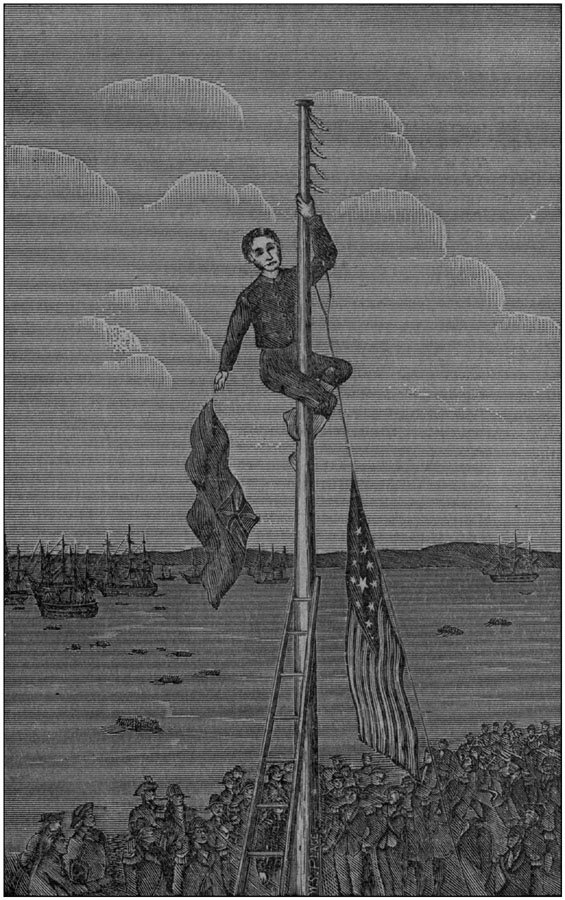

Sergeant Van Arsdale Tearing Down the British Flag.

Title: "Evacuation Day", 1783, Its Many Stirring Events

Author: James Riker

Release date: August 13, 2010 [eBook #33419]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Barbara Kosker and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

50 CENTS.

CRICHTON & CO.,

Printers,

221-225 Fulton St., N. Y.

Our memorable revolution, so prolific of grand and glorious themes, presents none more thrilling than is afforded by the closing scene in that stupendous struggle which gave birth to our free and noble Republic. New York City will have the honor of celebrating, on the 25th of November, the hundredth anniversary of this event, the most signal in its history; and which will add the last golden link to the chain of Revolutionary Centennials. A century ago, on "Evacuation Day," so called in our local calendar, the wrecks of those proud armies,—sent hither by the mother country to enforce her darling scheme of "taxation without representation,"—withdrew from our war-scarred city, with the honors of defeat thick upon them, but leaving our patriotic fathers happy in the enjoyment of their independence, so gloriously won in a seven years' conflict.

With the expiring century has also disappeared the host of brave actors in that eventful drama! Memory, if responsive, may bring up the venerable forms of the "Old Seventy Sixers," as they still lingered among us two score years ago; and perchance recall with what soul-stirring pathos they oft rehearsed "the times that tried men's souls." But they have fallen, fallen before the last great enemy, till not one is left to repeat the story of their campaigns, their sufferings, or their triumphs. But shall their memories perish, or their glorious deeds pass into oblivion? Heaven forbid! Rather let us treasure them in our heart of hearts, and speak their praises to our children; thus may we keep unimpaired our love of country, and kindle the patriotism of those who come after us. To-day they shall live again, in the event we celebrate. And what event can more strongly appeal to the popular gratitude than that which brought our city a happy deliverance from a foreign power, gave welcome relief to our patriot sires, who had fought for their country or suffered exile, and marked the close of a struggle which conferred the priceless blessings of peace and liberty, and a government which knows no sovereign but the people only. Our aim shall be, not so much to impress the reader with the moral grandeur of that day, or with its historic significance as bearing upon the subsequent growth and prosperity of our great metropolis; but the rather to [Pg 4]present a popular account of what occurred at or in connection with the evacuation; and also to satisfy a curiosity often expressed to know something more of a former citizen, much esteemed in his time, whose name, from an incident which then took place, is inseparably associated with the scenes of Evacuation Day.

At the period referred to, a century ago, the City of New York contained a population of less than twenty thousand souls, who mostly resided below Wall Street, above which the city was not compactly built; while northward of the City Hall Park, then known as the Fields, the Commons, or the Green, were little more than scattered farm houses and rural seats. The seven years' occupation by the enemy had reduced the town to a most abject condition; many of the church edifices having been desecrated and applied to profane uses; the dwellings, which their owners had vacated on the approach of the enemy, being occupied by the refugee loyalists, and officers and attachés of the British army, were despoiled and dilapidated; while a large area of the City, ravaged by fires, still lay in ruins!

The news of peace with Great Britain, which was officially published at New York on April 8th, 1783, was hailed with delight by every friend of his country. But it spread consternation and dismay among the loyalists. Its effects upon the latter class, and the scenes which ensued, beggar all description. The receipt of death warrants could hardly have been more appalling. Some of these who had zealously taken up commissions in the king's service, amid the excitement of the hour tore the lapels from their coats and stamped them under foot, crying out that they were ruined forever! Others, in like despair, uttered doleful complaints, that after sacrificing their all, to prove their loyalty, they should now be left to shift for themselves, with nothing to hope for, either from king or country. In the day of their power these had assumed the most insolent bearing towards their fellow-citizens who were suspected of sympathy for their suffering country; while those thrown among them as prisoners of war, met their studied scorn and abuse, and were usually accosted, with the more popular than elegant epithet, of "damned rebel!" The tables were now turned; all this injustice and cruelty stared them in the face, and, to their excited imaginations, clothed with countless terrors that coming day, when, their protectors being gone, they could expect naught but a dreadful retribution! Under such circumstances, Sir Guy Carleton, the English commander at New York, was in honor bound not to give up the City till he had provided the means of conveying away to places within the British possessions, all those who should decide to quit the country. It was not pure humanity, but shrewd policy as well, for the king, by his agents, thus to promote the settlement of portions of his [Pg 5]dominions which were cold, barren, uninviting, and but sparsely populated.

By the cessation of hostilities the barriers to commercial intercourse between the City and other parts of the State, &c., were removed, and the navigation of the Hudson, the Sound, and connected waters was resumed as before the war. Packets brought in the produce of the country, and left laden with commodities suited to the needs of the rural population, or with the British gold in their purses; for all the staples of food, as flour, beef, pork and butter, were in great demand, to victual the many fleets preparing to sail, freighted with troops, or with loyalists. The country people in the vicinity also flocked to the public markets, bringing all kinds of provisions, which they readily sold at moderate rates for hard cash; and thus the adjacent country was supplied and enriched with specie. The fall in prices, which during the war had risen eight hundred per cent, brought a most grateful relief to the consumers. Simultaneously with these tokens of better days, the order for the release of all the prisoners of war from the New York prisons and prisonships, with their actual liberation from their gloomy cells, came as a touching reminder that the horrors of war were at an end.

Many of the old citizens who had fled, on or prior to the invasion of the City by the British, and had purchased homes in the country, now prepared to return, by selling or disposing of these places, expecting upon reaching New York to re-occupy their old dwellings, without let or hindrance, but on arriving here were utterly astonished at being debarred their own houses; the commandant, General Birch, holding the keys of all dwellings vacated by persons leaving, and only suffering the owners to enter their premises as tenants, and upon their paying him down a quarter's rent in advance! Such apparent injustice determined many not to come before the time set for the evacuation of the City, while many others were kept back through fear of the loyalists, whose rage and vindictiveness were justly to be dreaded. Hence, though our people were allowed free ingress and egress to and from the City, upon their obtaining a British pass for that purpose, yet but few, comparatively, ventured to bring their families or remain permanently till they could make their entry with, or under the protection of, the American forces.

Never perhaps in the history of our City had there been a corresponding period of such incessant activity and feverish excitement. Stimulated by their fears, the loyalist families began arrangements in early spring for their departure from the land of their birth (indeed a company of six hundred, including women and children, had already gone the preceding fall) destined mainly for Port Roseway, in Nova Scotia, where they [Pg 6]ultimately formed their principal settlement, and built the large town of Shelburne. Those intending to remove were required to enter their name, the number in their family, &c., at the Adjutant-General's Office, that due provision might be made for their passage. They flocked into the City in such numbers from within the British lines (and many from within our lines also) that often during that season there were not houses enough to shelter them. Many occupied huts made by stretching canvass from the ruined walls of the burnt districts. They banded together for removing, and had their respective headquarters, where they met to discuss and arrange their plans. The first considerable company, some five thousand, sailed on April 27th, and larger companies soon followed. Many held back, hoping for some act of grace on the part of our Legislature which would allow them to stay. But the public sentiment being opposed to it, and expressed in terms too strong to be disregarded, these at last had to yield to necessity, and find new homes. The mass of the loyalists went to Nova Scotia and Canada; others to the Island of Abaco, in the Bahamas; while not a few of the more distinguished or wealthy retired to England. The bitterness felt towards this class was to be deplored, but, in truth, the active part taken by many of them during the war against their country, and above all the untold outrages committed upon defenceless inhabitants by tories (the zealous and active loyalists), often in league with Indians, had kindled a resentment towards all loyalists alike that stifled every philanthrophic feeling. This exodus was going on when General Carleton, about the beginning of August, received his final orders for the evacuation of the City; but it took nearly four months more to complete it, as a large number of vessels were required to transport the immense crowds of refugees who left with their families and effects during that brief period. Hundreds of slaves (ours being then a slave State) were also induced to go to Novy Koshee, as they called it. Their masters could do little to hinder it, though a committee appointed by both governments to superintend all embarkations did something towards preventing slaves and other property belonging to our people from being carried away. Such negroes as had been found in a state of freedom, General Carleton held, had a right to leave if they chose to do so, and many probably got away under this pretext; but to provide against mistakes the name of each negro (with that of his former owner) was registered, and also such facts as would fix his value, in case compensation were allowed. In this, as in the whole ordering of the evacuation, which was more than the work of a day, General Carleton must have credit for humanity and a disposition to pursue a fair and honorable course, which, under the extraordinary difficulties of [Pg 7]the situation, required rare tact and discretion. Of course he was blamed for much when he was not responsible (natural enough in those who suffered grievances), and especially for the great delay in giving up the City, which bore hard on virtuous citizens who had sacrificed opulence and ease at the shrine of liberty, and had now thrown themselves out of homes and business in the expectation of an early return to the City. Yet Carleton's fidelity to the various trusts committed to him, making one delay after another unavoidable, it may be doubted whether he could have surrendered the City at an earlier date.

Closing up the affairs of the army was truly a Herculean task. The shipment of the troops began early in the season. A portion of the army was disbanded to reduce it to a peace establishment pursuant to orders from England. Then there was the settlement of innumerable accounts, pertaining to every department, and the sale and disposal of surplus army property, as horses, wagons, harness and military stores, with several thousand cords of fire wood, which was sold off at half its cost. Even the prisonships were set up at auction. A sale of draft horses was begun, October 2d, at the Artillery Stables near St. Paul's church.

Auctions on private account were rife; daily, in every street, the red flag was seen hanging out. And it was alleged that a great deal of furniture was sold to which the venders had no good title; much of it being newly painted or otherwise disguised, that its proper owner might never know and reclaim it! We need not doubt it, for it seemed as if the refugees would strip the City of every portable article, even to the buildings, or the brick and lumber composing them; insomuch that the authorities, in formal orders, forbade the removal or demolition of any house till the right to do so was shown.

These irregularities, with the brag and bluster of the enraged tories, was enough to keep society in a broil. The uppermost themes were the evacuation, and the removal to Nova Scotia, or elsewhere. They were irritating topics, and gave rise to endless and hot discussions, in which tory vexed tory. While one maintained that Nova Scotia was a very Paradise, another denounced it as unfit for human beings to inhabit. Disappointed and chagrined at the issue of the war, they would curse the powers to whom they owed allegiance; as rebellious as those they called rebels. In other cases, the turn the war had taken had a magic effect upon their principles; once avowed loyalists, they suddenly became zealous patriots! It was a witty reply given by a tailor,—the tailor, in the olden time, we must premise, was often applied to, to rip up and turn a coat, when threadbare or faded. "How does business go on?" asked a friend. "Not very well," said he, "my customers have all learned to turn their own coats!" [Pg 8]The shrewd whigs were not to be deceived by these sudden conversions. They drew the line nicely at a meeting held on Nov. 18th, at Cape's Tavern, in Broadway, (site of the Boreel Building), to arrange plans for evacuation day. Before touching their business, they "Resolved. That every person, whatever his political character may be, who hath remained in this City during the late contest, be requested to leave the room forthwith."

Society could not be very secure, when, as is stated, scarcely a night passed without a robbery; scarcely a morning came, but corpses were found upon the streets, the work of the assassin or midnight revel. Indeed at this juncture, there was much underlying apprehension in the minds of good citizens; the situation was unprecedented, men's passions had been wrought up to a fearful pitch, and who could foresee the outcome! Sensible of the danger, and with the approval of the commandant, a large number of citizens lately returned from exile, organized as a guard and patrolled the streets, on the night preceding evacuation day. The vigilance of these returned patriots, and the protection it afforded, added greatly to the public security at this threatening crisis.

A word as to the aspect of the City; sanitary rules being suspended, the public streets were in a most filthy condition. All the churches, except the Episcopal, the Methodist, and the Lutheran (spared to please the Hessians), had been converted into hospitals, prisons, barracks, riding-schools, or storehouses; the pews, and in some the galleries, torn out, the window-lights broken, and all foul and loathsome. Fences enclosing the churches and cemeteries had disappeared, and the very graves and tombs lay hidden by rubbish and filth! No public moneyed or charitable institutions, no insurance offices existed; trade was at the lowest ebb, education wholly neglected, the schools and college shut up! But the long-wished-for event, which was to light up this dark picture, and work a happy transformation, was at hand.

Finally, the day fixed upon for the evacuation, and for the triumphal entry of Washington and the American army, to take possession of the city, was Tuesday, the 25th of November. At an early hour, on that cold, but radiant morning, the whole population seemed to be abroad, making ready for the great gala day, regardless of a keen nor'wester. During the forenoon many delegations from the suburban districts began to arrive, to share in the public festivities, or to witness the exit of the foreign troops, and the entrance of the victorious Americans; while with the latter was expected a host of patriots, to re-occupy their desolate dwellings, from which they had been so long cruelly exiled; or [Pg 9]otherwise, only to gaze upon the charred and blackened ruins of what was once their homes![1]

To guard against any disturbance which such an occasion might favor, in the interval between the laying down and the resumption of authority, and as rumors were afloat of an organized plot to plunder the town when the King's forces were withdrawn; the hour of noon had been set for the Royal troops to move, and by an understanding between the two commanders-in-chief, the Americans were to promptly advance and occupy the positions as the British vacated them; the latter, when ready to move, to send out an officer to notify our advance guard. There was no longer any antagonism between these, so recently hostile, forces; the plans for the evacuation, on the one part, and the occupation, on the other, being carried out in as orderly a manner, and to all appearance, with as friendly a spirit, as when, in time of peace, one guard relieves another at a military post.

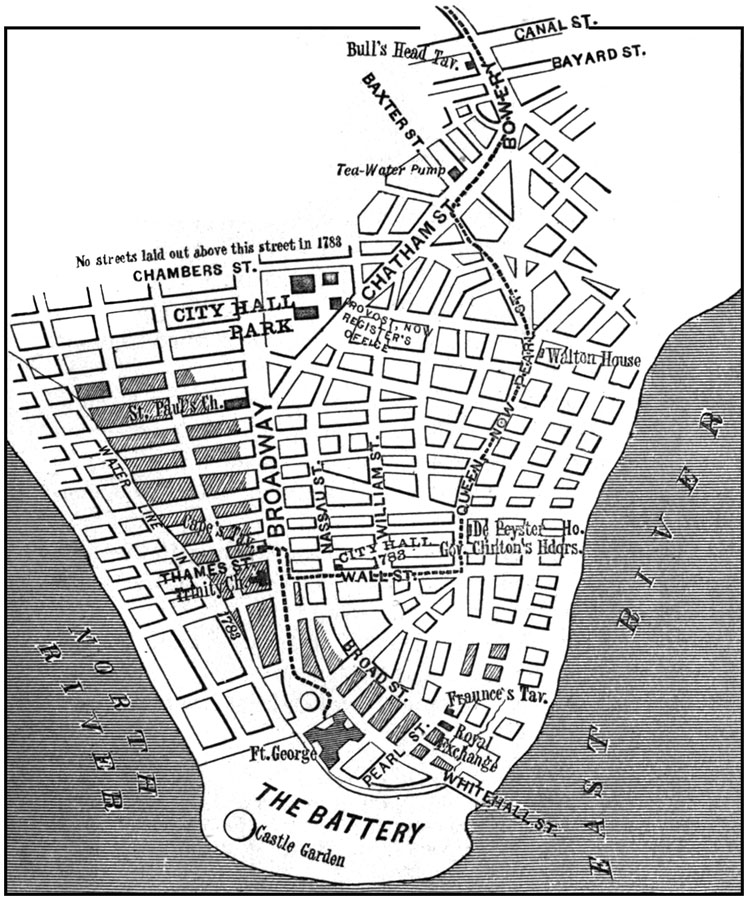

Major Gen. Knox, a large, fine looking officer, had been appointed to command the American troops which were first to enter and occupy the city. With his forces, consisting of a corps of dragoons, under Capt. John Stakes, another of artillery, and several battalions of infantry, with a rear guard under Major John Burnet, Knox marched from McGown's Pass, Harlem, early in the morning, halting at the present junction of the Bowery and Third Avenue. Here he waited—meanwhile holding a friendly parley with the English officers, whose forces were also resting a little in advance of him—until about one o'clock in the afternoon. The British then receiving orders to move, took up their march, passed down the Bowery and Chatham street, and wheeling into Pearl, finally turned off to the river, and went on shipboard. The American forces under Gen. Knox, following on, proceeded through Chatham street, into and down Broadway, and took possession. As they advanced, greeted with happy faces and joyful acclamations by crowds of freemen who lined the streets, or fairer [Pg 10]forms drawn to the windows and balconies by the beat of the American drums and the vociferous cheering, the march down Broadway to Cape's Tavern (on the site now of the Boreel Building), was indeed the triumphal march of conquerors!

Our troops having halted and taken their position opposite and below Cape's Tavern,[2] Gen. Knox quitted them, and heading a body of mounted citizens, lately returned from exile, and who had met by arrangement at the Bowling Green, each wearing in his hat a sprig of laurel, and on the left breast a Union cockade, made of black and white ribbon, rode up into the Bowery to receive their Excellencies General Washington and Governor George Clinton, who were at the Bull's Head Tavern (site of the Thalia Theatre), they having arrived at Day's Tavern, Harlem, on the 21st inst., the very day on which Carleton had drawn in his forces and abandoned the posts from Kingsbridge to McGown's Pass, inclusive.

At the Bull's Head, where the widow Varien presided as hostess, congratulations passed freely, and a series of hearty demonstrations began, on the part of the overjoyed populace, which continued along the whole line of Washington's march, and closed only with the day. The civic procession having formed began its grand entry in the following order:

General Washington, "straight as a dart and noble as he could be," riding a spirited gray horse, and Governor Clinton, on a splendid bay, with their respective suites also mounted; and having as escort a body of Westchester Light Horse, under the command of Capt. Delavan.

The Lieutenant Governor, Pierre Van Cortlandt, with the members of the Council for the temporary Government of the Southern District of New York; four abreast.

Major Gen. Knox, and the officers of the army; eight abreast.

Citizens on horseback; eight abreast.

The Speaker of the Assembly, and citizens on foot; eight abreast.

MAP

Showing Washington's line of march from Bull's Head (Bowery), to Cape's

Tavern, in Broadway; and thence to Fort George.

[Pg 13]Near the Tea-water Pump, (in Chatham street just above Pearl), where the citizens on foot had gathered to join the procession, Washington halted the column, while Gen. Knox and the officers of the Revolution drew out and, forming into line, marched down Chatham street, passing a body of the British troops which were still halting in the fields (now the City Hall Park); while Washington and the rest, turning down Pearl street, proceeded on to Wall street, and up Wall, then the seat of fashionable residences, to Broadway, where both companies again met, and while our troops in line fired a feu-de-joie, alighted at the popular tavern before mentioned, kept by John Cape, where now stands the Boreel Building.[3]

We must mention here, that when Gen. Knox reached the New Jail, then known as the Provost (and now the Hall of Records), Capt. Cunningham, the Provost Marshall, and his deputy and jailor Sergeant Keefe, both having held those positions during most of the war, and equally notorious for their brutal treatment of the American prisoners who were confined there, thought it about time to retreat; and quitting the jail, followed by the hangman in his yellow jacket, passed between a platoon of British soldiers and marched down Broadway, with the last detachment of their troops. When Sergeant Keefe was in the act of leaving the Provost, (says John Pintard), one of the few prisoners then in his custody for criminal offences, called out: "Sergeant, what is to become of us?" "You may all go to the devil together," was his surly reply, as he threw the bunch of keys on the floor behind him. "Thank you, Sergeant," was the cutting retort, "we have had too much of your company in this world, to wish to follow you to the next!" Another incident, which respected Cunningham, was witnessed (says Dr. Lossing), by the late Dr. Alexander Anderson. It was [Pg 14]during the forenoon, that a tavern keeper in Murray street hung out the Stars and Stripes. Informed of it, thither hastened Cunningham, who with an oath, and in his imperious tone, exclaimed, "Take in that flag, the City is ours till noon." Suiting the action to the word, he tried to pull down the obnoxious ensign; but the landlady coming to the rescue, with broom in hand, dealt the Captain such lusty blows, as made the powder fly in clouds from his wig, and forced him to beat a retreat! The Provost Guard, and the Main Guard at the City Hall (Wall street, opposite Broad, where the U. S. Treasury stands), were the last to abandon their posts, and repair on shipboard.

The brief reception being over, at Cape's Tavern, (with presenting of addresses to Gen. Washington and Gov. Clinton), the cavalcade again formed, and marched to the Battery, to enact the last formality in re-possessing the City, which was to unfurl the American flag over Fort George.[5] A great concourse of people had assembled, not only to witness this ceremony, but to obtain a sight of the illustrious Washington and other great generals, who had so nobly defended our liberties.

But now a sight was presented, which, as soon as fully understood, drew forth from the astonished and incensed beholders execrations loud and deep. The royal ensign was still floating [Pg 15]as usual over Fort George; the enemy having departed without striking their colors, though they had dismantled the fort and removed on shipboard all their stores and heavy ordnance, while other cannon lay dismounted under the walls as if thrown off in a spirit of wantonness. On a closer view it was found that the flag had been nailed to the staff, the halyards taken away, and the pole itself besmeared with grease; obviously to prevent or hinder the removal of the emblem of royalty, and the raising of the Stars and Stripes. Whether to escape the mortification of seeing our flag supplant the British standard, or to annoy and exasperate our people were the stronger impulse, it were hard to say. It was too serious for a joke, however, and the dilemma caused no little confusion. The artillery had taken a position on the Battery, the guns were unlimbered, and the gunners stood ready to salute our [Pg 16]colors. But the grease baffled all attempts to shin up the staff. To cut the staff down and erect another would consume too much time. Impatient of delay, "three or four guns were fired with the colors on a pole before they were raised on the flagstaff."[6] But this expedient was premature and humiliating, while the hostile flag yet waved as if in defiance. The scene grew exciting: and now appeared another actor, hitherto looking on, but no idle observer of what was passing. He was a young man of medium height, whose ruddy honest face, tarpaulin cap and pea-jacket told his vocation. Born neither to fortune nor to fame, yet by his own merits and exertions he had won the regard of some in that assembly, having served under McClaughry, and Willett, and Weissenfels, as also the Clintons, to whom he had lived neighbor, within that patriotic circle in old Orange, where these were the guiding spirits, and every yeoman with them, shoulder to shoulder, in the common cause. As a subaltern officer he had made a good record during the war, and none present, however superior in station, had sustained a better character or exhibited a purer patriotism. This was John Van Arsdale, late a Sergeant in Capt. Hardenburgh's company of New York Levies. At nineteen years of age, quitting his father's vessel, where he had been bred a sailor, he enlisted in the Continental Army at the beginning of the war, and had served faithfully till its close. Suffering cold and hardship in the Canada expedition, wounded and taken prisoner at the battle of Fort Montgomery, he had languished weary months in New York dungeons, and in the foul hold of a British prisonship, and subsequently braved the perils of Indian warfare in several campaigns. And with such a record, where expect to find him but among his old compatriots, on this day of momentous import, when the struggles of seven years were to culminate in a final triumph.

Van Arsdale volunteered to climb the staff, though with little prospect of succeeding better than others, especially when after making an attempt, sailor fashion, he was unable to maintain his grasp upon the slippery pole. Now it was proposed to replace the cleats which had been knocked off; and persons ran in haste to Peter Goelet's hardware store, in Hanover Square, and returned with a saw, hatchet, gimlets, and nails. Then willing hands sawed pieces of board, split and bored cleats, and began to nail them on. By this means Van Arsdale got up a short distance, with a line to which our flag was attached; but just then, a ladder being brought to his assistance, he mounted still higher, then completed the ascent in the usual way, and reaching the top of the staff, tore down the British standard, and rove the new halyards by which the [Pg 17]Star-spangled Banner was quickly run up by Lieut. Anthony Glean, and floated proudly, while the multitude gave vent to their joy in hearty cheers, and the artillery boomed forth a national salute of thirteen guns![7] On descending, Van Arsdale was [Pg 18]warmly greeted by the overjoyed spectators, for the service he had rendered; but some one proposing a more substantial acknowledgement than mere applause, hats were passed around, and a considerable sum collected, nearly all within reach contributing, even to the Commander-in-Chief. Though taken quite aback, Van Arsdale modestly accepted the gift, with a protest at being rewarded for so trivial an act. But the contributors were of another opinion; he had accomplished what was thought impracticable, and the occasion and the emergency made his success peculiarly gratifying to all present. On returning home to his amiable Polly (they had been married short of six months), the story of "Evacuation Day," and the silver money which he poured into her lap, caused her to open her eyes, and fixed the circumstance indelibly in her memory!

But to return: during the scene on the Battery, which consumed full an hour, the last squads of the British were getting into their boats, while many others, filled with soldiers, rested on their oars between the shore and their ships, anchored in the North River. They kept silence during this time, and watched our efforts to hoist the colors (no doubt enjoying our embarrassment), but when our flag was run up and the salute fired, they rowed off to their shipping, which soon weighed anchor and proceeded down the bay.[8]

This scene over, the Commander-in-Chief and the general officers, accompanied Gov. Clinton to Fraunces' Tavern, also a popular resort, and which still stands on the corner of Pearl and Broad streets. Here the Governor gave a sumptuous dinner. The repast over, then came "the feast of reason and the flow of soul," when the sentiments dearest to those brave and loyal men found utterance in the following admirable toasts:

1. The United States of America.

[Pg 19]2. His most Christian Majesty.

3. The United Netherlands.

4. The King of Sweden.

5. The American Army.

6. The Fleet and Armies of France, which have served in America.

7. The Memory of those Heroes who have fallen for our Freedom.

8. May our Country be grateful to her Military Children.

9. May Justice support what Courage has gained.

10. The Vindicators of the Rights of Mankind in every Quarter of the Globe.

11. May America be an Asylum to the Persecuted of the Earth.

12. May a close Union of the States guard the Temple they have erected to Liberty.

13. May the Remembrance of This Day, be a Lesson to Princes.

An extensive illumination of the buildings in the evening, a grand display of rockets, and the blaze of bonfires at every corner, made a fitting sequel to the events of the day.[9] Great as was the joy, and lively as were the demonstrations of it, not the slightest outbreak or disturbance occurred, to mar the public tranquility; and the happy citizens retired to rest in the sweet consciousness that the reign of martial law and of regal despotism had ended! But it was remarked, says an eye-witness of the time, that an unusual proportion of those who in '76 had fled from New York, had been cut off by death and denied a share in the general joy, which marked the return of their fellow citizens to their former habitations. And those habitations, such as had survived the fires, how marred and damaged, as before intimated; in many cases mere shells and wrecks. And the sanctuaries, where they and their fathers had worshipped, all despoiled, save St. Paul's, St. George's in Beekman street, the Dutch Church, Garden street, the Lutheran church, Frankfort street, the Methodist Meeting House in John street, (none remaining at present but the first and last), and some three or four small and obscure places. Years elapsed, before, in their poverty, the people were enabled fully to restore some of them to their former sacred uses. The churches which suffered most at the enemy's hands were the Middle and North Dutch churches, in Nassau and William streets, the two Presbyterian churches, in Wall and Beekman streets, the Scotch Presbyterian church, [Pg 20]in Cedar street, the French church in Pine street, the Baptist church, Gold street, and the Friends' new Meeting House, in Pearl street; all since removed to meet the demands of trade. Religious affairs were found in a sad plight when the evacuation took place. The Dutch, Presbyterian and Baptist ministers had gone into voluntary exile. The Rev. Charles Inglis, D.D., Rector of Trinity Parish, having made himself very obnoxious to the patriots, concluded to follow the loyalists of his flock to Nova Scotia, and therefore resigned his rectorship Nov. 1st, preceding the evacuation. Dr. John H. Livingston, arriving with our people, immediately resumed his services in Garden street. Other pastors were not so favored. Dr. John Rogers, of the Presbyterian church, returned on the day after the evacuation, and on the following Sabbath, Nov. 30th, preached in St. George's chapel, "to a thronged and deeply affected assembly," a discourse adapted to the occasion from Psalms cxvi, 12,—"What shall I render unto the Lord, for all His benefits towards me?" The vestry of Trinity church having kindly offered the use of their two chapels, St. Paul's and St. George's, the Presbyterians occupied these buildings a part of every Sabbath until June 27th, 1784, when they took possession of the Brick Church, Beekman street, which had been repaired.

On the Friday following the evacuation, the citizens lately returned from exile, gave an elegant entertainment, at Cape's Tavern, to his Excellency, the Governor, and the Council for governing the City; when Gen. Washington and the Officers of the Army, about three hundred gentlemen, graced the feast. The following Tuesday, Dec. 2d, another such entertainment was given by Gov. Clinton, at the same place, to the French Ambassador, Luzerne, and in the evening, at the Bowling Green, the Definitive Treaty of Peace was celebrated by "an unparallelled exhibition of fireworks," and when, says an account of it, "the prodigious concourse of spectators assembled on the occasion, expressed their plaudits in loud and grateful clangors!" On Thursday, the 4th, Gen. Washington bade a final adieu to his fellow officers at Fraunces' Tavern. The scene was most affecting. "With a heart full of love and gratitude," said he, "I now take leave of you, and most devoutly wish that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable." Embracing each one in turn, while tears coursed down their manly checks, he parted from them, and from the City, to resign his commission to Congress, and seek again the retirement of private life.

The following Thursday, Dec. 11th, was observed by appointment of Congress, "as a day of public Thanksgiving throughout the United States." On this occasion Dr. Rogers preached in [Pg 21]St. George's chapel, a sermon from Psalms cxxvi, 3,—"The Lord hath done great things for us, whereof we are glad." It was afterwards published with the title—"The Divine Goodness displayed in the American Revolution."

Thus just eight score years after Europeans first settled on this Island of Manhattan, our City had its new birth into freedom, and started on its unexampled career of prosperity and greatness. And as we contemplate the growth, enterprise, trade, commerce, credit, opulence and magnificence of the present City, with its hundreds of churches, schools and other noble institutions, and contrast it with the contracted, war-worn, desolate town, of which our fathers took possession on the 25th of November 1783, well may we exclaim—"What hath God wrought?" That day, whose memories were so fondly cherished by our grandsires while they lived, was one of great significance in the history of our City and Country. Its anniversary has ever since been duly celebrated by military parades, and a national salute fired on the Battery at sunrise, by the "Independent Veteran Corps of Heavy Artillery," composed at first of Revolutionary soldiers, and of which John Van Arsdale was long an efficient and honored member, and, at the time of his decease, its First Captain-Lieutenant.[10] For many [Pg 22]years the day was observed with great eclat; the troops, in parading, "went through the forms practiced on taking possession of the City, maneuvering and firing feux-de-joie, &c., as occurred on the evacuation." All shops and business places were closed, artisans and toilers ceased their work, and the streets, decorated with patriotic emblems, and alive with happy people, were given up to gaiety and mirth. To civic and military displays were added sumptuous dinners, and convivial parties, while the schoolboy rejoiced in a holiday; the whole bearing witness to a peoples' gratitude for the deliverance which that memorable day brought them. And boys of older growth may yet recall the simple distich:

In the evening every place of amusement was well attended, but none better than Peale's American Museum, because, as duly advertised:—"The Flag hoisted by order of Gen. Washington, on the Battery, the same day the British troops evacuated this city, is displayed in the upper hall, as a sacred memorial of that day." This flag was presented to the museum by the Common Council in 1819. It was raised on the Battery for the last time in 1846, and when the museum was burned the old flag perished!

Well deserves this day not merely a local but a national commemoration; since it inaugurated for the nation an era of freedom, the blessings of which all could not realize, while the chief city and seaport of our country were held by foreign armies.

Another chapter, introducing us to colonial and revolutionary times, will tell more of Capt. Van Arsdale, what he did and endured for his country, and ensure him a grateful remembrance so long as "Evacuation Day" shall cheer us by its annual return.

[1] The Great Fire, of September 20, 1776, beginning at Whitehall slip, swept along the river front and northward, consuming all the buildings between Whitehall street on the west and Broad street on the east, extending up Broadway to a point just below Rector street, and up Broad street as far as Beaver, above which the houses on Broad street escaped; the fire being confined to a line nearly straight from Beaver, near Broad, to the point it reached on Broadway. Crossing Broadway, it also swept everything north of Morris street, including Trinity Church; from which point passing behind the city (later Cape's) Tavern, it spared the line of buildings, mainly dwellings, facing Broadway, with a few joining them on the cross streets, but otherwise made a clean sweep as far up as Barclay street, where the College grounds stayed its further process.

The fire of August 3, 1778, which was confined to the blocks between Old slip and Coenties slip, reaching up to Pearl street, was a small affair in comparison.

[2] The orders of Nov. 24, to our troops read: "The Light Infantry will furnish a company for Main Guard to-morrow. As soon as the troops are formed in the city, the Main Guard will be marched off to Fort George; on their taking possession, an officer of artillery will immediately hoist the American standard. * * * On the standard being hoisted in Fort George, the artillery will fire thirteen rounds. Afterwards his Excellency Governor Clinton will be received on the right of the line. The officers will salute his Excellency as he passes them, and the troops present their arms by corps, and the drums beat a march. After his Excellency is past the line, and alighted at Cape's Tavern, the artillery will fire thirteen rounds."

As our flag was not raised on Fort George, nor the salute fired until after Gov. Clinton and Gen. Washington arrived there, the delay, and failure to carry out the orders strictly as issued, must be accounted for by the embarrassing incident hereafter noticed.

[3] Why "the officers of the Revolution" should have taken a different rout admits of this explanation. The officers referred to were no doubt the mounted citizens who had ridden up with Knox from Bowling Green, among whom were colonels, captains, etc., of the late army. The move was evidently made to reach Cape's Tavern first, and be in position ready to receive their Excellencies, Washington and Clinton, and present addresses, which had been prepared. This is referred to in a letter written by Elisha D. Whitlesey, dated Danbury, Conn., Aug. 24, 1821, "A committee had been appointed by the citizens to wait upon Gen. Washington and Gov. Clinton and other American officers, and to express their joyful congratulations to them upon the occasion. A procession for this purpose formed in the Bowery, marched through a part of the city, and halted at a tavern, then known by the name of Cooper's [Cape's] Tavern, in Broadway, where the following addresses were delivered.[4] Mr. Thomas Tucker, late of this town [Danbury], and at that time a respectable merchant in New York, a member of the committee, was selected to perform the office on the part of the committee."

[4] For that to Washington, and his reply, see next note.

[5] Address to General Washington,

Presented at Cape's Tavern.

To his Excellency George Washington, Esquire, General and Commander in Chief of the Armies of the United States of America:

The Address of the Citizens of New York, who have returned from exile, in behalf of themselves and their suffering brethren:

Sir:

At a moment when the arm of tyranny is yielding up its fondest usurpations, we hope the salutations of long suffering exiles, but now happy freemen, will not be deemed an unworthy tribute. In this place, and at this moment of exultation and triumph, while the ensigns of slavery still linger in our sight, we look up to you, our deliverer, with unusual transports of gratitude and joy. Permit us to welcome you to this City, long torn from us by the hard hand of oppression, but now by your wisdom and energy, under the guidance of Providence, once more the seat of peace and freedom. We forbear to speak our gratitude or your praise, we should but echo the voice of applauding millions; but the Citizens of New York are eminently indebted to your virtues, and we who have now the honor to address your Excellency, have been often companions of your sufferings, and witnesses of your exertions. Permit us therefore to approach your Excellency with the dignity and sincerity of freemen, and to assure you that we shall preserve with our latest breath our gratitude for your services, and veneration for your character. And accept of our sincere and earnest wishes that you may long enjoy that calm domestic felicity which you have so generously sacrificed; that the cries of injured liberty may nevermore interrupt your repose, and that your happiness may be equal to your virtues.

Signed at the request of the meeting.

Thomas Randall.

Dan. Phœnix.

Saml. Broome.

Thos. Tucker.

Henry Kipp.

Pat. Dennis.

Wm. Gilbert, Sr.

Wm. Gilbert, Jr.

Francis Van Dyck.

Jeremiah Wool.

Geo. Janeway.

Abra'm P. Lott.

Ephraim Brashier.

New York, Nov. 25th, 1783.

The General's Reply.

To the Citizens of New York who have returned from exile:

Gentlemen—

I thank you sincerely for your affectionate address, and entreat you to be persuaded that nothing could be more agreeable to me than your polite congratulations. Permit me in turn to felicitate you on the happy repossession of your City.

Great as your joy must be on this pleasing occasion, it can scarcely exceed that which I feel at seeing you, Gentlemen, who from the noblest motives have suffered a voluntary exile of many years, return again in peace and triumph, to enjoy the fruits of your virtuous conduct.

The fortitude and perseverance, which you and your suffering brethren have exhibited in the course of the war, have not only endeared you to your countrymen, but will be remembered with admiration and applause to the latest posterity.

May the tranquility of your City be perpetual,—may the ruins soon be repaired, commerce flourish, science be fostered, and all the civil and social virtues be cherished in the same illustrious manner which formerly reflected so much credit on the inhabitants of New York. In fine, may every species of felicity attend you, Gentlemen, and your worthy fellow citizens.

Geo. Washington.

[6] Gen. Jeremiah Johnson, who was present, so stated to the writer, Feb. 15, 1848.

[7] A patriotic song was composed for that day, entitled, "The Sheep Stealers," which was distributed and sung with immense gusto in the evening coteries. Coarse, but designed to cast ridicule on the enemy, it is given as a specimen of the popular songs of the period:

[8] The British troops did not take their final departure from Long Island and Staten Island till the 4th of December. Their flag waved over Governor's Island till the 3d, when the Island was formally given up to an officer sent over by Gov. Clinton, for that purpose. (Mag. of Am. Hist., 1883, p. 430.) Sir Guy Carleton and other officers and gentlemen sailed in the frigate Ceres, Capt. Hawkins.

[9] Among the more authentic newspaper accounts of the Evacuation, is one of which I have here availed myself, contained in the New York Sun of Nov. 27th, 1850, but copied from the Observer. Much valuable material is also brought together in the N. Y. Corp. Manual for 1870.

[10] It caused great surprise, in 1831, that an officer of the Revolution, Capt. John Van Dyck, of Lamb's artillery, who was present at the evacuation of New York, and "was on Fort George and within two feet of the flagstaff," should have stated in the most positive terms, that "there was no British flag on the staff to pull down:" also that no ladder was used, and besides, more than intimated that Van Arsdale did not perform the part ascribed to him! (His letter, in N. Y. Commercial Advertiser, of June 30th, 1831.) We well remember Capt. Van Dyck, and do not doubt the sincerity of his statements; but it only shows how effectually facts once well known may be obliterated from the memory by the lapse of time. For few facts in our history are better authenticated than that the royal standard was left flying at the evacuation; and it was afterwards complained of, as the able historian, Mr. Dawson writes me, by John Adams, our first embassador to England, as an unfriendly act, to evacuate the City without a formal surrender of it, or striking their colors. The fact is also mentioned in a pamphlet printed in 1808, by the "Wallabout Committee," (appointed to superintend the interment of the bones of American patriots who perished in the prison ships), and consisting of gentlemen who could not have all been ignorant on such a point, viz., Messrs. Jacob Vandervoort, John Jackson, Issachar Cozzens, Burdet Stryker, Robert Townsend, Jr., Benjamin Watson and Samuel Cowdrey. Hardie, who wrote his account prior to 1825, ("Description of New York," p. 107,) also makes the same statement, and so does Dr. Lossing: "Field Book of the Revolution," 2:633. A letter written in New York the day after the evacuation, says "they cut away the halyards from the flagstaff in the fort, and likewise greased the post; so that we were obliged to have a ladder to fix a new rope." The use of a ladder is attested by Lieut. Glean; and also by the late Pearson Halstead, who witnessed the ascent. Mr. Halstead stated this to me, in 1845, and that, about the year 1805, he was informed that Van Arsdale was the person who climbed the staff. His association with Mr. Van Arsdale, both in business and in the Veteran Corps, gave him the best means of knowing the common belief on that subject, and he said it was "a fact understood and admitted by the members of the Veteran Corps, who used often to speak of it." Capt. George W. Chapman, of the Veteran Corps, then 84 years of age, informed me, in 1845, that he commanded the Corps when Van Arsdale joined it, and that the fact ascribed to the latter was well known to the members of the Corps, and never disputed. John Nixon, a reliable witness, said to me, in 1844, that he saw the ascent, &c., "by a short thickset man in sailor's dress," and that ten years later (1793) he became acquainted with Van Arsdale, and then learned that "he was the person who tore down the British flag, in 1783." Gen. Jeremiah Johnson informed me, in 1846, that he "saw the sailor, in ordinary round jacket and seaman's dress, shin up the flagstaff; a middling sized man, well proportioned." Major Jonathan Lawrence, who was present; said "a sailor mounted the flagstaff, with fresh halyards, rigged it and hoisted the American flag."

The real conservators of the rights of mankind have rarely been found among the rich or titled aristocracy. They belong to the more ingenuous, sympathetic, and virtuous middle class of society, so called. This is not the less true because of the notable exceptions, where the endowments of wealth, rank, and influence, have added lustre to the names of some of earth's best benefactors. The fact must remain that the bone and sinew of a nation, and in which consists its safety in peace, and its defense in war, are its hardy yeoman who guide the plow, or wield the axe, or ply the anvil; and without whose practical ideas and well-directed energies, no community could protect itself, or make any real advancement. It was most fortunate that the founders of this nation were so largely of this sterling class; the architects of their own fortunes, no labor, no difficulties or dangers appalled them; the very men were they, to break by stalwart blows the fetters which despotism was fast riveting upon them.

Such was Captain John Van Arsdale, in the essentials of his character. It chafed his young, free spirit to see his country, the home of his ancestors for a century before his birth, bleeding under the iron hand of tyranny, and invoking the sturdy and the brave to come forth and strike the blow for freedom. He was one of the first to heed that call, and to fearlessly enter the lists; nor ceased to battle manfully till our independence was achieved! If honest, unswerving patriotism, standing the triple test of manifold hardships and dangers, long and cruel imprisonment and years of arduous, poorly-requited service, should entitle one to the love and gratitude of his country; then let such honor be awarded to the subject of this sketch, and the power of his example tell upon all those who may read it.

John Van Arsdale was the son of John and Deborah Van Arsdale, and was born in the town of Cornwall (then a part of Goshen), Orange County, N. Y., on Monday, January 5th, 1756.[11] His ancestors for four generations in this country, as mentioned in the records of their times, were men of intelligence and virtue, honored and trusted in the communities in which they lived, and on whom, as God-fearing men, rested the mantles of their fathers who had battled for their faith in the wars of the Netherlands. His grandsire, Stoffel Van Arsdalen (for so he and his Dutch [Pg 24]progenitors wrote the name), had removed from Gravesend, Long Island, to Somerset County, New Jersey, in the second decade of that century, and eventually purchased a farm of two hundred acres in Franklin township, where he lived, zealously devoted to the church, and highly esteemed, till his death near the beginning of the Revolution.[12] He married Magdalena, daughter of Okie Van Hengelen, and had several children, of whom, John, born 1722, and Cornelius, born 1729, removed to the County of Orange, aforesaid.[13] John, by trade a millwright, was engaged by Mr. Tunis Van Pelt to build a grist mill on Murderer's Creek, so called from an Indian tragedy of earlier times; and from which name softened to Murdner, in common usage, came the modern Moodna. While so occupied, and sharing the hospitalities of Mr. Van Pelt's house, he wooed and married his daughter, Deborah, in 1744. Associating with his father-in-law in the milling [Pg 25]business, Van Arsdale eventually became proprietor, assisted, we believe, by his brother Cornelius, who was a miller. Building up a large trade, he also became known for his private virtues and public spirit. A lieutenant's commission (in which he is styled "of Ulster County, Gentleman"), under Capt. Thomas Ellison, and dated October 10th, 1754, is now in the writer's possession. But misfortune, the loss of a vessel sent to the Bay of Honduras laden with flour, and where it was to ship a cargo of logwood, led him to give up the business and remove to New York, where he took charge of the Prison in the old City Hall, in Wall street, which was deemed a post of great responsibility. It was soon after this change that John, the subject of our sketch, was born, at Mr. Van Pelt's residence, at Moodna, where his mother had either remained, or was then making a visit. About six weeks thereafter, having come to the city, with her infant, she sickened and died of the small pox. After four years (in 1760), Mr. Van Arsdale married Catherine, daughter of James Mills, deputy-sheriff of New York. Ten years later, weary of his charge, then at the New Jail, built in 1757-9 (the Provost of the Revolution, and now the Hall of Records); he resigned it, bought a schooner, and engaged in the more congenial pursuit of marketing produce.

The Revolution coming on, Capt. Van Arsdale entered with his vessel into the American service, supplied our army at New York with fuel brought from Hackensack (the Asia man-of-war once taking his wood and paying him in continental bills), and afterwards helped to sink the chevaux-de-frize in the Hudson, opposite Fort Washington. In this arduous work he was aided by his son John, then lately returned from the Canada expedition. The day the enemy entered the City he conveyed his family to his vessel at Stryker's Bay, and, crowded with fugitives, made good his escape up the Hudson to Murdner's Creek. Here his companion, who had borne him eleven children, died in 1779; but he survived not only to witness the war brought to a happy close, but long enough to see much of the waste repaired, and the greatness of his country assured. Respected and beloved for his amiable qualities and exemplary christian character, Capt. Van Arsdale, the elder, died in 1798 at the residence of his son-in-law, Mr. William Sherwood, at "The Creek."

The junior Van Arsdale would have been unworthy of his honest ancestry had he not possessed in a good degree the same stability of character. Bereft of a mother's love at so early an age, John was tenderly reared at his grandfather Van Pelt's till his father married again. Then New York became his home for ten years or more, during which time his playground was the Green (now City Hall Park) with the fields adjacent to the New Jail, of which [Pg 26]his father still had the custody. The times were turbulent, and many stirring scenes passed under his boyish eyes. One was the Soldiers' Riot, in 1764, when the jail was assaulted and broken into by a party of riotous soldiers, with design to release a prisoner, and in which Mr. Mills, in resisting them, was rudely handled and wounded. And the gatherings, hardly less tumultuous, of the "Sons of Liberty" to oppose the Stamp Act, or celebrate its repeal, by raising liberty poles, which were several times cut down and replaced, all serving to implant in his young mind an abhorrence of foreign rule, with the germs of that patriotism which matured as he grew in years.[14] But an elder brother Tunis (his only own brother living, save Christopher, a brassfounder, who died, unmarried, in the West Indies in 1773), having served an apprenticeship with Fronce Mandeville, of Moodna, blacksmith, married, in 1771, Jennie Wear, of the town of Montgomery, and the next spring began married life on a farm of eighty acres, which he had purchased, lying in that part of Hanover Precinct (now Montgomery) called Neelytown. Much attached to Tunis, John thereafter spent several years with him, attending school.

But now the growing controversy between the Colonies and the mother country had ripened into actual hostilities; the first aggressive movement in which this Colony took part being the expedition against Canada, planned in the summer of 1775. It fired young Van Arsdale's patriotism, and about August 25th he enlisted under Capt. Jacobus Wynkoop, of the Fourth New York Regiment, James Holmes being the colonel and Philip Van Cortlandt the lieutenant-colonel. These forces, proceeding up the Hudson, entered Canada by way of lakes George and Champlain; part of the Fourth Regiment, under Major Barnabas Tuthill, taking part in the brilliant assault upon Quebec, December 31st, but unsuccessful, and fatal to the gallant leader, General Montgomery, and numbers of his men. On their way to Quebec, and especially in crossing the lakes on the ice, Van Arsdale and his comrades suffered so intensely from the extreme cold that the hardships and incidents of this, his first campaign, remained fresh in his memory even till old age. Van Arsdale having "served his time out in the year's service, returned to New York," where the Americans were [Pg 27]concentrating troops, in order to oppose the royal forces expected from Europe. Here he assisted his father on board the schooner in sinking the obstructions in the Hudson, as before noticed, and when the enemy captured the city, accompanied him to Orange County. It was on Sept. 16th, 1776, that the British forces landed at Kip's Bay, on the east side of the island, three miles out of the city. A great many of the citizens who were friends of their country, made a precipitate flight, and the roads were lined with vehicles of every kind, removing furniture, etc. The elder Van Arsdale, with difficulty, and only by paying down $200, got the use of a horse and wagon to take his family and effects from his house to the schooner lying in Stryker's Bay. While drawing a load, a spent cannon ball knocked off one of the wagon wheels, at which his little son Cornelius, but eight years old, was so frightened that he never forgot it. The schooner was crowded to excess with citizens and their families, all eager to get away, and for fear they might sink her, Capt. Van Arsdale was obliged to turn off some who applied for a passage. They left deeply loaded, and in their haste were obliged to take with them a lot of military stores which were on board. Arriving at Murdner's Creek, John, at his father's request, and taking his brother Abraham, set out afoot for Neelytown, to inform their brother Tunis of their arrival. The journey of twelve miles seemed short, and ere long the well-known farmhouse hove in sight, seated a little way back, and to which led a lane between rows of young cherry trees, and near it on the road the low, dusky smith-shop, with its debris of cinders, old wheel-tires and broken iron-work strewn about. Entering, as Tunis, with his back towards them, stood at the forge heating his iron, and his assistant, Aleck Bodle, lazily blowing the bellows, the first surprize was only surpassed, when after hearty greetings, they imparted the startling news of the capture of New York by the British, and that their father, having barely escaped with his vessel, had arrived at the Creek. At once out went the fire, and out went Tunis also to harness his horses, in order to go and bring up the rest of the family; but on second thought, as the day was far spent, he concluded to await the morrow. The next day there was a joyous reunion at the farmhouse, but tempered with many sad comments upon the doleful situation.

John spent the winter with his brother Tunis, aiding in farm work and at the forge; he had just reached his majority, and found congenial spirits in Alexander Bodle and Joseph Elder, then serving apprenticeships with Tunis, and afterwards much respected residents of Orange County. Around the evening fireside they indulged in many a joke, when laughter made the welkin ring, or behind the well-fed pacer, were borne in the clumsy [Pg 28]box sled, with the gingle of merry bells, to the rustic frolic; but the bounds of decorum were never exceeded, and lips which could tell all about it, bore us pleasing witness to Van Arsdale's correct habits and deportment at a stage of life so beset with syren snares for the unwary, and which commonly moulds the character.

But nevertheless the winter was one of great military activity, especially among the organized militia of Orange County, in which (in the town of New Windsor) was the sub-district of Little Britain, the home of the Clintons;[15] the menacing attitude of the enemy under Lord Howe, who had approached as near as Hackensack, and the protection of the passes of the Highlands, requiring frequent calls upon the yeomanry to take the field. The inhabitants of Hanover Precinct, which precinct joined on New Windsor, had from the first shown great spirit; their Association, dated May 8th, 1775, in which they pledge their support to the Continental Congress, &c., in resisting "the several arbitrary and oppressive acts of the British Parliaments," and "in the most solemn manner resolve never to become slaves," is signed first by Dr. Charles Clinton and presents 342 names. The Precinct in the winter of 1776-7, contained four militia companies, under Captains Matthew Felter, James Milliken, Hendrick Van Keuren and James McBride, and these were attached to a regiment of which that sterling patriot, James McClaughry, of Little Britain, brother in law to the Clintons, was lieutenant colonel commandant.[16] Tunis and John Van Arsdale lived in Capt. Van Keuren's beat. The Captain was a veteran of the last French war, and it gave him prestige, in the command to which he had been recently promoted. He had "warmly espoused the cause of his country, and evinced unshaken firmness throughout the whole of the contest." Col. McClaughry had taken the field with his regiment early in the winter, proceeding down into Jersey, and of which, on his return, Jan. 1st, he gave a humorous account to Gen. Clinton; but though highly probable, we have no positive evidence that John Van Arsdale went into actual service till the spring opened.

Forts Montgomery and Clinton, begun in 1775, stood on the west side of the Hudson, opposite Anthony's Nose, at a very important pass, where the river was narrow, easily obstructed, and [Pg 29]from the elevation which the forts occupied, was commanded a great distance up and down. Fort Clinton was below Fort Montgomery, distant only about six hundred yards, the Poplopen Kill running through a ravine between them; the fortress was small, but more complete than Fort Montgomery, and stood at a greater elevation, being 23 feet the highest, and 123 feet above the river. These posts were distant (southeast) from the Clinton mansion only about sixteen miles. The two fortresses required a thousand men for their proper defense, but till early in 1777, had usually been in charge of a very small force under Gen. James Clinton. The time of these soldiers expiring on the last day of March, Col. Lewis Dubois, with the Fifth New York Regiment was sent to garrison Fort Montgomery.

A meeting of the field officers of Orange and Ulster, was held at Mrs. Falls' in Little Britain, March 31st, 1777, pursuant to a resolve of the New York Convention empowering General George Clinton, lately appointed commandant of the forts in the Highlands, to call out the militia "to defend this State against the incursions of our implacable enemies, and reinforce the garrisons of Fort Montgomery, defend the post of Sidnam's Bridge (near Hackensack), and afford protection to the distressed inhabitants." It was there resolved, with great spirit, to call one-third of each of the several regiments into actual service, to the number of 1,200, and to form them into three temporary regiments, of which two should garrison Fort Montgomery, under Colonel Levi Pawling (with Lt. Col. McClaughry), and Col. Johannes Snyder. As the men were raised they were to march in detachments to that post, and were to serve till August 1st, and receive continental pay and rations. Each captain was forthwith directed to raise his quota, and "in the most just and equitable manner."

John Van Arsdale was among those chosen from his beat, and sometime in April, borrowing from his brother an old but trusty musket, proceeded to Fort Montgomery. Being of a resolute, active temperament, with a knowledge of tactics, and an aptness to command, he was made a corporal; an evidence of the good opinion entertained of him by his officers, flattering to one of his years. It was also in his favor that he was a good penman, and had acquired a fair English education for the times. Drilling his squad, placing and relieving the guards, and other daily routine duty, gave our young corporal enough to do, while the courts for the trial of some notorious tories, held at that post, during the spring and summer, added to frequent alarms due to indications that the enemy from below meditated an attack upon the forts, kept everything lively. On [Pg 30]July 2nd, Gen. Clinton, upon a hint from Washington that Lord Howe, in order to favor Burgoyne, might attempt to seize the passes of the Highlands, and "make him a very hasty visit," with which view, accounts given by deserters from New York coincided; immediately repaired to Fort Montgomery, after first ordering to that post the full regiment of Col. McClaughry, with those of Colonels William Allison, Jesse Woodhull, and Jonathan Hasbrouck. The militia came in with great alacrity, almost to a man. But ten days passed without a sign of the enemy. Parties went daily on the Dunderbergh (Thunder Mountain) to look down the river, but could not see a single vessel; then, as usual, when there was no immediate prospect of any thing to do, the transient militia became uneasy, and were allowed to go home in the belief that they would turn out more cheerfully the next time.

But as the term of service of those called out in April expired on August 1st, on that date another call was made by Gov. Clinton on the respective regiments, to make up eight companies, by ballot or other equitable mode, and to march with due expedition to Fort Montgomery, and there put themselves under command of Colonel Allison, with McClaughry as his Lieutenant Colonel. They were to draw continental pay, etc. In this instance no immediate danger being apprehended, the militia did not respond very promptly, although much needed to replace part of the continental force which had been withdrawn for other service. Again, on August 5th, Clinton, by virtue of threatening news from Gen. Washington, directed Allison and McClaughry to march all the militia to Fort Montgomery, except the frontier companies, which were to be left for home protection. But repeated orders to urge them forward were but partially successful. September closed, the quotas were far from complete, orders then issued by Allison, McClaughry, and Hasbrouck (by direction of Clinton) for half their regiments to repair to Fort Montgomery were but slowly complied with, and the delay was fatal! Van Arsdale had re-enlisted and held his former position. It was at this time that he made the acquaintance of Elnathan Sears, and which ripened into friendship under very trying circumstances.

Forts Montgomery and Clinton at this date mounted thirty-two cannon, rating from 6 to 32 pounders. The garrison consisted of two companies of Col. John Lamb's artillery, under Capts. Andrew Moodie and Jonathan Brown (one in each fort) and parts of the regiments of Cols. Dubois, Allison, Hasbrouck, Woodhull and McClaughry with a very few from other regiments. Thus matters stood on Sunday, October 5th, 1777.

Hark! what bustling haste—of people running to and fro,—has suddenly disturbed the Sabbath evening's repose at [Pg 31]Neelytown? Tidings have just reached them that the enemy's vessels are ascending the Hudson with the obvious design of attacking Fort Montgomery and the neighboring posts. The orders are for every man able to shoulder a musket to hasten to their assistance! This was grave intelligence for the inmates at the Van Arsdale home (and which may serve to represent many others), but the call of duty could not be disregarded. For most of the night the good wife was occupied in baking and putting up provisions for Tunis and his two apprentices to take with them, while these were as busy cleaning their muskets, moulding bullets, etc., that naught might be wanting for the stern business before them. Towards morning, taking one or two hours rest, they arose, equipped themselves, and made ready for the journey to the fort, which was full twenty miles distant. As the parting moment had come, the kind father kissed his three little ones tenderly, then uttered in the ear of his sorrowing Jennie the sad good-bye, and with the others hastened from the house, his wife attending him to the road, and weeping bitterly for she understood but too well that it might be the final parting. Her longing eyes followed them till they disappeared beyond an intervening hill. "Oh!" said she to the writer more than sixty years afterwards, as she related these facts, her eyes even then suffused with tears, "You may read of these things, but you can never feel them as I did. I wept much during those seven years."

During the day, those whose kinsmen had gone to the battle met here and there in little bands to condole with each other, and talk over the unhappy situation. Later, the boom of distant artillery awakened their worst fears, for now were they sure that those dear to them were engaged in a mortal conflict with the enemy. The shades of evening closing around, brought no relief to their burdened hearts; but, on the contrary, the most torturing suspense as to the issue of the battle. To make the situation more depressing, there came on a cold rain, and the dreariness without was a fit index of the desolate hearts within. At a late hour Mrs. Van Arsdale retired to her sleepless pillow; but her case found its counterpart in many an anxious household over a large section of country.

At length morning broke upon that unhappy neighborhood, and with it came persons from the battle bringing the appalling news that the Americans had been defeated, and many of them slain, or made prisoners, and that the enemy were in full possession of the forts. Then other parties arrived whose woe-stricken faces only confirmed the sad intelligence. Soon anxious inquiries sped from house to house where any lived who had escaped from the slaughter, to learn about this one and that, who had gone to the battle, but had not returned. Jennie could get no tidings of [Pg 32]her husband, though she spent the greater part of the day in watching on the road, and several times even fancied that she saw him coming; but alas! only to find it a delusion. It added to her fears for her husband, when a neighbor named Monell, at whose house she called, met her with the sorrowful news that his brother, Robert Monell, first lieutenant in Capt. Van Keuren's company, had been killed in the battle. At length the apprentices arrived, their faces begrimed with powder, and one of them crying for his brother, who had been shot down by his side, and died instantly.[17] The other, who was Joseph Elder, before spoken of, a young man of giant frame, had narrowly escaped death, having his hat and jacket pierced with bullets in the engagement! But having been separated from Mr. Van Arsdale, they had not seen him since the battle, and so were ignorant as to his fate. The wretched woman was in despair; many of her neighbors had now returned and the prolonged absence of her Tunis seemed to forbode that he had either been killed or captured by the enemy. But now still others arrive, and she is led from their statements, to hope that Tunis has escaped, and is making his way homeward through the mountains. Her heart leaps with joy, and she returns to the house, and even indulges a laugh as her eye gets a sight of the mush kettle still hanging on the trammel, as she placed it there in the morning; no meal stirred in, and she having eaten nothing the whole day. Towards night Tunis arrived, on horseback, with his brother-in-law William Wear, who at Jennie's request, had gone out some distance to look for him.[18] He was fast asleep from exhaustion when they reached the house, (Wear behind him and holding him on the horse), and his face so [Pg 33]blackened with powder that his wife hardly knew him. He was much depressed in spirits, but grateful to God who had preserved and restored him to his family and friends. That evening brought in his captain, Van Keuren, who for some cause was not in the fight, with his minister, Rev. Andrew King, and many other neighbors—a house full,—some to congratulate Van Arsdale on his escape, others, with anxious faces to inquire after missing friends, and others still to learn the particulars of the battle. The account he gave of what happened after leaving home for the scene of conflict, was briefly as follows:

A walk of several hours brought them to a little stream at the foot of the hill upon which Fort Montgomery stood, and where they had intended to stop and eat their dinner; but hearing a great deal of noise and bustle in the fort, they only took a drink from the brook, and hastened up into the works, when they soon learned that a large body of the enemy had landed below the Dunderbergh, and were advancing by a circuitous route to attack the fort in the rear. About the middle of the afternoon the British columns appeared, and pressed on to the assault with bayonets fixed. But our men poured down upon them such a destructive fire of bullets and grape shot that they fell in heaps, and were kept at bay till night-fall, when our folks, being worn out by continued fighting, and overpowered by numbers, were obliged to give way. Then Gov. Clinton told them to escape for their lives, when many fought their way out, or scrambled over the wall, and so got away. It must have fared badly with the rest, as the enemy after entering the fort continued to stab, knock down and kill our soldiers without pity. Favored by the darkness, Tunis attempted to escape through one of the entrances, though it was nearly blocked up by the assailing column, and the heaps of killed and wounded; but presently, as an English soldier held a militiaman bayoneted against the wall, Tunis, stooping down, slipped between the Briton's legs, and escaped around the fort toward the river. He said he had gone but a little way, when a cry of distress, evidently from a young person, arrested his attention. A poor boy, in making his escape, had fallen into a crevice in the rocks, and was unable to extricate himself. Tunis, at no little risk, crept down to where the lad was and drew him out, but in doing so hurt himself quite badly, by scraping one of his legs on a sharp rock. He then gained the river and found a skiff, in which he and two or three others crossed over. Then a party of them travelled in Indian file, through the darkness and cold drizzling rain, stopping once at the house of a friendly farmer, where they got some food, and as the day broke entered Fishkill; whence they crossed to New Windsor, and there met Gov. Clinton and many more who had made good their escape. All felt greatly [Pg 34]dispirited, but the Governor tried to cheer them, remarking: "Well, my boys, we've been badly beaten this time, but have courage, the next time the day may be ours." Without much delay Mr. Van Arsdale set out for home, as fast as his lameness admitted of, knowing how great anxiety would be felt on his account. But of his brother John; he had no knowledge of what had befallen him, and indulged the worst fears as to his fate.

Such in brief was Van Arsdale's account of that sanguinary affair, divested of many little particulars of the battle and its sequel. But his limited observation could include but a small part of what passed on that most eventful day, as we are now able to gather it from many sources.

With a view to coöperate with General Burgoyne, who had invaded the State from the north, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Clinton, having a force of about 3,000 men, sailed from New York on the 4th of October, with the design of reducing the forts in the Highlands, and, if possible, open communication with Burgoyne's army. The same night their advance as far as Tarrytown was known at Fort Montgomery, and that they had landed a large force at that place. The next morning (Sunday) advices were received that they had reached King's Ferry, connecting Verplank's and Stony Point. That afternoon they landed a large body of men on the east side of the river, to divert attention from the real point of attack, but they re-embarked in the night. An extract from Sir Henry Clinton's report to General Howe, dated Fort Montgomery, October 9th, will begin at this point, and form a proper introduction to our side of the story. Says he:

"At day-break on the 6th the troops disembarked at Stony Point. The avant-garde of 500 regulars and 400 provincials,[19] commanded by Lieut.-Col. Campbell, with Col. Robinson, of the provincials, under him, began its march to occupy the pass of Thunder-hill (Dunderbergh). This avant-garde, after it had passed that mountain, was to proceed by a detour of seven miles round the hill (called Bear Hill), and deboucher in the rear of Fort Montgomery; while Gen. Vaughan, with 1200 men,[20] was to continue his march towards Fort Clinton, covering the corps under Lieut.-Col. Campbell, and à portée to coöperate, by attacking Fort Clinton, or, in case of misfortune, to favor the retreat. Major-Gen. Tryon, with the remainder, being the rear guard,[21] to [Pg 35]leave a battalion at the pass of Thunder-hill, to open our communication with the fleet.