Title: John Deere's Steel Plow

Author: Edward C. Kendall

Release date: December 4, 2010 [eBook #34562]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Louise Pattison

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Edward C. Kendall

DEERE AND ANDRUS 17

THE FIRST PLOW 19

STEEL OR IRON 21

WHY A STEEL PLOW 23

RECONSTRUCTIONS 24

IN SUMMARY— 25

John Deere in 1837 invented a plow that could be used successfully in the sticky, root-filled soil of the prairie. It was called a steel plow. Actually, it appears that only the cutting edge, the share, on the first Deere plows was steel. The moldboard was smoothly ground wrought iron.

Deere's invention succeeded because, as the durable steel share of the plow cut through the heavy earth, the sticky soil could find no place to cling on its polished surfaces.

Americans moving westward in the beginning of the 19th century soon encountered the prairie lands of what we now call the Middle West. The dark fertile soils promised great rewards to the farmers settling in these regions, but also posed certain problems. First was the breaking of the tough prairie sod. The naturalist John Muir describes the conditions facing prairie farmers when he was a boy in the early 1850's as he tells of the use of the big prairie-breaking plows in the following words:[1]

They were used only for the first ploughing, in breaking up the wild sod woven into a tough mass, chiefly by the cord-like roots of perennial grasses, reinforced by the tap roots of oak and hickory bushes, called "grubs," some of which were more than a century old and four or five inches in diameter.... If in good trim, the plough cut through and turned over these grubs as if the century-old wood were soft like the flesh of carrots and turnips; but if not in good trim the grubs promptly tossed the plough out of the ground.

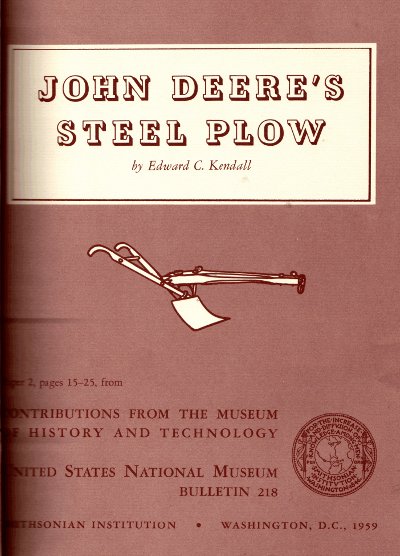

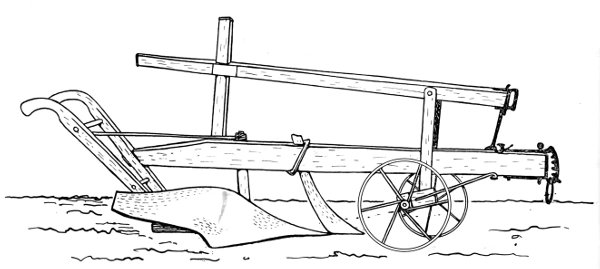

The second and greater problem was that the richer lands of the prairie bottoms, after a few years of continuous cultivation, became so sticky that they clogged the moldboards of the plows. Clogging was such a factor in prairie plowing that farmers in these regions carried a wooden paddle solely for cleaning off the moldboard, a task which had to be repeated so frequently that it seriously interfered with plowing efficiency. It seems probable that by the 1830's blacksmiths in the prairie country were beginning to solve the problem of continuous cultivation of sticky prairie soil by nailing strips of saw steel to the face of wooden moldboard of the traditional plows. Figure 1 is a photograph of an 18th century New England plow in the collection of the U. S. National Museum. This is one type of plow which was brought west by the settlers. It contributed to the development of the prairie breaker shown in figure 2. The first plow on record with strips of steel on the moldboard is attributed to John Lane in Chicago in 1833.[2] Steel presented a smoother surface which shed the sticky loam better than the conventional wooden moldboards covered with wrought iron, or the cast iron moldboards of the newer factory-made plows then coming into use.

It is generally accepted as historical fact that John Deere made his first steel plow in 1837 at Grand Detour, Illinois. The details of the construction of[Pg 17] this plow have been variously given by different writers. Ardrey[3] and Davidson[4] describe Deere's original plow as having a wooden moldboard covered with strips of steel cut from a saw, in the manner of the John Lane plow.

In recent years the 1837 Deere plow has been pictured quite differently. This has apparently come about as the result of the discovery of an old plow identified as one made by John Deere at Grand Detour in 1838 and sold to Joseph Brierton from whose farm it was obtained in 1901 by the maker's son, Charles H. Deere. He brought it to the office of Deere & Company at Moline, Illinois, for preservation and display. This plow is shown in figures 7 and 9. In 1938 Deere & Company presented it to the U. S. National Museum, where it is on display. It can be seen that the moldboard is made of one curved diamond-shaped metal slab. This plow bottom conforms to the description of the "diamond" plows manufactured by Deere in the 1840's.[5] The Company states that according to its records, this was one of three plows made by Deere in 1838 and that it was probably substantially identical with the first one made in 1837.[6] It may be difficult to prove that the Museum's specimen was made in 1838, but a comparison of this plow (fig. 7) with the 1847 moldboard (fig. 5) and the 1855 plow (fig. 6) suggests that the Museum's plow is the earliest of the three, since there is particularly evident an evolution of the shape of the moldboard from a simple, almost crude form to a more sophisticated shape.

Figure 1.—New England Strong Plow, Mid-18th Century. Colter locked into heavy, broad share; wooden moldboard covered with iron strips. (Cat. no. F1091; Smithsonian photo 13214.)

Writers of the 20th century describing the making of the first John Deere steel plow have in mind the 1838 plow. One[7] has John Deere pondering the local plowing problem and getting an idea from the polished surface of a broken steel mill saw. Another[8] claims that Leonard Andrus, the founder and leading figure of Grand Detour and part owner of the sawmill,[Pg 18] conceived the design of the plow and employed Deere, the blacksmith newly arrived from Vermont, to build it. This idea may have originated with and was certainly promoted by the late Fred A. Wirt, as advertising manager of the J. I. Case Company. It is difficult, at this distance, to determine the parts played at the beginning by Deere and Andrus.

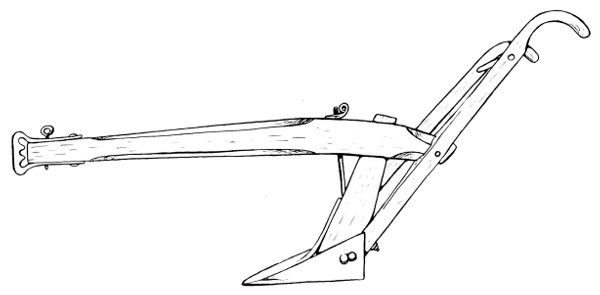

Figure 2.—Large Prairie-Breaking Plow, Mid-19th Century. Wheels underneath the beam regulate the depth of plowing; large wheel runs in the furrow, small wheel on the land. The colter is braced at the bottom as well as at the top. The share cuts a broad, shallow strip of sod which the long, gently curving moldboard turns over unbroken.

The earliest existing partnership agreement involving Andrus and Deere is dated March 20, 1843.[9] The existing copy is unsigned, but its conditions are the same as those in the agreements executed during the next few years. It began by stating that Deere and Andrus had agreed "to become copartners together in the art and trade of Blacksmithing, ploughmaking and all things thereto belonging at the said Grand Detour, and all other business that the said parties may hereafter deem necessary for their mutual interest and benefit ..." One of the terms was that the copartnership should continue from the date of the agreement "under the name and firm of Leonard Andrus."

A second agreement dated October 26, 1844,[10] which brought in a third partner, Horace Paine, described the business as "the art and trade of Blacksmithing Plough Making Iron Castings and all things thereto belonging ..." and stated that the copartnership should be conducted "under the name and firm of L. Andrus and Co." The third agreement, dated October 20, 1846, in which another man appeared in place of Paine, gave the name of the firm as Andrus, Deere, and Lathrop.[11] This carried an addendum dated June 22, 1847, in which Andrus and Deere bought out Lathrop's interest in the business and agreed to continue under the name of Andrus and Deere. This is the only mention of the firm of Andrus and Deere. It could only have lasted a few months because it was in 1847 that Deere moved to Moline and established his plow factory there.

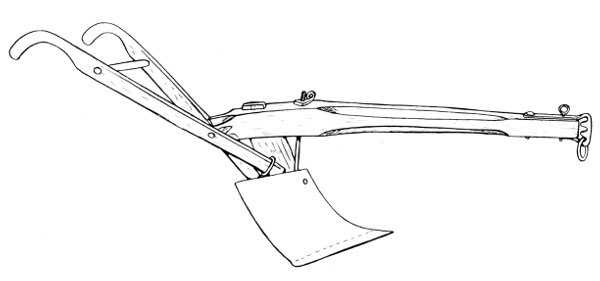

Figure 3.—Reconstructions of John Deere's 1837 Plow. For a discussion of the position and attachment of the handles see p. 24. (Deere & Company photo.)

These agreements suggest that Leonard Andrus was the capitalist of the young community of Grand Detour, as well as its founder. The dominance of the name Andrus tends to back up the opinion which holds that Andrus was the leading figure in the development of the successful prairie plow. On the other hand, the general tone of the agreements suggests that two or more people were participating in an enterprise in which each contributed to the business and shared in the results. Deere contributed his plow and his blacksmith shop, tools, and outbuildings;[Pg 19] Andrus contributed money and business experience. There is no indication that they were formally associated prior to the agreement of March 20, 1843. An advertisement (it is quoted later) dated February 3, 1843, and appearing in the March 10, 1843, issue of the Rock River Register, carries an announcement by John Deere that he is ready to fill orders for plows, which he then describes. There is no mention of Andrus or of an Andrus and Deere firm. I am inclined by the evidence to the view that Deere worked out his plow by himself, began to manufacture it in small numbers, needed money to enlarge and expand his operations, and went to the logical source of capital in the community, Leonard Andrus.

In support of this view I quote a statement by Mr. Burton F. Peek[12] who has spent most of his life in Deere & Company and who may now be the only person living who knew John Deere:

Andrus removed to Grand de Tour from some place in New York [Rochester, though originally from Vermont]. Some years later John Deere came along from Rutland, Vermont leaving his family behind him. Whether Deere ever heard of Andrus or Andrus of Deere no one knows.

Having decided to remain in Grand de Tour, Deere sent for his family asking my paternal grandfather, William Peek, to bring them and also the Peek family out to Grand de Tour. This was done via covered wagon the journey occupying some six weeks. My father, Henry C. Peek, was then an infant age six weeks and Charles Deere, the son of John, an infant of about the same age. Of course these infants came along sleeping in the feed box of the wagon. My grandfather "took up land" adjacent to Grand de Tour and John Deere continued in the manufacturing business.

Incidentally, John Deere and William Peek were brothers-in-law having married sisters and what I have said, and much more that I might say to you, is based upon what I have been told by my grandfather, by John Deere and by others who had a part in the early history of the company. So far as I know, I am the only living person who ever knew or saw John Deere....

... I joined the Deere Company on October 1, 1888, at the age of 16 and retired on the 28th of April, 1956—nearly 68 years. C. H. Deere was my great friend and benefactor. I was educated at his expense as a lawyer and practiced for thirteen years. During this time I was his personal attorney, I drew his will, was made trustee thereunder, and probably was more intimate with him than any living person. I have seen and read the manuscript of an early history of the company which he wrote, but never published and there was nothing in it to indicate that Andrus had any part in the manufacture of the first successful steel plow and it is my firm belief that he had no part other than perhaps a friendly interest in it.

Most writers describe Deere cutting a diamond-shaped piece out of a broken steel mill saw. There is usually no further identification of the type of saw beyond the statement that it came from the Andrus sawmill. Neil Clark, author of a brief biography of John Deere, states that the diamond-shaped piece was cut out of a circular saw.[13] There is no evidence given to support this. There are some powerful arguments against it. The circular saw, especially of the larger size, was probably not very common in America in the 1830's. Although an English patent for a circular saw was issued in 1777 the first circular saw in America is attributed to Benjamin Cummins of Bentonsville, New York, about 1814.[14]

In a small, new, pioneering community it seems unlikely that the local sawmill would have been equipped with the newer circular saw rather than the familiar up and down saw which remained in use[Pg 20] throughout the 19th century and, in places, well into the 20th century. The up and down saw was a broad strip of iron or steel with large teeth in one edge. Driven by water power it slowly cut large logs into boards. It is doubtful that the circular saws of that period were large enough for this kind of mill work. The second argument is the shape of the moldboard itself. The photograph of the 1838 plow in figure 7 shows that the shape of the moldboard is unconventional. It is essentially a parallelogram curved to present a concave surface to the furrow slice and thus to make a simple, small but workable plow. A parallelogram or diamond would be an easy shape to cut out of a mill saw with the teeth removed. The moldboard on the 1838 plow is from .228 to .238 inches thick and its width is 12 inches. These dimensions approximate those given in an 1897 Disston catalog[15] which describes mulay saws, a type of mill saw, from 10 to 12 inches wide and from 4 to 9 gauge. Gauge number 4 is the thickest and is .238 inches.

Examination of the 1838 plow suggests that Deere cut the moldboard and landside as one piece, which was then heated and bent to the desired form. The pattern of this piece is shown in figure 4. Some additional metal appears to be forged into the sharp bend at the junction of the moldboard and the landside apparently to strengthen this part, which may have begun to open during the bending. If, however, Deere had used a large circular saw with plenty of room for cutting out a moldboard of the usual shape and size, it seems likely that he would have made a plow of more conventional appearance. In any event his moldboard of one jointless piece of polished metal would scour better than one of wood covered with strips of steel since the nailheads and the joints between the strips would provide places for the earth to stick.[Pg 21]

Figure 6.—The Shape of the Moldboard continued to evolve, as illustrated by this 1855 John Deere plow. (Deere & Company photo 57192-A.)

A very great majority of writers describing John Deere and his plow attribute his fame to his development of a successful steel plow which made cultivation of rich prairie soil practical. The emphasis is always on the development of a steel moldboard and the assumption is that from the 1837 plow onward stretched an unbroken line of steel moldboard plows. An advertisement for John Deere plows in the March 10, 1843, issue of the Rock River Register, published weekly in Grand Detour, Illinois, gives a detailed description, here presented in full:

John Deere respectfully informs his friends and customers, the agricultural community, of this and adjoining counties, and dealers in Ploughs, that he is now prepared to fill orders for the same on presentation.

The Moldboard of this well, and so favorably known PLOUGH, is made of wrought iron, and the share of steel, 5/16 of an inch thick, which carries a fine sharp edge. The whole face of the moldboard and share is ground smooth, so that it scours perfectly bright in any soil, and will not choke in the foulest of ground. It will do more work in a day, and do it much better and with less labor, to both team and holder, than the ordinary ploughs that do not scour, and in consequence of the ground being better prepared, the agriculturalist obtains a much heavier crop.

The price of Ploughs, in consequence of hard times, will be reduced from last year's prices. Grand Detour, Feb. 3, 1843.

This raised two questions: Why, and for how long, was wrought iron used for the moldboards of the Deere plows? Of what material is the moldboard of the 1838 plow made? During the first few years, when production was very small, there were probably enough worn out mill saws available for the relatively few plows made. As production increased this source must have become inadequate. Ardrey gives the following figures for the production of plows by Deere and Andrus:[16] 1839, 10 plows; 1840, 40 plows; 1841, 75 plows; 1842, 100 plows; 1843, 400 plows. Ardrey states further that "by this time the difficulty of obtaining steel in the quantity and quality needed had become a serious obstacle in the way of further development." The statement, quoted above, that the moldboard was of wrought iron and the statistics on production of plows during the 1840's and 1850's belie Ardrey's claim that it was a serious obstacle, nor is there any suggestion in the advertisement that wrought iron was being substituted for steel.

In 1847 John Deere amicably severed relations with the firm of Andrus & Deere and moved to Moline, Illinois, to continue plow manufacturing in a site that had better transportation facilities than Grand Detour. The new firm produced 700 plows in the first year, 1600 in 1850, and 10,000 in 1857.[17] Swank[18] states that the first slab of cast plow steel ever rolled in the United States was in 1846 and that it was shipped to John Deere of Moline, Illinois. A little later he says that it was not until the early 1860's in this country that several firms succeeded in making high grade crucible cast steel of uniform quality as a regular product.[Pg 22]

Figure 7.—John Deere's 1838 Plow, Right Side, showing large iron staple used to fasten end of right handle to the standard. Note remains of wooden pin near rear end of plow beam. (Cat. no. F1111; Smithsonian photo 42639-A.)

Based on a visit to Deere's factory in 1857 the Country Gentleman[19] gave the yearly output as 13,400 plows. It pictured four of seven models and stated, "these are all made of cast steel, and perfectly polished before they are sent out, and are kept bright by use, so that no soil adheres to them." The article then gives the tonnages of iron and steel used by the Deere factory in a year. They are as follows: 50 tons cast steel, 40 tons German steel, 100 tons Pittsburgh steel, 75 tons castings, 200 tons wrought iron, 8 tons malleable castings in clevises, etc. In addition 100,000 plow bolts and 200,000 feet of oak plank were used.

These figures do not indicate what the different parts of the plows were made of but, if approximately correct, they do show that more than half the metal used was iron rather than steel. Steel accounts for 190 tons; wrought iron for 200. Although it is conceivable, under this weight distribution, that the shares and moldboards were made of steel while the landsides and standards were made of wrought iron, other distributions are also possible, and it is quite conceivable that at this period some of the plows had steel moldboards while others had wrought-iron ones. An analysis of the metal in different parts of an 1855 John Deere plow, now at the factory in Moline, may shed some light on this, but from these figures and dates it seems likely that most of John Deere's plows during the 1840's and 1850's had wrought-iron moldboards with steel shares. (It should be borne in mind that the poorer grades of steel available at this time were probably no more satisfactory than cast iron as far as scouring clean in sticky soil was concerned.)

Figure 8.—Reconstruction of Deere's 1838 Plow, right side, with handles shown in what is believed to be their original position. (Smithsonian photo 42647.)

The question of the material in the moldboard of the 1838 plow was answered when a spark-test analysis was made of the metal in the moldboard and share. In this test the color, shape, and pattern of the spark bursts produced by a high-speed grinding wheel indicate the type of iron or steel. Several spots along the edges and back surface of the moldboard were tested. [Pg 23]No carbon bursts were seen in the spark patterns, indicating that the material was wrought iron. The share consists of a piece, wedge shaped in cross section, welded on to the lower, or front, edge of the moldboard. This was tested at several spots along its sharp edge, all of which gave a pattern and color indicating that the material was medium high carbon steel. This test was corroborated by a chemical analysis of filings from the moldboard and share in a metallurgical laboratory. A small trace of carbon was found in the moldboard. It may be present as the result of contamination from several sources, a likely one being the charcoal fire in the forge when it was heated for bending and shaping.[20]

These tests agree perfectly with the description in the 1843 advertisement. It seems, therefore, that Deere's success in making plows that worked well in prairie bottom lands depended as much on the smooth surface he produced by grinding and polishing as on the material used.

The filing of the edge of the moldboard for the metallurgical test disclosed that the wrought-iron slab consisted of five thin laminations apparently forged together but with separations visible. The length and regularity of the lines of separation seem to preclude their being striations resulting from the fibrous structure of wrought iron. This calls into question the theory that the moldboard and landside were cut from a mill saw, since it hardly seems likely that a saw would be made of laminated material. The possibility exists that the body of the mill saw might have been made this way, with a tooth-bearing steel edge welded on, but there seems little reason for making a saw out of thin laminations. It is also possible that this laminated iron originally had been intended for some other purpose, such as boiler plate, and may have been available in rectangular pieces. In making the 1838 plow Deere followed a pattern (fig. 4), which suggests that he cut it out of such a piece.

Figure 9.—John Deere's 1838 Plow, Left Side, showing details of construction and relationship of landside to moldboard. (Cat. no. F1111; Smithsonian photo 42639.)

Since the moldboard of the 1838 plow is of wrought iron, and since this plow is thought to be essentially identical with the first one Deere made in 1837, it is highly probable that the 1837 plow also had a wrought-iron moldboard, a condition which appears to have been the basic pattern for John Deere plows until the middle 1850's.

In view of the facts and the probabilities based on them, how is the legend of the John Deere steel plow to be explained? There are several likely reasons. It is possible that the first plow, in 1837, was made from a broken steel mill saw. It is also possible that within a few years puddled iron came to be used for the moldboards because of the scarcity of suitable steel, either in the form of broken mill saws or as plates ordered from foundries in America (the high price of steel imported from England made this an impractical source). However, it seems more likely that it became known as a steel plow owing to the importance Deere attached to his plows having steel shares, as shown in his advertisement in 1843. A steel share, tougher than cast iron, would hold an edge much better than wrought iron, and John Muir's description of prairie plowing, quoted earlier, substantiates the importance of a tough, sharp share.

Deere's plows, probably distinctive by reason of their steel shares, may have been called "steel"[Pg 24] plows, in the regions where they were used, to distinguish them from the standard wooden plows and from the newer cast-iron implements. The term "wooden plow" has a similar history. For well over 2000 years in Europe some plows have been made with iron shares and the rest of the structure wood. Plows in 18th-century America were made principally of wood with iron shares, colters, and clevises, and with strips of iron frequently covering the wooden moldboard. These implements were called, simply, plows of various regional types. Not until the development and spread of the factory-made plows with cast-iron moldboards, landsides, and standards did the term "wooden plow" come into use to differentiate all these plows from the newer ones. Subsequently writers have been led to assume that "wooden plow" meant a plow with no iron parts and consequently to make unwarranted statements about the primitiveness of the 18th-century implements.

A second reason for use of the term "steel plow" may have developed from the supposition that the moldboards of the first John Deere plows were made of diamond-shaped sections cut from old mill saws, which later writers seem to have assumed were made of steel. (It is probable that from the late 1850's on Deere plows had steel moldboards.) However, mill saws of the early 19th century were not necessarily made of steel, which was then relatively expensive. I have been told of an old mill saw made of wrought iron on which was welded a steel edge that carried the teeth.[21] Rees' Cyclopaedia[22] describes saws as being made of either wrought iron or steel, the latter being preferable. Therefore, it seems most likely that Deere's plows, from his first until the middle 1850's were made with highly polished wrought-iron moldboards and steel shares.

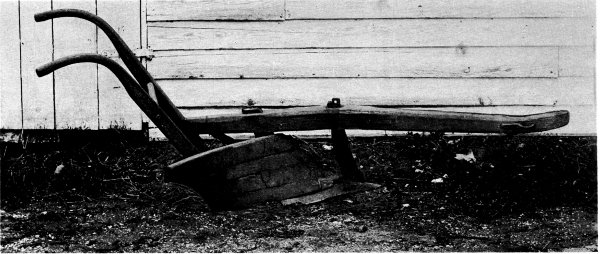

The remains of the 1838 plow are shown in figures 7 and 9. One's curiosity is aroused as to what the plow looked like in its original state, complete with handles. Several full-scale 3-dimensional reconstructions and a number of sketches of the 1837 plow have been made. The reconstructions all must have been based on the remains of the 1838 plow, since they resemble it closely and it is the only surviving plow of this type known.

Recently I received a photograph (fig. 3, right) of a plow which has been boxed and in storage for many years at Deere & Company which may be an early Deere plow. As it appears in the photograph, the plow looks unconvincing. The handles are fastened by bolts and nuts, a manner uncommon in American plow making in the early 19th century. The shape of the handles is that of stock handles available for small plows and cultivators in such a catalog as Belknap's. The plow seems very high and weakly braced. There is no logical reason for curving the end of the beam down and cutting it off at a slant if the handles are attached in the manner shown. The edges of the tenon on the upper end of the standard where it goes through the mortise in the beam have been neatly beveled in a manner I have never seen before on any other plow. All of this leads me to think that this is an early reconstruction based on the remains of the 1838 plow which it only roughly approximates in proportion and design.

Another of these reconstructions is shown in figure 3, left. Although superficially like the 1838 plow it varies considerably in its proportions, in the angular relations of its parts, and in other details such as the use of iron bolts and nuts in place of wooden pins. All these reconstructions agree in one thing. They show a plow with handles fastened to both sides of the plow beam and standard.

During an examination of the 1838 plow it occurred to me that there was no indication of an attachment of a handle on the landside in the same manner as on the furrow side. The position and attachment of the handle in figure 7 is clearly indicated by the remains of a wooden pin in the side of the plow beam near the rear end and by the large iron staple, in the side of the standard, which must have held the tapered lower end of the handle. Figure 8 is a sketch showing this handle in position. The landside view of this plow in figure 9 shows that the pin did not extend through the beam nor are there marks on the standard to indicate the position of a staple like that on the furrow side. The four holes approximately in line on the standard and beam show where a piece of sheet metal had been nailed to hold the beam and standard in about the right position. The outline of the sheet metal can be seen on the side of the beam. This was removed at the time this examination was made.[Pg 25]

How was the landside handle attached? W. E. Bridges of the National Museum suggests that it might have been attached to the lower side of the standard and the rear end of the plow beam. This seems, beyond doubt, to be correct. The wood has deteriorated considerably over the years and the joints are loose, but, within the limits of the existing structure, the plow beam can easily be set in such a position that its sloping rear end lines up with the slope of the underside of the standard. Furthermore, a long bolt runs from the upper part of the moldboard through the standard and projects quite far beyond its lower surface, as can be seen in figure 7. The end of the bolt is threaded only part way and it has been necessary to put a cylindrical metal spacer on it in order to draw up the nut snugly. This long bolt must originally have passed through the lower end of the handle, which, in turn, was fastened to the end of the plow beam by a tenon on the end of the beam, now broken off, passing through a mortise in the handle. This was the common method of fastening the handle to the beam. The square hole in the plow's iron landside (fig. 7), which at first might seem meant for another bolt passing through the lower end of the handle at right angles to the long bolt, seems too close to the other bolt and to the edges of the handle. It may simply be a first try for the bolt through the bottom of the standard. In this manner the handle would have been strongly attached to the plow frame and, at the same time, would have materially helped to make it rigid by forming one side of a triangular structure. Figures 8 and 10 show what I believe to be the correct reconstruction of the 1838 Deere plow along the lines just described and, therefore, the probable appearance of the 1837 plow.

Figure 10.—Reconstruction of Deere's 1838 Plow, left side, showing how left handle is believed to have been attached. (Smithsonian photo 42637.)

It should also be noted that it was general practice in making fixed moldboard plows to have the plow beam, standard, handle, and landside (or sharebeam, on the old plows) in the same plane. Symmetrical handles branching from both sides of the beam are found on cultivators, shovel plows, middle busters, and sidehill plows where the moldboard is turned alternately to each side.

The existing evidence, I believe, indicates that:

1. The successful prairie plow with a smooth one-piece moldboard and steel share was basically Deere's idea.

2. The moldboards of practically all of his plows, from 1837 and for about 15 years, were made of wrought iron rather than steel.

3. The success of his plows in the prairie soils depended on a steel share which held a sharp edge and a highly polished moldboard to which the sticky soils could not cling.

4. The importance attached to the steel share led to the plows being identified as steel plows.

5. The correct reconstruction of the 1838 plow, and, by inference, the 1837 plow, is shown in figures 8 and 10, previous reconstructions being wrong primarily in the position and attachment of the handles.

6. The Museum's John Deere plow (Cat. No. F1111), shown in figures 7 and 9, is a very early specimen, on the basis of a comparison of it with Deere moldboards of 1847 and 1855 and its conformity to Deere's description of his plows in an 1843 advertisement; and the 1838 date associated with it is plausible.

[1] John Muir (1838-1914), The story of my boyhood and youth, Boston, 1913, pp. 227, 228.

[2] R. L. Ardrey, American agricultural implements, Chicago, 1894, p. 14.

[3] Ibid., p. 16.

[4] J. B. Davidson, "Tillage machinery," in L. H. Bailey's Cyclopedia of American agriculture, New York, 1907, vol. 1, p. 389.

[5] Leo Rogin, The introduction of farm machinery in its relation to the productivity of labor in the agriculture of the United States during the nineteenth century, Berkeley, 1931, p. 33.

[6] U. S. National Museum records under accession 148904.

[7] Neil M. Clark, John Deere, Moline, 1937, pp. 34, 35.

[8] Stewart H. Holbrook, Machines of plenty, New York, 1955, pp. 178, 179. To an inquiry by this author, Mr. Holbrook replied that most if not all of the material about Andrus came from the files of the J. I. Case Company.

[9] Photographic copies of partnership agreements between Andrus, Deere, and others are in U. S. National Museum records under accession 148904.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Letter from Burton F. Peek to M. L. Putnam, December 18, 1957, in U. S. National Museum records under accession 148904.

[13] Clark, op. cit. (footnote 7), p. 34.

[14] E. H. Knight, American mechanical dictionary, Boston, 1884, vol. 3, p. 2033.

[15] Henry Disston & Sons, Price list, Philadelphia, 1897, p. 28.

[16] Ardrey, op. cit. (footnote 2), p. 166.

[17] Ibid., p. 166.

[18] James M. Swank, History of the manufacture of iron in all ages..., Philadelphia, 1892, pp. 390, 393.

[19] Country Gentleman, 1857, vol. 10, p. 129.

[20] Reports on spark test by E. A. Battison, U. S. National Museum, and on metallurgical investigation by A. H. Valentine, Metallographic Laboratory of the Bethlehem Steel Company's Sparrows Point Plant.

[21] For this information I am indebted to Mr. E. A. Battison of the U. S. National Museum staff.

[22] Abraham Rees, The cyclopaedia; or universal dictionary of arts, sciences, and literature, Philadelphia, 1810-1842, vol. 33, under saw.