Title: With Ring of Shield

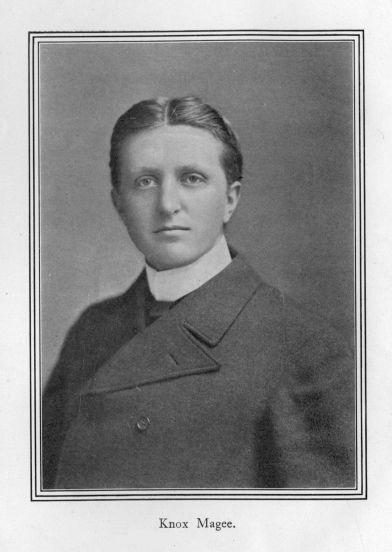

Author: Knox Magee

Illustrator: F. A. Carter

Release date: June 18, 2010 [eBook #32874]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

"On he came, and, to my great surprise and pleasure,

struck he my shield with the sharp point of his lance.

"Ah! my brave sons, ye all do know the pleasure 'tis

when, with ring of shield, ye are informed an enemy hath

come to do ye battle."

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | Sir Frederick Harleston |

| II. | The Maidens |

| III. | A First Brush with the Enemy |

| IV. | The Taking of Berwick |

| V. | From Berwick to Windsor |

| VI. | The King's Gifts |

| VII. | The Ball at the Castle |

| VIII. | The Duel |

| IX. | The King's Death |

| X. | I am Sent to Ludlow |

| XI. | Some Happenings at Windsor |

| XII. | Gloucester Shows his Hand |

| XIII. | The Flight from the Palace |

| XIV. | I Reach Westminster |

| XV. | Michael and Catesby |

| XVI. | My Dangerous Position |

| XVII. | At the Sanctuary |

| XVIII. | Richard Triumphs |

| XIX. | A Message is Sent to Richmond |

| XX. | Before the Tournament |

| XXI. | The Tournament |

| XXII. | A Midnight Adventure |

| XXIII. | The Arrest |

| XXIV. | In the Tower |

| XXV. | Michael and I |

| XXVI. | The House with the Flag |

| XXVII. | The Field of Bosworth |

| XXVIII. | Conclusion |

In these days, when the air is filled with the irritating, peevish sounds of chattering gossips, which tell of naught but the scandals of a court, where Queens are as faithless as are their lives brief, methinks it will not be amiss for me to tell a story of more martial days, when gossips told of armies marching and great battles fought, with pointed lance, and with the bright swords' flash, and with the lusty ring of shield.

Now, my friend Harleston doth contend, that peace and quiet, without the disturbing clamour of war's dread alarms, do help to improve the mind, and thus the power of thought is added unto. This, I doubt not, is correct in the cases of some men; but there are others, to whom peace and quiet do but bring a lack of their appreciation. I grant that to such a mind as Harleston's, peaceful and undisturbed meditation are the fields in which they love to stroll, and pluck, with tender hand, and thought-bowed head, the most beautiful and most rare of flowers: but then, such even-balanced brains as his are few and far between; and even he, so fond of thought and study, did love to dash, with levelled lance and waving plumes, against the best opponent, and hurl him from his saddle.

And there is Michael, which ever thinks the same as do myself, and longs for fresh obstacles to lay his mighty hand upon and crush, as he would a reed.

It is of those bygone days of struggle and deep intrigue that I now shall write. I do hope that some of ye—my sons and grandsons—may, after I am laid to rest, have some worthy obstacles to overcome, in order that ye may the better enjoy your happiness when it is allotted unto you. Still do I pray, with my old heart's truest earnestness, that no one of my blood may have as great trials as I went through; but in which I had the noble assistance and sympathy of the best friends ever man was blest with. I shall now tell of my meeting with the first of these, and later in the tale I shall tell ye of the other.

I, Walter Bradley, then a faithful servant of his Majesty King Edward IV, was sitting one evening in my room at the palace of the aforesaid King, at Windsor, engaged in the examination of some of mine arms, to make sure that my servants had put them all in proper order for our expedition into Scotland, with the King's brother, the Duke of Gloucester. A knock came at my door and, upon opening, I beheld Lord Hastings, then the Chancellor of the Kingdom, and at his side a gentleman which I had not before seen. This stranger was a man of splendid physique, about mine own height; long, light brown, waving hair; blue eyes, that looked me fairly in mine own; sharp features; and yet, with all his look of unbending will, and proud bearing, he had a kindly expression in his honest eyes.

"This is my young friend, Sir Frederick Harleston, just now arrived from Calais," said Hastings, as they both entered at mine invitation, and he introduced us to each other.

The Chancellor stayed but until he got our conversation running freely, and then he spoke of some business of state that did demand his immediate attention, and left us to become better acquainted.

Of course the expedition into Scotland was the chiefest subject of our conversation; and I learned from Harleston that he too did intend accompanying the Duke, as the King had that day granted him the desired permission.

"And what kind of man is Duke Richard?" asked my new acquaintance, when we had at length discussed the other leaders of our forces.

"Hast thou never seen him?"

"Ay, I have seen him, though I am unknown to him; but I mean what kind of man is he inwardly, not physically?"

"As for that, I do not care to speak. Thou, no doubt, hast heard of some of his Royal Highness' acts; men must be judged but by their acts, and not by the opinions of such an one as I," I replied cautiously; for I hesitated to express mine own opinion—the which, in this case, was not the most favourable—to one which I had but just met. Remember, my dears, those were times in which a silent tongue lived longer than did a loose one.

Harleston's color heightened, but with a smile, he said:—"Thou art in the right. 'Twas impertinent of me to ask thee, who know me not, a question of that sort. I had forgot that this is England, and not Calais; for there we discuss, freely, the King, as though he were but a plain man."

The frankness of this man, together with his polite and gentlemanly speech, made me to feel ashamed of my caution, so I said:—"Duke Richard hath never been popular with the friends of her Majesty the Queen; though of late he hath made himself liked better by them, than he was for many a long day."

"But he is a valiant soldier, is he not?"

"Ay, verily, that he is. He is as brave as the lions upon his banner, and besides, he knoweth well the properest way in which to distribute his forces in the field. There it is that the good qualities of Richard do show up like stars in a deep, dark sky."

"Then the sky is truly black?" asked Sir Frederick, with a smile.

I could not help but laugh at the way I had at last unconsciously expressed mine opinion of the Duke, after having declined to do so, but a breathing-space before. I cared not now that I had spoken my mind of Richard; for the more I looked into the honest face before me, the more did I trust to his discretion.

Then our conversation changed to the gossip of the court, of which I told him all. The only part of this in which he showed interest was when I spoke of the King's health.

"I fear," said he, "that his Majesty's reign is nearing an untimely end. When a man hath lived the life that the noble Edward hath, and kept up, with unbated vigor, his licentious habits, even when his body hath broken down, it doth take but little to blow the candle out. Some morning we shall awaken to find that Edward IV is dead, and his infant son is our new king."

"Yes, that is what we must soon expect, for kings must die as well as subjects; especially, as thou most wisely saidst, kings which insist upon living a life of three score and ten years in a trifle more than two score."

"And then God help poor England," said my new acquaintance devoutly.

"Why dost thou take such a pessimistic view of the situation in case of King Edward's death?" I asked; for the solemn manner in which Harleston had last spoken strangely thrilled me.

He regarded me thoughtfully whilst one might, with leisure, tell a score, ere he did answer my question; then he said:—"It hath ever been a rule of mine, as it evidently is of yours, to not speak mine opinions unto strangers; but on the contrary to let the other party speak his mind most freely. I have found this plan to be of exceeding worth in enabling me to gather most useful information, without a payment in return."

I felt my face flush red, and I was about to express, in no mild speech, mine opinion of his action in thus obtaining from me all the information that I did possess, and then, when I did ask him to explain the meaning of his own remarks, to thus answer me.

He took no notice of my movement or look, but continued speaking in that same quiet voice, that never did seem to be disturbed by passion, and yet had in it something of a force that ever made it to command attention.

"Many years have I spent in France, and therefore a stranger have I come to look on as a foreigner. Now that I am returned again unto my native land methinks that I will let my judgment take the place of mine old rule, and speak out freely to those whom I take to be honest. Thee do I place in this class, which I do regret is very small."

I was prodigiously surprised that a stranger would thus speak unto me as though I were some disinterested outsider of whom he was speaking. Again did I flush up and commence to attire myself in my dignity; but Harleston's honest and inoffensive look of candor did again disarm me, and he continued, uninterrupted, with his speech.

"For several years have I been acquainted with my Lord Hastings, whilst he was the governor of Calais. From him did I learn much of the situation here; but never did he speak of the characters of those in power; for Hastings, though a proper man, is still a politician and, as such, must keep his opinions to himself. It is a pleasure to me then to be permitted to thus discuss the probabilities of England's future with one not bound by the bonds of policy."

I bowed, and he continued:—

"So far as I can see, if the King dies ere the Prince of Wales be old enough to take full charge of the government, the people shall be obliged to choose a protector to rule in the young king's stead, until such time as the child doth come unto years of proper judgment."

"True," I assented.

"Do then but cast thine eye over the congregation of eager applicants for this seat of power, and thou shalt behold one whose advantage over the others doth raise him to a vast height above their heads, and consequently his chances of success in this great competition are assured; that one can be no other than Richard, Duke of Gloucester."

"Ay, truly, there is no other with sufficient power to rule England, in case the King should die."

"Now if Gloucester doth come thus into power will he not desire to have his revenge upon those which have ever been his enemies?"

"'Tis like he will."

"And will not this lead to uprisings throughout the land? Yea," he continued, "we have had one example of the troubles, and bloody wars brought about through the King dying and leaving a child to grasp with its weakly hands the sceptre and the sword of chastisement. Pray God we do not have another, and yet I fear that it will be unavoidable. I have expressed mine own poor opinion, without its being prejudiced by any others' thoughts; see whether I shall be right or wrong."

Now such a view of that which might soon happen had never been taken by me; and yet I had spent several years at court, and thought myself well acquainted with all the intrigues and possibilities of court life. And here was a young man—in fact not older than myself—which had never in his life lived at court, prophesying as to what the future would bring forth. His words were indeed bold, and yet I could not deny that they were reasonable, and liable to be fulfilled.

I now did admire this handsome and thoughtful stranger, and therefore methought it a duty put upon me to give him some warning that might serve to keep that well-shaped head, for a little longer space, upon its broad, square shoulders. I therefore said:—

"Thine opinions, I have a fear, stand in some likelihood of being proven true; yet do I pray with my full heart that they may be wrong. However, whether thou art right or wrong—the which time will prove—let me now warn thee, which art a stranger here, to keep those thoughts to thyself. There are those about this place—the more's the pity—whose shoulders are not bent by the weight of honor they carry, but from their habit of holding their ears to the keyhole."

"Thanks for thy kind intent," he replied. "After I have had some little experience at court I do hope that I may acquire the habit of smiling whilst, with my dagger, I kill my partner in the conversation. This, I have heard, is the fashion of the Duke of Gloucester; and if I do prove a true prophet all good courtiers must soon adopt it."

That night as Harleston was leaving my room I promised to see him early in the morning, and show him through the castle and parks.

As we shook hands at the door I felt as though I had known him for long, and that we had ever been the best of friends.

That, my dears, was how I became acquainted with Sir Frederick Harleston, who, since that day, hath ever been close by my side, through many harsh experiences, as well as through many sunny days of happiness.

Now we are sailing, side by side, down the mighty river, travelled by all wearing the fleshly habit. The great unknown sea of oblivion is now near at hand, and soon we shall both cross the bar and sail forth upon its smooth and peaceful surface.

But there I go passing over sixty years as lightly as a swallow doth skim the bosom of smooth waters. And indeed the waters o'er which I am skimming are not smooth, but rough and troubled. Come, come, Sir Walter, settle down and tell the tale of days before your hair had lost its raven hue. My head, as ye all know, is now well capped with snow; but yet the head itself doth still retain a deal of its wonted fire.

The next morning after Harleston had come unto my rooms I called at his apartments to see how he did like the way that he had been placed. I found him in the act of completing his toilet, and therefore, as he had not broken his fast, I invited him to come and breakfast with me; which invitation he did readily accept.

During our meal he asked me many questions as to the manner in which people conducted themselves at court, to which questions I gave him very complete answers, so that he might be able to manage without any breach of etiquette, which thing to do, at Edward's court, was not so easy as one might imagine.

"Now, in regard to your ladies," said he, "do they insist upon being worshiped, as do the ones of France, or are they cold and chilling, as are the fogs of mine almost forgotten native land?"

"Thou shalt have an opportunity for the satisfying of thyself as to that same, to-day; for I am about to take thee with me to see two of England's fairest primroses; the one, my cousin, Lady Mary Atherby, to whose tender care I will leave thee, and the other, Lady Hazel Woodville, to whose mercy I do entrust my soul—if she be pleased to take the present at my hands."

"Do these ladies live at court?"

"Yes," I replied. "They are both ladies-in-waiting to the Queen. And now, having done all the damage we can to the present repast, what dost thou say to a stroll through the park, where we are like to meet the ladies, and there satisfy thy curiosity as to their dispositions?"

"With all my heart," said he. "I have never been known to be elsewhere than in the front rank in such an attack, though ever do I meet with a repulse."

We then strolled forth into the park, and wandered through the walks, among the grand old trees, for some time, without meeting anyone.

"I fear that we are not destined to fall in with the enemy," said Harleston, after we had walked in silence for some time.

"Fear not," I replied; "we shall soon commence the encounter; for there, unless mine eyes do deceive me, is the first sign of danger."

"Thou meanest that fair outpost yonder, where those two oaks do meet above the path?"

"The same," I replied; "but it now looketh as though there are others there before us."

While this conversation was going on we had gradually approached a bench, placed behind a clump of bushes, through which we saw some fair, fresh, faces, watching our approach. Upon the bench, and talking with the girls, were two men, in which, as we drew closer, I recognized the Duke of Gloucester and the Duke of Buckingham. Richard was dressed—as was his wont—in the extreme of fashion and in the richest of materials. Buckingham, though not so showily attired, was magnificently dressed in black, figured velvet, with dark maroon facings.

After saluting the Prince, the ladies, and Buckingham, I introduced my new friend to them all. I then said unto his Royal Highness—"Sir Frederick, here, hath but yesterday been made a brother officer, by his Majesty."

"Yes," said Harleston, "the King did command me to report to your Royal Highness for service with thee in your expedition into Scotland."

"Much am I joyed, Sir Frederick, to have thy noble assistance in our chastisement of the insolent Scot: for England can ill afford to spare any brave knight from her expeditions, now that they have become so thinned out by our late, unhappy wars," said the Prince, with that heartiness he so well could use, and of which he knew the power.

"But let me warn ye both," he continued, with a mock gravity and a quick glance at the maidens, "that ye shall have short time in which to enjoy the pleasures of the court; for we march next week. Therefore make the most of your opportunities."

Buckingham, who ever smiled, but said little, though he was no mean orator, merely agreed with the Prince's remark, and with a pleasant bow they left us, the limping Prince leaning on the arm of Buckingham.

"Thank God!" I cried, with a sigh, when the two were out of earshot.

"Is he not most disrespectful?" laughed Hazel, as she turned to Harleston.

"Nay, of that I cannot judge, fair lady," replied he, with a smile. "The customs of the court I have yet before me to master. 'Tis possible that ere I have been here a week I will commend Sir Walter's act."

"Indeed thou shalt," cried both of the girls at once.

"Oh! those two are simply unbearable," said Hazel with a force that left no doubt as to her opinion. But then she hath ever been one which feared not to express her dislikes, and they are ever as passionate as are her likes.

"And so, Sir Frederick, thou hast come all the way from France merely for the pleasure of marching off to battle and slaughtering poor Scotchmen, or of being killed thyself?" said gentle cousin Mary. "Alas, when will ever you men learn that there are other things to live for, in which there is more glory, far, than in the cruel wars and slaughters."

Both Hazel and I did laugh at the little maid for the solemn way in which she said this; but Harleston did not smile, and on the contrary listened with attention. Mary without noticing us continued—"Look at Lord Rivers and behold what he hath accomplished: introduced printing, and by that one act hath done more real good for England than if he had won the greatest of all battles."

"I quite agree with thee, Lady Mary," Sir Frederick replied; "but battles are also necessary, in order that our homes and country may be protected, and that we may be permitted to enjoy those luxuries such as is the one which Lord Rivers hath taken the pains to introduce."

"Mayhap thou art right; I never looked at it in that way before; but still I do not like them," said Mary, wrinkling her little forehead, and shaking her pretty head in the most bewitching way, and causing some little golden curls to dance and lightly kiss her cheeks. I could tell by the look on Harleston's face, that he did envy those curls their position. And who would not? Had ye but seen Mary at that time, ye should have been changed from freemen into Mary's slave, and that quite freely, that is, had the Lady Hazel not been there: for had she been ye would love the one on which your eyes first fell.

Whilst the afore-put-down conversation was taking place we had been walking slowly through the park; and now Hazel and I began, gradually, to drop behind. Of course we had naught whatever to do with this; it must have been that Harleston and Mary did quicken their pace.

"What dost thou think of my new friend?" I asked, when they were out of ear-shot.

"Quite an acquisition to the court," Hazel replied. "Indeed 'tis time we had another handsome gentleman at court," (here my chest did begin to swell, and at least two inches were added unto my stature, which did not need it;) "besides the King," she added.

Since that day I have had the greatest sympathy with Lucifer. Verily, I never fell from such a height before, nor since. I have been thrown from my horse in battle, and had hundreds ride over me, yet have I felt better than I did that morning in the park. I stopped and stared at her, with my mouth open, like a bumpkin gazing at an army passing.

Now at that time (and I say it without conceit) there were few men at court who would not have been glad to change their looks with Walter Bradley; therefore the blow did fall with more stunning force. When I had somewhat recovered myself, I walked on, wishing every woman at the bottom of the sea, and swearing revenge on her, which was now walking by my side; yet cursing myself, silently, for having made a fool of myself by showing my surprise. Hazel, instead of laughing, which would have made me feel better, wore the most innocent look that it is possible to imagine: yet methought the look was overdone. However, I was now determined not to show my disappointment any more; so I continued the conversation, using the same subject.

"I do not believe Harleston need fear the Scottish arrows; for, unless I be a false prophet, he will leave the most vital part of his body, namely, the heart, here at Windsor. And yet," I continued, becoming bolder, and heaving a heavy sigh, "he shall not be the only one to do so."

"No," she replied; "the Duke of Gloucester said he was leaving his heart here."

"To whom said he that?" cried I, for the one danger of this accursed court life was the chance of men in high places casting a jealous eye on the maidens of the court.

"I heard him tell the Queen that he would leave his heart with the King and his family," answered Hazel, and she laughed at my apprehension of the danger which I thought threatened her.

"Why dost thou like to torment me so?" I asked.

"Because thou art so easily teased."

Why, oh why, did the Creator arm these fair creatures with such a power to make us happy or miserable, good or bad, send us to Heaven or to Hell, make us sensible men or the veriest of fools as best doth please their whims?

"But look, here cometh the Queen," said my fair companion. "I fear I shall get a scolding for leaving her, to walk with thee."

"Tell her that the Duke of Gloucester kept thee talking with him, the which is the truth," I said.

But when we met her Majesty, who was walking with her daughters and some others of her suite, she most kindly did receive us, and no thoughts of scolding were in her gracious mind. When we had spoken for some time, the Queen enquired as to where Mary was.

"She came on ahead of us, your Majesty," replied I, "and I had surely thought that thou must have met her."

"Do thou go, Hazel dear, and when thou hast found her, tell her that I wish to speak to her."

Hazel courtesied, I bowed, and we passed on, searching for Mary and Harleston.

"The Queen is the best mistress that any servant could wish for," said Hazel, when we had gone a few paces. "She is never angry, and so kind; she treats both Mary and me as though we were her own daughters."

I did not wonder that the Queen did use them both go well; for who could help loving either of those dear, dainty maidens?

We had not gone far ere we met Mary and Harleston returning.

"They seem to be getting on famously," observed Hazel; "for they are so preoccupied that they do not see us coming."

When they came near, Mary, who had evidently been listening with great attention to something that Harleston was telling to her, burst forth into her rippling, childlike laugh. Then, as she caught sight of us, she stopped suddenly and said:—

"Oh, here they come now!" Then, as we met them:—"We thought that ye must have turned back; so we were just coming to search for you."

"And what has Sir Frederick been telling thee that was so amusing?" I asked.

"Oh!" replied Harleston, "the Lady Mary hath been completing mine education, which thou, Sir Walter, didst start last night, and then I, in order to, in some small way, repay part of the debt, was telling her some of the stories that I had heard in France, where indeed they are most expert in story-telling, though not so accomplished with regard to the truth."

Here Hazel delivered the Queen's message, and we all started back to the Palace, laughing and chattering, like nothing more than school children. Upon reaching the castle I found some orders from Duke Richard, the fulfillment of which did keep me busy for the remainder of the day.

The next few days, Harleston and I spent in making ready for the march; so we did not see much of the ladies. However, the morning before we left Windsor, we met them in the park, whither we had gone in search of them. When they beheld us, they came forward to meet us, and methought that Hazel did not look as happy as was her wont; but it may have been that I was hoping to see her look sorrowful, and therefore, I did imagine it.

"We have come to receive the benediction," said Sir Frederick.

"And also a charm that will give unto us both charmed lives," I laughingly put in.

"Indeed thou needst not to laugh, Walter," said Mary, solemnly, and with reproof in her tone and manner. "I know that thou dost not believe in such things, and therefore they are worthless to thee; for in order to be protected by these mysterious benefactors, one must have unquestioned faith in their ability to protect. Now, Sir Frederick," she continued, with a slight hesitation, "if thou art not so skeptical as Walter there, and if thou wilt promise to keep it safe, and not to lose it, I will lend thee a charm that will indeed protect thee from all harm. I always have it with me, and nothing hath ever harmed me."

"'Twould truly be a fiendish fate which could send harm unto one so fair," said he. Then, as she did hand unto him, the charm (which was a scarf of scarlet silk, and had been given to her by her father, who had obtained it from a Turk,) he thanked her, and placing his hand over his heart, he swore to protect it as he would his life, and never to permit a thought of doubt, as to its ability to protect, to cross his mind.

"Wilt thou not give unto me a charm that I may take with me, Lady Hazel?" I asked, coaxingly, when we had gone some little way.

"Thou dost not believe in them, and therefore, as Mary doth say, it would do thee no good," she replied, with a toss of her pretty head, as much as to say, "Now, thou wouldst be skeptical."

"Do but give it me, and I do hereby swear to trust in it, and no doubt as to its virtues shall ever cross my mind; yes, this do I swear by all the saints of paradise." Now this did I consider an exceeding fine speech, and therefore I was not prepared for the reception that it did receive, which was a burst of laughter, and clapping of the hands from Hazel.

"Excellent! excellent!" laughed she; "Oh, Sir Walter, thou hast missed thy calling; thou wouldst have made such a splendid priest; thou saidst those words with such a religious tone, and looked so saintly." Then, as I showed my disappointment and annoyance, "Come, come," she added, "do not sulk; here is my glove, which I do now command to protect thee through all the dangers of this war. Now, am I not kind to thee?"

I nearly went wild with delight. I kissed that glove so fondly that Hazel had to warn me not to eat it, as it would not protect me if I did. And then I said a lot of things which all my male readers either have said or are only awaiting an opportunity to say. Presently I was interrupted in my avowals by coming suddenly upon Harleston and Mary, who were sitting on a bench beside the path.

"Is Sir Frederick telling thee some more stories, Mary?" asked Hazel, when we saw them.

"Not the kind I heard Walter telling thee, just now," replied Mary, as she looked at me, with a wicked little smile playing over her fair features. Then, as I reddened to the ears, both Harleston and Mary burst out a-laughing, and I, after stammering out some explanation about some messages I was leaving with Hazel, to deliver to the Queen,—which set them laughing louder than ever, thought it best to keep quiet.

However, as we were bidding good-by to the girls, Hazel said something that made me to forget mine embarrassment. It was just as we were leaving them that she called me back and said, as she kept her eyes staring fixedly at the ground:—"Remember, Walter, I think a great deal of that same glove, and do not want any harm to come to it; therefore try and keep it out of danger."

"Oh, fear not; I now do know that I shall return again." And ere she could prevent me I seized her hand and kissed it.

I went back to my rooms with my toes scarce touching the ground.

Our time was now but short; and soon we did mount our horses and set out in the train of the Duke of Gloucester, on our march to Scotland, and had soon left the castle behind.

However, so long as we could see the left wing, we watched two scarfs waving, to which we waved our lances in return.

And so we rode off to the wars.

Now I will not weary ye, my children, with a description of our march unto Scotland, as it was a wearisome one, without any adventures which might have relieved the tediousness of so long a journey. Indeed there was nought for us to do, but march all day, and when night did come, thank Heaven that we could forget our weariness in well earned rest and sleep.

At almost every town along the line of march we were joined by reinforcements; so, by the time we neared the border, we had an army strong enough to take a considerable fortress. However, as we did approach nigh unto Berwick, which place was the object of our attack, we learned that it should require all of our forces to subdue so formidable a stronghold. When within a few miles of this place, that hath been so many times the scene of struggle between our nation and our ever irritating neighbours of the North, and which, some score of years before, had been turned over unto our enemies, by that gentle and weak-minded King Henry VI, Duke Richard of Gloucester, on this, his second expedition unto this place—his first having miscarried—sent unto the garrison a messenger, under a flag of truce, to demand the surrender of Berwick, unto the army of its rightful owner. Whilst he was gone, the army went into camp; for although it was still early in the day, our leader had decided, in case the Scots did refuse to surrender—which, in all probability, would be their reply—that we were not to begin the attack until the morrow, in order that his army might have an opportunity to rest after their long, hard, march.

Oh, such a delightful evening did follow that long and weary day of labour. We were among that magnificent border scenery, where nature doth seem so busy with her work of carving herself into most fantastic, and yet admirable, ruggedness. How, in the evening, doth she cast her beauteous, drooping, eye aslant across her work; and her gentle breath dies out in hushed and satisfied, yet modest, admiration. The setting sun did seem to paint a hill, then step a vale and touch another with its golden brush.

Here may be seen many a place where nature's liquid emery hath ground the rocks asunder, and still some sparkling remnant goes trickling down the groove.

On this evening Harleston and I did take our usual walk through the camp and, as the night was glorious, it did tempt us to stray further from headquarters than might be considered safe. In fact, past the outposts did we go, and sat us down upon a hill that had seemed bolder than its comrades, so that we might the better see the surrounding country.

As we sat there, our backs were turned towards the camp, and our faces were tinted with the fading colors of the western sky. To right and left were hills and hollows of varying height and depth, but all having in common, shrubs and trees in unfailing irregularity, growing side by side, above and beneath each other, in the same disorder as had their seeds been flung there by the hand of the hurrying angel which did sow the whole of the earth's broad face. At our feet, and betwixt us and the sister to the hill on which we now were seated, was a smooth and undeceiving mirror, set, with bashful caution, between these obscuring hills, that nature's pardonable vanity might not with ease be gazed upon by the ignorant eye of man.

"I wonder when we shall be back at Windsor," said Sir Frederick, in a gentle tone, after we had sat in silence for some time, gazing at the soul-inspiring sight.

"Surely thou art not beginning to be homesick?" I asked; for this was the first time that I had heard my companion speak of the castle, since we had left it.

"Oh, no," he replied, "yet I wish that I might be there," and with this methought he did sigh.

Now, Heaven knows, no man could have wished to be in Windsor more than did I at that moment: yet, I had not liked to say so, for fear Harleston might think that I did relish the lazy life at court, more than I did that of the camp. But now that he had broken the ice it was the one subject on which I wished to talk.

"Well, Sir Frederick, and what dost thou think of her, now that thou hast had time to well consider?" I asked, coming out boldly.

"She is indeed perfection," he replied. And then, as though to himself:—"Eyes like the sky's deep and unfathomable blue, and hair like nothing more earthy than a sun-reflecting piece of well polished gold."

"Nay, not so; her hair is dark, and her eyes are hazel as her name," said I, in surprise;—and then, after staring at each other for a moment, we both did see our mistakes, and burst out a-laughing.

So Harleston and I sat talking on a subject that was very dear to us, until we did hear the bugles calling, which warned us that it was time to return and retire. We arose and started down the hill, and back to camp, both feeling in musing, more than talking, mood. We had not gone far, however, when my companion called my attention to something behind a clump of bushes, glistening in the moonlight.

"If I am not mistaken, there is danger yonder; for if ever I did see the glisten of a headpiece, I see it now. We had better put that hill between us and the enemy, if such they be, for, without our armour, a doublet doth afford but faint resistance to the steel head of an arrow."

We at once started to cross the low hill that Harleston did refer to. We had just reached the top, when two or three arrows struck the rocks at our feet.

"A good shot, for the distance, upon mine honour," cried Sir Frederick, as we leapt down behind the shelter of the friendly hill. We ran quickly along the ravine in the direction of the camp, but Harleston, suddenly stopping, said:—"Suppose we see from whom we are running, before we do go any further. If they be but a few archers or men-at-arms, two good knights should drive the rascals before them as doth the wind the crisp, dry leaves; ay, though we wear not our full armour. What dost thou say, Bradley, shall we try conclusions with them?"

Readily did I consent to the adventure; for never in my life have I been known to require a second invitation of this sort. We concealed ourselves behind some shrubs, and there we awaited our pursuers. Presently we beheld them approaching at a run; and, as they neared our hiding place, we could see what we should have to face. They were three men, armed with swords such as are used by the Scotch, and which they do manage more after the fashion of a club, than any other weapon one could compare their use with. Their bows they had evidently thrown aside, for their empty quivers still hung at their sides. However, they also carried a small, round shield, and this did give them an advantage over us, who had nothing but our good swords with which to protect ourselves. When they came near the place where we were concealed they stopped and held a short consultation.

"I saw them stop about this place," said one.

"No, methinks they went further on," said another.

"Well, we had better search here anyway," added the third, "for it will not be safe for us to venture much more close unto the outposts."

And then they did commence to search the shrubbery all around us. Nearer did they draw to where we waited, swords in hands. Presently one came and thrust his sword into the bushes behind which we were hiding. That was the last thrust he ever made. I was upon him in a moment, and buried my sword up to its hilt in the fellow's chest. He sank to the ground, but as he did so he uttered a gurgling yell, the which did bring his companions unto that spot.

"Now, Harleston, we shall have some sport," I cried out, as I did engage with the first of these new arrivals. My friend quickly met the other, and we fell to in a lively fashion. I soon forced my man to give ground, despite the difficulty I found in getting past his shield.

"Now, my brave Scot, I have thee in the right place," said I, as I prepared to give him his quietus. Then, just as I did step forward, to run the knave through, my foot slipped on one of those accursed stones, and I sat down as nicely as I could have done in mine own rooms at the castle. The fellow aimed a savage blow at my head, but, dropping the point of my sword to the ground and raising the hilt, I caught the stroke upon it. Then, reaching swiftly forward, I grasped him by the ankle and hurled him to the ground. Ere he could move I was upon him and, seizing his own dagger, I stabbed him to the heart.

When I had done for my man I turned to see how my friend was progressing with his. They were still at it for dear life and Sir Frederick did seem to be bothered with the way the Scotchman used the little shield. This fellow was much larger and more thick of frame than the one with which I had been engaged, and did seem to be giving Harleston all he could do to hold his ground. Still would I not interfere, for well did I know that my friend would rather die than have assistance when fighting against a single foe. At length the Scotchman made a swinging, backhand stroke, full at Sir Frederick's neck. It was a savage blow, and I did greatly fear me that I had lost a good comrade. Harleston, however, dropped quickly to one knee, and as his opponent's blade whistled harmlessly over his head he plunged his sword into his adversary's side.

"Well done!" cried I. "A pretty piece of work, upon my soul, was that fall of thine."

"I see that thou hast settled with thy man," said he; "but this one did compel me to use mine artifice."

With this we took their swords, as remembrances of this night's work, and walked slowly back to camp, glad at having been the first to draw blood, and for having found something to relieve the monotony, after our long and tedious journey.

When we reached camp we learned that the messenger had returned with an answer from the Scots, which message was evidently a refusal to comply with the Duke's demand; for we did at once receive orders to be in readiness to commence the attack at sunrise.

When we retired, Frederick and I occupied—as was our wont—the same tent; and the last thing I heard, as I fell into a peaceful sleep, was the sounds of the anvils of the armourers, as they worked, getting everything ready for a day of battle.

The next morning, just as day was breaking, we were aroused by our squires, who, after bringing us our breakfasts, of which we ate heartily, got our armour and laid it out and ready. So soon as we had finished with our repast, we were buckled and laced into our harness, and then, as everything was ready for the march, we did set forth.

We had not travelled above a mile when our advance guard sent us word that a strong force of the enemy was coming towards us, evidently with the intention of attacking our right flank. This was the part of the army in which Harleston and I were to play our part; we having been sent there with a body of other knights to add somewhat to its strength, the which was somewhat weak in comparison with the left wing, which was led by the Duke of Albany, who was a brother of the Scottish King, James, against whom he was now about to fight—but then, royal brothers are ever longing to kill each other.

As we came over the brow of a hill we could see a considerable body of knights and men-at-arms, preceded by a stronger force of archers, coming slowly towards us, as the messenger had said.

Our archers were now thrown out in front, the knights followed, and the men-at-arms brought up the rear. As we were drawing near unto the foe we beheld their main body advancing on our centre, which was led by the Duke of Gloucester himself. Soon we were engaged, and then we had not time to see how the Duke did receive the Scotchmen; for indeed we were too busy with the receiving of them, or rather their arrows, which poured down on either side like rain.

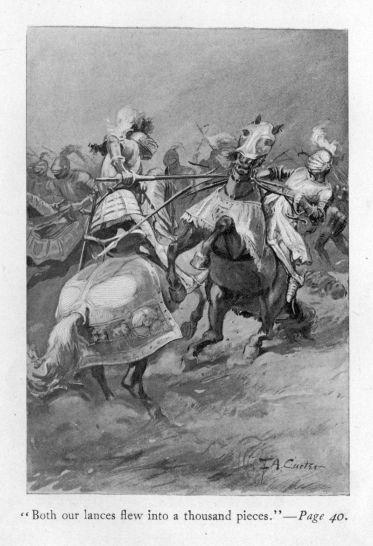

When this long distance battle had gone on for a short space we thought it time that we knights should take part, and not let all of the glory go to the archers. Therefore, the command was given to swing to the right, past them, and take the enemy in the flank. Around, as on a hinge, swung the double ranks of mail-clad figures, and then, when we had cleared our archers, we placed our lances in the rests, and came down upon the enemy like a thunderbolt. They, however, had seen us change position, and, though they be thick-skulled knaves, they did divine our object, ere our plan was carried out. Their knights dashed forward at the same time as did we, and we met before their archers with a crash that was heard for the distance of a mile.

I had singled out a knight, which, by his size, and the way he sat his horse, led me to think he should be a foeman worthy of my steel. In this I was not disappointed; for when we met in the front rank, each had aimed at the centre of the other's shield, and it is seldom that I have ever had so heavy a shock. Both our lances flew into a thousand pieces, as though they had been made of straw. Mine opponent's horse was forced back upon his haunches, and he was like to lose his seat. But he did recover himself with such dexterity as did show him to be a knight of great ability. I had scarce time in which to draw my sword ere he was upon me, hacking at my head so rapidly as to take all my time, and the use of all my knowledge, in defending myself. Round and round we rode, striking furiously at each other, which blows we guarded with equal quickness. Neither had any advantage, as we seemed to be both of nearly equal strength and skill. After forcing him closely he at length began to give ground, though whether from necessity or guile I do not know. I aimed a terrible blow at his head; he caught it upon the hilt of his sword. The force of the blow was so great that my weapon was broken in two, and I was unarmed. Verily I thought mine end had come, and that I should never see the Lady Hazel again. To my surprise the knight called out, in French, something to the effect that we should meet again, and rode off.

"That accounts for it," said I; "he is a Frenchman; and had he been a Scotchman, I had now been a corpse."

The enemy was now commencing to give way in places; yet the fight was still a goodly one.

Sir Frederick was nowhere to be seen; so I quickly secured a sword from a poor knight, who had still the head and part of the shaft of a lance sticking in his side, and then did I plunge into the fight once more. I forced my way through a struggling crowd of the enemies' foot soldiers, cutting them down as I went; when suddenly I espied a knight on foot, surrounded by a score or more of these rascals.

"To the rescue!" cried I, and dashed into the circle. The knight was standing beside his horse, which was dead, and making great strokes with his sword, in all directions. Thus he had kept a circle clear around him. Several corpses in that deadly circle told why the rest stood back. But, just as I came up, one of the knaves did venture to make a dash forward, when the brave champion's head was turned. I was upon him in an instant. "Ha! thou coward ruffian, take that!" I cried, as, with a straight downward stroke, I cleft his head from top to chin. Just then some of our men-at-arms came up, and the few Scots which escaped us did so by their fleetness of foot, and their knowledge of the country's many hiding-places.

"Thou art not too soon," said Harleston, for it was he, as he opened his visor and wiped his brow. "Indeed I was hard pressed by that pack of hyenas."

I quickly secured a horse for my friend, and again we plunged into the thick of the fight. We soon became engaged with three knights which were like to have done for us, had not,—when we were sorely pressed—an arrow struck one of their horses, causing it to fall. The rider fell with his leg underneath, and so was unable to take any further part in the fight. I pressed my opponent from the first, and soon had him at my mercy. I gave him an opportunity to surrender, but as he refused to do so, I waited until his arm was raised for a blow, when, with my shield held over my head, I drove my sword straight under his arm, where the armour divides. I heard my point strike his harness on the other side, as it went through his body, so great was the force of the blow.

Hot and furious was now the fight. The enemy were fleeing in all directions, and our gallant troops were pressing them full hard. Loud blew the trumpets, the signal for the continuance of the slaughter. Berwick itself must now be carried whilst our blood was still at fever heat. I looked around to see how fared my friend, in his contest with the knight with whom I had seen him engaged. No sight could I see of either of them; but there was Harleston's horse straying riderless about the field. I recognized it by the peculiarity of its housing. A great sadness did then possess me, for I did greatly fear that my dear friend must have fallen at the hand of his opponent. "Indeed he must be dead," said I; "else how could his steed be riderless?" Then did I swear a great and savage oath of vengeance. "For his life an hundred Scots shall die, and still shall he be but poorly paid for." Thus did I think; for during the short time in which I had known Sir Frederick I had learned to love this noble knight, better far than I would a brother.

Our forces came on, eager to avenge the loss of their comrades which had fallen that day, and these amounted to a considerable number. Now and then a small body of the foe were driven to bay, and seldom were they spared. I seemed to be changed into a demon, with the thirst for blood. Every one of the enemy that did fall into my hands, I slaughtered, and felt a savage delight in doing it. Ah! the fierce delirium of victory.

When we reached the walls of Berwick a white flag was flying from the Citadel; so the battle was over, and we were stopped from pursuing the fleeing foe. Berwick was taken, and the war was ended; though we did not know this latter at that time. That evening we took possession of the fortress, and the flag of England replaced that of the Scots.

After I had had my quarters allotted to me, and was just getting out of mine armour, who should walk into my room but my dear friend. He was still in his complete harness, and was covered with sand and blood, from head to foot.

"The saints be praised that thou art still alive!" cried I, as I rushed and grasped him by the hand. "I was sure thou must be dead, and many a poor Scot has paid dearly for my thought. But where, in the name of Heaven, hast thou been rolling?"

"Do but wait a moment and I will tell thee all," he replied. Then, when we were seated, he told me what had happened him. "You saw that knight, with whom I did engage when the three attacked us?" he asked.

I nodded, and he went on:—"He is a Frenchman, and he hath a knack of breaking his opponent's sword with the hilt of his own. He broke mine, as I aimed a blow at his head; but, before he could strike, I closed with him, and, putting mine arms around his waist, I threw myself from my horse and dragged him with me. Of course he fell on top, which shook me up a little and, as the ground was soaked with blood, I naturally do not look so clean as I might."

"And what about the Frenchman?" I asked; "didst thou kill him?"

"Oh, no," he replied, "he struck his head heavily on the ground, and as he was badly stunned, I took off his helmet to see what he did look like, and also to give the poor devil some air, which I was in much need of myself. He was a handsome man, and evidently he belongs unto a wealthy house; for his armour was richly inlaid with gold."

I then told Harleston of my encounter with the same knight earlier in the day, and when he had heard that the Frenchman had spared my life, he was glad that he had not given him his coup de grace.

The next morning, as we were dressing, a knock came at our door, and, upon opening it, a soldier handed unto me a message which, upon reading, I found to be an order from the Duke of Gloucester to prepare myself for a journey, and to report to him in an hour's time. I at once guessed my destination, which I thought to be Windsor; and in this I was not mistaken; for, on presenting myself at his Royal Highness' quarters, I was handed a packet and commanded to reach the castle in the shortest possible time. I then asked the Duke if Harleston might accompany me. He thought for a moment ere he answered, and then said:—"Yes, by Saint Paul, take the whole army, and thou wilt! we do not need them here; these Scotchmen will not dare to draw a sword, after the lesson we taught them yesterday, eh! Bradley?" and he slapped me on the shoulder. Of course I agreed with his Royal Highness, which is ever the proper thing to do, when dealing with a Prince.

Half an hour later Harleston and I were on our way to Windsor.

"Not so long a campaign as we had thought," said I, when we were fairly on the road.

"No," he replied; "my dream of last night is being now fulfilled."

And so we rode on, with our faces turned southward.

On this ride from Berwick to Windsor we had but one adventure to break the monotony of our journey, and that was of so little importance that I will not describe it at any great length. It was as we were nearing York, and passing through a great forest which lines that road on either side, like two great rustic walls placed there to screen Nature's lowliest children from the murderous hand of man, for a considerable distance, that we were attacked by a band of highwaymen, with which this forest doth abound. Indeed 'tis said that here they do grow upon the trees like poisonous fruit. We had been riding hard all day, and, as the evening was drawing nigh, we were walking our horses, in order to give them a rest in the cool of the forest, ere we should make our final effort, for that day, and dash into York at a gallop. Suddenly, about five score yards in front of us, two horsemen did ride out, one on each side of the great road, with drawn swords in their hands. They started to come in our direction, so we thought they meant mischief. Then two more followed, and these were dressed as were the first. We now became convinced that we were the attraction which seemed to be drawing these gentlemen of the greenwood. I glanced over my shoulder, and there, about the same distance behind us as were the others in front, were four more men, dressed in exactly the same manner and also carrying their swords in their hands.

"We are in for a skirmish now," said I.

"Yes," replied Harleston; "but if we be careful we can do for them yet. If they do attempt to stop us, cut down the one on the right, and I will do the same on the left, then dash forward and see if we cannot pass the others. The ones behind we need not bother with. However, use great caution and do not show signs of resistance too early in the game."

"I'll watch thee for the signal."

When the first two men were within a few paces of us, they suddenly wheeled their horses straight across the road, thus compelling us to stop.

"And what might you want, sirs?" asked Harleston, in his sweetest tone. The manner in which he spoke did seem to take their breath away; for they did nothing but stare for a moment. Then the first to recover himself answered:—

"All that thou hast, and be damned quick about the giving it." This in a voice that told, in the plainest terms, the life these fellows lead.

My companion fumbled with his purse for a moment, which example I followed. The two knaves eyed the bags as the wolf doth gaze in greedy admiration at a lamb. Then, when the outlaws were off their guards, our swords did leap from their scabbards, and we cleft their heads as though they had been made of putty—which, mayhap, they were. We now drove our spurs into the flanks of our horses and dashed at the other two. They waited until we were within a score of yards of them, and then they changed their minds, and did not seem to relish the idea of meeting the same fate as their fellows; for they turned their horses into the greenwood, and disappeared along one of those many narrow paths, with which these forests are burrowed, and which they know as well as I do the corridors of the palaces at Westminster or Windsor. We did not attempt to follow them, but rode on at full speed for the distance of a mile, and when we at length slackened our pace and looked back, not one of the six was to be seen.

They had evidently thought to overawe us by a great show of numbers and the copious use of bluster; but after two of their number had fallen the courage of the rest did forsake them, and they lost their appetites for our purses, for which they should have to pay such a price.

So we rode into York, nothing the worse for our little adventure which had helped to make us forget the weariness of our long, hard ride. When we had entered our inn, and were preparing us for our supper, a great crowd gathered about the door; for the news had soon leaked out, who we were and what our business was; for around inns every one doth know one's business better than that person does himself; for what they do not know they guess at. So we gave them the news of the great victory our army had won, and told them that the Duke of Gloucester now occupied Berwick. When they heard this they went wild with delight, and we had to shut ourselves in our rooms to keep from being carried, on their shoulders, all over the city; so great was the admiration of this sturdy, simple, congregation of England's stalwart sons.

Bonfires were lighted wherever they could find sufficient open space in which to build them. Processions were continually marching through the streets, singing and cheering.

We had intended staying here for a few hours, in order that we might get some much needed sleep; but we soon found this to be outside the bounds of possibility, on account of the uproar which was increasing every moment.

My friend and I, after cursing our folly in telling them the good news, decided to not wait for a longer time than should be necessary for us to get some supper and a change of horses, and then proceed on our journey.

Needless to say, we did eat ravenously, after the long ride we had had. When we had refreshed ourselves, all that it was possible for us to do, we mounted our horses and set out through the surging, screaming, half-drunken mass of humanity and made our way slowly towards the city gates.

One drunken fellow, which did recognize us as being the persons who had brought the good news, caught my horse by the head and insisted upon our joining him in a friendly bowl at a near by inn. When I tried to persuade him to let me go, and to excuse the duty that did make our presence with him impossible, he said:—

"No, by the Virgin, your Royal Highness shall not pass out of the old city of your father without drinking with some of its citizens. Were his Royal Highness, thy father, alive he would not pass out till he had made the whole town drunk, and so shall not you. Stay and revel with us, for this is a glorious day for England,—glorious day," and he did lean his head against the neck of my horse, and seemed inclined to spend the night thus.

I spurred my steed sharply and, as he bounded forward, the poor tradesman was thrown to the ground; but as we rode on we could still hear him calling out to "his Royal Highness," so long as he could make himself heard above the uproar that was going on around us. He evidently thought that I was the Duke of Gloucester, and he was most determined to show his patriotism and loyalty, by giving us what he considered a glorious time.

We were permitted to pass through the gates, when we had told our business; and so we rode forth from the city and on to the moon-lit road, upon a long night's ride, through alternate wood and open country.

All that long night we rode on, now dozing in our saddles, and then waking with a start, when an owl would break the stillness of the forest with his unearthly noise, which seemed to us to be in keeping with bats, serpents, brimstone, and all the general sounds of Hades, more than the peaceful quiet of our weary ride through the forest. Then, after cursing all these hideous disturbers, we would spur our horses on, and let the cool breezes, as they played against our faces and whistled past our ears and through our hair, refresh us and help to drive away those heavy veils that did seem ever to be settling down upon our brains and blotting out our consciousness with their soothing folds.

The wolves, as they howled in the distance, seemed to be humming some unearthly lullaby, in keeping with the scene and with our feelings; and so weird-sweet did it sound that we would surely have gone to sleep, had not our horses, which had better sense than their riders, quickened their paces at each of these, to us, melodious outbursts. How we kept our seats that night hath ever since been, to me, a mystery; for I have but scant recollection of that agonizing ride from York.

When we entered Northampton, early the next day (for this was the road we came), we had to be lifted from our saddles, so stiff were we, after that awful night. Here we did refresh ourselves with wine and food, and had about an hour's sleep. Then we were rubbed with strong waters, the which did greatly refresh us, and then, mounting our seventh pair of horses, we did set out for Windsor.

We stopped but twice before we reached our destination, and then only whilst we could get some refreshments and changes of horses.

We reached Windsor that evening, and were so exhausted that we had to be assisted into the palace, and to the King's apartments. When I saw the King, however, I remembered my mission, and this did seem to revive me; for I rushed forward and, dropping to one knee, presented the Duke of Gloucester's message to his Majesty. So soon as we had entered the room Harleston, regardless of etiquette, flung himself into a chair and was sound asleep almost the instant that he touched it. When I had handed the packet unto the King my duty was done and I had no ambition to support me further. Mine ears did ring; the room began to whirl all around me; weights then did seem to hang upon my weary eyelids; my head sank lower; and there, at the King's feet, I fell into a heavy sleep.

When I awoke I was in mine own sleeping room, undressed and in bed. My servant was standing by my bedside. The sun was shining into my room, and it was evidently well on in the day. I had to think for some moments before I could tell where I was. Then it all came to me like a flash of light. I remembered that terrible ride; kneeling at the King's feet, and from that moment everything was a blank.

I asked my servant what hour it was.

"Upon the stroke of three, sir," he replied.

"Is Sir Frederick Harleston yet stirring?"

"I think not, sir."

"Go call him, and ask him to breakfast with me, in my sitting room."

I dressed myself as quickly as my stiff limbs would permit, and soon Sir Frederick joined me at breakfast.

Whilst we were yet at our meal a page brought us word that the King did desire to see us in his apartments. We hastily followed the messenger and soon found ourselves in the presence of his Majesty, who did receive us most cordially.

"Ah! my dear Bradley, I hope thou hast quite recovered from the effects of thy journey." Then, looking at Harleston, he said:—"And thou, Sir Frederick, art not so sleep-weary as thou wast yesterday e'en? By the saints, we thought that ye both were done for! Ye would not even keep from dreamland for the sake of a flagon of wine. Truly, ye were greatly exhausted; and no small wonder, when one doth take into account the time ye made."

We bowed respectfully, in acknowledgment of this compliment, and he continued:—

"I hope that ye will now give me a description of the battle; for my brother doth send me the result only."

After we had described the battle, as well as might be, the King, with a complimentary expression of his thanks for our services, gave unto Harleston and me each a suit of the best of Spanish armour, richly inlaid with gold. I had seen the King wear suits like these, and I did guess that they were his Majesty's own. This surmise proved to be correct, for, as we hastened to thank him for his magnificent gift, he said:—

"I know that you will not prize them the less when ye learn that both of those suits have been worn by us."

We could not thank his Grace sufficiently for this marked favor: nor did he want our expressions of gratitude; for he stopped us with a wave of his hand:—

"No more, no more, I pray," said he. "The only thing that I do wish you to do is promise me that, in case anything should happen me, ye will ever be as true and faithful to my son, which is now Prince of Wales, as ye have been to me. Stand by him through his youth, and should any one—no matter who—wrong him, I wish ye now to swear to do all in your power to avenge his wrongs. Now, gentlemen, are ye willing to do this for your King?"

So there we swore, on the cross of his sword, to do that which the King had asked of us; and when we bowed ourselves out of the royal presence and went in search of the girls the thought furthest from our minds was that we should ever be called upon to fulfil our oaths made to our King that day.

Suddenly, as we were making our way slowly through the halls, Harleston quickened his pace and, without one word, left me, and hastened forward, almost at a run.

"I hope that our hard ride hath not turned my dear friend's mind," thought I, as I hurried after him. But when I turned a corner in the corridor I learned the reason of his haste. There, a few paces down the hall, and retreating from me, but with Frederick gaining rapidly upon them, were Hazel and Mary, walking arm in arm, unconscious of their pursuers—for by this time they had two. I reached them almost as soon as did Harleston, so great was my anxiety lest I should be considered negligent in finding them. When the maidens, hearing the hasty steps behind them, turned and beheld us, both did utter little screams of surprise. Then Mary quickly recovered herself and said:—

"Oh, dear Cousin Walter, I am so glad to see thee safe returned." And then, as though less concerned, "And thee, Sir Frederick. I hope thou hast come through the journey well, even though thou didst not have one of those grand campaigns that you so glory in."

I left it to him to explain to her that we did have one of those glorious "campaigns," of which she so sarcastically spoke; for I did turn to greet the dearest maid which ever drew the breath of life.

"Walter, I am glad that thou hast returned safe," said she, after I had told her when we did arrive, and how we came to be returned before the others. "Thou knowest,"—although I did not—"I had such a fearful dream about thee."

"Almost a confession," thought I.

"Methought I saw thee attacked by foes hidden in ambush, and thou wert fighting desperately for thy life. Then, in battle, I saw thee struggling against fearful odds, and then you seemed to be unarmed, and at the mercy of your foes. But in this dream I did awake to find myself in a tremble of excitement, and glad that it was but a dream. Yet it did trouble me, not to see what became of thee when thou wert in these great dangers; for I feared that mine awakening, ere I did see that which did happen, meant that thou wert killed."

"Well, Lady Hazel, thy dreams were true. Verily some angel did show unto thee the adventures I went through. Joyed am I, too, that thou wert kept in ignorance of my fate; for then thou hadst not been so pleased to see me now. And wert thou greatly troubled when thou didst see me beset by dangers?" And I drew a trifle closer unto her side.

"Art anxious to know?"

"Ay, Ay, so anxious, Lady Hazel," and I seized her pretty hand. She drew it quickly from my grasp, and motioned with her head in the direction of Mary and Harleston.

"Well, then," she said gently, "I was greatly troubled, for I knew not whether thou hadst been killed or no; and if thou wert dead I should then greatly miss one of my best friends," and her dark and beauteous eyes drooped, and she did seem to be greatly engaged in examining her dainty little slipper, as it nervously tapped the floor, and tempted me to drop on my knees and kiss that pretty foot. I was on the point of dropping on my knee and telling her how I did worship her, when I did hear Mary titter behind me as though she had read my thought. It had ever been my misfortune to have someone, or something, prevent me from taking advantage of a golden opportunity, such as was this, when it did present itself.

Then Mary and Harleston strolled off down the corridor, and I thought I should have another chance to complete the story I had started so well that morning, some weeks before, in the park. But it was too late. My tongue would not put into words the thoughts that I was dying to express. So I cursed myself for a dumb idiot, and was compelled to postpone my declarations until Erato saw fit to untie my stammering tongue.

Hazel seemed amused at mine annoyance, and laughed and blushed in my gloomy face.

We strolled on and into the library and, as the others were there, we sat and talked and told the girls all about the campaign and our little adventures and our ride from Berwick, and then they did tell us everything that had happened at court whilst we were away, and which is generally known as court gossip and, as it could not interest you, my dears, I will not put it down.

"See, I did not lose the charm thou gavest me when I left," I said, as I drew it from its hiding-place, over my heart.

She noticed the locality in which it had been carried, and her color heightened as I coolly put it back in its place, after I had let her see it.

"Art not going to return it?" she asked in a tone which assured me that she did not wish me to.

"Oh! no, I cannot tell what dangers may yet beset me; so I must keep it still, that I may come safely through."

To this she raised no objection; so it stayed there till another day, of which I will tell ye later.

Now I think I hear some one say, as he doth read these lines:—"Was he not simple, not to see that Hazel loved him?" To this I reply in advance, by reminding him to look back over his own experience—if he hath been so fortunate as to have had one—and try to recall how he did act, under the same trying circumstances. Then, if his memory will be as fresh as is mine, he will remember the times when he was almost sure that his lady loved him; yet, was there not a most tormenting uncertainty, and a doubt that he might be over confident, and so, by speaking too soon, he feared he might lose all? This I know was mine experience, and I preferred, like a general with an uncertain force, to wait until I should find some traitor within the strong fortress that I was to take, and so make sure of victory by one short, quick stroke. I now felt that I was winning over part of her garrison; still did I prefer to make still more certain that I was not deceiving myself with false hope.

Nor you, ye ones which have yet to experience this most perplexing, and yet most delightful of engagements, be not too hasty in your judgment of one—not the least distinguished of your house—for when ye are placed in the position in which he here found himself, if you do not feel, or act, any more foolish than did I, ye may congratulate yourselves for having conducted the enterprise in the most advantageous manner. However, in this case—but there, I am getting ahead of my story.

When I look back from the mountain of peace and happiness, upon which I am now sitting, and across the vale of years gone by, to that other, sun-topped hill of youth, I do not regret that I am no longer young. For in that valley, which separates the mountains, I see dark clouds, and storms, and armies marching and engaged in deadly contest. I hear the cheers of the living intermingled with the prayers and curses of the dying. Foul murders are being committed; dark plots being laid and executed by those which struggle in that dark and troubled valley. And through all this do I see that same group of young people, struggling with the rest. Another and grand soul hath been added unto their number; and their united trials seem, to my old eyes, to rank first in importance. Then, on the near side, those dark and heavy vapors, with which the depression is filled, are torn asunder by the united force of a giant arm betwixt two flashing swords, and the five walk out and take their seats upon this glorious hill, which is the goal of all; and yet, which so few do reach, whilst wearing the fleshly garment.

About a week after our return to Windsor I learned that there was to be a grand ball given by the King, in honor of our victory over the Scots. I at once found the girls and told them the good news.

"Ah!" cried Hazel; "will it not be delightful to be able to have some life at court, after all this quiet and monotony, with every one away and no music, but that which Mary and I do make for ourselves?" And she clapped her hands, and smiled and courtesied to me, as though I were her partner in the dance.

"Not a great compliment to me, nor to Sir Frederick neither, when thou dost say there is no one at court," said I; for I did not altogether relish Hazel's superabundance of delight at the prospect of the change. But the dear one was in one of those teasing fits of hers; so I knew full well it was useless to say much.

The only answer she did vouchsafe to my remark was a provoking little toss of her pretty head. She looked so lovely as she skipped about the room, that even an over-exacting lover could not help but be good-natured; even though he did try to be otherwise.

Mary was equally joyed when she heard that we were to have the dance.

"But when is it to be?" asked Hazel, stopping suddenly in the midst of her solitary performance and joining Mary and me.

"This day week, and the Duke of Gloucester and most of the court will have returned by then; so we will have a lively time. But here doth come Sir Frederick; so, Mary, thou hadst better inform him and give him the first chance to pick out his dances." Mary blushed; but however, she did go and meet Harleston, at which both Hazel and I laughed heartily.

Indeed it was a goodly sight to see those two standing side by side; the one tall, handsome, and built in the mould of a slightly reduced Hercules; and the other, small, dainty, and lovely, as a sweet flower growing beside an oak. I could see by the way in which Mary was drawn to him that it would take but a word from him, and she would surrender. And as for him,—well, he was hopelessly entangled in the silken meshes of love's all-powerful net from the first day on which he did lay eyes upon this beauteous lily-of-the-valley.

But why do I look to them for a picture? Had Harleston but cast his eyes in our direction (the which he did not) he should have beheld as great a contrast, and, to be modest, at least one as pleasing to the eye.

"And how many sets am I to have?" I asked of Hazel.

"Well, I shall consider, and take note of thy conduct, and, if it be good, I may give unto thee the second,—and the—"

"Nay, nay, by mine honour, I do insist upon having the first, and the second, and a great many more."

"Oh, Walter, such an appetite as thou hast developed."

"But remember, I have been fasting for a long time."

Then she wrinkled her little snow-white forehead, and seemed weighing the matter very deliberately. "Well," she said, after she had appeared to consider at great length, "thou mayst have the first; but I will not promise thee any more before the dance, and if I do like that one, mayhap I will give thee some others."

I knew full well what that meant; so I said no more, but made up my mind to have more when the time did come round. And the time soon did come; for in those days of happiness and youth the sun scarce seemed to stay in the heavens for more than an hour at a time; so quickly did those days of dreams pass by. And yet, though it may sound like a contradiction, the sun seemed ever to be shining; for we had it in our hearts. Oh, had we but known the clouds that were to pass over,— But there, I must draw the rein again, or I shall be telling the end of my story ere I shall have come unto it.

So the days flew past like sunbeams, and the evening when the great ball was to take place at length arrived.

Both Harleston and I had engaged the best tailor in London, and when we walked into the great audience hall that night there was not a soul in the place which could compete with us, for elegance of dress—except, perhaps, the Duke of Gloucester. And let me here put it down; that room contained all the best of fashion that English tailors could produce. The secret of our success lay in the fact that it was Gloucester's own tailor which did make our garments; he being not over busy whilst the Duke was absent in Scotland.

As the King (for some reason then unknown to us) had not yet arrived, the ladies and gentlemen, after having been presented to the Queen, were standing about, in groups of four or more, gossiping and making all manner of remarks as each of the guests arrived.

After we had been presented to her Majesty, and saluted the girls, we walked to the far end of the hall, where Gloucester, Buckingham, and a fellow by the name of Sir William Catesby, a lawyer, with whom I shall have to deal later on, were standing. The Prince was giving some instructions to the musicians as we came up, but when he saw us he turned, and in that voice, as smooth as the finest silk, he said:—"Ah! Bradley, my dear friend, I am delighted to see thee here this evening, and thee, Harleston. I have heard how swift were my messengers, and I assure you both that it shall be none the worse for you that it was so."

We thanked his Grace for his pretty speech, in which, however, I could not help but detect some insincerity; but could not, at that time, imagine what his object could be—for this man ever did have one,—when he acted in this manner. However, I learned it later.

Just then the King did enter, leaning upon the arm of Lord Hastings. He looked very pale and his magnificent form seemed tottering as though with age, and yet Edward was still a young man. I could scarce believe mine eyes, so greatly was he changed since last I had seen him. "If so short a time can work such a marvel, he must be nearing his end," thought I. Then Harleston's prophecy, when first I had met him, flashed through my mind, and I wondered if it were going to be fulfilled. "But yet, he may be suffering from some temporary attack, and it will soon pass off." Thus did I try to convince myself that all was well.

But Harleston nudged me with his elbow, and said, in a voice that no one else might hear:—"Dost thou observe the King? If he doth live a month it shall greatly surprise me; for if the stamp of death be not upon that brow, then there is no such thing."

Then Gloucester and Buckingham came forward and, when his Majesty was seated upon his throne, enquired as to how he did, and kissed his hand, as though they loved him; when, at the same time, I verily believe, one of them at least had been happy had the King been dead.

Every one remarked upon the great change in the noble Edward, and hastened forward to enquire as to his health; when, if they did use their eyes, they could see their answer writ in bold letters upon that pale, yet handsome face.

His Majesty did not seem to like these enquiries; for he frowned on some which expressed their hope that he was not ill. When my friend and I paid our homage to him, however, he smiled and spoke most kindly unto us. This action of the King's did not seem to please some of those which had met with a reception less warm; for I observed on the faces of some of these lords and others, sneers and smiles; then would they turn to each other and converse, and look in our direction, and shrug their shoulders, as much as to say:—"It matters not; those upon whom he smiles to-day may be in the Tower to-morrow."

But to this we paid little attention; for it was but natural for them to feel jealous, after their cold reception.