Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Bible" to "Bisectrix"

Author: Various

Release date: December 19, 2010 [eBook #34702]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

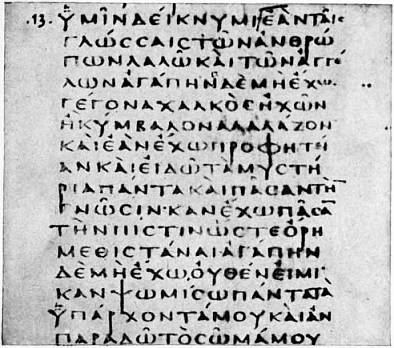

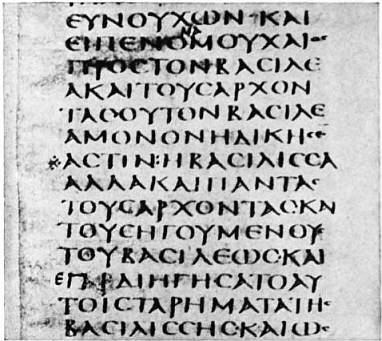

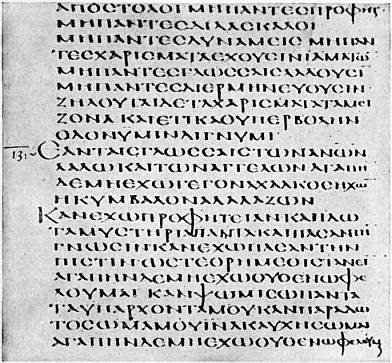

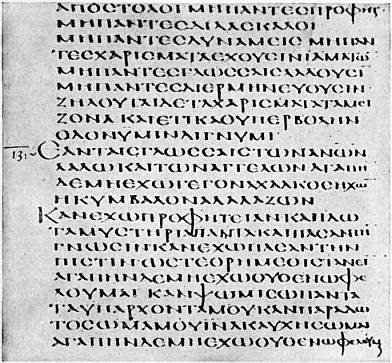

Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

BIBLE. The word “Bible,” which in English, as in medieval Latin, is treated as a singular noun, is in its original Greek form a plural, τὰ βιβλία, the (sacred) books—correctly expressing the fact that the sacred writings of Christendom (collectively described by this title) are made up of a number of independent records, which set before us the successive stages in the history of revelation. The origin of each of these records forms a distinct critical problem, and for the discussion of these questions of detail the reader is referred to the separate articles on the Biblical books. An account of the Bible as a whole involves so many aspects of interest, that, apart from the separate articles on its component books, the general questions of importance arising out of its present shape require to be discussed in separate sections of this article. They are here divided accordingly, into two main divisions:—(A) Old Testament, and (B) New Testament; and under each of these are treated (1) the Canon, (2) the texts and versions, (3) textual criticism, (4) the “higher criticism,” i.e. a general historical account (more particularly considered for separate books in the articles on them) of the criticism and views based on the substance and matter, as apart from criticism devoted to the correction and elucidation of the text, and (5) chronology. For the literary history of the translated English Bible, see the separate article under Bible, English.

(A) Old Testament

1. Canon.

We shall begin by giving a general account of the historical and literary conditions under which the unique literature of the Old Testament sprang up, of the stages by which it gradually reached its present form, and (so far as this is possible) of the way in which the Biblical books were brought together in a canonical collection. There exists no formal historical account of the formation of the Old Testament canon. The popular idea that this canon was closed by Ezra has no foundation in antiquity. Certainly in the apocryphal book of 2 Esdras, written towards the end of the 1st century A.D., we read (xiv. 20-26, 38-48), that, the law being burnt, Ezra, at his own request, was miraculously inspired to rewrite it; he procured accordingly five skilled scribes, and dictated to them for forty days, during which time they wrote 94 books, i.e. not only (according to the Jewish reckoning) the 24 books of the Old Testament, but 70 apocryphal books as well, which, being filled, it is said, with a superior, or esoteric wisdom, are placed upon even a higher level (vv. 46, 47) than the Old Testament itself. No argument is needed to show that this legend is unworthy of credit; even if it did deserve to be taken seriously, it still contains nothing respecting either a completion of the canon, or even a collection, or redaction, of sacred books by Ezra. Yet it is frequently referred to by patristic writers; and Ezra, on the strength of it, is regarded by them as the genuine restorer of the lost books of the Old Testament (see Ezra).

In 2 Macc. ii. 13 it is said that Nehemiah, “founding a library, gathered together the things concerning the kings and prophets, and the (writings) of David, and letters of kings about sacred gifts.” These statements are found in a part of 2 Macc. which is admitted to be both late and full of untrustworthy matter; still, the passage may preserve an indistinct reminiscence of an early stage in the formation of the canon, the writings referred 850 to being possibly the books of Samuel and Kings and some of the Prophets, a part of the Psalter, and documents such as those excerpted in the book of Ezra, respecting edicts issued by Persian kings in favour of the Temple. But obviously nothing definite can be built upon a passage of this character.

The first traces of the idea current in modern times that the canon of the Old Testament was closed by Ezra are found in the 13th century A.D. From this time, as is clearly shown by the series of quotations in Ryle’s Canon of the Old Testament, p. 257 ff. (2nd ed., p. 269 ff.), the legend—for it is nothing better—grew, until finally, in the hands of Elias Levita (1538), and especially of Johannes Buxtorf (1665), it assumed the form that the “men of the Great Synagogue,”—a body the real existence of which is itself very doubtful, but which is affirmed in the Talmud to have “written” (!) the books of Ezekiel, the Minor Prophets, Daniel and Esther—with Ezra as president, first collected the books of the Old Testament into a single volume, restored the text, where necessary, from the best MSS., and divided the collection into three parts, the Law, the Prophets and the “Writings” (the Hagiographa). The reputation of Elias Levita and Buxtorf led to this view of Ezra’s activity being adopted by other scholars, and so it acquired general currency. But it rests upon no authority in antiquity whatever.

The statement just quoted, however, that in the Jewish canon the books of the Old Testament are divided into three parts, though the arrangement is wrongly referred to Ezra, is in itself both correct and important. “The Law, the Prophets and the Writings (i.e. the Hagiographa)” is the standing Jewish expression for the Old Testament; and in every ordinary Hebrew Bible the books are arranged accordingly in the following three divisions:—

1. The Torah (or “Law”), corresponding to our “Pentateuch” (5 books).

2. The “Prophets,” consisting of eight books, divided into two groups:—

(a) The “Former Prophets”; Joshua, Judges, Samuel; Kings.1

(b) The “Latter Prophets”; Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, the Minor Prophets (called by the Jews “the Twelve,” and counted by them as one book).

3. The “Writings,” also sometimes the “Sacred Writings,” i.e., as we call them, the “Hagiographa,” consisting of three groups, containing in all eleven books:—

(a) The poetical books, Psalms, Proverbs, Job.

(b) The five Megilloth (or “Rolls”)—grouped thus together in later times, on account of the custom which arose of reading them in the synagogues at five sacred seasons—Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther.

(c) The remaining books, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah (forming one book), Chronicles.

There are thus, according to the Jewish computation, twenty-four “books” in the Hebrew canon. The threefold division of the canon just given is recognized in the Talmud, and followed in all Hebrew MSS., the only difference being that the books included in the Latter Prophets and in the Hagiographa are not always arranged in the same order. No book, however, belonging to one of these three divisions is ever, by the Jews, transferred to another. The expansion of the Talmudic twenty-four to the thirty-nine Old Testament books of the English Bible is effected by reckoning the Minor Prophets one by one, by separating Ezra from Nehemiah, and by subdividing the long books of Samuel, Kings and Chronicles. The different order of the books in the English Bible is due to the fact that when the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek between the 3rd and 1st centuries B.C., the Hebrew tripartite division was disregarded, and the books (including those now known as the “Apocrypha”) were grouped mostly by subjects, the historical books being placed first (Genesis—Esther), the poetical books next (Job—Song of Songs), and the prophetical books last (Isaiah—Malachi). Substantially the same order was followed in the Vulgate. The Reformers separated the books which had no Hebrew original (i.e. the Apocrypha) from the rest, and placed them at the end; the remaining books, as they stood in the Vulgate, were then in the order which they still retain in the English Bible.

The tripartite division of the Hebrew canon thus recognized by Jewish tradition can, however, be traced back far beyond the Talmud. The Proverbs of Jesus, the son of Sirach (c. 200 B.C.), which form now the apocryphal book Ecclesiasticus, were translated into Greek by the grandson of the author at about 130 B.C.; and in the preface prefixed by him to his translation he speaks of “the law, and the prophets, and the other books of our fathers,” and again of “the law, and the prophets, and the rest of the books,” expressions which point naturally to the same threefold division which was afterwards universally recognized by the Jews. The terms used, however, do not show that the Hagiographa was already completed, as we now have it; it would be entirely consistent with them, if, for instance, particular books, as Esther, or Daniel, or Ecclesiastes, were only added to the collection subsequently. Another allusion to the tripartite division is also no doubt to be found in the expression “the law, the prophets, and the psalms,” in Luke xxiv. 44. A collection of sacred books, including in particular the prophets, is also referred to in Dan. ix. 2 (R. V.), written about 166 B.C.

This threefold division of the Old Testament, it cannot reasonably be doubted, rests upon an historical basis. It represents three successive stages in the history of the collection. The Law was the first part to be definitely recognized as authoritative, or canonized; the “Prophets” (as defined above) were next accepted as canonical; the more miscellaneous collection of books comprised in the Hagiographa was recognized last. In the absence of all external evidence respecting the formation of the canon, we are driven to internal evidence in our endeavour to fix the dates at which these three collections were thus canonized. And internal evidence points to the conclusion that the Law could scarcely have been completed, and accepted formally, as a whole, as canonical before 444 B.C. (cf. Neh. viii.-x.); that the “Prophets” were completed and so recognized about 250 B.C., and the Hagiographa between about 150 and 100 B.C. (See further Ryle’s Canon of the Old Testament.)

Having thus fixed approximately the terminus ad quem at which the Old Testament was completed, we must now begin at the other end, and endeavour to sketch in outline the process by which it gradually reached its completed form. And here it will be found to be characteristic of nearly all the longer books of the Old Testament, and in some cases even of the shorter ones as well, that they were not completed by a single hand, but that they were gradually expanded, and reached their present form by a succession of stages.

Among the Hebrews, as among many other nations, the earliest beginnings of literature were in all probability poetical. At least the opening phrases of the song of Moses in Exodus xv.; the song of Deborah in Judges v.; the fragment from the “Book of the Wars of Yahweh,” in Numbers xxi. 14, 15; the war-ballad, celebrating an Israelitish victory, in Numbers xxi. 27-30; the extracts from the “Book of Jashar” (or “of the Upright,” no doubt a title of Israel) quoted in Joshua x. 12, 13 (“Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon,” &c.); in 2 Sam. i. (David’s elegy over Saul and Jonathan); and, very probably, in the Septuagint of 1 Kings viii. 13 [Sept. 53], as the source of the poetical fragment in vv. 12, 13, describing Solomon’s building of the Temple, show how great national occurrences and the deeds of ancient Israelitish heroes stimulated the national genius for poetry, and evoked lyric songs, suffused with religious feeling, by which their memory was perpetuated. The poetical descriptions of the character, or geographical position, of the various tribes, now grouped together as the Blessings of Jacob (Gen. xlix.) and Moses (Deut. xxxiii.), may be mentioned at the same time. These poems, which are older, and in most cases considerably older, than the narratives in which they are now embedded, if they were collected into books, must have been fairly numerous, 851 and we could wish that more examples of them had been preserved.

The historical books of the Old Testament form two series: one, consisting of the books from Genesis to 2 Kings (exclusive of Ruth, which, as we have seen, forms in the Hebrew canon part of the Hagiographa), embracing the period from the Creation to the destruction of Jerusalem by the Chaldaeans in 586 B.C.; the other, comprising the books of Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah, beginning with Adam and ending with the second visit of Nehemiah to Jerusalem in 432 B.C. These two series differ from one another materially in scope and point of view, but in one respect they are both constructed upon a similar plan; no entire book in either series consists of a single, original work; but older writings, or sources, have been combined by a compiler—or sometimes, in stages, by a succession of compilers—in such a manner that the points of juncture are often clearly discernible, and the sources are in consequence capable of being separated from one another. The authors of the Hebrew historical books, as we now have them, do not, as a rule, as a modern author would do, rewrite the matter in their own language; they excerpt from pre-existing documents such passages as are suitable to their purpose, and incorporate them in their work, sometimes adding at the same time matter of their own. Hebrew writers, however, exhibit usually such strongly marked individualities of style that the documents or sources, thus combined, can generally be distinguished from each other, and from the comments or other additions of the compiler, without difficulty. The literary differences are, moreover, often accompanied by differences of treatment, or representation of the history, which, where they exist, confirm independently the conclusions of the literary analysis. Although, however, the historical books generally are constructed upon similar principles, the method on which these principles have been applied is not quite the same in all cases. Sometimes, for instance, the excerpts from the older documents form long and complete narratives; in other cases (as in the account of the Flood) they consist of a number of short passages, taken alternately from two older narratives, and dovetailed together to make a continuous story; in the books of Judges and Kings the compiler has fitted together a series of older narratives in a framework supplied by himself; the Pentateuch and book of Joshua (which form a literary whole, and are now often spoken of together as the Hexateuch) have passed through more stages than the books just mentioned, and their literary structure is more complex.

The Hexateuch (Gen.-Josh.).—The traditions current among the Israelites respecting the origins and early history of their nation—the patriarchal period, and the times of Moses and Joshua—were probably first cast into a written form in the 10th or 9th century B.C. by a prophet living in Judah, who, from the almost exclusive use in his narrative of the sacred name “Jahveh” (“Jehovah”),—or, as we now commonly write it, Yahweh,—is referred to among scholars by the abbreviation “J.” This writer, who is characterized by a singularly bright and picturesque style, and also by deep religious feeling and insight, begins his narrative with the account of the creation of man from the dust, and tells of the first sin and its consequences (Gen. ii. 4b-iii. 24); then he gives an account of the early growth of civilization (Gen. iv.), of the Flood (parts of Gen. vi.-viii.), and the origin of different languages (xi. 1-9); afterwards in a series of vivid pictures he gives the story, as tradition told it, of the patriarchs, of Moses and the Exodus, of the journey through the wilderness, and the conquest of Canaan. It would occupy too much space to give here a complete list of the passages belonging to “J”; but examples of his narrative (with the exception here and there of a verse or two belonging to one of the other sources described below) are to be found, for instance, in Gen. xii., xiii., xviii.-xix. (the visit of the three angels to Abraham, and the judgment on Sodom and Gomorrah), xxiv. (Abraham’s servant sent to find a wife for Isaac), xxvii. 1-45 (Jacob obtaining his father’s blessing), xxxii., xliii., xliv. (parts of the history of Joseph); Ex. iv.-v. (mostly), viii. 20-ix. 7, x. 1-11, xxxiii. 12-xxxiv. 26 (including, in xxxiv. 17-26, a group of regulations, of a simple, undeveloped character, on various religious observances); Num. x. 29-36, and most of Num. xi.

Somewhat later than “J,” another writer, commonly referred to as “E,” from his preference for the name Elohim (“God”) rather than “Jehovah,” living apparently in the northern kingdom, wrote down the traditions of the past as they were current in northern Israel, in a style resembling generally that of “J,” but not quite as bright and vivid, and marked by small differences of expression and representation. The first traces of “E” are found in the life of Abraham, in parts of Gen. xv.; examples of other passages belonging to this source are:—Gen. xx. 1-17, xxi. 8-32, xxii. 1-14, xl.-xlii. and xlv. (except a few isolated passages); Ex. xviii., xx.-xxiii. (including the decalogue—in its original, terser form, without the explanatory additions now attached to several of the commandments—and the collection of laws, known as the “Book of the Covenant,” in xxi.-xxiii.), xxxii., xxxiii. 7-11; Num. xii., most of Num. xxii.-xxiv. (the history of Balaam); Josh. xxiv. “E” thus covers substantially the same ground as “J,” and gives often a parallel, though somewhat divergent, version of the same events. The laws contained in Ex. xx. 23-xxiii. 19 were no doubt taken by “E” from a pre-existing source; with the regulations referred to above as incorporated in “J” (Ex. xxxiv. 17-26), they form the oldest legislation of the Hebrews that we possess; they consist principally of civil ordinances, suited to regulate the life of a community living under simple conditions of society, and chiefly occupied in agriculture, but partly also of elementary regulations respecting religious observances (altars, sacrifices, festivals, &c.).

Not long, probably, after the fall of the northern kingdom in 722 B.C., a prophet of Judah conceived the plan of compiling a comprehensive history of the traditions of his people. For this purpose he selected extracts from the two narratives, “J” and “E,” and combined them together into a single narrative, introducing in some places additions of his own. This combined narrative is commonly known as “JE.” As distinguished from the Priestly Narrative (to be mentioned presently), it has a distinctly prophetical character; it treats the history from the standpoint of the prophets, and the religious ideas characteristic of the prophets often find expression in it. Most of the best-known narratives of the patriarchal and Mosaic ages belong to “JE.” His style, especially in the parts belonging to “J,” is graphic and picturesque, the descriptions are vivid and abound in detail and colloquy, and both emotion and religious feeling are warmly and sympathetically expressed in it.

Deuteronomy.—In the 7th century B.C., during the reign of either Manasseh or Josiah, the narrative of “JE” was enlarged by the addition of the discourses of Deuteronomy. These discourses purport to be addresses delivered by Moses to the assembled people, shortly before his death, in the land of Moab, opposite to Jericho. There was probably some tradition of a farewell address delivered by Moses, and the writer of Deuteronomy gave this tradition form and substance. In impressive and persuasive oratory he sets before Israel, in a form adapted to the needs of the age in which he lived, the fundamental principles which Moses had taught. Yahweh was Israel’s only god, who tolerated no other god beside Himself, and who claimed to be the sole object of the Israelite’s reverence. This is the fundamental thought which is insisted on and developed in Deuteronomy with great eloquence and power. The truths on which the writer loves to dwell are the sole godhead of Yahweh, His spirituality (ch. iv.), His choice of Israel, and the love and faithfulness which He had shown towards it, by redeeming it from slavery in Egypt, and planting it in a free and fertile land; from which are deduced the great practical duties of loyal and loving devotion to Him, an uncompromising repudiation of all false gods, the rejection of all heathen practices, a cheerful and ready obedience to His will, and a warm-hearted and generous attitude towards man. Love of God is the primary spring of human duty (vi. 5). In the course of his argument (especially in chs. xii.-xxvi.), the writer takes up most of the laws, both civil 852 and ceremonial, which (see above) had been incorporated before in “J” and “E,” together with many besides which were current in Israel; these, as a rule, he expands, applies or enforces with motives; for obedience to them is not to be rendered merely in deference to external authority, it is to be prompted by right moral and religious motives. The ideal of Deuteronomy is a community of which every member is full of love and reverence towards his God, and of sympathy and regard for his fellow-men. The “Song” (Deut. xxxii.) and “Blessing” (Deut. xxxiii.) of Moses are not by the author of the discourses; and the latter, though not Mosaic, is of considerably earlier date.

The influence of Deuteronomy upon subsequent books of the Old Testament is very perceptible. Upon its promulgation it speedily became the book which both gave the religious ideals of the age, and moulded the phraseology in which these ideals were expressed. The style of Deuteronomy, when once it had been formed, lent itself readily to imitation; and thus a school of writers, imbued with its spirit, and using its expressions, quickly arose, who have left their mark upon many parts of the Old Testament. In particular, the parts of the combined narrative “JE,” which are now included in the book of Joshua, passed through the hands of a Deuteronomic editor, who made considerable additions to them—chiefly in the form of speeches placed, for instance, in the mouth of Joshua, or expansions of the history, all emphasizing principles inculcated in Deuteronomy and expressed in its characteristic phraseology (e.g. most of Josh. i., ii. 10-11, iii. 2-4, 6-9, x. 28-43, xi. 10-23, xii., xiii. 2-6, 8-12, xxiii.). From an historical point of view it is characteristic of these additions that they generalize Joshua’s successes, and represent the conquest of Canaan, effected under his leadership, as far more complete than the earlier narratives allow us to suppose was the case. The compilers of Judges and Kings are also (see below) strongly influenced by Deuteronomy.

The Priestly sections of the Hexateuch (known as “P”) remain still to be considered. That these are later than “JE,” and even than Deut., is apparent—to mention but one feature—from the more complex ritual and hierarchical organization which they exhibit. They are to all appearance the work of a school of priests, who, after the destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C., began to write down and codify the ceremonial regulations of the pre-exilic times, combining them with an historical narrative extending from the Creation to the establishment of Israel in Canaan; and who completed their work during the century following the restoration in 537 B.C. The chief object of these sections is to describe in detail the leading institutions of the theocracy (Tabernacle, sacrifices, purifications, &c.), and to refer them to their traditional origin in the Mosaic age. The history as such is subordinate; and except at important epochs is given only in brief summaries (e.g. Gen. xix. 29, xli. 46). Statistical data (lists of names, genealogies, and precise chronological notes) are a conspicuous feature in it. The legislation of “P,” though written down in or after the exile, must not, however, be supposed to be the creation of that period; many elements in it can be shown from the older literature to have been of great antiquity in Israel; it is, in fact, based upon pre-exilic Temple usage, though in some respects it is a development of it, and exhibits the form which the older and simpler ceremonial institutions of Israel ultimately assumed. In “P’s” picture of the Mosaic age there are many ideal elements; it represents the priestly ideal of the past rather than the past as it actually was. The following examples of passages from “P” will illustrate what has been said:—Gen. i. 1-ii. 4a, xvii. (institution of circumcision), xxiii. (purchase of the cave of Machpelah), xxv. 7-17, xlvi. 6-27; Ex. vi. 2-vii. 13, xxv.-xxxi. (directions for making the Tabernacle, its vessels, dress of the priests, &c.), xxxv.-xl. (execution of these directions); Lev. (the whole); Num. i. 1-x. 28 (census of people, arrangement of camp, and duties of Levites, law of the Nazirite, &c.), xv., xviii., xix., xxvi.-xxxi., xxxiii.-xxxvi.; Josh. v. 10-12, the greater part of xv.-xix. (distribution of the land among the different tribes), xxi. 1-42. The style of “P” is strongly marked—as strongly marked, in fact, as (in a different way) that of Deuteronomy is; numerous expressions not found elsewhere in the Hexateuch occur in it repeatedly. The section Lev. xvii.-xxvi. has a character of its own; for it consists of a substratum of older laws, partly moral (chs. xviii.-xx. mostly), partly ceremonial, with a hortatory conclusion (ch. xxvi.), with certain very marked characteristics (from one of which it has received the name of the “Law of Holiness”), which have been combined with elements belonging to, or conceived in the spirit of, the main body of “P.”

Not long after “P” was completed, probably in the 5th century B.C., the whole, consisting of “JE” and Deuteronomy, was combined with it; and the existing Hexateuch was thus produced.

Judges, Samuel and Kings.—The structure of these books is simpler than that of the Hexateuch. The book of Judges consists substantially of a series of older narratives, arranged together by a compiler, and provided by him, where he deemed it necessary, with introductory and concluding comments (e.g. ii. 11-iii. 6, iii. 12-15a, 30, iv. 1-3, 23, 24, v. 31b). The compiler is strongly imbued with the spirit of Deuteronomy; and the object of his comments is partly to exhibit the chronology of the period as he conceived it, partly to state his theory of the religious history of the time. The compiler will not have written before c. 600 B.C.; the narratives incorporated by him will in most cases have been considerably earlier. The books of Samuel centre round the names of Samuel, Saul and David. They consist of a series of narratives, or groups of narratives, dealing with the lives of these three men, arranged by a compiler, who, however, unlike the compilers of Judges and Kings, rarely allows his own hand to appear. Some of these narratives are to all appearance nearly contemporary with the events that they describe (e.g. 1 Sam. ix. 1-x. 16, xi. 1-11, 15, xiii.-xiv., xxv.-xxxi.; 2 Sam. ix.-xx.); others are later. In 1 Sam. the double (and discrepant) accounts of the appointment of Saul as king (ix. 1-x. 16, xi. 1-11, 15, and viii., x. 17-27, xii.), and of the introduction of David to the history (xvi. 14-23 and xvii. 1-xviii. 5) are noticeable; in ix. 1-x. 16, xi. 1-11, 15, the monarchy is viewed as God’s gracious gift to His people; in viii., x. 17-27, xii., which reflect the feeling of a much later date, the monarchy is viewed unfavourably, and represented as granted by God unwillingly. The structure of the book of Kings resembles that of Judges. A number of narratives, evidently written by prophets, and in many of which also (as those relating to Elijah, Elisha and Isaiah) prophets play a prominent part, and a series of short statistical notices, relating to political events, and derived probably from the official annals of the two kingdoms (which are usually cited at the end of a king’s reign), have been arranged together, and sometimes expanded at the same time, in a framework supplied by the compiler. The framework is generally recognizable without difficulty. It comprises the chronological details, references to authorities, and judgments on the character of the various kings, especially as regards their attitude to the worship at the high places, all cast in the same literary mould, and marked by the same characteristic phraseology. Both in point of view and in phraseology the compiler shows himself to be strongly influenced by Deuteronomy. The two books appear to have been substantially completed before the exile; but short passages were probably introduced into them afterwards. Examples of passages due to the compiler: 1 Kings ii. 3-4, viii. 14-61 (the prayer of dedication put into Solomon’s mouth), ix. 1-9, xi. 32b-39, xiv. 7-11, 19-20, 21-24, 29-31, xv. 1-15, xxi. 20b-26; 2 Kings ix. 7-10a, xvii. 7-23.

The Latter Prophets.—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, the Twelve. The writings of the canonical prophets form another important element in the Old Testament, also, like the historical books, of gradual growth. Beginning with Amos and Hosea, they form a series which was not completed till more than three centuries had passed away. The activity of the prophets was largely called forth by crises in the national history. They were partly moral reformers, partly religious teachers, partly political advisers. They held up before a backsliding people the ideals of human duty, of religious truth and of national policy. They expanded and developed, and applied to new situations and 853 circumstances of the national life, the truths which in a more germinal form they had inherited from their ancestors. The nature and attributes of God; His gracious purposes towards man; the relation of man to God, with the practical consequences that follow from it; the true nature of religious service; the call to repentance as the condition of God’s favour; the ideal of character and action which each man should set before himself; human duty under its various aspects; the responsibilities of office and position; the claims of mercy and philanthropy, justice and integrity; indignation against the oppression of the weak and the unprotected; ideals of a blissful future, when the troubles of the present will be over, and men will bask in the enjoyment of righteousness and felicity,—these, and such as these, are the themes which are ever in the prophets’ mouths, and on which they enlarge with unwearying eloquence and power.

For the more special characteristics of the individual prophets, reference must be made to the separate articles devoted to each; it is impossible to do more here than summarize briefly the literary structure of their various books.

Isaiah.—The book of Isaiah falls into two clearly distinguished parts, viz. chs. i.-xxxix., and xl.-lxvi. Chs. xl.-lxvi., however, are not by Isaiah, but are the work of a prophet who wrote about 540 B.C., shortly before the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus, and whose aim was to encourage the Israelites in exile, and assure them of the certainty of their approaching restoration to Canaan. (According to many recent critics, this prophet wrote only chs. xl.-lv., chs. lvi.-lxvi. being added subsequently, some time after the return.) The genuine prophecies of Isaiah are contained in chs. i.-xii., xiv. 24-xxiii., xxviii.-xxxiii., xxxvii. 22-32,—all written between 740 and 700 B.C. (or a little later), and all (except ch. vi.) having reference to the condition of Judah and Israel, and the movements of the Assyrians during the reigns of Ahaz and Hezekiah. The opinion has, however, latterly gained ground that parts even of these chapters are of later origin than Isaiah’s own time. Of the rest of chs. i.-xxxix. this is generally admitted. Thus chs. xiii. 1-xiv. 23, xxi. 1-10, xxxiv.-xxxv. belong to the same age as chs. xl.-lxvi., xiii. 1-xiv. 23, and xxi. 1-10, looking forward similarly to the approaching fall of Babylon; chs. xxiv.-xxvii. have a character of their own, and form an apocalypse written not earlier than the 5th century B.C.; chs. xxxvi.-xxxix., describing incidents in which Isaiah took a part, consist of narratives excerpted from 2 Kings xviii. 13-xx. with the addition of Hezekiah’s song (xxxviii. 9-20). It is evident from these facts that the book of Isaiah did not assume its present form till considerably after the return of the Jews from exile in 537, when a compiler, or series of compilers, arranged the genuine prophecies of Isaiah which had come to his hands, together with others which at the time were attributed to Isaiah, and gave the book its present form.

Jeremiah.—Jeremiah’s first public appearance as a prophet was in the 13th year of Josiah (Jer. i. 2, xxv. 3), i.e. 626 B.C., and his latest prophecy (ch. xliv.) was delivered by him in Egypt, whither he was carried, against his will, by some of the Jews who had been left in Judah, shortly after the fall of Jerusalem in 586. Jeremiah was keenly conscious of his people’s sin; and the aim of most of his earlier prophecies is to bring his countrymen, if possible, to a better mind, in the hope that thereby the doom which he sees impending may be averted—an end which eventually he saw clearly to be unattainable. Jeremiah’s was a sensitive, tender nature; and he laments, with great pathos and emotion, his people’s sins, the ruin to which he saw his country hastening, and the trials and persecutions which his predictions of disaster frequently brought upon him. A large part of his book is biographical, describing various incidents of his ministry. Prophecies of restoration are contained in chs. xxx.-xxxiii. The prophecies of the first twenty-three years of his ministry, as we are expressly told in ch. xxxvi., were first written down in 604 B.C. by his friend and amanuensis Baruch, and the roll thus formed must have formed the nucleus of the present book. Some of the reports of Jeremiah’s prophecies, and especially the biographical narratives, also probably have Baruch for their author. But the chronological disorder of the book, and other indications, show that Baruch could not have been the compiler of the book, but that the prophecies and narratives contained in it were collected together gradually, and that it reached its present form by a succession of stages, which were not finally completed till long after Israel’s return from Babylon. The long prophecy (l. 1-li. 58), announcing the approaching fall of Babylon, is not by Jeremiah, and cannot have been written till shortly before 538 B.C.

Ezekiel.—Ezekiel was one of the captives who were carried with Jehoiachin in 597 B.C. to Babylonia, and was settled with many other exiles at a place called Tel-abib (iii. 15). His prophecies (which are regularly dated) are assigned to various years from 592 to 570 B.C. The theme of the first twenty-four chapters of his book is the impending fall of Jerusalem, which took place actually in 586, and which Ezekiel foretells in a series of prophecies, distinguished by great variety of symbolism and imagery. Chs. xxv.-xxxii. are on various foreign nations, Edom, Tyre, Egypt, &c. Prophecies of Israel’s future restoration follow in chs. xxxiii.-xlviii., chs. xl.-xlviii. being remarkable for the minuteness with which Ezekiel describes the organization of the restored community, as he would fain see it realized, including even such details as the measurements and other arrangements of the Temple, the sacrifices to be offered in it, the duties and revenues of the priests, and the redistribution of the country among the twelve tribes. The book of Ezekiel bears throughout the stamp of a single mind; the prophecies contained in it are arranged methodically; and to all appearance—in striking contrast to the books of Isaiah and Jeremiah—it received the form in which we still have it from the prophet himself.

The Twelve Minor Prophets.—These, as was stated above, were reckoned by the Jews as forming a single “book.” The two earliest of the Minor Prophets, Amos and Hosea, prophesied in the northern kingdom, at about 760 and 740 B.C. respectively; both foresaw the approaching ruin of northern Israel at the hands of the Assyrians, which took place in fact when Sargon took Samaria in 722 B.C.; and both did their best to stir their people to better things. The dates of the other Minor Prophets (in some cases approximate) are: Micah, c. 725-c. 680 B.C. (some passages perhaps later); Zephaniah, c. 625; Nahum, shortly before the destruction of Nineveh by the Manda in 607; Habakkuk (on the rise and destiny of the Chaldaean empire) 605-600; Obadiah, after the destruction of Jerusalem by the Chaldaeans in 586; Haggai, 520; Zechariah, i.-viii. (as in Haggai, promises and encouragements connected with the rebuilding of the Temple) 520 and 518; Malachi, c. 460-450; Joel, 5th century B.C.; Jonah, 4th century B.C. The latest prophecies in the book are, probably, those contained in Zech. ix.-xiv. which reflect entirely different historical conditions from Zech. i.-viii. (520 and 518 B.C.), and may be plausibly assigned to the period beginning with the conquests of Alexander the Great, between 332 and c. 300 B.C. Why these prophecies were attached to Zech. i.-viii. must remain matter of conjecture; but there are reasons for supposing that, together with the prophecy of Malachi, they came to the compiler of the “book” of the Twelve Prophets anonymously, and he simply attached them at the point which his collection had reached (i.e. at the end of Zech. viii.).

The Psalms.—The Psalter is that part of the Old Testament in which the devotional aspect of the religious character finds its completest expression; and in lyrics of exquisite tenderness and beauty the most varied emotions are poured forth by the psalmists to their God—despondency and distress, penitence and resignation, hope and confidence, jubilation and thankfulness, adoration and praise. The Psalter, it is clear from many indications, is not the work of a single compiler, but was formed gradually. A single compiler is not likely to have introduced double recensions of one and the same psalm (as Ps. liii. = Ps. xiv., Ps. lxx. = Ps. xi. 13-17, Ps. cviii. = Ps. lvii. 7-11 + lx. 5-12); in the Hebrew canon the Psalter is composed of five 854 books (i.-xli., xlii.-lxxii., lxxiii.-lxxxix., xc.-cvi., cvii.-cl.); and in many parts it is manifestly based upon independent smaller collections; for it contains groups of psalms headed “David,” the “sons of Korah,” “Asaph,” “Songs of Ascents.” Each of the five books of which it is composed contains psalms which show that its compilation cannot have been completed till after the return from the Captivity; and indeed, when the individual psalms are studied carefully it becomes apparent that in the great majority of cases they presuppose the historical conditions, or the religious experiences, of the ages that followed Jeremiah. Thus, though it is going too far to say that there are no pre-exilic psalms, the Psalter, as a whole, is the expression of the deeper spiritual feeling which marked the later stages of Israel’s history. It has been not inaptly termed the Hymn-book of the second Temple. Its compilation can hardly have been finally completed before the 3rd century B.C.; if it is true, as many scholars think, that there are psalms dating from the time of the Maccabee struggle (Ps. xliv., lxxiv., lxxix., lxxxiii, and perhaps others), it cannot have been completed till after 165 B.C.

The Book of Proverbs.—This is the first of the three books belonging to the “Wisdom-literature” of the Hebrews, the other two books being Job and Ecclesiastes. The Wisdom-literature of the Hebrews concerned itself with what we should call the philosophy of human nature, and sometimes also of physical nature as well; its writers observed human character, studied action in its consequences, laid down maxims for education and conduct, and reflected on the moral problems which human society presents. The book of Proverbs consists essentially of generalizations on human character and conduct, with (especially in chs. i.-ix.) moral exhortations addressed to an imagined “son” or pupil. The book consists of eight distinct portions, chs. i.-ix. being introductory, the proverbs, properly so called, beginning at x. 1 (with the title “The Proverbs of Solomon”), and other, shorter collections, beginning at xxii. 17, xxiv. 23, xxv. 1, xxx. 1, xxxi. 1, xxxi. 10 respectively. The book, it is evident, was formed gradually. A small nucleus of the proverbs may be Solomon’s; but the great majority represent no doubt the generalizations of a long succession of “wise men.” The introduction, or “Praise of Wisdom,” as it has been called (chs. i.-ix), commending the maxims of Wisdom as a guide to the young, will have been added after most of the rest of the book was already complete. The book will not have finally reached its present form before the 4th century B.C. Some scholars believe that it dates entirely from the Greek period (which began 332 B.C.); but it may be doubted whether there are sufficient grounds for this conclusion.

Job.—The book of Job deals with a problem of human life; in modern phraseology it is a work of religious philosophy. Job is a righteous man, overwhelmed with undeserved misfortune; and thus the question is raised, Why do the righteous suffer? Is their suffering consistent with the justice of God? The dominant theory at the time when Job was written was that all suffering was a punishment of sin; and the aim of the book is to controvert this theory. Job’s friends argue that he must have been guilty of some grave sin; Job himself passionately maintains his innocence; and on the issue thus raised the dialogue of the book turns. The outline of Job’s story was no doubt supplied by tradition; and a later poet has developed this outline, and made it a vehicle for expressing his new thoughts respecting a great moral problem which perplexed his contemporaries. A variety of indications (see Job) combine to show that the book of Job was not written till after the time of Jeremiah—probably, indeed, not till after the return from exile. The speeches of Elihu (chs. xxxii.-xxxvii.) are not part of the original poem, but were inserted in it afterwards.

There follow (in the Hebrew Bible) the five short books, which, as explained above, are now known by the Jews as the Megilloth, or “Rolls,” viz. Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes and Esther. Of these, the Song of Songs, in exquisite poetry, extols the power and sweetness of pure and faithful human love. The date at which it was written is uncertain; there are features in it which point to its having been the work of a poet living in north Israel, and writing at an early date; but most recent scholars, on account chiefly of certain late expressions occurring in it, think that it cannot have been written earlier than the 4th or 3rd century B.C. In the graceful and tender idyll of Ruth, it is told how Ruth, the Moabitess, and a native consequently of a country hostile theocratically to Israel, adopted Israel’s faith (i. 16), and was counted worthy to become an ancestress of David. The date of Ruth is disputed; Driver has defended a pre-exilic date for it, but the general opinion of modern scholars is that it belongs to the 5th century B.C. The Lamentations consist of five elegies on the fall of Jerusalem, and the sufferings which its people experienced in consequence; they must all have been composed not long after 586 B.C. Ecclesiastes, the third book belonging (see above) to the Wisdom-literature, consists of moralizings, prompted by the dark times in which the author’s lot in life was cast, on the disappointments which seemed to him to be the reward of all human endeavour, and the inability of man to remedy the injustices and anomalies of society. If only upon linguistic grounds—for the Hebrew of the book resembles often that of the Mishnah more than the ordinary Hebrew of the Old Testament—Ecclesiastes must be one of the latest books in the Hebrew canon. It was most probably written during the Greek period towards the end of the 3rd century B.C. The book of Esther, which describes, with many legendary traits, how the beautiful Jewess succeeded in rescuing her people from the destruction which Haman had prepared for them, will not be earlier than the closing years of the 4th century B.C., and is thought by many scholars to be even later.

The Book of Daniel.—The aim of this book is to strengthen and encourage the pious Jews in their sufferings under the persecution of Antiochus Epiphanes, 168-165 B.C. Chs. i.-vi. consist of narratives, constructed no doubt upon a traditional basis, of the experiences of Daniel at the Babylonian court, between 605 and 538 B.C., with the design of illustrating how God, in times of trouble, defends and succours His faithful servants. Chs. vii.-xii. contain a series of visions, purporting to have been seen by Daniel, and describing, sometimes (especially in ch. xi.) with considerable minuteness, the course of events from Alexander the Great, through the two royal lines of the Ptolemies and the Seleucidae, to Antiochus Epiphanes, dwelling in particular on the persecuting measures adopted by Antiochus against the Jews, and promising the tyrant’s speedy fall (see e.g. viii. 9-14, 23-25, xi. 21-45). Internal evidence shows clearly that the book cannot have been written by Daniel himself; and that it must in fact be a product of the period in which its interest culminates, and the circumstances of which it so accurately reflects, i.e. of 168-165 B.C.

Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah.—These books form the second series of historical books referred to above, Ezra and Nehemiah carrying on the narrative of Chronicles, and forming its direct sequel. 1 Chr. i.-ix. consists mostly of tribal genealogies, partly based upon data contained in the older books (Gen.-Kings), partly including materials found by the compiler elsewhere. 1 Chr. x.-2 Chr. xxxvi. consists of a series of excerpts from the books of Samuel and Kings—sometimes transcribed without substantial change, at other times materially altered in the process—combined with matter, in some cases limited to a verse or two, in others extending to several chapters, contributed by the compiler himself, and differing markedly from the excerpts from the older books both in phraseology and in point of view. The books of Ezra and Nehemiah are of similar structure; here the sources excerpted are the Memoirs of Ezra and Nehemiah, written by themselves in the first person; viz. Ezra vii. 12-ix. (including the decree of Artaxerxes, vii. 12-26); Neh. i. 1-vii. 73a, xii. 31-41, xiii.; and a narrative written in Aramaic (Ezra iv. 8-vi. 18); Ezra x. and Neh. viii.-x. also are in all probability based pretty directly upon the Memoirs of Ezra; the remaining parts of the books are the composition of the compiler. The additions of the compiler, especially in the Chronicles, place the old history in a new light; he invests it with the associations of his own day; and pictures pre-exilic Judah as already possessing the fully developed ceremonial 855 system, under which he lived himself, and as ruled by the ideas and principles current among his contemporaries. There is much in his representation of the past which cannot be historical. For examples of narratives which are his composition see 1 Chr. xv. 1-24, xvi. 4-42, xxii. 2-xxix.; 2 Chr. xiii. 3-22, xiv. 6-xv. 15, xvi. 7-11, xvii., xix. 1-xx. 30, xxvi. 16-20, xxix. 3-xxxi. 21. On account of the interest shown by the compiler in the ecclesiastical aspects of the history, his work has been not inaptly called the “Ecclesiastical Chronicle of Jerusalem.” From historical allusions in the book of Nehemiah, it may be inferred that the compiler wrote at about 300 B.C.

2. Texts and Versions.

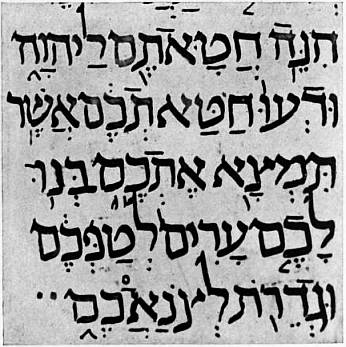

Text.—The form in which the Hebrew text of the Old Testament is presented to us in all MSS. and printed editions is that of the Massoretic text, the date of which is usually placed somewhere between the 6th and 8th centuries of the Christian era. It is probable that the present text became fixed as early as the 2nd century A.D., but even this earlier date leaves a long interval between the original autographs of the Old Testament writers and our present text. Since the fixing of the Massoretic text the task of preserving and transmitting the sacred books has been carried out with the greatest care and fidelity, with the result that the text has undergone practically no change of any real importance; but before that date, owing to various causes, it is beyond dispute that a large number of corruptions were introduced into the Hebrew text. In dealing, therefore, with the textual criticism of the Old Testament it is necessary to determine the period at which the text assumed its present fixed form before considering the means at our disposal for controlling the text when it was, so to speak, in a less settled condition.

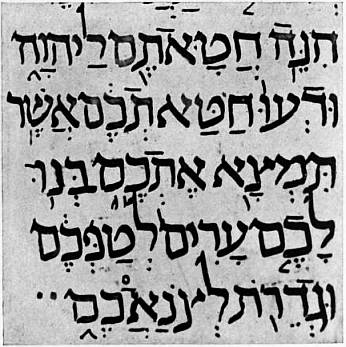

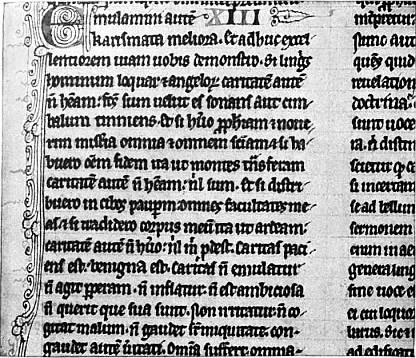

An examination of the extant MSS. of the Hebrew Old Testament reveals two facts which at first sight are somewhat remarkable. The first is that the oldest dated MS., the Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus, only goes back to the year A.D. 916, though it is probable that one or two MSS. Massoretic text. belong to the 9th century. The second fact is that all our Hebrew MSS. represent one and the same text, viz. the Massoretic. This text was the work of a special gild of trained scholars called Massoretes (בעלי המסרת) or “masters of tradition” (מסורה or less correctly מסרת),2 whose aim was not only to preserve and transmit the consonantal text which had been handed down to them, but also to ensure its proper pronunciation. To this end they provided the text with a complete system of vowel points and accents.3 Their labours further included the compilation of a number of notes, to which the term Massorah is now usually applied. These notes for the most part constitute a sort of index of the peculiarities of the text, and possess but little general interest. More important are those passages in which the Massoretes have definitely adopted a variation from the consonantal text. In these cases the vowel points attached to the written word (Kěthībh) belong to the word which is to be substituted for it, the latter being placed in the margin with the initial letter of Qěrē (= to be read) prefixed to it. Many even of these readings merely relate to variations of spelling, pronunciation or grammatical forms; others substitute a more decent expression for the coarser phrase of the text, but in some instances the suggested reading really affects the sense of the passage. These last are to be regarded either as old textual variants, or, more probably, as emendations corresponding to the errata or corrigenda of a modern printed book. They do not point to any critical editing of the text; for the aim of the Massoretes was essentially conservative. Their object was not to create a new text, but rather to ensure the accurate transmission of the traditional text which they themselves had received. Their work may be said to culminate in the vocalized text which resulted from the labours of Rabbi Aaron ben Asher in the 10th century.4 But the writings of Jerome in the 4th, and of Origen in the 3rd century both testify to a Hebrew text practically identical with that of the Massoretes. Similar evidence is furnished by the Mishna and the Gemara, the Targums, and lastly by the Greek version of Aquila,5 which dates from the first half of the 2nd century A.D. Hence it is hardly doubtful that the form in which we now possess the Hebrew text was already fixed by the beginning of the 2nd century. On the other hand, evidence such as that of the Book of Jubilees shows that the form of the text still fluctuated considerably as late as the 1st century A.D., so that we are forced to place the fixing of the text some time between the fall of Jerusalem and the production of Aquila’s version. Nor is the occasion far to seek. After the fall of Jerusalem the new system of biblical exegesis founded by Rabbi Hillel reached its climax at Jamnia under the famous Rabbi Aqiba (d. c. 132). The latter’s system of interpretation was based upon an extremely literal treatment of the text, according to which the smallest words or particles, and sometimes even the letters of scripture, were invested with divine authority. The inevitable result of such a system must have been the fixing of an officially recognized text, which could scarcely have differed materially from that which was finally adopted by the Massoretes. That the standard edition was not the result of the critical investigation of existing materials may be assumed with some certainty.6 Indeed, it is probable, as has been suggested,7 that the manuscript which was adopted as the standard text was an old and well-written copy, possibly one of those which were preserved in the Court of the Temple.

But if the evidence available points to the time of Hadrian as the period at which the Hebrew text assumed its present form, it is even more certain that prior to that date the various MSS. of the Old Testament differed very materially from one another. Sufficient proof of this statement is furnished by the Samaritan Pentateuch and the versions, more especially the Septuagint. Indications also are not wanting in the Hebrew text itself to show that in earlier times the text was treated with considerable freedom. Thus, according to Jewish tradition, there are eighteen8 passages in which the older scribes deliberately altered the text on the ground that the language employed was either irreverent or liable to misconception. Of a similar nature are the changes introduced into proper names, e.g. the substitution of bosheth (= shame) for ba’al in Ishbosheth (2 Sam. ii. 8) and Mephibosheth (2 Sam. ix. 6; cf. the older forms Eshbaal and Meribaal, 1 Chron. viii. 34, 35); the use of the verb “to bless” (ברך) in the sense of cursing (1 Kings xxi. 10, 13; Job i. 5, 11, ii. 5, 9; Ps. x. 3); and the insertion of “the enemies of” in 1 Sam. xxv. 22, 2 Sam. xii. 14. These intentional alterations, however, only affect a very limited portion of the text, and, though it is possible that other changes were introduced at different times, it is very 856 unlikely that they were either more extensive in range or more important in character. At the same time it is clear both from internal and external evidence that the archetype from which our MSS. are descended was far from being a perfect representative of the original text. For a comparison of the different parallel passages which occur in the Old Testament (e.g. 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, and 1 and 2 Chronicles; 2 Kings xviii. 13-xx. 19 and Isaiah xxxvi.-xxxix; 2 Sam. xxii. and Ps. xviii.; Ps. xiv. and liii., &c.) reveals many variations which are obviously due to textual corruption, while there are many passages which in their present form are either ungrammatical, or inconsistent with the context or with other passages. Externally also the ancient versions, especially the Septuagint, frequently exhibit variations from the Hebrew which are not only intrinsically more probable, but often explain the difficulties presented by the Massoretic text. Our estimate of the value of these variant readings, moreover, is considerably heightened when we consider that the MSS. on which the versions are based are older by several centuries than those from which the Massoretic text was derived; hence the text which they presuppose has no slight claim to be regarded as an important witness for the original Hebrew. “But the use of the ancient versions” (to quote Prof. Driver9) “is not always such a simple matter as might be inferred.... In the use of the ancient versions for the purposes of textual criticism there are three precautions which must always be observed; we must reasonably assure ourselves that we possess the version itself in its original integrity; we must eliminate such variants as have the appearance of originating merely with the translator; the remainder, which will be those that are due to a difference of text in the MS. (or MSS.) used by the translator, we must then compare carefully, in the light of the considerations just stated, with the existing Hebrew text, in order to determine on which side the superiority lies.”

Versions.—In point of age the Samaritan Pentateuch furnishes the earliest external witness to the Hebrew text. It is not a version, but merely that text of the Pentateuch which has been preserved by the Samaritan community since the time Samaritan. of Nehemiah (Neh. xiii. 23-31), i.e. about 432 B.C.10 It is written in the Samaritan script, which is closely allied to the old Hebrew as opposed to the later “square” character. We further possess a Samaritan Targum of the Pentateuch written in the Samaritan dialect, a variety of western Aramaic, and also an Arabic translation of the five books of the law; the latter dating perhaps from the 11th century A.D. or earlier. The Samaritan Pentateuch agrees with the Septuagint version in many passages, but its chief importance lies in the proof which it affords as to the substantial agreement of our present text of the Pentateuch, apart from certain intentional changes,11 with that which was promulgated by Ezra. Its value for critical purposes is considerably discounted by the late date of the MSS., upon which the printed text is based.

The Targums, or Aramaic paraphrases of the books of the Old Testament (see Targum), date from the time when Hebrew had become superseded by Aramaic as the language spoken by the Jews, i.e. during the period immediately preceding Aramaic. the Christian era. In their written form, however, the earlier Targums, viz. those on the Pentateuch and the prophetical books, cannot be earlier than the 4th or 5th century A.D. Since they were designed to meet the needs of the people and had a directly edificatory aim, they are naturally characterized by expansion and paraphrase, and thus afford invaluable illustrations of the methods of Jewish interpretation and of the development of Jewish thought. The text which they exhibit is virtually identical with the Massoretic text.

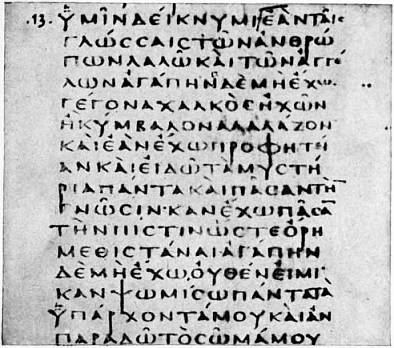

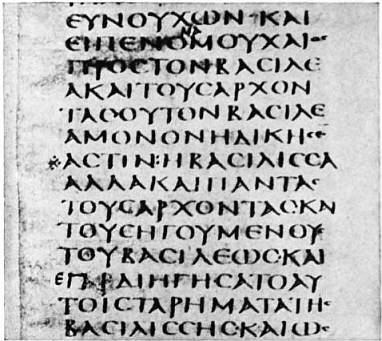

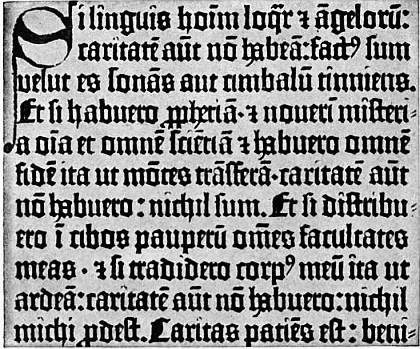

The earliest among the versions as well as the most important for the textual criticism of the Old Testament is the Septuagint. This version probably arose out of the needs of the Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria in the 3rd century B.C. Septuagint. According to tradition the law was translated into Greek during the reign of Ptolemy Philadelphus (284-247 B.C.), and, though the form (viz. the Letter of Aristeas) in which this tradition has come down to us cannot be regarded as historical, yet it seems to have preserved correctly both the date and the locality of the version. The name Septuagint, strictly speaking, only applies to the translation of the Pentateuch, but it was afterwards extended to include the other books of the Old Testament as they were translated. That the interval which elapsed before the Prophets and the Hagiographa were also translated was no great one is shown by the prologue to Sirach which speaks of “the Law, the Prophets and the rest of the books,” as already current in a translation by 132 B.C. The date at which the various books were combined into a single work is not known, but the existence of the Septuagint as a whole may be assumed for the 1st century A.D., at which period the Greek version was universally accepted by the Jews of the Dispersion as Scripture, and from them passed on to the Christian Church.

The position of the Septuagint, however, as the official Greek representative of the Old Testament did not long remain unchallenged. The opposition, as might be expected, came from the side of the Jews, and was due partly to the Versions of Aquila, Symmachus, Theodotion. controversial use which was made of the version by the Christians, but chiefly to the fact that it was not sufficiently in agreement with the standard Hebrew text established by Rabbi Aqiba and his school. Hence arose in the 2nd century A.D. the three new versions of Aquila, Symmachus and Theodotion. Aquila was a Jewish proselyte of Pontus, and since he was a disciple of Rabbi Aqiba (d. A.D. 135), and (according to another Talmudic account) also of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Joshua, the immediate predecessors of Aqiba, his version may be assigned to the first half of the 2nd century. It is characterized by extreme literalness, and clearly reflects the peculiar system of exegesis which was then in vogue among the Jewish rabbis. Its slavish adherence to the original caused the new translation to be received with favour by the Hellenistic Jews, among whom it quickly superseded the older Septuagint. For what remains of this version, which owing to its character is of the greatest value to the textual critic, we have until recently been indebted to Origen’s Hexapla (see below); for, though Jerome mentions a secunda editio, no MS. of Aquila’s translation has survived. Fragments12, however, of two codices were discovered (1897) in the genizah at Cairo, which illustrate more fully the peculiar features of this version.

The accounts given of Theodotion are somewhat conflicting. Both Irenaeus and Epiphanius describe him as a Jewish proselyte, but while the former calls him an Ephesian and mentions his translation before that of Aquila, the latter states that he was a native of Pontus and a follower of Marcion, and further assigns his work to the reign of Commodus (A.D. 180-192); others, according to Jerome, describe him as an Ebionite. On the whole it is probable that Irenaeus has preserved the most trustworthy account.13 Theodotion’s version differs from those of Aquila and Symmachus in that it was not an independent translation, but rather a revision of the Septuagint on the basis of the current Hebrew text. He retained, however, those passages of which there was no Hebrew equivalent, and added translations of the Hebrew where the latter was not represented in the Septuagint. A peculiar feature of his translation is his excessive use of transliteration, but, apart from this, his work has many points of contact with the Septuagint, which it closely resembles in style; hence it is not surprising to find that later MSS. of the Septuagint have been largely influenced by Theodotion’s translation. In the case of the book of Daniel, as we learn from Jerome (praefatio in Dan.), the translation of Theodotion was definitely adopted by the Church, and is accordingly found in the place of the original Septuagint in all MSS. and editions.14 It is interesting to note in this connexion that renderings which agree in the most remarkable manner with Theodotion’s version of Daniel are found not only in writers of the 2nd century but also in the New Testament. The most probable explanation of this phenomenon is that these renderings are derived from an early Greek translation, differing from the Septuagint proper, but closely allied to that which Theodotion used as the basis of his revision.

Symmachus, according to Eusebius and Jerome, was an Ebionite; Epiphanius represents him (very improbably) as a Samaritan who became a Jewish proselyte. He is not mentioned by Irenaeus and his date is uncertain, but probably his work is to be assigned to the 857 end of the 2nd century. His version was commended by Jerome as giving the sense of the original, and in that respect it forms a direct contrast with that of Aquila. Indeed Dr Swete15 thinks it probable that “he wrote with Aquila’s version before him, (and that) in his efforts to recast it he made free use both of the Septuagint and of Theodotion.”

As in the case of Aquila, our knowledge of the works of Theodotion and Symmachus is practically limited to the fragments that have been preserved through the labours of Origen. This writer (see Origen) conceived the idea of collecting all the Origen’s ‘Hexapla.’ existing Greek versions of the Old Testament with a view to recovering the original text of the Septuagint, partly by their aid and partly by means of the current Hebrew text. He accordingly arranged the texts to be compared in six16 parallel columns in the following order:—(1) the Hebrew text; (2) the Hebrew transliterated into Greek letters; (3) Aquila; (4) Symmachus; (5) the Septuagint; and (6) Theodotion. In the Septuagint column he drew attention to those passages for which there was no Hebrew equivalent by prefixing an obelus; but where the Septuagint had nothing corresponding to the Hebrew text he supplied the omissions, chiefly but not entirely from the translation of Theodotion, placing an asterisk at the beginning of the interpolation; the close of the passage to which the obelus or the asterisk was prefixed was denoted by the metobelus. That Origen did not succeed in his object of recovering the original Septuagint is due to the fact that he started with the false conception that the original text of the Septuagint must be that which coincided most nearly with the current Hebrew text. Indeed, the result of his monumental labours has been to impede rather than to promote the restoration of the genuine Septuagint. For the Hexaplar text which he thus produced not only effaced many of the most characteristic features of the old version, but also exercised a prejudicial influence on the MSS. of that version.

The Hexapla as a whole was far too large to be copied, but the revised Septuagint text was published separately by Eusebius and Pamphilus, and was extensively used in Palestine during the 4th century. During the same period two other Hesychius, Lucian. recensions made their appearance, that of Hesychius which was current in Egypt, and that of Lucian which became the accepted text of the Antiochene Church. Of Hesychius little is known. Traces of his revision are to be found in the Egyptian MSS., especially the Codex Marchalianus, and in the quotations of Cyril of Alexandria. Lucian was a priest of Antioch who was martyred at Nicomedia in A.D. 311 or 312. His revision (to quote Dr Swete) “was doubtless an attempt to revise the κοινή (or ’common text’ of the Septuagint) in accordance with the principles of criticism which were accepted at Antioch.” To Ceriani is due the discovery that the text preserved by codices 19, 82, 93, 108, really represents Lucian’s recension; the same conclusion was reached independently by Lagarde, who combined codex 118 with the four mentioned above.17 As Field (Hexapla, p. 87) has shown, this discovery is confirmed by the marginal readings of the Syro-Hexapla. The recension (see Driver, Notes on the Hebrew Text of the Books of Samuel, p. 52) is characterized by the substitution of synonyms for the words originally used by the Septuagint, and by the frequent occurrence of double renderings, but its chief claim to critical importance rests on the fact that “it embodies renderings not found in other MSS. of the Septuagint which presuppose a Hebrew original self-evidently superior in the passages concerned to the existing Massoretic text.”

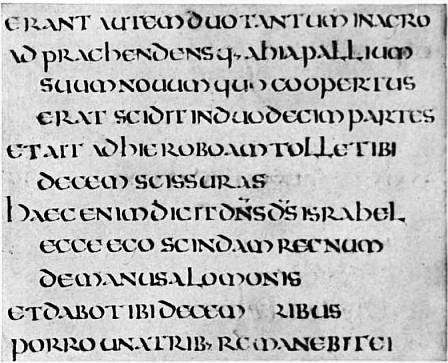

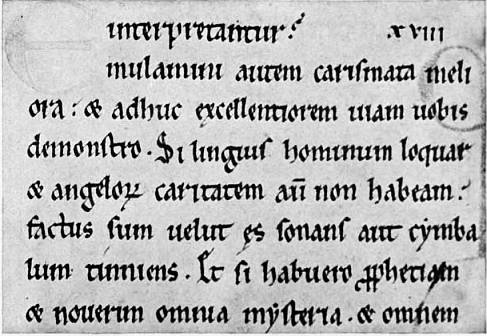

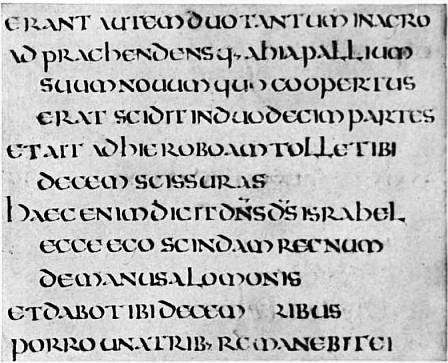

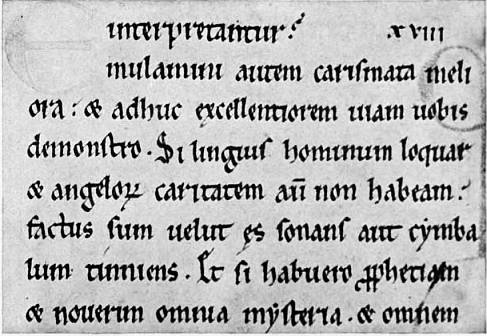

Latin Versions.—Of even greater importance in this respect is the Old Latin version, which undoubtedly represents a Greek original prior to the Hexapla. “The earliest form of the version” (to quote Dr Kennedy18) “to which we can assign a definite date, namely, that used by Cyprian, plainly circulated in Africa.” In the view of many authorities this version was first produced at Carthage, but recent writers are inclined to regard Antioch as its birthplace, a view which is supported by the remarkable agreement of its readings with the Lucianic recension and with the early Syriac MSS. Unfortunately the version is only extant in a fragmentary form, being preserved partly in MSS., partly in quotations of the Vulgate. Fathers. The non-canonical books of the Vulgate, however, which do not appear to have been revised by Jerome, still represent the older version. It was not until after the 6th century that the Old Latin was finally superseded by the Vulgate or Latin translation of the Old Testament made by Jerome during the last quarter of the 4th century. This new version was translated from the Hebrew, but Jerome also made use of the Greek versions, more especially of Symmachus. His original intention was to revise the Old Latin, and his two revisions of the Psalter, the Roman and the Gallican, the latter modelled on the Hexapla, still survive. Of the other books which he revised according to the Hexaplar text, that of Job has alone come down to us. For textual purposes the Vulgate possesses but little value, since it presupposes a Hebrew original practically identical with the text stereotyped by the Massoretes.

Syriac Versions.—The Peshito (P’shitta) or “simple” revision of the Old Testament is a translation from the Hebrew, though certain books appear to have been influenced by the Septuagint. Its date is unknown, but it is usually assigned to the 2nd century A.D. Its value for textual purposes is not great, partly because the underlying text is the same as the Massoretic, partly because the Syriac text has at different times been harmonized with that of the Septuagint.

The Syro-Hexaplar version, on the other hand, is extremely valuable for critical purposes. This Syriac translation of the Septuagint column of the Hexapla was made by Paul, bishop of Tella, at Alexandria in A.D. 616-617. Its value consists Syro-Hexaplar. in the extreme literalness of the translation, which renders it possible to recover the Greek original with considerable certainty. It has further preserved the critical signs employed by Origen as well as many readings from the other Greek versions; hence it forms our chief authority for reconstructing the Hexapla. The greater part of this work is still extant; the poetical and prophetical books have been preserved in the Codex Ambrosianus at Milan (published in photolithography by Ceriani, Mon. Sacr. et Prof.), and the remaining portions of the other books have been collected by Lagarde in his Bibliothecae Syriacae, &c.

Of the remaining versions of the Old Testament the most important are the Egyptian, Ethiopic, Arabic, Gothic and Armenian, all of which, except a part of the Arabic, appear to have been made through the medium of the Septuagint.

Authorities.—Wellhausen-Bleek, Einleitung in das alte Testament (4th ed., Berlin, 1878, pp. 571 ff., or 5th ed., Berlin, 1886, pp. 523 ff.); S.R. Driver, Notes on Samuel (Oxford, 1890), Introd. §§3 f.; W. Robertson Smith, Old Testament in the Jewish Church (2nd ed., 1895); F.G. Kenyon, Our Bible and the Ancient MSS. (London, 1896); T.H. Weir, A Short History of the Hebrew Text (London, 1896); H B. Swete, Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek (Cambridge, 1900); F. Buhl, Kanon u. Text des A.T. (English trans., Edinburgh, 1892); E. Schürer, Geschichte des jüdischen Volkes (3rd ed., 1902), vol. iii. § 33; C.H. Cornill, Einleitung in das alte Testament (4th ed., 1896), and Prolegomena to Ezechiel (Leipzig, 1886); H.L. Strack, Einleitung in das alte Testament, Prolegomena Critica in Vet. Test. (Leipzig, 1873); A. Loisy, Histoire critique du texte et des versions de la bible (Amiens, 1892); E. Nestle, Urtext und Übersetzungen der Bibel (Leipzig, 1897); Ed. König, Einleitung in das alte Testament (Bonn, 1893); F. Field, Origenis Hexaplorum quae supersunt, &c.; A. Dillmann and F. Buhl, article on “Bibel-text des A.T.” in P.R.E.³ vol. ii.; Ch. D. Ginsburg, Introduction to the Massoretico-critical edition of the Bible (London, 1897) and The Massorah (London, 1880-1885).

3. Textual Criticism.

The aim of scientific Old Testament criticism is to obtain, through discrimination between truth and error, a full appreciation of the literature which constitutes the Old Testament, of the life out of which it grew, and the secret of Distinction between Textual and Higher Criticism. the influence which these have exerted and still exert. For such an appreciation many things are needed; and the branches of Old Testament criticism are correspondingly numerous. It is necessary in the first instance to detect the errors which have crept into the text in the course of its transmission, and to recover, so far as possible, the text in its original form; this is the task of Textual, or as it is sometimes called in contradistinction to another branch, Lower Criticism. It then becomes the task of critical exegesis to interpret the text thus recovered so as to bring out the meaning intended by the original authors. This Higher Criticism partakes of two characters, literary and historical. One branch seeks to determine the scope, purpose and character of the various books of the Old Testament, the times in and conditions under which they were written, whether they are severally the work of a single author or of several, whether they embody earlier sources and, if so, the character of these, and the conditions under which they have reached us, whether altered and, if altered, how; this is Literary Criticism. A further task is to estimate the value of this literature as evidence for the history of Israel, to determine, as far as possible, whether such parts of the literature as are contemporary with the time described present correct, or whether 858 in any respect one-sided or biased or otherwise incorrect, descriptions; and again, how far the literature that relates the story of long past periods has drawn upon trustworthy records, and how far it is possible to extract historical truth from traditions (such as those of the Pentateuch) that present, owing to the gradual accretions and modifications of intervening generations, a composite picture of the period described, or from a work such as Chronicles, which narrates the past under the influence of the conception that the institutions and ideas of the present must have been established and current in the past; all this falls under Historical Criticism, which, on its constructive side, must avail itself of all available and well-sifted evidence, whether derived from the Old Testament or elsewhere, for its presentation of the history of Israel—its ultimate purpose. Finally, by comparing the results of this criticism as a whole, we have to determine, by observing its growth and comparing it with others, the essential character of the religion of Israel.

In brief, then, the criticism of the Old Testament seeks to discover what the words written actually meant to the writers, what the events in Hebrew history actually were, what the religion actually was; and hence its aim differs from the dogmatic or homiletic treatments of the Old Testament, which have sought to discover in Scripture a given body of dogma or incentives to a particular type of life or the like.

Biblical criticism, and in some respects more especially Old Testament criticism, is, in all its branches, very largely of modern growth. This has been due in part to the removal of conditions unfavourable to the critical study of the evidence that existed, in part to the discovery in recent times of fresh evidence. The unfavourable conditions and the critical efforts which were made in spite of them can only be briefly indicated.

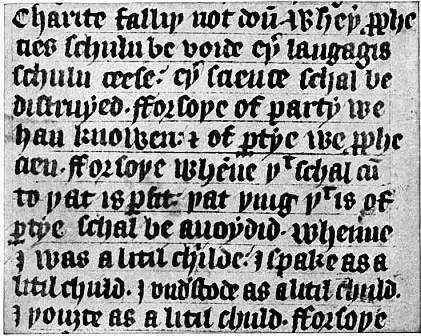

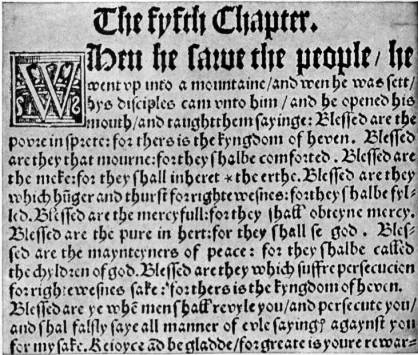

For a long time Biblical study lacked the first essential of sound critical method, viz. a critical text of the literature. Jewish study was exclusively based on the official Hebrew text, which was fixed, probably in the 2nd century A.D., Growth of criticism. and thereafter scrupulously preserved. This text, however, had suffered certain now obvious corruptions, and, probably enough, more corruption than can now, or perhaps ever will be, detected with certainty. The position of Christian (and Jewish Alexandrian) scholars was considerably worse; for, with rare exceptions, down to the 5th century, and practically without exception between the 5th and 15th centuries, their study was exclusively based on translations. Beneath the ancient Greek version, the Septuagint, there certainly underlay an earlier form of the Hebrew text than that perpetuated by Jewish tradition, and if Christian scholars could have worked through the version to the underlying Hebrew text, they would often have come nearer to the original meaning than their Jewish contemporaries. But this they could not do; and since the version, owing to the limitations of the translators, departs widely from the sense of the original, Christian scholars were on the whole kept much farther from the original meaning than their Jewish contemporaries, who used the Hebrew text; and later, after Jewish grammatical and philological study had been stimulated by intercourse with the Arabs, the relative disadvantages under which Christian scholarship laboured increased. Still there are not lacking in the early centuries A.D. important, if limited and imperfect, efforts in textual criticism. Origen, in his Hexapla, placed side by side the Hebrew text, the Septuagint, and certain later Greek versions, and drew attention to the variations: he thus brought together for comparison, an indispensable preliminary to criticism, the chief existing evidence to the text of the Old Testament. Unfortunately this great work proved too voluminous to be preserved entire; and in the form in which it was fragmentarily preserved, it even largely enhanced the critical task of later centuries. Jerome, perceiving the unsatisfactory position of Latin-speaking Christian scholars who studied the Old Testament at a double remove from the original—in Latin versions of the Greek—made a fresh Latin translation direct from the Hebrew text then received among the Jews. It is only in accordance with what constantly recurs in the history of Biblical criticism that this effort to approximate to the truth met at first with considerable opposition, and was for a time regarded even by Augustine as dangerous. Subsequently, however, this version of Jerome (the Vulgate) became the basis of Western Biblical scholarship. Henceforward the Western Church suffered both from the corruptions in the official Hebrew text and also from the fact that it worked from a version and not from the original, for a knowledge of Hebrew was rare indeed among Christian scholars between the time of Jerome and the 16th century.