Title: A Historical Geography of the British Colonies, Vol. V

Author: Sir Charles Prestwood Lucas

Release date: October 16, 2010 [eBook #34080]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ron Swanson

| CHAP. I. | EUROPEAN DISCOVERERS IN NORTH AMERICA TO THE END OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY |

| CHAP. II. | SAMUEL CHAMPLAIN AND THE FOUNDING OF QUEBEC |

| CHAP. III. | THE SETTLEMENT OF CANADA AND THE FIVE NATION INDIANS |

| CHAP. IV. | FRENCH AND ENGLISH DOWN TO THE PEACE OF UTRECHT |

| CHAP. V. | THE MISSISSIPPI AND LOUISIANA |

| CHAP. VI. | ACADIA AND HUDSON BAY |

| CHAP. VII. | LOUISBOURG |

| CHAP. VIII. | THE PRELUDE TO THE SEVEN YEARS' WAR |

| CHAP. IX. | THE CONQUEST OF CANADA |

| CHAP. X. | THE CONQUEST OF CANADA (continued) |

| CHAP. XI. | GENERAL SUMMARY |

| APPENDIX I. | LIST OF FRENCH GOVERNORS OF CANADA |

| APPENDIX II. | DATES OF THE PRINCIPAL EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF CANADA DOWN TO 1763 |

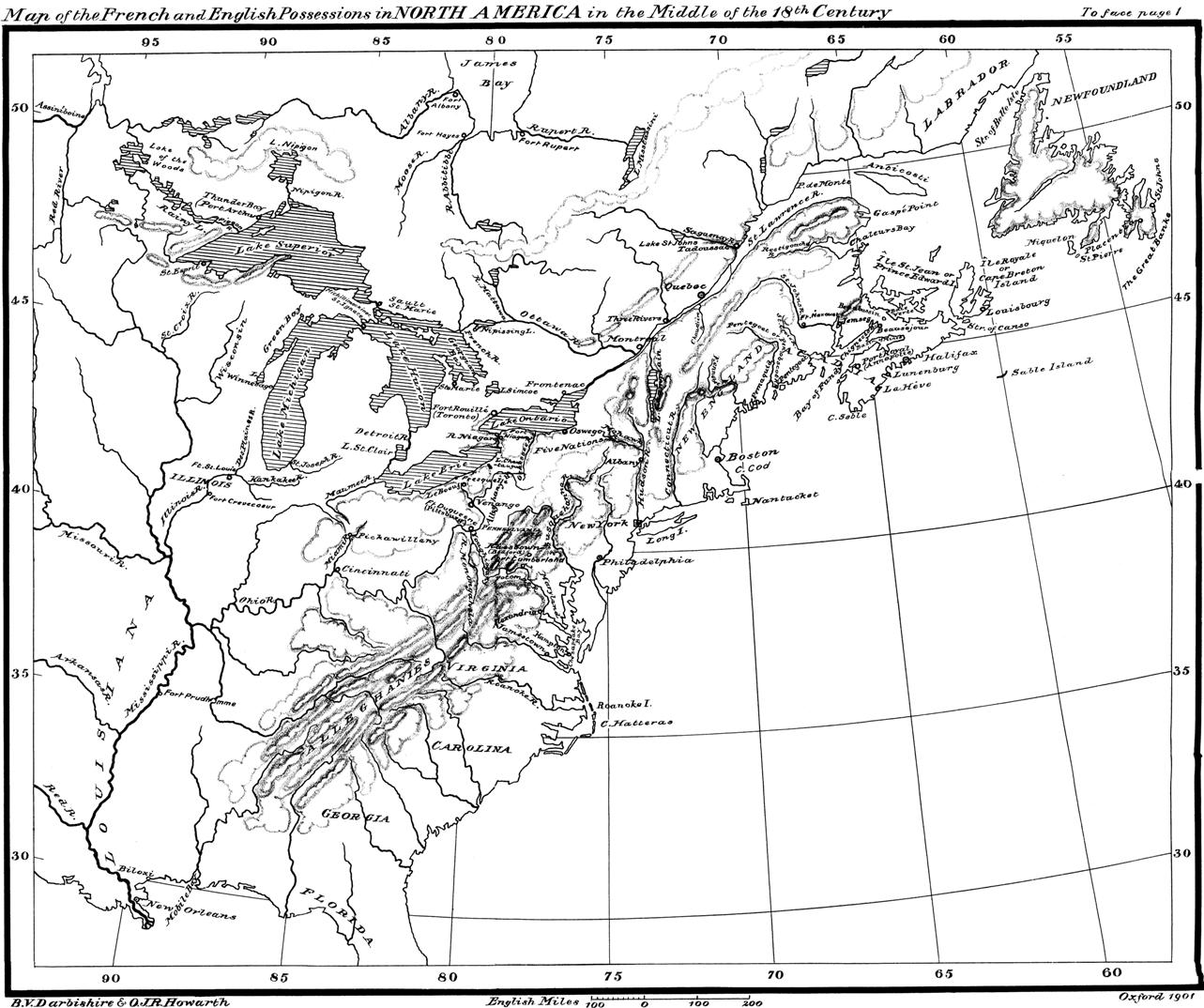

| 1. | Map of the French and English possessions in North America in the middle of the eighteenth century |

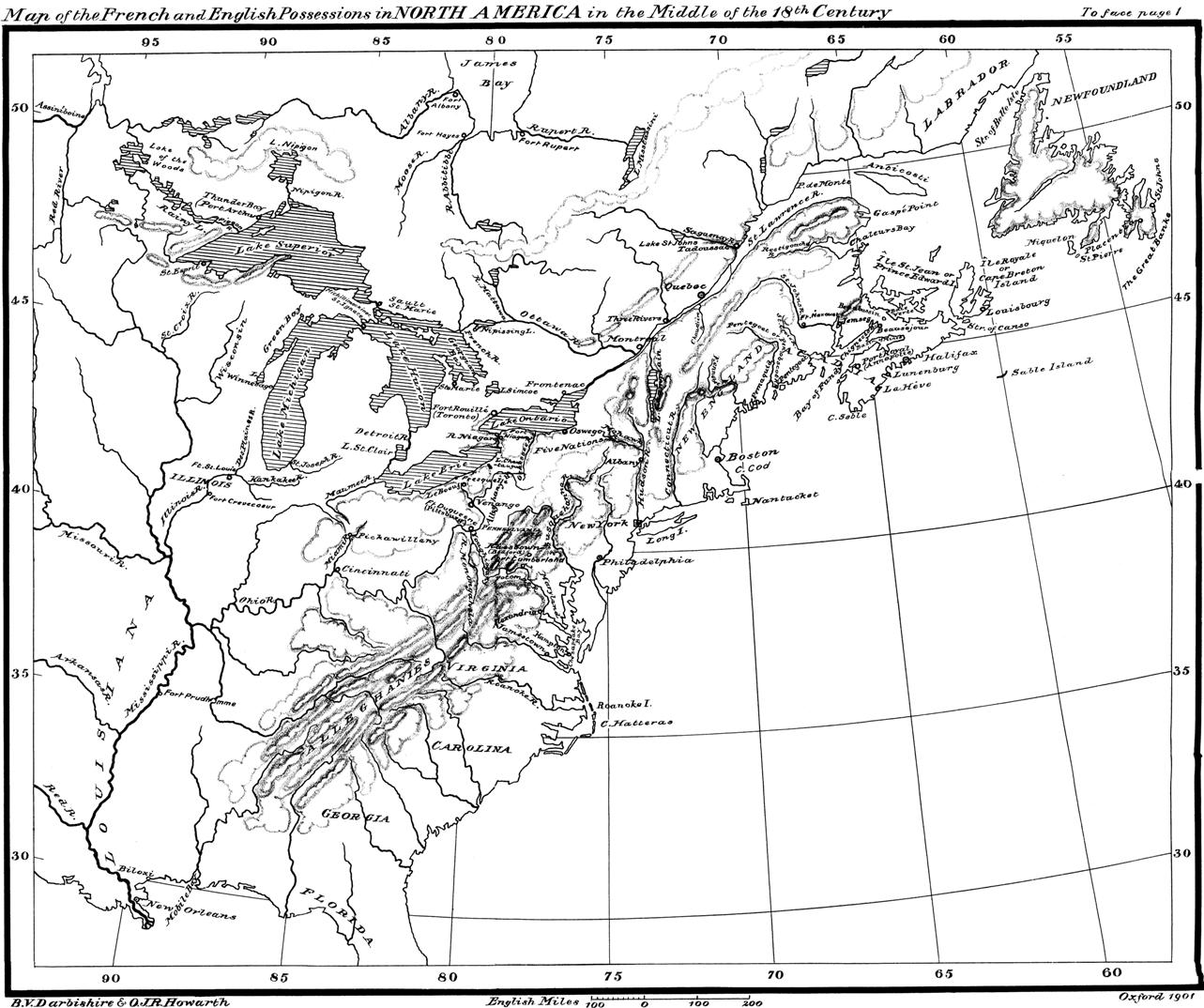

| 2. | Map of New England, New York, and Central Canada, showing the waterways |

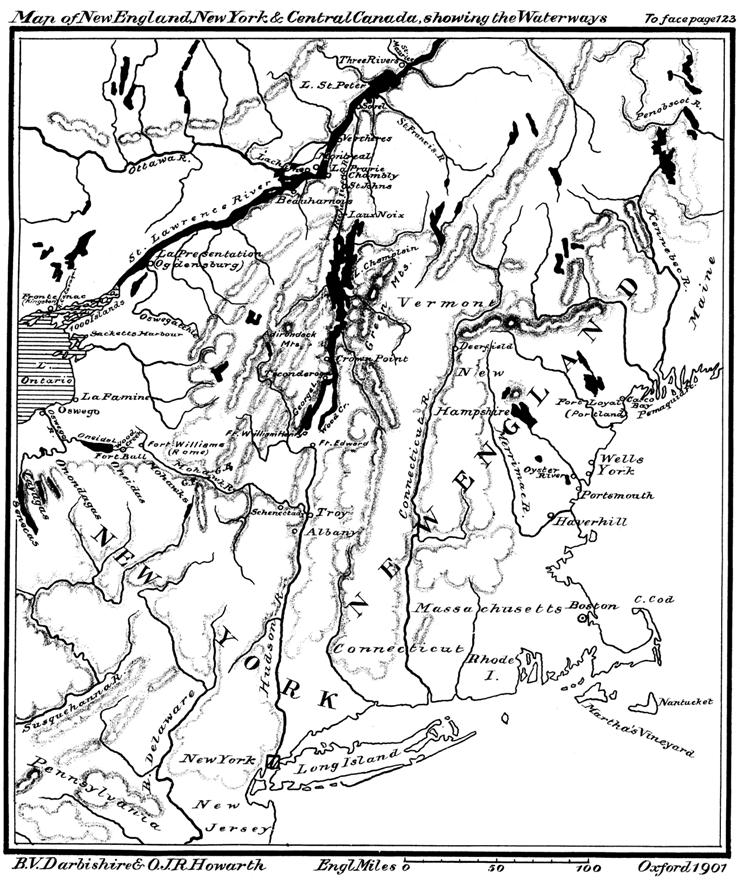

| 3. | Map of Louisbourg |

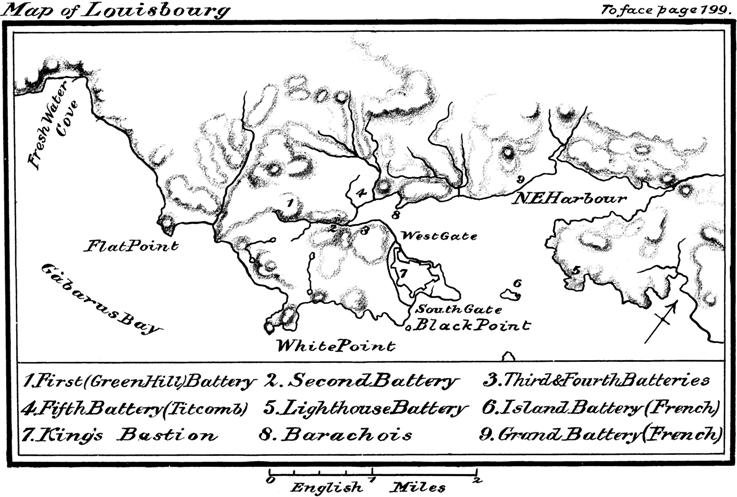

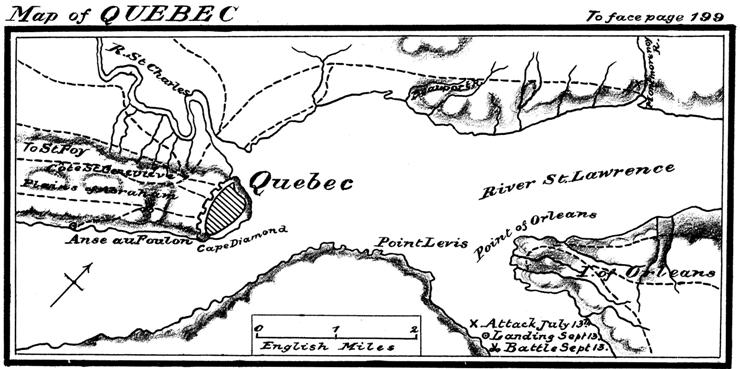

| 4. | Map of Quebec |

|

| The British possessions in North America. |

The British possessions in North America consist of Newfoundland and the Dominion of Canada. Under the Government of Newfoundland is a section of the mainland coast which forms part of Labrador, extending from the straits of Belle Isle on the south to Cape Chudleigh on the north.

The area of these possessions, together with the date and mode of their acquisition, is as follows:—

| Name. | How acquired. | Date. | Area in square miles. |

| Newfoundland and Labrador |

Settlement | 1583-1623 | 40,200 120,000 |

| Canada | Cession [Quebec] | 1763 | 3,653,946 |

| British possessions in North America and West Indies contrasted. |

In the Introduction to a previous volume,1 it was pointed out that all the British possessions in the New World have one common feature; viz. that they have been, in the main, fields of European settlement, and not merely trading stations or conquered dependencies; but that, in other respects—in climate, in geography, and in what may be called the strata of colonization—the West Indian and North American provinces of the Empire stand at opposite poles to each other. It may be added that, in North America, European colonization was later in time and slower in development than in the central and southern parts of the continent; and, in order to understand why this was the case, some reference must be made to the geography of North America, more especially in its relation to Europe, and also to its first explorers, their motives, and their methods.

1 Vol. ii, West Indies, pp. 3, 4.

| Geographical outline of America. |

The Old World lies west and east. In the New World the line of length is from north to south. The geographical outline of America, as compared with that of Europe and Asia, is very simple. There is a long stretch of continent, with a continuous backbone of mountains, running from the far north to the far south. The mountains line the western coast; on the eastern side are great plains, great rivers, broken shores, and islands. Midway in the line of length, where the Gulf of Mexico runs into the land, and where, further south, the Isthmus of Darien holds together North and South America by a narrow link, the semicircle of West Indian islands stand out as stepping-stones in the ocean for wayfarers from the old continent to the new.

| North and South America. |

The two divisions of the American continent are curiously alike. They have each two great river-basins on the eastern side. The basin of the St. Lawrence is roughly parallel to that of the Amazon; the basin of the Mississippi to that of La Plata. The North American coast, however, between the mouth of the St. Lawrence and that of the Mississippi, is more varied and broken, more easy of access, than the South American shores between the Amazon and La Plata. On the other hand, South America has an attractive and accessible northern coast, in strong contrast to the icebound Arctic regions; and the Gulf of Venezuela, the delta of the Orinoco, and the rivers of Guiana, have called in traders and settlers from beyond the seas.

| South America colonized from both sides, North America only from the eastern side. |

The history of colonization in North America has been, in the main, one of movement from east to west. In South America, on the other hand, the western side played almost from the first at least as important a part as the eastern. The story of Peru and its Inca rulers shows that in old times, in South America, there was a civilization to be found upon the western side of the Andes, and the shores of the Pacific Ocean. European explorers penetrated into and crossed the continent rather from the north and west than from the east; and Spanish colonization on the Pacific coast was, outwardly at least, more imposing and effective than Portuguese colonization on the Atlantic seaboard. The great mass of land on the earth's surface is in the northern hemisphere; and in the extreme north the shores of the Old and New Worlds are closest to each other. Here, where the Arctic Sea narrows into the Behring Straits, it is easier to reach America from the west than from the east, from Asia than from Europe; but to pass from the extremity of one continent to the extremity of another is of little avail for making history; and the history of North America has been made from the opposite side, which lies over against Europe, where the shores are indented by plenteous bays and estuaries, and where there are great waterways leading into the heart of the interior.

| The rivers of North America. English colonization in North America. |

The main outlets of North America are, as has been said, the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi; while, on the long stretch of coast between them, the most important river is the Hudson, whose valley is a direct and comparatively easy highroad from the Atlantic to Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence basin; and here it may be noticed that, though a Bristol ship first discovered North America, and though, from the time of Ralegh onwards, North America became the main scene of British colonization, the English allowed other nations to secure the keys of the continent, and ran the risk of being cut off from the interior. The French forestalled them on the St. Lawrence, and later took possession of the mouth of the Mississippi. The Dutch planted themselves on the Hudson between New England and the southern colonies, and New York, the present chief city of English-speaking America, was once New Amsterdam. Of all colonizing nations the English have perhaps been the least scientific in their methods; and in no part of the world were their mistakes greater than in North America, where their success was eventually most complete. There was, however, one principle in colonization to which they instinctively and consistently held. While they often neglected to safeguard the obvious means of access into new-found countries, and, as compared with other nations, made comparatively little use of the great rivers in any part of the world, they laid hold on coasts, peninsulas, and islands, and kept their population more or less concentrated near to the sea. Thus, when the time of struggle came, they could be supported from home, and were stronger at given points than their more scientific rivals. If the French laid their plans to keep in their own hands the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the St. Lawrence, and thereby to shut off the colonies of the Atlantic seaboard from the continent behind, those colonies had the advantage of close contact with the sea, of comparatively continuous settlement, and of yearly growing power to break through the weak and unduly extended line with which the competing race tried to hem them in.

But this contest between French and English, based though it was on geographical position, belongs to the Middle Ages of European colonization in America: let us look a little further back, and see how the Old and the New Worlds first came into touch with each other.

| Bacon on the discovery of North America. |

In his history of King Henry VII, Bacon refers to the 'memorable accident' of the Cabots' great discovery, in the following passage:—'There was one Sebastian Gabato, a Venetian living in Bristow, a man seen and expert in cosmography and navigation. This man, seeing the success and emulating perhaps the enterprise of Christopherus Columbus in that fortunate discovery towards the south-west, which had been by him made some six years before, conceited with himself that lands might likewise be discovered towards the north-west. And surely it may be he had more firm and pregnant conjectures of it than Columbus had of his at the first. For the two great islands of the Old and New World, being in the shape and making of them broad towards the north and pointed towards the south, it is likely that the discovery first began where the lands did nearest meet. And there had been before that time a discovery of some lands which they took to be islands, and were indeed the continent of America towards the north-west.'2 Bacon goes on to surmise that Columbus had knowledge of this prior discovery, and was guided by it in forming his own conjectures as to the existence of land in the far west; and it is at least not unlikely that, when he visited Iceland in 1477, he would have heard tales of the Norsemen's voyages to America.3

2 Spedding's edition of Bacon's works, 1870, vol. vi, p. 196.

3 For this visit, see Washington Irving's Life and Voyages of Columbus, bk. i, ch. vi.

| Pre-Columbian explorations. |

It would be out of place in this book to make more than a passing reference to the much-vexed question, how far the New World was known to Europeans before the days of Columbus and the Cabots. Indeed, if all the stories on the subject were proved, the fact would yet remain that, for all practical purposes, America was first revealed to the nations of Europe, when Columbus took his way across the Atlantic. It was likely that, when his discovery had been made, men would rise up to assert that it was not so great and not so new as had been at first imagined. The French claimed priority for a countryman of their own;4 stories of Welsh and Irish settlement in America passed into circulation; the romance of the brothers Zeni was published, a tale of supposed Venetian adventure in the fourteenth century to the islands of the far north; and it was contended, more prosaically and with greater show of reason, that Basque fishermen had frequented the banks of Newfoundland, before that island was discovered for England and thereby earned its present name.

4 Cousin of Dieppe, who claimed to have discovered America in 1488, four years before Columbus reached the West Indies.

| Voyages of the Norsemen. |

The story of the Norsemen's voyages has a sounder foundation than any other of these early traditions and tales. Iceland is nearer to Greenland than to Norway: it has been abundantly proved that colonies were established and fully organized in Greenland in the Middle Ages; and it seems on the face of it unlikely that the enterprise and adventure of the seafaring sons of the north would have stopped short at this point, instead of carrying them on to the mainland of America.

| Their alleged discovery of North America. |

The Norse are said to have come to Iceland about 875 A.D., where Christian Irish had already preceded them; and, in the following year, rocks far to the west were sighted by Gunnbiorn. A century later, in 984, Eric the Red came back from a visit to Gunnbiorn's land, calling it by the attractive name of Greenland. About 986, Bjarni Herjulfson, sailing from Iceland to Greenland, sighted land to the south-west; and, a few years later, about the year 1000, Leif, the son of Eric, who had brought the Christian religion to Greenland, sailed in search of the south-western land which Bjarni had seen. The record of his voyage claims to be the record of the discovery of America. He found the rocky barren shores of Labrador and Newfoundland, and called them from their appearance Helluland, or 'slateland.' He passed on to the mouth of the St. Lawrence and to Nova Scotia, calling it Markland, or the 'land of woods.' Then sailing still further south, he came to a land where vines grew wild, and which he called Vinland. This last was, it would seem, the New England coast, between Boston and New York; and here in after times, for a like reason, English settlers gave the name of Martha's or Martin's Vineyard to an island, which lies close to the shore south of Cape Cod.5 In Vinland, it is stated, a Norse colony was founded a few years after Leif's visit; and trade—mainly a timber trade—was carried on with Greenland down to the year 1347, after which all is a blank.

5 A little further to the south on the coast of New Jersey, or Maryland, Verrazano 'saw in this country many vines growing naturally' (Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 360, 1810 ed.).

No authentic inscriptions or remains, indicating Scandinavian discovery or settlement in America, have, it is said, been found anywhere outside Greenland, except at one point in the very far north;6 and in their absence these northern tales cannot be absolutely verified. It can only be said that, in all probability, America was known to the Northmen in the Middle Ages, but that what happened in these dark days in the extreme north of Europe and the extreme north of America has no direct bearing upon the history of European colonization.

6 See Justin Winsor's Narrative and Critical History of America, (vol. i, chap. ii) on 'Pre-Columbian Explorations.' The writer says, 'Nowhere in America, except on an island on the east shore of Baffin's Bay, has any authentic runic inscription been found outside of Greenland.' Reference should be made to the first chapter of Mr. Raymond Beazley's John and Sebastian Cabot ('Builders of Greater Britain' series, 1898), in which the dates and particulars of the Norse discovery of America, as given above, are somewhat modified.

| The way to the East. |

At the time when modern history opens, there were two parts of the world which were—to use the Greek philosopher's phrase—'ends in themselves.' One was Europe or rather Southern Europe, the other was the East Indies; and the great problem was to find the best and shortest way from the one point to the other.

| Africa and America places on the road. |

The overland trade routes through Syria and Egypt—by which Genoa, Venice, and the other city states of the Middle Ages had grown rich—had fallen in the main under Moslem control; and, accordingly, the growing nations of Europe began to take to the open sea. On the ocean, India can be reached from Europe either by going east or by going west. In the former case Africa comes in the way, in the latter America; and the position of these two continents in the modern history of the world is, in their earliest stage, that of having been places on the road, not final goals.

The Portuguese tried the way by Africa and succeeded. Vasco de Gama rounded the Cape, sailed up the eastern coast of Africa, and crossed to India. The Spaniards set sail in the opposite direction, and, failing in their original design, found instead a New World.

Let us suppose that the conditions had been reversed, that Southern Africa, when reached, had proved as attractive as the West Indies; that its shores had been fertile and easy of access; that its rivers had been navigable, and that its turning-point had been as distant as Cape Horn; that, on the contrary, Columbus had discovered a channel through America, where he sought for it at the Isthmus of Darien, had found the American coasts and islands as little inviting as Africa, and behind them an expanse of sea no wider than the Indian Ocean. In that case America would have remained the Dark Continent, to be passed by, as Africa was passed by, on the way to the East; and hinging on this one central fact, that the Indies were the goal of discovery, the whole history of colonization would have been changed. As it was, the Spaniards, in the first place, found their way barred by America; and, in the second place, found America too good to be passed by, even if a thoroughfare had been found. Thus they assumed that they had really reached the Indies on their furthest side; and, by the time that the mistake had been finally cleared up, the riches and wonders of the New World had given it a position and standing of its own, over and above all considerations respecting the best way to the East.

America then was discovered by being taken on the way to some other part of the world; it could not be passed by like Africa; and it was more attractive than Africa. Thus it was early colonized, while the great mass of the African continent was left, almost down to our own day, unexplored and unknown.

| Reasons why the discovery and settlement of North America was later than that of Central and South America. |

This statement, however, only holds true of that part of America which the Spaniards made their own; and the further question arises—Why was the discovery and settlement of North America a much slower process than the Spanish conquest and colonization of Central America and the West Indies? The north of Newfoundland is in the same latitude as the south of England; the mouth of the St. Lawrence lies directly over against the ports of Brittany; a line drawn due east from New York would almost pass through Madrid: therefore it seems as though sailors going westward from Europe would naturally make their way in the first instance to the North American coast; and, as a matter of fact, Cabot probably sighted the shores of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, or Labrador before Columbus set foot upon the mainland of South America.

| Spain and Portugal the natural centres for Western discovery. The Spaniards went to the south-west. |

There are, however, ample historical and geographical reasons for the fact that, at the beginning of modern history, the stream of European discovery and colonization took a south-westerly rather than a westerly direction. The main course of European civilization has on the whole been from south-east to north-west. Its centre gradually shifted from Asia Minor and Phoenicia to Greece, from Greece to Rome, and finally from the shores of the Mediterranean to those of the Atlantic. The peninsula of Spain and Portugal stands half-way between the inner and the outer sea, and accordingly geography marked out this country to be the birthplace of the new and wider history of the world. Further, at the time when modern history begins, the Spaniards and Portuguese were better trained, more consolidated, more nearly come to their prime, more full of expansive force than the peoples of Northern Europe; so that their history combined with their geographical position to place them in the front rank among the movers of the world. But Spain and Portugal look south-west: both countries are hot, sunny lands, and, while adventurers to the unknown would in any case be more attracted to regions where they would expect light and heat and tropical growth and colour, than to the bare, bleak stretches of the north, most of all would a southern race set out to find a new world in a southerly or south-westerly direction. Again, as has been seen, the early explorers were seeking for a sea-road to the Indies; and, as the tales of the Indies were glowing tales of glowing lands, men were more likely at first to start in search of them by way of the Equator than by way of the Pole.

And they had guidance in their course. The Canaries, Madeira, and the Azores, lying away in the ocean to the south-west, were the half-mythical goals of ancient navigation. The Spaniards would naturally make for them in the first instance, and so far help themselves on their westward way. Wind and tide would prescribe the same line of discovery. The way to the West Indies is made easy by the north-easterly trade winds, whereas the passage to North America is in the teeth of the prevailing wind from the west. Those who take ship from Europe to North America meet the opposing force of the Gulf Stream; voyagers to the south-west, on the contrary, are borne by the Equatorial Current from the African coast to the Caribbean Sea.

| The West Indies more attractive than North America. |

Easier to reach than North America, the West Indies and Central America were also more attractive when reached. The Spaniards found riches beyond their hopes, pearls in the sea, gold and silver in the land, and a race of natives who could be forced to fish for the one and to mine for the other. When they had discovered the New World, there was every inducement to make them forthwith conquer and colonize in countries where living promised to be more luxurious than in their own land. Adventurers to North America, on the contrary, found greater cold than they had left behind them in the same latitudes in Europe, desolate shores, little trace of precious metal, and natives whom it was dangerous to offend and impossible to enslave. In the far north the cod fisheries were discovered, and furs were to be obtained by barter from the North American Indians; but such trade was not likely to lead to permanent settlement in the near future. Its natural outcome was not the founding of colonies, the building of cities, and the subjugation of continents, but, at the most, repeated visits in the summer time to the Newfoundland banks, or spasmodic excursions up the course of the St. Lawrence. Thus, for a century after Columbus first sailed to the west, while Central and South America became organized into a collection of Spanish provinces, the extreme north was left to Basque, Breton, and English fishermen; and the coast between the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi, where the English race was eventually to make its greatest effort and achieve its greatest success—this, the present territory of the United States, was, with the exception of Florida, little visited and scarcely known.

| Effect of finding mineral wealth in Central America. |

The discovery of minerals in a district brings about dense population and a hurried settlement. Men come to fisheries or hunting-grounds at stated times, and leave to come again. The progress of agricultural colonization, if steady and continuous, is usually very slow. Thus, where Central America gave gold and silver, there adventurers from Europe hurried in and stayed. The fisheries of Newfoundland saw men come and go; the sea was there the attraction, not the land. The agricultural resources of Virginia and New England were left undeveloped by Europeans, until the time came when business-like companies were formed by men who could afford to wait, and when enthusiasts went over the Atlantic not so much to make money as to live patiently and in the fear of God.

| The North-West Passage. |

But, though the sixteenth century passed away before men's eyes, which were dazzled with the splendour of the tropics, had given more than passing glances to the sober landscape of North America, discoverers from Cabot onwards were not idle; and from the first, the ever powerful hope of finding a new road to the Indies took adventurers to the north-west in spite of cold and wind and tide. Because North America was unattractive in itself, therefore men seem to have imagined that it must be on the way to something better; and also, because it was unattractive in itself, they did not wait to see what could be made out of it, but kept perpetually pushing on to a further goal. They argued, as Bacon shows in the passage already quoted, and argued rightly, that in the north the Old and New Worlds were nearest together, and that here therefore was the point at which to cross from one to the other. They found sea channels evidently leading towards the west; they saw the great river of Canada7 come widening down from the same quarter; and thus, long after the quest of the Indies had in Central America been swallowed up in the riches found on the way, in North America it remained the one great object of the men who went out from Europe, and of the Kings who sent them out.

7 The idea that there was a way to the Indies by the St. Lawrence long continued. Thus Lescarbot writes (Nova Francia, Erondelle's translation, 1609, chap. xiii, p. 87) of the great river of Canada as 'taking her beginning from one of the lakes which do meet at the stream of her course (and so I think), so that it hath two courses, the one from the east towards France, the other from the west towards the south sea.'

As the first discoverer, Cabot, set sail to find the passage to Cathay, 'having great desire to traffic for the spices as the Portingals did,'8 so all who came after during the century of exploration kept the same end firmly in view. Francis I of France dispatched Verrazano to find the passage to the East; Cartier, the Breton sailor, came back from the St. Lawrence with tales which savoured of the Indies, of 'a river that goeth south-west, from whence there is a whole month's sailing to go to a certain land where there is neither ice nor snow seen'9—of a 'country of Saguenay, in which are infinite rubies, gold and other riches'10—of 'a land where cinnamon and cloves are gathered';11 and his third voyage was, in his King's words, 'to the lands of Canada and Hochelaga, which form the extremity of Asia towards the west.'12 Frobisher's voyage in 1576 led to the formation of a company of Cathay. As early as 1527, Master Robert Thorne wrote 'an information of the parts of the world' discovered by the Spaniards and Portuguese, and 'of the way to the Moluccas by the north.' Sir Humphrey Gilbert published 'a discourse' 'to prove a passage by the north-west to Cathaia and the East Indies'; and Richard Hakluyt himself, in the 'epistle dedicatory' to Philip Sydney, which forms the preface to his collection of Divers Voyages touching the discovery of America,13 sums up the arguments for the existence of 'that short and easy passage by the north-west which we have hitherto so long desired.' In short, the record of the sixteenth century in North America was, in the main, a record of successive voyagers seeking after a way to the East, supplemented by the fishing trade which was attracted to the shores of Newfoundland.

8 Gomara, quoted by Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 30 (1810 ed.).

9 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 278.

10 Ibid. p. 281.

11 Ibid. p. 285.

12 See Parkman's Pioneers of France in the New World (25th ed., 1888), p. 217.

13 Published in 1582; edited by the Hakluyt Society in 1850.

| The early voyagers to North America were of various nationalities. |

The two men who opened America to Europe were of Italian parentage—Columbus the Genoese, and Cabot, born at Genoa, domiciled at Venice.14 The two great trading republics of the Middle Ages at once crowned their work in the world, and signed their own death warrant, in providing Spain and England with the sailors whose discoveries transferred the centre of life and movement from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. The King of France too turned to Italy for a discoverer to rival Columbus and Cabot, and sent Verrazano the Florentine, at the end of 1523, to search out the coasts of North America.

14 As to Cabot's parentage see below. If the voyages of the Zeni were genuine, the Venetians could have claimed a yet older share in the record of European connexion with America.

At the first dawn of discovery those coasts were not wholly given over to French or English adventurers. Though Florida was the northern limit of Spanish conquest and settlement, Spanish claims extended indefinitely over the whole continent; and the French King's scheme for the colonization of Canada, in 1541, under the leadership of Cartier and Roberval, roused the suspicion of the Spanish court as an attempt to infringe an acknowledged monopoly. The Portuguese at the very first took part in north-western discovery, and with good reason; for it was their own Indies which were the final goal, and they could not afford to leave to other nations to find a shorter way thither than their own route round the Cape. Thus it was that Corte Real set out from Lisbon for the north-west in the year 1500, having 'craved a general license of the King Emmanuel to discover the Newfoundland,' and 'sailed unto that climate which standeth under the north in 50 degrees of latitude.'15 We find, too, records of Portuguese working in the same direction under foreign flags. In 1501 two patents were granted by Henry VII of England to English and Portuguese conjointly to explore, trade, and settle in America;16 and, in 1525, Gomez, who had served under Magellan, and who, like Magellan, was a Portuguese in the service of Spain, set out from the Spanish port of Corunna to search for the North-West Passage.17

15 See Purchas' Pilgrims, pt. 2, bk. x, chap. i. A brief 'collection of voyages, chiefly of Spaniards and Portugals, taken out of Antoine Galvano's Book of the Discoveries of the World.'

16 See Doyle's History of the English in America, vol. i, chap. iv.

17 See Justin Winsor, vol. iv, chap. i, p. 10.

| The Basque fishermen. |

Basque fishermen were among the very first visitors to Newfoundland, and, even after the North American continent was becoming a sphere of French and English colonization, to the exclusion of the southern nations of Europe, the Spaniards and Portuguese still held their own in the fisheries. The record of almost every voyage to Newfoundland notices Spanish or Portuguese ships plying their trade on the banks.18 A writer19 in the year 1578, on 'the true state and commodities of Newfoundland,' tells us that, according to his information, there were at that date above one hundred Spanish ships engaged in the cod fisheries, in addition to twenty or thirty whalers from Biscay; that the Portuguese ships did not exceed fifty, and that those owned by French and Bretons numbered about one hundred and fifty. Edward Hayes, the chronicler of Gilbert's last voyage in 1583, relates how the Portuguese at Newfoundland provisioned the English admiral's ships for their return voyage, and adds that 'the Portugals and French chiefly have a notable trade of fishing upon this bank.'20

18 See Parkman's Pioneers of France in the New World (25th ed., 1888), pp. 189, 190, and notes.

19 Anthony Parkhurst. The letter was written to Hakluyt, and published in his collection, vol. iii, p. 171.

20 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 190.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, the Spanish Government still claimed for its subjects the right to fish on the Newfoundland coast, among other grounds on that of prior discovery, a claim which was only finally relinquished under the provisions of the Peace of Paris in 1763;21 and, writing about the same date, the author of the European Settlements in America noted that the Spaniards still shared in the fishery.22

21 As to the question whether Basque fishermen had found their way to Newfoundland before Cabot, see the note to p. 189 of Mr. Parkman's Pioneers of France in the New World. The reasons for thinking that these fishermen forestalled Cabot seem to be—(1) the argument of probability; (2) assertions of old writers to that effect; (3) the application of the Basque name 'Baccalaos' to Newfoundland, and the statement of Peter Martyr that Cabot found that word in use for codfish among the natives; (4) the claim advanced by the Spanish Government to right of fishing at Newfoundland on the ground of prior discovery by Biscayan fishermen. As to this last point, see Papers relative to the rupture with Spain, 1762. One source of friction at this time between Great Britain and Spain was what Pitt styles in a dispatch (p. 3) 'the stale and inadmissible pretensions of the Biscayans and Guipuscoans to fish at Newfoundland.' As to this claim, the Earl of Bristol, British minister at Madrid, writes (p. 53), 'With regard to the Newfoundland fishery, Mr. Wall urged, what I have also conveyed in some former despatches, that the Spaniards indeed pleaded, in favour of their claim to a share of the Bacallao trade, the first discovery of that island.'

22 European Settlements in America, pt. 6, chap. xxviii, 'Newfoundland.' The author (? Burke) says, 'The French and Spaniards, especially the former, have a large share (in the fishery).'

Hayes, who has just been quoted, tells us that more than thirty years before he wrote, i.e. about 1550, the Portuguese had touched at Sable Island and left there 'both neat and swine to breed.' In the same way they left live stock at Mauritius on their way to and from the East; and in like manner the Spaniards landed pigs at the Bermudas23 on their early voyages to the West Indies.

23 See vol. i of this series, p. 163, and vol. ii, p. 6 and note. Lescarbot states that the French Baron de Léry, who attempted to found a colony in North America in 1518, left cattle on Sable Island. See Parkman's Pioneers of France, p. 193, and Doyle's History of the English in America, vol. i, chap. v, p. 111.

| Names in North America indicate visits from Southern Europe. |

If evidence were wanted that, in the oldest days of movement from Europe to the West, southern sailors did not go only to tropical America, it would be found in the naming of the North American coasts and islands. The first point on the coast of North America, sighted by the first discoverer—the Italian Cabot—was spoken of under the Italian name of Prima Terra Vista. The name Baccalaos24 tells of voyages of the Basques, as Cape Breton of visitors from Brittany; and, after Corte Real's voyages, the east coast of Newfoundland was, as old maps testify, christened for a while Terra de Corte Reall.25 Soon, however, the Spaniards found Mexico, Peru, and Central America enough and more than enough to absorb their whole attention; the Portuguese were over-weighted by their eastern empire and Brazil: and North America was given over, first to be explored and then to be settled, by the peoples of the north of Europe; who gathered strength as their southern rivals declined, and whose work was more lasting because more slow.

24 'Baccalaos' is the Spanish name for codfish. It is of Basque origin. Cabot, it is stated, gave the name generally to the lands which he found. The name was subsequently applied more especially to Newfoundland. Thus Edward Hayes in his account of Sir Humphrey Gilbert's last voyage, under the heading 'a brief relation of the Newfoundland and the commodities thereof' (Hakluyt, iii, 193), speaks of 'that which we do call the Newfoundland and the Frenchmen Bacalaos.' Various small islands, however, in these parts were also given this name by different writers. At the present day, on the maps of Newfoundland, an islet off the east coast, at the extreme north of the peninsula of Avalon, bears the name of Baccalieu. See Parkman, p. 189 note as above, and the chapter on the voyages of the Cabots in Justin Winsor's history, vol. iii.

25 The name 'Labrador' is supposed to have been derived from the fact that some North American natives, brought back in one of the ships which accompanied Corte Real on this second voyage, were said to be 'admirably calculated for labour and the best slaves I have ever seen.' Hence the name 'Laboratoris terra,' or Labrador. On Thorne's map (1527) printed in the Divers Voyages to America, there appears 'Nova terra Laboratorum dicta.' Sir Clements Markham, in his edition of the Journal of Columbus, Cabot, and Corte Real (Hakluyt Society, 1893, Int. p. 51, note), says: 'There is no reference to Labrador in any of the authorities for the voyages of Corte Real. The King of Portugal is said to have hoped to derive good slave labour from the lands discovered by Corte Real. That is all. The name Labrador is not Portuguese; and Corte Real was never on the Labrador coast.' Another derivation given is: 'This land was discovered by the English from Bristol, and named Labrador because the one who saw it first was a labourer from the Azores.' One more derivation is that Labrador was the name of the Basque captain of a fishing-vessel. See Justin Winsor, vol. iv, chap. i, pp. 2, 46, and Parkman's Pioneers of France in the New World, p. 216, note.

| The Cabots. |

On March 5, 1496, King Henry VII of England granted a patent to 'John Cabot, citizen of Venice,' and to his three sons—Lewis, Sebastian, and Sancius—empowering them 'to discover unknown lands under the king's banner.'26 Under this patent—'the earliest surviving document which connects England with the New World'27—North America was discovered.

26 Quoted from the marginal note to the patent. See Hakluyt's Divers Voyages touching the discovery of America, published by the Hakluyt Society, 1850, p. 21.

27 From Doyle's History of the English in America, vol. i, chap. iv.

Almost every point connected with the voyages of the Cabots is dark and doubtful. What the father did and what the son, whence they came, and whither they went, is all uncertain. The tale of Columbus and his voyages is known to all the world; but readers are left to grope after the Cabots, as the latter groped after the strange wild regions of the north-west.

John Cabot, it would seem, was a Genoese who settled in Venice. There he was admitted to the rights of citizenship. He married a Venetian lady, and in Venice probably his three sons were born and passed their childhood. He travelled on the sea, visiting the coasts of Arabia, and forming, it may be, schemes to discover a new route to the far East. He came to England, having previously attempted to gain support for his projected voyages in Spain and Portugal, and he took up his residence in either London or Bristol. The exact date of his arrival in this country is unknown; but, either shortly before or shortly after he came, Columbus crossed the Atlantic for the first time in 1492. The news gave a stimulus to other would-be discoverers, and encouraged the Kings of Europe to further their plans. Hence Cabot and his sons obtained their patent in 1496. It was little that King Henry VII gave to the Italian sailors. Their voyages were to be made 'upon their own proper costs and charges,' and in return for his licence, the King was to receive a fifth of the profits. The enterprise was countenanced but not supported by the state, and the English Government in these early days, as in the times which came after, left the work of discovery and colonization in the hands of private adventurers. Bristol was the port of departure, and a Bristol book contains the following notice of the voyage:—'In the year 1497, the 24th of June, on St. John's day, was Newfoundland found by Bristol men in a ship called the Matthew.'28 John Cabot and Sebastian his son probably both sailed in the Matthew, and they commanded a crew of English sailors. The voyage was a short summer venture, beginning in May and ending with the close of July or the beginning of August. America was seen and touched, the land-fall being either the northern end of Cape Breton island, or the coast of Labrador, or Cape Bonavista in Newfoundland. The English flag was planted on American soil, but no exploration took place; nothing was achieved but the one great fact of discovery. In the following February, new letters patent were issued—on this occasion to John Cabot alone; and a second time, in the summer of 1498, the ships started from Bristol. Again, it is conjectured, both father and son were on board; and this time the North American coast seems to have been skirted from the region of icebergs and the banks of Newfoundland as far south as the Carolinas. In reference to this second voyage, Sebastian Cabot wrote that he sailed 'unto the latitude of sixty-seven degrees and a half under the North Pole,' and 'finding still the open sea without any manner of impediment, he thought verily by that way to have passed on still the way to Cathaio which is in the East.'29 The way to the East, however, was left unopened, to tantalize after-comers, and to be a kind of 'will o' the wisp,' leading men on to barren shores and Arctic seas, though the continent which they had already found was worth all the riches of the Indies.

28 Barrett's History and Antiquities of Bristol (Bristol, 1789), p. 172.

29 From Ramusio, quoted in 'a note of Sebastian Cabot's voyage of discovery' (Hakluyt's Divers Voyages, p. 25). For the much-vexed question of the Cabots and their voyages, reference should be made to John Cabot the Discoverer of North America and Sebastian his son, by Henry Harrisse, London, 1896; to the Journal of Columbus, Cabot, and Corte Real, edited for the Hakluyt Society by Sir Clements Markham, 1893; to Doyle's History of the English in America, vol. i, Appendix B, 'The Cabots and their Voyages'; and to Mr. Raymond Beazley's John and Sebastian Cabot ('Builders of Greater Britain' series, 1898). The result of a great deal of learning is after all little but conjecture.

| Corte Real. |

The next great voyager to North America was Gaspar Corte Real, a Portuguese. Twice he sailed to the north-west, in 1500 and 1501, on the earlier voyage sighting Greenland and the east coast of Newfoundland, and on the later working north from Chesapeake Bay. He was lost on the second voyage; and his brother Miguel, who went in search of him in 1502, after finding 'many entrances of rivers and havens,' was lost also.30

30 The voyages of the Corte Reals are given in Purchas' Pilgrims, pt. 2, bk. x. See Justin Winsor, vol. iv, chap. i, on Cortereal, Verrazano, &c. See also the volume of the Hakluyt Society referred to in the previous note.

| French explorers. |

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, if not earlier, Frenchmen took their place among the explorers of the world, and the Norman and Breton seaports began to send their ships across the Atlantic. Denys of Honfleur is said to have reached the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1506; in 1508, Aubert of Dieppe brought American Indians back to France; and in 1518 Baron de Léry made the first, a stillborn, attempt to found a French colony in North America.31

31 See above, note 23.

| Verrazano. |

At the end of the fifteenth century, the consolidation of France had been completed by the marriage of Charles VIII with Anne of Brittany, and from this time France began to compete with Spain. Francis I came to the throne in 1515, and his personal rivalry with Charles V, German Emperor and Spanish King in one, quickened the competition between the French and Spanish peoples. Thus it was that the French court turned its attention to the work of exploration, and Francis sent forth the Italian Verrazano with four ships from Dieppe 'to discover new lands by the ocean.'32 Sailing at the end of 1523, Verrazano was driven back by tempest; but, starting again, he left Madeira to cross the Atlantic on January 17, 1524. He reached the shores of Carolina; then coasted northward, landing at various points; and, having sailed as far north as Newfoundland—'the land that in times past was discovered by the Britons (Bretons), which is in fifty degrees'—he 'concluded to return into France.'

32 From 'The relation of John Verarzanus,' given in Hakluyt's Divers Voyages, p. 55, and there also headed 'The Discovery of Morum Bega' (Norumbega). It is given too in the ordinary collection, vol. iii, p. 357.

He brought home to his King a sober and systematic report of the North American coast—a report which meant business, and was not tricked out with vague surmises and impossible tales; but, within a year from his return, the strength of France was for a while broken at the battle of Pavia. He himself died soon afterwards, hanged, it is said, by the Spaniards as a pirate; and for ten years there is no record of any French explorer following in his steps, though French ships found their way over the ocean to the cod-fisheries of Newfoundland.

| Cartier. |

The year 1534 is a memorable one in the annals alike of France and of North America. It is the year from which must be dated the first beginnings of New France on the banks of the St. Lawrence. The discoverer of Canada was Jacques Cartier, a Breton sailor of St. Malo. He went out to explore the unknown world, not at his own risk, but as the agent of Brian Chabot, High Admiral of France. Sailing from St. Malo, on April 20, 1534, he came to Newfoundland, passed through the straits of Belle Isle, and entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He sailed into Chaleurs Bay under the July sun, describing the country as 'hotter than the country of Spain, and the fairest that can possibly be found';33 and, having set up a cross on Gaspé Peninsula, he reached St. Malo again on September 5, bringing with him two Indian children as living memorials of his voyage.

33 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 257.

He had discovered a hot, fair land, widely different from the bleak and rock-bound coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador; and the good report which he brought of his discoveries was more than enough to find him backing for a second venture. Accordingly, in the following year, on May 19, 1535, he sailed again from St. Malo, and, reaching the straits of Belle Isle after storm and tempest, took his way, the first of European explorers, up the great river of Canada. He moored his three ships below the rock of Quebec—then the site of Stadaconé, a native Indian village, and the dwelling-place of a chief Donnaconna, who is styled in the narrative the Lord of Canada. There he left his two larger vessels, and pushed on in his pinnace and boats to the town of Hochelaga. That town, the Indians had told him, was the capital of the land; and he found it, palisaded and fortified in native fashion, where Montreal now stands.34 The Frenchmen were received as gods by the Indians; they were asked, like the Apostles of old, to touch and heal the sick; and, ever mindful of the duty of spreading the Christian religion, they read the gospel to their savage admirers in the strange French tongue, to cure their souls if they could not mend their bodies.

34 As Mr. Parkman points out (Pioneers of France, p. 212), Quebec and Montreal were in old days, as now, the centres of population in Lower Canada. 'Stadaconé and Hochelaga, Quebec and Montreal, in the sixteenth century, as in the nineteenth, were the centres of Canadian population.'

Returning down stream to their ships, they passed the winter underneath Quebec, amid ice and snow, stricken with scurvy, and distrustful of their Indian neighbours; and at length, on the return of summer, they set sail for France, carrying away the Indian chief Donnaconna and some of his companions, to die in a far-off land. They reached St. Malo in the middle of July, 1536, and so ended Cartier's second voyage to 'the New found lands by him named New France.'35

35 End of the narrative of Cartier's second voyage in Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 285.

| Failure of Roberval's attempt at colonization. |

Between four and five years passed, and then the Breton sailor set out again. This time a definite scheme of settlement was projected, the instructions were more elaborate than before, the preparations were on a larger scale. The money was found by the crown, and the King was to receive one-third of the profits. A French nobleman, De Roberval, was to go out as the King's lieutenant in the New World, and was given the title of Lord of Norumbega,36 while Cartier was appointed Captain-General. The objects of the expedition were to explore, to colonize, and to convert the heathen; and its leaders were, like Columbus, empowered to recruit colonists from the prisons at home. Cartier set out in advance of Roberval, in May, 1541. Again he sailed up the St. Lawrence, reached in his boats a point above Montreal, and, as before, wintered on the river; but this time at the mouth of the Cap Rouge, some way higher up than Quebec. His leader, Roberval, did not start till April, 1542; and, when in June he reached St. John's harbour in Newfoundland, he was met by Cartier, who had broken up his colony in disgust, and was on his way home to France. In spite of Roberval's remonstrances, Cartier left by night on his return voyage, and the Lord of Norumbega went on alone to the St. Lawrence. He planted his settlement at Cap Rouge, where Cartier had last sojourned, but it proved a miserable failure. The supplies were insufficient, the Governor turned out a savage despot, and after about a year the colony came to an end.

| Norumbega. |

36 As to Norumbega, see Parkman's Pioneers of France, pp. 216 and 253, notes, and Justin Winsor, vol. iii, chap. vi, on 'Norumbega and its English explorers.' The writer of this latter chapter (p. 185) says the territory of Norumbega never included Baccalaos, 'though Baccalaos, an old name of Newfoundland, sometimes included New England.' Norumbega, an Indian name, covered the district now included in the state of Maine, and was sometimes extended to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia on the north, and part of New England on the south. Michael Loki's map (1582) makes Norumbega the whole district between the river and gulf of St. Lawrence and the Hudson. The river of Norumbega was the Penobscot, and on it a city of Norumbega was given a fabulous existence. Lescarbot (Histoire de la Nouvelle France, 1609, bk. i, chap. i) speaks of 'pais qu'on a appellé d'un nom Alleman Norumbega, lequel est par les quarante cinq degrez.'

With this disappointing and disastrous failure, the curtain fell on the prologue of the great drama of New France, and did not rise again for more than fifty years. For the French, as for the English, the sixteenth century was a time of exploring, of training, of making experiments; and it was not till the seventeenth century dawned that permanent colonization began. Then in the Bourbons the French had rulers who, with all their faults, were abler and stronger than the princes of the house of Valois; and in Champlain they had a leader as daring as, and more statesmanlike than, Cartier. But it was by Cartier that the ground had been broken and the seed first sown. His voyages made Canada37 in some sort familiar to Europeans. He opened the St. Lawrence to be the highway into North America,38 and he gave to the hill above the native town of Hochelaga the name of the Royal Mount, which is still perpetuated in Montreal. He brought the French into Canada, and, though his settlement failed, the French connexion remained. Fishermen and fur-traders followed in his steps, and in fullness of time the New France, which his discoveries conceived, was brought to birth and grew to greatness.

37 For the meaning of the name 'Canada,' see Parkman's Pioneers of France, p. 202, note. It is of Indian origin, probably meaning 'town.' Cartier called the country about Quebec Canada, having Saguenay below and Hochelaga above. Donnaconna, the native chief at Quebec, was called Lord of Canada.

38 On his second voyage Cartier sailed into a bay at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, where he stayed from the eighth to the twelfth of August, and 'named the said gulf St. Lawrence his bay' (Hakluyt, iii, 263), St. Lawrence's Day being the 10th of August. Hence the river, which he called the river of Hochelaga or the great river of Canada, derived its name. See Parkman, p. 202.

| English exploration in North America in the sixteenth century. Hore's voyage. Acts of Parliament relating to the Newfoundland fisheries. |

A Bristol ship39 having first discovered North America, it might have been expected that the years succeeding Cabot's voyages would have been fruitful in English adventure to the West; but, as far as records show, little was done by Englishmen during the first half of the sixteenth century to open up the New World; and even Cartier's bold exploits roused little or no spirit of rivalry in Great Britain. Indeed, all through this century no English voyager seems to have turned his mind to Canada and its river. The explorers went to the Arctic seas, the would-be colonizers to Newfoundland or Virginia. Between 1500 and 1550 two voyages alone have been actually chronicled, though passing reference is made to others. Of these two, the first was in 1527, when Albert de Prado, a canon of St. Paul's, sailed with two ships in search of the Indies, reaching Newfoundland and the North American coast. The second was in 1536, under a leader named Hore—a voyage of which a graphic account is given in Hakluyt. On the coast of Newfoundland the adventurers suffered the last extremes of starvation, until at length even cannibalism began among them; and the survivors owed their safety to the coming of a French ship, which they seized and in which they returned home. It is clear, however, that before the middle of the century the Newfoundland fisheries had become a recognized branch of English trade, for the traffic was safeguarded by two Acts of Parliament, one passed in 1540, in Henry VIII's reign, the other in 1548, in the reign of King Edward VI. The object of the second Act was to prohibit the exaction of any dues by way of licence from men engaged in the Iceland or Newfoundland fishing trade, and Hakluyt's note upon it is that 'by this Act it appeareth that the trade out of England to Newfoundland was common and frequented about the beginning of the reign of Edward VI, namely, in the year 1548.'40

39 For this passage, see Doyle's History of the English in America, vol. i, chap. iv.

40 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 170.

| Return of Sebastian Cabot to England. |

About this date Sebastian Cabot again appears upon the scene. In 1512 he had entered the Spanish service; and, after a visit to England, had returned to Spain, where, from 1518 to 1547, he held the appointment of Pilot-Major to the King and Emperor Charles V.41 At the end of 1547 or the beginning of 1548, he was induced in his old age to come back to the land, for and from which, more than half a century before, his or his father's great discovery had been made; and King Edward VI rewarded his services by appointing him Grand Pilot in England. His mind was still set on finding a way to the Indies by the Northern Sea. He became governor of 'the mystery and company of the Merchant Adventurers for the discovery of regions, dominions, islands, and places unknown'; and in Hakluyt's pages42 may be found his instructions 'for the direction of the intended voyage for Cathay.'

41 See The Dictionary of National Biography, s. v.

42 Vol. i, p. 251.

| The North-East Passage and Sir Hugh Willoughby. The Muscovy Company. |

The company was not finally incorporated by royal charter till 1554-5, but in the preceding year, 1553, they sent out an expedition of three ships to try for a North-East Passage. The leader of the expedition, Sir Hugh Willoughby, was, with the crews of two ships, frozen to death on the coast of Lapland; but Richard Chancellor, the captain of the third ship, reached the port on which the town of Archangel now stands, and made his way overland to Moscow. This was the beginning of British trade with Russia. The Merchant Adventurers became known as the Muscovy Company, and their efforts were directed to the overland traffic between Asia and Europe, which came by Bokhara, Astrakhan, and the Volga, to the meeting of the east and west at Novgorod.

| Martin Frobisher. |

But, important as was this new development of trade, the British explorers, whose names have lived, still took their way for the most part over the Atlantic, making ever for the West. In June, 1576, Martin Frobisher sailed from Blackwall to the north-west 'for the search of the straight or passage to China.'43 He sighted Greenland; and, sailing west, came to the inlet in the American coast, north of the Hudson Straits, which, after him, was called Frobisher Bay. This arm of the sea he took to be a passage between the two continents, the right-hand coast, as he went west, seeming to be Asia, the left-hand coast America. He came back to Harwich in October, bringing with him a sample of black stone supposed to contain gold; and thus, to the vain hope of a short passage to the Indies, he added the more dangerous attraction of possible mineral wealth in the Arctic regions. Men's hopes were raised; a company of Cathay was formed, with Michael Lok for governor; and, as their Captain-General, Frobisher sailed again in May, 1577, 'for the further discovering of the passage to Cathay.'44 Again he sighted Greenland. Again he reached the bay which had been the turning-point of his former voyage. He took possession of the barren northern land in his Queen's name; and, when he came back in September, 'Her Majesty named it very properly Meta Incognita, as a mark and bound utterly hitherto unknown.'45 The voyage was fruitless, but the stones brought home were still thought to promise gold, and so, in the following May, Frobisher started once more on a third voyage to the north. Fifteen ships went with him from Harwich, bearing 'a strong fort or house of timber'46 to be set up on arrival in the Arctic regions, and intended to shelter one hundred men through the coming winter. The hundred men included miners, goldfiners, gentlemen, artisans, 'and all necessary persons'46—as though this desolate region were to become the scene of a thriving colony. They set sail, reached the coast of Greenland, and claimed it in the Queen's name. They fell in with the Esquimaux; they crossed the channel now known as Davis Strait to the Meta Incognita; and they came back in the autumn with no result beyond the report of a new imaginary island. This was the end of Frobisher's enterprise, but in the next forty years other English sailors followed where he had gone before, and opened up to geographical knowledge fresh stretches of icebound coast and wintry sea. Davis, Hudson, Baffin, and others, gave their names to straits and bays, but it is impossible here to trace the record of their courage and endurance. No quest has ever been so fruitful of daring, patient seamanship, none has ever been so barren of practical results, as that for the North-West Passage. What Frobisher went to find in the sixteenth century, Franklin still sought in the nineteenth: and through all the ages of British exploration has run the ever receding hope of finding a short way through ice and snow to the sunny lands of the East.

43 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 52.

44 Ibid. p. 56.

45 Ibid. p. 104.

46 Ibid. p. 105.

| Sir Humphrey Gilbert. |

In Great Britain the sixteenth century was the age of adventurers, casting about for ways to other worlds, or freebooting where Spain and Portugal claimed ownership of land and sea; but in that time two men stand out as having had definite views of settlement, and as having been colonizers in advance of their age. They are Sir Humphrey Gilbert and his half-brother, Sir Walter Ralegh. Edward Hayes, the author of a narrative of Gilbert's attempt to found a colony in Newfoundland, speaks of him as 'the first of our nation that carried people to erect an habitation and government in those northerly countries of America,'47 and no nobler Englishman could well be found to head the list of English colonizers of the New World. Chivalrous in nature, bold in action, he was at the same time 'famous for his knowledge both by sea and land';48 and it was his Discourse to prove a passage by the north-west to Cathaia and the East Indies, which is said to have determined Frobisher to explore the north.

47 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 185.

48 From Fuller's Worthies of Devonshire.

| His patent of colonization. |

In June, 1578, Gilbert obtained from Queen Elizabeth his celebrated patent 'for the inhabiting and planting of our people in America.'49 The grant was a wide one. It gave him full liberty to explore and settle in any 'remote heathen and barbarous lands, countries, and territories, not actually possessed of any Christian prince or people'; and it constituted him full owner of the land where he settled, within a radius of two hundred leagues from the place of settlement. It was subject only to a reservation to the Crown of one-fifth of the gold and silver found, and to a condition that advantage should be taken of the grant within six years. For three or four years Gilbert's efforts to colonize under this patent were fruitless; he organized an expedition which came to nothing, and other men, to whom he temporarily resigned his rights, were equally unsuccessful.

49 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 174.

| His voyage to Newfoundland. |

At length, on June 11, 1583, he set sail from Cawsand Bay, near Plymouth, to try his luck for the last time in the western world. There were five ships, one of which was fitted out by Ralegh,50 and one, the Golden Hind, had for its captain and owner, Edward Hayes, the chronicler of the voyage. The company numbered 260 men all told, including shipwrights, carpenters, and other artisans, 'mineral men and refiners,' 'morris dancers' and other caterers of amusement 'for solace of our people and allurement of the savages.'51 These last were evidence that more was projected than mere temporary exploration. It was intended, writes Hayes, 'to win' the savages 'by all fair means possible'; and with this end in view the freight of the ships included 'petty haberdashery wares to barter with those simple people.' On the third of August the little fleet entered the harbour of St. John's in Newfoundland, where they found thirty-six ships of all nations. They came expecting resistance, but met with none. When Gilbert made known his intention to proclaim British sovereignty over the island, the sailors and fishermen present seem to have willingly acquiesced; and when he wanted to revictual and refit his ships, the necessary supplies were readily forthcoming.52

50 This ship deserted soon after starting.

51 Hakluyt, vol. iii, pp. 189, 190.

52 Hayes says, 'The Portugals (above other nations) did most willingly and liberally contribute' (Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 192). See above.

| Newfoundland declared to be a British possession. |

The want of a settled authority, of some guarantee for law and order, in the harbours and on the coasts of Newfoundland, was no doubt felt by those who came year by year to the fisheries, and Sir Humphrey Gilbert's name and high repute may well have been known to others than his own countrymen. Two days after his arrival he took formal possession of the land, with ceremony of rod and turf, in the name of his sovereign; the arms of England were set up; three simple laws were enacted—providing that the recognized religion should be in accordance with the forms of the Church of England, safeguarding the sovereign rights of the Queen of England, and enjoining due respect for her name; and then Gilbert issued land grants as proprietor of the soil. In the words of one of the accounts which Hakluyt has preserved,53 'he did let, set, give, and dispose of many things as absolute Governor there, by virtue of Her Majesty's letters patents.'

53 Peckham's account, Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 209.

Thus was Newfoundland declared to be a British possession, and such are its claims to be our oldest colony. The annexation was complete in form and substance; no protest was entered against it by those whom it concerned; land was granted by the recognized proprietor, and nothing was wanting to constitute a claim which should last, and has lasted, to all time. Frobisher proclaimed the sovereignty of England over Arctic lands, but his proclamation was as barren as the shores over which it extended. Gilbert, on the contrary, went to a place where European sailors had long foregathered; he went there as an English Governor; his authority was unquestioned, his grants were accepted, and when he read his commission and set up the arms of England at the harbour of St. John, he took the first step, and a very long step, towards British dominion in the New World.

| Gilbert's death. |

Gilbert had great hopes of finding precious metal in Newfoundland; and his principal mining expert, a Saxon, promised him a rich yield of silver from the ore which was collected in the island. That ore, however, was lost early on the voyage home, and the miner himself was lost with it in the wreck of the largest ship—the Delight. A far greater loss, however, was in store for the ill-fated expedition. They left St. John's on August 20, making for Sable Island, which had been stocked years before by the Portuguese.54 In a few days the Delight foundered on a rock; and the weather became so bad that, at the end of the month, Gilbert consented to make for home. He was in the smallest ship, the Squirrel, a little ten-ton vessel, as being the best suited to explore the creeks and inlets of the American coast; and, in spite of the remonstrances of his companions, he would not leave her on the return voyage. 'We are as near heaven by sea as by land,' were his last words, before the ship went down in the middle of the Atlantic with all on board; and thus, fearless and faithful unto death, he found his resting-place in the sea. The story is one which stands out to all time in the annals of English adventure and English colonization. It was meet and right that the founder of the first English colony should be a Devonshire sailor of high repute, of stainless name, chivalrous, unselfish, strong in the fear of God. It was no less meet that his grave should be in the stormy Atlantic, midway between the Old World and the New. Thus those who came after had a forerunner of the noblest type; and the ships, which from that time to this have carried Englishmen to America, may ever have been passing by where Humphrey Gilbert went to his rest.

54 See above.

| Sir Walter Ralegh. His attempts to colonize Virginia. |

Gilbert's half-brother, Sir Walter Ralegh, was cast in the same mould, but the record of his doings lies in the main beyond the range of this book. Virginia and Guiana were the scenes of his attempts at colonization, not Newfoundland or the coasts and rivers of Canada. In 1584, the year after Gilbert had been lost at sea, Ralegh obtained from Queen Elizabeth a patent which was practically the same as Gilbert's grant of 1578; and, at the end of April, he sent out two ships, commanded by two captains named Amidas and Barlow, to explore and report upon a likely place for an English settlement.55

55 Accounts of this and the following voyages are given in the third volume of Hakluyt. See also the first book of John Smith's general history of Virginia, The English Voyages to the Old Virginia, in Mr. Arber's edition, The English Scholar's Library.

They sailed more towards the south than previous English explorers, and eventually reached the island of Roanoke, which is now within the limits of North Carolina. Everything seemed bright and sweet and healthful, and the natives of the country were friendly and hospitable, 'such as live after the manner of the golden age.'56 So they came back in the autumn with a story full of hope for the future, and the virgin Queen christened the land of promise Virginia.

56 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 304.

Ralegh lost no time in sending out settlers. In the next year, 1585, seven ships started with 108 colonists on board. The expedition was commanded by Sir Richard Grenville, and among other captains with him was Thomas Cavendish, afterwards celebrated, like Drake, for sailing round the world. Ralph Lane, a soldier of fortune, was chosen to remain in charge of the colony, and with him was Amidas, the explorer of the previous year, who was styled 'Admiral of the country.' They went by the West Indies, touching at the Spanish islands of Porto Rico and Hispaniola, and, at the end of June, they reached Roanoke. Here they formed their settlement, and, when Grenville and his ships left in August and September, they brought back as bright a report as Amidas and Barlow had given the year before.

Already, however, before Grenville's departure, there had been friction between the Indians and the new-comers; and, as months went on, the new-born colony became in constant danger of extermination. Still Lane contrived to hold his own, exploring north and west, gleaning reports of pearls and mines, and a possible passage to the south sea, until the winter and spring were past and the month of June had come again. A fleet of twenty-three ships was then seen out at sea, and, to the joy of the settlers, proved to be an English expedition under Sir Francis Drake, who was returning home laden with spoils from the Spanish main. Drake, at Lane's request, placed one of his ships with seamen and supplies at the disposal of the colony; but a storm arose, and the ship was blown out to sea. Daunted by this fresh trouble, the settlers determined to give up their enterprise and return home. They asked for passages on board Drake's vessels: the request was granted; and they abandoned Roanoke only a fortnight before Grenville arrived with relief, long expected and long delayed. Finding the island deserted, Grenville left fifteen men in possession and himself came home.

So far, Ralegh's scheme had failed; but the failure was due to untoward circumstances, not to the nature of the country, and he still persevered in his efforts. The very next year, in 1587, he sent out a fresh band of settlers, 150 in number; giving them for a leader John White, who had taken part in the former expedition. The arrangements for forming a colony were more fully organized than before; and to White and twelve Assistants Ralegh 'gave a charter and incorporated them by the name of Governor and Assistants of the city of Ralegh in Virginia.'57 When the colonists reached Roanoke, they found that the fifteen men left by Grenville had disappeared, driven out, as they learnt, by the Indians. Notwithstanding, they renewed the old settlement; and, in the face of native enmity, began again the work of colonizing America. Before the end of the summer, White sailed for England, to give an account of what had been done; and, on his return home, Ralegh prepared to send relief to the colony. But war with Spain was now on hand, freebooting was more attractive than colonizing, one attempt and another to send ships to Virginia miscarried; and when at length, late in 1589, White reached the scene of his settlement, he found it dismantled and deserted. So ended the first attempt to colonize Virginia. Success was not to come for a few more years, until the sixteenth century had passed and gone.

57 Hakluyt, vol. iii, p. 341.

| General results of the sixteenth century. |

Before 1600, Newfoundland had been annexed by Great Britain, but not one single English or French colony had as yet taken root in America. Nevertheless the century was far from barren of results. The way had been made plain, the ground had been cleared, the wild oats of adventure and knight-errantry had been sown, and the peoples were sobering down to steadier and more prudent enterprise. Beaten on the sea, raided and plundered in their own tropical domain, the Spaniards were ceasing to be a terror and a hindrance to the nations of Northern Europe; and, as the latter grew from youth to lusty manhood, the map of the great North American continent unfolded itself before their eyes. Then Champlain went to work in Canada, and John Smith in Virginia; Jesuits on the St. Lawrence, and Puritans in the New England states; and so the grain of mustard-seed, cast into American soil, grew into a great tree, which already, before three centuries have ended, bids fair to overshadow the earth.

N.B.—The references to Hakluyt made in the notes above are to the 1810 edition.

Among modern books most use has been made in this chapter of:—

PARKMAN'S Pioneers of France in the New World;

DOYLE'S History of the English in America, vol. i; and

JUSTIN WINSOR'S Narrative and Critical History of America.

Reference should also be made to Sir J. BOURINOT'S monograph on 'Cape Breton,' first published in the Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, vol. ix, 1891, and since published separately.

The history of Canada has been so often and so well told, that an attempt simply to reproduce the narrative would be worse than superfluous. The scheme of the present series is, in the field of colonization and within the present limits of the British Empire, to trace the connexion between history and geography; and from this point of view more especially the story of New France will be recorded.

| New France. |

Various parts of the world, now British possessions, were once owned by other European nations, notably by the Dutch or French. The last volume of the series dealt with what was in past times a dependency of the Netherlands, the Cape Colony, the mother colony of South Africa. The present volume deals with a land which the French made peculiarly their own; where, as hardly anywhere else, they settled, though not in large numbers; not merely conquering or ruling the conquered, not only leaving a permanent impress of manners, law, and religion, but slowly and partially colonizing a country and forming a nation.

Lower Canada, the basin of the St. Lawrence, was rightly included under the wider name of New France, for here France and the French were reproduced in weakness and in strength. It was a land well suited to the French character and physique. Much depended on tactful dealings with the North American Indians, a species of diplomacy in which Frenchmen excelled. The commercial value of Canada consisted mainly in the fur trade, an adventurous kind of traffic more attractive to the Frenchman of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than plodding agriculture or the life of a counting-house. On the rivers and lakes, coming and going was comparatively easy; the short bright summers and the long winters made the country one of strong contrasts. To a bold, imaginative, somewhat restless people there was much to charm in Canada.

But Canada meant far less in earlier days than now it means. It meant the banks of the St. Lawrence and its tributaries, and of the lakes from which it flows. The Maritime Provinces of the present Dominion, or at any rate Nova Scotia, were not in Canada properly so called, but bore the name of La Cadie or Acadia,1 and the great North-West was an unknown land.

1 For the derivation of the name 'Acadia,' see Parkman's Pioneers of France in the New World, p. 243, note. Cadie is an Indian word meaning place or region. 'It is obviously a Micmac or Souriquois affix used in connexion with other words to describe the natural characteristics of a place or locality' (Bourinot's monograph on 'Cape Breton,' Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, vol. ix, sec. 2, p. 185). For the name 'Canada,' see above, note 37.

By the end of the seventeenth century the French had three spheres of influence and colonization in North America—the country of the St. Lawrence, the seaboard between the mouth of the St. Lawrence and the New England colonies, and Louisiana at the mouth of the Mississippi. To join them and encircle the English colonies was the aim of French statesmanship. It was an impossible aim, inevitably frustrated by geographical conditions and by want of colonists; but the conception was a great one, large as the new continent in which it was framed, and able men tried to work it out, but tried in vain.

| The French as colonizers. |

Much has been written of French methods of colonization; writers have been at pains to enumerate the shortcomings of the French, and have carefully explained whence those mistakes arose. But there is less to wonder at in the failures than in the great successes to be credited to France. Being part of the continent of Europe, and ever embroiled in continental politics, when she competed with England as a colonizing power, she competed with one hand tied.2 Changeable, it is said, were the French and their policy; their kings and courtiers may have been changeable, but the charge does not lie against the French nation.

2 This is pointed out in Professor Seeley's Expansion of England, course i, lecture 5.

They were trading up the Senegal early in the seventeenth century, and there they are at the present day. From the dawn of their colonial enterprise they tried to obtain possession of Madagascar; they have their object now. Nearly four centuries ago they fished off the coasts of Newfoundland, and England has good cause to know that they fish there still. To the St. Lawrence went Cartier from St. Malo, and by the same route generations of Frenchmen entered steadily into America, until Quebec had fallen and the St. Lawrence was theirs no more. The French were versatile in their colonial dealings; they were quickly moving and constantly moving; but they saw clearly and they followed tenaciously; they were strong and staunch, and they proved themselves to be a wonderful people.

Yet there must have been some element of weakness in the French character, in that they bred and obeyed bad rulers who did not live for France, but for whom France was sacrificed; who crushed liberty, political and religious, who drove out industry with the Huguenots, and squandered the heritage of the nation. Englishmen, comparatively early in their history, reckoned with priests first and with kings afterwards. They did most of their work at home before they made their colonial empire; they colonized new worlds as a reformed people; the French tried to colonize under absolutism and priestcraft. It might not have been so, it probably would not have been so, if the religious policy of the French Government had been other than it was. The Huguenots, if not persecuted and eventually in great measure driven out, would have given France the one thing wanting to make her colonization successful, the spirit of private enterprise independent of court favour, the child and the parent of freedom, the determined foe of a deadening religious despotism.

| Attempts at French colonization in Brazil and Florida. |