VASCO NUÑEZ DE BALBOA

VASCO NUÑEZ DE BALBOA

Title: Vasco Nuñez de Balboa

Author: Frederick A. Ober

Release date: December 31, 2010 [eBook #34802]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

HEROES OF

AMERICAN HISTORY

DE BALBOA

BY

FREDERICK A. OBER

| HEROES OF AMERICAN HISTORY |

ILLUSTRATED

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

1906

| Copyright, 1906, by Harper & Brothers. |

| All rights reserved. |

| Published October, 1906. |

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Man-of-the-barrel | 1 |

| II. | Leader of a Forlorn Hope | 19 |

| III. | Balboa Asserts His Supremacy | 33 |

| IV. | Balboa Captures a Princess | 47 |

| V. | The Caciques of Darien | 64 |

| VI. | First Tidings of the Pacific | 81 |

| VII. | A Search for the Golden Temple | 95 |

| VIII. | Conspiracy of the Caciques | 106 |

| IX. | How the Conspiracy was Defeated | 120 |

| X. | Dissensions in the Colony | 134 |

| XI. | Balboa Strengthens His Arm | 148 |

| XII. | The Quest for the Austral Ocean | 162 |

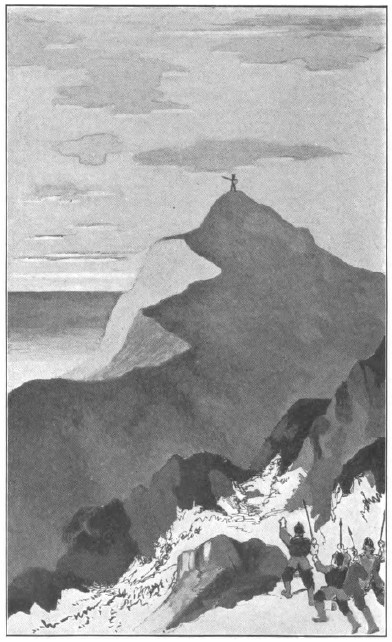

| XIII. | On the Shores of the Pacific | 175 |

| XIV. | A Rival in the Field | 193 |

| XV. | Pedrarias, the Scourge of Darien | 206 |

| XVI. | In the Domain of the Dragons | 220 |

| XVII. | A Compact with the Enemy | 234 |

| XVIII. | Building the Brigantines | 245 |

| XIX. | Imprisoned and in Chains | 258 |

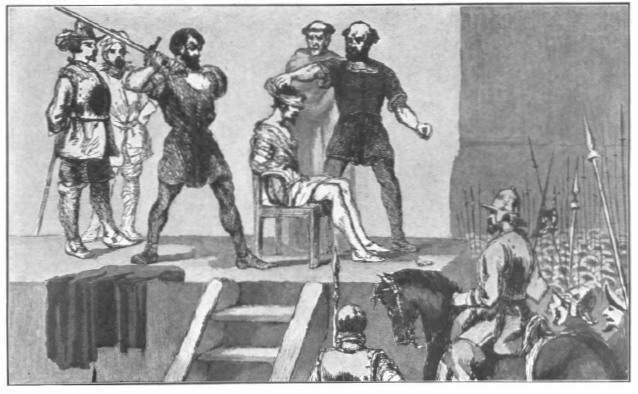

| XX. | The End of Vasco Nuñez de Balboa | 269 |

| VASCO NUÑEZ DE BALBOA | Frontispiece | |

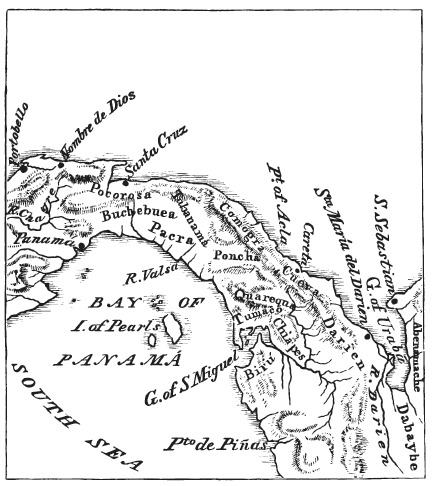

| PANAMA, DARIEN, AND THE SOUTH SEA | Facing p. | 1 |

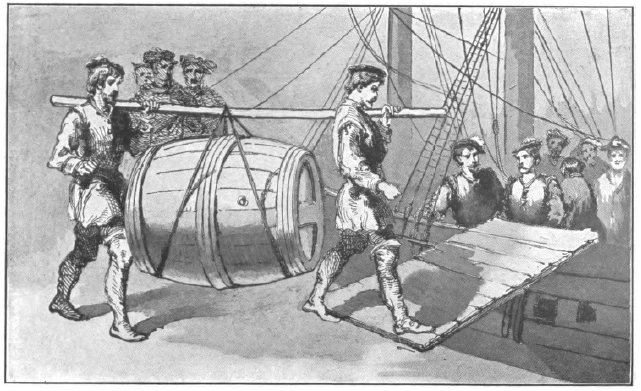

| BALBOA CARRIED ON SHIPBOARD | " | 16 |

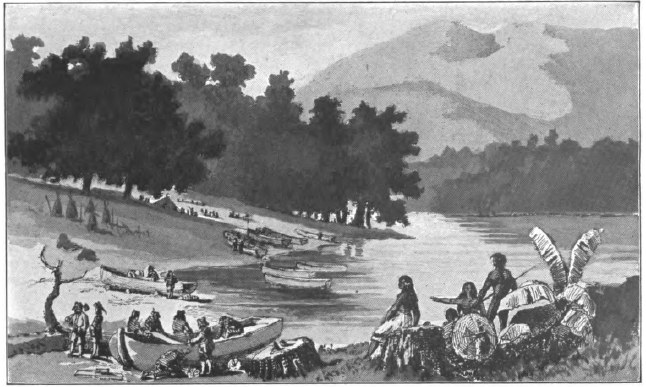

| VILLAGE ON RIVER OF DARIEN | " | 52 |

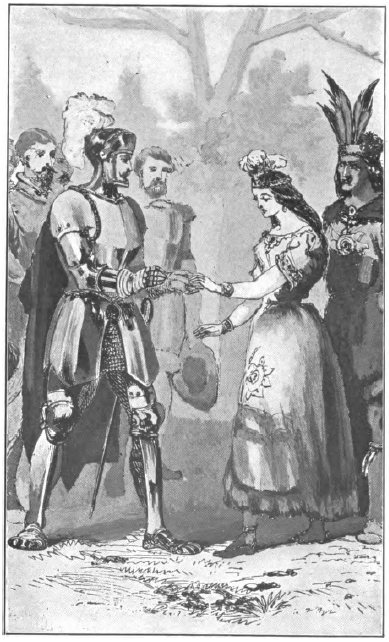

| BALBOA AND THE INDIAN PRINCESS | " | 68 |

| QUARREL FOR THE GOLD | " | 84 |

| DISCOVERY OF THE PACIFIC | " | 170 |

| EXECUTION OF BALBOA | " | 274 |

While Vasco Nuñez de Balboa may be reckoned among the greatest of the minor explorers, yet less has been written of him, perhaps, than of any other in his class except Juan Ponce de Leon. Both names are familiar to every student of history, both are well known even to the casual reader; but both have been strangely neglected by the biographer.

The only complete biography of Balboa (it was declared by an authority several years ago), is that of Don Manuel José de Quintana, who, between the years 1807 and 1834, published his "Spanish Plutarch," or Vidas de Españoles Célebres. This work is considered a classic, and its author (who was born in Madrid, 1772, and died in 1857) lived to see it receive high praise, and some of its subjects honored by translation into other languages than his own vernacular. An English edition, of Balboa and Pizarro, from Quintana's Celebrated Spaniards, was published in London, 1832, as translated by Mrs. Margaret Hodson, and dedicated to Robert Southey, then England's poet-laureate.

But there is much material elsewhere to be found pertaining to Balboa, as well as to Pizarro, and no lack of original documents, such as letters that passed between Vasco Nuñez and the Spanish crown, in the years 1513, 1514 and 1515. Mention is made of Balboa by all the early Spanish writers, of course, such as Martyr, Herrera, and Oviedo, the last named having been personally acquainted with him, as well as with Pedrarias, Pizarro, and all those who were concerned in the exploration and settlement of Darien, Panama, and Peru. Though Oviedo's great work, the Historia Natural y General de las Indias, remained in manuscript during three centuries, Quintana had free access to it and extracted much that was interesting and valuable.

PANAMA, DARIEN, AND THE SOUTH SEA

PANAMA, DARIEN, AND THE SOUTH SEA

SOMETIME in the summer of the year 1501 there landed on the southern coast of Santo Domingo one of the strangest expeditions that ever visited its shores. It was commanded by one Rodrigo de Bastidas, a rich notary of Seville, in Old Spain, who had become imbued with a passion for adventure, and so set forth, with a company contained in two caravels, over the route followed by Christopher Columbus in his third voyage to America. As he was guided by the skilled pilot Juan de la Cosa, who had been with Columbus in the West Indies, his voyage was in every respect successful, save in its ending. It included the entire length of Terra Firma (as the north coast of South America was then called), from the Gulf of Maracaibo to the Isthmus of Darien, whence, after profitable bartering with the Indians, Bastidas set sail for Spain.

He had sought traffic only, and not conquest, hence had been everywhere received with open arms by the natives, who poured out their treasures of gold and pearls most lavishly, so that he and all his comrades were enriched. Only one other venture to this region, that of Pedro Niño, the year previous, had yielded such rich returns, and it was with exultation that the members of this expedition turned the prows of their caravels homeward. When half-way across the Caribbean Sea, however, they discovered, to their great alarm, that their vessels were leaking in every part, and upon investigation found the hulls full of holes, made by the destructive teredo, or ship-worm, the existence of which they had not suspected. The nearest land was the island of Santo Domingo, then known as Hispaniola, and, bearing up for it, they found a harbor in the Bay of Ocoa. The caravels were hardly kept afloat until this haven was reached, and foundered in port before their cargoes were landed. All the arms and ammunition aboard, as well as much of the provisions, went down with the vessels; but no lives were lost, and the most precious portion of the cargoes was saved, to the last pearl and nugget of gold.

The governor of Santo Domingo at that time was Don Francisco de Bobadilla, who, though but a year or so in office, had already committed irreparable wrongs upon the natives of the island. But a few months had elapsed since he had sent Christopher Columbus and his brothers home to Spain in chains. Having sequestrated their effects, he was rapidly squandering his ill-gotten wealth, and actually living in the old admiral's castle.

One hot midsummer day, as Governor Bobadilla was enjoying his siesta, or noonday nap, he was rudely awakened by one of his mounted scouts, who had ridden all night and all morning, coming in from the westward. Pushing aside the sentinel on duty in the lower court, he sprang up the stone stairs with jangling spurs, and, making his way to the balcony overlooking the river Ozama, where the governor's hammock was swung, he exclaimed: "Your excellency, I have dire news to report. It calls for immediate action, too, hence my intrusion upon your privacy."

"Ha! it must be pressing, indeed," replied the governor, testily, rubbing his eyes and at the same time rolling out of his hammock. "Know you not, sirrah, that I could have you swung from the battlements—yea, dashed to the pavement of the court below? Ho, it is Enrique! Pardon me, man, I thought it must be some varlet of the admiral's scurvy gang. No chances lose the Colombinos [partisans of Columbus] to invade my castle and seek to press home their claims, perchance their rusty blades! But proceed. What is it, Enrique?"

"Your excellency, three bands of lawless adventurers, under one Bastidas and the pilot Juan de la Cosa, are marching through the country, with intent, most probably, of attacking the capital. Each band is provided with a coffer filled with gold and pearls, which they are bestowing upon the Indians in exchange for provisions. They are committing no ravage, being in the main unarmed; but I thought your excellency should be informed, and so have come, as you see, all the way from Azua, without rest."

"As a faithful retainer, Enrique, you have done well, and shall receive your reward. They can do no harm, doubtless, since we are here in force; but, laden with gold and pearls, say you?"

"Yes, your excellency, rioting in wealth, which they have obtained in Terra Firma. Not a man among them that has not great store."

"Ha! They come most opportunely, then, for this island of Hispaniola is wellnigh drained of its riches, what with the ravages of Roldan's men and the license permitted by Bartolomé Colon. Their wealth is, without doubt, ill-gotten, and we must see what can be done with it. Trading without permission, whether on Terra Firma or in the isles, is a serious offence."

"But, excellency, the commander of the expedition is Rodrigo Bastidas, a lawyer of note in Seville, and he claims to have had permission from the sovereigns. He comes not with intent to trade in this island, so he says, but, his vessels having foundered, he desires only assistance to proceed home to Spain."

"And he shall get it, forsooth; but not of the sort he may crave. A lawyer, say you? Well, since I have already incarcerated an admiral, an adelantado, and the governor of this very city of Santo Domingo, it seems not reasonable that I shall be bearded by a bachelor! The dungeon awaits him, and there is a place in my treasury for his store of gold and pearls, until it shall be shown that the royal fifth is secure. Go now and call the captain of the guard. Tell it not in the town; but I shall have my soldiers ready to arrest these marauders the moment they arrive."

The avaricious Bobadilla kept his word to the letter, for when, the next night, his shipwrecked countrymen arrived within sight of the city, they were met by an armed force and conducted, weak and famishing as they were, to the prison-pen, where they were herded like cattle. The rank and file were soon released, and allowed to wander at will about the island, but Bastidas and La Cosa were kept immured for many months. In June or July of the next year they were placed on board one of the ships comprising the large fleet collected by the governor to accompany him to Spain. Bobadilla embarked in another vessel, at the same time, but lost his life in a hurricane, which sank nearly every ship in his fleet.[1]

The vessel containing Bastidas and La Cosa survived the tempest, and they safely arrived in Spain with the greater portion of their treasure. Both received high honors at the hands of their sovereign, and returned to the scenes of their discoveries, on the coast of Terra Firma, where the gallant pilot was killed by a poisoned arrow. Bastidas was appointed governor of Santa Marta, where, because he treated the Indians justly and took their part against his ferocious followers, he was assassinated by some of his own men. His remains were taken to Santo Domingo, and in its cathedral is a chapel dedicated to the memory of "the Adelantado Rodrigo de Bastidas," who, together with his wife and child, there sleeps his last, in a tomb elaborately carved, as attested by an inscription on the chapel wall.

While the adventures of the humane Bastidas were sufficiently interesting to attract attention at the time of their occurrence, they might, possibly, have escaped the historian were it not for the fact that they were shared by a man whose subsequent fortunes were identified with one of the greatest events in American history. This man was Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who enlisted under Bastidas at Seville, and accompanied him throughout the voyage, with its consequent disasters. He was then an obscure individual, known only as a dependant of Don Pedro Puertocarrero, the mighty lord of Moguer. He was not a native of Moguer (that town near Palos so closely identified with Columbus and the discovery of America), but came from Xeres de los Caballeros, where his family was respected, though poor and untitled.

No mention is made of Balboa in the annals of the voyage, nor for years after the disbanding of the company at Santo Domingo do we find anything respecting the man who possessed those transcendent qualities that later marked him as a born leader of men. He was probably one of the unfortunates let loose upon the island when Bastidas was imprisoned by Bobadilla. At that time he was about twenty-six years of age, having been born in 1475. He was tall and robust, with a handsome, prepossessing countenance, and was one of the most expert swordsmen and archers in the island.

"His singular vigor of frame," says his Spanish biographer, Quintana, "rendered him capable of any degree of fatigue; his was the strongest lance, his was the surest arrow in the company; but his habits were loose and prodigal, though his nature was generous, his manners extremely affable."

He was, probably, just an average "soldier of fortune," and, finding Santo Domingo well suited to his tastes, took what came to him from his share in the voyage with Bastidas and spent it in riotous living. This one-time Indian Eden, or paradise, had been converted, by the passions of depraved men, into an abode fit only for the ruffian and libertine. With the farms and plantations assigned the new-coming settlers went large encomiendas, or slave-gangs, of unfortunate Indians, who belonged to their master utterly so long as they remained subject to his control. At the time of Balboa's advent the system was at its worst, for Bobadilla, knowing that his time was short, encouraged every Spaniard to make the most of his opportunities. Thus the poor Indians were worked beyond the limit of endurance, and died by thousands; thus the white men took to oppression as a matter of course, and became as fiends in human shape, with no regard for morals, for humanity, or the rights of their fellow-men.

Yet, with all the opportunities presumably given Balboa for acquiring a fortune, we find him, after several years in the island, deep in debt and seeking to avoid his creditors by flight. The first authentic notice of this former companion of Bastidas appears in a reference to him, in general terms, in the year 1510. At that time, four years after the death of Christopher Columbus, his only legitimate son, Don Diego, was governor of Santo Domingo and viceroy of the Indies. He had succeeded to the incompetent Bobadilla and the atrocious Ovando, who had left the island in such terrible condition that all his great energies were required to bring it under control.

Besides seeking to renovate the impoverished plantations and ameliorate the condition of the Indians, Don Diego also undertook the investigation of Santo Domingo's resources, and explorations in various regions of the Caribbean. He was especially interested in the development of Terra Firma, and encouraged expeditions thither, among them being the venture of Alonso de Ojeda, who, on one of his voyages, was accompanied by Francisco Pizarro, then unknown, but destined to become the conqueror of Peru. On his third voyage to Terra Firma, Ojeda left behind him in Santo Domingo one Martin Fernandez de Enciso, who was to follow after with a vessel freighted with supplies and reinforcements for a colony he had founded on the coast of Darien. It was on the occasion of Enciso's sailing that the reference, already alluded to, was made to Balboa and the class to which he then belonged: delinquent debtors who sought to evade their obligations by flight. Information having reached Don Diego, the admiral, that certain reckless men of this class meditated waylaying Enciso's ship when she called at some of the out-ports for final supplies, he issued a proclamation commanding them to desist from their purpose, and also sent an armed caravel with the vessel to escort her clear of the coast.

Vasco Nuñez de Balboa was then residing on a farm, which he nominally owned, near the sea-coast town of Salvatierra, at which place Enciso was to call for provisions. Indeed, some of the provisions were to come from Balboa's farm, and his own Indians were engaged in transporting them to the sea-shore. Late one afternoon, it is said, as Balboa and his mayordomo, or chief man, were walking on the sands near the mouth of the river that flowed through his farm, they saw Enciso's vessel and her escort standing into the bay. The sun was then not far above the western hills, beyond which towered the cloud-capped mountains of the interior, where lay the rugged region known as the Goldstone Country. The craft had scarcely furled their sails and dropped their anchors ere a puff of smoke shot out from the larger vessel, followed by the report of a cannon.

"Ha! that means haste!" exclaimed Balboa. "Bachelor Enciso is desirous that we send our supplies at once, so that he may lade to-night and sail to-morrow with the morning breeze."

"Well, master," said the mayordomo, "so far as our own provisions go, we are ready for him. These barrels on the beach, with what the Indians are now bearing hither on the road, make up our contribution to the cargo."

"Yes, Miguel," answered Balboa, "as thou sayest, we are ready. But, notwithstanding, there is one more contribution I fain would make to Bachelor Enciso's complement of soldiers, as well as add to his cargo. Dost understand me, Miguel mio?"

"I have heard, master, that thou art pressed for funds of late, and threatened with imprisonment provided money be not forthcoming for thy creditors."

"That is it. And dost know, Miguel, whence I may get that money—or, what is the same to me now, how I may evade payment for a while?"

"As to the dinero, master—'sooth, I know not where to find it; for if I did, certain thou shouldst have it. As to evading the payment, there is but one way open, and that—"

"Lies yonder," added Balboa, then continued, bitterly: "Yet it is not open, after all, for how can I get aboard the vessel? Don Diego—and may the devil get his soul in keeping, say I!—Don Diego has sent the caravel to prevent the escape of poor men like me who would redeem themselves in a far country. He would keep us here, it seems, to rot in misery, rather than afford us a chance to get gold for the payment of our debts."

"Don Diego is a fool!" exclaimed the mayordomo. "Yea, and so is the Bachelor Enciso. Faith, if we cannot outwit them both, thou mayst cut off my head and stick it on a pole! When canst thou be ready, my master?"

"In an hour, Miguel. But what will it avail?"

"Say no more, my master, but go to the rancho, and return to the beach within an hour or two. It were better if after dark; but not too late for getting aboard the ship."

"Oh no, not too late for boarding the ship," rejoined Balboa, derisively. "It hath ever been that, of late. But, what is thy scheme, Miguel?"

"Let not that concern thee, master. Go thou, and remember these proverbs: 'When the iron is hot, then is the time to strike'; and 'When the fool has made up his mind, the market is over!'"

Balboa laughed lightly as he hastened away to the rancho, whence he returned, two or three hours later, accompanied by an Indian porter with a full suit of armor on his back, and another with a large basket containing articles of wearing apparel.

Miguel was standing by a large cask, one end of which was open. Directing the Indians to deposit their burdens on the sand beside the cask, he sent them back to the rancho, thus leaving himself and Balboa alone. Not far away, though but dimly visible in the starlit night, a number of Indians were rolling casks of provisions into a small boat from the ship.

"They will be ready for this in about an hour," said the mayordomo, "so I fain must pack it quickly. What thinkst thou of thy quarters, master mine?"

"What? Is that thy scheme—to send me aboard packed like pork in a cask? Never, Miguel! The stigma would cling to me forever!"

"Not so closely, perhaps, as thy creditors, my master. But choose thou, and quickly, for time is no laggard. Meanwhile thou'rt making up thy mind, I'll pack this armor and clothing in the lower end of the cask. See, now, I shall secure it with braces, so the armor may not rattle; and observe thou that there are holes, which I have bored in the sides, to give thee air. Now, when quite ready, get therein, and I will head thee up, my master."

"But, Miguel, suppose the cask were to turn over? With the weight of my armor upon me, I should be suffocated, methinks."

"Nay, master, turned over thou shalt not be, for I shall give instructions to the crew to keep the top-end uppermost."

"But they may not observe them," groaned Balboa, as he clambered into the cask and settled himself in position.

"They will, master; trust me," said the faithful Miguel. "In the lading, they may roll thee about a bit, to be sure. Still, it will be better than to be squeezed by thy creditors."

"Well, as thou sayest, Miguel. In I go, perchance to a living tomb. A thousand ducats for thee, Miguel, if the venture prove successful."

"Ha! But when do I get it, master?"

"When I am lord of Terra Firma! But stay, Miguel. There is Leoncico. I cannot, must not, leave him behind."

"Truly thou sayest," replied the mayordomo; "but for the hound I have already provided. He goes aboard with Salvador Gonzalez, who, also, will have an eye on this cask, to open it at the proper time, which cannot be till to-morrow, know thou."

BALBOA CARRIED ON SHIPBOARD

BALBOA CARRIED ON SHIPBOARD

"Ah, well! get me aboard; and caution the men to handle me carefully. Adios, Miguel, good friend. May the Lord reward thee."

Enciso's vessel was laden by midnight, and before dawn of the next morning was well in the offing, from the shore appearing a mere speck upon the horizon. The bachelor was now in high feather, for he had, as he thought, completely outwitted the scheming debtors of the island, who intended boarding his vessel, and had dismissed the armed caravel with a message to Don Diego to this effect. What, then, was his astonishment, about mid-forenoon of the first day out, to be confronted by a mailed apparition, in the person of the most notorious debtor that Santo Domingo had known—Vasco Nuñez de Balboa!

Clad in full armor, with his good Toledo blade in one hand and the famous hound, Leoncico, by his side, the soldier-colonist strode aft to the quarter-deck where Enciso was standing. He had been released from his cramped quarters in the cask by his neighbor Gonzalez, guided by Leoncico, who picked out his master's place of imprisonment from among the freightage in the vessel's bows, and stood by solemnly until he was freed.

"Dios mio!" exclaimed Balboa, after the head of the cask had been removed and his own head took its place. "That was an experience I would not endure again for an empire! Give me to eat, friend Salvador, and something to drink, for of a truth I am perishing of hunger and thirst. My limbs, too, are as stiff as a stake, so rub me down, amigo, and then help me on with my armor."

WHEN the Bachelor Enciso beheld Vasco Nuñez before him, even though the stowaway removed his plumed hat and bowed obsequiously almost to the deck, he was exceedingly disturbed. As he gazed, open-mouthed, upon the handsome countenance of Balboa, wreathed as it was with a most provoking smile, which seemed to say, "Aha! I have outwitted you at last," his choler rose, so that at first he could not find words for his wrath.

Finally it was voiced, and he poured forth, upon the still smiling vagabond in armor before him, a torrent of words which, since they were not chosen with a view to being reproduced for posterity to peruse, will not be repeated herewith. Suffice it that, when at last his rage and his vocabulary were seemingly exhausted, he was somewhat mollified by Balboa's single remark: "Well, Señor Bachelor, after all, the island, it seemeth, has lost a bad citizen, while you have gained a good soldier. Yea, two good soldiers, for here behold my hound, Leoncico, who will do more than one man's work, I ween."

"Scoundrel!" sputtered the lawyer, "what bad citizen—and, faith, you are one—ever became a good soldier? I have a mind—yea, a mind almost made up for that—to leave you on the reefs of Roncador, there to subsist on such as the sea may yield. And your impudence, moreover, to force yourself upon my company, when, as you cannot truthfully deny, you owe me, myself, two hundred ducats!"

"Nor do I deny it," answered Balboa, with a winning smile. "And the fact that I do not—and, moreover, seek you out—and, as you say, force myself upon your company—would not that imply that my motives are most honorable? Why should I seek to ally with one to whom I am indeed in debt but for a desire to liquidate that obligation? You yourself know, Bachelor, that there are now no opportunities in Hispaniola: none for the planter, even—which I am not; and scarce any for the soldier—which I am. Take me with you, then, and but give me opportunity. From the first spoils I win of the heathen, you shall recoup yourself the two hundred ducats, and I shall not rest until all my creditors have likewise been repaid in full."

"I do not know," remarked Enciso dubiously. "I remember the proverb, 'When the devil says his prayers, he wants to cheat you.' I never knew you, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, to be over-anxious to discharge your debts. Still, since you are here, and if, before these men assembled, you will pledge your fealty, promising support and obedience to my commands, I will allow you to remain."

"I thank your excellency; and let me quote another proverb, which I verily believe in, 'Quien busca, halla—He who seeks, finds!' I have sought, I shall seek yet more, and—I shall find!"

With these words, Balboa bowed low to the lawyer-captain, turned on his heel, and walked forward to rejoin his friends. Enciso looked after him, noting his stalwart, muscular figure, his independent poise, and shook his head. He had, indeed, gained a sturdy recruit, but one of such lofty and intrepid spirit that he might not be content with a position in the ranks, and, perchance, might some time aspire to command. Lawyer that he was, he was provoked to think that he had, in a sense, compounded with felony, and allowed a man to join his company who was under the ban of the law. But, like the lawyer that he was, he shrugged his shoulders and hoped all would turn out for the best. Balboa had his permission to stay, and even if he had not given it, he could not get rid of the impudent rascal without throwing him overboard.

Balboa joined his friends in the prow of the ship, and, with something of a swagger, told of his reception by Enciso, whom he complimented for his good sense in securing a good recruit, even though it had gone against his prejudices to do so. Salvador Gonzalez and a few other soldier-settlers, who had enlisted for the voyage and a year thereafter of service on land, then informed Balboa of the nature of the expedition in which he had engaged. They had turned the empty cask bottom up, and, gathered around Balboa's erstwhile domicile of the night before, regaled themselves upon viands brought from their Dominican farms. A goat-skin of wine hung conveniently near, and as this was frequently resorted to, the spirits of the company rose with the progress of the meal.

"You may not understand, Vasco Nuñez mio," said Gonzalez, "that this expedition we are on is for the relief of Don Alonso de Ojeda, who has made, now, three voyages to Terra Firma, and has founded a colony on the Gulf of Urabá. He and Don Diego de Nicuesa were given by the sovereigns permission to settle the coast of Terra Firma, between Cape de la Vela and Gracias á Dios, and they sailed from Santo Domingo, as you know, at or about the same time. When Don Alonso left, he had arranged with this our commander, the Bachelor Enciso, to prepare a vessel and follow him, after a certain interval. That interval has elapsed, and, true to his pledge, Don Martin Fernandez has set sail, and here we are, you see, on the high seas between Santo Domingo and the continent of mysteries [South America]."

"And well pleased am I," responded Balboa, "to find myself loose from that island of plagues and poverty. Whate'er betide, meseems we cannot do worse on the continent than in Hispaniola. Well it is that I preserved my good sword all these years that I have played the planter in that island, for now I see my way to carve a fortune with it in a new land where gold abounds. Here, then, is to the success of our voyage! May we find gold galore, and caciques as rich as was Caonabo when Don Cristobal Columbus came first to Hispaniola!"

He filled a calabash with wine, which he quaffed at a draught, and his companions likewise drank most heartily to the toast he proposed.

"How many are there in our company?" asked Balboa.

"One hundred and fifty men," answered Gonzalez, "plus yourself."

"Then there are one hundred and fifty-two, for Leoncico is as good as any soldier, and shall share on equal terms with all."

This Balboa said with such determination that it was easy to see his dog stood only second to himself in his estimation.

"Ay, he is a fine brute," assented Gonzalez. "I know him well. He is a son of Ponce de Leon's dog, Becerrico, who performed such feats in the island San Juan, and well worthy of his sire. And, inasmuch as Becerrico received a soldier's full share, yielding his master more than two thousand pesos in gold, as prize-money for those he captured, I see not why Leoncico should not be received among us on the same terms."

"You shall never regret it!" exclaimed Balboa, eagerly, "for on occasions he can render the service of a dozen men. He is a sentinel that never sleeps. By day and by night, he is ever on the watch. And, mates, his instinct is most wonderful. He can distinguish between a peaceful and a warlike Indian merely by his smell. When we were hunting down the Indians of the Cibao, ten Christians escorted by this dog were in greater security than twenty were without him. Seeing an Indian at a distance, I have loosed him, saying, 'There he is, seek him,' and he hath so fine a scent that not one ever escaped him. Having overtaken an Indian, he will take him by the hand or sleeve or girdle, perchance he have anything upon him, and lead him gently towards me, without biting or annoying him at all; but should the savage resist, he would tear him to pieces. Look at the scars upon him," added Balboa, proudly, drawing the blood-hound towards him and pointing out the many places where he had been wounded. "Most of these wounds were made by Indian arrows; but here is where a javelin struck and tore him badly, and here again where a spear glanced from his ribs that might else have penetrated to his heart. Ah, you are a great dog, aren't you, Leoncico?" The hound raised his massive head and sent forth a roar that resounded through the ship. He was an ugly brute, even for a blood-hound, and few aboard ship cared to handle him; but with Balboa he was like a kitten.

Pursuing a course southwesterly across the Caribbean Sea, Enciso's ship finally arrived at the harbor of Cartagena, where, as the Spaniards attempted to land, they were set upon by a host of savages, who had been roused to exasperation by Ojeda and were burning for revenge. Balboa and the more fiery of the cavaliers were for attacking them forthwith; but Enciso was of a peaceable disposition and would not consent. He withdrew from the shore a little way, and parleyed with the Indians through an interpreter, with the consequence that they desisted from their hostile demonstrations and soon engaged in friendly barter with the Spaniards. Though they had suffered severely at the hands of Ojeda, who had killed many of their warriors, women, and children, as well as burned their town to ashes, these so-called savages forgot their wrongs and mingled freely with the countrymen of those who had ravaged their territory.

Enciso took occasion to point out the advantages the Spaniards might always gain if they would treat these simple people fairly instead of with rank injustice, as was usually the case when the two races met. Balboa, Gonzalez, and their like, who had been schooled in the barbarous savagery of Bobadilla and Ovando, dissented from the bachelor's opinion, and declared he was altogether too lenient with the Indians. Then and there, in fact, began the dissension among the soldiers which resulted in Enciso's overthrow. But of that anon.

As they were about to leave Cartagena harbor, a sail was descried at a distance, which proved to be a brigantine laden with soldiers who had enlisted with Ojeda. This was proven to the satisfaction of Enciso, and on coming to close quarters he hailed them and demanded why they had deserted their post. He was answered by the commander of the ship, who was no less than the subsequently renowned Francisco Pizarro, that famine and savages had combined to drive them away. Ojeda, said Pizarro, had departed two months before, in a pirate ship bound for Santo Domingo, leaving him in command. He was to wait fifty days, and if at the end of that time no supplies or reinforcements came, was at liberty to abandon the settlement. The stipulated time passed, and the survivors of the wretched colony embarked in two vessels. One of these was swallowed by the sea, and the terrified crew of the other vessel sought the harbor of Cartagena, intending to sail direct for Santo Domingo.

They had endured enough, all agreed, having lost more than a hundred comrades by drowning, starvation, and the Indians' poisoned arrows. Even the indomitable Pizarro was convinced that a return to the deserted settlement was useless, for the savages had burned their fort before they left the harbor, and everything would have to be done over anew. But Enciso, as alcalde mayor by appointment of Ojeda, was then ranking officer of the little squadron, and Pizarro was subject to his authority. He yielded to his superior as gracefully as might have been expected in the circumstances; but soon after it was noticed that he and Balboa (having previously met in Santo Domingo, where they were at one time boon companions, in fact) had their heads together, and it was surmised, not without reason, that a plot was hatching.

The Bachelor Enciso was not devoid of tact, however, and to divert the malcontents led them on an expedition inland, to ravage the territory of the cacique Zenu and ravish the sepulchres of his ancestors, which were said to be filled with gold and gems. It was Balboa who related the story of the golden sepulchres, which he recalled as having heard when he was on that very coast with Bastidas.

"And, moreover," said he, "I bethink me of what was related respecting the gold of that region. It is said to abound in such quantities that it may be picked up by the basketful. In the season of rains, which is now, gold, in great nuggets large as eggs, is washed down by the torrents, and all the natives do to collect it is to stretch nets across the streams. Going to them in the morning, as a fisherman would visit his nets in the sea, they find the precious metal in such abundance that they bear it away by the backload."

Thus discoursed the redoubtable Vasco Nuñez de Balboa to his commander, Enciso; and though there were those on board ship who, knowing him of old, declared that he was prone to "shoot with the long bow," or, in other words, tell incredible yarns, the bachelor believed his story, every word, and prepared to put it to the proof. As he, Enciso, was a man of peace, more learned in the law than versed in the practice of arms, he allowed Balboa to take charge of the expedition, though he himself went along in an advisory capacity.

The remarkable abilities of the Bachelor Enciso shone forth in a remarkable manner at the outset, for, meeting with two caciques in command of a large army of naked warriors, he insisted upon expounding to them the "why and wherefore" of the Spaniards having invaded their territory. He had with him the old formula, drawn up by the learned doctors of Spain, which recited that, in virtue of the world having been given by God to the pope, and by the latter the unexplored regions of America to the king of Spain, hence the inhabitants thereof, which included, of course, those same Indian caciques, should submit to the Spaniards, etc. But these two caciques were strangely stubborn, for they could not perceive the connecting links in an argument which was supposed to be final as to the rights of the Spaniards to territory which they and their ancestors had held beyond the memory of any living man. One of them, in fact, was so rude as to inform the bachelor that while he assented to the proposition that there was but one God, who lived in the heavens, they could not understand how it was He had given the world to the pope, who also must have been drunk, or crazy, to present to the king of Spain what did not belong to him. And he furthermore added that he and his friend were rulers over that golden province, and if Enciso persisted in his hostile action, they would be forced to cut off his head and stick it up on a pole. Then he and his warriors turned about and pointed to the palisaded fort behind them, where, over the gateway, ranged in grisly rows, Enciso and his men saw several heads that had once been carried on living shoulders.

This ghastly spectacle did not daunt Enciso, however, who said to Balboa and Pizarro, "Well, I have given them the law; now it only remains for you to give them what they can better understand, perhaps—that is, the sword and the lance."

The two dauntless fighters desired nothing better than the pretty fight that was promised with the caciques, and, with shouts to their followers, led them against the foe. The battle was short, but fierce. The two caciques were forced to retreat, leaving many of their men dead on the field; but two of the Spaniards were wounded with poisoned arrows, and died in torments. The province was ravaged, but no gold was found, either as ornaments in the sepulchres or nuggets in nets stretched across the roaring torrents.

THE barren victory at Zenu did not serve to greatly strengthen the authority of Enciso, and it required all his arts as a solicitor to induce Pizarro's disgusted soldiers to return to San Sebastian—as Ojeda's settlement was called. It was situated on the east side of an inlet from the Gulf of Darien known as Urabá, the currents of which were so swift and strong as to force Enciso's vessel upon a shoal, where she went to pieces, with the result that nearly all her precious freight was lost, the men on board barely escaping with their lives. They reached the shore nearly naked and destitute, only to find their fortress and former dwellings in ashes, and the rapacious savages lying in wait for them in the surrounding forest.

A party sent by Enciso to forage the country was waylaid by Indians, who wounded several Spaniards with their poisoned arrows, and compelled the command to retreat to the shore. There a consultation was held, at which all present were unanimous for abandoning a region where, in their own words, "Sea and land, the skies and the inhabitants, all unite to repulse us." But they knew not whither to go, unless it were back to Santo Domingo, which, under the circumstances, would not be likely to receive them hospitably. At this juncture, the one man of that company who had less to expect from a return to the island than from remaining away from it, stepped forth and, by his words of encouragement, kindled in the hearts of the despairing colonists new spirits and new hopes.

"Now I remember," said Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, "that some years ago when passing by this coast on a voyage of discovery with Rodrigo de Bastidas, we entered this very gulf and disembarked on its western shore. There we found a large river, and saw on its opposite bank an Indian town, the inhabitants of which do not poison their arrows. The country adjacent, moreover, was open and fertile, so that, doubtless, we shall find there great store of maize and cassava, as well as a good site for a settlement."

This welcome information at once placed Balboa upon a pinnacle of prominence, and he was urged to lead the starving band towards the promised land of abundance. As many as possible crowded into the remaining brigantine, and sailed across the gulf, where they found the river and the town, just as Vasco Nuñez had described them. They landed at once and took possession, for the town was abandoned of its inhabitants, who had retreated to the forest. The place, however, was rendered untenable at the moment by its brave cacique, named Zemaco, who, with five hundred warriors, had intrenched himself on a near-by hill, where he courageously awaited the invaders, determined to give them battle. With such men as Pizarro and Balboa in his command, and the latter already aspiring to leadership, it was not possible for Enciso to restrain the ardor of his men, who would not heed his desire to parley with the Indians, but immediately attacked them in their chosen stronghold.

The Indians fought for their homes, but the Spaniards for their very lives, and with such desperation they battled that the issue was not long in doubt. The cacique and his warriors were driven from the hill with slaughter, and the victorious though famishing Spaniards, unable to pursue and overtake them in their flight, remained in possession of the town, with its ample stores of provisions and its treasures. They found in the huts, thrust beneath thatched roofs of palm leaves, many quaint ornaments of gold, such as anklets and bracelets, nose and ear rings, altogether to the value of ten thousand crowns. In the reeds and canes along the river, also, were discovered many precious articles concealed there by the Indians in their flight, and the cacique, having been captured and put to the torture, revealed the hiding-place of many more.

Thus suddenly raised from poverty to affluence, with more than twelve thousand pieces of gold in their possession, the Spaniards entertained hopes of acquiring yet greater wealth, in a short time, by marauding expeditions. But their ardent expectations were suddenly dashed by Enciso, who not only claimed the right to hold in his keeping all the gold, in conformity to royal command, but imprudently prohibited all traffic with the Indians on individual account, under penalty of death. As the greater part of his command was composed of men like Balboa, who had left their country in the hope of bettering their fortunes by barter with the natives of this golden region, dissatisfaction was wide-spread and the murmurings loud as well as deep. It was instantly perceived that the bachelor would prove a captious, miserly master, and the bolder spirits of the company resolved upon resisting his authority.

All had agreed, meanwhile, that the Indian village was well situated for a permanent settlement, and, after sending for the remainder of his company at San Sebastian, Enciso commenced to lay the foundations of a town which, in fulfilment of a vow he had made, he called Antigua del Darien. He was the founder of the town of Antigua, but was not to remain long in control of it, for, having without sufficient force to back him attempted to restrain the passions of his followers and deprive them of their liberties, he was soon to be swept away when those pent-up passions burst their bounds.

The Spaniards of those days had a deep reverence for royal authority and fear of their king; but when it was casually discovered that Enciso had unwittingly settled upon territory which had been granted to Nicuesa, and over which neither Ojeda nor himself had any jurisdiction, he was promptly deposed by the soldiers, who refused him further allegiance. He was beaten by his own weapons—those of the law—which were turned against him by his chief opponent, Balboa, who had never forgotten Enciso's threat to throw him into the sea, or land him on a desert island, when he had first made his appearance on shipboard. The line of demarcation between the territories granted to Ojeda and Nicuesa respectively ran through the centre of the Gulf of Urabá, the eastern shores of which pertained to the former and the western to the latter.

As Antigua had been founded on the western shore, it undoubtedly lay within the limits of Nicuesa's grant, and hence the unfortunate Enciso was without a legal leg to stand on. "This miser who would deprive us of our gold," said Balboa, "and who covets for himself all the fruits of our efforts, would use to our prejudice an authority to which he has no just claim. Placed as we are, beyond the limits assigned to Ojeda's jurisdiction, his command as alcalde mayor is become null, together with our obligation to obedience."

Enciso could not refute this argument, and was set aside, in his place being elected as alcaldes, or magistrates, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa and a man named Zamudio. Though the majority of the company had chosen these two as their chiefs, there were still some discontented ones, and finally the altercations became so violent as to threaten the disruption of the little colony. In the midst of it, one day, as the disputants were hotly engaged in the market-place, they heard the sound of cannon and saw signal-smokes arising from the hills across the gulf from Antigua. They replied in like manner, with cannon and smoke-signals, and soon two ships were seen sailing from the eastward, which, on arrival in the river, proved to be in command of one Diego de Colmenares, who had come from Spain in search of Nicuesa, the long absence of whom without tidings had excited alarm.

Learning that opinion in the colony was divided as to the authority that should rule there, Colmenares agreed to remain and share his arms and supplies with the colonists, provided they would receive Nicuesa as their leader. This proposition having been acceded to (for the liberality of Colmenares had gained him universal favor), he and two others were deputed to go in search of the lost leader, who, with seven vessels and five hundred men, had disappeared, months before, and left no sign by which others could follow him. It was known that he had taken part with Ojeda in an attack upon the Indians at Cartagena, after which he had set sail for his allotted territory to the westward of Urabá. Since then nothing whatever had been heard from Nicuesa, but the search of Colmenares disclosed the details of a terrible narrative of suffering and fatal disasters, almost without a parallel in the annals of exploration. In short, at the time Colmenares set out from Antigua, only sixty men survived of the five hundred who had sailed from Spain with Nicuesa, and but one brigantine was left of his fleet.

The unfortunate explorer was finally found at a port on the north coast of the isthmus named Nombre de Dios, where he and the remnant of his band were existing in a state of utter despondency, unable to get away, and despairing of assistance from any quarter. This port had been discovered and named by Nicuesa himself, who, on reaching it when worn by fatigue and exhausted by hunger, had exclaimed: "En nombre de Dios—in the name of God—let us rest here!" There he and his companions gave up their battle against the elements and hostile savages, and in the apathy of despair awaited the end. From this situation they were rescued by the coming of Colmenares, who snatched them from the very jaws of death.

This Nicuesa had been a man of some distinction in Spain, where he had held the office of royal carver, and had amassed quite a fortune. He was just such a vivacious and testy cavalier as Ojeda himself, with whom, by-the-way, he came near fighting a duel over their respective boundaries. His reckless and generous disposition was made manifest by the bountiful dinner he ordered prepared from the stores brought by his rescuer, at which he proudly exhibited his skill as a carver, by slicing and disjointing a fowl while held in the air on a fork. His imprudence was shown by repeated boasts that he would promptly chastise those who had ventured to question his authority over Antigua, and would take from them all the gold of which, without his permission, they had possessed themselves. It belonged to the crown, he said, and to him, and those who held it must disgorge, even to the last centavo, which he would force them to do immediately on his arrival. Colmenares and his two companions were disgusted, and their apprehensions were further excited at the story told them by one Lope de Olano, who had formerly come to Nicuesa's relief, and had been imprisoned by him on a technical charge of desertion. "Take warning by my treatment," he said, privately, to the envoys. "I brought relief to Nicuesa, and rescued him from certain death when starving on a desert island; but behold my recompense! He repays me, as you see, with imprisonment and with chains. And such, believe me, is the gratitude the people of Darien may look for at his hands."

Colmenares continued loyal to his chief, but his companion envoys, Corral and Albitez, were so impressed by the avaricious disposition displayed by Nicuesa, that they hastened ahead of the brigantine in which he embarked, and, arriving at Antigua before him, warned the inhabitants against receiving the boastful ingrate into their midst. "A blessed change we shall make," they said, "in summoning this Diego de Nicuesa to take supreme command. We have called in King Stork with a vengeance, and he will not rest until he has devoured us. What folly is it, being our own masters, and in such free condition, to send for a tyrant to rule over us!"

Their words, indeed, produced a turmoil, and the two parties of Enciso and Balboa, though opposed to each other, quickly united in opposition to the landing of Nicuesa. When the man without a government arrived in the river opposite Antigua, the people sallied forth as if to receive him, but with loud cries and menaces warned him against disembarking, and ordered him back to Nombre de Dios. It was a desperate situation for Nicuesa, who felt, indeed, as if "the heavens were falling on his head." To be warned away from his own territory was humiliating, but to be sent back to the isthmus meant death by starvation. He entreated, then, to be allowed to land, though merely as an equal and companion; failing in that, he begged the heartless Spaniards to take and imprison him, since, though he should lose his liberty, his life might be saved thereby. But the factions were obdurate, and when, in spite of Balboa's warning, Nicuesa persisted in landing, a band of vagabonds pursued him along the shore until, by sheer fleetness of foot, he escaped from them and plunged into the forest.

At sight of this once respected cavalier, who had lost a fortune in his expedition, and was now reduced to the extremity of flight before a rabble crew, Balboa's heart misgave him. He had been foremost in exciting the populace against Nicuesa, but he had not expected such a tempest of disapproval as to threaten his life, and strove earnestly to allay it, though in vain. His fellow-alcalde Zamudio was the most demonstrative against the poor wretch, fearing to lose his position should he be allowed to assume the government. One of his most zealous supporters was a burly ruffian named Benitez, who was so vociferous that Balboa, after repeatedly warning him to desist, suddenly set in motion the machinery of the law, and, in his capacity of magistrate, ordered him to receive one hundred lashes on the bare shoulders. This act of lawful violence cooled the emotions of the mob somewhat, and poor Nicuesa was allowed to emerge from the forest and seek shelter on his brigantine. Here he received word from Balboa that his only safety lay in keeping out of sight aboard the vessel; but the next morning, while his friend's attention was attracted in another direction, he was lured on shore by a deputation assuming to have been sent to treat with him, and hastily cast into a small and unseaworthy vessel, which was set adrift upon the waters of the gulf. Together with seventeen comrades, who chose to accompany him on his perilous voyage, Nicuesa was thrust into the miserable craft, which, with scant provisions and little water, was sent forth to cross the Caribbean Sea, and was never heard of again.

Nicuesa was thus disposed of the first week in March, 1511. He was never to return; but a few years later his avengers exacted reparation for this barbarous deed, and Balboa lost his life partly in consequence. After ridding themselves of Nicuesa, the Antiguans resolved upon sending Enciso after him, and under form of the law succeeded in doing so. He was, however, better equipped for a voyage than his lamented predecessor, and in the caravel which conveyed him to Santo Domingo and Spain went also the alcalde Zamudio. He had been prevailed upon by his partner to take the voyage for the purpose of presenting their cause at court, and thus, at a single coup, the wily Balboa removed an enemy and a rival from the colony, and was left in sole and absolute command.

UNTIL the expulsion of Enciso, says a Spanish writer of the century in which the actions narrated occurred, Balboa might have been considered as a bold and factious intriguer who, aided by his popularity, aspired to the first place among his equals, and who endeavored, artfully and audaciously, to rid himself of all who might, with better title, have disputed it with him; but as soon as he found himself alone and unrivalled, he gave himself up solely to the preservation and improvement of the colony which had fallen into his hands. He then began to justify his ambition by his services, to raise his mind to a level with the dignity of his office, and to place himself, in the scale of public opinion, almost in comparison with Columbus himself.

The removal of the colony from San Sebastian to Darien had been done in pursuance of his advice, and the wisdom of this act being apparent to everybody, he was thereby raised above all others in the estimation of his companions. He was not made giddy by his elevation to supreme power, but, on the contrary, seemed sobered by it, as though he realized his responsibilities, and also wished to justify his comrades' confidence in him. Having been invested with the command, he became a real leader and actual head of affairs, always first in any toil and danger, and shrinking from no exposure, whether to the elements or the weapons of the savages. While frank and affable in common discourse, and ever accessible to the meanest and most humble colonist, yet he was a strict disciplinarian with reference to his soldiers, and insisted upon being treated with the deference due him as governor-general of the colony and captain of its forces. He fully recognized the necessity for collecting ample supplies of gold, to be forwarded to King Ferdinand of Spain, in order to purchase exemption from punishment for his expulsion of Enciso, a royal official; but he deprived no man of his portion in consequence. Balboa was probably one of the most generous and high-minded of the Spanish-American conquerors. While he sometimes treated the Indians with barbarity, and his exactions bore heavily upon them, yet he was never unfair to his comrades when it came to a division of spoils. He was known to have relinquished his own share on more than one occasion, in order that his followers might not lose their reward for the toils and dangers of an arduous campaign.

Having united the warring factions among the colonists, and secured the unswerving loyalty of his soldiers by offering them in himself an exemplar of soldierly qualities, Balboa turned his attention to establishing the colony on a basis of thrift and security. He built a stockaded fort, repaired the dilapidated brigantines, ordered extensive fields to be cleared for planting with corn, and drilled his soldiers constantly. No tidings coming from the exiled Nicuesa as the weeks went by, Balboa despatched vessels for the rescue of whatever survivors might be discovered at Nombre de Dios and along the intervening coast, thereby saving several half-starved wretches from death. Among others thus rescued were two Spaniards who had fled from the severities of Nicuesa more than a year before, and found refuge with the cacique of a province called Coyba. They were nearly naked, like the Indians, and their skins were painted, after the fashion in vogue among the savages; but they could still speak their native language, and thenceforth served Balboa as interpreters. They had been kindly treated by Careta, the cacique of Coyba, who had freely given them shelter, food, and clothing; but their first thought, when they found themselves safe at Darien, was how they might betray him and assist their countrymen to obtain his treasures. Shown into the presence of Captain Balboa, they eagerly offered to lead him to Coyba, where, they said, he would find an immense booty in gold as well as vast quantities of provisions.

"And this cacique Careta, you say, treated you well?" he asked.

"As well as he could, being a savage," answered one of the men. "He is naught but an Indian, half the time going naked, and with manners not of the best; but such as he had he freely gave us, and saved us both from death by starvation, most likely."

"And yet," rejoined Balboa, with a curl of his lip, "ye would have me attack this generous chieftain, lay his town in ashes, perchance kill him and some of his subjects?"

"We have naught against him," answered the man, evasively; "but, being possessed of gold, of which he knows not the use, and of provisions, which ye certainly need in this settlement, it seemed to us our duty to acquaint you with these things."

"And that was well," exclaimed Balboa, "for of a truth we need both gold and supplies for our larder, which is low, even near to being exhausted. As to gold—indeed, as you say, the savage knows not its value, while to us it is the greatest and best thing in the world. We are already under ban of the king, most probably, for hastening the departure of the Bachelor Enciso, and unless I can persuade his majesty, with a golden argument, of the justice of our doings, it may go hard with me and with us all. So now, as I say, this news comes most opportunely, and peradventure it turn out to be true, ye shall not suffer for the imparting of it. I will myself lead the way, with you as guides, and if we can accomplish our object without bloodshed, much better will I be suited than if violence be done."

Balboa was highly elated by the tidings of a golden country not far distant, and, selecting a hundred and thirty of his best men, embarked them in two brigantines for the province of Coyba. They were equipped with the best weapons the colony could supply, and also with utensils for opening roads into the mountains, as well as with merchandise for traffic should it seem better to barter with the Indians than attack them openly.

The swamps and forests adjacent to the colony were occupied by Indians of different tribes, some more warlike than others, but none of them so barbarous as the fierce Caribs of the eastern shore of the Urabá Gulf, who ate their prisoners, gave no quarter in battle, and made use of poisoned arrows. These terrible weapons, as already remarked, were not used by the Indians of the western shore, who were far less sanguinary, though obstinate in battle and even ferocious. They spared the lives of their captives, and, instead of eating or sacrificing them to their gods, branded them on the forehead, or knocked out a tooth, as a sign of servility, and kept them as slaves. Each tribe was governed by a cacique, or supreme chief, whose title and privileges were hereditary, and who was permitted to have numerous wives, while the common warrior had but a single helpmeet, unless he had won unusual distinction by great bravery in battle. Besides supporting their caciques, the Darien Indians allowed priests, or magicians, and doctors to exercise their arts, and they adored a supreme deity, known as Tuira, to whom the milder tribes offered spices, fruits, and flowers, while the more savage ones poured out blood upon their altars and made human sacrifices.

VILLAGE ON RIVER OF DARIEN

VILLAGE ON RIVER OF DARIEN

The houses of these people were mostly made of poles, or canes, loosely bound together with vines, and roofed with a thatch composed of grasses and palm leaves so thickly placed as to turn the tropical rains and afford a perfect shelter. When these structures were built on solid ground they were called bohios, as in the islands of the West Indies, and some of them were nearly a hundred feet in length, though not over twenty or thirty in breadth. The majority, however, were small huts, at a distance very much resembling hay-stacks, having a single opening only, as a doorway, and a clay or earthen floor, with a fire usually burning in the centre, the smoke from which escaped through the roof of thatch. There was another class of dwellings, either aerial or aquatic, depending upon whether they were built in trees, for safety from floods and wild beasts, or above the placid surface of some lake or gulf, and used as dwellings by fishermen. These were known as barbacoas; and it is worthy of note that we find the same name applied to certain elevated structures of a similar sort used as corn-cribs by the Indians of Florida in De Soto's time. Both bohios and barbacoas were subject to removal or abandonment whenever the game of the neighborhood grew scarce, the soil unfruitful, or a pestilence decimated the tribe, following the dictates of danger or necessity.

During the greater part of the year, in that tropical climate, clothing was rarely necessary for warmth, except at night, and the men and boys were nearly always naked, though the caciques sometimes wore breech-cloths, and cotton mantles over their shoulders as badges of distinction. All males, and especially the warriors, painted their bodies with ochreous earths, and stained their skin with the juice of the annotto, while they adorned their heads with plumes of feathers. Both sexes inserted tinted seashells in their ears and nostrils as "ornaments," and encircled their wrists and ankles with bracelets of native gold. The women, after reaching the marriageable age, wore cotton skirts from waist to knee, and broad bands of gold beneath their breasts. Their hair, which was very coarse and black, they cut off in front, even with their eyebrows, by means of sharp flints, but allowed the thick, luxuriant tresses to fall over their shoulders as far as the waist.

They were fine-looking people, especially the young girls and children, for, though their complexion was brown, or copper-colored, their forms were models of symmetry, their countenances pleasing, and their dispositions sweet and amiable. Their defects (for they were by no means devoid of them) were such as might be expected to arise from their barbarous mode of life, descended from ancestors who had never been instructed in morals or religion, save in their most brutish forms. They had, of course, no written language, nor even a hieroglyphic system, to perpetuate their thoughts or the traditions of their ancestors; but they were experts in the chant and dance known as the areito, which they performed to the rude music of drums made of hollowed logs, like the tambouyé, or "tom-tom," of the Africans.

Free from the cares of civilization, their occupations agricultural, with frequent forays into the forest for game and upon the river and gulf for fish, they passed much of their time in idleness, except when pressed for hunger or incited by passion to war upon their neighbors. They knew not, as has been said, the value of gold, for they were always willing to barter great nuggets for the veriest trifles and toys; but Careta, the cacique of Coyba, may have been instructed in its worth by the two Spaniards who had shared his hospitality, for when, under their guidance, Balboa appeared in his settlement and demanded his treasures, he declared he had none to supply. Neither had he any provisions, he said, except such as were necessary to carry his tribe over to the next planting season, for he had been engaged in a disastrous war with Ponca, a powerful cacique who lived in the mountains, and his people had been unable either to sow or to reap.

Then one of the traitors took Balboa aside, and said:

"Commander, believe him not. To my certain knowledge, he hath an abundant hoard of provisions in barbacoas concealed in the forest, and of gold, also, vast quantities hidden in the reeds and thickets. But it is best to dissemble, for behold, he is surrounded by two thousand warriors, and they will fight, as I know from having seen them combat with the tribe of Ponca. Appear to believe him, then, and pretend to depart for Antigua; but in the night return, take him by surprise, burn the village, and make the cacique prisoner, with all his family."

This advice seemed sound to Balboa, and he acted on it promptly, turning about that afternoon and making as though departing for Darien, after a cordial leave-taking, to the cacique's great delight. The unsuspecting chieftain watched the Spaniards out of sight, heard their drums and bugles resounding through the forest farther and farther away, and, convinced that they had indeed left him in good faith, retired to rest without setting scouts on their trail or posting sentinels about his camp. But the sagacious Balboa had no sooner placed a league or so of forest between himself and the unwary Careta than he ordered a halt. The wood was dense and dark, for the trees of the tropical forest are not only vast of bulk, but thickly held together by innumerable vines and bush-ropes, called lianas, seemingly miles in length, and forming impenetrable bulwarks, overtopped by canopies of foliage, through which the sun even at mid-day can hardly send a single ray.

Having with him, however, axes and machetes for cutting his way through the forest, the prudent Balboa had commanded his men to slash a broad path ahead of the company, and thus, when they halted for rest shortly after sunset, behind them lay an open, easy trail leading directly back to the cacique's village. After posting sentries roundabout the camp, Balboa ordered a bountiful meal to be served his hungry men, one hundred of whom were allowed to sleep for the space of two hours, after which the command was given to march.

Without bustle or confusion, the soldiers formed in loose order and commenced their retrograde march through the forest, thanks to the foresight of their commander, finding the return far easier than the advance. All was silent as they approached the village, and, as stealthily as jaguars about to leap on their prey, crept within bow-shot of the dwellings. Balboa had passed the order for his men to refrain from shedding blood, unless a fierce resistance were offered, and, whatever happened, to capture the cacique and his family alive. The royal dwelling was conspicuous from its size and its position on a mound raised somewhat above the general level of the town, and it was silently surrounded by a picked company.

Suddenly the twang of a cross-bow string broke the stillness of the night, followed by a sheet of fire from an arquebuse; for two of the soldiers had spied some Indians moving through a thicket, and concluded the whole village was alarmed. At once, in terrible confusion, from the surrounded houses outpoured swarms of startled savages, naked and weaponless, seeking security by flight, and with no intention of resisting the unexpected attack. Several of them were cut down by the swordsmen and halberdiers, and a few were transfixed by arrows from the cross-bows; but the greater number were allowed to dart into outer darkness and escape. Nearly all escaped, in fact, except the cacique's numerous family, who, surrounded by the soldiery, with naked swords and lighted fusees in their hands, cowered around their dwelling in affright.

One alone attempted to escape, and would have succeeded but for Leoncico, Balboa's faithful hound, who had effectively assisted at "rounding up" the band, and was keeping a vigilant watch at his master's side. With a leap and a growl, Leoncico sprang over the heads of the group in front of him and disappeared in the darkness of the wood. "Dios!" exclaimed Balboa, in alarm. "It was a woman—a maiden! God grant she may not resist him! I never knew Leoncico to harm a woman, but he has torn many a man to pieces. Gonzalez, take you command for the moment, while I follow the hound to see that he does no harm to the maiden." Saying this, he plunged into the wood, which grew close up to the cacique's dwelling, and with his sword and heavy armor cut and beat down the vines that stretched across the path his hound had taken. Soon he was surrounded by silence, as well as by darkness, for the Indians who had fled to the forest lay quiet, like hares in a form, and the turmoil of the village was left far behind him.

"Leon—Leoncico!" he shouted, "where art thou?" For a while there was no response, then a hoarse bark sounded in his ears. It came from a point well ahead, deep in the wood, but by dint of sword and armor he forced his way to it, and there found that of which he was in search. The darkness was intense, for the time was then about midnight; but as he pushed his way onward a stray gleam of moonlight thrust a lance-like shaft through the leafy canopy above, and he saw the form of Leoncico crouching in front of a cringing figure outlined against the trunk of a mighty tree. Then Balboa drew breath with great relief, for, despite the darkness, he could see that the captive was, apparently, unharmed. She was pressed close against the tree-trunk, clinging for support to a sturdy liana, and motionless, save for the trembling which shook her like a leaf.

She seemed, indeed, a statue cast in golden bronze. Fear had paralyzed her limbs so that she did not move, even when, approaching softly, Balboa called to her to be of good cheer and touched her reassuringly. She continued gazing at the hound with wide-staring eyes and parted lips, as though fascinated by that terrible apparition. She had never seen its like before, and could not but have been bereft of sense and motion when it had sprung upon her from the darkness of the forest, like a phantom of evil.

Realizing that his errand had been accomplished with the appearance of his master, Leoncico rose with a growl, and would have returned to the village had not Balboa halted him. "Lie down, brute," he cried, in a voice hoarse with rage. "What do you mean by pursuing a defenceless maiden? Were there not warriors enough for you to slay?"

The hound cringed before him and whined, as though to exculpate himself; but suddenly his whole attitude changed. Springing erect, and thrusting his nose into the air, while the hair on his neck bristled with rage, he uttered a low, deep growl. At the same instant the whistle of an arrow came to Balboa's ears and a missile struck him forcibly between the shoulders. But for his armor he might have been transfixed, so forcefully was the missile-weapon sent; but, as it was, it fell in fragments to the ground.

Then there was the sound of a scuffle, a shriek of agony pierced the air, followed by the ravening of Leoncico as he tore to pieces the victim of his rage. He had sprung upon the savage who in the darkness had approached and sped the arrow at his master, and, bearing him to the ground, made short work of the poor wretch, who was soon a mangled corpse. Stupefied as she was by fear, the maiden could not but have felt the horror of that terrible scene, and sank senseless to the ground. War's dread experiences had not so seared the heart of Balboa that he could be insensible to pity for his helpless captive, and, sheathing his sword, he gathered her in his arms. Preceded by Leoncico, he bore her tenderly through the forest, shielding her from harm in the darkness, and in due time joined his command at the village.

AS Vasco Nuñez burst into the circle of light shed by the flames of burning bohios, the red glare from which lighted up the steel-clad soldiers and their abject captives, he was greeted by glad exclamations from the former and cries of distress from the latter. He strode through the lines without a word, and, making for the group containing the cacique's family, he sought out an elderly female, whom he supposed to be the mother of the girl, and delivered his charge into her keeping. The cries of distress were instantly hushed as the happy mother gathered the girl in her arms, but as the minutes went by without any signs of recovery from the maiden, low moans broke from the captives, and many of them began to gash themselves and tear their hair.

The cacique had stood aloof, stoically refraining from uttering a sound; but after a while, as his daughter did not return to consciousness, he went to the side of Balboa, and, raising his manacled hands in the air, exclaimed:

"What have I done to thee, O thou terrible stranger, that thou shouldst treat me so cruelly? None of thy people ever came to my land that were not fed and sheltered and treated with loving kindness. When thou camest to my dwelling, did I meet thee with a javelin in my hand? Did I not set forth meat and drink, and welcome thee as a brother? Set me free, therefore, with my family and people, and we may yet remain as friends. We will supply thee with provisions and reveal to thee the riches of this land. But first restore to me my daughter, the light of my eyes, the pearl of my household, whom thou and that dread beast of thine have driven to the borderland of death."

During this impassioned speech by the outraged cacique, Balboa remained gazing first at the chieftain, then at his daughter, without uttering a word. The mother was chafing the wrists, bathing the forehead, and whispering tender words into the ears of the maiden, but without eliciting a response. A most pathetic spectacle mother and daughter presented, despite the savagery of the parent, her lack of clothing, and uncouth appearance, which but enhanced by contrast the beauty of the maiden.

Balboa had thought her beautiful, in the brief glimpses afforded in the moonlit forest, but now, with her form and features wrought upon radiantly by the flickering flames, he saw that she was ravishingly lovely. Touched by her beauty, then, and rendered compassionate by her helplessness, he allowed his heart to go out to her, and so far as his rough nature was susceptible to love he felt that sentiment for the cacique's daughter. Distressed by the silence with which his appeal had been received, the cacique added:

"Dost thou doubt my faith? Behold my daughter. I give her to thee, provided she shall be restored, as a pledge of friendship. Thou mayst take her for thy wife, and be thus assured of the friendship of her family and her people."

Balboa then awoke, as from a trance, and, grasping Careta's right hand, exclaimed: "I accept her, if she will but ratify thy offer, and henceforth there shall be no enmity between us. Men, cast off the chains from these people. Set them free; and bugler, order the recall, peradventure there be any in pursuit of our former enemies, now our friends."

With his own hands he removed the manacles from Careta's wrists, then, noting by the flickering of the maiden's eyelids that she was recovering, he hastened to her side. As her eyes opened, they rested in astonishment first upon the mailed cavalier, standing erect in the firelight, clad in shining armor from throat to foot, and with a smile upon his handsome features.

Then in the fulness of his manly powers, with a face and figure that would have wrought havoc among the dames of his sovereign's court, had he been favored with a presentation there, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa carried this untutored maiden's heart by storm. She uttered a low cry, and, leaping from her mother's lap, darted into the cacique's dwelling, as if for the first time realizing her lack of proper raiment and desiring to conceal herself from the eyes of her lover. At a word from the cacique, whose will was law with all his family, the mother went in after her and soon reappeared, holding her daughter by one hand. During the brief time at her disposal, she had found and arrayed herself in a flowing robe of cotton, embroidered in gold, and gathered at the waist by a golden girdle. This she clutched nervously, as, with dejected mien and downcast eyes, she stood before the man in whose sight she had found favor above all other women.

The marriage ceremony was simple and brief, consisting in the cacique's joining the right hands of these two so strangely brought together, and invoking his deity to bless the union, which, at a later period, Balboa intended to have sanctioned by a priest. Whether this intention was fulfilled, we will not at this moment inquire. Balboa was a man of many good resolves and promises, most of which seem to have been made only to be broken. But, in the sight of God, who sees into the souls of men, and in the presence of more than one hundred witnesses, who looked on in vast astonishment as the ceremony was performed, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa was "well and truly wedded" to the cacique's beautiful daughter. She, the simple child of nature, untaught by art, and with no moral law to guide her, knew and cared for naught except that she loved the gallant cavalier and sought no further.

BALBOA AND THE INDIAN PRINCESS

BALBOA AND THE INDIAN PRINCESS

Short and fierce had been the wooing of the fair Cacica, wild and weird the accessories of her wedding, with the accompaniment of burning dwellings and attendance of rude soldiers in armor bearing flaming torches. Brief and tempestuous was to be her life on earth thereafter. Balboa may have reckoned upon this alliance as attaching to his service one of the most powerful caciques of Darien; but by captivating the affections of the beautiful Cacica he had incurred the hatred and jealousy of certain young warriors, who were to cause him trouble in the near future. He had captured the wild beauty of the wilderness, but in so doing he enmeshed himself in troubles of far-reaching consequence. They reached, indeed, across the sea and ocean even to Spain, and in their train brought retribution, none the less certain because it was delayed for years.