Title: Notes on the Kiowa Sun Dance

Author: Leslie Spier

Release date: May 28, 2011 [eBook #36224]

Most recently updated: September 1, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tor Martin Kristiansen, Joseph Cooper and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Page. | |

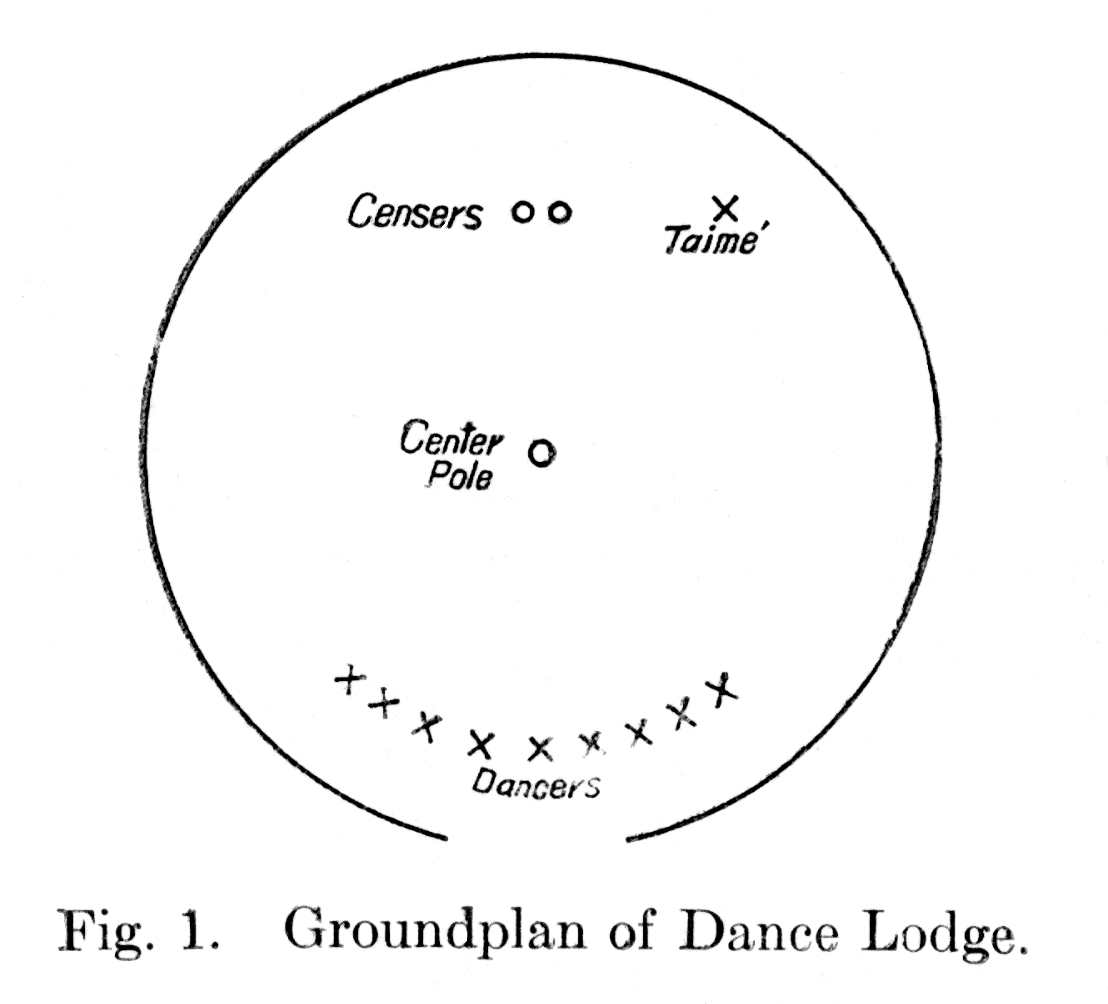

| 1. Groundplan of Dance Lodge | 441 |

The following notes were obtained from Andres Martinez (Andele, a Mexican captive of the Kiowa whose history[1] is well known) in August, 1919. Attention was directed in the first instance to the organization of the dance, but a brief description of the whole ceremony was also obtained, chiefly by way of comments on Scott's account.[2] The last Kiowa sun dance was held in 1887.[3]

The Kiowa sun dance is the prerogative of the individual who owns the sacred image, the tai'me. He deputes the ancillary offices where he sees fit, although there is a well-defined tendency for them to be hereditary. The predominant idea of this image is that of a war medicine. Thus the dance is fundamentally like that of the Crow, but it differs from it in two important respects. First, the Kiowa rites cluster about only one particular medicine, whereas among the Crow, any one of a number of medicine dolls may be used in the ceremony. The question arises whether the dozen minor Kiowa images, which are sometimes brought into the dance, were more recently acquired or constructed in order to reproduce the functions of the tai'me, or whether one medicine doll has completely overshadowed all the others, as seemed about to happen among the Crow. The evidence favors the first view, since no rites, other than those attendant on any personal medicine, are described, or even intimated, for the minor images. The second difference is, that while the Crow shaman invokes his medicine for any one who appeals to him for aid, acting only in a directive capacity, the Kiowa tai'me owner is himself the principal suppliant. Were it not for the hereditary bias in the distribution of ceremonial functions, the Kiowa sun dance would be the prerogative of one man as completely as that of the Crow is, when the latter is once under way. The hereditary principle does not appear in the military societies except in the ownership of the medicine lance or arrow (zë'bo).[4]

The Kiowa sun dance (k’oθdun specifically the name for the lodge) was an annual tribal affair, in which the associated Kiowa Apache freely joined.[5] It was danced in an effort to obtain material benefits from, or through, the medicine doll in the possession of the medicineman, who is at the same time director and principal performer.[Pg 438]

This is a small image, less than 2 feet in length, representing a human figure dressed in a robe of white feathers, with a headdress consisting of a single upright feather and pendants of ermine skin, with numerous strands of blue beads around its neck, and painted upon the face, breast, and back with designs symbolic of the sun and moon. [Martinez says the face is entirely obscured by hanging beads.] The image itself is of dark-green stone, in form rudely resembling a human head and bust, probably shaped by art like the stone fetishes of the Pueblo tribes. It is preserved in a rawhide box in charge of the hereditary keeper, and is never under any circumstances exposed to view except at the annual sun dance, when it is fastened to a short upright stick planted within the medicine lodge, near the western side.... The ancient tai'me image was of buckskin, with a stalk of Indian tobacco for a headdress. This buckskin image was left in the medicine lodge, with all the other adornments and sacrificial offerings, at the close of each ceremony. The present tai'me is one of three, two of which came originally from the Crows, through an Arapaho who married into the Kiowa tribe, while the third came by capture from the Blackfeet.[6]

The bundle containing the image is usually hung outside of its keeper's tipi. It is not customary to expose the image except at the sun dance, but tobacco is placed with it from time to time. Its function outside of the dance is identical with its use there: those who need its aid make vows to it, which they fulfil by sacrificing horses, etc., and making sweatlodges. The image is the property of one man, or more properly of his family, since it may be inherited by his blood relatives. If the transfer is made before the father's death, payment and a sweatlodge must be given by the son.[7] After Long Foot died about 1870, as he had no son, it passed into the possession of three of his nephews in succession, and reverted in 1894 to his daughter who still has it.[8] While she may handle the image, she would not be permitted to enter the dance with it.[9] There the functions which would normally devolve on her would be performed in their entirety by a captive. This captive has been trained to the position in order to take the place of the image keeper should he be sick. A captive is chosen for the substitute so that a calamity incurred by a mischance in the proceedings may fall on him alone and not on the Kiowa. The erstwhile substitute, a Mexican, is still living. The image keeper, like his four associates, must not look in a mirror, nor touch a skunk or jackrabbit. One who touches these animals cannot enter the tipi where the doll is housed until four days have elapsed. No dog is allowed in this tipi, nor is one permitted to jump over the keeper or his four associates, the g.uołg.uȧt`.[Pg 439]

There are ten or twelve minor images (tailyúkȧ) which strongly resemble the tai'me in function, as they are essentially war medicines. Most of them were in the keeping of men other than the sacred doll owner, but two were kept by him for a time.[10] They have little or no part in the sun dance.

The Gadômbítsoñhi, "Old-woman-under-the-ground," belonged to the Kiñep band of the Kiowa. It was a small image, less than a foot high, representing a woman with flowing hair. It was exposed in front of the tai'me at the great sun-dance ceremony, and by some unexplained jugglery the priest in charge of it caused it to rise out of the ground, dance in the sight of the people, and then again sink into the earth.[11]

The sun dance was normally an annual ceremony, but sometimes a year passed without one. The dance was theoretically dependent on someone going to the keeper and saying, "I dreamed of it (i.e., the sun dance)," or on the keeper himself dreaming of it. On two occasions a second dance was held in the dance lodge after the keeper had removed the sacred doll at the close of the first dance, because a second man had also dreamed of it.[12] After the dream is announced the keeper hangs the image on his back and rides out to all the camps, announcing, as he circles them, that he will conduct the ceremony the following spring (May or June). This announcement was sometimes made immediately after the close of the preceding dance, but usually it came just before they intended to hold the dance.[13] The keeper fasts while he is making the announcement, even if it takes three days, as may happen when the camps were scattered. When they know the dance is to be held, others vow to dance for a specified number of days, and all gather near the dance ground. No one may absent himself: they are all afraid of his medicine. When the tribe is assembled, the keeper circles the camp, again bearing the sacred doll on his back.

Two young men are selected by the keeper from one of the military societies[14] to scout for a tree to serve as center pole for the dance lodge. While searching, they must refrain from drinking. About this time all those intending to dance are building sweatlodges to purify themselves: the keeper must enter each of these to direct the proceedings; this entails considerable work on him. Should he be sick at this time, the doll is carried into the sweatlodge by the captive in his stead. It is incumbent on the tai'me shield owners to accompany this captive and help him[Pg 440] perform the necessary ceremonies. When the tree for the center pole has been selected, the whole camp moves after the keeper and his family to the dance ground. A dozen or more old men follow immediately after him. The main body is guarded front, rear, and both flanks by the military societies, as is customary when a camp moves.[15] The procession halts four times on its journey while the keeper smokes and prays. Next, the soldier societies charge on the dance ground, or rather on a pole erected there before the camp circle is established,[16] according to Methvin (p. 64), but on the newly established camp itself according to Scott's informants (p. 357).

The next morning the man who has that privilege sets out with his wife to get the hide of a young buffalo bull. When such a person dies, the keeper appoints one of his kin to take his place.[17] The couple must fast while on this hunt. If the buffalo is killed with a single arrow, it is a favorable omen, if many are needed, the opposite is indicated. The buffalo must be killed so that he falls on his belly with his head toward the east. A broad strip of back skin, with the tail and head skin attached is carried to the keeper's tipi, where feathers are tied to its head.[18]

The next morning they set out to fetch the center pole. Scott describes a parade around the camp circle by the military societies which then proceed to charge the tree selected for the center pole, which is defended in sham combat by one of the men's societies[19] (akiaik`to, war with the trees). After the chiefs have recited their coups, and prayers have been said by the sacred doll keeper and his wife, who have brought the doll there, the tree is chopped down by a captive Mexican woman. A captive is always selected for this difficult task, so that any harm due to an error on her part may not fall on a tribesman. This function is always performed by a Mexican woman: when she dies, the keeper appoints her successor. As the tree falls, they shout and shoot in the air. The pole is carried to the dance ground by a society designated by the keeper,[20] where a hole to receive it has been dug by a men's military society.[21] The pole is set upright by a single medicineman who owns this privilege. The buffalo hide is then fastened across the forks with its head to the[Pg 441] east and offerings of cloth, etc., brought by various individuals are tied to it. In 1873 Battey observed:—

The central post is ornamented near the ground with the robes of buffalo calves, their heads up, as if in the act of climbing it; each of the branches above the fork is ornamented in a similar manner, with the addition of shawls, calico, scarfs, &c., and covered at the top with black muslin. Attached to the fork is a bundle of cottonwood and willow limbs, firmly bound together, and covered with a buffalo robe, with head and horns, so as to form a rude image of a buffalo, to which were hung strips of new calico, muslin, strouding, both blue and scarlet, feathers, shawls, &c., of various lengths and qualities. The longer and more showy articles were placed near the ends. This image was so placed as to face the east.[22]

The center pole is not painted.

After the center pole is in place, everyone, but especially the military societies, assists in building the enclosing structure. The lodge is like those of the Arapaho and Cheyenne: it is circular, the rafters rest on the center pole, and the covering of boughs extends a third of the way to the center of the roof. An entrance is left on the east side. A flat stone is placed here so that every dancer passing through must set his foot on it. Wet sand is spread over the ground in the dance lodge[23] and heaped around the base of the center pole. Two little round holes, walled in with mud, are dug near the rear of the lodge to hold incense smudges. A screen of cottonwood and cedar branches is constructed just north of these.[Pg 442]

This business continued through the day, except for an hour or two in the middle of the afternoon, when the old women[24]—the grandmothers of the tribe—had a dance. The music consisted of singing and drumming, done by several old women, who were squatted on the ground in a circle. The dancers—old, gray-headed women, from sixty to eighty years of age—performed in a circle around them for some time, finally striking off upon a waddling run, one behind another; they formed a circle, came back and, doubling so as to bring two together, threw their arms around each other's necks, and trudged around for some time longer; then sat down, while a youngish man circulated the pipe, from which each in turn took two or three whiffs, and this ceremony ended.[25]

[When the dance lodge was completed] the soldiers of the tribe then had a frolic in and about it, running and jumping, striking and kicking, throwing one another down, stripping and tearing the clothes off each other.[26]... Before this frolic was over, a party of ten or twelve warriors appeared, moving a kind of shield to and fro before their bodies, making, in some manner (as I was not near enough to see how it was done), a grating sound, not unlike the filing of a mill-saw.[27]

In the afternoon, a party of a dozen or more warriors and braves proceeded to the medicine house, followed by a large proportion of the people of the encampment. They were highly painted, and wore shirts only, with head-dresses of feathers which extended down the backs to the ground, and were kept in their proper places by means of an ornamented strap clasping the waist. Some of them had long horns attached to their head-dresses. They were armed with lances and revolvers, and carrying a couple of long poles mounted from end to end with feathers, the one white and the other black. They also bore shields highly ornamented with paint, feathers, and hair.

They took their station upon the side opposite the entrance, the musicians standing behind them.

Many old women occupied a position to the right and near the entrance, who set up a tremulous shrieking; the drums began to beat, and the dance began, the party above described only participating in it.

They at first slowly advanced towards the central post, followed by the musicians several of whom carried a side of raw hide (dried), which was beaten upon with sticks, making about as much music as to beat upon the sole of an old shoe, while the drums, the voices of the women, and the rattling of pebbles in instruments of raw hide filled out the choir.

After slowly advancing nearly to the central post, they retired backward, again advanced, a little farther than before; this was repeated several times, each time advancing a little farther, until they crowded upon the spectators, drew their revolvers, and discharged them into the air.

Soon after, the women rushed forward with a shrieking yell, threw their blankets violently upon the ground, at the feet of the retiring dancers, snatched them up with the same tremulous shriek that had been before produced, and retired; which closed this part of the entertainment. The ornamented shields used on this occasion were afterwards hung up with the medicine.[28]

These may be the shields which are associated with the tai'me. Later, after the sacred doll has been brought into the lodge, they are either hung with it on the cedar screen as Battey observed,[29] or on stakes set up outside the dance lodge to the west, i.e., behind the image, where Martinez saw them. No offerings are made to them there. It is incumbent on a tai'me shield owner to dance with the associates (g.uołg.uȧt`) in every sun dance so long as he continues to own the shield. He is not considered one of the associates however. Shield owners always help the image keeper when he asks their aid. They must also assist his captive substitute when officiating in a sweatlodge. A shield owner cannot sell his shield, but he may give it to his son in anticipation of his death, receiving presents in return. Otherwise, on the death of its owner the shield is placed on his grave. Should a son or nephew dream of it, he has the right to make a duplicate with the help of the doll owner in order to keep it in the family. However, if any other man dreams of it and wants to make the duplicate, he must pay the owner.[30] The shield is usually hung outside of its owner's tipi. The shield owners "must not eat buffalo hearts, or touch a bearskin, or have anything to do with a bear." Like the associates, "they must not smoke with their moccasins on,[31] or kill, or eat any kind of rabbit, or kill or touch a skunk."[32] These shields are used only in war as their owner's personal medicine: no offerings are ever made to them.

Late in the day, a number of men who have vowed to take part in the subsequent dance, together with one woman who has the privilege,[33] are garbed in buffalo robes to represent the living animals. They gather to the east of the lodge where they simulate the actions of a herd of buffalo. A man, called a scout, starts from the entrance of the lodge with a firebrand and circles about the herd until he meets a second man, mounted and carrying a shield and a straight pipe, who thereupon drives the buffalo toward the dance lodge, which they circle several times before negotiating the entrance. Once inside they lie down; the man with the pipe dismounts and enters. Picking up the hairs on the back of first one animal and another, he says, "This is the fattest animal. He is our protector in war." Then he recites a coup. This[Pg 444] designated (or makes ?) a brave man of that buffalo.[34] Both the man with the firebrand and he with the pipe ought to be medicinemen. The present incumbent of the first office also has the privilege of erecting the center pole. When these men die, the sacred doll keeper selects successors from their families.[35]

That evening after sunset the dance proper begins, to last four nights and days, ending in the evening. The doll keeper proceeds to his own tipi, where, with the assistance of seven other medicinemen (tai'me shield keepers and some others not otherwise connected with the ceremony), he unwraps the tai'me. Carrying it on his back, he walks to the dance lodge, and, completely circles it four times, feigning to enter each time he passes the entrance. After entering, he goes around by the south side to the northwest quadrant, where he plants the image hanging on a staff. Formerly two or more of the minor images, tailyúkȧ, were placed with the tai'me. After the image is in place the dancers enter to perform for the night.

The keeper dances throughout the whole four-day period. He is painted yellow, with a design representing the sun, and sometimes another for the moon, drawn on his chest and back. "His face was painted, like that of the Taimay itself, with red and black zigzag lines downward from the eyes." He wears a yellow buckskin kilt, a jackrabbit skin cap with down attached, and sage wristlets. He is barefoot. He carries a bunch of cedar in his hand, and an eagle bone whistle from which an eagle feather is pendent. Battey observed that he was painted white at the "buffalo-herding" rite, and not painted at all in the dance proper.[36]

Beside the tai'me keeper there are three classes of persons who dance; the associates (g.uołg.uȧt`), the tai'me shield keepers, and the common dancers. The four associates (Scott's "keeper's assistants") must dance throughout the whole four day period. They appear in four successive dances (normally four years), after which they choose successors from among those young men, eighteen to thirty years old, who have made the best records in war. These young men, with the assistance of their relatives,[37] pay horses and buffalo robes for the privilege, receiving the[Pg 445] regalia in return.[38] One who is chosen cannot refuse: if he does, he may expect a calamity. The associate may belong to any of the military societies. His office does not impose obligations of foolhardiness in war (such as the no-flight idea), but he is obliged to act the part of an intrepid warrior, because he enjoys security in battle.[39] The associate must not look in a mirror lest he become blind,[40] nor can he touch a skunk or jackrabbit, nor remain near a fire where someone is cooking. Dogs must not be permitted to jump over an associate. He must remove his moccasins before he smokes, but others may keep theirs on when smoking in his presence. The associate dances in order to live long and to be a great warrior. His body is painted white or yellow: a round spot representing the sun is painted on the middle of his chest, with a crescent moon (the concavity upward) on both sides of the sun, and the same decoration is repeated on his back. The skin is cut away as a sacrifice and to make these designs permanent after his first dance. A scalp from a tai'me shield hangs on his breast with two eagle feathers; another on his back. His face is "ornamented with a green stripe across the forehead, and around down the sides of the cheeks, to the corners of the mouth, and meeting on the chin."[41] He wears a yellow buckskin kilt, with his breechclout hung outside, like the Arapaho and Cheyenne sun dancers. Bunches of sage are stuck into his belt, others tied around his wrists and ankles, and carried in each hand. On his head is either a cap of jackrabbitskin in which is stuck an eagle feather or a sage wreath with down attached. He carries a bone whistle. Like the sacred doll keeper and all other dancers, he is barefoot.[42] Battey saw three associates purify themselves in the incense from the censors, and then dance on piles of sage.[43]

The tai'me shield owners, who dance with the associates are sometimes painted yellow or green with pictures of the sun and moon on their bodies, but otherwise they wear the regalia of the common dancers.

The rank and file of the dancers are men, never women. Anyone may vow to dance a certain number of days, with the object of becoming a better warrior and living long.

They believe that it warded off sickness, caused happiness, prosperity, many children, success in war, and plenty of buffalo for all the people. It was frequently vowed by persons in danger from sickness or the enemy.[44]

Sometimes a medicineman danced to intercede for a sick man. A sick man who had vowed to attend the dance in order to be cured would be carried into the dance lodge, but he would not dance. These dancers make offerings to the tai'me. They do not pay the doll keeper in order to enter the dance, and they have no rights in any subsequent performance by reason of having once participated. Like all other dancers they must fast and go without water during the period that they dance; they can however, smoke, provided the proper rites are observed.

... The pipe was filled, brought forward, and laid upon the ground; the person, carefully turning the stem towards the fire, and bedding it in the sand, so that the bowl should remain in an upright position, arose and stood with his back towards it, or facing the medicine. It was then approached by one of the musicians, who, in a squatting position, raised his hand reverently towards the sun, the medicine, the top of the central post, or buffalo; then, passing his hands slowly over the pipe, took it up with his left hand, and taking a pinch from the bowl with the thumb and fore finger of the right, held it to the sun, the medicine, the top of the central post, then the bottom, and finally covered it up in the ground. He then proceeded to light the pipe, blowing a whiff of smoke towards the several objects of adoration, and placed it carefully where he found it, in reversed order, that is, with the stem from the fire. The person who brought it had stood waiting all this time for it. He now took it up and retired to the dancers, who, wrapped in buffalo robes, were waiting, in a squatting position, to receive it. The sand where the pipe had lain was carefully smoothed by the hand, and all marks of it wholly obliterated.[45]

These dancers are painted white; they wear white buckskin kilts, with the breechclout outside, carry bone whistles, and are barefoot. They have no headdress, wrist or ankle ornaments. They paint themselves.[46] There is only one style of paint used by either the principal or the common dancers throughout the sun dance.

The dancers form a line on the east side of the lodge facing the image. Their step is that characteristic of the sun dance of other tribes: they stand in place, alternately bending their knees and rising on their toes. They dance intermittently throughout four days and nights; the common dancers leave as the periods for which they have vowed to dance have elapsed or when they can no longer stand the combined strain of fasting, thirsting, and dancing. Martinez left after three days and nights. The "four days and nights" which are specified are in reality only three nights and days; evidently the first day of preliminary dancing is included to fill out the quota to the magic "four." In Scott's account, the dancers perform on the first day from evening to the middle of the night, and on the succeeding days from sunrise to the chorus's[Pg 447] breakfast, nine o'clock to dinner, four in the afternoon to sundown, and from evening to midnight, ending in the evening of the fourth day. The dance Battey describes evidently began in the evening of the 18th and continued intermittently to late afternoon of the 21st. Apparently the dancers do not leave the lodge during this entire period.

19th [June, 1873.]—Music and dancing continued in the medicine house through the night. At an early hour this morning I went thither with Couguet, and witnessed one dance throughout. The ground inside the enclosure had been carefully cleared of grass, sticks, and roots, and covered, several inches deep, with a clean, white sand. A screen had been constructed on the side opposite the entrance, by sticking small cottonwoods and cedars deep into the ground, so as to preserve them fresh as long as possible. A space was left, two or three feet wide, between it and the enclosing wall, in which the dancers prepared themselves for the dance, and in front of which was the medicine. This consisted of an image, lying on the ground, but so concealed from view, in the screen, as to render its form indistinguishable; above it was a large fan, made of eagle quills, [an error, these are crow feathers], with the quill part lengthened out nearly a foot, by inserting a stick into it, and securing it there. These were held in a spread form by means of a willow rod, or wire, bent in a circular form; above this was a mass of feathers, concealing an image, on each side of which were several shields, highly decorated with feathers and paint. Various other paraphernalia of heathen worship were suspended in the screen, among these shields or over them, impossible for me to describe so as to be comprehended. A mound had also been thrown up around the central post of the building, two feet high, and perhaps five feet in diameter.

The musicians, who, if I mistake not, are the war chiefs, were squatted on the ground, in true heathen style, to the left, and near the entrance, having Indian drums and rattles. The music was sounding when we entered.

Presently the dancers came from behind the screen; their faces, arms, and the upper part of their bodies were painted white; a soft, white buckskin skirt, secured about the loins, descended nearly to the ankles, while the breech-cloth,—blue on this occasion,—hanging to the ground, outside the skirt, both in front and behind, completed the dress. They faced the medicine—shall I say idols? for it was conducted with all the solemnity of worship,—jumping up and down in true time with the beating of the drums, while a bone whistle in their mouths, through which the breath escaped as they jumped about, and the singing of the women, completed the music. The dancers continued to face the medicine, with arms stretched upwards and towards it,—their eyes as it were riveted to it. They were apparently oblivious to all surroundings, except the music and what was before them.

After some time, a middle-aged man, painted as the others, but wearing a buffalo robe, issued from behind the screen, facing the entrance, but having his eyes fixed upon the sun, upon which he stood gazing, without winking or moving a muscle, for some time, then began slowly to incline his head from side to side, as if to avoid some obstruction in his view of it, swaying his body slightly, then, stepping slowly from side to side—forward—backward—increasing his motions, both in rapidity and extent, until in appearance nearly frantic, his robes fell off, leaving him—except his blue breechclout—entirely naked. In this condition he jumped and ran about the enclosure,—head, arms, and legs all equally participating in the violence of his gestures,[Pg 448]—every joint of his body apparently loosened, his eyes only fixed. I wondered how, with every joint apparently dislocated, and every muscular fibre relaxed, he could maintain the upright position.

Thus he continued to exercise without ceasing, or once removing his eyes from the sun, until the sweat ran down in great rolling drops, washing the white paint into streaks no more ornamental than the original painting, and he was at length compelled to retire, from mere exhaustion, the other dancers still continuing their exercises.

Presently another man [the tai'me keeper] entered from behind the screen, wearing an Indian fur cap and a blue breechcloth reaching to the ground. He was unpainted, and had a human scalp fastened to his scalplock, the soft, flowing hair of which, spreading out upon his naked back, bore mute testimony to the tragical death of some unfortunate white woman. This man, with a kind of half running jump, still in step with the music, went around all the dancers, who did not notice him, with one arm stretched out over his heads, first in one direction, then the other, turning his course at every time, after stopping in front of the medicine, and making some indescribable motions before it. He sometimes parted the feathers concealing the small image, appearing to examine it minutely, as if searching for something, and sometimes putting his lips to it, as if in the act of kissing it. [He takes some medicine root into his mouth, chews it and blows it on the dancers.][47] At length, after repeated examinations, he, apparently for the first time, discovered the fan, and took hold of it hesitatingly, and as if afraid.

This was loosed from its fastenings by a hand behind the screen, and he slowly raised it up, looking intently at it, while the expression of his countenance indicated a fearfulness of the result of handling an object whose hidden and mysterious powers were so far beyond his comprehension. He held it up before the medicine, waved it up and down, and from side to side, then, turning round so as to face the dancers and spectators, waved it from side to side near the ground, once around the dancers; then, raising it above his head, he waved it in the same manner, performing another circle around the dancers.

Then, with gestures of striking, and a countenance scowling as with fierce rage, he began to chase them around and around the ring, [i.e., around the center pole] from left to right. Finally, getting one of them separated from the rest, he pursued him with the most fiend-like attitude, fiercely striking at him with his fan. The pursued one fled from him with a countenance expressive of almost death-like terror, until, after several rounds, he stumbled and fell heavily to the ground. Another and another were thus separated from the dancers, pursued, and fell before the mystical power of the fan, and the act closed.[48]

The "feather-killing" (staiĕnkiăł, he runs after them with feathers) occurs every day in the late forenoon.[49] The associates as well as the other dancers, are fanned into unconsciousness.[50] In such a condition they would try to get visions: they would rise, call for a pipe, and announce what they had seen.[51]

Being called to a council of the war chiefs, I went no more to the medicine house to-day, though the music and dancing continued the whole time, by day and by night, with short intervals between the different acts, to give opportunity for rest, arranging dress, painting, and such other changes as the programme of the ceremony demanded.

20th.—Saw but one dance to-day. Quite a quantity of goods, such as blankets, strouding (blue and scarlet list-cloth), calico, shawls, scarfs, and other Indian wares, had been carried into the medicine house previous to my entrance. The dancers had been painted white, three of them [the g.uolg.uȧt`] ornamented with a green stripe across the forehead, and around down the sides of the cheeks, to the corner of the mouth, and meeting on the chin. A round green spot was painted on the back and breast, about three inches in diameter, while on either side of it, and somewhat elevated above it, was a crescent of the same size and color. Two small, hollow mounds of sand and clay had been made before the medicine, in which fire was placed, and kept just sufficiently burning, with the partially dried cottonwood leaves, cedar twigs, and probably tobacco, to produce a smoke. A small fire was burning near the musicians, for lighting pipes, tightening drums, &c.

When all was ready, the three young men, who were painted as described, were led, each by a man clad in a buffalo robe [possibly the former g.uolg.uȧt` who were transferring their privileges], near to the smoking mounds in front of the medicine. An ornamented fur cap was, with some ceremony, placed upon the head of one of them; wisps of green wild wormwood were fastened to the wrists and ankles, which being done, he reverently raised his hands above his head, leaning forward over one of the mounds, brought them down nearly to it; then, straightening up, passed his hands over his face and stroked his breast. This was repeated several times; then, after holding one foot, and the other, over the mound, as if to warm them, two or three times, he went around the central post, and back to the other mound, where the same ceremony was repeated. During this whole ceremony I could perceive that his lips moved, though he uttered nothing. I afterwards learned that it was in prayer to this effect: "May this medicine render me brave in war, proof against the weapons of my enemies, strong in the chase, wise in council; and, finally, may it preserve me to a good age, and may I at last die in peace among my own people." The others, one at a time, were similarly brought forward, and went through with the same ceremony. Three bunches of wild wormwood were then placed on the ground in a row, crossing the line of entrance, and between it and the central post, upon which the three young men were placed by their attendants, who stood behind them, with their hands upon their shoulders, the music playing all the time. Two or three men then approached the pile of goods, selected therefrom some plaid shawls, strouding, blankets, scarfs, and an umbrella, and hung them over the medicine; this being done, the six men began to dance,—the three foremost ones upon the wormwood, with their arms stretched towards the medicine, the three others with their hands still resting upon the shoulders of the former. After some time the latter retired; the other dancers came from behind the screen, and joined in the dance, which continued until they were driven off by the medicine chief, as described in yesterday's dance. All these ceremonies had a sacred significance, which I did not understand, but have been informed that they believe any article of wearing apparel, or of harness for their horses, hung up by the medicine during these ceremonies, receives a charmed power to protect their wearers from disease, or the assaults of their enemies, during the year.

21st.—At one of the dances to-day, all but one retired behind the screen, who continued to dance by himself for a long time. Various articles were brought forward, and laid upon the ground, which he took up and hung in proximity to the medicine. After along time, the other dancers reappeared, and he retired; these continued their exercises, until driven off as before. The last dance differed from the preceding in this: the last man selected and separated from the others by the medicine chief to be driven off, though he ran from him, did not appear terrified, and would not fall down, but retired, with the medicine chief, behind the screen.

At one of the dances to-day, five human scalps were exhibited,—one attached to each of the right wrists of two men, and one to each wrist of another, besides the one worn attached to the scalp lock of the medicine chief. Two of these scalps were from the heads of Indians. They had all been tanned, and evidently belonged with the medicine fixtures.

The whole ceremony closed about four o'clock in the afternoon. The medicine was packed away by the medicine chief, and the several articles which had been hung about it—medicated, I suppose, or, in other words, sanctified by proximity to the sacred things during the ceremonies, and consequently having power to protect their possessors from evil—were restored to the proper owners. They then packed them, took them upon their backs, formed into a procession, and marched, to the music of the drums, around and out of the medicine house, whence every one took the direction of his or her own lodge, and the ceremonies of the great medicine were ended.[52]

At the end of the ceremony, the image keeper chews up some medicine root and prepares a drink, of which the dancers are permitted to imbibe a little.[53]

After the image has been removed, old clothing is hung on the center pole as a sacrifice. Once Martinez saw a horse tied to the center pole as a sacrifice to the sun. It remained there until it starved to death. Horses were also painted and placed, together with blankets and similar valuables, on high hills as sacrifices. Others beside the associates sacrificed their flesh to the sun at this time, or in fact, whenever they wanted to, as Martinez has done. The Kiowa never suspended their dancers, as in the self-torture dance of other tribes, neither in the sun dance, nor when an individual sought a vision while fasting alone in the mountains.

The night the dance closes everyone joins in a hilarious time in the dance lodge. Next morning the camp circle breaks up, and the warriors soon go off to war.[54] They do not molest the dance lodge, though other tribes passing that way may do so: the Kiowa do not care.

[1] Methvin, J. J., Andele, or The Mexican-Kiowa Captive. A Story of Real Life among the Indians (Louisville, Kentucky, 1899).

[2] Scott, Hugh Lenox, "Notes on the Kado, or Sun Dance of the Kiowa" (American Anthropologist, N. S., vol. 13, pp. 345-379, 1911). The phonetic system used in the present paper is that of the "Phonetic Transcription of Indian Languages" (Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, vol. 66, no. 6, 1916), 2-7.

[3] Mooney, James, "Calendar History of the Kiowa Indians" (Seventeenth Annual Report, Bureau of American Ethnology, part 1, pp. 129-445, Washington, 1911), 385.

[4] Lowie, R. H., "Societies of the Kiowa" (this series, vol. 11), 847; Mooney, 325, 338.

[5] Mooney, 253, states the contrary.

[6] Mooney, 240; Plate LXIX shows a model (see Scott, 349).

[7] This coupling of purchase with inheritance is strictly comparable to the Hidatsa bundle (this volume, 416-417).

[8] Scott, 369, 373.

[9] If this is more than a general taboo against women handling sacred objects, it has its parallel in a similar Crow bias (this volume, 13).

[10] Mooney, 241, 323, 324.

[11] Mooney, 239.

[12] Mooney, 279, 343.

[13] Lowie, 842.

[14] Lowie, 843.

[15] Compare, Battey, Thomas C., The Life and Adventures of a Quaker among the Indians (Boston, 1876) 185.

[16] The Southern Cheyenne also charge and count coup on some sticks marking the site of the dance lodge (G. A. Dorsey, Cheyenne Sun Dance).

[17] Cf. 83, 109. Mooney, 349.

[18] Scott, 358-360, 365. In this account the hide is taken into a sweatlodge at this juncture.

[19] "Foot-soldiers," Scott, 360-361.

[20] Lowie, 843.

[21] Not by a woman's society as Scott's informant states (361).

[22] Battey, 170.

[23] By the "old women soldiers" according to Scott (361), but Martinez informs me that, with the exception of the dance described by Battey, the two women's societies have no significant part in the sun dance.

[24] The Old Woman society (Lowie, 850).

[25] Battey, 168.

[26] Cf. Lowie, 843.

[27] Battey, 169.

[28] Battey, 170-172. War singing gwudańke, was customary before an expedition set out for war (Lowie, 850).

[29] Scott, Pl. XXV.

[30] Evidently a shield of this type was made by Koñate, who was instructed to do so by the tai'me which appeared to him as he lay wounded (Mooney, 304).

[31] Lewis notes this custom for the Shoshoni, and Lowie for their medicinemen when treating the sick (Lowie, Northern Shoshone, 213-214). The Crow do not smoke where their moccasins are hung up, according to Maximilian, (Reise in das innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834 [Coblenz, 1841], I, 400).

[32] Scott, 373.

[33] Scott, 362.

[34] Martinez puts this performance after the image has been brought into the dance lodge: this does not seem correct.

[35] Battey has the keeper signal to the herd with a firebrand. Neither Battey nor Scott mention a mounted herder; the former puts the pipe in the hands of the keeper, and the latter in those of a third man who remains in the dance lodge, but in Scott's account also the function of the pipe is to force the buffalo to enter the lodge. In Battey's account two men assist the keeper in designating warriors, and in Scott's three men with straight pipes do it. (Battey, 172-173; Scott, 362-364).

[36] Battey, 173, 176; Scott, 351-352, 367, Pl. XXII; Methvin, 66, notes that his feet are painted black with sage wreaths about his ankles.

[37] Lowie, 843.

[38] Martinez, in Methvin's account, (71), states that the payment is made in four successive years.

[39] Methvin, 71; Scott, 352, states that these men directed the sun dance as substitutes for the keeper and did the ceremonial painting, but this is contrary to my information.

[40] Compare Mooney, 296.

[41] Battey, 178.

[42] Compare Scott, 352, 368, Pls. XVIII, XXII; Methvin, 70-71.

[43] Battey, 178-179.

[44] Scott, 347.

[45] Battey, 181-182.

[46] Mooney, 302, notes that one of these individuals carried his personal medicine in the dance.

[47] Methvin, 66; Scott, 366.

[48] Battey, 173-177.

[49] Once, not three times a day as Scott states (366).

[50] Scott, 366, places raven fans in hands of the associates.

[51] In the ghost dance a shaman hypnotizes the dancers by waving a feather or scarf before their faces. The subject staggers into the ring and falls (Mooney, Ghost dance, 925-926). This performance may not be related to that of the Kiowa, since it appeared among the Sioux before the southern Plains tribes took up the ghost dance. On the other hand, the Paiute, from whom the ghost dance was derived, did not hypnotize.

[52] Battey, 177-181.

[53] Scott, 365, 367.

[54] Mooney, Kiowa Calendar History, 282, 297, 304, 321, 322. Another suggestive similarity to the Crow is the assumption of "no-flight" obligations in both tribes at the sun dance (Ibid., 284, 287, 320).

In 1906 the present series of Anthropological Papers was authorized by the Trustees of the Museum to record the results of research conducted by the Department of Anthropology. The series comprises octavo volumes of about 350 pages each, issued in parts at irregular intervals. Previous to 1906 articles devoted to anthropological subjects appeared as occasional papers in the Bulletin and also in the Memoir series of the Museum. A complete list of these publications with prices will be furnished when requested. All communications should be addressed to the Librarian of the Museum.

The recent issues are as follows:—

I. Pueblo Ruins of the Galisteo Basin, New Mexico. By N.C. Nelson. Pp. 1-124, Plates 1-4, 13 text figures, 1 map, and 7 plans. 1914. Price, $.75.

II. (In preparation.)

I. The Sun Dance of the Crow Indians. By Robert H. Lowie. Pp. 1-50, and 11 text figures. 1915. Price, $.50.

II. The Sun Dance and Other Ceremonies of the Oglala Division of the Teton-Dakota. By J. R. Walker. Pp. 51-221. 1917. Price, $1.50.

III. The Sun Dance of the Blackfoot Indians. By Clark Wissler. Pp. 223-270, and 1 text figure. 1918. Price, $.50.

IV. Notes on the Sun Dance of the Sarsi. By Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 271-282. The Sun Dance of the Plains-Cree. By Alanson Skinner. Pp. 283-293. Notes on the Sun Dance of the Cree in Alberta. By Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 295-310, and 3 text figures. The Sun Dance of the Plains-Ojibway. By Alanson Skinner. Pp. 311-315. The Sun Dance of the Canadian Dakota. By W. D. Wallis. Pp. 317-380. Notes on the Sun Dance of the Sisseton Dakota. By Alanson Skinner. Pp. 381-385. 1919. Price, $1.50.

V. The Sun Dance of the Wind River Shoshoni and Ute. By Robert H. Lowie. Pp. 387-410, and 4 text figures. The Hidatsa Sun Dance. By Robert H. Lowie. Pp. 411-431. 1919. Price, $.50.

VI. Notes on the Kiowa Sun Dance. By Leslie Spier. Pp. 433-450, and 1 text figure. 1921. Price, $.25.

VII. The Sun Dance of the Plains Indians: Its Development and Diffusion. By Leslie Spier. Pp. 451-527, and 1 text figure. 1921. Price, $1.00.

I. The Whale House of the Chilkat. By George T. Emmons. Pp. 1-33. Plates I-IV, and 6 text figures. 1916. Price, $1.00.

II. The History of Philippine Civilization as Reflected in Religious Nomenclature. By A. L. Kroeber. Pp. 35-67. 1918. Price, $.25.

III. Kinship in the Philippines. By A. L. Kroeber. Pp. 69-84. Price, $.25.

IV. Notes on Ceremonialism at Laguna. By Elsie Clews Parsons. Pp. 85-131, and 21 text figures. 1920. Price $.50.

V. (In press.)

I. Tales of Yukaghir, Lamut, and Russianized Natives of Eastern Siberia. By Waldemar Bogoras. Pp. 1-148. 1918. Price, $1.50.

II. (In preparation.)

I. Notes on the Social Organization and Customs of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Crow Indians. By Robert H. Lowie. Pp. 1-99. 1917. Price, $1.00.

II. The Tobacco Society of the Crow Indians. By Robert H. Lowie. Pp. 101-200, and 13 text figures. 1920. Price, $1.25.

III. (In preparation.)

I. Contributions to the Archaeology of Mammoth Cave and Vicinity, Kentucky. By N. C. Nelson. Pp. 1-73, and 18 text figures. 1917. Price, $.75.

II. Chronology in Florida. By N. C. Nelson. Pp. 75-103, and 7 text figures. 1918. Price, $.25.

III. Archaeology of the Polar Eskimo. By Clark Wissler. Pp. 105-166, 33 text figures, and 1 map. 1918. Price, $.50.

IV. The Trenton Argillite Culture. By Leslie Spier. Pp. 167-226, and 11 text figures. 1918. Price, $.50.

V. (In preparation.)

I. Racial Types in the Philippine Islands. By Louis R. Sullivan, Pp. 1-61, 6 text figures, and 2 maps. 1918. Price, $.75.

II. The Evidence Afforded by the Boskop Skull of a New Species of Primitive Man (Homo capensis). By R, Broom. Pp. 33-79, and 5 text figures. 1918. Price, $.25.

III. Anthropometry of the Siouan Tribes. By Louis R. Sullivan. Pp. 81-174, 7 text figures, and 74 tables. 1920. Price, $1.25.

IV. (In press.)

I. Myths and Tales from the San Carlos Apache. By Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 1-86. 1918. Price, $.75.

II. Myths and Tales from the White Mountain Apache. By Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 87-139. 1919. Price, $.50.

III. San Carlos Apache Texts. By Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 141-367. 1919. Price, $2.50.

IV. White Mountain Apache Texts. By Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 369-527. 1920. Price $2.00.

I. Myths and Traditions of the Crow Indians. By Robert H. Lowie. Pp. 1-308. 1918. Price, $3.00.

II. (In preparation.)

I. The Aztec Ruin. By Earl H. Morris. Pp. 1-108, and 73 text figures. 1919. Price, $1.00.

II. (In press.)

I. Pueblo Bonito. By George H. Pepper. Pp. 1-490. Plates I-XII, and 155 text figures. 1920. Price $3.50.

Transcriber note: On page 443, 'the the' changed to 'the' (Once inside they lie down; the man with the pipe ...)