Ancient Manners

COMPLETE AND INTEGRAL TRANSLATION

INTO ENGLISH

by Pierre Louÿs

Illustrated by ED. ZIER

Privately printed for Subscribers only

PARIS

This

Translation of

Ancient Manners

was executed on the

Printing Presses of CHARLES

HERISSEY, at Evreux, (France),

for Mr. CHARLES CARRINGTON,

Paris, Bookseller et Publisher,

and is the only

complete English

version

extant.

This Edition on Large Paper,

is limited to 1000 copies of

which this is

No . . . . . . . .

Contents

PREFACE

The very ruins of the Greek

world instruct us how our

modern life might be made

supportable.

RICHARD WAGNER

The learned Prodicos of Ceos, who flourished towards the end of the fifth

century before our era, is the author of the celebrated apologue that Saint

Basil recommended to the meditations of the Christians: Heracles between

Virtue and Pleasure. We know that Heracles chose the former and was

therefore permitted to commit a certain number of crimes against the Arcadian

Stag, the Amazons, the Golden Apples, and the Giants.

Had Prodicos gone no further than this, he would simply have written a fable

marked by a certain cheap Symbolism; but he was a good philosopher, and his

collection of tales, The Hours, in three parts, presented the moral

truths under the various aspects that befit them, according to the three ages

of life. To little children he complacently held up the example of the austere

choice of Heracles; to young men, doubtless, he related the voluptuous choice

of Paris, and I imagine that to full-grown men he addressed himself somewhat as

follows:

“One day Odysseus was roaming about the foot of the mountains of Delphi,

hunting, when he fell in with two maidens holding one another by the hand. One

of them had glossy, black hair, clear eyes, and a grave look. She said to him:

‘I am Arete.’ The other had drooping eyelids, delicate hands, and

tender breasts. She said: ‘I am ‘Tryphe.’ And both exclaimed:

‘Choose between us.’ But the subtile Odysseus answered sagely.

‘How should I choose? You are inseparable. The eyes that have seen you

pass by separately have witnessed but a barren shadow. Just as sincere virtue

does not repel the eternal joys that pleasure offers it, in like manner

self-indulgence would be in evil plight without a certain nobility of spirit. I

will follow both of you. Show me the way.’ No sooner had he finished

speaking than the two visions were merged in one another, and Odysseus knew

that he had been talking with the great golden Aphrodite.”

The principal character of the novel which the reader is about to have under

his eyes is a woman, a courtesan of antiquity; but let him take heart of grace:

she will not be converted in the end.

She will be loved neither by a saint, nor by a prophet, nor by a god. In the

literature of to-day this is a novelty.

A courtesan, she will be a courtesan with the frankness, the ardour, and also

the conscious pride of every human being who has a vocation and has freely

chosen the place he occupies in society; she will aspire to rise to the highest

point; the idea that her life demands excuse or mystery will not even cross her

mind. This point requires elucidation.

Hitherto, the modern writers who have appealed to a public less prejudiced than

that of young girls and upper-form boys have resorted to a laborious stratagem

the hypocrisy of which is displeasing to me. “I have painted pleasure as

it really is,” they say, “in order to exalt virtue.” In

commencing a novel which has Alexandria for its scene, I refuse absolutely to

perpetuate this anachronism.

Love, with all that it implies, was, for the Greeks, the most virtuous of

sentiments and the most prolific in greatness. They never attached to it the

ideas of lewdness and immodesty which the Jewish tradition has handed down to

us with the Christian doctrine. Herodotos (I. 10) tells us in the most natural

manner possible, “Amongst certain barbarous peoples it is considered

disgraceful to appear in public naked.” When the Greeks or the Latins

wished to insult a man who frequented women of pleasure, they called him

μοἴχος or mœchus, which simply means

adulterer. A man and a woman who, without being bound by any tie, formed a

union with one another, whether it were in public or not, and whatever their

youth might be, were regarded as injuring no one and were left in peace.

It is obvious that the life of the ancients cannot be judged according to the

ideas of morality which we owe to Geneva.

For my part, I have written this book with the same simplicity as an Athenian

narrating the same adventures. I hope that it will be read in the same spirit.

In order to continue to judge of the ancient Greeks according to ideas at

present in vogue, it is necessary that not a single exact translation of

their great writers should fall in the hands of a fifth-form schoolboy. If M.

Mounet—Sully were to play his part of Œdipus without making any

omissions, the police would suspend the performance. Had not M. Leconte de

Lisle expurgated Theocritos, from prudent motives, his book would have been

seized the very day it was put on sale. Aristophanes is regarded as

exceptional! But we possess important fragments of fourteen hundred and forty

comedies, due to one hundred and thirty-two Greek poets, some of whom, such as

Alexis, Philetairos, Strattis, Euboulos, Cratinos, have left us admirable

lines, and nobody has yet dared to translate this immodest and charming

collection.

With the object of defending Greek morals, it is the custom to quote the

teaching of certain philosophers who reproved sexual pleasures. But there

exists a confusion in this matter. These rare moralists blamed the excesses of

all the senses without distinction, without setting up any difference between

the debauch of the bed and that of the table. A man who orders a solitary

dinner which costs him six louis, at a modern Paris restaurant, would have been

judged by them to be as guilty, and no less guilty, than a man who should make

a rendez-vous of too intimate a nature in the public street and should be

condemned therefore to a year’s imprisonment by the existing laws.

Moreover, these austere philosophers were generally regarded by ancient society

as dangerous madmen; they were scoffed at in every theatre; they received

thrashings in the street; the tyrants chose them for their court jesters, and

the citizens of free States sent them into exile, when they did not deem them

worthy of capital punishment.

It is, then, by a conscious and voluntary fraud, that modern educators, from

the Renaissance to the present day, have represented the ancient code of

morality as the inspiring source of their narrow virtues. If this code was

great, if it deserves to be chosen for a model and to be obeyed, it is

precisely because none other has more successfully distinguished the just from

the unjust according to a criterion of beauty; proclaimed the right of all men

to find their individual happiness within the bounds to which it is limited by

the corresponding right of others, and declared that there is nothing under

heaven more sacred than physical love, nothing more beautiful than the human

body.

Such were the ethics of the nation that built the Acropolis; and if I add that

they are still those of all great minds, I shall merely attest the value of a

common-place. It is abundantly proved that the higher intelligences of artists,

writers, warriors, or statesmen have never regarded the majestic toleration of

ancient morals as illegitimate. Aristotle began life by wasting his patrimony

in the society of riotous women; Sappho has given her name to a special vice;

Cæsar was the mœchus calvus; nor can we imagine Racine shunning the

stage-women nor Napoleon practicing abstinence. Mirabeau’s novels,

Chénier’s Greek verses, Diderot’s correspondence, and

Montesquieu’s minor works are as daring as the writings of Catullus

himself. And the most austere, saintly, and laborious of all French authors,

Button, would you know his maxim of advice in the case of sentimental

intrigues? “Love! why art thou the happiness of all beings and

man’s misfortune? Because only the physical part of this passion

is good, and the rest is worth nothing.”

Whence is this? And how comes it that in spite of the ruin of the ancient

system of thought, the grand sensuality of the Greeks has remained like a ray

of light upon the foreheads of the highest?

It is because sensuality is the mysterious but necessary and creative condition

of intellectual development. Those who have not felt the exigencies of the

flesh to the uttermost, whether for love or hatred, are incapable of

understanding the full range of the exigencies of the mind. Just as the beauty

of the soul illumines the whole face, in like manner virility of the body is an

indispensable condition of a fruitful brain. The worst insult that Delacroix

could address to men, the insult that he hurled without distinction against the

decriers of Rubens and the detractors of Ingres, was the terrible word:

eunuchs.

But furthermore, it would seem that the genius of peoples, like that of

individuals, is above all sensual. All the cities that have reigned over the

world, Babylon, Alexandria, Athens, Rome, Venice, Paris, have by a general law

been as licentious as they were powerful, as if their dissoluteness was

necessary to their splendour. The cities where the legislator has attempted to

implant a narrow, unproductive, and artificial virtue have seen themselves

condemned to utter death from the very first day. It was so with Lacedæmon,

which, in the centre of the most prodigious intellectual development that the

human spirit has ever witnessed, between Corinth and Alexandria, between

Syracuse and Miletus, has bequeathed us neither a poet, nor a painter, nor a

philosopher, nor an historian, nor a savant, barely the popular renown of a

sort of Bobillot who got killed in a mountain defile with three hundred men

without even succeeding in gaining the victory. And it is for this reason that

after two thousand years we are able to gauge the nothingness of Spartan

virtue, and declare, following Renan’s exhortation, that we “curse

the soil that bred this mistress of sombre errors, and insult it because it

exists no longer.”

Shall we see the return of the days of Ephesus and Cyrene? Alas! the modern

world is succumbing to an invasion of ugliness. Civilization is marching to the

north, is entering into mist, cold, mud. What night! A people clothed in black

fills the mean streets. What is it thinking of? We know not, but our

twenty-five years shiver at being banished to a land of old men.

But let those who will ever regret not to have known that rapturous youth of

the earth which we call ancient life, be allowed to live again, by a fecund

illusion, in the days when human nudity, the most perfect form that we can know

and even conceive of, since we believe it to be in God’s image, could

unveil itself under the features of a sacred courtesan, before the twenty

thousand pilgrims who covered the strands of Eleusis; when the most sensual

love, the divine love of which we are born, was without sin: let them be

allowed to forget eighteen barbarous, hypocritical, and hideous centuries.

Leave the quagmire for the pure spring, piously return to original beauty,

rebuild the great temple to the sound of enchanted flutes, and consecrate with

enthusiasm their hearts, ever charmed by the immortal Aphrodite, to the

sanctuaries of the true faith.

Pierre Louÿs.

I

CHRYSIS

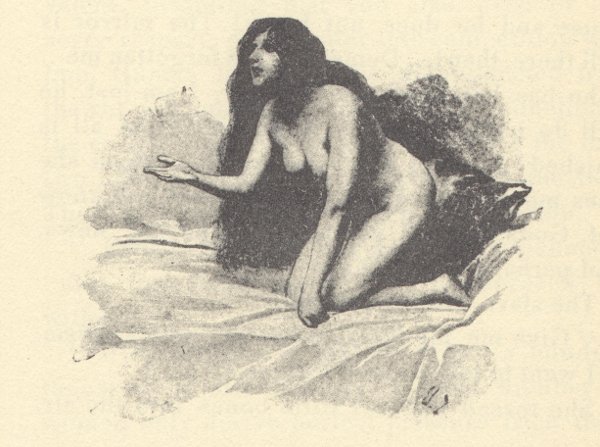

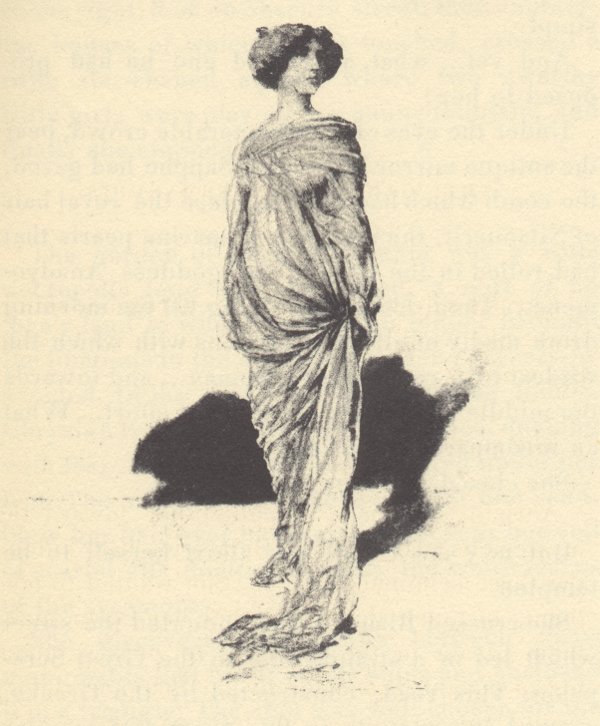

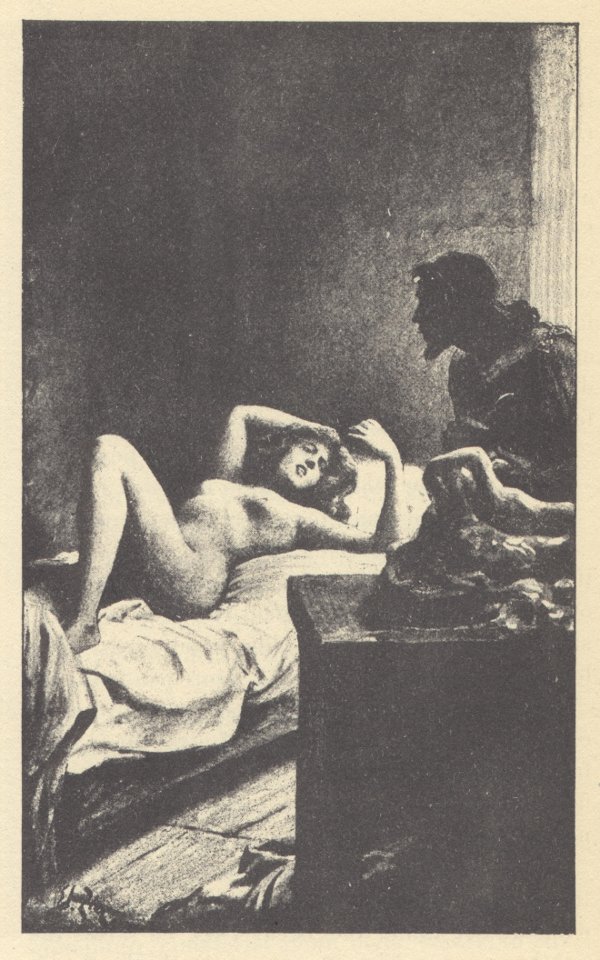

She lay upon her bosom, with her elbows in front of her, her legs wide apart

and her cheek resting on her hand, pricking, with a long golden pin, small

symmetrical holes in a pillow of green linen.

Languid with too much sleep, she had remained alone upon the disordered bed

ever since she had awakened, two hours after mid-day.

The great waves of her hair, her only garment, covered one of her sides.

This hair was resplendently opaque, soft as fur, longer than a bird’s

wing, supple, uncountable, full of life and warmth. It covered half her back,

flowed under her naked belly, glittered under her knees in thick, curling

clusters. The young woman was enwrapped in this precious fleece. It glinted

with a russet sheen, almost metallic, and had procured her the name of Chrysis,

given her by the courtesans of Alexandria.

It was not the sleek hair of the court-woman from Syria, or the dyed hair of

the Asiatics, or the black and brown hair of the daughters of Egypt. It was the

hair of an Aryan race, the Galilæans across the sands.

Chrysis. She loved the name. The young men who came to see her called her

Chryse like Aphrodite, in the verses they laid at her door, with rose-garlands,

in the morning. She did not believe in Aphrodite, but she liked to be compared

to the goddess, and she went to the temple sometimes, in order to give her, as

to a friend, boxes of perfumes and blue veils.

She was born upon the borders of Lake Gennesaret, in a country of sun and

shade, overgrown by laurel roses. Her mother used to go out in the evening upon

the Jerusalem road, and wait for the travelers and merchants. She gave herself

to them in the grass, in the midst of the silence of the fields. This woman was

greatly loved in Galilee. The priests did not turn aside from her door, for she

was charitable and pious. She always paid for the sacrificial lambs, and the

blessing of the Eternal abode upon her house. Now when she became with child,

her pregnancy being a scandal (for she had no husband), a man celebrated for

his gift of prophecy told her that she would give birth to a maiden who should

one day carry “the riches and faith of a people” around her neck.

She did not well understand how that might be, but she named the child Sarah,

that is to say princess in Hebrew. And that closed the mouth of slander.

Chrysis had always remained in ignorance of this incident, the seer having told

her mother how dangerous it is to reveal to people the prophecies of which they

are the object. She knew nothing of her future. That is why she often thought

about it. She remembered her childhood but little, and did not like to speak

about it. The only vivid sensation she had retained was the fear and disgust

caused her by the anxious surveillance of her mother, who, on the approach of

her time for going forth upon the road, shut her up alone in her chamber for

interminable hours. She also remembered the round window through which she saw

the waters of the lake, the blue-tinted fields, the transparent sky, the blithe

air of Galilee. The house was covered with tamarisks and rose-coloured flax.

Thorny caper-bushes reared their green heads in wild confusion, over-topping

the fine mist of the grasses. The little girls bathed in a limpid brook, where

they found red shells under the tufts of flowering laurels; and there were

flowers upon the water and flowers over all the mead and great lilies upon the

mountains.

She was twelve years old when she escaped from home to follow a troop of young

horsemen who were on their way to Tyre to sell ivory. She fell in with them

before a cistern. They were adorning their long-tailed horses with

multi-coloured tufts. She well remembered how she was carried off, pale with

joy upon their horses, and how they stopped a second time during the night, a

night so clear that the stars were invisible.

Neither had she forgotten how they entered Tyre: she in front, seated upon the

panniers of a pack-horse, holding on to its mane with her fists, and proudly

dangling her naked calves, to show the women of the town that she had pure

blood coursing in her well-shaped legs. They left for Egypt that same evening.

She followed the ivory-sellers as far as the market of Alexandria.

Greek harlots from the isles told her the

legend of Iphis.

And it was there, in a little white house with a terrace and tapering columns,

that they left her two months afterwards, with her bronze mirror, carpets, new

cushions, and a beautiful Hindoo slave who was learned in the dressing of

courtesans’ hair. Others came on the evening of their departure, and

others on the morrow.

As she lived at the extreme east of the town, a quarter disdained by the young

Greeks of Brouchion, she was long before she made the acquaintance of aught but

travellers and merchants, like her mother. Yet she inspired interminable

passions. Caravan-masters were known to sell their merchandise dirt cheap in

order to stay with her, and ruin themselves in a few nights. With these

men’s fortune she bought jewels, bed-cushions, rare perfumes, flowered

robes, and four slaves.

She gained a knowledge of many foreign languages, and knew the tales of all

countries. Assyrians told her the loves of Douzi and Ishtar; Phœnicians those

of Ashtaroth and Adonis. Greek harlots from the isles told her the legend of

Iphis, and taught her strange caresses which surprised her at first, but

afterwards enchanted her so much that she could not do without them for a whole

day. She also knew the loves of Atalanta, and how, like her, flute-girls, while

yet virgins, may tire out the strongest men. Finally, her Hindoo slave had

taught her patiently, during seven years, the minutest details of the complex

and voluptuous art of the courtesans of Palibothra.

For love is an art, like music. It gives emotions of the same order, equally

delicate, equally thrilling, sometimes perhaps more intense; and Chrysis, who

knew all its rhythms and all its subtilities, regarded herself, with good

reason, as a greater artist than Plango herself. Yet Plango was a musician of

the temple.

Seven years she lived thus, without dreaming of a life happier or more varied.

But shortly before her twentieth year, when she emerged from girlhood to

womanhood and saw the first charming line of nascent maturity take form under

her breasts, she suddenly conceived other ambitions.

And one morning, waking up two hours after mid-day, languid with too much

sleep, she turned over upon her breast, threw out her legs, leaned her cheek

upon her hand, and with a long golden pin, pricked little symmetrical holes

upon her pillow of green linen.

Her reflexions were profound.

First it was four little pricks which made a square, with a prick in the

centre. Then four other pricks to make a bigger square. Then she tried to make

a circle. But it was a little difficult. Then, she pricked away aimlessly and

began to call:

“Djala! Djala!”

Djala was her Hindoo slave, and was called Djalantachtchandratchapala, which

means: “Mobile as the image of the moon upon the water.” Chrysis

was too lazy to say the whole name.

The slave entered and stood near the door, without entirely closing it.

“Who came yesterday, Djala?”

“You do not know?”

“No, I did not look. He was handsome? I think I slept all the time; I was

tired. I remember nothing at all about it. At what time did he go away? This

morning early?”

“At sunrise, he said—”

“What did he leave me? Is it much? No, don’t tell me. It’s

all the same to me. What did he say? Has no one been since? Will he come back

again? Give me my bracelets.”

The slave brought a casket, but Chrysis did not look at it, and, raising her

arm as high as she could:

“Ah! Djala,” she said, “ah! Djala! I long for extraordinary

adventures.”

“Everything is extraordinary,” said Djala, “or nought. The

days resemble one another.”

“No, no. Formerly it was not like that. In all the countries of the world

gods came down to earth and loved mortal women. Ah! on what beds await them, in

what forest search for them that are a little more than men? What prayers shall

I put up for the coming of them that will teach me something new or oblivion of

all things? And if the gods will no longer come down, if they are dead or too

old, Djala, shall I too die without seeing a man capable of putting tragic

events into my life?”

She turned over upon her back and interlocked her fingers.

“If somebody adored me, I think it would give me such joy to make him

suffer till he died. Those who come here are not worthy to weep. And then, it

is my fault as well: it is I who summon them; how should they love me?”

“What bracelet to-day?”

“I shall put them all on. But leave me. I need no one. Go to the steps

before the door, and if anyone comes, say that I am with my lover, a black

slave whom I pay. Go.”

“You are not going out?”

“Yes, I shall go out alone. I shall dress myself alone. I shall not

return. Off with you! Off with you!”

She let one leg drop upon the carpet and stretched herself into a standing

posture. Djala had gone away noiselessly.

She walked very slowly about the room, with her hands crossed behind her neck,

entirely absorbed in the luxury of cooling the sweat of her naked feet by

stepping about on the tiles. Then she entered her bath.

It was a delight to her to look at herself through the water. She saw herself

like a great pearl-shell lying open on a rock. Her skin became smooth and

perfect; the lines of her legs tapered away into blue light; her whole form was

more supple; her hands were transfigured. The lightness of her body was such

that she raised herself on two fingers and allowed herself to float for a

little and fall gently back on the marble, causing the water to ripple softly

against her chin. The water entered her ears with the provocation of a kiss.

It was when taking her bath that Chrysis began to adore herself. Every part of

her body became separately the object of tender admiration and the motive of a

caress. She played a thousand charming pranks with her hair and her breasts.

Sometimes, even, she accorded a more direct satisfaction to her perpetual

desires, and no place of repose seemed to her more propitious for the minute

slowness of this delicate solace.

The day was waning. She sat up in the piscina, stepped out of the water, and

walked to the door. Her foot-marks shone upon the stones. Tottering, and as if

exhausted, she opened the door wide and stopped, holding the latch at

arm’s length; then entered, and, standing upright near her bed, and

dripping with water, said to the slave:

“Dry me.”

The Malabar woman took a large sponge and passed it over Chrysis’s golden

hair, which, being heavily charged with water, dripped streams down her back.

She dried it, smoothed it out, waved it gently to and fro, and, dipping the

sponge into a jar of oil, she caressed her mistress with it even to the neck.

She then rubbed her down with a rough towel which brought the colour to her

supple skin.

Chrysis sank quivering into the coolness of a marble chair and murmured:

“Dress my hair.”

In the level rays of evening her hair, still heavy and humid, shone like rain

illuminated by the sun: The slave took it in handfuls and entwined it. She

rolled it into a spiral and picked it out with slim golden pins, like a great

metal serpent bristling with arrows. She wound the whole around a triple fillet

of green in order that its reflections might be heightened by the silk.

Chrysis held a mirror of polished copper at arm’s length. She watched the

slave’s darting hands with a distracted eye, as she passed them through

the heavy hair, rounded off the clusters, captured the stray locks, and built

up her head-dress like a spiral rhytium of clay. When all was finished, Djala

knelt down on her knees before her mistress and shaved her rounded flesh to the

skin, in order that she might have the nudity of a statue in her lovers’

eyes.

Chrysis became graver and said in a low voice:

“Paint me.”

A little pink box from the island of Dioscoris contained cosmetics of all

colours. With a camel-hair brush, the slave took a little of a certain black

paste which she laid upon the long curves of the beautiful eye-lashes, in order

to heighten the blueness of the eyes. Two firm lines put on with a pencil

imparted increased length and softness to them; a bluish powder tinted the

eye-lids the colour of lead; two touches of bright vermilion accentuated the

tear-corners. In order to fix the cosmetics, it was necessary to anoint the

face and breast with fresh cerate. With a soft feather dipped in ceruse, Djala

painted trails of white along the arms and on the neck; with a little brush

swollen with carmine she reddened the mouth and touched up the nipples of the

breasts; with her fingers she spread a fine layer of red powder over the

cheeks, marked three deep lines between the waist and the belly, and in the

rounded haunches two dimples that sometimes moved; then with a plug of leather

dipped in cosmetics she gave a indefinable tint to the elbows and polished up

the ten nails. The toilette was finished.

The Chrysis began to smile, and said to the Hindoo woman:

“Sing to me.”

She sat erect in her marble chair. Her pins gleamed with a golden glint behind

her head. Her painted finger-nails, pressed to her neck from shoulder to

shoulder, broke the red line of her necklace, and her white feet rested close

together upon the stone.

Huddled against the wall, Djala bethought her of the love-songs of India.

“Chrysis . . .”

She sang in a monotonous chant.

“Chrysis, thy hair is like a swarm of bees hanging on a tree. The hot

wind of the south penetrates it with the dew of love-battles and the wet

perfume of night-flowers.”

The young woman alternated, in a softer, lower voice:

“My hair is like an endless river in the plain when the flame-lit evening

fades.”

And they sang, one after the other:

“Thine eyes are like blue water-lilies without stalks, motionless upon

the pools.”

“Mine eyes rest in the shadow of my lashes like deep lakes under dark

branches.”

“Thy lips are two delicate flowers stained with the blood of a

roe.”

“My lips are the edges of a burning wound.”

“Thy tongue is the bloody dagger that has made the wound of thy

mouth.”

“My tongue is inlaid with precious stones. It is red with the sheen of my

lips.”

“Thine arms are tapering as two ivory tusks, and thy armpits are two

mouths.”

“Mine arms are tapering as two lily-stalks and my fingers hang therefrom

like five petals.”

“Thy thighs are two white elephants’ trunks. They bear thy feet

like two red flowers.”

“My feet are two nenuphar-leaves upon the water: My thighs are two

bursting nenuphar buds.”

“Thy breasts are two silver bucklers with cusps steeped in blood.”

“My breasts are the moon and the reflection of the moon and the

water.”

Huddled against the wall, Djala bethought

herself of the love-songs of India.

“Thy navel is a deep pit in a desert of red sand, and thy belly a young

kid lying on its mother’s breast.”

“My navel is a round pearl on an inverted cup, and the curve of my belly

is the clear crescent of Phœbe in the forests.”

There was a silence. The slave raised her hands and bowed to the ground.

The courtesan proceeded:

“It is like a purple flower, full of perfumes and honey.”

“It is like a sea-serpent, soft and living, open at night.”

“It is the humid grotto, the ever-warm lodging, the Refuge where man

reposes from his march to death.”

The prostrate one murmured very low: “It is appalling. It is the face of

Medusa.”

Chrysis planted her foot upon the slave’s neck and said with trembling:

“Djala.”

The night had come on little by little, but the moon was so luminous that the

room was filled with blue light.

Chrysis looked at the motionless reflections of her naked body where the

shadows fell very black.

She rose brusquely:

“Djala, what are we thinking of? It is night, and I have not yet gone

out. There will be nothing left upon the heptastadion but sleeping sailors.

Tell me, Djala, I am beautiful?

“Tell me, Djala, I am more beautiful than ever to-night? I am the most

beautiful of the Alexandrian women, and you know it? Will not he who shall

presently pass within the sidelong glance of my eyes follow me like a dog?

Shall I not perform my pleasure upon him, and make a slave of him according to

my whim, and can I not expect the most abject obedience from the first man whom

I shall meet? Dress me, Djala.”

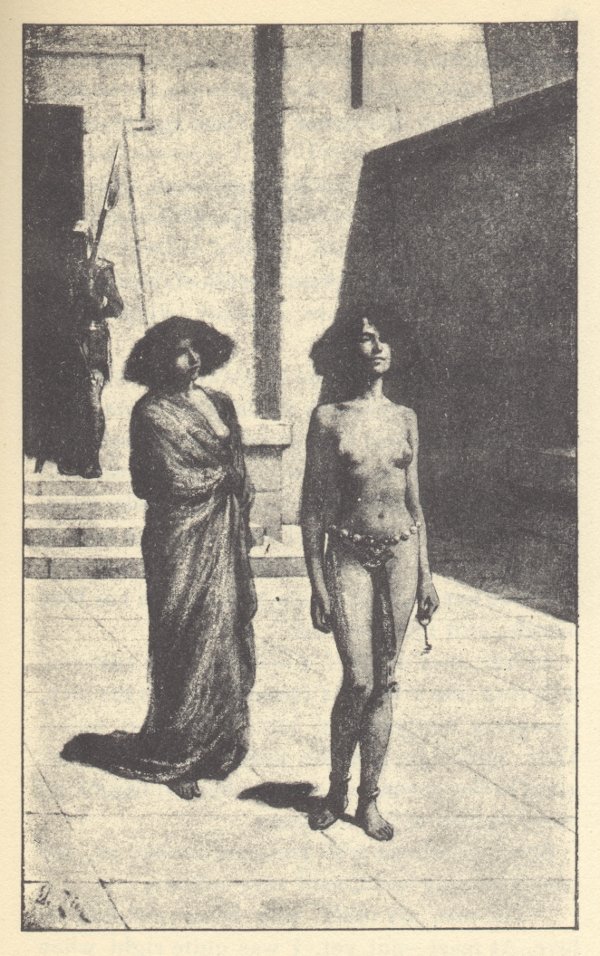

Djala twined two silver serpents about her arms. On her feet she fixed sandals

and attached them to her brown legs with crossed leather straps. Over her warm

belly Chrysis herself buckled a maiden’s girdle, which sloped down from

the upper part of the loins along the hollow line of the groins; in her ears

she hung great circular rings, on her neck three golden phallus-bracelets

enchased at Paphos by the hierodules. She contemplated herself for some time,

standing naked in her jewels; then, drawing from the coffer in which she had

folded it, a vast transparent stuff of yellow linen, she twisted it about her

and draped herself in it to the ground. Diagonal folds intersected the little

that one saw of her body through the light tissue; one of her elbows stood out

under the light tunic, and the other arm, which she had left bare, carried the

long train high out of reach of the dust.

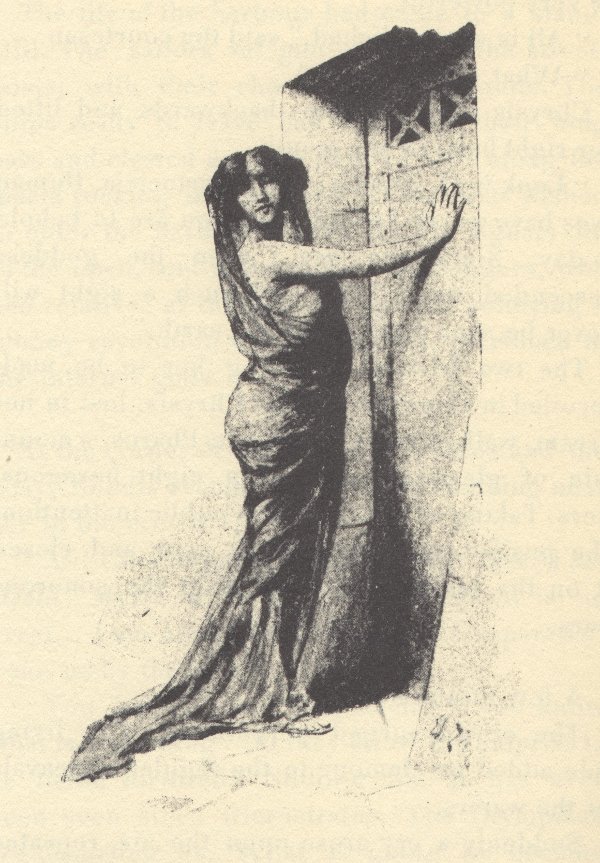

She took her feather fan in her hand, and carelessly sauntered forth.

Standing upon the steps of the threshold, with her hand leaning on the white

wall, Djala watched the courtesan’s retreating form.

She walked slowly past the houses, in the deserted street bathed in moonlight.

A little flickering shadow danced behind her.

II

THE QUAY AT ALEXANDRIA

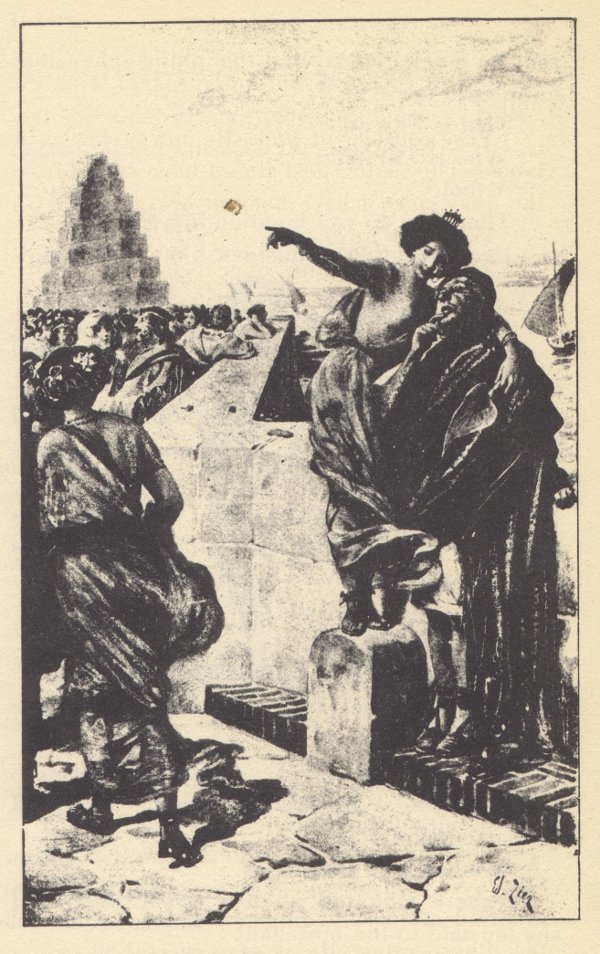

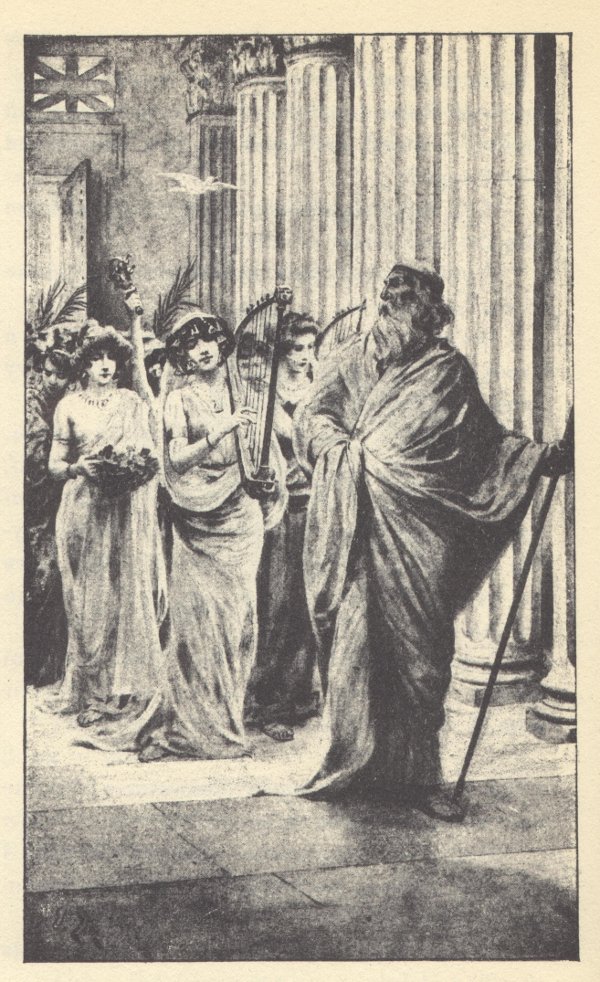

On the quay at Alexandria a singing-girl was standing singing. By her side were

two flute-girls, seated on the white parapet.

I

The satyrs pursue in the woods

The light-footed oreads.

They chase the nymphs upon the mountains,

They fill their eyes with affright,

They seize their hair in the wind,

They grasp their breasts in the chase,

And throw their warm bodies backwards

Upon the green dew-covered moss,

And the beautiful bodies, their beautiful bodies half divine,

Writhe with the agony . . .

O women! Eros makes your lips cry aloud

With dolorous, sweet Desire.

The flute-players repeated

“Eros

Eros!”

and wailed in their twin reeds.

II

Cybele pursues across the plain

Attys, beautiful as Apollo.

Eros has smitten her to the heart, and for him,

O Totoi! but not him for her,

Instead of love, cruel god, wicked Eros,

Thou counsellest but hatred . . .

Across the meads, the vast distant plains,

Cybele chases Attys;

And because she adores the scorned,

She infuses into his veins

The great cold breath, the breath of death.

O dolorous, sweet Desire!

“Eros!

Eros!”

Shrill wailings poured from the flutes.

III

The Goat-foot pursues to the river

Syrinx, the daughter of the fountain;

Pale Eros, that loves the taste of tears,

Kissed her as she ran, cheek to cheek;

And the frail shadow of the drowned maiden

Shivers, reeds, upon the waters.

But Eros kings it over the world and the gods.

He kings it over death itself.

On the watery tomb he gathered for us

All the reeds, and with them made the flute,

’Tis a dead soul that weeps here, women,

Dolorous, sweet Desire.

Whilst the flute prolonged the slow chant of the last line, the singer held out

her hand to the passers-by standing around her in a circle, and collected four

obols, which she slipped into her shoe.

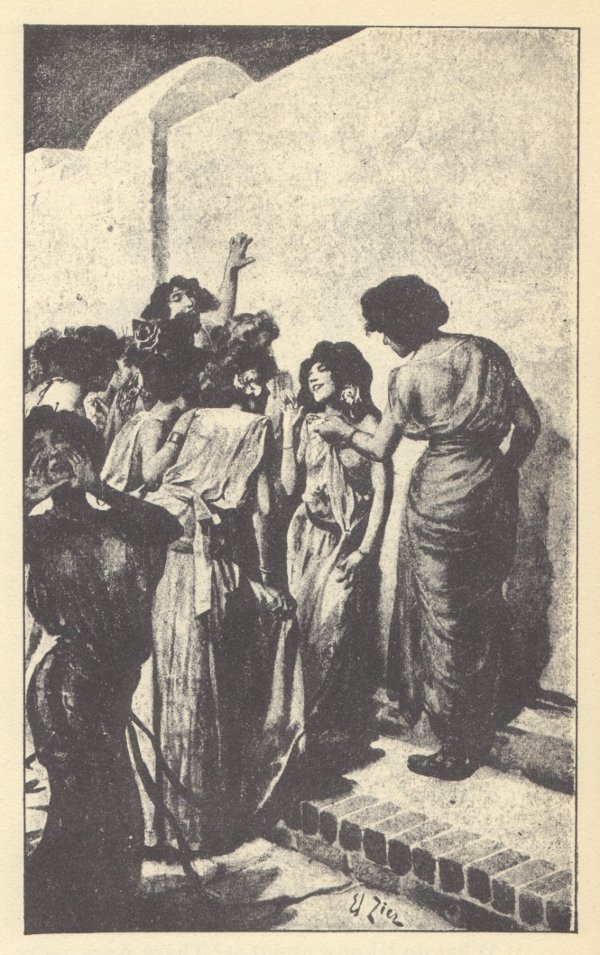

Groups formed in places, and women wandered amongst them

The crowd gradually melted away, innumerable, curious of itself and watching

its own movements. The noise of footsteps and voices drowned even the sound of

the sea. Sailors hauled their boats upon the quay with bowed shoulders.

Fruit-sellers passed to and fro with teeming baskets upon their arms. Beggars

begged for alms with trembling hand. Asses, laden with leathern bottles,

trotted in front of the goads of their drivers. But it was the hour of sunset;

and the crowd of idlers, more numerous than the crowd bent on affairs, covered

the quay. Groups formed in places, and women wandered amongst them. The names

of well-known characters passed from mouth to mouth. The young men looked at

the philosophers, and the philosophers looked at the courtesans.

The latter were of every kind and condition, from the most celebrated, dressed

in fine silks and wearing shoes of gilded leather, to the most miserable, who

walked barefooted. The poor ones were no less beautiful than the others, but

less fortunate only, and the attention of the sages was fixed by preference

upon those whose natural grace was not disfigured by the artifice of girdles

and weighty jewels. As it was the day before the Aphrodisiæ, these women had

every license to choose the dress which suited them the best, and some of the

youngest had even ventured to wear nothing at all. But their nudity shocked

nobody, for they would not thus have exposed all the details of their bodies to

the sun if they had possessed the slightest defect which might have rendered

them the laughing-stock of the married women.

“Tryphera! Tryphera!”

And a young courtesan of joyful mien elbowed her way through the crowd to join

a friend of whom she had just caught sight.

“Tryphera! are you invited?”

“Where, Seso?”

“To Bacchis’s.”

“Not yet. She is giving a dinner?”

“A dinner? A banquet, my dear. She is to liberate her most beautiful

slave, Aphrodisia, on the second day of the feast.”

“At last! She has perceived at last that people came to see her only for

the sake of her slave.”

“I think she has seen nothing. It is a whim of old Cheres, the ship-owner

on the quay. He wanted to buy the girl for ten minæ. Bacchis refused. Twenty

minæ; she refused again.”

“She must be crazy.”

“Why, pray? It was her ambition to have a freed-woman. Besides, she was

quite right to bargain. Cheres will give thirty-five minæ, and at that price

the girl becomes a freed-woman.”

“Thirty-five minæ? Three thousand five hundred drachmæ? Three thousand

five hundred drachmæ for a negress?”

“She is a white man’s daughter.”

“But her mother is black.”

“Bacchis declared that she would not part with her for less, and old

Cheres is so amorous that he consented.”

“I hope he is invited at any rate.”

“No! Aphrodisia is to be served up at the banquet as the last dish, after

the fruit. Everybody will taste of it at pleasure, and it is only on the morrow

that she is to be handed over to Cheres; but I am much afraid she will be tired

. . .”

“Don’t pity her. With him she will have time to recover. I know

him, Seso. I have watched him sleep.”

They laughed together at Cheres. Then they complimented one another. “You

have a pretty robe,” said Seso. “Did you have it trimmed at

home?”

Tryphera’s robe was of fine sea-green stuff entirely trimmed with

flowering iris. A carbuncle set in gold gathered it up into a spindle-shaped

pleat over the left shoulder; the robe fell slantingly between the two breasts,

leaving the entire right side of her body naked down to the metal girdle; a

narrow slit, that opened and closed at every step, alone revealed the whiteness

of the leg.

“Seso!” said another voice. “Seso and Tryphera, come with me

if you don’t know what to do. I am going to the Ceramic Wall to see

whether my name is written up.”

“Mousarion! Where have you come from, my dear?”

“From Pharos. There is nobody there.”

“What do you mean? There is nothing to do but fish, it is so full.”

“No turbots for me. I am off to the wall. Come.”

On the way, Seso told them about the projected banquet at Bacchis’s over

again.

“Ah! at Bacchis’s!” cried Mousarion. “You remember the

last dinner, Tryphera, and all the stories about Chrysis?”

“You must not repeat them. Seso is her friend.”

Mousarion bit her lips; but Seso had already taken the alarm.

“What did they say about her?”

“Oh! various ill-natured things.”

“Let people talk,” declared Seso. “We three together are not

worth Chrysis. The day she decides to leave her quarter and shew herself at

Brouchion, I know of some of our lovers whom we shall never see again.”

“Oh! Oh!”

“Certainly. I would commit any folly for that woman. Be sure that there

is none here more beautiful than she.”

The three girls had now arrived in front of the Ceramic Wall. Inscriptions

written in black succeeded one another along the whole length of its immense

white surface. When a lover desired to present himself to a courtesan, he had

merely to write up their two names, with the price he offered; if the man and

the money were approved of, the woman remained standing under the notice until

the lover re-appeared.

“Look, Seso,” said Tryphera, laughing.

“Who is the practical joker who has written that?”

And they read in huge letters:

BACCHIS

THERSIES

2 OBOLS

“It ought not to be allowed to make fun of the women like that. If I were

the rhymarch, I should already have held an enquiry.”

But further on, Seso stopped before an inscription more to the point:

SESO OF CNIDOS

TIMON THE SON OF LYSIAS

1 MINA

She turned slightly pale.

“I stay,” she said.

And she leaned her back against the wall under the envious glances of the women

that passed by.

A few steps further on Mousarion found an acceptable offer, if not as generous

an one. Tryphera returned to the quay alone.

As the hour was advanced, the crowd had become less compact. But the three

musicians were still singing and playing the flute.

Catching sight of a stranger whose clothes and rotundity were slightly

ridiculous, Tryphera tapped him on the shoulder.

“I say! Papa! I wager that you are not an Alexandrian, eh?”

“No indeed, my girl,” answered the honest fellow. “And you

have guessed rightly. I am quite astounded at the town and the people.”

“You are from Boubastis?”

“No. From Cabasa. I came here to sell grain, and I am going back again

to-morrow, richer by fifty-two minæ. Thanks be to the gods! it has been a good

year.”

Tryphera suddenly began to take an great interest in this merchant.

“My child,” he resumed timidly, “you can give me a great joy.

I don’t want to return to Cabasa to-morrow without being able to tell my

wife and three daughters that I have seen some celebrated men, You probably

know some celebrated men?”

“Some few,” she said, laughing.

“Good. Name them to me when they pass. I am sure that during the last two

days I have met the most influential functionaries. I am in despair at not

knowing them by sight.”

“You shall have your wish. This is Naucrates.”

“Who is Naucrates?”

“A philosopher.”

“And what does he teach?”

“Silence.”

“By Zeus, that is a doctrine that does not require much genius, and this

philosopher does not please me at all.”

“That is Phrasilas.”

“Who is Phrasilas?”

“A fool.”

“Then why do you mention him?”

“Because others consider him to be eminent.”

“And what does he say?”

“He says everything with a smile, and that enables him to pass off his

errors as international and common-places as subtile. He has all the advantage.

People have allowed themselves to be duped.”

“All this is beyond me, and I don’t quite understand. Besides, the

face of this Phrasilas is marked by hypocrisy.”

“This is Philodemos.”

“The strategist?”

“No. A Latin poet who writes in Greek.”

“My dear, he is an enemy. I am sorry to have seen him.”

At this point a flutter of excitement ran through the crowd and a murmur of

voices pronounced the same name:

“Demetrios . . . Demetrios . . .”

Tryphera mounted upon a street post, and she too said to the merchant:

“Demetrios . . . That is Demetrios. You were anxious to see celebrated

men.”

Tryphera mounted upon a street post.

“Demetrios? the Queen’s lover? Is it possible?”

“Yes, you are in luck. He never leaves his house. This is the first time

I have seen him on the quay since I have been at Alexandria.”

“Where is he?”

“That’s he, bending over to look at the harbour.”

“There are two men leaning over.”

“It is the one in blue.”

“I cannot see him very well. His back is turned to me.”

“Know you not? he is the sculptor to whom the queen offered herself for a

model when he carved the Aphrodite in the temple.”

“They say he is the royal lover. They say he is the master of

Egypt.”

“And he is as beautiful as Apollo.”

“Ah! he has turned round. I am very glad that I came. I shall say that I

have seen him. I have heard so much about him. It seems that no woman has ever

resisted him. He has had many love adventures, has he not? How is it that the

queen has not heard of them?”

“The queen knows of them as well as we do. She loves him too much to

speak of them. She is afraid of his returning to Rhodes, to his master,

Pherecrates. He is as powerful as she is, and it is she who desired him.”

“He does not look happy. Why does he look so sad? I think I should be

happy if I were in his place. I should like to be he, were it only for an

evening.”

The sun had set. The women gazed at this man, their common dream. He, without

appearing to be conscious of the stir he created, remained leaning over the

parapet, listening to the flute-girls.

The little musicians made another collection; then, they softly threw their

light flutes over their backs. The singing-girl placed her arms round their

necks and all three returned to the town.

At night-fall, the other women went back into immense Alexandria in little

groups, and the herd of men followed them; but all turned round as they walked,

and looked at Demetrios.

The last girl who passed softly cast her yellow flowers at him, and laughed.

Night fell upon the quays.

III

DEMETRIOS

Demetrios remained alone, leaning on his elbow, at the spot vacated by the

flute-girls. He listened to the murmur of the sea, to the slow creaking of the

ships, to the wind passing beneath the stars.

The town was illumined by a dazzling little cloud which lingered upon the moon,

and the sky was bathed in soft light.

The young man looked around him. The flute-girls’ tunics had left two

marks in the dust. He remembered their faces: they were two Ephesians. He had

thought the elder one pretty; but the younger was without charm, and, as

ugliness was a torture to him, he avoided thinking about her.

An ivory object gleamed at his feet. He picked it up: it was a writing-tablet,

with a silver style attached to it. The wax was almost worn away and it had

been necessary to go over the words several times in order to make them

legible. They were even scratched into the ivory.

There were only these words:

Myrtis Loves Rhodocleia

and he did not know to which of the two women this belonged, and whether the

other was the loved one, or whether it was some unknown girl left behind in

Ephesos. Then he thought for a moment of overtaking the two musicians in order

to restore them what was perhaps the souvenir of a cherished dead friend; but

he could not have found them without difficulty, and as he was already

beginning to lose interest in them, he turned round languidly and threw the

little object into the sea.

It fell rapidly, with a gliding motion like a white bird, and he heard the

splash it made away out in the black water. This little noise enhanced the

immense silence of the harbour. Leaning against the cold parapet, he tried to

drive away all thought, and began to look at the things around him.

He had a horror of life. He only left his house when the life of the day was

dying down, and he returned home when the dawn began to draw the fishermen and

market-gardeners to the town. The pleasure of seeing nought in the world but

the ghost of the town and his own stature had become a voluptuous passion with

him, and he did not remember having seen the mid-day sun for months.

He was wearied. The queen was tedious.

He could hardly understand, that night, the joy and pride that had possessed

him three years before, when the queen, bewitched perhaps by the stories of his

beauty and genius, had sent for him to the palace, and had heralded him to the

Evening Gate with the sound of the silver salpinx.

His arrival at the palace sometimes lighted up his memory with one of those

souvenirs which, through excess of sweetness, become gradually embittered in

the soul and then intolerable . . . The queen had received him alone, in her

private apartments, consisting of three rooms of incomparable luxury, where

every sound was muffled by cushions. She lay upon her left side, embedded, at

it were, in a litter of greenish silks which, by reflection, bathed the black

locks of her hair in purple. Her youthful body was arrayed in a daring

open-worked costume which she had had made before her eyes by a Phrygian

courtesan, and which exposed the twenty-two places where caresses are

irresistible. One had no need to take off that costume during a whole night,

even though one exhausted one’s amorous imagination beyond the most

extravagant dreams.

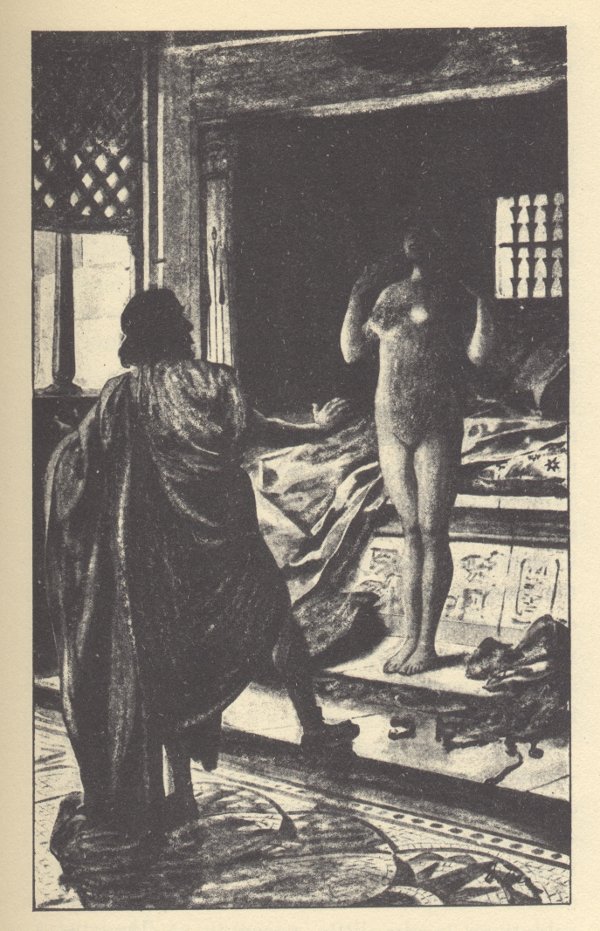

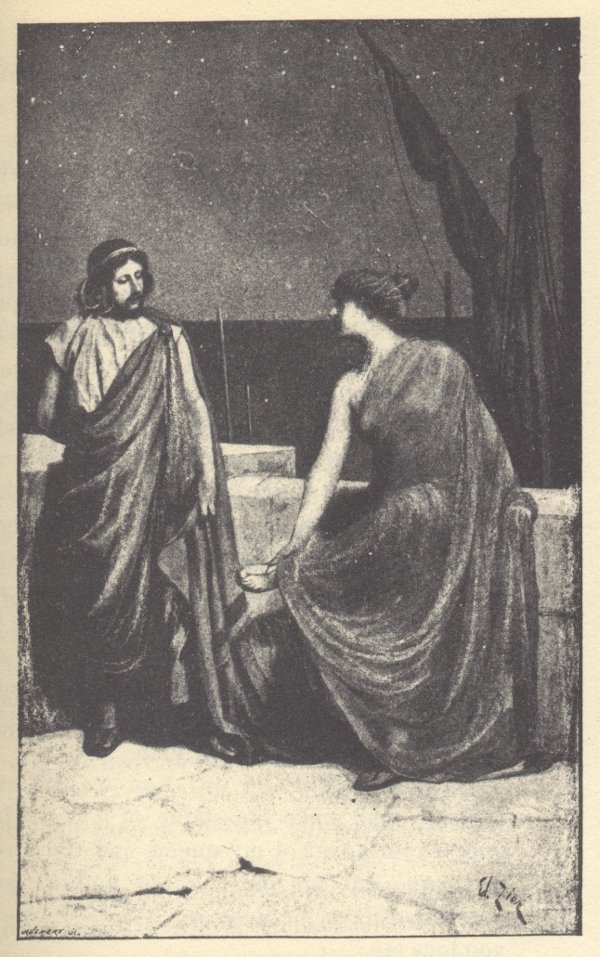

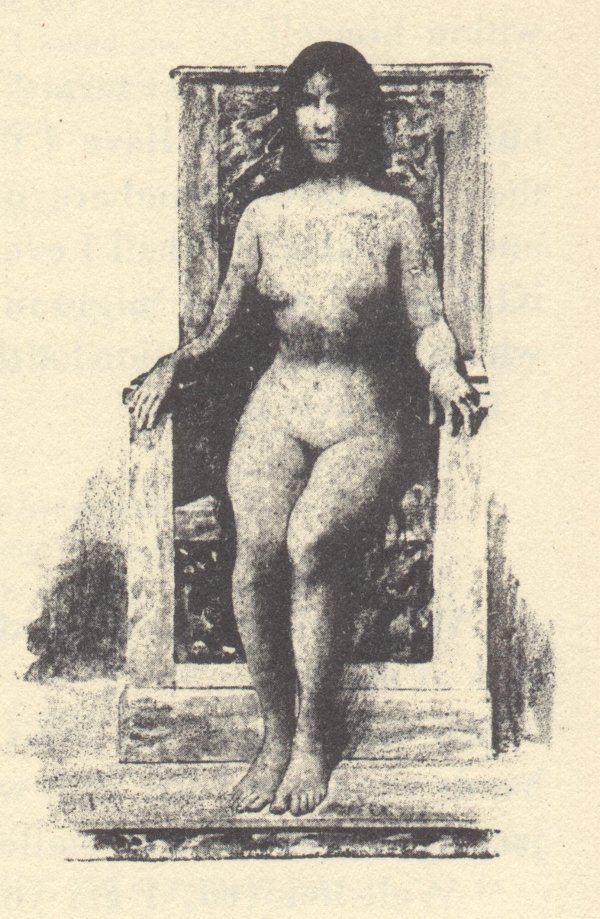

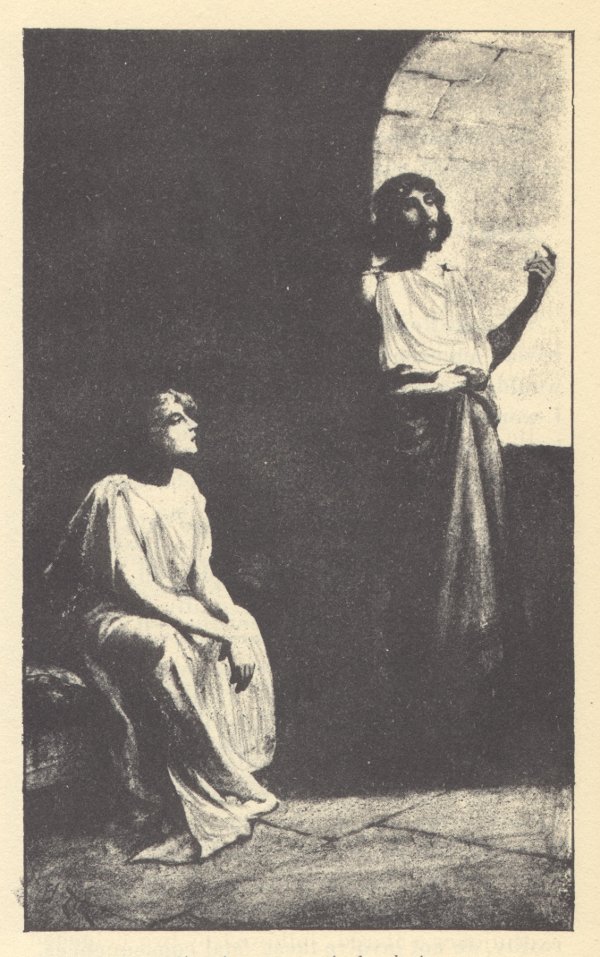

Demetrios fell respectfully on his knees, and took Queen Berenice’s naked

little foot in his hand, in order to kiss it, as one kisses an object delicate

and rare.

Then she rose.

Simply, like a beautiful slave posing, she undid her corselet, her bandelettes,

her open drawers, took off the very bracelets from her arms, the rings from her

ankles, and stood up erect, with her hands open before her shoulders, her head

slightly thrown back, and her coral coif trembling upon her cheeks.

She was the daughter of a Ptolemy and a Syrian princess descended from all the

gods, through Astarte, whom the Greeks call Aphrodite. Demetrios knew this, and

that she was proud of her Olympian lineage. Accordingly he was not disconcerted

when the queen said to him without moving: “I am Astarte. Take a block of

marble and your chisel and reveal me to the men of Egypt. I desire them to

worship my image.”

“I am Astarte. Take a block of marble and your chisel and

reveal me to the men of Egypt. I desire them to worship my image.”

Demetrios looked at her, and divined, unerringly, the artless, novel sensuality

with which this young girl’s body was animated. He said, “I am the

first to worship it,” and he took her in his arms. The queen was not

angry at this brusquerie, but stepped back a pace and asked, “You think

yourself Adonis, that you dare to lay hands on the goddess?” He answered,

“Yes.” She looked at him, smiled a little, and concluded.

“You are right.”

Thus was why he became insupportable, and his best friends left him; but he

ravished the hearts of all women.

When he entered one of the apartments of the palace, the women of the court

ceased talking, and the other women listened to him too, for the sound of his

voice was an ecstasy. If he took refuge with the queen, their persecution

followed him even there, under pretexts ever new. Did he wander through the

streets, the folds of his tunic became filled with little papyri on which the

women wrote their names with words of anguish. But he crumpled them up without

reading them. He was tired of all that. When his handiwork was set up in the

temple of Aphrodite, the sacred enclosure was invaded at every hour of the

night by the crowd of his feminine adorers, who came to read his name chiselled

in the stone and offer a wealth of doves and roses to their living god.

His house was soon encumbered with gifts, which he accepted at first out of

negligence, but ended by refusing all, when he understood what was desired of

him, and that he was being treated like a prostitute. His very slave-women

offered themselves. He had them whipped, and sold them to the little porneion

at Rhacotis. Then his men-slaves, seduced by presents, opened his door to

unknown women whom he found at his bed-side when he came home, and whose

attitude left no doubt as to their passionate intentions. The trinkets of his

toilet-table disappeared one after the other; more than one of the women of the

town had a sandal or a belt of his, a cup from which he had drunk, even the

stones of the fruit he had eaten. If he dropped a flower as he walked, he did

not find it again. The women would have picked up the very dust upon which his

shoes had trampled.

In addition to the fact that this persecution was becoming dangerous and

threatened to kill all his sensibility, he had reached the stage of manhood at

which a thinking man perceives the urgency of dividing his life into two parts,

and of ceasing to confound the things of the intellect with the exigencies of

the senses. The statue of Aphrodite was for him the sublime pretext of this

moral conversion. The highest realization of the queen’s beauty, all the

idealism it was possible to read into the supple lines of her body, Demetrios

had evoked it all from the marble, and from that day onward he imagined that no

other woman on earth would ever attain to the level of his dream. His statue

became the object of his passion. He adored it only, and madly divorced from

the flesh the supreme idea of the goddess, all the more immaterial because he

had attached it to life.

When he again saw the queen herself, she seemed to him destitute of everything

which had constituted her charm. She served for a certain time to hoodwink his

aimless desires, but she was at once too different from the Other, and too like

her. When she sank down in exhaustion after his embraces, and incontinently

went to sleep, he looked at her as if she were an intruder who had adopted the

semblance of the beloved one and usurped her place in his bed. The arms of the

Other were more slender, her breast more finely cut, her hips narrower than

those of the Real one. The latter did not possess the three furrows of the

groins, thin as lines, that he had graved upon the marble. He finally wearied

of her.

His feminine adorers were aware of it, and though he continued his daily visits

it was known that he ceased to be amorous of Berenice. And the enthusiasm on

his account doubled. He paid no attention to it. In point of fact, he had need

of a change of quite other importance.

It often happens that in the interval between two mistresses a man is tempted

and satisfied by vulgar dissipation. Demetrios succumbed to it. When the

necessity of going to the palace was more distasteful to him than usual, he

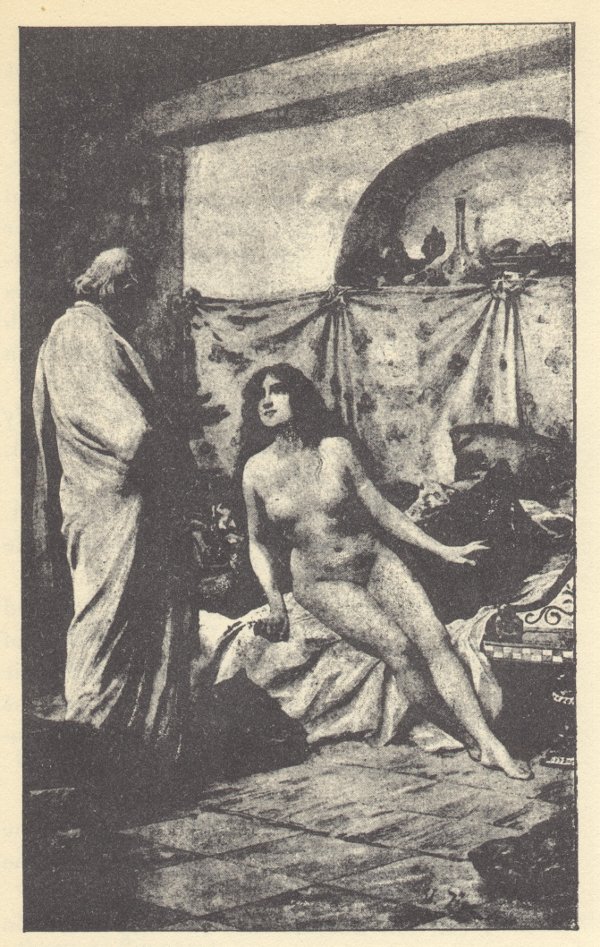

went off at night to the garden of the sacred courtesans. This garden

surrounded the temple on every side.

The women who frequented it did not know him. Moreover, they were so wearied by

the superfluity of their loves that they had neither exclamations nor tears,

and the satisfaction he was in search of was not dashed, in that quarter at

least, by those frenzied cat-cries with which the queen exasperated him.

His conversation with these fair, self-possessed ladies was idle and

unaffected. The day’s visitors, the probable weather on the morrow, the

softness of the grass, the mildness of the night—these were the charming

topics. They did not beg him to express his theories in statuary, and they did

not give their opinion upon the Achilleus of Scopas. If it befell that they

dismissed the lover who had chosen them, and that they thought him handsome and

told him so, he was quite at liberty not to believe in their disinterestedness.

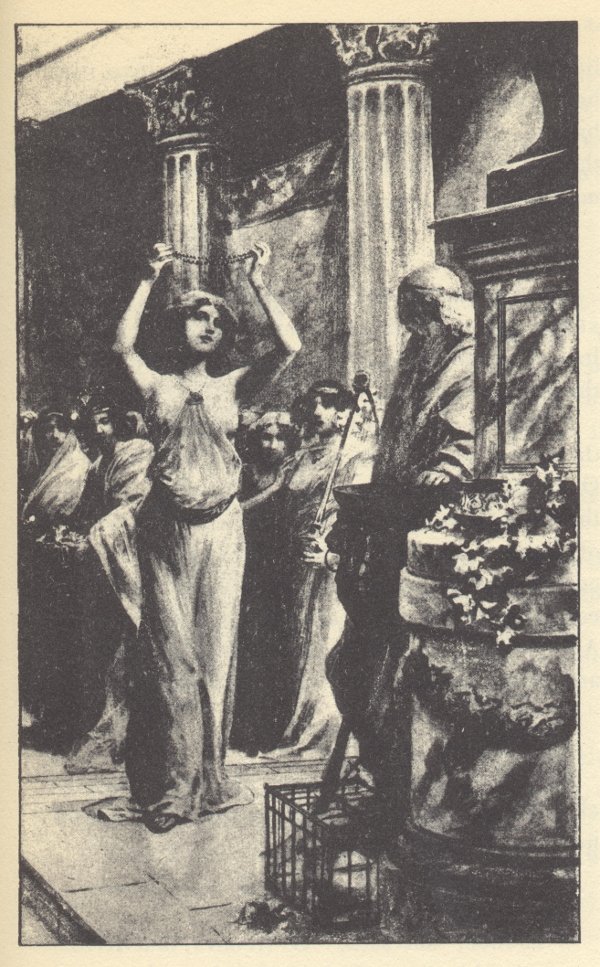

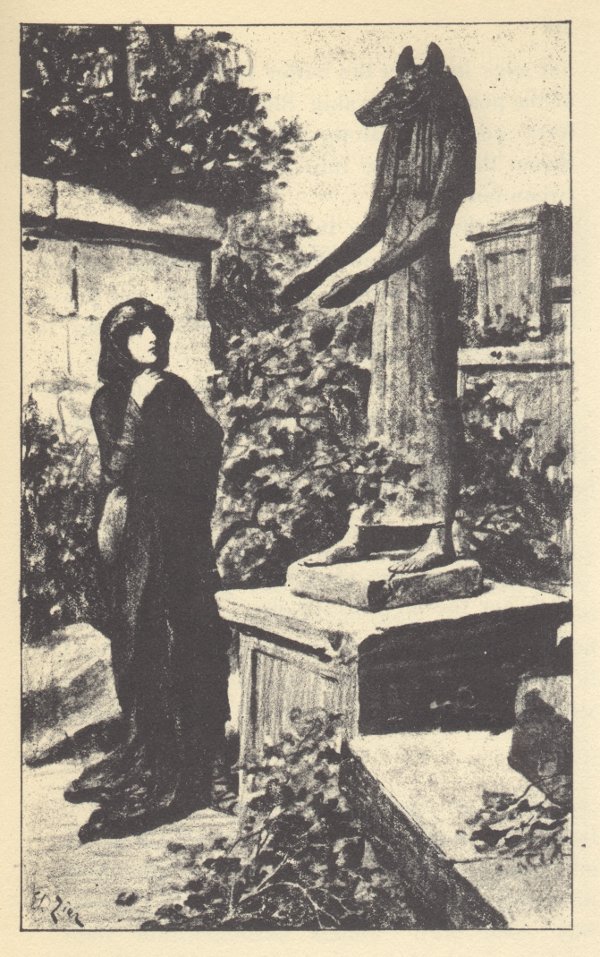

When freed from the embrace of their religious arms, he mounted the temple

steps and fell to an ecstatic contemplation of the statue.

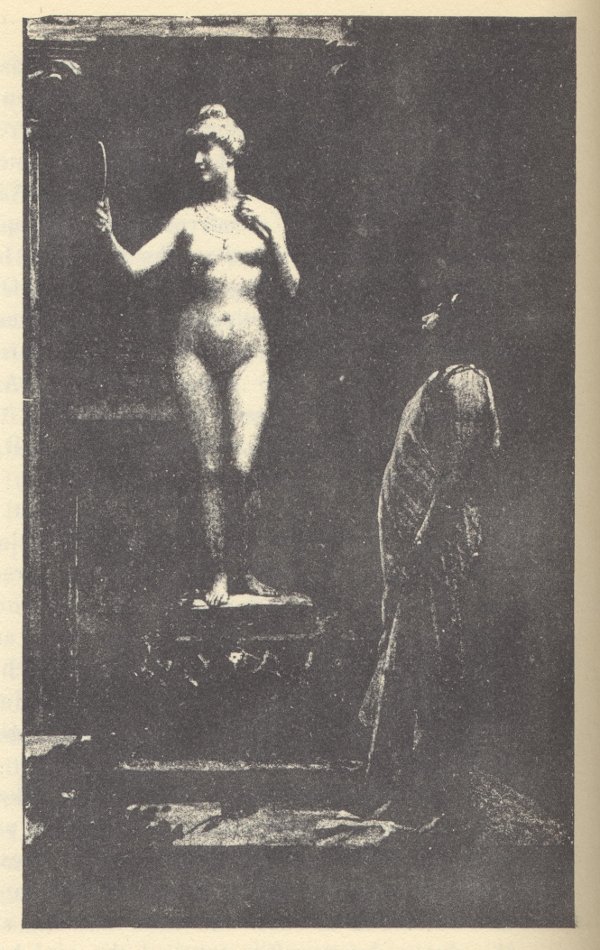

Between the slim columns crowned with Ionian volutes, the goddess stood

instinct with life upon a pedestal of rose-coloured stone laden with rich

votive offerings. She was naked and fully sexed, tinted vaguely and like a

woman. In one hand she held her mirror, the handle of which was a priapus, and

with the other she adorned her beauty with a pearl necklace of seven strings. A

pearl larger than the others, long and silvery, gleamed between her two

breasts, like the moon’s crescent between two round clouds.

Demetrios contemplated her tenderly, and would fain have believed, like the

common people, that they were real sacred pearls, born of the drops of water

which had rolled in the shell of Anadyomene.

“O divine sister!” he would say. “O flowered one! O

transfigured one! You are no longer the little Asiatic woman whom I made your

unworthy model. You are her immortal Idea, the terrestrial soul of Astarte, the

mother of her race. You shone in her blazing eyes, you burned in her sombre

lips, you swooned in her soft hands, you gaped in her great breasts, you

strained in entwining legs, long ago, before your birth; and the food which the

daughter of a sinner hungers for is your tyrant also, you, a goddess, the

mother of gods and men, the joy and anguish of the world. But I have seen you,

evolved you, caught you, O marvelous Cytherea! It is not to your image, it is

to yourself that I have given your mirror, and yourself that I have covered

with pearls, as on the day when you were born of the fiery heaven and the

laughing foam of the sea, like the dew-steeped dawn, and escorted with

acclamations by blue tritons to the shores of Cyprus.”

He had been adoring her after this fashion when he entered the quay, at the

hour when the crowd was melting away, and he heard the anguish and tears of the

flute-girls’ chant.

But he had spurned the courtesans of the temple that evening, because a glimpse

of a couple beneath the branches had stirred him with disgust and revolted him

to the soul.

The kindly influence of the night penetrated him little by little. He turned

his face of the wind, the wind that had passed over the sea and seemed to carry

to Egypt the lingering scent of the sweet-smelling roses of Amathus.

Beautiful feminine forms took shape in his brain. He had been asked for a group

of the three Charites, enclasping one another, for the garden of the goddess,

but it was distasteful to his youthful genius to copy conventions, and he

dreamed of bringing together on the same block of marble the three graceful

motions of woman. Two of the Charites were to be dressed, one holding a fan and

half closing her eyelids to the gently-swaying feathers; the other dancing in

the folds of her robe. The third should be standing naked behind her sisters,

and, with her uplifted arms, would be twisting the thick mass of her hair upon

her neck.

His mind conceived still other projects, as, for example, to erect, upon the

rocks of Pharos, an Andromeda of black marble confronting the tumultuous

monster of the sea, or to enclose the agora of Brouchion between the four

horses of the rising sun, like wrathful Pegasi; and what was not his exultant

rapture at the idea, which began to germinate within him, of a Zagreus

terror-stricken by the approaching Titans? Ah! how beauty had once more taken

him for its own! how he was escaping from the clutches of love! how he was

separating from the flesh the supreme idea of the goddess! In a word, how free

he felt!

Now, he turned his head towards the quays, and, in the distance, saw the yellow

shimmer of a woman’s veil.

IV

THE PASSER-BY

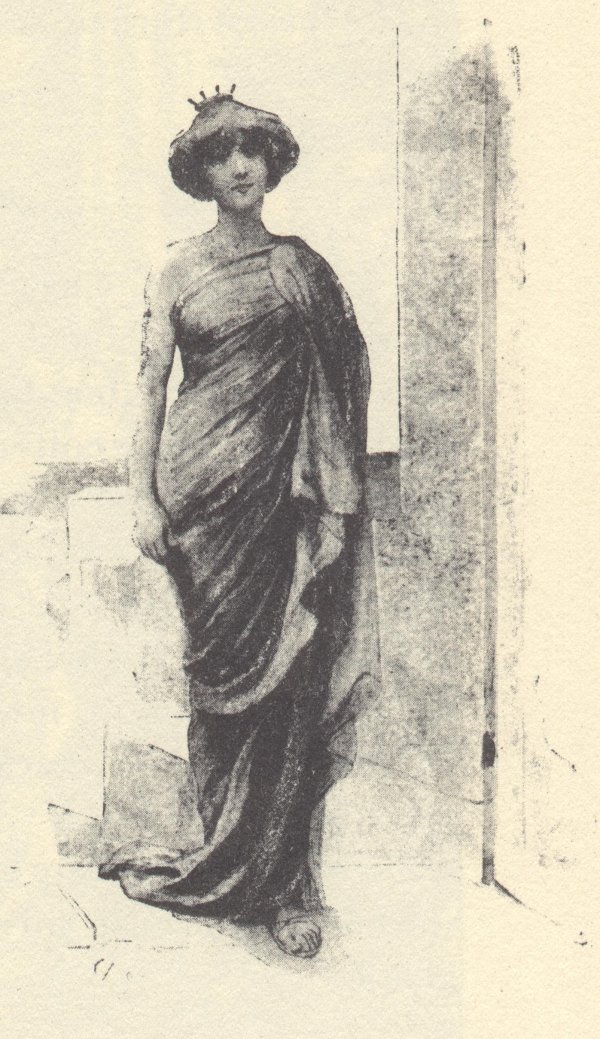

She carried slowly along the deserted quay, which was bathed in moonlight. Her

head leaned over one shoulder. A little shadow danced and flickered before her

footsteps.

Demetrios watched her as she drew near.

Diagonal folds intersected the little one saw of her body through the thin

tissue; one of her elbows stood out in relief under the tight tunic, and the

other arm, which she had left bare, carried the long train, holding it high out

of the dust.

He recognised by her jewels that she was a courtesan. In order to avoid her

salutation he crossed the road rapidly.

He did not want to look at her. He obstinately centered his thoughts upon the

rough plan of his Zagreus. Nevertheless his eyes turned in the direction of the

passer-by.

Then he saw that she did not stop, that she paid no attention to him, that she

did not even affect to look at the sea, or to raise the front of her veil, or

to absorb herself in her reflections; but that she was merely taking a walk by

herself and was in search of nothing but the freshness of the breeze, solitude,

abandonment, the subtle thrill of silence.

Demetrios did not take his eyes off her, and fell into a singular astonishment.

She continued to walk like a yellow shadow in the distance, nonchalant, and

preceded by the little black shadow.

He heard at each step the slight creak of her shoe in the dust.

She walked on as far as the island of Pharos and went up into the rocks.

Suddenly, and as if he had loved this unknown woman for a long time, Demetrios

ran after her, then stopped, retraced his steps, trembled, got angry with

himself, tried to leave the quay; but he had never utilised his will except in

the service of his pleasure, and when it was time to set it in motion for the

salvation of his character and the ordering of his life, he felt completely

powerless and nailed to the spot on which he stood.

As he could not throw off the thought of this woman, he tried to find excuses

in his own eyes for the preoccupation which was so violently distracting him.

He imagined that his admiration for the graceful apparition was due to a purely

æsthetic sentiment, and he said to himself that she would make a perfect model

for the Charis with the fan which he intended to design on the morrow.

Then, suddenly, all his thoughts became confused, and a crowd of anxious

questions surged up into his mind about this woman in yellow.

What was she doing in the island at this hour of the night? Why, for whom had

she left home so late? Why had she not addressed him? She had seen him,

certainly she had seen him while he was crossing the quay. Why had she gone her

way without a word of salutation? It was rumoured that certain women sometimes

chose the fresh hours before the dawn to bathe in the sea. But there was no

bathing at Pharos. The sea was too deep. Besides, how unlikely that a woman

would be covered with all those jewels for no other object than to go bathing!

Then what took her so far from Rhacotis? A rendezvous perhaps? Some young rake,

avid of variety, who had chosen for a temporary bed the great rocks polished by

the waves?

Demetrios wished to be certain. But the young woman was already returning, with

the same calm and indolent step. The sluggish radiance of the moon shone full

upon her face as she advanced, brushing the dust of the parapet with the end of

her fan.

V

THE MIRROR, THE COMB, AND THE NECKLACE

She had a special beauty of her own. Her hair seemed two masses of gold, but it

was too abundant, and it padded her low forehead with two heavy waves charged

with amber, which swallowed up the ears and twisted themselves into a

seven-fold coil upon the nape of the neck. The nose was delicate, with

expressive nostrils which palpitated sometimes, surmounting a thick and painted

mouth, with rounded mobile corners. The supple line of the body undulated at

every stop, receiving animation from the harmonious motion of her unfettered

breasts, or from the swing of the beautiful hips that supported her lissom

waist.

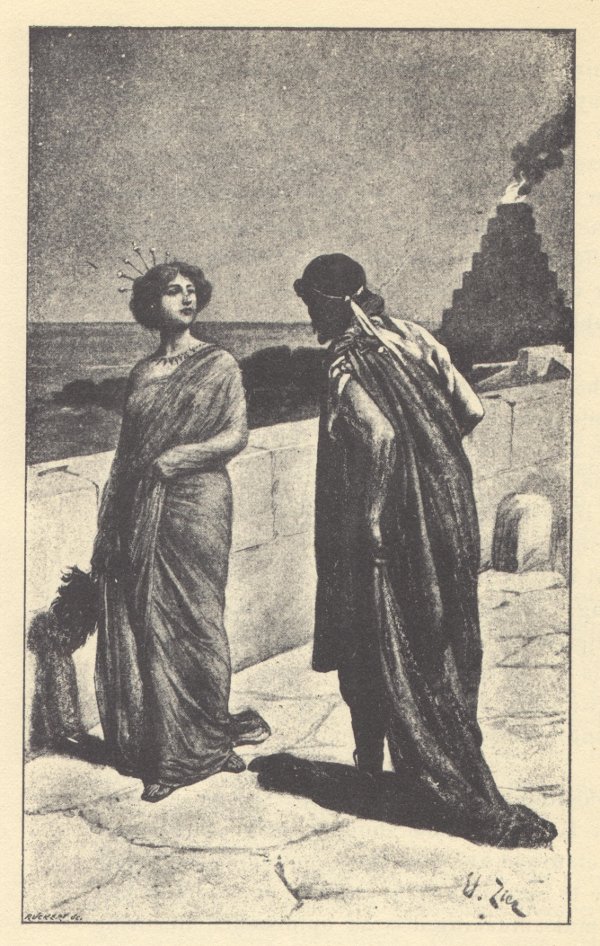

When she was within ten paces of the young man, she turned her eyes upon him.

Demetrios was seized with trembling. They were extraordinary eyes; blue, but

deep and brilliant at the same time, humid, weary, bathed in tears and flashing

fire, almost closed under the weight of the eyelids and eyelashes. The glance

of these eyes was like the siren’s song. Whosoever crossed their path was

inevitably a captive. She knew it well, and cunningly she used their virtue;

but she counted still more upon affected indifference as a weapon of attack

against the man whom so much sincere love had been incapable of touching

deeply.

The navigators who have sailed over the purple seas, beyond the Ganges, relate

that they have seen, beneath the water, rocks of magnetic stone. When ships

pass near them, the nails and iron fittings are wrenched down to the submarine

cliff and remain fixed to it for ever. And what was once a swift craft, a

habitation, a living being, becomes nought but a flotsam of planks, scattered

by the winds, tossed by the waves. Thus did Demetrios, in the presence of the

spell of two great eyes, lose his very self, and all his strength ebbed away.

She lowered her eyes and passed by close to him. He could have shouted with

impatience. He clenched his fists. He was afraid of not being able to recover a

calm attitude, for speak to her he must. Nevertheless he approached her with

the formula of convention.

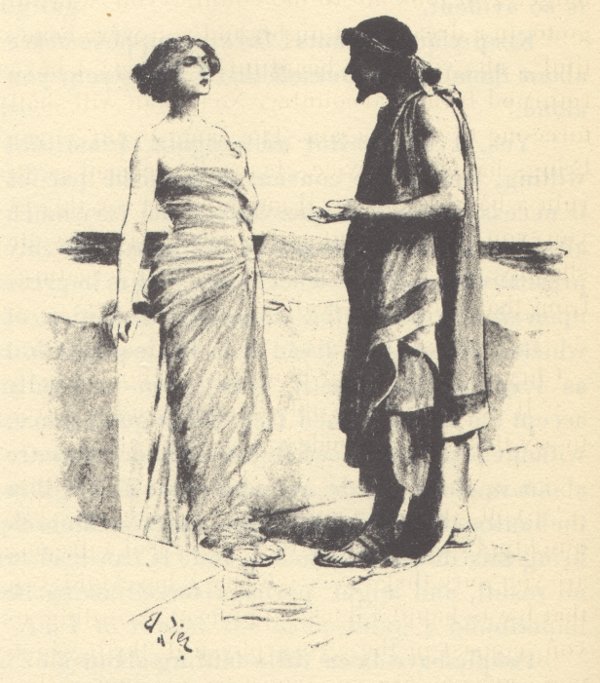

“I salute you,” said he.

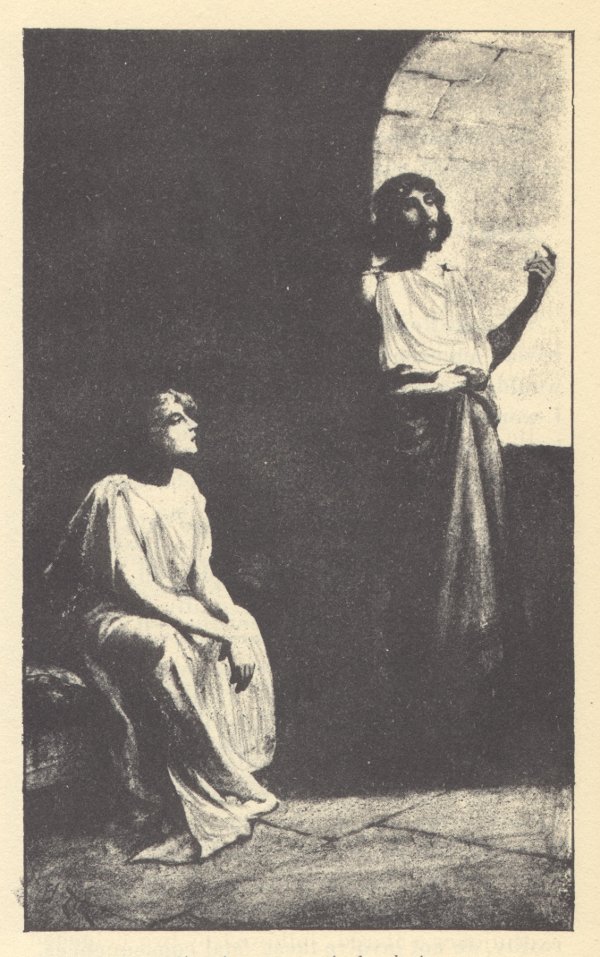

“I salute you,” said he. “I salute you also,”

answered the woman

“I salute you also,” answered the woman.

Demetrios continued:

“Where are you going to in so leisurely a fashion?”

“I am going home.”

“Alone?”

“Alone.”

And she made a movement as if to resume her walk.

Then Demetrios thought that perhaps he had made a mistake in taking her for a

courtesan. For some time past, the wives of the magistrates and functionaries

had taken to dressing and painting themselves like the women of pleasure. She

was probably a woman of honourable reputation, and it was not without irony

that he finished his question thus:

“To your husband?”

She put her two hands to her sides and began to laugh.

“I haven’t one this evening.”

Demetrios bit his lip and suggested, almost timidly:

“Don’t look for one. You have set to work too late. There is no one

about now.”

“Who told you that I was looking for one? I am taking a walk by myself,

and am looking for nothing.”

“Where have you come from then? You certainly have not put on all those

jewels for your own pleasure, and that silken veil. . .”

“Would you have me go out naked, or dressed in wool like a slave-woman? I

dress for my own benefit. I like to know that I am beautiful, and I look at my

fingers as I walk in order to recognise all my rings. . . . .”

“You ought to have a mirror in your hand and look at nothing but your

eyes. Those eyes did not see the light at Alexandria. You are a Jewess. I

recognise it by your voice, which is softer than ours.”

“No, I am not a Jewess. I am a Galilæn.”

“What is your name, Miriam or Noëmi?”

“My Syriac name you shall not know. It is a royal name which is not home

here. My friends call me Chrysis, and it is a compliment that you might have

paid me.”

He put his hand on her arm.

“Oh! no, no,” she said mockingly. “It is much too late for

this kind of trifling. Let me go home quickly. I have been up for nearly three

hours. I am dying of hunger.”

Bending down, she took her foot in her hand:

Bending down, she took her foot in her hand.

“See how my little thongs hurt me. They are too tightly strapped. If I do

not loose them in a moment, I shall have a mark on my foot, and that will be a

pretty object to kiss. Leave me quickly. Ah! what an ado! If I had known, I

would not have stopped. My yellow veil is all crumpled at the waist,

look.”

Demetrios passed his hand over his forehead; then, with the careless air of a

man who condescends to make his choice, he murmured:

“Show me the way.”

“I shall do nothing of the kind,” said Chrysis with a stupefied

air. “You do not even ask me whether it is my pleasure.

“Show me the way! Listen to him! Do you take me for a porneion-girl, who

puts herself on her back for three obols without looking to see who is

possessing her? Do you even know whether I am free? Do you know what

appointments I may have? Have you followed me in the street? Have you noted the

doors that open for me? Have you counted the men who think they are loved by

Chrysis? Show me the way! I shall not show it you, if you please. Stay here or

go away, but you shall not go home with me!”

“You do not know who I am.”

“You? Of course I do! You are Demetrios of Saïs; you made the statue of

my goddess; you are the lover of my queen and the lord of my town. But for me

you are nothing but a handsome slave, because you have seen me and you love

me.”

She came a little nearer to him, and went on in a caressing voice:

“Yes, you love me. Oh! don’t interrupt me. I know what you are

going to say: you love no one, you are loved. You are the Well-beloved, the

Darling, the Idol. You refused Glycera, who had refused Antiochus. Demonassa

the Lesbian, who had sworn to die a virgin, entered your bed during your sleep,

and would have taken you by force if your two Lybian slaves had not put her

naked into the street. Callistion, the well-named, despairing of approaching

you, has bought the house opposite yours, and shows herself at the open window

in the morning, as scantily dressed as Artemis in the bath. You think that I do

not know all that? But we courtesans hear of everything. I heard of you the

night of your arrival at Alexandria; and since then not a single day has passed

without your name being mentioned. I even know things you have forgotten. I

even know things that you do not yet know yourself. Poor little Phyllis hanged

herself the day before yesterday on your door-post, did she not? well, the

fashion is catching. Lyde has done like Phyllis: I saw her this evening as I

passed, she was quite blue, but the tears were not yet dry upon her cheeks. You

don’t know who Lyde is? a child, a little fifteen-year-old courtesan whom

her mother sold last month to a Samian shipwright who was passing the night at

Alexandria before going up the river to Thebes. She came to see me. I gave her

some advice; she knew absolutely nothing, not even how to play at dice. I often

took her in my bed, because, when she had no lover, she did not know where to

sleep. And she loved you! If you had seen her hug me to her and call me by your

name. She wanted to write to you. Do you understand? I told her it was not

worth while . . .”

Demetrios gazed at her without understanding.

“Yes, all that is a pure matter of indifference to you, is it not?”

continued Chrysis. “You did not love her. It is I that you love. You have

not even listened to what I have just told you. I am sure you could not repeat

a single word. You are absorbed in wondering how my eyelids are made up,

speculating on the sweetness of my mouth, on the softness of my hair. Ah! how

many others know all this! All who have desired me have had their pleasure upon

me: men, young men, old men, children, women, young girls. I have refused

nobody, do you understand? For seven years, Demetrios, I have only slept alone

three nights. Count how many lovers that makes. Two thousand five hundred and

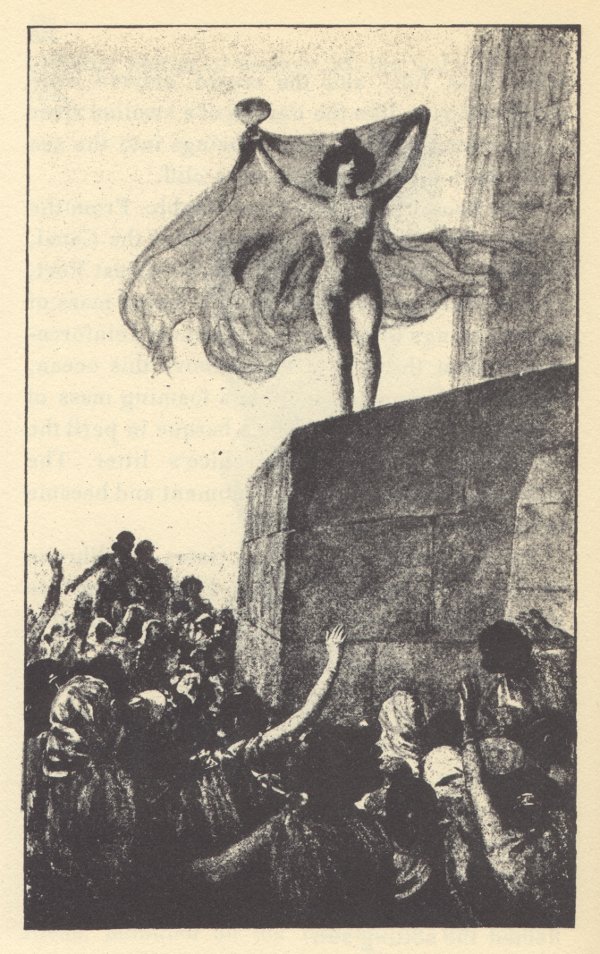

more. I do not include those that came in the daytime. Last year I danced naked

before twenty thousand persons, and I know that you were not one of them. Do

you think that I hide myself? Ah! for what, pray? All the women have seen me in

the bath. All the men have seen me in bed. You alone, you shall never see me. I

refuse you. I refuse you. You shall never know anything of what I am, of what I

feel, of my beauty, of my love! You are an abominable man, fatuous, cruel,

insensible, cowardly! I don’t know why one of us has not had enough

hatred to kill you both in one another’s arms, first you, and afterwards

the queen.”

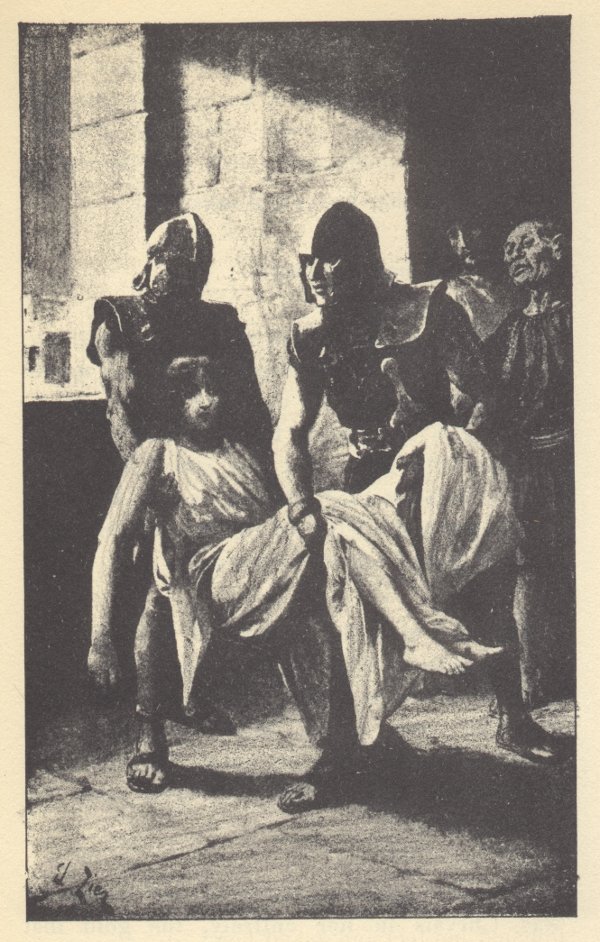

Demetrios quietly took her by the two arms, and, without answering a word, bent

her backwards with violence.

She had a moment’s anguish; but suddenly she stiffened her knees,

stiffened her elbows, backed a little, and said in a low voice:

“Ah! I am not afraid of that, Demetrios! you shall never take me by

force, were I as feeble as an amorous virgin and you as strong as a son of

Atlas. You desire not only the satisfaction of your own senses, but chiefly of

mine. Moreover, you want to see me from head to foot, because you believe that

I am beautiful, and I am beautiful indeed. Now the moon gives less light than

my twelve waxen torches. It is almost dark here. And then it is not customary

to undress upon the quay. I could not dress myself again without the help of my

slave. Let me free, you hurt my arms.”

They were silent for a few minutes; then Demetrios answered:

“We must have done with this, Chrysis. You know well that I shall not

force you. But let me follow you. However proud you are, you would pay dearly

for the glory of refusing Demetrios.”

Chrysis still kept silence. He continued more gently:

“What are you afraid of?”

“You are accustomed to the love of others. Do you know what ought to be

given to a courtesan who does not love?”

He became impatient.

“I do not ask you to love me. I am tired of being loved. I do not want to

be loved. I ask you to abandon yourself. For that, I will give you all the gold

in the world. I have it in Egypt.”

“I have it in my hair. I am tired of gold. I don’t want gold. I

want but three things. Will you give them to me?”

Demetrios felt that she was going to ask for the impossible. He looked at her

anxiously. But she began to smile, and said in slow tones:

“I want a silver mirror to gaze at my eyes within my eyes.”

“You shall have it. What else do you want? Quickly.”

“I want a carved ivory comb to plunge into my hair like a net into water

that sparkles in the sun.”

“And then?”

“You will give me my comb?”

“Yes, yes. Go on.”

“I want a pearl necklace to hang on my breast, when I dance you the

nuptial dances of my country in my chamber.”

He raised his eyebrows;

“Is that all?”

“You will give me my necklace?”

“Any you please.”

Her voice became very tender.

“Any I please? Ah! that is exactly what I wanted to ask you. Will you let

me choose my presents?”

“Of course.”

“You swear?”

“I swear.”

“What oath will you swear?”

“Dictate it to me.”

“By the Aphrodite you carved.”

“I swear by the Aphrodite. But why these precautions?”

“Ah! . . . I was uneasy; but now I am reassured”.

She raised her head.

“I have chosen my presents.”

Demetrios suddenly became anxious and asked:

“Already?”

“Yes. Do you think I shall accept any sort of silver mirror, bought of a

merchant of Smyrna, or some stray courtesan. I want the mirror of my friend

Bacchis, who stole a lover from me last week and jeered at me spitefully in a

little orgie she had with Tryphera, Mousarion, and some young fools who

repeated everything to me. It is a mirror she prizes greatly because it

belonged to Ithodopis, who was fellow-slave with æsop and was redeemed by

Sappho’s brother. You know that she is a very celebrated courtesan. Her

mirror is magnificent. It is said that Sappho used it, and it is for this

reason that Bacchis lays store on it. She has nothing more precious in the

world; but I know where you will find it. She told me one night, when she was

intoxicated. It is under the third stone of the altar. She puts it there every

evening when she leaves her house at sunset. Go to-morrow to her house at that

hour and fear nothing: she takes her slaves with her.”

“This is pure madness,” cried Demetrios. “Do you expect me to

steal?”

“Do you not love me? I thought that you loved me. And then, have you not

sworn? I thought you had sworn. If I am mistaken, let us say no more about

it.”

He understood that she was ruining him, but he yielded without a struggle,

almost willingly.

“I will do what you say,” he answered.

“Oh! I know well that you will. But you hesitate at first. I understand

that. It is not an ordinary present. I would not ask it of a philosopher. I ask

you for it. I know well that you will give it me.”

She toyed a moment with the peacock feathers of her round fan, and suddenly:

“Ah! . . . Neither do I wish for a common ivory comb bought at a

tradesman’s in the town. You told me I might choose, did you not? Well, I

want . . . I want the carved ivory comb in the hair of the wife of the high

priest. It is much more valuable than the mirror of Rhodopis. It came from a

queen of Egypt who lived a long time ago, and whose name is so difficult that I

cannot pronounce it. Consequently the ivory is very old, and as yellow as if it

were gilded. It has a carved figure of a young girl walking in a lotus-marsh.

The lotus is higher than she is, and she is stepping on tiptoe in order not to

get wet. . . . . It is really a beautiful comb. I am glad you are going to give

it to me. I have also some little grievances against its present possessor. I

had offered a blue veil to Aphrodite last month; I saw it on this woman’s

head next day. It was a little hasty, and I bore her a grudge for it. Her comb

will avenge me for my veil.”

“And how am I to get it?” asked Demetrios.

“Ah! that will be a little more difficult. She is an Egyptian, you know,

and she makes up her two hundred plaits only once a year, like the other women

of her race. But I want my comb to-morrow, and you must kill her to get it. You

have sworn an oath.”

She pouted at Demetrios, who was looking on the ground. Then she concluded very

quickly:

“I have chosen my necklace also. I want the seven-stringed pearl necklace

on the neck of Aphrodite.”

Demetrios started violently.

“Ah! this time, it is too much! You shall not have the laugh of me to the

end! Nothing, do you understand? neither the mirror, nor the comb, nor the

collar.”

But she closed his mouth with her hand and resumed her caressing tone:

But she closed his mouth with her hand.

“Don’t say that. You know well that you will give me this too. I am

sure of it. I shall have the three gifts. You will come to see me to-morrow

evening, and the day after to-morrow if you like, and every evening. I shall be

at home at any hour, in the costume you prefer, painted according to your

taste, with my hair dressed after your pleasure, ready for your most

extravagant caprices. If you desire but tender love, I will cherish you like a

child. If you thirst after rare sensations, I will not refuse you the most

agonising. If you wish for silence, I will hold my peace, when you want me to