From a painting by Theodore B. Pitman in possession of

Colonel Roosevelt.

On the brink of the Grand Canyon.

From a painting by Theodore B. Pitman in possession of

Colonel Roosevelt.

On the brink of the Grand Canyon.

Title: A Book-Lover's Holidays in the Open

Author: Theodore Roosevelt

Release date: October 26, 2010 [eBook #34135]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jana Srna, Carla Foust, David Edwards and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Minor punctuation errors have been changed without notice. Printer errors have been changed, and they are indicated with a mouse-hover and listed at the end of this book. All other inconsistencies are as in the original.

BOOKS BY THEODORE ROOSEVELT

PUBLISHED BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

A BOOK-LOVER'S HOLIDAYS IN THE OPEN.

Illustrated. 8vo $2.00 net

THROUGH THE BRAZILIAN WILDERNESS.

Illustrated. Large 8vo $3.50 net

LIFE-HISTORIES OF AFRICAN GAME ANIMALS.

With Edmund Heller. Illustrated. 2

vols. Large 8vo $10.00 net

AFRICAN GAME TRAILS. An account of the African

Wanderings of an American Hunter-Naturalist.

Illustrated. Large 8vo $4.00 net

OUTDOOR PASTIMES OF AN AMERICAN HUNTER.

New Edition. Illustrated. 8vo $3.00 net

HISTORY AS LITERATURE and Other Essays.

12mo $1.50 net

OLIVER CROMWELL. Illustrated. 8vo $2.00 net

THE ROUGH RIDERS. Illustrated. 8vo $1.50 net

THE ROOSEVELT BOOK. Selections from the Writings

of Theodore Roosevelt. 16mo 50 cents net

AMERICA AND THE WORLD WAR.

12mo 75 cents net

THE ELKHORN EDITION. Complete Works

of Theodore Roosevelt. 26 volumes. Illustrated.

8vo. Sold by subscription.

From a painting by Theodore B. Pitman in possession of

Colonel Roosevelt.

On the brink of the Grand Canyon.

From a painting by Theodore B. Pitman in possession of

Colonel Roosevelt.

On the brink of the Grand Canyon.

BY

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1916

Copyright, 1916, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Published March, 1916

To

ARCHIE AND QUENTIN

The man should have youth and strength who seeks adventure in the wide, waste spaces of the earth, in the marshes, and among the vast mountain masses, in the northern forests, amid the steaming jungles of the tropics, or on the deserts of sand or of snow. He must long greatly for the lonely winds that blow across the wilderness, and for sunrise and sunset over the rim of the empty world. His heart must thrill for the saddle and not for the hearthstone. He must be helmsman and chief, the cragsman, the rifleman, the boat steerer. He must be the wielder of axe and of paddle, the rider of fiery horses, the master of the craft that leaps through white water. His eye must be true and quick, his hand steady and strong. His heart must never fail nor his head grow bewildered, whether he face brute and human foes, or the frowning strength of hostile nature, or the awful fear that grips those who are lost in trackless lands. Wearing toil and hardship shall be his; thirst and famine he shall face, and burning fever. Death shall come to greet him with poison-fang[viii] or poison-arrow, in shape of charging beast or of scaly things that lurk in lake and river; it shall lie in wait for him among untrodden forests, in the swirl of wild waters, and in the blast of snow blizzard or thunder-shattered hurricane.

Not many men can with wisdom make such a life their permanent and serious occupation. Those whose tasks lie along other lines can lead it for but a few years. For them it must normally come in the hardy vigor of their youth, before the beat of the blood has grown sluggish in their veins.

Nevertheless, older men also can find joy in such a life, although in their case it must be led only on the outskirts of adventure, and although the part they play therein must be that of the onlooker rather than that of the doer. The feats of prowess are for others. It is for other men to face the peril of unknown lands, to master unbroken horses, and to hold their own among their fellows with bodies of supple strength. But much, very much, remains for the man who has "warmed both hands before the fire of life," and who, although he loves the great cities, loves even more the fenceless grass-land, and the forest-clad hills.

The grandest scenery of the world is his to look at if he chooses; and he can witness the[ix] strange ways of tribes who have survived into an alien age from an immemorial past, tribes whose priests dance in honor of the serpent and worship the spirits of the wolf and the bear. Far and wide, all the continents are open to him as they never were to any of his forefathers; the Nile and the Paraguay are easy of access, and the borderland between savagery and civilization; and the veil of the past has been lifted so that he can dimly see how, in time immeasurably remote, his ancestors—no less remote—led furtive lives among uncouth and terrible beasts, whose kind has perished utterly from the face of the earth. He will take books with him as he journeys; for the keenest enjoyment of the wilderness is reserved for him who enjoys also the garnered wisdom of the present and the past. He will take pleasure in the companionship of the men of the open; in South America, the daring and reckless horsemen who guard the herds of the grazing country, and the dark-skinned paddlers who guide their clumsy dugouts down the dangerous equatorial rivers; the white and red and half-breed hunters of the Rockies, and of the Canadian woodland; and in Africa the faithful black gun-bearers who have stood steadily at his elbow when the lion came on with coughing grunts, or[x] when the huge mass of the charging elephant burst asunder the vine-tangled branches.

The beauty and charm of the wilderness are his for the asking, for the edges of the wilderness lie close beside the beaten roads of present travel. He can see the red splendor of desert sunsets, and the unearthly glory of the afterglow on the battlements of desolate mountains. In sapphire gulfs of ocean he can visit islets, above which the wings of myriads of sea-fowl make a kind of shifting cuneiform script in the air. He can ride along the brink of the stupendous cliff-walled canyon, where eagles soar below him, and cougars make their lairs on the ledges and harry the big-horned sheep. He can journey through the northern forests, the home of the giant moose, the forests of fragrant and murmuring life in summer, the iron-bound and melancholy forests of winter.

The joy of living is his who has the heart to demand it.

Sagamore Hill, January 1, 1916.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Cougar Hunt on the Rim of the Grand Canyon | 1 |

| II. | Across the Navajo Desert | 29 |

| III. | The Hopi Snake-Dance | 63 |

| IV. | The Ranchland of Argentina | 98 |

| V. | A Chilean Rondeo | 117 |

| VI. | Across the Andes and Northern Patagonia | 130 |

| VII. | Wild Hunting Companions | 152 |

| VIII. | Primitive Man; and the Horse, the Lion, and the Elephant | 190 |

| IX. | Books for Holidays in the Open | 259 |

| X. | Bird Reserves at the Mouth of the Mississippi | 274 |

| XI. | A Curious Experience | 318 |

| Appendices | ||

| A | 359 | |

| B | 366 |

| On the brink of the Grand Canyon | Frontispiece |

From a painting by Theodore B. Pitman, reproduced in color.

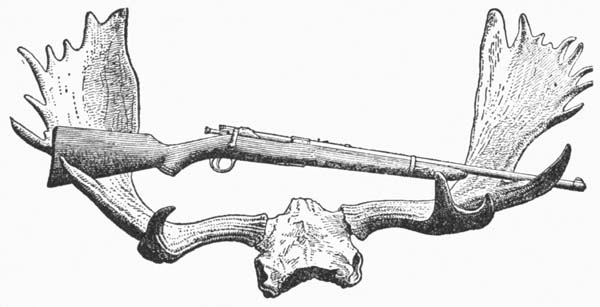

| Colonel Roosevelt and Arthur Lirette with antlers of moose shot | |

| September 19, 1915 | Facing page 348 |

From a photograph by Alexander Lambert, M.D.

| Antlers of moose shot September 19, 1915, with Springfield rifle | |

| No. 6000, Model 1903 | Page 356 |

On July 14, 1913, our party gathered at the comfortable El Tovar Hotel, on the edge of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, and therefore overlooking the most wonderful scenery in the world. The moon was full. Dim, vast, mysterious, the canyon lay in the shimmering radiance. To all else that is strange and beautiful in nature the Canyon stands as Karnak and Baalbec, seen by moonlight, stand to all other ruined temples and palaces of the bygone ages.

With me were my two younger sons, Archie and Quentin, aged nineteen and fifteen respectively, and a cousin of theirs, Nicholas, aged twenty. The cousin had driven our horses, and what outfit we did not ourselves carry, from southern Arizona to the north side of the can[2]yon, and had then crossed the canyon to meet us. The youngest one of the three had not before been on such a trip as that we intended to take; but the two elder boys, for their good fortune, had formerly been at the Evans School in Mesa, Arizona, and among the by-products of their education was a practical and working familiarity with ranch life, with the round-up, and with travelling through the desert and on the mountains. Jesse Cummings, of Mesa, was along to act as cook, packer, and horse-wrangler, helped in all three branches by the two elder boys; he was a Kentuckian by birth, and a better man for our trip and a stancher friend could not have been found.

On the 15th we went down to the bottom of the canyon. There we were to have been met by our outfit with two men whom we had engaged; but they never turned up, and we should have been in a bad way had not Mr. Stevenson, of the Bar Z Cattle Company, come down the trail behind us, while the foreman of the Bar Z, Mr. Mansfield, appeared to meet him, on the opposite side of the rushing, muddy torrent of the Colorado. Mansfield worked us across on the trolley which spans the river; and then we joined in and worked Stevenson, and some friends he had with him, across. Among[3] us all we had food enough for dinner and for a light breakfast, and we had our bedding. With characteristic cattleman's generosity, our new friends turned over to us two pack-mules, which could carry our bedding and the like, and two spare saddle-horses—both the mules and the spare saddle-horses having been brought down by Mansfield because of a lucky mistake as to the number of men he was to meet.

Mansfield was a representative of the best type of old-style ranch foreman. It is a hard climb out of the canyon on the north side, and Mansfield was bound that we should have an early start. He was up at half-past one in the morning; we breakfasted on a few spoonfuls of mush; packed the mules and saddled the horses; and then in the sultry darkness, which in spite of the moon filled the bottom of the stupendous gorge, we started up the Bright Angel trail. Cummings and the two elder boys walked; the rest of us were on horseback. The trail crossed and recrossed the rapid brook, and for rods at a time went up its bowlder-filled bed; groping and stumbling, we made our blind way along it; and over an hour passed before the first grayness of the dawn faintly lighted our footsteps.

At last we left the stream bed, and the trail[4] climbed the sheer slopes and zigzagged upward through the breaks in the cliff walls. At one place the Bar Z men showed us where one of their pack-animals had lost his footing and fallen down the mountainside a year previously. It was eight hours before we topped the rim and came out on the high, wooded, broken plateau which at this part of its course forms the northern barrier of the deep-sunk Colorado River. Three or four miles farther on we found the men who were to have met us; they were two days behindhand, so we told them we would not need them, and reclaimed what horses, provisions, and other outfit were ours. With Cummings and the two elder boys we were quite competent to take care of ourselves under all circumstances, and extra men, tents, and provisions merely represented a slight, and dispensable, increase in convenience and comfort.

As it turned out, there was no loss even of comfort. We went straight to the cabin of the game warden, Uncle Jim Owens; and he instantly accepted us as his guests, treated us as such, and accompanied us throughout our fortnight's stay north of the river. A kinder host and better companion in a wild country could not be found. Through him we hired a very[5] good fellow, a mining prospector, who stayed with us until we crossed the Colorado at Lee's Ferry. He was originally a New York State man, who had grown up in Montana, and had prospected through the mountains from the Athabaska River to the Mexican boundary. Uncle Jim was a Texan, born at San Antonio, and raised in the Panhandle, on the Goodnight ranch. In his youth he had seen the thronging myriads of bison, and taken part in the rough life of the border, the life of the cow-men, the buffalo-hunters, and the Indian-fighters. He was by instinct a man of the right kind in all relations; and he early hailed with delight the growth of the movement among our people to put a stop to the senseless and wanton destruction of our wild life. Together with his—and my—friend Buffalo Jones he had worked for the preservation of the scattered bands of bison; he was keenly interested not only in the preservation of the forests but in the preservation of the game. He had been two years buffalo warden in the Yellowstone National Park. Then he had come to the Colorado National Forest Reserve and Game Reserve, where he had been game warden for over six years at the time of our trip. He has given zealous and efficient service to the people as a whole; for[6] which, by the way, his salary has been an inadequate return. One important feature of his work is to keep down the larger beasts and birds of prey, the arch-enemies of the deer, mountain-sheep, and grouse; and the most formidable among these foes of the harmless wild life are the cougars. At the time of our visit he owned five hounds, which he had trained especially, as far as his manifold duties gave him the time, to the chase of cougars and bobcats. Coyotes were plentiful, and he shot these wherever the chance offered; but coyotes are best kept down by poison, and poison cannot be used where any man is keeping the hounds with which alone it is possible effectively to handle the cougars.

At this point the Colorado, in its deep gulf, bends south, then west, then north, and incloses on three sides the high plateau which is the heart of the forest and game reserve. It was on this plateau, locally known as Buckskin Mountain, that we spent the next fortnight. The altitude is from eight thousand to nearly ten thousand feet, and the climate is that of the far north. Spring does not come until June; the snow lies deep for seven months. We were there in midsummer, but the thermometer went down at night to 36, 34, and once[7] to 33 degrees Fahrenheit; there was hoarfrost in the mornings. Sound was our sleep under our blankets, in the open, or under a shelf of rock, or beneath a tent, or most often under a thickly leaved tree. Throughout the day the air was cool and bracing.

Although we reached the plateau in mid-July, the spring was but just coming to an end. Silver-voiced Rocky Mountain hermit-thrushes chanted divinely from the deep woods. There were multitudes of flowers, of which, alas! I know only a very few, and these by their vernacular names; for as yet there is no such handbook for the flowers of the southern Rocky Mountains as, thanks to Mrs. Frances Dana, we have for those of the Eastern States, and, thanks to Miss Mary Elizabeth Parsons, for those of California. The sego lilies, looking like very handsome Eastern trilliums, were as plentiful as they were beautiful; and there were the striking Indian paint-brushes, fragrant purple locust blooms, the blossoms of that strange bush the plumed acacia, delicately beautiful white columbines, bluebells, great sheets of blue lupin, and the tall, crowded spikes of the brilliant red bell—and innumerable others. The rainfall is light and the ground porous; springs are few, and brooks wanting; but the trees are[8] handsome. In a few places the forest is dense; in most places it is sufficiently open to allow a mountain-horse to twist in and out among the tree trunks at a smart canter. The tall yellow pines are everywhere; the erect spires of the mountain-spruce and of the blue-tipped Western balsam shoot up around their taller cousins, and the quaking asps, the aspens with their ever-quivering leaves and glimmering white boles, are scattered among and beneath the conifers, or stand in groves by themselves. Blue grouse were plentiful—having increased greatly, partly because of the war waged by Uncle Jim against their foes the great horned owls; and among the numerous birds were long-crested, dark-blue jays, pinyon-jays, doves, band-tailed pigeons, golden-winged flickers, chickadees, juncos, mountain-bluebirds, thistle-finches, and Louisiana tanagers. A very handsome cock tanager, the orange yellow of its plumage dashed with red on the head and throat, flew familiarly round Uncle Jim's cabin, and spent most of its time foraging in the grass. Once three birds flew by which I am convinced were the strange and interesting evening grosbeaks. Chipmunks and white-footed mice lived in the cabin, the former very bold and friendly; in fact, the chipmunks, of several species, were everywhere;[9] and there were gophers or rock-squirrels, and small tree-squirrels, like the Eastern chickarees, and big tree-squirrels—the handsomest squirrels I have ever seen—with black bodies and bushy white tails. These last lived in the pines, were diurnal in their habits, and often foraged among the fallen cones on the ground; and they were strikingly conspicuous.

We met, and were most favorably impressed by, the forest supervisor, and some of his rangers. This forest and game reserve is thrown open to grazing, as with all similar reserves. Among the real settlers, the home-makers of sense and farsightedness, there is a growing belief in the wisdom of the policy of the preservation of the national resources by the National Government. On small, permanent farms, the owner, if reasonably intelligent, will himself preserve his own patrimony; but everywhere the uncontrolled use in common of the public domain has meant reckless, and usually wanton, destruction. All the public domain that is used should be used under strictly supervised governmental lease; that is, the lease system should be applied everywhere substantially as it is now applied in the forest. In every case the small neighboring settlers, the actual home-makers, should be given priority of chance to lease the land in reasonable sized[10] tracts. Continual efforts are made by demagogues and by unscrupulous agitators to excite hostility to the forest policy of the government; and needy men who are short-sighted and unscrupulous join in the cry, and play into the hands of the corrupt politicians who do the bidding of the big and selfish exploiters of the public domain. One device of these politicians is through their representatives in Congress to cut down the appropriation for the forest service; and in consequence the administrative heads of the service, in the effort to be economical, are sometimes driven to the expedient of trying to replace the permanently employed experts by short-term men, picked up at haphazard, and hired only for the summer season. This is all wrong: first, because the men thus hired give very inferior service; and, second, because the government should be a model employer, and should not set a vicious example in hiring men under conditions that tend to create a shifting class of laborers who suffer from all the evils of unsteady employment, varied by long seasons of idleness. At this time the best and most thoughtful farmers are endeavoring to devise means for doing away with the system of employing farm-hands in mass for a few months and then discharging them; and the[11] government should not itself have recourse to this thoroughly pernicious system.

The preservation of game and of wild life generally—aside from the noxious species—on these reserves is of incalculable benefit to the people as a whole. As the game increases in these national refuges and nurseries it overflows into the surrounding country. Very wealthy men can have private game-preserves of their own. But the average man of small or moderate means can enjoy the vigorous pastime of the chase, and indeed can enjoy wild nature, only if there are good general laws, properly enforced, for the preservation of the game and wild life, and if, furthermore, there are big parks or reserves provided for the use of all our people, like those of the Yellowstone, the Yosemite, and the Colorado.

A small herd of bison has been brought to the reserve; it is slowly increasing. It is privately owned, one-third of the ownership being in Uncle Jim, who handles the herd. The government should immediately buy this herd. Everything should be done to increase the number of bison on the public reservations.

The chief game animal of the Colorado Canyon reserve is the Rocky Mountain blacktail, or mule, deer. The deer have increased greatly[12] in numbers since the reserve was created, partly because of the stopping of hunting by men, and even more because of the killing off of the cougars. The high plateau is their summer range; in the winter the bitter cold and driving snow send them and the cattle, as well as the bands of wild horses, to the lower desert country. For some cause, perhaps the limestone soil, their antlers are unusually stout and large. We found the deer tame and plentiful, and as we rode or walked through the forest we continually came across them—now a doe with her fawn, now a party of does and fawns, or a single buck, or a party of bucks. The antlers were still in the velvet. Does would stand and watch us go by within fifty or a hundred yards, their big ears thrown forward; while the fawns stayed hid near by. Sometimes we roused the pretty spotted fawns, and watched them dart away, the embodiments of delicate grace. One buck, when a hound chased it, refused to run and promptly stood at bay; another buck jumped and capered, and also refused to run, as we passed at but a few yards' distance. One of the most beautiful sights I ever saw was on this trip. We were slowly riding through the open pine forest when we came on a party of seven bucks. Four were yearlings or two-year-[13]olds; but three were mighty master bucks, and their velvet-clad antlers made them look as if they had rocking-chairs on their heads. Stately of port and bearing, they walked a few steps at a time, or stood at gaze on the carpet of brown needles strewn with cones; on their red coats the flecked and broken sun-rays played; and as we watched them, down the aisles of tall tree trunks the odorous breath of the pines blew in our faces.

The deadly enemies of the deer are the cougars. They had been very plentiful all over the table-land until Uncle Jim thinned them out, killing between two and three hundred. Usually their lairs are made in the well-nigh inaccessible ruggedness of the canyon itself. Those which dwelt in the open forest were soon killed off. Along the part of the canyon where we hunted there was usually an upper wall of sheer white cliffs; then came a very steep slope covered by a thick scrub of dwarf oak and locust, with an occasional pinyon or pine; and then another and deeper wall of vermilion cliffs. It was along this intermediate slope that the cougars usually passed the day. At night they came up through some gorge or break in the cliff and rambled through the forests and along the rim after the deer. They[14] are the most successful of all still-hunters, killing deer much more easily than a wolf can; and those we killed were very fat.

Cougars are strange and interesting creatures. They are among the most successful and to their prey the most formidable beasts of rapine in the world. Yet when themselves attacked they are the least dangerous of all beasts of prey, except hyenas. Their every movement is so lithe and stealthy, they move with such sinuous and noiseless caution, and are such past masters in the art of concealment, that they are hardly ever seen unless roused by dogs. In the wilds they occasionally kill wapiti, and often bighorn sheep and white goats; but their favorite prey is the deer.

Among domestic animals, while they at times kill all, including, occasionally, horned cattle, they are especially destructive to horses. Among the first bands of horses brought to this plateau there were some of which the cougars killed every foal. The big males attacked full-grown horses. Uncle Jim had killed one big male which had killed a large draft-horse, and another which had killed two saddle-horses and a pack-mule, although the mule had a bell on its neck, which it was mistakenly supposed would keep the cougar away. We saw the[15] skeleton of one of the saddle-horses. It was killed when snow was on the ground, and when Uncle Jim first saw the carcass the marks of the struggle were plain. The cougar sprang on its neck, holding the face with the claws of one paw, while his fangs tore at the back of the neck, just at the base of the skull; the other fore paw was on the other side of the neck, and the hind claws tore the withers and one shoulder and flank. The horse struggled thirty yards or so before he fell, and never rose again. The draft-horse was seized in similar fashion. It went but twenty yards before falling; then in the snow could be seen the marks where it had struggled madly on its side, plunging in a circle, and the marks of the hind feet of the cougar in an outside circle, while the fangs and fore talons of the great cat never ceased tearing the prey. In this case the fore claws so ripped and tore the neck and throat that it was doubtful whether they, and not the teeth, had not given the fatal wounds.

We came across the bodies of a number of deer that had been killed by cougars. Generally the remains were in such condition that we could not see how the killing had been done. In one or two cases the carcasses were sufficiently fresh for us to examine them carefully. One[16] doe had claw marks on her face, but no fang marks on the head or neck; apparently the neck had been broken by her own plunging fall; then the cougar had bitten a hole in the flank and eaten part of one haunch; but it had not disembowelled its prey, as an African lion would have done. Another deer, a buck, was seized in similar manner; but the death-wound was inflicted with the teeth, in singular fashion, a great hole being torn into the chest, where the neck joins the shoulder. Evidently there is no settled and invariable method of killing. We saw no signs of any cougar being injured in the struggle; the prey was always seized suddenly and by surprise, and in such fashion that it could make no counter-attack.

Few African leopards would attack such quarry as the big male cougars do. Yet the leopard sometimes preys on man, and it is the boldest and most formidable of fighters when brought to bay. The cougar, on the contrary, is the least dangerous to man of all the big cats. There are authentic instances of its attacking man; but they are not merely rare but so wholly exceptional that in practise they can be entirely disregarded. There is no more need of being frightened when sleeping in, or wandering after nightfall through, a forest infested by[17] cougars than if they were so many tom-cats. Moreover, when itself assailed by either dogs or men the cougar makes no aggressive fight. It will stay in a tree for hours, kept there by a single dog which it could kill at once if it had the heart—and this although if hungry it will itself attack and kill any dog, and on occasions even a big wolf. If the dogs—or men—come within a few feet, it will inflict formidable wounds with its claws and teeth, the former being used to hold the assailant while the latter inflict the fatal bite. But it fights purely on the defensive, whereas the leopard readily assumes the offensive and often charges, at headlong, racing speed, from a distance of fifty or sixty yards. It is absolutely safe to walk up to within ten yards of a cougar at bay, whether wounded or unwounded, and to shoot it at leisure.

Cougars are solitary beasts. When full-grown the females outnumber the males about three to one; and the sexes stay together for only a few days at mating-time. The female rears her kittens alone, usually in some cave; the male would be apt to kill them if he could get at them. The young are playful. Uncle Jim once brought back to his cabin a young cougar, two or three months old. At the time he had a[18] hound puppy named Pot—he was an old dog, the most dependable in the pack, when we made our hunt. Pot had lost his mother; Uncle Jim was raising him on canned milk, and, as it was winter, kept him at night in a German sock. The young cougar speedily accepted Pot as a playmate, to be enjoyed and tyrannized over. The two would lap out of the same dish; but when the milk was nearly lapped up, the cougar would put one paw on Pot's face, and hold him firmly while it finished the dish itself. Then it would seize Pot in its fore paws and toss him up, catching him again; while Pot would occasionally howl dismally, for the young cougar had sharp little claws. Finally the cougar would tire of the play, and then it would take Pot by the back of the neck, carry him off, and put him down in his box by the German sock.

When we started on our cougar hunt there were seven of us, with six pack-animals. The latter included one mule, three donkeys—two of them, Ted and Possum, very wise donkeys—and two horses. The saddle-animals included two mules and five horses, one of which solemnly carried a cow-bell. It was a characteristic old-time Western outfit. We met with the customary misadventures of such a trip, chiefly[19] in connection with our animals. At night they were turned loose to feed, most of them with hobbles, some of them with bells. Before dawn, two or three of the party—usually including one, and sometimes both, of the elder boys—were off on foot, through the chilly dew, to bring them in. Usually this was a matter of an hour or two; but once it took a day, and twice it took a half-day. Both breaking camp and making camp, with a pack-outfit, take time; and in our case each of the packers, including the two elder boys, used his own hitch—single-diamond, squaw hitch, cow-man's hitch, miner's hitch, Navajo hitch, as the case might be. As for cooking and washing dishes—why, I wish that the average tourist-sportsman, the city-hunter-with-a-guide, would once in a while have to cook and wash dishes for himself; it would enable him to grasp the reality of things. We were sometimes nearly drowned out by heavy rain-storms. We had good food; but the only fresh meat we had was the cougar meat. This was delicious; quite as good as venison. Yet men rarely eat cougar flesh.

Cougars should be hunted when snow is on the ground. It is difficult for hounds to trail them in hot weather, when there is no water and the ground is dry and hard. However, we[20] had to do the best we could; and the frequent rains helped us. On most of the hunting days we rode along the rim of the canyon and through the woods, hour after hour, until the dogs grew tired, or their feet sore, so that we deemed it best to turn toward camp; having either struck no trail or else a trail so old that the hounds could not puzzle it out. I did not have a rifle, wishing the boys to do the shooting. The two elder boys had tossed up for the first shot, Nick winning. In cougar hunting the shot is usually much the least interesting and important part of the performance. The credit belongs to the hounds, and to the man who hunts the hounds. Uncle Jim hunted his hounds excellently. He had neither horn nor whip; instead, he threw pebbles, with much accuracy of aim, at any recalcitrant dog—and several showed a tendency to hunt deer or coyote. "They think they know best and needn't obey me unless I have a nose-bag full of rocks," observed Uncle Jim.

Twice we had lucky days. On the first occasion we all seven left camp by sunrise with the hounds. We began with an hour's chase after a bobcat, which dodged back and forth over and under the rim rock, and finally escaped along a ledge in the cliff wall. At about[21] eleven we struck a cougar trail of the night before. It was a fine sight to see the hounds running it through the woods in full cry, while we loped after them. After one or two checks, they finally roused the cougar, a big male, from a grove of aspens at the head of a great gorge which broke through the cliffs into the canyon. Down the gorge went the cougar, and then along the slope between the white cliffs and the red; and after some delay in taking the wrong trail, the hounds followed him. The gorge was impassable for horses, and we rode along the rim, looking down into the depths, from which rose the chiming of the hounds. At last a change in the sound showed that they had him treed; and after a while we saw them far below under a pine, across the gorge, and on the upper edge of the vermilion cliff wall. Down we went to them, scrambling and sliding; down a break in the cliffs, round the head of the gorge just before it broke off into a side-canyon, through the thorny scrub which tore our hands and faces, along the slope where, if a man started rolling, he never would stop until life had left his body. Before we reached him the cougar leaped from the tree and tore off, with his big tail stretched straight as a bar behind him; but a cougar is a short-winded beast, and a[22] couple of hundred yards on, the hounds put him up another tree. Thither we went.

It was a wild sight. The maddened hounds bayed at the foot of the pine. Above them, in the lower branches, stood the big horse-killing cat, the destroyer of the deer, the lord of stealthy murder, facing his doom with a heart both craven and cruel. Almost beneath him the vermilion cliffs fell sheer a thousand feet without a break. Behind him lay the Grand Canyon in its awful and desolate majesty.

Nicholas shot true. With his neck broken, the cougar fell from the tree, and the body was clutched by Uncle Jim and Archie before it could roll over the cliff—while I experienced a moment's lively doubt as to whether all three might not waltz into the abyss together. Cautiously we dragged him along the rim to another tree, where we skinned him. Then, after a hard pull out of the canyon, we rejoined the horses; rain came on; and, while the storm pelted against our slickers and down-drawn slouch-hats, we rode back to our water-drenched camp.

On our second day of success only three of us went out—Uncle Jim, Archie, and I. Unfortunately, Quentin's horse went lame, that morning, and he had to stay with the pack-train.[23] For two or three hours we rode through the woods and along the rim of the canyon. Then the hounds struck a cold trail and began to puzzle it out. They went slowly along to one of the deep, precipice-hemmed gorges which from time to time break the upper cliff wall of the canyon; and after some busy nose-work they plunged into its depths. We led our horses to the bottom, slipping, sliding, and pitching, and clambered, panting and gasping, up the other side. Then we galloped along the rim. Far below us we could at times hear the hounds. One of them was a bitch, with a squealing voice. The other dogs were under the first cliffs, working out a trail, which was evidently growing fresher. Much farther down we could hear the squealing of the bitch, apparently on another trail. However, the trails came together, and the shrill yelps of the bitch were drowned in the deeper-toned chorus of the other hounds, as the fierce intensity of the cry told that the game was at last roused. Soon they had the cougar treed. Like the first, it was in a pine at the foot of the steep slope, just above the vermilion cliff wall. We scrambled down to the beast, a big male, and Archie broke its neck; in such a position it was advisable to kill it outright, as, if it struggled at all, it was likely[24] to slide over the edge of the cliff and fall a thousand feet sheer.

It was a long way down the slope, with its jungle of dwarf oak and locust, and the climb back, with the skin and flesh of the cougar, would be heart-breaking. So, as there was a break in the cliff line above, Uncle Jim suggested to Archie to try to lead down our riding animals while he, Uncle Jim, skinned the cougar. By the time the skin was off, Archie turned up with our two horses and Uncle Jim's mule—an animal which galloped as freely as a horse. Then the skin and flesh were packed behind his and Uncle Jim's saddles, and we started to lead the three animals up the steep, nearly sheer mountainside. We had our hands full. The horses and mule could barely make it. Finally the saddles of both the laden animals slipped, and Archie's horse in his fright nearly went over the cliff—it was a favorite horse of his, a black horse from the plains below, with good blood in it, but less at home climbing cliffs than were the mountain horses. On that slope anything that started rolling never stopped unless it went against one of the rare pine or pinyon trees. The horse plunged and reared; Archie clung to its head for dear life, trying to prevent it from turning down-hill, while Uncle[25] Jim sought to undo the saddle and I clutched the bridle of his mule and of my horse and kept them quiet. Finally the frightened black horse sank on his knees with his head on Archie's lap; the saddle was taken off—and promptly rolled down-hill fifty or sixty yards before it fetched up against a pinyon; we repacked, and finally reached the top of the rim.

Meanwhile the hounds had again started, and we concluded that the bitch must have been on the trail of a different animal, after all. By the time we were ready to proceed they were out of hearing, and we completely lost track of them. So Uncle Jim started in the direction he deemed it probable they would take, and after a while we were joined by Pot. Evidently the dogs were tired and thirsty and had scattered. In about an hour, as we rode through the open pine forest across hills and valleys, Archie and I caught, very faintly, a far-off baying note. Uncle Jim could not hear it, but we rode toward the spot, and after a time caught the note again. Soon Pot heard it and trotted toward the sound. Then we came over a low hill crest, and when half-way down we saw a cougar crouched in a pine on the opposite slope, while one of the hounds, named Ranger, uttered at short intervals a[26] husky bay as he kept his solitary vigil at the foot of the tree. Archie insisted that I should shoot, and thrust the rifle into my hand as we galloped down the incline. The cougar, a young and active female, leaped out of the tree and rushed off at a gait that for a moment left both dogs behind; and after her we tore at full speed through the woods and over rocks and logs. A few hundred yards farther on her bolt was shot, and the dogs, and we also, were at her heels. She went up a pine which had no branches for the lower thirty or forty feet. It was interesting to see her climb. Her two fore paws were placed on each side of the stem, and her hind paws against it, all the claws digging into the wood; her body was held as clear of the tree as if she had been walking on the ground, the legs being straight, and she walked or ran up the perpendicular stem with as much daylight between her body and the trunk as there was between her body and the earth when she was on the ground. As she faced us among the branches I could only get a clear shot into her chest where the neck joins the shoulder; down she came, but on the ground she jumped to her feet, ran fifty yards with the dogs at her heels, turned to bay in some fallen timber, and dropped dead.[27]

The last days before we left this beautiful holiday region we spent on the table-land called Greenland, which projects into the canyon east of Bright Angel. We were camped by the Dripping Springs, in singular and striking surroundings. A long valley leads south through the table-land; and just as it breaks into a sheer walled chasm which opens into one of the side loops of the great canyon, the trail turns into a natural gallery along the face of the cliff. For a couple of hundred yards a rock shelf a dozen feet wide runs under a rock overhang which often projects beyond it. The gallery is in some places twenty feet high; in other places a man on horseback must stoop his head as he rides. Then, at a point where the shelf broadens, the clear spring pools of living water, fed by constant dripping from above, lie on the inner side next to and under the rock wall. A little beyond these pools, with the chasm at our feet, and its opposite wall towering immediately in front of us, we threw down our bedding and made camp. Darkness fell; the stars were brilliant overhead; the fire of pitchy pine stumps flared; and in the light of the wavering flames the cliff walls and jutting rocks momentarily shone with ghastly clearness, and as instantly vanished in utter gloom.[28]

From the southernmost point of this table-land the view of the canyon left the beholder solemn with the sense of awe. At high noon, under the unveiled sun, every tremendous detail leaped in glory to the sight; yet in hue and shape the change was unceasing from moment to moment. When clouds swept the heavens, vast shadows were cast; but so vast was the canyon that these shadows seemed but patches of gray and purple and umber. The dawn and the evening twilight were brooding mysteries over the dusk of the abyss; night shrouded its immensity, but did not hide it; and to none of the sons of men is it given to tell of the wonder and splendor of sunrise and sunset in the Grand Canyon of the Colorado.

We dropped down from Buckskin Mountain, from the land of the pine and spruce and of cold, clear springs, into the grim desolation of the desert. We drove the pack-animals and loose horses, usually one of us taking the lead to keep the trail. The foreman of the Bar Z had lent us two horses for our trip, in true cattleman's spirit; another Bar Z man, who with his wife lived at Lee's Ferry, showed us every hospitality, and gave us fruit from his garden, and chickens; and two of the Bar Z riders helped Archie and Nick shoe one of our horses. It was a land of wide spaces and few people, but those few we met were so friendly and helpful that we shall not soon forget them.

At noon of the first day we had come down the mountainside, from the tall northern forest trees at the summit, through the scattered, sprawling pinyons and cedars of the side slopes, to the barren, treeless plain of sand and sage-brush[30] and greasewood. At the foot of the mountain we stopped for a few minutes at an outlying cow-ranch. There was not a tree, not a bush more than knee-high, on the whole plain round about. The bare little ranch-house, of stone and timber, lay in the full glare of the sun; through the open door we saw the cluttered cooking-utensils and the rolls of untidy bedding. The foreman, rough and kindly, greeted us from the door; spare and lean, his eyes bloodshot and his face like roughened oak from the pitiless sun, wind, and sand of the desert. After we had dismounted, our shabby ponies moped at the hitching-post as we stood talking. In the big corral a mob of half-broken horses were gathered, and two dust-grimed, hard-faced cowpunchers, lithe as panthers, were engaged in breaking a couple of wild ones. All around, dotted with stunted sage-brush and greasewood, the desert stretched, blinding white in the sunlight; across its surface the dust clouds moved in pillars, and in the distance the heat-waves danced and wavered.

During the afternoon we shogged steadily across the plain. At one place, far off to one side, we saw a band of buffalo, and between them and us a herd of wild donkeys. Otherwise the only living things were snakes and lizards.[31] On the other side of the plain, two or three miles from a high wall of vermilion cliffs, we stopped for the night at a little stone rest-house, built as a station by a cow outfit. Here there were big corrals, and a pool of water piped down by the cow-men from a spring many miles distant. On the sand grew the usual desert plants, and on some of the ridges a sparse growth of grass, sufficient for the night feed of the hardy horses. The little stone house and the corrals stood bare and desolate on the empty plain. Soon after we reached them a sand-storm rose and blew so violently that we took refuge inside the house. Then the wind died down; and as the sun sank toward the horizon we sauntered off through the hot, still evening. There were many sidewinder rattlesnakes. We killed several of the gray, flat-headed, venomous things; as we slept on the ground outside the house, under the open sky, we were glad to kill as many as possible, for they sometimes crawl into a sleeper's blankets. Except this baleful life, there was little save the sand and the harsh, scanty vegetation. Across the lonely wastes the sun went down. The sharply channelled cliffs turned crimson in the dying light; all the heavens flamed ruby red, and faded to a hundred dim hues of opal, beryl and amber, pale turquoise[32] and delicate emerald; and then night fell and darkness shrouded the desert.

Next morning the horse-wranglers, Nick and Quentin, were off before dawn to bring in the saddle and pack animals; the sun rose in burning glory, and through the breathless heat we drove the pack-train before us toward the crossing of the Colorado. Hour after hour we plodded ahead. The cliff line bent back at an angle, and we followed into the valley of the Colorado. The trail edged in toward the high cliffs as they gradually drew toward the river. At last it followed along the base of the frowning rock masses. Far off on our right lay the Colorado; on its opposite side the broad river valley was hemmed in by another line of cliffs, at whose foot we were to travel for two days after crossing the river.

The landscape had become one of incredible wildness, of tremendous and desolate majesty. No one could paint or describe it save one of the great masters of imaginative art or literature—a Turner or Browning or Poe. The sullen rock walls towered hundreds of feet aloft, with something about their grim savagery that suggested both the terrible and the grotesque. All life was absent, both from them and from the fantastic barrenness of the bowlder-strewn[33] land at their bases. The ground was burned out or washed bare. In one place a little stream trickled forth at the bottom of a ravine, but even here no grass grew—only little clusters of a coarse weed with flaring white flowers that looked as if it throve on poisoned soil. In the still heat "we saw the silences move by and beckon." The cliffs were channelled into myriad forms—battlements, spires, pillars, buttressed towers, flying arches; they looked like the ruined castles and temples of the monstrous devil-deities of some vanished race. All were ruins—ruins vaster than those of any structures ever reared by the hands of men—as if some magic city, built by warlocks and sorcerers, had been wrecked by the wrath of the elder gods. Evil dwelt in the silent places; from battlement to lonely battlement fiends' voices might have raved; in the utter desolation of each empty valley the squat blind tower might have stood, and giants lolled at length to see the death of a soul at bay.

As the afternoon wore on, storm boded in the south. The day grew sombre; to the desolation of the blinding light succeeded the desolation of utter gloom. The echoes of the thunder rolled among the crags, and lightning jagged the darkness. The heavens burst, and the[34] downpour drove in our faces; then through cloud rifts the sun's beams shone again and we looked on "the shining race of rain whose hair a great wind scattereth."

At Lee's Ferry, once the home of the dark leader of the Danites, the cliffs, a medley of bold colors and striking forms, come close to the river's brink on either side; but at this one point there is a break in the canyon walls and a ferry can be run. A stream flows into the river from the north. By it there is a house, and the miracle of water has done its work. Under irrigation, there are fields of corn and alfalfa, groves of fruit-trees, and gardens; a splash of fresh, cool green in the harsh waste.

South of the ferry we found two mule-wagons, sent for us by Mr. Hubbell, of Ganado, to whose thoughtful kindness we owed much. One was driven by a Mexican, Francisco Marquez; the other, the smaller one, by a Navajo Indian, Loko, who acted as cook; both were capital men, and we lived in much comfort while with them. A Navajo policeman accompanied us as guide, for we were now in the great Navajo reservation. A Navajo brought us a sheep for sale, and we held a feast.

For two days we drove southward through the desert country, along the foot of a range of red[35] cliffs. In places the sand was heavy; in others the ground was hard, and the teams made good progress. There were little water-holes, usually more or less alkaline, ten or fifteen miles apart. At these the Navajos were watering their big flocks of sheep and goats, their horses and donkeys, and their few cattle. They are very interesting Indians. They live scattered out, each family by itself, or two or three families together; not in villages, like their neighbors the Hopis. They are pastoral Indians, but they are agriculturists also, as far as the desert permits. Here and there, where there was a little seepage of water, we saw their meagre fields of corn, beans, squashes, and melons. All were mounted; the men usually on horses, the women and children often on donkeys. They were clad in white man's garb; at least the men wore shirts and trousers and the women bodices and skirts; but the shirts were often green or red or saffron or bright blue; their long hair was knotted at the back of the head, and they usually wore moccasins. The well-to-do carried much jewelry of their own make. They wore earrings and necklaces of turquoise; turquoises were set in their many silver ornaments; and they wore buttons and bangles of silver, for they are cunning silversmiths, as well as weavers of the famous[36] Navajo blankets. Although they practise polygamy, and divorce is easy, their women are usually well treated; and we saw evidences of courtesy and consideration not too common even among civilized people. At one halt a woman on a donkey, with a little boy behind her, rode up to the wagon. We gave her and the boy food. Later when a Navajo man came up, she quietly handed him a couple of delicacies. So far there was nothing of note; but the man equally quietly and with a slight smile of evident gratitude and appreciation stretched out his hand; and for a moment they stood with clasped hands, both pleased, one with the courtesy, and the other with the way the courtesy had been received. Both were tattered beings on donkeys; but it made a pleasant picture.

These are as a whole good Indians—although some are very bad, and should be handled rigorously. Most of them work hard, and wring a reluctant living from the desert; often their houses are miles from water, and they use it sparingly. They live on a reservation in which many acres are necessary to support life; I do not believe that at present they ought to be allotted land in severalty, and their whole reservation should be kept for them, if only they can be brought forward fast enough in stock-[37]raising and agriculture to use it; for with Indians and white men alike it is use which should determine occupancy of the soil. The Navajos have made progress of a real type, and stand far above mere savagery; and everything possible should be done to help them help themselves, to teach them English, and, above all, to teach them how to be better stock-raisers and food-growers—as well as smiths and weavers—in their desert home. The whites have treated these Indians well. They benefited by the coming of the Spaniards; they have benefited more by the coming of our own people. For the last quarter of a century the lawless individuals among them have done much more wrong (including murder) to the whites than has been done to them by lawless whites. The lawless Indians are the worst menace to the others among the Navajos and Utes; and very serious harm has been done by well-meaning Eastern philanthropists who have encouraged and protected these criminals. I have known some startling cases of this kind.

During the second day of our southward journey the Painted Desert, in gaudy desolation, lay far to our right; and we crossed tongues and patches of the queer formation, with its hard, bright colors. Red and purple, green[38] and bluish, orange and gray and umber brown, the streaked and splashed clays and marls had been carved by wind and weather into a thousand outlandish forms. Funnel-shaped sandstorms moved across the waste. We climbed gradually upward to the top of the mesa. The yellow sand grew heavier and deeper. There were occasional short streams from springs; but they ran in deep gullies, with nothing to tell of their presence; never a tree near by and hardly a bush or a tuft of grass, unless planted and tended by man. We passed the stone walls of an abandoned trading-post. The desert had claimed its own. The ruins lay close to a low range of cliffs; the white sand, dazzling under the sun, had drifted everywhere; there was not a plant, not a green thing in sight—nothing but the parched and burning lifelessness of rock and sand. This northern Arizona desert was less attractive than the southern desert along the road to the Roosevelt Dam and near Mesa, for instance; for in the south the cactus growth is infinitely varied in size and in fantastic shape.

In the late afternoon we reached Tuba, with its Indian school and its trader's store. Tuba was once a Mormon settlement, the Mormons having been invited thither by the people of a[39] near-by Hopi village—which we visited—because the Hopis wished protection from hostile Indian foes. As usual, the Mormon settlers had planted and cared for many trees—cotton-woods, poplars, almond-trees, and flowering acacias—and the green shade was doubly attractive in that sandy desert. We were most hospitably received, especially by the school superintendent, and also by the trader. They showed us every courtesy. Mentioning the abandoned trading-post in the desert to the wife of the trader, she told us that it was there she had gone as a bride. The women who live in the outposts of civilization have brave souls!

We rested the horses for a day, and then started northward, toward the trading-station of John Wetherill, near Navajo Mountain and the Natural Bridge. The first day's travel was through heavy sand and very tiring to the teams. Late in the afternoon we came to an outlying trader's store, on a sandy hillside. In the plain below, where not a blade of grass grew, were two or three permanent pools; and toward these the flocks of the Navajos were hurrying, from every quarter, with their herdsmen. The sight was curiously suggestive of the sights I so often saw in Africa, when the Masai and Samburu herdsmen brought their[40] flocks to water. On we went, not halting until nine in the evening.

All next day we travelled through a parched, monotonous landscape, now and then meeting Navajos with their flocks and herds, and passing by an occasional Navajo "hogan," or hovel-like house, with its rough corral near by. Toward evening we struck into Marsh Pass, and camped at the summit. Here we were again among the mountains; and the great gorge was wonderfully picturesque—well worth a visit from any landscape-lover, were there not so many sights still more wonderful in the immediate neighborhood. The lower rock masses were orange-hued, and above them rose red battlements of cliff; where the former broke into sheer sides there were old houses of the cliff-dwellers, carved in the living rock. The half-moon hung high overhead; the scene was wild and lovely, when we strolled away from the camp-fire among the scattered cedars and pinyons through the cool, still night.

Next morning we journeyed on, and in the forenoon we reached Kayentay, where John Wetherill, the guide and Indian trader, lives. We had been travelling over a bare table-land, through surroundings utterly desolate; and with startling suddenness, as we dropped over the edge,[41] we came on the group of houses—the store, the attractive house of Mr. and Mrs. Wetherill, and several other buildings. Our new friends were the kindest and most hospitable of hosts, and their house was a delight to every sense: clean, comfortable, with its bath and running water, its rugs and books, its desks, cupboards, couches and chairs, and the excellent taste of its Navajo ornamentation. Here we parted with our two wagons, and again took to pack-trains; we had already grown attached to Francisco and Loko, and felt sorry to say good-by to them.

On August 10, under Wetherill's guidance, we started for the Natural Bridge, seven of us, all told, with five pack-horses. We travelled light, with no tentage, and when it rained at night we curled up in our bedding under our slickers. I was treated as "the Colonel," and did nothing but look after my own horse and bedding, and usually not even this much; but every one else in the outfit worked! On the two days spent in actually getting into and out of the very difficult country around the Bridge itself we cut down our luggage still further, taking the necessary food in the most portable form, and, as regards bedding, trusting, in cowboy fashion, to our slickers and horse blankets. But we were comfortable,[42] and the work was just hard enough to keep us in fine trim.

We began by retracing our steps to the head of Marsh Pass and turning westward up Laguna Canyon. This was so named because it contained pools of water when, half a century ago, Kit Carson, the type of all that was best among the old-style mountain man and plainsman, traversed it during one of his successful Indian campaigns. The story of the American advance through the Southwest is filled with feats of heroism. Yet, taking into account the means of doing the work, even greater dangers were fronted, even more severe hardships endured, and even more striking triumphs achieved by the soldiers and priests who three centuries previously, during Spain's brief sunburst of glory, first broke through the portals of the thirst-guarded, Indian-haunted desert.

At noon we halted in a side-canyon, at the foot of a mighty cliff, where there were ruins of a big village of cliff-dwellers. The cliff was of the form so common in this type of rock formation. It was not merely sheer, but reentrant, making a huge, arched, shallow cave, several hundred feet high, and at least a hundred—perhaps a hundred and fifty—feet deep, the overhang being enormous. The stone houses[43] of the village, which in all essentials was like a Hopi village of to-day, were plastered against the wall in stories, each resting on a narrow ledge. Long poles permitted one to climb from ledge to ledge, and gave access, through the roofs, to the more inaccessible houses. The immense size of the cave—or overhanging, reentrant cliff, whichever one chooses to call it—dwarfed the houses, so that they looked like toy houses.

There were many similar, although smaller, villages and little clusters of houses among the cliffs of this tangle of canyons. Once the cliff-dwellers had lived in numbers in this neighborhood, sleeping in their rock aeries, and venturing into the valleys only to cultivate their small patches of irrigated land. Generations had passed since these old cliff-dwellers had been killed or expelled. Compared with the neighboring Indians, they had already made a long stride in cultural advance when the Spaniards arrived; but they were shrinking back before the advance of the more savage tribes. Their history should teach the lesson—taught by all history in thousands of cases, and now being taught before our eyes by the experience of China, but being taught to no purpose so far as concerns those ultra peace advocates whose[44] heads are even softer than their hearts—that the industrious race of advanced culture and peaceful ideals is lost unless it retains the power not merely for defensive but for offensive action, when itself menaced by vigorous and aggressive foes.

That night, having ridden only some twenty-five miles, we camped in Bubbling Spring Valley. It would be hard to imagine a wilder or more beautiful spot; if in the Old World, the valley would surely be celebrated in song and story; here it is one among many others, all equally unknown. We camped by the bubbling spring of pure cold water from which it derives its name. The long, winding valley was carpeted with emerald green, varied by wide bands and ribbons of lilac, where the tall ranks of bee-blossoms, haunted by humming-birds, grew thickly, often for a quarter of a mile at a stretch. The valley was walled in by towering cliffs, a few of them sloping, most of them sheer-sided or with the tops overhanging; and there were isolated rock domes and pinnacles. As everywhere round about, the rocks were of many colors, and the colors varied from hour to hour, so that the hues of sunrise differed from those of noonday, and yet again from the long lights of sunset. The cliffs seemed orange and purple; and again[45] they seemed vermilion and umber; or in the white glare they were white and yellow and light red.

Our routine was that usual when travelling with a pack-train. By earliest dawn the men whose duties were to wrangle the horses and cook had scrambled out of their bedding; and the others soon followed suit. There is always much work with a pack-outfit, and there are almost always some animals which cause trouble when being packed. The sun was well up before we started; then we travelled until sunset, taking out a couple of hours to let the hobbled horses and mules rest and feed at noon.

On the second day out we camped not far from the foot of Navajo Mountain. We came across several Indians, both Navajos and Utes, guarding their flocks and herds; and we passed by several of their flimsy branch-built summer houses, and their mud, stone, and log winter houses; and by their roughly fenced fields of corn and melons watered by irrigation ditches. Wetherill hired two Indians, a Ute and a Navajo, to go with us, chiefly to relieve us of the labor of looking after our horses at night. They were pleasant-faced, silent men. They wore broad hats, shirts and waistcoats, trousers, and red handkerchiefs loosely knotted round their necks; except for their moccasins, a feather in[46] each hat, and two or three silver ornaments, they were dressed like cowboys, and both picturesquely and appropriately. Their ornamented saddles were of Navajo make.

The second day's march was long. At one point we dropped into and climbed out of a sheer-sided canyon some twelve hundred feet deep. The trail, which zigzagged up and down the rocky walls, had been made by the Navajos. After we had led our horses down into the canyon, and were lunching by a spring, we were followed by several Indians driving large flocks of goats and sheep. They came down the trail at a good rate, many of them riding instead of leading their horses. One rather comely squaw attracted our attention. She was riding a weedy, limber-legged brood-mare, followed by a foal. The mare did not look as if it would be particularly strong even on the level; yet the well-dressed squaw, holding before her both her baby and her long sticks for blanket-weaving, and with behind her another child and a small roll of things which included a black umbrella, ambled down among the broken rocks with entire unconcern, and joked cheerily with us as she passed.

The night was lovely, and the moon, nearly full, softened the dry harshness of the land,[47] while Navajo Mountain loomed up under it. When we rose, we saw the pale dawn turn blood-red; and shortly after sunrise we started for our third and final day's journey to the Bridge. For some ten miles the track was an ordinary rough mountain trail. Then we left all our pack-animals except two little mules, and began the hard part of our trip. From this point on the trail was that followed by Wetherill on his various trips to the Bridge, and it can perhaps fairly be called dangerous in two or three places, at least for horses. Wetherill has been with every party that has visited the Bridge from the time of its discovery by white men four years ago. On that occasion he was with two parties, their guide being the Ute who was at this time with us. Mrs. Wetherill has made an extraordinarily sympathetic study of the Navajos and to a less extent of the Utes; she knows, and feelingly understands, their traditions and ways of thought, and speaks their tongue fluently; and it was she who first got from the Indians full knowledge of the Bridge.

The hard trail began with a twenty minutes' crossing of a big mountain dome of bare sheet rock. Over this we led our horses, up, down, and along the sloping sides, which fell away into cliffs that were scores and even hundreds[48] of feet deep. One spot was rather ticklish. We led the horses down the rounded slope to where a crack or shelf six or eight inches broad appeared and went off level to the right for some fifty feet. For half a dozen feet before we dropped down to this shelf the slope was steep enough to make it difficult for both horses and men to keep their footing on the smooth rock; there was nothing whatever to hold on to, and a precipice lay underneath.

On we went, under the pitiless sun, through a contorted wilderness of scalped peaks and ranges, barren passes, and twisted valleys of sun-baked clay. We worked up and down steep hill slopes, and along tilted masses of sheet-rock ending in cliffs. At the foot of one of these lay the bleached skeleton of a horse. It was one which Wetherill had ridden on one of his trips to the Bridge. The horse lost his footing on the slippery slide rock, and went to his death over the cliff; Wetherill threw himself out of the saddle and just managed to escape. The last four miles were the worst of all for the horses. They led along the bottom of the Bridge canyon. It was covered with a torrent-strewn mass of smooth rocks, from pebbles to bowlders of a ton's weight. It was a marvel that the horses got down without breaking their[49] legs; and the poor beasts were nearly worn out.

Huge and bare the immense cliffs towered, on either hand, and in front and behind as the canyon turned right and left. They lifted straight above us for many hundreds of feet. The sunlight lingered on their tops; far below, we made our way like pygmies through the gloom of the great gorge. As we neared the Bridge the horse trail led up to one side, and along it the Indians drove the horses; we walked at the bottom of the canyon so as to see the Bridge first from below and realize its true size; for from above it is dwarfed by the immense mountain masses surrounding it.

At last we turned a corner, and the tremendous arch of the Bridge rose in front of us. It is surely one of the wonders of the world. It is a triumphal arch rather than a bridge, and spans the torrent bed in a majesty never shared by any arch ever reared by the mightiest conquerors among the nations of mankind. At this point there were deep pools in the rock bed of the canyon, with overhanging shelves under which grew beautiful ferns and hanging plants. Hot and tired, we greeted the chance for a bath, and as I floated on my back in the water the Bridge towered above me. Then we made[50] camp. We built a blazing fire under one of the giant buttresses of the arch, and the leaping flame brought it momentarily into sudden relief. We white men talked and laughed by the fire, and the two silent Indians sat by and listened to us. The night was cloudless. The round moon rose under the arch and flooded the cliffs behind us with her radiance. After she passed behind the mountains the heavens were still brilliant with starlight, and whenever I waked I turned and gazed at the loom of the mighty arch against the clear night sky.

Next morning early we started on our toilsome return trip. The pony trail led under the arch. Along this the Ute drove our pack-mules, and as I followed him I noticed that the Navajo rode around outside. His creed bade him never pass under an arch, for the arch is the sign of the rainbow, the sign of the sun's course over the earth, and to the Navajo it is sacred. This great natural bridge, so recently "discovered" by white men, has for ages been known to the Indians. Near it, against the rock walls of the canyon, we saw the crumbling remains of some cliff-dwellings, and almost under it there is what appears to be the ruin of a very ancient shrine.

We travelled steadily at a good gait, and we[51] feasted on a sheep we bought from a band of Utes. Early on the afternoon of the sixth day of our absence we again rode our weary horses over the hill slope down to the store at Kayentay, and glad we were to see the comfortable ranch buildings.

Many Navajos were continually visiting the store. It seems a queer thing to say, but I really believe Kayentay would be an excellent place for a summer school of archæology and ethnology. There are many old cliff-dwellings, some of large size and peculiar interest, in the neighborhood; and the Navajos of this region themselves, not to mention the village-dwelling Hopis, are Indians who will repay the most careful study, whether of language, religion, or ordinary customs and culture. As always when I have seen Indians in their homes, in mass, I was struck by the wide cultural and intellectual difference among the different tribes, as well as among the different individuals of each tribe, and both by the great possibilities for their improvement and by the need of showing common sense even more than good intentions if this improvement is to be achieved. Some Indians can hardly be moved forward at all. Some can be moved forward both fast and far. To let them entirely alone usually[52] means their ruin. To interfere with them foolishly, with whatever good intentions, and to try to move all of them forward in a mass, with a jump, means their ruin. A few individuals in every tribe, and most of the individuals in some tribes, can move very far forward at once; the non-reservation schools do excellently for these. Most of them need to be advanced by degrees; there must be a half-way house at which they can halt, or they may never reach their final destination and stand on a level with the white man.

The Navajos have made long strides in advance during the last fifty years, thanks to the presence of the white men in their neighborhood. Many decent men have helped them—soldiers, agents, missionaries, traders; and the help has quite as often been given unconsciously as consciously; and some of the most conscientious efforts to help them have flatly failed. The missionaries have made comparatively few converts; but many of the missionaries have added much to the influences telling for the gradual uplift of the tribe. Outside benevolent societies have done some good work at times, but have been mischievous influences when guided by ignorance and sentimentality—a notable instance on this Navajo reservation is given by[53] Mr. Leupp in his book "The Indian and His Problem." Agents and other government officials, when of the best type, have done most good, and when not of the right type have done most evil; and they have never done any good at all when they have been afraid of the Indians or have hesitated relentlessly to punish Indian wrong-doers, even if these wrong-doers were supported by some unwise missionaries or ill-advised Eastern benevolent societies. The traders of the right type have rendered genuine, and ill-appreciated, service, and their stores and houses are centres of civilizing influence.

Good work can be done, and has been done, at the schools. Wherever the effort is to jump the ordinary Indian too far ahead and yet send him back to the reservation, the result is usually failure. To be useful the steps for the ordinary boy or girl, in any save the most advanced tribes, must normally be gradual. Enough English should be taught to enable such a boy or girl to read, write, and cipher so as not to be cheated in ordinary commercial transactions. Outside of this the training should be industrial, and, among the Navajos, it should be the kind of industrial training which shall avail in the home cabins and in tending flocks and herds and irrigated fields. The Indian should be en[54]couraged to build a better house; but the house must not be too different from his present dwelling, or he will, as a rule, neither build it nor live in it. The boy should be taught what will be of actual use to him among his fellows, and not what might be of use to a skilled mechanic in a big city, who can work only with first-class appliances; and the agency farmer should strive steadily to teach the young men out in the field how to better their stock and practically to increase the yield of their rough agriculture. The girl should be taught domestic science, not as it would be practised in a first-class hotel or a wealthy private home, but as she must practise it in a hut with no conveniences, and with intervals of sheep-herding. If the boy and girl are not so taught, their after lives will normally be worthless both to themselves and to others. If they are so taught, they will normally themselves rise and will be the most effective of home missionaries for their tribe.

In Horace Greeley's "Overland Journey," published more than half a century ago, there are words of sound wisdom on this subject. Said Greeley (I condense): "In future efforts to improve the condition of the Indians the women should be specially regarded and ap[55]pealed to. A conscientious, humane, capable Christian trader, with a wife thoroughly skilled in household manufactures and handicrafts, each speaking the language of the tribe with whom they take up their residence, can do [incalculable] good. Let them keep and sell whatever articles are adapted to the Indians' needs ... and maintain an industrial school for Indian women and children, which, though primarily industrial, should impart intellectual and religious instruction also, wisely adapted in character and season to the needs of the pupils.... Such an enterprise would gradually" [the italics here are mine] "mould a generation after its own spirit.... The Indian likes bread as well as the white; he must be taught to prefer the toil of producing it to the privation of lacking it." Mrs. Wetherill is doing, and striving to do, much more than Horace Greeley held up as an ideal. One of her hopes is to establish a "model hogan," an Indian home, both advanced and possible for the Navajos now to live up to—a half-way house on the road to higher civilization, a house in which, for instance, the Indian girl will be taught to wash in a tub with a pail of water heated at the fire; it is utterly useless to teach her to wash in a laundry with steam and cement bath[56]tubs and expect her to apply this knowledge on a reservation. I wish some admirer of Horace Greeley and friend of the Indian would help Mrs. Wetherill establish her half-way house.

Mrs. Wetherill was not only versed in archæological lore concerning ruins and the like, she was also versed in the yet stranger and more interesting archæology of the Indian's own mind and soul. There have of recent years been some admirable books published on the phase of Indian life which is now, after so many tens of thousands of years, rapidly drawing to a close. There is the extraordinary, the monumental work of Mr. E.S. Curtis, whose photographs are not merely photographs, but pictures of the highest value; the capital volume by Miss Natalie Curtis; and others. If Mrs. Wetherill could be persuaded to write on the mythology of the Navajos, and also on their present-day psychology—by which somewhat magniloquent term I mean their present ways and habits of thought—she would render an invaluable service. She not only knows their language; she knows their minds; she has the keenest sympathy not only with their bodily needs, but with their mental and spiritual processes; and she is not in the least afraid of them or sentimental about them when[57] they do wrong. They trust her so fully that they will speak to her without reserve about those intimate things of the soul which they will never even hint at if they suspect want of sympathy or fear ridicule. She has collected some absorbingly interesting reproductions of the Navajo sand drawings, picture representations of the old mythological tales; they would be almost worthless unless she wrote out the interpretation, told her by the medicine-man, for the hieroglyphics themselves would be meaningless without such translation. According to their own creed, the Navajos are very devout, and pray continually to the gods of their belief. Some of these prayers are very beautiful; others differ but little from forms of mere devil-worship, of propitiation of the powers of possible evil. Mrs. Wetherill was good enough to write out for me, in the original and in English translation, a prayer of each type—a prayer to the God of the Dawn and the Goddess of Evening Light, and a prayer to the great Spirit Bear. They run as follows:

(The Navajos believe in repeating a prayer, both in anticipatory and in realized form, four times, being firm in the faith that an adjuration four times repeated will bring the results they desire; the Pollen Boy is the God of Fertilization of the Flowers.)

(The fourfold repetition of "the evil has missed me" is held to insure the accomplishment in the future of what the prayer asserts of the past. Instead of "hat" we could say "helmet," as the Navajos once wore a black buckskin helmet; and the knife was of black flint. Black was the war color. This prayer was to ward off the effect of a bad dream.)

On August 17, we left Wetherill's with our pack-train, for a three days' trip across the Black Mesa to Walpi, where we were to witness the snake-dance of the Hopis. The desert valley where Kayentay stands is bounded on the south by a high wall of cliffs, extending for scores of miles. Our first day's march took us up this; we led the saddle-horses and drove the pack-animals up a very rough Navajo trail which zigzagged to the top through a partial break in the continuous rock wall. From the summit we looked back over the desert, barren, desolate, and yet with a curious fascination of its own. In the middle distance rose a line of[61] low cliffs, deep red, well-nigh blood-red, in color. In the far distance isolated buttes lifted daringly against the horizon; prominent among them was the abrupt pinnacle known as El Capitan, a landmark for the whole region.