Title: Mercedes of Castile; Or, The Voyage to Cathay

Author: James Fenimore Cooper

Illustrator: Felix Octavius Carr Darley

Release date: June 13, 2011 [eBook #36406]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHAPTER XXIX.

CHAPTER XXX.

CHAPTER XXXI.

"Columbus kneeled on the sands, and received the benediction."

"In vain Luis endeavored to persuade the devoted girl to withdraw."

So much has been written of late years, touching the discovery of America, that it would not be at all surprising should there exist a disposition in a certain class of readers to deny the accuracy of all the statements in this work. Some may refer to history, with a view to prove that there never were such persons as our hero and heroine, and fancy that by establishing these facts, they completely destroy the authenticity of the whole book. In answer to this anticipated objection, we will state, that after carefully perusing several of the Spanish writers—from Cervantes to the translator of the journal of Columbus, the Alpha and Omega of peninsular literature—and after having read both Irving and Prescott from beginning to end, we do not find a syllable in either of them, that we understand to be conclusive evidence, or indeed to be any evidence at all, on the portions of our subject that are likely to be disputed. Until some solid affirmative proof, therefore, can be produced against us, we shall hold our case to be made out, and rest our claims to be believed on the authority of our own statements. Nor do we think there is any thing either unreasonable or unusual in this course, as perhaps the greater portion of that which is daily and hourly offered to the credence of the American public, rests on the same species of testimony—with the trifling difference that we state truths, with a profession of fiction, while the great moral caterers of the age state fiction with the profession of truth. If any advantage can be fairly obtained over us, in consequence of this trifling discrepancy, we must submit.

There is one point, notwithstanding, concerning which it may be well to be frank at once. The narrative of the "Voyage to Cathay," has been written with the journal of the Admiral before us; or, rather, with all of that journal that has been given to the world through the agency of a very incompetent and meagre editor. Nothing is plainer than the general fact that this person did not always understand his author, and in one particular circumstance he has written so obscurely, as not a little to embarrass even a novelist, whose functions naturally include an entire familiarity with the thoughts, emotions, characters, and, occasionally, with the unknown fates of the subjects of his pen. The nautical day formerly commenced at meridian, and, with all our native ingenuity and high professional prerogatives, we have not been able to discover whether the editor of the journal has adopted that mode of counting time, or whether he has condescended to use the more vulgar and irrational practice of landsmen. It is our opinion, however, that in the spirit of impartiality which becomes an historian, he has adopted both. This little peculiarity might possibly embarrass a superficial critic; but accurate critics being so very common, we feel no concern on this head, well knowing that they will be much more apt to wink at these minor inconsistencies, than to pass over an error of the press, or a comma with a broken tail. As we wish to live on good terms with this useful class of our fellow-creatures, we have directed the printers to mis-spell some eight or ten words for their convenience, and to save them from headaches, have honestly stated this principal difficulty ourselves.

Should the publicity which is now given to the consequences of commencing a day in the middle have the effect to induce the government to order that it shall, in future, with all American seamen, commence at one of its ends, something will be gained in the way of simplicity, and the writing of novels will, in-so-much, be rendered easier and more agreeable.

As respects the minor characters of this work, very little need be said. Every one knows that Columbus had seamen in his vessels, and that he brought some of the natives of the islands he had discovered, back with him to Spain. The reader is now made much more intimately acquainted with certain of these individuals, we will venture to say, than he can be possibly by the perusal of any work previously written. As for the subordinate incidents connected with the more familiar events of the age, it is hoped they will be found so completely to fill up this branch of the subject, as to render future investigations unnecessary.

Whether we take the pictures of the inimitable Cervantes, or of that scarcely less meritorious author from whom Le Sage has borrowed his immortal tale, for our guides; whether we confide in the graver legends of history, or put our trust in the accounts of modern travellers, the time has scarcely ever existed when the inns of Spain were good, or the roads safe. These are two of the blessings of civilization which the people of the peninsula would really seem destined never to attain; for, in all ages, we hear, or have heard, of wrongs done the traveller equally by the robber and the host. If such are the facts to-day, such also were the facts in the middle of the fifteenth century, the period to which we desire to carry back the reader in imagination.

At the commencement of the month of October, in the year of our Lord 1469, John of Trastamara reigned in Aragon, holding his court at a place called Zaragosa, a town lying on the Ebro, the name of which is supposed to be a corruption of Cæsar Augustus, and a city that has become celebrated in our own times, under the more Anglicised term of Saragossa, for its deeds in arms. John of Trastamara, or, as it was more usual to style him, agreeably to the nomenclature of kings, John II., was one of the most sagacious monarchs of his age; but he had become impoverished by many conflicts with the turbulent, or, as it may be more courtly to say, the liberty-loving Catalonians; had frequently enough to do to maintain his seat on the throne; possessed a party-colored empire that included within its sway, besides his native Aragon with its dependencies of Valencia and Catalonia, Sicily and the Balearic Islands, with some very questionable rights in Navarre. By the will of his elder brother and predecessor, the crown of Naples had descended to an illegitimate son of the latter, else would that kingdom have been added to the list. The King of Aragon had seen a long and troubled reign, and, at this very moment, his treasury was nearly exhausted by his efforts to subdue the truculent Catalans, though he was nearer a triumph than he could then foresee, his competitor, the Duke of Lorraine, dying suddenly, only two short months after the precise period chosen for the commencement of our tale. But it is denied to man to look into the future, and on the 9th of the month just mentioned, the ingenuity of the royal treasurer was most sorely taxed, there having arisen an unexpected demand for a considerable sum of money, at the very moment that the army was about to disband itself for the want of pay, and the public coffers contained only the very moderate sum of three hundred Enriques, or Henrys—a gold coin named after a previous monarch, and which had a value not far from that of the modern ducat, or our own quarter eagle. The matter, however, was too pressing to be deferred, and even the objects of the war were considered as secondary to those connected with this suddenly-conceived, and more private enterprise. Councils were held, money-dealers were cajoled or frightened, and the confidants of the court were very manifestly in a state of great and earnest excitement. At length, the time of preparation appeared to be passed and the instant of action arrived. Curiosity was relieved, and the citizens of Saragossa were permitted to know that their sovereign was about to send a solemn embassy, on matters of high moment, to his neighbor, kinsman, and ally, the monarch of Castile. In 1469, Henry, also of Trastamara, sat upon the throne of the adjoining kingdom, under the title of Henry IV. He was the grandson, in the male line, of the brother of John II.'s father, and, consequently, a first-cousin once removed, of the monarch of Aragon. Notwithstanding this affinity, and the strong family interests that might be supposed to unite them, it required many friendly embassies to preserve the peace between the two monarchs; and the announcement of that which was about to depart, produced more satisfaction than wonder in the streets of the town.

Henry of Castile, though he reigned over broader and richer peninsular territories than his relative of Aragon, had his cares and troubles, also. He had been twice married, having repudiated his first consort, Blanche of Aragon, to wed Joanna of Portugal, a princess of a levity of character so marked, as not only to bring great scandal on the court generally, but to throw so much distrust on the birth of her only child, a daughter, as to push discontent to disaffection, and eventually to deprive the infant itself of the rights of royalty. Henry's father, like himself, had been twice married, and the issue of the second union was a son and a daughter, Alfonso and Isabella; the latter becoming subsequently illustrious, under the double titles of the Queen of Castile, and of the Catholic. The luxurious impotency of Henry, as a monarch, had driven a portion of his subjects into open rebellion. Three years preceding that selected for our opening, his brother Alfonso had been proclaimed king in his stead, and a civil war had raged throughout his provinces. This war had been recently terminated by the death of Alfonso, when the peace of the kingdom was temporarily restored by a treaty, in which Henry consented to the setting aside of his own daughter—or rather of the daughter of Joanna of Portugal—and to the recognition of his half-sister Isabella, as the rightful heiress of the throne. The last concession was the result of dire necessity, and, as might have been expected, it led to many secret and violent measures, with a view to defeat its objects. Among the other expedients adopted by the king—or, it might be better to say, by his favorites, the inaction and indolence of the self-indulgent but kind-hearted prince being proverbial—with a view to counteract the probable consequences of the expected accession of Isabella, were various schemes to control her will, and guide her policy, by giving her hand, first to a subject, with a view to reduce her power, and subsequently to various foreign princes, who were thought to be more or less suited to the furtherance of such schemes. Just at this moment, indeed, the marriage of the princess was one of the greatest objects of Spanish prudence. The son of the King of Aragon was one of the suitors for the hand of Isabella, and most of those who heard of the intended departure of the embassy, naturally enough believed that the mission had some connection with that great stroke of Aragonese policy.

Isabella had the reputation of learning, modesty, discretion, piety, and beauty, besides being the acknowledged heiress of so enviable a crown; and there were many competitors for her hand. Among them were to be ranked French, English, and Portuguese princes, besides him of Aragon to whom we have already alluded. Different favorites supported different pretenders, struggling to effect their several purposes by the usual intrigues of courtiers and partisans; while the royal maiden, herself, who was the object of so much competition and rivalry, observed a discreet and womanly decorum, even while firmly bent on indulging her most womanly and dearest sentiments. Her brother, the king, was in the south, pursuing his pleasures, and, long accustomed to dwell in comparative solitude, the princess was earnestly occupied in arranging her own affairs, in a way that she believed would most conduce to her own happiness. After several attempts to entrap her person, from which she had only escaped by the prompt succor of the forces of her friends, she had taken refuge in Leon, in the capital of which province, or kingdom as it was sometimes called, Valladolid, she temporarily took up her abode. As Henry, however, still remained in the vicinity of Granada, it is in that direction we must look for the route taken by the embassy.

The cortège left Saragossa, by one of the southern gates, early in the morning of a glorious autumnal day. There was the usual escort of lances, for this the troubled state of the country demanded; bearded nobles well mailed—for few, who offered an inducement to the plunderer, ventured on the highway without this precaution; a long train of sumpter mules, and a host of those who, by their guise, were half menials and half soldiers. The gallant display drew crowds after the horses' heels, and, together with some prayers for success, a vast deal of crude and shallow conjecture, as is still the practice with the uninstructed and gossiping, was lavished on the probable objects and results of the journey. But curiosity has its limits, and even the gossip occasionally grows weary; and by the time the sun was setting, most of the multitude had already forgotten to think and speak of the parade of the morning. As the night drew on, however, the late pageant was still the subject of discourse between two soldiers, who belonged to the guard of the western gate, or that which opened on the road to the province of Burgos. These worthies were loitering away the hours, in the listless manner common to men on watch, and the spirit of discussion and of critical censure had survived the thoughts and bustle of the day.

"If Don Alonso de Carbajal thinketh to ride far in that guise," observed the elder of the two idlers, "he would do well to look sharp to his followers, for the army of Aragon never sent forth a more scurvily-appointed guard than that he hath this day led through the southern gate, notwithstanding the glitter of housings, and the clangor of trumpets. We could have furnished lances from Valencia more befitting a king's embassy, I tell thee, Diego; ay, and worthier knights to lead them, than these of Aragon. But if the king is content, it ill becomes soldiers, like thee and me, to be dissatisfied."

"There are many who think, Roderique, that it had been better to spare the money lavished in this courtly letter-writing, to pay the brave men who so freely shed their blood in order to subdue the rebellious Barcelans."

"This is always the way, boy, between debtor and creditor. Don John owes you a few maravedis, and you grudge him every Enrique he spends on his necessities. I am an older soldier, and have learned the art of paying myself, when the treasury is too poor to save me the trouble."

"That might do in a foreign war, when one is battling against the Moor, for instance; but, after all, these Catalans are as good Christians as we are ourselves; some of them are as good subjects; and it is not as easy to plunder a countryman as to plunder an Infidel."

"Easier by twenty fold; for the one expects it, and, like all in that unhappy condition, seldom has any thing worth taking, while the other opens his stores to you as freely as he does his heart—but who are these, setting forth on the highway, at this late hour?"

"Fellows that pretend to wealth, by affecting to conceal it. I'll warrant you, now, Roderique, that there is not money enough among all those varlets to pay the laquais that shall serve them their boiled eggs, to-night."

"By St. Iago, my blessed patron!" whispered one of the leaders of a small cavalcade, who, with a single companion, rode a little in advance of the others, as if not particularly anxious to be too familiar with the rest, and laughing, lightly, as he spoke: "Yonder vagabond is nearer the truth than is comfortable! We may have sufficient among us all to pay for an olla-podrida and its service, but I much doubt whether there will be a dobla left, when the journey shall be once ended."

A low, but grave rebuke, checked this inconsiderate mirth; and the party, which consisted of merchants, or traders, mounted on mules, as was evident by their appearance, for in that age the different classes were easily recognized by their attire, halted at the gate. The permission to quit the town was regular, and the drowsy and consequently surly gate-keeper slowly undid his bars, in order that the travellers might pass.

While these necessary movements were going on, the two soldiers stood a little on one side, coolly scanning the group, though Spanish gravity prevented them from indulging openly in an expression of the scorn that they actually felt for two or three Jews who were among the traders. The merchants, moreover, were of a better class, as was evident by a follower or two, who rode in their train, in the garbs of menials, and who kept at a respectful distance while their masters paid the light fee that it was customary to give on passing the gates after nightfall. One of these menials, capitally mounted on a tall, spirited mule, happened to place himself so near Diego, during this little ceremony, that the latter, who was talkative by nature, could not refrain from having his say.

"Prithee, Pepe," commenced the soldier, "how many hundred doblas a year do they pay, in that service of thine, and how often do they renew that fine leathern doublet?"

The varlet, or follower of the merchant, who was still a youth, though his vigorous frame and embrowned cheek denoted equally severe exercise and rude exposure, started and reddened at this free inquiry, which was enforced by a hand slapped familiarly on his knee, and such a squeeze of the leg as denoted the freedom of the camp. The laugh of Diego probably suppressed a sudden outbreak of anger, for the soldier was one whose manner indicated too much good-humor easily to excite resentment.

"Thy gripe is friendly, but somewhat close, comrade," the young domestic mildly observed; "and if thou wilt take a friend's counsel, it will be, never to indulge in too great familiarity, lest some day it lead to a broken pate."

"By holy San Pedro!—I should relish—"

It was too late, however; for his master having proceeded, the youth pushed a powerful rowel into the flank of his mule, and the vigorous animal dashed ahead, nearly upsetting Diego, who was pressing hard on the pommel of the saddle, by the movement.

"There is mettle in that boy," exclaimed the good-natured soldier, as he recovered his feet. "I thought, for one moment, he was about to favor me with a visitation of his hand."

"Thou art wrong—and too much accustomed to be heedless, Diego," answered his comrade; "and it had been no wonder had that youth struck thee to the earth, for the indignity thou putt'st upon him."

"Ha! a hireling follower of some cringing Hebrew! He dare to strike a blow at a soldier of the king!"

"He may have been a soldier of the king himself, in his day. These are times when most of his frame and muscle are called on to go in harness. I think I have seen that face before; ay, and that, too, where none of craven hearts would be apt to go."

"The fellow is a mere varlet, and a younker that has just escaped from the hands of the women."

"I'll answer for it, that he hath faced both the Catalan and the Moor in his time, young as he may seem. Thou knowest that the nobles are wont to carry their sons, as children, early into the fight, that they may learn the deeds of chivalry betimes."

"The nobles!" repeated Diego, laughing. "In the name of all the devils, Roderique, of what art thou thinking, that thou likenest this knave to a young noble? Dost fancy him a Guzman, or a Mendoza, in disguise, that thou speakest thus of chivalry?"

"True—it doth, indeed, seem silly—and yet have I before met that frown in battle, and heard that sharp, quick voice, in a rally. By St. Iago de Compostello! I have it! Harkee, Diego!—a word in thy ear."

The veteran now led his more youthful comrade aside, although there was no one near to listen to what he said; and looking carefully round, to make certain that his words would not be overheard, he whispered, for a moment, in Diego's ear.

"Holy Mother of God!" exclaimed the latter, recoiling quite three paces, in surprise and awe. "Thou canst not be right, Roderique!"

"I will place my soul's welfare on it," returned the other, positively. "Have I not often seen him with his visor up, and followed him, time and again, to the charge?"

"And he setting forth as a trader's varlet! Nay, I know not, but as the servitor of a Jew!"

"Our business, Diego, is to strike without looking into the quarrel; to look without seeing, and to listen without hearing. Although his coffers are low, Don John is a good master, and our anointed king; and so we will prove ourselves discreet soldiers."

"But he will never forgive me that gripe of the knee, and my foolish tongue. I shall never dare meet him again."

"Humph!—It is not probable thou ever wilt meet him at the table of the king, and, as for the field, as he is wont to go first, there will not be much temptation for him to turn back in order to look at thee."

"Thou thinkest, then, he will not be apt to know me again?"

"If it should prove so, boy, thou need'st not take it in ill part; as such as he have more demands on their memories than they can always meet."

"The Blessed Maria make thee a true prophet!—else would I never dare again to appear in the ranks. Were it a favor I conferred, I might hope it would be forgotten; but an indignity sticks long in the memory."

Here the two soldiers moved away, continuing the discourse from time to time, although the elder frequently admonished his loquacious companion of the virtue of discretion.

In the mean time, the travellers pursued their way, with a diligence that denoted great distrust of the roads, and as great a desire to get on. They journeyed throughout the night, nor did there occur any relaxation in their speed, until the return of the sun exposed them again to the observations of the curious, among whom were thought to be many emissaries of Henry of Castile, whose agents were known to be particularly on the alert, along all the roads that communicated between the capital of Aragon and Valladolid, the city in which his royal sister had then, quite recently, taken refuge. Nothing remarkable occurred, however, to distinguish this journey from any other of the period. There was nothing about the appearance of the travellers—who soon entered the territory of Soria, a province of Old Castile, where armed parties of the monarch were active in watching the passes—to attract the attention of Henry's soldiers; and as for the more vulgar robber, he was temporarily driven from the highways by the presence of those who acted in the name of the prince. As respects the youth who had given rise to the discourse between the two soldiers, he rode diligently in the rear of his master, so long as it pleased the latter to remain in the saddle; and during the few and brief pauses that occurred in the travelling, he busied himself, like the other menials, in the duties of his proper vocation. On the evening of the second day, however, about an hour after the party had left a hostelry, where it had solaced itself with an olla-podrida and some sour wine, the merry young man who has already been mentioned, and who still kept his place by the side of his graver and more aged companion in the van, suddenly burst into a fit of loud laughter, and, reining in his mule he allowed the whole train to pass him, until he found himself by the side of the young menial already so particularly named. The latter cast a severe and rebuking glance at his reputed master, as he dropped in by his side, and said, with a sternness that ill comported with their apparent relations to each other—

"How now, Master Nuñez! what hath called thee from thy position in the van, to this unseemly familiarity with the varlets in the rear?"

"I crave ten thousand pardons, honest Juan," returned the master, still laughing, though he evidently struggled to repress his mirth, out of respect to the other; "but here is a calamity befallen us, that outdoes those of the fables and legends of necromancy and knight-errantry. The worthy Master Ferreras, yonder, who is so skilful in handling gold, having passed his whole life in buying and selling barley and oats, hath actually mislaid the purse, which it would seem he hath forgotten at the inn we have quitted, in payment of some very stale bread and rancid oil. I doubt if there are twenty reals left in the whole party!"

"And is it a matter of jest, Master Nuñez," returned the servant, though a slight smile struggled about his mouth, as if ready to join in his companion's merriment; "that we are penniless? Thank Heaven! the Burgo of Osma cannot be very distant; and we may have less occasion for gold. And now, master of mine, let me command thee to keep thy proper place in this cavalcade, and not to forget thyself by such undue familiarity with thy inferiors. I have no farther need of thee, and therefore hasten back to Master Ferreras and acquaint him with my sympathy and grief."

The young man smiled, though the eye of the pretended servant was averted, as if he cared to respect his own admonitions; while the other evidently sought a look of recognition and favor. In another minute, the usual order of the journey was resumed.

As the night advanced, and the hour arrived when man and beast usually betray fatigue, these travellers pushed their mules the hardest; and about midnight, by dint of hard pricking, they came under the principal gate of a small walled town, called Osma, that stood not far from the boundary of the province of Burgos, though still in that of Soria. No sooner was his mule near enough to the gate to allow of the freedom, than the young merchant in advance dealt sundry blows on it with his staff, effectually apprising those within of his presence. It required no strong pull of the reins to stop the mules of those behind; but the pretended varlet now pushed ahead, and was about to assume his place among the principal personages near the gate, when a heavy stone, hurled from the battlements, passed so close to his head, as vividly to remind him how near he might be to making a hasty journey to another world. A cry arose in the whole party, at this narrow escape; nor were loud imprecations on the hand that had cast the missile spared. The youth, himself, seemed the least disturbed of them all; and though his voice was sharp and authoritative, as he raised it in remonstrance, it was neither angry nor alarmed.

"How now!" he said; "is this the way you treat peaceful travellers; merchants, who come to ask hospitality and a night's repose at your hands?"

"Merchants and travellers!" growled a voice from above—"say, rather, spies and agents of King Henry. Who are ye? Speak promptly, or ye may expect something sharper than stones, at the next visit."

"Tell me," answered the youth, as if disdaining to be questioned himself—"who holds this borough? Is it not the noble Count of Treviño?"

"The very same, Señor," answered he above, with a mollified tone: "but what can a set of travelling traders know of His Excellency? and who art thou, that speakest up as sharply and as proudly as if thou wert a grandee?"

"I am Ferdinand of Trastamara—the Prince of Aragon—the King of Sicily. Go! bid thy master hasten to the gate."

This sudden announcement, which was made in the lofty manner of one accustomed to implicit obedience, produced a marked change in the state of affairs. The party at the gate so far altered their several positions, that the two superior nobles who had ridden in front, gave place to the youthful king; while the group of knights made such arrangements as showed that disguise was dropped, and each man was now expected to appear in his proper character. It might have amused a close and philosophical observer to note the promptitude with which the young cavaliers, in particular, rose in their saddles, as if casting aside the lounging mien of grovelling traders, in order to appear what they really were, men accustomed to the tourney and the field. On the ramparts the change was equally sudden and great. All appearance of drowsiness vanished; the soldiers spoke to each other in suppressed but hurried voices; and the distant tramp of feet announced that messengers were dispatched in various directions. Some ten minutes elapsed in this manner, during which an inferior officer showed himself on the ramparts, and apologized for a delay that arose altogether from the force of discipline, and on no account from any want of respect. At length a bustle on the wall, with the light of many lanterns, betrayed the approach of the governor of the town; and the impatience of the young men below, that had begun to manifest itself in half-uttered execrations, was put under a more decent restraint for the occasion.

"Are the joyful tidings that my people bring me true?" cried one from the battlements; while a lantern was lowered from the wall, as if to make a closer inspection of the party at the gate: "Am I really so honored, as to receive a summons from Don Ferdinand of Aragon, at this unusual hour?"

"Cause thy fellow to turn his lantern more closely on my countenance," answered the king, "that thou may'st make thyself sure. I will cheerfully overlook the disrespect, Count of Treviño, for the advantage of a more speedy admission."

"'Tis he!" exclaimed the noble: "I know those royal features, which bear the lineaments of a long race of kings, and that voice have I heard, often, rallying the squadrons of Aragon, in their onsets against the Moor. Let the trumpets speak up, and proclaim this happy arrival; and open wide our gates, without delay."

This order was promptly obeyed, and the youthful king entered Osma, by sound of trumpet, encircled by a strong party of men-at-arms, and with half of the awakened and astonished population at his heels.

"It is lucky, my Lord King," said Don Andres de Cabrera, the young noble already mentioned, as he rode familiarly at the side of Don Ferdinand, "that we have found these good lodgings without cost; it being a melancholy truth, that Master Ferreras hath, negligently enough, mislaid the only purse there was among us. In such a strait, it would not have been easy to keep up the character of thrifty traders much longer; for, while the knaves higgle at the price of every thing, they are fond of letting their gold be seen."

"Now that we are in thine own Castile, Don Andres," returned the king, smiling, "we shall throw ourselves gladly on thy hospitality, well knowing that thou hast two most beautiful diamonds always at thy command."

"I, Sir King! Your Highness is pleased to be merry at my expense, although I believe it is, just now, the only gratification I can pay for. My attachment for the Princess Isabella hath driven me from my lands; and even the humblest cavalier in the Aragonese army is not, just now, poorer than I. What diamonds, therefore, can I command?"

"Report speaketh favorably of the two brilliants that are set in the face of the Doña Beatriz de Bobadilla; and I hear they are altogether at thy disposal, or as much so as a noble maiden's inclinations can leave them with a loyal knight."

"Ah! my Lord King! if indeed this adventure end as happily as it commenceth, I may, indeed, look to your royal favor, for some aid in that matter."

The king smiled, in his own sedate manner; but the Count de Treviño pressing nearer to his side at that moment, the discourse was changed. That night Ferdinand of Aragon slept soundly; but with the dawn, he and his followers were again in the saddle. The party quitted Osma, however, in a manner very different from that in which it had approached its gate. Ferdinand now appeared as a knight, mounted on a noble Andalusian charger; and all his followers had still more openly assumed their proper characters. A strong body of lancers, led by the Count of Treviño in person, composed the escort; and on the 9th of the month, the whole cavalcade reached Dueñas, in Leon, a place quite near to Valladolid. The disaffected nobles crowded about the prince to pay their court, and he was received as became his high rank and still higher destinies.

Here the more luxurious Castilians had an opportunity of observing the severe personal discipline by which Don Ferdinand, at the immature years of eighteen, for he was scarcely older, had succeeded in hardening his body and in stringing his nerves, so as to be equal to any deeds in arms. His delight was found in the rudest military exercises; and no knight of Aragon could better direct his steed in the tourney or in the field. Like most of the royal races of that period, and indeed of this, in despite of the burning sun under which he dwelt, his native complexion was brilliant, though it had already become embrowned by exposure in the chase, and in the martial occupations of his boyhood. Temperate as a Mussulman, his active and well-proportioned frame seemed to be early indurating, as if Providence held him in reserve for some of its own dispensations, that called for great bodily vigor as well as for deep forethought and a vigilant sagacity. During the four or five days that followed, the noble Castilians who listened to his discourse, knew not of which most to approve, his fluent eloquence, or a wariness of thought and expression, which, while they might have been deemed prematurely worldly and cold-blooded, were believed to be particular merits in one destined to control the jarring passions, deep deceptions, and selfish devices of men.

While John of Aragon had recourse to such means to enable his son to escape the vigilant and vindictive emissaries of the King of Castile, there were anxious hearts in Valladolid, awaiting the result with the impatience and doubt that ever attend the execution of hazardous enterprises. Among others who felt this deep interest in the movements of Ferdinand of Aragon and his companions, were a few whom it has now become necessary to introduce to the reader.

Although Valladolid had not then reached the magnificence it subsequently acquired as the capital of Charles V., it was an ancient, and, for the age, a magnificent and luxurious town, possessing its palaces, as well as its more inferior abodes. To the principal of the former, the residence of John de Vivero—a distinguished noble of the kingdom—we must repair in imagination; where companions more agreeable than those we have just quitted, await us, and who were then themselves awaiting, with deep anxiety, the arrival of a messenger with tidings from Dueñas. The particular apartment that it will be necessary to imagine, had much of the rude splendor of the period, united to that air of comfort and fitness that woman seldom fails to impart to the portion of any edifice that comes directly under her control. In the year 1469, Spain was fast approaching the termination of that great struggle which had already endured seven centuries, and in which the Christian and the Mussulman contended for the mastery of the peninsula. The latter had long held sway in the southern parts of Leon, and had left behind him, in the palaces of this town, some of the traces of his barbaric magnificence. The lofty and fretted ceilings were not as glorious as those to be found further south, it is true; still, the Moor had been here, and the name of Veled Vlid—since changed to Valladolid—denotes its Arabic connection. In the room just mentioned, and in the principal palace of this ancient town—that of John de Vivero—were two females, in earnest and engrossing discourse. Both were young, and, though in very different styles, both would have been deemed beautiful in any age or region of the earth. One, indeed, was surpassingly lovely. She had just reached her nineteenth year—an age when the female form has received its full development in that generous climate; and the most imaginative poet of Spain—a country so renowned for beauty of form in the sex—could not have conceived of a person more symmetrical. The hands, feet, bust, and all the outlines, were those of feminine loveliness; while the stature, without rising to a height to suggest the idea of any thing masculine, was sufficient to ennoble an air of quiet dignity. The beholder, at first, was a little at a loss to know whether the influence to which he submitted, proceeded most from the perfection of the body itself, or from the expression that the soul within imparted to the almost faultless exterior. The face was, in all respects, worthy of the form. Although born beneath the sun of Spain, her lineage carried her back, through a long line of kings, to the Gothic sovereigns; and its frequent intermarriages with foreign princesses, had produced in her countenance that intermixture of the brilliancy of the north with the witchery of the south, that probably is nearest to the perfection of feminine loveliness.

Her complexion was fair, and her rich locks had that tint of the auburn which approaches as near as possible to the more marked color that gives it warmth, without attaining any of the latter's distinctive hue. "Her mild blue eyes," says an eminent historian, "beamed with intelligence and sensibility." In these indexes to the soul, indeed, were to be found her highest claims to loveliness, for they bespoke no less the beauty within, than the beauty without; imparting to features of exquisite delicacy and symmetry, a serene expression of dignity and moral excellence, that was remarkably softened by a modesty that seemed as much allied to the sensibilities of a woman, as to the purity of an angel. To add to all these charms, though of royal blood, and educated in a court, an earnest, but meek sincerity presided over every look and thought—as thought was betrayed in the countenance—adding the illumination of truth to the lustre of youth and beauty.

The attire of this princess was simple, for, happily, the taste of the age enabled those who worked for the toilet to consult the proportions of nature; though the materials were rich, and such as became her high rank. A single cross of diamonds sparkled on a neck of snow, to which it was attached by a short string of pearls; and a few rings, decked with stones of price, rather cumbered than adorned hands that needed no ornaments to rivet the gaze. Such was Isabella of Castile, in her days of maiden retirement and maiden pride—while waiting the issues of those changes that were about to put their seal on her own future fortunes, as well as on those of posterity even to our own times.

Her companion was Beatriz de Bobadilla, the friend of her childhood and infancy, and who continued, to the last, the friend of her prime, and of her death-bed. This lady, a little older than the princess, was of more decided Spanish mien, for, though of an ancient and illustrious house, policy and necessity had not caused so many foreign intermarriages in her race, as had been required in that of her royal mistress. Her eyes were black and sparkling, bespeaking a generous soul, and a resolution so high that some commentators have termed it valor; while her hair was dark as the raven's wing. Like that of her royal mistress, her form exhibited the grace and loveliness of young womanhood, developed by the generous warmth of Spain; though her stature was, in a slight degree, less noble, and the outlines of her figure, in about an equal proportion, less perfect. In short, nature had drawn some such distinction between the exceeding grace and high moral charms that encircled the beauty of the princess, and those which belonged to her noble friend, as the notions of men had established between their respective conditions; though, considered singly, as women, either would have been deemed pre-eminently winning and attractive.

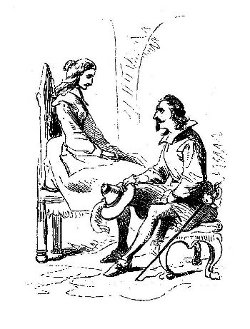

At the moment we have selected for the opening of the scene that is to follow, Isabella, fresh from the morning toilet, was seated in a chair, leaning lightly on one of its arms, in an attitude that interest in the subject she was discussing, and confidence in her companion, had naturally produced; while Beatriz de Bobadilla occupied a low stool at her feet, bending her body in respectful affection so far forward, as to allow the fairer hair of the princess to mingle with her own dark curls, while the face of the latter appeared to repose on the head of her friend. As no one else was present, the reader will at once infer, from the entire absence of Castilian etiquette and Spanish reserve, that the dialogue they held was strictly confidential, and that it was governed more by the feelings of nature, than by the artificial rules that usually regulate the intercourse of courts.

"I have prayed, Beatriz, that God would direct my judgment in this weighty concern," said the princess, in continuation of some previous observation; "and I hope I have as much kept in view the happiness of my future subjects, in the choice I have made, as my own."

"None shall presume to question it," said Beatriz de Bobadilla; "for had it pleased you to wed the Grand Turk, the Castilians would not gainsay your wish, such is their love!"

"Say, rather, such is thy love for me, my good Beatriz, that thou fanciest this," returned Isabella, smiling, and raising her face from the other's head. "Our Castilians might overlook such a sin, but I could not pardon myself for forgetting that I am a Christian. Beatriz, I have been sorely tried, in this matter!"

"But the hour of trial is nearly passed. Holy Maria! what lightness of reflection, and vanity, and misjudging of self, must exist in man, to embolden some who have dared to aspire to become your husband! You were yet a child when they betrothed you to Don Carlos, a prince old enough to be your father; and then, as if that were not sufficient to warm Castilian blood, they chose the King of Portugal for you, and he might well have passed for a generation still more remote! Much as I love you, Doña Isabella, and my own soul is scarce dearer to me than your person and mind, for nought do I respect you more, than for the noble and princely resolution, child as you then were, with which you denied the king, in his wicked wish to make you Queen of Portugal."

"Don Enriquez is my brother, Beatriz; and thine and my royal master."

"Ah! bravely did you tell them all," continued Beatriz de Bobadilla, with sparkling eyes, and a feeling of exultation that caused her to overlook the quiet rebuke of her mistress; "and worthy was it of a princess of the royal house of Castile! 'The Infantas of Castile,' you said, 'could not be disposed of, in marriage, without the consent of the nobles of the realm;' and with that fit reply they were glad to be content."

"And yet, Beatriz, am I about to dispose of an Infanta of Castile, without even consulting its nobles."

"Say not that, my excellent mistress. There is not a loyal and gallant cavalier between the Pyrenees and the sea, who will not, in his heart, approve of your choice. The character, and age, and other qualities of the suitor, make a sensible difference in these concerns. But unfit as Don Alfonso of Portugal was, and is, to be the wedded husband of Doña Isabella of Castile, what shall we say to the next suitor who appeared as a pretender to your royal hand—Don Pedro Giron, the Master of Calatrava! truly a most worthy lord for a maiden of the royal house! Out upon him! A Pachecho might think himself full honorably mated, could he have found a damsel of Bobadilla to elevate his race!"

"That ill-assorted union was imposed upon my brother by unworthy favorites; and God, in his holy providence, saw fit to defeat their wishes, by hurrying their intended bridegroom to an unexpected grave!"

"Ay! had it not pleased his blessed will so to dispose of Don Pedro, other means would not have been wanting!"

"This little hand of thine, Beatriz," returned the princess, gravely, though she smiled affectionately on her friend as she took the hand in question, "was not made for the deed its owner menaced."

"That which its owner menaced," replied Beatriz, with eyes flashing fire, "this hand would have executed, before Isabella of Castile should be the doomed bride of the Grand Master of Calatrava. What! was the purest, loveliest virgin of Castile, and she of royal birth—nay, the rightful heiress of the crown—to be sacrificed to a lawless libertine, because it had pleased Don Henry to forget his station and duties, and make a favorite of a craven miscreant!"

"Thou always forgettest, Beatriz, that Don Enriquez is our lord the king, and my royal brother."

"I do not forget, Señora, that you are the royal sister of our lord the king, and that Pedro de Giron, or Pachecho, whichever it might suit the ancient Portuguese page to style him, was altogether unworthy to sit in your presence, much less to become your wedded husband. Oh! what days of anguish were those, my gracious lady, when your knees ached with bending in prayer, that this might not be! But God would not permit it—neither would I! That dagger should have pierced his heart, before ear of his should have heard the vows of Isabella of Castile!"

"Speak no more of this, good Beatriz, I pray thee," said the princess, shuddering, and crossing herself; "they were, in sooth, days of anguish; but what were they in comparison with the passion of the Son of God, who gave himself a sacrifice for our sins! Name it not, then; it was good for my soul to be thus tried; and thou knowest that the evil was turned from me—more, I doubt not, by the efficacy of our prayers, than by that of thy dagger. If thou wilt speak of my suitors, surely there are others better worthy of the trouble."

A light gleamed about the dark eye of Beatriz, and a smile struggled toward her pretty mouth; for well did she understand that the royal, but bashful maiden, would gladly hear something of him on whom her choice had finally fallen. Although ever disposed to do that which was grateful to her mistress, with a woman's coquetry, Beatriz determined to approach the more pleasing part of the subject coyly, and by a regular gradation of events, in the order in which they had actually occurred.

"Then, there was Monsieur de Guienne, the brother of King Louis of France," she resumed, affecting contempt in her manner; "he would fain become the husband of the future Queen of Castile! But even our most unworthy Castilians soon saw the unfitness of that union. Their pride was unwilling to run the chance of becoming a fief of France."

"That misfortune could never have befallen our beloved Castile," interrupted Isabella with dignity; "had I espoused the King of France himself, he would have learned to respect me as the Queen Proprietor of this ancient realm, and not have looked upon me as a subject."

"Then, Señora," continued Beatriz, looking up into Isabella's face, and laughing—"was your own royal kinsman, Don Ricardo of Gloucester; he that they say was born with teeth, and who carries already a burthen so heavy on his back, that he may well thank his patron saint that he is not also to be loaded with the affairs of Castile."[1]

"Thy tongue runneth riot, Beatriz. They tell me that Don Ricardo is a noble and aspiring prince; that he is, one day, likely to wed some princess, whose merit may well console him for his failure in Castile. But what more hast thou to offer concerning my suitors?"

"Nay, what more can I say, my beloved mistress? We have now reached Don Fernando, literally the first, as he proveth to be the last, and as we know him to be, the best of them all."

"I think I have been guided by the motives that become my birth and future hopes, in choosing Don Ferdinand," said Isabella, meekly, though she was uneasy in spite of her royal views of matrimony; "since nothing can so much tend to the peace of our dear kingdom, and to the success of the great cause of Christianity, as to unite Castile and Aragon under one crown."

"By uniting their sovereigns in holy wedlock," returned Beatriz, with respectful gravity, though a smile again struggled around her pouting lips. "What if Don Fernando is the most youthful, the handsomest, the most valiant, and the most agreeable prince in Christendom, it is no fault of yours, since you did not make him, but have only accepted him for a husband!"

"Nay, this exceedeth discretion and respect, my good Beatriz," returned Isabella, affecting to frown, even while she blushed deeply at her own emotions, and looked gratified at the praises of her betrothed. "Thou knowest that I have never beheld my cousin, the King of Sicily."

"Very true, Señora; but Father Alonso de Coca hath—and a surer eye, or truer tongue than his, do not exist in Castile."

"Beatriz, I pardon thy license, however unjust and unseemly, because I know thou lovest me, and lookest rather at mine own happiness, than at that of my people," said the princess, the effect of whose gravity now was not diminished by any betrayal of natural feminine weakness—for she felt slightly offended. "Thou knowest, or ought'st to know, that a maiden of royal birth is bound principally to consult the interests of the state, in bestowing her hand, and that the idle fancies of village girls have little in common with her duties. Nay, what virgin of noble extraction, like thyself, even, would dream of aught else than of submitting to the counsel of her family, in taking a husband? If I have selected Don Fernando of Aragon, from among many princes, it is, doubtless, because the alliance is more suited to the interests of Castile, than any other that hath offered. Thou seest, Beatriz, that the Castilians and the Aragonese spring from the same source, and have the same habits and prejudices. They speak the same language"—

"Nay, dearest lady, do not confound the pure Castilian with the dialect of the mountains!"

"Well, have thy fling, wayward one, if thou wilt; but we can easier teach the nobles of Aragon our purer Spanish, than we can teach it to the Gaul. Then, Don Fernando is of my own race; the House of Trastamara cometh of Castile and her monarchs, and we may at least hope that the King of Sicily will be able to make himself understood."

"If he could not, he were no true knight! The man whose tongue should fail him, when the stake was a royal maiden of a beauty surpassing that of the dawn—of an excellence that already touches on heaven—of a crown"—

"Girl, girl, thy tongue is getting the mastery of thee—such discourse ill befitteth thee and me."

"And yet, Doña Ysabel, my tongue is close bound to my heart."

"I do believe thee, my good Beatriz; but we should bethink us both of our last shrivings, and of the ghostly counsel that we then received. Such nattering discourse seemeth light, when we remember our manifold transgressions, and our many occasions for forgiveness. As for this marriage, I would have thee think that it has been contracted on my part, with the considerations and motives of a princess, and not through any light indulgence of my fancies. Thou knowest that I have never beheld Don Fernando, and that he hath never even looked upon me."

"Assuredly, dearest lady and honored mistress, all this I know, and see, and believe; and I also agree that it were unseemly and little befitting her birth, for even a noble maiden to contract the all-important obligations of marriage, with no better motive than the light impulses of a country wench. Nothing is more just than that we are alike bound to consult our own dignity, and the wishes of kinsmen and friends; and that our duty, and the habits of piety and submission in which we have been reared, are better pledges for our connubial affection than any caprices of a girlish imagination. Still, my honored lady, it is most fortunate that your high obligations point to one as youthful, brave, noble, and chivalrous, as is the King of Sicily, as we well know, by Father Alonso's representations, to be the fact; and that all my friends unite in saying that Don Andres de Cabrera, madcap and silly as he is, will make an exceedingly excellent husband for Beatriz de Bobadilla!"

Isabella, habitually dignified and reserved as she was, had her confidants and her moments for unbending; and Beatriz was the principal among the former, while the present instant was one of the latter. She smiled, therefore, at this sally; and parting, with her own fair hand, the dark locks on the brow of her friend, she regarded her much as the mother regards her child, when sudden passages of tenderness come over the heart.

"If madcap should wed madcap, thy friends, at least, have judged rightly," answered the princess. Then, pausing an instant, as if in deep thought, she continued in a graver manner, though modesty shone in her tell-tale complexion, and the sensibility that beamed in her eyes betrayed that she now felt more as a woman than as a future queen bent only on the happiness of her people: "As this interview draweth near, I suffer an embarrassment I had not thought it easy to inflict on an Infanta of Castile. To thee, my faithful Beatriz, I will acknowledge, that were the King of Sicily as old as Don Alfonso of Portugal, or were he as effeminate and unmanly as Monsieur of Guienne; were he, in sooth, less engaging and young, I should feel less embarrassment in meeting him, than I now experience."

"This is passing strange, Señora! Now, I will confess that I would not willingly abate in Don Andres, one hour of his life, which has been sufficiently long as it is; one grace of his person, if indeed the honest cavalier hath any to boast of; or one single perfection of either body or mind."

"Thy case is not mine, Beatriz. Thou knowest the Marquis of Moya; hast listened to his discourse, and art accustomed to his praises and his admiration."

"Holy St. Iago of Spain! Do not distrust any thing, Señora, on account of unfamiliarity with such matters—for, of all learning, it is easiest to learn to relish praise and admiration!"

"True, daughter"—(for so Isabella often termed her friend, though her junior: in later life, and after the princess had become a queen, this, indeed, was her usual term of endearment)—"true, daughter, when praise and admiration are freely given and fairly merited. But I distrust, myself, my claims to be thus viewed, and the feelings with which Don Fernando may first behold me. I know—nay, I feel him to be graceful, and noble, and valiant, and generous, and good; comely to the eye, and strict of duty to our holy religion; as illustrious in qualities as in birth; and I tremble to think of my own unsuitableness to be his bride and queen."

"God's Justice!—I should like to meet the impudent Aragonese noble that would dare to hint as much as this! If Don Fernando is noble, are you not nobler, Señora, as coming of the senior branch of the same house; if he is young, are you not equally so; if he is wise, are you not wiser; if he is comely, are you not more of an angel than a woman; if he is valiant, are you not virtuous; if he is graceful, are you not grace itself; if he is generous, are you not good, and what is more, are you not the very soul of generosity; if he is strict of duty in matters of our holy religion, are you not an angel?"

"Good sooth—good sooth—Beatriz, thou art a comforter! I could reprove thee for this idle tongue, but I know thee honest."

"This is no more than that deep modesty, honored mistress, which ever maketh you quicker to see the merits of others, than to perceive your own. Let Don Fernando look to it! Though he come in all the pomp and glory of his many crowns, I warrant you we find him a royal maiden in Castile, who shall abash him and rebuke his vanity, even while she appears before him in the sweet guise of her own meek nature!"

"I have said naught of Don Fernando's vanity, Beatriz—nor do I esteem him in the least inclined to so weak a feeling; and as for pomp, we well know that gold no more abounds at Zaragosa than at Valladolid, albeit he hath many crowns, in possession, and in reserve. Notwithstanding all thy foolish but friendly tongue hath uttered, I distrust myself, and not the King of Sicily. Methinks I could meet any other prince in Christendom with indifference—or, at least, as becometh my rank and sex; but I confess, I tremble at the thought of encountering the eyes and opinions of my noble cousin."

Beatriz listened with interest; and when her royal mistress ceased speaking, she kissed her hand affectionately, and then pressed it to her heart.

"Let Don Fernando tremble, rather, Señora, at encountering yours," she answered.

"Nay, Beatriz, we know that he hath nothing to dread, for report speaketh but too favorably of him. But, why linger here in doubt and apprehension, when the staff on which it is my duty to lean, is ready to receive its burthen: Father Alonso doubtless waiteth for us, and we will now join him."

The princess and her friend now repaired to the chapel of the palace, where her confessor celebrated the daily mass. The self-distrust which disturbed the feelings of the modest Isabella was appeased by the holy rites, or, rather, it took refuge on that rock where she was accustomed to place all her troubles, with her sins. As the little assemblage left the chapel, one, hot with haste, arrived with the expected, but still doubted tidings, that the King of Sicily had reached Dueñas in safety, and that, as he was now in the very centre of his supporters, there could no longer be any reasonable distrust of the speedy celebration of the contemplated marriage.

Isabella was much overcome with this news, and required more than usual of the care of Beatriz de Bobadilla, to restore her to that sweet serenity of mind and air, which ordinarily rendered her presence as attractive as it was commanding. An hour or two spent in meditation and prayer, however, finally produced a gentle calm in her feelings, and these two friends were again alone, in the very apartment where we first introduced them to the reader.

"Hast thou seen Don Andres de Cabrera?" demanded the princess, taking a hand from a brow which had been often pressed in a sort of bewildered recollection.

Beatriz de Bobadilla blushed—and then she laughed outright, with a freedom that the long-established affection of her mistress did not rebuke.

"For a youth of thirty, and a cavalier well hacked in the wars of the Moors, Don Andres hath a nimble foot," she answered. "He brought hither the tidings of the arrival; and with it he brought his own delightful person, to show it was no lie. For one so experienced, he hath a strong propensity to talk; and so, in sooth, while you, my honored mistress, would be in your closet alone, I could but listen to all the marvels of the journey. It seems, Señora, that they did not reach Dueñas any too soon; for the only purse among them was mislaid, or blown away by the wind on account of its lightness."

"I trust this accident hath been repaired. Few of the house of Trastamara have much gold at this trying moment, and yet none are wont to be entirely without it."

"Don Andres is neither beggar nor miser. He is now in our Castile, where I doubt not he is familiar with the Jews and money-lenders; as these last must know the full value of his lands, the King of Sicily will not want. I hear, too, that the Count of Treviño hath conducted nobly with him."

"It shall be well for the Count of Treviño that he hath had this liberality. But, Beatriz, bring forth the writing materials; it is meet that I, at once, acquaint Don Enriquez with this event, and with my purpose of marriage."

"Nay, dearest mistress, this is out of all rule. When a maiden, gentle or simple, intendeth marriage against her kinsmen's wishes, it is the way to wed first, and to write the letter and ask the blessing when the evil is done."

"Go to, light-of-speech! Thou hast spoken; now bring the pens and paper. The king is not only my lord and sovereign, but he is my nearest of kin, and should be my father."

"And Doña Joanna of Portugal, his royal consort, and our illustrious queen, should be your mother; and a fitting guide would she be to any modest virgin! No—no—my beloved mistress; your royal mother was the Doña Isabella of Portugal—and a very different princess was she from this, her wanton niece."

"Thou givest thyself too much license, Doña Beatriz, and forgettest my request. I desire to write to my brother the king."

It was so seldom that Isabella spoke sternly, that her friend started, and the tears rushed to her eyes at this rebuke; but she procured the writing materials, before she presumed to look into Isabella's face, in order to ascertain if she were really angered. There all was beautiful serenity again; and the Lady of Bobadilla, perceiving that her mistress's mind was altogether occupied with the matter before her, and that she had already forgotten her displeasure, chose to make no further allusion to the subject.

Isabella now wrote her celebrated letter, in which she appeared to forget all her natural timidity, and to speak solely as a princess. By the treaty of Toros de Guisando, in which, setting aside the claims of Joanna of Portugal's daughter, she had been recognized as the heiress of the throne, it had been stipulated that she should not marry without the king's consent; and she now apologized for the step she was about to take, on the substantial plea that her enemies had disregarded the solemn compact entered into not to urge her into any union that was unsuitable or disagreeable to herself. She then alluded to the political advantages that would follow the union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, and solicited the king's approbation of the step she was about to take. This letter, after having been submitted to John de Vivero, and others of her council, was dispatched by a special messenger—after which act the arrangements necessary as preliminaries to a meeting between the betrothed were entered into. Castilian etiquette was proverbial, even in that age; and the discussion led to a proposal that Isabella rejected with her usual modesty and discretion.

"It seemeth to me," said John de Vivero, "that this alliance should not take place without some admission, on the part of Don Fernando, of the inferiority of Aragon to our own Castile. The house of the latter kingdom is but a junior branch of the reigning House of Castile, and the former territory of old was admitted to have a dependency on the latter."

This proposition was much applauded, until the beautiful and natural sentiments of the princess, herself, interposed to expose its weakness and its deformities.

"It is doubtless true," she said, "that Don Juan of Aragon is the son of the younger brother of my royal grandfather; but he is none the less a king. Nay, besides his crown of Aragon—a country, if thou wilt, which is inferior to Castile—he hath those of Naples and Sicily; not to speak of Navarre, over which he ruleth, although it may not be with too much right. Don Fernando even weareth the crown of Sicily, by the renunciation of Don Juan; and shall he, a crowned sovereign, make concessions to one who is barely a princess, and whom it may never please God to conduct to a throne? Moreover, Don John of Vivero, I beseech thee to remember the errand that bringeth the King of Sicily to Valladolid. Both he and I have two parts to perform, and two characters to maintain—those of prince and princess, and those of Christians wedded and bound by holy marriage ties. It would ill become one that is about to take on herself the duties and obligations of a wife, to begin the intercourse with exactions that should be humiliating to the pride and self-respect of her lord. Aragon may truly be an inferior realm to Castile—but Ferdinand of Aragon is even now every way the equal of Isabella of Castile; and when he shall receive my vows, and, with them, my duty and my affections"—Isabella's color deepened, and her mild eye lighted with a sort of holy enthusiasm—"as befitteth a woman, though an infidel, he would become, in some particulars, my superior. Let me, then, hear no more of this; for it could not nearly as much pain Don Fernando to make the concessions ye require, as it paineth me to hear of them."

"Nice customs curt'sy to great kings. Dear Kate, you and I cannot be confined within the weak list of a country's fashion. We are the makers of manners; and the liberty that follows our places, stops the mouths of all fault-finders."—Henry V.

Notwithstanding her high resolution, habitual firmness, and a serenity of mind, that seemed to pervade the moral system of Isabella, like a deep, quiet current of enthusiasm, but which it were truer to assign to the high and fixed principles that guided all her actions, her heart beat tumultuously, and her native reserve, which almost amounted to shyness, troubled her sorely, as the hour arrived when she was first to behold the prince she had accepted for a husband. Castilian etiquette, no less than the magnitude of the political interests involved in the intended union, had drawn out the preliminary negotiations several days; the bridegroom being left, all that time, to curb his impatience to behold the princess, as best he might.

On the evening of the 15th of October, 1469, however, every obstacle being at length removed, Don Fernando threw himself into the saddle, and, accompanied by only four attendants, among whom was Andres de Cabrera, he quietly took his way, without any of the usual accompaniments of his high rank, toward the palace of John of Vivero, in the city of Valladolid. The Archbishop of Toledo was of the faction of the princess, and this prelate, a warlike and active partisan, was in readiness to receive the accepted suitor, and to conduct him to the presence of his mistress.

Isabella, attended only by Beatriz de Bobadilla, was in waiting for the interview, in the apartment already mentioned; and by one of those mighty efforts that even the most retiring of the sex can make, on great occasions, she received her future husband with quite as much of the dignity of a princess as of the timidity of a woman. Ferdinand of Aragon had been prepared to meet one of singular grace and beauty; but the mixture of angelic modesty with a loveliness that almost surpassed that of her sex, produced a picture approaching so much nearer to heaven than to earth, that, though one of circumspect behavior, and much accustomed to suppress emotion, he actually started, and his feet were momentarily riveted to the floor, when the glorious vision first met his eye. Then, recovering himself, he advanced eagerly, and taking the little hand which neither met nor repulsed the attempt, he pressed it to his lips with a warmth that seldom accompanies the first interviews of those whose passions are usually so factitious.

"This happy moment hath at length arrived, my illustrious and beautiful cousin!" he said, with a truth of feeling that went directly to the pure and tender heart of Isabella; for no skill in courtly phrases can ever give to the accents of deceit, the point and emphasis that belong to sincerity. "I have thought it would never arrive; but this blessed moment—thanks to our own St. Iago, whom I have not ceased to implore with intercessions—more than rewards me for all anxieties."

"I thank my Lord the Prince, and bid him right welcome," modestly returned Isabella. "The difficulties that have been overcome, in order to effect this meeting, are but types of the difficulties we shall have to conquer as we advance through life."

Then followed a few courteous expressions concerning the hopes of the princess that her cousin had wanted for nothing, since his arrival in Castile, with suitable answers; when Don Ferdinand led her to an armed-chair, assuming himself the stool on which Beatriz de Bobadilla was wont to be seated, in her familiar intercourse with her royal mistress. Isabella, however, sensitively alive to the pretensions of the Castilians, who were fond of asserting the superiority of their own country over that of Aragon, would not quietly submit to this arrangement, but declined to be seated, unless her suitor would take the chair prepared for him also, saying—

"It ill befitteth one who hath little more than some royalty of blood, and her dependence on God, to be thus placed, while the King of Sicily is so unworthily bestowed."

"Let me entreat that it may be so," returned the king. "All considerations of earthly rank vanish in this presence; view me as a knight, ready and desirous of proving his fealty in any court or field of Christendom, and treat me as such."

Isabella, who had that high tact which teaches the precise point where breeding becomes neuter and airs commence, blushed and smiled, but no longer declined to be seated. It was not so much the mere words of her cousin that went to her heart, as the undisguised admiration of his looks, the animation of his eye, and the frank sincerity of his manner. With a woman's instinct she perceived that the impression she had made was favorable, and, with a woman's sensibility, her heart was ready, under the circumstances, to dissolve in tenderness at the discovery. This mutual satisfaction soon opened the way to a freer conversation; and, ere half an hour was passed, the archbishop—who, though officially ignorant of the language and wishes of lovers, was practically sufficiently familiar with both—contrived to draw the two or three courtiers who were present, into an adjoining room, where, though the door continued open, he placed them with so much discretion that neither eye nor ear could be any restraint on what was passing. As for Beatriz de Bobadilla, whom female etiquette required should remain in the same room with her royal mistress, she was so much engaged with Andres de Cabrera, that half a dozen thrones might have been disposed of between the royal pair, and she none the wiser.

Although Isabella did not lose that mild reserve and feminine modesty that threw so winning a grace around her person, even to the day of her death, she gradually grew more calm as the discourse proceeded; and, falling back on her self-respect, womanly dignity, and, not a little, on those stores of knowledge that she had been diligently collecting, while others similarly situated had wasted their time in the vanities of courts, she was quickly at her ease, if not wholly in that tranquil state of mind to which she had been accustomed.

"I trust there can now be no longer any delay to the celebration of our union by holy church," observed the king, in continuation of the subject. "All that can be required of us both, as those entrusted with the cares and interests of realms, hath been observed, and I may have a claim to look to my own happiness. We are not strangers to each other, Doña Isabella; for our grandfathers were brothers, and from infancy up, have I been taught to reverence thy virtues, and to strive to emulate thy holy duty to God."

"I have not betrothed myself lightly, Don Fernando," returned the princess, blushing, even while she assumed the majesty of a queen; "and with the subject so fully discussed, the wisdom of the union so fully established, and the necessity of promptness so apparent, no idle delays shall proceed from me. I had thought that the ceremony might be had on the fourth day from this, which will give us both time to prepare for an occasion so solemn, by suitable attention to the offices of the church."

"It must be as thou wiliest," said the king, respectfully bowing; "and now there remaineth but a few preparations, and we shall have no reproaches of forgetfulness. Thou knowest, Doña Isabella, how sorely my father is beset by his enemies, and I need scarce tell thee that his coffers are empty. In good sooth, my fair cousin, nothing but my earnest desire to possess myself, at as early a day as possible, of the precious boon that Providence and thy goodness"—

"Mingle not, Don Fernando, any of the acts of God and his providence, with the wisdom and petty expedients of his creatures," said Isabella, earnestly.

"To seize upon the precious boon, then, that Providence appeared willing to bestow," rejoined the king, crossing himself, while he bowed his head, as much, perhaps, in deference to the pious feelings of his affianced wife, as in deference to a higher Power—"would not admit of delay, and we quitted Zaragosa better provided with hearts loyal toward the treasures we were to find in Valladolid, than with gold. Even that we had, by a mischance, hath gone to enrich some lucky varlet in an inn."

"Doña Beatriz de Bobadilla hath acquainted me with the mishap," said Isabella, smiling; "and truly we shall commence our married lives with but few of the goods of the world in present possession. I have little more to offer thee, Fernando, than a true heart, and a spirit that I think may be trusted for its fidelity."

"In obtaining thee, my excellent cousin, I obtain sufficient to satisfy the desires of any reasonable man. Still, something is due to our rank and future prospects, and it shall not be said that thy nuptials passed like those of a common subject."

"Under ordinary circumstances it might not appear seemly for one of my sex to furnish the means for her own bridal," answered the princess, the blood stealing to her face until it crimsoned even her brow and temples; maintaining, otherwise, that beautiful tranquillity of mien which marked her ordinary manner—"but the well-being of two states depending on our union, vain emotions must be suppressed. I am not without jewels, and Valladolid hath many Hebrews: thou wilt permit me to part with the baubles for such an object."

"So that thou preservest for me the jewel in which that pure mind is encased," said the King of Sicily, gallantly, "I care not if I never see another. But there will not be this need; for our friends, who have more generous souls than well-filled coffers too, can give such warranty to the lenders as will procure the means. I charge myself with this duty, for henceforth, my cousin—may I not say my betrothed!"—

"The term is even dearer than any that belongeth to blood, Fernando," answered the princess, with a simple sincerity of manner that set at nought the ordinary affectations and artificial feelings of her sex, while it left the deepest reverence for her modesty—"and we might be excused for using it. I trust God will bless our union, not only to our own happiness, but to that of our people."

"Then, my betrothed, henceforth we have but a common fortune, and thou wilt trust in me for the provision for thy wants."

"Nay, Fernando," answered Isabella, smiling, "imagine what we will, we cannot imagine ourselves the children of two hidalgos about to set forth in the world with humble dowries. Thou art a king, even now; and by the treaty of Toros de Guisando, I am solemnly recognized as the heiress of Castile. We must, therefore, have our separate means, as well as our separate duties, though I trust hardly our separate interests."

"Thou wilt never find me failing in that respect which is due to thy rank, or in that duty which it befitteth me to render thee, as the head of our ancient House, next to thy royal brother, the king."

"Thou hast well considered, Don Fernando, the treaty of marriage, and accepted cheerfully, I trust, all of its several conditions?"

"As becometh the importance of the measures, and the magnitude of the benefit I was to receive."

"I would have them acceptable to thee, as well as expedient; for, though so soon to become thy wife, I can never cease to remember that I shall be Queen of this country."

"Thou mayest be assured, my beautiful betrothed, that Ferdinand of Aragon will be the last to deem thee aught else."

"I look on my duties as coming from God, and on myself as one rigidly accountable to him for their faithful discharge. Sceptres may not be treated as toys, Fernando, to be trifled with; for man beareth no heavier burden, than when he beareth a crown."

"The maxims of our House have not been forgotten in Aragon, my betrothed—and I rejoice to find that they are the same in both kingdoms."

"We are not to think principally of ourselves in entering upon this engagement," continued Isabella, earnestly—"for that would be supplanting the duties of princes by the feelings of the lover. Thou hast frequently perused, and sufficiently conned the marriage articles, I trust?"

"There hath been sufficient leisure for that, my cousin, as they have now been signed these nine months."

"If I may have seemed to thee exacting in some particulars," continued Isabella, with the same earnest and beautiful simplicity as usually marked her deportment in all the relations of life—"it is because the duties of a sovereign may not be overlooked. Thou knowest, moreover, Fernando, the influence that the husband is wont to acquire over the wife, and wilt feel the necessity of my protecting my Castilians, in the fullest manner, against my own weaknesses."

"If thy Castilians do not suffer until they suffer from that cause, Doña Isabella, their lot will indeed be blessed."

"These are words of gallantry, and I must reprove their use on an occasion so serious, Fernando. I am a few months thy senior, and shall assume an elder sister's rights, until they are lost in the obligations of a wife. Thou hast seen in those articles, how anxiously I would protect my Castilians against any supremacy of the stranger. Thou knowest that many of the greatest of this realm are opposed to our union, through apprehension of Aragonese sway, and wilt observe how studiously we have striven to appease their jealousies."

"Thy motives, Doña Isabella, have been understood, and thy wishes in this and all other particulars shall be respected."