Title: Pilgrim Trails: A Plymouth-to-Provincetown Sketchbook

Author: Frances Lester Warner

Illustrator: C. Scott White

Release date: January 31, 2011 [eBook #35136]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steve Mattern

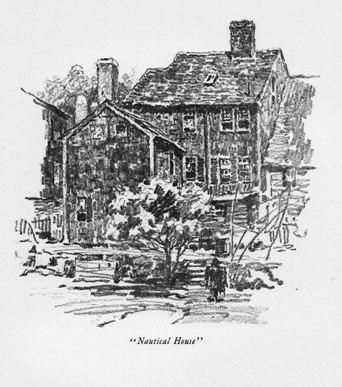

"There!" said the artist, "isn't that a nautical-looking house?"

When the artist says that a house is nautical, he means that it looks as if it had been built by seafaring men; not by wealthy ship-owners, but by generations of skippers and men before the mast. When you build a nautical house, you should begin more than a hundred years ago with a small cottage on the side-hill over the harbor, and add on a snug cabin now and then, tucking in a shipshape companionway here and there, and running a new section out along the slope. If you like to indulge your taste in roofs, you make a different kind for every addition. One section may be gable, another lean-to, and the one-story addition may run out as long as you please, shaped on top something like the roof of a barge. Simply fit your building to the ups and downs of the land and the ways of the wind. A bit of faded blue paint somewhere on the blinds or near the door, and all your roofing weathered by many hundred harbor gales, and your house is nautical.

There are not as many of these in Plymouth as in Gloucester, but there are a few. In fact, at Plymouth you may find almost any kind of building you look for, from Mansard roofs and bungalows, to the lobster-houses down by Eel River, the shooting-boxes out on the sand-spit, and the dark old structures beside Town Brook and around the region once known as Clamshell Alley.

We had left the car at the garage, and had walked along the upper streets over the hill. The artist was going sketching, his brother Alexander was meeting a business appointment, and Barbara and I had come to see Plymouth.

"I'm going in among those places on the other side of Town Brook," said the artist. "The only way to find something good is to go everywhere you're not supposed to."

"But you and Barbara," said Alexander, as he prepared to escort us out to the main street, "might as well go where you're supposed to."

He paused for a moment to let his words sink in.

"The best way," said Alexander, "is to follow your guide-book."

"The best way," said the artist over his shoulder, "is to explore."

Barbara receives advice from her two brothers with the air of a young empress listening to the remarks of two prime ministers, but makes her own decisions. I have acted as her confederate and chaperon on so many occasions that I know enough to be quiet until the prime ministers have gone.

"The best way," said Barbara when this had happened, "is to ask a little boy."

Doubtless any real expedition to Plymouth ought to begin with the Rock. We found our way down along the water-front, to the place where the Rock used to be, but it was nowhere in sight.

"When I was here before," said I, "the Rock was exactly here, under its canopy at the foot of Cole's Hill. You couldn't miss it."

Barbara looked out along the wharves. Some children were playing at the end of one of the piers.

"We'll ask a little boy," said Barbara, leading the way.

"They look like little foreigners," said I. "Do you think they would know?"

For answer, Barbara went out slowly to the edge of the pier, and stood watching the white seagulls flying over the harbor. The boys gave her a glance, made up their minds about her, and went on with their play.

"Where's the Rock?" said Barbara casually, over her shoulder.

"They're moving it," said one.

"It's all broke up," said another.

"Want us to show it to you?" said a third.

"Yes," said Barbara. "Where are they moving it to?"

"Down to the edge. When they get it there, we can swim right up to it," said our guide with unction. "But now it's all broke up."

He was leading us rapidly back to Water Street, to a great pile of masonry by the roadside. "That's the rock," said he. "Here's some, and here's some, and here's some more. All broke up."

The boys were scrambling over the arches and hopping about among the blocks of granite.

"Oh, yes," said Barbara tactfully, "this is the old canopy that used to be over the Rock, isn't it? And where's the real Rock?"

Our guide looked puzzled. Then light dawned. "The little one with 1620 on it? Down on the other side of the road." He waved a brown fist. "See?"

And there it was, the famous boulder, waiting to be taken to its new position at the water's edge. Plymouth Rock is a very satisfactory relic; just the shape of a Rock. Its prehistoric excursions with the glacier and its historic pilgrimages since 1620 have combined to lead it a roving life. In Revolutionary days it was on Town Square, with the Liberty Pole; then it migrated to the lawn in front of Pilgrim Hall; then it rested under its canopy at the foot of Cole's Hill—and in all these positions it inspired tourists to remarks about the agility of the Fathers in using it as a stepping-stone from the harbor to dry land. And now, in 1921, it goes back to the original landing-place, where the high tides will reach it again.

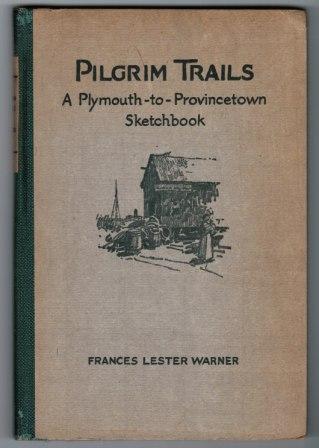

Plymouth Harbor

Plymouth Harbor

Barbara and I congratulated ourselves on our luck in arriving at the right time to catch it on the move. Probably its fourth century of fame will bring it more visitors than ever before, including our friends, the little delegates from Portugal and Italy, who hope to swim near by.

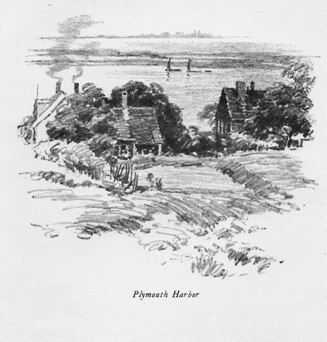

"Now," said Barbara, "let's go up to Leyden Street and see if we can imagine that it's First Street, with the first houses and all."

Taking our imaginations well in hand, we found Leyden Street and the site of the first house. Probably it is not necessary to be thrilled at every inch of Plymouth. No matter how many times we visit it, I think we expect to find it looking more gray and spectral than it does; just as children, from much study of the map, half expect to see the land of China look yellow. There are fishing-coves on the Maine coast that look a good deal more like our childhood idea of Plymouth—weatherbeaten houses, low roofs, and great dark cliffs with the surf pounding against them. Mrs. Felicia Hemans is not entirely responsible for our misconception. We know that we shall not see the original block-house, but we still have a lingering feeling that Plymouth ought to look gray.

And Leyden Street does not. It is old, but not decrepit. A very short street, with close-set houses, some of them painted white or yellow; and at the head of the street, on what used to be Elder Brewster's Meerstead, the fine Post-Office building—it is hard to realize that this is the place where the Mayflower settlers staked off their nineteen plots of ground. Even in winter, there is no sweeping impression that anything very grim or perilous ever happened here. But one impression we do feel strongly. If we stand at the head of the street by Elder Brewster's spring, and look down past the site of the first house, at the blue harbor, and then turn and look up at Burial Hill, we find ourselves thinking of the compactness of it all. Within a three-minute walk, we have caught a glimpse of the landing-place, Cole's Hill burying-ground, the site of the first house, the first street, and the hill where, as Governor Bradford says, "they built a fort, both strong & comly, made with a flate rofe & batllments, on which their ordnance were mounted, and wher they kepte constante watch, espetially in time of danger." The times of danger seem remote from Plymouth now, "espetially" at the corner of Leyden Street.

Site of First House, Leyden Street

Site of First House, Leyden Street

In order to feel the true sense of history,—not a worked-up sentiment, but the real thing,—you have to look at Plymouth, not in panorama but in detail. You have to accept with philosophy such modern phenomena as the Massasoit Shoe-Shine Parlors and the Plymouth Rock Garage, and keep your eyes open for certain types of old houses scattered in unexpected places everywhere.

One of these is a neat old house in excellent repair, the ends of the house of brick, the side toward the street of wood, plain gable roof, stout chimney, the whole thing painted white, and all fascinating within. This is Tabitha Plaskett's house, on Court Street, near Pilgrim Hall. It is not so very old,—only two hundred years come 1922,—but it is the one of its kind into which visitors are most naturally admitted, for they sell antiques there now. But before the Revolution it was the home of Mrs. Tabitha Plaskett, the first woman to keep a school in Plymouth.

Barbara and I went in, seeking gifts, and we stayed to look at the doors. They are plain one-paneled doors, each made of a single piece of wood, with old hand-made hinges,—some the H-hinge, some the H and L,—with irregular hand-wrought nails, and on each door a polished door-latch of slenderest design. The tiles around the fireplace are blue and white, the central one showing a dog running very fast, with all four feet off the ground, and all his legs held perfectly stiff like the legs of a rocking-horse.

We were shown the place where Tabitha Plaskett used to do her spinning and her school-teaching at the same time. Every legend-lover recalls the story of Tabitha's famous way of punishing children, by slipping a skein of yarn underneath their arms and hanging them up on a peg on the wall, much as Mrs. Peter Rabbit in the story hangs all her little rabbits on the clothes-line. The soft yarn probably did not hurt the children, though the position must have been, for the moment, embarrassing. We wonder whether Tabitha really did this often. If we remember our own schooldays, we know that the story of a punishment can take a fabulous turn in less than two hundred years. But from her epitaph on Burial Hill, we may be fairly sure that her relations with the public were not without an occasional breeze. She is supposed to have composed the epitaph herself, and it certainly sounds like the document of a vivid personality. We may read it now, carefully chiseled on her grave-stone, under an elaborate design of urn and weeping willow:—

Well, Tabitha's headstone now overlooks the place where the little children go along to school. If you should go into the primary rooms after school-hours, you would see the sand-tables and the little desks, and, hanging around the walls, a series of paper cut-outs of the Three Bears and the Little Red Hen. And if you should ask to be allowed to look at the register, you would find there some names that would remind you of the cabins of the Mayflower and the Fortune and the Ann, together with some that came over in a later ship. Surely the boys and girls of to-day will not object if we imagine Tabitha calling the roll of their last names in alphabetical order? She stands beside her spinning-wheel and begins: "Alden, Cook, Crane, Dante, Davenport, Deschamps, Donovan, Kitchin, Kerrigan, Locatelli, Malaguto, Metz, Morgan—" And she goes on, adjusting her voice to the musical variety of the names, until she ends the alphabet with "Thornhill, Vacchino, Wood, and Worcester." It is like a pleasant chant of the nations.

It is a very pretty question whether Tabitha Plaskett could maintain the quiet orderliness that we see now in these primary rooms, and make headway with her spinning at the same time. Would she apply the skeins of yarn internationally? And would she know just what to do with the sand-tables? If she could keep school again in her old house now, perhaps, instead of punishing the wicked, she would reward the just by letting them go into the front room, when they were very good, to look at the dog running like a rocking-horse on the blue tile.

"Nautical House"

"Nautical House"

Another kind of house that stirs our "sense of the past" is the sort that really does seem old on the outside. A little way down Sandwich Street is the Howland House, built in 1666, recently repaired and opened to visitors. If we are looking for a house that actually did come under the eye of the Pilgrims, this is one. A plain gable cottage, now painted the dull red that we associate with "little-red-schoolhouse" coloring, it stands a little back from the busy street, and the visitor goes in through a turnstile at the gate. Inside, all sorts of old furniture, including spinning-wheel and carriage-top bed, make it look as much as possible as if it were still inhabited. Other houses that were built in the sixteen hundreds, especially the Holmes House, also repay the trouble of searching them out. And when we find them, they look as if they had been built in the spirit of Governor Bradford's specifications about the colony's purpose in founding the Plymouth Plantation: "Not out of any newfanglednes or other such like giddie humor, by which men are oftentimes transported to their great hurt and danger, but for sundrie weightie & solid reasons." There is not much "giddie humor" about the old beams and rafters that have borne the solid weight of two hundred and fifty years.

In Plymouth there are many houses made partly of brick, with iron S-shaped anchors bolted through their brick-work to the beam inside. There are some of these on the side of Leyden Street near LeBaron Alley. And on North Street, there are great Santa Claus chimneys, with small low houses built around them, the structure of the house looking altogether too tiny to go with the generous flues.

Best of all, perhaps, because they have plenty of space around them, are the unpainted gambrel-roofed houses on the outskirts of the town. Now and then you find one where the shingles that cover the house from top to bottom have weathered a silver gray. Here and there the shingles have curled a trifle, so that they look like the bark of a shagbark walnut tree, in no danger of flying away with the wind, but making the house look crusted, picturesque. And there are some gabled houses where the long slope of the roof has sagged a little, just enough to make a place for moss and shadows, but not enough to look fallen in.

Barbara and I did not find all these the first day, or the next. We spent a good deal of time scouting over the moors, among the bayberry bushes and the pointed red cedars. Now and then we came upon a cranberry bog, hidden away behind what one geologist calls the "tumbled hills of Plymouth."

It was Alexander who showed us the best Colonial mansion. The frame was got out in England, and brought over in 1754, and, tradition says, was put upside down. It belonged to the Winslows—not the Edward Winslow who wrote "Good News From New England" in 1624, but a later branch of the family. The Winslow family seems to have prospered steadily in the early days—one of the cases where, in the elder Winslow's own words, "religion and profit jump together, which is rare."

"I want to show you the Winslow house," said Alexander; "the house where Emerson was married."

"I think we passed it on the corner of North and Winslow," said I. "Isn't it the fine square one, painted yellow and white, with the carving of fruit around the doorways?"

"That's it," admitted Alexander placidly, "but you don't know that house just by going past it on the street."

He led us down North Street to Winslow, and found the point where we could get the best view.

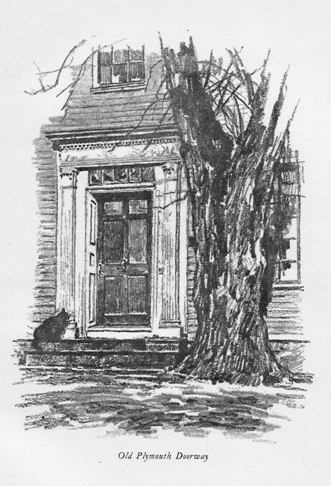

Old Plymouth Doorway

Old Plymouth Doorway

"Now," said he when he had planted us to his satisfaction, "notice the doorway, with those two immense linden-trees shading the path. The original shoots of the Winslow linden-trees were brought to this country in a raisin-box. Up on the front of the house, over the upstairs window, you see the carving of the British Lion and Unicorn. This branch of the Winslows in Revolutionary days remained Tories and were very loyal to the King; and after the war their property went into other hands. But their Lion and Unicorn are as good as ever."

"Is it really true," asked Barbara, "that the house is upside down?"

"Well," said Alexander, "the legend is very old. And the second-story rooms are a great deal higher-studded than the rooms downstairs. There's one door upstairs that looks as if it had been made for a giant. But they say that some of the English builders used to plan a house that way."

Whether the house is upside down or not, one thing is certain—that here Miss Lydia Jackson was married to Emerson. Once in a while an event in the world takes place in precisely the perfect setting. Emerson's marriage was one. The huge English door, almost as broad as it is tall, with its great brass knocker and deep paneling, knows how to swing wide open in a stately way of its own; a proper door to welcome Mr. Emerson. And the rooms inside, with their high white paneling and delicate beading around the top, have dignity in every line. In every room there is a fireplace, with tiles. In the room where Emerson was married, the tiles around the fireplace illustrate Scripture stories—the drawings exactly in the style of the pictures in the New England Primer. Jonah emerges from his specially constructed fish; Elijah sits under his juniper bush; Jacob awakens from his dream. Under each picture is a reference to the Bible, with chapter and verse; so that, if you should fail to recognize any Bible worthy from his picture, you could look him up.

In the hallway, the white staircase, with its mahogany rail, is deeply paneled at the sides, and if you stand beneath the stairway where it turns, you see still more careful paneling on the under side of each stair. The spindles of the balustrade are white and delicately carved, and the slender newel-post is twined with a perfectly proportioned white spiral, like a smooth round stem of a vine, running round and round it, and disappearing into the woodwork of the rail.

This house, with its linden trees, its traditions, its Lion and Unicorn rampant over the sea, was the best example of old-time royalist elegance that we saw.

"Are you going sketching this afternoon?" asked Barbara politely of the artist.

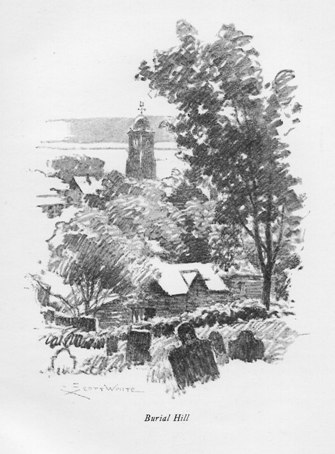

"Yes, on Burial Hill," said he. "Want to come?"

"Don't you ever carry a camp-chair?" said I. For days I had been longing to ask him that question, when I saw him starting out with no visible sketching equipment except a leather affair, which looked like a lawyer's brief-case, strapped over his shoulder.

"Yes, I always take a chair," said he. "It folds. It's in the leather case."

I, who remember the days when people went sketching with an immense French sketching-umbrella, a camp-chair, an easel, and a portfolio, looked with respect upon the leather case.

"Before we go up to the hill," said the artist, "don't you want me to show you the most stunning subject for a painting that I've found?"

Even Alexander rose to this. We followed our leader down past the old Junk Shop, in among the old houses at the water-front, and as we picked our way around the corner, the artist threw up his hands in despair.

"Oh, ye gods," we heard him say, "it's gone!"

We followed his tragic gaze out toward the harbor, expecting to find that an ancient landmark had been razed to the ground.

"What was it?" said Barbara anxiously. "Have they moved it somewhere else?"

"Yes," said the artist bitterly, "they've moved it somewhere else. It was the washing that was out on that line—the colors—all the accents—Portuguese as you can imagine—and they've taken it in!"

Alexander turned on his heel and left us to make our way back to Burial Hill. He sympathizes with his brother's sorrows when fishermen go down to their boats and change all the rigging the moment a marine sketch is half done; but he is not quite advanced enough to grieve because Portuguese laundry no longer flaps against the American blue.

"By the way," said the artist when we reached the Hill, "the lettering on these stones is something remarkably fine. Pemberton identifies it with Caslon lettering, Caslon the Elder, English typefounder in the sixteen hundreds. I '11 show you the article when we get home."

Barbara was examining a very old stone. "Listen," said she,—

As we made our way along the paths beside the family lots of the Bradfords, Cottons, Harlows, LeBarons, and Howlands, we began to notice how the wording varied with the relative age of the stones. For example, "Edward Gray, Gent." is older style than "Josiah Cotton, Esq." And "That Virtuous Woman, Mrs. Rebecca Turner" is of an earlier period than "Mary, Relict of Deac. Lot Harlow."

We found one very stately epitaph to a young wife, the simplest expression of the language of bereavement: "By this event a husband was deprived of his best friend."

Far more elaborate is the tribute to Mrs. Lucy Hammatt, Relict of the late Capt. Abraham Hammatt. Still clear and definite, the inscription, deeply lettered on the face of the worn slab, records the ideals of an exemplary life:—

But Barbara's favorite among the epitaphs was one on the stone of a young Southern bride:--

Phebe J. Bramhall

a Native of Virginia

and Wife of Benj. Bramhall

Possess'd of an Amiable Disposition

It suggests that our early ancestors were not impervious to Southern charm.

On our way down the Hill, we went around to see the harbor at sunset. Clark's Island in the distance, Captain's Hill, Manomet—we had begun to think of these as our own landmarks.

Burial Hill

Burial Hill

"Since this is our last night at Plymouth," said Alexander that evening, "don't you want to see the country by moonlight?"

"It's only a half-moon," said Barbara critically; but we went.

On our way, we went up to look at the town from the site of the old Watch-Tower, on the very top of Burial Hill. We climbed the Hill this time by the path nearest the sea. The low branches of the twisted tree over the flight of steps made strange patterns above us against the sky. There is one place on the summit where you can look out into the darkness of the country, not toward the lights of town. Here you can see only the shadows of the elm branches and the outlines of the slanting stones. And here, I think, we found the time for the spirit of place to be abroad. We did not see the kindly ghosts of Adoniram Judson and Bathsheba Bradford and Captain Jabez Harlow. But we were in the midst of something very real. All the odd phrasings of the epitaphs—the relicts and consorts and phyticians—were hidden now, translated by the shadows. We saw only the silhouette of the past; and it was not grim or gloomy, but only brave. The record of antique sorrow is a quieting thing. Every thought on this hill was thought a long time ago. The poignancy is out of it now. And as we stand on the spot where the Pilgrims once set watch every night for danger, we cannot help being stirred by the gray dignity of their thoughts about the continuity of life.

We stayed only a moment. Then we went down again, pausing only to watch the harbor lights.

Plymouth harbor is a quiet place by moonlight, and Burial Hill is a very quiet place. Yet it gave us the most direct message we had—of spacious thought dramatized in narrow setting, of definite achievement with inadequate equipment, of the resourceful valiance of those early people, and of what Governor Bradford calls "their great patience and allacritie of spirit" in the face of life, and death.

Duxbury, Duxberie, Duxborough, Ducksborrow: the early writers spelled it as they pleased. But the Duxbury Light, Duxbury ships, and Duxbury clam-flats have standardized the spelling for all time. This town, across the harbor from Plymouth, where grants of land were settled by Myles Standish, Elder Brewster, and John Alden, has been the home port of notable ships and men. Merchant-ships, brigs, and schooners—the Eliza Warwick and the Mary Chilton, the Oriole, the Lion, Boreas, and Seadrift, the Triton, Mattakeeset, and the Hitty Tom,—these and hundreds of sail besides were built here in the shipyards and manned by Duxbury boys. Among the early men of Duxbury were Benjamin Church, who captured Philip the Sachem; Major Judah Alden and Colonel Ichabod, descendants of John Alden and Priscilla; Colonel Gamaliel Bradford and Captain Gamaliel, his son; George Partridge, one of George Washington's Congressmen; and Ezra Weston, the King Caesar of the shipyards.

At one end of the town used to be the Ezra Weston ropewalk; and not too far away was the famous Duxbury Ordinary, the tavern where, in 1678, Mr. Seabury the landlord had license to "sell liquors unto such sober-minded naighbors, as hee shall think meet, so as he sell not less than the quantie of a gallon att a time to one prson and not in smaller quantities to the occationing of drunkenes." Mr. Seabury was evidently to use his own judgment as to which "naighbors" were sufficiently sober-minded to sustain the gallon.

But doubtless the oldest Duxbury settlers were the clams. The colonists called them, first, "sandgapers," then clamps, then clambs, clambes, slammes, and clammes. We surmise that the clam was not at first the Pilgrims' favorite dish, when we read Mr. John Pory's account of his visit to Plymouth in 1622. "Muskles and slammes they have all the yeare long, which being the meanest of God's blessings here, and such as these people fat their hogs with at low water, if ours upon any extremitie did enjoy in the South Colonie, they would never complain of famine or want, although they wanted bread." When we read this remark of Mr. Pory's, we wonder how it happened that the Pilgrims were reduced at one time to five grains of parched corn per meal per person. But suppose that you yourself had never tasted a clamb at a clam-bake, and had never been introduced to it in the right circumstances by the right people—would it naturally occur to you to steam it, and discard its little neck, and make a chowder of its straps? This would call for the strictly pioneering spirit, especially if, in the words of an early explorer, these clamps were ofttimes "as big as ye penny white loafe." In fact, the only Pilgrim who at all adequately celebrates the clam is Edward Winslow. "Indeed," says he, "had we not been in a place where divers sort of shell-fish are, that may be taken with the hand, we must have perished, unless God had raised up some unknown or extraordinary means for our preservation." And to-day, in certain spots along the Duxbury coast, from the Gurnet to the Nook, you may still find the descendants of those early sandgapers drawing down their necks at your approach, lest peradventure you take them with the hand.

Barbara and I explored Duxbury, not for clams, but for another sort of oldest inhabitant, the trailing arbutus. We did not explain to Alexander the object of our quiet trips to the woods, for it was the middle of winter, and we felt that he might not sympathize with our simple-minded quest. Of course, we did not expect to find flowers, but we thought that we might find a root or two of mayflower from John Alden's land, to transplant on our hill at home. We know that it does grow in Duxbury, but we must have looked in all the wrong places. Like many other great explorers, we found all sorts of things other than the thing we sought: charming patches of checkerberry and mosses; blueberry bushes growing where blueberries ought not to grow and arbutus ought; many pleasant views of Captain Standish's tall monument on the Hill, but not one stiff rusty leaf of a mayflower. Finally we decided to go to the present Mr. John Alden and inquire.

We hail from a part of the country where you would no sooner ask a person to direct you to his patch of trailing arbutus than you would ask him the combination of his safe. We therefore planned to word our question discreetly. "Do you know," we planned to say to Mr. John Alden, "whether any mayflower, or trailing arbutus, ever used to grow in Duxbury?"

That ought to give him a chance to tell us about contemporary mayflowers, if he cared to, at the same time giving him plenty of leeway if he preferred to dwell upon the past.

We were putting the finishing touches on our speech as we went up the path to the old John Alden house, when a great touring-car, with an Indiana number, went rocking past us up the uneven lane, and stopped.

"Can you tell us," said a gentleman, leaning out of the car and calling back to us, "whether this house is open to visitors?"

"We don't know," said I, "but we know that Mr. John Alden lives here."

"I'll ask him," said the gentleman from Indiana; and he went to the door.

"He says it's open to-day," reported our new guide in a moment, helping his family out of the car, and giving the youngest child a big jump up into his arms.

Barbara and I, abandoning trailing arbutus, merged ourselves with the family group, and went in at the front door.

The little hallway is papered with the kind of paper you sometimes see in houses where "George Washington spent the night"—gray, with landscapes. But, in addition to the landscapes in this paper, there are slender pillars in groups, a design that makes you think of a miniature Alma Tadema picture, all in gray. This wall-paper is, of course, not as old as the house, but it is old-fashioned enough to be interesting.

We threaded our way in single file around the door, into the hallway, and our host invited us first to go upstairs.

The stairs go straight up beside the great chimney, very steep and narrow, each stair twice as tall as a modern stair and half as deep. At the top, we went around the slope of the chimney and into the rooms above. Here, in these low square rooms, with the supporting beams still showing the marks of the broad-axe, and the wide boards of the floor attesting the size of timber-growth in the early days, we found a perfect paradise of old-time furniture stored away. We were allowed to stop and prowl among the old possessions. None of the things used by Priscilla are here, of course; these are the accumulations of generations that followed her.

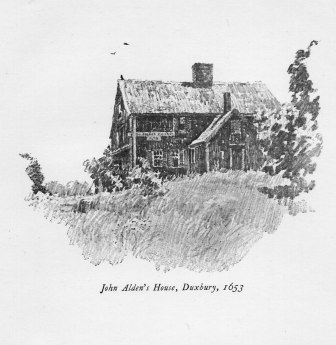

John Alden's House, Duxbury, (1653)

John Alden's House, Duxbury, (1653)

In the corner by the chimney, we saw a small wooden cradle, with its wooden roof sloping in three sections over the top. On the wall hung an old lantern made to hold a candle, the kind of "lanthorn" that might have been used by Moon in "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

We were looking at the churn and the yarn-winder, when one of the ladies called us to look at the strap-hinges on the door. These hinges, handmade of iron, long and narrow and pennant-shaped, run out almost a third of the way across the door. The iron latch, also hand-wrought, is worn where the bar slips into the hasp, and the downward curve of the lift of the latch is bent into a thin twisted shape. One of the doors, a curious, three-paneled affair, is supposed to have been saved from a former house of John Alden's.

The present house, built in 1653, was the place where John Alden spent his later years. Here he lived to the age of eighty-nine, holding important offices in Plymouth Colony up to the time of his death. He was one of the eight Purchasers who bought from the Merchant Adventurers their interest in the colony, after the expiration of seven years' copartnership. And in paying the required sum of eighteen hundred pounds, he, with Myles Standish and the other "Undertakers," must have been very busy managing the Plymouth trade, and "fraighting the White Angell, Frindship and others" with saxafrass, clapboards, and beaver. They were a busy brood, those old-comers; and John Alden, whom Bradford called "a hopfull young man," fulfilled the promise of his youth.

Ever since his death, his house has been lived in by Aldens. The present John Alden is a Grand Army veteran, son of a veteran of the Civil War, grandson of veterans of the Revolution, and grandfather of a veteran of the World War.

He led us downstairs, and out to the large room where they used to do their fireplace cooking. The fireplace is closed now, but the spirit of the house is still one of comfort and hospitable good cheer. From its windows you cannot quite see the place where Myles Standish lived; it is too far away. But it is pleasant to know that the Captain and John Alden were near neighbors, and that one of Myles Standish's sons married one of the daughters of Priscilla. All of Priscilla's eleven children turned out well; many of them were later called to "act in publick stations;" and the old house has been the homestead of her descendants all these years.

When we had signed our names in the big register, and turned to go, Barbara said, "Do you know why the Aldens and Standishes left Plymouth and came over here so far?"

"Why, they came over to settle it," said Mr. John Alden kindly; "to open it up."

The Myles Standish Monument

The Myles Standish Monument

As we went out down the lane, we turned to take one more look at John Alden's land. There, in the middle foreground, we saw the artist, sketching busily.

"How did you get here?" we asked in a breath.

"In the car. How did you get here?"

"We walked," said Barbara with emphasis.

"Like to go the rest of the way by stage?" inquired the artist affably, hoisting his sketching kit over his shoulder and pointing to the car at the foot of the lane. "I'm going over to the Standish house next."

"Did you know," said Barbara dreamily to the artist, as she seated herself in the car, "that the four most famous descendants of John Alden and Priscilla were John Quincy Adams, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, and Tom Thumb?"

"Barbara," said the artist gravely, "did you make that up?"

"No," said Barbara, clutching the seat as we went around the corner on one wheel, "I looked it up."

Country over which you have just been prowling on foot looks very different when viewed from a car. The blackberry tangles and wild rose-bushes, through which we had waded on our way to the woods, were now simply part of the scenery. And the Myles Standish monument, which had been our mariner's needle, one of the necessities of life, was now only a forsaken watch-tower, with a solitary figure on top of it against the sky. We went careening up the side-road to the Standish house, which was built in 1666, not by the captain himself, but by one of his sons.

It was closed. An old house, locked, with an open field around it and the sea below; a perfect place for sketching, and the rising wind from the sea. Barbara went softly up to the doorway and touched the rusty latch. On one side of the doorstep was a lilac bush, and on the other a wild birch.

The Standish House, Duxbury, (1666)

The Standish House, Duxbury, (1666)

This is probably the oldest of the gambrel-roofed houses on the harbor. There is something very strong and homely about the pitch of the roof—a balanced, firm old line, in splendid proportions with the huge chimney and low walls. A weathered gambrel has a way of looking at home in the fields, a sort of boulder-shape firmly settled. And the Standish house, with its flat field-rock for a doorstep, looks like a very old settler indeed.

For a long time we sat on the doorstep and watched the outline of Plymouth Town across the harbor, and the white gulls flying, and the crows. The son of Standish of Standish knew where to pitch a house.

Thoreau criticizes the Pilgrims for lacking the explorer's instinct. They were not woodsmen, he says, nor, except spiritually, pioneers at heart. He calls attention to the fact that it was long after the landing before they explored the woods and ponds back of Plymouth, territory "within the compass of an afternoon's ramble." "A party of emigrants to California or Oregon," says he, "with no less work on their hands and more hostile Indians, would do as much exploring the first afternoon, and the Sieur de Champlain would have sought an interview with the savages, and examined the country as far as the Connecticut, and made a map of it, before Billington had climbed his tree."

Well, the Sieur de Champlain had not with him such little travelers as Oceanus Hopkins and Peregrine White. After the deaths of the first winter, every one of the few grown men left in the colony was needed for immediate affairs. They could not afford to go exploring overmuch. With the exception of the madcap Billingtons and one boy Crackston, they ran very little risk of losing themselves in the woods. They went, as much as possible by sea, to Kennebeck, to Boston, to all parts of Cape Cod. But as to wandering through the woods on foot, that was done only for good and warrantable reasons, not to see what they could see.

Yet even here we find a paradox. They were so thinned in numbers that they had to be cautious, but in an emergency they knew how to be perfectly reckless and perfectly adequate to the occasion. In March, 1623, when news came that their friend Massasoit was "like to die," they knew that, if they were to be accounted loyal friends, they must follow the Indian custom of paying a visit to the chief in his last days. Therefore, Edward Winslow, with one Master John Hampden of London, and the Indian Hobbomock for guide, set out on foot around across the Cape, through what is now Eastham, to Mattapoisett, and thence to "Sowams," now the town of Warren, Rhode Island, the home of Massasoit. In spite of the protests of Hobbomock, part of the journey through the woods was made after nightfall, so eager were they to arrive before "Massassowat" died. And the accurate Winslow records and translates for us a sentence in Massasoit's own language, the very words of the great friendly sachem: "Matta neen wonckanet namen, Winsnow!" that is to say, 'O Winslow, I shall never see thee again.' Winslow tells us how he revived Massasoit by giving him a "confection of comfortable conserves on the point of my knife," and by performing other helpful offices, "which he took marvelous kindly"; and how he then set out on his homeward journey, after learning from the convalescent Massasoit of the plans of other tribes to destroy the paleface colony. On Winslow's return trip through the woods, the Indians themselves, he says, "demanded further how we durst, being but two, come so far into the country. I answered, where was true love, there was no fear."

They did explore. But their exploring was always for community purpose, whether for "true love," or for parleys with the French and Dutch, or for trade with Squanto's friends at Chatham, or for pasturage for their "katle," or for fish.

We do not know how La Salle and De Soto and the Sieur de Champlain would have looked upon the woods around Plymouth and the Cape. They would probably have thought of them as suburbs of the Mississippi. But as we sit on the Standish doorstep and glance out toward Plymouth, with the harbor between us and the Duxbury woods behind, we realize that the first settlers here were quite completely cut off from the shelter of that comely fort on Burial Hill. There was something very hardy and permanent about their pioneering, though there was always a reasonable explanation for the risks they undertook. There were no heroics about it. Their chronicler says simply, "now they must of necessitie goe to their great lots; they could not other wise keep their katle." They did not come over out of restlessness, or for adventure, or primarily for exploring the new continent, at all. Mr. John Alden spoke in the authentic colonial spirit. They came over to settle it—to open it up.

From John Alden's land, in early days, a footpath led out along the shore, over Stony Brook, by Duck's Hill, to Careswell, the "great lot" granted to Edward Winslow. The lot is now the town of Marshfield, made famous by Daniel Webster and by generations of notable Winslows.

The Pilgrim Winslow was Plymouth's favorite representative in foreign affairs, whether in dealings with the Dutch, or with the Indians, or with the English in London. His friendships were curiously varied and fortunate; he was admired and trusted by such forceful men as Roger Williams, Massasoit, and Oliver Cromwell—a vigorous trio. When he went plying back and forth on his diplomatic voyages between Plymouth and England, his duties varied from the responsibility of convoying twenty hogsheads of beaver to the old country and bringing back three heifers and a bull to the new, to defending the judicial policy of his friends in Boston, and writing such sprightly tracts as "Hypocrisie Unmasked" and "New England's Salamander Discovered." Oliver Cromwell appointed him Commissioner to go to Hispaniola and Jamaica, and to confer at Goldsmiths' Hall, London, on a question involving Denmark's seizure of English ships after the treaty of peace. The Commissioners were given a certain time to come to a decision; and if they could not agree by the day appointed, they were to be "shut up in a chamber, without fire, candles, meat, or drink, or any other refreshment, until they should agree." Cromwell believed in international agreements speedily arrived at.

On Winslow's land to-day stands the Winslow house, built on the old foundation by Isaac Winslow in 1699. This famous homestead, which a few years ago was going to wrack and ruin through sheer old age, has been restored as nearly as possible to its original state of comfort and dignity by the Winslow Associates, furnished throughout with a rare collection of antique furniture, and opened to the many visitors who come that way on their route to Plymouth. As you wander through the rooms, you find the place a perfect study in early building; every detail has been carefully preserved, from the "spatter-painted beams" in the kitchen and the old fire-back in the parlor, to the fine wood finish of the "Parlor Bedroom." You gain a notion of the interesting way in which the restoration was managed, when you learn that thirty-four coats of paint had to be removed from the woodwork of the entrance hallway, and that four fireplaces had to be taken out of the huge dining-room fireplace to bring it back to its original condition.

It is very fitting that this house, on the land of the most internationally minded man of the early colony, should be cordial to visitors now. Old houses make friends easily. They are like people who have known our grandfathers—able on that account to make us feel at home. And when an ancient house bears the name of one of the Pilgrim Forefathers, it plays homestead to the whole United States.

The Winslow House, Marshfield, (1699)

The Winslow House, Marshfield, (1699)

The Winslow mansion, with its great trees and its own broad hearths, has not grown bleak in its old age, or even austere. There is an Indian word preserved for us by Governor Winslow's friend, Roger Williams, that might serve as a motto for this house. "Nickquenum" says Roger Williams, "I am going home, is a solemn word with them; and no man will offer any hinderance to him, who after some absence is going to visit his family, and useth this word Nickquenum." As we go up the flagstone pathway and lift the Marshfield knocker, we can easily imagine that generations of famous Winslows, returning to their ancestral estate, must have approached this house somewhat in the spirit of that word used by their grandfather's friends the Indians: "Nickquenum, Winsnow!" which is to say, "O Winslow—I am going home."

If you come from the Firelands in the Middle West, if you discover Cape Cod, if you fall in love with a little empty ninety-five-year-old house there and buy it, with its three acres of pines and locust trees and arbutus and rose bushes—then you long to go to see it after the deed is filed. It may be the dead of winter, but you want to go. You do not want to be merely a "summer person." The sea is rocking with a February gale, and the rain drives over the dunes in slanting gusts. But you go cruising down the Cape in the evening train, disembark two or three stations short of Provincetown, make your way up your lane, unlock your door, light a fire in your stove, set a lamp in your window, and feel that the house has been waiting there all its ninety-five years, for you.

If you are generous with your share of the world, you invite your friends.

In just this way, our friend from the West filed her deed, built her fire with driftwood and pine cones, set her teakettle on the stove, and sent for Barbara and me to come.

We had known Cape Cod in summer, with its blueberries and its sailing-craft, its wharves and artist-colonies and ocean breezes. But we had never seen it in winter, with snow on the sand-dunes and the wind flying over with sleet and rain.

An old house with seafaring memories knows how to behave in a storm. At high tide, our house sits up not so very far above the level of the sea. A little Ark on a little Ararat, it was built nearly a century ago by Jonah Atkins for Noah Smith; Noah and Jonah—surely names of men equipped to go a voyage. The lumber for the house had to be brought by ship from Maine, thrown overboard off shore, rafted up to the land in time of high-course tide, spread out on the hill to dry, and then set solidly together, and pegged. Jonah Atkins made his wooden pegs to stay. The gale while we were there blew great ships far out of their course at sea, but there was not a shiver in the timbers of our roof.

We took the first stormy day to explore the house. To an inlander there is something magical about discovering seafaring implements and deep-sea fishing-gear of any kind about a house. You expect to find such things on ships and wharves; but when you find them high and dry, stowed away under rafters, they rouse your anchored spirit like a ship-ahoy. The corners under our roof were as full of treasures as a ship-chandler's loft: all sorts of stowaways that had been hidden for years in out-of-the-way nooks; a clam-fork under the eaves, for instance, and a net-shuttle on the sill. Up in the porch-attic, we found a wooden cradle becalmed under the rafters, left there probably when the last little Noah Smith grew too old to voyage in such small craft. Something glittered in the shadows under the hood of the cradle, and Barbara reached in to explore. She brought out a large globe of heavy glass—not a fish-globe, with an opening, but a perfect sphere. We all ventured guesses. It could not be a receptacle or lamp-accessory of any kind, for there was no entrance or exit to it, except a tiny pin-hole clogged up, at one point. Was it an ornament, or a toy, or a great lens of some kind, or perhaps a globe used by some old-time crystal-gazer? We found out later that it was a net-float—a glass buoy to bob on top of the waves, holding up a corner of the net at sea. You find them sometimes on the beach after a storm. An old glass net-float dry-docked under the hood of a cradle—we put it back where we found it.

One of our fence-posts was made of a piece of a mast, our clothes-horse of teakwood washed ashore after the wreck of the Portland, our stool of wreckage from the frigate Jason; and on the end of the string to which our back-door key was fastened, there hung a large snail-shell, like a seal on a fob.

But the most nautical of our possessions was the carpet on the floor of our kitchen; a carpet made of an old sail cut square and spread smoothly and painted gray—an old sail with all the wind taken out of it, spread, not this time for Java Head or Lisbon, but for our kitchen floor!

"Now," said our hostess, calling us to the window, "perhaps you can understand why they call this place The Point."

We looked out. The whole ocean was crowding up the valley,—foam and gulls and driftwood and all,—flooding the bed of the Pamet River. The marsh-grass and the bottom-lands, which had been solid ground two hours before, were the floor of the ocean now; the familiar winding channel of the Pamet, with its fish-weirs, eel-traps, and boundaries all submerged.

"Isn't this a sea-going promontory?" inquired our proud freeholder, as we watched a sea-gull flap its way up against the rain, alight on the water, and swim toward our territory over the gusty brine. "This, you see, is high-course tide," our friend went on, with that double vanity that comes from being the possessor of a new estate and a new vocabulary. "But it never makes in beyond this Point. The Indians used to have their wigwam here before the house was built."

Barbara and I instantly adopted for our own permanent possession the sea-going promontory, the gulls and the high tide sailing up around our premises, and the house itself.

"The Ark"

"The Ark"

During our sojourn on the Cape, we learned just one thing that we can be sure of: You should never make any general statement whatever about Cape Cod. If you do, you will find your statement disproved by the next turn of the tide, or turn of the road. You mention the fact that Bartholomew Gosnold discovered it in 1602, naming it Cape Cod because there his boat was so "pestered" with codfish. And a well-informed friend will set you right by explaining how the Vikings discovered it some six hundred years earlier. Or perhaps you are interested in weather-vanes. After inspecting them on all the barns down the Cape, you say that all weather-vanes here are codfish; some flat codfish, some solid, but all cod. Instantly you look up and see a beautiful swordfish afloat over the roof of your neighbor's barn. Perhaps you see Barnstable in midwinter, with its marshlands and shores packed with cakes of ice, pink and lavender in the sunset, with sea-gulls sitting upright on the edges, like so many penguins on an Arctic floe. You decide that the Cape harbors are full of ice. But if you inspect the harbor of Provincetown on that same day, you are likely to find not a scrap of ice on the premises.

You might as well confine yourself to particulars, and avoid large sayings of any sort. Thoreau is properly cautious about this. Even when he speaks of so simple a matter as the rarity of dogs and cats on the Atlantic side of the Cape, he guards his speech. "Still less," says he, "could you think of a cat bending her steps that way and shaking her wet foot over the Atlantic; yet even this happens sometimes, they tell me." They told him the truth. A fine, enormous, distinguished-looking white cat, sitting on your doorstep at the foot of the pilaster of your doorway, is as common on some parts of the Cape as the pointed Christmas-trees in green tubs on the doorsteps of old houses in certain cities inland. Remarkable cats, brindle or yellow or tiger or snowball or gray, they are loved while they live, lamented when they die. "If I could look out of the window," said a little boy whose favorite cat had died, "and see my Bobbie coming down the road, wouldn't I wun to let him in?" The Cape Cod cats are not confined to doorsteps. They catch the Cape Cod mice. And at least one elegant pure-white cat of our acquaintance goes stepping down the Cape with her master, shaking her wet foot over the Atlantic, perhaps, but waiting until it is time to go back, and then escorting him home.

Therefore, since it is so unsafe to generalize, we are resolved to make no sweeping statements about the Cape Cod house. You cannot be too sure even about your own. You discover this when you take its measurements for curtains and wall-paper; no two apertures and no two surfaces are alike.

But, with due reservations, there is one sort of old house that was most nearly standardized by the early builders: the low-studded, story-and-a-half house, with its long gable roof, its many little windows tucked up under the point of the gable, its front to the south, its "West Entry" at one side, and its six-panel door, with a row of little square glass panes above it—-sometimes a row of four lights, sometimes five. More rarely there is a fan-light over the door, curving out to the pilasters at each side.

All this varies a little, and most of the houses have been altered more or less by subsequent generations. But whenever you come upon the regulation, unspoiled Cape Cod house, there is a general plan that you recognize at once.

For example: the term "West Entry" is no idle phrase. West Entry means west entry, regardless of your angle to the road. Your house faces the south, and your side entry faces west, though the road may run at random on a wild slant, and though your west entry open on the midst of the sea. It does not matter whether you face the highway or not, does it? A road is a perishable and human thing at best; but the points of the compass mean business on the Cape.

Our own house is a perfect illustration of the results of this theory: if you should ever wish to reach our West Entry, you would have to circumnavigate our Point, and scale an all-but-inaccessible bank to the unused door. Because of this inconvenience of our "entry," we always expect callers to come in at the door of our kitchen—our porch. For the benefit of the uninstructed it may be well to say that when we speak of our "porch" on our part of the Cape, we mean the same thing as an ell. Our porch is an ell with an attic over it, a kitchen chimney, our stove, and our pump and major equipment for the industries of the day. It opens into the "winter kitchen," where they did their fireplace cooking years ago, before there was a stove in the porch.

The outside piazza arrangement, unroofed, we call our platform, or walk. Ours is very neatly made of matched planks, with one part at the end cleverly arranged to slide, so that you can draw out the planks a little and get down into the manhole that incloses the pipes from pump to drilled well. On cold winter nights, you let yourself down on the ladder twelve feet underground, to turn off the water in the pump, if you are afraid that the pipes are going to freeze. I shall never forget the sensation of usefulness that filled my beating heart when I disappeared down that hatchway one clear cold night and opened the little faucet far below. When you go down that neat, perfectly smooth tube, with the winter stars shining solemnly down on the top of your head, you feel like a more slender Saint Nicholas making his way down a sootless chimney.

The Cape Cod cellar is also interesting to a newcomer. It is a small circular dungeon-keep, solidly built of masonry, usually under the "east room." You go into it down a short flight of steps on the outside of the house, through a small entry which has the outer aspect of a tall dog-kennel, and the inner aspect of a Dutch interior, perfectly spotless. Some authorities say that the Cape cellars were made circular to prevent the heavy sand from breaking through by undue pressure on any one wall, as would happen in a four-cornered cellar. Others imagine that seafaring men made their cellars circular on the principle of the half-barrel in the sand. An old stone-mason says that they did it because firm corners of field-rock are so hard to make. But when you stand in these spick-and-span circles of solid masonry,—an interior like the inside of a bowl,—you suspect that the tidy housewives planned the rounded walls so as to leave no odd corners for spiders and cobwebs.

There may be square cellars on the Cape, and there certainly are some west entries that point the wrong way. But in general, when you enter a Cape Cod "three-quarters" house, you go in through the porch-door, you sit and visit in the winter kitchen, and you have your wedding in The Room. Porch, winter kitchen, pantry, east bedroom, The Room, the west bedroom near the west entry—it is a charming and compact arrangement for a little house, with regard for space and views and corners. Unless your "sight" from the windows is cut off by trees or hills, you have views of ocean dawns and sunsets framed in delicate white moulding, and seen through small square panes. The world outside appears like a series of pictures seen through an artist's finder. If your house tops a dune on the narrow part of the Cape, you may see the sails on the horizon of the Atlantic on the east, and the sails on the horizon of the Bay on the west; a clear view of the salt water straight across the Cape in both directions.

As you go down from Barnstable to Provincetown, in automobile or by train, you notice that there are more windows than you expect to see in the triangle under the slope of the roofs. Commonly, you see two large windows in the middle of the upper half-story, and on each side of these, under the slope of the roof, two much smaller windows in the corners. Perhaps there is even a fifth window, sometimes triangular, sometimes elongated, under the very peak of the roof. Thoreau was mightily pleased with these. He said that it looked as if every member of the family had punched a hole through the upper half-story, the better to see the view—large windows for Father and Mother, small windows for children, on the principle of large door for the cat and small door for the kitten. The two large windows light the one square room finished off under the peak of the roof. The other smaller windows are to ventilate the "open chambers"—the slope-roofed spaces left on either side of the finished room, under the rafters. In large families, in the early days, some of the children had to sleep out in these open chambers, under the slope of the roof. There is at least one noted man of affairs in the United States to-day who affirms that there is one rafter in the open chamber of a certain house on Cape Cod that has a slight but clearly defined hollow worn in it, where he used to collide with the roof when he got aboard his trundle-bed in the dark.

Old Fish Wharf, Cape Cod

Old Fish Wharf, Cape Cod

The Double House is different; the two-story house is different; the steep-roofed house is different; and so are the houses built by summer people. There are even a few houses made of old windmills, with three stories: living-room on the ground floor, little bedroom on the second floor, tiny bedroom up aloft, and a look-out that is almost level with the windmill sails.

But let us stick to our own experience. In our own house, and in those of the neighbors around us, you see delicate white paneling around the fireplace up to the ceiling; an antique china closet with its old copper-lustre and sprigged ware; white wainscoting around the room up to the level of the window-sills; exquisite moulding all around the windows and doors; in short, it is the simplest little house in the world, in plan, with unexpected beauty of detail. Braided mats on the floor, a fire in the stove, and a breeze from the Azores scudding over our roof—there certainly is good comfort even in dead of winter on the Cape.

We are glad that the Pilgrims were "joyfull" at the sight of "Cap-Codd." They decided not to pause there, but to "stande for ye southward to finde some place aboute Hudsons river for their habitation." But they were turned back by the "deangerous shoulds and roring breakers," and were thankful to bear up again along the Atlantic side of the Cape until they got into harbor, "wher they ridd in safetie."

In our intervals of fair weather, we visited the places where they stopped: Chatham where they were turned back, Provincetown where they waded ashore, Truro where they camped for the night and explored the Pamet River, and Corn Hill where they found "diverce faire Indean baskets filled with corne." All this country was as wintry as the Pilgrims found it, with long streaks of snow caught in the beach-grass on the tops of the camel-back dunes. From the crest of one dune, we watched the sun dropping over the harbor until it rested on the water, like a great luminous net-float drifting off to sea.

The Pilgrim Monument, Provincetown

The Pilgrim Monument, Provincetown

Provincetown we saw in a flying snow-squall, all the marine colors so loved by the artists softened in the snowy light, even the strange blue of a guineaboat by the fish-wharf. Hollyhock Lane was only a narrow passageway of frosty stubble, and the seagulls winging over looked ghostly against the pale sky. The wharves, the monument, the lighthouse, and the sails in the harbor were blurred by the fine flakes that filled the air.

But the snow soon changed to rain, the squall turned into a northeast wind, the wind rose to a gale, and Barbara and I decided to see the Atlantic in a real storm. We went home first for rubber coats, and then set off down the road to the ocean side of the Cape. The wind from the Atlantic goes over the Pamet valley in one great rush of invisible swiftness. As you lean forward against it, you feel that you must run to hold your own. If we had been going the other way, we could have spread our cloaks and gone flying home like witches, over the dunes. As it was, beating our way against it, we had to stop in the lee of the bayberry slopes to catch our breath. Ahead of us we saw only the wave-like crests of the dunes, one after another, with their patches of ruddy wild cranberry, and their streaks of sand and snow. And then, as we went battling over the top of the last rise in the road, we saw between two sand-dunes ahead of us a darker hill beyond, its peculiar heavy gray coloring dull and threatening; its crest lay straight against the sky, and all the snowy white streaks along it were in motion. It was the sea.

We made for the top of the nearest dune ahead. It rose up steep as a breaker itself, with a jagged edge at the top where the wind had scooped out sharp hollows at the roots of the beach-grass. We each made straight for one of these hollows, in one last determined dash up the sheer slope. All this time, the noise of tumult had been growing louder and louder, and when we reached the crest, there it was before us, the whole Atlantic ocean rearing toward our frail strip of sandy shore. We had the horrible impression that the whole roaring thing was one gray hill of water, coming in. The breakers were plunging along from sky to shore with no regard for order. You could not have watched for the ninth wave, for they were breaking in masses, three great thunderheads at a time crashing into each other from different directions and coming up the beach with a shout, still struggling together in foam. Before they were half-way in, another surge was almost on top of them, with a huge white-horse breaker rearing at one side—everywhere one rush of confusion and terrible tossing with white crests of spray. There was not a sail in sight, or a human being, or an island, or a bird; only a world of furious water and a ragged horizon of mist and trailing cloud as far as we could see in three directions.

It is hard to believe that the Mayflower came cruising over the Atlantic through just such winds. "In sundrie of these stormes," says Bradford, "the winds were so feirce & ye seas so high, as they could not beare a knote of sail, but were forced to hull, for diverce days togither." When we think how the sea can growl around an ocean-liner now, and then think how the little Mayflower went hulling for diverce days in "mighty storme," we wonder how it ever got here at all. And indeed, we are told that at one time in mid-ocean, when the main beam of the little craft buckled, there was nothing between the passengers and shipwreck except a certain "great iron scrue ye passengers brought from Holland which would raise ye beam to his place." They screwed up the scrue and calked the deck; and though they knew that "with the working of ye ship they would not long keep stanch," they hoped that she might weather the rest of the voyage if they did not overpress her with sails.

"So," remarks the Governor with fine simplicity, "they comited them selves to ye will of God, & resolved to proseede."

The whole story of that voyage has in it the vitality of the wind at sea. It has also the nobility always found when the human will goes somewhere and does something with the minimum of material equipment, alone, against odds, for the sake of a true conviction. Materially, the Pilgrims had the narrowest possible margin. A great iron screw to prop their beam; a great iron purpose to prop their souls.

We do well to hold in honor those who voyage alone through "crosse winds and feirce stormes into desperat and inevitable perill," in the power of a noble thought. We erect our monuments to those who, with discouragement and danger and threatened shipwreck all around them, valiantly prop up their beam, calk their decks, commit themselves to the will of God—and "resolve to proseede."