GEORGE PEABODY.

GEORGE PEABODY.

Title: Lives of Poor Boys Who Became Famous

Author: Sarah Knowles Bolton

Release date: April 24, 2011 [eBook #35950]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Darleen Dove, Sharon Verougstraete and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

"There is properly no History, only Biography." —Emerson.

Human portraits, faithfully drawn, are of all pictures the welcomest on human walls. —Carlyle.

FORTY-FIRST THOUSAND.

NEW YORK THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO. PUBLISHERS

Copyright,

By Thomas Y. Crowell & Co.

1885.

Norwood Press:

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith.

Boston, Mass., U.S.A.

TO

MY ONLY SISTER,

Mrs. Halsey D. Miller,

IN REMEMBRANCE OF

MANY HAPPY HOURS.

These characters have been chosen from various countries and from varied professions, that the youth who read this book may see that poverty is no barrier to success. It usually develops ambition, and nerves people to action. Life at best has much of struggle, and we need to be cheered and stimulated by the careers of those who have overcome obstacles.

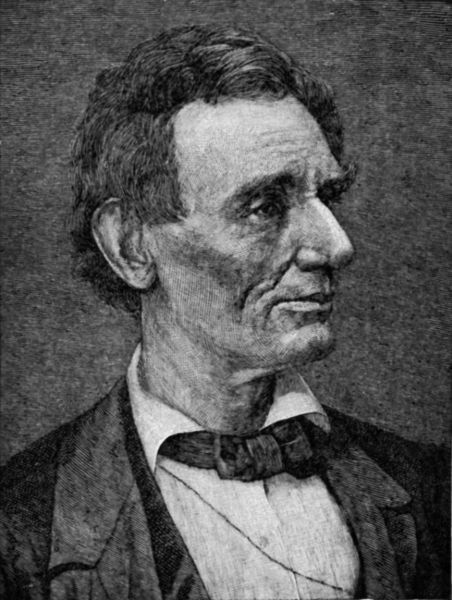

If Lincoln and Garfield, both farmer-boys, could come to the Presidency, then there is a chance for other farmer-boys. If Ezra Cornell, a mechanic, could become the president of great telegraph companies, and leave millions to a university, then other mechanics can come to fame. If Sir Titus Salt, working and sorting wool in a factory at nineteen, could build one of the model towns of the world for his thousands of workingmen, then there is[vi] encouragement and inspiration for other toilers in factories. These lives show that without WORK and WILL no great things are achieved.

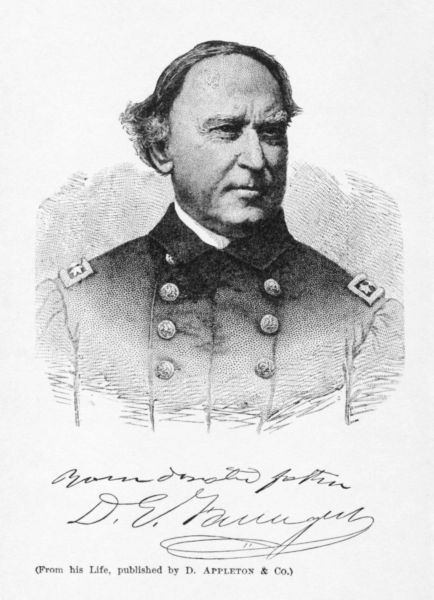

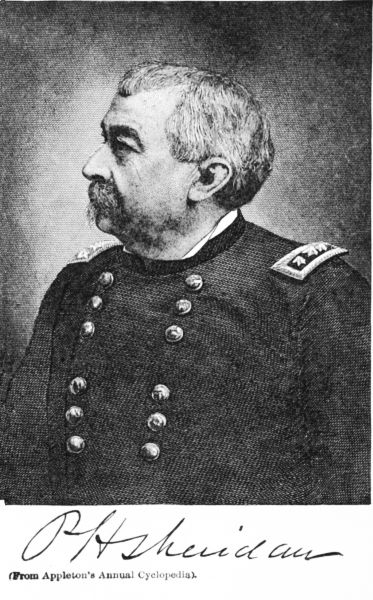

I have selected several characters because they were the centres of important historical epochs. With Garibaldi is necessarily told the story of Italian unity; with Garrison and Greeley, the fall of slavery; and with Lincoln and Sheridan, the battles of our Civil War.

S. K. B.

| PAGE | ||

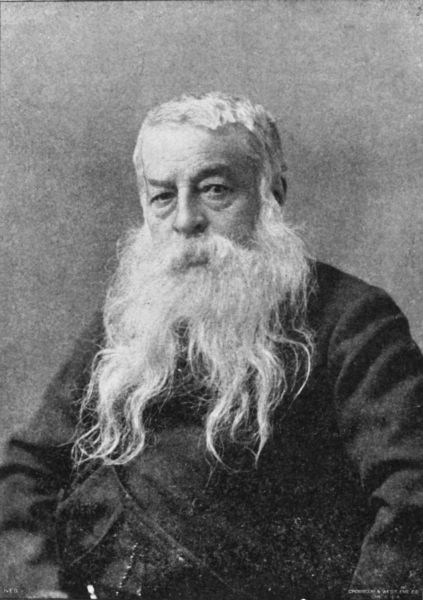

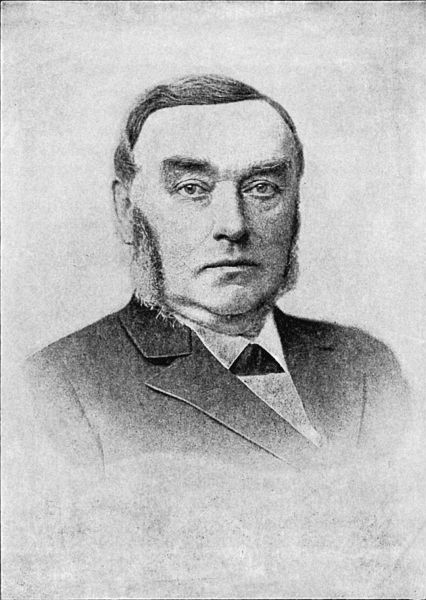

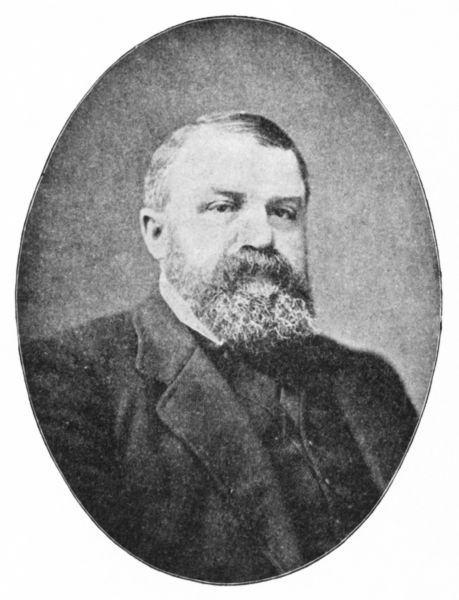

| George Peabody | Merchant | 1 |

| Bayard Taylor | Traveller | 13 |

| Captain James B. Eads | Civil Engineer | 26 |

| James Watt | Inventor | 33 |

| Sir Josiah Mason | Manufacturer | 46 |

| Bernard Palissy | Potter | 54 |

| Bertel Thorwaldsen | Sculptor | 65 |

| Wolfgang Mozart | Composer | 72 |

| Samuel Johnson | Author | 83 |

| Oliver Goldsmith | Poet and Writer | 90 |

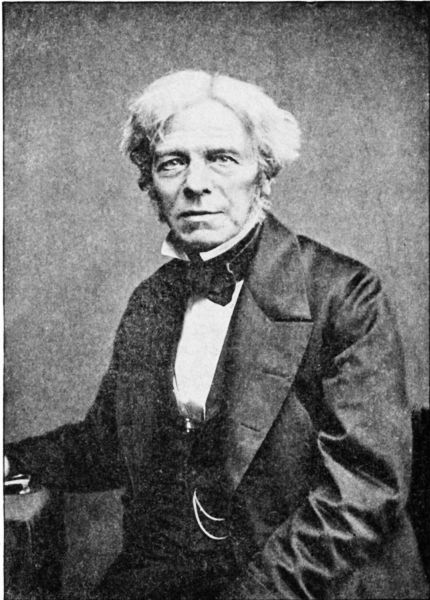

| Michael Faraday | Scientist | 96 |

| Sir Henry Bessemer | Maker of Steel | 112 |

| Sir Titus Salt | Philanthropist | 124 |

| Joseph Marie Jacquard | Silk Weaver | 130 |

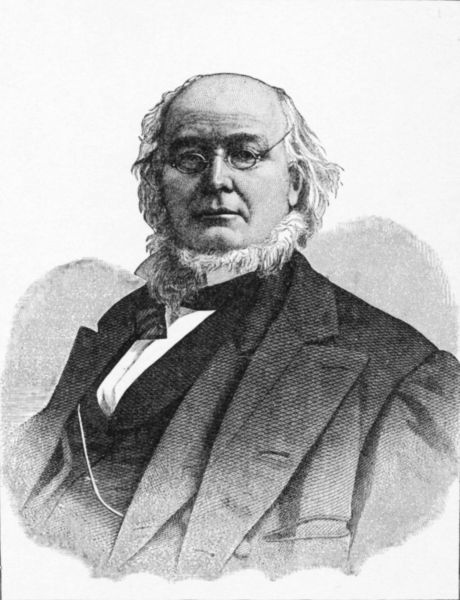

| Horace Greeley | Editor | 138 |

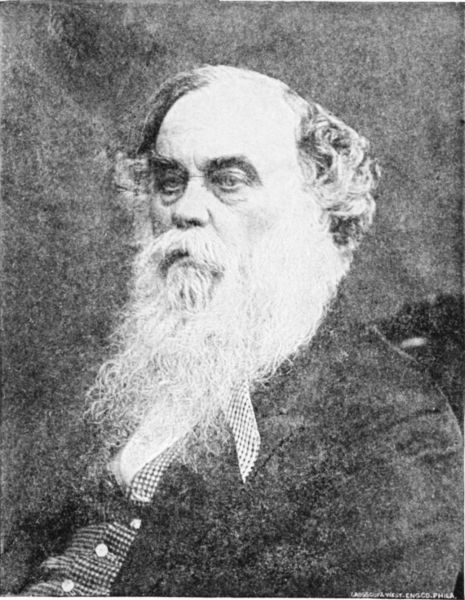

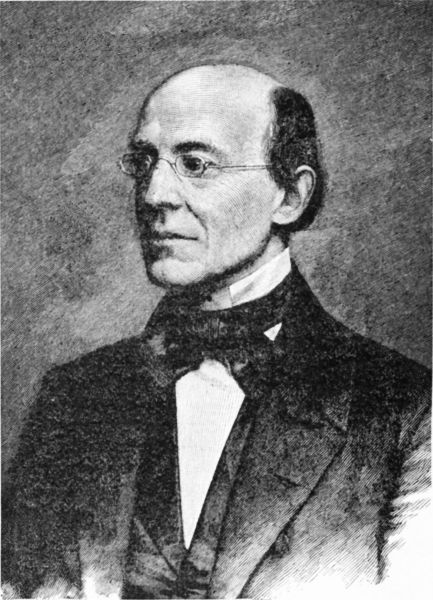

| William Lloyd Garrison | Reformer | 156 |

| Giuseppe Garibaldi | Patriot | 172 |

| Jean Paul Richter | Novelist | 187 |

| [viii]Leon Gambetta | Statesman | 204 |

| David G. Farragut | Sailor | 219 |

| Ezra Cornell | Mechanic | 238 |

| Lieut.-General Sheridan | Soldier | 251 |

| Thomas Cole | Painter | 270 |

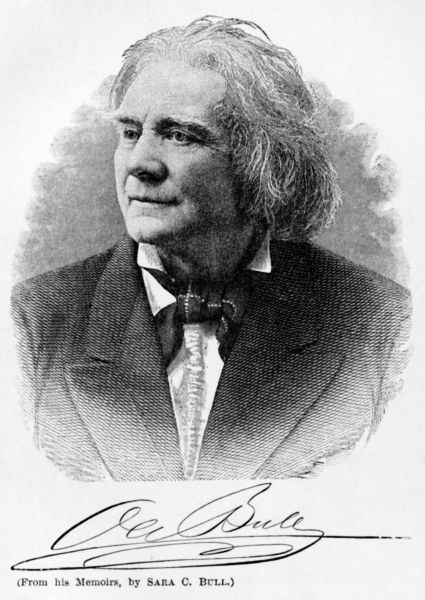

| Ole Bull | Violinist | 284 |

| Meissonier | Artist | 303 |

| Geo. W. Childs | Journalist | 313 |

| Dwight L. Moody | Evangelist | 323 |

| Abraham Lincoln | President | 342 |

GEORGE PEABODY.

GEORGE PEABODY.

If America had been asked who were to be her most munificent givers in the nineteenth century, she would scarcely have pointed to two grocer's boys, one in a little country store at Danvers, Mass., the other in Baltimore; both poor, both uneducated; the one leaving seven millions to Johns Hopkins University and Hospital, the other nearly nine millions to elevate humanity. George Peabody was born in Danvers, Feb. 18, 1795. His parents were respectable, hard-working people, whose scanty income afforded little education for their children. George grew up an obedient, faithful son, called a "mother-boy" by his companions, from his devotion to her,—a title of which any boy may well be proud.

At eleven years of age he must go out into the world to earn his living. Doubtless his mother wished to keep her child in school; but there was no money. A place was found with a Mr. Proctor in a grocery-store, and here, for four years, he worked day by day, giving his earnings to his mother, and winning esteem for his promptness and[2] honesty. But the boy at fifteen began to grow ambitious. He longed for a larger store and a broader field. Going with his maternal grandfather to Thetford, Vt., he remained a year, when he came back to work for his brother in a dry-goods store in Newburyport. Perhaps now in this larger town his ambition would be satisfied, when, lo! the store burned, and George was thrown out of employment.

His father had died, and he was without a dollar in the world. Ambition seemed of little use now. However, an uncle in Georgetown, D.C., hearing that the boy needed work, sent for him, and thither he went for two years. Here he made many friends, and won trade, by his genial manner and respectful bearing. His tact was unusual. He never wounded the feelings of a buyer of goods, never tried him with unnecessary talk, never seemed impatient, and was punctual to the minute. Perhaps no one trait is more desirable than the latter. A person who breaks his appointments, or keeps others waiting for him, loses friends, and business success as well.

A young man's habits are always observed. If he is worthy, and has energy, the world has a place for him, and sooner or later he will find it. A wholesale dry-goods dealer, Mr. Riggs, had been watching young Peabody. He desired a partner of energy, perseverance, and honesty. Calling on the young clerk, he asked him to put his labor against[3] his, Mr. Riggs's, capital. "But I am only nineteen years of age," was the reply.

This was considered no objection, and the partnership was formed. A year later, the business was moved to Baltimore. The boyish partner travelled on horseback through the western wilds of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, selling goods, and lodging over night with farmers or planters. In seven years the business had so increased, that branch houses were established in Philadelphia and New York. Finally Mr. Riggs retired from the firm; and George Peabody found himself, at the age of thirty-five, at the head of a large and wealthy establishment, which his own energy, industry, and honesty had helped largely to build. He had bent his life to one purpose, that of making his business a success. No one person can do many things well.

Having visited London several times in matters of trade, he determined to make that great city his place of residence. He had studied finance by experience as well as close observation, and believed that he could make money in the great metropolis. Having established himself as a banker at Wanford Court, he took simple lodgings, and lived without display. When Americans visited London, they called upon the genial, true-hearted banker, whose integrity they could always depend upon, and transacted their business with him.

In 1851, the World's Fair was opened at the[4] Crystal Palace, London, Prince Albert having worked earnestly to make it a great success. Congress neglected to make the needed appropriations for America; and her people did not care, apparently, whether Powers' Greek Slave, Hoe's wonderful printing-press, or the McCormick Reaper were seen or not. But George Peabody cared for the honor of his nation, and gave fifteen thousand dollars to the American exhibitors, that they might make their display worthy of the great country which they were to represent. The same year, he gave his first Fourth of July dinner to leading Americans and Englishmen, headed by the Duke of Wellington. While he remembered and honored the day which freed us from England, no one did more than he to bind the two nations together by the great kindness of a great heart.

Mr. Peabody was no longer the poor grocery boy, or the dry-goods clerk. He was fine looking, most intelligent from his wide reading, a total abstainer from liquors and tobacco, honored at home and abroad, and very rich. Should he buy an immense estate, and live like a prince? Should he give parties and grand dinners, and have servants in livery? Oh, no! Mr. Peabody had acquired his wealth for a different purpose. He loved humanity. "How could he elevate the people?" was the one question of his life. He would not wait till his death, and let others spend his money; he would have the satisfaction of spending it himself.[5]

And now began a life of benevolence which is one of the brightest in our history. Unmarried and childless, he made other wives and children happy by his boundless generosity. If the story be true, that he was once engaged to a beautiful American girl, who gave him up for a former poor lover, the world has been the gainer by her choice.

In 1852, Mr. Peabody gave ten thousand dollars to help fit out the second expedition under Dr. Kane, in his search for Sir John Franklin; and for this gift a portion of the newly-discovered country was justly called Peabody Land. This same year, the town of Danvers, his birthplace, decided to celebrate its centennial. Of course the rich London banker was invited as one of the guests. He was too busy to be present, but sent a letter, to be opened on the day of the celebration. The seal was broken at dinner, and this was the toast, or sentiment, it contained: "Education—a debt due from present to future generations." A check was enclosed for twenty thousand dollars for the purpose of building an Institute, with a free library and free course of lectures. Afterward this gift was increased to two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. The poor boy had not forgotten the home of his childhood.

Four years later, when Peabody Institute was dedicated, the giver, who had been absent from America twenty years, was present. New York and other cities offered public receptions; but he declined all save Danvers. A great procession[6] was formed, the houses along the streets being decorated, all eager to do honor to their noble townsman. The Governor of Massachusetts, Edward Everett, and others made eloquent addresses, and then the kind-faced, great-hearted man responded:—

"Though Providence has granted me an unvaried and unusual success in the pursuit of fortune in other lands, I am still in heart the humble boy who left yonder unpretending dwelling many, very many years ago.... There is not a youth within the sound of my voice whose early opportunities and advantages are not very much greater than were my own; and I have since achieved nothing that is impossible to the most humble boy among you. Bear in mind, that, to be truly great, it is not necessary that you should gain wealth and importance. Steadfast and undeviating truth, fearless and straightforward integrity, and an honor ever unsullied by an unworthy word or action, make their possessor greater than worldly success or prosperity. These qualities constitute greatness."

Soon after this, Mr. Peabody determined to build an Institute, combining a free library and lectures with an Academy of Music and an Art Gallery, in the city of Baltimore. For this purpose he gave over one million dollars—a princely gift indeed! Well might Baltimore be proud of the day when he sought a home in her midst.

But the merchant-prince had not finished his giv[7]ing. He saw the poor of the great city of London, living in wretched, desolate homes. Vice and poverty were joining hands. He, too, had been poor. He could sympathize with those who knew not how to make ends meet. What would so stimulate these people to good citizenship as comfortable and cheerful abiding-places? March 12, 1862, he called together a few of his trusted friends in London, and placed in their hands, for the erection of neat, tasteful dwellings for the poor, the sum of seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Ah, what a friend the poor had found! not the gift of a few dollars, which would soon be absorbed in rent, but homes which for a small amount might be enjoyed as long as they lived.

At once some of the worst portions of London were purchased; tumble-down structures were removed; and plain, high brick blocks erected, around open squares, where the children could find a playground. Gas and water were supplied, bathing and laundry rooms furnished. Then the poor came eagerly, with their scanty furniture, and hired one or two rooms for twenty-five or fifty cents a week,—cab-men, shoemakers, tailors, and needle-women. Tenants were required to be temperate and of good moral character. Soon tiny pots of flowers were seen in the windows, and a happier look stole into the faces of hard-working fathers and mothers.

Mr. Peabody soon increased his gift to the London poor to three million dollars, saying, "If judi[8]ciously managed for two hundred years, its accumulation will amount to a sum sufficient to buy the city of London."

No wonder that these gifts of millions began to astonish the world. London gave him the freedom of the city in a gold box,—an honor rarely bestowed,—and erected his bronze statue near the Royal Exchange. Queen Victoria wished to make him a baron; but he declined all titles. What gift, then, would he accept, was eagerly asked. "A letter from the Queen of England, which I may carry across the Atlantic, and deposit as a memorial of one of her most faithful sons," was the response. It is not strange that so pure and noble a man as George Peabody admired the purity and nobility of character of her who governs England so wisely.

A beautiful letter was returned by the Queen, assuring him how deeply she appreciated his noble act of more than princely munificence,—an act, as the Queen believes, "wholly without parallel," and asking him to accept a miniature portrait of herself. The portrait, in a massive gold frame, is fourteen inches long and ten inches wide, representing the Queen in robes of state,—the largest miniature ever attempted in England, and for the making of which a furnace was especially built. The cost is believed to have been over fifty thousand dollars in gold. It is now preserved, with her letter, in the Peabody Institute near Danvers.

Oct. 25, 1866, the beautiful white marble Insti[9]tute in Baltimore was to be dedicated. Mr. Peabody had crossed the ocean to be present. Besides the famous and the learned, twenty thousand children with Peabody badges were gathered to meet him. The great man's heart was touched as he said, "Never have I seen a more beautiful sight than this vast collection of interesting children. The review of the finest army, attended by the most delightful strains of martial music, could never give me half the pleasure." He was now seventy-one years old. He had given nearly five millions; could the world expect any more? He realized that the freed slaves at the South needed an education. They were poor, and so were a large portion of the white race. He would give for their education three million dollars, the same amount he had bestowed upon the poor of London. To the trustees having this gift in charge he said, "With my advancing years, my attachment to my native land has but become more devoted. My hope and faith in its successful and glorious future have grown brighter and stronger. But, to make her prosperity more than superficial, her moral and intellectual development should keep pace with her material growth. I feel most deeply, therefore, that it is the duty and privilege of the more favored and wealthy portions of our nation to assist those who are less fortunate." Noble words! Mr. Peabody's health was beginning to fail. What he did must now be done quickly. Yale College received a hundred and fifty[10] thousand dollars for a Museum of Natural History; Harvard the same, for a Museum of Archæology and Ethnology; to found the Peabody Academy of Science at Salem a hundred and forty thousand dollars; to Newburyport Library, where the fire threw him out of employment, and thus probably broadened his path in life, fifteen thousand dollars; twenty-five thousand dollars each to various institutions of learning throughout the country; ten thousand dollars to the Sanitary Commission during the war, besides four million dollars to his relatives; making in all thirteen million dollars. Just before his return to England, he made one of the most tender gifts of his life. The dear mother whom he idolized was dead, but he would build her a fitting monument; not a granite shaft, but a beautiful Memorial Church at Georgetown, Mass., where for centuries, perhaps, others will worship the God she worshipped. On a marble tablet are the words, "Affectionately consecrated by her children, George and Judith, to the memory of Mrs. Judith Peabody." Whittier wrote the hymn for its dedication:—

Nov. 4, 1869, Mr. Peabody lay dying at the house of a friend in London. The Queen sent a special telegram of inquiry and sympathy, and[11] desired to call upon him in person; but it was too late. "It is a great mystery," said the dying man feebly; "but I shall know all soon." At midnight he passed to his reward.

Westminster Abbey opened her doors for a great funeral, where statesmen and earls bowed their heads in honor of the departed. Then the Queen sent her noblest man-of-war, "Monarch," to bear in state, across the Atlantic, "her friend," the once poor boy of Danvers. Around the coffin, in a room draped in black, stood immense wax candles, lighted. When the great ship reached America, Legislatures adjourned, and went with Governors and famous men to receive the precious freight. The body was taken by train to Peabody, and then placed on a funeral car, eleven feet long and ten feet high, covered with black velvet, trimmed with silver lace and stars. Under the casket were winged cherubs in silver. The car was drawn by six horses covered with black and silver, while corps of artillery preceded the long procession. At sunset the Institute was reached, and there, surrounded by the English and American flags draped with crape, the guard kept silent watch about the dead. At the funeral, at the church, Hon. Robert C. Winthrop pronounced the eloquent eulogy, of the "brave, honest, noble-hearted friend of mankind," and then, amid a great concourse of people, George Peabody was buried at Harmony Grove, by the side of the mother whom he so tenderly loved. Doubtless he looked out upon[12] this greensward from his attic window when a child or when he labored in the village store. Well might two nations unite in doing honor to this man, both good and great, who gave nine million dollars to bless humanity.

[The building fund of £500,000 left by Mr. Peabody for the benefit of the poor of London has now been increased by rents and interest to £857,320. The whole of this great sum of money is in active employment, together with £340,000 which the trustees have borrowed. A total of £1,170,787 has been expended during the time the fund has been in existence, of which £80,903 was laid out during 1884. The results of these operations are seen in blocks of artisans' dwellings built on land purchased by the trustees and let to working men at rents within their means, containing conveniences and comforts not ordinarily attainable by them, thus fulfilling the benevolent intentions of Mr. Peabody. At the present time 4551 separate dwellings have been erected, containing 10,144 rooms, inhabited by 18,453 persons. Thirteen new blocks of buildings are now in course of erection and near completion. Indeed, there is no cessation in the work of fulfilling the intentions of the noble bequest.—Boston Journal, Mar. 7, 1885.]

BAYARD TAYLOR.

BAYARD TAYLOR.

Since Samuel Johnson toiled in Grub Street, London, literature has scarcely furnished a more pathetic or inspiring illustration of struggle to success than that of Bayard Taylor. Born of Quaker parentage in the little town of Kennett Square, near Philadelphia, Jan. 11, 1825, he grew to boyhood in the midst of fresh air and the hard work of farm-life. His mother, a refined and intelligent woman, who taught him to read at four, and who early discovered her child's love for books, shielded him as far as possible from picking up stones and weeding corn, and set him to rocking the baby to sleep. What was her amazement one day, on hearing loud cries from the infant, to find Bayard absorbed in reading, and rocking his own chair furiously, supposing it to be the cradle! It was evident, that, though such a boy might become a fine literary man, he could not be a successful baby-tender.

He was especially eager to read poetry and travels, and, before he was twelve years old, had devoured the contents of their small circulating library, as[14] well as Cooper's novels, and the histories of Gibbon, Robertson, and Hume. The few books which he owned were bought with money earned by selling nuts which he had gathered. He read Milton, Scott, Byron, and Wordsworth; and his mother would often hear him repeating poetry to his brother after they had gone to bed. He was always planning journeys in Europe, which seemed very far from being realized. At fourteen he began to study Latin and French, and at fifteen, Spanish; and a year later he assisted in teaching at the academy where he was attending school.

He was ambitious; but there seemed no open door. There is never an open door to fame or prosperity, except we open it for ourselves. The world is too busy to help others; and assistance usually weakens rather than strengthens us. About this time he received, through request, an autograph from Charles Dickens, then lecturing in this country. The boy of sixteen wrote in his journal: "It was not without a feeling of ambition that I looked upon it; that as he, a humble clerk, had risen to be the guest of a mighty nation, so I, a humble pedagogue, might, by unremitted and arduous intellectual and moral exertion, become a light, a star, among the names of my country. May it be!... I believe all poets are possessed in a greater or less degree of ambition. I think this is never given without a mind of sufficient power to sustain it, and to achieve its lofty object."[15]

At seventeen, Bayard's schooling was over. He sketched well, and would gladly have gone to Philadelphia to study engraving; but he had no money. One poem had been published in the "Saturday Evening Post." Those only who have seen their first poem in print can experience his joy. But writing poetry would not earn him a living. He had no liking for teaching, but, as that seemed the only thing at hand, he would try to obtain a school. He did not succeed, however, and apprenticed himself for four years to a printer. He worked faithfully, using all his spare hours in reading and writing poetry.

Two years later, he walked to Philadelphia and back—thirty miles each way—to see if fifteen of his poems could not be printed in a book! His ambition evidently had not abated. Of course no publisher would take the book at his own risk. There was no way of securing its publication, therefore, but to visit his friends, and solicit them to buy copies in advance. This was a trying matter for a refined nature; but it was a necessity. He hoped thus to earn a little money for travel, and "to win a name that the person who shall be chosen to share with me the toils of life will not be ashamed to own." This "person" was Mary Agnew, whose love and that of Bayard Taylor form one of the saddest and tenderest pictures in our literature.

At last the penniless printer boy had determined[16] to see Europe. For two years he had read every thing he could find upon travels abroad. His good mother mourned over the matter, and his acquaintances prophesied dire results from such a roving disposition. He would go again to Philadelphia, and see if the newspapers did not wish correspondence from Europe. All the editors politely declined the ardent boy's proposals. Probably he did not know that "unknown writers" are not wanted.

About to return home, "not in despair," he afterwards wrote, "but in a state of wonder as to where my funds would come from, for I felt certain they would come," the editor of the "Saturday Evening Post" offered him four dollars a letter for twelve letters,—fifty dollars,—with the promise of taking more if they were satisfactory. The "United States Gazette" made a similar offer, and, after selling a few manuscript poems which he had with him, he returned home in triumph, with a hundred and forty dollars in his pocket! "This," he says, "seemed sufficient to carry me to the end of the world."

Immediately Bayard and his cousin started on foot for Washington, a hundred miles, to see the member of Congress from their district, and obtain passports from him. Reaching a little village on their way thither, they were refused lodgings at the tavern because of the lateness of the hour,—nine o'clock!—and walked on till near midnight. Then seeing a house brilliantly lighted, as for a wedding, they approached, and asked the proprietor whether[17] a tavern were near by. The man addressed turned fiercely upon the lads, shouting, "Begone! Leave the place instantly. Do you hear? Off!" The amazed boys hastened away, and at three o'clock in the morning, footsore and faint, after a walk of nearly forty miles, slept in a cart standing beside an old farmhouse.

And now at nineteen, he was in New York, ready for Europe. He called upon the author, N. P. Willis, who had once written a kind note to him; and this gentleman, with a ready nature in helping others,—alas! not always found among writers—gave him several letters of introduction to newspaper men. Mr. Greeley said bluntly when applied to, "I am sick of descriptive letters, and will have no more of them. But I should like some sketches of German life and society, after you have been there, and know something about it. If the letters are good, you shall be paid for them; but don't write until you know something."

July 1, 1844, Bayard and two young friends, after paying ten dollars each for steerage passage, started out for this eventful voyage. No wonder that, as land faded from sight, and he thought of gentle Mary Agnew and his devoted mother, his heart failed him, and he quite broke down. After twenty-eight days they landed in Liverpool, strangers, poor, knowing almost nothing of the world, but full of hope and enthusiasm. They spent three weeks in Scotland and the north of England, and the[18]n travelled through Belgium to Heidelberg. Bayard passed the first winter in Frankfort, in the plainest quarters, and then, with his knapsack on his back, visited Leipzig, Dresden, Prague, Vienna, and Munich. After this he walked over the Alps, and through Northern Italy, spending four months in Florence, and then visiting Rome. Often he was so poor that he lived on twenty cents a day. Sometimes he was without food for nearly two days, writing his natural and graphic letters when his ragged clothes were wet through, and his body faint from fasting. But the manly, enthusiastic youth always made friends by his good cheer and unselfishness.

At last he was in London, with but thirty cents to buy food and lodging. But he had a poem of twelve hundred lines in his knapsack, which he supposed any London publisher would be glad to accept. He offered it; but it was "declined with thanks." The youth had not learned that Bayard Taylor unknown, and Bayard Taylor famous in two hemispheres, were two different names upon the title-page of a book. Publishers cannot usually afford to do missionary work in their business; they print what will sell. "Weak from sea-sickness," he says, "hungry, chilled, and without a single acquaintance in the great city, my situation was about as hopeless as it is possible to conceive."

Possibly he could obtain work in a printer's shop. This he tried hour after hour, and failed. Finally[19] he spent his last twopence for bread, and found a place to sleep in a third-rate chop-house, among sailors, and actors from the lower theatres. He rose early, so as not to be asked to pay for his bed, and again sought work. Fortunately he met an American publisher, who loaned him five dollars, and with a thankful heart he returned to pay for his lodging. For six weeks he staid in his humble quarters, wrote letters home to the newspapers, and also sent various poems to the English journals, which were all returned to him. For two years he supported himself on two hundred and fifty dollars a year, earning it all by writing. "I saw," he says, "almost nothing of intelligent European society; but literature and art were, nevertheless, open to me, and a new day had dawned in my life."

On his return to America he found that his published letters had been widely read. He was advised to put them in a book; and "Views Afoot," with a preface by N. P. Willis, were soon given to the world. Six editions were sold the first year; and the boy who had seen Europe in the midst of so much privation, found himself an author, with the prospect of fame. Not alone had poverty made these two years hard to bear. He was allowed to hold no correspondence with Mary Agnew, because her parents steadily refused to countenance the young lovers. He had wisely made his mother his confidante, and she had counselled patience and hope. The rising fame possibly smoothed the[20] course of true love, for at twenty-one, Bayard became engaged to the idol of his heart. She was an intelligent and beautiful girl, with dark eyes and soft brown hair, and to the ardent young traveller seemed more angel than human. He showed her his every poem, and laid before her every purpose. He wrote her, "I have often dim, vague forebodings that an eventful destiny is in store for me"; and then he added in quaint, Quaker dialect, "I have told thee that existence would not be endurable without thee; I feel further that thy aid will be necessary to work out the destinies of the future.... I am really glad that thou art pleased with my poetry. One word from thee is dearer to me than the cold praise of all the critics in the land."

For the year following his return home, he edited a country paper, and thereby became involved in debts which required the labors of the next three years to cancel. He now decided to go to New York if possible, where there would naturally be more literary society, and openings for a writer. He wrote to editors and publishers; but there were no vacancies to be filled. Finally he was offered enough to pay his board by translating, and this he gladly accepted. By teaching literature in a young ladies' school, he increased his income to nine dollars a week. Not a luxurious amount, surely.

For a year he struggled on, saving every cent possible, and then Mr. Greeley gave him a place on the "Tribune," at twelve dollars a week. He[21] worked constantly, often writing poetry at midnight, when his day's duties were over. He made true friends, such as Stedman and Stoddard, published a new book of poems; and in the beginning of 1849 life began to look full of promise. Sent by his paper to write up California, for six months he lived in the open air, his saddle for his pillow, and on his return wrote his charming book "El-dorado." He was now twenty-five, out of debt, and ready to marry Mary Agnew. But a dreadful cloud had meantime gathered and burst over their heads. The beautiful girl had been stricken with consumption. The May day bridal had been postponed. "God help me, if I lose her!" wrote the young author to Mr. Stoddard from her bedside. Oct. 24 came, and the dying girl was wedded to the man she loved. Four days later he wrote: "We have had some heart-breaking hours, talking of what is before us, and are both better and calmer for it." And, later still: "She is radiantly beautiful; but it is not the beauty of earth.... We have loved so long, so intimately, and so wholly, that the footsteps of her life have forever left their traces in mine. If my name should be remembered among men, hers will not be forgotten." Dec. 21, 1850, she went beyond; and Bayard Taylor at twenty-six was alone in the world, benumbed, unfitted for work of any kind. "I am not my true self more than half the time. I cannot work with any spirit: another such winter[22] will kill me, I am certain. I shall leave next fall on a journey somewhere—no matter where," he wrote a friend.

Fortunately he took a trip to the Far East, travelling in Egypt, Asia Minor, India, and Japan for two years, writing letters which made him known the country over. On his return, he published three books of travel, and accepted numerous calls in the lecture-field. His stock in the "Tribune" had become productive, and he was gaining great success.

His next long journey was to Northern Europe, when he took his brother and two sisters with him, as he could enjoy nothing selfishly. This time he saw much of the Brownings and Thackeray, and spent two days as the guest of Tennyson. He was no longer the penniless youth, vainly looking for work in London to pay his lodging, but the well-known traveller, lecturer, and poet. Oct. 27, 1857, seven years after the death of Mary Agnew, he married the daughter of a distinguished German astronomer, Marie Hansen, a lady of great culture, whose companionship has ever proved a blessing.

Tired of travel, Mr. Taylor now longed for a home for his wife and infant daughter, Lilian. He would erect on the old homestead, where he played when a boy, such a house as a poet would love to dwell in, and such as poet friends would delight to visit. So, with minutest care and thought, "Cedarcroft," a beautiful structure, was[23] built in the midst of two hundred acres. Every flower, every tree, was planted with as much love as Scott gave to "Abbotsford." But, when it was completed, the old story had been told again, of expenses going far beyond expectations, and, instead of anticipated rest, toil and struggle to pay debts, and provide for constant outgoes.

But Bayard Taylor was not the man to be disturbed by obstacles. He at once set to work to earn more than ever by his books and lectures. With his characteristic generosity he brought his parents and his sisters to live in his home, and made everybody welcome to his hospitality. The "Poet's Journal," a poem of exquisite tenderness, was written here, and "Hannah Thurston," a novel, of which fifteen thousand were soon sold.

Shortly after the beginning of our civil war, Mr. Taylor was made Secretary of Legation at Russia. He was now forty years of age, loved, well-to-do, and famous. His novels—"John Godfrey's Fortunes" and the "Story of Kennett"—were both successful. The "Picture of St. John," rich and stronger than his other poems, added to his fame. But the gifted and versatile man was breaking in health. Again he travelled abroad, and wrote "Byways in Europe." On his return he translated, with great care and study, "Faust," which will always be a monument to his learning and literary skill. He published "Lars, a Norway pastoral," and gave delightful lectures on German[24] literature at Cornell University, and Lowell and Peabody Institutes, at Boston and Baltimore.

At last he wearied of the care and constant expense of "Cedarcroft." He needed to be near the New York libraries. Mr. Greeley had died, his newspaper stock had declined, and he could not sell his home, as he had hoped. There was no alternative but to go back in 1871 into the daily work of journalism in the "Tribune" office. The rest which he had longed for was never to come. For four years he worked untiringly, delivering the Centennial Ode at our Exposition, and often speaking before learned societies.

In 1878, President Hayes bestowed upon him a well-deserved honor, by appointing him minister to Berlin. Germany rejoiced that a lover of her life and literature had been sent to her borders. The best of New York gathered to say good-by to the noted author. Arriving in Berlin, Emperor William gave him cordial welcome, and Bismark made him a friend. A pleasant residence was secured, and furniture purchased. At last he was to find time to complete a long-desired work, the Lives of Goethe and Schiller. "Prince Deukalion," his last noble poem, had just reached him. All was ready for the best and strongest work of his life, when, lo! the overworked brain and body gave way. He did not murmur. Only once, Dec. 19, he groaned, "I want—I want—oh, you know what I mean, that stuff of life!" It was too late. At fifty-three the great[25] heart, the exquisite brain, the tired body, were still.

Germany as well as America wept over the bier of the once poor Quaker lad, who travelled over Europe with scarce a shilling in his pocket, now, by his own energy, brought to one of the highest positions in the gift of his country. Dec. 22, the great of Germany gathered about his coffin, Bertold Auerbach speaking beautiful words.

March 13, 1879, the dead poet lay in state in the City Hall at New York, in the midst of assembled thousands. The following day the body was borne to "Cedarcroft," and, surrounded by literary associates and tender friends, laid to rest. Public memorial meetings were held in various cities, where Holmes, Longfellow, Whittier, and others gave their loving tributes. A devoted student, a successful diplomat, a true friend, a noble poet, a gifted traveller, a man whose life will never cease to be an inspiration.

On the steamship "Germanic" I played chess with the great civil engineer, Captain Eads, stimulated by the thought that to beat him was to defeat the man who had twice conquered the Mississippi. But I didn't defeat him.

The building of a ship-canal across the Isthmus of Suez made famous the Frenchman, Ferdinand de Lesseps: so the opening-up of the mouth of the Mississippi River has distinguished Captain Eads. To-day both these men are struggling for the rare honor of joining, at the Isthmus of Panama, the waters of the great Atlantic and Pacific; a magnificent scheme, which, if successful, will save annually thousands of miles of dangerous sea-voyage around Cape Horn, besides millions of money.

The "Great West" seems to delight in producing self-made men like Lincoln, Grant, Eads, and others.

James B. Eads was born in Indiana in 1820. He is slender in form, neat in dress, genial, courteous, and over sixty years of age. In 1833, his father started down the Ohio River with his family, pro[27]posing to settle in Wisconsin. The boat caught fire, and his scanty furniture and clothing were burned. Young Eads barely escaped ashore with his pantaloons, shirt, and cap. Taking passage on another boat, this boy of thirteen landed at St. Louis with his parents; his little bare feet first touching the rocky shore of the city on the very spot where he afterwards located and built the largest steel bridge in the world, over the Mississippi,—one of the most difficult feats of engineering ever performed in America.

At the age of nine, young Eads made a short trip on the Ohio, when the engineer of the steamboat explained to him so clearly the construction of the steam-engine, that, before he was a year older, he built a little working model of it, so perfect in its parts and movements, that his schoolmates would frequently go home with him after school to see it work. A locomotive engine driven by a concealed rat was one of his next juvenile feats in mechanical engineering. From eight to thirteen he attended school; after which, from necessity, he was placed as clerk in a dry-goods store.

How few young people of the many to whom poverty denies an education, either understand the value of the saying, "knowledge is power," or exercise will sufficient to overcome obstacles. Willpower and thirst for knowledge elevated General Garfield from driving canal horses to the Presidency of the United States.[28]

Over the store in St. Louis, where he was engaged, his employer lived. He was an old bachelor, and, having observed the tastes of his clerk, gave him his first book in engineering. The old gentleman's library furnished evening companions for him during the five years he was thus employed. Finally, his health failing, at the age of nineteen he went on a Mississippi River steamer; from which time to the present day that great river has been to him an all-absorbing study.

Soon afterwards he formed a partnership with a friend, and built a small boat to raise cargoes of vessels sunken in the Mississippi. While this boat was building, he made his first venture in submarine engineering, on the lower rapids of the river, by the recovery of several hundred tons of lead. He hired a scow or flat-boat, and anchored it over the wreck. An experienced diver, clad in armor, who had been hired at considerable expense in Buffalo, was lowered into the water; but the rapids were so swift that the diver, though incased in the strong armor, feared to be sunk to the bottom. Young Eads determined to succeed, and, finding it impracticable to use the armor, went ashore, purchased a whiskey-barrel, knocked out the head, attached the air-pump hose to it, fastened several heavy weights to the open end of the barrel; then, swinging it on a derrick, he had a practical diving-bell—the best use I ever heard made of a whiskey-barrel.

Neither the diver, nor any of the crew, would go[29] down in this contrivance: so the dauntless young engineer, having full confidence in what he had read in books, was lowered within the barrel down to the bottom; the lower end of the barrel being open. The water was sixteen feet deep, and very swift. Finding the wreck, he remained by it a full hour, hitching ropes to pig-lead till a ton or more was safely hoisted into his own boat. Then, making a signal by a small line attached to the barrel, he was lifted on deck, and in command again. The sunken cargo was soon successfully raised, and was sold, and netted a handsome profit, which, increased by other successes, enabled energetic Eads to build larger boats, with powerful pumps, and machinery on them for lifting entire vessels. He surprised all his friends in floating even immense sunken steamers—boats which had long been given up as lost.

When the Rebellion came, it was soon evident that a strong fleet must be put upon Western rivers to assist our armies. Word came from the government to Captain Eads to report in Washington. His thorough knowledge of the "Father of Waters" and its tributaries, and his practical suggestions, secured an order to build seven gunboats, and soon after an order for the eighth was given.

In forty-eight hours after receiving this authority, his agents and assistants were at work; and suitable ship-timber was felled in half a dozen Western States for their hulls. Contracts were awarded to large engine and iron works in St. Louis, Pitts[30]burgh, and Cincinnati; and within one hundred days, eight powerful ironclad gunboats, carrying over one hundred large cannon, and costing a million dollars, were achieving victories no less important for the Mississippi valley than those which Ericsson's famous "Cheese-box Monitor" afterwards won on the James River.

These eight gunboats, Commodore Foote ably employed in his brave attacks on Forts McHenry and Donaldson. They were the first ironclads the United States ever owned. Captain Eads covered the boats with iron: Commodore Foote covered them with glory.

Eads built not less than fourteen of these gunboats. During the war, the models were exhibited by request to the German and other governments. His next work was to throw across the mighty Mississippi River, nearly half a mile wide, at St. Louis, a monstrous steel bridge, supported by three arches, the spans of two being five hundred and two feet long, and the central one five hundred and twenty feet. The huge piles were ingeniously sunk in the treacherous sand, one hundred and thirty-six feet below the flood-level to the solid rock, through ninety feet of sand. This bridge and its approaches cost eighty millions of dollars, and is used by ten or twelve railroad companies. Above the tracks is a big street with carriage-roads, street-cars, and walks for foot-passengers.

The honor of building the finest bridge in the[31] world would have satisfied most men, but not ambitious Captain Eads. He actually loved the noble river in which De Soto, its discoverer, was buried, and fully realized the vast, undeveloped resources of its rich valleys. Equally well he understood what a gigantic work in the past the river and its fifteen hundred sizable tributaries had accomplished in times of freshets, by depositing soil and sand north of the original Gulf of Mexico, forming an alluvial plain five hundred miles long, sixty miles wide, and of unknown depth, and having a delta extending out into the Gulf, sixty miles long, and as many miles wide, and probably a mile deep. And yet this heroic man, although jealously opposed for years by West Point engineers, having a sublime confidence in the laws of nature, and actuated by intense desire to benefit mankind, dared to stand on the immense sand-bars at the mouth of this defiant stream, and, making use of the jetty system, bid the river itself dig a wide, deep channel into the seas beyond, for the world's commerce.

Captain Eads, who had studied the improvements on the Danube, Maas, and other European rivers, observed that all rivers flow faster in their narrow channels, and carry along in the swift water, sand, gravel, and even stones. This familiar law he applied at the South Pass of the Mississippi River, where the waters, though deep above, escaped from the banks into the Gulf, and spread sediment far and wide.[32]

The water on the sand-bars of the three principal passes varied from eight to thirteen feet in depth. Many vessels require twice the depth. Two piers, twelve hundred feet apart, were built from land's end, a mile into the sea. They were made from willows, timber, gravel, concrete, and stone. Mattresses, a hundred feet long, from twenty-five to fifty feet wide, and two feet thick, were constructed from small willows placed at right angles, and bound securely together. These were floated into position, and sunk with gravel, one mattress upon another, which the river soon filled with sand that firmly held them in their place. The top was finished with heavy concrete blocks, to resist the waves. These piers are called "jetties," and the swift collected waters have already carried over five million cubic yards of sand into the deep gulf, and made a ship-way over thirty feet deep. The five million dollars paid by the United States was little enough for so priceless a service.

In June, 1884, Captain Eads received the Albert medal of the British Society of Arts, the first American upon whom this honor has been conferred. Before his great enterprise of the Tehuantepec ship railroad had been completed, he died at Nassau, New Providence, Bahama Islands, March 8, 1887, after a brief illness, of pneumonia, at the age of sixty-seven.

JAMES WATT.

JAMES WATT.

The history of inventors is generally the same old struggle with poverty. Sir Richard Arkwright, the youngest of thirteen children, with no education, a barber, shaving in a cellar for a penny to each customer, dies worth two and one-half million dollars, after being knighted by the King for his inventions in spinning. Elias Howe, Jr., in want and sorrow, lives on beans in a London attic, and dies at forty-five, having received over two million dollars from his sewing-machines in thirteen years. Success comes only through hard work and determined perseverance. The steps to honor, or wealth, or fame, are not easy to climb.

The history of James Watt, the inventor of the steam-engine, is no exception to the rule of struggling to win. He was born in the little town of Greenock, Scotland, 1736. Too delicate to attend school, he was taught reading by his mother, and a little writing and arithmetic by his father. When six years of age, he would draw mechanical lines and circles on the hearth, with a colored piece of chalk. His favorite play was to take to pieces his[34] little carpenter tools, and make them into different ones. He was an obedient boy, especially devoted to his mother, a cheerful and very intelligent woman, who always encouraged him. She would say in any childish quarrels, "Let James speak; from him I always hear the truth." Old George Herbert said, "One good mother is worth a hundred schoolmasters"; and such a one was Mrs. Watt.

When sent to school, James was too sensitive to mix with rough boys, and was very unhappy with them. When nearly fourteen, his parents sent him to a friend in Glasgow, who soon wrote back that they must come for their boy, for he told so many interesting stories that he had read, that he kept the family up till very late at night.

His aunt wrote that he would sit "for an hour taking off the lid of the teakettle, and putting it on, holding now a cup and now a silver spoon over the steam, watching how it rises from the spout, and catching and condensing the drops of hot water it falls into."

Before he was fifteen, he had read a natural philosophy twice through, as well as every other book he could lay his hands on. He had made an electrical machine, and startled his young friends by some sudden shocks. He had a bench for his special use, and a forge, where he made small cranes, pulleys, pumps, and repaired instruments used on ships. He was fond of astronomy, and would lie on his back on the ground for hours, looking at the stars.[35]

Frail though he was in health, yet he must prepare himself to earn a living. When he was eighteen, with many tender words from his mother, her only boy started for Glasgow to learn the trade of making mathematical instruments. In his little trunk, besides his "best clothes," which were a ruffled shirt, a velvet waistcoat, and silk stockings, were a leather apron and some carpenter tools. Here he found a position with a man who sold and mended spectacles, repaired fiddles, and made fishing nets and rods.

Finding that he could learn very little in this shop, an old sea-captain, a friend of the family, took him to London. Here, day after day, he walked the streets, asking for a situation; but nobody wanted him. Finally he offered to work for a watchmaker without pay, till he found a place to learn his trade. This he at last obtained with a Mr. Morgan, to whom he agreed to give a hundred dollars for the year's teaching. As his father was poorly able to help him, the conscientious boy lived on two dollars a week, earning most of this pittance by rising early, and doing odd jobs before his employer opened his shop in the morning. He labored every evening until nine o'clock, except Saturday, and was soon broken in health by hunger and overwork. His mother's heart ached for him, but, like other poor boys, he must make his way alone.

At the end of the year he went to Glasgow to[36] open a shop for himself; but other mechanics were jealous of a new-comer, and would not permit him to rent a place. A professor at the Glasgow University knew the deserving young man, and offered him a room in the college, which he gladly accepted. He and the lad who assisted him could earn only ten dollars a week, and there was little sale for the instruments after they were made: so, following the example of his first master, he began to make and mend flutes, fiddles, and guitars, though he did not know one note from another. One of his customers wanted an organ built, and at once Watt set to work to learn the theory of music. When the organ was finished, a remarkable one for those times, the young machinist had added to it several inventions of his own.

This earning a living was a hard matter; but it brought energy, developed thought, and probably helped more than all else to make him famous. The world in general works no harder than circumstances compel.

Poverty is no barrier to falling in love, and, poor though he was, he now married Margaret Miller, his cousin, whom he had long tenderly loved. Their home was plain and small; but she had the sweetest of dispositions, was always happy, and made his life sunny even in its darkest hours of struggling.

Meantime he had made several intellectual friends in the college, one of whom talked much to him about a steam-carriage. Steam was not by any[37] means unknown. Hero, a Greek physician who lived at Alexandria a century before the Christian era, tells how the ancients used it. Some crude engines were made in Watt's time, the best being that of Thomas Newcomen, called an atmospheric engine, and used in raising water from coal-mines. It could do comparatively little, however; and many of the mines were now useless because the water nearly drowned the miners.

Watt first experimented with common vials for steam-reservoirs, and canes hollowed out for steam-pipes. For months he went on working night and day, trying new plans, testing the powers of steam, borrowing a brass syringe a foot long for his cylinder, till finally the essential principles of the steam-engine were born in his mind. He wrote to a friend, "My whole thoughts are bent on this machine. I can think of nothing else." He hired an old cellar, and for two months worked on his model. His tools were poor; his foreman died; and the engine, when completed, leaked in all parts. His old business of mending instruments had fallen off; he was badly in debt, and had no money to push forward the invention. He believed he had found the right principle; but he could not let his family starve. Sick at heart, and worn in body, he wrote: "Of all things in life there is nothing more foolish than inventing." Poor Watt!

His great need was money,—money to buy food, money to buy tools, money to give him leisure for[38] thought. Finally, a friend induced Dr. Roebuck, an iron-dealer, to become Watt's partner, pay his debts of five thousand dollars, take out a patent, and perfect the engine. Watt went to London for his patent, but so long was he delayed by indifferent officials, that he wrote home to his young wife, quite discouraged. With a brave heart in their pinching poverty, Margaret wrote back, "I beg that you will not make yourself uneasy, though things should not succeed to your wish. If the engine will not do, something else will; never despair."

On his return home, for six months he worked in setting up his engine. The cylinder, having been badly cast, was almost worthless; the piston, though wrapped in cork, oiled rags, and old hat, let the air in and the steam out; and the model proved a failure. "To-day," he said, "I enter the thirty-fifth year of my life, and I think I have hardly yet done thirty-five pence worth of good in the world: but I cannot help it." The path to success was not easy.

Dr. Roebuck was getting badly in debt, and could not aid him as he had promised; so Watt went sadly back to surveying, a business he had taken up to keep the wolf from the door. In feeble health, out in the worst weather, his clothes often wet through, life seemed almost unbearable. When absent on one of these surveying excursions, word was brought that Margaret, his beloved wife, was dead. He was completely unnerved. Who would care for his little[39] children, or be to him what he had often called her, "the comfort of his life"? After this he would often pause on the threshold of his humble home to summon courage to enter, since she was no longer there to welcome him. She had shared his poverty, but was never to share his fame and wealth.

And now came a turning-point in his life, though the struggles were by no means over. At Birmingham, lived Matthew Boulton, a rich manufacturer, eight years older than Watt. He employed over a thousand men in his hardware establishment, and in making clocks, and reproducing rare vases. He was a friend of Benjamin Franklin, with whom he had corresponded about the steam-engine, and he had also heard of Watt and his invention through Dr. Roebuck. He was urged to assist. But Watt waited three years longer for aid. Nine years had passed since he made his invention; he was in debt, without business, and in poor health. What could he do? He seemed likely to finish life without any success.

Finally Boulton was induced to engage in the manufacture of engines, giving Watt one-third of the profits, if any were made. One engine was constructed by Boulton's men, and it worked admirably. Soon orders came in for others, as the mines were in bad condition, and the water must be pumped out. Fortunes, like misfortunes, rarely come singly. Just at this time the Russian Government offered Watt five thousand dollars yearly if he[40] would go to that country. Such a sum was an astonishment. How he wished Margaret could have lived to see this proud day!

He could not well be spared from the company now; so he lived on at Birmingham, marrying a second time, Anne Macgregor of Scotland, to care for his children and his home. She was a very different woman from Margaret Miller; a neat housekeeper, but seemingly lacking in the lovable qualities which make sunshine even in the plainest home.

As soon as the Boulton and Watt engines were completed, and success seemed assured, obstacles arose from another quarter. Engines had been put into several Cornwall mines, which bore the singular names of "Ale and Cakes," "Wheat Fanny," "Wheat Abraham," "Cupboard," and "Cook's Kitchen." As soon as the miners found that these engines worked well, they determined to destroy the patent by the cry that Boulton and Watt had a monopoly of a thing which the world needed. Petitions were circulated, giving great uneasiness to both the partners. Several persons also stole the principle of the engine, either by bribing the engine-men, or by getting them drunk so that they would tell the secrets of their employers. The patent was constantly infringed upon. Every hour was a warfare. Watt said, "The rascality of mankind is almost past belief."

Meantime Boulton, with his many branches of business, and the low state of trade, had gotten[41] deeply in debt, and was pressed on every side for the tens of thousands which he owed. Watt was nearly insane with this trouble. He wrote to Boulton: "I cannot rest in my bed until these money matters have assumed some determinate form. I am plagued with the blues. I am quite eaten up with the mulligrubs."

Soon after this, Watt invented the letter-copying press, which at first was greatly opposed, because it was thought that forged names and letters would result. After a time, however, there was great demand for it. Watt was urged by Boulton to invent a rotary engine; but this was finally done by their head workman, William Murdock, the inventor of lighting by gas. He also made the first model of a locomotive, which frightened the village preacher nearly out of his senses, as it came puffing down the street one evening. Though devoted to his employers, sometimes working all night for them, they counselled him to give up all thought about his locomotive, lest by developing it he might in time withdraw from their firm. Alas for the selfishness of human nature! He was never made a partner, and, though he thought out many inventions after his day's work was done, he remained faithful to their service till the end of his life. Mr. Buckle tells this good story of Murdock. Having found that fish-skins could be used instead of isinglass, he came to London to inform the brewers, and took board in a handsome house. Fancying[42] himself in his laboratory, he went on with his experiments. Imagine the horror of the landlady when she entered his room, and found her elegant wall-paper covered with wet fish-skins, hung up to dry! The inventor took an immediate departure with his skins. When the rotary engine was finished, the partners sought to obtain a charter, when lo! The millers and mealmen all opposed it, because, said they, "If flour is ground by steam, the wind and water-mills will stop, and men will be thrown out of work." Boulton and Watt viewed with contempt this new obstacle of ignorance. "Carry out this argument," said the former, "and we must annihilate water-mills themselves, and go back again to the grinding of corn by hand labor." Presently a large mill was burned by incendiaries, with a loss of fifty thousand dollars.

Watt about this time invented his "Parallel Motion," and the Governor, for regulating the speed of the engine. Large orders began to come in, even from America and the West Indies; but not till they had expended two hundred thousand dollars were there any profits. Times were brightening for the hard-working inventor. He lost his despondency, and did not long for death, as he had previously.

After a time, he built a lovely home at Heathfield, in the midst of forty acres of trees, flowers, and tasteful walks. Here gathered some of the greatest minds of the world,—Dr. Priestley who[43] discovered oxygen, Sir William Herschel, Dr. Darwin, Josiah Wedgwood, and scores of others, who talked of science and literature. Mrs. Watt so detested dirt, and so hated the sight of her husband's leather apron and soiled hands, that he built for himself a "garret," where he could work unmolested by his wife, or her broom and dustpan. She never allowed even her two pug-dogs to cross the hall without wiping their feet on the mat. She would seize and carry away her husband's snuff-box, wherever she found it, because she considered snuff as dirt. At night, when she retired from the dining-room, if Mr. Watt did not follow at the time fixed by her, she sent a servant to remove the lights. If friends were present, he would say meekly, "We must go," and walk slowly out of the room. Such conduct must have been about as trying as the failure of his engines. For days together he would stay in his garret, not even coming down to his meals, cooking his food in his frying-pan and Dutch oven, which he kept by him. One cannot help wondering, whether, sometimes, as he worked up there alone, he did not think of Margaret, whose face would have brightened even that dingy room.

A crushing sorrow now came to him. His only daughter, Jessie, died, and then his pet son, Gregory, the dearest friend of Humphry Davy, a young man of brilliant scholarship and oratorical powers. Boulton died before his partner,[44] loved and lamented by all, having followed the precept he once gave to Watt: "Keep your mind and your heart pleasant, if possible; for the way to go through life sweetly is not to regard rubs."

Watt died peacefully Aug. 19, 1819, in his eighty-third year, and was buried in beautiful Handsworth Church. Here stands Chantrey's masterpiece, a sitting statue of the great inventor. Another is in Westminster Abbey. When Lord Brougham was asked to write the inscription for this monument, he said, "I reckon it one of the chief honors of my life." Sir James Mackintosh placed him "at the head of all inventors in all ages and nations"; and Wordsworth regarded him, "Considering both the magnitude and the universality of his genius, as perhaps the most extraordinary man that this country has ever produced."

After all the struggle came wealth and fame. The mine opens up its treasures only to those who are persevering enough to dig into it; and life itself yields little, only to such as have the courage and the will to overcome obstacles.

Heathfield has passed into other hands; but the quiet garret is just as James Watt left it at death. Here is a large sculpture machine, and many busts partly copied. Here is his handkerchief tied to the beam on which he rested his head. The beam itself is crumbling to dust. Little pots of chemicals on the shelves are hardened by age. A bunch of withered grapes is on a dish, and the[45] ashes are in the grate as when he sat before it. Close by is the hair trunk of his beloved Gregory, full of his schoolbooks, his letters, and his childish toys. This the noble old man kept beside him to the last.

One sunny morning in June, I went out five miles from the great manufacturing city of Birmingham, England, to the pretty town called Erdington, to see the Mason Orphanage. I found an immense brick structure, with high Gothic towers, in the midst of thirteen acres of velvety lawn. Over the portals of the building were the words, "DO DEEDS OF LOVE." Three hundred happy children were scattered over the premises, the girls in brown dresses with long white aprons: some were in the great play-room, some doing the housework, and some serving at dinner. Sly Cupid creeps into an orphan-asylum even; and the matron had to watch carefully lest the biggest pieces of bread and butter be given by the girls to the boys they liked best.

In the large grounds, full of flowers and trees, among the children he so tenderly loved and called by name, the founder, Sir Josiah Mason, and his wife, are buried, in a beautiful mausoleum, a Gothic chapel, with stone carving and stained-glass windows.

SIR JOSIAH MASON.

SIR JOSIAH MASON.

And who was this founder?

In a poor, plain home in Kidderminster, Feb. 23 1795, Sir Josiah Mason was born. His father was a weaver, and his mother the daughter of a laborer. At eight years of age, with of course little education, the boy began the struggle of earning a living. His mother fitted up two baskets for him, and these he filled with baker's cakes, and sold them about the streets. Little Joe became so great a favorite, that the buyers often gave him an extra penny. Finally a donkey was obtained; and a bag containing cakes in one end, and fruit and vegetables in the other, was strapped across his back. In this way, for seven years, Joe peddled from door to door. Did anybody ever think then that he would be rich and famous?

The poor mother helped him with her scanty means, and both parents allowed him to keep all he could make. His father's advice used to be, "Joe, thee'st got a few pence; never let anybody know how much thee'st got in thee pockets." And well the boy carried out his father's injunction in afterlife.

When he was fifteen, his brother had become a confirmed invalid, and needed a constant attendant. The father was away at the shop, and the mother busy with her cares: so Joe, who thought of others always before himself, determined to be nurse, and earn some money also. He set about becoming a shoemaker, having learned the trade from watching[48] an old man who lived near their house; but he could make only a bare pittance. Then he taught himself writing, and earned a trifle for composing letters and Valentines for his poor neighbors. This money he spent in books, for he was eager for an education. He read no novels nor poetry, but books of history, science, and theology.

Finally the mother started a small grocery and bakery, and Joe assisted. Many of their customers were tramps and beggars, who could buy only an ounce or half-ounce of tea; but even a farthing was welcome to the Masons. Later, Josiah took up carpet-weaving and blacksmithing; but he could never earn more than five dollars a week, and he became restless and eager for a broader field. He had courage, was active and industrious, and had good habits.

He was now twenty-one. He decided to go to Birmingham on Christmas Day, to visit an uncle whom he had never seen. He went, and this was the turning-point of his life. His uncle gave him work in making gilt toys; and, what was perhaps better still for the poor young man, he fell in love with his cousin Annie Griffiths, and married her the following year. This marriage proved a great blessing, and for fifty-two years, childless, they two were all in all to each other. For six years the young husband worked early and late, with the promise of succeeding to the small business; but at the end of these years the promise was broken, and[49] Mason found himself at thirty, out of work, and owning less than one hundred dollars.

Walking down the street one day in no very happy frame of mind, a stranger stepped up to him, and said, "Mr. Mason?"

"Yes," was the answer.

"You are now, I understand, without employment. I know some one who wants just such a man as you, and I will introduce him to you. Will you meet me to-morrow morning at Mr. Harrison's, the split-ring maker?"

"I will."

The next day the stranger said to Mr. Harrison, "I have brought you the very man you want."

The business man eyed Mason closely, saying, "I've had a good many young men come here; but they are afraid of dirtying their fingers."

Mason opened his somewhat calloused hands, and, looking at them, said, "Are you ashamed of dirtying yourselves to get your own living?"

Mason was at once employed, and a year later Mr. Harrison offered him the business at twenty-five hundred dollars. Several men, observing the young man's good qualities, had offered to loan him money when he should go into trade for himself. He bethought him of these friends, and called upon them; but they all began to make excuse. The world's proffers of help or friendship we can usually discount by half. Seeing that not a dollar could be borrowed, Mr. Harrison generously offered to wait[50] for the principal till it could be earned out of the profits. This was a noble act, and Mr. Mason never ceased to be grateful for it.

He soon invented a machine for bevelling hoop-rings, and made five thousand dollars the first year from its use. Thenceforward his life reads like a fairy-tale. One day, seeing some steel pens on a card, in a shop-window, he went in and purchased one for twelve cents. That evening he made three, and enclosed one in a letter to Perry of London, the maker, paying eighteen cents' postage, which now would be only two cents.

His pen was such an improvement that Mr. Perry at once wrote for all he could make. In a few years, Mason became the greatest pen-maker in the world, employing a thousand persons, and turning out over five million pens per week. Sixty tons of pens, containing one and a half million pens to the ton, were often in his shops. What a change from peddling cakes from door to door in Kidderminster!

Later he became the moneyed partner in the great electro-plating trade of the Elkingtons, whose beautiful work at the Centennial Exposition we all remember.

Mr. Mason never forgot his laborers. When he established copper-smelting works in Wales, he built neat cottages for the workmen, and schools for the three hundred and fifty children. The Welsh refused to allow their children to attend school where they would be taught English. Mr. Mason over[51]came this by distributing hats, bonnets, and other clothing to the pupils, and, once in school, they needed no urging to remain. The manufacturer was as hard a worker as any of his men. For years he was the first person to come to his factory, and the last to leave it. He was quick to decide a matter, and act upon it, and the most rigid economist of time. He allowed nobody to waste his precious hours with idle talk, nor did he waste theirs. He believed, with Shakespeare, that "Talkers are no good doers." His hours were regular. He took much exercise on foot, and lived with great simplicity. He was always cheerful, and had great self-control. Finally he began to ask himself how he could best use his money before he died. He remembered his poor struggling mother in his boyish days. His first gift should be a home for aged women—a noble thought!—his next should be for orphans, as he was a great lover of children. For eight years he watched the beautiful buildings of his Orphanage go up, and then saw the happy children gathered within, bringing many of them from Kidderminster, who were as destitute as himself when a boy. He seemed to know and love each child, for whose benefit he had included even his own lovely home, a million dollars in all. The annual income for the Orphanage is about fifty thousand dollars. What pleasure he must have had as he saw them swinging in the great playgrounds, where he had even thought to make triple columns[52] so that they could the better play hide-and-seek! At eight, he was trudging the streets to earn bread; they should have an easier lot through his generosity.

For this and other noble deeds Queen Victoria made him a knight. What would his poor mother have said to such an honor for her boy, had she been alive!

What would the noble man, now over eighty, do next with his money? He recalled how hard it had been for him to obtain knowledge. The colleges were patronized largely by the rich. He would build a great School of Science, free to all who depended upon themselves for support. They might study mathematics, languages, chemistry, civil engineering, without distinction of sex or race. For five years he watched the elegant brick and stone structure in Birmingham rise from its foundations. And then, Oct. 1, 1880, in the midst of assembled thousands, and in the presence of such men as Fawcett, Bright, and Max Muller, Mason Science College was formally opened. Professor Huxley, R. W. Dale, and others made eloquent addresses. In the evening, a thousand of the best of England gathered at the college, made beautiful by flowers and crimson drapery. On a dais sat the noble giver, in his eighty-sixth year. The silence was impressive as the grand old man arose, handing the key of his college, his million-dollar gift, to the trustees. Surely truth is stranger than fiction![53] To what honor and renown had come the humble peddler!

On the following 25th of June, Sir Josiah Mason was borne to his grave, in the Erdington mausoleum. Three hundred and fifty orphan-children followed his coffin, which was carried by eight servants or workingmen, as he had requested. After the children had sung a hymn, they covered the coffin-lid with flowers, which he so dearly loved. He sleeps in the midst of his gifts, one of England's noble benefactors.

In the Louvre in Paris, preserved among almost priceless gems, are several pieces of exquisite pottery called Palissy ware. Thousands examine them every year, yet but few know the struggles of the man who made such beautiful works of art.

Born in the south of France in 1509, in a poor, plain home, Bernard Palissy grew to boyhood, sunny-hearted and hopeful, learning the trade of painting on glass from his father. He had an ardent love for nature, and sketched rocks, birds, and flowers with his boyish hands. When he was eighteen, he grew eager to see the world, and, with a tearful good-by from his mother, started out to seek his fortune. For ten years he travelled from town to town, now painting on glass for some rich lord, and now sketching for a peasant family in return for food. Meantime he made notes about vegetation, and the forming of crystals in the mountains of Auvergne, showing that he was an uncommon boy.

BERNARD PALISSY.

BERNARD PALISSY.

Finally, like other young people, he fell in love, and was married at twenty-eight. He could not[55] travel about the country now, so he settled in the little town of Saintes. Then a baby came into their humble home. How could he earn more money, since the poor people about him had no need for painted glass? Every time he tried to plan some new way to grow richer, his daily needs weighed like a millstone around his neck.

About this time he was shown an elegant enamelled cup from Italy. "What if I could be the first and only maker of such ware in France?" thought he. But he had no knowledge of clay, and no money to visit Italy, where alone the secret could be obtained.

The Italians began making such pottery about the year 1300. Two centuries earlier, the Pagan King of Majorca, in the Mediterranean Sea, was said to keep confined in his dungeons twenty thousand Christians. The Archbishop of Pisa incited his subjects to make war upon such an infidel king, and after a year's struggle, the Pisans took the island, killed the ruler, and brought home his heir, and great booty. Among the spoils were exquisite Moorish plates, which were so greatly admired that they were hung on the walls of Italian churches. At length the people learned to imitate this Majolica ware, which brought very high prices.

The more Palissy thought about this beautiful pottery, the more determined he became to attempt its making. But he was like a man groping in the dark. He had no knowledge of what composed the[56] enamel on the ware; but he purchased some drugs, and ground them to powder. Then he bought earthen pots, broke them in pieces, spread the powder upon the fragments, and put them in a furnace to bake. He could ill afford to build a furnace, or even to buy the earthenware; but he comforted his young wife with the thought that as soon as he had discovered what would produce white enamel they would become rich.

When the pots had been heated sufficiently, as he supposed, he took them out, but, lo! the experiment had availed nothing. Either he had not hit upon the right ingredients, or the baking had been too long or too short in time. He must of course try again. For days and weeks he pounded and ground new materials; but no success came. The weeks grew into months. Finally his supply of wood became exhausted, and the wife was losing her patience with these whims of an inventor. They were poor, and needed present income rather than future prospects. She had ceased to believe Palissy's stories of riches coming from white enamel. Had she known that she was marrying an inventor, she might well have hesitated, lest she starve in the days of experimenting; but now it was too late.

His wood used up, Palissy was obliged to make arrangements with a potter who lived three miles away, to burn the broken pieces in his furnace. His enthusiasm made others hopeful; so that the promise to pay when white enamel was discovered[57] was readily accepted. To make matters sure of success at this trial, he sent between three and four hundred pieces of earthenware to his neighbor's furnace. Some of these would surely come back with the powder upon them melted, and the surface would be white. Both himself and wife waited anxiously for the return of the ware; she much less hopeful than he, however. When it came, he says in his journal, "I received nothing but shame and loss, because it turned out good for nothing."

Two years went by in this almost hopeless work, then a third,—three whole years of borrowing money, wood, and chemicals; three years of consuming hope and desperate poverty. Palissy's family had suffered extremely. One child had died, probably from destitution. The poor wife was discouraged, and at last angered at his foolishness. Finally the pottery fever seemed to abate, and Palissy went back to his drudgery of glass-painting and occasional surveying. Nobody knew the struggle it had cost to give up the great discovery; but it must be done.

Henry II., who was then King of France, had placed a new tax on salt, and Palissy was appointed to make maps of all the salt-marshes of the surrounding country. Some degree of comfort now came back to his family. New clothes were purchased for the children, and the overworked wife repented of her lack of patience. When the surveying was completed, a little money had been saved, but, alas! the pottery fever had returned.[58]