Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 93, October 15th 1887

Author: Various

Editor: F. C. Burnand

Release date: May 22, 2011 [eBook #36187]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jane Robins, Malcolm Farmer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Dear Charlie,

'Arry.

Turning To the Left.—At a recent meeting of the Court of Common Council (in the teeth of a strong opposition of some of the members of the Board) it was decided to exclude strangers and the Press during a part of the proceedings. The matter under secret consideration, it is said, was the appointment by the Recorder of the Assistant-Judge of the Mayor's Court. It is rumoured that, acting on the opinion of Mr. R. S. Wright, (with him the Attorney-General) the Court decided not to confirm that appointment. But why all this mystery? What had the Councillors to fear? Obviously, they could be doing nothing wrong if they were sustained by Wright!

"Who's that tiny little Gentleman talking to

Mamma, Tom?" "Mr. Scribbins, the Writing Master at our School."

"Ah! I suppose he teaches Short-hand!"

(A Lay of the Criminal Law Amendment Act.)

(Before Mr. Commissioner Punch.)

An Official of Epping Forest introduced.

The Commissioner. Now, Sir, what can I do for you?

Witness. You can confer a favour upon me, Sir, by correcting some sensational letters and paragraphs on "Deer-Maiming in Epping Forest," that have lately appeared in the newspapers.

The Commissioner. Always pleased to oblige the Corporation. Well, what is it?

Witness. I wish to say, Sir, that deer-shooting in Epping Forest, so far as its guardians are concerned, is not a sport, but a difficult and disagreeable duty?

The Commissioner. A duty?

Witness. Yes, Sir, a duty; because, in fulfilment of an agreement with the late Lords of the Forest Manors (to whom we have to supply annually a certain amount of venison), and in justice to the neighbouring farmers, whose crops are much damaged by the deer, we are obliged to keep down the herd to a fixed limit.

The Commissioner. But how about the stories of the wounded animals that linger and die?

Witness. We have nothing to do with them—we are not in fault. I mean by "we" those who have a right to shoot by the invitation of the proper Authorities.

The Commissioner. But are not the poor animals sometimes wounded?

Witness. Alas, yes! Unhappily the forest is infested by a gang of poachers of the worst type, and it is at their door that any charge of cruelty must be laid. So far as we are concerned, we kill the deer in the most humane manner. We use rifles and bullets, and our guns are excellent shots. As no doubt you will have seen from the report of the City Solicitor, such deer as it has been necessary to kill, have been shot by, or in the presence of, two of the Conservators renowned for their humanity and shooting skill.

The Commissioner. It seems to me that you should put down the poachers.

Witness. We do our best, Sir. You must remember the Corporation has not been in possession very long. We have to protect nearly ten square miles of forest land, close to a city whose population is counted by Millions.

The Commissioner. Very true. Can I do anything more for you?

Witness. Nothing, Sir. Pray accept my thanks for affording me this opportunity of offering an explanation. I trust the explanation is satisfactory?

The Commissioner. Perfectly. (The Witness then withdrew.)[171]

(As much Fact as Fancy.)

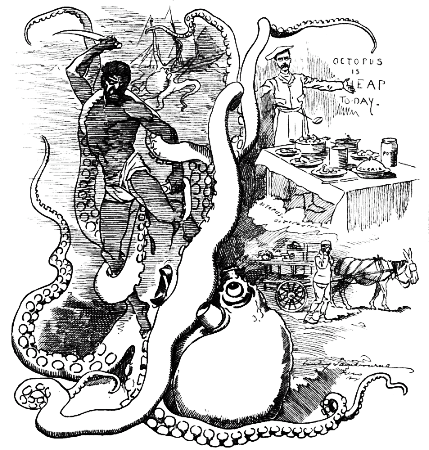

"I had one curried, and found it most

excellent—something like tender tripe."—Extract from Mr. Tuer's

Letter.

"I had one curried, and found it most

excellent—something like tender tripe."—Extract from Mr. Tuer's

Letter.

("Is this the Hend?"—Miss Squeers.)

Skurrie puts us in the train, gives us our Cook's tickets all ready stamped and dated. No trouble. Then he insists on comparing his notes of our route with mine, to see that all is correct.

"Wednesday," he says, "that's to-day. Geneva dep. 12, Bâle arr. 7.45." He speaks a Bradshaw abbreviated language. "Change twice, perhaps three times, Lausanne, Brienne, Olten. Not quite sure; but you must look out." Oh, the trouble and anxiety of looking out for where you change! "Then," he goes on, "Thursday, Bâle dep. 9.2 A.M., Heidelberg arr. 1.55."

"Any change?" I ask, as if I wanted twopence out of a shilling.

"No; at least I don't think so. But you had better ask," he replies. Ah! this asking! if you are not quite well, and don't understand the language (which I do not in German Switzerland), and get hold of an austere military station-master, or an imbecile porter, and then have to carry that most inconvenient article of all baggage, a hand-bag, which you have brought as "so convenient to hold everything you want for a night," and which is so light to carry until it is packed! "Then," goes on the imperturbable Skurrie, "you'll 'do' Heidelberg, dine there, sleep there, and on Friday Heidelberg dep. 6 A.M.——"

Here I interrupt with a groan—"Can't we go later?"

"No," says Skurrie, sternly. "Impossible. You'll upset all the calculations if you do."

Jane says, meekly, that when one is travelling, and going to bed early, it is not so difficult to get up very early, and, for her part, she knows she shall be awake all night. Ah! so shall I, I feel, and already the journey begins to weigh heavily on me, and I do not bless Skurrie and his plan. "But," I say aloud, knowing he has done it all for the best, and that I cannot now recede, "go on."

He does so, at railroad pace:—"Heidelberg dep. 6. Mannheim arr. 7.5, dep. 7.15. Mayence arr. 8.22, in time for boat down the Rhine 8.55. Cologne arr. 4.30. And there you are."

"Yes," I rejoin, rather liking the idea of Cologne, "there we are—and then?"

"Well, you'll have a longish morning at Cologne; rest, see Cathedral, breakfast," and here he refers to his notes, "Cologne dep. 1.13 P.M., and Antwerp arr. 6.34."

"Change anywhere?" I inquire, helplessly. "Yes," he answers, meditatively. "At this moment I forget where, but you've got examination of baggage on the Belgian frontier, and you have two changes, I think. However, it's all easy enough."

"I'm glad of that," I say, trying to cheer up a bit, only somehow I am depressed: and Cousin Jane isn't much better, though she tries to put everything in the pleasantest possible light, and remarks that at all events "the travelling will soon be over."

Skurrie continues reading off his paper and comparing the details with my notes, "Sunday—Antwerp dep. 6.34 P.M. Rosendael arr. 7.45—yes—then Rosendael dep. 8.44, and catch the 10.10 P.M. boat at Flushing. Queenborough arr. 5.50, fresh as a lark, and up to town by 7.55."

"But we don't want to go up to town, we want to go to Ramsgate."

"Ha!" he says slowly, giving this idea as just sprung upon him his full consideration. "Ha!—let me see——" Then, as if by inspiration, he continues quickly—"sacrifice your London tickets, book luggage for Flushing, only then at Flushing re-book it for Queenborough, and once you're there you catch an early train to Ramsgate, and you'll be there nearly as soon as you would have arrived in London. Train just off. Wish you bon voyage."

I thank him for all his trouble, and ask, with some astonishment, if he is not going to accompany us?

"Can't—wish I could," returns Skurrie, "but I've got to go off to Petersburgh by night mail. Business. Should have been delighted to have looked after you and seen you through, but you've got it all down and can't make any mistake. Au plaisir!"

And he is off. So are we.

Oh, this journey!! Everything changes. My health, the scenery, the weather, all becoming worse and worse. Poor Cousin Jane, too.

Oh, the changes of carriage! The rushing about from platform to platform, carrying that confounded bag, and sticks, and umbrellas, and small things, of which Jane—poor Jane!—has her share, and, but for her sticking to every basket and package, I should, in despair, have surrendered to chance, left them behind me somewhere, and should have never seen them again. All aches and pains, and weariness! At last at Bâle, rattled over stones and bridge in a jolting omnibus, through pouring rain to the hotel of "The Three Kings."

Our treatment in the salle-à-manger of that Monarchical Hostelrie is enough to make the most loyal turn republican. A willing head-waiter with insubordinate assistants—and we are miserable.

Off early to Heidelberg. Delighted, at all events, to bid farewell to the worthy Monarchs. This trip seemed to invigorate us, and if civility, polite attention, good rooms, and an excellent cuisine could make any invalid temporarily better, then our short stay at the Prinz Karl Hotel—a really perfectly managed establishment—ought to have revived us both considerably. And so it did. A lovely drive to the heights among the pine woods and in the purest air went for something, but alas the knowledge that we had to rise at 5 A.M., to be off by six—it turned out to be a 6.30 train—drove slumber from our eyes, and only by means of a cold bath, the first thing on tumbling out of bed, could I brace myself for the effort. Then on we went, taking Skurrie's pre-arranged tour.

Let the remainder be a blank.

When abroad I had bought a French one-volume novel which I had seen praised in the Figaro. I will not give its name, nor that of its author. If it indeed portrays persons really living in Paris, and if these persons are not wholly exceptional (but, if so, why this novel, which implies the contrary and denounces them?) then is the latest state of Republican Paris worse than its former state in the days of the dégringolade of the Empire, and Paris must undergo a fearful purgation before she will once again possess mens sana in corpore sano. I read this disgusting novel half-way through until its meaning became quite clear to me, and then I proceeded by leaps and bounds, landing on dry places and skipping over the filth in order to see how the author worked out a moral and punished his infamous scoundrel of a chief personage. No. Moral there was none, except an eloquent appeal to Paris to rise and crush these reptiles and their brood. On the wretched night when feverish, ill, and sleepless, I lay miserably in the saloon of the Flemish steamer crossing to Queenborough, I opened the porthole above me and threw this infernal book into the sea. After this I bore the sufferings of that night with a lighter heart.

Suffice it that I arrived at home—and how glad I was to get there—broken down, prostrate and only fit for bed——where with railways running round and round my head, steamboats dashing and thumping about my brain, the shrieks of German and Flemish porters ringing in my ears, Skurrie always forcing me to travel on, on, on, against my will, I remained for about three weeks.

Advice gratis to all Drinkers of Waters.—"The story shows," as the Moral to the fables of Æsop used to put it, that when you have finished your cure, make straight by the easiest stages for the seaside at home. Avoid all exertion: and ask your medical man before leaving to tell you exactly what to eat, drink, and avoid, for the next three weeks at least after the completion of your cure.

While ill, but when beginning to crave for some amusement or distraction, I asked that my dear old Boz's Sketches should be read to me, to which in years gone by I had been indebted for many a hearty laugh. Alas! what a disappointment! Except for a little descriptive bit here and there, the fun of these Sketches sounded as wearisome and old-fashioned as the humours of the now forgotten "Adelphi screamers" in which Messrs. Wright and Paul Bedford used to perform, and at which, as a boy, I used to scream with delight, when the strong-minded mistress of the house, speaking while the comic servant was laying the cloth for dinner, would say of her husband, "When I see him I'll give him——" "Pepper," says the comic servant, accidentally placing that condiment on the table. "He shan't," resumes the irate lady, "come over me with any——" "Butter," interrupts the comic servant, quite unconsciously, of course, as he deposits a pat of Dorset on the table. And so on. Later on, I tried Thackeray's Esmond. How tedious, how involved, and full of repetitions! It is enlivened here and there by the introduction of such real characters as Dick Steele, Lord Mohun, Dean Atterbury, and others, and by the mysterious melodramatic appearances and disappearances of Father Holt, a typical Jesuit of the "penny dreadful" style of literature. But the work had lost whatever charm it ever possessed for me, and, indeed, I had always considered it an over-rated book, not by any means to be compared with Vanity Fair, Pendennis, or even with Barry Lyndon, which last is repulsively clever.

Then I asked for a book that I never yet could get through, and to which I thought that now, with leisure and a craving for distraction, I might take a liking. This was Little Dorrit. I tried hard, but it made my head ache even more than Esmond had done, and I laid it down, utterly unable to comprehend the mystery which takes such an amount of dreary, broken-up, tedious dialogue in the closing chapters to unravel.

I took down Washington Irving's Sketch-book, and read it[173] with delight. Fresh as ever! It did me good. So did Charles Lamb's Essays. And then guess what moved me to laughter, to tears, and to real heartfelt gratitude that we should have had a writer who could leave us such an immortal work? What? It is a gem. It is very small, but to my mind, and not excepting any one of all he ever wrote, the most precious in every way for its true humour, for its natural pathos, and for its large-hearted Christian teaching, is The Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens. Had this been his only book, it would have sufficed for his imperishable fame.

And then what made me chuckle and laugh? Why,Thackeray's Sultan Stork, which, somehow or other, I never remembered having read before this time of convalescent leisure. It is Thackeray in his most frolicsome humour, and, therefore, Thackeray at his best.

I am almost recovered, and am finding my "Salubrity at Home."

From an Anxious Householder.

Dear Toby,—It was in my mind to write to you some days ago, but I have had my time much occupied with a subject of domestic interest. In fact, I have just been laying the carpet presented to me by our fellow-citizens of the ancient and important community of Kidderminster. The carpet, regarded individually, is a desirable and an acceptable thing. It is, as you have observed in the newspaper reports, woven of the wool known to the trade as the Queen's Clip. In colour it is a rich damson, and in quality Wilton. Apart from its suitability and acceptability, we here see in it the beginning of what I confess we should be inclined to regard as a pleasing habit on the part of our fellow-countrymen. As you are aware, my wife and myself have for some years been the recipients of gifts consisting of what a well-known person of the name of Wemmick was accustomed to call, articles of portable property. Our journeys to Scotland were always marked by the presentation of gifts that even became embarrassing by reason of their quantity and variety. We have quite a stock of Paisley shawls. Dundee marmalade is a drug in our domestic market. Plaids, snuff-boxes, walking-sticks, and, above all, axes I have in abundance. Through the medium of an interesting periodical, of which you may have heard—(it is known as Exchange and Mart)—we have managed to average our possessions, a process not entirely free from adventure. In one instance an unscrupulous individual, probably a member of the Primrose League, succeeded in obtaining a two-dozen case of marmalade and a Scotch plaid presented by the working-men of Glasgow, in promise, yet unfulfilled, of delivery of a bicycle warranted new. I have rather a hankering after trying a bicycle. Lowe gave his up with the ultimate remainder of his Liberal principles. But in old times I have heard him speak with enthusiasm of the exercise. When I noticed this person advertising in Exchange and Mart his desire of bartering his bicycle, we entered upon the negotiation which has ended so unfortunately. He has our Paisley plaid and Dundee marmalade, and we have not his bicycle.

This, however, by the way. What I had at heart to write to you about, suggested by the Kidderminster carpet, is the new opening here offered for manifestations of political sympathy at a serious political crisis. We are, to tell the truth, towards the close of a long career, a little overburdened with articles of portable property of the kind already indicated. But our residence is large, and, if I may say so, receptive. Carpets, though a not unimportant feature in the furnishing of a house, do not contain within themselves the full catalogue of a furnishing establishment.

If Kidderminster has its carpets, there are other localities throughout the Kingdom which have their tables and chairs, their bed-room furniture, their curtains, their brass stair-rods, and their gas-fittings. History will, I believe, look with indulgent eye upon an ex-Premier, the Counsellor of Kings, the leader of a great Party, assisting at the hauling in and laying down of an eleemosynary carpet, the wool of which is made from Queen's Clip, has a rich damson colour, and is of Wilton quality. Why should I not give a back to an arm-chair presented by an admiring Liberal Association? or walk upstairs with a bolster under either arm, token of the esteem and admiration of the West of England Home Rulers?

I throw out these thoughts to you, dear Toby, as I sit in my study and survey the carpet of Wilton quality, which covers the floor. As you will have seen in the newspaper reports, "on entering the room where the carpet was displayed the Right Honourable Gentleman remarked that it had a quiet tone, which was so pleasant to the eye; adding that it was a great mistake, (which used to be committed about fifty years ago) when carpets were made with staring patterns." It is, I need hardly say, the growth of Liberal principles which has effected this change in the public taste for carpets. Whether indeed, suppose we were in need of a battle-cry, "Our Quiet Tones and Our Liberal Principles," would not serve as opposed to "Toryism and Staring Patterns," I am not certain. These things we must leave to the evolution of time. Meanwhile I will not deny in the confidence of a friendly letter that we could very well do with a sofa, the tone and construction of which should, of course, match the carpet from Kidderminster. If you are attending any public meeting and you find the popular indignation against the Government of Lord Salisbury rising to an ungovernable pitch, you might gently and discreetly guide it in this direction.

Always yours faithfully,

H-w-rd-n C-stle. W. E. Gl-dst-ne.

P.S.—A mangle and a garden-roller might later, and in due order, occupy your kindly thought.

A Ballade for the Board.

"The lobby of the Metropolitan Board of Works offices was recently the scene of a serious assault, committed by Mr. Keevil, upon Mr. Shepherd."—Daily Paper.

Proud o' the Title."—The Bishop of Lichfield, in one of his speeches at the Church Congress last week, included the English Roman Catholics among the "other Nonconformists." Then his Lordship was graciously pleased to observe that he was very willing to acknowledge the Queen as supreme, but objected to the authority of Parliament, in Church matters. It is very evident on which side Dr. Maclagan would have been in the reign of the pure and pious Henry the Eighth, when that amiable monarch ordered the decapitation of those bigoted and obtuse "Nonconformists," Bishop Fisher, and Sir Thomas More.

A Colloquy on the Canadian Shore.

Loaded with Presents.—In the account given in the Times (Oct. 7) of the unveiling of Mr. Boehm's statue of the Queen in the presence of its donors, Her Majesty's tenants and servants on the Balmoral Estates assembled at Crathie, there is a funny misprint:—

"At this point (i.e. after Her Majesty's reply to the Prince of Wales's address) the soldiers saluted and fired a feu de foie."

As refreshments were supplied by the Queen's command immediately afterwards, perhaps the guns had been loaded with "foie gras," tightly compressed into cartridges.

Ethel Dering has not recognised me yet. Naturally she would not expect to find me being photographed on the beach with such a crew as this—but she will in another instant, unless,—ah, Louise's sunshade! my presence of mind never quite deserts me. There is a slit in the silk—through which I can see Ethel. As soon as she discovers what the excitement is all about, she turns away.... Thank goodness, she is gone! I have saved the situation—but ruined the group ... they are all annoyed with me. I had really no idea Louise looked so plain when out of temper!

As we go back, Alf wants to know whether I noticed that "clipping girl." He means Ethel. Louise says, he "ought to know better than to ask me such things, considering my situation." Agree with Louise.

Evening. I am staying at home; nominally, to work at the Drama (still in very elementary stage) really, to think out the situation. Remember now the Derings have a yacht; they may only have put in here for a day or two—if not, can I avoid being seen by her sooner or later? The mere idea of meeting her when I am with Alf or Ponking, and my Blazer acquaintances, makes me ill. (Not that I need distress myself, for she would probably cut me!) Can't think in Mrs. Surge's little front parlour. I must get out, into the air! Let me see, Louise and her Aunt (and no doubt Ponking and Alf) will be at the Music Hall this evening, as there is a "benefit" with the usual "galaxy of talent." If I keep away from the sands (where I might see Ethel), I shall be safe enough.

Turn into Public Gardens; nobody here just now, except a couple in front, who seem to have quarrelled—at least the lady's voice sounds displeased. Too dark to see, but as I come nearer—is it only my nervous fancy that—? No, I can't be mistaken, that is Ethel speaking now! "Why will you persist in speaking to me?" she is saying, "I don't know you—have the goodness to go away at once." Some impudent scoundrel is annoying her! Didn't know anything could make me so angry. I don't stop to think—before I know where I am, I have knocked the fellow down ... he can't be more surprised than I am! It is all very well—but what is to become of me when he gets up again? He is sure to make a row, and I can't go on knocking him down! Must get Ethel away first, should not like to be pounded into shapelessness before her eyes. "Miss Dering," I say, "you—you had better go on—leave him to me," (it will probably be the other way, though!) "Mr. Coney!" she cries. "Oh, I am so glad!—but don't hurt him any more—please." He is getting up, as well as I can make out in the darkness, I am not likely to hurt him any more ... I wish he would begin, this suspense is very trying. He has begun—to weep bitterly! Never was so surprised in my life; he is too much upset even to swear, simply sits in the gutter boohooing. If he knew how grateful I am to him! However, I tell him sternly to "think himself lucky it is no worse," and leave him to recover.

Must see Ethel safe home after this. She and her father did come in the yacht—they are at the Royal Hotel, and she missed her way and her maid somehow, trying to find a Circulating Library. She really seems pleased to meet me. It is not an original remark—but what a delight it is to listen to the clear fresh tones of a well-bred girl—not that Ethel's voice is anything to me now! She "can't imagine what I find to do in Starmouth,"—then she did not recognise me this afternoon, which is some comfort! I should like to tell her all, but it would be rather uncalled-for just now, perhaps. We talk on general matters, as we used to do. Singular how one can throw off one's troubles for the time—I am actually gay! I can make her laugh, and what a pretty rippling laugh she has! We have reached the Hotel—already!

Now I am here, it would be rude not to go in and see old Dering. I do. He is most cordial. Am I alone down here? Critical, this. After all, I am alone—in my lodgings. "Then I must come to luncheon on board the Amaryllis to-morrow." Ethel (I must get into the way of thinking of her as "Miss Dering") looks as if she expects me to accept. I had better go, and find an opportunity of telling her about Louise—who knows—they might become bosom friends. No, hang it, that's out of the question!

The Derings' private room opens on to the Esplanade; old Dering comes to the French windows, and calls out after me, "Don't forget. Lunch at two. On board the Amaryllis—find her at the quay." "Thanks very much—I won't forget. Good-night!" "Good-night!" Someone is waiting for me under a lamp. It is Alf, but I did not know him at first. "Why, where on earth!"—I begin. He regards me reproachfully with his one efficient eye, and I observe his nose is much swollen. Good heavens, I see it all—I have knocked down my future brother-in-law! Well, it serves him right.

He explains, sulkily; he meant no harm; never thought anyone would be offended by being spoken to civil; he never met girls like that before (which is likely enough); and to think I should have treated him that savage and brutal—it was that upset him. Tell him I am sorry, but I can't help it now. "Yes you can," he says, hoarsely. "You know this girl—this Miss Derin'," (he has followed us, it appears, and caught her name)—"you don't ought to play dog in the manger now—I want you to introduce me in a reg'lar way. I tell yer I'm down-right smitten." Introduce him—to Ethel! Never, not if I won the V.C. for it! "Then you look out!"

He has gone off growling—the cub! He will tell Louise. On second thoughts, his own share in the business may prevent that—but it is unfortunate.

Next Day.—Have got leave of absence (without mentioning reason). I believe I pleaded the Drama, as usual, and I have jotted down a line or two. Am dressing for luncheon—somehow I take longer than usual. Ready at last; the coast is clear, I am a trifle early, but I can stroll gently down to the quay.... Turn a corner, and come upon Ponking, with Louise. Fancy both look rather confused, but they are delighted to see me. "Was I going any where in particular?" "No—nowhere in particular." "Then I'd better come along with them—they have dined early, and are doing the lions." Louise makes such a point of it that I can't refuse—must watch my chance, and slip off when I can.

Later.—We have done an ancient gaol, the church, and a fishermen's almshouse—and I have not seen my chance yet. Ponking determined to see all he can for his money. Louise, more demonstrative than she has been of late, clings to my arm. It is past two, but we are working our way, slowly, towards the quay. Ponking suggests visit to Fisherring Establishment. Now is my chance; say I won't go in—don't like herrings—will wait outside. To my surprise, they actually meet me half-way! "If you want to get back to your play-writing, old chap," says Ponking (really not a bad fellow, Ponking!) "don't you mind us—we'll take care of one another!" Just as deliverance is at hand, that infernal Alf comes up from the quay, with an eye that is positively iridescent! "Oh, look at his poor eye!" cries Louise. I look—and I see that he means "being nasty." He addresses me: "Why ain't you on board your swell yacht, taking lunch along with that girl, eh?" he inquires. Exclamations from Louise: "Girl? yacht? who? what?" and then—it all comes out!

Painful scene; fortunate there are so few looking on. Louise renounces me for ever opposite the Town-hall. "She knew I was a muff, but she had thought I was too much the gentleman to act deceitful!" Ponking is of opinion I "haven't a gentlemanly action in me." So is Alf, who adds that he "always felt somehow he could never make a pal of me." There is balm in that!

Thank goodness, it is over! I am free—free to think of Ethel as much as I like! I see now what a wretched infatuation all this has been. I can tell her about it some day—if I think it necessary. I am not sure I shall think it necessary—at all events, just yet.

I am a little late, but I can apologise for that. Odd—but I can't find the Amaryllis anywhere! Ask. A seaman on a post says "There was a yacht he see being towed out 'bout 'arf an hour back—he didn't take no partickler notice of her name." No doubt I mistook the moorings—better ask at hotel, perhaps. I do. Waiter says if I am the gentleman by name of Coney, there are two notes for me in Coffee-Room.

Open first—from Mr. Dering.

"Regrets; unforeseen circumstances—compelled to sail at once, and give up pleasure, &c."

Second—from Ethel; there is hope still—or would she write?

"Dear Mr. Coney,—So sorry to go away without seeing you. You might have told me of your engagement yourself, I think—I should have been so interested. Your brother-in-law and his aunt thought it necessary to call and inform us. We are delighted that you are having a pleasanter time here than you gave us to understand last night. With best wishes for all possible happiness," &c.

So that was Alf's revenge—it was a good one! After that, I shake off the sand of Starmouth—for ever!

John Bull (loq). "Very kind of Her Majesty to let me see Her Jubilee Gifts; but I wonder when Her Advisers will allow me to see my Own!"

Crowd discovered besieging entrance to Staircase. Policeman examines bags for concealed Dynamite.

Loyal Old Lady (presenting reticule for inspection). Which there's nothing in it but a few cough-drops.

Policeman (exercising a very wise discretion). Pass on, Mother!

On the Stairs.

'Arry (to Halfred—taxing his memory). I dunno as I was ever 'ere before—was you?

Halfred (conscientiously). Not to remember.

A Deliberate Old Gentleman, full of suppressed general information (to

his two boys). Now, the great thing is not to hurry—we shall find

much deserving of careful study here.

[Faces of boys lengthen perceptibly.

An Aunt (to Niece). You'd better go first, Eliza; then you can read it all out to me as we go along.

Confused Murmurs—"Where's Grandma?"—"It is ridiklous to go pushing like that!"—"Well, the Pit's a joke to this!" &c., &c.

In the State Apartments.

Delib. O. G. This, boys, is the ante-room, and here, you see, is a

trophy presented by the Maha——

[Puts on glasses, to inspect label.

Policeman (loudly). Now then, Sir, don't block the way, please,—keep

moving!

[O. G. moves on, under protest, to secret relief of boys.

The Aunt (examining pair of Elephant Tusks set in carved Buffalo's

Head). They may call them "tusks" if they like, Eliza,—but anyone can

see they're horns. They belong to one of them "Cow-Elephants," depend

upon it!

[Peers anxiously about in vain attempt to discover it.

Loyal Old Lady. There's nothing here but these caskets. I thought they'd the Jubilee Cake on view!

Visitor (in state of general gratification). Ha! they've given her some nice things among 'em, I must say. There, you see,—an arm-chair,—always come in useful, they do!

Female V. Jane, come here, quick! (They gaze reverentially on carved chest full of slippers.) That's what I call a nice present, now,—but, if they were mine, I should unpick all that raised embroidery inside the soles before ever I put 'em on!

Jane. Well, I suppose she wouldn't only wear them when she's in state.

Policeman. Now, Ladies, please don't linger! Pass along, there!

The Well-informed Old G. You see this device, formed of green and yellow feathers, boys. Well, these feathers come from——

Policeman (as before). Don't stop the way, Sir, please!

Old G. (hanging on obstinately to barrier)——The Sandwich Islands, and are worn exclusively by—(is swept on by crowd, and wedged tightly against case containing samples of woollen products—boys dive under red cord, and escape).

Two Ladies (from the country). Those Policemen is like so many parrots, with their "Keep moving;" they don't give you time for a good look! That's a handsome pair of jugs the Crown Prince and Princess give her, a little like the pair old Mr. Spudder won with his Shorthorns at the Show, don't you think? Only more elaborate, p'raps. Tell me if you can see the Cake anywhere, my dear. I don't want to go away, and not see that!

Intelligent Visitor. That's a curious thing, now. Look at that label, "Presented by——" and the name left blank!

A Jocular Visitor (seeing an opportunity). Too bad, Maria! I'm sure we

wrote our names plainly enough!

[Sensation amongst bystanders, who regard the couple with respectful

interest.

Maria (who considers this trifling with a serious subject). If I had

known you were going to be so foolish, George, I should not have come!

[Collapse of George.

A Practical Visitor. Now, there's a neat idea—d'ye see? A crown, made all out of tobaccer. There's some sense in giving a thing like that!

The Jocular Visitor (reviving at sight of embroidered Child's Frock in case). Pretty costume, that, eh, Maria? But do you think Her Gracious Majesty will ever be able to get it on?

Maria (horrified). I tell you what it is, George, if you go on making these stupid jokes, you will get us both turned out—if not worse! I'm sure that Policeman heard!

Loyal Old Lady. They've given her scent, and little brass-nailed boots, and cotton reels enough to set her up for life. But there, she deserves it all, bless her!

Party of Philistines (to one another.) You don't want to go in there—there's only a lot of water-colours presented by the British Institute. Let's see if we can find the Jubilee Cake!

Final Tableau.—At the General Exit.

Crush of enthusiastic Britons, gazing at a gigantic ornament from the Jubilee Cake. Various exclamations. "All of it pure sugar, I shouldn't wonder!"—"What do you think of that for a cake, Jemmy?"—"Lift Joey up to have a look!"—"Well, I do call that grand!"

Loyal Old Lady (forcing her way to the front—disappointedly). But that's only the trimmings!

A Bystander (correctively). You can't expect any Cake to keep long, with so many in the family; and, even as it is, you get some ideer what it must have been!

All (deeply impressed). Ah, you do, indeed—you get that! Well, I'm

glad I came; I shan't forget this as long as I live!

[Exeunt awestruck—their places are taken by others, who gaze long and

respectfully on the Cake. Scene closes in.

(At the Middlesex Hospital.)

Just been given what the newspapers call "the privileges and status of a true Collegian,"—in other words find I'm no longer to be allowed to live in the jolly old free-and-easy way, in one's own diggings, but am to be boxed up inside the Hospital instead! Hang the Authorities! Should like to cup them all.

Anyhow, got a decent room: can show it off to visitors. Visit from Oxbridge friend. Seems surprised at smallness of my apartment. Says it's "not his idea of living in College: more like living in Quad," he adds, humorously. "Do I really mean to say," he asks, "that I am to sleep in same room I live in, with only a curtain between?" Have to confess such is the intention of the architect. He says, "if he was me, he'd complain to the Dean." Don't like to show ignorance—so don't ask him if he means Dean of Westminster or St. Paul's. Oxbridge friend declines my invitation to "dine in Hall," and disappears.

Ah! They've given us a Smoking-room, anyhow. Is it a smoking-room? No—a "Library and Reading-room." Disgusting! Ring for brandy-and-soda. Nobody answers the bell! It seems the "Collegiate servants" go out of College between meals. Nothing to do, so amuse myself for an hour in Dissecting-room. Pine for freedom. Go to entrance and am stopped by Porter. Porter says, "Gentlemen not allowed to leave Hospital after dark without leave of House Surgeon." Tell Porter I'm a child of nature, and that I want to visit a dying relative. Porter incredulous—proposes sending one of the resident Physicians instead. No, thanks! Retire to room and think of old rollicking days. Nothing to do. Wonder if Porter would let me bleed him. No, perhaps he's not in the vein.

Hall Dinner.—Hate dining in common—reminds one of the Zoo. Student next to me very sloppy. Brings a bone in with him, and puts it on table, studying it between courses. Tell him, pleasantly, it'll be a bone of contention if he does not remove it. He doesn't understand. Replies, quite seriously, that it's the "os humeri."

After Dinner.—Tedious. Just the time when the "Lion Comique" is "coming on" at the Parthenon Music Hall. And I can't get out to hear him!

Later.—Had jolly spree, after all—also after Hall. Tied new curtains together and let myself down into street, amid yells of large crowd. Rather damaged right scapula, but can't be helped. Went to Gaiety; jolly supper, met Ben Allen and a lot of chappies, who are at Bart's and haven't any of these ridiculous Collegiate regulations, and had high old time. How to get back, though? Ay, "there's the rub,"—worse than rubbing scapula, too.

Boldest plan best. Rap Porter up. Porter surprised to see me. Says it's "past one o'clock," and wants to know how I got out. Tell him I'm a child of nature, and if he reports me to House Surgeon I shall certainly cup him to-morrow. Porter asserts, quite untruly, that I am intoxicated.

Next Day.—Authorities have heard how I escaped from Hospital last night. Also Porter—the idiot!—has complained that he goes in fear of his life because of my threats. On the whole, Hospital Authorities come to conclusion to ask me to leave, as "they think I am not fitted for Collegiate life," and I quite agree with them. Pack up, and pack off.

Southerner (in Glasgow, to Friend). "By the way, do you know McScrew?" Northerner. "Ken McScrew?" Oo' fine! A graund man, McScrew! Keeps the Sawbath, —an' everything else he can lay his Hands on!"

Quite a little Holiday.—The unfortunate Vacation Judge this year has been detained at Court or Chambers five times a week instead of (as in the olden days) thrice a fortnight. He must appreciate the meaning of "getting his head into Chancery"—and his wig too!

An Old Fable with a New Application.

(For the benefit of Bolton.)

Two bellicose goats once encountered each other in the middle of a narrow bridge spanning a deep gulf and a raging torrent. To pass each other seemed (to them) impossible, at least without much more careful and courteous mutual self-adjustment than either was at all disposed for. For one or the other to make way by temporarily backing, was, of course—to bellicose goats—entirely out of the question. The only alternative was clearly a butting-match.

Our angry goats entered upon it with great gusto. Heads hotly encountered, horns angrily collided. The harder the hits the less did either feel disposed to give way.

But a narrow bridge over a deep gulf is a bad place for a battle à outrance. The infuriated animals quickly settled the point at issue, in a way as final as unpleasant, by butting each other over into the gulf, leaving the disputed path clear for the passage of creatures more conciliatory and less cantankerous.

Application.

Two objects cannot occupy the same space—even in Bolton. Battles upon bridges—even iron bridges—are bad things. A quarrel between two parties—even if they represent Capital and Labour—cannot be regarded as satisfactorily settled by the destruction of both—unless they are thieves, or Kilkenny cats. It is much easier to get into a gulf—even the gulf of Bankruptcy—than out of it. To parties expiring at the bottom of a gulf, into which they have hurled each other, it is small consolation to see more peaceful persons—though they be foreigners—making better use of the bridge which might have carried them both safely over.

A Collection of Thackeray's Letters (1847 to 1855. Smith & Elder).—It must have cost Mrs. Brookfield a good deal of mental anxiety before she decided upon giving publicity to this correspondence. But she has undoubtedly done well and wisely, as everybody interested in the personal Thackeray, outside and away from his works, will gratefully acknowledge. Thackeray was always fond of alluding to himself as the Showman with the puppets, or portraying himself as taking off the cap-and-bells when, from behind the grinning mask, peep out the sad eyes and the rueful countenance. Now in these Letters we are sometimes admitted behind the scenes, as, for instance, when he is just going to work; but, as a rule, we see him in his leisure, out for a holiday, amusing himself and others, and enjoying himself like an overgrown schoolboy full of fun and frolic, not a bit of a cynic, and there are no sad eyes and rueful countenance when the mask is off. The peculiar charm of these Letters is that they are so evidently private; there is nothing of the poseur about them. They were never intended to be addressed urbi et orbi.

One favourite style of amusing himself in writing he had, which, by the way, rather calls to mind the way Mr. Peter Magnus had of amusing his friends, and that was mis-spelling, and spelling in Cockney fashion. How he must have revelled in writing Jeames's Diary! The burlesque element of humour was irrepressible in Thackeray, and found vent through pen and pencil. Nearly all his sketches, with remarkable exceptions, are, more or less, grotesque. Many of his Vignettes, with which he illustrated his novels, cannot fail to suggest a kind of Dicky-Doyleian humour. Two characteristics of the man are brought out strongly in these letters; first, his humility as regards his own work (he was proud in other matters), and, secondly, his generosity as exhibited in his unaffected admiration for the work of Charles Dickens.

Occasionally we catch a glimpse of his religious tendencies, which are at one time influenced by J. H. Newman, at another by J. S. Mill; and it is interesting to read his naïve utterances about Scripture, showing that whatever lectures he may have attended at Cambridge, those on Divinity, or on the Greek Testament, could not have been among them. And this indeed is highly probable. His kindness of heart is evident throughout. His laughing at himself as a Snob when affecting the company of great people is delightful, though there seems to be in this self-ridicule something of the true word spoken in jest. He makes a burlesque flourish—so like him—about sending in "his resignation" to Mr. Punch. As a matter of fact, he remained an honorary member of Mr. Punch's Cabinet Council, and retained his seat at Mr. Punch's table, up to the time of his death. The present writer remembers William Makepeace Thackeray being frequently present in Mr. Punch's Council Chamber, Consule Marco. A most interesting, amusing, and instructive book, especially to literary men—(some novelists must be delighted at finding Thackeray reading over the previous portions of his own serial in order to recall the names of his characters, and his frantic joy at hitting on the title of Vanity Fair)—is this collection of Thackeray's Letters. To Mrs. Brookfield our heartiest thanks are due.

Like and Unlike. By Miss Braddon. Everybody who cares about a novel with a good plot so well worked out that the excitement is kept up through the three volumes and culminates with the last chapter of the story, must "Like" and can never again "Unlike," this the latest and certainly one of the best of Miss Braddon's novels. Miss Braddon is our most dramatic novelist. Her method is to interest the reader at once with the very first line, just as that Master-Dramatist of our time Dion Boucicault would rivet the attention of an audience by the action at the opening of the piece, even before a line of the dialogue had been spoken. This authoress never wastes her own time and that of her reader, by giving up any number of pages at the outset to a minute description of scenery, to a history of a certain family, to a wearisome account of the habits and customs of the natives, or to explaining peculiarities in manners and dialect which are to form one of the principal charms of the story. No: Miss Braddon is dramatic just as far as the drama can assist her, and then she is the genuine novelist. A few touches present her characters living before the reader, and the story easily developes itself in, apparently, the most natural manner possible. Like and Unlike will make many people late for dinner, and will keep a number of persons up at night when they ought to be soundly sleeping. These are two sure tests of a really well-told sensational novel. Vive Miss Braddon!

Your Own Book-Worm.

Shade of Boswell, awake, arise! Know that the Lord Mayor of Lichfield, Mr. A. C. Baxter, has announced in the Times that the house Dr. Johnson was born in is put up for sale by auction on the 20th inst. Now, then, is the time for a big brewer who would like to get bigger, or any licensed victualler, with command of a moderate capital, to invest it in the purchase of the premises in which the great Lexicographer and Moralist first saw the light, and in the conversion of them into a public-house, to be called and known by the sign and name of "The Johnson's Head." A likeness of Dr. Johnson, copied by a competent Artist from the best of Sir Joshua Reynolds's portraits, and mounted on the signboard, would be sure to attract multitudes of respectable people, and others, besides forming a decoration of the tavern at Lichfield, and an ornament to that town. A pub. associated with one of the highest names in literature could hardly fail to be frequented by numerous bookmakers. The memory of Dr. Johnson might, however, be honoured by the preservation of his home for what many may consider a nobler purpose than that of a liquor-shop; and those who are of that opinion should look sharp and secure his birthplace by coming forward, and taking care that, when under the hammer, it shall be knocked down on their own account to the highest bidder. "The man who could make a pun would pick a pocket;" true, but he might prefer putting his hand in his own to commemorate the name of the great Samuel, by helping to stand Sam.

Favourite Seasoning at the Guildhall Banquet on the 9th of November.—Sauce à la Maître d'Hôtel.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The remaining corrections made are indicated by dotted lines under the corrections. Scroll the mouse over the word and the original text will appear.

P. 179. changed 'shoppy' to 'sloppy'.

P. 180. 'developes' (sic). Probably not an error. "and the story easily developes itself"