Title: Handicraft for Girls

Author: Idabelle McGlauflin

Release date: January 5, 2011 [eBook #34854]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The exercises in this five-year course are based upon an estimated time of one hour per week in the first two years, and one and one-half hours in the last three, the school year consisting of thirty-eight weeks.

All materials, with the exception of that used for the full-sized garments and some of the Christmas gifts, are supposed to be furnished by the Board of Education. In many instances the pupils are allowed the privilege of supplying themselves with a better grade of material if they wish. In every case a substitute is given for the full-sized garment if the home cannot furnish the material. All supplies can be purchased by the class collectively or individually, if the Board of Education so desires.

Every exercise in handicraft should embody an educational principle, making sure the training of the judgment, the eye, or the memory, and tending to develop skill, patience, accuracy, perseverance, dexterity or artistic appreciation.

| CHAPTER I.—Suggestions to Teachers | 7 |

| General Directions for Pupils of Sewing Classes. Drills for Beginners. | |

CHAPTER II—Course of Instruction | 11 |

| First Year—Third Grade. Detailed Description of Exercises. | |

CHAPTER III.—Course of Instruction | 19 |

| Second Year—Fourth Grade. Detailed Description of Exercises. | |

CHAPTER IV.—Course of Instruction | 28 |

| Third Year—Fifth Grade. Detailed Description of Exercises. | |

CHAPTER V.—Course of Instruction | 39 |

| Fourth Year—Sixth Grade. Detailed Description of Exercises. | |

CHAPTER VI.—Course of Instruction | 50 |

| Fifth Year—Seventh Grade. Detailed Description of Exercises. | |

CHAPTER VII.—Description of Stitches | 62 |

| Stitches Used in Plain Sewing. Ornamental Stitches. Miscellaneous. | |

CHAPTER VIII.—Textile Fibers and Fabrics | 90 |

| Silk. Cotton. Flax. Wool. | |

CHAPTER IX.—Dress and Its Relation to Art | 98 |

CHAPTER X.—Paper, Cloth and Cardboard Construction | 101 |

CHAPTER XI.—Home Furnishing, Decoration and Care | 112 |

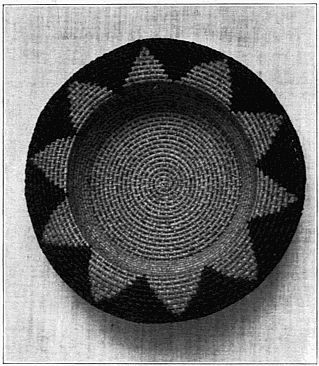

CHAPTER XII.—Basketry | 114 |

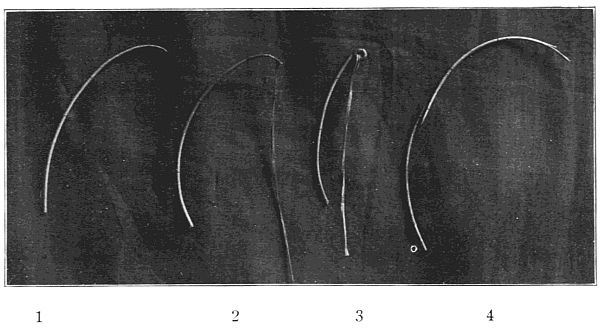

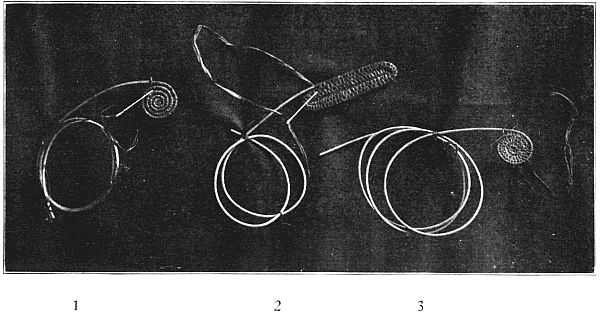

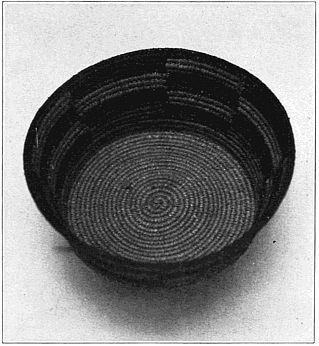

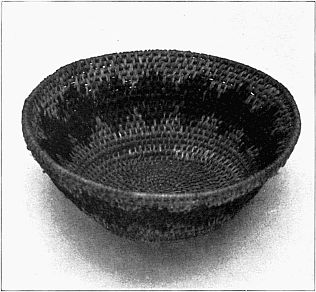

| General Directions for making the Coil Basket. The Sewed Baskets. |

The teacher's preparation for the lesson consists in doing each exercise before presenting the lesson to the class. It will take some of your time to do so, but it will save hours of time and much worry in the end, and you will thus discover how best to present the difficult points of the lesson. A well finished piece gives to the child a complete mental picture of what she is undertaking, and acts as an inspiration; she will work quicker, easier, and better because of it. This impulse and a clear demonstration of the method of doing, will enable her to work far more independently of the teacher than would otherwise be possible, and will give more satisfactory results.

What are designated as "electives" in this book are designed to meet the needs of classes or individuals doing the work a second time or of teachers who find the regular work too difficult.

Large classes can be handled with less wasted energy by dividing the class into groups that are doing the same work. This saves endless repetition and enables the teacher to give better general supervision. This is the most vulnerable point in class work. A teacher may work laboriously and still waste her own and the children's time by too close an adherence to the individual method of instruction. Those children whose turn comes toward the end of the line will have lost much of the value of the lesson. Children require constant supervision. It is not teaching to examine the work when finished and order it ripped out. The fault is then with the teacher and not with the child. Each successive step should be inspected and corrected before the next one is taken. I would go still farther and have every pupil, even in the advanced grades, submit a sample of her work on every stitch to be used in each exercise. Children are always eager to begin a new piece, and if required to practice until the result is satisfactory will very soon do good work. You then have this to refer to and can hold them to their best.

There is absolutely no value in poor, careless, puttering work. Unless the child has a high ideal and strives to reach it, the time of the lesson[8] is wasted. Encourage self-criticism. Work should be done to one's own satisfaction whether it is to be seen by others or not.

Do not allow pupils to take their work home unless it is some required practice work. It is not the object to cover a certain amount of ground, but to inculcate high standards of excellence and some technical skill. They cannot accomplish this by themselves. I would prefer that classes do not complete the entire course rather than have good work sacrificed to quantity. There is a difference between careful, painstaking effort, and the puttering away of valuable time.

Avoid delay in distributing supplies.

Be sure that every member of the class understands clearly the object of the lesson.

Do not encourage waste by a too liberal supply of material.

Too much stress cannot be laid upon the careful preparation of the cloth to be used. Trim all edges neatly before hemming, facing, gathering, etc. Do not allow children to sew without basting. The time required for careful basting is well spent.

It is not expected that the various pupils of the class will advance with the same degree of proficiency. Some will require a much longer time on an exercise than others. As it is greatly to the advantage of the class in the end, and saves time and tiresome repetition to give each new exercise or stitch as a class lesson, the average pupils should regulate the time for taking up new work. A teacher of resources will find ways and means of bringing up the work of slow pupils, and profitable 'busy work' for those who work more rapidly. For the former, a little extra time each day—not as a punishment, but as an opportunity to catch up—would be all that is necessary. For the latter, there is a great variety of interesting, useful work.

It is a pedagogic truism that every teacher, consciously or unconsciously, imparts to her class her own inclinations. An enthusiastic class indicates an ardent interest on the part of the teacher, and a distaste for work and a lack of zeal on the part of the pupils are equally indicative of the teacher's attitude. Bear in mind that an unprepared teacher or a poorly presented lesson can make almost any exercise difficult and distasteful to the class. Do not blame pupils for poor work for which you are yourself responsible.

1. Be sure that the hands are clean.

2. Always sit erect—well back in the seat—with the light coming over the left shoulder, both feet upon the floor, because the body will not become as tired, the hand will not shade the work and it is easier to see the stitches. Do not fasten the work to the knee, because a stooping position easily becomes a habit.

3. Place the thimble upon the second finger of the right hand. Either the side or end of the thimble can be used. Never sew without one.

4. Measure the thread either from shoulder to shoulder or from the end of the finger to the elbow. A long thread becomes soiled and worn before being used up and is more liable to knot.

5. Wind the thread once around the forefinger and break from the spool, because the broken thread twists more easily to a point than when cut. Cut the thread from the work when finished to avoid drawing the stitches or breaking at the wrong place.

6. Thread the needle from the end that hangs from the spool. In this way you are working with the twist of the thread and there is less danger of knotting and kinking.

7. Do not wet the thread in the mouth. Roll the end of the thread between the thumb and forefinger and place through the eye of the needle.

8. To tie a knot wind the thread around the forefinger once and a little over, and twist by rubbing the finger down the side of the thumb. With the nail of the second finger bring the knot thus formed to the end of the thread.

9. Hold the unfinished work in the left hand.

10. Do not bite the threads.

11. Trim the selvedge, as it is hard to sew through and draws up when washed.

12. The knot is always buried except in the basting which is to be removed.[10]

Drill 1. Threading the needle with cotton. Needle No. 8; colored thread.

Drill 2. Making the knot.

Drill 3. Use of the thimble.

Drill 4. Threading the yarn needle.

| Needles No. | 10 | will carry | thread No. | 100 | 90 | 80 | |

| Needles No. | 9 | will carry | thread No. | 90 | 80 | 70 | 60 |

| Needles No. | 8 | will carry | thread No. | 70 | 60 | 50 | 40 |

| Needles No. | 7 | will carry | thread No. | 50 | 40 | 30 | 20 |

| Needles No. | 6 | will carry | thread No. | 20 | 10 | ||

| Needles No. | 5 | will carry | Linen thread—Luster cotton | ||||

| EQUIPMENT. |

| Sewing box. |

| Pin cushion—20 pins. |

| Thimble. |

| Needles. |

| Scissors. |

| Thread cards. |

| Practice Piece—Unbleached muslin, 9" × 6". |

Prepare Thread Cards—Cardboard 4" × 4", designed and cut for four kinds of thread.

Teach: One inch, one-half inch, one-fourth inch.

Practice: "Drills for Beginners," page 10.

Materials: Unbleached muslin 5" × 8" stamped with the three basting stitches, No. 1, page 64; colored thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

Make pupils perfectly familiar with the name and use of this stitch. See "Description of Stitches Used in Plain Sewing," page 63.

Beginning at the right hand follow the lines of the design with the thread, placing the knots over the dots on the right hand side and fastening over the dots at the left. Under each stamped row of stitches put in one, two, three or more rows, depending upon the rapidity with which each individual works. This will help to keep the class uniform.

Materials: Stamped running design No. 1, page 12. Unbleached muslin 6" × 8"; colored thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

Make pupils perfectly familiar with the name and use of this stitch. See "Description of Stitches Used in Plain Sewing," page 63.

The object of this model is to give the pupils practice in the running stitch. These designs are more interesting than practicing on plain cloth, so if the work is not satisfactory, cut the knot, pull out the thread, and try again. Give special attention to the knots and the fastening of the threads and the general neatness of the work. Place the knot on the wrong side and follow the lines of the design with the running stitch.

Materials: Practice piece; colored thread No. 50; needle No. 7. Teach the Overhanding Stitch on the Practice Piece. See "Description of Stitches Used in Plain Sewing," page 63. Change the color of the[14] thread once or twice and teach the joining of the thread. Baste two folded edges together and insist upon neat, careful work.

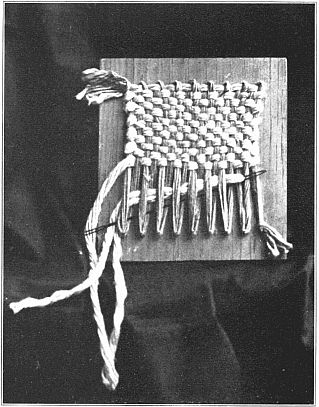

Materials: Weaving frame; netting needles; candle wicking in two colors; brass rings.

THE WOVEN POT HOLDER MADE OF CANDLE WICKING.

THE WOVEN POT HOLDER MADE OF CANDLE WICKING.

Teach the principles of cloth weaving and the terms warp, woof and selvedge.

The weaving frames are made from one-inch board, 8" × 8". Three-fourths of an inch from and parallel to the top and bottom drive a row of[15] nails, having very small heads, one-half inch apart, leaving an inch margin at both sides.

Tie a slip knot in the end of the wicking and slip it over one of the corner nails. Pass the wicking back and forth around the nails first on one side and then the other. This forms the warp. Draw the threads fairly tight and tie around the last nail. Thread the other color of wicking into the netting needles, weave across the warp threads alternately taking up and passing over them. In alternate rows take up the threads passed over in the preceding row. Do not draw the woof threads tight enough to draw the holder in at the sides. Slip from the frame and fasten the loose ends by weaving them back into the holder. Work a brass ring with the blanket stitch, using a strand of the wicking and sew it to one of the corners.

Materials: Running design No. 2, page 12, 6" × 8"; colored thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

Follow the lines of the design with the running stitch.

Materials: White thread No. 50; needle No. 7. Running designs 1 and 2 are to be overhanded together. Turn a quarter-inch fold on the long side of both pieces. Baste the folded edges together and overhand.

Materials: Running design No. 3, page 12, 6" × 8"; colored thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

Follow the lines of the design with the running stitch.[16]

Materials: Paper 4½" × 7".

Fold the long way of the paper. First fold of the hem, one-fourth of an inch. Turn half an inch hem on one side and an inch hem on the other. Have each child cut from a card a gauge for measuring the hems and insist that the hems be turned evenly.

Teach the hemming stitch on the Practice Piece with colored thread. Trim the edge neatly, fold the hem accurately and baste in place. Bad habits, that are hard to correct later, can so easily be formed in making this stitch that I wish to caution teachers in regard to the position of the needle in relation to the hem, the amount of cloth taken on the needle and the tendency toward making the blind stitch or the damask hem instead of the plain hemming stitch.

Materials: Crash, 9" woof, 6" warp; white thread No. 50; needle No. 7; tape 4½ inches.

Turn one-fourth inch fold on each side and across the bottom and baste. Turn the second fold one-fourth of an inch on the sides and baste. Hem the sides. Turn an inch hem at the bottom, baste and hem, giving special attention to the corners where the bottom hem is turned over the side hems. Hem the top with a quarter-inch hem if there is no selvedge. Sew a loop in the middle of the top on the selvedge edge as follows: Turn in one-fourth of an inch at both ends of the tape. Place the ends of the tape side by side and down one-fourth of an inch from the edge of the towel. Hem around the ends of the tape and back-stitch across the tape just at the edge of the towel.

Materials: Running design No. 4, page 12, 6" × 8"; colored thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

Follow the lines of the design with the running stitch.[17]

Materials: White thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

Running designs 3 and 4 are to be overhanded together. Turn a quarter-inch fold on the long sides of both pieces. Baste the folded edges together and overhand. Running designs 1 and 2 are to be overhanded to 3 and 4. Turn a quarter-inch fold at the top of one piece and the bottom of the other, baste the folded edges together and overhand.

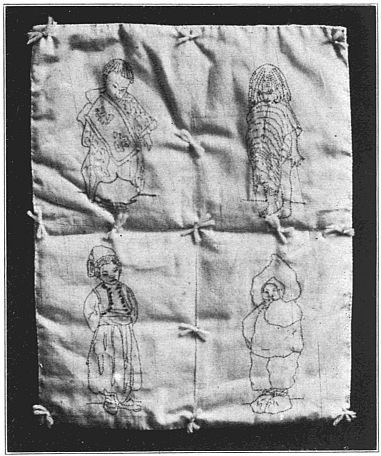

DOLL'S QUILT—ELECTIVE.

DOLL'S QUILT—ELECTIVE.

[5] Running designs No. 3 and 4 may be omitted, (this will also cut out Exercise No. 10) and selections from the following substituted to fill in the time, pupils furnishing their own materials and teachers planning their own designs:

| Pen wipers. |

| Pin disks. |

| Needle books. |

| Small pin cushions for the sewing box. |

| A wiper for eye-glasses. |

[6] The four running designs in Exercise No. 10 may be made into a doll's quilt by basting to a lining, turning in and overhanding the edges together and tacking. Pupils will furnish their own materials for the lining.

[7] Instead of the small towel encourage children to ask their mothers for a dish towel which they can bring from home to hem. Some house-keeper of the neighborhood might be glad to have her dish-towels hemmed for her by the class.

[8] Instead of the pot holder a child's picture-book may be substituted. See "Paper, Cloth and Cardboard Construction," page 101.

| EQUIPMENT. |

| Sewing box. |

| Pin cushion—20 pins. |

| Thimble. |

| Needles. |

| Scissors. |

| Thread cards. |

| Practice Piece—Unbleached muslin 9" × 12". |

Prepare Thread Cards—Cardboard 4" × 4", designed and cut for four kinds of thread.

Review: One inch, one-half inch, one-fourth inch.

Teach: One-eighth inch, three-eighths inch, seven-eighths inch.

Materials: Plain percale 10" warp, 12" woof; white thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

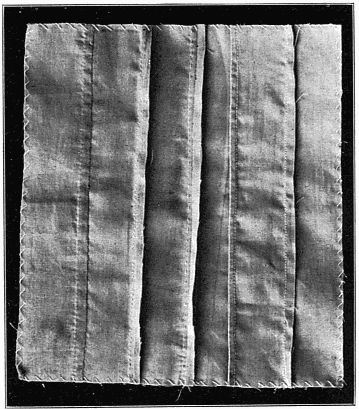

Five exercises of the Second Year Sewing will consist of seam work on the Seam Sampler. Each stitch will be first taught on the Practice Piece. Make pupils perfectly familiar with the names and uses of the different stitches as they are taught. As the year's work progresses compare the different seams and teach when, where and why these various seams are used in garment making. See "Description of Seams," page 85. That the pupils may not lose interest in their sewing the seam work is alternated with miscellaneous exercises.

Fold the percale with the warp into three equal pieces. Cut off one piece. Have each pupil label her large piece with her name. Collect and put them away until ready for Seam B. Do not leave them in the boxes or they will be lost, or soiled with too much handling.

See description of "Seam Sampler" given above.

Materials: First section of Seam Sampler.

Fold with the warp through the center, and cut on the fold. Baste these two edges together one-fourth of an inch from the edge. Sew with the Combination Stitch three-eighths of an inch from the edge.

Materials: Unbleached muslin, 6½" × 6½"; red cashmere 6½" × 6½" (this amount provides for four); thread, yellow, white and red; emery powder; needles No. 7 and No. 3; green luster cotton.

To cut the pattern of the strawberry emery ball: Draw a circle three inches in radius, and cut on the line.[21]

Cut a circle from the unbleached muslin for the lining and one a quarter of an inch larger from the cashmere for the outside; cut both into quarters.

To make the case: Fold the two edges of the muslin together and sew in a seam with the combination stitch, rounding the point to give the strawberry shape. Turn in a good seam at the top and gather. Fill with the powdered emery and fasten the gathering thread by overhanding over the top.

THE COMPLETED SEAM SAMPLER ILLUSTRATING EXERCISES NOS. 11, 13, 15, 17, AND 19.

THE COMPLETED SEAM SAMPLER ILLUSTRATING EXERCISES NOS. 11, 13, 15, 17, AND 19.

Before sewing up the outside put in the stitches, with yellow thread, to represent the seeds of the strawberry as follows: Hold the wrong side of the cloth toward you and put in a row of tiny stitches half an inch[22] apart. One-fourth of an inch above these put in another row with the stitches midway between those of the last row, and so continue. If desired these may be omitted and the seeds represented by French knots when the strawberry is finished.

Seam up the outside, slip it over the case, arranging the seams on opposite sides to avoid the possibility of powder sifting through. Overhand the top and cover with the green luster cotton to represent the calyx, leaving a loop for the stem.

Materials: Second section of Seam Sampler.

Fold with the warp through the center and cut on the fold. Baste these two edges together one-fourth of an inch from the edge. Stitch three-eighths of an inch from the edge.

The Christmas Piece will consist of bags of any size, shape or style for which the pupils wish to furnish their own materials. This gives the teacher an opportunity to exercise her own ingenuity and taste and to have some individuality in her work. There is a great variety, from the utility bag made of cheap, pretty material, costing only a few pennies, to the more elaborate ones made of dainty silk or ribbon. A little tact will easily adapt the style of bag to the home into which it is to go, for the purpose for which it is to be used, and the purse of the donor.

Following are the directions for a simple button-bag:

Materials: A soft washable fabric, 14" warp, 6" woof; thread; needles; narrow tape 26 inches.

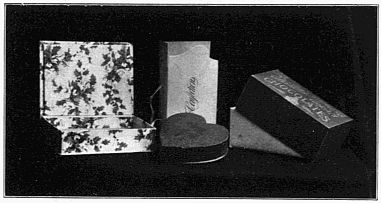

BAGS TO ILLUSTRATE EXERCISE NO. 14.

BAGS TO ILLUSTRATE EXERCISE NO. 14.

Crease an inch hem at each end. Fold the cloth with the two hems right sides together and baste from the lower edge of the hems to the bottom of the bag. Stitch a quarter-inch seam. Turn in the ends of the hems even with the sides of the bag and overhand from the top five-eighths of an inch, leaving an opening for the tapes three-eighths of an inch wide at the bottom of the hem. Baste and hem the hems, fastening securely[24] at each side of the tape openings, as there is considerable strain when the tapes are drawn. Put in a row of running stitches parallel to and five-eighths of an inch from the top of the bag, for the tape opening. With a tape needle draw in the two tapes, sew the ends of each together and draw out of opposite openings so that the place of joining will not show. Overcast the seams.

Materials: First and second sections of the Seam Sampler.

Baste the two sections together one-fourth of an inch from the edge. Sew with the half-back stitch three-eighths of an inch from the edge.

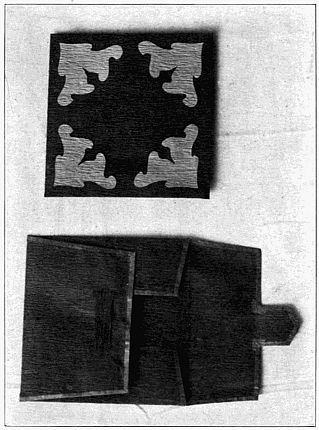

Materials: Imitation Butchers' Linen 9" × 9"; white luster cotton; needle No. 5.

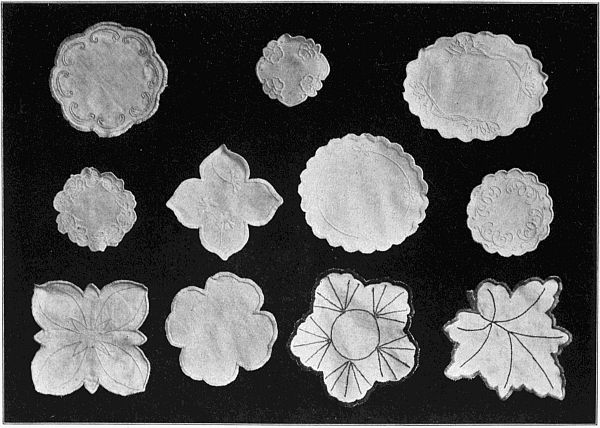

An exercise in paper cutting for the doily design. Have pupils provide themselves with ten or twelve pieces of paper eight inches square for practice cutting. Fold the first paper three times and cut a convex, concave or compound curve from corner to corner. Open and study these curved lines and select the most graceful. Cut again making corrections. Cut a design in straight lines. Cut one composed of both straight and curved lines. Do not work haphazard, but criticise, compare and reject. The surface requires little decoration if the doily is pleasing in outline. That which is placed upon it should have some relation to the outline. Study the space to be decorated and how it can be divided or ornamented by lines, curved or straight, that may serve as a real decoration, but avoid too elaborate designs. Before beginning the doily have a finished pattern. The pattern may be transferred to the cloth by tracing the pattern with a hard pencil, using carbon paper between pattern and cloth, or the pattern may be pinned on and the outline drawn and the design put on freehand.[25]

ORIGINAL DESIGNS FOR THE DOILY BY FOURTH GRADE GIRLS.

ORIGINAL DESIGNS FOR THE DOILY BY FOURTH GRADE GIRLS.

To work the Doily. Finish the edge with the blanket stitch. See "Blanket Stitch," page 73. Work the lines of the design with the Kensington Outline Stitch.

Materials: Third section of the Seam Sampler.

Fold with the warp through the center and cut on the fold. Follow the directions for the French Seam.

Materials: Two pieces bleached muslin 7½" warp, 8½" woof; white thread No. 50; needle No. 7.

In a pillow case the warp threads should run lengthwise of the pillow. Crease a quarter-inch fold across one end and on both sides. Fold with the warp through the center so that the seam just turned comes on the inside, baste the folded edges together on the right side. Overhand on the right side, using no knot, but sewing over the end of the thread. Turn a three-quarter inch hem, baste and hem. Trim the seam and overcast.

Materials: Seam Sampler.

Sew Section Three of the Seam Sampler to the others with the French Fell. Follow directions for the French Fell.

Under the heading "Textile Fibers and Fabrics," page 90, will be found subject matter which can be used in correlation with the geography, language and history work. The fourth grade subject is silk. Secure if possible the silk cocoon and make a collection of silk fabrics. Language papers on the subject can be illustrated with pictures cut from papers and magazines.[27]

[13] A choice may be had between the strawberry and the tomato emery ball.

Tomato Emery Ball—Materials: Unbleached muslin 6" × 3"; red cashmere 6" × 3"; emery powder; red thread No. 50; green luster cotton.

To cut the pattern: Draw a circle one and one-fourth inches in radius and cut on the line.

Cut the two pieces for the lining and the two for the outside of the same size. Place the right sides of the two pieces of cashmere together between the two pieces of lining. Baste all together. Sew with the back stitch one-fourth of an inch from the edge, leaving an opening for turning and filling. Turn in a seam at the opening, fill with powder and close by overhanding the edges together. Flatten as much as possible and make the creases seen in the tomato by tightly drawing the thread of luster cotton from the center around the outside and back to the center, repeating several times. Make a little tuft of the luster cotton in the middle at the top.

[14] The order of the doily and the bag may be reversed, using the doily for the Christmas piece instead of the bag, or the paper box may be substituted. See "Cloth and Cardboard Construction," page 102.

[15] Simple toilet articles in white, such as a handkerchief case, may be substituted for the doily, teachers planning their own designs.

[16] One pillow-case may be omitted and a pillow for the other case made instead. This may be stuffed with crumpled bits of paper. Use unbleached muslin for the pillow.

| EQUIPMENT. |

| Sewing box. |

| Pin cushion—30 pins. |

| Thimble. |

| Needles. |

| Scissors. |

| Thread cards. |

| Practice Piece—Unbleached muslin 9" × 12". |

Prepare Thread Cards—Cardboard 4" × 4" designed and cut for four kinds of thread.

Review the divisions of the inch.

Materials: Gingham 8" warp, 13" woof; white thread No. 60; needle No. 8.

It is desirable that each girl cut the two patches and the two pieces to be patched from the same piece of cloth, that there may be no difficulty in matching the pattern, when patching or when later sewing the two patched pieces together.

Fold the piece of gingham, eight inches by thirteen inches woof, with the warp into three sections, two of them eight inches warp by five inches woof, and the third eight inches warp by three inches woof. Fold the three-inch piece across the warp in the center for the two patches. Cut on the creases. Pin one patch to one of the large pieces, label with the girl's name and put it away for Exercise No. 23.

Materials: First section of Patching Sampler.

The hemmed patch is the strongest and the one most commonly used for repairing garments. The patch will not be noticeable if the pattern is skilfully matched. When matching stripes or plaids always turn on the line where the color changes, never through the middle of a stripe. Ten minutes spent on a paper pattern will prevent the mistakes beginners usually make in this exercise.

Trim the patch and crease a quarter-inch fold on the four sides. Place the patch in the center of the large piece (which we will imagine to be worn) and baste around it, matching the pattern carefully. Do not allow pupils to go any farther until the patch is basted on exactly right. Turn to the right side and cut out the part supposed to be worn by the following successive steps:

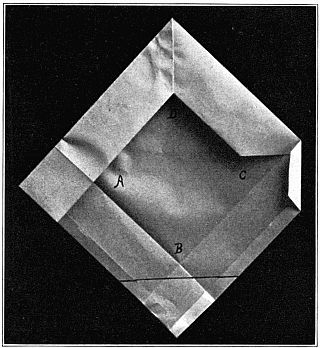

THE MITERED CORNER.

THE MITERED CORNER.

Materials: Paper.

Teach the mitered corner on paper only. Have it done over and over until every pupil understands how it is done, and can do it alone, rapidly and perfectly. Ask pupils to bring paper from home, as almost any kind[31] will do for this practice work. Have it made in hems of several widths. See description of "Miscellaneous" exercises, page 79.

Materials: Second section of the Patching Sampler.

The overhand patch is used on very thin material, such as lawn, dimity or organdy, where strength is not required and where the two thicknesses of cloth around the edge of the hemmed patch would be too noticeable. The pattern should be as carefully matched as in the hemmed patch and equal care given to the corners. A paper pattern will assist beginners.

Fold the large piece of gingham with the four corners together and clip off the point from the center. The following are the successive steps for making the overhand patch:

The two patched pieces are to be overhanded together. Turn a quarter-inch fold on each with the warp, matching the pattern, baste together and overhand.

Teach the Overcasting on the Practice Piece and overcast all raw edges on the Patching Sampler.

This subject has such limitless possibilities and its success or failure rests so entirely with the teacher that it will be necessary for each teacher to[32] prepare herself to teach it and decide upon the style, size and general character of the design of the baskets to be made by her class, allowing the pupils as far as possible to work out their individual tastes.

See chapter on "Basketry," page 114.

Materials: Damask 8½" × 8½"; white thread No. 60; needle No. 8.

See Description of the Damask Hem, page 70.

Trim the napkin square. Crease a half-inch hem on the four sides. The corners are to be mitered, and this is more easily done by basting the side hems in place, skipping across the corners when basting. Turn out the corners and miter them. Hem the corners with the flat hem and the sides with the damask hem.

Materials: Flannel 6½" × 6½", patch 3" × 3"; sewing silk; needle No. 8.

See description of the Herringbone Stitch, page 77.

Cut from the center of the large piece of flannel a two-inch square. Trim the patch square and place it over this hole. Baste at both edges. Teach the herringbone stitch on the practice piece, and herringbone over the raw edges of the patch. Turn one fold three-eighths of an inch wide on the four sides of the large piece, baste and herringbone stitch the raw edge. Keep the raw edges trimmed.

Materials: Cotton twill 8½" × 11"; tape 36"; ribbon elastic 4"; white thread No. 60; needle No. 8.

A COOKING SET, CONSISTING OF AN APRON (EXERCISE NO. 33), SLEEVE PROTECTORS (EXERCISE NO. 27), AND A HOLDER AND CASE (AN ELECTIVE FOR EXERCISE NO. 24).

A COOKING SET, CONSISTING OF AN APRON (EXERCISE NO. 33), SLEEVE PROTECTORS (EXERCISE NO. 27), AND A HOLDER AND CASE (AN ELECTIVE FOR EXERCISE NO. 24).

To cut the pattern of a sleeve protector: Cut an oblong eight inches by ten and one-half inches. Fold through the center the long way. Mark the top of the folded edge A, the bottom B, the upper right hand corner C and the lower D. Measure down on the folded edge from A four inches[34] and mark E. Measure down from C four inches and mark F. Measure up from D five inches and mark G. Measure on the line B D three and one fourth inches from B and mark H. Connect G and H with a straight line. With E as the center and E A as the radius draw a quarter of a circle connecting A and F. Cut on the lines H G, and A F.

Cut the sleeve protectors from the pattern. Beginning at the center of the bottom and holding the wrong side of the cloth next to you, baste the edge of the sleeve protector to the line running through the middle of the tape. Make a tiny pleat in the tape at each corner so that when doubled over it will round the corners smoothly. Join the ends of the tape by folding back both ends and overhanding them together on the wrong side. Hem the tape down on the right side. Before basting the tape down on the wrong side, fasten the elastic in place on one side of the sleeve protector. The elastic is in two pieces, two inches in length. Place the first piece one inch from the bottom and the second piece three inches above the first. Baste the tape down on the wrong side and hem, leaving the opening for the other end of the elastic, which is fastened in place after the hemming is done. Lay the binding smooth over the elastic and stitch along the edge of the tape, through the elastic, to hold in place.

Ask every pupil to bring some article from home, in preference a garment, to be mended. There is no home that cannot furnish a garment that needs repairing. This is a practical application of Exercises 21, 23 or 26, and is a valuable experience for the children.

Materials: These will be furnished by the pupils.

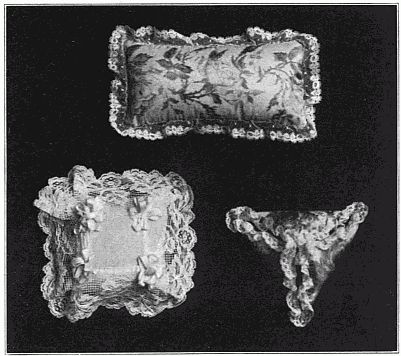

Pupils and teachers will plan their own designs, adapting them to the material furnished. The cushions may be of any size, shape or kind. Do not have the children incur expense, as small pieces of ribbon, silk or bright bits of many kinds of cloth can be made into attractive cushions. Hardwood sawdust, sifted, makes an excellent filling.[35]

Under the heading "Textile Fibers and Fabrics," page 92, will be found subject matter which can be used in correlation with the geography, language and history work. The fifth grade subject is cotton. Many interesting collections can be made that will be instructive for the children.

PIN CUSHIONS TO ILLUSTRATE EXERCISE NO. 29.

PIN CUSHIONS TO ILLUSTRATE EXERCISE NO. 29.

[21] The round holder and case may be substituted for the basketry, or a blank book with paper cover or the folding envelope case may be made instead. See "Paper, Cloth and Cardboard Construction," page 104.

[22] The pin cushion may be substituted for the basketry and the book cover, or the book bag, or the round holder given for Exercise No. 29.

[23] A book cover or a book bag for carrying books may be substituted for the pin cushion.

Materials: Unbleached muslin, 14" × 7"; bleached muslin 15" × 7¾"; strap 18" × 1½"; bias binding 25" × 1"; wadding.

To cut the Circular Pattern: Cut a square of paper eight inches by eight inches and fold it three times. Measure three and five-eighth inches from the point on each folded edge and once between these edges. Draw a curved line connecting these points and cut on the line. The case is cut from this pattern, a circle having a radius of three and five-eighth inches and the holder from a pattern one-fourth of an inch smaller with a radius of three and three-eighth inches.

The Holder: Cut from the unbleached muslin two circular pieces. Turn in one-fourth of an inch around both pieces. Place the wadding between them; pin and baste together. Overhand the folded edges. Quilt the holder in a simple pattern with the running stitch.

The Case: Cut from the bleached muslin two circular pieces. Fold one piece with the warp through the center and cut on the fold. Turn an eighth of an inch hem on each of the straight edges just cut, and hem. The pupils who work rapidly could design a simple decoration for the front of the case. This could be traced, or drawn with a hard pencil and worked with a coarse, colored thread in any decorative stitch, before making the case. Place the half circles on the large circle and baste around the edge. This will leave an opening of about half an inch into which the holder will easily slip. Make the strap by which the[37] holder case is hung from the belt, by folding in the edges at the sides and across one end and overhanding together. The raw end of the strap is then fastened at one end of the case-opening, so that it will come under the binding. See description of the Bias, page 79. Teach the cutting and joining of bias pieces, first with paper and then with the cloth. In order to give the pupil this valuable experience cut the binding in three pieces and join them together. Stitch along the edge of the binding where it folds back against the strap. Slip the holder into the case.

Materials: Grass linen or Holland 15" woof by 10" warp; white thread No. 60; needles Nos. 8 and 5; luster cotton.

The Design: Start several weeks before the class is ready to make it, arouse an interest, and study designs for book covers. Ask pupils to bring from home books having good designs on the covers. Have them tell why they like certain ones and do not favor others. In a word, educate their tastes in this line before expecting them to originate designs. Do not attempt anything elaborate. Many artistic effects can be obtained by interlacing straight lines and these have the advantage of being easily worked. Paper cutting is an excellent medium for experimenting, if a unit is to be repeated or if curves are desired in the outline. For example, fold an oblong, four and one-half by seven inches, through the center both ways, and cut on a slightly curving line from the folded edges to the corner. Quite a variety of simple, graceful outlines can be made by slightly varying these curves, which, with a simple unit repeated around the center or in each corner makes an effective design. Have the finished pattern before starting the book cover. Trace on the cloth by means of the carbon paper. It will be necessary to crease the cover over the book before putting on the design, so that it may be placed just right.

To Make the Book Cover: Work the design with the outline stitch before sewing up the seams. Overcast the raw edges at the top and bottom of the cover and hem with a quarter-inch hem the two ends that fold into the book. The raw-edged hem, finished with the herringbone[38] stitch, could be used in place of the plain hem, if desired. Turn in the top and bottom of the cover so that the book will slip in easily. Overhand that part which folds into the books to the outside, at top and bottom, thus forming the pockets into which the covers of the book slip. Do the overhanding on the wrong side and then turn it to the right side.

Materials: Galatea, kaiki or burlap 15" woof, 13" warp; two strips for handles 14" warp by 3" woof; thread No. 40; needle No. 7.

The decoration of the bag should be done before sewing up the ends. Very artistic effects can be obtained in the applique. See directions for the design of the book cover, page 37.

Cut a three-inch strip from the length of the piece for the end pieces. Divide this into two pieces seven and one-half by three inches. Find the middle of one end of both end pieces and notch them. Fold the large piece with the warp through the center and notch at both ends of the fold. Turn in a quarter of an inch around the large piece and baste. Turn in a quarter of an inch across the notched end and sides of the end pieces. Place the notch at the end of one side piece to one in the large piece, right sides together, and pin in place. Overhand on the wrong side the two together across the end and up both sides. Put in the other end piece in the same way. Trim the end pieces even with the top of the case. Turn a three-quarter inch hem at the top. Before hemming make the straps for the handles by turning in and overhanding the edges. Insert both ends of one strap under the hem of the right side of the bag, two inches from the middle or four inches apart and the other strap on the left side. Hem, and fasten the handles to the edge of the hem by backstitching.

[24] A cover for a pin cushion affords a good application for the mitered corner. This can be made any size, square or oblong. Ornament with fine feather stitching and the star stitch.

| Equipment. |

| Sewing box. |

| Pin cushion—30 pins. |

| Thimble. |

| Needles. |

| Scissors. |

| Thread cards. |

| Practice Piece—unbleached muslin 9" × 12". |

Prepare Thread Cards—Cardboard 4" × 4"—designed and cut for four kinds of thread.

Teach the yard measure and its divisions.

See note under Exercise No. 35—Buttonholes.

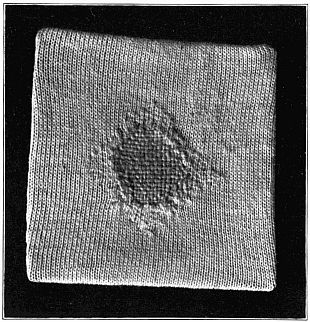

STOCKINET DARNING.

STOCKINET DARNING.

Materials: Stockinet 4" × 4"; cardboard 3" × 3"; darning cotton; darning needle; a pair of worn stockings.

See description of Stocking Darning, page 67.

Pupils will furnish their own cardboard and have it cut and ready for the lesson, also a pair of worn stockings.

The cardboard is a substitute for the darning ball. Do not stretch the cloth too tightly over the card, nor put in a needless number of stitches at the back to hold it on, five or six being sufficient to hold it temporarily[41] in place. The darning cotton winds from the spool in several strands loosely twisted together. Separate and use two, three or more strands, depending upon the texture of the cloth to be darned. Take care not to split the threads when weaving across them, and also avoid putting the threads so far apart that holes are left between them. In fact, try to have pupils understand that they are supplying a piece of cloth that has been worn away, and that when finished should match as nearly as possible in color and texture the cloth that is being repaired. Stockinet, like stockings, is a knitted, not a woven fabric, and as every stitch is drawn through the one below it, it is very necessary that the loops be caught before they ravel back. Prepare the hole for darning by whipping the edge with fine thread, catching up all the severed loops. Either a round or an oblong hole may be cut in the stockinet, the round hole being three-fourths of an inch across, and the oblong three-fourths of an inch by one inch.

Follow the exercise in stockinet darning, in which the principles of darning have been taught, with the darning of a pair of worn stockings that the pupils have brought from home. Every child in the class must be given this practical and useful experience. If there is difficulty in securing these stockings, members of the class or the teacher can readily supply the deficiency.

Materials: Calico 12" woof, 14" warp; facings and bands 58" × 2"; white thread No. 60; needle No. 8.

See description of Plackets, page 81.

Upon this sampler is taught the placket, the gusset, the nightgown opening and two different methods of putting on bands, and in addition a review of the French seam and the French fell. It is made in sections which are combined later. These lessons are interspersed with other exercises that the pupils may not become tired of this piece. Teach the placket and the nightgown opening first on paper. It will save time and trouble in the end. Fold the large piece of calico across the warp through the center and cut on the fold. Fold one of these pieces with the warp, through the center and cut. The first exercise of the "Placket Sampler"[42] is done on one of these quarters. As these sections are to be sewed together later each girl must have her own pieces. To avoid the possibility of their being lost or soiled, those not in use should be wrapped in paper, labeled and collected by the teacher and kept until ready for Exercise No. 34.

PLACKET SAMPLER (FRONT VIEW).

PLACKET SAMPLER (FRONT VIEW).

First section of the Placket Sampler: Fold the piece of calico with the warp, through the center and cut an opening on this fold five inches in length. Then follow the directions for making Placket B. Facing eleven inches by two inches.[43]

Materials: Pupils will select and furnish their own materials for an apron. This may be of any style or kind, and will afford an excellent opportunity for carrying out their individual tastes. This may necessitate the teaching of the principles of bands which can be done with the practice piece. See description of Bands, page 79.

PLACKET SAMPLER (BACK VIEW).

PLACKET SAMPLER (BACK VIEW).

APRONS—EXERCISE NO. 33.

APRONS—EXERCISE NO. 33.

Second section of the Placket Sampler.

Materials: The second quarter of the large piece of calico; a two-inch square of calico for the gusset.

Fold with the warp through the center, and cut an opening on this fold five inches in length. Then follow the directions for making the gusset. Sew the two sections together with the French fell. Hem the sides with a quarter-inch hem.

Materials: Blue Percale 9" woof by 4" warp; scraps of calico for practice pieces; white thread No. 40 and No. 80; needles No. 7 and No. 8.

Remember the old adage Practice Makes Perfect.

See description of the Buttonhole, page 63.

Note: Scraps and odd pieces of calico can be used for the practice work on buttonholes. As the buttonhole requires a great deal of practice it is well to keep these pieces in the sewing box and work at it at odd times during the progress of the years' work. Encourage the girls, too, to practice on the buttonhole for home work. In this way they will gradually acquire the skill which only comes with practice. Fold the cloth, wrong side out, with the woof and through the center, and baste the edges together. Begin with the blind buttonhole.

The buttonhole model is intended to show how much skill has been acquired. Fold the percale through the center, with the woof, and baste the edges together. Make the buttonholes three-fourths of an inch long and one inch apart.

Materials: Half of the large piece of calico; facing 18" × 2".

Fold with the warp through the center and cut an opening on this fold[46] five inches in length. Then follow the directions for the Nightgown Opening. Hem the side of the narrower part with a quarter-inch hem.

Materials: Butcher's linen, collar 15½" warp by 3" woof, India linen band 15½" warp by 1½" woof; practice piece 6" warp by 4" woof; white thread No. 80; needle No. 8.

Measure the neck and decide upon the length of collar and width of hem before trimming.

See directions for Hemstitching, page 76.

Put the collar band on the collar. The collars may be still further ornamented with fine feather stitching, the star stitch or French knots.

See description of Bands and Gathering, pages 68 and 79.

To avoid soiling the cloth put the bands on before seaming the halves of the Placket Sampler together. This can be done with the exception of the band on the long side of the nightgown opening, which will have to be done after this side is basted to the other section, cut off and hemmed, and will therefore be the last thing to be done on the Sampler. Put the hemmed bands on the side having the placket and the gusset, and the overhand bands on the side of the nightgown opening.

Length of bands: On the first half, short bands cut two inches, one and one-half inches finished; long band cut four inches, three and one-half inches finished; on the last half, bands cut three and three quarters inches, three and one-quarter inches finished.

Sew the two sections of the Sampler together with the French seam. The section having the two openings is a little narrower than the other. Baste the two sections together, basting the little pleats at the end of the placket and the nightgown opening, and sew them into the seam. Do not cut off the long side until basted nearly across, then cut off and hem the side. Finish with the last band.[47]

Materials: Pupils will furnish their own material for an underskirt for themselves. The patterns which their mothers use can be secured from the home, or one pattern used by all the members of the class. These skirts may be made plain or trimmed with tucked ruffles of cloth or with embroidery, depending upon the wishes of the mothers, the skill and taste of the individuals and the material furnished. Should there be difficulty in securing material for the garment, a small model on the half-inch scale or one of the electives can be substituted. Insist that the work be well done, neatly finished and first class throughout. Use sewing machines when available.

Points to emphasize in the making of a skirt:

Under the heading "Textile Fibers and Fabrics," page 94, will be found subject matter which can be used in correlation with the geography, language and history work. The sixth grade subject is Flax. Make a collection of the flax products, fabrics, etc. A class set of compositions, each member of the class taking different subdivisions of the subject, would make an interesting collection which could be put together in a simple binding done by members of the class.

See "Paper and Cardboard Construction," page 101.[48]

[28] Placket A may be substituted for the gusset, if desired.

[29] A pin cushion cover may be hemstitched in place of the collar. Make this a square seven inches by seven inches, or an oblong five inches by nine inches, or any size to fit a particular cushion that can be cut from these pieces, or any size for which the pupils furnish their own material.

ROUND BOTTOM BAG WITH RAFFIA COVERING.

ROUND BOTTOM BAG WITH RAFFIA COVERING.

[30] Pupils who desire to furnish their own materials for a linen handkerchief may substitute this for the hemstitched collar.

[31] Basketry may be substituted for the apron, or a clipping case or a postal-card album may be made instead.

See "Paper, Cloth and Cardboard Construction," page 107.[49]

Make the bag any size desired; a circle of three or four inches in diameter makes a practical one. Draw the pattern for the raffia covering on paper, the circle for the bottom being the same size as that of the bottom of the bag. The design for the sides may be in as many sections as desired. The tops of these sections may be shaped to suit one's taste—round, pointed or fancy. When the pattern is completed baste a strand of raffia on the pattern, following the lines of the design. Then closely blanket stitch with raffia on both sides of these strands. The spaces may then be filled with fancy lace stitches.

| EQUIPMENT. |

| Sewing box. |

| Pin cushion—30 pins. |

| Thimble. |

| Needles. |

| Scissors. |

| Thread cards. |

| Practice Piece—Unbleached muslin 12" × 9". |

Prepare Thread Cards—Cardboard 4" × 4", designed and cut for four kinds of thread.

Review Divisions of the Foot and Yard Measure.

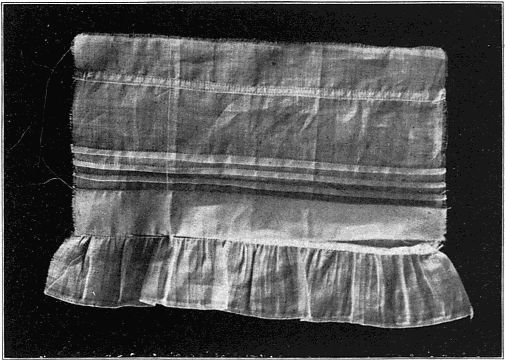

Materials: India linen 8" × 8", ruffle 12" woof, 2" warp; white thread No. 70; needle No. 8.

A TRIAL PIECE, GIVING PRACTICE ON THE HEMMED SEAM, TUCKING, AND PUTTING A RUFFLE INTO A HEM-TUCK.

A TRIAL PIECE, GIVING PRACTICE ON THE HEMMED SEAM, TUCKING, AND PUTTING A RUFFLE INTO A HEM-TUCK.

Hemmed Seam: One inch and a quarter from the top crease a fold with the warp. Cut on this crease.

See description of the Hemmed Seam, page 86.

Putting a ruffle into a hem-tuck and tucking: Measure up from the bottom two and one-fourth inches—or twice the width of the hem-tuck[52] plus one-fourth inch for the seam—and crease with the warp, across the piece. Stitch, or run by hand an inch tuck, taking care to measure and make perfectly even. Measure up three-eighths of an inch from this stitching and crease for another tuck. Stitch, or run by hand an eighth of an inch tuck. Measure up three-eighths of an inch for another tuck. Put in a cluster of three tucks. Hem the ruffle with an eighth of an inch hem, gather and stroke the gathers.

See description of gathering and sewing a ruffle to a straight edge, page 69.

Place the wrong sides of the cloth and ruffle together and baste to the edge extending below the hem-tuck, bringing the seam exactly to the edge of the tuck. Baste and stitch the edge of the hem-tuck over the seam of the ruffle.

Materials: Pupils may furnish their own materials for an underwaist such as they wear. This may be of any style. Patterns can be secured from the mothers. If there is any difficulty in securing supplies from the home, a child's waist on a small scale may be substituted.

Materials: Bleached muslin 24" woof by 10" warp, bias facings 54" by 1"; white thread No. 70; needle No. 8.

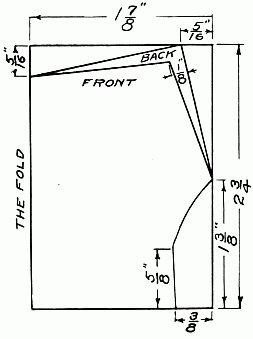

See the draft for the pattern of the small underwaist, page 53.

Patterns: Multiply all dimensions by four. Each girl can draft her pattern from the teacher's dictation, or one pattern can be drafted before the lesson and the members of the class cut their patterns from this one. Insist that the patterns be exact. Have the patterns pinned on, and submitted for inspection before the cutting is done, to avoid blunders and waste of material. Cut the front double. One inch has been allowed for the hem on the backs.

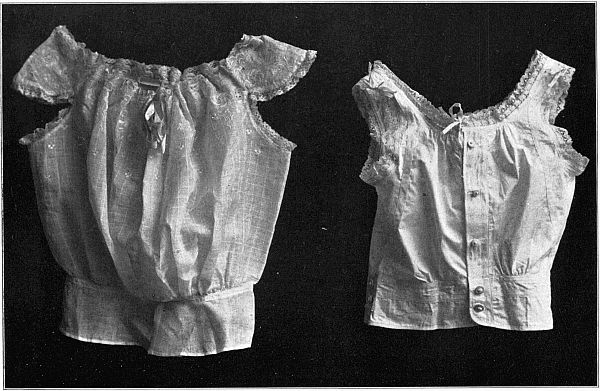

FRONT OF CORSET COVER AND BACK OF GIRL'S UNDERWAIST.

FRONT OF CORSET COVER AND BACK OF GIRL'S UNDERWAIST.

Baste, half-back stitch and fell the seams. Turn the hems at the back, baste and hem. See description of the Bias, page 79. Put the bias facing[55] on the bottom first, then around the neck, and last around the armholes. Teach the joining of the bias facing by having the bottom facing in two pieces and then insist that the ends of the armhole facing be joined in the same way. Overhand neatly the ends of the bottom and neck facings. Make four quarter-inch buttonholes and sew on the buttons.

The styles of dressing the neck vary greatly from season to season. This is also modified by the taste of individuals. Pupils may furnish their own material for any kind of collar desired, after thoughtful consideration of the prevailing styles. It is possible to make a great variety of useful and dainty articles at a trifling expense which will be most acceptable Christmas gifts. If so intended, lead the pupils to study the appropriateness of their gifts. Those pupils who find it difficult to furnish their own material may substitute a collar made from an imitation of linen which will afford the same experience in making, but will not be quite as desirable an article to wear.

Materials: Imitation linen 15" woof, 8" warp. This amount will cut either the Dutch collar by piecing the band, or the ordinary stiff collar. The patterns for both, or the collars from which patterns can be cut, can be brought from home by some member of the class. Be absolutely sure of the size before cutting out the collar, as a quarter of an inch will make a difference in the comfort and fit. It is an excellent plan to have collars of different sizes—12, 12½, 13, 13½—in the class, try them on, and mark the buttonholes on the bands from the right sized collars. The "Dutch" collar can be made with a plain hem and finished with the fine featherstitching or any of the ornamental stitches, or it can be embroidered in a simple pattern with the eyelet embroidery. This gives an excellent opportunity for an original design, or if so desired a pattern can be transferred by the use of the carbon paper. The stiff collar, if made double, is first sewed up on the wrong side and then turned and stitched along the edge on the right. It is then put into the double band, which has been made in the same way. If so desired the collar can be made of a single embroidered piece with the worked edge, or finished with the hemstitched edge and ornamented with fancy stitches.[56]

The success of this exercise will depend entirely upon the interest and ingenuity of the teacher.

See "Home Furnishing, Decoration and Care," page 112.

Materials: French flannel 3½" warp by 6½" woof; twist; sewing silk; needle No. 7 and No. 8.

See description of the Buttonhole, page 63.

Pupils will furnish their own twist and flannel for the practice work. It is not necessary that these should match in color. Double the flannel through the center the long way, baste along the folded edge and around the piece. Overcast the raw edges. Begin one-half inch from the top and make the buttonholes three-fourths of an inch long and three-fourths of an inch apart. Strand, overcast and finish with the bar.

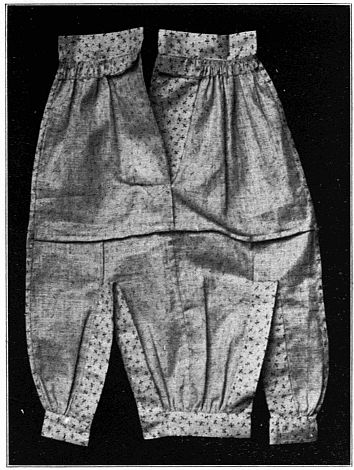

Materials: Pupils may furnish their own materials for a full-sized garment. This may be made in any style. Patterns can be secured from the mothers or exchanged among the members of the class, or a pattern may be drafted from the diagram. Secure the pattern first and have the girls measure it to determine the amount of material needed. If there is any difficulty in securing supplies from the home, a pair of child's drawers on a smaller scale may be substituted. The directions for making the small drawers will assist in making the full-sized garment.

Materials: Bleached muslin 36" woof, 11" warp; ruffling, India linen 36" woof, 1½" warp; white thread No. 70; needle No. 8.[57]

DRAFT FOR A PATTERN OF A PAIR OF DRAWERS.

DRAFT FOR A PATTERN OF A PAIR OF DRAWERS.Patterns: See the draft for the drawers pattern, page 57. Multiply the dimensions by four. Each girl can draft a pattern from the teacher's dictation, or one pattern can be drafted and cut before class time, and the members of the class cut their patterns from this one.

A strip of muslin thirty-six inches by eleven inches will cut the drawers by careful management. The lesson in economy and the experience of cutting from a close pattern is a valuable one for the girls, as it is a problem which will confront them many times in life. Fold the cloth the short way through the center, and pin the selvedge edges together. Allow three and one-half inches from the fold for the placket facings and bands, thus keeping the extra cloth in one large piece. Pin the pattern in position, and cut the two lengths, at the same time taking care that the lengthwise fold of the pattern is straight with the warp threads. If the pattern does not allow for hem and tucks, provide the extra length when cutting. The right sides are now together; mark them before separating, and avoid the chance of making both pieces for the same leg, a mistake easily made by more experienced needlewomen.

Finish the bottom of the drawer legs with one-eighth inch tucks, one-half inch hem-tuck and the ruffle as in Exercise No. 41. One-half inch in front of the side fold cut an opening, with the warp, four inches in length. This may be made in both legs or in the right one only, and may be finished with the gusset, placket A or placket B, keeping in mind that the back buttons over the front. Finish all seams with the French seam except where the ends of the ruffle are joined with the hemmed seam. Gather the fullness at the top on both sides of the front and the back seams, and draw up to the desired length of band. If two openings have been cut at the sides make the back band one inch longer than the front. Place buttons and make buttonholes where desired.

Materials: Albatros 4" × 5"; sewing silk; needle No. 8; beeswax.

See description of Cloth Darning, page 68.

Four holes, cut as follows, are to be darned on this piece of cloth:[59]

No. 1. In the lower left hand corner one inch from the bottom and the side, cut one inch straight with the warp. Darn with split sewing silk on the wrong side.

No. 2. In the upper left hand corner, one inch from the top and side, cut one inch with the warp and one inch with the woof. This will serve for a three-cornered tear. Darn on the right side with ravelings. Spread the stitches at the corner like the sticks of a fan.

No. 3. In the lower right-hand corner, one inch from the bottom and the side cut one inch on the bias. Darn with split sewing silk on the wrong side.

No. 4. In the upper right-hand corner, one inch from the top and the side cut one inch across the warp. This will serve for a worn place in the cloth. Place the patch under it and baste around the edge. Darn with ravelings on the right side. Trim the edges of the patch smooth and herringbone stitch with ravelings around it.

Finish the edge of the piece with the blanket stitch.

Follow this exercise with the repairing of some article brought from home that will give a practical experience in cloth darning. Should there be any difficulty in securing these articles there are plenty of homes that will supply enough for the entire class. This must be done under the teacher's supervision.

Under the heading "Textile Fibers and Fabrics," page 95, will be found subject matter which can be used in correlation with the geography, language and history work. The seventh grade subject is Wool.[60]

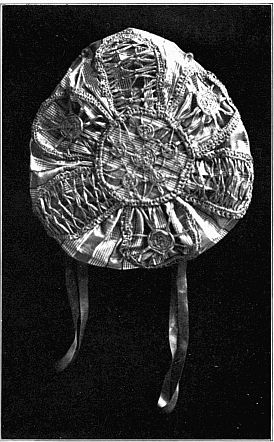

A SET OF UNDERWEAR.

A SET OF UNDERWEAR.[34] An exercise in paper and cardboard construction, adapted to the skill of the class, may be substituted for the Christmas Exercise. See chapter on "Paper and Cardboard Construction," page 101.

[35] In connection with the study of home furnishing and decoration an exercise in passepartout or the making of lamp shades would be excellent.

Stitches Used in Plain Sewing. | |

| 1. | Basting. |

| 2. | Blind Stitch. |

| 3. | Buttonholes. |

| 4. | Combination Stitch. |

| 5. | Darning. |

| 6. | Gathering. |

| 7. | Half-back Stitch. |

| 8. | Hemming. |

| 9. | Overcasting. |

| 10. | Overhanding. |

| 11. | Running. |

| 12. | Slip Stitch. |

| 13. | Stitching. |

Ornamental Stitches. | |

| 1. | Bands. |

| 2. | Blanket Stitch. |

| 3. | Chain Stitch. |

| 4. | Couching. |

| 5. | Feather Stitch. |

| 6. | French Knots. |

| 7. | Hemstitching. |

| 8. | Herringbone Stitch. |

| 9. | Kensington Outline. |

| 10. | Lazy Daisy or Star Stitch. |

Miscellaneous. | ||

| 1. | Bias. | |

| 2. | Cloth. | |

| 3. | Eyelets and Loops. | |

| 4. | Joining and Fastening Threads. | |

| 5. | Mitered Corner. | |

| 6. | Patterns. | |

| 7. | Plackets. | |

| 8. | Putting in Sleeves. | |

| 9. | Seams. | |

| A. Bound Seam. | ||

| B. Flannel Seam. | ||

| C. French Fell. | ||

| D. French Seam. | ||

| E. Hemmed Seam. | ||

| 10. | Sewing on Buttons. | |

| 11. | Sewing on Hooks and Eyes. | |

| 12. | Sewing on Lace. | |

| 13. | Tucking. | |

Basting.—Basting is temporary sewing used to hold the cloth in place while putting in permanent stitches. As the basting threads are to be removed, place the knot on the right side. Fasten the threads securely by taking two or three backstitches. In removing basting threads clip the threads at short intervals that they may be taken out easily. Much of the success of the work depends upon careful basting. The extra time required will be repaid ten-fold. One stitch at a time for beginners, later two or three stitches may be taken. In basting hems, baste not on the edge, but very near it. Do not baste on the line where you expect to stitch, but as near it as possible.

A. An even basting is used on hems, seams of garments, or wherever two pieces of cloth are to be held firmly together. Take up one-fourth of an inch and skip one-fourth.

B. Uneven basting is used where very careful basting is unnecessary, as in the seams of skirts, or in working on a material that clings together, as a guide for stitching. Take up an eighth of an inch and skip three-eighths. When only loose basting is required, as when holding the lining and outside together, a long stitch and two short ones may be used.

Blind Stitch.—The blind stitch and slip stitch are used to fasten a hem lightly where it is desired to conceal the stitches. To blind stitch a hem, turn back the edge of the hem to the basting and, holding the cloth along the edge of the finger, catch first cloth and then hem with a single stitch that does not show on either side. A slip stitch is a long stitch on the wrong side and a blind stitch on the hem. It is used on the milliner's fold.

Buttonholes.—A buttonhole is a slit cut and worked to admit a button for fastening purposes. It is much easier for beginners to commence on the blind buttonhole. This is made by working around a line instead of cutting the hole. The stitch, the fan, and the finishing can thus be learned without the care of the raw edge. The directions for making the buttonhole are as follows:[64]

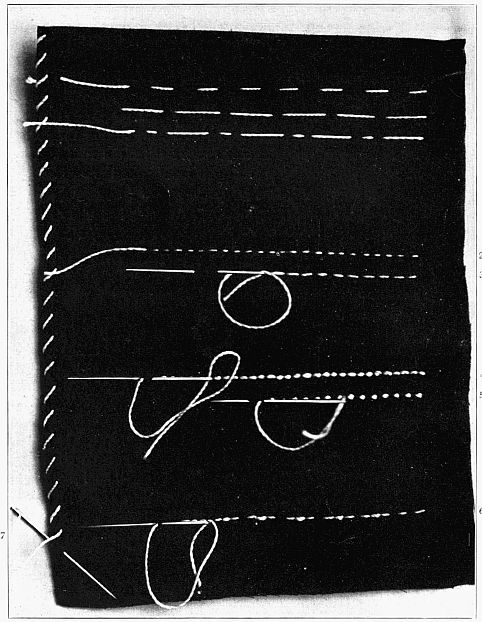

STITCHES USED ON PLAIN SEWING.

STITCHES USED ON PLAIN SEWING.

| 1—Three styles of basting. |

| 2—The running stitch. |

| 3—The gathering. |

| 4—The backstitch. |

| 5—The half-back stitch. |

| 6—The combination stitch. |

| 7—The overcasting. |

a. Cutting—With the buttonhole scissors cut the hole one-fourth of an inch from the folded edge and straight with the threads of the cloth.

b. Stranding—The strand consists of carrying the thread along the edge of the buttonhole near enough to be easily covered by the buttonhole stitch, for the purpose of adding strength to the buttonhole. Thread two needles, one with fine thread or sewing silk and the other with coarser thread or twist, depending upon the kind of buttonhole to be made. Place a knot in the coarse thread or twist, and with the folded edge of the cloth toward the left hand, bring the needle out just below the lower right hand end of the buttonhole, which is the end farthest from the folded edge. At the other end put the needle into the cloth just below the end of the cut and bring it out just above, which will carry the thread along the edge of the buttonhole. Repeat the same on the other side bringing the thread out at the point of starting. Do not cut this thread, as this is ready to begin the buttonhole stitch after the overcasting.

c. Overcasting—With the fine thread or sewing silk begin at the lower right-hand end. The object of the overcasting is to prevent raveling while working the buttonhole and the fewer stitches which will accomplish this purpose the better. As the overcasting must be covered by the buttonhole stitch do not take over two or three threads deep and just as few stitches on each side as is absolutely necessary to prevent the loosening of the threads. Some materials do not require overcasting.

a. The Stitch—Determine how deep a stitch is necessary so that the threads will not pull out, always keeping in mind that the shorter the stitch the better the buttonhole will look. This depends upon the kind of material in use. The first stitch begins one thread beyond the end of the slit. Holding the buttonhole along the cushion of the left forefinger with the folded edge of the cloth toward the left, place the needle into the slit under the lower edge of the buttonhole and draw the needle half way through. With the needle still[66] pointing toward the chest take up the double thread at the eye of the needle and place it under the point, passing from right to left. Draw the needle and thread out, and from you, so that the purl or twist comes to the edge of the slit. (This makes a firmer edge than when the thread is carried around the needle from left to right.) Each stitch is a repetition of the above. Place the stitches about the width of a thread apart, as this will avoid a crowded appearance and makes a firm, hard edge. Do not jerk the thread, but draw steadily and tight; otherwise the edge will be rough. Avoid stretching the buttonhole; the edges should touch when finished.

b. The Fan—At the end near the folded edge—the round end—spread the stitches like the sticks of a fan, drawing them closer at the top and spreading at the bottom. Five stitches will work nicely around the end, the third stitch being straight with the buttonhole.

a. The simplest manner of finishing is as follows: The buttonhole stitches at this end are at right angles to the slit, and not rounding as at the other end. After finishing the last buttonhole stitch, pass the needle down between the first and second stitch, and bring it out between the last and next to the last stitch. Draw the thread tight so as to bring the edges of the buttonhole together. Put in several stitches in the same place. Pass the needle to the under side and fasten the thread.

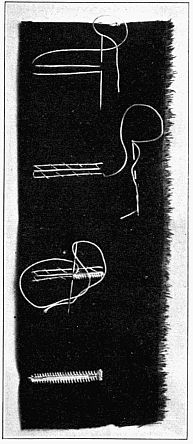

METHOD OF BUTTONHOLING.

METHOD OF BUTTONHOLING.

b. The Bar—The thread being at the top of the last stitch, pass the needle down between the first and second stitch and out at the bottom of the last stitch. Put in three threads across the width of the buttonhole, bringing the thread out at the bottom of the last buttonhole stitch. Turn the cloth so that the thumb covers the thread and the buttonhole, and work the bar by bringing the needle out each time over the thread, as in the blanket stitch. Draw the purl edge toward the buttonhole. Do not put in too many stitches, as it makes the loop stand away from the buttonhole. Near the middle of the bar take one stitch through the cloth to hold it down.

c. Caution—Be sure that the thread is long enough to work the buttonhole, but not over-long, as the thread wears and is more liable to break. Use care and not break the thread, but in case this happens, take out the last few stitches, thread the needle on this short end, pass through the last purl, and fasten the thread on the under side. With the new thread fasten without a knot on the wrong side, bring through the last purl at the edge of the buttonhole and continue.

On cloth that ravels badly put in two parallel rows of running stitches and then cut the buttonhole between the rows.

Combination Stitch.—The Combination stitch consists of three little running stitches and a backstitch over the last running stitch. Take three running stitches on the needle and pull it through. Take up the last running stitch for the first of the next group of three. It is a little stronger than the running stitch.

Darning.—The object in darning is to repair a rent, if possible so that it cannot be perceived. The warp and woof threads that have been worn away are to be rewoven into the cloth. No knots are needed. Leave a short end of thread to be clipped when the darn is finished.

Stockings should be darned on the wrong side. A square hole makes a more symmetrical darn than a round one, and should be used wherever there is no widening or narrowing in the knitting, as on the leg of a stocking. A round hole is better for the heel and toe. Cut away the part that is badly worn. First put in the warp threads, taking care to take up on the needle all the little loops around the hole and making the darn[68] symmetrical in shape. Then put in the woof threads, weaving carefully across the warp over the hole, passing over the threads that were taken up on the preceding row. Give special attention to the edge of the hole, passing first over and then under the edge, that there may be no ridge. If the hole is large or stretched out of shape, draw up the edges by whipping with fine thread. The darning stitches should extend only as far as the worn part. If the warp threads have strengthened the worn part sufficiently the woof threads may be extended only far enough over the edge to fasten securely. In darning a large hole it is sometimes wise to begin putting in the warp threads at the center first to prevent stretching. Do not draw the threads too tight, as they will shrink when washed.

This may be done with thread, ravelings or hair. In darning with thread darn on the wrong side, with ravelings or hair on the right. Darn at right angles to the tear or cut. Continue the darning stitches on each side of the tear only far enough to strengthen the worn part, usually a quarter, sometimes an eighth of an inch, is sufficient. Continue the darn an eighth of an inch beyond the end of the tear. The repairing shows less if the rows of darning stitches are of unequal length. In darning take up the threads of cloth passed over in the preceding row, slipping the needle over one edge of the tear and under the other going one way and reversing this order going the other way. This makes the edge smooth and does not throw it up in a ridge. If the material to be darned is thin or stretches easily, place the rent over a piece of glazed paper and baste around it before darning. If the cloth is worn and thin, place a piece of cloth under and darn through the two thicknesses. Take great care not to stretch the hole or to draw the threads tight enough to pucker.

Gathering.—Gathering is an uneven stitch made by passing over twice as much as is taken on the needle. When the thread is drawn up this gives the appearance of fine gathering on the right side and admits of considerable cloth being gathered into a small space.

Gathering is used in joining a full part to a straight piece, as the skirt to the band, etc. Gather with a strong single thread a little longer than than the space to be gathered. Never use a double thread. If the thread becomes knotted a new thread must be put in from the beginning. Hold[69] the cloth, as in the running stitch, with the right side toward you, using the wrist motion. Make a large knot in the thread so that it cannot slip through the cloth, and place the knot on the wrong side. At the end of the gathering slip the needle off and make a knot in the thread, that it may not pull out.

For stroking or placing gathers use a coarse needle or a pin. Draw up the gathering thread just tightly enough so that the pin can be easily inserted between the gathers and fasten by winding over a pin placed at right angles to the last stitch. Begin at the left hand, placing the pin in the fold of the first stitch and stroke gently downward, holding the pin obliquely. After each successive stroke press the pleat under the thumb of the left hand. Continue the same with every stitch.

Divide both into halves, quarters or eighths, depending upon the length, and pin the points of division together. Draw up the gathering thread to the proper length and fasten by winding over a pin. Arrange the gathers even before basting. Baste just above the gathers, holding the gathered piece next to you. Stitch just below the gathering thread.

Gauging or double gathering is done by having a second row of gathering stitches of equal length and directly below those of the first (so that when both threads are drawn up the cloth lies in pleats). In heavy material three or four threads may be put in. Gauging is usually used on heavy material or on a folded edge that is to be overhanded to a band.

Ruffles of lawn, linen or embroidery are sometimes put upon the edge instead of into a facing or seam, and when so placed it is desirable to avoid the raw edge on the under side. Hold the work over the left forefinger and roll the edge toward you between the thumb and forefinger. Place the needle under the roll on the right side, passing out at the top of the roll. Whip about one inch and draw up the thread. It is necessary to use a strong thread for whipping and gathering the edge of a ruffle.[70]

Half-Back Stitch.—Half-back stitching is similar to the stitching. The long forward stitch on the under side is three times the length of the backstitch on the upper side, and a space the length of the backstitch is left between the stitches. See Stitching, page 63.

Hemming.—A hem is a fold made by twice turning over the edge of a piece of cloth, and then sewing it down. The first fold is most important; if that is turned even there will be little trouble with the second. Trim the edge of the cloth before turning the hem. It is well to make and use a gauge of the required width. If a wide hem is turned, baste along the second fold or bottom of the hem first, and then at the top. On woolen goods or material that does not crease easily it is necessary to baste the first fold. Either bury the knot between the folds of the hem or leave one-half inch of thread and hem over it.

Hold the hem across the cushion of the left forefinger and point the needle a little to the left across the middle of the thumb. Take up a few threads of the cloth and a few threads of the fold and draw the needle through. Take care that the stitches are regular, of equal length and of equal distance apart. Do not confuse the hemming stitch with the blind stitch, or the damask hem. Join the threads by leaving a half-inch of the old thread and a half-inch of the new to be tucked under the edge of the hem and be hemmed over.

Teachers will find the following suggestions helpful in teaching the hemming stitch:

Put the needle in almost straight with the hem, not at right angles to it. Take up as little cloth on the needle as possible; bring the needle directly through the hem, making one stitch of it instead of dividing the stitch as in the blind stitch. Crowd the point of the needle under the edge of the hem. Do not insert the needle a distance from the hem, trusting to puckering it up.

Damask is a heavy fabric woven of heavy threads of one color in which the pattern is brought out by a change in the direction of the threads, and when new is stiff with much dressing. From the very nature[71] of the cloth it is impossible to hem well with the flat hem. The two folds of the hem are turned the desired width and the hem is then turned back flat to the cloth and creased. The edge of the hem and the crease thus formed are overhanded together with fine even stitches. When laundered this irons perfectly smooth and the stitches do not show on the right side. Do not confuse this method of hemming with the flat hem, as each has its own use.

Overcasting.—Overcasting is done by taking loose stitches over the raw edge of cloth from right to left to keep it from raveling. The depth of the stitch depends upon the material to be overcast, usually an eighth of an inch is sufficient. The stitches should be twice as far apart as they are deep. The needle is inserted from the under side of the cloth and points a little to the left, making a slanting stitch. Keep the spaces even and the stitches of equal length. Always trim the edges before overcasting. Do not overcast a selvedge edge. Take only one stitch at a time and be careful not to draw the edge of the cloth.

Overhanding.—Overhanding is done by sewing closely over two edges of cloth from right to left. The cloth may have a folded or selvedge edge. Careful basting is necessary to good overhanding. The needle is placed at a right angle to the seam and should point to the chest. No knot is used; a short end of the thread is left and overhanded under. Hold the work horizontally along the edge of the cushion of the left forefinger and the thumb. Do not wind the cloth over the end of the finger. The stitches are straight on the under side and slanting on the top. Do not draw the threads tight enough to make a hard seam and also avoid a loose stitch that will not hold the edges together when the seam is opened. A deep stitch is not necessary for strength and will not look well on the right side when opened. To join the threads leave a half-inch of the old and a half-inch of the new, lay them along the edge and overhand over them.

Running.—Running is done by taking up and slipping over an equal amount of cloth.

Running is used for seams that do not require great strength, and also for tucking. Care should be taken not to draw the thread tight enough[72] to pucker. Make a small knot in the thread and conceal it on the wrong side or in the folds of the cloth. Hold the work in the left hand between the thumb and cushion of the forefinger; hold the needle in the work between the thumb and forefinger of the right hand. Use the wrist motion.

Fasten the thread by passing the needle through to the wrong side and taking two backstitches.

Slip Stitch.—See Blind Stitch, page 63.