Transcriber's Note:

1. Page scan source: http://books.google.com/books?id=T8EDAAAAQAAJ&dq

GAUDEAMUS

Humorous Poems

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN OF

JOSEPH VICTOR SCHEFFEL

AND OTHERS.

BY

CHARLES G. LELAND.

LONDON:

TRÜBNER & CO., 8 & 60, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1872.

[All Rights reserved.]

JOHN CHILDS AND SON, PRINTERS.

CONTENTS.

Translator's Preface

Joseph Victor Scheffel. An Introductory Memoir

Granite

The Ichthyosaurus

The Tazzelworm

The Megatherium

The Basalt

The Boulder

The Comet

Guano Song

Asphaltum

The Pile Builder

Hesiod

Modern Greek

Translation

Pumpus of Perusia

The Teutoburger Battle

Old Assyrian--Jonah

By the Border

Hildebrand and Hadubrand

Song of the Travelling Students

The Cloister Cellar Master's Summer Morning Song

The Maulbronn Fugue

Der Enderle Von Ketsch

The Rodenstein Ballads.

The Three Villages

The Welcome

The Pawning

The Page

The Wild Army

Rodenstein and the Priest

Rodenstein

Heidelberg.

Number Eight

The Martin's Goose

The Last Trousers

The Last Postillion

Wine of Sixty-five

Perkêo

The Return Home

Miscellaneous.

Heinz Von Stein

The Holy Coat at Treves

Rambambo

Bibesco

The Jolly Brother

The Students Dress-coat

Ahasuerus

The Song of the Widow, Clara Bakethecakes

The Herring

From the German Gipsy

Brigand Song

Die Zwei Freunde

The Two Friends

To the Reader

This volume contains the greater portion of the poems which constitute

the Gaudeamus--'Let us be jolly'--of Joseph Victor Scheffel, who is at

present the most popular poet in Germany. Without being presented as

such, these ballads, though complete in themselves, form in their

connection a droll history of the world and of humanity--advancing from

the early outburst of Granite and Basalt, through the boulder of Gneiss

to the Ichthyosaurus and Megatherium. Man then appears as a dweller in

the pre-historic Swiss-Lacustrine-dwelling on poles, where he bitterly

bewails the misfortune of being a pioneer of civilization, and as one

born before the invention of modern comforts.

'In stocks I would gladly grow wealthy,

But exchange is not yet understood:

A good glass of beer would be healthy,

But never a drop has been brewed.'

The Early Phœnician is set forth in a droll song (originally

published under the title of Jonah) which describes the disasters that

befell a guest who could not pay his bill,--presented in arrow-head or

cuneiform characters on six tiles. The old Etruscan era and that of the

ancient German are also painted in a style which, could the truth be

known, would probably be found as genially true to life as it is to the

world-old, infinite spirit of Humour, which moved man in the same

measure in ancient Egypt as in modern England. In these, as in his

serious poems of a more ambitious nature, Joseph Victor Scheffel

manifests a remarkable insight into the inner real life of the past.

Like a geologist, or poet, he infers from trivial relics the probable

feelings and habits of obscure beings or races, or at least imagines

them, and assimilates them to modern usages with rare tact. These

ballads have been printed, sung, and imitated in Germany of late years

to a great extent. Scheffel has in fact founded a school of humorous

poetry--that of the burlesque-scientific and historical--which, though

by no means pretentious, has at least made the world laugh heartily. I

sincerely trust that the following translations will induce the reader

to become familiar with the original.

I have omitted a few poems from the Gaudeamus, as deficient in the

peculiar spirit of fun which characterises all that are here given;

but should the public manifest its approbation of this work, they may

be found in another edition. In their place I have given translations

of a number of eccentric German-student songs of the new school, nearly

all of which have found their way into the popular German song-books of

late years.

CHARLES G. LELAND.

London, October, 1871.

AN INTRODUCTORY MEMOIR.

Joseph Victor Scheffel was born in the year 1826, at Karlsruhe, in

Baden, where his father, a veteran officer, had taken up his residence.

He received his first instruction in the 'Lyceum' of his native place,

a high school which enjoyed at the time a splendid reputation, and was

considered the best in the Grand Duchy of Baden. Whatever may have been

said against one or the other of the professors, the majority were

remarkable men, knowing how to awaken the mental activity of their

pupils. The social life of the 'Lyceists' was free from ordinary

constraints; and the merry youths enjoyed many privileges, which at

other places were strictly reserved for University students.

Nor did they lack any opportunities for intellectual improvement in the

capital of Baden. The theatre was then excellent, and the 'Lyceists'

visited it regularly. Eyen politics agitated the mind of this young

generation. It must be remembered that thirty years ago Baden was the

focus of political life, to which the eyes of every German patriot was

directed; and although Mannheim was the seat of the agitation, the

chamber united at Karlsruhe a number of men, whose names will ever be

held in respect in Baden: Itzstein, Welcker, Bassermann, Hecker, Mathy,

Soiron.

Joseph Victor passed with all the honours, and as one of the best

pupils, all the classes of the Lyceum, and then devoted himself to the

study of law at the University of Heidelberg. There he joined a

so-called academical society of progress, without, however, taking part

in the Baden revolution, which drove so many of his comrades into

exile.

After having passed the Government examination we find our young poet

as 'Rechtspractikant' (practitioner of law) in the little town of

Säckingen. Well might the little provincial place appear dull to a

student coming from the liveliest university of Germany. Still the

splendid scenery of the environs of Säckingen compensated for many

shortcomings. With the numerous friends he won there, Scheffel made

frequent excursions through the valleys which stretch in all directions

from the Feldberg and the Rhine. He proved to be a bold and even

reckless swimmer, passing many a time through the bridge of Säckingen,

saluting the bystanders as he accomplished this daring feat.

In the office of his court, located in an old convent of nuns, Scheffel

found a number of old documents and MSS., and there his first poem was

written, based on one of them: 'Der Trompeter von Säckingen. Ein Sang

vom Oberrhein.'

The success of this first production was complete. It was published at

the time when the 'incense perfume of the pious soul,' as Scheffel

calls the poems of Oskar von Redwitz, had its firmest hold on the

misguided taste of the public. In comparison with this sickly,

effeminate poetry, the simple, natural, and yet intensely poetic

production of Scheffel afforded something like the enjoyment of fresh

mountain air after that of a hot-house. It is true, Scheffel was

at first entirely ignored by the Berlin and Leipzig critics who

assume to sit in judgment over modern German literature (he has,

up to the present day, not even found a place in Brockhaus's

Conversations-Lexicon), but the unsophisticated public recognized the

kernel of pure poetry in Scheffel's unpretentious verses; and his

'Trompeter' is at present the most popular poem in Germany. Its story

is told with extreme simplicity and humour, in blank trochees with

interspersed rhymed poems; it leads us to the forest-town of Säckingen

during the second half of the 17th century, and into the neighbouring

castle of a baron, whose only daughter is wooed and, at last, won by a

young musician, a merry youth, who had been expelled from the

University of Heidelberg on account of his noisy behaviour.

Nothing can be more humorous than the account of the ex-student's life

at Heidelberg, of his duels and his libations beneath the big tun of

the castle,

Bei dem Wunder unserer Tage,

Bei dem Kunstwerk deutschen Denkens,

Bei dem Heidelberger Fass,

or the historical episode of the foundation of Säckingen by Saint

Fridolin, an Irish apostle, sent by Chlodwig with the following message

to convert the Allemannic Germans:

Hatt' sonst nicht die grösste Vorlieb

Für die Kutten, für die Heil'gen,

Aber seit mir die verfluchten

Scharfen Alemannenspiesse

Allzunah um's Ohr gepfiffen,

Seit der schweren Schlacht bei Zülpich,

Bin ich and'rer Ansicht worden,

--Noth lehrt auch die Könige beten.

Schutz drum geb' ich, wo ihr hinzieht.

Und empfehl' hauptsächlich Euch am

Oberrhein die Alemannen.

Diese haben schwere Schädel,

Diese sind noch trotz'ge Heiden,

Macht mir diese fromm und artig--

or the meditations of the cat of the castle, which, as silent witness

of the caresses of the two lovers, thus broods over the enigma of the

kiss:

Warum küssen sich die Menschen?

S'ist nicht Hass, sie beissen sich nicht,

Hunger nicht, sie fressen sich nicht.

S'kann auch kein zweckloser blinder

Unverstand sein, denn sie sind sonst

Klug und selbstbewusst im Handeln;

Warum, also, frag' umsonst ich,

Warum küssen sich die Menschen?

Warum meistens nur die Jüngern?

Warum diese meist im Frühling?

Ueber diese Punkte werd' ich

Morgen auf des Daches Giebel

Etwas naher meditiren.

In the delineations of the various characters of the 'Trompeter'

Scheffel exhibits a gift of true poetical conception, a warmth of

feeling, and a power of description, equalled by few of our modern

poets; indeed, the characters rise before our mind with such

truthfulness, as the idealized types of the people in that corner of

Germany, that one might almost believe one had met all of them during

one's wanderings in the Black Forest, whether it be Werner, the merry

trumpeter, or the crusty old baron, or Anton, the respectable

'Hausknecht.'

Scheffel did not remain long in Säckingen. He quitted the Government

service, and, after passing some time in travels in South Germany,

settled at Donaueschingen as Keeper of the Archives of Prince

Fürstenberg. This town is likewise exceedingly small, the environs are

bare and not to be compared with the romantic scenery of the Upper

Rhine; but at the court of the refined princes of Fürstenberg there

were at all times remarkable men, and the library afforded, in MSS. and

documents, ample means for the study of Old German history, language,

and literature.

To this study Scheffel now devoted himself, and, in combining his

qualities as a poet with that of an historian, created his famous novel

Ekkehard. Based chiefly on the Chronicles of the Monastery of St.

Gallen, it gives us a faithful picture of the social life in South

Western Germany--the most ancient seat and nucleus of German

civilization during the tenth century,--in retaining and reproducing

all the naïveté, freshness, and simple-minded views which are the

charms of these celebrated chronicles, whilst the poet's figures are

marked with that distinct individuality which raises the dry chronicle

to a skilful and poetical tale of human passions and conflicts.

Ekkehard may be compared with the best of Sir Walter Scott's novels.

Another fruit of Scheffel's researches in mediæval literature is his

charming little volume 'Frau Aventiure,' and likewise, although

published much later, 'Juniperus,' the history of a German Crusader,

and his most recent work, 'Die Bergpsalmen.' Both these latter works

(the last one is written in verse) exhibit the same merits as Ekkehard,

but they are laid out on a smaller scale, and are of a more fragmentary

character. 'Frau Aventiure' is a collection of songs, partly jocose,

partly inspired by the most tender feelings, in the spirit of the poems

of the Minnesinger and wandering scholars of the Middle Ages, and is

based on a subtle knowledge of mediæval culture and poetry.

But to his second residence in Heidelberg we must trace the origin of

his most popular work, the collection of songs known under the title of

'Gaudeamus.' A small circle of friends, who met every Wednesday evening

at a supper in the Holländer Hof, near the bridge (and amongst whose

most conspicuous members were the celebrated historian Ludwig Haeusser,

and the venerable pastor of Ziegelhausen, Fr. Schmezer), kindled those

sparks of unequalled humour and merriment--the Rodensteiner, 'Im

Schwarzen Wallfisch zu Askalon,' and the geological songs, which

delighted readers of every class, and found their way into every

student's songbook of Germany. The geological songs owe their origin to

a course of lectures on geology which Pastor Schmezer delivered at the

time. Scheffel regularly attended these lectures of his friend, and the

latter was certain to find as regularly on the following morning of his

lecture a poetical resumé of it on his desk, in the form of a humorous

poem.

What gives such a high value to these songs, and indeed to all the

poetry of Scheffel, is the fact that they, in depicting the joyous vein

in human nature, set forth a faithful abstract, a true poetical

substratum, of the popular life and thought of South-Western Germany.

If any one should fail to comprehend the spirit of Scheffel's poetry

let him go to the 'joyful Palatinate,' and to its ancient capital,

Heidelberg. There he will find the frank, merry, and humorous

characters of Scheffel's poems, and especially the prototypes of that

thirsty soul, the Rodensteiner who pawned his three villages during the

revelries 'Zu Heidelberg im Hirschen,' and finally bequeathed his

thirst to the students. And looking from the ruins of the castle over

the beautiful valleys of the Neckar and the Rhine, he will perhaps

understand the enthusiasm which our poet has for this blessed spot, in

singing:

Und stechen mich die Dornen,

Und wird mir's draus zu kahl;

Geb' ich dem Pferd die Spornen,

Und reit' in's Neckarthal.

In unterirdischer Kammer

Sprach grollend der alte Granit:

'Da droben den wäss'rigen Jammer

Den mach' ich jetzt länger nicht mit.'

In his lair subterranean, grumbling

Old Granite said: 'One thing is sure,

That slopping and slippery tumbling

Up yonder, no more I'll endure.

So wearily wallows the water

His billows of brine o'er the land,

'Stead of prouder and fairer and better

All is turning to slime and to sand.

'That would be a nice limestony cover,

A sweet geological swash,

If the coat of the wide world all over

Were one sedimentary wash.

By and by 'twill be myth and no true thing

What were hills--what was high or was low.

The deuce take their drifting and smoothing;

Hurrah! far eruption I go!'

So he spoke, and to aid him, pro rata,

The brave-hearted Porphyry flew,

The weak-hearted crystalline strata

He scornfully shattered in two.

With flashing and crashing and bellow,

As though the world's end were to dread,

Even Graywack, that decent old fellow,

In terror stood up on his head.

Also Stonecoal and Limestone and Trias

Fast vanished, internally mined.

Loud wailed in the Jura, the Lias,

That the wild fire had scorched him behind.

And Limestone, the marl-plot of chalkers,

Said later, in deep earnest chimes,

'Was there no one, to stop, 'mong you talkers,

This wild revolution betimes?'

But upwards through strata and fountains

Passed the conquering hero with heat,

Until from the sunniest mountains

He gazed on the world at his feet.

Then he shouted with yodling and singing,

'Hurrah! 'Twas courageously done,

Even we can be doing and bringing

What it only needs pluck to be won.'

Es rauscht in den Schachtelhalmen,

Verdächtig leuchtet das Meer,

Da schwimmt mit Thränen im Auge

Ein Ichthyosaurus daher.

The rushes are strangely rustling,

The ocean uncannily gleams,

As with tears in his eyes down gushing,

An Ichthyosaurus swims.

He bewails the frightful corruption

Of his age, for an awful tone

Has lately been noticed by many

In the Lias formation shown.

'The Plesiosaurus, the elder,

Goes roaring about on a spree;

The Plerodactylus even

Comes flying as drunk as can be.

'The Iguanodon, the blackguard,

Deserves to be publicly hissed,

Since he lately in open daylight

The Ichthyosaura kissed.

'The end of the world is coming,

Things can't go on long in this way;

The Lias formation can't stand it,

Is all that I've got to say!'

So the Ichthyosaur went walking

His chalks in an angry mood;[1]

The last of his sighs extinguished

In the roar and the rush of the flood.

And all of the piggish Saurians[2]

Died, too, on that dreadful day;

There were too many chalks against them,

And of course they'd the devil to pay.

And this petrifideal ditty?[3]

Who was it this song did write?

'Twas found as a fossil album leaf

Upon a coprolite.

Als noch ein Bergsee klar und gross

In dieser Thäler Tiefen floss,

Hab'ich allhier in grober Pracht

Gelebt, geliebt und auch gedracht

Als Tazzelwurm.

Tazzelworm is a provincial German word for a dragon. This was a song

sung at the fête of hanging up the sign of the Fiery Tazzelworm at a

little mountain tavern in Rehau, on the road over the Audorfen mountain

meadows, in the Tyrol.

When yet a lake from mountains grand

Ran down yon valleys through the land,

Here I a great flash vulgar thing

Lived, loved, and went a-dragoning

As Tazzelworm,

From Pentling unto Wendelstein,

Were rock and air and water mine,

I walked and flew, and kicked and rolled,

And 'stead of hay I slept on gold,

As Tazzelworm.

My scaly skin was all of horn,

And fire I spit since I was born;

Whatever up the mountain came,

I killed and gobbled it for game,

As Tazzelworm.

But when I so forgot God's law,

And ate up shepherd maidens raw,

Came Noah's food, with all its fogs,

And knocked my business to the dogs,

As Tazzelworm.

And now you see me painted, shine

On Schweinesteiger's bran-new sign.

The shepherd maidens laugh in choir,

And not a mortal fears the fire

Of Tazzelworm.

And oft some learned chap will shout

Before my eyes: 'His games played out!

He lived before the flood washed round,

But men of science never found

A Tazzelworm.'

Weak-minded sceptic! enter here,

Mix up Tyróler wine and beer,

But ere you come to Kuffstein--whew!

You'll find that I have breathed on you,

As Tazzelworm.

And Klausen's landlord sad will say,

'By Jove--whence did those fellows stray?

Their legs are loose--their heads arn't firm,

They all have seen the Tazzelworm,

The Tazzelworm.'

Was hängt denn dort bewegungslos

Zum Knaul zusammgeballt

So riesenfaul und riesengross

Im Ururururwald?

Dreifach so wuchtig als ein Stier,

Dreifach so schwer und dumm--

Ein Kletterthier, ein Krallenthier:

Das Megatherium!

Vide Cuvier, Ossemens fossiles, v. 1, p. 174. tab. 61. The

Megatherium was a gigantic sloth.

What hangs there like a frozen pig,

Or knot all twisted rude?

So giant lazy, giant big,

In the prim--rim--æval wood?

Thrice bigger than a bull--at least

Thrice heavier, and dumb--

A climbing and a clawing beast,

The Megatherium!

All dreamily it opes its jaws

And glares so lazily,

Then digs with might its cutting claws

In the Embahuba tree.

It eats the fruit, it eats the leaf,

Soft, happy, grunting 'Ai!'

And when they're gone, as if with grief,

Occasionally goes 'Wai!'

But from the tree it never crawls.

It knows a shorter way;

For like a gourd adown it falls,

And will not hence away.

With owly eyes awhile it hums,

Smiles wondrously and deep;

For after good long feeding comes

Its main hard work--to sleep.

Oh, sceptic mortal--brassy, bold,

Wilt thou my words deride?

Go to Madrid and there behold

His bones all petrified.

And if thou hast before them stood,

Remember these my rhymes.

Such laziness held only good

In antdiluvian times.

Thou art no Megatherium,

Thy soul has aims divine,

Then mind your studies, all and some,

And eat not like a swine.

Use well your time--'tis money worth,

Yea, work till death you see.

And should you yield to sloth and mirth,

Do it not sloath--somely![4]

Mag der basaltene Mohrenstein

Zum Schreck es erzählen im Lande,

Wie er gebrodelt in Flammenschein

Und geschwärzt entstiegen dem Brande:

Brenn's drunten noch Jahr aus Jahr ein

Beim Wein soll uns nicht bange sein,

Nein, nein!

Soll uns nicht bange sein!

F. v. Kobell. Urzeit der Erde, p. 33.

Es war der Basalt ein jüngerer Sohn

Aus altvulcanischem Hause,

Er lebte lang verkannt und gedrückt

In erdtief verborgener Clause.

Sir basalt was a younger son

Of that oldest race, the Vulcanian,

And he lived for ages oppressed and unknown

In a cavern deep subterranean.

So they goaded and jeered the lover forlorn,--

'Art thou yearning for rainy weather?

You will get but a mitten, and the scorn

Of all the formations together.

'Uncle Rocksalt said to the Lime and smiled,

And the billows sneer it higher,

"How can the Ocean's third-born child

Be a bride to this scum of Fire?"'

What happened next was never known;

But at once into madness crashing,

In a fiery blaze he was upwards thrown,

His wild veins glaring and flashing.

Loud raving he sprang to the air in haste,

And scorching all, fast hurried;

Bursting the strata's mountain waste

Beneath which he long was buried.

And she whom he once had worshipped, broke,

And was crushed as a mere obstruction;

He laughed in scorn, and whirling in smoke,

Stormed on to fresh destruction.

And blow on blow--a terrible roar

Of thousands of storms wild crashing;

The earth burst open and trembled all o'er.

With a shaking and breaking and dashing.

Till in majesty the fiery flood

Flew up from the rifts in fountains,

And scattered with ruins land and flood

Bowed down to the columned mountains.

There he stood and gazed on the blue air free,

And the sun with its sweet attraction,

Then heavily sighed--it blew cool from the sea--

And he sank in petrifaction.

Yet still in the rock may be heard in rhyme

A wondrous tuning and ringing,

As though he would from his youthful time

A song of love be singing.

And a gold yellow drop of natrolite

From the dark stone oft comes peeping;

Those are the tears which Sir Basált

For his crushed love ever is weeping.

Einst ziert' ich, den Aether durchspähend,

Als Spitze des Urgebirg's Stock,

Ruhm, Hoheit und Stellung verschmähend,

Ward ich zum erratischen Block.

Once high on the mountain-peak rising,

In sunlight I shone like a flame;

But height and position despising,

A wandering boulder became.

They say of a thinker's bold sallies,

He goes where the ice will not bear;

I was beckoned to false hollow valleys,

By snow maids, seductive and fair.

Thus driven by furious fancies,

I went down the hill with a shout;

But atoned for my youthful romances

By a thousand years rolling about.

Cried the Glacier, his teeth sharply showing,

Here, my blade, you'll be polished right well,

And from my moraine-offal going,

As a stranger be borne from the dell.

Then be scratched and be scraped and be driven,

I rolled to a rock that was cracked,

But with blows was knocked upward to heaven,

Be twisted, be puffed, and be whacked.

Just try to be proper and decent

In chaotic upheavals of mud!

Down I sunk, down to periods recent,

When the ice wall went off in the flood.

And rough is the rôle he unravels

Who plays in an ice part--ah, me!

On a flake I set out on my travels,

And the ice cake soon melted at sea.

Plimp, plump! down I went to the bottom,

For ages lay sleeping in clay,

Until the heat finally caught 'em,

And Glacier and Flood dried away.

Then the Sun, with a hotter light blazing,

Shone down where the billows once played;

And with the rhinoceros grazing,

The mammoth was seen in the glade.

Now we from the driving ice fast-time

Are useful, although it be late,

And to heathen and Christian for pastime

Give stones for the Church and the State.

* * * * *

Two geologists made up this ditty

In the vale between Aaré and Reuss;

And the inn where they sang it, so witty,

Was all built of boulders of gneiss.

They sang with deep feeling dramatic,

To the landscape of Findling so fine;

Then went like two boulders erratic,

Both tumbling and stumbling with wine.

Ich armer Komet in dem himmlischen Feld

Wie ist's doch so windig mit mir bestellt!

Ich leb' in steten Sorgen,

Mein Licht selbst muss ich borgen ...

Ich erscheine nur von Zeit zu Zeit

Dann muss ich wieder fort in die Dunkelheit.

I a poor comet on high, you see,

How windy and wild is my destiny!

I live in constant sorrow,

My light e'en I must borrow;

I only appear from time to time,

Then must wander away in gloom and grime.

By lady Sun I'm ever distracted,

And to her by power magnetic attracted;

Yet she will not endure

That I should rise up to her,

I must long for her from flights afar,

For, alas! I'm in fact an eccentric star.

The fixed stars all in bitter fun

Declare I'm a lost and prodigal son.

They say I still go tottering

Here, there, among them pottering,

And where I once on my way have been

Nothing but dimness and darkness are seen.

The planets regard me with scorn, and say

That I always come bothering in their way.

Dame Venus and her sisters

Call me one of those crazy twisters,

'His tail is too great, and his nucleus too small.

Such an ill-made night stroller's worth nothing at all.'

That I'm a scandal they cry or lisp,

And call me a dreamer or Will-o'-the-wisp.

And down on earth a-squinting,

I see the learned ones printing,

'He's neither firm nor settled, nor would be,

Though he should spin to all eternity.'

E'en Humboldt, who handles nothing lightly,

Treats me in his Cosmos far from politely,

And should he write--I ask all--

And am I such a rascal?--

'The wandering comet, much thinner than foam,

With the smallest corps takes up the greatest room.'

But bide yon star-gazing spitefuls!--bide?

You don't know me yet from the innermost side.

Some day I'll catch you--curse ye?

And make you cry for mercy?

Then you'll go through me, and I'll meet your hope,

For with meteors I'll smash up your telescope.

Ich weiss eine friedliche Stelle

Im schweigenden Ocean,

Krystallhell schäumet die Welle

Zum Felsengestade hinan.

I know of a peaceful island

Afar in the silent sea,

Where around the rocky highland

Pure billows are foaming free.

In the harbour no ship is resting,

No sailor is on the strand;

And thousands of white birds nesting,

Are the guards of the lonely land.

Ever pondering pious questions,

They labour right faithfully,

For blessed are their digestions,

And flowing like poetry.

For the birds are all 'Philosophen,'

To the principal precept inclined;

If the body be properly open,

Then all will go well with the mind.

And the children pursue more enlightened

What their fathers in silence begun.

To a mountain it rises, and whitened

By rays of a tropical sun.

In the rosiest light these sages

Look down at the future and say,

In the course of historical ages

We shall fill up the ocean some day.

And the recognition of merit

Is theirs in these later days,

For in Suabian land we hear it

When the Böblinger Rapsbauer[5] says:

'God bless you--guano sea-gull,

Of the far away coast of the west:

In spite of my countryman Hegel,

The stuff which you make is the best.'

Bestreuet aie Häupter mit Asche,

Verhaltet die Nasen euch bang,

Heut giebt's bei trübfliessender Flasche

Einen bituminösen Gesang.

Strew, strew all your heads with ashes,

Hold your noses firmly and long;

I sing by the lightning's pale flashes

A wild and bituminous song.

The wind of the desert is sweeping,

Like fire by the dead Dead Sea;

There a Dervish appointment is keeping,

With a maiden from Galilee.

'Twas ever a salty engulpher,

In horrors excessively rich;

In Lot's time there were lots of sulphur,

And to-day it is piteous on pitch.

No washwoman comes with a bucket,

No thirsty man comes with a mug;

For the one who would venture to suck it

Would wish that his grave had been dug.

Not a breath of a breeze is blowing,

No waves on the waters fall,

Though a strong smell of naphtha is flowing,

They said, 'We don't mind it at all.'

Two dark brown lumps were lying

Like rocks on the Dead Sea shore,

And while tenderly loving and sighing

They sat down there--to rise no more.

For the rock was pitch-naphtha which would not

Allow them to stir e'en a stitch,

And seated in concert, they could not

Rise up above concert pitch.

Then all the disaster comprising,

They wailed aloud: 'Allah is great!

We stick and we stick--there's no rising,

We stick and forever must wait!'

There they sat like a lost pot and kettle,

Their wails o'er the wilderness passed;

They mummified little by little,

And were turned to Asphaltum at last.

A little bird flew for assistance,

Away to the townlet of Zoar;

But benumbed it fell down in the distance,

It smelt so, it fluttered no more.

And shuddering and pale as if flurried,

A pilgrim procession went in--

From the smell of the benzine it hurried

So fast you'd not say 't had been seen.

MORAL.

In love or in turning a penny

Always study the field of your luck;

In petroleum and naphtha full many

Ere now have been terribly 'stuck.'

A Lacustrine Lyric.

Dichtqualmende Nebel umfeuchten

Ein Pfahlbaugerüstwerk im See

Und fern ob der Waldwildniss leuchten

Die Alpen in ewigem Schnee.

Damp smoky-like vapour is streaming

O'er piles in the waters below.

And far o'er the forest are gleaming

The Alps in perpetual snow.

A man on a wood block is sitting

In furs, for the wind-draught is strong:

With a flint chip a deer-horn splitting,

While he mournfully murmurs a song:

'See my face swollen up like the devil!

Remark how in wind, as it spins,

The history of Europe primæval

With rheumatics and toothache begins!

'It is true that with stone-axe employment,

Or with celts I can hammer my way,

But no rational means of enjoyment

Is known to the world in this day.

'Wild animals, wolfish or beary,

Howl fierce round my forest-tree brown;

And when I build huts on the prairie

The buffaloes batter them down.

'And so, to the beaver a debtor,

I build for myself in the flood;

The further from firm land the better,

A pile-dam in shingle and mud.

'But much I am forced to dispense with

What ages to come will behold;

I'd be glad of a good sword to fence with,

But as yet there's no iron or gold.

'In stocks I would gladly grow wealthy,

But exchange is not yet understood:

A good glass of beer would be healthy;

But never a drop has been brewed.

'And then how my horror increases

To think of our cookery rude!

How we crack a pig's bones into pieces,

And suck out the marrow for food.

'And how can the soul be expected

To form an ideal of taste,

When nothing but poles are erected

Around in a watery waste?'

He sang With a voice hoarse and failing,

With rheumatics his temper was grim;

Two wild bears slipped over the poling,

And, climbing, came snapping at him.

Down he threw, as with anger he flushes,

Axe, deer-horn, and drink-cup of clay,

Sprang, splash! like a frog to the rushes,

And paddled with curses away.

Where once the Lacustrians plying,

Drove many a pillar or stake,

A strata of relics is lying

'Neath the mud and the turf of the lake.

And he who this song made for singing,

Himself through those layers has mined,

And the relics to daylight upbringing,

Felt pride as a mortal refined.

Licht glühte des Helicon Klippe

In Mittagspurpur und Blau.

Light gleamed upon Helicon's mountain

In the purple of mid-day and blue,

As by Aganippe's clear fountain

A shepherd boy slept in the dew.

In seeking the lambs of his master,

From Askra, he'd roamed through the wood,

But now all the strength of the pastor

By the heat of the sun was subdued.

Then from sun-lighted fields of old story,

Came Nine who were heavenly fair;

Their limbs were of beauty a glory,

And a glory of gold was their hair.

They moved as in musical numbers,

To the grove, Aganippe across,

And laid by the youth in his slumbers,

Their gifts in the emerald moss.

The first a bronze style like a feather,

The second an inkstand of brass,

The third a neat album in leather,

The fourth a Bohemian glass,

The fifth gave red wax and a taper,

The sixth a gold eye-glass and sheath,

The seventh cigars wrapped in paper,

The eighth a sweet asphodel wreath.

The ninth bent her knee in the heather,

And kissed him full tender and true,

Then vanished on high in the æther

As angels invariably do.

Up sprung the young dreamer and panted

And sang in a measure sublime,

And swung, like a creature enchanted,

A twig of wild laurel in time.

Then up came his friends 'mong the peasants

And praised his good fortune that day,

And led him with all his fine presents

To Askra in festive array:

And there all the wisest or rudest,

Considered the matter in doubt,

Until the Nomarchos as shrewdest

To Böotia this sentence gave out.

'To him heaven opens a portal,

No more at the flocks let him look.

He is destined to be an immortal,

Write poems--and publish a book.'

They found him a rod neat and slender,

In long garments they gave him to God;

Then he wrote them the Farmer's Calénder,

And Theogony too--Hesiod.

BY ATHANASIOS CHRISTOPOULOS.

πλουτον δεν θελω

Δοξαν δεν θελω

Ουτ'εξουσιαν

Ποτε καμμιαν.

Δεν θελω γνωσιν

ουτε καν τοσην

̔Οσ'ειν του φυλλου

Κι ̔οσ'ειν του ξυλου.

Τουτες ̔η κρυες

Η φαντασιες

̔Οσω ευφαινουν

Τοσω πικραινουν

Reichthum und Ehre

Nimmer ich 'gehre;

Herrschaft und Würde;

Wär mir nur Bürde.

I never desire

Wealth or fame to acquire

Honour and station

Were but vexation.

And to be learned

I'm no more concerned,

Than in the thicket

Are field-mouse and cricket.

All those cold cheating

Phantom forms fleeting,

'Stead of reviving,

Are vexing and driving.

θελω ειρηνην

Ψυχης γαληνην

Χορους ερωτων

Τρελαις και κροτον.

Θελο τραγουδια,

Κηπους, λουλουδια

Και χωραταδαις

Σταις πρασιναδαις.

Τουτα λατρευω

Τουτα γηλευω

Κ' ̔εις τουτ απανω

Θελ να ποθανω.]

To me be given

The sweet peace of heaven,

A heart quiet resting,

Frolic and jesting!

Dramas sweet ringing,

Ball play and singing,

Music entrancing,

Wild whirling dancing!

Such I require,

Such I desire,

Rose-crowned, so

To the bier I would go!

Feucht hing die Sonne. Des Novembers Schauer ging

Mit leisem Frösteln durch das Land Hetruria.

Anpumpen, to pump, is a German slang term for borrowing. Pumpus was

the name of an Etruscan prince.

Dim was the sunlight, and November shivering

Ran with a light frost o'er the land Etruria,

A gentle head-ache of the last night's origin,

Went threading through the air with weary pinion-beat;

A weak and bankrupt feeling lay on hill and dale,

The sacred olive tree, whose last thin yellow leaf

Thrilled in the wind, stretched mournfully its branches forth

Barren and bare, as wanting what was needfullest;

E'en the street pavement was suspicious. To the eye

The old primæval basalt's firm material

Seemed changed that day to very porous carbonate,

And all things--all things--all things had a seedy look.

Such was the day when, in the early morning hour,

A weary wight from Populonia's portal went;

In vain the guard on the Cyclopean city wall

Cast on the lord a hopeful glance for drink-money,--

He drew him back--and glared at him--and gave nothing.

There where the road goes winding towards Suessulæ,

And some old priest's strange ten-pin-towered monument

Mournfully casts a shadow o'er the bleaching field,

He paused awhile--in the reed grass stuck his javelin,

And in his chlamys foldings sadly sought awhile,

Then sought again--then made one more experiment--

Yet found not what he sought for.

Oh, who knows the pain

Which rears up horse-like in a brave Etruscan heart

When all things--all things--all things tend to poverty,

And the horror of the Empty in the pocket dwells

Where once the sesterce gaily by the denar rang!

The helm removing from his heavy-laden head,

He raised his right hand to his forehead thoughtfully,

His tearful glance went back to Populonia,

And lurid lightning flickered from his hero-eye.

'Oh thou Chimæra Tavern!' said he mournfully,

'Was that the end of 't? Meant that the flock of birds

Which three days past went croaking to the left hand side?

Said that the oxen's, entrails enigmatical?

Oh thou Chimæra Tavern, what is pleasanter

Than entering as a guest into thy guest-chamber?

There neatly waits the experienced tavern-keeper;

And heroes round the cool wine are convivial;

Around the noble hill-descended Dimeros.

From drinking mouths comes wisdom flowing thoughtfully,

While at the upper linen-covered long table,

Where Tegulinum's augur to the latest hour,

Sternly defying, stands it like a bronze column,

And sings in glees; that wonderful astrologer;--

Oh thou Chimæra Tavern, tell--if possible--

Whither goes hurrying?--ha! what was't I nearly spoke?--

What word--thrice god-curst word--on which--oh horrible!

Hangs the Etruscan fate--ay, that's it--Ready Money!

Oh Fufluns! Fufluns! Bacchus--dark and terrible!

Now all is gone--away and gone away--ha--hummm!

And yet a deed, I swear 't shall now by me be done,

Such as the stupid world in dream has never dreamed,

Shuddering and cold--my name shall to posterity

By this one deed be carried, awful, horrible,

As true as I by this priest's grave am standing now,

I--Pumpus of Perusia, the Etruscan prince.'

He said--and went. A sunbeam fell uncannily

On spear and helm. Cold light was o'er the cypresses,

Deep the gale sighed--grave-deep--like moaning far-away.

The world was innocent then. As yet no one had known

The law of contracts with its windings intricate,

And e'en the sage in silver beard was ignorant

Of loans or such a deed as money borrowing;

Yet on that day i' the forest by Suessulæ

One hero by another bold was borrowed from!

This is the song of Pumpus of Perusia.

Als die Römer frech geworden,

Zogen sie nach Deutschlands Norden,

Vorne beim Trompetenschall

Ritt der Generalfeldmarschall

Herr Quinctilius Varus.

When the Romans, rashly roving,

Into Germany were moving,

First of all--to flourish, partial--

Rode 'mid trumps the great field-martial,

Sir Quinctilius Varus.

But in the Teutoburgian forest

How the north wind blew and chor-rused;

Ravens flying through the air,

And there was a perfume there

As of blood and corpses.

All at once, in sock and buskins

Out came rushing the Cheruskins

Howling, 'Gott und Vaterland!'

They went in with sword in hand,

Against the Roman legions.

Ah, it was an awful slaughter,

And the cohorts ran like water;

But of all the foe that day,

The horsemen only got away,

Because they were on horseback.

O Quinctilius! wretched general,

Knowest thou not that such our men are all?

In a swamp he fell--how shocking!

Lost two boots, a left-hand stocking.

And, besides, was smothered.

Then, with his temper growing wusser.

Said to Centurion Titiusser,

'Pull your sword out--never mind,

And bore me through with it behind,

Since the game is busted.'

Scaevola, of law a student,

Fine young fellow--but imprudent

As a youth of tender years,

Served among the volunteers,--

He was also captured.

E'en his hoped-for death was baffled,

For ere they got him to the scaffold

He was stabbed quite unaware,

And nailed fast en derrière

To his Corpus Juris.

When this forest fight was over

Hermann rubbed his hands in clover;

And to do the thing up right,

The Cheruscans did invite

To a first-rate breakfast.

But in Rome the wretched varmints

Went to purchase morning garments;

Just as they had tapped a puncheon,

And Augustus sat at luncheon,

Came the mournful story.

And the tidings so provoked him,

That a peacock leg half choked him,

And he cried--beyond control--

'Varus--Varus--d--n your soul!

Redde legiones!'

His German slave, Hans Schmidt be-christened,

Who in the corner stood and listened,

Remarked, 'Der teufel take me wenn

He efer kits dose droops acain,

For tead men ish not lifin.'

Now, in honour of the story,

A monument they'll raise for glory.

As for pedestal--they've done it;

But who'll pay for a statue on it

Heaven alone can tell us.

Im schwarzen Wallfisch zu Ascalon

Da trank ein Mann drei Tag',

Bis dass er steif wie ein Besenstiel

Am Marmortische lag.

In the Black Whale at Ascalon

A man drank day by day,

Till, stiff as any broom-handle,

Upon the floor he lay.

In the Black Whale at Ascalon

The landlord said: 'I say,

He's drinking of my date-juice wine

Much more than he can pay!'

In the Black Whale at Ascalon

The waiters brought the bill,

In arrow-heads on six broad tiles

To him who thus did swill.

In the Black Whale at Ascalon

The guest cried out: 'O woe!

I spent in the Lamb at Nineveh

My money long ago!'

In the Black Whale at Ascalon

The clock struck half-past four

When the Nubian porter he did pitch

The stranger from the door.

In the Black Whale at Ascalon

No prophet hath renown;

And he who there would drink in peace

Must pay the money down.

Ein Römer stand in finstrer Nacht

Am deutschen Grenzwall Posten,

Fern vom Castell war seine Wacht,

Das Antlitz gegen Osten.

Barritum civere vel maximum. Qui clamor ipso fervore certaminum a

tenui susurro exoriens paullatimque adolescens situ extollitur fluctuum

cantibus illisorum.--Ammian. Marcellin. xvi. 12.

A Roman stood in midnight lost,

For the German line selected;

Far from the castle was his post,

His glances east directed.

He heard a murmur and a fuss,

And distant voices ringing--

No pæan of Horatius;

Right savage was the singing:

'Ha--haw--haw! we got ye safe at last,

Got ye by the skirt, too--got ye firm and fast,

You scamp, you!'

With a maiden of the Chatten race

He oft in love had meddled,

And sought her in a lonely place,

Disguised as one who peddled.

Now came the vengeance--one, two, three!

Now o'er the wall they're climbing,

Screeching like cats in agony,

With hatchet rattle chiming.

'Ha--haw--haw! we got you safe at last,

Got you by the skirt, too--got you firm and fast,

You scamp, you!'

He drew his sword, he blew his horn,

And like a warrior shook him;

But vain were pluck and Roman scorn--

The savage Deutschers took him.

They tied him fast, and in a word

Away with him went bounding,

And when the cohort came, it heard

Far through the pine-trees sounding:

'Ha--haw--haw I we've got him safe at last,

Got him by the skirt, too--got him firm and fast,

You scamp, you!'

In the holy grove, toward the east,

Were all the Chatten foemen,

To celebrate the Odin feast

Of Jul, with blood of Roman.

He felt himself like roasted meat

'Twixt savage grinders going;

Out sprang his blonde-haired darling sweet,

And cried with tears hot flowing:

Ha--haw--haw! I've got you safe at last,

Got you by the skirt, too--got you firm and fast,

You scamp, you!'

Then all the Chats were deeply moved

To see her thus accost him,

And said, 'Since they so well have loved,

'Twould be a shame to roast him,

Here let them wed.' This ends the tale.

'Yes, wed at once before us;

And all day long throughout the vale

We'll sing as bridal chorus,

"Ha--haw--haw! were got you safe at last,

Got you by the skirt, too--got you firm and fast,

You scamp, you!"'

DAS HILDEBRANDLIED.

.... Hiltibraht enti Hathubrant.

Hildebrand und sein Sohn Hadubrand,

Hadubrand,

Ritten selbander in Wuth entbrannt,

Wuth entbrannt,

Gegen die Seestadt Venedig.

Hildebrand und sein Sohn Hadubrand,

Hadubrand,

Keiner die Seestadt Venedig fand,

--nedig fand,

Da schimpften die beiden unfläthig.

Hildebrand and his son Hadubrand,

Hadubrand,

Rode off together with sword in hand,

Sword in hand,

All to make war upon Venice.

Hildebrand and his son Hadubrand,

Hadubrand,

Neither could find the Venetian land,

'Netian land,

Dire were their curses and menace.

Hildebrand and his son Hadubrand,

Hadubrand,

Got drunk as lords in a jolly band,

--jolly band--

All the while swearing and bawling;

Hildebrand and his son Hadubrand,

Hadubrand,

Drunk till they neither could walk or stand,

Walk or stand,

Home on all fours they went crawling.

O liberales clerics

Nû merchet rehte wi dem si

Date: vobis dabitur

Ir sült lan offen iwer tür

Vagis et egentibus

So gewinnet ihr das himelhûs,

Et in perenni gaudio

Alsus alsô, alsus alsô!

Pfarrherr, du kühler, öffne dein' Thor,

Fahrende Schüler stehen davor.

Fahrende Schüler, unstete Kind,

Singer und Spieler, wirbliger Wind.

Parson Sir Prudence, open your gate!

Travelling students your welcome await!

Travelling scholar, whimsical child!

Singer and stroller, the wind-whirling wild.

Iron throats for drinking--bellies like fires,

Gold souls unshrinking--which no one desires,

Thin garments sporting--weather so raw,

Ah--and our courting--on hay and in straw!

Parson, Sir Prudence, open your gate!

Travelling students your welcome await!

Suabia, Franconia have given us food,

Sans ceremonié--an all eating brood;

Fed us, rapacious, God keep them from harm!

Like the voracious and wild locust swarm,

What we've o'erpowered--once fertile and fair,

All is devoured--shorn barren and bare.

Parson Sir Prudence, open your gate!

Travelling students your welcome await!

Makest not thy oven free, miserly owl,

We'll haul thee to Coventry straight by the cowl.

Pull off your breeches, the shoes from your feet,

Hang them like fitches out here in the street;

He who would own it and do us a hurt,

He must atone it in stockings and shirt.

Parson Sir Prudence, open your tower!

Travelling students your bars will o'erpower!

Ho, ho, heiadihoh!

Avoy, avoy, alez avanz!

Alsus also, alsus alsus also!

Ho ho heiadihoh, hoh, ho, ho!

Hu weh! mir ist des Tages bang!

Tret ich hinaus in den schweigenden Bergwald

Den kaum das erste Frühlicht erhellet,

Wehe! noch lagert die Hitze von Gestern

Ueber versengtetn Moos und Gesträuch.

Ah me! what a dull day it is!

If I go out in the wood on the mountain

When the tops shine in the earliest sunlight,

Ah! there still lingers the dry heat of yestern

On the singed mosses and withering shrubs,

And all around me come m/idges by thousands,

Stinging and bold,

As if the hot sun were sprinkling in sparkles.

Wide gaping crevices split the earth round us;

Grass dries to hay before they can mow it,

And in the air sweeps

Dust ....

Ah me! what a dull day it is!

If I seek by the trunk of the giant-grown beech-tree

A cool place to sit on the rough-hewn stone bench,

Where by the eight-cornered slab of the table

The brethren merrily rest in the forest,

Ah! there the stone rays a heat that is horrible,

Cannot endure me!

All because I, when just seated, so nimbly

Jumped in a hurry.

Grasshoppers sit, sound asleep, by the road-side

Quiet as can be.

Dull ....

Ah me! what a dull day it is!

These are the times, hey, when people and cattle

Are scorching red-hot like the irons in a smithy!

Pour on them drops or long floods of cold water,

All would be swallowed and nothing be quenched.

Ah!--hey!--the matin bell still is a-ringing,

And I'm seized with a powerful yearning already

To go to the cloister, and down to the cellar!

Whether I'll tarry there steadily drinking

Until the night comes,

Or a loud clattering thunder in heaven

Breaks up this wearisome terrible heat,

I don't know,

Only my thirst is

Dreadful ....

Ah me! what a dull day it is.

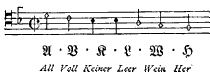

--'Wem das Kloster Maulbrunn bekandt, der hats können mit seinen Augen

sehen, wie in dem Vorhoff selbiger schönen erbauten Kirchen oben im

Schwibbogen unter anderen Gemälden auch eine Gans abgemalt steht, an

welcher eine Fläsch, Bratwürst, Bratspiss und dergleichen hangen, neben

einer zur nassen Andacht gar wohl componirten Fuga folgenden Tenors mit

ihrem unterlegten Text, gleichwohl nur den initialibus literis A. V. K.

L. W. H. welches villeicht dieser durstigen Münch und Religiosen

Commentarius gewest, über das Hohelied Salomonis: Comedite amici et

bibite et inebriamini charissimi, &c., &c.'--Tob. Wagner, Evangel.

Censur der Besoldischen Motiven, &c. Tübingen, 1640.

All Voll Keiner Leer Wein Her

[English.] He who knows the Abbey Maulbrunn may have seen with his own

eyes how in the fore court of this beautifully built church, above in

the double arch, there is painted, among other pictures, that of a

goose by which hang a bottle, sausages, a roasting spit, and like

things, near a well-composed fugue adapted to wet devotion, on the

following theme, with the subjoined text, although with only the

initial letters

A. V. K. L. W. H.

Or Alle Voll, Keiner Leer, Wein Her! meaning "All full, No one empty,

Bring Wine here!"--which was perhaps the commentary of these thirsty

monks and pious men on the Canticle of Solomon: Comedite amici et

bibite et inebriamini charissimi, &c, &c.--Tobias Wagner, Evangel.

Censur der Besoldischen Motiven, &c. Tübingen, 1640.

Im Winterrefectorium

Zu Maulbronn in dem Kloster

Da geht was um den Tisch herum

Klingt nicht wie Paternoster;

Die Martinsgans hat woklgethan,

Eilfinger blinkt im Kruge,

Nun hebt die nasse Andacht an

Und alles singt die Fuge:

A. V. K. L. W. H.

Complete Pocula!

In the winter refectorium

Of Maulbronn, in the cloister,

One hears a merry sound and hum,

Not like a paternoster.

The Martin's goose has tasted well,

Eilfinger wine they're bringing;

Now let the wet devotion swell,

While all the fugue are singing:

A. V. K. L. W. H.

Complete Pocula!

The Abbot Duckfoot--Holy John,

Came waddling in and grumbling:

'What is't so late, when the feast is done,

To fiddles ye are mumbling?

Cease! ye disturb the Doctor Faust,

In the garden tower behind there;

If from his studies he be roused,

No gold will he e'er find there.

A. V. K. L. W. H.

Cavete scandala!'

Herr Faust sat backwards by the wall,

Alone with pleasure-drinking,

But now the sorcerer, pale and tall,

Held forth the wine red blinking.

Said he: 'I've studied making gold,

By magic sought to win it;

But now I see that I am sold,

And that there's nothing in it.

A. V. K. L. W. H.

This is the gold--aha!

'I find from Hermes Trismegist

Gold yields itself unwilling;

The sun is the true alchemist,

All fluidly distilling.

When through our veins 't has glowed and relled;

With Eilfinger we try it;

Then you have gold, have real gold,

And honourably come by it.

A. V. K. L. W. H.

Hæc vera practica!'

Then laughed the Abbot. 'That sounds fair;

It sets me too to drinking,

For All Voll, Keiner Leer, Wein Her!

Is a wet fugue, I'm thinking.

As Faust's gold-proverb it shall be

Painted by the officials

In the transept. All the melody

Is found in the initials.

A. V. K. L. W. H.

Sit vino gloria!'

This ballad is founded on an incident narrated in the description of

the Palatinate by Merian (1645), where, speaking of the village Ketsch,

he tells us that--'The Counte Palatine Otto Heinrich, afterwards

Kurfürst, sailed in the yeere 1530 to the Holie Lande and to Jerusalem.

Returning thence, hee came over the greate open sea where a shipp from

Norwaie mett him, and from it there came this crye: "Flye, flye, for ye

fatt Enderle von Ketsch cometh!" Now, the Counte Palatine and his

Chancellor Mückenhäuser knew a godless wretche of this name who dwelte

at Ketsch, and therefore whenn they returned home they inquired of ye

fatt Enderle and of the tyme of his deathe, and observed that itt

agreed withe the tyme whenn they did heare the crye upon ye sea, as

Weyland, a Professor of Heidelberg; hath narrated in divers wrytings

which hee left behinde.'

The translator has endeavoured to give this version of the extract from

Merian in English corresponding to the style of the original old

German.

Jetzt weicht, jetzt flieht! Jetzt weicht, jetzt flieht

Mit Zittern und Zähnegefletsch:

Jetzt weicht, jetzt flieht! Wir singen das Lied

Vom Enderle von Ketsch!

CHORUS.

'Away--along! Away--along!

With, trembling, your jaws on the stretch.

Away--along! We sing the song

Of Enderle von Ketsch!

SOLO.

Ott Heinrich the Pfalzgrave of Rhine--oh!

Spoke out of a morning; 'Rem blem!

I'm tired of the sour Hock wine--oh!

I'm off for Jerusalem.

'Far lovelier, neater, and nicer

Are the maids there who give you the cup;

Oh, Chancellor! oh, Mückenhäuser,

Five thousand gold ducats pack up.'

And as before Joppa they anchored

The Chancellor held up his hand:

'Now drain to the dregs your last tankard,

For the ducats are come to an end.'

Ott Heinrich said, 'Well, and no wonder,--

Rem blem! what remains to be seen!

We'll paddle for Cyprus out yonder,

And make a small raise on the Queen.'

But just as the galley was dancing

By Cyprus, in beautiful night,

A storm o'er the billows came prancing,

With thunder and flashes of light.

In a ghastly wild glare, by the landing,

A black ship came rushing along;

There a ghost in his shirt-sleeves was standing,

And howling a horrible song.

CHORUS.

'Away--along! Away--along!

With trembling, your jaws on the stretch.

Away--along! I sing the song

Of Enderle von Ketsch!'

SOLO.

The thunder grew calmer and wiser,

Like oil lay the water below;

But oh, the old brave Mückenhäuser

The Chancellor felt sorrow and woe.

The Pfalzgrave stood up by the rudder,

And gazed on the billowy foam;

'Rem blem! all my soul's in a shudder,

Oh, Cyprus--I travel for home!

'God spare me such terrible menace--

I'm wiser through trial and pain;

Back, back on our course to old Venice--

I'll ne'er borrow money again.

'And he who 'mid heathens at table

His cash to the devil has slammed,

Let him hook it in peace while he's able,--

It sounds like all hell and be damned!'[6]

RODENSTEIN.

I.

Wer reit't mit zwanzig Knappen ein

Zu Heidelberg im Hirschen?

Das ist der Herr von Rodenstein,

Auf Rheinwein will er pirschen.

Who is it rides with twenty spears,

Straight to the Stag Inn going?

Von Rodenstein and cavaliers,

To set the Rhine wine flowing.

Hurrah! the tap! Give wine to me,

The best of all your tillage!

A whole year long we'll merry, merry be,

Although it cost a village.

I've Pfaffenbeerfurt, o' my soul!

And Reichelsheim so loyal.

The trumps and psaltery played to wine,

Although no drums were beating;

For six months sat the Rodenstein,

To Rhine wine measures treating.

And when six months in frolic fled

He for the reckoning halloed,

And 'Now the fun is o'er,' he said,

'For Reichelsheim is swallowed!

Reichelsheim's gone!

Gone with a race!

Reichelsheim loyal, the schnaps-making place,

Old Reichelsheim is swallowed!

'Hollaheh! it's gone, at worst;

We've all our way of thinking;

They never say a word for thirst,

But always talk of drinking.

Reichelsheim's gone!

Gone with a race!

Reichelsheim loyal, the schnaps-stilling place,

Old Reichelsheim is swallowed.'

Hol-li-roh!

III.

Wer wankt zu Fusse ganz allein

Gen Heidelberg zum Hirschen?

Das ist der Herr von Rodenstein,

Vorbei ist's mit dem Pirschen.

Who trots afoot alone to dine,

Still to the Stag a rover?

That is the Herr von Rodenstein,

But all his drinking's over.

'Landlord, your smallest beer for me

And one poor herring salted;

I've drunk so much of your Malvasie,

That all my taste has halted.

'What once the greatest thirst was called

At length has vanished hollow;

The last place in the Odenwald

I find I cannot swallow.

'Now call me in a notary

To write my will with prudence:

Pfaffenbeerfurt to the University,

And my thirst unto the students.

'It moves even me, though old and gray,

To see the cups they're swinging,

And if they drink like me, some day

They'll all in it be singing:

"Pfaffenbeerfurt is gone!

Pfaffenbeerfurt is done!

Pfaffenbeerfurt the dung-sparrow hole, as 'tis called,

Pfaffenbeerfurt the gem of the Odenwald,

Pfaffenbeerfurt is finished and swallowed.

"Hollaheh! it's gone at worst;

We've all our way of thinking;

They never say a word for thirst,

But always talk of drinking.

Pfaffenbeerfurt is gone!

Pfaffenbeerfurt is done!

Pfaffenbeerfurt the dung-sparrow hole, as 'tis called,

Pfaffenbeerfurt is finished and swallowed."'

Hol-li-roh!

Und als der Herr von Rodenstein

Zum Frankenstein sich wandte,

Empfing er seinen Ehrenwein

So wie es Brauch im Lande.

And as the Herr von Rodenstein

To Frankenstein was going,

They served the 'wine of honour' fine,

To him great honour showing.

In Beerbach by the Town Hall brought

The Zentgrave with the people,

The owl-jug. The old lord laughed out--

'Bring up your sour tipple!

Ye fellows, let your voices sound!

The welcome goes around, around;

Hallo! the peasants owl-cup

Goes round, goes round!'

And when in the Lime of Frankenstein

The merry riders found them,

The castle-youth in garments fine

Came thickly thronging round them.

A jack-boot made of porcelain

They brought--he did not falter,

But drained it as he drew the rein,

While all sang out the psalter;

'Ye fellows, let your voices sound!

The welcome goes around, around;

Holliro! the boot-cup

Goes round, goes round!'

In the castle-court another swarm

Came with loud musket-banging,

While on the castle-master's arm

The second boot was hanging.

With their finest wine they filled the boot,

And grandly spoke the Ritter--

'Sir Neighbour--not upon one foot!

And this does not taste bitter.

Ye fellows, let your voices sound!

The welcome goes around, around;

Holliro! the boot-cup

Goes round, goes round!'

The Rodenstein drank out the cup;

'God bless your nose for ever,

For mine was nearly doubled up

In such a flowing river.

Now to your castle-hall, and there

We'll rest from this pace so killing;

I think in it your lady fair

The Charlemagne's horn is filling.

So once more let your voices sound!

The welcome goes around, around;

Holliro! the emperor's drink-horn

Goes round, goes round!'

Next morning lay a mantle white

Of fog o'er hill and valley;

They brought the album to the knight,

And in't he wrote this sally

With trembling hand--' Be this in sign

I folded here my banners,

And praise the House of Frankenstein,

As one of taste and manners.

Their welcome cheered my heart and head

So much I could not find my bed!

Holliro! not only boot-cup,

But everything went around!'

Hol-li-roh!

Und wieder sass beim Weine

Im Waldhorn ob der Bruck

Der Herr vom Rodensteine

Mit schwerem Schluck und Gluck.

Again there sat hard drinking,

All in the Hunting Horn,

The Rodenstein ne'er winking,

Accurst with thirst forlorn.

The landlord wept the hour

He came his wine to try--

'He sits there like a tower,

And drinks me high and dry.

'How will it end? by thunder!

He never pays me--no!

I'll have to pawn his plunder,

Or else he will not go.'

The beadle went to work in

The tap-room of the Horn:

'Pull off your velvet jerkin,

Your boots, and all you've worn.

'Pull off the mantle round you,

Your gloves and sable hat;

Unto this host you've bound you

With all you have at that.'

Loud laughed the Rodensteiner--

'Go in!--that will not hurt.

It's airier and finer

To sit and drink in shirt!

'And till you pawn the swallow

Wherewith I drink my wine

I'll vex full many a fellow

In taverns on the Rhine.'

Der Herr vom Rodensteine

Sprach fiebrig und schabab:

'Ungern duld' ich alleine

Wo steckt mein treuer Knapp?

The Herr vom Rodensteine

Said, sick, in fever-rage,

'A lone in pain I pine--oh!

Where is my faithful page?

'I feel in head and belly

All pains that man annoy;

This time 'ts the neck, I tell ye;

Where is my jolly boy?'

Four of his men went riding--

Went riding at his beck:

They found the truant biding

By beer in Bremeneck.

He drank and spoke with sorrow:

'Brave Rodenstein--ah me!

Dark night and darker morrow!

I cannot come to thee.

'If you have had your stitches,

I, too, have grief, d'ye know?

They've got my coat and breeches,

And will not let me go!

The riders told, heart-breaking,

What they had witnessed there;

Their lord said, fever-shaking,

'Oh boy--that was not fair!

'And wilt thou leave me sweating

In need and pain away?

So shall thou stay there sitting

Until the Judgment Day!'

He spoke and died in fever--

His last sad word struck sore;

The page none can deliver--

He stays there evermore.

Of nights, like storm-winds howling,

You hear the knight in rage;

The Rodenstein loud growling,

Who asks, 'Where is my page?

Das war der Herr von Rodenstein,

Der sprach: 'Das Gott mir helf,

Giebt's nirgend mehr'n Tropfen Wein

Des Nachts um halber Zwölf?

'Raus da! 'Raus aus dam Haus da!

Herr Wirth, das Gott mir helf,

Giebt's nirgend 'nen Tropfen Wein

Des Nachts um halber Zwölf?'

It was the Herr von Rodenstein

Who cried, 'By God in Heaven,

Why can't I find a drop of wine

By night at half-past 'leven?

Rouse there! rouse out of the house, there!

Come, landlord! help me, Heaven!

Great God, is there no wine about

By night at half-past 'leven?'

He went road-up, road-down apace--

No landlord made it right;

Death-thirsty and with fading face

He sighed into the night:

'Rouse out! rouse out of the house there!

Hey, landlord! help me, Heaven!

Can no one get a drop of wine

By night at half-past 'leven?'

And as with spear and hunters' frock

They bore him to the tomb,

The Blackguard Bell i' the old town clock

Began untouched to boom.

'Rouse there! rouse out of the house, there!

Hey, landlord! help us, Heaven!

Can no one get a drop of wine

By night at half-past 'leven?'

But those 'tis known who die of thirst

Ne'er rest in quiet graves,

So now he storms with dryness curst

As ghost around and raves:

'Rouse there! rouse out of the house, there!

Hey, landlord! help me, Heaven!

Can no one get a drop of wine

By night at half-past 'leven?'

And all who in the Odenwald

At midnight still are dry

Rush after him when he has called,

And yell, and roar, and cry:

'Rouse there! rouse out of the house, there!

Hey, landlord! help us, Heaven!

Can no one get a drop of wine

By night at half-past 'leven?'

This song we sing when fun must stop,

To hosts who'll sell no wine,

Who too precisely shuts up shop

Will catch the Rodenstein:

'Rouse there! rouse out of the house, there!

Rum diri di--Free fight

Hoi diri do!--Free night!

Boots!--to the fore!

Open the door!

Rouse-rouse-rouse!

With all of his wild crew--halloo!

The roaring Rodenstein.'

Und wieder sprach der Rodenstein:

'Halloh, mein wildes Heer!

In Assmanshausen fall ich ein

Und trink' den Pfarrer leer.

'Raus da! 'raus aus dem Haus da!

Herr Pfarr', dass Gott Euch helf'.

Giebt's nirgends mehr ein' Tropfen Wein

Des Nachts um halber Zwölf?'

Again outspoke the Rodenstein--

'Hurrah! wild army:--fly!

In Assmanshausen there is wine;

Let's drink the parson dry!

Rouse there! rouse out o' th' house there!

Now, priest, God help your like

If there be left one drop of wine

When you hear midnight strike.'

The priest, a valiant clergyman,

Stood raging by the door;

With scapulary, cross, and bann,

He cursed the spirit o'er.

'Rouse there! rouse out o' th' house, there!

The devil help you delve,

If you dig out one drop of wine

Before the clock strikes twelve!'

But laughing growled the Rodenstein,

'Oh, priest, I'll catch you yet;

A ghost who's shut in front from wine,

Through the back door can get.

Fly'n there! fly'n there to the wine, there!

Hurrah--we're in! they shout.

His cellar is not badly filled!

Hurrah! we'll drink him out!'

Oh, poor and pious priestly heart!

Bad spirits rule this hour.

In vain he roared out cellar ward,

Till he cracked the vault with power--

'Swine there! swine there by the wine, there!

Is't decent, let me know?

Oh, can't you leave me wine enough

For a gentleman to show?'

And when the clock struck One, all rough

The ghosts began to cry,

'Ho, Parson! now we've got enough!

Ho, Parson! now good-bye!

Rouse there! rouse out o' th' house, there!

Now, Parson, all is sprung;

There runs no more one drop of wine

From spicket, jug, or bung!'

Then cursed the priest, 'My thanks to you,

Confound it!--All is gone.

Then I myself in your wild crew,

As chaplain will dash on!

Rouse there! rouse out o' th' house, there!

Sir Knight--at one we'll be.

If all my wine to the devil's gone,

The devil may preach for me!

Huzzah! Hallo!--Yo hi ha ho!

Rum diri di!--it's gone!

Hoy diri do!--I'm on!

In the devil's chorus--all before us,

Row--dow-dydow!'

Und wieder sprach der Rodenstein--

'Pelzkappenschwerenoth!

Hans Schleuning, Stabstrompeter mein,

Bist untreu oder todt?

Lebst noch? Lebst noch und hebst noch?

Man g'spürt dich nirgend mehr;

Schon naht die durf'tge Mainweinzeit,

Du musst mir wieder her!'

Again outspoke the Rodenstein--

'May thunder split my head!

Hans Schleuning, trumpeter of mine,

Art thou untrue or dead?

Art living man?--art moving?--

No trace I find of thee;

The thirsty May-wine time is near:--

Oh, come again to me!'

He rode till he to Darmstadt came,

And badly still he fared,

Till halting at The Old Black Lamb,

He through the window glared.

'He lives still!--thrives still!--lives still!

But ask not how from me.

How comes my brave old fugle-man

In such a company?'

Without a word, without a wink,

There sat a solemn crowd;

Small beer was all their evening drink,

There rang no word aloud.

'So-bri-ety, pro-pri-ety!

Is a great duty, sir!'

So whispered a small vestry-man

Unto a colporteur.

Among these half-glass tippling men

A silent guest there sat;

And as the clock struck eight just then,

He caught up stick and hat.

'What eight! what eight! Good-night! 'tis late!

I've learned good hours to keep;

Ah well!--a steady life's the best,

I'll go to bed and sleep!'

The Rodenstein in grimmest scorn

Glared o'er his horse's mane;

Then thrice he blew his hunting horn

With thundering refrain:

'Rouse there! rouse out o' th' house, there!

Rouse out your runaway!

That lame, tame guest, ye cursed crew,

Belongs to me, I say.'

A shudder swept across that guest

Like some strange sense of sin;

Then with a jug, like one possessed,

He smashed the window in.

'Rouse house, and curse the house, here!

Oh, horn and spur and scorn.

Oh Rodenstein! Oh, German wine!

I am not lost and lorn!

Rum diri di--all right,

Hey, diri da--free night!

Old patron mine--again I'm thine!

Huzza! Hallo!

Huzza! Hallo!

Yo hi a ho!--Arouse!

Hi--a-ho!

Hi--o!'

(IN THE COURT OF HOLLAND IN HEIDELBERG.)

Zwei Schatten seh' ich schweben

In später, später Nacht;

Wisst Ihr, wohin sie streben?--

--Beide auf Numero Acht!--

I see two shadows sweeping

In deep, deep night so late;

And know'st thou where they creeping?

--Both--both to Number Eight!

The porter hears them drumming,

And, waking, bids them wait:

He well knows who is coming,

Those two in Number Eight.

'Old Holland knows the crowd is

Right from the Wild Hunt straight!

Oh, owe, you gay old rowdies,

Who room in Number Eight!

'Is that the way a writer

Makes the world calls great?

You early-cock-tail-fighter,

You birds in Number Eight!

'Is't thus a pious pastor

On his flock should meditate?

You sinful-hearted master,

You rips in Number Eight!

The porter in his throttle

Deep grumbling holds debate,

And hears: 'Another bottle

Or two--for Number Eight!'

With a singing and a dinging,

And laughter long and great,

Till the landlord hears it ringing,

The two in Number Eight!

He spits and turns his nose up,

The bedstead groans with weight,

And then a snuff-pinch goes up,

'Those men in Number Eight!'

Der Mensch ist ein Barbar von Natur,

Er achtet nicht im mindesten die Nebencreatur,

Thut sieden sir und braten,

Verspeist sie mit Salaten,

Schütt't Wein oben drauf aus güldnem Gefäss

Und nennt das gelehrt: Ernährungsprocess.

All men are barbarous, 'tis true.

Nor care for their fellow-beings a sous.

They roast 'em, boil 'em, scour' em,

With salad then devour them;

Pour wine upon 'em in this condition,

And learnedly call the process nutrition.

I a good goose they have also caught,

Feathered and unto the table brought.

To King Gambrinus

Once spake Saint Martinus:

'This world, my lord, is nothing here,

But a priest's slice is good with wine or beer.'

The 'leventh November was the day

When he this with emphasis chanced to say,

'Therefore it is our use

To roast the Martin's Goose.'

I, poor bird, that is my reward,

And they eat me by a subscription card.

How different it was upon the heather,

When as gosling I stood for hours together,

On one foot resting,

My bill and eye twisting

Unto my true love, so handsome and fine,

Who had flown as a gander, of age, o'er the Rhine.

Oh, would that I ne'er in town had been,

Where never a cook of refinement is seen!

She laughed at me so rudely,

And pinched my legs so lewdly,

And said, 'Though you feel as if squeezed and jammed,

With Indian corn your crop must be crammed.'

So even while breathing and heaving sighs,

I am destined for roasts or Strasburg pies.

My mind is lost for ever,

I only grow in the liver;

They never ask, 'Is she gentle and fair?'

They only ask, 'What weight will she bear?

Is that our reward, because well behaved?

The world's capital one night we saved.

For, as they had been drinking,

All were asleep, unthinking;

Had it not been for our clatter and clack,

Rome had been French--yes, in Anno Tubak.

Save your scorn, gentlemen--take our advice,

We shall not save civilization twice;

And if to the Capitol,

Storm Claret, Hock, and Bowl,

No goose again will warn you from surprise,

Or hinder the red monkeys from dancing 'fore your eyes.

Melody,--''Tis the last Rose of Summer.'

Letzte Hose, die mich schmückte,

Fahre wohl! dein Amt ist aus,

Ach auch Dich, die mich entzückte,

Schleppt ein Andrer nun nach Haus.

'Tis my la-a-st pair of bre-e-eches

Le-e-ft sa-a-dly a-lone;

Ah--and she too with her riches,

With another hence has gone.

Oh, they seemed in one piece knitted,

Such a pair is seldom matched;