Title: The White Queen of Okoyong: A True Story of Adventure, Heroism and Faith

Author: W. P. Livingstone

Release date: July 21, 2010 [eBook #33214]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Rose Mawhorter and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

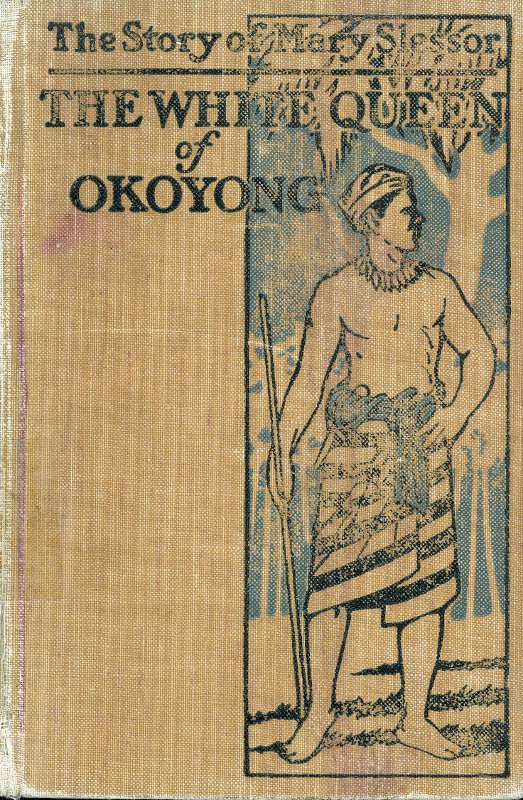

THE CANOE WAS ATTACKED BY A HUGE HIPPOPOTAMUS

THE CANOE WAS ATTACKED BY A HUGE HIPPOPOTAMUS

A TRUE STORY OF ADVENTURE HEROISM AND FAITH

NEW YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Chief Dates in Miss Slessor's Life | xi |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Tells how a little girl lived in a lowly home, and played, and dreamed dreams, and how a dark shadow came into her life and made her unhappy; how when she grew older she went into a factory and learned to weave, and how in her spare minutes she taught herself many things, and worked amongst wild boys; and how she was sent to Africa | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| How our heroine sailed away to a golden land of sunshine across the sea; how she found that under all the beauty there were terrible things which made life a misery to the dark-skinned natives; how she began to fight their evil ideas and ways and to rescue little children from death; how, after losing all her loved ones, she took a little twin-girl to her heart, and how she grew strong and calm and brave | 22 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Ma's great adventure: how she went up-river by herself in a canoe and lived in a forest amongst a savage tribe; how she fought their terrible customs and saved many lives; how she built a hut for herself and then a church, and how she took a band of the wild warriors down to the coast and got them to be friends with the people who had always been their sworn enemies | 45[Pg viii] |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Stories of how Ma kept an armed mob at bay and saved the lives of a number of men and women; how in answer to a secret warning she tramped a long distance in the dark to stop a war; how she slept by a camp-fire in the heart of the forest, and how she became a British Consul and ruled Okoyong like a Queen | 69 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Ma's great love for children; her rescue of outcast twins from death; the story of little Susie, the pet of the household; and something about a new kind of birthday that came oftener than once a year | 90 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| How the Queen of Okoyong brought a high British official to talk to the people; how she left her nice home and went to live in a little shed; how she buried a chief at midnight; how she took four black girls to Scotland, and afterwards spent three very lonely years in the forest | 105 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Tells of a country of mystery and a clever tribe who were slave-hunters and cannibals, and how they were fought and defeated by Government soldiers; how Ma went amongst them, sailing through fairyland, and how she began to bring them to the feet of Jesus | 120 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Ma learns to ride a bicycle and goes pioneering; the Government makes her a Judge again and she rules the people;[Pg ix] stories of the Court, and of her last visit to Scotland with a black boy as maid-of-all-work; and something about a beautiful dream which she dreamed when she returned, and a cow and a yellow cat | 140 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Ma goes farther up the Creek and settles in a heathen town in the wilds; she enters into happy friendships with young people in Scotland; has a holiday in a beautiful island, where she makes a secret compact with a lame boy; and is given a Royal Cross for the heroic work she has done | 163 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| This chapter tells how Ma became a gypsy again and lived on a hill-top, and how after a hard fight she won a new region for Jesus; gives some notes from her diary and letters to little friends at home, and pictures her amongst her treasures | 183 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| What happened when the Great War broke out. Ma's last voyage down the Creek; how her life-long dream came true | 198 |

| Index | 207 |

| YEAR | AGE |

| 1848. Born at Gilcomston, Aberdeen, December 2. | |

| 1856. Family went to Dundee. | 8 |

| 1859. Began work in a factory. | 11 |

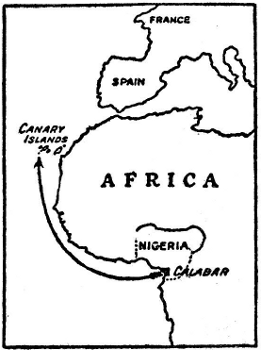

| 1876. Appointed by United Presbyterian Church to Calabar | |

| as missionary teacher, and sailed. | 28 |

| 1879. Paid her first visit home. | 31 |

| 1880. In charge at Old Town. | 32 |

| 1883. Second visit home with Janie. | 35 |

| 1885. In Creek Town. | 37 |

| 1886. Death of her mother and sister (Janie). | 38 |

| 1888. Entered Okoyong alone. | 40 |

| 1881. Third visit home with Janie. | 43 |

| 1892. Made Government Agent in Okoyong. | 44 |

| 1898. Fourth visit home, with Janie, Alice, Maggie, and Mary. 50 | |

| 1900. Union of United Presbyterian and Free Churches as | |

| United Free Church. | 52 |

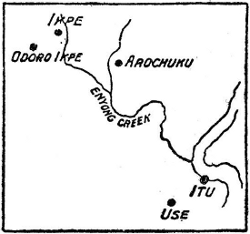

| 1902. Pioneering in Enyong Creek. | 54 |

| 1903. Started a Mission at Itu. Reached Arochuku. | 55 |

| 1904. Settled at Itu. | 56 |

| 1905. Settled at Ikotobong. | 57 |

| Appointed Vice-President of Native Court.[Pg xii] | |

| 1907. Fifth visit home with Dan. | 59 |

| Settled at Use. | |

| 1908. Began a home for women and girls. | 60 |

| 1909. Gave up Court work. | 61 |

| 1910. Began work at Ikpe. | 62 |

| 1912. Holiday at Grand Canary. | 64 |

| 1913. Visit to Okoyong. | 65 |

| Received Royal Medal. | |

| Began work at Odoro Ikpe. | |

| 1914. Last illness, August. | 65 |

| 1915. Died at Use, January 13. | 66 |

| Mary Slessor Memorial Home decided on by Women's | |

| Foreign Mission Committee. | |

| 1916. Issue of Appeal for £5000 for upkeep of Memorial | |

| Home and Missionary. |

Wishart Church, Dundee.

Wishart Church, Dundee.

Tells how a little girl lived in a lowly home, and played, and dreamed dreams, and how a dark shadow came into her life and made her unhappy; how when she grew older she went into a factory and learned to weave, and how in her spare minutes she taught herself many things, and worked amongst wild boys; and how she was sent to Africa.

One cold day in December, in the city of Aberdeen, a baby girl was carried by her mother into a church to be enrolled in the Kingdom of Jesus and given a name. As the minister went through the tender and beautiful ceremony the people in the pews looked at the tiny form in her robes of white, and thought of the long years that lay before her and wondered what she would become, because every girl and boy is like a shut casket full of mystery and promise and hope. No one knows what gifts may lie hidden within them, and what great and[Pg 2] surprising things they may do when they grow up and go out into the world.

The baby was christened "Mary Slessor," and then she was wrapped up carefully again and taken home. Surely no one present ever dreamed how much good little Mary would one day do for Africa.

It was not a very fine house into which Mary had been born, for her father, who was a shoemaker, did not earn much money; but her mother, a sweet and gentle woman, worked hard to keep it clean and tidy, and love makes even the poorest place sunshiny and warm. When Mary was able to run about she played a great deal with her brother Robert, who was older than she, but she liked to help her mother too: indeed she seemed to be fonder of doing things for others than for herself. She did not need dolls, for more babies came into the home, and she used to nurse them and dress them and hush them to sleep.

She was very good at make-believe, and one of her games was to sit in a corner and pretend that she was keeping school. If you had listened to her you would have found that the pupils she was busy teaching and keeping in order were children with skins as black as coal. The reason was this: Her mother took a great interest in all she heard on Sundays about the dark lands beyond the seas where millions of people had never heard of Jesus. The church to which she belonged, the United[Pg 3] Presbyterian Church, had sent out many brave men and women to various parts of the world to fight the evils of heathenism, and a new Mission had just begun amongst a savage race in a wild country called Calabar in West Africa, and every one in Scotland was talking about it and the perils and hardships of the missionaries. Mrs. Slessor used to come home with all the news about the work, and the children would gather about her knees and listen to stories of the strange cruel customs of the natives, and how they killed the twin-babies, until their eyes grew big and round, and their hearts raced with fear, and they snuggled close to her side.

Mary was very sorry for these helpless bush-children, and often thought about them, and that was why she made them her play-scholars. She dreamed, too, of going out some day to that terrible land and saving the lives of the twinnies, and sometimes she would look up and say:

"Mother, I want to be a missionary and go out and teach the black boys and girls—real ways."

Then Robert would retort in the tone that boys often use to their sisters:

"But you're only a girl, and girls can't be missionaries. I'm going to be one and you can come out with me, and if you're good I may let you up into my pulpit beside me."

Mrs. Slessor was amused at their talk, and well[Pg 4] pleased too, for she had a longing that her boy should work abroad in the service of Jesus when he became a man. But that was not to be, for soon afterwards Robert fell ill and died, so Mary became the eldest.

A dark shadow, darker than death, gathered over the home. Mr. Slessor learned the habit of taking strong drink and became a slave to it, and he began to spend a large part of his money in the public-house, and his wife and children had not the comfort they ought to have had. Matters became so bad that something had to be done. It was thought that if Mr. Slessor could be got away from the bad companions who led him astray, he might do better. So the home was broken up, and the family journeyed to Dundee, the busy smoky town on the River Tay, where there were many large mills and factories, and here, for a time, they lived in a little house with a bit of garden in front. That garden was at first a delight to Mary, but afterwards she lost her pleasure in it, for her father used to dig in it on Sunday, and make people think he did not love God's Day.

She was now old enough to look after the younger children, and very well she did it. Often she took them long walks, climbing the steep streets to see the green fields, or going down to feel the fresh smell of the sea. Sometimes her mother gave her a sixpence, and they went and had a ride on the[Pg 5] merry-go-round. It was the custom then for girls and boys to go bare-footed in the summer, and Mary liked it so much that she never afterwards cared to wear shoes and stockings.

On Sundays they all trotted away to church, clean and sweet, each with a peppermint to suck during the sermon, and afterwards they went to Sunday School. As a rule Mary was good and obedient, though, like most girls, she sometimes got into trouble. Her hair was reddish then, and her brothers would tease her and call her "Carrots," and she did not like that. She loved a prank too, and was sometimes naughty. Once or twice she played truant from the Sunday School. She was always very vexed afterwards, for she could not bear to see her mother's face when she heard of her wrong-doing—it was so white and sad. The quiet little mother did not punish her: she would draw her instead into a room and kneel down and pray for her. "Oh, mother!" Mary would say, "I would rather you whip me!"

But all that soon passed away, for she had been dreaming another dream, a very sweet one, which always set her heart a-longing and a-thrilling, and it now came true and changed her life. It was the biggest thing and the happiest that ever happened to her. She gave her heart to Jesus. Very shyly one night she crept up to her mother, nestled close[Pg 6] to her, and laid her head on her knee, and then whispered the wonderful news. "I'll try, mother," she said, "to be a good girl and a comfort to you." Her mother was filled with joy, and both went about for long afterwards singing in their hearts. If only the shadow would lift!

The Little House-Mother.

The Little House-Mother.

But it settled down more darkly than ever. We can change the place where we stay and wander far, but it is not so easy to change our habits. Mr. Slessor was now bringing in so little money that his wife was forced to go and work in one of the mills in order to buy food and clothes for the children. Mary became the little house-mother, and how busy her hands and feet were, how early she was up, and how late she tumbled into bed, and how bravely she met all her troubles! Tears might steal into her eyes when she felt faint and hungry, but it was always a bright and smiling face that welcomed the tired mother home at night.

Gloomier grew the shadow. More money was needed to keep the home, and Mary, a slim girl of eleven, was the next to go out and become a bread-winner. One morning she went into a big factory[Pg 7] and stood in the midst of machines and wheels and whirling belts, and at first was bewildered and a little afraid. But she was only allowed to stay for half a day: the other half she had to go to a school in the works where the girls were taught to read and write and count. She was fond of the reading, but did not like doing the sums: the figures on the board danced before her eyes, and she could not follow the working out of the problems, and sometimes the teacher punished her by making her stand until the lesson was finished.

But she was clever with her fingers, and soon knew all about weaving. How proud she was when she ran home with her first week's earnings! She laid them in the lap of her mother, who cried over them and wrapped them up and put them away: she could not, just then, find it in her heart to spend such precious money.

By the time she was fourteen Mary was working a large machine and being paid a good wage. But she had to toil very hard for it. She rose at five o'clock in the morning, when the factory whistle blew, and was in the works by six, and, except for two hours off for meals, she was busy at her task until six in the evening. In the warm summer days she did not go home, but carried her dinner with her and ate it sitting beside the loom; and sometimes she went away by herself and walked in the park. Saturday afternoons and Sundays were her[Pg 8] own, but they were usually spent in helping her mother. Her dress was coarse and plain, and she wore no pretty ornaments, though she liked them as much as her companions did, for she was learning to put aside all the things she did not really need, and by and by she came not to miss them, and found pleasure instead in making others happy. She would have been quite content if only her father had been different.

But there was no hope now of a better time. The shadow became so black that it was like night when there are no stars in the sky. Mrs. Slessor and Mary had a big burden to bear and a grim battle to fight. In their distress they clung to one another, and prayed to Jesus for help and strength, for they, of themselves, could do little. On Saturday nights Mr. Slessor came home late, and treated them unkindly, so that Mary was often forced to go out into the cold streets and wait until he had gone to sleep. As she wandered about she felt very lonely and very miserable, and sometimes sobbed as if her heart would break. When she passed the bright windows of the places where drink was sold, she wondered why people were allowed to ruin men and women in such a way, and she clenched her hands and resolved that when she grew up she would war against this terrible thing which destroyed the peace and happiness of homes.

But at last the trouble came to an end. One[Pg 9] tragic day Mary stood and looked down with a great awe upon the face of her father lying white and still in death.

What she went through in these days made her often sad and downcast, for she had a loving heart, and suffered sorely when any one was rough to her or ill-treated her. But good came out of it too. She was like a white starry flower which grows on the walls and verandahs of houses in the tropics. The hot sunshine is not able to draw perfume from it, but as soon as darkness falls its fragrance scents the air and comes stealing through the open windows and doors. So it was with Mary. She grew sweeter in the darkness of trouble; it was in the shadows of life that she learned to be patient and brave and unselfish.

We must not think less, but more, of her for coming out of such a home. It is not always the girls and boys who are highly favoured that grow up to do the best and biggest things in life. Some of the men and women to whom the world owes most had a hard time when they were young. The home life of President Lincoln, who freed millions of slaves in America, was like Mary's, yet his name has become one of the most famous in history. No girl or boy should despair because they are poor or lonely or crushed down in any way; let them fight on, quietly and patiently, and in the end better things and happier times will come.[Pg 10]

Mrs. Slessor now left the factory, and for a time kept a little shop, in which Mary used to help, especially on Saturday afternoons and nights, when trade was busiest. The girl was still dreaming dreams about the wonderful days that lay before her, but, unlike many others who do the same, she did her best to make hers come true. She wanted to learn things, and she found that books would tell her, and so she was led into the great world of knowledge. The more she read the more she wanted to know. So eager was she that when she left home for her work, she slipped a book into her pocket and glanced at it in the streets. She did not know then about Dr. Livingstone, the African missionary and traveller, but she did exactly what he had done when he was a boy: she propped a book on a corner of the loom in the factory, and read whenever she had a moment to spare. Her companions tell how they used to see her take out a little note-book, put it on the weaver's beam, and jot down her thoughts—she was always writing, they say; sometimes it was poetry, sometimes an essay, sometimes a letter to a friend. But she never neglected her work.

How different her lot was from that of most girls of to-day! They have leisure for their lessons, and they learn music and do fancy work and keep house and bake—and how many hate it all! Mary had only a few precious minutes, but she made the[Pg 11] most of them. The books she read were not stories, but ones like Milton's Paradise Lost and Carlyle's Sartor Resartus, and so deep did she become in them at night that sometimes she forgot everything, and read on and on through the quiet hours, and only came to herself with a start when she heard the warning whistle of the factory in the early morning.

She was fond of all good books, but the one she liked most and knew better than any was the Bible. She pored over it so often that she remembered much of it by heart. In the Bible Class she was so quick and so ready to answer questions that Mr. Baxter, her minister, used to say, "Now, Mary Slessor, don't answer any more questions till I bid you." When every one else failed he would turn to her with "Now, Mary," and she always had her reply ready. She was never tired of the story of Jesus, especially as it is told in the Gospel of St. John, for there He appeared to her so kind and winsome and lovable. When she thought of all He did, how He came from His own beautiful heaven to save the world from what is sinful and sad, and how He was made to suffer and at last was put to death, and how His teaching has brought peace and safety and sunshine into the lives of millions of women and girls, she felt she must do something for Him to show her love and thankfulness and devotion.

"He says we must do as He did and try to make[Pg 12] people better and happier, and so I, too, must do my best and join in the war against all that is evil and unlovely and unrestful in the world." So she thought to herself.

She did not say, "I am only a girl, what can I do?" She knew that when a General wanted an army to fight a strong enemy he did not call for officers only, but for soldiers—hosts of them, and especially for those who were young. "I can be a soldier," Mary said humbly. "Dear Lord, I will do what I can—here are my heart and head and hands and feet—use me for anything that I can do."

The first thing that she did was to take a class of little girls in the Sunday School, and thus she began to teach others before she was educated herself, but it is not always those who are best trained who can teach best. The heart of Mary was so full of deep true love for Jesus that it caused her face to shine and her eyes to smile and her lips to speak kind words, and that is the sort of learning that wins others to Him.

Wishart Church, to which she went, was built over shops, and looked down upon the old Port Gate and upon streets and lanes which were filled at night with big boys and girls who seemed to have no other place to go to, and nothing to do but lounge and swear and fight. Mary felt she would like to do something for them. By and by when a Mission was begun in a little house in Queen Street—there[Pg 13] is a brass inscription upon the wall, now, telling about Mary—she went to the superintendent and said, "Will you take me as a teacher?" "Gladly," he said, but she looked so small and frail that he was afraid the work would be too rough for her.

What a time she had at first! The boys and girls did not want anybody to bother about them: those who came to the meeting were wild and noisy; those who remained outside threw stones and mud and tried to stop the work. Mary faced them, smiling and unafraid, and dared them to touch her. Some grew ashamed of worrying the brave little teacher, and these she won over to her side. But there were others with sullen eyes and clenched fists who would not give in, and they did their best to make her life a misery.

One night a band of the most violent lay in wait for her, and she found herself suddenly in their midst. They hustled and threatened her.

"We'll do for you if you don't leave us alone," they cried.

She was quaking with fear, but she did not show it. She just breathed a prayer for help, and looked at them with her quiet eyes.

"I will not give up," she replied. "You can do what you like."

"All right," shouted the leader, a big hulking lad. "Here goes."[Pg 14]

Out of his pocket he took a lump of lead to which was tied a bit of cord, and began to swing it round her head. The rest of the gang looked on breathless, wondering at the courage of the girl. The lead came nearer and swished past her brow. Pale, calm, unflinching, she stood waiting for the blow that would fell her to the ground. Suddenly the lad jerked away the weapon and let it fall with a crash.

"We can't force her, boys," he cried, "she's game."

And, like beaten foes, they followed her, and went to the meeting and into her class, and after that there was no more trouble. The boys fell under her spell, grew fond of her, and in their shy way did all they could to help her. On Saturday afternoons she would take them into the country away from the temptations of the streets, and sought to make them gentle and kind and generous. Some of the most wayward amongst them gave their hearts to Jesus, and afterwards grew to be good and useful men.

What was it that gave her such an influence over these rude and unruly boys? They did not know. She was not what is called a pretty girl. She was plain and quiet and simple, and she was poorly clad. But she was somehow different from most teachers. Perhaps it was because she loved them so much, for the love that is real and pure and unselfish is the greatest power in the world.[Pg 15]

One of the "Pends" or "Closes" where Mary visited the

Boys in her Class.

One of the "Pends" or "Closes" where Mary visited the

Boys in her Class.

Through the hearts of the boys Mary found her way to their homes in the slums, and paid visits to their mothers and sisters, and saw that life to them was often very hard and wretched. The other Mission workers used to go two and two, but she often went alone. Once she was a long time away, and when she came back she said laughingly:

"I've been dining with the Macdonalds in Quarry Pend."

"Indeed," said some one, "and did you get a clean plate and spoon?"

"Oh, never mind that," replied Mary. "I've got into their house and been asked to come back, and that's all I care about."

She always went in the same spirit in which Jesus would have gone. Sometimes she would sit by the fire with the baby on her knees; sometimes she would take tea with the family, drinking out of a broken cup; sometimes she would help the mother to finish a bit of work. And always she cheered[Pg 16] up tired and anxious hearts, and left sunshine and peace where there had been only the blackness of despair.

No one could be long in her company without feeling better, and not a few of her friends came, through her, to know and love and work for Jesus. "Three weeks after I knew her," says one of her old factory mates, "I became a different girl." How eager and earnest she was! "Oh!" she said to a companion, "I wonder what we would do or dare for Jesus? Would we be burned at the stake? Would we give our lives for His sake?" "She did work hard," says another, "and whatever she did, she did with heart and soul."

When the Mission was removed to the rooms under the church, the superintendent said: "We shall need a charwoman to give the place a thorough cleaning."

"Nonsense," said Mary; "we will clean it ourselves."

"You ladies clean such a dirty hall!"

"Ladies!" cried Mary; "we are no ladies, we are just ordinary working folk."

Next night Mary and another teacher were found, with sleeves turned up and aprons on, busy with pails of water and brushes scrubbing out the rooms. Like other young people, she had her troubles, big and little, and these she met bravely. Evil-minded persons, jealous of her goodness, sometimes[Pg 17] said unkind things about her, but she never paid any heed to them. She always did what she thought was right, and went her own way. On Saturdays she used to put her hair in curlpapers, and her companions teased her a lot about it, and tried to laugh her out of the habit, but she just laughed back. When she and two or three friends met during the meal hour and held a little prayer meeting opposite the factory, the other girls would come and peep in, and one of her companions would be vexed and scold them. "Dinna bother, Janet," she would say quietly, "we needna mind what they do."

She was not always serious, but could enjoy fun and frolic with the wildest. Once while walking in the country with a girl she knocked playfully at some cottage doors and ran away. "Oh, Mary," said her friend, "I'm shocked at you!"

Mary only laughed, and said, "A little nonsense now and then is relished by the wisest men."

From one old friend we get a picture of her at this time. "Her face was always shining and happy. With her fresh skin, her short ringlets, and her firm mouth she somehow always made me think of a farmer's daughter coming to market with butter and eggs!"

Her life during these years was a training for what she had to do in the future. She must have had an inkling of it, for her dreams now were all of[Pg 18] service in the far lands beyond the seas. Through the gloom of the smoky streets she was always seeing visions of tropical rivers and tangled jungle and heathen huts amongst palm trees, and above the noise of the factory she was hearing the cries of the little bush-children; and she longed to leave busy Dundee with its churches and Sunday Schools and go out and help where help was most needed. She did not say anything, for she knew it was her brother John that her mother was anxious to make a missionary. He was a big lad, but very delicate, and there came a time when the doctor said he must leave the cold climate of Scotland or die. He sailed to New Zealand, but it was too late, and he passed away there. His mother grieved again over her lost hopes, and Mary, who was very fond of him, wept bitterly. As she went about her work she repeated the hymn, "Lead, kindly Light," to herself, finding comfort in the last two lines:

And then she came back to her dazzling day-dream. Could she not, after all, be the missionary? But she was not educated, and she was the chief breadwinner of the family, and her mother leant upon her so much. How could she manage it? She thought it all out, and at last said, "I can do it. I will do it." She was one of the cleverest[Pg 19] weavers in the factory, and she began to do extra work, thus earning a bigger wage and saving more money. She studied very hard. She practised speaking at meetings until she learned how to put her thoughts into clear and simple words.

But it was a weary, weary time, for she spent fourteen years within the walls of the factory. Thousands of other girls, of course, were doing the same, and sometimes they got very tired, but had just to go bravely on. In one of her poems Mrs. Browning tells us what it was like: how the revolving wheels seemed to make everything turn too—the heads and hearts of the girls, the walls, the sky seen out of the high windows, even the black flies on the ceiling—

But they never did stop, and the girls had only their hopes and dreams to make them patient and brave.

One day there flashed through the land a telegram which caused much excitement and sorrow. Africa was then an unknown country, vast and mysterious, and haunted by all the horrors of slavery and heathenism. For a long time there had been tramping through it a white man, a Scotsman, David Livingstone, hero of heroes, who had been[Pg 20] gradually finding out the secrets of its lakes and rivers and peoples. Sometimes he was lost for years. The telegram which came told of his lonely death in a hut in the heart of the continent. Every one asked, What is to be done now? who is to take up the work of the great pioneer and help to save the natives from misery and death? Amongst those whose hearts leapt at the call was Mary Slessor. She went to her mother.

"Mother," she said, "I am going to offer myself as a missionary. But do not fret. I will be able to give you part of my salary, and that, with the earnings of Susan and Janie, will keep the home in comfort."

"My lassie," was the reply, "I'll willingly let you go. You'll make a fine missionary, and I'm sure God will be with you."

Some of her friends wondered at her. They knew she was not specially brave; indeed, was not her timidity a joke amongst them? "Why," they said, "she is even afraid of dogs. When she sees one coming down the street she goes into a passage until it is past!" This was true, but they forgot that love can cast out all fear.

Tremblingly she waited for the answer to her letter to the Mission Board of the United Presbyterian Church in Edinburgh. When it arrived she rushed to her mother.

"I'm accepted! I'm going to Calabar as a[Pg 21] teacher." And then, strange to say, she burst into tears.

So she who had waited so long and so patiently, working within the walls of a factory, weaving the warp and woof in the loom, was now going to one of the wildest parts of Africa to weave there the lives of the people into new and beautiful patterns.

The House in Queen Street, Dundee, where Mary Slessor

first taught as a Mission Teacher.

The House in Queen Street, Dundee, where Mary Slessor

first taught as a Mission Teacher.

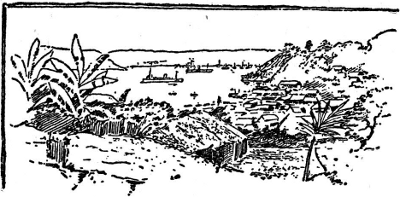

Duke Town, West Africa.

Duke Town, West Africa.

How our heroine sailed away to a golden land of sunshine across the sea; how she found that under all the beauty there were terrible things which made life a misery to the dark-skinned natives; how she began to fight their evil ideas and ways and to rescue little children from death; how, after losing all her loved ones, she took a little twin-girl to her heart, and how she grew strong and calm and brave.

On an autumn morning in 1876 Miss Slessor stood on the deck of the steamer Ethiopia in Liverpool docks and waved good-bye to two companions from Dundee who had gone to see her off. As the vessel cleared the land and moved out into the wide spaces of the waters she, who had always lived in narrow streets, felt as if she were on holiday, and was in as high spirits as any schoolgirl. She could not help being kind and helpful to others, and soon made friends with many of the passengers and crew.

One man drew her like a magnet, for he also was[Pg 23] a dreamer of dreams. This was Mr. Thomson, an architect from Glasgow, who was filled with the idea that the missionaries in West Africa would do better work and remain out longer if there were some cool place near at hand to which they could go for a rest and change. He had been all over the Coast, and explored the rivers and hills, and had at last found a healthy spot five thousand feet up on the Cameroon Mountains, where he decided to build a home. He had given up his business, and was now on his way out, with his wife and two workmen, to put his dream into shape. Mary's eyes shone as she listened to his tale of love and sacrifice; but, alas! the plan, so beautiful, so full of hope for the missionaries, came to nothing, for he died not long after landing.

It was from Mr. Thomson that she learned most about the strange country to which she was going. He told her how it was covered with thick bush and forest; how swift, mud-coloured rivers came out of mysterious lands which had never been seen by white men; how the sun shone like a furnace-fire, and how sudden hurricanes of rain and wind came and swept away huts and uprooted trees. He described the wild animals he had seen—huge hippopotami and crocodiles in the creeks; elephants, leopards, and snakes in the forests; and lovely hued birds that flashed in the sunlight—until her eyes sparkled and her cheeks flushed as they had done[Pg 24] in the old days when she listened to the stories told by her mother.

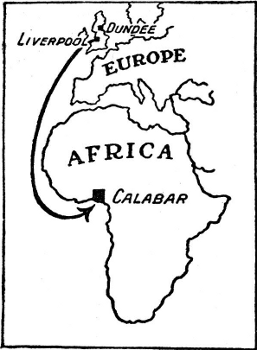

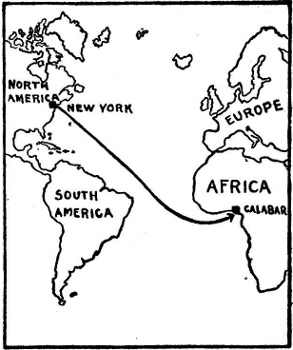

From Dundee to Calabar.

From Dundee to Calabar.

Within a week the steamer had passed out of the grey north, and was gliding through a calm sea beneath a blue and sunny sky. By and by Mary was seeking cool corners under the awning, and listening lazily to the swish of the waves from the bows and watching golden sunsets and big bright stars. Sometimes she saw scores of flying-fish hurry-scurrying over the shining surface, and at night the prow of the vessel went flashing through water that sparkled like diamonds.

By and by came the hot smell of Africa, long lines of surf rolling on lonely shores, white fortresses that spoke of the old slave days, and little port towns, half-hidden amongst trees, where she got her first glimpses of the natives, and was amused at the din they made as they came off to the steamer,[Pg 25] fearless of the sharks that swarmed in the water. It was all strange and unreal to the Scottish weaver-girl.

And when, after a month, the vessel came to the Calabar River and steamed through waters crowded with white cranes and pelicans, and past dark mangrove swamps and sand-banks where the crocodiles lay sunning themselves, and islands gay with parrots and monkeys, up to Duke Town, the queer huddle of mud huts amongst the palm trees that was to be her home, she was excited beyond telling. For at last that wonderful dream of hers, which she had cherished through so many long years, had come true, and so wonderful was it that it seemed to be still only a dream and nothing more.

Clear above the river and the town, like a lighthouse on a cliff, stood the Mission where "Daddy" and "Mammy" Anderson, two of its famous pioneers, lived, and with them Mary stayed until she[Pg 26] knew something about the natives and her work. She felt very happy; she loved the glowing sunshine, the gorgeous sunsets, the white moonlight, the shining river, the flaming blossoms amongst which the humming-birds and butterflies flitted, and all the sights and sounds that were so different from those in Scotland. She was so glad that she used to write poems, and in one of these she sings of the beauty of the land:

Her spirits, so long bottled up in Dundee, overflowed, and she did things which amused and sometimes vexed the older and more serious missionaries. She climbed trees and ran races with the black girls and boys, and was so often late at meals that Mrs. Anderson, by way of punishment, left her out nothing to eat. But "Daddy" was fond of the bright-eyed, warm-hearted lassie, and he always hid some bananas and other fruit and passed them to her in secret. There was no factory whistle to warn her in the morning, and sometimes she would start up in the middle of the night and, seeing her room almost as light as midday, would hastily put[Pg 27] on her clothes, thinking she had slept in, and run out to ring the first bell, only to find a very quiet world and the great round moon shining in the sky.

It was not long before all the light and colour and beauty of the land seemed to fade away, and only the horror of a great darkness remain. She was taken to the homes and yards of the natives in the town and out into the bush, and saw a savage heathenism that astonished and shocked her. She did not think that people could be so wretched and degraded and ignorant. At some of the places the naked children were so afraid of her that they ran away screaming. She herself shrank from the fierce men who thronged round her, but her winning way captured their hearts, and she was soon quite at home with them.

When she came back she was very thoughtful, and talked to Mrs. Anderson of the things she had seen.

"My lassie," said "Mammy," "you've seen nothing." And she began to tell her of the terrible evils that filled the land with misery and sorrow.

"All around us, in the bush and far away into the interior, there are millions of these black people. In every little village there is a Chief or Master, and a few free men and women, but the rest are slaves, and can be sold or flogged or killed at their owner's pleasure. It is all right when they are treated kindly, but think of the kind of men the masters[Pg 28] are. All the tribes are wild and cruel and cunning, and pass their days and nights in fighting each other and in dancing and drinking, and there are some that are cannibals and feast on the bodies of those they have slain. Their religion is the fear of spirits, one of blood and sacrifice, in which there is no love. When a chief dies, do you know what happens to his wives and slaves? Their heads are cut off and they are buried with him to be his companions in the spirit-land."

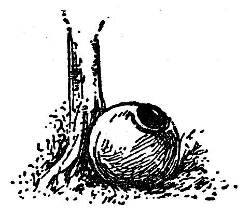

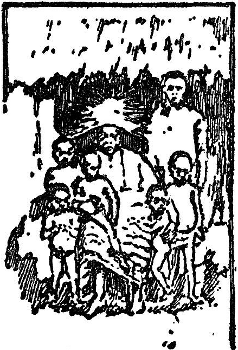

A Pot into which Twins were put.

A Pot into which Twins were put.

Mary shivered. "It must be awful for the children," she said.

"Ah, yes, nearly all are slaves, and their masters look upon them as if they were sheep or pigs. They are his wealth. As soon as they are able to walk they begin to carry loads on their heads, and paddle canoes and sweep and clean out the yards. Often they are beaten or branded with a hot iron, or get their ears cut off. They sleep on the ground without any covering. When the girls grow up they are hidden away in the ufök nkukhö, or 'house of seclusion,' and made very fat, and then become the slave-wives of the masters or freemen. And the twins! Poor mites. For some reason the people[Pg 29] fear them worse than death, and they are not allowed to live; they are killed and crushed into pots and thrown away for leopards to eat. The mother is hounded into the bush, where she must live alone. She, too, is afraid of the twin-babies, and she would murder them if others did not."

Mary cried out in hot rage against so cruel a system.

"Oh," she said, "I want to fight it; I want to save those innocent babes."

"Right, lassie," replied "Mammy," "and we need a hundred more like you to help."

Mary jumped to her feet. "The first thing I have to do," she said, "is to learn the language. I can do nothing until I know it well."

Efik is the chief tongue spoken in this part of Africa, and so quickly did she pick it up and master it that the people said she was "blessed with an Efik mouth"; and then her old dream came true, and she began to teach the black boys and girls in the day school. There were not many, for the chiefs did not believe in educating them. The bigger ones wore only a red or white shirt, while the wee ones had nothing on at all, and they carried their slates on their heads and their pencils in their woolly hair. In spite of everything they were a happy lot, with bright eyes and nimble feet, and Mary loved them, and those that were mischievous[Pg 30] most of all. She also went down to the yards out of which they came, and spoke to their fathers and mothers about Jesus, and begged them to come to the Mission church.

When she had been out three years she fell ill, and was home-sick for her mother and friends. Calabar then was like some of the flowers growing in the bush, very pretty but very poisonous. Mary had fever so badly and was so weak that she was glad to be put on board the steamer and taken away.

In Scotland the cool winds and the loving care of her mother soon made her strong again.

Sometimes she was asked to speak at meetings, but was very shy to face people. One Sunday morning in Edinburgh she went to a children's church. The superintendent asked her to come to the platform, but she would not go. Then he explained to the children who she was, and begged her to tell them something about Calabar. She blushed and refused. A hymn was given out, during which the superintendent pled with her to say a few words. "No, no, I cannot," she replied timidly. He was not to be beaten. "Let us pray," he said. He prayed that Miss Slessor might be able to give them a message. When he finished he appealed to her again. After a pause she rose, and, turning her head half-away, spoke, not about[Pg 31] Calabar, but about the free and glad life which children in a Christian land enjoyed, and how grateful they ought to be to Jesus, to whom they owed it all.

When she reached Calabar again she was made very happy, for her dream was to be a real missionary, and she found that she was to be in charge of the women's work at Old Town, a place two miles higher up the river, noted for its wickedness. She could now do as she liked, and save more money to send home to her mother and sisters, for they were always first in her thoughts. She lived in a hut built of mud and slips of bamboo, with a roof of palm leaves, wore old clothes, and ate the cheap food of the natives, yam and plantain and fish. Many white persons wondered why she did this, and made remarks, but she did not tell them the reason: she cared less than ever for the laughter and scorn of others.

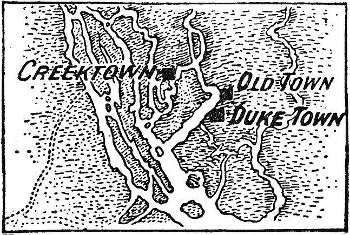

Towns in Calabar.

Towns in Calabar.She soon became a power in the district. The men in the town were selfish and greedy, and would[Pg 32] not let the inland natives come with their palm oil and trade with the factories, and fights often took place, and blood was shed. "This will never do," Mary said, and she began to help the country people, allowing them to steal down at night through the Mission ground, and guiding them past the sentries to the beach. The townsmen were angry, but they could not browbeat the brave white woman, and at last they gave in, and so the trading became free.

Then she began to oppose the custom of killing twins, and by and by she came to be known as "the Ma who loves babies." "Ma" in the Efik tongue is a title of respect given to women, and ever after she was known to all, white and black, as "Ma Slessor," or "Ma Akamba," the great Ma, or just simply "Ma," and we, too, may use the same name for her.

One day a young Scottish trader named Owen came to her with a black baby in his arms.

"Ma," he said, "I have found this baby thing lying away in the bush. It's a twin. The other has been killed. It would soon have died if I hadn't picked it up. I knew you'd like it, and so here it is."

Ma thanked the young man for his kindly act, and took the child, a bright and attractive girl, to her heart of hearts. "I'll call it Janie," she said, "after my sister."

She was delighted one day to hear that the[Pg 33] British Consul and the missionaries had at last coaxed the chiefs in the river towns to make a law after their own fashion against twin-murder. This was done through a secret society called Egbo, which was very powerful and ruled the land. Those who belonged to it sent out men with whips and drums, called runners, who were disguised in masks and strange dresses. When they appeared all women and children had to fly indoors. If caught they were flogged. It was these men who came to proclaim the new rules. Ma thus tells about the scene in a letter to Sunday School children in Dundee:

Just as it became dark one evening I was sitting in my verandah talking to the children, when we heard the beating of drums and the singing of men coming near. This was strange, because we are on a piece of ground which no one in the town has a right to enter. Taking the wee twin boys in my hands I rushed out, and what do you think I saw? A crowd of men standing outside the fence chanting and swaying their bodies. They were proclaiming that all twins and twin-mothers could now live in the town, and that if any one murdered the twins or harmed the mothers he would be hanged by the neck. If you could have heard the twin-mothers who were there, how they laughed and clapped their hands and shouted, "Sosoño! Sosoño!" ("Thank you! Thank you!"). You will not wonder that amidst all the noise I turned aside and wept tears of joy and thankfulness, for it was a glorious day for Calabar.

A few days later the treaties were signed, and at the same time a new King was crowned. Twin-mothers[Pg 34] were actually sitting with us on a platform in front of all the people. Such a thing had never been known before. What a scene it was! How can I describe it? There were thousands of Africans, each with a voice equal to ten men at home, and all speaking as loudly as they could. The women were the worst. I asked a chief to stop the noise. "Ma," he said, "how I fit stop them woman mouth?" The Consul told the King that he must have quiet during the reading of the treaties, but the King said helplessly, "How can I do? They be women—best put them away," and many were put away.

And the dresses! As some one said of a hat I trimmed, they were "overpowering." The women had crimson silks and satins covered with earrings and brooches and all kinds of finery. The men were in all sorts of uniform with gold and silver lace and jewelled hats and caps. Many naked bodies were covered with beadwork, silks, damask, and even red and green table-cloths trimmed with gold and silver. Their legs were circled with brass and beadwork, and unseen bells that tinkled all the time. The hats were immense affairs with huge feathers of all colours and brooches.

The Egbo men were the most gorgeous. Some had large three-cornered hats with long plumes hanging down. Some had crowns, others wore masks of animals with horns, and all were looped round with ever so many skirts and trailed tails a yard or two long with a tuft of feathers at the end. Such splendour is barbaric, but it is imposing in its own place.

Well, the people have agreed to do away with many of the bad customs they have that hinder the spread of the Gospel. You must remember that it is the long[Pg 35] and faithful teaching of God's word that is bringing the people to a state of mind fit for better things.

Now I am sleepy. Good-bye. May God make us all worthy of what He has done for us.

The people were good for a time, but soon fell back into the habit of centuries, and did in secret what they used to do openly. Ma saw that the struggle was only just beginning, and she threw herself into it with all her courage and strength.

She was always studying her Bible, and learning more of the love and power of Jesus, and so much did she lean on Him that she was growing quite fearless, and would go by herself into the vilest haunts in the town or far out into lonesome villages. Often she took a canoe and went up the river and into the creeks and visited places where no white woman had been before, healing the sick, sitting by the wayside listening to the tales of the people, and talking to them about the Saviour of the world. Sometimes there was so much to say and do that she could not get back the same day, and she slept on straw or leaves in the open air, or on a bundle of rags in an evil-smelling hut.

Once she took the house-children and went a long river journey to visit an exiled chief who lived in a district haunted by elephants. They were to start in the morning, but things are done very leisurely in Africa, and it was night before they set off by torchlight. Eyo Honesty VII., the negro king[Pg 36] of Creek Town, who was a Christian and always very kind to Ma, had sent a State canoe, brightly painted, with the message:

"Ma must not go as a nameless stranger to a strange people, but as a lady and our Mother, and she can use the canoe as long as she pleases."

There was a crew of thirty-three men dressed only in loin-cloths.

As they dipped the paddles and sped onwards over the quiet water, a drummer drummed his drum, and the crew chanted a song in her praise:

The motion of the canoe was like a cradle, and the song like a mother's crooning, and she fell asleep; and all through the night, amongst these wild black men, she lay in God's keeping like a little child.

At dawn they came to a beach and a village, where she was given a mud room in the chief's yard, and here for a whole fortnight she lived in the company of dogs, fowls, rats, lizards, and mosquitoes. Many of the people had never seen a white person, and were afraid to touch her. She was very sorry for them, they were so poor and naked and dirty, and she busied herself making clothes and healing the sick. So many were ill that a canoe had to be sent to the nearest Mission House for another supply of medicines.

One day the chief said to her, "Ma, two of my[Pg 37] wives have been doing wrong, and they are to get one hundred stripes each on their bare backs. It is the custom."

She was horrified. "Why, what have they done?"

"They went into a yard that is not their own. Of course," he added, "they are young and thoughtless, they are only sixteen years old, but they must learn."

"Oh, but that is a very cruel punishment for young girls."

"Ma, it is nothing; we shall also rub salt into the wounds and perhaps cut off their ears. That is the only way to make the women obey us."

"No, no, you must not do that," cried Ma. "Bring all the people together for a palaver."

The crowd gathered, and the two girls stood in front with sullen faces. Ma spoke to them.

"You have done wrong according to your law, and you will have to be punished."

At this, smiles broke over the faces of the men; but Ma turned to them swiftly and cried, "You are in the wrong too. Shame on you for making a law that marries girls so early! Why, these are still children who love fun and mischief. Their fault is a small one, and you must not punish them so cruelly."

The smiles fled, and the faces grew angry and defiant, and there were mutterings and threats.[Pg 38]

"Who are you to come and spoil our laws," said some of the big men; "the girls are ours, let us have them."

But Ma was firm, and as she was the guest of the village, and worthy of honour, they at length agreed to give a lighter punishment. The girls were handed over to two strong fellows, who flogged them with a whip. Ma heard their screams amidst the shouts and laughter of those who looked on, and was ready to attend to their bleeding bodies when they ran into her room. Then she gave them something which made them sleep and forget their pain and misery.

"What can you expect?" said she to herself; "they have never heard of God, they worship human skulls, and they don't know about love and compassion and mercy"—and she did her best to teach them.

In the quiet nights, when their work in the fields was over, they came and squatted on the ground, the big men in front, the slaves outside, and she stood beside a little table on which were a Bible and hymn-book and a lamp, and in her sweet and earnest voice told them the story of the gentle Jesus. She could not see anything but the dark mass of their bodies and the gleaming of their eyes, and they sat so still that when she stopped she could only hear the sighing of the wind among the palm tops. It was all very wonderful to them.[Pg 39] Sometimes they would ask questions, chiefly about the life after death, which was such a mystery to them, and, when they rose, they slipped away softly to their homes to talk about this strange new religion that was so different from their own.

It was the time of storms, and one day when Ma was sitting sewing the sky grew dark, lightning flashed, thunder crashed, and floods fell. The roof of the hut was blown away, and she was drenched to the skin, and for a time was ill with fever and nigh to death.

Mrs. Slessor and Janie.

Mrs. Slessor and Janie.

On the way back at night to Old Town another tornado burst, flooding the canoe, and tossing it about like a match-box on the raging waves. The crew lost their wits, and Ma thought they would be upset. But putting aside her own fear for the sake of others, she made the men paddle into the mangrove, where they jumped into the branches like monkeys and held on to the canoe until the danger was passed. All were sitting in water, and Ma was wet through and shaking with ague. She became so ill that when Old Town was reached she had to be carried up to the Mission House. Yet she did not go to bed until[Pg 40] she had made hot tea for the children, and tucked them snugly away for the night.

Soon afterwards another tornado destroyed her house, and she and the children escaped through the wind and rain to the home of some white traders who were very kind to her. But she was so ill after all she had gone through that she was ordered to Scotland, and had again to be carried on board the steamer. She would not leave Janie behind her, as she was afraid the people would murder her, and so the girl-twin also sailed with her across the sea.

Ma soon grew strong in her native air, and one Sunday she went to her old church in Dundee with Janie, and there that morning the little black child was given the name that had been chosen for her. With her black skin and her solemn eyes she was a curious sight to the boys and girls, and they came crowding round and begged to be allowed to hold her for a little. She appeared at many of the meetings to which Ma went, and during the address would sit on the platform munching biscuits, which she was always ready to share with every one near her.

One night Ma travelled to Falkirk to speak to a large class of girls taught by Miss Bessie Wilson, a well-known lady in the Church. She had a message that night, and her face shone and her words fell like stirring music on the young hearts before her.[Pg 41] Janie was passed round from one to another, and helped to make her story more real. So delighted were the girls with the black baby that they begged to be allowed to give something every month for her support.

Perhaps all this had nothing to do with what happened afterwards, but was it not strange that out of that class by and by no fewer than six members gave themselves to the work in Calabar, including Miss Wright and Miss Peacock, two of Ma's dearest friends and best helpers?

Ma had a wonderful power of drawing other people to her and of influencing them for good. On this visit one girl, Miss Hogg, was no sooner in her company than she decided to go to Calabar, and she went, and was for many years a much-loved missionary, whose name was familiar to the children of the Church at home.

Ma was anxious to be back at her work, but her sister Janie, who was delicate like her brothers, needed all her care, and was at last ordered by the doctor to live in a warmer climate. This set Ma dreaming again. "If only I could take her out to Calabar with me," she mused, "we could live cheaply in a native hut, and it might save her life." But the Mission Board did not think this would be right, and Mary, who had a quick brain as well as a warm heart, at once carried Janie off to Devonshire, that lovely county in the south of England,[Pg 42] where she rented a house with a garden and nursed and cared for the invalid. Very sorrowfully she gave up the work in Calabar she loved so much, but she felt that her sister needed her most. Then she brought down her mother, and they lived happily together, and Janie grew strong in the sunshine and fresh air. After a time Ma thought they could be left, and, after getting an old companion down from Dundee to look after them, she went out again to Africa.

Her new station was Creek Town, a little farther away, where the missionary was her dear friend Mr. Goldie, the etubom akamba, the "big master." Here she lived more plainly than ever, for she needed now to send a larger sum of money in order to keep the home in Devonshire. But she had not long to do this loving service, for first her mother, and then her sister, died. All the rest of the family of seven had now passed away, and Ma was alone in the world. She never quite got over her grief and her longing for them all, and to the end of her life was dreaming a sweet dream of the time when she would meet them again in heaven.

With no home-hearts to love she began to lavish her affection on the black children, and was specially fond of Janie, who trotted at her side all day and slept in her bed at night. She was a lively thing, full of fun and tricks, and it was curious that the[Pg 43] people should be so afraid of her. They would not touch her even if Ma was there.

One day a man came to the Mission House who said he was her father.

"Then," said Ma, "you will come and see her."

"Oh, no," he replied, with fear in his eyes, "I could not."

Ma looked at him with scorn. "What harm can a wee girlie do you?" she asked. "Come along."

"Well, I'll look from a distance."

"Hoots," she cried, and seizing him by the arm dragged him close to the child, who was alarmed and clung to Ma.

"My lassie, this is your father, give him a hug."

The child put her arms round the man's neck and he did not mind, and indeed his fierce face grew soft, and he sat down and took her gently on his knee and petted her, and was so delighted with her pretty ways that he would hardly give her up. After that he came often and brought her gifts of food. Thus Ma tried to show the people that there was nothing wrong with twins, and that it was a cruel and senseless thing to kill them.

There were other children, both boys and girls, in the home, whom Ma had saved from sickness or death, and these she trained to do housework and bake and go to market, and when their work was done she taught them from their Efik lesson books,[Pg 44] and by and by they were able to help her in school and church by looking after all the little things that needed to be done. The oldest was a girl of thirteen, a kind of Cinderella, who was always in the kitchen, but who was very honest and truthful and loved her Ma.

Besides these there were always a number of refugees in the yard-rooms outside, a woman, perhaps, who had been ill-used by her masters and had run away, or girls broken in body and mind, who had been brought down from the country to be sold as slaves and whom Ma had rescued, or sick people who came from far distances to get the white woman's medicine to be healed.

It was a busy life which Ma lived in and out amongst the huts and villages of the Creek; but she was happy, like all busy people who love their work and are doing good.[Pg 45]

The Landing Beach at Ekenge.

The Landing Beach at Ekenge.

Ma's great adventure: how she went up-river by herself in a canoe and lived in a forest amongst a savage tribe; how she fought their terrible customs and saved many lives; how she built a hut for herself and then a church, and how she took a band of the wild warriors down to the coast and got them to be friends with the people who had always been their sworn enemies.

Ma felt that she was not getting to the heart of things.

Behind that wall of bush, for hundreds of miles inland, lay a vast region of forest and river into which white men had not yet ventured. It was there that the natives lived almost like wild beasts, and where the most terrible crimes against women and children were done without any one lifting a finger to stop them. It was there that the biggest work for Jesus was to be carried on. "If only I could get amongst these people," she said, "and attack their customs at the root; that is where they must be destroyed."[Pg 46]

She dreamed of it night and day, and laid her plans.

One district lying between two rivers behind Creek Town, called Okoyong, was specially noted for its lawless heathenism. The tribe who lived there was strong, proud, warlike, and had become the terror of the whole country. Every man, woman, and child of them went about armed, and even ate and slept with their guns and swords by their side; they roamed about in bands watching the forest paths, and attacked and captured all whom they met, and sold them as slaves or sent them away to be food for the cannibals. They and the people of the coast were sworn enemies.

Ma knew all about them, and was eager to go into their midst to teach them better ways. She pled with the Mission leaders at Duke Town. "I am not afraid," she said; "I am alone now and have nobody to be anxious about me."

But the missionaries shook their heads. "No, no, it is too dangerous," they told her.

And her friends the traders said, "It is a gun-boat they want, Ma, not a missionary."

It was hard for her eager spirit to wait. For fourteen years she had worked in the factory at Dundee, for ten more she had toiled in the towns on the Calabar River, and she was now a grown woman. But God often keeps us at a task far longer than we ourselves think is good for us, for[Pg 47] He knows best, and if we are patient to the end He lets us do even more than we had hoped for. So it was with Mary Slessor. She was at last allowed to go.

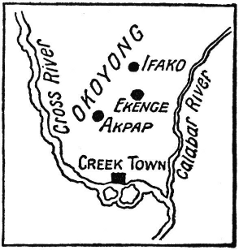

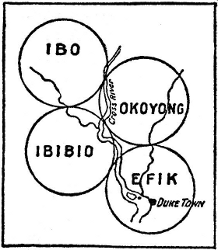

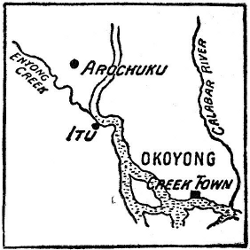

The Okoyong District.

The Okoyong District.

The Okoyong people, however, would not have her.

"We want no missionary, man or woman," they said sullenly.

For a whole year messengers went up and down the river, but the tribe remained firm. Then Ma said:

"I'll go myself and see them."

One hot June day she got the loan of King Eyo's canoe, a hollow tree-trunk twenty feet long, on which there was a little arch of palm leaves to shade her from the sun, and set out up the Calabar River. As she lay back on a pillow she thought how pretty and peaceful the scene was—the calm water gleaming in the light of the sky, the cotton trees and bananas and palms along the banks, the brilliant birds and butterflies flitting about. The only sound was the dip of the paddles and the soft voices of the men singing about their Ma. And[Pg 48] then she thought of what might lie before her, of the perils of the forest, and the anger of the blood-thirsty Okoyong, and wondered if she had done right.

"We'll have a cup of tea, anyhow," she said to herself, and got out an old paraffin stove, but found that matches had been forgotten. Coming to a farm the canoe swung into a mud-beach, and Ma went ashore, and was happy to find that the owner was a "big" man whom she knew. He gave her some matches, and on they went again. When the tea was ready Ma opened a tin of stewed steak and cut up a loaf of home-made bread.

"Boy," she said, "where is the cup?"

"No cup, Ma—forgotten."

"Bother! now what shall I do?"

"I wash out that steak tin, Ma."

"Right; if you use what you have you will never want."

But alas! the tin slipped out of his hand and sank.

Ma was a philosopher. "Ah, well," she said, "it cannot be helped. I'll drink out of the saucer."

Ma was really very timid. Just before leaving Devonshire she would not go out on Guy Fawkes' Day, because she shrank from the crowds who were parading the streets; and yet, here she was going alone into an unknown region in Africa to face untamed savages. What made her so courageous was her faith in God. She believed that He wanted[Pg 49] her to do this bit of work, and that therefore He would take care of her. She would not carry a weapon of any kind. Even David, when he went out to fight Goliath, had a sling and a stone as well as his faith. Ma was going to fight a much bigger giant, and she took nothing with her but a bright face and a heart full of love and sympathy. She was more like Jesus, who faced His enemies with nothing but the power of His spirit.

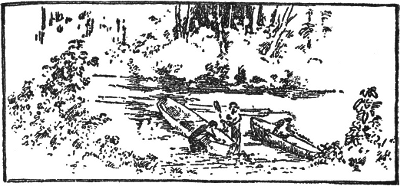

Canoe being made out of a Tree-trunk.

Canoe being made out of a Tree-trunk.

The paddlers landed her at a strip of beach on the river, and with a fast-beating heart she trudged along the forest path for about four miles until she reached a village called Ekenge.

Shouts arose: "Ma has come! Ma has come!" and a crowd rushed forward. To her surprise they seemed pleased to see her. "You are brave to come alone," they said; "that is good."

The chief, who was called Edem, was sober, and he would not allow her to go on farther, because the people at the next village were drunk and might harm her. So she stayed the night at Ekenge.

"I am not very particular about my bed nowadays,"[Pg 50] she told a friend, "but as I lay on a few dirty sticks laid across and across and covered with a litter of dirty corn-shells, with plenty of rats and insects, three women and an infant three days old alongside, and over a dozen goats and sheep and cows and countless dogs outside, you don't wonder that I slept little! But I had such a comfortable quiet night in my own heart."

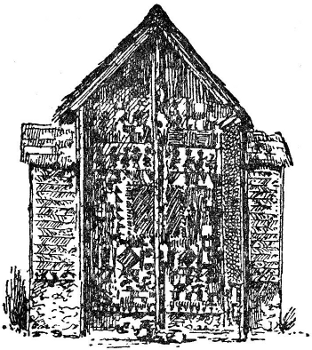

Next day all the big men of the district came to see her, and her winsome ways won them over, and they agreed to give her ground for a church and school, and promised that when these were built they would be places of refuge into which hunted people could fly and be safe.

She was so happy that she did not mind the rain, which came on and wetted her to the skin as she walked back through the forest to the river. The tide, too, was against the paddlers, so they had to put the canoe into a cove and tie it to a tree for two hours. Ma was cold and shivery, and lay watching the brown crabs fighting in the mud, but she dared not sleep in case a crocodile or snake might make an attack. The men kept very quiet, and sometimes she heard them whisper, "Speak softly and let Ma sleep," or "Don't shake the canoe and wake Ma." When they started again she gradually passed into sleep, and only wakened to see the friendly lamps of Creek Town gleaming like stars through the night.[Pg 51]

A month or two later she was ready to go and make her home among the Okoyong. The people of Creek Town were alarmed, and tried to make her give up the idea.

"Do you think any one will listen to you?"

"Do you think they will lay aside their weapons of war for you?"

"We shall never see you again."

"You are sure to be murdered."

Such were some of the things said to her. But she just smiled, and thought how little there was to fear when Jesus was with her.

"I am going," she wrote home, "to a new tribe up-country, a fierce, cruel people, and every one tells me they will kill me. But I don't fear any hurt. Only—to combat their savage customs will require courage and firmness on my part."

The night before she left she could not sleep for thinking and wondering about all that was before her, and lay listening to the dripping of the rain until daylight. When she heard the negro carriers coming for the packages she rose. It was still wet, and the men were miserable and grumbled and quarrelled amongst themselves until good King Eyo arrived and took them in hand. Seeing how nervous she was he sat down beside her and cheered her up, saying that he would send secret messengers from time to time to find out how she was getting on, and that she was to let him know if ever she[Pg 52] needed help. Her courage and smiles came back, and she jumped up, gathered her children together, and walked down to the beach. Amidst the sighs and sobs and farewells of the people she stepped into the canoe.

"Good-bye, good-bye," she cried to every one, and the canoe sped into the middle of the stream and was lost in the mist and the rain.

"Plunged into the Depths of the Forest."

"Plunged into the Depths of the Forest."

It was night when the landing-beach was reached, and the stars were hidden by rain-clouds. As Ma stepped ashore on the mud-bank and looked into the dark forest and thought of the long journey before her, and the end of it, her heart failed. She might lose her way in that unlit tangle of wood. She would meet wild beasts, the natives might be feasting and drinking and unwilling to receive her. A score of shadowy terrors arose in her imagination. For a moment she wished she could turn back to the safe shelter of her home, but when she thought of Jesus and what He had done for her sake, how He was never afraid, but went forward calm and fearless even to His death on the Cross,[Pg 53] she felt ashamed of her weakness, and, calling the children, she plunged stoutly into the black depths of the forest.

What a queer procession it was! The biggest boy, eleven years old, went first with a box of bread and tea and sugar on his head, next a laddie of eight with a kettle and pots, then a wee fellow of three sturdily doing his best, but crying as if his heart would break. Janie followed, also sobbing, and lastly the white mother herself carrying Annie, a baby slave-girl, on her shoulder, and singing gaily to cheer the others, but there was often a funny little break in her voice as she heard the scream of the vampire-bat or the stealthy tread and growling of wild animals close at hand.

Brushing against dripping branches, stumbling in the black and slippery mud, tired and hungry and wretched, they made their way to Ekenge. When they arrived all was quiet, and no one greeted them.

"Strange," said Ma to herself, for a village welcome is always a noisy one. She shouted, and two slaves appeared.

"Where is the chief? Where are the people?" she asked.

"Gone to the death-feast at Ifako, the next village, Ma."

"Then bring me some fire and water."

She made tea for the children, undressed them,[Pg 54] huddled them naked in a corner to sleep, and sat down in her wet things to wait for the carriers, who were bringing the boxes with food and dry clothes. A messenger arrived, but it was to tell her that the men were too worn out to carry anything that night. She jumped to her feet, and, bareheaded and barefooted, dived into the forest to return to the river. She had not gone far when she heard the pitter-patter of feet. She stopped.

"Ma! Ma!" a voice cried. It was the messenger. He loved Ma, and, unhappy at the thought of her tramping along that lonesome trail, he had followed her to keep her company. Together they ran, now tripping and falling, now dashing into a tree, now standing still trembling, as they heard some rushing sound or weird cry.

When she came to the beach she waded out to the canoe, lifted the covering, and roused the sleeping natives. They grumbled a good deal, but even these big rough men could not withstand Ma's coaxing, masterful ways, and they had soon the boxes on their heads and were marching merrily in single file along the wet and dark path to Ekenge. She made them put the packages into the hut which Edem, the chief, had allotted to her, a small, dirty place with mud walls, no window, and only an open space for a door. When everything was piled up inside there was hardly room for herself and the children, but she lay down on the boxes, and as it[Pg 55] was after midnight, and she was weary and foot-sore, she soon fell into a deep sleep.

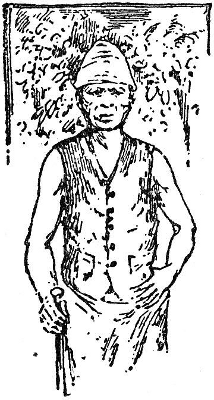

Ma Eme Ete.

Ma Eme Ete.

When the chief and his followers came back from the revels at Ifako they welcomed Ma, for it was an honour for a white woman to live in their midst. But they had no idea of changing their ways of life for her, and went on day and night drinking rum and gin, dancing, and making sacrifices to their jujus or gods. Sometimes the din was so great that Ma never got a wink of sleep. The yard was full of half-naked slave-women, who were always scolding and quarrelling. Some were wicked and hateful, and did not want such a good white Ma to be with them, and tried to force her to leave. But there was one who was kind to her, Eme Ete, a sister of the chief, who had a sad story. One day she told it to Ma. She had been married to a chief who had not treated her well. When he died his followers put the blame on his wives, and they were seized and brought to trial. It was an odd way they had of testing guilt or innocence. As each wife stepped forward the head of a fowl was[Pg 56] cut off, and the people watched to see how the body fell. If it lay in a certain way she was innocent; if in another way, she was guilty! How Eme Ete trembled when her turn came! When she knew she was safe she fainted.

Eme Ete was big in body and big in heart. To Ma she showed herself gentle and refined, and acted towards her as a white lady would, caring for her comfort, watching over her safety, going to her meetings, and helping her in her work. They grew to be like sisters. Yet Eme Ete was always a little bit of a mystery to Ma. She wanted the people to change their old ways, but she herself would not, and went on with her bush-worship and sacrifices, and never became a Christian. But of all the native women Ma ever met, there was none she loved so well as this motherly heathen soul.

In the yard there were also many boys and girls. Ma was fond of children, but these ones were not nice: they stole and lied and made themselves a trouble to everybody. "Oh, dear," she sighed, "what can I do with such bairns?" But she remembered what her Master said, "Suffer little children to come unto Me and forbid them not"; and she gathered them about her, took the wee ones in her arms and nursed them, made clothes for their bodies, and taught them what it was to be clean and sweet and good. When the sick babies died she would not let the people throw them away into[Pg 57] the bush, as they usually did, but put them into little boxes on which she laid some flowers, and buried them in a piece of ground that she chose for a cemetery. "Why, Ma," said the natives in wonder, "what is a dead child? You can have hundreds of them."

None of the children could read or write, nor, indeed, could any of the older people, and so Ma started schools, which she held in the open air in the shade of the forest trees. At first everybody came, even the grey-headed men and women, and learned A B C in Efik and sang the hymns that Ma taught them. The beautiful birds which flew above their heads must have wondered, for they had only been accustomed to the wild chant of war-songs. And at night the twinkling stars must have twinkled harder when they looked down and saw, not a crowd of people drinking and fighting, but a quiet company, and a white woman standing talking to them in grave sweet tones about holy things.

But when Ma spoke about their bad customs they would not listen. "Ma," they would say, "we like you and we want to learn book and wear clothes, but we don't want to put away our old fashions."

"Well," replied Ma patiently, "we shall see."

And so the battle began.

The first time she failed, because she did not know what was happening. A lad had been accused[Pg 58] of some fault, and she saw him standing, girt with chains, holding out his arms before a pot of boiling oil. A man took a ladle and dipped it into the burning stuff, which he began to pour over the boy's hands. Ma sprang forward, but was too late; the boy screamed and rolled on the ground in agony. She was very angry, especially when they told her the meaning of the thing. It was a test to show whether the boy was innocent or guilty of the charge brought against him. If he had not been guilty, they said, he would not have suffered.

"Oh, you stupid creatures," cried Ma. "Everybody will suffer if you do that to them. Let me try it on you," she said to the man with the ladle, but he rushed off amidst the laughter of the crowd.

Next time she did better. A slave was blamed for using witchcraft, and condemned to die. Ma knew he was innocent, and went and stood beside him in front of the armed warriors of the chief, and said:

"This man has done no wrong. You must not put him to death."

"Ho, ho," they cried, "that is not good speaking. We have said he shall die, and he must die."

"No, no; listen," and she tried to reason with them, but they came round her waving their swords and guns, and shouting at the pitch of their voices. She stood in the midst of them as she had stood in the midst of the Dundee roughs, pale, but calm and[Pg 59] unafraid. The more angry and excited and threatening they grew the cooler she became. Perhaps it was her wonderful courage which did not fail her even when the swords were flashing about her head, perhaps it was the strange light that shone in her face that awed and quietened them, but the confusion died down and ceased. Then the chiefs agreed for her sake not to kill the man, but they put heavy chains upon his arms and legs, and starved and flogged him until he was a mass of bleeding flesh. Ma felt she had not done much, but it was a beginning.

People at a distance heard of her, and one day messengers came from a township many miles away to ask her to visit their chief, who was believed to be dying.

"And what will happen if he dies?" asked Ma.

"All his wives and slaves will be killed," was the prompt reply.

"Then I will come at once," she said.

"Ma," put in Chief Edem, "you must not go. They are cruel people and may do you hurt. Then see the rain; all the rivers will be flowing and you cannot cross."