Title: King Spruce, A Novel

Author: Holman Day

Illustrator: E. Roscoe Shrader

Release date: January 13, 2011 [eBook #34948]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Audrey Longhurst, D Alexander and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

Author of

Copyright, 1908, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

Published April, 1908.

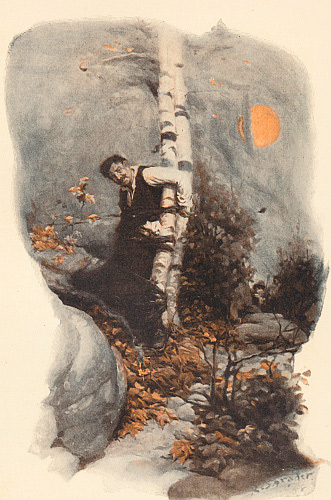

“‘I KNOW YOUR HEART’” [See p. 289

“‘I KNOW YOUR HEART’” [See p. 289

TO

A. B. D.

MY COMRADE OF

TRAIL AND CAMP

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Up in “Castle Cut ’Em” | 1 |

| II. | The Heiress of “Oaklands” | 17 |

| III. | The Making of a “Chaney Man” | 27 |

| IV. | The Boss of the “Busters” | 35 |

| V. | During the Pugwash Hang-up | 55 |

| VI. | As Fought before the “It-’ll-git-ye Club” | 62 |

| VII. | On Misery Gore | 78 |

| VIII. | The Torch, and the Lighting of It | 92 |

| IX. | By Order of Pulaski D. Britt | 104 |

| X. | “Ladder” Lane’s Soirée | 114 |

| XI. | In the Barony of “Stumpage John” | 127 |

| XII. | The Code of Larrigan-land | 142 |

| XIII. | The Red Throat of Pogey | 153 |

| XIV. | The Message of “Prophet Eli” | 164 |

| XV. | Between Two on Jerusalem | 174 |

| XVI. | In the Path of the Big Wind | 181 |

| XVII. | The Affair at Durfy’s Camp | 198 |

| XVIII. | The Old Soubungo Trail | 217 |

| XIX. | The Home-makers of Enchanted | 230 |

| XX. | The Ha’nt of the Umcolcus | 241 |

| XXI. | The Man Who Came from Nowhere | 256 |

| XXII. | The Hostage of the Great White Silence | 270 |

| XXIII. | In the Matter of John Barrett’s Daughter | 278 |

| XXIV. | The Cheese Rind that Needed Sharp Teeth | 293 |

| XXV. | Sharpening Teeth on Pulaski Britt’s Whetstone | 303 |

| XXVI. | The Devil of the Hempen Strands | 312 |

| XXVII. | The “Canned Thunder” of Castonia | 324 |

| XXVIII. | “’Twas Done by Tommy Thunder” | 341 |

| XXIX. | The Parade Past Rodburd Ide’s Platform | 352 |

| XXX. | The Pact with King Spruce | 361 |

| “‘I KNOW YOUR HEART’” | Frontispiece | |

| “WADE STOOD ABOVE THE FALLEN FOE” | Facing p. | 70 |

| “WRITHING AT HIS BONDS, HIS CONTORTED FACE TOWARDS THE RED FLAMES GALLOPING UP THE VALLEY” |

172 | |

| “‘WHAT I SAY ON THIS RIVER GOES!’” | 334 |

When the trees have been cut and trimmed in the winter’s work in the woods the logs are hauled in great loads to be piled at “landing-places” on the frozen streams, so that the spring floods will move them. Most of the streams have a succession of dams. On the spring drive the logs are floated to the dams, and then the gates are raised and the logs are “sluiced” through with a head of water behind them to carry them down-stream. Thus the drive is lifted along in sections from one dam to another. It will be seen that Pulaski D. Britt’s series of dams on Jerusalem constituted a valuable holding, and enabled him to control the water and leave the logs of rivals stranded if he wished. The collection of water and quick work in “sluicing” are most important, for the streams give down only about so much water in the spring.

When a load of logs is suddenly set free from the cable holding it back on a steep descent, as in Chapter XXVI., it is said to be “sluiced.”

When there is a jam of entangled logs as they are swept down-stream, if it is impossible to find and pry loose the “key-log,” it is sometimes necessary to blow up the restraining logs with dynamite.

When the floating logs are caught upon rocks, and the men are prying them loose, they are said to be “carding” the ledges.

A “jill-poke,” a pet aversion of drivers, is a log with one end lodged on the bank and the other thrust out into the stream.

The “cant-dog” is illustrated on the cover of the book.

The “peavy” is the Maine name for a slightly different variety of “cant-dog,” which takes its title from its maker in Old Town.

The “pick-pole” is an ashen pole ten to twelve feet long, shod with an iron point with a screw-tip, which enables a driver to pull a log towards him or to push it away.

“Oh, the road to ‘Castle Cut ’Em’ is mostly all uphill.

You can dance along all cheerful to the sing-song of a mill;

King Cole he wanted fiddles, and so does old King Spruce,

But it’s only gashin’-fiddles that he finds of any use.

“Oh, come along, good lumbermen, oh, come along I say!

Come up to ‘Castle Cut ’Em,’ and pull your wads and pay.

King Cole he liked his bitters, and so does old King Spruce,

But the only kind he hankers for is old spondulix-juice.”

—From song by Larry Gorman, “Woods Poet.”

The young man on his way to “Castle Cut ’Em” was a clean-cut picture of self-reliant youth. But he was not walking as one who goes to a welcome task. He saw two men ahead of him who walked with as little display of eagerness; men whose shoulders were stooped and whose hands swung listlessly as do hands that are astonished at finding themselves idle.

A row of mills that squatted along the bank of the canal sent after them a medley of howls from band-saws and circulars. The young man, with the memory of his college classics sufficiently fresh to make him [Pg 2]fanciful, found suggestion of chained monsters in the aspect of those shrieking mills, with slip-openings like huge mouths.

That same imagery invested the big building on the hill with attributes that were not reassuring. But he went on up the street in the sunshine, his eyes on the broad backs of the plodders ahead.

King Spruce was in official session.

Men who were big, men who were brawny, yet meek and apologetic, were daily climbing the hill or waiting in the big building to have word with the Honorable John Davis Barrett, who was King Spruce’s high chamberlain. Dwight Wade found half a dozen ahead of him when he came into the general office. They sat, balancing their hats on their knees, and each face wore the anxious expectancy that characterized those who waited to see John Barrett.

Wade had lived long enough in Stillwater to know the type of men who came to the throne-room of King Spruce in midsummer. These were stumpage buyers from the north woods, down to make another season’s contract with the lord of a million acres of timber land. Their faces were brown, their hands were knotted, and when one, in his turn, went into the inner office he moved awkwardly across the level tiles, as though he missed the familiar inequalities of the forest’s floor.

The others droned on with their subdued mumble about saw-logs, sleeper contracts, and “popple” peeling. The young man who had just entered was so plainly not of themselves or their interests that they paid no attention to him.

This was the first time Wade had been inside the doors of “Castle Cut ’Em,” the name the humorists of Stillwater had given the dominating block on the main street of the little city. The up-country men, with the bitterness of experience, and moved by somewhat [Pg 3]fantastic imaginings, said it was “King Spruce’s castle.”

In the north woods one heard men talk of King Spruce as though this potentate were a real and vital personality. To be sure, his power was real, and power is the principal manifestation of the tyrant who is incarnate. Invisibility usually makes the tyranny more potent. King Spruce, vast association of timber interests, was visible only through the affairs of his court administered by his officers to whom power had been delegated. And, viewed by what he exacted and performed, King Spruce lived and reigned—still lives and reigns.

Wade, not wholly at ease in the presence, for he had come with a petition like the others, gazed about the reception-room of the Umcolcus Lumbering and Log-driving Association, the incorporators’ more decorous title for King Spruce. It occurred to him that the wall-adornments were not reassuring. A brightly polished circular-saw hung between two windows. It was crossed by two axes, and a double-handled saw was the base for this suggestive coat of arms. The framed photographs displayed loaded log-sleds and piles of logs heaped at landings and similar portraiture of destruction in the woods. Everything seemed to accentuate the dominion of the edge of steel. The other wall-decorations were the heads of moose and deer, further suggestion of slaughter in the forest. A stuffed porcupine on the mantel above the great fireplace mutely suggested that the timber-owners would brook no rivalry in their campaign against the forest; they had asked the State to offer a bounty for the slaughter of this tree-girdler, and a card propped against the “quill-pig” instructed the reader that the State had already spent more than fifty thousand dollars in bounties.

The deification of the cutting-edge appealed to Wade’s abundant fancy. He had noticed, when he came past [Pg 4]the windows of the lumber company’s outfitting store on the first floor of the building, that the window displays consisted mostly of cutting tools.

When the door of the inner office opened and one of those big and awkward giants came out, Wade discovered that King Spruce had evidently placed in the hands of the Honorable John Davis Barrett something sharp with which to slash human feelings, also. The man’s face was flushed and his teeth were set down over his lower lip with manifest effort to dam back language.

“Didn’t he renew?” inquired one of the waiting group, solicitously.

“He turned me down!” muttered the other, scarcely releasing the clutch on his lip. “I’ve wondered sometimes why ‘Stumpage John’ hasn’t been over his own timber lands in all these years. If he has backed many out of that office feelin’ like I do, I reckon there’s a good reason why he doesn’t trust himself up in the woods.” He struck his soft hat across his palm. He did not raise his voice. But the venom in his tone was convincing. “By God, I’d relish bein’ the man that mistook him for a bear!”

“Give any good reason for not renewin’?” asked a man whose face showed his anxiety for himself.

“Any one who has been over my operation on Lunksoos,” declared the lumberman, answering the question in his own way—“any fair man knows I haven’t devilled: I’ve left short stumps and I ’ain’t topped off under eight inches, though you all know that their damnable scale-system puts a man to the bad when he’s square on tops. But I ’ain’t left tops to rot on the ground. I’ve been square!”

Wade did not understand clearly, but the sincerity of the man’s distress appealed to him.

One of the little group darted an uneasy look towards [Pg 5]the door of the inner office. It was closed tightly. But for all that he spoke in a husky whisper.

“It must be that you didn’t fix with What’s-his-name last spring—I heard you and he had trouble.”

The angry operator dared to speak now. He looked towards the door as though he hoped his voice would penetrate to King Spruce’s throne-room.

“Trouble!” he cried. “Who wouldn’t have trouble? I made up my mind I had divided my profits with John Barrett’s blackmailin’ thieves of agents for the last time. I lumbered square. And the agent was mad because I wasn’t crooked and didn’t have hush-money for him. And he spiked me with John Barrett; but you fellows, and all the rest that are willin’ to whack up and steal in company, will get your contracts all right. And I’m froze out, with camps all built and five thousand dollars’ worth of supplies in my depot-camp.”

“Hold on!” protested several of the men, in chorus, crowding close to this dangerous tale-teller. “You ain’t tryin’ to sluice the rest of us, are you, just because you’ve gone to work and got your own load busted on the ramdown?”

“I’d like to see the whole infernal game of graft, gamble, and woods-gashin’ showed up. Let John Barrett go up and look at his woods and he’ll see what you are doin’ to ’em—you and his agents! And the man that lumbers square, and remembers that there are folks comin’ after us that will need trees, gets what I’ve just got!” He shook his crumpled hat in their faces. “And I’m just good and ripe for trouble, and a lot of it.”

“Here, you let me talk with you,” interposed a man who had said nothing before, and he took the recalcitrant by the arm, led him away to a corner, and they entered into earnest conference. At the end of it the destructionist drove his hat on with a smack of his big palm and strode out, sullen but plainly convinced.

The other man returned to the group and spoke cautiously low, but in that big, bare room with its resonant emptiness even whispers travelled far.

“I’ll take a double contract and sublet to him,” he explained. “Barrett won’t know, and after this Dave will come back into line and handle the agent. I reckon he’s got well converted from honesty in a lumberin’ deal. It’s what we’re up against, gents, in this business; the patterns are handed to us and we’ve got to cut our conduct accordin’ to other men’s measurements. Barrett gets his first; the agent gets his; we get what we can squeeze out of a narrow margin—and the woods get hell.”

A man came out of the inner office stroking the folds of a stumpage permit preparatory to stuffing it into his wallet, and the peacemaker departed promptly, for it was now his turn to pay his respects to King Spruce.

In what he had seen and what he had heard, Dwight Wade found food for thought. The men so manifestly had accepted the stranger as some one utterly removed from comprehension of their affairs or interest in their talk that they had not been discreet. It occurred to him that his own present business with John Barrett would be decidedly furthered were he to utilize that indiscretion.

This thought occurred to him not because he intended for one instant to use his information, but because he saw now that his business with John Barrett was more to John Barrett’s personal advantage than that gentleman realized. This knowledge gave him more confidence. He was proposing something to the Honorable John Barrett that the latter, for his own good, ought to be pressed into accepting.

The earlier reflection which had made him uneasy, that a millionaire timber baron would not listen patiently to suggestions about his own business offered [Pg 7]by the principal of the Stillwater high-school, had now been modified by circumstances. Even that lurking fear, that awe of John Barrett which he had his peculiar and private reason for feeling and hiding, was not quite so nerve-racking.

Barrett left it to his clients to manage the order of precedence in the outer office. It was only necessary for the awaiting suppliant to note his place between those already there and those who came in after him; and Wade was prompt to accept his turn.

He knew the Honorable John Barrett. As mayor that gentleman had distributed the diplomas at the June graduation. And Mr. Barrett, after one first, sharp, scowling glance over his nose-glasses, hooking his chin to one side as he gazed, rose and greeted the young man cordially.

Then he wheeled his chair away from his desk to the window and sat down where he could feel the breeze.

Looking past him Wade saw the Stillwater saw-mills. There were five of them in a row along the canal. Each had a slip-opening in the end and it yawned wide like a mouth that stretched for prey.

The two windows pinched together in each gable gave to the end of the building likeness to a hideous face. From his seat Wade heard the screech of the band-saws. The sounds came out of those open mouths. The dripping logs went up the slips and into those mouths, like morsels sliding along a slavering tongue. Mingled with the fierce scream of the band-saws there were the wailings of the lath and clapboard saws. In that medley of sound the imagination heard monster and victims mingling howl of triumph and despairing cry.

The breeze that ruffled the awnings stirred the thin, gray hair of John Barrett, brought fresh scents of sawdust and sweeter fragrance of seasoning lumber. And [Pg 8]fainter yet came the whiff of resinous balsam from the vast fields of logs that crowded the booms.

With that picture backing him in the frame of the open window—mutilated trees, and mills yowling in chorus, and with the scent of the riven logs bathing him—the timber baron politely waited for the young man to speak. He had put off the brusqueness of his business demeanor, for it had not occurred to him that the principal of the Stillwater high school could have any financial errand. He played a little tattoo with his eye-glasses’ rim upon the second button of his frock-coat. One touch of sunshine on Barrett’s cheek showed up striated markings and the faint purpling that indulgence paints upon the skin. The way in which the shoulders were set back under the tightly buttoned frock-coat, the flashing of the keen eyes, and even the cock of the bristly gray mustache that crossed the face in a straight line showed that John Barrett had enjoyed the best that life had to offer him.

“I’ll make my errand a short one, Mr. Barrett,” began Wade, “for I see that others are waiting.”

“They’re only men who want to buy something,” said the baron, reassuringly—“men who have come, the whole of them, with the same growl and whine. It’s a relief to be rid of them for a few moments.”

Frankly showing that he welcomed the respite, and serenely indifferent to those who waited, he brought a box of cigars from the desk, and the young man accepted one nervously.

“I think I have noticed you about the city since your school closed,” Mr. Barrett proceeded. And without special interest he asked, whirling his chair and gazing out of the window at the mills: “How do you happen to be staying here in Stillwater this summer? I supposed pedagogues in vacation-time ran away from their schools as fast as they could.”

If John Barrett had not been staring at the mills he would have seen the flush that blazed on the young man’s cheeks at this sudden, blunt demand for the reasons why he stayed in town.

“If I had a home I should probably go there,” answered Wade; “but my parents died while I was in college—and—and high-school principals do not usually find summer resorts and European trips agreeing with the size of their purses.”

“Probably not,” assented the millionaire, calmly. A sudden recollection seemed to strike him. “Say, speaking of college—you’re the Burton centre, aren’t you—or you were? I was there a year ago when Burton clinched the championship. I liked your game! I meant to have said as much to you, but I didn’t get a chance, for you know what the push is on a ball-ground. I’m a Burton man, you know. I never miss a game. I’m glad to have such a chap as you at the head of our school. These pale fellows with specs aren’t my style!”

He turned and ran an approving gaze over Wade’s six feet of sturdy young manhood. With his keen eye for lines that revealed breeding and training, Barrett usually turned once to look after a handsome woman and twice to stare at a blooded horse. Men interested him, too—men who appealed to his sportsman sense. This young man, with the glamour of the football victories still upon him, was a particularly attractive object at that moment. He stared into Wade’s flushed face, evidently accepting the color as the signal that gratified pride had set upon the cheeks.

“You’ll weigh in at about one hundred and eighty-five,” commented the millionaire. It seemed to Wade that his tone was that of a judge appraising the points of a race-horse, and for an instant he resented the fact that Barrett was sizing him less as a man than as a [Pg 10]gladiator. “Old Dame Nature put you up solid, Mr. Wade, and gave you the face to go with the rest. I wish I were as young—and as free!” He gave another look at the mills and scowled when he heard the mumble of men’s voices in the outer room. “When a man is past sixty, money doesn’t buy the things for him that he really wants.” It was the familiar cant of the man rich enough to affect disdain for money, and Wade was not impressed.

“I’d like to take my daughter across the big pond this summer,” the land baron grumbled, discontentedly, “but I never was tied down so in my life. I am directing-manager of the Umcolcus Association, and I’ve got all my own lands to handle besides, and with matters in the lumbering business as they are just now there are some things that you can’t delegate to agents, Mr. Wade.”

This man, confiding his troubles, did not seem the ogre he had been painted.

The young man had flushed still more deeply at mention of Barrett’s daughter, but Barrett was again looking at his squalling mills.

The pause seemed a fair opportunity for the errand. The mention of agents revived the recollection that he was proposing something to John Barrett’s advantage.

“Mr. Barrett, you know it is pretty hard for any one to live in Stillwater and not take an interest in the lumbering business. I’ll confess that I’ve taken such interest myself. A few of my older boys have asked me to secure books on the science of forestry and help them study it.”

“A man would have pretty hard work to convince me that it is a science,” broke in Barrett, with some contempt. “As near as I can find out, it’s mostly guesswork, and poor guesswork at that.”

“Well, the fact remains,” hastened Wade, a little [Pg 11]nettled by the curtness that had succeeded the timber baron’s rather sentimental courtesy, “my boys have been studying forestry, and I have been keeping a bit ahead of them and helping them as I could. Now they need a little practical experience. But they are boys who are working their way through school, and as I had to do the same thing I’m taking an especial interest in them. They have been in your mills two summers.”

“Why isn’t it a good place for them to stay?” demanded Barrett. “They’re learning a side of forestry there that amounts to something.”

“The side that they want to learn is the side of the standing trees,” persisted Wade, patiently. “I thought I could talk it over with you a little better than they. I hoped that such a large owner of timber land had begun to take interest in forestry and would, for experiment’s sake, put these young men upon a section of timber land this summer and let them work up a map and a report that you could use as a basis for later comparison, if nothing else.”

“What do you mean, that I’m going to hire them to do it—pay them money?” demanded the timber baron, fixing upon the young man that stare that always disconcerted petitioners. At that moment Wade realized why those men whom he had seen waiting in the outer office were gazing at the door of the inner room with such anxiety.

“The young men will be performing a real service, for they will plot a square mile and—”

“If there’s any pay to it, I’d rather pay them to keep off my lands,” broke in Barrett. “Forestry—”

He in turn was interrupted. The man who came in entered with manifest belief in his right to interrupt.

“Forestry!” he cried, taking the word off Barrett’s lips—“forestry is getting your men into the woods, getting grub to ’em, hiring bosses that can whale spryness [Pg 12]into human jill-pokes, and can get the logs down to Pea Cove sortin’-boom before the drought strikes. That’s forestry! That’s my kind. It’s the kind I’ve made my money on. It’s the kind John Barrett made his on. What are you doin’, John—hirin’ a perfesser?” The new arrival asked this in a tone and with a glance up and down Wade that left no doubt as to his opinion of “perfessers.” “Are you one of these newfangled fellers that’s been studyin’ in a book how to make trees grow?” he demanded.

Wade had only a limited acquaintance with the notables of the State, but he knew this man. He had seen him in Stillwater frequently, and his down-river office was in “Castle Cut ’Em.” He was the Honorable Pulaski D. Britt. He had acquired that title—mostly for newspaper use—by serving many years in the State senate from Umcolcus County.

Wade gazed at the puffy red face, the bristle of gray beard, the hard little eyes—pupils of dull gray set in yellow eyeballs—and remembered the stories he had heard about this man who yelped his words with canine abruptness of utterance, who waved his big, hairy hands about his head as he talked, and with every gesture, every glance, every word revealed himself as a driver of men, grown arrogant and cruel by possession of power.

“Mr. Britt is executive officer for the lumber company in the north country,” explained Barrett, dryly. “We are all associated more or less closely, though many of our holdings are separate. We think it is quite essential to confer together when undertaking any important step.” His satiric dwelling on the word “important” was exasperating. “This young gentleman is the principal of our high-school, Pulaski, and he wants me to put a bunch of high-school boys in my woods as foresters—and pay ’em for it. You came in just as I was going [Pg 13]to give him my opinion. But it may be more proper for you to do it, for you are the woods executive, and are better posted on conditions up there than I am.” His drawled irony was biting.

The Honorable John Barrett enjoyed sport of all kinds, including badger-baiting. Now he leaned back in his swivel-chair with the air of a man about to enjoy the spectacle of a lively affair. But Wade, glancing from Barrett to Britt, was in no humor to be the butt of the millionaire.

“I don’t think I care to listen to Mr. Britt’s opinions,” he said, rising hastily.

“Why? Don’t you think I know what I’m talking about?” demanded the lumberman. He had missed the point of Barrett’s satire, being himself a man of the bludgeon instead of the rapier.

“I’m quite sure you know, Mr. Britt,” said the young man, bowing to Barrett and starting away.

“I’ve hired more men than any ten operators on the Umcolcus, put ’em all together,” declared Britt, following him, “and I’d ought to know something about whether a man is worth anything on a job or not. And rather than have any one of those squirt-gun foresters cuttin’ and caliperin’ over my lands, I’d—”

Wade shut the door behind him, strode through the outer office, and hurried down-stairs, his face very red and his teeth shut very tight. He realized that he had left the presence of King Spruce in most discourteous haste, but the look in John Barrett’s eyes when he had leaned back and “sicked on” that old railer of the rasping voice had been too much for Wade’s nerves. To be made an object of ridicule by her father was bitter, with the bitterness of banished hope that had sprung into blossom for just one encouraging moment.

When he came out into the sunlight he threw down the fat cigar—plump with a suggestion of the rich man’s [Pg 14]opulence—and ground it under his heel. In the anxiety of his intimate hopes, in the first cordiality of their interview, it had seemed as though the millionaire had chosen to meet him upon that common level of gentle society where consideration of money is banished. Now, in the passion of his disappointment, Wade realized that he had served merely as a diversion, as a prize pup or a game-cock would have served, had either been brought to “Castle Cut ’Em” for inspection.

Walking—seeking the open country and the comforting breath of the flowers—away from that sickly scent of the sawdust, his cheeks burned when he remembered that at first he had fearfully, yet hopefully, believed that John Barrett knew the secret that he and Elva Barrett were keeping.

Hastening away from his humiliation, he confessed to himself that in his optimism of love he had been dreaming a beautiful but particularly foolish dream; but having realized the blessed hope that had once seemed so visionary—having won Elva Barrett’s love—the winning of even John Barrett had not seemed an impossible task. The millionaire’s frank greeting had held a warmth that Wade had grasped at as vague encouragement. But now the clairvoyancy of his sensitiveness enabled him to understand John Barrett’s nature and his own pitiful position in that great affair of the heart; he had not dared to look at that affair too closely till now.

So he hurried on, seeking the open country, obsessed by the strange fancy that there was something in his soul that he wanted to take out and scrutinize, alone, away from curious eyes.

The Honorable Pulaski D. Britt had watched that hasty exit with sudden ire that promptly changed to amusement. He turned slowly and gazed at the timber baron with that amusement plainly showing—amusement spiced with a bit of malice. The reverse of Britt’s [Pg 15]hard character as bully and tyrant was an insatiate curiosity as to the little affairs of the people he knew and a desire to retail those matters in gossip when he could wound feelings or stir mischief. If one with a gift of prophecy had told him that his next words would mark the beginning of the crisis of his life, Pulaski Britt would have professed his profane incredulity in his own vigorous fashion. All that he said was, “Well, John, your girl has picked out quite a rugged-lookin’ feller, even if he ain’t much inclined to listen to good advice on forestry.”

Confirmed gossips are like connoisseurs of cheese: the stuff they relish must be stout. It gratified Britt to see that he had “jumped” his friend.

“I didn’t know but you had him in here to sign partnership papers,” Britt continued, helping himself to a cigar. “I wouldn’t blame you much for annexin’ him. You need a chap of his size to go in on your lands and straighten out your bushwhackin’ thieves with a club, seein’ that you don’t go yourself. As for me, I don’t need to delegate clubbers; I can attend to it myself. It’s the way I take exercise.”

“Look here, Pulaski,” Barrett replied, angrily, “a joke is all right between friends, but hitching up my daughter Elva’s name with a beggar of a school-master isn’t humorous.”

Britt gnawed off the end of the cigar, and spat the fragment of tobacco into a far corner.

“Then if you don’t see any humor in it, why don’t you stop the courtin’?”

“There isn’t any courting.”

“I say there is, and if the girl’s mother was alive, or you ’tending out at home as sharp as you ought to, your family would have had a stir-up long ago. If you ain’t quite ready for a son-in-law, and don’t want that young man, you’d better grab in and issue a family bulletin to that effect.”

“Damn such foolishness! I don’t believe it,” stormed Barrett, pulling his chair back to the desk; “but if you knew it, why didn’t you say something before?”

“Oh, I’m no gossip,” returned Britt, serenely. “I’ve got something to do besides watch courtin’ scrapes. But I don’t have to watch this one in your family. I know it’s on.”

Barrett hooked his glasses on his nose with an angry gesture, and began to fuss with the papers on his desk. But in spite of his professed scepticism and his suspicion of Pulaski Britt’s ingenuousness, it was plain that his mind was not on the papers.

He whirled away suddenly and faced Britt. That gentleman was pulling packets of other papers from his pocket.

“Look here, Britt, about this lying scandal that seems to be snaking around, seeing that it has come to your ears, I—”

“What I’m here for is to go over these drivin’ tolls so that they can be passed on to the book-keepers,” announced Mr. Britt, with a fine and brisk business air. He had shot his shaft of gossip, had “jumped” his man, and the affair of John Barrett’s daughter had no further interest for him. “You go ahead and run your family affairs to suit yourself. As to these things you are runnin’ with me, let’s get at ’em.”

In this manner, unwittingly, did Pulaski D. Britt light the fuse that connected with his own magazine; in this fashion, too, did he turn his back upon it.

“Pete Lebree had money and land, Paul of Olamon had none,

Only his peavy and driving pole, his birch canoe and his gun.

But to Paul Nicola, lithe and tall, son of a Tarratine,

Had gone the heart of the governor’s child, Molly the island’s

queen.”

—Old Town Ballads.

The coachman usually drove into town from the “Oaklands” to bring John Barrett home from his office, for Barrett liked the spirited rush of his blooded horses.

But when his daughter occasionally anticipated the coachman, he resigned himself to a ride in her phaeton with only a sleepy pony to draw them.

Once more absorbed in his affairs, after the departure of Pulaski Britt, Barrett had forgotten the unpleasant morsel of gossip that Britt had brought to spice his interview.

But a familiar trilling call that came up to him stirred that unpleasant thing in his mind. When Barrett walked to the window and signalled to her that he had heard and would come, his expression was not exactly that of the fond father who welcomes his only child. It was not the expression that the bright face peering from under the phaeton’s parasol invited. And as he wore his look of uneasiness and discontent when he took his seat beside her, her face became grave also.

“Is it the business or the politics, father?” she asked, [Pg 18]solicitously. “I’m jealous of both if they take away the smiles and bring the tired lines. If it’s business, let’s make believe we’ve got money enough. Haven’t we—for only us two? If it’s politics—well, when I’m a governor’s daughter I’ll be only an unhappy slave to the women, and you a servant of the men.”

But he did not respond to her rallying.

“I can’t get away from work this summer, Elva,” he said, with something of the curtness of his business tone. “I mean I can’t get away to go with you.”

“But I don’t want you to go anywhere, father,” protested the girl.

She was so earnest that he glanced sidewise at her. His air was that of one who is trying a subtle test.

“I feel that I must go north for a visit to my timber lands,” he went on; “I have not been over them for years. I’ve had pretty good proof that I am being robbed by men I trusted. I propose to go up there and make a few wholesome examples.”

He was accustomed to talk his business affairs with her. She always received them with a grave understanding that pleased him. Her dark eyes now met him frankly and interestedly. Looking at her as he did, with his strange thrill of suspicion that another man wanted her and that she loved the man, he saw that his daughter was beautiful, with the brilliancy of type that transcends prettiness. He realized that she had the wit and spirit which make beauty potent, and her eyes and bearing showed poise and self-reliance. Such was John Barrett’s appraisal, and John Barrett’s business was to appraise humankind. But perhaps he did not fully realize that she was a woman with a woman’s heart.

The pony was ambling along lazily under the elms, and the reflective lord of lands was silent awhile, glancing at his daughter occasionally from the corner of his eye. [Pg 19]He noted, with fresh interest, that she had greeting for all she met—as gracious a word for the tattered man from the mill as for the youth who slowed his automobile to speak to her.

“These gossips have misunderstood her graciousness,” he mused, the thought giving him comfort.

But he was still grimly intent upon his trial of her.

“Because I cannot go with you, and because I shall be away in the woods, Elva,” he said, after a time, “I am going to send you to the shore with the Dustins.”

There was sudden fire in her dark eyes.

“I do not care to go anywhere with the Dustins,” she said, with decision. “I do not care to go anywhere at all this summer. Father!” There was a volume of protest in the intonation of the word. She had the bluntness of his business air when she was aroused. “I would be blind and a fool not to understand why you are so determined to throw me in with the Dustins. You want me to marry that bland and blessed son and heir. But I’ll not do any such thing.”

“You are jumping at conclusions, Elva,” he returned, feeling that he himself had suddenly become the hunted.

“I’ve got enough of your wit, father, to know what’s in a barrel when there’s a knot-hole for me to peep through.”

“Now that you have brought up the subject, what reason is there for your not wanting to marry Weston Dustin? He’s—”

“I know all about him,” she interrupted. “There is no earthly need for you and me to get into a snarl of words about him, dadah! He isn’t the man I want for a husband; and when John Barrett’s only daughter tells him that with all her heart and soul, I don’t believe John Barrett is going to argue the question or ask for further reasons or give any orders.”

He bridled in turn.

“But I’m going to tell you, for my part, that I want you to marry Weston Dustin! It has been my wish for a long time, though I have not wanted to hurry you.”

She urged on the pony, as though anxious to end a tête-à-tête that was becoming embarrassing.

“It might be well to save our discussion of Mr. Dustin until that impetuous suitor has shown that he wants to marry me,” she remarked, with a little acid in her tone.

“He has come to me like a gentleman, told me what he wants, and asked my permission,” stated Mr. Barrett.

“Following a strictly business rule characteristic of Mr. Dustin—‘Will you marry your timber lands to my saw-mill, Mr. John Barrett, one daughter thrown in?’”

“At least he didn’t come sneaking around by the back door!” cried her father, jarred out of his earlier determination to probe the matter craftily.

“Intimating thereby that I have an affair of the heart with the iceman or the grocery boy?” she inquired, tartly.

She was looking full at him now with all the Barrett resoluteness shining in her eyes. And he, with only the vague and malicious promptings of Pulaski Britt for his credentials, had not the courage to make the charge that was on his tongue, for his heart rejected it now that he was looking into her face.

“In the old times stern parents married off daughters as they would dispose of farm stock,” she said, whipping her pony with a little unnecessary vigor. “But I had never learned that the custom had obtained in the Barrett family. Therefore, father, we will talk about something more profitable than Mr. Dustin.”

Outside the city, in the valley where the road curved to enter the gates of “Oaklands,” they met Dwight Wade returning, chastened by self-communion.

Barrett did not look at the young man. He kept his [Pg 21]eyes on his daughter’s face as she returned Wade’s bow. He saw what he feared. The fires of indignation quickly left the dark eyes. There was the softness of a caress in her gaze. Love displayed his crimson flag on her cheeks. She spoke in answer to Wade’s salutation, and even cast one shy look after him when he had passed. When she took her eyes from him she found her father’s hard gaze fronting her.

“Do you know that fellow?” he demanded, brusquely.

“Yes,” she said, her composure not yet regained; “when he was a student at Burton and I was at the academy I met him often at receptions.”

“What is that academy, a sort of matrimonial bureau?” His tone was rough.

“It is not a nunnery,” she retorted, with spirit. “The ordinary rules of society govern there as they do here in Stillwater.”

“Elva,” he said, emotion in his tones, “since your mother died you have been mistress of the house and of your own actions, mostly. Has that fellow there been calling on you?”

“He has called on me, certainly. Many of my school friends have called. Since he has been principal of the high-school I have invited him to ‘Oaklands.’”

“You needn’t invite him again. I do not want him to call on you.”

“For what reason, father?” She was looking straight ahead now, and her voice was even with the evenness of contemplated rebellion.

“As your father, I am not obliged to give reasons for all my commands.”

“You are obliged to give me a reason when you deny a young gentleman of good standing in this city our house. An unreasonable order like that reflects on my character or my judgment. I am the mistress of our home, as well as your daughter.”

“It’s making gossip,” he floundered, dimly feeling the unwisdom of quoting Pulaski Britt.

“Who is gossiping, and what is the gossip?” she insisted.

“I don’t care to go into the matter,” he declared, desperately. “If the young man is nothing to you except an acquaintance, and I have reasons of my own for not wanting him to call at my house, I expect you to do as I say, seeing that his exclusion will not mean any sacrifice for you.”

He was dealing craftily. She knew it, and resented it.

“I do not propose to sacrifice any of my friends for a whim, father. If your reasons have anything to do with my personal side of this matter, I must have them. If they are purely your own and do not concern me, I must consider them your whim, unless you convince me to the contrary, and I shall not be governed in my choice of friends. That may sound rebellious, but a father should not provoke a daughter to rebellion. You ought to know me too well for that.”

They were at the house, and he threw himself out of the phaeton and tramped in without reply. During their supper he preserved a resentful silence, and at the end went up-stairs to his den to think over the whole matter. It had suddenly assumed a seriousness that puzzled and frightened him. He had been routed in the first encounter. He resolved to make sure of his ground and his facts—and win.

Usually he did not notice who came or who went at his house. The still waters of his confidence in his daughter had never been troubled until the Honorable Pulaski D. Britt had breathed upon them.

This evening, when he heard a caller announced, he tiptoed to the head of the stairs and listened.

It was Dwight Wade, and at sight of him his pride took alarm, his anger flared. After the afternoon’s exasperating [Pg 23]talk, this seemed like open and insulting contempt for his authority. It was as though the man were plotting with a disobedient daughter to flout him as a father. His purpose of calm thought was swept away by an unreasoning wrath. Muttering venomous oaths, he stamped down the stairs, whose carpet made his approach stealthy, though he did not intend it, and he came upon the two as Wade, his great love spurred by the day’s opposition, despondent in the present, fearing for the future, reached out his longing arms and took her to his heart.

They faced him as he stood and glowered upon them, a pathetic pair, clinging to each other.

“You sneaking thief!” roared Barrett.

The girl did not draw away. Wade felt her trembling hands seeking his, and he pressed them and kept her in the circle of his arm.

“I don’t care to advertise this,” Barrett went on, choking with his rage, “but there’s just one way to treat you, you thief, and that’s to have you kicked out of the house. Elva, up-stairs with you!”

She gently put away her lover’s arm, but she remained beside him, strong in her woman’s courage.

“I have always been proud of my father as a gentleman,” she said. “It hurts my faith to have you say such things under your own roof.”

“That pup has come under my roof to steal,” raged the millionaire, “and he’s got to take the consequences. Don’t you read me my duty, girl!”

Even Barrett in his wrath had to acknowledge that simple manliness has potency against pride of wealth. Wade took two steps towards him, the instinctive movement of the male that protects his mate.

“Mr. Barrett,” he said, gravely, “give me credit for honest intentions. If it is a fault to love your daughter with all my heart and soul, I have committed that fault. [Pg 24]For me it’s a privilege—an honor that you can’t prevent.”

“What! I can’t regulate my own daughter’s marriage, you young hound?”

“You misunderstand me, Mr. Barrett. You cannot prevent me from loving her, even though I may never see nor speak to her again.”

And Elva, blushing, tremulous, yet determined, looked straight in her father’s eyes, saying, “And I love him.”

Barrett realized that his anger was making a sorry figure compared with this young man’s resolute calmness. With an effort he held himself in check.

“We won’t argue the love side of this thing,” he said, grimly. “I haven’t any notion of doing that with a nineteen-year-old girl and a pauper. But I want to inform you, young man, that the marriage of John Barrett’s only child and heir is a matter for my judgment to control. I’m taking it for granted that you are not sneak enough to run away with her, even if you have stolen her affections.”

The millionaire understood his man. He had calculated the effect of the sneer. He knew how New England pride may be spurred to conquer passion.

“These are wicked insults, sir,” said the young man, his face rigid and pale, “but I don’t deserve them.”

“I tell you here before my daughter that I have plans for her future that you shall not interfere with. This is no country school-ma’am, down on your plane of life—this is Elva Barrett, of ‘Oaklands,’ a girl who has temporarily lost her good sense, but who is nevertheless my daughter and my heiress. She will remember that in a little while. Take yourself out of the way, young man!”

The girl’s eyes blazed. Her face was transfigured with grief and love. She was about to speak, but Wade hastened to her and took her hand.

“Good-night, Elva.”

She understood him. His eyes and the quiver in his voice spoke to her heart. She clung to his hands when he would have withdrawn them. The look she gave her father checked that gentleman’s contemptuous mutterings.

“I am ashamed of my father, Mr. Wade,” she said, passionately. “I offer you the apologies of our home.”

“Say, look here!” snarled Barrett, this scornful rebelliousness putting his wits to flight, “if that’s the way you feel about me, put on your hat and go with him. I’ll be d—d if I don’t mean it! Go and starve.”

He realized the folly of his outburst as he returned their gaze. But he persisted in his puerile attack.

“Oh, you don’t want her that way, do you?” he sneered. “You want her to bring the dollars that go along with her!”

Then Wade forgot himself.

He wrested one hand from the gentle clasp that entreated him, and would have struck the mouth that uttered the wretched insult. The girl prevented an act that would have been an enormity. She caught his wrist, and when his arm relaxed he did not dare, at first, to look at her. Then he gave her one quick stare of horror and looked at his hand, dazed and ashamed.

Barrett, strangely enough, was jarred back to equanimity by the threat of that blow. He folded his arms, drew himself up, and stood there, the outraged master of the mansion restored to command, silent, cold, rigid, his whole attitude of indignant reproach more effective than all the curses in Satan’s lexicon.

Talk could not help that distressing situation. The young man’s white lips tried to frame the words “I apologize,” but even in his anguish the grim humor of this reciprocation of apology rose before his dizzy consciousness.

“Good-night!” he gasped.

Then he left her and went into the hall, John Barrett close on his heels. The millionaire watched him take his hat, followed him out upon the broad porch, and halted him at the edge of the steps.

“Mr. Wade,” he said, “you’d rather resign your position than be kicked out, I presume?”

“You mean that it is your wish that I should go away from Stillwater?”

“That is exactly what I mean. You resign, or I will have your resignation demanded by the school board.”

“I think my school relations are entirely my own business,” retorted the young man, fighting back his mounting wrath.

“I’ll make it mine, and have you kicked out of this town like a cur.”

Wade remembered at that instant the face of the man whom he had seen leave John Barrett’s office that morning. He recollected his words—“I’d relish bein’ the man that mistook him for a bear!” He knew now how that man felt. And feeling the lust of killing rise in his own soul for the first time, he clinched his fists, set his teeth, and strode away into the night.

“We’re bound for the choppin’s at Chamberlain Lake,

And we’re lookin’ for trouble and suthin’ to take.

We reckon we’ll manage this end of the train,

And we’ll leave a red streak up the centre of Maine.”

—Murphy’s “Come-all-ye.”

A company of reserves posted in a thicket, after valiantly withstanding the hammering of a battery, were suddenly routed by wasps. They broke and ran like the veriest knaves.

Dwight Wade had determined to face John Barrett’s battery of persecution. But at the end of a week he realized that the little city of Stillwater was looking askance at him. He knew that gossip attended his steps and stood ever at his shoulders, as one from the tail of the eye sees shadowy visions and, turning suddenly, finds them gone.

That John Barrett would deliberately start stories in which his daughter’s affairs were concerned seemed incredible to the lover who, for the sake of her fair fame and her peace of mind, had resolved to make fetish of duty, realizing even better than she herself that Elva Barrett’s sense of justice would weigh well her duties as daughter before she could be won to the duties of wife.

Yet Wade could hardly tell why he determined to stay in Stillwater. He wanted to console himself with the belief that a sudden departure would give gossip the [Pg 28]proof it wanted. For gossip, as he caught its vague whispers, said that John Barrett had kicked—actually and violently kicked—the principal of the Stillwater high-school out of his mansion. Wade did not like to think that Barrett, by himself or a servant, started that story. Yet the thought made Wade suspect that the bitterness of the night at “Oaklands” still rankled, and that he was remaining in Stillwater for the sake of defying John Barrett, and was not simply crucifying his spirit for the sake of the peace of John Barrett’s daughter.

For he confessed that his stay there would be martyrdom. He had resolved that he would not try to see her; that would only mean grief for her and humiliation for him. He was proud of his love for Elva Barrett, in spite of her father’s contempt and insults. He found no reproach for himself because he had loved her and had told her so. But for the rôle of a Lochinvar his New England nature had no taste. He realized, without arguing the question with himself, that Elva Barrett was not to be won by the impetuous folly that demanded blind sacrifice of name and position and father and friends.

There was no cowardice in this realization. It was rather a pathetic sacrifice on the part of simple loyalty and a love that was absolute devotion. In deciding to remain in Stillwater he kept his love alight like a flame before a shrine. But beyond his daily work and the unflinching purpose of his great love he could not see his way.

It was because his way was so obscure that the wasps found him an easier victim.

He heard the buzzings at street corners as he passed. There were stings of glances and of half-heard words.

Like the pastor of a church in a small place, the principal of a high-school is one in whom the community feels a sense of proprietorship, with full right to canvass his goings and comings and liberty to circumscribe and [Pg 29]control. For is he not the one that should “set example”?

The wasps would not accept his silent surrender. They suspected something hidden, and their imaginings saw the worst. They buzzed more busily every day. That they would not allow him the peace and the pathetic liberty of renunciation drove Wade frantic. With all the courage of his conscience, he still faced John Barrett’s battery. But the wasps he could not face.

And he fled. In the end it was nothing but that—he was put to flight! The people of Stillwater accepted it as flight, for he placed his resignation in the hands of the school board barely a week before the date for the opening of the autumn term. And on the train on which he fled was the Honorable Pulaski D. Britt, still unconscious that the word of gossip he had dropped was the match that lighted a fuse, and that the fuse was briskly burning.

Above the rumble of the starting car-wheels Wade heard the mills of Stillwater screaming their farewell taunt at him.

Then the Honorable Pulaski Britt came and sat down in his seat, penning him next to the window.

“Yes, sir,” said Britt, with keen memory as to where he had left off in his previous conversation and with dogged determination to have his say out, “a man that reads a book written by a perfesser that don’t know the difference between a ramdown and a dose of catnip tea, and then thinks he understands forestry of the kind that there’s a dollar in, needs to have his head examined for hollows. Do you find anything in them books about how to get the best figgers on dressed beef?—and when you are buyin’ it in fifty-ton lots for a dozen camps a half a cent on a pound means something! Is there anything about hirin’ men and makin’ ’em stay and work, gettin’ cooks and saw-filers that know their business, chasin’ thieves away from depot-camps, keepin’ crews [Pg 30]from losin’ half the tools? Forestry! Making trees grow! Gawd-amighty, young man, Nature will attend to the tree-growin’. That’s all Nature has got to do. She was doin’ it before we got here, and doin’ it well, and do you reckon we have any right to set up and tell Nature her business? I’ve got something else to think of besides tellin’ Nature how to run her end. I’d like to know how to grow men instead of trees. My Jerusalem boss, MacLeod, writes me he has been two weeks getting together his hundred men for that operation. He’ll meet me at the Umcolcus junction, up the line here a hundred miles. And I’ve been tryin’ most of that time to get hold of the right sort of a ‘chaney man.’”

Wade, in his resentment at Britt’s intrusion on his thoughts, was in no mood for philological research, but sudden and rather idle curiosity impelled him to ask what a “chaney man” was.

“Why, a clerk—a camp clerk, time-keeper, wangan store overseer, supply accountant, and all that,” snapped Britt, with small patience for the young man’s ignorance.

At that instant it came more plainly to Wade that he was a fugitive. When he had left Elva Barrett behind he had let go the strongest cable of hope. A day before—the day after—his manly spirit probably would not have allowed him to become a clerk for Pulaski Britt. This day the impetuous desire to hide in the woods, to escape the wasps of humanity, to be in some place where sneers and false pity and taunt could not reach him—that desire was coined into performance.

“Wouldn’t I fit into a job of that sort, Mr. Britt?” he asked, blurting the question. And when the lumberman stared at him with as much astonishment as Pulaski Britt ever allowed himself to display, Wade added, “I have given up school-teaching because—well, I want to get into the woods for my health!”

“It will be healthy, all right, but it won’t be dude work,” said Britt. “You’ll have to hump ’round on snow-shoes or a jumper to five camps. Board and thirty-five a month! What’s the particular ailment with you?” he demanded, rather suspiciously. “You look rugged enough.”

The young man did not reply, and the Honorable Pulaski stared at him, his eyes narrowing shrewdly. Mr. Britt had no very delicate notions of repressing an idea when it occurred to him “Say, look here, young man,” he cried, “I reckon I understand! The Barrett girl, hey? And John got after you! Well, he can make it hot for any one he takes a niff at.”

“Can’t I have that job, Mr. Britt, without a general discussion of my affairs?” asked Wade, with temper.

“You’re hired!” There was the click of business in Britt’s tone, but his gossip’s nature showed itself in the somewhat humorous drawl in which he added: “I’m glad to know that it’s only love that ails you. Outside of that, you strike me as bein’ a pretty rugged chap, and it’s rugged chaps we’re lookin’ for in ‘Britt’s Busters.’ If it’s only love that ails you, I reckon we won’t have any trouble about sendin’ you out cured in the spring.”

But noting the glitter in Wade’s eyes, Mr. Britt chuckled amiably and took himself off down the car to talk business with a man.

During the long ride to Umcolcus Junction, Wade sat revelling in the bitterness of his thoughts. He was not disturbed because he had given up his school. There was a relief in escaping from meddlesome backbiters. The school had been only a means to an end: it afforded revenue to attain certain cherished professional plans that loomed large in Wade’s prospects. Money earned honorably in any other fashion would count for as much. [Pg 32]But the fact remained that he was fleeing, was hiding. Britt’s rough and somewhat contemptuous proprietorship, so instantly displayed, wounded his pride. When he had passed the station to which he had purchased his ticket before he met Britt, he offered more pay to the conductor. He had seen Britt talking with the conductor a moment before, brandishing a hairy hand in his direction.

“It’s all settled by Mr. Britt,” the train officer stated, passing on. “You’re one of his men, he says.”

He growled under his breath as he accepted that label—“One of Britt’s men.”

There were one hundred more waiting for them at Umcolcus Junction, where they changed to the spur line that ran north.

Most of the men were in a state of social inebriety. A few fighters were sitting apart on their dunnage-bags, nursing bruises and grudges. Mindful of the State law that forbade the wearing of calked boots on board a railroad train, the men who owned only that sort of footgear were in their stocking feet. They carried their boots strung about their necks by lacings. Many were bareheaded, having thrown away their hats in their enthusiasm. Wade was not in a frame of mind to see any picturesqueness in that frowsy crowd. He was one of them; he walked dutifully behind his master, the Honorable Pulaski Britt.

A little man, with neck wattled blue and red with queer suggestion of a turkey’s characteristics, lurched out of a group and came at Pulaski Britt with a meek and watery smile of welcome. His knees doubled with a drunkard’s limpness, and he had to run to keep from falling. Britt evidently did not propose to serve as dock for this human derelict. He stepped to one side with an oath, and the man made a dizzy whirl and dove headforemost under the train on the main track, and [Pg 33]at that moment the train started. The man rolled over twice, and lay, serenely indifferent to death, on the outer rail.

After it was all over Wade sourly told himself that he acted as he did simply to avoid witnessing a hideous spectacle.

For, in spite of Britt’s yells of protest, he went under the car, missed the grinding wheels by an inch, and rolled out on the other side with the drunken man in his arms.

And when the train had drawn out of the station he came back across the track, lugging the little man as he would carry a gripsack, tossed him into the open door of the baggage-car of the waiting train, spatted the dust off his own clothes, and went into the coach, casting surly looks at the sputtering inebriates who attempted to shake hands with him.

When the train started Britt came again and penned the young man in his seat against the window-casing.

“You’ve started in makin’ yourself worth while, even if you are only the chaney man,” vouchsafed his employer. “You did an infernal fool trick, but you’ve saved me Tommy Eye, the best teamster on the Umcolcus waters. As he lies there now he ain’t worth half a cent a pound to feed to cats; when he’s on a load with the webbin’s in his hands I wouldn’t take ten thousand dollars for him.”

“Is he a sort of personal property of yours?” asked Wade, sullenly. He was venting his own resentment at Pulaski Britt’s airs of general proprietorship over men.

“Just the same as that,” replied Britt, complacently. “I’ve had him more than twenty years, and I’d like to see him try to go to work for any one else, or any one else try to hire him away.” He struck his hand on the young man’s knee. “Up this way, if you don’t make men know you own ’em, you’re missin’ one of the main [Pg 34]points of forestry!” He sneered this word every time he used it in his talk with Wade. The new chaney man began to wonder how much longer he could endure the Honorable Pulaski D. Britt without rising and cuffing those puffy cheeks.

“If you don’t like our looks nor ain’t stuck on our kind,

Git back with the dames in the next car behind.”

On and on went the yelping staccato of the Honorable Pulaski D. Britt. The Honorable Pulaski D. was discoursing on his favorite topic, and his voice was heard above the rattle and jangle of the shaky old passenger-coach that jolted behind some freight-cars.

“Forty years ago I rolled nigh onto a million feet into that brook there!” shouted the lumber baron of the Umcolcus. His knotted, hairy fist wagged under the young man’s nose as he pointed at the car window, his unwholesome breath fanned warmly on Wade’s cheek, and when he crowded over to look into the summer-dried stream his bristly chin-whiskers tickled his seat-mate’s ear. The September day was muggy and human contact disquieting. Wade shrank nearer the open window. The Honorable Pulaski did not notice the shrinking. He was accustomed to crowd folks. His self-assertiveness expected them to get out of the way.

“Yes, sir, nigh onto a million in one spring, and half of it ‘down pine’ and sounder’n a hound’s tooth. Nothing here now but sleeper stuff. It’s a good many miles to the nearest saw-log, and that’s where I’m cutting on [Pg 36]Jerusalem. I tell you, I’ve peeled some territory in forty years, young man.”

Wade looked at the red tongue licking lustfully between blue lips, and then gazed on the ragged, bush-grown wastes on either side. While he had been crowding men the Honorable Pulaski had been just as industriously crowding the forest off God’s acres. The “chock” of the axe sounded in his abrupt sentences, the rasp of saws in his voice.

“We left big stumps those days.” The hairy fist indicated the rotten monuments of moss-covered punk shouldering over the dwarfed bushes. “There was a lot of it ahead of us. Didn’t have to be economical. Get it down and yanked to the landings—that was the game! We’re cutting as small as eight-inch spruce at Jerusalem. Ain’t a mouthful for a gang-saw, but they taste good to pulp-grinders.”

The train began to groan and jerk to a stand-still, and the old man dove out of his seat and staggered down the aisle, holding to the backs of the seats. At the last station he had spent ten minutes of hand-brandishing colloquy on the platform with a shingle-mill boss whom he had summoned to the train by wire. He was to meet a birch-mill foreman here. Wade looked out at the struggling cedars and the white birches, “the ladies of the forest,” pathetic aftermath which was now falling victim to axe and saw, and wondered with a flicker of grim humor in his thoughts why the Honorable Pulaski did not set crews at work cutting the bushes for hoop-poles and then clean up the last remnant into toothpicks.

“He’s a driver, ain’t he?” sounded a voice in his ear. An old man behind him hung his grizzled whiskers over the seat-back and pointed an admiring finger at the retreating back of the lumber baron.

Wade wished that people would let him alone. He [Pg 37]had some thoughts—some very bitter thoughts—to think alone, and the world jarred on him. The yelp of the Honorable Pulaski’s monologue, that everlasting, insistent bellow of voices in the smoking-car ahead, where the ingoing crew of Britt’s hundred men were trying to sing with drunken lustiness, and now this amiable old fool of the grizzled whiskers, stung the dull pain of his resentment at deeper troubles into sudden and almost childish anger.

“Once when I was swamping for him on Telos stream, he says to me, ‘Man,’ he says, ‘remember that the time that’s lost when an axe is slicin’ air ain’t helping me to pay you day’s wages!’ And I says to him, ‘Mister Britt,’ says I—”

Dwight Wade, college graduate, former high-school principal, and at all times in the past a cultured and courteous young gentleman, did the first really rude and unpardonable act of his life. He twisted his chin over his shoulder, scowled into the mild, dim, and watery eyes of his interlocutor, and growled:

“Oh, cut it short! What in—” He checked the expletive, and snapped himself up and across the aisle, and slammed down into another seat. The red came over his face. He did not dare to look back at the old man. He hearkened to the rip-roaring chorus in the smoking-car, and reflected that as the new time-keeper he was now one of “Britt’s Busters,” and that the demoralizing license of the great north woods must have entered into his nature thus early. He grunted his disgust at himself under his breath, and hunched his head down between his shoulders.

In his nasty state of mind he glowered at a passenger who came into the car at the front. It was a girl, and a pretty girl at that. She nodded a cheery greeting to the old man of the grizzled whiskers, and with a smile still dimpling her cheeks flashed one glance at Wade. [Pg 38]It was not a bold look, and yet there was the least bit of challenge in it. The sudden pout on her lips might have been at thought of confiding her fresh, crisp skirts to the dusty seat; and yet, when she turned and shot one more quick glance at the young man’s sour countenance, the pout curled into something like disdain, and a little shrug of her shoulders hinted that she had not met the response that she was accustomed to find on the faces of young men who saw her for the first time.

While Wade was gazing gloomily and abstractedly at the fair profile and the nose, tip-tilted a wee bit above the big white bow of her veil tied under her chin, one of the crew lurched from the door of the smoking-car, caught off his hat, and bowed extravagantly. It was Tommy Eye. He had to clutch the brake-wheel to keep himself from falling. But his voice was still his own. He broke out lustily:

“Oh, there ain’t no girl, no pretty little girl,

That I have left behind me.

I’m all cut loose for to wrassle with the spruce,

Way up where she can’t find me.

Oh, there ain’t no—”

An angry face appeared over his shoulder in the door of the smoker, two big hands clutched his throat, jammed the melody into a hoarse squawk, and then the songster went tumbling backward into the car and out of sight.

Almost immediately his muscular suppressor crossed the platform and came into the coach, snatching the little round hat off the back of his head as he entered. Wade knew him. His employer had introduced them at the junction as two who should know each other. It was Colin MacLeod, the “boss.”

“And Prince Edward’s Island never turned out a smarter,” the Honorable Pulaski had said, not deigning [Pg 39]to make an aside of his remarks. “Landed four million of the Umcolcus logs on the ice this spring, busted her with dynamite, let hell and the drive loose, licked every pulp-wood boss that got in his way with their kindlings, and was the first into Pea Cove boom with every log on the scale-sheet. That’s this boy!” And he fondled the young giant’s arm like a butcher appraising beef.

Wade paid little attention to him then. With his ridged jaw muscles, his hard gray eyes, and the bullying cock of his head, he was only a part of the ruthlessness of the woods.

But now, as he came up the car aisle, his face flushed, his eyes eager, his embarrassment wrinkling on his forehead, Wade looked at him with the sudden thought that the boss of the “Busters” was merely a boy, after all.

“It was only Tommy Eye, Miss Nina,” explained MacLeod, his voice trembling, his abashed admiration shining in his face. “He’s just out of jail, you know.” He looked at Wade and then at the old man of the grizzled whiskers, and raised his voice as though to gain a self-possession he did not feel. “Tommy always gets into jail after the drive is down. He’s spent seventeen summers in jail, and is proud of it.”

“But there ain’t no better teamster ever pushed on the webbin’s,” said the old man, admiration for all the folks of the woods still unflagging.

The girl did not display the same enthusiasm, either for Tommy Eye’s mishaps or for the bashful giant who stood shifting from foot to foot beside her seat.

“Crews going into the woods ought to be nailed up in box-cars, that’s what father says. And when they go through Castonia settlement I wish they were in crates, the same as they ship bears.”

“How is your father since spring?” asked the young [Pg 40]boss, stammeringly, trying to appear unconscious of her scorn.

“Oh, he’s all right,” she returned, carelessly, patting her hand on her lips to repress a yawn.

“And is every one in Castonia all right?”

“You can ask them when you get there,” she replied, a bit ungraciously.

“I tell you, I was pretty surprised to see you get aboard the train down here at Bomazeen. I—”

She canted her head suddenly, and looked sidewise at him with an expression half satiric, half indignant.

“Do you think that all the folks who ever go anywhere in this world are river drivers and”—she shot a quick and disparaging glance at the still glowering Wade—“drummers?”

MacLeod noticed the look and its scorn with delight, and grasped at this opportunity to get outside the platitudes of conversation. But in his eagerness to be news-monger he did not soften his “out-door voice,” deepened by many years of bellowing above the roar of white water.

“Oh, that ain’t a drummer! That’s Britt’s new chaney man—the time-keeper and the wangan store clerk.” MacLeod knew that a girl born and bred in Castonia settlement, on the edge of the great forest, needed no explanation of “chaney man,” the only man in a logging crew who could sleep till daylight, and didn’t come out in the spring with callous marks on his hands as big as dimes. But he seemed to be hungry for an excuse to stay beside her, where he could gaze down on the brown hair looped over her forehead and her radiantly fair face, and could catch a glimpse of the white teeth. “Britt was tellin’ me on the side that he’s been teachin’ school or something like that, and—say, you’ve heard of old Barrett, who controls all the stumpage on the Chamberlain waters—that rich [Pg 41]old feller? Well, Britt, being hitched up with Barrett more or less, and knowin’ all about it—”

Wade was now upright in his seat, but the absorbed foreman, catching at last a gleam of interest in the gray eyes upraised to his, did not notice.

“—Britt says that Mister School-teacher there went to work and fell in love with Barrett’s girl, and now she’s goin’ to marry a rich feller in the lumberin’ line that her dad picked out for her, and instead of goin’ to war or to sea, like—”

Wade, maddened, sick at heart, furious at the old tattler who had thus canvassed his poor secret with his boss, had tried twice to cry an interruption. But his voice stuck in his throat.

Now he leaped up, leaned far over the seat-back in front of him, and shouted, with face flushed and eyes like shining steel:

“That’s enough of that, you pup!”

In the sudden, astonished silence the old man dragged his fingers through his grizzled whiskers and whined plaintively:

“Ain’t he peppery, though, about anybody talking? He shet me up, too!”

“It’s my business you’re talking!” shouted Wade, beating time with clinched fist. “Drop it.”

MacLeod, primordial in his instincts, lost sight of the provocation, and felt only the rebuff in the presence of the girl he was seeking to attract. He had no apology on his tongue or in his heart.

“It will take a better man than you to trig talk that I’m makin’,” he retorted. “This isn’t a district school, where you are licked if you whisper!” He sneered as he said it, and took one step up the aisle.

With the bitter anger that had been burning in him for many days now fanned into the white-heat of Berserker rage, Wade leaped out of his seat. Between them [Pg 42]sat the girl, looking from one to the other, her cheeks paling, her lips apart.

At the moment, with a drunken man’s instinctive knowledge of ripe occasions, Tommy Eye lurched out once more on the smoker platform and began to carol the lay that had consoled him on so many trips from town:

“Oh, there ain’t no girl, no pretty little girl,

That I have left behind me.”

There sounded the clang of the engine bell far to the front. There was the premonitory and approaching jangle of shacklings, as car after car took up its slack.

“Look after your man there, MacLeod!” cried the girl. “The yank will throw him off.”

“Let him go, then!” gritted the foreman. The flame in Wade’s eyes was like the red torch of battle to him. Not for years had a man dared to give him that look.

Suddenly the car sprang forward under their feet as the last shackle snapped taut. The boss was driven towards Wade, and let himself be driven. The other braced himself, blind in his fury, realizing at last the nature of the blood lust.

A squall, fairly demoniac in intensity, stopped them. MacLeod recognized the voice, and even his passion for battle yielded. When the Honorable Pulaski D. Britt, baron of the Umcolcus, yelled in that fashion it meant obedience, and on this occasion the squall was reinforced by a shriek from the girl. And MacLeod whirled, dropping his fists.

There on the platform stood Britt, clutching the limp and soggy Tommy Eye by the slack of his jacket. The Honorable Pulaski, jealous of every second of time, had remained in conversation to the last with his birch foreman. He stepped aboard just as Tommy, jarred from his feet, was pitching off the other side of the [Pg 43]platform. The Honorable Pulaski snatched for him and held on, at the imminent risk of his own life. Already both of them were leaning far out, for Tommy Eye, in the blissful calm of his spirit, was making no effort to help himself.

In an instant MacLeod was down the car aisle and had pulled both back to safety.

“Why in blastnation ain’t you staying in this hog-car here, where you belong, you long-legged P.I. steer?” roared the old man, his anger ready the moment his fright subsided. “What do I hire you for? You came near letting me lose the best teamster in my whole crew. Now get into that car and stay in that car till we get to the end of this railroad.”

He put his hands against MacLeod’s breast and shoved him backward into the door, where Tommy Eye, grinning in fatuous ignorance of the danger he had passed through, had just disappeared ahead of him. The angry shame of a man cruelly humiliated twisted MacLeod’s features, but he allowed his imperious despot to push him into the car, casting a last appealing look at the girl. Britt slammed the door and stood on the platform, bracing himself by a hand on either side the casing, and peered through the dingy glass to make sure that his crew was now under proper discipline.

“He’s a driver and a master,” piped up Grizzly Whiskers, with the appositeness of a Greek chorus.

“There’s the song about him, ye know:

“Oh, the night that I was married,

The night that I was wed,

Up there come Pulaski Britt

And stood at my bed-head.

Said he, ‘Arise, young married man,

And come along with me.

Where the waters of Umcolcus

They do roar along so free.’”

“I’ll bet he went, at that,” volunteered a man farther back in the car. “When Britt is after men he gits’ em, and when he gits ’em he uses ’em.”

“Mr. Britt,” he shouted down the car aisle as the old man entered, “that was brave work you done in savin’ Tommy’s life!”

“Go to the devil with your compliments!” snapped Britt. “If it wasn’t that I was losing my best teamster I wouldn’t have put out my little finger to save him from mince-meat.”

He saw the girl, turned over a seat to face her, and began to fire rapid questions at her regarding her father and mother and the latest news of Castonia settlement. When the conversation languished, as it did soon on account of the inattention of the young woman, the Honorable Pulaski caught the still flaming eye of Dwight Wade, and crooked his finger to summon him. Wade merely scowled the deeper. The Honorable Pulaski serenely disregarded this malevolence as a probable optical illusion, and when Wade did not start beckoned again.

“Come here, you!” he bellowed. “Can’t you see that I want you?”

With new accession of fury at being thus baited, the young man started up, resolved to take his employer aside and free his mind on that matter of news-mongering. But the bluff and busy tyrant was first, as he always was in his dealings with men.

“Here, Wade,” he shouted, “you shake hands with the prettiest girl in the north country! This is Miss Nina Ide, and this is my new time-keeper, Dwight Wade. He’s going to find that there’s more in lumbering than there is in being a college dude or teaching a school. Sit down, Wade.”

He pulled the young man into the seat.

“Entertain this young lady,” he commanded. “She [Pg 45]don’t want to talk with old chaps like me. Her father—well, I reckon you know her father! Oh, you don’t? Well, he’s first assessor of Castonia settlement, runs the roads, the schools, and the town, has the general store and post-office, and this pretty daughter that all the boys are in love with.”

And at the end of this delicate introduction he pushed brusquely between them, and went back to talk with his elderly admirer in the rear of the car.

Wade looked into the gray eyes of the girl sullenly. There was an angry sparkle in her gaze.

“Well, Mr. Wade, you may think from what that old fool said that I’m suffering to be entertained. If you think any such thing you can change your mind and go back.”

She had not a city-bred woman’s self-poise, he thought. Her manner was that of the country belle, spoiled the least bit by flattery and attention. And yet, as he looked at her, he thought that he had never seen fairer skin to set off the flush of angry beauty. For others there was something alluring in the absolute whiteness of her teeth, peeping under the curve of her lip, in the nose (the least bit retroussé), in the looped locks of brown hair crossing her temples. Yet there was no admiration in his eyes.