Title: Lost Man's Lane: A Second Episode in the Life of Amelia Butterworth

Author: Anna Katharine Green

Release date: July 31, 2010 [eBook #33305]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A word to my readers before they begin these pages.

As a woman of inborn principle and strict Presbyterian training, I hate deception and cannot abide subterfuge. This is why, after a year or more of hesitation, I have felt myself constrained to put into words the true history of the events surrounding the solution of that great mystery which made Lost Man's Lane the dread of the neighboring country. Feminine delicacy, and a natural shrinking from revealing to the world certain weaknesses on my part, inseparable from a true relation of this tale, led me to consent to the publication of that meagre and decidedly falsified account of the matter which has appeared in some of our leading papers.

But conscience has regained its sway in my breast, and with all due confidence in your forbearance, I herein take my rightful place in these annals, of whose interest and importance I now leave you to judge.

Amelia Butterworth.

Gramercy Park, New York.

BOOK I THE KNOLLYS FAMILY

I.—A VISIT FROM MR. GRYCE

II.—I AM TEMPTED

III.—I SUCCUMB

IV.—A GHOSTLY INTERIOR

V.—A STRANGE HOUSEHOLD

VI.—A SOMBRE EVENING

VII.—THE FIRST NIGHT

VIII.—ON THE STAIRS

IX.—A NEW ACQUAINTANCE

X.—SECRET INSTRUCTIONS

XI.—MEN, WOMEN, AND GHOSTS

XII.—THE PHANTOM COACH

XIII.—GOSSIP

XIV.—I FORGET MY AGE, OR, RATHER, REMEMBER IT

BOOK II THE FLOWER PARLOR

XV.—LUCETTA FULFILS MY EXPECTATION OF HER

XVI.—LOREEN

XVII.—THE FLOWER PARLOR

XVIII.—THE SECOND NIGHT

XIX.—A KNOT OF CRAPE

XX.—QUESTIONS

XXI.—MOTHER JANE

XXII.—THE THIRD NIGHT

BOOK III FORWARD AND BACK

XXIII.—ROOM 3, HOTEL CARTER

XXIV.—THE ENIGMA OF NUMBERS

XXV.—TRIFLES, BUT NOT TRIFLING

XXVI.—A POINT GAINED

XXVII.—THE TEXT WITNESSETH

XXVIII.—AN INTRUSION

XXIX.—IN THE CELLAR

XXX.—INVESTIGATION

XXXI.—STRATEGY

XXXII.—RELIEF

BOOK IV THE BIRDS OF THE AIR

XXXIII.—LUCETTA

XXXIV.—CONDITIONS

XXXV—THE DOVE

XXXVI.—AN HOUR OF STARTLING EXPERIENCES

XXXVII.—I ASTONISH MR. GRYCE AND HE ASTONISHES ME

XXXVIII.—A FEW WORDS

XXXIX.—UNDER A CRIMSON SKY

XL.—EXPLANATIONS

EPILOGUE

WORKS BY Anna Katharine Green

Ever since my fortunate—or shall I say unfortunate?—connection with that famous case of murder in Gramercy Park, I have had it intimated to me by many of my friends—and by some who were not my friends—that no woman who had met with such success as myself in detective work would ever be satisfied with a single display of her powers, and that sooner or later I would find myself again at work upon some other case of striking peculiarities.

As vanity has never been my foible, and as, moreover, I never have forsaken and never am likely to forsake the plain path marked out for my sex, at any other call than that of duty, I invariably responded to these insinuations by an affable but incredulous smile, striving to excuse the presumption of my friends by remembering their ignorance of my nature and the very excellent reasons I had for my one notable interference in the police affairs of New York City.

Besides, though I appeared to be resting quietly, if not in entire contentment, on my laurels, I was not so utterly removed from the old atmosphere of crime and its detection as the world in general considered me to be. Mr. Gryce still visited me; not on business, of course, but as a friend, for whom I had some regard; and naturally our conversation was not always confined to the weather or even to city politics, provocative as the latter subject is of wholesome controversy.

Not that he ever betrayed any of the secrets of his office—oh no; that would have been too much to expect—but he did sometimes mention the outward aspects of some celebrated case, and though I never ventured upon advice—I know too much for that, I hope—I found my wits more or less exercised by a conversation in which he gained much without acknowledging it, and I gave much without appearing conscious of the fact.

I was therefore finding life pleasant and full of interest, when suddenly (I had no right to expect it, and I do not blame myself for not expecting it or for holding my head so high at the prognostications of my friends) an opportunity came for a direct exercise of my detective powers in a line seemingly so laid out for me by Providence that I felt I would be slighting the Powers above if I refused to enter upon it, though now I see that the line was laid out for me by Mr. Gryce, and that I was obeying anything but the call of duty in following it.

But this is not explicit. One night Mr. Gryce came to my house looking older and more feeble than usual. He was engaged in a perplexing case, he said, and missed his early vigor and persistency. Would I like to hear about it? It was not in the line of his usual work, yet it had points—and well!—it would do him good to talk about it to a non-professional who was capable of sympathizing with its baffling and worrisome features and yet would never have to be told to hold her peace.

I ought to have been on my guard. I ought to have known the old fox well enough to feel certain that when he went so manifestly out of his way to take me into his confidence he did it for a purpose. But Jove nods now and then—or so I have been assured on unimpeachable authority,—and if Jove has ever been caught napping, surely Amelia Butterworth may be pardoned a like inconsistency.

"It is not a city crime," Mr. Gryce went on to explain, and here he was base enough to sigh. "At my time of life this is an important consideration. It is no longer a simple matter for me to pack up a valise and go off to some distant village, way up in the mountains perhaps, where comforts are few and secrecy an impossibility. Comforts have become indispensable to my threescore years and ten, and secrecy—well, if ever there was an affair where one needs to go softly, it is this one; as you will see if you will allow me to give you the facts of the case as known at Headquarters to-day."

I bowed, trying not to show my surprise or my extreme satisfaction. Mr. Gryce assumed his most benignant aspect (always a dangerous one with him), and began his story.

"Some ninety miles from here, in a more or less inaccessible region, there is a small but interesting village, which has been the scene of so many unaccountable disappearances that the attention of the New York police has at last been directed to it. The village, which is at least two miles from any railroad, is one of those quiet, placid little spots found now and then among the mountains, where life is simple, and crime, to all appearance, an element so out of accord with every other characteristic of the place as to seem a complete anomaly. Yet crime, or some other hideous mystery almost equally revolting, has during the last five years been accountable for the disappearance in or about this village of four persons of various ages and occupations. Of these, three were strangers and one a well-known vagabond accustomed to tramp the hills and live on the bounty of farmers' wives. All were of the male sex, and in no case has any clue ever come to light as to their fate. That is the matter as it stands before the police to-day."

"A serious affair," I remarked. "Seems to me I have read of such things in novels. Is there a tumbled-down old inn in the vicinity where beds are made up over trap-doors?"

His smile was a mild protest against my flippancy.

"I have visited the town myself. There is no inn there, but a comfortable hotel of the most matter-of-fact sort, kept by the frankest and most open-minded of landlords. Besides, these disappearances, as a rule, did not take place at night, but in broad daylight. Imagine this street at noon. It is a short one, and you know every house on it, and you think you know every lurking-place. You see a man enter it at one end and you expect him to issue from it at the other. But suppose he never does. More than that, suppose he is never heard of again, and that this thing should happen in this one street four times during five years."

"I should move," I dryly responded.

"Would you? Many good people have moved from the place I speak of, but that has not helped matters. The disappearances go on just the same and the mystery continues."

"You interest me," I said. "Come to think of it, if this street were the scene of such an unexplained series of horrors as you have described, I do not think I should move."

"I thought not," he curtly rejoined. "But since you are interested in this matter, let me be more explicit in my statements. The first person whose disappearance was noted——"

"Wait," I interrupted. "Have you a map of the place?"

He smiled, nodded quite affectionately to a little statuette on the mantel-piece, which had had the honor of sharing his confidences in days gone by, but did not produce the map.

"That detail will keep," said he. "Let me go on with my story. As I was saying, madam, the first person whose disappearance was noted in this place was a peddler of small wares, accustomed to tramp the mountains. On this occasion he had been in town longer than usual, and was known to have sold fully half of his goods. Consequently he must have had quite a sum of money upon him. One day his pack was found lying under a cluster of bushes in a wood, but of him nothing was ever again heard. It made an excitement for a few days while the woods were being searched for his body, but, nothing having been discovered, he was forgotten, and everything went on as before, till suddenly public attention was again aroused by the pouring in of letters containing inquiries in regard to a young man who had been sent there from Duluth to collect facts in a law case, and who after a certain date had failed to communicate with his firm or show up at any of the places where he was known. Instantly the village was in arms. Many remembered the young man, and some two or three of the villagers could recall the fact of having seen him go up the street with his hand-bag in his hand as if on his way to the Mountain-station. The landlord of the hotel could fix the very day at which he left his house, but inquiries at the station failed to establish the fact that he took train from there, nor were the most minute inquiries into his fate ever attended by the least result. He was not known to have carried much money, but he carried a very handsome watch and wore a ring of more than ordinary value, neither of which has ever shown up at any pawnbroker's known to the police. This was three years ago.

"The next occurrence of a like character did not take place till a year after. This time it was a poor old man from Hartford, who vanished almost as it were before the eyes of these astounded villagers. He had come to town to get subscriptions for a valuable book issued by a well-known publisher. He had been more or less successful, and was looking very cheerful and contented, when one morning, after making a sale at a certain farmhouse, he sat down to dine with the family, it being close on to noon. He had eaten several mouthfuls and was chatting quite freely, when suddenly they saw him pause, clap his hand to his pocket, and rise up very much disturbed. 'I have left my pocket-book behind me at Deacon Spear's,' he cried. 'I cannot eat with it out of my possession. Excuse me if I go for it.' And without any further apologies, he ran out of the house and down the road in the direction of Deacon Spear's. He never reached Deacon Spear's, nor was he ever seen in that village again or in his home in Hartford. This was the most astonishing mystery of all. Within a half-mile's radius, in a populous country town, this man disappeared as if the road had swallowed him and closed again. It was marvellous, it was incredible, and remained so even after the best efforts of the country police to solve the mystery had exhausted themselves. After this, the town began to acquire a bad name, and one or two families moved away. Yet no one was found who was willing to admit that these various persons had been the victims of foul play till a month later another case came to light of a young man who had left the village for the hillside station, and had never arrived at that or any other destination so far as could be learned. As he was a distant relative of a wealthy cattle owner in Iowa, who came on post-haste to inquire into his nephew's fate, the excitement ran high, and through his efforts and that of one of the town's leading citizens, the services of our office were called into play. But the result has been nil. We have found neither the bodies of these men nor any clue to their fate."

"Yet you have been there?" I suggested.

He nodded.

"Wonderful! And you came upon no suspicious house, no suspicious person?"

The finger with which he was rubbing his eyeglasses went round and round the rims with a slower and slower and still more thoughtful motion.

"Every town has its suspicious-looking houses," he slowly remarked, "and, as for persons, the most honest often wear a lowering look in which an unbridled imagination can see guilt. I never trust to appearances of that kind."

"What else can you trust in, when a case is as impenetrable as this one?" I asked.

His finger, going slower and slower, suddenly stopped.

"In my knowledge of persons," he replied. "In my knowledge of their fears, their hopes, and their individual concerns. If I were twenty years younger"—here he stole a glance at me in the mirror which made me bridle; did he think I was only twenty years younger than himself?—"I would," he went on, "make myself so acquainted with every man, woman, and child there, that—" Here he drew himself up with a jerk. "But the day for that is passed," said he. "I am too old and too crippled to succeed in such an undertaking. Having been there once, I am a marked man. My very walk betrays me. He whose good fortune it will be to get at the bottom of these people's hearts must awaken no suspicions as to his connection with the police. Indeed, I do not think that any man can succeed in doing this now."

I started. This was a frank showing of his hand at least. No man! It was then a woman's aid he was after. I laughed as I thought of it. I had not thought him either so presumptuous or so appreciative of talents of a character so directly in line with his own.

"Don't you agree with me, madam?"

I did agree with him; but I had a character of great dignity to maintain, so I simply surveyed him with an air of well-tempered severity.

"I do not know of any woman who would undertake such a task," I calmly observed.

"No?" he smiled with that air of forbearance which is so exasperating to me. "Well, perhaps there isn't any such woman to be found. It would take one of very uncommon characteristics, I own."

"Pish!" I cried. "Not so very!"

"Indeed, I think you have not fully taken in the case," he urged in quiet superiority. "The people there are of the higher order of country folk. Many of them are of extreme refinement. One family"—here his tone changed a trifle—"is poor enough and cultivated enough to interest even such a woman as yourself."

"Indeed!" I ejaculated, with just a touch of my father's hauteur to hide the stir of curiosity his words naturally evoked.

"It is in some such home," he continued with an ease that should have warned me he had started on this pursuit with a quiet determination to win, "that the clue will be found to the mystery we are considering. Yes, you may well look startled, but that conclusion is the one thing I brought away with me from—X., let us say. I regard it as one of some moment. What do you think of it?"

"Well," I admitted, "it makes me feel like recalling that pish I uttered a few minutes ago. It would take a woman of uncommon characteristics to assist you in this matter."

"I am glad we have got that far," said he.

"A lady," I went on.

"Most assuredly a lady."

I paused. Sometimes discreet silence is more sarcastic than speech.

"Well, what lady would lend herself to this scheme?" I demanded at last.

The tap, tap of his fingers on the rim of his glasses was my only answer.

"I do not know of any," said I.

His eyebrows rose perhaps a hair's-breadth, but I noted the implied sarcasm, and for an instant forgot my dignity.

"Now," said I, "this will not do. You mean me, Amelia Butterworth; a woman who—but I do not think it is necessary to tell you either who or what I am. You have presumed, sir—Now do not put on that look of innocence, and above all do not attempt to deny what is so manifestly in your thoughts, for that would make me feel like showing you the door."

"Then," he smiled, "I shall be sure to deny nothing. I am not anxious to leave—yet. Besides, whom could I mean but you? A lady visiting friends in this remote and beautiful region—what opportunities might she not have to probe this important mystery if, like yourself, she had tact, discretion, excellent understanding, and an experience which if not broad or deep is certainly such as to give her a certain confidence in herself, and an undoubted influence with the man fortunate enough to receive her advice."

"Bah!" I exclaimed. It was one of his favorite expressions. That was perhaps why I used it. "One would think I was a member of your police."

"You flatter us too deeply," was his deferential answer. "Such an honor as that would be beyond our deserts."

To this I gave but the faintest sniff. That he should think that I, Amelia Butterworth, could be amenable to such barefaced flattery! Then I faced him with some asperity, and said bluntly: "You waste your time. I have no more intention of meddling in another affair than——"

"You had in meddling in the first," he politely, too politely, interpolated. "I understand, madam."

I was angry, but made no show of being so. I was not willing he should see that I could be affected by anything he could say.

"The Van Burnams are my next-door neighbors," I remarked sweetly. "I had the best of excuses for the interest I took in their affairs."

"So you had," he acquiesced. "I am glad to be reminded of the fact. I wonder I was able to forget it."

Angry now to the point of not being able to hide it, I turned upon him with firm determination.

"Let us talk of something else," I said.

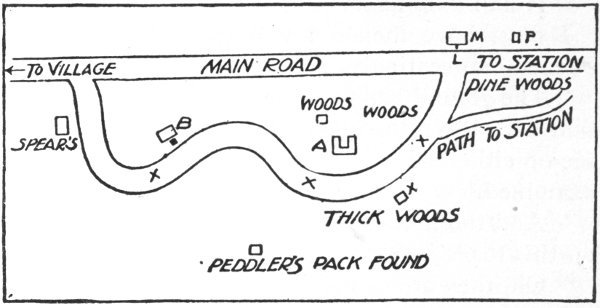

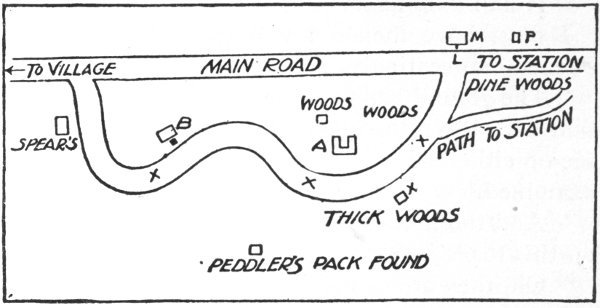

But he was equal to the occasion. Drawing a folded paper from his pocket, he opened it out before my eyes, observing quite naturally: "That is a happy thought. Let us look over this sketch you were sharp enough to ask for a few moments ago. It shows the streets of the village and the places where each of the persons I have mentioned was last seen. Is not that what you wanted?"

I know that I should have drawn back with a frown, that I never should have allowed myself the satisfaction of casting so much as a glance toward the paper, but the human nature which links me to my kind was too much for me, and with an involuntary "Exactly!" I leaned over it with an eagerness I strove hard, even at that exciting moment, to keep within the bounds I thought proper to my position as a non-professional, interested in the matter from curiosity alone.

This is what I saw:

"Mr. Gryce," said I, after a few minutes' close contemplation of this diagram, "I do not suppose you want any opinion from me."

"Madam," he retorted, "it is all you have left me free to ask for."

Receiving this as a permission to speak, I put my finger on the road marked with a cross.

"Then," said I, "so far as I can gather from this drawing, all the disappearances seem to have taken place in or about this especial road."

"You are as correct as usual," he returned. "What you have said is so true, that the people of the vicinity have already given to this winding way a special cognomen of its own. For two years now it has been called Lost Man's Lane."

"Indeed!" I cried. "They have got the matter down as close as that, and yet have not solved its mystery? How long is this road?"

"A half mile or so."

I must have looked my disgust, for his hands opened deprecatingly.

"The ground has undergone a thorough search," said he. "Not a square foot in those woods you see on either side of the road, but has been carefully examined."

"And the houses? I see there are three houses on this road."

"Oh, they are owned by most respectable people—most respectable people," he repeated, with a lingering emphasis that gave me an inward shudder. "I think I had the honor of intimating as much to you a few minutes ago."

I looked at him earnestly, and irresistibly drew a little nearer to him over the diagram.

"Have none of these houses been visited by you?" I asked. "Do you mean to say you have not seen the inside of them all?"

"Oh," he replied, "I have been in them all, of course; but a mystery such as we are investigating is not written upon the walls of parlors or halls."

"You freeze my blood," was my uncharacteristic rejoinder. Somehow the sight of the homes indicated on this diagram seemed to bring me into more intimate sympathy with the affair.

His shrug was significant.

"I told you that this was no vulgar mystery," he declared; "or why should I be considering it with you? It is quite worthy of your interest. Do you see that house marked A?"

"I do," I nodded.

"Well, that is a decayed mansion of imposing proportions, set in a forest of overgrown shrubbery. The ladies who inhabit it——"

"Ladies!" I put in, with a small shock of horror.

"Young ladies," he explained, "of a refined if not over-prosperous appearance. They are the interesting residue of a family of some repute. Their father was a judge, I believe."

"And do they live there alone," I asked,—"two young ladies in a house so large and in a neighborhood so full of mystery?"

"Oh, they have a brother with them, a lout of no great attractions," he responded carelessly—too carelessly, I thought.

I made a note of the house A in my mind.

"And who lives in the house marked B?" I now queried.

"A Mr. Trohm. You will remember that it was through his exertions the services of the New York police were secured. His place there is one of the most interesting in town, and he does not wish to be forced to leave it, but he will be obliged to do so if the road is not soon relieved of its bad name; and so will Deacon Spear. The very children shun the road now. I do not know of a lonelier place."

"I see a little mark made here on the verge of the woods. What does that mean?"

"That stands for a hut—it can hardly be called a cottage—where a poor old woman lives called Mother Jane. She is a harmless imbecile, against whom no one has ever directed a suspicion. You may take your finger off that mark, Miss Butterworth."

I did so, but I did not forget that it stood very near the footpath branching off to the station.

"You entered this hut as well as the big houses?" I intimated.

"And found," was his answer, "four walls; nothing more."

I let my finger travel along the footpath I have just mentioned.

"Steep," was his comment. "Up, up, all the way, but no precipices. Nothing but pine woods on either side, thickly carpeted with needles."

My finger came back and stopped at the house marked M.

"Why is a letter affixed to this spot?" I asked.

"Because it stands at the head of the lane. Any one sitting at the window L can see whoever enters or leaves the lane at this end. And some one is always sitting there. The house contains two crippled children, a boy and a girl. One of them is always in that window."

"I see," said I. Then abruptly: "What do you think of Deacon Spear?"

"Oh, he's a well-meaning man, none too fine in his feelings. He does not mind the neighborhood; likes quiet, he says. I hope you will know him for yourself some day," the detective slyly added.

At this return to the forbidden subject, I held myself very much aloof.

"Your diagram is interesting," I remarked, "but it has not in the least changed my determination. It is you who will return to X., and that, very soon."

"Very soon?" he repeated. "Whoever goes there on this errand must go at once; to-night, if possible; if not, to-morrow at the latest."

"To-night! to-morrow!" I expostulated. "And you thought——"

"No matter what I thought," he sighed. "It seems I had no reason for my hopes." And folding up the map, he slowly rose. "The young man we have left there is doing more harm than good. That is why I say that some one of real ability must replace him immediately. The detective from New York must seem to have left the place."

I made him my most ladylike bow of dismissal.

"I shall watch the papers," I said. "I have no doubt that I shall soon be gratified by seeing in them some token of your success."

He cast a rueful look at his hands, took a painful step toward the door, and dolefully shook his head.

I kept my silence undisturbed.

He took another painful step, then turned.

"By the way," he remarked, as I stood watching him with an uncompromising air, "I have forgotten to mention the name of the town in which these disappearances have occurred. It is called X., and it is to be found on one of the spurs of the Berkshire Hills." And, being by this time at the door, he bowed himself out with all the insinuating suavity which distinguishes him at certain critical moments. The old fox was so sure of his triumph that he did not wait to witness it. He knew—how, it is easy enough for me to understand now—that X. was a place I had often threatened to visit. The family of one of my dearest friends lived there, the children of Althea Knollys. She had been my chum at school, and when she died I had promised myself not to let many months go by without making the acquaintance of her children. Alas! I had allowed years to elapse.

That night the tempter had his own way with me. Without much difficulty he persuaded me that my neglect of Althea Burroughs' children was without any excuse; that what had been my duty toward them when I knew them to be left motherless and alone, had become an imperative demand upon me now that the town in which they lived had become overshadowed by a mystery which could not but affect the comfort and happiness of all its inhabitants. I could not wait a day. I recalled all that I had heard of poor Althea's short and none too happy marriage, and immediately felt such a burning desire to see if her dainty but spirited beauty—how well I remembered it—had been repeated in her daughters, that I found myself packing my trunk before I knew it.

I had not been from home for a long time—all the more reason why I should have a change now—and when I notified Mrs. Randolph and the servants of my intention of leaving on the early morning train, it created quite a sensation in the house.

But I had the best of explanations to offer. I had been thinking of my dead friend, and my conscience would not let me neglect her dear and possibly unhappy progeny any longer. I had purposed many times to visit X., and now I was going to do it. When I come to a decision, it is usually suddenly, and I never rest after having once made up my mind.

My sentiment went so far that I got down an old album and began hunting up the pictures I had brought away with me from boarding-school. Hers was among them, and I really did experience more or less compunction when I saw again the delicate yet daring features which had once had a very great influence over my mind. What a teasing sprite she was, yet what a will she had, and how strange it was that, having been so intimate as girls, we never knew anything of each other as women! Had it been her fault or mine? Was her marriage to blame for it or my spinsterhood? Difficult to tell then, impossible to tell now. I would not even think of it again, save as a warning. Nothing must stand between me and her children now that my attention has been called to them again.

I did not mean to take them by surprise—that is, not entirely. The invitation which they had sent me years ago was still in force, making it simply necessary for me to telegraph them that I had decided to make them a visit, and that they might expect me by the noon train. If in times gone by they had been properly instructed by their mother in regard to the character of her old friend, this need not put them out. I am not a woman of unbounded expectations. I do not look for the comforts abroad I am accustomed to find at home, and if, as I have reason to believe, their means are not of the greatest, they would only provoke me by any show of effort to make me feel at home in the humble cottage suited to their fortunes.

So the telegram was sent, and my preparations completed for an early departure.

But, resolved as I was to make this visit, my determination came near receiving a check. Just as I was leaving the house—at the very moment, in fact, when the hackman was carrying out my trunk, I perceived a man approaching me with every evidence of haste. He had a letter in his hand, which he held out to me as soon as he came within reach.

"For Miss Butterworth," he announced. "Private and immediate."

"Ah," thought I, "a communication from Mr. Gryce," and hesitated for a moment whether to open it on the spot or to wait and read it at my leisure on the cars. The latter course promised me less inconvenience than the first, for my hands were cumbered with the various small articles I consider indispensable to the comfortable enjoyment of the shortest journey, and the glasses without which I cannot read a word, were in the very bottom of my pocket under many other equally necessary articles.

But something in the man's expectant look warned me that he would never leave me till I had read the note, so with a sigh I called Lena to my aid, and after several vain attempts to reach my glasses, succeeded at last in pulling them out, and by their help reading the following hurried lines:

"Dear Madam:

"I send you this by a swifter messenger than myself. Do not let anything that I may have said last night influence you to leave your comfortable home. The adventure offers too many dangers for a woman. Read the inclosed. G."

The inclosed was a telegram from X., sent during the night, and evidently just received at Headquarters. Its contents were certainly not reassuring:

"Another person missing. Last seen in Lost Man's Lane. A harmless lad known as Silly Rufus. What's to be done? Wire orders. Trohm."

"Mr. Gryce bade me say that he would be up here some time before noon," said the man, seeing me look with some blankness at these words.

Nothing more was needed to restore my self-possession. Folding up the letter, I put it in my bag.

"Say to Mr. Gryce from me that my intended visit cannot be postponed," I replied. "I have telegraphed to my friends to expect me, and only a great emergency would lead me to disappoint them. I will be glad to receive Mr. Gryce on my return." And without further parley, I took my bundles back from Lena, and proceeded at once to the carriage. Why should I show any failure of courage at an event that was but a repetition of the very ones which made my visit necessary? Was I a likely person to fall victim to a mystery to which my eyes had been opened? Had I not been sufficiently warned of the dangers of Lost Man's Lane to keep myself at a respectable distance from the place of peril? I was going to visit the children of my once devoted friend. If there were perils of no ordinary nature to be encountered in so doing, was I not all the more called upon to lend them the support of my presence?

Yes, Mr. Gryce, and nothing now should hold me back. I even felt an increased desire to reach the scene of these mysteries, and chafed some at the length of the journey, which was of a more tedious character than I expected. A poor beginning for events requiring patience as well as great moral courage; but I little knew what was before me, and only considered that every moment spent on this hot and dusty train kept me thus much longer from the embraces of Althea's children.

I recovered my equanimity, however, as we approached X. The scenery was really beautiful, and the consciousness that I should soon alight at the mountain station which had played a more or less serious part in Mr. Gryce's narrative, awakened in me a pleasurable excitement which should have been a sufficient warning to me that the spirit of investigation which had led me so triumphantly through that affair next door had seized me again in a way that meant equal absorption if not equal success.

The number of small packages I carried gave me enough to think of at the moment of alighting, but as soon as I was safely again on terra firma I threw a hasty glance around to see if any of Althea's children were on hand to meet me.

I felt that I ought to know them at first glance. Their mother had been so characteristically pretty, she could not have failed to transmit some of her most charming traits to her offspring. But while there were two or three country maidens to be seen standing in and around the little pavilion known here as the Mountain-station, I saw no one who by any stretch of imagination could be regarded as of Althea Burroughs' blood or breeding.

Somewhat disappointed, for I had expected different results from my telegram, I stepped up to the station-master, and asked him whether I would have any difficulty in procuring a carriage to take me to Miss Knollys' house. He stared, it seemed to me, unnecessarily long, before replying.

"Waal," said he, "Simmons is usually here, but I don't see him around to-day. Perhaps some of these farmer lads will drive you in."

But they all drew back with a scared look, and I was beginning to tuck up my skirts preparatory to walking, when a little old man of exceedingly meek appearance drove up in a very old-fashioned coach, and with a hesitating air, springing entirely from bashfulness, managed to ask if I was Miss Butterworth. I hastened to assure him that I was that lady, whereupon he stammered out some words about Miss Knollys, and how sorry she was that she could not come for me herself. Then he pointed to his coach, and made me understand that I was to step into it and go with him.

This I had not counted upon doing, for I desired to both see and hear as much as possible before reaching my destination. There was but one way out of it. To his astonishment, I insisted that my belongings be put inside the coach, while I rode on the box.

It was an inauspicious beginning to a very doubtful adventure. I understood this when I saw the heads of the various onlookers draw together and many curious looks directed at both us and the conveyance that was to carry us. But I was in no mood to be daunted now, and mounting to the box with what grace I could, prepared myself for a ride into town.

But it seems I was not to be allowed to leave the spot without another warning. While the old man was engaged in fetching my trunk, the station-master approached me with great civility, and asked if it was my intention to spend a few days with the Misses Knollys. I told him that it was, and thinking it best to establish my position at once in the eyes of the whole town, added with a politeness equal to his own, that I was an old friend of the family, and had been coming to visit them for years, but had never found it convenient till now, and that I hoped they were all well and would be glad to see me.

His reply showed considerable embarrassment.

"Perhaps you have not heard that this village is under a cloud just now?"

"I have heard that one or two men have disappeared from here somewhat mysteriously," I returned. "Is that what you mean?"

"Yes, ma'am. One person, a boy, disappeared only two days ago."

"That's bad," I said. "But what has it to do with me?" I smilingly added, for I saw that he was not at the end of his talk.

"Oh, nothing," he eagerly replied, "only I didn't know but you might be timid——"

"Oh, I'm not at all timid," I hastened to interject. "If I were, I should not have come here at all. Such matters don't affect me." And I spread out my skirts and arranged myself for my ride with as much care and precision as if the horrors he had mentioned had made no more impression upon me than if his chat had been of the weather.

Perhaps I overdid it, for he looked at me for another moment in a curious, lingering way; then he walked off, and I saw him enter the circle of gossips on the platform, where he stood shaking his head as long as we were within sight.

My companion, who was the shyest man I ever saw, did not speak a word while we were descending the hill. I talked, and endeavored to make him follow my example, but his replies were mere grunts or half-syllables which conveyed no information whatever. As we cleared the thicket, however, he allowed himself an ejaculation or two as he pointed out the beauties of the landscape. And indeed it was well worth his admiration and mine had my mind been free to enjoy it. But the houses, which now began to appear on either side of the way, drew my attention from the mountains. Though still somewhat remote from the town, we were rapidly approaching the head of that lane of evil fame with whose awe-inspiring history my thoughts were at this time full. I was so anxious not to pass it without one look into its grewsome recesses that I kept my head persistently turned that way till I felt I was attracting the attention of my companion. As this was not desirable, I put on a nonchalant look and began chatting about what I saw. But he had lapsed into his early silence, and seemed wholly engrossed in his attempt to remove with the butt-end of his whip a bit of rag which had somehow become entangled in the spokes of one of the front wheels. The furtive look he cast me as he succeeded in doing this struck me oddly at the moment, but it was too small a matter to hold my attention long or to cause any cessation in the flow of small talk with which I was endeavoring to enliven the situation.

My desire for conversation lagged, however, as I saw rising up before us the dark boughs of a pine thicket. We were nearing Lost Man's Lane; we were abreast of it; we were—yes, we were turning into it!

I could not repress an exclamation of dismay.

"Where are we going?" I asked.

"To Miss Knollys' house," he found words to say, with a sidelong glance at me full of uneasy inquiry.

"Do they live on this road?" I cried, remembering with a certain shock Mr. Gryce's suspicious description of the two young ladies who with their brother inhabited the dilapidated mansion marked A in the map he had shown me.

"Where else?" was his laconic answer; and, obliged to be satisfied with this curtest of curt replies, I drew myself up with just one longing look behind me at the cheerful highway we were so rapidly leaving. A cottage, with an open window, in which a child's head could be seen nodding eagerly toward me, met my eyes and filled me with quite an odd sense of discomfort as I realized that I had caught the attention of one of the little cripples who, according to Mr. Gryce, always kept watch over this entrance into Lost Man's Lane. Another moment and the pine branches had shut the vision out, but I did not soon forget that eager, childish face and pointing hand, marking me out as a possible victim to the horrors of this ill-reputed lane. But I was aware of no secret flinching from the adventure into which I was plunging. On the contrary, I felt a strange and fierce delight in thus being thrust into the very heart of the mystery I had only expected to approach by degrees. The warning message sent me by Mr. Gryce had acquired a deeper and more significant meaning, as did the looks which had been cast me by the station-master and his gossips on the hillside, but in my present mood these very tokens of the serious nature of my undertaking only gave an added spur to my courage. I felt my brain clear and my heart expand, as if at this moment, before I had so much as set eyes on the faces of these young people, I recognized the fact that they were the victims of a web of circumstances so tragic and incomprehensible that only a woman like myself would be able to dissipate them and restore these girls to the confidence of the people around them.

I forgot that these girls had a brother and that—But not a word to forestall the truth. I wish this story to grow upon you just as it did upon me, and with just as little preparation.

The farmer who drove me, and who I afterwards learned was called Simsbury, showed a certain dogged interest in my behavior that would have amused me, or, at least, have awakened my disdain under circumstances of a less thrilling nature. I saw his eye roll in a sort of wonder over my person, which may have been held a little more stiffly than was necessary, and settle finally on my face, with a look I might have thought complimentary had I had any thought to bestow on such matters. Not till we had passed the path branching up through the woods toward the mountain did he see fit to withdraw it, nor did I fail to find it fixed again upon me as we rode by the little hut occupied by the old woman considered so harmless by Mr. Gryce.

Perhaps he had a reason for this, as I was very much interested in this hut and its occupant, about whom I felt free to cherish my own secret doubts—so interested that I cast it a very sharp glance, and was glad when I caught a glimpse through the doorway of the old crone mumbling over a piece of bread she was engaged in eating as we passed her.

"That's Mother Jane," explained my companion, breaking the silence of many minutes. "And yonder is Miss Knollys' house," he added, lifting his whip and pointing toward the half-concealed façade of a large and pretentious dwelling a few rods farther on down the road. "She will be powerful glad to see you, Miss. Company is scarce in these parts."

Astonished at this sudden launch into conversation by one whose reserve I had hitherto found it impossible to penetrate, I gave him the affable answer he evidently expected, and then looked eagerly toward the house. It was as Mr. Gryce had intimated, exceedingly forbidding even at that distance, and as we approached nearer and I was given a full view of its worn and discolored front, I felt myself forced to acknowledge that never in my life had my eyes fallen upon a habitation more given over to neglect or less promising in its hospitality.

Had it not been for the thin circle of smoke eddying up from one of its broken chimneys, I would have looked upon the place as one which had not known the care or presence of man for years. There was a riot of shrubbery in the yard, a lack of the commonest attention to order in the way the vines drooped in tangled masses over the face of the desolate porch, that gave to the broken pilasters and decayed window-frames of this dreariest of façades that look of abandonment which only becomes picturesque when nature has usurped the prerogative of man and taken entirely to herself the empty walls and falling casements of what was once a human dwelling. That any one should be living in it now and that I, who have never been able to see a chair standing crooked or a curtain awry, without a sensation of the keenest discomfort, should be on the point of deliberately entering its doors as an inmate, filled me at the moment with such a sense of unreality, that I descended from the carriage in a sort of a dream and was making my way through one of the gaps in the high antique fence that separated the yard from the gateway, when Mr. Simsbury stopped me and pointed out the gate.

I did not think it worth while to apologize for my mistake, for the broken palings certainly offered as good an entrance as the gate, which had slipped from its hinges and hung but a few inches open. But I took the course he indicated, holding up my skirts, and treading gingerly for fear of the snails and toads that incumbered such portions of the path as the weeds had left visible. As I proceeded on my way, something in the silence of the spot struck me. Was I becoming over-sensitive to impressions or was there something really uncanny in the absolute lack of sound or movement in a dwelling of such dimensions? But I should not have said movement, for at that instant I saw a flash in one of the upper windows as of a curtain being stealthily drawn and as stealthily let fall again, and though it gave me the promise of some sort of greeting, there was a furtiveness in the action, so in keeping with the suspicions of Mr. Gryce that I felt my nerves braced at once to mount the half-dozen uninviting-looking steps that led to the front door.

But no sooner had I done this, with what I am fain to consider my best air, than I suddenly collapsed with what I am bound to regard as a comprehensible and quite excusable fear; for, while I do not quail before men, and have a reasonable fortitude in the presence of most dangers, corporeal and moral, I am not quite myself in face of a rampant and barking dog. It is my one weakness, and while I usually can, and under most circumstances do, succeed in hiding my inner trepidation under the emergency just mentioned, I always feel that it would be a happy relief for me if the day should ever come when these so-called domestic animals would be banished from the affections and homes of men. Then I think I would begin to live in good earnest and perhaps enjoy trips into the country, which now, for all my apparent bravery, I regard more in the light of a penance than a pleasure.

Imagine, then, how hard I found it to retain my self-possession or even any appearance of dignity, when at the moment I was stretching forth my hand toward the knocker of this inhospitable mansion I heard rising from some unknown quarter a howl so keen, piercing, and prolonged that it frightened the very birds over my head and sent them flying from the vines in clouds.

It was the unhappiest kind of welcome for me. I did not know whether it came from within or without, and when after a moment of indecision I saw the door open, I am not sure whether the smile I called up to grace the occasion had any of the real Amelia Butterworth in it, so much was my mind divided between a desire to produce a favorable impression and a very decided and not-to-be-hidden fear of the dog who had greeted my arrival with such an ominous howl.

"Call off the dog!" I cried almost before I saw what sort of person I was addressing.

Mr. Gryce, when I saw him later, declared this to be the most significant introduction I could have made of myself upon entering the Knollys mansion.

The hall into which I had stepped was so dark that for a few minutes I could see nothing but the indistinct outline of a young woman with a very white face. She had uttered some sort of murmur at my words, but for some reason was strangely silent, and, if I could trust my eyes, seemed rather to be looking back over her shoulder than into the face of her advancing guest. This was odd, but before I could quite satisfy myself as to the cause of her abstraction, she suddenly bethought herself, and throwing open the door of an adjoining room, let in a stream of light by which we were enabled to see each other and exchange the greetings suitable to the occasion.

"Miss Butterworth, my mother's old friend," she murmured, with an almost pitiful effort to be cordial, "we are so glad to have you visit us. Won't you—won't you sit down?"

What did it mean? She had pointed to a chair in the sitting-room, but her face was turned away again as if drawn irresistibly toward some secret object of dread. Was there anyone or anything at the top of the dim staircase I could faintly see in the distance? It would not do for me to ask, nor was it wise for me to show that I thought this reception a strange one. Stepping into the room she pointed out, I waited for her to follow me, which she did with manifest reluctance. But when she was once out of the atmosphere of the hall, or out of reach of the sight or sound of whatever it was that frightened her, her face took on a smile that ingratiated her with me at once and gave to her very delicate aspect, which up to that moment had not suggested the remotest likeness to her mother, a piquant charm and subtle fascination that were not unworthy of the daughter of Althea Burroughs.

"You must not mind the poverty of your welcome," she said, with a half-proud, half-apologetic look around her, which I must say the bareness and shabby character of the room we were in fully justified. "We have not been very well off since father died and mother left us. Had you given us a chance we should have written you that our home would not offer many inducements to you after your own, but you have come unexpectedly and——"

"There, there," I put in, for I saw that her embarrassment would soon get the better of her, "do not speak of it. I did not come to enjoy your home, but to see you. Are you the eldest, my dear, and where are your sister and brother?"

"I am not the eldest," she said. "I am Lucetta. My sister"—here her head stole irresistibly back to its old position of listening—"will—will come soon. My brother is not in the house."

"Well," said I, astonished that she did not ask me to take off my things, "you are a pretty girl, but you do not look very strong. Are you quite well, my dear?"

She started, looked at me eagerly, almost anxiously, for a moment, then straightened herself and began to lose some of her abstraction.

"I am not a strong person," she smiled, "but neither am I so very weak either. I was always small. So was my mother, you know."

I was glad to have her talk of her mother. I therefore answered her in a way to prolong the conversation.

"Yes, your mother was small," I admitted, "but never thin or pallid. She was like a fairy among us schoolgirls. Does it seem odd to hear so old a woman as I speak of herself as a schoolgirl?"

"Oh, no!" she said, but there was no heart in her voice.

"I had almost forgotten those days till I happened to hear the name of Althea mentioned the other day," I proceeded, seeing I must keep up the conversation if we were not to sit in total silence. "Then my early friendship with your mother recurred to me, and I started up—as I always do when I come to any decision, my dear—and sent that telegram, which I hope I have not followed by an unwelcome presence."

"Oh, no," she repeated, but this time with some feeling; "we need friends, and if you will overlook our shortcomings—But you have not taken off your hat. What will Loreen say to me?"

And with a sudden nervous action as marked as her late listlessness, she jumped up and began busying herself over me, untying my bonnet and laying aside my bundles, which up to this moment I had held in my hands.

"I—I am so absent-minded," she murmured. "I—I did not think—I hope you will excuse me. Loreen would have given you a much better welcome."

"Then Loreen should have been here," I said, with a smile. I could not restrain this slight rebuke, yet I liked the girl; notwithstanding everything I had heard and her own odd and unaccountable behavior, there was a sweetness in her face, when she chose to smile, that proved an irresistible attraction. And then, for all her absent-mindedness and abstracted ways, she was such a lady! Her plain dress, her restrained manner, could not hide this fact. It was apparent in every line of her thin but graceful form and in every inflection of her musical but constrained voice. Had I seen her in my own parlor instead of between these bare and moldering walls, I should have said the same thing: "She is such a lady!" But this only passed through my mind at the time. I was not studying her personality, but trying to understand why my presence in the house had so visibly disturbed her. Was it the embarrassment of poverty, not knowing how to meet the call made so suddenly upon it? I hardly thought so. Fear would not enter into a sensation of this kind, and fear was what I had seen in her face before the front door had closed upon me. But that fear? Was it connected with me or with something threatening her from another portion of the house?

The latter supposition seemed the probable one. The way her ear was turned, the slight start she gave at every sound, convinced me that her cause of dread lay elsewhere than with myself, and therefore was worthy of my closest attention. Though I chatted and tried in every way to arouse her confidence, I could not help asking myself between the sentences, if the cause of her apprehension lay with her sister, her brother, or in something entirely apart from either, and connected with the dreadful matter which had drawn me to X. Or another supposition still, was it merely the sign of an habitual distemper which, misunderstood by Mr. Gryce, had given rise to the suspicions which it was my possible mission here to dispel?

Anxious to force things a little, I remarked, with a glance at the dismal branches that almost forced their way into the open casements: "What a scene for young eyes like yours! Do you never get tired of these pine-boughs and clustering shadows? Would not a little cottage in the sunnier part of the town be preferable to all this dreary grandeur?"

She looked up with sudden wistfulness that made her smile piteous.

"Some of my happiest days have been passed here and some of my saddest. I do not think I should like to leave it for any sunny cottage. We were not made for bonny homes," she continued. "The sombreness of this old house suits us."

"And of this road," I ventured. "It is the darkest and most picturesque I ever rode through. I thought I was threading a wilderness."

For a moment she forgot her cause of anxiety and looked at me quite intently, while a subtle shade of doubt passed slowly over her features.

"It is a solitary one," she acquiesced. "I do not wonder it struck you as dismal. Have you heard—has any one ever told you that—that it was not considered quite safe?"

"Safe?" I repeated, with—God forgive me!—an expression of mild wonder in my eyes.

"Yes, it has not the best of reputations. Strange things have happened in it. I thought that some one might have been kind enough to tell you this at the station."

There was a gentle sort of sarcasm in the tone; only that, or so it seemed to me at the time. I began to feel myself in a maze.

"Somebody—I suppose it was the station-master—did say something to me about a boy lost somewhere in this portion of the woods. Do you mean that, my dear?"

She nodded, glancing again over her shoulder and partly rising as if moved by some instinct of flight.

"They are dark enough, for more than one person to have been lost in their recesses," I observed with another look toward the heavily curtained windows.

"They certainly are," she assented, reseating herself and eying me nervously while she spoke. "We are used to the terrors they inspire in strangers, but if you"—she leaped to her feet in manifest eagerness and her whole face changed in a way she little realized herself—"if you have any fear of sleeping amid such gloomy surroundings, we can procure you a room in the village where you will be more comfortable, and where we can visit you almost as well as we can here. Shall I do it? Shall I call——"

My face must have assumed a very grim look, for her words tripped at that point, and a flush, the first I had seen on her cheek, suffused her face, giving her an appearance of great distress.

"Oh, I wish Loreen would come! I am not at all happy in my suggestions," she said, with a deprecatory twitch of her lip that was one of her subtle charms. "Oh, there she is! Now I may go," she cried; and without the least appearance of realizing that she had said anything out of place, she rushed from the room almost before her sister had entered it.

But not before their eyes had met in a look of unusual significance.

Had I not surprised this look of mutual understanding, I might have received an impression of Miss Knollys which would in a measure have counteracted that made by the more nervous and less restrained Lucetta. The dignified reserve of her bearing, the quiet way in which she approached, and, above all, the even tones in which she uttered her welcome, were such as to win my confidence and put me at my ease in the house of which she was the nominal mistress. But that look! With that in my memory, I was enabled to pierce below the surface of this placid nature, and in the very constraint she put upon herself, detect the presence of the same secret uneasiness which had been so openly, if unconsciously, manifested by her sister.

She was more beautiful than Lucetta in form and feature, and even more markedly elegant in her plain black gown and fine lawn ruffles, but she lacked her sister's evanescent charm, and though admirable to all appearance, was less lovable on a short acquaintance.

But this delays my tale, which is one of action rather than reflection. I had naturally expected that with the appearance of the elder Miss Knollys I should be taken to my room; but, on the contrary, she sat down and with an apologetic air informed me that she was sorry she could not show me the customary attentions. Circumstances over which she had no control had made it impossible, she said, for her to offer me the guest-chamber, but if I would be so good as to accept another for this one night, she would endeavor to provide me with better accommodations on the morrow.

Satisfied of the almost painful nature of their poverty and determined to submit to privations rather than leave a house so imbued with mystery, I hastened to assure her that any room would be acceptable to me; and with a display of good feeling not wholly insincere, began to gather up my wraps in anticipation of being taken at once up-stairs.

But Miss Knollys again surprised me by saying that my room was not yet ready; that they had not been able to complete all their arrangements, and begged me to make myself at home in the room where I was till evening.

As this was asking a good deal of a woman of my years, fresh from a railroad journey and with natural habits of great neatness and order, I felt somewhat disconcerted, but hiding my feelings in consideration of reasons before given, replaced my bundles on the table and endeavored to make the best of a somewhat trying situation.

Launching at once into conversation, I began, as with Lucetta, to talk about her mother. I had never known, save in the vaguest way, why Mrs. Knollys had taken the journey which had ended in her death and burial in a foreign land. Rumor had it that she had gone abroad for her health which had begun to fail after the birth of Lucetta; but as Rumor had not added why she had gone unaccompanied by her husband or children, there remained much which these girls might willingly tell me, which would be of the greatest interest to me. But Miss Knollys, intentionally or unintentionally, assumed an air so cold at my well meant questions, that I desisted from pressing them, and began to talk about myself in a way which I hoped would establish really friendly relations between us and make it possible for her to tell me later, if not at the present moment, what it was that weighed so heavily upon the household, that no one could enter this home without feeling the shadow of the secret terror enveloping it.

But Miss Knollys, while more attentive to my remarks than her sister had been, showed, by certain unmistakable signs, that her heart and interest were anywhere but in that room; and while I could not regard this as throwing any discredit upon my powers of pleasing—which have rarely failed when I have exerted them to their utmost,—I still could not but experience the dampening effect of her manner. I went on chatting, but in a desultory way, noting all that was odd in her unaccountable reception of me, but giving, as I firmly believe, no evidence of my concern and rapidly increasing curiosity.

The peculiarities observable in this my first interview with these interesting but by no means easily-to-be-understood sisters continued all day. When one sister came in, the other stepped out, and when dinner was announced and I was ushered down the bare and dismal hall into an equally bare and unattractive dining-room, it was to find the chairs set for four, and Lucetta only seated at the table.

"Where is Loreen?" I asked wonderingly, as I took the seat she pointed out to me with one of her faint and quickly vanishing smiles.

"She cannot come at present," my young hostess stammered with an unmistakable glance of distress at the large, hearty-looking woman who had summoned me to the dining-room.

"Ah," I ejaculated, thinking that possibly Loreen had found it necessary to assist in the preparation of the meal, "and your brother?"

It was the first time he had been mentioned since my first inquiries. I had shrunk from the venture out of a motive of pure compassion, and they had not seen fit to introduce his name into any of our conversations. Consequently I awaited her response, with some anxiety, having a secret premonition that in some way he was at the bottom of my strange reception.

Her hasty answer, given, however, without any increase of embarrassment, somewhat dispelled this supposition.

"Oh, he will be in presently," said she. "William is never very punctual."

But when he did come in, I could not help seeing that her manner instantly changed and became almost painfully anxious. Though it was my first meeting with the real head of the house, she waited for an interchange of looks with him before giving me the necessary introduction, and when, this duty performed, he took his seat at the table, her thoughts and attention remained so fixed upon him that she well-nigh forgot the ordinary civilities of a hostess. Had it not been for the woman I have spoken of, who in her good-natured attention to my wants amply made up for the abstraction of her mistress, I should have fared ill at this meal, good and ample as it was, considering the resources of those who provided it.

She seemed to dread to have him speak, almost to have him move. She watched him with her lips half open, ready, as it appeared, to stop any inadvertent expression he might utter in his efforts to be agreeable. She even kept her left hand disengaged, with the evident intention of stretching it out in his direction if in his lumbering stupidity he should utter a sentence calculated to open my eyes to what she so passionately desired to have kept secret. I saw it all as plainly as I saw his heavy indifference to her anxiety; and knowing from experience that it is in just such stolid louts as these that the worst passions are often hidden, I took advantage of my years and forced a conversation in which I hoped some flash of his real self would appear, despite her wary watch upon him.

Not liking to renew the topic of the lane itself, I asked with a very natural show of interest, who was their nearest neighbor. It was William who looked up and William who answered.

"Old Mother Jane is the nearest," said he; "but she's no good. We never think of her. Mr. Trohm is the only neighbor I care for. Such peaches as the old fellow raises! Such grapes! Such melons! He gave me two of the nicest you ever saw this morning. By Jupiter, I taste them yet!"

Lucetta's face, which should have crimsoned with mortification, turned most unaccountably pale. Yet not so pale as it had previously done when, a few minutes before, he began to say, "Loreen wants some of this soup saved for"—and stopped awkwardly, conscious perhaps that Loreen's wants should not be mentioned before me.

"I thought you promised me that you would never again ask Mr. Trohm for any of his fruit," remonstrated Lucetta.

"Oh, I didn't ask! I just stood at the fence and looked over. Mr. Trohm and I are good friends. Why shouldn't I eat his fruit?"

The look she gave him might have moved a stone, but he seemed perfectly impervious to it. Seeing him so stolid, her head drooped, and she did not answer a word. Yet somehow I felt that even while she was so manifestly a prey to the deepest mortification, her attention was not wholly given over to this one emotion. There was something else she feared. Hoping to relieve her and lighten the situation, I forced myself to smile on the young man as I said:

"Why don't you raise melons yourself? I think if I possessed your land I should be anxious to raise everything I could on it."

"Oh, you're a woman!" he retorted, almost roughly. "It's good business for women; and for men, too, perhaps, who love to see fruit hang, but I only care to eat it."

"Don't," Lucetta put in, but not with the vigor I had expected.

"I like to hunt, train dogs, and enjoy other people's fruit," he laughed, with a nod at the blushing Lucetta. "I don't see any use in a man's putting himself out for things he can get for the asking. Life's too short for such folly. I mean to have a good time while I'm on this blessed sphere."

"William!"

The cry was irresistible, yet it was not the cry I had been looking for. Painful as was this exhibition of his stupidity and utter want of feeling, it was not the one thing she stood in dread of, or why was her protest so much weaker than her appearance had given token of?

"Oh!" he shouted in great amusement, while she shrunk back with a horrified look. "Lucetta don't like to hear me say that. She thinks a man ought to work, plow, harrow, dig, make a slave of himself, to keep up a place that's no good anyway. But I tell her that work is something she'll never get out of me. I was born a gentleman, and a gentleman I will live if the place tumbles down over our heads. Perhaps it would be the best way to get rid of it. Then I could go live with Mr. Trohm, and have melons from early morn till late at night." And again his coarse laugh rang out.

This, or was it his words, seemed to rouse her as nothing had done before. Thrusting out her hand, she laid it on his mouth, with a look of almost frenzied appeal at the woman who was standing at his back.

"Mr. William, how can you!" that woman protested; and when he would have turned upon her angrily, she leaned over and whispered in his ear a few words that seemed to cow him, for he gave a short grunt through his sister's trembling fingers and, with a shrug of his heavy shoulders, subsided into silence.

To all this I was a simple spectator, but I did not soon forget a single feature of the scene.

The remainder of the dinner passed quietly, William and myself eating with more or less heartiness, Lucetta tasting nothing at all. In mercy to her I declined coffee, and as soon as William gave token of being satisfied, we hurriedly rose. It was the most uncomfortable meal I ever ate in my life.

The evening, like the afternoon, was spent in the sitting-room with one of the sisters. One event alone is worth recording. I had become excessively tired of a conversation that always languished, no matter on what topic it started, and, observing an old piano in one corner—I once played very well—I sat down before it and impulsively struck a few chords from the yellow keys. Instantly Lucetta—it was Lucetta who was with me then—bounded to my side with a look of horror.

"Don't do that!" she cried, laying her hand on mine to stop me. Then, seeing my look of dignified astonishment, she added with an appealing smile, "I beg pardon, but every sound goes through me to-night."

"Are you not well?" I asked.

"I am never very well," she returned, and we went back to the sofa and renewed our forced and pitiful attempts at conversation.

Promptly at nine o'clock Miss Knollys came in. She was very pale and cast, as usual, a sad and uneasy look at her sister before she spoke to me. Immediately Lucetta rose, and, becoming very pale herself, was hurrying toward the door when her sister stopped her.

"You have forgotten," she said, "to say good-night to our guest."

Instantly Lucetta turned, and, with a sudden, uncontrollable impulse, seized my hand and pressed it convulsively.

"Good-night," she cried. "I hope you will sleep well," and was gone before I could say a word in response.

"Why does Lucetta go out of the room when you come in?" I asked, determined to know the reason for this peculiar conduct. "Have you any other guests in the house?"

The reply came with unexpected vehemence. "No," she cried, "why should you think so? There is no one here but the family." And she turned away with a dignity she must have inherited from her father, for Althea Burroughs had every interesting quality but that. "You must be very tired," she remarked. "If you please we will go now to your room."

I rose at once, glad of the prospect of seeing the upper portion of the house. She took my wraps on her arm, and we passed immediately into the hall. As we did so, I heard voices, one of them shrill and full of distress; but the sound was so quickly smothered by a closing door that I failed to discover whether this tone of suffering proceeded from a man or a woman.

Miss Knollys, who was preceding me, glanced back in some alarm, but as I gave no token of having noticed anything out of the ordinary, she speedily resumed her way up-stairs. As the sounds I had heard proceeded from above, I followed her with alacrity, but felt my enthusiasm diminish somewhat when I found myself passing door after door down a long hall to a room as remote as possible from what seemed to be the living portion of the house.

"Is it necessary to put me off quite so far?" I asked, as my young hostess paused and waited for me to join her on the threshold of the most forbidding room it had ever been my fortune to enter.

The blush which mounted to her brow showed that she felt the situation keenly.

"I am sure," she said, "that it is a matter of great regret to me to be obliged to offer you so mean a lodging, but all our other rooms are out of order, and I cannot accommodate you with anything better to-night."

"But isn't there some spot nearer you?" I urged. "A couch in the same room with you would be more acceptable to me than this distant room."

"I—I hope you are not timid," she began, but I hastened to disabuse her mind on this score.

"I am not afraid of any earthly thing but dogs," I protested warmly. "But I do not like solitude. I came here for companionship, my dear. I really would like to sleep with one of you."

This, to see how she would meet such urgency. She met it, as I might have known she would, by a rebuff.

"I am very sorry," she again repeated, "but it is quite impossible. If I could give you the comforts you are accustomed to, I should be glad, but we are unfortunate, we girls, and—" She said no more, but began to busy herself about the room, which held but one object that had the least look of comfort in it. That was my trunk, which had been neatly placed in one corner.

"I suppose you are not used to candles," she remarked, lighting what struck me as a very short end, from the one she held in her hand.

"My dear," said I, "I can accommodate myself to much that I am not used to. I have very few old maid's ways or notions. You shall see that I am far from being a difficult guest."

She heaved a sigh, and then, seeing my eye travelling slowly over the gray discolored walls which were not relieved by so much as a solitary print, she pointed to a bell-rope near the head of the bed, and considerately remarked:

"If you wish anything in the night, or are disturbed in any way, pull that. It communicates with my room, and I will be only too glad to come to you."

I glanced up at the rope, ran my eye along the wire communicating with it, and saw that it was broken sheer off before it even entered into the wall.

"I am afraid you will not hear me," I answered, pointing to the break.

She flushed a deep scarlet, and for a moment looked as embarrassed as ever her sister had done.

"I did not know," she murmured. "The house is so old, everything is more or less out of repair." And she made haste to quit the room.

I stepped after her in grim determination.

"But there is no key to the door," I objected.

She came back with a look that was as nearly desperate as her placid features were capable of.

"I know," she said, "I know. We have nothing. But if you are not afraid—and of what could you be afraid in this house, under our protection, and with a good dog outside?—you will bear with things to-night, and—Good God!" she murmured, but not so low but that my excited sense caught every syllable, "can she have heard? Has the reputation of this place gone abroad? Miss Butterworth," she repeated earnestly, "the house contains no cause of terror for you. Nothing threatens our guest, nor need you have the least concern for yourself or us, whether the night passes in quiet or whether it is broken by unaccountable sounds. They will have no reference to anything in which you are interested."

"Ah, ha," thought I, "won't they! You give me credit for much indifference, my dear." But I said nothing beyond a few soothing phrases, which I made purposely short, seeing that every moment I detained her was just so much unnecessary torture to her. Then I went back to my room and carefully closed the door. My first night in this dismal and strangely ordered house had opened anything but propitiously.

I spoke with a due regard to truth when I assured Miss Knollys that I entertained no fears at the prospect of sleeping apart from the rest of the family. I am a woman of courage—or so I have always believed—and at home occupy my second floor alone without the least apprehension. But there is a difference in these two abiding-places, as I think you are ready by this time to acknowledge, and, though I felt little of what is called fear, I certainly did not experience my usual satisfaction in the minute preparations with which I am accustomed to make myself comfortable for the night. There was a gloom both within and without the four bare walls between which I now found myself shut, which I would have been something less than human not to feel, and though I had no dread of being overcome by it, I was glad to add something to the cheer of the spot by opening my trunk and taking out a few of those little matters of personal equipment without which the brightest room looks barren and a den like this too desolate for habitation.

Then I took a good look about me to see how I could obtain for myself some sense of security. The bed was light and could be pulled in front of the door. This was something. There was but one window, and that was closely draped with some thick, dark stuff, very funereal in its appearance. Going to it, I pulled aside the thick folds and looked out. A mass of heavy foliage at once met my eye, obstructing the view of the sky and adding much to the lonesomeness of the situation. I let the curtain fall again and sat down in a chair to think.

The shortness of the candle-end with which I had been provided had struck me as significant, so significant that I had not allowed it to burn long after Miss Knollys had left me. If these girls, charming, no doubt, but sly, had thought to shorten my watch by shortening my candle, I would give them no cause to think but that their ruse had been successful. The foresight which causes me to add a winter wrap to my stock of clothing even when the weather is at the hottest, leads me to place a half dozen or so of candles in my travelling trunk, and so I had only to open a little oblong box in the upper tray to have the means at my disposal of keeping a light all night.

So far, so good. I had a light, but had I anything else in case William Knollys—but with this thought Miss Knollys's look and reassuring words recurred to me. "Whatever you may hear—if you hear anything—will have no reference to yourself and need not disturb you."

This was comforting certainly, from a selfish standpoint; but did it relieve my mind concerning others?

Not knowing what to think of it all, and fully conscious that sleep would not visit me under existing circumstances, I finally made up my mind not to lie down till better assured that sleep on my part would be desirable. So after making the various little arrangements already alluded to, I drew over my shoulders a comfortable shawl and set myself to listen for what I feared would be more than one dreary hour of this not to be envied night.

And here just let me stop to mention that, carefully considered as all my precautions were, I had forgotten one thing upon leaving home which at this minute made me very nearly miserable. I had not included among my effects the alcohol lamp and all the other private and particular conveniences which I possess for making tea in my own apartment. Had I but had them with me, and had I been able to make and sip a cup of my own delicious tea through the ordeal of listening for whatever sounds might come to disturb the midnight stillness of this house, what relief it would have been to my spirits and in what a different light I might have regarded Mr. Gryce and the mission with which I had been intrusted. But I not only lacked this element of comfort, but the satisfaction of thinking that it was any one's fault but my own. Lena had laid her hand on that teapot, but I had shaken my head, fearing that the sight of it might offend the eyes of my young hostesses. But I had not calculated upon being put in a remote corner like this of a house large enough to accommodate a dozen families, and if ever I travel again——

But this is a matter personal to Amelia Butterworth, and of no interest to you. I will not inflict my little foibles upon you again.