Title: Fragments of an Autobiography

Author: Felix Moscheles

Release date: July 16, 2010 [eBook #33185]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Internet Archive.)

DEDICATED TO MY WIFE

BY

AUTHOR OF "IN BOHEMIA WITH DU MAURIER," ETC.

London

JAMES NISBET & CO., LTD.

21 BERNERS STREET

1899

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

HAVE often found it hard to read a preface; much harder do I find it

to-day to write one. If I do so, it is because it gives me an

opportunity of owning that I have strung these my reminiscences together

most unceremoniously and unsystematically. They are to be taken only as

"Fragments of an Autobiography," very much on the same lines as the

first volume which recorded my adventures in Bohemia with Du Maurier. If

the reader, thus duly forewarned, elects to follow me over the uneven

road, he will, I trust, not mind a little jolting. If, however, he

judges that the gaps and omissions in my life-story are unjustifiable,

he must not be surprised should I attempt to set things right in a third

volume. I should be all the more inclined to do so as there are some

other fragments and segments waiting to be pieced together which are

connected with the brightest days of my life.

HAVE often found it hard to read a preface; much harder do I find it

to-day to write one. If I do so, it is because it gives me an

opportunity of owning that I have strung these my reminiscences together

most unceremoniously and unsystematically. They are to be taken only as

"Fragments of an Autobiography," very much on the same lines as the

first volume which recorded my adventures in Bohemia with Du Maurier. If

the reader, thus duly forewarned, elects to follow me over the uneven

road, he will, I trust, not mind a little jolting. If, however, he

judges that the gaps and omissions in my life-story are unjustifiable,

he must not be surprised should I attempt to set things right in a third

volume. I should be all the more inclined to do so as there are some

other fragments and segments waiting to be pieced together which are

connected with the brightest days of my life.

The writing of the present chapters has often been a source of genuine pleasure to me, for I say with Bolingbroke in Richard II.: "I count myself in nothing else so happy as in a soul remembering my good friends."

And now that I have come to a full stop, I am left in that pleasant frame of mind in which I would fain believe in the proverbial kindness of the reader—that deity from times immemorial appealed to by the preface-writer,—a frame of mind unduly optimistic perhaps, but which emboldens me to hope that I may find some new friends amongst those who will care to read what I have to say about the old ones.

F. M.

London, February 1899.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Early Impressions | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Will you sit for me, Frida? | 58 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Leipsic in 1847 and 1848—Mendelssohn's Death | 92 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| My First Commission | 110 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Claude Raoul Dupont | 116 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| A Trip To America in 1883 | 208 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Grover Cleveland "Viewed" | 234 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Giuseppe Mazzini | 246 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Rossini | 271 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Paris after the Commune | 300 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Some Incidents of Robert Browning's Visits to the Studio | 317 |

![]() the terrors of a certain night when the wind was howling

and the rain was beating down in torrents over the arid plains of the

Lüneburger Haide; between them they had blown or blotted out the

flickering lights of a heavy, lumbering travelling carriage such as one

used to hire in the so-called good old times. The horses were plunging

in the mire, the postillion was swearing, and a very small boy was

howling. That boy was I, and the incident marks my first entrance into

that conscious life which registers events in our memories. Not that I

exactly remember what happened, and how we got out of the ankle-deep

mud, and finally reached our destination; but I have no doubt that my

father and the "brother-in-law," as the German postillion was addressed

in those days, had to get the wheels out of the ruts as best they could

without assistance, for there was no traveller, weary or otherwise, of

the regulation first-chapter pattern, to come to the rescue.

the terrors of a certain night when the wind was howling

and the rain was beating down in torrents over the arid plains of the

Lüneburger Haide; between them they had blown or blotted out the

flickering lights of a heavy, lumbering travelling carriage such as one

used to hire in the so-called good old times. The horses were plunging

in the mire, the postillion was swearing, and a very small boy was

howling. That boy was I, and the incident marks my first entrance into

that conscious life which registers events in our memories. Not that I

exactly remember what happened, and how we got out of the ankle-deep

mud, and finally reached our destination; but I have no doubt that my

father and the "brother-in-law," as the German postillion was addressed

in those days, had to get the wheels out of the ruts as best they could

without assistance, for there was no traveller, weary or otherwise, of

the regulation first-chapter pattern, to come to the rescue.

No—I remember but little of it, but I have lived it all over again every time I have heard the dramatic strains of Schubert's Erl-king. Great artists, gifted with the power of song, have depicted the whole scene to me in thrilling accents; dear old Rubinstein, the friend, alas, I lost all too soon—grand old Rubinstein, the master whose magic touch swept the keyboard as the hurricane sweeps the plain—could conjure up visions of a misty past in my mind. "My father, my father," I could have cried, as the Erl-king of Pianists pursued the doomed child with his giant strides and unrelenting touch, alternately letting loose the elements to rage in maddening tumult, and drawing uncanny whispers from his weird instrument.

Whatever I may have been prompted to cry when under the spell of Rubinstein's art, I do not think I invoked my father's aid on that night upon the heath; it was more likely "My mother, my mother," I called, and she just protected me, and so, fortunately for me, it all ended happily, and: "In her arms the child was not dead," but cried itself to sleep, and was put back into the little hammock that was slung across from side to side of our old-fashioned vehicle, and that temporarily replaced my cradle in 3 Chester Place, Regent's Park, London, the house I was born in.

My father was on a concert tour in Germany, reaping laurels and golden harvests, such as were rarely heard of in those days. From his wife he never parted if he could help it, even for a short time, and by way of an encumbrance he had on this occasion taken, besides the necessary luggage, us children—I think there were three of us then—and a little dumb keyboard on which he used to exercise his fingers to keep them up to concert pitch when pianos were out of reach. I hadn't seen any of those little finger-trainers for years, when I came across one on Robert Browning's writing-table; he always kept it by his side, and I wondered whether he used it to stimulate the fingers that had to keep pace with the poet's ever-flowing thoughts. But my earliest recollections are connected, not with dumb keyboards, but with very full-sounding and eloquent ones. My father was ever happiest when at the piano or composing. He was interested, oh yes, much interested in the sister arts, in science and politics, but he had a way of disappearing after a while when such matters were being discussed, or of getting lost when we had set out conscientiously to do museums or churches in Venice or Antwerp, or to visit crypts, shrines, bones of ancestors, and other historical relics above and below ground. We knew we should find him at home at the piano, or pen in hand composing, that is, if he had not perchance been stopped on the way by the sounds of music in some attractive shape. It was quite enough for him to hear such sounds proceeding from an open window, to make for the door, ring the bell, and ask for the "Maestro" or the "Herr Kapellmeister." He would introduce himself, and presently be making friends on a sound musical basis with his colleague. It would sometimes lead to a continental hug of the warmest description, when the surprised native would discover that his visitor was the pianist.

Sometimes my father did not wait for that finishing touch, as when on one occasion he invaded the room of an ill-fated lover of music. It was at Tetschen, on a journey through Saxony and Bohemia; we arrived one evening at the little hotel of that place, tired and hungry, and thinking only of supper and a good night's rest. Scarcely had we settled down to the former, when, separated from us only by a wooden partition, a neighbour commenced operations on the piano, slowly and carefully unwinding one bar after the other of that most brilliant of pieces, Weber's "Invitation à la Valse." "Dass dich das Mäuserle beisse!" exclaims my father, in terrible earnest. "May the little mouse bite you!" That was a favourite expression of his, when he found himself suddenly impelled to denounce somebody or something, and, as he accentuated it, it always seemed amply to replace those naughty words which are not admissible in daily life, and may only be used—and that, to be sure, for our benefit—on Sundays by the exponents of the Christian dogma.

The servant-girl was summoned, and she explained that the neighbour usually began at that time, and was in the habit of playing several hours. "Dass dich das Mäuserle" muttered my father with suppressed rage; "Dass dich" ... and with that he rushed out of the room. What would happen? We were about to tremble, when a meek, respectful knock at the neighbour's door happily reassured us. "Herein"—Come in. Enter my father suavely apologising for the interruption—we hear it all through the thin partition. He, too, is a lover of music; may he as such be allowed to listen for a while. Much pleased, the other offers him a chair and resumes his performance; my father listens patiently, and waits till the last bars are reached. "Delightful!" we hear him say, "a beautiful piece, is it not? I once learnt it too; may I try your piano?" And with that he pounces on the shaky old instrument, galvanising it into new life, as he starts off at a furious rate, and gives vent to his pent-up feelings in cascades of octaves and breakneck passages; never had he played that most brilliant of pieces more brilliantly. "Good-night," he said as he struck the last chord; "allow me once more to apologise." "Ach! thus I shall never be able to play it," answered the neighbour with a deep sigh, and he closed the piano, and spent the rest of the evening a sadder but a quieter man.

But it was not often my father was allowed an opportunity of watching over his own comforts. That was a duty my mother would not willingly share with him or with anybody else; quite apart from the affection she lavished on the husband, there was the tribute of respect she paid to the artist. His was a privileged position, she held, and his path should be kept clear of all annoyance. Petty troubles, at any rate, should not approach him, nor the serious ones either if it was within her power to shield him from them; if not, she would contrive to take the larger share of the burden upon herself.

From our earliest days, we children were trained to be on our best behaviour when our father came home, whatever our next best might have been previously. We were mostly happy little listeners when he was at the piano, and if he stopped too long for our juvenile faculties of enjoyment, why, our happiness gradually took the shape of respect for the musical function. It even turned into something akin to awe when he was composing. At such times I would not have whistled within his hearing to save my life. A wholesome fear of the Mäuserles that would assuredly sweep down upon me, if I disturbed the peace, would, I daresay, in a great measure account for my praiseworthy attitude, but, apart from any such practical considerations, it was the mystery connected with the evolution of the beautiful in art, which, from the first, held me in subjection.

The whooping-cough with which one of us children started, rapidly communicating it to the others, was also regulated in its outbursts with due regard to my father's peace. Whilst the fit was on us, it was a source of particular enjoyment to my sisters and myself, but we never freely indulged in it when my father was near. At other times we would come together, and wait for one another till the spirit moved us to whoop. Then I would wield the bâton in imitation of my betters at the conductor's desk, and we would have our solos and ensemble-pieces, our ritardandos and prestissimos, producing unexpected effects, and with the limited means at our disposal, making what I recollect as a very attractive and interesting performance. Edifying as it should have been to a parent, my mother could at first not see it in that light, but she had finally to give in, and to acknowledge that it was a bad cough that whooped no good.

I was an only son—an elder brother died some years before I was born—and it was but natural that my mother should look with indulgence on my delinquencies. I must sometimes have tried her and those around me sorely, as, for instance, when I hanged my little sister's favourite doll Anna Maria, from a knob of the chest of drawers, there to remain until she be dead.

Clara—that was my sister's name—was of a warm temperament, and fought for the release of her wax baby with all the passionate energy of the maternal instinct. I had to give way and cut down the victim, and then, all other means to pacify her having failed, I appealed to her imagination, and persuaded her to play at my having killed her in the battle we had just fought; it would be such a surprise for mamma. Ever sharp and quick as she was, she at once saw the far-reaching possibilities of my scheme, and allowed herself to be wrapped up in a bedsheet, as in a shroud, and to be laid out stiff and rigid as a corpse. I pulled down the blinds and shut the shutters; then I lit a candle which I placed by her side; when all was ready, I hid in a cupboard and set up a dismal wail that soon brought my mother to the spot. The effect upon her was all I could have desired, perhaps more so, for the first surprise once over, she expressed her disapproval of my conduct in terms suitable to the occasion, and thus quite spoilt the pleasure I had taken in the whole thing.

My mother was a remarkable woman,—a "lovely" woman, to use the word as the Americans do when they want a single epithet to describe alike the beauty of the body and the beauty of the soul, a word that shall tell of the brightness of the intellect and suggest the qualities of the heart.

There are those who think that when it comes to the selection of epithets applicable to a mother, however distinguished or worthy she may have been, the son is not the person to entrust with that selection. Perhaps they are right, and if in this case they care to do so, they must look round for corroborative evidence in her books. It is just their fault if they have never read them, or if they have never heard of her as Felix Mendelssohn's grandmother, a character in which she appeared with great advantage to the grandson when she was twenty-four, and he as a young man of nineteen paid his first visit to England. And it is just their loss if they never saw the jet-black plaits as she wore them coiled around her head when she was young, or the mass of silky, snow-white hair of her later days that, when set free, would cascade over and far below the shoulders that bore the weight of fourscore years. On her face Time had left its mark. Every line, every wrinkle gave character and expression to her features, and bore testimony to the truly beautiful life she had led. The picture reproduced on the first page of these reminiscences I painted when she was in her 83rd year.

But the story of my mother's life must be written in another volume. For the present I return to earlier recollections.

When I was ten years old, I was dubbed a big boy, too big to be tied to his mother's apron-strings, and I was sent to King's College to rough it with other boys. Opportunities were not wanting for the roughing it. On one occasion a boy called me a German sausage, and I retorted by punching his head; and on another I met a University College boy, called him a stinkermalee, and got my head punched in return. What the appellation precisely meant, I didn't know, nor do I now, but it was then the particular term, opprobrious and insulting, we King's College boys had adopted to express our unbounded contempt for the hated rivals in Gower Street.

I was generally allowed to walk to school and back by myself, for it formed part of the scheme of education mapped out for me by my parents, that I should start fair and see life for myself. My way lay through St. Giles's and the Seven Dials, and there I did see life and did hear English too, English as she was spoke in those parts, perhaps as she is to this day; but as I pass that way now, I don't come across it; the hand of Time has been moving across the Seven Dials, and all the old landmarks are gone. Where in these degenerate times can a schoolboy hope to see a bear, a real big brown bear, in a cage just in front of a barber's shop? only a penny-shave place to be sure, but bold in its advertisement, a notice in sprawling big characters proclaiming the superiority of the establishment's bear's grease over any other grease, whatever its kind might be. Where is the schoolboy to-day who can realise the pleasurable excitement of approaching such a caged bear in a public thoroughfare close enough to test the beast's good nature under circumstances of provocation, and his own adroitness in making good his retreat in case of retaliation?

In the streets and alleys of St. Giles's I was first initiated into the horrors of warfare, especially into the kind of warfare considered quite legitimate in those days. A quarrel first;—passions roused—words leading to blows. Coats off, fists clenched, and there, whilst two savages were trying the issue as to which could knock the other into a jelly, or, if luck would have it, into a coffin, we, the enlightened public, formed a ring and stood round, nominally to see fair-play, but virtually to back one or the other of the combatants, goading both on to fight like devils, and finally rejoicing over the survival of the fittest.

That kind of thing has been stopped in St. Giles's, but the devil doesn't mind; there is so much legitimate warfare, slaughter and massacre nowadays on a larger scale, that he is said to admit himself that he gets over and above the share he originally claimed; and as for the ring, why, that has grown apace; thanks to scientific progress, it is iron-bound now with telegraphic wires, and is known by the euphonious name of "the Concert of Europe."

How good man is, and how tender in his concern for his brother! More than once I saw him pick up the battered jelly and carry it with fraternal solicitude to the neighbouring chemist. How good we all are, stitching at Red Cross badges, chartering ambulances, and sending the hat round at the Mansion House and elsewhere to save the surviving fittest from starvation!

The question of woman's rights—and wrongs—was also occasionally raised and illustrated for my benefit in one or the other of the Seven Dials, the object lesson sometimes delaying me and getting me into trouble for being late at the hic-hæc-hoc business in the Strand. I particularly recollect a female fiend rushing after her wretched husband, who fled down the street from her, and from the blood-stained poker she savagely brandished.

But there were quieter corners too, not far from the lairs of the vicious, a dear old printshop for one, just by St. Giles' Church. The most tempting pictures were displayed in the windows: coloured prints of stage-coaches, cockatoos, prize-fighters, and racehorses; lovely female types, as originally published in Heath's Book of Beauty; there were fashion-plates next to Bartolozzi's, not in fashion, and I daresay many an undiscovered treasure besides. I used to spend my pennies on views of London, little steel-plate engravings, printed on a sort of shiny cardboard. Was it my innate love for London that made them so attractive, or my equally innate love of architecture? Probably both. I always was, and am still a cockney at heart, and as for the building craze, that has been on me from that day to this. Certainly no boy ever had such a collection of bricks as I had, and such a table to build on, specially constructed with drawers and divisions for all sizes and forms of my materials.

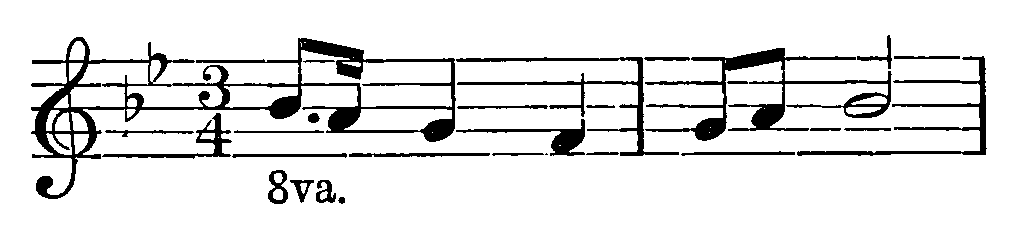

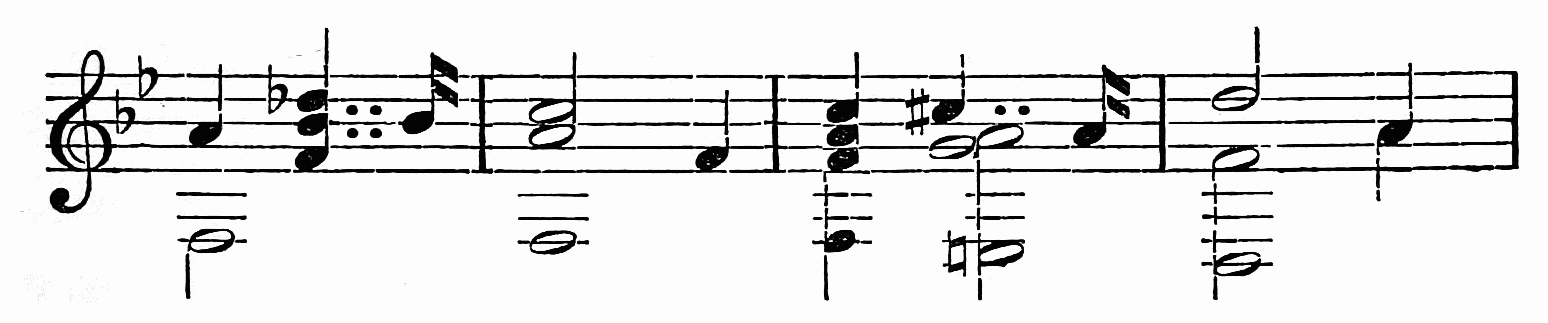

"I'm going to be an architect," I informed the old Duke of Cambridge on a gala occasion when he rode up to our house. "Right you are, my boy," said the Duke. "You'll be too late to build me a house, but you can build me a mausoleum." I've been planning mausoleums ever since, but unfortunately, not being an architect, I never have had a commission in that line. The Duke, who was an enthusiastic lover of music, had come on that occasion specially interested to hear Bach's Concerto in G minor, which my father played from a copy of the original manuscript he had received from his friend Professor Fischhof, of Vienna.

But to return from Royalty to the plebeian quarter of St. Giles, I must state that whatever of my pocket-money may have been invested in views of London, it was not that printshop, but the Lowther Arcade, which usually wrecked my finances. I could not resist the temptation which that short cut from the Strand to Catherine Street offered; my money went to the purchase of most fascinating articles, unfortunately at best of a twopenny-halfpenny character, things of beauty irresistibly suggesting themselves as presents for my sisters, things no girl should be without, wax angels under glass globes, bottle imps, china shepherdesses, or jumping frogs, the latter to be sprung upon the recipient unexpectedly. I brought them home and confided to my mother what bargains I had got. Unhappily the angels, frogs, imps, and the rest, however effective at first, were not long lived, or they proved themselves otherwise disappointing; so they were soon forgotten. Not so their cost.

My mother had carefully kept account of my wasteful expenditure for some weeks, and one day she confronted me with the sum total it had reached. It actually came within measurable distance of half-a-crown, an amount I had as yet never been able to call my own. I was overwhelmed by such proofs of my recklessness, and henceforth resisted the wiles of the Lowther Arcade. So the lesson was not lost on me; it sank deep into my heart, whence I have on more than one occasion been able to bring it to the surface. But I am bound to confess that I never was radically cured. I have periodical relapses when the old craving comes upon me, and the taste for beautifully fashioned angels, for china and for glass, and I revel in a bargain, and exult when I have picked up something every girl ought to have. Whilst the glorious fit is on, I am privileged to forget all I learnt in the sum-total lesson.

My experiences in the Lowther Arcade were soon to be suddenly interrupted, and for a long time it was even doubtful whether I should ever again be able to put in an appearance in that place or anywhere else. I caught the scarlet fever, not in the slums as it might be thought, but at school, where a regular epidemic had broken out. Our class-rooms in King's College were down in the basement, and those who knew said that the outbreak was due to the fact that the filth-laden river came right up to the feet of the grand old building, and washed them dirty day and night; other wiseacres contended that it was more likely to be the churchyard of St. Mary-le-Grand just opposite which had done the mischief. As far as I can remember, nobody mentioned the drains, which in those days had not yet come into notice and fashion, and could do their level best for the multiplication of bacilli without being hampered by meddlesome sanitary inspectors. Well, whatever may have been the malignant source which poisoned me, it had done its work thoroughly, and developed my scarlet fever in its most virulent form. It was a terrible time I went through. I was at death's door, but fortunately that sombre portal remained closed, and I was not bidden to cross the grim threshold.

No, I was destined to live and to fight the battle of life with whatever fighting powers I might possess. Later on I was to wrestle more than once with the grim immortal who only spares each of us mortals till his hour-glass tells him it is time to use his scythe. And if I wrestled well and am here to tell the tale, it is because by my side watched day and night that best of nurses, my mother.

I was never what is called a good patient, and to this day I am very much averse to sending for the doctor. I quite feel he indeed is a friend in need, and I do not wish to disparage his power for good, or to underrate his skill and judgment, but as a rule I make a point of not calling him in till I know what I want him to say. I think that doctors nowadays are more agreeable than they were formerly; the great and fashionable doctors, I mean. A man, to be up to date, had to be brief, brusque, and bumptious. He seemed to have learnt his stronger English from Dr. Johnson, and generally to have been trained in a Johnsonian atmosphere. He had to say smart things that could be quoted and hawked about, and to enunciate wise saws in imitation of the master whose sayings are so unmercifully inflicted on us to this day. He was in a hurry; he drove up in a big yellow carriage, and before the horses could pull up, his tiger had sprung from the footboard, and was giving the most tremendous double-knock, one evidently meant to awaken the dead, in case medical assistance had come too late.

To pass muster, the doctor's natural kindness had to be concealed beneath an outer coating of apparent roughness. Sometimes it was the roughness that was concealed only by a transparent veneer of amiability. Certain it is that in those days no doctor could look at a boy's tongue without at once declaring that he stood in immediate need of a black dose, and if that vile compound did not exceed every other mixture in nastiness, he did not believe it would be efficacious. He revelled in blue pills, and was happiest when he could pull out a little lancet and bleed you, or send round a man with a complete set of sharp blades, to do the thing wholesale, jerking them into some part of your precious self, and pumping a given number of ounces out of it and into his cupping-glasses.

All this is very ungrateful of me, for Dr. Stone was the best and kindest of men—and very undutiful, for he was my godfather (Felix Stone is my full name). To be sure he had a big yellow carriage, and a tiger whose main ambition in life it seemed to be to knock his master's patients up. To be sure Dr. Stone came coated with a veneer of roughness, but it was skin-deep; true, he gave me as many black doses and blue pills as he thought my robust constitution could stand, but in addition to these he made me many beautiful presents—a silver mug emblazoned with our family crest and the motto "Labore," a splendid family Bible of about my own weight and size, a costly edition of Byron's "Childe Harold" and ditto of Milton's "Paradise Lost and Regained," and a number of other things doubly delightful and gratifying to my juvenile mind, because they always came at least three or four years before I knew how to use them.

My good godfather had ushered me into this world, from which unfortunately he was himself called away before he had had many opportunities of performing the duties he had undertaken when he pledged himself to see to it that I should "renounce the devil and all his works."

When after many weeks of hard fighting with the scarlet enemy, and after having passed through various relapses and complications, I emerged from the sick-room, I was taken to Brighton for a complete change of air. There I soon found new life and strength. Dear old Brighton! I was to find new life and strength there once more, thirty years later, when I met the young lady who said she would—when I asked her to marry me.

My next station was Hamburg. I was sent there to get the benefit of a thorough change of air, and to improve my German. It was shortly after the terrible conflagration which had laid low a great part of the city.

The jagged walls, springing in fantastic forms from immense piles of crumbling masonry and charred timber, had a weird fascination for me. I was deeply in sympathy with my beloved friend Architecture, and deplored the fate that had overtaken some of the best buildings, but at the same time I was lost in admiration of the beauties, now picturesque, now awe-inspiring, which the caprice of the destructive element had stamped on crazy walls and tangled masses of wreckage.

I have since been similarly impressed; in Pompeii first, and again in Paris, after the Commune; only to be sure the former scene of devastation I saw neatly put in order and made presentable for the visitor, whereas the latter was yet smoking and all besmirched with the blood of the sorely visited Parisians.

My father had given a concert for the benefit of the sufferers in Hamburg, and was able to contribute a sum of £643 to the relief fund raised.

On my arrival I was received with open arms by my relatives. My grandfather, Adolf Embden, had been staying with us more than once, and he was particularly partial to his grandson, because he had a marked predilection for England and everything that was English. He knew more about British politics than most men born and bred in the country; he read all the big speeches delivered in Parliament, identified himself with the Whigs, and was a fervent disciple of Cobden and Bright. He did his best to train me in the way I should go, and his methods were quite congenial to my taste. We often took long walks together, and his peripatetic teachings are pleasantly blended in my mind with the half-way house at the corner of the Jungfernsteg and the Alster Bassin, then occupied by Giosti Giovanoli, the confectioner. He trained me just once too often, but that was in London, in a shop near Oxford Circus, and it was a Bath bun that made me restless. That shop was painted green and gold, and to this day I would not eat on green and gold premises if I were starving.

In Hamburg I was welcomed, too, by uncles and aunts, first and second cousins, male and female, and by a strong contingent of grandaunts. I am aware that most people have quite as many relatives of their own as they need for home consumption, and that being so, they are not pleasantly disposed towards the family history of their friends. So I mean to use my relatives sparingly, and only to bring them in where they are associated with things I well remember. My mother has penned most characteristic sketches of many of those worthy personalities in a MS. she has entitled "Early Recollections," and the grandaunts hold a prominent place in those papers; but for the reason just given, I refrain from transcribing her graphic descriptions of their doings. I would, however, record my own boyish impressions, to the effect that one or two of my grandaunts were a caution to rattle-snakes. I have learned since to see that they were nothing of the kind, but just old ladies of marked originality. It took some time before I could get to like being loved by them; I preferred making faces behind their backs, a pastime which I was joined in by a cousin about my own age. Cousin Carl got into trouble oftener than I did, and had more reason to regret it, for in one of the drawers of an old-fashioned mahogany secretary his father kept an orthodox cane which he would produce on special occasions—such were the unchallenged methods of training in those days. My uncle was the best of men, anxious only to chastise for the good of the young delinquent, whom he tenderly loved, but he might have saved himself the trouble, for poor Cousin Carl was never to reap the benefit of his training. He had at no time been robust, and was not to live long. That winter of 1842 was looking about for victims. The fearful mornings, when we had to get up in the dark, and wash by the flicker of a tallow candle—wash, that is if we succeeded in hacking up the ice in the jug, and in finding some water at the bottom of it—those fearful mornings proved too much for him. Poor Carl's faces, as he made them behind people's backs, grew longer and longer, his cough grew hollower and hollower, and he soon went to rest where there are no canes and no tallow dips, and all is peace, and even one's grandaunts are seraphs.

The sad event did not, however, take place during my stay in Hamburg. I spent some six or eight months with my uncle and aunt. She, my Tante Jaques, was my mother's only sister, and was deeply attached to her; on me she lavished unvarying kindness and affection. My cousins, all older than myself, were delighted to have the "little Englishman" in the house, and the friendship we struck up then has lasted through life.

One of the grandaunts was a sister of Heinrich Heine, the poet. She had married into the Embden family, and so Heinrich was a sort of cousin of my mother's. They saw a good deal of one another when my mother was in her teens, and he was a dreamy youth whom she and the other girls of the family circle delighted to chaff. His frequent headaches they not incorrectly ascribed to his mode of living; to be sure, they said, he looked pale and interesting, but that was only because he had eaten too much at yesterday's dinner party. "Now, what is the matter with you again to-day?" said my mother as he sat down opposite her one morning and watched her shelling peas. "How pale you are! it's that head again, I suppose?" "Yes, Lottchen, I am ill; it is the head again." "That is what you are always saying, but I'm sure it is not as bad as you make it out to be. Come now, am I not right?" "O Lottchen," he said, "you do not know how I suffer;" and as he sat there musing, she had not the heart further to chaff him. When the next volume of his poems appeared shortly afterwards, she knew what had passed through his mind on that occasion, and perhaps on others when she had shown him friendly sympathy.

He writes:—

| "When past thy house at morning |

| I take my way, to see |

| Thy face, child, at the window |

| Is deep delight to me. |

| Thy dark-brown eyes seem asking |

| As my sad, pale looks they scan, |

| Who art thou, and what ails thee, |

| Thou strange and woe-worn man! |

| 'I am a German poet, |

| Through Germany widely known; |

| When they name the names that are famous, |

| With them they will name my own. |

| 'And what I ail, oh many, |

| Dear little one, ail the same. |

| When they name the worst of sorrows, |

| Mine, too, they are sure to name.'" |

Sometimes he was in livelier moods, as one day, when he, my grandfather, and my mother were walking through the fields together, and were joined by a remarkably dull doctor of philology, whose company was particularly distasteful to Heine. Pointing to half-a-dozen cows and oxen that were grazing close by, he said in an undertone: "I say, Lottchen, now there are seven doctors on the meadow."

Salomon Heine, the poet's uncle, was a millionaire who spent his money right royally and philanthropically; a man who owed his fortune to his own exertions, and who, when he had made a million of marks for each of his children—I forget how many he had—devoted the next million he amassed to the foundation of a hospital. He was a delightful specimen of an uncle, too, for he would spend his money philonepotically as well as philanthropically. The nephew was ever ready to dive into the uncle's purse; equally ready to make literary capital out of him and his friends. Gumpel, another rich banker—we know him as Gumpelino—was his pet aversion, and specially suggestive to him as a butt for his satire. Gumpel, too, was a self-made man, a fact of which, however, he did not like to be reminded, quite unlike old Heine, who loved to bring up the subject to the annoyance of his friend, shouting across the table stories of the early days when they came to Hamburg with their bundles slung across their shoulders. To his nephew he was ever indulgent; he was proud of his rising popularity, and as a rule was not appealed to in vain when the young genius had got into money troubles. On one occasion, though, he lost patience when he had given him a round sum wherewith to defray the expenses of a journey to Norderney, a summer resort on the coast of the North Sea. Instead of devoting the money to the purpose of improving his health, he managed in one night to roll the round sum into other people's pockets at the gaming tables. This time the uncle was indignant, and Heinrich would probably never have gone to Norderney, and consequently never have written the "Nordsee-Lieder," had not the well-known firm of Hoffman & Campe come to the rescue with the necessary funds, in consideration of which they stipulated he should write a volume of songs for them.

In Hamburg I was sent to the Johanneum, a large public school. It was rather hard, after having been called a German sausage in England, to be derided as an English "Rossbiff" or "Shonebool," which was meant for John Bull. The whole class roared with laughter when I rose for the first time to decline ἡ Μοὑσα, pronouncing the defunct Greek language as it was spoken in King's College, and the jeers of that whole class so galled and stung me that I wished I could kill all German boys at a stroke, or at least maim those despicable ones within my reach for life. It was well I could not act upon the impulse, for many a German boy of that day was to be a staunch friend to me in after life. I had my troubles in those Teutonic school-days, and I thought the proceedings monotonous, but still there was pleasurable excitement to be had occasionally, as when old Hummel came along—a half-witted water-carrier whom every bad boy in Hamburg knew and hooted. Three words we would shout in his face, three words that meant absolutely nothing, but that sounded worse than any bad language I had ever heard. He was a shaky old man, and the water-pails suspended from his shoulders prevented his running after us, and so we could indulge with impunity in the exhilarating sport of mocking him to the fullest extent our wicked little human hearts desired.

I have also a pleasant recollection of caterpillar-hunting; we were spending the summer near Hamburg in a rustic retreat, and a regular plague of these insects made life a burden to some members of the family. They were larger than ordinary caterpillars and more hairy, and they were so numerous that much thought and care had to be bestowed on the methods of protecting ourselves against them; for they did not confine themselves to the garden, they made no difference between vegetable produce and grand-aunts, and would mistake the best bonnets of those worthies for cabbage leaves. There was even a rumour that one of these slimy crawlers had been crushed out of existence by my grandest-aunt, who chanced to be the heaviest one too. How that caterpillar found its way between that lady's bed-sheets, and whether it did so with or without assistance, was fortunately never ascertained, and as discreet silence has been maintained on the subject for years, it is not for me to solve the mystery to-day.

After an absence of some six or eight months I returned to London, to that 3 Chester Place so full of memories, personal and artistic.

There were quite as many infant prodigies in those days as there are now; little exotic plants, forced in artistic hothouses, artificially developed, and prematurely produced in drawing-rooms and concert halls; glittering little shooting-stars, nine-days' wonders, to be soon forgotten, and ere long to be buried.

But then, there were also wonder-children, as the Germans call them, who thrived and lived, and who seemed to combine in themselves all the qualities that had belonged to the little victims of forced training. Such a one was Joachim. He first appeared in public when he was seven; five years later be played in Leipsic at Madame Viardot's concert; and when he was not yet fourteen he gathered his first laurels in London at the Philharmonic. That year—it was 1844—Mendelssohn was in England, and mightily interested in the young violinist. One evening, after singing at our house, Mendelssohn wanted to take him to a musical party; a pair of gloves were deemed necessary to make him presentable, and we two boys were sent out to get them; we had a walk, and a talk besides, and I remember thinking what a nice sort of sensible boy he was; no nonsense about him and no affectation; not like the other clever ones I knew. The gloves we bought in a little shop in Albany Street, Regent's Park, and as these were the first pair of English gloves that Joseph wore, I duly record the historical fact for the benefit of all those who have at one time or the other been under the spell of the fingers we fitted that evening.

When two years later we met in Leipsic, it so happened that I was suddenly fired with the desire to play the violin too. My friend Joseph was quite ready to teach me, and we started operations, but two or three lessons were sufficient to convince him and me, that mine was an unholy desire, which, if gratified, would give me the power of inflicting much suffering on my fellow-creatures, and which therefore was calculated to lead me into trouble. So we gave it up, and Joachim has had to rely on other pupils for his reputation as a teacher.

Liszt too had been a juvenile phenomenon, but had long arrived at full maturity at the time I first remember him. I was then about ten, and he some twenty years older. I think I never knew anybody so calculated to fascinate man, woman, or child. He generally spoke in French, which I did not understand, but I had to listen to every word. His voice alone held me spell-bound; it rose and fell like a big wave, and I could tell that something unusual was going on; that voice was evidently scattering thought as the big wave scatters spray, and those clear-cut features of his were each in turn accentuating and emphasising his words. His grand leonine mane fascinated me as it started from the lofty forehead, and bounded Niagara-like with one leap to the nape of the neck.

My early recollections of his playing are rather limited. As a boy I was mainly impressed by his long chord-grasping fingers, contrasting as they did with my father's small, velvety hand. To see him play was quite as much as I could do, without particularly attending to what he played, to watch his hands fly up from one set of notes and pounce down on another, and generally to lie in wait for the outward manifestations of his genius. Later on I grew accustomed to the grand young man's ways, and just knelt at his shrine as everybody else did.

My father was not the least outspoken of his admirers. In the early days he mentions him as "that rare art-phenomenon," and tells how "he played Hummel's Septet with the most perfect execution, storming occasionally like a Titan, but still in the main free from extravagance." Later on, at the Musical Festival held in Bonn, he describes him as "the absolute monarch, by virtue of his princely gifts, outshining all else."

Half a century ago playing à quatre mains was much more popular than it is now; more pieces were written and more pianoforte arrangements were made for two performers. The full-fledged pianist of to-day thinks he is quite able to do the work of two, and sees no reason why he should share the keyboard with another; so he prefers to keep the whole function in his own hands. Formerly he was satisfied to give a concert; the very word implied concerted action of several artists; now he announces the one-man show called a Recital, in which he stars and shines by himself. He scorns assistance, for he wishes it to be understood that he can get through the most formidable programme without breaking down, and that he can rely on his ironclad instrument to hold out with him and lead him triumphantly to the finale.

Well, the great virtuosi of my early days certainly loved playing together, and many are the instances of such joint performances, both in private and in public, which I recollect. How my father enjoyed playing with Liszt he records when he says: "It was a genuine treat to draw sparks from the piano as we dashed along together. When we are harnessed together in a duet we make a very good pair; Apollo drives us without a whip."

If, as my father assumes, Apollo was really the driver on occasions of that kind, I feel sure that his favourite team must have been Mendelssohn and Moscheles; they certainly enjoyed being in harness together, sometimes playing, and sometimes improvising. Occasionally the humour of the moment would lead them to compose together, as when one evening they planned a piece for two performers to be played by them three days later at a concert my father had announced. The Gipsies' March from Weber's "Preziosa" being chosen as a subject for variations, a general scheme was agreed upon, and the parts were distributed. "I will write a variation in minor and growl in the bass," said Mendelssohn. "Will you do a brilliant one in major in the treble?" It was settled that the Introduction and first and second variations should fall to Mendelssohn's lot, the third and fourth to my father's. The finale they shared in, Mendelssohn starting with an allegro movement, and my father following with a "più-lento." Two days later they had a hurried rehearsal, and on the following day they played the concertante variations, "composed expressly for this occasion," as the programme had it, "and performed on Erard's new patent-action grand pianoforte." Nobody noticed that the piece had been only sketched, and that each of the performers was allowed to improvise in his own solo, till at certain passages agreed upon, both met again in due harmony. The Morning Post of the day tells us that "the subject was treated in the most profound and effective manner by each, and executed so brilliantly that the most rapturous plaudits were elicited from the delighted company."

Mendelssohn himself in a letter gives a graphic account of a rehearsal held at Clementi's pianoforte factory, when the two friends played his "Double Concerto in E."

"It was great fun," he says; "no one can have an idea how Moscheles and I coquetted together on the piano—how the one constantly imitated the other, and how sweet we were. Moscheles plays the last movement with wonderful brilliancy; the runs drop from his fingers like magic. When it was over, all said it was a pity that we had made no cadenza; so I at once hit upon a passage in the first part of the last Tutti, where the orchestra has a pause, and Moscheles had, nolens volens, to comply, and compose a grand cadenza. We now deliberated amid a thousand jokes whether the small last solo should remain in its place, since, of course, the people would applaud the cadenza. 'We must have a bit of Tutti between the cadenza and the solo,' said I. 'How long are they to clap their hands?' asked Moscheles. 'Ten minutes, I daresay,' said I. Moscheles beat me down to five. I promised to supply a Tutti; and so we took the measure, embroidered, turned and padded, put in sleeves à la Mameluke, and at last, with our tailoring, produced a brilliant concerto. We shall have another rehearsal to-day; it will be quite a picnic, for Moscheles brings the cadenza and I the Tutti."

That golden thread of "great fun," as he calls it, goes through the history of Mendelssohn's life. It intertwined itself with the sensitive fibres of his nature, thus becoming an element of strength, a factor that illuminated his path and spread bright sunshine wherever he went. In fact I always thought one of the most delightful traits of his character was a certain naïveté, which enabled him to appreciate the humour of a situation, and thoroughly to enjoy it with his friends. He would turn some trivial incident to the happiest account, and in his own peculiarly genial way, make it the starting-point for a standing joke, or a winged word, to be handed down from generation to generation in the families of his friends.

Amongst the many drawings of his we treasure in the family is one humorously illustrating my father's works. It takes the shape of an arabesque, artistically framing some lines written for the occasion of his birthday by Klingemann. A second verse was composed for a subsequent birthday.

When in later years, and with a view to publication, I ventured to ask Robert Browning for an English version of those lines, he, with his usual kindness, sent me the following letter:—

"29 De Vere Gardens,

Nov. 30, '87.

"My dear Moscheles,—Pray forgive my delay in doing the little piece of business with which you entrusted me: an unexpected claim on my mornings interfered with it till just now. Will this answer your purpose anyhow?—

"Were my version but as true to the original as your father's life was to his noble ideal, it would be good indeed. As it is, accept the best of yours truly ever,

Robert Browning."

Having started on my recollections of Mendelssohn, I am somewhat perplexed to know how many or how few of them I should record here. So much has been published about him, first by my mother in "The Life of Moscheles,"[1] where she has used my father's diaries and correspondence, and then by myself, when I translated and edited Mendelssohn's letters to my parents,[2] that perhaps I ought not to run the risk of telling what is already known. But, on the other hand, Mendelssohn plays so prominent a part in my early recollections, that I cannot write these without attempting to portray the principal figure, my father's most intimate friend and my very dear godfather.

I shall, at any rate, have to exercise due discretion and care, for Mendelssohn, and what he said and did, was such a constant theme of conversation in our family, that I grew up knowing my parents' friend nearly as well as they did themselves, and I may consider myself fortunate if, in recording my earliest impressions, I do not find myself remembering things that happened before I was born.

The very first letter which connects me with Mendelssohn is the one in which he congratulates my parents on the arrival of a son and heir. He heads it with a pen-and-ink drawing, representing a diminutive baby in a cradle, surrounded by all the instruments of the orchestra.

"Here they are, dear Moscheles," he says, "wind instruments and fiddles, for the son and heir must not be kept waiting till I come—he must have a cradle song, with drums and trumpets and janissary music; fiddles alone are not nearly lively enough. May every happiness and joy and blessing attend the little stranger; may he be prosperous, may he do well whatever he does, and may it fare well with him in the world!

"So he is to be called Felix, is he? How nice and kind of you to make him my godchild, in formâ! The first present his godfather makes him is the above entire orchestra; it is to accompany him through life—the trumpets when he wishes to become famous, the flutes when he falls in love, the cymbals when he grows a beard; the pianoforte explains itself, and should people ever play him false, as will happen to the best of us, there stand the kettle-drums and the big-drum in the background.

"Dear me! I am ever so happy when I think of your happiness, and of the time when I shall have my full share of it. By the end of April, at the latest, I intend to be in London, and then we will duly name the boy, and introduce him to the world at large. It will be grand!"

In a later letter he announces himself as arriving in June, "ready to act as a godfather, to play, conduct, and even to be a genius."

He came, and I was duly christened Felix Stone Moscheles in St. Pancras Church. Barry Cornwall wrote some lines commemorative of the occasion. Alluding to the date of my birth, he begins:—

| 1. (February). |

| Speak low! the days are dear, |

| Sing load! A child is born! |

| Music, the maid, is watching near, |

| To hide him in her bosom dear, |

| From sights and sounds forlorn. |

| Happy be his infant days! |

| Happy be his after ways! |

| Happy manhood! Happy age! |

| Happy all his pilgrimage. |

| 2. (June). |

| Breathe soft! the days grow mild, |

| The child hath gained a name! |

| Now sweet maid, Music! whisper wild |

| Thy blessings on the new-named child, |

| And lead him straight to fame. |

| "Felix" should be "happy" ever, |

| And his life be like a river, |

| Sweetness, freshness, always bringing, |

| And ever, ever, ever singing! |

Well, the "sweet maid, Music" never led the new-named one "straight to fame," nor did the child ever get there by any circuitous route, but Felix was certainly "happy ever."

In this, my case, there certainly must have been something in a name, for my good godfather endowed me with my full share of happiness.

In later years Berlioz wrote that well-known line of Horace's in my album:—

"Donec eris Felix, multos numerabis amicos."

(As long as you are happy you will number many friends.) And when I reflect how much friendship I have enjoyed from the day of my christening to the present hour, I feel certain that the name was of good augury, and that Horace and Mendelssohn were right.

If the complete orchestra was the first godfather's present, the little album was the second. It measures only six inches by four, but that small compass holds much that is of interest. The book is full now; it required about half a century to cover its pages, for they contain only the autographs of such celebrities as were my personal friends. Mendelssohn had appropriately inaugurated it with a composition, the "Wiegenlied" (slumber-song), now so popular.

There are also two drawings by him, one of 3 Chester Place, Regent's Park, and another of the Park close at hand. Mendelssohn must have sat out of doors to make these very faithful transcripts of nature, and I sometimes wonder how the street-boys of those days took it. Looking at those contributions, one cannot help being struck by the care which he bestowed on everything he did. His handwriting was always neat and clear, with just enough of flourish and swing to give it originality. His musical manuscripts vie in precision with the products of the engraver's art, and again there is a marked analogy between his style of drawing and the way in which he forms the letters of the alphabet, or the notes of the scales. As one peruses his manuscripts, one finds oneself admiring the artistic aspect of his well-balanced bars, and on the other hand, the harmonious treatment of his drawings recalls the appearance his pen gives to his scores. In the view he took of the Regent's Park, the leaves, so delicately and yet so firmly pencilled, seem to sway and rustle in unison with the sprightly melody of the scherzo in the "Midsummer-Night's Dream," and just as that melody is discreetly accompanied by the orchestra, so in the drawing, the houses, the old Colosseum in the background, and the trees in the middle-distance, are, one and all, made to keep their places, and deferentially to play second fiddle to the rustling leaves.

In due course of time, and after full enjoyment of the Slumber Song, I got out of my cradle and on to my legs, and it is from that stage in my development that I really date my recollections of my godfather. Some are hazy, others distinct. I am often surprised when I realise that he was short of stature; to me, the small boy, he appeared very tall. I looked upon him as my own special godfather, in whom I had a sort of vested interest, and I showed my annoyance when I was not allowed to monopolise him, or at least to remain near him. Being put to bed was at best a hateful process; how much more so, then, when I was just happily installed on my godfather's knee; occasions of that kind are connected in my mind with vociferous protests, followed by ignominious expulsion.

There were, however, happier times soon to follow, times which recall to me our exploits in the Park. He could throw my ball farther than anybody else; and he could run faster too, but then, to be sure, for all that, I could catch him. There were pitched battles with snowballs, and there was that memorable occasion when I got my first black eye. I remember it came straight from the bat, but—to tell the truth—I was never quite sure that Mendelssohn was in any way connected with that historical event, correctly located though it is, in the Regent's Park.

Our indoor sports must have been pretty lively too, for on one occasion my mother records how "in the evening Felix junior had such a tremendous romp with his godfather, that the whole house shook." And she adds: "One can scarcely realise that the man who would presently be improvising in his grandest style, was the Felix senior, the king of games and romps."

One of my achievements, when I was a little boy in a black velvet blouse, was the impersonation of what we called "the dead man"; the dying man would have been more correct. From my earliest days I evidently pitied the soldier dying a violent death on the battlefield. Since then I have learnt to extend my commiseration to the tax-payer, and to the many innocent victims of a barbarous and iniquitous system. Well, the dying man in the blouse was stretched full length—say some three feet—on the Brussels carpet. Mendelssohn or my father were at the piano improvising a running accompaniment to my performance, and between us we illustrated musically and dramatically the throes and spasms of the expiring hero. I was much offended once, because they told me I acted just like a little monkey; I did not know then, but I am quite sure now, that behind my back they said in a very different tone, admiring and affectionate: "He is such a little monkey."

That black velvet blouse I particularly remember, because John Horsley, now the veteran R. A., then but a rising artist, painted me in it; and also because Hensel, Mendelssohn's brother-in-law, made a sketch of it in my album, at my particular request, representing me on horseback.

What honours that garment might not further have attained I do not know, had I not once for all checked its career by climbing over some freshly painted green railings in the Park, and thus irreparably spoiling it.

The dead-man improvisations remind me of the marvellous way in which my father and godfather would improvise together, playing à quatre mains, or alternately, and pouring forth a never-failing stream of musical ideas. I have spoken of it before, but it was in a preface, and who reads a preface? So I may perhaps once more be allowed to describe it. A subject started, it was caught up as if it were a shuttlecock; now one of the players would seem to toss it up on high, or to keep it balanced in mid-octaves with delicate touch. Then the other would take it in hand, start it on classical lines, and develop it with profound erudition, until perhaps the two joining together in new and brilliant forms, would triumphantly carry it off to other spheres of sound. Four hands there might be, but only one soul, so it seemed, as they would catch with lightning speed at each other's ideas, each trying to introduce subjects from the works of the other.

It was exciting to watch how the amicable contest would wax hot, culminating occasionally in an outburst of merriment, when some conflicting harmonies met in terrible collision. I see Mendelssohn's air of triumph when he had succeeded in twisting a subject from a composition of his own into a Moscheles theme, while the latter was obliged to second him in the bass. But not for long. "Stop a minute," said the next few chords that my father struck. "There I have you, you have taken the bait." Soon they would be again fraternising in perfect harmonies, gradually leading up to the brilliant finale that sounded as if it had been so written, revised and corrected, and were now being interpreted from the score by two masters.

Besides my godfather there were many of my father's friends who were kindly disposed towards me. Malibran is one of those I associate with my earliest days. Perhaps I remember her, perhaps I but fancy I do, for I was only three or four years old when she died. But I have impressions of her sitting on the floor and painting pretty pictures for us children; a certain black silk bag, from the depths of which she produced paint-box, brushes, and other beautiful and mysterious things, had an irresistible charm for us, as had also her big dark eyes, and that wonderful mouth of hers, which she showed us could easily hold an orange. And then she would sing to us Spanish songs by her father, Manuel Garcia, and other celebrities. In my album she wrote, "Nei giorni tuoi felici ricordati di Marie de Beriot," and the flourish appended to the signature takes the shape of an apocryphal bird. For my father's album, one of the completest of its kind, she composed an Allegretto, a song which I believe has never been published.

The words, probably by herself, run thus:—

| "Il est parti sans voir sa fiancée |

| Lorsque le bal était prêt à s'ouvrir; |

| Si pour une autre il m'avait délaissée, |

| Malheur à moi, je n'ai plus qu'à mourir." |

It is dated July 16, 1836: she died on the 23rd of September following.

Thalberg was also a children's man. He was not much of a romp, but always full of jokes, musical and otherwise. Interested as I was in the outward appearance of my home pianists, I was duly impressed by Thalberg's rigid appearance at the piano, contrasting as it did with the lively ways of Liszt and others. He had trained himself to this truly military bearing by practising his most difficult passages whilst he smoked a long Turkish chibouk, the cup of which rested on the ground.

Another source of wonder, not unmixed with awe, was the bulky frame of Lablache, the great singer. It was indeed a basso profondo which emerged from the depths of his ponderous figure. The beauty of his voice, the perfection of his style, and his unconventional deportment on the stage, I learnt to appreciate in later years. I particularly recollect him as Bartolo in Rossini's "Barbiere," on an occasion when Sontag and Mario took the other leading parts. As a small boy I just liked to walk round him, and thought the hackney-coach driver, as they called the cabby then, was not far wrong when he inquired whether his fare expected to be conveyed in one lot.

One of the friends of those early days was Dante Gabriel Rossetti. His father was giving my elder sisters Italian lessons, and that led to most friendly intercourse with him and his two sons. I mention Gabriel's name with a twinge of regret, for the chief records of that intercourse, a number of drawings by his hand, are irretrievably lost. There were—I see them still—knights in armour, fair ladies, and graceful pages, bold pen-and-ink drawings, illustrating a story that ran through several numbers of our own special paper the "Weekly Critic." What, or by whom the story was, I do not recollect, probably by Chorley, who was a frequent contributor to that weekly publication of ours. The drawings in no way foreshadowed Gabriel's later manner; they were just what an imaginative young fellow of seventeen or eighteen would draw, but I feel sure there were no beautiful peculiarities or other poetical deviations from the natural in this his early work. I often wonder where the "Weekly Critic" is in hiding. If this should meet the eye of anybody who knows, I trust he will come forward and receive my blessing in exchange for the drawings which we will give to an expectant world.

When I was about twelve I made my first appearance on the stage under peculiar circumstances. My father had announced a concert in Baden, where we were spending the summer, he the centre of a musical circle, I a schoolboy enjoying my holidays, and specially devoted to the climbing of trees and the picking of blackberries. The impresario of the Court Theatre in Carlsruhe (he seemed to me a sort of Grand Mogul) had graciously permitted the stars of his Opera to sing at that concert of my father's. At the eleventh hour, however, there was a hitch, and the stars were needed to shine on their own Grand-Ducal boards. In the hope that matters might yet be settled in his favour, my father sent me to him with urgent messages. On my arrival I made straight for the theatre, and entering by an unguarded back door, I soon found myself in a maze of dark passages. The sounds of music guided me to the stage, where a rehearsal of the "Vier Haymons-Kinder" was going on, and from the wings I found my way into a rustic arbour destined for the trysting-place of the lovers in the particular scene which was being rehearsed; there I was biding my time when I was discovered by the lady who had come to meet the tenor. The performance was abruptly stopped; the lady was no other than the great prima donna and our old friend Madame Haizinger. Rushing at me with a cry of dramatic exultation, she seized me and carried me triumphantly on to the middle of the stage. "Here," she cried, holding me up to the assembled company, my arms and legs dangling in mid-air—"here, ladies and gentlemen, you see Felix, the son of my old friend Moscheles." The Grand Mogul sat at a table covered with papers to my left, and happily looked upon the interruption and the rapturous outburst as nothing uncommon. As soon as I was replaced on my feet, I delivered my messages, but my influence as a diplomatic agent was not proof against untoward circumstances, and I failed in my mission.

That same Court Theatre was destined soon to become the prey of flames; it was the scene of a terrible catastrophe when many lives were lost.

I was soon to see more of Carlsruhe. Chiefly with a view to improving my German, I was put to school there. Now Carlsruhe was in those days one of the dullest places rational man ever condescended to inhabit. I think it was Heine who said that the dogs came up to you in the street and begged as a favour that you would tread on their toes, just to relieve them of the intolerable monotony of their lives. How it is to-day I don't know; probably they now have music-halls and motor cars, jingoes and pickpockets, but in my time all was slow, sure, and safe. The Grand-Duke sat in his palace like a royal spider in his web; all the streets radiated fan-like from the centre he occupied. In the forest, at the back of the palace, the avenues were cut out so as to form a counterpart to the city, one and all converging towards the abode of the Ruler. A fine spacious market-place there was, however, with a town-hall and a church and a monument to a departed Markgraf, round which clustered on certain days quaint old apple-women whom we school-boys patronised to the fullest extent of our limited means. We were close at hand, for the "Gymnasium" was happily situated in this most attractive part of the town. For all that, it took me some time before I could get accustomed to my new home.

Professor Schummelig, to whose care I was entrusted, was good in his way; I give him a fictitious name, as I have to record that he could also be bad in his way. I don't think he made my lessons more tedious or my tasks more irksome than any other ordinary German professor would have done; but he was pedantic and I was imaginative, so we did not always give one another satisfaction. We had one or two grand rows, in which the wrongs cannot have been all on my side, for, as soon as convenient, he granted me a free pardon, in consideration of which I was required not to mention the unpleasant incident in my letters to my parents (my father paid a hundred florins per quarter). I acquiesced, and so we were soon on good terms again.

But I always felt he was an egoist. He would carve the daily little piece of boiled beef just so as to give himself the particular portion which I coveted. The bread, too, was under his control: he would never take much of it at a time, but he would just cut himself little titbits, crisp corners, and knotty excrescences, until the loaf took the appearance of a dismantled wreck. He also squinted, not with that broad outside squint, ever ready to see both sides, to embrace all things, but with a narrow selfish inside squint which slid down his nose, and from there watched the focussing and absorption of the titbits with keen interest and an irritating show of gratified tastes.

And not only was the professor's field of vision thus distressingly limited, but there was also some moral obliquity in his composition. He mistook certain piles of fire-logs, which had been stocked for the use of the public school, for his own private property. When this was discovered, the authorities, happily for the professor, winked at his delinquencies with an eye to avoiding a scandal—a course they might be well justified in taking, as Justice herself is admitted to be blind.

There were two female servants to minister to our wants—two female drudges, I should say. In lieu of their real names they had been dubbed "Die grosse Biene" and "Die kleine Biene"—the great bee and the little bee—with a view, I suppose, to encouraging them in the delusion that they were not born white slaves, one large and the other small, but busy bees whose nature it was to improve the shining hour, whether it shone by the light of the day or the oil of the night.

The German language, as spoken in the Fatherland, its irregularities, vagaries, and varieties, gave me much trouble. In Hamburg I had learnt to pronounce the words "stehen" and "stossen" with a sharp and incisive st; in the south, all the stiffness and stubbornness was taken out of it, and I had to say "schtehe" and "schtosse." Then the words themselves changed, and "laufen" stood for "gehen," "springen" for "laufen." This surprised me, as I did not know then that the Southerner generally calls running what the Northerner calls walking.

Titles, too, puzzled me, especially when applied to ladies. The first time I heard the "Frau Professorin" mentioned, I looked so blank, not to say shocked, that I evoked general mirth. (It is surprising how well one remembers the occasions when one was laughed at.) But the "Frau Professorin" seemed a strange creature to me in those days, and I little thought that for many a year I was to hear my own mother called by that title.

I had my first skirmishes with the French language too, and I certainly thought I was being made a fool of when I was told there was no word in French for our verb, "to stand." I had learnt the German "stehen" and the ditto "schtehe," and I had conjugated every tense of the Latin "stare," and now I refused to believe that the French language could have a locus standi amongst civilised nations without an equivalent for those words. I did not know then how much civilisation can put up with, and it took me a long while to overcome my mistrust of a language so evidently unsound at its base.

We all know to what wearisome length an average schoolmaster can draw out a single hour, and my teachers were no exception to the rule. Time went slowly, as did all things fifty years ago in Carlsruhe.

What a blessed relief it was then when a holiday came round! Perhaps it was when we were liberated in honour of our glorious Grand-Duke's birthday, perhaps when we were to join in the commemoration of some great deed or greater misdeed of one of his ancestors, or perhaps—best of all—when once or twice Mother Earth was clad in so much loveliness, that it was just impossible to keep masters and boys indoors, dissecting dead languages and putting historical bones together. Nature herself seemed to proclaim a free pardon for us prisoners and for our warders: off we went all together to the woods.

How we ran and shouted when we got into those avenues of trees behind the Grand-Ducal Palace, how madly we raced, how heroically we fought the boys we hated, and how solemnly we swore eternal friendship with the ones we loved! We climbed trees, cut sticks, and did what little harm we could to exuberant prolific Nature; we chased butterflies and deprived spiders of their legitimate prey, and then—selfish little lords of creation that we were—we settled down where the grass grew thickest, to discuss large haunches of bread and red-cheeked apples, and to crack nuts and jokes in true schoolboy fashion.

The masters forgot for the while that they were German professors, with spectacles on their noses and Latin quotations on their lips. They were just human, and felt themselves as much at home in the woods as we did, gratefully inhaling the same balmy air, and greedily swallowing the same glittering dust. They knew something, too, to tell us about God's creation, and in those blessed hours taught us wonderful and beautiful things that stirred our little souls, and made us glad to live and wonder and worship.

Oscar—I have forgotten his surname—was not a professor, and did not even wear spectacles, but he was a sort of monitor, had long silky eyelashes, and he certainly was in love. He never told me so, but I am sure he was, and remembering him and his eyelashes as I do, I can easily reconstruct the simple story of his love. She was a Gretchen, a sweet German maiden, blue-eyed and golden-haired. They first met at a Kränzchen where their feet waltzed to the same step and their hearts beat to the same tune. Then on two ever-to-be-remembered Sunday afternoons they took coffee together in the "Restauration zum blauen Stern," and on the second occasion, as they were going home through the pine-woods, he said something to her she had never heard before; her answer was inaudible, but I know she left her hand where he wanted it to remain, and the good old moon did the rest. They soon received the paternal and maternal blessings, and now they were happy in the knowledge that in six or eight years nothing would stand between them and their fondest hopes, when he probably would have passed his examinations and have secured his first appointment.

I must have caught the loving mood from Oscar, or else some wood-nymphs or sprites must have been trying their hands on me, or perhaps I was only tired and lagged behind. Certain it is that a new sort of feeling came over me, a semi-conscious yearning for an unknown quantity that was waiting for me somewhere; and as I lay on my back under the trees, my imagination shot upwards, starting from the gnarled roots by my side, along the mast-like perpendiculars the pines, past jolly little squirrels, patches of moss and garlands of creepers, right to the top where the sky's blue eyes were winking at me. Nature was whispering some secret and I was dreaming my first Midsummer-Day's Dream.

All around there was humming and buzzing, piping and singing; mysterious sounds, joyous notes, and pensive ditties. Some bird with a flute-like voice sang a pretty little musical phrase, just a bar of five or six notes, and kept on repeating it at intervals. Another little bird, deep down in the forest, answered it—birds of a feather flirt together—only there were so many chirping chatterboxes about, enjoying themselves in their way, that the warbling flirtation was carried on under difficulties. For all that, the flute-like voice never tired of saying its say, and putting its question, pleased as it evidently was with its mate's reply. I dare say it knew a good deal better than I did at the time what it was all about, and what was the grand and glorious answer inexhaustible Nature held in store for it.

For my part, I gazed upward at the patches of ultramarine, and longed for them, but it was not till years afterwards that they vouchsafed to come down. Then, when they took the shape of a pair of real blue eyes, it all dawned upon me, and I knew what Nature had been whispering, and understood that stately pine-forests, jolly little squirrels, and loving little birds, were only created to guide and direct good little boys to realms of joy and happiness.

Whilst I was sitting on school-forms puzzling over nouns and verbs, or lying on the grass communing with the birds, things were happening in my London home that were once more to lead to a change in my surroundings.

Another pleasant day-dream, one that my father and his friend Mendelssohn had for some time past been indulging in, was about to be realised. The frequent correspondence between them, delightful as it was, the exchange of views, musical and personal, and the occasional meetings in England or Germany, had only more saliently brought out the points in favour of a long-cherished scheme which should enable them to live and work together in the same town.

Mendelssohn had for some time been planning the formation of a School of Music in Leipsic, and his letters of this period are full of the warmest and most eloquent appeals to my father to give up his position in England, and to take up his residence in Leipsic. The outcome of it was, that the Conservatorio in that city was founded, and that my father was offered a professorship. In answer to his assumption that Mendelssohn would act as director, the latter answers: "I am not, and never shall be the director of the school. I stand in precisely the same kind of position that it is hoped you may occupy. The duties of my department are the reading of compositions, &c., and as I was one of the founders of the school, and am acquainted with its weak points, I lend a hand here and there until we are more firmly established."