Title: The Story of Norway

Author: Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen

Release date: December 14, 2010 [eBook #34646]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Steve Read and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE STORY OF GREECE. By Prof. Jas. A. Harrison

THE STORY OF ROME. By Arthur Gilman

THE STORY OF THE JEWS. By Prof. Jas. K. Hosmer

THE STORY OF CHALDEA. By Z. A. Ragozin

THE STORY OF NORWAY. By Prof. H. H. Boyesen

THE STORY OF GERMANY. By S. Baring-Gould

THE STORY OF SPAIN. By E. E. and Susan Hale

THE STORY OF HUNGARY. By Prof. A. Vámbéry

THE STORY OF CARTHAGE. By Prof. Alfred J. Church

THE STORY OF THE SARACENS. By Arthur Gilman

THE STORY OF ASSYRIA. By Z. A. Ragozin

THE STORY OF THE MOORS IN SPAIN. By Stanley Lane-Poole

THE STORY OF THE NORMANS. By Sarah O. Jewett

THE STORY OF PERSIA. By S. G. W. Benjamin

THE STORY OF ALEXANDER'S EMPIRE. By Prof. J. P. Mahaffy

THE STORY OF ANCIENT EGYPT. By Geo. Rawlinson

THE STORY OF THE GOTHS. By Henry Bradley

It has been my ambition for many years to write a history of Norway, chiefly because no such book, worthy of the name, exists in the English language. When the publishers of the present volume proposed to me to write the story of my native land, I therefore eagerly accepted their offer. The story, however, according to their plan, was to differ in some important respects from a regular history. It was to dwell particularly upon the dramatic phases of historical events, and concern itself but slightly with the growth of institutions and sociological phenomena. It therefore necessarily takes small account of proportion. In the present volume more space is given to the national hero, Olaf Tryggvesson, whose brief reign was crowded with dramatic events, than to kings who reigned ten times as long. For the same reason the four centuries of the Union with Denmark are treated with comparative brevity. Many things happened, no doubt, during those centuries, but "there were few deeds." Moreover, the separate history of Norway, in the time of her degradation, has never proved an attractive theme to[vi] Norse historians, for which reason the period has been generally neglected.

The principal sources of which I have availed myself in the preparation of the present volume, are Snorre Sturlasson: Norges Kongesagaer (Christiania, 1859, 2 vols.); P. A. Munch: Det Norske Folks Historie (Christiania, 1852, 6 vols.); R. Keyser: Efterladte Skrifter (Christiania, 1866, 2 vols.); Samlede Afhandlinger (1868); J. E. Sars: Udsigt over den Norske Historie (Christiania, 1877, 2 vols.); K. Maurer: Die Bekehrung des Norwegischen Stammes zum Christenthume (München, 1856, 2 vols.), and Die Entstehung des Isländischen Staates (München, 1852); G. Vigfusson: Sturlunga Saga (Oxford, 1878, 2 vols.); and Um tímatal í Islendinga sögum i fornöld (contained in Safn til sögu Islands, 1855); G. Storm: Snorre Sturlasson's Historieskrivning (Kjöbenhavn, 1878); C. F. Allen: Haandbog i Fædrelandets Historie (Kjöbenhavn, 1863); besides a large number of scattered articles in German and Scandinavian historical magazines. A question which has presented many difficulties is the spelling of proper names. To adopt in every instance the ancient Icelandic form would scarcely be practicable, because the names in their modernized forms are usually familiar and easy to pronounce, while, in their Icelandic disguises, they are to English readers nearly unpronounceable, and present a needlessly forbidding appearance. Where a name has no well-recognized English equivalent, I have therefore adopted the modern Norwegian form, which usually differs from the ancient, in having dropped a final letter. Thus Sigurdr (which with an[vii] English genitive would be Sigurdr's) becomes in modern Norwegian Sigurd, Eirikr, Erik, etc. Those surnames, which are descriptive epithets, I have translated where they are easily translatable, thus writing Harold the Fairhaired, Haakon the Good, Olaf the Saint, etc. Absolute consistency would, however, give to some names a too cumbrous look, as, for instance, Einar the Twanger of Thamb (Thamb being the name of his bow), and I have in such instances kept the Norse name (Thambarskelver).

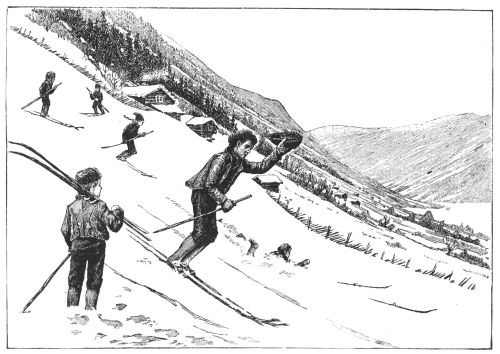

It is a pleasant duty to acknowledge my indebtedness for valuable criticism to my friends, E. Munroe Smith, J.U.D., Adjunct Professor of History in Columbia College, and Hon. Rasmus B. Andersen, United States Minister to Denmark, without whose kindly aid in procuring books, maps, etc., the difficulties in the preparation of the present volume would have been much increased. I am also under obligation to Dr. W. H. Carpenter, of Columbia College, and to the Norwegian artist, Mr. H. N. Gausta, of La Crosse, Wis., who has kindly sent me two spirited original compositions, illustrative of peasant-life in Norway.

Hjalmar H. Boyesen.

Columbia College,

New York, April 15, 1886.

| I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Who Were the Norsemen? | 1-12 |

| The Aryan migrations, 1-3—The physical characteristics of Norway, 4, 5—Early tribal organization and means of livelihood, 6-10—Sense of independence and aptitude for self-government, 10-12. | |

| II. | |

| The Religion of the Norsemen | 13-24 |

| Theories regarding the origin of the Scandinavian gods, 13-16—The Eddaic account of the creation of the world and of man, 16-18—The world-tree Ygdrasil, 18—The Aesir, their functions and their dwellings, 19-23—Loke the Evil-Doer and his terrible children, 23, 24. | |

| III. | |

| The Age of the Vikings.—Origin of the Viking Cruises | 25-44 |

| The Norsemen launch forth upon the arena of history, 25—The origin of the viking cruises, 25-27—Kingship among the Scandinavian tribes, 27, 28—The three periods of the viking age, 28-30—The contribution of the vikings to the political life of Europe, 30, 31—Sigfrid of Nortmannia, 31—Godfrey the Hunter, 31, 32—-Charlemagne's prophecy in regard to the vikings, 32-34—Hasting's stratagem, 34-36—Ragnar, Asgeir, and Rörek, 36, 37—Thorgisl in Ireland, 38, 39—Olaf the White, 40, 41—The vikings in England, 41—Simeon of Durham's account of the vikings, 42—The [x] character of the vikings at home and abroad, 43, 44. | |

| IV. | |

| Halfdan the Swarthy | 45-51 |

| The descent of the Yngling race, 45—The sacrifices of Aun the Old, 45—Olaf the Wood-cutter, Halfdan Whiteleg, and Godfrey the Hunter, 46—Birth of Halfdan the Swarthy, 46 Sigurd Hjort and the Berserk Hake, 47, 48—Halfdan the Swarthy weds Ragnhild, 48—Ragnhild's dream, 48—King Halfdan's dream, 49—Birth of Harold the Fairhaired, 49—The Finn's trick, 50—King Halfdan's death, 51. | |

| V. | |

| Harold the Fairhaired | 52-73 |

| Harold the Fairhaired woos Gyda, 52, 53—Harold's vow, 53—Herlaug and Rollaug, 54—Harold's policy toward the conquered kings, 54, 55—The feudal state, 55—Taxation and the peasants' loss of allodial rights, 55, 56—Haakon Grjotgardsson and Ragnvald, Earl of Möre, 56—Kveld-Ulf and his sons, 56, 57—Erik Eimundsson's invasion of Norway, 57—His meeting with King Harold, 58—The battle of Hafrs-Fjord, 59—Earl Ragnvald cuts King Harold's hair, 59—Harold marries Gyda, 59, 60—Harold's treachery to Thorolf Kveld-Ulf's son, 60-62—Kveld-Ulf's vengeance and migration to Iceland, 62, 63—Duke Rollo in Norway and France, 64, 65—Emigration of discontented magnates, 65, 66—Snefrid, 67—Queen Ragnhild, 68—Erik Blood-Axe's feuds with his brothers, 69-71—Guttorm Sindre, 71, 72—Birth of Haakon the Good, 72—Haakon is sent to Ethelstan, 72, 73—Death of Harold, 73. | |

| VI. | |

| Erik Blood-axe | 74-86 |

| Erik's meeting with Gunhild, 74-76—Erik kills his brothers, Sigfrid and Olaf, 76—Thorolf, Bald Grim's son, 77—Egil, Bald Grim's son, kills Baard, 78—Egil kills Berg-Anund, 79, 80—Egil's pole of dishonor, 80—Egil ransoms his head by a song, 81-85—Erik is exiled, 86. | |

| VII. | |

| Haakon the Good | 87-101 |

| [xi] Character of Haakon, 87—Proclaimed king of Norway, 88—Legislative reforms and restoration of allodium, 89—Signal fires, 90—First attempt to introduce Christianity, 90-92—Speech of Asbjörn of Medalhus, 92—The king eats horse-flesh, 92-94—The sons of Erik Blood-Axe make war upon Norway, 94, 95—Battles of Sotoness and Agvaldsness, 95, 96—Egil Woolsark, 96, 97—Battle of Fraedö, 96-98—Failure of attempt to Christianize the country, 98—Battle of Fitje (Eyvind Scald-Spoiler), 98-101—Death of Haakon the Good, 101. | |

| VIII. | |

| Harold Greyfell and his Brothers | 102-114 |

| Unpopularity of the sons of Erik, 102-104—Their characters, 104—Harold Greyfell and Eyvind Scald-Spoiler, 105—Treachery of Harold toward Earl Sigurd, 105, 106—Independence of Earl Haakon, 106, 107—Murder of Tryggve Olafsson, 107, 108—Birth of Olaf Tryggvesson, 108—Adventures of Aastrid and Thoralf Lousy-Beard, 108-110—Sigurd Sleva insults Aaluf, 111—Earl Haakon's intrigues in Denmark, 111, 112—Gold-Harold slays Harold Greyfell, 112—Expulsion of the sons of Erik, 113, 114. | |

| IX. | |

| Earl Haakon | 115-133 |

| Earl Haakon defends Dannevirke, 115, 116—Harold Bluetooth, 117—Haakon's devastations in Sweden and in Viken, 118—Earl Erik and Tiding-Skofte, 119—The funeral feast of the Jomsvikings, 120, 121—Battle in Hjörungavaag, 121-125—The Jomsvikings on the log, 125, 126—Haavard the Hewer, 127—The power and popularity of Earl Haakon, 127, 128—Gudrun Lundarsol, 129—Revolt of the peasants, 130—The earl hides under a pigsty, 130, 131—"Why art thou so pale, Kark?" 131—Kark murders the earl, 132—Haakon's character, 132, 133. | |

| X. | |

| The Youth of Olaf Tryggvesson | 134-142 |

| Aastrid's flight to Russia, 134, 135—Olaf is sold for a ram, [xii] 135—He is taken to Vladimir's court, 135, 136—King Burislav and Geira, 136, 137—The wooers' market in England, 137—Marriage with Gyda, 137, 138—Olaf's warfare in England, 138, 139—Thore Klakka tries to entrap Olaf, 139, 140—Return to Norway and proclamation as king, 140-142. | |

| XI. | |

| Olaf Tryggvesson | 143-172 |

| Olaf Christianizes Viken, 143, 144—Character of old Germanic Christianity, 144-146—Thangbrand the pugnacious priest, 147—The chiefs of Haalogaland, 148—Ironbeard and the peasants of Tröndelag, 149, 150—The Yule-tide feast at Möre, 150-152—Olaf woos Sigrid the Haughty, 152-154—He marries Thyra, 154—Thore Hjort, Eyvind Kinriva, and Haarek of Thjotta, 154-158—Thangbrand in Iceland, 158, 159—Olaf's character, 160—Thyra's tears for her lost possessions, 161—"The Long-Serpent," 161—King Olaf sails to Wendland, 162, 163—Earl Sigvalde's treachery, 163—Battle of Svolder, 164-172—King Olaf's death. 171, 172. | |

| XII. | |

| The Earls Erik and Sweyn.—Ihe Discovery of Vinland | 173-181 |

| Division of Norway between the victors at Svolder, 173—Erling Skjalgsson of Sole, 174-176—Earl Erik's character, 176—And attitude toward Christianity, 176, 177—Revival of the viking spirit, 177—Earl Erik abdicates in favor of his brother and son, 178, 179—Bjarne Herjulfsson's glimpse of America, 179—Leif Eriksson's expedition to Vinland, 180, 181—Thorfinn Karlsevne and Gudrid, 181. | |

| XIII. | |

| Olaf the Saint | 182-224 |

| Birth and childhood of Olaf the Saint, 182, 183—Viking cruises, 183—Return to Norway, 184—He captures Earl Haakon, 185—His reception by Aastrid and Sigurd Syr, 186, 187—Family council, 187, 188—Support of the shire-kings, 188—The Trönders recognize Olaf as king, 189—Surprised [xiii] by Earl Sweyn in Nidaros, 190—Battle of Nessje, 190, 192—Earl Sweyn's flight and death, 192—Quarrel with King Olaf the Swede, 193, 194—Björn Stallare's mission, 194-196—Speech of Thorgny the Lawman, 196, 197—Olaf marries Aastrid, 198—Conspiracy of the shire-kings and their punishments, 199—The play of the sons of Sigurd Syr, 199, 200—Rörek's hard fate, 201—His attempt to murder Olaf, 202—The attitude of the tribal aristocracy toward Olaf, 202, 203—Paganism versus Christianity, 204, 205—"Where are my ancestors?" 205—Olaf's character and appearance, 205-207—Dale-Guldbrand, 207-210—Slaying of Aasbjörn Sigurdsson, 211—Knut the Mighty bribes the Norse chieftains, 212, 213—Anund Jacob refuses the bribe, 213, 214—Battle of Helge-aa, 214, 215—Death of Erling Skjalgsson, 216—Olaf goes to Russia, 217—Björn Stallare's confession, 218—Olaf returns to Norway, 218—His vision, 220, 221—Battle of Sticklestad, 221, 222—Thormod Kolbruna-Scald, 222-224—Burial of St. Olaf, 224. | |

| XIV. | |

| Sweyn Alfifasson | 225-229 |

| Alfifa and the Norse chiefs, 225—Unpopular and oppressive laws, 226—King Olaf canonized, 227—Tryggve Olafsson's defeat, 228—Einar Thambarskelver rebukes Alfifa, 228—Magnus Olafsson returns from Russia, 229—Expulsion of Sweyn, 229. | |

| XV. | |

| Magnus the Good | 230-250 |

| Circumstances of Magnus' birth, 230—Magnus and Harthaknut, 231—Jealousies of the chieftains, 232—Magnus and Kalf Arnesson at Stiklestad, 233—Sighvat Scald's Lay of Candor, 234—Sweyn Estridsson rebels, 236, 237—Battle of Lyrskog's Heath, 237—Thorstein Side-Hall's son, 238—Einar Thambarskelver's disagreement and reconciliation with Magnus, 238, 239—Arrival of Harold Sigurdsson, 240—His adventures abroad, 240-242—Magnus' reception of Harold, 243—Harold's alliance with Sweyn Estridsson, 244—Agreement [xiv] to share the government, 245—The peasant Toke's speech, 246, 247—Expeditions of Magnus against Sweyn Estridsson, 247, 247—Death of Magnus the Good, 249, 250. | |

| XVI. | |

| Harold Hard-Ruler | 251-272 |

| The tribal chieftains and the hereditability of the crown, 251, 252—Harold decides to conquer Denmark, 252—Determination to break the power of the aristocracy, 253—Einar Thambarskelver's hostility, 254, 255—Harold marries Thora, 255—St. Hallvard and the founding of Oslo, 256—Burning of Heidaby, 257—Sweyn's pursuits and Harold's stratagems, 257-259—Battle of Nis-aa, 259—Peace of Götha Elv, 260—Feuds with Einar Thambarskelver, 260, 261—Harold tests the loyalty of the chieftains, 261, 262—Högne Langbjörnsson, 262, 263—Murder of Einar and his son, 264—Harold's treachery to Kalf Arnesson and Haakon Ivarsson, 265-267—Arrival of Earl Tostig in Norway, 268—Battles of Fulford and Stamford Bridge, 268-270—Styrkaar and the yeoman, 270-272—Position of the Norwegian Church, 272. | |

| XVII. | |

| Olaf the Quiet and Magnus Haroldsson, | 273-284 |

| Olaf and Magnus divide the country, 273—War with Sweyn Estridsson, 273, 274—Death of Magnus, 274—Character of Olaf the Quiet, 275, 276—Gradual cessation of viking cruises, 276, 277—Gradual abolition of serfdom, 278—Vikings and merchants, 278, 279—Appearance and appointments of dwellings, 280, 281—Increased splendor of the court, 281, 282—Establishment of guilds, 282, 283—Skule Tostigsson, 283—Death of Olaf the Quiet, 284. | |

| XVIII. | |

| Magnus Barefoot and Haakon Magnusson, | 285-290 |

| The Trönders proclaim Haakon king, 285—Magnus' expedition to Scotland and Ireland, 285, 286—Death of Haakon, 286—Punishment of his partisans, 286, 287—War-like spirit of Magnus, 287—War with Sweden, 288—War [xv] with Ireland, 289—Death of Magnus in Ulster, 290. | |

| XIX. | |

| Eystein Sigurd the Crusader and Olaf Magnusson | 291-305 |

| Division of the land, 291—Sigurd's crusade, 292, 293—Eystein's meritorious activity at home, 294—Hostility of the brothers, 295—The case of Sigurd Ranesson, 295, 296—Borghild of Dal, 297—The "man-measuring," 297-301—Death of Eystein, 301—Ottar Birting, 301-303—Arrival of Harold Gille, 303—Cecilia, 303—Death of Sigurd, 304, 305. | |

| XX. | |

| Magnus the Blind and Harold Gille | 306-310 |

| Character of Magnus and of Harold, 306—Battle of Fyrileiv, 307—Magnus captured and maimed, 307, 308—Sigurd Slembedegn, 308—Harold Gille murdered, 309—Burning of Konghelle by the Wends, 310. | |

| XXI. | |

| The Sons of Harold Gille | 311-321 |

| The sons of Harold Gille proclaimed kings, 311—Sigurd Slembedegn allies himself with Magnus the Blind, 311, 312—Inge Crookback's first experience of war, 312—Battles of Krokaskogen, 312, and Holmengraa, 313—Sigurd Slembedegn's fortitude, 313—Arrival of Eystein Haroldsson, 314—Feuds between the brothers, 314-316—Character and appearance of Sigurd Mouth, 314-316—Death of Sigurd, 316—Death of Eystein, 317—Erling Skakke and Gregorius Dagsson, 318-320—Fall of Inge at Oslo, 320—The cardinal's visit, 320, 321. | |

| XXII. | |

| Haakon the Broad-shouldered | 322-325 |

| Christina bribes the priest, 322—Erling Skakke's intrigues, 323—Seeks aid in Denmark, 323, 324—Battle of Sekken, 324. | |

| XXIII. | |

| Magnus Erlingsson | 326-349 |

| Rebellion of the "Sigurd party," 326, 327—Battle of Ree, [xvi] 327—Erling's alliance with Archbishop Eystein, 327—Magnus takes the land in fief from St. Olaf, 327, 328—Magnus crowned, 328—King Valdemar's expedition to Norway, 328, 329—The rebellion of the Hood-Swains, 329—Battle of Djursaa, 330—Erling accepts an earldom from Valdemar, 330—Kills his stepson Harold, 332—Eystein Meyla and the Birchlegs, 333, 334—Childhood and youth of Sverre Sigurdsson, 334-337—Sverre becomes the chief of the Birchlegs, 337—Vicissitudes and adventures of the Birchlegs, 337-341—Battle of Kalvskindet, 341-343—Death of Erling Skakke, 343—Social revolution inaugurated by Sverre, 343-345—Battle at Nordness, 346—Warfare between Birchlegs and Heklungs, 346-348—Battle of Norefjord and death of Magnus, 348, 349. | |

| XXIV. | |

| Sverre Sigurdsson | 350-378 |

| A dangerous precedent, 350—Erik Kingsson, 351—The lawmen and prefects, 351, 352—The new democracy, 352, 353—Rebellion of the Kuvlungs, 353, 354; the Varbelgs, 354; and the Oyeskeggs, 354-357—Sverre's controversy with the Church, 357, 358—Nicholas Arnesson, 358—Sverre is put in the ban, 359—Origin of the Bagler party, 360, 361—Nicholas shows the white feather, 361—Treason of Thorstein Kugad, 362—The Baglers besiege the block-house in Bergen, 362-365—Burning of Bergen, 365—The traitor's return, 366—The Papal bull and Sverre's defence, 366-368—The Bagler's defeated at Strindsö, 369—The great peasant rebellion, 370-373—Sverre's magnanimity, 374—Aristocracy versus Democracy, 374, 375—Siege and surrender of Tunsberg, 375, 376—Death of Sverre, 376, 377—His character, 377, 378. | |

| XXV. | |

| Haakon Sverresson | 379-384 |

| Peace with the Church, 379—Popularity of Haakon, 380—Discontent of the queen-dowager, 381—Abduction of Princess Christina, 381, 382—The fatal Yule-tide feast, 382, 383—Death of Haakon by poison, 383—Flight of Queen [xvii] Margaret, 384. | |

| XXVI. | |

| Guttorm Sigurdsson and Inge Baardsson, | 385-399 |

| The Bagler troop reorganized under Erling Stonewall, 385—Successful ordeal, 386—Death of Guttorm Sigurdsson by poison, 387—Inge Baardsson proclaimed king, 388—Society disorganized by the civil wars, 388, 389—Unbidden guests at the bridal feast, 389, 390—Philip Simonsson made king of the Baglers, 390—Birth and childhood of Haakon Haakonsson, 391, 392—Compromise of Hvitingsöe, 393—The intrigues of Haakon Galen, 394, 395—Helge Hvasse and the boy Haakon, 396, 397—Discontent of the Birchlegs, 398—Death of King Inge, 399. | |

| XXVII. | |

| Haakon Haakonsson the Old | 400-432 |

| Haakon proclaimed king, 400—Rebellion of the Slittungs, 401—Effects of the civil war, 401, 402—The intrigues of Earl Skule, 402-404—Inga of Varteig carries glowing irons, 404-406—Rebellion of the Ribbungs, 407, 408—Skule's double-dealing, 408-410—Assembly of notables in Bergen, 410—Bishop Nicholas' hypocrisy, 411—Sigurd Ribbung renews the rebellion, 412—Haakon's campaign in Vermeland, 412, 413—Duke Skule's leaky ships, 413—Death of Bishop Nicholas and Sigurd Ribbung, 414—Squire Knut as the chief of the Ribbungs, 416—Skule's "Crusade," 416, 417—Skule allies himself with Valdemar the Victorious, 417, 418—Skule called to account, 418-420—Intrigues at the Roman Curia, 420, 421—The plot revealed, 421, 422—Skule proclaims himself king, 423—Battle of Laaka, 424—Skule defeated at Oslo, 425—Death of Skule, 426, 427—Coronation of Haakon, 427-429—His power and fame at home and abroad, 429-431—Expedition to Scotland, and death, 431, 432. | |

| XXVIII. | |

| The Sturlungs in Iceland | 433-441 |

| Snorre Sturlasson's Heimskringla, 433, 434—Snorre's parentage and youth, 434—Character of Snorre, 434—Reykjaholt, [xviii] 436—Brother feuds, 436—Snorre's visit to Norway, 437—Plots and counterplots, 437-440—Snorre's death, 440—Sturla Thordsson, 440, 441. | |

| XXIX. | |

| Magnus Law-Mender | 442-450 |

| Cession of Man and the Shetland Isles to Scotland, 442—Reasons for and against the cession, 443—Condition of Icelandic society and submission of the island to Norway, 444—Magnus as a law-giver, 445-447—The tribal aristocracy and the court nobility, 447, 448—Concessions to the Church, 448, 449—Degeneracy of the old royal house, 450—Death of Magnus, 450. | |

| XXX. | |

| Erik Priest-Hater | 451-456 |

| The barons increase their power, 451—Quarrels with the clergy, 452—The false "Maid of Norway," 453—Depredations of "Little Sir Alf," 453, 454—War with Denmark and the Hansa, 454, 455—Capture and death of Little Sir Alf, 456—Death of King Erik, 456. | |

| XXXI. | |

| Haakon Longlegs | 457-460 |

| Sir Audun's treason, 457—The dukes Erik and Valdemar 458—Complications with Sweden, 459—War with Denmark, 460—Death of Haakon, 460. | |

| XXXII. | |

| Magnus Smek, Haakon Magnusson, and Olaf the Young | 461-466 |

| Magnus Smek becomes king of Norway and Sweden, 461—Duchess Ingeborg's unpopularity, 461, 462—Discontent with Magnus, 462—Alliance with Valdemar Atterdag, 462, 463—Magnus deposed in Sweden, 463—Haakon's war with Albrecht of Mecklenberg, 464—The power of the Hansa in Norway, 464—Death of Magnus, 465—The Black Death, [xix] 465, 466—Olaf the Young, 466. | |

| XXXIII. | |

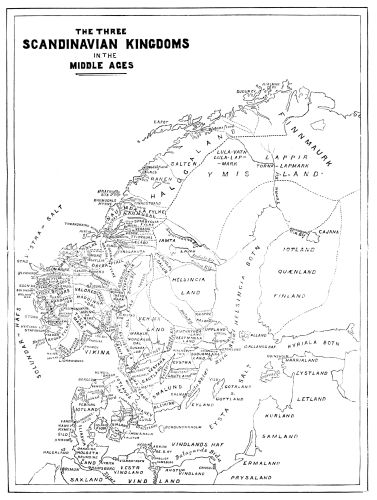

| Norway During the Kalmar Union | 467-474 |

| Margaret unites the three kingdoms, 467-469—The Kalmar Union, 469, 470—Reasons for its disastrous consequences, 470-472—Death of Margaret, 472—Erik of Pomerania's misrule and extortions, 472, 473—Christopher of Bavaria, 473, 474. | |

| XXXIV. | |

| The Union With Denmark | 475-488 |

| The condition of Norway and Denmark during the union compared, 475, 476—Charles Knuttson elected king of Sweden, 478—Christian I.'s war with Charles Knutsson, 479, 480—Misrule in Norway, 480—The Scottish Isles pawned, 480, 481—King Hans, 481, 482—Christian II.'s accession, 482—His attempt to humble the nobility, 483—The carnage of Stockholm, 483, 484—His vain appeal to the bourgeoisie, 484, 485—Christian's flight, 485—Frederick I., 485, 486—Struggle about the succession, 486, 487—Christian III., 487, 488—Norway becomes a province of Denmark, 488. | |

| XXXV. | |

| Norway As a Province of Denmark | 489-515 |

| The Reformation introduced, 489, 490—The power of the Hansa broken, 490-492—Frederick II., 492-494—Christian IV.'s interest in Norway, 494—The Kalmar War, 495—Participation in the Thirty Years' War, 495, 496—The Hannibal's feud, 496—Frederick III.'s disastrous war with Sweden, 498—Absolutism introduced, 499, 500—Christian V., 500, 501—Frederick IV.'s accession, 501—The Great Northern War, 502-504—Tordenskjold, 503, 504—Christian VI., 506-508—Frederick V, 508—Christian VII., 508-512—The armed neutrality, 509, 510—Frederick VI. mounts the throne, 512—War with Sweden, 512, 513—Christian August as viceroy, 512-514—The Treaty of Paris, 513—Protest of the Norsemen, 514—Separation from Denmark, 515. | |

| XXXVI. | |

| Norway Recovers Her Independence | 516-538 |

| [xx] Christian Frederick as viceroy, 516-518—Constitutional convention at Eidsvold, 518-520—War with Sweden, 520, 521—Armistice at Moss, 521—Charles XIII. accepts the constitution, 522—Charles XIV. John becomes king of Norway, 522—His controversies with the Storthing, 522-526—Henrik Wergeland, 526, 527—Count Wedel-Jarlsberg as viceroy, 527—Oscar I., 528-530—The character of the Norse peasantry, 528-530—Charles XV., 530, 531—Oscar II., and the constitutional struggle, 531-534—Impeachment of the ministry Selmer, 534—"The Pure Flag," 535—Present condition of Norway and her place among the nations, 536—Literature and science, 536-538. [xxi] |

| PAGE. | |

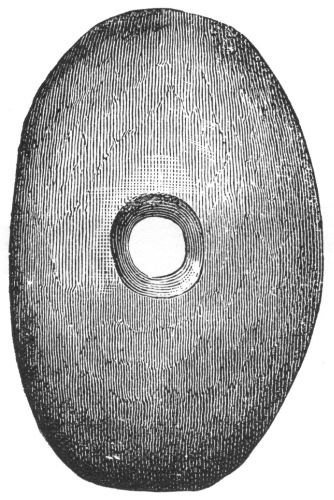

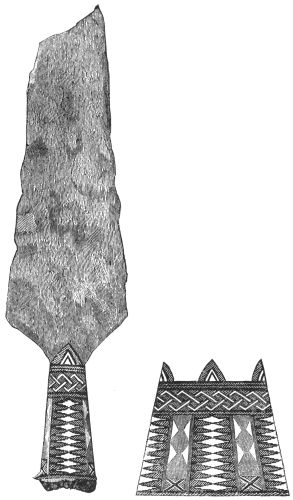

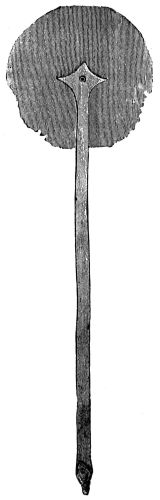

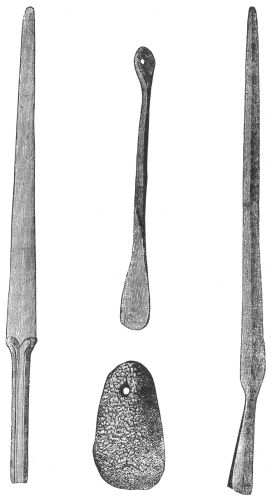

| STONE AXES FROM THE LATER STONE AGE | 5 |

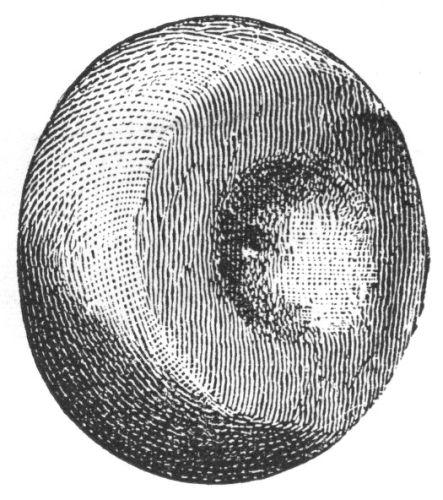

| STONE USED FOR SHAPING INSTRUMENTS | 7 |

| STONE HAMMER | 7 |

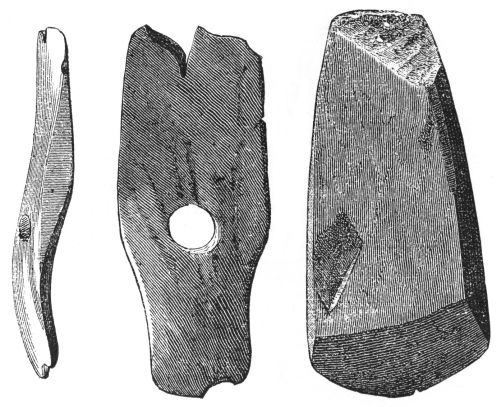

| STONE KNIFE | 8 |

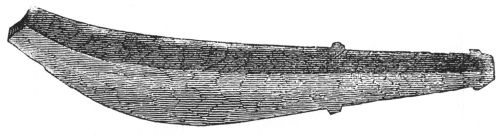

| ADZE OF ELK-HORN | 9 |

| STONE WEDGE | 9 |

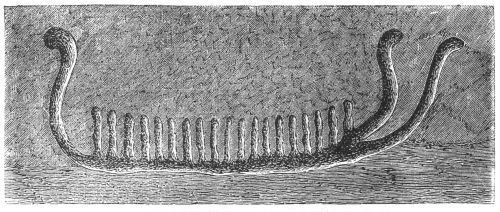

| ROCK PICTURE OF A SHIP AT LÖKEBERG | 10 |

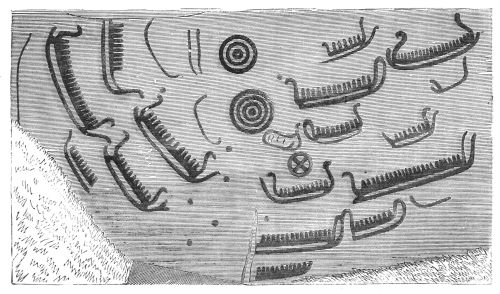

| ROCK PICTURE AT BORGEN | 11 |

| BRONZE SWORD | 14 |

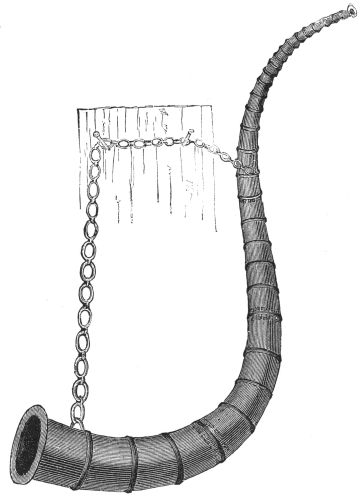

| LOOR OR WAR HORN OF BRONZE | 15 |

| BRONZE SWORD | 17 |

| BUCKLES FROM THE EARLY IRON AGE | 19 |

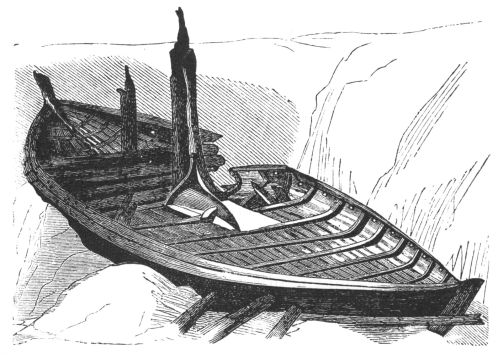

| THE VIKING SHIP RECENTLY UNEARTHED AT SANDEFJORD | 26 |

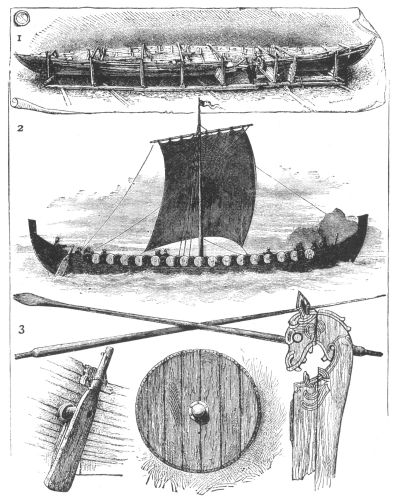

| THE VIKING SHIP, VARIOUS VIEWS OF | 29 |

| ST. ANSGARIUS THE APOSTLE OF THE NORTH | 33 |

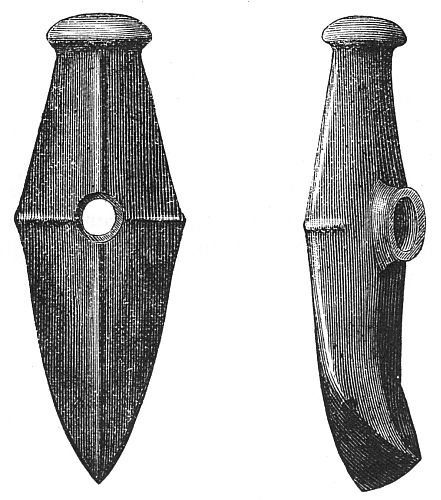

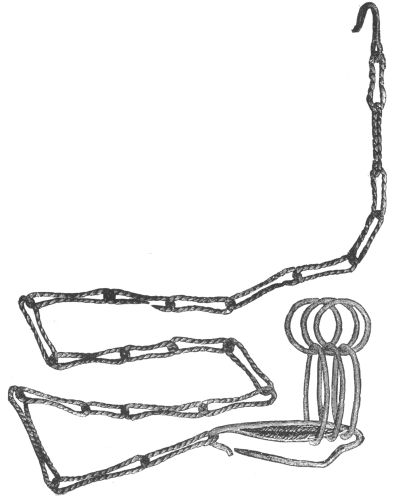

| IRON IMPLEMENT—USE UNKNOWN | 35 |

| TWO-EDGED SWORD | 37 |

| BUCKLE FROM THE IRON AGE | 39 |

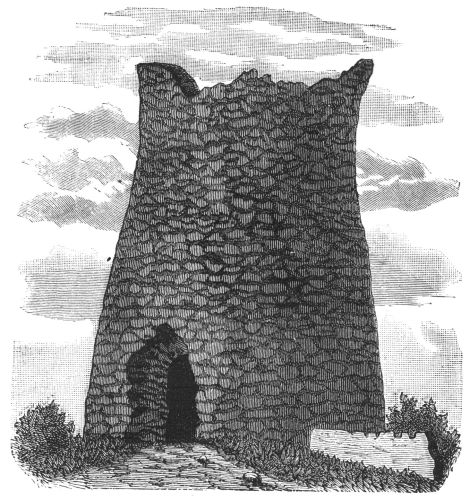

| RUIN OF NORSE TOWER AT MOSÖ | 43 |

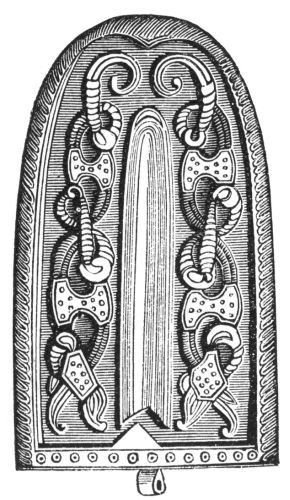

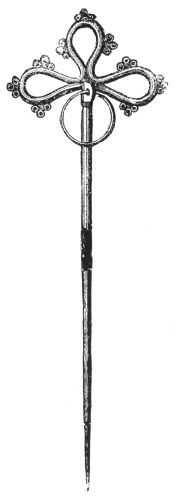

| BUCKLE WITH BYZANTINE ORNAMENTATION | 51 |

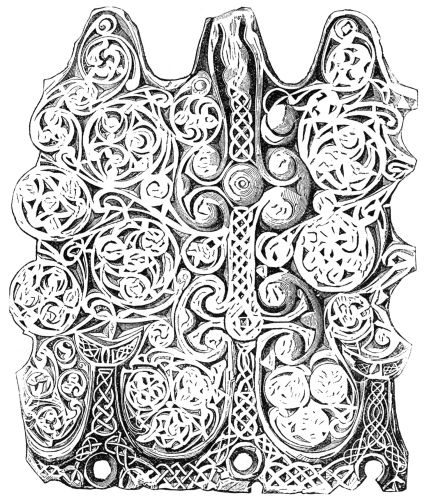

| GILT BUCKLE FOUND AT SKEDSMO | 72 |

| CYLINDRICAL MOUNTING IN BRONZE | 76 |

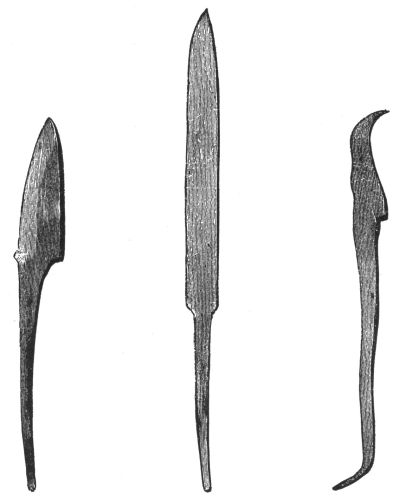

| IRON POINT OF SPEAR, IRON CHISEL | 84 |

| [xxii]FRYING-PAN OF BRONZE | 89 |

| BREASTPIN OF BRONZE | 91 |

| OVAL BRONZE BUCKLE | 93 |

| EGIL WOOLSARK'S MONUMENT | 96 |

| ORNAMENTAL BRONZE MOUNTING | 97 |

| CHURCH AT EGILÖ | 103 |

| SCISSORS AND ARROW-HEAD OF IRON | 107 |

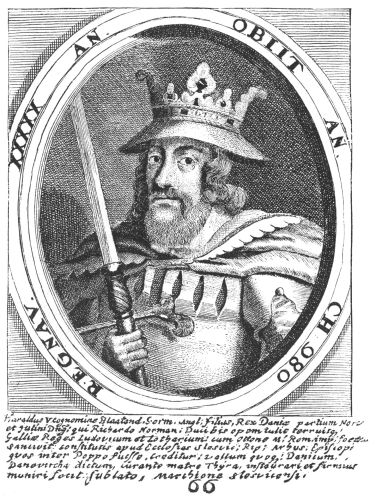

| HAROLD BLUETOOTH | 117 |

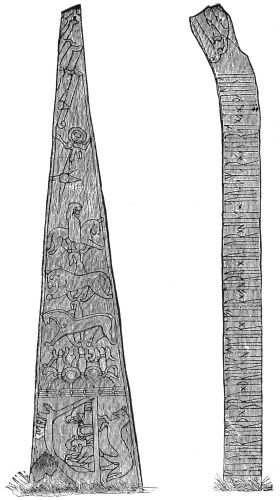

| RUNESTONE FROM STRAND IN RYFYLKE | 121 |

| OBLONG BUCKLE | 133 |

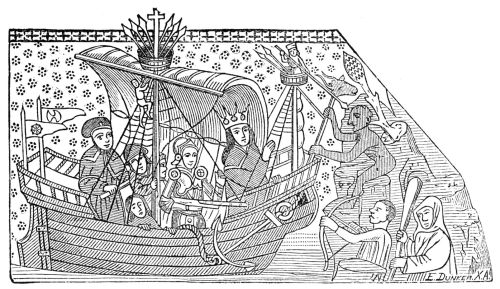

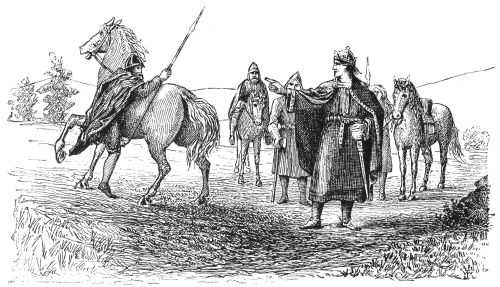

| OLAF TRYGGVESSON'S ARRIVAL IN NORWAY | 141 |

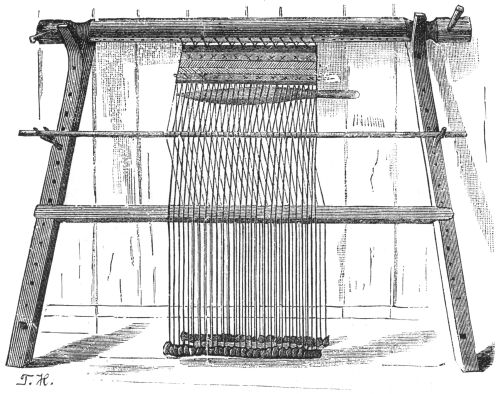

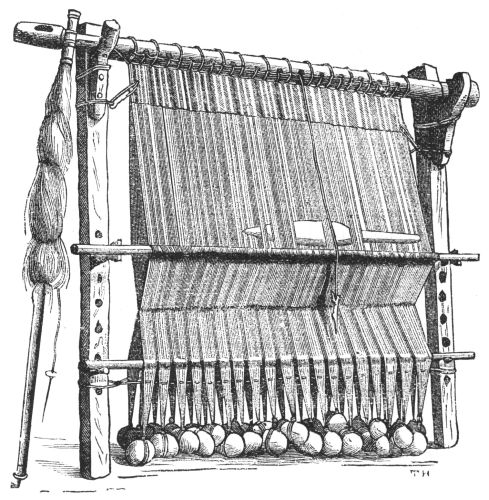

| OLD NORSE LOOM | 145 |

| RUNIC STONE FROM GRAN IN HADELAND | 153 |

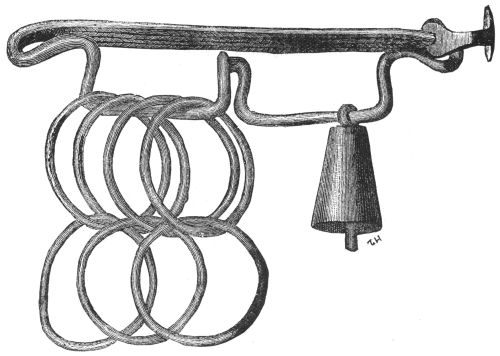

| INSTRUMENT OF UNKNOWN USE | 155 |

| OLD LOOM FROM THE FAEROE ISLANDS | 159 |

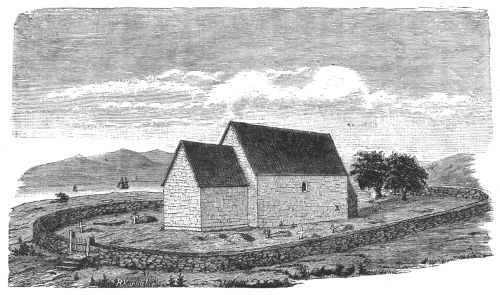

| CHURCH AT MOSTER ISLAND | 167 |

| SHUTTLES OF IRON AND WHALEBONE | 175 |

| KNIVES OF IRON FOUND IN HEDEMARK AND HADELAND | 208 |

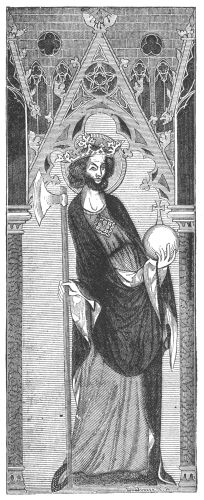

| ST. OLAF FROM DRONTHEIM CATHEDRAL | 219 |

| ST. OLAF AND THE TROLDS | 223 |

| MAGNUS THE GOOD AND KALF ARNESSON AT STIKLESTAD | 235 |

| MARBLE LION FROM THE PIRÆUS | 241 |

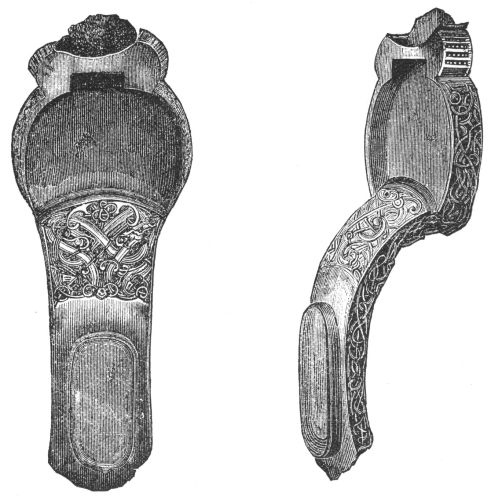

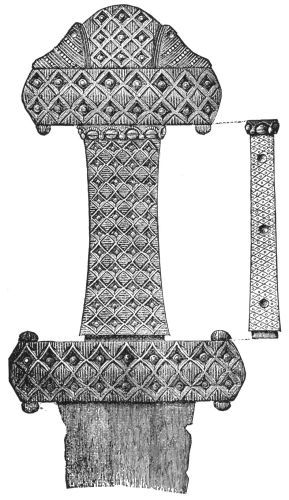

| POMMEL OF GILT BRONZE FROM THE VIKING AGE | 250 |

| THE OLD MAN OF HOY | 271 |

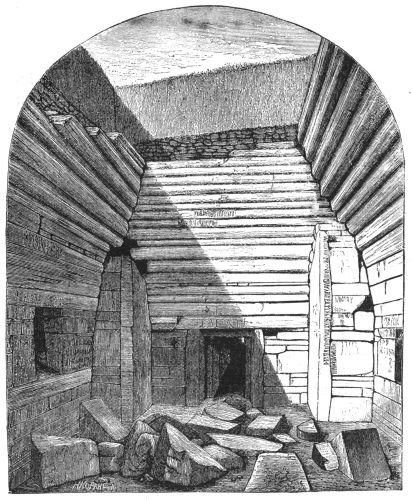

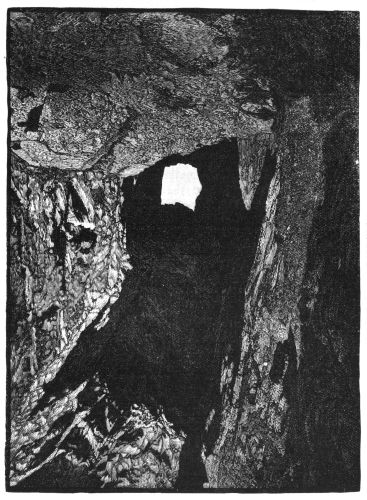

| INTERIOR OF ORKHAUGEN | 279 |

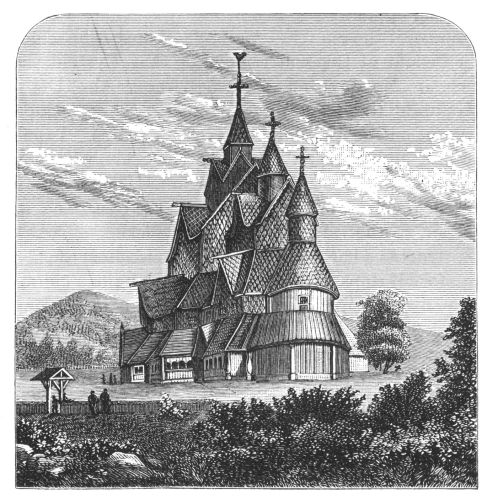

| HITTERDAL CHURCH | 299 |

| VILLAGE DURING FISHING SEASON | 315 |

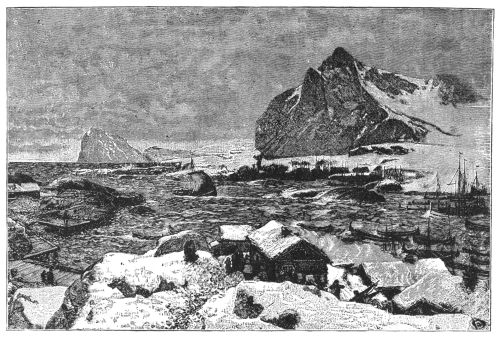

| THE RAFT SUND IN VESTFJORD | 331 |

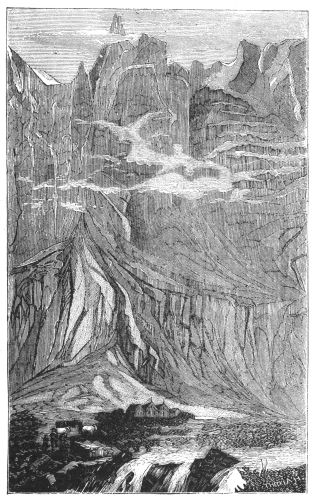

| HORNELEN | 339 |

| THORGHÄTTEN | 363 |

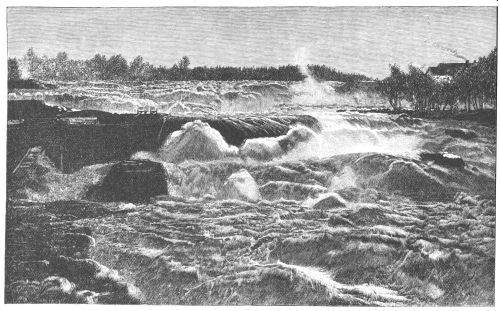

| HÖNEFOSS | 371 |

| HAAKON HAAKONSSON AND HELGE HVASSE | 397 |

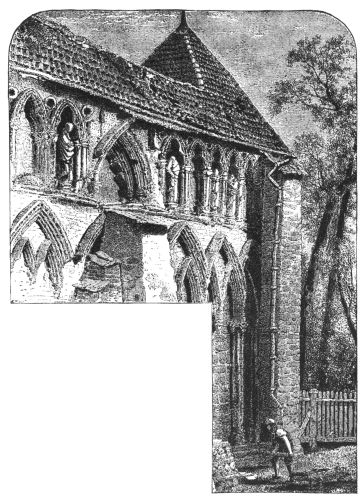

| [xxiii]WEST FRONT OF DRONTHEIM CATHEDRAL | 403 |

| OLD NORSE CAPITALS | 409 |

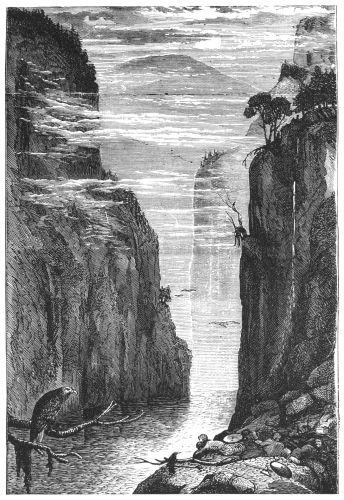

| ON THE SOGNE FJORD | 415 |

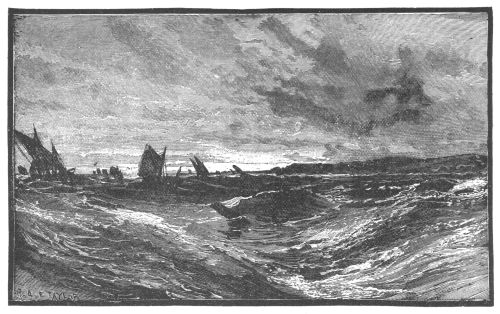

| A STORM ON THE FJORD | 419 |

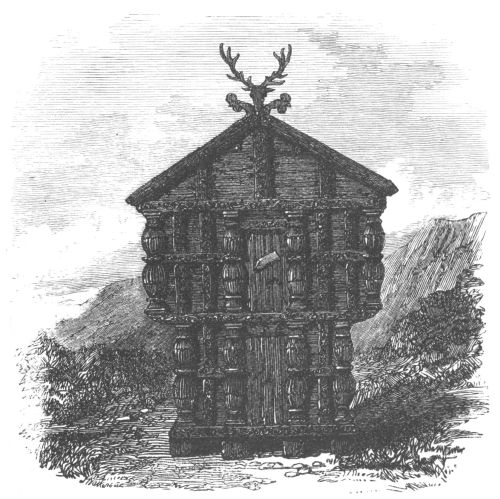

| NORWEGIAN STABBUR OR STORE-HOUSE | 431 |

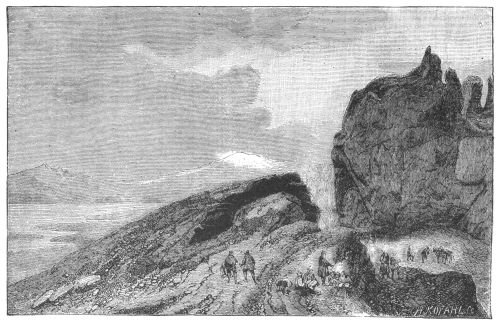

| HÖRGADAL IN THE NORTH OF ICELAND | 435 |

| ALMANNAGJAA WITH THE HILL OF LAWS | 439 |

| QUEEN MARGARET | 471 |

| CHRISTIAN I. | 479 |

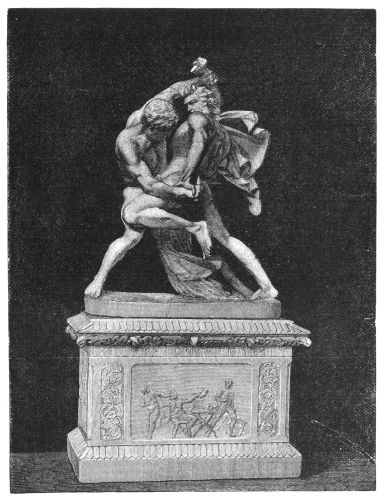

| BELT WRESTLING | 491 |

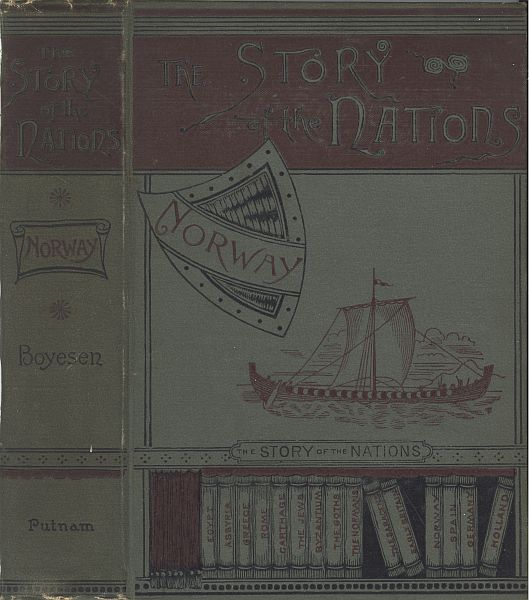

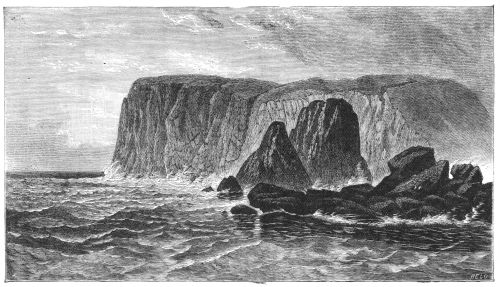

| THE NORTH CAPE | 493 |

| FREDERICK III., KING OF DENMARK AND NORWAY | 497 |

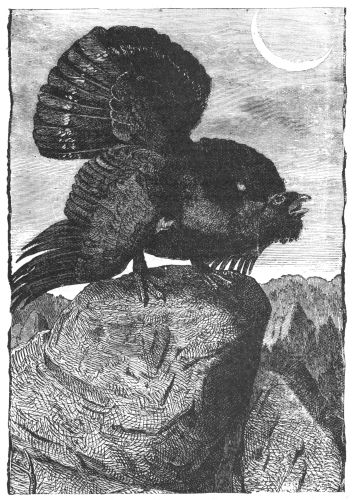

| THE CAPERCAILZIE IN NORWAY | 505 |

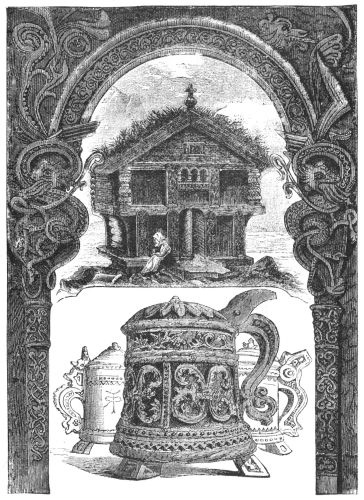

| CARVED LINTEL, STABBUR, AND BEER-MUGS | 507 |

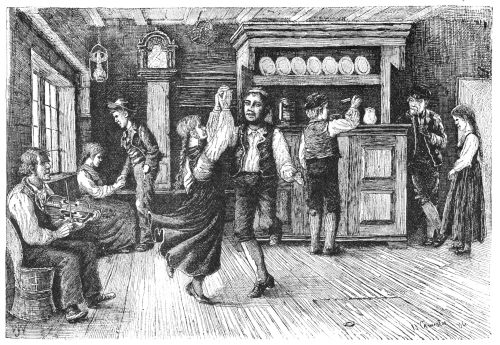

| PEASANTS DANCING | 511 |

| PRINCE CHRISTIAN FREDERICK, VICEROY OF NORWAY | 517 |

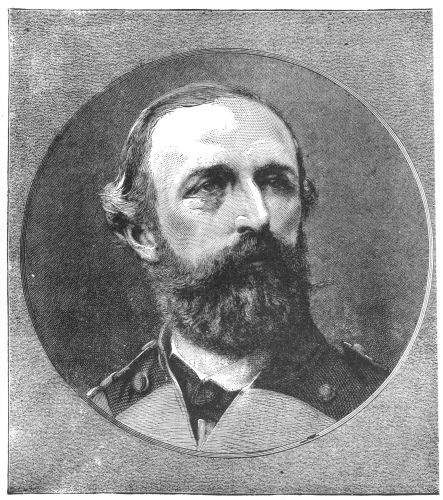

| CHARLES XIV. JOHN (BERNADOTTE) | 521 |

| SKEE-RUNNING | 525 |

| BRIDE AND GROOM | 529 |

| PORTRAIT OF OSCAR II. | 533 |

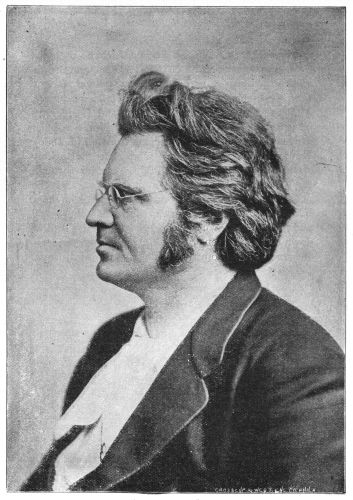

| BJÖRNSTJERNE BJÖRNSON | 537 |

The Norsemen are a Germanic race, and belong, accordingly, to the great Aryan family. Their next of kin are the Swedes and Danes. Their original home was Asia, and probably that part of Asia which the ancients called Bactria, near the sources of the rivers Oxus and Jaxartes. Not only the Norsemen are supposed to have come from this region, but the ancestors of all the Aryan nations which now inhabit the greater portion of the civilized world. Among the first to leave this cradle of nations were the tribes which settled upon the eastern islands and peninsulas of the Mediterranean, and, under the name of Hellenes, developed, long before the Christian era, an art and a literature which are, in some respects, yet unrivalled. The early Italic tribes, from which sprung in time the world-empire of Rome, trace their descent from the same ancestry; as do also the Kelts, who in ancient times inhabited England, Ireland, and France; the Slavs who settled in the present Russia, Bohemia, and the[2] northern Turkish provinces; and the Germans, who occupied the great central regions of the European continent. Among Asiatic nations, the Iranians inhabiting Persia, and the Hindoos in India, have Aryan blood.

It seems almost incredible that persons differing so widely in appearance, habits, and disposition, as, for instance, a Hindoo and an Englishman, should, if you go sufficiently far back, have the same ancestry. And yet there cannot be the slightest doubt that such is the case. The question, then, naturally arises: "If they were once alike, what can have made them so different?" And the answer is: "The climate, the soil, and the general character of the countries in which they settled."

The country from which the first Aryans emigrated was mountainous, with fertile valleys, and an even, temperate climate. There was no excessive heat to make men drowsy and indolent, nor excessive cold to stunt them in their growth and paralyze their energies. The earth did not, as in the tropics, produce a luxurious vegetation which would support the inhabitants without labor, but it offered sustenance to herds of cattle which, with the proper care, would supply the simple needs of primitive men. The race, thus situated, progressed physically as well as mentally, until it became superior to all the tribes inhabiting the neighboring regions. War followed, in which the weaker succumbed. The Aryans, increasing rapidly in numbers, took possession of the conquered territories, enslaved the indigenous population, or drove it back into locali[3]ties where the conditions of life were less favorable. It is not positively known when the first migration on a large scale took place; but some scholars have supposed that the Hindoos separated from the parent race as early as 1500 B.C. The dates of the Greek, Italic, Keltic, and Slavic migrations are likewise uncertain, and the period which has been fixed upon for the Aryan occupation of Germany is also conjectural. The same uncertainty prevails regarding the earliest history of the Scandinavian tribes; although there is a strong probability that their invasion of the countries which they now inhabit must have taken place during the second century preceding the Christian era. It is not unlikely that they left their Asiatic home simultaneously with the Germans, with whom they were then almost, if not entirely, identical, and that their conquering hordes spread northward, subduing the Finns and Lapps, whom they found in possession of the land, partly exterminating them, partly forcing them up into the barren mountains of the extreme North. Among the tribes whose path of conquest was turned in this direction, the Goths (Gauter), the Swedes (Svear), and the Danes (Daner) were the most prominent, though several other names are mentioned, both by native and foreign authors. The name Norseman, or Northman, is not found among these, because it refers not to any of the Aryan tribes, but is solely derived from the country in which they settled. Their country soon became known as Norway (Noregr or Norvegr), i. e., the Northern Way. It is the long strip of territory extending north and south[4] between the mountain chain Kjölen, which separates it from Sweden and the Arctic and Atlantic oceans. It looks on the map like a big bag slung across the shoulders of Sweden.

It is a wonderful country—this land of the Norsemen. The ocean roars along its rock-bound coast, and during the long, dark winter the storms howl and rage, and hurl the waves in white showers of spray against the sky. Great swarms of sea-birds drift like snow over the waters, and circle screaming around the lonely cliffs. The aurora borealis flashes like a huge shining fan over the northern heavens, and the stars glitter with a keen frosty splendor. But in the summer all this is changed, suddenly, as by a miracle. Then the sun shines warmly, even within the polar circle; innumerable wild flowers sprout forth, the swelling rivers dance singing to the sea, and the birches mingle their light-green foliage with the darker needles of the pines. In the northern districts it is light throughout the night, even during the few hours while the sun dips beneath the horizon; the ocean spreads like a great burnished mirror under the cloudless sky, the fishes leap, and the gulls and eider-ducks rock tranquilly upon the shining waters. All along the coast there are excellent harbors, which are free of ice both winter and summer. A multitude of islands, some rocky and barren, others covered with a scant growth of grass and trees, afford hiding-places for ships and pasturage for cattle. Moreover, long arms of the ocean—the so-called fiords—penetrate far into the country, and being filled with water from the gulf-stream[5] which strikes the western coast of Norway, tend greatly to moderate the climate. About the shores of these fiords narrow strips of arable land stretch themselves, with many interruptions, along the edge of the water, and here the early Germanic settlers built their houses and began their fight for existence. Behind them and before them the great snow-hooded mountains rose threateningly, sending down upon them avalanches, floods, and sudden whirlwinds. But, nothing daunted, they clung to the soil, explored the land and the sea, and selected the most favorable sites for their permanent dwellings.

It is tolerably certain that the Aryan settlers in Norway knew at that time very little of agriculture,[6] but made their living by hunting, fishing, and cattle-raising. The huts which they built of logs were rude contrivances which could be easily torn down and moved. But, as at a very early period, they began to devote themselves more to the culture of the ground, their dwellings were made larger, and were built with greater care. When a horde of warriors invaded a valley their first task was to clear away the forests which grew dense and dark up over the mountain sides. Their chieftain then built a hov or temple for the gods, where sacrifices were made at certain stated times. Whether it was the chieftain's task to allot to each his share of land, or whether each one chose according to his own preference, is not known, but the former is the more probable; for the Norsemen, proud and pugnacious as they were, subordinated themselves, in historic times, readily to their local chiefs, and accorded them great honor. This sense of kinship within the tribe and willing recognition of authority was the more important in Norway, because the character of the ground there compelled the people to live far apart on scattered gaards or farms, between which communication was often difficult. It would therefore have been easy for the bönder or peasants to forget all public concerns and gradually to lapse into isolation and savagery. But here their Germanic nature, which had in it the germs of social progress, asserted itself. As the centuries passed the people were bound more strongly together by common pursuits and common interests. First of all, their religious observances brought them together, then the[7] necessity of defence against external enemies. Life and property were in those days insecure possessions, and it was only by acting in concert, under the leadership of a valiant chief, that the scattered peasants could hope to preserve either. Men had then fiercer and more inflammable passions than they have now, and only fear of retaliation could teach them self-restraint.

It happened in this way that almost every separate valley in Norway became a little kingdom by itself. Such a diminutive kingdom was called a fylki. There was not always a king, but a chief there was always, and sometimes more than one. To the king belonged the leadership in war. He was in some district called a jarl or earl, though this name came[8] in later times to mean not an independent ruler, but rather a land-grave, a royal governor. The king could not tax the peasants for his support, nor impose any burden upon them which they did not of their own free choice accept. As a rule, his dignity was inherited by his son, though the people were at liberty, in case they disapproved of the heir, to select another. This right was repeatedly exercised in historic times, both in Sweden and Norway. Sometimes, when the crops failed or bad weather destroyed their herds, the peasants sacrificed their king to their gods. All public misfortunes they interpreted as a sign that the gods were angry, and craved bloody atonement. If the crops were good it was evident that their king was in favor with the gods.

It thus appears that the royal dignity among the early Norsemen was burdened with unpleasant responsibilities. It involved more duties than privileges, for, besides commanding in war, the king had also to conduct the public sacrifices at the great pagan festivals. He was thus priest as well as king. In fact, as before stated, he built the hov or temple himself, and it was chiefly his ownership of this, which raised him to a dignity superior to that of[9] other chieftains. It was by dint of this same authority that he acted as judge at the fylkis thing, or popular assembly, where all freeman met to consult concerning public and private affairs. The fylkis thing was neither a parliament nor a court of law, but both combined. Private quarrels were settled, blood-wites or fines agreed upon for homicides and other injuries, and resolutions taken concerning peace and war. It was not a representative assembly, the members of which were elected by vote, but rather a county meeting (shiremote) where every man who could bear arms had a right to make himself heard. You would scarcely wonder that where so many fierce and turbulent warriors were gathered, breaches of the[10] peace were frequent. But when swords were drawn, it was impossible to judge and deliberate. Therefore the fylkis thing was hallowed, and to break the peace of the thing was regarded as the greatest of crimes. If a man killed another, and publicly proclaimed himself his slayer, the crime could be atoned for by money (blood-wite) paid to the nearest surviving relative of the dead man. If the relatives accepted the blood-wite, they were not at liberty to seek revenge. But in ancient times it was regarded as more honorable to refuse the money and resort to the sword. If a man slew another secretly and denied the crime he was held to be a murderer, and could not offer blood-wite. He was then outlawed, and every man who saw him was at liberty to slay him.

Such were the Norsemen during the first centuries [12] after their settlement in their present home. In spite of their violence and proneness to bloodshed, you will yet admit that they had many traits which were admirable. They could recognize authority, and yet preserve their sturdy sense of independence. Simple and imperfect as their fylkis things were, they suffice to show an aptitude for self-government, and a recognition of the people itself, as the source of authority. These tall blonde men with their defiant blue eyes, who obeyed their kings while they had confidence in them, and killed them when they had forfeited their respect, were the ancestors of the Normans who under William the Conqueror invaded England, and founded the only European state which has since reached the highest civilization and the highest liberty, through slow and even stages of orderly development.

The Icelander Snorre Sturlasson wrote in the thirteenth century a very remarkable book, called the Heimskringla, or the Sagas of the Kings of Norway. In this book he says that Odin, the highest god of the Norsemen, was the chief who first led the Germanic tribes into Europe. He was a great warrior and was always victorious. Therefore, when he was dead, the people made sacrifices to him and prayed to him for victory. They did not believe, however, that he was actually dead, but that he had returned to his old home in Asia, whence he still watched their fortunes and occasionally visited them in person. Many tales are told in the sagas of people who had seen Odin, particularly when a great battle was to be fought. He was represented as a tall, bearded man with one eye, and clad as a warrior. He had two brothers, Vile and Ve, and many sons and daughters who were worshipped like him and became gods and goddesses. Odin and his children were called Aesir, which Snorre says means Asia-men; and their home Asgard, or Asaheim, likewise indicates their Asiatic origin. During their migrations the Aesir came in contact with another peo[14]ple, called the Vanir, with whom, after an indecisive battle, they formed an alliance. The Vanir then made common cause with the Aesir and were worshipped like them.

Whether there is any basis of truth in this tradition, is difficult to determine. We know that primitive nations usually make gods of their early kings and chieftains, and worship them after death. Every year that passes makes them look greater and more mysterious. In storms and earthquakes, in thunder and lightning, they hear their voices and see the manifestations of their power. More and more they become identified with the elements which they are supposed to rule; the mighty attributes of the sun, the sky, and the sea are given to them, and to each is allotted his particular sphere of action. The chieftain who has been a valiant warrior in his life-time is supposed to give victory to those who call upon him. He who has excelled in the arts of peace continues to rule over the seasons, and to give good crops and prosperity to those who, by sacrifices, secure his good-will. This may have been the origin of the Scandinavian gods; although many scholars maintain that they were from the beginning personifications of the elements, and have never had an actual existence on earth. But whether they were originally men or sun-myths, interesting legends [16]have been told about them which may be worth recounting.

In the beginning of time there were two worlds, Muspelheim, the world of fire, whose king was Surtur, and Niflheim, the world of frost and darkness. In Niflheim was the spring Hvergelmer, where dwelt the terrible dragon Nidhögger. Between these two worlds was the yawning chasm Ginnungagap. The spring Hvergelmer sent forth twelve icy rivers, which were called the Elivagar. These gradually filled up the chasm Ginnungagap. As the wild waters rushed into the abyss, they froze and were again thawed by the sparks that were blown from the fiery Muspelheim. The frozen vapors fell as hoar-frost, and the heat imparted life to them. They took shape and fashioned themselves into the Yotun or giant Ymer, from whom descends the evil race of frost-giants. Simultaneously with Ymer the cow Audhumbla came into being. She licked the briny hoar-frost, and a mighty being appeared with the shape of a man. He was large and beautiful, and was named Bure. His son was Bör, who married the daughter of a Yotun, and got three sons, Odin, Vile, and Ve. These three brothers slew the Yotun Ymer, and in his blood all the race of Yotuns was drowned except one couple, from whom a new race of giants descended. Then Odin and his brothers dragged the huge body of Ymer into the middle of Ginnungagap, and fashioned from it the world. Out of the flesh they made the earth, the bones became stones and lofty mountains, and his blood the sea. From his hair they made the trees, and from his[17] skull the great vault of the sky. His brain they scattered in the air, where its fragments yet float about in queer, fantastic shapes, and are called clouds. The flying sparks from Muspelheim they gathered up and fashioned them into sun, moon, and stars, which they flung up against the blue vault of the sky. Then they arranged land and water so that the ocean flowed round about the entire earth, and beyond the watery waste they fixed the abode of the Yotuns. This cold and barren realm beyond the sea is therefore called Utgard or Yotunheim. From the earth to the sky they suspended a bridge of many colors, which they named Bifrost or the rainbow. The Yotun woman Night married Delling (the Dawn) and became the mother of Day, who rode in his shining chariot across the sky, always followed by his dark mother. The latter drove a huge black horse named Hrimfaxe, from whose foamy bit dropped the dew that refreshed the grass during the hours of darkness, while Day's horse, Skinfaxe, spread from his radiant mane the glorious light over the earth. It is further told that the heat bred in Ymer's body a multitude of maggots, which assumed the shapes of tiny men and were called gnomes or dwarves. They live in caves and mountains, and know of all the treasures of gold and silver and precious stones in the[18] secret chambers of the rocks. They also have great skill in the working of metals, but they cannot endure the light of the sun. Last of all man was created. One day when the three gods, Odin, Höner, and Lodur were walking on the shores of the sea they found two trees, and from these they made a man and a woman, named Ask and Embla (ash and elm). Odin gave them the breath of life, Höner, speech and reason, Lodur, blood and fair complexions.

The old Norsemen conceived of the world as an enormous ash tree, named Ygdrasil, the three roots of which extend, one to the gods in Asgard, another to Yotunheim, the third to Niflheim. On the third gnaws continually the dragon Nidhögger. In the top of the tree sits an eagle; among the branches four stags are running; and up and down on the trunk frisks a squirrel who carries slander and endeavors to make mischief between the eagle and the dragon. Under the root which stretches to Yotunheim is the fountain of the wise Yotun Mimer, to whom Odin gave one of his eyes in return for a draught from his fountain. For whoever drank from its water became instantly wise. Under the second root of the ash, which draws its nourishment from heaven, is the sacred fountain of Urd, whither the gods ride daily over the bridge Bifrost. Here they meet the three Norns—Urd, Verdande, and Skuld (Past, Present, and Future), the august goddesses of Fate, whose decrees not even the gods are able to change. The Norns pour the water of the fountain over Ygdrasil's root, and thereby keep the world-tree alive. They govern the fates of gods[19] and men, giving life or death to whomever they please.

Odin dwells with all the other gods in Asgard, where he receives in his shining hall Valhalla all those who have died by the sword. He is therefore called Valfather, and those fallen warriors whom he chooses to be his guests, are known as einheriar, i. e., great champions. Valhalla is splendidly decorated with burnished weapons. The ceiling is made of spears, the roof is covered with shining shields,[20] and the walls are adorned with armor and coats of mail. Hence the champions issue forth every day and fight great battles, killing and maiming each other. But every night they wake up whole and unscathed and return to Odin's hall, where they spend the night in merry carousing. The maidens of Odin—the Valkyries, who, before every battle, select those who are to be slain, wait upon the warriors, fill their great horns with mead, and give them the flesh of swine to eat.

The great gathering-place of the gods in Asgard is the plains of Ida. Here is Odin's throne, where he sits looking out over the whole world. At his side sit the two wolves—Gere and Freke, and on his shoulders the ravens, Hugin and Munin, who daily fly forth and bear him tidings from the remotest regions of the earth. If he wishes to travel, he mounts his eight-footed horse Sleipner, which carries him far and wide with wonderful speed. When the father of gods and men rides to battle he wears a helmet of gold and a suit of mail, which shines dazzlingly from afar. He carries also his spear Gungner, which he sends forth whenever he wishes to arouse men to warfare and strife. But, besides being the god of war, Odin also delights in poetry and sage counsel. He is the god of the scalds or poets; for he had drunk of Suttung's mead, which imparted the gift of song. He is well skilled in sorcery, and has taught men the art of writing runes.

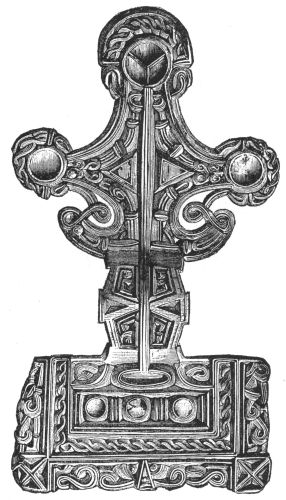

Thor, the son of Odin, lives in Thrudvang. He is the strongest of all the gods, and has an enormous hammer, Mjolner, with which he carries on a cease[21]less warfare against the Yotuns, or mist-giants. He rides in a cart drawn by two rams across the Gjallar bridge (the resounding bridge), which leads to Yotunheim, and the rattling of the cart and the noise of his hammer, as he hurls it at the heads of the fleeing giants, make the vault of the sky tremble. This is what men call thunder. When Thor is hungry, he kills his rams and eats their flesh, but he is always careful to gather up the bones and to throw them back into the skins. Then, the next morning, the rams are as frisky as ever and ready for service. Thor has a wife named Sif, whose hair is of gold.

Balder, the good and the beautiful, is also the son of Odin. He is wise and gentle, and kindness beams from his countenance. His wife is Nanna, and his dwelling Breidablik.

Njord is ruler of the sea, and can raise storms and calm the waves at his pleasure. He is of the race of the Vanir, but is yet worshipped as a god. He is the owner of great wealth, and can give prosperity to those who obtain his favor. Njord was married to the Yotun woman, Skade, but was again separated from her. His abode is at Noatun, from which he has wide view of the sea.

Frey, the son of Njord, rules over the seasons, and gives peace and good crops. Fields and pastures grow, and the cattle thrive in the sunshine of his favor. He lives with his wife Gerd in Alfheim. Tyr is the god of courage, whom men call upon as they are about to go into battle. He has but one hand, having thrust the other into the mouth of the Fenris-[22]Wolf, who bit it off. Brage is the god of song, and of vows and pledges. He has a long beard, and, is possessed of wisdom and eloquence. When men drained the horn in his honor, they made vows of daring deeds which they would perform, and called the god to witness that they would keep them. Many were those who, while drunk, pledged themselves to foolhardy undertakings, and perished in the attempt to carry them out. Brage's wife is the ever-young Idun. She has in her keeping the wonderful apples, which the gods eat to preserve the beauty and vigor of an eternal youth.

The watchman of the gods is named Heimdal. His senses are so keen that nothing can escape him. He can see hundreds of miles, and he can hear the grass grow. When he blows his Gjallar horn (the resounding horn), its rousing call is heard throughout the world. Heimdal's dwelling is Himinbjarg at the Bifrost Bridge.

Among gods of less consequence may be mentioned Uller, the step-son of Thor, who is a master in running on snow-shoes; Forsete, the son of Balder, who makes peace between those who have quarrelled; Höder, the blind god, who shot Balder; and the silent Vidar.

Foremost among the goddesses is Frigg, the wife of Odin, who dwells in Fensal. She shields from danger those who call upon her. Freya, the Northern Venus, is the goddess of beauty. She is the daughter of Njord, and was forsaken by her husband Odd, and is ever hoping for his return. She travelled far and wide in search of him, and wept because she could[23] not find him. Her tears turned into gold, and gold is therefore by the poets called the tears of Freya. Her chariot, in which she drives over the sky, is drawn by cats, though at times she flies in the guise of a swan and visits distant lands. Her necklace, Brising, made by wonder-working gnomes, is of dazzling splendor. The dwelling of Freya is Folkvang, and thither ascend the prayers of lovelorn swains and maidens. Freya's daughter, Hnos, is of marvellous beauty and a sweet disposition. Her name is still used in the nursery as a pet-name for babes.

The dominion of the sea does not belong entirely to Njord. The Yotun Aeger rules over the towering waves, and lashes them into fury, until Njord again curbs them and bids them be still. Yet Aeger is the friend of the gods, and is at times visited by them in his magnificent submarine hall, where ale and mead flow abundantly. He is himself peaceably disposed toward men, but is overruled by his terrible wife Ran, who with her nine daughters (the waves) causes shipwrecks and draws the drowned men down to her watery abode.

One dweller in Asgard is still to be mentioned, and that is the evil Loke, who disturbs the peace of the gods, and will work their final ruin. He was born among the Yotuns, but gained the confidence of Odin by his agreeable presence and his fair speech. He delighted in mischief and loved evil-doing. He had three terrible children—the wolf Fenris, the world-serpent, and Hel. As these monsters grew up, the gods foresaw that their presence in Asgard would cause trouble. The wolf Fenris was, therefore,[24] after having broken the strongest chains, tied with a magical cord, made of the noise of cats'-paws, women's beard, roots of mountains, and other equally intangible things. This cord he could not break. The world-serpent was thrown into the ocean, where it continued to grow until it encircled all the earth and at last bit its own tail. Hel was banished to Helheim, where she became the ruler of the dead, and the goddess of the under-world.

The Norsemen had up to the middle of the eighth century played no part in the world's history. Their very existence had been unknown or but vaguely known to the rest of Europe. But towards the close of the eighth century they broke like a destructive tempest over the civilized lands, spreading desolation in their path. When their fast-sailing ships with two square sails were sighted at the river-mouths, people fled in terror, and the priests prayed in vain: "Deliver us, O Lord, from the rage of the Norsemen."

There were several reasons for this sudden warlike activity on the part of the Norsemen. They had waged war from immemorial times; because war was with them the most honorable occupation. As Tacitus says of their kinsmen, the Germans: "They deemed it a disgrace to acquire by sweat what they might obtain by blood." But previous to the viking period they had fought each other. One earl or king made foraging expeditions into the land of his neighbors, and carried away with him whatever booty he could lay hands on. But in this perpetual warfare one or the other must at length become ex[26]hausted, and the stronger would be likely to oust or vanquish the weaker. This was what happened in the north. Large tracts of land, made up of small conquered kingdoms, were united under one successful chief, who, of course, made haste to prevent depredations within his own boundaries. With the growing power of these local kings, it became more and more risky to attack them, and the field for domestic warfare thus became constantly narrower. But war was the very condition of the chieftain's existence among the early Norsemen. His honor was dependent upon the number of his followers and the splendor of their equipments, and to gain the means to entertain and to equip them he was obliged to wage war. When he could no longer do[27] it at home, he naturally went abroad. It was neither ferocity nor excessive avarice which impelled him to draw the sword; but the desire to preserve his honor among men, which, in a warlike state, is merely another form of the instinct of self-preservation. The high-born chieftain had to make himself formidable in order to protect his life and property. He had to live in accordance with his rank, if he wished to live at all. His men-at-arms were his body-guard as well as his army. He had to behave royally toward them in order to preserve their good-will; and next to personal valor, liberality in giving was the first duty of a king. The king is therefore called the breaker of rings (large solid arm-rings of gold being used for purposes of payment) and the hater of gold.[A]

[A] Munch (Det Norske Folk's Historie, 1-124) derives the word king (old Norse, konungr; Anglo-Saxon, cyning; O. H. German, chuninc and chunig) from Kun or Kon, meaning race, descent; and interprets the word as meaning (like Lat., generosus) of high birth or descent.

There is in the earliest Germanic times no sharp distinction between the titles "earl" and "king." The viking cruises, however, helped to establish a distinction. The earl who, having gathered a large number of warriors about him, went abroad for purposes of conquest, was hailed by his men as king. A number of vikings, of high birth, assumed the name of kings, when starting on warlike expeditions; but were known as sea-kings, in contra-distinction to those who ruled at home over a fixed domain. The number of these sea-kings increased (for the reasons cited above) enormously toward the close of the eighth century. They harried not only the coasts [28]of the neighboring lands, but they crossed the North Sea and the Baltic, carrying away or slaughtering the inhabitants and destroying the cities. Churches and monasteries they plundered, scattering the bones of the saints to the four winds; all that Christian men held sacred they trod under foot. And yet we must bear in mind that all we know about these early vikings is derived from the writings of their enemies, who were smarting under the injury they had done them. That they were fierce and brutal is credible enough. The warlike state is in itself brutalizing. It arouses all the slumbering savagery in man, and smothers his gentler impulses. But certain moral qualities even their hostile chroniclers concede to them. They admit that the Norse barbarians were, as a rule, faithful to their oaths and kept their promises.

Three periods[A] are recognizable in the viking age, though there are, in point of time, no sharp divisions between them. It would, perhaps, be more correct to say that there were three kinds of vikings. The first cruises were more or less tentative and irregular. Chieftains gather about them crews for a few ships and sail over to England, Denmark, or Flanders, where they attack a city or a monastery, and return home with their booty. The second period shows an advance in the art of war and in military experience. Several vikings attack in company some exposed point, take possession of it, erect fortifications, and make forays into the surrounding country. During the third period the Norsemen abandon [30] their character of pirates and assume the rôle of conquerors. With large fleets, counting from one to five hundred ships, they storm and sack cities, assume the government of the conquered territories, treat, as regular belligerents, with kings and emperors, and establish themselves permanently in the conquered land. Of the two first classes of vikings we have only scattered and unreliable accounts. To go on viking cruises is a recognized occupation in the Norse sagas, and it was regarded as a kind of liberal education for a young man of good birth to spend some years of his youth on such expeditions. His honor was thereby greatly increased at home, and his position in society assured. Royal youths of twelve or fifteen years often went abroad as commanders of viking fleets, in order to test their manhood and accumulate experience and knowledge of men.

[A] Sars: "Udsigt over den Norske Historie," 1-90.

The third class of vikings, the conquerors, have found their historians both at home and abroad; and the different narratives, though not strictly accurate, supplement and correct each other. It is these conquering vikings who have demonstrated the historic mission of Norway, and doubly indemnified the world for the misery they brought upon it. The ability to endure discipline without loss of self-respect, voluntary subordination for mutual benefit, and the power of orderly organization, based upon these qualities, these were the contributions of the Norse vikings to the political life of Europe. The feudal state, which, with all its defects, is yet the indispensable basis of a higher civilization, has its root in the[31] Germanic instinct of loyalty—of mutual allegiance between master and vassal; and the noble spirit of independence which restrains and limits the power of the ruler, and at a later stage leads to constitutional government, is even a more distinctly Norse than Germanic characteristic. While Norway, up under the pole, has developed a democracy, Germany, coming at too early a period into contact with Rome, has developed a military despotism under constitutional forms. The breath of new life which the vikings infused into history lives to-day in Norway, in England, and in America.

Among the earliest conquests of the Norse vikings was a portion of the present Sleswick which after them was called Nortmannia. It is possible that they recognized the sovereignty of the kings of Denmark, though there is no direct evidence that they regarded themselves as vassals. The first intelligence we obtain concerning them is that their king Sigfrid, in the year 777, received hospitably the Saxon chieftain Widukind, who, when summoned to meet Charlemagne in Paderborn, fled northward and sought refuge with his Norse co-religionists. This Sigfrid belonged to the renowned race of the Ynglings, from whom descended Harold the Fairhaired, and through him a long line of Norwegian kings. A later king of Nortmannia, who also had great possessions in Norway, was Gudröd or Godfrey the Hunter. He came, through the friendship of the Saxons, repeatedly into collision with Charlemagne, and even threatened to attack the emperor in Aachen. It is told that he was killed by his own men in the[32] year 809. He had about a year before attacked and slain the king of Agder, whose daughter Aasa he married. She bore him a son named Halfdan the Swarthy, but avenged her father's death by inducing her servant to kill her husband while he was drunk. One of Godfrey's sons, Erik, carried on an intermittent warfare with Charlemagne's son, Louis the Pious, sent embassies to Aachen, and in 845, during the reign of Louis the German, sacked and burned the city of Hamburg. St. Ansgarius, the apostle of the North, who had been established by the emperor as archbishop of Hamburg, fled with all his priests; and the church and the monastery which he had founded were utterly destroyed.

It was not only in his remote northern domains that Charlemagne came in contact with the vikings. The chronicles of the Monks of St. Gall relate that he also encountered them in his Mediterranean provinces. Once, as he was visiting a city in Gallia Narbonensis, some fast-sailing Norse ships with square sails were seen out in the harbor. Soon a message was brought to the emperor that the crews had landed and were plundering the shore. Nobody then knew to what nationality these ships belonged, some conjecturing that they were Jewish, others African, and again others that they were British merchant vessels.

"No," said Charlemagne, "these ships are not filled with merchandise, but with the most pugnacious foes."

Hearing this everybody seized his weapons and hastened to the harbor; but the vikings had in the meanwhile learned that the emperor was in the city,[33] and as they were not strong enough to fight with him, they fled to sea.

It is related that Charlemagne, as he stood at his window and watched their flight, wept. Remarking the wonder of his men, he said:

"I do not weep because I fear that these miscreants can do me any harm; but I am grieved that, while I am alive, they have dared to show themselves[34] upon this coast; and I foresee with dread all the evil they will do to my descendants."[A]

[A] Munch (Det. Norske Folks Historie 1-414) questions the credibility of this story, because the Norsemen did not show themselves in the Mediterranean as early as the chronicle here indicates; in fact not before 800 A.D.

This story, endowing the emperor with prophetic vision, has a certain legendary flavor, and may be a monkish invention. Similar prophecies, dating after the event, are found in other ecclesiastical authors, and show sufficiently the feeling with which the Norsemen were regarded. It is especially one typical viking, the renowned Hasting, who figures both in sacred and profane chronicles. He sailed up the Loire in 841, with a large fleet, burned the city of Amboise, and besieged Tours. The inhabitants, however, carried the bones of their patron saint up on the walls; and, according to the story, by the intervention of the saint, the vikings were put to flight. In 845, Hasting is reported to have attacked Paris, in company with Björn Ironside, the son of Ragnar Lodbrok. To the Baltic and even to the shore of the Mediterranean this fearless marauder extended his ravages, and as success attended his banner, he grew more daring and determined to lay siege to Rome.

He even aspired to put the imperial crown upon his brow. With as large a fleet as he could muster he sailed through the Pillars of Hercules, but before he reached the mouth of the Tiber, a storm drove his ships to the city of Luna, near Carrara. Being poorly versed in geography, Hasting mistook this city for Rome, and resolved to capture it by strategem.

He sent word to the bishop that he was very ill and desired to be baptized, so that he might die a Christian. The bishop, as well as the commander of the town, fell into the trap. Delighted at the prospect of gaining so valuable a convert, they opened the gates and invited the Norsemen to enter. These, in the meanwhile, declared, that since sending his message, Hasting had died; and with great pomp they bore his coffin, followed by a funeral procession of enormous length, into the cathedral where the bishop stood ready to read the mass for the repose of the viking's soul. Suddenly, however, as the coffin was deposited before the altar and the mass commenced, Hasting sprang up, flung away his shroud, and stood in flashing armor before the astonished populace. His men, at this signal, also flung off their mourning cloaks and drew their[36] swords. The bishop and his priests were killed, and blood flowed in torrents through the sacred aisles. A terrible carnage ensued, and the city was captured. Having accomplished this enterprise, Hasting discovered that, while deceiving, he had himself been deceived. It was not Rome he had taken after all. Whether he accepted this as an omen or not, he lost his desire to make his entry into the eternal city. Content with the booty he had accumulated, he turned his prows toward France where he became the vassal of Charles the Bald, from whom he received valuable fiefs.[A]

[A] The Norse Sagas make no mention of Hasting, and Munch (1-429) gives several reasons for questioning whether he was an historical character.

Many other vikings are mentioned in chronicles of later date, who by their incessant attacks upon the coasts, taxed the energy of the weak Carolingian kings to the utmost. One of them, named Ragnar, is said to have plundered Paris in 845, and another, named Asgeir, had four years earlier sacked and burned Rouen and the monastery Jumièges. He spent eleven years ravaging the coasts of France, and finally, in 851, sailed up the Seine, destroyed the monastery Fontenelle and burned Beauvois. On his return to the sea he was defeated by the French, and had to hide with his men in the woods, but succeeded in recapturing his ships and making good his escape. Of a third one, Rörek, it is told that about the year 862 he accepted Christianity, without, as it appears, experiencing any perceptible change of heart. After having ravaged Dorestad and Nimwegen, [37]two flourishing cities on the Rhine, and having defended himself heroically against King Lothair, the younger, he made peace (873) with Louis the German, and refrained from further depredations.

There is a certain uniformity in the deeds of the vikings, whether they be Norsemen or Danes, which makes further description superfluous. Only a few of their more daring enterprises may be briefly alluded to.

To Ireland the Norsemen had been attracted at a comparatively early period. In the last decade of the eighth century they destroyed the monastery of Iona or Icolmkill, and between the years 810 and 830 they spread terror and devastation along the entire coast. In the year 838 they sailed with one hundred and twenty ships up to Dublin and conquered the city, under the leadership of Thorgisl, who still lives in Irish song and story under the names of Turges and Turgesius.

"After many sharp fights," says an old author,[A] "he conquered in a short time all Ireland, and erected, wherever he went, high fortifications of masonry with deep moats, of which many ruins are yet to be seen in the country." At last he fell in love with the daughter of Maelsechnail, king in Meath, and demanded of him that he should send her to him, attended by fifteen young maidens. Thorgisl promised to meet her with the same number of high-born Norsemen on an island in Loch Erne. But instead of maidens Maelsechnail sent fifteen beardless young men, disguised as women and armed with daggers. When Thorgisl arrived he was attacked by these and slain. On a previous occasion Maelsechnail had asked Thorgisl what he should do [39]to get rid of some strange and injurious birds that had got into the country. "Destroy their nests," said Thorgisl. Accordingly Maelsechnail began at once to destroy the Norse castles, while the Irish slew or chased away the Norsemen.

[A] Giraldus Cambrensis, De Topogr. Hiberniæ, cap. 37. Quoted from Munch, 1-438.

It appears probable that Thorgisl's reign in Ireland lasted from 838 to 846, although a much longer period is given by the above-quoted chronicler. A more enduring sway over the country was gained by the Norse sea-king Olaf the White, who belonged to the great Yngling race. In 852 a company of Danish vikings had possession of Dublin; but Olaf defeated them and compelled them to send him hostages. He then established himself in the city, built castles, and taxed the surrounding country. Two other Norsemen, the brothers Sigtrygg and Ivar, founded about the same time kingdoms—the former in Waterford, the latter in Limerick—without, however, being able to compete with Olaf in splendor and power. The dominion of the Norsemen in Dublin is said to have lasted for three hundred and fifty years. From Irish sources a somewhat different account is derived of these remarkable events. It is told that the Norsemen often sailed up the rivers, not as warriors, but as peaceful merchants, and that the Irish found it advantageous to trade with them. They thus gained considerable possessions in the cities, and when the vikings came there was already a party in the larger cities who favored them and made their conquests easy.

From Dublin Olaf the White made two cruises to Scotland, laid siege to Dumbarton, sailed southward to England, plundering and ravaging, and returned to Dublin with two hundred ships laden with precious booty. The Orkneys, the Hebrides, and the Faroe Isles were also, during this period, repeatedly visited by the vikings, and even to Iceland expedi[41]tions were made, which did not, however, result in permanent settlement. The Irish hermits and pious monks, who had retired from the world into the Arctic solitude, were disturbed in their devotions by the unwelcome visitors, and the majority returned to Ireland, while some are said to have remained until the island was regularly settled by the Norsemen.

To England the Norsemen went for the first time with hostile intent in 787. During the reign of King Beorthric in Wessex a small flock of vikings landed in the neighborhood of Dorchester, killed some people, and were driven away again. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle[A] relates the incident in these words:

[A] Monum. Hist. Brit., pp. 336, 337. Quoted from Munch, i., 416.

"In this year (787) King Beorthric married Eadburg, daughter of King Offa. In those days came for the first time Northmen and ships from Heredhaland. The gerêfa (commander) rode down to them and wished to drive them to the king's dwelling. For he knew not who they were; but they slew him there. These were the first ships belonging to Danish men which visited England."

It is noticeable that the ships are said in the same breath to have belonged to Northmen and to Danes, and it is obvious that the chronicler supposes the terms to be synonymous. The Heredhaland from which the men came was in all probability Hardeland in Jutland, where the Norsemen had at that time a colony.

The next attack of which we have an account was directed against the coast of Northumberland, and [42]took place in the year 794. The monk Simeon of Durham,[A] who lived in the beginning of the twelfth century, writes as follows:

[A] Simeon of Durham, Monum. Hist. Brit., p. 668. Quoted from Munch, i., 417.

"The heathen came from the northern countries to Britain like stinging wasps, roamed about like savage wolves, robbing, biting, killing not only horses, sheep, and cattle, but also priests, acolytes, monks, and nuns. They went to Lindisfarena church, destroying every thing in the most miserable manner, and trod the sanctuary with their profane feet, threw down the altars, robbed the treasures of the church, killed some of the brothers, carried others away in captivity, mocked many and flung them away naked, and threw some into the ocean. In 794 they harried King Ecgfridh's harbor, and plundered the monastery of Donmouth. But St. Cuthbert did not permit them to escape unpunished; for their chieftain was visited with a cruel death by the English and, a short time after, their ships were destroyed by a storm, and many of them perished; a few who swam ashore were killed without pity."

It is an odd circumstance that while an incessant stream of Norse vikings, during the first half of the ninth century, poured southward, devastating the shores of the Baltic and the Mediterranean, only a comparatively small number found their way to England. We hear in the Sagas of many individual warriors who visited the Saxon kings in England and took service under them, and of several who sailed up the Thames and put an embargo on the trade of the river, capturing every ship [43]that ventured into their clutches. But as a field for conquest they left England (probably not from any fraternal consideration) to their kinsmen, the Danes, while they themselves turned their attention to France, Ireland, and the isles north of Scotland. In the Hebrides, the Orkneys, the Shetland Islands, and the Faeroe Isles, their descendants are still living, and Norse names are yet frequent.

Another notable circumstance in connection with[44] the vikings is, that the very men whom foreign chroniclers describe as stinging wasps and savage wolves, and of whom the greatest atrocities are related during their sojourn abroad, became, as a rule, after their return home, men of weight and influence, with respect for tradition and law—men who, according to the standard of the time, were moral and honorable. There were exceptions, of course, but they go to prove the rule. The explanation is not far to seek. Religion in those days was tribal, and morality had no application outside the tribe. Every people is the chosen people of its own god or gods. As the Jews divided humanity into Jews and Gentiles, and the Greeks into Greeks and barbarians, so the Norsemen retaliated towards Jews and Greeks, by including them with all other nations in the Norse equivalent for barbarians. English, Irish, and Germans, often men of high birth, were constantly brought to Norway by the vikings as thralls, bartered and sold and forced to menial tasks. No law extended its protection to them; and yet maltreatment of thralls was, both in Iceland and Norway, regarded as unworthy of a freeman. For all that, the vikings were children of their age, and practised only the rude morality which their religion prescribed. The humanitarian sentiment which regards all men as brethren and creatures of the same God is a comparatively modern growth, and it would be unfair to judge the old Norsemen by any such advanced standard. It is therefore quite credible that the vikings may have been guilty of deeds abroad which they would not have committed at home.[45]

The Yngling race traced its ancestry from the god Frey. Snorre Sturlasson, in his famous work, "The Sagas of the Kings of Norway,"[A] mentions a long line of kings who were descended from Fjölne, a son of Frey, and reigned in Sweden having their residence in Upsala. Yngve was one of the god's surnames, and Yngling means a descendant of Yngve. One of the Ynglings, named Aun the Old, sacrificed every ten years one of his sons to Odin, having been promised that for every son he sacrificed, ten years should be added to his life. When he had thus slain seven sons, and was so old that he had to be fed like an infant, his people grew weary of him and saved the eighth son, whom he was about to sacrifice. Ingjald Ill-Ruler, when he took the kingdom on the death of his father Anund, sixth in descent from Aun the Old, made a great funeral feast, to which he invited all the neighboring kings. When he rose to drink the Brage goblet,[B] he vowed that he would increase[46] his kingdom by one half toward all the four corners of the heavens, or die in the attempt. As a preliminary step he set fire to the hall, burned his guests, and took possession of their lands. When he died, about the middle of the seventh century, he was so detested by his people that they would not accept his son, nor any of his race, as his successor. The son, whose name was Olaf, therefore gathered about him as many as would follow him, and emigrated to the great northern forests, where he felled the trees, gained much arable lands, and thereby acquired the nickname The Wood-cutter.[C] He and his people became prosperous, and a great influx of the discontented from the neighboring lands followed. In fact, so great was the number of immigrants that the country could not feed them, and they were threatened with famine. This they attributed, however, to the fact that Olaf was not in the favor of the gods, and they sacrificed him to Odin.

[A] "The Heimskringla, or the Sagas of the Kings of Norway," by the Icelander Snorre Sturlasson, was written in the twelfth century, and continued by his nephew Sturla Thordsson, is the principal source of the history of Norway up to the middle of the thirteenth century.

[B] The toast to the god Brage.

[C] Tretelgja.