Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Drama" to "Dublin"

Author: Various

Release date: June 11, 2010 [eBook #32783]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

DRAMA. (Continued from Volume 8 Slice 6.)

10. Medieval Drama

While the scattered and persecuted strollers thus kept alive something of the popularity, if not of the loftier traditions, of their art, neither, on the other hand, was there an utter absence of written compositions to bridge the Ecclesiastical and monastic literary drama. gap between ancient and modern dramatic literature. In the midst of the condemnation with which the Christian Church visited the stage, its professors and votaries, we find individual ecclesiastics resorting in their writings to both the tragic and the comic form of the ancient drama. These isolated productions, which include the Χριστὀς πάσχων (Passion of Christ) formerly attributed to St Gregory Nazianzen, and the Querolus, long fathered upon Plautus himself, were doubtless mostly written for educational purposes—whether Euripides and Lycophron, or Menander, Plautus and Terence, served as the outward models. The same was probably Hrosvitha. the design of the famous “comedies” of Hrosvitha, the Benedictine nun of Gandersheim, in Eastphalian Saxony, which associate themselves in the history of Christian literature with the spiritual revival of the 10th century in the days of Otto the Great. While avowedly imitated in form from the comedies of Terence, these religious exercises derive their themes—martyrdoms,1 and miraculous or otherwise startling conversions2—from the legends of Christian saints. Thus, from perhaps the 9th to the 12th centuries, Germany and France, and through the latter, by means of the Norman Conquest, England, became acquainted with what may be called the literary monastic drama. It was no doubt occasionally performed by the children under the care of monks or nuns, or by the religious themselves; an exhibition of the former kind was that of the Play of St Katharine, acted at Dunstable about the year 1110 in “copes” by the scholars of the Norman Geoffrey, afterwards abbot of St Albans. Nothing is known concerning it except the fact of its performance, which was certainly not regarded as a novelty.

These efforts of the cloister came in time to blend themselves with more popular forms of the early medieval drama. The natural agents in the transmission of these popular forms were those mimes, whom, while the representatives The joculatores, jongleurs, minstrels. of more elaborate developments, the “pantomimes” in particular, had inevitably succumbed, the Roman drama had left surviving it, unextinguished and unextinguishable. Above all, it is necessary to point out how in the long interval now in question—the “dark ages,” which may, from the present point of view, be reckoned from about the 6th to the 11th century—the Latin and the Teutonic elements of what may be broadly designated as medieval “minstrelsy,” more or less imperceptibly, coalesced. The traditions of the disestablished and disendowed mimus combined with the “occupation” of the Teutonic scôp, who as a professional personage does not occur in the earliest Teutonic poetry, but on the other hand is very distinctly traceable under this name or that of the “gleeman,” in Anglo-Saxon literature, before it fell under the control of the Christian Church. Her influence and that of docile rulers, both in England and in the far wider area of the Frank empire, gradually prevailed even over the inherited goodwill which neither Alfred nor even Charles the Great had denied to the composite growth in which mimus and scôp alike had a share.

How far the joculatores—which in the early middle ages came to be the name most widely given to these irresponsible transmitters of a great artistic trust—kept alive the usage of entertainments more essentially dramatic than the minor varieties of their performances, we cannot say. In different countries these entertainers suited themselves to different tastes, and with the rise of native literatures to different literary tendencies. The literature of the troubadours of Provence, which communicated itself to Spain and Italy, came only into isolated contact with the beginnings of the religious drama; in northern France the jongleurs, as the joculatores were now called, were confounded with the trouvères, who, to the accompaniment of vielle or harp, sang the chansons de geste commemorative of deeds of war. As appointed servants of particular households they were here, and afterwards in England, called menestrels (from ministeriales) or minstrels. Such a histrio or mimus (as he is called) was Taillefer, who rode first into the fight at Hastings, singing his songs of Roland and Charlemagne, and tossing his sword in the air and catching it again. In England such accomplished minstrels easily outshone the less versatile gleemen of pre-Norman times, and one or two of them appeared as landholders in Domesday Book, and many enjoyed the favour of the Norman, Angevin and Plantagenet kings. But here, as elsewhere, the humbler members of the craft spent their lives in strolling from castle to convent, from village-green to city-street, and there exhibiting their skill as dancers, tumblers, jugglers proper, and as masquers and conductors of bears and other dumb contributors to popular wonder and merriment. Their only chance of survival finally came to lie in organization under the protection of powerful nobles; but when, in the 15th century in England, companies of players issued forth from towns and villages, the profession, in so far as its members had not secured preference, saw itself threatened with ruin.

In any attempt to explain the transmission of dramatic elements from pagan to Christian times, and the influence exercised by this transmission upon the beginnings of the medieval drama, account should finally be taken Survivals and adaptations of pagan festive ceremonies and usages. of the pertinacious survival of popular festive rites and ceremonies. From the days of Gregory the Great, i.e. from the end of the 6th century onwards, the Western Church tolerated and even attracted to her own festivals popular customs, significant of rejoicing, which were in truth relics of heathen ritual. Such were the Mithraic feast of the 25th of December, or the egg of Eostre-tide, and a multitude of Celtic or Teutonic agricultural ceremonies. These rites, originally symbolical of propitiation or of weather-magic, were of a semi-dramatic nature—such as the dipping of the neck of corn in water, sprinkling holy drops upon persons or animals, processions of beasts or men in beast-masks, dressing trees with flowers, and the like, but above all ceremonial dances, often in disguise. The sword-dance, recorded by Tacitus, of which an important feature was the symbolic threat of death to a victim, endured (though it is rarely mentioned) to the later middle ages. By this time it had attracted to itself a variety of additional features, and of characters familiar as pace-eggers, mummers, morris-dancers (probably of distinct origin), who continually enlarged the scope of their performances, especially as regarded their comic element. The dramatic “expulsion of death,” or winter, by the destruction of a lay-figure—common through western Europe about the 8th century—seems connected with a more elaborate rite, in which a disguised performer (who perhaps originally represented summer) was slain and afterwards revived (the Pfingstl, Jack in the Green, or Green Knight). This representation, after acquiring a comic complexion, was annexed by the character dancers, who about the 15th century took to adding still livelier incidents from songs treating of popular heroes, such as St George and Robin Hood; which latter found a place in the festivities of May Day with their central figure, the May Queen. The earliest ceremonial observances of this sort were clearly connected with pastoral and agricultural life; but the inhabitants of the towns also came to have a share in them; and so, as will be seen later, did the clergy. They were in particular responsible for the buffooneries of the feast of fools (or asses), which enjoyed the greatest popularity in France (though protests against it are on record from the 11th century onwards to the 17th), but was well known from London to Constantinople. This riotous New Year’s celebration was probably derived from the ancient Kalend feasts, which may have bequeathed to it both the hobby-horse and the lord, or bishop, of misrule. In the 16th century the feast of fools was combined with the elaborate festivities of courts and cities during the twelve Christmas feast-days—the season when throughout the previous two centuries the “mummers” especially 498 flourished, who in their disguisings and “viseres” began as dancers gesticulating in dumb-show, but ultimately developed into actors proper.

Thus the literary and the professional element, as well as that of popular festive usages, had survived to become tributaries to the main stream of the early Christian drama, which had its direct source in the liturgy of the Church The liturgy the main source of the medieval religious drama. itself. The service of the Mass contains in itself dramatic elements, and combines with the reading out of portions of Scripture by the priest—its “epical” part—a “lyrical” part in the anthems and responses of the congregation. At a very early period—certainly already in the 5th century—it was usual on special occasions to increase the attractions of public worship by living pictures, illustrating the Gospel narrative and accompanied by songs; and thus a certain amount of action gradually introduced itself into the service. The insertion, before or after sung portions Tropes. of the service, of tropes, originally one or more verses of texts, usually serving as introits and in connexion with the gospel of the day, and recited by the two halves of the choir, naturally led to dialogue chanting; and this was frequently accompanied by illustrative fragments of action, such as drawing down the veil from before the altar.

This practice of interpolations in the offices of the church, which is attested by texts from the 9th century onwards (the so-called “Winchester tropes” belong to the 10th and 11th), progressed, till on the great festivals of the The liturgical mystery. church the epical part of the liturgy was systematically connected with spectacular and in some measure mimical adjuncts, the lyrical accompaniment being of course retained. Thus the liturgical mystery—the earliest form of the Christian drama—was gradually called into existence. This had certainly been accomplished as early as the 10th century, when on great ecclesiastical festivals it was customary for the priests to perform in the churches these offices (as they were called). The whole Easter story, from the burial to Emmaus, was thus presented, the Maries and the angel adding their lyrical planctus; while the surroundings of the Nativity—the Shepherds, the Innocents, &c.—were linked with the Shepherds of Epiphany by a recitation of “Prophets,” including Vergil and the Sibyl. Before long, from the 11th century onwards, mysteries, as they were called, were produced in France on scriptural subjects unconnected with the great Church festivals—such as the Wise and Foolish Virgins, Adam (with the fall of Lucifer), Daniel, Lazarus, &c. Compositions on the last-named two themes remain from the hand of one of the very earliest of medieval play-writers, Hilarius, who may have been an Englishman, and who certainly studied under Abelard. He also wrote a “miracle” of St Nicholas, one of the most widely popular of medieval saints. Into the pieces founded on the Scripture narrative outside characters and incidents were occasionally introduced, by way of diverting the audience.

These mysteries and miracles being as yet represented by the clergy only, the language in which they were usually written is Latin—in many varieties of verse with occasional prose; but already in the 11th century the further The collective mystery. step was taken of composing these texts in the vernacular—the earliest example being the mystery of the Resurrection. In time a whole series of mysteries was joined together; a process which was at first roughly and then more elaborately pursued in France and elsewhere, and finally resulted in the collective mystery—merely a scholars’ term of course, but one to which the principal examples of the English mystery-drama correspond.

The productions of the medieval religious drama it is usual technically to divide into three classes. The mysteries proper deal with scriptural events only, their purpose being to set forth, with the aid of the prophetic or preparatory Mysteries, miracles, and morals distinguished. history of the Old Testament, and more especially of the fulfilling events of the New, the central mystery of the Redemption of the world, as accomplished by the Nativity, the Passion and the Resurrection. But in fact these were not kept distinctly apart from the miracle-plays, or miracles, which are strictly speaking concerned with the legends of the saints of the church; and in England the name mysteries was not in use. Of these species the miracles must more especially have been fed from the resources of the monastic literary drama. Thirdly, the moralities, or moral-plays, teach and illustrate the same truths—not, however, by direct representation of scriptural or legendary events and personages, but allegorically, their characters being personified virtues or qualities. Of the moralities the Norman trouvères had been the inventors; and doubtless this innovation connects itself with the endeavour, which in France had almost proved victorious by the end of the 13th century, to emancipate dramatic performances from the control of the church.

The attitude of the clergy towards the dramatic performances which had arisen out of the elaboration of the services of the church, but soon admitted elements from other sources, was not, and could not be, uniform. As the plays grew The clergy and the religious drama. longer, their paraphernalia more extensive, and their spectators more numerous, they began to be represented outside as well as inside the churches, at first in the churchyards, and the use of the vulgar tongue came to be gradually preferred. A Beverley Resurrection play (1220 c.) and some others are bilingual. Miracles were less dependent on this connexion with the church services than mysteries proper; and lay associations, gilds, and schools in particular, soon began to act plays in honour of their patron saints in or near their own halls. Lastly, as scenes and characters of a more or less trivial description were admitted even into the plays acted or superintended by the clergy, as some of these characters came to be depended on by the audiences for conventional extravagance or fun, every new Herod seeking to out-Herod his predecessor, and the devils and their chief asserting themselves as indispensable favourites, the comic element in the religious drama increased; and that drama itself, even where it remained associated with the church, grew more and more profane. The endeavour to sanctify the popular tastes to religious uses, which connects itself with the institution of the great festival of Corpus Christi (1264, confirmed 1311), when the symbol of the mystery of the Incarnation was borne in solemn procession, led to the closer union of the dramatic exhibitions (hence often called processus) with this and other religious feasts; but it neither limited their range nor controlled their development.

It is impossible to condense into a few sentences the extremely varied history of the processes of transformation undergone by the medieval drama in Europe during the two centuries—from about 1200 to about 1400—in which it ran Progress of the medieval drama in Europe. a course of its own, and during the succeeding period, in which it was only partially affected by the influence of the Renaissance. A few typical phenomena may, however, be noted in the case of the drama of each of the several chief countries of the West; where the vernacular successfully supplanted Latin as the ordinary medium of dramatic speech, where song was effectually ousted by recitation and dialogue, and where finally, though the emancipation was on this head nowhere absolute, the religious drama gave place to the secular.

In France, where dramatic performances had never fallen entirely into the hands of the clergy, the progress was speediest and most decided towards forms approaching those of the modern drama. The earliest play in the French France. tongue, however, the 12th-century Adam, supposed to have been written by a Norman in England (as is a fragmentary Résurrection of much the same date), still reveals its connexion with the liturgical drama. Jean Bodel of Arras’ miracle-play of St Nicolas (before 1205) is already the production of a secular author, probably designed for the edification of some civic confraternity to which he belonged, and has some realistic features. On the other hand, the Theophilus of Rutebeuf (d. c. 1280) treats its Faust-like theme, with which we meet again in Low-German dramatic literature two centuries later, in a rather lifeless form but in a highly religious spirit, and belongs to the cycle of miracles of the Virgin of which examples abound throughout 499 this period. Easter or Passion plays were fully established in popular acceptance in Paris as well as in other towns of France by the end of the 14th century; and in 1402 the Confrérie de la Passion, who at first devoted themselves exclusively to the performance of this species, obtained a royal privilege for the purpose. These series of religious plays were both extensive and elaborate; perhaps the most notable series (c. 1450) is that by Arnoul Greban, who died as a canon of Le Mans, his native town. Its revision, by Jean Michel, containing much illustrative detail (first performed at Angers in 1486), was very popular. Still more elaborate is the Rouen Christmas mystery of 1474, and the celebrated Mystère du vieil testament, produced at Abbeville in 1458, and performed at Paris in 1500. Most of the Provençal Christmas and Passion plays date from the 14th century, as well as a miracle of St Agnes. The miracles of saints were popular in all parts of France, and the diversity of local colouring naturally imparted to these productions contributed materially to the growth of the early French drama. The miracles of Ste Geneviève and St Denis came directly home to the inhabitants of Paris, as that of St Martin to the citizens of Tours; while the early victories of St Louis over the English might claim a national significance for the dramatic celebration of his deeds. The local saints of Provence were in their turn honoured by miracles dating from the 15th and 16th centuries.

It is less easy to trace the origins of the comic medieval drama in France, connected as they are with an extraordinary variety of associations for professional, pious and pleasurable purposes. The ludi inhonesti in which the students of a Paris college (Navarre) were in 1315 debarred from engaging cannot be proved to have been dramatic performances; the earliest known secular plays presented by university students in France were moralities, performed in 1426 and 1431. These plays, depicting conflicts between opposing influences—and at bottom the struggle between good and evil in the human soul—become more frequent from about this time onwards. Now it is (at Rennes in 1439) the contention between Bien-avisé and Mal-avisé (who at the close find themselves respectively in charge of Bonne-fin and Male-fin); now, one between l’homme juste and l’homme mondain; now, the contrasted story of Les Enfants de Maintenant, who, however, is no abstraction, but an honest baker with a wife called Mignotte. Political and social problems are likewise treated; and the Mystère du Concile de Bâle—an historical morality—dates back to 1432. But thought is taken even more largely of the sufferings of the people than of the controversies of the Church; and in 1507 we even meet with a hygienic or abstinence morality (by N. de la Chesnaye) in which “Banquet” enters into a conspiracy with “Apoplexy,” “Epilepsy” and the whole regiment of diseases.

Long before this development of an artificial species had been consummated—from the beginning of the 14th century onwards—the famous fraternity or professional union of the Basoche (clerks of the Parlement and the Châtelet) had been entrusted with the conduct of popular festivals at Paris, in which, as of right, they took a prominent personal share; and from a date unknown they had performed plays. But after the Confrérie de la Passion had been allowed to monopolize the religious drama, the basochiens had confined themselves to the presentment of moralities and of farces (from Italian farsa, Latin farcita), in which political satire had as a matter of course when possible found a place. A third association, calling themselves the Enfans sans souci, had, apparently also early in the 15th century, acquired celebrity by their performances of short comic plays called soties—in which, as it would seem, at first allegorical figures ironically “played the fool,” but which were probably before long not very carefully kept distinct from the farces of the Basoche, and were like these on occasion made to serve the purposes of State or of Church. Other confraternities and associations readily took a leaf out of the book of these devil-may-care good-fellows, and interwove their religious and moral plays with comic scenes and characters from actual life, thus becoming more and more free and secular in their dramatic methods, and unconsciously preparing the transition to the regular drama.

The earliest example of a serious secular play known to have been written in the French tongue is the Estoire de Griseldis (1393); which is in the style of the miracles of the Virgin, but is largely indebted to Petrarch. The Mystère du siege d’Orléans, on the other hand, written about half a century later, in the epic tediousness of its manner comes near to a chronicle history, and interests us chiefly as the earliest of many efforts to bring Joan of Arc on the stage. Jacques Milet’s celebrated mystery of the Destruction de Troye la grant (1452) seems to have been addressed to readers and not to hearers only. The beginnings of the French regular comic drama are again more difficult to extract from the copious literature of farces and soties, which, after mingling actual types with abstract and allegorical figures, gradually came to exclude all but the concrete personages; moreover, the large majority of these productions in their extant form belong to a later period than that now under consideration. But there is ample evidence that the most famous of all medieval farces, the immortal Maistre Pierre Pathelin (otherwise L’Avocat Pathelin), was written before 1470 and acted by the basochiens; and we may conclude that this delightful story of the biter bit, and the profession outwitted, typifies a multitude of similar comic episodes of real life, dramatized for the delectation of clerks, lawyers and students, and of all lovers of laughter.

In the neighbouring Netherlands many Easter and Christmas mysteries are noted from the middle of the 15th century, attesting the enduring popularity of these religious plays; and with them the celebrated series of the Seven Joys of The Netherlands. Maria—of which the first is the Annunciation and the seventh the Ascension. To about the same date belongs the small group of the so-called abele spelen (as who should say plays easily managed), chiefly on chivalrous themes. Though allegorical figures are already to be found in the Netherlands miracles of Mary, the species of the moralities was specially cultivated during the great Burgundian period of this century by the chambers or lodges of the Rederijkers (rhetoricians)—the well-known civic associations which devoted themselves to the cultivation of learned poetry and took an active share in the festivals that formed one of the most characteristic features of the life of the Low Countries. Among these moralities was that of Elckerlijk (printed 1495 and presumably by Peter Dorlandus), which there is good reason for regarding as the original of one of the finest of English moralities, Everyman.

In Italy the liturgical drama must have run its course as elsewhere; but the traces of it are few, and confined to the north-east. The collective mystery, so common in other Western countries, is in Italian literature Italy. represented by a single example only—a Passione di Gesù Cristo, performed at Revello in Saluzzo in the 15th century; though there are some traces of other cyclic dramas of the kind. The Italian religious plays, called figure when on Old, vangeli when on New, Testament subjects, and differing from those of northern Europe chiefly by the less degree of coarseness in their comic characters, seem largely to have sprung out of the development of the processional element in the festivals of the Church. Besides such processions as that of the Three Kings at Epiphany in Milan, there were the penitential processions and songs (laude), which at Assisi, Perugia and elsewhere already contained a dramatic element; and at Siena, Florence and other centres these again developed into the so-called (sacre) rappresentazioni, which became the most usual name for this kind of entertainment. Such a piece was the San Giovanni e San Paolo (1489), by Lorenzo the Magnificent—the prince who afterwards sought to reform the Italian stage by paganizing it; another was the Santa Teodora, by Luigi Pulci (d. 1487); San Giovanni Gualberto (of Florence) treats the religious experience of a latter-day saint; Rosana e Ulimento is a love-story with a Christian moral. Passion plays were performed at Rome in the Coliseum by the Compagnia del Gonfalone; but there is no evidence on this head before the end of the 15th century. In general, the spectacular magnificence of Italian theatrical displays accorded with the growing pomp of the processions both ecclesiastical and lay—called trionfi 500 already in the days of Dante; while the religious drama gradually acquired an artificial character and elaboration of form assimilating it to the classical attempts, to be noted below, which gave rise to the regular Italian drama. The poetry of the Troubadours, which had come from Provence into Italy, here frequently took a dramatic form, and may have suggested some of his earlier poetic experiments to Petrarch.

It was a matter of course that remnants of the ancient popular dramatic entertainments should have survived in particular abundance on Italian soil. They were to be recognized in the improvised farces performed at the courts, in the churches (farse spirituali), and among the people; the Roman carnival had preserved its wagon-plays, and various links remained to connect the modern comic drama of the Italians with the Atellanes and mimes of their ancestors. But the more notable later comic developments, which belong to the 16th century, will be more appropriately noticed below. Moralities proper had not flourished in Italy, where the love of the concrete has always been dominant in popular taste; more numerous are examples of scenes, largely mythological, in which the influence of the Renaissance is already perceptible, of eclogues, and of allegorical festival-plays of various sorts.

In Spain hardly a monument of the medieval religious drama has been preserved. There is manuscript evidence of the 11th century attesting the early addition of dramatic elements to the Easter office; and a Spanish fragment Spain. of the Three Kings Epiphany play, dating from the 12th century, is, like the French Adam, one of the very earliest examples of the medieval drama in the vernacular. But that religious plays were performed in Spain is clear from the permission granted by Alphonso X. of Castile (d. 1284) to the clergy to represent them, while prohibiting the performance by them of juegos de escarnio (mocking plays). The earliest Spanish plays which we possess belong to the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century, and already show humanistic influence. In 1472 the couplets of Mingo Revulgo (i.e. Domingo Vulgus, the common people), and about the same time another dialogue by the same author, offer examples of a sort resembling the Italian contrasti (see below).

The German religious plays in the vernacular, the earliest of which date from the 14th and 15th centuries, and were produced at Trier, Wolfenbuttel, Innsbruck, Vienna, Berlin, &c., were of a simple kind; but in some of them, though Germany. they were written by clerks, there are traces of the minstrels’ hands. The earliest complete Christmas play in German, contained in a 14th-century St Gallen MS., has nothing in it to suggest a Latin original. On the other hand, the play of The Wise and the Foolish Virgins, in a Thuringian MS. thought to be as early as 1328, a piece of remarkable dignity, was evidently based on a Latin play. Other festivals besides Christmas were celebrated by plays; but down to the Reformation Easter enjoyed a preference. In the same century miracle-plays began to be performed, in honour of St Catherine, St Dorothea and other saints. But all these productions seem to belong to a period when the drama was still under ecclesiastical control. Gradually, as the liturgical drama returned to the simpler forms from which it had so surprisingly expanded, and ultimately died out, the religious plays performed outside the churches expanded more freely; and the type of mystery associated with the name of the Frankfort canon Baldemar von Peterweil communicated itself, with other examples, to the receptive region of the south-west. The Corpus Christi plays, or (as they were here called) Frohnleichnamsspiele, are notable, since that of Innsbruck (1391) is probably the earliest extant example of its class. The number of non-scriptural religious plays in Germany was much smaller than that in France; but it may be noted that (in accordance with a long-enduring popular notion) the theme of the last judgment was common in Germany in the latter part of the middle ages. Of this theme Antichrist may be regarded as an episode, though in 1469 an Antichrist appears to have occupied at Frankfort four days in its performance. The earlier (12th century) Antichrist is a production quite unique of its kind; this political protest breathes the Ghibelline spirit of the reign (Frederick Barbarossa’s) in which it was composed.

Though many of the early German plays contain an element of the moralities, there were few representative German examples of the species. The academical instinct, or some other influence, kept the more elaborate productions on the whole apart from the drolleries of the professional strollers (fahrende Leute), whose Shrove-Tuesday plays (Fastnachtsspiele) and cognate productions reproduced the practical fun of common life. Occasionally, no doubt, as in the Lübeck Fastnachtsspiel of the Five Virtues, the two species may have more or less closely approached to one another. When, in the course of the 15th century, Hans Rosenplüt, called Schnepperer—or Hans Schnepperer, called Rosenplüt—the predecessor of Hans Sachs, first gave a more enduring form to the popular Shrove-Tuesday plays, a connexion was already establishing itself between the dramatic amusements of the people and the literary efforts of the “master-singers” of the towns. But, while the main productivity of the writers of moralities and cognate productions—a species particularly suited to German latitudes—falls into the periods of Renaissance and Reformation, the religious drama proper survived far beyond either in Catholic Germany, and, in fact, was not suppressed in Bavaria and Tirol till the end of the 18th century.3

It may be added that the performance of miracle-plays is traceable in Sweden in the latter half of the 14th century; and that the German clerks and laymen who immigrated into the Carpathian lands, and into Galicia in particular, Sweden, Carpathian lands, &c. in the later middle ages, brought with them their religious plays together with other elements of culture. This fact is the more striking, inasmuch as, though Czech Easter plays were performed about the end of the 14th century, we hear of none among the Magyars, or among their neighbours of the Eastern empire.

Coming now to the English religious drama, we find that from its extant literature a fair general idea may be derived of the character of these medieval productions. The miracle-plays, miracles or plays (these being the terms used in Religious drama in England. England) of which we hear in London in the 12th century were probably written in Latin and acted by ecclesiastics; but already in the following century mention is made—in the way of prohibition—of plays acted by professional players. (Isolated moralities of the 12th century are not to be regarded as popular productions.) In England as elsewhere, the clergy either sought to retain their control over the religious plays, which continued to be occasionally acted in churches even after the Reformation, or else reprobated them with or Cornish miracle-plays. without qualifications. In Cornwall miracles in the native Cymric dialect were performed at an early date; but those which have been preserved are apparently copies of English (with the occasional use of French) originals; they were represented, unlike the English plays, in the open country, in extensive amphitheatres constructed for the purpose—one of which, at St Just near Penzance, has recently been restored.

The flourishing period of English miracle-plays begins with the practice of their performance by trading-companies in the towns, though these bodies were by no means possessed of any special privileges for the purpose. Of this practice Localities of the performance of miracle-plays. Chester is said to have set the example (1268-1276); it was followed in the course of the 13th and 14th centuries by many other towns, while in yet others traces of such performances are not to be found till the 15th, or even the 16th. These towns with their neighbourhoods include, starting from East Anglia, where the religious drama was particularly at home, Wymondham, Norwich, Sleaford, Lincoln, Leeds, Wakefield, Beverley, York, Newcastle-on-Tyne, with a deviation across the border to Edinburgh and Aberdeen. In the north-west they are found at Kendal, Lancaster, Preston, 501 Chester; whence they may be supposed to have migrated to Dublin. In the west they are noticeable at Shrewsbury, Worcester and Tewkesbury; in the Midlands at Coventry and Leicester; in the east at Cambridge and Bassingbourne, Heybridge and Manningtree; to which places have to be added Reading, Winchester, Canterbury, Bethesda and London, in which last the performers were the parish-clerks. Four collections, in addition to some single examples of such plays, The York, Towneley, Chester and Coventry plays. have come down to us, the York plays, the so-called Towneley plays, which were probably acted at the fairs of Widkirk, near Wakefield, and those bearing the names of Chester and of Coventry. Their dates, in the forms in which they have come down to us, are more or less uncertain; that of the York may on the whole be concluded to be earlier than that of the Towneley, which were probably put together about the middle of the 14th century; the Chester may be ascribed to the close of the 14th or the earlier part of the 15th; the body of the Coventry probably belongs to the 15th or 16th. Many of the individual plays in these collections were doubtless founded on French originals; others are taken direct from Scripture, from the apocryphal gospels, or from the legends of the saints. Their characteristic feature is the combination of a whole series of plays into one collective whole, exhibiting the entire course of Bible history from the creation to the day of judgment. For this combination it is unnecessary to suppose that they were generally indebted to foreign examples, though there are several remarkable coincidences between the Chester plays and the French Mystère du vieil testament. Indeed, the oldest of the series—the York plays—exhibits a fairly close parallel to the scheme of the Cursor mundi, an epic poem of Northumbrian origin, which early in the 14th century had set an example of treatment that unmistakably influenced the collective mysteries as a whole. Among the isolated plays of the same type which have come down to us may be mentioned The Harrowing of Hell (the Saviour’s descent into hell), an East-Midland production which professes to tell of “a strif of Jesu and of Satan” and is probably the earliest dramatic, or all but dramatic, work in English that has been preserved; and several belonging to a series known as the Digby Mysteries, including Parfre’s Candlemas Day (the massacre of the Innocents), and the very interesting miracle of Mary Magdalene. Of the so-called “Paternoster” and “Creed” plays (which exhibit the miraculous powers of portions of the Church service) no example remains, though of some we have an account; the Croxton Play of the Sacrament, the MS. of which is preserved at Dublin, and which seems to date from the latter half of the 15th century, exhibits the triumph of the holy wafer over wicked Jewish wiles.

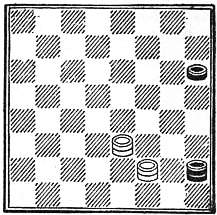

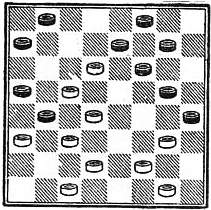

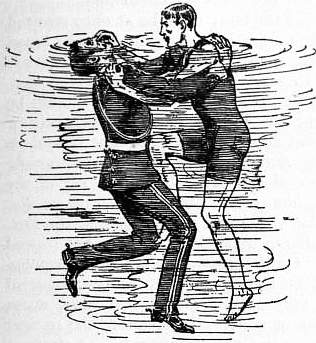

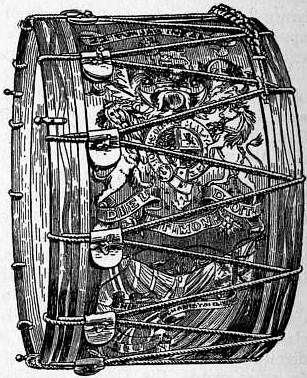

To return to the collective mysteries, as they present themselves to us in the chief extant series. “The manner of these plays,” we read in a description of those at Chester, dating from the close of the 16th century, “were:—Every English collective mysteries. company had his pageant, which pageants were a high scaffold with two rooms, a higher and a lower, upon four wheels. In the lower they apparelled themselves, and in the higher room they played, being all open at the top, that all beholders might hear and see them. The places where they played them was in every street. They began first at the abbey gates, and when the first pageant was played, it was wheeled to the high cross before the mayor, and so to every street, and so every street had a pageant playing before them at one time till all the pageants appointed for the day were played; and when one pageant was near ended, word was brought from street to street, that so they might come in place thereof, exceedingly orderly, and all the streets have their pageants afore them all at one time playing together; to see which plays was great resort, and also scaffolds and stages made in the streets in those places where they determined to play their pageants.”

Each play, then, was performed by the representative of a particular trade or company, after whom it was called the fishers’, glovers’, &c., pageant; while a general prologue was spoken by a herald. As a rule the movable stage sufficed for the action, though we find horsemen riding up to the scaffold, and Herod instructed to “rage in the pagond and in the strete also.” There is no probability that the stage was, as in France, divided into three platforms with a dark cavern at the side of the lowest, appropriated respectively to the Heavenly Father and his angels, to saints and glorified men, to mere men, and to souls in hell. But the last-named locality was frequently displayed in the English miracles, with or without fire in its mouth. The costumes were in part conventional,—divine and saintly personages being distinguished by gilt hair and beards, Herod being clad as a Saracen, the demons wearing hideous heads, the souls black and white coats according to their kind, and the angels gold skins and wings.

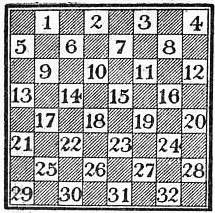

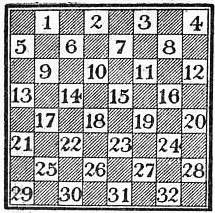

Doubtless these performances abounded in what seem to us ludicrous features; and, though their main purpose was serious, they were not in England at least intended to be devoid of fun. But many of the features in question Character of the Plays. are in truth only homely and naïf, and the simplicity of feeling which they exhibit is at times pathetic rather than laughable. The occasional grossness is due to an absence of refinement of taste rather than to an obliquity of moral sentiment. These features the four series have more or less in common, still there are certain obvious distinctions between them. The York plays (48), which were performed at Corpus Christi, are comparatively free from the tendency to jocularity and vulgarity observable in the Towneley; several of the plays concerned with the New Testament and early Christian story are, however, in substance common to both series. The Towneley Plays or Wakefield Mysteries (32) were undoubtedly composed by the friars of Widkirk or Nostel; but they are of a popular character; and, while somewhat over-free in tone, are superior in vivacity and humour to both the later collections. The Chester Plays (25) were undoubtedly indebted both to the Mystère du vieil testament and to earlier French mysteries; they are less popular in character than the earlier two cycles, and on the whole undistinguished by original power of pathos or humour. There is, on the other hand, a notable inner completeness in this series, which includes a play of Antichrist, devoid of course of any modern application. While these plays were performed at Whitsuntide, the Coventry Plays (42) were Corpus Christi performances. Though there is no proof that the extant series were composed by the Grey Friars, they reveal a considerable knowledge of ecclesiastical literature. For the rest, they are far more effectively written than the Chester Plays, and occasionally rise to real dramatic force. In the Coventry series there is already to be observed an element of abstract figures, which connects them with a different species of the medieval drama.

The moralities corresponded to the love for allegory which manifests itself in so many periods of English literature, and which, while dominating the whole field of medieval literature, was nowhere more assiduously and effectively Moralities. cultivated than in England. It is necessary to bear this in mind, in order to understand what to us seems so strange, the popularity of the moral-plays, which indeed never equalled that of the miracles, but sufficed to maintain the former species till it received a fresh impulse from the connexion established between it and the “new learning,” together with the new political and religious ideas and questions, of the Reformation age. Moreover, a specially popular element was supplied to these plays, which in manner of representation differed in no essential point from the miracles, in a character borrowed from the latter, and, in the moralities, usually provided with a companion The Devil and the Vice. whose task it was to lighten the weight of such abstractions as Sapience and Justice. These were the Devil and his attendant the Vice, of whom the latter seems to have been of native origin, and, as he was usually dressed in a fool’s habit, was probably suggested by the familiar custom of keeping an attendant fool at court or in great houses. The Vice had many aliases (Shift, Ambidexter, Sin, Fraud, Iniquity, &c.), but his usual duty is to torment and tease the Devil his master for the edification and diversion of the audience. 502 He was gradually blended with the domestic fool, who survived in the regular drama. There are other concrete elements in the moralities; for typical figures are often fitted with concrete names, and thus all but converted into concrete human personages.

The earlier English moralities4—from the reign of Henry VI. to that of Henry VII.—usually allegorize the conflict between good and evil in the mind and life of man, without any side-intention of theological controversy. Such also Groups of English moralities. is still essentially the purpose of the extant morality by Henry VIII.’s poet, the witty Skelton.5 Everyman (pr. c. 1529), perhaps the most perfect example of its class, with which the present generation has fortunately become familiar, contains passages certainly designed to enforce the specific teaching of Rome. But its Dutch original was written at least a generation earlier, and could have no controversial intention. On the other hand, R. Wever’s Lusty Juventus breathes the spirit of the dogmatic reformation of the reign of Edward VI. Theological controversy largely occupies the moralities of the earlier part of Elizabeth’s reign,6 and connects itself with political feeling in a famous morality, Sir David Lyndsay’s Satire of the Three Estaitis, written and acted (at Cupar, in 1539) on the other side of the border, where such efforts as the religious drama proper had made had been extinguished by the Reformation. Only a single English political morality proper remains to us, which belongs to the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth.7 Another series connects itself with the ideas of the Renaissance rather than the Reformation, treating of intellectual progress rather than of moral conduct;8 this extends from the reign of Henry VIII. to that of his younger daughter. Besides these, there remain some Elizabethan moralities which have no special theological or scientific purpose, and which are none the less lively in consequence.9

The transition from the morality to the regular drama in England was effected, on the one hand, by the intermixture of historical personages with abstractions—as in Bishop Bale’s Kyng Johan (c. 1548)—which easily led over to Heywood’s interludes. the chronicle history; on the other, by the introduction of types of real life by the side of abstract figures. This latter tendency, of which instances occur in earlier plays, is observable in several of the 16th-century moralities;10 but before most of these were written, a further step in advance had been taken by a man of genius, John Transition from the morality to the regular drama. Heywood (b. c. 1500, d. between 1577 and 1587), whose “interludes”11 were short farces in the French manner. The term “interludes” was by no means new, but had been applied by friend and foe to religious plays, and plays (including moralities) in general, already in the 14th century. But it conveniently serves to designate a species which marks a distinct stage in the history of the modern drama. Heywood’s interludes dealt entirely with real—very real—men and women. Orthodox and conservative, he had at the same time a keen eye for the vices as well as the follies of his age, and not the least for those of the clerical profession. Other writers, such as T. Ingeland,12 took the same direction; and the allegory of abstractions was thus undermined on the stage, very much as in didactic literature the ground had been cut from under its feet by the Ship of Fooles. Thus the interludes facilitated the advent of comedy, without having superseded the earlier form. Both moralities and miracle-plays survived into the Elizabethan age after the regular drama had already begun its course.

Such, in barest outline, was the progress of dramatic entertainments in the principal countries of Europe, before the revival of classical studies brought about a return to the examples of the classical drama, or before this return had Pageants. distinctly asserted itself. It must not, however, be forgotten that from an early period in England as elsewhere had flourished a species of entertainments, not properly speaking dramatic, but largely contributing to form and foster a taste for dramatic spectacles. The pageants—as they were called in England—were the successors of those ridings from which, when they gladdened “Chepe,” Chaucer’s idle apprentice would not keep away; but they had advanced in splendour and ingenuity of device under the influence of Flemish and other foreign examples. Costumed figures represented before gaping citizens the heroes of mythology and history, and the abstractions of moral, patriotic, or municipal allegory; and the city of London clung with special fervour to these exhibitions, which the Elizabethan drama was neither able nor—as represented by most of its poets who composed devices and short texts for these and similar shows—willing to oust from popular favour. Some of the greatest and some of the least of English dramatists were the ministers of pageantry; and perhaps it would have been an advantage for the future of the theatre if the legitimate drama and the Triumphs of Old Drapery had been more jealously kept apart. With the reign of Henry VIII. there also set in a varied succession of entertainments at court and in the houses of the great nobles, which may be said to have lasted through the Tudor and early Stuart periods; but it would be an endless task to attempt to discriminate the dramatic elements contained in these productions. The “mask,” stated to have been introduced from Italy into England as a new diversion in 1512-1513, at first merely added a fresh element of “disguising” to those already in use; as a quasi-dramatic species (“mask” or “masque”) capable of a great literary development it hardly asserted itself till quite the end of the 16th century.

11. The Modern National Drama

The literary influence which finally transformed the growths noticed above into the national dramas of the several countries of Europe, was that of the Renaissance. Among the remains of classical antiquity which were studied, Influence of the Renaissance. translated and imitated, those of the drama necessarily held a prominent place. Never altogether lost sight of, they now became subjects of devoted research and models for more or less exact imitation, first in Greek or Latin, then in modern tongues; and these essentially literary endeavours came into more or less direct contact with, and acquired more or less control over, dramatic performances and entertainments already in existence. This process it will be most convenient to pursue seriatim, in connexion with the rise and progress of the several dramatic literatures of the West. For no sooner had the stream of the modern drama, whose source and contributories have been described, been brought back into the ancient bed, than its flow diverged into a number of national currents, unequal in impetus and strength, and varying in accordance with their manifold surroundings. And even of these it is only possible to survey the most productive or important.

(a) Italy.

The priority in this as in most of the other aspects of the Renaissance belongs to Italy. In ultimate achievement the Italian drama fell short of the fulness of the results obtained elsewhere—a surprising fact when it is The modern Italian drama. considered, not only that the Italian language had the vantage-ground of closest relationship to the Latin, but that the genius of the Italian people has at all times led it to love the drama. The cause is doubtless to be sought in the lack, noticeable in Italian national life during a long period, and more especially during the troubled days of division and strife coinciding with the rise and earlier promise of Italian dramatic literature, of those loftiest and most potent impulses of popular feeling to which a national drama owes so much of its strength. This deficiency was due partly to the peculiarities of the Italian 503 character, partly to the political and ecclesiastical experiences which Italy was fated to undergo. The Italians were alike strangers to the enthusiasm of patriotism, which was as the breath in the nostrils of the English Elizabethan age, and to the religious devotion which identified Spain with the spirit of the Catholic revival. The clear-sightedness of the Italians had something to do with this, for they were too intelligent to believe in their tyrants, and too free from illusions to deliver up their minds to their priests. Finally, the chilling and enervating effects of a pressure of foreign domination, such as no Western people with a history and a civilization like those of Italy has ever experienced, contributed to paralyse for many generations the higher efforts of the dramatic art. No basis was permanently found for a really national tragedy; while literary comedy, after turning from the direct imitation of Latin models to a more popular form, lost itself in an abandoned immorality of tone and in reckless insolence of invective against particular classes of society. Though its productivity long continued, the poetic drama more and more concentrated its efforts upon subordinate or subsidiary species, artificial in origin and decorative in purpose, and surrendered its substance to the overpowering aids of music, dancing and spectacle. Only a single form of the Italian drama, improvised comedy, remained truly national; and this was of its nature dissociated from higher literary effort. The revival of Italian tragedy in later times is due partly to the imitation of French models, partly to the endeavour of a brilliant genius to infuse into his art the historical and political spirit. Comedy likewise attained to new growths of considerable significance, when it was sought to accommodate its popular forms to the representation of real life in a wider range, and again to render it more poetical in accordance with the tendencies of modern romanticism.

The regular Italian drama, in both its tragic and its comic branches, began with a reproduction, in the Latin language, of classical models—the first step, as it was to prove, towards the transformation of the medieval into the modern drama, and the birth of modern dramatic literature. But the process was both tentative and tedious, and must have died away but for the pomp and circumstance with which some of the patrons of the Renaissance at Florence, Rome and elsewhere surrounded these manifestations of a fashionable taste, and for the patriotic inspiration which from the first induced Italian writers to dramatize themes of national historic interest. Greek tragedy had been long forgotten, and one or two indications in the earlier part of the 16th century of Italian interest in the Greek drama, chiefly due to the printing presses, may be passed by.13 To the later middle ages classical tragedy meant Seneca, and even his plays remained unremembered till the study of them was revived by the Paduan judge Lovato de’ Lovati (Lupatus, d. 1309). Of the comedies of Plautus three-fifths were not rediscovered till 1429; and though Terence was much read in the schools, he found no dramatic imitators, pour le bon motif or otherwise, since Hrosvitha.

Thus the first medieval follower of Seneca, Albertino Mussato (1261-1330) may in a sense be called the father of modern dramatic literature. Born at Padua, to which city all his services were given, he in 1315 brought out his Eccerinis, a Latin tragedy very near to the confines of epic poetry, intended to warn the Paduans against the designs of Can Grande della Scala by the example of the tyrant Ezzelino. Other tragedies of much the same type followed during the ensuing century; such as L. da Fabiano’s De casu Caesenae (1377) a sort of chronicle history in Latin prose on Cardinal Albornoz’ capture of Caesena.14 Purely classical themes were treated in the Achilleis of A. de’ Loschi of Vicenza (d. 1441), formerly attributed to Mussato, several passages of which are taken verbally from Seneca; in the celebrated Progne of the Venetian Gregorio Cornaro, which is dated 1428-1429, and in later Latin productions included among the translations and imitations of Greek and Latin tragedies and comedies by Bishop Martirano (d. 1557), the friend of Pope Leo X.,15 and the efforts of Pomponius Laetus and his followers, who, with the aid of Cardinal Raffaele Riario (1451-1521), sought to revive the ancient theatre, with all its classical associations, at Rome.

In this general movement Latin comedy had quickly followed suit, and, as just indicated, it is almost impossible, when we reach the height of the Italian Renaissance under the Medici at Florence and at Rome in particular, to review the progress of either species apart from that of the other. If we possessed the lost Philologia of Petrarch, of which, as of a juvenile work, he declared himself ashamed, this would be the earliest of extant humanistic comedies. As it is, this position is held by Paulus, a Latin comedy of life on the classic model, by the orthodox P. P. Vergerio (1370-1444); which was followed by many others.16

Early in the 16th century, tragedy began to be written in the native tongue; but it retained from the first, and never wholly lost, the impress of its origin. Whatever the source of its subjects—which, though mostly of classical Italian tragedy in the 16th century. origin, were occasionally derived from native romance, or even due to invention—they were all treated with a predilection for the horrible, inspired by the example of Seneca, though no doubt encouraged by a perennial national taste. The chorus, stationary on the stage as in old Roman tragedy, was not reduced to a merely occasional appearance between the acts till the beginning of the 17th century, or ousted altogether from the tragic drama till the earlier half of the 18th. Thus the changes undergone by Italian tragedy were for a long series of generations chiefly confined to the form of versification and the choice of themes; nor was it, at all events till the last century of the course which it has hitherto run, more than the aftergrowth of an aftergrowth. The honour of having been the earliest tragedy in Italian seems to belong to A. da Pistoia’s Pamfila (1499), of which the subject was taken from Boccaccio, introduced by the ghost of Seneca, and marred in the taking. Carretto’s Sofonisba, which hardly rises above the art of a chronicle history, though provided with a chorus, followed in 1502. But the play usually associated with the beginning of Italian tragedy—that with which “th’ Italian scene first learned to glow”—was another Sofonisba, acted before Leo X. in 1515, and written in blank hendecasyllables instead of the ottava and terza rima of the earlier tragedians (retaining, however, the lyric measures of the chorus), by G. G. Trissino, who was employed as nuncio by that pope. Other tragedies of the former half of the 16th century, largely inspired by Trissino’s example, were the Rosmunda of Rucellai, a nephew of Lorenzo the Magnificent (1516); Martelli’s Tullia, Alamanni’s Antigone (1532); the Canace of Sperone Speroni, the envious Mopsus of Tasso, who, like Guarini, took Sperone’s elaborate style for his model; the 504 Orazia, the earliest dramatic treatment of this famous subject by the notorious Aretino (1549); and the nine tragedies of G. B. Giraldi (Cinthio) of Ferrara, among which L’Orbecche (1541) is accounted the best and the bloodiest. Cinthio, the author of those Hecatommithi to which Shakespeare was indebted for so many of his subjects, was (supposing him to have invented these) the first Italian who was the author of the fables of his own dramas; he introduced some novelties into dramatic construction, separating the prologue and probably also the epilogue from the action, and has by some been regarded as the inventor of the pastoral drama. But his style was arid. In the latter half of the 16th century may be mentioned the Didone and the Marianna of L. Dolce, the translator of Euripides and Seneca (1565); A. Leonico’s Il Soldato (1550); the Adriana (acted before 1561 or 1586) of L. Groto, which treats the story of Romeo and Juliet; Tasso’s Torrismondo (1587); the Tancredi of Asinari (1588); and the Merope of Torelli (1593), the last who employed the stationary chorus (coro fisso) on the Italian stage. Leonico’s Soldato is noticeable as supposed to have given rise to the tragedia cittadina, or domestic tragedy, of which there are few examples in the Italian drama, and De Velo’s Tamar (1586) as written in prose. Subjects of modern historical interest were in this period treated only in isolated instances.17

The tragedians of the 17th century continued to pursue the beaten track, marked out already in the 16th by rigid prescription. In course of time, however, they sought by the introduction of musical airs to compromise with the Italian tragedy in the 17th and 18th centuries. danger with which their art was threatened of being (in Voltaire’s phrase) extinguished by the beautiful monster, the opera, now rapidly gaining ground in the country of its origin. (See Opera.) To Count P. Bonarelli (1589-1659), the author of Solimano, is on the other hand ascribed the first disuse of the chorus in Italian tragedy. The innovation of the use of rhyme attempted in the learned Pallavicino’s Erminigildo (1655), and defended by him in a discourse prefixed to the play, was unable to achieve a permanent success in Italy any more than in England; its chief representative was afterwards Martelli (d. 1727), whose rhymed Alexandrian verse (Martelliano), though on one occasion used in comedy by Goldoni, failed to commend itself to the popular taste. By the end of the 17th century Italian tragedy seemed destined to expire, and the great tragic actor Cotta had withdrawn in disgust at the apathy of the public towards the higher forms of the drama. The 18th century was, however, to witness a change, the beginnings of which are attributed to the institution of the Academy of the Arcadians at Rome (1690). The principal efforts of the new school of writers and critics were directed to the abolition of the chorus, and to a general increase of freedom in treatment. Maffei. Before long the marquis S. Maffei with his Merope (first printed 1713) achieved one of the most brilliant successes recorded in the history of dramatic literature. This play, which is devoid of any love-story, long continued to be considered the masterpiece of Italian tragedy; Voltaire, who declared it “worthy of the most glorious days of Athens,” adapted it for the French stage, and it inspired a celebrated production of the English drama.18 It was followed by a tragedy full of horrors,19 noticeable as having given rise to the first Italian dramatic parody; and by the highly esteemed productions of Metastasio. Granelli (d. 1769) and his contemporary Bettinelli. P. T. Metastasio (1698-1782), who had early begun his career as a dramatist by a strict adherence to the precepts of Aristotle, gained celebrity by his contributions to the operatic drama at Naples, Venice and Vienna (where he held office as poeta cesareo, whose function was to arrange the court entertainments). But his libretti have a poetic value of their own;20 and Voltaire pronounced much of him worthy of Corneille and of Racine, when at their best. The influence of Voltaire had now come to predominate over the Italian drama; and, in accordance with the spirit of the times, greater freedom prevailed in the choice of tragic themes. Thus the greatest of Italian tragic poets. Alfieri. Count V. Alfieri (1749-1803), found his path prepared for him. Alfieri’s grand and impassioned treatment of his subjects caused his faultiness of form, which he never altogether overcame, to be forgotten. His themes were partly classical;21 but the spirit of a love of freedom which his creations22 breathe was the herald of the national ideas of the future. Spurning the usages of French tragedy, his plays, which abound in soliloquies, owe part of their effect to an impassioned force of declamation, part to those “points” by which Italian acting seems pre-eminently capable of thrilling an audience. He has much besides the subjects of two of his dramas23 in common with Schiller, but his amazon-muse (as Schlegel called her) was not schooled into serenity, like the muse of the German poet. Among his numerous plays (21), Merope and Saul, and perhaps Mirra, are accounted his masterpieces.

The political colouring given by Alfieri to Italian tragedy reappears in the plays of U. Foscolo and A. Manzoni, both of whom are under the influence of the romantic school of modern literature; and to these names must be Tragedians since Alfieri. added those of S. Pellico and G. B. Niccolini (1785-1861), Paolo Giacometti (b. 1816) and others, whose dramas24 treat largely national themes familiar to all students of modern history and literature. In their hands Italian tragedy upon the whole adhered to its love of strong situations and passionate declamation. Since the successful efforts of G. Modena (1804-1861) renovated the tragic stage in Italy, the art of tragic acting long stood at a higher level in this than in almost any other European country; in Adelaide Ristori (Marchesa del Grillo) the tragic stage lost one of the greatest of modern actresses; and Ernesto Rossi (1827-1896) and Tommaso Salvini long remained rivals in the noblest forms of tragedy.

In comedy, the efforts of the scholars of the Italian Renaissance for a time went side by side with the progress of the popular entertainments noticed above. While the contrasti of the close of the 15th and of the 16th century were Italian comedy; popular forms. disputations between pairs of abstract or allegorical figures, in the frottola human types take the place of abstractions, and more than two characters appear. The farsa (a name used of a wide variety of entertainments) was still under medieval influences, and in this popular form Alione of Asti (soon after 1500) was specially productive. To these popular diversions a new literary as well as social significance was given by the Neapolitan court-poet Sannazaro (c. 1492); about the same time a capitano valoroso, Venturino of Pesara, first brought on the modern stage the capitano glorioso or spavente, the military braggart, who owed his origin both to Plautus25 and to the Spanish officers who abounded in the Italy of those days. The popular character-comedy, a relic of the ancient Atellanae, likewise took a new lease of life—and this in a double form. The improvised comedy (commedia a soggetto) was now as a rule performed by professional actors, members of a craft, and was Commedia dell’ arte. thence called the commedia dell’ arte, which is said to have been invented by Francesco (called Terenziano) Cherea, the favourite player of Leo X. Its scenes, still unwritten except in skeleton (scenario), were connected together by the ligatures or links (lazzi) of the arlecchino, the descendant of the ancient Roman sannio (whence our zany). Harlequin’s summit of glory was probably reached early in the 17th century, when he was ennobled in the person of Cecchino by the emperor Matthias; of Cecchino’s successors, Zaccagnino and Truffaldino, Masked comedy. we read that “they shut the door in Italy to good harlequins.” Distinct from this growth is that of the masked comedy, the action of which was chiefly carried on by certain 505 typical figures in masks, speaking in local dialects,26 but which was not improvised, and indeed from the nature of the case hardly could have been. Its inventor was A. Beolco of Padua, who called himself Ruzzante (joker), and is memorable under that name as the first actor-playwright—a combination of extreme significance for the history of the modern stage. He published six comedies in various dialects, including the Greek of the day (1530). This was the masked comedy to which the Italians so tenaciously clung, and in which, as all their own and imitable by no other nation, they took so great a pride that even Goldoni was unable to overthrow it. Improvisation and burlesque, alike abominable to comedy proper, were inseparable from the species.

Meanwhile, the Latin imitations of Roman, varied by occasional translations of Greek, comedies early led to the production of Italian translations, several of which were performed at Ferrara in the last quarter of the 15th century, Early Italian regular comedy. whence they spread to Milan, Pavia and other towns of the north. Contemporaneously, imitations of Latin comedy made their appearance, for the most part in rhymed verse; most of them applying classical treatment to subjects derived from Boccaccio’s and other novelle, some still mere adaptations of ancient models. In these circumstances it is all but idle to assign the honour of having been “the first Italian comedy”—and thus the first comedy in modern dramatic literature—to any particular play. Boiardo’s Timone (before 1494), for which this distinction was frequently claimed, is to a large extent founded on a dialogue of Lucian’s; and, since some of its personages are abstractions, and Olympus is domesticated on an upper stage, it cannot be regarded as more than a transition from the moralities. A. Ricci’s I Tre Tiranni (before 1530) seems still to belong to the same transitional species. Among the earlier imitators of Latin comedy in the vernacular may be noted G. Visconti, one of the poets patronized by Ludovico il Moro at Milan;27 the Florentines G. B. Araldo, J. Nardi, the historian,28 and D. Gianotti.29 The step—very important had it been adopted consistently or with a view to consistency—of substituting prose for verse as the diction of comedy, is sometimes attributed to Ariosto; but, though his first two comedies were originally written in prose, the experiment was not new, nor did he persist in its adoption. Caretto’s I Sei Contenti dates from the end of the 15th century, and Publio Filippo’s Formicone, taken from Apuleius, followed quite early in the 16th. Machiavelli, as will be seen, wrote comedies both in prose and in verse.

But, whoever wrote the first Italian comedy, Ludovico Ariosto was the first master of the species. All but the first two of his comedies, belonging as they do to the field of commedia erudita, or scholarly comedy, are in blank verse, to which he gave a singular mobility by the dactylic ending of the line (sdrucciolo). Ariosto’s models were the masterpieces of the palliata, and his morals those of his age, which emulated those of the worst days of ancient Rome or Byzantium in looseness, and surpassed them in effrontery. He chose his subjects accordingly; but his dramatic genius displayed itself in the effective drawing of character,30 and more especially in the skilful management of complicated intrigues.31 Such, with an additional brilliancy of wit and lasciviousness of tone, are likewise the characteristics of Machiavelli’s famous prose comedy, the Mandragola (The Magic Draught);32 and at the height of their success, of the plays of P. Aretino,33 especially the prose Marescalco (1526-1527) whose name, it has been said, ought to be written in asterisks. It may be added that the plays of Ariosto and his followers were represented with magnificent scenery and settings. Other dramatists of the 16th century were B. Accolti, whose Virginia (prob. before 1513) treats the story from Boccaccio which reappears in All’s Well that Ends Well; G. Cecchi, F. d’Ambra, A. F. Grazzini, N. Secco or Secchi and L. Dolce—all writers of romantic comedy of intrigue in verse or prose.

During the same century the “pastoral drama” flourished in Italy. The origin of this peculiar species—which was the bucolic idyll in a dramatic form, and which freely lent itself to the introduction of both mythological The pastoral drama. and allegorical elements—was purely literary, and arose directly out of the classical studies and tastes of the Renaissance. It was very far removed from the genuine peasant plays which flourished in Venetia and Tuscany early in the 16th century. The earliest example of the artificial, but in some of its productions exquisite, growth in question was the renowned scholar A. Politian’s Orfeo (1472), which begins like an idyll and ends like a tragedy. Intended to be performed with music—for the pastoral drama is the parent of the opera—this beautiful work tells its story simply. N. da Correggio’s (1450-1508) Cefalo, or Aurora, and others followed, before in 1554 A. Beccari produced, as totally new of its kind, his Arcadian pastoral drama Il Sagrifizio, in which the comic element predominates. But an epoch in the history of the species is marked by the Aminta of Tasso (1573), in whose Arcadia is allegorically mirrored the Ferrara court. Adorned by choral lyrics of great beauty, it presents an allegorical treatment of a social and moral problem; and since the conception of the characters, all of whom think and speak of nothing but love, is artificial, the charm of the poem lies not in the interest of its action, but in the passion and sweetness of its sentiment. This work was the model of many others, and the pastoral drama reached its height of popularity in the famous Pastor fido (written before 1590) of G. B. Guarini, which, while founded on a tragic love-story, introduces into its complicated plot a comic element, partly with a satirical intention. It is one of those exceptional works which, by circumstance as well as by merit, have become the property of the world’s literature at large. Thus, both in Italian and in other literatures, the pastoral drama became a distinct species, characterized, like the great body of modern pastoral poetry in general, by a tendency either towards the artificial or towards the burlesque. Its artificiality affected the entire growth of Italian comedy, including the commedia dell’ arte, and impressed itself in an intensified form upon the opera. The foremost Italian masters of the last-named species, so far as it can claim to be included in the poetic drama, were A. Zeno (1668-1750) and P. Metastasio.

The comic dramatists of the 17th century are grouped as followers of the classical and of the romantic school, G. B. della Porta (q.v.) and G. A. Cicognini (whom Goldoni describes as full of whining pathos and commonplace Comedy in the 17th and 18th centuries. drollery, but as still possessing a great power to interest) being regarded as the leading representatives of the former. But neither of these largely intermixed groups of writers could, with all its fertility, prevail against the competition, on the one hand of the musical drama, and on the other of the popular farcical entertainments and those introduced in imitation of Spanish examples. Italian comedy had fallen into decay, when its reform was undertaken by the wonderful Goldoni. theatrical genius of C. Goldoni. One of the most fertile and rapid of playwrights (of his 150 comedies 16 were written and acted in a single year), he at the same time pursued definite aims as a dramatist. Disgusted with the conventional buffoonery, and ashamed of the rampant 506 immorality of the Italian comic stage, he drew his characters from real life, whether of his native city (Venice)34 or of society at large, and sought to enforce virtuous and pathetic sentiments without neglecting the essential objects of his art. Happy and various in his choice of themes, and dipping deep into a popular life with which he had a genuine sympathy, he produced, besides comedies of general human character,35 plays on subjects drawn from literary biography36 or from fiction.37 Goldoni, whose style was considered defective by the purists whom Italy has at no time lacked, met with a severe critic and a temporarily successful Gozzi. rival in Count C. Gozzi (1722-1806), who sought to rescue the comic drama from its association with the actual life of the middle classes, and to infuse a new spirit into the figures of the old masked comedy by the invention of a new species. His themes were taken from Neapolitan38 and Oriental39 fairy tales, to which he accommodated some of the standing figures upon which Goldoni had made war. This attempt at mingling fancy and humour—occasionally of a directly satirical turn40—was in harmony with the tendencies of the modern romantic school; and Gozzi’s efforts, which though successful found hardly any imitators in Italy, have a family resemblance to those of Tieck and of some more recent writers whose art wings its flight, through the windows, “over the hills and far away.”

During the latter part of the 18th and the early years of the 19th century comedy continued to follow the course marked out by its acknowledged master Goldoni, under the influence of the sentimental drama of France and other Comedians after Goldoni. countries. Abati Andrea Villi, the marquis Albergati Capacelli, Antonio Simone Sografi (1760-1825), Federici, and Pietro Napoli Signorelli (1731-1815), the historian of the drama, are mentioned among the writers of this school; to the 19th century belong Count Giraud, Marchisio (who took his subjects especially from commercial life), and Nota, a fertile writer, among whose plays are three treating the lives of poets. Of still more recent date are L. B. Bon and A. Brofferio. At the same time, the comedy of dialect to which the example of Goldoni had given sanction in Venice, flourished there as well as in the mutually remote spheres of Piedmont and Naples. Quite modern developments must remain unnoticed here; but the fact cannot be ignored that they signally illustrate the perennial vitality of the modern drama in the home of its beginnings. A new realistic style set fully in about the middle of the 18th century with P. Ferrari and A. Torelli; and though an historical reaction towards classical and medieval themes is associated with the names of P. Cossa and G. Giacosa, modernism reasserted itself through P. Bracco and other dramatists. It should be noted that the influence of great actors, more especially Ermete Novelli and Eleanora Duse, must be credited with a large share of the success with which the Italian stage has held its own even against the foreign influences to which it gave room. And it would seem as if even the paradoxical endeavour of the poet Gabrielle d’ Annunzio to lyricize the drama by ignoring action as its essence were a problem for the solution of which the stage can furnish unexpected conditions of its own. In any event, both Italian tragedy and Italian comedy have survived periods of a seemingly hopeless decline; and the fear has vanished that either the opera or the ballet might succeed in ousting from the national stage the legitimate forms of the national drama.

(b) Greece.