Title: The History of Painting in Italy, Vol. 1 (of 6)

Author: Luigi Lanzi

Translator: Thomas Roscoe

Release date: November 29, 2010 [eBook #34479]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Barbara Tozier, Carol Brown, Bill Tozier and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

J. M'Creery, Tooks Court,

Chancery Lane,

London.

After the very copious and excellent remarks upon the objects of the present history contained in the Author's Preface, the Translator feels that it would be useless on his part to add any further explanation.

It would not be right, however, to close these volumes without some acknowledgment of the valuable assistance he has received. Amongst others, he is particularly indebted to Dr. Traill, of Liverpool, who after proceeding to some length with a translation of this work, kindly placed what he had completed in the hands of the Translator, with liberty to make such use of it as might be deemed advantageous to the present undertaking. To Mr. W. Y. Ottley, who also contemplated, and in part executed, a version of the same author, the Translator has to express his obligations for several explanations of terms of art, which the intimacy of that gentleman with the fine arts, in all their branches, peculiarly qualifies him to impart.[1] Similar acknowledgments are[Pg iv] due to an enlightened and learned foreigner, Mr. Panizzi, of Liverpool, for his kind explanation of various obscure phrases and doubtful passages.

Notwithstanding the anxious desire and unremitting endeavours of the Translator to render this work, in all instances, as accurate as the nature of the subject, and the numerous difficulties he had to surmount would allow, yet, in dismissing it from his hands, he cannot repress the feeling that he must throw himself upon the indulgence of the public to excuse such errors as may be discoverable in the text. He trusts, however, that where it may be found incorrect, it will for the most part be in those passages where doubtful terms of art lay in his way, intelligible only to the initiated, and which perhaps many of the countrymen of Lanzi themselves might not be able very readily to explain.

[1] The following are among the valuable works which have been given to the public by Mr. Ottley:—The Italian School of Design, being a series of Fac-similes of Original Drawings, &c.—An Inquiry into the History of Engraving.—The Stafford Gallery.—A Series of Plates engraved after the Paintings and Sculptures of the most eminent masters of the early Florentine School, during the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries. This work forms a complete illustration of the first volume of Lanzi.—A Catalogue of the National Gallery.—Fac-similes of Specimens of Early Masters, &c.

| Page | |

| Advertisement | iii |

| Preface by the Author | i |

| Biographical Notice by the Translator | xli |

HISTORY OF PAINTING IN LOWER ITALY.

BOOK I.

FLORENTINE SCHOOL.

| Epoch I. | Origin of the revival of painting—Association and methods of the old painters—Series of Tuscan artists before the time of Cimabue and Giotto. Sect. I. | 1 |

| Florentine painters who lived after Giotto to the end of the fifteenth century. Sect. II. | 51 | |

| Origin and progress of engraving on copper and wood. Sect. III. | 105 | |

| Epoch II. | Vinci, Bonarruoti, and other celebrated artists, form the most flourishing era of this school | 147 |

| Epoch III. | The imitators of Michelangiolo | 229 |

| Epoch IV. | Cigoli and his Associates improve the style of painting | 280 |

| Epoch V. | Pietro da Cortona and his followers | 335 |

BOOK II.

SIENESE SCHOOL.

| Epoch I. | The old masters | 372 |

| Epoch II. | Foreign painters at Siena—Origin and progress of the modern style in that city | 406 |

| Epoch III. | The art having declined through the disasters of the state, is revived by the labours of Salimbeni and his sons | 433 |

When detached or individual histories become so numerous that they can neither be easily collected nor perused, the public interest requires a writer capable of arranging and embodying them in the form of a general historical narrative; not, indeed, by a minute detail of their whole contents, but by selecting from each that which appears most interesting and instructive. Hence it mostly happens, that the diffuse compositions of earlier ages are found to give place to compendiums, and to succinct history. If this desire has prevailed in former times, it has been, and now is, more especially the characteristic of our own. We live in an age highly favourable, in one sense at least, to the cultivation of intellect: the boundaries of science are now extended beyond what our forefathers could have hoped, much less foreseen; and we become anxious only to discover the readiest methods of obtaining a competent knowledge, at least, of several sciences, since it is impossible to acquire them all. On the other hand, the ages [Pg ii]preceding ours, since the revival of learning, being more occupied about words than things, and admiring certain objects that now seem trivial to the generality of readers, have produced historical compositions, the separate nature of which demands combination, no less than their prolixity requires abridgment.

If these observations are applicable to other branches of history, they are especially so to the history of painting. Its materials are found ready prepared, scattered through numerous memoirs of artists of every school which, from time to time, have been given to the public: and additional articles are supplied by dictionaries of art, letters on painting, guides to several cities, catalogues of various collections, and by many tracts relating to different artists, which have been published in Italy. But these accounts, independent of want of connexion, are not useful to the generality of readers. Who, indeed, could form a just idea of painting in Italy by perusing the works of certain historians of latter ages, and some even of our own time, which abound in invectives, and in attempts to exalt favourite masters above the artists of all other schools; and which confer eulogies indiscriminately upon professors of first, second, or third-rate merit?[2] How few are there who feel[Pg iii] interested in knowing all that is said of artists with so much verbosity by Vasari, Pascoli, or Baldinucci; their low jests, their amours, their private affairs, and their eccentricities? What do we learn by being informed of the jealousies of the Florentine artists, the quarrels of the Roman, or the boasts of the Bolognian schools? Who can endure the verbal accuracy with which their wills and testaments are recorded, even to the subscription of the notary, as if the author had been drawing up a legal document; or the descriptions of their stature and physiognomy, more minute than the ancients afford us of Alexander or Augustus?[3] Not that I object to the introduction of such particulars in the lives of the great luminaries of art: in a Raffaello or a Caracci minute circumstances derive interest from the subject; but how intolerable do they become [Pg iv]in the life of an ordinary individual, where the principal incidents are but little interesting? Suetonius has not written the lives of his Cæsars and his grammarians in the same manner: the former he has rendered familiar to the reader; the latter are merely noticed and passed over.

The tastes of individuals, however, are different, and some people delight in minutiæ, as it regards both the present and the past; and since it may be of utility to those who may hereafter be inclined to give a very full and perfect history of every thing relating to Italian painting, let us view with indulgence those who have employed themselves in compiling lives so copious, and let those who have time to spare, beguile it with their perusal. At the same time, due regard should be paid to that very respectable class of readers, who, in a history of painting, would rather contemplate the artist than the man; and who are less solicitous to become acquainted with the character of a single painter, whose solitary and insulated history cannot prove instructive, than with the genius, the method, the invention, and the style of a great number of artists, with their characteristics, their merits, and their rank, the result of which is a history of the whole art.

To this object there is no one whom I know who has hitherto dedicated his pen, although it seems to be recommended no less by the passion [Pg v]indulged by princes for the fine arts, than by the general diffusion of a knowledge of them among all ranks. The habit of travelling, rendered more familiar to private persons by the example of many great sovereigns, the traffic in pictures, now become a branch of commerce important to Italy, and the philosophic genius of this age, which shuns prolixity in every study, and requires systematic arrangement, are additional incentives to the task. It is true that very pleasing and instructive biographical sketches of the most celebrated painters have been published by M. d'Argenville, in France; and various epitomes have since appeared, in which the style of painting alone is discussed.[4] But without taking into account the corruptions of the names of our countrymen in which their authors have indulged, or their omission of celebrated Italians, while they record less eminent artists of other countries, no work of this sort, and still less any dictionary, can afford us a systematic history of painting: none of these exhibit those pictures, if we may be allowed the[Pg vi] expression, in which we may, at a glance, trace the progress and series of events; none of them exhibit the principal masters of the art in a sufficiently conspicuous point of view, while inferior artists are reduced to their proper size and station: far less can we discover in them those epochs and revolutions of the art, which the judicious reader most anxiously desires to know, as the source from which he may trace the causes that have contributed to its revival or its decline; or from which he may be enabled to recollect the series, and the arrangement of the facts narrated. The history of painting has a strong analogy to literary, to civil, and to sacred history; it too requires, from time to time, the aid of certain beacons, some particular distinction in regard to places, times, or events, that may serve to divide it into epochs, and mark its successive stages. Deprive it of these, and it degenerates, like other history, into a chaos of names more calculated to load the memory than to inform the understanding.

To supply this hitherto neglected branch of Italian history, to contribute to the advancement of the art, and to facilitate the study of the different styles in painting, were the three objects I proposed to myself when I began the work which I am now about to lay before the indulgent reader. My intention was to form a compendious history of all our schools, in two volumes; adopting, with [Pg vii]little variation, Pliny's division of the country into Upper and Lower Italy. It was my design to comprehend in the first volume the schools of Lower Italy; because in it the reviving arts came earlier to maturity; and in the second to include the schools of Upper Italy, which were more tardy in attaining to celebrity. The first part of my work appeared at Florence in 1792: the second I was obliged to defer to another opportunity, and the succeeding years have so shaken my constitution, that I have scarcely been able to bring it to a conclusion, even with the assistance of many amanuenses and correctors of the press.[5] One advantage, however, has been derived from this delay; and that is, a knowledge of the opinion of [Pg viii]the public, a tribunal from which no writer can appeal; and I have been thus enabled to prepare a new edition conformable to its decision.[6] I have understood through various channels, that an additional number of names and of notices were necessary to afford satisfaction to the public; and this I have accomplished, without abandoning my plan of a compendious history. Nor does the Florentine edition on this account become useless: it will even be preferred by many to that published at Bassano; the inhabitants, for instance, of Lower Italy will be pleased to possess a work on their most illustrious painters, without concerning themselves about accounts of other places.

To a new work, then, so much more extensive than the former, I prefix a preface almost entirely new. The plan is not wholly my own, nor altogether that of others. Richardson[7] suggested that some historian should collect the scattered remarks on art, especially on painting, and should point out its progress and decline through successive ages. He has not even omitted to give us a sketch, which he brought down to the time of Giordano. [Pg ix]Mengs[8] accomplished the task more perfectly in the form of a letter, where he judiciously distinguished all the periods of the art, and has thus laid the foundations of a more enlarged history. Were I to follow their example, the chief masters of every school would be considered together, and we should be under the necessity of passing from one country to another, according as painting acquired a new lustre from their talents, or was debased by a wrong use of the great example of those artists. This method might be easily pursued, if the subject were to be treated in a general point of view, such as Pliny has considered and transmitted it to posterity; but it is not equally adapted to the arrangement of a history so fully particular as Italy seems to require. Besides the styles introduced by the most celebrated painters, such infinite diversities of a mixed character, often united with originality of manner, have arisen in every school, that we cannot easily reduce them to any particular standard: and the same artists at different periods, and in different pictures, have adopted styles so various, that at one time they appear imitators of Titian, at another of Raffaello, or of Correggio. We cannot, therefore, adopt the method of the naturalist, who having arranged the vegetable kingdom, for example, in classes more or less numerous, according to the systems of [Pg x]Tournefort or of Linnæus, can easily reduce a plant, wherever it may happen to grow, to a particular class, adding a name and description, at once precise, characteristic, and permanent. In a complete history it is necessary to distinguish each style from every other: nor do I know any more eligible method of performing this task, than by composing a separate history of each school. In this I follow Winckelmann, the best historian of ancient art in design, who specified as many different schools as the nations that produced them. A similar plan seems to me to have been pursued by Rollin, in his History of Nations, who has thus been enabled to record a prodigious mass of names and events within the compass of a few volumes, in the clearest order.

The method I follow in treating of each school is analogous to that prescribed to himself by Sig. Antonio Maria Zanetti,[9] in his Pittura Veneziana, [Pg xi]a work of its kind highly instructive, and well arranged. What he has done, in speaking of his own, I have attempted in the other schools of Italy. I accordingly omit the names of living painters, and do not notice every picture of deceased artists, as it would interrupt the connexion of the narrative, and would render the work too voluminous, but content myself with commending some of their best productions. I first give a general character of each school; I then distinguish it into three, four, or more epochs, according as its style underwent changes with the change of taste, in the same way that the eras of civil history are deduced from revolutions in governments, or other remarkable events. A few celebrated painters, who have swayed the public taste, and given a new tone to the art, are placed at the head of each epoch; and their style is particularly described, because the general and characteristic taste of the age has been formed upon their models. Their immediate pupils, and other disciples of the school, follow their great masters; and without a repetition of the general character, reference is made to what each has borrowed, altered, or added to the style of the founder of the school, or at most such character is cursorily noticed. This method, though not susceptible of a strict chronological order, is, on account of the connexion of ideas, much better adapted to [Pg xii]a history of art than an alphabetic arrangement, which too frequently interrupts the notices of schools and eras; or than the method pursued in annals, by which we are often compelled to make mention of the scholar before the master, should he survive the former; or that of separate lives, which introduces much repetition, by obliging the writer to bestow praises on the pupil for the same style which he also commends in the master, and to notice in each individual that which was the general character of the age in which he lived.

For the sake of perspicuity, I have generally separated from historical painters artists in inferior branches, such as painters of portraits, of landscape, of animals, of flowers and of fruit, of sea-pieces, of perspectives, of drolls, and all who merit a place in such classes. I have also taken notice of some arts which are analogous to painting, and though they differ from it in the materials employed, or the manner of using them, may still be included in the art; for example, engraving of prints, inlaid and mosaic work, and embroidering tapestry. Vasari, Lomazzo, and several other writers on the fine arts, have mentioned them; and I have followed their example; contenting myself with noticing, in each of those arts, only what has appeared most worthy of being recorded. Each might be the subject of a separate work; [Pg xiii]and some of them have long had their own peculiar historians, and in particular the art of engraving. By this method, in which I may boast such great examples, I am not without hopes of affording satisfaction to my readers. I am, however, more apprehensive in regard to my selection of artists; the number of whom, whatsoever method is adopted, may to some appear by far too limited, and to others too greatly extended. But criticism will not so readily apply to the names of the most illustrious artists, whom I have included, nor to those of very inferior character, whom I trust I have omitted; except a few that have some claim to be mentioned, from their connexion with celebrated masters.[10] The accusation then of having noticed some, and omitted others, will apply to me only on account of artists of a middle class, that can be neither well reckoned among the senate, the equestrian order, nor vulgar herd of painters; they constitute the class of mediocrity. The adjustment of limits is a frequent cause of legal contention; and the subject of art now under [Pg xiv]discussion, may be considered like a dispute concerning boundaries. It may often admit of doubt whether a particular artist approaches more nearly to the class of merit or of insignificance; which is, in other words, whether he should or should not obtain a place in a history of the art. Under such uncertainty, which I have several times encountered, I have more usually inclined to the side of lenity than of severity; especially when the artist has been noticed with a degree of commendation by former authors. We ought to bow to public opinion, which rarely blames us for noticing mediocrity, but frequently for passing it over in silence. Books on painting abound with complaints against Orlandi and Guarienti, for their omissions of certain artists. Still more frequently are authors censured, when the Guide to a city points out some altar-piece by a native artist, who is not named in our Dictionaries of Painting. The describers of collections repeat similar complaints in regard to every painting bearing the signature of an artist whose name appears in no work of art. Collectors of prints do the same when they discover the name of some designer, of whom history is silent, affixed to an engraving. Thus, were we to consult the opinion of the public, the majority would be inclined to recommend copiousness, rather than to express satisfaction at a more discriminating [Pg xv]selection of names. Almost all artists and amateurs belonging to every city, would be desirous that I should commemorate as many of their second rate painters as possible; and our selection, therefore, in this respect, nearly resembles the exercise of justice, which is generally applauded as long as it visits only the dwellings of others, but is cried down by each individual when it knocks at his own door. Thus a writer who is bound to observe impartiality towards every city, can scarcely shew great severity to artists of mediocrity in any. This too is not without reason; for to pass mediocrity in silence may be the study of a good orator, but not the office of a good historian. Cicero himself, in his treatise De claris Oratoribus, has given a place to less eloquent orators, and it may be observed that, after this example, the literary history of every people does not merely include its most classic writers, and those who approached nearest to them; but it adds short and concise accounts of authors less celebrated; and in the Iliad, which is a history of the heroic age, there are a few eminent leaders, many valiant soldiers, and a prodigious crowd of others, whom the poet has transiently noticed. In our case, it is still more incumbent on the historian to give mediocrity a place along with the eminent and most excellent. Many books describe that class in terms so vague, and sometimes [Pg xvi]so discordant, that to form a proper estimate of their claims, we must introduce them among superior artists, as a sort of performers in third-rate parts. Such, however, I am not solicitous to exhibit very minutely, more especially when treating of painters in fresco, and generally of other artists, whose works are now unknown in collections, or add more to the bulk than the ornament of a gallery. Thus also in point of number, my work has maintained the character of a compendium: but if any of my readers, adopting the rigid maxim of Bellori, that, in the fine arts, as in poetry, mediocrity is not to be tolerated,[11] should disdain the middle class of artists, he must look [Pg xvii]for the heads of schools, and for the most eminent painters: to these he may dedicate his attention, and turn his regard from the others like one,

Having described my plan, let us next consider the three objects originally proposed, of which the first was to present Italy with a history that may prove important to her fame. This delightful country is already indebted to Tiraboschi for a history of her literature, but she is still in want of a history of her arts. The history of painting, an art in which she is confessedly without a rival, I propose to supply, or at least to facilitate the attempt. In some departments of literature, and of the fine arts, we are equalled, or even surpassed by foreigners; and in others the palm is yet doubtful: but in painting, universal consent now yields the triumph to Italian genius, and foreigners are the more esteemed in proportion to their approach towards us. It is time then, for the honour of Italy, to collect in one point of view, those observations on her painting, scattered through upwards of a hundred volumes, and to embody them in what Horace terms series et junctura; without which the work cannot be pronounced a history. I [Pg xviii]will not conceal, that the author of the "History of Italian Literature" above mentioned, frequently animated me to this undertaking, as a sequel to his own work. He also wished me to subjoin other anecdotes to those already published, and to substitute more authentic documents for the inaccuracies abounding in our Dictionaries of painting. I have attended to both these objects. The reader will here find various schools never hitherto illustrated, and an entire school, that of Ferrara, now first described from the manuscripts of Baruffaldi and of Crespi; and in other schools he will often observe names of fresh artists, which I have either collected from ancient MSS.[13] and the correspondence of my learned friends, or deciphered on old paintings. Although such pictures are confined to cabinets, it cannot prove useless to extend a more intimate acquaintance with their authors. The reader will also meet with many new observations on the origin of painting, and on its diffusion in [Pg xix]Italy, formerly a fruitful subject of debate and contention; and likewise here and there with some original reflections on the masters, to whom various disciples may be traced; a branch of history, the most uncertain of any. Old writers of respectability often mention Raffaello, Correggio, or some other celebrated artist, as the master of a painter, without any better foundation than a similarity of style; just as the credulous heathens imagined one hero to be the son of Hercules, because he was strong; another of Mercury, because he was ingenious; a third of Neptune, because he had performed several long voyages. Errors like these are easily corrected when they are accompanied by some inadvertency in the writer; as for instance, where he has not been aware that the age of the disciple does not correspond with that of his supposed master. Occasionally, however, their detection is attended with more difficulty; and in particular when the artist, whose reputation is wholly founded upon that of his master, represented himself in foreign parts, as the disciple of men of celebrity, whom he scarcely knew by sight. Of this we have an example in Agostino Tassi, and more recently in certain soidisant disciples of Mengs; to whom it scarcely appears that he ever so much as said, "Gentlemen, how do you do?"

Finally, the reader will find some less obvious notices relating to the name, the country, and [Pg xx]the age of different artists. The deficiency of our Dictionaries in interesting names, together with their inaccuracy, are common subjects of complaint. I can excuse the compilers of these works; I know how easily we may be misled in regard to names which have been often gathered from vulgar report, or even from authors who differ in point of orthography, some giving opposite readings of the same name. But it is quite necessary that such mistakes should once for all be cleared up. The index of this work will form a new Dictionary of Painters, certainly more copious, and perhaps more accurate than usual, although it might be still further improved, especially by consulting archives and manuscripts.[14]

[Pg xxi]The second object which I had in view was to advance the interests of the art as much as lay in my power. It was of old observed that examples have a more powerful influence on the arts than any precepts can possess; and this is particularly true in respect to painting. Whoever writes history upon the model of the learned ancients, ought not only to narrate events, but to investigate their secret sources and their causes. Now these will be here developed, tracing the progress of painting as it advanced or declined in each school; and these causes being invariable, point out the means of its improvement, by shewing what ought to be[Pg xxii] pursued and what avoided. Such observations are not of importance to the artist alone, but have a reference also to other individuals. In the Roman school, during its second epoch, I perceive that the progress of the arts invariably depends on certain principles universally adopted in that age, according to which artists worked, and the public decided. A general history, by pointing out the best maxims of art, may contribute considerably to make them known and regarded; and hence artists can execute, and others approve or direct, on principles no longer uncertain and questionable, nor deduced from the manner of a particular school, but founded on maxims unerring and established, and strengthened by the uniform practice of all schools and all ages. We may add, that in a history so diversified, numerous examples occur suited to the genius of different students, who have often to lament their want of success from this circumstance alone, that they had neglected to follow the path in which nature had destined them to tread. On the influence of examples I shall add no more: should any one be desirous also of precepts under every school, he will find them given, not indeed by me, but by those who have written more ably on the art, and whom I have diligently consulted with regard to different masters, as I shall hereafter mention.

My third object was to facilitate an acquaintance with the various styles of painting. The artist or [Pg xxiii]amateur indeed, who has studied the manner of all ages and of every school, on meeting with a picture can very readily assign it, if not to a particular master, at least to a certain style, much as antiquarians, from a consideration of the paper and the characters, are enabled to assign a manuscript to a particular era; or as critics conjecture the age and place in which an anonymous author flourished, from his phraseology. With similar lights we proceed to investigate the school and era of artists; and by a diligent examination of prints, drawings, and other relics belonging to the period, we at length determine the real author. Much of the uncertainty, with regard to pictures, arises from a similitude between the style of different masters: these I collect together under one head, and remark in what one differs from the other. Ambiguity often arises from comparing different works of the same painter, when the style of some of them does not seem to accord with his general manner, nor with the great reputation he may have acquired. On account of such uncertainty, I usually point out the master of each artist, because all at the outset imitate the example offered by their teachers; and I, moreover, note the style formed, and adhered to by each, or abandoned for another manner; I sometimes mark the age in which he lived, and his greater or less assiduity in his profession. By an attentive consideration of [Pg xxiv]such circumstances, we may avoid pronouncing a picture spurious, which may have been painted in old age, or negligently executed. Who, for instance, would receive as genuine all the pictures of Guido, were it not known that he sometimes affected the style of Caracci, of Calvart, or of Caravaggio; and at other times pursued a manner of his own, in which, however, he was often very unequal, as he is known to have painted three or four different pieces in a single day? Who would suppose that the works of Giordano were the production of the same artist, if it were not known that he aspired to diversify his style, by adopting the manner of various ancient artists? These are indeed well known facts, but how many are there yet unnoted that are not unworthy of being related, if we wish to avoid falling into error? Such will be found noticed in my work, among other anecdotes of the various masters, and the different styles.

I am aware that to become critically acquainted with the diversity of styles is not the ultimate object to which the travels and the eager solicitude of the connoisseur aspire. His object is to make himself familiar with the handling of the most celebrated masters, and to distinguish copies from originals. Happy should I be, could I promise to accomplish so much! Even they might consider themselves fortunate, who dedicate their lives to [Pg xxv]such pursuits, were they enabled to discover any short, general, and certain rules for infallibly determining this delicate point! Many rely much upon history for the truth. But how frequently does it happen that the authority of an historian is cited in favour of a family picture, or an altar-piece, the original of which having been disposed of by some of the predecessors, and a copy substituted in its place, the latter is supposed to be a genuine painting! Others seem to lay great stress on the importance of places, and hesitate to raise doubts respecting any specimen they find contained in royal and select galleries, assuming that they really belong to the artists referred to in the gallery descriptions and catalogues. But here too they are liable to mistake; inasmuch as many private individuals, as well as princes, unable to purchase ancient pictures at any price, contented themselves with such copies of their imitators as approached nearest to the old masters. Some indeed were made by professors purposely despatched by princes in search of them; as in the instance of Rodolph I., who employed Giuseppe Enzo, a celebrated copyist. (See Boschini, p. 62, and Orlandi, on Gioseffo Ains di Berna.) External proofs, therefore, are insufficient, without adding a knowledge of different manners. The acquisition of such discrimination is the fruit only of long experience, and deep reflection on the style of each master: [Pg xxvi]and I shall endeavour to point out the manner in which it may be obtained.[15]

To judge of a master we must attend to his design, and this is to be acquired from his drawings, from his pictures, or, at least, from accurate engravings after them. A good connoisseur in prints is more than half way advanced in the art of judging pictures; and he who aims at this must study engravings with unremitting assiduity. It is thus his eye becomes familiarized to the artist's method of delineating and foreshortening the figure, to the air of his heads and the casting of his draperies; to that action, that peculiarity of conception, of disposing, and of contrasting, which are habitual to his character. Thus is he, as it were, introduced to the different families of youths, of children, of women, of old men, and of individuals in the vigour of life, which each artist has adopted as his own, and has usually exhibited in his pictures. We cannot be too well versed in such matters, so minute or almost insensible are the distinctions between the imitators of one master, (such as Michelangiolo, for example,) who have perhaps studied the same cartoon, or the same statues, and, as it were, learned to write after the same model.

More originality is generally to be discovered in[Pg xxvii] colouring, a branch of the art formed by a painter rather on his own judgment, than by instruction. The amateur can never attain experience in this branch who has not studied many pictures by the same master; who has not observed his selection of colours, his method of separating, of uniting, and of subduing them; what are his local tints, and what the general tone that harmonizes the colours he employs. This tint, however clear and silvery in Guido and his followers, bright and golden in Titiano and his school, and thus of the rest, has still as many modifications as there are masters in the art. The same remark extends to middle tints and to chiaroscuro, in which each artist employs a peculiar method.

These are qualities which catch the eye at a distance, yet they will not always enable the critic to decide with certainty; whether, for instance, a certain picture is the production of Vinci, or Luini, who imitated him closely; whether another be an original picture by Barocci, or an exact copy from the hand of Vanni. In such cases judges of art approach closer to the picture with a determination to examine it with the same care and accuracy as are employed in a judicial question, upon the recognition of hand-writing. Fortunately for society, nature has granted to every individual a peculiar character in this respect, which it is not easy to counterfeit, nor to mistake [Pg xxviii]for any other person's writing. The hand, habituated to move in a peculiar manner, always retains it: in old age the characters may be more slowly traced, may become more negligent or more heavy; but the form of the letters remains the same. So it is in painting. Every artist not only retains this peculiarity, but one is distinguished by a full charged pencil; another by a dry but neat finish; the work of one exhibits blended tints, that of another distinct touches; and each has his own manner of laying on the colours:[16] but even in regard to what is common to so many, each has a peculiar handling and direction of the pencil, a marking of his lines more or less waved, more or less free, and more or less studied, by which those truly skilled from long experience are enabled, after a due consideration of all circumstances, to decide who was the real author. Such judges do[Pg xxix] not fear a copyist, however excellent. He will, perhaps, keep pace with his model for a certain time, but not always; he may sometimes shew a free, but commonly a timid, servile, and meagre pencil; he will not be long able, with a free hand, to keep his own style concealed under the manner of another, more especially in regard to less important points, such as the penciling of the hair, and in the fore- and back-grounds of the picture.[17] Certain observations on the canvas and the priming ground may sometimes assist inquiry; and hence some have endeavoured to attain greater certainty by a chemical analysis of the colours. Diligence is ever laudable when exerted on a point so nice as ascertaining the hand-work of a celebrated master. It may prevent our paying ten guineas for what may not be worth two; or placing in a choice collection pictures that will not do it credit; while to the curious it affords scientific views, instead of creating prejudices that often engender errors. That mistakes should happen is not surprising. A true connoisseur is still more rare than a good artist. His skill is the result of only indirect application; it is acquired amidst other pursuits, and divides the attention with other objects; the means of attaining it fall to the lot of few; and still fewer practise it successfully. [Pg xxx]Among the number of the last I do not reckon myself. By this work I pretend not, I repeat it, to form an accomplished connoisseur in painting: my object is to facilitate and expedite the acquisition of such knowledge. The history of painting is the basis of connoisseurship; by combining it, I supersede the necessity of referring to many books; by abbreviating it I save the time and labour of the student; and by arranging it in a proper manner on every occasion, I present him with the subject ready prepared and developed before him.

It remains, in the last place, that I should give some account of myself; of the criticisms that I, who am not an artist, have ventured to pass upon each painter: and, indeed, if the professors of the art had as much leisure and experience in writing as they have ability, every author might resign to them the field. The propriety of technical terms, the abilities of artists, and the selection of specimens of art, are usually better understood, even by an indifferent artist, than by the learned connoisseur: but since those occupied in painting have not sufficient leisure to write, others, assisted by them, may be permitted to undertake the office.[18]

[Pg xxxi]By the mutual assistance which the painter has afforded to the man of letters, and the man of letters to the artist, the history of painting has been greatly advanced. The merits of the best painters are already so ably discussed that a modern historian can treat the subject advantageously. The criticisms I most regard are those that come directly from professors of the art. We meet with few from the pen of Raphael, of Titian, of Poussin, and of other great masters; such as exist, however, I regard as most precious, and deserving the most careful preservation; for, in general, those who can best perform can likewise judge the best. Vasari, Lomazzo, Passeri, Ridolfi, Boschini, Zanotti, and Crespi, require, perhaps, to be narrowly watched in some passages where they allowed themselves to be surprised by a spirit of party: but, on the whole, they have an undoubted right to dictate to us, because they were themselves painters. Bellori, Baldinucci, Count Malvasia, Count Tassi, and similar writers, hold an inferior rank; but are not wholly destitute of authority: for though mere dilettanti, they have collected [Pg xxxii]both the opinions of professors and of the public. This will at present suffice, with regard to the historians of the art: we shall notice each of them particularly under the school which he has described.

In pronouncing a criticism upon each artist I have adopted the plan of Baillet, the author of a voluminous history of works on taste, where he does not so frequently give his own opinion as that of others. Accordingly, I have collected the various remarks of connoisseurs, which were scattered through the pages of history; but I have not always cited my authorities, lest I should add too much to the dimensions of my book;[19] nor have I regarded their opinion when they seemed to me to have been influenced by prejudice. I have availed myself of the observations of some approved critics, like Borghini, Fresnoy, Richardson, Bottari, Algarotti, Lazzarini, and Mengs; with others who have rather criticised our painters than written their lives. I have also respected the opinions of[Pg xxxiii] living critics, by consulting different professors in Italy: to them I have submitted my manuscript; I have followed their advice, especially when it related to design, or any other department of painting, in which artists are almost the only adequate judges. I have conversed with many connoisseurs, who, in some points, are not less skilful than the professors of the art, and are even consulted by artists with advantage; as, for instance, on the suitableness of the subject, on the propriety of the invention and the expression, on the imitation of the antique, on the truth of the colouring. Nor have I failed to study the greatest part of the best productions of the schools of Italy; and to inform myself in the different cities what rank their least known painters hold among their connoisseurs; persuaded, as I am, that the most accurate opinion of any artist is formed where the greatest number of his works are to be seen, and where he is most frequently spoken of by his fellow citizens and by strangers. In this way, also, I have been enabled to do justice to the merits of several artists who had been passed over, either because the historian of their school had never beheld their productions, or had merely met with some early and trivial specimens in one city, being unacquainted with the more perfect and mature specimens they had produced elsewhere.

Notwithstanding my diligence I do not presume[Pg xxxiv] to offer this as a work to which much might not be added. It has never happened that a history, embracing so many objects, is at once produced perfect; though it may gradually be rendered so. The history earliest in point of time, becomes, in the end, the least in authority; and its greatest merit is in having paved the way to more finished performances. Perfection is still less to be expected in a compendium. The reader is here presented with the names of many artists and authors; but many others might have been admitted, whom want of leisure or opportunity, but not of respect, has obliged us to omit. Here he will find a variety of opinions; but to these many others might have been added. There is no man, of whom all think alike. Baillet, just before mentioned, is a proof of this, with regard to writers on literary subjects; and he who thinks the task worthy of his pains might demonstrate it much more fully with respect to different painters. Each judges by principles peculiar to himself: Bonarruoti stigmatized as drivelling, Pietro Perugino and Francia, both luminaries of the art; Guido, if we may credit history, was disapproved of by Cortona; Caravaggio by Zucchero; Guercino by Guido; and, what seems more extraordinary, Domenichino by most of the artists who flourished at Rome, when he painted his finest pictures.[20] Had these artists written of [Pg xxxv]their rivals they either would have condemned them, or spoken less favourably of them than unprejudiced individuals. Hence it is that connoisseurs will frequently be found to approach nearer the truth, in forming their estimate, than artists; the former adopt the impartial feelings of the public, while the latter allow themselves to be influenced by motives of envy or of prejudice. Innumerable similar disputes are still maintained concerning several artists, who, like different kinds of aliment, are found to be disagreeable or grateful to different palates. To hold the happy mean, exempted from all party spirit, is as impossible as to reconcile the opinions of mankind, which are as multifarious as are the individuals of the species.

Amid such discrepancy of opinion I have judged it expedient to avoid the most controverted points; in others, to subscribe to the decision of the majority; [Pg xxxvi]to allow to each his particular opinion;[21] but not, if possible, to disappoint the reader, desirous of learning what is most authentic and generally received. Ancient writers appear to have pursued this plan when treating of the professors of any art, in which they themselves were mere amateurs; nor could it arise from any other circumstance that Cicero, Pliny, and Quintilian, express themselves upon the Greek artists in the same manner. Their opinions coincide, because[Pg xxxvii] that of the public was unanimous. I am aware that it is difficult to obtain the opinion of the public concerning the more modern artists, but it is not difficult with regard to those on whom much has been already written. I am also aware that public opinion accords not at all times with truth, because "it often happens to incline to the wrong side of the question." This, however, is a rare occurrence in the fine arts,[22] nor does it militate against an historian who aims more at fidelity of narrative, and impartiality of public opinion, than the discussion of the relative merit or correctness of tastes.

My work is divided into six volumes; and I commence by treating in the two first volumes of that part of Italy, which, through the genius of Da Vinci, Michelangiolo, and Raffaello, became first conspicuous, and first exhibited a decided character in painting. Those artists were the ornaments of the Florentine and Roman schools, from which I proceed to two others, the Sienese and Neapolitan. About the same time Giorgione, Tiziano, and Coreggio, began to flourish in Italy; three artists, who as much advanced the art of [Pg xxxviii]colouring, as the former improved design; and of these luminaries of Upper Italy I treat in the third and fourth volumes; since the number of the names of artists, and the many additions to this new impression, have induced me to devote two volumes to their merits. Then follows the school of Bologna, in which the attempt was made to unite the excellences of all the other schools: this commences the fifth volume; and on account of proximity it is succeeded by that of Ferrara, and Upper and Lower Romagna. The school of Genoa, which was late in acquiring celebrity, succeeds, and we conclude with that of Piedmont, which, though it cannot boast so long a succession of artists as those of the other states, has merits sufficient to entitle it to a place in a history of painting. Thus the five most celebrated schools will be treated of in the order in which they arose; in like manner as the ancient writers on painting began with the Asiatic school, which was followed by the Grecian, and this last was subdivided into the Attic and Sicyonian; to which in process of time succeeded the Roman school.[23] The sixth and last volume contains an ample index to the whole, quite indispensable to render the work more extensively useful, and to give it its[Pg xxxix] full advantage. In assigning artists to any school I have paid more regard to other circumstances than the place of their nativity; to their education, their style, their place of residence in particular, and the instruction of their pupils: circumstances, indeed, which are sometimes found so blended and confused, that several cities may contend for one painter, as they are said to have done for Homer. In such cases I do not pretend to decide; the object of my labours being only to trace the vicissitudes of the art in various places, and to point out those artists who have exercised an influence over them; not to determine disputes, unpleasant in themselves, and wholly foreign to my undertaking.

[2] See Algarotti, Saggio sopra la Pittura, in the chapter Della critica necessaria al Pittore.

[3] For this fault, which the Greeks used to call Acribia, Pascoli has been sharply reproved. He has, in fact, informed us which among the several artists could boast a becoming and proportionate nose, which had it short or long, aquiline or snubbed, very sharp or very hollow. He most generally observes that such an artist was neither tall nor large of stature, neither handsome nor plain in his physiognomy; and who would have thought it worth his while to inquire about it? The sole utility that can possibly attend such inquiries is, the chance of detecting some impostor, who might attempt to palm upon us for a genuine portrait the likeness of some other individual. Engravings, however, are the best security against similar impositions.

[4] In the Magasin Encyclopédique of Paris, (An. viii. tom. iv. p. 63), there is a work in two volumes, edited in the German language at Gottingen, announced as well as commended. The first volume is dated 1798, the second 1801, from the pen of note the learned Sig. Florillo, the title of which we insert in the second index. It consists of a history of painting upon the plan of the present one; but there is some variation in the order of the schools.

[5] It was finished in the year 1796, and it is now given, with various additions and corrections throughout. Many churches, galleries, and pictures, are here mentioned which are no longer in existence; but this does not interfere with its truth, inasmuch as the title of the work is confined to the before mentioned year. Numerous friends have lent me their assistance in the completion of this edition, and in particular the cavalier Gio. de' Lazara, a gentleman of Padua, who possesses a rich collection, both in books and MSS., and displays the utmost liberality in affording others the use of them. To this merit, in regard to the present work, he has likewise added that of revising and correcting it through the press, a favour which I could not have more highly estimated from any other hand, deeply versed as he is in the history of the fine arts.

[6] "Ut enim pictores, et qui signa faciunt, et vero etiam poetæ suum quisque opus à vulgo considerari vult, ut si quid reprehensum sit à pluribus id corrigatur ... sic aliorum judicio permulta nobis et facienda et non facienda, et mutanda et corrigenda sunt." Cicero De Officiis, ii. c. 41.

[7] Treatise on Painting, tom. ii. p. 166.

[8] Opere, tom. ii. p. 108.

[9] A learned Venetian, skilled in the practice of design and of painting. He must not be confounded with Antonio Maria Zanetti, an eminent engraver, who revived the art of taking prints from wooden blocks with more than one colour, which was invented by Ugo da Carpi, but afterwards lost. He also wrote works, serviceable to the fine arts; and several of his letters may be seen in the second volume of Lettere Pittoriche. They are subscribed Antonio Maria Zanetti, q. Erasmo; but this is an error of the editor: it ought to be q. Girolamo, to distinguish him from the other, who was called del q. Alessandro. This mistake was detected by the accurate Vianelli, in his Diario della Carriera, p. 49.

[10] An amateur, who happens to be unacquainted with the fact, that there were various artists of the same name, as the Vecelli, Bassani, and Caracci, will never become properly acquainted with these families of painters; neither will he be competent to judge of certain pictures, which only attract the regard of the vulgar, because they truly boast the reputation of a great name.

[11] I do not admit this principle. Horace laid it down for the art of poetry alone, because it is a faculty that perishes when it ceases to give delight. Architecture, on the other hand, confers vast utility when it does not please, by presenting us with habitations; and painting, and sculpture, by preserving the features of men, and illustrious actions. Besides, let us recollect, that Horace denounces the production of inferior verses, because there is not space enough for them; "Non concessere columnæ," but it is not so with paintings of mediocrity. In any country Petrarch, Ariosto, and Tasso, may be read, and he who has never read a poor poet, will write better than if he had read a hundred. But it is not every one who can boast either in the houses or temples of his country, of possessing the works of good artists; and for purposes of worship or of ornament, the less excellent ones may suffice; wherefore these also produce some advantage.

[12] Like one who thinks of some other person than he that is before him.

[13] For the improvement of my latest edition, I am greatly indebted to the Prince Filippo Ercolani, who, having purchased from the heirs of Signor Marcello Oretti fifty-two manuscript volumes, which that indefatigable amateur, in the course of his studies, journeys, and observations, had compiled respecting the professors of the fine arts, their eras, and their labours, allowed materials to be drawn from them for various notes, by the Sig. Lazara, who superintended the edition. To the devoted attachment of these gentlemen to the fine arts, the public are indebted for much information, either wholly new, or hitherto little known.

[14] Vasari, from whom several epochs are taken, is full of errors in dates, as may be every where perceived. See Bottari's note on tom. ii. p. 79. The same observation applies generally to other authors, as Bottari remarks in a note on Lettere Pittoriche, tom. iv. p. 366. A similar objection is made to the Dictionary of P. Orlandi in another letter, tom. ii. p. 318, where it is termed "a useful work, but so full of errors, that one can derive no benefit from it without possessing the books there quoted." After three editions of this work, a fourth was printed in Venice, in 1753, corrected and enlarged by Guarienti, "but enough still remains to be done after his additions, even to increase it twofold." Bottari, Lett. Pitt. tom. iii. p. 353. See also Crespi Vite de' Pittori Bolognesi, p. 50. No one, who has not perused this book, would believe how often he defaces Orlandi in presuming to correct him; multiplying artists for every little difference with which authors wrote the name of the same man. Thus Pier Antonio Torre, and Antonio Torri, are with him two different men. Many of the articles, however, added by him, relating to artists unknown to P. Orlandi, are useful; so that this second Dictionary ought to be consulted with caution, not altogether rejected. The last edition, printed at Florence, in two volumes, contains the names of many painters, either lately dead, or still living, and often of very inferior merit, and on this account is little noticed in my history. This Dictionary, moreover, affords little satisfaction to the reader concerning the old masters, unless he possess a work printed at Florence in twelve volumes, entitled Serie degli Uomini più illustri in Pittura, to which the articles in it often refer. The Dizionario Portatile, by Mr. La Combe, is also a book of reference, not very valuable to those who look for exact information. We give a single instance of his inaccuracy in regard to the elder Palma; but our emendations have been chiefly directed towards the writers of Italy, from whom foreigners have, or ought to have borrowed, in writing respecting our artists.

[15] See Mr. Richardson's Treatise on Painting, tom. ii. p. 58; and M. D'Argenville's Abrégé de la Vie des plus fameux Peintres, tom. i. p. 65.

[16] "Some made use of pure colours, without blending one with the other; a practice well understood in the age of Titiano: others, as Coreggio, adopted a method totally opposite: he laid on his admirable colours in such a manner, that they appear as if they had been breathed without effort on the canvas; so soft and so clear, without harshness of outline, and so relieved, that he seems the rival of nature. The elder Palma and Lorenzo Lotto coloured freshly, and finished their pictures as highly as Giovanni Bellini; but they have loaded and overwhelmed them with outline and softness in the style of Titiano and Giorgione. Some others, as Tintoretto, to a purity of colour not inferior to the artists above mentioned, have added a boldness as grand as it is astonishing;" &c. Baldinucci, Lett. Pittor. tom. ii. lett. 126.

[17] See Baldinucci in Lett. Pittor. tom. ii. lett. 126, and one by Crespi, tom. iv. lett. 162.

[18] We must recollect that "de pictore, sculptore, fusore, judicare nisi artifex non potest," (Plin. Jun. i. epist. 10); which must be understood of certain refinements of the art that may escape the eye of the most learned connoisseur. But have we any need of a painter to whisper in our ear whether the features of a figure are handsome or ugly, its colouring false or natural, whether it has harmony and expression, or whether its composition be in the Roman or Venetian taste? And where it is really expedient to have the opinion of an artist, which we therefore report as we have either read it or heard it, will that opinion have less authority in my pages than on his own tongue?

[19] Abundance of quotations, and descriptions of the minutest particulars from rarer works is a characteristic of the present day, to which I think I have sufficiently conformed in my second Index. But in a history expressly composed to instruct and please, I have judged it right not to interrupt the thread of the narrative too frequently with different authorities. The works from which I draw my account of each artist are indicated in the body of the history and in the first index: to make continual allusion to them might please a few, but would prove very disagreeable to many.

[20] Pietro da Cortona told Falconieri that when the celebrated picture of S. Girolamo della Carità was exhibited, "it was so abused by all the eminent painters, of whom many then flourished, that he himself joined in its condemnation, in order to save his credit." See Falconieri, Lett. Pittor. tom. ii. lett. 17. He continues: "Is not the tribune of the church of S. Andrea della Valle, ornamented by Domenichino, among the finest specimens of painting in fresco? and yet they talked of sending masons with hammers to knock it down after he had displayed it. When Domenichino afterwards passed through the church, he stopped with his scholars to view it; and, shrugging up his shoulders, observed, 'After all, I do not think the picture so badly executed.'"

[21] The most singular and novel opinions concerning our painters are contained in the volumes published by M. Cochin, who is confuted in the Guides to the cities of Padua and Parma, and is often convicted of erroneous statements in matter of fact. He is reproved, with regard to Bologna, by Crespi, in Lett. Pittor. tom. vii.; and for what he has said of Genoa, by Ratti, in the lives of the painters of that city. Commencing with his preface, they point out the grossest errors in Cochin. It is there also observed that his work was disapproved of by Watellet, by Clerisseau, and other French connoisseurs then living: nor do I believe it would have pleased Filibien, De Piles, and such masters of the critical art. Italy also, at a later period, has produced a book, which aims at overturning the received opinions on subjects connected with the fine arts. It is entitled Arte di vedere secondo i principii di Sulzer e di Mengs. The author, who in certain periodical works at Rome, was called the modern Diogenes, has been honoured with various confutations. (See Lettera in Difesa del Cav. Ratti, p. 11.) Authors like these launch their extravagant opinions, for the purpose of attracting the gaze of the world; but men of letters, if they cannot pass them over in silence, ought not to be very anxious to gratify their wishes—"Opinionum commenta delet dies." Cicero.

[22] Of Apelles himself Pliny observes, "Vulgum diligentiorem judicem quam se præferens." Examine also Carlo Dati in Vite de' Pittori Antichi, p. 99, where he proves, by authority and examples, that judgment, in the imitative arts, is not confined to the learned. See also Junius, De Pictura Veterum, lib. i. cap. 5.

[23] See Mons. Agucchi, in a fragment preserved by Bellori, in Vite de' Pittori, Scultori, e Architetti moderni, p. 190.

Luigi Lanzi was born in the year 1732, at Monte dell' Olmo, in the diocese of Fermo, of an ancient family, which is said to have enjoyed some of the chief honours of the municipality to which it belonged. His father was a physician, and also a man of letters: his mother, a truly excellent and pious woman, was allied to the family of the Firmani. How deeply sensible the subject of this memoir was of the advantages he derived, in common with many illustrious characters, from early maternal precepts and direction, he has shewn in a beautiful Latin elegy to her memory, which appeared in his work, entitled Inscriptionum et Carminum.

Possessed of a naturally lively and penetrating turn of mind, he began early to investigate the [Pg xlii]merits of the great writers of his own country; alike in poetry, in history, and in art. His poetical taste was formed on the models of Petrarch and of Dante, and he was accustomed, while yet a child, to repeat their finest passages to his father, an enthusiastic admirer of Italy's old poets, who took pride in cultivating the same fervour in the mind of his son, a fervour of which in more northern climates, we can form little idea. His imitations of these early poets, whose spirit he first imbibed at the fountain head, before he grew familiar with the corrupt and tasteless compositions of succeeding eras, are said to have frequently been so bold and striking, as to deceive the paternal eye. To these, too, he was perhaps mainly indebted for that energy of feeling, and solidity of judgment, as well as that richness of illustration and allusion, which confer attractions upon his most serious and elaborate works. He was no less intimate with the best political and literary historians at an early age; with Machiavelli, Davila, and Guicciardini; with Muratori and Tiraboschi; whose respective compositions he was destined to rival in the world of art.

Lanzi's first studies were pursued in the Jesuits' College at Fermo, where an Italian Canzone, written in praise of the Beata Vergine, is said to have acquired for him, as a youth of great promise, the highest degree of regard. Under the care of his spiritual instructor, father Raimondo Cunich, Lanzi likewise became deeply versed in all the excellences[Pg xliii] of classical literature, not as a vain parade of words and syllables; for along with the technical skill of the scholar, he imbibed the spirit of the ancient writers. In his succeeding philosophical and mathematical studies he was assisted by Father Boscovich, one of the first mathematicians of his day. Thus to a keen and fertile intellect, animated by enthusiasm for true poetry and the beauties of art, was added that regular classical and scientific learning, inducing a love of order and of truth, capable of applying the clear logic derived from Euclid to advantage, in subjects of a less tangible and demonstrative nature. The value of such preliminary acquirements to the examination of antiquarian and scientific remains, which can only be conducted on uncertain data and a calculation of possibilities, as in ancient specimens of art, can bear no question; and of this truth Lanzi was fully aware. To feel rightly, to reason clearly, to decide upon probabilities, to distinguish degrees, resemblances, and differences, comparing and weighing the whole with persevering accuracy; these were among the essentials which Lanzi conceived requisite to prepare a writer upon works of art.

These qualities, too, will be found finely relieved and elevated by frequent and appropriate passages of eloquent feeling; flowing from that sincere veneration for his subject, and that love which may be termed the religion of the art to which he became so early attached. How intimately [Pg xliv]such a spirit is connected with the best triumphs of the art of painting, is seen in the angelic faces of Da Vinci, of Raffaello, and Coreggio; and the same enthusiasm must have been felt by a true critic, such as Lanzi. Far, however, from impeding him in the acquisition of his stores of antiquarian knowledge, and in his scientific arrangements, his enthusiasm conferred upon him only an incredible degree of diligence and despatch. He was at once enabled to decipher the age and character, to arrange in its proper class, and to give the most exact description of every object of art which passed under his review.

Lanzi thus came admirably prepared to his great task, one of the most complete models of sound historical composition, of which the modern age can boast. It was written in the full maturity of his powers; no hasty or isolated undertaking, it followed a series of other excellent treatises, all connected with some branches of the subject, and furnishing materials for his grand design. Circumstances further contributed to promote his views. Shortly after the dissolution of the order of Jesuits, to which he belonged, he was recommended by his friend Fabroni, prior of the church of S. Lorenzo, to the grand duke Leopold of Florence, who, in 1775, appointed him to the care of his cabinet of medals and gems, in the gallery of Florence. This gave rise to one of his first publications, entitled, A Description of the Florentine Gallery, which he sent in 1782 to the same friend,[Pg xlv] Angiolo Fabroni, then General Provveditore of the Studio at Pisa, and who conducted the celebrated Literary Journal of that place, in which Lanzi's Description appeared.

His next dissertation, still more enriched with antiquarian illustration and research, was his Essay on the Ancient Italian dialects, which contains a curious account of old Etruscan monuments, and the ducal collection of classical vases and urns. This was followed by his Preliminary Notices respecting the Sculpture of the Ancients, and their various Styles, put forth in the year 1789, in which he pursues the same plan which he subsequently perfected in the history before us, of allotting to each style its respective epochs, to each epoch its peculiar characters, these last being exemplified by their leading professors, most celebrated in history. He farther adduces examples of his system as he proceeds, from the various cabinets of the Royal Museum, which he explains to the reader as a part of his chief design in illustrating them. He enters largely into the origin and character of the Etruscan School, and examines very fully the criticisms, both on ancient and Italian art, by Winckelmann and Mengs.

From the period of these publications, the Grand Duke, entertaining a high opinion of Lanzi's judgment, was in the habit of consulting him before he ventured to add any new specimens to his cabinet of antiquities. He was also entrusted with a fresh arrangement of some new cabinets belonging[Pg xlvi] to the gallery, which together with the latter, he finally completed, on a system which it is said never fails to awaken the admiration of all scientific visitors at Florence. During this task, his attention had been particularly directed to the interpretation of the monuments and Etruscan inscriptions contained in the ducal gallery, which, together with the ancient Tuscan, the Umbrian, and other obsolete dialects, soon grew familiar to him, and led to the composition of his celebrated Essay upon the Tuscan Tongue. For the purpose of more complete research and illustration, he obtained permission from the duke to visit Rome, in order to consult the museums, and prepare the way for his essay, which he published there in 1789; a work of immense erudition and research.

It was here Lanzi first appeared as the most profound antiquarian of modern Italy, by his successful explanation of some ancient Etruscan inscriptions and remains of art, which had baffled the skill of a number of his most distinguished countrymen. Upon presenting it to the grand duke, after his return from Rome, Lanzi was immediately appointed his head antiquary and director of the Florentine gallery; while the city of Gubbio raised him to the rank of their first patrician order, on account of his successful elucidation of the famous Eugubine Tables. In one of his Dissertations upon a small Tuscan Urn, he triumphantly refuted some charges which had been invidiously advanced against him, and defended his[Pg xlvii] principles of antiquarian illustration by retorting the charge of fallacy upon his adversaries.

In the year 1790, Lanzi, at the request of the Gonfaloniere and priors of Monte dell'Olino, published an inquiry into the Condition and Site of Pausula, an ancient City of Piceno; said to be written with surprising ingenuity, yet with equal fairness; uninfluenced by any prejudices arising from national partiality, or from the nature of the commission with which he had been honoured. This was speedily followed by a much more important undertaking, connected with the prosecution of his great design, which it would appear he had already for some time entertained.

During the period of his travels through Italy in pursuit of antiquities, he had carefully collected materials for a general History of Painting, which was meant to comprize, in a compendious form, whatever should be found scattered throughout the numerous authors who had written upon the art. These materials, as well as the work itself, had gradually grown upon his hands, as might be expected from a man so long accustomed to method, to criticism, to perspicuity; in short, to every quality requisite in the philosophical treatment of a great subject. The artists and literati of Italy, then, were not a little surprised at the appearance of the first portion of the Storia Pittorica, comprehending Lower Italy; or the Florentine, Sienese, Roman, and Neapolitan Schools, reduced to a compendious and methodical form,[Pg xlviii] adapted to facilitate a knowledge of Professors and of their Styles, for the lovers of the art. It was dedicated to the grand duchess Louisa Maria of Bourbon, in a style, observes the Cav. Bossi, "which recalls to mind the letters of Pliny to Trajan, composed with mingled dignity and respect; with genuine feeling, and with true, not imaginary, commendations." Elogio, p. 127.

But the unfeigned pleasure and admiration expressed in the world of literature and art, on being presented with the Pictorial History of Lower Italy, was almost equalled by its disappointment at the delay experienced with regard to the appearance of the second part; and which it was feared would never see the light. Lanzi's state of health had, some time subsequent to 1790, been very precarious; and he suffered severely from a distressing complaint,[25] which frequently interrupted his travels in which he was then engaged, collecting further materials for his History of Painting in Upper Italy. While thus employed, on his return from Genoa in December, 1793, he experienced a first attack of apoplexy, as he was passing the mountains of Massa and Carrara. After his recovery, and return to Florence, he was advised in the ensuing spring to visit the baths of Albano, which being situated near Bassano, afforded him an opportunity of superintending the publication of his history, in the Remondini [Pg xlix]Press, and on a more extensive scale than he had at first contemplated. He likewise obtained permission from the grand duke Leopold to absent himself, during some time, from his charge at Florence, in September, 1793. The first portion of his labours he conceived to be too scanty in point of names and notices to satisfy public taste, so that upon completing the latter part upon a more full and extensive scale, he gave a new edition of that already published, very considerably altered and augmented.

To these improvements he invariably contributed, both in notes and text, at every subsequent edition, a number of which appeared in the course of a few years, until the work attained a degree of completeness and correctness seldom bestowed upon labours of such incredible difficulty and extent. The last which received the correction and additions of the author was published at Bassano, in the year 1809.

That a work upon such a scale was a great desideratum, no less to Italy than to the general world of art, would appear evident from the character of the various histories and accounts of painting which had preceded it. They are rather valuable as records, than as real criticism or history; as annals of particular characters and productions derived from contemporary observation, than as sound and enlightened views, and a dispassionate estimate of individual merits. Full of errors, idle prejudices, and discussions foreign to the subject, a [Pg l]large portion of their pages is taken up in vapid conceits, personal accusations, and puerile reasoning, destitute of method.

The work of Lanzi, on the other hand, as it is well remarked by the Cav. Boni, observes throughout the precept of the serie et junctura of Horace. It brings into full light the leading professors of the art, exhibits at due distance those of the second class, and only glances at mediocrity and inferiority of character, insomuch as to fill up the great pictoric canvas with its just lights and shades. The true causes of the decline and revival of the art at certain epochs are pointed out, with those that contribute to preserve the fine arts in their happiest lustre; in which, recourse to examples more than to precepts is strongly recommended. The best rules are unfolded for facilitating the study of different manners, some of which are known to bear a resemblance, though by different hands, and others are opposed to each other, although adopted by the same artist; a species of knowledge highly useful at a period when the best productions are eagerly sought after at a high rate. It is a history, in short, worthy of being placed at the side of that on the Literature of Italy by Tiraboschi, who having touched upon the fine arts at the outset of his labours, often urged his ancient friend and colleague to dilate upon a subject in every way so flattering to the genius of Italy; to Italy which, however rivalled by other nations in science and in literature, [Pg li]stands triumphant and alone in its creative mind of art.

It is, however, difficult to convey a just idea of a work composed upon so enlarged and complete a scale; which embraces a period of about six centuries, and fourteen Italian schools, but treated with such rapidity and precision, as to form in itself a compendium of whatever we meet with in so many volumes of guides, catalogues, descriptions of churches and palaces, and in so many lives of artists throughout the whole of Italy. (pp. 130-1.)

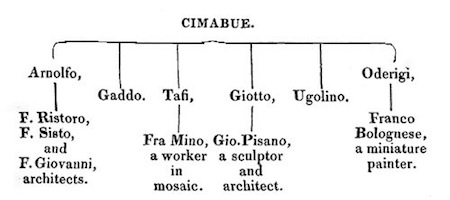

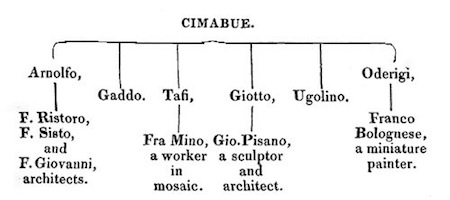

It is known that Richardson expressed a wish that some historian would collect these scattered accounts relating to the art of painting, at the same time noting down its progress and decline in every age, a desideratum which Mengs in part supplied in one of his letters, briefly marking down all the respective eras. Upon this plan, as far as regarded Venetian painting, Zanetti had partially proceeded; but the general survey, in its perfect form, of the whole of the other schools, was destined to be completed by the genius of Lanzi. Here he first gives the general character of each, distinguishing its particular epochs, according to the alterations in taste which it underwent. A few artists of distinguished reputation, whose influence gave a new impulse and new laws to the art, stand at the head of each era, which they may be said to have produced, with a full description of their style. To these great masters, their respective pupils are annexed, with the progress of their [Pg lii]school, referring to such as may have more or less added to, or altered the manner of their prototype. For the sake of greater perspicuity, the painters of history are kept distinct from the artists in inferior branches; among whom are classed portrait and landscape painters, those of animals, of flowers, of fruits, &c. Nor are such as bear an affinity to the art, like engraving, inlaying, mosaic work, and embroidery, wholly excluded. Being doubtful whether he should make mention of those artists who belong neither to the senatorial, the equestrian, nor the popular order of the pictorial republic, and have no public representation, such as the names of mediocrity; Lanzi finally decided to introduce them among their superiors, like third-rate actors, whose figures may just be seen, in order to preserve the entireness of the story. To this he was farther induced by the general appearance of their names in the various dictionaries, guides, and descriptions of cities and of galleries; and by the example of Homer, Cicero, and most great writers; Homer himself commemorating, along with the wise and brave also the less valiant—the fools and the cowards. (Elogio, pp. 129, 130, 131.)

After having resided during a considerable period at Bassano, occupied in the superintendence of the first edition of his great work, Lanzi found himself compelled to retire to Udine, in 1796, from the more immediate scene of war; a war which subsequently involved other cities of Italy [Pg liii]in its career. From Udine he shortly returned to Florence, where he again resumed his former avocations in the ducal gallery, about the period of the commencement of the Bourbon government.

Lanzi's next literary undertaking was three Dissertations upon Ancient painted Vases, commonly called Etruscan; and he subsequently published a very excellent and pleasing work, entitled, Aloisii Lanzii Inscriptionum et Carminum Libri Tres: works which obtained for him the favourable notice of the Bourbon court. Nor was he less distinguished by that of the new French dynasty, which shortly obtained the ascendancy throughout all Italy, as well as at Florence, and by which Lanzi was appointed President of the Cruscan Academy.

Among Lanzi's latest productions may be classed his edition and translations of Hesiod; entitled I Lavori, e le Giornate di Esiodo Ascreo opera con L. Codici riscontrata, emendata la versione latina, aggiuntavi l'Italiana in Terze Rime con annotazioni. In this he had been engaged as far back as the year 1785, and it had been then announced in a beautiful edition of Hesiod, translated into Latin by Count Zamagua.