Museum of Natural History

Chautauqua, Cowley and

Elk Counties, Kansas

ARTIE L. METCALF

Lawrence

1959

Title: Fishes of Chautauqua, Cowley and Elk Counties, Kansas

Author: Artie L. Metcalf

Release date: November 30, 2010 [eBook #34523]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

ARTIE L. METCALF

ARTIE L. METCALF

Volume 11, No. 6, pp. 345-400, 2 plates, 2 figs. in text, 10 tables

University of Kansas

A Contribution From

| Introduction | 347 | |

| Physical characteristics of the streams | 351 | |

| Climate | 351 | |

| Present flora | 353 | |

| History | 354 | |

| Conservation | 357 | |

| Previous ichthyological collections | 357 | |

| Acknowledgments | 358 | |

| Materials and methods | 358 | |

| Collecting stations | 359 | |

| Annotated list of species | 362 | |

| Fishes of doubtful or possible occurrence | 383 | |

| Faunal comparisons of different streams | 384 | |

| Distributional variations within the same stream | 387 | |

| Faunas of intermittent streams | 390 | |

| East-west distribution | 392 | |

| Summary | 394 | |

| Literature cited | 397 |

Aims of the distributional study here reported on concerning the fishes of a part of the Arkansas River Basin of south-central Kansas were as follows:

(1) Ascertain what species occur in streams of the three counties.

(2) Ascertain habitat preferences for the species found.

(3) Distinguish faunal associations existing in different parts of the same stream.

(4) Describe differences and similarities among the fish faunas of the several streams in the area.

(5) Relate the findings to the over-all picture of east-west distribution of fishes in Kansas.[Pg 348]

(6) List any demonstrable effects of intermittency of streams on fish distribution within the area.

Cowley and Chautauqua counties form part of the southern border of Kansas, and Elk County lies directly north of Chautauqua. The following report concerns data only from those three counties unless otherwise noted. They make up an area of 2,430 square miles having a population of 50,960 persons in 1950 (55,552 in 1940, and 60,375 in 1930). The most populous portion of the area is western Cowley County where Arkansas City with 12,903 inhabitants and Winfield with 10,264 inhabitants are located. Each of the other towns has less than 2,000 inhabitants. In the Flint Hills, which cross the central portion of the area surveyed, population is sparse and chiefly in the valleys.

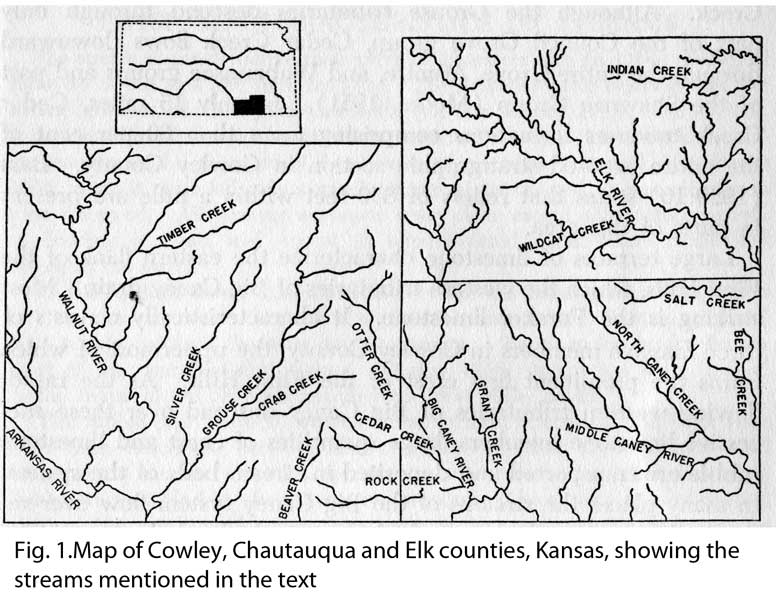

Topographically, the area is divisible into three general sections: the extensive Wellington formation and the floodplain of the Arkansas River in western Cowley County; the Flint Hills in the central part of the area; and the "Chautauqua Hills" in the eastern part. The drainage pattern is shown in Figure 1.

The Wellington formation, which is devoid of sharp relief, borders the floodplain of the Arkansas River through most of its course in Cowley County. A short distance south of Arkansas City, however, the Arkansas is joined by the Walnut River and enters a narrow valley walled by steep, wooded slopes. Frye and Leonard (1952:198) suggest that this valley was originally carved by the Walnut River, when the Arkansas River flowed southward west of its present course. They further suggest that during Nebraskan glacial time the Arkansas probably was diverted to the rapidly downcutting Walnut. The Arkansas River has a gradient of 3.0 ft. per mile in Cowley County. This gradient and others cited were computed, by use of a cartometer, from maps made by the State Geological Survey of Kansas and the United States Geological Survey.

Northward along the Walnut, steep bluffs and eroded gulleys characterize both sides of the river, especially in southern Cowley County. Two massive limestones, the Fort Riley and the Winfield, form the bluffs in most places. The well-defined Winfield limestone is persistent on the west bank of the river across the entire county. The Walnut has only a few small tributaries in the southern half of Cowley County (Fig. 1). In the northern half, however, it is joined from the east by Timber Creek and Rock Creek. Timber Creek drains a large level area, formed by the eroded upper [Pg 349] portion of the Fort Riley limestone, in the north-central portion of the county. The gradient of Timber Creek is 12.9 feet per mile. The gradient of the Walnut River is only 2.3 ft. per mile from its point of entrance into the county to its mouth.

Fig. 1. Map of Cowley, Chautauqua and Elk counties,

Kansas, showing the streams mentioned in the text

Fig. 1. Map of Cowley, Chautauqua and Elk counties,

Kansas, showing the streams mentioned in the text

Grouse Creek, like the Walnut, has formed a valley of one to three miles in width, rimmed by prominent wooded bluffs. Those on the west side are capped by the Fort Riley limestone with the resistant Wreford and Crouse limestones forming lower escarpments. On the east side the Wreford and Crouse limestones provide the only escarpments along the stream above the Vinton community, except for occasional lower outcrops of Morrill limestone. Below Vinton the Fort Riley limestone again appears, capping the hills above the Wreford limestone. The headwaters of the western tributaries of Grouse Creek are generally in the Doyle shale formation; the eastern tributaries are in the Wreford limestone, Matfield shale, and Barnestone limestone formations. The gradient of Grouse Creek is 9 ft. per mile, of Silver Creek 14.6 ft. per mile, and of Crab Creek 14.4 ft. per mile.

The Big Caney River (Fig. 1), having a gradient of 15.4 ft. per mile in the area studied, drains an area with considerable geological and topographic variation. The main stream and its western tributaries [Pg 350] originate in Permian formations, whereas the eastern tributaries originate in Pennsylvanian formations. Cedar Creek is exemplary of western tributaries of Big Caney. This creek arises in the Wreford limestone, as do several nearby tributaries of Grouse Creek. Although the Grouse tributaries descend through only part of the Council Grove group, Cedar Creek flows downward through the entire Grove, Admire, and Wabaunsee groups and part of the Shawnee Group (Moore, 1951). In only 15 miles, Cedar Creek traverses formations comprising more than 60 per cent of the entire exposed stratigraphic section in Cowley County. Bass (1929:16) states that reliefs of 350 feet within a mile are present in parts of this area.

Large terraces of limestone characterize the eastern flank of the Flint Hills, which the western tributaries of Big Caney drain. Most striking is the Foraker limestone. It characteristically consists of three massive members in Cowley County, the uppermost of which forms the prominent first crest of the Flint Hills. As the rapid-flowing western tributaries of Big Caney descend over these successive limestone members, large quantities of chert and limestone rubble are transported and deposited in stream beds of the system. In many places the streams of the Big Caney system flow over resistant limestone members, which form a bedrock bottom. The eastern tributaries of Big Caney drain, for the most part, formations of the Wabaunsee group of the Pennsylvanian. Most of these streams have lower gradients than those entering Big Caney from the west. The tributaries of Big Caney, along with length in miles and gradient in feet per mile, are as follows: Spring Creek, 7.1, 54.5; Union Creek, 6.3, 42.9; Otter Creek, 14.6, 27.4; Cedar Creek, 11.6, 31.0; Rock Creek, 15.9, 26.5; Wolf Creek, 9.3, 17.2; Turkey Creek, 8.5, 26.4; Grant Creek, 13.9, 23.4; and Sycamore Creek, 8.9, 27.0.

Spring Creek and Union Creek are short and have formed no extensive floodplain. The high gradients of these creeks are characteristic also of the upper portions of several other tributaries such as Cedar Creek and Otter Creek.

Middle Caney Creek (Fig. 1) has its source in the Wabaunsee and Shawnee groups of the Pennsylvanian but its watershed is dominated by the "Chautauqua Hills" of the Douglas Group. This area is described by Moore (1949:127) as "an upland formed by hard sandstone layers." The rough rounded hills supporting thick growths of oaks differ in appearance from both the Big Caney watershed on the west and the Verdigris River watershed on the east. The gradient of Middle Caney in Chautauqua County is [Pg 351] 10.8 feet per mile. Its largest tributary, North Caney Creek, has a gradient of 15.5 feet per mile.

The Elk River Basin resembles the Big Caney River Basin topographically. Elk River has a gradient of 14.4 feet per mile.

The stream channels derive their physical characteristics from the geological make-up of the area and from land-use. The Arkansas River typically has low banks; however, in a few places, as in the NE ¼ of Section 21, T. 33 S, R. 3 E, it cuts into limestone members to form steep rocky banks. The bottom is predominantly sand. In years of heavy rainfall the river is turbid, but during 1956, when it occupied only a small portion of its channel, it was clear each time observed. All streams surveyed were clear except after short periods of flooding in June, and except in some isolated pools where cattle had access to the water.

In the Walnut River, sand bottoms occur in the lower part of the stream but the sand is coarser than that of the Arkansas River. Upstream, gravel and rubble bottoms become more common. Steep rocky banks border most of the course of the Walnut. During 1956, stream-flow was confined to the center of the channel, remote from these rocky banks.

The rubble and bedrock bottoms found in most streams of the Flint Hills have been described. In the alluvial valleys of their lower courses mud bottoms are found. Gravel is present in some places but sand is absent. Banks are variable but often steep and wooded. Along east- or west-flowing streams the north bank characteristically is low and sloping whereas the south bank is high, rises abruptly, and in many places is continuous with wooded hills. The lower sections of Otter Creek, Cedar Creek, and Rock Creek fit this description (Bass, 1929:19) especially well, as does Elk River near Howard.

Streams in the Chautauqua Hills resemble those of the Flint Hills in physical characteristics, except that a larger admixture of sandstone occurs in the rubble.

The climate of the area is characterized by those fluctuations of temperature, wind, and rainfall typical of the Great Plains. The mean annual temperature is 58 degrees; the mean July temperature is 81 degrees; the mean January temperature is approximately 34 degrees. The mean annual precipitation is 32.9 in Cowley County, 38.5 in Chautauqua County, and 35.1 in Elk County. Wind movement is great; Flora (1948:6) states that south-central Kansas ranks close to some of the windiest inland areas in the United States.

The area has been periodically subjected to droughts and floods. Such phenomena are of special interest to ichthyological workers in the area. At the time of this study drought conditions, which began in 1952, prevailed. Even in this period of drought, however, flooding occurred on Grouse Creek and water was high in Big Caney River after heavy local rains on the headwaters of these streams on June 22, 1956. Some of the lower tributaries of these same streams (such as Crab Creek and Cedar Creek) did not flow while the mainstreams were flooding. This illustrates the local nature of many of the summer rains in the area.

Table 1 indicates maximum, minimum, and average discharges in cubic feet per second at several stations in the area and on nearby streams. These figures were provided by the U. S. Geological Survey.

| Gauging station | Drainage area (sq. mi.) | Avg discharge | Maximum discharge | Date | Minimum discharge | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas River at Arkansas City | 43,713 | 1,630 | 103,000 | June 10, 1923 | 1 | October 9, 1921 |

| Walnut River at Winfield | 1,840 | 738 | 105,000 | April 23, 1944 | 0 | 1928, 1936 |

| Big Caney River at Elgin | 445 | 264 | 35,500 | April 10, 1944 | 0 | 1939, 1940, 1946, 1947 |

| Elk River near Elk City | 575 | 393 | 39,200 | April 16, 1945 | 0 | 1939, 1940, 1946 |

| Fall River near Fall River | 591 | 359 | 45,600 | April 16, 1945 | 0 | 1939, 1940, 1946 |

| Verdigris River at Independence | 2,892 | 1,649 | 117,000 | April 17, 1945 | 0 | 1932, 1934, 1936, 1939, 1940 |

Something of the effect that drought and flash-flood have had on Big Caney River is shown by the monthly means of daily discharge from October, 1954, to September, 1956, at the stream-gauging station near Elgin, Kansas (Table 2). Within these monthly variations there are also pronounced daily fluctuations; on Big Caney River approximately ¼ mile south of Elgin, Kansas, discharge in cubic feet per second for May, 1944, ranged from .7 to 9,270.0 and for May, 1956, from .03 to 20.0.

| Month | 1954-55 | 1955-56 |

|---|---|---|

| October | 103.00 | 69.60 |

| November | .31 | .78 |

| December | .18 | 1.92 |

| January | .78 | 1.65 |

| February | 4.76 | 2.08 |

| March | 3.37 | 1.27 |

| April | 4.91 | .47 |

| May | 624.00 | 7.37 |

| June | 51.30 | 35.20 |

| July | 1.20 | 1.85 |

| August | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| September | .04 | 0.00 |

The flora of the region varies greatly at the present time. Land-use has altered the original floral communities, especially in the intensively cultivated area of western Cowley County and in the river valleys.

The sandy Arkansas River floodplain exhibits several stages ranging from sparsely vegetated sandy mounds near the river through stages of Johnson grass, willow, and cottonwood, to an elm-hackberry fringe-forest. The Wellington formation bordering the floodplain supports a prairie flora where not disturbed by cultivation; Gates (1936:15) designates this as a part of the mixed bluestem and short-grass region. Andropogon gerardi Vitman., Andropogon scoparius Michx., Sorghastrum nutans (L.), and Panicum virgatum L. are important grasses in the hilly pasture-lands. Although much of this land is virgin prairie, the tall, lush condition of the grasses described by early writers such as Mooso (1888:304), and by local residents, is not seen today. These residents speak of slough grasses (probably Tripsacum dactyloides L. and Spartina pectinata Link.) that originally formed rank growths. These no doubt helped conserve water and stabilize flow in small headwater creeks. Remnants of some of these sloughs can still be found. The streams in the Flint Hills have fringe-forests of elm, hackberry, walnut, ash, and willow.

Eastward from the Flint Hills these fringe-forests become thicker with a greater admixture of hickories and oaks. The north slopes of hills also become more wooded. However, grassland remains predominant over woodland in western Chautauqua and Elk counties, whereas in the eastern one-half of Chautauqua County and the eastern one-third of Elk County the wooded Chautauqua Hills prevail. This is one of the most extensive wooded upland areas in Kansas. Hale (1955:167) describes this woodland as part of an ecotonal scrub-oak forest bordering the Great Plains south through Texas. He found stand dominants in these wooded areas to be Quercus marilandica Muenchh., Quercus stellata Wang., and Quercus velutina Lam.

Few true aquatic plants were observed in the Arkansas River although mats of duckweed were found in shallow backwater pools at station A-3 (Fig. 2) on December 22, 1956. In the Walnut River Najas guadalupensis Spreng. was common at station W-2. Stones were usually covered with algae in both the Arkansas and Walnut rivers. A red bloom, possibly attributable to Euglena rubra (Johnson), was observed on a tributary of the Walnut River on July 9, 1956, at station W-4.

Green algae were abundant at all stations in the Caney, Elk, and Grouse systems during May and June, 1956, and reappeared late in September. Chara sp. was common in these streams in April and May.

The most characteristic rooted aquatic of streams in the Flint Hills was Justicia americana L. At station G-7 on Grouse Creek and Station C-8 on Big Caney River (Fig. 3), Nelumbo lutea (Willd.) was found. Myriophyllum heterophyllum Michx. formed dense floating mats at a number of stations. Other aquatic plants observed in the Caney, Elk, and Grouse systems included Potamogeton gramineus L., Potamogeton nodosus Poir., Potamogeton foliosus Raf., Sagittaria latifolia Willd., Typha latifolia L., and Jussiaea diffusa Forsk.

In 1857, a survey was made of the southern boundary of Kansas. Several diaries (Miller, 1932; Caldwell, 1937; Bieber, 1932) were kept by members of the surveying party, which traveled from east to west. These accounts contain complaints of difficulty in traversing a country of broken ridges and gulleys as the party approached the area now comprising Chautauqua County. One account by Hugh Campbell, astronomical computer for the party (Caldwell, 1937) mentions rocky ridges covered with dense growth of "black jack," while another by Col. Joseph Johnson, Commander (Miller, 1932) speaks of "a good deal of oakes in the heights"—indicating that the upland oak forest of the Chautauqua Hills was in existence at that time. On reaching Big Caney River near Elgin, Campbell wrote of a stream with very high banks and of a valley timbered with oak and black walnut. While the party was encamped on Big Caney River some fishing was done. Campbell (Caldwell, 1937:353) described the fish taken as "Cat, Trout or Bass, Buffalo and Garr." Eugene Bandel (Bieber, 1932:152) wrote, "This forenoon we did not expect to leave camp, and therefore we went fishing. In about two hours we caught more fish than the whole company could eat. There were some forty fish caught, some of them weighing over ten pounds." It was noted that the waters of Big Caney and its tributaries were "very clear." Progressing up Rock Creek, Johnson wrote of entering a high rolling plain covered with fine grass, and crossed occasionally by clear wooded streams (probably Big and Little Beaver Creeks and Grouse Creek). The diary of Hugh Campbell (Caldwell, 1937:354) contains a description of the Arkansas River Valley near the Oklahoma border. "The Arkansas River at this point is about 300 yards wide, its waters are muddy, not quite so much so, as those of the Mississippi or Rio Bravo. Its valley is wooded and about two miles in width, the main bottom here, being on the east side. On the west it is a rolling prairie as far as the eye can see, affording excellent grass." Some seining was done while encamped on the Arkansas River and "buffalo, catfish, sturgeons, and gars" were taken (Bieber, 1932:156).

An editorial in the Winfield Courier of November 16, 1899, vigorously registers concern about a direct effect of settlement on fish populations in rivers of the area:

"The fish in the streams of Cowley County are being slaughtered by the thousands, by the unlawful use of the seine and the deadly hoop net. Fish are sold on the market every day, sometimes a tubful at a time, which never swallowed a hook.

"The fish law says it is unlawful to seine, snare, or trap fish but some of the smaller streams in the county, it is said are so full of hoop and trammel nets that a minnow cannot get up or down stream. These nets not only destroy what fish there are in the streams but they keep other fish from coming in, they are not operated as a rule by farmers to supply their own tables but by fellows who catch the fish to sell with no thought or care for the welfare of others who like to catch and eat fish.

"If there is a fishwarden in Cowley County so far as his utility goes the county would be as well off without him and his inactivity has caused many of those interested to get together for the purpose of seeing that the law is enforced.

"Depredations like this work injury in more ways than one. They not only deplete the streams of fish large enough to eat and destroy the source of supply but if the U. S. Fish Commission discovers that the law is not enforced and the fish not protected, there will be no free government fish placed in Cowley County streams. It is useless for the Government to spend thousands of dollars to keep the streams well supplied if a few outlaws are allowed to ruthlessly destroy them. The new organization has its eye on certain parties now and something is liable to drop unexpectedly soon."

Graham (1885:78) listed 13 species of fish that had already been introduced into Kansas waters prior to 1885 by the State Fish Commission.

These early references indicate that direct effects of settlement on the native flora and fauna were recognized early. Concern such as that expressed in the editorial above persists today; however, it is not clear whether the fish fauna of the streams of the area has been essentially changed by man's predation. The indirect effects through human modifications of the environment seem to be of much importance. Three modifications which have especially affected streams have been agricultural use, urbanization, and industrialization.

The effect of land-use on streams is closely related to its effect on the flora of the watershed. Turbidity, sedimentation, and the rate, periodicity, and manner of flow all bear some relationship to the land-use of the watershed. Stream-flow in the area has been discussed in the section on climate.

The effects of urbanization are more tangible and better recognized than those of agricultural land-use. Streams that flow through cities and other populous areas undergo some modification, especially of the streamside flora. Another effect of urbanization has been increased loads of sewage discharged into the streams. The combined populations of Arkansas City and Winfield rose from 3,986 in 1880 to 23,167 in 1950. Arkansas City found it necessary to construct a sewage system in 1889; Winfield in 1907.

There are, at the present time, nine towns within the area that have municipal sewage systems. The State Training Home at Winfield also has a sewage system. The Kansas State Board of Health, Division of Sanitation, has provided information concerning adequacy of these systems and certain others in nearby counties as of February 5, 1957. This information is shown in Table 3.

Representatives of the Division of Sanitation, Kansas State Board of Health, expressed the belief that pollution by both domestic sewage and industrial wastes would be largely eliminated in the "lower Arkansas" and in the Walnut watershed by 1959.

Important oil and gas resources have been discovered in each of the three counties. The first producing wells were drilled between 1900 and 1902 (Jewett and Abernathy, 1945:24). The Arkansas River flows through several oilfields in its course across Cowley County (Jewett and Abernathy, 1945:97). A number of producing wells have been drilled in the Grouse Creek watershed since 1939 and many of these wells are near the banks of the creek. In the Big Caney watershed of Cowley and Chautauqua counties there has been little oil production in recent years; however, a few small pools are presently producing in southwestern Elk County.

Clapp (1920:33) stated that "Many of the finest streams of our state are now destitute of fish on account of oil and salt pollution. The Walnut River, once as fine a bass stream as could be found anywhere, and a beautiful stream, too, is now a murky oil run, and does not contain a single fish so far as I know. The Fall and Verdigris rivers are practically ruined. Both the Caney rivers are affected, and may soon be ruined for fishing." Doze (1924:31) noted "Some of the finest streams in the state have been ruined as habitat for wild life, the Walnut River is probably the most flagrant example."

| Community | Status on February 5, 1957 | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Cowley County: | ||

| Arkansas City | Discharging raw sewage | Adequate plant in design stage. |

| Geuda Springs | Discharging raw sewage | |

| Winfield | Inadequate | |

| State training school | Adequate | |

| Udall | Adequate | |

| Chautauqua County: | ||

| Cedar Vale | Inadequate | |

| Sedan | Adequate | In operation 30 days. |

| Elgin | Adequate | |

| Elk County: | ||

| Moline | Inadequate | |

| Howard | Adequate | |

| Sumner County: | ||

| Belle Plaine | Discharging raw sewage | Adequate plant under construction. |

| Mulvane | Discharging raw sewage | Adequate plant under construction. |

| Oxford | Discharging raw sewage | Construction on adequate plant to start soon. |

| Butler County: | ||

| Augusta | Adequate | |

| El Dorado | Discharging raw sewage | Adequate plant under construction. |

| Douglass | Discharging raw sewage | Adequate plant to go into operation within 30 days. |

Pollution by petroleum wastes from refineries has also affected the streams studied. The only refinery within the area is at Arkansas City. In Butler County there are four refineries on the Walnut watershed upstream from the area surveyed. Metzler (1952) noted that "fish-kills" occurred from the mid-1940's until 1952 in connection with wastes periodically discharged from these refineries. However, the largest kill, in 1944, was attributed to excessive brine pollution.

In Arkansas City a meat-packing plant, a large railroad workshop, two flour mills, two milk plants, and several small manufacturing plants contribute wastes which may figure in industrial pollution. There are milk plants and small poultry processing plants at Winfield. In Chautauqua and Elk Counties there is little industrial activity.

In recent years several measures have been implemented or proposed to conserve the water and land resources of the Arkansas River Basin. Droughts and floods have focused public attention on such conservation. Less spectacular, but nevertheless important, problems confronting conservationists include streambank erosion, channel deterioration, silting, recreational demands for water, and irrigation needs.

Congress has authorized the U. S. Corps of Engineers (by the Flood Control Act of 1941) to construct six dam and reservoir projects in the Verdigris watershed. Two of these—Hulah Reservoir in Osage County, Oklahoma, on Big Caney River, and Fall River Reservoir in Greenwood County, Kansas—have been completed. Other reservoirs authorized in the Verdigris watershed include Toronto, Neodesha, and Elk City (Table Mound) in Kansas and Oologah in Oklahoma. Construction is underway on the Toronto Reservoir and some planning has been accomplished on the Neodesha and Elk City projects.

The possibilities of irrigation projects in the Verdigris and Walnut River basins are under investigation by the United States Bureau of Reclamation (Foley, et al., 1955:F18).

An area of 11 square miles in Chautauqua and Montgomery Counties is included in the Aiken Creek "Pilot Watershed Project," a co-operative effort by federal, state, and local agencies to obtain information as to the effects of an integrated watershed protection program (Foley, et al., 1955:131).

Few accounts of fishes in the area here reported on have been published. Evermann and Fordice (1886:184) made a collection from Timber Creek at Winfield in 1884.

The State Biological Survey collected actively from 1910 to 1912, but localities visited in the Arkansas River System were limited to the Neosho and Verdigris River basins (Breukelman, 1940:377). The only collection made in the area considered here was on the Elk River in Elk County on July 11, 1912. The total species list of this collection is not known.

In the years 1924-1929 Minna E. Jewell collected at various places in central Kansas. On June 30, 1925, Jewell and Frank Jobes made collections on Timber Creek and Silver Creek in Cowley County.

Hoyle (1936:285) mentions collections made by himself and Dr. Charles E. Burt, who was then Professor of Biology at Southwestern College, Winfield, Kansas. Records in the Department of Biology, Kansas State Teachers College at Emporia, indicate that Dr. Burt and others made collections in the area which have not been published on.

| Collection number | Date | River | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-131 | April 5, 1955 | Elk | Sec. 3, T31S, R11E |

| C-132 | April 5, 1955 | Sycamore | Sec. 5, T34S, R10E |

| C-133 | April 5, 1955 | Big Caney | Sec. 12, T34S, R8E |

| C-136 | April 6, 1955 | Walnut | Sec. 29 or 32, T32S, R4E |

Claire Schelske (1957) studied fishes of the Fall and Verdigris Rivers in Wilson and Montgomery counties from March, 1954, to February, 1955.

In the annotated list of species that follows, records other than mine are designated by the following symbols:

E&F—Evermann and Fordice

SBS—State Biological Survey (1910-1912)

J&J—Jewell and Jobes (collection on Silver Creek)

C—Collection number—Cross (State Biological Survey, 1955)

UMMZ—University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

OAM—Oklahoma A&M College Museum of Zoology

I am grateful to Professor Frank B. Cross for his interest in my investigation, for his counsel, and for his penetrating criticism of this paper. This study would have been impossible without the assistance of several persons who helped in the field. Mr. Artie C. Metcalf and Mr. Delbert Metcalf deserve special thanks for their enthusiastic and untiring co-operation in collecting and preserving of specimens. Mrs. Artie C. Metcalf, Miss Patricia Metcalf, Mr. Chester Metcalf, and Mr. Forrest W. Metcalf gave help which is much appreciated. I am indebted to the following persons for numerous valuable suggestions: Dr. John Breukelman, Kansas State Teachers College, Emporia, Kansas; Dr. George Moore, Oklahoma A&M College, and Mr. W. L. Minckley, Lawrence, Kansas.

Collections were made by means of: (1) a four-foot net of nylon screen; (2) a 10×4-foot "common-sense" woven seine with ¼-inch mesh; (3) a 15×4-foot knotted mesh seine; (4) a 20×5-foot ¼-inch mesh seine; (5) pole and line (natural and artificial baits). At most stations the four-foot, ten-foot, and twenty-foot seines were used; however, the equipment that was used varied according to the size of pool, number of obstructions, nature of bottom, amount of flow, and type of streambank. Usually several hours were spent at each station and several stations were revisited from time to time. Percentages noted in the List of Species represent the relative number taken in the first five seine-hauls at each station.

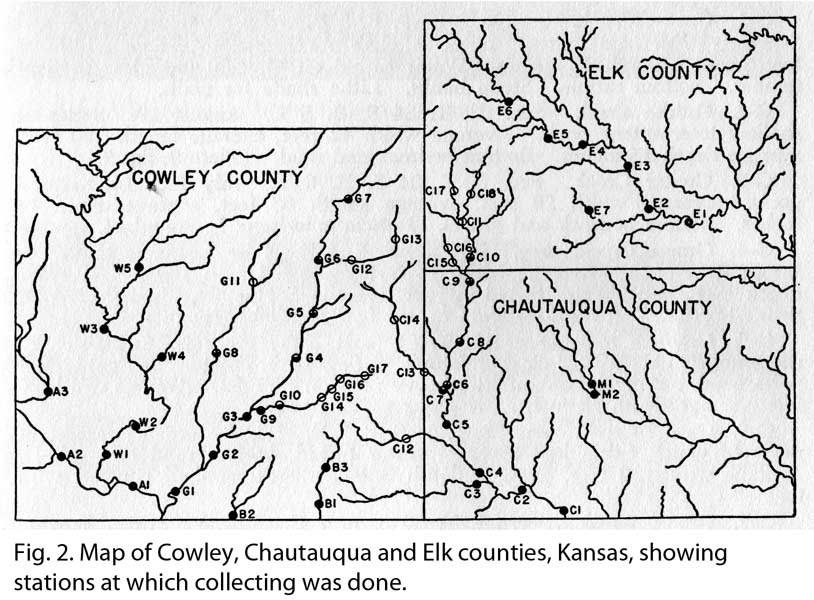

Collecting was done at stations listed below and shown in Fig. 2. Each station was assigned a letter, designating the stream system on which the station was located, and a number which indicates the position of the station on the stream. This number increases progressively upstream from mouth to source. Code letters used are as follows: A&Mdash;Arkansas River; W—Walnut River System; B—Beaver Creek System; C—Big Caney River System; G—Grouse Creek System; M—Middle Caney Creek System; E—Elk River System. All dates are in the year 1956.

Fig. 2. Map of Cowley, Chautauqua and Elk counties,

Kansas, showing stations at which collecting was done.

Fig. 2. Map of Cowley, Chautauqua and Elk counties,

Kansas, showing stations at which collecting was done.

A-1. Arkansas River. Sec. 2 and 3, T. 35 S, R. 4 E. June 14 and August 20. Braided channel with sand bottom. Water slightly turbid, with layer of oil sludge on bottom.

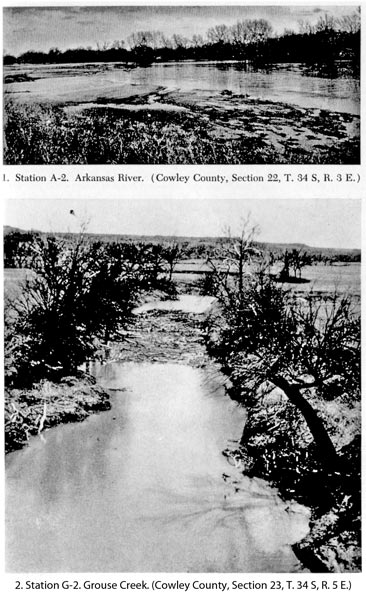

A-2. Arkansas River. Sec. 22, T. 34 S, R. 3 E. August 25. Flowing through diverse channels. Average depth 12 inches. Bottom sand. (Plate 9, fig. 1.)

A-3. Arkansas River. Sec. 21, T. 33 S, R. 3 E. August 27 and December 22. Flowing over fine sand. Average depth 11 inches. Some areas of backwater with oil sludge on bottom.

W-1. Walnut River. Sec. 20, T. 34 S, R. 4 E. July 7. Flowing rapidly, with large volume, because of recent rains. Average width 300 feet. Bottom gravel. Water turbid.

W-2. Walnut River. Sec. 11, T. 34 S, R. 4 E. July 20. Rubble riffles and large shallow pools with gravel bottoms. Average width, 100 feet. Water clear.

W-3. Walnut River. Sec. 29, T. 32 S, R. 4 E. July 17. Pools and riffles below Tunnel Mill Dam at Winfield. Water clear.

W-4. Badger Creek. Sec. 6, T. 33 S, R. 5 E. July 17. Small pools. Average width 7 feet, average length 40 feet, average depth 8 inches. Water turbid and malodorous. Bottoms and banks mud. Much detritus present.

W-5. Timber Creek. Sec. 35, T. 31 S, R. 4 E. June 6. Intermittent pools, widely separated. Average width 9 feet, average depth 8 inches. Bottom mud and gravel.

B-1. Big Beaver Creek. Sec. 8, T. 35 S, R. 7 E. May 28. Isolated pools. Average width 10 feet, average depth one foot. Water turbid. Bottom rubble.

B-2. Little Beaver Creek. Sec. 18, T. 35 S, R. 6 E. July 21. Intermittent pools. Average width 10 feet, average length 35 feet, average depth 10 inches. Bottoms rubble, mud, and bedrock.

B-3. Big Beaver Creek. Sec. 28, T. 34 S, R. 7 E. July 22. Series of small turbid pools.

G-1. Grouse Creek. Sec. 5, T. 35 S, R. 5 E. May 30, September 5, and September 24. Intermittent pools in close succession. Average width 22 feet, average depth 16 inches. Water turbid on May 30 but clear in September. Bottom rubble. Steep banks. Little shade for pools.

G-2. Grouse Creek. Sec. 23, T. 34 S, R. 5 E. August 29. Series of shallow intermittent pools. Average width 42 feet, average length 120 feet, average depth 15 inches. Bottom bedrock and mud. (Plate 9, fig. 2.)

G-3. Grouse Creek. Sec. 6, T. 34 S, R. 6 E. July 12. Intermittent pools. Average width 20 feet, average length 65 feet, average depth 14 inches. Bottom bedrock and gravel. Justicia americana L. abundant.

G-4. Grouse Creek. Sec. 12, T. 33 S, R. 6 E. June 1 and September 7. Intermittent pools. Average width 15 feet, average length 100 feet, average depth 18 inches. Water turbid in June, clear in September. Najas guadalupensis Spreng., and Myriophyllum heterophyllum Michx. common.

G-5. Grouse Creek. Sec. 19, T. 32 S, R. 7 E. July 2. Succession of riffles and pools. Water clear. Volume of flow approximately one cubic foot per second, but creek bankful after heavy rains on June 22. Average width 20 feet, average depth 18 inches.

G-6. Grouse Creek. Sec. 32, T. 31 S, R. 7 E. July 8. Small intermittent pools to which cattle had access. Water turbid, bottom mud and rubble. Average width 10 feet, average depth 8 inches. Stream-bed covered with tangled growths of Sorghum halepense (L.).

G-7. Grouse Creek. Sec. 34, T. 30 S, R. 7 E. July 8. Stream flowing slightly. Water clear. Average width of pools 30 feet; average depth 20 inches. Bottom bedrock and gravel. Myriophyllum heterophyllum Michx., Nelumbo lutea (Willd.), and Justicia americana L. common in shallow water.

G-8. Silver Creek. Sec. 1, T. 33 S, R. 5 E. July 17. Intermittent pools. Average width 30 feet, average length 120 feet, average depth 12 inches. Water clear.

G-9. Silver Creek. Sec. 4, T. 32 S, R. 6 E. July 17. Small upland brook with volume less than one-half cfs. Average width 12 feet, average depth 10 inches. Water clear, bottom mostly rubble.

G-10. Crab Creek. Sec. 33, T. 33 S, R. 6 E. June 24. Intermittent pools, showing evidence of having flowed after rains on June 22. Average width 15 feet, average depth 16 inches.

G-11. Crab Creek. Sec. 35, T. 33 S, R. 6 E. July 16. Small intermittent pools. Average width 13 feet, average length 55 feet, average depth 11 inches. Water clear. Bottom rubble and mud.

G-12. Crab Creek. Sec. 28, T. 33 S, R. 7 E. June 2 and July 20. Isolated pools. Average width 18 feet, average depth one foot. Water turbid. Bottom bedrock and rubble. Myriophyllum heterophyllum and Justicia americana abundant.

G-13. Crab Creek. Sec. 21, T. 33 S, R. 7 E. July 29. Isolated pools 300 feet by 24 feet. Average depth 12 inches. Water turbid.

G-14. Unnamed creek (hereafter called Grand Summit Creek). Sec. 26, T. 31 S, R. 7 E. August 30. Intermittent pools. Average width 15 feet, average length 45 feet, average depth 11 inches. Water clear. Bottom rubble.

1. Station A-2. Arkansas River. (Cowley County, Section 22, T. 34 S, R.

3 E.)

2. Station G-2. Grouse Creek. (Cowley County, Section 23, T. 34 S, R. 5

E.)

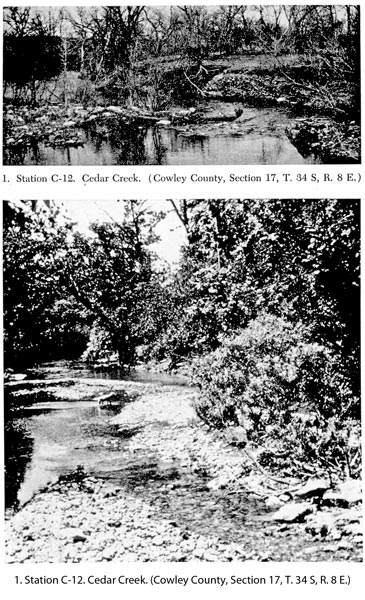

1. Station C-12. Cedar Creek. (Cowley County, Section 17, T. 34 S, R. 8

E.)

2. Station C-16. Spring Creek. (Elk County, Section 26, T. 31 S, R. 8

E.) Volume of flow of this small creek is indicated by riffle in

foreground.

G-15. Unnamed creek (same as above). Sec. 17, T. 31 S, R. 8 E. July 27. Small upland creek bordered by bluestem pastures. Pools with average width of 10 feet, average length 30 feet, average depth 9 inches. Water slightly turbid. Bottom rubble and mud.

G-16. Crab Creek. Sec. 22, T. 33 S, R. 7 E. July 25. Small isolated pools. Average width 17 feet, average length 58 feet, average depth 9 inches. Water turbid.

G-17. Crab Creek. Sec. 23, T. 33 S, R. 7 E. July 25. Upland brook bordered by bluestem pastures. Unshaded intermittent pools. Average width 7 feet, average length 40 feet, average depth 9 inches. Water turbid.

C-1. Big Caney River. Sec. 16, T. 33 S, R. 10 E. July 19. Intermittent pools. Average width 47 feet, average length 90 feet, average depth 13 inches. Bottom rubble and bedrock. Water clear to slightly turbid.

C-2. Big Caney River. Sec. 1, T. 35 S, R. 9 E. September 5. Series of intermittent pools. Bottom rubble and large stones.

C-3. Big Caney River. Sec. 29, T. 34 S, R. 9 E. June 17. Large shallow pool below ledge 3 feet high forming "Osro Falls." Bottom bedrock.

C-4. Big Caney River. Sec. 32, T. 34 S, R. 9 E. June 3. Three large pools (50 feet by 300 feet) with connecting riffles. Water turbid. Bottom bedrock and rubble.

C-5. Big Caney River. Sec. 11 and 12, T. 34 S, R. 8 E. May 27, May 29, June 11, June 18, June 19, and June 27. From a low-water dam, 6 feet high, downstream for ¼ mile. Pools alternating with rubble and bedrock riffles. Collecting was done at different times of day and night, and when stream was flowing and intermittent.

C-6. Big Caney River. Sec. 26, T. 33 S, R. 8 E. June 16. Intermittent pools with bedrock bottom. Water slightly turbid. Average width 16 feet, average depth 10 inches.

C-7. Otter Creek. Sec. 26, T. 33 S, R. 8 E. June 16. Pools and riffles. Water clear. Algae abundant. Average width 10 feet, average depth 10 inches.

C-8. Big Caney River. Sec. 1, T. 33 S, R. 8 E. June 10. Intermittent pools. Average width 10 feet, average depth 14 inches. Water clear. Bottom rubble and gravel. Aquatic plants included Chara sp., Sagittaria latifolia Willd., Jussiaea diffusa Forsk., and Nelumbo lutea (Willd.).

C-9. Big Caney River. Sec. 6 and 7, T. 32 S, R. 9 E. June 27. Clear, flowing stream, 20 feet wide, volume estimated at 5 cfs. Bottom gravel and rubble. Extensive gravel riffles.

C-10. Big Caney River. Sec. 29 and 32, T. 31 S, R. 9 E. June 27. Water clear and flowing rapidly, volume estimated at 5-6 cfs. Bottom rubble with a few muddy backwater areas.

C-11. Big Caney River. Sec. 7, T. 31 S, R. 9 E. July 26. Flowing, with less than 1 cfs. Average width 20 feet, average depth 22 inches. Water extremely clear. Bottom gravel and rubble. Myriophyllum heterophyllum, Potamogeton foliosus, and Justicia americana common.

C-12. Cedar Creek. Sec. 17, T. 34 S, R. 8 E. March 10, April 2, June 1, June 6, and August 24. Pools and riffles along ¼ mile of stream were seined in the early collections. In August only small isolated pools remained. Bottom bedrock and rubble. Much detritus along streambanks. (Plate 10, fig. 1.)

C-13. Otter Creek. Sec. 16, T. 33 S, R. 8 E. June 15. Flowing, less than 1 cfs. Pools interspersed with rubble riffles. Water clear.

C-14. Otter Creek. Sec. 30, T. 32 S, R. 8 E. May 31, and September 3. Series of small pools. Average width 10 feet, average depth 15 inches. Shallow rubble riffles. Water extremely clear. Temperature 68° at 6:30 p.m. on May 31; 78° at 2:00 p.m. on September 3.

C-15. Spring Creek. Sec. 35, T. 31 S, R. 8 E. June 28. Small, clear, [Pg 362] upland brook with rubble bottom. Pools 10 feet in average width and 11 inches in average depth. Numerous shallow rubble riffles.

C-16. Spring Creek. Sec. 26, T. 31 S, R. 8 E. July 9. Small intermittent pools. Average width 10 feet; average depth 8 inches. Bottom gravel. (Plate 10, fig. 2.)

C-17. West Fork Big Caney River. Sec. 36, T. 30 S, R. 8 E. July 27. Small pool below low-water dam. Pool 20 feet by 30 feet with average depth of 20 inches.

C-18. East Fork Big Caney River. Sec. 31, T. 30 S, R. 9 E. July 27. Isolated pool 25 feet by 25 feet with an average depth of 15 inches.

M-1. Middle Caney Creek. Sec. 23, T. 33 S, R. 10 E. July 4. Intermittent pools. Average width 45 feet, average depth 15 inches. Water stained brown. Oil fields nearby but no sludge or surface film of oil noted. Bottom rubble and bedrock.

M-2. Pool Creek. Sec. 25, T. 33 S, R. 10 E. May 26. Pool 120 feet by 40 feet below limestone ledge approximately 12 feet high forming Butcher's Falls. Other smaller pools sampled. Water clear. Bottom bedrock and rubble.

E-1. Elk River. Sec. 12, T. 31 S, R. 11 E. July 9. Four intermittent pools seined. Average width 32 feet, average depth 13 inches. Bottom bedrock, rubble, and mud. Water turbid.

E-2. Elk River. Sec. 3, T. 31 S, R. 11 E. June 28. Intermittent pools below and above sandstone ledge approximately 6 feet high forming "falls" at Elk Falls. Average width 33 feet, average depth 15 inches. Bottom bedrock, rubble and mud. Water slightly turbid.

E-3. Elk River. Sec. 21, T. 30 S, R. 11 E. June 28. Two small pools, 10 feet by 30 feet with average depth of 6 inches. Bottom bedrock.

E-4. Elk River. Sec. 12, T. 30 S, R. 10 E. June 28. One long pool 500 feet by 50 feet with a variety of depths and bottom conditions ranging from mud to bedrock. Average depth 18 inches. Water turbid and pools unshaded.

E-5. Elk River. Sec. 32, T. 29 S, R. 10 E. August 30. Intermittent pools. Average width 21 feet, average depth 20 inches. Bottom rubble. Water clear.

E-6. Elk River. Sec. 23, T. 29 S, R. 9 E. August 30. Small isolated pools. River mostly dry. Bottom bedrock. Water slightly turbid with gray-green "bloom."

E-7. Wildcat Creek. Sec. 11, T. 31 S, R. 10 E. Volume of flow less than one cfs. Average width 20 feet, average depth 18 inches. Domestic sewage pollution from town of Moline suspected.

Lepisosteus osseus oxyurus (Linnaeus): Stations A-1, W-2, W-3, G-2, G-3, G-4, C-1, C-2, C-3, C-5, C-8.

Of 34 longnose gar taken, 27 were young-of-the-year. The latter were from shallow isolated pools (bedrock bottom at C-1, C-3, C-4; gravel bottom at C-6). At station W-1 in moderate flood conditions several young-of-the-year were found in the most sheltered water next to the banks.

The longnose gar was found only in the lower parts of the streams surveyed (but were observed by me in smaller tributaries of these streams in years when the streams had a greater volume of flow). A preference for downstream habitat is suggested in several other surveys: Cross (1950:134, 1954a:307) on the South Fork of the [Pg 363] Cottonwood and on Stillwater Creek; Cross and Moore (1952:401) on the Poteau and Fourche Maline rivers; Moore and Buck (1953:21) on the Chikaskia River.

Lepisosteus platostomus Rafinesque: One shortnose gar (K. U. 3157) has been taken from the Arkansas River in Cowley County. This gar was taken by Mr. Richard Rinker on a bank line on April 10, 1955, at station A-3.

Dorosoma cepedianum (Le Sueur): Stations W-3, G-4, C-4, C-5, M-1, E-1, E-4.

In smaller streams such as the Elk and Caney rivers adult gizzard shad seemed scarce. They were more common in collections made in larger rivers (Walnut, Verdigris, and Neosho). In impoundments of this region shad often become extremely abundant. Schoonover (1954:173) found that shad comprised 97 per cent by number and 83 per cent by weight of fishes taken in a survey of Fall River Reservoir.

Carpiodes carpio carpio (Rafinesque): Stations A-1, A-2, A-3, W-3, G-1, C-3.

Hubbs and Lagler (1947:50) stated that the river carpsucker was "Mostly confined to large silty rivers." Of the stations listed above C-3 least fits this description being a large shallow pool about ⅓ acre in area having bedrock bottom and slightly turbid water. The other stations conform to conditions described by Hubbs and Lagler (loc. cit.).

Carpiodes velifer (Rafinesque): SBS. Three specimens of the highfin carpsucker (K. U. 177-179) were collected on July 11, 1912, from an unspecified location on Elk River in Elk County.

Ictiobus bubalus (Rafinesque): Stations W-3, G-1, G-2, C-1, C-3, C-4, C-6, E-1, E-2, E-3.

The smallmouth buffalo shared the downstream proclivities of the river carpsucker. In half of the collections (G-2, C-1, E-1, E-2, E-3) only large juveniles were taken; in the other half only young-of-the-year were found. In one pool at station C-1 hundreds of young buffalo and gar were observed. This large shallow pool was 100 × 150 feet, with an average depth of 8 inches. The bottom consisted of bedrock. Station C-6 was a small pool with bedrock bottom, eight feet in diameter, with an average depth of only 4 inches. Station E-3 was also a small isolated pool with bedrock bottom and an average depth of 6 inches.

Ictiobus niger (Rafinesque): Station C-5.

Only two specimens of the black buffalo were taken. An adult [Pg 364] was caught on spinning tackle, with doughballs for bait. The second specimen was a juvenile taken by seining one mile below Station C-5 on September 22.

Ictiobus cyprinella (Valenciennes): Station G-2.

Two juvenal bigmouth buffalo were taken in a shallow pool, along with several juvenal smallmouth buffalo.

Moxostoma aureolum pisolabrum Trautman and Moxostoma carinatum (Cope): SBS.

Two specimens of Moxostoma aureolum pisolabrum (K. U. 242-243) and one specimen of Moxostoma carinatum (K. U. 223) were taken from an unspecified locality on Elk River in Elk County on July 11, 1912. There are no other records for any of these fish in the collection area. M. aureolum pisolabrum has been taken in recent years in eastern Kansas (Trautman, 1951:3) and has been found as far west as the Chikaskia drainage in northern Oklahoma by Moore and Buck (1953:21). That occasional northern redhorse enter the larger rivers of the area here reported on seems probable.

M. carinatum has been reported only a few times from Kansas. The only recent records are from the Verdigris River (Schelske, 1957:39). Elkins (1954:28) took four specimens of M. carinatum from cutoff pools on Salt Creek in Osage County, Oklahoma, in 1954. This recent record suggests that occurrences in southern Kansas are probable.

Moxostoma erythrurum (Rafinesque): Stations G-5, G-7, G-10, G-12, C-4, C-5, C-6, C-8, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-13, C-15, E-1, E-2, E-4 (C-131, C-133, C-136).

The golden redhorse was common in several of the streams surveyed, and utilized the upland parts of streams more extensively than any of the other catostomids occurring in the area. M. erythrurum and Ictiobus bubalus were taken together at only two stations. In no case was I. bubalus taken from a tributary of Grouse Creek or of Big Caney River. In contrast M. erythrurum reached its greatest concentrations in such habitat, although it was always a minor component of the total fish population. Stations C-5 and E-2 were the lowermost environments in which this redhorse was taken.

The largest relative number of golden redhorse was found at station G-12 on Crab Creek where 7.5 per cent of the fishes taken were of this species. This station consisted of intermittent pools averaging one foot in depth. Bottoms were bedrock and rubble and the water was clear and shaded. The fish were consistently [Pg 365] taken in the deeper, open part of the pool where aquatic vegetation, which covered most of the pool, was absent.

Another station at which M. erythrurum was abundant was C-12 on Cedar Creek. Here a long, narrow, clear pool was the habitat, with average depth of 17 inches, and bottom of bedrock.

Minytrema melanops (Rafinesque): Stations G-10, C-4, C-12, E-1.

Occurrences of the spotted sucker were scattered. At stations C-4 and G-10 single specimens were taken. At station E-1 (July 9) one specimen was taken at the mouth of a small tributary where water was turbid and quiet. This specimen (K. U. 3708) was the largest (9⅜ inches total length) found, and possessed pits of lost tubercles.

Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus: Stations A-1, W-1, W-2, W-3, W-4, G-3, G-4, G-6, G-8, C-3, C-5, E-4.

Carp were taken most often in downstream habitat. No carp were taken above station C-5 on Big Caney River.

The earliest date on which young were taken was July 7, when 46 specimens, approximately ½ inch in total length, were taken from the Walnut River at station W-1. The small carp showed a preference for small shallow pools; adults were found in deeper pools.

Hybopsis aestivalis tetranemus (Gilbert): Station A-3.

Only one specimen of the speckled chub was taken. The species has been recorded from nearby localities in the Arkansas River and its tributaries both in Kansas and Oklahoma. Its habitat seems to be shallow water over clean, fine sand, and it occurs in strong current in mid-channel in the Arkansas River. Suitable habitat does not occur in other parts of the area covered by this report.

Notropis blennius (Girard): Stations A-1, A-2, A-3.

The river shiner was taken only in the Arkansas River and in small numbers. In all instances N. blennius was found over sandy bottom in flowing water. Females were gravid at station A-1 on June 14. To my knowledge there are no published records of this shiner from the Arkansas River Basin in Kansas. In Oklahoma this species prefers the large, sandy streams such as the Arkansas River. Cross and Moore (1952:403) found it in the Poteau River only near the mouth.

Notropis boops Gilbert: Stations G-5, G-7, C-3, C-5, C-8, C-9, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-15, C-16, E-4, E-5, M-1, M-2.

Widespread occurrence of the bigeye shiner in this area seems surprising. Except for this area it is known in Kansas only from [Pg 366] the Spring River drainage in the southeastern corner of the state (Cross, 1954b:474). N. boops chose habitats that seemed most nearly like Ozarkian terrain. The largest relative number of bigeye shiners was taken at C-11 in a clear stream described in the discussion of Notropis rubellus. At this station N. boops comprised 14.11 per cent, and N. boops and N. rubellus together comprised 24.78 per cent of all fish taken.

At station G-7 on Grouse Creek the percentage of N. boops was 7.15. Here, as at station C-11, water was clear. At both stations Myriophyllum heterophyllum was abundant and at G-7 Nelumbo lutea was also common. At G-7 N. boops seemed most abundant in the deeper water, but at C-11 most shiners were found in the shallower part of a large pool.

Two other collections in which N. boops were common were from Spring Creek. It is a small, clear Flint Hills brook running swiftly over clean gravel and rubble. It had, however, been intermittent or completely dry in its upper portion throughout the winter of 1955-'56 and until June 22, 1956. In collections at C-15 on June 28, N. boops formed 6.5 per cent of the fish taken. Farther upstream, at C-16 on July 9, in an area one mile from the nearest pool of water that existed prior to the rains of June 22, N. boops made up 7.2 per cent of the fish taken.

In streams heading in the hilly area of western Elk County, the relative abundance of Notropis boops decreased progressively downstream. On upper Elk River percentages were lower than on upper Grouse Creek and upper Big Caney River.

Hubbs and Lagler (1947:66) characterize the habitat of this species as clear creeks of limestone uplands. There are numerous records of the bigeye shiner from extreme eastern Oklahoma. It has been reported as far west as Beaver Creek in Osage County, Oklahoma. Beaver Creek originates in Cowley County, Kansas, near the origin of Cedar Creek and Crab Creek. Drought had left a few pools of water in Beaver Creek in Kansas at the time of my survey. The fish-fauna seemed sparse and N. boops was not among the species taken. Of interest in considering the somewhat isolated occurrence of the bigeye shiner in the Flint Hills area of Kansas is a record of it by Ortenburger and Hubbs (1926:126) from Panther Creek, Comanche County, Oklahoma, in the Wichita Mountain area of that state.

Notropis buchanani Meek: Stations G-1, E-4 (C-131).

At station G-1 the ghost shiner was taken in small numbers in the shallow end of a long pool (150 × 40 feet.) The three individuals taken at station E-4 were in an isolated pool (50 × 510 feet) averaging [Pg 367] 1½ feet in depth. Water was turbid, and warm due to lack of shade.

The habitat preferences of this species and of the related species N. volucellus have been described as follows by Hubbs and Ortenburger (1929b:68): "It seems probable that volucellus when occurring in the range of buchanani occupies upland streams, whereas buchanani is chiefly a form of the large rivers and adjacent creek mouths." The results of this survey and impressions gained from other collections, some of which are unpublished, are in agreement with this view. A collection on the Verdigris River at Independence, Kansas, directly downstream from the mouth of the Elk River, showed N. buchanani to be common while N. volucellus was not taken. At station E-5 upstream from E-4, however, N. volucellus was taken but N. buchanani was not found.

In the upper Neosho basin, Cross (1954a:310) took N. volucellus but not N. buchanani. Other collections have shown N. buchanani to be abundant in the lower Neosho River in Kansas. Moore and Paden (1950:85) observe that N. buchanani was found only near the mouth of the Illinois River in Oklahoma and was sharply segregated ecologically from N. volucellus that occupied a niche in the clear main channels in contrast to the more sluggish waters inhabited by N. buchanani.

Notropis camurus (Jordan and Meek): Stations C-3, C-4, C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, C-9, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-13, E-1, E-5 (C-131).

Highest concentrations of the bluntface shiner were found close to the mouths of two tributaries of Big Caney River: Rock Creek and Otter Creek. On Rock Creek (Station C-4) this shiner was abundant in a shallow pool below a riffle where water was flowing rapidly. Many large males in breeding condition were taken (June 3). The species formed 20.2 per cent of the fish taken.

On Otter Creek (Station C-13) the species was common in shallow bedrock pools below riffles. It formed 12.1 per cent of the fish taken.

At station C-5, N. camurus was characteristically found in an area of shallow pools and riffles. At station C-10 it was found in clear flowing water over rubble bottom and in small coves over mud bottom. At C-11 (July 26) N. camurus was taken only in one small pool with rapidly flowing water below a riffle. In this pool N. camurus was the dominant fish. At station C-12, on April 2, N. camurus was abundant in the stream, which was then clear and flowing. On August 24, it was not taken from the same pool, which was then turbid and drying.

The frequent occurrence of this species in clear, flowing water [Pg 368] seems significant. Cross (1954a:309) notes that the bluntface shiner prefers moderately fast, clear water. Hall (1952:57) found N. camurus only in upland tributaries east of Grand River and not in lowland tributaries west of the river. Moore and Buck (1953:22) took this species in the Chikaskia River, which was at that time a clear, flowing stream. They noted that in Oklahoma it seems to be found only in relatively clear water.

N. camurus did not seem to ascend the smaller tributaries of Big Caney River as did N. rubellus and N. boops even when these tributaries were flowing.

Notropis deliciosus missuriensis (Cope): Stations A-1, A-2, A-3, W-1, W-2, W-3 (C-136).

Sand shiners seemed to be abundant in the Arkansas River, rare in the Walnut River and absent from other streams surveyed. This shiner was most abundant in shallow, flowing water in the Arkansas River; in backwaters, where Gambusia affinis prevailed, N. deliciosus formed only a small percentage of the fish population.

Notropis girardi Hubbs and Ortenburger: Stations A-2 and A-3.

At station A-2 the Arkansas River shiner made up 14.6 per cent of all fish taken. At A-2, it was found only in rapidly-flowing water over clean sand in the main channels. It was absent from the shallow, slowly-flowing water where N. deliciosus missuriensis was abundant. At A-3 N. girardi made up 22 per cent of the total catch, and again preferred the deeper, faster water over clean-swept sand. Failure to find N. girardi at station A-1 is not understood.

Females were gravid in both collections (August 25 and 27). In neither collection were young-of-the-year taken. Moore (1944:210) has suggested that N. girardi requires periods of high water and turbidity to spawn. Additional collecting was done at station A-3 on December 22, 1957. A few adults were taken in flowing water but no young were found.

In this area, N. girardi showed no tendency to ascend tributaries of the Arkansas River. Not far to the west, however, this pattern changes as shown by Hubbs and Ortenburger (1929a:32) who took this fish at seven of ten stations on the Cimarron, Canadian, and Salt Fork of the Arkansas. N. girardi was taken only in the lowermost stations on both Stillwater Creek (Cross, 1950:136) and the Chikaskia River (Moore and Buck, 1953:22). In the next major stream west of the Chikaskia, the Medicine River, N. girardi seems to occur farther upstream than in the Chikaskia. (Collection C-5-51 by Dr. A. B. Leonard and Dr. Frank B. Cross on Elm Creek near Medicine Lodge on July 20, 1951.)

Notropis lutrensis (Baird and Girard): Stations A-1, A-2, W-1, W-2, W-3, W-4, G-1, G-2, G-4, G-5, G-8, G-9, G-10, G-11, G-12, G-13, G-14, G-15, G-16, B-1, B-2, B-3, C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, C-5, C-6, C-9, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-13, C-14, M-1, E-1, E-2, E-4, E-7 (E&F, C-131, C-133, C-136).

The red shiner was taken in every stream surveyed. The relative abundance seemed to be greatest in two types of habitat which were separated geographically. The first habitat was in large rivers such as the Arkansas and Walnut. In the Arkansas River the red shiner consistently made up 20 per cent to 25 per cent of the catch. On the Walnut River percentages ranged from 10 per cent (station W-3) to 45 per cent (station W-2).

The second habitat in which numbers of N. lutrensis reached high proportions was in the upper parts of the most intermittent tributaries. At the uppermost station in Silver Creek this species formed 30 per cent of the fish taken. In Crab Creek the following percentages were taken in six collections from mouth to source: 20.6%, 26.1%, 25%, 85%, 14.6%, and 1%. In the mainstream of Grouse Creek the highest percentage taken was 19.27 near the mouth at station G-1. In middle sections of Grouse Creek this species was either absent or made up less than 2 per cent of the fish taken.

At no station on Big Caney River was the red shiner abundant. The smallest relative numbers were found at upstream stations, in contrast to collections made on tributaries of Grouse Creek. This distributional pattern possibly may be explained by the severe conditions under which fish have been forced to live in the upper tributaries of Grouse Creek. Water was more turbid, and pools were smaller than in Big Caney. These factors possibly decimate numbers of the less hardy species permitting expansion by more adaptable species, among which seems to be N. lutrensis. In the upper tributaries of Big Caney River conditions have not been so severe due to greater flow from springs and less cultivation of the watershed in most places. Under such conditions N. lutrensis seems to remain a minor faunal constituent.

Notropis percobromus (Cope): Stations A-1, A-2, W-1, W-2, W-3, G-1.

At station W-1 the plains shiner constituted 20 per cent of the fish taken. The river was flowing rapidly with large volume at the time of this collection, and all specimens were taken near the bank in comparatively quiet water over gravel bottom. At station W-3, below Tunnel Mill Dam at Winfield, N. percobromus comprised 18.7 per cent of the fish taken, second only to Lepomis humilis in [Pg 370] relative abundance. Immediately below the west end of the dam, plains shiners were so concentrated that fifty or more were taken in one haul of a four-foot nylon net. The amount of water overflowing the dam at this point was slight. Water was shallow (8-12 inches) and the bottom consisted of the pitted apron or of fine gravel. At the east end of the dam where water was deeper (1-3 feet) and the flow over the dam greater, large numbers of Lepomis humilis were taken while N. percobromus was rare.

In the Arkansas River smaller relative numbers of this shiner were obtained. At station A-2, it formed 4.68 per cent of the total. At this station N. percobromus was taken with N. lutrensis in water about 18 inches deep next to a bank where the current was sluggish and tangled roots and detritus offered some shelter.

At station G-1 on Grouse Creek the plains shiner made up 7.68 per cent of the fish taken. The habitat consisted of intermittent pools with rubble bottoms at this station, which was four miles upstream from the mouth of the creek. The plains shiner seems rarely to ascend the upland streams of the area.

Notropis rubellus (Agassiz): Stations C-3, C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-13, C-14 (J&J).

No fish in these collections showed a more persistent preference than Notropis rubellus for clear, cool streams. All collections of the rosyface shiner were in the Big Caney River system, but at only four stations in this system was it common. At station C-11 the highest relative numbers (10.6 per cent) were obtained. This site possessed the most limpid water of any station on the mainstream of Big Caney. Aquatic plants (Myriophyllum heterophyllum and Potamogeton nodosus) were common. Other fishes that flourished at this station were N. boops, N. camurus, Campostoma anomalum, and Etheostoma spectabile. The water temperature was 86° at surface and 80° at bottom whereas air temperature was 97°.

N. rubellus was common at all stations in Otter Creek, the clear, upland character of which has been discussed. In May and June only adults were found. On September 1, examination of several pools in upper Otter Creek revealed numerous young-of-the-year in small spring-fed pools.

Literature is scarce concerning this shiner in Kansas. Cross (1954a:308) stated that it was abundant in the South Fork of the Cottonwood River and was one of those fishes primarily associated with the Ozarkian fauna, rather than with the fauna of the plains. Elliott (1947) found N. rubellus in Spring Creek, a tributary of [Pg 371] Fall River which seems similar to Otter Creek in physical features. Between the Fall River and Big Caney River systems is the Elk River, from which there is no record of the rosyface shiner. Perhaps its absence is related to the intermittent condition of this stream at present. The Elk River is poor in spring-fed tributaries, which seem to be favorite environs of the rosyface shiner.

N. rubellus was taken by Minna Jewell and Frank Jobes in Silver Creek on June 30, 1925 (UMMZ 67818). The shiner was not found in any stream west of the Big Caney system in my collections.

In Oklahoma, Hall (1952:57) found N. rubellus in upland tributaries on the east side of Grand River and not in the lowland tributaries on the west side. Martin and Campbell (1953:51) characterize N. rubellus as preferring riffle channels in moderate to fast current in the Black River, Missouri. It is the only species so characterized by them which was taken in my collections. Moore and Paden (1950:84) state "Notropis rubellus is one of the most abundant fishes of the Illinois River, being found in all habitats but showing a distinct preference for fast water...."

Notropis topeka (Gilbert): Two specimens (formerly Indiana University 4605) of the Topeka shiner labeled "Winfield, Kansas" are now at the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Collector and other data are not given. Evermann and Fordice (1886:185) noted that two specimens of N. topeka were taken from Sand Creek near Newton in Harvey County, but do not list it from Cowley County near Winfield. They deposited their fish in the museum of Indiana University.

Notropis umbratilis (Girard): Stations G-1, G-3, G-4, G-7, G-8, G-9, G-12, G-14, B-2, B-3, C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, C-9, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-13, C-14, C-15, C-16, E-1, E-2, E-4, E-5, M-1, M-2 (J&J, C-131, C-132).

The redfin shiner flourished in all the streams surveyed except the Arkansas and Walnut Rivers. N. umbratilis has been found in upland tributaries of the Walnut River, some of which originate in terrain similar to that in which Elk River, Big Caney River, and Grouse Creek originate. (Collection C-26-51 by Cross on Durechon Creek, October 7, 1951.) This suggests downstream reduction in relative numbers of this species, a tendency which also seemed to exist on both Big Caney River and Grouse Creek. N. umbratilis was the most abundant species in Big Caney River except at the lowermost stations where it was surpassed in relative abundance by N. lutrensis and Gambusia affinis.

N. umbratilis was a pool-dweller, becoming more concentrated in the deeper pools as summer advanced. In May and early June, large concentrations of adult N. umbratilis were common in the shallow ends of pools together with N. rubellus, N. boops, Pimephales notatus, and Pimephales tenellus. By July and August, only young of the year were taken in shallow water, and adults were scarcely in evidence.

Notropis volucellus (Cope): Stations G-5, G-8, C-3, C-5, C-7, C-8, C-9, C-10, M-1, E-4, E-5.

The mimic shiner was a minor element in the fauna, 2.02 per cent at station C-5 being the largest percentage taken. In the Big Caney River system N. volucellus was taken only in the main stream. In the Grouse Creek drainage it was found at two stations in the upper part of the watershed, where water is clearer, gradient greater, and pools well-shaded and cool.

In the Elk River the mimic shiner was taken only in the upper part of the main stream. The dominant shiner in situations where N. volucellus was taken was, in all cases, N. umbratilis. Elliott (1947) found N. volucellus in Spring Creek, a tributary of Fall River. Farther north in the Flint Hills region, N. volucellus was reported by Cross (1954a:310).

Notemigonus crysoleucas (Mitchell): Station W-5.

This isolated record for the golden shiner consisted of nine specimens collected on June 6 in Timber Creek, a tributary of the Walnut River. Most of the creek was dry. N. crysoleucas was taken in one pool with dimensions of 8 feet by 4 feet with an average depth of 4 inches. This creek is sluggish and silt-laden, even under conditions of favorable precipitation. Hubbs and Ortenburger (1929b:89) observed that the golden shiner prefers sluggish water. Hall (1952:58) took the golden shiner only in the lowland tributaries west of Grand River and not east of the river in upland tributaries.

Phenacobius mirabilis Girard: Stations W-3, C-3.

In no case was the suckermouth minnow common; it never comprised more than 1 per cent of the fish population.

Pimephales notatus (Rafinesque): Stations W-4, G-5, G-7, G-9, G-12, G-13, B-3, C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, C-9, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-13, C-14, C-15, C-16, C-17, C-18, M-1, M-2, E-1, E-2, E-4, E-5, E-7 (J&J, C-131, C-132, C-133).

This was much the most abundant of the four species of Pimephales in this area. It was taken at 33 stations as compared with 10 for P. tenellus, 8 for P. promelas, and 3 for P. vigilax.

The bluntnose minnow was taken almost everywhere except in the main stream of the Arkansas and Walnut rivers and in lower Grouse Creek. P. notatus seemed to prefer clearer streams of the Flint Hills part of my area. There was a marked increase in percentages taken in the upland tributaries of both Caney River and Grouse Creek. In the Elk River, too, higher concentrations were found upstream.

The highest relative numbers of bluntnose minnows were taken at station G-12 on Crab Creek, station C-12 on Cedar Creek and station C-16 on Spring Creek. At G-12, this minnow was abundant in the deeper isolated pools. Males in breeding condition were taken on June 9. In Cedar Creek the population of bluntnose minnows was observed periodically in one pool in which they were dominant. This pool was 100 feet by 50 feet, shallow, and with bedrock bottom. At its upper end, however, there was a small area of heavily-shaded deeper water. Throughout the spring bluntnose minnows were found in large schools in the shallow area. As the summer progressed they were no longer there, but seining revealed their presence in the deeper, upper end.

At station C-16 on Spring Creek on July 9 male P. notatus were taken in extreme breeding condition, being light brick-red in color and with large tubercles.

Pimephales tenellus (Girard): Stations G-1, C-2, C-3, C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, M-1, E-2, E-4 (C-131 C-133).

The mountain minnow was never taken far from the mainstream of Big Caney, Middle Caney, or Elk River. In this respect it differed from P. notatus, which reached large concentrations in the small upland tributaries. On the other hand, P. tenellus was not so abundant as P. vigilax in the silty larger streams. In no collection was the mountain minnow common. The highest percentages were 2.4 per cent (Station C-5), and 2.1 per cent (Station C-7) on Big Caney River. These stations consisted of clear, flowing water over rubble bottoms. Males at C-7 (June 16) were in breeding condition.

Moore and Buck (1953:23) reported finding this species among rocks in very fast water rather than in the quiet backwaters frequented by P. vigilax. Other records of the mountain minnow from the Flint Hills indicate that it seeks areas of maximum gradient and flow; in this distributional respect it is like Notropis camurus. The two species are recorded together from other streams in this region such as the Chikaskia (Moore and Buck, 1953:23), Cottonwood (Cross, 1954a:310), and Spring Creek, tributary of Fall River (Elliott, 1947). It is conceivable that a preference for flowing [Pg 374] water might explain its restriction to the medium-sized, less intermittent streams in this area. The only tributary which the species seemed to ascend to any extent was Otter Creek, which is seldom intermittent downstream.

Pimephales vigilax perspicuus (Girard): Stations A-3, C-1, C-4.

The parrot minnow was found only in downstream habitats. Collection C-4 (June 3) on Rock Creek was made about ½ mile from the mouth of this tributary of Big Caney and the creek here had almost the same character as the river proper. The presence of other channel fishes such as Ictiobus bubalus indicates the downstream nature of the creek. Some males of P. vigilax in breeding condition were taken in this collection.

At C-1, only one specimen was found in a turbid, isolated pool with bedrock bottom. At A-1 only one parrot minnow was taken; it was in deep, fairly quiet water near the bank.

Other collections outside the three-county area revealed the following: In the Neosho River, several parrot minnows were found in quiet backwaters and in shallow pools. In the Verdigris River three were taken directly under water spilling over the dam at this station, while others were found, together with P. promelas, in the mouth of a small creek that provided a backwater habitat with mud bottom.

Cross and Moore (1952:405) found this species only at stations in the lower portion of the Poteau River. Farther west the minnow may ascend the smaller sandy streams to greater distances. Moore and Buck (1953:23) took parrot minnows at six of 15 stations on the Chikaskia River and found the species as far upstream as Drury, Kansas. Elliott (1947), in comparing the South Ninnescah and Spring Creek fish faunas, found only P. vigilax and P. promelas on the sandy, "flatter" Ninnescah and only P. notatus and P. tenellus on Spring Creek, an upland, Flint Hills stream in Greenwood County.

Pimephales promelas Rafinesque: Stations A-2, A-3, W-3, W-4, G-9, B-1, M-1, E-4 (E&F, C-136).

Occurrences of the fathead minnow were scattered, but included all streams sampled except Big Caney.

Three of the collections were in small intermittent streams where conditions were generally unfavorable for fishes and in one instance extremely foul. Two of these stations had turbid water and all suffered from siltation.

In Middle Caney Creek the species was rare but in the Elk River [Pg 375] (June 28) more than 100 specimens, predominantly young, were taken. This station consisted of a large isolated pool with a variety of bottom types. Water was turbid and the surface temperature was high (93° F.). In different parts of the pool the following numbers of specimens were taken in single seine-hauls: 15 over shallow bedrock; 35 over gravel (1½ feet deep); 50 over mud bottom (1 foot deep).

P. promelas was found also in the large, flowing rivers: Arkansas, Walnut, Verdigris, and Neosho. The species was scarce in the Arkansas River, and was found principally in muddy coves. In the Walnut (W-3), this minnow comprised 7.65 per cent of the fish taken and was common in quiet pools.

Campostoma anomalum Rafinesque: Stations W-4, G-4, C-1, C-3, C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, C-9, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-13, C-14, C-15, C-16, C-17, C-18, B-3 (E&F, C-131, C-136).

Although the stoneroller was found in most streams surveyed, it was taken most often in the Big Caney system, where it occurred at 16 of the 18 stations. In contrast, it was represented at only one of 17 stations on Grouse Creek. High percentages were found in three creeks—Cedar, Otter, and Spring. As noted above, these streams are normally clear, swift and have steep gradients and many rubble and gravel riffles. On these riffles young stonerollers abounded. Station C-16 on Spring Creek typifies the habitat in which this species was most abundant. The stream has an average width of 10 feet and depth of a few inches. The volume of flow was less than 1 cubic foot per second but turbulence was great. Water was clear and the bottom was gravel and rubble. Following rains in June, stonerollers quickly occupied parts of Spring Creek (upstream from C-16) that had been dry throughout the previous winter.

On April 2 many C. anomalum and Etheostoma spectabile were taken in shallow pools and riffles in an extensive bedrock-riffle area on Cedar Creek near station C-12. Most of the females were gravid and the males were in breeding condition. On June 6 these pools were revisited. Flow had ceased and the pools were drying up. Young-of-the-year of the two species were abundant, but only a few mature stonerollers were taken. On August 24, prolonged drought had drastically altered the stream and all areas from which stonerollers and darters had been taken were dry. Seining of other pools which were almost dry revealed no stonerollers.

Collections on May 31, June 15, and June 16 in Otter Creek [Pg 376] revealed large numbers of stonerollers. They were found in riffle areas, in aquatic vegetation, and especially in detritus alongside banks. Most of the specimens were young-of-the-year.

Anguilla bostoniensis (Le Sueur): An American eel was caught by me in Grouse Creek in 1949.

Gambusia affinis (Baird and Girard): Stations A-1, A-2, A-3, W-1, W-2, W-3, W-4, W-5, G-1, G-2, G-3, G-4, G-5, G-7, G-8, G-9, C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, C-6, C-15, E-1.

Mosquitofish occurred widely but in varied abundance. Huge populations were in the shallow sandy backwaters and cut-off pools of the Arkansas River. In the shallow pools of several intermittent streams such as station G-8 on Silver Creek this fish also flourished.

G. affinis was taken at every station in the Arkansas, Walnut and Grouse systems except those stations on two upland tributaries of Grouse Creek (Crab Creek and Grand Summit Creek). The mosquitofish was not observed in the clear upland tributaries of Big Caney, nor on upper Big Caney River itself in May, June, and July. On September 3, however, Gambusia were taken at station C-15 on Otter Creek and others were seen at station C-14 on the same date.

Hubbs and Ortenburger (1929b:99) and Cross and Moore (1952:407) observed that G. affinis usually was absent from small upland tributaries, even though it was abundant in lower parts of the same river systems.

Fundulus kansae (Garman): Stations A-2, A-3, Evermann and Fordice as Fundulus zebrinus.

At station A-2, seven plains killifish were taken together with a great many Notropis deliciosus and Gambusia affinis in a shallow, algae-covered channel with slight flow and sand bottom. At station A-3 many young killifish were taken in small shallow pools on December 22. Fundulus kansae has been found in the lower part of the Walnut River Basin, especially where petroleum pollution was evident. Eastward from the Walnut River plains killifish have not been taken.

Fundulus notatus (Rafinesque): Stations B-1, G-1, G-2, G-3, G-4, G-5, G-7, G-8, G-10, G-11, G-14, C-1, M-1, E-1, Evermann and Fordice as Zygonectes notatus.

The black-banded topminnow was not taken in the Arkansas River but was common in the Walnut and Grouse systems. It was common also in Middle Caney, but in Big Caney and Elk River it was taken only at the lowermost stations.

This species did not seem to ascend far into smaller tributaries of Grouse Creek. In Crab Creek it was taken at the lower two of six stations and in Grand Summit Creek at the lower of two stations.

The highest relative numbers were taken at stations G-3 (17.5 per cent), G-4 (24 per cent), G-10 (25.75 per cent) and G-11 (41.52 per cent), on Crab Creek and Grouse Creek. Both upstream and downstream from these stations, which were within five miles of each other, the relative abundance dropped off sharply. The bottoms at these stations were mostly rubble and mud, and water was turbid at three of the stations. At G-10 (June 24) and G-11 (July 16) young-of-the-year were abundant.