W.H.G. Kingston

"Among the Red-skins"

Chapter One.

Missing.

An Unexpected Return—Hugh is Absent—No Knowledge of his Whereabouts—Uncle Donald’s Apprehensions—A Hurried Supper, and Preparations for a Search.

“Hugh, my lad! Hugh, run and tell Madge we have come back,” cried Uncle Donald, as he and I entered the house on our return, one summer’s evening, from a hunting excursion in search of deer or any other game we could come across, accompanied by three of our dogs, Whiskey, Pilot, and Muskymote.

As he spoke, he unstrapped from his shoulders a heavy load of caribou meat. I, having a similar load, did the same—mine was lighter than his—and, Hugh not appearing, I went to the door and again called. No answer came.

“Rose, my bonnie Rose! Madge, I say! Madge! Where are you all?” shouted Uncle Donald, while he hung his rifle, with his powder-horn and shot-pouch, in their accustomed places on the wall.

On glancing round the room he seemed somewhat vexed to perceive that no preparations had been made for supper, which we expected to have found ready for us. It was seldom, however, that he allowed himself to be put out. I think I can see him now—his countenance, though weather-beaten and furrowed by age, wearing its usual placid and benignant expression; while his long silvery beard and the white locks which escaped from beneath his Highland bonnet gave him an especially venerable appearance. His dress was a plaid shooting-coat, and high leggings of well-tanned leather, ornamented with fringe after the fashion of the Indians. Upright as an arrow, with broad shoulders and wiry frame, he stood upwards of six feet in his mocassins, nor did he appear to have lost anything of the strength and energy of youth.

As no one appeared, I ran round to the back of the house, thinking that Rose and Madge, accompanied by Hugh, had gone to bring in the milk, which it was the duty of Sandy McTavish to draw from our cows, and that he, for some cause or other, being later than usual, they had been delayed. I was not mistaken. I presently met them, Madge carrying the pails, and Rose, a fair-haired, blue-eyed little maiden, tripping lightly beside her. She certainly presented a great contrast in appearance to the gaunt, dark-skinned Indian woman, whose features, through sorrow and hardship, had become prematurely old. I inquired for Hugh.

“Is he not with you?” asked Rose, in a tone of some little alarm. “He went off two hours ago, saying that he should be sure to fall in with you, and would assist in bringing home the game you might have killed.”

“Yes, Hugh would go. What he will he do,” said the Indian woman, in the peculiar way of speaking used by most of her people.

“He felt so much better in the afternoon that he was eager to go out and help you,” said Rose. “He thought that Uncle Donald would not be angry with him, though he had told him to remain at home.”

We soon got back to the house. When Uncle Donald heard where Hugh had gone, though he expressed no anger, he looked somewhat troubled. He waited until Rose had gone out of the room, then he said to me—

“I noticed, about four miles from home, as we went out in the morning, the marks of a ‘grizzly,’ which had been busy grubbing up a rotten log, but as his trail appeared to lead away up the mountains to the eastward I did not think it worth my while to chase him; and you having just before separated from me, I forgot to mention the fact when you came back. But vexed would I be if Hugh should have fallen in with the brute. He’s too venturesome at times; and if he fired and only wounded it, I doubt it would be a bad job for him. Don’t you let Rose hear a word about the ‘grizzly,’ Archie,” he hastily added, as she re-entered the room.

Both Madge and Rose were, however, very anxious when they found that Hugh had not returned with us. There was still an hour or so of daylight, and we did not therefore abandon the hope that he would return before dark. Uncle Donald and I were both very hungry, for we had been in active exercise the whole of the day, and had eaten nothing.

Madge knowing this set about preparing supper with all haste. She could not, however, help running to the door every now and then to ascertain if Hugh were coming. At length Sandy McTavish came in. He was something like Uncle Donald in figure, but though not so old, even more wiry and gaunt, looking as if he were made of bone and sinews covered with parchment.

He at once volunteered to set out and look for Hugh.

“Wait till we get our supper, and Archie and I will go too. What’s the use of man or boy with an empty stomach?” said Uncle Donald.

“’Deed an’ that’s true,” observed Sandy, helping himself from the trencher which stood in the centre of the table. “It’s a peety young Red Squirrel isna’ here; he would ha’ been a grand help if Maister Hugh’s missin’. But I’m thinkin’ he’s no far off, sir. He’ll have shot some beast likely, and be trying to trail it hame; it wud be a shame to him to hae lost his way! I canna believe that o’ Maister Hugh.”

Sandy said this while we were finishing our supper, when, taking down our rifles, with fresh ammunition, and bidding Rose and Madge “cheer up,” we three set out in search of Hugh.

Fortunately the days were long, and we might still hope to discover his track before darkness closed upon the world.

Chapter Two.

An Indian Raid.

Scene of the Story—History of Archie and Hugh—A Journey Across the Prairie—A Village Burnt by the Indians—Uncle Donald pursues the Blackfeet—Arrival at the Indian Camp.

But where did the scene just described occur? And who were the actors?

Take a map of the world, run your eye over the broad Atlantic, up the mighty St. Lawrence, across the great lakes of Canada, then along well-nigh a thousand miles of prairie, until the Rocky Mountains are reached, beyond which lies British Columbia, a region of lakes, rivers, and streams, of lofty, rugged, and precipitous heights, the further shores washed by the Pacific Ocean.

On the bank of one of the many affluents of its chief river—the Fraser—Uncle Donald had established a location, called Clearwater, far removed from the haunts of civilised man. In front of the house flowed the ever-bright current (hence the name of the farm), on the opposite side of which rose rugged pine-crowned heights; to the left were others of similar altitude, a sparkling torrent running amid them into the main stream. Directly behind, extending some way back, was a level prairie, interspersed with trees and bordered by a forest extending up the sides of the variously shaped hills; while eastward, when lighted by the rays of the declining sun, numberless snow-capped peaks, tinged with a roseate hue, could be seen in the far distance. Horses and cattle fed on the rich grass of the well-watered meadows, and a few acres brought under cultivation produced wheat, Indian corn, barley, and oats sufficient for the wants of the establishment.

Such was the spot which Uncle Donald, who had won the friendship of the Sushwap tribe inhabiting the district, had some years ago fixed on as his abode. He had formerly been an officer in the Hudson’s Bay Company, but had, for some reason or other, left their service. Loving the country in which he had spent the best years of his life, and where he had met with the most strange and romantic adventures, he had determined to make it his home. He had not, however, lost all affection for the land of his birth, or for his relatives and friends, and two years before the time I speak of he had unexpectedly appeared at the Highland village from which, when a young man, more than a quarter of a century before, he had set out to seek his fortune. Many of his relatives and the friends of his youth were dead, and he seemed, in consequence, to set greater value on those who remained, who gave him an affectionate reception. Among them was my mother, his niece, who had been a little blooming girl when he went away, but was now a staid matron, with a large family.

My father, Mr Morton, was a minister, but having placed himself under the directions of a Missionary Society, he was now waiting in London until it was decided in what part of the world he should commence his labours among the heathen. My two elder brothers were already out in the world—one as a surgeon, the other in business—and I had a fancy for going to sea.

“Let Archie come with me,” said Uncle Donald. “I will put him in the way of doing far better than he ever can knocking about on salt water; and as for adventures, he’ll meet with ten times as many as he would if he becomes a sailor.” He used some other arguments, probably relating to my future advantage, which I did not hear. They, at all events, decided my mother; and my father, hearing of the offer, without hesitation gave his consent to my going. It was arranged, therefore, that I should accompany Uncle Donald back to his far-off home, of which he had left his faithful follower, Sandy McTavish, in charge during his absence.

“I want to have you with me for your own benefit, Archie; but there is another reason. I have under my care a boy of about your own age, Hugh McLellan, the son of an old comrade, who died and left him to my charge, begging me to act the part of a father to him. I have done so hitherto, and hope to do so as long as I live; you two must be friends. Hugh is a fine, frank laddie, and you are sure to like one another. As Sandy was not likely to prove a good tutor to him, I left him at Fort Edmonton when I came away, and we will call for him as we return.”

I must pass over the parting with the dear ones at home, the voyage across the Atlantic, and the journey through the United States, which Uncle Donald took from its being in those days the quickest route to the part of the country for which we were bound.

After descending the Ohio, we ascended the Mississippi to its very source, several hundred miles, by steamboat; leaving which, we struck westward, passing the head waters of the Bed River of the north, on which Fort Garry, the principal post of the Hudson’s Bay Company, is situated, but which Uncle Donald did not wish to visit.

We had purchased good saddle-horses and baggage animals to carry our goods, and had engaged two men—a French Canadian, Pierre Le Clerc, and an Irishman, Cornelius Crolly, or “Corney,” as he was generally called. Both men were known to Uncle Donald, and were considered trustworthy fellows, who would stick by us at a pinch. The route Uncle Donald proposed taking was looked upon as a dangerous one, but he was so well acquainted with all the Indian tribes of the north that he believed, even should we encounter a party of Blackfeet, they would not molest us.

We had been riding over the prairie for some hours, with here and there, widely scattered, farms seen in the distance, and were approaching the last frontier settlement, a village or hamlet on the very outskirts of civilisation, when we caught sight of a column of smoke ascending some way on directly ahead of us.

“Can it be the prairie on fire?” I asked, with a feeling of alarm; for I had heard of the fearful way in which prairie fires sometimes extend for miles and miles, destroying everything in their course.

Uncle Donald stood up in his stirrups that he might obtain a better view before us.

“No; that’s not the smoke of burning grass. It looks more like that from a building, or may be from more than one. I fear the village itself is on fire,” he answered.

Scarcely had he spoken when several horsemen appeared galloping towards us, their countenances as they came near exhibiting the utmost terror. They were passing on, when Uncle Donald shouted out, “Hi! where are you going? What has happened?” On hearing the question, one of the men replied, “The Indians have surprised us. They have killed most of our people, set fire to our houses, and carried off the women and children.”

“And you running away without so much as trying to recover them? Shame upon ye!” exclaimed Uncle Donald. “Come on with me, and let’s see what can be done!”

The men, however, who had scarcely pulled rein, were galloping forward. Uncle Donald shouted to them to come back, but, terror-stricken, they continued their course, perhaps mistaking his shouts for the cries of the Indians.

“We must try and save some of the poor creatures,” said Uncle Donald, turning to our men. “Come on, lads! You are not afraid of a gang of howling red-skins!” and we rode on, making our baggage horses move much faster than they were wont to do under ordinary circumstances.

Before reaching the village we came to a clump of trees. Here Uncle Donald, thinking it prudent not to expose his property to the greedy eyes of the Indians, should we overtake them, ordered Corney and Pierre to halt and remain concealed, while he and I rode forward. By the time we had got up to the hamlet every farm and log-house was burning, and the greater part reduced to ashes.

No Indians were to be seen. According to their custom, after they had performed their work they had retreated.

I will pass over the dreadful sights we witnessed. Finding no one alive to whom we could render assistance, we pushed on, Uncle Donald being anxious to come up with the enemy before they had put their captives to death. Though darkness was approaching, we still rode forward.

“It’s likely they will move on all night, but, you see, they are loaded, and we can travel faster than they will. They are sure to camp before morning, and then we’ll get up with them,” observed Uncle Donald.

“But what will become of our baggage?” I asked.

“Oh, that will be safe enough. Pierre and Corney will remain where we left them until we get back,” he answered.

I was certain that Uncle Donald knew what he was about, or I should have been far from easy, I confess.

We went on and on, the Indians keeping ahead of us. From this circumstance, Uncle Donald was of opinion that they had not taken many prisoners. At length we came to a stream running northward, bordered by willows poplars, and other trees. Instead of crossing directly in front of us, where it was somewhat deep, we kept up along its banks. We had not got far when we saw the light of a fire, kindled, apparently, at the bottom of the hollow through which the stream passed.

“If I’m not far wrong, that fire is in the camp of their rear guard. Their main body cannot be far off,” observed Uncle Donald. “Dismount here, Archie, and you hold the horses behind these trees, while I walk boldly up to them. They won’t disturb themselves much for a single man.”

I dismounted as he desired, and he proceeded toward the fire. I felt very anxious, for I feared that the Blackfeet might fire and kill him without stopping to learn who he was.

Chapter Three.

With the Red-skins.

Uncle Donald and the Blackfeet—The Chief’s Speech—A Fortunate Recognition—Ponoko gives up a Little Girl to Uncle Donald—Impossible to do any more—Ponoko urges Departure—Rose is Adopted by Uncle Donald—Hugh McLellan—Madge—Story of a Brave Indian Mother—Red Squirrel—The Household at Clearwater.

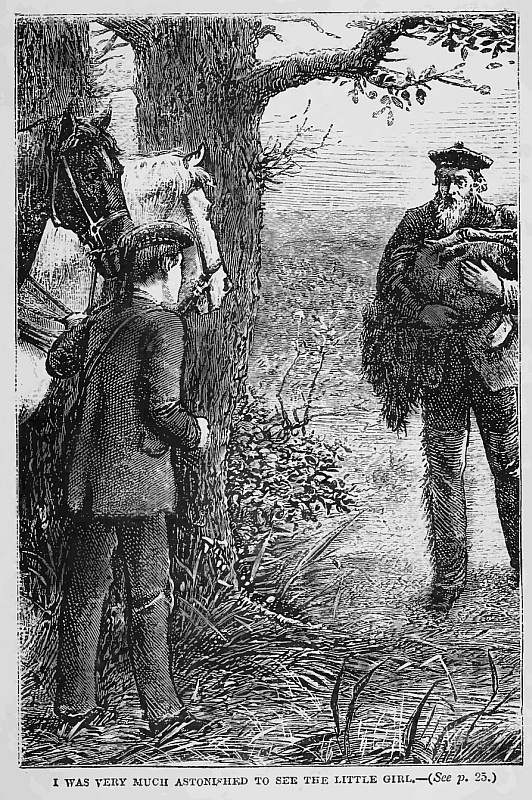

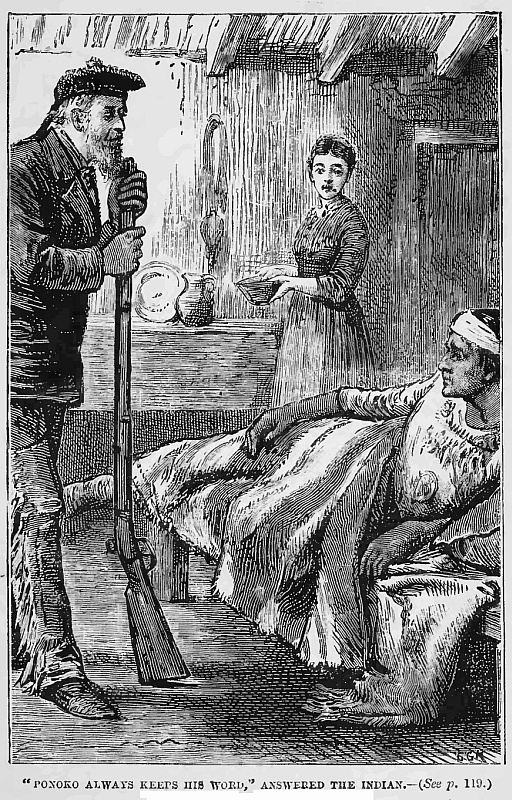

I waited with intense anxiety for Uncle Donald who appeared to have been a long time absent. I dared not disobey his orders by moving from the spot, yet I felt eager to creep up and try and ascertain what had happened. I thought that by seeming the horses to the trees, I might manage to get near the Indian camp without being perceived, but I overcame the temptation. At length I heard footsteps approaching, when, greatly to my relief, I saw Uncle Donald coming towards me, carrying some object wrapped up in a buffalo-robe in his arms.

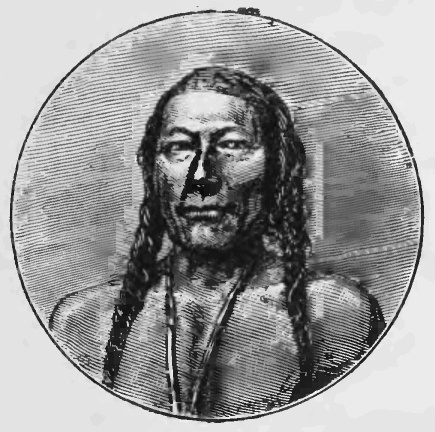

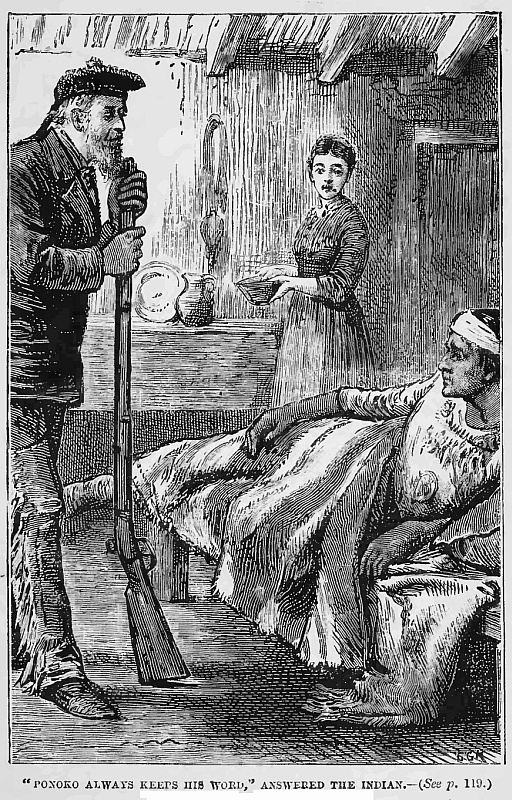

I will now mention what occurred to him. He advanced, as he told me afterwards, without uttering a word, until he was close up to the fire round which the braves were collected, then seating himself opposite the chief, whom he recognised by his dress and ornaments, said, “I have come as a friend to visit my red brothers; they must listen to what I have to say.” The chief nodded and passed the pipe he was smoking round to him, to show that he was welcome as a friend. Uncle Donald then told them that he was aware of their attack upon the village, which was not only unjustifiable, but very unwise, as they would be certain to bring down on their heads the vengeance of the “Long-knives”—so the Indians call the people of the United States. That wide as was the country, the arm of the Long-knives could stretch over it; that they had fleet horses, and guns which could kill when their figures appeared no larger than musk rats; and he urged them, now that the harm was done, to avert the punishment which would overtake them by restoring the white people they had captured.

When he had finished, the chief rose and made a long speech, excusing himself and his tribe on the plea that the Long-knives had been the aggressors; that they had killed their people, driven them from their hunting-grounds, and destroyed the buffalo on which they lived. No sooner did the chief begin to speak than Uncle Donald recognised him as a Sioux whose life he had saved some years before. He therefore addressed him by his name of Ponoko, or the Red Deer, reminding him of the circumstance. On this the chief, advancing, embraced him; and though unwilling to acknowledge that he had acted wrongly, he expressed his readiness to follow the advice of his white friend. He confessed, however, that his hand had only one captive, a little girl, whom he was carrying off as a present to his wife, to replace a child she had lost. “She would be as a daughter to me; but if my white father desires it, I will forego the pleasure I expected, and give her up to him. As for what the rest of my people may determine I cannot be answerable; but I fear that they will not give up their captives, should they have taken any alive,” he added.

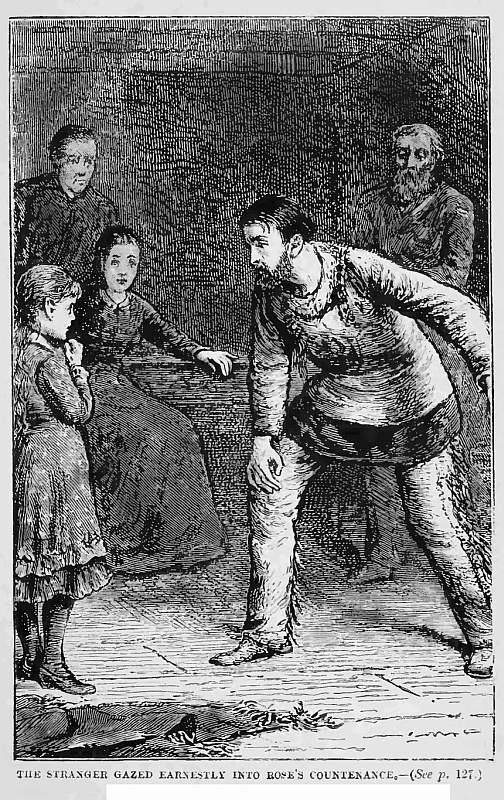

“It would have been a terrible thing to have left the little innocent to be brought up among the savages and taught all their heathen ways, though they, no doubt, would have made much of her, and treated her like a little queen,” said Uncle Donald to me; “so I at once closed with the chief’s offer. Forthwith, a little girl, some five years of age, was brought out from a small hut built of boughs, close to where the party was sitting. She appeared almost paralysed with terror; but when, looking up, she saw that Uncle Donald was a white man, and that he was gazing compassionately at her, clinging to his hand, she entreated him by her looks to save her from the savages. She had been so overcome by the terrible scenes she had witnessed that she was unable to speak.”

Uncle Donald, lifting her up in his arms, endeavoured to calm her fears, promising that he would take care of her until he had restored her to her friends. He now expressed his intention of proceeding to the larger camp, but Ponoko urged him on no account to make the attempt, declaring that his life would not be safe, as several of their fiercest warriors were in command, who had vowed the destruction of all the Long-knives or others they should encounter.

“But the prisoners! What will they do with them?” asked Uncle Donald. “Am I to allow them to perish without attempting their rescue?”

“My white father must be satisfied with what I’ve done for him. I saw no other prisoners taken. All the pale-faces in the villages were killed,” answered Ponoko. “For his own sake I cannot allow him to go forward; let him return to his own country, and he will there be safe. I know his wishes, and will, when the sun rises, go to my brother chiefs and tell them what my white father desires.”

Ponoko spoke so earnestly that Uncle Donald, seeing that it would be useless to make the attempt, and fearing that even the little girl might be taken from him, judged that it would be wise to get out of the power of the savages; and carrying the child, who clung round his neck, he bade the other braves farewell, and commenced his return to where he had left me. He had not got far when Ponoko overtook him, and again urged him to get to a distance as soon as possible.

“Even my own braves cannot be trusted,” he said. “I much fear that several who would not smoke the pipe may steal out from the camp, and try to kill my white father if he remains longer in the neighbourhood.”

Brave as Uncle Donald was, he had me to look after as well as the little girl. Parting with the chief, therefore, he hurried on, and told me instantly to mount.

I was very much astonished to see the little girl, but there was no time to ask questions; so putting spurs to our horses, we galloped back to where we had left our men and the baggage.

As both we and our horses required rest, we camped on the spot, Pierre and Corney being directed to keep a vigilant watch.

The little girl lay in Uncle Donald’s arms, but she had not yet recovered sufficiently to tell us her name, and it was with difficulty that we could induce her to take any food.

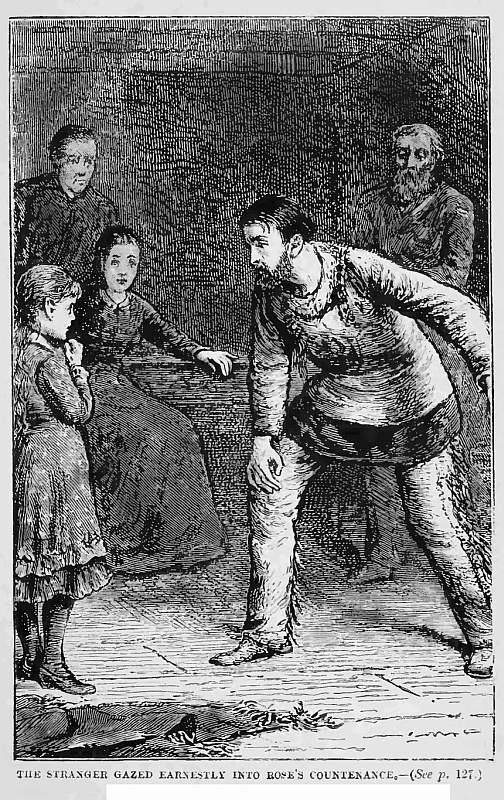

Late in the day we met a party going out to attack the Indians; but, as Uncle Donald observed, “they might just as well have tried to catch the east wind. We waited to see the result of the expedition. They at length returned, not having come near the enemy. The few men who had escaped the massacre were unable to give any information about the little girl or her friends, nor could we learn to whom she belonged. All we could ascertain from her was that her name was Rose, for her mind had sustained so fearful a shock that, even after several days had passed, she was unable to speak intelligibly.

“Her fate among the Indians would have been terrible, but it would be almost as bad were we to leave her among the rough characters hereabouts,” observed Uncle Donald. “As none of her friends can be found, I will be her guardian, and, if God spares my life, will bring her up as a Christian child.”

It was many a long day, however, before Rose recovered her spirits. Her mind, indeed, seemed to be a blank as to the past, and Uncle Donald, afraid of reviving the recollection of the fearful scenes she must have witnessed, forbore to say anything which might recall them. However, by the time we reached Fort Edmonton, where Hugh McLellan had been left, she was able to prattle away right merrily. The officers at the fort offered to take charge of her, but Uncle Donald would not consent to part with his little “Prairie Rose,” as he called her; and after a short stay we set out again, with Hugh added to our party, across the Rocky Mountains, and at length arrived safely at Clearwater.

Corney and Pierre remained with us, and took the places of two other men who had left.

Hugh McLellan was a fine, bold little fellow, not quite two years my junior; and he and I—as Uncle Donald had hoped we should—soon became fast friends.

He had not much book learning, though he had been instructed in the rudiments of reading and writing by one of the clerks in the fort, but he rode fearlessly, and could manage many a horse which grown men would fear to mount.

“I want you, Archie, to help Hugh with his books,” said Uncle Donald. “I believe, if you set wisely about it, that he will be ready to learn from you. I would not like for him to grow up as ignorant as most of the people about us. It is the knowledge we of the old country possess which gives us the influence over these untutored savages; without it we should be their inferiors.”

I promised to do my best in fulfilling his wishes, though I took good care not to assert any superiority over my companion, who, indeed, though I was better acquainted with literature than he was, knew far more about the country than I did.

But there was another person in the household whose history is worthy of narration—the poor Indian woman—“Madge,” as we called her for shortness, though her real name was Okenmadgelika. She also owed her life to Uncle Donald.

Several years before this, she, with her two children, had accompanied her husband and some other men on an expedition to trap beavers, at the end of autumn, towards the head waters of the Columbia. While she was seated in her hut late in the evening, one of the men staggered in desperately wounded, and had just time to tell her that her husband and the rest were murdered, when he fell dead at her feet. She, instantly taking up her children—one a boy of six years of age, the other a little girl, an infant in arms—fled from the spot, with a horse and such articles as she could throw on its back, narrowly escaping from the savages searching for her.

She passed the winter with her two young ones, no human aid at hand. On the return of spring she set off, intending to rejoin her husband’s people far away to the westward. After enduring incredible hardships, she had been compelled to kill her horse for food. She had made good some days’ journey, when, almost sinking from hunger, and fearing to see her children perish, she caught sight of her relentless foes, the Blackfeet. In vain she endeavoured to conceal herself. They saw her and were approaching, when, close to the spot where she was standing, a tall white man and several Indians suddenly emerged from behind some rocks. The Blackfeet came on, fancying that against so few they could gain an easy victory; but the rifles of the white man and his party drove them back, and Uncle Donald—for he was the white man—conveyed the apparently dying woman and her little ones to his camp.

The house at Clearwater had not yet been built. By being well cared for the Indian woman and her children recovered; but though the boy flourished, the little girl seemed like a withered flower, and never regained her strength.

Grateful for her preservation, the poor woman, when she found that Uncle Donald was about to settle at Clearwater, entreated that she might remain with her children and labour for him, and a faithful servant she had ever since proved.

Her little girl at length died. She was for a time inconsolable, until the arrival of Rose, to whom she transferred all her maternal feelings, and who warmly returned her affection.

But her son, whose Indian name translated was Red Squirrel, by which appellation he was always known, had grown up into a fine lad, versed in all Indian ways, and possessing a considerable amount of knowledge gained from his white companions, without the vices of civilisation. He was a great favourite with Uncle Donald, who placed much confidence in his intelligence, courage, and faithfulness.

Nearly two years had passed since Rose, Hugh, and I had been brought to Clearwater, and by this time we were all much attached to each other. We had also learned to love the place which had become our home; but we loved Uncle Donald far more.

Chapter Four.

Three Grizzlies.

The Start after Hugh—A Foot-print—Following the Trail—Archer meets a Grizzly—A Miss-fire—Discretion the Better Part of Valour—Far more Bears—Help, and a Joint Attack—Hugh up in a Tree—The Result of Disobedience.

I must now continue my narrative from the evening Hugh was missing.

The moment we had finished our hurried meal we set out. Sandy, in case we should be benighted, had procured a number of pine torches, which he strapped on his back; and Uncle Donald directed Corney and Pierre who came in as we were starting, to follow, keeping to the right by the side of the torrent, in case Hugh should have taken that direction.

Whiskey, Pilot, Muskymote followed closely at our heels—faithful animals, ready to drag our sleighs in winter, or, as now, to assist us in our search. We walked on at a rapid rate, and were soon in a wild region of forests, rugged hills, and foaming streams. As we went along we shouted out Hugh’s name, and searched about for any signs of his having passed that way. At length we discovered in some soft ground a foot-print, which there could be no doubt was his, the toe pointing in the direction we were going.

“Now we have found the laddie’s trail we must take care not to lose it,” observed Uncle Donald. “It leads towards the very spot where I saw the grizzly this morning.”

On and on we went. Soon another foot-print, and then a mark on some fallen leaves, and here and there a twig bent or broken off, showed that we were on Hugh’s trail.

But the sun had now sunk beneath the western range of mountains, and the gloom of evening coming on would prevent us from tracing our young companion much further. Still, as we should have met him had he turned back, we followed the only track he was likely to have taken.

We were approaching the spot where Uncle Donald had seen the bear, near a clump of trees with a thick undergrowth, a rugged hill riding beyond. We were somewhat scattered, hunting about for any traces the waning light would enable us to discover. I half feared that I should come upon his mangled remains, or some part of his dress which might show his fate. I had my rifle, but was encumbered with no other weight, and in my eagerness, I ran on faster than my companions. I was making my way among some fallen timber blown down by a storm, when suddenly I saw rise up, just before me, a huge form. I stopped, having, fortunately, the presence of mind not to run away, for I at once recognised the animal as a huge grizzly, which had been engaged in tearing open a rotten trunk in search of insects. I remembered that Uncle Donald had told me, should I ever find myself face to face with a grizzly, to throw up my arms and stand stock still.

The savage brute, desisting from its employment, came towards me, growling terribly, and displaying its huge teeth and enormous mouth.

I was afraid to shout, lest it might excite the animal’s rage; but I acted as Uncle Donald had advised me. As I lifted up my rifle and flourished it over my head, the creature stopped for a moment and got up on its hind legs.

Now or never was my time to fire, for I could not expect to have a better opportunity, and bringing my rifle, into which I had put a bullet, to my shoulder, I took a steady aim and pulled the trigger. To my dismay, the cap snapped. It had never before played me such a trick. Still the bear kept looking at me, apparently wondering what I was about. Mastering all my nerve, and still keeping my eye fixed on the shaggy monster in front of me, I lowered my rifle, took out another cap, and placed it on the nipple. I well knew that should I only wound the bear my fate would be sealed, for it would be upon me in an instant. I felt doubly anxious to hill it, under the belief that it had destroyed my friend Hugh; but still it was sufficiently far off to make it possible for me to miss, should my nerves for a moment fail me. As long as it remained motionless I was unwilling to fire, in the hope that before I did so Uncle Donald and Sandy might come to my assistance.

Having re-capped my rifle, I again lifted it to my shoulder. At that moment Bruin, who had grown tired of watching me, went down on all fours. The favourable opportunity was lost; for although I might still lodge a bullet in its head, I might not kill it at once, and I should probably be torn to pieces. I stood steady as before, though sorely tempted to run. Instead, however, of coming towards me, to my surprise, the bear returned to the log, and recommenced its occupation of scratching for insects.

Had it been broad daylight I might have had a fair chance of shooting it; but in the obscurity, as it scratched away among the fallen timber, from which several gnarled and twisted limbs projected upwards, I was uncertain as to the exact position of its head. Under the circumstances, I considered that discretion was the better part of valour; and feeling sure that Uncle Donald and Sandy would soon come up and settle the bear more effectually than I should, I began slowly to retreat, hoping to get away unperceived. I stepped back very cautiously, scarcely more than a foot at a time, then stopped. As I did so I observed a movement a little distance off beyond the big bear, and presently, as I again retreated, two other bears came up, growling, to the big one, and, to my horror, all three moved towards me.

Though smaller than their mother, each bear was large enough to kill me with a pat of its paw; and should I even shoot her they would probably be upon me. Again, however, they stopped, unwilling apparently to leave their dainty feast.

How earnestly I prayed for the arrival of Uncle Donald and Sandy! I had time, too, to think of poor Hugh, and felt more convinced than ever that he had fallen a victim to the ferocious grizzlies. I still dared not cry out, but seeing them again turn to the logs, I began, as before, to step back, hoping at length to get to such a distance that I might take to my heels without the risk of being pursued. In doing as I proposed I very nearly tumbled over a log, but recovering myself, I got round it. When I stopped to see what the bears were about they were still feeding, having apparently forgotten me. I accordingly turned round and ran as fast as I could venture to go among the trees and fallen trunks, till at length I made out the indistinct figures of Uncle Donald and Sandy, with the dogs, coming towards me.

“I have just seen three bears,” I shouted. “Come on quickly, and we may be in time to kill them!”

“It’s a mercy they did not catch you, laddie,” said Uncle Donald, when he got up to me. “With the help of the dogs we’ll try to kill them, however. Can you find the spot where you saw them?”

“I have no doubt about that,” I answered.

“Well, then, before we go further we’ll just look to our rifles, and make sure that there’s no chance of their missing fire.”

Doing as he suggested, we moved on, he in the centre and somewhat in advance, Sandy and I on either side of him, the dogs following and waiting for the word of command to rush forward.

The bears did not discover us until we were within twenty yards of them, when Uncle Donald shouted to make them show themselves.

I fancied that directly afterwards I heard a cry, but it might only have been the echo of Uncle Donald’s voice. Presently a loud growl from the rotten log showed us that the bears were still there, and we soon saw all three sitting up and looking about them.

“Sandy, do you take the small bear on the right; I will aim at the big fellow, and leave the other to you, Archie; but do not fire until you are sure of your aim,” said Uncle Donald. “Now, are you ready?”

We all fired at the same moment. Sandy’s bear dropped immediately, but the big one, with a savage growl, sprang over the logs and came towards us, followed by the one at which I had fired.

Uncle Donald now ordered the dogs, which had been barking loudly, to advance to the fight; but before they reached the larger bear she fell over on her side, and giving some convulsive struggles, lay apparently dead. The dogs, on this, attacked the other bear, which, made furious by its wound, was coming towards us, growling loudly. On seeing the dogs, however, the brute stopped, and sat up on its hind legs, ready with its huge paws to defend itself from their attacks. We all three, meantime, were rapidly reloading, and just as the bear had knocked over Whiskey and seized Muskymote in its paws, Uncle Donald and Sandy again fired and brought it to the ground, enabling Muskymote, sorely mauled, to escape from its deadly embrace.

I instinctively gave a shout, and was running on, when Uncle Donald stopped me.

“Stay!” he said; “those brutes play ‘possum’ sometimes, and are not to be trusted. If they are not shamming, they may suddenly revive and try to avenge themselves.”

“We’ll soon settle that,” said Sandy, and quickly reloading, he fired his rifle into the head of the fallen bear.

“Have you killed them all?” I heard a voice exclaim, which seemed to come from the branches of a tree some little distance off.

I recognised it as Hugh’s. “Hurrah!” I shouted; “are you all right?”

“Yes, yes,” answered Hugh, “only very hungry and stiff.”

We quickly made our way to the tree, where I found Hugh safe and sound, and assisted him to descend. He told us that he had fallen in with the bears on his way out, and had just time to escape from them by climbing up the tree, where they had kept him a prisoner all day.

“I am thankful to get ye back, Hugh. You disobeyed orders, and have been punished pretty severely. I hope it will be a lesson to you,” was the only remark Uncle Donald made as he grasped Hugh’s hand. I judged, by the tone of his voice, that he was not inclined to be very angry.

Having flayed the bears by the light of Sandy’s torches, we packed up as much of the meat as we could carry, and hung up the remainder with the skins, intending to send for it in the morning. We then, having met the other two men, hastened homewards with Hugh; and I need not say how rejoiced Rose and Madge were to see him back safe.

Chapter Five.

An Expedition.

Waiting for the Messengers—Two Tired Indians—Bad News of Archie’s Father—Uncle Donald Determines to Cross the Rocky Mountains—Preparations—News of the Blackfeet—Indian Canoes—The Expedition Starts.

Summer was advancing, and we had for some time been expecting the return of Red Squirrel and Kondiarak, another Indian, who had been sent in the spring to Fort Edmonton with letters, and directions to bring any which might have come for us. At length we became somewhat anxious at their non-appearance, fearing that some serious accident might have happened to them, or that they might have fallen into the hands of the savage Blackfeet, the chief predatory tribe in the country through which they had to pass.

Hugh and I were one evening returning from trapping beaver, several of which we carried on our backs. Though the skins are the most valued, the meat of the animal serves as food. We were skirting the edge of the prairie, when we caught sight of two figures descending the hills to the east by the pass which led from Clearwater towards the Rocky Mountains.

“They are Indians,” cried Hugh, “What if they should be enemies?”

“It is more likely that they are friends,” I answered. “If they were enemies they would take care not to show themselves. Let us go to meet them.”

The two men made their way slowly down the mountains and had got almost up to us before we recognised Red Squirrel, and his companion Kondiarak (“the rat”), so travel-stained, wan, and haggard did they look.

They had lost their horses, they said, after our first greetings were over. One had strayed, the other had been stolen by the Blackfeet, so that they had been compelled to perform the greater part of the journey on foot; and having exhausted their ammunition, they had been almost starved. They had succeeded, however, in preserving the letters confided to them, and they had brought a packet, for Uncle Donald, from a white stranger at whose hut they had stopped on the way.

On seeing the beavers we carried they entreated that we would give them some meat without delay, saying that they had had no food for a couple of days.

Their countenances and the difficulty with which they dragged their feet along corroborated their assertions. We, therefore, at once collecting some fuel, lighted a fire, and having skinned and opened one of the beavers, extended it, spread-eagle fashion, on some sticks to cook. They watched our proceedings with eager eyes; but before there was time to warm the animal through their hunger made them seize it, when tearing off the still uncooked flesh, they began to gobble it up with the greatest avidity.

I was afraid they would suffer from over eating, but nothing Hugh or I could say would induce them to stop until they had consumed the greater part of the beaver. They would then, had we allowed them, have thrown themselves on the ground and gone to sleep; but anxious to know the contents of the packets they had brought, relieving them of their guns, we urged them to lean upon us, and come at once to the farm. It was almost dark before we reached home.

Madge embraced her son affectionately, and almost, wept when she observed the melancholy condition to which he was reduced. He would not, however, go to sleep, as she wanted him to do, until he had delivered the packets to Uncle Donald, who was still out about the farm.

He in the meantime squatted down near the fire, where he remained with true Indian patience till Uncle Donald came in, when, rising to his feet, he gave a brief account of his adventures, and produced the packets, carefully wrapped up in a piece of leather.

To those which came by way of Edmonton I need not further refer, as they were chiefly about business. One, however, was of great interest; it was in answer to inquiries which Uncle Donald had instituted to discover any relatives or friends of little Rose. To his secret satisfaction he was informed that none could be found, and that he need have no fear of being deprived of her. As he read the last packet his countenance exhibited astonishment and much concern.

“This letter is from your mother, Archie,” he said, at length, when he had twice read it through. “Your father has brought her and the rest of the family to a mission station which has been established for the benefit of the Sercies, on the other side of the Rocky Mountains. Scarcely had they been settled for a few months, and your father had begun to win the confidence of the tribe among whom he had come to labour, than the small-pox broke out in their village, brought by the Blackfeet from the south; and their medicine-men, who had from the first regarded him with jealous eyes, persuaded the people that the scourge had been sent in consequence of their having given a friendly reception to the Christian missionary. Some few, whose good will he had gained, warned him that his life was in danger, and urged him to make his escape from the district. Though unwilling himself to leave his post, he had proposed sending your mother and the children away, when he was attacked by a severe illness. She thus, even had she wished it, could not have left him, and they have remained on at the station, notwithstanding that she fears they may at any time be destroyed by the savages, while the medicine-men have been using all their arts to win over the few Indians who continue faithful. These have promised to protect them to the best of their power, but how long they will be able to do so is doubtful. Their cattle and horses have been stolen, and they have for some time been short of provisions; thus, even should your father regain his health, they will be unable to travel. He, like a true missionary of the Gospel, puts his confidence in God, and endeavours, your mother says, ever to wear a cheerful countenance. She does not actually implore me to come to her assistance, for she knows the length and difficulties of the journey; and she expresses her thankfulness that you are safe on this side of the mountains, but I see clearly that she would be very grateful if I could pay her a visit; and I fear, indeed, unless help reaches your family, that the consequences may be serious. I have, therefore, made up my mind to set off at once. We may manage to get across the mountains before the winter sets in, though there is no time to be lost. I will take Pierre and Corney, with Red Squirrel and a party of our own Indians, and leave Sandy, with Hugh and you, in charge of Clearwater.”

“May I not go, also?” I asked, in a tone of disappointment. “Surely I may be able to help my father and mother, and Hugh would be very sorry to be left behind.”

“It is but natural that you should wish to go; and Hugh, too, maybe of assistance, for I can always trust to your discretion and judgment should any difficulty occur,” he observed.

“Then you will take us, won’t you?” we both cried at once.

“Yes,” he answered. “I would not take one without the other, so Hugh may go if he wishes it.”

“Thank you, thank you!” I exclaimed, gratified at Uncle Donald’s remark; “we will try to deserve your confidence. What shall we do first?”

“We must have the canoes got ready, and lay in a stock of provisions so that we may not be delayed by having to hunt; indeed, except some big-horns, and perhaps a grizzly, we shall not find much game on the mountains,” he remarked.

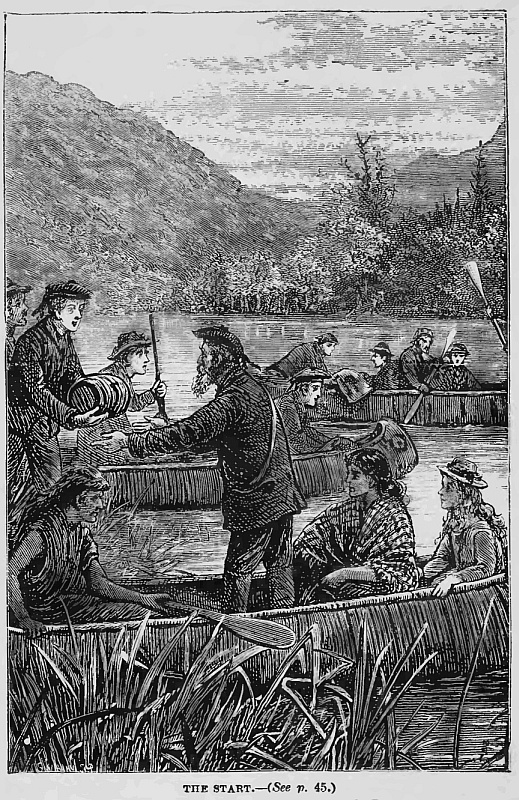

That evening all our plans were completed, and Sandy and the other men received their directions. Saddle and pack horses were at once to be started off by a circuitous route, carrying only light loads however, and were to meet us at the head of the river navigation, however, while we were to go as far up the stream as we could in canoes, with as large a supply of provisions as they could convey.

The very next morning at daybreak while we were engaged in preparing the birch bark canoes by covering the seams with gum, and sewing on some fresh pieces of bark with wattap, which is formed of the flexible roots of the young spruce tree, an Indian was seen on the opposite side of the river making a signal to us that he desired to cross. One of the canoes which was ready for launching was sent for him and brought him over.

“He had come,” he said, “to bring us information that a large body of Blackfeet were on the war-path, having crossed the Rocky Mountains at one of the southern passes, and that having attacked the Sinapools, their old enemies on the Columbia, they were now bending their steps northward in search of plunder and scalps. He came to tell his white friends to be prepared should they come so far north.”

On hearing this I was afraid that Uncle Donald would give up the expedition and remain to defend Clearwater, but on cross-questioning the Indian, he came to the conclusion that the Blackfeet were not at all likely to come so far, and Sandy declared that if they did he would give a very good account of them.

Still, as it was possible that they might make their appearance, Uncle Donald considered that it was safer to take Rose with us notwithstanding the hardships to which she might be exposed.

“Then Madge will go too,” exclaimed Rose; “poor Madge would be very unhappy at being left alone without me.”

“Madge shall go with us,” said Uncle Donald; and Rose, highly delighted, ran off to tell her to get ready.

The horses had been sent off at dawn, but we were not able to start until the following morning as it took us the whole day to prepare the packages of dried fish, pemmican, and smoked venison and pork, which were to serve us as provisions.

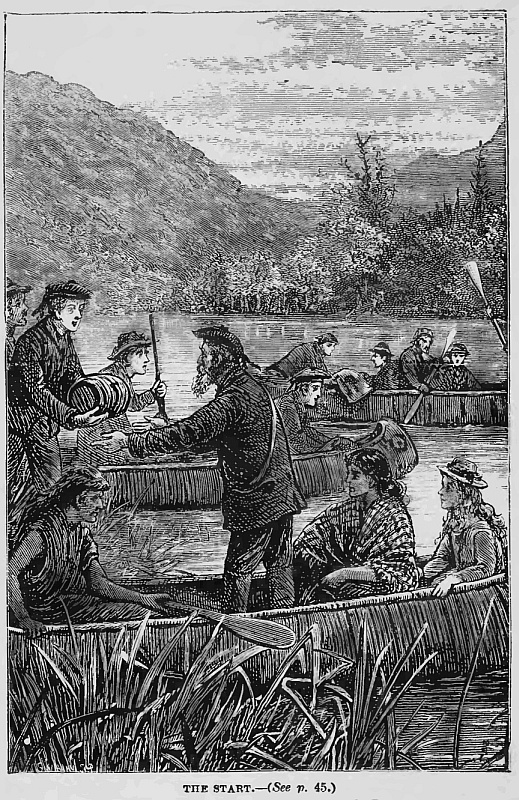

On a bright clear morning, just before the sun rose over the hills to the east, we pushed off from the bank in four canoes. In each were five people, one to steer and the others to paddle. Uncle Donald took Rose in his as a passenger.

Hugh and I went together with Red Squirrel to steer for us, and Corney and Pierre had each charge of another canoe.

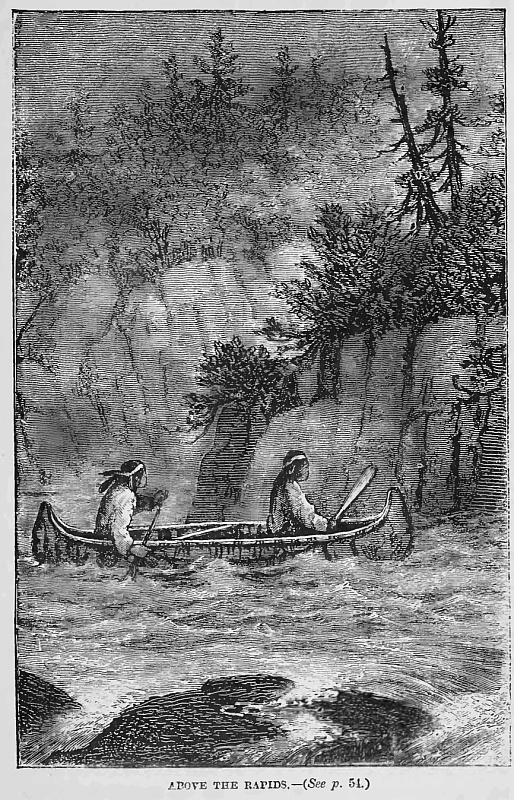

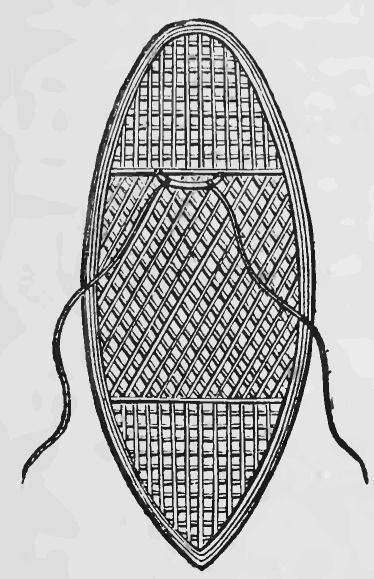

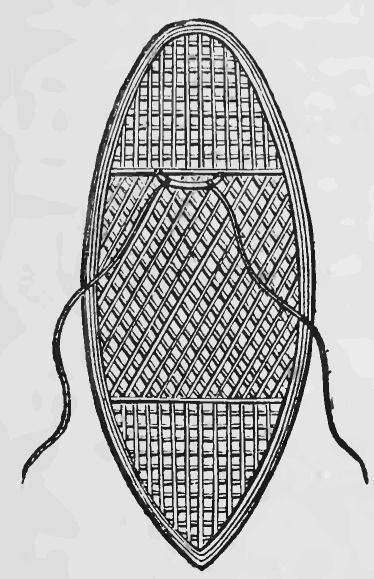

I will describe our canoes, which were light, elegant, and wonderfully strong, considering the materials of which they were formed. They were constructed of the bark of the white birch-tree. This had been peeled from the tree in large sheets, which were bent over a slender frame of cedar ribs, confined by gunwales, and kept apart by thin bars of the same wood. The ends were alike, forming wedge-like points, and turned over from the extremities towards the centre so as to look somewhat like the handle of a violin. The sheets of bark were then fastened round the gunwales by wattap, and sewn together with the same materials at the joinings. These were afterwards covered by a coat of pine pitch, called gum. The seats for the paddlers were made by suspending a strip of board with cords from the gunwales in such a manner that they did not press against the sides of the canoe. At the second cross-bar from the bow a hole was cut for a mast, so that a sail could be hoisted when the wind proved favourable. Each canoe carried a quantity of spare bark, wattap, gum, a pan for heating the gum, and some smaller articles necessary for repairs. The canoes were about eighteen feet long, yet so light that two men could carry one with ease a considerable distance when we had to make a “portage.” A “portage,” I should say, is the term used when a canoe has to be carried over the land, in consequence of any obstruction in the river, such as rapids, falls, or shallows.

As soon as we were fairly off Pierre struck up a cheerful song, in which we, Corney, and the Indians joined, and lustily plying our paddles we urged our little fleet up the river.

Chapter Six.

Paddling up Stream.

The First Camp—Rapids—A Portage—Indians Attack the Canoes—A Race for Life—He’s Won just in Time—More Rapids in an Awkward Place—The Canoes Poled up Stream—An Upset—The Indians Again, and Hugh in Danger—Other Canoes to the Rescue.

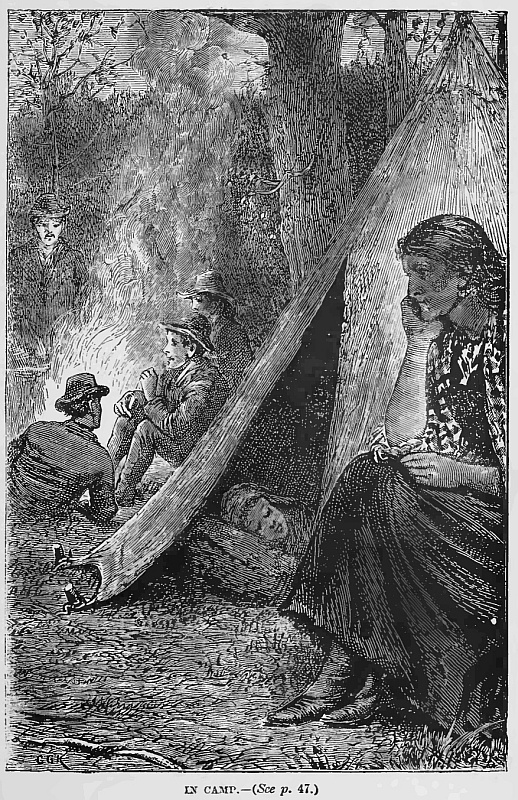

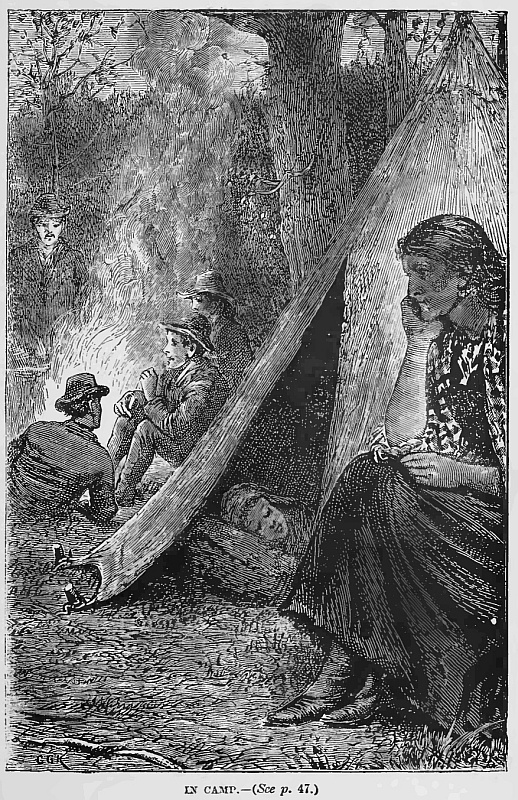

For the first day we made good progress, stopping only a short time to land and cook our provisions. We then paddled on until nearly dark, when we went on shore, unloaded our canoes, hauled them up, lighted a fire for cooking, and pitched a small tent for Rose, in front of which Madge, as she always afterwards did, took up her post to be ready to guard her in case of danger.

As soon as supper was over, two men were placed on watch, and the rest of the party lay down round the fire with our buffalo-robes spread on fresh spruce or pine boughs as beds. Before dawn we were aroused by Uncle Donald.

The morning was calm, the stars were slightly paling, a cold yellow light began to show itself. Above the river floated a light mist through which objects on the opposite bank were dimly seen, while on the land side a wall of forest rose up impenetrable to the eye. From the dying embers of the camp fire a thin column of smoke rose high above the trees, while round it were the silent forms of the Indians, lying motionless at full length on their backs, enveloped in their blankets. To stretch my legs I walked a few paces from the camp, when I was startled by a sudden rush through the underbrush. For a moment I thought of the Blackfeet, but the movement proved to be made by a minx or marten, which had been attracted to the spot by the remains of last night’s meal.

On hearing Uncle Donald’s voice the Indians started to their feet, and after a hurried breakfast, the canoes being launched and the baggage stowed on board, we proceeded on our voyage. The mist by degrees cleared away, the sun mounting over the hills, lighted up the scenery, and our crews burst into one of the songs with which they were wont to beguile the time while plying their paddles. Having stopped as before to dine we were paddling on, when we heard a low ceaseless roar coming down between the high banks. In a short time we saw the waters rushing and foaming ahead of us, as they fell over a broad ledge of rocks.

“Can we get over there?” asked Hugh.

“No,” I answered; “see, Uncle Donald is steering in for the shore.”

We soon landed, the canoes were unloaded, and being hauled up the bank, each was placed on the shoulders of two men, who trotted off with them by a path parallel to the river; the rest loaded themselves with the bales. Hugh and I imitated their example, Madge carried as heavy a package as any of the men, and Rose begged that she might take charge of a small bundle, with which she trotted merrily off, but did not refuse to let Madge have it before she had gone half-way. After proceeding for nearly a mile among rocks and trees, the canoes were placed on the banks where the river flowed calmly by, and the men returned for the remainder of the baggage. Three trips had to be made to convey the whole of the cargoes above the falls. This is what is called “making a portage.”

Re-embarking, on we went until nightfall. During the next few days we had several such portages to make. We were at times able to hoist our sails, but when the stream became more rapid and shallow, we took to poling, a less pleasant way of progressing, though under these circumstances the only one available. Occasionally the river opened out, and we were able to resume our paddles.

We had just taken them in hand and were passing along the east bank when Hugh exclaimed, “I see some one moving on shore among the trees! Yes, I thought so; he’s an Indian,” and he immediately added, “there are several more.”

I shouted to Uncle Donald to tell him, and then turned to warn Pierre and Corney.

Scarcely had I spoken than well-nigh fifty savages appeared on the banks, and, yelling loudly, let fly a cloud of arrows towards us, while one of them shouted to us to come to shore.

“Very likely we’ll be after doin’ that, Mister Red-skins,” cried Corney.

And we all, following Uncle Donald’s example, turning the heads of our canoes, paddled towards the opposite bank.

We were safe for the present, and might, had we chosen, have picked off several of the savages with our rifles; Corney and Pierre had lifted theirs for the purpose, but Uncle Donald ordered them not to fire.

“Should we kill any of them we should only find it more difficult to make peace afterwards,” he observed.

The river was here wide enough to enable us to keep beyond range of their arrows, and we continued our course paddling along close to the western bank. After going a short distance we saw ahead of us a lake, which we should have to cross. The Indians had disappeared, and I hoped we had seen the last of them, when Corney shouted out that he had caught sight of them running alone; the shore of the lake to double round it. Their object in so doing was evident, for on the opposite side of the upper river entered the lake, rounding a point by a narrow passage, and this point they hoped to gain before we could get through, so that they might stop our progress.

“Paddle, lads—paddle for your lives!” cried Uncle Donald. “We must keep ahead of the red-skins if we wish to save our scalps.”

We did paddle with might and main, making the calm water bubble round the bows of our canoes.

Looking to our right, we every now and then caught a glimpse of the Blackfeet, for such we knew they were by their dress. They were bounding along in single file among the trees, led apparently by one of their most nimble warriors. It seemed very doubtful whether we could pass the point before they could reach it. We persevered, for otherwise we should be compelled either to turn back, or to run the risk of being attacked at one of the portages, or to land at the western side of the lake, and to throw up a fort in which we could defend ourselves should the Blackfeet make their way across the river. It was not likely, however, that they would do this. They had already ventured much farther to the north than it was their custom to make a raid; and should they be discovered, they would run the risk of being set upon by the Shoushwaps, the chief tribe inhabiting that part of the country, and their retreat cut off. Still it was of the greatest importance to lose no time, and we redoubled our efforts to get by the point. The Indians had a greater distance to go; but then they ran much faster than we could paddle our canoes. As we neared the point, I kept looking to the right to see how far our enemies had got. Again I caught a glimpse of their figures moving among the trees, but whether or not they were those of the leaders I could not distinguish.

Uncle Donald reached the point, and his canoe disappeared behind it. Hugh and I next came up, closely followed by the other two. We could hear the savage shouts and cries of the red-skins; but there was now a good chance of getting beyond their reach.

“There goes the captain’s canoe,” I heard Corney sing out; “paddle, boys, paddle, and we’ll give them the go-by!”

We had entered the upper branch of the river; the current ran smoothly. Still we were obliged to exert ourselves to force our canoes up against it. Looking back for a moment over my shoulder, I could see the leading Indians as they reached the point we had just rounded. Enraged at being too late to stop us, they expended another flight of arrows, several of which struck the water close to us, and two went through the after end of Pierre’s canoe, but fortunately above water.

Though we had escaped for the present, they might continue along the eastern bank of the river, and meet us at the next portage we should have to make. The day was wearing on, and ere long we should have to look out for a spot on which to camp, on the west bank, opposite to that where we had seen the Indians.

We had got four or five miles up the river when the roaring sound of rushing waters struck our ears, and we knew that we should have to make another portage. The only practicable one was on the east bank, and as it would occupy us the greater part of an hour, we could scarcely hope to escape the Indians, even should they not already have arrived at the spot. On the left rose a line of precipitous rocks, over which we should be unable to force our way. At length we got up to the foot of the rapids. Uncle Donald took a survey of them. I observed on the west side a sheet of water flowing down smoother and freer from rocks than the rest.

“We must pole up the rapids, but it will need caution; follow me,” said Uncle Donald.

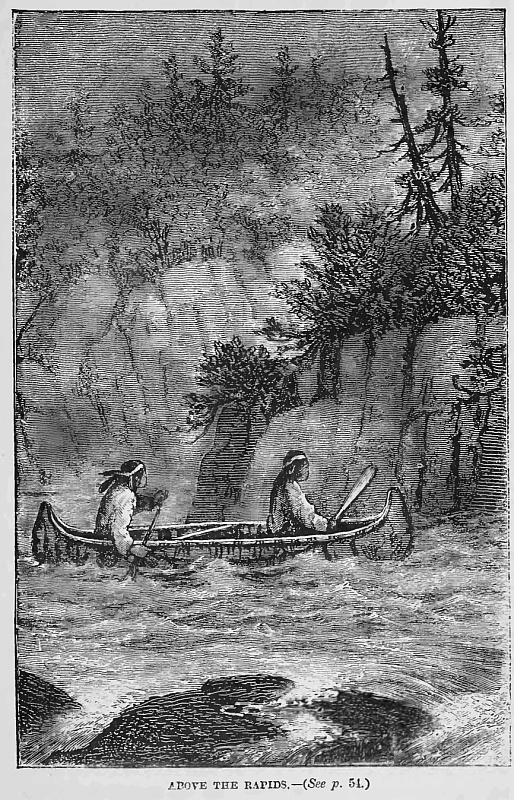

We got out our long poles, and Uncle Donald leading the way, we commenced the ascent.

While resting on our paddles Corney and Pierre had overtaken us, and now followed astern of Uncle Donald, so that our canoe was the last. We had got nearly half-way up, the navigation becoming more difficult as we proceeded. The rocks extended farther and farther across the channel, the water leaping and hissing and foaming as it rushed by them. One of our Indians sat in the bows with a rope ready to jump out on the rocks and tow the canoe should the current prove too strong for us. Red Squirrel stood aft with pole in hand guiding the canoe, while Hugh and I worked our poles on either side. Corney and Pierre were at some little distance before us, while Uncle Donald, having a stronger crew, got well ahead.

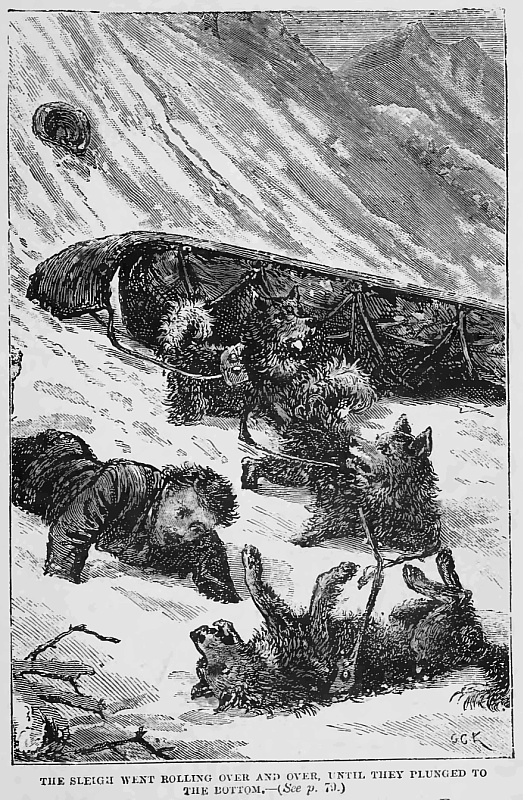

“We shall soon be through this, I hope,” cried Hugh; “pretty tough work though.”

As he spoke he thrust down his pole, which must have been jammed in a hole, and his weight being thrown upon it, before he could recover it broke, and over he went; I in my eagerness, leaning on one side, attempted to grasp at him, the consequence was that the canoe, swinging round, was driven by the current against the rock. I heard a crash, the foaming water washed over us, and I found myself struggling in its midst. My first impulse was to strike out, for I had been a swimmer from childhood.

Notwithstanding, I found myself carried down. I looked out for Hugh, but the bubbling water blinded my eyes, and I could nowhere see him nor my Indian companions; still I instinctively struggled for life. Suddenly I found myself close to a rugged rock, whose sides afforded the means of holding on to it. By a violent effort I drew myself out of the water and climbed to the top. I looked round to see what had become of the rest of the crew; my eye first fell on the canoe, to which Hugh was clinging. It was being whirled hurriedly down the rapids; and some distance from it, indeed, almost close to where I now was, I saw the head of an Indian. His hands and feet were moving; but instead of trying to save himself by swimming towards the rock on which I was seated, he was evidently endeavouring to overtake the canoe. I could nowhere see our other companion; he had, I feared, sunk, sucked under by the current. A momentary glance showed me what I have described.

Directly I had recovered breath I shouted to Pierre and Corney, but the roar of the waters prevented them from hearing my voice; and they and their companions were so completely occupied in poling on their canoes that they did not observe what had occurred. Again and again I shouted; then I turned round, anxiously looking to see how it fared with Hugh and the Indian.

The canoe had almost reached the foot of the rapids, but it went much faster than the Indian, who was still bravely following it. He had caught hold of one of the paddles, which assisted to support him. I was now sure that his object was to assist Hugh, for he might, as I have said, by swimming to the rock and clutching it, have secured his own life until he could be taken off by Corney or Pierre. Hugh still held tight hold of the canoe, which, however, the moment it reached the foot of the rapids, began to drift over to the eastern shore.

Just then what was my dismay to see a number of red-skins rush out from the forest towards the bank. They were those, I had no doubt, from whom we were endeavouring to escape. They must have seen the canoe, and were rejoicing in the thoughts of the capture they were about to make. Hugh’s youth would not save him from the cruel sufferings to which they were wont to put their prisoners, should they get hold of him, and that they would do this seemed too probable. I almost wished, rather than he should have had to endure so cruel a fate, that he had sunk to the bottom. Even now the Indian might come up with the canoe, but would it be possible for him to tow it to the west bank, or support Hugh while swimming in the same direction. Though the rock was slippery I at length managed to stand up on it, and as I did so I gave as shrill a shout as I could utter. One of the Indians in Corney’s canoe glanced at me for a moment. He at once saw what had happened, and I guessed from his gestures was telling Pierre as well as Corney of the accident. In an instant the poles were thrown in, and the Indians seizing their paddles, the canoes, their heads turned round, were gliding like air bubbles down the torrent.

Chapter Seven.

A Narrow Escape.

Hugh’s Canoe Arrested by Red Squirrel just in Time—The Canoe Saved—All got up the Rapids at Last—Camp at the Top—The Blackfeet reach the Camp to find the Party gone—The Indians Pursue, and Uncle Donald lies by for Two Days on an Island—End of the Water Passage—The Horses do not Appear.

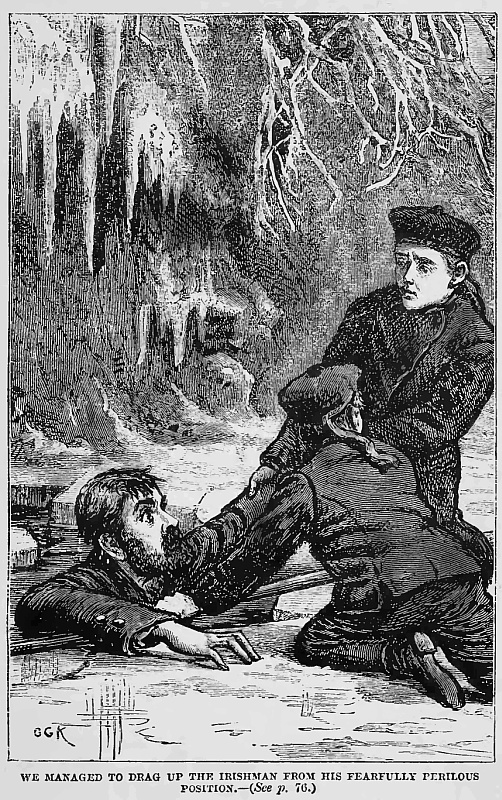

As Corney and Pierre approached I waved to them to go on, pointing to the canoe to which Hugh was clinging. They saw the necessity of at once going to his rescue, and so left me on the rock, where I was perfectly safe for the present. There was need, in truth, for them to make haste, for already Hugh was drifting within range of the Indians’ arrows, and they might shoot him in revenge for the long run we had given them.

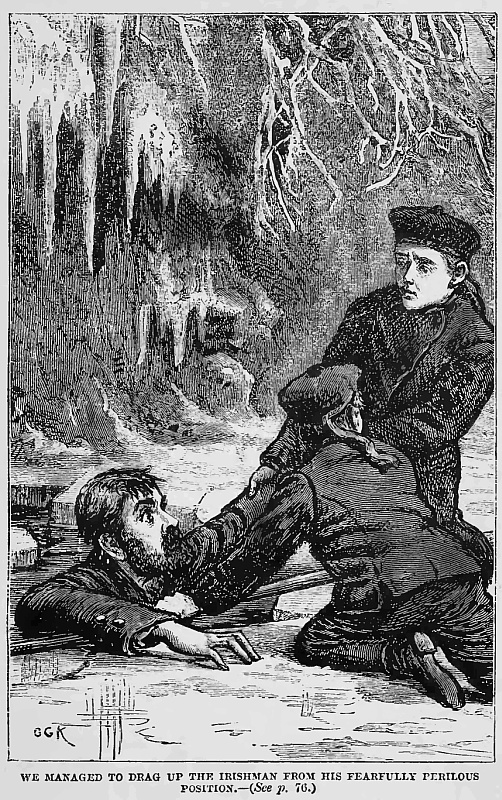

The overturned canoe seemed to be gliding more and more rapidly towards them, when I saw its progress arrested.

The brave Indian had seized it, and was attempting to tow it away from the spot where the savages were collected. But all his efforts could scarcely do more than stop its way, and he apparently made but little progress towards the west shore. Corney and Pierre were, however, quickly getting up to it. I shouted with joy when I saw Hugh lifted into Corney’s canoe, and the Indian with some assistance clambering into that of Pierre. Not satisfied with this success they got hold of the canoe itself, determined to prevent it from falling into the hands of the enemy. This done, they quickly paddled over to the west shore, where a level spot enabled them to land. They had not forgotten me; and presently I saw Corney’s canoe, with three people in her, poling up towards the rock on which I stood, while Pierre’s was engaged in picking up such of the articles of baggage as had floated. It was not without some difficulty that I got on board. My first inquiry was to ascertain which of the Indians had assisted to save Hugh, and I was thankful to hear, as I had expected, that it was Bed Squirrel who had behaved so gallantly.

We then had to decide what to do—whether to continue our course upwards, to let Uncle Donald know what had happened, or to rejoin Pierre. Though I had managed to cling on to the rock I found my strength so much exhausted that I could afford but little help in poling up the canoe. While we were discussing the matter, what was my dismay to see an Indian on the top of the western cliff.

“Our enemies must have crossed, and we shall be attacked,” I exclaimed.

“Sure no, it’s one of Mr Donald’s men who has been sent to see what has become of us,” answered Corney.

Such I saw was the case. We could not hear his voice, but getting closer to us he made signs which his own people understood, that he would go back to Uncle Donald and learn what we were to do. In reply our two Indians pointed down to where Pierre’s party were now on shore, letting him understand exactly what had happened.

He quickly disappeared, and we had to wait some time, hanging on to a rock by a rope, until he returned with two other men. They then pointed up the stream as a sign to us that we were to proceed. We accordingly did so, poling up as before. By the time we got to the head of the rapids we saw that Pierre was coming after us, apparently towing the shattered canoe.

Above the rapids we discovered a small bay, towards which Uncle Donald’s voice summoned us. As we landed he grasped my hand, showing his joy at my escape. It was some time before Pierre arrived. Hugh came in his canoe, while the rest of the men had arrived over land with the luggage which had been saved, as also with our rifles, which, having been slung under the thwarts, had fortunately not slipped out.

We immediately began our preparations for camping, but had, besides doing what was usual, to collect materials for a stockade, which might enable us to resist a sudden onslaught of the Blackfeet should they cross the river. One of the men was also placed on watch all the time to prevent surprise.

While most of the party were thus engaged, Red Squirrel and Jock, who were the best canoe builders, were employed in repairing the shattered canoe, and making some fresh paddles and poles; indeed there was so much work to be done, that none of us got more than a few hours’ rest. We had also to keep a vigilant watch, and two of the men were constantly scouting outside the camp, to guard in more effectually from being taken by surprise.

All was ready for a start some time before daylight, when Uncle Donald, awakening the sleepers, ordered every one to get on board as noiselessly as possible. He, as usual, led the way, the other canoes following close astern. The last man was told to make up the fire, which was left burning to deceive the enemy, who would suppose that we were still encamped.

We had got some distance, the wind being up stream, when just at dawn I fancied that I heard a faint though prolonged yell. We stopped paddling for a moment, I asked Red Squirrel if he thought that the Blackfeet had got across to our camp. He nodded, and uttered a low laugh, significant of his satisfaction that we had deceived them. Daylight increasing, we put up our masts and hoisted the light cotton sails, which sent our canoes skimming over the water at a far greater speed than we had hitherto been able to move.

Another lake appeared before us. By crossing it we should be far ahead of the Blackfeet. We had brought some cooked provisions, so that we were able to breakfast in the canoes. It was long past noon before, the river having again narrowed, we ventured on shore for a brief time only to dine.

The next portage we came to was on the east bank. It was fortunately a short one, and Uncle Donald kept some of the men under arms, a portion only being engaged in carrying the canoes and their cargoes. No Indians, however, appeared.

“I hope that we have given them the go-by,” said Hugh, “and shall not again see their ugly faces.”

“We must not be too certain; I’ll ask Red Squirrel what he thinks,” I replied.

“Never trust a Blackfoot,” was the answer. “They are as cunning as serpents, and, like serpents, they strike their enemies from among the grass.”

We expected in the course of two or three days more to come to an end of the river navigation at a spot where Uncle Donald had directed that the horses should meet us. We were not without fear, however, that some, if not the whole of the animals, might have been stolen by the Blackfeet should they by any means have discovered them.

Occasionally sailing, sometimes paddling and poling, and now and then towing the canoes along the banks, we continued our progress. As we went along we kept a look-out for the Blackfeet, as it was more than possible that they might pursue us. We accordingly, in preference to landing on either bank, selected an island in the centre of the stream for our camping-ground.

We had just drawn up the canoes among the bushes and formed our camp in an open spot near the middle of the island, when one of the men who was on the lookout brought word that he saw a large number of savages passing on the east bank. We were, however, perfectly concealed from their keen eyes. Watching them attentively, we guessed by their gestures that they were looking for us, and not seeing our canoes, fancied that we had passed on. Night was now approaching. We were afraid of lighting a fire, lest its glare might betray our position to our pursuers. They would, however, on not discovering us, turn back, so that we should thus meet them, and Uncle Donald resolved, therefore, to remain where we were, until they had retreated to the southward. Even should they discover us we might defend the island more easily than any other spot we could select. We had plenty of provisions, so that we could remain there without inconvenience for several days, except that we should thus delay our passage over the mountains. Hugh and I were, much to our satisfaction, appointed by Uncle Donald to keep watch, Hugh on one side of the island and I on the other, for fear lest, should the red-skins find out where we were, they might attempt, by swimming across, to take us by surprise.

None appeared, however, and two more days went by. At last Uncle Donald began to hope that they, supposing we had taken another route, were on their way back. We accordingly, seeing no one the next morning, embarked, and the river here expanding into a lake, we were able to paddle on without impediment across it, and a short distance up another stream, when we came to a fall of several feet, beyond which our canoes could not proceed. This was the spot where we had expected to find the horses, but they had not arrived. We were greatly disappointed, for, having been much longer than we had calculated on coming up, we naturally expected that they would have been ready for us. Winter was rapidly approaching, and in the autumn before the streams are thoroughly frozen the dangers of crossing the mountains are greater than at any other period.

As the canoes could go no higher we took them up the stream and placed them “en cache,” where there was little chance of their being discovered. They were to remain there until the return of our men, who would accompany us to the foot of the mountains and go back again that autumn.

On not finding the horses Uncle Donald went to the highest hill in the neighbourhood, overlooking the country through which they had to pass, in the hopes of seeing them approach. He came back saying that he could perceive no signs of them, and he ordered us forthwith to camp in such a position that we might defend ourselves against any sudden attack of hostile Indians.

Chapter Eight.

Among the Mountains.

The Horse Party arrives at last, but with half the Horses Stolen—The Start Across the Mountains—More Blackfeet in the way oblige the Party to take a Strange Pass—It becomes Colder—Snow comes on—A Pack of Wolves—Sleighs and Snow-Shoes—In the Heart of the “Rockies”—Corney has a Narrow Escape and a Cold Bath—Snow in the Canoes—Difficulties of the Way—The Pass at Last—A fearful Avalanche.

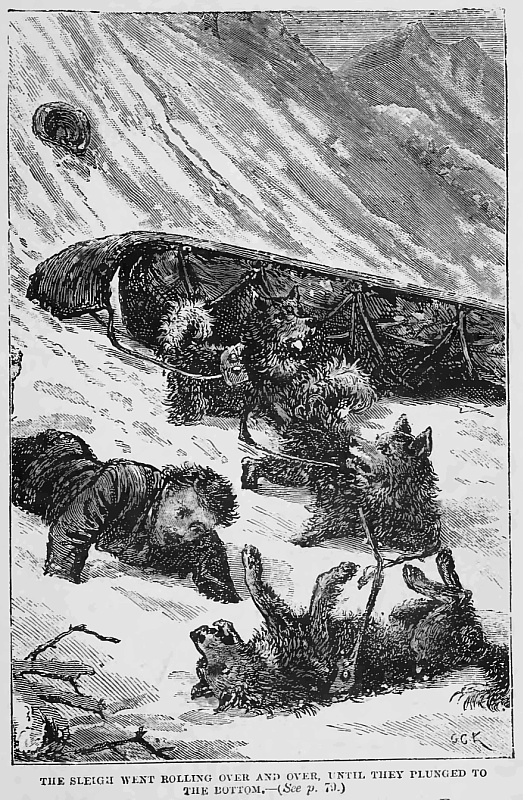

Several days passed by. We were not molested by the Indians, but the horses did not arrive. Uncle Donald never fretted or fumed, though it was enough to try his temper. I asked him to allow me to set off with Corney and Pierre to ascertain if they had gone by mistake to any other place. We were on the point of starting when we saw a party of horses and men approaching. They proved to be those we were expecting, but there were only eight horses, less than half the number we had sent off. The men in charge had a sad account to give. The rest had been stolen by Indians, and one of their party had been killed, while they had to make a long round to escape from the thieves, who would otherwise very likely have carried off the remainder. The men also had brought a dozen dogs—our three especial favourites being among them—to be used in dragging our sleighs in case the horses should be unable to get through. We had carried the materials for forming sleighs with us in the canoes, while the harness had been transported thus far with the other packages by the horses. The poor beasts, though very thin, were better than no horses at all. There were a sufficient number to convey our stores and provisions, one for Uncle Donald, who carried Rose on his saddle, and two others for Hugh and me. The rest of the party had to proceed on foot. I offered mine to Madge, but she declared that she could walk better than I could.

We made a short day’s journey, but the poor animals were so weak that we were compelled to camp again at a spot where there was plenty of grass. It was here absolutely necessary to remain three days to enable them to regain their strength.

While we were in camp Uncle Donald sent out Pierre and one of our Indians to try and ascertain if any of the Blackfeet were still hovering in the direction we proposed taking across the mountains. We did not wait for the return of our scouts, but started at the time proposed, expecting to meet them on the road we should travel.

We were engaged in forming our camp, collecting wood for the fires, and putting up rough huts, or rather arbours of boughs, as a protection from the wind—which here coming off the snowy mountains was exceedingly cold at night—while the gloom of evening was coming on, when one of the men on watch shouted—

“The enemy! the enemy are upon us!”

While some of our people ran out intending to bring in the horses, the rest of us flew to our arms.

Uncle Donald, taking his rifle, at once went out in the direction in which the sentry declared he had seen the band of savages coming over the hill.

Our alarm was put an end to when, shortly afterwards, he came back accompanied by Pierre and his companion, who brought the unsatisfactory intelligence that a large body of Blackfeet were encamped near the pass by which we had intended to descend into the plains of the Saskatchewan.

Ever prompt in action, Uncle Donald decided at once to take a more northerly pass.

The country through which we were travelling was wild and rugged in the extreme; frequently we had to cross the same stream over and over again to find a practicable road. Now we had to proceed along the bottom of a deep valley among lofty trees, then to climb up a steep height by a zigzag course, and once more to descend into another valley. Heavily laden as were both horses and men, our progress was of necessity slow. Sometimes after travelling a whole day we found that we had not made good in a straight line more than eight or ten miles.

The weather hitherto had been remarkably fine, and Hugh and Rose and I agreed that we enjoyed our journey amazingly. Our hunters went out every day after we had camped, and sometimes before we started in the morning, or while we were moving along, and never failed to bring in several deer, so that we were well supplied with food. The cold at night was very considerable; but with good fires blazing, and wrapped up in buffalo-robes, we did not feel it; and when the sun shone brightly the air was so pure and fresh that we were scarcely aware how rapidly winter was approaching.

It should be understood that there are several passes through the lofty range it was our object to cross. These passes had been formed by the mountains being rent asunder by some mighty convulsion of nature. All of them are many miles in length, and in some places several in width; now the pass presents a narrow gorge, now expands into a wide valley. The highest point is called the watershed, where there is either a single small lake, or a succession of lakelets, from which the water flows either eastward through the Saskatchewan or Athabasca rivers, to find its way ultimately into the Arctic Ocean, or westward, by numberless tributaries, into the Fraser or Columbia rivers, which fall, after making numerous bends, into the Pacific.

We had voyaged in our canoes up one of the larger tributaries of the Fraser, and had now to follow to its source at the watershed one of the smaller streams which flowed, twisting and turning, through the dense forests and wild and rugged hills rising on every side.

The country had become more and more difficult as we advanced, and frequently we had to wind our way in single file round the mountains by a narrow path scarcely affording foothold to our horses. Sometimes on one side, sometimes on the other were steep precipices, over which, by a false step, either we or our animals might be whirled into the roaring torrent below. Now we had to force a road through the tangled forest to cut off an angle of the stream, and then to pass along narrow gorges, beetling cliffs frowning above our heads, and almost shutting out the light of day.

At length we camped on higher ground than any we had yet reached. On one side was a forest, on the other a rapid stream came foaming by. The sky was overcast, so that, expecting rain, we put up all the shelter we could command.

The hunters having brought in a good supply of meat, our people were in good spirits, and seemed to have forgotten the dangers we had gone through, while they did not trouble themselves by thinking of those we might have to encounter. We had no longer hostile Indians to fear; but we still kept a watch at night in case a prowling grizzly or pack of hungry wolves might pay the camp a visit. The wind blew cold; not a star was visible. The light from our fire threw a lurid glare on the stems and boughs of the trees and the tops of the rugged rocks which rose beyond.

Having said good night to Rose, whom we saw stowed away in her snug little bower, Hugh and I lay down a short distance from the fire, sheltered by some of the packages piled up at our heads. Uncle Donald was not far from us. On the other side were Pierre and Corney and Red Squirrel, while Madge took her post, disdaining more shelter than the men, close to Rose’s hut. Two of the men kept awake, one watching the camp, the other the horses, and the rest lay in a row on the opposite side of the fire.