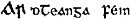

Title: Sinn Fein: An Illumination

Author: P. S. O'Hegarty

Release date: November 28, 2010 [eBook #34464]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian

Libraries.)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

THE INDESTRUCTIBLE NATION: A Survey of Irish History from the Invasion. The First Phase: The Overthrow of the Clans.

JOHN MITCHEL: An Appreciation. With some Account of Young Ireland.

IN PREPARATION:

ULSTER: A Brief Statement of Fact.

MAUNSEL & CO., LTD.,

DUBLIN AND LONDON

1919

I was a member of the “National Council” formed in 1902 by Mr. Arthur

Griffith on the occasion of the visit of the late Queen Victoria, and of

the Executives of “Cumann na nGaedheal,” the “Dungannon Clubs,” and the

“Sinn Fein League,” by the fusion of which the old “Sinn Fein”

organisation was formed. I was a member of the Sinn Fein Executive until

1911, and from 1903 to the present time I have been closely connected with

every Irish movement of what I might call the Language Revival current.

This book is therefore, so far as the matters of fact referred to therein

are concerned, a book based upon personal knowledge.

My object in writing it has not been to give a history of Sinn Fein, but to give an account of its historical evolution, to place it in relation to the antecedent history of Ireland, above all to show it in its true light as an attempt, inspired by the Language revival, to place Ireland in touch with the historic Irish Nation which went down in the seventeenth century under the Penal Laws and was forced, when it emerged in the nineteenth, to reconstitute itself on the framework which had been provided for the artificial State which had been superimposed on the Irish State with the Penal Laws. The quarrel between Sinn Fein and the Irish Parliamentary Party is really the quarrel between the historic Irish Nation and the artificial English garrison State; the quarrel between de-Anglicisation and Anglicisation.

The scope of the book precluded any detail in regard to the evolution of events since 1916, as it precluded any mention of individuals, save Mr. Arthur Griffith, who is the Hamlet of the piece.

(As Passed by Censor.)

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE POLICY OF PEACEFUL PENETRATION IN IRELAND | 1 |

| II. | THE TURNING POINT | 6 |

| III. | THE GENESIS OF THE SINN FEIN MOVEMENT | 13 |

| IV. | THE SINN FEIN POLICY | 19 |

| V. | ARTHUR GRIFFITH—THE TRUTH | 28 |

| VI. | THE SINN FEIN MOVEMENT—1905 TO 1913 | 34 |

| VII. | THE IRISH VOLUNTEERS | 41 |

| VIII. | SINN FEIN | 49 |

Note.—The first seven chapters were written in October, 1917, and passed for publication in November, 1918. Chapter viii represents a re-arrangement of such portions of the last three chapters of the original manuscript as it is permissible to publish at the present time.

When Pitt and Castlereagh forced through the Act of Union, they forged a

weapon with the potentiality of utterly subjecting the Irish nation, of

extinguishing wholly its civilisation, its name, and its memory; for they

made possible that policy of peaceful penetration which in less than a

century brought Ireland lower than she had been brought by five centuries

of war and one century of almost incredibly severe penal legislation. In

the history of the connexion between England and Ireland the vital dates

are 1691, 1800, and 1893: in 1691 Ireland lay for the first time unarmed

under the heel of the invader; in 1800 began the peaceful penetration of

Irish civilisation by English civilisation; and in 1893 by the foundation

of the Gaelic League Ireland turned once more to her own culture and her

own past, alive to her separateness, her distinctiveness, alive also to

her danger.

The defences of a nation against annihilation are two, physical and spiritual. Until 1691 Ireland retained and used both, and not even Cromwell was able to deprive her of her fighting men and their arms. But when Sarsfield signed the Treaty of Limerick in 1691 and carried the bulk of the fighting men out of Ireland, and when those remaining in Ireland suffered themselves to be disarmed, Ireland was left to rely[Pg 2] upon spiritual defence only—upon language, culture, and memory. And these sufficed. Not even the Penal Laws could penetrate them, and behind the sure rampart of the language the Irish people, without leaders and notwithstanding the Penal Laws, re-knit their social order and peacefully penetrated the Garrison, so that at the end of the century they emerged from the ruins of the Penal Laws a Nation in bondage but still a Nation, with the language, culture, traditions and hopes of a Nation, and with the single will of a Nation.

Up to that time there had been nothing to turn their attention out of Ireland, and all their hopes of action, political or otherwise, naturally centred within Ireland. They had had little cause to love the Dublin Parliament of the eighteenth century, in which they had neither representation nor franchise, but they had had no cause whatever to be hopefully conscious of the existence of the London Parliament. The Penal Legislation inevitably threw them back on themselves, preserved their language, culture, and traditions, preserved their national continuity. And as the century wore on the more conscious and strengthened Irish Nation swayed the Garrison into something which, in time, would have developed into complete nationalism and fusion.

By changing the seat of government from Dublin to London, the Act of Union not alone killed the incipient Nationalism of the Garrison, but it, in time, totally alienated them from the Nation, by attaching them to English Parties, English ways, and making their centre London, and not Dublin. The landed proprietors[Pg 3] and aristocracy followed the seat of government, and London became their capital also. So that, early in the nineteenth century, the Garrison classes, which towards the end of the eighteenth century had come dangerously near to making common cause with the Nation, had shifted their political and social centre to London, and became a strength to England and a weakness to Ireland.

At the same tame the relaxation, and eventual abolition, of the Penal Laws manœuvred the mass of the Irish People also Londonwards. English was the language of the courts, of the professions, of commerce, the language of preferment, and the newly-emancipated people embraced English with a rush, and with English there came a dimming of their national consciousness, a peaceful penetration of Irish culture by English culture in every particular. The middle and upper classes were the first to be caught by it, but every influence in the country favoured it, all the popular political movements being carried on in English, and having the London Parliament as their field of operations. O’Connell, who was a native speaker of Irish, but one without any reasoned consciousness of nationality, refused to speak anything but English, the newspapers printed nothing but English, the Repeal Movement and the Young Ireland Movement, both appealing to a people which was still seventy per cent. Irish speaking, used nothing but English, and the National Schools, also using nothing but English, imposed English culture from the first on the children and set the feet of the Nation more and more steadily Londonwards.

[Pg 4]The English attack upon Ireland had begun with the most obvious and the most easily disturbed portions of the National machinery, and then, as it developed strength, it struck at other portions. It began by obstructing, and continued obstruction eventually annihilated, the then dawning political unity of Ireland as exemplified in the growing power of the Ard-Ri, and even when its own strength was weakest it managed to upset all subsequent attempts at Irish unity. It went from that to the development of an actual grip over the whole soil of Ireland, which it got in 1691, and ensured by the planting of a resident Garrison, not military only, but social also, and the placing of all place and power under the Garrison constitution in their hands. It followed that by the Penal Laws, which were an attempt to crush a whole people out, to degrade them bodily and mentally, so that they would ever afterwards be negligible. And when that failed, because of the spiritual resources of the people, it attacked those resources. The granting of the franchise to the Irish gave them an interest, even the interest of a spectator, in Parliamentary elections and happenings: the removal of that Parliament to London did not abate that interest: O’Connell’s proceedings intensified it: the “emancipation” of 1829, by conceding representation in the London Parliament, and doing so after a struggle and in the guise of an Irish victory, set the people’s imagination fatally outside their own country, and every other movement of the century, save the Young Ireland and Fenian Movements, was just an additional chain binding the Irish imagination to London. At the same time there[Pg 5] flowed over from England the English language, and English culture, habits, customs, dress, prejudices, newspapers. And transit developments, telegraph and telephone developments, trust developments—the whole modern development of machinery to render nugatory space and time—all these combined to throw English civilisation with an impetus on our shores. And right through the century it attacked, with ever increasing success and vehemence, every artery of National life.

And so the nineteenth century, which on the surface saw the development of an Ireland intensely conscious of its nationality, merely saw an Ireland intensely conscious of one manifestation of it, and that the least essential, and increasingly unconscious of the realities of nationality. While Ireland, as the century wore on, grew more vocal about political freedom, all the essentials of its nationality—language, culture, memory—faded away into the highlands and islands of Kerry and Donegal and the bare West Coast. Assimilation proceeded apace, London was as near as Dublin, and the end of the century saw the popular Political Party merely the tail of an English Party. In the islands and bleak places of the bare West Coast the remnants of the Irish-speaking Nation still kept their language and their memory, and lived a life apart, but away towards the East there was only a people who were rapidly being assimilated by England, unconsciously but none the less certainly. One century of peaceful penetration had done more to blot out the Nation than five centuries of war and one century of incredible Penal Legislation.

It is not easy to say whether the policy of peaceful penetration which was

pursued in Ireland in the nineteenth century was planned beforehand,

whether Pitt actually carried the Union with a comprehensive assimilating

policy in his mind. The probabilities are against that, and in favour of

the supposition that, the one vital step of the Union having been taken,

the rest of the policy followed inevitably. At any rate, once it did get

going, its operations continued and developed logically and methodically,

with ever-increasing ramifications, until it had the whole of Ireland in a

strangle grip, a grip mental as well as physical. And while the political

fervour of the people, under Parnell, seemed to be most strongly and

determinedly pro-Irish, yet in reality they were becoming less and less

Irish with every year. Silently but relentlessly English culture flowed in

and attacked every artery of Ireland’s national life.

Up to the Sinn Fein Movement Irish Patriotic Movements have all been specialist rather than comprehensive. They aimed at political freedom, or they aimed at the control of the land, or they had some definite one object which at the time stood for everything, and often they mistook the one thing for the whole. Their non-comprehensiveness has been made a reproach to[Pg 7] them in certain Nationalist speculations of recent years, but this cannot with justice be done. The first thing which Ireland lost was her political independence and naturally it was the thing she then tried to recover. She had not lost her language, or her culture, or her memory, and naturally she could only frame a movement for the recovery of what she had actually lost. In the eighteenth century, which in some ways was the darkest, she was yet much more of a Nation than ever she was in the nineteenth; for, even though her thoughts in that century were directed to the bare hope of keeping herself alive, of not starving and not becoming a herd of illiterates and degenerates, even then her full National consciousness went on, en rapport with her past and undisturbed in the broad sense by the froth and fustian of the Garrison persecutions: and at the end of the century she had lost nothing but her political independence and her ownership of the land. The nineteenth century, therefore, saw her devoted to the recovery of these two things, of the loss of which she was conscious; and the closing years of the century, which brought her the perception of the loss of other things, of language and all that goes with it, brought with them for the first time the possibility of a comprehensive movement for the recovery of everything lost, for an attack upon the dominant civilisation at every point of contact. And the twentieth century brought the movement itself in the Sinn Fein movement.

There were throughout the nineteenth century various short and ineffective attempts at a revival of Irish industries, but the first [Pg 8]evidence of a sense of spiritual loss was the successful attempt in the eighties at a revival and strengthening of Irish games and athletics, which resulted in the removal of English games and athletics from the dominant position and their gradual decline to their proper position as the games of a Garrison. But the turning point of all modern Irish development was the foundation of the Gaelic League in 1893. That definitely and irrevocably, insignificant though it seemed at the time and for a long time, arrested the assimilating process, provided a last fortification, as it were, behind which the still unassimilated forces of the Nation gathered strength, and unity, and courage, and turned the mind of Ireland away from everything foreign and inward towards herself and her own concerns. There had always been in Ireland Archæological Associations and learned persons who studied Irish as a dead language, and there actually was in existence at the time the present “Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language”: but the Gaelic League was a League of common men and women who took up Irish not for antiquarian or academical reasons, but because it was the national language of Ireland, and because they were convinced that Ireland would be irrevocably lost if she lost it. They were seers and enthusiasts, not archæologists, and in twenty years they had all Ireland, all Nationalist Ireland at any rate, behind their banner.

It would be difficult to over-emphasise the influence which the Gaelic

League has had upon Ireland. It may be said with absolute truth that it

stemmed the onflowing tide of assimilation to English civilisation,[Pg 9] and

not alone stemmed it but turned it back. Its fight for the Irish language

reacted upon everything else in Ireland, set up influences, currents, out

of nowhere, which fought firmly for this or that Irish characteristic,

dinned into the ears of the people everywhere an insistence upon things

Irish as apart from things foreign. And it gave the first great example of

the support of a thing because it is Irish. The Gaelic Leaguer had, and

has, many weapons in his armoury, and the reasons for the revival of Irish

are many. But although in case of necessity he is prepared to justify the

revival upon utilitarian grounds, upon philological grounds, and upon

historical grounds, the chief weapon in his armoury is a sentimental one,

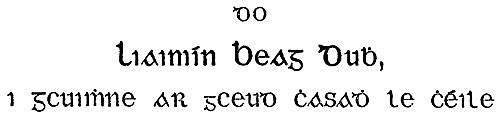

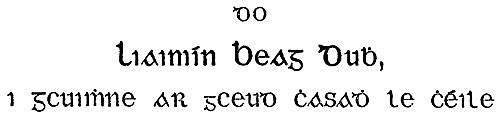

being “  ”—Our own language. That is the

battle-cry which has appealed irresistibly to the man in the street, and

the principle behind it, first enunciated as a fighting principle by the

Gaelic League, has come to be applied to all Irish questions and

practically to mould the thoughts of the present generation.

”—Our own language. That is the

battle-cry which has appealed irresistibly to the man in the street, and

the principle behind it, first enunciated as a fighting principle by the

Gaelic League, has come to be applied to all Irish questions and

practically to mould the thoughts of the present generation.

The foundation of the Gaelic League has been attributed to the debâcle which had just then overwhelmed the Parliamentarian Movement, but the two things had no connexion. The young men who founded the Gaelic League, and who did the desperate work of its early years, were men whose interests were intellectual rather than political, and who neither had, nor were likely to have, any intimate connexion with any political movement such as the then Parliamentarian Movement. The origin of the Gaelic League goes farther back, back to the early days of the century when the Nation began to lose the language. Once[Pg 10] the people began to shed their own language a movement for its recovery was inevitable if the Nation was not to be wholly annihilated; and as in other things a perception of loss rarely arises until a thing is either lost or well on the way to it, so in this case a perception of the meaning of the loss of the language did not come until the language was almost lost. But it did come. And to a few young men it was given to see that Ireland might gain riches, gain empire, gain everything, but that if she lost her language she lost her soul. And they raised their battle-cry accordingly, and led their Nation out of the bog of Anglicisation, took the people’s eyes from the ends of the earth and turned them towards the West, where their language still lived and their national life kept its continuity.

The Gaelic League was not, is not, a mere movement for the revival of a language. Literally it is that, but philosophically it is a movement for the revival of a Nation. Resurrecting, as it did, the chief essential to Nationality, it inevitably resurrected also the subsidiary ones. Its constitution debars it from taking any part in politics, and it holds within its ranks men and women of all parties, but no constitution can prevent the leaven of the language working on the individual to its fullest extent once it gets into him. And the language brought with it old ideas, old values, old traditions. There is in the very sound of Irish music a quality which wipes out at once the whole of the nineteenth century and brings one face to face with the days when Ireland had an individuality and a proud civilisation: the roots of the language are away back in the very golden age of Irish civilisation;[Pg 11] and the enthusiast who began with the language has been irresistibly impelled to a quest which embraces many things besides, industries, games, government—everything which concerns a Nation.

Since its inception the Gaelic League has influenced, in one way or another, the best of the young men and women of Ireland. It has set them thinking, with the language firm in them. And it has led them irresistibly to disregard altogether the whole current of Irish evolution since 1800, to realise that when Ireland began to lose her language she began to lose her Nationality, and to send them back to take up the broken thread of Irish civilisation where the English onrush broke it, and rebuild it.

That force has worked just as all-embracingly as the English aggressive onrush of the nineteenth century worked. It has neglected nothing. And while the older politicians went on in their well-worn grooves, uneasy at the apathy of the young people towards them, but ignorantly content so long as they were undisturbed, the leaven of the Gaelic League self-reliance principle was undermining their political foundations, in common with all other foundations in Ireland which were the result of a bastard connexion with any of the manifestations of English civilisation in Ireland. That is also the secret of the Irish Literary Movement in English. It gets its inspiration from Irish tradition, Irish convention, Irish speech, and even though it expresses itself in English it is an English which is half Irish. Its whole spirit is the spirit of an Ireland which is looking back to Eoghan Ruadh and Keating rather than forward to a development of the perfectly [Pg 12]reputable, perfectly colourless, and perfectly uninspiring work of, say, Mr. Edward Dowden. That work is the work of a mind perfectly assimilated to English civilisation, and it has no future save absorption. The Gaelic League leaven has driven it home to the people of Ireland that any similar work or effort in any sphere has no future save absorption, and it has sent them, in everything, in literature, politics, economics, back to their native culture and its traditions.

It may be asserted with truth that the youth of Ireland, in every

generation, are by instinct Separatist, that “their dream is of the swift

sword-thrust,” and that therefore in every generation there is the full

material for a Separatist Movement. The question, then, of the adhesion of

any given generation to a Separatist Movement resolves itself practically

into the question of the formation, at the right time, of a Separatist

Movement with an open policy; and practically any generation of Irishmen

is liable to be drawn from a moderate movement to a Separatist Movement if

the Separatists should develop a sufficiently attractive and workable open

policy. But, in the absence of that, or in the presence of a more workable

or attractive moderate policy, the mass of the people are more liable to

be deflected to the moderate policy and to leave Separatist principles to

the minority who will not compromise and who will carry on a secret

movement in default of an open one. That minority always exists, and the

key to Irish political history in the years since Fenianism may be found

in the fact that Fenianism has never died out of Ireland since its

foundation in 1858 by James Stephens and Thomas Clarke Luby, and that[Pg 14] the

Separatist Minority had always worked through it. Given a suitable open

policy, that minority may become a majority at any time.

Now a Separatist Movement may have a choice of open policies, but it can have only one kind of secret policy, viz., a policy of arming and insurrection. And that is why insurrectionary movements which failed at an attempted insurrection and had no open policy to fall back upon have invariably been succeeded by moderate movements. Emmet was followed by O’Connell, Young Ireland by the Tenant Right Parliamentarian Movement, Fenianism by Parnell.

Fenianism held the field, as a partly secret and partly open movement, although it had no open policy, for many years after ’67, because there was no moderate policy either workable or attractive put forward. But when Parnell developed his machine of Opposition in Parliament and Organisation outside Parliament, and demonstrated that that policy, at any rate, held some possibility of wresting material concessions from England, there was a great landslide from the Separatist Movement, which finally went underground and became again a Separatist minority working in secret. With the death of Parnell died all chance of the policy of Parliamentarianism achieving anything for Ireland, but his fighting personality and record cast a glamour over the Nation for many a year after his death and secured to his successors something of his authority if, unfortunately, it could not secure to them his courage or his ability.

The Separatists, however, were reviving, and gradually the younger generation came into play. The[Pg 15] Gaelic League had turned men’s thoughts towards the old independent Ireland when the language and with it native culture were secure, and that spirit when it sought political expression naturally found it in Separatist form, and as naturally in literary form. So that there came a Separatist revival, largely in literary form, and Literary Societies were established in Dublin, Cork and Belfast which preached Separation and which fell back upon the propaganda methods of the Young Irelanders—ballad, lecture, history, with the significant addition of the language. The movement was to some extent drawn together by the publication (January, 1896, to March, 1899) at Belfast of the “Shan Van Vocht,” a monthly journal projected and edited by Miss Alice Milligan, which printed both literary and political matter, but in form was preponderatingly literary, printed notes of the doings of the various clubs and societies, and in general kept the scattered outposts of the movement in touch with one another. The celebration throughout Ireland of the centenary of ’98 gave further impetus to the growing Separatist sentiment, and when, in 1899, some of the Dublin Separatists established “The United Irishman,” with Mr. Arthur Griffith as editor, the modern Separatist Movement was definitely on its feet.

The influence of the “United Irishman” in accelerating the development of the movement and in drawing it together was immediate. Its chief writers were William Rooney, whose character and whose work were akin to those of Thomas Davis, with again the significant addition that he knew Irish fluently, but of course far behind him in ability, and Mr. Griffith, who[Pg 16] brought to the paper a clear, logical, virile and convincing style which is the best that has come out of Ireland since John Mitchel. The paper gave the movement expression, acted, so to speak, both as secretary and organiser, and was very soon in touch with every club and every convinced Separatist in Ireland, holding them together, encouraging them, increasing them. Clubs grew, and were gathered together in convention and formed into an organisation, “Cumann na nGaedheal,” which took up organisation work vigorously, and which, though at the outset in 1902 it had the misfortune to lose William Rooney, who was its chief inspiration, yet made progress. Separatists grew more confident, more informed, and more numerous.

The propaganda of Cumann na nGaedheal consisted of the Irish language, history study, Irish industries, and self reliance generally, with a pious expression of opinion that everybody ought to have arms. Arming was, however, no portion of its policy, nor had it any public policy in the nature of a platform policy. It was, practically speaking, an educational movement, on the same lines as the Gaelic League, save with a definite political basis, and was carried on on identical lines—classes (language and history), lectures, national concerts, and celebrations of national anniversaries. As such, its influence was limited, and the great majority of the people, who will not go to classes or lectures and are reachable only through some public platform and platform policy, were quite untouched by it. Its members were practically wholly young men and young women with a studious or intellectual bent, and although the “United Irishman” was a very severe[Pg 17] and very pungent critic of the Irish Parliamentary Party, yet “Cumann na nGaedheal” and the Party never crossed swords, because their spheres of action were so widely different that they had no point of contact. Neither set of followers was reachable by the other propaganda.

Although, however, they had no direct point of contact, the Parliamentarian movement began to be conscious of the growing Separatist movement. Its Press sparred a little with the “United Irishman,” and individual members occasionally met and argued. At that time neither the Parliamentary Party nor its Press had developed any open Imperialism: and while in conversation Parliamentarians generally admitted that the Parliamentarian policy was a compromise and indefensible as such, they vigorously defended it on the ground that it was the only alternative to insurrection, which was impracticable: and Separatists, while maintaining that insurrection was the natural and inevitable culmination of any national policy, and that all plans and preparations should have it in view as the ultimate plan, yet could not well contest the argument that in the then state of the country insurrection was impracticable. After a couple of years of intensive educational work, therefore, there sprang up in the rank and file a demand for the framing of a public policy which should preserve principles and yet be a workable alternative to the Parliamentarian policy. And that policy was produced by Mr. Arthur Griffith. He had made, in the “United Irishman,” constant references to the policy by which Hungary had won her freedom from Austria, had constantly recommended[Pg 18] the Parliamentarians—who at the time, be it remembered, defended their policy only on the ground that there was no alternative but insurrection—to adopt a similar policy for Ireland. For a long time he and his friends did not wish to initiate any such policy for Ireland, holding that it was a policy to be initiated and carried on by moderate men rather than by extreme men, but one in which all extreme men might without any sacrifice of principle join. In the first six months of 1904, however, he wrote in the “United Irishman” a series of articles entitled the “Resurrection of Hungary,” in which the history of Hungary’s struggle with and victory over Austria is told with the closest possible analogy to the affairs of Ireland, and containing a final chapter showing how a similar policy, applied to Ireland, could be made equally successful. These articles were republished as a pamphlet and had a wide circulation, with the result that a demand went up from the readers of the “United Irishman” that the “Hungarian Policy,” as it was then called, should be adopted as the alternative to armed insurrection and should be propagated against Parliamentarianism. And, after some manœuvring, that was done, and all public Separatist organisations were fused together in one organisation called “Sinn Fein,” governed by an executive called the “National Council,” with its policy as the “Sinn Fein Policy,” as the “Hungarian Policy” had now been renamed.

“The policy of Sinn Fein purposes to bring Ireland out of the corner and make her assert her existence to the world. I have spoken of an essential; but the basis of the policy is national self-reliance. No law and no series of laws can make a Nation out of a People which distrusts itself.”—Arthur Griffith (1906).

While the immediate inspiration of the Sinn Fein policy may be held to be

Mr. Griffith’s study of Hungary, it is no less undeniable that the roots

of the policy are already in Nationalist writings and proceedings. Swift,

and the 1782 Volunteers, and Davis, and Mitchel, and Lalor, all had some

one or other of the points which make up the modern Sinn Fein policy. And,

had there never been a Hungary, yet the Sinn Fein policy would have come

into being in or about the period at which it actually did. The Gaelic

League had made it inevitable. Supporters of the Parliamentary Party have

at various times accused the Gaelic League of being a political body, of

being anti-Party, and have felt very sore over its alleged breaches of its

non-political constitution. But the Gaelic League is actually

non-political, and rigidly so. It and the [Pg 20]Parliamentarian people do not

mix, and cannot mix, because they represent totally opposite views of

Ireland. It is an impossibility for a supporter of the Parliamentarian

policy to be at the same time a sincere believer in Gaelic League policy.

He will find that his Parliamentarian convictions will vanish, not because

of any propaganda within the Gaelic League, but because the Gaelic League

philosophy, its aggressive self-reliance, its faith in itself, and in

Ireland, these create an outlook and a conviction which, without being

political, are fatal to the Parliamentarian atmosphere and show it for the

helpless, foolish thing it is. In the “Shan Van Vocht” for March, 1897,

Dr. Douglas Hyde, who will not be accused by anybody of being a

politician, has a poem in Irish, “Waiting for Help,” of which the last

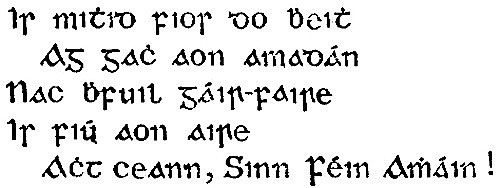

verse is—

(It is time for every fool to recognise that there is only one watchword which is worth anything—Ourselves alone.) This contains the essence of the Sinn Fein policy.

Sinn Fein means ourselves, and the Sinn Fein policy is founded on the faith that the Irish people have the strength to free themselves without any outside aid of any description, if they will only use their strength. To the policy of building up the Nation from without it opposes the policy of building it from within, and[Pg 21] against Freedom by Legislation it puts Freedom by National Self-Development. It takes the motto of Davis, “Educate, that you may be free,” and it applies it to every Irish problem; it takes the Gaelic League principle of developing Irish distinctive features, and it declares war on everything imported, resurrecting Swift’s dictum to “burn everything English save their coals.” The nineteenth century, as I have pointed out, was a century wherein English civilisation attacked Irish civilisation at every possible point of contact: in the twentieth century the Sinn Fein policy reverses that process, and under its banner it is Irish civilisation which is the attacking party.

To regard the Sinn Fein policy as a mere political device is a grave mistake. It is more than politics: it is a national philosophy. Its purely political side has been most prominent because it attacked the existing dominant political party, and because before it can be generally effective it must establish dominance over every other political policy. Nationalists of all shades of opinion would subscribe to a great deal of its constructive programme, and these have often asked why does Sinn Fein not confine itself to those points upon which general agreement can be reached. The answer is that the political policy of Sinn Fein is an integral portion of its general national policy, and that its adoption by the majority of the Irish people is essential to the effective operation of its non-political constructive policy.

The case for the policy of Parliamentarianism, the policy of acquiescing in the Act of Union and sending Irish Nationalist representatives to sit in the English[Pg 22] Parliament, must rest upon one thing, and one alone, upon its effectiveness. It has already against it the damning fact that the sending of Irish representatives to the English Parliament is a giving away of Ireland’s whole case, is an acceptance of the Act of Union, and is a recognition of the authority of the English Parliament to legislate for Ireland. Of itself, argues Sinn Fein, that fact discredits the Parliamentarian policy, even if it were effective, but it is not, and it never has been effective. The “remedial legislation” which the English Parliament has passed for Ireland has been passed in response to agitation in Ireland, and not in response to agitation in Parliament. The only way to set the legislative machine working is to hamper the machine of government in Ireland, and the more effectively that machine is hampered the more drastic the resultant legislation. Instead of London being the lever to work Ireland, Ireland is the lever to work London. No measure of remedial legislation can be pointed to which was passed as the result, directly or indirectly, of parliamentary action. The Catholic Associations of O’Connell, culminating in the Clare election and the ferment it set up, passed the Catholic Emancipation Act; Carrickshock and similar acts of resistance to the collection of tithes passed the Tithes Act; Fenianism disestablished the “Irish” Church and passed the Land Acts; and the Local Government Act was passed by a Unionist Government which had a clear majority over all parties, avowedly as a sop to try and pacify Ireland, and not in response to any pressure of any kind in Parliament, or any Parliamentarian manœuvres. In none of these things had[Pg 23] action in the Parliament of England the least share. It is the agitation at home, and not the agitation in Westminster, that is effective. The only possible function which Irish representatives in London can fulfil is to record Irish opinion, to speak for it, negotiate for it, make it articulate; and that function can be performed much more effectively by representatives living and meeting in Ireland itself.

Sinn Fein thus scores two points against the Parliamentarian policy, that it is a betrayal of Ireland’s case, and that it is totally ineffective. But it is not content with that. It scores yet another point. Not alone is the Parliamentarian policy totally ineffective, but it is hurtful to the Nation. It has turned the imagination of the people away from Ireland towards parliamentary happenings in a foreign Parliament: it has kept their minds on the one phase of activity, the oratorical phase, while language, traditions, and industries vanished from the land, while at every national artery English civilisation entered: it has gradually whittled down the national demand, as the Party gradually became less Irish and more English, until it was ready to accept any shameful settlement as a just settlement: it has been a force, unconscious perhaps but powerful, towards making London the capital of Ireland: under its sway in Ireland the population of Ireland has steadily decreased and the taxation of Ireland has as steadily increased.

That is the Sinn Fein case against the policy of Parliamentarianism, and it is an overwhelming case.

The Sinn Fein policy, on the other hand, reverses the policy of Parliamentarianism, and relies upon[Pg 24] focussing the attention and the strength of the Irish people upon action within Ireland. As a first step towards the resurrection of Ireland it would deny the authority of the English Parliament to legislate for Ireland, and it would refuse to send any representatives whatever to that Parliament. It would assemble in Dublin a National Assembly, elected by the people, to act as a de facto Parliament, which should take within its purview all Ireland and plan for the conservation and development of national resources. The Sinn Fein policy would

(a) Deny the legality of the Act of Union and refuse to send representatives to the English Parliament, thereby cutting the ground at once from under the Union.

(b) Establish Irish as the national language of Ireland; teaching through Irish only in the Irish-speaking districts, and bilingually in the non-Irish-speaking districts.

(c) Remodel the Irish educational chaos, and frame a system based upon Irish culture, and as national as the educational systems of other countries are.

(d) Establish an Irish mercantile marine.

(e) Establish Irish courts of arbitration, to supersede the Law Courts.

(f) Improve transit facilities, cut down internal rates, and overhaul and extend the canal system.

(g) Establish in foreign countries Irish representatives specially trained who would act in the same capacity as consuls.

(h) Direct the strength of the Irish people generally as that of one man in any given direction

(i) Build up Ireland’s manufacturing arm by protection—voluntary or legal—developing also Ireland’s mineral resources, especially her coal and iron.

The Sinn Fein Movement, as such, did not contemplate an appeal to arms, believing that its policy, with the majority of Ireland behind it, would be irresistible on a passive resistance basis. It was really composed of two sections—one, led by Mr. Griffith, wished to base the movement definitely on the Constitution of 1782 and the Renunciation Act of 1783, and the other composed of the Separatists was for independence pure and simple. As a compromise, the object of the movement was defined as “the re-establishment of the Independence of Ireland,” which satisfied the Separatists, with an addendum committing it, as a minimum, to the “King, Lords and Commons” solution, which satisfied the others. Both sections were agreed as to the general lines of policy.

Upon every Irish question, and every possible development in Ireland, Sinn Fein would operate on the same lines as those I have enumerated above. It would build up Ireland from within, strengthening everything Irish and attacking everything foreign, eliminating everything which would send Irish thoughts wandering in search of foreign aid and teaching the people by precept and example that a Nation’s salvation can only be worked out by itself and on its own soil. It would substitute for petitions and resolutions and manœuvres in a foreign Parliament work and more work and still[Pg 26] more work in Ireland. To the Irish people it says in effect: “Turn your eyes and your thoughts away from London and concentrate them on your own concerns. You are of right a free people, and no bonds can affect that right, though they may hamper it. Assert it, not by empty words, but by deeds, so far as you can within the limits of your bonds. Suffer Anglicising and anti-national things only when you must. You send representatives to the English Parliament, testifying to the world an acceptance of your bonds. There is no power that can compel you to send them. Withdraw them, and your honour is once more clean and your case becomes an International one, as of right, not a provincial one, which your Parliamentary manœuvres have almost made it. Establish a National Assembly in Dublin and let it speak for you. You need not speak English, you have your own language; you need not base your education on English culture; you have your own culture. There is no law to compel you to have resource to English law courts, establish voluntary courts of arbitration; there is no law compelling you to buy English manufactures, buy your own; there is no law compelling you to carry on your trade in English ships, establish your own mercantile marine. Stand together, the whole people as one unit, stand up for everything native and reject everything foreign, and freedom is yours.”

The Sinn Fein policy is not a policy that could be made effective by a minority, though even a minority, determined and well led, could make it felt: but if adopted by the majority of the Irish people there is no doubt of its effectiveness. It would make government[Pg 27] impossible: for it must always be remembered that in modern times a subject nation remains a subject nation only because it accepts, in some way or other, its government. A nation which will resolutely and unitedly, on the lines of the Sinn Fein policy, ignore its Government and proceed to the formation of a voluntary (so to speak) Government, would force the occupying power either to give in or to provide an armed guard for every unit of the subject nation.

And, as a matter of historical fact, it was the unconscious application of the Sinn Fein policy that originated all the remedial legislation of the nineteenth century. The Catholic Association of O’Connell, for instance, was practically a Sinn Fein Association, and the records and memoirs of that time show that it had made the ordinary government of Ireland a nullity, and that it forced the Emancipation Act. But when Ireland accepted the Emancipation Act and recognised the Act of Union the process of degeneration set in.

A small man, very sturdily built, nothing remarkable about his appearance

except his eyes, which are impenetrable and steely, taciturn, deliberate,

speaking when he does speak with the authority and the finality of genius,

totally without rhetoric, under complete self-control, and the coolest and

best brain in Ireland.

Griffith is not alone the ablest Irishman now alive, but the ablest Irishman since John Mitchel, and the only political thinker since Mitchel who has displayed the statesman’s mind. He is the master of a style which is more nearly akin to that of Mitchel, and that of Swift, than to any modern style, and is certainly the greatest political writer now concerned with Ireland, and far and away the most potent political influence. Parnell, in his day, said that the Fenians were the backbone of Nationalism in Ireland, and that saying stands as true to-day as it was then. Political parties, and political movements, come and go, but the uncompromising Separatists, the Fenians, are always there, thrusting, it may be, from behind the mask of an open organisation, but always there directing and planning. Griffith can hardly be numbered amongst them. He has never believed in physical force, but has always believed that all Ireland standing together[Pg 29] could force an honourable settlement without physical force. And yet it may be said that no man alive is more responsible for the Fenian spirit in Ireland than Griffith. From 1899 to 1911 the “United Irishman” and its successor, “Sinn Fein,” were the chief inspiration of all extreme propaganda and extreme discussion in Ireland, and although from 1911 until 1914 “Irish Freedom” more properly represented the Fenian element, yet the influence of Griffith has gone heavily in the same direction. It is pretty safe to say that it was the rallying point which the “United Irishman” provided in the early critical days of the movement, its circulation into places where an organiser, even if they had one, could not penetrate, its examination and vindication of the whole case for Ireland, its inculcation of self-reliance and work, and its comprehensive national philosophy generally, that made the later developments of militant nationalism possible.

Arthur Griffith knows Ireland as no other man of his time does, or did, save perhaps his early comrade, William Rooney. There is no epoch of Irish History, no phase of the many-sided Irish problem, that he cannot elucidate. History, biography, economics, politics, literature, in their Irish connexion he has at his fingers’ ends. And outside Ireland he is widely read and far flung. When a comparatively young man he emigrated to the Transvaal, but Ireland drew him and drew him, and he returned to edit the “United Irishman” and to write, when Kruger declared war, that it would take the whole strength of England to win the war—probably the only true prophet amongst the publicists of the time.

[Pg 30]England in Ireland he loves to refer to, following John Mitchel, as “Carthage,” and in all his writing and all his thinking the great battle is the battle between Ireland and Carthage. Every sentence of his is as clean as a sword-cut, and as terrible in its effect as a battle-axe, and his genius for marshalling facts, like artillery, and concentrating them all at once in the direction he is working at is unequalled. His domestic policy for Ireland is the policy of Sinn Fein, and his foreign policy for Ireland is equally logical and equally inevitable. Ireland, he holds, has no business having, at present, any kind of a foreign policy but a defensive one: that is to say that while its domestic policy ought always to be governed by the fact that it is in bondage and fighting for its life, its foreign policy should be governed by precisely the same considerations. In these circumstances abstract right and wrong in continental matters are luxuries he cannot afford to take to his heart. And whenever any event outside Ireland seems worth his comment, he sits down, scalpel in hand, and analyses patiently until he has discovered where England is. And then he has also discovered where Ireland ought to be, and, in so far as he can, he places her there.

He is naturally a believer in evolutionary methods in politics rather than in revolutionary methods, and, in a free Ireland, would I think be found on the side of what the “Times” would call “stability.” He is no great believer in the rights of man, and modern radical catch-cries leave him cold: his creed being rather the rights of nations and the duties of man, the rights of a nation being the right to freedom and[Pg 31] the right to the allegiance and service of all its children, and the duties of man being to fear God and serve his nation. He believes in the State as against the individual, and when in 1913 the great Dublin strike was on foot he opposed it unflinchingly, unheeding the unpopularity of that course, because he believed that the strike was injurious to Ireland. Poverty and sweated labour and social problems generally he would remedy, not by strikes or sabotage, but by State action, and in such action he would have as little leaning towards employers as towards employées, his one guiding principle being the good of the nation.

He believes intensely in himself, and he has no real faith in anybody else, so that he is always more or less cold towards anybody who tries to do any political work on his own, in or about his own particular sphere. And this unfortunate tendency in him has been strengthened by the fact that his immediate friends and co-workers in Dublin are all far below his level in intellect and outlook, follow him blindly, and are equally suspicious of any other attempt to do similar work. He has never had any hero-worship for anybody save William Rooney, and for him he, as well as all Rooney’s co-workers, had the affection and the awe which the Young Irelanders had for Davis. Since the death of Rooney he has been alone intellectually, and while that has doubtless strengthened him, it has also strengthened the difficulty of working with him amicably without being a mere echo. When he got married, everybody gasped, but whatever he may be as a family man, in public life he has continued to be just the same aloof, impenetrable sphinx as before.

[Pg 32]It is a pity that circumstances have put him in the way of making propagandist speeches extensively, for it is not his work. He is an effective speaker. He will stand on a platform and, coolly and without the least trace of passion or emotion, will be more effective in the pungent deadliness of half-a-dozen sentences, without word painting or ornamentation of any kind, than the most flambuoyant orator. But his weapon is the pen, and one article in his best style is worth more than a dozen of his platform speeches. As leader-writer he is unequalled, and as a writer of obituary notices he is unsurpassable.

Once he has made up his mind on anything he never changes. In controversy he is like a bull-dog; he is always the last to let go, and by that time there isn’t much left of the other man’s case. As a controversialist he is able and totally unscrupulous, but he is nearly always right.

Until the recent strenuous period set in, his paper was like a huge magnet which attracted to itself from the length and breadth of Ireland all the poets and budding litterateurs. Its contributors have included W. B. Yeats and Æ and John Eglinton; Seumas O’Sullivan and Padraic Colum; Thomas Boyd and Alice Milligan and Ethna Carbery; finally James Stephens. But in his heart he believes that

“The poets all are foolish

And some of them are wild,”

and eventually there comes an estrangement, if not a quarrel. He has held the minor poets, but the major poets, after doing their best work in his company, have escaped.

[Pg 33]In addition to the poets, the paper attracts to itself first-hand information about all political moves in Ireland and suggested moves. Upon these things his information is usually premature, startling, and eventually extraordinarily accurate. He has his finger on all the strings that control Irish political happenings, and seems to know secret political history almost as well as those who make it.

He always splits his infinitives.

In the years to come, when we his contemporaries and himself are all dead, the historian will attempt to analyse the rapid Anglicisation of Ireland in the nineteenth century, and the desperate struggle at its close to arrest and reverse that Anglicisation. He will give the greater praise to that small company of men and women who formed the Gaelic League in 1893 and by their hard work saved the language and arrested the tide of Anglicisation; but, without detracting from either, he will dwell perhaps most lovingly on the work of Arthur Griffith from 1899 to 1911, upon the brain that took the several strands of the Irish Ireland movement, took every constructive and quickening national idea there was, and wove them all into the most complete and comprehensive national philosophy that has been given to Ireland.

The Sinn Fein movement may be said to have begun in 1905 with, the general

adoption by the Separatist organisations in that year of the “Sinn Fein

Policy” as a basis of operations, and with the combination of all the

organisations into one, and a consequent more effective distribution of

energy, it made rapid progress. Branches of Sinn Fein were quickly formed

in all the larger towns, and more slowly in the smaller towns and in some

country districts. But at first it did not cause much fluttering in the

Parliamentarian dovecote, because its members were nearly altogether apart

from the people, upon whom the Parliamentarians relied for their strength.

Sinn Fein found its expounders and its followers almost wholly amongst

young men and young women of the intellectual order, who were more or less

in the general current set up by the language movement, which was then at

full strength, and who, were it not for Sinn Fein, would not bother

themselves with any political movement—save, of course, the Fenian

minority. It made no attack upon the mainsprings of the Parliamentarian

power, the daily press and the platform, and its propaganda was almost

wholly educational, and was wholly carried on in rooms and debating

societies, with an occasional public[Pg 35] celebration of a national

anniversary. It was, in effect, creating an atmosphere which would

eventually have brought about the complete collapse of the Parliamentarian

power, even without any direct attack, and Mr. Griffith was very much in

favour of continuing the organisation upon that educational basis and

refraining from any incursion into platform politics. Circumstances,

however, proved too strong for him, and a beginning was made with

municipal representation. In Dublin the tide ran very strongly in a Sinn

Fein direction and some ten or a dozen seats were captured at the

municipal elections. Some seats in the provinces were also captured, but

in these cases I think the elections were not won upon a clear political

issue, but upon the personal popularity of the candidates. Wherever

possible the Branches of Sinn Fein inveigled the local Branches of the

United Irish League into debates on their respective policies, and usually

had no difficulty in pulverising them. Many attempts were made, also, to

inveigle members of the Party, but the only member who accepted a Sinn

Fein invitation was Mr. Stephen Gwynn, who was rather severely handled in

debate by the London Central Branch of Sinn Fein; while the “Irish

Parliament” Branch of the U.I.L., in a two nights’ debate, conducted with

great vehemence and in the presence of a huge crowd, was practically

argued out of existence altogether.

The cumulative effect of all this was to set the name Sinn Fein reverberating, ever so slightly but still clearly, in Ireland. The Parliamentarian Press began to be conscious of its existence and it was [Pg 36]understood that it formed a lively topic of discussion, in private, amongst the younger members of the Party. The Party were at the time in very low water. The Liberals had come into power in 1906 with a majority over all parties combined, and they promptly removed Home Rule from their programme, offering instead the Devolution Bill, a plan for appeasing Ireland with a number of glorified County Councils without an Irish Parliament, and which was rejected even by a United Irish League Convention although the Party were understood to be working for its acceptance until the last moment. This offer and its rejection, and the obvious refusal of the Liberal Party to carry out their implied promises with regard to Ireland, and the helplessness of the Parliamentary Party, led to the beginnings of a revolt in the ranks of the Parliamentary Party. Mr. C. J. Dolan, member for North Leitrim, declared himself to be a Sinn Feiner; Sir Thomas Esmonde, a Party Whip at the time, followed suit; and others of the younger members were known, or were credibly believed, to be considering the same course. All the influence which the Party could muster was immediately brought to bear upon the two rebels, and in the case of Sir Thomas Esmonde with complete success. He remained a Sinn Feiner, if my memory is accurate, for about a week, and then recanted. Mr. Dolan, however, proved to have more conviction. He not alone refused to be cajoled, but he resigned his seat and contested it again as a Sinn Feiner. It was the first definite challenge since the Union to the theory of Parliamentarianism.

[Pg 37]The Sinn Fein Executive at the time did not want an election on its hands. It was not ready for it. It knew that the movement, so far as a policy of Parliamentary elections was concerned, was only in its initial stages, that a Sinn Fein candidate outside Dublin stood no chance, and that a Sinn Fein defeat would react unfavourably on the movement, even though a good fight were made. But the circumstances gave them no choice, and both sides did their best in North Leitrim. The Parliamentary Party had all the advantage that money, organisation, and Press could give them; whereas the Sinn Feiners had no money, no organisation in the county, which, up to Mr. Dolan’s conversion, did not contain a single Sinn Feiner, few speakers, no Press save the weekly “United Irishman”—in fact, they had nothing save logic and courage. Mr. Dolan polled 1,200 votes and his opponent some 800 or 900 more, a result which, considering that all the big-wigs of the Party had been sent down to the campaign, was a moral victory for Sinn Fein and heartened the movement immensely; but it undoubtedly set going a reaction against it in the country, and it arrested the flow of converts from the Parliamentarian policy.

A daily paper had long been a cherished project of Mr. Griffith, and during the North Leitrim election he became so sensible of the part played by the daily press in that election that after it was over he set about the establishment of a daily. By sheer obstinacy he talked over the Sinn Fein Executive, none of whom viewed the project with anything but apprehension, and an appeal for funds was made. It was an[Pg 38] inopportune time for such an appeal, as the slender purses of Sinn Feiners had just been emptied in order to defray the expenses of North Leitrim; but enthusiasm was high, and sufficient capital was subscribed for the modest venture it was intended to be. The paper, however, never had a chance of succeeding, its slender capital being counted in hundreds instead of in thousands, and it subsisted for some months only by a periodical call on the purses of its readers, and then collapsed, with adverse results. Its failure not alone damned the chance of the Sinn Fein policy sweeping the country—which chance had looked a sporting one—but it damped the enthusiasm of the individual Sinn Feiners and arrested the movement. And it was followed by another fatal complication. Some individuals who were half Sinn Feiners and half followers of Mr. William O’Brien, one foot in each camp, set on foot the idea of a combination between the two forces, with a mixture of policies, viz., that there should be a Parliamentary Party but that it should be subsidiary, and should be controlled by a National Executive sitting in Dublin, which latter body should decide, as a matter of tactics, whether the Party should attend Parliament or withdraw from Parliament on any particular occasion. (This, it will be noticed, was the after policy of the “Irish Nation League.”) Mr. O’Brien was understood to be favourable to the project, and certain of the Sinn Fein leaders were also said to be not ill-disposed to it: but it was publicly exposed, and as the result the Sinn Fein Executive definitely repudiated it. The mischief had, however, been done: the Sinn Fein credit went[Pg 39] lower and lower in the country, and the Fenian element, to all intents and purposes, withdrew their active support. Finally, when the General Election of January, 1910, gave Mr. Redmond’s Party the balance of power, and the Liberals promised Home Rule, the country definitely threw off the Sinn Fein idea and the organisation dwindled down to a Branch in Dublin, and perhaps two or three in the provinces. From 1910 to 1913 the skeleton of the Sinn Fein organisation continued in existence; the Dublin Central Branch met regularly; the paper appeared regularly; annual conventions were held; but no political work other than indoor educational and propagandist work was done. Even though most of the country branches were moribund, however, the framework of the organisation was still there: it merely marked time until there should be some issue to Mr. Redmond’s balance of power. The Sinn Feiners knew well that that issue would be unfavourable to the continued adhesion of the country to the Parliamentarian policy, and they marked time.

The movement was, properly speaking, the political expression of the spirit which was rendered permanent in Irish evolution by the establishment of the Gaelic League, and its distinguishing characteristic is in the permanence of its principles and of its policy. Its principles and its policy are applicable at any stage of the struggle for Irish freedom and under any conditions, and cannot be overwhelmed. They are based upon ideas rather than on rhetoric, and they appeal to the intellect rather than the passions. They emphasize the distinctive nationality of Ireland, not so[Pg 40] much by talking about it as by producing and strengthening the evidences of that distinctive nationality: and in the brain of Mr. Griffith they evolved a comprehensive and unconquerable national policy, a policy to which all who believe in Ireland a Nation can subscribe without compromising either extreme or moderate degrees of that belief, a policy which, applied by a subject nation, gives the occupying nation three alternatives, viz.: (1) extermination; (2) a permanent army of occupation and the permanent suspension of all pretence at constitutional government; (3) evacuation.

From the beginning the movement was crippled for want of money. Its members, with the exception of Mr. Edward Martyn and Mr. John Sweetman, were all young men and women, earning low wages, whose shillings and sixpences, cheerfully given, only sufficed to keep the paper going, to defray office expenses, and to finance the solitary organiser the Organisation boasted in its best days. Had it had the money in 1907 or 1908, its two best years, to take the best of its young men and let them loose upon Ireland at the work which was nearest their hearts, even Mr. Redmond’s balance of power would not have deferred his eclipse. But its executive knew, and every member knew, that that day was only deferred, and that the Policy of Self-Reliance would hold the field some day.

The English people, either collectively or individually, do not want to

give Ireland freedom. Some of them are willing to concede the name of

freedom whilst reserving its machinery, but they are few. Most of them do

not understand the Irish question, which is an international one, as being

a dispute between two Sovereign Nations, and not an Imperial or Domestic

one, and none of them want to understand it.

Similarly with English political parties. Neither the Liberal Party nor the Tory Party desires to give Ireland freedom, and if they have coquetted with various schemes for extending local government, they have only done so because it was necessary, owing to the Irish vote in the English constituencies or in Parliament, to their retention in office, or because the situation in Ireland necessitated some kind of sop to the sentiment there, and they have taken good care that these coquettings came to nothing. In Mr. Gladstone’s case he could coquet with Home Rule with a perfectly easy mind, because he knew that no Home Rule Bill introduced by a Liberal Government would ever pass the House of Lords. So that he had not to[Pg 42] take any special measures to ensure that the Bill did not pass; all he had to do was to let events take their normal course, and blame the House of Lords. How a man like Parnell could have believed that a Liberal Government, even if it wanted to pass a Home Rule Bill, could do so has always astonished me.

When Mr. Asquith, in order to ensure the passing of advanced Radical legislation, upon the passing of which the continued existence of his Party depended, weakened the House of Lords, the situation changed, and it became necessary to seek some new method of insuring that the Bill should not pass into law, at any rate in any form which would be of the least benefit to Ireland. And that method was provided, possibly at the instance of both parties in England acting together for the benefit of England, and certainly with the full connivance of the Liberal Government, by Sir Edward Carson and his friends in the organisation of the Ulster Volunteers. Mr. Redmond was assured, while the Volunteers were being formed, that the Government would not permit any threats to influence them with regard to the Bill, and then at the last moment they took refuge behind the Ulster Volunteers and regretted that they could give Ireland Home Rule only by Partition. And Partition it would have been were it not for the Irish Volunteers.

The idea of a Volunteer force under Irish control was not a new thing in Ireland. Such a force had made history in the years 1779 to 1782, and there has probably been no generation of Nationalists since which has not at some time or other gone into the possibility of the establishment of a Volunteer force. And[Pg 43] long before the Ulster Volunteers were started, one of the things which Nationalists looked forward to as amongst the first to be done under any Irish government was the establishment of a Volunteer force, whether that power came with the Bill or not. But the objection that had always met any schemes for the establishment of Volunteers, or for any public arming or drilling, was the certainty that, whatever the law on the subject might be, no Irish Volunteer force or analogous body would be permitted by England to come into being. But with the establishment and arming of the Ulster Volunteers, with the connivance of England, it dawned upon many people that there was a sporting chance that, in order to keep up the semblance of impartiality, England would find herself unable to suppress an Irish Volunteer force, unless at any rate the Ulster force were at the same time suppressed. And accordingly the Irish Volunteers were established.

To Sir Edward Carson let the greater praise belong.

The men who established the Irish Volunteers were drawn from several sources. There were some Fenians, some Sinn Feiners, some Parliamentarians, and some who had not hitherto been identified at all with politics. They did not establish the Volunteers as a counterblast to the Ulster Volunteers, or with any idea of either fighting or overawing Ulster. No member of the Irish Volunteers would ever have fired a shot against an Ulster Volunteer for refusing to acknowledge an Act of the English Parliament, even though that Act were a Home Rule Act. Nor were they established to help Mr. Redmond to achieve[Pg 44] Home Rule. They had a vision which went a long way beyond Home Rule. They were established because half-a-dozen Irishmen had the inspiration at about the same time that here was a God-given opportunity of providing Ireland with an armed Volunteer force, which should do as much for Ireland to-day as the Irish Volunteers of 1779-1782 had done for the Ascendancy Parliament. These men were, as the “Freeman’s Journal” put it, “nobodies,” but their work has endured.

The Irish Parliamentary Party did not want an Irish Volunteer movement, not even under their own control. They had degenerated into such ineffective and incapable politicians that they had no glimmering of the way in which they were being fooled, and they were still convinced that speech-making in the House of Commons was the only way to help the Home Rule Bill. And when, at the outset, they and their chief supporters were invited to identify themselves with the movement, in which they would of course have a majority, they peremptorily refused. They believed then that the movement, without their sanction, would not come to anything.

The Government evidently thought so, too, for it allowed the movement to develop, although, in order to be on the safe side, it prohibited the importation into Ireland of arms and ammunition a week after the formation of the first corps. But it soon became evident that the movement was going to be a force to be reckoned with, as parish after parish fell into line, and the Party began to be concerned for their power. In public they made no pronouncement as a Party[Pg 45] against the Volunteer movement, but in private they did their best against it, to no purpose. Then there were some open attacks, by Mr. Hazleton and Mr. Lundon (I think), and still the Volunteers grew. Then a secret order was issued to the A.O.H. Branches to go into the Volunteers and get control of them, but they were refused affiliation as Branches and their members had to come in as individuals, and were posted haphazard to the various companies, thus breaking up their solidarity.

The Parliamentary Party were now seriously alarmed about the Volunteer movement. It continued to grow, and its recruits included not alone men who had never been members of the U.I.L. or A.O.H., but men who were actually members of these organisations and who now gave their first allegiance to the Volunteers. Public opinion had swung over to the Volunteers, and the Party were faced with practical extinction unless they could in some way manage to “get in” on the Volunteer Executive. And therefore a new move was tried. Mr. Redmond opened up secret negotiations with the Volunteers, or rather with Eoin MacNeill, and made various demands for the representation of the Parliamentary Party on the Volunteer Executive. While these negotiations were still in progress, the Press machine and the “public men” machine were set going all over the country, and from all quarters the Party supporters began to bombard the public with statements to the effect that Volunteering was quite the right thing, but that the men in control were unknown and inexperienced men, and that the movement would be safer and more stable, and,[Pg 46] it was whispered, more effective, in the hands of the “elected representatives” of the people. After this had gone on for some little time, Mr. Redmond suddenly delivered an ultimatum to the Volunteer Committee to accept a nomination of 25 representatives from him or else he would instantly split the Volunteers. This nomination would give him a controlling majority on the Volunteer Executive, but it was accepted as the lesser of two evils.

Mr. Redmond’s objects in securing control were three: first, to prevent any further development of the movement on lines which constituted a menace to his own power; second, to prevent the arming of the movement and confine it to a paper Volunteer movement with the sole purpose of establishing a counterpoise to the Ulster Volunteers; and, third, to ensure that any arms which were obtained should be placed with safe men—men, that is, who would place the Irish Parliamentary Party first and the Volunteers second. But in none of these objects was he successful. The Volunteer movement continued to grow, and continued to grow on its own lines, and its own lines naturally led it away from the whole atmosphere and philosophy on which the Parliamentary Party depend: and arms were got in and were placed in the hands of men whose first allegiance was to Ireland and not to Mr. Redmond; for in ability, even the ability to run committees and to organise, Mr. Redmond’s nominees were handsomely outweighted by the original members.

Then came the incidents connected with the gun-running at Howth, to set all Ireland aflame. In the[Pg 47] week which followed it the whole of Nationalist Ireland swerved into the Volunteer ranks, in thousands in the cities, and in hundreds in the country places, and “respectable men, with a stake in the country” offered motor cars, yachts, transit contrivances of all kinds, for Volunteer purposes. Ireland stirred and raised itself, as if out of a long sleep, as if the touch of the steel at Clontarf, the feel of the rifle in the hands of the Volunteers after Howth and Kilcool, had roused her, had brought back to her some of the old outlook. And it was a Volunteer force of perhaps 250,000 men, not armed to any extent, and not well drilled, but the best raw material in the world, that, with the reverberation of the Scottish Borderers’ volley at Bachelor’s Walk not yet banished from their ears, heard suddenly the rumble of the guns of the war. Mr. Redmond, however, thought otherwise.

Had there been no war, the split in the Volunteer movement might have been postponed for some time, might even have been postponed indefinitely, if other events had taken a favourable turn; but the altered situation caused by the war very soon upset the patched-up peace. When Mr. Redmond abrogated the Irish claim, on behalf of his Party and of all the influence he could control in Ireland, the Volunteer Committee trembled but it did not erupt; but when at Woodenbridge he also pledged the Volunteers to a similar abrogation, the Volunteer Committee erupted violently, and the original members expelled Mr. Redmond’s nominees and resumed control. Mr. Redmond immediately formed an Executive of his own, and the Volunteer split was an accomplished[Pg 48] fact: Mr. Redmond had his paper Organisation, but he had not succeeded in destroying the real Organisation, though he had badly hampered it. He had diverted the Irish Volunteers from being a movement representative of the whole of Nationalist Ireland, with the highest ideals and the broadest national principles, into a movement with the original ideals and principles, but representative now only of a minority of the people and, consequently, no longer commanding the same general respect. The after history of the Irish National Volunteers, as Mr. Redmond’s organisation was called, is the history of a make-believe, of a paper Volunteer force, whose only public appearance was one which will be for all time execrated by the people of Ireland.

The promoters of the Volunteer movement had not contemplated insurrection,

nor had they identified themselves with any extreme or physical force

policy. They were not committed to Separation, to Sinn Fein, or to

Parliamentarianism, but to the defence of Irish rights, and to the

obtaining of arms and ammunition for that purpose. Each of them had his

own idea of what exactly the movement stood for, as had the rank and file,

but all were content to sink differences and subscribe to the simple

formula of defending Irish rights, which embraced them all and embraced

all their policies. Upon that basis they carried Ireland with them,

united, despite political machines and jealousies, for the first time for

generations.

The outbreak of war however changed that, and made it imperative on every section to reconsider the position, and to revise policy. The Parliamentarians and the Fenians were the first to make up their minds, the one to work for an insurrection and the other not alone to suspend Ireland’s claims but actively to support England. The resultant split left Mr. Redmond with an imposing organisation, on paper, but left only one genuine body of Nationalist Volunteers in Ireland—the original Irish Volunteers. But its membership was[Pg 50] now reduced to the extreme men—using the term to denote every school of Nationalist thought which went beyond Parliamentarianism. And that inevitably ensured the controlling influence to the Fenians, the only men who were out with a definite policy. The campaign which, immediately after the expulsion of Mr. Redmond and his followers, was carried on against the Volunteers by the united forces of the Government and of the Parliamentary Party hardened them and inclined the whole body towards the policy on which the Fenians were building, and although there were to the end two sections in the Volunteers, one which wanted an insurrection and one which only contemplated it in the event of Partition or Conscription and desired to keep the organisation intact with a view to its weight being used in any post-bellum attempt at settlement, yet the temper of the whole body was such that the Fenian element dominated it for all practical purposes. The self-denying ordinance under which they had at the beginning refrained from being prominently identified with the movement had no further justification, and they controlled the Executive, as representing the majority opinion of the organisation. The result we know.

When the Volunteers expelled Mr. Redmond’s nominees it was considered good tactics by the Parliamentarian press to dub the original Irish Volunteers the “Sinn Fein” Volunteers, the Party having judged that Sinn Fein as a policy was beyond the possibility of resurrection: and in course of time the name “Sinn Feiner” came to be used where up to that time “Factionist” had been the favourite term. When the [Pg 51]insurrection occurred it was promptly labelled a “Sinn Fein” insurrection, and the papers were full of stories about the “Sinn Fein” colours, stamps, commandoes, and desperadoes. All this with the object of discrediting the insurrection, the name “Sinn Fein” not being in good odour in the country. Thus Sinn Fein, from being politics, and discredited politics, suddenly became history. And at the same time the Unionists made their contribution to its rehabilitation.