Plate I.—Dodge-Shreves Doorway. Built in 1816.

Plate I.—Dodge-Shreves Doorway. Built in 1816.

Title: Colonial Homes and Their Furnishings

Author: Mary Harrod Northend

Release date: January 9, 2011 [eBook #34897]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire. This book was produced from

scanned images of public domain material from the Internet

Archive.

Copyright, 1912,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

The wonderfully good collection of antiques for which Salem is noted was of great interest to me, being owned by personal friends who kindly consented to allow me for the first time to go through their homes and pick out the cream of their inheritance. If the readers are half as interested in these objects as I have become,—growing enthusiastic in the work through the valuable pieces found,—they will enjoy the pictures of colonial furnishings, many of which cannot be duplicated in any other collection of antiques. Family bits, wonderful old Lowestoft, and other treasures are included, all brought over in the holds of cumbersome ships, at the time when the commerce of Salem was at high tide.

To Mr. Charles R. Waters, Mrs. Nathan C. Osgood, Mrs. Henry P. Benson, Mrs. William C. West, Mrs. Nathaniel B. Mansfield, Miss A. Grace Atkinson, Mrs. Walter C. Harris, Dr. Hardy Phippen, Mrs. McDonald White, and Mr. Horatio P. Peirson, as well as many others in my native city, I owe acknowledgment for their kindness in opening their houses and letting me in, as well as to[Pg viii] Mrs. George Rogers of Danvers, Mrs. D. P. Page, Dr. Ernest H. Noyes, and Mrs. Charles H. Perry of Newburyport, Mrs. Walter J. Mitchell of Manchester, Mrs. Prescott Bigelow and Mrs. William O. Kimball of Boston, Mrs. A. A. Lord of Newton, Mrs. Charles M. Stark of Dunbarton, N.H., and the late Mr. Daniel Low.

The work was commenced at first through ill health and the desire for occupation, and has met with such good results through an interest in the story of antiques, that I have to-day one of the most valuable collections of photographs to be found in New England.

MARY H. NORTHEND.

August 1, 1912.

| Preface | |

| I. | Old Houses |

| II. | Colonial Doorways |

| III. | Door Knockers |

| IV. | Old-Time Gardens |

| V. | Halls and Stairways |

| VI. | Fireplaces and Mantelpieces |

| VII. | Old-Time Wall Papers |

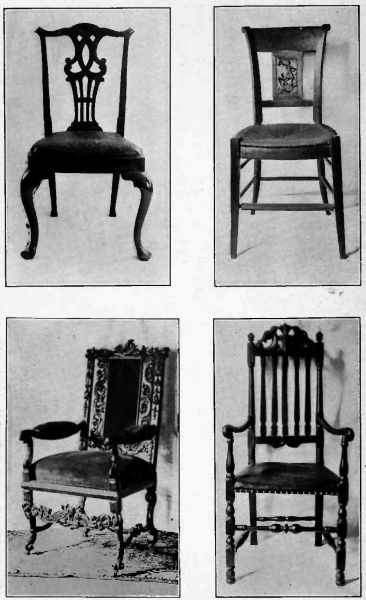

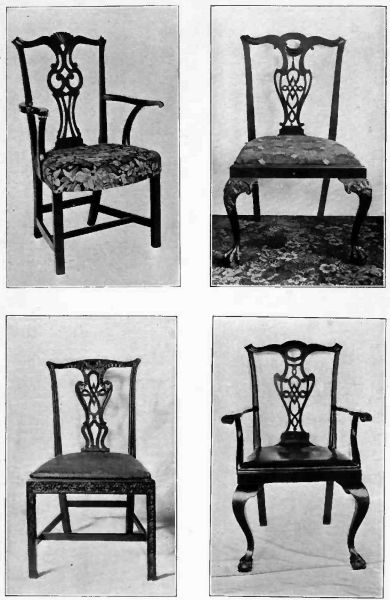

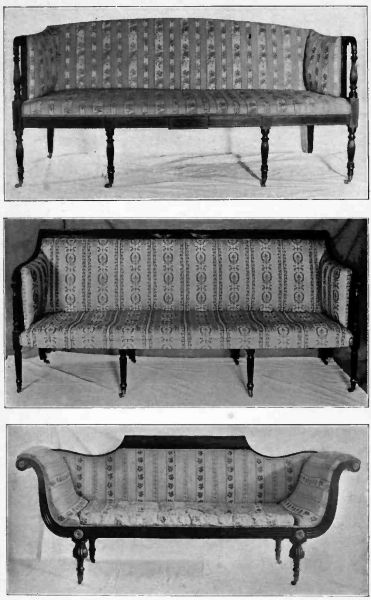

| VIII. | Old Chairs and Sofas |

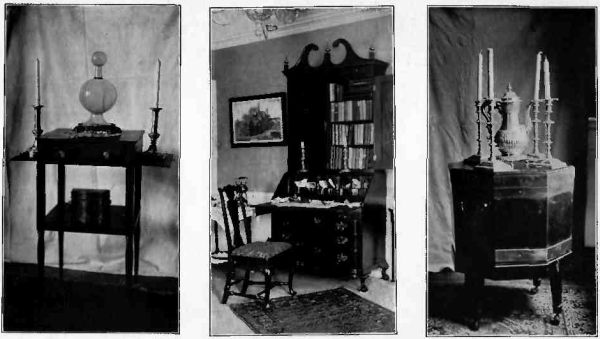

| IX. | Sideboards, Bureaus, Tables, etc. |

| X. | Four-Posters |

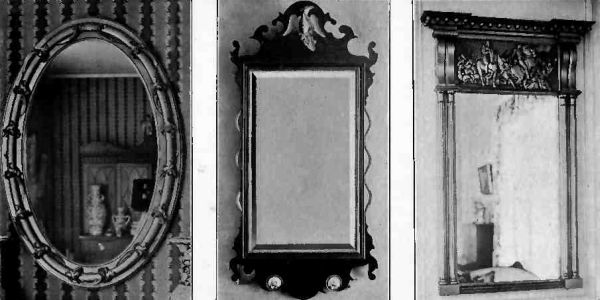

| XI. | Mirrors |

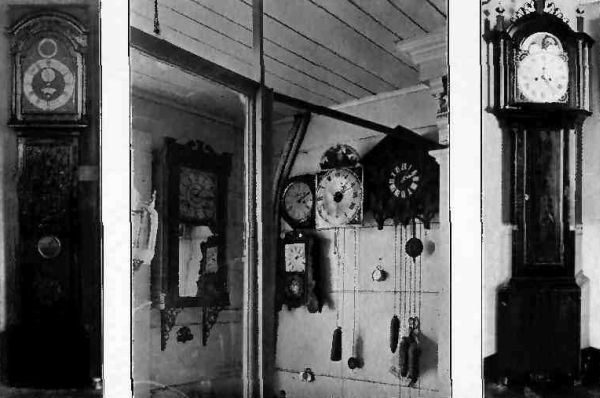

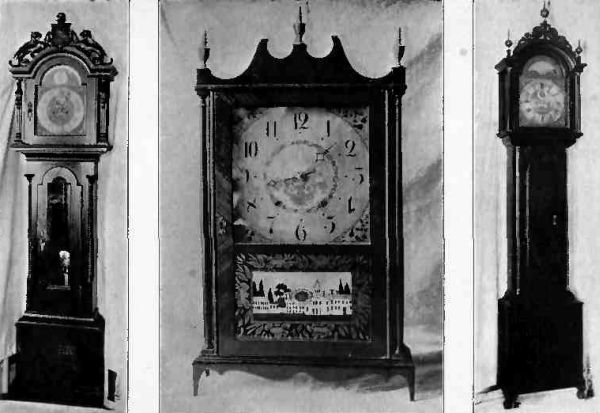

| XII. | Old-Time Clocks |

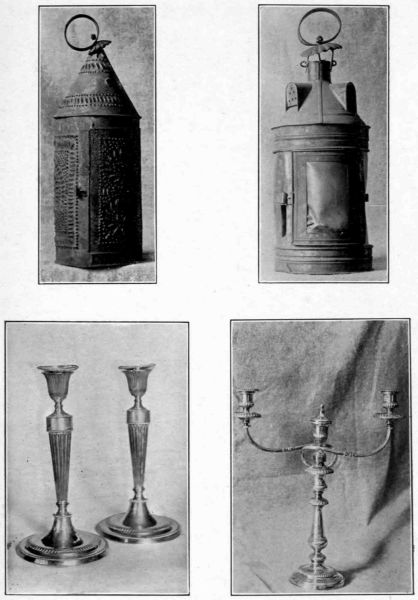

| XIII. | Old-Time Lights |

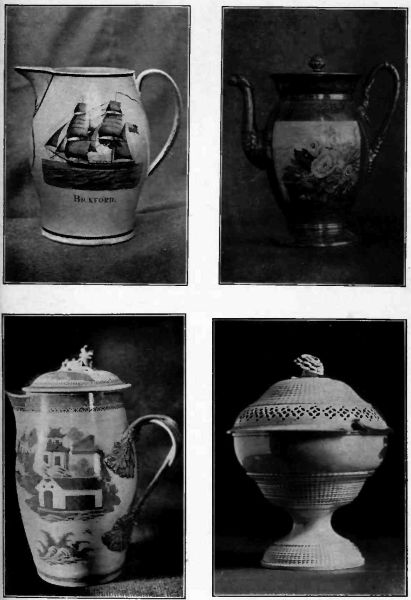

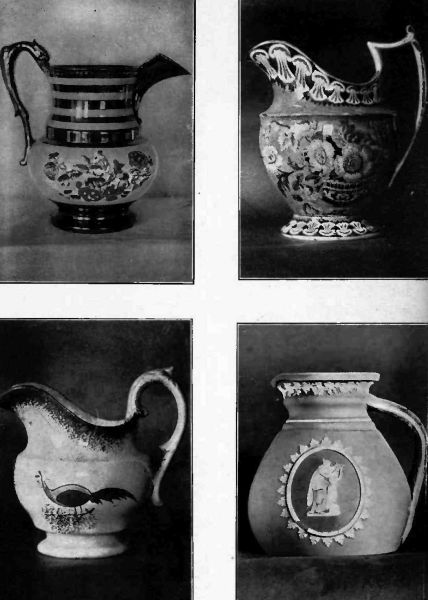

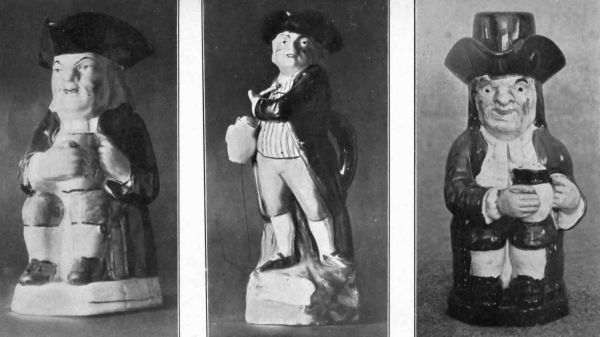

| XIV. | Old China |

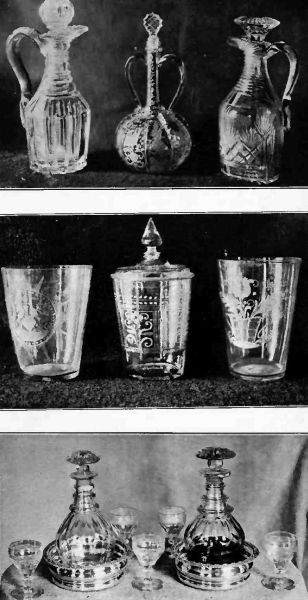

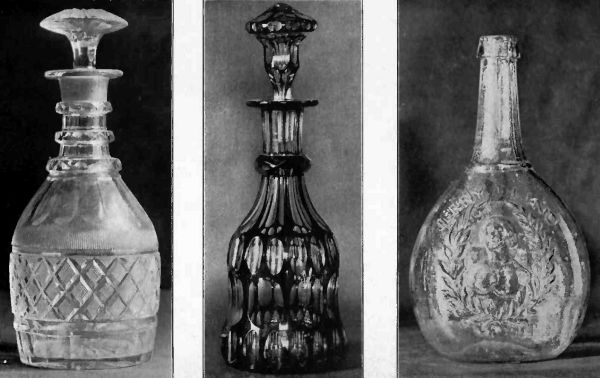

| XV. | Old Glass |

| XVI. | Old Pewter |

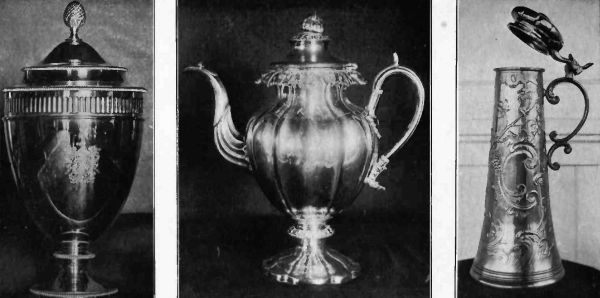

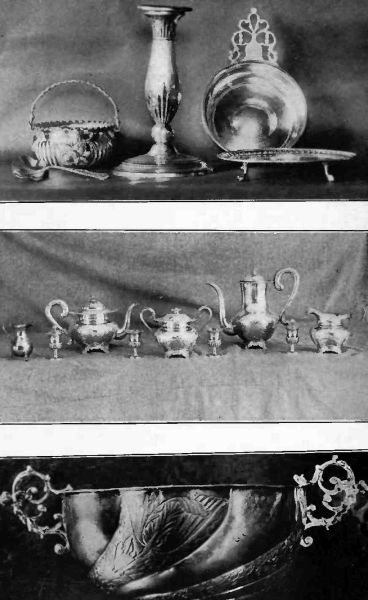

| XVII. | Old Silver |

There is an indescribable charm surrounding colonial houses, especially if historic traditions are associated with them. Many of an early date of erection are still to be found throughout New England towns, where the Puritan and the Pilgrim first settled, and not a few have remained in the same families since their construction. Some are still in an excellent state of preservation, though the majority show weather-beaten exteriors, guiltless of paint, with broken windows and sagging sills, speaking forcibly of a past prosperity, and mutely appealing through their forlornness for recognition.

These are not, however, the first homes built by the colonists, and, indeed, it is doubtful if any examples of the earliest type are still standing.[Pg 2] These were rude cabins built of logs, kept together by daubings of clay thrust into their chinks, and showing roofs finished with thatch. Great chimneys were characteristic of all these cabins, built of stone, lengthened at the top with wood, and best known by the name Catted Chimneys. In the rude interiors of the old-time fireplaces hung soot-blackened cranes, while on cold, cheerless nights the blaze of logs on the hearths

"Made the rude, bare, raftered room

Burst, flowerlike, into rosy bloom."

The next type was the frame house, built large or small according to the means of the owner, and constructed through the influence of Governor John Endicott, who sent to England for skilled workmen. Generally, these dwellings were two stories in height, the more pretentious ones showing peaks on either side to accommodate chambers, and their marked superiority over the first type soon resulted in their adoption throughout New England. In design they bore some resemblance to the Dutch architecture of the period, the outcome doubtless of many of the early settlers' long sojourn in Holland. Many of the frames were of white wood brought from the mother country in the incoming[Pg 3] ships, and the low ceilings invariably present were crossed with the heavy beams of the floors above, projecting through the timbers.

The lean-to, characteristic of some houses of this type, did not come into vogue until about the middle of the seventeenth century, and its adoption is generally believed to have been for the use of the eldest son of the family, who, according to the law of England, would inherit the homestead, and until such inheritance, could remain, with his family, beneath the ancestral roof.

The third type, the gambrel-roofed house, was at the height of its popularity about the time of the Revolutionary War, and continued in favor until the tide of commercial prosperity sweeping through the land brought in its wake the desire for more pretentious dwellings. Then came into fashion the large, square, wooden mansion, later followed by that of stately brick, excellent examples of both types being still extant.

Like the Egyptian Isis who went forth to gather up the scattered fragments of her husband Osiris, fondly hoping that she might be able to bring back his former beauty, so we of to-day are endeavoring in New England to gather and bring into unison portions of the early homes, that we may eventually[Pg 4] restore them to their original charm and dignity. Outwardly these dwellings appear much as they did when built, more than a century ago, but inwardly sad changes have been wrought, leaving scarcely a trace of their old-time beauty. Yet beneath this devastation one versed in house lore can read many a tale of interest, for old houses, like old books, secrete between their covers many a story that is well worth while.

Among the carefully preserved specimens, none of the earlier type is more interesting than the Pickering house at Salem, Massachusetts, built in 1660, more than a hundred years before the Revolution. The land on which it stands is part of the twenty acres' grant which was a portion of Governor's Field, originally owned by Governor Endicott, and conveyed by him to Emanuel Downing, who, in order to pay for his son George's commencement dinner at Harvard, disposed of it to John Pickering, the builder of the home, in 1642.

In design, the dwelling is Gothic, a popular type in the Elizabethan period, and closely resembles the Peacock Inn at Rouseley, England. The timbers used in its construction were taken from a near-by swamp, and when it was first built it showed on the northern side a sloping roof affording[Pg 5] but a single story at that end. In 1770, the then owner, Timothy Pickering, decided to raise this end to make room for three chambers, and the new portion was built to conform exactly with the old part, the windows equipped with the same quaint panes, set in leaded strips, which were finely grooved to receive the glass, on which the lead was pressed down and soldered together. It was found when the weatherboards were ripped off that the sills were sound, and it was decided to continue to use them, feeling they would last longer than those that could then be obtained. Two of the peaks found to be leaky were removed at this time, and they were not replaced until 1840, when Colonel Timothy Pickering's son, John, had reproductions set in place. The house has never been out of the Pickering family, and, with one exception, has descended to a John Pickering ever since its erection.

Distinctly a New England landmark is the Colonel Jeremiah Page house at Danvers, Massachusetts, erected in the year 1750. It occupies a site that at the time of its construction was on the highway between Ipswich and Boston, now broadened at this point and known as Danvers Square. Originally, it consisted of four rooms, but these were[Pg 6] later moved back and a new front added, the ell being replaced by a larger one.

From a historic point of view, the roof is probably the most interesting feature of this old home, for here occurred the famous tea-party that Lucy Larcom has forever immortalized. During the troublous times of 1775, when all good patriots scorned the use of tea, Colonel Page demanded that it should not be drunk beneath his roof. Mistress Page had acceded to his request, but she did not promise that she would not drink it on his roof, so with a few friends she repaired one afternoon to the rail-enclosed roof, and here brewed and distributed the much liked beverage. The secret of the tea-party did not leak out until after her death, when one of the party, visiting at the house, asked to be taken to the roof, at the same time relating the, till then unknown, experience.

Antedating the Page house some twenty-five years is the home of the Stearns family on Essex Street, Salem, erected by Joseph Sprague, a prominent old-time merchant, whose warehouse occupied the present site at the corner of North and Federal streets. This dwelling is of spacious dimensions, excellently proportioned, and it is especially interesting from the fact of its unusual interior arrangement,[Pg 7] which provides on each floor for three rooms at the back and only two at the front. The original owner was captain of the first uniformed company of militia organized in Salem, April 22, 1776, and he was also the first American to spill his blood in the Revolution, receiving a slight wound at the time of Leslie's retreat, while scuttling his gondola so it should not fall into the hands of the enemy.

Another fine old home is the Cabot house, also in Salem. This dwelling, erected in 1745 by one Joseph Cabot, is considered by experts to be of the purest colonial type, and it has proved a subject of unusual interest to any number of artists and architects.

No modern touch has been allowed to mar the old-time aspect of the Whipple house at Ipswich, Massachusetts, built in 1760, and which remains wholly unchanged from its original construction. It stands to-day almost alone in its picturesque antiquity, its huge central chimney, tiny window-panes, plain front door, guiltless of porch, with iron knocker, steep-pitched roof with lean-to at the back nearly sweeping the ground,—all betokening its age. Little wonder it is the haunt of tourists, for it presents a picture in its old-time beauty that modern architecture can never duplicate.[Pg 8]

In the historic town of Marblehead, in Massachusetts, is one of the most interesting of old-time homes,—the Colonel Jeremiah Lee mansion, built in 1768, and considered at the time of its erection the finest house in the Colonies. It was designed by an English architect at a cost of ten thousand pounds, and the timber and finish used in its construction were brought from England in one of the colonel's ships. It stands well to the front of the lot of which it forms a part, with scarcely any yard space separating it from the sidewalk, and it boasts a handsome porch supported by finely carved pillars, approached by a flight of steps. The broad entrance door, with its brass latch and old-time knob, swings easily upon its great hinges into a spacious hall that extends the length of the dwelling, affording access to the finely finished interior apartments.

Equally as interesting as these old homes are several houses in New Hampshire, one of the most prominent being the Stark mansion at Dunbarton. This was built in 1785 by Major Caleb Stark of Revolutionary fame, and it is approached to-day through the original tree-lined avenue, a mile in length. In construction it is of the mansion type, two stories in height, with gambrel roof, twelve[Pg 9] dormer windows, and a large, two-storied ell. Its entrance door is nearly three inches through, with handsome, hand-made panels, and it swings on wrought-iron hinges two feet either way. It is adorned with a knocker and latch that were brought from England by the major. Ever since its erection, this house has been occupied by a member of the Stark family, and the present owner, Charles Morris Stark, boasts the distinction of being of Revolutionary stock on both sides of the family, his mother being a lineal descendant of Robert Morris, the great financier of the Revolution.

Another interesting colonial home is the Warner house at Portsmouth, occupying a corner section on one of the city's main thoroughfares. This fine dwelling was erected by Captain Macpheadris, a wealthy merchant who came to this country from Scotland, and it is built of Dutch bricks that were imported from Holland, with walls eighteen inches thick. It stands firmly on its foundation, a magnificent specimen of early construction; and its gambrel roof, Lutheran windows, quaint cupola, and broad simplicity of entrance door, suggest the old-time hospitality that was so freely dispensed here. After the captain's death, the house came to his daughter, Mary, who[Pg 10] had married Hon. Jonathan Warner, a member of the King's Council until the outbreak of the Revolution, and it is by his name that the fine old home is known.

Two miles from Portsmouth, at Little Harbor, is the old home of Governor Benning Wentworth, built in 1750. In general, this dwelling is two stories in height, with wings that form three sides of a hollow square, though it boasts no particular style of architecture, appearing to be rather a group of buildings added to the main structure from time to time. It is screened from the roadway by great trees, and on the north and east faces the water. Originally it had fifty-two rooms, but some of these have been combined, so to-day there are but forty-five. The cellar is particularly large, and here in times of danger the governor hid his horses. After the governor's death, his widow married John Wentworth, and it was during the occupancy of Sir John and his wife that Washington was entertained here.

Typical of the wooden mansion type, that succeeded in favor the gambrel-roofed dwellings, is the house now known as the Endicott house, at Danvers, Massachusetts. This building, constructed about 1800, was purchased about 1812 by Captain Joseph[Pg 11] Peabody, a Salem merchant, and grandfather of the present owner, as a place of refuge for himself and family during the embargo. In design, it is most imposing, and the front now shows a wide veranda, with the entrance dignified by a porte-cochère, supported by high columns, between each two of which a great bay tree is set. Sweeps of smooth lawn afford an attractive setting, and great trees, here and there, bestow protecting shade. The dwelling is surrounded by beautiful gardens, the most interesting from a historic point of view being the old-fashioned posy plot laid out at the time of the erection of the house.

Not unlike in type to this fine home is "Hey Bonnie Hall" in Rhode Island, the residence of the Misses Middleton. Built in 1808, it stands to-day in all its original beauty, the pure white of its exterior admirably set off by the great green sweeps of sward, dotted with fine trees, that surround it on all sides. It was erected from plans of Russell Warren, who designed the White House at Washington, and it is renowned not only for its beautiful colonial architecture, but also for the wonderful collection of old-time furniture and objects of art that it contains.

In type, it is very similar to a Maryland manor,[Pg 12] with projecting wings, the service portion in a separate building connected with the main house by a covered passage, after the Southern fashion. In this passage is the well room, so called from the fact that a well of pure spring water is located here. In length the house is one hundred and forty feet, its front just enough broken to avoid monotony, and its spaciousness affording an air of comfort. Two Corinthian columns, as high as the house itself, support the roof over the entrance porch, and on either side are well-protected verandas, overlooking beds of old-fashioned flowers and smooth stretches of sward. In front lies the harbor, and beyond is the picturesque town of Bristol, affording a most pleasing prospect.

Unlike these latter-day types, in fact unlike any set design, is the low, rambling house at West Newbury, Massachusetts, known as Indian Hill, and so called from the location that it occupies. In appearance, this dwelling is most picturesque, resembling in design a castle, and it is as historic as it is interesting. The site that it occupies is the last reservation of the Indians in the neighborhood, the land having been sold by Old Tom, the Indian chieftain, to the town, and the deed of the sale being still preserved by the present owners.[Pg 13]

Viewed from any angle, the house presents a series of pictures, each equally as interesting as the other, and its irregular roof lines, gables and bays, quaint, diamond-paned windows, and chimneys adorned with chimney pots, are further embellished by the flowering vines of a rambler rose, perhaps the finest in the country. While the house can be seen from the road, it is only when one drives under the archway into the courtyard, bounded on three sides by barn, stables, and house, that he can realize its true worth.

Salem, fortunate in specimens of early construction, is also fortunate in examples of latter-day types, and here are to be found several of the fine brick dwellings, built at the time of her greatest commercial prosperity. One of these is the Andrews house, located on Washington Square, and one of the three dwellings erected in 1818. Its brick exterior gives no hint of its age other than the softening dignity that time bequeaths, and it stands to-day, tall and broad, its gray-faced bricks brightened by white trimmings, and its beauty emphasized by a fine circular porch supported by white columns, topped with a high balustrade. At one side is a charming old-fashioned garden, laid out in prim, box-bordered beds, and all about its fence[Pg 14] inclosure flowering vines clamber. Complete, the dwelling cost forty thousand dollars,—a large sum for the time of its erection.

Every brick used in its construction was first dipped into boiling oil to render it impervious to moisture, and all the framework is of timbers seasoned by long exposure to the sun and rain. On one brick is cut the date of erection, the work of the master builder under whose supervision the dwelling was erected. The great pillars of the side porch, overlooking the garden, are packed, so the story goes, with rock salt—not an uncommon process at that time—to keep out dampness and to save the wood from being eaten by worms.

Some years previous to the erection of this dwelling, Mr. Nathan Robinson had constructed on Chestnut Street a brick dwelling, considered by connoisseurs to be one of the finest specimens to-day extant. The porch, at the front, is wonderfully fine, and has attracted the attention of any number of students and architects, who have made a careful study of it.

And so we might go on and on, singling out particularly good specimens here and there, but when all is said and done, it is undeniable that all old houses afford interesting study. Architects of[Pg 15] the present are coming to appreciate their worth, and into many modern homes features of early construction are being incorporated. Naturally, to the antiquarian, nothing can ever take the place of these bygone specimens, and as he paces the main thoroughfares of historic cities, now lined with stores, he sees in fancy the stately homes with their fragrant garden plots, which modern demand has superseded. Pausing on the curbing near the old State House in Boston, what an array of bygone dwellings in fancy can be conjured, and how many of the old-time dignitaries can be recalled. So vivid is the picture that one might almost expect to see old Thomas Leverett saunter by, or perchance hear the rattle of wheels as the carriage of Dr. Elisha Cook lumbered on its way. It is a pleasant picture to contemplate, and the lover of the old breathes a sigh of regret at the passing of such picturesqueness.[Pg 16]

No type of architecture to-day holds such a distinctive place in the minds of architects and home builders as does that of the colonial period. This is especially true concerning the porch or doorway, for this feature, affording as it does entrance to the home, called for most careful thought, that it might be made harmonious and artistic, and expressive of the sentiment which it embodies. The straight lines and ample dimensions which characterized it required skill to arrange properly, and, considering the limitations of the period in which it was constructed, the results obtained were remarkable.

These porches and doorways were designed at a time when our country was young, and the builders were not finished architects like the designers of to-day; but they were planned and built by men who were masters in their line, and who taxed their skill to the utmost that results might be artistic and varied, individualizing each home so that[Pg 17] the entrance porch should express both hospitality and refinement.

In the holds of the cumbersome ships that plied between the new country and the motherland were placed as cargoes, pillars, columns, and bits of shaped wood, all to be used in the construction of the new home, and incidentally in the porch. It was no easy task to devise from these fragments a complete and artistic whole, and to the ingenuity of the builders great credit is due.

In contour and construction, these porches differ greatly. Those found in New England depict a stateliness that savors of Puritanical influence, while those in the South convey, through their breadth, an impression of the cordiality which is characteristic of that section. Some are semicircular, others square; a few are oblong, and some are three-cornered, fitting into two sides of the entrance, and in each case giving to the dwelling a congruous appearance that is refreshing to contemplate in an age like ours, when so many different periods are combined in a finished whole.

All these porches show a harmony of form and proportion that gives just the right effect, and many are embellished by wonderful wood carving. The Grecian column, in its many forms, lends itself[Pg 18] in a great degree to artistic effects, often bestowing an originality of finish that is most pleasing, and one that differs in every respect from the modern broad veranda, and the stately porte-cochère.

The art of hand carving reached its highest state of perfection about the year 1811, during which period the best types of porches were erected. The results are shown not only in the capitals of the columns and on the architrave, but on the pediments and over the entrance door as well. A good example of the decoration of the architrave is seen on the old Assembly House on Federal Street, in Salem, Massachusetts, where the carving takes the form of a grapevine, with bunches of the hanging fruit, and also over the door of the Kimball house, in the same city, where Samuel McIntyre, one of the most noted wood carvers, lived.

It can be well and correctly said that the colonial porch embodied not only the characteristics of the period in which it was built, but the personality of the owner as well. Should the unobservant person feel that this statement is far-fetched, let him take a stroll through some tree-shaded street of an old New England village, and the truth of the assertion is readily revealed. Though the house[Pg 19] itself may be old and battered, and fast falling into decay, yet the porch greets one with a simple welcome that breathes of former hospitality, and, in admiration of this feature, the shabbiness of the rest of the exterior sinks into oblivion.

Broadly speaking, porches are divided into three types or classes. The first belong to the period beginning with the year 1745 and continuing until the year 1785, a space of time marked by stirring events, culminating in the Revolutionary War, and the birth of the new republic. Houses of this period are of the gambrel-roofed type. The second class adorn the succeeding type of dwelling,—the large, square, colonial house, built by the merchant prince, whose ships circumnavigated the globe, and who filled his home with foreign treasures; while the third type is that which ornamented the brick mansion which came into vogue about 1818. As many of these were erected during the commercial period, they cannot, strictly speaking, be called colonial; they belong rather to the Washingtonian time, and reflect in their construction the gracious hospitality of that day.

Porches of varied colonial types are found in most of the New England cities and towns, in the Middle States, and in the South, and particularly[Pg 20] fine examples can be seen in Salem, Massachusetts. There is about all of these a dignity and refinement that is unmistakable, bespeaking a culture that is felt at once, and a stranger wandering through Salem's streets cannot help but be impressed with the fact.

Adorning the three-storied houses with their flat roofs, they give an artistic touch to what would otherwise be plain exteriors. From step to knocker, from leaded glass to the arched or square roof of the doorway, there is a plainness and simplicity which betokens art, but of such a quiet, unpretentious type that by the untrained eye it is hardly appreciated, though to the architect it brings inspiration and affords study for classic detail, the result of which is shown in the modified colonial homes of to-day.

Romance and history are strangely intermingled in these old-time porches and doorways. Under their stately portals has passed many a colonial lover, doffing his cocked hat to his lady fair, who, with silken gown, powdered hair and patches, sat at the window awaiting his coming. Those were Salem's halcyon days, when the tide of life ebbed and flowed in uneventful harmony, free from the disturbing elements of latter-day life.[Pg 21]

To attempt even a brief description of each and every doorway would be a herculean task. Rather, it is better to depict the different types, studying with critical eye the various examples. One is the semicircular entrance, with its rounded front, a type shown in many a New England home. The Andrew porch, numbered among the finest in the city, belongs to this class. Under this doorway passed the late war governor, John Andrew, during visits to his uncle, John Andrew, builder of the dwelling, that he always coveted for his own. The dwelling was one of three built in 1818 on three sides of a training field, which is now the Common. The fine elm trees that characterize the Common were planted in the same year. The other two houses were the John Forrester dwelling and the Nathaniel Silsbee house. The Andrew porch shows straight columns, and a roof topped with a balustrade; the simplicity of outline renders it most attractive.

Another porch of the same type is that of the John Gardiner house on Essex Street, built in 1804. Here is an entrance considered by good judges of architecture to be one of the best examples of its type, characterized by perfect symmetry of outline. Numbered among its features are quaint[Pg 22] indentations in the door head. This dwelling was formerly the home of Captain Joseph White, one of the worthy and noted Salem merchants. Other porches of similar contour, though differently ornamented, are to be found on Chestnut Street.

It is only when one carefully studies doorways such as these, contrasting them with latter-day porches, which are often little more than holes in the wall, fitted with a cheap framing and entirely out of keeping with the exterior, that their worth is viewed in the true light, and the opportunity to turn to the old-time types for inspiration is appreciated.

Perhaps the most Puritanical of all the doorways are the simple narrow ones that generally stand at one side of the house, although sometimes they are used as the main entrance. These show either fluted side pilasters, or severely plain columns, surmounted by a pediment. The door is always dark in coloring, trimmed with a polished brass knocker and often with a brass latch.

One of the most elaborate of these is that of the dwelling known as the Cabot house on Essex Street. This house was designed in 1745 by an English architect for Joseph Choate, and later came into the possession of Joseph Cabot.

Another notable entrance is that of the Lord[Pg 23] house on Washington Square. This is a side entrance, and is said to be one of the finest of its type in Salem. This house was at one time occupied by Stephen White, a man of worth, who was falsely accused of the murder of his uncle, and who engaged as counsel Daniel Webster. While this case was in progress, Webster brought his son, Fletcher, to the White home, where he met and fell in love with the daughter of the house, later making her his bride. Thus were romance and law strangely intermingled! The house was afterwards the home of Nathaniel Lord, one of the most brilliant jurists of his time.

The inclosed porch is another phase of old Salem doorways. There are several interesting examples of this type still to be seen here, perhaps the most noted being the one on Charter Street, on a three-story, wooden building, about a century and a half old, low of stud, with square front, standing directly on a shabby little by-street, and cornered in a graveyard. This porch, inclosing the entrance door, is lighted by small, oval windows, one on either side, affording glimpses up and down the street. It has been graphically described by a silent, dark-browed man, who, with two women, came to the dwelling in the dusk of an evening[Pg 24] in 1838, and, lifting the old-time knocker, announced his arrival. The door was opened by Elizabeth Peabody, who graciously admitted Nathaniel Hawthorne and his sisters, showed them into the parlor, and then ran up-stairs to tell her sister Sophia of the handsome young man—handsomer than Lord Byron—who had just arrived. As the door closed behind him that evening, Hawthorne shut out forever the dreary solitude of his life, and we read that he came again and again to the old home, where he played the principal part in one of the most idyllic of courtships, ending in his marriage two years later with the fair Sophia. This dwelling he made the scene of Dr. Grimshawe's Secret, and the old porch has taken on a dignity and historic interest that will live forever.

But perhaps one loves to dwell longest on the doorway of the Assembly House on Federal Street, for it is full of vivid memories. It is an oddly shaped porch, beautifully carved, and under its portals the daughters of Salem's merchant princes passed, holding in their slender hands the skirts of their silken gowns, as they gayly mounted the broad stone steps. On the evening of October 29, 1784, Lafayette was entertained in this old[Pg 25] home, and five years later, Washington, who had just been inaugurated as the first President of the United States, came here. Concerning his visit, he wrote in his diary: "Between 7 and 8 I went to an Assembly, where there were at least a hundred handsome young ladies." With one of these, the daughter of General Abbot, Washington opened the ball, and for her later, as he did not dance, he secured as a partner General Knox.

Other types of porches still seen in Salem include the Dutch porch, quaint and comely in its construction, an excellent example of which is seen on the Whipple house on Andover Street, while surrounding the Common on Washington Square are many rare and picturesque porches of various dates of erection.

Considered by experts to excel them all is the porch that adorns the Pierce-Jahonnot house on Federal Street. This dwelling was erected by Mr. Pierce, of Pierce and Waitte, merchants, in the year 1782, and beside the main entrance it boasts a fine example of the narrow doorway at one side. In the early spring, crocuses clustering about the base of the porch add a touch that is decorative and charming, and the box-bordered garden beds, just in front, filled with masses of pure white[Pg 26] bloom, complete a wholly delightful setting. There is about this particular doorway a touch of sentiment felt by every Salemite. It is a piece of architecture of which any one might feel proud, and in its beauty and dignity it stands distinctive in the midst of many fine bits. It is the Mecca of architects, who delight in the exquisite blending of doorway and entrance.

There is a touch of the old Witchcraft Days connected with a doorway at Number 23 Summer Street, that resembles in type the one immortalized by Hawthorne. More than two hundred years ago, this porch was the site of an event that culminated in tragedy. Bridget Bishop, the first victim of the terrible delusion of 1692, kept a tavern here, and in her gay light-heartedness, she scorned the dictates of the church and insisted upon wearing on Sabbath Day a black hat and a red paragon bodice, bordered and looped with different colors. Her boldness in defying the rigid doctrines made the dignitaries suspicious of her, and at her trial, when one witness told of meeting her before the site of the present doorway where his horse stopped, and the buggy he was driving flew to pieces,—she of course having bewitched it,—was condemned to death.[Pg 27]

Individual types found throughout the city show a variety of construction and ornamentation, and many of these are most unique, although they do not belong to any special period. Prominent among these is the Pineapple doorway on Brown Street Court, an excellently proportioned and finely adorned entrance, which, through the remoteness of its location, is rarely seen by tourists. The dwelling of which it is a part was built in 1750 by Captain Thomas Poynton, and this feature, unlike the old Benjamin Pickman porch on Essex Street, which shows a codfish, has nothing about it suggestive of New England. The pineapple, which is set in a broken pediment, was brought over from England in one of the captain's own ships, and in the days of his occupancy it was kept brightly gilded, its leaves painted green.

Many of the doorways show an innovation in the presence of the climbing vine, which winds its tendrils about the pillar supports, emphasizing their beauty. It is not definitely known whether the early owners encouraged the vine-covered porch or not, but they probably did, as they delighted in the vine-covered summer-house, which was a feature of nearly every old-time garden.

While Salem may hold a prominent rank in[Pg 28] attractive porches, many fine examples are to be found in Philadelphia, and though these specimens differ radically in design, they are most attractive. One is to be seen on Independence Hall on Chestnut Street, while others are found on churches and houses.

These doorways illustrate a phase of architectural construction totally different from the porches of New England and those of the South, yet they combine features of the other types, while at the same time displaying a certain definite style of their own which gives to them as great distinctiveness as characterizes Salem porches.

If the twentieth-century architect desires studies of truly attractive doorways, the seaport towns of New England will afford him excellent models. There is enough variety here in porches which are still preserved to give him any number of models from which to devise an entrance that will serve its purpose in every sense of the word.

For the home builder, it will not be amiss to carefully consider the best type of porch before he goes to the architect to develop his plans; he can be assured that study will develop ideas that will give to his home an individuality that will embody his ideas and personality.[Pg 29]

There is no more decorative feature of the entrance door than the old-time door knocker, especially if in conjunction with it are used a latch and hinge. It possesses a dignity and charm that is most attractive, and when shown in brass, brightly burnished, it forms a most effective foil for the dark or polished surface of the wood.

Door knockers have been in use, save for short periods during the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, since their invention, early in the world's history, although they were most freely used during the Romanesque, the Gothic, and the Renaissance periods. For easy identification they may be divided into three classes, the first characterized by a ring, the second by a hammer, and the third by human figures and animals' heads. The first two types show a much larger surface of plate than the third, and the designs employed are often most elaborate.

Door knockers in use during the Medieval[Pg 30] period were perhaps the most carefully designed, while those of the Renaissance period showed the most fanciful treatment. It must be remembered, when considering the ornamental qualities of both these types of knockers, and comparing them with latter-day productions, that they were made at a time when designers were practically unknown, artists being employed to draw patterns which were worked out by assistants under the supervision of master smiths, which method resulted in a greater diversity of treatment.

Iron was at first used in the construction of knockers, partly on account of its inexpensiveness, and the results secured from this seemingly ugly material were both artistic and beautiful. Later, brass came into favor for the purpose, and it has since remained the principal knocker material, as no better substitute has been found. Brightly polished, a brass knocker undeniably adds to the decorative attractiveness of any door.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, knockers were used on all classes of houses. These for the most part were very elaborate in design, showing a wonderful delicacy of workmanship, and they were in many instances larger than those found on modern colonial homes.[Pg 31]

Except for the period during the seventeenth century, as above mentioned, door knockers remained in favor until the middle of the nineteenth century, when a wave of modernity, sweeping the length and breadth of the land, brought in its wake an overthrow of colonial ideas and furnishings. Modern doors, plain of surface, replaced the finely paneled old-time ones, and with their coming disappeared the knocker and the latch. Probably the principal cause of this was the demolition of many of the old landmarks, and the substitution of dwellings of an entirely different architectural type. This innovation for a second time consigned the knocker to oblivion, and many there were who, not realizing its artistic value, cast it into the scrap heap. Others, with a veneration for heirlooms, packed the knockers away in old hair trunks under the eaves of the spacious attic, together with other antiques of varying character.

No doubt the greatest number were saved by the wise and far-sighted collector, who, realizing the artistic beauty of the knocker, felt that it would in time come to its own again. Quietly he purchased them and stored them away, awaiting the day of their revival, and his foresight was amply repaid when the modified colonial house came into vogue,[Pg 32] demanding that the knocker should again be the doorway's chief feature. Many of those now shown are genuine antiques, while others are reproductions, but so carefully copied that only to one who has made a study of antiques is the difference discernible.

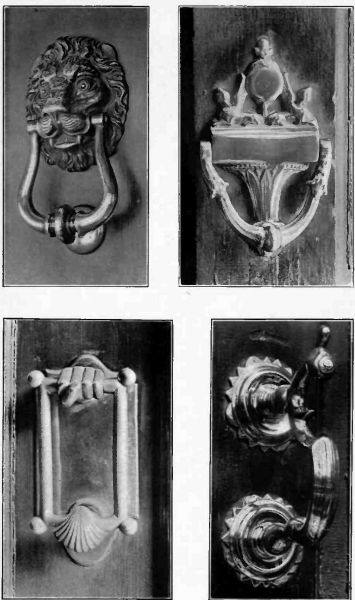

Plate VIII.—16th Century Knocker, Lion type, Striker of first type; Georgian Urn type, in use on modern house; Mexican Knocker of the Hammer type; Hammer type Knocker, 18th Century, Charles P. Waters House.

Plate VIII.—16th Century Knocker, Lion type, Striker of first type; Georgian Urn type, in use on modern house; Mexican Knocker of the Hammer type; Hammer type Knocker, 18th Century, Charles P. Waters House.

Old door knockers vary as to size according to the date of their construction. Many are of odd design, having been made to fit doors of unusual shapes, and the ornamentation is as varied as the shapes. The most elaborate knockers depict such ideas as Medusa's head, Garlands of Roses, and, in many cases, animals' heads, while the simple ones show oval or plain shapes, with border decorated with bead or fretwork.

The shape of the knocker is of great assistance in classification, as is the metal used. The most common type has the striker round or stirrup-shaped. This is either plain or ornamented with twisted forms, with wreathing or masks, and the plate is formed of a rosette or lion's head.

In the second type, the striker is hammer-shaped, the handle often showing a split and straplike formation, while the plate and knob are plain. This is an early type, as is shown from the fact that specimens still exist that are not unlike Byzantine[Pg 33] and Saracenic forms. It is to this type that the exquisite iron-chiseled knockers of Henry II and Louis XIV belong.

The lyre or elongated loop drawn down to form the striker constitute the third style. Masks, snakes, dragons, and human figures belong to this class, and, on account of the elaborate workmanship employed, these are often found in brass and bronze. This type shows ornamentation lavished on the striker, while the plate is very plain.

The greatest difference noted in all these classes is that in the third type the escutcheon or plate by which the knocker is fastened to the door is of little importance, while in the first two types it is the leading motive.

During the Gothic period, the design was diamond-shape, richly decorated with pierced work, and while this same motif was retained in the making of the Renaissance knocker, it was frequently varied by the double-headed or some similar style.

What is correct concerning the design of the Medieval knocker holds good in that of to-day. No door knocker ever designed was ugly, even at the time of the earliest manufacture, when so little was known concerning architectural construction. There is a[Pg 34] fine individuality in the style of all knockers, and singularly enough one fails to find duplicates of even the most admirable specimens. Another fact that seems strange is that reproductions often sell for as much as genuine antiques. It would seem that the price of the old knocker would be high, on account of its historical value, and yet this type of knockers sells at a lower price than present-day specimens. Old brass examples can be purchased as low as two dollars and fifty cents, while large and elaborate ones bring only ten dollars. This is not on account of their true value not being known, but because there is, as yet, comparatively little demand for them; and their sale at the best is limited, for where a person could use twenty candlesticks, two knockers would suffice for door ornamentation.

There is an important phase of the copied specimens that must be taken into consideration, and that is that they have no historic value. This fact has made reproductions of no appeal to either the collector or the antiquarian, unless there is some special interest in the model from which they have been copied.

Whether a knocker is a reproduction or a genuine antique can often be told by examining the plate[Pg 35] and noting if it is forged to the ring or flat plate. If so, it is a fine piece of workmanship and a genuine antique; otherwise, it is spurious.

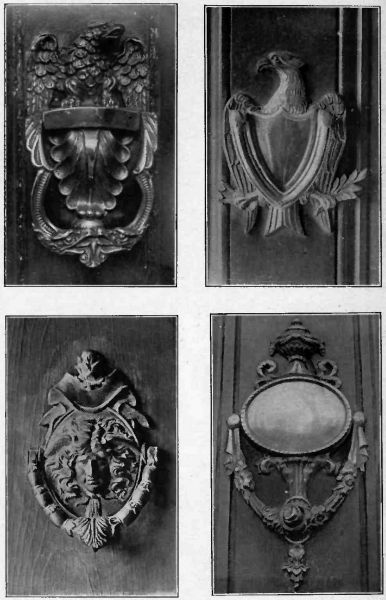

Plate IX.—Eagle Knocker; Eagle Knocker, Rogers House, Danvers, Mass.; Medusa head, elaborate early type; Garland type of Knocker.

Plate IX.—Eagle Knocker; Eagle Knocker, Rogers House, Danvers, Mass.; Medusa head, elaborate early type; Garland type of Knocker.

The best place to purchase genuine old knockers is in the curio shops, where only such things are for sale. Even in this event, it is well to know the earmarks, for if one is anxious for a real antique, he should be posted on the characteristics, as a spurious specimen is apt to find its way even here.

The door knockers in general use to-day are the Georgian urn or vase, the thumb latch, and the eagle. Such designs as Medusa's head, and the head of Daphne with its wreath of laurel leaves are also sometimes found.

The lion with ring has always been more popular in England than in our country, and, indeed, during the Revolutionary War and for fifty years after, it was not even tolerated here, being superseded by the eagle, which came into vogue about 1775.

The garland knocker, which belongs to the early type, is still sometimes found to-day. One such specimen is shown on a modern colonial home at Wayland, Massachusetts. This originally graced the doorway of one of Salem's merchant prince's[Pg 36] homes, but it was purchased by a dealer in antiques at the time of the decline in favor of the knocker, later finding its original resting place, from which it has only recently been removed.

Another rare and unusual knocker is shown on a house on Lynde Street, Salem, Massachusetts. This is of Mexican type, and has been on the house since its erection. It was painted over some years ago by an owner who cared little for its worth, and it was not until a comparatively short time ago that it was discovered to be a fine example of a rare type.

The horseshoe knocker, a specimen of the hammer class, is a prized relic of many old homes. Like all true colonial specimens, it is made of wrought iron, painfully hammered by hand upon the forge in the absence of machinery for working iron, as even nails had to be hammered out in those early times. This is one of the quaintest and most original knockers, and is after the pattern of the earliest designed. Subsequent specimens were more elaborate, colonial craftsmen bestowing upon them their greatest skill. Among the most ornate were the purely Greek or Georgian vases or urns, eagles in all possible and impossible positions, heads of Medusa, Ariadne, and other mythological ladies,[Pg 37] and Italian Renaissance subjects, such as nymphs, mermaids, and dolphins, with ribbons, garlands, and streamers.

Not a few of these knockers have wonderfully interesting histories. Scenes have been enacted about them, which, could they be but known, would make thrilling tales. Take, for instance, the knocker on the Craigie House at Cambridge, Massachusetts. How many men of letters from all over the world have lifted the knocker to gain admittance to our late loved poet's home, and think what stories such visits could furnish!

On the Whittier homestead at Amesbury, Massachusetts, is still to be seen the knocker which was on the door during the poet's life. This is of eagle design, probably chosen on account of its patriotic significance. Another interesting knocker formerly graced the house wherein the "Duchess" lived, on Turner Street, in Salem, many times lifted by Hawthorne, who was a frequent visitor to this dwelling, and who forever immortalized it in his famous romance, The House of Seven Gables. This is now replaced by another of different design.

Considered to be one of the oldest knockers in this section is that on the door of the May house at Newton, Massachusetts. Be that as it may, it is[Pg 38] certainly unique. The plate shows a phœnix rising from the plain brass surface, while the knocker has for ornamentation a Medieval head. This knocker has attracted the attention of antiquarians throughout the country, who have given it much study in attempts to find out the period in which it was made.

Thumb latches are not so common as the hammer and ring class. Two of these specially unique show wonderful cutting. One is found on the front door of the Waters house on Washington Square, Salem, being brought from the John Crowninshield dwelling, while the other is seen on the side porch of this same residence, having been placed there at the time of the building's erection in 1795.

England is the seat of most of the old-time knockers, although they are still found in almost every part of the globe. Threading the narrow by-streets of London, one finds many historic specimens replaced by simple modern affairs. Some have become the prey of avaricious tourists, while others, because of their owners' little regard for their value, have been relegated to ash heaps and thrown away.

This is true of the knocker made famous by Dickens in the Christmas Carol. On the polished[Pg 39] surface of this, Scrooge was said to have thought he saw reflected the face of Marley "like a bad lobster in a dark cellar." Later he spoke of it as follows: "I shall love it as long as I live. I scarcely ever looked at it before. What an honest expression it has in its face. It is a wonderful knocker." Clasped hands holding a ring of laurel is the form of the knocker still seen on the door of the famous Dr. Johnson house, and, as one gazes at it, he can in fancy see David Garrick and Sir Joshua Reynolds ascending the steps, and if he pauses a moment longer he can no doubt even hear the metallic ring of the knocker, as it responds to the vigorous raps that they give.

The most beautiful knocker left in London is the one shown on the outer gate of the Duke of Devonshire's house at Piccadilly. The design here, as unique as it is beautiful, shows an angelic head with flowing hair.

Chapels and cathedrals in England have many examples of this type of door decoration, one being a knocker handle with pierced tracery seen on Stogumber Church in Somerset.

The history of door knockers is practically unwritten, and little is known concerning their make. The revival of antiques is responsible for[Pg 40] their present popularity, and gives them an importance in house ornamentation little dreamed of a few years ago. To be sure, the coming of electric bells has precluded their necessity, but, on account of their ornamental value, it is doubtful if they ever become obsolete. The variety of design, the many artistic shapes to which they can be adapted, and, more than all, their decorative qualities, make them particularly valuable.[Pg 41]

There was a restful charm and dignity surrounding the garden of olden times that is lacking in the formal ones of to-day. This effect was gained partly from the prim box borders and the straight, central path, and partly from the stateliness of the old-fashioned flowers. Gardens formed a distinctive feature in the colonists' home grounds, from the time of their landing on unknown soil. At first they were very small, and consisted mostly of wild flowers and plants that had been brought from their homes in England and Holland. The early settlers brought with them to this new land a deep love for floriculture, and the earliest garden plots filled with flowering plants, though rude in construction, saved the house mother many a heartache, reminding her as they did of the beautiful gardens in the motherland left behind.

We find in the earliest records of the new settlers allusions to flowers, and Reverend Francis Higginson speaks of the wild flowers which he[Pg 42] saw blossoming near the shore. He considered them of enough importance to record in his diary on June 24, 1629, writing "that wild flowers of yellow coloring resembling Gilliflowers were seen near the shore as they sighted land, and that as they came closer they saw many of these flowers scattered here and there, some of the plots being from nine to ten feet in size."

Four of the men who went ashore on the twenty-seventh of that month found on the headlands of Cape Cod single wild roses. Later on he tells again of the number of plants found growing, giving their names. These facts have enabled people in later years to locate the same flowers growing near the same places as when they were first discovered.

Governor Bradford also considered the flowers of importance, and in his historical account of the Colonies of New England, he tells us that "here grow many fine flowers, among them the fair lily and the fragrant rose."

On Governors Island in Boston Harbor were rich vineyards and orchards, as well as many varieties of flowers. Governor Winthrop, inserting a clause in the grant, said that vineyards and orchards should be planted here; that this was complied[Pg 43] with is shown from the fact that the rent in 1634 was paid with a hogshead of wine.

Following the growth of colonist gardens, we find that John Josslyn arrived in Boston four years later, in 1638, and that soon after his arrival he visited his brother's plantation in Black Point, Maine. He made a careful list of plants that he found here, each one of which he carefully described and sent in part to England, and it is interesting to note that in those days, the colonists in the spring gathered hepaticas, bloodroot, and numerous other wild flowers.

His description of the pitcher plant is graphic: "Hollow leaved lavender is a plant that grows in the marshes, overgrown with moss, with one straight stalk about the bigness of an oat straw. It is better than a cubic high, and upon the top is found one single fantastic flower. The leaves grow close to the root in shape like a tankard, hollow, tight, and always full of water." The whole plant, so he says, comes into perfection about the middle of August, and has leaves and stalks as red as blood, while the flower is yellow.

Mr. Josslyn also speaks of the fact that shrubs and flowers brought from England and Holland by the Puritans as early as 1626 were the nucleus of[Pg 44] old-fashioned gardens, and that woadwaxen, now a pest covering acres of ground and showing during the time of blossoming a brilliant yellow, was kept in pots by Governor Endicott, while the oxeye daisy and whiteweed were grown on Governor Endicott's Danvers farm.

He also tells us of the gardens with "their pleasant, familiar flowers, lavender, hollyhocks, and satin." "We call this herbe in Norfolke sattin," says Gerard, "and among our women, it is called honestie and gillyflowers, which meant pinks as well, and dear English roses and eglantine."

The evolution of the garden commenced at this time, and from then until fifty years ago the old-fashioned garden was in vogue. There was much sameness to this kind of garden; each one had its central path of varying width, generally with a box border on either side, while inside were sweet-smelling flowers, such as mignonette, heliotrope, and sweet alyssum. Vine-covered arbors were the central feature, and at the end of the walk stood a summer-house of simple proportions, sometimes so covered with trailing vines as to be almost unseen.

It was here on summer afternoons that our grandmothers loved to come for a social cup of tea,[Pg 45] knitting while breathing in the sweet-scented air, permeated with the fragrance of single and double peonies, phlox, roses, and bushes of syringa. Tall hollyhocks swayed in the breeze, holding their stately cups stiff and upright, and there were tiger lilies, as well as the dielytra, with its row of hanging pink and white blossoms, from which the children made boats, rabbits, and other fantastic figures.

In some of the old-time gardens, the small, thorny Scotch roses intermingled with the red and white roses of York and Lancaster. Little wonder that the perfume of their blooms was wafted through the air, although they were hidden among the taller roses, and there was no visible trace of their presence.

One walked along the broad sidewalks of the old-time cities, expecting to find at every turn a garden of flowers. Not even a glimpse did they obtain, for the gardens of those days were not in view, but hidden away behind high board fences which have now in many cases been changed for iron ones, thus giving to the public glimpses of the central arbor and the long line of path with brilliant bloom on either side.

One reason that the gardens in the olden days[Pg 46] were hidden from view was that the houses, more especially the Salem ones, were built close to the sidewalk, and there was no chance for flowers in front or at either side.

Most of the noted old gardens have long since become things of the past, but a few are still left to give hints of the many that long ago were the pride of New England housewives. The estate of the late Captain Joseph Peabody at Danvers, Massachusetts, was at one time famed for its old-fashioned garden. This lay to the right of the avenue of trees that formed the driveway to the house. These trees were planted in 1816 by Joseph Augustus Peabody, the elder son of the owner. The garden proper was hidden from view, as one passed up the driveway, but lay at the front of the house. In its center was a large tulip tree, which still stands, said to be one of the oldest and largest in the country. One of the unique features of the grounds, and one that has existed since the days of Captain Peabody's occupancy, is a small summer-house, showing lattice work and graceful arches. Its top is dome-shaped, surmounted by a gilded pineapple.

There is, however, another historic summer-house on this estate. It was formerly on the[Pg 47] Elias Hasket Derby property, and was built about 1790. This was purchased by the present owner of the estate, who had it moved to her grounds, a distance of four miles, without a crack in the plaster. It was built by Samuel McIntyre, and is decorated with the pilaster and festoons that are characteristic of his workmanship. Four urns and a farmer whetting his scythe adorn the top. Originally a companion piece was at the other end, representing a milkmaid with her pail. This latter figure was long ago sold by the former owner and placed with a spindle in its hand on the Sutton Mills at Andover, Massachusetts, where it stood for many years until destroyed by fire. The house itself contains a tool room on the lower floor, while at the head of the staircase is a large room, sixteen feet square, containing eight windows and four cupboards. It is hung with Japanese lanterns, and the closets are filled with wonderful old china. Its setting of flowers is most appropriate.

At Oak Knoll in Danvers is still left the garden that the poet Whittier so much loved. It stands at the side of the house, bordering the avenue that leads from the entrance gate. The paths have box borders, and inside is a wealth of bloom, the[Pg 48] central feature being a fountain which was a gift from Whittier to the mistress of the home. It was here he loved to come during the warm summer afternoons to pace up and down, doubtless thinking over and shaping many of his most noted poems. The garden has been carefully tended, and it shows to-day the same flowers that were in their prime during his life.

Another fine example of a box-bordered, old-time garden is seen at Newburyport, Massachusetts, on the estate of Mrs. Charles Perry. Here the colonial house stands back from the main road, with a long stretch of lawn at the front. Passing out of the door at the rear, one comes upon a courtyard with moss-grown flagging that leads directly to the garden itself, fragrant with the incense of old-time blooms.

At Indian Hill, the summer home of the late Major Benjamin Perley Poore at West Newbury, much care has been given to the gardens to keep the flowers as they were in the olden days. A feature of this estate, in addition to the gardens, is a shapely grove of trees at the rear of the mansion, that took first prize years ago as being the finest and best-shaped specimens in the county. Many of these trees were named for the major's[Pg 49] friends, and they bear names well known to New Englanders.

More than a century ago, when Salem was the trade center of the world, her gardens were renowned. These gardens were at the rear of the dwellings, and it was here that the host and his guests came for their after-dinner smoke, surrounded by the flowers that they loved.

The first improvements in garden culture were made by one George Heussler, who, according to Captain Jonathan P. Felt, came to America in 1780, bringing with him a diploma given him by his former employers. Previous to this period he had served an apprenticeship in the gardens of several German princes, as well as in that of the king of Holland, and was, in consequence, well qualified for the work. The first experience he had in America in gardening was at the home of John Tracy in Newburyport, where he worked faithfully for several years. Ten years afterwards he came to Salem to take charge of the farm and garden of Elias Hasket Derby, Senior, at Danvers, and later worked in other gardens in the city of Salem, where he lived until his death in 1817.

From the records we glean that on October 21, 1796, Mr. Heussler gave notice that he had choice[Pg 50] fruit trees for sale at Mr. Derby's farm, while a newspaper of that date informs us that the latter gentleman had recently imported valuable trees from India and Africa and that he had "an extensive nursery of useful plants in the neighborhood of his rich garden." His son, E. Hersey Derby, had a garden of great dimensions at his estate in South Salem, or, as it was then called, South Fields. This was in 1802, and for a long time the fame of this rare and beautiful garden was retained.

Both of the Derby gardens were worthy of attention, and it is said by those in authority that in the Derby greenhouse the first night-blooming cereus blossomed. This was in 1790, and the flower was the true cereus grande flora, not the flat-leaved cactus kind that is now cultivated under that name. It was largely the influence of the beautiful Derby gardens that gave to Salem its impetus for fine garden culture.

Who knows how many romances have been enacted in the old-fashioned gardens of long ago! They were fascinating places for lovers to wander and in their vine-clad summer-houses many a love-tale was told. The sight of an old-time garden recalls to-day the early owners, and in imagination one can hear the swish of silken[Pg 51] skirts as the mistress of the home saunters down the central path to take tea with friends in her beloved arbor. There were warm friendships among neighbors in those days, and the summer season was marked by a daily interchange of visits; and so the old-time garden is fraught with memories of bygone festivities and perchance of gossip.

After the close of commerce, the Derby Street houses, formerly occupied by the old merchants, gradually became deserted, and new houses were sought in different parts of the town, farther removed from shipping interests. Chestnut Street was the location of many of these new homes, and here the beautiful old-fashioned gardens were shown at their best. These were usually inclosed, and were reached by a side door, opening directly into a veritable wealth of bloom.

Among the extensive gardens cultivated here was a smaller one containing a greenhouse. This was owned by John Fiske Allen. Mr. Allen was an ardent lover of flowers, and was always interested in adding some new and rare specimen to his collection. From Caleb Ropes in Philadelphia he purchased seed of the Victoria Regia, the water lily of the Amazon. These plants blossomed for the second time in our country on[Pg 52] July 28, 1833, the grounds being thronged with visitors during the time of their blossoming. This fact was called to the attention of William Sharp, who had illustrations made for a book on the subject. The following year an extension was made to the greenhouse, and more seed was planted, which had come from England, and, in addition, orchids and other plants were grown.

The Humphrey Devereux house stands almost directly across the street from the Allen house. This garden, under the care of the next owner, Captain Charles Hoffman, became famous, for here the first camellias and azaleas in this country were planted. One of the former plants is still seen in a greenhouse in Salem. Captain Hoffman had a well-trained gardener, named Wilson, whose care gave this garden a distinctive name in the city. This garden is now the property of Dr. James E. Simpson, and it shows like no other the direct influence of olden times. There is the same vine-clad arbor for the central figure, and the plants which are grown behind box borders are the same that grew in our grandmothers' time. This scheme has been carefully carried out by the mistress of the house, who is passionately fond of the old-time blossoms.[Pg 53]

In the garden of the Cabot house on Essex Street, the first owner of the house imported tulips from Holland, and, during the time of their blossoming, threw open the garden to friends. The later owners improved the garden by adding rare specimens of peonies and other plants, and have kept the same effects, adding to the gardens' beauty each year.

While the old-fashioned garden has gone into decline, yet the modern-day enthusiast has brought into his formal gardens the flowers of yesterday. The artistic possibilities of these have appealed so strongly to the flower lover that they have been restored to their own once more. The box border is practically a thing of the past, having been replaced by flower borders of mignonette and sweet alyssum, which afford a fine setting for the beds. Like pictures seem these old-fashioned gardens, framed with thoughts of days long gone by, and one unconsciously sighs for those days that are gone, taking with them the sweet odor of the flowers that grew in our grandmothers' time.[Pg 54]

The colonial hall as we have come to think of it—dignified and spacious, with characteristics of unrivaled beauty—was not the type in vogue in the first years of the country's settlement, but rather was the outgrowth of inherent tendencies, reflecting in a measure the breadth and attractiveness of the English hallway.

The earliest dwellings were built for comfort, with little regard for effect, and they showed no hallways, only a rude entrance door giving directly upon the general and often only apartment. Sometimes this door was sheltered on the outside by a quaint closed porch, which afforded additional warmth and protection from the driving storms of rain or snow; but it was never anything more than a mere comfort-seeking appendage, boasting no pretentions whatever to architectural merit. Crude, indeed, such entrances must have seemed to the stern Puritan dwellers, in comparison with[Pg 55] those of their ancestral abodes; and it is not to be wondered at if in secret they sometimes longed for the hallways of their boyhood, where, after the evening meal in the winter season, the family was wont to gather about the roaring fire, perchance to listen to some tale of thrilling adventure.

The first American hall came in with the building of the frame house, erected after the early hardships were over, and the colonists could afford to abandon their rude cabin domiciles. This was really little more than an entry, rarely characterized by any unusual features, but it served as a sort of introduction to the home proper, and was dignified by the title of hallway. The hall in the old Capen house at Topsfield, Massachusetts, belongs to this type.

Later came the more pretentious hall, typical of the gambrel roof house, that enjoyed so long a period of popularity. This was generally a narrow passage, with doors opening at either side into the main front apartments, and with the staircase at the end rising in a series of turns to the rooms above. The first turn often contained in one corner a small table, which held a candlestick and candle used to light a guest to bed, or a grandfather's clock, the dark wood of[Pg 56] its casing serving as an effective contrast to the otherwise light finish of the apartment.

Not infrequently the hall was solidly paneled, and a built-in cupboard or like device was sometimes concealed behind the paneling; or, as in a dwelling in Manchester, Massachusetts, it contained an innovation in the form of a broad space opened between two high beams, halfway up the staircase, arranged, no doubt, for the display of some choice possession, and showing beneath a motto of religious import.

In the better class of houses of this period, the hallway sometimes extended the width of the dwelling, opening at the rear on to the yard space. This type was the forerunner of the stately attractive hall that came into vogue in the last half of the eighteenth century, and continued in favor during the first years of the nineteenth century, with the advent of the wooden and brick mansion.

Belonging to the earlier class are the Warner and Stark halls in New Hampshire. The former is paneled from floor to ceiling, the white of the finish now mellowed to ivory tones, and serving to display to advantage the fine furnishings with which it is equipped. At the rear it opens upon a grassy yard space, shaded by tall trees, thought[Pg 57] to be the site of the old slave quarters, long since demolished. The walls show several adornments, among the most interesting being the enormous antlers of an elk, which, tradition tells, were presented to the builder of the dwelling by some of the Indians with whom he traded, as an evidence of their friendship and good will. The latter hall is of similar type, entered through a narrow door space and continuing the width of the dwelling; it ends at the rear in a quaint old door that shows above its broad wooden panels a row of green bull's eyes, specimens of early American glass manufacture, still rough on the inside where detached from the molding bar. This door gives upon an old-time garden plot, fragrant with the blooms of its original planting, and preserving intact its early features. Rare bits of old furniture are used in the equipment of this hall, and the paneled walls are hung with family portraits.

When unwearied toil had made living considerably easier, and many of the merchants had amassed fortunes, there sprang up, in both the North and the South, those charming colonial mansions that were the fit abode of a brave race. They demanded hallways of spacious dimensions, and into favor then came the broad and lofty[Pg 58] hall, embodying in its construction the highest development of the colonial type. Quite through the center of the house this hall extended, from the pillared portico and stately entrance door, with its fan lights and brazen knocker, to another door at the rear, through the glazed upper panels of which tantalizing glimpses could be obtained of tall hollyhocks and climbing roses growing in the old-fashioned garden just without.

In a measure this hall was a reproduction of the English type, particularly in its spaciousness of dimension. Unlike this type, however, it lacked the dominant influence of the fireplace, and in its construction it showed several independent features, all tending to emphasize the attractive dignity suggested in the broadness of outline. Often an elliptical arch spanned the width at about one third the length, generally serving to frame the staircase, and tending to make dominant the attractiveness of this feature. This was usually little more than a skeleton arch, being a suggestion, rather than a reality, sometimes plain, and sometimes slightly ornamental. This feature is shown in the Lee hall at Salem, and in the main hall of the old Governor Wentworth house at Little Harbor, New Hampshire. This latter hall[Pg 59] is particularly interesting, not only for its beauty of construction, but also for its historic associations. Under its arch, framing the fine old staircase, men prominent in the history of the State and country have passed, and on the walls and over the door are still seen stacks of arms, thirteen in number, the muskets of the governor's guard, so long dismissed.

The most important feature of all these halls was the staircase, and in its construction the greatest interest was centered. Generally it ascended by broad, low treads to a landing lighted by a window of artistic design, and continued in a shorter flight to the second floor apartments. It was always located at one side, and generally near the rear, to allow the placing of furniture without crowding. The balusters were usually beautifully carved and hand turned, with newel posts of graceful design; and sometimes even the risers showed carved effects. The cap rail was usually of mahogany. Hard wood was sometimes used in the construction of the staircase, the treads in this event being dark and polished, while soft wood painted white was also much used.

The finish of the walls in this type of hall varied. Some were entirely paneled, others showed a[Pg 60] quaint landscape paper above a low white wainscot, and still others showed hangings of pictorial import, framed like great pictures. To the last-named class belongs the Lee hall at Marblehead, considered to be one of the finest examples of its type extant. Black walnut is the wood finish here, and the hangings, designed by a London artist, are in soft tones of gray, beautifully blended, and represent scenes of ruined Greece, each set in a separate panel, handsomely carved.

Occasionally, to-day, a staircase of the spiral type is found,—a type that possesses certain satisfying characteristics, but which never enjoyed the popularity of the straight staircase. Some few of the staircases in the old Derby Street mansions at Salem are of this type, as is the staircase at Oak Knoll, in Danvers, the poet Whittier's last residence. The common name for this type of staircase was winder.

A large number of representatives of the finest type of the colonial hall are scattered throughout the North and South, and their sturdiness of construction bids fair to make them valued examples indefinitely. One particularly good example is shown at Hey Bonnie Hall, in Bristol, Rhode Island, a mansion built on Southern lines, and[Pg 61] suggesting in its construction the hospitality of that section. Here the hall is twenty feet wide; the walls are tinted their original coloring, a soft rich green, that harmonizes perfectly with the white woodwork and the deep, mellow tones of the priceless old mahogany of the furnishings. A well-designed, groined arch forming a portion of the ceiling, and supported at the corners by four slender white pillars, is one of the apartment's attractive adjuncts, while the dominant feature is the staircase that rises at the farther end, five feet in width, with treads of solid mahogany and simple but substantial balusters of the same wood on either side. The upper hall is as distinctive as the lower one, and exactly corresponds in length and width. Wonderful old furnishings are placed here, and at one end is displayed a fine bit of architectural work in a fanlight window, overlooking the garden.

One wonders, when viewing such a hall as this, how this type could ever have been superseded in house construction, but with the gradual decline in favor of the colonial type of dwelling, it was abolished, and in place of its lofty build and attractive spaciousness, halls of cramped dimensions came into vogue, culminating in the entry[Pg 62] passage typical of houses built toward the middle of the nineteenth century. Happily, present-day house builders are coming to a realizing sense of the importance of the hallway, and are beginning to appreciate the fact that, to be attractive, the hall must be ample, well lighted, and of pleasing character. With this realization the beauty of the colonial hall has again demanded attention, and in a large number of modern homes it has been copied in a modified degree.[Pg 63]

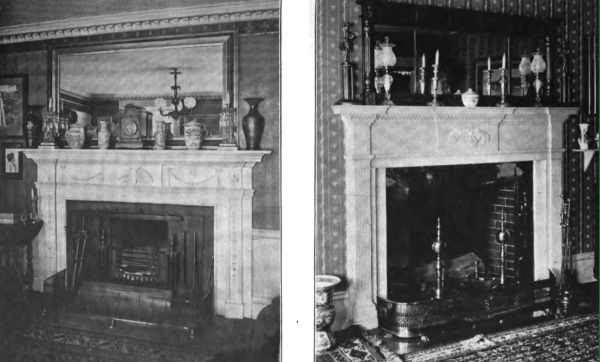

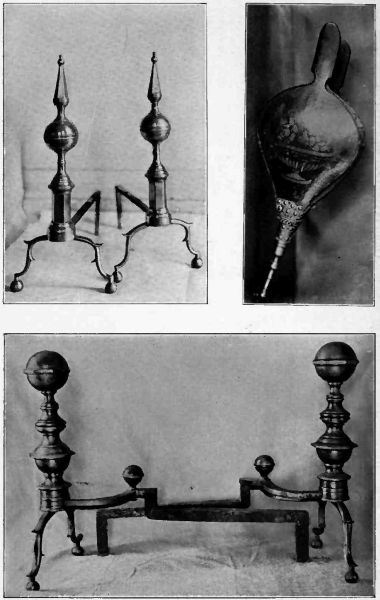

It is a far cry from the fireplaces of early times to those of the present, when elaborate fittings make them architecturally notable. We read that in the Middle Ages, the fire in the banquet hall was laid on the floor in the center of the large apartment, the smoke from the blazing logs, as it curled slowly upward, escaping through a hole cut in the ceiling. Later, during the Renaissance period, the fire was laid close to the wall, the space set apart for it framed with masonry jambs that supported a mantel shelf. A projecting hood of stone or brick carried the smoke away, and the jambs were useful, inasmuch as they protected the fire from draughts. From this time, the evolution of the fireplace might be said to date, improvement in its arrangement being worked out gradually, until to-day it is numbered among the home's most attractive features. It is interesting to note, in reference to these latter-day specimens, that many of them are similar in design[Pg 64] to those of the Renaissance, Louis Sixteenth, and colonial periods.

Not a few of the early fireplaces were of the inglenook type, a fad that has been revived and is much in evidence in modern dwellings; and many of them followed certain periods, such as the Queen Anne style and the Elizabethan design. Several, too, were topped with mantels, features practical as well as ornamental, which are almost always associated with the fireplaces of to-day. Many of the old mantels were very narrow, prohibiting ornamentation with pottery or small bits of bric-a-brac; they were so built, because the designers of early times considered them sufficiently decorative in themselves without any additional embellishment, and their sturdiness and architectural regularity seem to justify this opinion. Mantels and fireplaces of early Renaissance type show in detail an elegance that is characteristic of all the work of that period, the Italian designers being masters in their line.

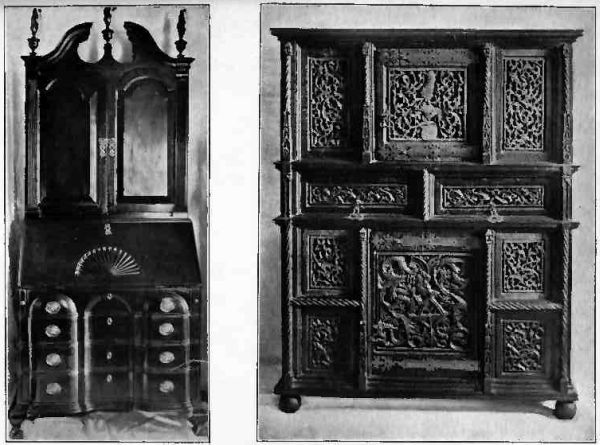

In the baronial halls of Merrie England, we find huge fireplaces, wide enough to hold the Yule log, around which, after the chase, the followers gathered to drink deep of the wassail bowl. Such pictures must have lingered long in the minds of[Pg 65] the colonists in their new surroundings, and to us they are suggestive of the Squire in "Old Christmas," who, seated in his great armchair, close by the fire, contentedly smoked his pipe and gazed into the heart of the flickering flames, filled with the joy of his ancestral possessions.