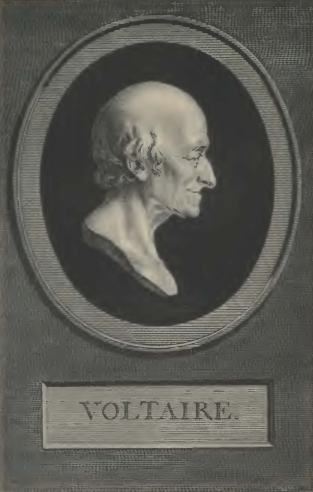

Voltaire: The Houdon Bust.

Voltaire: The Houdon Bust.

Title: A Philosophical Dictionary, Volume 09

Author: Voltaire

Commentator: Oliver Herbrand Gordon Leigh

John Morley

T. Smollett

Translator: William F. Fleming

Release date: March 28, 2011 [eBook #35629]

Most recently updated: April 2, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Andrea Ball, Christine Bell & Marc D'Hooghe (From images generously made available by the Internet Archive.)

"Between two servants of Humanity, who appeared eighteen hundred years apart, there is a mysterious relation. * * * * Let us say it with a sentiment of profound respect: JESUS WEPT: VOLTAIRE SMILED. Of that divine tear and of that human smile is composed the sweetness of the present civilization."

VICTOR HUGO.

VOLTAIRE: THE HOUDON BUST—Frontispiece

GENIUS INSPIRING THE MUSES

SAMSON DESTROYING THE TEMPLE

JOHN LOCKE

"Liberty and property" is the great national cry of the English. It is certainly better than "St. George and my right," or "St. Denis and Montjoie"; it is the cry of nature. From Switzerland to China the peasants are the real occupiers of the land. The right of conquest alone has, in some countries, deprived men of a right so natural.

The general advantage or good of a nation is that of the sovereign, of the magistrate, and of the people, both in peace and war. Is this possession of lands by the peasantry equally conducive to the prosperity of the throne and the people in all periods and circumstances? In order to its being the most beneficial system for the throne, it must be that which produces the most considerable revenue, and the most numerous and powerful army.

We must inquire, therefore, whether this principle or plan tends clearly to increase commerce and population. It is certain that the possessor of an estate will cultivate his own inheritance better than that of another. The spirit of property doubles a man's strength. He labors for himself and his family both with more vigor and pleasure than he would for a master. The slave, who is in the power of another, has but little inclination for marriage; he often shudders even at the thought of producing slaves like himself. His industry is damped; his soul is brutalized; and his strength is never exercised in its full energy and elasticity. The possessor of property, on the contrary, desires a wife to share his happiness, and children to assist in his labors. His wife and children constitute his wealth. The estate of such a cultivator, under the hands of an active and willing family, may become ten times more productive than it was before. The general commerce will be increased. The treasure of the prince will accumulate. The country will supply more soldiers. It is clear, therefore, that the system is beneficial to the prince. Poland would be thrice as populous and wealthy as it is at present if the peasants were not slaves.

Nor is the system less beneficial to the great landlords. If we suppose one of these to possess ten thousand acres of land cultivated by serfs, these ten thousand acres will produce him but a very scanty revenue, which will be frequently absorbed in repairs, and reduced to nothing by the irregularity and severity of the seasons. What will he in fact be, although his estates may be vastly more extensive than we have mentioned, if at the same time they are unproductive? He will be merely the possessor of an immense solitude. He will never be really rich but in proportion as his vassals are so; his prosperity depends on theirs. If this prosperity advances so far as to render the land too populous; if land is wanting to employ the labor of so many industrious hands—as hands in the first instance were wanting to cultivate the land—then the superfluity of necessary laborers will flow off into cities and seaports, into manufactories and armies. Population will have produced this decided benefit, and the possession of the lands by the real cultivators, under payment of a rent which enriches the landlords, will have been the cause of this increase of population.

There is another species of property not less beneficial; it is that which is freed from payment of rent altogether, and which is liable only to those general imposts which are levied by the sovereign for the support and benefit of the state. It is this property which has contributed in a particular manner to the wealth of England, of France, and the free cities of Germany. The sovereigns who thus enfranchised the lands which constituted their domains, derived, in the first instance, vast advantage from so doing by the franchises which they disposed of being eagerly purchased at high prices; and they derive from it, even at the present day, a greater advantage still, especially in France and England, by the progress of industry and commerce.

England furnished a grand example to the sixteenth century by enfranchising the lands possessed by the church and the monks. Nothing could be more odious and nothing more pernicious than the before prevailing practice of men, who had voluntarily bound themselves, by the rules of their order, to a life of humility and poverty, becoming complete masters of the very finest estates in the kingdom, and treating their brethren of mankind as mere useful animals, as no better than beasts to bear their burdens. The state and opulence of this small number of priests degraded human nature; their appropriated and accumulated wealth impoverished the rest of the kingdom. The abuse was destroyed, and England became rich.

In all the rest of Europe commerce has never flourished; the arts have never attained estimation and honor, and cities have never advanced both in extent and embellishment, except when the serfs of the Crown and the Church held their lands in property. And it is deserving of attentive remark that if the Church thus lost rights, which in fact never truly belonged to it, the Crown gained an extension of its legitimate rights; for the Church, whose first obligation and professed principle it is to imitate its great legislator in humility and poverty, was not originally instituted to fatten and aggrandize itself upon the fruit of the labors of mankind; and the sovereign, who is the representative of the State, is bound to manage with economy, the produce of that same labor for the good of the State itself, and for the splendor of the throne. In every country where the people labor for the Church, the State is poor; but wherever they labor for themselves and the sovereign, the State is rich.

It is in these circumstances that commerce everywhere extends its branches. The mercantile navy becomes a school for the warlike navy. Great commercial companies are formed. The sovereign finds in periods of difficulty and danger resources before unknown. Accordingly, in the Austrian states, in England, and in France, we see the prince easily borrowing from his subjects a hundred times more than he could obtain by force while the people were bent down to the earth in slavery.

All the peasants will not be rich, nor is it necessary that they should be so. The State requires men who possess nothing but strength and good will. Even such, however, who appear to many as the very outcasts of fortune, will participate in the prosperity of the rest. They will be free to dispose of their labor at the best market, and this freedom will be an effective substitute for property. The assured hope of adequate wages will support their spirits, and they will bring up their families in their own laborious and serviceable occupations with success, and even with gayety. It is this class, so despised by the great and opulent, that constitutes, be it remembered, the nursery for soldiers. Thus, from kings to shepherds, from the sceptre to the scythe, all is animation and prosperity, and the principle in question gives new force to every exertion.

After having ascertained whether it is beneficial to a State that the cultivators should be proprietors, it remains to be shown how far this principle may be properly carried. It has happened, in more kingdoms than one, that the emancipated serf has attained such wealth by his skill and industry as has enabled him to occupy the station of his former masters, who have become reduced and impoverished by their luxury. He has purchased their lands and assumed their titles; the old noblesse have been degraded, and the new have been only envied and despised. Everything has been thrown into confusion. Those nations which have permitted such usurpations, have been the sport and scorn of such as have secured themselves against an evil so baneful. The errors of one government may become a lesson for others. They profit by its wise and salutary institutions; they may avoid the evil it has incurred through those of an opposite tendency.

It is so easy to oppose the restrictions of law to the cupidity and arrogance of upstart proprietors, to fix the extent of lands which wealthy plebeians may be allowed to purchase, to prevent their acquisition of large seigniorial property and privileges, that a firm and wise government can never have cause to repent of having enfranchised servitude and enriched indigence. A good is never productive of evil but when it is carried to a culpable excess, in which case it completely ceases to be a good. The examples of other nations supply a warning; and on this principle it is easy to explain why those communities, which have most recently attained civilization and regular government, frequently surpass the masters from whom they drew their lessons.

This word, in its ordinary acceptation, signifies prediction of the future. It is in this sense that Jesus declared to His disciples: "All things must be fulfilled which were written in the law of Moses, and in the Prophets, and in the Psalms, concerning Me. Then opened He their understanding that they might understand the Scriptures."

We shall feel the indispensable necessity of having our minds opened to comprehend the prophecies, if we reflect that the Jews, who were the depositories of them, could never recognize Jesus for the Messiah, and that for eighteen centuries our theologians have disputed with them to fix the sense of some which they endeavor to apply to Jesus. Such is that of Jacob—"The sceptre shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come." That of Moses—"The Lord thy God will raise up unto thee a prophet like unto me from the nations and from thy brethren; unto Him shall ye hearken." That of Isaiah—"Behold a virgin shall conceive and bring forth a son, and shall call his name Immanuel." That of Daniel—"Seventy weeks have been determined in favor of thy people," etc. But our object here is not to enter into theological detail.

Let us merely observe what is said in the Acts of the Apostles, that in giving a successor to Judas, and on other occasions, they acted expressly to accomplish prophecies; but the apostles themselves sometimes quote such as are not found in the Jewish writings; such is that alleged by St. Matthew: "And He came and dwelt in a city called Nazareth, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophets, He shall be called a Nazarene."

St. Jude, in his epistle, also quotes a prophecy from the book of "Enoch," which is apocryphal; and the author of the imperfect work on St. Matthew, speaking of the star seen in the East by the Magi, expresses himself in these terms: "It is related to me on the evidence of I know not what writing, which is not authentic, but which far from destroying faith encourages it, that there was a nation on the borders of the eastern ocean which possessed a book that bears the name of Seth, in which the star that appeared to the Magi is spoken of, and the presents which these Magi offered to the Son of God. This nation, instructed by the book in question, chose twelve of the most religious persons amongst them, and charged them with the care of observing whenever this star should appear. When any of them died, they substituted one of their sons or relations. They were called magi in their tongue, because they served God in silence and with a low voice.

"These Magi went every year, after the corn harvest, to a mountain in their country, which they called the Mount of Victory, and which is very agreeable on account of the fountains that water and the trees which cover it. There is also a cistern dug in the rock, and after having there washed and purified themselves, they offered sacrifices and prayed to God in silence for three days.

"They had not continued this pious practice for many generations, when the happy star descended on their mountain. They saw in it the figure of a little child, on which there appeared that of the cross. It spoke to them and told them to go to Judæa. They immediately departed, the star always going before them, and were two days on the road."

This prophecy of the book of Seth resembles that of Zorodascht or Zoroaster, except that the figure seen in his star was that of a young virgin, and Zoroaster says not that there was a cross on her. This prophecy, quoted in the "Gospel of the Infancy," is thus related by Abulpharagius: "Zoroaster, the master of the Magi, instructed the Persians of the future manifestation of our Lord Jesus Christ, and commanded them to offer Him presents when He was born. He warned them that in future times a virgin should conceive without the operation of any man, and that when she brought her Son into the world, a star should appear which would shine at noonday, in the midst of which they would see the figure of a young virgin. 'You, my children,' adds Zoroaster, 'will see it before all nations. When, therefore, you see this star appear, go where it will conduct you. Adore this dawning child; offer it presents, for it is the word which created heaven.'"

The accomplishment of this prophecy is related in Pliny's "Natural History"; but besides that the appearance of the star should have preceded the birth of Jesus by about forty years, this passage seems very suspicious to scholars, and is not the first nor only one which might have been interpolated in favor of Christianity. This is the exact account of it: "There appeared at Rome for seven days a comet so brilliant that the sight of it could scarcely be supported; in the middle of it a god was perceived under the human form; they took it for the soul of Julius Cæsar, who had just died, and adored it in a particular temple."

M. Assermany, in his "Eastern Library," also speaks of a book of Solomon, archbishop of Bassora, entitled "The Bee," in which there is a chapter on this prediction of Zoroaster. Hornius, who doubted not its authenticity, has pretended that Zoroaster was Balaam, and that was very likely, because Origen, in his first book against Celsus, says that the Magi had no doubt of the prophecies of Balaam, of which these words are found in Numbers: "There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel." But Balaam was no more a Jew than Zoroaster, since he said himself that he came from Aram—from the mountains of the East.

Besides, St. Paul speaks expressly to Titus of a Cretan prophet, and St. Clement of Alexandria acknowledged that God, wishing to save the Jews, gave them prophets; with the same motive, He ever created the most excellent men of Greece; those who were the most proper to receive His grace, He separated from the vulgar, to be prophets of the Greeks, in order to instruct them in their own tongue. "Has not Plato," he further says, "in some manner predicted the plan of salvation, when in the second book of his 'Republic,' he has imitated this expression of Scripture: 'Let us separate ourselves from the Just, for he incommodes us'; and he expresses himself in these terms: 'The Just shall be beaten with rods, His eyes shall be put out, and after suffering all sorts of evils, He shall at last be crucified.'"

St. Clement might have added, that if Jesus Christ's eyes were not put out, notwithstanding the prophecy, neither were His bones broken, though it is said in a psalm: "While they break My bones, My enemies who persecute Me overwhelm Me with their reproaches." On the contrary, St. John says positively that the soldiers broke the legs of two others who were crucified with Him, but they broke not those of Jesus, that the Scripture might be fulfilled: "A bone of Him shall not be broken."

This Scripture, quoted by St. John, extended to the letter of the paschal lamb, which ought to be eaten by the Israelites; but John the Baptist having called Jesus the Lamb of God, not only was the application of it given to Him, but it is even pretended that His death was predicted by Confucius. Spizeli quotes the history of China by Maitinus, in which it is related that in the thirty-ninth year of the reign of King-hi, some hunters outside the gates of the town killed a rare animal which the Chinese called kilin, that is to say, the Lamb of God. At this news, Confucius struck his breast, sighed profoundly, and exclaimed more than once: "Kilin, who has said that thou art come?" He added: "My doctrine draws to an end; it will no longer be of use, since you will appear."

Another prophecy of the same Confucius is also found in his second book, which is applied equally to Jesus, though He is not designated under the name of the Lamb of God. This is it: We need not fear but that when the expected Holy One shall come, all the honor will be rendered to His virtue which is due to it. His works will be conformable to the laws of heaven and earth.

These contradictory prophecies found in the Jewish books seem to excuse their obstinacy, and give good reason for the embarrassment of our theologians in their controversy with them. Further, those which we are about to relate of other people, prove that the author of Numbers, the apostles and fathers, recognized prophets in all nations. The Arabs also pretend this, who reckon a hundred and eighty thousand prophets from the creation of the world to Mahomet, and believe that each of them was sent to a particular nation. We shall speak of prophetesses in the article on "Sibyls."

Prophets still exist: we had two at the Bicêtre in 1723, both calling themselves Elias. They were whipped; which put it out of all doubt. Before the prophets of Cévennes, who fired off their guns from behind hedges in the name of the Lord in 1704, Holland had the famous Peter Jurieu, who published the "Accomplishment of the Prophecies." But that Holland may not be too proud, he was born in France, in a little town called Mer, near Orleans. However, it must be confessed that it was at Rotterdam alone that God called him to prophesy.

This Jurieu, like many others, saw clearly that the pope was the beast in the "Apocalypse," that he held "poculum aureum plenum abominationum," the golden cup full of abominations; that the four first letters of these four Latin words formed the word papa; that consequently his reign was about to finish; that the Jews would re-enter Jerusalem; that they would reign over the whole world during a thousand years; after which would come the Antichrist; finally, Jesus seated on a cloud would judge the quick and the dead.

Jurieu prophesies expressly that the time of the great revolution and the entire fall of papistry "will fall justly in the year 1689, which I hold," says he, "to be the time of the apocalyptic vintage, for the two witnesses will revive at this time; after which, France will break with the pope before the end of this century, or at the commencement of the next, and the rest of the anti-Christian empire will be everywhere abolished."

The disjunctive particle "or," that sign of doubt, is not in the manner of an adroit man. A prophet should not hesitate; he may be obscure, but he ought to be sure of his fact.

The revolution in papistry not happening in 1689, as Peter Jurieu predicted, he quickly published a new edition, in which he assured the public that it would be in 1690; and, what is more astonishing, this edition was immediately followed by another. It would have been very beneficial if Bayle's "Dictionary" had had such a run in the first instance; the works of the latter have, however, remained, while those of Peter Jurieu are not even to be found by the side of Nostradamus.

All was not left to a single prophet. An English Presbyterian, who studied at Utrecht, combated all which Jurieu said on the seven vials and seven trumpets of the Apocalypse, on the reign of a thousand years, the conversion of the Jews, and even on Antichrist. Each supported himself by the authority of Cocceius, Coterus, Drabicius, and Commenius, great preceding prophets, and by the prophetess Christina. The two champions confined themselves to writing; we hoped they would give each other blows, as Zedekiah smacked the face of Micaiah, saying: "Which way went the spirit of the Lord from my hand to thy cheek?" or literally: "How has the spirit passed from thee to me?" The public had not this satisfaction, which is a great pity.

It belongs to the infallible church alone to fix the true sense of prophecies, for the Jews have always maintained, with their usual obstinacy, that no prophecy could regard Jesus Christ; and the Fathers of the Church could not dispute with them with advantage, since, except St. Ephrem, the great Origen, and St. Jerome, there was never any Father of the Church who knew a word of Hebrew.

It is not until the ninth century that Raban the Moor, afterwards bishop of Mayence, learned the Jewish language. His example was followed by some others, and then they began disputing with the rabbi on the sense of the prophecies.

Raban was astonished at the blasphemies which they uttered against our Saviour; calling Him a bastard, impious son of Panther, and saying that it is not permitted them to pray to God without cursing Jesus: "Quod nulla oratio posset apud Deum accepta esse nisi in ea Dominum nostrum Jesum Christum maledicant. Confitentes eum esse impium et filium impii, id est, nescio cujus æthnici quern nominant Panthera, a quo dicunt matrem Domini adulteratam."

These horrible profanations are found in several places in the "Talmud," in the books of Nizachon, in the dispute of Rittangel, in those of Jechiel and Nachmanides, entitled the "Bulwark of Faith," and above all in the abominable work of the Toldos Jeschut. It is particularly in the "Bulwark of Faith" of the Rabbin Isaac, that they interpret all the prophecies which announce Jesus Christ by applying them to other persons.

We are there assured that the Trinity is not alluded to in any Hebrew book, and that there is not found in them the slightest trace of our holy religion. On the contrary, they point out a hundred passages, which, according to them, assert that the Mosaic law should eternally remain.

The famous passage which should confound the Jews, and make the Christian religion triumph in the opinion of all our great theologians, is that of Isaiah: "Behold a virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel. Butter and honey shall he eat, that he may know how to refuse the evil, and choose the good. For before the child shall know how to refuse the evil and choose the good, the land that thou abhorrest shall be forsaken of both her kings. And it shall come to pass in that day, that the Lord shall whistle for the flies that are in the brooks of Egypt, and for the bees that are in the land of Assyria. In the same day shall the Lord shave with a razor that is hired, namely, by them beyond the river, by the king of Assyria, the head and the hair of the genitals, and he will also consume the beard.

"Moreover, the Lord said unto me, take thee a great roll, and write in it with a man's pen concerning Maher-shalal-hash-baz. And I took unto me faithful witnesses to record, Uriah the priest, and Zachariah the son of Jeberechiah. And I went in unto the prophetess; and she conceived and bare a son; then said the Lord to me, call his name Maher-shalal-hash-baz. For before the child shall have knowledge to cry my father and my mother, the riches of Damascus, and the spoil of Samaria, shall be taken away before the king of Assyria."

The Rabbin Isaac affirms, with all the other doctors of his law, that the Hebrew word "alma" sometimes signifies a virgin and sometimes a married woman; that Ruth is called "alma" when she was a mother; that even an adulteress is sometimes called "alma"; that nobody is meant here but the wife of the prophet Isaiah; that her son was not called Immanuel, but Maher-shalal-hash-baz; that when this son should eat honey and butter, the two kings who besieged Jerusalem would be driven from the country, etc.

Thus these blind interpreters of their own religion, and their own language, combated with the Church, and obstinately maintained, that this prophecy cannot in any manner regard Jesus Christ. We have a thousand times refuted their explication in our modern languages. We have employed force, gibbets, racks, and flames; yet they will not give up.

"He has borne our ills, he has sustained our griefs, and we have beheld him afflicted with sores, stricken by God, and afflicted." However striking this prediction may appear to us, these obstinate Jews say that it has no relationship to Jesus Christ, and that it can only regard the prophets who were persecuted for the sins of the people.

"And behold my servant shall prosper, shall be honored, and raised very high." They say, further, that the foregoing passage regards not Jesus Christ but David; that this king really did prosper, but that Jesus, whom they deny, did not prosper. "Behold I will make a new pact with the house of Israel, and with the house of Judah." They say that this passage signifies not, according to the letter and the sense, anything more than—I will renew my covenant with Judah and with Israel. However, this pact has not been renewed; and they cannot make a worse bargain than they have made. No matter, they are obstinate.

"But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, though thou be little among the thousands of Judah, yet out of thee shall come forth a ruler in Israel; whose goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting."

They dare to deny that this prophecy applies to Jesus Christ. They say that it is evident that Micah speaks of some native captain of Bethlehem, who shall gain some advantage in the war against the Babylonians: for the moment after he speaks of the history of Babylon, and of the seven captains who elected Darius. And if we demonstrate that he treated of the Messiah, they still will not agree.

The Jews are grossly deceived in Judah, who should be a lion, and who has only been an ass under the Persians, Alexander, the Seleucides, Ptolemys, Romans, Arabs, and Turks.

They know not what is understood by the Shiloh, and by the rod, and the thigh of Judah. The rod has been in Judæa but a very short time. They say miserable things; but the Abbé Houteville says not much more with his phrases, his neologism, and oratorical eloquence; a writer who always puts words in the place of things, and who proposes very difficult objections merely to reply to them by frothy discourse, or idle words!

All this is, therefore, labor in vain; and when the French abbé would make a still larger book, when he would add to the five or six thousand volumes which we have on the subject, we shall only be more fatigued, without advancing a single step.

We are, therefore, plunged in a chaos which it is impossible for the weakness of the human mind to set in order. Once more, we have need of a church which judges without appeal. For in fact, if a Chinese, a Tartar, or an African, reduced to the misfortune of having only good sense, read all these prophecies, it would be impossible for him to apply them to Jesus Christ, the Jews, or to anyone else. He would be in astonishment and uncertainty, would conceive nothing, and would not have a single distinct idea. He could not take a step in this abyss without a guide. With this guide, he arrives not only at the sanctuary of virtue, but at good canon-ships, at large commanderies, opulent abbeys, the crosiered and mitred abbots of which are called monseigneur by his monks and peasants, and to bishoprics which give the title of prince. In a word, he enjoys earth, and is sure of possessing heaven.

The prophet Jurieu was hissed; the prophets of the Cévennes were hanged or racked; the prophets who went from Languedoc and Dauphiny to London were put in the pillory; the Anabaptist prophets were condemned to various modes and degrees of punishment; and the prophet Savonarola was baked at Florence. If, in connection with these, we may advert to the case of the genuine Jewish prophets, we shall perceive their destiny to have been no less unfortunate; the greatest prophet among the Jews, St. John the Baptist, was beheaded.

Zachariah is stated to have been assassinated; but, happily, this is not absolutely proved. The prophet Jeddo, or Addo, who was sent to Bethel under the injunction neither to eat nor drink, having unfortunately tasted a morsel of bread, was devoured in his turn by a lion; and his bones were found on the highway between the lion and his ass. Jonah was swallowed by a fish. He did not, it is true, remain in the fish's stomach more than three days and three nights; even this, however, was passing threescore and twelve hours very uncomfortably.

Habakkuk was transported through the air, suspended by the hair of his head, to Babylon; this was not a fatal or permanent calamity, certainly; but it must have been an exceedingly uncomfortable method of travelling. A man could not help suffering a great deal by being suspended by his hair during a journey of three hundred miles. I certainly should have preferred a pair of wings, or the mare Borak, or the Hippogriffe.

Micaiah, the son of Imla, saw the Lord seated on His throne, surrounded by His army of celestial spirits; and the Lord having inquired who could be found to go and deceive King Ahab, a demon volunteered for that purpose, and was accordingly charged with the commission; and Micaiah, on the part of the Lord, gave King Ahab an account of this celestial adventure. He was rewarded for this communication by a tremendous blow on his face from the hand of the prophet Zedekiah, and by being shut up for some days in a dungeon. His punishment might undoubtedly have been more severe; but still, it is unpleasant and painful enough for a man who knows and feels himself divinely inspired to be knocked about in so coarse and vulgar a manner, and confined in a damp and dirty hole of a prison.

It is believed that King Amaziah had the teeth of the prophet Amos pulled out to prevent him from speaking; not that a person without teeth is absolutely incapable of speaking, as we see many toothless old ladies as loquacious and chattering as ever; but a prophecy should be uttered with great distinctness; and a toothless prophet is never listened to with the respect due to his character.

Baruch experienced various persecutions. Ezekiel was stoned by the companions of his slavery. It is not ascertained whether Jeremiah was stoned or sawed asunder. Isaiah is considered as having been incontestably sawed to death by order of Manasseh, king of Judah.

It cannot be denied, that the occupation of a prophet is exceedingly irksome and dangerous. For one who, like Elijah, sets off on his tour among the planets in a chariot of light, drawn by four white horses, there are a hundred who travel on foot, and are obliged to beg their subsistence from door to door. They may be compared to Homer, who, we are told, was reduced to be a mendicant in the same seven cities which afterwards sharply disputed with each other the honor of having given him birth. His commentators have attributed to him an infinity of allegories which he never even thought of; and prophets have frequently had the like honor conferred upon them. I by no means deny that there may have existed elsewhere persons possessed of a knowledge of the future. It is only requisite for a man to work up his soul to a high state of excitation, according to the doctrine of one of our doughty modern philosophers, who speculates upon boring the earth through to the Antipodes, and curing the sick by covering them all over with pitch-plaster.

The Jews possessed this faculty of exalting and exciting the soul to such a degree that they saw every future event as clearly as possible; only unfortunately, it is difficult to decide whether by Jerusalem they always mean eternal life; whether Babylon means London or Paris; whether, when they speak of a grand dinner, they really mean a fast, and whether red wine means blood, and a red mantle faith, and a white mantle charity. Indeed, the correct and complete understanding of the prophets is the most arduous attainment of the human mind.

There is likewise a further difficulty with respect to the Jewish prophets, which is, that many among them were Samaritan heretics. Hosea was of the tribe of Issachar, which dwelt in the Samaritan territory, and Elisha and Elijah were of the same tribe. But the objection is very easily answered. We well know that "the wind bloweth where it listeth," and that grace lights on the most dry and barren, as well as on the most fertile soil.

I was at the grate of the convent when Sister Fessue said to Sister Confite: "Providence takes a visible care of me; you know how I love my sparrow; he would have been dead if I had not said nine ave-marias to obtain his cure. God has restored my sparrow to life; thanks to the Holy Virgin."

A metaphysician said to her: "Sister, there is nothing so good as ave-marias, especially when a girl pronounces them in Latin in the suburbs of Paris; but I cannot believe that God has occupied Himself so much with your sparrow, pretty as he is; I pray you to believe that He has other matters to attend to. It is necessary for Him constantly to superintend the course of sixteen planets and the rising of Saturn, in the centre of which He has placed the sun, which is as large as a million of our globes. He has also thousands and thousands of millions of other suns, planets, and comets to govern. His immutable laws, and His eternal arrangement, produce motion throughout nature; all is bound to His throne by an infinite chain, of which no link can ever be put out of place!" If certain ave-marias had caused the sparrow of Sister Fessue to live an instant longer than it would naturally have lived, it would have violated all the laws imposed from eternity by the Great Being; it would have deranged the universe; a new world, a new God, and a new order of existence would have been rendered unavoidable.

SISTER FESSUE.—What! do you think that God pays so little attention to Sister Fessue?

METAPHYSICIAN.—I am sorry to inform you, that like myself you are but an imperceptible link in the great chain; that your organs, those of your sparrow, and my own, are destined to subsist a determinate number of minutes in the suburbs of Paris.

SISTER FESSUE.—If so, I was predestined to say a certain number of ave-marias.

METAPHYSICIAN.—Yes; but they have not obliged the Deity to prolong the life of your sparrow beyond his term. It has been so ordered, that in this convent at a certain hour you should pronounce, like a parrot, certain words in a certain language which you do not understand; that this bird, produced like yourself by the irresistible action of general laws, having been sick, should get better; that you should imagine that you had cured it, and that we should hold together this conversation.

SISTER FESSUE.—Sir, this discourse savors of heresy. My confessor, the reverend Father de Menou, will infer that you do not believe in Providence.

METAPHYSICIAN.—I believe in a general Providence, dear sister, which has laid down from all eternity the law which governs all things, like light from the sun; but I believe not that a particular Providence changes the economy of the world for your sparrow or your cat.

SISTER FESSUE.—But suppose my confessor tells you, as he has told me, that God changes His intentions every day in favor of the devout?

METAPHYSICIAN.—He would assert the greatest absurdity that a confessor of girls could possibly utter to a being who thinks.

SISTER FESSUE.—My confessor absurd! Holy Virgin Mary!

METAPHYSICIAN.—I do not go so far as that. I only observe that he cannot, by an enormously absurd assertion, justify the false principles which he has instilled into you—possibly very adroitly—in order to govern you.

SISTER FESSUE.—That observation merits reflection. I will think of it.

It is very singular that the Protestant churches agree in exclaiming that purgatory was invented by the monks. It is true that they invented the art of drawing money from the living by praying to God for the dead; but purgatory existed before the monks.

It was Pope John XIV., say they, who, towards the middle of the tenth century, instituted the feast of the dead. From that fact, however, I only conclude that they were prayed for before; for if they then took measures to pray for all, it is reasonable to believe that they had previously prayed for some of them; in the same way as the feast of All Saints was instituted, because the feast of many of them had been previously celebrated. The difference between the feast of All Saints and that of the dead, is, that in the first we invoke, and that in the second we are invoked; in the former we commend ourselves to the blessed, and in the second the unblessed commend themselves to us.

The most ignorant writers know, that this feast was first instituted at Cluny, which was then a territory belonging to the German Empire. Is it necessary to repeat, "that St. Odilon, abbot of Cluny, was accustomed to deliver many souls from purgatory by his masses and his prayers; and that one day a knight or a monk, returning from the holy land, was cast by a tempest, on a small island, where he met with a hermit, who said to him, that in that island existed enormous caverns of fire and flames, in which the wicked were tormented; and that he often heard the devils complain of the Abbot Odilon and his monks, who every day delivered some soul or other; for which reason it was necessary to request Odilon to continue his exertions, at once to increase the joy of the saints in heaven and the grief of the demons in hell?"

It is thus that Father Gerard, the Jesuit, relates the affair in his "Flower of the Saints," after Father Ribadeneira. Fleury differs a little from this legend, but has substantively preserved it. This revelation induced St. Odilon to institute in Cluny the feast of the dead, which was then adopted by the Church.

Since this time, purgatory has brought much money to those who possess the power of opening the gates. It was by virtue of this power that English John, that great landlord, surnamed Lackland, by declaring himself the liegeman of Pope Innocent III., and placing his kingdom under submission, delivered the souls of his parents, who had been excommunicated: "Pro mortuo excommunico, pro quo supplicant consanguinei."

The Roman chancery had even its regular scale for the absolution of the dead; there were many privileged altars in the fifteenth century, at which every mass performed for six liards delivered a soul from purgatory. Heretics could not ascend beyond the truth, that the apostles had the right of unbinding all who were bound on earth, but not under the earth; and many of them, like impious persons, doubted the power of the keys. It is however to be remarked, that when the pope is inclined to remit five or six hundred years of purgatory, he accords the grace with full power: "Pro potestate a Deo accepta concedit."

Of the Antiquity of Purgatory.

It is pretended that purgatory was, from time immemorial, known to the famous Jewish people, and it is founded on the second book of the Maccabees, which says expressly, "that there being found concealed in the vestments of the Jews (at the battle of Adullam), things consecrated to the idols of Jamma, it was manifest that on that account they had perished; and having made a gathering of twelve thousand drachms of silver, Judas, who thought religiously of the resurrection, sent them to Jerusalem for the sins of the dead."

Having taken upon ourselves the task of relating the objections of the heretics and infidels, for the purpose of confounding them by their own opinions, we will detail here these objections to the twelve thousand drachms transmitted by Judas; and to purgatory. They say: 1. That twelve thousand drachms of silver was too much for Judas Maccabeus, who only maintained a petty war of insurgency against a great king.

2. That they might send a present to Jerusalem for the sins of the dead, in order to bring down the blessing of God on the survivors.

3. That the idea of a resurrection was not entertained among the Jews at this time, it being ascertained that this doctrine was not discussed among them until the time of Gamaliel, a little before the ministry of Jesus Christ.

4. As the laws of the Jews included in the "Decalogue," Leviticus and Deuteronomy, have not spoken of the immortality of the soul, nor of the torments of hell, it was impossible that they should contain the doctrine of purgatory.

5. Heretics and infidels make the greatest efforts to demonstrate in their manner, that the books of the Maccabees are evidently apocryphal. The following are their pretended proofs:

The Jews have never acknowledged the books of the Maccabees to be canonical, why then should we acknowledge them? Origen declares formally that the books of the Maccabees are to be rejected, and St. Jerome regards them as unworthy of credit. The Council of Laodicea, held in 567, admits them not among the canonical books. The Athanasiuses, the Cyrils, and the Hilarys, have also rejected them. The reasons for treating the foregoing books as romances, and as very bad romances, are as follows:

The ignorant author commences by a falsehood, known to be such by all the world. He says: "Alexander called the young nobles, who had been educated with him from their infancy, and parted his kingdom among them while he still lived." So gross and absurd a lie could not issue from the pen of a sacred and inspired writer.

The author of the Maccabees, in speaking of Antiochus Epiphanes, says: "Antiochus marched towards Elymais, and wished to pillage it, but was not able, because his intention was known to the inhabitants, who assembled in order to give him battle, on which he departed with great sadness, and returned to Babylon. Whilst he was still in Persia, he learned that his army in Judæa had fled ... and he took to his bed and died."

The same writer himself, in another place, says quite the contrary; for he relates that Antiochus Epiphanes was about to pillage Persepolis, and not Elymais; that he fell from his chariot; that he was stricken with an incurable wound; that he was devoured by worms; that he demanded pardon of the god of the Jews; that he wished himself to be a Jew: it is there where we find the celebrated versicle, which fanatics have applied so frequently to their enemies; "Orabet scelestus ille veniam quam non erat consecuturus." The wicked man demandeth a pardon, which he cannot obtain. This passage is very Jewish; but it is not permitted to an inspired writer to contradict himself so flagrantly.

This is not all: behold another contradiction, and another oversight. The author makes Antiochus die in a third manner, so that there is quite a choice. He remarks that this prince was stoned in the temple of Nanneus; and those who would excuse the stupidity pretend that he here speaks of Antiochus Eupator; but neither Epiphanes nor Eupator was stoned.

Moreover, this author says, that another Antiochus (the Great) was taken by the Romans, and that they gave to Eumenes the Indies and Media. This is about equal to saying that Francis I. made a prisoner of Henry VIII., and that he gave Turkey to the duke of Savoy. It is insulting the Holy Ghost to imagine it capable of dictating so many disgusting absurdities.

The same author says, that the Romans conquered the Galatians; but they did not conquer Galatia for more than a hundred years after. Thus the unhappy story-teller did not write for more than a hundred years after the time in which it was supposed that he wrote: and it is thus, according to the infidels, with almost all the Jewish books.

The same author observes, that the Romans every year nominated a chief of the senate. Behold a well-informed man, who did not even know that Rome had two consuls! What reliance, say infidels, can be placed in these rhapsodies and puerile tales, strung together without choice or order by the most imbecile of men? How shameful to believe in them! and the barbarity of persecuting sensible men, in order to force a belief of miserable absurdities, for which they could not but entertain the most sovereign contempt, is equal to that of cannibals.

Our answer is, that some mistakes which probably arose from the copyists may not affect the fundamental truths of the remainder; that the Holy Ghost inspired the author only, and not the copyists; that if the Council of Laodicea rejected the Maccabees, they have been admitted by the Council of Trent; that they are admitted by the Roman Church; and consequently that we ought to receive them with due submission.

Of the Origin of Purgatory.

It is certain that those who admitted of purgatory in the primitive church were treated as heretics. The Simonians were condemned who admitted the purgation of souls—Psuken Kadaron.

St. Augustine has since condemned the followers of Origen who maintained this doctrine. But the Simonians and the Origenists had taken their purgatory from Virgil, Plato and the Egyptians. You will find it clearly indicated in the sixth book of the "Æneid," as we have already remarked. What is still more singular, Virgil describes souls suspended in air, others burned, and others drowned:

Aliæ panduntur inanes

Suspensæ ad ventos: aliis sub gurgite vasto

Infectum eluitur scelus, aut exuritur igni.

—&ÆNEID, Book vi, 740-742.

For this are various penances enjoined,

And some are hung to bleach upon the wind;

Some plunged in waters, others purged in fires,

Till all the dregs are drained, and all the rust expires.

—DRYDEN.

And what is more singular still, Pope Gregory, surnamed the great, not only adopts this doctrine from Virgil, but in his theology introduces many souls who arrive from purgatory after having been hanged or drowned.

Plato has spoken of purgatory in his "Phædon," and it is easy to discover, by a perusal of "Hermes Trismegistus" that Plato borrowed from the Egyptians all which he had not borrowed from Timæus of Locris.

All this is very recent, and of yesterday, in comparison with the ancient Brahmins. The latter, it must be confessed, invented purgatory in the same manner as they invented the revolt and fall of the genii or celestial intelligences.

It is in their Shasta, or Shastabad, written three thousand years before the vulgar era, that you, my dear reader, will discover the doctrine of purgatory. The rebel angels, of whom the history was copied among the Jews in the time of the rabbin Gamaliel, were condemned by the Eternal and His Son, to a thousand years of purgatory, after which God pardoned and made them men. This we have already said, dear reader, as also that the Brahmins found eternal punishment too severe, as eternity never concludes. The Brahmins thought like the Abbé Chaulieu, and called upon the Lord to pardon them, if, impressed with His bounties, they could not be brought to conceive that they would be punished so rigorously for vain pleasures, which passed away like a dream:

Pardonne alors, Seigneur, si, plein de tes bontés,

Je n'ai pu concevoir que mes fragilités,

Ni tous ces vains plaisirs que passent comme un songe,

Pussent être l'objet de tes sévérités;

Et si j'ai pu penser que tant des cruautés.

Puniraient un peu trop la douceur d'un mensonge.

—EPITRE SUR LA MORT, au Marquis de la Fare.

The abode of physicians is in large towns; there are scarcely any in country places. Great towns contain rich patients; debauchery, excess at the tables, and the passions, cause their maladies. Dumoulin, the physician, who was in as much practice as any of his profession, said when dying that he left two great physicians behind him—simple diet and soft water.

In 1728, in the time of Law, the most famous of quacks of the first class, another named Villars, confided to some friends, that his uncle, who had lived to the age of nearly a hundred, and who was then killed by an accident, had left him the secret of a water which could easily prolong life to the age of one hundred and fifty, provided sobriety was attended to. When a funeral passed, he affected to shrug up his shoulders in pity: "Had the deceased," he exclaimed, "but drank my water, he would not be where he is." His friends, to whom he generously imparted it, and who attended a little to the regimen prescribed, found themselves well, and cried it up. He then sold it for six francs the bottle, and the sale was prodigious. It was the water of the Seine, impregnated with a small quantity of nitre, and those who took it and confined themselves a little to the regimen, but above all those who were born with a good constitution, in a short time recovered perfect health. He said to others: "It is your own fault if you are not perfectly cured. You have been intemperate and incontinent, correct yourself of these two vices, and you will live a hundred and fifty years at least." Several did so, and the fortune of this good quack augmented with his reputation. The enthusiastic Abbé de Pons ranked him much above his namesake, Marshal Villars. "He caused the death of men," he observed to him, "whereas you make men live."

It being at last discovered that the water of Villars was only river water, people took no more of it, and resorted to other quacks in lieu of him. It is certain that he did much good, and he can only be accused of selling the Seine water too dear. He advised men to temperance, and so far was superior to the apothecary Arnault, who amused Europe with the farce of his specific against apoplexy, without recommending any virtue.

I knew a physician of London named Brown, who had practised at Barbadoes. He had a sugar-house and negroes, and the latter stole from him a considerable sum. He accordingly assembled his negroes together, and thus addressed them: "My friends," said he to them, "the great serpent has appeared to me during the night, and has informed me that the thief has at this moment a paroquet's feather at the end of his nose." The criminal instantly applied his hand to his nose. "It is thou who hast robbed me," exclaimed the master; "the great serpent has just informed me so;" and he recovered his money. This quackery is scarcely condemnable, but then it is applicable only to negroes.

The first Scipio Africanus, a very different person from the physician Brown, made his soldiers believe that he was inspired by the gods. This grand charlatanism was in use for a long time. Was Scipio to be blamed for assisting himself by the means of this pretension? He was possibly the man who did most honor to the Roman republic; but why the gods should inspire him has never been explained.

Numa did better: he civilized robbers, and swayed a senate composed of a portion of them which was the most difficult to govern. If he had proposed his laws to the assembled tribes, the assassins of his predecessor would have started a thousand difficulties. He addressed himself to the goddess Egeria, who favored him with pandects from Jupiter; he was obeyed without a murmur, and reigned happily. His instructions were sound, his charlatanism did good; but if some secret enemy had discovered his knavery, and had said, "Let us exterminate an impostor who prostitutes the names of the gods in order to deceive men," he would have run the risk of being sent to heaven like Romulus. It is probable that Numa took his measures ably, and that he deceived the Romans for their own benefit, by a policy adapted to the time, the place, and the early manners of the people.

Mahomet was twenty times on the point of failure, but at length succeeded with the Arabs of Medina, who believed him the intimate friend of the angel Gabriel. If any one at present was to announce in Constantinople that he was favored by the angel Raphael, who is superior to Gabriel in dignity, and that he alone was to be believed, he would be publicly empaled. Quacks should know their time.

Was there not a little quackery in Socrates with his familiar dæmon, and the express declaration of Apollo, that he was the wisest of all men? How can Rollin in his history reason from this oracle? Why not inform youth that it was a pure imposition? Socrates chose his time ill: about a hundred years before he might have governed Athens.

Every chief of a sect in philosophy has been a little of a quack; but the greatest of all have been those who have aspired to govern. Cromwell was the most terrible of all quacks, and appeared precisely at a time in which he could succeed. Under Elizabeth he would have been hanged; under Charles II., laughed at. Fortunately for himself he came at a time when people were disgusted with kings: his son followed, when they were weary of protectors.

Of the Quackery of Sciences and of Literature.

The followers of science have never been able to dispense with quackery. Each would have his opinions prevail; the subtle doctor would eclipse the angelic doctor, and the profound doctor would reign alone. Everyone erects his own system of physics, metaphysics, and scholastic theology; and the question is, who will value his merchandise? You have dependants who cry it up, fools who believe you, and protectors on whom to lean. Can there be greater quackery than the substitution of words for things, or than a wish to make others believe what we do not believe ourselves?

One establishes vortices of subtile matter, branched, globular, and tubular; another, elements of matter which are not matter, and a pre-established harmony which makes the clock of the body sound the hour, when the needle of the clock of the soul is duly pointed. These chimeras found partisans for many years, and when these ideas went out of fashion, new pretenders to inspiration mounted upon the ambulatory stage. They banished the germs of the world, asserted that the sea produced mountains, and that men were formerly fishes.

How much quackery has always pervaded history: either by astonishing the reader with prodigies, tickling the malignity of human nature with satire, or by flattering the families of tyrants with infamous eulogies!

The unhappy class who write in order to live, are quacks of another kind. A poor man who has no trade, and has had the misfortune to have been at college, thinks that he knows how to write, and repairing to a neighboring bookseller, demands employment. The bookseller knows that most persons keeping houses are desirous of small libraries, and require abridgments and new tables, orders an abridgment of the history of Rapin Thoyras, or of the church; a collection of bon mots from the Menagiana, or a dictionary of great men, in which some obscure pedant is placed by the side of Cicero, and a sonneteer of Italy as near as possible to Virgil.

Another bookseller will order romances or the translation of romances. If you have no invention, he will say to his workman: You can collect adventures from the grand Cyrus, from Gusman d'Alfarache, from the "Secret Memoirs of a Man of Quality" or of a "Woman of Quality"; and from the total you will make a volume of four hundred pages.

Another bookseller gives ten years' newspapers and almanacs to a man of genius, and says: You will make an abstract from all that, and in three months bring it me under the name of a faithful "History of the Times," by M. le Chevalier ——, Lieutenant de Vaisseau, employed in the office for foreign affairs.

Of this sort of books there are about fifty thousand in Europe, and the labor still goes on like the secret for whitening the skin, blackening the hair, and mixing up the universal remedy.

I knew in my infancy a canon of Péronne of the age of ninety-two years, who had been educated by one of the most furious burghers of the League—he always used to say, the late M. de Ravaillac. This canon had preserved many curious manuscripts of the apostolic times, although they did little honor to his party. The following is one of them, which he bequeathed to my uncle:

Dialogue of a Page of the Duke of Sully, and of Master Filesac, Doctor of the Sorbonne, one of the two Confessors of Ravaillac.

MASTER FILESAC.—God be thanked, my dear page, Ravaillac has died like a saint. I heard his confession; he repented of his sin, and determined no more to fall into it. He wished to receive the holy sacrament, but it is not the custom here as at Rome; his penitence will serve in lieu of it, and it is certain that he is in paradise.

PAGE.—He in paradise, in the Garden of Eden, the monster!

MASTER FILESAC.—Yes, my fine lad, in that garden, or heaven, it is the same thing.

PAGE.—I believe so; but he has taken a bad road to arrive there.

MASTER FILESAC.—You talk like a young Huguenot. Learn that what I say to you partakes of faith. He possessed attrition, and attrition, joined to the sacrament of confession, infallibly works out the salvation which conducts straightway to paradise, where he is now praying to God for you.

PAGE.—I have no wish that he should address God on my account. Let him go to the devil with his prayers and his attrition.

MASTER FILESAC.—At the bottom, he was a good soul; his zeal led him to commit evil, but it was not with a bad intention. In all his interrogatories, he replied that he assassinated the king only because he was about to make war on the pope, and that he did so to serve God. His sentiments were very Christian-like. He is saved, I tell you; he was bound, and I have unbound him.

PAGE.—In good faith, the more I listen to you the more I regard you as a man bound yourself. You excite horror in me.

MASTER FILESAC.—It is because that you are not yet in the right way; but you will be one day. I have always said that you were not far from the kingdom of heaven; but your time is not yet come.

PAGE.—And the time will never come in which I shall be made to believe that you have sent Ravaillac to the kingdom of heaven.

MASTER FILESAC.—As soon as you shall be converted, which I hope will be the case, you will believe as I do; but in the meantime, be assured that you and the duke of Sully, your master, will be damned to all eternity with Judas Iscariot and the wicked rich man Dives, while Ravaillac will repose in the bosom of Abraham.

PAGE.—How, scoundrel!

MASTER FILESAC.—No abuse, my little son. It is forbidden to call our brother "raca," under the penalty of the gehenna or hell fire. Permit me to instruct without enraging you.

PAGE.—Go on; thou appearest to me so "raca," that I will be angry no more.

MASTER FILESAC.—I therefore say to you, that agreeably to faith you will be damned, as unhappily our dear Henry IV. is already, as the Sorbonne always foresaw.

PAGE.—My dear master damned! Listen to the wicked wretch! A cane! a cane!

MASTER FILESAC.—Be patient, good young man; you promised to listen to me quietly. Is it not true that the great Henry died without confession? Is it not true that he died in the commission of mortal sin, being still amorous of the princess of Condé, and that he had not time to receive the sacrament of repentance, God having allowed him to be stabbed in the left ventricle of the heart, in consequence of which he was instantly suffocated with his own blood? You will absolutely find no good Catholic who will not say the same as I do.

PAGE.—Hold thy tongue, master madman; if I thought that thy doctors taught a doctrine so abominable, I would burn them in their lodgings.

MASTER FILESAC.—Once again, be calm; you have promised to be so. His lordship the marquis of Cochini, who is a good Catholic, will know how to prevent you from being guilty of the sacrilege of injuring my colleagues.

PAGE.—But conscientiously, Master Filesac, does thy party really think in this manner?

MASTER FILESAC.—Be assured of it; it is our catechism.

PAGE.—Listen; for I must confess to thee, that one of thy Sorbonnists almost seduced me last year. He induced me to hope for a pension or a benefice. Since the king, he observed, has heard mass in Latin, you who are only a petty gentleman may also attend it without derogation. God takes care of His elect, giving them mitres, crosses, and prodigious sums of money, while you of the reformed doctrine go on foot, and can do nothing but write. I own I was staggered; but after what thou hast just said to me, I would rather a thousand times be a Mahometan than of thy creed.

The page was wrong. We are not to become Mahometans because we are incensed; but we must pardon a feeling young man who loved Henry IV. Master Filesac spoke according to his theology; the page attended to his heart.

At the time that all France was carried away by the system of Law, and when he was comptroller-general, a man who was always in the right came to him one day and said:

"Sir, you are the greatest madman, the greatest fool, or the greatest rogue, who has yet appeared among us. It is saying a great deal; but behold how I prove it. You have imagined that we may increase the riches of a state ten-fold by means of paper. But this paper only represents money, which is itself only a representative of genuine riches, the production of the earth and manufacture. It follows, therefore, that you should have commenced by giving us ten times as much corn, wine, cloth, linen, etc.; this is not enough, they must be certain of sale. Now you make ten times as many notes as we have money and commodities; ergo, you are ten times more insane, stupid, or roguish, than all the comptrollers or superintendents who have preceded you. Behold how rapidly I will prove my major."

Scarcely had he commenced his major than he was conducted to St. Lazarus. When he came out of St. Lazarus, where he studied much and strengthened his reason, he went to Rome. He demanded a public audience, and that he should not be interrupted in his harangue. He addressed his holiness as follows:

"Holy father, you are Antichrist, and behold how I will prove it to your holiness. I call him ante-Christ or antichrist, according to the meaning of the word, who does everything contrary to that which Christ commanded. Now Christ was poor, and you are very rich. He paid tribute, and you exact it. He submitted himself to the powers that be, and you have become one of them. He wandered on foot, and you visit Castle Gandolfo in a sumptuous carriage. He ate of all that which people were willing to give him, and you would have us eat fish on Fridays and Saturdays, even when we reside at a distance from the seas and rivers. He forbade Simon Barjonas using the sword, and you have many swords in your service, etc. In this sense, therefore, your holiness is Antichrist. In every other sense I exceedingly revere you, and request an indulgence 'in articulo mortis.'"

My free speaker was immediately confined in the castle of St. Angelo. When he came out of the castle of St. Angelo, he proceeded to Venice, and demanded an audience of the doge. "Your serenity," he exclaimed, "commits a great extravagance every year in marrying the sea; for, in the first place, people marry only once with the same person; secondly, your marriage resembles that of Harlequin, which was only half performed, as wanting the consent of one of the parties; thirdly, who has told you that, some day or other, the other maritime powers will not declare you incapable of consummating your marriage?"

Having thus delivered his mind, he was shut up in the tower of St. Mark. When he came out of the tower of St. Mark, he proceeded to Constantinople, where he obtained an interview with the mufti, and thus addressed him: "Your religion contains some good points, such as the adoration of the Supreme Being, and the necessity of being just and charitable; nevertheless, it is a mere hash composed out of Judaism and a wearisome heap of stories from Mother Goose. If the archangel Gabriel had brought from some planet the leaves of the Koran to Mahomet, all Arabia would have beheld his descent. Nobody saw him, therefore Mahomet was a bold impostor, who deceived weak and ignorant people."

He had scarcely pronounced these words before he was empaled; nevertheless, he had been all along in the right.

By this name are designated the remains or remaining parts of the body, or clothes, of a person placed after his death by the Church in the number of the blessed.

It is clear that Jesus condemned only the hypocrisy of the Jews, in saying: "Woe unto you, Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! because ye build the tombs of the prophets, and garnish the sepulchres of the righteous." Thus orthodox Christians have an equal veneration for the relics and images of saints, and I know not what. Doctor Henry ventures to say that when bones or other relics are changed into worms, we must not adore these worms; the Jesuit Vasquez decided that the opinion of Henry is absurd and vain, for it signifies not in what manner corruption takes place; "consequently," says he, "we can adore relics as much under the form of worms as under that of ashes."

However this may be, St. Cyril of Alexandria avows that the origin of relics is Pagan; and this is the description given of their worship by Theodoret, who lived in the commencement of the Christian era: "They run to the temples of martyrs," says this learned bishop, "some to demand the preservation of their health, others the cure of their maladies; and barren women for fruitfulness. After obtaining children, these women ask the preservation of them. Those who undertake voyages, pray the martyrs to accompany and conduct them; and on their return they testify to them their gratitude. They adore them not as gods, but they honor them as divine men; and conjure them to become their intercessors.

"The offerings which are displayed in their temples are public proofs that those who have demanded with faith, have obtained the accomplishment of their vows and the cure of their disorders. Some hang up artificial eyes, others feet, and others hands of gold and silver. These monuments publish the virtue of those who are buried in these tombs, as their influence publishes that the god for whom they suffered is the true God. Thus Christians take care to give their children the names of martyrs, that they may be insured their protection."

Finally, Theodoret adds, that the temples of the gods were demolished, and that the materials served for the construction of the temples of martyrs: "For the Lord," said he to the Pagans, "has substituted his dead for your gods; He has shown the vanity of the latter, and transferred to others the honors paid to them." It is of this that the famous sophist of Sardis complains bitterly in deploring the ruin of the temple of Serapis at Canopus, which was demolished by order of the emperor Theodosius I. in the year 389.

"People," says Eunapius, "who had never heard of war, were, however, very valiant against the stones of this temple; and principally against the rich offerings with which it was filled. These holy places were given to monks, an infamous and useless class of people, who provided they wear a black and slovenly dress, hold a tyrannical authority over the minds of the people; and instead of the gods whom we acknowledge through the lights of reason, these monks give us heads of criminals, punished for their crimes, to adore, which they have salted in order to preserve them."

The people are superstitious, and it is superstition which enchains them. The miracles forged on the subject of relics became a loadstone which attracted from all parts riches to the churches. Stupidity and credulity were carried so far that, in the year 386, the same Theodosius was obliged to make a law by which he forbade buried corpses to be transported from one place to another, or the relics of any martyr to be separated and sold.

During the first three ages of Christianity they were contented with celebrating the day of the death of martyrs, which they called their natal day, by assembling in the cemeteries where their bodies lay, to pray for them, as we have remarked in the article on "Mass." They dreamed not then of a time in which Christians would raise temples to them, transport their ashes and bones from one place to another, show them in shrines, and finally make a traffic of them; which excited avarice to fill the world with false relics.

But the Third Council of Carthage, held in the year 397, having inserted in the Scriptures the Apocalypse of St. John, the authenticity of which was till then contested, this passage of chapter vi., "I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God"—authorized the custom of having relics of martyrs under the altars; and this practice was soon regarded so essential that St. Ambrose, notwithstanding the wishes of the people, would not consecrate a church where there were none; and in 692, the Council of Constantinople, in Trullo, even ordered all the altars to be demolished under which it found no relics.

Another Council of Carthage, on the contrary, in the year 401, ordered bishops to build altars which might be seen everywhere, in fields and on high roads, in honor of martyrs; from which were here and there dug pretended relics, on dreams and vain revelations of all sorts of people.

St. Augustine relates that towards the year 415, Lucian, the priest of a town called Caphargamata, some miles distant from Jerusalem, three times saw in a dream the learned Gamaliel, who declared to him that his body, that of Abibas his son, of St. Stephen, and Nicodemus, were buried in a part of his parish which he pointed out to him. He commanded him, on their part and his own, to leave them no longer neglected in the tomb in which they had been for some ages, but to go and tell John, bishop of Jerusalem, to come and dig them up immediately, if he would prevent the ills with which the world was threatened. Gamaliel added that this translation must be made in the episcopacy of John, who died about a year after. The order of heaven was that the body of St. Stephen should be transported to Jerusalem.

Either Lucian did not clearly understand, or he was unfortunate—he dug and found nothing; which obliged the learned Jew to appear to a very simple and innocent monk, and indicate to him more precisely the place where the sacred relics lay. Lucian there found the treasure which he sought, according as God had revealed it unto him. In this tomb there was a stone on which was engraved the word "cheliel," which signifies "crown" in Hebrew, as "stephanos" does in Greek. On the opening of Stephen's coffin the earth trembled, a delightful odor issued, and a great number of sick were cured. The body of the saint was reduced to ashes, except the bones, which were transported to Jerusalem, and placed in the church of Sion. At the same hour there fell a great rain, until which they had had a great drouth.

Avitus, a Spanish priest who was then in the East, translated into Latin this story, which Lucian wrote in Greek. As the Spaniard was the friend of Lucian, he obtained a small portion of the ashes of the saint, some bones full of an oil which was a visible proof of their holiness, surpassing newly-made perfumes, and the most agreeable odors. These relics, brought by Orosius into the island of Minorca, in eight days converted five hundred and forty Jews.

They were afterwards informed by divers visions that some monks of Egypt had relics of St. Stephen which strangers had brought there. As the monks, not then being priests, had no churches of their own, they took this treasure to transport it to a church which was near Usala. Above the church some persons soon saw a star which seemed to come before the holy martyr. These relics did not remain long in this church; the bishop of Usala, finding it convenient to enrich his own, transported them, seated on a car, accompanied by a crowd of people, who sang the praises of God, attended by a great number of lights and tapers.

In this manner the relics were borne to an elevated place in the church and placed on a throne ornamented with hangings. They were afterwards put on a little bed in a place which was locked up, but to which a little window was left, that cloths might be touched, which cured several disorders. A little dust collected on the shrine suddenly cured one that was paralytic. Flowers which had been presented to the saint, applied to the eyes of a blind man, gave him sight. There were even seven or eight corpses restored to life.

St. Augustine, who endeavors to justify this worship by distinguishing it from that of adoration, which is due to God alone, is obliged to agree that he himself knew several Christians who adored sepulchres and images. "I know several who drink to great excess on the tombs, and who, in giving entertainments to the dead, fell themselves on those who were buried."

Indeed, turning fresh from Paganism, and charmed to find deified men in the Christian church, though under other names, the people honored them as much as they had honored their false gods; and it would be grossly deceiving ourselves to judge of the ideas and practices of the populace by those of enlightened and philosophic bishops. We know that the sages among the Pagans made the same distinctions as our holy bishops. "We must," said Hierocles, "acknowledge and serve the gods so as to take great care to distinguish them from the supreme God, who is their author and father. We must not too greatly exalt their dignity. And finally the worship which we give them should relate to their sole creator, whom you may properly call the God of gods, because He is the Master of all, and the most excellent of all." Porphyrius, who, like St. Paul, terms the supreme God, the God who is above all things, adds that we must not sacrifice to Him anything that is sensible or material, because, being a pure Spirit, everything material is impure to Him. He can only be worthily honored by the thoughts and sentiments of a soul which is not tainted with any sinful passion.

In a word, St. Augustine, in declaring with naïveté that he dared not speak freely on several similar abuses on account of giving opportunity for scandal to pious persons or to pedants, shows that the bishops made use of the artifice to convert the Pagans, as St. Gregory recommended two centuries after to convert England. This pope, being consulted by the monk Augustine on some remains of ceremonies, half civil and half Pagan, which the newly converted English would not renounce, answered, "We cannot divest hard minds of all their habits at once; we reach not to the top of a steep rock by leaping, but by climbing step by step."

The reply of the same pope to Constantina, the daughter of the emperor Tiberius Constantine, and the wife of Maurice, who demanded of him the head of St. Paul, to place in a temple which she had built in honor of this apostle, is no less remarkable. St. Gregory sent word to the princess that the bodies of saints shone with so many miracles that they dared not even approach their tombs to pray without being seized with fear. That his predecessor (Pelagius II.) wishing to remove some silver from the tomb of St. Peter to another place four feet distant, he appeared to him with frightful signs. That he (Gregory) wishing to make some repairs in the monument of St. Paul, as it had sunk a little in front, and he who had the care of the place having had the boldness to raise some bones which touched not the tomb of the apostle, to transport them elsewhere, he appeared to him also in a terrible manner, and he died immediately. That his predecessor also wishing to repair the tomb of St. Lawrence, the shroud which encircled the body of the martyr was imprudently discovered; and although the laborers were monks and officers of the church, they all died in the space of ten days because they had seen the body of the saint. That when the Romans gave relics, they never touched the sacred bodies, but contented themselves with putting some cloths, with which they approached them, in a box. That these cloths have the same virtue as relics, and perform as many miracles. That certain Greeks, doubting of this fact, Pope Leo took a pair of scissors, and in their presence cutting some of the cloth which had approached the holy bodies, blood came from it. That in the west of Rome it is a sacrilege to touch the bodies of saints; and that if any one attempts, he may be assured that his crime will not go unpunished. For which reason the Greeks cannot be persuaded to adopt the custom of transporting relics. That some Greeks daring to disinter some bodies in the night near the church of St. Paul, intending to transport them into their own country, were discovered, which persuaded them that the relics were false. That the easterns, pretending that the bodies of St. Peter and St. Paul belonged to them, came to Rome to take them to their own country; but arriving at the catacombs where these bodies repose, when they would have taken them, sudden lightning and terrible thunder dispersed the alarmed multitude and forced them to renounce their undertaking. That those who suggested to Constantina the demand of the head of St. Paul from him, had no other design than that of making him lose his favor. St. Gregory concludes with these words: "I have that confidence in God, that you will not be deprived of the fruit of your good will, nor of the virtue of the holy apostles, whom you love with all your heart and with all your mind; and that, if you have not their corporeal presence, you will always enjoy their protection."

Yet the ecclesiastical history pretends that the translation of relics was equally frequent in the East and West; and the author of the notes to this letter further observes that the same St. Gregory afterwards gave several holy bodies, and that other popes have given so many as six or seven to one individual.