Title: The Reclaimers

Author: Margaret Hill McCarter

Illustrator: George W. Gage

Release date: September 30, 2010 [eBook #33959]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Darleen Dove, Roger Frank, Mary Meehan and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

PART I. JERRY

I. The Heir Apparent

II. Uncle Cornie's Throw

III. Hitching the Wagon to a Star

IV. Between Edens

V. New Eden's Problem

VI. Paradise Lost

PART II. JERRY AND JOE

VII. Unhitching the Wagon from a Star

VIII. If a Man Went Right with Himself

IX. If a Woman Went Right with Herself

X. The Snare of the Fowler

XI. An Interlude in "Eden"

XII. This Side of the Rubicon

PART III. JERRY AND EUGENE—AND JOE

XIII. How a Good Mother Lives On

XIV. Jim Swaim's Wish

XV. Drawing Out Leviathan with a Hook

XVI. A Postlude in "Eden"

XVII. The Flesh-pots of the Winnwoc

XVIII. The Lord Hath His Way in the Storm

XIX. Reclaimed

Only the good little snakes were permitted to enter the "Eden" that belonged to Aunt Jerry and Uncle Cornie Darby. "Eden," it should be explained, was the country estate of Mrs. Jerusha Darby—a wealthy Philadelphian—and her husband, Cornelius Darby, a relative by marriage, so to speak, whose sole business on earth was to guard his wife's wealth for six hours of the day in the city, and to practise discus-throwing out at "Eden" for two hours every evening.

Of course these two were never familiarly "Aunt" and "Uncle" to this country neighborhood, nor to any other community. Far, oh, far from that! They were Aunt and Uncle only to Jerry Swaim, the orphaned and only child of Mrs. Darby's brother Jim, whose charming girlish presence made the whole community, wherever she might chance to be. They were cousin, however, to Eugene Wellington, a young artist of more than ordinary merit, also orphaned and alone, except for a sort of cousinship with Uncle Cornelius.

"Eden" was a beautifully located and handsomely appointed estate of two hundred acres, offering large facilities to any photographer seeking magazine illustrations of country life in America. Indeed, the place was, as Aunt Jerry Darby declared, "summer and winter, all shot up by camera-toters and dabbed over with canvas-stretchers' paints," much to the owner's disgust, to whom all camera-toters and artists, except Cousin Eugene Wellington, were useless idlers. The rustic little railway station, hidden by maple-trees, was only three or four good discus-throws from the house. But the railroad itself very properly dropped from view into a wooded valley on either side of the station. There was nothing of cindery ugliness to mar the spot where the dwellers in "Eden" could take the early morning train for the city, or drop off in the cool of the afternoon into a delightful pastoral retreat. Beyond the lawns and buildings, gardens and orchards, the land billowed away into meadow and pasture and grain-field, with an insert of leafy grove where song-birds builded an Eden all their own. The entire freehold of Aunt Jerry Darby and Uncle Cornie, set down in the middle of a Western ranch, would have been a day's journey from its borders. And yet in it country life was done into poetry, combining city luxuries and conveniences with the dehorned, dethorned comfort and freedom of idyllic nature. What more need be said for this "Eden" into which only the good little snakes were permitted to enter?

In the late afternoon Aunt Jerry sat in the rose-arbor with her Japanese work-basket beside her, and a pearl tatting-shuttle between her thumb and fingers. One could read in a thoughtful glance all there was to know of Mrs. Darby. Her alert air and busy hands bespoke the habit of everlasting industry fastened down upon her, no doubt, in a far-off childhood. She was luxurious in her tastes. The satin gown, the diamond fastening the little cap to her gray hair, the elegant lace at her throat and wrists, the flashing jewels on her thin fingers, all proclaimed a desire for display and the means wherewith to pamper it. The rest of her story was written on her wrinkled face, where the strong traits of a self-willed youth were deeply graven. Something in the narrow, restless eyes suggested the discontented lover of wealth. The lines of the mouth hinted at selfishness and prejudice. The square chin told of a stubborn will, and the stern cast of features indicated no sense of humor whereby the hardest face is softened. That Jerusha Darby was rich, intolerant, determined, unimaginative, self-centered, unforgiving, and unhappy the student of character might gather at a glance. Where these traits abide a second glance is unnecessary.

Outside, the arbor was aglow with early June roses; within, the cushioned willow seats invite to restful enjoyment. But Jerusha Darby was not there for pleasure. While her pearl shuttle darted in and out among her fingers like a tiny, iridescent bird, her mind and tongue were busy with important matters.

Opposite to her was her husband, Cornelius. It was only important matters that called him away from his business in the city at so early an hour in the afternoon. And it was only on business matters that he and his wife ever really conferred, either in the rose-arbor or elsewhere. The appealing beauty of the place indirectly meant nothing to these two owners of all this beauty.

The most to be said of Cornelius Darby was that he was born the son of a rich man and he died the husband of a rich woman. His life, like his face, was colorless. He fitted into the landscape and his presence was never detected. He had no opinions of his own. His father had given him all that he needed to think about until he was married. "Was married" is well said. He never courted nor married anybody. He was never courted, but he was married by Jerusha Swaim. But that is all dried stuff now. Let it be said, however, that not all the mummies are in Egyptian tombs and Smithsonian Institutions. Some of them sit in banking-houses all day long, and go discus-throwing in lovely "Edens" on soft June evenings. And one of them once, just once, broke the ancient linen wrappings from his glazed jaws and spoke. For half an hour his voice was heard; and then the bandages slipped back, and the mummy was all mummy again. It was Jerry Swaim who wrought that miracle. But then there is little in the earth, or the waters under the earth, that a pretty girl cannot work upon.

"You say you have the report on the Swaim estate that the Macpherson Mortgage Company of New Eden, Kansas, is taking care of for us?" Mrs. Darby asked.

"The complete report. York Macpherson hasn't left out a detail. Shall I read you his description?" her husband replied.

"No, no; don't tell me a thing about it, not a thing. I don't want to know any more about Kansas than I know already. I hate the very name of Kansas. You can understand why, when you remember my brother. I've known York Macpherson all his life, him and his sister Laura, too. And I never could understand why he went so far West, nor why he dragged that lame sister of his out with him to that Sage Brush country."

"That's because you won't let me tell you anything about the West. But as a matter of business you ought to understand the conditions connected with this estate."

"I tell you again I won't listen to it, not one word. He is employed to look after the property, not to write about it. None of my family ever expects to see it. When we get ready to study its value we will give due notice. Now let the matter of description, location, big puffing up of its value—I know all that Kansas talk—let all that drop here." Jerusha Darby unconsciously stamped her foot on the cement floor of the arbor and struck her thin palm flat upon the broad arm of her chair.

"Very well, Jerusha. If Jerry ever wants to know anything about its extent, agricultural value, water-supply, crop returns, etc., she will find them on file in my office. The document says that the land in the Sage Brush Valley in Kansas is now, with title clear, the property of the estate of the late Jeremiah Swaim and his heirs and assigns forever; that York Macpherson will, for a very small consideration, be the Kansas representative of the Swaim heirs. That is all I have to say about it."

"Then listen to me," Mrs. Darby commanded. And her listener—listened. "Jerry Swaim is Brother Jim and Sister Lesa's only child. She's been brought up in luxury; never wanted a thing she didn't get, and never earned a penny in her life. She couldn't do it to save her life. If I outlive you she will be my heir if I choose to make my will in her favor. She can be taken care of without that Kansas property of hers. That's enough about the matter. We will drop it right here for other things. There's your cousin Eugene Wellington coming home again. He's a real artist and hasn't any property at all."

A ghost of a smile flitted across Mr. Darby's blank face, but Mrs. Darby never saw ghosts.

"Of course Jerry and Gene, who have been playmates in the same game all their lives, will—will—" Mrs. Darby hesitated.

"Will keep on playing the same game," Cornelius suggested. "If that's all about this business, I'll go and look after the lily-ponds over yonder, and then take a little exercise before dinner. I'm sorry I missed Jerry in the city. She doesn't know I am out here."

"What difference if you did? She and Eugene will be coming out on the train pretty soon," Mrs. Darby declared.

"She doesn't know he's there, maybe. They may miss each other," her husband replied.

Then he left the arbor and effaced himself, as was his custom, from his wife's presence, and busied himself with matters concerning the lily-ponds on the far side of the grounds where pink lotuses were blooming.

Meantime Jerusha Darby's fingers fairly writhed about her tatting-work, as she waited impatiently for the sound of the afternoon train from the city.

"It's time the four-forty was whistling round the curve," she murmured. "My girl will soon be here, unless the train is delayed by that bridge down yonder. Plague on these June rains!"

Mrs. Darby said "my girl" exactly as she would have said "my bank stock," or "my farm." Hers was the tone of complete possession.

"She could have come out in the auto in half the time, the four-forty creeps so, but the roads are dreadfully skiddy after these abominable rains," Mrs. Darby continued.

The habit of speaking her thoughts aloud had grown on her, as it often does on those advanced in years who live much alone. The little vista of rain-washed meadows and growing grain that lay between tall lilac-trees was lost to her eyes in the impatience of the moment's delay. What Jerusha Darby wanted for Jerusha Darby was vastly more important to her at any moment than the abstract value of a general good or a common charm.

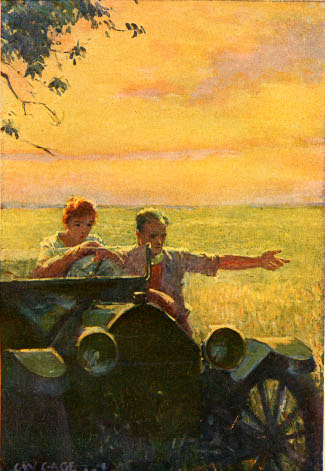

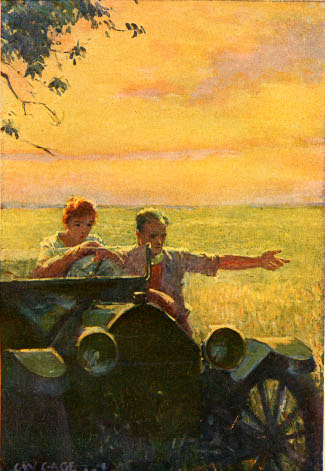

As she leaned forward, listening intently for the rumble of the train down in the valley, a great automobile swung through the open gateway of "Eden" and rounded the curves of the maple-guarded avenue, bearing down with a birdlike sweep upon the rose-arbor.

"Here I am, Aunt Jerry," the driver's girlish voice called. "Uncle Cornie is coming out on the train. I beat him to it. I saw the old engine huffing and puffing at the hill beyond the third crossing of the Winnowoc. It is bank-full now from the rains. I stopped on that high fill and watched the train down below me creeping out on the trestle above the creek. When it got across and went crawling into the cut on this side I came on, too. I had my hands full then making this big gun of a car climb that muddy, slippery hill that the railroad cuts through. But I'd rather climb than creep any old day."

"Jerry Swaim," Mrs. Darby cried, staring up at her niece in amazement, "do you mean to say you drove out alone over that sideling, slippery bluff road? But you wouldn't be Lesa Swaim's daughter if you weren't taking chances. You are your mother's own child, if there ever was one."

"Well, I should hope I am, since I've got to be classified somewhere. I came because I wanted to," Jerry declared, with the finality of complete excuse in her tone. All her life what Jerry Swaim had wanted was abundant reason for her having. "It was dreadfully hot and sticky in the city, and I knew it would be the bottom deep of mugginess on that crowded Winnowoc train. The last time I came out here on it I had to sit beside a dreadful big Dutchman who had an old hen and chickens in a basket under his feet. He had had Limburger cheese for his dinner and had used his whiskers for a napkin to catch the crumbs. Ugh!" Jerry gave a shiver of disgust at the recollection. "An old lady behind us had 'sky-atick rheumatiz' and wouldn't let the windows be opened. I'd rather have any kind of 'rheumatiz' than Limburger for the same length of time. The Winnowoc special ought to carry a parlor coach from the city and set it off at 'Eden' like it used to do. The agent let me play in it whenever I wanted to when I was a youngster. I'm never going to ride on any train again unless I go in a Pullman."

The girl struck her small gloved fist, like a spoiled child, against the steering-wheel of her luxuriously appointed car, but her winsome smile was all-redeeming as she looked down at her aunt standing in the doorway of the rose-arbor.

"Come in here, Geraldine Swaim. I want to talk to you." Mrs. Darby's affectionate tones carried also a note of command.

"Means business when she 'Geraldine Swaims' me," Jerry commented, mentally, as she gave the car to the "Eden" man-of-all-work and followed her aunt to a seat inside the blossom-covered retreat, where the pearl shuttle began to grow tatting again beneath the thin, busy fingers.

It always pleased Jerusha Darby to be told that there was a resemblance between these two. But, although the older woman's countenance was an open book holding the story of inherited ideas, limited and intensified, and the young face unmistakably perpetuated the family likeness, yet Jerry Swaim was a type of her own, not easy to forejudge. In the shadows of the rose-arbor her hair rippled back from her forehead in dull-gold waves. One could picture what the sunshine would do for it. Her big, dark-blue eyes were sometimes dreamy under their long lashes, and sometimes full of sparkling light. Her whole atmosphere was that of easeful, dependent, city life; yet there was something contrastingly definite in her low voice, her firm mouth and square-cut chin. And beyond appearances and manner, there was something which nobody ever quite defined, that made it her way to walk straight into the hearts of those who knew her.

"Where were you in the city to-day?" Mrs. Darby asked, abruptly, looking keenly at the fair-faced girl much as she would have looked at any other of her goodly possessions.

"Let me see," Jerry Swaim began, meditatively. "I was shopping quite a while. The stores are gorgeous this June."

"Yes, and what else?" queried the older woman.

"Oh, some more shopping. Then I lunched at La Señorita, that beautiful new tea-house. Every room represents some nationality in its decoration. I was in the Delft room—Holland Dutch—whiskers and Limburger"—there was a gleam of fun in the dark-blue eyes—"but it is restful and charming. And the service is perfect. Then I strolled off to the Art Gallery and lost myself in the latest exhibit. Cousin Gene would like that, I'm sure. It was so cool and quiet there that I stayed a long time. The exhibit is mostly of landscapes, all of them as beautiful as 'Eden' except one."

There was just a shade of something different in the girl's tone when she spoke her cousin's name.

"And that one?" Mrs. Darby inquired. She did not object to shopping and more shopping, but art was getting outside of her dominion.

"It was a desert-like scene; just yellow-gray plains, with no trees at all. And in the farther distance the richest purples and reds of a sunset sky into which the land sort of diffused. No landscape on this earth was ever so yellow-gray, or any sunset ever so like the Book of Revelation, nor any horizon-line so wide and far away. It was the hyperbole of a freakish imagination. And yet, Aunt Jerry, there was a romantic lure in the thing, somehow."

Jerry Swaim's face was grave as she gazed with wide, unseeing eyes at the vista of fresh June meadows from which the odor of red clover, pulsing in on the cool west breeze of the late afternoon, mingled with the odor of white honeysuckle that twined among the climbing rose-vines above her.

"Humph! What else?" Aunt Jerry sniffed a disapproval of unpleasant landscapes in general and alluring romances in particular. Love of romance was not in her mental make-up, any more than love of art.

"I went over to Uncle Cornie's bank to tell him to take care of my shopping-bills. He wasn't in just then and I didn't wait for him. By the way"—Jerry Swaim was not dreamy now—"since all the legal litigations and things are over, oughtn't I begin to manage my own affairs and live on my own income?"

Sitting there in the shelter of blossoming vines, the girl seemed far too dainty a creature, too lacking in experience, initiative, or ability, to manage anything more trying than a big allowance of pin-money. And yet, something in her small, firm hands, something in the lines of her well-formed chin, put the doubt into any forecast of what Geraldine Swaim might do when she chose to act.

Aunt Jerry wrapped the lacy tatting stuff she had been making around the pearl shuttle and, putting both away in the Japanese work-basket, carefully snapped down the lid.

"When Jerusha Darby quits work to talk it's time for me to put on my skid-chains," Jerry said to herself as she watched the procedure.

"Jerry, do you know why I called you your mother's own child just now?" Mrs. Darby asked, gravely.

"From habit, maybe, you have said it so often." Jerry's smile took away any suggestion of pertness. "I know I am like her in some ways."

"Yes, but not altogether," the older woman continued. "Lesa Swaim was a strange combination. She was made to spend money, with no idea of how to get money. And she brought you up the same way. And now you are grown, boarding-school finished, and of age, you can't alter your bringing up any more than you can change your big eyes that are just like Lesa's, nor your chin that you inherited from Brother Jim. I might as well try to give you little black eyes and a receding chin as to try to reshape your ways now. You are as the Lord made you, and Providence molded you, and your mother spoiled you."

"Well, I don't want to be anything different. I'm happy as I am."

"You won't need to be, unless you choose. But being twenty-one doesn't make you too old to listen to me—and your uncle Cornie."

In all her life Jerry had never before heard her uncle's name brought in as co-partner of Jerusha Darby's in any opinion, authority, or advice. It was an unfortunate slip of the tongue for Uncle Cornie's wife, one of those simple phrases that, dropped at the right spot, take root and grow and bear big fruit, whether of sweet or bitter taste.

"Your mother was a dreamer, a lover of romance, and all sorts of adventures, although she never had a chance to get into any of them. That's why you went skidding on that sideling bluff road to-day; that and the fact that she brought you up to have your own way about everything. But, as I say, we can't change that now, and there's no need to if we could. Lesa was a pretty woman, but you look like the Swaims, except right across here."

Aunt Jerry drew her bony finger across the girl's brows, unwilling to concede any of the family likeness that could possibly be retained. She could not see the gleam of mischief lurking under the downcast eyelashes of Lesa Swaim's own child.

"Your father was a good business man, level-headed, shrewd, and honest"—Mrs. Darby spoke rapidly now—"but things happened in the last years of his life. Your mother took pneumonia and died, and you went away to boarding-school. Jim's business was considerably involved. I needn't bother to tell you about that. It doesn't matter now, anyhow. And then one night he didn't come home, and the next morning your uncle found him sitting in his office, just as he had left him the evening before. He had been dead several hours. Heart failure was what the doctor said, but I reckon everybody goes of heart failure sooner or later."

A bright, hard glow came into Jerry Swaim's eyes and the red lips were grimly pressed together. In the two years since the loss of her parents the girl had never tried to pray. As time went on the light spirit of youth had come back, but something went out of her life on the day of her father's death, leaving a loss against which she stubbornly rebelled.

"To be plain, Jerry," Mrs. Darby hurried on, "you have your inheritance all cleared up at last, after two whole years of legal trouble."

"Oh, it hasn't really bothered me," Jerry declared, with seeming flippancy. "Just signing my name where somebody pointed to a blank line, and holding up my right hand to be sworn—that's all. I've written my full name and promised that the writing was mine, 's'welp me Gawd,' as the court-house man used to say, till I could do either one under the influence of ether. Nothing really bothersome about it, but I'm glad it's over. Business is so tiresome."

"It's not so large a fortune, by a good deal, as it would have been if your father had listened to me." Mrs. Darby spoke vaguely. "But you will be amply provided for, anyhow, unless you yourself choose to trifle with your best interest. You and I are the only Swaims living now. Some day, if I choose, I can will all my property to you."

The square-cut chin and the deep lines around the stern mouth told plainly that obedience to this woman's wishes alone could make a beneficiary to that will.

"You may be a dreamer, and love to go romancing around into new scrapes like your mother would have done if she could. But she was as soft-hearted as could be, with all that. That's why she never denied you anything you wanted. She couldn't do a thing with money, though, as I said, except spend it. You are a good deal like your father, too, Jerry, and you'll value property some day as the only thing on earth that can make life anything but a hard grind. If you don't want to be like that bunch of everlasting grubs that ride on the Winnowoc train every afternoon, or the poor country folks around here that never ride in anything but a rickety old farm-wagon, you'll appreciate what I—and Uncle Cornie—can do for you."

Uncle Cornie again, and he never had shared in any equal consideration before. It was a mistake.

"There's the four-forty whistling for the curve at last. It's time it was coming. I must go in and see that dinner is just right. You run down and meet it. Cousin Eugene is coming out on it. Your uncle Cornie is here on the place somewhere. He came out after lunch on some business we had to fix up. No wonder you missed him. But, Jerry"—the stern-faced woman put a hand on the girl's shoulder with more of command than caress in the gesture—"Eugene is a real artist with genius, you know."

"Yes, I know," Jerry replied, a sudden change coming into her tone. "What of that?"

"You've always known him. You like him very much?" Jerusha Darby was as awkward in sentiment as she was shrewd in a bargain.

The bloom on the girl's cheek deepened as she looked away toward the brilliantly green meadows across which the low sun was sending rays of golden light.

"Oh, I like him as much as he likes me, no doubt. I'll go down to the station and look him over, if you say so."

Beneath the words lay something deeper than speech—something new even to the girl herself.

As Jerry left the arbor Mrs. Darby said, with something half playful, half final, in her tone: "You won't forget what I've said about property, you little spendthrift. You will be sensible, like my sensible brother's child, even if you are as idealizing as your sentimental mother."

"I'll not forget. I couldn't and be Jerry Darby's niece," the last added after the girl was safely out of her aunt's hearing. "My father and mother both had lots of good traits, it seems, and a few poor ones. I seem to be really heir to all the faulty bents of theirs, and to have lost out on all the good ones. But I can't help that now. Not till after the train gets in, anyhow."

Her aunt watched her till the shrubbery hid her at a turn in the walk. Young, full of life, dainty as the June blossoms that showered her pathway with petals, a spoiled, luxury-loving child, with an adventurous spirit and a blunted and undeveloped notion of human service and divine heritage, but with a latent capacity and an untrained power for doing things, that was Jerry Swaim—whom the winds of heaven must not visit too roughly without being accountable to Mrs. Jerusha Darby, owner and manager of the universe for her niece.

Jerry was waiting at the cool end of the rustic station when the train came in. How hot and stuffy it seemed to her as it puffed out of the valley, and how tired and cross all the bunch of grubs who stared out of the window at her. It made them ten times more tired and cross and hot to see that girl looking so cool and rested and exquisitely gowned and crowned and shod. The blue linen with white embroidered cuffs, the rippling, glinting masses of hair, the small shoes, immaculately white against the green sod—little wonder that, while the heir apparent to the Darby wealth felt comfortably indifferent toward this uninteresting line of nobodies in particular, the bunch of grubs should feel only envy and resentment of their own sweaty, muscle-worn lot in life.

Jerry and Eugene Wellington were far up the shrubbery walk by the time the Winnowoc train was on its way again, unconscious that the passengers were looking after them, or that the talk, as the train slowly got under way, was all of "that rich old codger of a Darby and his selfish old wife"; of "that young dude artist, old Wellington's kid, too lazy to work"; of "that pretty, frivolous girl who didn't know how to comb her own hair, Jim Swaim's girl—poor Jim!" "Old Corn Darby was looking yellow and thin, too. He would dry up and blow away some day if his money wasn't weighting him down so he couldn't."

At the bend in the walk, the two young people saw Uncle Cornie crossing the lawn.

"Going to get his discus. He'll have no appetite for dinner unless he gets in a few dozen slings," the young man declared. "Let's turn in here at the sign of the roses, Jerry. I'm too lazy to take another step."

"You should have come out with me in the car," Jerry replied as they sat down in the cool arbor made for youth and June-time. "I didn't know you were in the city."

"Well, little cousin girl, I'll confess I didn't dare," the young man declared, boldly. "I've been studying awfully hard this year, and, now I'm needed to paint The Great American Canvas, I can't end my useful career under a big touring-car at the bottom of an embankment out on the Winnowoc bluff road. So when I saw you coming into Uncle Cornie's office in the bank I slipped away."

"And as to my own risk?" Jerry asked.

"Oh, Jerry Swaim, you would never have an accident in a hundred years. There's nobody like you, little cousin mine, nobody at all."

Eugene Wellington put one well-formed hand lightly on the small white hand lying on the wicker chair-arm, and, leaning forward, he looked down into the face of the girl beside him. A handsome, well-set up, artistic young fellow he was, fitted to adorn life's ornamental places. And if a faint line of possible indecision of character might have suggested itself to the keen-eyed reader of faces, other traits outweighed its possibility. For his was a fine face, with a sort of gracious gentleness in it that grows with the artist's growth. A hint of deeper spirituality, too, that marks nobility of character, added to a winning personality, put Eugene Wellington above the common class. He fitted the rose-arbor, in "Eden" and the comradeship of good breeding. When a man finds his element, all the rest of the world moves more smoothly therefor.

"Nobody like me," Jerry repeated. "It's a good thing I'm the only one of the kind. You'd say so if you knew what Aunt Jerry thinks of me. She has been analyzing me and filing me away in sections this afternoon."

"What's on her mind now?" Eugene Wellington asked, as he leaned easefully back in his chair.

"She says I am heir—" Jerry always wondered what made her pause there. Years afterward, when this June evening came back in memory, she could not account for it.

"Heir to what?" the young artist inquired, a faint, shadowy something sweeping his countenance fleetly.

also to my father's entire estate that's left after some two years of litigation. I hate litigations."

"So do I, Jerry. Let's forget them. Isn't 'Eden' beautiful? I'm so glad to be back here again." Eugene Wellington looked out at the idyllic loveliness of the place which the rose-arbor was built especially to command. "Nobody could sin here, for there are no serpents busy-bodying around in such a dream of a landscape as this. I'm glad I'm an artist, if I never become famous. There's such a joy in being able to see, even if your brush fails miserably in trying to make others see."

Again the man's shapely hand fell gently on the girl's hand, and this time it stayed there.

"You love it all as much as I do, don't you, Jerry?" The voice was deep with emotion. "And you feel as I do, how this lifts one nearer to God. Or is it because you are here with me that 'Eden' is so fair to-night? May I tell you something, Jerry? Something I've waited for the summer and 'Eden' to give me the hour and the place to say? We've always known each other. We thought we did before, but a new knowing came to me the day your father left us. Look up, little cousin. I want to say something to you."

June-time, and youth, and roses, and soft, sweet air, and nobody there but blossoms, and whispering breezes, and these two. And they had known each other always. Oh, always! But now—something was different now, something that was grander, more beautiful in this place, in this day, in each other, than had ever been before—the old, old miracle of a man and a maid.

Suddenly something whizzed through the air and a snakelike streak of shadow cut the light of the doorway. Out in the open, Uncle Cornie came slowly stepping off the space to where his discus lay beside the rose-arbor—one of the good little snakes. Every Eden has them, and some are much better than others.

The discus-ground was out on a lovely stretch of shorn clover sod. Why the discus should wander from the thrower's hand through the air toward the rose-arbor no wind of heaven could tell. Nor could it tell why Uncle Cornie should choose to follow it and stand in the doorway of the arbor until the "Eden" dinner-hour called all three of the dwellers, Adam and Eve and this good little snake, to the cool dining-room and what goes with it.

Twilight and moonlight were melting into one, and all the sweet odors of dew-kissed blossoms, the good-night twitter of homing birds, the mists rising above the Winnowoc Valley, the shadows of shrubbery on the lawn, and the darkling outline of the tall maples made "Eden" as beautiful now as in the full sunlight.

Jerry Swaim sat in the doorway of the rose-arbor, watching Uncle Cornie throwing his discus again along the smooth white clover sod. Aunt Jerry had trailed off with Eugene to the far side of the spacious grounds to see the lily-ponds where the pink lotuses were blooming.

"Young folks mustn't be together too much. They'll get tired of each other too quickly. I used to get bored to death having Cornelius forever around." Aunt Jerry philosophized, considering herself as wise in the affairs of the heart as she was shrewd in affairs of the pocketbook. She would make Jerry and Gene want to be together before they had the chance again.

So Jerry Swaim sat alone, watching the lights and shadows on the lawn, only half conscious of Uncle Cornie's presence out there, until he suddenly followed his discus as it rolled toward the arbor and lay flat at her feet. Instead of picking it up, he dropped down on the stone step beside his niece and sat without speaking until Jerry forgot his presence entirely. It was his custom to sit without speaking, and to be forgotten.

Jerry's mind was full of many things. Life had opened a new door to her that afternoon, and something strange and sweet had suddenly come through it. Life had always opened pleasant doors to her, save that one through which her father and mother had slipped away—a door that closed and shut her from them and God, whose Providence had robbed her so cruelly of what was her own. But no door ever showed her as fair a vista as the one now opening before her dreamy gaze.

She glanced unseeingly at the old man sitting beside her. Then across her memory Aunt Jerry's words came drifting, "Being twenty-one doesn't make you too old to listen to me—and your uncle Cornie," and, "You'll appreciate what I—and Uncle Cornie—can do for you."

Uncle Cornie was looking at her with a face as expressionless as if he were about to say, "The bank doesn't make loans on any such security," yet something in his eyes drew her comfortably to him and she mechanically put her shapely little hand on his thin yellow one.

"I want to talk to you before anything happens, Jerry," he began, and then paused, in a confused uncertainty that threatened to end his wanting here.

And Jerry, being a woman, divined in an instant that it was to talk to her before anything happened that he had thrown that discus out of its way when she and Gene had thought themselves alone in the arbor before dinner. It was to talk to her that the thing had been rolled purposely to her feet now. Queer Uncle Cornie!

"I'm not too old to listen to you. I appreciate what you can do for me." Jerry was quoting her aunt's admonitions exactly, which showed how deeply they had unconsciously impressed themselves on her mind. Her words broke the linen bands about Uncle Cornie's glazed jaws, and he spoke.

"Your estate is all settled now. What's left to you after that rascally John—I mean after two years of pulling and hauling through the courts, is a 'claim,' as they call it, in the Sage Brush Valley in Kansas. It has never been managed well, somehow. There's not been a cent of income from it since Jim Swaim got hold of it, but that's no fault of the man who is looking after it—a York Macpherson. He's a gentleman you can trust anywhere. That's all there is of your own from your father's estate."

Jerry Swaim's dark-blue eyes opened wide and her face was lily white under the shadow of dull-gold hair above it.

"You are dependent on your aunt for everything. Well, she's glad of that. So am I, in a way. Only, if you go against her will you won't be her heir any more. You mightn't be, anyhow, if she—went first. The Darby estate isn't really Jerusha Swaim's; it's mine. But she thinks it's hers and it's all right that way, because, in the end, I do control it." Uncle Cornie paused.

Jerry sat motionless, and, although it was June-time, the little white hand on the speaker's thin yellow one was very cold.

"If you are satisfied, I'm glad, but I won't let Jim Swaim's child think she's got a fortune of her own when she hasn't got a cent and must depend on the good-will of her relatives for everything she wants. Jim would haunt me to my grave if I did."

Jerry stared at her uncle's face in the darkening twilight. In all her life she had never known him to seem to have any mind before except what grooved in with Aunt Jerry's commanding mind. Yet, surprised as she was, she involuntarily drew nearer to him as to one whom she could trust.

"We agreed long ago, Jim and I did, when Jim was a rich man, that some day you must be shown that you were his child as well as Lesa's—I mean that you mustn't always be a dependent spender. You must get some Swaim notions of living, too. Not that either of us ever criticized your mother's sweet spirit and her ideal-building and love of adventure. Romance belongs to some lives and keeps them young and sweet if they live to be a million. I'm not down on it like your Aunt Jerry is."

Romance had steered wide away from Cornelius Darby's colorless days. And possibly only this once in the sweet stillness of the June twilight at "Eden" did that hungering note ever sound in his voice, and then only for a brief space.

"Jim would have told you all this himself if he had got his affairs untangled in time. And he'd have done that, for he had a big brain and a big heart, but God went and took him. He did. Don't rebel always, Jerry. God was good to him—you'll see it some day and quit your ugly doubting."

Who ever called anything ugly about Jerry Swaim before? That a creature like Cornelius Darby should do it now was one of the strange, unbelievable things of this world.

"I just wanted to say again," Uncle Cornie continued, "if I go first you'd be Jerusha's heir. We agreed to that long ago. That is, if you don't cross her wishes and start her to make a will against you, as she'd do if you didn't obey her to the last letter in the alphabet. If I go after she does, the property all goes by law to distant relatives of mine. That was fixed before I ever got hold of it—heirs of some spendthrifts who would have wasted it long ago if they'd lived and had it themselves."

The sound of voices and Eugene Wellington's light laughter came faintly from the lily-pond.

"Eugene is a good fellow," Uncle Cornie said, meditatively. "He's got real talent and he'll make a name for himself some day that will be stronger, and do more good, and last longer than the man's name that's just rated gilt-edged security on a note, and nowhere else. Gene will make a decent living, too, independent of any aunts and uncles. But he's no stronger-willed, nor smarter, nor better than you are, Jerry, even if he is a bit more religious-minded, as you might say. You try awfully hard to think you don't believe in anything because just once in your life Providence didn't work your way. You can't fool with your own opinions against God Almighty and not lose in the deal. You'll have to learn that some time. All of us do, sooner or later."

"But to take my father—all I had—after I had given up mother, I can't see any justice nor any mercy in it," Jerry broke out.

Uncle Cornie was no comforter with words. He had had no chance to practise giving sympathy either before or after marriage. Mummies are limited, whether they be in sealed sarcophagi or sit behind roller-top desks and cut coupons. Something in his quiet presence, however, soothed the girl's rebellious spirit more than words could have done. Cornelius Darby did not know that he could come nearer to the true measurement of Jerry's mind than any one else had ever done. People had pitied her when her mother passed away and her father died a bankrupt—which last fact she must not be told—but nobody understood her except Uncle Cornie, and he had never said a word until now. He seemed to know now just how her mind was running. The wisdom of the serpent—even the good little snakes, of this "Eden"—is not to be misjudged.

"Jerry"—the old man's voice had a strange gentleness in that hour, however flat and dry it was before and afterward—"Jerry, you understand about things here."

He waved his hand as if to take in "Eden," Aunt Jerry and Cousin Eugene strolling leisurely away from the lily-pond, himself, the Darby heritage, and the unprofitable Swaim estate in the Sage Brush Valley in far-away Kansas.

"You've never been crossed in your life except when death took Jim. You don't know a thing about business, nor what it means to earn the money you spend, and to feel the independence that comes from being so strong in yourself you don't have to submit to anybody's will." Cornelius Darby spoke as one who had dreamed of these things, but had never known the strength of their reality. "And last of all," he concluded, "you think you are in love with Eugene Wellington."

Jerry gave a start. Uncle Cornie and love! Anybody and love! Only in her day-dreams, her wild flights of adventure, up to castles builded high in air, had she really thought of love for herself—until to-day. And now—Aunt Jerry had hinted awkwardly enough here in the late afternoon of what was on her mind. Cousin Gene had held her hand and said, "I want to say something to you." How full of light his eyes had been as he looked at her then! Jerry felt them on her still, and a tingle of joy went pulsing through her whole being. Then the discus had hurtled across the doorway and Uncle Cornie had come, not knowing that these two would rather be alone. At least he didn't look as if he knew. And now it was Uncle Cornie himself who was talking of love.

"You think you are in love with Eugene Wellington," Uncle Cornie repeated, "but you're not, Jerry. You're only in love with Love. Some day it may be with Gene, but it's not now. He just comes nearer to what you've been dreaming about, and so you think you are in love with him. Jerry, I don't want you to make any mistakes. I've lived a sort of colorless life"—the man's face was ashy gray as he spoke—"but once in a while I've thought of what might be in a man's days if things went right with him and if he went right with himself."

How often the last words came back to Jerry Swaim when she recalled the events of this evening—"if he went right himself."

"And I don't want any mistakes made that I can help."

Uncle Cornie's other hand closed gently about the little hand that lay on one of his. How firm and white and shapely it was, and how determined and fearless the grip it could put on the steering-wheel when the big Darby car skidded dangerously! And how flat and flabby and yellow and characterless was the hand that held it close!

"Come on, folks, we are going to the house to have some music," Aunt Jerry called, as she and Eugene Wellington came across the lawn from the lily-pond.

Mrs. Darby, sure of the fruition of her plans now, was really becoming pettishly jealous to-night. A little longer she wanted to hold these two young people under her absolute dominion. Of course she would always control them, but when they were promised to each other there would arise a kingdom within a kingdom which she could never enter. The angry voice of a warped, misused, and withered youth was in her soul, and the jealousy of loveless old age was no little fox among her vines to-night. Let them wait on her a little while. One evening more wouldn't matter.

As the two approached the rose-arbor Jerry's hand touched Uncle Cornie's cheek in a loving caress—the first she had ever given him.

"I won't forget what you have said, Uncle Cornie," she murmured, softly, as she rose to join her aunt and Eugene.

The moonlight flooding the lawn touched Jerry's golden hair, and the bloom of love and youth beautified her cheeks, as she walked away beside the handsome young artist into the beauty of the June night.

"Come on, Cornelius." Mrs. Darby's voice put the one harsh note into the harmony of the moment.

"As soon as I put away my discus. That last throw was an awkward one, and a lot out of line for me," he answered, in his dry, flat voice, stooping to pick up the implement of his daily pastime.

Up in the big parlor, Eugene and Jerry played the old duets they had learned together in their childhood, and sang the old songs that Jerusha Darby had heard when she was a girl, before the lust for wealth had hardened her arteries and dimmed her eyes to visions that come only to bless. But the two young people forgot her presence and seemed to live the hours of the beautiful June night only for each other.

It was nearly midnight when a peal of thunder boomed up the Winnowoc Valley and the end of a perfect day was brilliant in the grandeur of a June shower, with skies of midnight blackness cloven through with long shafts of lightning or swept across by billows of flame, while the storm wind's strong arms beat the earth with flails of crystal rain.

"Where is Uncle Cornie? I hadn't missed him before," Jerry asked as the three in the parlor watched the storm pouring out all its wrath upon the Winnowoc Valley.

"Oh, he went to put up his old discus, and then he went off to bed I suppose," Aunt Jerry replied, indifferently.

Nothing was ever farther from his wife's thought than the presence of Cornelius Darby. The two had never lived for each other; they had lived for the accumulation of property that together they might gather in.

It was long after midnight before the family retired. The moon came out of hiding as the storm-cloud swept eastward. The night breezes were cool and sweet, scattering the flower petals, that the shower had beaten off, in little perfumy cloudlets about the rose-arbor and upon its stone door-step.

It was long after Jerry Swaim had gone to her room before she slept. Over and over the events of the day passed in review before her mind: the city shopping; the dainty lunch in the Delft room at La Señorita; the art exhibit and that one level gray landscape with the flaming, gorgeous sunset so unlike the green-and-gold sunset landscape of "Eden"; the homeward ride with all its dangerous thrills; the talk with Aunt Jerry; Eugene, Eugene, Eugene; Uncle Cornie with his discus, at the door of the rose-arbor, and all that he had said to her; the old, old songs, and the thunder-storm's tremendous beauty, and Uncle Cornie again—and dreams at last, and Jim Swaim, big, strong, shrewd; and Lesa, sweet-faced, visionary; and then sound slumber bringing complete oblivion.

Last to sleep and first to waken in the early morning was Jerry. Happy Jerry! Nobody as happy as she was could sleep—and yet—Uncle Cornie's last discus-throw had brought new thoughts that would not slip away as the storm had slipped up the Winnowoc into nowhere. A rift in the lute, a cloud speck in a blue June sky, was the memory of what Uncle Cornie had told her when he let his discus roll up to her very feet by the door of the rose-arbor. Jerry Swaim must not be troubled with lute rifts and cloud specks. The call of the early morning was in the air, the dewy, misty, rose-hued dawning of a beautiful day in a beautiful "Eden" where only beautiful things belong. And loveliest among them all was Jerry Swaim in her pink morning dress, her glorious crown of hair agleam in the sun's early rays, her blue eye full of light.

The sweetest spot to her in all "Eden" on this morning was the rose-arbor. It belonged to her now by right of Eugene and—Uncle Cornie. The snatches of an old love-ballad, one of the songs she had sung with Eugene the night before, were on her lips as she left the veranda and passed with light step down the lilac walk toward the arbor. The very grass blades seemed to sing with her, and all the rain-washed world glowed with green and gold and creamy white, pink and heliotrope and rose.

At the turn of the walk toward the arbor Jerry paused to drink in the richness of all this colorful scene. And then, for no reason at all, she remembered what Uncle Cornie had said about his colorless life. Strange that she had never, in her own frivolous existence, thought of him in that way before. But with the alchemy of love in her veins she began to see things in a new light. His had been a dull existence. If Aunt Jerry ever really loved him she must have forgotten it long ago. And he made so little noise in the world, anyhow, it was easy to forget that he was in it. She had forgotten him last night even after all that he had said. He had had no part in their music, nor the beauty of the storm.

But here he was up early and sitting at the doorway of the rose-arbor just as she had left him last night. He was leaning back in the angle of the slightly splintered trellis, his colorless face gray, save where a blue line ran down his cheek from a blue-black burn on his temple, his colorless eyes looking straight before him; the discus he had stooped to pick up in the twilight last night clasped in his colorless hands; his colorless life race run. His clothing, soaked by the midnight storm, clung wet and sagging about his shrunken form. But the rain-beaten rose-vines had showered his gray head with a halo of pink petals, and about his feet were drifts of fallen blossoms flowing out upon the rich green sod. Nature in loving pity had gently decked him with her daintiest hues, as if a world of lavish color would wipe away in a sweep of June-time beauty the memory of the lost drab years.

Behind the most expensive mourner's crape to be had in Philadelphia Jerusha Darby hid the least mournful of faces. Not that she had not been shocked that one bolt out of all that summer storm-cloud, barely splintering the rose-arbor, should strike the head leaning against it with a blow so faint and yet so fatal; nor that she would not miss Cornelius and find it very inconvenient to fill his place in her business management. Every business needs some one to fetch and carry and play the watch-dog. And in these days of expensive labor watch-dogs come high and are not always well trained. But everybody must go sometime. That is, everybody else. To Mrs. Darby's cast of mind the scheme of death and final reckoning as belonging to a general experience was never intended for her individually. After all, things work out all right under Providential guidance. Eugene Wellington was a fortunate provision of an all-wise Providence. Eugene had some of his late cousin's ability. He would come in time to fill the vacant chair by the roll-top desk in the city banking and business house. Moreover, to the eyes of age he was a thousandfold more interesting and resourceful than the colorless quiet one whose loss would be felt of course, of course.

The reddest roses of "Eden" bloomed the next June on Cornelius Darby's grave, the brightest leaves of autumn covered him warmly from the winter's snows, and the places that had never felt his living presence missed him no more forever.

There was a steady downpour of summer rain on the day following the funeral at "Eden." Mrs. Darby was very busy with post-mortem details and Eugene Wellington's services were in constant demand by her, while Jerry Swaim wandered aimlessly about the house with a sense of the uselessness of her existence forcing itself upon her for the first time. Late in the afternoon, when the big rooms with all their luxurious appointments seemed unbearable, she slipped down the sodden way to the rose-arbor. There was a shower of new buds showing now under the beneficence of the warm rain, and all the withered petals of fallen blossoms were swept from sight.

As Jerry dropped into an easy willow rocker her eye fell on the splintered angle of the trellis by the doorway where Uncle Cornie had sat when the last summons came to him. A folded paper lay under the seat, inside the door, as if it had been blown from his pocket by a whirl of wind in that midnight thunder-storm.

Jerry stared at the paper a long time before it occurred to her to pick it up. At last, in a mechanical way, she took it from under the seat and spread it out on the broad arm of her chair. As she read its contents her listlessness fell away, the dreamy blue eyes glowed with a new light, the firm mouth took on a bit more of firmness, and the strong little hands holding the paper did not tremble.

"A claim in the Sage Brush Valley in Kansas." Jerry spoke slowly. "It lies in Range—Township—Oh, that's all Greek to me! They must number land out there like lots in the potter's-field corner of the cemetery that we drove by yesterday. Maybe they may all be dead ones, paupers at that, in Kansas. It is controlled, or something, by York Macpherson of the Macpherson Mortgage Company of New Eden—New Eden—Kansas. Uncle Cornie told me it hadn't brought any income, but that wasn't York Macpherson's fault. Strange that I remember all that Uncle Cornie said here the other night."

The girl read the document spread out before her a second time. When she lifted her face again it was another Jerry Swaim who looked out through the dark-blue eyes. The rain had ceased falling. A cool breeze was playing up the Winnowoc Valley, and low in the west shafts of sunlight were piercing the thinning gray clouds.

"Twelve hundred acres! A prince's holdings! Why 'Eden' has only two hundred! And that is at New Eden. It 'hasn't been well managed.' I know who's going to manage it now. I'm the daughter of Jim Swaim. He was a good business man. And Aunt Darby—" A smile broke the set line about the red lips. "I'd never dare to say she didn't understand how to manage things, Chief of Staff to the General who runs the Universe, she is."

Then the serious mood came back as the girl stared out at the meadows and growing grain of the "Eden" farmland. A sudden resolve had formed in her mind—Jerry Swaim the type all her own, not possible to forecast.

"Father wanted me to know what it means to be independent. I'll find out. If this 'Eden' can be so beautiful and profitable, what can I not make out of twelve hundred acres, in a New Eden? And it will be such a splendid lark, just the kind of thing I have always dreamed of doing. Aunt Jerry will say that I'm crazy, or that I'm Lesa Swaim's own child. Well, I am, but there's a big purpose back of it all, too, the purpose my father would have approved. He was all business—all money-making—in his purposes, it seemed to some folks, but I think mother knew how to keep him sweet. Maybe her adventurous spirit, and all that, kept her interesting to him, and her romancing kept him her lover, instead of their growing to be like Uncle Cornie and Aunt Jerry. There's something else in the world besides just getting property—'if a man went right with himself,' Uncle Cornie said. There was a good sermon in those seven words. Uncle Cornie preached more to me than the man who officiated at the funeral yesterday could ever do. 'If a man went right with himself.' And Eugene." A quick change swept Jerry Swaim's countenance. "He said he wanted to say something to me. I think I know what he wanted to say. Maybe he will say it some day, but not yet, not yet. Here he comes now."

There was a something new, unguessable, and very sweet in Jerry Swaim's face as Eugene Wellington came striding down the walk to the rose-arbor.

"I'm through at last, little cousin," he declared, dropping into a seat beside her. "Really, Aunt Jerry is a wonderful woman. She seems to know most of the details of Uncle Cornie's business since he began in business. But now and then she runs against something that takes her breath away. Evidently Uncle Cornie knew a lot of things he didn't tell her or anybody else. She doesn't like to meet these things. It makes her cross. She sent me away just now in a huff because she was opening up a new line that I think she didn't want me to know anything about. Something that took her breath away at first glance. But she didn't have to coax me off the place. I ran out here when the chance came."

How handsome and well-groomed he was sitting there in the easy willow seat! And how good he had been to Mrs. Darby in these trying days! A dozen little services that her niece had overlooked had come naturally to his hand and mind.

The words of Uncle Cornie came into Jerry Swaim's mind as she looked at him: "He's a good fellow, with real talent, and he'll make a name for himself some day. He'll make a decent living, too, independent of anybody's aunts and uncles, but he's no stronger-willed nor smarter nor better than you are." A thrill of pleasure quickened her pulse at the recollection, making this new decision of hers the more firm.

"It has seemed like a month since we sat here the evening before Uncle Cornie passed away," Eugene began. "He made a bad discus-throw and came over here just as I began to tell you something, Jerry. Do you remember what we were saying when he appeared on the scene?"

"Yes, I remember." Jerry's voice was low, but there was no quaver in it.

Her face, as she lifted it, seemed to his eyes the one face he could never paint. For him it was the fulfilment of a man's best dream.

"There's only one grief in my heart at this minute—that I can never put your face as it is now on any canvas. But let me tell you some things that Aunt Jerry has been telling me. She seems so fond of you, and she says that after all the claims against your father's estate are settled there is really no income left for you. But she assures me that it makes no difference, because you can go on living with her exactly as you have always done. She told me she had never failed in the fruition of a single plan of hers, and she is too old to fail now. She has some plan for you—" The young artist hesitated.

Jerry had never thought much about his good looks until in these June days in "Eden" when Love had come noiselessly down the way to her. And yet—a little faint, irresolute line in the man's face—a mere shadow, a ghost of nothing at all, fixed itself in her image of his countenance. A quick intuition flashed into her mind with the last words.

"Aunt Jerry is too old for lots of things besides the failure of her plans. I know what she said, Gene, because I know what she thinks. She isn't exactly fond of me; she wants to control me. I believe there are only two planes of existence with her—one of absolute rule, and the other of absolute submission. She couldn't conceive of me in the first plane, of course, so I must be in the second."

"Why, Geraldine Swaim, I never heard you speak so of your aunt before!" Eugene Wellington exclaimed. He had caught a new and very real line in the girl's face as she spoke.

"Maybe not. But don't go Geraldine-ing me. It's too Aunt Jerry-ish. I'm coming to understand her better because I'm doing my own thinking now," Jerry replied.

"As if you hadn't always done that, you little tyrant! I bear the scars of your teeth on my arms now—or I would bear them if I hadn't given up to you a thousand times years ago," Eugene declared, laughingly.

"That's just it," Jerry replied. "I've been let to have my own way until Aunt Jerry thinks I must go on having just what she thinks I want, and to do that I must be dependent on her. And—Wait a minute, Gene—you will be dependent on her, too. You have only your gift. So both of us are to be pensioners of hers. That's her plan."

"I won't be," Eugene Wellington declared, stoutly. And then, in loving thought of Jerry, he added: "I don't want to, Jerry. I want to do great things, the best that God has given me to do, not merely for myself, but for your sake—and for all the world. That seems to me to be what artists are for."

"And I won't be, either," Jerry insisted. "I won't. You needn't look so incredulous. Let me tell you something. The evening before Uncle Cornie died—" Jerry broke off suddenly.

It seemed unfair to betray the one burst of confidence that the colorless old man had given up to on the last evening of his earthly life. Jerry knew that it was to her, and for her alone, that he had spoken.

"This is what I want to tell you. I have no income now. Aunt Jerry is right, although she never told me that herself. But I have a plan to make a living for myself."

Eugene Wellington leaned back and laughed aloud. "You, Miss Geraldine Swaim, who never earned a dollar in your precious life! I always knew you were a dreamer, but you are going wrong now, Jerry. You must look out for belfry bats under that golden thatch of yours. Only artists dare those wild flights so far—and they do it only on canvas and then get rejected by the hanging committee."

Jerry paid no heed to his bantering words as she went on with serious earnestness: "My estate—from my father—is a claim out at New Eden, Kansas. Twelve hundred acres. It has never been managed well, consequently it has never paid well. Look at 'Eden' here"—Jerry lifted a hand for silence as Eugene was about to speak—"it has only two hundred acres. Now multiply it by six and you'll have New Eden out in Kansas. And I own it. And I am going to manage it. And I am not going to be dependent on anybody. Won't it be one big lark for me to go clear to the Sage Brush Valley? If it is as beautiful as the Winnowoc, just think of its possibilities. It will be perfectly grand to feel oneself so free and self-reliant. And when we have won out, you by your brush and I by my Kansas farm, then, oh, Gene, how splendid life will be!"

The big, dreamy eyes were full of light. The level beams of the sun stretched far across green meadows and shaven lawns, between tall lilac-trees, to the rose-arbor, just to glorify that rippling mass of brown-shadowed golden hair.

"Jerry"—Eugene Wellington's voice trembled—"you are the most wonderful girl in the world. I am so proud of you. But, dear girl, it is an old, threadbare fancy, this going to Kansas to get rich. My father tried it years ago. He had a vision of great things, too. He failed. Not only that, he ruined everybody connected with him. That's why I'm poor to-day. Truly, little cousin mine, I don't believe the good Lord, who makes Edens like this in the Winnowoc Valley, ever intended for well-bred people to leave them and go New-Eden-hunting in the Sage Brush Valley. We belong here where all the beauty of nature is about us and the care of a loving God is over us. Why do you want to go to Kansas? I wouldn't know how to pray out there where my father made such a botch of living. I really wouldn't."

"I don't know how to pray here, Gene," Jerry said, softly, with no trace of flippant irreverence in her tone. "I forgot how to do that when God took my father away. But listen to me." The imperious power of the uncontrolled will was Jerry's always. "You don't live here; you stay here. And you take a piece of canvas and go to the ends of the earth on it, or down to the deeps, or into the heavens. You make what never did and never will be, with your free brush. And folks call it good and you earn a living by it. You are an artist. I am a foolish dreamer, but I am going out to Kansas and work my dreams into reality and beauty—and money—in a New Eden. If the Lord isn't there, I shall not mind any more than I do here. I am going to Kansas, though, because I want to."

"Look, Jerry, at the sunset yonder," Eugene said, gently, knowing of old what "I want" meant. "They couldn't have such pictures of green and gold out West as we see framed in here by the lilacs. You always have been a determined little girl, so you will have your own way now, I suppose. We can try it, anyhow, for a while. And if you find your way a rocky road you must come back to 'Eden.' When your new playthings fail, you can play with the old ones. But I really love your spirit of self-reliance. I don't want you ever to be dependent. I don't want any other Jerry than I have always known. And I want to work hard and make my little talent pay me big, and make you proud of me."

"We are living a real romance, Gene. And we'll be true to our word to make the best of ourselves and not let Aunt Jerry frighten us into changing our plans, will we, Gene? My father's wish for me was that I should not always be a spender of other folks's incomes, but that I would find out what it means to live my own life. I never knew that until last week. Everything seems changed for me since Uncle Cornie died. Isn't it strange how suddenly we drop off one life and take up another?" Jerry's eyes were on the deepening gold of the sunset sky.

"Yes, we have been two idlers. I'm glad to quit the job. But, somehow, for you I could wish that you would stay here, if you were only satisfied to do it," Eugene replied.

"I don't wish it." Jerry spoke decisively. "I couldn't be happy, now I've this splendid Kansas thing to think about. Let's go and tell Aunt Jerry and have it out with her."

"And if she says no?" the young man queried.

Jerry Swaim paused in the doorway and looked straight into Eugene Wellington's face, without saying a word.

"Geraldine Swaim, there was a big mistake made in your baptismal ceremony. You should have been christened 'The Sphinx.' Some day I'll make a canvas of the Egyptian product and put your face on it. After all, are you really in earnest about this Sage Brush Valley New Eden? It is so lovely here, I want you to stay here."

Again Jerry looked at him without speaking, and that faint line of indecision that scarcely hinted at its own existence fixed itself in the substratum of her memory.

Mrs. Darby met the young people in the parlor, where only a few nights ago the three had watched the summer storm, not knowing that it was beating down on the unconscious form of Cornelius Darby. Mrs. Darby felt sure that the young people would be coming to her to-night. Well—the end of her plan was in sight now. Really, it may have been better for Cornelius to have gone when he did, since we must all go sometime. Indeed, it would have been better—only Jerusha Darby never knew that—if Cornelius had gone before that discus-throw. Everything might have been different if he had gone earlier. But he lost the opportunity of his life to serve his wife by staying over and making one awkward fling too many.

The June evening was cool after the long rains. Aunt Jerry had a tiny wood fire burning in the parlor grate, and the tall lamps with the rose-colored shades lighted to add a touch of twilight charm to the place, when the young lovers came in.

"Aunt Jerry, we want to tell you what we have been talking about," Eugene began, when the three were seated together. "Jerry and I have decided that we must look on life differently now since—" Eugene hesitated.

"Yes, I know." Mrs. Darby spoke briskly. "We must face the truth now and speak of Cornelius freely. He was fond of both of you. Poor Cornelius!"

"Poor Cornelius," Jerry Swaim repeated, under her breath.

"Of course I know it is difficult for a girl reared as Jerry has been—" Eugene began again.

"She can go on living just as she has been. This will be her home always," Mrs. Darby broke in, abruptly.

"And I know that I have nothing but the prospect of earning a living and winning to a successful career in my line—" the young man went on.

"Hasn't Jerry the prospect of enough for herself? I'll need you to help me for several months. You know, Eugene, that I must have some one who understands Cornelius's way of doing things." There was more of command than request in the older woman's voice.

"I'll be glad to help you as long as I am needed, but I am speaking now of my life-work. When I cannot serve you any longer I must begin on my own career. I have some hopes and plans for the future."

"Humph! What's the use of talking about it? I tell you Jerry will have enough for all her needs, and I want you here. I shall not consider any more such notions, Eugene. You are both going to stay right here as you have done. Let's talk of something else."

"We can't yet, Aunt Jerry, because I have not enough for myself, even if Gene would accept a living from you," Jerry Swaim declared.

Jerusha Darby opened her narrow eyes and stared at her niece. If the older woman had made one plea of loneliness, if she had even hinted at sorrow for the loss of the companion of her business transactions, Jerry Swaim would have felt uncomfortable, even though she knew her aunt too well to be deceived by any such demonstration.

"Geraldine Swaim, what are you saying?" Mrs. Darby demanded, in a hard, even voice. Something in her manner and face could always hold even the brave-spirited in frightened awe of her.

Eugene Wellington lost courage to go on, and the same thing came again that Jerry Swaim had twice seen on his face in the rose-arbor this evening. The two were looking straight at the girl now. The firelight played with the golden glory of her hair and deepened the rose hue of her round cheeks. The dark-blue eyes seemed almost black, with a gleam in their depths that meant trouble, and there was a strength in the low voice as Jerry went on:

"I'm talking about what I know, Aunt Jerry. All there is of my heritage from my father is a 'claim,' they call it, at New Eden, in the Sage Brush Valley in Kansas; twelve hundred acres. I'm going out there to manage it myself and support myself on an income of my own."

For a long minute Jerusha Darby looked steadily at her niece, her own face as hard and impenetrable as if it were carven out of flint. Then she said, sharply:

"Where did you find out all this?"

"It is all in a document here that I found in the rose-arbor this afternoon," the girl replied. "Aunt Jerry, I must use what is mine. I wouldn't be a Swaim if I didn't."

"You won't stay there two weeks." Mrs. Darby fairly clicked out the words. Her face was very pale and something like real fright looked through her eyes as she took the paper from her niece's hand.

"And then?" Jerry inquired, demurely.

"And then you will come back here where you belong and live as you always have lived, in comfort."

"And if I do not come?"

Jerusha Darby's face was not pleasant to see just then. The firelight that made the girl more winsomely pretty seemed to throw into relief all the hard lines of a countenance which selfishness and stubbornness and a dictatorial will had graven there.

"Jerry Swaim, you are building up a wild, adventurous dream. You are Lesa Swaim over and over. You want a lark, that's what you want. And it's you who have put Eugene up to his notions of a career and all that. Listen to me. Nothing talks in this world like money. That you have to have for your way of living, and that he's got to have if he wants to be what he should be. Well, go on out to Kansas. You know more of that prosperous property out there than I do. I'll let you find it out to the last limit. But when you come back you must promise me never to take another such notion. I won't stand this foolishness forever. I'll give you plenty of money to get there. You can write me when you need funds to come back. It won't take long to get that letter here."

"And if I shouldn't come?" Jerry asked, calmly.

"Look what you are giving up. All this beautiful home, to say nothing of the town house—and Eugene—and other property."

"No, no; you don't count him as your property, do you?" Jerry cried, turning to the young artist, whose face was very pale.

"Jerry, must you make this sacrifice?" he asked, in a voice of tenderness.

"It isn't a sacrifice; it's just what I want to do," Jerry declared, lightly.

Jerusha Darby's face darkened. The effect of a long and absolute exercise of will, coupled with ample means, can make the same kind of a tyrant out of a Kaiser and a rich aunt. The determination to have her own way in this matter, as she had had in all other matters, became at once an unbreakable purpose in her. She wanted to keep fast hold of these young people for her own sake, not for theirs. For a little while she sat measuring the two with her narrow, searching eyes.

"I can manage him best," she concluded to herself. At last she asked, plaintively, "With all you have here, Jerry, why do you go hunting opportunities in Kansas?"

"Because I want to," Jerry replied, and her aunt knew that, so far as Jerry was concerned, everything was settled.

"Then we'll drop the matter here. I can wait for you to come to your senses. Eugene, if you can give her up, when you've always been chums, I certainly can."

With these words Mrs. Darby rose and passed out, leaving the two alone under the rose-colored lights of the richly furnished parlor.

It was not like Jerusha Darby to make such a concession, and Jerry Swaim knew it, but Eugene Wellington, who was of alien blood, did not know it.

The room was much more beautiful without her presence; and her sordid hinting at the Darby wealth which Jerry must count on, and Eugene must meekly help to guard for future gain, rasped harshly against their souls, for they were young and more sentimental than practical. Left alone to their youth, and strength, and nobler ideals, they vowed that night to hold to better things. Together they builded a dream of a rainbow-tinted world which they were going bravely forth to create. Of what should follow that they did not speak, yet each one guessed what was in the other's mind, as men and maidens have always guessed since love began. And on this night there were no serpents at all in their Eden.

The sun of a mid-June day glared down pitilessly on the little station at the junction of the Sage Brush branch with the main line. There was not a tree in sight. The south wind was raving across the prairie, swirling showers of fine sand before it. Its breath came hot against Jerry Swaim's cheek as she stood in the doorway of the station or wandered grimly down between the shining rails that stretched toward a boundless nowhere whither the "through" train had vanished nearly two hours ago. As Jerry watched it leaving, a sudden heaviness weighed down upon her. And when the Pullman porter's white coat on the rear platform of the last coach melted into the dull, diminishing splotch on the western distance, she felt as if she were shipwrecked in a pathless land, with the little red station house, reefed about by cinders, as the only resting-place for the soles of her feet. When her eyes grew weary of the monotonous landscape, Jerry rested them with what she called "A Kansas Interior." The rustic station under the maples at "Eden" was always clean and comfortably appointed. Big flower-beds outside, Uncle Cornie's gift, belonged to the station and its guests, with the spacious grounds of "Eden," at which the travelers might gaze without cost, lying just beyond it.

This "Kansas Interior" seemed only a degree less inviting than the whole monotonous universe outside. The dust of ages dimmed the windows that were propped and nailed and otherwise secured against the entrance of cool summer breezes, or the outlet of bad, overheated air in winter. Iron-partitioned seats, invention of the Evil One himself, stalled off three sides of the room, intending to prove the principle that no one body can occupy two spaces at the same time. In the center of the room a "plain, unvarnished" stove, bare and bald, stood on a low pedestal yellowed with time and tobacco juice. A dingy, fly-specked map of the entire railway system hung askew on the wall—very fat and foreshortened as to its own extent, very attenuated and ill-proportioned as to other insignificant systems cutting spidery lines across it.

Behind a sealed tomb of a ticket-window Jerry could hear the "tick-tick, tick-a-tick-tick, tick-tick" of a telegraph-wire. Somebody must be in there who at set times, like a Saint Serapion from his hermit cell, might open this blank wall and speak in almost human tones. Just now the solitude of the grave prevailed, save for that everlasting "tick-a-tick" behind the wall.

When Jerry Swaim gripped her hands on the plow handles, there would be no looking back. She persuaded herself that she wasn't going to die of the jiggermaroos in the empty nothingness here. It would be very different at New Eden, she was sure of that. And this York Macpherson must be a nice old man, honest and easy-going, because he had never realized any income from her big Kansas estate. She pictured York easily—a short, bald-headed old gentleman with gray burnsides and benevolent pale-blue eyes behind gold-rimmed glasses, driving a fat sorrel nag to an easy-going old Rockaway buggy, carrying a gold-headed cane given him by the Sunday-school. Jerry had seen his type all her life in the business circles of Philadelphia and among the better-to-do country-dwellers around "Eden."

At last it was only fifteen minutes till the Sage Brush train would be due; then she could find comfort in her Pullman berth. She wondered what Aunt Jerry and Eugene were doing now. She had slipped away from "Eden" on her wild adventure in the early dawn. She had taken leave of Aunt Jerry the night before. Old women need their beauty sleep in the morning, even if foolish young things are breaking all the laws by launching out to hunt their fortunes. Eugene had been hurriedly sent away on Darby estate matters without the opportunity of a leave-taking, two days before Jerry was ready to start for Kansas. Everything was prearranged, evidently, to make this going a difficult one. So, without a single good-by to speed her on her quest, the young girl had gone out from a sheltering Eden of beauty and idleness. But the tears that had dimmed her eyes came only when she left the lilac walk to the station to slip around by Uncle Cornie's grave beside the green-coverleted resting-places of Jim and Lesa Swaim.

"Maybe mother would glory in what I am doing, and father might say I had the right stuff in me. And Uncle Cornie—'If a man went right with himself'—Uncle Cornie might have said 'if a woman went right with herself,' too. I'm going to put that meaning into his words, even if he never seemed to think much of women. Oh, father! Oh, mother! You lived before you died, anyhow, and I'm going to do the same. Uncle Cornie died before he ever really lived."

Jerry stretched out her hands to the one good-by in "Eden" coming to her from these silent ripples of dewy green sod. Then youth and the June morning and the lure of adventure into new lands came with their triple strength to buoy her up to do and dare. Behind her were her lover to be—for Eugene must love her—her home ties, luxury, dependent inactivity. Before her lay the very ends of the earth, the Kansas end especially. The spirit of Sir Galahad, of Robinson Crusoe, of Don Quixote, combined with the spirit of a self-willed, inexperienced girl, but dimly conscious yet of what lay back of her determination to go forth—because she wanted to go.

Chicago and Kansas City offered easy ports for clearing. And the Kaw Valley, unrolling its broad acres along the way, gave larger promise than Jerry had yet dared to dream of for the New Eden farther west. The train service, after the manner of a Pacific Coast limited, had been perfect in every appointment. And then—this junction episode.

Two eternity-long hours before the Sage Brush branch could take her to New Eden were almost ended.

"It's not so terrifying, after all." Jerry was beginning to "see things again." "It's all in the game—and I am going to be as 'game' as the thing I am playing. Things always come round all right for me. They must."