Title: The New Gresham Encyclopedia. Atrebates to Bedlis

Author: Various

Release date: October 15, 2010 [eBook #34075]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. |

PLATES

| Page | |

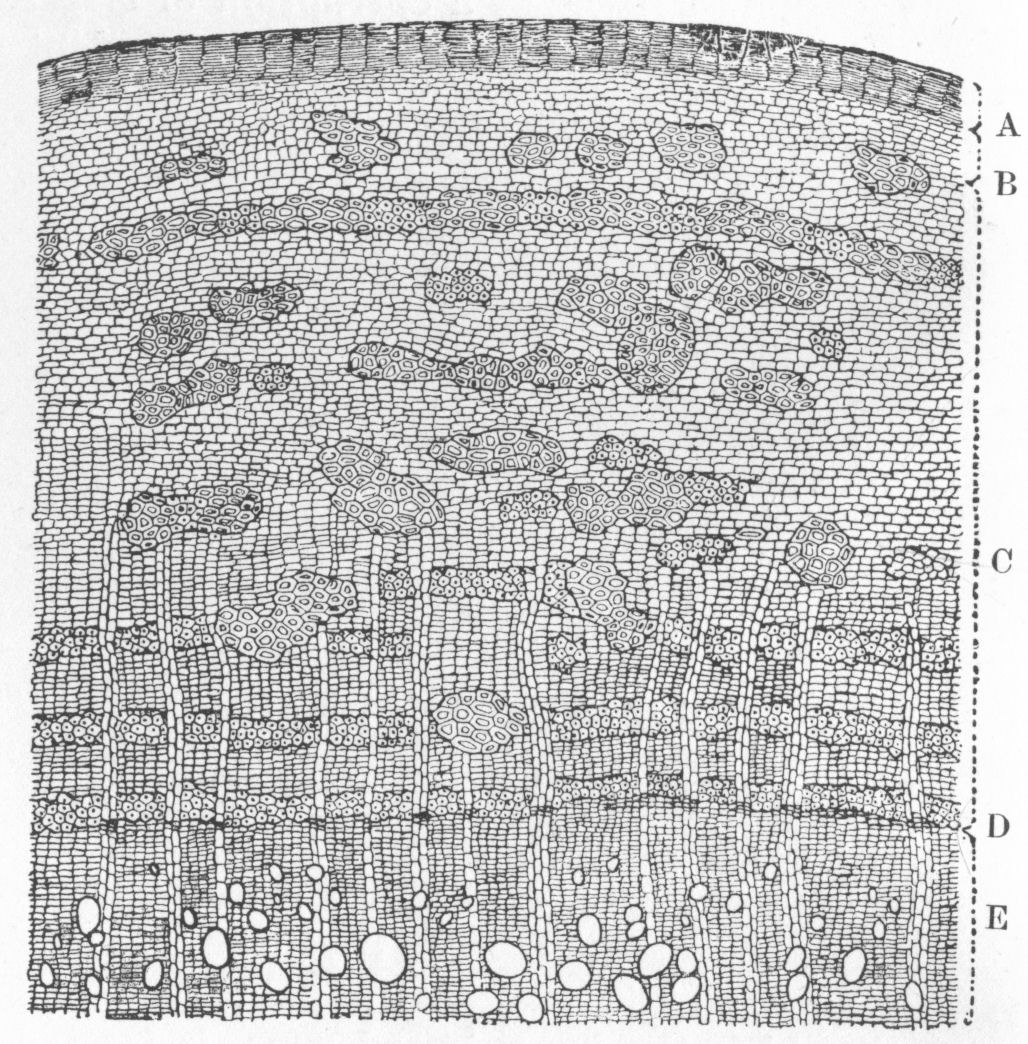

| Bacteria | 348 |

MAPS IN COLOUR

| Australia | 316 |

The method of marking pronunciations here employed is either (1) by marking the syllable on which the accent falls, or (2) by a simple system of transliteration, to which the following is the Key:—

ā, as in fate, or in bare.

ä, as in alms, Fr. âme, Ger. Bahn = á of Indian names.

a˙, the same sound short or medium, as in Fr. bal, Ger. Mann.

a, as in fat.

a¨, as in fall.

a, obscure, as in rural, similar to u in but, ė in her: common in Indian names.

ē, as in me = i in machine.

e, as in met.

ė, as in her.

ī, as in pine, or as ei in Ger. mein.

i, as in pin, also used for the short sound corresponding to ē, as in French and Italian words.

eu, a long sound as in Fr. jeûne = Ger. long ö, as in Söhne, Göthe (Goethe).

eu, corresponding sound short or medium, as in Fr. peu = Ger. ö short.

ō, as in note, moan.

o, as in not, soft—that is, short or medium.

ö, as in move, two.

ū as in tube.

u, as in tub: similar to ė and also to a.

u¨, as in bull.

ü, as in Sc. abune = Fr. û as in dû, Ger. ü long as in grün, Bühne.

u˙, the corresponding short or medium sound, as in Fr. but, Ger. Müller.

oi, as in oil.

ou, as in pound; or as au in Ger. Haus.

Of the consonants, b, d, f, h, j, k, l, m, n, ng, p, sh, t, v, z, always have their common English sounds, when used to transliterate foreign words. The letter c is not used by itself in re-writing for pronunciation, s or k being used instead. The only consonantal symbols, therefore, that require explanation are the following:—

ch is always as in rich.

d, nearly as th in this = Sp. d in Madrid, &c.

g is always hard, as in go.

h represents the guttural in Scotch loch, Ger. nach, also other similar gutturals.

n˙, Fr. nasal n as in bon.

r represents both English r, and r in foreign words, which is generally much more strongly trilled.

s, always as in so.

th, as th in thin.

th, as th in this.

w always consonantal, as in we.

x = ks, which are used instead.

y always consonantal, as in yea (Fr. ligne would be re-written lēny).

zh, as s in pleasure = Fr. j.

Atreb´ates, ancient inhabitants of that part of Gallia Belgica, afterwards called Artois. A colony of them settled in Britain, in a part of Berkshire and Oxfordshire.

At´rek, a river of Asia, forming the boundary between Persia and the Russian Transcaspian territory, and flowing into the Caspian; length 250 miles.

Atreus (at´rūs), in Greek mythology, a son of Pelops and Hippodamīa, and grandson of Tantălus. Atreus was the father of Agamemnon, according to Homer; other writers call him Agamemnon's grandfather. He succeeded Eurystheus, his father-in-law, as King of Mycēnæ, and in revenge for the seduction of his wife by his brother Thyestes gave a banquet at which the latter partook of the flesh of his own sons. Atreus was killed by Ægisthus, a son of Thyestes. The tragic events connected with this family furnished materials to some of the great Greek dramatists.

Atri (ancient, Hadria), an episcopal city in the province of Teramo, Italy, 8 miles from the Adriatic. It has an old (thirteenth century) Gothic cathedral, ruins of ancient Roman walls and buildings, and a palace of the Agraviva family, who were Dukes of Atri from 1398 to 1775. Pop. 14,043.

At´riplex. See Orache.

A´trium, the entrance-hall and most important apartment of a Roman house, generally ornamented with statues, pictures, and imagines or ancestral likenesses, which were portrait masks in wax kept in cases. The atrium formed the reception-room for visitors and clients. It was lighted by the compluvium, an opening in the roof, towards which the roof sloped so as to throw the rainwater into a cistern in the floor called the impluvium.

In zoology the term is applied to the large chamber or 'cloaca' into which the intestine opens in the Tunicata.

At´ropa, the nightshade genus of plants. See Belladonna.

At´rophy, a wasting of the flesh due to some interference with the nutritive processes. It may arise from a variety of causes, such as permanent, oppressive, and exhausting passions, organic disease, a want of proper food or of pure air, suppurations in important organs, copious evacuations of blood, saliva, semen, &c., and it is also sometimes produced by poisons, for example arsenic, mercury, lead, in miners, painters, gilders, &c. In old age the whole frame except the heart undergoes atrophic change, and it is of frequent occurrence in infancy as a consequence of improper, unwholesome food, exposure to cold, damp, or impure air, &c. Single organs or parts of the body may be affected irrespective of the general state of nutrition; thus local atrophy may be superinduced by palsies, the pressure of tumours upon the nerves of the limbs, or by artificial pressure, as in the feet of Chinese ladies.

At´ropin, or At´ropine, a crystalline alkaloid obtained from the deadly nightshade (Atrŏpa Belladonna). It is very poisonous, and produces persistent dilation of the pupil.

At´ropos, the eldest of the three Fates (the others being Clotho and Lachĕsis), who cuts the thread of life with her shears.

Attaché (at´a-shā), a junior member of the diplomatic services attached to an embassy or legation.

Attach´ment, in English law, a taking of the person, goods, or estate by virtue of a writ or precept. It is distinguished from an arrest by proceeding out of a higher court by precept or writ, whereas the latter proceeds out of an inferior court by precept only. An arrest lies only against the body of a man, whereas an attachment lies often against the goods only, and sometimes against the body and goods. It differs from a distress in that an attachment does not extend to lands, while a distress cannot touch the body.—Foreign attachment answers to what in Scotland is termed arrestment, by means of which a creditor may obtain the security of the goods or other personal property of his debtor in the hands of a third person for the purpose of enforcing the appearance of the debtor to answer to an action, and afterwards, upon his continued default, of obtaining the property absolutely in satisfaction of the demand.

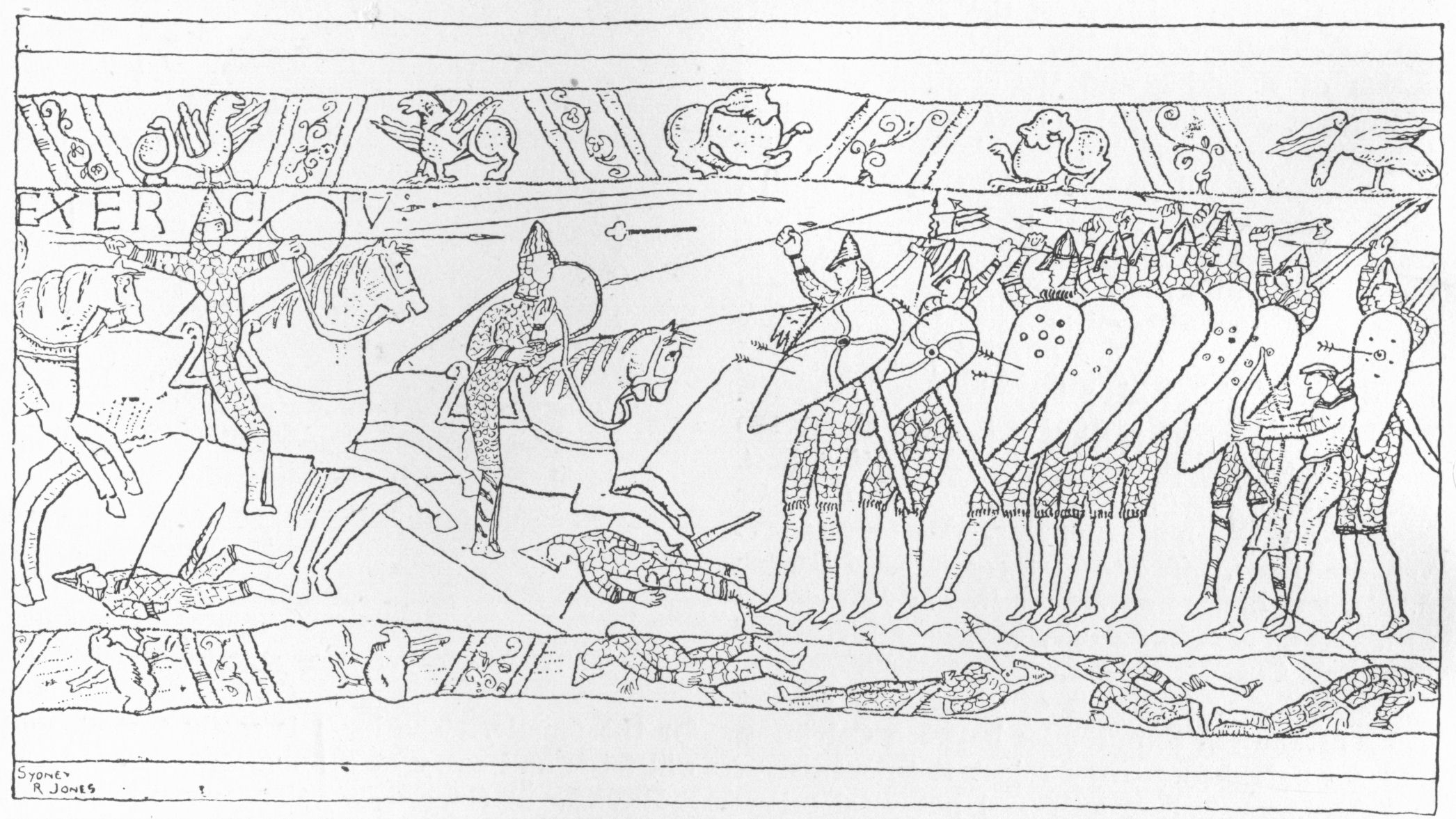

Attack´, the opening act of hostility by a force seeking to dislodge an enemy from its position. It is considered more advantageous to offer than to await attack, even in a defensive war. The historic forms of attack are: (1) the parallel; (2) the form in which both wings attack and the centre is kept back; (3) the form in which the centre is pushed forward and the wings kept back; (4) the famous oblique mode, dating at least from Epaminondas, and employed by Frederick the Great, where one wing advances to engage, whilst the other is kept back, and occupies the attention of the enemy by pretending an attack. Napoleon preferred to mass heavy columns against an enemy's centre. The forms of attack have changed with the weapons used. In the days of the pike heavy masses were the rule, but the use of the musket led to an extended battle-front to give effect to the fire. The advance in long and slender lines which grew out of this has been not less famous in the annals of British attack than the square formation in those of defence. In the European War (1914-18) the Germans often attacked in mass-formation; but British attacks were usually carried out by successive waves; one wave secured its objective [304]and consolidated it while another wave passed through to attack a more advanced objective. Artillery preparation became of increasingly great importance; it broke down the enemy's wire, counteracted his artillery-fire, and made his infantry keep under cover. In trench-to-trench attacks machine-guns and trench-mortars were of great value, and many casualties were avoided by the skilful use of tanks in the attack. But it is still a fundamental principle of tactics that the infantry is the chief factor in the attack, and that no attack can be considered overwhelmingly successful without the use of the bayonet.

Attain´der, the legal consequences of a sentence of death or outlawry pronounced against a person for treason or felony, the person being said to be attainted. It resulted in forfeiture of estate and 'corruption of blood', rendering the party incapable of inheriting property or transmitting it to heirs; but these results now no longer follow. Formerly persons were often subjected to attainder by a special Bill or Act passed in Parliament called Bills of Attainder, the last being passed in 1798, in the case of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, one of the Irish rebel leaders.

Attaint´, a writ at common law against a jury for a false verdict, finally abolished in England in 1825.

Attale´a, a genus of American palms, comprising the piassava palm, which produces coquilla-nuts.

Att´alus, the names of three kings of ancient Pergamus (241-133 B.C.), the last of whom bequeathed his kingdom to the Romans. They were all patrons of art and literature.

At´tar, in the East Indies, a general term for a perfume from flowers; in Europe generally used only of the attar or otto of roses, an essential oil made from Rosa centifolia, the hundred-leaved or cabbage-rose, R. damascēna, or damask-rose, R. moschāta, or musk-rose, &c., 100,000 roses yielding only 180 grains of attar. Cashmere, Shiraz, and Damascus are celebrated for its manufacture, and there are extensive rose farms in the valley of Kezanlik in Roumelia and at Ghazipur in Benares. The oil is at first greenish, but afterwards it presents various tints of green, yellow, and red. It is concrete at all ordinary temperatures, but becomes liquid about 84° F. It consists of two substances, a hydrocarbon and an oxygenated oil, and is frequently adulterated with the oils of rhodium, sandal-wood, and geranium, with the addition of camphor or spermaceti.

At´terbury, Francis, an English prelate, born in 1662, and educated at Westminster and Oxford. In 1687 he took his degree of M.A., and appeared as a controversialist in a defence of the character of Luther, entitled, Considerations on the Spirit of Martin Luther, &c. He also assisted his pupil, the Hon. Charles Boyle, in his famous controversy with Bentley on the Epistles of Phalaris. Having taken orders in 1691 he settled in London, became chaplain to William and Mary, preacher of Bridewell, and lecturer of St. Bride's. Controversy was congenial to him, and in 1706 he commenced one with Dr. Wake, which lasted four years, on the rights, privileges, and powers of convocations. For this service he received the thanks of the lower house of convocation and the degree of Doctor of Divinity from Oxford. Soon after the accession of Queen Anne he was made Dean of Carlisle, aided in the defence of the famous Sacheverell, and wrote A Representation of the Present State of Religion. In 1712 he was made Dean of Christ Church, and in 1713 Bishop of Rochester and Dean of Westminster. After the death of the queen in 1714 he distinguished himself by his opposition to George I; and, having entered into a correspondence with the Pretender's party, was apprehended in Aug., 1722, and committed to the Tower. Being banished the kingdom, he settled in Paris, where he chiefly occupied himself in study and in correspondence with men of letters. But even here, in 1725, he was actively engaged in fomenting discontent in the Scottish Highlands. He died in 1731, and his body was privately interred in Westminster Abbey. His sermons and letters are marked by ease and grace; but as a critic and a controversialist he is rather dexterous and popular than accurate and profound.

Attercliffe, a parliamentary division of the borough of Sheffield.

Attic, an architectural term variously used. An Attic base is a peculiar kind of base, used by the ancient architects in the Ionic order and by Palladio and some others in the Doric. An Attic story is a low story in the upper part of a house rising above the main portion of the building. In ordinary language an attic is an apartment lighted by a window in the roof.

At´tica, a State of ancient Greece, the capital of which is Athens. The territory was triangular in shape, with Cape Sunium (Colonna) as its apex and the ranges of Mounts Cithæron and Parnes as its base. On the north these ranges separated it from Bœotia; on the west it was bounded by Megaris and the Saronic Gulf; on the east by the Ægean. Its most marked physical divisions consisted of the highlands, midland district, and coast district, with the two famous plains of Eleusis and of Athens. The Cephissus and Ilissus, though small, were its chief streams; its principal hills, Cithæron, Parnes, Hymettus, Pentelicus, and Laurium. Its soil has probably undergone considerable deterioration, but produced good fruit, especially [305]olives and figs. These are still cultivated, as well as the vine and cereals, but Attica is better suited for pasture than tillage. According to tradition the earliest inhabitants of Attica lived in a savage manner until the time of Cecrops, who came, 1550 B.C., with a colony from Egypt, taught them all the essentials of civilization, and founded Athens. One of Cecrops' descendants founded eleven other cities in the regions round, and there followed a period of mutual hostility. To Theseus is assigned the honour of uniting these cities in a confederacy, with Athens as the capital, thus forming the Attic State. After the death of Codrus, 1068 B.C., the monarchy was abolished, and the government vested in archons elected by the nobility, at first for life, in 752 B.C. for ten years, and in 683 B.C. for one year only. The severe constitution of Draco was succeeded in 594 by the milder code of Solon, the democratic elements of which, after the brief tyranny of the Pisistratids, were emphasized and developed by Clisthenes. He divided the people into ten classes, and made the Senate consist of 500 persons, establishing as the Government an oligarchy modified by popular control. Then came the splendid era of the Persian War, which elevated Athens to the summit of fame. Miltiades at Marathon, and Themistocles at Salamis, conquered the Persians by land and by sea. The chief external danger being removed, the rights of the people were enlarged; the archons and other magistrates were chosen from all classes without distinction. The period from the Persian War to the time of Alexander (500 to 336 B.C.) was most remarkable for the development of the Athenian constitution. Attica appears to have contained a territory of nearly 850 sq. miles, with some 500,000 inhabitants, 360,000 of whom were slaves, while the inhabitants of the city numbered 180,000. Cimon and Pericles (444 B.C.) raised Athens to its point of greatest splendour, though under the latter began the Peloponnesian War, which ended with the conquest of Athens by the Lacedæmonians. The succeeding tyranny of the Thirty, under the protection of a Spartan garrison, was overthrown by Thrasybulus, with a temporary partial restoration of the power of Athens; but the battle of Cheronæa (338 B.C.) made Attica, in common with the rest of Greece, a dependency of Macedon. The attempts at revolt after the death of Alexander were crushed, and in 260 B.C. Attica was still under the sway of Antigonus Gonatas, the Macedonian king. A period of freedom under the shelter of the Achæan League then ensued, but their support of Mithridates led, in 146 B.C., to the subjugation of the Grecian States by Rome. After the division of the Roman Empire, Attica belonged to the Empire of the East until, in A.D. 396, it was conquered by Alaric the Goth and the country devastated. Attica and Bœotia now form a nome or province of the kingdom of Greece, with a population of 407,063.—Bibliography: Sir J. G. Frazer, Pausanias's Description of Greece, vols. ii and v; C. Wordsworth, Athens and Attica.

At´ticus, Titus Pomponius, a Roman of great wealth and culture, born 109 B.C., and died 32 B.C. On the death of his father he removed to Athens to avoid participation in the civil war, to which his brother Sulpicius had fallen a victim. There he so identified himself with Greek life and literature as to receive the surname Atticus. It was his principle never to mix in politics, and he lived undisturbed amid the strife of factions. Sulla and the Marian party, Cæsar and Pompey, Brutus and Antony, were alike friendly to him, and he was in favour with Augustus. Of his close friendship with Cicero proof is given in the series of letters addressed to him by Cicero. He married at the age of fifty-three, and had one daughter, Pomponia, named by Cicero Atticula and Attica. He reached the age of seventy-seven years without sickness, but, being then attacked by an incurable disease, ended his life by voluntary starvation. He was a type of the refined Epicurean, and an author of some contemporary repute, though none of his works have reached us.—The name Atticus was given to Addison by Pope, in a well-known passage (Prologue to the Satires, addressed to Dr. Arbuthnot).

At´tila (in Ger. Etzel), the famous leader of the Huns, was the son of Mundzuk, and the successor, in conjunction with his brother Bleda, of his uncle Roua. The rule of the two leaders extended over a great part of Northern Asia and Europe, and they threatened the Eastern Empire, and twice compelled the weak Theodosius II to purchase an inglorious peace. Attila caused his brother Bleda to be murdered (444), and in a short time extended his dominion over all the peoples of Germany and exacted tribute from the Eastern and Western emperors. The Vandals, the Ostrogoths, the Gepidæ, and a part of the Franks united under his banners, and he speedily formed a pretext for leading them against the Empire of the East. He laid waste all the countries from the Black to the Adriatic Sea, and in three encounters defeated the Emperor Theodosius, but could not take Constantinople. Thrace, Macedonia, and Greece all submitted to the invader, who destroyed seventy flourishing cities; and Theodosius was obliged to purchase a peace. Turning to the west, the 'scourge of God', as his defeated enemies termed him, crossed with an immense army the Rhine, the Moselle, and the Seine, came to the Loire, and laid siege to Orleans. The inhabitants of this city repelled the first attack, and the united forces of the Romans under Aetius, and of the Visigoths under [306]their king, Theodoric, compelled Attila to raise the siege. He retreated to Champagne, and waited for the enemy in the plains of Châlons. In apparent opposition to the prophecies of the soothsayers the ranks of the Romans and Goths were broken; but when the victory of Attila seemed assured, the Gothic prince Thorismond, the son of Theodoric, poured down from the neighbouring height upon the Huns, who were defeated with great slaughter. Rather irritated than discouraged, he sought in the following year a new opportunity to seize upon Italy, and demanded Honoria, the sister of Valentinian III, in marriage, with half the kingdom as a dowry. When this demand was refused he conquered and destroyed Aquileia, Padua, Vicenza, Verona, and Bergamo, laid waste the plains of Lombardy, and was marching on Rome when Pope Leo I went with the Roman ambassadors to his camp and succeeded in obtaining a peace. Attila went back to Hungary, and died on the night of his marriage with Hilda or Ildico (453), either from the bursting of a blood-vessel or by her hand. The description that Jordanès (or Jornandes) has left us of him is in keeping with his Kalmuck-Tartar origin. He had a large head, a flat nose, broad shoulders, and a short and ill-formed body; but his eyes were brilliant, his walk stately, and his voice strong and well-toned.—Bibliography: Thierry, Koenig Attila und seine Zeit; E. Hutton, Attila and the Huns.

Attilly, a village in France. See Scarpe, Battle of the.

Attleborough, a manufacturing town of the United States, in Massachusetts. Pop. 19,731.

At´tock, a town and fort in Rawal Pindi district, Punjab, overhanging the Indus at the point where it is joined by the Kabul River. It is at the head of the steam navigation of the Indus, and is connected with Lahore by railway. It is an important post on the military road to the frontier. Pop. 2822.

Attor´ney, a person appointed to do something for and in the stead and name of another. An attorney may have general powers to act for another; or his power may be special, and limited to a particular act or acts. A special attorney is appointed by a deed called a power or letter of attorney, specifying the acts which he is authorized to do. An attorney at law is a person qualified to appear for another before a court of law to prosecute or defend any action on behalf of his client. The term in England was formerly applied especially to those practising before the supreme courts of common law at Westminster, and corresponded to the term solicitor used in courts of Chancery; but this distinction was abolished in 1873, and solicitor is now the regular term for all such legal agents. In the United States the term is in common use, and is wide enough to include what in England would be called barristers (or counsel), in Scotland advocates, having indeed the general sense of lawyer. In America women are admitted as attorneys.

Attorney-General, in England and Ireland, the first law-officer and legal adviser of the Crown, acting on its behalf in its revenue and criminal proceedings, carrying on prosecutions in crimes that have a public character, guarding the interests of charitable endowments, and granting patents. He is ex officio the leader of the bar, and, as a member of Parliament, has charge of all Government measures on legal questions. The Solicitor-General holds a similar position, and may act in his place. In Scotland the Attorney-General is called Lord-Advocate. There are also Attorneys-General in the colonies. In the United States he is head of the Department of Justice. The individual States have also an Attorney-General.

Attrac´tion, the tendency of all material bodies, whether masses or particles, to approach each other, to unite, and to remain united. Newton was the first to adopt the theory of a universal attractive force, and to determine its laws. When bodies tend to come together from sensible distances the tendency is termed either the attraction of gravitation, magnetism, or electricity, according to circumstances; when the attraction operates at insensible distances it is known as adhesion with respect to surfaces, as cohesion with respect to the particles of a body, and as affinity when the particles of different bodies tend together. It is by the attraction of gravitation that all bodies fall to the earth when unsupported.—Bibliography: Newton, Principia; Thomson and Tait, Natural Philosophy; Laplace, Mécanique Céleste; Poynting, The Mean Density of the Earth.

Attrek. See Atrek.

At´tribute, in philosophy, a quality or property of a substance, as whiteness or hardness. A substance is known to us only as a congeries of attributes.

In the fine arts an attribute is a symbol regularly accompanying and marking out some personage. Thus the caduceus, purse, winged hat, and sandals are attributes of Mercury, the trampled dragon that of St. George.

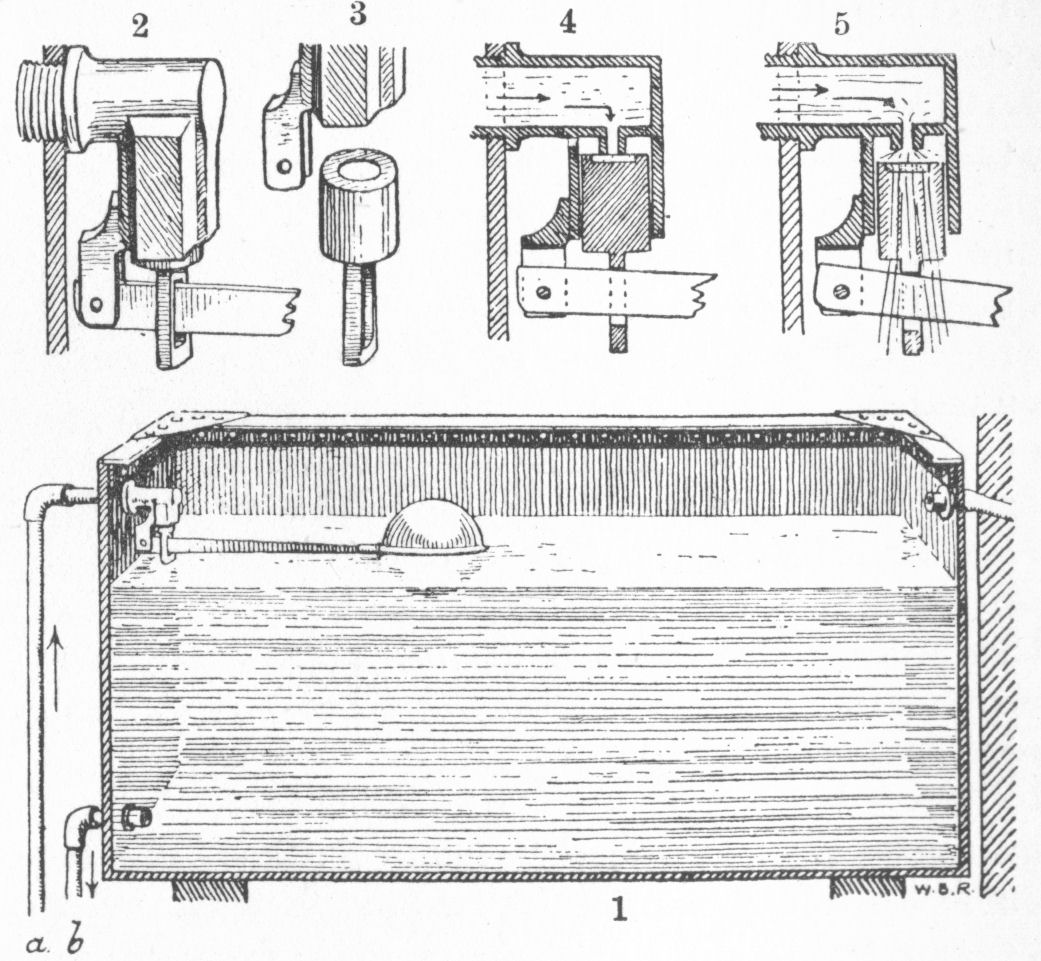

Attwood, George, F.R.S., an English mathematician, born 1746, died 1807, best known by his invention, called after him Attwood's Machine, for verifying the laws of falling bodies. It consists essentially of a freely-moving pulley over which runs a fine cord with two equal weights suspended from the ends. A small additional weight is laid upon one of them, causing it to descend with uniform acceleration. Means are provided by which the added weight can be removed at any point of the descent, thus [307]allowing the motion to continue from this point onward with uniform velocity. See Gravitation.

Atys, or Attis (at'is), in classical mythology, the shepherd lover of Cybĕle, who, having broken the vow of chastity which he made her, castrated himself. In Asia Minor Atys seems to have been a deity, with somewhat of the same character as Adonis. Catullus has written a celebrated poem (Carmen 63) on the subject of Attis.

Aubagne (ō-ba˙n-yė), a town in France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône, with manufactures of cottons, pottery, cloth. Pop. 8800.

Aubaine, Droit d' (drwä dō-bān). See Droit d'Aubaine.

Aube (ōb), a north-eastern French department; area 2326 sq. miles; pop. 227,745. The surface is undulating, and watered by the Aube, &c. The N. and N.W. districts are bleak and infertile, the southern districts remarkably fertile. A large extent of ground is under forests and vineyards, and the soil is admirable for grain, pulse, and hemp. The chief manufactures are worsted and hosiery. Troyes is the capital.—The River Aube, which gives name to the department, rises in Haute-Marne, flows N.W., and after a course of 113 miles joins the Seine.

Aubenas (ōb-nä), a town of France, department Ardèche, with a trade in coal, silk, &c. Pop. 7206.

Auber (ō-bār), Daniel François Esprit, a French operatic composer, born 1782, at Caen, in Normandy, died at Paris 1871. He was originally intended for a mercantile career, but devoted himself to music, studying under Cherubini. His first great success was his opera La Bergère Châtelaine, produced in 1820. In 1822 he had associated himself with Scribe as librettist, and other operas now followed in quick succession. Chief among them were Masaniello or La Muette de Portici (1828), Fra Diavolo (1830), Lestocq (1834), L'Ambassadrice (1836), Le Domino Noir (1837), Les Diamants de la Couronne (1841), Marco Spada (1853), La Fiancée du Roi de Garbe (1864). Despite his success in Masaniello, his peculiar field was comic opera, in which his charming melodies, bearing strongly the stamp of the French national character, his uniform grace and piquancy, won him a high place.

Aubergine (ō'bėr-zhēn), the fruit of the eggplant (q.v.).

Aubervilliers (ō-bār-vēl-yā), a suburban locality of Paris, with a fort belonging to the defensive works of the city. Pop. 37,558.

Aubigné, Merle d'. See Merle d'Aubigné.

Aubin (ō-ban˙), a town of Southern France, department of Aveyron, 20 miles N.E. of Villefranche; mining district: coal, sulphur, alum, and iron. Pop. 9574.

Au´brey, John, F.R.S., an English antiquary, born in Wiltshire in 1625 or 1626, died about 1700. He was educated at Oxford; collected materials for the Monasticon Anglicanum, and afforded important assistance to Wood, the antiquary. He left large collections of manuscripts, which have been used by subsequent writers. His Miscellanies (London, 1696) contain much curious information, but display credulity and superstition. His Survey of Surrey was incorporated in Rawlinson's Natural History and Antiquities of the County of Surrey, which was published in 1719.

Au´burn, the name of many places in America, the chief being a handsome city of New York State, at the north end of Owasco Lake. It is chiefly famous for its State prison, large enough to receive 1000 prisoners. In the town or vicinity various manufactures are carried on. Pop. 36,142.—Another Auburn is in Maine, on the Androscoggin River, a manufacturing town. Pop. (1920), 16,985.

Aubusson (ō-bu˙-sōn), a town of the interior of France, department Creuse, celebrated for its carpets. Pop. 7211.

Aubusson (ō-bu˙-sōn), Pierre d', grand-master of the knights of St. John of Jerusalem, born in 1423 of a noble French family, served in early life against the Turks, then entered the order of St. John, obtained a commandery, was made grand-prior, and in 1476 succeeded the Grand-master Orsini. In 1480 the Island of Rhodes, the head-quarters of the order, was invaded by a Turkish army of 100,000 men. The town was besieged for two months and then assaulted, but the Turks were obliged to retire with great loss. He died at Rhodes in 1503.

Auch (ōsh), a town in S.W. France, capital of department Gers; the seat of an archbishop, with one of the finest Gothic cathedrals in France; manufactures linens, leather, &c. Pop. 13,638.

Auchenia (a¨-kē'ni-a). See Llama.

Auchterar´der, a town, Perthshire, Scotland, with manufactures of tweeds, tartans, &c. The opposition to the presentee to the church of Auchterarder (1839) originated the struggle which ended in the formation of the Free Church of Scotland. Pop. (1921), 3151.

Auck´land, a town of New Zealand, in the North Island, founded in 1840, and situated on Waitemata Harbour, one of the finest harbours of New Zealand, where the island is only 6 miles across, there being another harbour (Manukau) on the opposite side of the isthmus. At dead low water there is sufficient depth in the harbour for the largest steamers. The working ship channel has an average depth of 36 feet, and varies in width from 1 to 2 miles. The harbour has two good entrances, with a lighthouse; and is defended by batteries. There are numerous wharves and jetties, and two graving-docks, one of [308]which—the Calliope Dock, opened in 1887—is one of the largest in the whole of the Southern Seas. Its site is picturesque, the streets are spacious, and the public buildings—churches, educational establishments, including a university college—are numerous and handsome. It has a large and increasing trade, there being connection with the chief places on the island by rail, and regular communication with the other ports of the colony, Australia, and Fiji by steam. It was formerly the capital of the colony. Pop. (including suburbs) 157,750.—The provincial district of Auckland forms the northern part of North Island, with an area of 25,364 sq. miles. Pop. 308,766. The surface is very diversified; volcanic phenomena are common, including geysers, hot lakes, &c.; rivers are numerous; wool, timber, kauri-gum, &c., are exported. Much gold has been obtained in the Thames Valley and elsewhere.

Auckland, William Eden, Lord, an English statesman, born 1744; educated at Eton and Oxford, called to the bar 1768, Under-Secretary of State 1772, and in 1776 a lord of the Board of Trade. In 1778 he was nominated in conjunction with Lord Howe and others to act as mediator between Britain and the insurgent American colonies. He was afterwards Secretary of State for Ireland, Ambassador Extraordinary to France, Ambassador Extraordinary to the Netherlands, &c. He was raised to the peerage in 1788, and died in 1814.

Auckland Islands, a group of islands about 180 miles S. of New Zealand, discovered in 1806, and belonging to Britain. They are of volcanic origin and fertile; and the largest, which is 30 miles by 15, has two good harbours. There are no settled inhabitants.

Auction is a public sale to the party offering the best price where the buyers bid against each other, or to the bidder who first accepts the terms offered by the vendor where he sells by reducing his terms until someone accepts them. The latter form is known as a Dutch Auction. A sale by auction must be conducted in the most open and public manner possible; and there must be no collusion on the part of the buyers. Puffing, or mock bidding, to raise the value by apparent competition, is illegal.

Auctioneer´, a person who conducts sales by auction. It is his duty to state the conditions of sale, to declare the respective biddings, and to terminate the sale by knocking down the thing sold to the highest bidder. In Britain an auctioneer must have a licence (for which he pays £10), renewable annually. Verbal declarations by an auctioneer are not suffered to control the printed conditions of sale. The Auctioneers' Institute of the United Kingdom was founded in 1886.

Au´cuba, a genus of plants, ord. Cornaceæ, one species of which, A. japoníca, a laurel-like shrub with spotted leaves, a native of Japan and China, is now common in ornamental grounds in Europe. The flowers are diœcious and inconspicuous. For a long time only the female plant, introduced into Britain from Japan in 1783, was cultivated, but in 1850 the male was introduced, and the fruit, which consists of beautiful coral-red berries, is now frequently developed, and adds greatly to the attractiveness of the plant. A. himalaica, also brought to Europe, is less hardy.

Aude (ōd), a maritime department in the S. of France; area 2448 sq. miles, mainly covered by hills belonging to the Pyrenees or the Cevennes, and traversed W. to E. by a valley drained by the Aude. The loftier districts are bleak and unproductive; the others tolerably fertile, yielding good crops of grain. The wines, especially the white wines, are famous; olives and other fruits are also cultivated. The manufactures are varied; the trade is facilitated by the Canal du Midi. Carcassonne is the capital; other towns are Narbonne and Castelnaudary. Pop. 286,552. The River Aude rises in the Eastern Pyrenees, and, flowing nearly parallel to the Canal du Midi, falls into the Mediterranean after a course of 130 miles.

Audebert (ōd-bār), Jean Baptiste, French engraver and naturalist, born in 1759, died in 1800; published Histoire Naturelle des Singes, des Makis, et des Galéopithèques; Histoire des Colibris, &c.; and began Histoire des Grimpereaux et des Oiseaux de Paradis, finished by Desray—all finely-illustrated works.

Au´denshaw, a town of England, in Lancashire, 4 miles E. of Manchester, with cotton-mills, engineering-works, &c. Pop. (1921), 7878.

Audiometer, an instrument for the measurement of hearing, invented by Professor D. E. Hughes, of London, in 1879.

Au´diphone, an acoustic instrument by means of which deaf persons are enabled to hear. It consists essentially of a fan-shaped plate of hardened caoutchouc, which is bent to a greater or less degree by strings, and is very sensitive to sound-waves. When used, the up edge is pressed against the upper front teeth, with the convexity outward, and the sounds being collected are conveyed from the teeth to the auditory nerve without passing through the external ear.

Au´dit, an examination into accounts or dealings with money or property, along with vouchers or other documents connected therewith, especially by proper officers, or persons appointed for the purpose. Also the occasion of receiving the rents from the tenants on an estate.

Au´ditor, a person appointed to examine accounts, public or private, to see whether they [309]are correct and in accordance with vouchers. In Britain the public accounts are audited by the Exchequer and Audit Department, Somerset House, at the head of it being a comptroller and auditor-general, and an assistant-comptroller and auditor, with a large staff of clerks. In Scotland there is an auditor attached to the Court of Session appointed to tax costs in litigation.

Auditory Nerves. See Ear.

Audley, a town (urban district) of England, in Staffordshire, to the north-west of the district of The Potteries, with coal and iron mines. Pop. (1921), 14,751.

Audran (ō-drän), Gerard, a celebrated French engraver, born 1640; studied at Rome; was appointed engraver to Louis XIV; died at Paris 1703. He engraved Le Brun's Battles of Alexander, two of Raphael's cartoons, Poussin's Coriolanus, &c., and takes a first place among historical engravers. Other members of the family were successful in the same profession: Benoît, 1661-1721; Claude père, 1592-1677; Claude fils, 1640-84; Germain, 1631-1710; Jean, 1667-1756.

Au´dubon, John James, an American naturalist of French extraction, born near New Orleans in 1775, was educated in France, and studied painting under David. In 1798 he settled in Pennsylvania, but having a great love for ornithology he set out in 1810 with his wife and child, descended the Ohio, and for many years roamed the forests in every direction, drawing the birds which he shot. In 1826 he came to England, exhibited his drawings in Liverpool, Manchester, and Edinburgh, and finally published them in an unrivalled work of double-folio size, with 435 coloured plates of birds the size of life (The Birds of America, 4 vols., 1827-39), with an accompanying text (Ornithological Biography, 5 vols., 8vo, partly written by Professor Macgillivray). On his final return to America he laboured with Dr. Bachman on a finely-illustrated work entitled The Quadrupeds of America (1843-50, 3 vols.). He died at New York in 1851.

Auerbach, a manufacturing town of Germany, in Saxony. Pop. 2200.

Auerbach (ou'ėr-bäh), Berthold, a distinguished German author of Jewish extraction, born 1812, died 1882. He abandoned the study of Jewish theology in favour of philosophy, publishing in 1836 his Judaism and Modern Literature, and a translation of the works of Spinoza with critical biography (5 vols., 1841). His later works were tales or novels, and his Village Tales of the Black Forest (Schwarzwälder Dorfgeschichten), as well as others of his writings, have been translated into several languages. Other works: Barfüssele, Joseph im Schnee, Edelweiss, Auf der Höhe, Das Landhaus am Rhein, Waldfried, Brigitta.

Auerstädt (ou'ėr-stet), battle at, 14th Oct., 1806. See Jena.

Augeas (a¨-jē'as), a fabulous king of Elis, in Greece, whose stable contained 3000 oxen, and had not been cleaned for thirty years. Hercules undertook to clear away the filth in one day in return for a tenth part of the cattle, and executed the task by turning the River Alphēus through it. Augeas, having broken the bargain, was deposed and slain by Hercules.

Auger (a¨'gėr), an instrument for boring holes considerably larger than those bored by a gimlet, used by carpenters and joiners, ship-wrights, &c.

Augereau (ōzh-rō), Pierre François Charles, Duke of Castiglione, Marshal of France, son of a mason, born at Paris 1757. He adopted the life of a soldier, and by 1796 had reached the rank of general of division in the army of Italy. At Casale, Lodi, Castiglione, and Arcole he highly distinguished himself. In 1797 he was at Paris, and was the instrument of the coup d'état of the 18th of Fructidor (4th Sept.). In 1799 he was chosen a member of the Council of Five Hundred. He then obtained the command of the army in Holland, and fought till the end of the campaign. In 1803 he was appointed to lead the army collected at Bayonne against Portugal. In 1804 he was named marshal of the empire, and grand officer of the Legion of Honour. He subsequently took part in the battles of Jena and Eylau, held a command in Spain, and in July, 1813, led the army in Bavaria against Saxony, taking part in the battle of Leipzig. On Napoleon's abdication he submitted to Louis XVIII, who named him a peer. He died 1816.

Aughrim, a village in Co. Galway, Ireland, memorable for the decisive victory gained in the neighbourhood, 12th July, 1691, by the forces of William of Orange, under Ginkel, over the Irish and French troops, under St. Ruth. The total English casualties were about 1700, while the Irish lost at least 7000 men as well as all their war material. This battle caused the complete submission of the country.

Augier (ō-zhi-ā), Emile, noted French dramatist, born 1820, came young to Paris, entered a lawyer's office, but relinquished law for literature; elected an academician in 1857, in 1868 a commander of the Legion of Honour. His first and one of his best dramas was the comedy La Ciguë (1844); among his other works are L'Aventurière, Gabrielle, Paul Forestier, Le Mariage d'Olympe, Le Gendre de M. Poirier, Les Effrontés, Le Fils de Giboyer, Les Lions et les Renards, Maître Guérin, Les Fourchambault, &c. He died in 1889.

Augite (a¨'jīt) is the commonest member of the pyroxene group of minerals; a constituent of many igneous rocks, such as basalt, gabbro, &c. It crystallizes in short almost rectangular [310]prisms of the monoclinic system, modifying planes causing cross-sections to be eight-sided. Its specific gravity is about 3.2; lustre vitreous; hardness sufficient to scratch glass; colour usually dark. It is a silicate of calcium, magnesium, iron, and aluminium, and alters in geological time by slow recrystallization into hornblende, possibly with some loss of calcium. It may be imitated by the artificial fusion of its constituents. A transparent, green, non-aluminous variety found at Zillertal, in Tyrol, is used in jewellery.

Augsburg (ougz'bu¨rh; Lat. Augusta Vindelicorum), a city of Bavaria, at the junction of the Wertach and Lech, antique in appearance, but with some fine streets, squares, and handsome or interesting buildings, including a splendid town hall, a lofty belfry (Perlach Tower), cathedral, with paintings by Domenichino, Holbein, &c.; St. Ulrich's Church; the bishop's palace, where the Augsburg Confession was presented to the Diet, afterwards a royal residence; the Fugger Palace, or mansion of the celebrated Fugger family; the public library; the theatre; the Academy of Arts; and the Fuggerei, a separate quarter of the city, consisting of fifty-three small houses, tenanted at a merely nominal rent by indigent Roman Catholics. Augsburg was a renowned commercial centre in the Middle Ages, and is still an important emporium of South German and Italian trade; industries: cotton spinning and weaving, dyeing, woollen manufacture, machinery and metal goods, books and printing, chemicals, &c. The Emperor Augustus established a colony here about 12 B.C. In 1276 it became a free city, and, besides being a great mart for the commerce between the north and south of Europe, it was a great centre of German art in the Middle Ages. It early took a conspicuous part in the Reformation. (See next article.) In 1806 it was incorporated in Bavaria. Pop. (1919), 154,555.

Augsburg Confession, a document which was presented by the Protestants at the Diet of Augsburg, 1530, to the Emperor Charles V and the Diet, and being signed by the Protestant States was adopted as their creed. Luther made the original draft; but as its style appeared too violent it was given to Melanchthon for amendment. The original is to be found in the imperial Austrian archives. Afterwards Melanchthon arbitrarily altered some of the articles, and there arose a division between those who held the original and those who held the altered Augsburg Confession. The former is received by the Lutherans, the latter by the German Reformed.

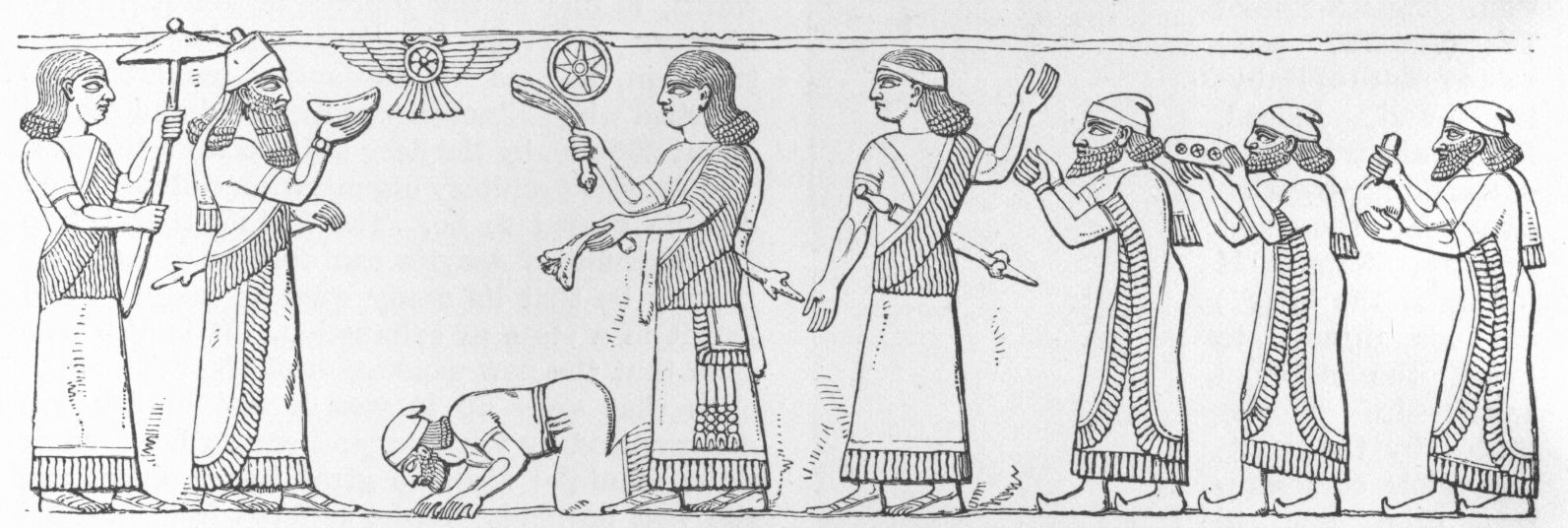

Au´gurs, a board or college of diviners who, amongst the Romans, predicted future events and announced the will of the gods from the occurrence of certain signs. These consisted of signs in the sky, especially thunder and lightning; signs from the flight and cries of birds; from the feeding of the sacred chickens; from the course taken or sounds uttered by various quadrupeds or by serpents; from accidents or occurrences, such as spilling the salt, sneezing, &c. The answers of the augurs as well as the signs by which they were governed were called auguries, but bird-predictions were properly termed auspices. Nothing of consequence could be undertaken without consulting the augurs, and by the mere utterance of the words alio die ('meet on another day') they could dissolve the assembly of the people and annul all decrees passed at the meeting.

Au´gust, the eighth month from January. It was the sixth of the Roman year, and hence was called Sextīlis till the Emperor Augustus affixed to it his own name.

Augus´ta, the name of many ancient places, as Augusta Trevirorum, now Trèves; Augusta Taurinorum, now Turin; Augusta Vindelicorum, now Augsburg; &c.

Augusta (ou-gu¨s'ta˙), or Agos´ta, a seaport in the south-east of Sicily, 12 miles north of Syracuse. It exports salt, oil, honey, &c. Pop. 17,250.

Augus´ta, capital of Maine, United States, on the River Kennebec, which is crossed by a bridge and is navigable for small vessels 43 miles from its mouth, while a dam enables steamboats to ply for 20 miles farther up and furnishes immense water-power. Pop. (1920), 14,144.

Augusta, the capital of Richmond county, Georgia, United States, on the left bank of the Savannah River, 231 miles from its mouth; well built, and connected with the river by high-level canals; an important manufacturing centre, having cotton-mills, machine-shops, and railroad works, &c. Pop. (1920), 52,548.

Au´gustine (Aurelius Augustinus), St., a renowned father of the Christian Church, was born at Tagaste, in Africa, in 354, his mother Monica being a Christian, his father Patricius a pagan. His parents sent him to Carthage to complete his education, but he disappointed their expectations by his neglect of serious study and his devotion to pleasure. A lost book of Cicero's, called Hortensius, led him to the study of philosophy; but dissatisfied with this he went over to the Manichæans. He was one of their disciples for nine years, but left them, went to Rome, and thence to Milan, where he announced himself as a teacher of rhetoric. St. Ambrose, the bishop of this city, converted him to the faith of his boyhood, and the reading of Paul's Epistles wrought an entire change in his life and character. He retired into solitude, and prepared himself for baptism, which he received in his thirty-third year from the hands of Ambrose. Returning to [311]Africa, he sold his estate and gave the proceeds to the poor, retaining only enough to support him. At the desire of the people of Hippo, Augustine became the assistant of the bishop of that town, preached with extraordinary success, and in 395 succeeded to the see. He entered into a warm controversy with Pelagius concerning the doctrines of free-will, grace, and predestination, and wrote treatises concerning them, but of his various works his Confessions is most secure of immortality. He died 28th Aug., 430, while Hippo was besieged by the Vandals. He was a man of great enthusiasm, self-devotion, zeal for truth, and powerful intellect, and though there have been fathers of the Church more learned, none have wielded a more powerful influence. His doctrine of grace, which was an important contribution to Christian thought, triumphed at last in the Reformation and evangelical religion. His writings are partly autobiographical, as the Confessions, partly polemical, homiletic, or exegetical. The greatest is the City of God (De Civitate Dei), a vindication of Christianity.—Bibliography: Joseph McCabe, St. Augustine and his Age; Nourrisson, La Philosophie de St. Augustin.

Au´gustine, or Austin, St., the Apostle of the English, first Archbishop of Canterbury, flourished at the close of the sixth century, was sent, in 596, with forty monks by Pope Gregory I to introduce Christianity into Saxon England, and was kindly received by Ethelbert, King of Kent, whom he converted, baptising 10,000 of his subjects in one day. In acknowledgment of his tact and success Augustine received the archiepiscopal pall from the Pope, with instructions to establish twelve sees in his province, but he could not persuade the British bishops in Wales to unite with the new English Church. He died in 604 or 605. Cf. Sir H. H. Howorth, St. Augustine of Canterbury.

Au´gustins, or Augustines, members of several monastic fraternities who follow rules framed by the great St. Augustine, or deduced from his writings, of which the chief are the Canons Regular of St. Augustine, or Austin Canons, and the Begging Hermits or Austin Friars. The Austin Canons were introduced into Britain about 1100, and had about 170 houses in England and about twenty-five in Scotland. They took the vows of chastity and poverty, and their habit was a long black cassock with a white rochet over it, having over that a black cloak and hood. The Austin Friars, originally hermits, were a much more austere body, went barefooted, and formed one of the four orders of mendicants. An order of nuns had also the name of Augustines. Their garments, at first black, were afterwards violet.

Augusto´vo, a town of Poland, formerly in Russia, in the government of Suwalki, founded in 1557 by Sigismund II. Pop. 11,797. The battle of Augustovo was fought between the Russians and the Germans between 14th Sept and 3rd Oct., 1914.

Augus´tulus, Romulus, the last of the Western Roman emperors; reigned for one year (475-6), when he was overthrown by Odoacer and banished.

Augus´tus, Gaius Julius Cæsar Octavianus (originally called Gaius Octavius), Roman emperor, was the son of Gaius Octavius and Atia, a daughter of Julia, the sister of Julius Cæsar. He was born 63 B.C., and died A.D. 14. Octavius was at Apollonia, in Epirus, when he received news of the death of his uncle (44 B.C.), who had previously adopted him as his son. He returned to Rome to claim Cæsar's property and avenge his death, and now took, according to usage, his uncle's name with the surname Octavianus. He was aiming secretly at the chief power, but at first he joined the republican party, and assisted at the defeat of Antony at Mutina. He got himself chosen consul in 43. Soon after the second triumvirate was formed between him and Antony and Lepidus, and this was followed by the conscription and assassination of three hundred Senators and two thousand knights of the party opposed to the triumvirate. Next year Octavianus and Antony defeated the republican army under Brutus and Cassius at Philippi. The victors now divided the Roman world between them, Octavianus getting the West, Antony the East, and Lepidus Africa. Sextus Pompeius, who had made himself formidable at sea, had now to be put down; and Lepidus, who had hitherto retained an appearance of power, was deprived of all authority (36 B.C.) and retired into private life. Antony and Octavianus now shared the Empire between them; but while the former, in the East, gave himself up to a life of luxury, and alienated the Romans by his alliance with Cleopatra and his adoption of Oriental manners, Octavianus skilfully cultivated popularity, and soon declared war ostensibly against the Queen of Egypt. The naval victory of Actium, in which the fleet of Antony and Cleopatra was defeated, made Octavianus master of the world, 31 B.C. He returned to Rome, 29 B.C., celebrated a splendid triumph, and caused the temple of Janus to be closed in token of peace being restored. Gradually all the highest offices of State, civil and religious, were united in his hands, and the new title of Augustus was also assumed by him, being formally conferred by the Senate in 27 B.C. Great as was the power given to him, he exercised it with wise moderation, and kept up the show of a republican form of government. Under him successful wars were carried on in Africa and Asia (against the Parthians), in Gaul [312]and Spain, in Pannonia, Dalmatia, &c.; but the defeat of Varus by the Germans under Arminius with the loss of three legions, A.D. 9, was a great blow to him in his old age. Many useful decrees proceeded from him, and various abuses were abolished. He gave a new form to the Senate, employed himself in improving the morals of the people, enacted laws for the suppression of luxury, introduced discipline into the armies, and order into the games of the circus. He adorned Rome in such a manner that it was said: "He found it of brick, and left it of marble". The people erected altars to him, and, by a decree of the Senate, the month Sextilis was called Augustus (our August). He was a patron of literature; Virgil and Horace were befriended by him, and their works and those of their contemporaries are the glory of the Augustan Age. His death, which took place at Nola, plunged the Empire into the greatest grief. He was thrice married, but had no son, and was succeeded by his stepson Tiberius, whose mother Livia he had married after prevailing on her husband to divorce her.—Bibliography: J. B. Firth, Augustus Cæsar (in Heroes of the Nations series); E. S. Shuckburgh, Augustus.

Augustus II (or Frederick Augustus I), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, second son of John George III, Elector of Saxony, was born at Dresden in 1670, died at Warsaw 1733. He succeeded his brother in the Electorate in 1694, and the Polish throne having become vacant, in 1696, by the death of John Sobieski, Augustus presented himself as a candidate for it and was successful. He joined with Peter the Great in the war against Charles XII of Sweden, invaded Livonia, but was defeated by Charles near Riga, and at Clissow, between Warsaw and Cracow. In 1704 he was deposed, and two years later formally resigned the crown to Stanislaus I, now devoting himself to his Saxon dominions. In 1709, after the defeat of Charles at Poltava, the Poles recalled Augustus, who united himself anew with Peter. The two monarchs, in alliance with Denmark, sent troops into Pomerania, but the Swedish general Steinbock defeated the allies at Gadebusch, 20th Dec., 1712. The death of Charles XII put an end to the war, and Augustus concluded a peace with Sweden. A confederation was now formed in Poland against the Saxon troops, but through the mediation of Peter an arrangement was concluded by which the Saxon troops were removed from the kingdom. Augustus now gave himself up to voluptuousness and a life of pleasure. His Court was one of the most splendid and polished in Europe. The Poles yielded but too readily to the example of their king, and the last years of his reign were characterized by boundless luxury and corruption of manners. His wife left him one son. The Countess of Königsmark bore him the celebrated commander Marshal Saxe (Maurice of Saxony).

Augustus III (or Frederick Augustus II), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, son of Augustus II, born at Dresden 1696, succeeded his father as Elector in 1733, and was chosen King of Poland through the influence of Austria and Russia. He closely followed the example of his father, distinguishing himself by the splendour of his feasts and the extravagance of his Court. He preferred Dresden to Warsaw, and through his long absence from Poland the government sank into entire inactivity. During the first Silesian war he formed a secret alliance with Austria. The consequence was that during the second Silesian war Frederick the Great of Prussia pushed on into Saxony, and occupied the capital, from which Augustus fled. By the peace of Dresden, 25th Dec., 1745, he was reinstated in the possession of Saxony. In 1756 he was involved anew in a war against Prussia. When Frederick declined his proposal of neutrality he left Dresden, and entered the camp at Pirna, where 17,000 Saxon troops were assembled. Frederick surrounded the Saxons, who were obliged to surrender, and Augustus fled to Poland. On the threat of invasion by Russia he returned to Dresden, where he died in 1763. His son, Frederick Christian, succeeded him as Elector of Saxony, and Stanislaus Poniatowski as King of Poland.

Auk, a name of certain swimming birds, family Alcidæ, including the great auk, the little auk, the puffin, &c. The genus Alca, or auks proper, contains only two species, the great auk (Alca impennis), and the razor-bill (Alca torda). The great auk or gair-fowl, a bird about 3 feet in length, used to be plentiful in northerly regions, and also visited the British shores, but has become extinct. Some seventy skins, about as many eggs, with bones representing perhaps a hundred individuals, are preserved in various [313]museums. Though the largest species of the family, the wings were only 6 inches from the carpal joint to the tip, totally useless for flight, but employed as fins in swimming, especially under water. The tail was about 3 inches long; the beak was high, short, and compressed; the head, neck, and upper parts were blackish; a large spot under each eye, and most of the under parts white. Its legs were placed so far back as to cause it to sit nearly upright. The razor-bill is about 15 inches in length, and its wings are sufficiently developed to be used for flight. It is found in numbers on some parts of the British shores, as the Isle of Man.

Aulap´olay, or Alleppi, a seaport on the south-west coast of Hindustan, Travancore, between the sea and a lagoon, with a safe roadstead all the year round; exports timber, coir, coconuts, &c. Pop. 24,918.

Auld Lichts. See Presbyterianism.

Aulic (Lat. aula, a court or hall), an epithet given to a council (the Reichshofrath) in the old German Empire, one of the two supreme courts of the German Empire, the other being the court of the imperial chamber (Reichskammergericht). It had not only concurrent jurisdiction with the latter court, but in many cases exclusive jurisdiction, in all feudal processes, and in criminal affairs, over the immediate feudatories of the Emperor and in affairs which concerned the imperial Government.

Au´lis, in ancient Greece, a seaport in Bœotia, on the strait called Euripus, between Bœotia and Eubœa. See Iphigenia.

Aullagas (ou-lyä'gäs), a salt lake of Bolivia, which receives the surplus waters of Lake Titicaca through the Rio Desaguadero, and has only one perceptible insignificant outlet, so that what becomes of its superfluous water is still a matter of uncertainty.

Aulnoy (ō-nwä), Countess d', French writer, born 1650, died 1705, was the author of Contes des Fées (Fairy Tales), many of which, such as The White Cat, The Yellow Dwarf, &c., have been translated into English. She also wrote a number of novels, historical memoirs, &c.

Aumale (ō-mäl), a small French town, department of Seine Inférieure, 35 miles N.E. of Rouen, which has given titles to several notables in French history.—Jean d'Arcourt, Eighth Count d'Aumale, fought at Agincourt, and defeated the English at Gravelle (1423).—Claude II, Duc d'Aumale, one of the chief instigators of the massacre of St. Bartholomew, was killed 1573.—Charles de Lorraine, Duc d'Aumale, was an ardent partisan of the League in the politico-religious French wars of the sixteenth century.—Henri-Eugene-Philippe Louis d'Orleans, Duc d'Aumale, son of Louis Philippe, king of the French, was born in 1822. In 1847 he succeeded Marshal Bugeaud as Governor-General of Algeria, where he had distinguished himself in the war against Abd-el-Kader. After the revolution of 1848 he retired to England; but he returned to France in 1871, and was elected a member of the Assembly; became Inspector-General of the army in 1879, and was expelled along with the other royal princes in 1886, but was allowed to return. Author of a History of the House of Condé, &c. He died in 1897.

Aun´gerville, Richard, known as Richard de Bury (from his birthplace Bury St. Edmund's), English statesman, bibliographer, and correspondent of Petrarch, born 1281, died 1345. He entered the order of Benedictine monks, and became tutor to the Prince of Wales, afterwards Edward III. Promoted to several offices of dignity, he ultimately became Bishop of Durham, and Lord Chancellor of England. During his frequent embassies to the Continent he made the acquaintance of many of the eminent men of the day. He was a diligent collector of books, and formed a library at Oxford. Author of Philobiblon, printed at Cologne in 1473; Epistolœ Familiarium, including letters to Petrarch, &c.

Aurangabad´, a town of India, in the territory of the Nizam of Hyderabad, 175 miles from Bombay. It contains a ruined palace of Aurangzib and a mausoleum erected to the memory of his favourite wife. It was formerly a considerable trading centre, but its commercial importance decreased when Hyderabad became the capital of the Nizam. Pop. 34,000.

Aurangzib ('ornament of the throne'), one of the greatest of the Mogul emperors of Hindustan, born in Oct. 1618 or 1619. When he was nine years old his weak and unfortunate father, Shah Jehan, succeeded to the throne. Aurangzib was distinguished, when a youth, for his serious look, his frequent prayers, his love of solitude, his profound hypocrisy, and his deep plans. In his twentieth year he raised a body of troops by his address and good fortune, and obtained the government of the Deccan. He stirred up dissensions between his brothers, made use of the assistance of one against the other, and finally shut his father up in his harem, where he kept him prisoner. He then murdered his relatives one after the other, and in 1659 ascended the throne. Notwithstanding the means by which he had got possession of power, he governed with much wisdom. Two of his sons, who endeavoured to form a party in their own favour, he caused to be arrested and put to death by slow poison. He carried on many wars, conquered Golconda and Bijapur, and drove out, by degrees, the Mahrattas from their country. After his death, on 4th March, 1707, the Mogul Empire declined.

Aurantia´ceæ, the orange tribe, a nat. ord. of [314]plants, polypetalous dicotyledons, with leaves containing a fragrant essential oil in transparent dots, and a superior pulpy fruit, originally natives of India; examples comprise the orange, lemon, lime, citron, and shaddock.

Auray (ō-rā), a seaport of North-West France, department Morbihan, with a deaf and dumb institute, and within 2 miles of St. Anne of Auray, a famous place of pilgrimage. Pop. 6653.

Aure´lian, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus, Emperor of Rome, of humble origin, was born about A.D. 212, rose to the highest rank in the army, and on the death of Claudius II (270) was chosen emperor. He delivered Italy from the barbarians (Alemanni and Marcomanni), and conquered the famous Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra. He followed up his victories by the reformation of abuses, and the restoration throughout the Empire of order and regularity. He lost his life, A.D. 275, by assassination, when heading an expedition against the Persians.

Aure´lius Antoni´nus, Marcus, often called simply Marcus Aurelius, Roman emperor and philosopher, son-in-law, adopted son, and successor of Antoninus Pius, born A.D. 121, succeeded to the throne 161, died 180. His name originally was Marcus Annius Verus. He voluntarily shared the government with Lucius Verus, whom Antoninus Pius had also adopted. Brought up and instructed by Plutarch's nephew, Sextus, the orator Herodes Atticus, and L. Volusius Mecianus, the jurist, he had become acquainted with learned men, and formed a particular love for the Stoic philosophy. A war with Parthia broke out in the year of his accession, and did not terminate till 166. A confederacy of the northern tribes now threatened Italy, while a frightful pestilence, brought from the East with the army, raged in Rome itself. Both emperors set out in person against the rebellious tribes. In 169 Verus died, and the sole command of the war devolved on Marcus Aurelius, who prosecuted it with the utmost rigour, and nearly exterminated the Marcomanni. His victory over the Quadi (174) is connected with a famous legend. Dion Cassius tells us that the twelfth legion of the Roman army was shut up in a defile, and reduced to great straits for want of water, when a body of Christians enrolled in the legion prayed for relief. Not only was rain sent, which enabled the Romans to quench their thirst, but a fierce storm of hail beat upon the enemy, accompanied by thunder and lightning, which so terrified them that a complete victory was obtained, and the legion was ever after called The Thundering Legion (Legio Fulminatrix). After this victory the Marcomanni, the Quadi, as well as the rest of the barbarians, sued for peace. The sedition of the Syrian governor Avidius Cassius, with whom Faustina, the empress, was in treasonable communication, called off the emperor from his conquests, but before he reached Asia the rebel was assassinated. Aurelius returned to Rome, after visiting Egypt and Greece, but soon new incursions of the Marcomanni compelled him once more to take the field. He defeated the enemy several times, but was taken sick at Sirmium, and died at Vindobona (Vienna) in 180. His only extant work is the Meditations, written in Greek. It has been translated into most modern languages (into English first by George Long in 1862, and by J. Jackson in 1906). This may be regarded as a manual of practical morality, in which wisdom, gentleness, and benevolence are combined in the most fascinating manner. Many believe it to have been intended for the instruction of his son Commodus. Aurelius was one of the best emperors Rome ever saw, although his philosophy and the magnanimity of his character did not restrain him from the persecution of the Christians, whose religious doctrines he was led to believe were subversive of good government, and whom he charged, therefore, with obstinacy, the greatest social crime in the eyes of Roman authority. Marcus Aurelius was not so much a philosopher as a seeker after righteousness.—Bibliography: P. B. Watson, M. Aurelius Antoninus; Sir Samuel Dill, Roman Society from Nero to Marcus Aurelius; Translations of the Meditations by G. H. Kendall, and J. Jackson.

Aurengzebe. See Aurangzib.

Aure´ola, or Au´reole, in paintings, an illumination surrounding the whole figure of a holy person, as Christ, a saint, or a martyr, intended to represent a luminous cloud or haze emanating from him. It is generally of an oval shape, or may be nearly or quite circular, and is of similar character with the nimbus surrounding the heads of sacred personages.

Au´rĕus, the first gold coin which was coined at Rome, 207 B.C. Its value varied at different times, from about 12s. to £1, 4s. See Numismatics.

Aurich (ou´rēh), a German town, province of Hanover. Pop. 6070.

Au´ricle. See Heart.

Auric´ula, a garden flower derived from the yellow Primŭla Auricŭla, found native in the Swiss Alps, and sometimes called bear's-ear from the shape of its leaves. It has for over three centuries been an object of cultivation by florists, who have succeeded in raising from seed a great number of beautiful varieties. Its leaves are obovate, entire or serrated, and fleshy, varying, however, in form in the numerous varieties. The flowers are borne on an erect umbel and central scape with involucre. The original colours of the corolla are yellow, purple, and [315]variegated, and there is a mealy covering on the surface. There are auricula clubs and societies in the north of England.

Auricular Confession. See Confession.

Au´rifaber, the Latinized name of Johann Goldschmidt, one of Luther's companions, born 1519, became pastor at Erfurt in 1566, died there in 1579. He collected the unpublished MSS. of Luther, and edited the Epistolæ and the Table-talk.

Auriflamme. See Oriflamme.

Auri´ga, in astronomy, the Waggoner, a constellation of the northern hemisphere, containing Capella, a star of the first magnitude. Nova Aurigæ, a temporary star, appeared in the constellation in 1892.

Aurillac (ō-rē-ya˙k), a town of France, capital of the department Cantal, in a valley watered by the Jordanne, about 270 miles S. of Paris; well built, with wide streets; copper-works, paper-works, manufactures of lace, tapestry, leather, &c. Pop. 18,036.

Aurochs (a¨'roks), a species of wild bull or buffalo, the urus of Cæsar, bison of Pliny, the European bison, Bos or Bonassus Bison of modern naturalists. The animal was once abundant in Europe, but were it not for the protection afforded by the late Emperor of Russia to a few herds which inhabit the forests of Lithuania it would before this have been extinct.

Auro´ra, an American city, of Kane county, Illinois, on Fox River, 40 miles W. by S. of Chicago; it has flourishing manufactures, railway-works, and a considerable trade. Pop. (1920), 36,265.

Auro´ra (Gr. Eōs), in classical mythology, the goddess of the dawn, daughter of Hyperion and Theia, and sister of Helios and Selēnē (Sun and Moon). She was represented as a charming figure, 'rosy-fingered', clad in a yellow robe, rising at dawn from the ocean and driving her chariot through the heavens. Among the mortals whose beauty captivated the goddess, poets mentioned Orion, Tithōnus, and Cephălus.

Auro´ra, one of the New Hebrides Islands, S. Pacific Ocean, about 30 miles long by 5 wide. It rises to a considerable elevation, and is covered with a luxuriant vegetation.

Auro´ra Borea´lis, a luminous meteoric phenomenon appearing in the north, most frequently in high latitudes, the corresponding phenomenon in the southern hemisphere being called Aurora Australis, and both being also called Polar Light, Streamers, &c. The northern aurora has been far the most observed and studied. It usually manifests itself by streams of light ascending towards the zenith from a dusky line of cloud or haze a few degrees above the horizon, and stretching from the north towards the west and east, so as to form an arc with its ends on the horizon, and its different parts and rays are constantly in motion. Sometimes it appears in detached places; at other times it almost covers the whole sky. It assumes many shapes and a variety of colours, from a pale red or yellow to a deep red or blood colour; and in far northern latitudes serves to illuminate the earth and cheer the gloom of the long winter nights. The appearance of the aurora borealis so exactly resembles the effects of experimental electrical phenomena that there is every reason to believe that their causes are similar. When electricity passes through rarefied air it exhibits a diffused luminous stream which has all the characteristic appearances of the aurora, and hence it is highly probable that this natural phenomenon is occasioned by the passage of electricity through the upper regions of the atmosphere. The synchronism of auroral display with disturbances of the magnetic needle is an ascertained fact, and the connection between auroræ and magnetism is further evident from the fact that the beams or coruscations [316]issuing from a point in the horizon west of north are frequently observed to run in the magnetic meridian. What are known as magnetic storms are invariably connected with exhibitions of the aurora, and with spontaneous galvanic currents in the ordinary telegraph wires; and this connection is found to be so certain that, upon remarking the display of one of the three classes of phenomena, we can at once assert that the other two are also present. In recent years it has been established that auroræ wax and wane in frequency pari passu with sun-spots in an 11-year cycle, and that they often manifest themselves about the time of transit of a conspicuous spot across the sun's central meridian. Also they frequently recur at successive intervals of about 27 days, which is the period of a solar rotation relative to the earth. It is therefore inferred that auroræ are largely excited by influences proceeding from the sun, and it is suggested that they are the result of the impinging upon our upper atmosphere of streams of electric corpuscles expelled from the solar orb, these streams when approaching our planet being mainly directed to its higher latitudes as a consequence of its magnetic polarity. The aurora borealis is said to be frequently accompanied by sound, which is variously described as resembling the rustling of pieces of silk against each other, or the sound of wind against the flame of a candle. The aurora of the southern hemisphere is quite a similar phenomenon to that of the north.—Bibliography: A. Angot, Les Aurores Polaires; Captain H. P. Dawson, Observations of the International Polar Expeditions, 1882-3, Fort Rae.

Aurungabad. See Aurangabad.

Aurungzebe. See Aurangzib.

Ausculta´tion, a method of distinguishing the state of the internal parts of the body, particularly of the thorax and abdomen, by observing the sounds arising in the part either through the immediate application of the ear to its surface (immediate auscultation), or by applying the stethoscope to the part, and listening through it (mediate auscultation). Auscultation may be used with more or less advantage in all cases where morbid sounds are produced, but its general applications are: the auscultation of respiration, the auscultation of the voice; auscultation of coughs; auscultation of sounds foreign to all these, but sometimes accompanying them; auscultation of the actions of the heart; obstetric auscultation. The parts when struck also give different sounds in health and disease.

Auso´nia, an ancient poetical name of Italy.

Auso´nius, Decimus Magnus (c. A.D. 310-395), Roman poet, born at Burdigala (Bordeaux). Valentinian entrusted to him the education of his son Gratian, and appointed him afterwards quæstor and pretorian prefect. Gratian appointed him consul in Gaul, and after this emperor's death he lived upon an estate at Bordeaux, devoted to literary pursuits. He wrote epigrams, idyls, eclogues, letters in verse, &c., still extant, and was probably a Christian. He was rather a man of letters than a poet, and his poems are devoid of inspiration.

Aus´pices, among the ancient Romans strictly omens or auguries derived from birds, though the term was also used in a wider sense. Nothing of importance was done without taking the auspices, which, however, simply showed whether the enterprise was likely to result successfully or not, without supplying any further information. Magistrates possessed the right of taking the auspices, in which they were usually assisted by an augur. Before a war or campaign a Roman general always took the auspices, and hence the operations were said to be carried out 'under his auspices'. See Augur.

Aus´sig, a town in Bohemia, in the republic of Czecho-Slovakia, formerly in Austria, near the junction of the Bila with the Elbe, 42 miles N.N.W. of Prague; has large manufactures of woollens, chemicals, &c. The town is now known as Ousti nad Labem. Pop. 40,000.

Aus´ten, Jane, English novelist, born 1775, at Steventon, in Hants, of which parish her father was rector. Her principal novels are, Sense and Sensibility; Pride and Prejudice, which Disraeli is said to have read seventeen times; Mansfield Park; and Emma. Two more were published after her death, entitled Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, which were, however, her most early attempts. Her novels are marked by ease, humour, and a complete knowledge of the domestic life of the English middle classes of her time. She died in 1817.

Austenite, a constituent of high-carbon steel (q.v.).

Aus´terlitz, a town with 3703 inhabitants, in Moravia, 10 miles E. of Brünn, famous for the battle of 2nd Dec., 1805, fought between the French (70,000 in number) and the allied Austrian and Russian armies (95,000). The decisive victory of the French led to the Peace of Pressburg between France and Austria.

Aus´tin, capital of the State of Texas, on the Colorado, about 200 miles from its mouth, and accessible to steamboats during certain seasons. There is a State university and other institutions, and a splendid capitol built of red granite. Pop. (1920), 34,876.

Austin, Alfred, English poet, born at Hedingley, near Leeds, in 1835, educated at Stonyhurst and St. Mary's College, Oscott; took the degree of B.A. at London in 1853, was called to the bar and practised, but gave up law for literature in 1861. He published, in 1861, a [317]satire called The Season, followed by many poems, including The Human Tragedy, The Golden Age, Savonarola (a tragedy), English Lyrics, Fortunatus the Pessimist, Lyrical Poems, Narrative Poems, Prince Lucifer, Alfred the Great, A Tale of True Love, Flodden Field (a tragedy), &c. His works in prose include The Garden that I love, In Veronica's Garden, Spring and Autumn in Ireland, Haunts of Ancient Peace, The Bridling of Pegasus, &c. He was made Poet Laureate in 1896, about four years after the death of Tennyson. He died in 1913.

Aus´tin, John, an English writer on jurisprudence, born 1790, died 1859. From 1826 to 1835 he filled the chair of jurisprudence at London University. He served on several royal commissions, one of which took him to Malta; lived for some years on the Continent, and finally settled at Weybridge, in Surrey. His fame rests solely on his great works: The Province of Jurisprudence Determined, published in 1832; and his Lectures on Jurisprudence, published by his widow between 1861 and 1863.—His wife, Sarah, one of the Taylors of Norwich, produced translations of German works, and other books bearing on Germany or its literature; also, Considerations on National Education, &c. Born 1793, died 1867. Her daughter, Lady Duff Gordon, translated Meinhold's Mary Schweidler, the Amber Witch, and other German works.

Austin, St. See Augustine.

Austin Friars. See Augustins.

Australasia, a division of the globe usually regarded as comprehending the Islands of Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, New Caledonia, the New Hebrides, the Solomon Islands, New Ireland, New Britain, the Admiralty Islands, New Guinea, and the Arru Islands, besides numerous other islands and island groups; estimated area, 3,400,000 sq. miles; pop. 6,000,000. It forms one of the three portions into which some geographers have divided Oceania, the other two being Malaysia and Polynesia. The British territories in Australasia comprise the Commonwealth of Australia, the Australian dependencies of Papua and Northern Territory, New Zealand and adjacent islands, and the crown colony of Fiji.

Australia (older name, New Holland), the largest island in the world, a sea-girt continent, lying between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, S.E. of Asia; between lat. 10° 39' and 39° 11' S.; long. 113° 5' and 153° 16' E.; greatest length, from W. to E., 2400 miles; greatest breadth, from N. to S., 1700 to 1900 miles. It is separated from New Guinea on the north by Torres Strait, from Tasmania on the south by Bass Strait. It is divided into two unequal parts by the Tropic of Capricorn, and consequently belongs partly to the South Temperate, partly to the Torrid Zone. It is occupied by five British colonies, namely, New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland in the east; South Australia in the middle, stretching from sea to sea; and Western Australia in the west, which, with the Island of Tasmania, form the Commonwealth of Australia. Their area and population are as follows:—

| Area in sq. m. | Pop. in 1920 | |

| New South Wales | 309,432 | 2,091,115 |

| Victoria | 87,884 | 1,528,151 |

| Queensland | 670,500 | 752,245 |

| South Australia | 380,070 | 491,177 |

| Western Australia | 975,920 | 330,819 |

| Tasmania | 26,215 | 212,847 |

| Northern Territory | 523,620 | 3,992 |

| Federal Territory | 940 | 1,972 |

Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane, and Perth are the chief towns. The population of the Commonwealth of Australia was 4,895,894 in 1917 and 5,412,318 in 1920.