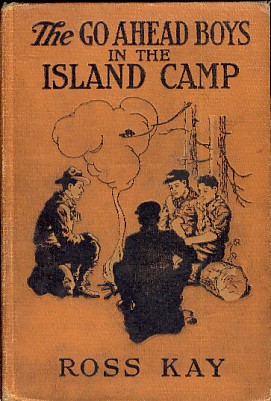

Title: The Go Ahead Boys in the Island Camp

Author: Ross Kay

Release date: April 25, 2011 [eBook #35957]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by RStephen Hutcheson, Roger Frank and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE GO AHEAD BOYS IN THE ISLAND CAMP

THE GO AHEAD BOYS

IN

THE ISLAND CAMP

BY

ROSS KAY

Author of “The Search for the Spy,” “The Air Scout,”

“With Joffre on the Battle Line,” “Dodging the

North Sea Mines,” “The Go Ahead Boys

on Smugglers’ Island,” “The Go

Ahead Boys and the

Treasure Cave,”

etc., etc.

PREFACE

Every one who loves outdoor life knows the charm and the pleasures of camping. To look back on the days passed in a tent by the shore of some forest lake or stream is a source of never-ending enjoyment to those of us who have had that experience. In this book I have tried to describe the adventures of four boys who spent a vacation camping in the Adirondacks, and who indulged in water sports of various kinds while there. Many of the episodes are true or at least founded on the experiences of former boys who enjoyed them. If the boys who may read this tale will derive some of the pleasure in hearing about them that the real boys did in participating in them I shall feel repaid.

—Ross Kay

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I—MAKING CAMP

CHAPTER II—A MISHAP

CHAPTER III—JOHN HEARS SOMETHING

CHAPTER IV—SETTING SAIL

CHAPTER V—THE UNEXPECTED HAPPENS

CHAPTER VI—ADRIFT

CHAPTER VII—AN UNEXPECTED MEETING

CHAPTER VIII—A PREDICAMENT

CHAPTER IX—DANGER

CHAPTER X—WAIT AND SEE

CHAPTER XI—WHAT GEORGE DID

CHAPTER XII—A CHALLENGE

CHAPTER XIII—THE OUTCAST

CHAPTER XIV—TALKING IT OVER

CHAPTER XV—PREPARATION

CHAPTER XVI—GRANT MISSES

CHAPTER XVII—GEORGE’S STRATEGY

CHAPTER XVIII—A CLOSE MATCH

CHAPTER XIX—A CLOSE SHAVE

CHAPTER XX—GEORGE SURPRISES HIS FRIENDS

CHAPTER XXI—HOW THE PLAN WORKED

CHAPTER XXII—A STRANGE PERFORMANCE

CHAPTER XXIII—AN UNEXPECTED HONOR

CHAPTER XXIV—IN QUEST OF GAME

CHAPTER XXV—THE WORM TURNS

CHAPTER XXVI—AN UNEXPECTED ENCOUNTER

CHAPTER XXVII—CONCLUSION

THE GO AHEAD BOYS IN THE ISLAND CAMP

“Here is the place to put the tent, String.”

“I think this spot is better.”

“Not at all. It’s higher over here and consequently we won’t be flooded by every rain that comes along and besides that, the flies won’t be so apt to bother us.”

“All right, just as you say.”

The boy addressed as “String” had been named John Clemens by his parents. He was six feet three inches tall, however, and extremely thin so that the nickname applied to him seemed quite appropriate. At any rate his friends thought so and that was the name by which he usually was called.

Talking with him and arguing about the location of the tent was Fred Button, a boy as short as John was tall. He was so small that the nicknames of Stub, Pewee and Pygmy had all been applied to him, the last one sometimes shortened to Pyg much to Fred’s disgust. He had found out long ago, however, that there was no use in showing his irritation at this for it only served to increase the frequency with which the name was applied to him.

These two boys, together with two of their friends, were pitching camp preparatory to spending a summer on one of the Adirondack lakes. Grant Jones was one of these boys and the other was George Washington Sanders. Grant was the most serious-minded of the four and everything he did he did with all his heart. As a result he was a leader not only on the athletic field but in his studies as well. The other boys usually came to him for advice and looked up to him in many ways. The fact that he was of a serious nature, however, did not mean that he was not oftentimes just as full of fun as anybody.

George Washington Sanders having been named after the father of his country, had acquired the name of Pop. He was often in mischief and took especial delight in teasing his three friends. It was almost out of the question to be angry at him, however, for he never lost his temper for more than a moment himself and was always bubbling over with spirits and fun. He was the life of any crowd he was in.

While the argument between John and Fred was in progress Grant and George approached.

“What are you two arguing about?” demanded Grant.

“We’re trying to decide where to put the tent,” replied Fred. “What have you two been doing all this time?”

“Putting the canoes away,” said Grant. “Where are you going to locate the tent, anyway?”

“Well,” said Fred, “John wants it over in that hollow, but I say it ought to be up on this little plateau.”

“I think you’re right, Fred,” said George. “We won’t get so many flies up there.”

“Just what I said,” exclaimed Fred triumphantly. “What do you think about it, Grant?”

“I think your place is better,” said Grant. “Besides everything else we’ll have a good view of the lake from there.”

“All right,” said John, pretending to be very sad. “You all seem to be against me so I guess I’ll have to give in.”

“You see, String,” exclaimed George with a sly twinkle in his eye, “we all know so very much more about this business than you do that you might just as well take our advice in everything.”

“You talk too much, Pop,” said John shortly, which remark drew a laugh of glee from George who had tried to irritate his friend and was delighted at having succeeded.

“I say we all stop talking and get to work on the tent,” said Grant. “We can do all the fooling we want later.”

“Great idea, Grant,” exclaimed George, who was in excellent spirits at the prospect of all the good times ahead of them. “You’re a wonder.”

“You were right when you said Pop talked too much, String,” laughed Grant. “We’ll put him to work now, though.”

In an incredibly short time the white tent was erected on the little bluff overlooking the lake. It was spacious with plenty of room for the four young campers and all their equipment, which was speedily stored away inside.

“How about a few fish for dinner?” exclaimed George, when the tent was in place. “Personally I think they’d taste pretty good.”

“Go ahead and catch some, then,” urged John. “I’ll help you eat them.”

“Oh, I didn’t worry about your not helping me out in that way,” laughed George. “That’s the least of my troubles. What bothers me is who is to clean the fish.”

“The man who catches them always cleans them,” said Fred.

“Oh, no, he doesn’t,” laughed George. “Not in this case, anyway.”

“How about the cook doing it?” inquired John.

“As I am to do the cooking all summer I can’t say I approve of that plan,” laughed Grant. “That seems a little bit too much.”

“Well, he hasn’t caught any fish yet, anyway,” said Fred. “Let him do that first and we’ll argue about them afterwards.”

“Where are you going to fish, Pop?” asked Grant.

“I thought I’d try it off those rocks down on the point there,” said George. “That looks like a likely spot.”

“While you’re fishing I’ll cut some balsam boughs and make four beds in the tent,” said John.

“And I’ll get a place ready to make a fire in,” said Grant. “That’ll take a little time.”

“How about you, Fred?” demanded George. “It looks as if you were about the only loafer in the whole crowd.”

“I’ll help String cut balsam.”

“Very good,” said George haughtily. “You may go now.”

“I’ll put you in the lake if you’re not more careful,” said John threateningly, but he laughed in spite of himself.

A few moments later every boy was busied with his appointed task. George, armed with his fishing rod, made off for the end of the little wooded island. John and Fred disappeared in search of balsam boughs, while Grant remained behind to make a fireplace. This was an interesting piece of work, the secret of which he had learned from a guide some few summers before during a sojourn in the woods.

First he selected eight or ten rocks as nearly the size and shape of cobblestones as he could find. These he placed on the ground in two parallel rows some twelve inches apart. Both little stone walls thus formed he endeavored to make as nearly the same height as possible and before long his fireplace was complete. Between the two rows of stones the fire was to be made; pots and pans could thus be set over the fire and rest upon the rocks which formed the walls of the fireplace; in this way they could be kept from actual contact with the coals and at the same time most of the heat from the fire was concentrated upon them.

This is a very efficient method of making a camp-fire as Grant had learned from previous experience. Of course, in the case of a temporary camp or unless there are plenty of rocks close at hand, it is hardly worth while and it is not the kind of a fire that campers like to sit around in the evening. As a cooking fire, however, it is one of the best.

Grant had hardly finished this task when John and Fred returned to the camp. They were loaded down with balsam boughs and staggered under the weight of the loads they were carrying. With a sigh of relief each boy dropped his bundle on the ground and sat down to regain his breath.

“You fellows look as if you’d been working hard,” laughed Grant.

“We have,” panted John. “Just carry a load like that for a while and see what you think of it.”

“I’ll take your word for it,” said Grant. “Have you got all you want?”

“All the balsam, you mean?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I should hope so,” exclaimed Fred. “At any rate I refuse to go back after any more. My fingers are all gummy and sticky, too.”

“The boughs smell great, though,” said Grant admiringly.

“Don’t they?” exclaimed John. “They’ll be wonderful to sleep on.”

“You see, Grant,” remarked Fred, “String here is so tall we had to cut an extra supply to make a bed long enough for him. I’m really quite worried, too, for fear his feet may stick out beyond the flap of the tent, anyway.”

“I’m not as bad as that I hope,” laughed John. “It would be awful, wouldn’t it, if I couldn’t keep out of the rain?”

“You might stand on your head,” suggested Fred. “Your feet sticking straight up in the air could take the place of umbrellas. They’re big enough so that they’d shelter you, all right.”

“Look here,” exclaimed John, “that sounds like one of Pop’s remarks. I hope you’re not getting as bad as he is.”

“By the way,” said Fred, “where is he? He ought to be back pretty soon.”

“He’s still fishing,” said Grant. “I guess he hasn’t had very good luck.”

“He ought to have taken one of the canoes, anyway,” said John. “He can’t catch anything just standing on the shore.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Grant. “He might get some small perch or bass.”

“What I want is a good big trout,” exclaimed Fred. “I’ll consider this summer a failure unless I get one.”

“Maybe we’ll each get one,” said Grant. “They say there are lots of them around here.”

“Not so much in the lake as in the streams running into it, I guess,” remarked John. “It seems to me that the big trout are always in small pools.”

“Well, I’ll try them all,” said Fred eagerly. “I don’t want just to catch trout; any one can do that. What I want is a big one.”

“One you can take home stuffed, I suppose,” suggested Grant.

“That’s it exactly. I mean to have one, too.”

“Well, we might fix up the beds first,” said John. “It won’t take long. All we want is four piles and we can spread the blankets out on them when we are ready to turn in. Just think of it; a nice soft sweet-smelling bed to sleep on and we won’t feel any of the rocks and roots and bumps that may be under us.”

“It sounds fine all right,” laughed Grant. “We’d better get to work soon, too, for it’ll be dark before long.”

“I should think Pop would be back by now, too,” said John. “You don’t suppose anything could have happened to him, do you?”

“Why, I don’t see how—” began Fred, when he suddenly ceased speaking and listened intently.

“What’s the matter?” demanded Grant.

“Ssh,” whispered Fred. “I thought I heard some one call.”

All three boys bent their heads and listened intently. The only sound that came to them, however, was the soft sighing of the breeze through the treetops and the occasional call of some bird preparing to settle down for the night. The sun was low in the west, just sinking below the fringe of the forest which skirted the little lake. All seemed quiet and serene.

“What did you think you heard, Fred?” demanded Grant after the lapse of several moments.

“I thought I heard a call. In fact I was almost—”

Once more he stopped suddenly and listened. “What was that?” he exclaimed.

“I heard something, too,” whispered John excitedly. “Listen!”

“I don’t hear a thing,” muttered Grant. “I must be deaf.”

“There it is again,” cried Fred suddenly.

“I heard it, too,” exclaimed John. “It came from that end of the island.”

“That’s the direction Pop took,” said Grant in alarm. “Perhaps there has something happened to him.”

“We’ll soon find out anyway,” cried Fred. “Come along!” and he began to run at top speed in the direction George had gone a short time before.

Close behind him followed Grant and John. Every boy was worried and beset with a thousand and one evil thoughts as to what might have befallen their light-hearted and well-loved comrade. Almost everything conceivable in the way of misfortune suggested itself to their anxious minds.

“Keep close to the shore, Fred,” called Grant. “He was fishing, you know.”

Fred did keep as close to the shore as possible, but it was no easy task a great many times. The island was rough and rocky and heavily wooded, the trees growing down to the water’s edge in many places. Crashing through the underbrush and making a great deal of noise the three boys raced along. Whether or not the cry which John and Fred had heard was repeated they could not say, for the tumult of their own mad course drowned out all other noises.

After what seemed a long time they came to the end of the island. Here the forest gave way to the rocks which ran out a considerable distance, forming a small peninsula. At the tip end were several big boulders which had become separated from the main island after long years of action by the water and in order to reach them it was necessary to jump across several feet from one to the other. Towards these boulders the three boys made their way.

“I don’t see anybody,” panted John.

“Nor I,” agreed Fred. “I don’t hear anything, either.”

“Listen,” warned Grant, holding up his hand.

“And look, too,” murmured Fred under his breath.

Suddenly John started forward excitedly. “Look,” he cried, “there he is.”

“Where? Where?” demanded Grant.

“Down there in the water. Don’t you see him?”

“Help! Help!” came the call, and John, Fred and Grant sped to the assistance of their comrade. His head showed above the water and he splashed a great deal in an effort to remain afloat. That he was very rapidly becoming weaker, however, was plain to be seen.

“Give me a hand, somebody,” cried George.

“All right, Pop. We’ll be right with you,” Grant reassured him.

George was struggling in the water close to one of the big boulders. Its sides were so steep and high, however, that he was unable to climb out. From his actions it also appeared as if he were keeping himself afloat merely with his hands.

“Get a stick, Grant,” cried Fred. “You can hold it out for him to take hold of.”

“Where is one? Find one, quick!” exclaimed Grant excitedly.

“Here you are,” said John. “This one will do. Take this.”

He held out a stick some six or eight feet long which had been lying on the shore at his feet. Grant seized it eagerly and hastened to George’s assistance.

“Hurry up, Grant!” called George. “I can’t last much longer!”

“Here you are!” cried Grant, leaning out from the shore as far as he dared and holding the stick toward his friend. “Grab hold of this.”

After one or two unsuccessful attempts George succeeded in catching hold of the stick. Grant drew him up as close to the rock as possible and then Fred and John bending down over the edge seized him by his arms and quickly pulled him out of the water and to safety.

“How did you happen to—” began Fred, when John suddenly interrupted him.

“What have you got around your legs?” he demanded in astonishment.

“My fishing line,” said George, smiling weakly. “It tripped me up.”

“Well, I should think it might,” exclaimed John. “How in the world did you ever get it wound around you like that?”

“I had my rod in one hand,” said George, “and I tried to jump from that rock over there to this one. I landed here all right, but when I jumped the line got twisted around my ankles and I lost my balance. It finally tripped me up and I fell into the water. When I got there the line kept getting more and more tangled up the harder I kicked, until finally I could hardly move my feet at all. I had to keep afloat just by using my hands.”

“That was certainly a bright trick,” exclaimed Fred. “Why, you might have drowned.”

“I thought I was going to be,” said George grimly. “I was getting pretty tired.”

“Where’s your rod?” inquired Fred.

“At the other end of the line. A steel rod doesn’t float, you know.”

“That’s true,” laughed Fred. “Haul in that line, John.”

Of course all the line unrolled from the reel before the rod was rescued but it was finally brought safely to shore. A large section of the line, however, had to be sacrificed as it was found almost impossible to untangle the mass that had wound itself around George’s legs and ankles, and a knife was necessary to free him.

“Where are your fish, Pop?” inquired Fred. “I suppose you dropped them all when you fell in,” and he nudged Grant as he spoke.

“I had only one,” replied George ruefully. “He did fall in and I lost him.”

“What kind was it?”

“A black bass.”

“A big one, I suppose.”

“No, he wasn’t either. He was pretty small. I didn’t have any luck at all.”

“You ought to have taken one of the canoes,” said Grant. “You can’t expect to catch anything from the shore.”

“He’d probably upset the canoe,” said Fred. “I don’t think we should allow him to do anything alone after this.”

“Huh!” was George’s only reply to this sally.

“Feel like walking, Pop?” asked Grant. “If you do we’d better go back to camp and get some dry clothes for you.”

“I was just thinking that,” said George. “I’m commencing to feel chilly. These nights in the Adirondacks are pretty cool, I find.”

“They certainly are,” John agreed. “Let’s go back.”

“I could eat something, too,” remarked Fred. “The cool air also seems to give you an appetite.”

“Come on,” cried Grant, and a moment later the four young campers were retracing their steps to the tent.

Arriving there, George made haste to change his wet garments for some dry ones. Fred and John collected wood for the fire while Grant made ready to cook the dinner. A short time later the odor of sizzling bacon filled the air, lending an even keener edge to four appetites that were sharp already. The first meal in camp was voted a great success by every member of the party, and all agreed that Grant was a wonderful cook.

“Isn’t this great!” exclaimed George, when the dishes had all been washed.

The four young friends were seated around a camp-fire crowned by a great birch log that blazed so brightly it lighted up everything for a considerable distance round about them.

“It surely is,” agreed John. “I don’t see how you could beat this.”

“Just think of it,” said Fred. “We’re here for all summer, too.”

“Oh, the summer will go fast enough. Don’t worry about that,” Grant warned him. “It’ll be over before we know it.”

At last the fire burned low until it was nothing but a mass of glowing embers. John arose to his feet and yawned. “I’m going in and try those new beds we made this afternoon,” he said. “I’m tired.”

“I’m sleepy, too,” exclaimed Grant. “Let’s all turn in.”

The few remaining coals from the fire were carefully scattered so that they could do no damage during the night. These four friends had had enough experience in the woods to know what a forest fire means. They also knew that all good woodsmen were careful about such things and always had regard for the rights of others.

Every one was sleepy and it was not long before four tired and happy boys were stretched upon four sweet-smelling balsam beds, sound asleep. How long he slept John could not tell when he suddenly awoke with the feeling that he had heard a cry for help.

John sat upright and peered about him in the darkness, every nerve alert. He heard nothing, however. Perhaps he had been mistaken after all. George’s mishap that afternoon had been on his mind and probably he had dreamed of it.

Somehow the feeling that he had heard a cry still seemed very distinct, however, and it gave him a most unpleasant sensation. He listened intently. He could hear the deep and steady breathing of his three comrades lying asleep around him, and he heaved a sigh of relief. At least nothing had happened to them.

Not a sound came to break the silence of the night and John began to feel sure that he had been deceived. He prepared himself to lie down again and go to sleep. He must have had a nightmare, he thought. Who could be in trouble on a calm, still night like this? At any rate it was none of their party and undoubtedly was no one at all. It had all been a dream, though a most unpleasant one, and John shivered unconsciously at the recollection. His nerves had all been set on edge, but gradually he quieted down and once more settled himself to rest.

Barely had he closed his eyes, however, when the cry was repeated. There was no mistaking it this time, and John instantly was wide awake once more, the cold shivers dancing up and down his spine. Never had he heard such a voice. Some one evidently was in terrible distress mingled with fear with which hopelessness seemed combined. The voice trailed off in a wail of despair that brought John’s heart up into his mouth.

It seemed to him that the cry must have awakened his companions as well, but no, he could still hear their regular breathing even above the violent pounding of his heart. What should he do? There was no question about it this time; it had not been a dream. Some one was in trouble and needed help, and evidently needed it badly. Consequently it was needed quickly, too, and John was determined to do his best.

He leaned over in the darkness and felt for the boy who was lying next to him.

“Grant,” he whispered. “Grant, wake up.”

Grant merely groaned and stirred uneasily.

“Wake up, Grant,” he repeated, shaking his friend by his shoulder. “Wake up, I tell you.”

“What do you want?” demanded Grant sleepily. “What’s the matter?”

“Matter enough,” exclaimed John. “There’s somebody in trouble out here on the lake and he’s calling for help.”

“Is that so?” cried Grant, now wide awake. “Are you sure?”

“I heard him call twice.”

“Was it a man?”

“I think so. I never heard such a voice. It was awful.”

“We’d better go see what we can do then,” exclaimed Grant. “Which direction did the voice come from?”

“I couldn’t say; it seemed to come from all over. Oh, Grant, it was awful.”

“Sure you didn’t dream it?”

“Positive. I know I heard it.”

“Come along then,” said Grant. “We’ll go outside and get one of the canoes and see what we can find. Maybe we’ll hear it again.”

“I don’t know; it sounded to me as though it was the death cry of some one. I never heard such a thing in all my life.”

“Get your sweater and some trousers,” directed Grant. “Don’t wake Fred and Pop yet. We’ll see what we can do first.”

John and Grant rose carefully to their feet and laid aside their blankets. Feeling their way, they soon located their clothes and a moment later, partly dressed, they stepped forth from the tent. The night was clear, and the moon, in its last quarter, lighted up the trees and the water in a ghostly manner.

“Are the paddles—” began Grant, when the cry was repeated. This time it seemed only a short distance from their camp and out on the lake. Perhaps some one had upset a boat and was struggling in the water.

“There it is,” cried John, clutching Grant excitedly by the arm. “Did you hear that? Isn’t that terrible?”

“Is that what you heard before?” demanded Grant.

“Yes, the same voice. Hurry! We mustn’t waste a second.”

“Wait a minute, String,” and in Grant’s voice was the suggestion of a laugh.

“What’s the matter?”

“Well, if that’s what you heard the other times, I wouldn’t be in a great hurry if I were you.”

“Why not? Are you crazy, Grant? Can’t you tell by that voice that some one is in trouble? Aren’t you going to help him?”

“Did you ask me if I was crazy?”

“I did, and I think you are, too. Please hurry, Grant.”

“Oh, no, I’m not crazy,” said Grant, and there was no mistaking the fact that he was laughing now. “I’m not crazy, but you’re loony.”

“What do you mean?”

“That’s a loon you hear out there.”

“A loon,” exclaimed John in amazement. “What are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about a bird. That noise you hear is made by a bird named a loon. Haven’t you ever heard one before?”

“Never. I don’t see how a bird could sound so like a human being.”

“That’s what it is just the same,” said Grant, and he was almost doubled up with laughter now. “I think I’d better wake up Pop and Fred and tell them about your friend that’s calling for help.”

“Are you positive it’s a loon?”

“Absolutely.”

“Then don’t ever tell a soul,” begged John eagerly. “I’d never hear the last of it as long as I lived. It would be awful if George ever knew.”

“You’re not the first one who’s ever been fooled,” laughed Grant. “You probably won’t be the last, either.”

“Please don’t tell on me, though, Grant. Promise me you won’t.”

“We’ll see,” said Grant evasively. “I can’t make any promises though.”

“How should I know that it was a loon?” demanded John. “I never heard one before and you yourself say that other people have been fooled the same way.”

“That’s true. Still it’s almost too good a joke on you to keep.”

“What is a loon, anyway?”

“It’s a bird; it belongs to the duck family, I guess. They live around on lakes and ponds like this and spend their nights waking people up and scaring them.”

“I should say they did,” exclaimed John with a shudder. “I never heard such a lonesome-sounding, terrible wail in all my life.”

“There it is again,” said Grant laughingly, as once more the cry of the loon came to their ears across the dark waters of the little lake.

“Let’s go back to sleep,” exclaimed John earnestly. “That sound makes my blood run cold, even though I know it is made by a bird.”

“Don’t you think we ought to tell Fred and Pop about it?” inquired Grant mischievously. “It seems to me they ought to be warned.”

“You can tell them about it if you don’t mention my name in connection with it,” said John. “If you tell on me though, I swear I’ll get even with you if it takes me a year.”

“All right,” laughed Grant, “I won’t say anything about it. At least, not yet,” he added under his breath.

“What did you say?” demanded John, not having caught the last sentence.

“I said, ‘let’s go to bed.’”

“That suits me,” exclaimed John, and a few moments later they had once more crawled quietly over their sleeping comrades and again rolled in their blankets, were sound asleep.

The sun had not been up very long before the camp was astir. Sleepy-eyed the boys emerged from the tent, blinking in the light of the new day. A moment later, however, four white bodies were splashing and swimming around in the cool waters of the lake, and all the cobwebs of sleep were soon brushed away.

“That’s what makes you feel fine,” exclaimed George when they had all come out and were dressing preparatory to eating breakfast. “A swim like that makes me feel as if I could lick my weight in wildcats.”

“You must have slept pretty well last night, Pop,” remarked Grant.

“I did. Never slept harder in my life.”

“Well, I didn’t,” exclaimed Fred. “It seemed to me I was dreaming all night long. Maybe my bed wasn’t fixed just right.”

“What did you dream about, Fred?” asked Grant curiously.

“Oh, all sorts of things. I thought I heard people calling for help. That seemed to be my principal dream for some reason.”

“That’s funny,” said Grant. “You didn’t dream anything like that, did you, String?”

“No, I didn’t,” said John shortly.

“What shall we do to-day?” exclaimed George when breakfast was over.

“We might go fishing,” suggested Fred. “I want a big trout some time this summer, you know.”

“Oh, it’s too sunny for trout to-day,” Grant objected.

“All right then,” said Fred. “What do you want to do?”

“How about taking a sail?”

“Is there enough wind?”

“Of course there is, and unless I’m very much mistaken its going to get stronger all the time.”

“Suppose we take our lunch along,” said John. “We can be gone as long as we want then and can go ashore and eat wherever we happen to be.”

“Good idea, String,” cried George heartily. “I do believe you’re getting smarter every day.”

“What do you think of my scheme?” demanded John, completely ignoring his friend’s sarcasm.

“It’s all right,” said Grant. “I’m in favor of doing it.”

“We can take a couple of rods with us, can’t we?” said Fred. “We might get a few fish for dinner.”

“That’s right,” agreed Grant. “We can anchor and fish from the boat if we want.”

“Let’s get started,” exclaimed John.

A small catboat was a part of the equipment the boys had in order to help them enjoy their summer more thoroughly. It now lay at anchor in a little cove a short distance from the place where the tent was located. It was a natural harbor and afforded excellent shelter for the boats from the squalls and not infrequent storms that were apt to spring up during this season of the year. The lake was between two and three miles in length so that a comparatively heavy sea could be stirred up by the winds.

The island on which the four boys had pitched their tent was the only one in the lake and it was very nearly in the center. It was owned by a friend of John’s father who had obtained permission for his son and his three friends to camp on it that summer. The sailboat and two canoes were included with the island, so that there was no question but that these four boys were very fortunate indeed to be able to enjoy it all.

For months they had been looking forward to this summer and they had planned innumerable excursions and expeditions as part of their camping experiences. Now that the time was really at hand they meant to enjoy every minute of it to the utmost.

“Fred and I will get the boat ready,” exclaimed John. “You two can collect the rods and fix up the lunch.”

“Put me near the food and I’m satisfied,” said George. “Come on, Grant.”

John and Fred made their way down to the spot where the canoes were hauled up on the shore. The catboat lay moored at anchor some fifty or sixty feet out from the bank so that it was necessary to paddle to reach her. One of the canoes was selected and the two boys soon pushed off from shore.

“That’s a pretty good looking boat I should say,” remarked Fred as he glanced approvingly at the little white catboat. “I wonder if she’s fast.”

“She looks so,” said John.

“You can’t always tell by the looks though, you know.”

“That’s true too. We ought to be able to tell pretty soon though.”

“I wonder if they have water sports or anything like that up here in the summer,” said Fred. “If they do it would be fun to enter.”

“It certainly would,” agreed John. “I don’t believe there are enough people on this lake though. As far as I can see we are about the only people here.”

“I thought you said there was another camp down at the north end of the lake.”

“That’s right, there is. I don’t know who’s in it though.”

“We might sail down and find out.”

“Let’s do that; it won’t take long.”

They had now arrived alongside the catboat, which was named the Balsam, and after having made fast the canoe, they quickly climbed on board.

“Any water in her?” exclaimed John.

“I don’t know. I was just going to look.”

“Lift up the flooring there and you can tell. It must have rained since she’s been out here and we’ll probably have to use the pump.”

“We certainly shall,” said Fred, who had raised up the flooring according to John’s suggestion. “Where is the pump anyway?”

“Up there under the deck. You can pump while I get the cover off the sail here and get things in shape a little, or would you rather have me pump?”

“No, I’ll do it. If I get tired, I’ll let you know.”

It did not take long to bail out the boat, however, and before many moments had elapsed the mainsail was hoisted and the Balsam was ready to weigh her anchor and start. The sail flapped idly in the breeze which seemed to be dying down instead of freshening as Grant had predicted. The boom swung back and forth, the pulleys rattling violently as the sheet dragged them first to one side and then the other.

John and Fred sat on the bottom of the boat and waited for their companions to appear with the luncheon. The two boys were dressed in bathing jerseys and white duck trousers. At least they had formerly been white, but constant contact with boats and rocks had colored them considerably. The feet of the young campers were bare, they having removed the moccasins which they usually wore. The day was warm and in fact the sun was quite hot. The previous night had been so cool it did not seem possible that it could be followed by a warm day, but such is often the case in the Adirondacks.

“Where do you suppose they are?” exclaimed Fred at length. “It seems to me they ought to have been ready by this time.”

“Here they come now,” said John. “Look at Pop; that basket is almost as heavy as he is.”

“He’s got lots of food in it, I guess. I’m glad too for I’m hungry already.”

“Why, you finished breakfast only about an hour ago.”

“I can’t help that. I’m always hungry in this place.”

“Ahoy there!” shouted George from the shore. “Come in and get us.”

“The other canoe doesn’t leak you know,” replied John, neither he nor Fred making any move to do as George had asked.

“We know that,” called George. “What’s the use of taking them both out there though?”

“Why not?” demanded John. “The exercise will do you good.”

“Are you coming after us?” asked Grant.

“Not that we know,” laughed Fred.

“I guess we paddle ourselves then, Pop,” said Grant to his companion.

“All right,” agreed George. “I’ll get square with them though.”

“How are you going to do it?”

“You let me paddle and I’ll show you.”

They spoke in a low tone of voice so that their friends on board the Balsam could not hear them and in silence they embarked upon the second canoe. Grant sat in the bow while George wielded the paddle in the stern. They approached the catboat rapidly where John and Fred sat waiting for them with broad grins upon their faces.

“You must think we run a ferry,” exclaimed Fred as the canoe drew near.

“Not at all,” said Grant. “We just thought that perhaps you’d be glad to do a good turn for us.”

“We’re tired,” grinned John. “Think how hard we had to work to get the sail up and to pump out—”

“Oh, look at that water bug,” cried George suddenly, striking at some object in the water with his paddle. Whether he hit or even saw any bug or not will always remain a mystery. One thing is sure, however, and that is, that a great sheet of water shot up from under the blade of the paddle and completely drenched both John and Fred.

“What are you trying to do?” demanded Fred angrily.

“He did that on purpose,” exclaimed John. “Soak him, Fred.”

“Look out,” cried George, “you’ll get the lunch all wet.”

“You meant to wet us,” Fred insisted.

“Why, Fred,” said George innocently; “I just tried to hit that water bug. How should I know that you would be splashed?”

“Huh,” snorted John. “Just look at me.”

“That’s too bad,” said George with a perfectly straight face. “If you had come in after us we’d have all been in the same canoe and you probably wouldn’t have gotten wet.”

“You admit you did it on purpose then?”

“I don’t at all. I just thought perhaps it was some sort of punishment inflicted on you for being so lazy.”

“Didn’t he do it on purpose, Grant?” demanded Fred.

“I don’t know,” replied Grant, striving desperately to keep from smiling. “I know he didn’t tell me he was going to do it.”

“Well, it was just like him anyway,” said John. “He knew we couldn’t splash him back because he had the lunch in the canoe with him.”

“Take it, will you?” asked Grant, holding the basket up to John. “Here are the fishing rods too.”

George and Grant followed soon after and the second canoe was made fast to one of the thwarts of the other.

“I’ll put the lunch up here,” said Fred, at the same time depositing the basket up forward under the protection of the deck.

“Slide the rods in there too, will you?” exclaimed George. “Look out for the reels that they don’t get caught under anything.”

“Everything ready?” asked John.

“Let ‘er go,” cried George enthusiastically. “I’m ready.”

“Come and help me pull up the anchor then,” said John.

“I’m your man,” cried George. “You know I’m always looking for work.”

“I’ve noticed that,” laughed Grant. “You’re always looking for work so that you’ll know what places to keep away from.”

Four light hearted young campers were now on board the Balsam. In spite of their words a few moments before not one of them had lost his temper. They knew each other too well and were far too sensible not to be able to take a joke. Outsiders, listening to their conversation, might have thought them angry at times, but such was never the case.

“Get your back in it there,” shouted Grant gayly to John and George who were busily engaged in hauling in the anchor chain. George stood close to the bow with John directly behind him as hand-over-hand they pulled in the wet, cold chain.

“This deck is getting slippery,” exclaimed George. “All this water that has splashed up here from the chain has made it so I can scarcely keep my feet.”

“I should say so,” agreed John earnestly and as he spoke one foot slid out from beneath him. He lurched heavily against his companion, and George thrown completely off his balance, waved his arms violently about his head in an effort to save himself, but all to no avail. He fell backward and striking the water with a great splash disappeared from sight.

“Man overboard!” shouted Grant, running forward as he called. He did not know whether to laugh or to be worried. One thing was certain though and that was that George like his three companions was perfectly at home in the water. All four were expert swimmers so that barring accidents they had little to fear from falling overboard.

“He’s all right,” cried John. “Help me hold this anchor, somebody.”

Grant grasped the chain and one more heave was sufficient to bring the anchor up on the deck of the Balsam. Before this could be done, however, George came to the surface choking and spluttering.

“I’ll fix you for that, String,” he gasped, shaking his fist at John.

“For what?” demanded John.

“You know all right.”

“Why, Pop,” said John reprovingly.

“Keep her up into the wind, Fred,” shouted Grant who was seated at the tiller. “Let your sheet run. Here, Pop, give me your hand.”

“I’d better go down to the stern and get aboard there,” said George. “I think it will be a little easier.”

“All right; go ahead.”

George floated alongside the Balsam until he came to the stern and a moment later had swung himself on board the boat. He was drenched to the skin but laughing in spite of himself.

“Do you want to change your clothes, Pop?” asked Grant.

“No, it’s hot to-day. They’ll dry out in no time.”

“Ease her off then, Fred,” Grant directed. “We may as well get started.”

Fred put the helm over, the sail filled and the Balsam began to slip through the water at a good rate. The four boys sat around the tiny cockpit, Fred at the tiller and Grant tending sheet. In a few moments they had emerged from the little harbor and had entered upon the open waters of the lake.

“Well, String,” observed George who was busily engaged in wringing water from the bottoms of his duck trousers, “you certainly did it well.”

“Did what well?” demanded John.

“Don’t pretend you don’t know.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You meant to shove me overboard and I know it so there’s no use in you trying to bluff. You were very skillful about it and I guess you got square with me all right. We’ll call it even and quit.”

“I did do it pretty well, didn’t I?” grinned John.

“Yes, you did, but I think the way I soaked you and Fred was just as good.”

“You didn’t see a water bug then?”

“No, and you didn’t slip either.”

“Yes, I did; on purpose though. Let’s call it off now.”

“I’m agreeable,” laughed George, “even if you did get the better of me.”

“How about me?” demanded Fred. “Pop wet me just as much as he did String and I don’t see that I am even with him yet.”

“You ‘tend to your sailing,” laughed George. “That’ll have to satisfy you.”

“I can steer you on a rock you know,” warned Fred.

“Don’t do it though,” begged Grant. “I’m an innocent party and I’d suffer just as much as the others.”

“Where shall we sail?” asked George.

“Fred and I thought we might go down to the other end of the lake,” said John. “There’s a camp down there, I believe, and we might see who is in it.”

“Go ahead,” exclaimed George. “Meanwhile I think I’ll try to get my clothes dry,” and suiting the action to the word he divested himself of everything he had on, which was not much. The few articles of clothing thus taken off he spread flat on the deck of the boat so that they might get the full benefit of the sun’s rays.

The day was bright and not a cloud appeared in the sky. A gentle breeze blew across the lake barely ruffling the water. Consequently the Balsam sailed on an even keel and scant attention was necessary to keep her pointing in the right direction.

“How about trolling?” exclaimed Fred all at once.

“What do you mean by that?” asked George.

“You mean to say you don’t know what trolling is?”

“If I had I wouldn’t have asked you, would I?” laughed George.

“Well, I’ll tell you,” said Fred. “Trolling is fishing in a certain way. When you troll you sit in a moving boat and trail your line out behind you. As a rule you use a spoon or live bait so that it gives the appearance of swimming. People usually fish for pickerel that way.”

“Let’s try it,” cried George enthusiastically. “Who’s got a spoon?”

“I have,” said Grant. “Hold this sheet and I’ll put it on my line.”

“Any pickerel in this lake, I wonder,” remarked John.

“There ought to be lots of them,” said Fred.

“Bass and perch too, I guess,” John added.

“Perch are fine eating,” exclaimed George. “I’ve eaten them cooked in a frying pan with lots of butter and bacon,” and he sighed blissfully at the recollection.

“Did you ever eat brook trout fried in bacon and rolled in corn meal?” asked Fred.

“Not yet,” laughed George. “I hope to before long, though.”

“Well when you do you’ll know you’ve tasted the finest thing in the world there is to eat,” said Fred with great conviction.

“Is it better than musk melon?”

“A thousand times.”

“Whew!” whistled George. “Is it better than turkey?”

“A million times.”

“Say,” exclaimed George. “Is it better than ice cream?”

“It’s better than anything, I tell you,” Fred insisted.

“I’ll take your word for it,” laughed George. “I’d like to try it myself pretty soon though.”

“Here’s your spoon,” said Grant, holding out the rod to George.

“You’re going to fish, yourself,” said George firmly.

“Not at all. I got it for you.”

“Why should I try it any more than you?”

“Because I want you to. Go ahead.”

“If you insist, I suppose I’ll have to,” laughed George and dropping the spoon overboard he let the line run out.

“How much line do I need?” he asked.

“Oh, about fifty or sixty feet I should think,” said Grant.

“Well, I don’t know much about it,” remarked John breaking in on the conversation; “but it doesn’t seem to me that we are making enough headway to keep that metal spoon from sinking.”

“I’m afraid not myself,” agreed Grant. “The wind seems to be dying down all the time and we’ll be becalmed if we’re not careful.”

“I’ll try it a few minutes anyway,” said George. “I might get something.”

“All you’ll get is sunburned, I guess,” laughed Fred. “You’d better put your clothes on or you’ll be blistered to-morrow.”

“That’s right, Pop,” said Grant. “I’d get dressed if I were you.”

“Perhaps you’re right,” George agreed. “Here, String, you take the rod.”

Scarcely had John taken the rod in his hands when he felt a violent tug at the line. The reel sang shrilly and then was still.

“You’ve hooked one,” cried Fred excitedly. “Reel in as fast as you can.”

“Bring the boat around, Fred,” shouted Grant. “Come up into the wind.”

Fred did as he was directed, while John strove desperately to reel in his line. At first there was no resistance and then all at once the rod bent double.

“Say!” exclaimed George, “it must be a whale!”

“It’s bottom,” said John disgustedly. “The old spoon sank just as I said it would and I’ve caught a log.”

“Don’t break the line whatever you do,” warned Grant. “Swish your rod back and forth.”

“It’s caught fast,” said John, following Grant’s directions.

“Keep it up, you’ll get it loose yet.”

Suddenly the hook was released and as John reeled in there was no resistance to be felt at all. A moment later the spoon appeared and pierced by the hook was a small chip of water-soaked wood showing that it was some sunken log that had deceived the boys at first.

“That trolling business is great all right, isn’t it?” laughed George, now completely dressed once more and ready for anything.

“I’ll take you out in one of the canoes some day and prove to you that it’s all right,” said Fred warmly. “You—”

He suddenly stopped speaking and looked up. “I thought I felt a drop of rain,” he remarked in surprise.

“You did,” exclaimed Grant. “Just look there. Here comes a squall and we’re in for it all right. This is no joke.”

“Quick, Fred!” cried Grant. “Bring her up into the wind. You help me let down this sail, Pop.”

An angry gust of wind scudding across the lake, caught the catboat and made her heel far over.

“Let go your sheet, Fred!” shouted Grant. “Quick or we’ll upset.”

He and George sprang forward and feverishly tried to loosen the ropes that held the sail aloft. The wind was increasing in strength now, however, and the boat was becoming more difficult to manage every moment. The sky was inky black and sharp flashes of lightning cut the clouds from end to end. The thunder roared and echoed and reëchoed over the wooded mountains round about. It was now raining hard.

“Keep that sheet clear of everything,” cried Grant, who usually assumed command in every crisis. “Let it run free whatever you do.”

“You hurry with that sail,” retorted Fred.

“They’re doing their best I guess,” said John.

“If they don’t get it down soon we’ll go over,” cried Fried. “I can hardly hold her now.”

“Can I help you, Grant?” asked John, striving to make his way forward. The boom, however, swung violently back and forth threatening to knock him overboard every second. It was almost impossible to keep out of its way in the tiny catboat.

“Go sit down,” cried Grant. “We’ll get it down in a second.”

The rain now fell in torrents. The wind whistled and shrieked all about them and it seemed as if at any moment the sail must be torn to shreds and the mast ripped from its socket. Lucky it was that Fred was an experienced sailor and endowed with nerve as well. The squall drove the boat backwards but Fred managed to keep her nose pointed straight into the teeth of the gale. Otherwise the Balsam could not have lived two minutes.

“Why don’t they hurry with that sail?” exclaimed Fred peevishly.

“They are hurrying,” said John. “The ropes are wet and they’re nervous.”

“Ah, there it comes,” cried Fred suddenly. “Now we’ll stand a chance.”

With a rush the sail came down, its folds almost completely covering the four boys in the boat. The strain on the tiller was greatly relieved however and the Balsam maintained a more even keel.

“Whew!” exclaimed George, groping his way astern. “What a storm this is!”

“I never saw it rain so hard,” said John. “Just look; you can’t see more than about ten feet.”

“We’ll go aground if we’re not careful.”

“How can we stop it?” demanded Fred. “We’re at the mercy of the storm.”

“Throw the anchor overboard,” suggested George.

“A good idea, Pop,” exclaimed Grant. “Come along and I’ll help you.”

“You’ll get struck by lightning,” warned Fred, half seriously. The flashes were blinding and almost continuous. The thunder ripped and roared all around and so near at hand was the center of the storm that sometimes the smell as of something burning could be detected in the air.

“That anchor will never hold us,” said John who sat in the stern, huddled close to Fred. Grant and George were feeling their way forward.

“Don’t throw the lunch basket over by mistake,” called Fred.

“The lunch won’t be worth much now, I’m afraid,” said John ruefully.

“Oh, I don’t know; it’s under the deck.”

“I know, but the boat has a lot of water in her now and if it touches that basket it will soon soak through.”

“How deep is this lake?”

“I’ve no idea. I don’t even know where we are.”

“I’m afraid we’re going to run ashore all of a sudden somewhere.”

“The anchor ought to catch before that happens,” said John. “It’s trailing now you know.”

“I know it is, but suppose we hit a lone rock.”

“We’re running that chance. I don’t know what we can do about it.”

“Are you trying to steer, Fred?” asked Grant who together with George had now crawled back to the stern of the boat.

“I’m trying to keep her headed with the waves; that’s all I can do.”

“I know it. I think the squall’s letting up some though.”

“Perhaps it is,” agreed John. “It does seem a little bit lighter.”

“It isn’t raining so hard either,” observed Grant. “These squalls stop just as quickly as they start sometimes.”

“The lake must be deep here,” said Fred. “How long is that anchor chain?”

“About fifteen feet I guess,” said John.

“That ought to keep us from going ashore anyway,” exclaimed Fred. “Who said this storm was over?”

“It must be coming back,” said Grant. “It certainly let up for awhile though.”

“But it’s making up for it now all right,” observed George. “I’m so glad I took all that trouble to get my clothes dry.”

The four boys looked at one another and could not help laughing. Every one of them was drenched through to the skin and no one had a dry stitch of clothes on. The rain pelted them mercilessly and the water ran off their faces in streams. All huddled together, they made a forlorn looking party.

“This is what all campers get I suppose,” remarked George.

“They certainly do,” agreed Grant. “Some of them get it worse than this too.”

“Do you suppose our tent is still there?” inquired John.

“Let’s hope so,” exclaimed George fervently. “We’d be in a nice fix if we found it blown away when we got back.”

“If we do get back,” said Fred dolefully.

“What’s the matter with you, Fred?” demanded Grant. “You don’t think we’re all going to die or be killed, do you?”

“I don’t know. This is a bad storm and we can’t see where we are.”

“But the anch—”

There was a sudden jolt. Every boy was almost thrown from his seat as the boat came to a quick stop. Then the bow swung slowly around and a moment later the Balsam was pointed straight into the wind, her anchor chain taut.

“We’re aground,” cried George.

“Not at all,” corrected Grant. “The anchor chain has caught, that’s all.”

“Where are we?”

“I can’t see.”

“We must be somewhere near shore,” said John.

“We might be on a shoal.”

“No, there’s land,” cried John. “I can see it.”

“Maybe it’s on our island,” said George. “Wouldn’t that be queer.”

“Well, I wish the old storm would be over so we can see just where we are located,” exclaimed Fred. “I’ve had enough of this.”

“You’d better be thankful the anchor holds and not worry about anything else,” observed Grant. “So far we can’t complain.”

“It’s stopping,” said George suddenly. “The sun will be out in a minute.”

“If it comes out it had better bring an umbrella, that’s all I can say,” observed John.

“A pretty poor joke, String,” said George. “Try another one; it might be better.”

“The sun is coming out,” cried Grant. “The storm is almost over, I guess.”

“Thank goodness!” exclaimed Fred. “Now we can see where we are.”

Little by little the rain abated, the wind died down and the thunder melted away in the distance. Before many moments had passed the sun broke forth from behind a cloud and blue sky appeared.

“Do they have many of these squalls around here, I wonder?” said George. “I don’t think very highly of them myself.”

“Nor I,” agreed Grant. “Just look where it carried us.”

“There’s our island,” exclaimed Fred. “I thought it was in the other direction though.”

“So it was,” said John. “We traveled the whole length of the lake, I guess.”

“Right past our camp?”

“It looks so.”

“Suppose we had hit one of those big rocks where I fell in,” said George. “Our anchor wouldn’t have done us very much good there.”

“I should say not,” agreed Grant. “Isn’t that a camp over there?”

His three companions gazed in the direction he indicated and sure enough a big white tent very similar to their own appeared on shore, a short distance from the spot where the Balsam lay at anchor.

“I don’t see anybody around,” remarked Fred. “Do you suppose they’re all away?”

“The best way to find out is to go and see for ourselves,” exclaimed Grant.

“That’s right,” observed George. “Let’s get the anchor up and sail in.”

“There’s a dock there too, where we can land,” said Fred. “Perhaps the people who are camping here have been caught out in the storm.”

“We’ll soon know anyway,” said Grant, making his way forward to assist George in getting up the anchor.

A few moments later the Balsam was making its way towards the tiny wharf in the little harbor. Two canoes lay bottom up on the shore but no sign of any living being appeared.

“Perhaps they’ve gone to the ball game,” remarked George.

“Ball game!” exclaimed Fred. “What are you talking about?”

“I was just fooling and trying to get a rise out of somebody. Of course I knew I could make somebody bite with you on board.”

“Huh,” snorted Fred. “I thought you’d gone crazy, talking about ball games up here in the woods.”

“You two are always wrangling,” exclaimed Grant. “Stop it.”

“I can’t resist trying to get rises out of Fred,” said George. “He’s so easy.”

“Leave him alone,” said Grant. “I wonder where the people are who own this tent. There doesn’t seem to be a soul around.”

“Let’s go up to the tent and peek in,” suggested John.

“Do you think we ought to do that?” Fred protested.

“Why not? We’re not going to steal anything are we?”

“I’m not,” laughed Fred. “Of course I don’t know about you.”

“Come ahead,” urged George. “We’ll just take one look.”

They made their way up from the dock towards the tent. Still no sign of life appeared and when John had stolen one hasty glance inside the tent he reported that no one was in there either.

“Let’s go back,” exclaimed Fred. “There’s no use in staying around here any longer.”

“Come on,” said Grant. “It’s time to eat too.”

“We might eat our luncheon over on that point,” suggested George, indicating a spot about a mile or so distant from the place where they were.

“Eating suits me all right,” exclaimed John. “I must say I’m hungry.”

“And I’d like to get my clothes dry,” added Fred. “I’m sort of cold.”

Once more they set sail on the Balsam without having caught sight of a single occupant of the camp they had just visited. The sun was now shining brightly and the sky was as blue as ever. No trace of the recent storm remained to mar the beautiful day. It was not long before all four boys were in excellent spirits again and their appetites became keener with each passing moment.

Landing on the point where they had decided to eat their luncheon, they quickly set about making preparations for the meal. A fire was soon started and with every one assisting, the meal was quickly under way.

“How soon will it be ready, Grant?” asked George of the cook.

“Oh, in half an hour.”

“Come on then, String,” exclaimed George. “Let’s go back into the woods here and see if we can’t find some berries or something.”

“Don’t get lost,” warned Grant. “Fred and I are too hungry to spend a lot of time looking for you, you know.”

“Don’t worry about us,” laughed John. “We’ll be gone only a few minutes.”

Leaving Grant and Fred busy with the cooking the two boys plunged into the woods and disappeared from view. The trees were still dripping from the heavy rain, but the fragrant odor of spruce and balsam was stronger than ever. The thick carpet of pine needles under their feet was wet, so that their advance was noiseless.

Suddenly, up from its hiding place almost under their feet, a grouse arose with a roar and whirr of wings. Booming off through the trees it quickly disappeared from view leaving the forest as silent as before. The spell of it was on the two young campers as they stood still and gazed all about them. The green leafy aisles of the woods stretched in all directions around them most beautiful and inviting to the eye. A catbird whined from a nearby tree, but otherwise all was still.

“Did you ever see anything more beautiful?” asked John in a low voice.

“I never did,” replied George solemnly. The beauty and the grandeur of it all made them feel as though they really should not speak above a whisper.

“I don’t see any berries though,” continued John.

“Nor I,” said George. “There’s an open space ahead of us though; perhaps we’ll find some there.”

“Some blueberries wouldn’t taste bad just now.”

In silence they continued their walk, even taking care to step softly so as not to disturb the solemnity of the woods. Ahead of them appeared a break in the trees and an open space showed. Here was the place to find blueberries if any grew in that neighborhood at all. A moment later the two boys came to the edge of the clearing which was perhaps a hundred yards square.

As they were about to step out from the shelter of the trees George suddenly clutched his companion by the arm.

“Look there,” he whispered.

Following George’s directions John saw something that caused his face to grow white and his heart to jump. In the center of the clearing and busily engaged in eating the blueberries which grew in abundance all about was a large black bear.

He seemed entirely oblivious to his surroundings and as the wind blew from him towards the two boys he was not aware of their presence. With one great paw he stripped the berries from the low-lying bushes and with his long, eager tongue he licked them up greedily. That his ancient enemy, man, might be lurking nearby apparently did not occur to him. The two boys stood and watched him, fascinated, not knowing whether to run or whether to hold their ground. The bear was scarcely a hundred feet distant from the spot where they were standing.

“What shall we do?” whispered George.

“Wait.”

“Suppose he comes after us.”

“If he does we’ll run.”

All at once the bear looked up. Perhaps some eddying current of wind had betrayed the presence of the two boys to his sensitive nostrils. It is a well known fact that the eyesight of most wild animals is comparatively poor; their sense of smell, however, is correspondingly sharp and it is on this that they must rely to a large extent for safety.

All around him old bruin gazed while the hearts of the two young campers almost stood still. There they were standing within plain sight, right at the edge of the forest and they could not possibly escape being seen. Anxiety as to what the bear would do made the next few moments very nervous ones.

Suddenly he saw them. George and John held their breath and waited. He looked at them steadily for a moment, one paw held poised in the air. Then he turned and with that clumsy lumbering gait common to his kind ambled off across the clearing. Arriving at the opposite side he turned his head and glanced back at the two boys, still standing in the shadow of the trees. Then he continued his way once more and quickly disappeared from sight.

“Well,” exclaimed George. “What do you think about that?”

“Suppose he’d chased us.”

“He’d never have caught me,” said George grimly. “With a bear after me I know I could at least equal the world’s record for the half-mile.”

“Even so, you’d have finished second,” laughed John.

“What do you mean?”

“Why, I’d have beaten you out, of course.”

“Maybe so,” said George laughingly. “At any rate I guess it would have been a pretty close finish. Imagine what Grant and Fred would have thought if they’d seen us coming, tearing out of the woods with a big black bear after us.”

“I’d have gone right on across the lake too,” said John.

“Do you want some berries?”

“It’s pretty late now I’m afraid. I think perhaps we’d better go back.”

“Perhaps so. Let’s go anyway; we can come back here after luncheon.”

“That bear might have the same idea.”

“That’s true too,” admitted George. “We can bring Fred and Grant along with us if they want to come.”

The two boys made their way back through the forest towards the lake. Knowing that there were such things as bears in the neighborhood they kept a sharp watch all about them. If they had only realized it, no bear was half as anxious to meet them as they were to meet a bear. Wild animals seldom if ever seek trouble of their own accord.

A few moments later George and John emerged from the woods and caught sight of the fire and their two companions.

“Hey, you two!” called Fred. “Where have you been?”

“Are we late?” asked John.

“I should say you were. Grant and I were just about to eat up all the food and not save any for you at all.”

“Thank goodness you didn’t,” exclaimed George, fervently.

“Did you find any berries?” demanded Grant.

“Lots of them. A good many of them are still on the bushes.”

“Didn’t you bring any back?”

“Not a single one.”

“What do you think of that, Fred?” demanded Grant. “These fellows go back in the woods and stuff themselves with a lot of berries and don’t even bring one back to the two who are working hard to prepare food for them.”

“We didn’t eat any ourselves.”

“You didn’t?” exclaimed Grant. “What was the matter with them; weren’t they good?”

“I guess they were,” said John. “We didn’t try any though.”

“What’s the matter?” inquired Fred. “What are you two trying to say anyway? You found a lot of berries but you didn’t bring any back and you didn’t eat any yourself. What’s the reason you didn’t?”

“Somebody was there ahead of us,” said George.

“The owner you mean?” asked Grant. “Wouldn’t he give you any?”

“It wasn’t the owner,” said George. “It was somebody else.”

“I wish you’d stop talking in riddles,” exclaimed Grant impatiently. “Why don’t you tell us what happened!”

“There was a bear there,” said John. “He liked berries too.”

“A bear!” cried Grant and Fred in one breath. “What do you mean?”

“There was a big black bear eating the blueberries,” said George, “so we just decided we didn’t care very much for berries ourselves.”

“Tell us about it,” demanded Grant eagerly.

“I can’t talk unless I have something to eat first,” replied George firmly.

“Nor I,” agreed John.

“Come and eat then,” laughed Fred. “We too have got something to tell you two when you’ve finished.”

While all four boys were doing full justice to the meal which Grant had prepared, George and John related the story of their meeting with the bear.

“And now,” exclaimed John when he had finished, “you tell us what you have to say. Fred said there was something.”

“We had an idea while you were gone, that’s all,” said Grant.

“Tell us what it was.”

“Go ahead, Fred.”

“No, you tell them,” urged Fred.

“Well,” said Grant, “it was only this. Fred and I were talking things over and we thought it might be good fun if we took the two canoes and went off on a little trip for a couple of days. What do you think about it?”

“I think it would be great,” exclaimed John heartily. “How about you, Pop?”

“It suits me first rate,” said George eagerly. “Why can’t we start to-night?”

“That’s a little soon I should think,” laughed Grant. “We can go to-morrow though if you say so.”

“We can get some good trout fishing up these streams, you know,” said Fred. “I want to get that big trout.”

“If there’s any big trout caught I expect to be the one to do it,” said George very pompously.

“Huh,” snorted Fred disgustedly, “you couldn’t catch cold.”

“You just wait and see,” muttered George under his breath.

“Do you know anything about trout fishing?” insisted Fred.

“I never did any in my life.”

“And you expect to catch a big trout?” said Fred derisively. “Why, Pop, you’re sort of out of your head, aren’t you?”

“Wait and see,” repeated George confidently.

“Do you know how hard it is to cast a trout fly when you’re standing in the middle of a clump of bushes and the branches of trees are in your way all around you?” continued Fred. “Don’t you know that it takes almost years of practice to do it so that you are accurate and don’t catch your hook on everything in sight?”

“Wait and see,” insisted George. “I have a new system.”

“Ha! ha! ha!” laughed Fred. “You’re a joke.”

“Let’s go back to camp and stop these two arguing,” exclaimed Grant. “They’re at it all day long.”

“We like each other all the more because we do it, don’t we, Pop?” demanded Fred laughingly.

“Yes,” admitted George, “except that you’re awfully conceited at times.”

“Come on,” urged Grant. “They’ll be at it again if we’re not careful.”

Before many moments had passed the Balsam was once more sailing over the clear waters of the lake and in a short time the four boys arrived back at camp. The remainder of the day was spent in planning for the trip they were about to take and in discussing just where they should go. At length an agreement satisfactory to every one was reached, the arrangements were all completed and there was nothing left to do but wait for the morrow in order to start.

The sun had been up but a short time before the camp was astir. Grant set about preparing breakfast while his three companions packed supplies into the two canoes. Food sufficient for three days was loaded on board; blankets were taken along, and trout rods with numerous flies of course were included.

“Breakfast’s ready,” announced Grant as soon as the work of loading was complete.

“So am I,” exclaimed George heartily. “I’m always ready to eat up here.”

“Not only ‘up here’ either,” muttered Fred.

“What did you say?” demanded George, wheeling around so as to face the speaker.

“Nothing.”

“As usual,” laughed George. “Where’s the food?”

“Right here,” exclaimed Grant. “Let’s see you get rid of it.”

No second invitation was needed and it was not long before every crumb and morsel that Grant had prepared had disappeared.

“Let’s get started,” exclaimed George. “All the food is gone so there is no point in staying around here any longer.”

“You’re right, Pop,” laughed John. “I say we go too.”

A few moments later the two canoes emerged from the little harbor and started out across the lake, headed northward. Grant and Fred occupied one of them while George and John paddled the other.

“I’m glad you’re not in my canoe, Fred,” called George gayly. “Small as you are, I’d soon get tired of paddling you around all day.”

“Is that so?” snorted Fred. “Well, you’re not half as glad as I am for I know that I’d be the one that would have to do all the work and you’re too big and fat to make the work pleasant.”

“They’re at it again, String,” laughed Grant. “What shall we do with them?”

“Leave them home,” suggested John.

“Oh, we couldn’t do that. They’d be like the Kilkenny cats.”

“Who were they?” demanded Fred.

“Didn’t you ever hear about them?”

“No. Tell me who they were.”

“I guess you mean what they were.”

“All right, what they were, then.”

“Why,” said Grant, “they were a couple of cats that loved to fight. One day somebody tied their tails together and hung them over a clothes line. Of course they began to fight right away and they fought so furiously that when it was all over there wasn’t a thing left of either of them.”

“I suppose you expect me to believe that story,” snorted Fred.

“I don’t care whether you believe it or not,” laughed Grant. “You wanted to hear it, so I told it to you.”

“Grant says we’re like a couple of cats, Pop,” called Fred.

“Tell him he’d better be careful,” replied George. “Just because we call each other names doesn’t mean that we allow other people to do it.”

“Excuse me for interrupting,” said John laughingly, “but does any one know where we are going?”

“I do,” replied Grant. “We’re going up that river you see straight ahead.”

“Do you know where that leads to?” inquired Fred.

“Yes. We can paddle up it for about two miles and then we have to make a carry over to another river.”

“How long is the carry?” demanded George.

“Oh, about half a mile, I guess.”

“Whew!” exclaimed George; “that’s a long distance to carry canoes and all the stuff we have in them.”

“Getting ready to shirk already, are you?” demanded Fred teasingly.

“Shirk nothing,” said George. “Wait and see if I don’t do my share.”

“Yes and ‘wait and see’ if you don’t catch the biggest trout too,” taunted Fred. “Why, Pop, you’ll be lucky if you catch your breath.”

“Wait and see,” muttered George darkly.

“Yes, ‘wait and see’,” echoed Fred. “If you don’t stop saying that we’ll have to call you, ‘Wait and See.’”

Just at this moment, however, they came to the mouth of the river and the argument was abandoned, for the time being at least.

“This is great!” exclaimed John. “I always did like paddling in a narrow space rather than on a lake or some place like that.”

“I do too,” agreed Grant. “You feel closer to things somehow.”

“You’re no closer to the water, you know,” remarked George with a wink at Fred.

“Don’t pay any attention to him, Grant,” said John. “I think we ought to throw both of them overboard anyway.”

As they progressed, the stream became narrower and the current swifter. Evidently they would be unable to paddle very much farther upstream and the young campers began to keep a sharp lookout for the carry.

“There it is,” exclaimed Fred, suddenly pointing to a small sandy beach a short distance ahead of them.

They soon landed and emptying the canoes, they started off through the woods to transfer them to the next river. It was necessary to leave the baggage behind to await their coming back for it. Two boys to each canoe they set out, the light boats turned upside down and bearing them aloft on their shoulders. In spite of many groanings from George they reached their destination before much time had elapsed, and then resting the canoes on the bank of the stream they returned for the baggage. This was more quickly and more easily transferred so that a short time later they were once more making their way by paddling.

“Say, Grant,” exclaimed John when they had covered a few hundred yards, “how do you know all about these rivers?”

“Didn’t you see that map I have?”

“No. I kept wondering how you knew so much about the country around here. I didn’t know you had a map.”

“Of course I have. I wouldn’t know anything any other way for I’ve never been up here in my life before.”

“String thought you guessed at it,” laughed George.

“No, I didn’t at all,” protested John. “I just didn’t think about it.”

“Does your map say that there are rapids ahead?” asked Fred.

“I didn’t notice. Why?”

“Because I think there are. It seems to me that the current is getting swifter all the time and I think you’ll find that when we go around that bend up yonder you’ll find rapids ahead of us.”

“Shall we run them?” demanded George excitedly.

“We’ll probably be wrecked if we try it,” said Grant.

“We can see how bad they are, anyway,” John suggested.

“Yes,” agreed Fred. “We’ll ‘wait and see.’”

“‘Go ahead’ is my motto when rapids are concerned,” said George.

Rounding the curve in the river they discovered that scarcely a hundred yards farther was another bend in the stream. Meanwhile the current was rapidly becoming swifter and stronger.

“We can’t see yet,” exclaimed George. “We’ll have to go ahead.”

All four boys were excited now, and there was an eager light in every one’s eyes as they were carried along by the swiftly-flowing stream.

Suddenly they came around the second bend, and spread out before their eyes appeared a long stretch of white water. It foamed and danced, here and there broken by a huge rock, black and ugly looking.

“We can’t run those,” cried Grant. “We’ll drown sure.”

“Go ashore then,” shouted Fred, and he drove his paddle desperately into the water. John and George also fought valiantly to divert their course and avoid the rapids. Too late, however, for the current was stronger than they, and with ever increasing speed they were drawn swiftly towards the foaming waters below.

“Work, Fred! Work!” urged Grant desperately.

“I’m doing my best,” panted Fred, and from the way he drove his paddle into the water it was evident that what he said was true.

They made a little progress towards the shore. They moved still more swiftly downstream, however, for the current was powerful here. For every foot that they progressed towards shore they were drawn a yard closer to the rapids. Unless they reached the bank very soon they were certain to be forced to run the rapids whether they desired to or not.

George and John in the other canoe were in the same predicament. The two frail little craft seemed no stronger than shells and it was almost unbelievable that they could traverse that foaming stretch of water in safety. No one spoke now; every boy was too busily employed in the desperate struggle he was waging against the river.

The current eddied and swirled. From below came the roar of the water as it raced along in its mad course. Beside them was the shore and safety; below was danger, accident, and possible death.

When the two canoes had rounded the bend in the river the one which John and George occupied had been a trifle closer to shore. Consequently it had just that much advantage over the other. The occupants of the two canoes were too engrossed in their own struggles to take much notice of their companions, but out of the corner of his eye Grant saw that the other canoe had nearly reached its goal.

A moment later he heard a call from the shore sounding above the roar of the rapids below. It was George’s voice.

“Keep it up, Grant!” he shouted. “You’ll make it yet.”

“Stick to it, Fred!” cried Grant, encouraged by the knowledge that their companions had reached safety. “We can make it.”

“I’m sticking to it all right,” replied Fred grimly.

Closer and closer to shore they came. Nearer and nearer sounded the noise of the rapids. Could they win out? Certainly they could if nerve and determination were to count for anything.

Ahead of them Grant could see George frantically urging them on. He was so excited that he had run down into the water, where he stood knee-deep, begging and imploring his comrades to come to him. Inch by inch they seemed to move towards shore. Their muscles were aching from the strain now and it was agony for both boys to keep up the fight, but neither one gave even the slightest thought to quitting.

It almost seemed as if they were going to win out now. George was scarcely ten feet distant; arms outstretched he eagerly awaited a chance to seize the bow of the canoe and draw it and its occupants to safety. His chance did not come, however.

Just out of his eager reach a whirlpool caught the canoe. The bow swung suddenly around and Fred’s paddle was almost wrested from his grasp. In vain he and Grant fought. Twice the frail little boat spun around and then seized by a sudden eddy in the current was borne swiftly and relentlessly towards the rapids below.

“We’re goners!” cried Fred.

“Keep your nerve!” shouted Grant fiercely. “You do the steering from the bow. You can see the rocks from there.”

At racehorse speed the canoe shot forward. With every second its momentum increased until it seemed fairly to fly over the water. White-lipped and with jaws set the two boys sat and awaited their fate. From the shore George and John watched with feverish anxiety.