Title: That Little Beggar

Author: Edith King Hall

Release date: May 19, 2011 [eBook #36166]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Dave Morgan, Kerry Tani and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

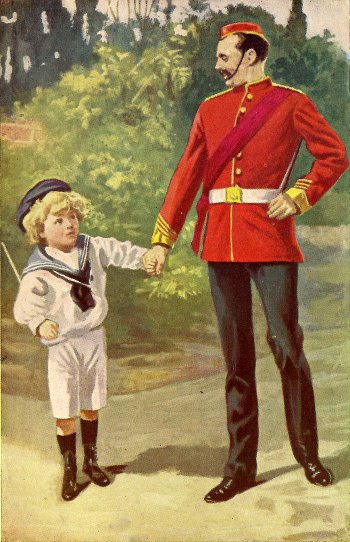

CHRIS IS BROUGHT BACK BY HIS FRIEND THE SERGEANT

| Page | ||

| CHAPTER I. | JACK AND HIS MASTER. | 161 |

| CHAPTER II. | A SONG AND A STORY. | 172 |

| CHAPTER III. | CONCERNING EIGHT FLIES. | 189 |

| CHAPTER IV. | TEACHING JACKY TO SWIM. | 201 |

| CHAPTER V. | THE DOCTOR'S HEAD! | 218 |

| CHAPTER VI. | A PASTE-MAN AND A PAINT-BOX. | 232 |

| CHAPTER VII. | CHRIS AND HIS UNCLE. | 244 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | "I'M A SOLDIER NOW." | 259 |

| CHAPTER IX. | THE GOLDEN FARTHING. | 274 |

"No carriage! Are you quite sure? Mrs. Wyndham told me that she would send to meet this train."

I looked anxiously at the station-master as I spoke. I was feeling tired, having had a very long journey; and now, to find that I had the prospect of a good walk before me was not pleasant.

"I'll go and have another look, mum," he said civilly as he turned away; "it may have driven up since the train came in. It weren't there before, I know that."

Presently he returned, and shook his head.

"There's nothing from the Hall," he remarked; "nothing to be seen nowhere."

I looked round despairingly, first at the deserted-looking little [Pg 162]country station with its gay flower-beds, decorated with ornamental devices in dazzling white stones, then at the long, white country road, stretching away in the distance with the July sun beating down upon it, and sighed. The outlook was not cheering.

"Is there no inn near at which I could find some sort of conveyance?" I asked, though without much hope of receiving a satisfactory reply.

"None but the White Hart at Teddington, and that's a matter of four miles off," he replied. "It would take less time to send to the Hall."

"How far off is that?" I inquired.

"It's two miles and a bit. By the fields it's less, but as you are a stranger in these parts, I take it, mum, you'd do better to keep to the road if you think of walking," he answered.

"It seems to me the best thing to do," I replied with resignation.

"Well, it's a beautiful afternoon for a walk, if it is a bit hot," he said consolingly, and, retiring to his office, left me to my own devices.

I started very slowly, determined not to waste any energy, with that long and hot walk before me.

Strolling gently on I fell to thinking over my past life—the quiet, peaceful life in the country rectory, where I had lived for so many years, and which had only ended with the death of my dear old father two months ago. Now middle-aged—yes,[Pg 163] I called myself middle-aged, though I daresay you at the age of eight, ten, fourteen (what is it?) would have called me a Methuselah—now I had to earn my own living, and start a fresh life. I don't want to make you sad, for I am quite of the opinion that it is better to make people laugh than cry, but I will confess that as I walked along that sunny afternoon, with the recollection of my great sorrow still fresh in my mind, the tears came to my eyes. You see, my father and I loved each other so much, and he was all that I had in the world; I had no brothers and sisters to share my sorrow with me.

I had gone some distance on my way, when I heard the sound of loud and bitter sobbing. Hastening my steps, I turned a bend of the road, and saw a little boy lying full length on the roadside, his face buried in the dusty, long grass, as he gave vent to the loud and uncontrolled grief which had attracted my attention; whilst a few yards off stood a little wire-haired fox-terrier, regarding him with a perplexed and wondering eye.

"What is the matter, dear?" I asked the distressed little mortal, whose tears were flowing so fast.

But he only mumbled something unintelligible, then burst into renewed sobs.

"Get up from that dusty grass and tell me[Pg 164] what it is all about," I said encouragingly, as I stooped down and took hold of his hand.

He rose slowly from the ground and looked at me doubtfully, half sobbing the while; then I saw how pretty he was. Such a pretty little boy, but oh! such a dirty one. He had the sweetest violet eyes, the prettiest golden curls, the most rosy of rosy checks that you can imagine, and he was dressed in the dearest little white-duck sailor's suit that any little boy ever wore. But at that moment the violet eyes were all swollen with crying, the golden curls were all tumbled and tossed, the rosy cheeks all smudged where dirty fingers had been rubbing away the tears, whilst as for the white-duck suit—well, to be accurate, I ought not to call it white. But as the small person inside of it had apparently been recklessly rolling on the ground, it was not surprising that something of its original purity had departed.

"What is the matter?" I asked again.

"I took Jack out for a walk and he runned away and I runned after him, but he wouldn't stop!" he sobbed vehemently.

Then, leaving go of my hand, he made a sudden dash towards the truant, who as suddenly ran off. My small friend wept afresh.

"He thinks that you are playing with him," I said; "that's why he runs away. Wait a moment!"[Pg 165] seeing he made a movement as if he were again about to chase the dog.

"Look!" I went on, and going gently towards Jack, I picked him up and placed him beside his little master.

"Come along, you little beggar!" the indignant little fellow exclaimed, and, seizing hold of the cause of the commotion, he walked, or rather staggered, off with him.

Poor Jack! He did look so unhappy. I think you would have been as sorry for him if you had seen him, as I was. Hugged closely in his master's arms, his hind-legs hanging down in a helpless, dislocated fashion, he gazed after me piteously over his master's shoulder, as if to say, "Can you do nothing to help me?"

He looked so funny and so miserable I could not help laughing. "What!" you say with some surprise, "and you were crying a little while before?"

Yes, my dear child; yet I could laugh in spite of that, for, you know, there is no better way of drying our own tears than to wipe away the tears of another—though they be but the ready tears of a little child.

So I laughed, and I laughed very heartily too.

"Wait," I said. "I fancy Jack is as uncomfortable as you, and that looks to me very uncomfortable.[Pg 166] Supposing we see if both you and he cannot get home in an easier fashion. Why don't you put him on the ground? I think if you were to walk back quietly Jack would follow you now."

My new acquaintance wrinkled his dirty little tear-stained countenance doubtfully.

"P'r'aps he'll run away, 'cause he's runned away often and often whilst he's been out with me, and I sha'n't be able to catch him," he said woefully.

"Put him down and see," I suggested. And Jack was dropped on the ground, though as much I fancy from necessity as choice, since his weight was evidently becoming too much for his master.

"Are you far from home?" I asked.

"A long, long way," he replied forlornly. "All the way from Skeffington."

"That's where I'm going," I said, "so we can go together."

"Are you the lady what's coming to live with my Granny?" he asked, slipping his hand confidingly in mine, as we turned our steps homewards.

"Yes," I replied.

"I'm called Chris, but my proper name is Christopher," he stated, pronouncing it slowly and with some difficulty.

"It's very pretty," I answered, smiling at the[Pg 167] diminutive little figure by my side, "but a very long name for such a little person."

"That's not my only name," he said proudly. "Did you think it was?"

And he laughed pityingly at my ignorance.

"What is your other?" I inquired, as I was intended to.

"Why, I have two others," he answered with still greater pride. "Three names altogether. Christopher, that's only like myself; and Godfrey, that's like my Uncle Godfrey; and Wyndham, that's like my Uncle Godfrey and my Granny too. All our names is Wyndham. What's your name?"

"Baggerley."

"Beggarley! That's something like what Uncle Godfrey calls me. He says I'm a little beggar."

"Baggerley, not Beggarley," I corrected him.

"But I would like to call you Beggarley, 'cause then you'd be called something the same as me. Mayn't I?"

A suspicious tremble in his voice warned me to give way, unless I was prepared for another outcry from that healthy little pair of lungs. The tears were evidently still near the surface. I therefore weakly yielded.

"Very well, dear," I replied in a resigned voice; and Chris, brightening at once, continued his conversation.[Pg 168]

"I'm seven years of age. How old are you?" he next remarked, regarding me with interest.

"Too old to tell my age," I replied evasively.

"As old as my Granny?"

"I don't think so."

"Then how old?"

"Chris, you shouldn't ask so many questions," I said, with a touch of severity.

"I only wanted to know if you was too old to play with me," he said, looking at me reproachfully out of his great violet eyes.

"I will certainly play with you if you are a good boy," I replied, in a mollified voice.

"Oh, I'm so glad!" he exclaimed, dancing by my side with pleasure; "'cause I have no one to play with me. Granny is too old, and Briggs says when she runs it makes her legs ache as if they will break."

"I will run a little sometimes, but I can't promise to do much," I said cautiously.

"Oh, you needn't always run," he said, encouragingly. "There is one or two games where you needn't hardly move. Just a little tiny bit, you know. Will you play at trains?"

"What is it?"

"Oh, such a nice game! and you needn't run unless you like. I'll be the train and the engine, and you can be the guard and the steam-engine whistle. Then you need only walk about at[Pg 169] the station and take the tickets, and just scream high up in your head like this" (and Chris gave vent to a loud and piercing scream—so unexpectedly loud and piercing that I almost started). "That's like the steam-engine goes, you know," he explained.

"I couldn't do that," I said with decision, when I had recovered from the shock.

"Then p'r'aps you'd like to play at lame horses," he suggested. "You needn't scream then, only jog up and down as if you'd got a stone in your foot. I'll be the coachman, but I won't make you run fast, 'cause it would be very cruel of me if you had a stone in your foot; wouldn't it?" he continued, virtuously.

"Very," I agreed, as we turned into the lodge-gates of Skeffington, and pursued our way up the drive.

"There's my Granny," he remarked presently, leaving go of my hand and running towards an old lady, who, with her work-table by her side and her knitting in her lap, was dozing comfortably in a big wicker chair on the shady side of the lawn.

"Granny! Granny!" shouted Chris excitedly, and at the top of his voice. "Here's the lady what's coming to live with you."

At the sound of his voice the old lady gave a nervous jump, opened her eyes, and, replacing her[Pg 170] spectacles which had fallen off her nose, arose, looking round as she did so with a bewildered air.

"Miss Baggerley, I presume," she said with an old-fashioned courtesy of manner, and advancing towards me with outstretched hand. "But how is it that you are walking? Was not the carriage at the station to meet you?"

"No, she walked all the way; and she didn't know the way, and I showed it to her," Chris put in eagerly. "I showed it to her all myself."

"The carriage was not at the station. But it was not of the slightest consequence, I assure you," I replied, as soon as Chris allowed me to speak.

"But two miles and a half in this hot sun, and after your long journey too!" Mrs. Wyndham said apologetically. "I am most distressed, I am indeed. I have a new coachman who is not very bright. He has doubtless made some stupid mistake. Dear me, how unfortunate!"

"It didn't matter, 'cause I found her and I showed her the way," Chris reiterated with pride.

"Hush, my dear child!" Granny said gently. Then, for the first time becoming fully aware of his very unkempt condition, "What have you been doing, my darling?" she exclaimed with surprise; "and what do you mean by saying you met Miss Baggerley? Where did you meet her?"

"I took Jack for a walk and he runned away,[Pg 171] and was such a naughty little dog. And I felled down and hurted myself, and I cried," Chris concluded with much pathos, as he saw Granny shake her head at the account of his doings.

"My darling, it was very wrong of you to leave the garden," she said. "You know when Briggs left you, she never thought for a moment that you would go outside the gates. And, oh, how dirty you are! Your nice white suit is all black! Miss Baggerley, I fear you met a disobedient, a very disobedient little boy indeed."

"I hurted myself very much," Chris remarked, in the most pathetic of voices.

Granny relented. "Where did you hurt yourself, my dear child?" she asked, with some anxiety.

"On my knee, and on my face, and on my hand," he replied still with melancholy.

"Go at once, darling, to Briggs, and ask her to bathe all your bruises with warm water," she said. "Or, if they are very bad, tell her that she will find some lotion in my room."

"Wasn't Jack a naughty little dog?" he asked, recovering, as he held up a smudgy little face to be kissed.

"I'm afraid it was someone else who was naughty," she answered, with an attempt at severity; "yes, very naughty indeed. But we'll say no more about it, for I think you are sorry; are you not, my Chris?"[Pg 172]

"Very, very sorry, Granny," he replied, but more cheerfully than penitently, as he ran off, relieved at the matter ending in so easy and pleasant a fashion.

"I'm afraid I spoil him dreadfully," Granny said, looking fondly after the retreating little figure. 'You're ruining the little beggar'; that's what my son Godfrey tells me. But then my Chris has no father or mother, so I feel very tenderly towards him. He has such a lovable nature too, it is difficult not to spoil him. You have doubtless seen that for yourself already, have you not?

"And now, my dear," she added kindly, "I'm sure you must want your tea after your long journey, and that hot walk afterwards. It was a most unfortunate mistake about the carriage. I cannot tell you how distressed, how very distressed, I am about it."

Yes, Granny was quite right. It was difficult not to spoil that little beggar. Everyone helped to do so; everyone, that is to say, but one person. That one person was Briggs, Chris's dignified[Pg 173] and severe nurse. The whole household concurred in petting and spoiling him in every possible way. Briggs alone maintained her course of justice, inflexible and unbending. Her yoke was not one under which the little beggar willingly bowed his head. He was not accustomed to any yoke, and Briggs' was not at all to his taste.

In consequence of this state of affairs, nursery rows were by no means infrequent; nor was it very long before I witnessed one. It was but a few days after I had arrived, and I was sitting one afternoon in the library reading the Morning Post to Granny, who was busy with some work she was doing for the poor.

It was a quiet and peaceful state of affairs which we were both enjoying. Suddenly, however, we were interrupted by a tap at the door, and the entrance of Briggs, flushed, heated, and slightly panting.

"If you please, mum," she began, a little breathlessly, and placing her hand on her side as if to still the beating of her heart, "I wish to know if Master Chris is to be allowed to speak to me as he likes?"

"Certainly not, certainly not," Granny replied, raising herself straight in her arm-chair, and trying to assume the severity of manner she felt was suitable to the occasion. "What has he been saying?"[Pg 174]

"It was just this, mum," Briggs started, with the air of resolving to give a full, true, and particular account; "it was just this. We were down in the village, and I stepped into the post-office to buy a few reels of black cotton, which it so happens I have run out of. Likewise, I wanted to buy some blue sewing-silk, which you may remember, mum, you asked me to keep in mind next time I happened to be that way."

"Yes, I remember, Briggs. And Master Chris was naughty?" Granny said, gently trying to bring her to the point.

"Well, mum, I was going to tell you," she continued, without hurrying, "when I had bought the cotton and the silk, it came to my mind to buy a packet of post-cards and two shillings' worth of stamps. But the rector's young ladies had come in, and being pressed for time, Mrs. Thompson, she says to me, 'I make no doubt but that you will let me serve the young ladies first'; to which I made answer, 'I wait your pleasure'. But Master Chris he gets cross, because he wants to go on home at once and roll his new hoop. 'Come along, old Briggs!' he says; 'come along, you old slow-coach!' Such behaviour, such language! Before the young ladies from the rectory, too! Where he learnt it I'm sure I can't tell. Not from me, I do assure you, mum," she concluded with indignation.[Pg 175]

"It was very naughty of him," Granny remarked mildly.

"But that was not all, mum," the irate Briggs continued; "for all the way home he walks in front of me, tossing his head and singing as loud as possible, 'For I'm a jolly good fellow'; and Jack there barking and making such a row alongside of him; it was for all the world like a wild-beast show. Nothing I could say could stop the pair of them."

She paused to allow Granny to take in the full extent of Chris's enormity. As she did so, a scampering of little feet was heard outside, the handle of the door was impatiently turned—first the wrong way, and then rattled angrily. Finally the door itself was burst open, and that little beggar ran in, with excited countenance; the big holland pinafore, in which Briggs insisted upon enveloping him, and his especial detestation, half dropping off him, and trailing behind on the ground.

"Granny," he began immediately, "is 'For he's a jolly good fellow', that Uncle Godfrey sings, a wicked song?"

"It's very naughty of you to behave rudely to Briggs," she replied gravely.

Looking round, Chris's eyes fell upon Briggs, whom at first he had not noticed; then, realizing that she had been first in the field, he burst into a loud, tearless wail.[Pg 176]

"Briggs, you're a nasty, nasty thing, and I hate you!" he cried vehemently, stamping his foot as he spoke.

"There, mum! Is that the way for a young gentleman to speak?" she asked, not without a certain triumph.

"I don't like you!" Chris cried, stamping his foot again. "You are always cross! Nasty, cross, old Briggs!"

"Chris, I am shocked, very, very shocked," Granny said gravely. "You must stand in the corner for a quarter of an hour."

The little beggar wailed again; real, unfeigned tears this time.

"I don't—want to—go into—the corner," he said sobbing. "It's all—your fault, Briggs."

Briggs shook her head slowly and solemnly from side to side.

"Oh, Master Chris!" she exclaimed, "is that a way for a nice young gentleman to speak?" Then she left the room with dignity.

Chris, looking after her with impotent anger, moved towards the corner with laggard steps, crying bitterly as he did so.

"Must I go into the corner, my Granny?" he wailed. "Uncle Godfrey is never sent into the corner."

"Yes, yes, you must, Chris," she said, obliging herself to be firm.[Pg 177]

The little beggar looked entreatingly with large tearful eyes at her, as he crept towards the hated corner. But she would not allow herself to relent. Justice, in the form of the deeply offended Briggs, had to be propitiated, and Chris had to bear the punishment for his misdeeds.

At the same time, I believe Granny would joyfully have gone into the corner herself, if by so doing she could have spared her darling this wound to his pride, and yet have satisfied her own conscience. I think, indeed, in her sympathy for Chris in his disgrace, she really suffered more than he. It was therefore with relief, and as a welcome diversion that, when the footman came to announce the arrival of visitors, she rose to go to the drawing-room.

"I must go, Miss Baggerley," she said. "Will you be so kind as to see that Chris stays in the corner for a quarter of an hour? Only for a quarter of an hour, if he is good; but I know that he will be good, for he does not want to make his Granny unhappy any more. I am sure of that." With which gentle persuasion she went.

For a time Chris wept loudly and sorely, after which he was silent, save for an occasional sniff. This silence continued uninterrupted for so long that it at last aroused my suspicions. Turning my head the better to see him, I found that he was engaged in drawing strange and mystic signs[Pg 178] upon the wall, by the simple process of wetting his finger in his mouth.

Hence the explanation of this sudden calm; for so absorbing, apparently, was this occupation, that it had had the effect of drying up all those bitter tears which, but a few minutes earlier, had flowed so freely.

"What are you doing?" I asked. "You must not dirty the wall like that."

"I am writing my name," the little beggar said with much pathos. "Chris-to-pher God-frey Wyndham. Then when I'm dead and gone far away over the sea, Granny will see it, and she'll be sorry she was so cross."

"Jane will wash out those dirty marks," I replied, ruthlessly destroying his mournful hopes. "They will not remain there."

At this the little beggar desisted from disfiguring the wall, but reiterated, though more weakly, "Granny will be very sorry by and by; she was cross, and she'll wish she hadn't put me in the corner."

"No, she won't," I answered decisively; "she'll be sorry that you were naughty, but she won't wish that she had not punished you. You deserved to be punished."

Feeling that I did not regard him as the ill-used little being that he considered himself, and that there was a want of sympathy about my[Pg 179] remarks that was not altogether to his taste, Chris once more was silent.

Ten minutes elapsed, broken only by an occasional sigh from the occupant of the corner. Then I was asked wearily:

"Is it nearly time for me to come away?"

"Yes," I said, as I looked at my watch, "you may come out now."

A forlorn little figure came towards me, and crept on my knee.

"Was I very naughty?" he asked, deprecatingly.

"Yes, dear, I am afraid you were," I answered. I should have liked to speak more severely, but that was a difficult matter with Chris.

"Briggs is a nasty thing," he said, nestling his head contentedly on my shoulder.

"Granny will send you back to the corner if she hears you speak like that," I said, with more confidence than I felt upon the subject.

"She was so unkind to me; she isn't a kind Briggs," he said. "Do you like her?"

Then without waiting for an answer he went on: "I love my Granny best, and Uncle Godfrey next, and you next, and Briggs last,—the most last."

"If you were good to Briggs you would love her more," I said.

"Would I?" he asked doubtfully.[Pg 180]

"Yes," I answered; "and though you are a happy little boy now, you would be still happier then. There is nothing that makes us happier than to love people very much and try to be kind to them."

"Even Briggs?" he inquired, thoughtfully.

"You should not talk of her like that," I said, trying not to smile. "She is really very fond of you, and very kind to you. If she was angry, it was because you were rude."

Chris moved impatiently. He did not like that view of the case. There was a pause, then: "Shall I tell you a story?" I asked. "I shall just have time before you go to your tea."

"I don't know," he answered, with some indifference. "I've heard them all lots of times. Briggs has told them to me often and often—'Jack the Giant-Killer', and 'Jack and the Beanstalk', and 'Red Riding-Hood', and 'Cinderella' ("I don't much like those two," he put in, with a touch of masculine contempt, "'cause they're all about girls"), and 'Hop o' my Thumb.' And the story of the Good Boy who had a cake, and gave it all away to the Blind Beggar and his dog, except a tiny, weeny piece for himself; and the Bad Boy who had a cake, and told a wicked story, and said there never was one, 'cause he didn't want anyone else to have it; and the Greedy Boy who had a cake, and ate it all up so fast he was dreadfully[Pg 181] sick. Briggs has told them all to me, and she says there ain't no more stories to tell; leastways, if there are, she's never heard tell of them."

"If I were you I shouldn't say 'leastways', 'never heard tell', or 'ain't no more'," I remarked as he paused, out of breath.

"Why not?" he asked.

"They are not the expressions a gentleman uses," I answered.

"Does a lady?" he asked with curiosity; "'cause Briggs does."

"My dear child, never mind what Briggs does. We were not talking of her," I replied. "You know I have told you before you should not always ask so many questions. It is a troublesome habit."

"Is it?" he said, with the utmost innocence.

"Decidedly," I replied, and once more struggling not to mar the effects of my words by smiling. "Well, about my story. It is not one of those you have spoken of. I don't think that you have heard it."

"Then tell it to me, please," he said, with a touch of condescension.

"Well, once upon a time," I began, in the most approved fashion, "there were two men who had a great hill to climb. It was a long and difficult climb, but, if they only reached the top of that hill, they would be fully rewarded for all their[Pg 182] pains. I will tell you why. There was there a beautiful country, where they would live and be happy for evermore. It was such a beautiful country! The trees were always green, the flowers never withered, and it was always sunny,—never a cloud to be seen. The Lord of that country was not only very great and powerful, but He was also very loving and good. He knew how wearying and difficult that uphill journey was to the dwellers in the valley beneath. So, in His love, He sent messengers to tell the travellers how they must journey if they hoped ever to reach the beautiful country over which He ruled.

"One of these messengers came to the two men of whom I have spoken just before they started on their journey, with these plain and simple directions:

"Follow the straight and narrow path that leads up-hill; you cannot mistake it, for it goes right on without any curves or twists. You will come across many rough and difficult places, but do not turn aside, though the path leads you over them. You may see other paths that lead round them, but don't turn off from the narrow one. Don't take the others; they don't lead up, they lead down. The straight path is the only right one. Go straight on, don't be afraid. These are my Lord's directions.[Pg 183]

"'The journey is very tiring,' went on the messenger, 'and the sun will beat down by and by with much fierceness, so that you will suffer at times from great thirst. But, see, my Lord has sent you these!' As he spoke, he held out two flasks. You cannot imagine anything so beautiful as they were. They were made of pure gold, bright and shining, and ornamented with diamonds that flashed and sparkled in the light like fire. To each of the men the messenger gave a flask.

"'Look,' he said, 'and you will find that they are filled with fresh, clear water. This water is magic; it will never come to an end, and you will never suffer from thirst, so long as you obey the order which my Lord sends you. This is the order. Drink none yourself, but give of it to all who need it. If you do so, your thirst will never overpower you. But if you are churlish, and wish to keep it for yourself, some day you will suffer—suffer terribly. By and by you will find, too, that there is no water left, for the magic will all have gone! The beauty also of your flasks will have all disappeared; the gold will have become dim, the diamonds will have lost their sparkle, and you yourself will have no power to go onwards and climb higher. Good-bye—remember that my Lord waits to welcome you with love.'

"Now, when he had given them these directions,[Pg 184] the messenger went, and after a while the two men started on their journey.

"At first the hill went up so gently that they hardly noticed the incline. The way did not appear very difficult in the beginning. They went through a wood where the trees were all young, and the leaves a tender green, as you see in the springtime, Chris, my dear. And the sunlight fell through the trees and made a pattern on the ground, which moved slowly and gracefully as the gentle breezes swayed the branches. There were no rough places then, or, if there were, they were so slight that the two travellers hardly remarked them. And as they walked along they sang in the joy of their hearts; the sunshine, the soft light breezes, the pretty wild flowers, the trees—all made them so glad and so happy. Nor did they forget to give to all who passed by some of the fresh, pure water out of their golden flasks.

"By and by they came out of the pretty little wood, and the hill became steeper, the rough places rougher and more frequent.

"Then one grew impatient. He wanted to go on more quickly than he had done hitherto. It seemed to him a waste of time to stop so often to give to the passers-by that pure, refreshing water. Besides, he began to doubt the truth of the message he had received. It did not seem possible to him that he could give away the water[Pg 185] in his flask and yet not suffer from thirst. He resolved to keep it all for himself. Nor could he believe that it was always necessary to follow the narrow path. It was a different thing when it led through the pretty wood, but now that it led so often over such difficult places, he determined to find an easier one. Therefore he separated from his companion, and went his own way, avoiding all the roughnesses of the road, and taking the paths that seemed less hard. Nor did he any longer stop to offer to others the magical water of his golden flask, he kept it all for himself, and let the wearied and sad ones pass him by without compassion.

"But he never remarked how dim the gold of the flask was growing, nor how fast the water was diminishing. Nor did he see that instead of going up he was really going down-hill, and that the paths he chose were misleading him. In his hurry he never noticed this, till one sad day it came upon him.

"He had been feeling very tired and out of heart, for the way seemed so long and tiring. Yet, he had been struggling on, hoping to find his rest at last. On this day, however, he found that his strength had gone; he could climb no further. He took out his flask, now so dim, hoping to quench the terrible thirst that was overpowering him; but alas! alas! there was hardly any water[Pg 186] left; not nearly enough to revive him. So there, by himself, sad and disappointed—for he knew that now he would never see the happy land he had started for with such glorious hopes,—he died—died all alone and uncared for!

"And the other traveller? Well, he went straight on as the good Lord had directed. Often the rough places were terribly rough, and the sharp stones in the pathway wounded his feet sadly. Nevertheless, he never turned aside; he went right on as he had been directed, whilst to all those who passed by, thirsting for some of the beautiful, clear water from his golden flask, he gave freely and willingly. Little children who met him with tearful eyes went on their way laughing and singing. Older people, also, who were too tired to cry, whose hearts were heavy with many sorrows, drank of that water and went on their way refreshed. And his golden flask remained bright, and the water within it undiminished, right to the very end.

"What was the end? Ah, it came sooner than he thought it would! The journey was not so very long after all! And when he arrived at that beautiful country, and his eyes saw 'The King in His beauty', he forgot all about the rough places, and all about his past weariness. It was the land of sunlight, you see, and the land of shadows passed from his recollection for ever."[Pg 187]

"Is that all?" Chris inquired, as I paused.

"Yes, that's all," I replied.

"It's a very nice story," he said, patronizingly. "I like it almost as much as 'Jack the Giant Killer' and 'Jack and the Beanstalk', and better than 'Cinderella'."

"Shall I tell you what it means?" I asked.

He looked at me doubtfully.

"Are you going to scold me?" he asked, moving restlessly on my knee; "'cause I'm going to be a good boy now."

"No, my dear, I'm not going to scold you," I said reassuringly. "I only want to tell you what I mean by my story."

"Will it take long?" he asked; "'cause I'm hungry, and want my tea."

"No, it won't take long," I answered persuasively. "I will tell it to you quickly. This is what it means. You know, Chris, God wants us all to go to heaven and live with Him by and by. In His great love He has shown us all the way; it is the way that the blesséd Jesus went; a way that sometimes takes us over hard and difficult places, but that always goes up—never down. It is a way that leads us higher and higher, right away to the happy land you were singing of last Sunday. But there is one thing God has told us to do if we ever hope to reach that happy land—we must love everyone. Just[Pg 188] as the man who in my story reached the beautiful land at last, just as he gave freely of the water in his flask, so must we give freely of the love God has put into our hearts. He has put it there, not that we should spend it on ourselves, but that we should spend it on others. So long as we do that, so long will our hearts remain pure and good as God wants them to be. And the more we love everyone, the more we shall know of God, and the nearer we shall be to heaven; for you see, dear, to know God is Heaven, and God is Love."

I paused, and Chris looked contemplative.

"I'm going to be like the good man, who gave away the water out of his flask," he said, with the air of one taking a great resolution. "I'm going to love everyone, and Briggs too."

"I like to hear you say that," I said, stroking his head, with the tumbled, golden curls. "Now, I think you had better go to your tea. Briggs will be waiting for you."

He jumped off my knee and went as far as the door, then came back to my side.

"Miss Beggarley," he said, putting his arms round my neck, "I want to give you a great, good hug like I give my Granny. I love you very, very much."

"If you please, mum, what am I to do about Master Chris's lessons? You said you wished me to look over his clothes this morning, and I haven't time for that and lessons too." Briggs looked inquiringly at Granny as she spoke.

"Of course not, of course not," said Granny. "Bring me his books, Briggs; I will give them to him to-day."

"Yes, Granny, you give me my lessons," exclaimed Chris, dancing with glee and clapping his hands, evidently looking forward to a frivolous hour in her company.

"I hope, mum, you'll see he does no tricks," Briggs said, when she returned with Chris's books. "He's very fond of them. He'll read over what he's read before, with a face as innocent as a lamb's, and if I don't remember he'll never say a word to remind me."

"Go away, Briggs; I don't want you," the little beggar remarked with more truth than politeness.

"Master Chris, I shall always stay where my duty calls me," she answered with loftiness, "as my mistress knows."

"Certainly," Granny replied soothingly. "Chris,[Pg 190] I cannot permit you to speak to Briggs in such a way. Where are your lesson-books?"

"Here, mum," Briggs said, producing two or three diminutive red books and a tiny slate.

"Thank you. Then you had better go and get on with your work," said Granny, and Briggs left, with a last admonitory look at the little beggar, which he received with one of defiance.

"May Jack do lessons too? He's just outside," he asked as Granny opened his reading-book.

"Very well," she agreed, and he ran off to fetch him. He returned presently, followed by his four-legged friend, who, selecting a sunny spot near the window, lay basking there, blinking at us lazily with sleepy eyes, as from time to time he roused himself to snap at the flies within reach.

"I want to get on your knee, my Granny," Chris said, suiting the action to the word.

"I don't think you will do your lessons so well," she said, doubtfully.

"Oh yes, I will!" he replied coaxingly, and was allowed to remain.

"Let us read this," he proposed, opening his book and pointing to a page.

"What is it? A little dialogue?" answered Granny. "Yes; it looks very nice."

"It's very difficult. So will you be the lady, and me the gentleman?"[Pg 191]

"Yes, if you would like that. But as I am helping you, you must be very good, and read your very best."

"My very, very best."

There was a pause.

"Now begin, my darling; we are losing so much time," Granny remarked.

"Why, it's you to begin," Chris replied, with a touch of reproach at having been unjustly censured. "Don't you see? You are Sue!"

"Quite true, to be sure, so I am," the old lady said apologetically, then began gently and precisely:

"'She. Sir! sir! I am Sue. See me! see me! The cow has hit my leg! She has hit her leg out up to my leg, and she has hit it and I cry! Boo! boo!'"

To this announcement of woe, Chris replied, or rather chanted in a sing-song tone, and as loudly and rapidly as he could:

"'He. Why, Sue, how is it? Why do you cry so? You are not to cry, Sue. It is bad to cry. Put the cry out and let me see you gay.'"

"Not so fast," Granny here remarked mildly; "not so fast, and not so loud."

"I want to finish it," he explained. "I want to get my lessons done very quickly."

"Ah! but they must be done properly. You[Pg 192] see that, my darling, don't you?" she said. Then continued:

"'She. I am to cry, and to cry all the day. I am so bad and so ill, and my leg is hit, and it is too bad of the cow to hit my leg.'"

"'He. Did she hit you on the toe?'"

"'She. No. She hit me by the hip, and it is a bad hip now, and she is a bad, old, big cow, and she is not to eat rye or hay; no, not a bit of it all the day.'"

"'He. Not eat all the day! not eat rye, not eat hay!'"

At this point, Granny stroked Chris's head and said commendingly:

"You are reading very well now, very well indeed. You have made great progress since I last heard you."

The little beggar wagged his head solemnly. "I want to read well," he stated gravely. "I want to read very well; then I shall read big books like my Uncle Godfrey."

"You are a good little boy," she said. "I am very pleased with the pains my little Chris is taking."

A suspicion crossed my mind. Was he indulging in one of the tricks of which Briggs had forewarned Granny?

"Have you ever read this before, Chris?" I asked.[Pg 193]

"Oh, yes; often and often!" he replied, with the utmost candour.

"Oh, my darling, why did you ask me to let you read it now?" Granny said, looking grieved.

"'Cause I read it so well," he explained, without exhibiting any proper shame.

"Ah! but you might have known Granny didn't want an old lesson," she said gravely. "It wasn't quite right; was it, Miss Baggerley?"

"No; it wasn't fair," I assented.

Chris hung his head. "I didn't mean not to be fair," he said, with touching contrition.

Granny's heart softened. "I don't believe you did, my Chris," she remarked gently.

Chris put his arms round her neck and hid his face on her shoulder. "I'm very sorry," he mumbled. Then raising his head:

"I am going to be a very fair boy," he said magnanimously, touched by Granny's forgiveness; "I'm going to be a very fair boy, and I am going to tell you that I don't know the lady's part as well as I know the gentleman's part. Shall I be Sue, my Granny?"

"Yes. Now that's an excellent idea," she said, with much satisfaction, and glancing at me with a look of pride in her darling's noble repentance. "I consider that an excellent idea, indeed; and I am very pleased that you should have proposed it."[Pg 194]

Chris's face fell. "Don't you think that it is silly for a big boy like me to be Sue?" he asked, with evident disappointment that his offer had been accepted.

"Not at all," Granny said. "It's only in a book, you see, my pet."

"I don't like being a girl," he murmured. "I don't want to be Sue."

"I thought, though, that you wanted to show Granny you were sorry for not having told her you were reading an old lesson," I remarked.

He sighed, without answering me; then after a pause, continued with an effort and a hesitation that offered a striking contrast to the glib manner of his previous reading:

"'She. Yes; for why did she hit me? She is a big and bad old cow. See her! See how fat she is! She is as fat as a sow. She has a fat hip, and a fat rib, and a fat ear, and a fat leg, and a fat all.'"

As he came to the end of the sentence he sighed once more, very heavily and sadly, then waited.

"Yes, yes, go on," Granny said, as he looked at her expectantly; "read to the end, like my good little boy."

He obeyed, but with a look of protest on his face, which changed to one of injury, when, at the close of the one lesson, he found that Granny intended him to read another.[Pg 195]

This was not what he had expected, and he was disappointed with her accordingly.

"That is just as much as I read with Briggs," he said, looking at her with a world of reproach.

"But you must read as much with me as you do with Briggs," she said, looking slightly fatigued with the arduous duty of giving the little beggar his lessons.

"Why must I?" he asked.

"Now, now, don't ask so many questions," she said slightly flustered. "Begin here, my dear child."

"'Ben! Ben! I can see a fly!'" he started impatiently, and stumbling over the words in his haste; "'and the fly can fly, and the fly can die, and the fly is shy, and can get to the pie, and can get on the rye! and the fly can run, and can get on the bun, all for its fun! and the fly is gay all the day, and oh, Ben! Ben! the fly is in my ear, so do put it out of my ear.'"... Chris came to a stop, and leant his head back on Granny's shoulder.

"What a funny thing it must be to have a fly in your ear," he remarked thoughtfully. "Have you ever had a fly in your ear, Granny?"

"Never, my darling," said the long-suffering old lady patiently; "go on."

Chris obeyed; now, however, reading in a listless fashion, as if he had no further energy left.[Pg 196]

He continued without a breath, until he reached the following: "Ah, but now it has got in the oil. Oh, fly, fly, why do you go to the oil?"

This was too good an opportunity to be lost.

"Granny," he said idly, and yawning as he spoke, "I want to ask you something."

"Yes, my Chris," she said inquiringly.

"Why did the fly go to the oil?" he asked with feigned interest.

"My darling, how can I possibly tell you?" she exclaimed. "See, you are slipping right off my knee. You can't read properly so."

Chris scrambled back to his former position, and then continued reading in a desultory fashion.

"'Oil is bad for a fly. So, now I put you out of the oil, and now I say you are to get dry. Ah! but now the fly is on the pot of jam, and it is on the jar and in the jam. The red jam, the new jam, the big jar of jam.'"

"How nice!" he exclaimed, with more enthusiasm. "May I have some red jam for my tea to-day?"

"If you are a good boy, and read right on to the end of the lesson without stopping," she replied. Thus encouraged, Chris with an effort toiled to the conclusion without any further pauses.

"'By, by! Wee fly!' Now must I do my sums?" he asked all in a breath as he came to the end.

"Yes; I think you had better," Granny replied,[Pg 197] holding the slate-pencil between her fingers and looking meditatively at the slate. "I will write you out one."

"Sometimes Briggs doesn't write horrid sums on the slate; sometimes she asks me sums she makes up out of her head," he said, insinuatingly. "I like that better, it is much, much nicer."

"Sometimes Briggs asks you sums out of her head, does she?" Granny repeated, putting down the slate-pencil. "Well, now, what shall I ask you?"

"Something about Jack," he said, getting off her knee and sitting on the ground beside the dog. "He's such a naughty, lazy, little doggie; he's done no lessons at all. Now, listen, Jackie, and do a sum with me. If Granny asks me something about you, you must think just as much as me. Mustn't he, Granny?"

"Of course, of course," she replied absently. "I'm to ask you something about Jack, my darling. Let me see, what shall it be?"

She looked at Jack for a moment as she spoke, who blinked back at her inquiringly, as if to ask, "What are you all talking so much about me for?"

Then with a look of inspiration:

"I know," she said. "There were six—no, there were eight flies. Jack swallowed one—yes, he swallowed one, he ate another—let me see, how[Pg 198] many flies did I say? Eight flies? Yes, eight. Well, he swallowed one, and he ate one, and"—she took off her spectacles and thought a moment—"he bit another in halves.

"Yes, that will do," she said with satisfaction. "He swallowed one, he ate another, and he bit another in halves. How many flies were left to fly away?"

Chris knitted his brows. "Lots," he replied, as he pulled one of Jack's ears.

"Come, come, think," Granny said reprovingly. "He swallowed one—that left how many?"

"Seven," said Chris.

"Very good. He ate another?" she went on—

"That left six," the little beggar said, looking very astute.

"That's right. And he bit another in halves. Then, how many were left to fly away?" she asked with mild triumph.

"Five and a half," answered Chris. Then thoughtfully: "How did the half-fly fly away, my Granny? P'r'aps Jack only ate the body and left the wings. Was that how it happened?"

"My pet shouldn't ask such silly questions," Granny said, speaking more testily than she generally did. "I only said, supposing there were eight flies."

"Well, supposing," Chris persisted; "how would the half-fly fly away then?"[Pg 199]

"It wouldn't, it couldn't. You see, my darling, it would be dead," the old lady said, becoming flurried.

"But you said it would," Chris said with some perplexity.

"There, there, that will do," she said. "You are a silly little boy to think such a thing. We must get on with your other lessons, for the time is passing."

"Shall I have a holiday now?" he suggested lazily.

"No, no; that would never do," she said. "You had better do some more sums; but on the slate. Miss Baggerley, will you be so kind as to give them to him. That, with a little spelling and a copy, will, I think, be sufficient for to-day;" and the old lady, leaning back in her arm-chair, closed her eyes with an exhausted expression.

"Miss Beggarley," said Chris in a coaxing voice—he never failed thus to distort my name—"may I get on your knee and do my lessons, like I did on Granny's?"

"No, you had better not," I said, hardening my heart. "How do you expect to write well if you sit on my knee?"

"'Cause I know I could," he replied confidently.

"No, no," I said firmly; "we won't try. Come here; you sit on this chair and write this copy. Now show me how well you can write and spell.[Pg 200] I know a boy no older than you, and he writes and spells beautifully for his age."

"Better than me?" Chris asked anxiously.

"Well, write and spell your very best, and then I shall be able to tell," I replied with caution. The mention of my small friend of advanced powers as scribe and speller proved a happy thought on my part. The effect was excellent. Chris's mood changed; his lazy fit passed away in a burning desire to emulate—not to say outdistance—his unknown rival. With frowning brow and tongue between his teeth, he laboured assiduously at his copy, without uttering a word, whilst Granny, lulled by the quiet which prevailed, slept the sleep of the just.

I felt, indeed I had cause to be, fully satisfied with the result of my remark, for its effects lasted not only whilst the copy was being written but even through the spelling-lesson; an effect that could hardly have been anticipated when the varying moods of that little beggar were taken into consideration.

As I closed the spelling-book, "Miss Beggarley," he said, gazing at me with anxious eyes, "have I written my writing and spelt my spelling as well as that other boy?"

"Yes, I really think you have; at least very nearly."

"P'r'aps I shall quite, to-morrow."[Pg 201]

"Perhaps you will—if you take great pains."

"Shall I kiss my Granny?"

"No, you will wake her up."

"Why does she want to go to sleep? She often goes to sleep when she does my lessons. Do boys' lessons always make old people sleepy?"

"That depends on the little boy who does them," I replied gravely. "If he tires his granny very much, it is not surprising that she should go to sleep."

Chris looked thoughtful.

"Have I been a good boy?" he said.

"You were inattentive at the beginning, dear," I replied, "but you were good afterwards."

"Then I shall tell Briggs I have been a good boy," he remarked with satisfaction. And with a certain expression of anticipated triumph upon his face, he walked off, followed by Jack, his constant and faithful companion.

"Tell you a story? What shall it be about? I thought you were tired of stories." Granny spoke a trifle drowsily. It was very warm that[Pg 202] September afternoon—an afternoon that made you feel more inclined to sleep than to tell stories.

But Chris was not to be denied.

"I want a story very much," he said; "very much indeed."

"Perhaps Miss Baggerley would tell you one," suggested Granny. "I am sure it would be a more interesting one than any I could think of."

"I don't want anyone to tell me a story but you," answered the little tyrant wilfully; "only you, my Granny."

"Then I will, my darling," she replied, plainly gratified at this preference so strongly expressed. "But you must wait a moment," she went on, "I shall have to think."

She closed her eyes as she spoke, and there was silence, broken only by the sounds of the world without carried through the open windows—the lazy hum of the bees amongst the flowers, the gentle, monotonous cooing of the wood-pigeons in the trees, the far-off voices of children at play.

Presently the little beggar became impatient.

"Why don't you begin, Granny?" he asked, pulling her sleeve as he leant against her knee.

She started from a slight doze into which she had fallen.

"Let me see," she said with a start; "I had[Pg 203] just thought of a very nice story, but I was trying to recollect the end. I think I remember it now."

"There was once a very beautiful Newfoundland dog," she began hurriedly. "Yes, he was a very beautiful dog indeed."

"How beautiful?" interrupted Chris, with his usual aptitude for asking questions. "As beautiful as Jacky?"

"I think more beautiful," she replied, without pausing to consider.

"Then he was a nasty dog," he said, with vehemence. "I don't like a dog what is more beautiful than my Jacky."

"He was such a different kind of dog," she said deprecatingly. "A Newfoundland dog cannot very well be compared with a fox-terrier, my pet."

"What was his name?" asked the little beggar, accepting Granny's explanation and letting the matter pass.

"Rover; that was what he was called," she replied. "His little mistress loved him dearly," she continued.

"Did he belong to a girl?" Chris inquired, with some contempt on the substantive.

"Yes; and they always used to go out for pleasant walks together," she went on. "But never near the river, for she had said many a[Pg 204] time, 'Don't go near the river, my darling, for it is not safe; not for a little girl like you'."

"Who said that?" he asked, speaking with some impatience. "The little girl—or what?"

"The little girl's mother," replied Granny, a trifle drowsily.

"You're going to sleep again!" Chris exclaimed reproachfully. "Oh, Granny, how can you tell me a story when you're asleep?"

"Asleep! Oh no, my darling," she said opening her eyes. "Well, one day, I am sorry, very sorry to say, Eliza—"

"Was that the little girl's name?" inquired Chris.

"Yes," she answered. "Didn't I tell you her name was Eliza? Dear, dear, how forgetful of me! As I was saying, Eliza thought, in spite of her father's and mother's command, she would go to the river, for she wished to pick some of the water-lilies which grew there in such profusion."

"How naughty of Eliza!" exclaimed Chris, with virtuous indignation.

"Yes, very naughty; very naughty indeed," agreed Granny, her voice again becoming sleepy. "It was sadly disobedient."

There was another pause, during which Chris listened expectantly, and the old lady once more closed her eyes.[Pg 205]

"Oh, Granny! do go on," said the anxious little listener fervently.

"She picked several which grew near the river's brink," the old lady continued with an effort, "and at first all went well. But at last she saw a beautiful—a remarkably beautiful one that grew just out of her reach. It was a most dangerous thing to attempt to pick it, but she did not think of that, for she was very, very thoughtless as well as disobedient. Bending forward, heedless of her father's warning call, and her poor dear mother's sorrowful cry, she lost her balance, and—fell—right—into—the—river."

The last few words were uttered in a whisper, Granny's sleepiness having once more overtaken her, bravely as she struggled against it.

"How drefful!" said Chris, with wide-open eyes. "Was poor Eliza drownded? Oh, I hope she wasn't! Did she get out? Oh, say yes, Granny! And where did her father and mother call to her from? Right from the house? 'Cause I thought you said she was alone."

But the only answer to his torrent of questions was a gentle snore. The time he had occupied in pouring forth these queries had sufficed to send Eliza's historian asleep.

Chris's little face fell.

"My Granny has gone quite asleep," he remarked with much disappointment. "Now I[Pg 206] shall never know if Eliza was drownded or not. P'r'aps she's only pretending. I'll see if her eyes are fast-shut," he added, preparing to put Granny to the test by lifting one of her eyelids.

"Don't do that, Chris," I said hastily. "Come here, I'll tell you the rest of the story."

"Do you know it?" he asked doubtfully.

"I can guess it," I replied, as he crossed the room to my side.

"Then what happened to poor Eliza?" he inquired anxiously; "and did Rover help her? Oh! I do hope he did."

"Well," I started, taking up the story at the point at which Granny had dozed off, "when her father and mother—who were near enough to see what had occurred—realized the danger their little daughter was in, they were filled with horror. It seemed as if they were going to see her die before their eyes; for they were so far off that it looked as if it were not possible to get to her before she sunk. And this is just what would have taken place had not help been at hand. Eliza, her water-lilies, and her disobedient, little heart would have sunk to the bottom of the river for ever, had it not been for—what do you think Chris?"

"I know, I know!" he cried, clapping his hands. "It was Rover; the good dog. He swam after her."

"You are right," I said. "There was a plunge,[Pg 207] and there was Rover swimming to the help of his little mistress. For a minute it appeared as if the current was carrying her away, and as if he would not reach her in time. How, then, shall I describe her father and her mother's joy when they saw him succeed in doing so, and, seizing her by the dress, bring her safely to the river's bank! No," as Chris looked at me with inquiring eyes, "she was not hurt; only very wet, and very frightened."

"I 'spect she was very, very frightened," Chris said, loudly and eagerly; "and I 'spect she never, never went near the river again,—never again. Did she?"

"No, my darling," Granny said, awakened by his loud and eager tones in time to hear his last question, and sitting up and rubbing her eyes; "she was never such a naughty little girl again. She expressed great sorrow for what had occurred, and she learnt to be more obedient for the future. Indeed, she became so remarkable for her obedience, my pet, that they always called her by the name of 'the obedient little Eliza'."

"Now nice!" Chris remarked with unction. "You've been fast asleep, my Granny," he informed her, with a laugh—pitying and amused.

"Dear, dear, is it possible?" she said.

"Yes, and Miss Beggarley had to finish the story," he continued.[Pg 208]

"I'm much obliged to you, my dear, I'm sure," Granny said gratefully.

"I hope I told it as you intended it to be told," I said laughing.

"You told it just as it should have been, I am fully convinced," she answered with gentle politeness; "much better than I should have myself."

"But she never told me what happened to Rover afterwards," put in Chris.

"He lived to a great age," answered Granny, adjusting her spectacles and resuming her knitting, "and was loved and honoured by all. And when he died he was beautifully stuffed and put into a glass case."

"I wish he hadn't died, my Granny," said the little beggar mournfully, unconsoled by the honour paid to Rover's remains. Then, with a sudden change of thought: "Can Jack swim like he did, I wonder."

"That I can't say, my darling," Granny replied, intent on her work.

"I think I had better teach him," the little beggar said, looking very wise; "'cause if you, or Miss Beggarley, or me, or Briggs felled into the water like Eliza, Jacky could bring us out, and save us from being drownded."

"Twenty-seven, twenty-eight, twenty-nine," murmured Granny, busy counting the stitches on her sock, and too much occupied to pay attention[Pg 209] to what Chris said. "Twenty-nine! Now, how have I gone wrong? Miss Baggerley, my dear, would you be so kind as to see if you can find out my mistake?"

"I know!" exclaimed Chris, as Granny handed me her work; "I know very well what I will do. I'll—," and he stopped short.

"What will you do, my pet?" asked Granny, a little absently, watching me as I put her knitting right.

But Chris shook his head. "A surprise!" he said, and closed his lips firmly.

I felt that it would be safer for the interests of all to probe the matter further, and was about to do so, when there was a tap at the door, and Briggs entered.

"Master Chris," she said, "it's time for your walk."

Now, generally the little beggar murmured much and loudly when he was interrupted by Briggs. On this occasion, however, he showed no disinclination to go with her, but on the contrary went with alacrity.

"I think he is really becoming fond of her," Granny remarked with some satisfaction when they had gone. "Perhaps, after all, I shall not have to send her away at Christmas, as I feared I should have to if she and Chris did not understand each other better. I shall be very glad if[Pg 210] I can let her stay, for although she has an unsympathetic manner—yes, I must say that she strikes me as being extremely unsympathetic to the darling at times; don't you think so, my dear?—yet I know that she is thoroughly reliable and trustworthy."

"I wonder if Chris's readiness to go with her had anything to do with his 'surprise'," I answered. "It looks to me a little suspicious, I must own. I hope he has not any mischievous idea in his little head."

"Oh, no, my dear!" she replied, almost reproachfully; "the darling is as good as gold. There never was a better child when he likes. No, no, he is not at all inclined to be troublesome to-day; I think you are mistaken."

I kept silence, for I saw that dear old Granny was not altogether pleased at my suggestion. Nevertheless, in spite of her reassuring words, I did not feel convinced that the little beggar was not going to give us some fresh proof of his remarkable powers for getting into mischief. And further events justified my fears.

I will tell you how this happened.

About half an hour later I was taking a stroll in the garden, when, turning my steps in the direction of the pond, I suddenly came upon Chris, accompanied by Briggs. That something was amiss was at once evident. Briggs was[Pg 211] walking along, with her air of greatest dignity—and that, I assure you, was very great indeed,—whilst Chris, by her side, was also making his little attempt at being dignified.

But it was the sorriest attempt you can imagine!

Dripping from head to foot, water running in little rivulets from his large straw hat upon his face, water dripping from his clothes soaked through and through, and making little pools on the garden-path as he pursued his way—a more forlorn, miserable-looking little object it was impossible to conceive.

In spite of this, however, he would not let go of that attempt at dignity. With his hands in his pockets, and his head thrown back, he whistled as he walked along, with the most defiant expression he could assume upon that naughty little face of his.

And the procession was brought up by Jack, with his tail between his legs, also dripping and shivering violently.

Directly Chris saw me the defiant expression instantly vanished, and running to me, he buried his face in my dress and wept at the top of his voice.

"What is the matter, Chris?" I asked. "What has happened? What have you been doing?"

"What hasn't happened, and what hasn't he[Pg 212] been doing?" said Briggs, coming up and speaking very angrily. "And what will happen next? That's what I ask."

"What has happened now?" I repeated.

"One of Master Chris's tricks again, that's all," she said, still angrily, as we all walked on to the house.

"I was—teach-teach—teaching J-J-Jack to—to swim—like Ro-Ro—Rover," the little beggar said between violent sobs, and bringing out the last word with a great gasp.

"Teaching Jack to swim like Rover!" I repeated.

"Yes," exclaimed Briggs, with much sarcasm; "and it was a mighty clever thing for Master Chris to do, seeing as how he can't swim himself.

"It was just like this, mum," she explained, as she hastened her steps, "(I think we had better hurry a bit if Master Chris isn't to take his death of cold. He'll be in bed to-morrow unless I'm much mistaken!) I was just speaking to one of the gardeners about a pot of musk we wanted in the nursery. I hadn't turned my back two minutes before I hear a splash and Master Chris crying out at the top of his voice, and when I look around there he is struggling nearly up to his neck in water, and Jacky struggling along by his side. Well, here we are back; we'll see[Pg 213] what my mistress thinks of it all. I'll be bound she won't be over and above pleased. As for me, I can only say I am more than thankful it was at the shallow part of the pond; if it had been at the deep end, there's no saying if he wouldn't have been lying there now stiff and stark."

At this woeful picture of himself, Chris's grief, which had become slightly subdued, burst forth afresh, and as we entered the hall he sobbed more loudly and more violently than before. So loudly and so violently that the sound of his grief penetrated to the library where Granny was sitting, and brought her out into the hall, frightened and anxious to know what was wrong.

"He nearly drowned himself, that's what is the matter, mum," answered Briggs, with a certain gloomy satisfaction, in reply to the old lady's anxious questions. "It's nothing but a chance he isn't at the bottom of the deepest end of the pond at this very same minute that I speak to you!"

At this startling, not to say overwhelming statement, Granny became quite white, and, holding on to a chair near at hand, did not speak.

"There is nothing for you to alarm yourself about, Mrs. Wyndham," I said quietly.—"Chris, stop crying; you are frightening Granny.—He managed to fall into the pond, trying to teach Jack to swim, but it was at the shallow end, so there was no danger."[Pg 214]

Thus reassured, Granny looked at me with relief.

"Thank God!" she said earnestly, as she kissed the little beggar thankfully, all wet and tear-stained as he was.

Then, with an attempt to control her emotion, but speaking in a voice that trembled in spite of herself:

"Come, come," she said to Briggs, "we must not waste time in talking. We must put Master Chris to bed at once, and get him warm. See how he shivers. Yes, come upstairs at once, my darling, and I will hear all about it by and by."

And, together with Briggs and the cause of all the confusion, she went upstairs to take precautions for the prevention of the ill consequences likely to follow upon his rash deed. It was some time before she came downstairs again, and when she did so she looked worried.

"I am afraid, very much afraid, he has caught a chill," she remarked. "He so easily does that."

"Perhaps you may have prevented it," I said hopefully.

"I wish I could think so," she replied, shaking her head; "but I much fear that it cannot be altogether prevented. He is not strong, you see, my dear."

"And to think," she went on admiringly; "to think the darling ran that risk all because of his[Pg 215] loving little heart; because he feared that some day we might be in danger of being drowned, and that if Jack could swim we should be rescued. Isn't it just like the pet to think of it?"

"It is," I agreed with conviction; adding cautiously, "It would have been better, I think, if he had told you of his idea before trying to put it into effect. It would have given everyone less trouble."

"He wished to surprise us all by showing us he had by himself taught Jack to swim," Granny returned, quick to defend her darling. "No, no, I see how it happened; he was thoughtless but not naughty. Indeed, I take what blame there is to myself. I should have considered, before I told him the story of Eliza and her dog Rover, the effect it was likely to have upon an active, quick little brain like his."

I smiled. It was quite plain that dear old Granny in her loving way wished to take all the blame upon her own willing shoulders, and to spare that incorrigible little beggar....

It was some three days after this, and I was sitting in the nursery by Chris's crib, trying to amuse him and wile away the time until Briggs came back with the lamp, when it would be the hour for him to say good-night and go to sleep. The bright September afternoon was drawing to a close, and twilight was beginning to fall.[Pg 216]

In spite of all Granny's precautions he had not escaped from the consequences of his tumble into the pond, but had caught a severe chill, and so had had to stay in bed for these last three days. He was very sweet and gentle in his weakness, that poor little beggar; partly, I think, because he felt too tired to be mischievous, and also, I am glad to say, because he loved his Granny very dearly and was truly sorry for the fright he had given her. I had been telling him stories for the last half-hour, but having now come to the end of my resources, for the moment we were quiet.

With his hand in mine, Chris lay looking out through the window at the stars as they came out slowly, slowly in the gathering darkness.

Presently he asked:

"Do you like the stars? I like them very much."

"Yes, Chris," I answered; "so do I."

"I think they are the most beautifullest things," he remarked with enthusiasm.

"Yes, they are," I replied. "They are like the great and loving deeds of God, falling in a bright shower from heaven upon the earth beneath."

"When I go to heaven, will God give me some stars if I ask Him very much?" Chris inquired, most seriously. "P'r'aps if I ask Him every day in my prayers till I'm dead He will then."[Pg 217]

I smiled a little.

"No, darling," I said, smoothing his hair gently; "the stars are not the little things they seem to you. You see, they are worlds like our world. It is only because they are such thousands and thousands of miles away that they look to you so small."

Chris pondered over this for a moment or two, then he said thoughtfully:

"Miss Beggarley, I want to ask you, when the good man got to the top of the hill, did he see that the stars were big worlds and not little, tiny things?"

"Yes," I replied, half to him, half to myself; "he saw then that those things which, at the foot of the hill, had seemed to him so small and so far away he had given them but little consideration, were in reality great, and beautiful, and worlds in their importance. And he saw, too, that the things which in the valley beneath had appeared to him of such infinite value were by comparison poor and valueless, not worthy the thought he had given them or the pain they had so often caused him...."

I heard a footstep, and looking round, saw that Briggs had come back.

"I must go now," I said to Chris, kissing him. "It is time for you to sleep. Good-night, dear!"

"Good-night!" he said, then turned his head[Pg 218] towards the window and lay still, gazing solemnly with big, sleepy eyes at the stars that shone without.

As Chris regained his strength he also regained his love of mischief—a state of affairs that proved somewhat trying. To keep him in bed and to keep him good was not a very easy task.

"The trouble it is, mum, words can't tell," Briggs said to me with fervour one evening when I had come upstairs to see that Chris was comfortably settled for the night. "If I turn my back for a moment he is half out of bed," she said, as she detained me for a moment as I went through the day-nursery. "He is that full of mischief I hardly know what to do with him."

"It shows he is getting strong again," I said, half smiling.

"It's the only way I can get any comfort," she said, sighing.

Poor Briggs! She really looked tired as she spoke, and I felt sorry for her.

"You look very tired," I remarked.[Pg 219]

"I've had bad enough nights lately to make me so," she replied. "Master Chris—he is always waking up and coughing and coughing till I'm nearly driven wild. It's my belief it's the barley-sugar has got something to do with it. Ever since the doctor said some had better be given to him when he got coughing it seems to me his cough has got a deal worse."

"Why don't you put a little by his crib?" I suggested; "then he needn't wake you up when he wants it."

"I did try that last night," she answered, "but by the time I went to bed myself he had eaten it all up, and there wasn't a scrap of it left."

"I think he will be well enough to get up soon," I said hopefully.

"I think so too," she replied. "It was only yesterday I said so to Dr. Saunders, but he didn't seem to think the same.

"I don't altogether hold with him," she continued, with a return of her usual dignified manner; "and so I told my mistress this morning. He is over-careful, and I've no belief in these medical gentlemen who are given that way. When he comes to-morrow—There, if I didn't forget!" she interrupted herself to exclaim.

"What have you forgotten, Briggs?" I asked.

"My mistress asked me in particular to remind[Pg 220] the doctor that he said Master Chris would be the better of a tonic, but he had forgotten to leave the prescription," she answered. "I never thought of it this morning when he was here."

"I should make a note of it," I suggested.

"Which is the very thing I'll do," she assented. "I'll write it down now on Master Chris's slate whilst it is in my mind. It's the only way to remember things, I do believe.

"Though it is my opinion, mum," she added, as she carried out her intention; "though it's my opinion a physician should not need reminding of such things. But there! he is always forgetting something. He has no head! I should like to know where it is sometimes, for it isn't always on his shoulders, I'll be bound!"

"How can the doctor's head not be on his shoulders?" asked a puzzled little voice. "'Cause he'd be quite dead if he had no head."

At this unexpected interruption Briggs and I looked in the direction whence the voice proceeded, and saw a little figure standing on the threshold of the door that led into the night-nursery. A little figure, in a long white nightgown, with tumbled, golden hair falling about the flushed little face, and two great violet eyes shining like stars, and dancing with mischief and glee.

I confess I felt a weak desire to take that[Pg 221] naughty but bewitching little beggar in my arms, and kiss him in spite of all his sins. But Briggs experienced no such weakness.

"Master Chris!" she exclaimed in horrified amazement; "what next, I should like to know? This is past everything."

Then snatching him up in her arms, she carried him back to bed, struggling and vehemently protesting at being treated in so summary and undignified a fashion.

As for me, I presently went downstairs laughing, with the sound of Chris's voice still ringing in my ears:

"Put me down, Briggs. I will be a good boy. I don't want to be carried like a baby." Then with his usual persistency: "But I want to know—why do you say that the doctor sometimes has no head on his shoulders, 'cause how could he live without a head?" Then again, in the most insinuating of voices: "Shall I tell the doctor about the medicine he forgot, and shall I write down all the things you want to know, and all the things I want to know, and everything. Would I be a good boy if I did? I want some barley-sugar, 'cause my cough's drefful bad."

"Chris is certainly recovering," I said to Granny when I joined her in the drawing-room, and told her what had occurred. "He is quite in his usual spirits again."[Pg 222]

"His is a happy disposition, is it not?" she said, with satisfaction. "The child is like a sunbeam in the house; so merry, so bright!"

The next morning, however, the sunbeam was comparatively still; not dancing, gay, and restless, as sunbeams often are.

The little beggar was in one of his quiet moods—moods of rare occurrence with him, as you will have gathered.

"The darling is like a lamb," Granny remarked when she came downstairs; "very gentle and so good. He wants you to go and sit with him a little, if you are not busy, my dear."

"Certainly," I said, and went up to the nursery to see Chris in this edifying rôle.

I found him busy, drawing strange hieroglyphics on a large sheet of foolscap paper with a red-lead pencil. As I entered he looked up at me for a moment with a preoccupied expression, then said mysteriously:

"Miss Beggarley, what do you think I am doing?"

"I don't know," I replied. "What is it? Let me see."

"No, no, no!" he cried, bending over the paper, "you mustn't see. I don't want you to know."

"Then why did you ask me?" I inquired.

"'Cause I wanted to see if you could guess," he said.[Pg 223]

"It's nothing naughty, is it?" I asked.

"Oh no!" he replied in the most virtuous of voices, "it's very good.

"I've done now," he remarked a few minutes later, sitting up and putting the sheet of foolscap and the red-lead pencil under his pillow. "When I get better will you play horses with me? You said you would, and you never have."

"That is very wrong of me," I answered. "Yes, I will play with you when you are better."

"When will the doctor come?" he suddenly asked with some eagerness.

"Very soon now, I think," I replied. "It is just about his time."

"Will you be a lame horse when you play, or a well horse?"

"Which of the two horses has the least work?"

"The lame horse."

"Then I'll be the lame horse."

"Is that the doctor?"

I listened. "Wait a moment, I'll see," I replied, and went to the day-nursery.

Yes, it was the doctor. I could hear him and Granny talking as they walked along the passage; Granny on her favourite topic—the virtues of her darling.

"Yes," she was saying, in answer to some observation of her companion's, "he really shows a great deal of character for one so young. But[Pg 224] he has done that from the earliest, from the very earliest age. When he was a baby of but a few weeks old, he would clutch hold of his bottle with such resolution, such tenacity, that it was, I assure you, a difficult matter to take it from him."

"Quite so, quite so," the doctor answered blandly as they entered; "as you say, great tenacity of purpose.

"Well," I heard him continue, after having passed through the day-nursery to the one beyond; "well, and how are we to-day?"

"Quite well," answered the little beggar's voice cheerfully.

"Quite well? We couldn't be better, could we?" he said jocularly. "Yes, I think we are looking so much better we may get up to-day, and go for a walk in the sun to-morrow. What do you say, Master Chris?"

"I want to ask you a lot," I heard Chris say importantly.

"Very well," replied the doctor good-naturedly, "let us hear it;" at which point curiosity prompted me to go to the door of the night-nursery and look in.

Chris was in the act of drawing, with no little pomp, the large sheet of foolscap from beneath his pillow.

"Read it," he said, handing it to the doctor with pride. "I've printed it all myself."[Pg 225]

The doctor laughed as he glanced at it.

"I think," he said, "you had better read it to me yourself, my little man."

"All right!" answered Chris. "It's all questions I want to ask you. I've written them down in case I forget them."