Title: Danger at the Drawbridge

Author: Mildred A. Wirt

Release date: December 3, 2010 [eBook #34552]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Brenda Lewis and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

By

MILDRED A. WIRT

Author of

MILDRED A. WIRT MYSTERY STORIES

TRAILER STORIES FOR GIRLS

Illustrated

CUPPLES AND LEON COMPANY

Publishers

NEW YORK

PENNY PARKER

MYSTERY STORIES

Large 12 mo. Cloth Illustrated

TALE OF THE WITCH DOLL

THE VANISHING HOUSEBOAT

DANGER AT THE DRAWBRIDGE

BEHIND THE GREEN DOOR

CLUE OF THE SILKEN LADDER

THE SECRET PACT

THE CLOCK STRIKES THIRTEEN

THE WISHING WELL

SABOTEURS ON THE RIVER

GHOST BEYOND THE GATE

HOOFBEATS ON THE TURNPIKE

VOICE FROM THE CAVE

GUILT OF THE BRASS THIEVES

SIGNAL IN THE DARK

WHISPERING WALLS

SWAMP ISLAND

THE CRY AT MIDNIGHT

COPYRIGHT, 1940, BY CUPPLES AND LEON CO.

Danger at the Drawbridge

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

The speeding automobile careened down the bank.

“Danger at the Drawbridge” (See Page 157)

Penny Parker, leaning indolently against the edge of the kitchen table, watched Mrs. Weems stem strawberries into a bright green bowl.

“Tempting bait for Dad’s jaded appetite,” she remarked, helping herself to the largest berry in the dish. “If he can’t eat them, I can.”

“I do wish you’d leave those berries alone,” the housekeeper protested in an exasperated tone. “They haven’t been washed yet.”

“Oh, I don’t mind a few germs,” laughed Penny. “I just toss them off like a duck shedding water. Shall I take the breakfast tray up to Dad?”

“Yes, I wish you would, Penny,” sighed Mrs. Weems. “I’m right tired on my feet this morning. Hot weather always did wear me down.”

She washed the berries and then offered the tray of food to Penny who started with it toward the kitchen vestibule.

“Now where are you going, Penelope Parker?” Mrs. Weems demanded suspiciously.

“Oh, just to the automatic lift.” Penny’s blue eyes were round with innocence.

“Don’t you dare try to ride in that contraption again!” scolded the housekeeper. “It was never built to carry human freight.”

“I’m not exactly freight,” Penny said with an injured sniff. “It’s strong enough to carry me. I know because I tried it last week.”

“You walk up the stairs like a lady or I’ll take the tray myself,” Mrs. Weems threatened. “I declare, I don’t know when you’ll grow up.”

“Oh, all right,” grumbled Penny good-naturedly. “But I do maintain it’s a shameful waste of energy.”

Balancing the tray precariously on the palm of her hand she tripped lightly up the stairway and tapped on the door of her father’s bedroom.

“Come in,” he called in a muffled voice.

Anthony Parker, editor and owner of the Riverview Star sat propped up with pillows, reading a day-old edition of the newspaper.

“’Morning, Dad,” said Penny cheerfully. “How is our invalid today?”

“I’m no more an invalid than you are,” returned Mr. Parker testily. “If that old quack, Doctor Horn, doesn’t let me out of bed today—”

“You’ll simply explode, won’t you, Dad?” Penny finished mischievously. “Here, drink your coffee and you’ll feel less like a stick of dynamite.”

Mr. Parker tossed the newspaper aside and made a place on his knees for the breakfast tray.

“Did I hear an argument between you and Mrs. Weems?” he asked curiously.

“No argument, Dad. I just wanted to ride up in style on the lift. Mrs. Weems thought it wasn’t a civilized way to travel.”

“I should think not.” The corners of Mr. Parker’s mouth twitched slightly as he poured coffee from the silver pot. “That lift was built to carry breakfast trays, but not in combination with athletic young ladies.”

“What a bore, this business of growing up,” sighed Penny. “You can’t be natural at all.”

“You seem to manage rather well with all the restrictions,” her father remarked dryly.

Penny twisted her neck to gaze at her reflection in the dresser mirror beyond the footboard of the big mahogany bed.

“I won’t mind growing up if only I’m able to develop plenty of glamour,” she said speculatively. “Am I getting any better looking, Dad?”

“Not that I’ve noticed,” replied Mr. Parker gruffly, but his gaze lingered affectionately upon his daughter’s golden hair. She really was growing prettier each day and looked more like her mother who had died when Penny was a little girl. He had spoiled her, of course, for she was an only child, but he was proud because he had taught her to think straight. She was deeply loyal and affectionate and those who loved her overlooked her casual ways and flippant speech.

“What happened to the paper boy this morning?” Mr. Parker asked between bites of buttered toast.

“It isn’t time for him yet, Dad,” said Penny demurely. “You always expect him at least an hour early.”

“First edition’s been off the press a good half hour,” grumbled the newspaper owner. “When I get back to the Star office, I’ll see that deliveries are speeded up. Just wait until I talk with Roberts!”

“Haven’t you been doing a pretty strenuous job of running the paper right from your bed?” inquired Penny as she refilled her father’s cup. “Sometimes when you talk with that poor circulation manager I think the telephone wires will burn off.”

“So I’m a tyrant, am I?”

“Oh, everyone knows your bark is worse than your bite, Dad. But you’ve certainly not been at your best the last few days.”

Mr. Parker’s eyes roved about the luxuriously furnished bedroom. Tinted walls, chintz draperies, the rich, deep rug, were completely lost upon him. “This place is a prison,” he grumbled.

For nearly a week the household had been thrown completely out of its usual routine by the editor’s illness. Overwork combined with an attack of influenza had sent him to bed, there to remain until he should be released by a doctor’s order. With a telephone at his elbow, Mr. Parker had kept in close touch with the staff of the Riverview Star but he fretted at confinement.

“I can’t half look after things,” he complained. “And now Miss Hilderman, the society editor, is sick. I don’t know how we’ll get a good story on the Kippenberg wedding.”

Penny looked up quickly. “Miss Hilderman is ill?”

“Yes, DeWitt, the city editor, telephoned me a few minutes ago. She wasn’t able to show up for work this morning.”

“I really don’t see why he should bother you about that, Dad. Can’t Miss Hilderman’s assistant take over the duties?”

“The routine work, yes, but I don’t care to trust her with the Kippenberg story.”

“Is it something extra special, Dad?”

“Surely, you’ve heard of Mrs. Clayton Kippenberg?”

“The name is familiar but I can’t seem to recall—”

“Clayton Kippenberg made a mint of money in the chain drug business. No one ever knew exactly the extent of his fortune. He built an elaborate estate about a hundred and twenty-five miles from here, familiarly called The Castle because of its resemblance to an ancient feudal castle. The estate is cut off from the mainland on three sides and may be reached either by boat or by means of a picturesque drawbridge.”

“Sounds interesting,” commented Penny.

“I never saw the place myself. In fact, Kippenberg never allowed outsiders to visit the estate. Less than a year ago a rumor floated around that he had separated from his wife. There also was considerable talk that he had disappeared because of difficulties with the government over income tax evasion and wished to escape arrest. At any rate, he faded out of the picture while his wife remained in possession of The Castle.”

“And now she is marrying again?”

“No, it is Mrs. Kippenberg’s daughter, Sylvia, who is to be married. The bridegroom, Grant Atherwald, comes from a very old and distinguished family.”

“I don’t see why the story should be so difficult to cover.”

“Mrs. Kippenberg has ruled that no reporters or photographers will be allowed on the estate,” explained Mr. Parker.

“That does complicate the situation.”

“Yes, it may not be easy to persuade Mrs. Kippenberg to change her mind. I rather doubt that our assistant society editor has the ingenuity to handle the story.”

“Then why don’t you send one of the regular reporters? Jerry Livingston, for instance?”

“Jerry couldn’t tell a tulle wedding veil from one of crinoline. Nor could any other man on the staff.”

“I could get that story for you,” Penny said suddenly. “Why don’t you try me?”

Mr. Parker gazed at his daughter speculatively.

“Do you really think you could?”

“Of course.” Penny spoke with assurance. “Didn’t I bring in two perfectly good scoops for your old sheet?”

“You certainly did. Your Vanishing Houseboat yarn was one of the best stories we’ve published in a year of Sundays. And the town is still talking about Tale of the Witch Doll.”

“After what I went through to get those stories, a mere wedding would be child’s play.”

“Don’t be too confident,” warned Mr. Parker. “If Mrs. Kippenberg doesn’t alter her decision about reporters, the story may be impossible to get.”

“May I try?” Penny asked eagerly.

Mr. Parker frowned. “Well, I don’t know. I hate to send you so far, and then I have a feeling—”

“Yes, Dad?”

“I can’t put my thoughts into words. It’s just that my newspaper instinct tells me this story may develop into something big. Kippenberg’s disappearance never was fully explained and his wife refused to discuss the affair with reporters.”

“Kippenberg might be at the wedding,” said Penny, thinking aloud. “If he were a normal father he would wish to see his daughter married.”

“You follow my line of thought, Penny. When you’re at the estate—if you get in—keep your eyes and ears open.”

“Then you’ll let me cover the story?” Penny cried in delight.

“Yes, I’ll telephone the office now and arrange for a photographer to go with you.”

“Tell them to send Salt Sommers,” Penny suggested quickly. “He doesn’t act as know-it-all as some of the other lads.”

“I had Sommers in mind,” her father nodded as he reached for the telephone.

“And I have a lot more than Salt Sommers in my mind,” laughed Penny.

“Meaning?”

“Another big story, Dad! A scoop for the Star and this for you.”

Penny implanted a kiss on her father’s cheek and skipped joyously from the room.

In the editorial room of the Riverview Star heads turned and eyebrows lifted as Penny, decked in her best silk dress and white picture hat, clicked her high-heeled slippers across the bare floor. Jerry Livingston, reporter, stopped pecking at his typewriter and stared in undisguised admiration.

“Well, if it isn’t our Bright Penny,” he bantered. “Didn’t recognize you for a minute in all those glad rags.”

“These are my work clothes,” replied Penny. “I’m covering the Kippenberg wedding.”

Jerry pushed his hat farther back on his head and grinned.

“Tough assignment. From what I hear of the Kippenberg family, you’ll be lucky if they don’t throw the wedding cake at you.”

Penny laughed and went on, winding her way through a barricade of desks to the office of the society editor. Miss Arnold, the assistant, was talking over the telephone, but in a moment she finished and turned to face the girl.

“Good morning, Miss Parker,” she said stiffly. An edge to her voice told Penny more clearly than words that the young woman was nettled because she had not been trusted with the story.

“Good morning,” replied Penny politely. “Dad said you would be able to give me helpful suggestions about covering the Kippenberg wedding.”

“There’s not much I can tell you, really. The ceremony is to take place at two o’clock in the garden, so you’ll have ample time to reach the estate. If you get in—” Miss Arnold placed an unpleasant emphasis upon the words—“take notes on Miss Kippenberg’s gown, the flowers, the decorations, the names of her attendants. Try to keep your facts straight. Nothing infuriates a bride more than to read in the paper that she carried a bouquet of lilies-of-the-valley and roses while actually it was a bouquet of some other flower.”

“I’ll try not to infuriate Miss Kippenberg,” promised Penny.

Miss Arnold glanced quickly at her but the girl’s face was perfectly serene.

“That’s all I can tell you, Miss Parker,” she said shortly. “Bring in at least a column. For some reason the city editor rates the wedding an important story.”

“I’ll do my best,” responded Penny, and arose.

Salt Sommers was waiting for her when she came out of the office. He was a tall, spare young man, with a deep scar down his left cheek. He talked nearly as fast as he walked.

“If you’re all set, let’s go,” he said.

Penny found herself three paces behind but she caught up with the photographer as he waited for the elevator.

“I’m taking Minny along,” Salt volunteered, holding his finger steadily on the signal bell. “May come in handy.”

“Minny?” asked Penny, puzzled.

“Miniature camera. You can’t always use the Model X.”

“Oh,” murmured Penny. Deeply embarrassed, she remained silent as the elevator shot them down to the ground floor.

Salt loaded his photographic equipment into a battered press car which was parked near the loading dock at the rear of the building. He slid in behind the wheel and then as an afterthought swung open the car door for Penny.

Salt seemed to know the way to the Kippenberg estate. They shot through Riverview traffic, shaving red lights and tooting derisively at slow drivers. In open country he pressed the accelerator down to the floor and the car roared down the road, only slackening speed as it raced through a town.

“How do you travel when you’re in a hurry?” Penny gasped, clinging to her flopping hat.

Salt grinned and lifted his foot from the gasoline pedal.

“Sorry,” he said. “I get in the habit of driving fast. We have plenty of time.”

As they rode, Penny gathered scraps of information. The Kippenberg estate was located six miles from the town of Corbin and was cut off from the mainland on three sides by the joining of two wide rivers, one with a direct outlet to the ocean. Salt did not know when the house had been built but it was considered one of the show places of the locality.

“Do you think we’ll have much trouble getting our story?” Penny asked anxiously.

“All depends,” Salt answered briefly. He slammed on the brake so suddenly that Penny was flung forward in the seat.

Another car coming from the opposite direction had pulled up at the side of the road. Penny did not recognize the three men who were crowded into the front seat, but the printed placard, Ledger which was pasted on the windshield told her they represented a rival newspaper in Riverview.

“What luck, Les?” Salt called, craning his neck out the car window.

“You may as well turn around and go back,” came the disgusted reply. “The old lady won’t let a reporter or a photographer on the estate. She has a guard stationed on the drawbridge to see that you don’t get past.”

The car drove on toward Riverview. Salt sat staring down the road, drumming his fingers thoughtfully on the steering wheel.

“Looks like we’re up against a tough assignment,” he said. “If Les can’t get in—”

“I’m not going back without at least an attempt,” announced Penny firmly.

“That’s the spirit!” Salt cried with sudden approval. “We’ll get on the estate somehow if we have to swim over.”

He jerked the press card from the windshield, and reaching into the back seat of the car, covered the Model X camera with an old gunny sack. The miniature camera he placed in his coat pocket.

“No use advertising our profession too early in the game,” he remarked.

Twelve-thirty found Penny and Salt in the sleepy little town of Corbin. Fortifying themselves with a lunch of hot dog sandwiches and pop, they followed a winding, dusty highway toward the Kippenberg estate.

Presently, through the trees, marking the end of the road, an iron drawbridge loomed up. It stood in open position so that boats might pass on the river below. A wooden barrier had been erected across the front of the structure which bore a large painted sign. Penny read the words aloud.

“‘DANGEROUS DRAWBRIDGE—KEEP OFF.’”

Salt drew up at the side of the road. “Looks as if this is as far as we’re going,” he said in disgust. “There’s no other road to the estate. I’ll bet that ‘dangerous drawbridge’ business is just a dodge to keep undesirables away from the place until after the wedding.”

Penny nodded gloomily. Then she brightened as she noticed an old man who obviously was an estate guard standing at the entrance to the bridge. He stared toward the old car as if trying to ascertain whether or not the occupants were expected guests.

“I’m going over to talk with him,” Penny said.

“Pretend that you’re a guest,” suggested Salt. “You look the part in that fancy outfit of yours.”

Penny walked leisurely toward the drawbridge. Appraisingly, she studied the old man who leaned comfortably against the gearhouse. A dilapidated hat pulled low over his shaggy brows seemed in keeping with the rest of his wardrobe—a blue work shirt and a pair of grease-smudged overalls. A charred corn-cob pipe, thrust at an angle between his lips, provided sure protection against the mosquitoes swarming up from the river below.

“Good afternoon,” began Penny pleasantly. “My friend and I are looking for the Kippenberg estate. We were told at Corbin to take this road but we seem to have made a mistake.”

“You ain’t made no mistake, Miss,” the old man replied.

“Then is the estate across the river?”

“That’s right, Miss.”

“But how are guests to reach the place? I see the sign says the bridge is out of commission. Are we supposed to swim over?”

“Not if you don’t want to,” the old man answered evenly. “Mrs. Kippenberg has a launch that takes the folks back and forth. It’s on the other side now but will be back in no time at all.”

“I’ll wait in the car out of the hot sun,” Penny said. She started away, then paused to inquire casually: “Is this drawbridge really out of order?”

The old man was deliberate in his reply. He blew a ring of smoke into the air, watched it hover like a floating skein of wool and finally disintegrate as if plucked to pieces by an unseen hand.

“Well, yes, and no,” he said. “It ain’t exactly sick but she sure is ailin’. I wouldn’t trust no heavy contraption on this bridge.”

“Condemned by the state, I suppose?”

“No, Miss, and I’ll tell you why. This here bridge doesn’t belong to the state. It’s a private bridge on a private road.”

“Odd that Mrs. Kippenberg never had it repaired,” Penny remarked. “It must be annoying.”

“It is to all them that don’t like launches. As for Mrs. Kippenberg, she don’t mind. Fact is, she ain’t much afraid of the bridge. She drives her car across whenever she takes the notion.”

“Then the bridge does operate!” Penny exclaimed.

“Sure it does. That’s my job, to raise and lower it whenever the owner says the word. But the bridge ain’t fit for delivery trucks and such-like. One of them big babies would crack through like goin’ over sponge ice.”

“Well, I rather envy your employer,” said Penny lightly. “It isn’t every lady who has her own private drawbridge.”

“She is kind of exclusive-like that way, Miss. Mrs. Kippenberg she keeps the drawbridge up so she’ll have more privacy. And I ain’t blamin’ her. These here newspaper reporters always is a-pesterin’ the life out of her.”

Penny nodded sympathetically and walked back to make her report to Salt.

“No luck?” he demanded.

“Guess twice,” she laughed. “The old bridgeman just took it for granted I was one of the wedding guests. It will be all right for us to go over in the guest launch as soon as it arrives.”

Salt gazed ruefully at his clothes.

“I don’t look much like a guest. Think I’ll pass inspection?”

“Maybe you could get by as one of the poor relations,” grinned Penny. “Pull your hat down and straighten your tie.”

Salt shook his head. “A business suit with a grease spot on the vest isn’t the correct dress for a formal wedding. You might get by but I won’t.”

“Then should I try it alone?”

“I’ll have to get those pictures somehow,” stated Salt grimly.

“Maybe we could hire a boat of our own,” Penny suggested. “Of course it wouldn’t look as well as if we arrived on the guest launch.”

“Let’s see what we can line up,” Salt said, swinging open the car door.

They walked to the river’s edge and looked in both directions. There were no small boats to be seen. The only available craft was a large motor boat which came slowly downstream toward the open drawbridge. Penny caught a glimpse of the pilot, a burly man with a red, puffy face.

Salt slid down the bank toward the water’s edge, and hailed the boat.

“Hey, you, Cap’n!” he called. “Two bucks to take me across the river.”

The man inclined his head, looked steadily at Salt for an instant, then deliberately turned his back.

“Five!” shouted Salt.

The pilot gave no sign that he had heard. Instead, he speeded up the boat which passed beneath the drawbridge and went on down the river.

“Perhaps he didn’t hear you,” said Penny, peering after the retreating boat.

“He heard me all right,” growled Salt as he scrambled back up the high bank.

Noticing a small boy in dirty overalls who sat at the water’s edge fishing, he called to him: “Say, sonny, who was that fellow, do you know?”

“Nope,” answered the boy, barely turning his head, “but his boat has been going up and down the river all morning. That’s why I can’t catch anything.”

The boat rounded a bend of the river and was lost to view. Only one other craft appeared on the water, a freshly painted white motor launch which could be seen coming from the far shore.

“That must be the guest boat now,” remarked Penny, shading her eyes against the glare of the sun. “It seems to be our only hope.”

“Let’s try to get aboard and see what happens,” proposed the photographer.

They walked leisurely back toward the guard at the drawbridge, timing their arrival just as the launch swung up to the landing. With a cool assurance which Penny tried to duplicate, Salt stepped aboard, nodded indifferently to the wheelsman, and slumped down in one of the leather seats.

Penny waited uneasily for embarrassing questions which did not come. Gradually she relaxed as the boatman took no interest in them and the guard’s attention was fully occupied with other cars which had driven up to the drawbridge.

A few minutes later, two elderly women, both elegantly gowned, were helped aboard the boat by their chauffeur. One of the women stared disapprovingly at Salt through her lorgnette and then ignored him.

“We’ll get by all right,” Salt whispered confidently.

“Wait until Mrs. Kippenberg sees us,” warned Penny.

“Oh, we’ll keep out of her way until we have our story and plenty of pictures. Once we’re across the river it will be easy.”

“I hope you’re right,” muttered Penny.

While Salt’s task of taking pictures might prove relatively simple, she realized that her own work would be anything but easy. She could not hope to gather many facts without talking to a member of the family, and the instant she admitted her identity she likely would be ejected from the grounds.

“I boasted I’d bring in a front page story,” she thought ruefully. “I’ll be lucky if I get a column of routine stuff.”

The boat was moving slowly away from the landing when the guard at the drawbridge called in a loud voice: “Hold it, Joe!”

Penny and Salt stiffened in their chairs, fearing they were to be exposed. But they were both greatly relieved to see that a long, black limousine had drawn up at the end of the road. The launch had been stopped so that additional passengers might be accommodated.

Salt nudged Penny’s elbow.

“Grant Atherwald,” he contributed, jerking his head toward a tall, well-built young man who had stepped from the car. “I’ve seen his picture plenty of times.”

“The bridegroom?” Penny turned to stare.

“Sure. He’s one of the blue-bloods, but they say he’s a little short on ready cash.”

The young man, dressed immaculately in formal day attire, and accompanied by two other men, came aboard the launch. He bowed politely to the elderly women and his gaze fell questioningly upon Penny and Salt. But if he wondered why they were there, he did not voice his thought.

As the boat put out across the river Penny watched Grant Atherwald curiously. It seemed to her that he appeared nervous and preoccupied. He stared straight before him, clenching and unclenching his hands. His face was colorless and drawn.

“He’s nervous and worried,” thought Penny. “I guess all bridegrooms are like that.”

A sharp “click” sounded in her ear. Penny did not turn toward Salt, but she caught her breath, knowing what he had done. He had dared to take a picture of Grant Atherwald!

She waited, feeling certain that the sound must have been heard by everyone in the boat. A full minute elapsed and no one spoke. When Penny finally glanced at Salt he was gazing serenely out across the muddy water, his miniature camera shielded behind a felt hat which he held on his knees.

The boat docked. Salt and Penny allowed the others to go ashore first, and then followed a narrow walk which wound through a deep lane of evergreen trees.

“Salt,” Penny asked abruptly, “how did you get that picture of Atherwald?”

“Snapped it through a hole in the crown of my hat. It’s an old trick. I always wear this special hat when I’m sent out on a hard assignment.”

“I thought a cannon had gone off when the shutter clicked,” Penny laughed. “We were lucky you weren’t caught.”

Emerging from behind the trees, they obtained their first view of the Kippenberg house. Sturdily built of brick and stone, it stood upon a slight hill, its many turrets and towers commanding a view of the two rivers.

“Nice layout,” Salt commented, pausing to snap a second picture. “Wish someone would give me a castle for a playhouse.”

They crossed the moat and found themselves directly behind Grant Atherwald again. Before the bridegroom could enter the house a servant stepped forward and handed him a sealed envelope.

“I was told to give this to you as soon as you arrived, sir,” he said.

Grant Atherwald nodded, and taking the letter, quickly opened it. A troubled expression came over his face as he scanned the message. Without a word he thrust the paper into his pocket. Turning, he walked swiftly toward the garden.

“Salt, did you notice how queerly Atherwald looked—” Penny began, but the photographer interrupted her.

“Listen,” he said, “we haven’t a Chinaman’s chance of getting in the front door. That boy in the fancy knickers is giving everyone the once over. Let’s try a side entrance.”

Without attracting attention they walked quickly around the house and located a door where no servant had been posted. Entering, they passed through a marble-floored vestibule into a breakfast room crowded with serving tables. Salt nonchalantly helped himself to an olive from one of the large glass dishes and led Penny on toward the main hall where many of the guests had gathered to admire the wedding gifts.

“Now don’t swipe any of the silver,” Salt said jokingly. “I think that fellow over by the stairway is a private detective.”

“He seems to be looking at us with a suspicious gleam in his eyes,” Penny replied. “I hope we don’t get tossed out of here.”

“We’ll be all right if Mrs. Kippenberg doesn’t see us before the ceremony.”

“Do you suppose Mr. Kippenberg could be here, Salt?”

“Not likely. It’s my guess that fellow will never be seen again.”

“Dad doesn’t share your opinion.”

“I know,” Salt admitted. “We’ll keep watch for him, but it would just be a lucky break if it turns out he’s here.”

Mingling with the guests, they walked slowly about a long table where the wedding gifts were displayed. Penny gazed curiously at dishes of solid silver, crystal bowls, candlesticks, jade ornaments, tea sets and service plates encrusted with gold.

“Nothing trashy here,” muttered Salt.

“I’ve never seen such an elegant display,” Penny whispered in awe. “Do you suppose that picture is one of the gifts?”

She indicated an oil painting which stood on an easel not far from the table. So many guests had gathered about the picture that she could not see it distinctly. But at her elbow, a woman in rustling silk, said to a companion:

“My dear, a genuine Van Gogh! It must have cost a small fortune!”

When the couple had moved aside, Penny and Salt drew closer to the easel. One glance assured them that the painting had been executed by a master. However, it was the subject of the picture which gave Penny a distinct start.

“Will you look at that!” she whispered to Salt.

“What about it?” he asked carelessly.

“Don’t you notice anything significant?”

“Can’t say I do. It’s just a nice picture of a drawbridge.”

“That’s just the point, Salt!” Penny’s eyes danced with excitement. “A drawbridge!”

The photographer glanced again at the painting, this time with deeper interest.

“Say, it looks a lot like the bridge which was built over the river,” he observed. “You think this picture is a copy of it?”

Penny shook her head impatiently. “Salt, your knowledge of art is dreadful. This Van Gogh was painted ages ago and is priceless. Don’t you see, the drawbridge has to be a copy of the picture?”

“Your theory sounds reasonable,” Salt admitted. “I wonder who gave the painting to the bride? There’s no name attached.”

“Can’t you guess why?”

“I never was good at kid games.”

“Why, it’s clear as crystal,” Penny declared, keeping her voice low. “This estate with the drawbridge was built by Clayton Kippenberg. He must have been familiar with the Van Gogh painting, and had the real bridge modeled after the picture. For that matter, the painting may have been in his possession—”

“Then you think the picture was presented to Sylvia Kippenberg by her father?” Salt broke in quickly.

“Yes, I do. Only a person very close to the bride would have given such a gift.”

“H-m,” said Salt, squinting at the picture thoughtfully. “If you’re right it means that Clayton Kippenberg’s whereabouts must be known to his family. His disappearance may not be such a deep mystery to Mamma Kippenberg and daughter Sylvia.”

“Oh, Salt, wouldn’t it make a grand story if only we could learn what became of him?”

“Sure. Front page stuff.”

“We simply must get the story somehow! If Mrs. Kippenberg would just answer our questions about this drawbridge painting—”

“I’m afraid Mamma Kippenberg isn’t going to break down and tell all,” Salt said dryly. “But buckle on your steel armor, little girl, because here she comes now!”

A large, middle-aged woman in rose-colored silk, crossed the room directly toward Salt and Penny. Her pale blue eyes glinted with anger and there were hard lines about her mouth. She walked haughtily, but with grim purpose.

“Unless we do some fast talking, out we go!” muttered Salt. “It’s Mrs. Kippenberg, all right.”

They stood their ground, knowing they had been recognized as intruders. But before the woman could reach them she was stopped by a servant who spoke a few words in a low tone. For a moment Mrs. Kippenberg forgot about Penny and Salt as a new problem presented itself.

“I can’t talk with anyone now,” she said in an agitated voice. “Tell them to come back later.”

“They insist upon talking with you now, Madam,” replied the servant. “Unless you see them they say they will look around for themselves.”

“Oh!” Mrs. Kippenberg drew herself up sharply as if from a physical blow. “Where are they now?”

“In the library, Madam.”

Penny did not hear the woman’s reply, but she turned and followed the servant.

“Saved by the bell,” mumbled Salt. “Now let’s get away from here before she comes back.”

They pushed through the throng and reached a long hallway. Mrs. Kippenberg had disappeared, but as they drew near an open door they caught sight of her again. She stood just inside the library, her back toward them, talking with two men who wore plain gray business suits.

Penny half drew back, fearing discovery, but Salt pulled her along. As they went quietly past the door they heard Mrs. Kippenberg say in an excited voice:

“No, no, I tell you he isn’t here! Why should I try to deceive you? We have nothing to hide. You are most inconsiderate to annoy me at such a time!”

Penny and Salt did not hear the reply. They reached an outside door and stepped down on a flagstone terrace which overlooked the garden at the rear of the grounds.

“Who were those men, do you suppose?” Penny whispered, fearful that her voice might betray them.

“Officers of the law, I should guess,” Salt replied in an undertone.

“Government men?”

“Likely as not. I don’t believe the locals would bother her. Anyway she’s got the wind up and you can tell she’s scared silly in spite of all her back talk.”

“You know what I think they’re after?” Penny said thoughtfully.

“Well, if I had just one guess,” Salt replied, “I’d say they are after Mr. Kippenberg.”

“I agree with you there.”

“Sure, why else would they come sleuthing around at a time like this? The answer is simple. Daughter gets married. Papa wants to see his darling do it. Therefore, boys, we’ll spread a net for Daddy and he might plump right into it.”

“So that’s the way a G man’s mind works?” laughed Penny.

“But I would take it that Kippenberg is no fool,” Salt went on. “If they really have a ‘man wanted’ sign hung on him he would be too cagey to come around here today.”

They were standing beside the stone balustrade which bounded the terrace. Below them the green foliage of the gardens formed a dark background for the playing fountains. A cool breeze drifted in from the river and rattled a window awning just over their heads.

“We’re in an exposed place here,” observed Salt uneasily. “Maybe we ought to find a hole somewhere.”

“We’ll never learn anything in a hole,” Penny objected. “In fact, we’re not making much progress in running down any sort of story. I do wish we could have heard more of that conversation.”

“And get thrown out on our collective ear before we even have a chance to snap a picture of the blushing bride!”

“Pictures! Pictures!” exclaimed Penny. “That’s all you photographers think about. How about poor little me and my story? After all, you can’t bring out a paper full of nothing but pictures and cigarette ads. You need a little news to go with it.”

“You like to work too fast,” complained Salt. “Right now the thing to do is to keep out of sight. I’m telling you the minute Mrs. Kippy finishes with those men she’ll be gunning for us.”

“Then I suppose we’ll have to go into hiding.”

“First, let’s mosey out into the rose garden,” Salt proposed. “I’ll take a few shots and then we’ll duck under somewhere and wait until the ceremony starts.”

“That’s all very well for you,” grumbled Penny, “but I can’t write much of a story without talking to some member of the family.”

Salt started off across the velvety green lawn toward the rose arbor where the service was to be held. Penny followed reluctantly. She watched the photographer take several pictures before a servant approached him.

“I beg your pardon,” the man said coldly, “but Mrs. Kippenberg gave orders no pictures were to be taken. If you are from one of the papers—”

“Oh, I saw her in the house just a minute ago,” Salt replied carelessly.

“Sorry, sir,” the servant apologized, retreating.

Salt finished taking the pictures and slipped the miniature camera back into his pocket.

“Now let’s amble down toward the river and wait,” he said to Penny. “We’ll blossom forth just as the ceremony starts. Mrs. Kippy won’t dare interrupt it to have us thrown off the grounds.”

They walked down a sloping path, past a glass-enclosed hothouse and on toward a grove of giant oak and maple trees.

“It’s pleasant here when you’re away from the crowd,” Penny remarked, gazing up at the leafy canopy. “I wonder where this path leads?”

“Oh, down to the river probably. With water on three sides of us that’s a fairly safe guess.”

“Which rivers flow past the estate, Salt?”

“The Big Bear and the Kobalt.”

“The same old muddy Kobalt which is near our town,” said Penny in surprise. “I’ll always think of it as a river of adventure.”

“Because of Mud-Cat Joe and his Vanishing Houseboat?”

Penny nodded and a dreamy look came into her eyes. “So much happened on the Kobalt, Salt. Remember that big party Dad threw at the Comstock Inn?”

“Do I? Jerry Livingston decided to sleep in Room Seven where so many persons had disappeared.”

“And then he was spirited away almost before our very eyes,” added Penny. “Days later Mud-Cat Joe helped me fish him out of this same old Kobalt. For awhile we didn’t think he’d ever pull through or be able to tell what had happened to him.”

“But as the grand finale you and your friend, Louise Sidell, solved the mystery and secured a dandy story for the Star. Those were the days!”

“You talk as if they were gone forever,” laughed Penny. “Other good stories will come along.”

“Maybe,” said Salt, “but covering a wedding is pretty tame in comparison.”

“Yet this one does have interesting angles,” Penny insisted. “Can’t you almost feel mystery lurking about the place?”

“No, but I do feel a mosquito sinking his stinger into me.” Salt slapped vigorously at his ankle.

They followed the path on toward the river, coming soon to a trail which branched off to the right. Across it had been stretched a wire barrier and a neatly lettered sign read:

NO ADMITTANCE BEYOND THIS POINT.

“Why do you suppose the path is blocked off?” Penny speculated.

“Let’s find out,” Salt suggested with a sudden flare of interest. “Maybe we’ll run into something worth a picture.”

Penny hesitated, not wishing to disregard the sign, yet eager to learn what lay beyond the barrier.

“Listen,” said Salt, “just put your little conscience on ice. We’re here to get the ‘who, when, why and where.’ You’ll never be a first class newspaper reporter if you stifle your curiosity.”

“Lead on,” laughed Penny. “I will follow. Only isn’t it getting late?”

Salt looked at his watch. “We still have a safe fifteen minutes.”

He started to step over the wire, only to have Penny reach out and grasp his hand.

“Wait!” she whispered.

“What’s the idea?” Salt turned toward her in astonishment.

“I think someone is watching us! I’m sure I saw the bushes move.”

“Your nerves are jumpy,” Salt jeered. “It’s only the wind.”

Even as he spoke the foliage to the left moved ever so slightly and a dark form could be seen creeping stealthily away along the ground.

Salt acted instinctively. Leaping over the wire barrier he dived into the bushes. Hurling himself upon the man who crouched there, he pinned him to the ground. The fellow gave a choked cry and tried to pull free.

“Oh, no, you don’t,” Salt muttered, coolly sitting down on his stomach. “Snooping, eh?”

“You let me up!” the man cried savagely. “Let me up, I say!”

“I’ll let you up when you explain what you were doing here.”

“Why, you impudent young pup!” the man spluttered. “You’re the one who will explain. I am Mrs. Kippenberg’s head gardener.”

Salt’s hand fell from the old man’s collar and he apologetically helped him to his feet. Penny, who had reached the scene, stooped down and recovered a trowel which had slipped from the gardener’s grasp.

“It was just a little mistake on my part,” Salt mumbled. “I hope I didn’t hurt you.”

“No fault of yours you didn’t,” the old man snapped. “A fine howdydo when a person can’t even loosen earth around a shrub without being assaulted by a ruffian!”

The gardener was a short, stout man with graying hair. He wore coarse garments, a loose fitting pair of trousers, a dark shirt and battered felt hat. But Penny noticed that his hands and fingernails were clean and there were no trowel marks around any of the shrubs.

“Salt isn’t exactly a ruffian,” she said as the photographer offered no defense. “After all, from where we stood it looked exactly as if you were hiding in the bushes.”

“Then you both need glasses,” the man retorted rudely. “A person can’t work without getting down on his hands and knees.”

“Where were you digging?” Penny asked innocently.

“I was just starting in when this young upstart leaped on my back!”

“Sorry,” said Salt, “but I thought you were trying to get away.”

“Who are you anyway?” the gardener demanded bluntly. “You’re not guests. I can tell that.”

“You have a very discerning eye,” replied Salt smoothly. “We’re from the Riverview Star.”

“Reporters, eh?” The old man scowled unpleasantly. “Then you’ve no business being here at all. You’re not wanted, so get out!”

“We’re only after a few facts about the wedding,” Penny said. “Perhaps you would be willing to tell me—”

“I’ll tell you nothing, Miss! If anything is given out to the papers it will have to come from Mrs. Kippenberg.”

“Fair enough,” Salt acknowledged. He glanced curiously down the path which had been blocked off. “What’s down there?”

“Nothing.” The gardener spoke irritably. “This part of the estate hasn’t been fixed up. That’s why it’s closed.”

Penny had bent down, pretending to examine a shrub at the edge of the path.

“What is the name of this bush?” she inquired casually.

“An azalea,” the gardener replied after a slight hesitation. “Now get out of here, will you? I have my work to do.”

“Oh, all right,” Salt rejoined as he and Penny moved away. “No need to get so tough.”

They stepped over the barrier wire and retraced their way toward the house. Several times Penny glanced back but she could not see the old man. He had slipped away somewhere among the trees.

“I don’t believe that fellow was a gardener,” she said suddenly.

“What makes you think not?”

“Didn’t you notice his nice clean hands and fingernails? And then when I asked him the name of that bush he hesitated and called it an azalea. I saw another long botanical name attached to it.”

“Maybe he just made a mistake, or said the first thing that came into his head. He wanted to get rid of us.”

“I know he did,” nodded Penny. “Yet, when he found out we were from the Star he didn’t threaten to report us to Mrs. Kippenberg.”

“That’s so.”

“He was afraid to report us,” Penny went on with conviction. “I’ll bet a cent he has no more right here than we have.”

Salt had lost all interest in the gardener. He glanced at his watch and quickened his step.

“Is it two o’clock yet?” Penny asked anxiously.

“Just. After all the trouble we’ve had getting here we can’t afford to miss the big show.”

Emerging from the grove, Salt and Penny were relieved to see that the ceremony had not yet started. The guests were gathered in the garden, the minister stood waiting, musicians were in their places, but the bridal party had not appeared.

“We’re just in time,” Salt remarked.

Penny observed Mrs. Kippenberg talking with one of the ushers. Even from a distance it was apparent that the woman had lost her poise. Her hands fluttered nervously as she conferred with the young man and a worried frown puckered her eyebrows.

“Something seems to be wrong,” said Penny. “I wonder what is causing the delay?”

Before Salt could reply, the usher crossed the lawn, and came directly toward them. Penny and Salt instantly were on guard, thinking that he had been sent by Mrs. Kippenberg to eject them from the grounds. But although the young man paused, he did not look squarely at them.

“Have you seen Mr. Atherwald anywhere?” he questioned.

“The bridegroom?” Salt asked in astonishment. “What’s the matter? Is he missing?”

“Oh, no, sir,” the young man returned stiffly. “Certainly not. He merely went away for a moment.”

“Mr. Atherwald came over on the same boat with us,” Penny volunteered.

“And did you see him enter the house?”

“No, he spoke to one of the servants and then went toward the garden.”

“Did you notice which path he took?”

“I believe it was this one.”

“We’ve just come from down by the river,” added Salt. “We didn’t see him there. The only person we met was an old gardener.”

The usher thanked them for the information and hurried on. When the man was beyond hearing, Salt turned to Penny, saying jubilantly:

“Say, maybe we’ll get a big story after all! Sylvia Kippenberg jilted at the altar! Hot stuff!”

“Aren’t you jumping to swift conclusions, Salt? He must be around here somewhere.”

“It’s always serious business when a man is late for his wedding. Even if he does show up, daughter Sylvia may take offense and call the whole thing off.”

“Oh, you’re too hopeful,” Penny laughed. “He’ll probably be here in another minute. I don’t believe he would have come at all if he had intended to slip away.”

“He may have lost his nerve at the last minute,” Salt insisted.

“Atherwald did act strangely on the boat,” Penny said reflectively. “And then that message he received—”

“He may have sent it to himself.”

“As an excuse for getting away?”

“Why not?”

“I can’t see any reason for going to so much unnecessary trouble,” Penny argued. “If he intended to jilt Miss Kippenberg how much easier it would have been not to come here at all.”

“Well, let’s see what we can learn,” Salt suggested.

Their interest steadily mounting, they went on toward the house and stationed themselves where they could see advantageously. It was evident by this time that the guests suspected something had gone amiss. Significant glances were exchanged, a few persons looked at their watches, and all eyes focused upon Mrs. Kippenberg who tried desperately to carry off an embarrassing situation.

Minutes passed. The crowd became increasingly restless. Finally, the usher returned and spoke quietly to Mrs. Kippenberg. They both retired to the house.

“It looks as if there will be no wedding today,” Salt declared. “Atherwald hasn’t been located.”

“I won’t dare use the story unless I’m absolutely certain of my facts,” Penny said anxiously.

“We’ll get them, never fear.”

Mrs. Kippenberg and the usher had stepped into the breakfast room. Posting Penny at the outside door, Salt followed the couple. From the hallway he could hear their conversation distinctly.

“But he must be somewhere on the grounds,” the matron argued.

“I can’t understand it myself,” the young man replied. “Grant’s disappearance is very mysterious to say the least. Several persons saw him arrive here and everything seemed to be all right.”

“What time is it now?”

“Two thirty-five, Mrs. Kippenberg.”

“So late? Oh, this is dreadful! How can I face them?”

“I know just how you feel,” the young man said with sympathy. “If you wish I will explain to the guests.”

“No, no, this will disgrace us,” Mrs. Kippenberg murmured. “Wait until I have talked with Sylvia.”

She turned suddenly and reached the hall door before Salt could escape. Her eyes blazed with wrath as she faced him.

“So here you are!” she cried furiously. “How dare you disregard my orders? I will have no reporters on the grounds!”

“I’m only a photographer,” Salt said meekly enough. “Sorry to intrude but I’ve been assigned to get a picture of the bride. It won’t take a minute—”

“Indeed it won’t,” Mrs. Kippenberg broke in, her voice rising higher. “You’ll take no pictures here. Not one! Now get out.”

“A picture might be better than a story that the bridegroom had skipped out,” Salt said persuasively.

“Why, you—you!” Mrs. Kippenberg’s face became fiery red. She choked as she tried to speak. “Get out, I say!”

Salt did not retreat. Instead he took his camera from his pocket.

“Just one picture, Mrs. Kippenberg. At least of you.”

Realizing that the photographer meant to take it whether or not she gave permission, the woman suddenly lost all control over her temper.

“Don’t you dare!” she cried furiously. “Don’t you dare!”

Whirling about, she seized an empty plate from the tall stack on the serving table.

“Hold that pose!” chortled Salt, goading her on.

The woman hurled the plate straight at him. Salt gleefully snapped a picture and dodged. The plate crashed into the wall behind him, splintering into a half dozen pieces.

“Swell action picture!” he grinned.

“Don’t you dare try to use it!” screamed Mrs. Kippenberg. “I’ll telephone your editor! I’ll have you discharged!”

“See here,” offered the usher, taking out his wallet. “I’ll give you ten dollars for that picture.”

Salt shook his head, still smiling broadly.

The sound of the crash had brought servants running to the scene.

“Have this person ejected from the grounds,” Mrs. Kippenberg ordered harshly. “And see that he doesn’t get back.”

Just outside the house, Penny huddled against the wall, trying to make herself as inconspicuous as possible. She had heard everything. As Salt backed out the door he did not glance at her but he muttered for her ears alone:

“You’re on your own now, kid. I’ll be waiting at the drawbridge.”

An instant later two servants seized him roughly by the arms and escorted him down the walk to the boat landing.

Penny waited anxiously, but Mrs. Kippenberg did not come to the outside door. Nor had it occurred to the two servants that the girl was connected in any way with the photographer.

“On my own,” she repeated to herself. “On my own with a vengeance.”

Salt had his picture and it was up to her to get a good story. Until now she had depended upon his guidance. With all support withdrawn she suddenly felt uncertain and incompetent.

Penny waited a few minutes before gathering sufficient courage to enter the long hallway. One glance assured her that the breakfast room was deserted.

“Mrs. Kippenberg probably went upstairs to talk with her daughter,” she reasoned. “I’d like to hear what they say to each other.”

With the guests assembled in the garden, only a few persons lingered in the house. No one paid heed to Penny as she moved noiselessly up the spiral stairway.

A bedroom door stood slightly ajar. Hearing a low murmur of voices, Penny paused. Framed against the leaded windows she saw Sylvia Kippenberg talking with her mother. Despite a tear-streaked face the girl was very lovely. She wore a long flowing gown of white satin and the flowers at the neckline were outlined with real pearls. Her net veil had been discarded. A bouquet of flowers lay on the floor.

“How could Grant do such a cruel thing?” Penny heard her sob. “I just can’t believe it of him, Mother. Surely he will come.”

Mrs. Kippenberg held the girl in her arms, trying to comfort her.

“It is nearly three now, Sylvia. The servants have searched everywhere. A man of his type isn’t worthy of you.”

“But I love him, Mother. And I am sure he loves me. It doesn’t seem possible he would do such a thing without a word of explanation.”

“He will explain, never fear,” Mrs. Kippenberg said grimly. “But now, we must think what has to be done. The guests must be told.”

“Oh, Mother!” Sylvia went into another paroxysm of crying.

“There is no other way, my dear. Leave everything to me.”

Before Penny realized that the interview had ended, Mrs. Kippenberg stepped out into the hall. Her eyes focused hard upon the girl.

“You are a reporter!” she accused harshly. “I remember, you were with that photographer!”

“Please—” began Penny.

“I’ll tell you nothing,” the woman cried. “How dare you intrude in my home and go about listening at bedroom doors!”

“Mrs. Kippenberg, if only you will calm yourself, I may be able to help you.”

“Help me?” the woman demanded. “What do you mean?”

“I may be able to give you a clue as to what became of Grant Atherwald.”

The anger faded from Mrs. Kippenberg’s face. She came close to Penny, grasping her arm with a pressure which hurt.

“You have seen him? Tell me!”

“He came over in the same boat.”

“How long ago was that?”

“Shortly after one o’clock. He was stopped at the front door by a servant who handed him a note. Mr. Atherwald read it and walked down toward the garden.”

“I wonder which one of the servants spoke to him? It was at the front door, you say?”

“Yes.”

“Then it must have been Gregg. I’ll talk with him.”

Forgetting Penny, Mrs. Kippenberg hastened down the stairway. She jangled a bell and asked that the manservant be sent to her. Unnoticed, Penny lingered to hear the interview.

The man came into the room. “You sent for me, Mrs. Kippenberg?” he inquired.

“Yes, Gregg. You were at the door when Mr. Atherwald arrived?”

“I was, Madam.”

“I understand you handed him a note which he read.”

“Yes, Madam.”

“Who gave you the note?”

“Mrs. Latch, the cook. She told me it was brought to the kitchen door early this morning by a most disreputable looking boy.”

“He had been hired to deliver it for another person, I suppose?”

“Yes, Madam. The boy told Mrs. Latch that the message came from a friend of Mr. Atherwald’s and should be given to him as soon as he arrived.”

“You have no idea what the note contained?”

“No, Mrs. Kippenberg, the envelope was sealed.”

Sensing that when the interview ended Mrs. Kippenberg’s wrath might again descend upon her, Penny decided not to tempt fate. While the woman was still talking with the servant, she slipped out of the house.

“Atherwald might have had that note sent to himself, but I doubt it,” she told herself. “Either he is still on the estate, or the boatman would have had to take him back across the river.”

She walked quickly down to the dock and was elated to find the guest launch tied up there. The boatman answered her questions readily. He had not seen Grant Atherwald since early in the afternoon. Salt was the only person he had taken back across the river.

“Have you noticed any other boat leaving the estate?” inquired Penny.

“Boats have been going up and down the river all day,” the man answered with a shrug. “I didn’t notice any particular one.”

Penny glanced across the water. She could see Salt perched on the drawbridge waiting for her. But she was not yet ready to leave the estate.

Ignoring his shout to “come on,” she turned and walked back toward the house. Deliberately, she chose the same path which she and Salt had followed earlier in the afternoon.

A swift walk brought her to the forbidden trail with the barrier sign. Penny glanced around to be certain she was not under observation. Then she stepped boldly over the wire.

Passing the place where she and Salt had talked with the gardener, she noticed his trowel lying on the ground. There was no evidence that he had done any work.

However, all along the path flowering shrubs were well trimmed and tended.

“So this part of the estate isn’t fixed up,” Penny mused. “It’s much nicer than the other section in my opinion. I wonder why that gardener told so many lies?”

The path led deeper into the woods. Rustic benches invited one to linger, but Penny walked rapidly onward.

Unexpectedly, she came to a little clearing, and saw before her a large, circular pool. From a gap in the trees, warm sunshine poured down upon the bed of flowers which flanked the cement sides, making a circle of brilliant color.

“So this is where the path leads,” thought Penny. “No mystery here after all.”

She was at a loss to understand why this portion of the estate had been closed to visitors for certainly it was the most beautiful part. Yet there was a quality to the beauty which the girl did not like.

As she stood staring at the pool, she was fully aware of an uneasy feeling which had taken possession of her. It was almost as if she stood in the presence of something sinister and unknown. The gentle rustling of the tree leaves, the cool river air blowing against her cheek, only served to heighten the feeling.

She drew closer and peered down into the blue depths of the pool. She could not see the bottom plainly for the water was choked with a tangle of feathery plants. A few yellow lilies floated on the surface.

Penny absently reached out to pluck one. But as the stem snapped off, she gave a little scream and dropped the flower. She had seen a large, shadowy form slithering through the water beneath her.

Penny backed a step away from the pool. From among the lily pads an ugly head emerged and a broad snout was raised above the surface for an instant. Powerful jaws opened and closed, revealing jagged teeth set in deep pits.

“An alligator!” Penny exclaimed aloud. “Such a horrid, ugly creature! And to think, I nearly put my hand in that water.”

She shivered and watched the movements of the alligator. Its head scooted smoothly over the water for a short distance. Then with a swish of its tail, the reptile submerged and the pool was as placid as before.

“Eight feet long if it’s an inch,” estimated Penny. “Why would any person in his right mind keep such a creature here? Why, it’s dangerous.”

She felt enraged, thinking how close she had come to touching the alligator. Yet justice compelled her to admit that she had only herself to blame. Deliberately, she had disregarded the warning not to explore the forbidden trail.

“The Kippenbergs keep nice pets,” she thought ironically. “If anyone fell into that pool it would be just too bad.”

Now that her curiosity was satisfied, Penny had not the slightest desire to linger near the lily pool. With another glance down into the murky depths she turned away, but she had taken less than a dozen steps when she paused. Her attention was held by a bright and shiny object which lay in the dust at her feet.

With a low cry of surprise she reached down and picked up a plain band of white gold. Obviously, it was a wedding ring.

“Now where did this come from?” Penny turned it over on the palm of her hand.

Startled thoughts leaped into her mind. She felt certain Grant Atherwald had taken this same path earlier in the afternoon. It was logical to believe that the ring had been his, intended for Sylvia Kippenberg. Had he lost the band accidentally or deliberately thrown it away?

Slowly, Penny’s gaze roved to the lily pond. She noted that the coping was so low that one who walked carelessly might easily stumble and fall into the water. It made her shudder to think of such a gruesome possibility, yet she could not avoid giving it consideration. For that matter, Grant Atherwald might have been lured to this isolated spot. The mysterious message—

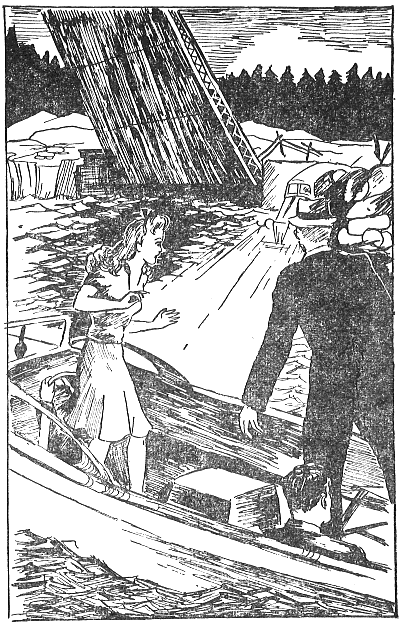

Penny delved no deeper into the problem for suddenly she felt someone grasp her arms. With a terrified cry she whirled about to face her assailant.

A wave of relief surged over Penny as she saw that it was the old gardener who held her fast.

“Oh, it’s only you,” she laughed shakily, trying to pull away. “For a second I thought the Bogey Man had me for sure.”

The gardener did not smile.

“Didn’t I tell you to keep away from here?” he demanded, giving her a hard shake.

“I’m not doing any h-harm,” Penny stammered. She kept her hand closed over the white gold ring so that the old man would not see what she had found. “I just wanted to learn what was back in here.”

“And you found out?”

The gardener’s tone warned Penny to be cautious in her reply.

“Oh, the pool is rather pretty,” she answered carelessly. “But I’ve seen much nicer ones.”

“How long have you been here?”

“Only a minute or two. I really came to search for Grant Atherwald.”

“Atherwald? What would he be doing here?”

“He disappeared an hour or so ago,” revealed Penny. “The servants have been searching everywhere for him.”

“He disappeared?” the gardener repeated incredulously.

“Yes, it’s very peculiar. Mr. Atherwald arrived at the estate in ample time for the wedding. But after he read a note which was delivered to him he walked off in this direction and was seen no more.”

“Down this path, you mean?”

“I couldn’t say as to that, but he started this way. I know because I saw him myself.”

“Atherwald didn’t come here,” the gardener said with finality. “I’ve been working around the lily pond all afternoon and would have seen him.”

Penny’s fingers closed tightly about the white gold ring which she kept shielded from the man’s gaze. In her opinion the trinket offered almost conclusive proof that the bridegroom had visited the locality. Because she could not trust the gardener she kept her thoughts strictly to herself.

The man stared down at his feet, obviously disturbed by the information Penny had given him.

“Do you suppose harm could have befallen Mr. Atherwald?” she asked after a moment.

“Harm?” he demanded irritably. “That’s sheer nonsense. The fellow probably skipped out. He ought to be tarred and feathered!”

“And you would enjoy doing it?” Penny interposed slyly.

The gardener glared at her, making no attempt to hide his dislike.

“Such treatment would be too good for anyone who hurt Miss Sylvia. Now will you get out of here? I have my orders and I mean to enforce them.”

“Oh, all right,” replied Penny. “I was going anyway.”

This was not strictly true, for had the gardener not been there she would have made a more thorough investigation of the locality near the lily pool. But now she had no hope of learning more, and so turned away.

Emerging from among the trees, she glanced toward the rose garden. Nearly all of the wedding guests had departed. Penny considered whether or not she should speak to Mrs. Kippenberg about finding the ring. Deciding against it, she joined a group of people at the boat dock and was ferried across the river.

Salt awaited her at the drawbridge.

“I just about gave you up,” he complained. “It’s time for us to get back to the office or our news won’t be news. The wedding is definitely off?”

“Yes, Atherwald can’t be found.”

“We’ll stop at a drug store and telephone,” Salt said, pulling her toward the car. “Learn anything more after I left?”

“Well, I found a wedding ring and was nearly chewed up by an alligator,” laughed Penny. “It seemed rather interesting at the time.”

The photographer gave her a queer look as he started the automobile.

“Imagination and journalism never mix,” he said.

“Does this look like imagination?” Penny countered, showing him the plain band ring.

“Where did you find it?”

“Beside a lily pond in the forbidden part of the estate. I feel certain it must have been dropped by Grant Atherwald.”

“Thrown away?”

“I don’t know exactly what to think,” Penny replied soberly.

Salt steered the car into the main road which led back to Corbin. Then he inquired: “Did you notice any signs of a struggle? Grass trampled? Footprints?”

“I didn’t have a chance to do any investigating. That bossy old gardener came and drove me away.”

“What were you saying about alligators?”

“Salt, I saw one swimming around in the lily pool,” Penny told him earnestly. “It was an ugly brute, at least twelve feet long.”

“How long?”

“Well, eight anyway.”

“You’re joking.”

“I am not,” Penny said indignantly.

“Maybe it was only a big log lying in the water.”

Penny gave an injured sniff. “Have it your own way. But it wasn’t a log. I guess I can tell an alligator when I see one.”

“If you’re actually right,” Salt said unmoved, “I’d like to have snapped a picture of it. You know, this story might develop into something big.”

“I have a feeling it will, Salt.”

“If Atherwald really has disappeared it should create a sensation!”

“And if the poor fellow had the misfortune to fall or be pushed into the lily pool Dad wouldn’t have headlines large enough to carry it!”

“Say, get a grip on yourself,” Salt advised. “The Riverview Star prints fact, not fancy.”

“That’s because so many of Dad’s reporters are stodgy old fellows,” laughed Penny. “But I’ll admit it isn’t very likely Grant Atherwald was devoured by the alligator.”

The car had reached Corbin. Salt drew up in front of a drug store.

“Run in and telephone DeWitt,” he said, opening the door for her. “And remember, stick to facts.”

Penny was a little frightened as she entered the telephone booth and placed a long distance call to the Riverview Star. She never failed to feel nervous when she talked with DeWitt, the city editor, for he was not a very pleasant individual.

She jumped as the receiver was taken down and a voice barked: “City desk.”

“This is Penny Parker over at Corbin,” she began weakly.

“Can’t hear you,” snapped DeWitt. “Talk up.”

Penny repeated her name and DeWitt’s voice lost some of its edge. Gathering courage, she started to tell him what she had learned at the Kippenberg estate.

“Hold it,” interrupted DeWitt. “I’ll switch you over to a rewrite man.”

The connection was made and Penny began a second time. Now and then the rewrite man broke into the narrative to ask a question.

“All right, I think I have it all,” he said finally and hung up.

Penny went back to the car looking as crestfallen as she felt.

“I don’t know what they thought of the story,” she told Salt. “DeWitt certainly didn’t waste any words of praise.”

“He never does,” chuckled the photographer. “You’re lucky if you don’t get fired.”

“That’s one consolation,” returned Penny, settling herself for the long ride home. “He can’t fire me. Being the editor’s daughter has its advantages.”

The regular night edition of the Riverview Star was on the street by the time they reached the city. Salt signaled a newsboy and bought a paper while the car waited for a traffic light. He tossed it over to Penny.

“Here it is! My story!” she cried, and then her face fell.

“What’s the matter?” asked Salt. “Did they garble it all up?”

“They’ve cut it down to three inches! And not a word about the alligator or the lost wedding ring! I could cry! Why, I told that rewrite man enough to fill at least a column!”

“Well, anyway you made the front page,” the photographer consoled. “They may build the story up in the next edition after they get my pictures.”

Penny said nothing, remaining in deep gloom during the remainder of the ride to the Star office. Salt let her out at the front door. She debated for a moment whether or not to go on home, but finally entered the building.

DeWitt was busy at his desk as she walked stiffly past. She hoped that he would notice how she ignored him, but he did not glance up from the copy before him.

Penny opened the door of her father’s private office and stopped short.

“Why, Dad?” she cried. “What are you doing here? You’re supposed to be home in bed.”

“I finally persuaded the doctor to let me out,” Anthony Parker replied, swinging around in his swivel chair. “How did you get along with your assignment?”

“I thought I did very well,” Penny said aloofly. “But from now on I’ll not telephone anything in. I’ll write the story myself.”

“Now don’t blame DeWitt or the rewrite man,” said Mr. Parker, smiling. “A paper has to be careful in what it publishes, especially about a wedding. Alligators are a bit too—shall we say sensational?”

“You made a similar remark about witch dolls,” Penny reminded him.

“I did eat my words that time,” Mr. Parker admitted, “but this is different. If we build up a big story about Grant Atherwald’s disappearance, and then tomorrow he shows up at his own home, we’ll appear pretty ridiculous.”

“I guess you’re right,” Penny said, turning away. “Well, I’m happy to see you back in the office again.”

Mr. Parker watched her speculatively. When she reached the door he inquired: “Aren’t you forgetting something?”

“What, Dad?”

“Today is Thursday.” The editor took a sealed envelope from the desk drawer. “This is the first time you have failed to collect your allowance in over a year.”

“I must be slipping.” Penny grinned as she pocketed the envelope.

“Why don’t you open it?”

“What’s the use?” Penny asked gloomily. “It’s always the same. Anyway, I borrowed two dollars last week so this doesn’t really belong to me.”

“You might be pleasantly surprised.”

Penny stared at her father with disbelief. “Dad! You don’t mean you’ve given me a raise!”

Eagerly, she ripped open the envelope. Three crisp dollar bills fluttered into her hand. With a shriek of delight, Penny flung her arms about her father’s neck.

“I always try to reward a good reporter,” he chuckled. “Now take yourself off because my work is stacked a mile high.”

Penny tripped gaily toward the door but it opened before she could cross the room. An office boy came in with a message for Mr. Parker.

“Man to see you named Atherwald,” he announced.

The name produced an electrifying effect upon both Penny and her father.

“Atherwald!” Mr. Parker exclaimed. “Then he hasn’t disappeared after all! Show him in.”

“And I’m staying right here,” Penny declared, easing herself into the nearest chair. “I have a hunch that this interview may concern me.”

In a few minutes the office boy returned, followed by a distinguished, middle-aged man who carried a cane. Penny gave him an astonished glance for she had expected to see Grant Atherwald. It had not occurred to her that there might be two persons with the same surname.

“Mr. Atherwald?” inquired her father, waving the visitor into a chair.

“James Atherwald.”

The man spoke shortly and did not sit down. Instead he spread out a copy of the night edition of the Star and pointed to the story which Penny had covered. She quaked inwardly, wondering what error of hers was to be exposed.

“Do you see this?” Mr. Atherwald demanded.

“What about it?” inquired the editor pleasantly.

“You are holding my family up to ridicule by printing such a story! Grant Atherwald is my son!”

“Is the story incorrect?”

“Yes, you imply that my son deliberately jilted Sylvia Kippenberg!”

“And actually he didn’t?” Mr. Parker inquired evenly.

“Certainly not. My son is a man of honor and had a very deep regard for Sylvia. Under no circumstance would he have jilted her.”

“Still, the wedding did not take place.”

“That is true,” Mr. Atherwald admitted.

“Perhaps you can explain why it was postponed?”

“I don’t know what happened to Grant,” Mr. Atherwald said reluctantly. “He left our home in ample time for the ceremony, and I might add, was in excellent spirits. I believe he must have been the victim of a stupid, practical joke.”

“Well, that suggests a new angle,” Mr. Parker remarked thoughtfully. “Did your son have friends who might be apt to play such a joke on him?”

“No one of my acquaintance,” Mr. Atherwald answered unwillingly. “Of course, he had many young friends who were not in my circle.”

Penny had listened quietly to the conversation. She now arose and came over to the desk. From her pocket she took the white gold wedding ring.

“Mr. Atherwald,” she said, “I wonder if you could identify this.”

The man studied the trinket for a moment.

“It looks very much like a ring which Grant purchased for Sylvia,” he declared. “Where did you get it?”

“I found it lying on the ground at the Kippenberg estate,” Penny replied vaguely. She had no intention of divulging the exact locality where she had picked up the ring.

“You see,” said Mr. Parker, “we have supporting facts in our possession which were not published. All in all, I think the story was handled discreetly, with due regard for the feelings of those involved.”

“Then you refuse to retract the story?”

“I should like to oblige you, Mr. Atherwald, but you realize such a story as this is of great interest to our readers.”

“You care only for sensationalism!”

“On the contrary, we try to avoid it,” Mr. Parker corrected. “In this particular case, we deliberately played the story down. If it develops that your son actually has disappeared—”

“I tell you it was only a practical joke,” Mr. Atherwald interrupted. “No doubt my son is at home by this time. The wedding has merely been postponed.”

“You are entitled to your opinion,” said Mr. Parker. “And I sincerely hope that you are right.”

“At least do not use that picture which your photographer took of Mrs. Kippenberg. I’ll pay you for it.”

Mr. Parker smiled and shook his head.

“I might have expected such an attitude!” Mr. Atherwald exclaimed angrily. “Good afternoon.”

He left the office, slamming the door behind him.

“Well, you’ve lost another subscriber, Dad,” said Penny flippantly.

“He’s not the first,” returned her father.

“I intended to give Mr. Atherwald the wedding ring, but he went off in too big a hurry. Should I go after him?”

“No, don’t bother, Penny. You might take it around to the picture room and have it photographed. We may use it as Exhibit A if the story develops into anything.”

“How about the alligator?” Penny asked. “Would you like to have me bring that to the office, too?”

“Move out of here and let me work,” her father retorted.

Penny went to the photographic department and made her requirements known.

“I’ll wait for the ring,” she announced. “You don’t catch me trusting you boys with any jewelry.”

While the picture was being taken Salt came by with several damp prints in his hand.

“Take a look at this one, Penny,” he said proudly. “Mrs. Kippenberg wielding a wicked plate. Will she burn up when she sees it on the picture page?”

“She will, indeed,” agreed Penny. “Nice going.”

When the ring had been returned to her she slipped it into her pocket and left the newspaper office. Her next stop was at a corner hamburger shop where she fortified herself with two large sandwiches.

“That ought to hold me until the dinner bell rings,” she thought. “And now to pay my honest debts.”

A trolley ride and a short walk brought Penny to the home of her chum, Louise Sidell. As she came within sight of the front porch she saw her friend sitting on the steps, reading a movie magazine. Louise threw it aside and sprang to her feet.

“Oh, Penny, I’m glad you came over. I telephoned your house and Mrs. Weems said you had gone away somewhere.”

“Official business for Dad,” Penny laughed. She dropped two dollars into Louise’s hand. “Here’s what I owe you. But don’t go spend it because I may need to borrow it back in a couple of days.”

“Is Leaping Lena running up huge garage bills again?” Louise inquired sympathetically.

Penny’s second-hand car was a joke to everyone save herself. She was a familiar figure at nearly every garage in Riverview, for the vehicle had a disconcerting way of breaking down.

“I had to buy new spark plugs this time,” sighed Penny. “But then, I should get along better from now on. Dad raised my allowance.”

“Doesn’t that call for a celebration? Rini’s have a special on today. A double chocolate sundae with pineapple and nuts, cherry and—”

“Oh, no, you don’t! I’m saving my dollar for the essentials of life. I may need it for gasoline if I decide to drive over to Corbin again.”

“Again?” Louise asked alertly.

“I was over there today, covering the Kippenberg wedding,” Penny explained. “Only it turned out there was no ceremony. Grant Atherwald jilted his bride, or was spirited away by persons unknown. He was last seen near a lily pool in an isolated part of the estate. I picked up a wedding ring lying on the ground close by. And then as a climax Mrs. Kippenberg hurled a plate at Salt.”

“Penny Parker, what are you saying?” Louise demanded. “It sounds like one of those two-reel thrillers they show over at the Rialto.”

“Here is the evidence,” Penny said, showing her the white gold ring.

“It’s amazing how you get into so much adventure,” Louise replied enviously as she studied the trinket. “Start at the beginning and tell me everything.”

The invitation was very much to Penny’s liking. Perching herself on the highest porch step she recounted her visit to the Kippenberg estate, painting an especially romantic picture of the castle dwelling, the moat, and the drawbridge.

“Oh, I’d love to visit the place,” Louise declared. “You have all the luck.”

“I’ll take you with me if I ever get to go again,” promised Penny. “Well, I’ll see you tomorrow.”

And with this careless farewell, she sprang to her feet, and hastened on home.

The next morning while Mrs. Weems was preparing breakfast, Penny ran down to the corner to buy the first edition of the Star. As she spread it open a small headline accosted her eye.

“NO TRACE OF MISSING BRIDEGROOM.”

Penny read swiftly, learning that Grant Atherwald had not been seen since his strange disappearance from the Kippenberg estate. Members of the family refused to discuss the affair and had made no report to the police.

“This story is developing into something big after all,” she thought with quickening pulse. “Now if Dad will only let me work on it!”

At home she gave the newspaper to her father, remarking rather pointedly: “You see, your expert reporters haven’t learned very much more than I brought in yesterday. Why wouldn’t it be a good idea to send me out there again today?”

“Oh, I doubt if you could get into the estate, Penny.”

“Salt and I managed yesterday.”

“You did very well, but you weren’t known then. It will be a different matter today since we antagonized the family by using the story. I’ll suggest that Jerry Livingston be assigned to it.”

“With Penny as first assistant?”

Mr. Parker smiled and shook his head. “This isn’t your type of story. Now if you would like to cover a lecture at the Women’s Club—”

“Or a nice peppy meeting of the Ladies Sewing Circle,” Penny finished ironically. “Thank you, no.”