, for when she was only ten years old, she took all the care of her dear brother David, who was sick for nearly two years. She really knew just exactly what sick people needed.

Clara worked in hospitals, camps, and battlefields all the time the four years' war lasted. Sometimes she had to jump on to a horse whose rider had been shot and dash away for bandages or a surgeon, and she was glad enough that David had taught her to be such a fine horsewoman.

Clara helped every sick and wounded man she came across, and some people thought she should only help the northerners. But she did not mind what anybody said or thought. She made all the soldiers as comfortable as she could. And she was delighted when, four years later, while she was in beautiful Switzerland for a rest, she heard of the Red Cross Society. This society helped every wounded person, no matter what color he was, no matter what cause or country he fought for.[80]

Clara Barton worked with this Swiss society all through the war between France and Prussia. The foreigners called her the Angel.

When Clara Barton came back to America, she tried a long time to have a branch of the Swiss society started in this country, but it was eight years before the Red Cross Society was actually formed in America. Then, because there was often sickness and suffering from fires and floods, as well as from wars, Miss Barton persuaded Congress to say that the society might help wherever there had been any great disaster.

Miss Barton's name is known in Europe as well as in America. She did Red Cross work until she was eighty years old. Almost every country on the globe gave her a present or medal. When we think what a heroine Clara Barton proved herself, it would seem as if the little girl born on the sunny December morning was a Christmas present to the whole world.

The more you find out about Abraham Lincoln, the more you will love him.

Abraham was born in Kentucky and lived in that State with his parents and his one sister until he was eight years old.